The Invention of America

La invención de América

The Invention of America: Research on the Historical Structure of the New World and the Meaning of its Future is a book by Mexican historian Edmundo O'Gorman, published in 1958. With this book, O'Gorman attacked the Mexican historiographical establishment in the 1940s, claiming that professional historiography in his country was hopelessly stuck in an outdated methodology and uninterested in philosophy. [1]

| La

invención de América: Investigación acerca de la estructura histórica

del Nuevo Mundo y del sentido de su devenir

es un libro del historiador mexicano Edmundo O'Gorman, publicado en

1958. Con este libro, O'Gorman atacó el establecimiento historiográfico

mexicano en los años 1940 afirmando que la historiografía profesional

de su país se hallaba atascada irremediablemente en una metodología

pasada de moda y desinteresada por la filosofía.1 |

The Invention of America: Research on the Historical Structure of the New World and the Meaning of its Future is a book by Mexican historian Edmundo O'Gorman, published in 1958. With this book, O'Gorman attacked the Mexican historiographical establishment in the 1940s, claiming that professional historiography in his country was hopelessly stuck in an outdated methodology and uninterested in philosophy. [1] |

| Contexto Es a estas ideas a lo que responde O' Gorman, mostrando cómo a América se le ve meramente como un objeto esperando a ser encontrado por los demás, se le desprestigia su estatus de civilización. A diferencia de autores tradicionales, no usa las fuentes convencionales e inaugura así este estilo de escritura junto con obras como: La disputa del Nuovo Mondo. Storia di una polémica, The Aztec Image in Western Thought, The First Images of America y The Impact of the New World on the Old. A este nuevo estilo se le suma la ola de novelas de ficción de América Latina que reflexionaron sobre su historia y su presente. Estos autores causaron revuelo en Europa y fueron percibidas, en su mayoría, más como historia que como ficción: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes u Octavio Paz. |

Context It is to these ideas that O'Gorman responds, showing how America is seen merely as an object waiting to be found by others, its status as a civilization being discredited. Unlike traditional authors, he does not use conventional sources and thus inaugurates this style of writing with works such as: La disputa del Nuovo Mondo. Storia di una polemica, The Aztec Image in Western Thought, The First Images of America, and The Impact of the New World on the Old. Added to this new style is the wave of Latin American fiction novels that reflected on their history and present. These authors caused a stir in Europe and were perceived, for the most part, more as history than fiction: García Márquez, Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, and Octavio Paz. |

| Síntesis El historiador mexicano Edmundo O'Gorman utilizando el término invención, pone en discusión el descubrimiento de América, y lo relata en su obra llamada la invención de América. Los viajes de Cristóbal Colón no fueron a América ya que la interpretación con el pasado no puede tener efectos retroactivos y afirmar lo contrario, quitar a la historia la luz que ilumina su propio devenír, todos parten de una América ya hecha, pero hay que empezar por una América vacía, estudiando el proyecto de Colón que se basaba en atravesar el océano en dirección de occidente para alcanzar desde España, los litorales extremos orientales y así unir Europa y Asia. Colón se basó en dos supuestos y concluyó que el globo terráqueo era mucho más pequeño de lo que decían y que el Theatrum Orbis Terrarum era mucho más largo de lo que se pensaba. Él consideraba la proximidad de las costas atlánticas de Europa y Asia pero algo andaba mal ya que la longitud de la tierra debería alargarse para hacerlo plausible y el riesgo era que las costas de África no terminaran arriba de Ecuador. Recibió la ayuda de los reyes católicos ya que, éstos tenían rivalidad con Portugal y también porque era poco lo que podían ganar y perder, además tenían la posibilidad de obtener algunas islas ubicadas en el atlántico, con el fin de ejercer un acto de soberanía sobre las aguas del océano. |

Summary Mexican historian Edmundo O'Gorman uses the term invention to question the discovery of America, recounting his argument in his work entitled The Invention of America. The voyages of Christopher Columbus did not go to America, since interpretations of the past cannot have retroactive effects, and to assert the contrary would be to strip history of the light that illuminates its own unfolding. All of them set out from an America that was already there, but we must start with an empty America, studying Columbus's project, which was based on crossing the ocean westward to reach the eastern coastlines from Spain and thus unite Europe and Asia. Columbus based his conclusions on two assumptions: that the globe was much smaller than people said and that the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum was much longer than previously thought. He considered the proximity of the Atlantic coasts of Europe and Asia, but something was wrong, since the length of the earth would have to be extended to make it plausible, and the risk was that the coasts of Africa would not end up above Ecuador. He received help from the Catholic monarchs, as they were rivals with Portugal and also because there was little to gain or lose, and they had the possibility of obtaining some islands located in the Atlantic, in order to exercise sovereignty over the waters of the ocean. |

| En

1492, Colón pensó haber llegado a Asia, a pesar de haber visto

indígenas desnudos, no se quitaba la idea de estar en Asia y con esa

idea persistió. Por esto Bartolomé de las Casas atribuye esta frase a

Colon: «cosa maravillosa como lo que el hombre mucho desea y asienta

una vez con firmeza en su imaginación, todo lo que oye y ve ser en su

favor en cada paso se le antoja»[cita requerida] .Colón no encontró

estas tierras por error, la corona lo impulsó pensando que estas

tierras le iban a ser provechosas, por este motivo las querían asegurar

jurídicamente el señorío sobre ellas, pero no podían suponer que la

isla encontrada eran las indias ya que corrían el riesgo de que no

fuese así y perdieran el poder sobre ellas, por esto se esclareció el

poder que tenían dejando lugar a la duda. En la segunda parte del libro O'Gorman explica que muchas personas no creían la teoría de Colón, sino que se trataba de una idea sin fundamentos y que la supuesta longitud de la Isla de la tierra era una posibilidad, pero por otro lado, Colón tenía todo el apoyo de la corona y de los teóricos que creían que su hipótesis era correcta, fue ahí cuando la corona pidió a Colón una serie de pruebas que ayudarían a determinar si de verdad llegó a India como él pensaba o se trataba de otra cosa. En su segundo viaje él tenía que demostrar que su teoría era una verdad científicamente comprobada, si no lograba las consecuencias podían ser muy graves. El fracaso de este viaje, iniciado el 25 de septiembre de 1493, se tradujo inmediatamente en desprecio por Colón y en un creciente desprestigio de la empresa. O'Gorman también explica que a pesar de que Colón había visto que su teoría podía estar equivocada, tuvo la idea de hacer que la tripulación testifique bajo juramento, en el cual decía que lo que habían explorado era demasiado para ser una sola isla y los obligó a decir que "antes de muchas leguas, navegando por la dicha costa (es decir, la que Colón tenía por ser la del Quersoneso Áureo), se hallaría tierra donde tratan gente política, y que saben del mundo" y que la ilusión de regresar fue sin duda el motivo que persuadió a todos a firmar tan extraordinario documento y cuando Colón mencionó la idea de continuar el viaje y circunnavegar el globo aumentaba la grave condición de los navíos y la falta de alimento, esto debió asustar mucho a la tripulación. Poco tiempo después se enfermó de fiebre amarilla y estuvo al borde de la muerte en la Villa de la Isabela, donde lo esperaba su hermano Bartolomé con todo su apoyo y junto a él lo esperaba la dura mirada de la corona y de la sociedad española. |

In

1492, Columbus thought he had reached Asia. Despite seeing naked

indigenous people, he could not shake the idea that he was in Asia, and

he persisted with this belief. For this reason, Bartolomé de las Casas

attributes this phrase to Columbus: "It is a marvelous thing how much a

man desires and firmly settles in his imagination, everything he hears

and sees in his favor at every turn seems to him to be so." Columbus

did not find these lands by mistake; the crown encouraged him, thinking

that these lands would be profitable, and for this reason they wanted

to legally secure their dominion over them, but they could not assume

that the island they found was the Indies, as they ran the risk of it

not being so and losing power over them. For this reason, the power

they had was clarified, leaving room for doubt. In the second part of the book, O'Gorman explains that many people did not believe Columbus' theory, considering it to be an unfounded idea and that the supposed length of the island of Earth was a possibility, but on the other hand, Columbus had the full support of the crown and of theorists who believed that his hypothesis was correct. It was then that the crown asked Columbus for a series of tests that would help determine whether he had really reached India as he thought, or whether it was something else. On his second voyage, he had to prove that his theory was scientifically proven; if he failed, the consequences could be very serious. The failure of this voyage, which began on September 25, 1493, immediately resulted in contempt for Columbus and a growing discredit of the enterprise. O'Gorman also explains that even though Columbus had seen that his theory might be wrong, he had the idea of having the crew testify under oath, in which he stated that what they had explored was too much to be a single island and forced them to say that "before many leagues, sailing along the said coast (that is, the one Columbus believed to be the Golden Chersonese), they would find land where people were political and knew about the world." The illusion of returning was undoubtedly the reason that persuaded everyone to sign such an extraordinary document, and when Columbus mentioned the idea of continuing the voyage and circumnavigating the globe, the serious condition of the ships and the lack of food must have greatly frightened the crew. Shortly thereafter, he fell ill with yellow fever and was on the verge of death in the town of La Isabela, where his brother Bartolomé awaited him with his full support, along with the harsh gaze of the crown and Spanish society. |

| En

1496, en el regreso de Colón a España, nadie sabía de la existencia de

una nueva tierra. En su tercer viaje, el 30 de mayo de 1498, Colón se

formó el proyecto de navegar hacia el sur hasta alcanzar regiones

ecuatoriales. Pretendía, establecer contacto con Asia y buscar el paso

al Océano Índico que, según la imagen que tenía de ellos, estaría por

esas latitudes. En el paralelo 9° de latitud norte aportó en una isla

bastante poblada por gente más blanca por lo que bautizo a la isla como

la isla Trinidad. Colón pensó que estaba en un archipiélago adyacente

al extremo meridional del orbis terrarum pero al explorarlo se dio

cuenta de su error y de que la ubicación de lo que pensaba no existía

donde el suponía. Para evitarse la hipótesis de que había encontrado

una gran tierra y tener que dar explicaciones asumió que había

encontrado una parte del Paraíso Terrenal donde existía una fuente de

donde procedían los cuatro grandes ríos del orbis terrarum. Colón pensó

que la Tierra no era una esfera perfecta sino de forma de pera. Para saber cual fue el planteamiento de Colón se necesita examinar más de sus cartas. Tanto en la carta al rey católico, 18 de octubre de 1498, como en otra carta que Colón dirigió a doña Juana de la Torre, o en su carta dirigida al papa en 1502, Colón expone los descubrimientos y logros de sus viajes y plantea el haber encontrado una nueva tierra. Pero este planteo le podía acarrear nuevos problemas a los papas, al tener que plantear la existencia de un "otro mundo", aunque finalmente lo hace, con cierta timidez. |

In

1496, when Columbus returned to Spain, no one knew of the existence of

a new land. On his third voyage, on May 30, 1498, Columbus formed a

plan to sail south until he reached equatorial regions. He intended to

establish contact with Asia and search for the passage to the Indian

Ocean, which, according to his image of them, would be at those

latitudes. At the 9th parallel north latitude, he landed on an island

populated by people with lighter skin, so he named the island Trinidad.

Columbus thought he was in an archipelago adjacent to the southern end

of the orbis terrarum, but upon exploring it, he realized his mistake

and that the location he thought existed did not exist where he had

assumed. To avoid the hypothesis that he had found a large landmass and

having to provide explanations, he assumed that he had found a part of

the Earthly Paradise where there was a source from which the four great

rivers of the orbis terrarum originated. Columbus thought that the

Earth was not a perfect sphere but pear-shaped. To understand Columbus's approach, we need to examine more of his letters. In his letter to the Catholic King dated October 18, 1498, in another letter Columbus wrote to Doña Juana de la Torre, and in his letter to the Pope in 1502, Columbus describes the discoveries and achievements of his voyages and suggests that he has found a new land. But this claim could cause new problems for the popes, as it would mean positing the existence of "another world," although he ultimately does so, with some timidity. |

| Al

enfocarnos en el cuarto y último viaje de Colón, se entiende claramente

cómo él comprendió lo establecido por Américo Vespucio para encaminarse

en su exploración, aquella enfocada en una península más en Asia,

mientras que Vespucio también comprendió la tesis establecida por Colón

en la cual menciona la realidad existente de ese nuevo mundo. Colón

había regresado con la idea de que todo era un mismo mundo, por su

parte Vespucio regresó con la idea de que había dos mundos. En concreto

Colón afirmaba que aquella tierra firme austral era el “nuevo mundo”

pero esta concepción discrepaba con la idea de Vespucio ya que según

él, este término desbordaba el marco de concepciones e indicios

habituales. En este punto se termina la idea de Colón para enfocarnos

en la promesa histórica de Vespucio. Las nuevas tierras fueron

comprendidas como dos islas oceánicas, este fue un primer intento para

declararlas como entidades geográficas independientes una de la otra,

aunque fue una noción inaceptable para el cristianismo debido a la

variedad de mundos. Este primer intento, fue muy cierto ya que se

concibe la idea de que esta era una gran isla en un principio pero que

con el tiempo se fue desprendiendo en su totalidad, esto permite

conceder a cada una un sentido propio. Por otra parte, es importante

recurrir al texto de Vespucio conocida como Lettera en la cual se

retomó la crisis que presentó Colón al verse forzado a reconocer que la

tierra que él encontró no era perteneciente al Orbis Terrarum. Vespucio

por su parte no interfirió en cuanto a esta implicación, que era muy

necesaria y que provocaría en este punto que América fuese inventada.

Por último ya se entiende cómo América llegó a ser una invención y cómo

apareció en la cultura como en la historia, esto llegó a nosotros no

desde la perspectiva de Colón sino desde una perspectiva universal

basada en una serie de hipótesis que se basan en conceder un sentido

propio que lo enfoca como “la cuarta parte del mundo”, aunque es

importante recalcar que se desconoce por qué fueron concedidas esas

tierras bajo ese nombre lo cual abre nuevas puertas a nuevas

investigaciones. |

By

focusing on Columbus' fourth and final voyage, it is clear how he

understood what Amerigo Vespucci had established in order to guide his

exploration, which focused on a peninsula in Asia, while Vespucci also

understood Columbus' thesis in which he mentioned the existing reality

of that new world. Columbus had returned with the idea that everything

was one world, while Vespucci returned with the idea that there were

two worlds. Specifically, Columbus claimed that the southern mainland

was the "new world," but this conception differed from Vespucci's idea,

since, according to him, this term went beyond the framework of usual

conceptions and indications. At this point, Columbus' idea ends and we

focus on Vespucci's historical promise. The new lands were understood

as two oceanic islands, which was a first attempt to declare them as

geographical entities independent of each other, although this was an

unacceptable notion for Christianity due to the variety of worlds. This

first attempt was very accurate, as it was conceived that this was

originally one large island but that over time it broke off completely,

allowing each one to be given its own meaning. On the other hand, it is

important to refer to Vespucci's text known as Lettera, which revisited

the crisis presented by Columbus when he was forced to recognize that

the land he found did not belong to the Orbis Terrarum. Vespucci, for

his part, did not interfere with this implication, which was very

necessary and would lead to the invention of America at this point.

Finally, we can now understand how America came to be an invention and

how it appeared in culture and history. This came to us not from

Columbus's perspective but from a universal perspective based on a

series of hypotheses that focus on giving it its own meaning as "the

fourth part of the world," although it is important to emphasize that

it is unknown why these lands were given that name, which opens new

doors for further research. |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/La_invenci%C3%B3n_de_Am%C3%A9rica |

References "Hale, C. EDMUNDO O'GORMAN AND NATIONAL HISTORY.". Archived from the original on July 3, 2011. Accessed May 13, 2010. Published in June 2000. Op.cit. p.15 |

| Bibliography O'Gorman (1995). The Invention of America. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica. |

Links

Bibliography

other informations

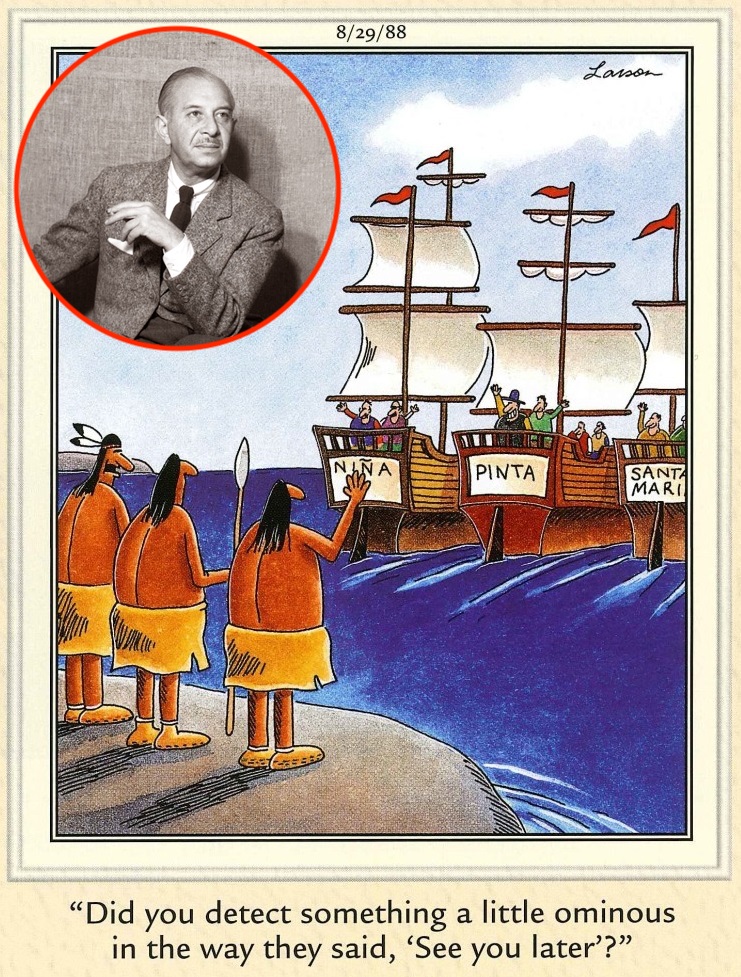

Did you detect something a little ominous in the way they said, "See you later'?"

彼 らが「また後でね」と言った口調に、何か不吉な予感を感じなかった?

¿Notaste

algo un poco siniestro en la forma en que dijeron «hasta luego»?

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099