インテル・カエテラ

Inter caetera, 教皇子午線

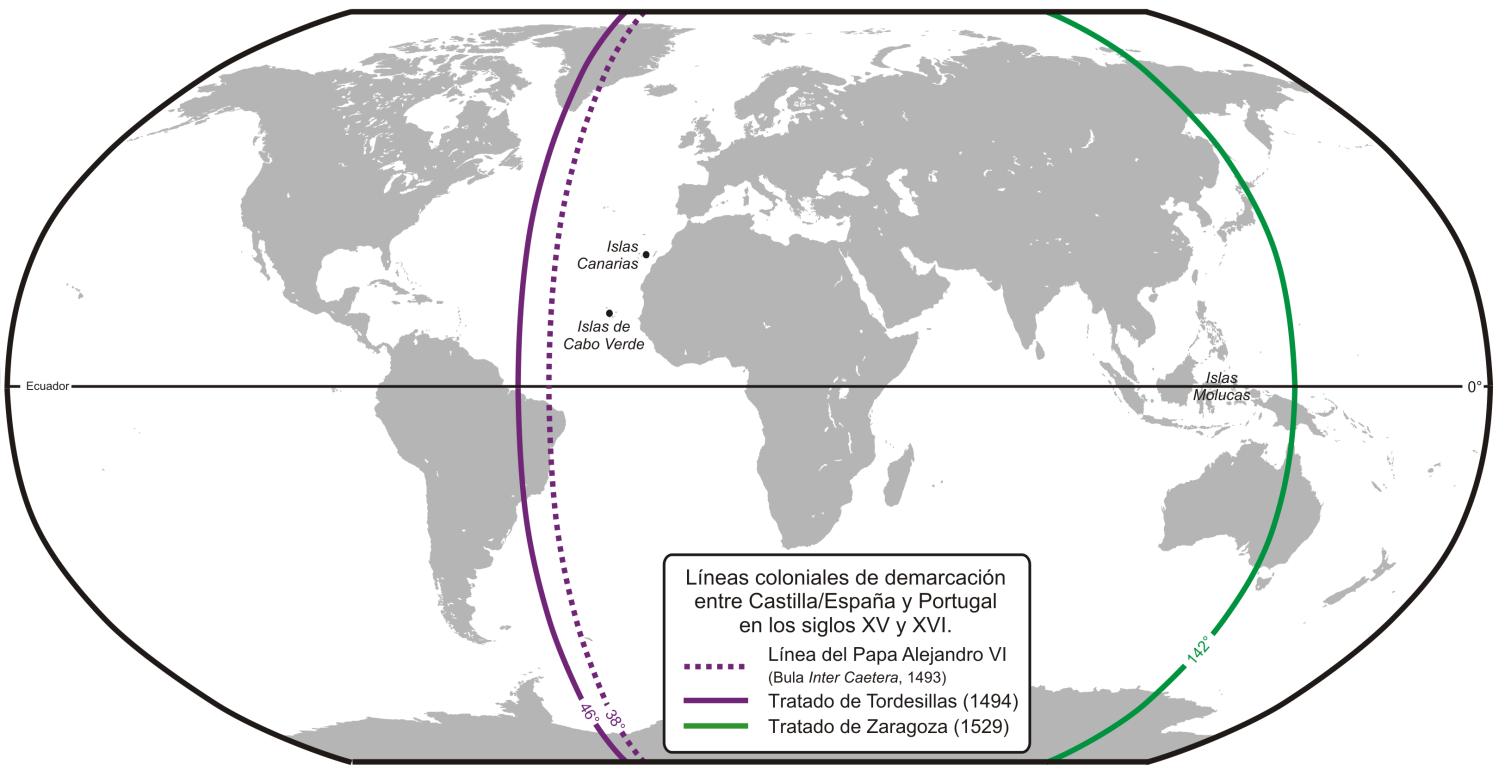

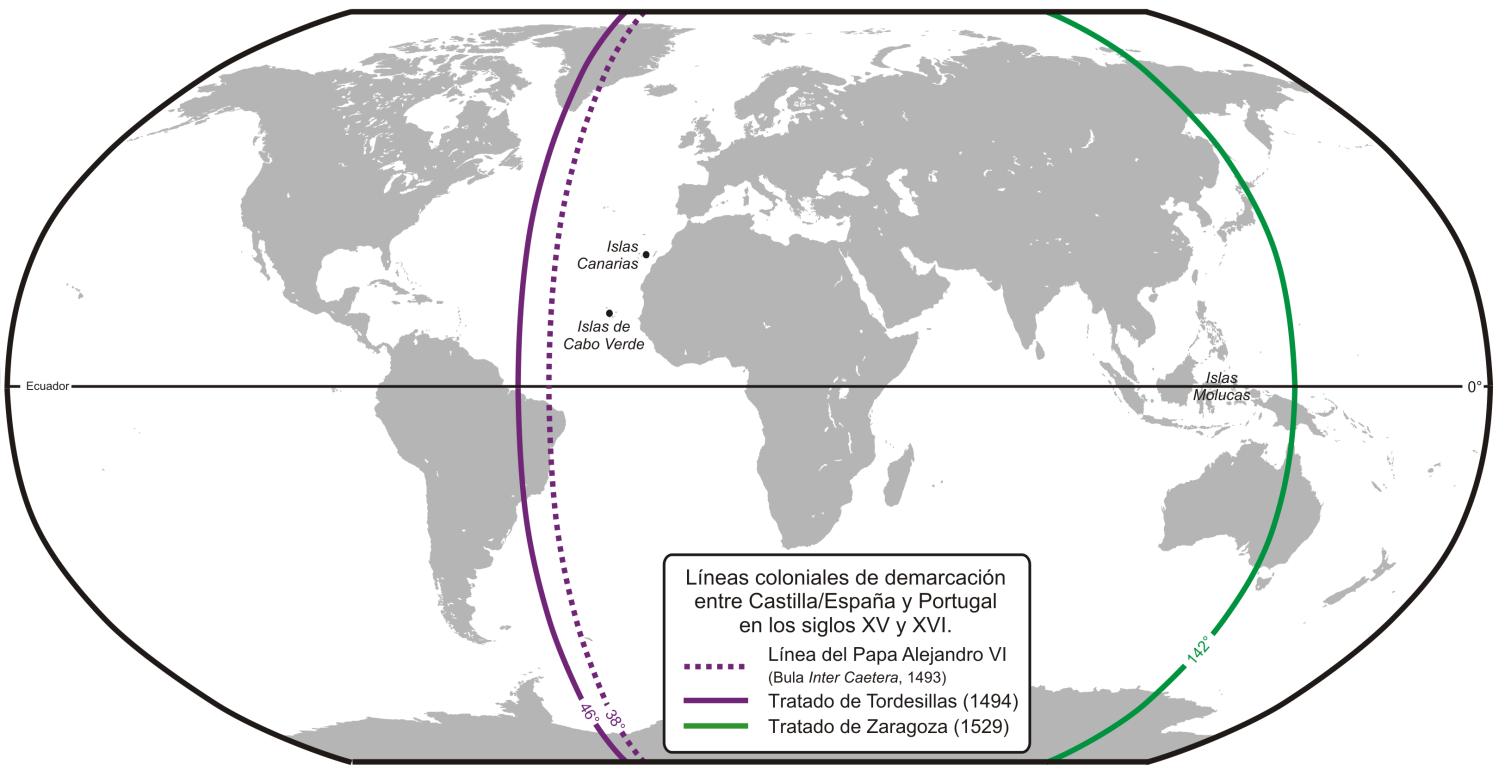

★インテル・カエテーラ Inter caetera(「他の(作品)の中で」)は、1493年5月4日に教皇アレクサンダー6世が発行した教皇勅書であり、カトリック両王であるアラゴン王 フェルディナンド2世とカスティーリャ女王イサベル1世に、アゾレス諸島またはカーボベルデ諸島のいずれかの島から西および南に100リーグの極から極へ の線より「西および南」のすべての土地を付与した。[1] 教皇が主権の「寄進」を意図していたのか、それとも封建的領有権や叙任を意図していたのかは、依然として不明である。この勅書が発行されて以来、さまざま な解釈が議論されており、土地の所有と占領を合法的な主権に変えることを意図しただけだと主張する者もいる。一方、スペイン王室や征服者たちを含む他の者 たちは、この勅書を可能な限り広い意味で解釈し、スペインに完全な政治的主権を与えたと結論づけた。[2] 『インター・カエテラ』とその補遺『ドゥドゥム・シキデム』(1493年9月)は、二つの「寄付教皇勅書」である。[3] これらの勅書はスペインとポルトガル間の紛争を解決する意図であったが、他の諸国の探検的・植民地的野心には言及しておらず、これは宗教改革後に一層問題 となった.

☆教皇子午線(きょうこうしごせん)は、

1492年のクリストファー・コロンブスによる「アジア」到達[注釈

1]の知らせを受けて、ローマ教皇アレクサンデル6世が1493年5月4日に発行した教皇勅書「インテル・カエテラ」(ラテン語: Inter

caetera、贈与大勅書[1])によって規定された、ポルトガル・スペイン両国の勢力分界線である。アフリカのヴェルデ岬西方の子午線で、大西洋のア

ゾレス諸島とヴェルデ諸島の間の海上を通過する経線より東側をポルトガルの、その西側をスペインの勢力圏とした。

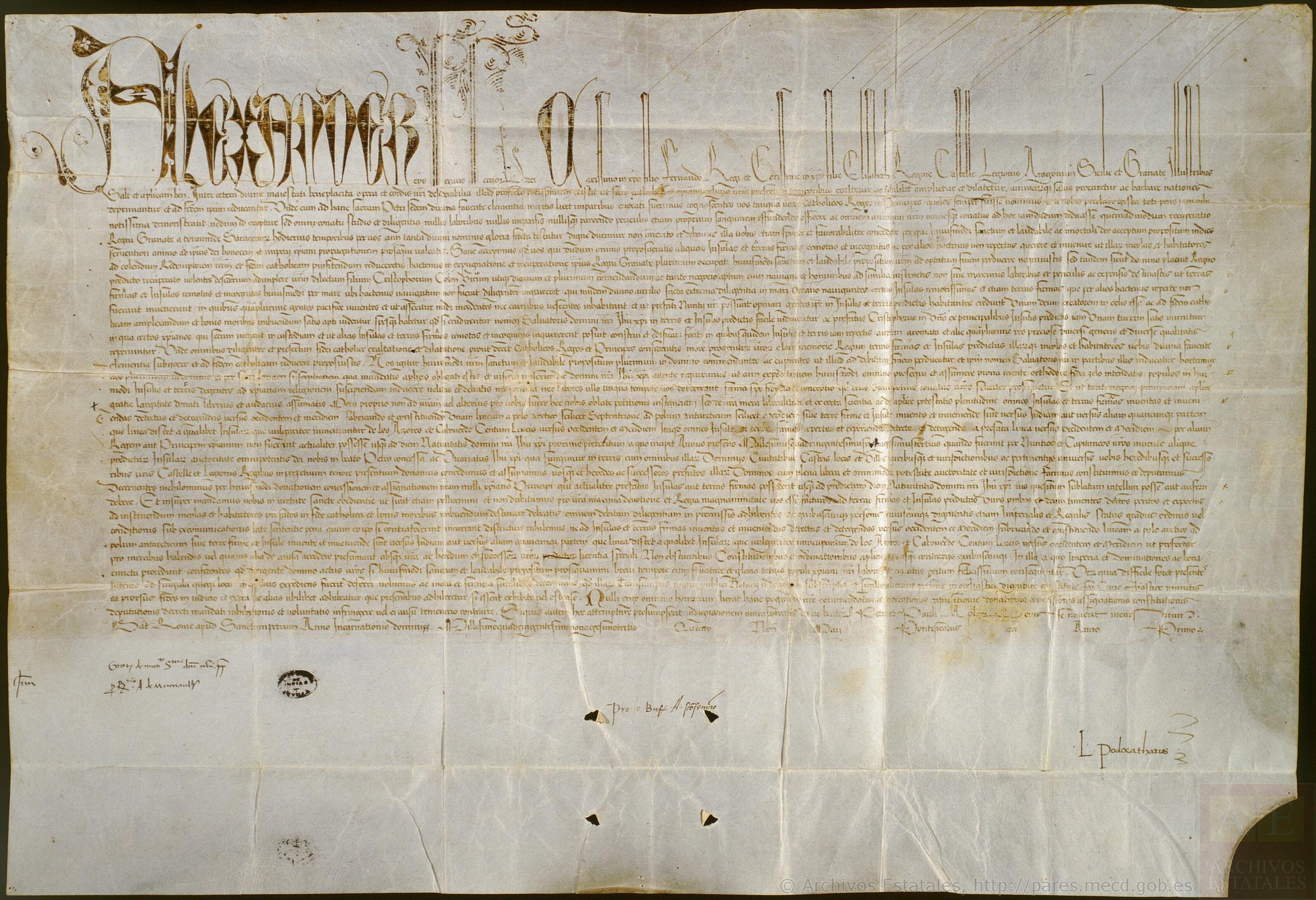

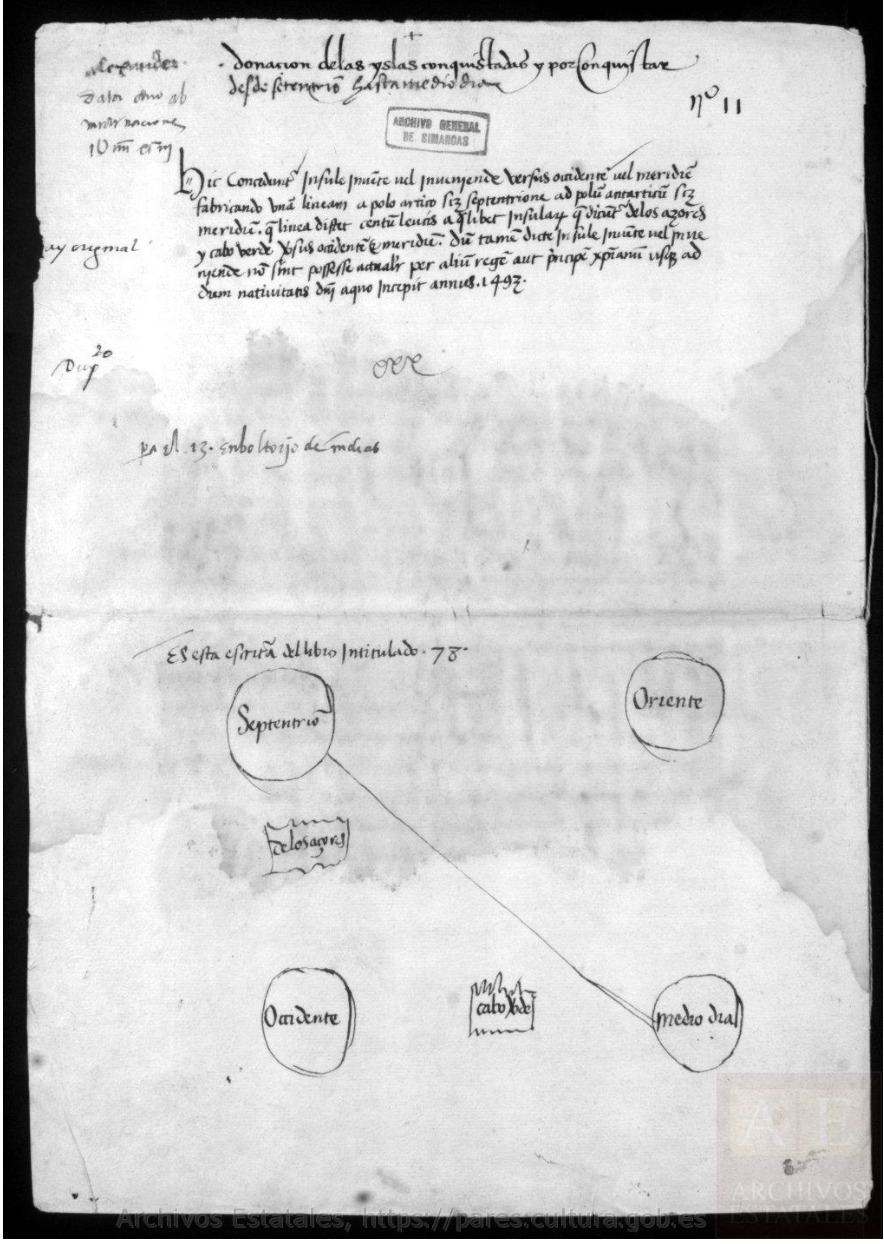

| La bula menor Inter caetera II

(en español, Entre otros II) fue otorgada por el papa Alejandro VI en

1493 en favor de Fernando e Isabel, reyes de Castilla y Aragón. La bula lleva fecha de 4 de mayo de 1493 pero se cree que realmente fue redactada más tarde, en el mes de junio. Su texto coincide en gran parte con el del breve Inter caetera del 3 de mayo de 1493, anterior a ella y que probablemente fue considerado insuficiente por los Reyes Católicos.[1] La novedad más importante que introdujo esta bula fue la definición de un meridiano al oeste del cual todas las tierras «halladas y por hallar» pertenecerían a los reyes de Castilla y Aragón. Esto supuso un cambio muy favorable para los Reyes Católicos respecto al breve Inter caetera, el cual había estipulado que pertenecerían a la Corona castellana sólo las tierras que fuesen descubiertas por navegantes castellanos.[2] Otros añadidos menores fueron una referencia más clara a tierras continentales (terras firmas) y unas palabras de elogio a Colón.[n. 1] Esta bula no menciona en ningún momento a Portugal y sólo se refiere al resto de los estados de la época al indicar que quedarían excluidos de la posesión castellana los territorios que ya perteneciesen a algún príncipe cristiano, al 25 de diciembre de 1492.[2] El manuscrito original de la bula promulgada se encuentra en el Archivo de Indias de Sevilla.[2] |

小教皇勅書「Inter caetera II」(スペイン語で「その他 II」の意)は、1493年に教皇アレクサンデル6世によってカスティーリャとアラゴンの王フェルナンドとイサベルに授与された。 この教皇勅書は1493年5月4日付であるが、実際には6月に作成されたと考えられている。その内容は、1493年5月3日付の「Inter caetera」と大部分が一致している。後者はそれより前に発布されたものだが、カトリック両王はそれを不十分だと考えたのだろう。[1] この教皇勅書がもたらした最も重要な新要素は、西経線以西の「発見済みおよび未発見の」すべての土地がカスティーリャとアラゴンの国王に属すると定義した ことだ。これは、カスティーリャの航海者によって発見された土地のみがカスティーリャ王冠に属すると規定していた「Inter caetera」に比べ、カトリック両王にとって非常に有利な変更であった。[2]その他の小さな追加点としては、大陸の土地(terras firmas)へのより明確な言及と、コロンブスへの賛辞が挙げられる。[n. 1] この教皇勅書は、ポルトガルについて一切言及しておらず、1492年12月25日時点で、すでにキリスト教の君主に属している領土はカスティーリャの所有から除外される、と当時の他の国家について言及しているだけだ。[2] 公布された教皇勅書の原文書は、セビリアのインディアス文書館に保管されている。[2] |

| Contexto histórico Véase también: Tratado de Alcaçovas Véase también: Cristóbal Colón  Líneas de demarcación entre Castilla/España y Portugal en los siglos xv y xvi, ubicadas según la teoría más extendida. Entre 1474 y 1479 se enfrentaron por la sucesión al trono de Castilla y León dos bandos: de un lado los partidarios de Juana la Beltraneja, hija del difunto rey Enrique IV y casada con Alfonso V de Portugal; del otro los de Isabel I de Castilla, hermanastra de Enrique IV y cuyo marido era Fernando, heredero de la Corona de Aragón. El 4 de septiembre de 1479 se selló la paz entre los reinos ibéricos mediante el Tratado de Alcáçovas. Además de acordar el fin de la guerra y la renuncia de Juana al trono castellano, el Tratado estableció un reparto del océano Atlántico entre Portugal y Castilla. Portugal obtuvo el reconocimiento de su dominio sobre Madeira, las Azores, Cabo Verde, Guinea y en general con todo lo que es hallado e se hallare, conquistase o descubriere en los dichos términos, allende de que es hallado ocupado o descubierto, mientras que Castilla se vio limitada a las Islas Canarias. Durante los años siguientes, Isabel y Fernando (conocidos posteriormente como los Reyes Católicos) concentraron sus esfuerzos militares en la conquista del reino musulmán de Granada. Granada se rindió finalmente el 2 de enero de 1492. Unos meses más tarde los reyes aceptaron el proyecto propuesto por Cristóbal Colón de navegar con tres barcos hacia Occidente por "el Mar Océano" para «descubrir y ganar» ciertas "islas y tierra firme".[n. 2] La expedición partió del puerto de Palos en agosto y llegó a tierras americanas en octubre. Tras explorar las islas de Cuba y La Española, los descubridores regresaron a Europa en marzo de 1493. Mientras que Martín Alonso Pinzón arribó a las costas gallegas e informó a los Reyes Católicos,[3] Colón desembarcó en Lisboa y se entrevistó con el rey portugués Juan II. Se inició entonces una intensa negociación diplomática entre ambas coronas para determinar quién controlaría las tierras descubiertas.[4] |

歴史的背景 関連項目:アルカソバス条約 関連項目:クリストファー・コロンブス  15世紀から16世紀にかけてのカスティーリャ/スペインとポルトガルの境界線。最も広く受け入れられている説に基づく。 1474年から1479年にかけて、カスティーリャ・レオン王位継承をめぐって、2つの陣営が対立した。一方は、故エンリケ4世の娘でポルトガルのアル フォンソ5世と結婚したフアナ・ラ・ベルトラーネハの支持者たち。もう一方は、エンリケ4世の異母妹で、アラゴン王冠の継承者フェルナンドの妻であるカス ティーリャのイサベル1世の支持者たちである。 1479年9月4日、アルカソバス条約によってイベリア半島の王国間の和平が締結された。この条約では、戦争の終結とフアナのカスティーリャ王位継承権の 放棄が合意されたほか、大西洋の領有権がポルトガルとカスティーリャの間で分割された。ポルトガルは、マデイラ、アゾレス諸島、カーボベルデ、ギニア、そ して一般的に、その地域で見つかったもの、征服したもの、発見したもの、占領されているもの、発見されているものすべてに対する支配権を認められた。一 方、カスティーリャはカナリア諸島に限定された。その後数年間、イサベルとフェルナンド(後にカトリック両王として知られる)は、イスラム教徒の王国グラ ナダの征服に軍事力を集中させた。 グラナダは1492年1月2日にようやく降伏した。その数ヶ月後、国王夫妻はクリストファー・コロンブスが提案した、3隻の船で「大西洋」を西へ航海し、 特定の「島々や陸地」を「発見し、獲得する」という計画を受け入れた。[n. 2] 遠征隊は8月にパロス港を出発し、10月にアメリカ大陸に到達した。キューバ島とイスパニョーラ島を探検した後、探検者たちは1493年3月にヨーロッパ に戻った。マルティン・アロンソ・ピンソンはガリシアの海岸に到着し、カトリック両王に報告したが、コロンブスはリスボンに上陸し、ポルトガルの王ジャン 2世と面会した。その後、発見された土地の支配権を決定するため、両王室間で激しい外交交渉が始まった。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bula_menor_Inter_caetera_de_1493 |

|

https://x.gd/wPqii |

|

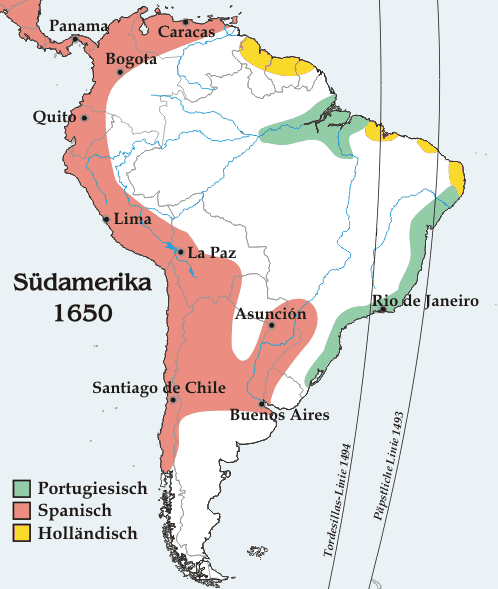

| Inter caetera

('Among other

[works]') was a papal bull issued by Pope Alexander VI on 4 May 1493,

which granted to the Catholic Monarchs King Ferdinand II of Aragon and

Queen Isabella I of Castile all lands to the "west and south" of a

pole-to-pole line 100 leagues west and south of any of the islands of

the Azores or the Cape Verde islands.[1] It remains unclear whether the pope intended a "donation" of sovereignty or an infeudation or investiture. Differing interpretations have been argued since the bull was issued, with some arguing that it was only meant to transform the possession and occupation of land into lawful sovereignty. Others, including the Spanish crown and the conquistadors, interpreted it in the widest possible sense, deducing that it gave Spain full political sovereignty.[2] Inter caetera and its supplement Dudum siquidem (September 1493) are two of the Bulls of Donation.[3] While these bulls purported to settle disputes between Spain and Portugal, they did not address the exploratory and colonial ambitions of other nations, which became more of an issue after the Protestant Reformation.  Map of South America; the meridian to the right was defined by Inter caetera (1493), the one to the left by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494). Modern boundaries and cities are shown for purposes of illustration. |

Inter

caetera(「他の(作品)の中で」)は、1493年5月4日に教皇アレクサンダー6世が発行した教皇勅書であり、カトリック両王であるアラゴン王

フェルディナンド2世とカスティーリャ女王イサベル1世に、アゾレス諸島またはカーボベルデ諸島のいずれかの島から西および南に100リーグの極から極へ

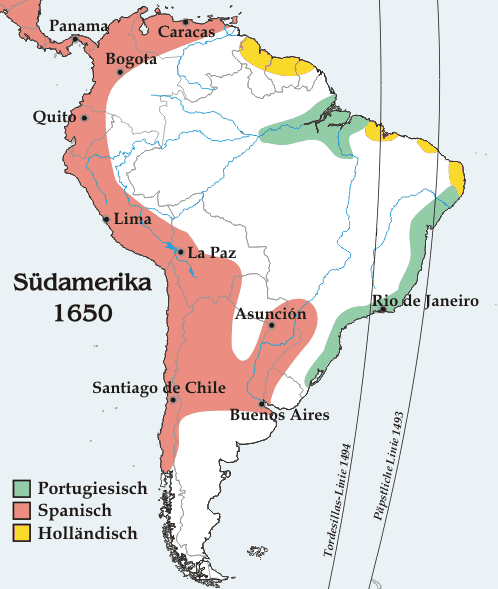

の線より「西および南」のすべての土地を付与した。[1] 教皇が主権の「寄進」を意図していたのか、それとも封建的領有権や叙任を意図していたのかは、依然として不明である。この勅書が発行されて以来、さまざま な解釈が議論されており、土地の所有と占領を合法的な主権に変えることを意図しただけだと主張する者もいる。一方、スペイン王室や征服者たちを含む他の者 たちは、この勅書を可能な限り広い意味で解釈し、スペインに完全な政治的主権を与えたと結論づけた。[2] 『インター・カエテラ』とその補遺『ドゥドゥム・シキデム』(1493年9月)は、二つの「寄付教皇勅書」である。[3] これらの勅書はスペインとポルトガル間の紛争を解決する意図であったが、他の諸国の探検的・植民地的野心には言及しておらず、これは宗教改革後に一層問題 となった.  南アメリカの地図。右側の経線は『インター・カエテラ』(1493年)で定められたもの、左側の経線は『トルデシージャス条約』(1494年)で定められ たものである。現代の国境と都市は説明のために示されている。 |

| Background Further information: Age of Discovery, Portuguese discovery of the sea route to India, Voyages of Christopher Columbus, and Portugal–Spain relations Before Christopher Columbus received support for his voyage from Queen Isabella and King Ferdinand of Spain, he had first approached King John II of Portugal. The king's scholars and navigators reviewed Columbus's documentation, determined that his calculations grossly underestimated the diameter of the Earth and thus the length of the voyage, and recommended against subsidizing the expedition. Upon Columbus's return from his first voyage to the Americas, his first landing was made in the Portuguese Azores; a subsequent storm drove his ship to Lisbon on 4 March 1493. Hearing of Columbus's discoveries, the Portuguese king informed him that he believed the voyage to be in violation of the 1479 Treaty of Alcáçovas. The treaty had been ratified with the 1481 papal bull Aeterni regis, which confirmed previous bulls of 1452 (Dum diversas), 1455 (Romanus Pontifex), and 1456 (Inter caetera),[2] recognizing Portuguese territorial claims along the West African coast. It was the King's understanding that the terms of the treaty acknowledged Portuguese claims to all territory south of the Canary Islands (which had been ceded to Spain).[4] Columbus's arrival in supposedly Asiatic lands in the western Atlantic Ocean in 1492 threatened the unstable relations between Portugal and Spain. With word that King John was preparing a fleet to sail to the west, the King and Queen of Spain initiated diplomatic discussions over the rights to possess and govern the newly found lands.[5] Spanish and Portuguese delegates met and debated from April to November 1493, without reaching an agreement. Columbus was still in Lisbon when he sent a report of his success to the Spanish monarchs. On 11 April, the Spanish ambassador conveyed the news to Pope Alexander VI, a Spaniard and the former Administrator of Valencia, and urged him to issue a new bull favorable to Spain.[6] At the time, Pope Alexander, as ruler of the Papal States, was embroiled in a territorial dispute with Ferdinand's first cousin, Ferdinand I, King of Naples, hence he was amicable to any requests of Isabella and Ferdinand, to the extent that they could write to Columbus saying that if he thought it necessary, one of the bulls would be modified. They were at Barcelona, in close touch with Rome. The camera apostolica became almost an extension of the Spanish Court, which secured a rapid succession of bulls virtually liquidating Portuguese claims.[7] The Pope issued edicts dated 3 and 4 May 1493. The third superseded the first two. A final edict, Dudum siquidem of 26 September 1493, supplemented the Inter caetera.[2] The first bull, Inter caetera, dated 3 May, recognized Spain's claim to any discovered lands not already held by a Christian prince, and protected Portugal's previous rights. Both parties found this too vague. The second bull, Eximiae devotionis, also dated 3 May, granted to the kings of Castile and León and their successors the same privileges in the newly discovered land that had been granted to the kings of Portugal in the regions of Africa, and Guinea.[8] The third bull, also entitled Inter caetera, dated 4 May, exhorts the Spanish monarchs to spread the faith west from a line drawn "one hundred leagues towards the west and south from any of the islands commonly known as the Azores and Cape Verde". Diffie notes that it has been suggested that this change may have been prompted by the Portuguese ambassador.[4] The Inter caetera and the following Treaty of Tordesillas defined and delineated a zone of Spanish rights exclusive of Portugal. In relation to other states the agreement was legally ineffective (res inter alios acta). Spain's attempts to persuade other European powers on the legal validity of the Inter caetera were never successful.[2] |

背景 詳細情報:大航海時代、ポルトガルによるインドへの海路発見、クリストファー・コロンブスの航海、ポルトガルとスペインの関係 クリストファー・コロンブスがスペインのイサベル女王とフェルナンド王から航海支援を得る前に、彼はまずポルトガルのジョアン2世に接触した。国王の学者 や航海士たちはコロンブスの資料を検討し、彼の計算が地球の直径を大幅に過小評価しており、したがって航海距離も過小評価していると判断した。彼らは遠征 への資金援助を認めないよう勧告した。コロンブスがアメリカ大陸への最初の航海から帰還した際、最初に上陸したのはポルトガル領アゾレス諸島であった。そ の後嵐に遭い、1493年3月4日に船はリスボンへ漂着した。コロンブスの発見を知ったポルトガル国王は、この航海が1479年のアルカソバス条約に違反 すると彼に伝えた。この条約は1481年の教皇勅書『エテルニ・レギス』で批准され、1452年(『ドゥム・デヴェルサ』)、1455年(『ロマーヌス・ ポンティフェクス』)、1456年(『インター・カエテラ』)の勅書を再確認し、西アフリカ沿岸におけるポルトガルの領有権を認めていた。国王は、この条 約の条項がカナリア諸島(スペインに割譲済み)以南の全領土に対するポルトガルの主張を認めるものと理解していた。[4] 1492年、コロンブスが西大西洋の、おそらくはアジアの土地に到達したことで、ポルトガルとスペインの不安定な関係に脅威が訪れた。ジョン王が西へ航海 するための艦隊を準備しているという情報を受け、スペイン国王と王妃は、新たに発見された土地の所有権と統治権について外交交渉を開始した。[5] 1493年4月から11月にかけて、スペインとポルトガルの代表者が会談し、議論を交わしたが、合意には至らなかった。 コロンブスは、リスボンに滞在しながら、スペイン国王夫妻に成功の報告を送った。4月11日、スペイン大使は、スペイン人であり、かつてバレンシアの行政 官であった教皇アレクサンダー6世にこの知らせを伝え、スペインに有利な新しい教皇勅書を発行するよう強く求めた。当時、教皇アレクサンダーは教皇領の支 配者として、フェルディナンドの従兄弟であるナポリ王フェルディナンド1世との領土紛争に巻き込まれていたため、イサベラとフェルディナンドの要求には友 好的な態度を示し、コロンブスに「必要であれば教皇勅書を修正する」と書簡で伝えるほどであった。彼らはバルセロナに滞在し、ローマと緊密に連絡を取り 合っていた。教皇庁は、スペイン宮廷の延長のような存在となり、ポルトガルの主張を事実上無効にする教皇勅書を次々と発行した。教皇は 1493 年 5 月 3 日と 4 日に勅書を発行した。3 番目の勅書は、最初の 2 つに取って代わった。1493 年 9 月 26 日の「Dudum siquidem」という最終的な勅書は、「Inter caetera」を補完するものであった。[2] 最初の教皇勅書『インター・カエテラ』(5月3日付)は、キリスト教君主が未占領の発見地に対するスペインの権利を認めつつ、ポルトガルの既存権利を保護 した。両国ともこの内容は曖昧すぎると感じた。 第二の勅書『エクシミエ・デヴォティオニス』(同じく5月3日付)は、カスティリャ・レオン両王及びその後継者に対し、ポルトガル王がアフリカ及びギニア 地域で認められていたのと同等の特権を新発見地において付与した。[8] 第三の教皇勅書『インター・カエテラ』(5月4日付)は、スペイン君主に対し「アゾレス諸島及びカーボベルデ諸島として一般に知られる諸島のいずれかから 西及び南へ百リーグの線」を基準に、西方の信仰普及を勧告した。ディフィーは、この変更がポルトガル大使の働きかけによる可能性が指摘されていると記して いる。[4] 『インター・カエテラ』と続くトルデシリャス条約は、ポルトガルを排除したスペインの権利区域を定義・画定した。他国との関係では、この合意は法的効力を 有さなかった(res inter alios acta)。スペインが他欧州列強に『インター・カエテラ』の法的有効性を説得しようとした試みは、決して成功しなかった。[2] |

| Provisions Inter caetera states: Among other works well pleasing to the Divine Majesty and cherished of our heart, this assuredly ranks highest, that in our times especially the Catholic faith and the Christian religion be exalted and be everywhere increased and spread, that the health of souls be cared for and that barbarous nations be overthrown and brought to the faith itself. ...[W]e ... assign to you and your heirs and successors, kings of Castile and Leon, ... all islands and mainlands found and to be found, discovered and to be discovered towards the west and south, by drawing and establishing a line from ... the north, ...to ...the south, ... the said line to be distant one hundred leagues towards the west and south from any of the islands commonly known as the Azores and Cape Verde.[9] The bull notes that the Isabella and Ferdinand "had intended to seek out and discover certain islands and mainlands remote and unknown" but had been otherwise engaged in the conquest of Granada.[9] The line of demarcation divided Atlantic zones only.[7] Spain and Portugal could pass each other toward the west or east, respectively, on the other side of the globe and still possess whatever lands they were first to discover. The bull was silent regarding whether lands to the east of the line would belong to Portugal, which had only recently reached the southern tip of Africa (1488) and had not yet reached India (1498). These lands yet "to be discovered" lay beyond those along the west coast of Africa as far as Guinea, and were given to Portugal via the 1481 bull Aeterni regis, which had ratified the Treaty of Alcáçovas.[10] For the time being, the question was in abeyance. |

規定 とりわけ次のように定めている: 神の御威光に喜ばれ、我らの心に愛される諸事業の中でも、とりわけこの事業は最高位にある。すなわち我らの時代に特にカトリックの信仰とキリスト教の宗教 が高められ、あらゆる場所で増し広められ、魂の健康が顧みられ、野蛮な諸国民が打ち倒され、信仰そのものへと導かれることである。...我々は...カス ティリャとレオンの王たる汝と汝の子孫及び後継者に対し...西と南の方角において発見され、また今後発見されるであろう全ての島々及び大陸を、...北 から...南へと引かれる線を基準として、... 北から...南へ...引かれた線は、アゾレス諸島及びカーボベルデ諸島として一般に知られる諸島のいずれからも、西及び南へ百リーグの距離を保つものと する。[9] 教皇勅書は、イサベルとフェルナンドが「遠隔かつ未知の諸島及び大陸を探求し発見する意図を持っていた」が、グラナダ征服に忙殺されていたと記している。 [9] この境界線は大西洋域のみを分けた。[7]スペインとポルトガルは地球の反対側で互いに西進・東進しても、それぞれが最初に発見した土地を所有できた。教 皇勅書は境界線東側の土地がポルトガルに帰属するか否かについて言及しておらず、当時ポルトガルはアフリカ最南端(1488年)に到達したばかりで、イン ド(1498年)にはまだ到達していなかった。これらの「未発見の」土地は、アフリカ西海岸のギニアに至る地域を超えて存在し、1481年の教皇勅書『エ テルニ・レギス』によってポルトガルに与えられていた。この勅書はアルカソバス条約を批准したものである。[10] 当面の間、この問題は保留状態にあった。 |

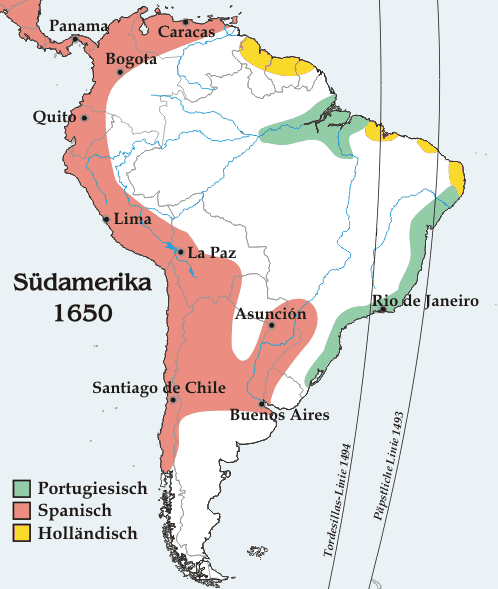

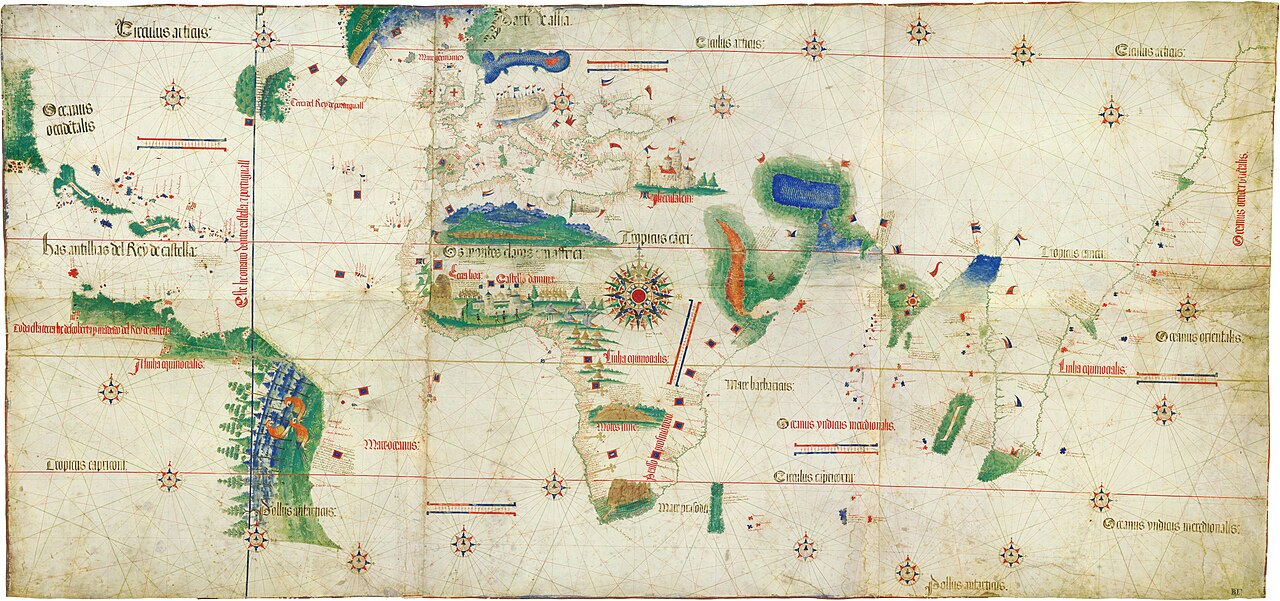

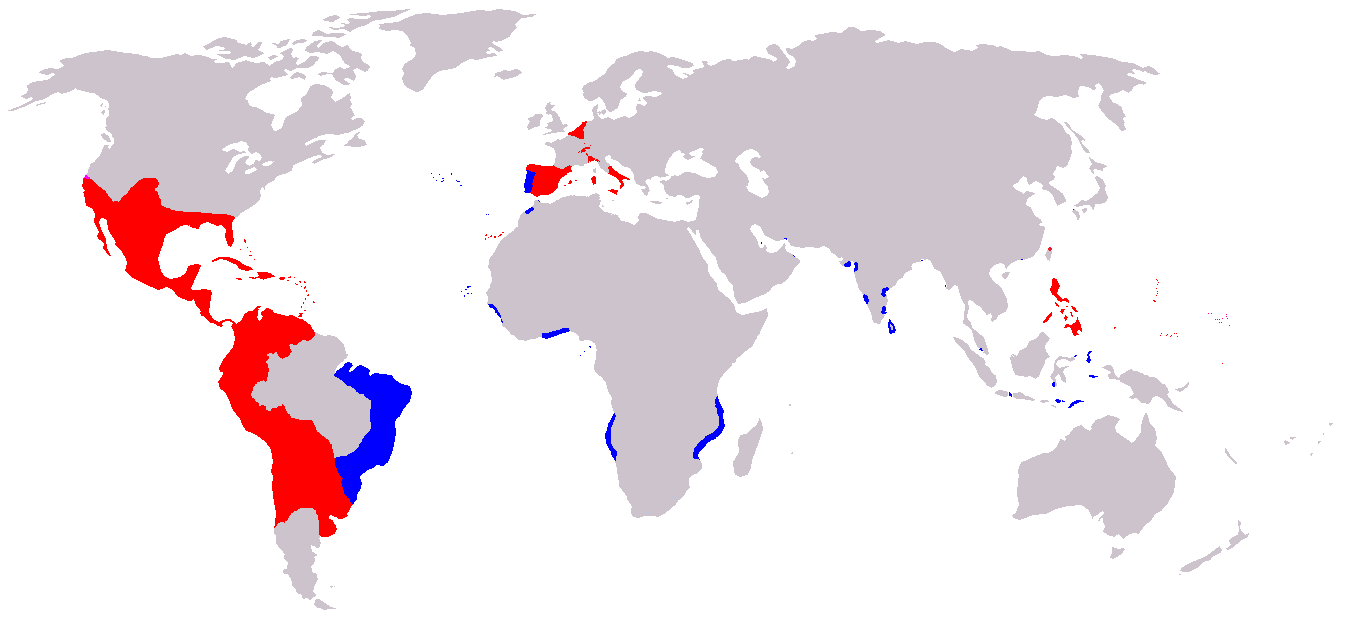

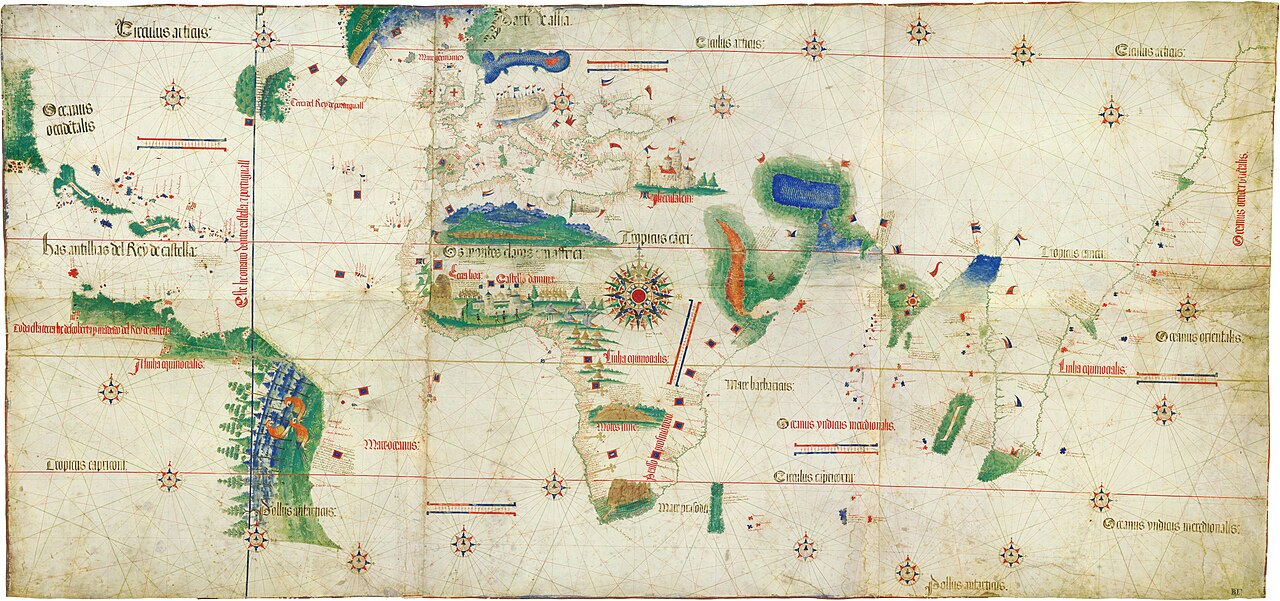

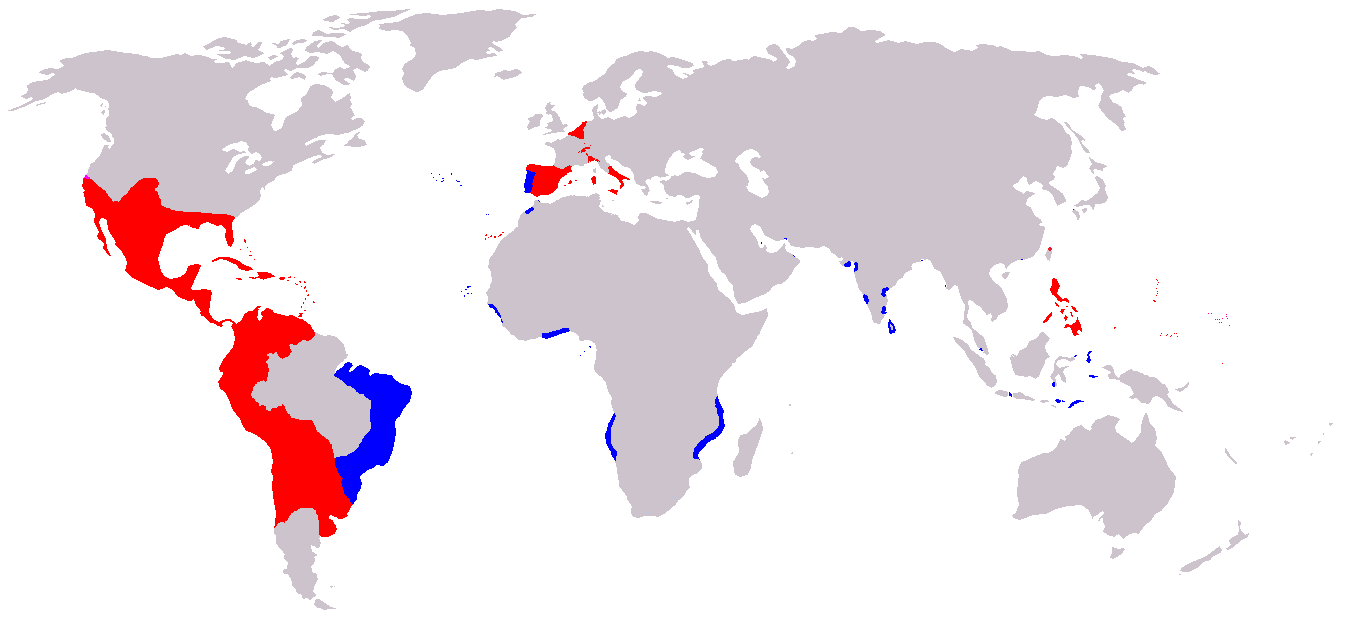

| Effects and aftermath See also: Treaty of Tordesillas  The Cantino planisphere of 1502 shows the line of the Treaty of Tordesillas. An important but unanticipated effect of this papal bull and the Treaty of Tordesillas was that nearly all the Pacific Ocean and the west coast of North America were given to Spain. King John II naturally declined to enter into a hopeless competition at Rome, and simply ignored the bulls, thus neither admitting their authority nor defying the Church. According to Oskar Spate, if Rome was in Ferdinand's pocket, highly placed personages at the Spanish Court were in King John's, and kept him well informed of its moves.[7] Controlling the sea lanes from Spain to the Antilles and in possession of bases in the Azores and Madeira, Portugal occupied a strategic naval position and he chose to pursue negotiations.  A map of the Spanish (red) and Portuguese Empires (blue) in the period of their personal union (1581–1640) Neither side paid any attention to Pope Alexander's bulls.[7] Instead, they negotiated the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, which moved the line further west to a meridian 370 leagues west of the Portuguese Cape Verde Islands, now explicitly giving Portugal all newly discovered lands east of the line.[11] In response to Portugal's discovery of the Spice Islands in 1512, the Spanish put forward the idea, in 1518, that Pope Alexander had divided the world into two halves.[12] By this time, however, other European powers had overwhelmingly rejected the notion that the Pope had the right to convey sovereignty of regions as vast as the New World. Even within Spain, influential voices such as Francisco de Vitoria had denounced the validity of the Inter caetera. While Spain never gave up its claims based on papal bulls, neither did the Spanish crown seek papal sanctions over the Atlantic Ocean line of demarcation. Rather, Spain negotiated directly with Portugal.[2] Piis fidelium On 25 June 1493, King Ferdinand secured another papal bull, Piis fidelium, appointing him apostolic vicar in the Indies. Father Bernardo Buil of the Order of Minims left Cádiz for America on 25 September 1493, on the second Columbus expedition. Once on the island of Hispaniola, Buil saw the effects of the conquistadors and quarreled with Columbus over the harsh treatment of colonists and Indians. Seeing that the situation for evangelization and catechizing was impossible, Buil left for Spain, defeated, within six months on 3 December 1494.[13] Two other friars whom he had left in the Americas returned to Spain in 1499. |

影響と余波 関連項目: トルデシリャス条約  1502年のカンティーノ世界地図には、トルデシリャス条約の境界線が示されている。 この教皇勅書とトルデシリャス条約がもたらした重要だが予期せぬ影響は、太平洋のほぼ全域と北米西海岸がスペインに与えられたことである。ジョン2世は当 然、ローマでの絶望的な競争に参加することを拒否し、教皇勅書を単に無視した。したがって、その権威を認めることも、教会に反抗することもなかった。オス カー・スペイトによれば、ローマがフェルディナンドの手中にあったのに対し、スペイン宮廷の高位の人物はジョン王の手中にあり、その動きを王にしっかりと 報告していた。[7] スペインからアンティル諸島への海路を支配し、アゾレス諸島とマデイラに拠点を所有していたポルトガルは、戦略的に重要な海軍の地位を占めており、交渉を 続けることを選んだ。  スペイン帝国(赤)とポルトガル帝国(青)が個人的な同君立国(1581年~1640年)だった時代の地図 両国とも、教皇アレクサンダーの勅書にはまったく注意を払わなかった[7]。その代わりに、1494年にトルデシリャス条約を締結し、境界線をさらに西、 ポルトガルのカーボベルデ諸島の西370リーグの経線まで移動させ、この境界線の東に新たに発見された土地はすべてポルトガルに属することを明確に定め た。[11] 1512年にポルトガルがスパイス諸島を発見したことを受け、スペインは1518年、教皇アレクサンダーが世界を2つに分割したという考えを打ち出した。 [12] しかし、この頃には、他のヨーロッパ列強は、教皇が新世界のような広大な地域の主権を譲渡する権利を持つという考えを圧倒的に拒否していた。スペイン国内 でさえ、フランシスコ・デ・ビトリアなどの影響力のある人物が、インター・カエテラ(Inter caetera)の有効性を非難していた。スペインは教皇勅書に基づく主張を決して放棄しなかったが、大西洋の境界線について教皇の認可を求めることもな かった。むしろ、スペインはポルトガルと直接交渉を行った。[2] Piis fidelium 1493年6月25日、フェルナンド王は新たな教皇勅書『Piis fidelium』を獲得し、自身をインド諸島の使徒座代理に任命した。ミニム会のベルナルド・ブイル神父は1493年9月25日、コロンブスの第二回遠 征に同行し、カディスからアメリカへ向けて出航した。イスパニョーラ島に到着したブイルは、征服者たちの所業を目の当たりにし、入植者や先住民への苛酷な 扱いを巡ってコロンブスと対立した。伝道と教理指導が不可能な状況と判断したブイルは、挫折して6ヶ月も経たない1494年12月3日にスペインへ帰還し た[13]。彼がアメリカ大陸に残した他の二人の修道士も、1499年にスペインへ戻った。 |

| Legacy and reaction This authorization to take non-Christian peoples' lands was cited by U.S. Chief Justice John Marshall almost 300 years later as he was developing the discovery doctrine in international law.[14] In the 21st century, groups such as the Shawnee, Lenape, Taíno, and Kanaka Maoli organised protests and raised petitions seeking to repeal the papal bull Inter caetera, and to remind Catholic leaders of "the record of conquest, disease and slavery in the Americas, sometimes justified in the name of Christianity", which they say has a devastating effect on their cultures today.[15] |

遺産と反響 この非キリスト教徒の土地を接収する権限は、約300年後、米国最高裁長官ジョン・マーシャルが国際法における発見主義を確立する際に引用された。 [14] 21世紀に入り、ショーニー族、レナペ族、タイノ族、カナカ・マオリ族などの集団は抗議行動を組織し、教皇勅書『インター・カエテラ』の廃止を求める請願 書を提出した。彼らはカトリック指導者に対し、「キリスト教の名のもとに正当化されることもあった、アメリカ大陸における征服、伝染病、奴隷制の歴史」を 想起させようとしている。彼らは、この歴史が今日の自らの文化に壊滅的な影響を与えていると主張している。[15] |

| Catholic Church and the Age of

Discovery Portuguese colonization of the Americas Treaty of Zaragoza |

カトリック教会と発見の時代 ポルトガルによるアメリカ大陸の植民地化 サラゴサ条約 |

| Notes 1. A single meridian is excluded because no lands can be south of it. Two partial meridians are possible, one extending north from a point west of the Azores and another extending south from a point south of the Cape Verde Islands, the two being connected by a north-northwest south-southeast line segment. Another possibility is a rhumb line west and south of the islands extending north-northwest and south-southeast. All rhumb lines reach both poles by spiraling into them. 2. Verzijl, Jan Hendrik Willem; W.P. Heere; J.P.S. Offerhaus (1979). International Law in Historical Perspective. Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 230–234, 237. ISBN 978-90-286-0158-1.. Online, Google Books entry 3. "The Möbius strip: a spatial history of colonial society in Guerrero, Mexico", Jonathan D. Amith, p. 80, Stanford University Press, 2005 ISBN 0-8047-4893-4 4. Diffie, Bailey Wallys (1977). Foundations of the Portuguese Empire, 1415–1580. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 9780816607822 – via Google Books. 5. Kirkpatrick Sale The Conquest of Paradise, p. 123, ISBN 0333574796 6. A copy of Columbus's letter is known to have arrived in Rome by mid-April (it is mentioned in a Venetian chronicle dated 18 April), Kirkpatrick Sale, p. 124 7. Spate, O. H. K. (1979). "Chapter 2 The Alexandrine Bulls and the Treaty of Tordesillas". The Spanish Lake. Canberra: Australian National University Press. ISBN 0-7081-0727-3. 8. Pope Alexander VI, Eximiae Devotionis, 1493 9. "Inter Caetera". 4 May 1493. 10. "The Philippine Islands, 1493–1803 by Emma Helen Blair – Full Text Free Book (Part 1/5)". www.fullbooks.com. 11. The Treaty of Tordesillas did not specify any longitude, thus writers have proposed several, beginning with Jaime Ferrer's 1495 opinion provided at the request of and to the Spanish king and queen. 12. Edward Gaylord Bourne, "Historical Introduction", in The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 by Emma Helen Blair. 13. "Ecomienda Casas". California State University at Northridge. 14. "The Doctrine of Discovery Helped Define Native American Policies". 15. "Indigenous demand revocation of 1493 papal bull", National Catholic Reporter, 27 October 2000, John L. Jr. Allen |

注記 1. 単一の経線は除外される。その南側に陸地が存在し得ないためである。二つの部分的な経線が考えられる。一つはアゾレス諸島の西側地点から北へ延びるもの、 もう一つはカーボベルデ諸島の南側地点から南へ延びるもので、両者は北北西-南南東の線分によって接続される。別の可能性として、諸島の西側及び南側を北 北西-南南東方向に延びるロム線がある。すべてのロム線は、螺旋状に両極に向かって伸びている。 2. Verzijl, Jan Hendrik Willem; W.P. Heere; J.P.S. Offerhaus (1979). International Law in Historical Perspective. Martinus Nijhoff. pp. 230–234, 237. ISBN 978-90-286-0158-1.. オンライン、Google Books エントリ 3. 「メビウス帯:メキシコ、ゲレロにおける植民地社会の空間的歴史」、ジョナサン・D・アミス、80 ページ、スタンフォード大学出版、2005 年 ISBN 0-8047-4893-4 4. ディフィー、ベイリー・ウォーリス(1977)。『ポルトガル帝国の基礎、1415–1580』。ミネソタ大学出版局。ISBN 9780816607822 – Google Books経由。 5. カークパトリック・セール『楽園の征服』、p. 123、ISBN 0333574796 6. コロンブスの手紙の写しが 4 月中旬までにローマに到着したことが知られている(4 月 18 日付のヴェネツィアの年代記に言及がある)。カークパトリック・セール、124 ページ 7. スペイト、O. H. K. (1979). 「第 2 章 アレクサンダーの勅書とトルデシリャス条約」. 『スペインの湖』. キャンベラ: オーストラリア国立大学出版局. ISBN 0-7081-0727-3。 8. 教皇アレクサンダー6世、Eximiae Devotionis、1493年 9. 「Inter Caetera」。1493年5月4日。 10. 「フィリピン諸島、1493年~1803年、エマ・ヘレン・ブレア著 – フルテキスト無料書籍(パート1/5)」。www.fullbooks.com。 11. トルデシリャス条約は経度を特定していなかったため、作家たちは、スペイン国王と王妃の要請に応じてハイメ・フェレールが1495年に提出した意見をはじ め、いくつかの経度を提案している。 12. エドワード・ゲイロード・ボーン、「歴史的紹介」、エマ・ヘレン・ブレア著『フィリピン諸島 1493-1803』所収。 13. 「エコミエンダ・カサス」。カリフォルニア州立大学ノースリッジ校。 14. 「発見の教義はネイティブアメリカン政策の定義に役立った」。 15. 「先住民が1493年教皇勅書の撤回を要求」。ナショナル・カトリック・レポーター、2000年10月27日、ジョン・L・アレン・ジュニア。 |

| References Emma H. Blair, The Philippine Islands 1493–1803 Linden, H. Vander (1916). "Alexander VI. and the Demarcation of the Maritime and Colonial Domains of Spain and Portugal, 1493-1494". The American Historical Review. 22 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2307/1836192. ISSN 0002-8762. JSTOR 1836192. Scott, William Henry (1987). "Demythologizing the Papal Bull 'Inter Caetera'". Philippine Studies. 35 (3): 348–356. ISSN 0031-7837. JSTOR 42633027. |

参考文献 エマ・H・ブレア『フィリピン諸島 1493-1803』 リンデン、H. ヴァンダー (1916). 「アレクサンダー 6 世とスペインおよびポルトガルの海洋および植民地領域の境界設定、1493-1494」. 『アメリカ歴史評論』. 22 (1): 1–20. doi:10.2307/1836192。ISSN 0002-8762。JSTOR 1836192。 スコット、ウィリアム・ヘンリー (1987). 「教皇勅書『Inter Caetera』の神話解体」. フィリピン研究. 35 (3): 348–356. ISSN 0031-7837. JSTOR 42633027. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inter_caetera |

デマルカシオン トルデシリャス条約 サラゴサ条約 スブリミス・デウス 奴隷制度に対するキリスト教徒の見解 大航海時代 ポルトガル海上帝国 スペイン帝国 |

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099