批判的人種理論

Critical Race Theory

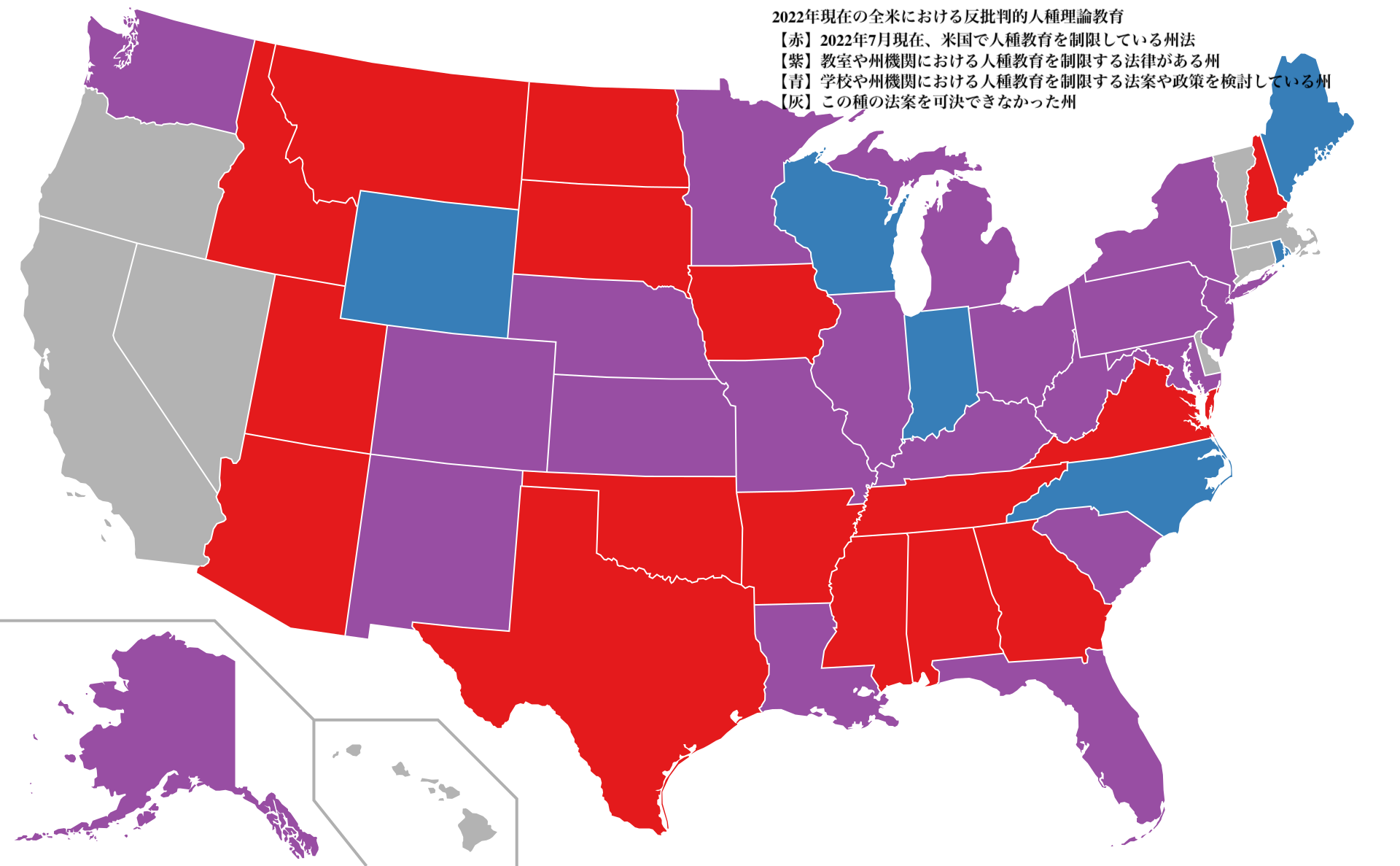

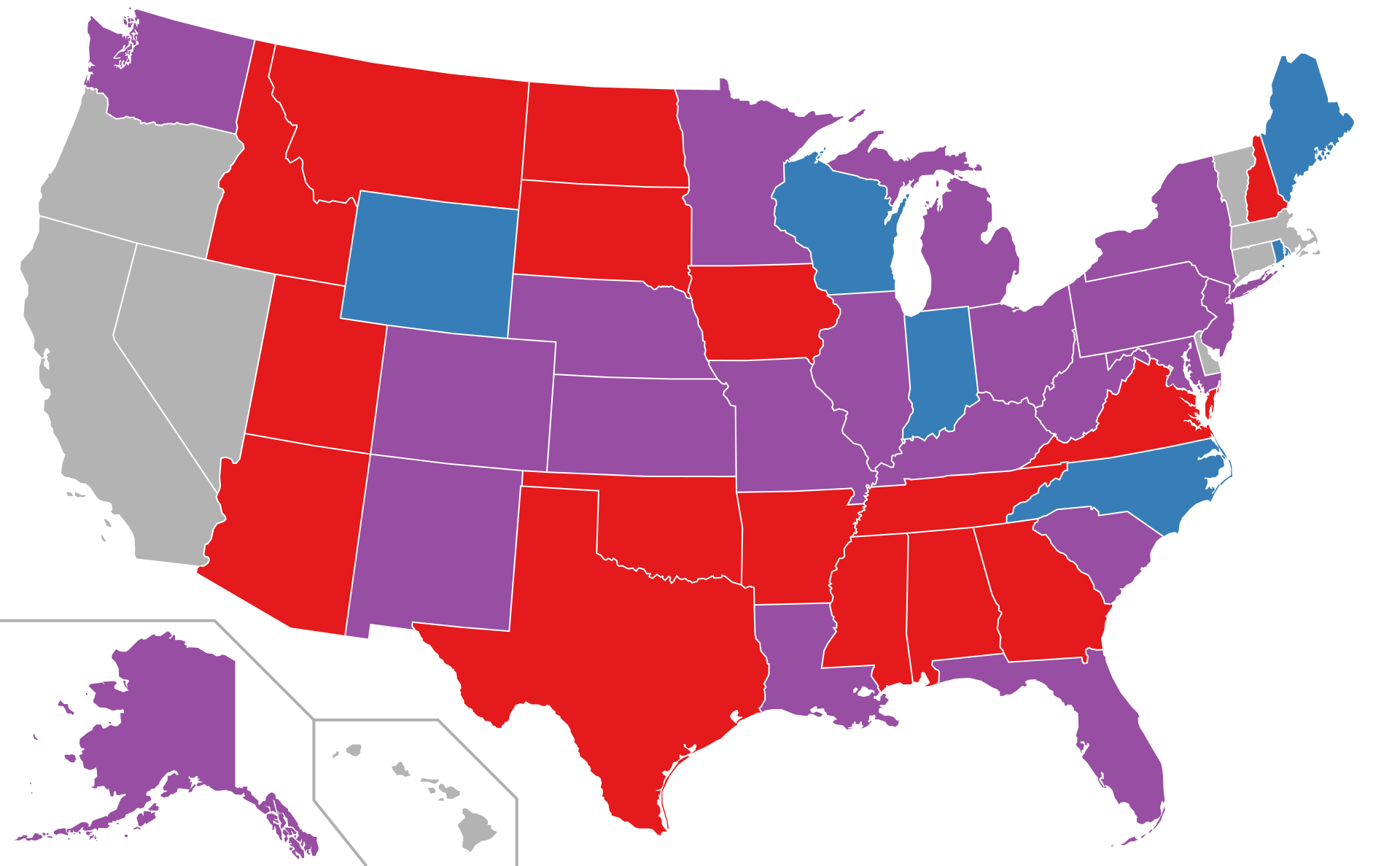

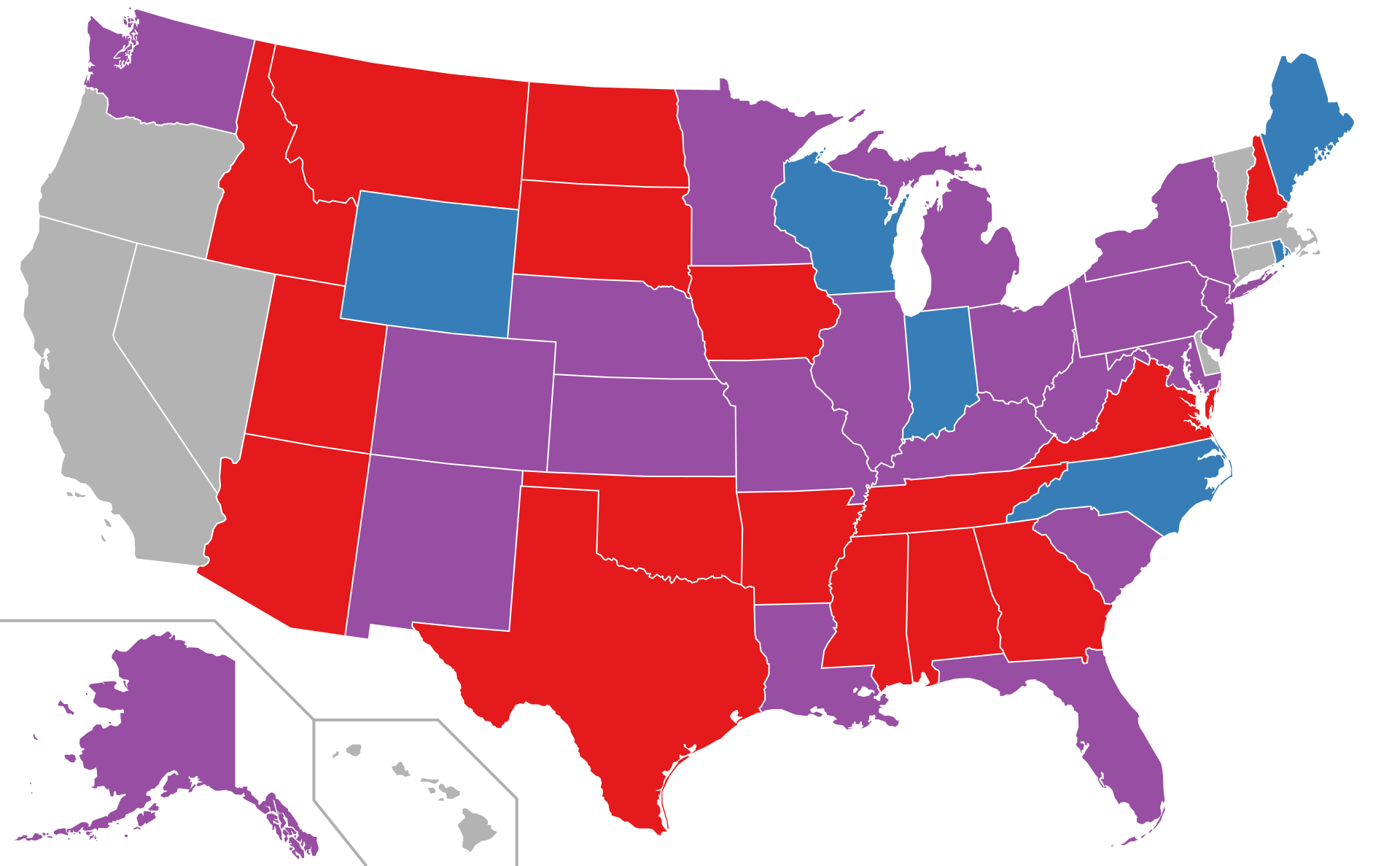

☆ 批判的人種理論(Critical Race Theory)、略してCRTは、人種、人種差 別、そして構造(特に法的構造)におけるその定着の関係を扱い、批判する、特にアメリカの法曹界か らの運動 であり、理論的アプローチの集まりである。アメリカの公的・政治的領域では、CRTをめぐって、あるいはむしろCRTとして誤って分類されている概念をめ ぐって集中的な議論が展開されており、そのなかで批判的人種理論は闘争用語となっている。他方で、2020年以降から全米でCRTを公教育の場で禁止した り、制限する州法の立法化がなされた。

★The

critical race theory (CRT) movement is a collection of

activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the

relationship among race, racism, and power. (Delgado and Stefancic

2001:2)[pdf]

★CRT は人 種差別(Racial discrimination)が個人の偏見に基づくだけでなく、様々な法律やルールの中に制度的に存在すると 考える。名前にあるcriticalという単語は、個人を批判したり非難したりするのではなく、批判的な理論に対する学術的な言及である。

★Goldberg, David Theo, The war on critical race theory : or, the remaking of racism, 2023

書 籍紹介:「「批 判的人種理論」は保守的なアメリカを蝕んでいる。かつては目立たなかった法理論への攻撃が強まり、公立学校教育を根底から覆し、検閲を法制化し、選挙を動 かし、地域社会を分断している。本書では、著名な学者デイヴィッド・セオ・ゴールドバーグが、こうした攻撃で表明されている主張の核心に切り込む。批判的 人種理論の悪者化に風穴を開け、誰がこの攻撃を組織し、資金を提供し、メッセージを熱心に配信しているのかを明らかにする。本書は、構造的人種差別の永続 的な性質を、保守的な色盲の主張がそれに対して何かをする可能性を沈黙させるのに役立つとしても、豊かに示している。重要なのは、ゴールドバーグが、激し い攻撃の政治的目的と効果を暴露していることである。CRTが標的にした結果は、人種差別を新たに解き放ち、人種差別と闘おうとする試みを妨害することで あり、すべては白人マイノリティの支配を守るためである、と彼は主張する。」

Preface 1. What’s Going On? PART I: PRINCIPLES AND PRINCIPALS 2. The Headliners 3. Critical Race Theory PART II: FABRICATIONS 4. A Method of Misreading 5. Structural Racism? 6. The Gospel of Colorblindness 7. Fictive Histories 8. Sounds of Silencing PART III: THE POLITICS OF “CRT” 9. Deregulating Racism 10. Executing Critical Race Theory

★Critical race theory :

an introduction / Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic ;

foreword by Angela Harris, New York University Press , 2023

書

籍紹介:「クリティカル・レース・セオリー(批判的人種理論)」の代表的テキストの新版

クリティカル・レース・セオリー(批判的人種理論)」の第3版が出版されて以来:

2017年に『批評的人種理論:入門』が出版されて以来、米国では人種差別を動機とする銃乱射事件が激増し、医療における人種差別がいかに深く根付いてい

るか、そして公共災害がいかにマイノリティのコミュニティに不釣り合いな影響を及ぼすかを明らかにするパンデミックが発生した。また、批判的人種理論に対

する急激な反発や、人種差別を過去のものとみなす一方で、人種的不寛容の炎をあおり、信奉者の間で民族主義的感情を助長する大統領も見られた。いまやかつ

てないほど、公的生活のあらゆる側面における人種格差が際立っている。この第4版では、こうした動きすべてを踏まえ、さまざまな新しいトピックや出来事を

取り上げ、右派のウェブサイトやシンクタンク、財団などからの激しい批判の高まりに対処している。受賞歴のある著者、リチャード・デルガドとジーン・ステ

ファンチックは、幼稚園から高校までの人種史教育を抑制しようとする立法措置の増加にも言及している。クリティカル・レース理論』第4版は、他の学問分野

や国にも広がりつつあるこの急成長分野の発展を理解するために不可欠である。新版では、他の社会や学問分野がその教えをどのように適応させているのかも取

り上げ、進歩的な人種アジェンダを推進したい読者のために、この目的を達成するための実践的なステップを概説することを目的とした新しい読み物やディス

カッションのための質問も収録している。」

★

批判的人種理論(CRT)がでてきた背景には、人種概念を批判する人種差別批判をアメリカ合衆国において、いくら啓蒙しても、差別構造がつづいたままであ

り、ある部分でアメリカの白人の文化・経済・社会構造のなかに組み込まれているからではないかという反省があっただろう。また、高等教育の研究や教育の現

場においても、依然として「科学的レイシズム・科学的人種主義」のトレンド

が一向に改まらない。人種主義は、社会に組み込まれた構造的なしぶとさがある、という批判的観点(これが「批判的」人種理論の言葉の由来)から解明すべき

だという強い意識があったのだろう。

★CRT の理論整理(英語ウィキペディアより)

| Tenets Scholars of CRT say that race is not "biologically grounded and natural";[9][10] rather, it is a socially constructed category used to oppress and exploit people of color;[35] and that racism is not an aberration,[36] but a normalized feature of American society.[35] According to CRT, negative stereotypes assigned to members of minority groups benefit white people[35] and increase racial oppression.[37] Individuals can belong to a number of different identity groups.[35] The concept of intersectionality—one of CRT's main concepts—was introduced by legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw.[38] Derrick Albert Bell Jr. (1930 – 2011), an American lawyer, professor, and civil rights activist, wrote that racial equality is "impossible and illusory" and that racism in the US is permanent.[36] According to Bell, civil-rights legislation will not on its own bring about progress in race relations;[36] alleged improvements or advantages to people of color "tend to serve the interests of dominant white groups", in what Bell called "interest convergence".[35] These changes do not typically affect—and at times even reinforce—racial hierarchies.[35] This is representative of the shift in the 1970s, in Bell's re-assessment of his earlier desegregation work as a civil rights lawyer. He was responding to the Supreme Court's decisions that had resulted in the re-segregation of schools.[39] The concept of standpoint theory became particularly relevant to CRT when it was expanded to include a black feminist standpoint by Patricia Hill Collins. First introduced by feminist sociologists in the 1980s, standpoint theory holds that people in marginalized groups, who share similar experiences, can bring a collective wisdom and a unique voice to discussions on decreasing oppression.[40] In this view, insights into racism can be uncovered by examining the nature of the US legal system through the perspective of the everyday lived experiences of people of color.[35] According to Encyclopedia Britannica, tenets of CRT have spread beyond academia, and are used to deepen understanding of socio-economic issues such as "poverty, police brutality, and voting rights violations", that are affected by the ways in which race and racism are "understood and misunderstood" in the United States.[35] |

テネット(=教義、信条) (Delgado and Stefancic 2023:8-11) CRTの研究者は、人種は「生物学的に根拠のある自然なもの」ではなく[9][10]、むしろ有色人種 を抑圧し搾取するために使用される社会的に構築され たカテゴリーであり[35]、人種差別は異常ではなく[36]、アメリカ社会の常態化した特徴であると述べている。 [35]CRTによれば、マイノリティ・グループのメンバーに割り当てられた否定的なステレオタイプは白人に利益をもたらし[35]、人種的抑圧を増大さ せる[37]。 個人は多くの異なるアイデンティティ・グループに属することができる[35]。CRTの主要概念の一つである交差性の概念は、法学者のキンバーレ・クレン ショーによって導入された[38]。 アメリカの弁護士、教授、公民権活動家であるデリック・アルバート・ベル・ジュニア(1930年 - 2011年)は、人種的平等は「不可能かつ幻想的」であり、アメリカにおける人種差別は永続的であると書いている[36]。ベルによれば、公民権法はそれ だけでは人種関係に進歩をもたらすことはなく、[36]有色人種に申し立てられた改善や利点は、ベルが「利害の収束」と呼ぶところの「支配的な白人集団の 利益に奉仕する傾向がある」。 [35]このような変化は通常、人種階層に影響を与えることはなく、時には人種階層を強化することさえある。彼は、学校の再分離をもたらした最高裁の判決 に対応していた[39]。 立場論(standpoint theory)の概念は、パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズによって黒人フェミニストの立場を含むように拡張されたときに、CRTと特に関連するようになった。 1980 年代にフェミニストの社会学者によって初めて導入された立場理論は、同じような経験 を共有する疎外された集団の人々が、抑圧の減少に関する議論に集合的な 知恵と独自の声をもたらすことができるとするものである[40]。この見解では、人種差別に関する洞察は、有色人種の日常的な生活体験の視 点を通してアメ リカの法制度の本質を検証することによって明らかにすることができる[35]。 ブリタニカ百科事典によれば、CRTの信条は学界を超えて広がっており、「貧困、警察の横暴、投票権の侵害」といった社会経済的問題の理解を深めるために 使用されており、それらはアメリカにおける人種と人種差別が「理解され、誤解される」方法によって影響を受けている[35]。 |

| Themes Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic published an annotated bibliography of CRT references in 1993, listing works of legal scholarship that addressed one or more of the following themes: "critique of liberalism"; "storytelling/counterstorytelling and 'naming one's own reality'"; "revisionist interpretations of American civil rights law and progress"; "a greater understanding of the underpinnings of race and racism"; "structural determinism"; "race, sex, class, and their intersections"; "essentialism and anti-essentialism"; "cultural nationalism/separatism"; "legal institutions, critical pedagogy, and minorities in the bar"; and "criticism and self-criticism".[41] When Gloria Ladson-Billings introduced CRT into education in 1995, she cautioned that its application required a "thorough analysis of the legal literature upon which it is based".[33] |

テーマ リチャード・デルガドとジーン・ステファンチックは1993年にCRT の参考文献の注釈付き書誌を出版し、以下のテーマの1つ以上を扱った法学の著作を列挙した:「 リベラリズム批判」、「ストーリーテリング/カウンターストーリーテリングと『自分自身の現実に名前をつけること』」、「アメリカの公民権法と進歩の修正 主義的解釈」、「人種と人種差別の根底にあるものに対するより深い理解」、「構造的決定論」、「人種、性、階級とそれらの交差」、「本質主義と反本質主 義」、「文化的ナショナリズム/分離主義」、「法制度、批判的教育法、法曹界におけるマイノリティ」、「批判と自己批判」である。 [41] 1995年にグロリア・ラドソン=ビリングスがCRTを教育に導入した際、彼女はその適用には「根拠となる法的文献の徹底的な分析」が必要であると注意を 促している[33]。 |

| Critique of liberalism First and foremost to CRT legal scholars in 1993 was their "discontent" with the way in which liberalism addressed race issues in the US. They critiqued "liberal jurisprudence", including affirmative action,[42] color-blindness, role modeling, and the merit principle.[43] Specifically, they claimed that the liberal concept of value-neutral law contributed to maintenance of the US's racially unjust social order.[15] An example questioning foundational liberal conceptions of Enlightenment values, such as rationalism and progress, is Rennard Strickland's 1986 Kansas Law Review article, "Genocide-at-Law: An Historic and Contemporary View of the Native American Experience". In it, he "introduced Native American traditions and world-views" into law school curriculum, challenging the entrenchment at that time of the "contemporary ideas of progress and enlightenment". He wrote that US laws that "permeate" the everyday lives of Native Americans were in "most cases carried out with scrupulous legality" but still resulted in what he called "cultural genocide".[44] In 1993, David Theo Goldberg described how countries that adopt classical liberalism's concepts of "individualism, equality, and freedom"—such as the United States and European countries—conceal structural racism in their cultures and languages, citing terms such as "Third World" and "primitive".[45]: 6–7 In 1988, Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw traced the origins of the New Right's use of the concept of color-blindness from 1970s neoconservative think tanks to the Ronald Reagan administration in the 1980s.[46] She described how prominent figures such as neoconservative scholars Thomas Sowell[47] and William Bradford Reynolds,[48] who served as Assistant Attorney General for the Civil Rights Division from 1981 to 1988,[48] called for "strictly color-blind policies".[47] Sowell and Reynolds, like many conservatives at that time, believed that the goal of equality of the races had already been achieved, and therefore the race-specific civil rights movement was a "threat to democracy".[47] The color-blindness logic used in "reverse discrimination" arguments in the post-civil rights period is informed by a particular viewpoint on "equality of opportunity", as adopted by Sowell,[49] in which the state's role is limited to providing a "level playing field", not to promoting equal distribution of resources. Crenshaw claimed that "equality of opportunity" in antidiscrimination law can have both an expansive and a restrictive aspect.[49] Crenshaw wrote that formally color-blind laws continue to have racially discriminatory outcomes.[16] According to her, this use of formal color-blindness rhetoric in claims of reverse discrimination, as in the 1978 Supreme Court ruling on Bakke, was a response to the way in which the courts had aggressively imposed affirmative action and busing during the Civil Rights era, even on those who were hostile to those issues.[46] In 1990, legal scholar Duncan Kennedy described the dominant approach to affirmative action in legal academia as "colorblind meritocratic fundamentalism". He called for a postmodern "race consciousness" approach that included "political and cultural relations" while avoiding "racialism" and "essentialism".[50] Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva describes this newer, subtle form of racism as "color-blind racism", which uses frameworks of abstract liberalism to decontextualize race, naturalize outcomes such as segregation in neighborhoods, attribute certain cultural practices to race, and cause "minimization of racism".[51] In his influential 1984 article, Delgado challenged the liberal concept of meritocracy in civil rights scholarship.[52] He questioned how the top articles in most well-established journals were all written by white men.[53] |

リベラリズム批判 1993年当時、CRTの法学者たちにとって何よりもまず重要だったのは、リベラリズムがアメリカにおける人種問題に対処する方法に対する「不満」であっ た。彼らはアファーマティブ・アクション、[42]カラーブラインド、役割モデル、功績主義を含む「リベラルな法学」を批判した[43]。具体的には、価 値中立法とい うリベラルな概念がアメリカの人種的に不公正な社会秩序の維持に寄与していると主張した[15]。 合理主義や進歩といった啓蒙主義的価値観の基礎となるリベラルな概念に疑問を投げかけている例として、レナード・ストリックランドによる1986年のカン ザス法学論集の論文「Genocide-at-Law: An Historic and Contemporary View of the Native American Experience」である。この論文の中で彼は、ロースクールのカリキュラムに「ネイティブ・アメリカンの伝統と世界観を導入」し、当時定着していた 「進歩と啓蒙の現代的思想」に異議を唱えた。彼は、ネイティブ・アメリカンの日常生活に「浸透」しているアメリカの法律は、「ほとんどの場合、細心の注意 を払って合法的に実施」されているが、それでもなお、彼が「文化的ジェノサイド」と呼ぶ結果をもたらしていると書いた[44]。 1993年、デイヴィッド・セオ・ゴールドバーグは、「個人主義、平 等、自由」という古典的な自由主義の概念を採用している国、例えばアメリカやヨーロッ パ諸国が、「第三世界」や「原始的」といった言葉を引用しながら、その文化や言語においていかに構造的な人種差別を隠蔽しているかについて述べている [45]。 1988年、キンバー・ウィリアムズ・クレンショーは、1970年代の新保守主義シンクタンクから1980年代のロナルド・レーガン政権に至るまで、新右 翼がカラーブラインドの概念を使用した起源をたどっている[46]。 彼女は、新保守主義の学者であるトーマス・ソーウェル[47]や、1981年から1988年まで公民権部門の司法次官補を務めたウィリアム・ブラッド フォード・レイノルズ[48]のような著名な人物が、「厳密にカラーブラインドの政策」を求めたことを述べている[48]。 [47]ソウェルとレイノルズは、当時の多くの保守派と同様に、人種の平等という目 標はすでに達成されており、したがって人種に特化した公民権運動は「民 主主義への脅威」であると信じていた[47]。 公民権運動後の「逆差別」の議論において使用されるカラーブラインドの論理は、ソウェルによって採用された「機会の平等」に関する特定の視点[49]に よってもたらさ れており、そこでは国家の役割は「公平な競技場」を提供することに限定されており、資源の平等な分配を促進することには限定されていない。 クレンショーは、差別禁止法における「機会の平等」は、拡大的な側面と制限的な側面の両方を持ち得ると主張している[49]。クレンショーは、形式的には カラーブラインド法が人種差別的な結果をもたらし続けていると書いている。 [16] クレンショーによれば、1978年のバッケ最高裁判決のように、逆差別の主張において形式的なカラーブラインドのレトリックが用いられるのは、公民権時代 に裁判所がア ファーマティブ・アクションやバッシングを、それらの問題に敵対的であった人々に対しても積極的に課してきたことへの反応であった[46]。 1990年、法学者のダンカン・ケネディは、法学アカデミズムにおけるアファーマティブ・アク ションへの支配的なアプローチを「カラーブラインド功利主義原理主義」と 表現した。彼は「人種主義」と「本質主義」を避けつつ、「政治的・文化的関係」を含むポストモダンの「人種意識」アプローチを求めた [50]。 社会学者のエドゥアルド・ボニーヤ=シルヴァ(Eduardo Bonilla-Silva)は、この人種主義の新しく微妙な形態を「カ ラーブラインド人種主義」と表現しており、抽象的な自由主義の枠組みを用いて人 種を非文脈化し、近隣における分離のような結果を自然化し、特定の文化的慣習を人種に帰結させ、「人種主義の最小化」を引き起こしている[51]。 1984年の影響力のある論文において、デルガドは公民権研究における実力主義というリベラルな概念に異議を唱えた[52]。 彼はほとんどの定評のあるジャーナルの上位の論文がすべて白人男性によって書かれていることに疑問を呈した[53]。 |

| Storytelling/counterstorytelling

and "naming one's own reality" This refers to the use of narrative (storytelling) to illuminate and explore lived experiences of racial oppression.[41] One of the prime tenets of liberal jurisprudence is that people can create appealing narratives to think and talk about greater levels of justice.[54] Delgado and Stefancic call this the empathic fallacy—the belief that it is possible to "control our consciousness" by using language alone to overcome bigotry and narrow-mindedness.[55] They examine how people of color, considered outsiders in mainstream US culture, are portrayed in media and law through stereotypes and stock characters that have been adapted over time to shield the dominant culture from discomfort and guilt. For example, slaves in the 18th-century Southern States were depicted as childlike and docile; Harriet Beecher Stowe adapted this stereotype through her character Uncle Tom, depicting him as a "gentle, long-suffering", pious Christian.[56] Following the American Civil War, the African-American woman was depicted as a wise, care-giving "Mammy" figure.[57] During the Reconstruction period, African-American men were stereotyped as "brutish and bestial", a danger to white women and children. This was exemplified in Thomas Dixon Jr.'s novels, used as the basis for the epic film The Birth of a Nation, which celebrated the Ku Klux Klan and lynching.[58] During the Harlem Renaissance, African-Americans were depicted as "musically talented" and "entertaining".[59] Following World War II, when many Black veterans joined the nascent civil rights movement, African Americans were portrayed as "cocky [and] street-smart", the "unreasonable, opportunistic" militant, the "safe, comforting, cardigan-wearing" TV sitcom character, and the "super-stud" of blaxploitation films.[60] The empathic fallacy informs the "time-warp aspect of racism", where the dominant culture can see racism only through the hindsight of a past era or distant land, such as South Africa.[61] Through centuries of stereotypes, racism has become normalized; it is a "part of the dominant narrative we use to interpret experience".[62] Delgado and Stefancic argue that speech alone is an ineffective tool to counter racism,[61] since the system of free expression tends to favor the interests of powerful elites[63] and to assign responsibility for racist stereotypes to the "marketplace of ideas".[64] In the decades following the passage of civil rights laws, acts of racism had become less overt and more covert—invisible to, and underestimated by, most of the dominant culture.[65] |

ストーリーテリング/カウンターストーリーテリングと

"自分自身の現実の命名" これは、人種的抑圧の生きた経験を照らし出し、探求するための物語(ストーリーテリング)の使用を指す[41]。 リベラルな法学の主要な信条の1つは、人々はより大きなレベルの正義について考え、語るために魅力的なナラティブを作り出すことができるというものであ る。 [55]彼らは、米国の主流文化においてアウトサイダーとみなされる有色人種が、支配文化を不快感や罪悪感から守るために長い時間をかけて適応されたステ レオタイプやストックキャラクターを通して、メディアや法律においてどのように描かれているかを検証している。例えば、18世紀の南部諸州の奴隷は、子供 のようにおとなしく描かれていた。ハリエット・ビーチャー・ストウは、アンクル・トムというキャラクターを通してこのステレオタイプを適応させ、彼を「優 しく、長く苦しむ」敬虔なクリスチャンとして描いた[56]。 アメリカ南北戦争の後、アフリカ系アメリカ人の女性は、賢明で世話を焼く「マミー」のような人物として描かれた[57]。 復興期には、アフリカ系アメリカ人の男性は「残忍で獣のような」、白人の女性や子どもにとって危険な存在としてステレオタイプ化された。これは、クー・ク ラックス・クランとリンチを賛美した大作映画『国民の誕生』の原作として使われたトーマス・ディクソン・ジュニアの小説に例証されている[58]。ハーレ ム・ルネッサンス期には、アフリカ系アメリカ人は「音楽的才能があり」「エンターテイナー」として描かれた。 [第二次世界大戦後、多くの黒人退役軍人が公民権運動の萌芽に参加したとき、アフリカ系アメリカ人は「生意気な(そして)ストリート・スマート」、「理不 尽で日和見主義的な」過激派、「安全で心地よくカーディガンを羽織る」テレビのシットコムのキャラクター、そしてブラックスプロイテーション映画の「スー パースタッド」として描かれた[60]。 [59] Delgado & Stefancic 1992, p. 1266.Delgado, Richard; Stefancic, Jean (1992). "Images of the Outsider in American Law and Culture: Can Free Expression Remedy Systemic Social Ills?" (PDF). Cornell Law Review. 77 (6): 1258–1297. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.946.7275. SSRN 2095316 |

| the empathic fallacy Since racism makes people feel uncomfortable, the empathic fallacy helps the dominant culture to mistakenly believe that it no longer exists, and that dominant images, portrayals, stock characters, and stereotypes—which usually portray minorities in a negative light—provide them with a true image of race in America.[citation needed] Based on these narratives, the dominant group has no need to feel guilty or to make an effort to overcome racism, as it feels "right, customary, and inoffensive to those engaged in it", while self-described liberals who uphold freedom of expression can feel virtuous while maintaining their own superior position.[66] +++++++++++++++++++++ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_race_theory +++++++++++++++++++++ What is the empathy fallacy? The argument goes like this: “If you are not part of the group you are criticizing or affecting, you do not have legitimate grounds on which to stand because you cannot empathize with them.” Interestingly, this idea overlaps with the popular theory of oppression known as “intersectionality.” 2 3 Essentially, since people are multifaceted, oppressed minorities overlap and must be considered as a whole. So for example, we can’t consider women’s issues or racial minorities merely individually – many people are in both groups. Oppression is a quilt of overlapping issues. This is true. But one misapplication of the empathy fallacy with intersectionality is that you have to be in ONE of the groups to be able to propose solutions. And the one group that is universally excluded as oppressed? White males. So the king of all outgroups who cannot affect anyone else with their censure or approval? White males. More specifically? White ‘cis’ males, meaning heterosexuals. Since they don’t intersect with any supposed oppressed minority, they have absolutely no right to speak on any of these issues. This is just a very narrow and specific case of the empathy fallacy. But while it may be true that it is harder to empathize with a group you are not part of, or if you yourself have not experienced marginalization, this does not make your arguments or causes illogical or incorrect. This is a form of the genetic fallacy – you arrived at your position illegitimately, and in this case, without the required perspective of the oppressed. +++++++++++++++++++++ https://x.gd/4yku7 +++++++++++++++++++++ |

共感的誤謬 人 種主義は人民を不快にさせるため、共感の誤謬は支配的文化が「もはや人種主義は存在しない」と誤って信じ込むのを助ける。そして支配的なイメージ、描写、 類型化されたキャラクター、ステレオタイプ——これらは通常マイノリティを否定的に描く——が、アメリカにおける人種の真実の姿を伝えていると信じ込ませ るのだ。[出典が必要] こうした物語に基づき、支配的集団は「正しい、慣習的であり、関与する者にとって不快ではない」と感じるため、罪悪感を抱く必要も人種主義を克服する努力 も不要となる。一方、表現の自由を擁護する自称リベラル派は、自らの優位な立場を維持しながら道徳的優越感を抱くことができるのである。[66] +++++++++++++++++++++ https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_race_theory +++++++++++++++++++++ 共感の誤謬とは何か? その主張はこうだ:「批判したり影響を与えたりする集団の一員でないなら、彼らに共感できない以上、正当な立場に立つ根拠はない」 興味深いことに、この考え方は「交差性」として知られる抑圧理論と重なる。 2 3 基本的に、人間は多面的であるため、抑圧された少数派は重なり合い、全体として考慮されねばならない。例えば、女性問題や人種的少数派を単に個別に考える ことはできない——多くの人々が両方のグループに属しているからだ。抑圧は重なり合う問題のパッチワークである。これは真実だ。しかし交差性理論における 共感の誤謬の誤用の一つは、解決策を提案するにはいずれかのグループに属していなければならないという主張である。そして、抑圧された者として普遍的に排 除される唯一のグループとは?白人男性だ。 つまり、非難や承認で他者に影響を与えられない、あらゆるアウトグループの王様とは?白人男性だ。より具体的には?白人「シス」男性、つまり異性愛者だ。 彼らは抑圧されたとされるいかなる少数派とも交差しないため、これらの問題について発言する権利は全くない。これは共感の誤謬の極めて狭く特化した事例に 過ぎない。 しかし、自分が属さない集団や、自ら境界を経験したことのない集団への共感は確かに難しいかもしれない。だが、だからといって、その主張や大義が非論理的 あるいは誤っているわけではない。これは一種の発生の誤謬だ——つまり、お前は正当な方法でその立場に至ったわけではなく、この場合、抑圧された者たちの 視点という必須条件を満たしていないというわけだ。 +++++++++++++++++++++ https://x.gd/4yku7 +++++++++++++++++++++ |

| Standpoint epistemology This is the view that members of racial minority groups have a unique authority and ability to speak about racism. This is seen as undermining dominant narratives relating to racial inequality, such as legal neutrality and personal responsibility or bootstrapping, through valuable first-hand accounts of the experience of racism.[67] |

立場認識論( Standpoint epistemology) これは、人種的マイノリティ・グループのメンバーは人種差別について語る独自の権威と能力を持っているという見解である。これは人種差別の経験についての 貴重な生の証言を通じて、法的中立性や個人的責任、あるいはブートストラップといった人種的不平等に関する支配的な物語を弱体化させると考えられている [67]。 |

| Revisionist interpretations of

American civil rights law and progress Interest convergence is a concept introduced by Derrick Bell in his 1980 Harvard Law Review article, "Brown v. Board of Education and the Interest-Convergence Dilemma".[68] In this article, Bell described how he re-assessed the impact of the hundreds of NAACP LDF de-segregation cases he won from 1960 to 1966, and how he began to believe that in spite of his sincerity at the time, anti-discrimination law had not resulted in improving Black children's access to quality education.[69] He listed and described how Supreme Court cases had gutted civil rights legislation, which had resulted in African-American students continuing to attend all-black schools that lacked adequate funding and resources.[68] In examining these Supreme Court cases, Bell concluded that the only civil-rights legislation that was passed coincided with the self-interest of white people, which Bell termed interest convergence.[68][70][71] One of the best-known examples of interest convergence is the way in which American geopolitics during the Cold War in the aftermath of World War II was a critical factor in the passage of civil rights legislation by both Republicans and Democrats. Bell described this in numerous articles, including the aforementioned, and it was supported by the research and publications of legal scholar Mary L. Dudziak. In her journal articles and her 2000 book Cold War Civil Rights—based on newly released documents—Dudziak provided detailed evidence that it was in the interest of the United States to quell the negative international press about treatment of African-Americans when the majority of the populations of newly decolonized countries which the US was trying to attract to Western-style democracy, were not white. The US sought to promote liberal values throughout Africa, Asia, and Latin America to prevent the Soviet Union from spreading communism.[72] Dudziak described how the international press widely circulated stories of segregation and violence against African-Americans. The Moore's Ford lynchings, where a World War II veteran was lynched, were particularly widespread in the news.[73] American allies followed stories of American racism through the international press, and the Soviets used stories of racism against Black Americans as a vital part of their propaganda.[74] Dudziak performed extensive archival research in the US Department of State and Department of Justice and concluded that US government support for civil-rights legislation "was motivated in part by the concern that racial discrimination harmed the United States' foreign relations".[41][75] When the National Guard was called in to prevent nine African-American students from integrating the Little Rock Central High School, the international press covered the story extensively.[74] The then-Secretary of State told President Dwight Eisenhower that the Little Rock situation was "ruining" American foreign policy, particularly in Asia and Africa.[76] The US's ambassador to the United Nations told President Eisenhower that as two-thirds of the world's population was not white, he was witnessing their negative reactions to American racial discrimination. He suspected that the US "lost several votes on the Chinese communist item because of Little Rock."[77] |

アメリカ公民権法の修正主義的解釈と進歩 利益収斂(Interest convergence)は、 デリック・ベルが1980年のハーバード・ロー・レビューの論文「ブラウン対教育委員会と利益収斂のジレンマ」[68]の中で紹介した概念で ある。この論文の中でベルは、1960年から1966年にかけて彼が獲得した何百件ものNAACPのLDFによる人種差別撤廃裁判の影響をどのように再評 価し、当時の彼の誠実さにもかかわらず、差別撤廃法は黒人の子どもたちの質の高い教 育へのアクセスを改善する結果にはなっていないと考えるようになったと 述べている。 [69]彼は、最高裁の判例が公民権法を根底から覆し、その結果、アフリカ系アメリカ人の生徒が、十分な資金と資源を持たない黒人だけの学校に通い続ける ことになったことを列挙し、説明した[68]。 利益収斂(Interest convergence)の 最もよく知られた例のひとつは、第二次世界大戦後の冷戦期におけるアメリカの地政学が、共和党と民主党の双方による公民権法成立の重要な要因と なった方法である。ベルは前述の論文を含む数多くの論文でこのことを述べており、法学者メアリー・L・ダジアックの研究や出版物によって裏付けられてい る。新たに公開された文書に基づく彼女の雑誌記事と2000年の著書『Cold War Civil Rights』の中で、ダジアックは、米国が西欧式の民主主義に引き込もう としていた脱植民地化されたばかりの国々の人口の大 多数が白人ではなかったとき、アフリカ系アメリカ人の扱いに関する否定的な国際的報道を鎮めることが米国の利益につながったという詳細な証拠を示してい る。アメリカは、ソ連が共産主義を広めるのを防ぐために、アフリカ、アジア、ラテンアメリカ全体にリベラルな価値観を広めようとしていた。 第二次世界大戦の退役軍人がリンチされたムーアズ・フォードのリンチ事件は特に広く報道された[73]。アメリカの同盟国は国際的な報道を通じてアメリカ の人種差別の物語を追いかけ、ソビエトはアメリカ黒人に対する人種差別の物語を彼らのプロパガンダの重要な一部として利用した[74]。 ダジアックはアメリカ国務省と司法省で広範なアーカイブ調査を行い、公民権法に対するアメリカ政府の支援は「人種差別がアメリカの外交関係を害するという 懸念によって動機づけられた部分もある」と結論づけた。 [当時の国務長官はドワイト・アイゼンハワー大統領に、リトルロックの事態がアメリカの外交政策、特にアジアとアフリカの外交政策を「台無し」にしている と述べた[76]。 アメリカの国連大使はアイゼンハワー大統領に、世界人口の3分の2は白人ではなく、アメリカの人種差別に対する彼らの否定的な反応を目の当たりにしている と述べた。彼はアメリカが「リトル・ロックのせいで中国共産党の項目でいくつかの票を失った」と疑っていた[77]。 |

| Intersectional theory This refers to the examination of race, sex, class, national origin, and sexual orientation, and how their intersections play out in various settings, such as how the needs of a Latina are different from those of a Black male, and whose needs are promoted.[41][78][further explanation needed] These intersections provide a more holistic picture for evaluating different groups of people. Intersectionality is a response to identity politics insofar as identity politics does not take into account the different intersections of people's identities.[79] |

交差理論( Intersectional theory) これは、人種、性、階級、出身国、性的指向を検討し、ラティーナのニーズと黒人男性のニーズがどのように異なるか、誰のニーズが促進されるかなど、それら の交差が様々な場面でどのように作用するかを指す[41][78][さらに説明が必要]。インターセクショナリティは、アイデンティティ政治が人々のアイ デンティティの様々な交差を考慮していない限りにおいて、アイデンティティ政治に対する反応である[79]。 |

| Essentialism vs.

anti-essentialism Delgado and Stefancic write, "Scholars who write about these issues are concerned with the appropriate unit for analysis: Is the black community one, or many, communities? Do middle- and working-class African-Americans have different interests and needs? Do all oppressed peoples have something in common?" This is a look at the ways that oppressed groups may share in their oppression but also have different needs and values that need to be analyzed differently. It is a question of how groups can be essentialized or are unable to be essentialized.[41][80][further explanation needed] From an essentialist perspective, one's identity consists of an internal "essence" that is static and unchanging from birth, whereas a non-essentialist position holds that "the subject has no fixed or permanent identity."[81] Racial essentialism diverges into biological and cultural essentialism, where subordinated groups may endorse one over the other. "Cultural and biological forms of racial essentialism share the idea that differences between racial groups are determined by a fixed and uniform essence that resides within and defines all members of each racial group. However, they differ in their understanding of the nature of this essence."[82] Subordinated communities may be more likely to endorse cultural essentialism as it provides a basis of positive distinction for establishing a cumulative resistance as a means to assert their identities and advocacy of rights, whereas biological essentialism may be unlikely to resonate with marginalized groups as historically, dominant groups have used genetics and biology in justifying racism and oppression. Essentialism is the idea of a singular, shared experience between a specific group of people. Anti-essentialism, on the other hand, believes that there are other various factors that can affect a person's being and their overall life experience. The race of an individual is viewed more as a social construct that does not necessarily dictate the outcome of their life circumstances. Race is viewed as "a social and historical construction, rather than an inherent, fixed, essential biological characteristic."[83][84] Anti-essentialism "forces a destabilization in the very concept of race itself…"[83] The results of this destabilization vary on the analytic focus falling into two general categories, "... consequences for the analytic concepts of racial identity or racial subjectivity."[83] |

本質主義〈対〉反本質主義 デルガドとステファンチッチは、「これらの問題について書いている学者たちは、分析の適切な単位に関心を持っている: 黒人社会はひとつの共同体なのか、それとも多くの共同体なのか。アフリカ系アメリカ人の中産階級と労働者階級では、関心やニーズが異なるのだろうか?抑圧 された人々には共通点があるのか?これは、抑圧された集団は抑圧を共有しているかもしれないが、同時に異なるニーズや価値観を持っており、異なる分析が必 要であるという見方である。それは、集団がいかに本質化されうるか、あるいは本質化することができないかという問題である[41][80][さらに説明が 必要]。 本質主義の観点からは、人のアイデンティティは静的で生まれながらにして変わらない内的 な「本質」から構成されているのに対し、非本質主義の立場は「主体 は固定的または永続的なアイデンティティを持たない」とする[81]。人種的本質主義は生物学的本質主義と文化的本質主義に分岐し、従属集団は他方よりも 一方を支持することがある。「人種本質主義の文化的および生物学的形態は、人種集団間の相違は、各人種集団のすべての構成員の中に存在し、それを定義する 固定された均一な本質によって決定されるという考えを共有している。一方、生物学的本質主義は、歴史的に支配的集団が人種差別や抑圧を正当化するために遺 伝学や生物学を利用してきたため、周縁化された集団とは共鳴しにくいかもしれない。 本質主義とは、特定のグループ間で共有される唯一の経験という考え方である。一方、反本質主義は、人のあり方や人生経験全体に影響を与える様々な要因が他 にもあると考える。個人の人種は、必ずしもその人の生活環境の結果を左右するものではない、社会的な構成要素としてとらえられている。人種は「固有の、固 定された、本質的な生物学的特性ではなく、社会的かつ歴史的な構築物」とみなされている[83][84] 反本質主義は「人種という概念そのものに不安定化を強いる」[83] この不安定化の結果は、「......人種的アイデンティティや人種的主観性の分析的概念に対する帰結」[83]という2つの一般的なカテゴリーに分類さ れる分析焦点によって異なる。 |

| Cultural nationalism/separatism This refers to the exploration of more radical views that argue for separation and reparations as a form of foreign aid (including black nationalism).[41][example needed] |

文化的ナショナリズム/分離主義 これは対外援助の一形態として分離と賠償を主張する(黒人ナショナリズムを含む)より急進的な見解の探求を指す[41][要出典]。 |

| Legal institutions, critical

pedagogy, and minorities in the bar Camara Phyllis Jones defines institutionalized racism as "differential access to the goods, services, and opportunities of society by race. Institutionalized racism is normative, sometimes legalized and often manifests as inherited disadvantage. It is structural, having been absorbed into our institutions of custom, practice, and law, so there need not be an identifiable offender. Indeed, institutionalized racism is often evident as inaction in the face of need, manifesting itself both in material conditions and in access to power. With regard to the former, examples include differential access to quality education, sound housing, gainful employment, appropriate medical facilities, and a clean environment."[88] |

法制度、批判的教育学、法曹界におけるマイノリティ カマラ・フィリス・ジョーンズは、制度化された人種差別を「人種による社会の財、サービス、機会へのアクセスの差」と定義している。制度化された人種差別 は規範的であり、時に合法化され、しばしば受け継がれた不利益として現れる。慣習、慣行、法律といった制度に吸収された構造的なものであるため、加害者を 特定する必要はない。実際、制度化された人種差別は、多くの場合、必要性に直面したときの不作為として明らかになり、物質的条件と権力へのアクセスの両方 に現れる。前者に関しては、質の高い教育、健全な住宅、有給の雇用、適切な医療施設、清潔な環境へのアクセスの差などがその例である」[88]。 |

| Black–white binary Main article: Black–white binary The black–white binary is a paradigm identified by legal scholars through which racial issues and histories are typically articulated within a racial binary between black and white Americans. The binary largely governs how race has been portrayed and addressed throughout US history.[89] Critical race theorists Richard Delgado and Jean Stefancic argue that anti-discrimination law has blindspots for non-black minorities due to its language being confined within the black–white binary.[90] |

黒人と白人の二元論 主な記事 黒人と白人の二元論 黒人と白人の二元論とは、法学者によって特定されたパラダイムであり、人種問題や歴史は通常、アメリカ人の黒人と白人の間の人種的二元論の中で明確化され る。批判的人種理論家のリチャード・デルガドとジーン・ステファンチッチは、差別禁止法は黒人と白人の二元論に縛られているため、黒人以外のマイノリティ にとって盲点になっていると主張している[90]。 |

★

批判的人種理論(ドイツ語ウィキペディアより)

| Critical

Race Theory

(englisch für kritische „Rassen“-Theorie[Anm. 1]), kurz CRT, wird eine

Bewegung und Sammlung von Theorieansätzen, insbesondere aus der

US-amerikanischen Rechtswissenschaft, genannt, die sich mit dem

Zusammenhang zwischen Rasse (race), Rassismus und dessen Verankerung in

– insbesondere rechtlichen – Strukturen befasst und diese kritisiert.

In der amerikanischen Öffentlichkeit und Politik hat sich um CRT, bzw.

um Konzepte, die fälschlich der CRT zugeordnet werden, eine intensive

Debatte entwickelt, in der Critical Race Theory zum Kampfbegriff

geworden ist.[1][2] |

批

判的人種理論(Critical Race

Theory)、略してCRTは、人種、人種差別、そして構造(特に法的構造)におけるその定着の関係を扱い、批判する、特にアメリカの法曹界からの運動

であり、理論的アプローチの集まりである。アメリカの公的・政治的領域では、CRTをめぐって、あるいはむしろCRTとして誤って分類されている概念をめ

ぐって集中的な議論が展開されており、そのなかで批判的人種理論は闘争用語となっている[1][2]。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Geschichte 2 Grundannahmen 2.1 race ist sozial konstruiert 2.2 Struktureller Rassismus ist Teil der gesellschaftlichen Normalität 2.3 Wissenschaft kann und soll in Bezug auf Rassismus nicht neutral sein 2.4 Intersektionalität 2.5 Kritik am Liberalismus 3 Critical Philosophy of Race 4 Akademische Rezeption 5 (Neo-)Marxistische Kritik 6 Politische Kontroversen 6.1 Auseinandersetzung über CRT an Schulen und Universitäten 6.2 Einordnung der Kampagne gegen CRT 7 Literatur 7.1 Allgemein 7.2 Anthologien 7.3 Einführungen 8 Weblinks 9 Einzelnachweise 10 Anmerkungen |

目次 1 歴史 2 基本的前提 2.1 人種は社会的に構築されたものである 2.2 構造的人種差別は社会的規範の一部である 2.3 科学は人種差別に対して中立ではありえないし、そうあるべきでもない 2.4 交差性 2.5 リベラリズム批判 3 人種に関する批判的哲学 4 学術的受容 5 (ネオ)マルクス主義批判 6 政治的論争 6.1 学校や大学におけるCRT論争 6.2 CRT反対運動の分類 7 文献 7.1 一般 7.2 アンソロジー 7.3 紹介 8 ウェブリンク 9 個々の参考文献 10 ノート |

Geschichte Kimberlé Crenshaw gilt als eine Begründerin der CRT Critical Race Theory wurde in den 1970er-Jahren zunächst von Anwälten, Aktivisten und Rechtswissenschaftlern in den USA entwickelt, die in Anbetracht der unzureichenden Fortschritte nach den anfänglichen Erfolgen der Bürgerrechtsbewegung nach neuen Theorien und Strategien suchten. Eine Gruppe um Autoren wie Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, Kimberlé Crenshaw und Richard Delgado veranstaltete 1989 ihre erste Konferenz und nachfolgend weitere Treffen und Veranstaltungen.[3][4] Viele der Professoren, die an der ersten Konferenz teilnahmen, lehrten an überwiegend weißen Law Schools und viele von ihnen waren an den entsprechenden Institutionen die ersten Fakultätsmitglieder, die nicht weiß waren. Einen starken Einfluss auf die CRT übten die Critical Legal Studies und linke Bewegungen innerhalb der Rechtswissenschaft aus, wobei aber von Vertretern der CRT (häufig Crits genannt) bemängelt wurde, dass die Critical Legal Studies wegen ihres Fokus auf Klassen nicht geeignet seien, Rassismus zu analysieren.[5][6] Heute gibt es an den meisten Elite-Law-Schools CRT-Vertreter und Konferenzen zu Critical Race Theory.[7] Es haben sich auch neue Subdisziplinen wie LatCrit (mit Schwerpunkt auf Latinos) gebildet.[8] Auch AsianCrit mit Bezug auf Asian Americans ist im Entstehen.[9] In jüngerer Vergangenheit konzentrierten sich ClassCrits erneut verstärkt auf materielle und ökonomische Faktoren sowie den Zusammenhang von race und Klasse. Mit der Erweiterung des inhaltlichen Fokus erweiterte sich auch der geographische Fokus, der sich zuvor stark auf die Vereinigten Staaten konzentriert hatte.[10][11] Critical Race Theory diffundierte in andere akademische Disziplinen, etwa in die Erziehungswissenschaft,[5] Soziologie[12] oder in die Philosophie, wo entsprechende Ansätze unter dem Begriff Critical Philosophy of Race gefasst werden.[13] |

歴史 クリティカル・レース理論(CRT)の創始者の一人とされるキンバレ・クレンショー。 クリティカル・レース・セオリー(批判的人種理論)は当初、1970年代にアメリカの弁護士、活動家、法学者によって提唱された。デリック・ベル、アラ ン・フリーマン、キンバレ・クレンショー、リチャード・デルガドといった著者に率いられたグループは、1989年に最初の会議を開催し、その後も会議やイ ベントを開催した[3][4]。CRTに強い影響を与えたのは批判的法学と法学界の左派運動であったが、CRT擁護者(しばしばクリッツと呼ばれる)は批 判的法学が階級に焦点を当てているために人種差別の分析には適していないと批判した。 [7]ラテンアメリカ人に焦点を当てたラト・クリット(LatCrit)のような新しいサブディシプリンも出現しており[8]、アジア系アメリカ人に焦点 を当てたアジアン・クリット(AsianCrit)も出現している[9]。 最近では、クラス・クリット(ClassCrit)が再び物質的・経済的要因や人種と階級の関係に焦点を当てるようになってきている。批判的人種理論は、 教育科学[5]、社会学[12]、哲学[13]などの他の学問分野にも拡散し、対応するアプローチは人種批判哲学[13]という用語でまとめられている。 |

| Grundannahmen Eine Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Ansätze fällt unter den Überbegriff Critical Race Theory. CRT ist interdisziplinär angelegt und baut u. a. auf Erkenntnissen des Liberalismus, des Poststrukturalismus, des Feminismus, des Marxismus, der Critical Legal Studies, des Postmodernismus und des Pragmatismus auf.[10] Trotz der Vielzahl unterschiedlicher Ansätze und Sichtweisen lassen sich einige Grundannahmen identifizieren, die von den meisten Theoretikern geteilt werden: race ist sozial konstruiert CRT geht davon aus, dass race sozial konstruiert ist und keine biologische Kategorie sei. Das Recht trage zur Entstehung und Aufrechterhaltung von race bei, etwa durch die Klassifizierung von Menschen in Kategorien wie „Schwarz“ oder „Weiß“.[14] Auch wenn race keine biologische oder naturwissenschaftliche Kategorie sei, habe die entsprechende Kategorisierung weitreichende Folgen für die Gesellschaft.[15] Fragen, die in der CRT behandelt (und von unterschiedlichen Theoretikern jeweils unterschiedlich beantwortet) werden, sind zum Beispiel, wie genau durch das Recht race hervorgebracht wird, wie durch das Recht Rassismus verteidigt wurde oder wie das Recht zur Reproduktion von Ungleichheit beitrage. Als Beispiele für die Bedeutung von Recht und Gerichten für die Konstruktion von race werden beispielsweise Gerichtsprozesse herangeführt, in denen explizit über die race von Individuen entschieden wurde, etwa wenn Sklaven vor Gericht feststellen lassen wollten, dass sie weiß seien und somit fälschlicher- und illegalerweise versklavt worden seien. In der Gegenwart seien beispielsweise Immigrationsgesetze an der Konstruktion von race beteiligt.[16] Struktureller Rassismus ist Teil der gesellschaftlichen Normalität Rassismus wird in der Theoriebildung der CRT nicht als Ausnahme, sondern als Norm betrachtet, die tief in gesellschaftlichen Strukturen und Institutionen verankert sei und die People of Color regelmäßig erführen.[16] Weil Rassismus die Interessen von weißen Eliten (materiell) und weißen Angehörigen der Arbeiterklasse (psychologisch) voranbringe, gebe es wenig Interesse an seiner Beseitigung seitens Weißer. Im Umkehrschluss entstünden Fortschritte bei der rechtlichen Gleichbehandlung nur, wenn die Interessen von Schwarzen mit den Interessen von Weißen, zum Beispiel durch eine veränderte sozioökonomische Situation, übereinstimmten (interest convergence).[17] Die ungleiche Verteilung von Reichtum, Macht und Ansehen in den USA lasse sich nicht alleine durch unterschiedliche Leistungen der entsprechenden Gruppen erklären.[18] Rassismus wird entsprechend nicht primär als falsches Handeln oder Denken von Individuen betrachtet und analysiert, sondern auf der Ebene von gesellschaftlichen Strukturen und Institutionen. Deshalb vertreten Critical Race Theorists auch die präskriptive Annahme, dass Systeme, die zur Unterdrückung von People of Color beitragen, benannt und bekämpft werden müssen.[16] Wissenschaft kann und soll in Bezug auf Rassismus nicht neutral sein In der Tradition der Kritischen Theorie sieht sich die CRT auch als Theorie sozialen Wandels. Als kritische Theorie versteht sich die CRT aber auch deshalb, weil sie die eigene Einbettung in rassistische Strukturen zu reflektieren versucht und die Norm wissenschaftlicher Neutralität als unerreichbar und nicht erstrebenswert verwirft.[19] CRT geht davon aus, dass Wissen stets politisch ist, und dass Forschung, die race ignoriert, weder objektiv noch neutral sei, sondern selbst durch diese Auslassung Position beziehe.[16] Intersektionalität Ein weiterer Fokus der CRT liegt auf Intersektionalität, einem Konzept, das von einer frühen Vertreterin der Disziplin, Kimberlé Crenshaw, geprägt wurde und darauf verweist, dass Identitäten jeweils vielschichtig sind und dass dementsprechend unterschiedliche Menschen in unterschiedlichen Situationen unterschiedliche Diskriminierungserfahrungen machen. Rassismus wird deshalb im Zusammenwirken mit anderen Diskriminierungsformen wie Sexismus oder Klassismus betrachtet.[6][3] Dass die Zuordnung zu bestimmten Gruppen selbst arbiträr erscheint und Fragen nach der Privilegierung bestimmter Kategorien („Ist Geschlecht oder race wichtiger?“) werden dabei selbst zum Gegenstand der Analyse in der CRT.[15] Kritik am Liberalismus Die Kritik der CRT an einem liberalen Rechtsverständnis richtet sich vor allem gegen dessen Glauben an neutrale Prozesse und die Doktrin formaler Gleichheit. Die Vorstellung von Neutralität und Objektivität wird nicht nur als unerreichbar verworfen, sondern sogar als schädlich bezeichnet, weil sie die dem Rechtssystem und der amerikanischen Gesellschaft inhärente Bevorzugung von Weißsein verschleiere.[20] Die „Farbenblindheit“ vieler liberaler Theoretiker, die davon ausgehen, dass die Justiz race nicht berücksichtigen solle, kritisieren Vertreter der CRT als unzureichend, um Rassismus, der nicht offensichtlich ist, zu bekämpfen. Die liberale Konzentration auf Rechte und Gesetze erlaube es zudem nicht, nachhaltig Ungerechtigkeit zu bekämpfen, weil trotz ungleicher Ausgangsbedingungen nur auf Chancengleichheit, aber nicht auf ähnliche Ergebnisse verschiedener races geachtet werde.[3] Es reiche nicht, den Fokus auf abstrakte Vorstellungen von Individuen zu legen, sondern der soziale und historische Kontext müsse in die Analyse einbezogen werden.[21] Das Rassismusverständnis der CRT in Abgrenzung von einem individualisierenden, liberalen Rassismusverständnis erläutert Khiara M. Bridges am Beispiel des Todes von Eric Garner. Anstatt sich auf den Polizisten zu konzentrieren, der Garner in den Würgegriff genommen hatte, und zu versuchen, diesen des Rassismus zu überführen, stelle die CRT Fragen wie: Warum gilt das Verkaufen einzelner Zigaretten (deswegen kam der Polizeikontakt zustande) in New York als illegal? Warum musste ein gesunder Mann überhaupt Zigaretten verkaufen, um Geld zu verdienen? Wie hat sich eine Interpretation des vierten Zusatzartikels zur Verfassung der Vereinigten Staaten durchgesetzt, die der Polizei in entsprechenden Situationen erlaubt, aktiv zu werden? Wieso litt Garner, wie viele andere Schwarze in den USA, unter Asthma, Hypertonie und einer Herzkrankheit? Die Antworten auf diese Fragen finde die CRT nicht im Handeln einzelner böswilliger Akteure, sondern in Systemen und Strukturen.[16] Auch die von einigen Liberalen vertretene Vorstellung, Meinungsfreiheit müsse unbegrenzt gelten, wird von Anhängern der CRT in Frage gestellt, die stärkere juristische Maßnahmen gegen rassistische Hassrede fordern.[22][23] Insbesondere weil der Konservatismus im Vergleich zum Liberalismus in den USA an Bedeutung gewonnen hat, aber teilweise auch aus persönlicher Überzeugung hat der Fokus der CRT auf den Liberalismus in den letzten Jahren nachgelassen.[3] |

基本的前提 批評的人種理論(Critical Race Theory)には、さまざまなアプローチが含まれる。CRTは学際的な性格を持ち、リベラリズム、ポスト構造主義、フェミニズム、マルクス主義、批判的 法学、ポストモダニズム、プラグマティズムなどの見識に基づいている[10]。さまざまなアプローチや視点があるにもかかわらず、ほとんどの理論家に共通 するいくつかの基本的な前提を特定することができる: 人種は社会的に構築される CRTは、人種は社会的に構築されたものであり、生物学的カテゴリーではないと仮定している。人種は社会的に構築されたものであり、生物学的なカテゴリー ではないとしている。人種が生物学的あるいは科学的なカテゴリーではないとしても、それに対応するカテゴライゼーションは社会に対して広範囲に及ぶ結果を もたらす[15]。例えば、奴隷が法廷で、自分は白人であり、したがって不当に違法に奴隷にされたのだと立証することを望んだ場合などである。現代では、 例えば移民法が人種の構築に関わっている[16]。 構造的人種主義は社会的規範の一部である CRTの理論化においては、人種差別は例外としてではなく、社会構造や制度に深く埋め込まれ、有色人種が定期的に経験する規範として捉えられている [16]。人種差別は(物質的に)白人エリートや(心理的に)労働者階級の白人の利益を促進するため、白人の側ではその撤廃にほとんど関心がない。逆に、 法的平等の進展は、例えば社会経済状況の変化によって黒人の利益が白人の利益と一致したときにのみ起こる(利益の収斂)[17]。アメリカにおける富、権 力、名声の不平等な分配は、それぞれの集団の業績の違いだけでは説明できない[18]。 したがって、人種差別は主に個人の誤った行動や考えとしてではなく、社会構造や制度のレベルでとらえられ、分析される。したがって批判的人種理論家はま た、有色人種の抑圧を助長するシステムは名指しされ、闘われなければならないという規定的な前提を提唱している[16]。 人種差別との関係において、科学は中立ではありえないし、そうあるべきでもない。 批判的理論の伝統において、CRTもまた自らを社会変革の理論として捉えている。しかしながら、CRTはまた、人種差別的な構造への自らの埋め込みを反省 しようとし、科学的中立性の規範を達成不可能であり、努力する価値がないとして拒絶することから、自らを批判的理論であるとみなしている[19]。CRT は、知識は常に政治的であり、人種を無視する研究は客観的でも中立的でもないと仮定しているが、この省略を通じて自らの立場をとっている。 交差性 CRTのさらなる焦点は、交差性にある。交差性とは、この学問分野の初期の代表者であるキンバーレ・クレンショーによって作られた概念であり、アイデン ティティは多層的であり、それに応じて、異なる状況にある異なる人々が異なる差別の経験を持っていることを指摘している。したがって人種差別は、性差別や 階級差別といった他の形態の差別と結びつけて考えられている[6][3]。特定の集団に分類されること自体が恣意的に見えるという事実や、特定のカテゴ リーの特権化に関する疑問(「ジェンダーと人種のどちらがより重要なのか」)は、それ自体がCRTにおける分析の対象である[15]。 リベラリズム批判 CRTの自由主義的な法理解に対する批判は、主として中立的なプロセスと形式的平等の教義に対するものである。中立性と客観性という概念は、達成不可能な ものとして否定されるだけでなく、法制度とアメリカ社会に内在する白人性への選好を曖昧にするため、有害ですらある[20]。司法制度は人種を考慮すべき ではないとする多くの自由主義理論家の「カラーブラインド」は、CRTの代表者たちによって、明白ではない人種差別と闘うには不十分であると批判される。 さらに、権利 と法律に焦点を当てたリベラル派は、不公正に対する持続可能な闘いを可能にしない。なぜなら、出発条件が不平等であるにもかかわらず、機会均等にのみ注意 が向けられ、異なる人種による同様の結果には注意が向けられないからである[3]。個人の抽象的な考えに焦点を当てるだけでは不十分であり、社会的・歴史 的背景が分析に含まれなければならない。 キアラ・M・ブリッジスは、エリック・ガーナーの死を例に、個人化するリベラルな人種主義理解とは対照的なCRTの人種主義理解を説明している。CRT は、ガーナーの首を絞めた警察官に焦点を当て、彼を人種差別で有罪にしようとする代わりに、次のような質問をした: なぜニューヨークではタバコの個別販売が違法とされているのか?そもそも、なぜ健康な男性がお金を稼ぐためにタバコを売らなければならなかったのか?合衆 国憲法修正第4条について、警察が適切な状況下で行動を起こすことを認める解釈が、どのようにして優勢になったのか?なぜガーナーは、米国の他の多くの黒 人男性と同様、喘息、高血圧、心臓病を患っていたのか?CRTはこれらの疑問に対する答えを、個々の悪意ある行為者の行動ではなく、システムと構造に見出 す[16]。 CRTの支持者たちはまた、一部のリベラル派が持つ、言論の自由は無制限であるべきだという考え方に疑問を呈し、人種差別的なヘイトスピーチに対する法的 措置の強化を求めている[22][23]。特に、アメリカではリベラリズムに対して保守主義が相対的に優勢になっているため、しかし個人的な信念から、 CRTがリベラリズムに焦点を当てることは近年減少している[3]。 |

| Critical Philosophy of Race Innerhalb der Philosophie hat sich aus der CRT heraus die Subdisziplin einer Critical Philosophy of Race (englisch: „Kritische Race-Philosophie“) entwickelt. Da es sich um ein relativ junges Feld handelt, ist die Abgrenzung zu anderen Fächern und Disziplinen nicht in Gänze geklärt und teilweise werden sehr unterschiedliche Ansätze unter der Bezeichnung gefasst. „Kritisch“ ist die Critical Philosophy of Race in mehrfachem Sinne: Sie ist einerseits kritisch gegenüber Rassismus, andererseits gegenüber naturalistischen Verständnissen von „Rasse“ und zuletzt auch gegenüber einem Ausblenden der Bedeutung von race in der Entstehung der modernen Welt.[13] Entsprechende Beiträge finden sich z. B. im Bereich der Ontologie und der Metaphysik, wo über die Existenz und das Wesen von race als Kategorie diskutiert wird. Im Bereich der Epistemologie wird beispielsweise untersucht, wie die Philosophie an der Entstehung des Konzepts race teilhatte und wie unterschiedliche Verständnisse von race selbst Verstehensprozesse beeinflussen.[24] Insbesondere das von Miranda Fricker entwickelte Konzept der epistemischen Ungerechtigkeit spielt im Feld eine herausgehobene Rolle.[25] In der praktischen Philosophie werden normative Fragen im Zusammenhang mit Rassismus analysiert.[24] Während die Critical Philosophy of Race also auf die Methodologie der Philosophie zurückgreift und auch zentrale philosophische Fragestellungen in den Blick nimmt, ist sie auch interdisziplinär geprägt und stellt Bezüge zu Disziplinen wie Soziologie, Anthropologie, Geschichte oder African-American Studies her.[26] In der US-amerikanischen Philosophie hat die Gründung der Zeitschrift Critical Philosophy of Race 2013 sowie die Veröffentlichung von Handbücher und Einführungsbüchern zur Etablierung des Felds beigetragen. Auch wenn es sich um eine hauptsächlich US-amerikanisch geprägte Disziplin handelt, gibt es Versuche, ihre Erkenntnisse auch für einen deutschsprachigen Kontext fruchtbar zu machen und gleichzeitig die Besonderheiten etwa der deutschen Geschichte zu beachten.[25] |

人種批評哲学 哲学の中でも、人種批評哲学(Critical Philosophy of Race)という下位分野は、CRTから発展したものである。これは比較的若い分野であるため、他の主題や学問分野との区別は完全には明確ではなく、全く 異なるアプローチがこの用語の下に包含されることもある。人種批評哲学はいくつかの意味で「批評的」であり、一方では人種差別を、他方では「人種」の自然 主義的理解を、そして最終的には、近代世界の出現における人種の意義のフェードアウトを批判している。例えば認識論の分野では、哲学が人種概念の出現にど のように関与したのか、また人種そのものに対する異なる理解が理解のプロセスにどのような影響を及ぼすのかが検討されている[24]。特に、ミランダ・フ リッカーによって開発された認識論的不公正の概念は、この分野において重要な役割を果たしている[25]。実践哲学においては、人種差別に関連する規範的 な問題が分析されている。 [24]このように人種批評哲学は哲学の方法論を利用し、哲学の中心的な問題にも焦点を当てているが、学際的な性質も持っており、社会学、人類学、歴史 学、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究などの学問分野とのつながりを確立している[26]。 米国哲学においては、2013年にジャーナル「Critical Philosophy of Race」が創刊され、ハンドブックや入門書の出版がこの分野の確立に貢献している。主にアメリカ合衆国の学問分野であるにもかかわらず、その知見をドイ ツ語圏の文脈で実りあるものにし、同時に例えばドイツ史の特殊性を考慮に入れる試みがなされている[25]。 |

| Akademische Rezeption Die Betonung von race und Rassismus wird von Kritikern mit anderen Sichtweisen häufig als fehlgeleitet oder sogar gefährlich empfunden.[6] Die Tatsache, dass CRT als Überbegriff für eine Vielzahl höchst unterschiedlicher Ansätze dient, ist selbst Gegenstand der Kritik.[14] Innerhalb der Theorieschule wurde die Kritik vorgebracht, dass die CRT essenzialistische Konzepte vertrete, woraufhin intersektionale Ansätze gestärkt werden sollten. Als Reaktion auf die Kritik, dass CRT sich zu stark auf schwarze Perspektiven beziehe und z. B. die Perspektiven von Native Americans vernachlässige, entwickelte sich eine größere Zahl von Subdisziplinen und Strängen der CRT, die diese Gruppen in den Blick nehmen.[10] Vehemente Kritik richtete sich vor allem gegen die als Angriffe auf ein liberales Rechtsverständnis wahrgenommene Infragestellung der Bedeutung von Objektivität, Neutralität und Universalismus, wobei besonders befürchtet wurde, die CRT würde zu einer Zersplitterung des gesellschaftlichen Zusammenhalts durch den Fokus auf einzelne Gruppen führen. Gegen Ende der 1990er Jahre schrieb beispielsweise der Richter Richard Posner, Anhänger der CRT seien „Geisteskranke“, die „den Postmodernismus mit Haut und Haaren geschluckt haben.“[16] Der Jura-Professor Randall Kennedy, der selbst zu juristischer Benachteiligung von Afro-Amerikanern forscht und in vielen Punkten mit CRT-Vertretern übereinstimmt,[8] warf der CRT vor, Komplikationen zu vernachlässigen, die ihre Schlüsse in Frage stellten, und nicht überzeugend zu argumentieren, dass es innerhalb der Rechtswissenschaft zu Benachteiligung von nicht-weißen Wissenschaftlern komme.[27] Besonders einflussreiche Kritik gegen CRT stammte von Daniel A. Farber und Suzanna Sherry, die sie durch einen „radikalen Multikulturalismus“ geprägt sehen, der tendenziell antisemitische Implikationen mit sich bringe und die Rolle asiatischer Amerikaner nicht ausreichend berücksichtige. Leistung erscheine zudem auch innerhalb des Felds nur als Ergebnis von Privilegien, was zu einer „Subkultur, in der Bildung und andere Zeichen von Leistung als Ausdrücke von ,Weißsein‘ zurückgewiesen werden“, führen könnte. Sie betonen aber, dass es innerhalb der CRT auch viele hilfreiche Ansätze gebe, mit denen der Dialog lohne.[28] Von Vertretern der CRT wurde Farber und Sherry wiederum vorgeworfen, ungenau zu argumentieren und CRT falsch darzustellen.[8] Weitere Kritik richtete sich dagegen, dass einige CRT-Vertreter Methoden des Storytellings, also die Inklusion von Narrativen wie autobiographischen Geschichten, Parabeln oder fiktionalen Werken in die rechtswissenschaftliche Forschung, anwenden. Die Befürworter der Methode heben ihre pädagogische Funktion hervor, weil Geschichten Rassismus anschaulich darstellen könnten. Einige Critical Race Theorists argumentieren außerdem, dass Geschichten bei den Lesern eine stärkere Resonanz erzeugen könnten als Statistiken und strenge Analysen und dass sie die Idee, dass es eine einzige, objektive Wahrheit geben könne, wirksam in Frage stellten und nichtweißen Menschen zeigen könnten, dass andere Menschen ihre Erfahrungen teilen. Kritiker hingegen verweisen auf das Problem, dass sich ausgehend von Geschichten nur schwer Verallgemeinerungen ableiten lassen könnten, dass Geschichten versuchten, emotional statt rational zu überzeugen, dass sich aus Geschichten keine klaren Regeln ableiten ließen und dass persönliche Geschichten das Äußern von Kritik erschwerten, weil diese nun leicht als Kritik an der erzählenden Person gedeutet werden könne.[16] Die Jura-Professorin Eleanor Marie Brown argumentierte, dass CRT große Beiträge zur Rechtswissenschaft geleistet habe und dass viele Kritikpunkte an der Disziplin sich auf eher unwichtige Aspekte der CRT bezögen, wofür sie einen fehlenden Austausch zwischen CRT-Vertretern und Kritikern verantwortlich macht. Es gelte, wahrzunehmen, wie sich weiße Einstellungen gegenüber Rassismus entwickelt hätten, um gegenseitige Vorurteile abzubauen und den Austausch zu fördern.[10] |

学術的受容 人種と人種差別の強調は、他の視点を持つ批評家からはしばしば見当違い、あるいは危険とさえ受け取られている[6]。 理論学派の中では、CRTは本質主義的な概念を表しており、交差的なアプローチを強化すべきだという批判がなされている。CRTは黒人の視点に強く焦点を 当てすぎており、例えばネイティブ・アメリカンの視点を軽視しているという批判に応えて、CRTの多くのサブディシプリンやストランドが、これらのグルー プを考慮に入れて発展した[10]。 熱心な批判は、とりわけ、法のリベラルな理解に対する攻撃と受け止められたものに向けられており、客観性、中立性、普遍性の重要性が疑問視され、特に、 CRTが個々の集団に焦点を当てることによって社会的結束の分断につながることが懸念されていた。例えば、1990年代末には、判事のリチャード・ポズ ナーが、CRTの支持者は「ポストモダニズムを丸呑みした狂人」であると書いた。 「自身もアフリカ系アメリカ人に対する法的差別を研究しており、多くの点でCRTの支持者と同意見であるランダル・ケネディ法学教授は[8]、CRTがそ の結論に異議を唱えるような複雑な問題を軽視しており、法曹界において非白人学者に対する差別が起きていることを説得力を持って論じていないと非難した [27]。 [27]CRTに対する特に影響力のある批判は、ダニエル・A・ファーバーとスザンナ・シェリーによるものであり、彼らはCRTを、反ユダヤ主義的な意味 合いを持ちがちで、アジア系アメリカ人の役割を十分に考慮していない「急進的多文化主義」によって特徴づけられていると見ている。また、この分野では達成 は特権の結果としてしか現れないため、「教育やその他の達成の証が『白人らしさ』の表現として拒絶されるサブカルチャー」につながりかねない。しかし彼ら は、CRTの中にも対話する価値のある多くの有益なアプローチがあることを強調している[28]。CRTの代表者たちは、ファーバーとシェリーがCRTを 不正確に論じ、誤って表現していると再び非難した。 さらに、CRTの代表者の中には、ストーリーテリング手法、すなわち、自伝的物語、たとえ話、フィクション作品などの物語を法的研究に取り入れるという手 法を用いる者がいるという事実に対しても批判がなされた。この手法の支持者は、物語は人種差別を説明できるため、その教育的機能を強調している。また、批 判的人種理論家の中には、ストーリーは統計や厳密な分析よりも読者の心に強く響くことがあり、単一で客観的な真実が存在しうるという考えに効果的に挑戦 し、非白人にも他の人々が自分たちの経験を共有していることを示すことができると主張する者もいる。一方、批評家たちは、物語から一般論を導き出すのは困 難であること、物語は理性的ではなく感情的に納得させようとするものであること、物語から明確なルールを導き出すことはできないこと、そして個人的な物語 は、その物語を語る人物への批判と解釈されやすくなるため、批判を表明するのが難しくなるという問題点を指摘している。 法学部のエレノア・マリー・ブラウン教授は、CRTは法学に多大な貢献をしてきたとし、CRTに対する多くの批判はCRTの重要でない部分に関連してお り、その原因はCRTの代表者と批判者の間の交流の欠如にあると主張した。相互の偏見を減らし、交流を促進するためには、人種差別に対する白人の態度がど のように発展してきたかを認識することが重要である[10]。 |

| (Neo-)Marxistische Kritik Obwohl CRT zumindest teilweise durch neomarxistische Gedanken geprägt wurde, entwickelten sich aus dem marxistischen Fokus auf Klassen und dem CRT-Fokus auf race Spannungen, insbesondere in Hinblick auf das Konzept der White Supremacy.[29][30] So kritisiert z. B. Mike Cole den Vorrang von race vor sozialer Klasse bei der Beschreibung von gesellschaftlichen Gegensätzen sowie eine zu geringe Beachtung von politischen und materiellen Bedingungen für Rassismus. Für Cole sind Rassismus und die (sozial konstruierte) „Rassifizierung“ eng mit dem Kapitalismus verbunden, der eine solche Spaltung der Arbeiterklasse als Teile-und-Herrsche-Strategie verfolge. Jedoch sei eine Einheit der Arbeiterklasse notwendig, um sich diesem System entgegenzustellen, wofür er die von der CRT vertretenen Konzepte wie White Supremacy eher als hinderlich ansieht. Das Konzept erlaube es zudem nicht, Rassismus zwischen nicht-weißen Akteuren zu verstehen, entspreche nicht dem Alltagsverständnis und könne die Motivation Weißer, sich gegen Rassismus zu engagieren, schwächen.[31][30] Vertreter der CRT verwiesen auf die Möglichkeit, marxistische Analysen in die CRT zu inkorporieren und durch Ansätze der CRT zu erweitern. Dass Autoren wie W.E.B. DuBois und Frantz Fanon, die Cole (ohne diese Auswahl weiter zu begründen) als Vordenker der CRT sieht, sich explizit auf marxistische Theorien bezogen, lasse die These einer Unvereinbarkeit der Theorien fragwürdig erscheinen.[12][32][30] Auch Cole stellt heraus, dass die Beiträge der CRT progressive Politik unterstützen könnten, wenn ihre Stärken durch marxistische Analysen erweitert würden.[33] |

(新)マルクス主義批判 CRTは少なくとも部分的にはネオ・マルクス主義の思想によって形成されていたが、階級に焦点を当てたマルクス主義と人種に焦点を当てたCRTから、特に 白人至上主義の概念に関して緊張が生まれた。コールにとって、人種差別と(社会的に構築された)「人種化」は、分断統治戦略として労働者階級の分断を追求 する資本主義と密接に結びついている。しかし、この体制に対抗するためには労働者階級の団結が必要であり、そのためには白人至上主義のようなCRTが提唱 する概念は妨げになると彼は考えている。この概念はまた、非白人行為者間の人種主義 を理解することを許さず、日常的な理解に対応せず、人種主義に反対する白人の動機づけを弱める可能性がある[31][30]。W.E.B.デュボイスやフ ランツ・ファノンのような著者が(この選択をさらに正当化することなく)CRTのパイオニアであると見なしており、マルクス主義の理論に明確に言及してい るという事実は、理論の非互換性というテーゼを疑わしいものにしている[12][32][30]。 コールはまた、CRTの貢献は、その長所がマルクス主義の分析によって拡張されれば進歩的な政治を支援することができると強調している。 |

| Politische Kontroversen Schon 1997 stellte Charles R. Lawrence III fest, dass es seit Beginn der CRT energische Angriffe gegen sie gegeben habe, die er als Teil eines „durch die Rechten geführten ideologischen Kriegs“ bezeichnete.[34] Insbesondere nach der amerikanischen Präsidentschaftswahl 2020 nahm die Intensität der Auseinandersetzung zu.[35] Im öffentlichen Diskurs sind Missverständnisse über CRT (z. B. die falsche Annahme, dass CRT alle weißen Menschen als Rassisten betrachte) verbreitet.[6] In einer Umfrage der Agentur Reuters konnten nur 5 % der befragten US-Amerikaner, die angaben, CRT zu kennen, alle sieben gestellten Fragen zum Thema korrekt beantworten, nur etwa ein Drittel beantwortete fünf von sieben Fragen korrekt.[36] Häufig richtet sich die Kritik auch gegen Ansätze wie Antirassismus-Trainings oder gegen Personen wie Ibram X. Kendi oder Robin DiAngelo, die nicht der CRT im engeren Sinne als rechtswissenschaftliches Feld zugeordnet werden[37] und die in rechtswissenschaftlichen Fachzeitschriften, in denen Beiträge aus der CRT meistens erscheinen, nur selten zitiert werden.[35] Christopher Rufo vom christlich-konservativen Discovery Institute, der als wichtige Figur hinter der Gegenbewegung zu CRT gilt, sieht diese als „Bedrohung der amerikanischen Lebensweise“.[22] Rufo behauptete ohne Begründung im Gespräch mit dem New Yorker, dass CRT „der perfekte Buhmann“ sei, um konservative US-Amerikaner im Kulturkampf um den Umgang mit Rassismus zu mobilisieren.[38] Auf Twitter schrieb er: „Wir haben den Begriff ‚Critical Race Theory‘ in die öffentliche Diskussion eingebracht und verstärken nun seine negative Wahrnehmung.“[1] Ziel sei es, „dass die Öffentlichkeit irgendetwas Verrücktes in der Zeitung liest und denkt ‚Critical Race Theory‘“.[35] Laut der Jura-Professorin Khiara Bridges hätten diese Versuche unsachlichen und unbelegten Framings insofern Erfolg gezeigt, als dass weite Teile der US-Öffentlichkeit unter Critical Race Theory nicht mehr eine rechtswissenschaftliche Theorie oder ein intellektuelles Werkzeug verstehen würden. Der Begriff sei vielmehr zu einem leeren Signifikanten geworden, der von verschiedenen Akteuren mit verschiedenen Bedeutungen versehen werde. Für die politische Rechte stehe er inzwischen für „jeden Gedanken, der es wagt vorzuschlagen, dass race heute noch eine bedeutungsvolle Kategorie ist.“[35] Laut David Theo Goldberg fungiere die Bezeichnung für „jegliches Reden über Rasse und Rassismus, als ein Schreckgespenst, das ‚Multikulturalismus‘, ‚Wokeism‘, ‚Antirassismus‘ und ‚Identitätspolitik‘ in einen Topf wirft.“[37] Victor Ray bezeichnet sie als Dog Whistle, die für eine Vielzahl von mit People of Color assoziierten vermeintlichen Problemen stehe.[39] |

政治的論争 1997年の時点で、チャールズ・R・ローレンス3世は、CRTの設立以来、CRTに対する激しい攻撃があったことを指摘し、それは「右派が仕掛けたイデ オロギー戦争」の一環であると述べている[34]。論争の激しさは、特に2020年の米国大統領選挙後に増した[35]。 CRTに関する誤解(例えば、CRTはすべての白人を人種差別主義者とみなしているという誤った思い込み)は、公の言説の中で広まっている[6]。 ロイターの調査では、CRTを知っていると答えた米国の回答者のうち、CRTに関する7つの質問にすべて正しく答えることができたのはわずか5%であり、 7つの質問のうち5つに正しく答えることができたのは3分の1程度であった[36]。批判はまた、反人種主義トレーニングのようなアプローチや、イブラ ム・X. KendiやRobin DiAngeloのような、法学分野としての狭義のCRTに配属されておらず[37]、CRTからの論文が通常掲載される法学ジャーナルで引用されること はほとんどない[35]。 キリスト教保守派であるディスカバリー研究所のクリストファー・ルフォは、CRTを「アメリカの生活様式に対する脅威」[22]とみなしている。ルフォは 『ニューヨーカー』誌のインタビューで、CRTは人種差別にどう対処すべきかをめぐる文化戦争において保守的なアメリカ人を動員するための「完璧な厄介 者」であると正当性もなく主張している[38]。 その狙いは、「一般市民が新聞でおかしなことを読んで『批判的人種理論』と思うようにすること」[35]である。キアラ・ブリッジス法学教授によれば、客 観的で根拠のないフレーミングのこうした試みは、批判的人種理論が法学的理論や知的ツールであると米国民の大部分がもはや理解していないという点で成功し ている。その代わりに、この用語は空虚な記号となり、異なるアクターによって異なる意味を与えられている。政治的右派にとって、この言葉は今や「人種が今 日でも意味のあるカテゴリーであることをあえて示唆するあらゆる思想」を意味する。 デイヴィッド・セオ・ゴールドバーグによれば、この用語は「人種と人種差別に関するあらゆる話、『多文化主義』、『ウォーキズム』、『反人種主義』、『ア イデンティティ政治』をひとまとめにした妖怪」として機能している。 |

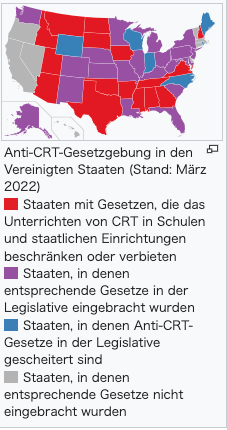

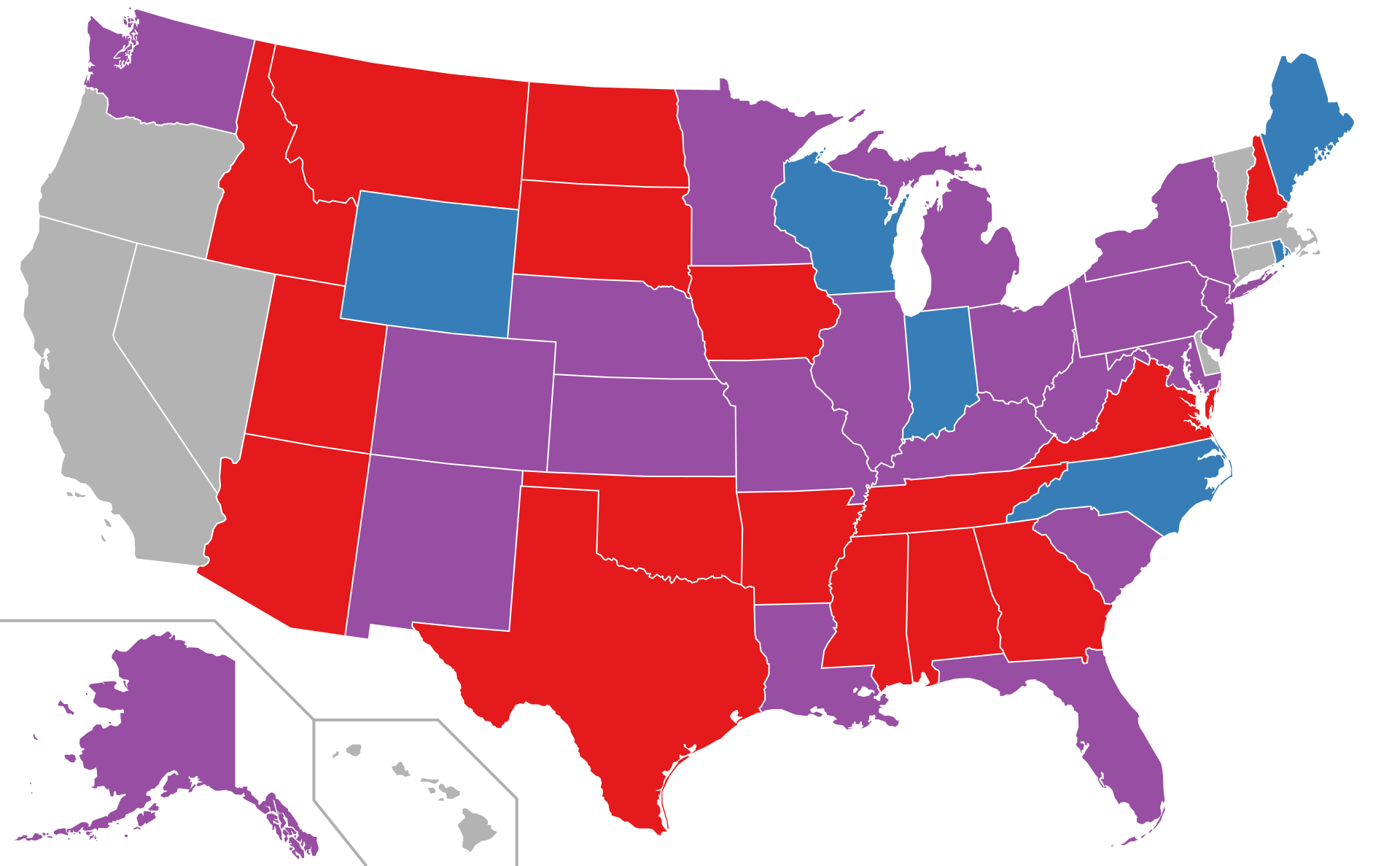

Auseinandersetzung über CRT an

Schulen und Universitäten Anti-CRT-Gesetzgebung in den Vereinigten Staaten (Stand: März 2022) Staaten mit Gesetzen, die das Unterrichten von CRT in Schulen und staatlichen Einrichtungen beschränken oder verbieten Staaten, in denen entsprechende Gesetze in der Legislative eingebracht wurden Staaten, in denen Anti-CRT-Gesetze in der Legislative gescheitert sind Staaten, in denen entsprechende Gesetze nicht eingebracht wurden  CRT wurde vielfach von konservativen Politikern attackiert: US-Präsident Donald J. Trump, der Rufos Aufrufe gegen CRT in Tucker Carlsons Show auf Fox News gesehen hatte,[40] bezeichnete CRT als „toxische Propaganda“, die das Land „zerstören“ würde.[4] In mehreren US-Bundesstaaten gab und gibt es politische Bemühungen, CRT aus den Curricula öffentlicher Schulen und Universitäten zu verbannen. Der republikanische Gouverneur von Florida Ron DeSantis sprach sich für ein Verbot aus, weil „die woke Klasse“ Kindern lieber „einander zu hassen beibringen“ wolle, „anstatt das Lesen“.[41] Dabei ist allerdings sogar umstritten, ob an Schulen tatsächlich CRT gelehrt wird.[42] In einer Umfrage der Association of American Educators gaben mehr als 96 % der befragten Lehrer an, dass an ihren Schulen nicht von ihnen erwartet würde, CRT zu unterrichten.[43] Die ACLU betrachtet Gesetzesvorhaben, die das Unterrichten von CRT verbieten sollen, als Versuch, Lehrer und Schüler zum Verstummen zu bringen.[42] Eine Vielzahl von Fachverbänden, darunter die American Historical Association, die American Association of University Professors, die American Federation of Teachers und PEN America, bezeichnete die Vorhaben in einem gemeinsamen Statement als gravierende Einschränkung der akademischen Freiheit mit dem Ziel, „das Lehren und Lernen über die Bedeutung von Rassismus in der Geschichte der Vereinigten Staaten zu unterdrücken“.[41] Viele juristische Experten gehen davon aus, dass die entsprechenden Gesetze nicht verfassungskonform seien.[40] Auch in Großbritannien, Australien und Frankreich gibt es Versuche, CRT und Aktivitäten, die der CRT zugerechnet werden, zu verbieten.[22][44] Einordnung der Kampagne gegen CRT Der Publizist Josef Joffe, der CRT als „Rückschritt und Irrweg zugleich“ bezeichnet, sieht im Widerstand gegen CRT „brave Bürger“, die sich „gegen Bildersturm und Agitprop“ wehrten.[45] Der Philosoph Jason Stanley bezeichnet die republikanischen Angriffe gegen CRT hingegen als „Rundumschlag gegen Wahrheit und Geschichte in der Bildung“.[46] David Theo Goldberg hält sie einerseits für eine Ablenkung „von der Ideenarmut der Rechten“ und andererseits für den Versuch, Rassismus zu neoliberalisieren, also auf persönliche Einstellungen und Vorurteile zu reduzieren, ohne gesellschaftliche Strukturen in den Blick zu nehmen. Zuletzt sei die politische Mobilisierung gegen CRT auch deshalb für Konservative attraktiv, weil sie „weiße Ressentiments entfacht, während sie von den Verwüstungen, die konservative Politik für alle außer die Reichen mit sich bringt, ablenkt“.[37] Der Politologe Cas Mudde hält die Kritik der Republikaner an CRT für Kritik an einem Strohmann. Er warnt Linke und Liberale davor, sich mit dieser oberflächlichen Kritik gemein zu machen und sich so zu „nützlichen Idioten der extremen Rechten zu machen“. In Gesetzesform gegossen würden die Attacken gegen CRT eine Gefährdung der US-amerikanischen Demokratie darstellen.[47] Victor Ray hält es für ironisch, dass sich in der moralischen Panik viele Befunde der CRT, etwa über die zentrale Bedeutung von Rassismus für die amerikanische Gesellschaft, bestätigten.[39] |

学校・大学でのCRTに関する議論 【赤】米国における反CRT法(2022年3月現在) 【紫】学校や州機関におけるCRT教育を制限または禁止する法律がある州 【青】対応する法案が議会に提出された州 【灰】反CRT法案が議会で否決された州 そのような法案が提出されていない州  CRTは、保守的な政治家によって広く攻撃されてきた: ドナルド・J・トランプ米大統領は、フォックス・ニュースのタッカー・カールソンの番組でルフォがCRTに反対する呼びかけを見たことがあり[40]、 CRTを「有害なプロパガンダ」であり、国を「破壊する」と呼んだ[4]。米国のいくつかの州では、公立学校や大学のカリキュラムからCRTを禁止しよう とする政治的な取り組みが行われており、現在も行われている。共和党のフロリダ州知事ロン・デサンティスは、「識者層」は「子供たちに読書を教える」より もむしろ「子供たちに憎しみ合うことを教える」だろうという理由で、禁止に賛成すると発言した[41]。しかし、CRTが実際に学校で教えられているかど うかについては論争さえある。 [42] 米国教育者協会の調査では、調査対象となった教師の96%以上が、自分の学校でCRTを教えることは期待されていないと回答している。 43] ACLUは、CRTの教育を禁止する法律案を、教師と生徒を黙らせようとする試みとみなしている。 [42]アメリカ歴史学会、アメリカ大学教授協会、アメリカ教員連盟、PENアメリカを含む多くの専門家団体は共同声明の中で、この計画は「アメリカ合衆 国の歴史における人種差別の意味についての教育と学習を抑制する」ことを目的とした学問の自由の重大な制限であると述べている[41]。 多くの法律専門家は、関連する法律は合憲ではないと信じている。] イギリス、オーストラリア、フランスでもCRTやCRTに関連する活動を禁止しようとする動きがあった[22][44]。 CRT反対キャンペーンの分類 ジャーナリストのヨゼフ・ヨッフェは、CRTを「退行であると同時に異常」であるとし、CRTに対する抵抗運動を「イコノクラスムとアジトプロップから」 自らを守った「品行方正な市民」と見ている[45]。一方、哲学者のジェイソン・スタンリーは、CRTに対する共和主義的な攻撃を「教育における真実と歴 史に対する徹底的な攻撃」と表現している。 [デイヴィッド・セオ・ゴールドバーグは、CRTへの攻撃を、一方では「右派の思想の貧困からの」目くらましであり、他方では人種差別を新自由主義化する 試み、すなわち社会構造を考慮に入れずに個人的な態度や偏見に還元する試みであると考えている。最後に、CRTに対する政治的動員は保守派にとっても魅力 的であり、それは「保守的な政策が富裕層以外のすべての人々にもたらす荒廃から目をそらしながら、白人の憤りを煽る」からである[37]。政治学者のカ ス・マッデは、共和党のCRT批判は藁人形に対する批判であると考えている。彼は、左翼やリベラルがこのような表面的な批判に加わることで、自分たちが 「極右の役に立つ馬鹿」になってしまうことに警鐘を鳴らしている。ビクター・レイは、アメリカ社会における人種差別の中心的重要性など、CRTの発見の多 くがモラル・パニックの中で確認されたことは皮肉だと考えている。 |

| Literatur Allgemein Francisco Valdes, Jerome McCristal Culp, und Angela P. Harris (Hg.): Crossroads, Directions, and a New Critical Race Theory. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 2002. ISBN 978-1-56639-930-2 Kristina Lepold und Marina Martinez Mateo (Hg.): Schwerpunkt: Critical Philosophy of Race, in: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie 67. 4 (2019) Anthologien Kimberlé Crenshaw et al. (Hrsg.): Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement, New Press, New York 1996 Richard Delagado, Jean Stefancic : critical race theory. the cutting edge, Temple University Press, Philadelphia 3. Auflage 2013 Einführungen Jean Stefancic, Richard Delgado: Critical Race Theory: An Introduction. 3. Aufl., New York University Press, New York 2017. ISBN 978-1-4798-0276-0 Alessandra Raengo: Critical Race Theory and Bamboozled (Film Theory in Practice), Bloomsbury, New York etc. 2016, ISBN 978-1-5013-0579-5 Weblinks Linda Martín Alcoff: Critical Philosophy of Race. In: Edward N. Zalta (Hrsg.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. |

全般 Francisco Valdes, Jerome McCristal Culp, und Angela P. Harris (Hg.): Crossroads, Directions, and a New Critical Race Theory. Temple University Press, Philadelphia 2002. ISBN 978-1-56639-930-2 Kristina Lepold und Marina Martinez Mateo (Hg.): Schwerpunkt: 人種批評哲学, in: Deutsche Zeitschrift für Philosophie 67. 4 (2019) アンソロジー キンバーレ・クレンショウ他(Hrsg:) 批判的人種理論: The Key Writings That Formed the Movement, New Press, New York 1996(クリティカル・レース・セオリー:運動を形成した重要な著作)。 リチャード・デラガド、ジーン・ステファンチック:批判的人種理論:最先端、テンプル大学出版、フィラデルフィア 3. 2013年 はじめに ジャン・ステファンチッチ、リチャード・デルガド 批判的人種理論: イントロダクション 3. Aufl., New York University Press, New York 2017. ISBN 978-1-4798-0276-0 アレッサンドラ・ラエンゴ Critical Race Theory and Bamboozled (Film Theory in Practice), Bloomsbury, New York 他。2016, ISBN 978-1-5013-0579-5 ウェブリンク リンダ・マルティン・アルコフ 人種の批評哲学。In: Edward N. Zalta (Hrsg.): Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_Race_Theory |

|

| Critical race theory (CRT Critical race theory (CRT) is an interdisciplinary academic field focused on the relationships between social conceptions of race and ethnicity, social and political laws, and media. CRT also considers racism to be systemic in various laws and rules, and not only based on individuals' prejudices.[1][2] The word critical in the name is an academic reference to critical theory rather than criticizing or blaming individuals.[3][4] CRT is also used in sociology to explain social, political, and legal structures and power distribution as through a "lens" focusing on the concept of race, and experiences of racism.[5][6] For example, the CRT conceptual framework examines racial bias in laws and legal institutions, such as highly disparate rates of incarceration among racial groups in the United States.[7] A key CRT concept is intersectionality—the way in which different forms of inequality and identity are affected by interconnections of race, class, gender, and disability.[8] Scholars of CRT view race as a social construct with no biological basis.[9][10] One tenet of CRT is that racism and disparate racial outcomes are the result of complex, changing, and often subtle social and institutional dynamics, rather than explicit and intentional prejudices of individuals.[10][3][11] CRT scholars argue that the social and legal construction of race advances the interests of white people[9][12] at the expense of people of color,[13][14] and that the liberal notion of U.S. law as "neutral" plays a significant role in maintaining a racially unjust social order,[15] where formally color-blind laws continue to have racially discriminatory outcomes.[16] CRT began in the United States in the post–civil rights era, as 1960s landmark civil rights laws were being eroded and schools were being re-segregated.[17][18] With racial inequalities persisting even after civil rights legislation and color-blind laws were enacted, CRT scholars in the 1970s and 1980s began reworking and expanding critical legal studies (CLS) theories on class, economic structure, and the law[19] to examine the role of US law in perpetuating racism.[20] CRT, a framework of analysis grounded in critical theory,[21] originated in the mid-1970s in the writings of several American legal scholars, including Derrick Bell, Alan Freeman, Kimberlé Crenshaw, Richard Delgado, Cheryl Harris, Charles R. Lawrence III, Mari Matsuda, and Patricia J. Williams.[22] CRT draws from the work of thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, and W. E. B. Du Bois, as well as the Black Power, Chicano, and radical feminist movements from the 1960s and 1970s.[22] Academic critics of CRT argue it is based on storytelling instead of evidence and reason, rejects truth and merit, and undervalues liberalism.[17][23] Since 2020, conservative US lawmakers have sought to ban or restrict the instruction of CRT education in primary and secondary schools,[3][24] as well as relevant training inside federal agencies.[25] Advocates of such bans argue that CRT is false, anti-American, villainizes white people, promotes radical leftism, and indoctrinates children.[17][26] Advocates of bans on CRT have been accused of misrepresenting its tenets, and of having the goal to broadly silence discussions of racism, equality, social justice, and the history of race.[27][28] |

批判的人種理論(Critical Race

Theory、CRT) 批判的人種理論(Critical Race Theory、CRT)とは、人種や民族に対する社会的概念、社会的・政治的法、メディアとの関係に焦点を当てた学際的な学問分野である。また、CRTは 人種差別が個人の偏見に基づくだけでなく、様々な法律やルールの中に制度的に存在すると考える[1][2]。名前にあるcriticalという単語は、個 人を批判したり非難したりするのではなく、批判的な理論に対する学術的な言及である[3][4]。 CRTは社会学においても、人種という概念や人種差別の経験に焦点を当てた「レン ズ」を通して、社会的、政治的、法的な構造や権力の分配を説明するために 使用されている[5][6]。例えば、CRTの概念的枠組みは、アメリカにおける人種グループ間で非常に格差のある収監率など、法律や法的 制度における人 種的偏見を検証している。 [7]CRTの重要な概念は交差性(intersectionality)であり、人種、階級、ジェンダー、障害の相互関係によって様々な形態の不平等や アイデンティティが影響を受ける方法である[8]。 [9][10]CRTの1つの信条は、人種差別と人種間の格差は、個人の明確で意図 的な偏見というよりも、複雑で変化し、しばしば微妙な社会的・制度的力 学の結果であるということである。 [10][3][11]CRTの研究者たちは、人種の社会的・法的構築は有色人種を犠牲にして白人の利益[9][12]を促進し[13][14]、米国の 法律が「中立」であるというリベラルな概念は人種的に不公正な社会秩序を維持する上で重要な役割を果たしており[15]、そこでは形式的にはカラーブライ ンドな法律が 人種差別的な結果をもたらし続けていると主張している[16]。 ※カラーブラインドな法律とは、「人種」の違いを意図的に無視して人種差を超えて「平等に取り扱っている」かのように振る舞う法律体系のこと。 CRTは1960年代の画期的な公民権法が侵食され、学校が再分別され つつあった公民権後の時代に米国で始まった[17][18]。公民権法やカラーブラインドな法が制 定された後も人種的不平等が存続していることから、1970年代から1980年代に かけてCRTの研究者たちは人種差別の永続における米国法の役割を検討 するために、階級、経済構造、法に関する批判的法学研究(CLS)の理論を再編集し、拡張し始めた[19]。 [20] 批判的理論に基づく分析の枠組みであるCRTは[21]、1970年代半ばにデリック・ベル、アラン・フリーマン、キンバレ・クレンショー、リチャード・ デルガド、シェリル・ハリス、チャールズ・R. CRTは、アントニオ・グラムシ、ソジャーナー・トゥルース、フレデリック・ダグラス、W・E・B・デュボワなどの思想家や、1960年代から1970年 代にかけてのブラックパワー運動、チカーノ運動、急進的なフェミニスト運動などの活動を参考にしている[22]。 CRTに対する学術的な批判者は、CRTは証拠や理性の代わりにストー リーテリングに基づいており、真実や功利を否定し、リベラリズムを過小評価していると主張 している[17][23]。 2020年以降、米国の保守的な議員 たちは、初等・中等学校におけるCRT教育の指導を禁止または制限しようとしている[3][24]。 [25]このような禁止の擁護者はCRTは虚偽であり、反アメリカ的であり、白人を悪者扱いし、急進的な左翼主義を促進し、子供たちを教化していると主張 している[17][26]。CRTの禁止の擁護者はその信条を誤って伝えており、人種差別、平等、社会正義、人種の歴史についての議論を広く沈黙させる目 的を持っていると非難されている[27][28]。 |

| In his introduction to the

comprehensive 1995 publication of critical race theory's key writings,

Cornel West described CRT as "an

intellectual movement that is both particular to our postmodern (and

conservative) times and part of a long tradition of human resistance

and liberation."[29] Law professor Roy L. Brooks defined

critical race theory in 1994 as "a collection of critical stances

against the existing legal order from a race-based point of view".[30] [29]West, Cornel (1995). "Foreword" in Crenshaw, Kimberlé; Gotanda, Neil; Peller, Gary (eds.). Critical Race Theory: The Key Writings that Formed the Movement. The New Press. Gloria Ladson-Billings, who—along with co-author William Tate—had introduced CRT to the field of education in 1995,[31] described it in 2015 as an "interdisciplinary approach that seeks to understand and combat race inequity in society."[32] Ladson-Billings wrote in 1998 that CRT "first emerged as a counterlegal scholarship to the positivist and liberal legal discourse of civil rights."[33] In 2017, University of Alabama School of Law professor Richard Delgado, a co-founder of critical race theory,[citation needed] and legal writer Jean Stefancic define CRT as "a collection of activists and scholars interested in studying and transforming the relationship among race, racism, and power".[34] In 2021, Khiara Bridges, a law professor and author of the textbook Critical Race Theory: A Primer,[11] defined critical race theory as an "intellectual movement", a "body of scholarship", and an "analytical toolset for interrogating the relationship between law and racial inequality."[20] The 2021 Encyclopaedia Britannica described CRT as an "intellectual and social movement and loosely organized framework of legal analysis based on the premise that race is not a natural, biologically grounded feature of physically distinct subgroups of human beings but a socially constructed (culturally invented) category that is used to oppress and exploit people of colour."[17][35] |

コーネル・ウェストは1995年に出版された批判的人種理論の主要な著

作を包括的に紹介する中で、CRTを「ポストモダンの(そして保守的な)現代に特有

であると同時に、人間の抵抗と解放の長い伝統の一部でもある知的運動」[29]と表現している。法学教授のロイ・L・ブルックスは1994

年に批判的人種理論を「人種に基づく視点から既存の法秩序に対して批判的なスタンスを集めたもの」と定義している[30]。 1995年に共著者であるウィリアム・テイトとともにCRTを教育分野に導入したグロリア・ラドソン=ビリングスは[31]、2015年にCRTを「社会 における人種間の不公平を理解し、それに対抗しようとする学際的アプローチ」と表現している[32]。 ラドソン=ビリングスは1998年にCRTが「公民権に関する実証主義的でリベラルな法学的言説に対する対抗的な法学として最初に登場した」と書いている [33]。 2017年、批判的人種理論の共同創設者であるアラバマ大学ロースクール教授のリチャード・デルガド[要出典]と法律作家のジーン・ステファンチッチは CRTを「人種、人種差別、権力の関係を研究し、変革することに関心を持つ活動家と学者の集まり」と定義している[34]。 2021年、法学教授であり、教科書『批判的人種理論』の著者であるキアラ・ブリッジスは、CRTを「人種、人種差別、権力の関係を研究し、変革すること に関心を持つ活動家と学者の集まり」と定義している: 入門書」[11]であるキアラ・ブリッジスは、批判的人種理論を「知的運動」、「学問の体系」、「法と人種的不平等の関係を問うための分析ツールセット」 と定義している[20]。 2021年のブリタニカ百科事典は、CRTを「人種は人間の物理的に異なるサブグループの自然で生物学的に根拠のある特徴ではなく、有色人種を抑圧し搾取 するために使用される社会的に構築された(文化的に発明された)カテゴリーであるという前提に基づく、知的で社会的な運動であり、緩やかに組織された法的 分析の枠組み」と説明している[17][35]。 |

| ★上掲の「CRTの理論整理(英語ウィキペディアより)」で記載済 | ★上掲の「CRTの理論整理(英語ウィキペディアより)」で記載済 |

| Applications and adaptations Scholars of critical race theory have focused, with some particularity, on the issues of hate crime and hate speech. In response to the opinion of the US Supreme Court in the hate speech case of R.A.V. v. City of St. Paul (1992), in which the Court struck down an anti-bias ordinance as applied to a teenager who had burned a cross, Mari Matsuda and Charles Lawrence argued that the Court had paid insufficient attention to the history of racist speech and the actual injury produced by such speech.[91] Critical race theorists have also argued in favor of affirmative action. They propose that so-called merit standards for hiring and educational admissions are not race-neutral and that such standards are part of the rhetoric of neutrality through which whites justify their disproportionate share of resources and social benefits.[92][93][94] In his 2009 article "Will the Real CRT Please Stand Up: The Dangers of Philosophical Contributions to CRT", Curry distinguished between the original CRT key writings and what is being done in the name of CRT by a "growing number of white feminists".[95] The new CRT movement "favors narratives that inculcate the ideals of a post-racial humanity and racial amelioration between compassionate (Black and White) philosophical thinkers dedicated to solving America's race problem."[96] They are interested in discourse (i.e., how individuals speak about race) and the theories of white Continental philosophers, over and against the structural and institutional accounts of white supremacy which were at the heart of the realist analysis of racism introduced in Derrick Bell's early works,[97] and articulated through such African-American thinkers as W. E. B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, and Judge Robert L. Carter.[98] |

応用と適応 批判的人種理論の研究者たちは、ヘイトクライムとヘイトスピーチの問題に、いくつかの特殊性をもって焦点を当ててきた。R.A.V.対セントポール市のヘ イトスピーチ事件(1992年)における連邦最高裁判所の意見に対して、裁判所は十字架を燃やしたティーンエイジャーに適用された反偏見条例を取り下げた が、マリ・マツダとチャールズ・ローレンスは、裁判所は人種差別的言論の歴史とそのような言論によって生み出された実際の傷害に対して十分な注意を払って いな かったと主張した[91]。 批判的人種理論家もまた、アファーマティブ・アクションを支持している。彼らは、雇用や教育入学のためのいわゆるメリット基準は人種に中立的ではなく、そ のような基準は、白人が資源や社会的利益の不釣り合いな分配を正当化するための中立性のレトリックの一部であると提唱している[92][93][94]。 2009年の論文「Will the Real CRT Please Stand Up: The Dangers of Philosophical Contributions to CRT」において、カリーはオリジナルのCRTの主要な著作と「増え続ける白人フェミニスト」によってCRTの名の下に行われていることを区別している。 [新しいCRT運動は、「アメリカの人種問題の解決に献身する思いやりのある(黒人と白人の)哲学的思想家たちの間で、ポスト人種的人間性と人種的改善の 理想を植え付ける物語を好んでいる」[96]、 デリック・ベルの初期の著作で紹介され[97]、W・E・B・デュボイス、ポール・ロベソン、ロバート・L・カーター判事といったアフリカ系アメリカ人の 思想家たちを通して明確にされた人種主義のリアリズム分析の核心であった白人至上主義の構造的・制度的な説明に対して、彼らは言説(すなわち、個人が人種 についてどのように語るのか)と白人大陸哲学者たちの理論に関心を持っている[98]。 |