ハコボ・アルベンス

Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán,

1913-1971

☆フアン・ハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン(スペイン語発音: [xwaŋ xaˈkoβo ˈaɾβens ɣusˈman]、1913年9月14日 - 1971年1月27日)は、グアテマラの軍人・政治家であり、同国第25代大統領を務めた。1944年から1950年まで国防大臣を務めた後、1951年 から1954年までグアテマラで2人目の民主的に選出された大統領となった。彼は10年にわたるグアテマラ革命の主要人物であり、この革命はグアテマラ史 上数少ない代表民主制の時代を象徴していた。アルベンスが大統領として実施した画期的な農地改革プログラムは、ラテンアメリカ全域に大きな影響を与えた。

| Juan

Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán (Spanish: [xwaŋ xaˈkoβo ˈaɾβens ɣusˈman]; 14

September 1913 – 27 January 1971) was a Guatemalan military officer and

politician who served as the 25th president of Guatemala. He was

Minister of National Defense from 1944 to 1950, before he became the

second democratically elected President of Guatemala, from 1951 to

1954. He was a major figure in the ten-year Guatemalan Revolution,

which represented some of the few years of representative democracy in

Guatemalan history. The landmark program of agrarian reform Árbenz

enacted as president was very influential across Latin America.[2] Árbenz was born in 1913 to a wealthy family, son of a Swiss German father and a Guatemalan mother. He graduated with high honors from a military academy in 1935, and served in the army until 1944, quickly rising through the ranks. During this period, he witnessed the violent repression of agrarian laborers by the United States-backed dictator Jorge Ubico, and was personally required to escort chain-gangs of prisoners, an experience that contributed to his progressive views. In 1938, he met and married María Vilanova, who was a great ideological influence on him, as was José Manuel Fortuny, a Guatemalan communist. In October 1944, several civilian groups and progressive military factions led by Árbenz and Francisco Arana rebelled against Ubico's repressive policies. In the elections that followed, Juan José Arévalo was elected president, and began a highly popular program of social reform. Árbenz was appointed Minister of Defense, and played a crucial role in putting down a military coup in 1949.[3][4][5][6] After the death of Arana, Árbenz ran in the presidential elections that were held in 1950 and without significant opposition defeated Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, his nearest challenger, by a margin of over 50%. He took office on 15 March 1951, and continued the social reform policies of his predecessor. These reforms included an expanded right to vote, the ability of workers to organize, legitimizing political parties, and allowing public debate.[7] The centerpiece of his policy was an agrarian reform law under which uncultivated portions of large land-holdings were expropriated in return for compensation and redistributed to poverty-stricken agricultural laborers. Approximately 500,000 people benefited from the decree. The majority of them were indigenous people, whose forebears had been dispossessed after the Spanish invasion. His policies ran afoul of the United Fruit Company, which lobbied the United States government to have him overthrown. The U.S. was also concerned by the presence of communists in the Guatemalan government, and Árbenz was ousted in the 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état engineered by the government of U.S. president Dwight D. Eisenhower through the U.S. Department of State and the Central Intelligence Agency. Árbenz went into exile through several countries, where his family gradually fell apart, and his daughter committed suicide. He died in Mexico in 1971. In October 2011, the Guatemalan government issued an apology for Árbenz's overthrow. |

フ

アン・ハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン(スペイン語発音: [xwaŋ xaˈkoβo ˈaɾβens ɣusˈman]、1913年9月14日 -

1971年1月27日)は、グアテマラの軍人・政治家であり、同国第25代大統領を務めた。1944年から1950年まで国防大臣を務めた後、1951年

から1954年までグアテマラで2人目の民主的に選出された大統領となった。彼は10年にわたるグアテマラ革命の主要人物であり、この革命はグアテマラ史

上数少ない代表民主制の時代を象徴していた。アルベンスが大統領として実施した画期的な農地改革プログラムは、ラテンアメリカ全域に大きな影響を与えた。

[2] アルベンスは1913年、裕福な家庭に生まれた。父はスイス系ドイツ人、母はグアテマラ人である。1935年に軍事アカデミーを優秀な成績で卒業し、 1944年まで軍に勤務、急速に出世した。この期間、彼はアメリカ合衆国が支援する独裁者ホルヘ・ウビコによる農地労働者への暴力的な弾圧を目の当たりに し、自らも囚人連行の護送を命じられる経験をした。この経験が彼の進歩的な思想形成に寄与した。1938年にはマリア・ビラノバと出会い結婚する。彼女は グアテマラの共産主義者ホセ・マヌエル・フォルトゥーニと同様、彼に大きな思想的影響を与えた。1944年10月、アルベンスとフランシスコ・アラナ率い る複数の市民団体と進歩的な軍部勢力が、ウビコの抑圧政策に反旗を翻した。続く選挙でフアン・ホセ・アレバロが大統領に選出され、大衆に支持された社会改 革プログラムを開始した。アルベンスは国防相に任命され、1949年の軍事クーデター鎮圧で重要な役割を果たした。[3][4][5] [6] アラナの死後、アルベンスは1950年に実施された大統領選挙に出馬し、実質的な対抗馬がいない中で最有力候補ミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスを50% 以上の境界で破った。1951年3月15日に就任し、前任者の社会改革政策を継続した。これらの改革には、選挙権の拡大、労働者の団結権、政党の合法化、 公開討論の許可などが含まれていた。[7] 政策の核心は農地改革法であり、これにより大規模土地所有者の未耕作地は補償と引き換えに収用され、貧困に苦しむ農業労働者に再分配された。約50万人が この法令の恩恵を受けた。その大半は先住民であり、彼らの祖先はスペインの侵略後に土地を奪われていた。 彼の政策はユナイテッド・フルーツ社と対立し、同社は米国政府に働きかけて彼の転覆を図った。米国はまたグアテマラ政府内の共産主義者の存在を懸念してお り、アルベンスは1954年のグアテマラクーデターで追放された。このクーデターはドワイト・D・アイゼンハワー米大統領政権が国務省と中央情報局を通じ て仕組んだものだった。アルベンスは亡命を余儀なくされ、いくつかの国を渡り歩いた。その間、家族は次第に崩壊し、娘は自殺した。彼は1971年にメキシ コで死去した。2011年10月、グアテマラ政府はアルベンスの失脚について謝罪した。 |

Early life Árbenz's parents, Hans Jakob Arbenz and Octavia Guzmán Caballeros Árbenz was born in Quetzaltenango, the second-largest city in Guatemala, in 1913. He was the son of a Swiss German pharmacist, Hans Jakob Arbenz Gröbli,[8][9] who immigrated to Guatemala in 1901. His mother, Octavia Guzmán Caballeros, was a Ladino woman from a middle-class family who worked as a primary school teacher.[9] His family was relatively wealthy and upper-class; his childhood has been described as "comfortable".[10] At some point during his childhood, his father became addicted to morphine and began to neglect the family business. He eventually went bankrupt, forcing the family to move to a rural estate that a wealthy friend had set aside for them "out of charity". Jacobo had originally desired to be an economist or an engineer, but since the family was now impoverished, he could not afford to go to a university. He initially did not want to join the military, but there was a scholarship available through the Polytechnic School of Guatemala for military cadets. He applied, passed all of the entrance exams, and became a cadet in 1932. His father committed suicide two years after Árbenz entered the academy.[10] |

幼少期 アルベンスの両親は、ハンス・ヤコブ・アルベンスとオクタビア・グスマン・カバジェロスであった。 アルベンスは1913年、グアテマラ第2の都市ケツァルテナンゴで生まれた。父はスイス・ドイツ系の薬剤師ハンス・ヤコブ・アルベンツ・グレーブリ[8] [9]で、1901年にグアテマラへ移住した。母オクタビア・グスマン・カバジェロスは中流階級のラディーノ系女性で、小学校教師を務めていた[9]。家 族は比較的裕福で上流階級に属し、彼の幼少期は「恵まれた環境」と評されている。[10] 幼少期のある時点で、父親がモルヒネ中毒になり、家業を顧みなくなった。結局破産し、裕福な友人が「慈善」で用意した田舎の土地に家族は移住せざるを得な かった。ヤコボはもともと経済学者か技術者になることを望んでいたが、家族が貧困に陥ったため、大学に進学する余裕はなかった。当初は軍隊に入ることを望 んでいなかったが、グアテマラ工科大学が軍事士官候補生向けに奨学金を提供していた。彼は応募し、全ての入学試験に合格して1932年に士官候補生となっ た。アルベンスが士官学校に入学してから2年後、父親は自殺した。[10] |

Military career and marriage Jacobo Árbenz seated next to his wife María Vilanova Árbenz seated next to his wife Maria Cristina Vilanova in 1944. His wife was a great ideological influence upon him, and they shared a desire for social reform. Árbenz excelled in the academy, and was deemed "an exceptional student". He became "first sergeant", the highest honor bestowed upon cadets; only six people received the honor from 1924 to 1944. His abilities earned him an unusual level of respect among the officers at the school, including Major John Considine, the US director of the school, and of other US officers who served at the school. A fellow officer later said that "his abilities were such that the officers treated him with a respect that was rarely granted to a cadet."[10] Árbenz graduated in 1935.[10] After graduating, he served a stint as a junior officer at Fort San José in Guatemala City and later another under "an illiterate Colonel" in a small garrison in the village of San Juan Sacatepéquez. While at San José, Árbenz had to lead squads of soldiers who were escorting chain gangs of prisoners (including political prisoners) to perform forced labor. The experience traumatized Árbenz, who said he felt like a capataz (i.e., a "foreman").[10] During this period he first met Francisco Arana.[10] Árbenz was asked to fill a vacant teaching position at the academy in 1937. Árbenz taught a wide range of subjects, including military matters, history, and physics. He was promoted to captain six years later, and placed in charge of the entire corps of cadets. His position was the third highest in the academy and was considered one of the most prestigious positions a young officer could hold.[10] In 1938 he met his future wife María Vilanova, the daughter of a wealthy Salvadoran landowner and a Guatemalan mother from a wealthy family. They were married a few months later, without the approval of María's parents, who felt she should not marry an army lieutenant who was not wealthy.[10] María was 24 at the time of the wedding, and Jacobo was 26. María later wrote that, while the two were very different in many ways, their desire for political change drew them together. Árbenz stated that his wife had a great influence on him.[10] It was through her that Árbenz was exposed to Marxism. María had received a copy of The Communist Manifesto at a women's congress and left a copy of it on Jacobo's bedside table when she left for a vacation. Jacobo was "moved" by the Manifesto, and he and María discussed it with each other. Both felt that it explained many things they had been feeling. Afterwards, Jacobo began reading more works by Marx, Lenin, and Stalin and by the late 1940s was regularly interacting with a group of Guatemalan communists.[11] |

軍歴と結婚 ハコボ・アルベンスは妻マリア・ビラノバの隣に座っている 1944年、アルベンスは妻マリア・クリスティーナ・ビラノバの隣に座っている。妻は彼に大きな思想的影響を与え、二人は社会改革への志を共有していた。 アルベンスは士官学校で優秀な成績を収め、「傑出した学生」と評された。彼は士官候補生に授与される最高の栄誉である「一等軍曹」となった。1924年か ら1944年にかけてこの栄誉を受けたのはわずか6人々である。その能力は、学校長を務めたジョン・コンシディン少佐をはじめ、学校に勤務した他の米国人 将校たちからも、異例の尊敬を集めた。後に同僚将校は「彼の能力は、士官候補生にはめったに与えられないほどの敬意を将校たちが彼に払うほどだった」と述 べている[10]。アルベンスは1935年に卒業した[10]。 卒業後、彼はグアテマラシティのサン・ホセ要塞で下級将校として勤務し、その後サン・フアン・サカテペケスの村にある小さな駐屯地で「文盲の大佐」の下で 勤務した。サン・ホセ駐屯中、アルベンスは囚人(政治犯を含む)の連行隊を率いて強制労働に従事させなければならなかった。この経験はアルベンスに深いト ラウマを残し、彼は自分がカパタス(つまり「監督役」)のように感じたと語っている[10]。この時期に彼は初めてフランシスコ・アラナと出会った。 [10] 1937年、アルベンスは士官学校の教員の空席を埋めるよう要請された。アルベンスは軍事、歴史、物理学など幅広い科目を教えた。6年後には大尉に昇進 し、士官候補生全体の責任者を任された。彼の地位は学校内で三番目に高く、若い将校が就ける最も名誉ある地位の一つと見なされていた。[10] 1938年、彼は将来の妻となるマリア・ビラノバと出会った。彼女はエルサルバドルの富裕な地主の娘で、母はグアテマラの裕福な家系の出身であった。数か 月後、マリアの両親の反対を押し切って二人は結婚した。両親は、裕福でない陸軍中尉との結婚を娘に許さなかったのである。[10] 結婚式当時、マリアは24歳、ハコボは26歳だった。マリアは後に、二人は多くの点で大きく異なる存在であったが、政治的変革への渇望が彼らを結びつけた と記している。アルベンスは妻が自分に大きな影響を与えたと述べている[10]。アルベンスがマルクス主義に触れたのは彼女を通じてであった。マリアは女 性会議で『共産党宣言』の写しを受け取り、休暇で家を離れる際にその写しをハコボの枕元に置いていったのである。ヤコボは『宣言』に「心を動かされた」と 述べ、夫妻は互いに議論を交わした。二人はこの書物が自分たちが抱いていた多くの感情を説明していると実感した。その後、ヤコボはマルクス、レーニン、ス ターリンの著作をさらに読み進め、1940年代後半にはグアテマラの共産主義者グループと定期的に交流するようになった[11]。 |

October revolution and defense ministership President Jorge Ubico in the 1930s. Like his predecessors, he gave a number of concessions to the United Fruit Company and supported their harsh labor practices. He was forced out of power by a popular uprising in 1944. Further information: Guatemalan Revolution Historical background In 1871 the government of Justo Rufino Barrios passed laws confiscating the lands of the native Mayan people and compelling them to work in coffee plantations for minimal compensation.[3] Several United States-based companies, including the United Fruit Company, received this public land, and were exempted from paying taxes.[12][13] In 1929 the Great Depression led to the collapse of the economy and a rise in unemployment, leading to unrest among workers and laborers. Fearing the possibility of a revolution, the landed elite lent their support to Jorge Ubico, who won the election that followed in 1931, an election in which he was the only candidate.[14][13] With the support of the United States, Ubico soon became one of Latin America's most brutal dictators.[15] Ubico abolished the system of debt peonage introduced by Barrios and replaced it with a vagrancy law, which required all men of working age who did not own land to perform a minimum of 100 days of hard labor.[16][3] In addition, the state made use of unpaid Indian labor to work on public infrastructure such as roads and railroads. Ubico also froze wages at very low levels, and passed a law allowing landowners complete immunity from prosecution for any action they took to defend their property,[16] including allowing them to execute workers as a "disciplinary" measure.[17][18][19][20] The result of these laws was a tremendous resentment against him among agricultural laborers.[21] Ubico was highly contemptuous of the country's indigenous people, once stating that they resembled donkeys.[22] He gave away 200,000 hectares (490,000 acres) of public land to the United Fruit Company, and allowed the US military to establish bases in Guatemala.[17][18][19][20][23][24] |

十月革命と国防相職 1930年代のホルヘ・ウビコ大統領。前任者たちと同様、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社に数々の特権を与え、同社の過酷な労働慣行を支持した。1944年の民衆蜂起により権力から追放された。 詳細情報:グアテマラ革命 歴史的背景 1871年、フスト・ルフィーノ・バリオス政権は、先住民マヤ人民の土地を没収し、最低限の報酬でコーヒー農園での労働を強制する法律を制定した[3]。 ユナイテッド・フルーツ・カンパニーを含む米国系企業数社がこの公有地を取得し、税金の支払いを免除された。[12][13] 1929年、世界恐慌により経済が崩壊し失業率が上昇、労働者や農民の間で不安が広がった。革命の可能性を恐れた土地所有者層はホルヘ・ウビコを支援し、 1931年の選挙で彼は唯一の候補者として当選した。[14][13] アメリカ合衆国の支援を得て、ウビコは間もなくラテンアメリカで最も残虐な独裁者の一人となった。[15] ウビコはバリオスが導入した債務農奴制を廃止し、代わりに浮浪者法を制定した。この法律は土地を所有しない労働年齢の男性全員に、最低100日間の重労働 を義務付けた。[16][3] さらに国家は、道路や鉄道などの公共インフラ建設に無給のインドの労働力を動員した。ウビコは賃金を極度に低い水準で凍結し、土地所有者が財産防衛のため に行ったあらゆる行為(労働者を「懲戒」として処刑することも含む)について完全な免責を認める法律を制定した。[16][17][18][19] [20] こうした法律の結果、農業労働者たちの間で彼に対する強い反感が高まった。[21] ウビコは国内の先住民を強く軽蔑し、かつて「彼らはロバに似ている」と発言したことがある。[22] 彼は20万ヘクタール(49万エーカー)の公有地をユナイテッド・フルーツ社に無償譲渡し、米軍がグアテマラに基地を設置することを許可した。[17] [18][19][20][23][24] |

October revolution Árbenz, Toriello and Arana Árbenz, Jorge Toriello (center), and Francisco Arana (right) in 1944. The three men formed the junta that ruled Guatemala from the October Revolution until the election of Arévalo. In May 1944 a series of protests against Ubico broke out at the university in Guatemala City. Ubico responded by suspending the constitution on 22 June 1944.[25][26][27] The protests, which by this point included many middle-class members and junior army officers in addition to students and workers, gained momentum, eventually forcing Ubico's resignation at the end of June.[28][17][29] Ubico appointed a three-person junta led by General Federico Ponce Vaides to succeed him. Although Ponce Vaides initially promised to hold free elections, when the congress met on 3 July soldiers held everyone at gunpoint and forced them to appoint Ponce Vaides interim president.[29] The repressive policies of the Ubico administration were continued.[17][29] Opposition groups began organizing again, this time joined by many prominent political and military leaders, who deemed the Ponce regime unconstitutional. Árbenz had been one of the few officers in the military to protest the actions of Ponce Vaides.[30] Ubico had fired Árbenz from his teaching post at the Escuela Politécnica, and since then Árbenz had been living in El Salvador, organizing a band of revolutionary exiles.[31] Árbenz was one of the leaders of the plot within the army, along with Major Aldana Sandoval. Árbenz insisted that civilians also be included in the coup, over the protests of the other military men involved. Sandoval later said that all contact with the civilians during the coup was through Árbenz.[30] On 19 October 1944, a small group of soldiers and students led by Árbenz and Francisco Javier Arana attacked the National Palace in what later became known as the "October Revolution".[31] Arana had not initially been a party to the coup, but his position of authority within the army meant that he was key to its success.[32] They were joined the next day by other factions of the army and the civilian population. Initially, the battle went against the revolutionaries, but after an appeal for support their ranks were swelled by unionists and students, and they eventually subdued the police and army factions loyal to Ponce Vaides. On 20 October, the next day, Ponce Vaides surrendered unconditionally.[33] Árbenz and Arana both fought with distinction during the revolt,[32] and despite the idealistic rhetoric of the revolution, both were also offered material rewards: Árbenz was promoted from captain to lieutenant colonel, and Arana from major to full colonel.[34] The junta promised free and open elections to the presidency and the congress, as well as for a constituent assembly.[35] The resignation of Ponce Vaides and the creation of the junta has been considered by scholars to be the beginning of the Guatemalan Revolution.[35] However, the revolutionary junta did not immediately threaten the interests of the landed elite. Two days after Ponce Vaides' resignation, a violent protest erupted at Patzicía, a small Indian hamlet. The junta responded with swift brutality, silencing the protest. The dead civilians included women and children.[36] Elections subsequently took place in December 1944. Although only literate men were allowed to vote, the elections were broadly considered free and fair.[37][38][39] Unlike in similar historical situations, none of the junta members stood for election.[37] The winner of the 1944 elections was a teacher named Juan José Arévalo, who ran under a coalition of leftist parties known as the "Partido Acción Revolucionaria'" ("Revolutionary Action Party", PAR), and won 85% of the vote.[38] Arana did not wish to turn over power to a civilian administration.[32] He initially tried to persuade Árbenz and Toriello to postpone the election, and after Arévalo was elected, he asked them to declare the results invalid.[32] Árbenz and Toriello insisted that Arévalo be allowed to take power, which Arana reluctantly agreed to, on the condition that Arana's position as the commander of the military be unchallenged. Arévalo had no choice but to agree to this, and so the new Guatemalan constitution, adopted in 1945, created a new position of "Commander of the Armed Forces", a position that was more powerful than that of the defense minister. He could only be removed by Congress, and even then only if he was found to have broken the law.[40] When Arévalo was inaugurated as president, Arana stepped into this new position, and Árbenz was sworn in as defense minister.[32] |

十月革命 アルベンス、トリエリョ、アラナ 1944年のアルベンス、ホルヘ・トリエリョ(中央)、フランシスコ・アラナ(右)。この三人は十月革命からアレバロの選挙までの間、グアテマラを統治した軍事政権を形成した。 1944年5月、グアテマラシティの大学でウビコに対する一連の抗議活動が発生した。ウビコはこれに対し、1944年6月22日に憲法を停止した[25] [26][27]。この時点で学生や労働者に加え、多くの中産階級や下級将校も参加するようになった抗議活動は勢いを増し、6月末にはウビコの辞任を迫る こととなった。[28][17][29] ウビコは後継としてフェデリコ・ポンセ・バイデス将軍を首班とする3人格による軍事政権を任命した。ポンセ・バイデスは当初自由選挙の実施を約束したが、 7月3日に議会が開かれた際、兵士たちが全員を銃口で脅してポンセ・バイデスを暫定大統領に任命させた。[29] ウビコ政権の抑圧的政策は継続された。[17][29] 反対派グループは再び組織化を開始し、今回は多くの著名な政治・軍事指導者が加わった。彼らはポンセ政権を違憲と見なしていた。アルベンスは軍内でポン セ・バイデス将軍の行動に抗議した数少ない将校の一人だった。[30] ウビコはアルベンスをポリテクニック校の教職から解雇しており、それ以来アルベンスはエルサルバドルに亡命し、革命的な亡命者たちのグループを組織してい た。[31] アルベンスはアルダナ・サンドバル少佐と共に、軍内部の陰謀の指導者の一人であった。アルベンスは、他の関与した軍人たちの反対を押し切って、クーデター に民間人も参加させることを主張した。サンドバルは後に、クーデター中の民間人との全ての連絡はアルベンスを通じて行われたと述べている。[30] 1944年10月19日、アルベンスとフランシスコ・ハビエル・アラナ率いる少数の兵士と学生が国立宮殿を襲撃した。この事件は後に「十月革命」として知 られるようになった。[31] アラナは当初クーデターに加わっていなかったが、軍内での権威ある立場から、クーデター成功の鍵を握る存在となった。[32] 翌日には他の軍部勢力や市民層が合流した。当初は革命派が劣勢だったが、支援要請後、労働組合員や学生が加わり、ポンセ・バイデスに忠実な警察・軍部勢力 を制圧した。翌10月20日、ポンセ・バイデスは無条件降伏した。[33] アルベンスとアラナは反乱で顕著な戦功を立てた[32]。革命の理想主義的な主張にもかかわらず、両者には物質的報酬も与えられた。アルベンスは大尉から 中佐に、アラナは少佐から大佐に昇進した[34]。軍事評議会は大統領選挙、議会選挙、憲法制定議会選挙の自由かつ公正な実施を約束した[35]。ポン セ・バイデス辞任と軍事評議会設立は、学者らによってグアテマラ革命の始まりと見なされている[35]。しかし革命評議会は、直ちに土地所有エリートの利 益を脅かすことはなかった。ポンセ・バイデス辞任の2日後、小さなインドの集落パツィシアで暴動が発生した。評議会は即座に残忍な弾圧で抗議を鎮圧した。 犠牲者には女性や子供も含まれていた。[36] その後、1944年12月に選挙が実施された。投票権は識字能力のある男性に限られていたが、この選挙は概ね自由かつ公正と評価された。[37][38] [39] 類似の歴史的事例とは異なり、軍事政権のメンバーは誰も立候補しなかった。[37] 1944年選挙の勝者はフアン・ホセ・アレバロという教師だった。彼は「革命行動党(PAR)」として知られる左派政党連合から立候補し、85%の得票率 で勝利した。[38] アラナは権力を文民政権に引き渡すことを望まなかった。[32] 彼は当初、アルベンスとトリエロに選挙延期を働きかけ、アレバロ当選後は結果無効を要求した。[32] アルベンスとトリエロはアレバロの政権樹立を主張し、アラナは軍司令官としての地位が揺るがないことを条件に渋々同意した. アレバロはこれを受け入れるしかなく、こうして1945年に採択されたグアテマラ新憲法は「軍司令官」という新たな地位を創設した。この地位は国防相より も強力なもので、議会によってのみ罷免され、しかも法律違反が認められた場合に限られた。[40] アレバロが大統領に就任すると、アラナはこの新職に就き、アルベンスは国防相として宣誓した。[32] |

| Government of Juan José Arévalo Arévalo described his ideology as "spiritual socialism". He was anti-communist and believed in a capitalist society regulated to ensure that its benefits went to the entire population.[41] Arévalo's ideology was reflected in the new constitution that was ratified by the Guatemalan assembly soon after his inauguration, which was one of the most progressive in Latin America. It mandated suffrage for all but illiterate women, a decentralization of power, and provisions for a multiparty system. Communist parties were forbidden.[41] Once in office, Arévalo implemented these and other reforms, including minimum wage laws, increased educational funding, and labor reforms. The benefits of these reforms were largely restricted to the upper-middle classes and did little for the peasant agricultural laborers who made up the majority of the population.[42][43] Although his reforms were based on liberalism and capitalism, he was viewed with suspicion by the United States government, which would later portray him as a communist.[42][43] When Árbenz was sworn in as defense minister under President Arévalo, he became the first to hold the portfolio, since it had previously been known as the Ministry of War. In the fall of 1947, Árbenz, as defense minister, objected to the deportation of several workers after they had been accused of being communists. Well-known communist José Manuel Fortuny was intrigued by this action and decided to visit him, and found Árbenz to be different from the stereotypical Central American military officer. That first meeting was followed by others until Árbenz invited Fortuny to his house for discussions that usually extended for hours. Like Árbenz, Fortuny was inspired by a fierce nationalism and a burning desire to improve the conditions of the Guatemalan people, and, like Árbenz, he sought answers in Marxist theory. This relationship would strongly influence Árbenz in the future.[44] On 16 December 1945, Arévalo was incapacitated for a while after a car accident.[45] The leaders of the Revolutionary Action Party (PAR), which was the party that supported the government, were afraid that Arana would take the opportunity to launch a coup and so struck a deal with him, which later came to be known as the Pacto del Barranco (Pact of the Ravine).[45] Under the terms of this pact, Arana agreed to refrain from seizing power with the military; in return, the PAR agreed to support Arana's candidacy in the next presidential election, scheduled for November 1950.[45] Arévalo himself recovered swiftly, but was forced to support the agreement.[45] However, by 1949 the National Renovation Party and the PAR were both openly hostile to Arana due to his lack of support for labor rights. The leftist parties decided to back Árbenz instead, as they believed that only a military officer could defeat Arana.[46] In 1947 Arana had demanded that certain labor leaders be expelled from the country; Árbenz vocally disagreed with Arana, and the former's intervention limited the number of deportees.[46] The land reforms brought about by the Arévalo administration threatened the interests of the landed elite, who sought a candidate who would be more amenable to their terms. They began to prop up Arana as a figure of resistance to Arévalo's reforms.[47] The summer of 1949 saw intense political conflict in the councils of the Guatemalan military between supporters of Arana and those of Árbenz, over the choice of Arana's successor.[a] On 16 July 1949, Arana delivered an ultimatum to Arévalo, demanding the expulsion of all of Árbenz's supporters from the cabinet and the military; he threatened a coup if his demands were not met. Arévalo informed Árbenz and other progressive leaders of the ultimatum; all agreed that Arana should be exiled.[48] Two days later, Arévalo and Arana had another meeting; on the way back, Arana's convoy was intercepted by a small force led by Árbenz. A shootout ensued, killing three men, including Arana. Historian Piero Gleijeses stated that Árbenz probably had orders to capture, rather than to kill, Arana.[48] Arana's supporters in the military rose up in revolt, but they were leaderless, and by the next day the rebels asked for negotiations. The coup attempt left approximately 150 dead and 200 wounded.[48] Árbenz and a few other ministers suggested that the entire truth be made public; however, they were overruled by the majority of the cabinet, and Arévalo made a speech suggesting that Arana had been killed for refusing to lead a coup against the government.[48] Árbenz kept his silence over the death of Arana until 1968, refusing to speak out without first obtaining Arévalo's consent. He tried to persuade Arévalo to tell the entire story when the two met in Montevideo in the 1950s, during their exile: however, Arévalo was unwilling, and Árbenz did not press his case.[49] |

フアン・ホセ・アレバロ政権 アレバロは自らの思想を「精神的社会主義」と称した。彼は反共主義者であり、資本主義社会の利益が全人口に還元されるよう規制された社会を信奉していた [41]。アレバロの思想は、就任直後にグアテマラ議会で批准された新憲法に反映され、これはラテンアメリカで最も進歩的な憲法の一つであった。この憲法 は、文盲の女性を除く全員の選挙権、権力の分散化、複数政党制の規定を義務付けた。共産党は禁止された。[41] 政権掌握後、アレバロはこれらの改革に加え、最低賃金法、教育資金の増額、労働改革などを実施した。しかしこれらの改革の恩恵は主に中流階級以上に限定さ れ、人口の大多数を占める農民や農業労働者にはほとんど及ばなかった。[42][43] 彼の改革は自由主義と資本主義に基づくものだったが、米国政府からは疑いの目で見られ、後に共産主義者として描かれることになる。[42][43] アルベンスがアレバロ大統領の下で国防大臣に就任した時、彼はこの職に就いた最初の人物となった。それまでは戦争省と呼ばれていたからだ。1947年秋、 国防相としてのアルベンスは、共産主義者との嫌疑をかけられた数名の労働者の国外追放に異議を唱えた。著名な共産主義者ホセ・マヌエル・フォルトゥーニは この行動に興味を惹かれ、アルベンスを訪ねることを決めた。そして彼は、アルベンスが中米の軍人という固定観念とは異なる人物であることを知った。この初 対面を皮切りに交流は続き、やがてアルベンスはフォルトゥーニを自宅に招いて数時間に及ぶ議論を重ねた。アルベンス同様、フォルトゥーニも激しいナショナ リズムとグアテマラの人民の生活改善への強い情熱に駆られており、マルクス主義理論に答えを求めていた。この関係は後にアルベンスに多大な影響を与えるこ とになる。[44] 1945年12月16日、アレバロは自動車事故で一時的に職務遂行不能となった[45]。政府を支持する革命行動党(PAR)の指導者たちは、アラナが クーデターを起こす機会を狙うことを恐れ、彼と取引を結んだ。これが後に「渓谷の協定(Pacto del Barranco)」として知られるようになった。この協定により、アラナは軍による権力掌握を控えることに同意した。その見返りとして、PARは 1950年11月に予定されていた次期大統領選挙におけるアラナの立候補を支持することを約束した。[45] アレバロ自身はすぐに回復したが、この協定を支持せざるを得なかった。[45] しかし1949 年までに、国民革新党とPAR党は、労働権を支持しないアラナに対して公然と敵対するようになった。左派政党は代わりにアルベンスを支援することを決め た。軍人だけがアラナを倒せると考えたからだ。[46] 1947年、アラナは特定の労働指導者を国外追放するよう要求した。アルベンスはアラナに公然と反対し、彼の介入によって国外退去者の数は制限された。 [46] アレバロ政権による土地改革は、土地所有エリートの利益を脅かした。彼らは自らの条件に順応しやすい候補者を探し、アレバロの改革に対する抵抗勢力として アラナを支援し始めた。[47] 1949年の夏、グアテマラ軍内部ではアラナ支持派とアルベンス支持派の間で、アラナの後継者選びを巡り激しい政治的対立が起きた。1949年7月16 日、アラナはアレバロに対し、アルベンス支持派を内閣と軍部から全員追放するよう最後通告を突きつけた。要求が受け入れられなければクーデターを起こすと 脅したのである。アレバロはこの最後通告をアルベンスら進歩派指導者に伝えた。全員がアラナの追放に同意した。二日後、アレバロとアラナは再び会談した。 帰路、アラナの車列はアルベンス率いる小部隊に襲撃された。銃撃戦が発生し、アラナを含む3名が死亡した。歴史家ピエロ・グレイヘセスは、アルベンスはお そらくアラナを殺害ではなく捕縛するよう命令を受けていたと述べている[48]。軍内のアラナ支持派は反乱を起こしたが、指導者を失っていたため、翌日に は反乱軍は交渉を求めた。このクーデター未遂事件では約150名が死亡、200名が負傷した[48]。アルベンスと数名の閣僚は真相の完全な公表を提案し たが、内閣の多数派に否決された。アレバロは演説で、アラナが政府に対するクーデターを指揮することを拒否したために殺害されたと示唆した。 |

| 1950 election Árbenz's role as defense minister had already made him a strong candidate for the presidency, and his firm support of the government during the 1949 uprising further increased his prestige.[50] In 1950 the economically moderate Partido de Integridad Nacional (PIN) announced that Árbenz would be its presidential candidate in the upcoming election. The announcement was quickly followed by endorsements from most parties on the left, including the influential PAR, as well as from labor unions.[50] Árbenz carefully chose the PIN as the party to nominate him. Based on the advice of his friends and colleagues, he believed it would make his candidacy appear more moderate.[50] Árbenz himself resigned his position as Defense Minister on 20 February and declared his candidacy for the presidency. Arévalo wrote him an enthusiastic personal letter in response but publicly only reluctantly endorsed him, preferring, it is thought, his friend Víctor Manuel Giordani, who was then Health Minister. It was only the support Árbenz had, and the impossibility of Giordani being elected, that led to Arévalo deciding to support Árbenz.[51] Prior to his death, Arana had planned to run in the 1950 presidential elections. His death left Árbenz without any serious opposition in the elections (leading some, including the CIA and US military intelligence, to speculate that Árbenz personally had him eliminated for this reason).[52] Árbenz had only a couple of significant challengers in the election, in a field of ten candidates.[50] One of these was Jorge García Granados, supported by some members of the upper-middle class who felt the revolution had gone too far. Another was Miguel Ydígoras Fuentes, who had been a general under Ubico and had the support of the hardline opponents of the revolution. During his campaign, Árbenz promised to continue and expand the reforms begun under Arévalo.[53] Árbenz was expected to win the election comfortably because he had the support of both major political parties of the country, as well as that of the labor unions, which campaigned heavily on his behalf.[54] In addition to political support, Árbenz had great personal appeal. He was described as having "an engaging personality and a vibrant voice".[55] Árbenz's wife María also campaigned with him; despite her wealthy upbringing she had made an effort to speak for the interests of the Mayan peasantry and had become a national figure in her own right. Árbenz's two daughters also occasionally made public appearances with him.[56] The election was held on 15 November 1950, with Árbenz winning more than 60% of the vote, in elections that were largely free and fair with the exception of the disenfranchisement of illiterate female voters.[50] Árbenz got more than three times as many votes as the runner-up, Ydígoras Fuentes, who claimed electoral fraud had benefited Árbenz. Scholars have pointed out that while fraud may possibly have given Árbenz some of his votes, it was not the reason that he won the election.[57] Árbenz's promise of land reform played a large role in ensuring his victory.[58] The election of Árbenz alarmed US State Department officials, who stated that Arana "has always represented the only positive conservative element in the Arévalo administration" and that his death would "strengthen Leftist [sic] materially", and that "developments forecast sharp leftist trend within the government."[59] Árbenz was inaugurated as president on 15 March 1951.[50] |

1950年の選挙 アルベンスは国防相としての役割で既に大統領選の有力候補となっており、1949年の反乱時に政府を断固として支持したことでさらに威信を高めた。 [50] 1950年、経済的に穏健な国民統合党(PIN)は、アルベンスを次期大統領選の党候補に指名すると発表した。この発表後、影響力のあるPARを含む左派 政党の大半や労働組合が相次いで支持を表明した。[50] アルベンスは自らを指名する政党としてPINを慎重に選んだ。友人や同僚の助言に基づき、これにより自身の立候補がより穏健に見えると考えていたのであ る。[50] アルベンス自身は2月20日に国防相の職を辞し、大統領選への出馬を宣言した。アレバロは熱烈な私信で応じたが、公の場では渋々支持を表明した。当時健康 大臣だった友人ビクトル・マヌエル・ジョルダーニを支持していたと考えられる。アルベンスの支持基盤とジョルダーニ当選の可能性の低さこそが、アレバロの 支持決定の決め手となった。[51] アラナは死の直前まで、1950年の大統領選挙への出馬を計画していた。彼の死により、アルベンスは選挙で実質的な対抗馬を失った(このため、CIAや米 軍情報部を含む一部の関係者は、アルベンスの人格が個人的に彼を排除したのではないかと推測している)。[52] アルベンスは10人の候補者が立候補した選挙で、実質的な対抗馬はわずか2人しかいなかった。[50] その一人がホルヘ・ガルシア・グラナドスで、革命が行き過ぎたと感じる上流中産階級の支持を得ていた。もう一人はミゲル・イディゴラス・フエンテスで、ウ ビコ政権下の将軍であり、革命強硬派の支持を受けていた。選挙運動中、アルベンスはアレバロ政権下で始まった改革を継続・拡大すると約束した。[53] アルベンスは国内の主要政党両方の支持に加え、労働組合の強力な支援を受けていたため、楽勝が予想されていた。[54] 政治的支持に加え、アルベンスは強い人格の魅力を持っていた。彼は「人を惹きつける人格と力強い声の持ち主」と評された[55]。妻のマリアも選挙運動に 同行した。裕福な家庭に育ったにもかかわらず、マリアはマヤ系農民の利益を代弁するよう努め、自らも国民的人物となっていた。二人の娘たちも時折、父と共 に公の場に登場した[56]。 選挙は1950年11月15日に実施され、アルベンスは60%以上の得票率で勝利した。この選挙は、文盲の女性有権者の選挙権剥奪を除けば、おおむね自由 かつ公正なものであった[50]。アルベンスは次点のイドイゴラス・フエンテスの3倍以上の票を獲得し、フエンテスは選挙不正がアルベンスに有利に働いた と主張した。学者らは、不正がアルベンスに票をもたらした可能性はあるものの、それが当選の決定的要因ではなかったと指摘している[57]。アルベンスの 土地改革公約が勝利を確実にする上で大きな役割を果たしたのだ[58]。アルベンスの当選は米国務省当局者を警戒させた。彼らはアラナについて「アレバロ 政権において常に唯一の建設的な保守派要素であった」と述べ、彼の死は「左派を実質的に強化する」とし、「政府内で急進的な左傾化傾向が予測される」と指 摘した[59]。アルベンスは1951年3月15日に大統領に就任した[50]。 |

Presidency Colonel Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán addressing the crowd at his inauguration as the President of Guatemala in 1951 Inauguration and ideology See also: José Manuel Fortuny In his inaugural address, Árbenz promised to convert Guatemala from "a backward country with a predominantly feudal economy into a modern capitalist state".[60] He declared that he intended to reduce dependency on foreign markets and dampen the influence of foreign corporations over Guatemalan politics.[61] He said that he would modernize Guatemala's infrastructure without the aid of foreign capital.[62] Based on advice from the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development, he set out to build more houses, ports, and roads.[60] Árbenz also set out to reform Guatemala's economic institutions; he planned to construct factories, increase mining, expand transportation infrastructure, and expand the banking system.[63] Land reform was the centerpiece of Árbenz's election campaign.[64][65] The revolutionary organizations that had helped put Árbenz in power kept constant pressure on him to live up to his campaign promises regarding land reform.[66] Agrarian reform was one of the areas of policy which the Arévalo administration had not ventured into;[63] when Árbenz took office, only 2% of the population owned 70% of the land.[67] Historian Jim Handy described Árbenz's economic and political ideals as "decidedly pragmatic and capitalist in temper".[68] According to historian Stephen Schlesinger, while Árbenz did have a few communists in lower-level positions in his administration, he "was not a dictator, he was not a crypto-communist". Schlesinger described him as a democratic socialist.[69] Nevertheless, some of his policies, particularly those involving agrarian reform, would be branded as "communist" by the Guatemalan upper class and the United Fruit Company.[70][71] Historian Piero Gleijeses has argued that although Árbenz's policies were intentionally capitalist in nature, his personal views gradually shifted towards communism.[72][73] His goal was to increase Guatemala's economic and political independence, and he believed that to do this Guatemala needed to build a strong domestic economy.[74] He made an effort to reach out to the indigenous Mayan people, and sent government representatives to confer with them. From this effort he learned that the Maya held strongly to their ideals of dignity and self-determination; inspired in part by this, he stated in 1951 that "If the independence and prosperity of our people were incompatible, which for certain they are not, I am sure that the great majority of Guatemalans would prefer to be a poor nation, but free, and not a rich colony, but enslaved."[75] Although the policies of the Árbenz government were based on a moderate form of capitalism,[76] the communist movement did grow stronger during his presidency, partly because Arévalo released its imprisoned leaders in 1944, and also through the strength of its teachers' union.[77] Although the Communist party was banned for much of the Guatemalan Revolution,[50] the Guatemalan government welcomed large numbers of communist and socialist refugees fleeing the dictatorial governments of neighboring countries, and this influx strengthened the domestic movement.[77] In addition, Árbenz had personal ties to some members of the communist Guatemalan Party of Labour, which was legalized during his government.[50] The most prominent of these was José Manuel Fortuny. Fortuny played the role of friend and adviser to Árbenz through the three years of his government, from 1951 to 1954.[78] Fortuny wrote several speeches for Árbenz, and in his role as agricultural secretary[79] helped craft the landmark agrarian reform bill. Despite his position in Árbenz's government, however, Fortuny never became a popular figure in Guatemala, and did not have a large popular following like some other communist leaders.[80] The communist party remained numerically weak, without any representation in Árbenz's cabinet of ministers.[80] A handful of communists were appointed to lower-level positions in the government.[69] Árbenz read and admired the works of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin (before Khrushchev's report); officials in his government eulogized Stalin as a "great statesman and leader ... whose passing is mourned by all progressive men".[81] The Guatemalan Congress paid tribute to Joseph Stalin with a "minute of silence" when Stalin died in 1953, a fact that was remarked upon by later observers.[82] Árbenz had several supporters among the communist members of the legislature, but they were only a small part of the government coalition.[69] |

大統領職 1951年、グアテマラ大統領就任式で群衆に演説するハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン大佐 就任とイデオロギー 関連項目: ホセ・マヌエル・フォルトゥーニ アルベンスは就任演説で、グアテマラを「封建経済が支配的な後進国から近代的な資本主義国家へ転換する」と約束した。[60] 彼は外国市場への依存を減らし、グアテマラ政治に対する外国企業の影響力を弱める意向を表明した。[61] 外国資本の援助なしにグアテマラのインフラを近代化すると述べた。[62] 国際復興開発銀行の助言に基づき、彼は住宅・港湾・道路の建設に着手した。[60] アルベンスはグアテマラの経済制度改革にも着手し、工場建設、鉱業拡大、交通インフラ拡充、銀行システム拡大を計画した。[63] 土地改革はアルベンス選挙運動の核心であった。[64] [65] アルベンス政権の樹立を支援した革命組織は、土地改革に関する選挙公約の履行を絶えず迫った。[66] 農業改革はアレバロ政権が手を出さなかった政策分野の一つであった。[63] アルベンスが政権を掌握した時点で、人口のわずか2%が国土の70%を所有していた。[67] 歴史家ジム・ハンディは、アルベンスの経済・政治理念を「明らかに現実主義的で資本主義的傾向が強い」と評した。[68] 歴史家スティーブン・シュレジンガーによれば、アルベンス政権の下級職に共産主義者が数名いたものの、彼は「独裁者でもなければ、隠れ共産主義者でもな かった」。シュレジンガーは彼を民主的社会主義者と評した[69]。しかしながら、彼の政策の一部、特に農地改革に関わるものは、グアテマラの上流階級や ユナイテッド・フルーツ社によって「共産主義的」とレッテルを貼られることになった[70][71]。歴史家ピエロ・グレイヘセスは、アルベンスの政策は 意図的に資本主義的性質を持っていたものの、彼の個人的な見解は次第に共産主義へと移行していったと主張している[72][73]。彼の目標はグアテマラ の経済的・政治的自立を高めることであり、そのためにはグアテマラが強力な国内経済を構築する必要があると信じていた[74]。彼はグアテマラの経済的自 立を高めるために、国内経済を強化する努力をした。[72][73] 彼の目標はグアテマラの経済的・政治的自立を高めることであり、そのためには強固な国内経済を構築する必要があると信じていた。[74] 彼は先住民マヤ人民への働きかけに努め、政府代表を派遣して協議させた. この取り組みを通じて、マヤ族が尊厳と自己決定の理念を強く堅持していることを知った。このことに一部触発され、彼は1951年にこう述べた。「もし我々 の国民の独立と繁栄が両立しないものなら―確かにそうではないが―大多数のグアテマラ人は、貧しいが自由な国であり、豊かだが奴隷化された植民地であるよ りは、貧しいが自由な国を選ぶだろう」[75] アルベンス政権の政策は穏健な資本主義を基盤としていたが[76]、その大統領任期中に共産主義運動は確かに勢力を増した。その一因は、アレバロが 1944年に投獄されていた共産党指導者たちを釈放したこと、そして教師組合の力強さにもあった。[77] グアテマラ革命の大部分において共産党は禁止されていたが[50]、グアテマラ政府は近隣諸国の独裁政権から逃れてきた多数の共産主義者・社会主義者難民 を受け入れ、この流入が国内運動を強化した[77]。さらにアルベンスは、政権下で合法化されたグアテマラ労働党(共産主義系)の党員数名と個人的な繋が りを持っていた[50]。中でも最も著名な人物がホセ・マヌエル・フォルトゥーニであった。フォルトゥーニは1951年から1954年までのアルベンス政 権3年間、友人兼顧問として活動した[78]。アルベンスの演説原稿を複数執筆し、農業大臣として[79]画期的な農地改革法案の策定に貢献した。しかし アルベンス政権での地位にもかかわらず、フォルトゥーニはグアテマラで人気者になることはなく、他の共産主義指導者のように大衆的な支持基盤も持たなかっ た[80]。共産党は数的に弱く、アルベンス内閣には代表者を一人も送り込めなかった。[80] 政府の下級職に任命された共産党員はごく少数だった。[69] アルベンスはマルクス、レーニン、スターリン(フルシチョフの批判以前)の著作を読み賞賛した。彼の政府高官はスターリンを「偉大な政治家であり指導者… その死をすべての進歩的な人々が悼む」と称賛した。[81] グアテマラ議会は1953年にスターリンが死去した際、「黙祷の一分間」をもって彼に敬意を表した。この事実は後の観察者たちによって指摘されている。 [82] アルベンスには議会内の共産党員支持者が数名いたが、彼らは政府連立の一部に過ぎなかった。[69] |

Land reform Farmland in the Quetzaltenango Department, in western Guatemala Main article: Decree 900 The biggest component of Árbenz's project of modernization was his agrarian reform bill.[83] Árbenz drafted the bill himself with the help of advisers that included some leaders of the communist party as well as non-communist economists.[84] He also sought advice from numerous economists from across Latin America.[83] The bill was passed by the National Assembly on 17 June 1952, and the program went into effect immediately. It transferred uncultivated land from large landowners to their poverty-stricken laborers, who would then be able to begin a viable farm of their own.[83] Árbenz was also motivated to pass the bill because he needed to generate capital for his public infrastructure projects within the country. At the behest of the United States, the World Bank had refused to grant Guatemala a loan in 1951, which made the shortage of capital more acute.[85] The official title of the agrarian reform bill was Decree 900. It expropriated all uncultivated land from landholdings that were larger than 673 acres (272 ha). If the estates were between 672 acres (272 ha) and 224 acres (91 ha) in size, uncultivated land was expropriated only if less than two-thirds of it was in use.[85] The owners were compensated with government bonds, the value of which was equal to that of the land expropriated. The value of the land itself was the value that the owners had declared in their tax returns in 1952.[85] The redistribution was organized by local committees that included representatives from the landowners, the laborers, and the government.[85] Of the nearly 350,000 private land-holdings, only 1,710 were affected by expropriation. The law itself was cast in a moderate capitalist framework; however, it was implemented with great speed, which resulted in occasional arbitrary land seizures. There was also some violence, directed at landowners as well as at peasants who had minor landholdings of their own.[85] Árbenz himself, a landowner through his wife, gave up 1,700 acres (7 km2) of his own land in the land reform program.[86] By June 1954, 1.4 million acres of land had been expropriated and distributed. Approximately 500,000 individuals, or one-sixth of the population, had received land by this point.[85] The decree also included provision of financial credit to the people who received the land. The National Agrarian Bank (Banco Nacional Agrario, or BNA) was created on 7 July 1953, and by June 1951 it had disbursed more than $9 million in small loans. 53,829 applicants received an average of 225 US dollars, which was twice as much as the Guatemalan per capita income.[85] The BNA developed a reputation for being a highly efficient government bureaucracy, and the United States government, Árbenz's biggest detractor, did not have anything negative to say about it.[85] The loans had a high repayment rate, and of the $3,371,185 handed out between March and November 1953, $3,049,092 had been repaid by June 1954.[85] The law also included provisions for nationalization of roads that passed through redistributed land, which greatly increased the connectivity of rural communities.[85] Contrary to the predictions made by detractors of the government, the law resulted in a slight increase in Guatemalan agricultural productivity, and to an increase in cultivated area. Purchases of farm machinery also increased.[85] Overall, the law resulted in a significant improvement in living standards for many thousands of farmer families, the majority of whom were native Guatemalans.[85] Gleijeses stated that the injustices corrected by the law were far greater than the injustice of the relatively few arbitrary land seizures.[85] Historian Greg Grandin stated that the law was flawed in many respects; among other things, it was too cautious and deferential to the planters, and it created communal divisions among farmers. Nonetheless, it represented a fundamental power shift in favor of those that had been marginalized before then.[87] In 1953 the reform was ruled unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, but the Guatemalan Congress later impeached four judges associated with the ruling.[88] |

土地改革 グアテマラ西部ケツァルテナンゴ県の農地 詳細記事: 政令900号 アルベンスの近代化計画の最大の要素は、彼の農地改革法案であった。[83] アルベンスは、共産党の指導者や非共産主義の経済学者を含む助言者の助けを借りて、自らこの法案を起草した. [84] またラテンアメリカ各地の多数の経済学者にも助言を求めた。[83] 法案は1952年6月17日に国民議会で可決され、計画は直ちに施行された。これにより大土地所有者から耕作されていない土地が貧困に苦しむ労働者へ移譲 され、彼らは自らが営む持続可能な農場を始められるようになった。[83] アルベンスがこの法案を通した動機には、国内の公共インフラ事業に必要な資金を調達する必要性もあった。1951年、米国の要請を受けて世界銀行がグアテ マラへの融資を拒否したため、資金不足が深刻化していたのである。[85] 農地改革法案の正式名称は法令900号であった。この法令は、673エーカー(272ヘクタール)を超える大土地所有者から、耕作されていない土地を全て 収用した。672エーカー(272ヘクタール)から224エーカー(91ヘクタール)の土地所有者については、耕作されていない土地の3分の2未満しか利 用されていない場合に限り収用が行われた。[85] 所有者への補償は国債で行われ、その価値は収用された土地と同額であった。土地の価値自体は、所有者が1952年の納税申告書で申告した金額に基づいた。 [85] 再分配は、地主、労働者、政府の代表者からなる地方委員会によって組織された。[85] 約35万件の私有地のうち、収用対象となったのはわずか1,710件であった。法律自体は穏健な資本主義的枠組みで制定されたが、その実施は極めて迅速に 行われたため、時折恣意的な土地接収が発生した。また、地主だけでなく、わずかな土地を所有する農民に対しても暴力が振るわれた。[85] 妻を通じて地主であったアルベンス自身も、土地改革プログラムにおいて自身の土地1,700エーカー(7平方キロメートル)を放棄した。[86] 1954年6月までに、140万エーカーの土地が収用され分配された。この時点で約50万人の個人、つまり人口の6分の1が土地を受け取っていた [85]。法令には土地受領者への金融信用供与も含まれていた。国立農業銀行(Banco Nacional Agrario、BNA)は1953年7月7日に設立され、1951年6月までに900万ドル以上の小口融資を実行した。53,829人の申請者が平均 225米ドルを受け取ったが、これはグアテマラの一人当たり所得の2倍に相当した[85]。BNAは極めて効率的な政府機関として評価され、アルベンス政 権の最大の批判者である米国政府すら、これについて否定的な見解を示さなかった。[85] 融資の返済率は高く、1953年3月から11月にかけて支給された3,371,185ドルのうち、1954年6月までに3,049,092ドルが返済され た。[85] この法律には、再分配された土地を通る道路の国有化に関する規定も含まれており、これにより農村地域の接続性が大幅に向上した。[85] 政府批判派の予測に反し、この法律はグアテマラの農業生産性をわずかに向上させ、耕作面積の増加をもたらした。農業機械の購入も増加した。[85] 全体として、この法律は数万の農家世帯(その大半がグアテマラ先住民)の生活水準を大幅に改善した。[85] グレイヘセスは、この法律が是正した不正は、比較的少数の恣意的な土地収用による不正をはるかに上回ると述べた。[85] 歴史家グレッグ・グランディンは、この法律には多くの欠陥があったと指摘している。特に、プランター層に対して過度に慎重かつ従順であり、農民間の共同体 分裂を生んだ点などが挙げられる。とはいえ、それまでは境界化されていた者たちにとって、この法律は根本的な権力シフトを意味していた。[87] 1953年、最高裁はこの改革を違憲と判断したが、グアテマラ議会は後にこの判決に関わった4人の判事を弾劾した。[88] |

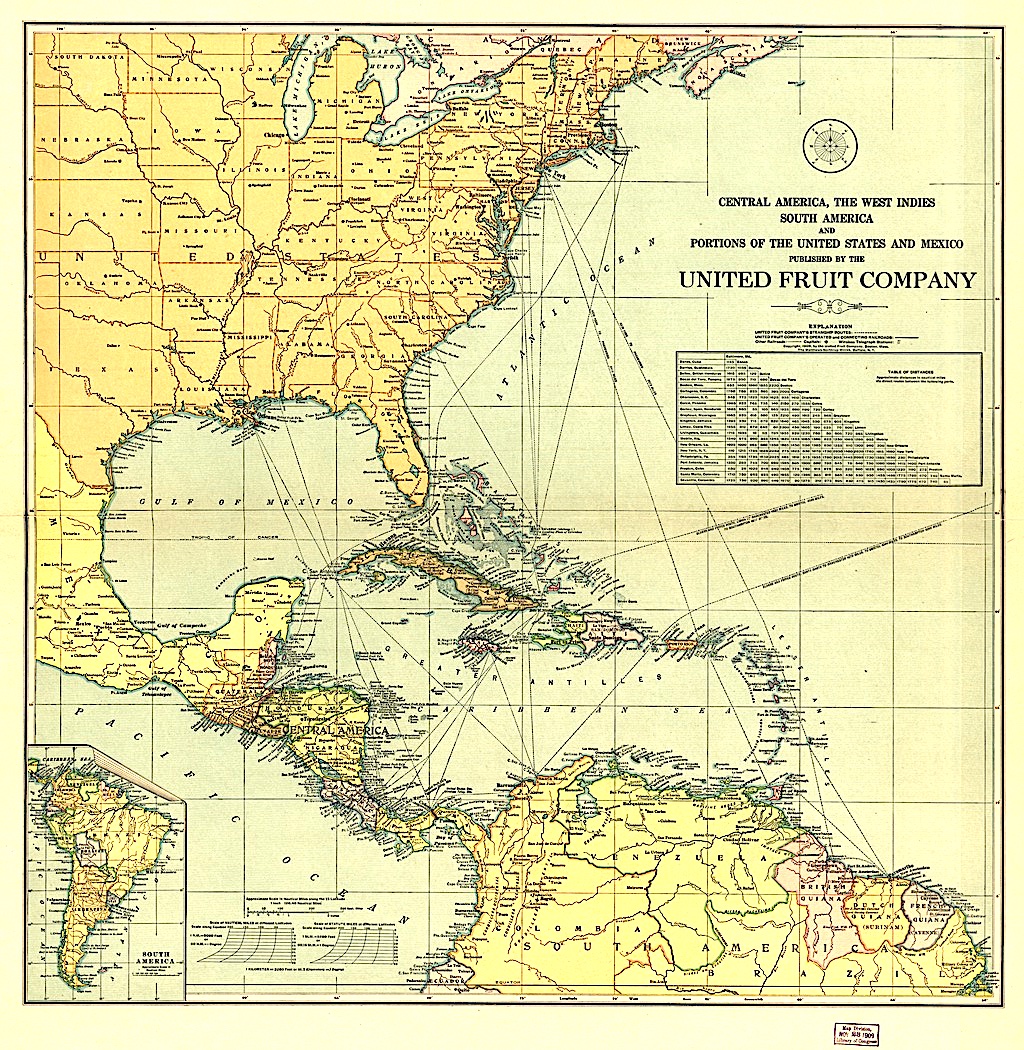

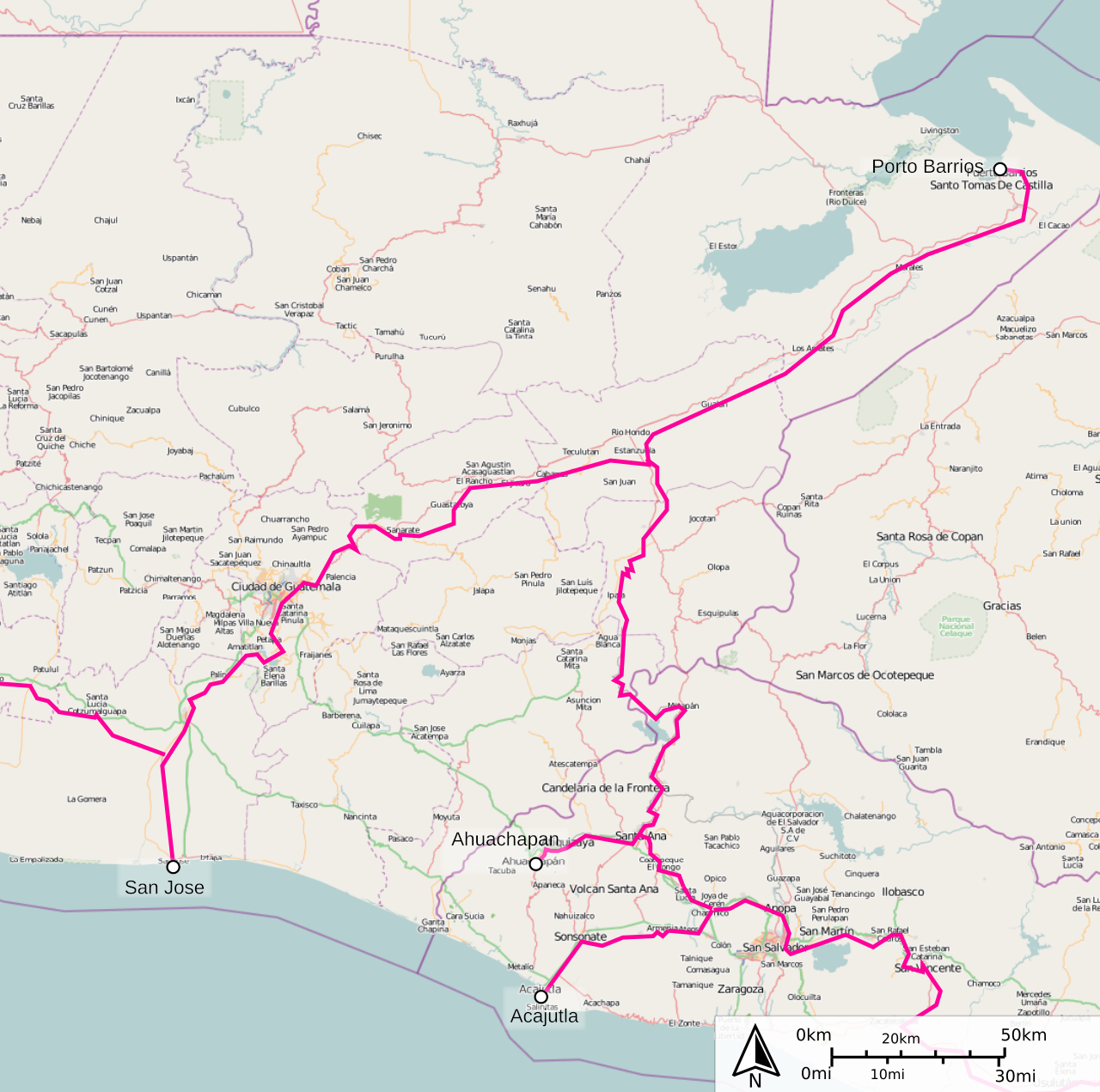

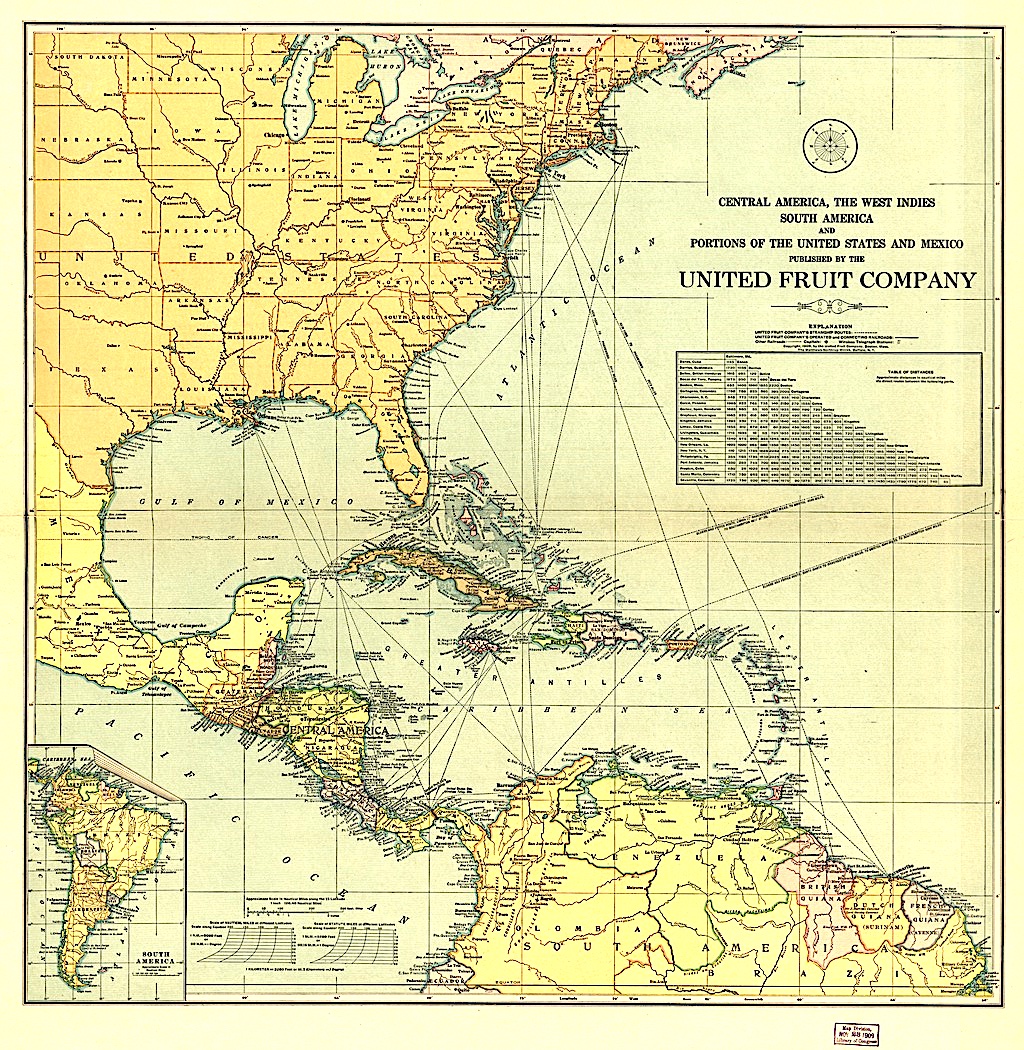

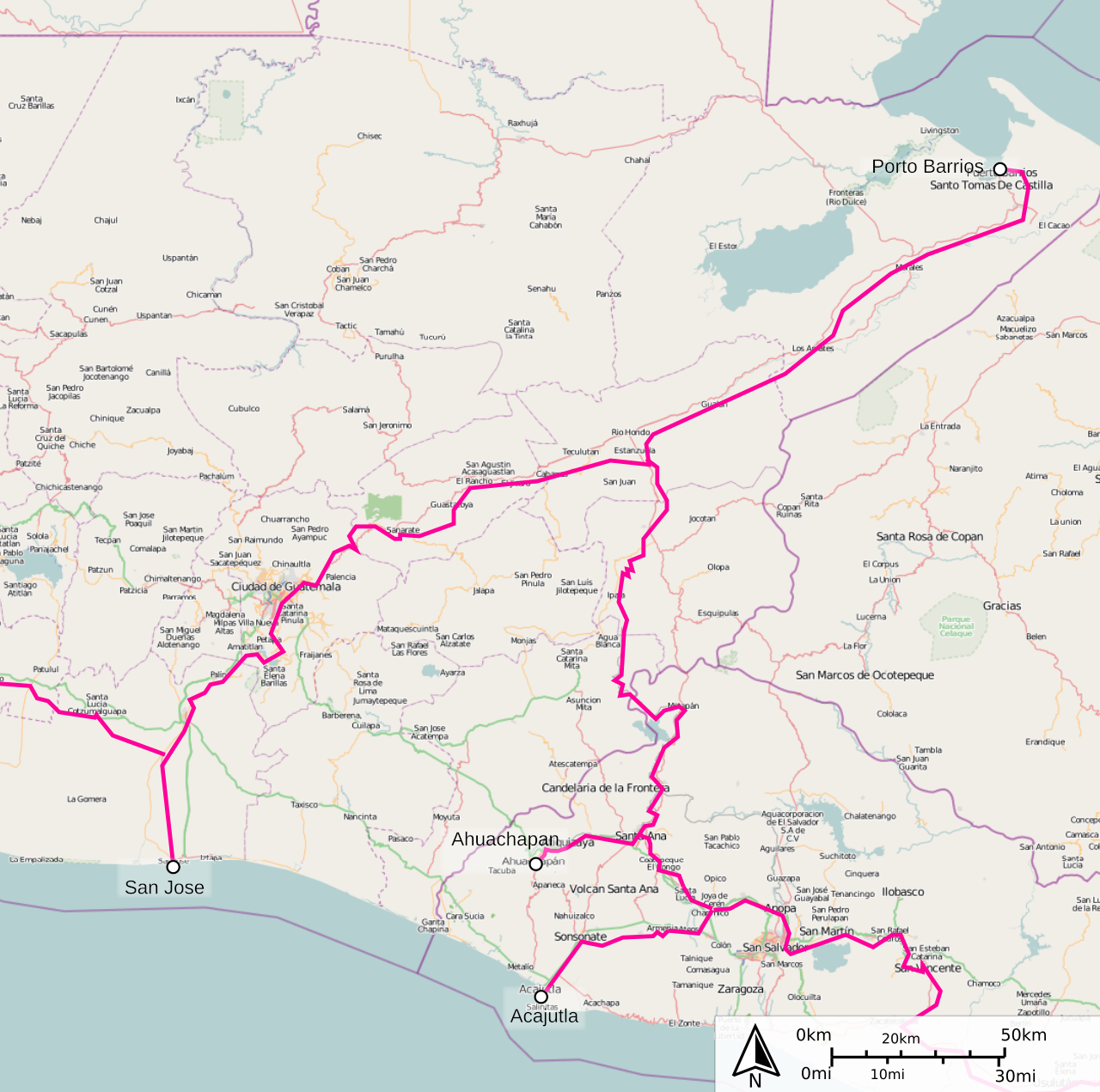

| Relationship with the United Fruit Company Further information: United Fruit Company  Route Map of the Great White Fleet of the United Fruit Company. The company had held the monopoly of freight and passenger maritime transportation to and from Puerto Barrios in Guatemala since 1903.  Map of railway lines in Guatemala and El Salvador. The lines were owned by the IRCA, the subsidiary of the United Fruit Company that controlled the railroad in both countries; the only Atlantic port was controlled by the Great White Fleet, also a UFC subsidiary. The relationship between Árbenz and the United Fruit Company has been described by historians as a "critical turning point in US dominance in the hemisphere".[89] The United Fruit Company, formed in 1899,[90] had major holdings of land and railroads across Central America, which it used to support its business of exporting bananas.[91] By 1930, it had been the largest landowner and employer in Guatemala for several years.[92] In return for the company's support, Ubico signed a contract with it that included a 99-year lease to massive tracts of land, and exemptions from virtually all taxes.[93] Ubico asked the company to pay its workers only 50 cents a day, to prevent other workers from demanding higher wages.[92] The company also virtually owned Puerto Barrios, Guatemala's only port to the Atlantic Ocean.[92] By 1950, the company's annual profits were 65 million US dollars, twice the revenue of the Guatemalan government.[94] As a result, the company was seen as an impediment to progress by the revolutionary movement after 1944.[94][95] Thanks to its position as the country's largest landowner and employer, the reforms of Arévalo's government affected the UFC more than other companies, which led to a perception by the company that it was being specifically targeted by the reforms.[96] The company's labor troubles were compounded in 1952 when Árbenz passed Decree 900, the agrarian reform law. Of the 550,000 acres (220,000 ha) that the company owned, 15% were being cultivated; the rest of the land, which was idle, came under the scope of the agrarian reform law.[96] Additionally, Árbenz supported a strike of UFC workers in 1951, which eventually compelled the company to rehire a number of laid-off workers.[97] The United Fruit Company responded with an intensive lobbying campaign against Árbenz in the United States.[98] The Guatemalan government reacted by saying that the company was the main obstacle to progress in the country. American historians observed that "to the Guatemalans it appeared that their country was being mercilessly exploited by foreign interests which took huge profits without making any contributions to the nation's welfare."[98] In 1953 200,000 acres (81,000 ha) of uncultivated land was expropriated under Árbenz's agrarian reform law, and the company was offered compensation at the rate of 2.99 US dollars to the acre, twice what it had paid when buying the property.[98] This resulted in further lobbying in Washington, particularly through Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, who had close ties to the company.[98] The company had begun a public relations campaign to discredit the Guatemalan government; overall, the company spent over a half-million dollars to influence both lawmakers and members of the public in the US that the Guatemalan government of Jacobo Árbenz needed to be overthrown.[99] |

ユナイテッド・フルーツ社との関係 詳細情報:ユナイテッド・フルーツ社  ユナイテッド・フルーツ社所有のグレート・ホワイト・フリートの航路図。同社は1903年以降、グアテマラのプエルト・バリオスへの貨物・旅客海上輸送を独占していた。  グアテマラとエルサルバドルの鉄道線路図。これらの路線は両国の鉄道を支配するユナイテッド・フルーツ社の子会社IRCAが所有していた。唯一の大西洋岸港湾は、同じくUFC子会社であるグレート・ホワイト・フリートが支配していた。 アルベンスとユナイテッド・フルーツ社の関係は、歴史家によって「米州における米国の支配力の重大な転換点」と評されている[89]。1899年に設立さ れたユナイテッド・フルーツ社[90]は、中米全域に広大な土地と鉄道網を保有し、バナナ輸出事業を支える基盤としていた。[91] 1930年までに、同社は数年にわたりグアテマラ最大の土地所有者かつ雇用主となっていた。[92] 支援の見返りとして、ウビコは同社と契約を結び、広大な土地の99年リース権と、事実上全ての税金の免除を認めた。[93] ウビコは、他の労働者が賃上げを要求するのを防ぐため、同社に労働者への日給をわずか50セントに抑えるよう求めた。[92] 同社はまた、グアテマラ唯一の大西洋港であるプエルト・バリオスを事実上所有していた。[92] 1950年までに、同社の年間利益は6500万米ドルに達し、グアテマラ政府の歳入の2倍となった。[94] その結果、1944年以降の革命運動は同社を進歩の妨げと見なすようになった。[94] [95] 国内最大の土地所有者かつ雇用主という立場ゆえ、アレバロ政権の改革は他企業よりUFCに深刻な影響を与えた。これにより同社は改革の標的とされていると 認識した。[96] 1952年、アルベンスが農地改革法である法令900号を公布したことで、同社の労使問題はさらに悪化した。同社が所有する55万エーカー(22万ヘク タール)のうち、耕作されていたのは15%に過ぎず、残りの遊休地は農地改革法の適用対象となった[96]。さらにアルベンスは1951年にUFC労働者 のストライキを支援し、最終的に同社は解雇した労働者の再雇用を余儀なくされた。[97] ユナイテッド・フルーツ社はこれに対し、米国でアルベンスに対する強力なロビー活動を展開した。[98] グアテマラ政府は、同社が国内発展の主要な障害であると反論した。米国の歴史家たちは「グアテマラ人にとって、自国が外国資本によって容赦なく搾取され、 莫大な利益を得ているにもかかわらず、国民の福祉には何の貢献もしていないように見えた」と指摘している。[98] 1953年、アルベンスの農地改革法に基づき20万エーカー(81,000ヘクタール)の未耕作地が収用され、同社には1エーカーあたり2.99米ドルの 補償金が提示された。これは同社が土地を購入した際の価格の2倍に相当した. [98] これによりワシントンでのロビー活動がさらに活発化した。特に同社と密接な関係にあったジョン・フォスター・ダレス国務長官を通じて行われた。[98] 同社はグアテマラ政府の信用を傷つけるための広報キャンペーンを開始。総額50万ドル以上を投じ、米国の議員や一般市民に対し、ハコボ・アルベンス政権を 打倒すべきだと訴えたのである。[99] |

| Coup d'état Main article: 1954 Guatemalan coup d'état A CIA memorandum dated May 1975 which describes the role of the Agency in deposing the Guatemalan government of President Jacobo Árbenz Guzmán in June 1954 (1–5) Political motives Several factors besides the lobbying campaign of the United Fruit Company led the United States to launch the coup that toppled Árbenz in 1954. The US government had grown more suspicious of the Guatemalan Revolution as the Cold War developed and the Guatemalan government clashed with US corporations on an increasing number of issues.[100] The US was also concerned that it had been infiltrated by communists[101] although historian Richard H. Immerman argued that during the early part of the Cold War, the US and the CIA were predisposed to see the revolutionary government as communist, despite Arévalo's ban of the communist party during his 1945–1951 presidency.[100] Additionally, the US government was concerned that the success of Árbenz's reforms would inspire similar movements elsewhere.[102] Until the end of its term, the Truman administration relied on purely diplomatic and economic means to attempt to reduce communist influences.[103] Árbenz's enactment of Decree 900 in 1952 provoked Truman to authorize Operation PBFortune, a covert operation to overthrow Árbenz.[104] The plan had originally been suggested by the US-backed dictator of Nicaragua, Anastasio Somoza García, who said that if he were given weapons, he could overthrow the Guatemalan government.[104] The operation was to be led by Carlos Castillo Armas.[105] However, the US state department discovered the conspiracy, and secretary of state Dean Acheson persuaded Truman to abort the plan.[104][105] After being elected president of the US in November 1952, Dwight Eisenhower was more willing than Truman to use military tactics to remove regimes he disliked.[106][107] Several figures in his administration, including Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother and CIA director Allen Dulles, had close ties to the United Fruit Company.[108][109] John Foster Dulles had previously represented United Fruit Company as a lawyer, and his brother, then-CIA director Allen Dulles was on the company's board of directors. Thomas Dudley Cabot, a former CEO of United Fruit, held the position of director of International Security Affairs in the State Department.[110] Undersecretary of State Bedell Smith later became a director of the UFC, while the wife of the UFC public relations director was Eisenhower's personal assistant. These connections made the Eisenhower administration more willing to overthrow the Guatemalan government.[108][109] |

クーデター 主な記事: 1954年グアテマラクーデター 1975年5月付のCIA覚書。1954年6月にグアテマラのハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン大統領政権を転覆させた際のCIAの役割を記述したもの(1–5) 政治的動機 ユナイテッド・フルーツ社のロビー活動以外にも、1954年にアルベンス政権を打倒するクーデターを米国が実行に移すに至った要因は複数あった。冷戦が進 行するにつれ、米国政府はグアテマラ革命への疑念を強め、グアテマラ政府は米国企業との対立を数多くの問題で深めていた。[100] 米国はまた、共産主義者に浸透されていることを懸念していた[101]。ただし歴史家リチャード・H・イマーマンは、冷戦初期には米国とCIAが、アレバ ロ大統領が1945年から1951年の在任中に共産党を禁止したにもかかわらず、革命政府を共産主義者と見なす傾向があったと論じている。[100] さらに米国政府は、アルベンスの改革の成功が他地域で同様の運動を刺激する可能性を懸念していた[102]。トルーマン政権は任期終了まで、共産主義の影 響力を減らすため純粋に外交的・経済的手段に頼った[103]。 1952年にアルベンスが布告900号を発令したことで、トルーマンはアルベンス打倒を目的とした秘密作戦「PBFortune作戦」を承認した。 [104] この計画は当初、米国が支援するニカラグアの独裁者アナスタシオ・ソモサ・ガルシアが提案したもので、武器を与えられればグアテマラ政府を打倒できると主 張していた. [104] この作戦はカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスが指揮する予定だった。[105] しかし米国務省が陰謀を察知し、ディーン・アチソン国務長官がトルーマンに計画中止を説得した。[104][105] 1952年11月に米国大統領に選出されたドワイト・アイゼンハワーは、トルーマンよりも軍事手段を用いて好ましくない政権を排除することに積極的だっ た。[106][107] 彼の政権内には、国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスやその弟でCIA長官のアレン・ダレスなど、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社と密接な関係を持つ人物が複数 いた。[108][109] ジョン・フォスター・ダレスは以前、ユナイテッド・フルーツ社の弁護士を務めており、弟で当時のCIA長官アレン・ダレスは同社の取締役を務めていた。ユ ナイテッド・フルーツの元最高経営責任者(CEO)であるトーマス・ダドリー・キャボットは、国務省の国際安全保障問題担当局長を務めていた。[110] 国務次官のベデル・スミスは後にユナイテッド・フルーツの取締役となり、同社の広報部長の妻はアイゼンハワー大統領の個人秘書を務めていた。こうした繋が りが、アイゼンハワー政権にグアテマラ政府の転覆をより積極的に行わせる要因となった。[108][109] |

Operation PBSuccess Gloriosa victoria (in English, Glorious victory) by Diego Rivera, circa 1954. It shows General Castillo Armas making a pact with members of the U.S. government at the time, such as US ambassador to Guatemala John Peurifoy, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles and his brother, CIA Director Allen Dulles, with the face of the bomb alluding to President Eisenhower. In the background is shown a United Fruit Company ship exporting bananas, as well as the figure of Archbishop Mariano Rossell y Arellano officiating a mass over the massacred bodies of the workers. Castillo Armas would lead the overthrow of Árbenz. The CIA operation to overthrow Jacobo Árbenz, code-named Operation PBSuccess, was authorized by Eisenhower in August 1953.[111] Carlos Castillo Armas, once Arana's lieutenant, who had been exiled following the failed coup in 1949, was chosen to lead the coup.[112] Castillo Armas recruited a force of approximately 150 mercenaries from among Guatemalan exiles and the populations of nearby countries.[113] In January 1954, information about these preparations were leaked to the Guatemalan government, which issued statements implicating a "Government of the North" in a plot to overthrow Árbenz. The US government denied the allegations, and the US media uniformly took the side of the government; both argued that Árbenz had succumbed to communist propaganda.[114] The US stopped selling arms to Guatemala in 1951, and soon after blocked arms purchases from Canada, Germany, and Rhodesia.[115] By 1954, Árbenz had become desperate for weapons, and decided to acquire them secretly from Czechoslovakia, an action seen as establishing a communist beachhead in the Americas.[116][117] The shipment of these weapons was portrayed by the CIA as Soviet interference in the United States' backyard, and acted as the final spur for the CIA to launch its coup.[117] Árbenz had intended the shipment of weapons from the Alfhem to be used to bolster peasant militia, in the event of army disloyalty, but the US informed the Guatemalan army chiefs of the shipment, forcing Árbenz to hand them over to the military, and deepening the rift between him and the chiefs of his army.[118] Castillo Armas' forces invaded Guatemala on 18 June 1954.[119] The invasion was accompanied by an intense campaign of psychological warfare presenting Castillo Armas' victory as a fait accompli, with the intent of forcing Árbenz to resign.[111][120] The most wide-reaching psychological weapon was the radio station known as the "Voice of Liberation", whose transmissions broadcast news of rebel troops converging on the capital, and contributed to massive demoralization among both the army and the civilian population.[121] Árbenz was confident that Castillo Armas could be defeated militarily,[122] but he worried that a defeat for Castillo Armas would provoke a US invasion.[122] Árbenz ordered Carlos Enrique Díaz, the chief of the army, to select officers to lead a counter-attack. Díaz chose a corps of officers who were all known to be men of personal integrity, and who were loyal to Árbenz.[122] By 21 June, Guatemalan soldiers had gathered at Zacapa under the command of Colonel Víctor M. León, who was believed to be loyal to Árbenz.[123] The leaders of the communist party also began to have their suspicions, and sent a member to investigate. He returned on 25 June, reporting that the army was highly demoralized, and would not fight.[124][125] PGT Secretary General Alvarado Monzón informed Árbenz, who quickly sent another investigator of his own, who brought back a message asking Árbenz to resign. The officers believed that given US support for the rebels, defeat was inevitable, and Árbenz was to blame for it.[125] The message stated that if Árbenz did not resign, the army was likely to strike a deal with Castillo Armas.[125][124] On 25 June, Árbenz announced that the army had abandoned the government, and that civilians needed to be armed in order to defend the country; however, only a few hundred individuals volunteered.[126][121] Seeing this, Díaz reneged on his support of the president, and began plotting to overthrow Árbenz with the assistance of other senior army officers. They informed US ambassador John Peurifoy of this plan, asking him to stop the hostilities in return for Árbenz's resignation.[127] Peurifoy promised to arrange a truce, and the plotters went to Árbenz and informed him of their decision. Árbenz, utterly exhausted and seeking to preserve at least a measure of the democratic reforms that he had brought, agreed. After informing his cabinet of his decision, he left the presidential palace at 8 pm on 27 June 1954, having taped a resignation speech that was broadcast an hour later.[127] In it, he stated that he was resigning in order to eliminate the "pretext for the invasion," and that he wished to preserve the gains of the October Revolution.[127] He walked to the nearby Mexican Embassy, seeking political asylum.[128] |

オペレーション・PBSuccess ディエゴ・リベラ作『栄光の勝利』(1954年頃)。グアテマラのキャスティージョ・アルマス将軍が当時の米国政府関係者——駐グアテマラ米国大使ジョ ン・ピュリフォイ、国務長官ジョン・フォスター・ダレスとその弟でCIA長官のアレン・ダレス——と協定を結ぶ場面を描いている。爆弾の顔はアイゼンハ ワー大統領を暗示している。背景にはユナイテッド・フルーツ社のバナナ輸出船と、虐殺された労働者の遺体の上でミサを執り行うマリアーノ・ロセル・イ・ア レジャーノ大司教の姿が描かれている。カスティージョ・アルマスは後にアルベンス政権打倒を主導する。 ヤコボ・アルベンス政権打倒のためのCIA作戦(コードネーム「PBSuccess」)は、1953年8月にアイゼンハワーによって承認された [111]。1949年のクーデター失敗後に亡命していた、かつてアラナの副官だったカルロス・カスティーヨ・アルマスがクーデター指導者に選ばれた。 [112] カスティージョ・アルマスはグアテマラ亡命者や近隣諸国の人々から約150名の傭兵部隊を募集した。[113] 1954年1月、この準備情報がグアテマラ政府に漏洩し、政府は「北の政府」がアルベンス打倒の陰謀に関与していると示唆する声明を発表した. 米国政府はこれらの主張を否定し、米国メディアも政府側を一様に支持した。双方ともアルベンスが共産主義プロパガンダに屈したと主張した。[114] 米国は1951年にグアテマラへの武器販売を停止し、その後間もなくカナダ、ドイツ、ローデシアからの武器購入も阻止した。[115] 1954年までにアルベンスは武器の確保に追い詰められ、チェコスロバキアから密かに調達することを決断した。この行動はアメリカ大陸における共産主義の 前哨基地を確立するものと見なされた[116][117]。CIAはこの武器輸送を「米国の裏庭におけるソ連の干渉」と表現し、クーデター実行の最終的な 引き金となった[117]。 アルフェム号からの武器輸送は、軍が反旗を翻した場合に備え農民民兵を強化する目的でアルベンスが計画したものだったが、米国はグアテマラ軍首脳部にこの 輸送を通知。アルベンスは武器を軍に引き渡すことを余儀なくされ、軍首脳部との亀裂は深まった。[118] カスティージョ・アルマス軍は1954年6月18日にグアテマラへ侵攻した。[119] この侵攻は、アルベンスの辞任を迫る意図で、カスティージョ・アルマス軍の勝利を既成事実として提示する激しい心理戦キャンペーンを伴っていた。 [111][120] 最も広範な心理兵器は「解放の声」と呼ばれるラジオ局であった。その放送は反乱軍が首都に集結しているというニュースを流し、軍と民間人の双方に大規模な 士気低下をもたらした。[121] アルベンスはカスティージョ・アルマスを軍事的に打ち負かせると確信していたが、[122] 彼の敗北が米国の侵攻を招くことを懸念していた. [122] アルベンスはカルロス・エンリケ・ディアス陸軍司令官に対し、反撃を指揮する将校を選抜するよう命じた。ディアスは、人格として誠実であり、かつアルベン スに忠実な将校たちで構成される部隊を選んだ。[122] 6月21日までに、グアテマラ軍兵士はザカパに集結した。指揮官はアルベンスに忠実とされたビクトル・M・レオン大佐であった。[123] 共産党指導部も疑念を抱き始め、調査員を派遣した。調査員は6月25日に帰還し、軍隊の士気が著しく低下しており、戦闘を拒否すると報告した。[124] [125] PGT書記長アルバラド・モンソンはアルベンスにこの情報を伝えた。アルベンスは直ちに別の調査員を派遣し、その調査員はアルベンスに辞任を求めるメッ セージを持ち帰った。将校たちは、反乱軍に対する米国の支援を考慮すれば敗北は避けられず、その責任はアルベンスにあると考えていた。[125] メッセージには、アルベンスが辞任しなければ、軍はカスティーヨ・アルマスと取引する可能性が高いと記されていた。[125][124] 6月25日、アルベンスは軍が政府を見捨てたと発表し、国を守るために市民の武装が必要だと訴えた。しかし志願者は数百人に留まった。[126] [121] この状況を見てディアスは大統領支持を撤回し、他の上級将校らと共謀してアルベンス打倒を画策し始めた. 彼らはこの計画を米国大使ジョン・ピュリフォイに伝え、アルベンスの辞任と引き換えに戦闘停止を要請した。[127] ピュリフォイは休戦の手配を約束し、謀議者たちはアルベンスのもとへ赴き決定を伝えた。極度の疲労状態にあり、自らが推進した民主的改革の少なくとも一部 を存続させたいと考えていたアルベンスは、これに同意した。 |

| Later life Beginning of exile After Árbenz's resignation, his family remained for 73 days at the Mexican embassy in Guatemala City, which was crowded with almost 300 exiles.[129] During this period, the CIA initiated a new set of operations against Árbenz, intended to discredit the former president and damage his reputation. The CIA obtained some of Árbenz's personal papers, and released parts of them after doctoring the documents. The CIA also promoted the notion that individuals in exile, such as Árbenz, should be prosecuted in Guatemala.[129] When they were finally allowed to leave the country, Árbenz was publicly humiliated at the airport when the authorities made the former president strip before the cameras,[130] claiming that he was carrying jewelry he had bought for his wife, María Cristina Vilanova, at Tiffany's in New York City, using funds from the presidency; no jewelry was found but the interrogation lasted for an hour.[131] Through this entire period, coverage of Árbenz in the Guatemalan press was very negative, influenced largely by the CIA's campaign.[130] The family then initiated a long journey in exile that would take them first to Mexico, then to Canada, where they went to pick up Arabella (the Árbenzes' oldest daughter), and then to Switzerland via the Netherlands and Paris.[132] They hoped to obtain citizenship in Switzerland based on Árbenz's Swiss heritage. However, the former president did not wish to renounce his Guatemalan nationality, as he felt that such a gesture would have marked the end of his political career.[133] Árbenz and his family were the victims of a CIA-orchestrated and intense defamation campaign that lasted from 1954 to 1960.[134] A close friend of Árbenz, Carlos Manuel Pellecer, turned out to be a spy working for the CIA.[135] |

晩年 亡命の始まり アルベンスが辞任した後、彼の家族はグアテマラシティのメキシコ大使館に73日間滞在した。そこには約300人の亡命者が詰めかけていた。[129] この期間中、CIAはアルベンスに対する新たな作戦を開始した。その目的は、元大統領の信用を傷つけ、評判を損なうことだった。CIAはアルベンスの私文 書の一部を入手し、改ざんした上でその一部を公開した。またCIAは、アルベンスのような亡命者をグアテマラで起訴すべきだという主張を推進した。 [129] 国外退去が最終的に許可された際、アルベンスは空港で公然と辱めを受けた。当局が元大統領にカメラの前で服を脱ぐよう強要したのである[130]。当局 は、大統領職の資金を使ってニューヨークのティファニーで妻マリア・クリスティーナ・ビラノバに購入した宝石類を所持していると主張した。宝石類は発見さ れなかったが、尋問は1時間に及んだ。[131] この全期間を通じて、グアテマラの報道機関によるアルベンスの報道は極めて否定的であり、その背景にはCIAのキャンペーンが大きく影響していた。 [130] その後、家族は亡命の長い旅を始めた。まずメキシコへ、次にカナダへ渡り(そこでアルベンス家の長女アラベラを迎えに行った)、さらにオランダとパリを経 由してスイスへ向かった。[132] 彼らはアルベンスのスイス系血統を根拠にスイス国籍取得を望んだ。しかし元大統領は、グアテマラ国民を放棄すれば政治生命の終焉を意味すると考え、これを 拒んだ[133]。アルベンス一家は1954年から1960年まで続いた、CIAが仕組んだ激しい中傷キャンペーンの犠牲者であった。[134] アルベンスの親友カルロス・マヌエル・ペレセルは、CIAのスパイとして働いていたことが判明した。[135] |

| Europe and Uruguay After being unable to obtain citizenship in Switzerland, the Árbenz family moved to Paris, where the French government gave them permission to live for a year, on the condition that they did not participate in any political activity,[133] then to Prague, the capital of Czechoslovakia. After only three months, he moved to Moscow, which came as a relief to him from the harsh treatment he received in Czechoslovakia.[136] While traveling in the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, he was constantly criticized in the press in Guatemala and the US, on the grounds that he was showing his true communist colors by going there.[136] After a brief stay in Moscow, Árbenz returned to Prague and then to Paris. From there he separated from his wife: María traveled to El Salvador to take care of family affairs.[136] The separation made life increasingly difficult for Árbenz, and he slipped into depression and took to drinking excessively.[136] He tried several times to return to Latin America, and was finally allowed in 1957 to move to Uruguay.[137] The CIA made several attempts to prevent Árbenz from receiving a Uruguayan visa, but these were unsuccessful, and the Uruguayan government allowed Árbenz to travel there as a political refugee.[138] Árbenz arrived in Montevideo on 13 May 1957, where he was met by a hostile "reception committee" organized by the CIA. However, he was still a figure of some note in leftist circles in the city, which partially explained the CIA's hostility.[139] While Árbenz was living in Montevideo, his wife came to join him. He was also visited by Arévalo a year after his own arrival there. Although the relationship between Arévalo and the Árbenz family was initially friendly, it soon deteriorated due to differences between the two men.[140] Arévalo himself was not under surveillance in Uruguay and was occasionally able to express himself through articles in the popular press. He left for Venezuela a year after his arrival to take up a position as a teacher.[139] During his stay in Uruguay, Árbenz was initially required to report to the police on a daily basis; eventually, however, this requirement was relaxed somewhat to once every eight days.[139] María Árbenz later stated that the couple was pleased by the hospitality they received in Uruguay, and would have stayed there indefinitely had they received permission to do so.[139] |

ヨーロッパとウルグアイ スイスでの市民権取得に失敗した後、アルベンス一家はパリに移住した。フランス政府は彼らに1年間の居住許可を与えたが、その条件として政治活動への参加 を禁じた[133]。その後、チェコスロバキアの首都プラハへ移った。わずか3か月後、彼はモスクワへ移った。チェコスロバキアでの厳しい扱いから解放さ れたことで、彼は安堵した。ソ連と東欧を移動中、彼はグアテマラと米国のメディアから絶えず批判された。そこへ行くことで共産主義の本性を露わにしている という理由からである。モスクワでの短期間の滞在後、アルベンスはプラハに戻り、その後パリへ向かった。そこで彼は妻と別れた。マリアは家族の問題を処理 するためエルサルバドルへ向かったのである。この別離はアルベンスの生活を次第に困難にし、彼は鬱状態に陥り、過度の飲酒に走るようになった。[136] 彼は何度かラテンアメリカへの帰国を試み、1957年にようやくウルグアイへの移住が許可された。[137] CIAはアルベンスがウルグアイのビザを取得するのを阻止しようと幾度か試みたが、これらは失敗に終わり、ウルグアイ政府はアルベンスを政治亡命者として 同国へ渡航させることを認めた。[138] アルベンスは1957年5月13日にモンテビデオに到着したが、そこではCIAが組織した敵対的な「出迎え委員会」が待っていた。しかし彼は依然として同 市の左翼勢力において一定の存在感を保っており、これがCIAの敵意の一因であった。[139] アルベンスがモンテビデオに滞在中、妻が合流した。また、アレバロも自身到着から1年後に彼を訪ねた。当初アレバロとアルベンス家の関係は友好的だった が、両者の意見の異なる点からすぐに悪化した。[140] アレバロ自身はウルグアイで監視下に置かれておらず、大衆紙への寄稿を通じて時折意見を表明できた。彼は到着から1年後にベネズエラへ移り、教師の職に就 いた。[139] ウルグアイ滞在中、アルベンスは当初、毎日警察に出頭するよう義務付けられていた。しかし、やがてこの義務は8日に1回へと緩和された。[139] マリア・アルベンスは後に、夫妻はウルグアイで受けた歓待に満足しており、許可さえ得られれば無期限に滞在していたと述べている。[139] |

| Daughter's suicide and death After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, a representative of the Fidel Castro government asked Árbenz to come to Cuba, to which he readily agreed, sensing an opportunity to live with fewer restrictions on himself. He flew to Havana in July 1960, and, caught up in the spirit of the recent revolution, began to participate in public events.[141] His presence so close to Guatemala once again increased the negative coverage he received in the Guatemalan press. He was offered the leadership of some revolutionary movements in Guatemala but refused, as he was pessimistic about the outcome.[141] In 1965 Árbenz was invited to the Communist Congress in Helsinki.[141] Soon afterwards, his daughter Arabella committed suicide in Bogotá, an incident that badly affected Árbenz. Following her funeral, the Árbenz family remained indefinitely in Mexico City, while Árbenz himself spent some time in France and Switzerland, with the ultimate objective of settling down in Mexico.[141] On one of his visits to Mexico, Árbenz contracted a serious illness, and by the end of 1970 he was very ill. He died soon after. Historians disagree as to the manner of his death: Roberto García Ferreira stated that he died of a heart attack while taking a bath,[141] while Cindy Forster wrote that he committed suicide.[142] On 19 October 1995, Árbenz's remains were repatriated to Guatemala, accompanied by his widow María.[143] After his remains were returned to Guatemala, Árbenz was given a military honor as military officers fired cannons in salute as Árbenz's coffin was placed onto a horse-drawn carriage and transported to San Carlos University, where students and university officials paid posthumous homage to the former president.[143][144] The Universidad de San Carlos de Guatemala, which previously held autonomy following the 1944 Guatemala Revolution,[143] awarded Árbenz with a posthumous decoration soon after.[141] After departing from the university, the coffin containing Árbenz's remains was then taken to the National Palace, where it would remain until midnight.[143] On 20 October 1995, thousands of Guatemalans flocked to the Guatemala City General Cemetery for his burial service.[144] During the burial service, then-Guatemala Defense Minister Gen. Marco Antonio González, who received Árbenz's remains after they were returned to the country, stayed in his car after crowds booed and screamed, "Army of assassins get out of the country."[144] |

娘の自殺と死 1959年のキューバ革命後、フィデル・カストロ政権の代表者がアルベンスにキューバへの渡航を要請した。彼は自身への制約が少なくなる機会と捉え、快諾 した。1960年7月にハバナへ飛んだ彼は、革命直後の熱気に触発され、公的な行事への参加を始めた。[141] グアテマラに近い場所で彼の姿が目撃されたことで、グアテマラの報道機関による彼への批判的な報道が再び増加した。グアテマラ国内のいくつかの革命運動の 指導者となるよう打診されたが、彼は結果に悲観的だったためこれを断った。[141] 1965年、アルベンスはヘルシンキで開催された共産主義者会議に招待された。[141] その後間もなく、娘のアラベラがボゴタで自殺した。この事件はアルベンスに深刻な打撃を与えた。葬儀後、アルベンス一家はメキシコシティに無期限滞在し た。一方アルベンス自身はフランスとスイスで時間を過ごし、最終的にはメキシコに定住するつもりだった。[141] メキシコ滞在中、アルベンスは重い病にかかり、1970年末には病状が深刻化した。その後まもなく死去した。死因については歴史家の見解が分かれる。ロベ ルト・ガルシア・フェレイラは入浴中の心臓発作と記し[141]、シンディ・フォスターは自殺と記している[142]。1995年10月19日、アルベン スの遺骨は未亡人マリアに付き添われてグアテマラに返還された。[143] 遺骨がグアテマラに返還された後、アルベンスには軍による栄誉が捧げられた。軍将校たちが礼砲を放ち、アルベンスの棺が馬車に乗せられてサン・カルロス大 学へ運ばれる間、学生や大学関係者が元大統領に死後の敬意を表したのである。[143][144] 1944年のグアテマラ革命後に自治権を獲得していたサンカルロス大学[143]は、間もなくアルベンスに死後勲章を授与した[141]。大学を出発した アルベンスの遺体を収めた棺は、その後国立宮殿へ運ばれ、深夜まで安置された[143]。1995年10月20日、数千人のグアテマラ人がグアテマラシ ティ総合墓地に集まり、彼の埋葬式に参列した[144]。埋葬式中、遺体が帰国後に受け取った当時のグアテマラ国防相マルコ・アントニオ・ゴンサレス将軍 は、群衆が「殺人者の軍隊は国から出て行け」と野次や叫び声を上げたため、車内に留まった。[144] |

| Guatemalan government apology In 1999, the Árbenz family went before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR) to demand an apology from the Guatemalan government for the 1954 coup which saw him ousted.[145] Following years of campaigning, the Árbenz Family took the Guatemalan Government to Inter-American Commission on Human Rights in Washington, D.C. It accepted the complaint in 2006, leading to five years of stop-and-start negotiations.[146][147] In May 2011 the Guatemalan government signed an agreement with Árbenz's surviving family to restore his legacy and publicly apologize for the government's role in ousting him. This included a financial settlement to the family, as well as the family's insistence on social reparations and policies for the future of the Guatemalan people, a first for a judgement of this kind from the OAS. The formal apology was made at the National Palace by Guatemalan President Alvaro Colom on 20 October 2011, to Jacobo Árbenz Vilanova, the son of the former president, and a Guatemalan politician.[70] Colom stated, "It was a crime to Guatemalan society and it was an act of aggression to a government starting its democratic spring."[70] The agreement established several forms of reparation for the next of kin of Árbenz Guzmán. Among other measures, the state:[70][148] held a public ceremony recognizing its responsibility sent a letter of apology to the next of kin named a hall of the National Museum of History and the highway to the Atlantic after the former president revised the basic national school curriculum (Currículo Nacional Base) established a degree program in Human Rights, Pluriculturalism, and Reconciliation of Indigenous Peoples held a photographic exhibition on Árbenz Guzmán and his legacy at the National Museum of History recovered the wealth of photographs of the Árbenz Guzmán family published a book of photos reissued the book Mi esposo, el presidente Árbenz (My Husband President Árbenz) prepared and published a biography of the former president, and issued a series of postage stamps in his honor. The official statement issued by the government recognized its responsibility for "failing to comply with its obligation to guarantee, respect, and protect the human rights of the victims to a fair trial, to property, to equal protection before the law, and to judicial protection, which are protected in the American Convention on Human Rights and which were violated against former President Juan Jacobo Árbenz Guzman, his wife, María Cristina Villanova, and his children, Juan Jacobo, María Leonora, and Arabella, all surnamed Árbenz Villanova."[148] |

グアテマラ政府の謝罪 1999年、アルベンス家は米州人権委員会(IACHR)に申し立てを行い、1954年のクーデターで彼を追放した件についてグアテマラ政府に謝罪を要求 した。[145] 長年の運動を経て、アルベンス家はグアテマラ政府をワシントンD.C.の米州人権委員会に提訴した。同委員会は2006年に申し立てを受理し、その後5年 間にわたり断続的な交渉が続いた。2011年5月、グアテマラ政府はアルベンスの生存家族と合意書に署名した。内容は彼の功績を回復すること、政府が彼を 追放した役割について公に謝罪することである。これには家族への金銭的補償に加え、家族が主張した社会的賠償とグアテマラ人民の未来に向けた政策が含まれ ており、OAS(米州機構)によるこの種の判断としては初めての事例となった。2011年10月20日、グアテマラ大統領アルヴァロ・コロンは国立宮殿に おいて、元大統領の息子でありグアテマラの政治家であるハコボ・アルベンス・ビラノバに対し、公式に謝罪した[70]。コロンは「これはグアテマラ社会に 対する犯罪であり、民主主義の春を迎えようとしていた政府への侵略行為であった」と述べた[70]。合意により、アルベンス・グスマンの遺族に対する複数 の賠償形態が確立された。主な措置として、国家は以下を実施した[70][148]: 責任を認める公的式典を開催 遺族へ謝罪書簡を送付 国立歴史博物館のホール及び大西洋への幹線道路に元大統領の名を命名 国家基本教育課程を改訂 (Currículo Nacional Base) 人権・多文化主義・先住民和解に関する学位課程を設置した 国立歴史博物館でアルベンス・グスマンとその遺産に関する写真展を開催した アルベンス・グスマン一家の貴重な写真群を回収した 写真集を出版した 『私の夫、大統領アルベンス』を再版した (My Huspo, el Presidente Arbenz)を再版した。 元大統領の伝記を準備・出版し、 彼を称える一連の切手を発行した。 政府が発表した公式声明は、次のような責任を認めた。「アメリカ人権条約で保護されている公正な裁判を受ける権利、財産権、法の下の平等な保護、司法保護 といった被害者の人権を保障し、尊重し、保護する義務を履行しなかったこと。この義務は、元大統領フアン・ハコボ・アルベンス・グスマン、その妻マリア・ クリスティーナ・ビジャノバ、そして子供たちであるフアン・ハコボ、 マリア・レオノーラ、アラベラ(全員姓はアルベンス・ビジャノバ)に対して侵害された」と認めた。[148] |

Legacy Photo of Árbenz projected on the National Palace during the official events commemorating the Revolution, 2024 Historian Roberto García Ferreira wrote in 2008 that Árbenz's legacy was still a matter of great dispute in Guatemala itself, while arguing that the image of Árbenz was significantly shaped by the CIA media campaign that followed the 1954 coup.[149] García Ferreira said that the revolutionary government represented one of the few periods in which "state authority was used to promote the interests of the nation's masses."[150] Forster described Árbenz's legacy in the following terms: "In 1952 the Agrarian Reform Law swept the land, destroying forever the hegemony of the planters. Árbenz in effect legislated a new social order ... The revolutionary decade ... plays a central role in twentieth-century Guatemalan history because it was more comprehensive than any period of reform before or since."[151] She added that even within the Guatemalan government, Árbenz "gave full compass to Indigenous, campesino, and labor demands" in contrast to Arévalo, who had remained suspicious of these movements.[151] Similarly, Greg Grandin stated that the land reform decree "represented a fundamental shift in the power relations governing Guatemala".[152] Árbenz himself once remarked that the agrarian reform law was "most precious fruit of the revolution and the fundamental base of the nation as a new country."[153] However, to a large extent the legislative reforms of the Árbenz and Arévalo administrations were reversed by the US-backed military governments that followed.[154] |

遺産 革命記念公式行事中に国立宮殿に投影されたアルベンスの写真、2024年 歴史家ロベルト・ガルシア・フェレイラは2008年、アルベンスの遺産はグアテマラ国内でも依然として大きな論争の的であると記した。同時に彼は、アルベ ンスのイメージは1954年のクーデター後にCIAが展開したメディアキャンペーンによって大きく形作られたと主張した[149]。ガルシア・フェレイラ は、革命政府は「国民権力が国民大衆の利益を促進するために用いられた」数少ない時期の一つであったと述べた。[150] フォースターはアルベンスの遺産を次のように表現した。「1952年、農地改革法が国土を席巻し、プランター階級のヘゲモニーを永遠に打ち砕いた。アルベ ンスは事実上、新たな社会秩序を法制化した…革命の10年間…は20世紀グアテマラ史において中心的な役割を果たす。なぜなら、それ以前のいかなる改革期 よりも包括的だったからだ。」 [151] 彼女はさらに、グアテマラ政府内部においても、アルベンスは「先住民、農民、労働者の要求を全面的に受け入れた」と付け加えた。これは、これらの運動に疑 念を抱き続けたアレバロとは対照的であった。[151] 同様に、グレッグ・グランディンは、土地改革令が「グアテマラを支配する権力関係における根本的な転換を表していた」と述べている。[152] アルベンス自身もかつて、農地改革法は「革命の最も貴重な成果であり、新たな国民としての国の基盤である」と述べたことがある。[153] しかし、アルベンス政権とアレバロ政権による立法改革の多くは、その後続いた米国支持の軍事政権によって覆された。[154] |

| In popular culture The Guatemalan movie The Silence of Neto (1994), filmed on location in Antigua Guatemala, takes place during the last months of the government of Árbenz. It follows the life of a fictional 12-year-old boy who is sheltered by the Árbenz family, set against a backdrop of the struggle in which the country is embroiled at the time.[155] The story of Árbenz's life and subsequent overthrow in the CIA-sponsored coup d'état has been the subject of several books, notably PBSuccess: The CIA's covert operation to overthrow Guatemalan president Jacobo Arbenz June–July 1954[156] by Mario Overall and Daniel Hagedorn (2016), American Propaganda, Media, And The Fall Of Jacobo Arbenz Guzman by Zachary Fisher (2014),[157] as well as New York Times best seller The Devil's Chessboard by David Talbot (HarperCollins 2015). The Árbenz story was also the subject of the multi award-winning 1997 documentary by Andreas Hoessli Devils Don't Dream![158] |

大衆文化において グアテマラ映画『ネトの沈黙』(1994年)は、アンティグア・グアテマラでロケ撮影された。アルベンス政権の最後の数ヶ月を舞台に、当時国が巻き込まれた闘争を背景に、架空の12歳の少年がアルベンス一家に保護される様子を描く。[155] アルベンスの生涯と、CIAが支援したクーデターによるその後の転覆の物語は、いくつかの書籍の主題となっている。特に『PBSuccess: CIAによるグアテマラ大統領ヤコボ・アルベンツの転覆工作 1954年6月~7月[156](マリオ・オーバーオール、ダニエル・ヘイゲドルン著、2016年)、『アメリカのプロパガンダ、メディア、そしてヤコ ボ・アルベンツ・グスマンの没落』(ザカリー・フィッシャー著、2014年)[157]、そしてニューヨーク・タイムズのベストセラー『悪魔のチェス盤』 (デビッド・タルボット著 (HarperCollins 2015)。アルベンスの物語は、アンドレアス・ヘスリによる、数々の賞を受賞した 1997 年のドキュメンタリー映画『悪魔は夢を見ない![158]』の題材にもなった。 |

| Salvador Allende - Socialist president of Chile who was ousted in a US-supported coup Juan José Torres - Socialist president of Bolivia ousted by a US-supported coup Ernest V. Siracusa - Embassy official in Guatemala who later was ambassador in Bolivia during the coup against Torres |

サルバドール・アジェンデ - チリの社会主義大統領。米国が支援したクーデターで追放された フアン・ホセ・トーレス - ボリビアの社会主義大統領。米国が支援したクーデターで追放された アーネスト・V・シラクーサ - グアテマラ駐在大使館職員。後にボリビア駐在大使となり、トーレスに対するクーデター時に在任していた |

| a. In order to run for election,

the constitution required that Arana resign his military position by

May 1950, and that his successor be chosen by Congress from a list

submitted by the Consejo Superior de la Defensa, or CSD.[48] Elections

for the CSD were scheduled for July 1949. The months before this

election saw intense wrangling, as Arana supporters tried to gain

control over the election process. Specifically, they wanted the

election to be supervised by regional commanders loyal to Arana, rather

than centrally dispatched observers.[48] |

a. 選挙に出馬するためには、憲法によりアラナは1950年5月までに軍職を辞任し、後任は国防最高評議会(CSD)が提出した名簿から議会が選出することが 求められていた。[48] CSDの選挙は1949年7月に予定されていた。この選挙前の数ヶ月間、アラナ支持派が選挙プロセスを掌握しようと激しく争った。具体的には、中央から派 遣された監視員ではなく、アラナに忠実な地域司令官による選挙監督を求めていたのである。[48] |