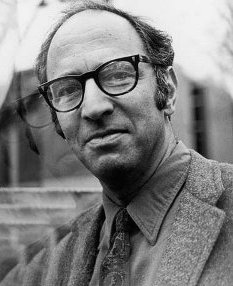

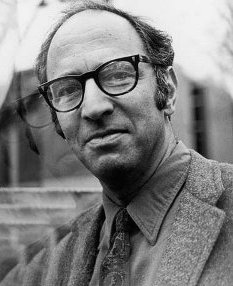

トーマス・クーン

Thomas Samuel Kuhn, 1922-1996

☆ トマス・サミュエル・クーン(Thomas Samuel Kuhn, /ku↪Lm_, 1922年7月18日 - 1996年6月17日)は、アメリカの歴史学者、科学哲学者であり、1962年に出版した『科学革命の構造(The Structure of Scientific Revolutions)』は学術界と大衆界に大きな影響を与え、パラダイムシフトという言葉と概念を紹介した。

| Thomas Samuel Kuhn

(/kuːn/; July 18, 1922 – June 17, 1996) was an American historian and

philosopher of science whose 1962 book The Structure of Scientific

Revolutions was influential in both academic and popular circles,

introducing the term paradigm shift, which has since become an

English-language idiom. Kuhn made several claims concerning the progress of scientific knowledge: that scientific fields undergo periodic "paradigm shifts" rather than solely progressing in a linear and continuous way, and that these paradigm shifts open up new approaches to understanding what scientists would never have considered valid before; and that the notion of scientific truth, at any given moment, cannot be established solely by objective criteria but is defined by a consensus of a scientific community. Competing paradigms are frequently incommensurable; that is, they are competing and irreconcilable accounts of reality. Thus, our comprehension of science can never rely wholly upon "objectivity" alone. Science must account for subjective perspectives as well, since all objective conclusions are ultimately founded upon the subjective conditioning/worldview of its researchers and participants. |

ト

マス・サミュエル・クーン(Thomas Samuel Kuhn, /ku↪Lm_, 1922年7月18日 -

1996年6月17日)は、アメリカの歴史学者、科学哲学者であり、1962年に出版した『科学革命の構造(The Structure of

Scientific Revolutions)』は学術界と大衆界に大きな影響を与え、パラダイムシフトという言葉と概念を紹介した。 クーンは、科学的知識の進歩に関して次のような主張を行った。科学分野は、直線的かつ連続的に進歩するのではなく、定期的に「パラダイムシフト」を起こ し、パラダイムシフトによって、科学者が以前は有効だと考えもしなかったことを理解するための新しいアプローチが開かれる。競合するパラダイムはしばしば 両立不可能である。したがって、私たちの科学に対する理解は、決して「客観性」だけに頼ることはできない。科学は主観的な視点も考慮しなければならない。 なぜなら、客観的な結論はすべて、最終的には研究者や参加者の主観的な条件や世界観に基づいているからである。 |

| Early life, family and education Kuhn was born in Cincinnati, Ohio, to Minette Stroock Kuhn and Samuel L. Kuhn, an industrial engineer, both Jewish.[9] From kindergarten through fifth grade, he was educated at Lincoln School, a private progressive school in Manhattan, which stressed independent thinking rather than learning facts and subjects. The family then moved 40 mi (64 km) north to the small town of Croton-on-Hudson, New York where, once again, he attended a private progressive school – Hessian Hills School. It was here that, in sixth through ninth grade, he learned to love mathematics. He left Hessian Hills in 1937. He graduated from The Taft School in Watertown, Connecticut, in 1940.[10] He obtained his BSc degree in physics from Harvard College in 1943, where he also obtained MSc and PhD degrees in physics in 1946 and 1949, respectively, under the supervision of John Van Vleck. [11] As he states in the first few pages of the preface to the second edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, his three years of total academic freedom as a Harvard Junior Fellow were crucial in allowing him to switch from physics to the history and philosophy of science. |

幼少期、家族、教育 クーンはオハイオ州シンシナティで、工業エンジニアのミネット・ストロック・クーンとサミュエル・L・クーンの間に生まれた。 幼稚園から小学5年生まで、事実や教科を学ぶよりも自主的な思考を重視するマンハッタンの私立進学校、リンカーン・スクールで教育を受けた。その後、一家 は40マイル(64km)北のニューヨーク州クロトン・オン・ハドソンという小さな町に引っ越し、再び私立の進歩的学校ヘシアン・ヒルズ・スクールに通っ た。6年生から9年生まで、彼はここで数学の素晴らしさを学んだ。1937年にヘシアン・ヒルズを退学。1940年、コネチカット州ウォータータウンのタ フト・スクールを卒業[10]。 1943年にハーバード・カレッジで物理学の理学士号を取得し、1946年と1949年には、ジョン・ヴァン・ヴレックの指導の下、それぞれ物理学の修士 号と博士号を取得した。[11]『科学革命の構造』第2版の序文の最初の数ページで述べているように、ハーバード大学のジュニア・フェローとして学問の自 由を完全に享受した3年間は、物理学から科学史・科学哲学に転向する上で極めて重要であった。 |

| Career Kuhn taught a course in the history of science at Harvard from 1948 until 1956, at the suggestion of university president James Conant. After leaving Harvard, Kuhn taught at the University of California, Berkeley, in both the philosophy department and the history department, being named Professor of the history of science in 1961. Kuhn interviewed and tape recorded Danish physicist Niels Bohr the day before Bohr's death.[12] At Berkeley, he wrote and published (in 1962) his best known and most influential work:[13] The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. In 1964, he joined Princeton University as the M. Taylor Pyne Professor of Philosophy and History of Science. He served as the president of the History of Science Society from 1969 to 1970.[14] In 1979 he joined the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) as the Laurance S. Rockefeller Professor of Philosophy, remaining there until 1991. |

経歴 ジェームズ・コナント学長の勧めで、1948年から1956年までハーバード大学で科学史の講義を担当。ハーバード大学を去った後、クーンはカリフォルニ ア大学バークレー校の哲学科と歴史学科で教鞭をとり、1961年に科学史教授に就任した。バークレー校では、彼の最もよく知られ、最も影響力のある著作 『科学革命の構造』[13]を執筆し、出版した(1962年)。1964年、プリンストン大学にM.テイラー・パイン哲学・科学史教授として着任。 1979年、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)に哲学教授(Laurance S. Rockefeller)として着任し、1991年まで在籍。 |

| The Structure of Scientific Revolutions Main article: The Structure of Scientific Revolutions The Structure of Scientific Revolutions (SSR) was originally printed as an article in the International Encyclopedia of Unified Science, published by the logical positivists of the Vienna Circle. In this book, heavily influenced by the fundamental work of Ludwik Fleck (on the possible influence of Fleck on Kuhn see[15]), Kuhn argued that science does not progress via a linear accumulation of new knowledge, but undergoes periodic revolutions, also called "paradigm shifts" (although he did not coin the phrase, he did contribute to its increase in popularity),[16] in which the nature of scientific inquiry within a particular field is abruptly transformed. In general, science is broken up into three distinct stages. Prescience, which lacks a central paradigm, comes first. This is followed by "normal science", when scientists attempt to enlarge the central paradigm by "puzzle-solving".[6]: 35–42 Guided by the paradigm, normal science is extremely productive: "when the paradigm is successful, the profession will have solved problems that its members could scarcely have imagined and would never have undertaken without commitment to the paradigm".[6]: 24–25 In regard to experimentation and collection of data with a view toward solving problems through the commitment to a paradigm, Kuhn states: The operations and measurements that a scientist undertakes in the laboratory are not "the given" of experience but rather "the collected with difficulty." They are not what the scientist sees—at least not before his research is well advanced and his attention focused. Rather, they are concrete indices to the content of more elementary perceptions, and as such they are selected for the close scrutiny of normal research only because they promise opportunity for the fruitful elaboration of an accepted paradigm. Far more clearly than the immediate experience from which they in part derive, operations and measurements are paradigm-determined. Science does not deal in all possible laboratory manipulations. Instead, it selects those relevant to the juxtaposition of a paradigm with the immediate experience that that paradigm has partially determined. As a result, scientists with different paradigms engage in different concrete laboratory manipulations.[6]: 126 During the period of normal science, the failure of a result to conform to the paradigm is seen not as refuting the paradigm, but as the mistake of the researcher, contra Karl Popper's falsifiability criterion. As anomalous results build up, science reaches a crisis, at which point a new paradigm, which subsumes the old results along with the anomalous results into one framework, is accepted. This is termed revolutionary science. The difference between the normal and revolutionary science soon sparked the Kuhn-Popper debate. In SSR, Kuhn also argues that rival paradigms are incommensurable—that is, it is not possible to understand one paradigm through the conceptual framework and terminology of another rival paradigm. For many critics, for example David Stove (Popper and After, 1982), this thesis seemed to entail that theory choice is fundamentally irrational: if rival theories cannot be directly compared, then one cannot make a rational choice as to which one is better. Whether Kuhn's views had such relativistic consequences is the subject of much debate; Kuhn himself denied the accusation of relativism in the third edition of SSR, and sought to clarify his views to avoid further misinterpretation. Freeman Dyson has quoted Kuhn as saying "I am not a Kuhnian!",[17] referring to the relativism that some philosophers have developed based on his work. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions is the single most widely cited book in the social sciences.[18] The enormous impact of Kuhn's work can be measured in the changes it brought about in the vocabulary of the philosophy of science: besides "paradigm shift", Kuhn popularized the word paradigm itself from a term used in certain forms of linguistics and the work of Georg Lichtenberg to its current broader meaning, coined the term "normal science" to refer to the relatively routine, day-to-day work of scientists working within a paradigm, and was largely responsible for the use of the term "scientific revolutions" in the plural, taking place at widely different periods of time and in different disciplines, as opposed to a single scientific revolution in the late Renaissance. The frequent use of the phrase "paradigm shift" has made scientists more aware of and in many cases more receptive to paradigm changes, so that Kuhn's analysis of the evolution of scientific views has by itself influenced that evolution.[citation needed] Kuhn's work has been extensively used in social science; for instance, in the post-positivist/positivist debate within International Relations. Kuhn is credited as a foundational force behind the post-Mertonian sociology of scientific knowledge. Kuhn's work has also been used in the Arts and Humanities, such as by Matthew Edward Harris to distinguish between scientific and historical communities (such as political or religious groups): 'political-religious beliefs and opinions are not epistemologically the same as those pertaining to scientific theories'.[19] This is because would-be scientists' worldviews are changed through rigorous training, through the engagement between what Kuhn calls 'exemplars' and the Global Paradigm. Kuhn's notions of paradigms and paradigm shifts have been influential in understanding the history of economic thought, for example the Keynesian revolution,[20] and in debates in political science.[21] A defense Kuhn gives against the objection that his account of science from The Structure of Scientific Revolutions results in relativism can be found in an essay by Kuhn called "Objectivity, Value Judgment, and Theory Choice."[22] In this essay, he reiterates five criteria from the penultimate chapter of SSR that determine (or help determine, more properly) theory choice: Accurate – empirically adequate with experimentation and observation Consistent – internally consistent, but also externally consistent with other theories Broad Scope – a theory's consequences should extend beyond that which it was initially designed to explain Simple – the simplest explanation, principally similar to Occam's razor Fruitful – a theory should disclose new phenomena or new relationships among phenomena He then goes on to show how, although these criteria admittedly determine theory choice, they are imprecise in practice and relative to individual scientists. According to Kuhn, "When scientists must choose between competing theories, two men fully committed to the same list of criteria for choice may nevertheless reach different conclusions."[22] For this reason, the criteria still are not "objective" in the usual sense of the word because individual scientists reach different conclusions with the same criteria due to valuing one criterion over another or even adding additional criteria for selfish or other subjective reasons. Kuhn then goes on to say, "I am suggesting, of course, that the criteria of choice with which I began function not as rules, which determine choice, but as values, which influence it."[22] Because Kuhn utilizes the history of science in his account of science, his criteria or values for theory choice are often understood as descriptive normative rules (or more properly, values) of theory choice for the scientific community rather than prescriptive normative rules in the usual sense of the word "criteria", although there are many varied interpretations of Kuhn's account of science. |

科学革命の構造 主な記事 科学革命の構造 科学革命の構造(SSR)は、ウィーン・サークルの論理実証主義者たちによって出版された『統一科学国際百科事典』に論文として掲載されたものである。ル ドウィク・フレックの基本的な研究(クーンに対するフレックの影響については[15]を参照)に大きな影響を受けたこの本の中で、クーンは、科学は新しい 知識の直線的な蓄積によって進歩するのではなく、「パラダイムシフト」とも呼ばれる周期的な革命(彼はこの言葉を造語したわけではないが、この言葉の普及 に貢献した)を経て、特定の分野における科学的探究の性質が突然変容すると主張した[16]。一般的に、科学は3つの異なる段階に分けられる。中心的なパ ラダイムを欠く「予知科学」が最初に来る。これに続くのが「通常の科学」であり、科学者は「謎解き」によって中心的なパラダイムを拡大しようとする [6]: 35-42 パラダイムに導かれた通常の科学は、極めて生産的である。「パラダイムが成功したとき、その専門職は、そのメンバーがほとんど想像することもできず、パラ ダイムへのコミットメントなしには決して引き受けなかったであろう問題を解決したことになる」[6]: 24-25 パラダイムへのコミットメントを通じた問題解決を視野に入れた実験やデータ収集に関して、クーンは次のように述べている: 科学者が実験室で行う操作や測定は、経験の "与えられたもの "ではなく、むしろ "苦労して集めたもの "である。それらは科学者が目にするものではない-少なくとも、彼の研究が十分に進み、彼の注意が集中するまでは。むしろそれらは、より初歩的な知覚の内 容に対する具体的な指標であり、そのようなものが通常の研究の綿密な精査の対象に選ばれるのは、受け入れられたパラダイムを実りあるものに練り上げる機会 が約束されているからにほかならない。操作と測定は、それらが部分的に由来する直接的な経験よりもはるかに明確に、パラダイムによって決定される。科学 は、実験室で可能なすべての操作を扱うわけではない。むしろ、あるパラダイムと、そのパラダイムが部分的に決定している身近な経験との並置に関連するもの を選択するのである。その結果、異なるパラダイムを持つ科学者は、異なる具体的な実験操作を行うことになる[6]: 126 通常の科学の時代には、結果がパラダイムに適合しないことは、パラダイムを否定するものではなく、カール・ポパーの反証可能性基準に反して、研究者の過ち とみなされる。異常な結果が積み重なると、科学は危機的状況に達し、その時点で、古い結果と異常な結果を1つの枠組みに包含する新しいパラダイムが受け入 れられる。これを革命的科学と呼ぶ。通常の科学と革命的科学の違いは、やがてクーンとポッパーの論争に火をつけた。 すなわち、あるパラダイムを、他の対立するパラダイムの概念的枠組みや用語を通して理解することは不可能であるということである。例えば、David Stove (Popper and After, 1982)のような多くの批評家にとって、このテーゼは、理論の選択が根本的に非合理的であることを意味しているように思われた。クーンの見解がこのよう な相対主義的な帰結をもたらすものであったかどうかは、多くの議論の対象となっている。クーン自身、『SSR』第3版で相対主義への非難を否定し、さらな る誤解を避けるために自身の見解を明らかにしようと努めた。フリーマン・ダイソンはクーンの言葉を引用し、「私はクーニアンではない!」と述べており [17]、クーンの著作に基づいて一部の哲学者が展開している相対主義について言及している。 科学革命の構造』は、社会科学の分野で最も広く引用されている唯一の本である。 [18]クーンの著作の多大な影響は、科学哲学の語彙にもたらした変化で測ることができる: パラダイムシフト」以外にも、クーンはパラダイムという言葉自体を、言語学の特定の形態やゲオルク・リヒテンベルクの研究で使われていた用語から、現在の より広い意味へと広めた。また、パラダイムの中で働く科学者の比較的日常的な仕事を指すために「通常の科学」という用語を作り出し、後期ルネサンスにおけ る単一の科学革命とは対照的に、広く異なる時代や異なる分野で起こる複数の「科学革命」という用語の使用に大きく関与した。パラダイムシフト」という言葉 が頻繁に使われるようになったことで、科学者たちはパラダイムの変化をより意識するようになり、多くの場合、パラダイムの変化を受け入れるようになった。 例えば、国際関係論におけるポスト実証主義/ポスト実証主義の議論などである。クーンは、マートン以後の科学的知識社会学の基礎を築いたと評価されてい る。クーンの研究はまた、マシュー・エドワード・ハリスが科学的共同体と歴史的共同体(政治団体や宗教団体など)を区別するために用いたように、芸術や人 文科学の分野でも用いられている: 政治的・宗教的な信念や意見は、認識論的に科学的理論に関わるものと同じではない」[19]。これは、クーンが「模範」と呼ぶものとグローバル・パラダイ ムとの関わりを通じて、科学者になろうとする者の世界観が厳しい訓練によって変化するためである。パラダイムとパラダイムシフトに関するクーンの概念は、 例えばケインズ革命のような経済思想の歴史を理解する上で、また政治学における議論において影響力を持っている[20]。 科学革命の構造』からの彼の科学に関する説明が相対主義をもたらすという反論に対するクーンの弁明は、「客観性、価値判断、理論選択」[22]と呼ばれる クーンによるエッセイに見出すことができる。このエッセイにおいて、彼はSSRの最後の章から、理論選択を決定する(あるいは、より適切に決定する手助け をする)5つの基準を繰り返し述べている: 正確 - 実験と観察によって経験的に適切であること。 一貫性 - 内部的に一貫しているだけでなく、外部的にも他の理論と一貫している。 広範な範囲-理論の帰結は、それが最初に説明するために設計された範囲を超えるべきである。 単純 - 最も単純な説明、主にオッカムの剃刀に似ている。 実りあるもの-理論は新しい現象や現象間の新しい関係を開示すべきである。 そして、これらの基準が理論の選択を決定することは認めるが、実際には不正確であり、個々の科学者にとっては相対的なものであることを示す。クーンによれ ば、「科学者が競合する理論の間で選択しなければならないとき、選択のための同じ基準のリストに完全にコミットした2人の人間が、それにもかかわらず異な る結論に達することがある」[22]。このため、個々の科学者が別の基準よりもある基準を重視したり、利己的な理由やその他の主観的な理由で追加的な基準 を加えたりすることによって、同じ基準で異なる結論に達するため、基準は依然として通常の意味での「客観的」ではないのである。クーンはさらに、「もちろ ん、私は、私が始めた選択の基準が、選択を決定する規則としてではなく、それに影響を与える価値として機能することを示唆している」と述べている [22]。クーンは科学についての説明において科学史を利用しているため、理論選択のための彼の基準や価値は、通常の「基準」という言葉の意味における規 定的な規範的規則というよりも、科学コミュニティのための理論選択の記述的な規範的規則(より適切には価値)として理解されることが多いが、クーンの科学 についての説明には様々な解釈がある。 |

| Post-Structure philosophy Years after the publication of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Kuhn dropped the concept of a paradigm and began to focus on the semantic aspects of scientific theories. In particular, Kuhn focuses on the taxonomic structure of scientific kind terms. In SSR he had dealt extensively with "meaning-changes". Later he spoke more of "terms of reference", providing each of them with a taxonomy. And even the changes that have to do with incommensurability were interpreted as taxonomic changes.[23] As a consequence, a scientific revolution is not defined as a "change of paradigm" anymore, but rather as a change in the taxonomic structure of the theoretical language of science.[24] Some scholars describe this change as resulting from a 'linguistic turn'.[25][26] In their book, Andersen, Barker and Chen use some recent theories in cognitive psychology to vindicate Kuhn's mature philosophy.[27] Apart from dropping the concept of a paradigm, Kuhn also began to look at the process of scientific specialisation. In a scientific revolution, a new paradigm (or a new taxonomy) replaces the old one; by contrast, specialisation leads to a proliferation of new specialties and disciplines. This attention to the proliferation of specialties would make Kuhn's model less 'revolutionary' and more "evolutionary". [R]evolutions, which produce new divisions between fields in scientific development, are much like episodes of speciation in biological evolution. The biological parallel to revolutionary change is not mutation, as I thought for many years, but speciation. And the problems presented by speciation (e.g., the difficulty in identifying an episode of speciation until some time after it has occurred, and the impossibility even then, of dating the time of its occurrence) are very similar to those presented by revolutionary change and by the emergence and individuation of new scientific specialties.[28] Some philosophers claim that Kuhn attempted to describe different kinds of scientific change: revolutions and specialty-creation.[29] Others claim that the process of specialisation is in itself a special case of scientific revolutions.[30] It is also possible to argue that, in Kuhn's model, science evolves through revolutions.[31] |

ポスト構造哲学 科学革命の構造』の出版から数年後、クーンはパラダイムの概念を捨て、科学理論の意味論的側面に焦点を当て始めた。特にクーンは、科学的な種類の用語の分 類学的構造に焦点を当てている。SSRでは、彼は「意味の変化」を広範囲に扱っていた。その後、彼は「参照項」についてより詳しく語り、それぞれに分類学 を提供した。その結果、科学革命はもはや「パラダイムの変化」としては定義されず、むしろ科学の理論的言語の分類学的構造の変化として定義されるように なった[24] 。 パラダイムの概念を取り下げたこととは別に、クーンは科学的な専門化のプロセスに注目し始めた。科学革命においては、新しいパラダイム(あるいは新しい分 類法)が古いパラダイムに取って代わる。このように専門分野の拡散に注目することで、クーンのモデルは「革命的」ではなく、より「進化的」なものとなる。 [科学の発展において分野間に新たな区分を生み出す「革命」は、生物学的進化における種分化のエピソードによく似ている。革命的な変化と生物学的に類似し ているのは、私が長年考えてきたような突然変異ではなく、種分化である。そして、種分化がもたらす問題(例えば、種分化が起こってからしばらく経たない と、種分化のエピソードを特定することが困難であること、また、その場合でも、種分化が起こった時期を特定することが不可能であること)は、革命的変化や 新しい科学的専門分野の出現と個別化がもたらす問題と非常に似ている[28]。 哲学者の中には、クーンは革命と専門性の創造という異なる種類の科学的変化を記述しようとしたと主張する者もいる[29]。また、専門化のプロセス自体が 科学的革命の特殊なケースであると主張する者もいる[30]。クーンのモデルでは、科学は革命を通じて進化すると主張することも可能である[31]。 |

| Polanyi–Kuhn debate Although they used different terminologies, both Kuhn and Michael Polanyi believed that scientists' subjective experiences made science a relativized discipline. Polanyi lectured on this topic for decades before Kuhn published The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Supporters of Polanyi charged Kuhn with plagiarism, as it was known that Kuhn attended several of Polanyi's lectures, and that the two men had debated endlessly over epistemology before either had achieved fame. After the charge of plagiarism, Kuhn acknowledged Polanyi in the Second edition of The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.[6]: 44 Despite this intellectual alliance, Polanyi's work was constantly interpreted by others within the framework of Kuhn's paradigm shifts, much to Polanyi's (and Kuhn's) dismay.[32] |

ポランニー=クーン論争 クーンとミヒャエル・ポランニーは、用語こそ違えど、科学者の主観的経験が科学を相対化された学問にしていると考えていた。ポランニーは、クーンが『科学革命の構造』を出版する数十年前から、このテーマで講義を行っていた。 ポランニーの支持者たちは、クーンがポランニーの講義に何度か出席していたこと、そして二人が名声を得る前から認識論をめぐって延々と議論していたことが 知られていたため、クーンを盗作で告訴した。盗作疑惑の後、クーンは『科学革命の構造』の第2版でポランニーを認めた[6]: 44 この知的同盟にもかかわらず、ポランニーの仕事は常にクーンのパラダイム・シフトの枠組みの中で他の人々によって解釈されており、ポランニー(そしてクー ン)は大いに落胆していた[32]。 |

| Honors Kuhn was named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1954, elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1963,[33] elected to the American Philosophical Society in 1974,[34] elected to the United States National Academy of Sciences in 1979,[35] and, in 1982 was awarded the George Sarton Medal by the History of Science Society. He also received numerous honorary doctorates. In honor of his legacy, the Thomas Kuhn Paradigm Shift Award is awarded by the American Chemical Society to speakers who present original views that are at odds with mainstream scientific understanding. The winner is selected based on the novelty of the viewpoint and its potential impact if it were to be widely accepted.[36] Personal life Thomas Kuhn was married twice, first to Kathryn Muhs with whom he had three children, then to Jehane Barton Burns (Jehane B. Kuhn). In 1994, Kuhn was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died in 1996. |

名誉 クーンは1954年にグッゲンハイム・フェローに選ばれ、1963年にはアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーに選出され[33]、1974年にはアメリカ哲学協会 に選出され[34]、1979年にはアメリカ科学アカデミーに選出され[35]、1982年には科学史学会からジョージ・サートン・メダルを授与された。 また、数多くの名誉博士号も授与されている。 彼の遺産を称え、トーマス・クーン・パラダイムシフト賞は、主流派の科学的理解と対立する独創的な見解を発表した講演者にアメリカ化学会から授与される。受賞者は、その視点の斬新さと、それが広く受け入れられた場合の潜在的な影響力に基づいて選ばれる[36]。 私生活 トーマス・クーンは2度結婚し、最初はキャサリン・ムースと3人の子供をもうけ、その後ジェハネ・バートン・バーンズ(ジェハネ・B・クーン)と結婚した。 1994年、クーンは肺がんと診断された。1996年に死去。 |

| Bibliography Kuhn, T. S. The Copernican Revolution: Planetary Astronomy in the Development of Western Thought. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1957. ISBN 0-674-17100-4 Kuhn, T. S. The Function of Measurement in Modern Physical Science. Isis, 52 (1961): 161–193. Kuhn, T. S. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1962. ISBN 0-226-45808-3 Kuhn, T. S. "The Function of Dogma in Scientific Research". pp. 347–369 in A. C. Crombie (ed.). Scientific Change (Symposium on the History of Science, University of Oxford, July 9–15, 1961). New York and London: Basic Books and Heineman, 1963. Kuhn, T. S. The Essential Tension: Selected Studies in Scientific Tradition and Change. Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 1977. ISBN 0-226-45805-9 Kuhn, T. S. Black-Body Theory and the Quantum Discontinuity, 1894-1912. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987. ISBN 0-226-45800-8 Kuhn, T. S. The Road Since Structure: Philosophical Essays, 1970–1993. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 0-226-45798-2 Kuhn, T. S. The Last Writings of Thomas S. Kuhn. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022. |

参考文献 クーン, T. S. 『コペルニクス的転回:西洋思想の発展における惑星天文学』ケンブリッジ:ハーバード大学出版局, 1957年. ISBN 0-674-17100-4 クーン, T. S. 「現代物理学における測定の機能」『アイシス』52号 (1961年): 161–193頁. クーン, T. S. 『科学革命の構造』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局, 1962. ISBN 0-226-45808-3 クーン, T. S. 「科学研究におけるドグマの機能」. pp. 347–369 in A. C. クロムビー (編). 『科学的変化』(オックスフォード大学科学史シンポジウム、1961年7月9日~15日)。ニューヨーク・ロンドン:ベーシック・ブックス・アンド・ハイ ネマン、1963年。 クーン、T. S. 『本質的緊張:科学的伝統と変化に関する選集』。シカゴ・ロンドン:シカゴ大学出版局、1977年。ISBN 0-226-45805-9 クーン, T. S. 『黒体理論と量子不連続性, 1894-1912』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局, 1987. ISBN 0-226-45800-8 クーン, T. S. 『構造以降の道:哲学的随筆集, 1970–1993』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局, 2000. ISBN 0-226-45798-2 クーン, T. S. 『トマス・S・クーンの遺稿集』. シカゴ: シカゴ大学出版局, 2022. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Kuhn |

|

| Born Thomas Samuel Kuhn July 18, 1922 Cincinnati, Ohio, US Died June 17, 1996 (aged 73) Cambridge, Massachusetts, US Education Education Harvard University (BSc, MSc, PhD) Thesis The Cohesive Energy of Monovalent Metals as a Function of Their Atomic Quantum Defects Philosophical work Era 20th-century philosophy Region Western philosophy American philosophy School Analytic Historical turn[1] Historiographical externalism[2] Institutions Harvard University University of California, Berkeley Princeton University Massachusetts Institute of Technology Main interests Philosophy of science History of science Notable ideas Paradigm shiftIncommensurabilityNormal scienceKuhn loss[3]Transcendental nominalism[4] |

トーマス・サミュエル・クーン 1922年7月18日 アメリカ合衆国オハイオ州シンシナティ 1996年6月17日(73歳で死去) マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ 学歴 学歴 ハーバード大学(理学士、理学修士、博士号) 学位論文 原子量子欠陥の関数としての単価金属の凝集エネルギー 哲学的業績 時代 20世紀哲学 地域 西洋哲学 アメリカ哲学 学派 分析哲学 歴史的転換[1] 歴史的外部主義[2] 所属機関 ハーバード大学 カリフォルニア大学バークレー校 プリンストン大学 マサチューセッツ工科大学 主な関心分野 科学哲学 科学史 主な思想 パラダイム転換非通約性通常科学クーンの損失[3]超越的唯名論[4] |

| Further reading Hanne Andersen, Peter Barker, and Xiang Chen. The Cognitive Structure of Scientific Revolutions, Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0521855754 Alexander Bird. Thomas Kuhn. Princeton and London: Princeton University Press and Acumen Press, 2000. ISBN 1-902683-10-2 Steve Fuller. Thomas Kuhn: A Philosophical History for Our Times. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2000. ISBN 0-226-26894-2 Matthew Edward Harris. The Notion of Papal Monarchy in the Thirteenth Century: The Idea of Paradigm in Church History. Lampeter and Lewiston, New York: Edwin Mellen Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7734-1441-9. Paul Hoyningen-Huene Reconstructing Scientific Revolutions: Thomas S. Kuhn's Philosophy of Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0226355511 Jouni-Matti Kuukkanen, Meaning Changes: A Study of Thomas Kuhn's Philosophy. AV Akademikerverlag, 2012. ISBN 978-3639444704 Errol Morris. The Ashtray (Or the Man Who Denied Reality). Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-226-51384-3 Sal Restivo, The Myth of the Kuhnian Revolution. Sociological Theory, Vol. 1, (1983), 293–305. |

さらに読む ハンネ・アンデルセン、ピーター・バーカー、シャン・チェン著。『科学革命の認知構造』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、2006年。ISBN 978-0521855754 アレクサンダー・バード著『トーマス・クーン』プリンストン大学出版局、2000年。ISBN 1-902683-10-2 スティーブ・フラー著『トーマス・クーン:現代のための哲学史』シカゴ大学出版局、2000年。ISBN 0-226-26894-2 マシュー・エドワード・ハリス著『13 世紀の教皇君主制の概念:教会史におけるパラダイムという考え方』ランプターおよびルイストン、ニューヨーク:エドウィン・メレン・プレス、2010 年。ISBN 978-0-7734-1441-9。 ポール・ホイニンゲン=ヒューネ著『科学革命の再構築:トーマス・S・クーンの科学哲学』 シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、1993年。ISBN 978-0226355511 ヨウニ=マッティ・クッカネン『意味の変化:トマス・クーンの哲学研究』。AVアカデミカーヴェルラフ、2012年。ISBN 978-3639444704 エロール・モリス『灰皿(あるいは現実を否定した男)』。シカゴ:シカゴ大学出版局、2018年。ISBN 978-0-226-51384-3 サル・レスティヴォ「クーン的革命の神話」。『社会学理論』第1巻(1983年)、293–305頁。 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆