ジョン・ロックの政治哲学

John Locke's Philosophy, or People's Right to resist

☆ジョン・ロック(John Locke、1632 年8月29日 - 1704年10月28日)は、イギリスの哲学者。哲学者としては、イギリス経験論の父と呼ばれ、主著『人間悟性論』(『人間知性論』)において経験論的認 識論を体系化した。また、「自由主義の父」とも呼ばれ[2][3][4]、政治哲学者としての側面も非常に有名である。『統治二論』などにおける彼の政治 思想は名誉革命を理論的に正当化するものとなり、その中で示された社会契約や抵抗権についての考えはアメリカ独立宣言、フランス人権宣言に大きな影響を与 えた。

| Two Treatises of

Government (full title: Two Treatises of Government: In the Former, The

False Principles, and Foundation of Sir Robert Filmer, and His

Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The Latter Is an Essay

Concerning The True Original, Extent, and End of Civil Government) is a

work of political philosophy published anonymously in 1689 by John

Locke. The First Treatise attacks patriarchalism in the form of

sentence-by-sentence refutation of Robert Filmer's Patriarcha, while

the Second Treatise outlines Locke's ideas for a more civilized society

based on natural rights and contract theory. The book is a key

foundational text in the theory of liberalism. This publication contrasts with former political works by Locke himself. In Two Tracts on Government, written in 1660, Locke defends a very conservative position; however, Locke never published it.[1] In 1669, Locke co-authored the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which endorses aristocracy, slavery and serfdom.[2][3] Some dispute the extent to which the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina portray Locke's own philosophy, vs. that of the Lord proprietors of the colony; the document was a legal document written for and signed and sealed by the eight Lord proprietors to whom Charles II had granted the colony. In this context, Locke was only a paid secretary, writing it much as a lawyer writes a will. |

「政府論」(原題:Two Treatises of

Government: In the Former, The False Principles, and Foundation of Sir

Robert Filmer, and His Followers, Are Detected and Overthrown. The

Latter Is an Essay Concerning The True Original, Extent, and End of

Civil

Government)は、1689年にジョン・ロックが匿名で発表した政治哲学の著作である。第一論は、ロバート・フィルマーの『家父長論』を一文一文

反駁する形で家父長制を攻撃し、第二論は自然権と契約理論に基づくより文明化された社会のためのロックの考え方を概説している。この本は自由主義理論の重

要な基礎となるテキストである。 この出版物は、ロック自身による以前の政治的な著作とは対照的である。1660年に書かれた『政府論二篇』では、ロックは非常に保守的な立場を擁護してい るが、ロックはこれを出版することはなかった[1]。1669年、ロックは『カロライナ根本憲法』を共同執筆したが、この憲法は貴族制、奴隷制、農奴制を 是認するものだった[ 2][3] キャロライナ基本憲法が、植民地の領主たちの哲学ではなく、ロック自身の哲学をどの程度反映しているかという点で、議論がある。この文書は、チャールズ2 世が植民地を認めた8人の領主のために書かれた法的文書であり、彼らによって署名され、封印された。この文脈において、ロックは報酬を受け取る秘書であ り、弁護士が遺言状を書くのと同じようにそれを書いたにすぎない。 |

| Historical context King James II of England (VII of Scotland) was overthrown in 1688 by a union of Parliamentarians and the stadtholder of the Dutch Republic William III of Oranje-Nassau (William of Orange), who as a result ascended the English throne as William III of England. He ruled jointly with Mary II, as Protestants. Mary was the daughter of James II, and had a strong claim to the English Throne. This is now known as the Glorious Revolution, also called the Revolution of 1688. Locke claims in the "Preface" to the Two Treatises that its purpose is to justify William III's ascension to the throne, though Peter Laslett suggests that the bulk of the writing was instead completed between 1679–1680 (and subsequently revised until Locke was driven into exile in 1683).[4] According to Laslett, Locke was writing his Two Treatises during the Exclusion Crisis, which attempted to prevent James II from ever taking the throne in the first place. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 1st Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke's mentor, patron and friend, introduced the bill, but it was ultimately unsuccessful. Richard Ashcraft, following in Laslett's suggestion that the Two Treatises were written before the Revolution, objected that Shaftesbury's party did not advocate revolution during the Exclusion Crisis. He suggests that they are instead better associated with the revolutionary conspiracies that swirled around what would come to be known as the Rye House Plot.[5] Locke, Shaftesbury and many others were forced into exile; some, such as Sidney, were even executed for treason. Locke knew his work was dangerous—he never acknowledged his authorship within his lifetime. |

歴史的背景 イングランド王ジェームズ2世(スコットランド王としてはジェームズ7世)は、1688年に議会派とオランダ共和国の執政官ウィリアム3世(オラニエ= ナッサウのウィリアム)の連合軍によって廃位され、その結果、イングランド王ウィリアム3世としてイングランド王位に就いた。彼はプロテスタントとしてメ アリー2世と共同統治を行った。メアリーはジェームズ2世の娘であり、イングランド王位継承権を有していた。 これは現在、名誉革命、または1688年の革命として知られている。ロックは『二論文』の「序文」で、その目的はウィリアム3世の王位継承を正当化するこ とだと主張しているが、ピーター・ラスレットは、大部分の執筆は1679年から1680年にかけて完了したのではないかと示唆している (その後、1683年にロックが亡命するまで改訂が続けられた)[4]。ロックは、ジェームズ2世がそもそも王位につくことを防ぐことを目的とした排除危 機(Exclusion Crisis)の最中に『二論文』を執筆していたとラスレットは述べている。ロックの師であり、パトロンであり友人でもあったアンソニー・アッシュリー= クーパー(第1代シャフツベリー伯爵)が法案を提出したが、最終的には不成立に終わった。リチャード・アッシュクラフトは、ロックの『二論文』は革命前に 書かれたというラスレットの主張に同意し、シャフツベリー派は排除危機に際して革命を主張しなかったと反論した。彼は、それよりもむしろ、後にライ・ハウ ス陰謀として知られることになる事件をめぐる革命陰謀と関連があるのではないかと示唆している[5]。ロック、シャフトスベリー、そしてその他大勢の人々 は亡命を余儀なくされ、シドニーのように反逆罪で処刑された者もいた。ロックは自分の作品が危険なものだと知っていた。彼は生前、自分の著作であることを 認めなかった。 |

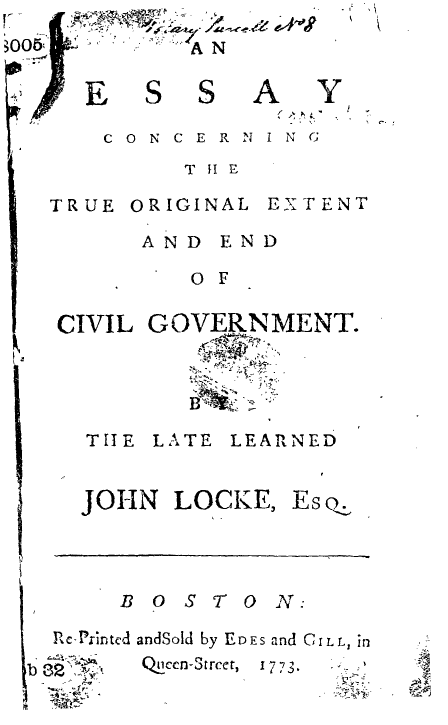

Publication history The only edition of the Treatises published in America during the 18th century (1773) Two Treatises was first published anonymously in December 1689 (following printing conventions of the time, its title page was marked 1690). Locke was dissatisfied with the numerous errors and complained to the publisher. For the rest of his life, he was intent on republishing the Two Treatises in a form that better reflected its intended meaning. Peter Laslett, one of the foremost Locke scholars, has suggested that Locke held the printers to a higher "standard of perfection" than the technology of the time would permit.[6] Be that as it may, the first edition was indeed replete with errors. The second edition was even worse, in addition to being printed on cheap paper and sold to the poor. The third edition was much improved, but still deemed unsatisfactory by Locke.[7] He manually corrected the third edition by hand and entrusted the publication of the fourth to his friends, as he died before it could be brought out.[8] Two Treatises is prefaced with Locke announcing what he aims to achieve, also mentioning that more than half of his original draft, occupying a space between the First and Second Treatises, has been irretrievably lost.[9] Peter Laslett maintains that, while Locke may have added or altered some portions in 1689, he did not make any revisions to accommodate for the missing section; he argues, for example, that the end of the First Treatise breaks off in mid-sentence.[10] In 1691 Two Treatises was translated into French by David Mazzel, a French Huguenot living in the Netherlands. This translation left out Locke's "Preface," all of the First Treatise, and the first chapter of the Second Treatise (which summarised Locke's conclusions in the First Treatise). It was in this form that Locke's work was reprinted during the 18th century in France and in this form that Montesquieu, Voltaire and Rousseau were exposed to it.[11] The only American edition from the 18th century was printed in 1773 in Boston; it, too, left out all of these sections. There were no other American editions until the 20th century.[12] |

出版の歴史 18世紀(1773年)にアメリカで出版された『二論文』の唯一の版 『二論文』は、1689年12月に匿名で初めて出版された(当時の印刷慣習に従い、タイトルページには1690年と記されていた)。ロックは、数多くの誤 りに不満を持ち、出版社に苦情を申し立てた。彼は生涯を通じて、『二論文』を本来の意味をより反映した形で再出版することに専念した。ロック研究者の第一 人者であるピーター・ラスレットは、ロックは当時の技術水準よりも高い「完璧さの基準」を印刷業者に求めていたのではないかと指摘している[6]。それは ともかく、初版には間違いだらけだった。第2版はさらにひどく、安い紙で印刷され、貧しい人々に販売されていた。第3版は大幅に改善されたが、それでも ロックにとっては満足のいくものではなかった[7]。彼は第3版を手作業で修正し、第4版の出版は友人たちに任せたが、第4版が出版される前に彼は亡く なった[8]。 「二論文」は、ロックが達成しようとしていることを前置きで述べ、また、第1論文と第2論文の間に位置する、彼の草稿の半分以上が、取り返しのつかない形 で失われていることも述べている[9]。 。ピーター・ラスレットは、1689年にロックがいくつかの部分を追加または変更した可能性はあるが、失われた部分に対応するための修正は一切行わなかっ たと主張している。例えば、第1論の終わりは文の途中で途切れていると主張している[10]。 1691年、オランダ在住のフランス人ユグノー教徒、デビッド・マゼルによって『二論』がフランス語に翻訳された。この翻訳では、ロックの「序文」、第一 論説の全文、第二論説の第一章(第一論説におけるロックの結論を要約したもの)が省略されていた。18世紀にフランスで再版されたのもこの形であり、モン テスキュー、ヴォルテール、ルソーがこれに触れたのもこの形であった[11]。18世紀のアメリカ版は1773年にボストンで印刷されたものが唯一であ り、これもこれらのセクションはすべて省略されていた。20世紀になるまで、アメリカ版はこれ以外にはなかった[12]。 |

| Main ideas Two Treatises is divided into the First Treatise and the Second Treatise. typically shortened to "Book I" and "Book II" respectively. Before publication, however, Locke gave it greater prominence by (hastily) inserting a separate title page: "An Essay Concerning the True Original, Extent and End of Civil Government."[13] The First Treatise is focused on the refutation of Sir Robert Filmer, in particular his Patriarcha, which argued that civil society was founded on divinely sanctioned patriarchalism. Locke proceeds through Filmer's arguments, contesting his proofs from Scripture and ridiculing them as senseless, until concluding that no government can be justified by an appeal to the divine right of kings. The Second Treatise outlines a theory of civil society. Locke begins by describing the state of nature, and appeals to god's creative intent in his case for human equality in this primordial context. From this, he goes on to explain the hypothetical rise of property and civilization, in the process explaining that the only legitimate governments are those that have the consent of the people. Therefore, any government that rules without the consent of the people can, in theory, be overthrown, i.e. revolutions just. |

主なアイデア 「二論文」は「第一論文」と「第二論文」に分かれている。それぞれ「第一編」と「第二編」と略称されることが多い。しかし、出版前に、ロックは(急いで) 別のタイトルページを挿入することで、この論文をより目立つようにした。「市民政府の本質、範囲、および目的に関する小論」[13]。第1論では、特に 『家父長論』で、市民社会は神聖な家父長制に基づいて設立されたと主張したロバート・フィルマー卿の反論に焦点を当てている。ロックは、フィルマーの主張 を聖書の証明と矛盾していると論じ、無意味であると嘲笑しながら、王の神の権利を主張することで正当化できる政府はないと結論づける。 「第二論文」は市民社会の理論を概説している。ロックは自然の状態について述べ、この根源的な文脈における人間の平等のために、神の創造意図に訴えること から始める。そこから、彼は財産と文明の仮説上の発生について説明し、その過程で、合法的な政府とは国民の同意を得ている政府のみであると説明する。した がって、国民の同意を得ずに統治する政府は、理論的には転覆されうる。すなわち、革命は正当である。 |

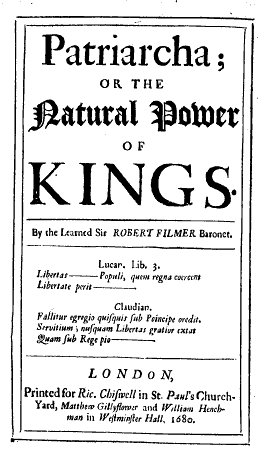

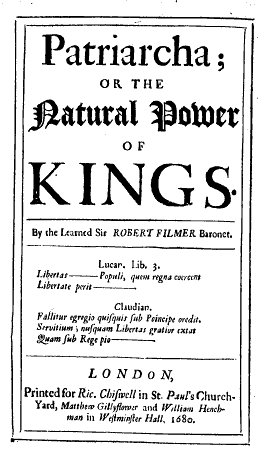

First Treatise Title page from Filmer's Patriarcha (1680) The First Treatise is an extended attack on Sir Robert Filmer's Patriarcha. Locke's argument proceeds along two lines: first, he undercuts the Scriptural support that Filmer had offered for his thesis, and second he argues that the acceptance of Filmer's thesis can lead only to slavery (and absurdity). Locke chose Filmer as his target, he says, because of his reputation and because he "carried this Argument [jure divino] farthest, and is supposed to have brought it to perfection" (1st Tr., § 5). Filmer's text presented an argument for a divinely ordained, hereditary, absolute monarchy. According to Filmer, the Biblical Adam in his role as father possessed unlimited power over his children and this authority passed down through the generations. Locke attacks this on several grounds. Accepting that fatherhood grants authority, he argues, it would do so only by the act of begetting, and so cannot be transmitted to one's children because only God can create life. Nor is the power of a father over his children absolute, as Filmer would have it; Locke points to the joint power parents share over their children referred to in the Bible. In the Second Treatise Locke returns to a discussion of parental power. (Both of these discussions have drawn the interest of modern feminists such as Carole Pateman.) Filmer also suggested that Adam's absolute authority came from his ownership over all the world. To this, Locke responds that the world was originally held in common (a theme that will return in the Second Treatise). But, even if it were not, he argues, God's grant to Adam covered only the land and brute animals, not human beings. Nor could Adam, or his heir, leverage this grant to enslave mankind, for the law of nature forbids reducing one's fellows to a state of desperation, if one possesses a sufficient surplus to maintain oneself securely. And even if this charity were not commanded by reason, Locke continues, such a strategy for gaining dominion would prove only that the foundation of government lies in consent. Locke intimates in the First Treatise that the doctrine of divine right of kings (jure divino) will eventually be the downfall of all governments. In his final chapter he asks, "Who heir?" If Filmer is correct, there should be only one rightful king in all the world—the heir of Adam. But since it is impossible to discover the true heir of Adam, no government, under Filmer's principles, can require that its members obey its rulers. Filmer must therefore say that men are duty-bound to obey their present rulers. Locke writes: I think he is the first Politician, who, pretending to settle Government upon its true Basis, and to establish the Thrones of lawful Princes, ever told the World, That he was properly a King, whose Manner of Government was by Supreme Power, by what Means soever he obtained it; which in plain English is to say, that Regal and Supreme Power is properly and truly his, who can by any Means seize upon it; and if this be, to be properly a King, I wonder how he came to think of, or where he will find, an Usurper. (1st Tr., § 79) Locke ends the First Treatise by examining the history told in the Bible and the history of the world since then; he concludes that there is no evidence to support Filmer's hypothesis. According to Locke, no king has ever claimed that his authority rested upon his being the heir of Adam. It is Filmer, Locke alleges, who is the innovator in politics, not those who assert the natural equality and freedom of man. |

第一論文 フィルマー著『家父長』(1680年)のタイトルページ 第一論文は、ロバート・フィルマー卿の『家父長』に対する長文の攻撃である。ロックの議論は2つの論点に沿って進められる。まず、フィルマーが自身の論文 の根拠として聖書から引用した箇所を否定し、次に、フィルマーの論文を受け入れることは奴隷制(と不条理)につながるだけだと主張する。ロックは、フィル マーを標的に選んだ理由として、彼の名声と、「この議論(神権説)を最も遠くまで推し進め、それを完璧なものにしたとされている」(『第一論』第5条)こ とを挙げている。 フィルマーの著作は、神によって定められた世襲の絶対君主制を主張していた。フィルマーによれば、聖書のアダムは父親として子供たちに無制限の権力を持っ ており、その権威は世代を超えて受け継がれていった。ロックはこれをいくつかの根拠から攻撃している。父権が権威を付与するという考えを受け入れると、そ れは子を産むという行為によってのみ付与されることになるが、生命を創造できるのは神だけなので、父権は子に受け継がれることはない。また、フィマーが主 張するように、父親が子供に対して持つ権力が絶対的なものでもない。ロックは、聖書で言及されている、両親が子供に対して共有する共同の権力を指摘してい る。第2論説でロックは、親の権力についての議論に戻っている。(これらの議論は、キャロル・パテマンなどの現代のフェミニストたちの関心を集めてい る。) フィマーは、アダムの絶対的権威は彼が全世界の所有権を持つことから来ているとも主張した。これに対し、ロックは、世界はもともと共有されていたと反論し た(このテーマは『第二論考』で再び取り上げられる)。しかし、たとえそうではなかったとしても、ロックは、神がアダムに与えたものは土地と家畜だけで、 人間には及んでいないと主張した。また、アダムやその相続人は、この権利を利用して人類を奴隷にすることはできない。なぜなら、自然法では、自分が安全に 維持できるだけの十分な余剰物を持っている場合、仲間を絶望的な状態に陥れることを禁じているからだ。そして、たとえこの慈善が理性によって命じられてい なかったとしても、ロックは続ける。このような支配権を得るための戦略は、政府の基盤が同意にあることを証明するのみであると。 ロックは『第一論考』の中で、王の神の権利(jure divino) の教義がいずれはすべての政府を崩壊させるだろうとほのめかしている。 最終章で彼は「誰が後継者か」と問う。 フィルマーの主張が正しいなら、世界にはただ一人の正当な王しかいないはずである。アダムの後継者だ。 しかし、アダムの真の相続人を見つけることは不可能であるため、フィルマーの原則の下では、いかなる政府も、その構成員に統治者に服従することを要求する ことはできない。したがって、フィルマーは、人間は現在の支配者に従う義務がある、と言わざるを得ない。ロックはこう書いている。 私は、真の基盤の上に政府を樹立し、合法的な王の王座を確立すると見せ かけながら、自分が王であり、その統治方法は最高の権力によっており、その権力をどのような手段で獲得したかは問わないと世界に語った最初の政治家だと思 う。つまり、王権と最高権力は、どのような手段を用いてでもそれを手に入れることができる者が、正しく真に所有するものである。そして、これが王としてふ さわしいものであるとするならば、私は、彼がどのようにして、あるいはどこで、簒奪者を思い付いたのか不思議でならない。(第1章第79節) ロックは、聖書で語られている歴史とそれ以降の世の中の歴史を検証し、フィルマーの仮説を裏付ける証拠はないと結論づけて第1章を終えている。ロックによ れば、アダムの末裔であるという理由で王位を主張した王は一人もいない。ロックは、政治における革新者とは、人間の自然平等と自由を主張する人々ではな く、フィルマーであると主張している。 |

| Second Treatise In the Second Treatise, Locke develops a number of notable themes. It begins with a depiction of the state of nature, wherein individuals are under no obligation to obey one another but are each themselves judge of what the law of nature requires. It also covers conquest and slavery, property, representative government, and the right of revolution. State of Nature Locke defines the state of nature thus: To properly understand political power and trace its origins, we must consider the state that all people are in naturally. That is a state of perfect freedom of acting and disposing of their own possessions and persons as they think fit within the bounds of the law of nature. People in this state do not have to ask permission to act or depend on the will of others to arrange matters on their behalf. The natural state is also one of equality in which all power and jurisdiction is reciprocal and no one has more than another. It is evident that all human beings—as creatures belonging to the same species and rank and born indiscriminately with all the same natural advantages and faculties—are equal amongst themselves. They have no relationship of subordination or subjection unless God (the lord and master of them all) had clearly set one person above another and conferred on him an undoubted right to dominion and sovereignty.[14][15] In 17th-century England, the work of Thomas Hobbes popularized theories based upon a state of nature, even as most of those who employed such arguments were deeply troubled by his absolutist conclusions. Locke's state of nature can be seen in light of this tradition. There is not and never has been any divinely ordained monarch over the entire world, Locke argues. However, the fact that the natural state of humanity is without an institutionalized government does not mean it is lawless. Human beings are still subject to the laws of God and nature. In contrast to Hobbes, who posited the state of nature as a hypothetical possibility, Locke takes great pains to show that such a state did indeed exist. Actually, it still exists in the area of international relations where there is not and is never likely to be any legitimate overarching government (i.e., one directly chosen by all the people subject to it). Whereas Hobbes stresses the disadvantages of the state of nature, Locke points to its good points. It is free, if full of continual dangers (2nd Tr., § 123). Finally, the proper alternative to the natural state is not political dictatorship/tyranny but a government that has been established with consent of the people and the effective protection of basic human rights to life, liberty, and property under the rule of law. Nobody in the natural state has the political power to tell others what to do. However, everybody has the right to authoritatively pronounce justice and administer punishment for breaches of the natural law. Thus, men are not free to do whatever they please. "The state of nature has a law of nature to govern it, which obliges every one: and reason, which is that law, teaches all mankind, who will but consult it, that... no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty, or possessions" (2nd Tr., § 6). The specifics of this law are unwritten, however, and so each is likely to misapply it in his own case. Lacking any commonly recognised, impartial judge, there is no way to correct these misapplications or to effectively restrain those who violate the law of nature. The law of nature is therefore ill enforced in the state of nature. IF man in the state of nature be so free, as has been said; if he be absolute lord of his own person and possessions, equal to the greatest, and subject to no body, why will he part with his freedom? Why will he give up this empire, and subject himself to the dominion and control of any other power? To which it is obvious to answer, that though in the state of nature he hath such a right, yet the enjoyment of it is very uncertain, and constantly exposed to the invasion of others: for all being kings as much as he, every man his equal, and the greater part no strict observers of equity and justice, the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, very unsecure. This makes him willing to quit a condition, which, however free, is full of fears and continual dangers: and it is not without reason, that he seeks out, and is willing to join in society with others, who are already united, or have a mind to unite, for the mutual preservation of their lives, liberties and estates, which I call by the general name, property. (2nd Tr., § 123) It is to avoid the state of war that often occurs in the state of nature, and to protect their private property that men enter into civil or political society, i.e., state of society. Conquest and slavery Ch. 4 ("Of Slavery") and Ch. 16 ("Of Conquest") are sources of some confusion: the former provides a justification for slavery that can nonetheless never be met, and thus constitutes an argument against the institution, the latter concerns the rights of conquerors, which Locke seeks to challenge. In the rhetoric of 17th-century England, those who opposed the increasing power of the kings claimed that the country was headed for a condition of slavery. Locke therefore asks, facetiously, under what conditions such slavery might be justified. He notes that slavery cannot come about as a matter of contract (which became the basis of Locke's political system). To be a slave is to be subject to the absolute, arbitrary power of another; as men do not have this power even over themselves, they cannot sell or otherwise grant it to another. One that is deserving of death, i.e., who has violated the law of nature, may be enslaved. This is, however, but the state of war continued (2nd Tr., § 24), and even one justly a slave therefore has no obligation to obedience. In providing a justification for slavery, he has rendered all forms of slavery as it actually exists invalid. Moreover, as one may not submit to slavery, there is a moral injunction to attempt to throw off and escape it whenever it looms. Most scholars take this to be Locke's point regarding slavery: submission to absolute monarchy is a violation of the law of nature, for one does not have the right to enslave oneself. The legitimacy of an English king depended on (somehow) demonstrating descent from William the Conqueror: the right of conquest was therefore a topic rife with constitutional connotations. Locke does not say that all subsequent English monarchs have been illegitimate, but he does make their rightful authority dependent solely upon their having acquired the people's approbation. Locke first argues that, clearly, aggressors in an unjust war can claim no right of conquest: everything they despoil may be retaken as soon as the dispossessed have the strength to do so. Their children retain this right, so an ancient usurpation does not become lawful with time. The rest of the chapter then considers what rights a just conqueror might have. The argument proceeds negatively: Locke proposes one power a conqueror could gain, and then demonstrates how in point of fact that power cannot be claimed. He gains no authority over those that conquered with him, for they did not wage war unjustly: thus, whatever other right William may have had in England, he could not claim kingship over his fellow Normans by right of conquest. The subdued are under the conqueror's despotical authority, but only those who actually took part in the fighting. Those who were governed by the defeated aggressor do not become subject to the authority of the victorious aggressor. They lacked the power to do an unjust thing, and so could not have granted that power to their governors: the aggressor therefore was not acting as their representative, and they cannot be punished for his actions. And while the conqueror may seize the person of the vanquished aggressor in an unjust war, he cannot seize the latter's property: he may not drive the innocent wife and children of a villain into poverty for another's unjust acts. While the property is technically that of the defeated, his innocent dependents have a claim that the just conqueror must honour. He cannot seize more than the vanquished could forfeit, and the latter had no right to ruin his dependents. (He may, however, demand and take reparations for the damages suffered in the war, so long as these leave enough in the possession of the aggressor's dependants for their survival). In so arguing, Locke accomplishes two objectives. First, he neutralises the claims of those who see all authority flowing from William I by the latter's right of conquest. In the absence of any other claims to authority (e.g., Filmer's primogeniture from Adam, divine anointment, etc.), all kings would have to found their authority on the consent of the governed. Second, he removes much of the incentive for conquest in the first place, for even in a just war the spoils are limited to the persons of the defeated and reparations sufficient only to cover the costs of the war, and even then only when the aggressor's territory can easily sustain such costs (i.e., it can never be a profitable endeavour). Needless to say, the bare claim that one's spoils are the just compensation for a just war does not suffice to make it so, in Locke's view. Property In the Second Treatise, Locke claims that civil society was created for the protection of property.[16] In saying this, he relies on the etymological root of "property," Latin proprius, or what is one's own, including oneself (cf. French propre). Thus, by "property" he means "life, liberty, and estate."[17] In A Letter Concerning Toleration, he wrote that the magistrate's power was limited to preserving a person's "civil interest", which he described as "life, liberty, health, and indolency of body; and the possession of outward things".[18] By saying that political society was established for the better protection of property, he claims that it serves the private (and non-political) interests of its constituent members: it does not promote some good that can be realised only in community with others (e.g. virtue). For this account to work, individuals must possess some property outside of society, i.e., in the state of nature: the state cannot be the sole origin of property, declaring what belongs to whom. If the purpose of government is the protection of property, the latter must exist independently of the former. Filmer had said that, if there even were a state of nature (which he denied), everything would be held in common: there could be no private property, and hence no justice or injustice (injustice being understood as treating someone else's goods, liberty, or life as if it were one's own). Thomas Hobbes had argued the same thing. Locke therefore provides an account of how material property could arise in the absence of government. He begins by asserting that each individual, at a minimum, "owns" himself, although, properly speaking, God created man and we are God's property;[19] this is a corollary of each individual's being free and equal in the state of nature. As a result, each must also own his own labour: to deny him his labour would be to make him a slave. One can therefore take items from the common store of goods by mixing one's labour with them: an apple on the tree is of no use to anyone—it must be picked to be eaten—and the picking of that apple makes it one's own. In an alternate argument, Locke claims that we must allow it to become private property lest all mankind have starved, despite the bounty of the world. A man must be allowed to eat, and thus have what he has eaten be his own (such that he could deny others a right to use it). The apple is surely his when he swallows it, when he chews it, when he bites into it, when he brings it to his mouth, etc.: it became his as soon as he mixed his labour with it (by picking it from the tree). This does not yet say why an individual is allowed to take from the common store of nature. There is a necessity to do so to eat, but this does not yet establish why others must respect one's property, especially as they labour under the like necessity. Locke assures his readers that the state of nature is a state of plenty: one may take from communal store if one leaves a) enough and b) as good for others, and since nature is bountiful, one can take all that one can use without taking anything from someone else. Moreover, one can take only so much as one can use before it spoils. There are then two provisos regarding what one can take, the "enough and as good" condition and "spoilage." Gold does not rot. Neither does silver, or any other precious metal or gem. They are, moreover, useless, their aesthetic value not entering into the equation. One can heap up as much of them as one wishes, or take them in trade for food. By the tacit consent of mankind, they become a form of money (one accepts gold in exchange for apples with the understanding that someone else will accept that gold in exchange for wheat). One can therefore avoid the spoilage limitation by selling all that one has amassed before it rots; the limits on acquisition thus disappear. In this way, Locke argues that a full economic system could, in principle, exist within the state of nature. Property could therefore predate the existence of government, and thus society can be dedicated to the protection of property. Representative government Locke did not demand a republic. Rather, Locke felt that a legitimate contract could easily exist between citizens and a monarchy, an oligarchy or some mixed form (2nd Tr., sec. 132). Locke uses the term Common-wealth to mean "not a democracy, or any form of government, but any independent community" (sec. 133) and "whatever form the Common-wealth is under, the Ruling Power ought to govern by declared and received laws, and not by extemporary dictates and undetermined resolutions." (sec 137) Locke does, however, make a distinction between an executive (e.g. a monarchy), a "Power always in being" (sec 144) that must perpetually execute the law, and the legislative that is the "supreme power of the Common-wealth" (sec 134) and does not have to be always in being. (sec 153) Furthermore, governments are charged by the consent of the individual, "i.e. the consent of the majority, giving it either by themselves, or their representatives chosen by them." (sec 140) His notions of people's rights and the role of civil government provided strong support for the intellectual movements of both the American and French Revolutions. Right of revolution The concept of the right of revolution was also taken up by John Locke in Two Treatises of Government as part of his social contract theory. Locke declared that under natural law, all people have the right to life, liberty, and estate; under the social contract, the people could instigate a revolution against the government when it acted against the interests of citizens, to replace the government with one that served the interests of citizens. In some cases, Locke deemed revolution an obligation. The right of revolution thus essentially acted as a safeguard against tyranny. Locke affirmed an explicit right to revolution in Two Treatises of Government: “whenever the Legislators endeavor to take away, and destroy the Property of the People, or to reduce them to Slavery under Arbitrary Power, they put themselves into a state of War with the People, who are thereupon absolved from any farther Obedience, and are left to the common Refuge, which God hath provided for all Men, against Force and Violence. Whensoever therefore the Legislative shall transgress this fundamental Rule of Society; and either by Ambition, Fear, Folly or Corruption, endeavor to grasp themselves, or put into the hands of any other an Absolute Power over the Lives, Liberties, and Estates of the People; By this breach of Trust they forfeit the Power, the People had put into their hands, for quite contrary ends, and it devolves to the People, who have a Right to resume their original Liberty". (sec. 222) |

第二論 第二論では、ロックはいくつかの重要なテーマを展開している。それは、自然の状態についての描写から始まる。自然の状態では、個々人は互いに従う義務を 負っていないが、それぞれが自然法に則った行動をとるべきであると考える。また、征服と奴隷制、財産、代議制政府、革命の権利についても述べている。 自然の状態 ロックは自然の状態を次のように定義している。 政治権力を正しく理解し、その起源をたどるためには、人間が本来的に置 かれている状態を考慮しなければならない。それは、自然法の範囲内で、自分の所有物や人を思い通りに行動し処分する完全な自由の状態である。この状態にあ る人々は、行動する許可を求めたり、他人の意志に頼って物事を処理したりする必要はない。自然状態は、すべての権力と管轄が相互であり、ある人が他の人よ りも優位になることがない平等な状態でもある。同じ種に属し、同じ階級に生まれ、同じ自然の利点と能力を持って無差別に生まれた人間である以上、すべての 人が平等であることは明らかである。神(万物の主であり支配者)が誰かを他の誰よりも上位に定め、その者に疑いようのない支配権と主権を授けた場合を除 き、人間は互いに従属や服従の関係にはない[14][15]。 17世紀のイギリスでは、トマス・ホッブズの著作により自然状態に基づく理論が普及したが、このような議論を展開した人々の大半は、ホッブズの絶対主義的 な結論に深く悩んでいた。ロックの自然状態は、この伝統の観点から理解することができる。ロックは、全世界を統治する神聖な君主は存在したこともなけれ ば、今後も存在することはないと主張している。しかし、人間の自然な状態が制度化さ れた政府を持たないからといって、無法状態ということにはならない。人間は依然として神と自然の法に従う。自然状態を仮説上の可能性として想定したホッブ ズとは対照的に、ロックは自然状態が実際に存在したことを示すことに多大な労力を費やした。実際、国際関係においては、正当な包括的政府 (すなわち、その政府に従属するすべての国民が直接選んだ政府)が存在しない、また今後も存在しそうにないという状況において、自然状態は今もなお存在し ている。ホッ ブズが自然状態の欠点を強調する一方、ロックはその長所について指摘している。それは自由であるが、絶え間ない危険に満ちている(第2回弁論、第123 条)。最後に、自然状態に代わる適切な選択肢は、政治的な独裁や専制ではなく、人々の同意を得て設立され、法の支配のもとで生命、自由、財産に対する基本 的人権が効果的に保護される政府である。 自然状態では、他人に何をすべきかを命じる政治的な力を持つ者はいない。しかし、誰もが自然法に違反した場合、権威を持って正義を言い渡し、刑罰を執行す る権利を持っている。したがって、人間は自分の好きなように行動できるわけではない。 「自然の状態にはそれを統治する自然法があり、それはすべての人に義務を課している。そして、その法である理性は、それを考慮するすべての人類に、... 誰も他人の生命、健康、自由、財産を害してはならないと教えている」(第2次弁論、第6条)。しかし、この法律の具体的な内容は書かれていないため、各自 が自分のケースに当てはめて誤用してしまう可能性が高い。一般的に認められた公平な裁判官がいないため、これらの誤用を修正したり、自然法に違反する人々 を効果的に抑制する方法がない。 したがって、自然法の状態では自然法は適切に施行されない。 自然の状態にある人間が、これまで言われてきたように本当に自由であり、自分自身の身体と所有物を完全に支配し、最も偉大な者と同等であり、いかなる権力 にも服従しないのであれば、なぜその自由を手放すだろうか? なぜその帝国を手放し、他の権力の支配と管理に身を委ねるだろうか?この問いに対する答えは明らかである。自然状態ではそのような権利を持つが、その享受 は非常に不安定であり、常に他者の侵略にさらされている。なぜなら、誰もが彼と同じくらい王であり、誰もが彼と対等であり、大部分は公平と正義を厳格に 守っているわけではないため、この状態で彼が所有する財産の享受は非常に不安定で、非常に安全ではない。このことから、彼は、たとえ自由であっても、恐怖 と絶え間ない危険に満ちた状態を辞めることを望むようになる。そして、すでに結束している、あるいは結束しようとしている人々とともに社会に参加し、互い の生命、自由、財産(私が総称して「財産」と呼ぶもの)を守ることを望むようになるのは、理由のないことではない。(第2章第123条) 自然の状態においてしばしば起こる戦争状態を回避し、私有財産を守るために、人々は市民社会や政治社会、すなわち社会状態に入るのである。 征服と奴隷制 第4章(「奴隷制について」)と第16章(「征服について」)は、いくつかの混乱を招く原因となっている。前者は、奴隷制を正当化するものであるが、その 正当性は決して満たされることはなく、奴隷制に対する反論となっている。後者は、征服者の権利に関するもので、ロックが挑戦しようとしているものである。 17世紀のイングランドの修辞学では、王の権力増大に反対する人々は、国が奴隷制の状態に向かっていると主張した。そのためロックは、皮肉をこめて、どの ような状況であればそのような奴隷制が正当化されるのかを問うている。彼は、奴隷制 は契約によって生じるものではないと指摘している(これはロックの政治システムの基礎となった)。 奴隷となるということは、他者の絶対的で恣意的な権力に従うことである。人間は自分自身に対してもそのような権力を持たないため、それを他人に売ったり、 与えたりすることはできない。死刑に値する者、すなわち自然法に背いた者は奴隷にすることができる。しかし、これは戦争状態が続いているにすぎない(第2 次弁論、第24条)。したがって、たとえ正当に奴隷となった者であっても服従の義務はない。 奴隷制を正当化することで、彼は実際に存在するあらゆる形態の奴隷制を無効にした。さらに、奴隷制に従うことはできないため、奴隷制が迫ってきたときに は、それを振り払い逃れようとする道徳的な義務が生じる。ほとんどの学者は、絶対君主制に従うことは自然法に違反する、なぜなら、人は自分自身を奴隷にす る権利を持たないからだ、とロックが奴隷制について述べていると考えている。 イングランド王の正当性は、(何らかの形で)征服王ウィリアムからの血筋を証明することにかかっていた。そのため、征服権は憲法上の意味合いを帯びたテー マであった。ロックは、その後のイングランド君主すべてが正当性を持たないとは言っていないが、彼らの正当な権威は、国民の承認を得たことのみに依存する と述べている。 ロックはまず、明らかに、不正な戦争における侵略者は征服権を主張できないと主張する。彼らが奪ったものはすべて、奪われた者が奪い返す力さえあればすぐ に奪い返される可能性がある。彼らの子孫はこの権利を保持するため、古代の簒奪は時間の経過とともに合法化されることはない。その後、この章の残りの部分 では、正当な征服者が持つ可能性のある権利について考察する。 議論は否定的な方向で進む。ロックは征服者が得ることができる権力を一つ提案し、その権力が実際には主張できないことを示す。 彼と一緒に征服した人々に対しては、彼らが不当な戦争を行っていないため、彼は何の権限も得られない。したがって、ウィリアムがイングランドでどのような 他の権利を持っていたとしても、征服の権利によってノルマン人の仲間に対して王権を主張することはできない。征服された人々は征服者の専制的な権威下に置 かれるが、実際に戦闘に参加した人々だけである。敗北した侵略者に支配されていた人々は、勝利した侵略者の権威に従うことはない。彼らは不正を行う力を 持っていなかったため、統治者にその力を与えることはできなかった。したがって侵略者は彼らの代表として行動していたわけではなく、侵略者の行為に対して 彼らを罰することはできない。征服者は、不正な戦争において敗者の侵略者の人質を捕らえることはできるが、その財産を没収することはできない。悪人の罪の ない妻や子供を、他人の不正行為のために貧困に追いやることはできない。財産は技術的には敗者のものであるが、罪のない扶養家族には、正義の征服者が尊重 すべき権利がある。征服者は、敗者が没収できる以上の財産を没収することはできず、敗者には扶養家族を困窮させる権利はなかった。(ただし、侵略者の扶養 家族が生活できるだけの財産が残る限り、戦争で受けた損害に対する賠償を要求し、受け取ることはできる)。 このように主張することで、ロックは2つの目的を達成した。まず、ウィリアム1世の征服権によってすべての権威がウィリアム1世から派生するという主張を 無効にした。権威を主張できる根拠が他にない場合(例えば、アダムからの長子相続権、神の任命など)、すべての王は統治される側の同意に基づいて権威を確 立しなければならない。第二に、彼はそもそも征服の動機の大半を取り除く。たとえ正義の戦争であっても、戦利品は敗者の生命のみに限定され、賠償金は戦争 の費用に充てるのに十分な額にすぎない。しかも、それは侵略者の領土が容易にその費用を負担できる場合(つまり、決して利益を生む事業ではない場合)に限 られる。言うまでもなく、戦利品が正当な戦争に対する正当な補償であるという主張だけでは、それを正当化するには不十分であるとロックは考えている。 財産 第2論考において、ロックは市民社会は財産を保護するために作られたと主張している[16]。この主張の根拠として、彼は「財産」の語源であるラテン語の 「proprius」(自分を含む自分のもの)を挙げている(フランス語の「propre」を参照)。したがって、彼が「財産」と呼ぶものは、「生命、自 由、財産」を意味する[17]。『寛容に関する書簡』の中で、彼は、裁判官の権限は個人の「市民的利益」の保護に限定されると述べている。彼はそれを「生 命、自由、健康、身体の無気力、 外的なものの所有」[18]。政治社会は財産をよりよく保護するために設立されたと述べたことで、彼は、政治社会は構成員の私的(非政治的)な利益に奉仕 するものであると主張している。つまり、他者との共同社会においてのみ実現できる何らかの善(例えば徳)を促進するものではない。 この説明が成り立つためには、個々人が社会の外側、すなわち自然の状態において何らかの財産を所有していなければならない。国家が財産の唯一の起源とな り、誰に何が帰属するかを宣言することはできない。政府の狙いが財産の保護であるならば、財産は政府の保護とは無関係に存在していなければならない。フィ ルマーは、仮に自然状態が存在したとしても(彼はその存在を否定していたが)、すべてのものは共有物であり、私有財産は存在せず、したがって正義も不正義 も存在しないだろう(不正義とは、他人の財産、自由、生命をあたかも自分のもののように扱うことである)と述べていた。トマス・ホッブズも同じことを主張 していた。そのためロックは、政府が不在の場合に物質的財産がどのようにして生じるかを説明している。 彼はまず、厳密に言えば人間は神によって創造され、神の所有物であるにもかかわらず、最低限、各個人は自分自身を「所有」していると主張する[19]。こ れは、自然の状態において各個人が自由かつ平等であるという帰結である。その結果、各個人は自分の労働も所有しなければならない。自分の労働を否定するこ とは、その人を奴隷にすることである。したがって、自分の労働を商品と混ぜ合わせることによって、共有財産から商品を取り出すことができる。木になってい るリンゴは誰の役にも立たない。食べるためにはリンゴを摘まなければならない。リンゴを摘むことによって、リンゴは自分のものになる。別の議論として、 ロックは、世界の恵みにもかかわらず、人類全員が飢えることのないよう、私有財産を認める必要があると主張している。人は食べることが許され、食べたもの は自分のものとなる(つまり、他人がそれを使う権利を否定できる)。リンゴは、飲み込んだとき、噛んだとき、かじったとき、口に入れたときなど、リンゴが 自分のものとなる。リンゴを木から摘み取るという労働をリンゴと組み合わせた瞬間に、リンゴは自分のものとなる。 しかし、これはまだ、個人が自然の共有財産から何かを奪うことが許される理由を説明しているわけではない。食べるためにはそうする必要があるが、他人が自 分の所有物を尊重しなければならない理由はまだ説明されていない。特に、他人も同じ必要性のもとで労働しているのである。ロックは、自然の状態は豊かであ る、と読者に保証している。共同の貯蔵所から取ることができるのは、a) 十分な量、b) 他の人のためにも十分な量、を残した場合のみであり、自然は豊かであるから、他の誰かのものを奪うことなく、自分が使えるだけの量をすべて取ることができ る。さらに、腐ってしまう前に自分が使える量だけを、取ることができる。人が持ち出せるものには、「十分かつ同等の」条件と「腐敗」という2つの前提条件 がある。 金は腐らない。銀も、その他の貴金属や宝石も腐らない。それらはさらに、美的価値を考慮する必要がないため、無用の長物である。人は好きなだけそれらを積 み上げたり、食料と交換したりできる。人類の暗黙の了解により、それらは貨幣の一種となる(誰かが小麦と交換するためにその金を引き受けることを理解した 上で、リンゴと交換するために金を引き受ける)。したがって、腐敗する前に自分が集めたものをすべて売れば、腐敗の制限を回避できる。 このように、ロックは、完全な経済システムは原則として自然の状態の中で存在しうる、と論じている。したがって、財産は政府の成立に先立つものであり、社 会は財産の保護に専念できる。 代議制政府 ロックは共和制を求めたわけではない。むしろロックは、市民と君主制、寡頭制、あるいはその混合形態の間には、正当な契約が容易に成立すると考えていた (第2次弁論、第132項)。ロックは「コモンウェルス」という用語を、「民主主義やいかなる形態の政府ではなく、独立した共同体」 (第 133 項) 、「コモンウェルスがどのような形態であろうとも、統治権力は、即席の指示や未決定の決議ではなく、宣言され、受け入れられた法律によって統治すべきであ る」 (第 137 項) と定義している。(第 137 条) しかし、ロックは、法律を永遠に執行しなければならない「常に存在する権力」(第 144 条)である行政(例えば君主制)と、「連邦の最高権力」(第 134 条)であり、常に存在する必要のない立法とを区別している。(第 153 条)さらに、政府は個人の同意によって成り立つ。すなわち、「多数派の同意、すなわち、彼ら自身、または彼らによって選ばれた代表者によって与えられる同 意」である(第 140 条)。 彼の考える国民の権利と市民政府の役割は、アメリカ独立革命とフランス革命の両方の知的運動を強力に支えた。 革命権 革命権という概念は、ジョン・ロックの『政府論』でも取り上げられ、社会契約論の一部として扱われた。ロックは、自然法の下では、すべての人々は生命、自 由、財産に対する権利を有しており、社会契約の下では、政府が市民の利益に反する行動を取った場合、市民は政府に革命を起こし、市民の利益にかなう政府に 取って代わることができると主張した。場合によっては、ロックは革命を義務と考えていた。革命権は、このように専制政治に対する防波堤としての役割を果た していた。 ロックは『政府論』の中で革命の明確な権利を肯定し、「立法者が人民の財産を奪い、破壊し、あるいは恣意的な権力の下で人民を奴隷状態に陥れようとすると き、人民は彼らと戦争状態に入り、それにより、それ以上の服従義務から解放され、神が万人のために用意した、力や暴力に対する共通の避難所へと導かれる」 と述べた。したがって立法府がこの社会の根本的規則に背く場合、野望、恐怖、愚かさや腐敗によって、自らを支配しようとしたり、あるいは国民の生命、自 由、財産に対する絶対的権力を他者に委ねたりする。このような背信行為によって、国民が自らのために委ねた権力を失うことになり、本来の自由を取り戻す権 利を持つ国民にその権限が委ねられることになる。(第222条) |

| Reception and influence Britain Although the Two Treatises would become well known in the second half of the 18th century, they were somewhat neglected when published. Between 1689 and 1694, around 200 tracts and treatises were published concerning the legitimacy of the Glorious Revolution. Three of these mention Locke, two of which were written by friends of Locke.[20] When Hobbes published the Leviathan in 1651, by contrast, dozens of texts were immediately written in response to it. As Mark Goldie explains: "Leviathan was a monolithic and unavoidable presence for political writers in Restoration England in a way that in the first half of the eighteenth the Two Treatises was not."[21] While the Two Treatises did not become popular until the 1760s, ideas from them did start to become important earlier in the century. According to Goldie, "the crucial moment was 1701" and "the occasion was the Kentish petition." The pamphlet war that ensued was one of the first times Locke's ideas were invoked in a public debate, most notably by Daniel Defoe.[22] Locke's ideas did not go unchallenged and the periodical The Rehearsal, for example, launched a "sustained and sophisticated assault" against the Two Treatises and endorsed the ideology of patriarchalism.[23] Not only did patriarchalism continue to be a legitimate political theory in the 18th century, but as J. G. A. Pocock and others have gone to great lengths to demonstrate, so was civic humanism and classical republicanism. Pocock has argued that Locke's Two Treatises had very little effect on British political theory; he maintains that there was no contractarian revolution. Rather, he sees these other long-standing traditions as far more important for 18th-century British politics.[24] In the middle of the 18th century, Locke's position as a political philosopher suddenly rose in prominence. For example, he was invoked by those arguing on behalf of the American colonies during the Stamp Act debates of 1765–66.[25] Marginalized groups such as women, Dissenters and those campaigning to abolish the slave trade all invoked Lockean ideals. But at the same time, as Goldie describes it, "a wind of doubt about Locke's credentials gathered into a storm. The sense that Locke's philosophy had been misappropriated increasingly turned to a conviction that it was erroneous".[26] By the 1790s Locke was associated with Rousseau and Voltaire and being blamed for the American and French Revolutions as well as for the perceived secularisation of society.[27] By 1815, Locke's portrait was taken down from Christ Church, his alma mater (it was later restored to a position of prominence, and currently hangs in the dining hall of the college). North America Locke's influence during the American Revolutionary period is disputed. While it is easy to point to specific instances of Locke's Two Treatises being invoked, the extent of the acceptance of Locke's ideals and the role they played in the American Revolution are far from clear. The Two Treatises are echoed in phrases in the Declaration of Independence and writings by Samuel Adams that attempted to gain support for the rebellion. Of Locke's influence Thomas Jefferson wrote: "Bacon, Locke and Newton I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical & Moral sciences".[28][29] The colonists frequently cited Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, which synthesised Lockean political philosophy with the common law tradition. Louis Hartz, writing at the beginning of the 20th century, took it for granted that Locke was the political philosopher of the revolution. This view was challenged by Bernard Bailyn and Gordon S. Wood, who argued that the revolution was not a struggle over property, taxation, and rights, but rather "a Machiavellian effort to preserve the young republic's 'virtue' from the corrupt and corrupting forces of English politics."[30] Garry Wills, on the other hand, maintains that it was neither the Lockean tradition nor the classical republican tradition that drove the revolution, but instead Scottish moral philosophy, a political philosophy that based its conception of society on friendship, sensibility and the controlled passions.[30] Thomas Pangle and Michael Zuckert have countered, demonstrating numerous elements in the thought of more influential founders that have a Lockean pedigree.[31] They argue that there is no conflict between Lockean thought and classical Republicanism.[32][33][34][35] Locke's ideas have not been without criticism with Howard Zinn arguing that the treatise "ignored the existing inequalities in property. And how could people truly have equal rights, with stark differences in wealth"?[36] and others taking issue with his Labour theory of property. |

受容と影響 イギリス 『統治二論』は18世紀後半に広く知られるようになったが、出版当時はほとんど顧みられることはなかった。1689年から1694年にかけて、名誉革命の 正当性に関する小論文や論文が200編ほど発表された。そのうち 3 冊はロックについて言及しており、そのうちの 2 冊はロックの友人によって書かれたものである[20]。一方、ホッブスが『リヴァイアサン』を出版した 1651 年には、それに対する反論として数十冊の著作がすぐに書かれた。マーク・ゴルディは次のように説明している。「『リヴァイアサン』は、18世紀前半の『二 論文』とは異なり、王政復古期のイギリスの政治思想家にとって、不可避かつ圧倒的な存在であった」[21]。 『二論文』が広く知られるようになったのは1760年代になってからだが、それ以前の世紀の初頭には、すでにその思想が重要なものになり始めていた。ゴー ルドによると、「決定的な瞬間は1701年」であり、「きっかけはケント州の嘆願書」であった。その後起こったパンフレット戦争は、ロックスの思想が公の 場で初めて議論されたもののひとつであり、特にダニエル・デフォーによって行われた。ロックスの思想は異論を唱えられることもなく、例えば定期刊行誌『リ ハーサル』は『二論文』に対して「持続的で洗練された攻撃」を開始し、 『二論文』に対して「持続的で洗練された攻撃」を仕掛けたほか、家父長制のイデオロギーを支持した[23]。家父長制は18世紀においても正当な政治理論 であり続けただけでなく、J. G. A. ポックや他の研究者が長々と論証してきたように、市民的人間主義や古典的共和主義も同様であった。ポコックは、ロックの『二論文』はイギリスの政治理論に ほとんど影響を与えていないと主張している。彼は、契約革命は存在しなかったと主張している。むしろ、彼はこれらの他の長年にわたる伝統の方が、18世紀 のイギリスの政治にとってはるかに重要だと考えている[24]。 18世紀半ば、ロックの政治哲学者としての地位は突然注目されるようになった。例えば、1765年から66年にかけての印紙税法に関する議論において、ア メリカ植民地側の主張を裏付けるために彼の思想が引用された[25]。女性、異端者、奴隷貿易廃止運動を行う人々など、社会的に疎外された集団が、ロック の理想を掲げていた。しかし同時に、ゴールディが述べるように、「ロックの信憑性に対する疑念の風が吹き荒れ、嵐となった。ロックの哲学が誤用されている という感覚は、次第にそれが誤っているという確信へと変わっていった」[26]。1790年代までにロックはルソーやヴォルテールと結びつけられ、アメリ カ革命やフランス革命、 社会の世俗化も非難された[27]。1815年、ロックの肖像画は母校であるクライストチャーチから取り外された(その後、再び目立つ場所に掛けられ、現 在は大学の食堂に飾られている)。 北米 アメリカ独立戦争期のロックの影響については議論がある。ロックの『二論文』が引用された具体的な事例を挙げるのは簡単だが、ロックの理想がどの程度受け 入れられ、それがアメリカ独立革命に果たした役割については明らかではない。二論文』の考え方は、独立宣言やサミュエル・アダムスの反乱を支持する文章に も反映されている。ロックの影響力について、トーマス・ジェファーソンは次のように書いている。「ベーコン、ロック、ニュートンは、私が考えるに、例外な くこれまで生きてきた中で最も偉大な3人の人物であり、物理科学と道徳科学において築かれた上層構造の基礎を築いた人物である」[28][29]。植民地 人は、ロックの政治哲学とコモンローの伝統を統合したブラックストーンの『イングランド法論』を頻繁に引用していた。20世紀初頭に執筆したルイ・ハーツ は、ロックが革命の政治哲学者であったことを当然のこととして受け止めていた。 この見解は、バーナード・ベイリンとゴードン・S・ウッドによって疑問視された。彼らは、革命は財産、課税、権利をめぐる争いではなく、「腐敗し、腐敗さ せるイギリスの政治勢力から、若い共和国の『美徳』を守るためのマキャベリ的な努力」[30] だったと主張した。一方、ギャリー・ウィルズは、 一方、ギャリー・ウィルズは、革命の原動力となったのはロックの伝統でも古典的共和主義の伝統でもなく、友情、感受性、抑制された情熱を社会の概念の基盤 とする政治哲学であるスコットランドの道徳哲学だったと主張している[30]。トーマス・パングルとマイケル・ズッカーはこれに反論し、より影響力の強い 建国者の思想にはロックの系譜を持つ要素が数多く存在することを示している より影響力の強い創設者たちの思想には、ロックの血統を引くものが数多くあると反論している[31]。彼らは、ロックの思想と古典的共和主義の間に矛盾は ないと主張している[32][33][34][35]。 ロックの思想は批判を免れてはいない。ハワード・ジンは、この論文は「財産における既存の不平等を無視している。そして、富に著しい格差がある中で、人々 が本当に平等な権利を持つことができるだろうか」[36]と。また、彼の労働理論にも異論を唱える者もいる。 |

| Controversies regarding

interpretation Locke's political philosophy is often compared and contrasted with Thomas Hobbes’ Leviathan. The motivation in both cases is self-preservation with Hobbes arguing the need of an absolute monarch to prevent the war of "all against all" inherent in anarchy while Locke argues that the protection of life, liberty, and property can be achieved by a parliamentary process that protects, not violates, one's rights. Leo Strauss and C. B. Macpherson stress the continuity of thought. In their view Locke and Hobbes describe an atomistic man largely driven by a hedonistic materialistic acquisitiveness. Strauss' Locke is little more than Hobbes in "sheep’s clothing".[37] C. B. Macpherson argued in his Political Theory of Possessive Individualism that Locke sets the stage for unlimited acquisition and appropriation of property by the powerful creating gross inequality. Government is the protector of interests of capitalists while the "labouring class [are] not considered to have an interest".[38][39] Unlike Macpherson, James Tully finds no evidence that Locke specifically advocates capitalism. In his A Discourse on Property, Tully describes Locke's view of man as a social dependent, with Christian sensibilities, and a God-given duty to care for others. Property, in Tully's explanation of Locke, belong to the community as the public commons but becomes "private" so long as the property owner, or more correctly the "custodian", serves the community.[40] Zuckert believes Tully is reading into Locke rights and duties that just aren’t there.[41] Huyler finds that Locke explicitly condemned government privileges for rich, contrary to Macpherson's pro-capitalism critique, but also rejected subsidies to aid the poor, in contrast to Tully's social justice apologetics.[42] *Tully, James (1980), A Discourse on Property: John Locke and his Adversaries, Cambridge University Press The Cambridge School of political thought, led principally by Quentin Skinner, J. G. A. Pocock, Richard Ashcraft, and Peter Laslett, uses a historical methodology to situate Locke in the political context of his times. But they also restrict his importance to those times.[43] Ashcraft's Locke takes the side of the burgeoning merchant class against the aristocracy.[44] Neal Wood puts Locke on the side of the agrarian interests, not the manufacturing bourgeoisie.[45] Jerome Huyler and Michael P. Zuckert approach Locke in the broader context of his oeuvre and historical influence. Locke is situated within changing religious, philosophical, scientific, and political dimensions of 17th century England. Objecting to the use of the contemporary concept of economic man to describe Locke's view of human nature, Huyler emphases the "virtue of industriousness" of Locke's Protestant England. Productive work is man's earthly function or calling, ordained by God and required by self-preservation. The government's protection of property rights insures that the results of industry, i.e. "fruits of one’s labor", are secure. Locke's prohibition of ill-gotten gains, whether for well-connected gentry or the profligate, is not a lack of Locke's foresight to the problems in the latter stages of liberalism but an application of equal protection of the law to every individual.[33] Richard Pipes argues that Locke holds a labor theory of value that leads to the socialist critique that those not engaging in physical labor exploit wage earners.[46] Huyler, relying on Locke's Essays on the Law of Nature shows that reason is the most fundamental virtue, underwrites all productive virtue, and leads to human flourishing or happiness in an Aristotelean sense.[47] |

解釈をめぐる論争 ロックの政治哲学は、しばしばトマス・ホッブズの『リヴァイアサン』と比較対照される。いずれの場合も、その動機は自己保存であり、ホッブズは、無政府状 態に内在する「全員対全員」の戦争を防ぐために絶対君主制が必要だと主張する一方、ロックは、議会のプロセスによって、個人の権利を侵害するのではなく保 護することで、生命、自由、財産の保護が実現できると主張する。 レオ・シュトラウスとC.B.マクファーソンは、思想の連続性を強調している。彼らの見解では、ロックとホッブズは快楽主義的唯物論的な物欲に駆り立てら れた原子論的人間を表現している。シュトラウスのロックは、ホッブズを「羊の皮を被ったオオカミ」にすぎない[37]。C.B.マクファーソンは『所有的 個人主義の政治理論』の中で、ロックは強大な権力者による財産の無制限な取得と収奪の舞台を設定し、深刻な不平等を生み出すと主張した。政府は資本家の利 益の擁護者であり、「労働階級には利益があるとは考えられていない」[38][39]。 マクファーソンとは異なり、ジェームズ・タリーは、ロックが特に資本主義を擁護しているという証拠はないとしている。タ リーは『財産論』の中で、ロックの人間観を、キリスト教的な感受性を持つ社会的依存者であり、他人を気遣う義務を神から与えられた存在であると説明してい る。タリーの説明によると、財産は公共の共有地として共同体に帰属するが、財産所有者、より正確には「管理人」が共同体に奉仕する限り、「私有」となる[40]。 ズッカーは、タリーがロックの権利と義務に存在しないものを読み込んでいると考えている[41]。ホイラーは、ロックが富裕層に対する政府の特権を明確に 非難し、マッカーソンの資本主義擁護の批判とは対照的に マクファーソンの資本主義擁護の批判とは対照的に、ロックは富裕層向けの政府特権を明確に非難したが、タリーの社会正義擁護論とは対照的に、貧困層支援の ための補助金も否定していた[42]。 *Tully, James (1980), A Discourse on Property: John Locke and his Adversaries, Cambridge University Press ケンブリッジ学派は、クエンティン・スキナー、J.G.A.ポックック、リチャード・アッシュクラフト、ピーター・ラスレットを中心に、ロックを当時の政 治的文脈に位置づけるために歴史的方法論を用いている。しかし、彼らはまた、ロックの重要性をその時代のものに限定している[43]。アッシュクラフトの ロックは、貴族階級に対して台頭しつつあった商人階級の側に立つ[44]。ニール・ウッドは、ロックを製造業ブルジョワジーではなく農業利益の側につける [45]。 ジェローム・ホイラーとマイケル・P・ズッカーは、ロックの著作と歴史的影響力のより広い文脈からロックにアプローチしている。ロックは、17世紀イギリ スの宗教、哲学、科学、政治の変遷の中で位置づけられる。ロックの人間性に関する見解を説明するのに、現代の経済人概念を用いることに異議を唱える Huylerは、ロックのプロテスタントイングランドにおける「勤勉の徳」を強調する。生産的な労働は、神によって定められた、自己保存のために必要な、 人間の地上的な機能または天職である。政府が財産権を保護することで、産業の成果、すなわち「労働の成果」が保証される。ロックスが不正な利益の獲得を禁 じたのは、有力な貴族であろうと浪費家であろうと関係なく、自由主義の後期における問題に対するロックスの洞察力の欠如ではなく、すべての個人に対する法 の平等な保護の適用である[33]。 リチャード・パイプス(Richard Pipes)は、ロックスは労働価値説を主張しており、 労働に従事しない者が賃金労働者を搾取しているという社会主義的批判につながる価値論を唱えていると、リチャード・パイプス(Richard Pipes)は主張している[46]。ホイラー(Huyler)は、ロックの『自然法論』を引用しながら、理性は最も根本的な美徳であり、生産的な美徳の すべてを支え、アリストテレス的な意味での人間の繁栄や幸福につながる、と論じている[47]。 |

| United

Kingdom constitutional law |

イギリス憲法 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Two_Treatises_of_Government |

|

++

| Two Treatises In the late 17th and early 18th centuries, Locke's Two Treatises were rarely cited. Historian Julian Hoppit said of the book, "except among some Whigs, even as a contribution to the intense debate of the 1690s it made little impression and was generally ignored until 1703 (though in Oxford in 1695 it was reported to have made 'a great noise')."[26] John Kenyon, in his study of British political debate from 1689 to 1720, has remarked that Locke's theories were "mentioned so rarely in the early stages of the [Glorious] Revolution, up to 1692, and even less thereafter, unless it was to heap abuse on them" and that "no one, including most Whigs, [was] ready for the idea of a notional or abstract contract of the kind adumbrated by Locke".[27]: 200 In contrast, Kenyon adds that Algernon Sidney's Discourses Concerning Government were "certainly much more influential than Locke's Two Treatises."[i][27]: 51 In the 50 years after Queen Anne's death in 1714, the Two Treatises were reprinted only once (except in the collected works of Locke). However, with the rise of American resistance to British taxation, the Second Treatise of Government gained a new readership; it was frequently cited in the debates in both America and Britain. The first American printing occurred in 1773 in Boston.[28] Locke exercised a profound influence on political philosophy, in particular on modern liberalism. Michael Zuckert has argued that Locke launched liberalism by tempering Hobbesian absolutism and clearly separating the realms of Church and State. He had a strong influence on Voltaire, who called him "le sage Locke". His arguments concerning liberty and the social contract later influenced the written works of Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, and other Founding Fathers of the United States. In fact, one passage from the Second Treatise is reproduced verbatim in the Declaration of Independence, the reference to a "long train of abuses". Such was Locke's influence that Thomas Jefferson wrote:[29][30][31] Bacon, Locke and Newton… I consider them as the three greatest men that have ever lived, without any exception, and as having laid the foundation of those superstructures which have been raised in the Physical and Moral sciences. However, Locke's influence may have been even more profound in the realm of epistemology. Locke redefined subjectivity, or self, leading intellectual historians such as Charles Taylor and Jerrold Seigel to argue that Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689/90) marks the beginning of the modern Western conception of the self.[32][33] Locke's theory of association heavily influenced the subject matter of modern psychology. At the time, Locke's recognition of two types of ideas, simple and complex—and, more importantly, their interaction through association—inspired other philosophers, such as David Hume and George Berkeley, to revise and expand this theory and apply it to explain how humans gain knowledge in the physical world.[34] |

『統治二論』 17世紀末から18世紀初頭にかけて、ロックの『統治二論』が引用されることはほとんどなかった。歴史家のジュリアン・ホピットはこの本について、「一部 のホイッグの間を除いて、1690年代の激しい議論への 貢献としても、ほとんど印象に残らず、1703年まで一般に無視された(ただし1695年のオックスフォードでは『大きな音』を立てたと報告されてい る)」と述べている[26]。 「1689年から1720年までのイギリスの政治的議論に関する研究において、ジョン・ケニオンは、ロックの理論が「(栄光)革命の初期段階において、 1692年まではほとんど言及されず、それ以降は、彼らを罵倒するためでなければ、さらに少なくなった」、「ほとんどのウィッグを含めて、誰もロックが提 唱したような観念的あるいは抽象的契約という考えには(中略)賛成しなかった」、としている[26]...これとは反対に、ロックが提唱していたような契 約の概念には、1692年から1720年までの間、誰も言及しなかった...[26]...[26]...[26][27][28 [これに対して、ケニヨンは、アルジャーノン・シドニーの『政府に関する言説』が「ロックの『二論』よりもはるかに影響力があったのは確かである」と付け 加えている[i][27]。 51 1714年のアン女王の死後50年間、『統治二論』は一度だけ再版された(ロック著作集を除く)。しかし、イギリスの課税に対するアメリカの抵抗が高まる と、『統治二論』は新たな読者を獲得し、米英両国の議論に頻繁に引用されるようになった。アメリカでの最初の印刷は、1773年にボストンで行われた [28]。 ロックは政治哲学、特に近代自由主義に大きな影響を及ぼした。マイケル・ズッカートは、ロックがホッブズ絶対主義を和らげ、教会と国家の領域を明確に分け ることによって自由主義を打ち立てたと論じている。ロックはヴォルテールに強い影響を与え、ヴォルテールはロックを「ロック賢者」と呼んだ。自由と社会契 約に関する彼の主張は、後にアレクサンダー・ハミルトン、ジェームズ・マディソン、トーマス・ジェファーソンらアメリカ建国の父たちの著作に影響を与え た。実際、独立宣言には、第二条約の一節、「長い悪習」についての記述がそのまま引用されている。このようなロックの影響力は、トーマス・ジェファーソン が次のように書いている[29][30][31]。 ベーコン、ロック、ニュートン......私は彼らを、例外なく、これまでに生きた三人の偉大な人物と考え、物理学と道徳科学の分野で育てられたこれらの 上部構造の基礎を築いたと考える。 しかし、ロックの影響は認識論の領域でさらに深かったと思われる。ロックは主観性または自己を再定義し、チャールズ・テイラーやジェロルド・シーゲルなど の知的歴史家は、ロックの『人間の理解に関する試論』(1689/90)が近代西洋における自己の概念の始まりになると論じている[32][33]。 ロックの連合論は近代心理学の主題に大きく影響を及ぼしていた。当時、ロックの単純なものと複雑なものという2種類の観念の認識、そしてより重要なのは連 想によるそれらの相互作用は、デビッドヒュームやジョージバークレーといった他の哲学者にこの理論の修正と拡張を促し、人間が物理世界で知識を得る方法を 説明するためにそれを適用するように仕向けた[34]。 |

| Religious tolerance Writing his Letters Concerning Toleration (1689–1692) in the aftermath of the European wars of religion, Locke formulated a classic reasoning for religious tolerance, in which three arguments are central:[35] earthly judges, the state in particular, and human beings generally, cannot dependably evaluate the truth-claims of competing religious standpoints; even if they could, enforcing a single 'true religion' would not have the desired effect, because belief cannot be compelled by violence; coercing religious uniformity would lead to more social disorder than allowing diversity. With regard to his position on religious tolerance, Locke was influenced by Baptist theologians like John Smyth and Thomas Helwys, who had published tracts demanding freedom of conscience in the early 17th century.[36][37][38][39] Baptist theologian Roger Williams founded the colony of Rhode Island in 1636, where he combined a democratic constitution with unlimited religious freedom. His tract, The Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644), which was widely read in the mother country, was a passionate plea for absolute religious freedom and the total separation of church and state.[40] Freedom of conscience had had high priority on the theological, philosophical, and political agenda, as Martin Luther refused to recant his beliefs before the Diet of the Holy Roman Empire at Worms in 1521, unless he would be proved false by the Bible.[41] |

宗教的寛容 ヨーロッパの宗教戦争の余波の中でLetters Concerning Toleration (1689-1692)を書いたロックは、宗教的寛容のための古典的な理由を策定しており、その中では以下の3つの議論が中心となっている[35]。 地上の裁判官、特に国家、そして一般的に人間は、競合する宗教的立場の真実の主張を信頼できる形で評価することはできない。 たとえできたとしても、単一の「真の宗教」を強制することは、暴力によって信仰を強制することができないため、望ましい効果をもたらさない。 宗教的な統一性を強制することは、多様性を認めることよりも社会的な混乱を招くだろう。 宗教的寛容性に関する彼の立場に関して、ロックは17世紀初頭に良心の自由を要求する小冊子を出版していたジョン・スマイスやトマス・ヘルウィスなどのバ プテスト神学者の影響を受けていた[36][37][38][39] バプティスト神学者ロジャー・ウィリアムズは1636年にロードアイランドの植民地を設立し、民主憲法と無限の信仰の自由を組み合わせている。彼のトラク トであるThe Bloudy Tenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience (1644)は母国で広く読まれ、絶対的な信仰の自由と教会と国家の完全な分離を熱く訴えていた[40]。 マルティンルターが1521年にワームスでの神聖ローマ帝国の国会において、聖書によって間違っていると証明されなければ自分の信念を撤回することを拒否 したように、良心的自由の優先度は神学、哲学、政治課題上で高く設定されていた[41]。 |

| Slavery and child labour Locke's views on slavery were multifaceted and complex. Although he wrote against slavery in general, Locke was an investor and beneficiary of the slave trading Royal Africa Company. In addition, while secretary to the Earl of Shaftesbury, Locke participated in drafting the Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, which established a quasi-feudal aristocracy and gave Carolinian planters absolute power over their enslaved chattel property; the constitutions pledged that "every freeman of Carolina shall have absolute power and authority over his negro slaves". Philosopher Martin Cohen notes that Locke, as secretary to the Council of Trade and Plantations and a member of the Board of Trade, was "one of just half a dozen men who created and supervised both the colonies and their iniquitous systems of servitude".[42][43] According to American historian James Farr, Locke never expressed any thoughts concerning his contradictory opinions regarding slavery, which Farr ascribes to his personal involvement in the slave trade.[44] Locke's positions on slavery have been described as hypocritical, and laying the foundation for the Founding Fathers to hold similarly contradictory thoughts regarding freedom and slavery.[45] Locke also drafted implementing instructions for the Carolina colonists designed to ensure that settlement and development was consistent with the Fundamental Constitutions. Collectively, these documents are known as the Grand Model for the Province of Carolina.[citation needed] Historian Holly Brewer has argued, however, that Locke's role in the Constitution of Carolina has been exaggerated and that he was merely paid to revise and make copies of a document that had already been partially written before he became involved; she compares Locke's role to a lawyer writing a will.[46] She further notes that Locke was paid in Royal African Company stock in lieu of money for his work as a secretary for a governmental sub-committee and that he sold the stock after only a few years.[47] Brewer likewise argues that Locke actively worked to undermine slavery in Virginia while heading a Board of Trade created by William of Orange following the Glorious Revolution. He specifically attacked colonial policy granting land to slave owners and encouraged the baptism and Christian education of the children of enslaved Africans to undercut a major justification of slavery—that they were heathens that possessed no rights.[48] Locke also supported child labour. In his "Essay on the Poor Law", he turns to the education of the poor; he laments that "the children of labouring people are an ordinary burden to the parish, and are usually maintained in idleness, so that their labour also is generally lost to the public till they are 12 or 14 years old".[49]: 190 He suggests, therefore, that "working schools" be set up in each parish in England for poor children so that they will be "from infancy [three years old] inured to work".[49]: 190 He goes on to outline the economics of these schools, arguing not only that they will be profitable for the parish, but also that they will instill a good work ethic in the children.[49]: 191 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke ++++++++++++++++++ "Locke owned stock in slave trading companies and was secretary of the Lords Proprietors of the Carolinas, where slavery was constitutionally permitted. He had two notions of slavery: legitimate slavery was captivity with forced labor imposed by the just winning side in a war; illegitimate slavery was an authoritarian deprivation of natural rights. Locke did not try to justify either black slavery or the oppression of Amerindians. In The Two Treatises of Government, Locke argued against the advocates of absolute monarchy. The arguments for absolute monarchy and colonial slavery turn out to be the same. So in arguing against the one, Locke could not help but argue against the other. Examining the natural rights tradition to which Locke’s work belongs confirms this. Locke could have defended colonial slavery by building on popular ideas of his colleagues and predecessors, but there is no textual evidence that he did that or that he advocated seizing Indian agricultural land." https://academic.oup.com/edited-volume/28299/chapter-abstract/214977811?redirectedFrom=fulltext |

奴隷制と児童労働 ロックの奴隷制度に対する考え方は多面的で複雑であった。ロックは奴隷制度に反対していたが、奴隷貿易会社であるロイヤル・アフリカ会社の出資者であり、 その恩恵を受けていた。この憲法では、「カロライナのすべての自由民は、その黒人奴隷に対して絶対的な権力と権威を持つ」ことがうたわれている。哲学者の マーティン・コーエンは、ロックが貿易・農園評議会の秘書として、また貿易委員会のメンバーとして、「植民地とその不義な隷属制度の両方を作り、監督した わずか6人のうちの1人」であると指摘している[42][43]。アメリカの歴史家ジェームズ・ファーによれば、ロックは奴隷制に関する彼の矛盾した意見 について考えを示すことはなく、ファーが奴隷貿易への彼の個人的関与によるものとしている[44]。 [ロックはまた、カロライナ植民者のために、入植と開発が基本憲法と一致することを保証するための実施要領を起草した[45]。これらの文書はまとめて、 カロライナ州のグランドモデルとして知られている[citation needed]。 しかし、歴史家のホリー・ブリューワーは、カロライナ憲法におけるロックの役割は誇張されており、ロックが関与する前にすでに部分的に書かれていた文書の 改訂とコピーを作るために支払われただけだと主張し、ロックの役割を遺言書を書く弁護士に例えている[46]。 [さらに、ロックは政府の小委員会の秘書としての仕事に対して、お金の代わりにロイヤル・アフリカ会社の株で支払われ、その株は数年後に売却したと述べて いる[47]。ブリュワーは同様に、ロックが栄光革命後にオレンジ公ウィリアムが設立した貿易委員会を率いながらバージニア州の奴隷制度を弱めるために活 発に働いたと主張している。彼は特に奴隷所有者に土地を与える植民地政策を攻撃し、奴隷にされたアフリカ人の子供たちに洗礼とキリスト教教育を奨励し、彼 らが権利を持たない異教徒であるという奴隷制の主要な正当性を弱体化させた[48]。 ロックはまた児童労働を支持していた。彼は「貧民法に関するエッセイ」において、貧民の教育に目を向け、「労働者の子どもは教区にとって普通の負担であ り、通常怠惰に維持されているため、彼らの労働も一般的には12歳か14歳になるまで失われる」ことを嘆いている[49]。 したがって、彼は、貧しい子 供たちのために、イングランドの各教区に「労働学校」を設立し、彼らが「乳児(3歳)から労働に慣れるようにする」ことを提案する[49]。 190 彼はさらにこれらの学校の経済的な概要を述べ、教区にとって有益であるばかりでなく、子供たちに優れた労働倫理を身につけさせることができると主張する [49]。 191 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_Locke +++++++++++++++++++ 「ロッ クは奴隷貿易会社の株式を所有し、奴隷制が憲法で認められていたカロライナ植民地の領主会の書記でもあった。ロックには奴隷制に対する2つの考え方があっ た。すなわち、合法的な奴隷制とは戦争に勝利した側が強制労働を課す捕虜制度であり、非合法的な奴隷制とは権力による自然権の剥奪である。ロックは黒人奴 隷制もアメリカ先住民の抑圧も正当化しようとはしなかった。ロックは『統治二論』の中で絶対王政の擁護者たちに対して反論した。絶対君主制と植民地奴隷制 の 主張は、結局のところ同じものであることが判明した。そのため、一方を否定する議論を展開するにあたり、ロックは必然的に他方を否定せざるを得なかった。 ロックの著作が属する自然権説の伝統を検証すると、このことが確認できる。ロックは、同僚や先人たちの一般的な考え方を踏まえて植民地奴隷制を擁護するこ とも可能だったが、ロックがそうしたことや、インドの農地を接収することを提唱したとする証拠は、文章上にはない。」 |

| Government Locke's political theory was founded upon that of social contract. Unlike Thomas Hobbes, Locke believed that human nature is characterised by reason and tolerance. Like Hobbes, however, Locke believed that human nature allows people to be selfish. This is apparent with the introduction of currency. In a natural state, all people were equal and independent, and everyone had a natural right to defend his "life, health, liberty, or possessions".[50]: 198 Most scholars trace the phrase "Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" in the American Declaration of Independence to Locke's theory of rights,[51] although other origins have been suggested.[52] Like Hobbes, Locke assumed that the sole right to defend in the state of nature was not enough, so people established a civil society to resolve conflicts in a civil way with help from government in a state of society. However, Locke never refers to Hobbes by name and may instead have been responding to other writers of the day.[53] Locke also advocated governmental separation of powers and believed that revolution is not only a right but an obligation in some circumstances. These ideas would come to have profound influence on the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States. |

政府 ロックの政治理論は、社会契約論を基礎としている。ホッブズとは異なり、ロックは人間の本性は理性と寛容に特徴づけられると考えた。しかし、ホッブズと同 様に、ロックは人間の本性は利己的であることを許容すると考えた。これは通貨の導入で明らかになった。自然状態においては、すべての人は平等であり、独立 しており、誰もが自分の「生命、健康、自由、または所有物」を守る自然権を有していた[50]。 198 アメリカ独立宣言における「生命、自由及び幸福の追求」という文言は、他の起源が示唆されているものの、ほとんどの学者がロックの権利論にたどっている [51]。 ホッブズのように、ロックは自然状態における唯一の防衛権だけでは不十分であり、人々は社会状態において政府の助けを借りて市民的な方法で対立を解決する ために市民社会を設立したと仮定していた。しかし、ロックはホッブズを名指ししておらず、その代わりに当時の他の作家に対して応答していたのかもしれない [53]。またロックは政府の三権分立を唱え、革命はある状況下では権利だけでなく義務であると信じた。これらの考えは後に独立宣言やアメリカ合衆国憲法 に大きな影響を与えることになる。 |

| Accumulation of wealth According to Locke, unused property is wasteful and an offence against nature,[54] but, with the introduction of "durable" goods, men could exchange their excessive perishable goods for those which would last longer and thus not offend the natural law. In his view, the introduction of money marked the culmination of this process, making possible the unlimited accumulation of property without causing waste through spoilage.[55] He also includes gold or silver as money because they may be "hoarded up without injury to anyone",[56] as they do not spoil or decay in the hands of the possessor. In his view, the introduction of money eliminates limits to accumulation. Locke stresses that inequality has come about by tacit agreement on the use of money, not by the social contract establishing civil society or the law of land regulating property. Locke is aware of a problem posed by unlimited accumulation, but does not consider it his task. He just implies that government would function to moderate the conflict between the unlimited accumulation of property and a more nearly equal distribution of wealth; he does not identify which principles that government should apply to solve this problem. However, not all elements of his thought form a consistent whole. For example, the labour theory of value in the Two Treatises of Government stands side by side with the demand-and-supply theory of value developed in a letter he wrote titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money. Moreover, Locke anchors property in labour but, in the end, upholds unlimited accumulation of wealth.[57] |

富の蓄積 ロックによれば、未使用の財産は浪費であり、自然に対する違反であるが[54]、「耐久財」の導入によって、人間は過剰な腐敗する財をより長持ちする財と 交換することができ、したがって自然法則に違反することがない。彼の見解では、貨幣の導入はこのプロセスの頂点であり、腐敗による浪費を引き起こすことな く財産の無制限の蓄積を可能にした[55]。また彼は金や銀を貨幣として含んでいるが、それはそれらが所有者の手の中で腐敗したり腐ったりしないので「誰 にも害を与えずにため込む」ことができる[56]からであった。彼の見解では、貨幣の導入は蓄積に対する制限をなくすものである。ロックは、不平等が市民 社会を確立する社会契約や財産を規制する土地法によってではなく、貨幣の使用に関する暗黙の合意によってもたらされたことを強調している。ロックは、無制 限の蓄積がもたらす問題を認識しているが、それを自分の課題とは考えていない。彼は、無制限の財産の蓄積とより平等な富の分配との間の対立を緩和するため に政府が機能することを示唆するだけで、この問題を解決するために政府が適用すべき原則を特定することはしていない。しかし、彼の思想のすべての要素が一 貫して全体を形成しているわけではない。例えば、『政体論』における労働価値説は、『利子の低下と貨幣価値の上昇の結果に関する若干の考察』と題する書簡 で展開された需要供給価値説と並存しているのである。さらに、ロックは財産を労働に固定するが、最終的には富の無制限な蓄積を支持する[57]。 |

| Economics On price theory Locke's general theory of value and price is a supply-and-demand theory, set out in a letter to a member of parliament in 1691, titled Some Considerations on the Consequences of the Lowering of Interest and the Raising of the Value of Money.[58] In it, he refers to supply as quantity and demand as rent: "The price of any commodity rises or falls by the proportion of the number of buyers and sellers" and "that which regulates the price…[of goods] is nothing else but their quantity in proportion to their rent." The quantity theory of money forms a special case of this general theory. His idea is based on "money answers all things" (Ecclesiastes) or "rent of money is always sufficient, or more than enough" and "varies very little". Locke concludes that, as far as money is concerned, the demand for it is exclusively regulated by its quantity, regardless of whether the demand is unlimited or constant. He also investigates the determinants of demand and supply. For supply, he explains the value of goods as based on their scarcity and ability to be exchanged and consumed. He explains demand for goods as based on their ability to yield a flow of income. Locke develops an early theory of capitalisation, such as of land, which has value because "by its constant production of saleable commodities it brings in a certain yearly income". He considers the demand for money as almost the same as demand for goods or land: it depends on whether money is wanted as medium of exchange. As a medium of exchange, he states, "money is capable by exchange to procure us the necessaries or conveniences of life" and, for loanable funds, "it comes to be of the same nature with land by yielding a certain yearly income…or interest". |

経済学 価格理論について ロックは、1691年に国会議員に宛てた書簡「利子の低下と貨幣価値の上昇の結果に関する若干の考察」の中で、供給を量、需要を家賃とし、「あらゆる商品 の価格は、買い手と売り手の数の割合によって上昇または下落する」、「価格・・・(商品)を調節するものは、その家賃に比例した量に他ならない」と言って いる[58] 。 貨幣数量説は、この一般理論の特殊なケースを形成している。彼の考えは、「貨幣は万物に答える」(『伝道者の書』)、あるいは「貨幣の賃借料は常に十分 か、あるいは十二分にある」、「ほとんど変化しない」ことに基づくものである。ロックは、貨幣に関する限り、その需要が無制限であるか一定であるかにかか わらず、その量によって排他的に規制されると結論付けている。彼はまた、需要と供給の決定要因についても調査している。供給については、財の価値は、その 希少性と交換・消費される能力に基づいていると説明する。また、財の需要については、財が所得の流れを生み出す能力に基づいて説明する。ロックは、「販売 可能な商品を絶えず生産することによって、一定の年間所得をもたらす」ために価値を持つ土地などの資本化に関する初期の理論を展開している。彼は、貨幣の 需要は、財や土地の需要とほとんど同じであり、貨幣が交換媒体として必要とされるかどうかにかかっていると考えている。交換媒体としては、「貨幣は交換に よって生活必需品や便益を調達することができる」とし、貸付可能な資金としては、「一定の年収...あるいは利子をもたらすことによって、土地と同じ性質 を持つようになる」と述べている。 |

| Monetary thoughts Locke distinguishes two functions of money: as a counter to measure value, and as a pledge to lay claim to goods. He believes that silver and gold, as opposed to paper money, are the appropriate currency for international transactions. Silver and gold, he says, are treated to have equal value by all of humanity and can thus be treated as a pledge by anyone, while the value of paper money is only valid under the government which issues it. Locke argues that a country should seek a favourable balance of trade, lest it fall behind other countries and suffer a loss in its trade. Since the world money stock grows constantly, a country must constantly seek to enlarge its own stock. Locke develops his theory of foreign exchanges, in addition to commodity movements, there are also movements in country stock of money, and movements of capital determine exchange rates. He considers the latter less significant and less volatile than commodity movements. As for a country's money stock, if it is large relative to that of other countries, he says it will cause the country's exchange to rise above par, as an export balance would do. He also prepares estimates of the cash requirements for different economic groups (landholders, labourers, and brokers). In each group he posits that the cash requirements are closely related to the length of the pay period. He argues the brokers—the middlemen—whose activities enlarge the monetary circuit and whose profits eat into the earnings of labourers and landholders, have a negative influence on both personal and the public economy to which they supposedly contribute.[citation needed] |

貨幣思想 ロックは、貨幣の機能を、価値を計るためのカウンターとしての機能と、財を要求するための質料としての機能の二つに分類している。彼は、国際的な取引には 紙幣ではなく、銀と金が適切な通貨であると考える。銀と金は人類が等しく価値を持つものとして扱われるため、誰にでも質草として扱うことができるが、紙幣 の価値はそれを発行する政府の下でのみ有効である、と彼は言っている。 ロックは、一国は他国に遅れをとって貿易で損をしないように、有利な貿易収支を追求すべきだと主張する。世界の貨幣在庫は絶えず増加するので、一国は常に 自国の貨幣在庫を増加させようとしなければならない。ロックは外国為替に関する理論を展開し、商品の動きだけでなく、国の貨幣ストックの動きもあり、資本 の動きが為替レートを決定するとした。彼は、後者については、商品の動きよりも重要性が低く、変動も少ないと考えている。マネーストックについては、他国 のマネーストックと比較して大きい場合、輸出収支のように為替が額面以上に上昇する原因になるという。 また、経済グループ別(土地所有者、労働者、仲介業者)の現金必要量の試算も行っている。それぞれのグループにおいて、現金必要額は給与期間の長さと密接 な関係があると仮定している。彼は、仲介者-その活動が貨幣回路を拡大し、その利益が労働者や土地所有者の収入を食い潰すため、個人と彼らが貢献している はずの公共経済の両方に悪影響を及ぼすと主張している[citation needed]。 |

| Theory of value and property Locke uses the concept of property in both broad and narrow terms: broadly, it covers a wide range of human interests and aspirations; more particularly, it refers to material goods. He argues that property is a natural right that is derived from labour. In Chapter V of his Second Treatise, Locke argues that the individual ownership of goods and property is justified by the labour exerted to produce such goods—"at least where there is enough [land], and as good, left in common for others" (para. 27)—or to use property to produce goods beneficial to human society.[59] Locke states in his Second Treatise that nature on its own provides little of value to society, implying that the labour expended in the creation of goods gives them their value. From this premise, understood as a labour theory of value,[59] Locke developed a labour theory of property, whereby ownership of property is created by the application of labour. In addition, he believed that property precedes government and government cannot "dispose of the estates of the subjects arbitrarily". Karl Marx later critiqued Locke's theory of property in his own social theory.[citation needed] |

価値と財産の理論 ロックは、財産という概念を広義にも狭義にも用いている。広義には、人間の利益や願望を幅広くカバーし、より狭義には、物質的な財を指している。彼は、財 産は労働に由来する自然権であると主張する。第二論文集の第五章において、ロックは財と財産の個人の所有は、そのような財を生産するために発揮される労働 -「少なくとも、十分な(土地)、そして善として、他人のために共有で残される場合」(パラグラフ27)、または人間社会に有益な財を生産するために財産 を使用するために発揮される労働によって正当化されると論じている[59]。 ロックは『統治二論』において、自然はそれ自体では社会に対してほとんど価値を提供しないと述べており、財の創造に費やされる労働がその価値を与えること を 暗示している。この前提から、ロックは価値の労働理論として理解し[59]、財産の所有は労働の適用によって生み出されるという財産の労働理論を展開し た。さらに彼は、財産は政府に先行し、政府は「臣民の財産を恣意的に処分する」ことができないと考えた。カール・マルクスは後に、自身の社会理論において ロックの財産論を批判した[citation needed]。 |

| The self Locke defines the self as "that conscious thinking thing, (whatever substance, made up of whether spiritual, or material, simple, or compounded, it matters not) which is sensible, or conscious of pleasure and pain, capable of happiness or misery, and so is concerned for itself, as far as that consciousness extends".[60] He does not, however, wholly ignore "substance", writing that "the body too goes to the making the man".[61] In his Essay, Locke explains the gradual unfolding of this conscious mind. Arguing against both the Augustinian view of man as originally sinful and the Cartesian position, which holds that man innately knows basic logical propositions, Locke posits an 'empty mind', a tabula rasa, which is shaped by experience; sensations and reflections being the two sources of all of our ideas.[62] He states in An Essay Concerning Human Understanding: This source of ideas every man has wholly within himself; and though it be not sense, as having nothing to do with external objects, yet it is very like it, and might properly enough be called 'internal sense.'[63] Locke's Some Thoughts Concerning Education is an outline on how to educate this mind. Drawing on thoughts expressed in letters written to Mary Clarke and her husband about their son,[64] he expresses the belief that education makes the man—or, more fundamentally, that the mind is an "empty cabinet":[65] I think I may say that of all the men we meet with, nine parts of ten are what they are, good or evil, useful or not, by their education. Locke also wrote that "the little and almost insensible impressions on our tender infancies have very important and lasting consequences".[65] He argues that the "associations of ideas" that one makes when young are more important than those made later because they are the foundation of the self; they are, put differently, what first mark the tabula rasa. In his Essay, in which both these concepts are introduced, Locke warns, for example, against letting "a foolish maid" convince a child that "goblins and sprites" are associated with the night, for "darkness shall ever afterwards bring with it those frightful ideas, and they shall be so joined, that he can no more bear the one than the other".[66] This theory came to be called associationism, going on to strongly influence 18th-century thought, particularly educational theory, as nearly every educational writer warned parents not to allow their children to develop negative associations. It also led to the development of psychology and other new disciplines with David Hartley's attempt to discover a biological mechanism for associationism in his Observations on Man (1749). Dream argument Locke was critical of Descartes's version of the dream argument, with Locke making the counter-argument that people cannot have physical pain in dreams as they do in waking life.[67] |

自己 ロックは自己を「意識的に考えるもの、(精神的であろうと物質的であろうと、単純であろうと複合的であろうと、どんな物質で構成されていようと関係ない) 感覚を持ち、喜びと痛みを意識し、幸福と不幸を可能にし、その意識が及ぶ限り、自分自身に関心を持つ」と定義している[60]。 しかし彼は「肉体も人間を作るために行く」、と書いていて完全に「物質」を無視はしていない[61]。 ロックは『エッセイ』の中で、この意識的な心が徐々に展開されることを説明している。ロックは『人間の理解に関するエッセイ』の中で、人間をもともと罪深 いものとするアウグスティヌス派の見解と、人間が基本的な論理命題を生得的に知っているとするデカルト派の立場の両方に反論して、経験によって形作られる 「空の心」、タブラ・ラサ、感覚と反射が人間のすべての考えの二つの源であると仮定している[62]。 この発想の源はすべての人が完全に自分の中に持っており、それは外部の対象とは何の関係もないので感覚ではないが、しかしそれに非常に似ており、適切に十 分に「内的感覚」と呼ばれるかもしれない[63]」。 ロックの『教育に関するいくつかの考え』は、この心をどのように教育するかについての概要である。メアリー・クラークとその夫に息子について書かれた手紙 に表現された考えを引き合いに出して、彼は教育が人間を作るという信念、より根本的には心が「空のキャビネット」であるという信念を表明している [64]:[65]。 私たちが出会うすべての人間のうち、10人のうち9人は教育によって、善であれ悪であれ、有用であれそうでないものであると言うことができると思う」。 ロックはまた、「幼少期の小さな、ほとんど気づかないような印象が非常に重要で永続的な結果をもたらす」と書いており[65]、幼少期に作る「考えの連 想」が後に作るものよりも重要であると論じている、それはそれが自己の基盤であり、別の言葉で言えば、それが最初にタブラ・ラサをマークするものだからで ある。この両方の概念が導入された『エッセイ』において、ロックは例えば「愚かな女中」が子供に「妖怪や精霊」が夜と関連していると信じ込ませることに対 して警告しており、「暗闇はその後、それらの恐ろしい考えをもたらすであろうし、それらはとても結合されて、彼は他よりも一方に耐えられなくなるだろうか ら」と述べている[66]。 この理論は連合主義と呼ばれるようになり、18世紀の思想、特に教育論に強い影響を与えるようになり、ほぼすべての教育作家が子供に負の連想を持たせない ように親に警告していた。また、デイヴィッド・ハートリーが『人間観察』(1749年)で連合論の生物学的メカニズムを発見しようとしたことで、心理学な どの新しい学問の発展にもつながった。 夢の議論 ロックはデカルト版の夢論に批判的であり、ロックは夢の中で人は起きている時のような肉体的苦痛を持つことはできないという反論を行った[67]。 |