個人あるいは個体

(パーソン=人格を含む)

Individual, including

Person

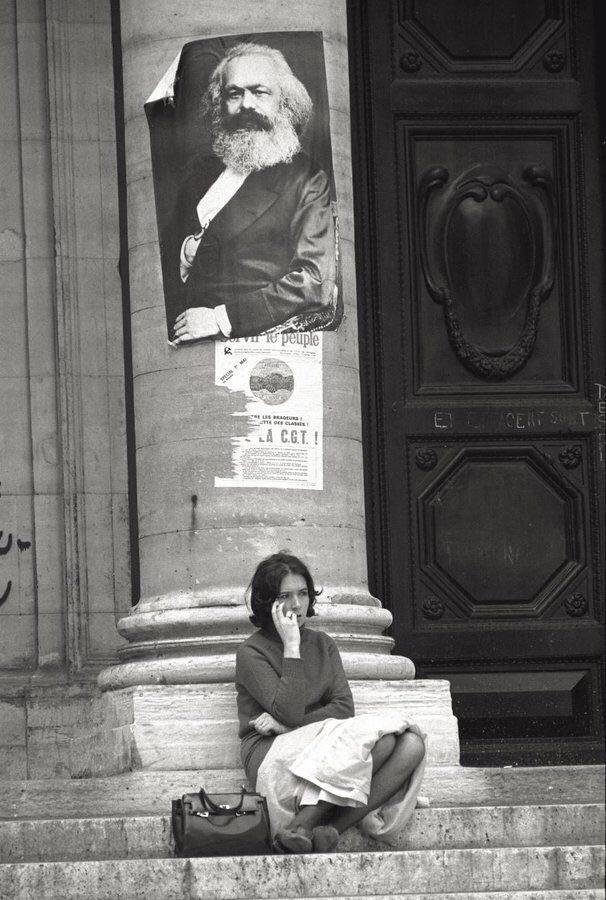

ソ

ルボンヌ 1968.

☆ 個人(individual)とは、 別個の存在として存在するものである。個性(または自我)とは、個人として生きている状態や資質のことで、特に(人間の場合)他の人とは違う、 自分だけのニーズや目標、権利や責任を持つ人のことである。個人という概念は、生物学、法律、哲学など多くの分野で見られる。すべての個人は文明の発展に 大きく貢献している。社会は多面的な概念であり、人間の行動、態度、考え方など、さまざまなものによって形成され、影響を受ける。他人の文化、道徳、信 念、そして社会の全般的な方向性や軌跡はすべて、個人の活動によって影響を受け、形成される可能性がある。

☆パーソン(person)における人や個人は、その人を人間と認めるか?という問題(=外延的範囲)になり、パーソンフッド(personhood) は、それを人として認める際における属性(=内包的定義)のことである。

| An individual

is one that exists as a distinct entity. Individuality (or self-hood)

is the state or quality of living as an individual; particularly (in

the case of humans) as a person unique from other people and possessing

one's own needs or goals, rights and responsibilities. The concept of

an individual features in many fields, including biology, law, and

philosophy. Every individual contributes significantly to the growth of

a civilization. Society is a multifaceted concept that is shaped and

influenced by a wide range of different things, including human

behaviors, attitudes, and ideas. The culture, morals, and beliefs of

others as well as the general direction and trajectory of the society

can all be influenced and shaped by an individual's activities.[1] |

個

人とは、別個の存在として存在するものである。個性(または自我)とは、個人として生きている状態や資質のことで、特に(人間の場合)他の人とは違う、自

分だけのニーズや目標、権利や責任を持つ人のことである。個人という概念は、生物学、法律、哲学など多くの分野で見られる。すべての個人は文明の発展に大

きく貢献している。社会は多面的な概念であり、人間の行動、態度、考え方など、さまざまなものによって形成され、影響を受ける。他人の文化、道徳、信念、

そして社会の全般的な方向性や軌跡はすべて、個人の活動によって影響を受け、形成される可能性がある[1]。 |

| Etymology From the 15th century and earlier (and also today within the fields of statistics and metaphysics) individual meant "indivisible", typically describing any numerically singular thing, but sometimes meaning "a person". From the 17th century on, an individual has indicated separateness, as in individualism.[2] |

語源 15世紀以前から(そして今日、統計学や形而上学の分野でも)individualは「不可分な」という意味で、一般的には数値的に単一なものを表すこと が多いが、「人」を意味することもある。17世紀以降、individualは個人主義のように分離性を示すようになった[2]。 |

| Biology In biology, the question of the individual is related to the definition of an organism, which is an important question in biology and the philosophy of biology, despite there having been little work devoted explicitly to this question.[3] An individual organism is not the only kind of individual that is considered as a "unit of selection".[3] Genes, genomes, or groups may function as individual units.[3] Asexual reproduction occurs in some colonial organisms so that the individuals are genetically identical. Such a colony is called a genet, and an individual in such a population is referred to as a ramet. The colony, rather than the individual, functions as a unit of selection. In other colonial organisms, individuals may be closely related to one another but may differ as a result of sexual reproduction. |

生物学 生物学において、個体という問題は生物の定義に関連しており、この問題に明確に費やされた研究はほとんどないにもかかわらず、生物学や生物学の哲学におい て重要な問題である[3]。個体というのは、「選択の単位」とみなされる唯一の種類の個体というわけではない。 いくつかのコロニー生物では無性生殖が行われ、個体は遺伝的に同一である。そのようなコロニーはゲネと呼ばれ、そのような集団の個体はラメットと呼ばれ る。個体ではなくコロニーが選択の単位として機能する。他のコロニー生物では、個体同士は近縁であっても、有性生殖の結果異なる場合がある。 |

| Law Although individuality and individualism are commonly considered to mature with age/time and experience/wealth, a sane adult human being is usually considered by the state as an "individual person" in law, even if the person denies individual culpability ("I followed instructions"). An individual person is accountable for their actions/decisions/instructions, subject to prosecution in both national and international law, from the time that they have reached the age of majority, often though not always more or less coinciding with the granting of voting rights, responsibility for paying tax, military duties, and the individual right to bear arms (protected only under certain constitutions). |

法律 一般に、個性や個人主義は、年齢・時間や経験・富によって成熟すると考えられているが、まともな成人であれば、たとえ本人が個人の責任を否定していたとし ても(「私は指示に従った」)、法律上は「個人」として国家にみなされるのが普通である。 選挙権、納税義務、兵役義務、武器を持つ個人の権利(特定の憲法の下でのみ保護される)の付与と多かれ少なかれ一致することが多いが、必ずしも一致するわ けではない。 |

Philosophy Individuals may stand out from the crowd, or may blend in with it. Buddhism In Buddhism, the concept of the individual lies in anatman, or "no-self." According to anatman, the individual is really a series of interconnected processes that, working together, give the appearance of being a single, separated whole. In this way, anatman, together with anicca, resembles a kind of bundle theory. Instead of an atomic, indivisible self distinct from reality, the individual in Buddhism is understood as an interrelated part of an ever-changing, impermanent universe (see Interdependence, Nondualism, Reciprocity). Empiricism Empiricists such as Ibn Tufail[4] in early 12th century Islamic Spain and John Locke in late 17th century England viewed the individual as a tabula rasa ("blank slate"), shaped from birth by experience and education. This ties into the idea of the liberty and rights of the individual, society as a social contract between rational individuals, and the beginnings of individualism as a doctrine. Hegel Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel regarded history as the gradual evolution of the Mind as it tests its own concepts against the external world.[5] Each time the mind applies its concepts to the world, the concept is revealed to be only partly true, within a certain context; thus the mind continually revises these incomplete concepts so as to reflect a fuller reality (commonly known as the process of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis). The individual comes to rise above their own particular viewpoint,[6] and grasps that they are a part of a greater whole[7] insofar as they are bound to family, a social context, and/or a political order. Existentialism With the rise of existentialism, Søren Kierkegaard rejected Hegel's notion of the individual as subordinated to the forces of history. Instead, he elevated the individual's subjectivity and capacity to choose their own fate. Later Existentialists built upon this notion. Friedrich Nietzsche, for example, examines the individual's need to define his/her own self and circumstances in his concept of the will to power and the heroic ideal of the Übermensch. The individual is also central to Sartre's philosophy, which emphasizes individual authenticity, responsibility, and free will. In both Sartre and Nietzsche (and in Nikolai Berdyaev), the individual is called upon to create their own values, rather than rely on external, socially imposed codes of morality. Objectivism Ayn Rand's Objectivism regards every human as an independent, sovereign entity that possesses an inalienable right to their own life, a right derived from their nature as a rational being. Individualism and Objectivism hold that a civilized society, or any form of association, cooperation or peaceful coexistence among humans, can be achieved only on the basis of the recognition of individual rights — and that a group, as such, has no rights other than the individual rights of its members. The principle of individual rights is the only moral base of all groups or associations. Since only an individual man or woman can possess rights, the expression "individual rights" is a redundancy (which one has to use for purposes of clarification in today's intellectual chaos), but the expression "collective rights" is a contradiction in terms. Individual rights are not subject to a public vote; a majority has no right to vote away the rights of a minority; the political function of rights is precisely to protect minorities from oppression by majorities (and the smallest minority on earth is the individual).[8][9]  |

哲学 個人は群衆から際立つかもしれないし、群衆に溶け込むかもしれない。 仏教 仏教では、個人の概念はアートマン(無我)にある。アートマンによると、個人は実際には一連の相互接続されたプロセスであり、それらが一緒に働くことで、 単一の分離された全体であるかのように見える。このように、アートマンはアニッカとともに、一種の束理論に似ている。現実とは異なる原子的で不可分な自己 の代わりに、仏教における個人は、絶えず変化する無常な宇宙の相互に関連する部分として理解される(相互依存、非二元論、互恵を参照)。 経験主義 12世紀初頭のイスラム・スペインのイブン・トゥファイル[4]や17世紀後半のイギリスのジョン・ロックのような経験主義者は、個人をタブラ・ラサ (「白紙」)とみなし、生まれながらにして経験と教育によって形成されると考えた。これは個人の自由と権利、理性的な個人間の社会契約としての社会、そし て教義としての個人主義の始まりという考え方に結びついている。 ヘーゲル ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルは、歴史とは、外界に対して自らの概念をテストする際の、心の段階的な進化であると考えた[5]。個人は 自分自身の特定の視点[6]を超えるようになり、家族、社会的文脈、政治的秩序に縛られている限りにおいて、自分がより大きな全体[7]の一部であること を把握する。 実存主義 実存主義の台頭とともに、セーレン・キルケゴールは、歴史の力に従属する個人というヘーゲルの概念を否定した。その代わりに、彼は個人の主体性と自らの運 命を選択する能力を高めた。後の実存主義者たちは、この考え方を基礎とした。例えば、フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、権力への意志とユーベルメンシュの英雄的 理想の概念において、個人が自己と状況を定義する必要性を検討している。個人はまた、個人の真正性、責任、自由意志を強調するサルトルの哲学の中心でもあ る。サルトルとニーチェの両者(そしてニコライ・ベルジャエフ)において、個人は社会的に押し付けられた道徳規範に依存するのではなく、自らの価値観を創 造するよう求められている。 目的論 アイン・ランドの目的論は、すべての人間を、自らの人生に対する不可侵の権利、すなわち理性的存在としての本性に由来する権利を有する、独立した主権的存 在とみなす。個人主義と目的論は、文明社会、あるいは人間同士のあらゆる形態の連合、協力、平和的共存は、個人の権利の承認に基づいてのみ達成されるもの であり、そのような集団は、その構成員の個人の権利以外の権利を有しないとする。個人の権利の原則は、すべての集団や団体の唯一の道徳的基盤である。権利 を所有できるのは個人の男性または女性だけであるため、「個人の権利」という表現は冗長である(今日の知的混沌の中では、明確化のために使わざるを得な い)が、「集団の権利」という表現は矛盾している。権利の政治的機能とは、まさに多数派による抑圧から少数派を守ることである(そして地球上で最小の少数 派は個人である)[8][9]。  |

| Action theory Autonomy Consciousness Cultural identity Identity Independent Individual time trial Person Self (philosophy) Self (psychology) Self (sociology) Self (spirituality) Structure and agency Will (philosophy) |

行動理論 自律 意識 文化的アイデンティティ アイデンティティ 自立 個人のタイムトライアル 個人 自己(哲学) 自己(心理学) 自己(社会学) 自己(スピリチュアリティ) 構造と主体性 意志(哲学) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Individual |

|

| A person (pl.: people or

persons, depending on context) is a being who has certain capacities or

attributes such as reason, morality, consciousness or

self-consciousness, and being a part of a culturally established form

of social relations such as kinship, ownership of property, or legal

responsibility.[1][2][3][4] The defining features of personhood and,

consequently, what makes a person count as a person, differ widely

among cultures and contexts.[5][6] In addition to the question of personhood, of what makes a being count as a person to begin with, there are further questions about personal identity and self: both about what makes any particular person that particular person instead of another, and about what makes a person at one time the same person as they were or will be at another time despite any intervening changes. The plural form "people" is often used to refer to an entire nation or ethnic group (as in "a people"), and this was the original meaning of the word; it subsequently acquired its use as a plural form of person. The plural form "persons" is often used in philosophical and legal writing. |

人あるいは人格(複数形:peopleまたはpersons、文脈によ

る)とは、理性、道徳、意識、自己意識などの特定の能力や属性を持ち、親族関係、財産所有、法的責任などの文化的に確立された社会関係の一部である存在で

ある。[1][2][3][4] 人格の定義となる特徴、そして結果的に人を人として数えるものは、文化や文脈によって大きく異なる。[5][6] そもそも人間とは何かという問題に加え、個人のアイデンティティや自己についてもさらに疑問が残る。特定の個人を他の誰でもないその個人たらしめているも のは何か、また、その個人が別の時間において、その間に変化があったにもかかわらず、ある時点ではある特定の個人であり、また別の時点では別の個人である ようにしているものは何か、という疑問である。 複数形の「people」は、国民や民族全体を指す場合にもよく用いられる(「a people」のように)。これはこの単語の本来の意味であり、後に「person」の複数形としての用法が生まれた。複数形の「persons」は、哲 学や法律の文章でよく用いられる。 |

Personhood An abstract painting of a person by Paul Klee. The concept of a person can be very challenging to define. Main article: Personhood The criteria for being a person... are designed to capture those attributes which are the subject of our most humane concern with ourselves and the source of what we regard as most important and most problematical in our lives. — Harry G. Frankfurt Personhood is the status of being a person. Defining personhood is a controversial topic in philosophy and law, and is closely tied to legal and political concepts of citizenship, equality, and liberty. According to common worldwide general legal practice, only a natural person or legal personality has rights, protections, privileges, responsibilities, and legal liability. Personhood continues to be a topic of international debate, and has been questioned during the abolition of slavery and the fight for women's rights, in debates about abortion, fetal rights, and in animal rights advocacy.[7][6] Various debates have focused on questions about the personhood of different classes of entities. Historically, the personhood of women, and slaves has been a catalyst of social upheaval. In most societies today, postnatal humans are defined as persons. Likewise, certain legal entities such as corporations, sovereign states and other polities, or estates in probate are legally defined as persons.[8] However, some people believe that other groups should be included; depending on the theory, the category of "person" may be taken to include or not pre-natal humans or such non-human entities as animals, artificial intelligences, or extraterrestrial life. |

人格 パウル・クレーによる人物の抽象画。 人格の概念を定義することは非常に難しい。 詳細は「人格」を参照 人格であるための基準は、私たちが自分自身に対して最も人間らしい関心を抱く対象であり、私たちの生活において最も重要かつ最も問題となるものとしてみな すものの源である、それらの属性を捉えるように設計されている。 — ハリー・G・フランクフルト 人格とは、人としての地位である。人格の定義は哲学や法律の分野で議論の的となっており、法や政治における市民権、平等、自由の概念と密接に関連してい る。世界的な一般的な法律実務では、自然人または法人格のみに権利、保護、特権、責任、法的責任がある。人格は国際的な議論のテーマであり続け、奴隷制度 廃止や女性の権利獲得の闘い、中絶や胎児の権利に関する議論、動物愛護の主張の中で疑問視されてきた。 さまざまな議論が、異なるクラスの実体の人格に関する疑問に焦点を当ててきた。歴史的に、女性や奴隷の人格は社会の激変のきっかけとなってきた。今日で は、ほとんどの社会において、出生後の人間は「人」として定義されている。同様に、法人、主権国家、その他の政治体、または遺言検認における財産などの特 定の法人も、法的に「人」として定義されている。[8] しかし、一部の人々は、他のグループも含まれるべきだと考えている。理論によっては、「人」のカテゴリーには出生前の人間や、動物、人工知能、地球外生命 体などの非人間的存在も含まれる場合と含まれない場合がある。 |

Personal identity What does it take for individuals to persist from moment to moment – or in other words, for the same individual to exist at different moments? Main article: Personal identity Personal identity is the unique identity of persons through time. That is to say, the necessary and sufficient conditions under which a person at one time and a person at another time can be said to be the same person, persisting through time. In the modern philosophy of mind, this concept of personal identity is sometimes referred to as the diachronic problem of personal identity. The synchronic problem is grounded in the question of what features or traits characterize a given person at one time. Identity is an issue for both continental philosophy[citation needed] and analytic philosophy.[citation needed] A key question in continental philosophy is in what sense we can maintain the modern conception of identity, while realizing many of our prior assumptions about the world are incorrect.[citation needed] Proposed solutions to the problem of personal identity include continuity of the physical body, continuity of an immaterial mind or soul, continuity of consciousness or memory,[9] the bundle theory of self,[10] continuity of personality after the death of the physical body,[11] and proposals that there are actually no persons or selves who persist over time at all.[citation needed] |

個人の同一性 個人が瞬間から瞬間へと存続する、つまり異なる瞬間に同一の個人が存在するためには何が必要だろうか? 詳細は「個人の同一性」を参照 個人の同一性とは、時間を通じての個人の唯一無二の同一性である。つまり、ある時点での個人と別の時点での個人が、時間を通じて同一人物であると言えるた めの必要十分条件である。現代の心の哲学では、この個人の同一性の概念は、個人の同一性の通時的問題として言及されることがある。共時的問題は、ある時点 での個人を特徴づける特徴や特性が何であるかという疑問に基づいている。 アイデンティティは、大陸哲学[要出典]と分析哲学[要出典]の両方における問題である。大陸哲学における重要な問題は、世界に関する我々の多くの前提が 誤っていることを認識しながら、どのような意味で我々はアイデンティティの現代的概念を維持できるかということである。[要出典] 個人の同一性に関する問題の解決策として提案されているものには、肉体の連続性、非物質的な心や魂の連続性、意識や記憶の連続性[9]、自己の束理論 [10]、肉体の死後の人格の連続性[11]、そして、時間的に持続する個人や自己は実際には存在しないという提案などがある[要出典]。 |

| Development of the concept In ancient Rome, the word persona (Latin) or prosopon (πρόσωπον; Ancient Greek) originally referred to the masks worn by actors on stage. The various masks represented the various "personae" in the stage play.[12] The concept of person was further developed during the Trinitarian and Christological debates of the 4th and 5th centuries in contrast to the word nature.[13] During the theological debates, some philosophical tools (concepts) were needed so that the debates could be held on common basis to all theological schools. The purpose of the debate was to establish the relation, similarities and differences between the logos (Ancient Greek: Λóγος, romanized: Lógos/Verbum) and God. The philosophical concept of person arose, taking the word "prosopon" (Ancient Greek: πρόσωπον, romanized: prósōpon) from the Greek theatre. Therefore, the logos (the Ancient Greek: Λóγος, romanized: Lógos/Verbum), which was identified with the Christ, was defined as a "person" of God. This concept was applied later to the Holy Ghost, the angels and to all human beings. Trinitarianism holds that God has three persons. Since then, a number of important changes to the word's meaning and use have taken place, and attempts have been made to redefine the word with varying degrees of adoption and influence. According to Jörg Noller, at least six approaches can be distinguished: 1. "The ontological definition of the person as "an individual substance of a rational nature" (Boethius). 2. The self-consciousness-based definition of the person as a being that "can conceive itself as itself" (John Locke). 3. The moral-philosophical definition of the person as "an end in itself" (Immanuel Kant). In current analytical debate, the focus has shifted to the relationship between bodily organism and person. 4. The theory of animalism (Eric T. Olson) states that persons are essentially animals and that mental or psychological attributes play no role in their identity. 5. Constitution theory (Lynne Baker), on the other hand, attempts to define the person as a natural and at the same time self-conscious being: the bodily organism constitutes the person without being identical to it. Rather, it forms with it a "unity without identity". 6. [... Another idea] for conceiving the natural-rational unity of the person has emerged recently in the concept of the "person life" (Marya Schechtman)."[14] Other theories attribute personhood to those states that are viewed to possess intrinsic or universal value. Value theory attempts to capture those states that are universally considered valuable by their nature, allowing one to assign the concept of personhood upon those states. For example, Chris Kelly argues that the value that is intuitively bestowed upon humans, their possessions, animals, and aspects of the natural environment is due to a value monism known as "richness." Richness, Kelly argues, is a product of the "variety" and the "unity" within an entity or agent. According to Kelly, human beings and animals are morally valued and entitled to the status of persons because they are complex organisms whose multitude of psychological and biological components are generally unified towards a singular purpose in any moment, existing and operating with relative harmony.[15] Primus defines people exclusively as their desires, whereby desires are states which are sought for arbitrary or nil purpose(s). Primus views that desires, by definition, are each sought as ends in and of themselves and are logically the most precious (valuable) states that one can conceive. Primus distinguishes states of desire (or 'want') from states which are sought instrumentally, as a means to an end (on the basis of perceived 'need'). Primus' approach can thus be contrasted to Kant's moral-philosophical definition of a person: whereas Kant's second formulation of the categorical imperative states that rational beings must never be treated merely as a means to an end and that they must also always be treated as an end, Primus offers that the aspects that humans (and some animals) desire, and only those aspects, are ends, by definition.[16] |

概念の展開 古代ローマでは、ペルソナ(ラテン語)またはプロソポン(πρόσωπον;古代ギリシャ語)という言葉は、もともと舞台で俳優が着用する仮面を指してい た。さまざまな仮面は、舞台劇におけるさまざまな「ペルソナ」を表していた。 パーソナ(person)という概念は、4世紀から5世紀にかけての三位一体論やキリスト論の論争の中で、さらに発展した。これは、言葉の本質 (nature)に対するものである。神学論争においては、すべての神学派に共通する基盤の上で論争を行うために、いくつかの哲学的なツール(概念)が必 要とされた。論争の目的は、ロゴス(古代ギリシア語:Λóγος、ローマ字表記:Lógos/Verbum)と神の関係、類似点、相違点を明らかにするこ とであった。ギリシア演劇から「prosopon」(古代ギリシア語:πρόσωπον、ローマ字表記:prósōpon)という語を取り入れた「人」と いう哲学概念が生まれた。したがって、キリストと同一視されていたロゴス(古代ギリシャ語:Λóγος、ローマ字表記:Lógos/Verbum)は、神 の「人」として定義された。この概念は後に聖霊、天使、そして全人類にも適用されるようになった。三位一体説では、神には3つの位格があるとされる。 それ以来、この言葉の意味と用法には多くの重要な変化が起こり、この言葉を再定義する試みも行われてきたが、その採用と影響力には程度の差がある。イェル ク・ノラー(Jörg Noller)によると、少なくとも6つのアプローチに区別できるという。 1. 「人間とは、理性的な本質を持つ個々の実体である」という存在論的な定義(ボエティウス)。 2. 「自己を自己として認識できる存在」という自己意識に基づく定義(ジョン・ロック)。 3. 「人間とは、それ自体が目的である」という道徳哲学的な定義(イマニュエル・カント)。現在の分析的議論では、焦点は身体と人間の関係に移っている。 4. アニマリズム(Eric T. Olson)の理論では、人間は本質的には動物であり、精神や心理的特性はアイデンティティには何ら影響しないと主張する。 5. 一方、憲法理論(Lynne Baker)では、人間を自然かつ同時に自己意識を持つ存在として定義しようとする。身体は人間を構成するが、同一ではない。むしろ、身体は人間と「同一 性なき統一」を形成する。 6. [... もう一つの考え方として、] 自然と理性の統一という観点から人間を捉える考え方が、最近「人格の生命」という概念(マリア・シェヒトマン)として登場している。 他の理論では、本質的または普遍的な価値を持つと見なされる状態に人格を帰属させている。価値理論は、本質的に普遍的に価値があると見なされる状態を捉え ようとするものであり、それらの状態に人格の概念を割り当てることができる。例えば、クリス・ケリーは、人間、所有物、動物、自然環境の側面に対して直観 的に与えられる価値は、「豊かさ」と呼ばれる価値一元論によるものであると主張している。ケリーは、豊かさは、実体または作用体における「多様性」と「統 一性」の産物であると主張している。ケリーによれば、人間と動物は道徳的に価値があり、人格者としての地位を認められるのは、それらが複雑な有機体であ り、その多数の心理学的および生物学的構成要素が、あらゆる瞬間において単一の目的に向かって概ね統一され、相対的な調和を保ちながら存在し、機能してい るからである。 プリムスは、人間をその欲求のみによって定義する。すなわち、欲求とは、任意の目的または目的なしに求められる状態である。プリムスは、定義上、欲求はそ れぞれそれ自体が目的として求められるものであり、論理的には人が考え得る中で最も貴重(価値がある)な状態であると考える。プリムスは、欲求の状態(ま たは「欠乏」)を、手段として求められる状態(「必要性」として認識されるもの)とは区別する。したがって、プリムスのアプローチは、カントの道徳哲学的 な人間定義とは対照的である。カントの定言命法の第二の定式化では、理性的存在は決して単なる手段として扱われるべきではなく、常に目的としても扱われな ければならないとされているが、プリムスは、人間(および一部の動物)が望む側面、そしてそれらの側面のみが、定義上、目的であると主張している。 [16] |

| Animal liberation Animal rights Anthropocentrism Anthropology Beginning of human personhood Being Capitis deminutio Character Consciousness Corporate personhood Great Ape personhood Human Hypostasis (philosophy and religion) Identity Individual Immanuel Kant Juridical person Legal personality Legal fiction Natural person in French law People Person (Catholic canon law) Personality Personhood movement Personoid Phenomenology Subject (philosophy) Surety Theory of mind Value Theory |

動物解放 動物権利 人間中心主義 人類学 人間としての始まり 存在 capitis deminutio 性格 意識 法人格 大型類人猿の人格 人間 下位概念(哲学および宗教 同一性 個人 イマヌエル・カント 法人 法人格 法的虚構 フランス法における自然人 人々 人(カトリック教会法) 人格 人格運動 ペルソノイド 現象学 主語(哲学) 保証人 心の理論 価値理論 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Person |

|

| Cornelia J. de Vogel (1963). The

Concept of Personality in Greek and Christian Thought. In Studies in

Philosophy and the History of Philosophy. Vol. 2. Edited by J. K. Ryan,

Washington: Catholic University of America Press. pp. 20– Grant, Patrick. Personalism and the Politics of Culture. New York: St Martin's Press 1996. ISBN 031216176X Grant, Patrick. Spiritual Discourse and the Meaning of Persons. New York: St Martin's Press 1994. ISBN 031212077X Grant, Patrick. Literature and Personal Values. London: MacMillan 1992. ISBN 1-349-22116-3 Lukes, Steven; Carrithers, Michael; Collins, Steven, eds. (1987). The Category of the Person: Anthropology, Philosophy, History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27757-4. Puccetti, Roland (1968). Persons: A Study of Possible Moral Agents in the Universe. London: Macmillan and Company. Stephens, William O. (2006). The Person: Readings in Human Nature. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-184811-5. Korfmacher, Carsten (May 29, 2006). "Personal Identity". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 2011-03-09. Jörg Noller (2019). Person. In: Thomas Kirchhoff (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg: https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66403. Eric T. Olson (2019). "Personal Identity". In: Edward N. Zalta (ed.): The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2019 Edition). |

コーネリア・J・デ・フォーゲル(1963年)。ギリシャとキリスト教

思想における人格の概念。哲学と哲学史研究。第2巻。J. K. ライアン編、ワシントン:アメリカ・カトリック大学出版。20ページ グラント、パトリック。個人主義と文化の政治。ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス、1996年。ISBN 031216176X グラント、パトリック著『スピリチュアル・ディスコースと人格の意味』ニューヨーク:セント・マーティンズ・プレス、1994年。ISBN 031212077X グラント、パトリック著『文学と個人的価値』ロンドン:マクミラン、1992年。ISBN 1-349-22116-3 Lukes, Steven; Carrithers, Michael; Collins, Steven, eds. (1987). The Category of the Person: Anthropology, Philosophy, History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-27757-4. Puccetti, Roland (1968). Persons: A Study of Possible Moral Agents in the Universe. London: Macmillan and Company. Stephens, William O. (2006). The Person: Readings in Human Nature. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson. ISBN 978-0-13-184811-5. Korfmacher, Carsten (2006年5月29日). 「Personal Identity」. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. 2011年3月9日閲覧。 Jörg Noller (2019). 人格. In: Thomas Kirchhoff (ed.): Online Encyclopedia Philosophy of Nature / Online Lexikon Naturphilosophie. Heidelberg, Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg: https://doi.org/10.11588/oepn.2019.0.66403. エリック・T・オルソン (2019) 「人格の同一性」 エドワード・N・ザルタ(編)『スタンフォード哲学事典』(2019年秋版)。 |

****

| Personhood

is the status of being a person. Defining personhood is a controversial

topic in philosophy and law and is closely tied with legal and

political concepts of citizenship, equality, and liberty. According to

law, only a legal person (either a natural or a juridical person) has

rights, protections, privileges, responsibilities, and legal

liability.[1] Personhood continues to be a topic of international debate and has been questioned critically during the abolition of human and nonhuman slavery, in debates about abortion and in fetal rights and/or reproductive rights, in animal rights activism, in theology and ontology, in ethical theory, and in debates about corporate personhood, and the beginning of human personhood.[2] In the 21st century, corporate personhood is an existing Western concept; granting non-human entities personhood, which has also been referred to a "personhood movement", can bridge Western and Indigenous legal systems.[3] Processes through which personhood is recognized socially and legally vary cross-culturally, demonstrating that notions of personhood are not universal. Anthropologist Beth Conklin has shown how personhood is tied to social relations among the Wari' people of Rondônia, Brazil.[4] Bruce Knauft's studies of the Gebusi people of Papua New Guinea depict a context in which individuals become persons incrementally, again through social relations.[5] Likewise, Jane C. Goodale has also examined the construction of personhood in Papua New Guinea.[6] |

人格とは、人としての地位である。人格の定義は、哲学や法律の分野で議論の的となるトピックであり、法的な概念や政治的な概念である市民権、平等、自由と密接に関連している。法律上、権利、保護、特権、責任、法的責任を有するのは、法人(自然人または法人)のみである。 人格は国際的な議論のテーマであり続け、人間および人間以外の奴隷制度の廃止、中絶に関する議論、胎児の権利および/または生殖に関する権利、動物愛護活 動、神学および存在論、倫理理論、法人格に関する議論 。21世紀において、法人格は西洋の概念であり、非人間的存在に人格を付与する「人格化運動」は、西洋と先住民の法体系を橋渡しすることができる。 人格が社会的に、また法的にどのように認められるかは文化によって異なり、人格の概念が普遍的ではないことを示している。人類学者のベス・コンクリンは、 ブラジルのロンドニア州に住むワリ族の人格が社会関係とどのように結びついているかを示している。[4] また、ブルース・ナウフトによるパプアニューギニアのゲブシ族の研究では、個人が徐々に人格を持つようになる過程が、やはり社会関係を通じて描かれてい る。[5] 同様に、ジェーン・C・グッドールもパプアニューギニアにおける人格の形成について調査している。[6] |

| In

philosophy, the word "person" may refer to various concepts. The

concept of personhood is difficult to define in a way that is

universally accepted, due to its historical and cultural variability

and the controversies surrounding its use in some contexts. Capacities

or attributes common to definitions of personhood can include human

nature, agency, self-awareness, a notion of the past and future, and

the possession of rights and duties, among others.[7] Boethius, a philosopher of the early 6th century CE, gives the definition of "person" as "an individual substance of a rational nature" ("Naturæ rationalis individua substantia").[8] According to the naturalist epistemological tradition, from Descartes through Locke and Hume, the term may designate any human or non-human agent who possesses continuous consciousness over time; and is therefore capable of framing representations about the world, formulating plans and acting on them.[9] According to Charles Taylor, the problem with the naturalist view is that it depends solely on a "performance criterion" to determine what is an agent. Thus, other things (e.g. machines or animals) that exhibit "similarly complex adaptive behaviour" could not be distinguished from persons. Instead, Taylor proposes a significance-based view of personhood: What is crucial about agents is that things matter to them. We thus cannot simply identify agents by a performance criterion, nor assimilate animals to machines... [likewise] there are matters of significance for human beings which are peculiarly human, and have no analogue with animals. — Charles Taylor, "The Concept of a Person"[10] Relatedly, Martin Heidegger developed his understanding of the distinctive kind of being which a person is as Dasein. The term's literal means an existence as a "being-there" or "there-being." Heidegger writes that, "Dasein itself has a special distinctiveness as compared with other entities; [...] it is ontically distinguished by the fact that, in its very Being, that Being is an issue for it."[11] For Heidegger, the way in which Being is an issue for a person as Dasein is their future oriented caring. This distinguishes Dasein from function or performance criteria of personhood. Others also dispute functional criteria of personhood, such as philosopher Francis J. Beckwith, who argues that it is rather the underlying personal unity of the individual: What is crucial morally is the being of a person, not his or her functioning. A human person does not come into existence when human function arises, but rather, a human person is an entity who has the natural inherent capacity to give rise to human functions, whether or not those functions are ever attained. ...A human person who lacks the ability to think rationally (either because she is too young or she suffers from a disability) is still a human person because of her nature. Consequently, it makes sense to speak of a human being’s lack if and only if she is an actual person. — Francis Beckwith, "Abortion, Bioethics, and Personhood: A Philosophical Reflection"[12] This belief in the underlying unity of an individual is a metaphysical and moral[13] belief referred to as the substance view of personhood.[14] Philosopher J. P. Moreland clarifies this point: It is because an entity has an essence and falls within a natural kind that it can possess a unity of dispositions, capacities, parts and properties at a given time and can maintain identity through change. — J. P Moreland, "James Rachels and the Active Euthanasia Debate"[15] Harry Frankfurt writes that, in reference to a definition by P. F. Strawson, "What philosophers have lately come to accept as analysis of the concept of a person is not actually analysis of that concept at all." He suggests that the concept of a person is intimately connected to free will, and describes the structure of human volition according to first- and second-order desires: Besides wanting and choosing and being moved to do this or that, [humans] may also want to have (or not to have) certain desires and motives. They are capable of wanting to be different, in their preferences and purposes, from what they are. Many animals appear to have the capacity for what I shall call "first-order desires" or "desires of the first order," which are simply desires to do or not to do one thing or another. No animal other than man, however, appears to have the capacity for reflective self-evaluation that is manifested in the formation of second-order desires. — Harry G. Frankfurt, "Freedom of the Will and the Concept of a Person"[16] The criteria for being a person... are designed to capture those attributes which are the subject of our most humane concern with ourselves and the source of what we regard as most important and most problematical in our lives. — Harry G. Frankfurt[17] According to Nikolas Kompridis, there might also be an intersubjective, or interpersonal, basis to personhood: What if personal identity is constituted in, and sustained through, our relations with others, such that were we to erase our relations with our significant others we would also erase the conditions of our self-intelligibility? As it turns out, this erasure... is precisely what is experimentally dramatized in the “science fiction” film, Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, a far more philosophically sophisticated meditation on personal identity than is found in most of the contemporary literature on the topic. — Nikolas Kompridis, "Technology's Challenge to Democracy: What of the Human?"[18] Mary Midgley defines a "person" as being a conscious, thinking being, which knows that it is a person (self-awareness). She also wrote that the law can create persons.[19] Philosopher Thomas I. White argues that the criteria for a person are: is alive, is aware, feels positive and negative sensations, has emotions, has a sense of self, (controls its own behaviour, recognises other persons and treats them appropriately, and has a variety of sophisticated cognitive abilities. While many of White's criteria are somewhat anthropocentric, some animals such as dolphins would still be considered persons.[20] Some animal rights groups have also championed recognition for animals as "persons".[21] Another approach to personhood, Paradigm Case Formulation, used in descriptive psychology and developed by Peter Ossorio, involves the four interrelated concepts of 1) The Individual Person, 2) Deliberate Action, 3) Reality and the Real World, and 4) Language or Verbal Behavior. All four concepts require full articulation for any one of them to be fully intelligible. More specifically, a Person is an individual whose history is, paradigmatically, a history of Deliberate Action in a Dramaturgical pattern. Deliberate Action is a form of behavior in which a person (a) engages in an Intentional Action, (b) is cognizant of that, and (c) has chosen to do that. A person is not always engaged in a deliberate action but has the eligibility to do so. A human being is an individual who is both a person and a specimen of Homo sapiens. Since persons are deliberate actors, they also employ hedonic, prudent, aesthetic and ethical reasons when selecting, choosing or deciding on a course of action. As part of our "social contract" we expect that the typical person can make use of all four of these motivational perspectives. Individual persons will weigh these motives in a manner that reflects their personal characteristics. That life is lived in a "dramaturgical" pattern is to say that people make sense, that their lives have patterns of significance. The paradigm case allows for nonhuman persons, potential persons, nascent persons, manufactured persons, former persons, "deficit case" persons, and "primitive" persons. By using a paradigm case methodology, different observers can point to where they agree and where they disagree about whether an entity qualifies as a person.[22][23] |

哲学において、「人格」という言葉

はさまざまな概念を指すことがある。人格の概念は、歴史的および文化的な多様性や、文脈によってはその使用をめぐる論争があるため、普遍的に受け入れられ

る定義を定めることは難しい。人格の定義に共通する能力や属性には、人間性、行動、自己認識、過去と未来の概念、権利と義務の保有などがある。 西暦6世紀初頭の哲学者ボエティウスは、「人格」を「理性を有する個々の実体」と定義している(「Naturæ rationalis individua substantia」)。 自然主義的認識論の伝統によれば、デカルトからロック、ヒュームに至るまで、この用語は、時間的に連続した意識を持つ人間または非人間的な作用者を指し、したがって、世界についての表現を構築し、計画を立て、それに基づいて行動することが可能である。 チャールズ・テイラーによると、自然主義的な見解の問題点は、それが「パフォーマンス基準」のみに依存して、何が主体であるかを決定していることである。 したがって、「同様に複雑な適応行動」を示す他のもの(例えば機械や動物)は、人格と区別することができない。代わりに、テイラーは、意味に基づく人格観 を提案している。 エージェントにとって重要なのは、物事が彼らにとって重要であるということである。したがって、私たちは単純にパフォーマンス基準によってエージェントを 識別することはできないし、動物と機械を同一視することもできない。同様に、人間にとって重要な事柄には、動物には類似するものがない、人間特有のものが ある。 —チャールズ・テイラー、『人格の概念』[10] 関連して、マルティン・ハイデガーは、人格がダーザイン(現存在)として存在するという独自の理解を展開した。この用語の文字通りの意味は、「そこに存在 する」あるいは「存在するそこ」としての存在である。ハイデガーは、「現存在それ自体は、他の実体と比較して特別な独自性を持っている。[...] その存在の本質において、その存在がそのものにとっての問題であるという事実によって、存在論的に区別される」と書いている。[11] ハイデガーにとって、現存在としての人がその存在を問題とする方法は、未来志向の思いやりである。これが、現存在を人格の機能やパフォーマンスの基準と区 別するものである。 また、哲学者フランシス・J・ベックウィズのように、人格の機能的基準を疑問視する者もいる。ベックウィズは、むしろ個人の根底にある個人的な統一性こそが重要であると主張している。 道徳的に重要なのは、その人の存在であって、その人の機能ではない。人間としての機能が生じるからといって、人間としての存在が生まれるわけではない。む しろ、人間としての機能が生じるかどうかに関わらず、人間としての機能を生み出す自然に備わった能力を持つ存在が人間である。... 合理的に考える能力を欠く人間(幼すぎるか、障害を抱えているため)であっても、その本質から人間であることに変わりはない。したがって、人間が実際に存 在する場合にのみ、その欠如について語ることに意味がある。 —フランシス・ベックウィズ、「中絶、生命倫理、人格:哲学的考察」[12] この個人の根底にある統一性に関する信念は、人格の実体論的・道徳的信念[13]であり、人格の実体論的見解[14]と呼ばれるものである。 哲学者のJ. P. モアランドは、この点を次のように明確にしている。 実体が本質を持ち、自然種に属しているからこそ、ある時点で性質、能力、部分、および特性の統一性を持ち、変化を経験しながらも同一性を維持することができるのである。 — J. P. モアランド、「ジェームズ・レイチェルズと積極的安楽死の議論」[15] ハリー・フランクフルトは、P. F. ストローソンの定義を参照しながら、「哲学者たちが最近、人格の概念の分析として受け入れ始めたものは、実際にはその概念の分析とはまったく言えない」と 書いている。彼は、人格の概念は自由意志と密接に関連していると示唆し、第一および第二の欲求に従って人間の意志の構造を次のように説明している。 人間は、あれがしたい、これがしたい、そうしたい、そうしたくないと思うだけでなく、特定の欲求や動機を持ちたい(あるいは持ちたくない)と思うこともあ る。人間は、自分の好みや目的において、今とは異なる存在になりたいと思うこともできる。多くの動物は、私が「第一級の欲求」または「第一級の欲求」と呼 ぶ能力を持っているように見える。これは、単に何かをしたい、あるいは何かをしたくないという欲求である。しかし、人間以外の動物には、2次的な欲求の形 成に現れるような、自己を反省的に評価する能力はないように見える。 — ハリー・G・フランクフルト、『自由意志と人格概念』[16] 人格であるための基準は...、自分自身に対する最も人間的な関心の対象であり、人生において最も重要かつ最も問題となるものとしてみなすものの源である、それらの属性を捉えるように設計されている。 — ハリー・G・フランクフルト[17] ニコラス・コンプリディスによると、人格には相互主観的、つまり対人関係的な基盤もあるかもしれない。 もし個人のアイデンティティが他者との関係性によって構成され、維持されているとしたら、重要な他者との関係を消し去ることは、自己理解の条件をも消し去 ることになるのではないか?結論から言えば、この消去こそが、まさに「SF」映画『エターナル・サンシャイン』で実験的にドラマ化されているものであり、 このテーマに関する現代の文学作品の多くよりもはるかに哲学的に洗練された人格の考察である。 —ニコラス・コンプリディス、「テクノロジーが民主主義に突きつける課題:人間はどうなるのか」[18] メアリー・ミドゲリーは、「人格」を、意識を持ち、思考する存在であり、自分が人格であることを認識している存在(自己認識)と定義している。彼女はまた、法律によって人格が創出される可能性もあると述べている。[19] 哲学者のトーマス・I・ホワイトは、人格の基準として、生きていること、意識があること、ポジティブな感覚とネガティブな感覚を感じること、感情があるこ と、自己認識があること(自身の行動を制御し、他者を認識し、適切に扱うこと)、そして高度な認知能力をさまざまに備えていることを挙げている。ホワイト の基準の多くは、やや人間中心主義的であるが、イルカなどの一部の動物は依然として人格者とみなされる。[20] 動物愛護団体の中には、動物に「人格」を認めることを主張する団体もある。[21] 人格に関するもう一つのアプローチである「パラダイムケースの形成」は、記述心理学で用いられ、ピーター・オソリオによって開発されたもので、相互に関連 する4つの概念、すなわち、1)個人、2)意図的な行動、3)現実と現実の世界、4)言語または言語行動、を含んでいる。4つの概念すべてが完全に理解さ れるためには、それぞれが完全に明確にされなければならない。より具体的には、人格とは、その歴史がドラマツルギーのパターンにおける意図的行動の歴史で ある個人のことである。意図的行動とは、(a) 意図的行動に従事し、(b) それを認識し、(c) それを選択する行動様式である。人格は常に意図的行動に従事しているわけではないが、そうする資格を有している。人間とは、人格とホモ・サピエンスの標本 である個人のことである。人格は熟慮した行動を取るため、行動を選択、決定する際には快楽的理由、慎重な理由、審美的な理由、倫理的理由も用いる。「社会 契約」の一部として、典型的な人間はこれら4つの動機づけの観点すべてを活用できると期待されている。個々の人格は、これらの動機を、その人格の特性を反 映する形で評価する。人生が「ドラマツルギー的」パターンで生きられるということは、人々が意味を見出し、その人生に意義のあるパターンがあるということ である。典型的な事例では、非人間的存在、潜在的存在、初期段階にある存在、人工的に作られた存在、元存在、欠損事例の存在、および「原始的」存在が想定 される。典型事例の方法論を用いることで、異なる観察者は、ある実体が人格として認められるかどうかについて、同意する点と反対する点を指摘することがで きる。[22][23] |

| Research As an application of social psychology and other disciplines, phenomena such as the perception and attribution of personhood have been scientifically studied.[24][25] Typical questions addressed in social psychology are the accuracy of attribution, processes of perception and the formation of bias. Various other scientific and medical disciplines address the myriad of issues in the development of personality. |

研究 社会心理学やその他の学問分野の応用として、人格の知覚や帰属などの現象が科学的に研究されてきた。[24][25] 社会心理学で扱われる典型的な問題は、帰属の正確さ、知覚のプロセス、偏りの形成などである。人格の形成に関する無数の問題については、さまざまな科学や 医学の分野で研究されている。 |

| Unborn Ireland In 1983, the people of Ireland added the Eighth Amendment to their constitution that "acknowledges the right to life of the unborn and, with due regard to the equal right to life of the mother, guarantees in its laws to respect, and, as far as practicable, by its laws to defend and vindicate that right." This was repealed in 2018 by the Thirty-sixth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland. United States A person is recognized by law as such, not because they are human, but because rights and duties are ascribed to them. The person is the legal subject or substance of which the rights and duties are attributes. An individual human being considered to be having such attributes is what lawyers call a "natural person".[26] According to Black's Law Dictionary,[27] a person is: In general usage, a human being (i.e. natural person), though by statute term may include a firm, labor organizations, partnerships, associations, corporations, legal representatives, trustees, trustees in bankruptcy, or receivers. In Federal law, the concept of legal personhood is formalized by statute (1 USC § 8) to include "every infant member of the species homo sapiens who is born alive at any stage of development." That statute also states that "Nothing in this section shall be construed to affirm, deny, expand, or contract any legal status or legal right applicable to any member of the species homo sapiens at any point prior to being 'born alive' as defined in this section." According to the National Conference of State Legislatures,[28] many US States have their own definition of personhood which expands upon the federal definition of personhood, and Webster v. Reproductive Health Services declined to overturn the state of Missouri's law stating that The life of each human being begins at conception ... Effective January 1, 1988, the laws of this state shall be interpreted and construed to acknowledge on behalf of the unborn child at every stage of development, all the rights, privileges, and immunities available to other persons, citizens, and residents of this state, unborn children have protectable interests in life, health, and well-being. The beginning of human personhood is a concept long debated by religion and philosophy. With respect to the abortion debate, personhood is the status of a human being having individual human rights. The term was used by Justice Blackmun in Roe v. Wade.[29] Personhood protest in front of the United States Supreme Court A political movement in the United States seeks to define the beginning of human personhood as starting from the moment of fertilization with the result being that abortion, as well as forms of birth control that act to deprive the human embryo of necessary sustenance in implantation, could become illegal.[30][31] Supporters of the movement also state that it would have some effect on the practice of in-vitro fertilization (IVF), but would not lead to the practice being outlawed.[32] Jonathan F. Will says that the personhood framework could produce significant restrictions on IVF to the extent that reproductive clinics find it impossible to provide the services.[33] Currently, the personhood movement is led by the Personhood Alliance, a coalition of state and national personhood organizations headquartered in Washington DC. The Personhood Alliance was founded in 2014 and currently has 22 affiliated organizations.[34] A significant number of the state affiliates of the Personhood Alliance were once affiliates of National Right to Life. Organizations like Georgia Right to Life,[35] Cleveland Right to Life, and Alaska Right to Life left National Right to Life and joined the Personhood Alliance after refusing to support National Right to Life's proposed legislation that included exceptions like the rape and incest exceptions. The Personhood Alliance describes itself as "a Christ-centered, biblically informed organization dedicated to the non-violent advancement of the recognition and protection of the God-given, inalienable right to life of all human beings as legal persons, at every stage of their biological development and in every circumstance."[36] A precursor to the Personhood Alliance was Personhood USA, a Colorado-based umbrella group with a number of state-level affiliates,[37] which describes itself as a nonprofit Christian ministry.[38] and seeks to ban abortion.[39] Personhood USA was co-founded by Cal Zastrow and Keith Mason[40] in 2008 following the Colorado for Equal Rights campaign to enact a state constitutional personhood amendment.[41] Proponents of the movement regard personhood as an attempt to directly challenge the Roe v. Wade U.S. Supreme Court decision, thus filling a legal void left by Justice Harry Blackmun in the majority opinion when he wrote: "If this suggestion of personhood is established, the appellant's case, of course, collapses, for the fetus' right to life would then be guaranteed specifically by the Amendment."[29] Some medical organizations have described the potential effects of personhood legislation as potentially harmful to patients and the practice of medicine, particularly in the cases of ectopic and molar pregnancy.[42] Susan Bordo has suggested that the focus on the issue of personhood in abortion debates has often been a means for depriving women of their rights. She writes that "the legal double standard concerning the bodily integrity of pregnant and nonpregnant bodies, the construction of women as fetal incubators, the bestowal of 'super-subject' status to the fetus, and the emergence of a father's-rights ideology" demonstrate "that the current terms of the abortion debate – as a contest between fetal claims to personhood and women's right to choose – are limited and misleading."[43] Others, such as Colleen Carroll Campbell, say that the personhood movement is a natural progression of society in protecting the equal rights of all members of the human species. She writes, "The basic philosophical premise behind these [personhood] amendments is eminently reasonable. And the alternative on offer – which severs humanity from personhood – is fraught with peril. If being human is not enough to entitle one to human rights, then the very concept of human rights loses meaning. And all of us – born and unborn, strong and weak, young and old – someday will find ourselves on the wrong end of that cruel measuring stick."[44] Father Frank Pavone agrees, adding, "Nor is this a dispute about the state imposing a religious or philosophical view. After all, your life and mine are not protected because of some religious or philosophical belief that others are required to have about us. More accurately, the law protects us precisely in spite of the beliefs of others who, in their own worldview, may not value our lives. …To support Roe vs. Wade is not merely to allow a medical procedure. It is to acknowledge that the government has the power to say who is a person and who is not. Who, then, is to limit the groups to whom it is applied? This is what makes "personhood" such an important public policy issue.[45] In March 2007 Georgia became the first state in the nation to introduce a legislative resolution to amend the state constitution to define and recognize the personhood of fetuses.[46] The Georgia Catholic Conference and National Right to Life supported the effort. The resolution failed to attract the super majority in both chambers required for it to be placed on the ballot.[47] Georgia legislators have filed a personhood resolution every session since 2007.[48][49][50] In May 2008 Georgia Right to Life hosted the first nationwide Personhood Symposium targeting anti-abortion activists.[51] This symposium was instrumental in spawning the group Personhood USA and the various state personhood efforts that followed. Voters in 46 Georgia counties approved personhood during the 2010 primary election with 75% in favor of a non-binding resolution declaring that the "right to life is vested in each human being from their earliest biological beginning until natural death".[52] During the 2012 Republican primary a similar question was placed on the ballot statewide and passed with a super-majority (66%) of the vote in 158 of 159 counties.[53] In the summer of 2008 a citizen initiated amendment was proposed for the Colorado constitution.[54] Three attempts to enact the from-fertilization definition of personhood into U.S. state constitutions via referendums have failed.[55] Following two attempts to enact similar changes in Colorado in 2008 and 2010, a 2011 initiative to amend the state constitution by referendum in the state of Mississippi also failed to gain approval with around 58% of voters disapproving.[55][56] In an interview after the referendum, Mason ascribed the failure of the initiative to a political campaign run by Planned Parenthood.[57] Personhood proponents in Oklahoma sought to amend the state constitution to define personhood as beginning at conception. The state Supreme Court, citing the U.S. Supreme Court's 1992 decision in Planned Parenthood v. Casey, ruled in April 2012 that the proposed amendment was unconstitutional under the federal Constitution and blocked inclusion of the referendum question on the ballot.[58] In October 2012, the U.S. Supreme Court declined to hear an appeal of the state Supreme Court's ruling.[59] In 2006, a 16-year-old girl was charged in Mississippi with murder for the still-birth of her daughter on the basis that the girl had smoked cocaine while pregnant.[60] These charges were later dismissed.[61] In February 2024, the Supreme Court of Alabama ruled that frozen embryos were "extrauterine children" subject to the Wrongful Death of a Minor Act, based on protections for unborn children in the state constitution[62][63] These protections were added in 2018 by ballot referendum, as Amendment 930 to the Alabama Constitution of 1901, and gained relevance when the 2022 U.S. Supreme Court decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization returned full control over regulation of abortion to the states.[64] The concurring decision of Justice Tom Parker cited Christian theology to support the decision, raising complaints about separation of church and state[65] Vatican The Vatican has advanced a human exceptionalist understanding of personhood. Catechism 2270 reads: "Human life must be respected and protected absolutely from the moment of conception. From the first moment of his existence, a human being must be recognized as having the rights of a person – among which is the inviolable right of every innocent being to life."[66] |

胎児 アイルランド 1983年、アイルランド国民は憲法に第8条を追加し、「胎児の生命に対する権利を認め、母親の生命に対する平等な権利を十分に考慮した上で、法律によっ てその権利を尊重し、また法律によって可能な限りその権利を擁護し、正当性を主張することを保証する」と定めた。これは2018年にアイルランド憲法の第 36条によって廃止された。 アメリカ合衆国 人は、人間であるからという理由ではなく、権利と義務が与えられるからこそ、法律によって人格として認められる。 人格とは、権利と義務が帰属する法的主体または実体である。 このような属性を持つとみなされる個々の人間は、法律家が「自然人」と呼ぶものである。[26] Black's Law Dictionaryによると、[27] 人格とは、 一般的な用法では、人間(すなわち自然人)を指すが、法令上の用語としては、会社、労働組合、パートナーシップ、協会、法人、法定代理人、受託者、破産管財人、または管財人を含む場合もある。 連邦法では、法人格の概念は法令(1 USC § 8)によって「生存して生まれたホモ・サピエンスの幼児」を含むように正式に規定されている。その法令には、「本条のいかなる規定も、本条で定義された 『生存して生まれた』以前のいかなる時点においても、ホモ・サピエンスの種に属するいかなる個人にも適用される法的地位または法的権利を、肯定、否定、拡 大、または縮小するものと解釈されてはならない」とも記載されている。 全米州議会議員会議によると、[28] 多くの米国の州では、連邦政府の人格の定義を拡大した独自の定義を定めている。Webster v. Reproductive Health Servicesは、ミズーリ州法を覆すことを拒否し、 人間の生命は受胎の瞬間から始まる... 1988年1月1日より、この州の法律は、胎児が発育のあらゆる段階において、この州の他の市民や居住者が有するすべての権利、特権、および免除を認める ように解釈および解釈されるものとする。胎児には、生命、保健、および幸福において保護されるべき利益がある。 人間としての人格の始まりは、宗教や哲学において長い間議論されてきた概念である。中絶の是非をめぐる議論において、人格とは個人の人権を有する人間の地位を指す。この用語は、ロー対ウェイド訴訟においてブラックマン判事によって使用された。[29] 米国連邦最高裁判所前での「人格」抗議活動 米国では、人間の「人格」の始まりを受精の瞬間と定義する政治運動が展開されており、その結果、中絶や、着床に必要な栄養を人間の胚から奪う避妊方法が違 法となる可能性がある。[30][31] この運動の支持者らは、 体外受精(IVF)の実施に何らかの影響を与える可能性はあるが、実施が違法化されることはないだろうと述べている。[32] ジョナサン・F・ウィルは、人格の枠組みによって体外受精に重大な制限が課され、生殖医療クリニックがサービスを提供できなくなる可能性があると述べてい る。[33] 現在、人格運動はワシントンD.C.に本部を置く州および国民の人格団体連合である「Personhood Alliance(人格同盟)」が主導している。2014年に設立された「Personhood Alliance」には現在、22の関連団体がある。[34] 「Personhood Alliance」の州レベルの関連団体の多くは、かつて「National Right to Life」の関連団体であった。「Georgia Right to Life」[35]、「Cleveland Right to Life」、「Alaska Right to Life」などの団体は、「National Right to Life」の提案した法案への支持を拒否した後、「Personhood Alliance」に参加した。この法案には、レイプや近親姦の例外規定が含まれていた。Personhood Allianceは、自らを「キリスト中心で聖書に精通した団体であり、生物学的発達段階のあらゆる段階において、またあらゆる状況下において、法的な人 格として神から与えられ、譲渡不可能な生命の権利を、非暴力で認識し、保護することに専念している」と説明している。[36] Personhood Allianceの前身は、コロラド州を拠点とする傘下団体を多数有する連合体Personhood USAである。[37] 自身をキリスト教系の非営利団体と称し、[38] 中絶の禁止を求めている。[39] Personhood USAは、2008年にコロラド州の平等権キャンペーンに続いて、州憲法に人格権修正条項を制定するために、Cal ZastrowとKeith Masonによって共同設立された。[40] この運動の推進派は、この運動を「ロー対ウェイド事件」の連邦最高裁判決に直接対抗する試みとみなしており、ハリー・ブラックマン判事が多数意見の中で 「もしこの『人格』の提案が認められれば、もちろん、上訴人の訴えは潰える。なぜなら、胎児の生命に対する権利は、この修正案によって明確に保証されるこ とになるからだ」と述べたことによって生じた法的な空白を埋めるものだと考えている。 一部の医療団体は、胎児の人格権法が患者や医療行為に有害な影響を及ぼす可能性があると指摘している。特に、子宮外妊娠や胞状奇胎の場合にその可能性が高いとされている。[42] スーザン・ボルドは、中絶に関する議論で人格権の問題に焦点を当てることは、しばしば女性から権利を奪う手段として用いられてきたと指摘している。彼女 は、「妊娠中と妊娠していない女性の身体の完全性に関する法的な二重基準、女性を胎児の保育器として見る考え方、胎児に『超主体』の地位を与えること、父 親の権利を主張するイデオロギーの出現」は、「中絶に関する議論の現状、すなわち胎児の人格に対する主張と女性の選択の権利との対立という形での議論は限 定的で誤解を招くものである」ことを示していると書いている。 コリーン・キャロル・キャンベル(Colleen Carroll Campbell)のような人々は、人権運動は人類のすべての構成員の平等な権利を保護する社会の自然な発展であると主張している。彼女は次のように書い ている。「これらの(人権)修正条項の背後にある基本的な哲学的前提は極めて合理的である。そして、人権から人間性を切り離すという代替案は危険をはらん でいる。人間であるというだけでは人権を享受する資格がないのであれば、人権という概念そのものが意味を失うことになる。そして、生まれてきた者も生まれ てくるべき者も、強い者も弱い者も、若者も年長者も、いずれは自分たちがその残酷な物差しによって不当に扱われていることに気づくだろう。」[44] フランク・パヴォーネ神父も同意見で、さらに次のように付け加えている。「これは、州が宗教的または哲学的見解を押し付けることに関する論争でもない。結 局のところ、私たちや私の人生が保護されているのは、他人が私たちについて持つべきだという宗教的あるいは哲学的信念があるからではない。より正確に言え ば、法律は、自分たちの世界観において私たちの命を尊重しないかもしれない他人の信念にもかかわらず、私たちを守っているのだ。... ロー対ウェイドを支持することは、単に医療処置を許可することではない。それは、政府には誰が人格者で誰がそうでないかを決定する権限があることを認める ことである。では、その適用対象を誰が制限するのか? これが「人格」が重要な公共政策問題となる理由である。[45] 2007年3月、ジョージア州は胎児の人格を定義し、それを認める州憲法改正の立法決議案を国民で初めて提出した。[46] ジョージア・カトリック会議と全米生命権協会がこの取り組みを支持した。この決議案は、投票にかけるために必要な両院での3分の2以上の賛成を得ることが できなかった。[47] ジョージア州の議員たちは、2007年以降、毎回の議会で「人間性」決議案を提出している。[48][49][50] 2008年5月には、ジョージア州の反中絶活動家を対象とした初の全国的な「人間性」シンポジウムがジョージア州の「生命の権利」によって主催された。 [51] このシンポジウムは、グループ「人間性 USA」や、それに続くさまざまな州の「人間性」の取り組みを生み出すきっかけとなった。2010年の予備選挙では、ジョージア州の46郡の有権者が、拘 束力のない決議案として「生命に対する権利は、生物学的誕生から自然死を迎えるまで、各人間に与えられている」という内容のものを75%の賛成多数で承認 した 。[52] 2012年の共和党予備選挙では、同様の質問が州全体の投票用紙に記載され、159郡中158郡で賛成票が66%を占め可決された。[53] 2008年夏には、コロラド州憲法の改正案が市民によって提案された。[54] 受精卵を「人」と定義する条項を米国の州憲法に住民投票で盛り込もうとする試みが3度行われたが、いずれも失敗している。[55] 2008年と2010年にコロラド州で同様の改正案が2度提出されたが、 2011年にはミシシッピ州でも住民投票による州憲法改正の試みが行われたが、有権者の約58%が反対票を投じ、承認を得ることはできなかった。[55] [56] 住民投票後のインタビューでメイソンは、このイニシアティブの失敗は、家族計画連盟による政治キャンペーンのせいだと述べた。[57] オクラホマ州では、妊娠の瞬間から「人」と定義するよう州憲法を改正しようとする動きがあった。オクラホマ州最高裁は、1992年の連邦最高裁の 「Planned Parenthood v. Casey」判決を引用し、2012年4月に、この憲法改正案は連邦憲法に反するとして違憲判決を下し、住民投票の実施を阻止した。[58] 2012年10月、連邦最高裁は州最高裁の判決に対する上訴を受理しないことを決定した。[59] 2006年、ミシシッピ州で16歳の少女が、妊娠中にコカインを吸引したことを理由に、死産した自身の娘の殺人容疑で起訴された。[60] これらの容疑は後に却下された。[61] 2024年2月、アラバマ州最高裁判所は、州憲法における胎児の保護を根拠に、凍結胚は「子宮外の子供」であり、未成年者の不法死亡法の対象であるとの判 決を下した[62][63]。これらの保護は、2018年の投票による住民投票で、1901年アラバマ州憲法の修正第930条として追加されたものであり 。2022年の米国最高裁判所によるDobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organizationの判決により、中絶の規制に関する完全な管理権が州に戻されたことで、この保護規定の重要性が高まった。[64] トム・パーカー判事の同意判決では、キリスト教神学を引用してこの判決を支持し、政教分離に関する苦情が寄せられた。[65] バチカン バチカンは、人間を例外的な人格として理解する立場を推進している。カテキズム2270には次のように書かれている。「人間の生命は受胎の瞬間から絶対的 に尊重され、保護されなければならない。存在の最初の瞬間から、人間は人格としての権利を有することが認められなければならない。その中には、いかなる無 実の存在にも侵すことのできない生命に対する権利が含まれる」[66] |

| Women In the United States, the personhood of women has important legal consequences. Although in 1920 the 19th Amendment guaranteed women in the right to vote, it was not until 1971 that the US Supreme Court ruled in Reed v. Reed[67] that the law cannot discriminate between the sexes because the 14th amendment grants equal protection to all "persons".[68][69] In 2011, Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia disputed the conclusion of Reed v. Reed, arguing that women do not have equal protection under the 14th amendment as "persons"[70][71] because the Constitution's use of the gender-neutral term "Person" means that the Constitution does not require discrimination on the basis of sex, but also does not prohibit such discrimination, adding "Nobody ever thought that that's what it meant. Nobody ever voted for that."[72] Many others, including law professor Jack Balkin disagree with this assertion. Balkin states that, at a minimum "the fourteenth amendment was intended to prohibit some forms of sex discrimination – discrimination in basic civil rights against single women."[73] Many local marriage laws at the time the 14th Amendment was ratified (as well as when the original Constitution was ratified) had concepts of coverture and "head-and-master", which meant that women legally lost rights upon marriage, including rights to ownership of property and other rights of adult participation in the political economy; single women retained these rights, however, and voted in some jurisdictions. Other commentators have noted that some of the ratifiers of the US Constitution (in 1787) also, in contemporaneous contexts, ratified state level Constitutions that saw women as Persons and required them to be treated as such, including granting women rights such as the right to vote.[74][75] Professor Jane Calvert argues that the 17th and 18th Century Quaker concept of Personhood applied to women, and the prevalence of Quakers in the population of several colonies, such as New Jersey and Pennsylvania, at the time that the original Constitution was drafted and ratified likely influenced the choice of the term "Person" for the Constitution instead of the term "Man", which was used in the Declaration of Independence and in the contemporaneously drafted French Constitution of 1791.[76] The personhood of women also has consequences for the ethics of abortion. For example, in "A Defense of Abortion", Judith Jarvis Thomson argues that one person's right to bodily autonomy trumps another's right to life, and therefore abortion does not violate a fetus's right to life: Instead abortion should be understood as the pregnant women withdrawing her own body from use, which causes the fetus to die.[77] Questions pertaining to the personhood of women and the personhood of fetuses have legal and ethical consequences for reproductive rights beyond abortion as well. For example, some fetal homicide laws have resulted in jail time for women suspected of drug use during a pregnancy that ended in a miscarriage, like one Alabama woman who was sentenced to ten years.[78] |

女性 米国では、女性の法的地位は重要な法的影響をもたらす。1920年に19条修正が女性の選挙権を保証したものの、米国最高裁が1971年のリード対リード 事件[67]において、14条修正がすべての人格に平等な保護を保証しているため、法律は性別による差別をしてはならないと裁定を下すまでは、そうした状 況が続いていた[68][69]。2011年、最高裁判事のアントニン・スカリアは Scaliaは、女性は「人」として憲法修正第14条による平等な保護を受けていないと主張し、Reed v. Reedの結論に異議を唱えた。[70][71] 憲法が性別に関係のない「人」という用語を使用しているのは、憲法が性別に基づく差別を要求していないが、そのような差別を禁止していないことも意味して いる。「誰もそんな意味だと思ったことはない。誰もそんなことを考えたことはないし、誰もそんなことを投票で選んだこともない」と主張している。[72] 法律学教授のジャック・バルキンをはじめ、この主張に反対する意見も多い。 バルキンは、少なくとも「第14修正条項は、ある種の性差別、つまり独身女性に対する基本的な市民権における差別を禁止することを意図していた」と述べて いる。[73] 第14修正条項が批准された当時(および当初の憲法が批准された当時も)、多くの地域の結婚法には 結婚により女性は法的権利を失うことを意味し、財産の所有権や政治経済への成人としての参加権なども含まれていた。しかし、独身女性はこれらの権利を保持 しており、一部の管轄区域では投票権もあった。 他の論者たちは、1787年の米国憲法批准者の中には、同時代の文脈において、女性を「人格」として認め、投票権などの権利を付与し、そのように扱うこと を求める州レベルの憲法も批准していたことを指摘している。[74][75] ジェーン・カルヴァート教授は、17世紀と18世紀のクエーカー教徒の 人格の概念を女性にも適用し、また、独立宣言や同時期に起草された1791年のフランス憲法で使用されていた「男性」という用語ではなく、「人」という用 語が憲法で使用されることになったのは、憲法が起草・批准された当時、ニュージャージーやペンシルベニアなどいくつかの植民地でクエーカー教徒が人口に占 める割合が高かったことが影響している可能性があると、ジェーン・カルヴァート教授は主張している。 女性の「人格」は、中絶の倫理にも影響を及ぼす。例えば、ジュディス・ジャヴィス・トムソンは著書『中絶の擁護』の中で、ある人物の身体の自律に対する権 利は、他の人物の生命に対する権利よりも優先されるべきであり、したがって中絶は胎児の生命に対する権利を侵害するものではないと主張している。むしろ、 中絶とは、妊娠した女性が自分の身体を胎児の成長に利用しないことを意味し、それによって胎児が死に至るのである。 女性の尊厳と胎児の尊厳に関する問題は、中絶以外の生殖に関する権利についても、法的および倫理的な影響を及ぼす。例えば、流産に至った妊娠中に薬物を使用した疑いのある女性に対して実刑判決が下された例もある。アラバマ州のある女性は10年の実刑判決を受けた。[78] |

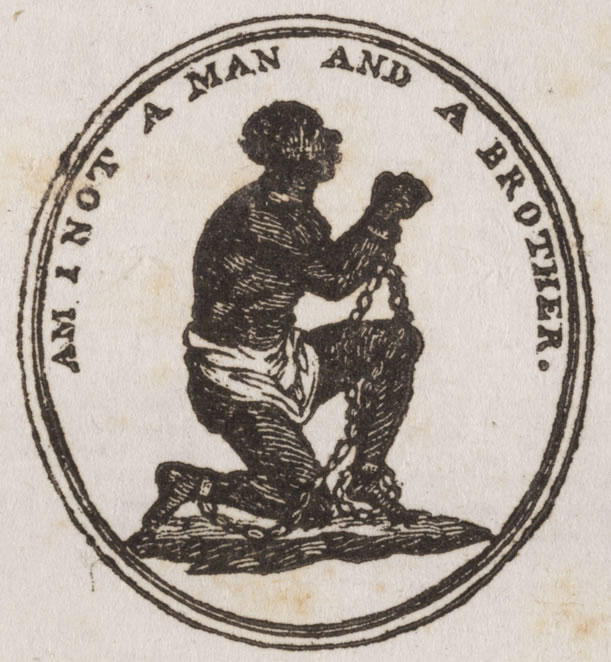

Slavery Am I not a man emblem used during the campaign to abolish slavery In 1772, Somersett's Case determined that slavery was unsupported by law in England and Wales, but not elsewhere in the British Empire. In 1868, under the 14th Amendment, black men in the United States became citizens. In 1870, under the 15th Amendment, black men got the right to vote. In 1853, Sojourner Truth became famous for asking Ain't I a Woman? and after slavery was abolished, black men continued to fight for personhood by claiming, I Am A Man!. |

奴隷制度 「私は人間ではないのか?」というスローガンは、奴隷制度廃止運動のキャンペーンで使用された 1772年、サマセット事件により、奴隷制度はイングランドおよびウェールズでは法律で支持されていないが、それ以外の英領では支持されていると判断され た。1868年、修正第14条により、米国の黒人男性は市民権を得た。1870年、修正第15条により、黒人男性に選挙権が与えられた。 1853年、ソジャーナ・トゥルースは「私は女ではないのか?」と問いかけたことで有名になった。奴隷制度が廃止された後、黒人男性は「私は男だ!」と主張し、市民権獲得のために戦い続けた。 |

| Original peoples The legal definition of "person" has excluded indigenous peoples in some countries.[example needed] Children The legal definition of persons may include or exclude children depending on the context. The US Born-Alive Infants Protection Act of 2002 provides a legal structure that those born at any gestational stage that are either breathing, have heartbeat, umbilical cord pulsation, or any voluntary muscle movement are living, individual human persons.[79] Disabled Adults with cognitive disabilities are regularly denied rights generally granted to all adult persons such as the right to marry and consent to sex,[80] and the right to vote. They may also lack legal competence. Philosophical arguments have been made against the cognitively disabled being able to have moral agency.[81] In many countries, including the US, psychiatric illness can be cited to imprison an adult without due process. Those who become disabled later in life often experience a change in how they are perceived, including others infantilizing them or assuming cognitive disability due to the existence of physical disability.[82] The concept of disability as being worse than death can be seen as a denial of disabled people's personhood, such as when medical professionals suggest euthanasia to non-suicidal disabled patients.[83] |

先住民 「人格」の法的定義は、いくつかの国々では先住民を除外している。[要出典] 子供 文脈によっては、法的定義における「人格」に子供を含める場合と除外する場合がある。2002年の米国「出生時生存児保護法」は、妊娠のどの段階で生まれ たとしても、呼吸、心拍、臍帯の脈動、随意筋運動のいずれかが見られる場合は、生存している個々の人間として扱うという法的構造を規定している。[79] 障害を持つ 成人 認知障害を持つ成人は、結婚する権利や性行為への同意[80]、投票する権利など、一般的に成人に認められている権利を定期的に否定されている。また、法 的責任能力を欠く場合もある。 認知障害を持つ成人が道徳的責任能力を持つことができるかについては、哲学的な議論がなされている。[81] 米国を含む多くの国々では、精神疾患を理由に適正手続きを経ずに成人を投獄することがある。 人生の後半で障害を持つようになった人々は、他人から子供扱いされたり、身体障害の存在によって認知障害があると決めつけられたりするなど、周囲の受け止 め方に変化が生じることが多い。[82] 障害は死よりも悪いという考え方は、医療関係者が自殺願望のない障害患者に安楽死を勧めるなど、障害者の人格を否定するものとして捉えられることがある。 [83] |

| Non-human animals See also: Great ape personhood Some philosophers and those involved in animal welfare, ethology, the rights of animals, and related subjects, consider that certain or even all animals should also be considered to be persons and thus granted legal personhood. Commonly named species in this context include the apes, cetaceans, parrots, cephalopods, corvids, elephants, bears, pigs, leporids and rodents, because of their apparent intelligence, sentience, and intricate social rules. The idea of extending personhood to all animals has the support of legal scholars such as Alan Dershowitz[84] and Laurence Tribe of Harvard Law School,[85] and animal law courses are (as of 2008) taught in 92 out of 180 law schools in the United States.[86] On May 9, 2008, Columbia University Press published Animals as Persons: Essays on the Abolition of Animal Exploitation by Professor Gary L. Francione of Rutgers University School of Law, a collection of writings that summarizes his work to date and makes the case for non-human animals as persons. Those who oppose personhood for non-human animals are known as human exceptionalists or human supremacists, and more pejoratively speciesists.[87] Other theorists attempt to demarcate between degrees of personhood. For example, Peter Singer's two-tiered account distinguishes between basic sentience and the higher standard of self-consciousness which constitutes personhood. His approach has been criticized for accepting the personhood of some animals, but rejecting the personhood of people with disabilities such as dementia.[88] It has also been given as an example of the limits of a capacities-based definition of personhood, in that they tend to be defined in ways that reinforce existing systems of power and privilege by preferring the capacities that are valued by those who write the definitions.[88] A squirrel would value agility and balance in defining personhood; a tree might grant personhood on the basis of height and longevity, and a long-time academic, "a human being with a fully functioning cerebral cortex who resides in a social context where the workings of this part of the brain are particularly prized", would just as predictably value the qualities that benefited his own life and overlook the ones that had little relationship to his own life.[88] Wynn Schwartz has offered a Paradigm Case Formulation of Persons as a format allowing judges to identify qualities of personhood in different entities.[23][17][89] Julian Friedland has advanced a seven-tiered account based on cognitive capacity and linguistic mastery.[90] Amanda Stoel suggested that rights should be granted based on a scale of degrees of personhood, allowing entities currently denied any right to be recognized some rights, but not as many.[91] In 1992, Switzerland amended its constitution to recognize animals as beings and not things.[92] A decade later, Germany guaranteed rights to animals in a 2002 amendment to its constitution, becoming the first European Union member to do so.[92][93][94] The New Zealand parliament included restrictions on the use of 'non-human hominids'[95] in research or teaching when passing the Animal Welfare Act (1999).[96] In 2007, the parliament of the Balearic Islands, an autonomous province of Spain, passed the world's first legislation granting legal rights to all great apes.[97] In 2013, India's Ministry of Forests and Environment banned the importation or capture of cetaceans (whales and dolphins) for entertainment, exhibition, or interaction purposes, on the basis that "cetaceans in general are highly intelligent and sensitive" and that it "is morally unacceptable to keep them captive for entertainment." It noted that "various scientists" have argued they should be seen as "non-human persons" with commensurate rights, but did not take an official position on this, and indeed did not have the legal authority to do so.[98][99] In 2014, a hybrid, zoo-born orangutan named Sandra was termed by the court in Argentina as a "non-human subject" in an unsuccessful habeas corpus case regarding the release of the orangutan from captivity at the Buenos Aires zoo. The status of the orangutan as a "non-human subject" needed to be clarified by the court. Court cases relevant to this orangutan were continuing in 2015.[100] Finally, in 2019, Sandra was granted nonhuman personhood and freed from captivity to a Florida sanctuary.[citation needed] In 2015, for the first time, two chimpanzees, Hercules and Leo, were thought to be "legal persons", having been granted a writ of habeas corpus. This meant their detainer, Stony Brook University, had to provide a legally sufficient reason for their imprisonment.[101] This view was rejected and the writ was reversed by the officiating judge shortly thereafter.[102] |

人間以外の動物 関連情報:類人猿の人格 一部の哲学者や動物福祉、動物行動学、動物の権利、関連分野に携わる人々は、特定の動物、あるいはすべての動物も人格として認め、法的にも人格として扱わ れるべきであると考えている。一般的にこの文脈で挙げられる種には、類人猿、クジラ、オウム、頭足類、カラス、ゾウ、クマ、ブタ、ウサギ、ネズミなどが含 まれる。これらの動物は、明らかな知性、感覚、複雑な社会規則を持っているためである。すべての動物に人格を認めるという考え方は、ハーバード大学法科大 学院のアラン・ダーショウィッツ[84]やローレンス・トライブ[85]などの法学者から支持されており、動物法の講座は(2008年現在)米国の180 の法科大学院のうち92校で開講されている。[86] 2008年5月9日、コロンビア大学出版局は、 ラトガース大学法学部のゲリー・L・フランシオーネ教授による著作で、同教授のこれまでの研究をまとめたもので、非ヒト動物に人格を認めるべきであるとい う主張を展開している。 非人間動物に人格を認めることに反対する人々は、人間至上主義者または人間優越主義者として知られており、さらに悪く言えば種差別主義者である。 他の理論家は、人格の程度を区別しようとしている。例えば、ピーター・シンガーの2段階のアプローチでは、基本的な感覚と、人格を構成するより高度な自己 意識の基準を区別している。彼の考え方は、一部の動物の人格を認める一方で、認知症などの障害を持つ人々の人格を否定しているとして批判されている。 [88] また、能力に基づく人格の定義には限界があるという例として、定義を定める人々が評価する能力を優先することで、既存の権力や特権のシステムを強化するよ うな定義のされ方になる傾向があるという指摘もある。[88] リスの場合、 敏捷性やバランスを重視するだろう。樹木は高さや寿命を基準に人格を認めるかもしれないし、長年学問を究めた人物は「大脳皮質が完全に機能し、その働きが 特に重んじられる社会環境に存在する人間」と定義するかもしれない。この人物は、自身の人生に役立つ性質を重視し、自身の人生とはほとんど関係のない性質 は見落とすだろう。 ウィン・シュワルツは、異なる実体に人格の特性を特定するフォーマットとして、パラダイム事例の定式化を提示している。[23][17][89] ジュリアン・フリードランドは、認知能力と言語習得能力に基づく7段階のアカウントを提示している。[90] アマンダ・ストールは、人格の程度を段階的に評価し、現在いかなる権利も認められていない実体にも、ある程度の権利を認めるべきであると提案している。た だし、多くの権利を認めるべきではない。[91] 1992年、スイスは憲法を改正し、動物は「物」ではなく「存在」であると認めた。[92] 10年後、ドイツは2002年の憲法改正で動物に権利を保証し、欧州連合(EU)加盟国で初めての国となった。[92][93][94] ニュージーランド議会は、 研究や教育における「非ヒト類人猿」の使用制限を盛り込んだ動物福祉法(1999年)を可決した。[96] 2007年には、スペインの自治州であるバレアレス諸島の議会が、世界で初めて類人猿に法的権利を認める法律を可決した。[97] 2013年、インドの森林環境省は、「鯨類は一般的に非常に知能が高く、感受性も強い」こと、および「娯楽目的で捕獲することは道徳的に容認できない」こ とを理由に、娯楽、展示、または交流目的での鯨類(クジラとイルカ)の捕獲または輸入を禁止した。「さまざまな科学者」が、クジラやイルカはそれにふさわ しい権利を持つ「非人間的人格」としてみなされるべきだと主張していることを指摘したが、この件について公式な立場は示さず、実際、そうする法的権限も 持っていなかった。[98][99] 2014年、ブエノスアイレス動物園で飼育されていたオランウータンのサンドラという名の雑種で動物園生まれのオランウータンが、同動物園での飼育からの 解放を求める人身保護令状請求の裁判で、アルゼンチンの裁判所によって「非人間的存在」とみなされた。このオランウータンの「非人間的存在」としての地位 は、裁判所によって明確にされる必要があった。このオランウータンに関連する裁判は2015年も継続していた。[100] 最終的に2019年、サンドラは非人間としての地位を認められ、フロリダの保護施設に収容されていたがそこから解放された。[要出典] 2015年には、初めて2匹のチンパンジー、ヘラクレスとレオに「法人格」が認められ、人身保護令状が発行された。これにより、彼らの拘束者であるストー ニー・ブルック大学は、彼らを拘束する法的根拠を提示しなければならなくなった。[101] この見解は却下され、その直後に裁判官が人身保護令状を取り消した。[102] |

| Corporations Main articles: Juridical person, Corporate personhood, University, Voluntary association, and Foundation (nonprofit) In statutory and corporate law, certain social constructs are legally considered persons. In many jurisdictions, some corporations and other organizations are considered juridical persons (a subtype of legal persons) with standing to own, possess, enter contracts, as well as to sue or be sued in court, or even to be indicted, in selected jurisdictions. This is known as legal or corporate personhood. In 1819, the US Supreme Court ruled in Dartmouth College v. Woodward, that corporations have the same rights as natural persons to enforce contracts. |

法人 詳細は「法人」、「法人格」、「大学」、「任意団体」、および「財団(非営利)」を参照 会社法や法人法では、特定の社会的構成物が法的に人格としてみなされる。多くの管轄区域では、一部の企業やその他の組織は法人格(法人格のサブタイプ)と してみなされ、所有、保有、契約締結の資格を有し、また、特定の管轄区域では、訴訟を起こしたり、訴訟を起こされたり、起訴されたりすることもある。これ は法人格または企業人格として知られている。 1819年、米国最高裁判所はDartmouth College v. Woodwardの判決で、企業は自然人と同様に契約を執行する権利を有すると裁定した。 |

| Environmental entities Since the new millennium, treating parts of nature like waterways as persons has become increasingly popular. Bolivia In 2006, Bolivia passed a law recognizing the rights of nature "to not be affected by mega-infrastructure and development projects that affect the balance of ecosystems and the local inhabitant communities".[103] Canada In February 2021, the Magpie River (Quebec) became the first river in Canada to be granted legal personhood, after the local municipality of Minganie and the Innu Council of Ekuanitshit passed joint resolutions.[104] The goal is to protect it long-term given its appeal for energy producers like Hydro-Quebec and Innergex Renewable Energy.[105] It has since the right to flow, maintain biodiversity, be free from pollution, and to sue.[3] Colombia In 2016, the Constitutional Court of Colombia granted legal rights to the Rio Atrato; in 2018, the Supreme Court of Colombia granted the Amazon river ecosystem legal rights.[106] Ecuador Main article: Sumac Kawsay In 2008, Ecuador approved a constitution to recognize that nature "...has the right to exist, persist, maintain and regenerate its vital cycles, structure, functions and its processes in evolution."[107] India In 2017, a court in the northern Indian state of Uttarakhand recognized the Ganges and Yamuna as legal persons. The judges cited Whanganui river in New Zealand as precedent for the action.[108] New Zealand The Whanganui River of New Zealand is revered by the local Māori people as Te Awa Tupua, sometimes translated as "an integrated, living whole". Efforts to grant it special legal protection have been pursued by the Whanganui iwi since the 1870s. In 2012, an agreement to grant legal personhood to the river was signed between the New Zealand government and the Whanganui River Māori Trust. One guardian from the Crown and one from the Whanganui are responsible for protecting the river.[109] United States In 2019, the Klamath River has been granted personhood by the Yurok Tribe.[110] Also in February 2019, voters in Toledo, Ohio passed the "Lake Erie Bill of Rights" (LEBOR), which granted personhood rights to Lake Erie.[111] The law was challenged in federal court on constitutional grounds by Drewes Farms Partnership, with the state government of Ohio joining as an intervenor. The law was overturned due to the vagueness of at least three portions of the law, with the court also criticizing the applicability of the law to other Lake Erie-bordering jurisdictions' laws regarding the lake.[112][113] |

環境保護団体 新世紀以降、水路のように自然の一部を人格として扱うことがますます一般的になっている。 ボリビア 2006年、ボリビアは「生態系のバランスや地域住民コミュニティに影響を与える大規模インフラや開発プロジェクトの影響を受けない」という自然の権利を認める法律を可決した。[103] カナダ 2021年2月、ケベック州のカササギ川が、地元自治体ミンガニーとエカンニシット・イヌー評議会による共同決議を経て、カナダで初めて法人格を付与され た川となった。 。その目的は、ハイドロ・ケベックやインナージェックス・リニューアブル・エナジーのようなエネルギー生産者にとって魅力的な存在であるこの川を長期的に 保護することである。[105] それ以来、この川には流れる権利、生物多様性を維持する権利、汚染から免れる権利、訴訟を起こす権利がある。[3] コロンビア 2016年、コロンビアの憲法裁判所はリオ・アトラト川に法的権利を認めた。2018年には、コロンビア最高裁がアマゾン川の生態系に法的権利を認めた。 エクアドル 詳細は「スーマ・カウサイ」を参照 2008年、エクアドルは「自然は...存在し、持続し、維持し、進化の過程におけるその生命のサイクル、構造、機能、プロセスを再生する権利を有する」ことを認める憲法を承認した。 インディアン 2017年、インド北部のウッタラーカンド州の裁判所は、ガンジス川とヤムナー川を法人として認めた。 裁判官は、ニュージーランドのワングヌイ川をこの措置の先例として挙げた。[108] ニュージーランド ニュージーランドのワングヌイ川は、地元のマオリ族の人々によって「統合された、生きている全体」という意味の「テ・アワ・トゥプア」として崇められてい る。1870年代から、ワングヌイ族は、この川に特別な法的保護を与えるための取り組みを進めてきた。2012年には、ニュージーランド政府とワングヌ イ・リバー・マオリ・トラストの間で、この川に法人格を与える合意が締結された。王冠とワングヌイ族からそれぞれ1名ずつ選出された保護者が、この川の保 護を担当している。 アメリカ 2019年、クラマス川はユロック族によって法人格を認められた。[110] 同じく2019年2月、オハイオ州トレドの有権者は「エリー湖権利章典」(LEBOR)を可決し、エリー湖に法人格の権利を認めた。[111] この法律は、ドリューズ・ファームズ・パートナーシップが憲法上の理由で連邦裁判所に提訴し、オハイオ州政府が訴訟参加した。この法律は、少なくとも3つ の条項が曖昧であることを理由に覆された。また、裁判所は、エリー湖に接する他の管轄区域の法律がエリー湖に関する法律に適用できるかどうかについても批 判した。[112][113] |

| Modified humans This section may need to be rewritten to comply with Wikipedia's quality standards, as Most sentences are questions; should be rewritten as statements.. You can help. The talk page may contain suggestions. (February 2024) The theoretical landscape of personhood theory has been altered recently by controversy in the bioethics community concerning an emerging community of scholars, researchers, and activists identifying with an explicitly transhumanist position, which supports morphological freedom, even if a person changed so much as to no longer be considered a member of the human species. For example, how much of a human can be artificially replaced before one loses their personhood? also in the case for cyborgs If people are considered persons because of their brains, then what if the brain's thought patterns, memories and other attributes could be transposed into a device? Would the patient still be considered a person after the operation?[according to whom?] |

改造人間 この節は、ウィキペディアの品質基準に準拠するために、ほとんどの文章が質問であるため、文章として書き直す必要があるかもしれません。 あなたも編集に参加できます。 ノートページには提案が含まれている場合があります。 (2024年2月) 人格論の理論的背景は、最近、明確なトランスヒューマニストの立場を表明する学者、研究者、活動家からなる新興コミュニティに関する生命倫理コミュニティ での論争によって変化した。この立場は、たとえその人物がもはやヒトの種に属するとはみなされないほど変化したとしても、形態学的自由を支持するものであ る。例えば、人工的にどれだけ人間を置き換えると、その人の人格が失われるのだろうか? サイボーグの場合も同様である。 人間が脳を持っているから人格があるとみなされるとすると、脳の思考パターンや記憶、その他の属性が装置に転送されるとしたらどうだろうか? その場合、手術を受けた患者は依然として人格者とみなされるのだろうか?[誰によると?] |

| Hypothetical beings This article's tone or style may not reflect the encyclopedic tone used on Wikipedia. See Wikipedia's guide to writing better articles for suggestions. (February 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Speculatively, there are several other likely categories of beings where personhood is at issue.[23] Aliens If alien life were found to exist, under what circumstances would they be counted as "persons"? Do we have to consider any "willing and communicative (capable to register its own will) autonomous body" in the universe, no matter the species, an individual (a person)? Do they deserve equal rights with the human race? Artificial intelligence or life See also: Ethics of artificial intelligence § Robot rights If artificial intelligences, intelligent and self-aware system of hardware and software, are eventually created, what criteria would determine their personhood? Likewise, at what point would human-created biological life achieve personhood? Digital technologies have been argued to hold the potential to give rise to notions of posthumous personhood, where the digital remains of the dead are reanimated through artificial intelligence and allow the dead to maintain interactions with the living. If they were to closely resemble a person in its interaction with others, they could be considered persons.[114][115] |

仮説上の存在 この記事のトーンやスタイルは、ウィキペディアで使用される百科事典的なトーンやスタイルを反映していない可能性がある。ウィキペディアでより良い記事を 書くためのガイドを参照。 (2024年2月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください) 推測上、人格が問題となる可能性のある存在のカテゴリーは他にもいくつかある。[23] 宇宙人 もし宇宙生命体が存在することが判明した場合、どのような状況下で「人」として数えられるのだろうか? 宇宙の「意思を持ち、意思疎通が可能な(自身の意思を登録できる)自律的な存在」は、その種に関わらず、すべて個人(人)としてみなさなければならないの だろうか? それらは人類と平等な権利を持つに値するのだろうか? 人工知能または生命 参照:人工知能の倫理 § ロボットの権利 もし、ハードウェアとソフトウェアからなる知能と自己認識能力を備えた人工知能がいずれ誕生したとしたら、その人格を決定する基準は何であろうか? 同様に、人間が作り出した生物生命が人格を獲得する時点とはいつであろうか? デジタル技術は、死者のデジタル上の痕跡が人工知能によって蘇り、死者と生者の交流を可能にするという、死後の人格概念を生み出す潜在的可能性を持つと主 張されている。もし、死者と生者の交流が、死者と生者の交流と極めて類似している場合、死者を人格とみなすことができる。[114][115] |