ジム・クロウ法

Jim Crow laws

☆ジム・クロウ法は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてアメリカ南部に導入された州法および地方法であり、人種差別を正当化し人種隔離を強制するものであった。「ジム・ク ロウ」はアフリカ系アメリカ人を蔑称する言葉である[1]。このような法律は1965年まで有効であった[2]。公的な施設や投票における差別を禁止して いた南部以外のいくつかの州があったにもかかわらず、公式および非公式の隔離政策はアメリカ国内の他の地域にも存在していた[ 3][4] 南部の法律は、再建時代にアフリカ系アメリカ人が獲得した政治的・経済的権利を奪い、排除するために、白人優位の州議会(Redeemers)によって制 定された。ジム・クロウ法は、1896年のプレッシー対ファーガソン事件で最高裁により支持された。この事件で最高裁は、アフリカ系アメリカ人向けの施設 に関する「分離だが平等」の法理を提示した。さらに、1861年から1865年の南北戦争後の南部では、公立教育は基本的に分離されていた。付随する法律 により、南部ではアフリカ系アメリカ人のほぼ全員が投票権を奪われ、代表制政府から排除された。

| The

Jim Crow laws were state and local laws introduced in the Southern

United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced

racial segregation, "Jim Crow" being a pejorative term for an African

American.[1] Such laws remained in force until 1965.[2] Formal and

informal segregation policies were present in other areas of the United

States as well, even as several states outside the South had banned

discrimination in public accommodations and voting.[3][4] Southern laws

were enacted by white-dominated state legislatures (Redeemers) to

disenfranchise and remove political and economic gains made by African

Americans during the Reconstruction era.[5] Such continuing racial

segregation was also supported by the successful Lily-white movement.[6] In practice, Jim Crow laws mandated racial segregation in all public facilities in the states of the former Confederate States of America and in some others, beginning in the 1870s. Jim Crow laws were upheld in 1896 in the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, in which the Supreme Court laid out its "separate but equal" legal doctrine concerning facilities for African Americans. Moreover, public education had essentially been segregated since its establishment in most of the South after the Civil War in 1861–1865. Companion laws excluded almost all African Americans from the vote in the South and deprived them of any representative government. Although in theory, the "equal" segregation doctrine governed public facilities and transportation too, facilities for African Americans were consistently inferior and underfunded compared to facilities for white Americans; sometimes, there were no facilities for the black community at all.[7][8] Far from equality, as a body of law, Jim Crow institutionalized economic, educational, political and social disadvantages and second class citizenship for most African Americans living in the United States.[7][8][9] After the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was founded in 1909, it became involved in a sustained public protest and campaigns against the Jim Crow laws, and the so-called "separate but equal" doctrine. In 1954, segregation of public schools (state-sponsored) was declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court in the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka.[10][11][12] In some states, it took many years to implement this decision, while the Warren Court continued to rule against Jim Crow legislation in other cases such as Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v. United States (1964).[13] In general, the remaining Jim Crow laws were overturned by the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. |

ジ

ム・クロウ法は、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてアメリカ南部に導入された州法および地方法であり、人種隔離を強制するものであった。「ジム・クロ

ウ」はアフリカ系アメリカ人を蔑称する言葉である[1]。このような法律は1965年まで有効であった[2]。公的な施設や投票における差別を禁止してい

た南部以外のいくつかの州があったにもかかわらず、公式および非公式の隔離政策はアメリカ国内の他の地域にも存在していた[ 3][4]

南部の法律は、再建時代にアフリカ系アメリカ人が獲得した政治的・経済的権利を奪い、排除するために、白人優位の州議会(Redeemers)によって制

定された。ジム・クロウ法は、1896年のプレッシー対ファーガソン事件で最高裁により支持された。この事件で最高裁は、アフリカ系アメリカ人向けの施設

に関する「分離だが平等」の法理を提示した。さらに、1861年から1865年の南北戦争後の南部では、公立教育は基本的に分離されていた。付随する法律

により、南部ではアフリカ系アメリカ人のほぼ全員が投票権を奪われ、代表制政府から排除された。 理論的には、「平等」な隔離の原則は公共施設や交通機関にも適用されていたが、アフリカ系アメリカ人向けの施設は、白人向けの施設に比べて常に劣悪で資金 不足であり、時には黒人コミュニティ向けの施設が全くないこともあった[7][8]。平等とは程遠い法律として、ジム・クロウ法は、経済、教育、政治、社 会における不利な条件を そして、米国に住むほとんどの黒人に対する経済的、教育的、政治的、社会的劣位と二級市民権を制度化していた[7][8][9]。1909年に全米有色人 地位向上協会(NAACP)が設立されると、同協会はジム・クロウ法や「分離だが平等」の原則に対する抗議運動やキャンペーンに継続的に取り組んだ。 1954年、公立学校(州立)の分離は、トピカ教育委員会対ブラウン事件という画期的な裁判で、合衆国最高裁判所により違憲であると宣言された[10] [11][12]。一部の州では、この判決を施行するまでには長い年月を要したが、一方でウォーレン 裁判所は、ハート・オブ・アトランタ・モーテル社対アメリカ合衆国事件(1964年)など、他の裁判でもジム・クロウ法に反対する判決を下し続けた [13]。一般的に、残るジム・クロウ法は、1964年の公民権法と1965年の投票権法によって覆された。 |

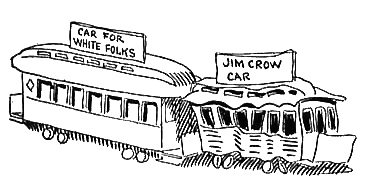

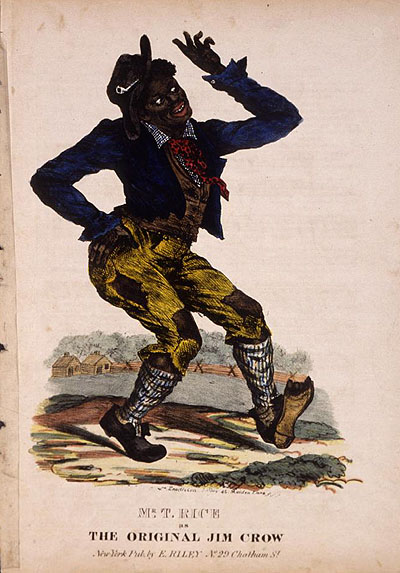

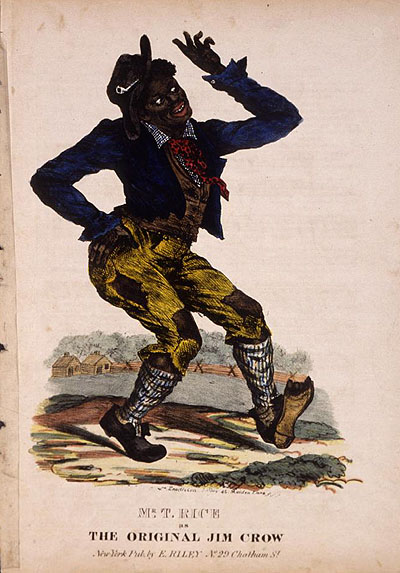

| Etymology The earliest known use of the phrase "Jim Crow law" can be dated to 1884 in a newspaper article summarizing congressional debate.[14] The term appears in 1892 in the title of a New York Times article about Louisiana requiring segregated railroad cars.[15][16] The origin of the phrase "Jim Crow" has often been attributed to "Jump Jim Crow", a song-and-dance caricature of black people performed by white actor Thomas D. Rice in blackface, first performed in 1828. As a result of Rice's fame, Jim Crow had become by 1838 a pejorative expression meaning "Negro". When southern legislatures passed laws of racial segregation directed against African Americans at the end of the 19th century, these statutes became known as Jim Crow laws.[15] |

語源 「ジム・クロウ法」という表現が最初に使用されたのは、1884年の議会討論をまとめた新聞記事である[14]。この言葉は、ルイジアナ州が鉄道車両を人 種別に分けることを義務付けたことについて書かれた1892年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙の記事のタイトルにも登場する [15][16]「ジム・クロウ」という表現の起源は、しばしば白人俳優トーマス・D・ライスが黒人役で演じた歌と踊りの風刺劇「ジャンプ・ジム・クロ ウ」に由来すると考えられている。ライスが有名になった結果、1838年までにジム・クロウは「黒人」を意味する蔑称となった。19世紀末に南部議会がア フリカ系アメリカ人に対する人種隔離法を可決すると、これらの法律はジム・クロウ法として知られるようになった[15]。 |

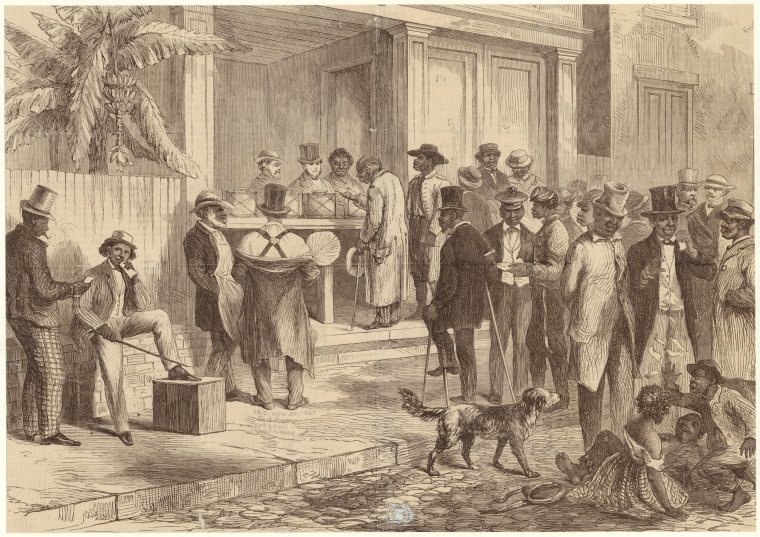

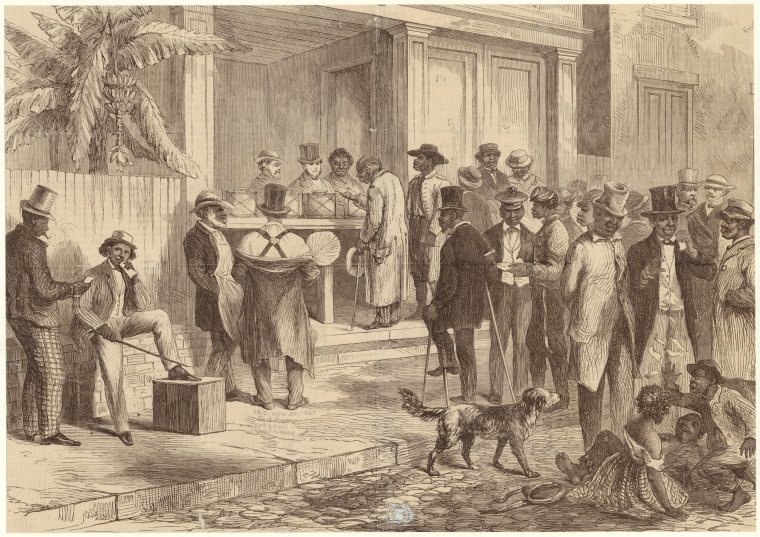

| Origins Main article: Disfranchisement after the Reconstruction era In January 1865, an amendment to the Constitution abolishing slavery in the United States was proposed by Congress and ratified as the Thirteenth Amendment on December 18, 1865.[17]  Cover of an early edition of "Jump Jim Crow" sheet music (c. 1832)  Freedmen voting in New Orleans, 1867 During the Reconstruction era of 1865–1877, federal laws provided civil rights protections in the U.S. South for freedmen, African Americans who were former slaves, and the minority of black people who had been free before the war. In the 1870s, Democrats gradually regained power in the Southern legislatures[18] as violent insurgent paramilitary groups, such as the Ku Klux Klan, White League, and Red Shirts disrupted Republican organizing, ran Republican officeholders out of town, and lynched black voters as an intimidation tactic to suppress the black vote.[19] Extensive voter fraud was also used. In one instance, an outright coup or insurrection in coastal North Carolina led to the violent removal of democratically elected Republican party executive and representative officials, who were either hunted down or hounded out. Gubernatorial elections were close and had been disputed in Louisiana for years, with increasing violence against black Americans during campaigns from 1868 onward.[20] The Compromise of 1877 to gain Southern support in the presidential election resulted in the government withdrawing the last of the federal troops from the South. White Democrats had regained political power in every Southern state.[21] These Southern, white, "Redeemer" governments legislated Jim Crow laws, officially segregating the country's population. Jim Crow laws were a manifestation of authoritarian rule specifically directed at one racial group.[22] Black people were still elected to local offices throughout the 1880s in local areas with large black populations, but their voting was suppressed for state and national elections. States passed laws to make voter registration and electoral rules more restrictive, with the result that political participation by most black people and many poor white people began to decrease.[23][24] Between 1890 and 1910, ten of the eleven former Confederate states, beginning with Mississippi, passed new constitutions or amendments that effectively disenfranchised most black people and tens of thousands of poor white people through a combination of poll taxes, literacy and comprehension tests, and residency and record-keeping requirements.[23][24] Grandfather clauses temporarily permitted some illiterate white people to vote but gave no relief to most black people. Voter turnout dropped dramatically through the South as a result of these measures. In Louisiana, by 1900, black voters were reduced to 5,320 on the rolls, although they comprised the majority of the state's population. By 1910, only 730 black people were registered, less than 0.5% of eligible black men. "In 27 of the state's 60 parishes, not a single black voter was registered any longer; in 9 more parishes, only one black voter was."[25] The cumulative effect in North Carolina meant that black voters were eliminated from voter rolls during the period from 1896 to 1904. The growth of their thriving middle class was slowed. In North Carolina and other Southern states, black people suffered from being made invisible in the political system: "[W]ithin a decade of disfranchisement, the white supremacy campaign had erased the image of the black middle class from the minds of white North Carolinians."[25] In Alabama, tens of thousands of poor whites were also disenfranchised, although initially legislators had promised them they would not be affected adversely by the new restrictions.[26] Those who could not vote were not eligible to serve on juries and could not run for local offices. They effectively disappeared from political life, as they could not influence the state legislatures, and their interests were overlooked. While public schools had been established by Reconstruction legislatures for the first time in most Southern states, those for black children were consistently underfunded compared to schools for white children, even when considered within the strained finances of the postwar South where the decreasing price of cotton kept the agricultural economy at a low.[27] Like schools, public libraries for black people were underfunded, if they existed at all, and they were often stocked with secondhand books and other resources.[8][28] These facilities were not introduced for African Americans in the South until the first decade of the 20th century.[29] Throughout the Jim Crow era, libraries were only available sporadically.[30] Prior to the 20th century, most libraries established for African Americans were school-library combinations.[30] Many public libraries for both European-American and African-American patrons in this period were founded as the result of middle-class activism aided by matching grants from the Carnegie Foundation.[30] In some cases, progressive measures intended to reduce election fraud, such as the Eight Box Law in South Carolina, acted against black and white voters who were illiterate, as they could not follow the directions.[31] While the separation of African Americans from the white general population was becoming legalized and formalized during the Progressive Era (1890s–1920s), it was also becoming customary. Even in cases in which Jim Crow laws did not expressly forbid black people from participating in sports or recreation, a segregated culture had become common.[15] In the Jim Crow context, the presidential election of 1912 was steeply slanted against the interests of African Americans.[32] Most black Americans still lived in the South, where they had been effectively disfranchised, so they could not vote at all. While poll taxes and literacy requirements banned many poor or illiterate people from voting, these stipulations frequently had loopholes that exempted European Americans from meeting the requirements. In Oklahoma, for instance, anyone qualified to vote before 1866, or related to someone qualified to vote before 1866 (a kind of "grandfather clause"), was exempted from the literacy requirement; but the only men who had the franchise before that year were white or European-American. European Americans were effectively exempted from the literacy testing, whereas black Americans were effectively singled out by the law.[33] Woodrow Wilson was a Democrat elected from New Jersey, but he was born and raised in the South, and was the first Southern-born president of the post-Civil War period. He appointed Southerners to his Cabinet. Some quickly began to press for segregated workplaces, although the city of Washington, D.C., and federal offices had been integrated since after the Civil War. In 1913, Secretary of the Treasury William Gibbs McAdoo – an appointee of the President – was heard to express his opinion of black and white women working together in one government office: "I feel sure that this must go against the grain of the white women. Is there any reason why the white women should not have only white women working across from them on the machines?"[34] The Wilson administration introduced segregation in federal offices, despite much protest from African-American leaders and white progressive groups in the north and midwest.[35] He appointed segregationist Southern politicians because of his own firm belief that racial segregation was in the best interest of black and European Americans alike.[36] At the Great Reunion of 1913 at Gettysburg, Wilson addressed the crowd on July 4, the semi-centennial of Abraham Lincoln's declaration that "all men are created equal": How complete the union has become and how dear to all of us, how unquestioned, how benign and majestic, as state after state has been added to this, our great family of free men![37] In sharp contrast to Wilson, a Washington Bee editorial wondered if the "reunion" of 1913 was a reunion of those who fought for "the extinction of slavery" or a reunion of those who fought to "perpetuate slavery and who are now employing every artifice and argument known to deceit" to present emancipation as a failed venture.[37] Historian David W. Blight observed that the "Peace Jubilee" at which Wilson presided at Gettysburg in 1913 "was a Jim Crow reunion, and white supremacy might be said to have been the silent, invisible master of ceremonies".[37] In Texas, several towns adopted residential segregation laws between 1910 and the 1920s. Legal strictures called for segregated water fountains and restrooms.[37] The exclusion of African Americans also found support in the Republican lily-white movement.[38] |

起源 メイン記事: 再建時代以降の公民権剥奪 1865年1月、米国議会は合衆国憲法修正第13条として奴隷制を廃止する憲法修正案を提案し、1865年12月18日に批准された[17]。  「Jump Jim Crow」楽譜の初期版の表紙(1832年頃 1832年頃  ニューオーリンズで投票する解放奴隷、1867年 1865年から1877年の再建時代、連邦法はアメリカ南部に住む解放奴隷、すなわち元奴隷のアフリカ系アメリカ人と、戦前に自由民であった少数派の黒人 に対して公民権保護を提供した。1870年代、民主党は南部議会で徐々に力を取り戻していった[18]。ク・クラックス・クラン、ホワイトリーグ、レッド シャツといった暴力的な反乱軍準軍事組織が、共和党の組織化を妨害し、共和党の公職者を町から追い出し、黒人票を抑制するための威嚇戦術として黒人有権者 をリンチした[19]。大規模な選挙不正も利用された。一例を挙げると、ノースカロライナ州沿岸部では、民主的に選出された共和党党幹部や代表幹部が、暴 力的手段で排除されるという、事実上のクーデターや暴動が発生した。ルイジアナ州では、知事選が接戦となり、長年にわたり論争が繰り返されていた。 1868年以降、選挙戦では黒人に対する暴力が増加していた[20]。 大統領選挙で南部からの支持を得るために1877年に妥協案が結ばれ、政府は南部から最後の連邦軍を撤退させた。白人民主党は南部各州で再び政治権力を 握った[21]。これらの南部白人「救世主」政府は、ジム・クロウ法を制定し、公式に人種隔離政策を実施した。ジム・クロウ法は、特定の人種集団を標的に した権威主義的支配の表れであった[22]。 1880年代を通じて、黒人人口の多い地方では黒人が地方議員に選出されることはあったが、州や全国レベルの選挙では黒人の投票権は抑圧された。各州は、 有権者登録や選挙規則をより厳しくする法律を制定し、その結果、ほとんどの黒人と多くの貧しい白人の政治参加は減少し始めた[23][24]。1890年 から1910年の間に、ミシシッピ州を皮切りに、かつての南部連合11州のうち10州が、 これは、人頭税、識字・理解力テスト、居住要件、記録保管要件を組み合わせることで、ほとんどの黒人と数万人の貧しい白人の選挙権を事実上剥奪するもの だった[23][24]。祖父条項により、一時的に一部の識字能力のない白人への投票が許可されたが、ほとんどの黒人には何の救済措置も与えられなかっ た。 これらの措置の結果、南部では投票率が大幅に低下した。ルイジアナ州では、1900年までに黒人有権者は5,320人にまで減少したが、彼らは州人口の大 半を占めていた。1910年には、登録されている黒人はわずか730人となり、有権者登録できる黒人男性の0.5%にも満たなかった。「州の60教区のう ち27教区では、黒人の有権者は一人も登録されておらず、さらに9教区では、黒人の有権者は一人しか登録されていなかった」[25]。ノースカロライナ州 では、1896年から1904年にかけて、累積的な影響により黒人の有権者が選挙人名簿から排除された。黒人の中産階級の成長は鈍化した。ノースカロライ ナ州や他の南部諸州では、黒人たちは政治システムの中で存在を無視されるという苦境に立たされていた。「選挙権剥奪から10年も経たないうちに、白人至上 主義運動によって、ノースカロライナ州の白人の心の中から黒人の中流階級のイメージが消え去ってしまった」[25]。アラバマ州では、当初、立法府が新し い制限によって不利な影響を受けないことを約束していたにもかかわらず、何万人もの貧しい白人が選挙権を奪われた[26]。 投票できない人々は陪審員を務めることも、地方選挙に立候補することもできなかった。彼らは州議会に影響を与えることができず、自分たちの利益も無視され たため、事実上政治生活から姿を消した。ほとんどの南部州で再建議会により公立学校が初めて設立されたが、綿花の価格低下により農業経済が低調な戦後の南 部の厳しい財政状況を考えたとしても、黒人の子供たちのための学校は白人の子供たちのための学校に比べて常に資金不足であった[27]。 学校と同様に、黒人のための公立図書館 黒人向けの公立図書館も、存在していたとしても資金不足で、中古の本やその他の資料で満たされていたことが多い[8][28]。これらの施設が南部アフリ カ系アメリカ人のために導入されたのは、20世紀最初の10年間になってからであった[29]。ジム・クロウ時代を通じて、図書館は不定期にしか利用でき なかった [30] 20世紀以前、アフリカ系アメリカ人のために設立された図書館のほとんどは、学校と図書館が合体した施設であった[30]。この時代のヨーロッパ系アメリ カ人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の両方を利用する多くの公立図書館は、カーネギー財団からのマッチンググラント(同額助成金)による中産階級の活動の結果とし て設立された[30]。 例えば、サウスカロライナ州の「エイトボックス法」のような選挙不正を減らすための進歩的な措置は、指示に従うことができない識字能力のない黒人および白 人の有権者に対して逆効果となった[31]。進歩主義の時代(1890年代~1920年代)にアフリカ系アメリカ人と白人の一般人口の分離が合法化され、 正式なものとなっていく一方で、それが習慣化していった。ジム・クロウ法が黒人のスポーツや娯楽への参加を明示的に禁止していない場合でも、隔離された文 化が一般的になっていた[15]。 ジム・クロウ法のもとで、1912年の大統領選挙はアフリカ系アメリカ人の利益に著しく不利な結果となった[32]。ほとんどの黒人アメリカ人は依然とし て南部に住んでおり、事実上選挙権を奪われていたため、投票することはできなかった。投票税と識字要件により、多くの貧困層や非識字者は投票権を奪われて いた。しかし、これらの規定には抜け穴があり、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は要件を満たさなくても投票できた。例えば、オクラホマ州では、1866年以前に投 票資格があった者、または1866年以前に投票資格があった者の親族(一種の「祖父条項」)は、識字要件を免除されていた。しかし、その年以前に選挙権を 持っていたのは白人やヨーロッパ系アメリカ人の男性だけだった。ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人は事実上識字テストが免除されていたのに対し、黒人アメリカ人は事 実上法律で差別されていた[33]。 ウッドロウ・ウィルソンはニュージャージー州選出の民主党員だったが、南部で生まれ育ち、南北戦争後の南部出身の初代大統領となった。彼は南部出身者を閣 僚に任命した。南北戦争後、ワシントンD.C.や連邦政府機関では人種統合が進められていたが、一部の者はすぐに職場での人種隔離を要求し始めた。 1913年、大統領の任命を受けたウィリアム・ギブス・マッカーサー財務長官は、ある政府機関で黒人と白人の女性が一緒に働いていることについて、次のよ うに意見を述べた。「これは白人女性の気分を害するにちがいない。白人女性が向かい側に座って作業する機械には、白人女性しか座ってはいけない理由がある のだろうか?」[34] ウィルソン政権は、北部と中西部のアフリカ系アメリカ人指導者および白人進歩派グループからの多くの抗議にもかかわらず、連邦政府機関に人種隔離を導入し た[35]。彼は人種隔離主義の南部政治家を任命したが、それは 人種的隔離は黒人とヨーロッパ系アメリカ人双方にとって最善の利益である、という彼の確固たる信念によるものであった[36]。1913年のゲティスバー グでの「大再統一」において、ウィルソンは7月4日、エイブラハム・リンカーンの「すべての人間は平等に創造された」という宣言から半世紀を迎えた日に、 群衆に向けて演説を行った。 この自由人の偉大な家族に加わる州が次々と加わるにつれ、この連合がいかに完全なものとなり、私たち皆にとっていかにかけがえのないものとなり、いかに疑いの余地のないものとなり、いかに善良で威厳のあるものとなったか![37] ウィルソンとは対照的に、ワシントン・ビー紙の社説は、1913年の「再会」が「奴隷制度の廃止」のために戦った人々の再会なのか、それとも「奴隷制度の 永続」のために戦った人々の再会であり、今では 奴隷制の廃止を失敗に終わらせた」として、あらゆる策略や論拠を駆使して奴隷制の存続を主張している人々との再会だった。歴史家のデビッド・W・ブライト は、ウィルソンが1913年にゲティスバーグで主宰した「平和の祝祭」について、「ジム・クロウの同窓会であり、白人至上主義が、目に見えない司会の主 だったと言えるかもしれない」と述べた。 テキサス州では、1910年から1920年代にかけて、いくつかの都市が居住区隔離法を採択した。法律上の制約により、水飲み場とトイレは分離されていた[37]。アフリカ系アメリカ人の排除は、共和党の白人至上主義運動からも支持されていた[38]。 |

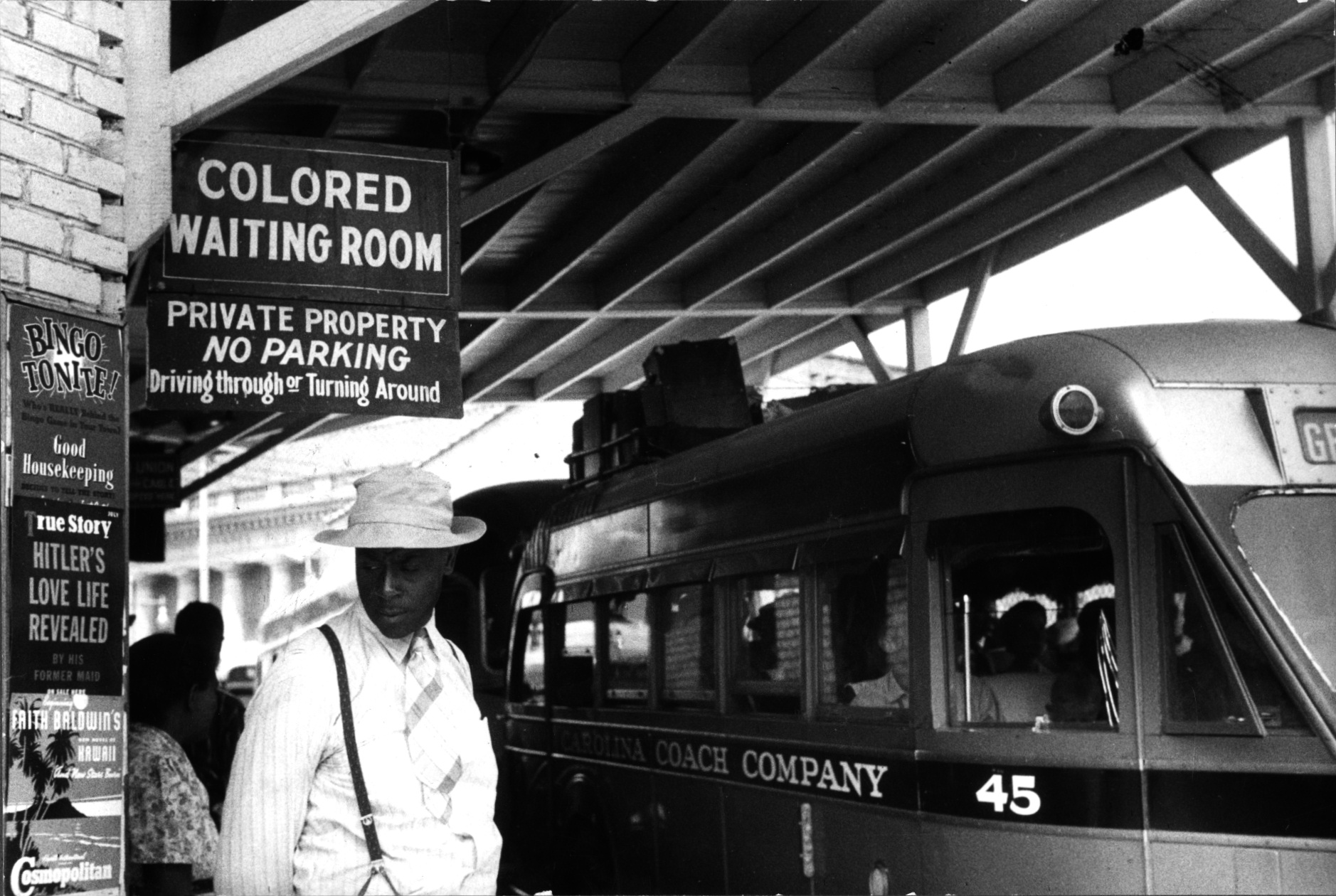

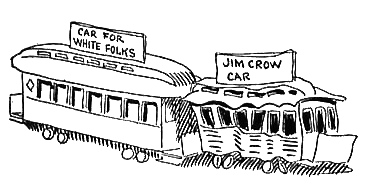

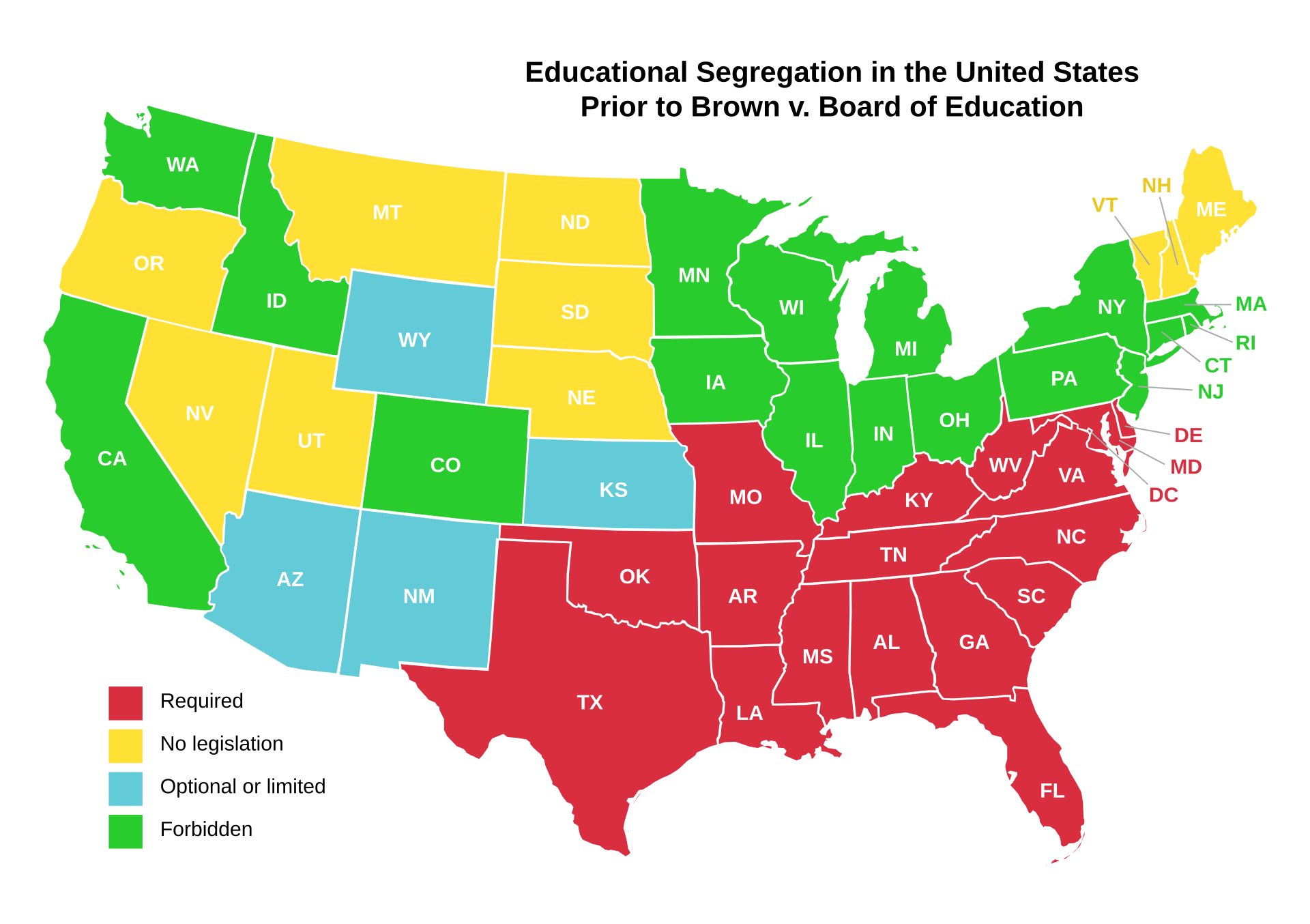

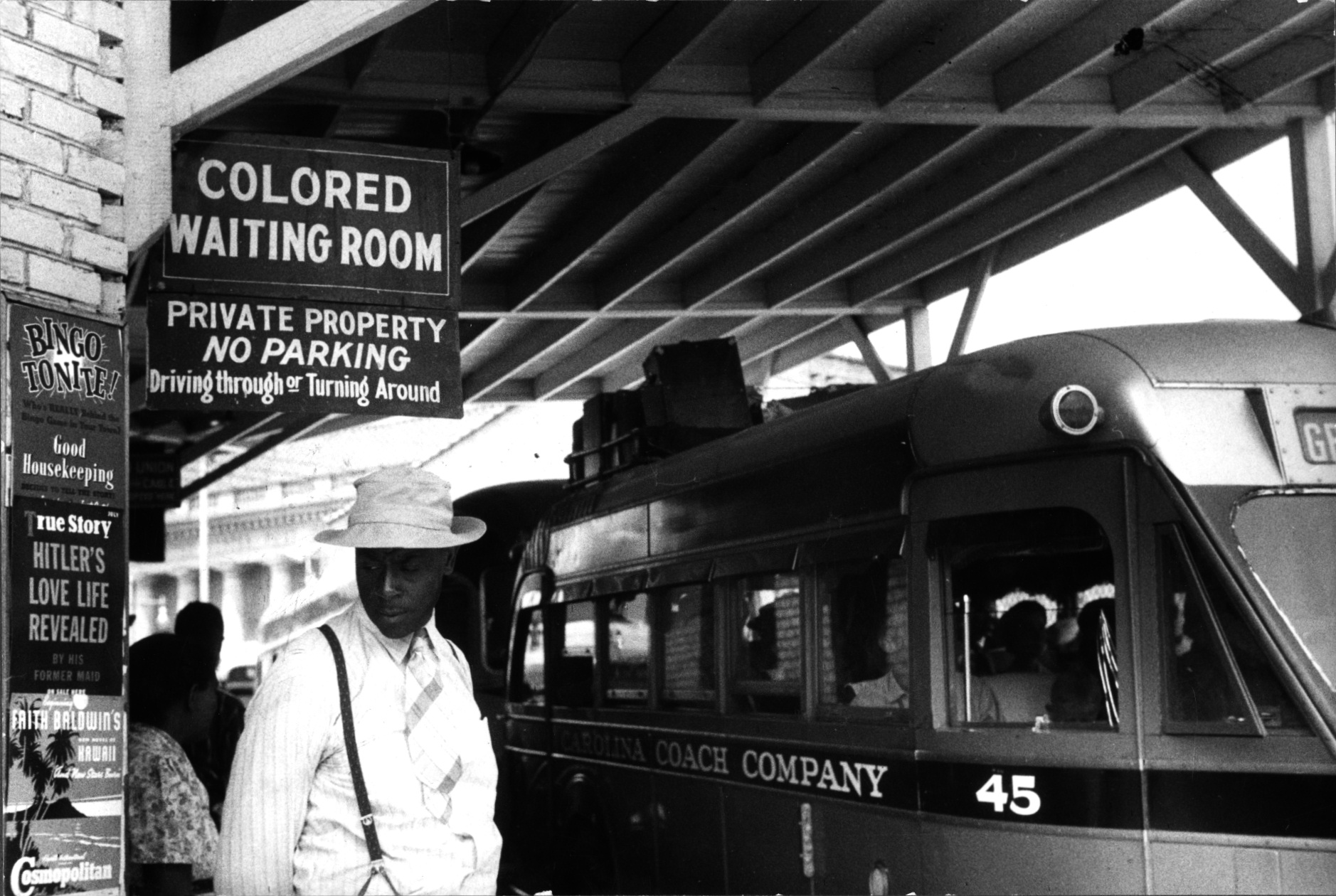

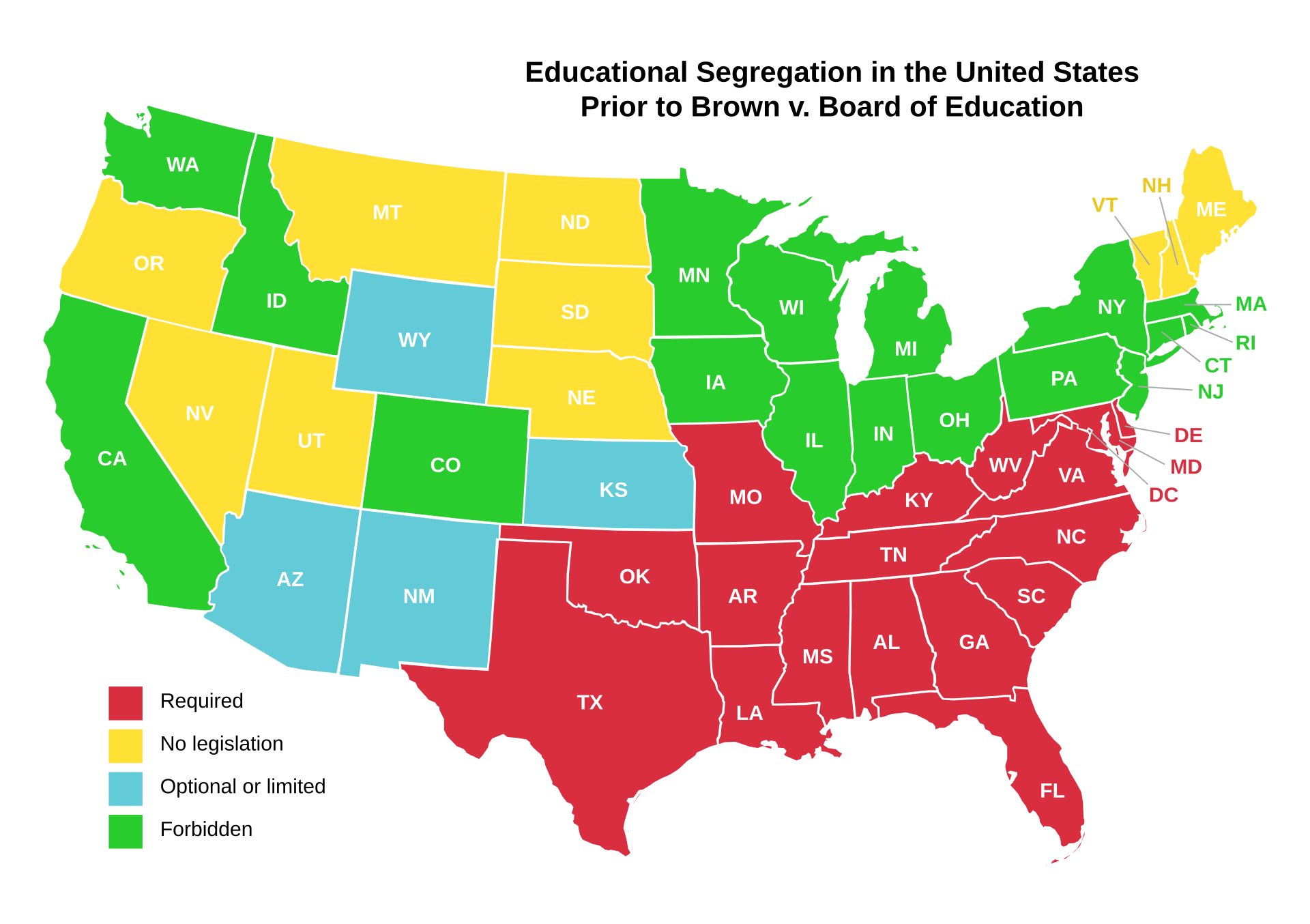

| Historical development Early attempts to break Jim Crow  Sign for the "colored" waiting room at a bus station in Durham, North Carolina, May 1940 The Civil Rights Act of 1875, introduced by Charles Sumner and Benjamin F. Butler, stipulated a guarantee that everyone, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, was entitled to the same treatment in public accommodations, such as inns, public transportation, theaters, and other places of recreation. This Act had little effect in practice.[39] An 1883 Supreme Court decision ruled that the act was unconstitutional in some respects, saying Congress was not afforded control over private persons or corporations. With white southern Democrats forming a solid voting bloc in Congress, due to having outsize power from keeping seats apportioned for the total population in the South (although hundreds of thousands had been disenfranchised), Congress did not pass another civil rights law until 1957.[40] In 1887, Rev. W. H. Heard lodged a complaint with the Interstate Commerce Commission against the Georgia Railroad company for discrimination, citing its provision of different cars for white and black/colored passengers. The company successfully appealed for relief on the grounds it offered "separate but equal" accommodation.[41] In 1890, Louisiana passed a law requiring separate accommodations for colored and white passengers on railroads. Louisiana law distinguished between "white", "black" and "colored" (that is, people of mixed European and African ancestry). The law had already specified that black people could not ride with white people, but colored people could ride with white people before 1890. A group of concerned black, colored and white citizens in New Orleans formed an association dedicated to rescinding the law. The group persuaded Homer Plessy to test it; he was a man of color who was of fair complexion and one-eighth "Negro" in ancestry.[42] In 1892, Plessy bought a first-class ticket from New Orleans on the East Louisiana Railway. Once he had boarded the train, he informed the train conductor of his racial lineage and took a seat in the whites-only car. He was directed to leave that car and sit instead in the "coloreds only" car. Plessy refused and was immediately arrested. The Citizens Committee of New Orleans fought the case all the way to the United States Supreme Court. They lost in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the Court ruled that "separate but equal" facilities were constitutional. The finding contributed to 58 more years of legalized discrimination against black and colored people in the United States.[42] In 1908, Congress defeated an attempt to introduce segregated streetcars into the capital.[43] Racism in the United States and defenses of Jim Crow  1904 caricature of "White" and "Jim Crow" rail cars by John T. McCutcheon. Despite Jim Crow's legal pretense that the races be "separate but equal" under the law, non-whites were given inferior facilities and treatment.[44] White Southerners encountered problems in learning free labor management after the end of slavery, and they resented African Americans, who represented the Confederacy's Civil War defeat: "With white supremacy being challenged throughout the South, many whites sought to protect their former status by threatening African Americans who exercised their new rights."[45] White Southerners used their power to segregate public spaces and facilities in law and reestablish social dominance over black people in the South. One rationale for the systematic exclusion of African Americans from southern public society was that it was for their own protection. An early 20th-century scholar suggested that allowing black people to attend white schools would mean "constantly subjecting them to adverse feeling and opinion", which might lead to "a morbid race consciousness".[46] This perspective took anti-black sentiment for granted, because bigotry was widespread in the South after slavery became a racial caste system. Justifications for white supremacy were provided by scientific racism and negative stereotypes of African Americans. Social segregation, from housing to laws against interracial chess games, was justified as a way to prevent black men from having sex with white women and in particular the rapacious Black Buck stereotype.[47] World War II and post-war era In 1944, Associate Justice Frank Murphy introduced the word "racism" into the lexicon of U.S. Supreme Court opinions in Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944).[48] In his dissenting opinion, Murphy stated that by upholding the forced relocation of Japanese Americans during World War II, the Court was sinking into "the ugly abyss of racism". This was the first time that "racism" was used in Supreme Court opinion (Murphy used it twice in a concurring opinion in Steele v Louisville & Nashville Railway Co 323 192 (1944) issued that day).[49] Murphy used the word in five separate opinions, but after he left the court, "racism" was not used again in an opinion for two decades. It next appeared in the landmark decision of Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967).  Educational segregation in the US prior to Brown. All the states of the "South" or with the longest histories of slavery (in red) segregated schools by law statewide. Numerous boycotts and demonstrations against segregation had occurred throughout the 1930s and 1940s. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had been engaged in a series of litigation cases since the early 20th century in efforts to combat laws that disenfranchised black voters across the South. Some of the early demonstrations achieved positive results, strengthening political activism, especially in the post-World War II years. Black veterans were impatient with social oppression after having fought for the United States and freedom across the world. In 1947 K. Leroy Irvis of Pittsburgh's Urban League, for instance, led a demonstration against employment discrimination by the city's department stores. It was the beginning of his own influential political career.[50] After World War II, people of color increasingly challenged segregation, as they believed they had more than earned the right to be treated as full citizens because of their military service and sacrifices. The civil rights movement was energized by a number of flashpoints, including the 1946 police beating and blinding of World War II veteran Isaac Woodard while he was in U.S. Army uniform. In 1948 President Harry S. Truman issued Executive Order 9981, ending racial discrimination in the armed services.[51] That same year, Silas Herbert Hunt enrolled in the University of Arkansas, effectively starting the desegregation of education in the South.[52] As the civil rights movement gained momentum and used federal courts to attack Jim Crow statutes, the white-dominated governments of many of the southern states countered by passing alternative forms of resistance.[53] |

歴史的発展 ジム・クロウを打破する初期の試み  1940年5月、ノースカロライナ州ダーラムのバス停の「有色人種」待合室への看板 1875年にチャールズ・サムナーとベンジャミン・F・バトラーによって提出された公民権法は、人種、肌の色、従属的地位の如何に関わらず、誰もが旅館、 公共交通機関、劇場、その他の娯楽施設などの公共施設において同じ待遇を受ける権利を保証することを規定していた。この法律は実際にはほとんど効果を示さ なかった[39]。1883年の最高裁判決では、この法律はいくつかの点で違憲であるとされ、連邦議会は個人や企業を統制する権限を有していないとされ た。白人南部民主党が議会で強固な票田を形成していたため、南部における総人口に比例した議席配分を維持することで議会に絶大な力があった(数十万人が選 挙権を奪われていたにもかかわらず)。議会は、1957年まで新たな公民権法を制定しなかった[40]。1957年である[40]。 1887年、W.H.ハード牧師は、ジョージア鉄道会社が白人と黒人・有色人種の乗客に異なる車両を提供していることを理由に、州際通商委員会に同社を差別行為で訴えた。同社は「分離だが平等」な宿泊施設を提供していることを理由に、救済措置を申請し、成功した[41]。 1890年、ルイジアナ州は、鉄道で有色人種と白人の乗客に別々の宿泊施設を提供することを義務付ける法律を制定した。ルイジアナ州法は、「白人」、「黒 人」、「有色人種」(つまり、ヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人の血を引く人々)を区別していた。この法律では、黒人は白人と一緒に乗車できないと規定されていた が、1890年以前は有色人種は白人と一緒に乗車することができた。ニューオーリンズの黒人、有色人種、白人の市民有志が、この法律を廃止することを目的 とした協会を結成した。このグループは、ホマー・プレッシーにこの法律をテストするよう説得した。彼は色白で、先祖の8分の1が「黒人」の血を引いていた 有色人種の男性だった[42]。 1892年、プレッシーはルイジアナ東部鉄道のニューオーリンズ発の一等車チケットを購入した。列車に乗り込んだ後、彼は車掌に自分の人種的出自を伝え、 白人専用車両に座った。彼はその車両を離れ、「有色人種専用」車両に座るように指示された。プレッシーはそれを拒否し、すぐに逮捕された。ニューオーリン ズ市民委員会は、この件を合衆国最高裁まで争った。しかし、プレッシー対ファーガソン事件(1896年)で敗訴し、最高裁は「分離だが平等」な施設は合憲 であると判決を下した。この判決により、米国では黒人や有色人種に対する合法的な差別がさらに58年間も続くことになった[42]。 1908年、連邦議会は首都に人種隔離路面電車を導入する試みを否決した[43]。 米国における人種差別とジム・クロウの擁護  1904年、ジョン・T・マックチュンによる「白人」と「ジム・クロウ」の車両を描いた風刺画。ジム・クロウ法は人種間の関係を「分離するが平等」と法律上規定していたが、非白人種には劣悪な施設や待遇が与えられた[44]。 奴隷制廃止後、南部の白人は自由な労働管理を学ぶ上で問題を抱え、南部連合の南北戦争での敗北を象徴する存在であるアフリカ系アメリカ人に対して憤慨し た。 「南部全域で白人至上主義が問われる中、多くの白人は、新しい権利を行使するアフリカ系アメリカ人を脅すことで、自分たちの以前の地位を守ろうとした」 [45]。白人南部は、法律で公共スペースや施設を隔離し、南部で黒人に対する社会的優位性を再確立するためにその権力を行使した。 南部社会からアフリカ系アメリカ人を組織的に排除する理由の一つは、彼ら自身の保護のためであった。20世紀初頭の学者は、黒人に白人の学校への入学を許 可することは、「常に彼らに否定的な感情や意見を植え付ける」ことになり、「病的な人種意識」につながるかもしれないと指摘した[46]。奴隷制が人種的 カースト制度となった後、南部では偏見が広まっていたため、このような見方は当然のことのように受け止められた。 白人至上主義の正当性は、科学的人種差別とアフリカ系アメリカ人に対する否定的な固定観念によって支えられていた。住宅から人種間チェスゲームに対する法 律まで、社会的隔離は、黒人男性が白人女性と性交渉を持つことを防ぐ方法として、また特に貪欲なブラックバックのステレオタイプとして正当化された [47]。 第二次世界大戦と戦後 1944年、フランク・マーフィー連邦最高裁判所陪席判事は、コレマツ対アメリカ合衆国事件(323 U.S. 214 (1944))において、「人種差別」という言葉を 1944年の最高裁判決、Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214(1944)においてである[48]。反対意見の中で、マーフィーは、第二次世界大戦中の日系アメリカ人の強制収容を支持することで、裁判所は「人 種差別という醜い奈落の底」に沈んでしまうと述べた。「人種差別」という言葉が最高裁の判決で使用されたのはこれが初めてであった(マーフィーは同日出さ れたSteele v Louisville & Nashville Railway Co 323 192 (1944)の同意意見で2度使用している)[49]。マーフィーは5つの異なる意見で「人種差別」という言葉を使用したが、彼が裁判所を去った後、20 年間「人種差別」という言葉は判決で使用されなくなった。次にこの言葉が使われたのは、画期的な判決となった「Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967)」である。  ブラウン判決以前の米国の教育における人種隔離。 「南部」の州、または奴隷制の歴史が最も長い州(赤)では、全州で法律により学校が人種隔離されていた。 1930年代から1940年代にかけて、人種隔離に対する数多くのボイコットやデモが行われた。全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)は、20世紀初頭か ら、南部全域で黒人有権者の選挙権を剥奪する法律に対抗すべく、一連の訴訟に取り組んできた。初期のデモの一部は成果を上げ、特に第二次世界大戦後の数年 間は、政治的な活動が強まった。黒人退役軍人は、アメリカと自由のために戦った後、社会的な抑圧に我慢ならなかった。例えば、ピッツバーグのアーバンリー グに所属する K. レイロイ・アーヴィスは、1947年に市内のデパートによる雇用差別に対してデモを率いた。これが彼の影響力ある政治キャリアの始まりとなった[50]。 第二次世界大戦後、有色人種の人々は、軍務や犠牲によって完全な市民として扱われる権利を十分に得たと考え、人種隔離にますます異議を唱えるようになっ た。公民権運動は、1946年に第二次世界大戦の退役軍人アイザック・ウッダードが軍服姿で暴行を受け、失明するという事件など、多くの火種によって活性 化された。1948年、ハリー・S・トルーマン大統領は行政命令9981号を発令し、軍における人種差別を廃止した[51]。同年、サイラス・ハーバー ト・ハントがアーカンソー大学に入学し、南部の教育における人種隔離の解消が実質的に始まった[52]。 公民権運動が勢いを増し、連邦裁判所を利用してジム・クロウ法に異議を申し立てるようになったため、白人が支配する南部諸州の政府も対抗措置として別の抵 抗形態を導入した[53]。 |

| Decline and removal Historian William Chafe has explored the defensive techniques developed inside the African American community to avoid the worst features of Jim Crow as expressed in the legal system, unbalanced economic power, and intimidation and psychological pressure. Chafe says "protective socialization by black people themselves" was created inside the community in order to accommodate white-imposed sanctions while subtly encouraging challenges to those sanctions. Known as "walking the tightrope", such efforts at bringing about change were only slightly effective before the 1920s. However, this did build the foundation for later generations to advance racial equality and de-segregation. Chafe argued that the places essential for change to begin were institutions, particularly black churches, which functioned as centers for community-building and discussion of politics. Additionally, some all-black communities, such as Mound Bayou, Mississippi and Ruthville, Virginia served as sources of pride and inspiration for black society as a whole. Over time, pushback and open defiance of the oppressive existing laws grew, until it reached a boiling point in the aggressive, large-scale activism of the 1950s civil rights movement.[54] Brown v. Board of Education Main article: Brown v. Board of Education  In the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education (1954), the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled unanimously that public school segregation was unconstitutional. The NAACP Legal Defense Committee (a group that became independent of the NAACP) – and its lawyer, Thurgood Marshall – brought the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) before the U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren.[10][11][12] In its pivotal 1954 decision, the Warren Court unanimously (9–0) overturned the 1896 Plessy decision.[11] The Supreme Court found that legally mandated (de jure) public school segregation was unconstitutional. The decision had far-reaching social ramifications.[55] Integrating collegiate sports Racial integration of all-white collegiate sports teams was high on the Southern agenda in the 1950s and 1960s. Involved were issues of equality, racism, and the alumni demand for the top players needed to win high-profile games. The Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC) of flagship state universities in the Southeast took the lead. First they started to schedule integrated teams from the North. Finally, ACC schools – typically under pressure from boosters and civil rights groups – integrated their teams.[56] With an alumni base that dominated local and state politics, society and business, the ACC schools were successful in their endeavor – as Pamela Grundy argues, they had learned how to win: The widespread admiration that athletic ability inspired would help transform athletic fields from grounds of symbolic play to forces for social change, places where a wide range of citizens could publicly and at times effectively challenge the assumptions that cast them as unworthy of full participation in U.S. society. While athletic successes would not rid society of prejudice or stereotype – black athletes would continue to confront racial slurs...[minority star players demonstrated] the discipline, intelligence, and poise to contend for position or influence in every arena of national life.[57] Public arena In 1955, Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat on a city bus to a white man in Montgomery, Alabama. This was not the first time this happened – for example, Parks was inspired by 15-year-old Claudette Colvin doing the same thing nine months earlier[58] – but the Parks act of civil disobedience was chosen, symbolically, as an important catalyst in the growth of the post-1954 civil rights movement; activists built the Montgomery bus boycott around it, which lasted more than a year and resulted in desegregation of the privately run buses in the city. Civil rights protests and actions, together with legal challenges, resulted in a series of legislative and court decisions which contributed to undermining the Jim Crow system.[59] End of legal segregation  President Johnson signs the Civil Rights Act of 1964 The decisive action ending segregation came when Congress in bipartisan fashion overcame Southern filibusters to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. A complex interaction of factors came together unexpectedly in the period 1954–1965 to make the momentous changes possible. The Supreme Court had taken the first initiative in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), declaring segregation of public schools unconstitutional. Enforcement was rapid in the North and border states, but was deliberately stopped in the South by the movement called Massive Resistance, sponsored by rural segregationists who largely controlled the state legislatures. Southern liberals, who counseled moderation, were shouted down by both sides and had limited impact. Much more significant was the civil rights movement, especially the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) headed by Martin Luther King Jr. It largely displaced the old, much more moderate NAACP in taking leadership roles. King organized massive demonstrations, that seized massive media attention in an era when network television news was an innovative and universally watched phenomenon.[60] SCLC, student activists and smaller local organizations staged demonstrations across the South. National attention focused on Birmingham, Alabama, where protesters deliberately provoked Bull Connor and his police forces by using young teenagers as demonstrators – and Connor arrested 900 on one day alone. The next day Connor unleashed billy clubs, police dogs, and high-pressure water hoses to disperse and punish the young demonstrators with a brutality that horrified the nation. It was very bad for business, and for the image of a modernizing progressive urban South. President John F. Kennedy, who had been calling for moderation, threatened to use federal troops to restore order in Birmingham. The result in Birmingham was compromise by which the new mayor opened the library, golf courses, and other city facilities to both races, against the backdrop of church bombings and assassinations.[61] In summer 1963, there were 800 demonstrations in 200 southern cities and towns, with over 100,000 participants, and 15,000 arrests. In Alabama in June 1963, Governor George Wallace escalated the crisis by defying court orders to admit the first two black students to the University of Alabama.[62] Kennedy responded by sending Congress a comprehensive civil rights bill, and ordered Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy to file federal lawsuits against segregated schools, and to deny funds for discriminatory programs. Martin Luther King launched a huge march on Washington in August 1963, bringing out 200,000 demonstrators in front of the Lincoln Memorial, at the time the largest political assembly in the nation's history. The Kennedy administration now gave full-fledged support to the civil rights movement, but powerful southern congressmen blocked any legislation.[63] After Kennedy was assassinated, President Lyndon B. Johnson called for immediate passage of Kennedy civil rights legislation as a memorial to the martyred president. Johnson formed a coalition with Northern Republicans that led to passage in the House, and with the help of Republican Senate leader Everett Dirksen with passage in the Senate early in 1964. For the first time in history, the southern filibuster was broken and the Senate finally passed its version on June 19 by vote of 73 to 27.[64] The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was the most powerful affirmation of equal rights ever made by Congress. It guaranteed access to public accommodations such as restaurants and places of amusement, authorized the Justice Department to bring suits to desegregate facilities in schools, gave new powers to the Civil Rights Commission; and allowed federal funds to be cut off in cases of discrimination. Furthermore, racial, religious and gender discrimination was outlawed for businesses with 25 or more employees, as well as apartment houses. The South resisted until the last moment, but as soon as the new law was signed by President Johnson on July 2, 1964, it was widely accepted across the nation. There was only a scattering of diehard opposition, typified by restaurant owner Lester Maddox in Georgia.[65][66][67][68] In January 1964, President Lyndon Johnson met with civil rights leaders. On January 8, during his first State of the Union address, Johnson asked Congress to "let this session of Congress be known as the session which did more for civil rights than the last hundred sessions combined." On June 21, civil rights workers Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney disappeared in Neshoba County, Mississippi, where they were volunteering in the registration of African American voters as part of the Freedom Summer project. The disappearance of the three activists captured national attention and the ensuing outrage was used by Johnson and civil rights activists to build a coalition of northern and western Democrats and Republicans and push Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[69] On July 2, 1964, Johnson signed the historic Civil Rights Act of 1964.[69][70] It invoked the Commerce Clause[69] to outlaw discrimination in public accommodations (privately owned restaurants, hotels, and stores, and in private schools and workplaces). This use of the Commerce Clause was upheld by the Warren Court in the landmark case Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States 379 US 241 (1964).[71] By 1965, efforts to break the grip of state disenfranchisement by education for voter registration in southern counties had been underway for some time, but had achieved only modest success overall. In some areas of the Deep South, white resistance made these efforts almost entirely ineffectual. The murder of the three voting-rights activists in Mississippi in 1964 and the state's refusal to prosecute the murderers, along with numerous other acts of violence and terrorism against black people, had gained national attention. Finally, the unprovoked attack on March 7, 1965, by county and state troopers on peaceful Alabama marchers crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge en route from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery, persuaded the President and Congress to overcome Southern legislators' resistance to effective voting rights enforcement legislation. President Johnson issued a call for a strong voting rights law and hearings soon began on the bill that would become the Voting Rights Act.[72] The Voting Rights Act of 1965 ended legally sanctioned state barriers to voting for all federal, state and local elections. It also provided for federal oversight and monitoring of counties with historically low minority voter turnout. Years of enforcement have been needed to overcome resistance, and additional legal challenges have been made in the courts to ensure the ability of voters to elect candidates of their choice. For instance, many cities and counties introduced at-large election of council members, which resulted in many cases of diluting minority votes and preventing election of minority-supported candidates.[73] In 2013, the Roberts Court, in Shelby County v. Holder, removed the requirement established by the Voting Rights Act that Southern states needed Federal approval for changes in voting policies. Several states immediately made changes in their laws restricting voting access.[74] |

衰退と排除 歴史家のウィリアム・チェイフは、法制度、経済力の不均衡、威圧や心理的圧力といった、ジム・クロウの最も悪質な特徴を回避するために、アフリカ系アメリ カ人コミュニティ内で開発された防御的手法について研究している。チェイフは、白人による制裁を受け入れつつ、その制裁にさりげなく異議を申し立てること を促すために、コミュニティ内で「黒人による保護社会化」が生み出されたと語る。綱渡り」として知られるこうした変革への取り組みは、1920年代までは ほとんど効果が見られなかった。 しかし、これは後の世代が人種的平等を推進し、分離政策を撤廃するための基盤を築くこととなった。 チャフェは、変革のきっかけとなる重要な場所として、特に黒人教会などのコミュニティ形成や政治議論の中心として機能する機関を挙げている。さらに、ミシ シッピ州のマウンド・バヨウやバージニア州ルースビルなどの黒人だけのコミュニティは、黒人社会全体の誇りとインスピレーションの源となった。時が経つに つれ、抑圧的な既存の法律に対する反発や公然たる反抗が高まり、1950年代の公民権運動における攻撃的で大規模な活動で沸点に達した[54]。 ブラウン対教育委員会事件 メイン記事: ブラウン対教育委員会  1954年のブラウン対教育委員会という画期的な裁判で、最高裁長官アール・ウォーレン率いる米国最高裁は、公立学校の分離は違憲であると満場一致で判決を下した。 NAACP 法律擁護委員会(NAACP から独立した団体)と、その弁護士サーグッド・マーシャルは、最高裁長官アール・ウォーレンの下で、トピカ教育委員会対ブラウン事件(347 U.S. 483 (1954))という画期的な訴訟を提起した。最高裁長官アール・ウォーレンの下で、この画期的なブラウン対トピカ教育委員会事件(Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U.S. 483 (1954))を最高裁に提訴した。この判決は、社会的に大きな影響を与えた[55]。 大学スポーツの統合 1950年代から1960年代にかけて、南部の大学スポーツ界では、白人だけのチームを人種的に統合することが大きな課題となっていた。そこには、平等、 人種差別、そして注目度の高い試合で勝利を収めるために必要なトップ選手を求める卒業生たちの要求といった問題が含まれていた。南東部の主要州立大学が加 盟するアトランティック・コースト・カンファレンス(ACC)が先陣を切った。まず、北部の統合チームとの対戦スケジュールを組んだ。最終的に、ACC校 は、後援者や公民権団体からの圧力を受けて、チームを統合した[56]。地元や州の政治、社会、ビジネス界を支配する卒業生を擁するACC校は、その努力 を成功させた。パメラ・グランディが主張するように、彼らは勝利する方法を学んだのだ。 運動能力に対する幅広い称賛は、運動場を象徴的な遊びの場から社会変革の原動力へと変えるのに役立つだろう。そこでは、幅広い市民が公然と、時には効果的 に、米国社会への完全な参加に値しないと見なされているという前提に異議を申し立てることができる。スポーツの成功が社会の偏見や固定観念をなくすわけで はない。黒人アスリートは人種差別的な中傷に直面し続けるだろう。しかし、[マイノリティのスター選手たちは]、規律、知性、落ち着きを身につけ、国家生 活のあらゆる分野で地位や影響力を争うことができるようになった[57]。 公共の場 1955年、アラバマ州モンゴメリーで、ローザ・パークスは市バスの席を白人に譲ることを拒んだ。このような出来事は初めてではなかった。例えば、9か月 前に同じことをした15歳のクロデット・コルビンにパークスは感銘を受けていた[58]。しかし、パークスの市民的不服従の行為は、象徴的に、1954年 以降の公民権運動の成長における重要なきっかけとして選ばれた。 象徴的に、パークスの市民的不服従は、1954年以降の公民権運動の成長における重要なきっかけとして選ばれた。活動家たちはこれをきっかけにモンゴメ リー・バス・ボイコット運動を起こし、1年以上続いた結果、同市の民間バス会社のバスから人種差別が撤廃された。公民権運動の抗議や行動、法的挑戦は、一 連の立法や判決につながり、ジム・クロウ制度を弱体化させる一因となった[59]。 法的分離の終焉  ジョンソン大統領が1964年公民権法に署名 分離を終わらせる決定的な行動は、超党派の議会が南部議会の妨害を乗り越え、1964年公民権法と1965年投票権法を可決したときに起こった。1954 年から1965年にかけて、さまざまな要因が複雑に絡み合い、歴史的な変革を可能にしました。最高裁判所はブラウン対教育委員会事件(1954年)で先陣 を切り、公立学校の分離を違憲と宣言しました。北部および国境沿いの州では、分離撤廃の動きが急速に進みましたが、南部では、州議会を支配していた農村部 の分離主義者たちが主導した「大規模抵抗」と呼ばれる運動によって、意図的に阻止されました。穏健な対応を勧めた南部リベラル派は、双方から非難を浴び、 影響力は限定的だった。それよりもはるかに重要なのは、公民権運動、特にマーティン・ルーサー・キング・ジュニアが率いる南部キリスト教指導者会議 (SCLC)だった。SCLCは、より穏健な立場だった全米有色人地位向上協会(NAACP)に代わって指導的役割を担うようになった。キングは大規模な デモを組織し、ネットワークテレビニュースが画期的で誰もが視聴する現象だった時代に、メディアの注目を集めた[60]。 SCLC、学生活動家、小規模な地域組織は、南部各地でデモを行った。全国的な注目はアラバマ州バーミングハムに集中した。抗議者たちは、10代の若者た ちをデモ参加者に仕立て、ブル・コナーと警察を意図的に挑発した。コナーは1日で900人を逮捕した。翌日、コナーは警棒、警察犬、高圧放水ホースを駆使 し、若者たちを散らし、残虐な手段で罰した。それはビジネスにとっても、近代化を進め進歩的な都市南部というイメージにとっても非常に悪影響だった。穏健 な対応を求めていたジョン・F・ケネディ大統領は、バーミンガムに秩序を回復するために連邦軍を出動させることをちらつかせていた。バーミンガムでの妥協 の結果、新市長は、教会爆破事件や暗殺事件を背景に、図書館やゴルフコース、その他の市の施設を両人種に開放した[61]。 1963年夏、南部200都市と町で800件のデモが行われ、10万人以上が参加し、1万5000人が逮捕された。1963年6月、アラバマ州知事ジョー ジ・ウォレスは、アラバマ大学に最初の2人の黒人学生を受け入れるよう裁判所命令に背くことで、危機をエスカレートさせた[62]。ケネディはこれに対 し、包括的な公民権法案を議会に提出し、ロバート・F・ケネディ司法長官に人種隔離学校に対する連邦訴訟を起こし、差別的プログラムへの資金援助を拒否す るよう命じた。マーティン・ルーサー・キングは1963年8月、ワシントンで大規模な行進を行い、リンカーン記念館前に20万人のデモ参加者を集めた。こ れは当時、アメリカ史上最大の政治集会であった。ケネディ政権は公民権運動に全面的な支援を与えたが、南部有力議員の妨害により法案は成立しなかった [63]。 ケネディ暗殺後、リンドン・B・ジョンソン大統領は殉職した大統領を追悼するため、ケネディ公民権法案の即時成立を求めた。ジョンソンは北部共和党と連立 を組み、下院での法案成立を実現。共和党上院院内総務エバレット・ダークセンの協力により、1964年初頭に上院での法案成立に至った。史上初めて南部議 員の議事妨害が破られ、上院は6月19日、73対27の投票で法案を可決した[64]。 1964年公民権法は、議会が制定した最も強力な平等の権利の主張であった。この法律は、レストランや娯楽施設などの公共施設の利用を保証し、司法省に学 校施設の差別撤廃を求める訴訟を起こす権限を与え、公民権委員会に新たな権限を付与し、差別行為があった場合には連邦政府からの資金援助を打ち切ることを 認めた。さらに、従業員数25人以上の企業や集合住宅では、人種、宗教、性別による差別が違法となった。南部では最後まで抵抗が続いたが、1964年7月 2日にジョンソン大統領が署名した新法が公布されると、たちまち全米で広く受け入れられるようになった。ジョージア州のレスター・マドックスというレスト ラン経営者を代表とする一部の頑固な反対派は散見された程度であった[65][66][67][68]。 1964年1月、リンドン・ジョンソン大統領は公民権運動の指導者たちと会談した。1月8日、大統領就任後初の一般教書演説で、ジョンソンは議会に対し、 「今国会を、過去100回の議会を合わせたよりも多くの公民権改善を実現した議会として歴史に刻むべきである」と述べた。6月21日、公民権運動家のマイ ケル・シュワーナー、アンドリュー・グッドマン、ジェームズ・チェイニーの3人が、ミシシッピ州ネショーバ郡で失踪した。3人の活動家の失踪は全米民の注 目を集め、それに続く怒りの声は、ジョンソンと公民権活動家たちが北部および西部民主党と共和党の連合を構築し、議会に1964年公民権法の成立を迫るの に利用された[69]。 1964年7月2日 1964年7月2日、ジョンソンは歴史的な公民権法(1964年)に署名した[69][70]。この法律は、公共施設(個人経営のレストラン、ホテル、店 舗、私立学校、職場)における差別を違法とするために、通商条項[69]を適用した。この商務条項の適用は、ウォーレン最高裁によって画期的な判例となっ たハート・オブ・アトランタ・モーテル対アメリカ合衆国事件(Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States 379 US 241 (1964))で支持された[71]。 1965年までに、南部諸州における有権者登録のための教育を通じて、州による選挙権の剥奪の支配を打破する努力がしばらくの間進められていたが、全体と してはささやかな成功しか収められなかった。ディープサウスの一部の地域では、白人の抵抗によりこれらの取り組みはほとんど効果がなかった。1964年に ミシシッピ州で3人の投票権活動家が殺害され、州が殺人犯を起訴しないことに加え、黒人に対する数々の暴力行為やテロ行為が全国的に注目を集めた。 1965年3月7日、セルマから州都モンゴメリーに向かう途中、エドマンド・ペタス橋を渡ろうとした平和的なデモ行進に参加していたアラバマ州民に対し て、州警察と州兵が理由もなく攻撃を仕掛けたことで、大統領と議会は南部議員の抵抗を乗り越え、有効な投票権行使法制定に踏み切った。ジョンソン大統領は 強力な投票権法の制定を要請し、投票権法が成立する法案の公聴会がすぐに始まった[72]。 1965年の公民権法は、連邦、州、地方選挙における投票に対する法的障壁を撤廃した。また、歴史的にマイノリティの投票率が低い郡に対して、連邦政府に よる監督と監視を行うことも規定した。抵抗を克服するには長年の施行が必要であり、有権者が自分の支持する候補者を確実に選ぶことができるように、法廷で さらなる法的挑戦が行われた。例えば、多くの市や郡で議員を無作為抽出で選出する制度が導入されたが、その結果、少数派の票が希釈され、少数派が支持する 候補者の当選が妨げられるケースが数多く発生した[73]。 2013年、ロバーツ最高裁はシェルビー郡対ホルダー事件において、南部諸州が投票政策を変更する際に連邦政府の承認を必要としていた投票権法に定められた要件を撤廃した。 複数の州が直ちに投票へのアクセスを制限する法律を改正した[74]。 |

| Influence and aftermath African American life  An African American man drinking at a "colored" drinking fountain in a streetcar terminal in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, 1939 The Jim Crow laws and the high rate of lynchings in the South were major factors that led to the Great Migration during the first half of the 20th century. Because opportunities were very limited in the South, African Americans moved in great numbers to cities in Northeastern, Midwestern, and Western states to seek better lives. African American athletes faced much discrimination during the Jim Crow era with white opposition leading to their exclusion from most organized sporting competitions. The boxers Jack Johnson and Joe Louis (both of whom became world heavyweight boxing champions) and track and field athlete Jesse Owens (who won four gold medals at the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin) gained prominence during the era. In baseball, a color line instituted in the 1880s had informally barred black people from playing in the major leagues, leading to the development of the Negro leagues, which featured many famous players. A major breakthrough occurred in 1947, when Jackie Robinson was hired as the first African American to play in Major League Baseball; he permanently broke the color bar. Baseball teams continued to integrate in the following years, leading to the full participation of black baseball players in the Major Leagues in the 1960s.[citation needed] Interracial marriage Main article: Anti-miscegenation laws in the United States See also: Interracial marriage in the United States Although sometimes counted among Jim Crow laws of the South, statutes such as anti-miscegenation laws were also passed by other states. Anti-miscegenation laws were not repealed by the Civil Rights Act of 1964, but were declared unconstitutional by the U.S. Supreme Court (the Warren Court) in a unanimous ruling Loving v. Virginia (1967).[69][75][76] Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote in the court opinion that "the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual, and cannot be infringed by the State."[76] Jury trials The Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution grants criminal defendants the right to a trial by a jury of their peers. While federal law required that convictions could only be granted by a unanimous jury for federal crimes, states were free to set their own jury requirements. All but two states, Oregon and Louisiana, opted for unanimous juries for conviction. Oregon and Louisiana, however, allowed juries of at least 10–2 to decide a criminal conviction. Louisiana's law was amended in 2018 to require a unanimous jury for criminal convictions, effective in 2019. Prior to that amendment, the law had been seen as a remnant of Jim Crow laws, because it allowed minority voices on a jury to be marginalized. In 2020, the Supreme Court found, in Ramos v. Louisiana, that unanimous jury votes are required for criminal convictions at state levels, thereby nullifying Oregon's remaining law, and overturning previous cases in Louisiana.[77] Later court cases In 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court (the Burger Court), in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, upheld desegregation busing of students to achieve integration. Interpretation of the Constitution and its application to minority rights continues to be controversial as Court membership changes. Observers such as Ian F. Lopez believe that in the 2000s, the Supreme Court has become more protective of the status quo.[78] Felony disenfranchisement Mississippi Today discusses the present-day Jim Crow legacy of felony disenfranchisement, and states that part of Mississippi’s 1890 constitution was not erased by the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s. The article states the constitutional felony disenfranchisement clause "takes away — for life — the right to vote upon conviction for several low-level crimes, like theft and bribery, that the 1890 drafters felt would be mostly committed by Black people."[79] International [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2024) There is evidence that the government of Nazi Germany took inspiration from the Jim Crow laws when writing the Nuremberg Laws.[80] Remembrance Ferris State University in Big Rapids, Michigan, houses the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia, an extensive collection of everyday items that promoted racial segregation or presented racial stereotypes of African Americans, for the purpose of academic research and education about their cultural influence.[81] |

影響とその後 アフリカ系アメリカ人の生活  1939年、オクラホマ州オクラホマシティの路面電車ターミナルにある「有色人種」用の飲み場で水を飲むアフリカ系アメリカ人男性 ジム・クロウ法と南部でのリンチ事件の高発率が、20世紀前半の大移動の主な要因となった。南部ではチャンスが非常に限られていたため、アフリカ系アメリカ人はより良い生活を求めて、北東部、中西部、西部各州の都市へと大量に流入した。 ジム・クロウ法時代、アフリカ系アメリカ人アスリートは多くの差別を受け、白人の反対によりほとんどの組織スポーツ競技から排除された。 ボクサーのジャック・ジョンソンとジョー・ルイス(ともに世界ヘビー級ボクシングチャンピオン)、陸上競技選手のジェシー・オーエンス(1936年のベル リン夏季オリンピックで4つの金メダルを獲得)は、この時代に有名になった。野球では、1880年代に導入された人種隔離政策により、黒人は非公式にメ ジャーリーグでプレーすることを禁じられていたが、これにより、多くの有名選手を擁するニグロリーグが発展した。1947年、ジャッキー・ロビンソンがメ ジャーリーグ史上初の黒人選手として採用されたことは、大きな飛躍となった。彼は人種差別を完全に撤廃した。その後、野球チームは黒人選手を続々と採用 し、1960年代には黒人選手もメジャーリーグでプレーするようになった。 異人種間結婚 メイン記事:アメリカ合衆国の異人種間結婚禁止法 関連項目: アメリカ合衆国における異人種間結婚 南部のジム・クロウ法に含まれることもあるが、異人種間結婚禁止法のような法律は他の州でも制定されていた。1964年の公民権法では人種混合禁止法は廃 止されなかったが、最高裁判所(ウォーレン最高裁)は、1967年の「バージニア州対ロバーツ事件」で満場一致で違憲判決を下した[69][75] [76]。アール・ウォーレン最高裁長官は判決文の中で、「他民族の人と結婚する自由、あるいは結婚しない自由は個人に属し、国家によって侵害されること はない」と述べた[76]。 陪審裁判 合衆国憲法修正第6条は、刑事被告人に陪審員による裁判を受ける権利を保障している。連邦法では、連邦犯罪の有罪判決は陪審員全員一致で下すことになって いたが、陪審員要件の設定については各州に任されていた。オレゴン州とルイジアナ州を除くすべての州は、有罪判決には陪審員全員一致を義務づけていた。し かし、オレゴン州とルイジアナ州では、陪審員10人に対して有罪判決を下す陪審員は少なくとも2人必要とされていた。ルイジアナ州法は2018年に改正さ れ、2019年より刑事有罪判決には陪審員全員一致が必要となった。この改正前は、陪審員に少数派の意見が反映されない可能性があるため、この法律は人種 隔離政策の名残と見なされていた。2020年、最高裁判所は、ラモス対ルイジアナ事件において、州レベルの刑事有罪判決には陪審員の全員一致の投票が必要 であると裁定し、オレゴン州の残存する法律を無効化し、ルイジアナ州の過去の判例を覆した[77]。 その後の裁判例 1971年、米国最高裁判所(バーガー裁判所)は、スワン対シャーロット・メクレンバーグ教育委員会事件において、統合を達成するための生徒のバスによる隔離を認めた。 憲法解釈とマイノリティの権利への適用は、最高裁判事の交代に伴い、現在もなお議論の的となっている。イアン・F・ロペスなどの観察者たちは、2000年代に入ってから、最高裁は現状維持の姿勢を強めていると考えている[78]。 重罪による公民権剥奪 ミシシッピ・トゥデイは、重罪による公民権剥奪という、現代に残るジム・クロウ法の遺産について論じ、ミシシッピ州1890年憲法の条文の一部は、 1960年代の公民権運動によっても削除されなかったと述べている。この記事では、憲法上の重罪による公民権剥奪条項について、「1890年の起草者が黒 人が主に犯すと考えた窃盗や贈収賄などの軽犯罪で有罪判決を受けた場合、その有罪判決により投票権が終身剥奪される」[79] と述べている。 国際 [icon] このセクションは拡大が必要です。 追加することで貢献できます。(2024年5月) ナチス・ドイツの政府がニュルンベルク法を作成する際に、ジム・クロウ法から着想を得たという証拠がある[80]。 追悼 ミシガン州ビッグラピッズにあるフェリス州立大学には、人種的分離を促進したり、アフリカ系アメリカ人に対する固定観念を提示したりする日常用品の広範な コレクションであるジム・クロウ人種差別記念品博物館があり、その文化的影響に関する学術研究と教育を目的としている[81]。 |

| Anti-miscegenation laws Apartheid Black Codes in the United States Disenfranchisement after the Reconstruction era Group Areas Act Jim Crow economy List of Jim Crow law examples by state Lynching Mass racial violence in the United States Penal labor Racial segregation in the United States Racism in the United States Second-class citizen Sundown town Timeline of the civil rights movement The New Jim Crow |

異人種間結婚禁止法 アパルトヘイト アメリカ合衆国の黒人法典 再建時代以降の公民権剥奪 グループエリア法 ジム・クロウ経済 州別のジム・クロウ法例一覧 リンチ アメリカ合衆国における集団的人種的暴力 懲役労働 アメリカ合衆国における人種的隔離 アメリカ合衆国における人種差別 二級市民 サンダウンタウン 公民権運動の年表 新ジム・クロウ法 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Crow_laws |

|

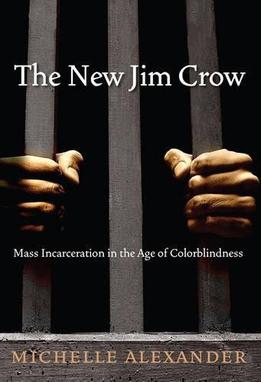

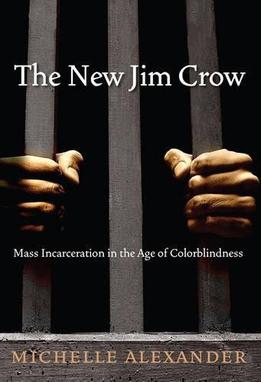

The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

is a 2010 book by Michelle Alexander, a civil rights litigator and

legal scholar. The book discusses race-related issues specific to

African-American males and mass incarceration in the United States, but

Alexander noted that the discrimination faced by African-American males

is prevalent among other minorities and socio-economically

disadvantaged populations. Alexander's central premise, from which the

book derives its title, is that "mass incarceration is, metaphorically,

the New Jim Crow".[1] The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

is a 2010 book by Michelle Alexander, a civil rights litigator and

legal scholar. The book discusses race-related issues specific to

African-American males and mass incarceration in the United States, but

Alexander noted that the discrimination faced by African-American males

is prevalent among other minorities and socio-economically

disadvantaged populations. Alexander's central premise, from which the

book derives its title, is that "mass incarceration is, metaphorically,

the New Jim Crow".[1]Overview Though the conventional point of view holds that systemic racial discrimination mostly ended with the civil rights movement reforms of the 1960s, Alexander posits that the U.S. criminal justice system uses the War on Drugs as a primary tool for enforcing traditional, as well as new, modes of discrimination and oppression.[2] These new modes of racism have led to not only the highest rate of incarceration in the world, but also a disproportionately large rate of imprisonment for African American men. Were present trends to continue, Alexander writes, the United States would imprison one third of its African American population. When combined with the fact that whites are more likely to commit drug crimes than people of color, the issue becomes clear for Alexander: "the primary targets of [the penal system's] control can be defined largely by race".[3] This ultimately leads Alexander to argue that mass incarceration is "a stunningly comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized social control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow".[4] The culmination of this social control is what Alexander calls a "racial caste system", a type of stratification wherein people of color are kept in an inferior position. Its emergence, she believes, is a direct response to the civil rights movement. It is because of this that Alexander argues for issues with mass incarceration to be addressed as issues of racial justice and civil rights. To approach these matters as anything but would be to fortify this new racial caste. Thus, Alexander aims to mobilize the civil rights community to move the incarceration issue to the forefront of its agenda and to provide factual information, data, arguments and a point of reference for those interested in pursuing the issue. Her broader goal is the revamping of the prevailing mentality regarding human rights, equality and equal opportunities in America, to prevent future cyclical recurrence of what she sees as "racial control under changing disguise".[1] According to the author, what has been altered since the collapse of Jim Crow is not so much the basic structure of US society, as the language used to justify its affairs. She argues that when people of color are disproportionately labeled as "criminals", this allows the unleashing of a whole range of legal discrimination measures in employment, housing, education, public benefits, voting rights, jury duty, and so on.[5] Alexander explains that it took her years to become fully aware and convinced of the phenomena she describes, despite her professional civil rights background. She expects similar reluctance and disbelief on the part of many of her readers. She believes that the problems besetting African American communities are not merely a passive, collateral side effect of poverty, limited educational opportunity or other factors, but a consequence of purposeful government policies. Alexander has concluded that mass incarceration policies, which were swiftly developed and implemented, are a "comprehensive and well-disguised system of racialized control that functions in a manner strikingly similar to Jim Crow".[6] Alexander contends that in 1982 the Reagan administration began an escalation of the War on Drugs, purportedly as a response to a crack cocaine crisis in black ghettos, which was (she claims) announced well before crack cocaine arrived in most inner city neighborhoods. During the mid-1980s, as the use of crack cocaine increased to epidemic levels in these neighborhoods, federal drug authorities publicized the problem, using scare tactics to generate support for their already-declared escalation.[7] The government's successful media campaign made possible an unprecedented expansion of law enforcement activities in America's urban neighborhoods, and this aggressive approach fueled widespread belief in conspiracy theories that posited government plans to destroy the black population. (Black genocide) [citation needed] In 1998, the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) acknowledged that during the 1980s the Contra faction—covertly supported by the US in Nicaragua—had been involved in smuggling cocaine into the US and distributing it in US cities. Drug Enforcement Administration efforts to expose these illegal activities were blocked by Reagan officials, which contributed to an explosion of crack cocaine consumption in America's urban neighborhoods. More aggressive enforcement of federal drug laws resulted in a dramatic increase in street level arrests for possession. Disparate sentencing policies (the crack cocaine v. powdered cocaine penalty disparity was 100-1 by weight and remains 18-1 even after recent reform efforts) meant that a disproportionate number of inner city residents were charged with felonies and sentenced to long prison terms, because they tended to purchase the more affordable crack version of cocaine, rather than the powdered version commonly consumed in the suburbs.[8][9] Alexander argues that the War on Drugs has a devastating impact on inner city African American communities, on a scale entirely out of proportion to the actual dimensions of criminal activity taking place within these communities. During the past three decades, the US prison population exploded from 300,000 to more than two million, with the majority of the increase due to drug convictions.[10] This led to the US having the world's highest incarceration rate. The US incarceration rate is eight times that of Germany, a comparatively developed large democracy.[11] Alexander claims that the US is unparalleled in the world in focusing enforcement of federal drug laws on racial and ethnic minorities. In the capital city of Washington, D.C., three out of four young African American males are expected to serve time in prison.[12] While studies show that quantitatively Americans of different races consume illegal drugs at similar rates,[13][verification needed] in some states black men have been sent to prison on drug charges at rates twenty to fifty times those of white men.[14] The proportion of African American men with some sort of criminal record approaches 80% in some major US cities, and they become marginalized, part of what Alexander calls "a growing and permanent undercaste".[15][16] Alexander maintains that this undercaste is hidden from view, invisible within a maze of rationalizations, with mass incarceration its most serious manifestation. Alexander borrows from the term "racial caste", as it is commonly used in scientific literature, to create "undercaste", denoting a "stigmatized racial group locked into inferior position by law and custom". By mass incarceration she refers to the web of laws, rules, policies and customs that make up the criminal justice system and which serve as a gateway to permanent marginalization in the undercaste. Once released from prison, new members of this undercaste face a "hidden underworld of legalized discrimination and permanent social exclusion".[17] According to Alexander, crime and punishment are poorly correlated, and the present US criminal justice system has effectively become a system of social control unparalleled in any other Western democracy, with its targets largely defined by race. The rate of incarceration in the US has soared, while its crime rates have generally remained similar to those of other Western countries, where incarceration rates have remained stable. The current rate of incarceration in the US is six to ten times greater than in other industrialized nations, and Alexander maintains that this disparity is not correlated to the fluctuation of crime rates, but can be traced mostly to the artificially invoked War on Drugs and its associated discriminatory policies.[18] The US embarked on an unprecedented expansion of its juvenile detention and prison systems.[19][20] Alexander notes that the civil rights community has been reluctant to get involved in this issue, concentrating primarily on protecting affirmative action gains, which mainly benefit an elite group of high-achieving African Americans. At the other end of the social spectrum are the young black men who are under active control of the criminal justice system (currently in prison, or on parole or probation)—approximately one-third of the young black men in the US. Criminal justice was not listed as a top priority of the Leadership Conference on Civil Rights in 2007 and 2008, or of the Congressional Black Caucus in 2009. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) have been involved in legal action, and grassroots campaigns have been organized, however Alexander feels that generally there is a lack of appreciation of the enormity of the crisis. According to her, mass incarceration is "the most damaging manifestation of the backlash against the Civil Rights Movement", and those who feel that the election of Barack Obama represents the ultimate "triumph over race", and that race no longer matters, are dangerously misguided.[21] Alexander writes that Americans are ashamed of their racial history, and therefore avoid talking about race, or even class, so the terms used in her book may seem unfamiliar to many. Americans want to believe that everybody is capable of upward mobility, given enough effort on his or her part; this assumption forms a part of the national collective self-image. Alexander points out that a large percentage of African Americans are hindered by the discriminatory practices of an ostensibly colorblind criminal justice system, which end up creating an undercaste where upward mobility is severely constrained.[citation needed] Alexander believes that the existence of the New Jim Crow system is not disproved by the election of Barack Obama and other examples of exceptional achievement among African Americans, but on the contrary the New Jim Crow system depends on such exceptionalism. She contends that the system does not require overt racial hostility or bigotry on the part of another racial group or groups. Indifference is sufficient to support the system. Alexander argues that the system reflects an underlying racial ideology and will not be significantly disturbed by half-measures such as laws mandating shorter prison sentences. Like its predecessors, the new system of racial control has been largely immune from legal challenge. She writes that a human tragedy is unfolding, and The New Jim Crow is intended to stimulate a much-needed national discussion "about the role of the criminal justice system in creating and perpetuating racial hierarchy in the United States".[22] |

『新ジム・クロウ:人種差別のない時代における大量投獄』(The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness)

は、公民権運動の弁護士であり法律学者でもあるミシェル・アレクサンダーが2010年に発表した著書である。この本は、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性特有の人

種差別問題と、米国における大量投獄について論じているが、アレクサンダーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性が直面する差別は、他の少数民族や社会経済的に恵

まれない人々にも広く見られるものであると指摘している。アレクサンダーの主要な前提は、この本のタイトルにもなっているが、「大量投獄は、比喩的に言え

ば、新しいジム・クロウ(Jim Crow)である」[1]ということである。 『新ジム・クロウ:人種差別のない時代における大量投獄』(The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness)

は、公民権運動の弁護士であり法律学者でもあるミシェル・アレクサンダーが2010年に発表した著書である。この本は、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性特有の人

種差別問題と、米国における大量投獄について論じているが、アレクサンダーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性が直面する差別は、他の少数民族や社会経済的に恵

まれない人々にも広く見られるものであると指摘している。アレクサンダーの主要な前提は、この本のタイトルにもなっているが、「大量投獄は、比喩的に言え

ば、新しいジム・クロウ(Jim Crow)である」[1]ということである。概要 従来の見方では、組織的な人種差別は1960年代の公民権運動による改革でほぼ終結したと考えられているが、アレクサンダーは、 米国の刑事司法制度は、伝統的な差別や抑圧だけでなく、新しい差別や抑圧の手段としても麻薬戦争を利用している[2]。こ うした新しい形態の人種差別は、世界最高水準の投獄率だけでなく、アフリカ系アメリカ人男性の不均衡な投獄率にもつながっている。アレクサンダーは、現在 の傾向が続けば、米国はアフリカ系アメリカ人人口の3分の1を投獄することになるだろうと書いている。白人は有色人種よりも薬物犯罪を犯しやすいという事 実と合わせると、アレクサンダーにとってこの問題は明らかになる。「(刑務所の)管理の対象となるのは、人種によってほぼ決まっている」[3]。 このことから、アレクサンダーは、大量投獄は「驚くほど包括的で巧妙に隠蔽された人種差別的社会統制システムであり、その機能はジム・クロウ法と驚くほど 似ている」[4]と主張する。この社会統制の頂点にあるのが、アレクサンダーが「人種的カースト制度」と呼ぶ、有色人種を劣等な立場に置く階層化である。 アレクサンダーは、その出現は公民権運動への直接的な反応であると信じている。 そのため、アレクサンダーは、大量投獄の問題を人種的正義と公民権の問題として取り上げるべきだと主張している。 そうしないことは、この新たな人種カースト体制を強化することになる。そのため、アレクサンダーは公民権運動のコミュニティを動員し、投獄問題を最優先課 題として取り上げ、この問題に関心を持つ人々に事実に基づく情報やデータ、議論、参考資料を提供することを目的としている。彼女のより広範な目標は、アメ リカにおける人権、平等、機会均等に関する一般的な考え方を一新し、「変装した人種差別」[1]と彼女が考えるものの将来的な循環的再発を防ぐことであ る。著者によると、ジム・クロウ法廃止後に変化したのは、アメリカ社会の基本的な構造というよりも、その状況を正当化するために使用される言葉である。彼 女は、有色人種の人々が「犯罪者」として不均衡にレッテルを貼られることで、雇用、住宅、教育、公的給付、投票権、陪審員義務など、あらゆる法的差別措置 が横行すると主張している[5]。 アレクサンダーは、自身の公民権運動家としての経歴にもかかわらず、彼女が記述する現象を完全に理解し確信するまでには何年もかかったと説明している。彼 女は、多くの読者が同様の消極性や不信感を抱くだろうと予想している。彼女は、アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティが抱える問題は、貧困や教育機会の制限と いった要因の単なる受動的な副次的な影響ではなく、意図的な政府政策の結果であると確信している。アレクサンダーは、急速に策定・実施された大量投獄政策 は、「人種差別的な統制の包括的で巧妙に隠蔽されたシステムであり、その機能はジム・クロウ法と驚くほど類似している」と結論づけている[6]。 アレクサンダーは、 1982年、レーガン政権は、黒人居住区におけるコカイン危機への対応策として、麻薬戦争の拡大に乗り出した。アレクサンダーは、コカインがほとんどの都 心部に流入するかなり前から、この危機が宣言されていたと主張している。1980年代半ば、これらの地域でのコカイン・クラックの蔓延が深刻化するにつ れ、連邦麻薬取締当局は、すでに宣言していた取締強化への支持を集めるために恐怖戦術を用いてこの問題を公表した[7]。政府のメディアキャンペーンが成 功を収めたことで、アメリカの都市部における法執行活動がかつてないほど拡大し、この積極的なアプローチが、政府が黒人人口を根絶やしにしようとしている という陰謀説を広く信じさせることにつながった。(黒人大量虐殺) [出典が必要] 1998年、中央情報局(CIA)は、1980年代にニカラグアでアメリカが秘密裏に支援していたコントラ派が、アメリカへのコカイン密輸とアメリカ国内 の都市部でのコカインの流通に関与していたことを認めた。麻薬取締局(DEA)がこれらの違法行為を摘発しようとしたが、レーガン政権の官僚によって妨害 され、その結果、アメリカの都市部でのコカインの消費量が爆発的に増加した。連邦麻薬法のより積極的な施行により、所持容疑での逮捕が劇的に増加した。量 刑のばらつき(粉コカインとクラックコカインの刑罰の格差は重量比で 100 対 1 であり、最近の改革努力後も 18 対 1 のままである)により、郊外で一般的に消費されている粉コカインではなく、より手頃な価格のクラックコカインを購入する傾向があることから、都市部の住民 が不当に重罪で起訴され、長期の懲役刑に処せられるケースが相次いだ[8][9]。 アレクサンダーは、麻薬戦争は、都市部のアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティに壊滅的な影響を与えていると主張している。その影響は、これらのコミュニティ で実際に起きている犯罪活動の規模とはまったく釣り合わないほど甚大なものである。過去30年間で、米国の刑務所人口は30万人から200万人以上に急増 したが、その大半は薬物犯罪によるものである[10]。その結果、米国は世界一の収監率を持つ国となった。米国の投獄率は、比較的発展した民主主義国家で あるドイツの8倍である[11]。アレクサンダーは、米国は連邦薬物法執行を人種的および民族的マイノリティに重点的に行う点で、世界でも類を見ないと主 張している。首都ワシントンD.C.では、アフリカ系アメリカ人の若い男性の4人中3人が刑務所で服役することが予想されている[12]。研究では、異な る人種のアメリカ人が違法薬物を摂取する頻度はほぼ同じであることが示されているが[13][検証が必要]、一部の州では黒人男性が薬物犯罪で刑務所に送 られる割合は白人男性の20~50倍となっている[14]。 ] 犯罪歴のあるアフリカ系アメリカ人男性の割合は、米国の主要都市では80%に迫っており、彼らは社会から疎外され、アレクサンダーが「拡大し、恒久的な下 層階級」と呼ぶものの一部となっている[15][16]。 アレクサンダーは、この下層階級は隠されており、合理化の迷路の中で目に見えず、大量投獄がその最も深刻な現れであると主張している。アレクサンダーは、 科学文献で一般的に使用されている「人種カースト」という用語を借用し、「アンダーキャスト」という用語を作り出した。アンダーキャストとは、「法律や慣 習によって劣等な立場に閉じ込められた烙印を押された人種グループ」を指す。アレクサンダーが言うところの大量投獄とは、刑事司法制度を構成する法律、規 則、政策、慣習の網を指し、アンダーキャストの永久的な疎外への入り口となっている。刑務所から釈放されたばかりのアンダーキャストの新メンバーは、「合 法化された差別と永久的な社会的排除の隠された裏社会」に直面する[17]。 アレクサンダーによると、犯罪と刑罰にはほとんど相関関係がなく、現在の米国の刑事司法制度は、他のどの西洋民主主義国にも類を見ない、人種によってター ゲットがほぼ定義された社会統制システムとなっている。米国の投獄率は急上昇しているが、犯罪率は他の西側諸国とほぼ同じ水準にとどまっている。これらの 国々では投獄率は安定している。現在の米国の投獄率は、他の先進国の6~10倍であり、アレクサンダーは、この格差は犯罪率の変動とは相関関係がなく、主 に人為的に引き起こされた麻薬戦争とその関連差別政策に起因すると主張している[18]。米国は、少年拘置所と刑務所のシステムについて、かつてないほど の拡大に乗り出した[19][20]。 アレクサンダーは、公民権団体がこの問題に関与することをためらっており、主にアファーマティブアクションの成果を守ることに集中していると指摘してい る。その一方で、刑事司法制度(現在服役中、または仮釈放中、保護観察中)の積極的な管理下にある黒人男性の若者は、米国の黒人男性の約3分の1を占めて いる。2007年と2008年の公民権指導者会議、2009年の連邦議会黒人議員連盟では、刑事司法は最優先課題として取り上げられなかった。全米有色人 地位向上協会(NAACP)やアメリカ自由人権協会(ACLU)は法的措置を講じ、草の根運動も組織されているが、アレクサンダーは一般的にこの危機がど れほど深刻なものか理解されていないと感じている。彼女によると、大量投獄は「公民権運動に対する反発の最も有害な現れ」であり、バラク・オバマ大統領の 当選を「人種に対する究極の勝利」と捉え、人種はもはや重要ではないと考える人々は、危険なまでに誤った考えを持っているという。 アレクサンダーは、アメリカ人は人種差別的な歴史を恥じているため、人種や階級について話すことを避けていると述べている。そのため、彼女の著書で使用さ れている用語は、多くの人にとって聞き慣れないもののように感じられるかもしれない。アメリカ人は、誰もが努力さえすれば社会的地位を向上させることがで きると信じたいと思っている。この思い込みは、国民が抱く集団的自己イメージの一部となっている。アレクサンダーは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の大部分が、表 面上は人種差別をしない刑事司法制度の差別的慣行によって妨げられており、その結果、上昇志向が著しく制限される下層階級が生み出されていると指摘してい る[出典が必要]。 アレクサンダーは、バラク・オバマ大統領の当選やアフリカ系アメリカ人の間で見られる例外的な成功例によって、ニュー・ジム・クロウ制度の存在が否定され るわけではないが、それどころかニュー・ジム・クロウ制度はこのような例外性に依存していると信じている。彼女は、この制度は他民族グループや他民族グ ループからのあからさまな人種的敵意や偏見を必要としない、と主張している。無関心でいれば、この制度を維持できる。アレクサンダーは、この制度は根底に ある人種的イデオロギーを反映しており、刑期短縮を義務付ける法律のような中途半端な手段では大きく揺るぐことはない、と主張している。先代と同様、人種 的支配の新しい制度は、法的な挑戦からほぼ免れている。彼女は、人類の悲劇が展開されていると書き、The New Jim Crowは「米国における人種的ヒエラルキーの創出と永続化における刑事司法制度の役割」について、必要とされている国民的議論を喚起することを目的とし ていると書いている[22]。 |

| Defining "incarceration" Alexander states in the book that she was: "careful to define 'mass incarceration' to include those who were subject to state control outside of prison walls, as well as those who were locked in literal cages."[23] The scope of Alexander's definition of "incarceration" includes people who have been arrested (but not tried), people on parole and people who have been released but labelled as "criminals". Alexander's definition is intentionally much broader than the subset of individuals currently in physical detention. Reception Michelle Alexander presenting The New Jim Crow at the Miller Center of Public Affairs in 2011 Darryl Pinckney, writing in The New York Review of Books, called the book one that would "touch the public and educate social commentators, policymakers, and politicians about a glaring wrong that we have been living with that we also somehow don't know how to face... [Alexander] is not the first to offer this bitter analysis, but NJC is striking in the intelligence of her ideas, her powers of summary, and the force of her writing".[24] Jennifer Schuessler, writing in The New York Times, notes that Alexander presents voluminous evidence in the form of both statistics and legal cases to argue that the tough-on-crime policies begun under the Nixon administration and amplified under Reagan's war on drugs have devastated black America, where nearly one-third of black men are likely to spend time in prison during their lifetimes, and where many of these men will be second-class citizens afterwards. Schuessler also notes that Alexander's book goes further, by asserting that the increase in incarceration was a deliberate effort to roll back civil rights gains, rather than a true response to increased rates of violent crime. Schuessler notes that the book has galvanized both black and white readers, some of whom view the work as giving voice to deep feelings that the criminal justice system is stacked against blacks, while others might question its portrayal of anti-crime policies as primarily motivated by racial animus.[25] Forbes wrote that Alexander "looks in detail at what economists usually miss", and "does a fine job of truth-telling, pointing the finger where it rightly should be pointed: at all of us, liberal and conservative, white and black".[26] The book received a starred review in Publishers Weekly, saying that Alexander "offers an acute analysis of the effect of mass incarceration upon former inmates" who will be legally discriminated against for the rest of their lives, and described the book as "carefully researched, deeply engaging, and thoroughly readable".[27] James Forman Jr. argues that though the book has value in focusing scholars (and society as a whole) on the failures of the criminal justice system, it obscures African-American support for tougher crime laws and downplays the role of violent crime in the story of incarceration.[28] John McWhorter, writing in The New Republic, praised the book for its criticism of the Drug War, but argued that Alexander had simplified the causes of the mass incarceration problem, noting that many Black leaders favored escalating the War on Drugs in the 1990’s.[29] John Pfaff, in his book Locked In: The True Causes of Mass Incarceration and How to Achieve Real Reform, criticizes Alexander's assertion that the Drug War is responsible for mass incarceration. Among his findings are that drug offenders make up only a small part of the prison population, and non-violent drug offenders an even smaller portion; that people convicted of violent crimes make up the majority of prisoners; that county and state justice systems account for the large majority of American prisoners and not the federal system that handles most drug cases; and, subsequently, "national" statistics tell a distorted story when differences in enforcement, conviction, and sentencing are widely disparate between states and counties.[30] The Brookings Institution reconciles the differences between Alexander and Pfaff by explaining two ways to look at the prison population as it relates to drug crimes, concluding "The picture is clear: Drug crimes have been the predominant reason for new admissions into state and federal prisons in recent decades" and "rolling back the war on drugs would not, as Pfaff and Urban Institute scholars maintain, totally solve the problem of mass incarceration, but it could help a great deal, by reducing exposure to prison."[31] The 10th Anniversary Edition (2020) was discussed with Ellen DeGeneres on The Ellen Show on network TV, and reviewed on the front page of the New York Times Book Review section on January 19, 2020. The New Jim Crow was listed in The Chronicle of Higher Education as one of the 11 best scholarly books of the 2010s, chosen by Stefan M. Bradley.[32] In 2024, it was ranked #69 in the New York Times list of best 100 books of the 21st century.[33] Awards Winner, NAACP Image Awards (Outstanding Non-fiction, 2011) Winner of the National Council on Crime and Delinquency's Prevention for a Safer Society (PASS) Award Winner of the Constitution Project's 2010 Constitutional Commentary Award 2010 IPPY Award: Silver Medal in Current Events II (Social Issues/Public Affairs/Ecological/Humanitarian) category Winner of the 2010 Association of Humanist Sociology Book Award Finalist, Silver Gavel Award Finalist, Phi Beta Kappa Emerson Award Finalist, Letitia Woods Brown Book Award |

「投獄」の定義 アレクサンダーは著書の中で、「『大量投獄』の定義には、刑務所の壁の外で国家の管理下に置かれている人々だけでなく、文字通り檻に閉じ込められている人 々も含めるように注意した」と述べている[23]。アレクサンダーの定義する「投獄」の範囲には、逮捕された(ただし裁判はされていない)人々、仮釈放中 の人々、釈放されたが「犯罪者」というレッテルを貼られた人々などが含まれる。アレクサンダーの定義は、現在物理的に拘束されている人々のサブセットより も意図的に広範囲に及ぶ。 評価 ミシェル・アレクサンダーが 2011年に ミラー・センター・オブ・パブリック・アフェアーズで 『新ジム・クロウ』を発表 ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』のダリル・ピンクニーは、この本を「一般の人々の心に訴え、社会評論家、政策立案者、政治家たちに、私たちがこ れまで生きてきて、どう向き合えばいいのかわからないままにしてきた、目も当てられないほどの誤りを知らしめる」本だと評した。[アレクサンダー]はこの ような辛辣な分析を提示した最初の人物ではないが、NJCは彼女のアイデアの知性、要約力、そして文章の力強さが印象的である」。[24] ニューヨーク・タイムズ』紙のジェニファー・シュッセルラーは、アレクサンダーが統計と ニクソン政権下で始まり、レーガン政権下の麻薬戦争で拡大された厳罰化政策が、黒人のアメリカを荒廃させたという主張を裏付けるために、統計と法的事例の 両方の形で膨大な証拠を提示している。黒人の男性のほぼ3分の1が一生のうちで刑務所に服役する可能性があり、服役した多くの男性がその後二級市民となる 黒人のアメリカを荒廃させたというのだ。シューレスラーは、アレクサンダーの著書ではさらに踏み込んで、投獄の増加は暴力犯罪の増加に対する真の対応では なく、公民権獲得を後退させる意図的な試みだったと主張していると指摘している。シュースラーは、この本が黒人と白人の両方の読者の関心を呼び起こしたと 指摘している。この本を読んだ人の中には、刑事司法制度が黒人に不利に働いているという深い感情を代弁するものだと考える人もいれば、反犯罪政策が人種的 憎悪を主な動機としているという描写に疑問を抱く人もいるだろう[25]。 フォーブスは、アレクサンダーは「経済学者が見逃しがちなことを詳細に調べ」、 真実を伝え、指弾すべきところを正しく指弾している。それは、リベラル派も保守派も、白人も黒人も、私たち全員を指弾しているのだ」[26]。 この本は『Publishers Weekly』で星5つの評価を受け、「アレクサンダーは、集団収容が元受刑者に及ぼす影響を鋭く分析している」と評された。 、そしてこの本を「綿密な調査に基づく、非常に興味深い、そして読み応えのある」と評した[27]。 ジェームズ・フォーマン・ジュニアは、この本は学者(そして社会全体)に刑事司法制度の失敗に焦点を当てるという価値はあるが、アフリカ系アメリカ人の厳 罰化法支持を曖昧にし、投獄の背景における暴力犯罪の役割を過小評価していると主張している ジョン・マクウォーターは『ニュー・リパブリック』誌で、この本が麻薬戦争を批判している点を評価したが、アレクサンダーは大量投獄問題の要因を単純化し すぎていると主張した。 ジョン・パフは著書『Locked In: 『大量投獄の真の要因と真の改革の実現方法』の中で、ジョン・パファフは、アレクサンダーの「麻薬戦争が大量投獄の原因である」という主張を批判してい る。彼の調査結果によると、薬物犯罪者は刑務所人口のほんの一部に過ぎず、非暴力的な薬物犯罪者はさらに少ない割合を占めている。暴力犯罪で有罪判決を受 けた人々が囚人の大半を占めている。郡や州の司法制度がアメリカの囚人の大半を占めており、ほとんどの薬物事件を扱う連邦制度ではない。その結果、「全 国」の統計は、州や郡間で執行、有罪判決、 、量刑が州や郡によって大きく異なる場合、[30]「全国」の統計は歪んだ結果を伝えることになる。ブルッキングス研究所は、アレクサンダーとファフの相 違点を、薬物犯罪に関連する受刑者人口を2つの観点から見ることで調整し、「状況は明らかである。薬物犯罪は、ここ2、30年の間、州立および連邦刑務所 への新規入所者の主な理由となっている」と結論付け、「薬物戦争を後退させることは、ファフや アーバン研究所の研究者が主張するように、麻薬戦争を撤回しても、大量投獄の問題が完全に解決されるわけではないが、刑務所への収容を減らすことで、大い に役立つだろう」[31]。 10周年記念版(2020年)は、ネットワークテレビの『エレン・デジェネレス・ショー』でエレン・デジェネレスと議論され、2020年1月19日付の『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』ブックレビュー欄の1ページ目にレビューが掲載された。 『ニュー・ジム・クロウ』は、ステファン・M・ブラッドリーが選んだ2010年代の学術書ベスト11に『The Chronicle of Higher Education』で挙げられた[32]。2024年には、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙が選ぶ21世紀のベスト100書籍で69位にランクインした [33]。[33]。 受賞 NAACPイメージ賞(優れたノンフィクション部門)受賞(2011年) 全米犯罪防止評議会より「より安全な社会のための犯罪防止(PASS)賞」受賞 憲法プロジェクトより「2010年憲法解説賞」受賞 2010年IPPY賞: 時事問題II(社会問題/公共問題/環境問題/人道問題)部門銀賞 2010年ヒューマニスト社会学協会図書賞受賞 シルバーガベル賞最終候補 ファイ・ベータ・カッパ・エマーソン賞最終候補 レティシア・ウッズ・ブラウン賞最終候補 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_New_Jim_Crow |

|