情報・インフォメーション

Information

☆情報(Information)とは、情報を与える力を持つものを指す抽象的な概念である。最も基本的なレベルでは、知覚されたもの、あるいはその抽象化されたものを(おそらく形式 的に)解釈することに関係する。完全にランダムでない自然のプロセスや、あらゆる媒体における観察可能なパターンは、ある程度の情報を伝えると言える。デ ジタル信号やその他のデータが情報を伝達するために離散的な符号を使用するのに対し、アナログ信号、詩、絵、音楽やその他の音、潮流などのその他の現象や 人工物は、より連続的な形で情報を伝達する[1]。情報とは知識そのものではなく、解釈を通じて表現から導き出される可能性のある意味である[2]。

| Information

is an abstract concept that refers to something which has the power to

inform. At the most fundamental level, it pertains to the

interpretation (perhaps formally) of that which may be sensed, or their

abstractions. Any natural process that is not completely random and any

observable pattern in any medium can be said to convey some amount of

information. Whereas digital signals and other data use discrete signs

to convey information, other phenomena and artifacts such as analogue

signals, poems, pictures, music or other sounds, and currents convey

information in a more continuous form.[1] Information is not knowledge

itself, but the meaning that may be derived from a representation

through interpretation.[2] The concept of information is relevant or connected to various concepts,[3] including constraint, communication, control, data, form, education, knowledge, meaning, understanding, mental stimuli, pattern, perception, proposition, representation, and entropy. Information is often processed iteratively: Data available at one step are processed into information to be interpreted and processed at the next step. For example, in written text each symbol or letter conveys information relevant to the word it is part of, each word conveys information relevant to the phrase it is part of, each phrase conveys information relevant to the sentence it is part of, and so on until at the final step information is interpreted and becomes knowledge in a given domain. In a digital signal, bits may be interpreted into the symbols, letters, numbers, or structures that convey the information available at the next level up. The key characteristic of information is that it is subject to interpretation and processing. The derivation of information from a signal or message may be thought of as the resolution of ambiguity or uncertainty that arises during the interpretation of patterns within the signal or message.[4] Information may be structured as data. Redundant data can be compressed up to an optimal size, which is the theoretical limit of compression. The information available through a collection of data may be derived by analysis. For example, a restaurant collects data from every customer order. That information may be analyzed to produce knowledge that is put to use when the business subsequently wants to identify the most popular or least popular dish.[citation needed] Information can be transmitted in time, via data storage, and space, via communication and telecommunication.[5] Information is expressed either as the content of a message or through direct or indirect observation. That which is perceived can be construed as a message in its own right, and in that sense, all information is always conveyed as the content of a message. Information can be encoded into various forms for transmission and interpretation (for example, information may be encoded into a sequence of signs, or transmitted via a signal). It can also be encrypted for safe storage and communication. The uncertainty of an event is measured by its probability of occurrence. Uncertainty is proportional to the negative logarithm of the probability of occurrence. Information theory takes advantage of this by concluding that more uncertain events require more information to resolve their uncertainty. The bit is a typical unit of information. It is 'that which reduces uncertainty by half'.[6] Other units such as the nat may be used. For example, the information encoded in one "fair" coin flip is log2(2/1) = 1 bit, and in two fair coin flips is log2(4/1) = 2 bits. A 2011 Science article estimates that 97% of technologically stored information was already in digital bits in 2007 and that the year 2002 was the beginning of the digital age for information storage (with digital storage capacity bypassing analogue for the first time).[7] |

情報とは、情報

を与える力を持つものを指す抽象的な概念である。最も基本的なレベルでは、知覚されたもの、あるいはその抽象化されたものを(おそらく形式的に)解釈する

ことに関係する。完全にランダムでない自然のプロセスや、あらゆる媒体における観察可能なパターンは、ある程度の情報を伝えると言える。デジタル信号やそ

の他のデータが情報を伝達するために離散的な符号を使用するのに対し、アナログ信号、詩、絵、音楽やその他の音、潮流などのその他の現象や人工物は、より

連続的な形で情報を伝達する[1]。情報とは知識そのものではなく、解釈を通じて表現から導き出される可能性のある意味である[2]。 情報の概念は、制約、コミュニケーション、制御、データ、形式、教育、知識、意味、理解、精神的刺激、パターン、知覚、命題、表現、エントロピーを含む様々な概念[3]と関連している。 情報はしばしば反復的に処理される: あるステップで利用可能なデータは、次のステップで解釈され処理される情報に加工される。例えば、書かれた文章では、各記号や文字がその一部である単語に 関連する情報を伝え、各単語がその一部である語句に関連する情報を伝え、各語句がその一部である文に関連する情報を伝え......といった具合に、最終 段階で情報が解釈され、与えられた領域の知識になるまで繰り返される。デジタル信号では、ビットは次のレベルで利用可能な情報を伝える記号、文字、数字、 構造に解釈される。情報の主体性は、解釈と処理の対象となることである。 信号やメッセージからの情報の導出は、信号やメッセージ内のパターンの解釈中に生じる曖昧さや不確実性の解決と考えることができる[4]。 情報はデータとして構造化されることがある。冗長なデータは、圧縮の理論的限界である最適サイズまで圧縮することができる。 データの収集によって得られる情報は、分析によって導き出されることがある。例えば、レストランでは客の注文ごとにデータを収集する。その情報を分析することで、最も人気のある料理や最も人気のない料理を特定したい場合に利用できる知識を得ることができる。 情報は、メッセージの内容として、あるいは直接的または間接的な観察を通じて表現される。知覚されるものは、それ自体がメッセージと解釈することができ、その意味で、すべての情報は常にメッセージの内容として伝達される。 情報は、伝達や解釈のために様々な形に符号化することができる(例えば、情報は符号の列に符号化されたり、信号によって伝達されたりする)。また、安全な保管や通信のために暗号化することもできる。 事象の不確実性は、その発生確率によって測定される。不確実性は発生確率の負の対数に比例する。情報理論はこれを利用し、不確実な事象ほど、その不確実性 を解決するために多くの情報を必要とすると結論付けている。ビットは情報の典型的な単位である。これは「不確実性を半分にするもの」である[6]。nat のような他の単位が使われることもある。例えば、1回の「公平な」コ インフリップで符号化される情報はlog2(2/1)=1ビットであり、2回のコ インフリップで符号化される情報はlog2(4/1)=2ビットである。2011年のScience誌の記事によると、技術的に保存された情報の97% は、2007年にはすでにデジタルビットになっており、2002年が情報ストレージのデジタル時代の始まりだった(デジタルストレージの容量が初めてアナ ログを凌駕した)[7]。 |

| Etymology and history of the concept This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages) This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (August 2025) You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (August 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions. The English word "information" comes from Middle French enformacion/informacion/information 'a criminal investigation' and its etymon, Latin informatiō(n) 'conception, teaching, creation'.[8] In English, "information" is an uncountable mass noun. References on "formation or molding of the mind or character, training, instruction, teaching" date from the 14th century in both English (according to Oxford English Dictionary) and other European languages. In the transition from Middle Ages to Modernity the use of the concept of information reflected a fundamental turn in epistemological basis – from "giving a (substantial) form to matter" to "communicating something to someone". Peters (1988, pp. 12–13) concludes: Information was readily deployed in empiricist psychology (though it played a less important role than other words such as impression or idea) because it seemed to describe the mechanics of sensation: objects in the world inform the senses. But sensation is entirely different from "form" – the one is sensual, the other intellectual; the one is subjective, the other objective. My sensation of things is fleeting, elusive, and idiosyncratic. For Hume, especially, sensory experience is a swirl of impressions cut off from any sure link to the real world... In any case, the empiricist problematic was how the mind is informed by sensations of the world. At first informed meant shaped by; later it came to mean received reports from. As its site of action drifted from cosmos to consciousness, the term's sense shifted from unities (Aristotle's forms) to units (of sensation). Information came less and less to refer to internal ordering or formation, since empiricism allowed for no preexisting intellectual forms outside of sensation itself. Instead, information came to refer to the fragmentary, fluctuating, haphazard stuff of sense. Information, like the early modern worldview in general, shifted from a divinely ordered cosmos to a system governed by the motion of corpuscles. Under the tutelage of empiricism, information gradually moved from structure to stuff, from form to substance, from intellectual order to sensory impulses.[9] In the modern era, the most important influence on the concept of information is derived from the Information theory developed by Claude Shannon and others. This theory, however, reflects a fundamental contradiction. Northrup (1993)[10] wrote: Thus, actually two conflicting metaphors are being used: The well-known metaphor of information as a quantity, like water in the water-pipe, is at work, but so is a second metaphor, that of information as a choice, a choice made by :an information provider, and a forced choice made by an :information receiver. Actually, the second metaphor implies that the information sent isn't necessarily equal to the information received, because any choice implies a comparison with a list of possibilities, i.e., a list of possible meanings. Here, meaning is involved, thus spoiling the idea of information as a pure "Ding an sich." Thus, much of the confusion regarding the concept of information seems to be related to the basic confusion of metaphors in Shannon's theory: is information an autonomous quantity, or is information always per SE information to an observer? Actually, I don't think that Shannon himself chose one of the two definitions. Logically speaking, his theory implied information as a subjective phenomenon. But this had so wide-ranging epistemological impacts that Shannon didn't seem to fully realize this logical fact. Consequently, he continued to use metaphors about information as if it were an objective substance. This is the basic, inherent contradiction in Shannon's information theory." (Northrup, 1993, p. 5) In their seminal book The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages,[11] Almach and Mansfield (1983) collected key views on the interdisciplinary controversy in computer science, artificial intelligence, library and information science, linguistics, psychology, and physics, as well as in the social sciences. Almach (1983,[12] p. 660) himself disagrees with the use of the concept of information in the context of signal transmission, the basic senses of information in his view all referring "to telling something or to the something that is being told. Information is addressed to human minds and is received by human minds." All other senses, including its use with regard to nonhuman organisms as well to society as a whole, are, according to Machlup, metaphoric and, as in the case of cybernetics, anthropomorphic. Hjørland (2007) [13] describes the fundamental difference between objective and subjective views of information and argues that the subjective view has been supported by, among others, Bateson,[14] Yovits,[15][16] Span-Hansen,[17] Brier,[18] Buckland,[19] Goguen,[20] and Hjørland.[21] Hjørland provided the following example: A stone on a field could contain different information for different people (or from one situation to another). It is not possible for information systems to map all the stone's possible information for every individual. Nor is any one mapping the one "true" mapping. But people have different educational backgrounds and play different roles in the division of labor in society. A stone in a field represents typical one kind of information for the geologist, another for the archaeologist. The information from the stone can be mapped into different collective knowledge structures produced by e.g. geology and archaeology. Information can be identified, described, represented in information systems for different domains of knowledge. Of course, there are much uncertainty and many and difficult problems in determining whether a thing is informative or not for a domain. Some domains have high degree of consensus and rather explicit criteria of relevance. Other domains have different, conflicting paradigms, each containing its own more or less implicate view of the informativeness of different kinds of information sources. (Hjørland, 1997, p. 111, emphasis in original). |

コンセプトの語源と歴史 このセクションには複数の問題がある。改善するか、トークページで議論してほしい。(これらのメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) この記事は引用が多すぎるか、長すぎる。(2025年8月) ロシア語の対応する記事から翻訳したテキストで、このセクションを拡張するのを手伝うことができる。(2025年8月) [表示]をクリックすると、重要な翻訳指示が表示される。 英語の「information」は中フランス語のenformacion/informacion/information「犯罪捜査」とその語源であるラテン語のinformatiō(n)「構想、教育、創造」に由来する[8]。 英語では、「情報」は不可算の大量名詞である。 心や性格の形成、訓練、指導、教育」については、英語(オックスフォード英語辞典による)でも他のヨーロッパ言語でも14世紀から言及されている。中世か ら近代への移行において、情報という概念の使用は、認識論的基礎の根本的な転換を反映したものであった-「物質に(実質的な)形を与える」から「誰かに何 かを伝える」へと。Peters(1988、12-13頁)はこう結論づける: なぜなら、情報とは感覚のメカニズムを説明するものであり、世界の対象が感覚に情報を与えるものだからである。しかし、感覚は「形」とはまったく異なる。 一方は感覚的で、他方は知的であり、一方は主観的で、他方は客観的である。私の感覚は儚く、とらえどころがなく、特異である。特にヒュームにとって、感覚 的経験とは、現実世界との確かなつながりから切り離された印象の渦である...。いずれにせよ、経験主義者が問題にしたのは、心が世界の感覚からどのよう な情報を得ているかということだった。当初、「知らされる」とは「形づくられる」という意味だったが、後には「報告を受ける」という意味になった。その作 用の場が宇宙から意識へと移るにつれて、この用語の意味も単一性(アリストテレスの形式)から(感覚の)単位へと変化していった。経験主義は感覚それ自体 の外側に既存の知的形式を認めなかったため、情報は内的な秩序や形成を指すことが少なくなっていった。その代わりに、情報は断片的で、変動的で、行き当た りばったりの感覚的なものを指すようになった。一般的な近世の世界観と同様に、情報は、神によって秩序づけられた宇宙から、筋肉の運動によって支配される システムへと移行した。経験主義の指導の下、情報は構造から物質へ、形から実体へ、知的秩序から感覚的衝動へと徐々に移行していった[9]。 現代において、情報の概念に最も重要な影響を与えたのは、クロード・シャノンらによって開発された情報理論である。しかし、この理論は根本的な矛盾を反映している。Northrup(1993)[10]はこう書いている: したがって、実際には相反する2つの隠喩が使われている: よく知られているように、情報は量であり、水道管の中の水のようなものであるという隠喩が働いているが、第二の隠喩、すなわち情報は選択であり、情報提供 者によってなされる選択であり、情報受信者によってなされる強制的な選択であるという隠喩も働いている。実際、第二の隠喩は、送信された情報が受信した情 報と必ずしも等しいとは限らないことを暗示している。なぜなら、どのような選択も可能性のリスト、すなわち可能な意味のリストとの比較を意味するからであ る。ここでは、意味が関与しているため、純粋な 「Ding an sich 」としての情報という考え方が台無しになっている。このように、情報の概念に関する混乱の多くは、シャノン理論における隠喩の基本的な混乱に関連している ように思われる:情報は自律的な量なのか、それとも情報は常に観測者にとってのSE情報なのか?実際、シャノン自身が2つの定義のどちらかを選んだとは思 えない。論理的に言えば、彼の理論は情報を主体性ある現象として含意していた。しかし、このことは認識論的に広範な影響を及ぼすため、シャノンはこの論理 的事実を十分に理解していなかったようだ。その結果、彼は情報をあたかも客観的な物質であるかのように隠喩し続けた。これがシャノンの情報理論に内在する 基本的な矛盾である。(Northrup, 1993, p. 5) 彼らの代表的な著書『情報の研究』(The Study of Information)[11]では、次のように述べられている: Almach and Mansfield (1983)は、コンピュータ科学、人工知能、図書館情報学、言語学、心理学、物理学、そして社会科学における学際的論争に関する主要な見解を集めた。 Almach(1983、[12] p.660)自身は、情報という概念を信号伝達の文脈で使用することに同意していない。彼の見解では、情報の基本的な意味はすべて「何かを伝えること、あ るいは伝えられている何かを伝えること」を指している。情報は人間の心に向けられ、人間の心によって受け取られる。それ以外の感覚は、人間以外の生物や社 会全体に対する使用も含め、マッハループによれば、隠喩であり、サイバネティクスの場合と同様、擬人化されたものである。 Hjørland(2007)[13]は、情報の客観的な見方と主観的な見方の根本的な違いについて述べ、主観的な見方がとりわけBateson、 [14] Yovits、[15][16] Span-Hansen、[17] Brier、[18] Buckland、[19] Goguen、[20] そしてHjørlandによって支持されてきたと論じている: 畑の石は、人々によって(あるいは状況によって)異なる情報を含んでいる可能性がある。情報システムは、すべての個人に対して、その石が持つ可能性のある 情報をすべてマッピングすることは不可能である。また、一つのマッピングが一つの「真の」マッピングというわけでもない。しかし、人々には異なる教育背景 があり、社会の分業において異なる役割を担っている。野原にある石は、地質学者にとっては典型的な一種類の情報を表し、考古学者にとっては別の種類の情報 を表す。石から得られる情報は、例えば地質学と考古学によって生み出される異なる集合的知識構造にマッピングすることができる。情報は識別され、記述さ れ、異なる知識領域の情報システムで表現される。もちろん、あるものがある領域にとって有益か否かを判断するには、多くの不確実性と多くの困難な問題があ る。ドメインによっては、高度なコンセンサスがあり、関連性の基準が明確なものもある。他の領域では、異なる相反するパラダイムが存在し、それぞれが多か れ少なかれ、さまざまな種類の情報源の情報性についての独自の見解を含んでいる(Hjørland, 1997)。(Hjørland, 1997, p. 111, 強調は原文)。 |

| Information theory Main article: Information theory Information theory is the scientific study of the quantification, storage, and communication of information. The field itself was fundamentally established by the work of Claude Shannon in the 1940s, with earlier contributions by Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley in the 1920s.[22][23] The field is at the intersection of probability theory, statistics, computer science, statistical mechanics, information engineering, and electrical engineering. A key measure in information theory is entropy. Entropy quantifies the amount of uncertainty involved in the value of a random variable or the outcome of a random process. For example, identifying the outcome of a fair coin flip (with two equally likely outcomes) provides less information (lower entropy) than specifying the outcome from a roll of a die (with six equally likely outcomes). Some other important measures in information theory are mutual information, channel capacity, error exponents, and relative entropy. Important sub-fields of information theory include source coding, algorithmic complexity theory, algorithmic information theory, and information-theoretic security.[citation needed] Applications of fundamental topics of information theory include source coding/data compression (e.g. for ZIP files), and channel coding/error detection and correction (e.g. for DSL). Its impact has been crucial to the success of the Voyager missions to deep space, the invention of the compact disc, the feasibility of mobile phones and the development of the Internet. The theory has also found applications in other areas, including statistical inference,[24] cryptography, neurobiology,[25] perception,[26] linguistics, the evolution[27] and function[28] of molecular codes (bioinformatics), thermal physics,[29] quantum computing, black holes, information retrieval, intelligence gathering, plagiarism detection,[30] pattern recognition, anomaly detection[31] and even art creation. |

情報理論 主な記事 情報理論 情報理論とは、情報の定量化、保存、伝達に関する科学的研究である。この分野自体は1940年代のクロード・シャノンの研究によって基本的に確立された が、それ以前には1920年代にハリー・ナイキストとラルフ・ハートリーが貢献している[22][23]。この分野は確率論、統計学、コンピュータサイエ ンス、統計力学、情報工学、電気工学の交差点にある。 情報理論における重要な尺度はエントロピーである。エントロピーは、確率変数の値やランダムプロセスの結果に含まれる不確実性の量を定量化する。例えば、 公平なコインフリップ(2つの可能性が等しい)の結果を特定することは、サイコロの目(6つの可能性が等しい)の結果を特定することよりも少ない情報(よ り低いエントロピー)を提供する。情報理論における他の重要な尺度には、相互情報量、チャンネル容量、誤差指数、相対エントロピーなどがある。情報理論の 重要な下位分野には、情報源符号化、アルゴリズム複雑性理論、アルゴリズム情報理論、情報理論的セキュリティなどがある[要出典]。 情報理論の基本的なトピックの応用には、ソース符号化/データ圧縮(ZIPファイルなど)、チャネル符号化/エラー検出と訂正(DSLなど)などがある。 その影響は、深宇宙へのボイジャー・ミッションの成功、コンパクト・ディスクの発明、携帯電話の実現可能性、インターネットの発展に極めて重要であった。 この理論はまた、統計的推論、[24]暗号、神経生物学、[25]知覚、[26]言語学、分子コードの進化[27]と機能[28](バイオインフォマティ クス)、熱物理学、[29]量子コンピューティング、ブラックホール、情報検索、情報収集、盗作検出、[30]パターン認識、異常検出[31]、さらには 芸術の創造など、他の分野にも応用されている。 |

| As sensory input Often information can be viewed as a type of input to an organism or system. Inputs are of two kinds. Some inputs are important to the function of the organism (for example, food) or system (energy) by themselves. In his book Sensory Ecology[32] biophysicist David B. Dusenbery called these causal inputs. Other inputs (information) are important only because they are associated with causal inputs and can be used to predict the occurrence of a causal input at a later time (and perhaps another place). Some information is important because of association with other information but eventually there must be a connection to a causal input. In practice, information is usually carried by weak stimuli that must be detected by specialized sensory systems and amplified by energy inputs before they can be functional to the organism or system. For example, light is mainly (but not only, e.g. plants can grow in the direction of the light source) a causal input to plants but for animals it only provides information. The colored light reflected from a flower is too weak for photosynthesis but the visual system of the bee detects it and the bee's nervous system uses the information to guide the bee to the flower, where the bee often finds nectar or pollen, which are causal inputs, a nutritional function. |

感覚入力として 多くの場合、情報は生物あるいはシステムへの入力の一種とみなすことができる。入力には2種類ある。入力の中には、それ自体が生物(例えば食物)やシステ ム(エネルギー)の機能にとって重要なものもある。生物物理学者デビッド・B・デュッセンベリーは著書『感覚生態学』[32]の中で、これらの入力を「因 果的入力」と呼んでいる。その他のインプット(情報)は、因果的インプットに関連付けられ、後日(そしておそらくは別の場所での)因果的インプットの発生 を予測するために使用できるという理由でのみ重要である。いくつかの情報は、他の情報との関連性から重要であるが、最終的には原因 となる入力との関連性がなければならない。 実際には、情報は弱い刺激によって伝達されるのが普通であり、それらは生物やシステムにとって機能的なものとなる前に、特殊な感覚システムによって検出さ れ、エネルギー入力によって増幅されなければならない。例えば、光は植物にとっては主に(それだけではないが、例えば植物は光源の方向に成長することがで きる)原因入力であるが、動物にとっては情報を提供するだけである。花から反射される色のついた光は光合成には弱すぎるが、ミツバチの視覚系はそれを検出 し、ミツバチの神経系はその情報を使ってミツバチを花に導き、そこでミツバチは多くの場合、原因入力である栄養機能である蜜や花粉を見つける。 |

| As an influence that leads to transformation Information is any type of pattern that influences the formation or transformation of other patterns.[33][34] In this sense, there is no need for a conscious mind to perceive, much less appreciate, the pattern. Consider, for example, DNA. The sequence of nucleotides is a pattern that influences the formation and development of an organism without any need for a conscious mind. One might argue though that for a human to consciously define a pattern, for example a nucleotide, naturally involves conscious information processing. However, the existence of unicellular and multicellular organisms, with the complex biochemistry that leads, among other events, to the existence of enzymes and polynucleotides that interact maintaining the biological order and participating in the development of multicellular organisms, precedes by millions of years the emergence of human consciousness and the creation of the scientific culture that produced the chemical nomenclature. Systems theory at times seems to refer to information in this sense, assuming information does not necessarily involve any conscious mind, and patterns circulating (due to feedback) in the system can be called information. In other words, it can be said that information in this sense is something potentially perceived as representation, though not created or presented for that purpose. For example, Gregory Bateson defines "information" as a "difference that makes a difference".[35] If, however, the premise of "influence" implies that information has been perceived by a conscious mind and also interpreted by it, the specific context associated with this interpretation may cause the transformation of the information into knowledge. Complex definitions of both "information" and "knowledge" make such semantic and logical analysis difficult, but the condition of "transformation" is an important point in the study of information as it relates to knowledge, especially in the business discipline of knowledge management. In this practice, tools and processes are used to assist a knowledge worker in performing research and making decisions, including steps such as: Review information to effectively derive value and meaning Reference metadata if available Establish relevant context, often from many possible contexts Derive new knowledge from the information Make decisions or recommendations from the resulting knowledge Stewart (2001) argues that transformation of information into knowledge is critical, lying at the core of value creation and competitive advantage for the modern enterprise. In a biological framework, Mizraji [36] has described information as an entity emerging from the interaction of patterns with receptor systems (eg: in molecular or neural receptors capable of interacting with specific patterns, information emerges from those interactions). In addition, he has incorporated the idea of "information catalysts", structures where emerging information promotes the transition from pattern recognition to goal-directed action (for example, the specific transformation of a substrate into a product by an enzyme, or auditory reception of words and the production of an oral response) The Danish Dictionary of Information Terms[37] argues that information only provides an answer to a posed question. Whether the answer provides knowledge depends on the informed person. So a generalized definition of the concept should be: "Information" = An answer to a specific question". When Marshall McLuhan speaks of media and their effects on human cultures, he refers to the structure of artifacts that in turn shape our behaviors and mindsets. Also, pheromones are often said to be "information" in this sense. |

変容をもたらす影響力として 情報とは、他のパターンの形成や変容に影響を与えるあらゆるタイプのパターンである[33][34]。この意味で、パターンを知覚したり、ましてや理解し たりするために意識的な心は必要ない。例えばDNAを考えてみよう。ヌクレオチドの配列は、意識的な思考を必要とすることなく、生物の形成と発達に影響を 与えるパターンである。しかし、人間が意識的にパターン、例えばヌクレオチドを定義するには、当然ながら意識的な情報処理が必要だと主張する人もいるかも しれない。しかし、単細胞生物と多細胞生物が存在し、とりわけ、生物学的秩序を維持し、多細胞生物の発達に関与する酵素とポリヌクレオチドの相互作用につ ながる複雑な生化学が存在することは、人間の意識の出現と化学命名法を生み出す科学文化の創造に何百万年も先行している。 システム理論では、このような意味で情報に言及することもあるようだが、情報には必ずしも意識は含まれず、システム内を(フィードバックによって)循環す るパターンを情報と呼ぶことができるとしている。言い換えれば、この意味での情報とは、そのために創造されたり提示されたりしているわけではないが、表象 として知覚される可能性のあるものであるとも言える。例えば、グレゴリー・ベイトソンは「情報」を「差異を生み出す差異」と定義している[35]。 しかし、「影響力」の前提が、情報が意識的な心によって知覚され、またそれによって解釈されたことを意味するのであれば、この解釈に関連する特定の文脈 が、情報を知識へと変容させるかもしれない。情報」と「知識」の両方の定義が複雑であるため、このような意味論的・論理的分析は困難であるが、「変換」と いう条件は、知識と関連する情報の研究、特にナレッジ・マネジメントというビジネス分野においては重要なポイントである。このパフォーマティビティでは、 ナレッジワーカーが調査や意思決定を行う際に、以下のようなステップを含むツールやプロセスが支援される: 価値と意味を効果的に導き出すために情報をレビューする メタデータがあれば参照する。 多くの可能なコンテクストから、関連するコンテクストを確立する。 情報から新しい知識を引き出す 得られた知識から意思決定や推奨を行う Stewart(2001)は、情報を知識に変換することが重要であり、現代企業の価値創造と競争優位の中核にあると論じている。 生物学的な枠組みでは、Mizraji [36]が情報をパターンと受容体システムとの相互作用から出現する実体として説明している(例えば、特定のパターンと相互作用できる分子や神経の受容体 では、情報はそれらの相互作用から出現する)。さらに、彼は「情報触媒」という考え方を取り入れており、出現した情報がパターン認識から目標指向の行動へ の移行を促進する構造(例えば、酵素による基質から生成物への特異的な変換や、聴覚による言葉の受信と口頭での反応の生成など)を示している。 デンマーク情報用語辞典[37]は、情報は提起された質問に対する答えを提供するだけであると論じている。その答えが知識を提供するかどうかは、情報を得 た人格次第である。したがって、この概念の一般化された定義は次のようになる: 「情報」=特定の質問に対する答え」である。 マーシャル・マクルーハンがメディアとそれが人間の文化に与える影響について語るとき、彼は人工物の構造を指しており、それがひいては私たちの行動や考え方を形成している。また、フェロモンもこの意味で「情報」であるとよく言われる。 |

| Technologically mediated information Further information: Information Age These sections are using measurements of data rather than information, as information cannot be directly measured. As of 2007 It is estimated that the world's technological capacity to store information grew from 2.6 (optimally compressed) exabytes in 1986 – which is the informational equivalent to less than one 730-MB CD-ROM per person (539 MB per person) – to 295 (optimally compressed) exabytes in 2007.[7] This is the informational equivalent of almost 61 CD-ROM per person in 2007.[5] The world's combined technological capacity to receive information through one-way broadcast networks was the informational equivalent of 174 newspapers per person per day in 2007.[7] The world's combined effective capacity to exchange information through two-way telecommunication networks was the informational equivalent of 6 newspapers per person per day in 2007.[5] As of 2007, an estimated 90% of all new information is digital, mostly stored on hard drives.[38] As of 2020 The total amount of data created, captured, copied, and consumed globally is forecast to increase rapidly, reaching 64.2 zettabytes in 2020. Over the next five years up to 2025, global data creation is projected to grow to more than 180 zettabytes.[39] |

技術的に媒介された情報 さらに詳しい情報 情報化時代 情報は直接測定することができないため、これらのセクションでは情報ではなくデータの測定値を使用している。 2007年現在 世界の情報保存技術容量は、1986年の2.6(最適圧縮)エクサバイトから、2007年には295(最適圧縮)エクサバイトに増加したと推定されている[7]。これは、2007年の人格一人当たりほぼ61枚のCD-ROMに相当する情報容量である[5]。 一方向放送ネットワークを通じて情報を受信する世界の技術的能力を合計すると、2007年には、人格1人当たり1日あたり新聞174紙分の情報量に相当する[7]。 双方向の電気通信ネットワークを通じて情報を交換する世界の有効な能力を合計すると、2007年には、人格1人当たり1日当たり新聞6紙に相当する情報量であった[5]。 2007年現在、すべての新しい情報の推定90%がデジタル化されており、そのほとんどがハードディスクに保存されている[38]。 2020年現在 世界中で作成、取得、コピー、消費されるデータの総量は急速に増加し、2020年には64.2ゼタバイトに達すると予測されている。2025年までの今後5年間で、世界のデータ作成量は180ゼタバイト以上に増加すると予測されている[39]。 |

| As records Records are specialized forms of information. Essentially, records are information produced consciously or as by-products of business activities or transactions and retained because of their value. Primarily, their value is as evidence of the activities of the organization but they may also be retained for their informational value. Sound records management ensures that the integrity of records is preserved for as long as they are required.[citation needed] The international standard on records management, ISO 15489, defines records as "information created, received, and maintained as evidence and information by an organization or person, in pursuance of legal obligations or in the transaction of business".[40] The International Committee on Archives (ICA) Committee on electronic records defined a record as, "recorded information produced or received in the initiation, conduct or completion of an institutional or individual activity and that comprises content, context and structure sufficient to provide evidence of the activity".[41] Records may be maintained to retain corporate memory of the organization or to meet legal, fiscal or accountability requirements imposed on the organization. Willis expressed the view that sound management of business records and information delivered "...six key requirements for good corporate governance...transparency; accountability; due process; compliance; meeting statutory and common law requirements; and security of personal and corporate information."[42] |

記録されたものとして 記録は情報の特殊な形態である。基本的に、記録は、意識的に、又は、事業活動や取引の副産物として生成され、その価値のために保持される情報である。その 価値は主として、組織の活動の証拠であるが、情報的価値のために保持されることもある。健全な記録管理は、必要とされる限り記録の完全性が保たれることを 保証する[要出典]。 記録管理に関する国際規格であるISO 15489は、記録を「組織又は人格が、法的義務の履行又は業務処理において、証拠及び情報として作成し、受領し、維持する情報」と定義している [40]。電子記録に関する国際公文書館委員会(ICA)委員会は、記録を「組織又は個人の活動の開始、実施又は完了において作成又は受領された記録され た情報であって、その活動の証拠を提供するのに十分な内容、文脈及び構造からなるもの」と定義している[41]。 記録は、組織の企業的記憶を保持するため、又は組織に課された法的、財政的又は説明責任要件を満たすために維持されることがある。ウィリスは、業務記録と 情報の健全な管理は、「...優れたコーポレート・ガバナンスのための6つの重要な要件...透明性、説明責任、デュー・プロセス、コンプライアンス、法 令及びコモンロー上の要件の充足、並びに人格及び企業情報のセキュリティ」を実現するものであるとの見解を表明している[42]。 |

| Semiotics Michael Buckland has classified "information" in terms of its uses: "information as process", "information as knowledge", and "information as thing".[43] Beynon-Davies[44][45] explains the multi-faceted concept of information in terms of signs and signal-sign systems. Signs themselves can be considered in terms of four inter-dependent levels, layers or branches of semiotics: pragmatics, semantics, syntax, and empirics. These four layers serve to connect the social world on the one hand with the physical or technical world on the other. Pragmatics is concerned with the purpose of communication. Pragmatics links the issue of signs with the context within which signs are used. The focus of pragmatics is on the intentions of living agents underlying communicative behaviour. In other words, pragmatics link language to action. Semantics is concerned with the meaning of a message conveyed in a communicative act. Semantics considers the content of communication. Semantics is the study of the meaning of signs – the association between signs and behaviour. Semantics can be considered as the study of the link between symbols and their referents or concepts – particularly the way that signs relate to human behavior. Syntax is concerned with the formalism used to represent a message. Syntax as an area studies the form of communication in terms of the logic and grammar of sign systems. Syntax is devoted to the study of the form rather than the content of signs and sign systems. Nielsen (2008) discusses the relationship between semiotics and information in relation to dictionaries. He introduces the concept of lexicographic information costs and refers to the effort a user of a dictionary must make to first find, and then understand data so that they can generate information. Communication normally exists within the context of some social situation. The social situation sets the context for the intentions conveyed (pragmatics) and the form of communication. In a communicative situation intentions are expressed through messages that comprise collections of inter-related signs taken from a language mutually understood by the agents involved in the communication. Mutual understanding implies that agents involved understand the chosen language in terms of its agreed syntax and semantics. The sender codes the message in the language and sends the message as signals along some communication channel (empirics). The chosen communication channel has inherent properties that determine outcomes such as the speed at which communication can take place, and over what distance. |

記号論 マイケル・バックランドは「情報」をその用途の観点から分類している: 「プロセスとしての情報」、「知識としての情報」、「モノとしての情報」である[43]。 Beynon-Davies[44][45]は情報の多面的な概念をサインと信号-サインシステムの観点から説明している。記号そのものは、語用論、意味 論、統語論、経験論という記号論の4つの相互依存的なレベル、層、あるいは枝分かれという観点から考えることができる。これらの4つの層は、一方では社会 的世界と、他方では物理的あるいは技術的な世界とを結びつける役割を果たしている。 語用論はコミュニケーションの目的に関わる。語用論は記号の問題を、記号が使用される文脈と結びつける。語用論の焦点は、コミュニケーション行動の根底にある生活主体の意図主義にある。言い換えれば、語用論は言語と行動を結びつける。 意味論は、コミュニケーション行為において伝達されるメッセージの意味に関係する。意味論はコミュニケーションの内容を考察する。意味論は記号の意味を研 究する学問であり、記号と行動の関連性を研究する学問である。意味論は、記号とその参照元や概念との関連性、特に記号と人間の行動との関連性を研究する学 問と考えることができる。 統語論は、メッセージを表現するために使用される形式論に関するものである。統語論は、記号体系の論理と文法の観点からコミュニケーションの形式を研究する分野である。統語論は記号や記号体系の内容よりもむしろ形式の研究に専念している。 Nielsen (2008)は、記号論と情報の関係を辞書との関連で論じている。ニールセンは辞書的情報コストという概念を導入し、辞書の利用者が情報を生成するために、まずデータを見つけ、次に理解する努力をしなければならないことに言及している。 コミュニケーションは通常、何らかの社会的状況の中で行われる。社会的状況は、伝達される意図(語用論)およびコミュニ ケーションの形態の文脈を設定する。コミュニケーション状況において意図は、コミュニケーションに関わるエージェントが相互に理解する言語から取られた、 相互に関連する記号の集まりからなるメッセージを通して表現される。相互理解とは、関係するエージェントが、合意された構文と意味論の観点から、選択され た言語を理解していることを意味する。送信者はその言語でメッセージをコード化し、何らかの通信チャネル(経験論)に沿って信号としてメッセージを送信す る。選択された通信チャネルは、通信が行われる速度や距離などの結果を決定する固有の特性を持っている。 |

| Physics and determinacy The existence of information about a closed system is a major concept in both classical physics and quantum mechanics, encompassing the ability, real or theoretical, of an agent to predict the future state of a system based on knowledge gathered during its past and present. Determinism is a philosophical theory holding that causal determination can predict all future events,[46] positing a fully predictable universe described by classical physicist Pierre-Simon Laplace as "the effect of its past and the cause of its future".[47] Quantum physics instead encodes information as a wave function, a mathematical description of a system from which the probabilities of measurement outcomes can be computed. A fundamental feature of quantum theory is that the predictions it makes are probabilistic. Prior to the publication of Bell's theorem, determinists reconciled with this behavior using hidden variable theories, which argued that the information necessary to predict the future of a function must exist, even if it is not accessible for humans, a view expressed by Albert Einstein with the assertion that "God does not play dice".[48] Modern astronomy cites the mechanical sense of information in the black hole information paradox, positing that, because the complete evaporation of a black hole into Hawking radiation leaves nothing except an expanding cloud of homogeneous particles, this results in the irrecoverability of any information about the matter to have originally crossed the event horizon, violating both classical and quantum assertions against the ability to destroy information.[49][50] |

物理学と決定性 閉じた系に関する情報の存在は、古典物理学と量子力学の両方における主要な概念であり、過去と現在の間に収集された知識に基づいて系の将来の状態を予測す るエージェントの能力を、現実的または理論的に包含している。決定論は、因果的な決定が将来のすべての出来事を予測できるとする哲学的理論であり [46]、古典物理学者のピエール=シモン・ラプラスによって「過去の結果であり、未来の原因である」と説明された完全に予測可能な宇宙を仮定している [47]。 量子物理学はその代わりに、情報を波動関数として符号化し、そこから測定結果の確率を計算することができるシステムの数学的記述とする。量子論の基本的な 特徴は、量子論が行う予測が確率的であるということである。ベルの定理が発表される以前は、決定論者は隠れ変数理論を使ってこの振る舞いと和解していた。 隠れ変数理論とは、ある関数の未来を予測するのに必要な情報は、たとえ人間にはアクセスできなくても存在するはずだと主張するもので、アルベルト・アイン シュタインが「神はサイコロを振らない」という主張で表現した見解である[48]。 現代の天文学は、ブラックホールの情報パラドックスにおいて情報の機械的な意味を引用し、ブラックホールがホーキング放射に完全に蒸発すると、膨張する均 質な粒子の雲以外何も残らないため、事象の地平線を元々横切っていた物質に関するいかなる情報も回復不可能となり、情報を破壊する能力に対する古典的・量 子的な主張の両方に違反すると仮定している[49][50]。 |

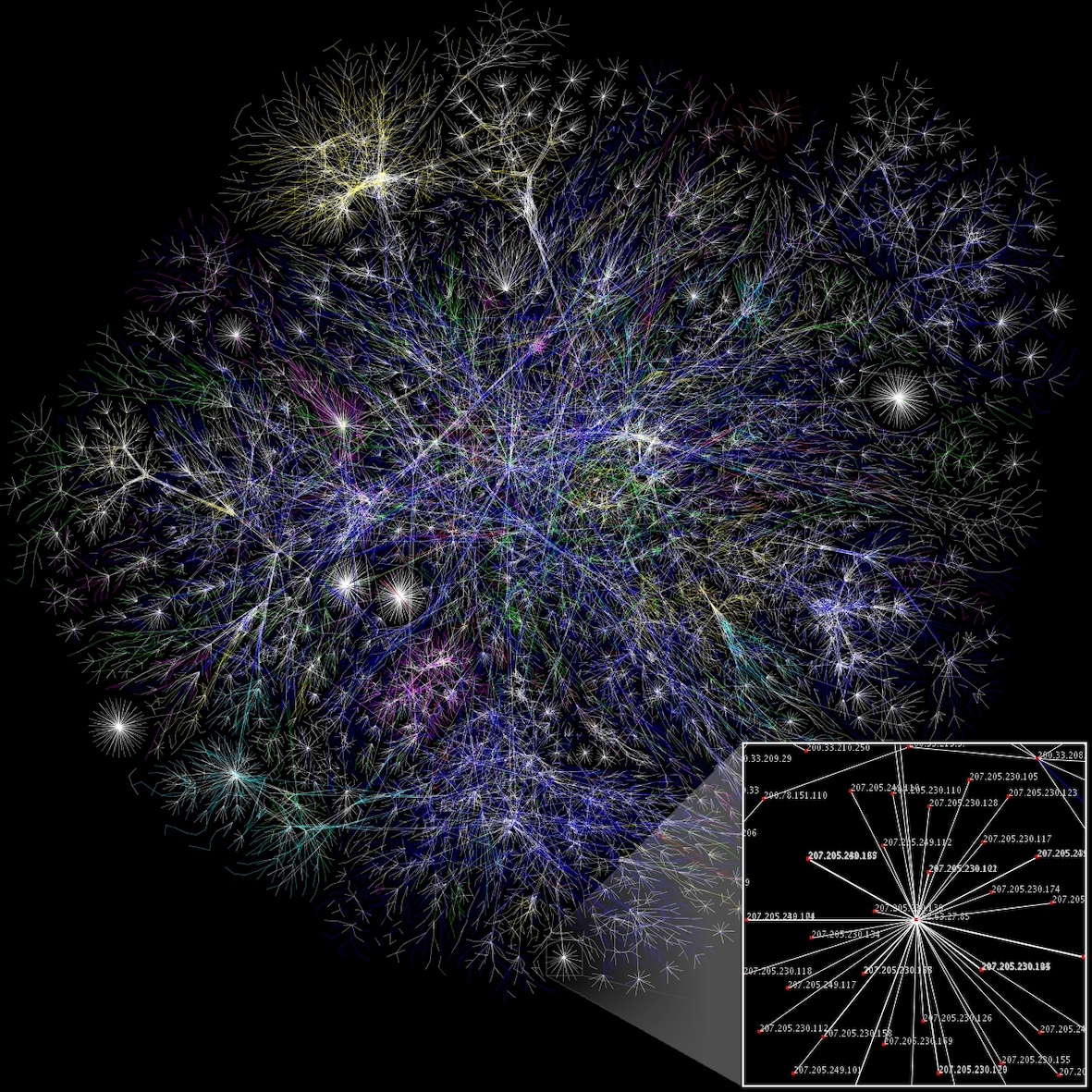

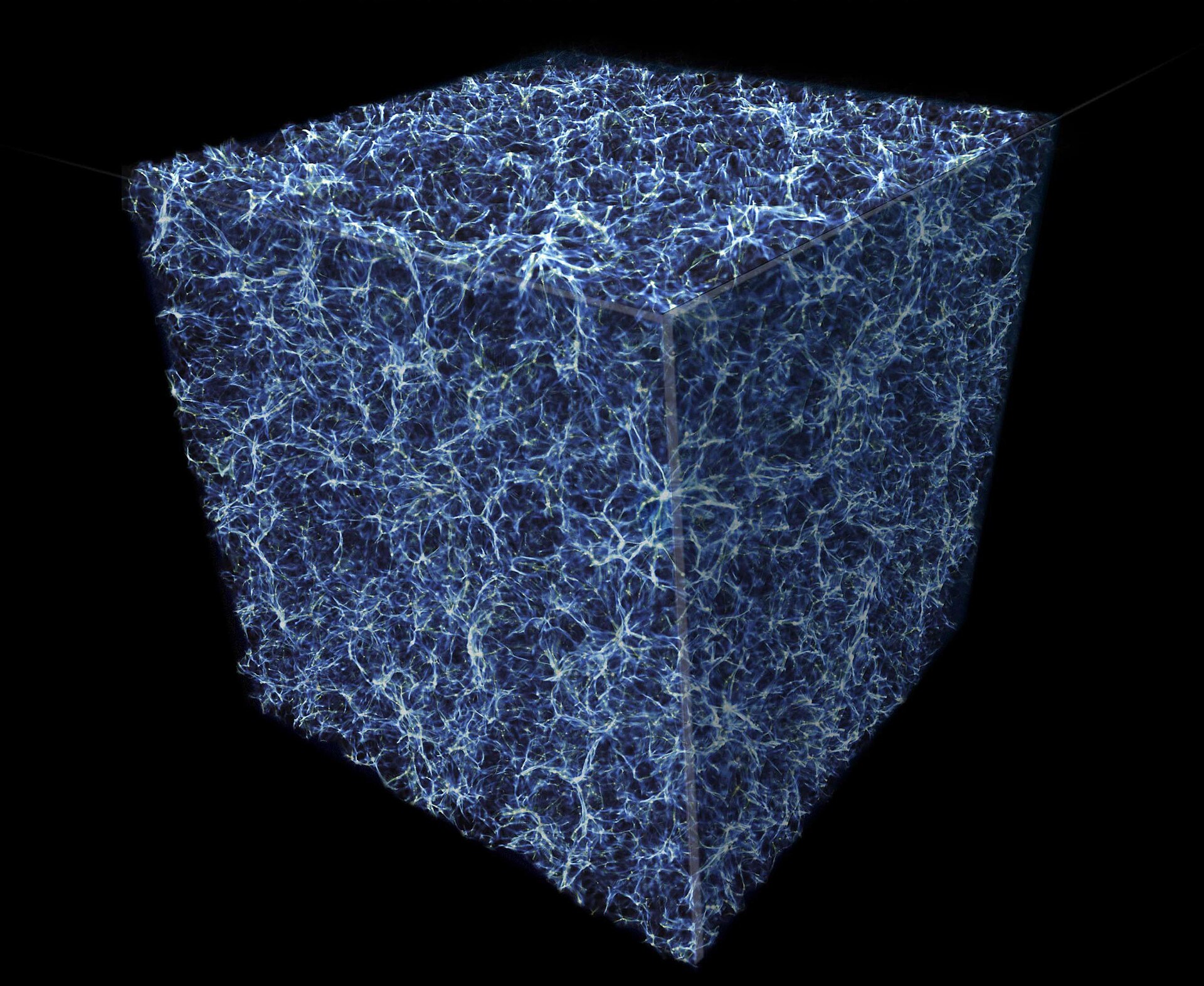

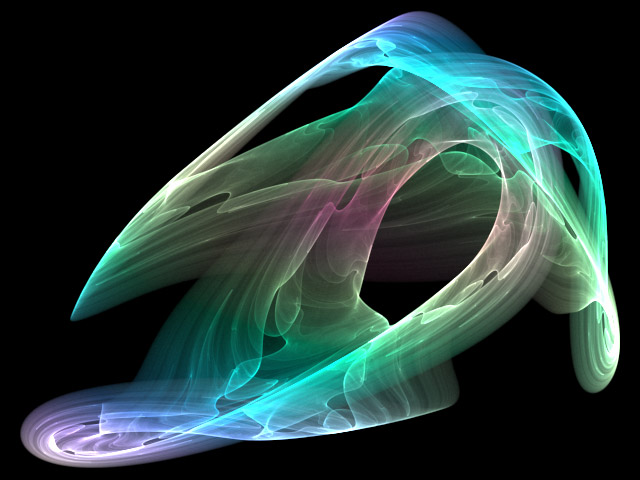

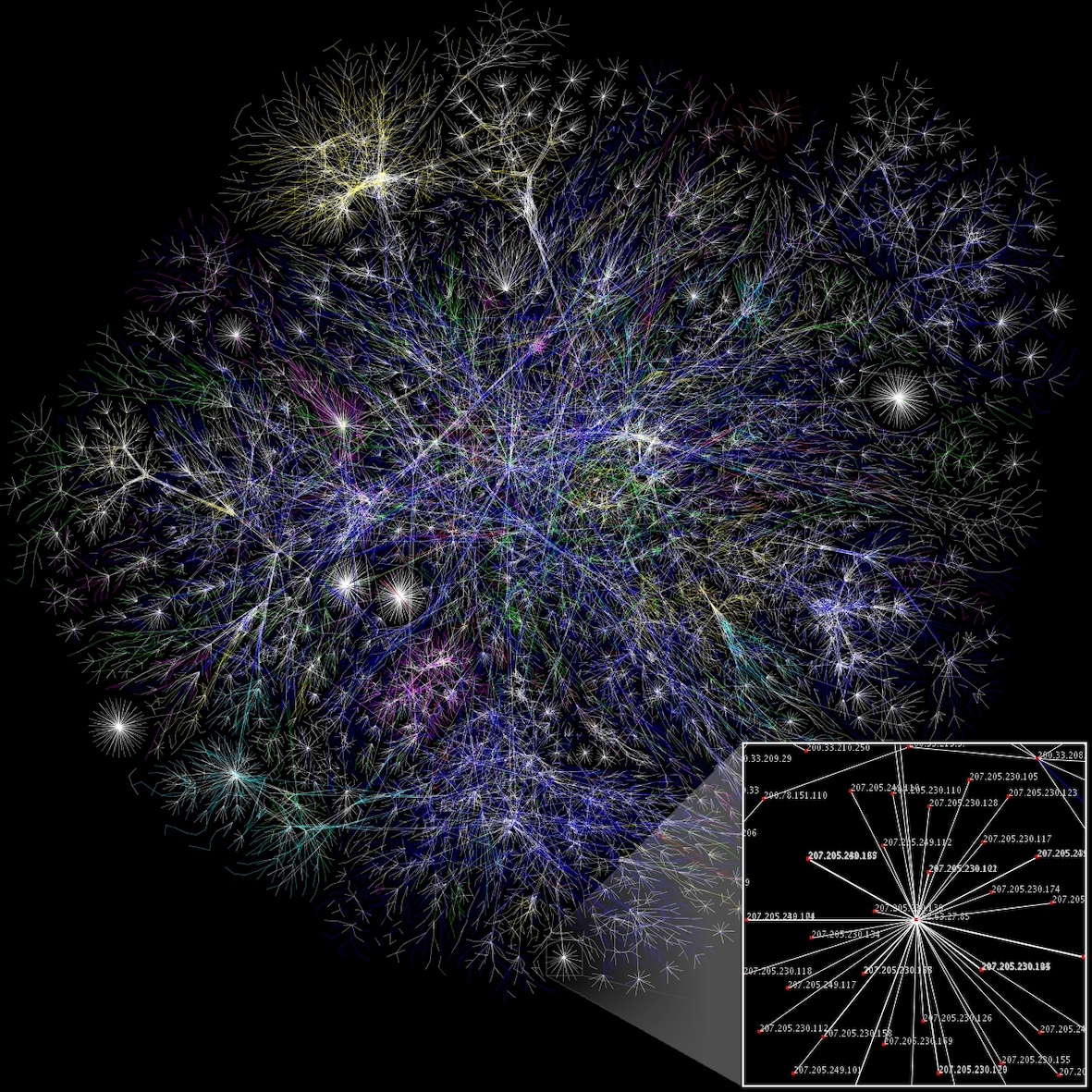

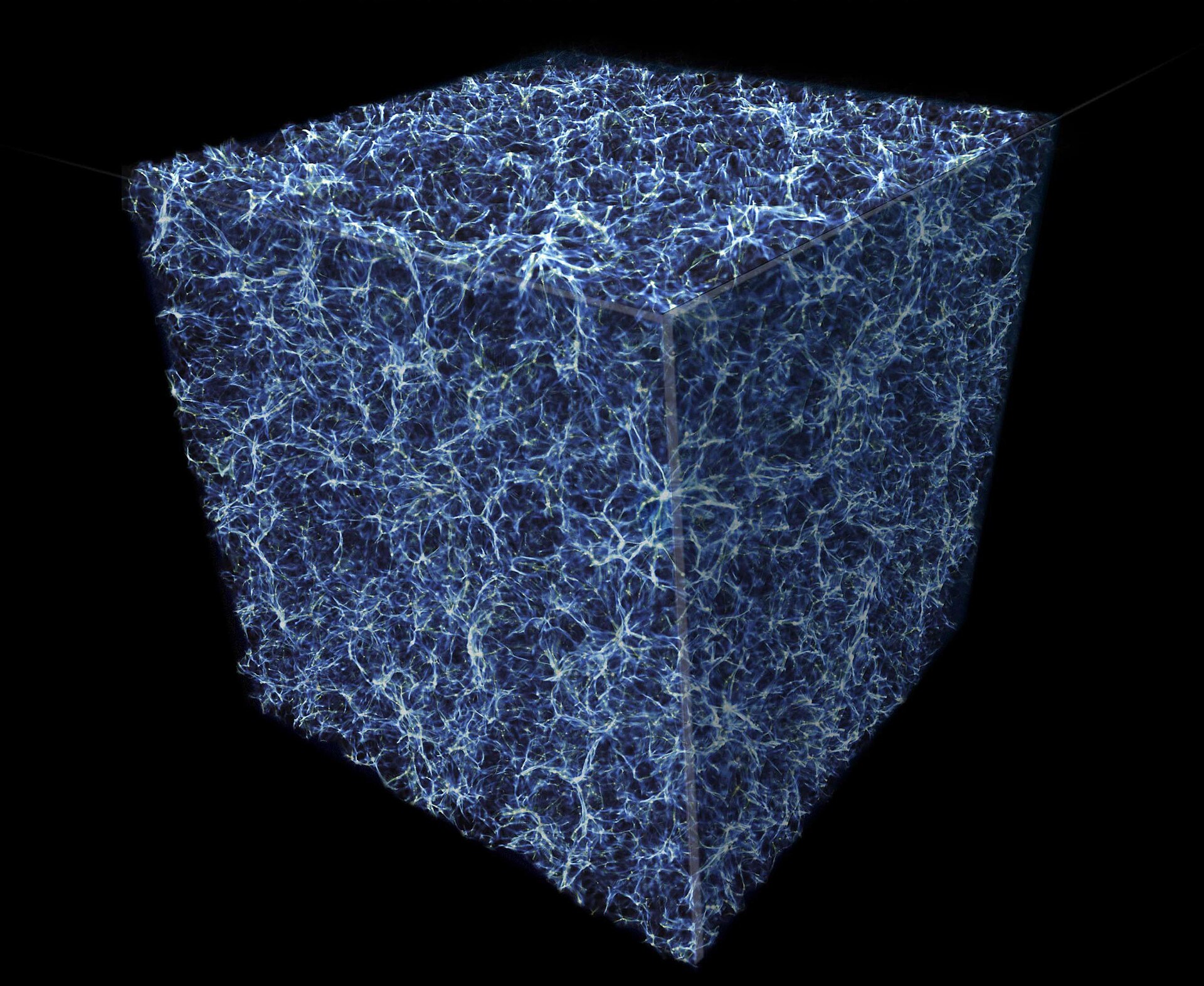

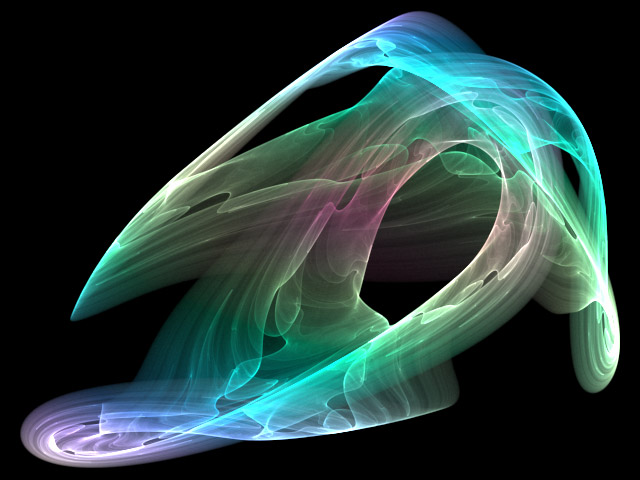

| The application of information study The information cycle (addressed as a whole or in its distinct components) is of great concern to information technology, information systems, as well as information science. These fields deal with those processes and techniques pertaining to information capture (through sensors) and generation (through computation, formulation or composition), processing (including encoding, encryption, compression, packaging), transmission (including all telecommunication methods), presentation (including visualization / display methods), storage (such as magnetic or optical, including holographic methods), etc. Information visualization (shortened as InfoVis) depends on the computation and digital representation of data, and assists users in pattern recognition and anomaly detection.  Partial map of the Internet, with nodes representing IP addresses Partial map of the Internet, with nodes representing IP addresses  Galactic (including dark) matter distribution in a cubic section of the Universe Galactic (including dark) matter distribution in a cubic section of the Universe  Visual representation of a strange attractor, with converted data of its fractal structure Visual representation of a strange attractor, with converted data of its fractal structure Information security (shortened as InfoSec) is the ongoing process of exercising due diligence to protect information, and information systems, from unauthorized access, use, disclosure, destruction, modification, disruption or distribution, through algorithms and procedures focused on monitoring and detection, as well as incident response and repair. Information analysis is the process of inspecting, transforming, and modeling information, by converting raw data into actionable knowledge, in support of the decision-making process. Information quality (shortened as InfoQ) is the potential of a dataset to achieve a specific (scientific or practical) goal using a given empirical analysis method. Information communication represents the convergence of informatics, telecommunication and audio-visual media & content. |

情報学の応用 情報サイクル(全体として、あるいは個別の構成要素として)は、情報技術、情報システム、情報科学にとって大きな関心事である。これらの分野は、情報の捕 捉(センサーによる)および生成(計算、定式化、構成による)、処理(符号化、暗号化、圧縮、パッケージングを含む)、伝送(すべての電気通信方式を含 む)、提示(視覚化/表示方式を含む)、保存(磁気的または光学的、ホログラフィック方式を含む)などに関連するプロセスと技術を扱う。 情報可視化(InfoVisと略される)は、データの計算とデジタル表現に依存し、パターン認識と異常検出においてユーザーを支援する。  ノードはIPアドレスを表す。 ノードはIPアドレスを表す。  宇宙の立方断面における銀河系(暗黒物質を含む)の物質分布 宇宙の立方体断面における銀河系(暗黒物質を含む)の物質分布  奇妙なアトラクターの視覚的表現(フラクタル構造の変換データ付き ストレンジアトラクターの視覚的表現とフラクタル構造の変換データ 情報セキュリティ(略称:インフォセック)とは、監視と検知、インシデント対応と修復に重点を置いたアルゴリズムと手順を通じて、不正アクセス、不正使 用、不正開示、不正破壊、不正改変、不正破壊、不正配布から情報および情報システムを保護するために、デューディリジェンスを実施する継続的なプロセスで ある。 情報分析とは、意思決定プロセスを支援するために、生データを実用的な知識に変換することによって、情報を検査、変換、モデル化するプロセスである。 情報の質(InfoQと略される)とは、特定の(科学的または実用的な)目標を達成するために、与えられた経験的な分析方法を用いたデータセットの可能性のことである。 情報コミュニケーションは、情報学、電気通信、オーディオ・ビジュアル・メディアとコンテンツの融合である。 |

| Accuracy and precision Complex adaptive system Complex system Data storage Engram Free Information Infrastructure Freedom of information Informatics Information and communication technologies Information architecture Information broker Information continuum Information ecology Information engineering Information geometry Information inequity Information infrastructure Information management Information metabolism Information overload Information quality (InfoQ) Information science Information sensitivity Information technology Information theory Information warfare Infosphere Lexicographic information cost Library science Meme Philosophy of information Quantum information Receiver operating characteristic Satisficing |

精度と正確さ 複雑な適応システム 複雑なシステム データ保存 エングラム 自由な情報インフラ 情報の自由 情報学 情報通信技術 情報アーキテクチャ 情報ブローカー 情報連続体 情報エコロジー 情報工学 情報幾何学 情報の不公平 情報インフラ 情報管理 情報代謝 情報の過負荷 情報の質(InfoQ) 情報科学 情報感度 情報技術 情報理論 情報戦争 情報圏 語彙情報コスト 図書館学 ミーム 情報の哲学 量子情報 受信者動作特性 サティスフィシング |

| Further reading Liu, Alan (2004). The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information. University of Chicago Press. Bekenstein, Jacob D. (August 2003). "Information in the holographic universe". Scientific American. 289 (2): 58–65. Bibcode:2003SciAm.289b..58B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0803-58. PMID 12884539. Gleick, James (2011). The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York, NY: Pantheon. Lin, Shu-Kun (2008). "Gibbs Paradox and the Concepts of Information, Symmetry, Similarity and Their Relationship". Entropy. 10 (1): 1–5. arXiv:0803.2571. Bibcode:2008Entrp..10....1L. doi:10.3390/entropy-e10010001. S2CID 41159530. Floridi, Luciano (2005). "Is Information Meaningful Data?" (PDF). Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 70 (2): 351–370. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x. hdl:2299/1825. S2CID 5593220. Floridi, Luciano (2005). "Semantic Conceptions of Information". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Floridi, Luciano (2010). Information: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Logan, Robert K. What is Information? – Propagating Organization in the Biosphere, the Symbolosphere, the Technosphere and the Econosphere. Toronto: DEMO Publishing. Machlup, F. and U. Mansfield, The Study of information : interdisciplinary messages. 1983, New York: Wiley. xxii, 743 p. ISBN 978-0471887171 Nielsen, Sandro (2008). "The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Dictionary Making and Use". Lexikos. 18: 170–189. Stewart, Thomas (2001). Wealth of Knowledge. New York, NY: Doubleday. Young, Paul (1987). The Nature of Information. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-92698-4. Kenett, Ron S.; Shmueli, Galit (2016). Information Quality: The Potential of Data and Analytics to Generate Knowledge. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118890622. ISBN 978-1-118-87444-8. |

さらに読む リュー、アラン (2004). クールの法則: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information. シカゴ大学出版局。 Bekenstein, Jacob D. (August 2003). 「ホログラフィック宇宙の情報". Scientific American. 289 (2): 58-65. Bibcode:2003SciAm.289b..58B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0803-58. PMID 12884539. Gleick, James (2011). 情報: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York, NY: Pantheon. Lin, Shu-Kun (2008). 「ギブスのパラドックスと情報、対称性、類似性の概念とその関係". Entropy. 10 (1): 1-5. arXiv:0803.2571. Bibcode:2008Entrp..10....1L. doi:10.3390/entropy-e10010001. s2cid 41159530. Floridi, Luciano (2005). 「情報は意味のあるデータなのか?」. (PDF). Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 70 (2): 351–370. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x. hdl:2299/1825. S2CID 5593220. Floridi, Luciano (2005). 「情報の意味論的概念". を参照。The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Floridi, Luciano (2010). 情報: A Very Short Introduction. オックスフォード: Oxford University Press. 情報とは何か?- 生物圏、象徴圏、技術圏、経済圏における組織の伝播. トロント: DEMO Publishing. Machlup, F. and U. Mansfield, The Study of information : interdisciplinary messages. 1983年、ニューヨーク: Wiley. xxii, 743 p. ISBN 978-0471887171. Nielsen, Sandro (2008). 「The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Making Dictionary and Use". Lexikos. 18: 170-189. Stewart, Thomas (2001). Wealth of Knowledge. New York, NY: Doubleday. Young, Paul (1987). 情報の本質. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-92698-4. Kenett, Ron S.; Shmueli, Galit (2016). Information Quality: The Potential of Data and Analytics to Generate Knowledge. 英国、チチェスター: doi:10.1002/9781118890622. ISBN 978-1-118-87444-8. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information |

Library

and information science compilation picture of library and information

spaces over time. First picture: Duke Humfrey's Library Interior,

Bodleian Library, Oxford, UK. Second picture: University of Texas at

Arlington Library, woman working at early version of computers. Third

picture: National Library of China Phase II Interior. Last picture:

Central Library Oodi in Helsinki.

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099