植民地主義に対する先住民の反応

Indigenous response to colonialism

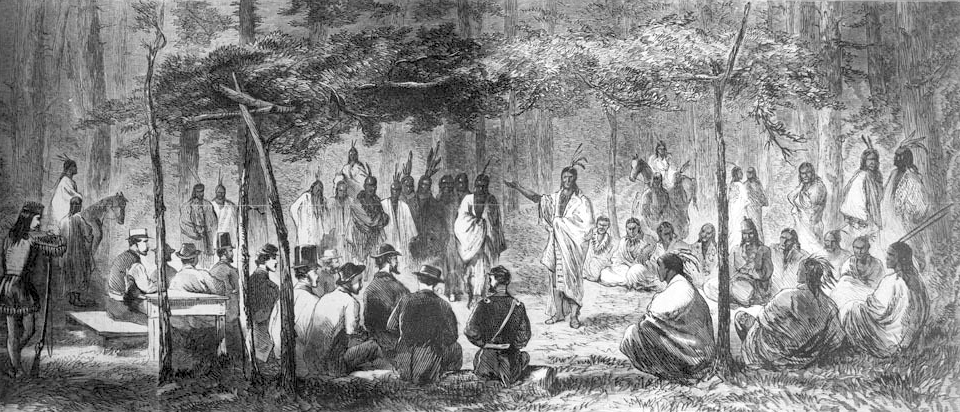

The

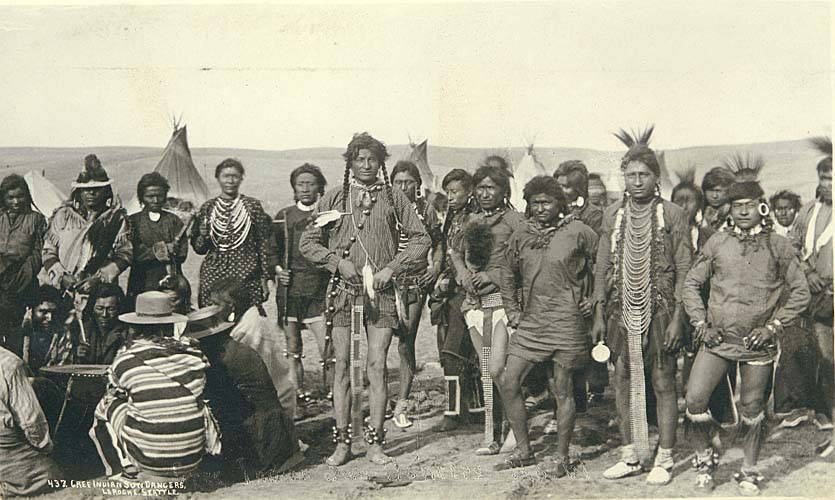

Kiowa, Comanche, Plains Apache, Cheyenne and Arapaho signed three

successive treaties with the United States government, 1867.

☆ 先住民の植民地主義に対する反応(Indigenous response to colonialism)は、先住民グループ、歴史的時代、領土、そして彼らが交流した植民地国家によって様々であった。先住民は植民地主義に対す る反応において、主体性を持っていた。彼らは武装抵抗、外交、法的手段を用いた。また、紛争を避けるために、不毛で好ましくない、あるいは辺境の地へと逃 れた者もいた。しかし、一部の先住民は保留地や削減地への移住を余儀なくされ、鉱山、農園、建設、家事労働に従事させられた。彼らは部族としての独自性を 失い、植民地社会に文化的に同化させられた。場合によっては、先住民は他の先住民や非先住民の国家と同盟を結んだ。全体として、この時期における先住民の 植民地主義に対する反応は多様であり、その有効性も様々であった。 先住民の抵抗には何世紀にもわたる複雑な歴史があり、現代にも続いている。

★現代の対応(後述)

++

Indigenous response to colonialism

has varied depending on the Indigenous group, historical period,

territory, and colonial state(s) they have interacted with. Indigenous

peoples have had agency in their response to colonialism. They have

employed armed resistance, diplomacy, and legal procedures. Others have

fled to inhospitable, undesirable or remote territories to avoid

conflict. Nevertheless, some Indigenous peoples were forced to move to

reservations or reductions, and work in mines, plantations,

construction, and domestic tasks. They have detribalized and culturally

assimilated into colonial societies. On occasion, Indigenous peoples

have formed alliances with one or more Indigenous or non-Indigenous

nations. Overall, the response of Indigenous peoples to colonialism

during this period has been diverse and varied in its effectiveness.[5]

Indigenous resistance has a centuries-long history that is complex and

carries on into contemporary times.[6] The Kiowa, Comanche, Plains Apache, Cheyenne and Arapaho signed three successive treaties with the United States government, 1867. |

先住民の植民地主義に対する反応

は、先住民グループ、歴史的時代、領土、そして彼らが交流した植民地国家によって様々であった。先住民は植民地主義に対する反応において、主体性を持って

いた。彼らは武装抵抗、外交、法的手段を用いた。また、紛争を避けるために、不毛で好ましくない、あるいは辺境の地へと逃れた者もいた。しかし、一部の先

住民は保留地や削減地への移住を余儀なくされ、鉱山、農園、建設、家事労働に従事させられた。彼らは部族としての独自性を失い、植民地社会に文化的に同化

させられた。場合によっては、先住民は他の先住民や非先住民の国家と同盟を結んだ。全体として、この時期における先住民の植民地主義に対する反応は多様で

あり、その有効性も様々であった。[5] 先住民の抵抗には何世紀にもわたる複雑な歴史があり、現代にも続いている。[6] 1867年、カイオワ族、コマンチ族、プレーンズ・アパッチ族、シャイアン族、アラパホ族は、米国政府と3つの条約を相次いで締結した。 |

| Background Indigenous peoples are the earliest known inhabitants of a territory that was or remains colonized by a dominant group.[7] Before the age of colonialism, there were hundreds of nations and tribes throughout the territories that would be colonized, with diverse languages, religions and cultures.[8] The peoples that would come to be known as Indigenous had large cities, city-states, chiefdoms, states, kingdoms, republics, confederacies, and empires. These societies had varying degrees of knowledge of the arts, agriculture, engineering, architecture, mathematics, astronomy, writing, physics, medicine, irrigation, geology, mining, weather forecasting, navigation, metallurgy and more.[9] Their population would experience a significant collapse due to the effects of colonization. Most Indigenous groups in the world today have been displaced from some or all of their ancestral lands.[10][11][12] Indigenous peoples have existed in a context of colonialism, as they are not "Indigenous" without experiencing the practice of colonialism, that is, when their sovereignty and self-determination are realized.[13] In recent decades, non-Indigenous historiography has paid increased attention to Indigenous agency. Before, Indigenous peoples were studied as passive objects of colonial policy and administration, but now the growing areas of borderland studies and Indigenous agency have emerged.[19] As European colonialism has spread throughout the world, settlers have become dominant through conquest, occupation, or invasion. In this process, there has been and continues to be conflict between settlers and Indigenous peoples. For hundreds of years in recent history, Indigenous groups have been the target of a number of atrocity crimes including multiple genocides that have destroyed entire nations. In spite of this, Indigenous peoples survive and some are thriving. They account for a population of 476 million, residing in 90 countries around the world and speaking over 5000 languages from several language families, even though hundreds of Indigenous groups are extinct.[20][21] Some examples of important surviving Indigenous languages include Aymara, Guaraní, Quechua and Mapuche in South America; Lakota and Navajo in North America; Maya and Nahua in Central America; Inuit in the circumpolar region; Sámi in northwest Eurasia; and Torres Strait Islanders and Māori in Oceania.[22][23][24] For comparison, at the time of contact in 1492, there were 40 to 70 languages spoken in Europe, mostly from the Indo-European language family.[25] Indigenous peoples continue to struggle as they suffer discrimination in most countries where they coexist with non-Indigenous peoples. The majority of the world's Indigenous peoples are among the poorest groups within the states where they live, and they amount to 19% of the world's poor.[26][2][27] |

背景 先住民族とは、支配的な集団によって植民地化された、または現在も植民地化されている領土において、最も早くから居住していたことが知られている人々であ る。[7] 植民地主義の時代以前には、植民地化されることになる領土全体に、多様な言語、宗教、文化を持つ数百もの国家や部族が存在していた。[8] 先住民族として知られるようになった人々は、大都市、都市国家、首長国、国家、王国、共和国、連邦、帝国を有していた。これらの社会は、芸術、農業、工 学、建築、数学、天文学、文字、物理学、医学、灌漑、地質学、採鉱、天気予報、航海術、冶金など、さまざまな知識を有していた。[9] 植民地化の影響により、これらの社会の人口は大幅に減少した。今日、世界の先住民のほとんどのグループは、先祖伝来の土地の一部または全部から追われた経 験を持っている。[10][11][12] 先住民は、植民地主義の実践を経験せずに「先住民」であることはできないため、植民地主義の文脈の中で存在してきた。つまり、彼らの主権と自己決定が実現 されたときである。[13] ここ数十年の間、非先住民の歴史学では、先住民の主体性への注目が高まっている。以前は、先住民は植民地政策や行政の受動的な対象として研究されていたが、現在では国境地域研究や先住民の主体性の分野が拡大している。 ヨーロッパの植民地主義が世界中に広がるにつれ、征服、占領、侵略によって入植者が優勢となった。この過程において、入植者と先住民との間で紛争が起こ り、現在も続いている。近年の歴史において、先住民グループは何百年もの間、国家全体を破壊する複数の大量虐殺を含む、数々の残虐犯罪の標的となってき た。それにもかかわらず、先住民は生き残り、中には繁栄している民族もある。彼らは世界90カ国に居住し、5000以上の言語を話し、その言語はいくつか の言語グループに属している。数百の先住民グループが絶滅しているにもかかわらず、彼らの人口は4億7600万人に上る。[20][21] 重要な先住民の言語の例としては、南米のアイマラ語、グアラニー語、ケチュア語、マプチェ語、北米のラコタ語、ナバホ語、中央アメリカのマヤ語 、北米のラコタ族やナバホ族、中米のマヤ族やナワ族、北極圏のイヌイット族、ユーラシア北西部のサーミ族、オセアニアのトレス海峡諸島民やマオリ族などで ある。[22][23][24] 比較のために、1492年の接触当時、ヨーロッパでは主にインド・ヨーロッパ語族に属する40から70の言語が話されていた。[25] 先住民は、非先住民と共存するほとんどの国々で差別を受け、苦闘を続けている。世界の先住民の大多数は、居住する国家の中で最も貧しいグループに属しており、世界の貧困層の19%を占めている。[26][2][27] |

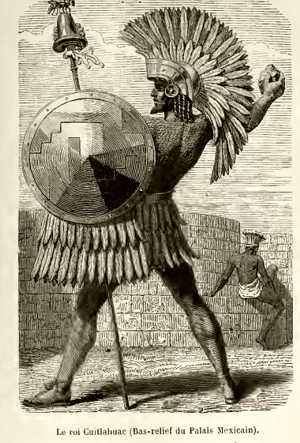

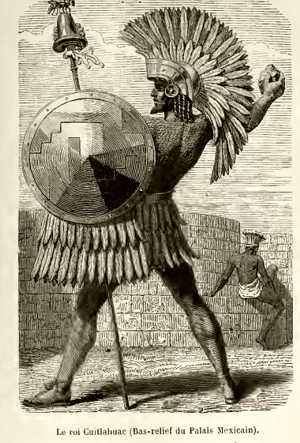

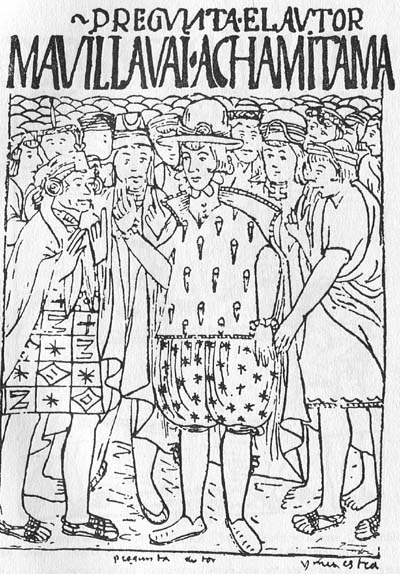

Contact and conquest Aztec warriors led by an eagle knight, each holding a macuahuitl club. Florentine Codex, book IX, F, 5v. Manuscript written by Bernardino de Sahagún. Before Europeans set out to discover what had been populated by others in their Age of Discovery and before the European colonization, Indigenous peoples resided in a large proportion of the world's territory. For example, in the Americas, there are estimates of a population of up to 100 million people.[28][29] The Indigenous response to colonization has been varied and also changed over time as each group chose to flee, fight, submit, support or seek diplomatic solutions. One example of an Indigenous group that fled is the Beothuk in Newfoundland, which is now practically extinct. The Charrúa were massacred in what is now Uruguay and were completely destroyed. In contrast, the Nenets have accommodated the Russian state.[30][16]  Malinche translating for Hernán Cortés For a long time, scholars have explained that the large fatality rates of Indigenous peoples upon contact with settlers have been caused by new infectious diseases brought to Indigenous territories from overseas. Recent scholarship has shifted to explore the nature of the difficult conditions of life imposed on Indigenous peoples due to colonization itself, which made Indigenous peoples more vulnerable to any disease, including new diseases. In other words, causes of death such as forced labor combined with hunger that converged during the colonization process made Indigenous peoples weaker and less resistant to disease.[36] For example, scholars maintain that smallpox probably killed a third of the population in colonial Mexico but admit that there is no evidence to quantify the impact with certainty.[37]  Cuitláhuac, Aztec Tlatoani who led to victory in battle During the colonization of New Spain from the 16th to the 18th centuries, the focus of the colonizers was to practice agriculture, farming, mining, and infrastructure construction while exploiting Indigenous labor.[38] Slavery was one of the main factors that decimated the Indigenous population of North America. Indigenous slavery predated and outlasted the African slave trade until the 20th century. The Spanish crown allowed slavery of Indigenous peoples captured in "just wars", which included Indigenous resistance to colonialism, such as religious conversion or forced labor. Indigenous forced labor took place in repartimientos, encomiendas, Spanish missions and haciendas. Indigenous women and children were forced to do domestic work. Even after slavery was outlawed by the Spanish Empire, and then ex-colonies such as the Mexican and United States governments, those that benefitted from slavery used legal frameworks to avoid enforcement such as vagrancy laws, convict leasing, and debt peonage.[39]  Francisco Tenamaztle, Indigenous leader in the Mixtón War, statue on the main square of Nochistlán de Mejía, Zacatecas. Indigenous nations sought diplomacy or military alliances to survive, seeking allies in other nations, including neighbouring Indigenous nations and other colonizing powers, as in the French and Indian War and the War of 1812. In Central America, Miskito people allied with the English to resist Spanish colonialism.[40] Indigenous peoples have sought alliances if the alliance has improved their chances of survival or worked to their advantage. Some Indigenous nations attempted to show their allegiance to the colonizing power by becoming a military ally in the attacks of other Indigenous nations, as in the case of the Tlaxcalans in the central valley of Mexico.[41] Other times, they would ally themselves with escaped African slaves, as in the case of the Seminoles.[42] On rare occasions, Indigenous peoples would be successful in battle against European armies. Examples include the Battle of Curalaba, La Noche Triste, Chichimeca War and the Battle of Big Horn. The Mapuche in Chile,[43] the Māori in New Zealand, the Yaquis in Mexico, and the Seminoles in Florida resisted for decades or even centuries.[44] However, in many parts of the world, Indigenous peoples moved away from fertile, resource-rich territories to inaccessible and inhospitable territories such as swamps, deserts and jungles.[45] They were displaced from fertile places in Argentina, Brazil, the Philippines and temperate Africa. Some examples include small Indigenous groups moving to parts of the Amazon basin, Australia, Central America, the Arctic and Siberia. Others came into conflict with other Indigenous groups as they were forcefully displaced and occupied territory that was inhabited by other Indigenous groups.[46] On occasions, the reaction of Indigenous peoples to attacks resulted in their transformation into warrior horse cultures that used European fire guns to resist further invasion of their territories. Even today, the stereotypical Native American depicted in Indian Wars is riding on a horse. For example, the people of the Great Plains[47] and Mapuche[48] adopted the horse into their everyday cultures.  Lautaro and Guacolda Indigenous peoples also adopted newly introduced domestic animals in their diet as Europeans introduced chicken, cattle, pigs, goats, and sheep in the Columbian exchange. Indigenous peoples have hunted their territory for centuries or millennia, and many times killed the animals belonging to settlers, and this has been the cause of much conflict between settlers and Indigenous peoples.[49][50] Indigenous peoples were not always conquered militarily, as in the case of treaties made between Great Britain and France with Indigenous peoples.[51][52] The 1840 Treaty of Waitangi of the Maori, and the 1868 Treaty of Bosque Redondo of the Navajo are two examples of treaties that remain important today.[53] |

接触と征服 ワシの騎士に率いられたアステカの戦士たち。それぞれがマクアウィトルの棍棒を持っている。 フィレンツェ写本、第9巻、F、5v。 ベルナルディーノ・デ・サアグンによる手稿。 ヨーロッパ人が大航海時代に他者が居住していた地域を発見し、ヨーロッパによる植民地化が始まる前、先住民は世界の領土の大部分に居住していた。例えば、 アメリカ大陸では、最大で1億人もの人口がいたと推定されている。[28][29] 植民地化に対する先住民の反応は様々であり、また、各グループが逃亡、戦闘、服従、支援、外交的解決の模索のいずれかを選択したため、時代とともに変化し た。逃亡した先住民の一例としては、ニューファンドランドのベオトゥク族が挙げられるが、現在ではほぼ絶滅している。チャルーア族は現在のウルグアイで虐 殺され、完全に滅びた。一方、ネネツ族はロシア国家に順応した。  マリンチェがヘルナン・コルテスの通訳を務めた 長い間、学者たちは、入植者との接触による先住民の死亡率の高さは、海外から先住民の領土に持ち込まれた新しい感染症が原因であると説明してきた。最近の 研究では、入植そのものによって先住民に課せられた生活の困難な条件の性質を解明することに重点が移っており、それによって先住民は新しい病気を含むあら ゆる病気に対してより脆弱になった。言い換えれば、植民地化の過程で重なった強制労働と飢餓が原住民をより弱くし、病気に対する抵抗力も弱めたのである。 [36] たとえば、学者たちは、おそらく天然痘が植民地時代のメキシコの人口の3分の1を殺したと主張しているが、その影響を定量的に明確にする証拠はないことを 認めている。[37]  アステカのトラントアニ(最高君主)であり、戦いに勝利を導いたクイトラワク 16世紀から18世紀にかけてのヌエバ・エスパーニャの植民地化の時代、植民地支配者たちは先住民の労働力を搾取しながら、農業、農耕、鉱業、インフラ建 設を実践することに重点を置いていた。先住民の奴隷制は、20世紀まで続くことになるアフリカ奴隷貿易よりも古く、長期間にわたって続いた。スペイン王 は、宗教改宗や強制労働といった植民地主義に対する先住民の抵抗を含む「正義の戦争」で捕らえた先住民の奴隷化を認めていた。先住民の強制労働は、レパル ティミエント、エンコミエンダ、スペインの宣教所、ハシエンダで行われた。先住民の女性や子供たちは家事労働を強いられた。スペイン帝国、そしてメキシコ やアメリカ合衆国などの旧植民地政府によって奴隷制度が廃止された後も、奴隷制度から利益を得ていた人々は、浮浪者取締法、囚人リース、債務奴隷制度など の法的枠組みを利用して、その施行を回避していた。  フランシスコ・テナマステル、ミクストーン戦争における先住民の指導者、サカテカス州ノチストラ・デ・メヒアのメイン広場にある銅像 先住民国家は生き残りをかけて外交や軍事同盟を求め、近隣の先住民国家や他の植民地支配国など、他国に同盟を求めた。中央アメリカでは、ミスキート族がス ペインの植民地主義に抵抗するためにイギリスと同盟を結んだ。[40] 先住民は、同盟が生存の可能性を高めたり、自分たちに有利に働くのであれば、同盟を求めてきた。メキシコ中央部の高原地帯に暮らしたトラスカラン族のよう に、他の先住民の攻撃に軍事同盟者として加わることで、植民地支配勢力への忠誠を示そうとした先住民国家もあった。[41] また、セミノール族のように、逃亡したアフリカ人奴隷と手を組むこともあった。[42] まれにではあるが、先住民がヨーロッパの軍隊との戦いに勝利した例もある。 その例としては、クララバの戦い、悲しみの夜、チチメカ戦争、ビッグホーンの戦いなどがある。チリのマプチェ族[43]、ニュージーランドのマオリ族、メ キシコのヤキ族、フロリダのセミノール族は、数十年あるいは数世紀にわたって抵抗を続けた[44]。しかし、世界の多くの地域では、先住民は肥沃で資源が 豊富な地域から、湿地、砂漠、ジャングルといったアクセスが困難で不毛な地域へと移動した[45]。彼らはアルゼンチン、ブラジル、フィリピン、温帯アフ リカの肥沃な土地から追われた。例えば、アマゾン川流域、オーストラリア、中央アメリカ、北極圏、シベリアなどに移住した小規模な先住民グループがある。 また、他の先住民グループが強制的に移住させられ、他の先住民グループが居住する地域を占領したため、他の先住民グループと対立するようになった例もあ る。[46] 攻撃に対する先住民の反応により、彼らは戦士と馬の文化へと変貌し、ヨーロッパの火縄銃を使って、彼らの領土へのさらなる侵略に抵抗するようになった。今 日でも、インディアン戦争で描かれたステレオタイプなネイティブアメリカンは馬に乗っている。例えば、グレートプレインズの人々[47]やマプチェ族 [48]は、馬を日常文化に取り入れた。  ラウタロとグアコルダ コロンブス交換によってヨーロッパ人が家畜としてニワトリ、牛、豚、ヤギ、羊を導入した際、先住民も新たに導入された家畜を食料として取り入れた。先住民 は何世紀、何千年もの間、自分たちの領土で狩猟を行ってきたが、入植者の所有する動物を殺すことも多く、これが入植者と先住民の間の多くの紛争の原因と なっている。 先住民は、イギリスとフランスが先住民と結んだ条約のように、常に軍事的に征服されたわけではない。[51][52] 1840年のワイタンギ条約(マオリ族)と1868年のボスク・レドンド条約(ナバホ族)は、今日でも重要な条約の2つの例である。[53] |

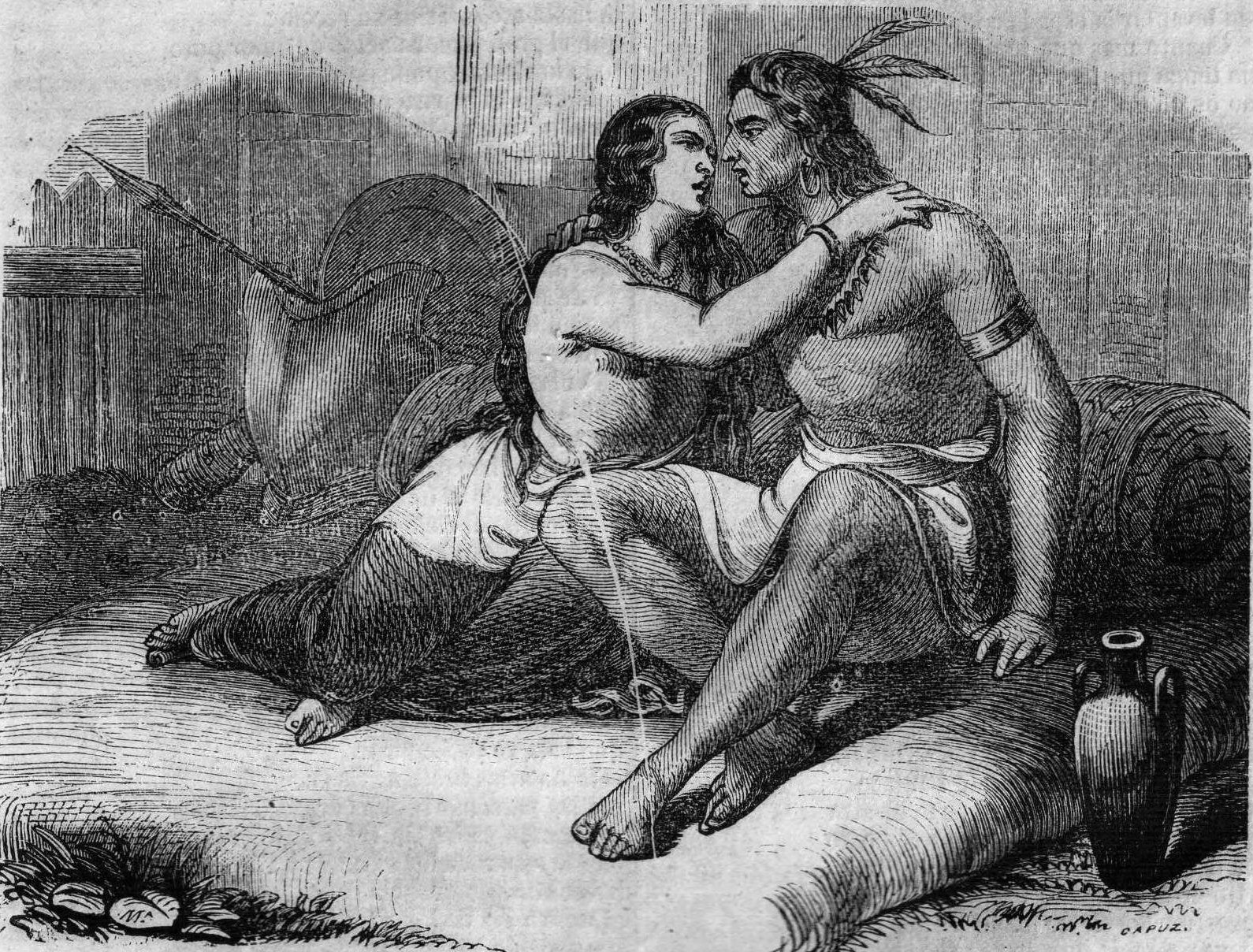

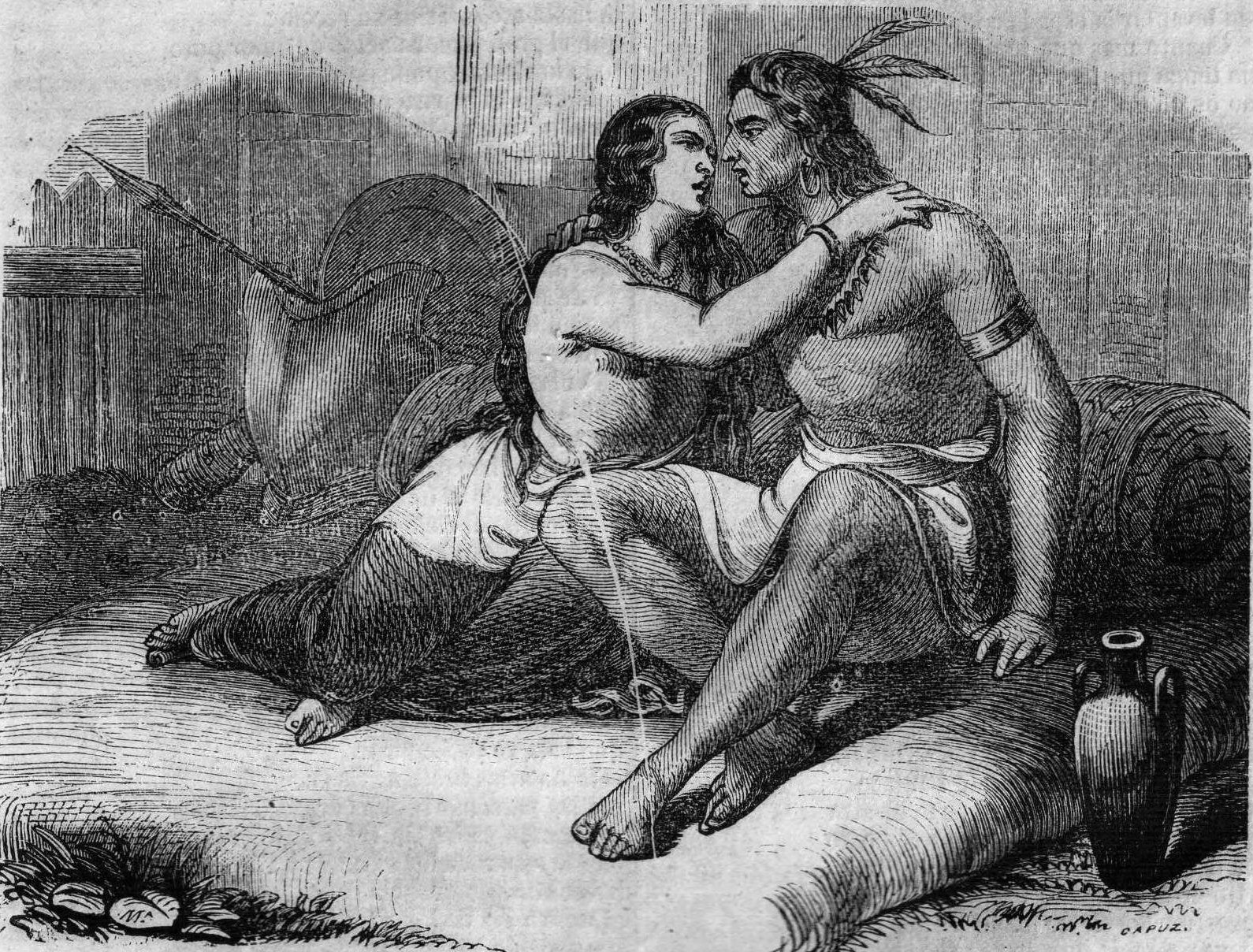

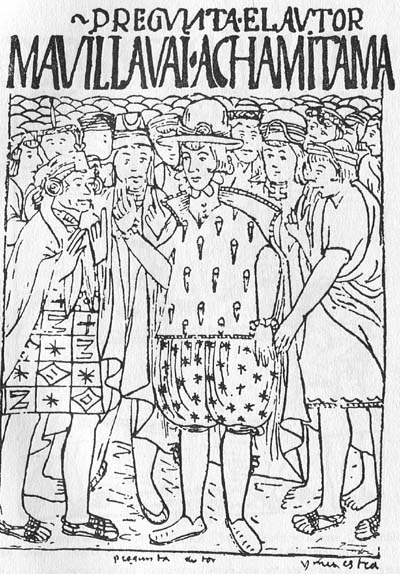

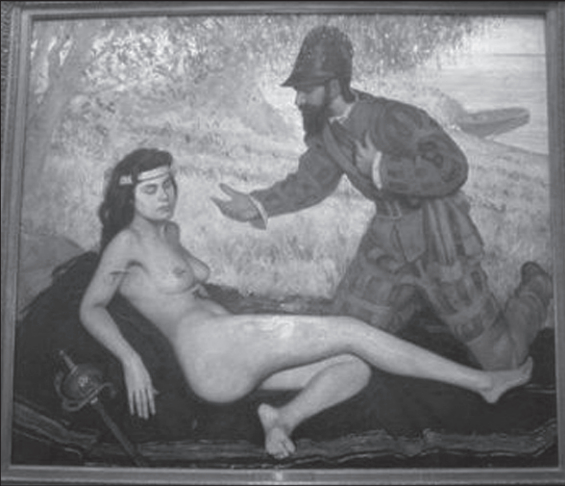

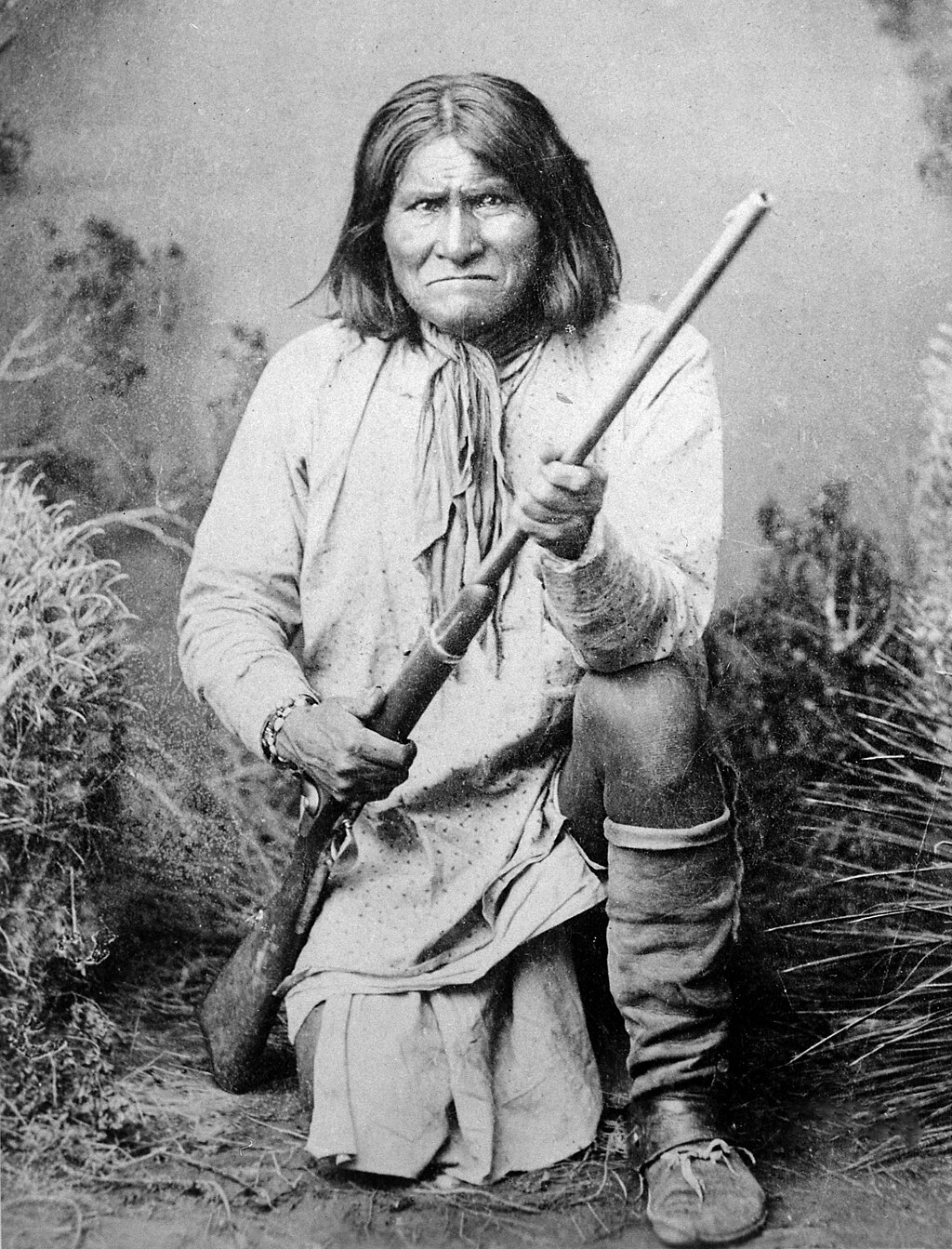

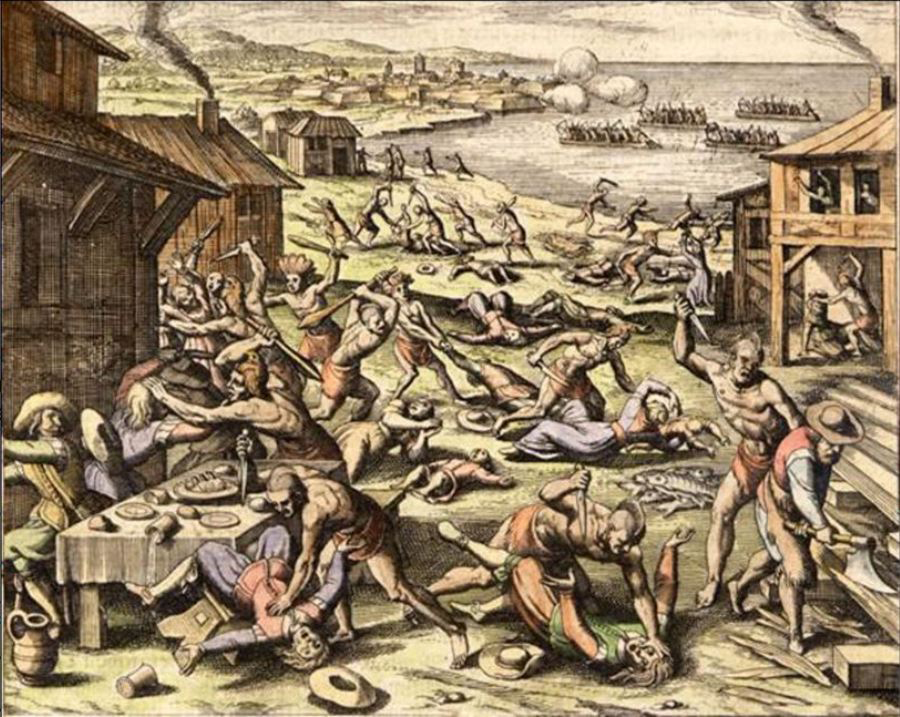

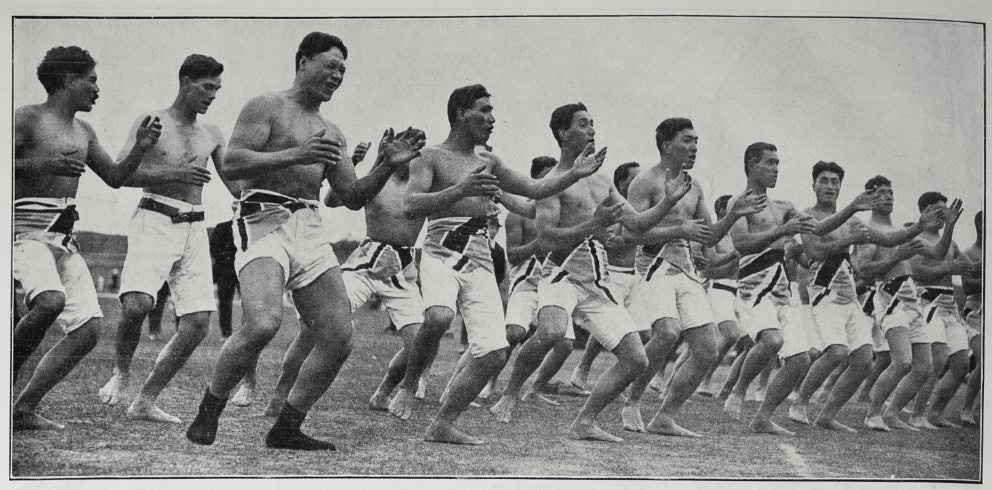

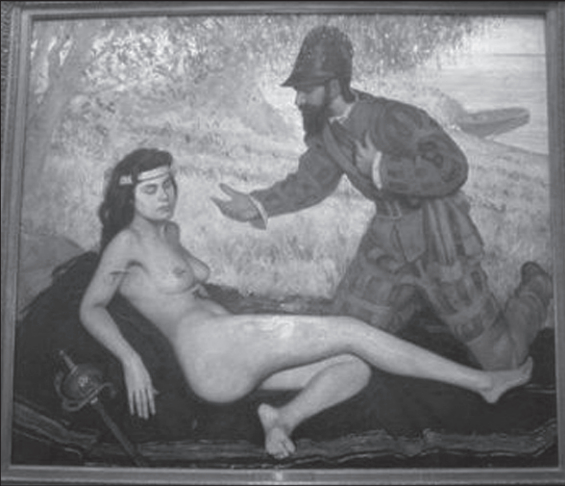

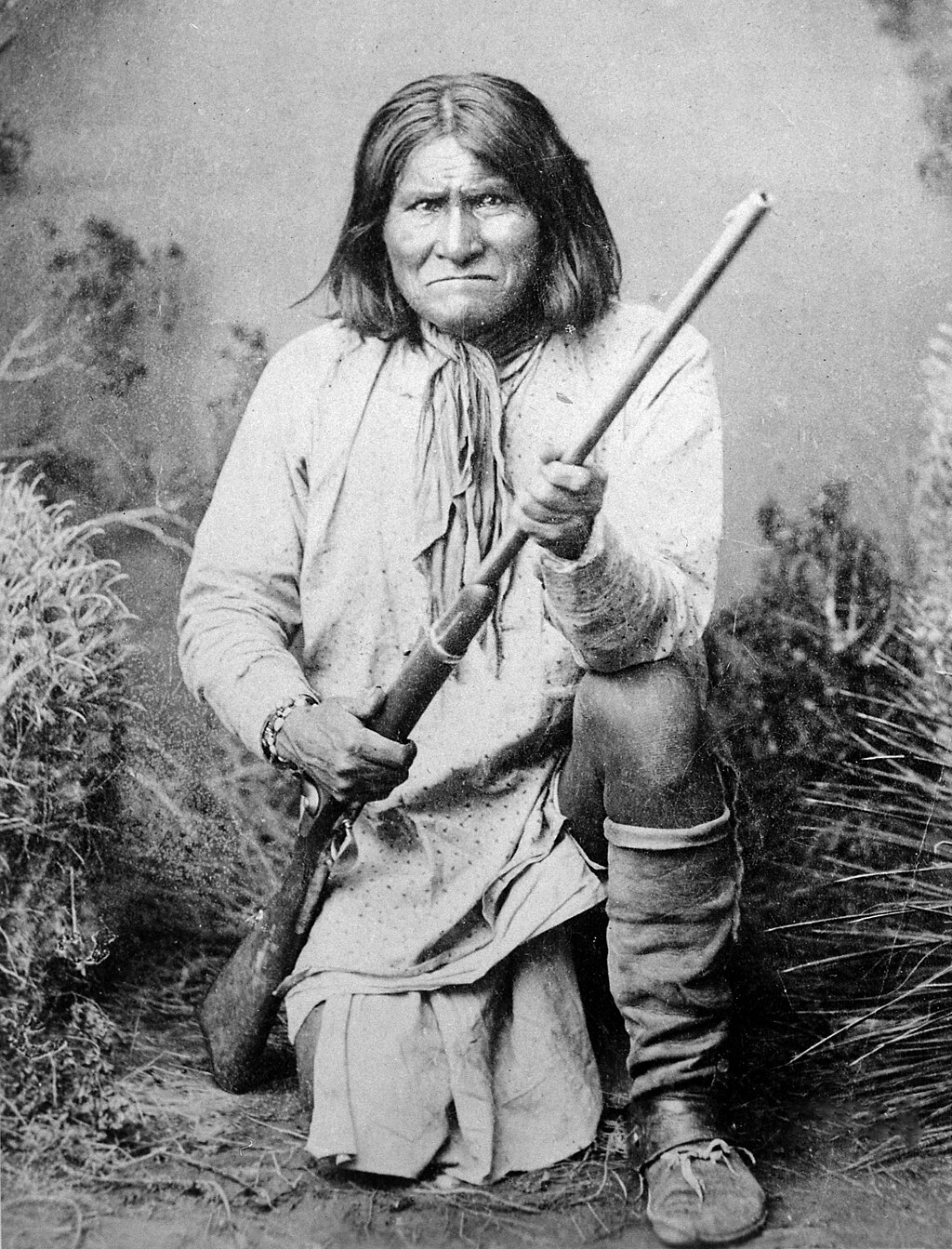

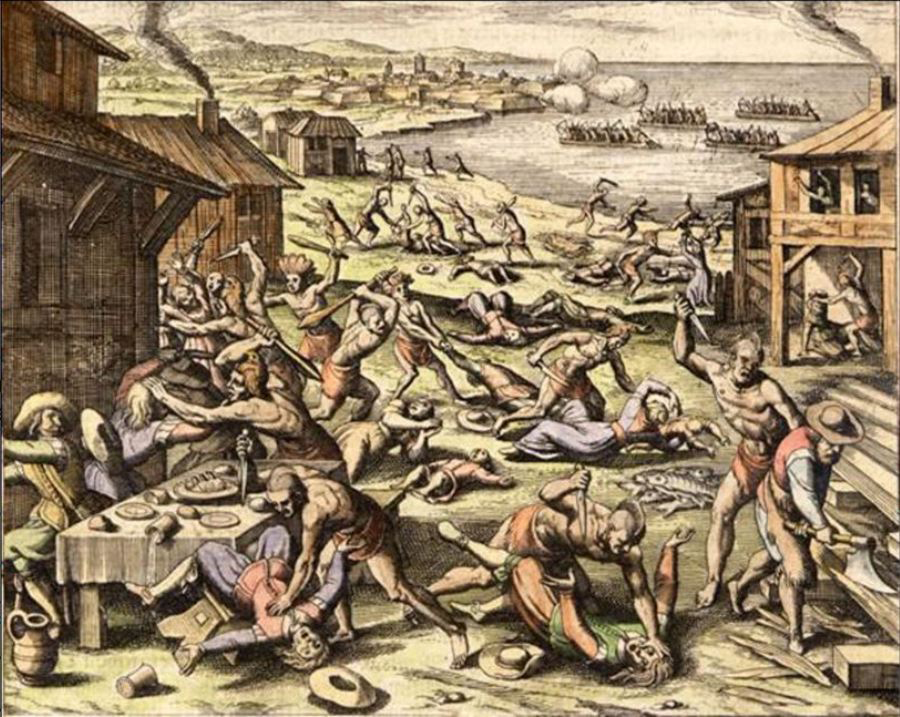

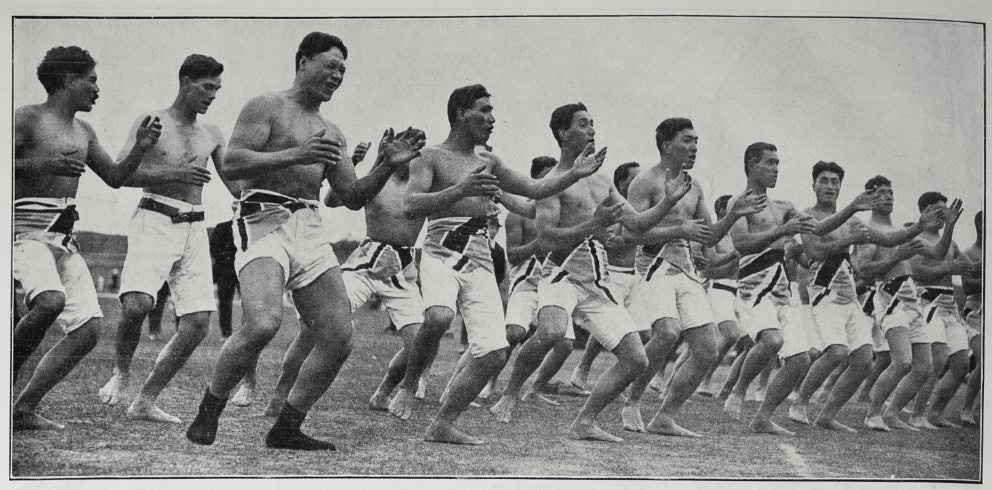

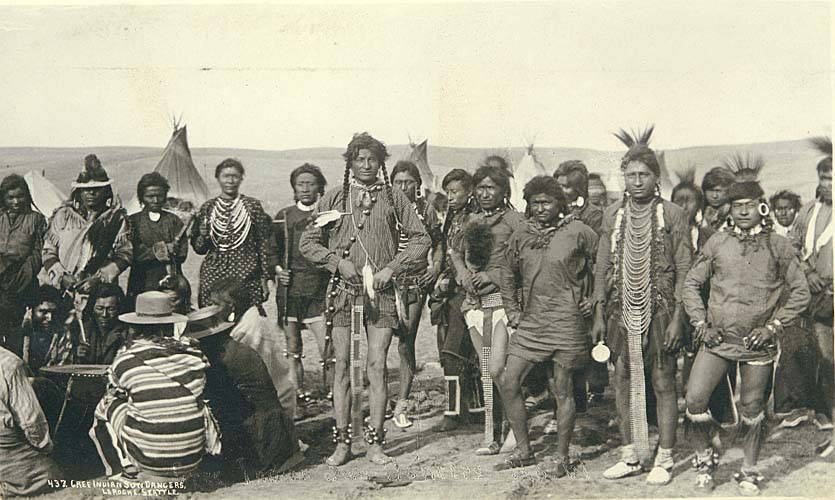

Colonization Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala Modern colonialism that started in the 15th century, along with European transatlantic navigation, resulted in the expansion of European empires and the associated settler colonialism that occurred in the Americas, Oceania, South Africa and beyond. According to historian Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz, the fact that Indigenous peoples survive today against genocidal attacks is proof of resistance:[54] Native nations and communities, while struggling to maintain fundamental values and collectivity, have from the beginning resisted modern colonialism using both defensive and offensive techniques, including the modern forms of armed resistance of national liberation movements and what now is called terrorism. In every instance they have fought for survival as peoples.  Charrua and soldier. Dunbar-Ortiz sets examples of resistance in North America in the cases of the Pueblo Revolt, the Pequot War, King Philip's War, and the Seminole Wars.[34]  Geronimo, Apache leader  Statue of Lempira, Plaza Central de Tambla Historical Indigenous resistance leaders throughout the world include Cajemé, Caupolican, Dundalli, Geronimo, Lautaro, Lempira, Mangas Coloradas, Manco Inca, Tupac Amaru II, Tecumseh, and Tenskwatawa. At times, Indigenous peoples used violent resistance, at times successfully or at times involving two or more Indigenous allies. Examples include the Mixton rebellion, the Zapatista uprising, the Caste War of Yucatán, Rebellion of Tupac Amaru II, the Tzeltal Rebellion of 1712, Pontiac's War and the North-West Rebellion.[1][55] Academic Benjamin Madley said that throughout the world, groups targeted for annihilation resist, often violently. He details the case of the Modoc War comparing the casualties of the conflict. Furthermore, he says that "The Modoc genocide is hardly the only genocide against Indigenous people that has been sanitized as war."[56] According to Frank Chalk, in the 19th century United States, the federal government policy toward Native Americans was ethnocide, but when they resisted, the result sometimes was genocidal.[57] Historically, victims of genocide have resisted, and this resistance has been criminalized to justify massacres.[58]  1622 Jamestown massacre. The image is largely considered conjecture. According to Ken Coates, sexual relations between Indigenous women and non-Indigenous men took place to some extent in New Zealand, New Spain, the Metis in Canada, whereas they generally did not take place in other places such as Australia and British North America. People of mixed settler-Indigenous ancestry have been discriminated against. The mixing blurred the lines between Indigenous and newcomer populations, and most learned the language of the colony, which was a European language.[59][60] Some scholars have argued that the concept of mestizaje, the process of transcultural mixing, has been used to promote assimitionalism and monoculturalism in Latin America.[61][62]  Maori soldiers, 1915 In North America, where the British made treaties with Indigenous peoples, they learned that these treaties could be broken and would not protect their communities.[63][64] Faced with the risk that their people would be destroyed, leaders of Indian resistance agreed to treaties requiring land cessions, and the redefinition of borders in the hope that the settlers would not encroach further on Indigenous territory.[6] One of such examples is the Pokagon Band of Potawatomi Indians, a federally recognized Indian Nation, which was led by Potawatomi leader Leopold Pokagon. Other times, treaties were signed under coercion or right after Indigenous groups suffered massacres, such as in the case of the Treaty of Hartford of 1638.[65] Colonial powers also sought control of new territories by appropriating the Indigenous elite through bribery and assimilation.[66] In North America, the United States and Canada established residential schools, removing Indigenous children from their families for years while prohibiting the use of their Indigenous language and cultural practices. Australia focused on children with mixed ethnicity and removed children to be placed in residential schools or to be adopted by non-Indigenous families.[67] Canada and the United States have assimilated Indigenous peoples via Indian termination policies, in which incentives are offered for Indigenous peoples to renounce Indigenous rights in exchange for benefits such as citizenship rights. Furthermore, Canada removed Indigenous rights if an Indigenous woman married a non-Indigenous person, an Indigenous person graduated from university, or joined the military.[68] The Cherokee Nation is one of the federally recognized tribes within the United States. It is now located in Oklahoma after being forcefully removed in the Trail of Tears along with other Indigenous groups. Indigenous groups in North America were assigned to small reservations, typically on remote and economically marginal territories that would not support crops, fishing or hunting. Some of the reservations were then dismantled through an allotment process such as the Dawes act in North America, but some Indigenous peoples refused to sign.[69]  Cree Indian sun dancers, ca 1893 A 2009 United Nations report stated that Indigenous peoples have "...documented histories of resistance, interface or cooperation with states...Indigenous peoples were often recognized as sovereign peoples by states, as witnessed by the hundreds of treaties concluded between Indigenous peoples and the governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and others".[70] |

植民地化 フェリペ・グアマン・ポマ・デ・アヤラ 15世紀に始まった近代植民地主義は、ヨーロッパによる大西洋横断航海とともに、ヨーロッパの帝国の拡大と、アメリカ、オセアニア、南アフリカ、その他の地域で発生した入植者による植民地主義をもたらした。 歴史家のロクサンヌ・ダンバー=オルティスによると、先住民が今日まで大量虐殺の攻撃に耐えて生き残っているという事実は、抵抗の証であるという。 先住民の国家やコミュニティは、基本的価値観や集団性を維持するために苦闘しながら、当初から防御的・攻撃的な技術を駆使して近代の植民地主義に抵抗して きた。その中には、民族解放運動の近代的な武力抵抗や、現在ではテロリズムと呼ばれるものも含まれている。いずれの場合も、彼らは民族として生き残りをか けて戦ってきた。  チャルーア族と兵士 ダンバー=オルティスは、北米における抵抗の例として、プエブロの反乱、ペコット戦争、フィリップ王戦争、セミノール戦争を挙げている。[34]  ジェロニモ、アパッチ族の指導者  レムピラの像、タンブラ中央広場 世界中の歴史的な先住民の抵抗指導者には、カジェメ、カウポリカン、ダンダリ、ジェロニモ、ラウタロ、レムピラ、マンガス・カラーダス、マンコ・インカ、トゥパック・アマルー2世、テカムセ、テンズワタワなどがいる。 先住民は時に暴力的な抵抗を行い、時には成功を収め、時には2人以上の先住民の同盟者を巻き込んだ。ミクストンの反乱、サパティスタ蜂起、ユカタンでの カースト戦争、トゥパック・アマルー2世の反乱、1712年のツェルタル族の反乱、ポンティアク戦争、北西戦争などがその例である。[1][55] 学術研究者のベンジャミン・マドレーは、世界中で、絶滅の対象となった集団はしばしば暴力的に抵抗したと述べている。彼はモドック戦争の事例を詳しく説明 し、その紛争による死傷者数を比較している。さらに、彼は「モドック族の大量虐殺は、戦争として正当化された先住民に対する大量虐殺の唯一の例ではない」 と述べている。[56] フランク・チョークによると、19世紀のアメリカでは、連邦政府のネイティブ・アメリカンに対する政策は民族抹殺であったが、彼らが抵抗した場合には、結 果として大量虐殺となることもあった。[57] 歴史的に、大量虐殺の犠牲者は抵抗し、この抵抗が大量虐殺を正当化するために犯罪化されてきた。[58]  1622年のジェームズタウン虐殺。この画像は、概ね推測であると考えられている。 ケン・コーツによると、先住民女性と非先住民男性との性的関係は、ニュージーランド、ヌエバ・エスパーニャ、カナダのメティスではある程度見られたが、 オーストラリアやイギリス領北アメリカなど他の地域では一般的ではなかった。入植者と先住民の混血の人々は差別されてきた。混血により先住民と入植者の境 界線は曖昧になり、ほとんどの者が入植地の言語、すなわちヨーロッパの言語を習得した。[59][60] 一部の学者は、混血の概念、すなわち異文化間の混血のプロセスは、ラテンアメリカにおける同化主義と単一文化主義を推進するために利用されてきたと主張し ている。[61][62]  1915年のマオリ族兵士 イギリスが先住民と条約を結んだ北アメリカでは、条約は破られる可能性があり、自分たちのコミュニティを守ることはできないことを学んだ。入植者たちが先 住民の領土をこれ以上侵害しないことを期待して、土地の割譲と国境の再定義を要求する条約に合意したのである。[6] そのような例のひとつに、ポタワトミ族のリーダー、レオポルド・ポカゴンが率いた、連邦政府に承認されたポタワトミ族インディアン部族、ポカゴン・バンド がある。また、1638年のハートフォード条約のように、先住民グループが虐殺された直後に、強制的に条約が締結された例もある。[65] 植民地支配国は、贈収賄や同化政策によって先住民エリートを取り込むことでも、新たな領土の支配を狙った。[66] 北米では、米国とカナダが寄宿学校を設立し、先住民の子供たちを家族から引き離し、先住民の言語や文化の実践を禁止した。オーストラリアは、複数の民族の 血を引く子供たちに焦点を当て、寄宿学校に入学させたり、先住民ではない家庭に養子に出したりした。[67] カナダと米国は、インディアン終結政策を通じて先住民を同化してきた。この政策では、市民権などの利益と引き換えに、先住民に先住民としての権利を放棄す るよう奨励している。さらに、カナダでは、先住民の女性が非先住民と結婚した場合、先住民の人が大学を卒業した場合、軍に入隊した場合、先住民の権利は剥 奪された。[68] チェロキー族は、アメリカ合衆国で連邦政府に認定された部族のひとつである。他の先住民グループとともに「涙の小道」で強制移住させられた後、現在はオク ラホマ州に居住している。北米の先住民グループは、作物や漁業、狩猟には適さない遠隔地や経済的に不利な地域にある小さな保留地に割り当てられた。保留地 の一部は、北米のドーズ法のような割当プロセスによって解体されたが、一部の先住民は署名を拒否した。  クリー族のサンダンサー、1893年頃 2009年の国連報告書は、「先住民には、国家に対する抵抗、交流、協力の歴史が記録されている。先住民は、米国、カナダ、ニュージーランドなどの政府と 結ばれた数百の条約が示すように、国家によって主権を有する民族として認められることが多かった」と述べている。[70] |

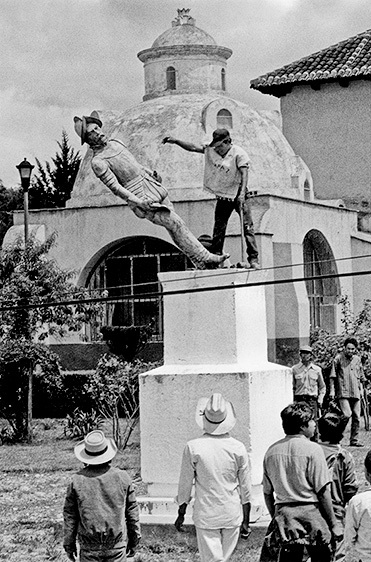

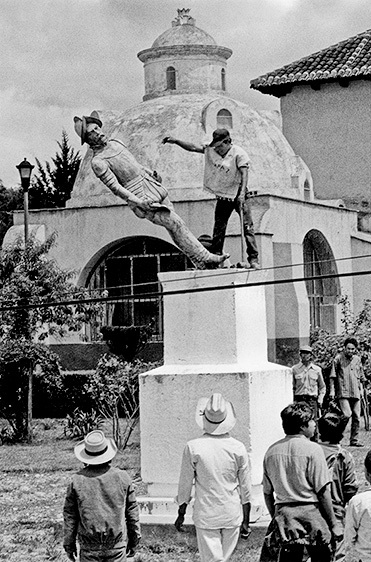

| Contemporary response Strategies Indigenous strategies continue to pursue Indigenous rights and freedom and seek to rebuild their nations and cultures to maintain national groups with distinct cultural identities. Indigenous nations continue to pursue self-determination and sovereignty.[71][72]  Protesters toppled a statue of Diego de Mazariegos, a Spanish conquistador. 1992.[73] Contemporary Indigenous strategies have included negotiations, mediation, arbitration, political statements, blockades, legal challenges, activism, political demonstrations and civil disobedience. A few have worked on the removal from public spaces of symbols of Indigenous oppression, such as monuments to Christopher Columbus, John A. Macdonald, and Junipero Serra. Much resistance has also been used to bring Indigenous issues to public attention.[78] Indigenous peoples commemorate historical events and processes on an annual or periodic basis. Examples include Unthanksgiving Day and Indigenous Peoples Day.[83] Activists have also protested what they consider controversial colonial holidays, such as Australia Day,[84][85] and Columbus Day and its quincentenary celebration.[86][87][88] Erich Steinman has compiled a record of Native American resistance processes and responses that he says are not well studied by American sociology.[89] In New Zealand and Ecuador, Indigenous peoples have formed political parties, Te Pāti Māori and Pachakutik respectively. Bolivia has had an Indigenous president, Evo Morales.[8] Indigenous nations and peoples have managed to survive despite sustained long-term attacks to their survival as Indigenous nations, cultures or as members of an Indigenous group.[90][91] Hall argues that Indigenous peoples challenge the idea that the state is the basic form of political organization. He argues that the Indigenous fight for self-determination today is part of a cycle of centuries of resistance to colonialism.[92] Views on ongoing colonialism Elaine Coburn and historian Lorenzo Veracini say that colonialism is present in contemporary settler colonial states, including Canada, New Zealand, Australia, and the United States.[93][94] Michael Grewcock has argued that in Australia, there are Indigenous peoples "who still resist the colonization of country that was never ceded".[95] Native American anthropologist Audra Simpson argues that the colonial project is ongoing, as the case of the Mohawks of Kahnawake, a self-governing territory of the Mohawk Nation within the borders of Canada.[96] Pablo G. Casanova has said that in Mexico there has been a practice of internal colonialism.[97][98] According to sociologist Anibal Quijano, Bolivia and Mexico have undergone limited decolonialization through a revolutionary process.[99] In Mexico, the case of the Ejercito Zapatista de Liberación Nacional (EZLN) denotes resistance in many areas, including education, territorial, epistemological, political and economic terms. EZLN is viewed as a continuation of the struggle against more than 500 years of oppression of Indigenous peoples.[100] According to Ken Coates, liberal democracies do not like being called up on internal human rights abuses "when these same governments are often prominent in criticizing other nations for abuses of human and civil rights". Furthermore, post-independence era countries such as Malaysia and Indonesia have been dismissive of Indigenous rights as much as colonial empires.[101] Indigenous storytelling Oral storytelling is important to Indigenous culture, but it has been underepresented.[102] Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz has said that when Howard Zinn wrote his United States' history book, he did not include the history of the Indigenous peoples, so he said that she could write what would become such a book: An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States.[103][104] Rigoberta Menchu published an essay about her life with personal experiences directly related to the Guatemalan genocide and went on to win the Nobel Peace Prize.[11] Truth commissions There are Truth Commissions that have investigated and reported on Indigenous atrocities. Some of them include the Guatemala Historical Clarification Commission, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Norway.[109] Museums In Latin America, there are only a few museums whose central theme is that of colonization and history of Indigenous peoples.[110] Indigenous peoples and others have protested against museum´s exhibitions.[119] Notable examples of Indigenous museums are Museu do Índio (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil),[120] Royal Museum for Central Africa (Brussels, Belgium),[121][122] Musée du Quai Branly (Paris, France),[123] National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico City), Museum of the Tropics (Amsterdam, Netherlands),[124] Museo Nacional de Antropología and Museo de América (Madrid, Spain), American Indian Genocide Museum (Houston, USA), George Gustav Heye Center (New York City, USA), and National Museum of the American Indian (Washington, D.C., USA).[125] Many smaller European colonial museums have closed after the end of European colonization.[126] According to Pascal Blanchard, the political climate in France has not allowed the emergence of a museum about French colonialism.[127] In Bristol, England, the only museum dedicated to colonialism, British Empire and Commonwealth Museum, has been closed after operating for just 6 years.[128][129] In North America, American Museum of Natural History in New York, Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, Harvard University’s Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology and Cleveland Museum of Art have begun to close exhibits with Indigenous themes to comply with federal regulations that mandate tribal consent and repatriation of human remains.[130][131] Indigenous media There are a number of Indigenous broadcasting organizations from countries serving Indigenous themes, including APTN, First Nations Experience, NITV, NRK Sami and Whakaata Māori.[132] Language Some movements, such as the Hawaiian sovereignty movement, have sought to promote the use of Indigenous languages in educational programs.[133] In recent years, there has been a revival in the use of Māori language in New Zealand, where it is an official language and taught in 350 schools.[134][11] New technologies are making access to educational language programs accessible to the general public.[135] Furthermore, there are examples of Indigenous schools that move away from Eurocentric curriculums while considering the graduates' future prospects within a non-Indigenous majority state.[136] In Paraguay, Guaraní is the official language and is spoken by 6.5 million people in the region. Quechua and Aymara are official languages in Peru and Bolivia and are spoken by 8 and 2.5 million people, respectively.[137] Nationalism has promoted the use of local languages in most of Eurasia, but in the rest of the world, European languages remain dominant in mass media, education and the internet.[138] Culture Today, Indigenous peoples can react to cultural processes in various ways, including acculturation, transculturation, assimilation, and cultural loss, while some remain separated from the dominant culture or marginalized from any group, including their own. In Hispanic America, Indigenous peoples have adopted Spanish religion, institutions, language, and literature, as well as non-endemic domestic animals and crops.[139][140] Some scholars and Indigenous peoples argue that renaming geographical entities should be part of a reclaiming process of Indigenous cultures.[141][142] International law In the area of international law, the Working Group on Indigenous Populations participated directly in the development of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and worked on the development of the Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention of 1989.[143] Indigenous scholar Jeff Corntassel said that article 46 of UNDRIP may be detrimental to some Indigenous rights: "...the restoration of their land-based and water-based cultural relationships and practices is often portrayed as a threat to the territorial integrity of the country(ies) in which they reside, and thus, a threat to state sovereignty".[144] For decades, Indigenous peoples had demanded that the Catholic Church rescind the Doctrine of Discovery theories that justified the seizure of Indigenous land and supported a legal basis.[145] |

現代の対応 戦略 先住民の戦略は、先住民の権利と自由を追求し続け、独自の文化アイデンティティを持つ民族集団を維持するために、彼らの国家と文化の再建を目指している。先住民の国家は、自己決定と主権を追求し続けている。[71][72]  抗議者たちは、スペインの征服者ディエゴ・デ・マサリエゴスの像を倒した。1992年。[73] 現代の先住民の戦略には、交渉、調停、仲裁、政治的声明、封鎖、法的措置、活動、政治的デモ、市民的不服従などが含まれる。少数ではあるが、クリスト ファー・コロンブス、ジョン・A・マクドナルド、ジュニペロ・セラの記念碑など、先住民弾圧の象徴となっているものを公共の場から撤去する活動に取り組ん でいる者もいる。先住民問題を世間の注目を集めるために、多くの抵抗活動も行われている。 先住民は、歴史的な出来事や過程を毎年または定期的に記念している。例としては、感謝祭反対の日や先住民の日などがある。[83] 活動家たちは、オーストラリア・デー[84][85]やコロンブス・デーおよびその500周年記念[86][87][88]など、論争の的となっている植 民地時代の祝日と見なされるものにも抗議している。 エーリッヒ・スタインマンは、アメリカ社会学では十分に研究されていないとされる、アメリカ先住民の抵抗の過程と対応の記録をまとめている。 ニュージーランドとエクアドルでは、先住民がそれぞれテ・パティ・マオリとパチャクティクという政党を結成している。ボリビアでは、先住民出身の大統領エボ・モラレスが誕生した。 先住民の国家や民族は、先住民としての国家、文化、あるいは先住民グループのメンバーとしての存続を長期間にわたって継続的に攻撃されながらも、なんとか 生き残ってきた。[90][91] ホールは、先住民は国家が政治組織の基本形態であるという考えに異議を唱えていると主張している。 また、今日の先住民による自己決定の闘いは、植民地主義に対する数世紀にわたる抵抗のサイクルの一部であると主張している。[92] 現在進行中の植民地主義に関する見解 Elaine Coburnと歴史学者のLorenzo Veraciniは、植民地主義は現代の入植植民地国家、すなわちカナダ、ニュージーランド、オーストラリア、アメリカ合衆国にも存在していると述べてい る。[93][94] マイケル・グロウコックは、オーストラリアには「いまだに領有権が譲渡されていない国土の植民地化に抵抗している」先住民がいると主張している。[95] アメリカ先住民人類学者のオードラ・シンプソンは、カナダの国境内に位置するモホーク族の自治領であるモホーク・カナーウェイの事例を挙げ、植民地化計画は現在も進行中であると主張している。 パブロ・G・カサノヴァは、メキシコでは国内植民地主義が実践されていると述べている。[97][98] 社会学者のアナバル・キハノによると、ボリビアとメキシコは革命的プロセスを通じて限定的な脱植民地化を経験している。[99] メキシコでは、サパティスタ民族解放軍(EZLN)の事例は、教育、領土、認識論、政治、経済など、多くの分野における抵抗を示している。EZLNは、先 住民に対する500年以上にわたる抑圧に対する闘争の継続と見なされている。[100] ケン・コーツによると、自由民主主義国家は、自国の政府が他国の人権侵害を批判する際に、自国の人権侵害を指摘されることを嫌う。さらに、マレーシアやインドネシアなどの独立後の国々は、植民地帝国と同様に先住民の権利を軽視してきた。 先住民の語り継ぎ 口頭による語り継ぎは先住民の文化にとって重要であるが、これまで十分に表現されてこなかった。[102] ロクサンヌ・ダンバー=オルティスは、ハワード・ジンが米国の歴史の教科書を執筆した際、先住民の歴史を盛り込まなかったため、彼女がそのような教科書と なるものを執筆できるだろうと述べた。先住民のアメリカ史』を書くことができるだろうと述べた。[103][104] リゴベルタ・メンチュは、グアテマラの大虐殺に直接関連する個人的な経験を交えた自伝を発表し、その後ノーベル平和賞を受賞した。[11] 真実究明委員会 先住民による残虐行為を調査し報告した真実究明委員会が存在する。その中には、グアテマラ歴史解明委員会、カナダの真実・和解委員会、ノルウェーの真実・和解委員会などがある。[109] 博物館 ラテンアメリカには、植民地化と先住民の歴史を主題とする博物館は数館しかない。[110] 先住民やその他の人々は、博物館の展示内容に対して抗議を行っている。[119] 先住民博物館の著名な例としては、ブラジルのリオ・デ・ジャネイロにある「インディオ博物館(Museu do Índio)」[120]、ベルギーのブリュッセルにある「中央アフリカ王立博物館(Royal Museum for Central Africa)」[121][122]、フランスのパリにある「ケ・ブランリー美術館(Musée du Quai Branly)」[123]、 国立人類学博物館(メキシコシティ)、熱帯博物館(オランダ・アムステルダム)[124]、国立人類学博物館およびアメリカ博物館(スペイン・マドリー ド)、アメリカ・インディアン大量虐殺博物館(アメリカ・ヒューストン)、ジョージ・グスタフ・ハイ・センター(アメリカ・ニューヨーク市)、国立アメリ カ・インディアン博物館(アメリカ・ワシントンD.C.)などがある。[125] ヨーロッパの植民地支配が終結した後、ヨーロッパの多くの小規模な植民地博物館が閉鎖された。[126] パスカル・ブランチャードによると、フランスの政治情勢は、フランス植民地主義に関する博物館の出現を許さなかった。[127] イギリス、ブリストルにある唯一の植民地主義に関する博物館、大英帝国・英連邦博物館は、開館からわずか6年で閉館した。[128][129] 北米では、ニューヨークのアメリカ自然史博物館、シカゴのフィールド自然史博物館、ハーバード大学のピーボディ考古学・民族学博物館、クリーブランド美術館が、部族の同意と人骨の返還を義務付ける連邦法に従い、先住民をテーマにした展示の閉鎖を開始した。 先住民メディア 先住民をテーマとする国々には、APTN、First Nations Experience、NITV、NRK Sami、Whakaata Māori など、多数の先住民向け放送組織がある。 言語 ハワイの主権運動などの一部の運動では、教育プログラムにおける先住民言語の使用を促進しようとしている。[133] 近年、ニュージーランドではマオリ語の使用が復活しており、マオリ語は公用語であり、350の学校で教えられている。[134][11] 新技術により、 教育用言語プログラムへのアクセスが一般市民にも可能になっている。[135] さらに、先住民学校の中には、非先住民が多数派を占める国家における卒業生の将来の展望を考慮しながらも、ヨーロッパ中心主義のカリキュラムから離れる例 もある。[136] パラグアイではグアラニー語が公用語であり、650万人がこの言語を話す。ケチュア語とアイマラ語はペルーとボリビアの公用語であり、それぞれ800万人 と250万人の人々によって話されている。[137] 民族主義は、ユーラシアの大半において現地語の使用を促進してきたが、その他の地域では、マスメディア、教育、インターネットでは依然としてヨーロッパの 言語が優勢である。[138] 文化 今日、先住民は文化過程に対して様々な反応を示しており、同化、異文化化、同化、文化の喪失などがある。一方で、支配的文化から隔絶されたり、自身のグ ループを含め、あらゆるグループから疎外されたままの人々もいる。ラテンアメリカでは、先住民はスペインの宗教、制度、言語、文学、および非土着の家畜や 作物を受け入れてきた。 一部の学者や先住民は、地理的な名称の変更は先住民文化の回復プロセスの一部であるべきだと主張している。 国際法 国際法の分野では、先住民に関する作業部会が国連先住民族の権利に関する宣言(UNDRIP)の策定に直接参加し、1989年の先住民族及び種族民に関す る条約の策定に取り組んだ。[143] 先住民の学者であるジェフ・コーンタッセルは、UNDRIPの第46条が一部の先住民の権利を損なう可能性があると述べている。「彼らの土地や水に関する 文化的な関係や慣習の復元は、しばしば彼らが居住する国の領土保全に対する脅威として描かれ、国家主権に対する脅威とみなされる」と述べている。 [144] 先住民は数十年にわたり、カトリック教会に対して、先住民の土地の収用を正当化し、法的根拠を支持する「発見の教義」理論を撤回するよう要求してきた。[145] |

| American Indian Movement Analysis of Western European colonialism and colonization Apologies to Indigenous peoples Denial of genocides of Indigenous peoples Decolonization Genocide of Indigenous peoples Indigenous and Tribal Peoples Convention, 1989 List of battles won by Indigenous peoples of the Americas List of Indigenous rebellions in Mexico and Central America List of Indian massacres in North America Native American genocide in the United States Racism against Native Americans in the United States |

アメリカン・インディアン運動 西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の分析 先住民への謝罪 先住民に対する大量虐殺の否定 脱植民地化 先住民に対する大量虐殺 先住民及び種族民に関する条約(1989年) アメリカ大陸の先住民が勝利した戦いの一覧 メキシコおよび中央アメリカにおける先住民の反乱の一覧 北アメリカにおけるインディアンの虐殺の一覧 アメリカ合衆国におけるネイティブ・アメリカン大量虐殺 アメリカ合衆国におけるネイティブ・アメリカンに対する人種差別 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indigenous_response_to_colonialism |

|

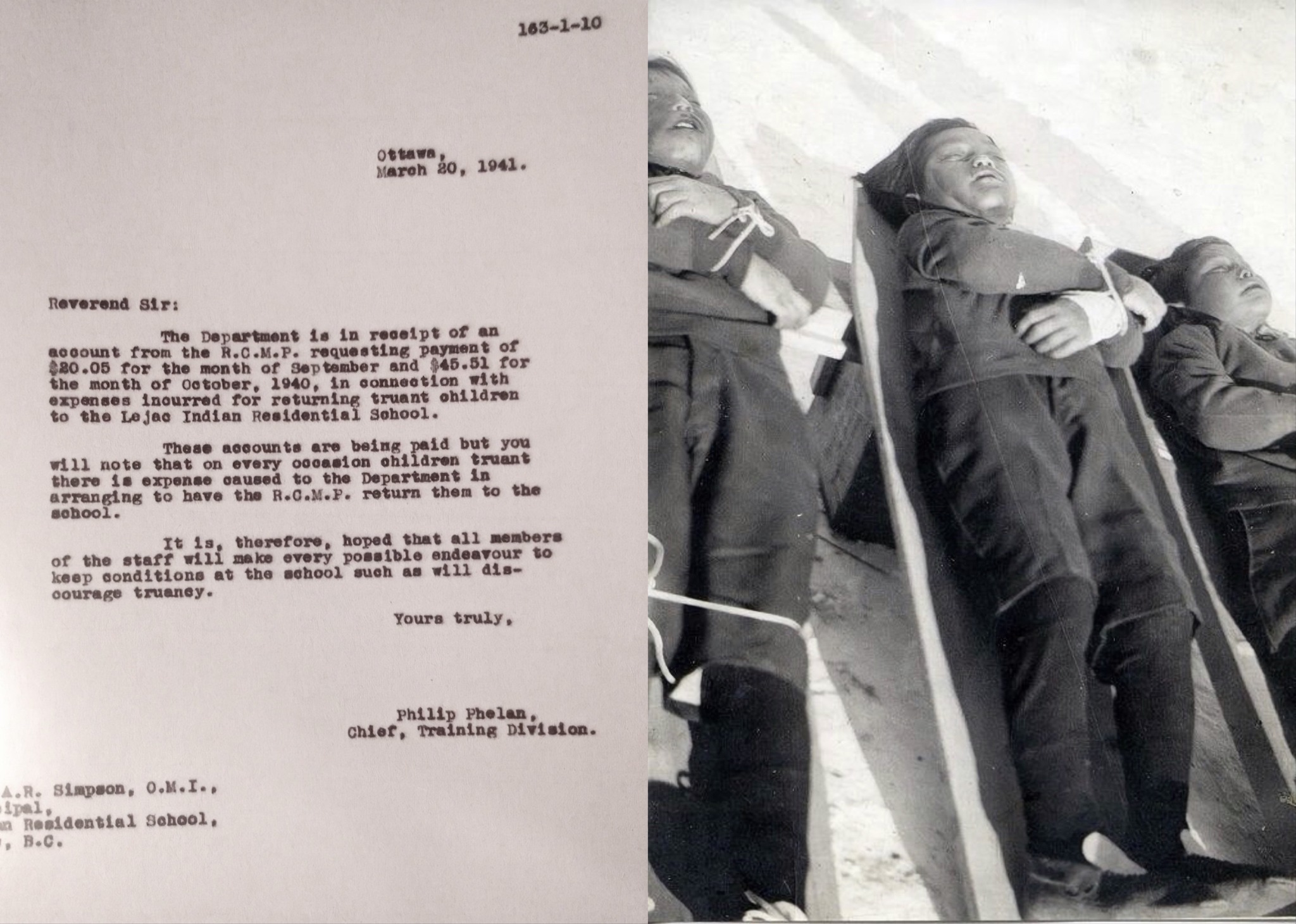

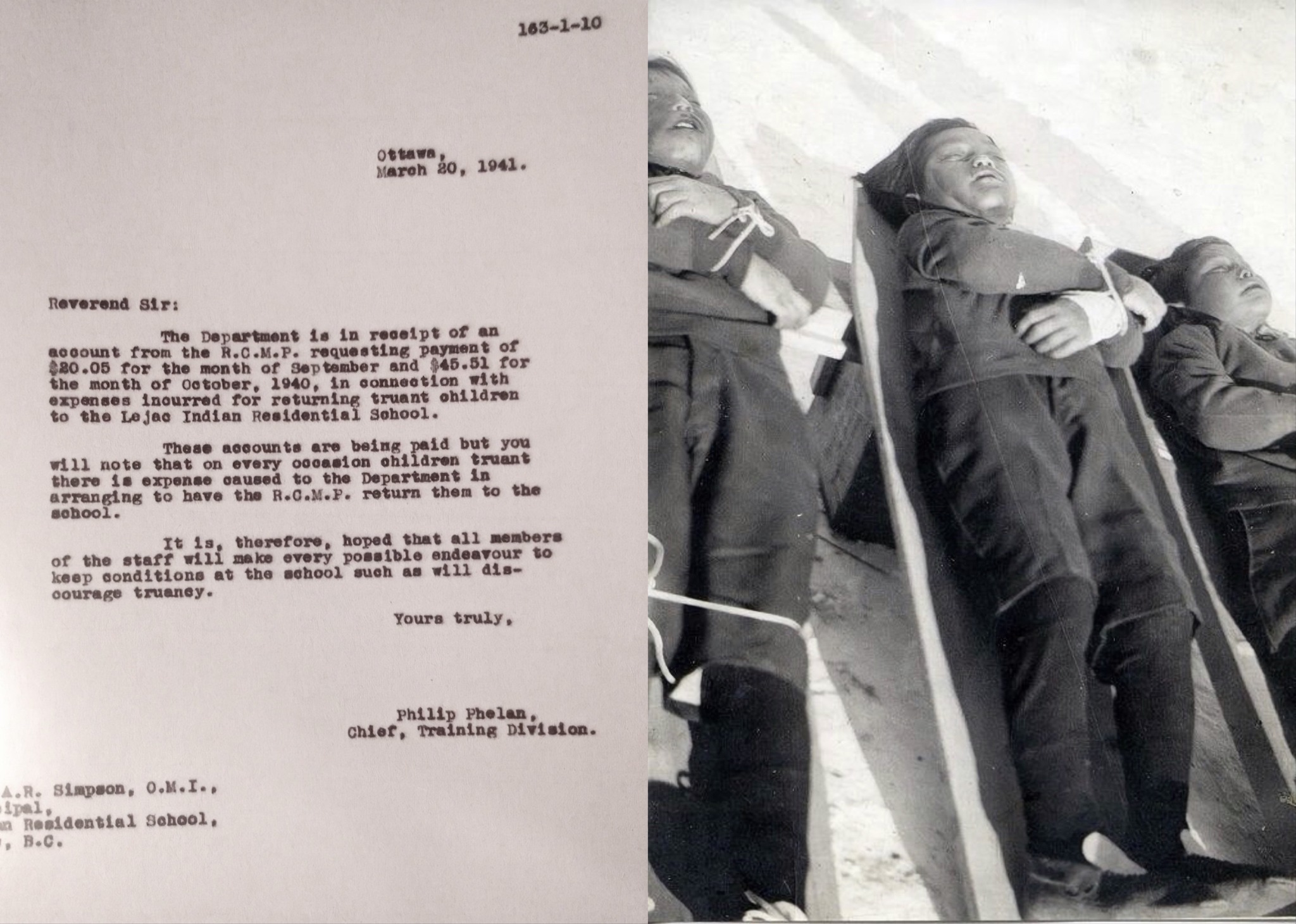

| The

Royal Canadian Mounted Police colluded with the Canadian Government and

the Church to return Indigenous children who desperately ran away from

the notorious Lejac school as revealed in this genocidally brutal

archived Indian Affairs of Canada document. “Ottawa, March 20, 1941. Reverend Sir: The Department is in receipt of an account from the R.C.M.P. requesting payment of $20.05 for the month of September and $45.51 for the month of October, 1940, in connection with expenses incurred for returning truant children to the Lejac Indian Residential School. These accounts are being paid but you will note that on every occasion children truant there is expense caused to the Department in arranging to have the R.C.M.P . return them to the school. It is, therefore, hoped that all members of the staff will make every possible endeavour to keep conditions at the school such as will discourage truancy. Yours truly, Philip Phelan, chief, Training Division.” Never forget…,Survivors want their stories told. 1937, sometime between 4:30 and 5 o’clock on New Year's Day, five homesick young native boys ran away from the notorious Lajac indian residential School in British Columbia, located within Stellat'en First Nation territory. Lejac Indian Residential school enrolled many Carrier, and neighbouring Sekani and Gitksan Nation Children. Desperately missing home, the children’s earlier request to visit home for the holidays was denied them. It was dark, temperatures 20 below zero when the youngest of the boys, seven years old, the eldest, age ten, snuck out of the school, walking in the direction toward home on the Nadleh reserve, "without caps and lightly clad". By 6pm the school noticed the boys were missing when they did not appear for dinner. One mile into the desperate journey, one of the five, Paul Alex, aged 10, turned back to the school. The four boys continued on, freezing to death, within a mile of their destination. A confidential Department of Indian Affairs Canada report prepared by the Indian Commissioner of British Columbia on, March 25, 1937 concludes, “…The children, with great difficulty reached a point on the lake approximately one quarter of a mile from Beaumonts Beach. The snow at this point was found to have been trampled over a small area and in places brushed aside by the children indicating they were nearing the point of exhaustion and unable to go on, wanted to rest; it was here they collapsed and died and their frozen bodies were found by Indian Charley at 5.30 P.M. on January 2nd. The total distance covered by the children would be approximately eight miles and the time taken to reach the spot where their bodies were found is estimated at seven hours; on this basis it is concluded the children perished at midnight on January lst. or there-after, or between seven and eight hours after they left the school.” They were, Andrew Paul 8, John Michel Jack 7, Maurice Justice 8, Alan Willie 9. Through statements issued later in the media, Lejac Indian Residential school placed the blame upon the boys for their own deaths, as well as upon the students own grieving community. The Lejac Residential School was part of the Canadian residential school system and one of the 130 boarding schools for First Nations children that operated across Canada between 1874 and 1996. Operated by the Roman Catholic Church under contract with the government of Canada. As with most other residential schools, students at Lejac were physically and sexually abused. What remains at the site are a cemetery, a memorial, the school closed in 1976 and the school buildings were demolished. Thousands of Indigenous children died in residential schools that failed to keep them safe from fires, protected from abusers, and healthy from infectious deadly diseases. It was also well known that schools were locking kids in their dormitories because they didn’t want them to escape. Many perished in fires despite repeated warnings in external audits that called for fire escapes and sprinklers but were routinely ignored. Tragedies in residential schools are not suddenly flushed out by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s findings and report that was issued in 2015. In 1909, Dr. Peter Bryce, general medical superintendent in the Department of Indian Affairs, warned the government that between 1894 and 1908, the death rate among native children of school age ranged between 30 and 60 per cent. The governments of the day paid little attention. In 1986, the United Church of Canada issued its apology specifically “to those individuals who were physically, sexually and mentally abused as students” in schools in which the United Church was involved. Suddenly, Christian leaders were sorry however, none of them, from infallible Pope to Presbyterian preacher, explained how a group of religious leaders with such devoutly held views on Christian love, got it so universally wrong when it came to applying belief to life towards the lives of tens of thousands of indigenous children. ~ "Many of my community members were brought there[Lejac], including my older brother and sisters, It was quite a notorious school... they witnessed a lot of abuse." ~ B.C. Assembly of First Nations regional chief Terry Teegee, January, 2018. ~ "Always telling us how we're gonna be so useless. For seven years, every day we hear that, I still haven't gotten over those... I feel ashamed of my life. They tell you every day that you'll amount to nothing, it sort of sticks with you and you just don't care about yourself the way you should. They need to understand how we grew up, being in residential school and stuff, and the violence that we had to go through after…,I'm glad that my story is out." ~ Marlene Jack. September 28, 2017 testifying to the national inquiry into missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls from her childhood attending Lejac residential school, being homeless in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside to the 1989, to the disappearance of her sister Doreen, Doreen's husband Ronald and their two children, from Prince George, British Columbia. ~ “It is so important to know how we came to this place of collective grief. If we have these figures, then our people can begin to talk about their own holocaust.” ~ “native activist, Maggie Hodgson. Truth is not negotiable. Healing begins with naming the harm and acknowledging it fully. Memory is resistance. Remember the children’s names: Andrew Paul, John Michel Jack, Maurice Justice, Alan Willie. They matter. They always will. Justice is sacred work. Reconciliation without accountability is hollow; honoring the children means standing with survivors, fighting for structural change, and carrying the memory forward.  |

カナダ王立騎馬警察は、カナダ政府および教会と共謀し、悪名高いレジャック学校から必死に逃げ出した先住民の子供たちを連れ戻した。これはカナダ先住民問題省のアーカイブ文書に記録された、虐殺的な残虐行為として明らかになった事実である。 「オタワ、1941年3月20日。 牧師殿:当省はカナダ王立騎馬警察(RCMP)より、1940年9月分20ドル5セント、10月分45ドル51セントの支払いを求める請求書を受領した。これはレジャック・インディアン寄宿学校へ無断離脱児童を連れ戻す際に発生した経費に関するものである。 これらの請求は支払われるが、児童が不登校となる度に、RCMPに学校へ連れ戻させる手配で当省に費用が発生していることに留意されたい。 よって、教職員全員が不登校を防止するような学校環境維持に最大限の努力を払うことを望む。 敬具 フィリップ・フェラン訓練部長」 決して忘れるな…生存者たちは自らの物語を語ってほしいと願っている。 1937年、元旦の午前4時半から5時の間に、5人の郷愁に駆られた先住民の少年たちが、ブリティッシュコロンビア州ステラテン・ファースト・ネイション 領内にある悪名高いレジャック・インディアン寄宿学校から脱走した。ラジャック・インディアン寄宿学校には、キャリヤー族や近隣のセカニ族、ギトクサン族 の子供たちが多数在籍していた。故郷を渇望する子供たちは、休暇中の帰郷を事前に申請していたが却下されていた。暗闇の中、気温は零下20度。最年少の7 歳から最年長の10歳までの少年たちは「帽子も被らず、薄着のまま」学校を抜け出し、ナドレー保留地にある故郷へ向かって歩き出した。午後6時、夕食に現 れないことに学校は少年たちの不在に気づいた。必死の旅路を1マイル進んだところで、5人組のうち10歳のポール・アレックスが学校へ引き返した。残る4 人の少年たちは目的地まであと1マイルの地点で凍死した。 1937年3月25日、ブリティッシュコロンビア州インディアン委員が作成したカナダ先住民省の機密報告書は次のように結論づけている。「…子供たちは、 ボーモント・ビーチから約400メートル離れた湖上の地点に、大変な苦労の末に到達した。この地点の雪は狭い範囲で踏み固められ、所々で子供たちが雪をか き分けていた。これは彼らが疲労の極限に達し、これ以上進めず休息を求めていたことを示している。ここで彼らは倒れ、死亡した。凍死した遺体は1月2日午 後5時30分、インディアン・チャーリーによって発見された。 子供たちが移動した総距離は約 8 マイルで、遺体が発見された地点に到達するのにかかった時間は 7 時間と推定される。このことから、子供たちは 1 月 1 日の深夜、あるいはそれ以降、学校を出発してから 7 時間から 8 時間の間に死亡したと結論づけられる。 彼らは、アンドルー・ポール(8 歳)、ジョン・ミシェル・ジャック(7 歳)、モーリス・ジャスティス(8 歳)、アラン・ウィリー(9 歳)であった。 後にメディアで発表された声明の中で、レジャック・インディアン寄宿学校は、少年たちの死の責任を彼ら自身と、悲嘆に暮れる生徒たちのコミュニティに負わせた。 レジャック寄宿学校は、カナダの寄宿学校制度の一部であり、1874年から1996年にかけてカナダ全土で運営されていた先住民児童のための130の寄宿 学校のうちの1つであった。カナダ政府との契約に基づき、ローマカトリック教会によって運営されていた。他のほとんどの寄宿学校と同様、レイジャックの生 徒たちも身体的・性的虐待を受けていた。現在、敷地に残っているのは墓地と記念碑だけで、学校は1976年に閉鎖され校舎は取り壊された。 数千人の先住民の子どもたちが寄宿学校で命を落とした。学校は火災から彼らを守れず、虐待者から保護できず、致死性の感染症から健康を保てなかった。ま た、子どもたちが逃げ出さないよう寮に閉じ込めることも周知の事実だった。外部監査で繰り返し警告された避難階段やスプリンクラーの設置は常習的に無視さ れ、多くの命が火災で消えた。 寄宿学校の悲劇は、2015年に発表された真実和解委員会の調査結果と報告書によって突然明るみに出たわけではない。1909年、インディアン事務局の医 療総監ピーター・ブライス博士は政府に対し、1894年から1908年にかけて就学年齢の先住民児童の死亡率が30~60%に達していると警告していた。 当時の政府はほとんど注意を払わなかった。 1986年、カナダ合同教会は、同教会が関与した学校において「身体的、性的、精神的虐待を受けた生徒たち」に対して特に謝罪を発表した。 突然、キリスト教指導者たちは謝罪した。しかし、絶対的な権威を持つ教皇から長老派の説教者に至るまで、キリスト教の愛をこれほど熱心に信奉する宗教指導 者たちが、何万人もの先住民児童の命に関わる現実において、なぜこれほどまでに普遍的に誤った対応を取ったのか、誰も説明しなかった。 ~「私のコミュニティの多くの人々が、兄や姉たちも含めて、あの学校(レジャック)に連れて行かれた。かなり悪名高い学校だった…彼らは多くの虐待を目撃した」~ ブリティッシュコロンビア州先住民議会地域長 テリー・ティーギー、2018年1月 ~「いつも『お前たちは絶対に役に立たない』と言われ続けた。7年間、毎日それを聞かされた。今でもそのトラウマは消えない…自分の人生が恥ずかしい。毎 日『お前はろくなものになれない』と言われると、それが染みついて、自分を大切にする気持ちが失せるんだ。彼らは理解すべきだ。私たちが寄宿学校で育ち、 その後も耐えねばならなかった暴力について…。自分の体験が公になったのは良かった。」 ~ マーリーン・ジャック。2017年9月28日、先住民の女性や少女たちの失踪および殺害に関する全国調査で、レジャック寄宿学校に通った子供時代、バン クーバーのダウンタウン・イーストサイドでホームレスだった1989年、そしてブリティッシュコロンビア州プリンスジョージから失踪した姉ドリーン、ド リーンの夫ロナルド、そして2人の子供たちについて証言。 「私たちが、どうしてこの集団的悲嘆の場所にたどり着いたのかを知ることは、とても重要だ。こうした数字が分かれば、私たちの人々は、自分たちのホロコーストについて話し始めることができる」と、先住民活動家のマギー・ホジソンは言う。 真実は交渉の余地がない。癒しは、害を名指し、それを完全に認めることから始まる。 記憶は抵抗だ。子供たちの名前を覚えておいてほしい。アンドルー・ポール、ジョン・ミシェル・ジャック、モーリス・ジャスティス、アラン・ウィリー。彼らは重要だ。これからもずっと重要だ。 正義は神聖な仕事だ。説明責任のない和解は空虚だ。子供たちを称えることは、生存者たちと一緒に立ち、構造的な変化のために戦い、記憶を未来へ引き継ぐことを意味する。  |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆