五月革命

May 68

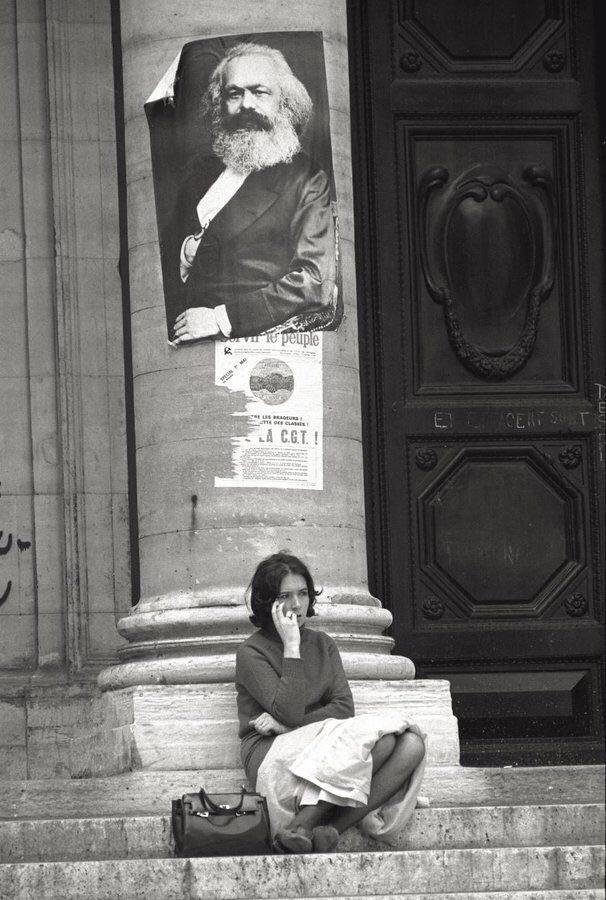

五月革命あるいは、「1968年5月(May 68)」とは、フランス全土でデモ、ゼネスト、大学や工場の占拠などの市民運動が7週間続いた。抗議運動は政治指導者たちに内戦や革命を恐れさせるまで になり、シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領が29日に密かにフランスから西ドイツに逃亡した後、国家政府は一時機能停止に陥った。この抗議運動は、歌、想像力豊 かな落書き、ポスター、スローガンなどの形で抗議芸術の世代を鼓舞した、世界同時期の同様の運動と関連付けられることもある。

| May 68 Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, and the occupation of universities and factories. At the height of events, which have since become known as May 68 (French: Mai 68), the economy of France came to a halt.[2] The protests reached a point that made political leaders fear civil war or revolution; the national government briefly ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France to West Germany on the 29th. The protests are sometimes linked to similar movements around the same time worldwide[3] that inspired a generation of protest art in the form of songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans.[4][5] The unrest began with a series of far-left student occupation protests against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism and traditional institutions. Heavy police repression of the protesters led France's trade union confederations to call for sympathy strikes, which spread far more quickly than expected to involve 11 million workers, more than 22% of France's population at the time.[2] The movement was characterized by spontaneous and decentralized wildcat disposition; this created contrast and at times even conflict among the trade unions and leftist parties.[2] It was the largest general strike ever attempted in France, and the first nationwide wildcat general strike.[2] The student occupations and general strikes across France met with forceful confrontation by university administrators and police. The de Gaulle administration's attempts to quell the strikes by police action only inflamed the situation, leading to street battles with the police in Paris's Latin Quarter. By late May the flow of events had changed. The Grenelle accords, concluded on 27 May between the government, trade unions and employers, won significant wage gains for workers. A counter-demonstration organised by the Gaullist party on 29 May in central Paris gave De Gaulle the confidence to dissolve the National Assembly and call parliamentary elections for 23 June 1968. Violence evaporated almost as quickly as it arose. Workers returned to their jobs, and after the June elections, the Gaullists emerged stronger than before. The events of May 1968 continue to influence French society. The period is considered a cultural, social and moral turning point in the nation's history. Alain Geismar, who was one of the student leaders at the time, later said the movement had succeeded "as a social revolution, not as a political one".[6] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_68 |

1968年5月(五月革命、五月危機) 1968年5月、フランス全土でデモ、ゼネスト、大学や工場の占拠などの市民運動が7週間続いた。抗議運動は政治指導者たちに内戦や革命を恐れさせるまで になり、シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領が29日に密かにフランスから西ドイツに逃亡した後、国家政府は一時機能停止に陥った。この抗議運動は、歌、想像力豊 かな落書き、ポスター、スローガンなどの形で抗議芸術の世代を鼓舞した、世界同時期の同様の運動[3]と関連付けられることもある[4][5]。 この騒乱は、資本主義、消費主義、アメリカ帝国主義、伝統的制度に反対する一連の極左学生占拠抗議行動から始まった。デモ参加者に対する警察の激しい弾圧 により、フランスの労働組合総連合は同情ストライキを呼びかけ、このストライキは予想をはるかに上回る速さで広がり、当時のフランス人口の22%以上にあ たる1,100万人の労働者を巻き込んだ。この運動は、自然発生的で分散的な山猫的気質を特徴としていた。このため、労働組合と左派政党の間にコントラス トが生まれ、時には対立さえ生じた。フランスで試みられた最大のゼネストであり、初の全国的な山猫ゼネストであった。 フランス全土の学生占拠とゼネストは、大学当局と警察による強硬な対立に見舞われた。ド・ゴール政権が警察によってストライキを鎮圧しようとしたことは事 態を悪化させ、パリのラテン地区では警察との路上戦闘に発展した。 5月下旬には流れが変わった。5月27日に政府、労働組合、使用者の間で締結されたグルネル協定により、労働者の大幅な賃上げが実現した。5月29日にパ リ中心部でゴーリスト党が組織した反対デモは、ドゴールに国民議会を解散し、1968年6月23日に議会選挙を実施する自信を与えた。暴力は発生とほぼ同 時に消滅した。労働者は職場に戻り、6月の選挙後、ゴーリスト派は以前よりも強くなった。 1968年5月の出来事はフランス社会に影響を与え続けている。この時期は、国の歴史における文化的、社会的、道徳的な転換点とみなされている。当時の学 生指導者の一人であったアラン・ガイスマールは後に、この運動は「政治革命としてではなく、社会革命として」成功したと述べている[6]。 |

| Les

événements de mai-juin 1968, ou plus brièvement Mai 68, désignent une

période durant laquelle se déroulent, en France, des grandes

manifestations ainsi qu'une grève générale et sauvage, accompagnée

d'occupations d'usines et de bâtiments administratifs, de la

généralisation de forums de discussions et propositions sociales et

politiques, d'une paralysie presque complète du système économique et

de l'administration, et d'une ébauche d'organisation de relations

sociétales égalitaires dans toute la France. Précédés par le mouvement de 1967 contre les ordonnances sur la sécurité sociale, les événements de mai-juin 1968 apparaissent d'abord comme une rupture fondamentale dans l'histoire de la société française, matérialisant une remise en cause des institutions traditionnelles, mais l'historiographie de Mai 68 a ensuite rappelé aussi, à partir des années 1990, que près de dix millions de personnes ont fait grève juste avant la négociation des accords de Grenelle qui actent un relèvement de 35 % du SMIG, le salaire minimum. La révolte étudiante parisienne et dans les villes universitaires, a gagné le monde ouvrier et pratiquement toutes les catégories de population sur l'ensemble du territoire, pour constituer le plus important mouvement social du xxe siècle en France. https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mai_68 |

1968年5月から6月にかけての出来事(略して68年5

月)は、フランスにおける大規模なデモと山猫ゼネストの期間であり、工場や行政施設の占拠、社会的・政治的議論や提案のための広範なフォーラム、経済シス

テムと行政のほぼ完全な麻痺、フランス全土における平等主義的社会関係の始まりを伴っていた。 1967年の社会保障条例反対運動に先立つ1968年5月から6月にかけての出来事は、当初、フランス社会の歴史における根本的な断絶であり、伝統的な制 度への挑戦であるかのように思われたが、1990年代以降、68年5月の歴史学は、最低賃金を35%引き上げるグレネル協定の交渉の直前に1000万人近 い人々がストライキに突入したことも想起した。パリと大学都市における学生の反乱は、フランス全土の労働者階級と事実上すべての国民に広がり、フランスに おける20世紀最大の社会運動となった。 |

| 共産主義・新左翼の影響 五月革命では、キューバ革命のチェ・ゲバラと文化大革命の毛沢東ら共産主義者が運動のアイコンとして掲げられた。背景にはフランス革命からロシア革命、 キューバ革命、文化大革命へと至る「革命の歴史」があり、それを高度経済成長に湧くパリの学生が導き、各国の学生運動に熱をふりまき、より拍車をかけた。 1960年代後半、欧米、日本を中心とした世界の新左翼若者は、学生運動によってお互いの理念、思想、哲学を共有し、激しい政治運動を行った。これによっ て国の枠組みにおさまらない対抗文化(カウンターカルチャー)や反体制文化(ヒッピー文化)を構成するユートピアスティックな「世界的な同世代」という世 代的な視座が加速度を増してゆく。以降、より自由に世界とコミュニケーションできるようになった学生は発言権を強めるようになり、フランスの現代化を推進 させたとの意見もある[2]。それはロックや映画、ファッション[3]、アニメ、アートなどに影響を与えたとされる[4]。 デモ支持派における毛沢東主義への憧れ 文化大革命の紅衛兵。五月革命当時のフランスではまだ文化大革命の実態は知らされておらず、フランス人のあいだでは毛思想への過剰な期待がふくらんでい た。 当時のフランスでは赤い中国のGrand Timonier[5]こと毛沢東の著書「Le petit livre rouge de mao」(「毛主席語録」)が流行していた。それはパリのENS(高等師範学校)[6]の学生たちを通じてひろまり、左派知識人たちを活気づけ、学生や労 働者を団結させる思想だった。学生はアメリカの覇権主義に反対するモデルとして毛沢東思想の書籍を読んだ。したがって中国への憧れも「五月革命」には投影 されている。ただその憧れは思想的に深められることがなく、ロマンチシズムの色彩が濃かった。さらに当然なことながら、学生には政府を転覆させる力はな かった。つまり本物の武力による革命ではなくて、学生時代のモラトリアムな革命[7]だった。 https://x.gd/NEUdl |

|

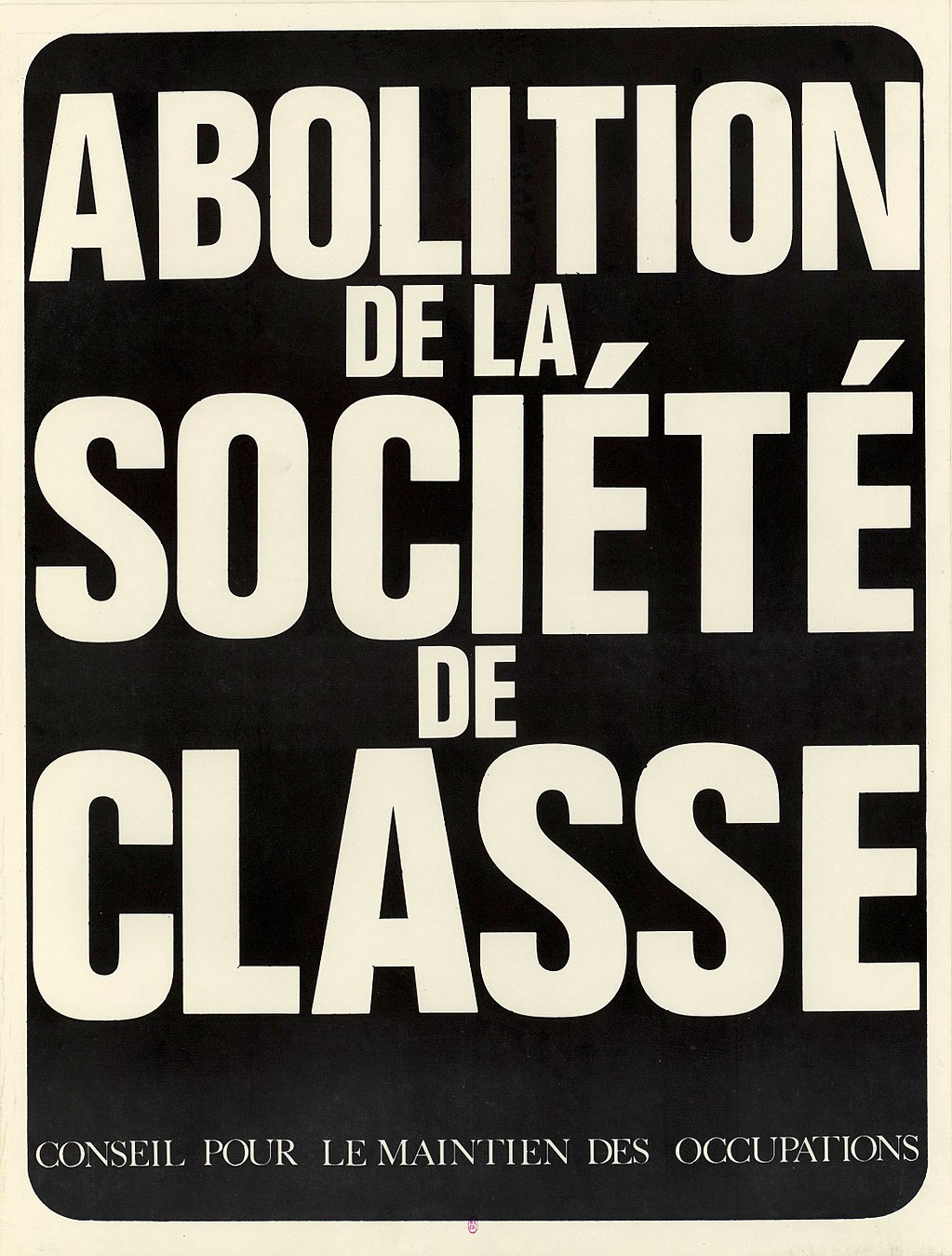

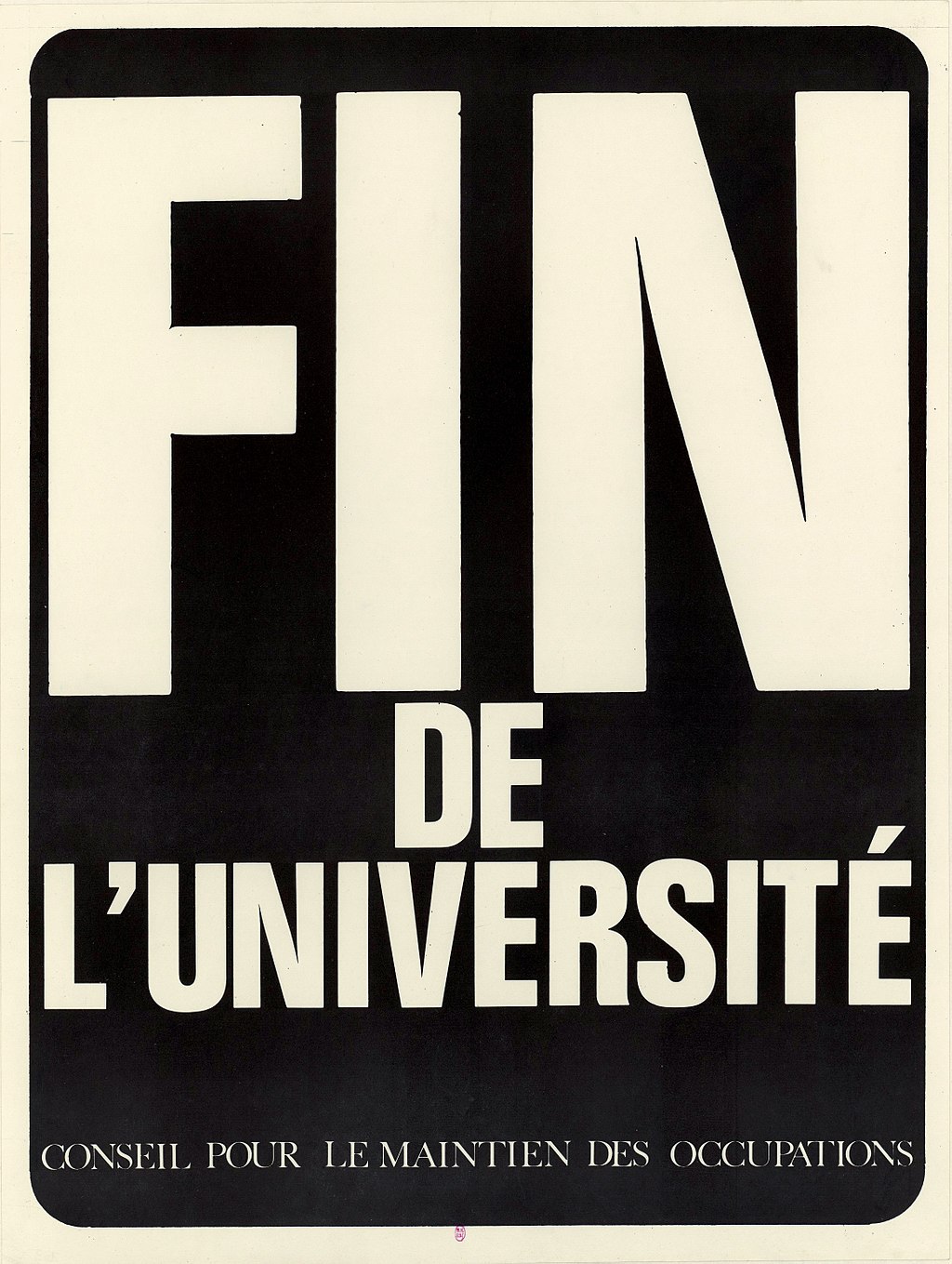

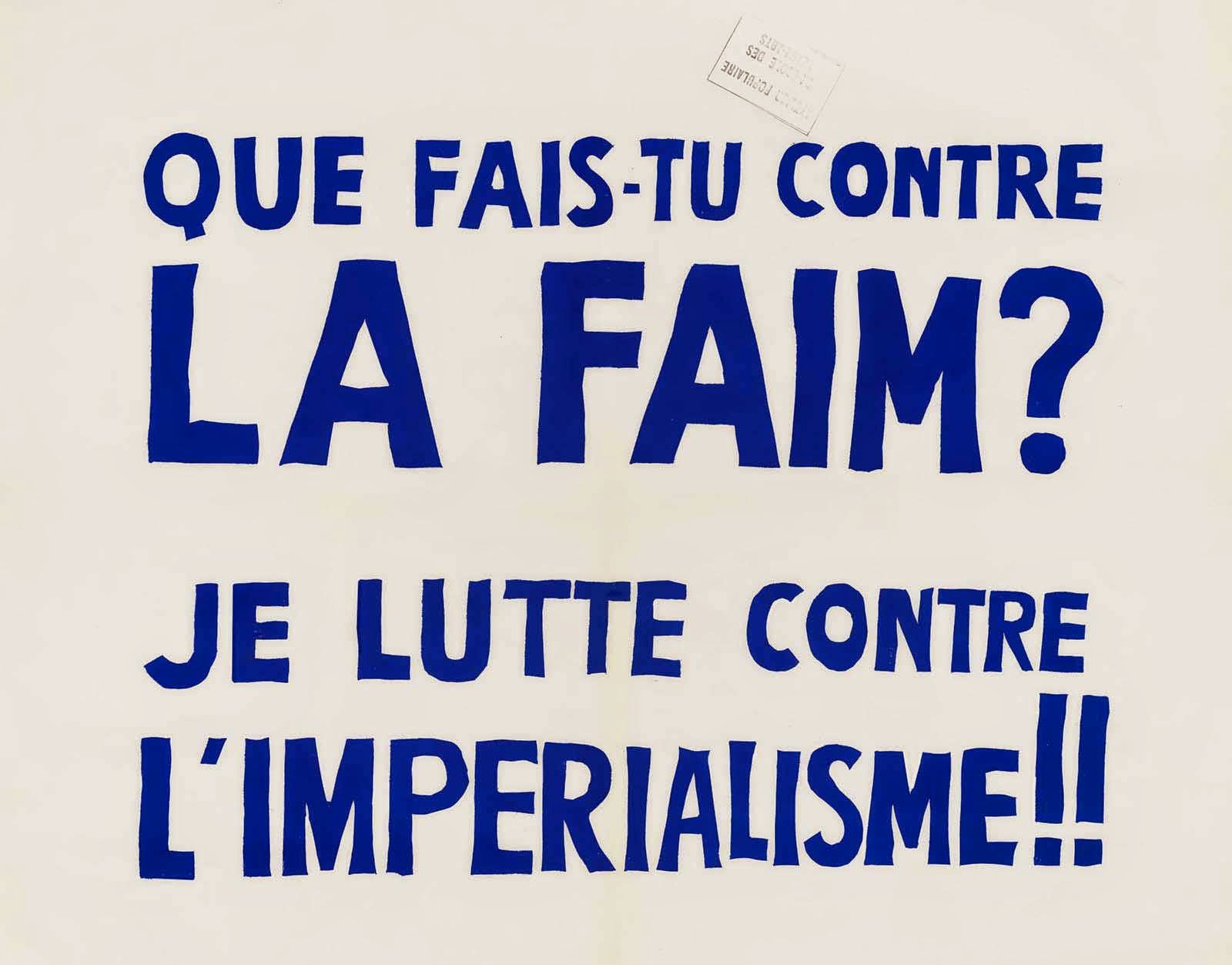

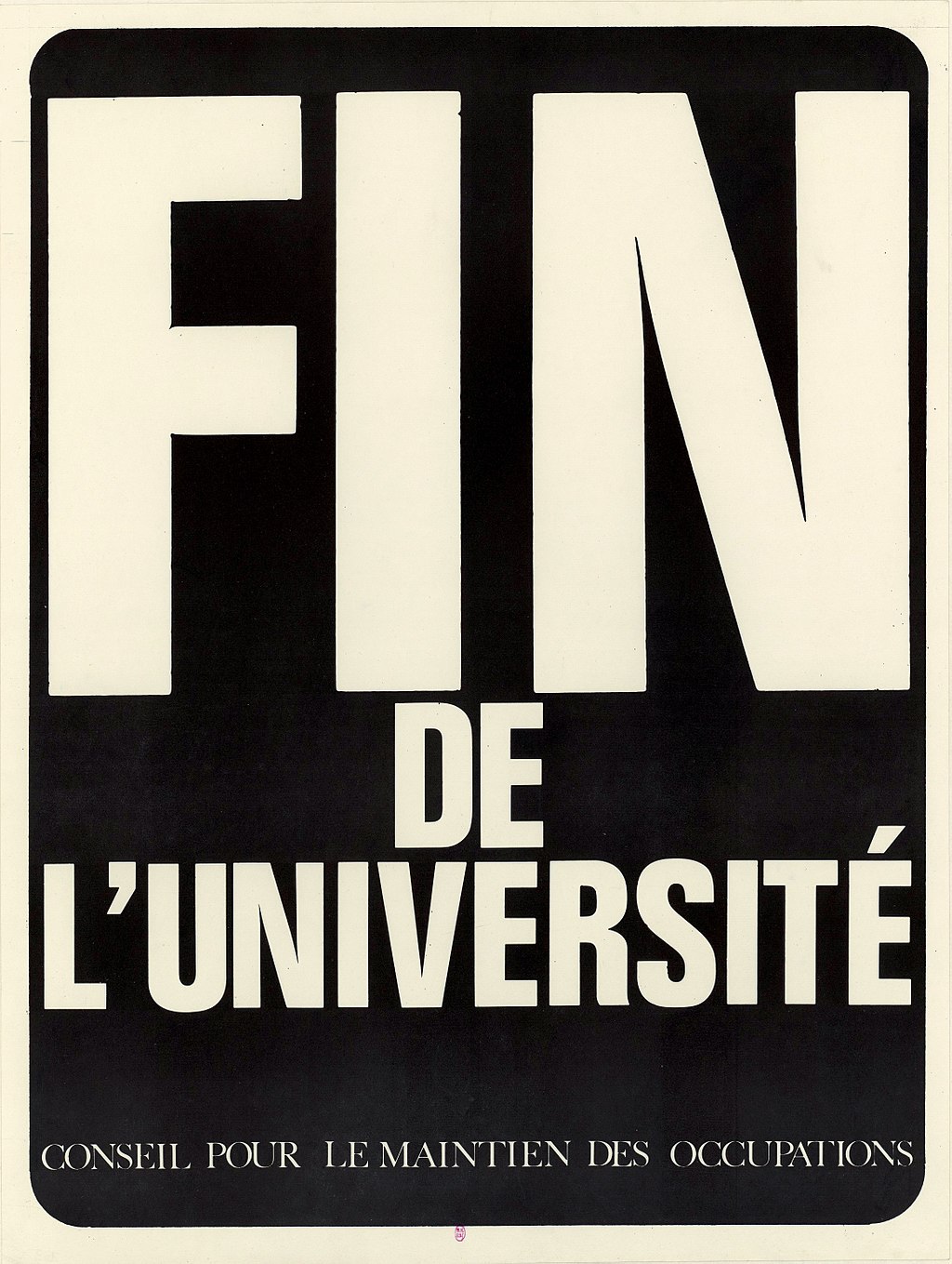

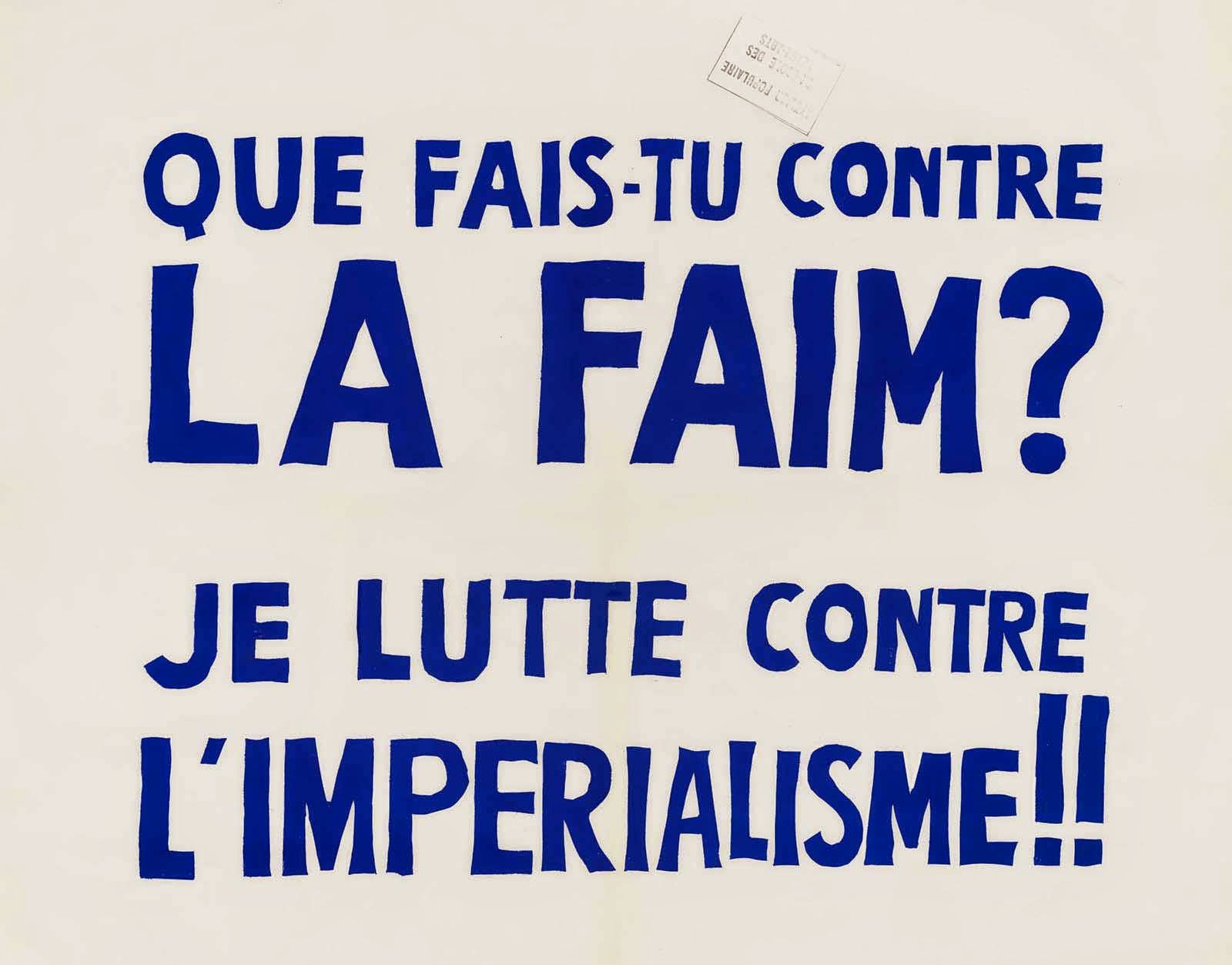

| Se

conoce como Mayo francés o Mayo de 1968 a la cadena de protestas

estudiantiles, principalmente universitarias, y posteriormente

sindicales que se llevaron a cabo en Francia y, especialmente, en París

durante los meses de mayo y junio de 1968. Esta serie de protestas espontáneas fue iniciada por grupos estudiantiles contrarios a la sociedad de consumo, el capitalismo, el imperialismo, el autoritarismo, y que en general desautorizaban las organizaciones políticas y sociales de la época, como los partidos políticos, el gobierno, los sindicatos o la propia universidad. Al movimiento estudiantil inicial pronto se unieron grupos de obreros industriales, los sindicatos y el Partido Comunista Francés,1 aunque con objetivos principalmente laborales, no plenamente coincidentes en otros aspectos con los grupos estudiantiles. Ambos movimientos dieron como resultado la mayor revuelta estudiantil y la mayor huelga general de la historia de Francia, y posiblemente de Europa occidental, secundada por más de nueve millones de trabajadores.2 El movimiento estudiantil tuvo influencias del movimiento hippie que se extendía entonces. La magnitud de las protestas no había sido prevista por el gobierno francés, y puso contra las cuerdas al gobierno de Charles de Gaulle, que llegó a temer una insurrección de carácter revolucionario tras la extensión de la huelga general. Sin embargo, la mayor parte de los sectores participantes en la protesta no llegaron a plantearse la toma del poder ni la insurrección abierta contra el Estado, y ni tan siquiera el Partido Comunista Francés llegó a considerar seriamente esa salida.2 El grueso de las protestas finalizó cuando De Gaulle anunció las elecciones anticipadas que tuvieron lugar el 23 y 30 de junio.  Cartel de mayo 68 que dice "Abolición de la sociedad de clases" (CMDO). Los sucesos de mayo y junio en Francia se encuadran dentro de una ola de protestas protagonizadas, principalmente, por sectores politizados de la juventud, cuya ideología recorrió el mundo durante 1968. Estos sucesos se extendieron por la República Federal Alemana, Suiza, España, México, Argentina, Uruguay, Estados Unidos, Checoslovaquia e Italia, lo cual ampliaba la escala del antiguo refrán del siglo xix afirmando que cuando París estornuda, toda Europa se resfría.  "Fin de la universidad". La novedad de 1968, con respecto a otras luchas anteriores, proviene de los puntos de intersección y del cruce de compromisos: de Vietnam a Japón, pasando por Alemania, se encuentran lazos y puentes construidos entre los pueblos insurrectos, los estudiantes disidentes y los trabajadores sublevados. Globalidad y transmisión operan de forma circular: el acontecimiento es global, porque sus protagonistas viajan, transmiten, se apropian y revelan el desafío más allá de la patria. El internacionalismo apareció como un principio activo, un motor político decisivo. Ese saber se impregnó con descubrimientos, con la circulación de informaciones y transmisiones. Los estudiantes estaban más al tanto que los obreros de sus vecinos europeos, e incluso miraban más allá, hacía ese vasto mundo, donde encontraban compromisos similares. Esto se explica debido a razones prácticas: originarios de medios sociales relativamente privilegiados, gozaban frecuentemente de los medios financieros para viajar; sus estudios los llevaban a tomar en cuenta otras culturas, practicar otras lenguas, a recibir en sus propias bancas a pares originarios de cualquier parte del mundo. Fue así como se puso en marcha la circulación de prácticas, ideas y solidaridades.3  «¿Qué haces contra el hambre? ¡Yo lucho contra el imperialismo!» https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mayo_de_1968_en_Francia |

フレンチ・メイまたは1968年5月とは、1968年5月から6月にか

けてフランス、特にパリで起こった学生、主に大学、後に労働組合の抗議行動の連鎖につけられた名称である。 この一連の自然発生的な抗議運動は、消費社会、資本主義、帝国主義、権威主義に反対し、政党、政府、労働組合、大学といった当時の政治・社会組織を否定す る学生グループによって始められた。当初の学生運動は、すぐに産業労働者のグループ、労働組合、フランス共産党1が加わったが、主に労働を目的としてお り、他の点では学生グループと完全には一致しなかった。学生運動は、当時広がっていたヒッピー運動の影響を受けていた。 学生運動は、当時広まっていたヒッピームーブメントの影響を受けていた。抗議行動の規模はフランス政府も予想していなかったもので、シャルル・ド・ゴール 政権を窮地に追い込み、ゼネストの広がりを受けて革命的な反乱を恐れるようになった。しかし、抗議行動に参加したほとんどの部門は、権力の掌握や国家に対 する公然たる反乱を検討するまでには至らず、フランス共産党でさえ、そのような退場を真剣に検討することはなかった2。抗議行動の大部分は、ド・ゴールが 6月23日と30日に実施された早期選挙を発表したときに終わった。  「階級社会の廃止」と書かれた68年5月のポスター(CMDO)。 フランスの5月と6月の出来事は、主に政治化された若者の一部によって引き起こされた抗議行動の波の一部であり、そのイデオロギーは1968年に世界を席 巻した。これらの出来事は、ドイツ連邦共和国、スイス、スペイン、メキシコ、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイ、アメリカ、チェコスロバキア、イタリアへと広が り、「パリがくしゃみをするとヨーロッパ全体が風邪をひく」という19世紀の古いことわざの規模を拡大した。  「大学の終焉」 ベトナムからドイツを経由して日本まで、反乱を起こした民族、反体制派の学生、蜂起した労働者たちの間にリンクと橋が架けられた。グローバル性と伝達は循 環的に作用する。主人公たちが祖国を越えて旅し、伝達し、適切化し、課題を明らかにするからこそ、このイベントはグローバルなのだ。国際主義は、積極的な 原則、決定的な政治的原動力として登場した。この知識は、情報の循環と伝達という発見を孕んでいた。学生たちは、労働者たちよりもヨーロッパの近隣諸国を 意識し、さらに遠く、広大な世界に目を向けていた。比較的恵まれた社会的背景を持つ彼らは、しばしば旅行する経済的な余裕を持っていた。こうして、実践、 アイデア、連帯感の循環が始まったのである3。  「私は帝国主義と戦っているんだ!」 |

| Background Political climate In February 1968, the French Communist Party and the French Section of the Workers' International formed an electoral alliance. Communists had long supported Socialist candidates in elections, but in the "February Declaration" the two parties agreed to attempt to form a joint government to replace President Charles de Gaulle and his Gaullist Party.[7] University demonstration On 22 March, far-left groups, a small number of prominent poets and musicians, and 150 students occupied an administration building at Paris University at Nanterre and held a meeting in the university council room about class discrimination in French society and the political bureaucracy that controlled the university's funding. The university's administration called the police, who surrounded the university. After the publication of their wishes, the students left the building without any trouble. After this, some leaders of what was named the "Movement of 22 March" were called together by the disciplinary committee of the university. |

背景 政治情勢 1968年2月、フランス共産党と労働者インターナショナル・フランス支部は選挙同盟を結んだ。共産主義者は長い間選挙で社会党候補を支持していたが、 「2月宣言」で両党はシャルル・ド・ゴール大統領と彼のゴーリスト党に代わる共同政権を樹立しようとすることに合意した[7]。 大学デモ 3月22日、極左団体、少数の著名な詩人や音楽家、150人の学生がパリ大学ナンテール校の管理棟を占拠し、大学の会議室でフランス社会における階級差別 や大学の資金を管理する政治官僚制について会議を開いた。大学当局は警察に通報し、警察は大学を包囲した。大学側は警察に通報し、警察は大学を包囲した。 この後、「3月22日運動」と名づけられたいくつかの指導者たちが、大学の懲罰委員会に呼び出された。 |

| Events of May Student protests Public square of the Sorbonne, in the Latin Quarter of Paris After months of conflicts between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris (now Paris Nanterre University), the administration shut the university down on 2 May 1968.[8] Students at the University of Paris's Sorbonne campus (today Sorbonne University) met on 3 May to protest the closure and the threatened expulsion of several Nanterre students.[9] On 6 May, the national student union, the Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (UNEF, the National Union of Students of France)—still France's largest student union today—and the union of university teachers called a march to protest the police invasion of the Sorbonne. More than 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched toward the Sorbonne, still sealed off by the police, who charged, wielding their batons, as soon as the marchers approached. While the crowd dispersed, some began to create barricades out of whatever was at hand, while others threw paving stones, forcing the police to retreat for a time. The police then responded with tear gas and charged the crowd again. Hundreds more students were arrested. Graffiti in a classroom Graffiti on the school of law, "Vive de Gaulle" (Long live De Gaulle) with, at left, the word "A bas" (down with) written across "Vive" University of Lyon during student occupation, May–June 1968 High school student unions spoke in support of the riots on 6 May. The next day, they joined the students, teachers and increasing numbers of young workers who gathered at the Arc de Triomphe to demand that (1) all criminal charges against arrested students be dropped, (2) the police leave the university, and (3) the authorities reopen Nanterre and Sorbonne. Escalating conflict Negotiations broke down, and students returned to their campuses after a false report that the government had agreed to reopen them, only to discover the police still occupying the schools. This led to near revolutionary fervor among the students. On 10 May, another huge crowd congregated on the Rive Gauche. When the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité again blocked them from crossing the river, the crowd again threw up barricades, which the police then attacked at 2:15 a.m. after negotiations once again floundered. The confrontation, which produced hundreds of arrests and injuries, lasted until dawn. The events were broadcast on radio as they occurred and the aftermath shown on television the next day. It was alleged that the police had participated in the riots, through agents provocateurs, by burning cars and throwing Molotov cocktails.[10] The government's heavy-handed reaction brought on a wave of sympathy for the strikers. Many of the nation's more mainstream singers and poets joined after the police brutality came to light. American artists also began voicing support of the strikers. The major left union federations, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) and the Force Ouvrière (CGT-FO), called a one-day general strike and demonstration for Monday, 13 May. Well over a million people marched through Paris that day; the police stayed largely out of sight. Prime Minister Georges Pompidou personally announced the release of the prisoners and the reopening of the Sorbonne. However, the surge of strikes did not recede. Instead, the protesters became even more active. When the Sorbonne reopened, students occupied it and declared it an autonomous "people's university". Public opinion at first supported the students, but turned against them after their leaders, invited to appear on national television, "behaved like irresponsible utopianists who wanted to destroy the 'consumer society'".[11] Nonetheless, in the weeks that followed, approximately 401 popular action committees were set up in Paris and elsewhere to take up grievances against the government and French society, including the Sorbonne Occupation Committee. Worker strikes Strikers in Southern France with a sign reading "Factory Occupied by the Workers." Behind them is a list of demands, June 1968. By the middle of May, demonstrations extended to factories, though workers' demands significantly varied from students'. A union-led general strike on 13 May included 200,000 in a march. The strikes spread to all sectors of the French economy, including state-owned jobs, manufacturing and service industries, management, and administration. Across France, students occupied university structures and up to one-third of the country's workforce was on strike.[12] These strikes were not led by the union movement; on the contrary, the CGT tried to contain this spontaneous outbreak of militancy by channeling it into a struggle for higher wages and other economic demands. Workers put forward a broader, more political and more radical agenda, demanding an ouster of de Gaulle's government and attempting, in some cases, to run their factories. When the trade union leadership negotiated a 35% increase in the minimum wage, a 7% wage increase for other workers, and half normal pay for the time on strike with the major employers' associations, the workers occupying their factories refused to return to work and jeered their union leaders.[13][14] In fact, the May 68 movement included substantial "anti-unionist euphoria"[15] against the mainstream unions, the CGT, FO and CFDT, that were more willing to compromise with the government than enact the will of the base.[2] On 24 May, two people died at the hands of out-of-control rioters. In Lyon, Police Inspector Rene Lacroix died when he was crushed by a driverless truck rioters sent careering into police lines. In Paris, Phillipe Metherion, 26, was stabbed to death during an argument among demonstrators.[1] As the upheaval reached its apogee in late May, major trade unions met with employers' organizations and the French government to produce the Grenelle agreements, which would increase the minimum wage 35% and all salaries 10%, and granted employee protections and a shortened working day. The unions were forced to reject the agreement, based on opposition from their members, underscoring a disconnect in organizations that claimed to reflect working class interests.[16] The UNEF student union and CFDT trade union held a rally in the Charléty stadium with about 22,000 attendees. Its range of speakers reflected the divide between student and Communist factions. While the rally was held in the stadium partly for security, the speakers' insurrectionist messages were dissonant with the relative amenities of the sports venue.[17] Calls for new government The Socialists saw an opportunity to act as a compromise between de Gaulle and the Communists. On 28 May, François Mitterrand of the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left declared that "there is no more state" and said he was ready to form a new government. He had received a surprisingly high 45% of the vote in the 1965 presidential election. On 29 May, Pierre Mendès France also said he was ready to form a new government; unlike Mitterrand, he was willing to include the Communists. Although the Socialists lacked the Communists' ability to form large street demonstrations, they had more than 20% of the country's support.[11][7] De Gaulle flees On the morning of 29 May, de Gaulle postponed the meeting of the Council of Ministers scheduled for that day and secretly removed his personal papers from Élysée Palace. He told his son-in-law Alain de Boissieu: "I do not want to give them a chance to attack the Élysée. It would be regrettable if blood were shed in my personal defense. I have decided to leave: nobody attacks an empty palace." De Gaulle refused Pompidou's request that he dissolve the National Assembly, as he believed that their party, the Gaullists, would lose the resulting election. At 11:00 am, he told Pompidou, "I am the past; you are the future; I embrace you."[11] The government announced that de Gaulle was going to his country home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises before returning the next day, and rumors spread that he would prepare his resignation speech there. However, the presidential helicopter did not arrive in Colombey, and de Gaulle had told no one in the government where he was going. For more than six hours the world did not know where he was.[18] The canceling of the ministerial meeting and de Gaulle's mysterious disappearance stunned the French,[11] including Pompidou, who shouted, "He has fled the country!"[19] Government collapse With de Gaulle's closest advisors saying they did not know what he intended, Pompidou scheduled a tentative appearance on television at 8 p.m.[18] The national government had effectively ceased to function. Édouard Balladur later wrote that as prime minister, Pompidou "by himself was the whole government", as most officials were "an incoherent group of confabulators" who believed that revolution would soon occur. A friend of Pompidou offered him a weapon, saying, "You will need it"; Pompidou advised him to go home. One official reportedly began burning documents, while another asked an aide how far they could flee by automobile should revolutionaries seize fuel supplies. Withdrawing money from banks became difficult, gasoline for private automobiles was unavailable, and some people tried to obtain private planes or fake national identity cards.[11] Pompidou unsuccessfully requested that military radar be used to follow de Gaulle's two helicopters, but soon learned that he had gone to the headquarters of the French Forces in Germany, in Baden-Baden, to meet General Jacques Massu. Massu persuaded the discouraged de Gaulle to return to France; now knowing that he had the military's support, de Gaulle rescheduled the meeting of the Council of Ministers for the next day, 30 May,[11] and returned to Colombey by 6:00 pm.[18] However, his wife Yvonne gave the family jewels to their son and daughter-in-law—who stayed in Baden for a few more days—for safekeeping, indicating that the de Gaulles still considered Germany a possible refuge. Massu kept as a state secret de Gaulle's loss of confidence until others disclosed it in 1982; until then most observers believed that his disappearance was intended to remind the French people of what they might lose. Although the disappearance was real and not intended as motivation, it indeed had such an effect on France.[11] Revolution prevented  Pierre Messmer On 30 May, 400,000 to 500,000 protesters (many more than the 50,000 the police were expecting) led by the CGT marched through Paris, chanting: "Adieu, de Gaulle!" ("Farewell, de Gaulle!"). Maurice Grimaud, head of the Paris police, played a key role in avoiding revolution by both speaking to and spying on the revolutionaries, and by avoiding the use of force. While Communist leaders later denied that they had planned an armed uprising, and extreme militants only comprised 2% of the populace, they had overestimated de Gaulle's strength, as shown by his escape to Germany.[11] One scholar, otherwise skeptical of French Communists' willingness to maintain democracy after forming a government, claims that the "moderate, nonviolent and essentially antirevolutionary" Communists opposed revolution because they sincerely believed that the party must come to power through legal elections, not armed conflict that might provoke harsh repression from political opponents.[7] Not knowing that the Communists did not intend to seize power, officials prepared to position police forces at the Élysée with orders to shoot if necessary. That it did not also guard Paris City Hall despite reports that it was the Communists' target was evidence of governmental chaos.[18] The Communist movement largely centered around the Paris metropolitan area, and not elsewhere. Had the rebellion occupied key public buildings in Paris, the government would have had to use force to retake them. The resulting casualties could have incited a revolution, with the military moving from the provinces to retake Paris as in 1871. Minister of Defence Pierre Messmer and Chief of the Defence Staff Michel Fourquet prepared for such an action, and Pompidou had ordered tanks to Issy-les-Moulineaux.[11] While the military was free of revolutionary sentiment, using an army mostly of conscripts the same age as the revolutionaries would have been very dangerous for the government.[7][18] A survey conducted immediately after the crisis found that 20% of Frenchmen would have supported a revolution, 23% would have opposed it, and 57% would have avoided physical participation in the conflict. 33% would have fought a military intervention, while only 5% would have supported it and a majority of the country would have avoided any action.[11] Election called At 2:30 p.m. on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded de Gaulle to dissolve the National Assembly and call a new election by threatening to resign. At 4:30 pm, de Gaulle broadcast his refusal to resign. He announced an election, scheduled for 23 June, and ordered workers to return to work, threatening to institute a state of emergency if they did not. The government had leaked to the media that the army was outside Paris. Immediately after the speech, about 800,000 supporters marched through the Champs-Élysées waving the national flag; the Gaullists had planned the rally for several days, which attracted a crowd of diverse ages, occupations, and politics. The Communists agreed to the election, and the threat of revolution was over.[11][18][20] |

5月の出来事 学生による抗議行動 パリのラテン地区にあるソルボンヌ大学の広場 1968年5月2日、パリ大学ナンテール校(現パリ・ナンテール大学)の学生と当局との数ヶ月にわたる対立の後、大学は閉鎖された[8]。5月3日、パリ 大学ソルボンヌ校(現ソルボンヌ大学)の学生は、閉鎖とナンテール校の学生数名の追放の危機に抗議するために集会を開いた。 [5月6日、現在もフランス最大の学生組合であるフランス全国学生組合(UNEF)と大学教員組合は、ソルボンヌ大学への警察の侵入に抗議するデモ行進を 呼びかけた。20,000人以上の学生、教師、支援者が、警察によって封鎖されたままのソルボンヌ大学に向かって行進し、行進者が近づくや否や、警察は警 棒を振り回して突撃した。群衆が散り散りになる中、手近なものでバリケードを作る者や敷石を投げる者が現れ、警察は一時退却を余儀なくされた。警察は催涙 ガスで応戦し、群衆を再び攻撃した。さらに数百人の学生が逮捕された。 教室の落書き 法学部の落書き。"Vive de Gaulle"(ド・ゴール万歳)と書かれ、左側には "Vive "の横に "A bas"(共に倒れろ)と書かれている。 学生占拠中のリヨン大学(1968年5月~6月 高校の学生組合は5月6日、暴動を支持する演説を行った。翌日、彼らは凱旋門に集まった学生、教師、そして増え続ける若年労働者とともに、(1)逮捕され た学生に対するすべての刑事責任を取り下げ、(2)警察が大学から立ち去り、(3)当局がナンテールとソルボンヌを再開することを要求した。 激化する対立 交渉は決裂し、政府が再開に同意したという虚偽の報告の後、学生たちはキャンパスに戻った。このため、学生たちの間では革命熱に近いものが起こった。 5月10日、リヴ・ゴーシュにまた大群衆が集まった。警備隊が川を渡るのを再び阻止すると、群衆は再びバリケードを築き、交渉が再び難航したため、警察は 午前2時15分にバリケードを攻撃した。何百人もの逮捕者と負傷者を出したこの対立は、夜明けまで続いた。その模様はラジオで放送され、翌日にはテレビで その余波が放映された。警察は挑発工作員を通じて、車を燃やしたり火炎瓶を投げたりして暴動に参加したとされた[10]。 政府の強硬な反応は、ストライキ参加者への同情の波をもたらした。警察の蛮行が明るみに出た後、アメリカの主流派の歌手や詩人の多くが参加した。アメリカ の芸術家たちもストライキ参加者への支持を表明し始めた。主要な左派労組連合である労働総同盟(CGT)と労働総同盟(CGT-FO)は、5月13日 (月)の1日ゼネストとデモを呼びかけた。 その日、100万人を超える人々がパリ市内を行進したが、警察はほとんど姿を見せなかった。ポンピドゥー首相は自ら囚人の釈放とソルボンヌ大学の再開を発 表した。しかし、ストライキの波は収まることはなかった。それどころか、デモ隊はさらに活発になった。 ソルボンヌ大学が再開されると、学生たちはそこを占拠し、「人民大学」の自治を宣言した。世論は当初学生たちを支持していたが、国営テレビに招かれた指導 者たちが「『消費社会』の破壊を望む無責任なユートピア主義者のように振る舞った」[11]ことから、学生たちに反感を抱くようになった。それでも、その 後の数週間で、ソルボンヌ占拠委員会を含め、政府やフランス社会に対する不満を取り上げる約401の民衆行動委員会がパリやその他の地域に設置された。 労働者のストライキ "労働者によって占拠された工場 "と書かれた看板を掲げる南フランスのストライキ参加者。背後には要求リスト(1968年6月)。 5月中旬までに、デモは工場にまで拡大したが、労働者の要求は学生の要求とは大きく異なっていた。5月13日の組合主導のゼネストには20万人が行進し た。ストライキは国有企業、製造業、サービス業、経営者、管理者などフランス経済のあらゆる部門に広がった。フランス全土で、学生が大学の建物を占拠し、 国内の労働者の3分の1までがストライキに突入した[12]。 これらのストライキは組合運動が主導したものではなく、それどころかCGTは、この自然発生的な戦闘性の発生を、賃上げやその他の経済的要求を求める闘争 に誘導することによって封じ込めようとした。労働者はより広範で、より政治的で、より急進的なアジェンダを打ち出し、ドゴール政権の退陣を要求し、場合に よっては工場の経営を試みた。労働組合の指導部が主要な使用者団体と最低賃金の35%引き上げ、その他の労働者の賃金の7%引き上げ、ストライキ期間中の 通常の賃金の半額を交渉したとき、工場を占拠していた労働者たちは職場復帰を拒否し、組合指導者を嘲笑した[13][14]。 事実、5月68日運動には、基層の意思を実現するよりも政府との妥協を厭わない主流派組合であるCGT、FO、CFDTに対する実質的な「反組合主義者の 陶酔」[15]が含まれていた[2]。 5月24日、制御不能に陥った暴徒によって2人が死亡した。リヨンでは、ルネ・ラクロワ警部が、暴徒が警察の列に突っ込ませた運転手のいないトラックに押 しつぶされて死亡した。パリでは、フィリップ・メテリオン(26歳)がデモ隊同士の口論中に刺殺された[1]。 騒乱が頂点に達した5月下旬、主要な労働組合は使用者団体およびフランス政府と会談し、最低賃金を35%、すべての給与を10%引き上げ、従業員保護と労 働時間の短縮を認めるグレネル協約を作成した。労働組合は組合員の反対により協約の拒否を余儀なくされ、労働者階級の利益を反映すると主張する組織の断絶 が浮き彫りになった[16]。 UNEF学生組合とCFDT労働組合はシャルレティ・スタジアムで集会を開き、約22,000人が参加した。演説者の顔ぶれは、学生派と共産主義派の分裂 を反映していた。集会がスタジアムで開催されたのは警備のためでもあったが、演説者たちの反乱主義的なメッセージは、スポーツ会場の比較的快適な環境と不 協和だった[17]。 新政府への要求 社会党は、ドゴールと共産主義者の妥協案として行動する機会を得た。5月28日、民主・社会主義左翼連合のフランソワ・ミッテランは「もう国家は存在しな い」と宣言し、新政権を樹立する用意があると述べた。ミッテランは1965年の大統領選挙で45%という驚異的な得票率を獲得していた。5月29日、ピ エール・メンデス・フランスも新政権を樹立する用意があると述べた。ミッテランとは異なり、彼は共産党を取り込むことを望んでいた。社会党には共産党のよ うな大規模な街頭デモを行う能力はなかったが、国内の20%以上の支持を得ていた[11][7]。 ドゴールの逃亡 5月29日の朝、ドゴールはその日に予定されていた閣僚会議を延期し、エリゼ宮から私物を密かに持ち出した。彼は義理の息子アラン・ド・ボワシューに言っ た: 「私は彼らにエリゼを攻撃する機会を与えたくない。私の個人的な防衛のために血が流されるのは残念なことだ。空っぽの宮殿を攻撃する者などいない"。ド ゴールはポンピドゥーからの国民議会解散の要求を拒否した。午前11時、彼はポンピドゥーに「私は過去であり、あなたは未来である。 政府は、ドゴールが翌日帰国する前にコロンビー・レ・ドゥ・エグリーズの別荘に向かうと発表し、そこで辞任演説の準備をするという噂が広まった。しかし、 大統領専用ヘリコプターはコロンビーに到着せず、ドゴールは政府の誰にも行き先を告げていなかった。閣僚会議の中止とド・ゴールの謎の失踪は、ポンピ ドゥーをはじめとするフランス人[11]を驚愕させ、ポンピドゥーは「彼は国外に逃亡した!」と叫んだ[19]。 政府崩壊 ドゴールの最側近たちは、ドゴールが何を意図しているのかわからないと言っていたが、ポンピドゥーは午後8時にテレビに仮出演する予定だった[18]。後 にエドゥアール・バラデュールは、首相であったポンピドゥーは「自分ひとりが政府のすべてであった」と記している。ほとんどの官僚は「支離滅裂な合議者の 集団」であり、革命がすぐに起こると信じていたからである。ポンピドゥーの友人が「君には必要だろう」と武器を差し出したが、ポンピドゥーは「家に帰れ」 と忠告した。ある役人は書類を燃やし始め、別の役人は革命派が燃料を押収した場合、自動車でどこまで逃げられるかを側近に尋ねたという。銀行からの引き出 しは困難になり、自家用車用のガソリンは手に入らなくなり、自家用飛行機や偽の国民IDカードを手に入れようとする者もいた[11]。 ポンピドゥーは、ドゴールの2機のヘリコプターを追跡するために軍のレーダーを使うよう要求したが失敗し、すぐに彼がバーデンバーデンの在ドイツフランス 軍司令部に行き、ジャック・マス将軍に会ったことを知った。マスー将軍は落胆していたドゴールにフランスに戻るよう説得し、ドゴールは軍の支持を得ている ことを知ったため、閣僚会議の予定を翌日の5月30日に変更し[11]、午後6時までにコロンビーに戻った[18]。しかし、妻のイヴォンヌは、さらに数 日間バーデンに滞在していた息子夫婦に家族の宝石を預けており、ドゴール夫妻がまだドイツを避難先として考えていたことを示していた。マスーは、1982 年に他人が暴露するまで、ド・ゴールの失脚を国家機密としていた。それまでは、彼の失踪は、フランス国民が失うかもしれないものを思い起こさせるためのも のだと、ほとんどのオブザーバーは考えていた。失踪は現実のものであり、動機付けのためのものではなかったが、フランスにそのような影響を与えたのは事実 である[11]。 革命の阻止  ピエール・メスメール 5月30日、CGTに率いられた40万から50万のデモ隊(警察が予想していた5万人よりも多かった)が、「アデュー、ドゴール」と唱えながらパリ市内を 行進した: "さらば、ド・ゴール! (さらば、ド・ゴール!)」と唱和しながら行進した。パリ警察のモーリス・グリモーは、革命派との対話とスパイ活動、そして武力行使の回避によって、革命 回避に重要な役割を果たした。共産主義指導者たちは後に武装蜂起を計画していたことを否定し、極端な過激派は民衆の2%に過ぎなかったが、ドイツへの逃亡 で示されたように、彼らはド・ゴールの力を過大評価していた。 [11] ある学者は、フランス共産主義者が政権を樹立した後も民主主義を維持しようとしたことに懐疑的であったが、「穏健で、非暴力的で、本質的に反革命的」な共 産主義者が革命に反対したのは、党が政敵からの厳しい弾圧を引き起こす可能性のある武力衝突ではなく、合法的な選挙を通じて政権を獲得しなければならない と心から信じていたからだと主張している[7]。 共産主義者が権力を掌握するつもりがないことを知らなかった官憲は、必要であれば発砲せよとの命令とともに警察部隊をエリゼに配置する準備をした。パリ市 庁舎が共産主義者の標的であるとの報告にもかかわらず、市庁舎も警備しなかったことは、政府の混乱の証拠であった[18]。もし反乱軍がパリの主要な公共 施設を占拠していたら、政府は武力で奪還しなければならなかっただろう。その結果、死傷者が出て、1871年のように軍隊が地方からパリを奪還するために 動き出し、革命を引き起こす可能性もあった。ピエール・メスメール国防大臣とミシェル・フルケ国防参謀総長はそのような事態に備えており、ポンピドゥーは イッシー・レ・ムリノーに戦車を派遣するよう命じていた[11]。軍部には革命的感情はなかったが、革命家と同年代の徴兵兵を中心とした軍隊を使用するこ とは政府にとって非常に危険なことであった[7][18]。 危機直後に実施された調査によると、フランス人の20%が革命を支持し、23%が反対し、57%が紛争への物理的参加を避けたという。33%は軍事介入を 支持し、5%のみが軍事介入を支持し、国民の大多数はいかなる行動も回避していた[11]。 選挙公示 5月30日午後2時30分、ポンピドゥーは辞任をちらつかせることで、国民議会を解散し、新たな選挙を招集するようドゴールを説得した。午後4時30分、 ドゴールは辞任を拒否する声明を発表した。ドゴールは6月23日に予定されていた選挙を告げ、労働者たちに職場復帰を命じ、もしそうしなければ非常事態宣 言を出すと脅した。政府は、軍隊がパリ郊外にいることをメディアにリークしていた。演説の直後、約80万人の支持者が国旗を振りながらシャンゼリゼ通りを 行進した。ガリア派は数日前からこの集会を計画しており、年齢も職業も政治もさまざまな人々が集まった。共産党は選挙に同意し、革命の危機は去った [11][18][20]。 |

| Aftermath Protest suppression and elections From that point, the revolutionary feeling of the students and workers faded away. Workers gradually returned to work or were ousted from their plants by police. The national student union called off street demonstrations. The government banned several leftist organizations. The police retook the Sorbonne on 16 June. Contrary to de Gaulle's fears, his party won the greatest victory in French parliamentary history in the legislative election held in June, taking 353 of 486 seats to the Communists' 34 and the Socialists' 57.[11] The February Declaration and its promise to include Communists in government likely hurt the Socialists in the election. Their opponents cited the example of the Czechoslovak National Front government of 1945, which led to a Communist takeover of the country in 1948. Socialist voters were divided; in a February 1968 survey a majority had favored allying with the Communists, but 44% believed that Communists would attempt to seize power once in government (30% of Communist voters agreed).[7] On Bastille Day, there were resurgent street demonstrations in the Latin Quarter, led by socialist students, leftists and communists wearing red armbands and anarchists wearing black armbands. The Paris police and the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS) harshly responded starting around 10 pm and continuing through the night, on the streets, in police vans, at police stations, and in hospitals where many wounded were taken. There was, as a result, much bloodshed among students and tourists there for the evening's festivities. No charges were filed against police or demonstrators, but the governments of Britain and West Germany filed formal protests, including for the indecent assault of two English schoolgirls by police in a police station. National feelings Despite the size of de Gaulle's triumph, it was not a personal one. A post-crisis survey conducted by Mattei Dogan showed that a majority of the country saw de Gaulle as "'too sure of himself' (70%), 'too old to govern' (59%), 'too authoritarian' (64%), 'too concerned with his personal prestige' (69%), 'too conservative' (63%), and 'too anti-American' (69%)"; as the April 1969 referendum would show, the country was ready for "Gaullism without de Gaulle".[11] |

余波 抗議弾圧と選挙 その時点から、学生や労働者の革命的感情は薄れていった。労働者は徐々に職場に戻り、あるいは警察によって工場から追い出された。全国学生組合は街頭デモ を中止した。政府はいくつかの左翼団体を禁止した。警察は6月16日にソルボンヌ大学を奪還した。ドゴールの懸念に反して、6月に行われた議会選挙でド ゴール党は486議席中353議席を獲得し、共産党34議席、社会党57議席というフランス議会史上最大の勝利を収めた[11]。反対派は、1945年の チェコスロバキア国民戦線政権が1948年に共産党に占領された例を引き合いに出した。1968年2月の調査では、社会党の有権者の過半数が共産党との同 盟に賛成していたが、44%が共産党が政権を握れば政権を奪取しようとすると考えていた(共産党員の30%が賛成)[7]。 バスティーユの日、ラテン地区では、赤い腕章をつけた社会主義学生、左翼、共産主義者、黒い腕章をつけたアナキストたちによる街頭デモが復活した。パリ警 察と治安警備隊(CRS)は、午後10時頃から夜通し、路上、警察車両、警察署、負傷者が多数収容された病院などで厳しく対応した。その結果、夜のお祭り に来ていた学生や観光客の間で多くの流血が発生した。警察やデモ参加者に罪は問われなかったが、イギリスと西ドイツの両政府は、警察署内で2人のイギリス 人女子学生に警察が強制わいせつを働いたことなどに対し、正式な抗議を行った。 国民感情 ド・ゴールの勝利の大きさにもかかわらず、それは個人的なものではなかった。マッテイ・ドガンが危機後に行った調査によると、国民の大多数がドゴールを 「『自分に自信がありすぎる』(70%)、『統治するには年を取りすぎている』(59%)、『権威主義的すぎる』(64%)、『個人的な威信を気にしすぎ ている』(69%)、『保守的すぎる』(63%)、『反米的すぎる』(69%)」と見ており、1969年4月の国民投票が示すように、国民は「ドゴール抜 きのゴーリズム」の用意ができていた[11]。 |

| May 1968 is an important

reference point in French politics, representing for some the

possibility of liberation and for others the dangers of anarchy.[6] For

some, May 1968 meant the end of traditional collective action and the

beginning of a new era to be dominated mainly by the so-called new

social movements.[21] Someone who took part in or supported this period of unrest is known as a soixante-huitard (a "68-er")—a term that has entered the English language. |

1968年5月はフランス政治における重要な参照点であり、ある者に

とっては解放の可能性を、またある者にとっては無政府状態の危険性を表している[6]。ある者にとっては、1968年5月は伝統的な集団行動の終焉を意味

し、いわゆる新しい社会運動が主に支配する新しい時代の始まりを意味した[21]。 この不安の時代に参加した、あるいは支援した人物は、ソワサント・ユイタール(「68年派」)として知られ、この言葉は英語にもなっている。 |

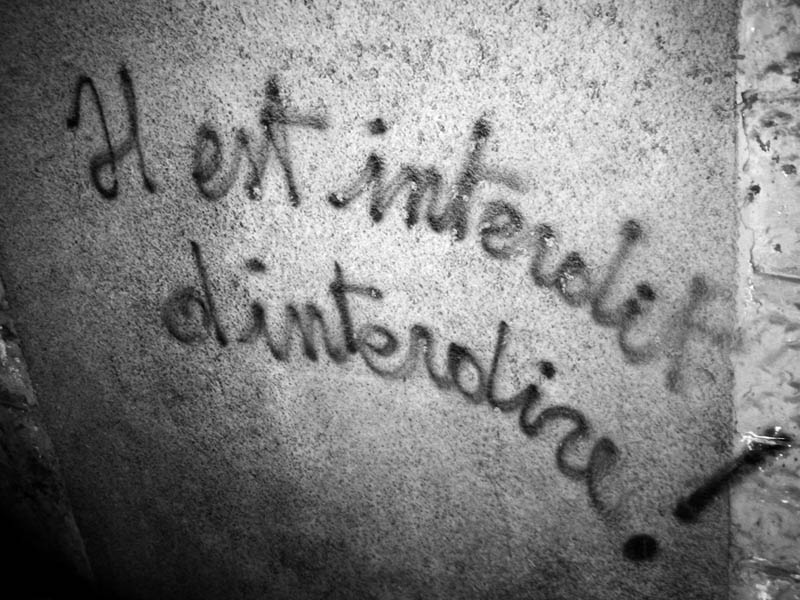

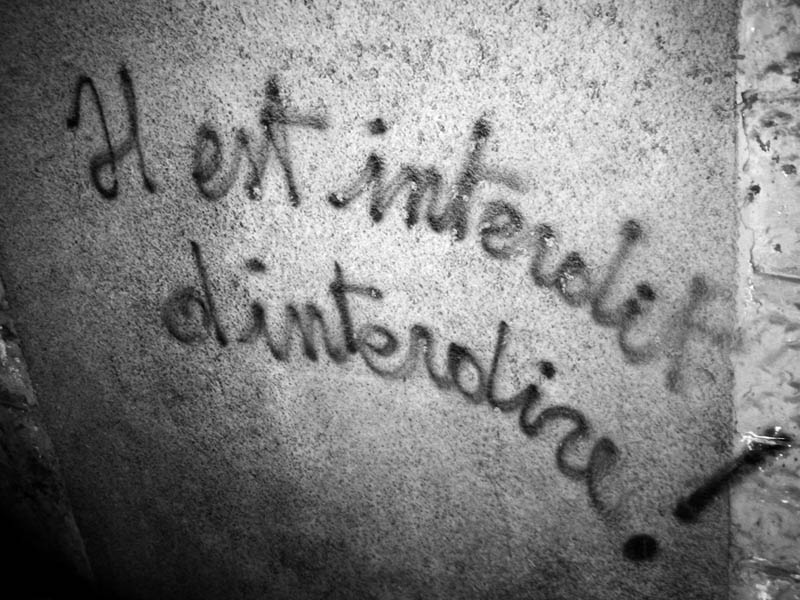

| Slogans and graffiti May 1968 slogan. Paris. "It is forbidden to forbid." Sous les pavés, la plage! ("Under the paving stones, the beach!") is a slogan coined by student activist Bernard Cousin[22] in collaboration with public relations expert Bernard Fritsch.[23] The phrase became an emblem of the events and movement of the spring of 1968, when the revolutionary students began to build barricades in the streets of major cities by tearing up street pavement stone. As the first barricades were raised, the students recognized that the stone setts were placed atop sand. The slogan encapsulated the movement's views on urbanization and modern society both literally and metaphorically. Other examples:[24]  Il est interdit d'interdire ("It is forbidden to forbid")[25] Jouissez sans entraves ("Enjoy without hindrance")[25] Élections, piège à con ("Elections, a trap for idiots")[26] CRS = SS[27] Je suis Marxiste—tendance Groucho ("I'm a Marxist—of the Groucho persuasion")[28] Marx, Mao, Marcuse![29][30][31] Also known as "3M".[32] Cela nous concerne tous. ("This concerns all of us") Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible ("Be realistic, demand the impossible")[33] "When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theater, all the bourgeois theaters should be turned into national assemblies." (Written above the entrance of the occupied Odéon Theater)[34] "I love you!!! Oh, say it with paving stones!!!"[35] "Read Reich and act accordingly!" (University of Frankfurt; similar Reichian slogans were scrawled on the walls of the Sorbonne, and in Berlin students threw copies of Reich's The Mass Psychology of Fascism at the police)[36] Travailleurs la lutte continue[;] constituez-vous en comité de base. ("Workers[,] the fight continues; form a basic committee.")[37][38] or simply La lutte continue ("The struggle continues")[38] |

スローガンと落書き 1968年5月のスローガン。パリ。"禁じることは禁じられている" 敷石の下は、海辺!(敷石の下には浜辺がある!)」は、学生運動家のベルナール・クーザン[22]が広報専門家のベルナール・フリッチュと共同で作ったス ローガンである[23]。このフレーズは、革命的な学生たちが主要都市の通りにバリケードを築き始めた1968年春の出来事と運動の象徴となった。最初の バリケードが築かれたとき、学生たちは石畳が砂の上に置かれていることを認識した。このスローガンは、文字通りの意味でも比喩的な意味でも、都市化と現代 社会に対する運動の見解を凝縮したものだった。 他の例:[24]  Il est interdit d'interdire(「禁止することは禁じられている」)[25]。 Jouissez sans entraves(「支障なく楽しむ」)[25]。 Élections, piège à con(「選挙、バカの罠」)[26]。 CRS = SS[27] Je suis Marxiste-tendance Groucho(「私はグルーチョ派のマルクス主義者だ」)[28]。 マルクス、毛沢東、マルクーゼ![29][30][31] 「3M」とも呼ばれる[32]。 Cela nous concerne tous. (これは私たち全員に関係する) Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible(「現実的であれ、不可能を要求せよ」)[33]。 「国民議会がブルジョア劇場になったら、すべてのブルジョア劇場を国民議会に変えるべきだ。(占拠されたオデオン劇場の入り口の上に書かれた)[34]。 「愛している! ああ、敷石で言ってみろ!!!」[35]。 "ライヒを読み、それに従って行動せよ!" (フランクフルト大学。同様のライヒのスローガンがソルボンヌ大学の壁に落書きされ、ベルリンでは学生がライヒの『ファシズムの大衆心理学』のコピーを警 察に投げつけた)[36]。 労働者よ、闘いは続く。(労働者たちよ、闘いは続く。基本委員会を結成せよ」)[37][38]、あるいは単にLa lutte continue(「闘いは続く」)[38]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_68 |

|

| Japanese

description on May 68. 日本語ウィキペディアの説明:五月革命ではなく「五月危機」 フランスの五月革命(ごがつかくめい)は、1968年5月に起きた、フランスのパリ で行われた新左翼主導の一斉蜂起の開始から、翌月の議会選挙で シャルル・ド・ゴール政権への多数派国民による支持が判明し、急速に鎮静するまでの期間を指す[1]。五月危機ともいう。 パリ郊外に1963年に新設されたパリ大学ナンテール校にて、1968年3月新左翼学生による占拠事件が発生し、同年5月10日には大学当局による学校閉 鎖へ抗議する新左翼学生たちがパリ市内に結集し、警官隊と衝突した。同年5月13日には新左翼学生を支持する一部の労働者・市民が学生支援デモを行い、混 迷は5月末まで続いた。ド=ゴールは5月30日に国民議会を解散し、世論の実態を問う総選挙を行うことを宣言し、事態の収拾にあたった。ジョルジュ・ポン ピドゥー首相はフランスを「共産主義の脅威」に直面してるため、デモに参加していないサイレント・マジョリティーに「共和国防衛」を訴え、声を上げようと 呼びかけた。翌6月に行われた総選挙はフランス国民多数派による新左翼暴動への反発からド=ゴール派が圧勝し、危機は去った(en:1968 French legislative election)[1]。フランス語では「Mai 68」、英語では「May 68」と表記する。 「パリ五月革命が直接シャルル・ド・ゴール政権を倒した」という言説は誤謬であり、ド・ゴール政権は共産主義者の脅威にフランス国民が選挙でNOを突き付 けるように呼びかけた。そして、5月危機最中の民意を問う1968年6月の国会選挙でも圧勝し、新左デモ側はフランス国民のノイジーマイノリティであるこ とを示した。ド・ゴールの辞任は、「1969年3月の金価格高騰」によるゼネストが巻き起こったことにある。同年翌4月にド・ゴールはこれを受けて、辞任 することになった[1]。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| 五

月革命では、キューバ革命のチェ・ゲバラと文化大革命の毛沢東ら共産主義者が運動のアイコンとして掲げられた。背景にはフランス革命からロシア革命、

キューバ革命、文化大革命へと至る「革命の歴史」があり、それを高度経済成長に湧くパリの学生が導き、各国の学生運動に熱をふりまき、より拍車をかけた。 1960年代後半、欧米、日本を中心とした世界の新左翼若者は、学生運動によってお互いの理念、思想、哲学を共有し、激しい政治運動を行った。これによっ て国の枠組みにおさまらない対抗文化(カウンターカルチャー)や反体制文化(ヒッピー文化)を構成するユートピアスティックな「世界的な同世代」という世 代的な視座が加速度を増してゆく。以降、より自由に世界とコミュニケーションできるようになった学生は発言権を強めるようになり、フランスの現代化を推進 させたとの意見もある[2]。それはロックや映画、ファッション[3]、アニメ、アートなどに影響を与えたとされる[4]。 当時のフランスでは赤い中国のGrand Timonier[5]こと毛沢東の著書「Le petit livre rouge de mao」(「毛主席語録」)が流行していた。それはパリのENS(高等師範学校)[6]の学生たちを通じてひろまり、左派知識人たちを活気づけ、学生や労 働者を団結させる思想だった。学生はアメリカの覇権主義に反対するモデルとして毛沢東思想の書籍を読んだ。したがって中国への憧れも「五月革命」には投影 されている。ただその憧れは思想的に深められることがなく、ロマンチシズムの色彩が濃かった。さらに当然なことながら、学生には政府を転覆させる力はな かった。つまり本物の武力による革命ではなくて、学生時代のモラトリアムな革命[7]だった。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| 第二次大戦が終わって植民地帝国だったフランスは第四共和政という政権

の安定しない政治体制に移行した(1946-1958)。このあいだにベトナムとアルジェリアという2つの旧植民地独立の挑戦をうけ、インドシナ戦争

(1946-1954)とアルジェリア戦争(1954-1962)に派兵した。インドシナ戦争で苦戦を強いられたフランス軍は1953年ディエンビエン

フーで敗れ、ベトナムからの撤退を余儀なくされる。さらにフランスはアルジェリアの植民地維持に固執し、議会の混乱を招くと、泥沼のアルジェリア戦争

(1954)へと突入してゆく。第四共和政が明確なリーダーシップを採りえない体制であったことから、第二次大戦の国民的英雄ド・ゴール将軍[8]はより

大統領権限の強化された第五共和政を樹立(1958)し、アルジェリアやアフリカ各国の独立を容認した。 1968年3月15日付日刊紙ル・モンドにジャーナリスト、ピエール・ヴィアンソン=ポンテは「現在、私たちの生活を定義するものは退屈だ」、「フランス 人は退屈だ。彼らは世界を揺るがす激動に参加していない」と書いた。その後の出来事は、「退屈」が反乱の強力な触媒として作用したことを示唆している [9]。 1968年5月1日 極右の学生組織「オキシデンタル・グループ(Occidental group)」がナンテール校を攻撃しようとしているという噂が広まり、緊張が高まった。 1968年5月2日 ソルボンヌの学生組合ビルの一部が燃え、オキシデンタル・グループによって非難される。ダニエル・コーン=ベンディットを含む7名ものメンバーは3月22 日の運動の件で懲戒委員会に呼び出される。 1968年5月3日 ナンテール校の学部長はキャンパスの閉鎖を決定する。追放された学生およそ500名は、ソルボンヌ校を占拠する。それを追い払おうとする警察、フランス共 和国保安機動隊(CRS)、大学当局と対立。100名以上の負傷者、20名の重傷者、数百名の逮捕者をだす。ソルボンヌ校は閉鎖された。学生はパリ市街ラ テン地区のストリートへと雪崩れこみ、バリケードを築いた。オデオン座、カルチエ・ラタンを含むパリ中心部で大規模なデモがおこなわれ、警察がカルチェ・ ラタンへ踏みこんでこれを弾圧、いわゆる普通の学生もデモに参加し、区別のつかなくなった警察に無関係な一般市民も巻きこまれた。 1968年5月6日 再びカルチエ・ラタンおよびラテン地区で激しい衝突がおき、600名の学生と345名の警察官が負傷、422名が逮捕された。フランスの各地で高校生や大 学生による連帯ストライキがおきた。7日、全学連(UNEF)が呼びかけた4万人デモがおこり、大学の再開を主張した。警察はカルチエ・ ラタンから撤退し、学生たちの「解放区」になった。9日、労働総同盟(CGT)とフランス民主労働総同盟 (CFDT) とが会合する。 1968年5月10・11日 米国とベトナムの交渉に参加する代表団の安全確保のため、警察の増員部隊がパリに到着した。全国高等教育職員組合 (SNES[13]) が警察による抑圧を非難し、高校生によるさまざまな行動委員会が組織された。フランス放送協会 (ORTF) は、一連の出来事の放送を禁止した。国民教育相と学生の交渉が行われるが,これは決裂に終わる。学生、労働者バリケードを築き、カルチエ・ラタン一帯を占 拠し(「バリケードの夜」)、転がされた車が燃えた。警察251名、学生102名など計377人が重傷、418名が逮捕され、およそ60台もの車が燃やさ れた。警察の強硬な反応に学生と一般市民は団結を強めた。11日、それぞれの組合が共同で13日のデモ、ゼネスト決行を宣言した。フランス各地でのデモや 占拠は続く。ポンピドゥー首相は学生達の要求に譲歩を見せた。 1968年5月13日 労働組合(CGT、CFDT、FEN)と左派政党は学生支援のために24時間のストライキを呼びかけた。約80万人もの教師、組合員、政治家がパリの通り に集まる。ジョルジュ・ポンピドゥ首相は、ソルボンヌの再開を発表することで状況を落ち着かせようとした。学生は恒久的な占拠を宣言する。討論と会議は昼 夜を問わずに行なわれた。 1968年5月14日 シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領は、ルーマニアに公式訪問。ストライキは多くのルノー工場に波及し、およそ50もの工場が労働者に占拠され、工場の責任者は労 働者の手によって拘束され、工場に「赤い旗」が掲げられた。5月17日までに20万人がストライキを決行、この数字は翌日のストライキで200万人にふく れあがり、その後1週間でフランス人労働者のおよそ2/3にあたるおよそ1千万人が参加したと言われる。 1968年5月15・16日 学生に占拠され、旗がひるがえるパリ・オデオン座。パリは瞬間的に新勢力に占拠され、またもとの日常へともどっていった。 レ・フィガロ紙が「権力はストリートにある」と報道。パリ、オデオン座を学生が占拠。タクシ―運転手たちがストライキを宣言。16日、より広域にデモとス トがひろがる。 1968年5月17・18・19日 17日、フランス共産党が左派の共通プログラムを呼びかけ、鉄道(SNCF[14])もストライキ。18日、極右勢力による反共産主義デモが行われ、スト ラスブール大学で自治が宣言される。19日、フランス国鉄・パリ市交通公団・郵便通信電話局でストライキ、燃料不足が始まる。 1968年5月20日 ほとんど全てのセクターでゼネストに近い状態になった。全学連(UNEF) とフランス民主労働総同盟(CFDT)(英語版)が記者会見をひらき、談上の「労働者と学生の闘争は同じである」という語はスローガンとなり、教師達の組 合の枠を超えてストライキがひろがるきっかけとなった。フランス放送協会(ORTF)は放送を中止する。 1968年5月21日 銀行や繊維産業等も含めた大規模なゼネスト、フランスの交通システムはすべて麻痺状態に陥った。 1968年5月22日 フランスでは800万人以上の人々がストライキを行なった。ドイツを旅していたダニエル・コーン=ベンディットはフランスへの再入国を拒否される。 1968年5月24日 パリ市庁舎や証券取引所を学生が襲撃、20万人の農業労働者や各大学もストライキに突入し、カトリック教会でも学生の要求に親和的な意見が高まる。デモは パリ市街をまわり「人民政府」を要求。はじめて2人の死者を出す。テレビ演説でド・ゴール大統領は国民投票を提案して世論を取り戻そうとしたが、演説はほ とんど影響を及ぼさず、抗議者は辞表を要求した。ラテン地区での衝突で456人が負傷し、795人が逮捕された。ストラスブール、ボルドー、ナント、リヨ ンでも衝突が起こり、警察官がトラックで押しつぶされ、死亡している。 1968年5月25日 ド・ゴール主義の国務長官ジャック・シラクが主宰で労働者、国、雇用主組織のあいだでの三者間会議が催される。 1968年5月27日 政府、労働組合、および雇用主連合間の交渉が社会雇用省(Minister of Social Affairs and Employment)にて行われる。交渉の結果、最低賃金が3分の1上昇し、労働組合への公的権利が確立される「グルネル協定(Grenell agreements)」が締結された。一部強硬派は合意を不服とし、ストライキを続けた。ダニエル・コーン=ベンディットは秘密裏にフランスに戻る。 1968年5月29日 全国規模でデモがおき、パリに共産主義者80万人が集まり、「人民政府!」を連呼した。ド・ゴールは秘密会議を招集する。 1968年5月30日 ド・ゴール大統領はドイツから帰国し、フランス軍のジャック・マシュ将軍の支援を求めた。ド・ゴールはラジオ放送を行ない、辞任を拒否するが、国会を解散 すると述べた。その夜、何十万人ものド・ゴールの支持者、いわゆる「サイレント・マジョリティ」がパリのシャンゼリゼ通りを行進した。 1968年6月 公共および民間労働者の大部分は仕事に戻ったが、余波としての散発的な暴力は続いた。警察、学生、労働者が別の事件で、3人が死亡した。 6月23日および30日の第1回、第2回の総選挙で、ド・ゴールに近い政党が大勝利を収めた。 1968年7月10日 ド・ゴール大統領はモーリス・クーヴ・ド・ミュルヴィルを首相に任命した[15]。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| デモ参加学生の内部 1938年、フランスの大学生は6万人にすぎなかった。それが1961年に24万人、1968年時点には60万5,000人にまでふくれあがっていた [16]。 新左翼と左翼の混在 実際に五月革命を主導していたのは、「反スターリニズム」的、「反ソヴィエト連邦」的な新左翼グループだった。デモはトロツキスト、マオイスト(毛沢東主 義者)、アナーキスト、学生、労働者、市民、状況主義者(シチュアニスト)らと、フランス社会党やフランス共産党など旧来の左翼の混合部隊だった。これら の性質の違う、さまざまなグループが雑多に集まり、運動を高揚させていったところに、この革命の特徴がある。 新左翼(反ソ連共産党) 「赤毛のダニー」こと、ダニエル・コーン・ベンディット。五月革命というとフランス人が先導していたと思いがちだが、先導していたのはドイツ人移民だっ た。 ソ連と関係が深かった「スターリン主義」的なフランス共産党は、当初は影響下にある労働総同盟(CGT)を通じて労働者のストライキを組織した。だが、当 時の共産党幹部ジョルジュ・マルシェは運動のリーダーであるダニエル・コーン=ベンディットら”ソ連を非難する急進的な学生運動”を「アナーキストのドイ ツ人」と否定、バリケードを構築しての衝突や街頭占拠をすすめる学生や労働者を「トロツキスト」と非難した。党や労働総同盟には学生主導のストライキを組 織する力はなく、逆に学生や労働者のほうがより時代にあった根本的な要求をかかげていた。さらに五月革命には党や組合によって、組織されたものではない運 動の自由で自発的な性質があり、「反=組合」「反=共産党」の幸福感があった。同じようにスターリン主義に幻滅していた、無神論的実存主義の哲学者ジャ ン・ポール・サルトルが学生運動家に接近した。 政権との総選挙と最低賃金引き上げ約束 政治生命の危機に直面したシャルル・ド・ゴール大統領は、国民議会を解散し、あくる6月に総選挙をすることを約束した。解散にさきだつ5月27日、政府は 労働組合との賃上げ交渉に寛大にこたえるかたちで事態の鎮静化をはかった。その結果、学生と労働組合はよりよい条件の「グルネル協定」(すべての賃金の 10%上乗せと最低賃金の35%引き上げ[17])を締結した 著名人の反応 ジャン・ポール・サルトル=戦後フランスを代表する哲学者。左翼だが、ソヴィエト政権に批判的だったサルトルは五月革命を熱烈に支持した。革命運動のリー ダー、ベンディットとインタヴューもしている。サルトルはキューバにも訪れ、カストロやチェ・ゲバラを知っており、学生の革命に肯定的だった。 アンドレ・マルロー=保守派で反ファシズムの文学者。1968年当時文化大臣だったマルローは同時にレジスタンス時代に知り合ったド・ゴール大統領の熱心 な支持者でもあった。マルローの忠誠心は5月30日の「ドゴール支持」のデモへとつづく。終生をつうじてその熱い忠誠の思いはかわることはなかった。 ヌーベルバーグを代表する映画監督ジャン・リュック・ゴダール。時代の空気を読むことに長けていたゴダールはそれ以前から五月革命を予見するような作品を 撮っていた。著書「ミル・プラトー」で有名なポストモダン哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズはゴダールの姿勢を擁護している。 ジャン・リュック・ゴダール=ヌーベルバーグ(新しい波)の映画監督。すこしづつ政治的なモチーフに関心を示すようになったゴダールは、五月革命に先だつ 1967年に「中国女」というマオイズム的な映画をつくった。この映画はナンテール校の生徒たちに強い影響を与えた。実際五月革命はゴダールのイメージで 充満していた。ちょうど五月に開催予定だったカンヌ国際映画祭に対し、トリュフォーやポランスキーらと祭の中止を要求したが認められず、彼らの作品の上映 はなくなった(カンヌ映画祭粉砕事件)。 ルイ・アルチュセール=マルクス主義の哲学者。アンチ=スターリニスト。思想面で大きな影響を五月革命に与えたとされる。アルチュセールの生徒たちは青年 共産主義マルクスレーニン連盟(UJC(ml))を結成。革命中、大学やストリートで活発に活動する。 ギ―・ドゥボールの著書「スペクタクルの社会」。この本は消費される商品と人間との関係性を分析し、五月革命に強い影響を与えた。 ギー・ドゥボール=左派系の詩人、映像作家、著述家。ドゥボールもまた五月革命に強い影響を与えた一人だった。彼はその著書「スペクタクルの社会」 (1967)のなかで、新しい市民社会はスペクタクル(光景、ショー)化する商品を通じて人間疎外をうむことを指摘した。商品の語る真実っぽさ(スペクタ クル)に囲まれ、個人そのものは商品のなかに解消されてしまう。このようなスペクタクルとリアルの境界を線引きすることが難しい状況が消費社会なのであ り、それは新しい「状況」をつくることによって批判されなくてはならない(「状況主義」)。ドゥボールの提示したテーゼは68年を経て、いま現在のコン ピューター情報社会を鋭く言いあらわしている。 1968年当時、パリ、エコール・ド・ボザールの准教授だったブルーノ・ケサンヌは高揚をまじえながら、五月革命について以下のように述べている [18]。 「革命に参加したそれぞれの人は、ずっとその人自身と積極的に関わっていたんだ。それは不公平に妨害工作をしてやろうとしたのでなく、どうやったらフラン スが走ることを止めることができるのかということだった。全世界は、彼らがいったん立ち止まって、その存在条件を社会に反映すべきなんだということに同意 していたのさ」 騒動後のフランス国内― 70年代パンク・ムーブメント 英国人デザイナーのヴィヴィアン・ウエストウッド。ロンドン・パンクはファッションに大きな影響を与えた。とくにセックス・ピストルズとヴィヴィアン・ウ エストウッドのファッションは衝撃的で、当時産業ロックなどで停滞していたロック界や、ファッション界に新たなる風をもたらした。 五月革命からしばらくのちの1970年代中盤に入ると、アメリカやイギリスのユースカルチャーの世界に「パンク」が登場する。パンクはアナーキズム、左 翼、ダダ、ニヒリズムなどの傾向があり、権力に対する挑戦、不満、退屈によるストレスの爆発、DIY精神など、その精神そのものは五月革命と通底するとこ ろがある。もっともパンクは音楽であり、国家機能を停止させ、政府と直接的な政治交渉をするほどの集合的な力は生みださず、ある局所的なムーブメントで あった。つまりファッションとしてのヴィジュアル面の影響が強く、真似しやすく、記号としての流通が簡単にできた。そのため政治思想としての反映ではな く、パンク・ファッション的が、おおくのデザイナーにインスピレーションを与えることとなった。マルコム・マクラレーンと組んでブティック「SEX」のデ ザイナーをし、セックス・ピストルズの衣装を手がけた英国のヴィヴィアン・ウエストウッドは億万長者になった後も、保守党のキャメロンに激しい抗議行動を おこなったり、緑の党を支持したりした。 レゲエやヒップホップの流行も起きた。米ソ冷戦構造下で発生したパンク革命は、資本主義社会体制下で実現が難しい、永遠の憧れとしての革命、実現しない ユートピアへの憧れの側面が強かった。 パンクはアナーキストになりたい―(I wanna be anarchist[19](Anarchy in the UK-The Sex Pistols))若者だったが、五月革命の学生や知識人も社会主義に憧れを抱き、叶わぬユートピア実現のために戦ったのである。 セックス革命とアンチセックス 映画プロデューサーのハーヴェイ・ワインスタイン。有名プロデューサーのハーヴェイ・ワインシュタインは、女性へのセクハラやレイプを繰り返していた。権 力をカサに着たその手口はMe Too運動によって告発され、厳しく非難され追放された。 68年当時、欧米においても性そのものは現在より抑圧されており、性表現や性関係は比較的につつましやかなものだった。 聖書の価値観、キリスト教の教義では、婚前性交渉、婚外性交渉(不倫)、同性愛は罪であるからだ。 ヒッピーのフリーラブスピリットや五月革命などの対抗文化を受けて性はより広範にわたって「表現されるもの」となり、映画、小説、文学、舞踏、アニメ、 ゲームなどのカルチャーを通じて一般にひろまり、身体意識の高まりを生むこととなった。また避妊具の発展、ファッションの簡易化、下着化、性映像の情報 化、パーソナルメディアの発達とともに異性間での性交渉も日常に解放され、現在に至っている。一方で60年代の左翼的ウーマンリブとは正反対の、新しい規 制を良しとする保守的フェミニストは性が搾取されるものと主張した。これは右派政治家と一致していた。また一方、対象となる女性の人権を無視した「セクハ ラ」はMe too運動のような新しいカウンター運動を生んだ。 文化大革命の実態報道 当時フランスで盛り上がった「毛沢東への憧れ」はやがて文化大革命の実情が明らかになるにつれて、「毛沢東への幻滅」へとかわった。文化大革命とは「下か らの革命」ではなく、毛沢東の権力闘争に利用された「上からの革命」であり、それは五月革命が志向した精神とはかけ離れたところにあった。その意味でフラ ンスのマオイストたちはそれほど誠実に毛沢東と向きあってはいなかったと言える。フランス人によくあるように、漠然としたユートピアを東洋に夢見ていた。 もっとも、実際にそれに罪があるというわけではないが、あまりにも無邪気かつ無知でもあり、反=スターリニズムの機運のなかで学生や思想家の体のいい希望 の星となった感は否めない。 また、ベトナムと同じフランスの植民地であったカンボジアからの留学生であるポル・ポトらによって結成されたクメール・ルージュが文化大革命の影響を受け て築いた民主カンプチアで行ったその徹底的な重農主義・農本主義による恐怖政治と大量虐殺も報じられ、ディストピアをもたらした毛沢東主義者は大粛清を 行ったスターリニストと同列視されることとなった。反帝国主義に固執してポル・ポト派を擁護して名声を失った有名な弁護士ジャック・ベルジェス(英語版) はその後のフランス社会では、独裁者と戦争犯罪人やテロリストなどの弁護も請け負ったことで「悪魔の弁護人」「恐怖の弁護士」と蔑まれるようになった。 サブカルチャーの流行 サブカルチャーはマンガ、アニメだけでなく、ヘヴィメタルなどのロックや麻薬、フリーセックスもふくまれた。キリスト教の影響が強い欧米社会において、 セックス革命というのは「社会の世俗化(vulgar)」を意味する。キリスト教(とくにカトリック)や、キリスト教原理主義者はその教義のなかで「中 絶」、「同性愛」を厳しく戒めてきた。なお中絶禁止は聖書には書かれていない。いまだ性をマイナス・イメージでとらえる信者も多い。したがって、このよう な社会の「世俗化」は、保守派の眉を顰めさせるような出来ごとであり、従来の価値を愛する保守の市民の根強い反発もある。くわえてサブカルチャーと結びつ いた麻薬やセックスの自由は、「中毒」や「依存症」になる危険もある。革命以後、アメリカのみならず、ヨーロッパも革新と保守の乖離の問題を抱えることと なった。 パリ五月革命と黄色いベスト運動 フランスはデモが多い国である。パリ五月革命は成功したストライキであり、フランス大衆のあいだでストライキが多く発生するようになった。五月革命という 成功体験で市民はその再現を望むようになった。フランス社会は個人の自由や尊厳が尊重される社会となった。パリ五月革命の精神は、ネオ・リベラリストのマ クロンに反対する「黄色いベスト運動」に、引き継がれている。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099