トーマス・クーン『科学革命の構造』ノート

On Thomas " The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions," 1962.

トーマス・クーン『科学革命の構造』ノート

On Thomas " The

Structure of Scientific Revolutions," 1962.

Discovery

commences with the awareness of anomaly, i.e., with the recognition

that nature has somehow violated the paradigm-induced expectations that

govern normal science. - Anomaly and

the Emergence of Scientific Discoveries

| The Structure of Scientific Revolutions

is a 1962 book about the history of science by the philosopher Thomas

S. Kuhn. Its publication was a landmark event in the history,

philosophy, and sociology of science. Kuhn challenged the then

prevailing view of progress in science in which scientific progress was

viewed as "development-by-accumulation" of accepted facts and theories.

Kuhn argued for an episodic model in which periods of conceptual

continuity and cumulative progress, referred to as periods of "normal

science", were interrupted by periods of revolutionary science. The

discovery of "anomalies" accumulating and precipitating revolutions in

science leads to new paradigms. New paradigms then ask new questions of

old data, move beyond the mere "puzzle-solving"[1] of the previous

paradigm, alter the rules of the game and change the "map" directing

new research.[2] |

『科学革命の構造』は、哲学者トーマス・S・クーンによる1962年の

科学史に関する著作である。その出版は科学史・科学哲学・科学社会学における画期的な出来事となった。クーンは当時主流だった科学進歩観、すなわち科学の

進歩を既成の事実や理論の「蓄積による発展」と見なす見解に異議を唱えた。クーンは、概念的連続性と累積的進歩の期間(「通常科学」の時期)が、革命的科

学の時期によって中断されるという、エピソード的モデルを主張した。科学における「異常」の発見が蓄積し、革命を引き起こすことで新たなパラダイムが生ま

れる。新たなパラダイムは古いデータに新たな問いを投げかけ、従来のパラダイムにおける単なる「パズル解き」[1]を超え、ゲームのルールを変え、新たな

研究を導く「地図」を変えるのである。[2] |

| For example, Kuhn's analysis of the Copernican Revolution emphasized that, in its beginning, it did not offer more accurate predictions of celestial events, such as planetary positions, than the Ptolemaic system, but instead appealed to some practitioners based on a promise of better, simpler solutions that might be developed at some point in the future. Kuhn called the core concepts of an ascendant revolution its "paradigms" and thereby launched this word into widespread analogical use in the second half of the 20th century. Kuhn's insistence that a paradigm shift was a mélange of sociology, enthusiasm and scientific promise, but not a logically determinate procedure, caused an uproar in reaction to his work. Kuhn addressed concerns in the 1969 postscript to the second edition. For some commentators The Structure of Scientific Revolutions introduced a realistic humanism into the core of science, while for others the nobility of science was tarnished by Kuhn's introduction of an irrational element into the heart of its greatest achievements. | 例えばクーンのコペルニクス的革命分析は、その初期段階において、惑星の位置など天体現象の予測精度がプトレマイオス体系を上回るわけではなく、将来的に 開発される可能性のあるより優れた簡潔な解決策を約束することで一部の実践者に訴求したと強調している。クーンは台頭する革命の中核概念を「パラダイム」 と呼び、この言葉を20世紀後半に広く比喩的に使われるようにした。パラダイム転換が社会学・熱意・科学的約束の混合物であって論理的に決定された手順で はないというクーンの主張は、彼の著作への反発として大騒ぎを引き起こした。クーンは1969年の第二版追記でこうした懸念に応えた。一部の評論家にとっ て『科学革命の構造』は科学の核心に現実的なヒューマニズムを導入した。一方で他の者にとっては、科学の偉業の核心に非合理的な要素を導入したことで、科 学の尊厳が損なわれたとされた。 |

| History The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was first published as a monograph in the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, then as a book by University of Chicago Press in 1962. In 1969, Kuhn added a postscript to the book in which he replied to critical responses to the first edition. A 50th Anniversary Edition (with an introductory essay by Ian Hacking)[3] was published by the University of Chicago Press in April 2012. Kuhn dated the genesis of his book to 1947, when he was a graduate student at Harvard University and had been asked to teach a science class for humanities undergraduates with a focus on historical case studies. Kuhn later commented that until then, "I'd never read an old document in science." Aristotle's Physics was astonishingly unlike Isaac Newton's work in its concepts of matter and motion. Kuhn wrote: "as I was reading him, Aristotle appeared not only ignorant of mechanics, but a dreadfully bad physical scientist as well. About motion, in particular, his writings seemed to me full of egregious errors, both of logic and of observation." This was in an apparent contradiction with the fact that Aristotle was a brilliant mind. While perusing Aristotle's Physics, Kuhn formed the view that in order to properly appreciate Aristotle's reasoning, one must be aware of the scientific conventions of the time. Kuhn concluded that Aristotle's concepts were not "bad Newton," just different.[4] This insight was the foundation of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.[5] Central ideas regarding the process of scientific investigation and discovery had been anticipated by Ludwik Fleck in Fleck (1935).[6] Fleck had developed the first system of the sociology of scientific knowledge. He claimed that the exchange of ideas led to the establishment of a thought collective, which, when developed sufficiently, separated the field into esoteric (professional) and exoteric (laymen) circles. Kuhn wrote the foreword to the 1979 edition of Fleck's book, noting that he read it in 1950 and was reassured that someone "saw in the history of science what I myself was finding there."[7] Kuhn was not confident about how his book would be received. Harvard University had denied his tenure a few years prior. By the mid-1980s, however, his book had achieved blockbuster status.[8] When Kuhn's book came out in the early 1960s, "structure" was an intellectually popular word in many fields in the humanities and social sciences, including linguistics and anthropology, appealing in its idea that complex phenomena could reveal or be studied through basic, simpler structures. Kuhn's book contributed to that idea.[9] One theory to which Kuhn replies directly is Karl Popper's "falsificationism," which stresses falsifiability as the most important criterion for distinguishing between that which is scientific and that which is unscientific. Kuhn also addresses verificationism, a philosophical movement that emerged in the 1920s among logical positivists. The verifiability principle claims that meaningful statements must be supported by empirical evidence or logical requirements. |

歴史 『科学革命の構造』は、最初に『統一科学国際百科事典』の単行本として出版され、その後1962年にシカゴ大学出版局から単行本として出版された。 1969年、クーンは、初版に対する批判的な反応に答える形で、この本にあとがきを加えた。2012年4月には、シカゴ大学出版局から50周年記念版(イ アン・ハッキングによる序論付き)[3]が出版された。 1947年、ハーバード大学の大学院生であったクーンは、人文系の学部生を対象に、歴史的事例研究に焦点を当てた科学の授業を担当することになった。クー ンは後に、それまで 「科学で古い文献を読んだことがなかった 」とコメントしている。アリストテレスの『物理学』は、物質と運動の概念において、アイザック・ニュートンの著作とは驚くほど異なっていた。クーンは次の ように書いている。「私が読んでいたとき、アリストテレスは力学に無知であっただけでなく、物理科学者としてもひどく劣っているように見えた。特に運動に ついて、彼の著作は論理的にも観察的にも、ひどい間違いに満ちているように私には思えた」。これは、アリストテレスが優れた頭脳の持ち主であったという事 実とは明らかに矛盾していた。アリストテレスの『物理学』を熟読するうちに、クーンは、アリストテレスの推論を正しく理解するためには、当時の科学的常識 を認識していなければならないという見解を得た。この洞察は『科学革命の構造』の基礎となった[5]。 科学的な調査や発見のプロセスに関する中心的な考え方は、ルドウィク・フレックによって『フレック』(1935年)の中で先取りされていた[6]。彼は、 アイデアの交換が思想集団の確立につながり、それが十分に発展すると、その分野が秘教的(専門家)なサークルと外教的(素人)なサークルに分かれると主張 した。クーンは1979年版のフレックの本の序文を書いており、1950年にこの本を読み、「私自身がそこに見出していたものを科学の歴史の中に見出して いる人がいる」と安心したと述べている[7]。 クーンは自分の本がどのように受け入れられるかについては自信がなかった。ハーバード大学は数年前、彼の終身在職権を拒否していた。しかし1980年代半 ばまでに、彼の著書は超大作の地位を獲得していた[8]。 クーンの著書が世に出た1960年代初頭、「構造」は言語学や人類学など、人文科学や社会科学の多くの分野で知的人気を博していた言葉であり、複雑な現象 が基本的で単純な構造によって明らかにされたり、研究されたりするという考え方に魅力を感じていた。クーンの著書はその考えに貢献した[9]。 クーンが直接反論している理論の一つはカール・ポパーの「反証主義」であり、科学的なものと非科学的なものを区別するための最も重要な基準として反証可能 性を強調している。クーンはまた、1920年代に論理実証主義者の間で生まれた哲学運動である検証主義も取り上げている。検証可能性原理は、意味のある記 述は経験的証拠や論理的要件によって裏付けられていなければならないと主張する。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions |

☆

この本(第2版、下記のpdfによる)の章立ては、 以下のとおりである。

| PREFACE (Kuhn_Revolutions.) |

序文︎_revolution_jap_Part1.pdf |

| I. INTRODUCTION: A ROLE FOR HISTORY | 1.導入部:歴史の役割 |

| II. THE ROUTE TO NORMAL SCIENCE | 2.通常科学(ノーマルサイエンス)の道

すじ |

| III. THE NATURE OF

NORMAL SCIENCE |

3.通常科学(ノーマルサイエンス)の本 性(=基本的性質) |

| IV. NORMAL SCIENCE

AS PUZZLE-SOLVING |

4.パズル解きゲームとしての通常科学 (ノーマルサイエンス) |

| V. THE PRIORITY OF

PARADIGMS |

5.パラダイム(論)の優位性 |

| VI. ANOMALY AND

THE EMERGENCE OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES |

6.異様性(アノマリー)と科学的発見の

登場 |

| VII. CRISIS AND

THE EMERGENCE OF SCIENTIFIC THEORIES |

7.危機と科学的理論の登場 |

| VIII. THE RESPONSE

TO CRISIS |

8.危機への反応=対応 kuhn_revolution_jap_Part2.pdf |

| IX. THE NATURE AND

NECESSITY OF SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTIONS |

9.科学革命の性質とその必要性(必然

性) |

| X. REVOLUTIONS AS

CHANGES OF WORLD VIEW |

10.世界観の変化としての革命 |

| XI. THE

INVISIBILITY OF REVOLUTIONS |

11.革命の不可視性 |

| XII. THE

RESOLUTION OF REVOLUTIONS |

12.革命の解決(解消) |

| XIII. PROGRESS

THROUGH REVOLUTIONS |

13.革命を通した進歩 |

| Postscript-1969 |

1969年のあとがき kuhn_revolution_jap_Part3.pdf |

トーマス・クーン(Thomas Kuhn,

1922-1996)によるパラダイム・チェインジ(パ

ラダイムの変更)こそが小文字の科学革命においておこることである。この場合の革命は、政治革命に似て、当該科学領域のものの見方(=科学の認識論)や方

法論(=科学の実践方法)が根本的に変わって、変わる前と変わった後には、断絶が生じているというものである。天動説から地動説への変化には、断絶がある

というのがもっともよく言われる例である。

トーマス・クーン(Thomas Kuhn,

1922-1996)によるパラダイム・チェインジ(パ

ラダイムの変更)こそが小文字の科学革命においておこることである。この場合の革命は、政治革命に似て、当該科学領域のものの見方(=科学の認識論)や方

法論(=科学の実践方法)が根本的に変わって、変わる前と変わった後には、断絶が生じているというものである。天動説から地動説への変化には、断絶がある

というのがもっともよく言われる例である。

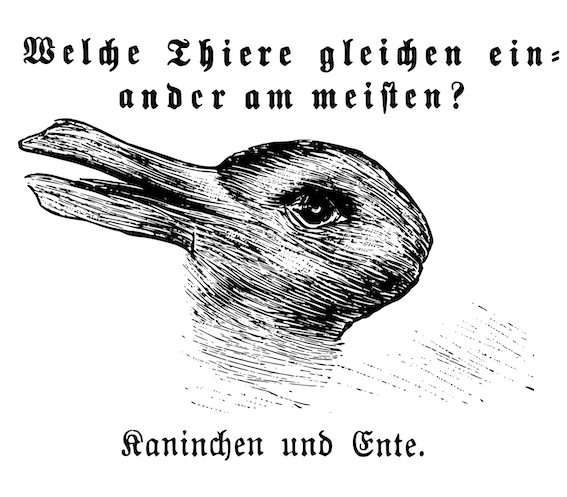

パラダイムとは、もと もとも文法規則による活用表の ようなルールの体系である。 革命的変化のない状態を、通常科学(ノーマル)サイエンスという。通常科学においては、学者はまさに品詞の活用 のように、ルー ルにしたがって、それがなんであるかを分析する。そこでは、微妙な問題や、解法の際は、そのようなルールにしたがって解く。したがって、ノーマルサイエン スにおける科学者の営為は、パズル解きのような、既約にしたがった手続きに従う。実験や検証もまた、その考え方の中から導かれる。このパラダイムの発想 は、トーマス・クーン自身の発言によれば、ニュートンの力学(=重力による落下速度は一定)を前提してしていると、アリストテレスの力学(=物体の落下速 度は質量に比例する)がさっぱりわからないというエピソードに代表される(『本質的緊張』『構造以来の道』)。また、野家啓一によると、ウィトゲンシュタインの 「アスペクト知覚」の考察(『探究』第二部xi章)——ジャストロウ図形においてウサギとアヒルの顔が同時に見えることはない。つまり2つの認識の間には 跳躍がある——が、その影響を与えたという(野家はハンソンの「観察の理論負荷」にもこのアスペクト知覚の考察が影響を与えたという)。

革命において、ルールによって解けない問題の発生は 重要であるが、多くの学者たちがそのアノマリーに直面しない限りは、例外として誰も真面目に取り扱わない。しかし、より多くの研究者による「アノマリーの 認識」だらけでにっちもさっちもいかなくなるとき、みんなは手詰まりになる。それをブレイクスルー(かのような)科学的手法や集団が、クーンがいうところ の「異常科学(アブノーマル・サイエンス)である。しかし、アブノーマルサイエンスに、みなが一斉にくら替えすることはまずありえない。科学者集団に対し てアノマリーのインパクトが多く、かつ、多くの科学者集団が、そのアノマリーに取り組まないと革命は進行しない。しかし、それが多数の科学者による集団改 宗の事態になれば、一気にアブノーマルサイエンスは、革命の様相を呈す。

かつてアブノーマルサイエンス(地動説)だったもの が、より改宗者を得て、最初は、中途半端な成果しかえなかったものが、次第に精緻化すると、そのサイエンスはノーマル化への道をすすむことになる。した がって、過去のノーマルサイエンスと、未来のノーマルサイエンスの間のパラダイムのコミュニケーションは不可能であり、両者の間には断絶がある。

パラダイム内における、研究者の間の理解可能な地平 を、通約可能だが、パラダイム間ではコミュニケーションできないことを「通約不可能性」と呼ぶ。

ざっと、このような説明が、クーンの科学革命の構造

のあらましである。したがって、クーンは、それ以前の、科学的真理はまがりなりにも漸進的に獲得されうるというカール・ポパーらの「反証可能性」の議論とは、そりがあわない。また、クーンの考え方を真面目

にうけると、科学革命を通して、人間は無知蒙昧から叡知あるものへと直線的に進むというわけでもない。あるのは、科学的認識論における断絶だけであるとい

う立場をとる。

「科学革命の構造」ならびに、イアン・ハッキングに よるその解説を翻訳紹介してくださった。京大哲学研究会からピックアップした キーワード集

●パラダイム概念(ウィキペディアのparadigm shiftよ り)

| Paradigm shift A paradigm shift, a concept identified by the American physicist and philosopher Thomas Kuhn, is a fundamental change in the basic concepts and experimental practices of a scientific discipline. Even though Kuhn restricted the use of the term to the natural sciences, the concept of a paradigm shift has also been used in numerous non-scientific contexts to describe a profound change in a fundamental model or perception of events. Kuhn presented his notion of a paradigm shift in his influential book The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1962). Kuhn contrasts paradigm shifts, which characterize a scientific revolution, to the activity of normal science, which he describes as scientific work done within a prevailing framework or paradigm. Paradigm shifts arise when the dominant paradigm under which normal science operates is rendered incompatible with new phenomena, facilitating the adoption of a new theory or paradigm.[1:Kuhn, Thomas (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. pp. 54] |

パ

ラダイムシフト パ ラダイムシフトとは、アメリカの物理学者・哲学者であるトーマス・クーンが提唱した概念で、ある科学分野の基本的な概念や実験方法が根本的に変わることを 指す。クーンはこの言葉を自然科学に限定して使用したが、パラダイムシフトの概念は非科学的な文脈でも数多く使用されており、基本的なモデルや事象の認識が大きく変化することを表している。クーンは『科学 革命の構造』(1962年)でパラダイムシフトの概念を提示した。クーンは、科学革 命を特徴づけるパラダイムシフトと、既存の枠組みやパラダイムの中で行われる科学的作業である通常の科学とを対比させている。パラダイムシ フトとは、通常の科学が支配しているパラダイムが新しい現象と相容れず、新しい理論やパラダイムの採用が促進される場合に生じる。 |

| Kuhn

acknowledges having used the term "paradigm" in two different meanings.

In the first one, "paradigm" designates what the members of a certain

scientific community have in common, that is to say, the whole of

techniques, patents and values shared by the members of the community.

In the second sense, the paradigm is a single element of a whole, say

for instance Newton’s Principia, which, acting as a common model or an

example... stands for the explicit rules and thus defines a coherent

tradition of investigation. Thus the question is for Kuhn to

investigate by means of the paradigm what makes possible the

constitution of what he calls "normal science". That is to say, the

science which can decide if a certain problem will be considered

scientific or not. Normal science does not mean at all a science guided

by a coherent system of rules, on the contrary, the rules can be

derived from the paradigms, but the paradigms can guide the

investigation also in the absence of rules. This is precisely the

second meaning of the term "paradigm", which Kuhn considered the most

new and profound, though it is in truth the oldest.[2: Agamben,

Giorgio. "What is a Paradigm?] |

クーンは、「パラダイム」という言葉を2つの異なる意味で使ったことを

認めている。最初の意味では、「パラダイム」は、ある科学コミュニティのメンバーが

共通に持つもの、つまり、そのコミュニティのメンバーが共有する技術、特許、価値観の全体を指す。もうひとつの意味では、パラダイムは全体

の中の一つの要素であり、例えばニュートンの『プリンキピア』のように、共通のモデ

ルや例として機能し、明示的な規則を表し、それによって調査の首尾一貫した伝統を定義するものである。このように、クーンはパラダイムを用

いて、彼が「ノーマルサイエンス(正常な科学)」と呼ぶものの構成を可能にするものを調査することが問題だとする。つまり、ある問題が科学的であるとみなされるかどうかを決定できる科学である。通常の科学とは、一貫し

た規則の体系によって導かれる科学を意味するのではなく、逆に規則はパラダイムから導き出されるが、パラダイムは規則がない場合にも調査を導くことができ

るのである。これはまさに「パラダイム」という言葉の第2の意味であり、クーンはこれを最も新しく深遠なものと考えているが、実際には最も

古いものである。 |

| ウィキペディアのparadigm shiftよ り | |

| Synopsis | あらすじ |

| Basic approach | 基本的アプローチ |

| Kuhn's approach to the history and philosophy of science focuses on

conceptual issues like the practice of normal science, influence of

historical events, emergence of scientific discoveries, nature of

scientific revolutions and progress through scientific revolutions.[10]

What sorts of intellectual options and strategies were available to

people during a given period? What types of lexicons and terminology

were known and employed during certain epochs? Stressing the importance

of not attributing traditional thought to earlier investigators, Kuhn's

book argues that the evolution of scientific theory does not emerge

from the straightforward accumulation of facts, but rather from a set

of changing intellectual circumstances and possibilities.[11] Kuhn did not see scientific theory as proceeding linearly from an objective, unbiased accumulation of all available data, but rather as paradigm-driven: The operations and measurements that a scientist undertakes in the laboratory are not "the given" of experience but rather "the collected with difficulty". They are not what the scientist sees—at least not before his research is well advanced and his attention focused. Rather, they are concrete indices to the content of more elementary perceptions, and as such they are selected for the close scrutiny of normal research only because they promise opportunity for the fruitful elaboration of an accepted paradigm. Far more clearly than the immediate experience from which they in part derive, operations and measurements are paradigm-determined. Science does not deal in all possible laboratory manipulations. Instead, it selects those relevant to the juxtaposition of a paradigm with the immediate experience that that paradigm has partially determined. As a result, scientists with different paradigms engage in different concrete laboratory manipulations.— Kuhn (1962, p. 216) Historical examples of chemistry Kuhn explains his ideas using examples taken from the history of science. For instance, eighteenth-century scientists believed that homogenous solutions were chemical compounds. Therefore, a combination of water and alcohol was generally classified as a compound. Nowadays it is considered to be a solution, but there was no reason then to suspect that it was not a compound. Water and alcohol would not separate spontaneously, nor will they separate completely upon distillation (they form an azeotrope). Water and alcohol can be combined in any proportion. Under this paradigm, scientists believed that chemical reactions (such as the combination of water and alcohol) did not necessarily occur in fixed proportion. This belief was ultimately overturned by Dalton's atomic theory, which asserted that atoms can only combine in simple, whole-number ratios. Under this new paradigm, any reaction which did not occur in fixed proportion could not be a chemical process. This type of world-view transition among the scientific community exemplifies Kuhn's paradigm shift.[12] Copernican Revolution  Motion of the Sun (yellow), Earth (blue), and Mars (red). At left, Copernicus's heliocentric motion. At right, traditional geocentric motion, including the retrograde motion of Mars. For simplicity, Mars's period of revolution is depicted as 2 years instead of 1.88, and orbits are depicted as perfectly circular or epitrochoid. Main article: Copernican Revolution A famous example of a revolution in scientific thought is the Copernican Revolution. In Ptolemy's school of thought, cycles and epicycles (with some additional concepts) were used for modeling the movements of the planets in a cosmos that had a stationary Earth at its center. As accuracy of celestial observations increased, complexity of the Ptolemaic cyclical and epicyclical mechanisms had to increase to maintain the calculated planetary positions close to the observed positions. Copernicus proposed a cosmology in which the Sun was at the center and the Earth was one of the planets revolving around it. For modeling the planetary motions, Copernicus used the tools he was familiar with, namely the cycles and epicycles of the Ptolemaic toolbox. Yet Copernicus' model needed more cycles and epicycles than existed in the then-current Ptolemaic model, and due to a lack of accuracy in calculations, his model did not appear to provide more accurate predictions than the Ptolemy model.[14] Copernicus' contemporaries rejected his cosmology, and Kuhn asserts that they were quite right to do so: Copernicus' cosmology lacked credibility. Kuhn illustrates how a paradigm shift later became possible when Galileo Galilei introduced his new ideas concerning motion. Intuitively, when an object is set in motion, it soon comes to a halt. A well-made cart may travel a long distance before it stops, but unless something keeps pushing it, it will eventually stop moving. Aristotle had argued that this was presumably a fundamental property of nature: for the motion of an object to be sustained, it must continue to be pushed. Given the knowledge available at the time, this represented sensible, reasonable thinking. Galileo put forward a bold alternative conjecture: suppose, he said, that we always observe objects coming to a halt simply because some friction is always occurring. Galileo had no equipment with which to objectively confirm his conjecture, but he suggested that without any friction to slow down an object in motion, its inherent tendency is to maintain its speed without the application of any additional force. The Ptolemaic approach of using cycles and epicycles was becoming strained: there seemed to be no end to the mushrooming growth in complexity required to account for the observable phenomena. Johannes Kepler was the first person to abandon the tools of the Ptolemaic paradigm. He started to explore the possibility that the planet Mars might have an elliptical orbit rather than a circular one. Clearly, the angular velocity could not be constant, but it proved very difficult to find the formula describing the rate of change of the planet's angular velocity. After many years of calculations, Kepler arrived at what we now know as the law of equal areas. Galileo's conjecture was merely that – a conjecture. So was Kepler's cosmology. But each conjecture increased the credibility of the other, and together, they changed the prevailing perceptions of the scientific community. Later, Newton showed that Kepler's three laws could all be derived from a single theory of motion and planetary motion. Newton solidified and unified the paradigm shift that Galileo and Kepler had initiated. Coherence One of the aims of science is to find models that will account for as many observations as possible within a coherent framework. Together, Galileo's rethinking of the nature of motion and Keplerian cosmology represented a coherent framework that was capable of rivaling the Aristotelian/Ptolemaic framework. Once a paradigm shift has taken place, the textbooks are rewritten. Often the history of science too is rewritten, being presented as an inevitable process leading up to the current, established framework of thought. There is a prevalent belief that all hitherto-unexplained phenomena will in due course be accounted for in terms of this established framework. Kuhn states that scientists spend most (if not all) of their careers in a process of puzzle-solving. Their puzzle-solving is pursued with great tenacity, because the previous successes of the established paradigm tend to generate great confidence that the approach being taken guarantees that a solution to the puzzle exists, even though it may be very hard to find. Kuhn calls this process normal science. As a paradigm is stretched to its limits, anomalies – failures of the current paradigm to take into account observed phenomena – accumulate. Their significance is judged by the practitioners of the discipline. Some anomalies may be dismissed as errors in observation, others as merely requiring small adjustments to the current paradigm that will be clarified in due course. Some anomalies resolve themselves spontaneously, having increased the available depth of insight along the way. But no matter how great or numerous the anomalies that persist, Kuhn observes, the practicing scientists will not lose faith in the established paradigm until a credible alternative is available; to lose faith in the solvability of the problems would in effect mean ceasing to be a scientist. In any community of scientists, Kuhn states, there are some individuals who are bolder than most. These scientists, judging that a crisis exists, embark on what Kuhn calls revolutionary science, exploring alternatives to long-held, obvious-seeming assumptions. Occasionally this generates a rival to the established framework of thought. The new candidate paradigm will appear to be accompanied by numerous anomalies, partly because it is still so new and incomplete. The majority of the scientific community will oppose any conceptual change, and, Kuhn emphasizes, so they should. To fulfill its potential, a scientific community needs to contain both individuals who are bold and individuals who are conservative. There are many examples in the history of science in which confidence in the established frame of thought was eventually vindicated. It is almost impossible to predict whether the anomalies in a candidate for a new paradigm will eventually be resolved. Those scientists who possess an exceptional ability to recognize a theory's potential will be the first whose preference is likely to shift in favour of the challenging paradigm. There typically follows a period in which there are adherents of both paradigms. In time, if the challenging paradigm is solidified and unified, it will replace the old paradigm, and a paradigm shift will have occurred. Phases Kuhn explains the process of scientific change as the result of various phases of paradigm change. Phase 1 – It exists only once and is the pre-paradigm phase, in which there is no consensus on any particular theory. This phase is characterized by several incompatible and incomplete theories. Consequently, most scientific inquiry takes the form of lengthy books, as there is no common body of facts that may be taken for granted. When the actors in the pre-paradigm community eventually gravitate to one of these conceptual frameworks and ultimately to a widespread consensus on the appropriate choice of methods, terminology and on the kinds of experiment that are likely to contribute to increased insights, the old schools of thought disappear. The new paradigm leads to a more rigid definition of the research field, and those who are reluctant or unable to adapt are isolated or have to join rival groups.[15] Phase 2 – Normal s cience begins, in which puzzles are solved within the context of the dominant paradigm. As long as there is consensus within the discipline, normal science continues. Over time, progress in normal science may reveal anomalies, facts that are difficult to explain within the context of the existing paradigm.[16] While usually these anomalies are resolved, in some cases they may accumulate to the point where normal science becomes difficult and where weaknesses in the old paradigm are revealed.[17] Phase 3 – If the paradigm proves chronically unable to account for anomalies, the community enters a crisis period. Crises are often resolved within the context of normal science. However, after significant efforts of normal science within a paradigm fail, science may enter the next phase.[18] Phase 4 – Paradigm shift, or scientific revolution, is the phase in which the underlying assumptions of the field are reexamined and a new paradigm is established.[19] Phase 5 – Post-revolution, the new paradigm's dominance is established and so scientists return to normal science, solving puzzles within the new paradigm.[20] A science may go through these cycles repeatedly, though Kuhn notes that it is a good thing for science that such shifts do not occur often or easily. Incommensurability According to Kuhn, the scientific paradigms preceding and succeeding a paradigm shift are so different that their theories are incommensurable—the new paradigm cannot be proven or disproven by the rules of the old paradigm, and vice versa. (A later interpretation by Kuhn of "commensurable" versus "incommensurable" was as a distinction between "languages", namely, that statements in commensurable languages were translatable fully from one to the other, while in incommensurable languages, strict translation is not possible.[21] The paradigm shift does not merely involve the revision or transformation of an individual theory, it changes the way terminology is defined, how the scientists in that field view their subject, and, perhaps most significantly, what questions are regarded as valid, and what rules are used to determine the truth of a particular theory. The new theories were not, as the scientists had previously thought, just extensions of old theories, but were instead completely new world views. Such incommensurability exists not just before and after a paradigm shift, but in the periods in between conflicting paradigms. It is simply not possible, according to Kuhn, to construct an impartial language that can be used to perform a neutral comparison between conflicting paradigms, because the very terms used are integral to the respective paradigms, and therefore have different connotations in each paradigm. The advocates of mutually exclusive paradigms are in a difficult position: "Though each may hope to convert the other to his way of seeing science and its problems, neither may hope to prove his case. The competition between paradigms is not the sort of battle that can be resolved by proofs."[22] Scientists subscribing to different paradigms end up talking past one another. Kuhn states that the probabilistic tools used by verificationists are inherently inadequate for the task of deciding between conflicting theories, since they belong to the very paradigms they seek to compare. Similarly, observations that are intended to falsify a statement will fall under one of the paradigms they are supposed to help compare, and will therefore also be inadequate for the task. According to Kuhn, the concept of falsifiability is unhelpful for understanding why and how science has developed as it has. In the practice of science, scientists will only consider the possibility that a theory has been falsified if an alternative theory is available that they judge credible. If there is not, scientists will continue to adhere to the established conceptual framework. If a paradigm shift has occurred, the textbooks will be rewritten to state that the previous theory has been falsified. Kuhn further developed his ideas regarding incommensurability in the 1980s and 1990s. In his unpublished manuscript The Plurality of Worlds, Kuhn introduces the theory of kind concepts: sets of interrelated concepts that are characteristic of a time period in a science and differ in structure from the modern analogous kind concepts. These different structures imply different "taxonomies" of things and processes, and this difference in taxonomies constitutes incommensurability.[23] This theory is strongly naturalistic and draws on developmental psychology to "found a quasi-transcendental theory of experience and of reality."[23] Exemplar Kuhn introduced the concept of an exemplar in a postscript to the second edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1970). He noted that he was substituting the term "exemplars" for "paradigm", meaning the problems and solutions that students of a subject learn from the beginning of their education. For example, physicists might have as exemplars the inclined plane, Kepler's laws of planetary motion, or instruments like the calorimeter.[24][25] According to Kuhn, scientific practice alternates between periods of normal science and revolutionary science. During periods of normalcy, scientists tend to subscribe to a large body of interconnecting knowledge, methods, and assumptions which make up the reigning paradigm (see paradigm shift). Normal science presents a series of problems that are solved as scientists explore their field. The solutions to some of these problems become well known and are the exemplars of the field.[25] Those who study a scientific discipline are expected to know its exemplars. There is no fixed set of exemplars, but for a physicist today it would probably include the harmonic oscillator from mechanics and the hydrogen atom from quantum mechanics.[26] |

科学の歴史と哲学に対するクーンのアプローチは、通常の科学の実践、歴史的出来事の影響、科学的発見の出現、科学革命の性質、科学革命による進歩といった

概念的な問題に焦点を当てている[10]。ある時代には、どのような種類の辞書や専門用語が知られ、使われていたのか。伝統的な思想を初期の研究者に帰結

させないことの重要性を強調するクーンの著書は、科学理論の進化は事実の直接的な蓄積からではなく、むしろ変化する一連の知的状況と可能性から生まれると

主張している[11]。 クーンは科学理論が、利用可能なすべてのデータの客観的で偏りのない蓄積から直線的に進行するものではなく、むしろパラダイムに駆動されるものであると考 えていた: 科学者が実験室で行う操作や測定は、経験の「与えられたもの」ではなく、むしろ「苦労して集めたもの」である。それらは科学者が目にするものではなく、少 なくとも彼の研究が十分に進み、注意が集中するまでは目にすることはない。むしろそれらは、より初歩的な知覚の内容を示す具体的な指標であり、通常の研究 で精査の対象に選ばれるのは、受容されたパラダイムを実りあるものに練り上げる機会が約束されているからにほかならない。操作と測定は、それらが部分的に 由来する直接的な経験よりもはるかに明確に、パラダイムによって決定される。科学は、実験室で可能なすべての操作を扱うわけではない。むしろ、あるパラダ イムと、そのパラダイムが部分的に決定している身近な経験との並置に関連するものを選択するのである。その結果、異なるパラダイムを持つ科学者は、異なる 具体的な実験操作を行うことになる。- クーン (1962, p. 216) 化学の歴史的例 クーンは、科学の歴史から抜粋した例を用いて自分の考えを説明している。例えば、18世紀の科学者は、均質な溶液は化合物であると信じていた。したがっ て、水とアルコールの組み合わせは、一般に化合物として分類された。現在では溶液と考えられているが、当時は化合物ではないと疑う理由はなかった。水とア ルコールは自然には分離しないし、蒸留しても完全には分離しない(共沸物を形成する)。水とアルコールはどのような割合でも結合できる。 このパラダイムの下で、科学者たちは(水とアルコールの組み合わせのような)化学反応は必ずしも一定の割合で起こるわけではないと信じていた。この考え方 は、最終的にダルトンの原子論によって覆された。ダルトンは、原子は単純な整数比でしか結合できないと主張したのである。この新しいパラダイムのもとで は、一定の割合で起こらない反応は化学的プロセスとは言えなかった。科学界におけるこの種の世界観の変遷は、クーンのパラダイム・シフトを例証している [12]。 コペルニクス的革命  太陽(黄色)、地球(青色)、火星(赤色)の運動。左側はコペルニクスの太陽中心運動。右側は伝統的な地球中心運動で、火星の逆行運動を含む。簡略化のた め、火星の公転周期は1.88年ではなく2年として描かれ、軌道は完全な円軌道またはエピトロコイドとして描かれている。 主な記事 コペルニクス的革命 科学思想における革命の有名な例は、コペルニクス的革命である。プトレマイオスの一派の思想では、地球を中心とする宇宙における惑星の動きをモデル化する ために、周期とエピシクル(いくつかの概念が追加されている)が使用されていた。天体観測の精度が上がるにつれて、計算された惑星の位置を観測された位置 に近づけるために、プトレマイオス流の周期とエピシクルのメカニズムは複雑さを増していった。コペルニクスは、太陽が中心にあり、地球はその周りを回る惑 星のひとつであるという宇宙論を提唱した。惑星の運動をモデル化するために、コペルニクスは慣れ親しんだ道具、すなわちプトレマイオスの道具箱の周期とエ ピシクルを使った。しかし、コペルニクスのモデルは、当時のプトレマイオスのモデルに存在するよりも多くの周期とエピシクルを必要とし、計算の精度不足の ために、彼のモデルはプトレマイオスのモデルよりも正確な予測を提供するようには見えなかった: コペルニクスの宇宙論は信頼性に欠けていた。 クーンは、後にガリレオ・ガリレイが運動に関する新しい考え方を導入したときに、パラダイムシフトがどのように可能になったかを説明している。直感的に言 えば、物体が動き出すと、すぐに停止する。よくできた荷車は、止まるまでに長い距離を走るかもしれないが、何かに押され続けない限り、やがて動かなくな る。アリストテレスは、これはおそらく自然の基本的な性質であると主張していた。物体の運動が維持されるためには、物体は押され続けなければならない。物 体の運動が持続するためには、物体は押され続けなければならない。当時利用可能だった知識を考慮すれば、これは常識的で合理的な考え方であった。 ガリレオは大胆な別の推測を提唱した。物体が停止するのを常に観察するのは、単に摩擦が常に起こっているからだと。ガリレオは、自分の推測を客観的に確認 する装置を持ち合わせていなかったが、運動している物体を減速させる摩擦がなければ、その物体固有の傾向として、付加的な力を加えなくても速度を維持する ことを示唆した。 周期とエピシクルを用いたプトレマイオス流のアプローチは窮屈になりつつあった。観測可能な現象を説明するために必要な複雑さは、キノコのように増え続 け、終わりがないように思えた。ヨハネス・ケプラーは天動説のパラダイムを捨てた最初の人物である。彼は、火星が円軌道ではなく楕円軌道を描いている可能 性を探り始めた。角速度が一定であるはずがないのは明らかだが、惑星の角速度の変化率を表す公式を見つけるのは非常に難しいことがわかった。何年にもわた る計算の末、ケプラーは現在の等面積の法則にたどり着いた。 ガリレオの推測は単なる推測に過ぎなかった。ケプラーの宇宙論もそうだった。しかし、それぞれの推測は他の推測の信憑性を高め、共に科学界の一般的な認識 を変えた。その後、ニュートンはケプラーの3つの法則が、運動と惑星運動に関する1つの理論から導き出されることを示した。ニュートンは、ガリレオとケプ ラーが起こしたパラダイムシフトを確固たるものにし、統一したのである。 一貫性 科学の目的のひとつは、首尾一貫した枠組みの中で、できるだけ多くの観測結果を説明できるモデルを見つけることである。ガリレオによる運動の本質の再考と ケプラー宇宙論は、共にアリストテレス/天動説の枠組みに匹敵する首尾一貫した枠組みであった。 パラダイムシフトが起こると、教科書は書き換えられる。科学の歴史もしばしば書き換えられ、現在の確立された思考の枠組みに至る必然的なプロセスとして紹 介される。これまで説明のつかなかった現象はすべて、やがてこの確立された枠組みで説明されるようになるという考えが広まっている。クーンは、科学者はそ のキャリアのほとんど(すべてではないにせよ)をパズル解きのプロセスに費やしていると述べている。というのも、確立されたパラダイムの過去の成功体験 が、たとえそれが非常に見つけにくいものであったとしても、そのアプローチによってパズルの解が存在することが保証されるという大きな自信を生みがちだか らである。クーンはこのプロセスを通常の科学と呼んでいる。 パラダイムがその限界まで引き伸ばされると、観測された現象を考慮するための現在のパラダイムの失敗であるアノマリーが蓄積されていく。その重要性を判断 するのは、その分野の実務者である。ある異常は観測の誤りとして片付けられるかもしれないし、またある異常は、現在のパラダイムにわずかな調整を加えるだ けで、やがて解明されるであろうとして片付けられるかもしれない。また、その過程で洞察の深みが増し、自然に解決するものもある。しかし、どんなに大き な、あるいは多くの異常が残っていたとしても、信頼できる代替案が利用可能になるまでは、実践的な科学者は確立されたパラダイムへの信頼を失うことはな い。 どのような科学者のコミュニティにも、他の誰よりも大胆な個人が存在するとクーンは述べる。このような科学者は、危機が存在すると判断し、クーンが革命的 科学と呼ぶものに着手し、長年信じられてきた自明と思われる仮定に代わるものを探求する。その結果、既成の思考の枠組みに対抗するものが生まれることもあ る。新しいパラダイムの候補は、まだ新しく不完全であることもあって、多くの変則性を伴っているように見えるだろう。科学界の大多数は、どのような概念的 変化にも反対するだろうし、そうあるべきだとクーンは強調する。潜在能力を発揮するためには、科学界には大胆な個人と保守的な個人の両方が必要である。科 学の歴史には、既成概念への信頼が最終的に正当化された例が数多くある。新しいパラダイムの候補における異常が最終的に解決されるかどうかを予測すること は、ほとんど不可能である。ある理論の可能性を認識する卓越した能力を持つ科学者たちは、真っ先に挑戦的なパラダイムを支持するようになるだろう。通常、 両方のパラダイムの信奉者が存在する期間が続く。やがて、挑戦的なパラダイムが固まり、統一されれば、古いパラダイムに取って代わり、パラダイムシフトが 起こる。 段階(諸フェーズ) クーンは科学的変化のプロセスを、パラダイム・チェンジの様々なフェーズの結果として説明している。 第1段階 - 一度しか存在せず、特定の理論についてコンセンサスが得られていないプレパラダイム段階である。この段階では、互換性のない不完全な理論がいくつか存在す るのが特徴である。その結果、ほとんどの科学的探究は、当然とされるような共通の事実が存在しないため、長大な書物の形をとる。プレパラダイム・コミュニ ティーの関係者が、やがてこれらの概念的枠組みのいずれかに引き寄せられ、最終的には、適切な手法や用語の選択、そして洞察力の向上に貢献しそうな実験の 種類について、広くコンセンサスが得られるようになると、古い学派は消滅する。新しいパラダイムは、研究分野をより厳格に定義することにつながり、適応に 消極的な人々や適応できない人々は孤立するか、対立するグループに参加しなければならなくなる[15]。 第2段階-通常の科学が始まり、支配的なパラダイムの文脈の中でパズル が解かれる。学問分野内にコンセンサスがある限り、通常の科学は継続する。通常、こ れらの異常は解決されるが、場合によっては、正常な科学が困難になり、古いパラダイムの弱点が明らかになるまでに蓄積されることもある[17]。 第3段階-パラダイムが慢性的に異常を説明できないと証明された場合、 コミュニティは危機の時期に入る。危機は多くの場合、通常の科学の文脈の中で解決される。しかし、パラダイム内での通常の科学の重要な努力が失敗した後、 科学は次の段階に入ることがある[18]。 第4段階-パラダイムシフト、または科学革命は、その分野の根本的な前 提が再検討され、新たなパラダイムが確立される段階である[19]。 第5段階-革命後、新しいパラダイムの優位性が確立されるため、科学者 は通常の科学に戻り、新しいパラダイムの中でパズルを解く[20]。 科学はこのようなサイクルを繰り返すかもしれないが、クーンはこのようなシフトが頻繁に、あるいは容易に起こらないことは科学にとって良いことであると指 摘している。 インコンシュメラヴィリティ(共約不可能性) クーンによれば、パラダイムシフトに先行する科学的パラダイムとそれを継承する科学的パラダイムは非常に異なっており、それらの理論は非可換である。(つ まり、通約可能な言語における言明は、一方から他方へ完全に翻訳可能であるが、非通約可能な言語においては、厳密な翻訳は不可能である。 [パラダイムシフトは、単に個々の理論の修正や変容を伴うだけでなく、用語の定義の仕方や、その分野の科学者が自分たちの対象をどのように見るか、そして おそらく最も重要なこととして、どのような疑問が妥当とみなされるか、特定の理論の真理を決定するためにどのようなルールが用いられるかをも変えるのであ る。新しい理論は、それまで科学者たちが考えていたような、古い理論の延長線上にあるものではなく、まったく新しい世界観なのである。このような矛盾は、 パラダイムシフトの前後だけでなく、相反するパラダイムの間にも存在する。クーンによれば、相反するパラダイム間で中立的な比較を行うための公平な言語を 構築することは不可能である。互いに排他的なパラダイムの提唱者は、難しい立場に立たされている: 「それぞれが、科学とその問題に対する自分の見方に相手を変えることを望むかもしれないが、どちらも自分の主張を証明することは望めない。パラダイム間の 競争は、証明によって解決できるような戦いではない」[22]。 クーンは、検証主義者が使用する確率論的なツールは、彼らが比較しようとするパラダイムそのものに属するものであるため、対立する理論間を決定する作業に は本質的に不適切であると述べている。同様に、ある言明を反証するための観察も、比較に役立つはずのパラダイムのいずれかに該当するため、この作業には不 適切である。クーンによれば、科学がなぜ、そしてどのように発展してきたかを理解する上で、反証可能性の概念は役に立たない。科学の実践において、科学者 が理論が反証された可能性を考慮するのは、自分たちが信頼できると判断する代替理論がある場合だけである。そうでない場合、科学者は確立された概念的枠組 みに固執し続ける。パラダイムシフトが起こった場合、教科書はそれまでの理論が反証されたと書き直される。 クーンは1980年代から1990年代にかけて、非整合性に関する考えをさらに発展させた。未発表の原稿『The Plurality of Worlds(世界の複数性)』の中で、クーンは類概念の理論を紹介している。類概念とは、ある科学のある時代に特徴的で、現代の類概念とは構造が異な る、相互に関連する概念の集合である。この理論は強く自然主義的であり、「経験と現実の準超越論的理論を見出す」ために発達心理学を利用している [23]。 模範 クーンは『科学革命の構造』第2版(1970年)のあとがきで模範の概念を導入した。彼は「模範」という用語を「パラダイム」に置き換えており、ある分野 の学生が教育の初期から学ぶ問題や解決策を意味していると述べている。例えば、物理学者は傾斜面やケプラーの惑星運動の法則、あるいは熱量計のような機器 を模範として持っているかもしれない[24][25]。 クーンによれば、科学的実践は、通常の科学と革命的な科学の時期を交互に繰り返す。通常の科学の時期には、科学者たちは、支配的なパラダイム(パラダイム シフトを参照)を構成する、相互に関連する知識、方法、仮定の大きな体を支持する傾向がある。通常の科学は、科学者がその分野を探求する過程で解決される 一連の問題を提示する。これらの問題のいくつかの解決策はよく知られるようになり、その分野の模範となる。 ある科学分野を研究する者は、その模範を知ることが期待されている。定まった模範解答はないが、今日の物理学者にとっては、力学の調和振動子や量子力学の 水素原子などがそれにあたるだろう[26]。 |

| Kuhn on scientific progress The first edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions ended with a chapter titled "Progress through Revolutions", in which Kuhn spelled out his views on the nature of scientific progress. Since he considered problem solving (or "puzzle solving")[1] to be a central element of science, Kuhn saw that for a new candidate paradigm to be accepted by a scientific community, "First, the new candidate must seem to resolve some outstanding and generally recognized problem that can be met in no other way. Second, the new paradigm must promise to preserve a relatively large part of the concrete problem-solving ability that has accrued to science through its predecessors. Novelty for its own sake is not a desideratum in the sciences as it is in so many other creative fields. As a result, though new paradigms seldom or never possess all the capabilities of their predecessors, they usually preserve a great deal of the most concrete parts of past achievement and they always permit additional concrete problem-solutions besides."— Kuhn (1962, p. 169) In the second edition, Kuhn added a postscript in which he elaborated his ideas on the nature of scientific progress. He described a thought experiment involving an observer who has the opportunity to inspect an assortment of theories, each corresponding to a single stage in a succession of theories. What if the observer is presented with these theories without any explicit indication of their chronological order? Kuhn anticipates that it will be possible to reconstruct their chronology on the basis of the theories' scope and content, because the more recent a theory is, the better it will be as an instrument for solving the kinds of puzzle that scientists aim to solve. Kuhn remarked: "That is not a relativist's position, and it displays the sense in which I am a convinced believer in scientific progress."[27][28] |

科学的進歩についてのクーン 科学革命の構造』の初版は「革命による進歩」と題された章で終わっており、その中でクーンは科学的進歩の本質についての見解を述べている。彼は問題解決 (あるいは「謎解き」)[1]が科学の中心的要素であると考えていたため、クーンは新しいパラダイム候補が科学コミュニティに受け入れられるためには、次 のように考えていた、 「第一に、その新しい候補は、他の方法では満たすことのできない、何か傑出した、一般に認識されている問題を解決しているように見えなければならない。第 二に、新しいパラダイムは、その前身を通じて科学に蓄積されてきた具体的な問題解決能力の比較的大きな部分を維持することを約束しなければならない。他の 多くの創造的分野のように、それ自体のための新奇性は科学では望まれていない。その結果、新しいパラダイムが前任者の能力をすべて備えていることはめった にないか、あるいは決してないとしても、通常、過去の業績の最も具体的な部分の多くを維持し、さらに具体的な問題解決を常に可能にする。"- クーン (1962, p. 169) 第2版では、クーンは科学の進歩の本質に関する彼の考えを詳しく説明する追記を加えた。クーンは、観察者がさまざまな理論を点検する機会を持つという思考 実験について説明した。もし観察者が、時系列的な順序を明示することなく、これらの理論を提示されたらどうなるだろうか。理論が新しければ新しいほど、科 学者が解決しようとするパズルを解く道具として優れているからである。クーンはこう述べている: 「それは相対主義者の立場ではなく、私が科学的進歩を確信していることを示すものである」[27][28]。 |

| Influence and reception The Structure of Scientific Revolutions has been credited with producing the kind of "paradigm shift" Kuhn discussed.[5] Since the book's publication, over one million copies have been sold, including translations into sixteen different languages.[29] In 1987, it was reported to be the twentieth-century book most frequently cited in the period 1976–1983 in the arts and the humanities.[30] Philosophy The first extensive review of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was authored by Dudley Shapere, a philosopher who interpreted Kuhn's work as a continuation of the anti-positivist sentiment of other philosophers of science, including Paul Feyerabend and Norwood Russell Hanson. Shapere noted the book's influence on the philosophical landscape of the time, calling it "a sustained attack on the prevailing image of scientific change as a linear process of ever-increasing knowledge".[31] According to the philosopher Michael Ruse, Kuhn discredited the ahistorical and prescriptive approach to the philosophy of science of Ernest Nagel's The Structure of Science (1961).[32] Kuhn's book sparked a historicist "revolt against positivism" (the so-called "historical turn in philosophy of science" which looked to the history of science as a source of data for developing a philosophy of science),[33] although this may not have been Kuhn's intention; in fact, he had already approached the prominent positivist Rudolf Carnap about having his work published in the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science.[34] The philosopher Robert C. Solomon noted that Kuhn's views have often been suggested to have an affinity to those of Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel.[35] Kuhn's view of scientific knowledge, as expounded in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, has been compared to the views of the philosopher Michel Foucault.[36] Sociology The first field to claim descent from Kuhn's ideas was the sociology of scientific knowledge.[37] Sociologists working within this new field, including Harry Collins and Steven Shapin, used Kuhn's emphasis on the role of non-evidential community factors in scientific development to argue against logical empiricism, which discouraged inquiry into the social aspects of scientific communities. These sociologists expanded upon Kuhn's ideas, arguing that scientific judgment is determined by social factors, such as professional interests and political ideologies.[38] Barry Barnes detailed the connection between the sociology of scientific knowledge and Kuhn in his book T. S. Kuhn and Social Science.[39] In particular, Kuhn's ideas regarding science occurring within an established framework informed Barnes's own ideas regarding finitism, a theory wherein meaning is continuously changed (even during periods of normal science) by its usage within the social framework.[40][41] The Structure of Scientific Revolutions elicited a number of reactions from the broader sociological community. Following the book's publication, some sociologists expressed the belief that the field of sociology had not yet developed a unifying paradigm, and should therefore strive towards homogenization. Others argued that the field was in the midst of normal science, and speculated that a new revolution would soon emerge. Some sociologists, including John Urry, doubted that Kuhn's theory, which addressed the development of natural science, was necessarily relevant to sociological development.[42] Economics Developments in the field of economics are often expressed and legitimized in Kuhnian terms. For instance, neoclassical economists have claimed "to be at the second stage [normal science], and to have been there for a very long time – since Adam Smith, according to some accounts (Hollander, 1987), or Jevons according to others (Hutchison, 1978)".[43] In the 1970s, post-Keynesian economists denied the coherence of the neoclassical paradigm, claiming that their own paradigm would ultimately become dominant.[43] While perhaps less explicit, Kuhn's influence remains apparent in recent economics. For instance, the abstract of Olivier Blanchard's paper "The State of Macro" (2008) begins: For a long while after the explosion of macroeconomics in the 1970s, the field looked like a battlefield. Over time however, largely because facts do not go away, a largely shared vision both of fluctuations and of methodology has emerged. Not everything is fine. Like all revolutions, this one has come with the destruction of some knowledge, and suffers from extremism and herding.— Blanchard (2009, p. 1) Political science In 1974, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was ranked as the second most frequently used book in political science courses focused on scope and methods.[44] In particular, Kuhn's theory has been used by political scientists to critique behavioralism, which claims that accurate political statements must be both testable and falsifiable.[45] The book also proved popular with political scientists embroiled in debates about whether a set of formulations put forth by a political scientist constituted a theory, or something else.[46] The changes that occur in politics, society and business are often expressed in Kuhnian terms, however poor their parallel with the practice of science may seem to scientists and historians of science. The terms "paradigm" and "paradigm shift" have become such notorious clichés and buzzwords that they are sometimes viewed as effectively devoid of content.[47][48] |

影響と受容 『科学革命の構造』は、クーンが論じたような「パラダイムシフト」をもたらしたと評価されている[5]。 同書の出版以来、16カ国語への翻訳を含め、100万部以上が販売されている[29]。 1987年には、同書は1976年から1983年の間に芸術と人文科学において最も頻繁に引用された20世紀の書籍であると報告されている[30]。 哲学 科学革命の構造』の最初の広範な書評は、ポール・ファイヤーアベンドやノーウッド・ラッセル・ハンソンなど、他の科学哲学者の反実証主義的感情の継続とし てクーンの仕事を解釈した哲学者、ダドリー・シェイプルによって執筆された。哲学者のマイケル・リューズ(Michael Ruse)によれば、クーンはアーネスト・ネーゲル(Ernest Nagel)の『科学の構造』(The Structure of Science、1961年)の非歴史的で杓子定規な科学哲学のアプローチを否定していた。 [32]クーンの著書は歴史主義者の「実証主義に対する反乱」(科学哲学を発展させるためのデータ源として科学史に注目した、いわゆる「科学哲学における 歴史的転回」)を巻き起こした[33]。 [34]哲学者のロバート・C・ソロモンは、クーンの見解がしばしばゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルの見解と親和性があることが示唆され ていると指摘している[35]。 科学革命の構造』で説かれたクーンの科学的知識に対する見解は、哲学者のミシェル・フーコーの見解と比較されている[36]。 社会学 ハリー・コリンズやスティーヴン・シャピンを含むこの新分野で活動する社会学者は、科学的コミュニティの社会的側面への探究を抑制する論理的経験主義に反 論するために、科学的発展における非立会的コミュニティ要因の役割に対するクーンの強調を利用した。これらの社会学者はクーンの考えを発展させ、科学的判 断は専門的利益や政治的イデオロギーなどの社会的要因によって決定されると主張していた[38]。 バリー・バーンズはその著書『T. S. Kuhn and Social Science』において、科学的知識の社会学とクーンとのつながりを詳述している[39]。特に、確立された枠組みの中で発生する科学に関するクーンの 考え方は、社会的枠組みの中で使用されることによって意味が(通常の科学の期間中であっても)継続的に変化するという理論である有限論に関するバーンズ自 身の考え方に影響を与えていた[40][41]。 科学革命の構造』はより広範な社会学コミュニティから多くの反応を引き出した。この本の出版後、何人かの社会学者は、社会学の分野はまだ統一的なパラダイ ムを確立しておらず、それゆえ均質化に向けて努力すべきだという信念を表明した。また、この分野は正常な科学の真っ只中にあり、やがて新たな革命が起こる だろうと推測する者もいた。ジョン・アーリーを含む何人かの社会学者は、自然科学の発展を扱ったクーンの理論が、社会学の発展に必ずしも関連するものであ ることに疑問を抱いていた[42]。 経済学 経済学の分野における発展は、しばしばクーン的な用語で表現され、正当化される。例えば、新古典派経済学者は「第二段階(通常の科学)にあり、非常に長い 間そこにいた-ある説によればアダム・スミス以来(Hollander, 1987)、他の説によればジェヴォンズ以来(Hutchison, 1978)」と主張してきた[43]。 1970年代には、ポスト・ケインズ派の経済学者は新古典派パラダイムの一貫性を否定し、自分たちのパラダイムが最終的に支配的になると主張していた [43]。 おそらくあまり明確ではないが、クーンの影響は最近の経済学においても明らかである。例えば、オリヴィエ・ブランシャールの論文「マクロの現状」 (2008年)の要旨はこう始まっている: 1970年代にマクロ経済学が爆発的に発展してからしばらくの間、この分野はまるで戦場のようだった。しかし、時が経つにつれ、事実が消えないことが主な 理由で、変動と方法論の両方について、ほぼ共有されたビジョンが現れてきた。すべてがうまくいっているわけではない。すべての革命がそうであるように、こ の革命もいくつかの知識の破壊を伴い、過激主義と群れ主義に苦しんでいる。- ブランチャード (2009, p. 1) 政治科学 1974年、『科学的革命の構造』は、範囲と方法に焦点を当てた政治学の講義で2番目に頻繁に使用される本としてランク付けされた[44]。特に、クーン の理論は、正確な政治的主張は検証可能かつ反証可能でなければならないと主張する行動主義を批判するために政治学者によって使用された[45]。 政治、社会、ビジネスにおいて起こる変化は、科学者や科学史家にとっては科学の実践との並列性が乏しいと思われるかもしれないが、しばしばクーン的な用語 で表現される。パラダイム」や「パラダイムシフト」という用語は、悪名高い決まり文句や流行語となっており、事実上内容がないとみなされることもある [47][48]。 |

Criticisms Front cover of Imre Lakatos and Alan Musgrave, ed., Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge The Structure of Scientific Revolutions was soon criticized by Kuhn's colleagues in the history and philosophy of science. In 1965, a special symposium on the book was held at an International Colloquium on the Philosophy of Science that took place at Bedford College, London, and was chaired by Karl Popper. The symposium led to the publication of the symposium's presentations plus other essays, most of them critical, which eventually appeared in an influential volume of essays. Kuhn expressed the opinion that his critics' readings of his book were so inconsistent with his own understanding of it that he was "tempted to posit the existence of two Thomas Kuhns", one the author of his book, the other the individual who had been criticized in the symposium by "Professors Popper, Feyerabend, Lakatos, Toulmin and Watkins.[49] A number of the included essays question the existence of normal science. In his essay, Feyerabend suggests that Kuhn's conception of normal science fits organized crime as well as it does science.[50] Popper expresses distaste with the entire premise of Kuhn's book, writing, "the idea of turning for enlightenment concerning the aims of science, and its possible progress, to sociology or to psychology (or ... to the history of science) is surprising and disappointing."[51] Concept of paradigm Stephen Toulmin defined paradigm as "the set of common beliefs and agreements shared between scientists about how problems should be understood and addressed". In his 1972 work, Human Understanding, he argued that a more realistic picture of science than that presented in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions would admit the fact that revisions in science take place much more frequently, and are much less dramatic than can be explained by the model of revolution/normal science. In Toulmin's view, such revisions occur quite often during periods of what Kuhn would call "normal science". For Kuhn to explain such revisions in terms of the non-paradigmatic puzzle solutions of normal science, he would need to delineate what is perhaps an implausibly sharp distinction between paradigmatic and non-paradigmatic science.[52] Incommensurability of paradigms In a series of texts published in the early 1970s, Carl R. Kordig asserted a position somewhere between that of Kuhn and the older philosophy of science. His criticism of the Kuhnian position was that the incommensurability thesis was too radical, and that this made it impossible to explain the confrontation of scientific theories that actually occurs. According to Kordig, it is in fact possible to admit the existence of revolutions and paradigm shifts in science while still recognizing that theories belonging to different paradigms can be compared and confronted on the plane of observation. Those who accept the incommensurability thesis do not do so because they admit the discontinuity of paradigms, but because they attribute a radical change in meanings to such shifts.[53] Kordig maintains that there is a common observational plane. For example, when Kepler and Tycho Brahe are trying to explain the relative variation of the distance of the sun from the horizon at sunrise, both see the same thing (the same configuration is focused on the retina of each individual). This is just one example of the fact that "rival scientific theories share some observations, and therefore some meanings". Kordig suggests that with this approach, he is not reintroducing the distinction between observations and theory in which the former is assigned a privileged and neutral status, but that it is possible to affirm more simply the fact that, even if no sharp distinction exists between theory and observations, this does not imply that there are no comprehensible differences at the two extremes of this polarity. At a secondary level, for Kordig there is a common plane of inter-paradigmatic standards or shared norms that permit the effective confrontation of rival theories.[53] In 1973, Hartry Field published an article that also sharply criticized Kuhn's idea of incommensurability.[54] In particular, he took issue with this passage from Kuhn: Newtonian mass is immutably conserved; that of Einstein is convertible into energy. Only at very low relative velocities can the two masses be measured in the same way, and even then they must not be conceived as if they were the same thing.— Kuhn (1970) Field takes this idea of incommensurability between the same terms in different theories one step further. Instead of attempting to identify a persistence of the reference of terms in different theories, Field's analysis emphasizes the indeterminacy of reference within individual theories. Field takes the example of the term "mass", and asks what exactly "mass" means in modern post-relativistic physics. He finds that there are at least two different definitions: Relativistic mass: the mass of a particle is equal to the total energy of the particle divided by the speed of light squared. Since the total energy of a particle in relation to one system of reference differs from the total energy in relation to other systems of reference, while the speed of light remains constant in all systems, it follows that the mass of a particle has different values in different systems of reference. "Real" mass: the mass of a particle is equal to the non-kinetic energy of a particle divided by the speed of light squared. Since non-kinetic energy is the same in all systems of reference, and the same is true of light, it follows that the mass of a particle has the same value in all systems of reference. Projecting this distinction backwards in time onto Newtonian dynamics, we can formulate the following two hypotheses: HR: the term "mass" in Newtonian theory denotes relativistic mass. Hp: the term "mass" in Newtonian theory denotes "real" mass. According to Field, it is impossible to decide which of these two affirmations is true. Prior to the theory of relativity, the term "mass" was referentially indeterminate. But this does not mean that the term "mass" did not have a different meaning than it now has. The problem is not one of meaning but of reference. The reference of such terms as mass is only partially determined: we do not really know how Newton intended his use of this term to be applied. As a consequence, neither of the two terms fully denotes (refers). It follows that it is improper to maintain that a term has changed its reference during a scientific revolution; it is more appropriate to describe terms such as "mass" as "having undergone a denotional refinement".[54] In 1974, Donald Davidson objected that the concept of incommensurable scientific paradigms competing with each other is logically inconsistent.[55] In his article Davidson goes well beyond the semantic version of the incommensurability thesis: to make sense of the idea of a language independent of translation requires a distinction between conceptual schemes and the content organized by such schemes. But, Davidson argues, no coherent sense can be made of the idea of a conceptual scheme, and therefore no sense may be attached to the idea of an untranslatable language."[56] Incommensurability and perception The close connection between the interpretationalist hypothesis and a holistic conception of beliefs is at the root of the notion of the dependence of perception on theory, a central concept in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Kuhn maintained that the perception of the world depends on how the percipient conceives the world: two scientists who witness the same phenomenon and are steeped in two radically different theories will see two different things. According to this view, our interpretation of the world determines what we see.[57] Jerry Fodor attempts to establish that this theoretical paradigm is fallacious and misleading by demonstrating the impenetrability of perception to the background knowledge of subjects. The strongest case can be based on evidence from experimental cognitive psychology, namely the persistence of perceptual illusions. Knowing that the lines in the Müller-Lyer illusion are equal does not prevent one from continuing to see one line as being longer than the other. This impenetrability of the information elaborated by the mental modules limits the scope of interpretationalism.[58] In epistemology, for example, the criticism of what Fodor calls the interpretationalist hypothesis accounts for the common-sense intuition (on which naïve physics is based) of the independence of reality from the conceptual categories of the experimenter. If the processes of elaboration of the mental modules are in fact independent of the background theories, then it is possible to maintain the realist view that two scientists who embrace two radically diverse theories see the world exactly in the same manner even if they interpret it differently. The point is that it is necessary to distinguish between observations and the perceptual fixation of beliefs. While it is beyond doubt that the second process involves the holistic relationship between beliefs, the first is largely independent of the background beliefs of individuals. Other critics, such as Israel Scheffler, Hilary Putnam and Saul Kripke, have focused on the Fregean distinction between sense and reference in order to defend scientific realism. Scheffler contends that Kuhn confuses the meanings of terms such as "mass" with their referents. While their meanings may very well differ, their referents (the objects or entities to which they correspond in the external world) remain fixed.[59] |

批評 イムレ・ラカトス、アラン・マスグレイヴ編『批判と知識の成長』表紙 科学革命の構造』は、科学史や科学哲学の分野でクーンの同僚たちからすぐに批判された。1965年、ロンドンのベッドフォード・カレッジで開催された科学 哲学国際コロキウムで、カール・ポパーが座長を務めたこの本に関する特別シンポジウムが開かれた。このシンポジウムは、シンポジウムでの発表に加え、他の エッセイ、そのほとんどが批判的なものであったが、最終的には影響力のあるエッセイ集として出版された。クーンは、批評家たちによる自著の読解が彼自身の 理解とはあまりにも矛盾していたため、「2人のトマス・クーンの存在を仮定したくなる」という意見を表明しており、1人は自著の著者であり、もう1人はシ ンポジウムで「ポパー教授、ファイヤアーベント教授、ラカトス教授、トゥールミン教授、ワトキンス教授」によって批判された人物であった[49]。 収録されたエッセイの多くは、通常の科学の存在に疑問を投げかけている。ポパーはクーンの本の前提全体に嫌悪感を示しており、「科学の目的とその可能な進 歩に関する啓蒙のために、社会学や心理学(あるいは...科学史)に目を向けるという考えは驚きであり、失望させられる」と書いている[51]。 パラダイムの概念 スティーヴン・トゥールミンはパラダイムを「問題がどのように理解され、対処されるべきかについての科学者間で共有される共通の信念と合意の集合」と定義 した。彼は1972年の著作『人間理解』において、『科学革命の構造』で提示されたものよりも現実的な科学の姿は、科学における改訂が革命/通常の科学の モデルで説明されるよりもはるかに頻繁に行われ、劇的なものではないという事実を認めるものであると主張した。トゥールミンの見解では、このような修正 は、クーンが「正常な科学」と呼ぶような時期に頻繁に起こる。クーンがこのような改訂を通常の科学の非パラダイム的なパズルの解法という観点から説明する ためには、パラダイム的な科学と非パラダイム的な科学との間のおそらくあり得ないほど鋭い区別を明確にする必要がある[52]。 パラダイムの共約不可能性 1970年代初頭に出版された一連のテキストの中で、カール・R・コーディグはクーンと旧来の科学哲学の中間の立場を主張していた。彼のクーン的立場に対 する批判は、非競合性テーゼは急進的すぎるというもので、そのために実際に起こっている科学理論の対立を説明できないというものであった。コーディッヒに よれば、科学における革命やパラダイムシフトの存在を認めつつ、異なるパラダイムに属する理論が観測の平面上で比較され、対立しうることを認識することは 実際可能である。非同一性テーゼを受け入れる人々は、パラダイムの不連続性を認めるからそうするのではなく、そのようなシフトに意味の根本的な変化を帰結 させるからそうするのである[53]。 コーディグは、共通の観測平面が存在すると主張している。例えば、ケプラーとティコ・ブラーエが日の出の地平線からの太陽の距離の相対的な変化を説明しよ うとしているとき、両者は同じものを見ている(同じ配置がそれぞれの網膜に焦点を合わせている)。これは、「ライバルとなる科学理論は、いくつかの観察結 果を共有し、したがっていくつかの意味を共有する」という事実の一例にすぎない。コルディッヒは、このアプローチによって、前者が特権的で中立的な地位を 与えられるような観察と理論の区別を再び導入しているのではなく、理論と観察の間に鋭い区別が存在しないとしても、この両極端に理解可能な差異が存在しな いことを意味するわけではないという事実を、より単純に肯定することが可能であることを示唆している。 二次的なレベルでは、コーディグにとって、対立する理論の効果的な対立を可能にするパラダイム間の基準や共有された規範という共通の平面が存在する [53]。 1973年、ハートリー・フィールドはクーンの非整合性の考え方を鋭く批判する論文を発表している[54]: ニュートンの質量は不変に保存され、アインシュタインの質量はエネルギーに変換される。ニュートンの質量は不変に保存され、アインシュタインの質量はエネ ルギーに変換される。この2つの質量を同じ方法で測定できるのは、相対速度が非常に低い場合だけであり、その場合でも、あたかも同じものであるかのように 考えてはならない。- クーン (1970) フィールドは、異なる理論における同じ用語間の非整合性というこの考え方をさらに一歩進めた。フィールドの分析は、異なる理論における用語の言及の持続性 を特定しようとする代わりに、個々の理論における言及の不確定性を強調する。フィールドは「質量」という用語を例にとり、現代のポスト相対論的物理学にお いて「質量」とは一体何を意味するのかを問う。彼は、少なくとも2つの異なる定義があることを発見した: 相対論的質量:粒子の質量は、粒子の全エネルギーを光速の2乗で割ったものに等しい。ある参照系における粒子の全エネルギーは、他の参照系における全エネ ルギーとは異なるが、光速はすべての参照系で一定であるため、粒子の質量は参照系によって異なる値を持つことになる。 「本当の "質量:粒子の質量は、粒子の非運動エネルギーを光速の2乗で割ったものに等しい。非運動エネルギーはすべての参照系で同じであり、光についても同じこと が言えるので、粒子の質量はすべての参照系で同じ値を持つことになる。 この区別をニュートンの力学に遡及させると、次の2つの仮説を立てることができる: HR:ニュートン理論における「質量」という用語は相対論的質量を表す。 Hp:ニュートン理論における「質量」という用語は「現実の」質量を表す。 フィールドによれば、この2つの主張のどちらが正しいかを決めることは不可能である。相対性理論以前は、「質量」という用語は参照的に不確定であった。し かし、これは「質量」という用語が現在とは異なる意味を持っていなかったことを意味しない。問題は意味の問題ではなく、参照の問題である。質量のような用 語の参照は部分的にしか決定されない。ニュートンがこの用語をどのように適用するつもりで使ったのか、私たちは本当のところは知らないのである。その結 果、2つの用語のどちらも完全に示す(参照する)ことはできない。その結果、ある用語が科学革命の間にその参照を変えたと主張することは不適切であり、 「質量」のような用語を「否定的な洗練を経た」と表現する方が適切であるということになる[54]。 1974年、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソンは、互いに競合する非保有可能な科学的パラダイムという概念は論理的に矛盾していると異議を唱えた[55]。彼の 論文においてデイヴィッドソンは非保有可能性テーゼの意味論的なバージョンをはるかに超えている。しかしデイヴィッドソンは、概念スキームという考え方に 首尾一貫した意味を持たせることはできず、したがって翻訳不可能な言語という考え方に意味を持たせることはできないと主張している。 共約不可能性と知覚 解釈主義的仮説と信念の全体論的概念との密接な関係は、『科学革命の構造』の中心的概念である、知覚の理論への依存という概念の根底にある。同じ現象を目 の当たりにしても、根本的に異なる2つの理論に浸っている2人の科学者は、2つの異なるものを見ることになる。この見解によれば、私たちの世界に対する解 釈が、私たちが見るものを決定するのである[57]。 ジェリー・フォドーは、知覚が被験者の背景知識に対して不可侵であることを示すことによって、この理論的パラダイムが誤りであり、誤解を招くものであるこ とを立証しようと試みている。最も強力なケースは、実験的認知心理学からの証拠、すなわち知覚の錯覚の持続性に基づくことができる。ミュラー・リヤー錯視 の線が等しいことを知っていても、一方の線が他方の線より長く見え続けることを妨げることはない。精神モジュールによって精緻化された情報のこの不可解さ は、解釈主義の範囲を限定する[58]。 例えば認識論においては、フォーダーが解釈論的仮説と呼ぶものに対する批判は、現実が実験者の概念カテゴリーから独立しているという常識的直観(ナイーブ な物理学が基礎としている)を説明するものである。もし心的モジュールの精緻化の過程が実際には背景理論から独立しているのであれば、2つの根本的に異な る理論を抱く2人の科学者が、たとえ解釈は異なっていても、世界をまったく同じように見ているという現実主義的な見方を維持することは可能である。重要な のは、観察と信念の知覚的固定化を区別する必要があるということである。二つ目のプロセスが信念間の全体的な関係を含んでいることは疑いようもないが、一 つ目のプロセスは個人の背景にある信念とはほとんど無関係である。 イスラエル・シェフラー、ヒラリー・パットナム、ソウル・クリプキといった他の批評家たちは、科学的実在論を擁護するために、感覚と参照の間のフレーゲ的 区別に注目している。シェフラーは、クーンは「質量」のような用語の意味とその参照とを混同していると主張する。それらの意味が異なることは大いにありう るが、それらの参照(それらが外界において対応する対象や実体)は固定されたままである[59]。 |

| Subsequent commentary by Kuhn In 1995 Kuhn argued that the Darwinian metaphor in the book should have been taken more seriously than it had been.[60] |

クーンによるその後の解説 1995年、クーンは、この本の中のダーウィンの比喩は、それまでよりももっと真剣に受け止められるべきであったと主張した[60]。 |

| Awards and honors 1998 Modern Library 100 Best Nonfiction: The Board's List (69) 1999 National Review 100 Best Nonfiction Books of the Century (25)[61] 2015 Mark Zuckerberg book club selection for March.[62][63] Publication history Kuhn, Thomas S. (1962). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (1st ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 172. LCCN 62019621. Kuhn, Thomas S. (1970). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Enlarged (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. pp. 210. ISBN 978-0-226-45803-8. LCCN 70107472. Kuhn, Thomas S. (1996). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (3rd ed.). University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-45807-6. LCCN 96013195. Kuhn, Thomas S. (2012). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. 50th anniversary. Ian Hacking (intro.) (4th ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-226-45811-3. LCCN 2011042476. Kuhn, Thomas S. (2020). The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Marcus du Sautoy (foreword); Ian Hacking (intro.) (Folio Society ed.). Folio Society (licensed by The University of Chicago Press). p. 169. |

受賞歴と栄誉 1998年 モダン・ライブラリー選定「100冊のベストノンフィクション」:編集委員会選定リスト(69位) 1999年 ナショナル・レビュー選定「世紀のベストノンフィクション100冊」(25位)[61] 2015年 マーク・ザッカーバーグのブッククラブ3月選定作品[62][63] 刊行履歴 クーン, トーマス・S. (1962). 『科学革命の構造』(初版)。シカゴ大学出版局。172ページ。LCCN 62019621。 クーン、トーマス・S. (1970). 『科学革命の構造』。増補版(第2版)。シカゴ大学出版局。210ページ。ISBN 978-0-226-45803-8。 LCCN 70107472。 クーン、トーマス・S. (1996)。『科学革命の構造』(第3版)。シカゴ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-226-45807-6。LCCN 96013195. クーン, トーマス・S. (2012). 『科学革命の構造』50周年記念版. イアン・ハッキング (序文) (第4版). シカゴ大学出版局. p. 264. ISBN 978-0-226-45811-3. LCCN 2011042476. クーン, トーマス・S. (2020). 『科学革命の構造』. マーカス・デュ・ソトーイ (序文); イアン・ハッキング (序文) (フォリオ・ソサエティ版). フォリオ・ソサエティ (シカゴ大学出版局よりライセンス取得). p. 169. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions |

|

| Bibliography Barnes, Barry (1982). T. S. Kuhn and Social Science. New York City: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231054362. Bilton, Tony; et al. (2002). Introductory Sociology (4th ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 422. ISBN 978-0-333-94571-1.* Bird, Alexander (2013). "Thomas Kuhn". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved September 23, 2017. Bird, Alexander; Ladyman, James (2013). Arguing about Science. Routledge. ISBN 9780415492294. Retrieved September 23, 2017. Blanchard, Olivier J. (2009). "The State of Macro". Annual Review of Economics. 1 (1): 209–228. doi:10.3386/w14259. Conant, James; Haugeland, John (2002). "Editors' introduction". The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970-1993, with an Autobiographical Interview (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0226457994. Daston, Lorraine (2012). "Structure". Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences. 42 (5): 496–499. doi:10.1525/hsns.2012.42.5.496. JSTOR 10.1525/hsns.2012.42.5.496. Davidson, Donald (1973). "On the Very Idea of a Conceptual Scheme". Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association. 47: 5–20. doi:10.2307/3129898. JSTOR 3129898. de Gelder, Beatrice (1989). "Granny, The Naked Emperor and the Second Cognitive Revolution". The Cognitive Turn: Sociological and Psychological Perspectives on Science. Sociology of the Sciences Yearbook. Vol. 13. Springer Netherlands. pp. 97–100. ISBN 978-0-7923-0306-0. Dolby, R. G. A. (1971). "Reviewed Work: Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. Proceedings of the International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London 1965, Volume 4". The British Journal for the History of Science. 5 (4): 400. doi:10.1017/s0007087400011626. JSTOR 4025383. S2CID 246613909. Feloni, Richard (March 17, 2015). "Why Mark Zuckerberg wants everyone to read this landmark philosophy book from the 1960s". Business Insider. Retrieved July 19, 2023. Ferretti, F. (2001). Jerry A. Fodor. Rome: Editori Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-6220-2. Field, Hartry (August 1973). "Theory Change and the Indeterminacy of Reference". The Journal of Philosophy. 70 (14): 462–481. doi:10.2307/2025110. JSTOR 2025110. Fleck, Ludwik (1979). Genesis and Development of a Scientific Fact. Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press. Fleck, Ludwik (1935). Entstehung und Entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen Tatsache. Einführung in die Lehre vom Denkstil und Denkkollektiv [Genesis and development of a scientific fact. Introduction to the study of thinking style and thinking collective] (in German). Verlagsbuchhandlung, Basel: Schwabe. Flood, Alison (March 19, 2015). "Mark Zuckerberg book club tackles the philosophy of science". The Guardian. Retrieved July 19, 2023. Forster, Malcolm. "Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions". philosophy.wisc.edu. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017. Fox, Charles (1974). "Whose Works Must Graduate Students Read?". A NEW Political Science: 19. Fulford, Robert (June 5, 1999). "Robert Fulford's column about the word "paradigm"". Globe and Mail. Retrieved February 28, 2023. Fuller, Steve (1992). "Being There with Thomas Kuhn: A Parable for Postmodern Times". History and Theory. 31 (3): 241–275. doi:10.2307/2505370. JSTOR 2505370. Garfield, Eugene (April 20, 1987). "A Different Sort of Great Books List: The 50 Twentieth-Century Works Most Cited in the Arts & Humanities Citation Index, 1976–1983" (PDF). Essays of an Information Scientist (1987 Current Contents). 10 (16): 3–7. Gattei, Stefano (2008). Thomas Kuhn's 'Linguistic Turn' and the Legacy of Logical Empiricism: Incommensurability, Rationality and the Search for Truth (1 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 292. doi:10.4324/9781315236124. ISBN 9781315236124. Horgan, John (May 1991). "Profile: Reluctant Revolutionary—Thomas S. Kuhn Unleashed 'Paradigm' on the World". Scientific American. 40. Hoyningen-Huene, Paul (March 19, 2015). "Kuhn's Development Before and After Structure". In Devlin, W.; Bokulich, A. (eds.). Kuhn's Structure of Scientific Revolutions - 50 Years on. Boston Studies in the Philosophy and History of Science. Vol. 311. Springer International Publishing. pp. 185–195. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13383-6_13. ISBN 978-3-319-13382-9. Kaiser, David (2012). "In retrospect: the structure of scientific revolutions". Nature. 484 (7393): 164–166. Bibcode:2012Natur.484..164K. doi:10.1038/484164a. hdl:1721.1/106157. King, J. E. (2002). A History of Post Keynesian Economics Since 1936. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar. p. 250. ISBN 978-1843766506. Kordig, Carl R. (December 1973). "Discussion: Observational Invariance". Philosophy of Science. 40 (4): 558–569. doi:10.1086/288565. JSTOR 186288. S2CID 224833690. Korta, Kepa; Larrazabal, Jesus M., eds. (2004). Truth, Rationality, Cognition, and Music: Proceedings of the Seventh International Colloquium on Cognitive Science. Kluwer Academic Publishers. Kuhn, Thomas (1987), "What Are Scientific Revolutions?", in Kruger, Lorenz; Daston, Lorraine J.; Heidelberger, Michael (eds.), The Probabilistic Revolution, vol. 1: Ideas in History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, pp. 719–720 Kuhn, Thomas; Baltas, Aristides; Gavroglu, Kostas; Kindi, Vassiliki (October 1995). A Discussion with Thomas S. Kuhn (Interview). Athens. Event occurs at 1m41s. Archived from the original on November 8, 2020. I would now argue very strongly that the Darwinian metaphor at the end of the book is right, and should have been taken more seriously than it was – and nobody took it seriously. Lakatos, Imre; Musgrave, Alan, eds. (1970). Criticism and the Growth of Knowledge. International Colloquium in the Philosophy of Science, London, 1965. Vol. 4. Cambridge University Press. p. 292. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139171434. ISBN 9780521096232. Longino, Helen (April 12, 2002). "The Social Dimensions of Scientific Knowledge". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. The Metaphysics Research Lab, Center for the Study of Language and Information (CSLI), Stanford University. Retrieved July 19, 2023. McFedries, Paul (May 7, 2001). The Complete Idiot's Guide to a Smart Vocabulary (1st ed.). Alpha Books. pp. 142–143. ISBN 978-0-02-863997-0. Mößner, Nicola (June 2011). "Thought styles and paradigms—a comparative study of Ludwik Fleck and Thomas S. Kuhn". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science. 42 (2): 362–371. Bibcode:2011SHPSA..42..362M. doi:10.1016/j.shpsa.2010.12.002. S2CID 146515142. National Review (May 3, 1999). "The 100 Best Non-Fiction Books of The Century". National Review. Retrieved July 19, 2023. Naughton, John (August 18, 2012). "Thomas Kuhn: the man who changed the way the world looked at science". The Guardian. Retrieved August 24, 2016. Ricci, David (1977). "Reading Thomas Kuhn in the Post-Behavioral Era". The Western Political Quarterly. 30 (1): 7–34. doi:10.1177/106591297703000102. JSTOR 448209. S2CID 144412975. Ruse, Michael (2005). Honderich, Ted (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. Scheffler, Israel (January 1, 1982). Science and Subjectivity. Indianapolis, Indiana: Hackett Publishing Company. p. 166. ISBN 9780915145300. Shapere, Dudley (1964). "The Structure of Scientific Revolutions". The Philosophical Review. 73 (3): 383–394. doi:10.2307/2183664. JSTOR 2183664. Shea, William (April 2001). Copernico (in Italian). Milan: Le Scienze. Solomon, Robert C. (1995). In the Spirit of Hegel: A Study of G. W. F. Hegel's Phenomenology of Spirit. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 359. ISBN 978-0-19-503650-3. Stephens, Jerome (1973). "The Kuhnian Paradigm and Political Inquiry: An Appraisal". American Journal of Political Science. 17 (3): 467–488. doi:10.2307/2110740. JSTOR 2110740. Toulmin, Stephen (1972). Human Understanding. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-824361-8. Urry, John (1973). "Thomas S. Kuhn as Sociologist of Knowledge". The British Journal of Sociology. 24 (4): 463–464. doi:10.2307/589735. JSTOR 589735. Weinberger, David (April 22, 2012). "Shift Happens". The Chronicle of Higher Education. Wray, K. Brad (2011). Kuhn's Evolutionary Social Epistemology. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781139503464. Ziman, J. M. (1982). "T. S. Kuhn and Social Science. Barry Barnes". Isis (book review). 73 (4). University of Chicago Press: 572. doi:10.1086/353123. |

参考文献 バーンズ、バリー (1982)。T. S. クーンと社会科学。ニューヨーク市:コロンビア大学出版局。ISBN 9780231054362。 ビルトン、トニーほか (2002)。入門社会学 (第 4 版)。ニューヨーク:パームグレイブ・マクミラン。422 ページ。ISBN 978-0-333-94571-1。* バード、アレクサンダー (2013). 「トーマス・クーン」. 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』. スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. 2017年9月23日取得。 バード、アレクサンダー; レディマン、ジェームズ (2013). 『科学について論じる』. ラウトレッジ. ISBN 9780415492294。2017年9月23日取得。 ブランチャード、オリヴィエ J. (2009). 「マクロ経済学の現状」 『Annual Review of Economics』 1 (1): 209–228. doi:10.3386/w14259. コナント、ジェームズ; ハウゲランド、ジョン (2002). 「編集者による序文」. 『構造以来の道:哲学的エッセイ集、1970-1993、自伝的インタビュー付き』(第2版). シカゴ大学出版局. p. 4. ISBN 978-0226457994. ダストン、ロレイン(2012)。「構造」。『自然科学の歴史研究』42巻5号:496–499頁。doi:10.1525/hsns.2012.42.5.496。JSTOR 10.1525/hsns.2012.42.5.496。 デイヴィッドソン、ドナルド(1973)。「概念体系という概念そのものについて」。『アメリカ哲学協会会議録および講演録』。47: 5–20。doi:10.2307/3129898。JSTOR 3129898。 デ・ゲルダー、ベアトリス(1989)。「おばあさん、裸の皇帝、そして第二の認知革命」。『認知への転換:科学に対する社会学的・心理学的視点』。『科 学社会学年報』第13巻。スプリンガー・ネザーランズ。97–100頁。ISBN 978-0-7923-0306-0。 ドルビー、R. G. A. (1971). 「書評対象:批評と知識の成長。1965年ロンドン国際科学哲学コロキウム議事録、第4巻」。『英国科学史ジャーナル』。5巻4号:400頁。doi: 10.1017/s0007087400011626。JSTOR 4025383. S2CID 246613909. フェローニ、リチャード (2015年3月17日). 「マーク・ザッカーバーグが、1960年代のこの画期的な哲学書を皆に読んでもらいたい理由」. ビジネスインサイダー. 2023年7月19日取得. フェレッティ、F. (2001). ジェリー・A・フォドル. ローマ: エディトリー・ラテルツァ. ISBN 978-88-420-6220-2. フィールド、ハートリー (1973年8月). 「理論の変化と参照の不確定性」. 哲学ジャーナル. 70 (14): 462–481. doi:10.2307/2025110. JSTOR 2025110. フレック、ルドウィック (1979). 科学的事実の生成と発展. イリノイ州シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局. フレック、ルドウィック (1935). Entstehung und Entwicklung einer wissenschaftlichen Tatsache. Einführung in die Lehre vom Denkstil und Denkkollektiv [科学的事実の生成と発展。思考様式と思考集団の研究入門](ドイツ語)。バーゼル:シュヴァーベ出版社。 フラッド、アリソン(2015年3月19日)。「マーク・ザッカーバーグの読書会が科学哲学に取り組む」。ガーディアン。2023年7月19日閲覧。 フォースター、マルコム。「クーンの『科学革命の構造』」philosophy.wisc.edu。2017年9月24日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年9月23日閲覧。 フォックス、チャールズ(1974)。「大学院生は何を読むべきか?」『A NEW Political Science』19号。 フルフォード、ロバート(1999年6月5日)。「ロバート・フルフォードの『パラダイム』という言葉に関するコラム」。グローブ・アンド・メール。2023年2月28日閲覧。 フラー、スティーブ(1992)。「トーマス・クーンと共に在ること:ポストモダン時代のための寓話」。『歴史と理論』。31巻3号:241–275頁。doi:10.2307/2505370。JSTOR 2505370。 ガーフィールド、ユージーン(1987年4月20日)。「異色の偉大な書物リスト:1976年から1983年にかけて芸術・人文科学引用索引で最も多く引 用された20世紀の著作50選」 (PDF). 『情報科学者のエッセイ』 (1987年 現行目録). 10巻16号: 3–7頁. ガッテイ、ステファノ (2008年). トーマス・クーンの『言語学的転回』と論理実証主義の遺産:非共測性、合理性、そして真実の探求(第1版)。ロンドン:ラウトリッジ。p. 292。doi:10.4324/9781315236124。ISBN 9781315236124。 ホーガン、ジョン(1991年5月)。「人物紹介:不本意な革命家―トーマス・S・クーンが世界に『パラダイム』を解き放った」。『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン』。40号。 ホイニンゲン=ヒューネ、ポール(2015年3月19日)。「構造論以前と以後のクーンの発展」。デヴリン、W.; ボクリッチ, A. (編). 『クーンの科学革命の構造―50年後の再考』. ボストン科学哲学・科学史研究叢書. 第311巻. スプリンガー・インターナショナル・パブリッシング. pp. 185–195. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-13383-6_13. ISBN 978-3-319-13382-9。 カイザー、デイヴィッド(2012)。「振り返って:科学革命の構造」。ネイチャー。484 (7393): 164–166。Bibcode:2012Natur.484..164K。doi:10.1038/484164a. hdl:1721.1/106157. キング, J. E. (2002). 『1936年以降のポスト・ケインズ経済学の歴史』. 英国チェルトナム: エドワード・エルガー. p. 250. ISBN 978-1843766506. Kordig, Carl R. (1973年12月). 「討論:観察不変性」. Philosophy of Science. 40 (4): 558–569. doi:10.1086/288565. JSTOR 186288. S2CID 224833690. コルタ、ケパ;ララサバル、ヘスス・M.(編)(2004)。『真実、合理性、認知、そして音楽:第7回認知科学国際コロキウム議事録』。クルワー・アカデミック・パブリッシャーズ。 クーン、トーマス(1987)、「科学革命とは何か?」、クルーガー、ローレンツ;ダストン、ロレイン・J.; ハイデルベルガー、マイケル(編)、『確率論的革命』第1巻:歴史における思想、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス、719–720頁 クーン、トーマス;バルタス、アリスティデス;ガヴログル、コスタス;キンディ、ヴァシリキ(1995年10月)。トーマス・S・クーンとの対話(インタ ビュー)。アテネ。イベント発生時刻:1分41秒。2020年11月8日時点のオリジナルからアーカイブ。今や私は強く主張する。本書の末尾にあるダー ウィニズムの比喩は正しいものであり、当時より真剣に受け止められるべきだったと——しかし誰も真剣に受け止めなかったのだ。 ラカトシュ、イムレ;マスグレイブ、アラン編(1970)。『批判と知識の成長』。1965年ロンドン国際科学哲学コロキウム。第4巻。ケンブリッジ大学 出版局。p. 292. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139171434. ISBN 9780521096232. ロンジーノ、ヘレン(2002年4月12日)。「科学的知識の社会的次元」。スタンフォード哲学百科事典。スタンフォード大学言語情報研究センター(CSLI)形而上学研究所。2023年7月19日閲覧。 マクフェドリーズ、ポール(2001年5月7日)。『スマート語彙完全ガイド』(第1版)。アルファブックス。142–143頁。ISBN 978-0-02-863997-0。 メッサーナー、ニコラ(2011年6月)。「思考様式とパラダイム―ルドヴィク・フレックとトーマス・S・クーンの比較研究」。『科学史・科学哲学研究』 42巻2号:362–371頁。Bibcode:2011SHPSA..42..362M。doi: 10.1016/j.shpsa.2010.12.002. S2CID 146515142. ナショナル・レビュー (1999年5月3日). 「世紀を代表するノンフィクション100選」. ナショナル・レビュー. 2023年7月19日閲覧。 ノートン、ジョン(2012年8月18日)。「トーマス・クーン:世界の科学観を変えた男」。ガーディアン。2016年8月24日閲覧。 リッチ、デイヴィッド(1977)。「行動主義後の時代にトーマス・クーンを読む」。ザ・ウエスタン・ポリティカル・クォータリー。30 (1): 7–34。doi:10.1177/106591297703000102. JSTOR 448209. S2CID 144412975. ルース、マイケル(2005年)。ホンデリッチ、テッド(編)。『オックスフォード哲学事典』。オックスフォード:オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-926479-7. シェフラー、イスラエル(1982年1月1日)。『科学と主観性』。インディアナ州インディアナポリス:ハケット出版会社。p. 166. ISBN 9780915145300. シェイパー、ダドリー(1964)。「科学革命の構造」。『フィロソフィカル・レビュー』73巻3号:383–394頁。doi:10.2307/2183664。JSTOR 2183664。 シーア、ウィリアム(2001年4月)。コペルニコ(イタリア語)。ミラノ:ル・シエンツェ。 ソロモン、ロバート・C.(1995)。『ヘーゲルの精神において:G. W. F. ヘーゲルの「精神の現象学」研究』。ニューヨーク:オックスフォード大学出版局。p. 359。ISBN 978-0-19-503650-3。 スティーブンス、ジェローム(1973)。「クーン的パラダイムと政治学研究:評価」。『アメリカ政治学ジャーナル』。17巻3号:467–488頁。doi:10.2307/2110740。JSTOR 2110740。 Toulmin, Stephen (1972). 『人間の理解』. オックスフォード: クレアンドン・プレス. ISBN 978-0-19-824361-8. Urry, John (1973). 「知識の社会学者としてのトーマス・S・クーン」. 『英国社会学雑誌』. 24 (4): 463–464. doi:10.2307/589735. JSTOR 589735. ワインバーガー、デイヴィッド (2012年4月22日). 「変化は起こる」. 『高等教育クロニクル』. レイ、K. ブラッド (2011). 『クーンの進化的社会認識論』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 9781139503464。 ジマン、J. M. (1982). 「T. S. クーンと社会科学。バリー・バーンズ」. Isis (書評). 73 (4). シカゴ大学出版局: 572. doi:10.1086/353123. |

| Epistemological rupture Groupthink Scientific Revolution |

認識論的断絶(認識論的切断) 集団思考 科学革命 |

| Further reading Wray, K. Brad, ed. (2024). Kuhn's The Structure of Scientific Revolutions at 60. Cambridge University Press. |

参考文献 レイ、K. ブラッド編(2024)。『クーンの「科学革命の構造」60周年』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Structure_of_Scientific_Revolutions |

■引用

「『科学革命の構造』は統一科学百科事典の第二号第 二巻として発表された。初版と第二班は両方ともタイトルが第1ページ、目次が第3ページである。第2ページは百科事典についてのいくつかの紹介である。 21人の編集者とアドバイザーの名前が載っている。50年後もよく知られているビッグネームを挙げれば、アルフレッド・タルスキー、バートランド・ラッセ ル、ジョン・デューイ、ルドルフ・カルナップ、ニールス・ボーア。/この百科事典はオットー・ノイラートとウィーン学団の同僚によってはじめられたプロ ジェクトの一環であった。ナチズムからの亡命者は、ヨーロッパからシカゴに移った。ノイラートは専門家による多くの短い論文を集めて、少なくとも40巻ほ どにすることを思い描いていた。クーンが彼の草稿を送る前には、二巻目も第一論文も出ていなかった。その後、統一科学百科事典は消滅した。今 になって振り返ってみると、多くのひとはクーンが『構造』をこの媒体で出版したのはかなり皮肉なことだったと考える。なぜなら、まさに『構造』が、このプ ロジェクトのもとになっている実証主義の教義のすべてを掘り崩したのだから。私はすでに反対の意見を示しておいた。クーンはウィーン学団やその同時代の人 々の前提を受け継いだのであり、その基礎を不滅のものとしたのである。/国際百科事典の以前の論文の印刷部数は専門家の小さなグループのた めのものだった。シカゴ大学出版はそれが大きな事件であることが分かっていたのだろうか。1962-1963年では919部が、1963-1964年では 774部が売れた。その翌年にペーパーバックで4,825部が売れ、その後はもう調べられない。1971年までに、初版は9万部を売り上げ、補遺をつけた 第二版はそれを超えた。出版から25年後、1987年までの発行部数の総計は少なくとも65万部である」イ アンハッキング(村上訳)「京大哲学研究会」より

Thomas S. Kuhn, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

- INTERNATIONAL ENCYCLOPEDIA of UNIFIED SCIENCE, 1962,1970. THE

UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

この本(第2版、下記のpdfによる)

| PREFACE (Kuhn_Revolutions.pdf) |

序文 ︎kuhn_revolution_jap_Part1.pdf | まえがき ・コイレ、ラヴジョイ、ピアジェ、ウォーフ、クワイン、(pp.ii-iii) ・パラダイム(p.v) ・統一科学事典 ・1962年2月バークレー |

| I. INTRODUCTION: A ROLE FOR HISTORY | 1.導入部:歴史の役割 |

・科学にとっての位相 ・通常の科学革命の意味、コペルニクス、ニュートン、ラヴォアジェ、アインシュタイン(7) ・科学革命と通常科学(8) |

| II. THE ROUTE TO NORMAL SCIENCE | 2.通常科学(ノーマルサイエンス)の道

すじ |

・通常科学の定義:「特定の研究者が一定

期間、一定の過去の科学的業績を受け入れ、それが基礎として進行させる研究」(12) ・具体的な科学の維持運営のほうが重要 ・切断面としてのニュートンの大きさ(15) ・電気派(17) ・プリニウスやベーコンのカオス(19) ・専門家はどのようにして再生産されるようになるのか?(23) ・アノマリーから生じてパラダイムが新たに獲得される(25) |

| III. THE NATURE OF

NORMAL SCIENCE |

3.通常科学(ノーマルサイエンス)の本 性(=基本的性質) | ・パラダイムの元々の意味は文法の活用表

(26) ・パラダイムは便利で、考えなくてもよい部分をスルーして先に議論をすすめる「生産的」側面がある(29) ・パラダイムの蓄積とその証明には膨大な時間がかかる(30) ・理論が発見されても、証明までにタイムラグがある(30) ・常数の決定もパラダイム内の作業(32) ・パラダイムの整備や再構成という作業もある(37) |

| IV. NORMAL SCIENCE

AS PUZZLE-SOLVING |

4.パズル解きゲームとしての通常科学 (ノーマルサイエンス) | ・通常科学は斬新なものを生み出さぬ

(39) ・なぜ革新をうみださないのに、パラダイムの整備や再構成に血道をあげるのか?それは「パズル解き」の面白さを提示するから(40)——科学は認識論的な ゲームである. ・パズル解きはなぜたのしいか?——それは解が出るから(43) ・付加的なルールの豊饒さ(44) ・「ルールはパラダイムから得られるが、パラダイムはルールがなくても研究を導きうる」(47)のテーゼを優しく説明してくれたまえ。 |

| V. THE PRIORITY OF

PARADIGMS |

5.パラダイム(論)の優位性 |

・パラダイムの比較(48-49) ・ウィトゲンシュタインの引用(50) ・パラダイムはルールの介在なしに通常科学を規定できる |

| VI. ANOMALY AND

THE EMERGENCE OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERIES |

6.異様性(アノマリー)と科学的発見の

登場 |

・アノマリーのこの章は、クリステンセン

にも影響を与えた ・他のルールが生まれることが、パラダイムチェインジの契機かも?(58) ・酸素の発見の物語(60-) ・X線(66) ・ライデン瓶(68) ・ブルーナーとポストマンの実験(70):変則的なカードを含ませておいても、少数なら、既存のカテゴリーに分けて気づかないが、数が増えると、ようやく 変則性に気づく |

| VII. CRISIS AND

THE EMERGENCE OF SCIENTIFIC THEORIES |

7.危機と科学的理論の登場 |

・パラダイムの変革の第一歩は変則性の

「発見」(74) ・気づいても、より深く認識することが重要(75) ・コペルニクス(76) ・相対論(81) ・太陽中心説(84) ・複数のデータがあれば、複数の理論構造の創案が可能(85) |

| VIII. THE RESPONSE