交差性=インターセクショナリティ

Intersectionality

☆ インターセクショナリティ(Intersectionality )とは、集団や個人の社会的・政治的アイデンティティが、どのように差別や特権の独 特な組み合わせをもたらすかを理解するための社 会学的な分析枠組みである。これらの要因の例としては、ジェンダー、カースト、性別、人種、民族性、階級、セクシュアリティ、宗教、障害、 身長、年齢、体 重、外見などが挙げられる。これらの交差し重なり合う社会的アイデンティティ(intersecting and overlapping social identities)は、 力を与えるものであると同時に抑圧するものであるかもしれな い。

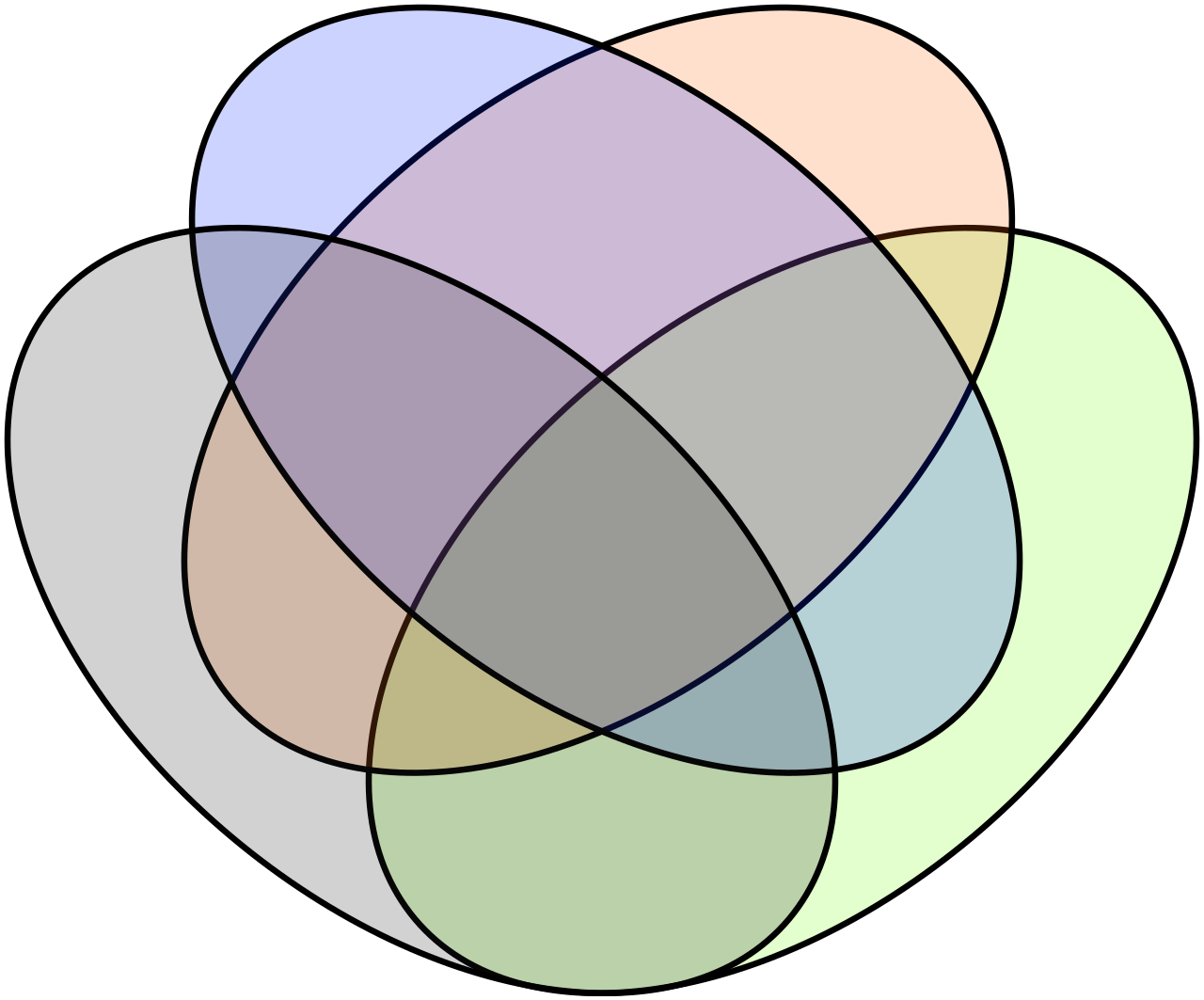

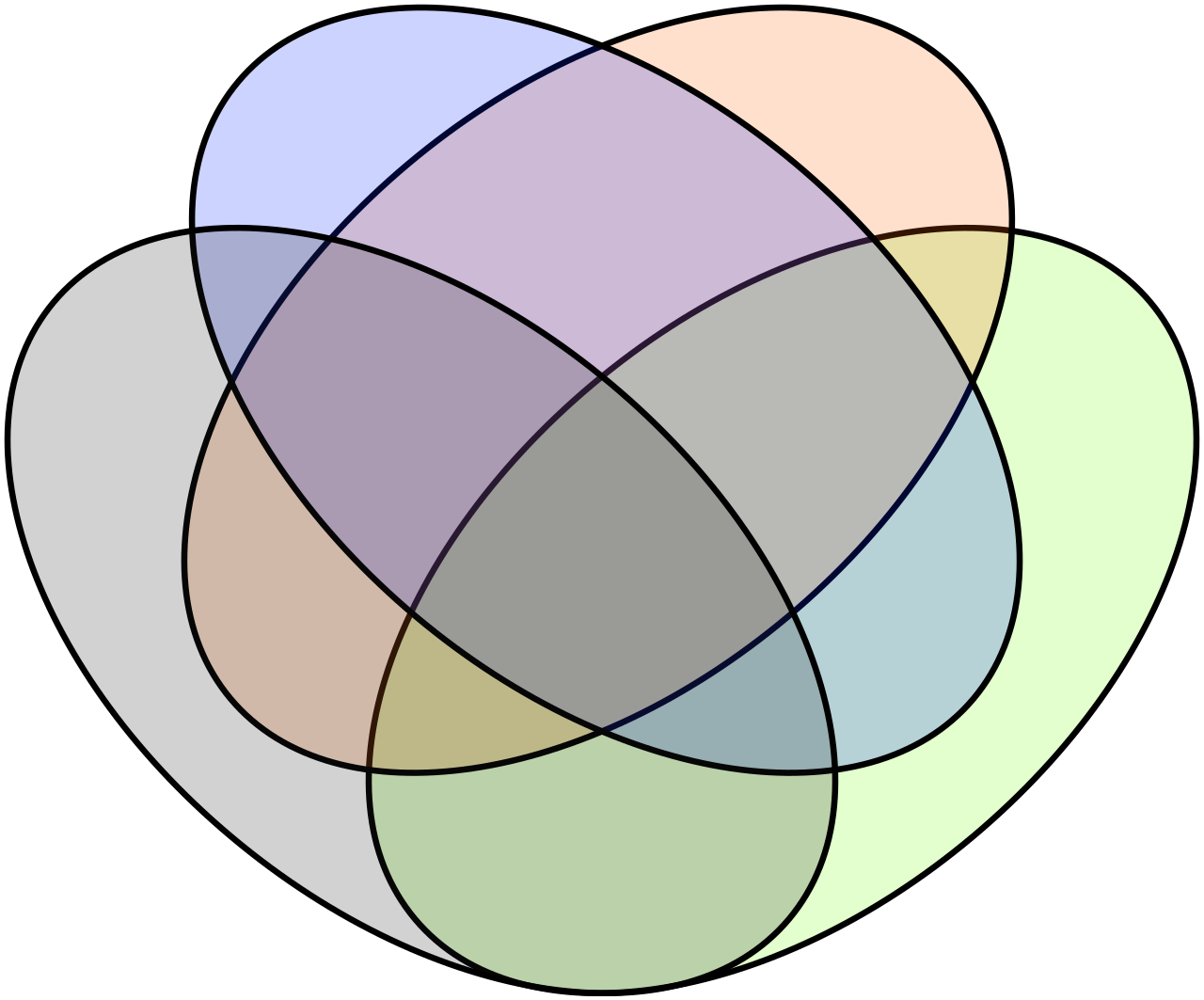

☆インターセクショナルな要素間の間に階層性を発見できる場合があったり(左)、ある差別を受けている時にインターセクショナルな関連性が2つないしはそれ以上の重なりあいで表出(=分析可能な実態として立ち現れること)することがある(右)

★ 交差性への批判には、このフレームワークが個人を特定の人口統計学的要因に還元する傾向があることや、他のフェミニズム理論に対するイデオロギー 的な道具として使用されていることが含まれる。スタンドポイント・セオリーすなわち立場理論(standpoint theory)に基づいているため、主観的な経験に焦点を当てることで矛盾が生じ、抑圧の共通の原因を特定することができないと批判されている。 2019年12月までに発表された学術論文の分析では、交差性から得たリサーチクエスチョンを調査するために広く採用されている定量的手法は存在しないこ とが判明し、今後の研究のための分析的ベストプラクティスに関する提言がなされた。 2020年5月までに発表された学術論文の分析では、理論を定量的方法論に橋渡しする際に、交 差性がしばしば誤解されていることが判明した*。2022年には、情報理論、特に相乗的情報に基づいて、交差性への定量的アプローチが提案された:このフレーミングでは、交差性は、複数のアイデン ティティ(例えば、人種と性別)が一緒に知られている場合にのみ知ることができ、個別に考慮された個々のアイデンティティの分析からは抽出できない、ある 結果(例えば、収入など)に関する情報と識別される。

*Bauer,

Greta R.; Churchill, Siobhan M.; Mahendran, Mayuri; Walwyn, Chantel;

Lizotte, Daniel; Villa-Rueda, Alma Angelica (June 2021).

"Intersectionality in quantitative research: A systematic review of its

emergence and applications of theory and methods". SSM - Population

Health. 14: 100798. doi:10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798. PMC 8095182. PMID

33997247

☆ 交差性の概念は、フェミニズムの理論や運動によってしばしば見落とされてきた原動力を明らかにすることを意図している。人種的不平等は、主に白人男性と白人女性の間の政治的平等を得ることに関心があった第一波フェ ミニズムによってほとんど無視されてきた要因であった。初期の女性の権利運動は、しばしば白人女性のメンバーシップ、関心事、闘争にのみ関 係していた[32]: 59-60 第二波フェミニズムは、女性の家庭内での目的 に関連する性差別の解体に取り組んだ。 この時期のフェミニストたちは、1963年の同一賃金法、タイトルIX、そしてロー対ウェイド事件を通してアメリカにおける成功を収めたが、主流派運動の プラットフォームから黒人女性を大きく遠ざけてしまった。 [しかし、1980年代後半に交差性という用語が造語された直後に出現した第三波フェミニズムは、初期のフェミニズム運動における人種、階級、性的指向、ジェンダー・ア イデンティティへの関心の欠如に注目し、政治的・社会的格差に対処するチャンネルを提供しようとした。 レスリー・マッコールのような最近の学者の多くは、交差性理論の導入は社会学にとって不可欠であり、この理論の発展以前には、社会の中で複数の抑圧を受け る人々の経験を具体的に取り上げた研究はほとんどなかったと主張している。この考え方の一例はアイリス・マリオン・ヤングによって提唱されたものであり、社会をより良い方向へ変化させる助けとなる連合を生み出す社会正義の統一 的な問題を見出すためには、違いを認めなければならないと主張している。より具体的には、これは全米黒人女性協議会(NCNW)の理想と関連して いる。

| Intersectionality

is

a sociological analytical framework for understanding how groups' and

individuals' social and political identities result in unique

combinations of discrimination and privilege. Examples of these factors

include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality,

religion, disability, height, age, weight[1] and physical

appearance.[2] These intersecting and overlapping social identities may

be both empowering and oppressing.[3][4] However, little good-quality

quantitative research has been done to support or undermine the

practical uses of intersectionality.[5] Intersectionality broadens the scope of the first and second waves of feminism, which largely focused on the experiences of women who were white, middle-class and cisgender,[6] to include the different experiences of women of color, poor women, immigrant women, and other groups. Intersectional feminism aims to separate itself from white feminism by acknowledging women's differing experiences and identities.[7] The term intersectionality was coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989.[8]: 385 She describes how interlocking systems of power affect those who are most marginalized in society.[8] Activists and academics use the framework to promote social and political egalitarianism.[7] Intersectionality opposes analytical systems that treat each axis of oppression in isolation. In this framework, for instance, discrimination against black women cannot be explained as a simple combination of misogyny and racism, but as something more complicated.[9] Intersectionality engages in similar themes as triple oppression, which is the oppression associated with being a poor or immigrant woman of color. Criticism includes the framework's tendency to reduce individuals to specific demographic factors,[10] and its use as an ideological tool against other feminist theories.[11] Critics have characterized the framework as ambiguous and lacking defined goals. As it is based in standpoint theory, critics say the focus on subjective experiences can lead to contradictions and the inability to identify common causes of oppression. An analysis of academic articles published through December 2019 found that there are no widely adopted quantitative methods to investigate research questions informed by intersectionality and provided recommendations on analytic best practices for future research.[12] An analysis of academic articles published through May 2020 found that intersectionality is frequently misunderstood when bridging theory into quantitative methodology.[5] In 2022, a quantitative approach to intersectionality was proposed based on information theory, specifically synergistic information: in this framing, intersectionality is identified with the information about some outcome (e.g. income, etc.) that can only be learned when multiple identities (e.g. race and sex) and known together, and not extractable from analysis of the individual identities considered separately.[13]  An intersectional analysis considers a collection of factors that affect a social individual in combination, rather than considering each factor in isolation, as illustrated here using a Venn diagram. |

インターセクショナリティとは、集団や個人の社会的・政治的アイデン

ティティが、どのように差別や特権の独特な組み合わせをもたらすかを理解するための社会学的な分析枠組みである。これらの要因の例としては、ジェンダー、

カースト、性別、人種、民族性、階級、セクシュアリティ、宗教、障害、身長、年齢、体重[1]、外見などが挙げられる[2]。これらの交差し重なり合う社

会的アイデンティティは、力を与えるものであると同時に抑圧するものであるかもしれない[3][4]。 交差性は、主に白人、中流階級、シスジェンダーである女性の経験に焦点を当てていたフェミニズムの第一波と第二波の範囲を広げ[6]、有色人種の女性、貧 困層の女性、移民の女性、その他のグループの様々な経験を含むようにした。インターセクショナル・フェミニズムは、女性の異なる経験やアイデンティティを 認めることで、ホワイト・フェミニズムから分離することを目指している[7]。 交差性という用語は1989年にキンバーレ・クレンショーによって作られた[8]: 385 彼女は、権力の連動システムが社会で最も疎外されている人々にどのような影響を与えるかを説明している[8]。活動家や学者は、社会的・政治的平等主義を 促進するためにこの枠組みを使用している。この枠組みでは、例えば黒人女性に対する差別は、女性差別と人種差別の単純な組み合わせとして説明することはで きず、もっと複雑なものとして説明される。 交差性への批判には、このフレームワークが個人を特定の人口統計学的要因に還元する傾向があること[10]や、他のフェミニズム理論に対するイデオロギー 的な道具として使用されていること[11]が含まれる。スタンドポイント・セオリーすなわち立場理論(standpoint theory)に基づいているため、主観的な経験に焦点を当てることで矛盾が生じ、抑圧の共通の原因を特定することができないと批判している。 2019年12月までに発表された学術論文の分析では、交差性から得たリサーチクエスチョンを調査するために広く採用されている定量的手法は存在しないこ とが判明し、今後の研究のための分析的ベストプラクティスに関する提言がなされた[12]。 2020年5月までに発表された学術論文の分析では、理論を定量的方法論に橋渡しする際に、交 差性がしばしば誤解されていることが判明した。 [5]2022年には、情報理論、特に相乗的情報に基づいて、交差性への定量的アプローチが提案された:このフレーミングでは、交差性は、複数のアイデン ティティ(例えば、人種と性別)が一緒に知られている場合にのみ知ることができ、個別に考慮された個々のアイデンティティの分析からは抽出できない、ある 結果(例えば、収入など)に関する情報と識別される[13]。  交差分析では、社会的な個人が受ける影響を及ぼす要因の集合を、それぞれを個別にではなく、組み合わせて考慮する。これは、ベン図を用いて上のように例示 されている。 |

| The

concept of intersectionality was introduced to the field of legal

studies by black feminist scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw,[15] who used the

term in a pair of essays[16][17] published in 1989 and 1991.[8] Intersectionality originated in critical race studies and demonstrates a multifaceted connection between race, gender, and other systems that work together to oppress, while also allowing privilege in other areas. Intersectionality is relative because it displays how race, gender, and other components "intersect" to shape the experiences of individuals. Crenshaw used intersectionality to denote how race, class, gender, and other systems combine to shape the experiences of many by making room for privilege.[18] Crenshaw used intersectionality to display the disadvantages caused by intersecting systems creating structural, political, and representational aspects of violence against minorities in the workplace and society.[18] Crenshaw explained the dynamics that using gender, race, and other forms of power in politics and academics plays a big role in intersectionality.[19] However, long before Crenshaw, W. E. B. Du Bois theorized that the intersectional paradigms of race, class, and nation might explain specific aspects of the black political economy. Collins writes: "Du Bois saw race, class, and nation not primarily as personal identity categories but as social hierarchies that shaped African-American access to status, poverty, and power."[20]: 44 Du Bois nevertheless omitted gender from his theory and considered it more of a personal identity category. In the 1970s, a group of black feminist women organized the Combahee River Collective in response to what they felt was an alienation from both white feminism and the male-dominated black liberation movement, citing the "interlocking oppressions" of racism, sexism and heteronormativity.[21] In DeGraffenreid v. General Motors (1976), Emma DeGraffenreid and four other black female auto workers alleged compound employment discrimination against black women as a result of General Motors' seniority-based system of layoffs. The courts weighed the allegations of race and gender discrimination separately, finding that the employment of African-American male factory workers disproved racial discrimination, and the employment of white female office workers disproved gender discrimination. The court declined to consider compound discrimination, and dismissed the case.[22][23] Crenshaw argued that in cases such as this, the courts have tended to ignore black women's unique experiences by treating them as only women or only black.[24][25]: 141–143 The ideas behind intersectional feminism existed long before the term was coined. For example, Sojourner Truth exemplifies intersectionality in her 1851 "Ain't I a Woman?" speech, in which she spoke from her racialized position as a former slave to critique essentialist notions of femininity.[26] Similarly, in her 1892 essay "The Colored Woman's Office", Anna Julia Cooper identifies black women as the most important actors in social change movements because of their experience with multiple facets of oppression.[27] Patricia Hill Collins has located the origins of intersectionality among black feminists, Chicana and other Latina feminists, indigenous feminists and Asian American feminists between the 1960s and 1980s. Collins has noted the existence of intellectuals at other times and in other places who discussed similar ideas about the interaction of different forms of inequality, such as Stuart Hall and the cultural studies movement, Nira Yuval-Davis, Anna Julia Cooper and Ida B. Wells. She noted that, as second-wave feminism receded in the 1980s, feminists of color such as Audre Lorde, Gloria E. Anzaldúa and Angela Davis entered academic environments and brought their perspectives to their scholarship. During this decade, many of the ideas that would together be labeled as intersectionality coalesced in U.S. academia under the banner of "race, class and gender studies".[28] As articulated by author bell hooks, the emergence of intersectionality "challenged the notion that 'gender' was the primary factor determining a woman's fate".[29] The historical exclusion of black women from the feminist movement in the United States resulted in many black 19th- and 20th-century feminists, such as Anna Julia Cooper, challenging their historical exclusion. This disputed the ideas of earlier feminist movements, which were primarily led by white middle-class women, suggesting that women were a homogeneous category who shared the same life experiences.[30] However, once established that the forms of oppression experienced by white middle-class women were different from those experienced by black, poor, or disabled women, feminists began seeking ways to understand how gender, race, and class combine to "determine the female destiny".[29] The concept of intersectionality is intended to illuminate dynamics that have often been overlooked by feminist theory and movements.[31] Racial inequality was a factor that was largely ignored by first-wave feminism, which was primarily concerned with gaining political equality between white men and white women. Early women's rights movements often exclusively pertained to the membership, concerns, and struggles of white women.[32]: 59–60 Second-wave feminism worked to dismantle sexism relating to the perceived domestic purpose of women. While feminists during this time achieved success in the United States through the Equal Pay Act of 1963, Title IX, and Roe v. Wade, they largely alienated black women from platforms in the mainstream movement.[33] However, third-wave feminism—which emerged shortly after the term intersectionality was coined in the late 1980s—noted the lack of attention to race, class, sexual orientation, and gender identity in early feminist movements, and tried to provide a channel to address political and social disparities.[32]: 72–73 Intersectionality recognizes these issues which were ignored by early social justice movements. Many recent academics, such as Leslie McCall, have argued that the introduction of the intersectionality theory was vital to sociology and that before the development of the theory, there was little research that specifically addressed the experiences of people who are subjected to multiple forms of oppression within society.[34] An example of this idea was championed by Iris Marion Young, arguing that differences must be acknowledged in order to find unifying social justice issues that create coalitions that aid in changing society for the better.[35] More specifically, this relates to the ideals of the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW).[36] The term also has historical and theoretical links to the concept of simultaneity, which was advanced during the 1970s by members of the Combahee River Collective in Boston, Massachusetts.[37] Simultaneity is the simultaneous influences of race, class, gender, and sexuality, which informed the member's lives and their resistance to oppression.[38] Thus, the women of the Combahee River Collective advanced an understanding of African-American experiences that challenged analyses emerging from black and male-centered social movements, as well as those from mainstream cisgender, white, middle-class, heterosexual feminists.[39]  A crowd of people in a Black Lives Matter protest in 2015. The main focus is four black women, one holding a sign. Since the term was coined, many feminist scholars have emerged with historical support for the intersectional theory. These women include Beverly Guy-Sheftall and her fellow contributors to Words of Fire: An Anthology of African-American Feminist Thought, a collection of articles describing the multiple oppressions black women in America have experienced from the 1830s to contemporary times. Guy-Sheftall speaks about the constant premises that influence the lives of African-American women, saying, "black women experience a special kind of oppression and suffering in this country which is racist, sexist, and classist because of their dual race and gender identity and their limited access to economic resources."[40] Other writers and theorists were using intersectional analysis in their work before the term was coined. For example, Pauli Murray used the phrase "Jane Crow" in 1947 while at Howard University to describe the compounded challenges faced by black women in the Jim Crow south.[41] Deborah K. King published the article "Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology" in 1988, just before Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality. In the article, King addresses what soon became the foundation for intersectionality, saying, "black women have long recognized the special circumstances of our lives in the United States: the commonalities that we share with all women, as well as the bonds that connect us to the men of our race."[42] Additionally, Gloria Wekker describes how Gloria Anzaldúa's work as a Chicana feminist theorist exemplifies how "existent categories for identity are strikingly not dealt with in separate or mutually exclusive terms, but are always referred to in relation to one another".[43] Wekker also points to the words and activism of Sojourner Truth as an example of an intersectional approach to social justice.[43] In her speech, "Ain't I a Woman?", Truth identifies the difference between the oppression of white and black women. She says that white women are often treated as emotional and delicate, while black women are subjected to racist abuse. However, this was largely dismissed by white feminists who worried that this would distract from their goal of women's suffrage and instead focused their attention on emancipation.[44] |

インターセクショナリティすなわち交差性という概念は、1989年と

1991年に出版された一組のエッセイ[16][17]でこの用語を使用した黒人フェミニスト学者キンバーレ・クレンショー[15]によって法学の分野に

導入された[8]。 インターセクショナリティは批判的人種研究に端を発し、人種、ジェンダー、その他抑圧するために共に働くシステム間の多面的なつながりを示す一方で、他の 領域における特権を認めるものでもある。インターセクショナリティが相対的であるのは、人種、ジェンダー、その他の要素がどのように「交差」して個人の経 験を形成しているかを示すからである。クレンショーは交差性を用いて、人種、階級、ジェ ンダー、その他のシステムがどのように組み合わさって、 特権の余地を作ることで多くの人の経験を形成している かを示した[18]。クレンショーは交差するシステムが、職場 や社会におけるマイノリティに対する暴力の構造的、政治的、 表象的側面を作り出すことによって引き起こされる不利を 表現した[18]。 しかし、クレンショーよりもずっと前に、W・E・B・デュボイスは、人種、階級、国家の交差パラダイムが黒人の政治経済の特定の側面を説明するかもしれない と理論化していた。コリンズは、「デュボイスは、人種、階級、国家を、主として個人的なアイデンティティのカテゴリーとしてではなく、地位、貧困、権力への アフリカ系アメリカ人のアクセスを形成する社会的階層としてとらえていた」と書いている[20]: 44 デュボイスはそれにもかかわらず、ジェンダーを彼の理論から省き、より個人的なアイデンティティのカテゴリーとみなしていた。1970年代、黒人フェミニス トの女性グループは、白人フェミニズムと男性優位の黒人解放運動の両方から疎外されていると感じ、人種差別、性差別、ヘテロ規範の「連動する抑圧」を挙げ て、コンバヒー・リバー・コレクティブを組織した[21]。 デグラフェンレイド対ゼネラル・モーターズ事件(1976年)では、エマ・デグラフェンレイドをはじめとする4人の黒人女性自動車労働者が、ゼネラル・ モーターズの年功序列に基づく解雇制度の結果として黒人女性に対する複合的な雇用差別を主張した。裁判所は、人種差別と男女差別の申し立てを別々に検討 し、アフリカ系アメリカ人の男性工場労働者の雇用は人種差別を否定し、白人女性事務職の雇用は男女差別を否定すると判断した。クレンショーは、このような ケースにおいて、裁判所は黒人女性のみを女性として、あるいは黒人のみを黒人として扱うことで、黒人女性特有の経験を無視する傾向があると主張した [24][25]: 141-143 交差点フェミニズムの背後にある考え方は、この言葉が作られるずっと前から存在していた。例えば、ソジャーナー・トゥルースは1851年に行った "Ain't I a Woman? "というスピーチで交差性を例証している。 [同様に、アンナ・ジュリア・クーパーは1892年に発表したエッセイ "The Colored Woman's Office "において、黒人女性は抑圧の多面性を経験しているため、社会変革運動において最も重要なアクターであるとしている[27]。パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズ は、1960年代から1980年代にかけて、黒人フェミニスト、チカーナやその他のラティーナ・フェミニスト、先住民フェミニスト、アジア系アメリカ人 フェミニストの間に交差性の起源を見出した。コリンズは、スチュアート・ホールやカルチュラル・スタディーズ運動、ニラ・ユヴァル=デイヴィス、アンナ・ ジュリア・クーパー、アイダ・B・ウェルズなど、さまざまな不平等の相互作用について同様の考えを論じた知識人が、他の時代や他の場所にも存在したことを 指摘している。1980年代に第二波フェミニズムが後退すると、オードレ・ローデ、グロリア・E・アンザルドゥア、アンジェラ・デイヴィスといった有色人 種のフェミニストたちがアカデミックな環境に入り、彼らの視点を学問に持ち込んだと彼女は指摘した。この10年の間に、「人種・階級・ジェンダー研究」の 旗印のもと、米国の学術界において、共に交差性というラベルを貼られることになる多くの考え方がまとまった[28]。 作家のベル・フックスが明確に述べているように、交差性の出現は「『ジェンダー』が女性の運命を決定する主要な要因であるという概念に異議を唱えた」 [29]。アメリカにおけるフェミニズム運動から黒人女性が歴史的に排除された結果、アンナ・ジュリア・クーパーなどの多くの19世紀と20世紀の黒人 フェミニストが、その歴史的排除に異議を唱えた。これは、主に白人中産階級の女性によって主導され、女性は同じ人生経験を共有する同質のカテゴリーである ことを示唆していた以前のフェミニズム運動の考え方に異議を唱えるものであった[30]。しかし、白人中産階級の女性が経験する抑圧の形態が、黒人、貧困 層、あるいは障害を持つ女性が経験するものとは異なることが確立されると、フェミニストたちはジェンダー、人種、階級がどのように組み合わさって「女性の 運命を決定する」のかを理解する方法を模索し始めた[29]。 交差性の概念は、フェミニズムの理論や運動によってしばしば見落とされてきた原動力を明らかにすることを意図している[31]。人種的不平等は、主に白人男性と白人女性の間の政治的平等を得ることに関心があった第一波フェ ミニズムによってほとんど無視されてきた要因であった。初期の女性の権利運動は、しばしば白人女性のメンバーシップ、関心事、闘争にのみ関 係していた[32]: 59-60 第二波フェミニズムは、女性の家庭内での目的 に関連する性差別の解体に取り組んだ。 この時期のフェミニストたちは、1963年の同一賃金法、タイトルIX、そしてロー対ウェイド事件を通してアメリカにおける成功を収めたが、主流派運動の プラットフォームから黒人女性を大きく遠ざけてしまった。 [しかし、1980年代後半に交差性という用語が造語された直後に出現した第三波フェミニズムは、初期のフェミニズム運動における人種、階級、性的指向、ジェンダー・ア イデンティティへの関心の欠如に注目し、政治的・社会的格差に対処するチャンネルを提供しようとした。 レスリー・マッコールのような最近の学者の多くは、交差性理論の導入は社会学にとって不可欠であり、この理論の発展以前には、社会の中で複数の抑圧を受け る人々の経験を具体的に取り上げた研究はほとんどなかったと主張している。 [この考え方の一例はアイリス・マリオン・ヤングによって提唱されたものであり、社会をより良い方向へ変化させる助けとなる連合を生み出す社会正義の統一 的な問題を見出すためには、違いを認めなければならないと主張している[35]。より具体的には、これは全米黒人女性協議会(NCNW)の理想と関連して いる[36]。 この言葉はまた、1970年代にマサチューセッツ州ボストンのコンバヒー・リバー・コレクティブのメンバーによって提唱された同時性の概念とも歴史的・理 論的なつながりがある。 [したがって、コンバヒー・リヴァー・コレクティブの女性たちは、黒人や男性中心の社会運動から生まれた分析や、主流派のシスジェンダー、白人、中流階 級、異性愛者のフェミニストから生まれた分析に挑戦するアフリカ系アメリカ人の経験についての理解を進めた[39]。  2015年、ブラック・ライブズ・マターの抗議デモに集まった群衆。主役は4人の黒人女性で、1人は看板を持っている。 この言葉ができて以来、多くのフェミニスト学者が交差理論を歴史的に支持するようになった。その中には、ビバリー・ガイ=シェフトールや、『Words of Fire』に寄稿した仲間も含まれる: アフリカ系アメリカ人フェミニスト思想のアンソロジー』は、1830年代から現代に至るまで、アメリカの黒人女性が経験してきた複数の抑圧を記述した論文 集である。ガイ・シェフトールは、アフリカ系アメリカ人女性の生活に影響を与える絶え間ない前提について語り、「黒人女性は、人種とジェンダーの二重のア イデンティティと、経済的資源への限られたアクセスのために、人種差別的、性差別的、階級差別的な、この国における特別な抑圧と苦しみを経験している」と 述べている[40]。例えば、ポーリ・マレイはハワード大学在学中の1947年に、ジム・クロウ制の南部で黒人女性が直面する複合的な課題を表現するため に「ジェーン・クロウ」という言葉を用いている[41]: デボラ・K・キングは、クレンショーがインターセクショナリティという言葉を作る直前の1988年に、"Multiple Jeopardy, Multiple Consciousness: The Context of a Black Feminist Ideology "という論文を発表している。黒人女性は長い間、アメリカにおける私たちの生活の特別な状況、すなわち私たちがすべての女性と共有している共通点と、私た ちを私たちの人種の男性と結びつけている絆を認識してきた。 「さらにグロリア・ウェッカーは、チカーナ・フェミニストの理論家としてのグロリア・アンザルドゥアの仕事が、「アイデンティティのために存在するカテゴ リーが、別個の、あるいは相互に排他的な用語で扱われるのではなく、常に互いに関連して言及される」ことを例証していると述べている。 [43]ウェッカーはまた、社会正義に対する交差的アプローチの例として、ソジャーナー・トゥルースの言葉や活動を指摘している[43]。トゥルースは、 彼女の演説「私は女性ではないのか」の中で、白人女性と黒人女性の抑圧の違いを明らかにしている。白人女性は感情的でデリケートな存在として扱われること が多いが、黒人女性は人種差別的な虐待を受けているという。しかしこれは、女性参政権という目標から目をそらされることを心配した白人フェミニストたちに よってほとんど否定され、代わりに奴隷解放に関心が向けられた[44]。 |

| In

1989, Kimberlé Crenshaw coined the term intersectionality as a way to

help explain the oppression of African-American women in her essay

"Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A black Feminist

Critique of Anti-discrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and

Antiracist Politics".[25] Crenshaw's term has risen to the forefront of

national conversations about racial justice, identity politics, and

policing—and over the years has helped shape legal discussions.[45][23]

In her work, Crenshaw discusses Black feminism, arguing that the

experience of being a black woman cannot be understood in terms

independent of either being black or a woman. Rather, it must include

interactions between the two identities, which, she adds, should

frequently reinforce one another.[46] In order to show that non-white women have a vastly different experience from white women due to their race and/or class and that their experiences are not easily voiced or amplified, Crenshaw explores two types of male violence against women: domestic violence and rape. Through her analysis of these two forms of male violence against women, Crenshaw says that the experiences of non-white women consist of a combination of both racism and sexism.[18] She says that because non-white women are present within discourses that have been designed to address either race or sex—but not both at the same time—non-white women are marginalized within both of these systems of oppression as a result.[18] In her work, Crenshaw identifies three aspects of intersectionality that affect the visibility of non-white women: structural intersectionality, political intersectionality, and representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality deals with how non-white women experience domestic violence and rape in a manner qualitatively different from white women. Political intersectionality examines how laws and policies intended to increase equality have paradoxically decreased the visibility of violence against non-white women. Finally, representational intersectionality delves into how pop culture portrayals of non-white women can obscure their own authentic lived experiences.[18] Within Crenshaw's work, she delves into a few legal cases that exhibit the concept of political intersectionality and how anti-discrimination law has been historically limited. These cases include DeGraffenreid v Motors, Moore v Hughes Helicopter Inc., and Payne v Travenol. There are two commonalities, amongst others, that exist between these cases with the first being each respective court's inability to fully understand the multidimensionality of the plaintiff's intersecting identities. Second is the limited ability that the plaintiffs had to argue their case due to restrictions created by the very legislation that exists in opposition to discrimination such as Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 as used against the plaintiffs in the DeGraffenreid v Motors case.[47] The term gained prominence in the 1990s, particularly in the wake of the further development of Crenshaw's work in the writings of sociologist Patricia Hill Collins. Crenshaw's term, Collins says, replaced her own previous coinage "black feminist thought", and "increased the general applicability of her theory from African American women to all women".[48]: 61 Much like Crenshaw, Collins argues that cultural patterns of oppression are not only interrelated, but are bound together and influenced by the intersectional systems of society, such as race, gender, class, and ethnicity.[20]: 42 Collins describes this as "interlocking social institutions [that] have relied on multiple forms of segregation... to produce unjust results".[49] Collins sought to create frameworks to think about intersectionality, rather than expanding on the theory itself. She identified three main branches of study within intersectionality. One branch deals with the background, ideas, issues, conflicts, and debates within intersectionality. Another branch seeks to apply intersectionality as an analytical strategy to various social institutions in order to examine how they might perpetuate social inequality. The final branch formulates intersectionality as a critical praxis to determine how social justice initiatives can use intersectionality to bring about social change.[28] One writer who focused on intersectionality was Audre Lorde, who was a self-proclaimed "Black, Lesbian, Mother, Warrior, Poet".[50] Even in the title she gave herself, Lorde expressed her multifaceted personhood and demonstrated her intersectional struggles with being a black, gay woman. Lorde commented in her essay The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house, that she was living in "a country where racism, sexism, and homophobia are inseparable".[51] Here, Lorde outlines the importance of intersectionality, while acknowledging that different prejudices are inherently linked.[52] Lorde's formulation of this linkage remains seminal in intersectional feminism.[52][a] Though intersectionality began with the exploration of the interplay between gender and race, over time other identities and oppressions were added to the theory. For example, in 1981 Cherríe Moraga and Gloria Anzaldúa published the first edition of This Bridge Called My Back. This anthology explored how classifications of sexual orientation and class also mix with those of race and gender to create even more distinct political categories. Many black, Latina, and Asian writers featured in the collection stress how their sexuality interacts with their race and gender to inform their perspectives. Similarly, poor women of color detail how their socio-economic status adds a layer of nuance to their identities, ignored or misunderstood by middle-class white feminists.[53][page needed] Asian American women often report intersectional experiences that set them apart from other American women.[54] For example, several studies have shown that East Asian women are considered more physically attractive than white women, and other women of color. Taken at face value, this may seem like a social advantage. However, if this perception is inspired by stereotypes of Asian women as "hyperfeminine", it can serve to perpetuate racialized stereotypes of Asian women as subordinate or oversexualized.[55] Robin Zheng writes that widespread fetishization of East Asian women's physical features leads to "racial depersonalization": the separation of Asian women from their own individual attributes.[56] According to black feminists such as Kimberle Crenshaw, Audre Lorde, bell hooks, and Patricia Hill Collins, experiences of class, gender, and sexuality cannot be adequately understood unless the influence of racialization is carefully considered. This focus on racialization was highlighted many times by scholar and feminist bell hooks, specifically in her 1981 book Ain't I A Woman: Black Women and Feminism.[57][page needed] Patricia Hill Collins's essay "Gender, black feminism, and black political economy" highlights her theory on the sociological crossroads between modern and post-modern feminist thought.[20] Black feminists argue that an understanding of intersectionality is a vital element of gaining political and social equity and improving the societal structures that oppress individuals.[58] Chiara Bottici has argued that criticisms of intersectionality that find it to be incomplete, or argue that it fails to recognize the specificity of women's oppression, can be met with an anarcha-feminism that recognizes "that there is something specific about the oppression of women and that in order to fight it you have to fight all other forms of oppression."[59] Cheryl Townsend Gilkes expands on this by pointing out the value of centering on the experiences of black women. Joy James takes things one step further by "using paradigms of intersectionality in interpreting social phenomena". Collins later integrated these three views by examining a black political economy through the centering of black women's experiences and the use of a theoretical framework of intersectionality.[20]: 44 Collins uses a Marxist feminist approach and applies her intersectional principles to what she calls the "work/family nexus and black women's poverty". In her 2000 article "Black Political Economy" she describes how, in her view, the intersections of consumer racism, gender hierarchies, and disadvantages in the labor market can be centered on black women's unique experiences. Considering this from a historical perspective and examining interracial marriage laws and property inheritance laws creates what Collins terms a "distinctive work/family nexus that in turn influences the overall patterns of black political economy".[20]: 45–46 For example, anti-miscegenation laws effectively suppressed the upward economic mobility of black women. The intersectionality of race and gender has been shown to have a visible impact on the labor market. "Sociological research clearly shows that accounting for education, experience, and skill does not fully explain significant differences in labor market outcomes."[60]: 506 The three main domains in which we see the impact of intersectionality are wages, discrimination, and domestic labor. Those who experience privilege within the social hierarchy in terms of race, gender, and socio-economic status are less likely to receive lower wages, to be subjected to stereotypes and discriminated against, or to be hired for exploitative domestic positions. Studies of the labor market and intersectionality provide a better understanding of economic inequalities and the implications of the multidimensional impact of race and gender on social status within society.[60]: 506–507 |

1989年、キンバーレ・クレンショーは、アフリカ系アメ

リカ人女性の抑圧を説明するための方法として交差性という言葉を作り、彼女のエッセイ「人種と性の交差を非限界化する:

クレンショーの用語は、人種的正義、アイデンティティ政治、そして警察に関する国民的な会話の最前線に立ち、長年にわたって法的な議論を形成するのに役

立ってきた。むしろ、それは2つのアイデンティティの間の相互作用を含むものでなければならず、それは頻繁に互いを補強しあうものでなければならないと彼

女は付け加えている[46]。 非白人女性が、人種や階級によって白人女性とは大きく異なる経験をしていること、そしてその経験が容易に声に出されたり増幅されたりしないことを示すため に、クレンショーは女性に対する2種類の男性の暴力、ドメスティック・バイオレンスとレイプを探求している。この2つの女性に対する男性の暴力の分析を通 して、クレンショーは、非白人女性の経験は人種差別と性差別の両方が組み合わさって構成されていると述べている[18]。彼女は、非白人女性は、人種か性 差別のどちらかに対処するように設計された言説の中に存在しているが、両方同時に対処することはできないため、非白人女性は、結果としてこれらの抑圧のシ ステムの両方の中で疎外されていると述べている[18]。 クレンショーは、非白人女性の可視性に影響を与える交差性の3つの側面、すなわち構造的交差性、政治的交差性、表象的交差性を明らかにしている。構造的交 差性は、非白人女性がどのように白人女性とは質的に異なる方法でDVやレイプを経験するかを扱う。政治的交差性は、平等性を高めることを意図した法律や政 策が、逆説的に非白人女性に対する暴力の可視性をどのように低下させてきたかを検証する。最後に、表象的交差性は、非白人女性に対するポップカルチャーの 描写が、いかに彼女たち自身の本物の生きた経験を曖昧にしてしまうかを掘り下げている[18]。 クレンショーの著作の中で、彼女は政治的交差性の概念と差別禁止法が歴史的にどのように制限されてきたかを示すいくつかの法的事例を掘り下げている。これ らの判例には、デグラフェンレイド対モーターズ事件、ムーア対ヒューズ・ヘリコプター事件、ペイン対トラベノール事件などがある。これらの事件には、とり わけ2つの共通点が存在する。1つ目は、それぞれの裁判所が、原告の交差するアイデンティティの多次元性を十分に理解できなかったことである。二つ目は、 デグラフェンレイド対モーターズ事件で原告に対して用いられた1964年公民権法タイトルVIIのような差別に反対するために存在する法律そのものによっ て作られた制限のために、原告が自分たちの訴えを主張する能力が制限されていたことである[47]。 この用語は1990年代、特に社会学者パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズの著作の中でクレンショーの研究がさらに発展したことをきっかけに注目されるようになっ た。コリンズによれば、クレンショーの用語は、彼女自身の以前の造語である「黒人フェミニスト思想」に取って代わり、「アフリカ系アメリカ人女性からすべ ての女性へと彼女の理論の一般的な適用可能性を高めた」[48]: 61 クレンショーと同様に、コリンズは抑圧の文化的パターンは相互に関連しているだけでなく、人種、ジェンダー、階級、民族性といった社会の交差システムに よって結びつけられ、影響を受けていると主張している[20]: 42 コリンズはこれを「不公正な結果を生み出すために...複数の形態の分離に依存してきた[連動する]社会制度」と表現している[49]。 コリンズは、理論そのものを拡張するのではなく、交差性について考える枠組みを作ろうとした。彼女は、交差性の中で3つの主要な研究分野を特定した。ひと つは、交差性における背景、考え方、問題、対立、議論を扱うものである。もうひとつは、社会的不平等をどのように永続させるかを検討するために、さまざま な社会制度に分析戦略として交差性を適用しようとするものである。最後の枝は、社会正義のイニシアチブが社会変革をもたらすために交差性をどのように用い ることができるかを決定するために、批判的実践として交差性を定式化するものである[28]。 交差性に焦点を当てた作家の一人に、「黒人、レズビアン、母親、戦士、詩人」を自称するオードレ・ロードがいる。ロードはエッセイ『The master's tools will never dismantle the master's house』の中で、自分が「人種差別、性差別、同性愛嫌悪が切り離せない国」に住んでいるとコメントしている[51]。ここでロードは、異なる偏見が本 質的に結びついていることを認めながら、交差性の重要性を概説している[52]。 交差性はジェンダーと人種間の相互作用の探求から始まったが、時を経て他のアイデンティティや抑圧が理論に加えられた。例えば、1981年にチェリー・モ ラガとグロリア・アンザルドゥアは、『This Bridge Called My Back』の初版を出版した。このアンソロジーは、性的指向や階級の分類が、人種やジェンダーの分類とどのように混ざり合い、さらに明確な政治的カテゴ リーを作り出しているかを探求した。このアンソロジーに登場する黒人、ラテン系、アジア系の作家の多くは、自分たちのセクシュアリティが人種やジェンダー とどのように影響し合って、自分たちの視点を形成しているかを強調している。同様に、貧しい有色人種の女性たちは、中流階級の白人フェミニストたちに無視 されたり誤解されたりしている社会経済的地位が、いかに自分たちのアイデンティティにニュアンスの層を加えているかを詳述している[53][要ページ]。 例えば、いくつかの研究によれば、東アジアの女性は白人女性や他の有色人種の女性よりも肉体的に魅力的であると考えられている。額面通りに受け取れば、こ れは社会的に有利なことのように思えるかもしれない。しかし、この認識がアジア人女性を「ハイパーフェミニン」とするステレオタイプに触発されたものであ る場合、アジア人女性を従属的あるいは性的に過度なものであるとする人種的ステレオタイプを永続させる役割を果たすことになる。 キンブル・クレンショー、オードレ・ロード、ベル・フックス、パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズといった黒人フェミニストによれば、階級、ジェンダー、セクシュ アリティの経験は、人種化の影響が注意深く考慮されない限り、適切に理解されることはない。このような人種差別の焦点は、学者でありフェミニストであるベ ル・フックスによって何度も強調され、特に1981年に出版された彼女の著書『Ain't I A Woman: 黒人女性とフェミニズム」[57][page needed] パトリシア・ヒル・コリンズのエッセイ「ジェンダー、黒人フェミニズム、黒人政治経済」は、現代とポストモダンのフェミニズム思想の間の社会学的交差点に 関する彼女の理論を強調している[20]。黒人フェミニストは、交差性の理解が政治的・社会的公平性を獲得し、個人を抑圧する社会構造を改善するために不 可欠な要素であると主張している[58]。 Chiara Botticiは、交差性が不完全であるとする批判や、女性の抑圧の特異性を認識できていないと主張する批判は、「女性の抑圧には特異なものがあり、それ と闘うためには他のすべての抑圧と闘わなければならない」と認識するアナーカ・フェミニズムで対応することができると主張している[59]。 シェリル・タウンゼント・ギルクスは、黒人女性の経験を中心に据えることの価値を指摘することで、これを発展させている。ジョイ・ジェイムズは、「社会現 象を解釈する際に交差性のパラダイムを用いる」ことによって、さらに一歩踏み込んでいる。コリンズは後に、黒人女性の経験を中心に据え、交差性の理論的枠 組みを用いることで黒人政治経済を検証し、これら3つの見解を統合した[20]: 44 コリンズはマルクス主義的なフェミニズムのアプローチを用い、彼女が「仕事と家庭の結びつきと黒人女性の貧困」と呼ぶものに交差性の原則を適用している。 2000年の論文「Black Political Economy」において、彼女は、消費者人種差別、ジェンダー階層、労働市場における不利の交錯が、黒人女性特有の経験を中心にどのように考えられるか を述べている。これを歴史的な観点から考察し、異人種間結婚法や財産相続法を検証することで、コリンズが言うところの「仕事と家族の結びつきが、ひいては 黒人の政治経済の全体的なパターンに影響を与える」というものを作り出している[20]: 例えば、混血禁止法は黒人女性の経済的上昇を効果的に抑制し た。 人種とジェンダーの交差性は、労働市場に目に見える影響を与えることが示されている。「社会学的研究は、学歴、経験、技能を考慮しても、労働市場の結果に おける有意な差異を完全に説明することはできないことを明確に示している」[60]: 506 交差性の影響が見られる3つの主な領域は、賃金、差別、家事労働である。人種、ジェンダー、社会経済的地位の点で社会階層の中で特権を経験している人は、 低賃金を受け取ったり、ステレオタイプや差別を受けたり、搾取的な家事労働に雇われたりする可能性が低い。労働市場とインターセクショナリティに関する研 究は、経済的不平等と、社会内での社会的地位に対する人種とジェンダーの多次元的影響の意味合いについて、より良い理解を提供する[60]: 506- 507 |

| Forms: structural, political,

representational Kimberlé Crenshaw, in "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color",[18] uses and explains three different forms of intersectionality to describe the violence that women experience. According to Crenshaw, there are three forms of intersectionality: structural, political, and representational intersectionality. Structural intersectionality is used to describe how different structures work together and create a complex which highlights the differences in the experiences of women of color with domestic violence and rape. Structural intersectionality entails the ways in which classism, sexism, and racism interlock and oppress women of color while molding their experiences in different arenas. Crenshaw's analysis of structural intersectionality was used during her field study of battered women. In this study, Crenshaw uses intersectionality to display the multilayered oppressions that women who are victims of domestic violence face.[61] Political intersectionality highlights two conflicting systems in the political arena, which separates women and women of color into two subordinate groups.[61] The experiences of women of color differ from those of white women and men of color due to their race and gender often intersecting. White women suffer from gender bias, and men of color suffer from racial bias; however, both of their experiences differ from that of women of color, because women of color experience both racial and gender bias. According to Crenshaw, a political failure of the antiracist and feminist discourses was the exclusion of the intersection of race and gender that places priority on the interest of "people of color" and "women", thus disregarding one while highlighting the other. Political engagement should reflect support of women of color; a prime example of the exclusion of women of color that shows the difference in the experiences of white women and women of color is the women's suffrage march.[42] Representational intersectionality advocates for the creation of imagery that is supportive of women of color. Representational intersectionality condemns sexist and racist marginalization of women of color in representation. Representational intersectionality also highlights the importance of women of color having representation in media and contemporary settings. |

形態:構造的、政治的、表象的 Kimberlé Crenshawは『Mapping the Margins: Mapping Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence Against Women of Color」[18]では、女性が経験する暴力を説明するために、3つの異なる形態の交差性を用いて説明している。クレンショーによれば、交差性には構造 的交差性、政治的交差性、表象的交差性の3つの形態がある。 構造的交差性は、さまざまな構造がどのように組み合わさって複合体を作り出し、有色人種の女性のドメスティック・バイオレンスやレイプの経験の違いを浮き 彫りにしているかを説明するために用いられる。構造的交差性とは、階級主義、性差別、人種差別が連動し、有色人種の女性たちを抑圧する一方で、彼女たちの 経験をさまざまな場で形成する方法を意味する。クレンショーの構造的交差性の分析は、被虐待女性のフィールド調査において用いられた。この研究でクレン ショーは、ドメスティック・バイオレンスの被害者である女性が直面する重層的な抑圧を示すために交差性を用いている[61]。 政治的交差性は、女性と有色人種の女性を2つの従属的な集団に分離する、政治の場における2つの相反するシステムを強調する[61]。有色人種の女性の経 験は、人種とジェンダーがしばしば交差するため、白人女性や有色人種の男性の経験とは異なる。白人女性はジェンダー・バイアスに苦しみ、有色人種男性は人 種的バイアスに苦しんでいる。しかし、有色人種の女性は人種的バイアスとジェンダー・バイアスの両方を経験しているため、彼女たちの経験はどちらも有色人 種の女性のそれとは異なる。クレンショーによれば、反人種主義的言説とフェミニスト的言説の政治的失敗は、人種とジェンダーの交差を排除することである。 政治的関与は有色人種の女性の支持を反映すべきである。白人女性と有色人種の女性の経験の違いを示す有色人種の女性の排除の典型的な例は、女性参政権行進 である[42]。 表象的交差性は、有色人種の女性を支持するイメージの創造を提唱する。表象的交差性は、表象における有色人種の女性の性差別的、人種差別的疎外を非難す る。表象的交差性はまた、有色人種の女性がメディアや現代的な場面で表象されることの重要性を強調する。 |

| Key concepts Interlocking matrix of oppression Collins refers to the various intersections of social inequality as the matrix of domination. These are also known as "vectors of oppression and privilege".[62]: 204 These terms refer to how differences among people (sexual orientation, class, race, age, etc.) serve as oppressive measures towards women and change the experience of living as a woman in society. Collins, Audre Lorde (in Sister Outsider), and bell hooks point towards either/or thinking as an influence on this oppression and as further intensifying these differences.[63] Specifically, Collins refers to this as the construct of dichotomous oppositional difference. This construct is characterized by its focus on differences rather than similarities.[64]: S20 Lisa A. Flores suggests, when individuals live in the borders, they "find themselves with a foot in both worlds". The result is "the sense of being neither" exclusively one identity nor another.[65] Standpoint epistemology and the outsider within Both Collins and Dorothy Smith have been instrumental in providing a sociological definition of standpoint theory. A standpoint is an individual's world perspective. The theoretical basis of this approach views societal knowledge as being located within an individual's specific geographic location. In turn, knowledge becomes distinct and subjective; it varies depending on the social conditions under which it was produced.[66]: 392 The concept of the outsider within refers to a standpoint encompassing the self, family, and society.[64]: S14 This relates to the specific experiences to which people are subjected as they move from a common cultural world (i.e., family) to that of modern society.[62]: 207 Therefore, even though a woman—especially a Black woman—may become influential in a particular field, she may feel as though she does not belong. Her personality, behavior, and cultural being overshadow her value as an individual; thus, she becomes the outsider within.[64]: S14 Resisting oppression Speaking from a critical standpoint, Collins points out that Brittan and Maynard say that "domination always involves the objectification of the dominated; all forms of oppression imply the devaluation of the subjectivity of the oppressed".[64]: S18 She later notes that self-valuation and self-definition are two ways of resisting oppression, and claims the practice of self-awareness helps to preserve the self-esteem of the group that is being oppressed while allowing them to avoid any dehumanizing outside influences. Marginalized groups often gain a status of being an "other".[64]: S18 In essence, you are "an other" if you are different from what Audre Lorde calls the mythical norm. Gloria Anzaldúa, scholar of Chicana cultural theory, theorized that the sociological term for this is "othering", i.e. specifically attempting to establish a person as unacceptable based on a certain, unachieved criterion.[62]: 205 Intersectionality and gender Intersectional theories in relation to gender recognize that each person has their own mix of identities which combine to create them, and where these identities "meet in the middle"[67] therein lies each person's intersectionality. These intersections lie between components such as class, race, religion, ethnicity, ability, income, indignity, and any other part of a person's identity which shapes their life, and the way others treat them. Stephanie A. Shields in her article on intersectionality and gender[68] explains how each part of someones identity "serve as organizing features of social relations, mutually constitute, reinforce, and naturalize one another."[68] Shields explains how one aspect can not exist individually, rather it "takes its meaning as a category in relation to another category."[68] |

主要概念 抑圧の連動マトリックス コリンズは、社会的不平等の様々な交差点を支配のマトリックスと呼んでいる。これらは「抑圧と特権のベクトル」とも呼ばれる[62]: 204。これらの用語は、人々の間の差異(性的指向、階級、人種、年齢など)がいかに女性に対する抑圧的な手段として機能し、社会の中で女性として生きる 経験を変化させるかを指している。コリンズ、オードレ・ローデ(『シスター・アウトサイダー』所収)、ベル・フックスは、この抑圧に影響を与え、これらの 差異をさらに激化させるものとして、どちらか/あるいはどちらか一方という思考を指摘している。この構成概念は、類似性よりもむしろ差異に焦点を当てるこ とを特徴としている[64]: S20リサ・A・フローレスは、個人が境界の中で生きるとき、「両方の世界に足を踏み入れていることに気づく」と示唆して いる。その結果、「どちらでもないという感覚」が生じる。 立脚点認識論と内なるアウトサイダー コリンズとドロシー・スミスの両氏は、立場論の社会学的定義を提供することに尽力してきた。立場とは個人の世界観である。このアプローチの理論的基礎は、 社会的知識が個人の特定の地理的位置の中にあるとみなす。その結果、知識は明確で主観的なものとなり、それが生み出された社会的条件によって変化する [66]: 392 内なる部外者という概念は、自己、家族、社会を包含する立場を指す[64]: S14 これは、人々が共通の文化的世界(つまり家族)から現代社会の世界へと移行する際に受ける具体的な経験に関するものである[62]: 207 したがって、ある女性(特に黒人女性)が特定の分野で影響力を持つようになっても、自分の居場所がないように感じることがある。彼女の性格、行動、文化的 存在が、個人としての彼女の価値を覆い隠してしまうのであり、その結果、彼女は内なるアウトサイダーとなってしまうのである[64]: S14 抑圧への抵抗 批判的な立場から言えば、コリンズはブリタンとメイナードが「支配は常に被支配者の客観化を伴い、あらゆる形態の抑圧は被抑圧者の主観性の切り捨てを意味 する」と述べていることを指摘している[64]: S18 彼女は後に、自己評価と自己定義は抑圧に抵抗する2つの方法であると指摘し、自己認識の実践は、抑圧されている集団の自尊心を維持するのに役立つと主張す る一方で、非人間的な外部からの影響を避けることを可能にしている。 疎外された集団はしばしば「他者」としての地位を得る: S18 要するに、オードレ・ローデが神話的規範と呼ぶものと異なっていれば、あなたは「他者」なのだ。チカーナ文化論の研究者であるグロリア・アンザルドゥア は、このことを社会学用語で「他者化」、つまり、ある特定の、達成されていない基準に基づいて、ある人物を受け入れがたい存在として具体的に確立しようと することだと理論化している[62]: 205。 交差性とジェンダー ジェンダーに関連する交差理論は、各人が自分自身のアイデンティティのミックスを持っており、それが組み合わさって自分自身を作り出していること、そして これらのアイデンティティが「中間で出会う」[67]ところに各人の交差性があることを認識している。これらの交差は、階級、人種、宗教、民族性、能力、 収入、屈辱、その他、その人の人生や他者からの扱われ方を形成する、その人のアイデンティティのあらゆる部分の間にある。ステファニー・シールズ (Stephanie A. Shields)は、交差性とジェンダーに関する論文[68]の中で、ある人のアイデンティティの各部分がどのように「社会関係の組織的特徴として機能 し、相互に構成し、補強し、自然化する」のかについて説明している[68]。 |

| Practical applications The examples and perspective in this section deal primarily with the United States and do not represent a worldwide view of the subject. You may improve this section, discuss the issue on the talk page, or create a new section, as appropriate. (March 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Intersectionality has been applied in many fields from politics,[69][70] education[34][27][71] healthcare,[72][73] and employment, to economics.[74] For example, within the institution of education, Sandra Jones' research on working-class women in academia takes into consideration meritocracy within all social strata, but argues that it is complicated by race and the external forces that oppress.[71] Additionally, people of color often experience differential treatment in the healthcare system. For example, in the period immediately after 9/11 researchers noted low birth weights and other poor birth outcomes among Muslim and Arab Americans, a result they connected to the increased racial and religious discrimination of the time.[75] Some researchers have also argued that immigration policies can affect health outcomes through mechanisms such as stress, restrictions on access to health care, and the social determinants of health.[73] The Women's Institute for Science, Equity and Race advocates for the disaggregation of data in order to highlight intersectional identities in all kinds of research.[76] Additionally, applications with regard to property and wealth can be traced to the American historical narrative that is filled "with tensions and struggles over property—in its various forms. From the removal of Native Americans (and later Japanese Americans) from the land, to military conquest of the Mexicans, to the construction of Africans as property, the ability to define, possess, and own property has been a central feature of power in America ... [and where] social benefits accrue largely to property owners."[74] One could apply the intersectionality framework analysis to various areas where race, class, gender, sexuality and ability are affected by policies, procedures, practices, and laws in "context-specific inquiries, including, for example, analyzing the multiple ways that race and gender interact with class in the labor market; interrogating the ways that states constitute regulatory regimes of identity, reproduction, and family formation";[19] and examining the inequities in "the power relations [of the intersectionality] of whiteness ... [where] the denial of power and privilege ... of whiteness, and middle-classness", while not addressing "the role of power it wields in social relations".[77] Intersectionality in a global context  Intersectionality at a Dyke March in Hamburg, Germany, 2020 Over the last couple of decades in the European Union (EU), there has been discussion regarding the intersections of social classifications. Before Crenshaw coined her definition of intersectionality, there was a debate on what these societal categories were. The once definite borders between the categories of gender, race, and class have instead fused into a multidimensional intersection of "race" that now includes religion, sexuality, ethnicities, etc. In the EU and UK, these intersections are referred to as the notion of "multiple discrimination". Although the EU passed a non-discrimination law which addresses these multiple intersections; there is however debate on whether the law is still proactively focusing on the proper inequalities.[78] Outside of the EU, intersectional categories have also been considered. In Analyzing Gender, Intersectionality, and Multiple Inequalities: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts, the authors argue: "The impact of patriarchy and traditional assumptions about gender and families are evident in the lives of Chinese migrant workers (Chow, Tong), sex workers and their clients in South Korea (Shin), and Indian widows (Chauhan), but also Ukrainian migrants (Amelina) and Australian men of the new global middle class (Connell)." This text suggests that there are many more intersections of discrimination for people around the globe than Crenshaw originally accounted for in her definition.[79] Chandra Mohanty discusses alliances between women throughout the world as intersectionality in a global context. She rejects the western feminist theory, especially when it writes about global women of color and generally associated "third world women". She argues that "third world women" are often thought of as a homogeneous entity, when, in fact, their experience of oppression is informed by their geography, history, and culture. When western feminists write about women in the global South in this way, they dismiss the inherent intersecting identities that are present in the dynamic of feminism in the global South. Mohanty questions the performance of intersectionality and relationality of power structures within the US and colonialism and how to work across identities with this history of colonial power structures.[80] This lack of homogeneity and intersecting identities can be seen through feminism in India, which goes over how women in India practice feminism within social structures and the continuing effects of colonization that differ from that of Western and other non-Western countries. This is elaborated on by Christine Bose, who discusses a global use of intersectionality which works to remove associations of specific inequalities with specific institutions while showing that these systems generate intersectional effects. She uses this approach to develop a framework that can analyze gender inequalities across different nations and differentiates this from an approach (the one that Mohanty was referring to) which, one, paints national-level inequalities as the same and, two, differentiates only between the global North and South. This is manifested through the intersection of global dynamics like economics, migration, or violence, with regional dynamics, like histories of the nation or gendered inequalities in education and property education.[81] There is an issue globally with the way the law interacts with intersectionality. For example, the UK's legislation to protect workers' rights has a distinct issue with intersectionality. Under the Equality Act 2010, the things that are listed as 'protected characteristics' are "age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage or civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation".[82] "Section 14 contains a provision to cover direct discrimination on up to two combined grounds—known as combined or dual discrimination. However, this section has never been brought into effect as the government deemed it too 'complicated and burdensome' for businesses."[82] This demonstrates systematic neglect of the issues that intersectionality presents, because the UK courts have explicitly decided not to cover intersectional discrimination in their courts. This neglect of an intersectional framework can often lead to dire consequences. The African American Policy Forum (AAPF) describes a certain example where immigrant women's lives are threatened by their abusive citizen spouses. In A primer on intersectionality, the authors argue that earlier immigration reform (which required spouses who immigrated to the US to marry American citizens to remain properly married for two years before they were eligible to receive permanent resident status) provided "no exceptions for battered women who often faced the risk of serious injury and death on the one hand, or deportation on the other." They continue to argue that advocates of several kinds hadn't originally considered this particular struggle many immigrant women face, including advocates for fairer immigration policies and advocates for domestic violence survivors.[83] Marie-Claire Belleau argues for "strategic intersectionality" in order to foster cooperation between feminisms of different ethnicities.[84]: 51 She refers to different nat-cult (national-cultural) groups that produce different types of feminisms. Using Québécois nat-cult as an example, Belleau says that many nat-cult groups contain infinite sub-identities within themselves, arguing that there are endless ways in which different feminisms can cooperate by using strategic intersectionality, and that these partnerships can help bridge gaps between "dominant and marginal" groups.[84]: 54 Belleau argues that, through strategic intersectionality, differences between nat-cult feminisms are neither essentialist nor universal, but should be understood as resulting from socio-cultural contexts. Furthermore, the performances of these nat-cult feminisms are also not essentialist. Instead, they are strategies.[84] Transnational intersectionality Postcolonial feminists and transnational feminists criticize intersectionality as a concept emanating from WEIRD (Western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic)[85] societies that unduly universalizes women's experiences.[86][87] Postcolonial feminists have worked to revise Western conceptualizations of intersectionality that assume all women experience the same type of gender and racial oppression.[86][88] Shelly Grabe coined the term transnational intersectionality to represent a more comprehensive conceptualization of intersectionality. Grabe wrote, "Transnational intersectionality places importance on the intersections among gender, ethnicity, sexuality, economic exploitation, and other social hierarchies in the context of empire building or imperialist policies characterized by historical and emergent global capitalism."[89] Both Postcolonial and transnational feminists advocate attending to "complex and intersecting oppressions and multiple forms of resistance".[86][88] Vrushali Patil argues that intersectionality ought to recognize transborder constructions of racial and cultural hierarchies. About the effect of the state on identity formation, Patil says: "If we continue to neglect cross-border dynamics and fail to problematize the nation and its emergence via transnational processes, our analyses will remain tethered to the spatialities and temporalities of colonial modernity."[90] Social work In the field of social work, proponents of intersectionality hold that unless service providers take intersectionality into account, they will be of less use for various segments of the population, such as those reporting domestic violence or disabled victims of abuse. According to intersectional theory, the practice of domestic violence counselors in the United States urging all women to report their abusers to police is of little use to women of color due to the history of racially motivated police brutality, and those counselors should adapt their counseling for women of color.[91] Women with disabilities encounter more frequent domestic abuse with a greater number of abusers. Health care workers and personal care attendants perpetrate abuse in these circumstances, and women with disabilities have fewer options for escaping the abusive situation.[92] There is a "silence" principle concerning the intersectionality of women and disability, which maintains an overall social denial of the prevalence of abuse among the disabled and leads to this abuse being frequently ignored when encountered.[93] A paradox is presented by the overprotection of people with disabilities combined with the expectations of promiscuous behavior of disabled women.[92][93] This leads to limited autonomy and social isolation of disabled individuals, which place women with disabilities in situations where further or more frequent abuse can occur.[92] Situated intersectionality Expanding on Crenshaw's framework, migration researcher Nira Yuval-Davis proposed the concept of situated intersectionality as a theoretical framework that can encompass different types of inequalities, simultaneously (ontologically), but enmeshed (concretely), and based on a dialogical epistemology which can incorporate "differentially located situated gazes" at these inequalities.[94] Reilly, Bjørnholt and Tastsoglou note that "Yuval-Davis shares Fineman's critical stance vis-à-vis the fragmentising and essentialising tendencies of identity politics, but without resorting to a universalism that eschews difference."[95] Implementation within organizations Practices referred to as intersectionality may be implemented in different ways in different organizations. Within the context of the UK charity sector, Christoffersen identified five different conceptualizations of intersectionality. "Generic intersectionality" was observed in policy areas, where intersectionality was conceptualized as developing policies to be in everyone's universal interest rather than being targeted to particular groups. "Pan equality" was concern for issues that affected most marginalised groups. "Multi-strand intersectionality" attempted to consider different groups when making a decision, but rarely viewed the groups as overlapping or focused on issues for a particular group. "Diversity within" considered one main form of identity, such as gender, as most important while occasionally considering other aspects of identity, with these different forms of identity sometimes seen as detracting from the main identity. "Intersections of equality strands" considered the intersection of identities but no form of identity was seen as more relevant. In this approach it was sometimes felt that if one dealt with the most marginalised identity the system would tend to work for all people. Christoffersen referred to some of these meanings given to intersectionality as "additive" where inequalities are thought to be able to be added to and subtracted from one another. .[96] Remediation To provide sufficient preventive, redressive and deterrent remedies, judges in courts and others working in conflict resolution mechanisms take into account intersectional dimensions. [97] |

実用的なアプリケーション このセクションの例と見解は、主に米国を扱ったものであり、世界的な見 解を示すものではありません。適宜、このセクションを改善したり、トークページで議論したり、新しいセクションを作ったりしてください。(2017年3 月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) インターセクショナリティは政治、[69][70]教育[34][27][71]医療、[72][73]雇用、経済まで多くの分野で応用されている [74]。例えば教育制度においては、学術界における労働者階級の女性に関するサンドラ・ジョーンズの研究は、あらゆる社会階層における実力主義を考慮に 入れているが、人種や抑圧する外的な力によって複雑になると主張している[71]。さらに、有色人種は医療制度においてしばしば差別的な扱いを経験する。 例えば、9.11直後の時期に、研究者たちはイスラム教徒やアラブ系アメリカ人の出生時の低体重やその他の出生アウトカムの悪さを指摘したが、この結果は 当時の人種的・宗教的差別の高まりと関連している[75]。また、移民政策が、ストレス、医療へのアクセスの制限、健康の社会的決定要因などのメカニズム を通じて、健康アウトカムに影響を与える可能性があると主張する研究者もいる[73]。 さらに、財産と富に関する応用は、「様々な形で財産をめぐる緊張と闘争に満ちている」アメリカの歴史的な物語にまで遡ることができる。アメリカ先住民(後 に日系アメリカ人)の土地からの排除から、メキシコ人の軍事征服、そしてアフリカ人を所有物として構築することに至るまで、所有物を定義し、所有し、所有 する能力は、アメリカにおける権力の中心的な特徴であった。[そして]社会的便益は財産所有者に主に生じている」[74]。人種、階級、ジェンダー、セク シュアリティ、能力が政策、手続き、慣行、法律によって影響を受ける様々な領域に対して、「例えば、労働市場における人種とジェンダーが階級と相互作用す る複数の方法を分析すること、国家がアイデンティティ、再生産、家族形成の規制体制を構成する方法を問うこと」[19]、「白人性の[交差性の]力関係」 における不公正を検証することなど、文脈に特化した探求」において、交差性の枠組み分析を適用することができる。[そこでは]権力と特権の否 定......白人性、そして中流階級性」、一方で「社会関係においてそれが行使する権力の役割」には触れていない[77]。 グローバルな文脈におけるインターセクショナリティ  2020年、ドイツ、ハンブルグでのダイク・マーチにおけるインターセクショナリティ 欧州連合(EU)ではここ数十年、社会的分類の交差に関する議論が行われてきた。クレンショーがインターセクショナリティの定義を作る以前は、社会的分類 が何であるかについての議論があった。かつては明確だったジェンダー、人種、階級というカテゴリーの境界線は、現在では宗教、セクシュアリティ、民族など を含む「人種」という多次元的な交差点へと融合している。EUや英国では、こうした交差点は「多重差別」という概念で呼ばれている。EUでは、こうした複 数の交差点に対応する非差別法が成立したが、この法律が依然として適切な不平等に積極的に焦点を当てているかどうかについては議論がある[78]。ジェン ダー、交差性、複数の不平等を分析する: Global, Transnational and Local Contexts)』では、著者は次のように論じている: 「家父長制とジェンダーと家族に関する伝統的な思い込みの影響は、中国の移民労働者(チョウ、トン)、韓国のセックスワーカーとその顧客(シン)、インド の未亡人(チャウハン)だけでなく、ウクライナからの移民(アメリナ)、新しいグローバル中産階級のオーストラリア人男性(コネル)の生活にも現れてい る」。この文章は、クレンショーが当初その定義で説明した以上に、世界中の人々にとって差別の交差点が多く存在することを示唆している[79]。 チャンドラ・モハンティは、グローバルな文脈における交差性として、世界中の女性間の同盟について論じている。彼女は西洋のフェミニズム理論、特にグロー バルな有色人種の女性や一般的に関連する「第三世界の女性」について書かれたものを否定している。彼女は、「第三世界の女性」はしばしば同質的な存在とし て考えられているが、実際には、彼女たちの抑圧の経験は、その地理的、歴史的、文化的背景によって左右されると主張する。西洋のフェミニストたちがこのよ うに第三世界の女性について書くとき、彼らは第三世界のフェミニズムのダイナミズムに内在する、交差するアイデンティティを否定してしまう。この同質性の 欠如と交差するアイデンティティはインドのフェミニズムを通して見ることができ、インドの女性たちが社会構造の中でどのようにフェミニズムを実践している のか、また西洋や他の非西洋諸国とは異なる植民地化の継続的な影響について考察している。 これはクリスティン・ボースによって詳しく説明され、特定の不平等と特定の制度との関連性を排除する一方で、これらの制度が交差効果を生み出していること を示す、交差性の世界的な利用法について論じている。彼女はこのアプローチを用いて、異なる国家間のジェンダーの不平等を分析できる枠組みを開発し、1つ には国家レベルの不平等を同じものとして描き、2つには世界の北と南だけを区別するアプローチ(Mohantyが言及していたもの)と区別している。これ は、経済、移民、暴力のようなグローバルな力学と、国家の歴史や教育や財産教育におけるジェンダーによる不平等のような地域的な力学が交差することによっ て現れている[81]。 法律が交差性とどのように相互作用するかについては、世界的に問題がある。例えば、労働者の権利を保護するためのイギリスの法律は、交差性と明確な問題を 抱えている。2010年平等法では、「保護される特性」として挙げられているのは、「年齢、障害、性別変更、結婚またはシビルパートナーシップ、妊娠・出 産、人種、宗教または信念、性別、性的指向」である[82]。しかし、この条項は、政府が企業にとってあまりにも『複雑で負担が大きい』と判断したため、 発効されることはなかった」[82] 。 このような交差性の枠組みの軽視は、しばしば悲惨な結果を招きかねない。アフリカン・アメリカン・ポリシー・フォーラム(AAPF)は、移民女性が市民権 を持つ配偶者に虐待され、生活を脅かされている例を紹介している。著者は『A primer on intersectionality』の中で、以前の移民制度改革(アメリカ市民と結婚するためにアメリカに移住した配偶者は、永住権を取得する前に2年 間きちんと結婚生活を続けることが義務付けられていた)では、"一方では重傷を負ったり死亡したりするリスクに、他方では国外追放のリスクにしばしば直面 していた被虐待女性には例外がなかった "と論じている。彼らは、より公平な移民政策を求める擁護者やドメスティック・バイオレンス生存者の擁護者など、いくつかの種類の擁護者が、多くの移民女 性が直面するこの特別な闘いをもともと考慮していなかったと主張し続けている[83]。 Marie-Claire Belleauは異なる民族のフェミニズム間の協力を促進するために「戦略的交差性」を主張している[84]: 51 彼女は異なるタイプのフェミニズムを生み出す異なる民族文化(nat-cult)グループに言及している。ベローは、ケベコイのナチュラ ル・カルトを例にとり、多くのナチュラ ル・カルト・グループはそれ自身の中に無限のサブ・ アイデンティティを内包しているとし、戦略的交 差性を用いることで異なるフェミニズムが 協力する方法は無限にあり、こうしたパートナーシップ は「支配的なもの」と「周縁的なもの」の間の溝を埋める のに役立つと論じている[84]: 54 Belleauは、戦略的交差性を通して、自然文化的フェミニズム間の相違は本質主義的でも普遍的でもなく、社会文化的文脈から生じたものとして理解され るべきであると論じている。さらに、これらの自然文化的フェミニズムのパフォーマンスもまた本質主義的なものではない。むしろそれらは戦略なのである [84]。 トランスナショナルな交差性 ポストコロニアル・フェミニストとトランスナショナル・フェミニストは、交差性を女性の経験を不当に普遍化するWEIRD(西洋、教育を受けた、工業化さ れた、豊かな、民主的な)社会[85]から生まれた概念として批判している[86][87]。ポストコロニアル・フェミニストは、すべての女性が同じタイ プのジェンダーと人種的抑圧を経験すると仮定する交差性の西洋的概念化を修正するために働いてきた[86][88]。グレイブは、「トランスナショナルな 交差性は、歴史的かつ出現的なグローバル資本主義によって特徴づけられる帝国構築や帝国主義的政策の文脈におけるジェンダー、エスニシティ、セクシュアリ ティ、経済的搾取、その他の社会的ヒエラルキーの間の交差を重要視している」と書いている[89]。ポストコロニアルフェミニストもトランスナショナル フェミニストも、「複雑で交差する抑圧と複数の抵抗の形態」に注目することを提唱している[86][88]。ヴルシャリー・パティルは、交差性は人種的・ 文化的ヒエラルキーの国境を越えた構築を認識すべきだと主張している。アイデンティティの形成における国家の影響について、パティルは次のように述べてい る。「もし私たちが国境を越えたダイナミクスを無視し続け、トランスナショナルなプロセスを介した国家とその出現を問題化できなければ、私たちの分析は植 民地的近代の空間性と時間性に縛られたままになってしまうだろう」[90]。 ソーシャルワーク ソーシャルワークの分野では、交差性の支持者は、サービス提供者が交差性を考慮に入れない限り、ドメスティック・バイオレンスを訴える人々や虐待の被害者 である障害者など、様々な層の人々にとってあまり役に立たないとしている。交差理論によれば、米国のDVカウンセラーは、すべての女性に加害者を警察に通 報するよう促しているが、人種差別を動機とした警察の残虐行為の歴史があるため、有色人種の女性にはほとんど役に立たず、カウンセラーは有色人種の女性の ためにカウンセリングを適応させるべきである[91]。 障害のある女性は、より多くの加害者と、より頻繁な家庭内虐待に遭遇する。このような状況では、医療従事者や介護付き添い人が虐待を行い、障害を持つ女性 は虐待の状況から逃れるための選択肢が少なくなる[92]。女性と障害の交差性に関する「沈黙」の原則があり、この原則は障害者の虐待の蔓延に対する社会 全体の否定を維持し、この虐待に遭遇してもしばしば無視されることにつながっている。 [93] 障害者に対する過保護と障害女性の乱暴な行動に対する期待との組み合わせによって逆説が提示されている[92][93]。これは障害者の自律性の制限と社 会的孤立につながり、障害女性をさらに、あるいはより頻繁に虐待が起こりうる状況に置くことになる[92]。 状況化された交差性 クレンショーの枠組みを発展させ、移住研究者のニラ・ユヴァル=デイヴィスは、異なるタイプの不平等を同時に(存在論的に)、しかし絡み合いながら(具体 的に)包含することができる理論的枠組みとして、またこれらの不平等に対する「異なる位置にある状況的な視線」を取り入れることができる対話的認識論に基 づく理論的枠組みとして、状況的交差性という概念を提唱した。 [Reilly, Bjørnholt and Tastsoglouは、「ユヴァル=デイヴィスは、アイデンティティ・ポリティクスの断片化し本質化する傾向に対するファインマンの批判的スタンスを共 有しているが、差異を排除する普遍主義に頼ることはない」と指摘している[95]。 組織内での実践 交差性と呼ばれる実践は、組織によって異なる方法で実施されることがある。英国のチャリティ・セクターの文脈の中で、クリストファーセンは、交差性の5つ の異なる概念化を特定した。「ジェネリック・インターセクショナリティ(一般的な交差性)」は、政策分野において観察され、交差性は、特定のグループを対 象とするのではなく、すべての人の普遍的な利益になるように政策を策定することとして概念化された。「汎的平等」は、最も周縁化された集団に影響を与える 問題に対する懸念であった。「マルチストランド・インターセクショナリティ」は、意思決定をする際にさまざまなグループを考慮しようとするものだが、グ ループを重複して捉えたり、特定のグループの問題に焦点を当てたりすることはほとんどなかった。「内なる多様性」は、ジェンダーなど、アイデンティティの ひとつの主要な形態を最も重要視する一方で、アイデンティティの他の側面を考慮することもあり、こうした異なる形態のアイデンティティが主要なアイデン ティティを損なうと見なされることもあった。「平等の諸側面の交差」は、アイデンティティの交差を考慮したが、どの形のアイデンティティもより関連性があ るとは見なされなかった。このアプローチでは、最も疎外されたアイデンティティに対処すれば、システムはすべての人のために機能する傾向があると感じられ ることがあった。クリストファーセン(Christoffersen)は、交差性に与えられたこれらの意味のいくつかを、不平等が互いに足したり引いたり できると考えられる「加算的(additive)」と呼んでいる。.[96] 是正 十分な予防的、是正的、抑止的救済を提供するために、裁判所の裁判官や紛争解決メカニズムに携わるその他の人々は、交差性の次元を考慮に入れている。 [97] |

| Criticism Lisa Downing argues that intersectionality focuses too much on group identities, which can lead it to ignore the fact that people are individuals, not just members of a class. Ignoring this can cause intersectionality to lead to a simplistic analysis and inaccurate assumptions about how a person's values and attitudes are determined.[10] Some conservatives and moderates believe that intersectionality allows people of color and women of color to victimize themselves and let themselves submit to special treatment. Instead, they classify the concept of intersectionality as a hierarchy of oppression determining who will receive better treatment than others. American conservative commentator Ben Shapiro stated in 2019 that "I would define intersectionality as, at least the way that I've seen it manifest on college campuses, and in a lot of the political left, as a hierarchy of victimhood in which people are considered members of a victim class by virtue of membership in a particular group, and at the intersection of various groups lies the ascent on the hierarchy".[24] Barbara Tomlinson, of the Department of Feminist Studies at University of California, Santa Barbara, has been critical of the applications of intersectional theory to attack other ways of feminist thinking.[11] Critics include Marxist historians and sociologists, some of whom claim that the contemporary applications of intersectional theory fail to adequately address economic class and wealth inequality.[98][99] Additionally, philosopher Tommy Curry recently published several works charging intersectional feminism with implicitly adopting, and thereby perpetuating, harmful stereotypes of Black men.[100] In so doing, Curry argues that the intersectional feminist concept "Double Jeopardy" is fundamentally mistaken.[101] Rekia Jibrin and Sara Salem argue that intersectional theory creates a unified idea of anti-oppression politics that requires a lot out of its adherents, often more than can reasonably be expected, creating difficulties achieving praxis. They also say that intersectional philosophy encourages a focus on the issues inside the group instead of on society at large, and that intersectionality is "a call to complexity and to abandon oversimplification... this has the parallel effect of emphasizing 'internal differences' over hegemonic structures".[102] (See Hegemony and Cultural hegemony.) Darren Hutchinson argues that "it is impossible to theorize about or study a group when each person in that group is 'composed of a complex and unique matrix of identities that shift in time, is never fixed, is constantly unstable and forever distinguishable from everyone else in the universe."[103] Brittney Cooper approaches Crenshaw's original idea of intersectionality with more nuance. In Mary Hawkesworth and Lisa Disch's The Oxford Handbook of feminist theory, Cooper points to Kimberlé Crenshaw's argument that the "failure to begin with an intersectional frame would always result in insufficient attention to black women's experiences of subordination." Cooper's main issue lies in the converse of Crenshaw's argument, where she feels that Crenshaw does not properly address intersectionality as a framework that is both "an effective tool of accounting for identities at any level beyond the structural," and a framework that would "fully and wholly account for the range or depth of black female experiences."[104] Methodology Generating testable predictions from intersectionality theory can be complex;[105][5] postintersectional critics of intersectional theory[who?] fault its proponents for inadequately explained causal methodology and say they have made incorrect predictions about the status of some minority groups.[106] For example, despite facing centuries of persecution and antisemitism rising across the globe, Jews are often excluded from intersectionality movements on the grounds that they are not sufficiently oppressed. Kathy Davis asserts that intersectionality is ambiguous and open-ended, and that its "lack of clear-cut definition or even specific parameters has enabled it to be drawn upon in nearly any context of inquiry".[107] A review of quantitative studies seeking evidence on intersectional issues published through May 12, 2020 found that many quantitative methods were simplistic and were often misapplied or misinterpreted.[5] |

批判 リサ・ダウニングは、交差性は集団のアイデンティティに焦点を当てすぎているため、人々は単なる階級の一員ではなく、個人であるという事実を無視すること につながると主張している[10]。このことを無視することで、交差性は単純化された分析や、人の価値観や態度がどのように決定されるのかについての不正 確な仮定につながる可能性がある[10]。 一部の保守派や穏健派は、交差性によって有色人種や有色人種の女性が自分自身を犠牲にし、特別扱いを受けることを許してしまうと考えている。その代わり に、彼らは交差性の概念を、誰が他の人より良い待遇を受けるかを決定する抑圧の階層として分類している。アメリカの保守的なコメンテーターであるベン・ シャピロは、2019年に「私は交差性を、少なくとも私が大学キャンパスや政治的左派の多くで見てきたように、人々が特定の集団に属していることを理由に 被害者階級の一員とみなされ、様々な集団の交差点に階層上の上昇があるという被害者意識の階層として定義したい」と述べている[24]。 カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校フェミニスト学科のバーバラ・トムリンソンは、フェミニストの他の思考方法を攻撃するための交差点理論の応用に批判的 である[11]。 批評家にはマルクス主義の歴史家や社会学者が含まれ、その中には交差理論の現代的な応用が経済階級や富の不平等に適切に対処できていないと主張する者もい る[98][99]。 さらに哲学者のトミー・カリーは最近、黒人男性に対する有害なステレオタイプを暗黙的に採用し、それによって永続させているとして交差フェミニズムを告発 するいくつかの著作を発表している[100]。そうすることで、カリーは交差フェミニズムの概念である「ダブル・ジョパディ」が根本的に間違っていると主 張している[101]。 Rekia JibrinとSara Salemは、交差論的理論が反抑圧政治学の統一的な考え方を作り出し、その信奉者に多くのことを要求し、しばしば合理的に期待される以上のことを要求 し、実践を達成することを困難にすると論じている。彼らはまた、交差性哲学は社会全体ではなく、集団内部の問題に焦点を当てることを奨励し、交差性は「複 雑性への呼びかけであり、単純化しすぎることを放棄することである...これは覇権的構造よりも「内部の違い」を強調するという並行効果をもたらす」と述 べている[102](「覇権」と「文化的覇権」を参照)。 ダレン・ハッチンソンは「その集団の各人が『時間的に移り変わり、決して固定されず、常に不安定で、宇宙の他の誰とも永遠に区別可能な、複雑でユニークな アイデンティティのマトリックスで構成されている』とき、その集団について理論化したり、研究したりすることは不可能である」と論じている[103]。 ブリットニー・クーパーは、クレンショーのインターセクショナリティの最初の考えに、よりニュアンスを加えてアプローチしている。メアリー・ホークスワー スとリサ・ディッシュの『The Oxford Handbook of feminist theory』の中で、クーパーはキンバレ・クレンショーの「交差性のフレームから始めなければ、黒人女性の従属体験への関心が常に不十分なものとなる」 という主張を指摘している。クーパーの主な論点はクレンショーの主張の逆であり、クレンショーが「構造的なものを超えたあらゆるレベルでのアイデンティ ティを説明する効果的なツール」であり、「黒人女性の経験の範囲や深さを完全かつ完全に説明する」フレームワークとしての交差性を適切に扱っていないと感 じている[104]。 方法論 交錯性理論から検証可能な予測を生み出すことは複雑である[105][5]。交錯性理論のポスト交錯性批評家[誰?]は、交錯性理論の支持者たちが因果関 係の方法論の説明が不十分であることを非難し、いくつかのマイノリティ・グループの地位について誤った予測をしていると述べている[106]。例えば、何 世紀にもわたる迫害や世界中で台頭する反ユダヤ主義に直面しているにもかかわらず、ユダヤ人は十分に抑圧されていないという理由で交錯性運動から排除され ることが多い。キャシー・デイヴィスは、インターセクショナリティは曖昧でオープンエンドなものであり、「明確な定義や具体的なパラメーターの欠如によっ て、ほとんどあらゆる文脈の調査において引き出される」ものであると主張している[107]。 2020年5月12日までに発表された交差性の問題に関する証拠を求める量的研究のレビューでは、多くの量的手法が単純化されており、しばしば誤った適用 や誤った解釈がなされていることが判明している[5]。 |

| Intersectionality and education This section is written like a personal reflection, personal essay, or argumentative essay that states a Wikipedia editor's personal feelings or presents an original argument about a topic. Please help improve it by rewriting it in an encyclopedic style. (March 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) Different methods of teaching/accessibility Laura Gonzales and Janine Butler argue that intersectionality can be helpful to provide an open perspective that helps study multiple inclusive learning processes, formalities, and strategies in order to decrease the risk of academic disadvantages/inequity because of anyone's social, economic, or class level. Inclusivity in education is a direct product of intersectionality, as it takes into consideration elements of peoples' identity. Different, more inclusive styles of teaching have gained traction as teachers continue to work towards accessibility for a wider range of students, specifically those affected by disability. These teaching styles also embrace multilingualism, multimodality, and accessibility.[108] As Laura Gonzales and Janine Butler explain in their article, when common language is unable to be reached, students may need to use other methods of communication such as gestures, visuals, or even technology.[108] The research conducted on these students by both authors promote the strengths of bilingual education and disability in writing. Teachers in their classrooms also incorporate pedagogical methods for multimodal composition, which create safe and productive learning environments for students while also promoting intersectional methods of learning.[108] Both Gonzales and Butler incorporate their social justice movements for inclusion in their own classrooms. Gonzales explains an introduction writing course to English majors where students were able to compile and film short videos of interviews with Indigenous people and interpreters. The purpose of the project served as a form of representation for an underrepresented group of people. In many instances, such as medical consultations, Indigenous people are not offered interpreters, even when they are supposed to.[108] Gonzales uses this course as an example and opportunity for community engagement where multiple forms of language were utilized, including digital media, readings, and conversations. Another example is Butler's pedagogical approach to incorporating intersectionality, focusing on letting her disabled students communicate through a variation of assignments. Examples of these variations are video reflections or an analysis of digital spaces. The video reflections are more geared towards mindful interactions. The students first must consider their own environment and methods of communication and either work with individuals who use the same methods of communication or explore a new genre of communication from a different community. After, the student must create a multimodal and multilingual reflection of the interview in order to interpret and process their own experiences and takeaways.[108] Next is the analysis of digital spaces, where students must take into consideration how their publications or organizations properly reach their target audience. Students are able to use their own identities as inspiration for picking an organization/publication. Then, they must write an in-depth report on Medium (a social platform) on how the digital platform communicates with their audience, or doesn't.[108] If published, this creates "an online audience"[108] where students and other peers can directly interact and discuss with one another. Both of these examples are ways Gonzales and Butler incorporate their research into their own classrooms in order to engage with their communities and incorporate intersectionality. Writing programs on race and gender Inclusion of intersectionality is meant to "Trouble the Boundaries" and pave the way for a more diverse writing program in Predominantly White Institutions (PWI). Writing programs are very closely linked by the influence of race and gender. Both of the authors Collin Lamout Craig and Staci Maree write about their experiences in writing program's as administrators in a predominantly white midwestern institution. One big culture shock to them was the underrepresentation of people of color and minorities in the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA) meetings. The CWPA oversee the evolution of the program, introduce revisions, implement university writing standards etc. Therefore, reprogramming and the addressing of issues must first and foremost go through the CWPA.[109] That is not to say any of the council members are at fault, it is a mere observation to shed light on the issue at hand, power dynamics and how they affect writing programs.[109] Dominant and minority relationships serve as a dimension that pushes for change in order to reach common language. Consequently, a broader composition in understanding helps construct identity politics in order to reach an agreement.[109] Craig then goes on to share her story when a well known professor approaches her and takes on an "It's not my problem"[109] or "I can't teach these people"[109] attitude when he has an issue with another black RA. The professor then goes on to say "He might take constructive criticism better from a pretty woman like you than an old white guy like me."[109] Her example is one of many given in the article that address the issue at hand with power dynamics within writing programs and PWI's. It doesn't allow room for advice or consultation from those of other races or gender. Instead, it simply passes on one problem from one demographic to another.[109] In these cases taking into consideration intersectionality and how prevalent they are in academia can help set up a system of acknowledgment and understanding. |

インターセクショナリティと教育 このセクションは、ウィキペディア編集者の個人的な感想を述べたり、あ るトピックについて独自の議論を提示したりする、個人的な考察、個人的なエッセイ、または議論的なエッセイのように書かれています。百科事典のようなスタ イルで書き直すことで、改善にご協力ください。(2023年3月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 異なる教授法/アクセシビリティ ローラ・ゴンザレスとジャニーン・バトラーは、社会的、経済的、階級的レベルの違いによる学業上の不利益/不公平のリスクを減らすために、複数のインク ルーシブな学習プロセス、形式、戦略を研究するのに役立つオープンな視点を提供するために、交差性が役立つと主張している。教育における包括性は、人々の アイデンティティの要素を考慮することから、交差性の直接的な産物である。教師がより幅広い生徒、特に障害の影響を受けている生徒のためにアクセシビリ ティを追求し続ける中で、異なる、よりインクルーシブな授業スタイルが支持を集めている。ローラ・ゴンザレスとジャニーン・バトラーが論文で説明している ように、共通言語に到達できない場合、生徒はジェスチャー、視覚、あるいはテクノロジーなど、他のコミュニケーション方法を使う必要がある[108]。ま た、彼らの教室の教師は、マルチモーダル作文のための教育方法を取り入れており、生徒にとって安全で生産的な学習環境を作ると同時に、交差的な学習方法を 促進している[108]。 ゴンザレスもバトラーも、インクルージョンのための社会正義運動を自分の教室に取り入れている。 ゴンザレスは、英語専攻の学生を対象としたライティング入門コースについて説明し、そこで学生は先住民や通訳へのインタビューを短いビデオにまとめ、撮影 することができた。このプロジェクトの目的は、十分に代表されていない人々の代表としての役割を果たすことだった。ゴンザレスは、このコースを、デジタ ル・メディア、朗読、会話など、複数の言語形態が活用されたコミュニティ・エンゲージメントの例と機会としている。 もうひとつの例は、バトラーの交差性を取り入れる教育学的アプローチであり、障害のある学生にさまざまな課題を通してコミュニケーションをとらせることに 重点を置いている。これらのバリエーションの例としては、ビデオによる振り返りやデジタル空間の分析がある。ビデオによる振り返りは、よりマインドフルな 相互作用に向けられている。生徒はまず、自分自身の環境とコミュニケーション方法を考え、同じコミュニケーション方法を使う個人と協力するか、異なるコ ミュニティからの新しいコミュニケーションジャンルを探求しなければならない。次にデジタルスペースの分析で、学生は出版物や組織がターゲットとする読者 にどのようにリーチするかを考慮しなければならない。生徒は、組織や出版物を選ぶ際のインスピレーションとして、自分自身のアイデンティティを使うことが できる。そして、Medium(ソーシャル・プラットフォーム)で、そのデジタル・プラットフォームがどのように聴衆とコミュニケーションをとっている か、あるいはとっていないかについて、詳細なレポートを書かなければならない。 これらの例はいずれも、ゴンザレスとバトラーが自分たちのコミュニティと関わり、交差性を取り入れるために、自分たちの研究を自分たちの授業に取り入れる 方法である。 人種とジェンダーに関するライティング・プログラム インターセクショナリティを取り入れることは、"Trouble the Boundaries "を意味し、Predominantly White Institutions (PWI)において、より多様なライティング・プログラムへの道を開くものである。ライティング・プログラムは、人種とジェンダーの影響によって非常に密 接に結びついている。著者のコリン・ラムアウト・クレイグとステイシー・マリーはともに、白人の多い中西部の教育機関の管理者として、ライティング・プロ グラムでの経験について書いている。彼らにとって大きなカルチャーショックだったのは、ライティング・プログラム管理者協議会(CWPA)の会議におい て、有色人種やマイノリティの代表が少ないことだった。CWPAはプログラムの進化を監督し、改訂を導入し、大学のライティング基準などを実施する。従っ て、プログラムの改訂や問題への対処は、何よりもまずCWPAを通さなければならない[109]。これは、評議会メンバーの誰かが悪いということではな く、目下の問題、パワー・ダイナミクス、そしてそれらがライティング・プログラムにどのような影響を与えるかに光を当てるための単なる観察に過ぎない。そ の結果、理解におけるより広い構図は、合意に達するためにアイデンティティ・ポリティクスを構築するのに役立つ[109]。クレイグはさらに、ある有名な 教授が彼女に近づき、他の黒人RAと問題を起こしたときに「私の問題ではない」[109]、「私はこの人たちを教えることはできない」[109]という態 度をとったときの話をする。そして教授は、「彼は私のような年老いた白人男性よりも、あなたのようなきれいな女性の方が建設的な批評を受け止めるかもしれ ない」[109]と言った。それは、他の人種や性別の者からのアドバイスや相談の余地を与えない。109]このような場合、交差性を考慮し、それらがアカ デミアでどの程度普及しているかを考慮することで、認識と理解のシステムを構築することができる。 |