ジャンキー

Junkie: Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict, by William S. Burroughs.

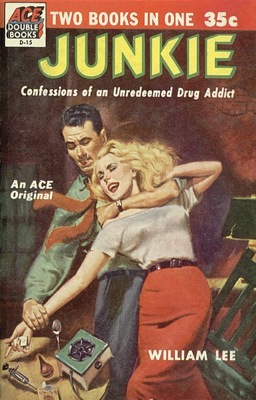

1953 Ace Double edition, credited to William Lee

☆ 『ジャンキー: 贖われざる薬物中毒者の告白』(原題:Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict)は、アメリカのビート世代作家ウィリアム・S・バロウズによる1953年の小説である。「ウィリアム・リー」がモルヒネとヘロインへの依存 と闘う姿を描いている。バロウズは自身のドラッグ体験をもとにこの物語を書き、ウィリアム・リーというペンネームで発表した。批評家の中には、ウィリア ム・リーという人物を単にバロウズ自身とみなす者もいる。この読み方では、『ジャンキー』はほぼ自伝的な回顧録である。この読み方では、『ジャンキー』は ほぼ自伝的回顧録である。また、リーを作者をモデルにした架空の人物とみなす者もいる。 『ジャンキー』はバロウズが初めて出版した小説である(それ以前にジャック・ケルアックと未発表の小説を書いていたが)。当初は1953年にエース・ブッ クスから出版された。エースは大幅な変更を要求し、いくつかの箇所を検閲し、連邦麻薬局に関する本と同梱した。このバージョンは商業的には成功したが、発 表当初は批評家の注目を浴びることはなかった。1977年、ペンギン・ブックスはこの小説のノーカット版をJunkyという別綴りで出版した。 批評家たちは、『裸のランチ』のようなバロウズの後期の、より実験的な小説に照らして『ジャンキー』を分析している。この本は、『ジャンキー』のテーマで ある薬物中毒と支配を拡大したそれらの後期の作品と比べると、辛口で明晰でわかりやすいと考えられている。この本のグロテスクな描写や幻覚的なイメージ も、後の作品への前兆とみなされている。

| Junkie: Confessions

of an Unredeemed Drug Addict, or Junky, is a 1953 novel by American

Beat generation writer William S. Burroughs. The book follows "William

Lee" as he struggles with his addiction to morphine and heroin.

Burroughs based the story on his own experiences with drugs, and he

published it under the pen name William Lee. Some critics view the

character William Lee as simply Burroughs himself; in this reading,

Junkie is a largely-autobiographical memoir. Others view Lee as a

fictional character based on the author. Junkie was Burroughs' first published novel (although he had previously written an unpublished novel with Jack Kerouac). It was initially published by Ace Books in 1953. Ace demanded substantial changes, censored some passages, and bundled it with a book about the Federal Bureau of Narcotics. This version was commercially successful, but did not receive critical attention when first released. In 1977, Penguin Books published an uncensored version of the novel under the alternate spelling Junky. Critics have analyzed Junkie in the light of Burroughs' later and more experimental novels, such as Naked Lunch. The book is considered dry, lucid, and straightforward compared to those later works, which expand on Junkie's themes of drug addiction and control. The book's grotesque descriptions and hallucinatory imagery are also seen as precursors to his later work. |

『ジャンキー: 贖われざる薬物中毒者の告白』(原題:Confessions of

an Unredeemed Drug

Addict)は、アメリカのビート世代作家ウィリアム・S・バロウズによる1953年の小説である。ウィリアム・リー」がモルヒネとヘロインへの依存と

闘う姿を描いている。バロウズは自身のドラッグ体験をもとにこの物語を書き、ウィリアム・リーというペンネームで発表した。批評家の中には、ウィリアム・

リーという人物を単にバロウズ自身とみなす者もいる。この読み方では、『ジャンキー』はほぼ自伝的な回顧録である。この読み方では、『ジャンキー』はほぼ

自伝的回顧録である。また、リーを作者をモデルにした架空の人物とみなす者もいる。 『ジャンキー』はバロウズが初めて出版した小説である(それ以前にジャック・ケルアックと未発表の小説を書いていたが)。当初は1953年にエース・ブッ クスから出版された。エースは大幅な変更を要求し、いくつかの箇所を検閲し、連邦麻薬局に関する本と同梱した。このバージョンは商業的には成功したが、発 表当初は批評家の注目を浴びることはなかった。1977年、ペンギン・ブックスはこの小説のノーカット版をJunkyという別綴りで出版した。 批評家たちは、『裸のランチ』のようなバロウズの後期の、より実験的な小説に照らして『ジャンキー』を分析している。この本は、『ジャンキー』のテーマで ある薬物中毒と支配を拡大したそれらの後期の作品と比べると、辛口で明晰でわかりやすいと考えられている。この本のグロテスクな描写や幻覚的なイメージ も、後の作品への前兆とみなされている。 |

| Synopsis You become a narcotics addict because you do not have strong motivations in any other direction. Junk wins by default. — William S. Burroughs, Junkie In New York City, 1944, William Lee[note 1] is offered a job selling stolen morphine syrettes. He tries the drug for the first time, keeps some syrettes for himself, and sells the rest to a buyer named Roy, who warns him about the dangers of addiction. Over the next month, Lee gradually uses up what he saved and becomes dependent. As their addictions worsen, Lee and Roy resort to "doctor shopping", convincing a series of physicians to prescribe them morphine. However, their scheme is risky; Lee is eventually arrested for using a fake name on a prescription. His wife bails him out, and he receives a suspended sentence. Experiencing withdrawal symptoms, including hallucinations, Lee begins searching for an alternative to morphine. Roy connects him to a heroin supplier, and the two initially support their habit by pickpocketing drunk subway riders. Later, Lee forms a partnership with a dealer named Bill Gains, buying, cutting, and reselling heroin while keeping a portion for himself. As police crack down on the drug trade, paranoia spreads among his circle of addicts and customers. Eventually, Gains decides his lifestyle has become too dangerous and checks himself into the Lexington Medical Center, a government-run facility for treating addiction. Lee attempts to quit heroin on his own but fails. Following Gains’ lead, he enters Lexington in late 1945, where he listens to other patients’ stories of addiction and undergoes methadone treatment, which he considers a success. After four months, he leaves to start over in New Orleans. While there, Lee visits a gay bar and is invited to have sex, only to be robbed instead. That evening, he relapses and quickly resumes selling heroin. His addiction worsens, and by 1947, he is arrested again. In jail, Lee suffers severe withdrawal symptoms, including rapid weight loss and hallucinations. His lawyer secures his transfer to a sanitorium for an experimental addiction cure, but his struggle with addiction continues. After his release, Lee moves to Texas, where he attempts to support himself by growing cotton. This endeavor fails, leaving him financially desperate. Unable to maintain a stable life, he moves to Mexico City in 1948 and relapses once more, much to his wife’s distress. Lee spends the next year in Mexico, making repeated but unsuccessful attempts to quit opioids. To manage his addiction, he begins drinking heavily, which only worsens his paranoia and deteriorating health. He eventually develops uremia, and later, his doctor warns him that he is drinking himself to death. His wife, realizing the hopelessness of his situation, leaves town with their children. As anti-narcotics enforcement intensifies in the U.S., Bill Gains flees to Mexico and reunites with Lee. He informs him that Roy was arrested and died in prison. Lee helps Gains secure a heroin supply, but the drug is so heavily adulterated that Gains nearly dies from it. By 1950, Lee’s marriage has completely collapsed, and he reflects on his separation from his wife. Seeking something beyond the emptiness of addiction, he reads about yagé (ayahuasca), a drug rumored to grant telepathic abilities. Hopeful that it will fill the void that “junk” could not, Lee leaves Mexico City a year later in search of it. |

あらすじ 麻薬中毒になるのは、他の方向に強い動機がないからだ。ジャンクはデフォルトで勝つ。 - ウィリアム・S・バロウズ『ジャンキー』 1944年のニューヨークで、ウィリアム・リー[注釈 1]は盗んだモルヒネのシレットを売る仕事を依頼される。初めてモルヒネを試したリーは、いくつかのモルヒネを自分のものにし、残りをロイというバイヤーに売る。 その後1ヶ月の間に、リーは貯めた分を徐々に使い果たし、依存症になっていく。依存症が悪化するにつれ、リーとロイは 「ドクターショッピング 」に頼り、モルヒネを処方するよう何人もの医師を説得する。しかし、彼らの計画は危険で、リーは最終的に処方箋に偽名を使ったとして逮捕される。妻が保釈 し、リーは執行猶予付きの判決を受ける。 幻覚などの禁断症状を経験したリーは、モルヒネに代わるものを探し始める。ロイは彼にヘロイン・サプライヤーを紹介し、ふたりは当初、地下鉄の酔客をスリ をすることで習慣を支えていた。その後、リーはビル・ゲインズという売人とパートナーシップを結び、ヘロインを購入、カット、転売しながら、一部を自分の ものにする。 警察が麻薬取引を取り締まるにつれ、ゲインズの仲間や客の間にパラノイアが広がっていく。やがてゲインズは自分のライフスタイルが危険すぎると判断し、政府が運営する依存症治療施設レキシントン・メディカル・センターに身を寄せる。 リーは自力でヘロインをやめようとするが失敗する。ゲインズに従って1945年末にレキシントンに入り、他の患者の中毒の話を聞き、メサドン治療を受け る。4ヵ月後、彼はニューオーリンズで再出発する。そこでゲイバーを訪れ、セックスに誘われるが、代わりに強盗に襲われる。その晩、彼は再発し、すぐにヘ ロインの販売を再開する。 中毒は悪化し、1947年には再び逮捕される。刑務所でリーは、急激な体重減少や幻覚など、ひどい禁断症状に苦しむ。彼の弁護士は、実験的な中毒治療のための療養所への移送を確保するが、彼の中毒との闘いは続く。 釈放後、リーはテキサスに移り住み、綿花栽培で生計を立てようとする。この試みは失敗に終わり、リーは経済的に絶望する。安定した生活を維持できなくなっ た彼は、1948年にメキシコ・シティに移り住み、妻を苦しめることになる。リーはその後1年間をメキシコで過ごし、オピオイドをやめようと何度も試みた がうまくいかなかった。 依存症に対処するため、彼は大量の飲酒を始めたが、それは彼のパラノイアと健康悪化を悪化させるだけだった。やがて尿毒症を発症し、後に主治医から「死ぬまで酒を飲んでいる」と警告される。絶望的な状況を悟った妻は、子供を連れて町を出て行く。 アメリカで麻薬取締りが強化される中、ビル・ゲインズはメキシコに逃れ、リーと再会する。彼はロイが逮捕され、刑務所で死んだことを告げる。リーはゲインズがヘロインの供給を確保するのを手伝うが、その麻薬は不純物が多く、ゲインズは危うくヘロインで死にそうになる。 1950年になると、リーの結婚生活は完全に破綻し、彼は妻との別れを思い返す。依存症の虚しさを超える何かを求めて、彼はテレパシー能力を与えるという噂の薬物、ヤヘ(アヤワスカ)について本を読む。「ジャンク」では埋められなかった空虚感をヤヘが埋めてくれることを期待したリーは、1年後、ヤヘを求めてメキシコシティを後にする。 |

| Background William S. Burroughs was the grandson of William Seward Burroughs I, who founded the Burroughs Corporation. Burroughs' family was financially comfortable, and he received an allowance for most of his life.[1][2] Burroughs volunteered for the army in 1942, but he was discharged for mental instability. In September 1943, he moved to New York, following his friends Lucien Carr and David Kammerer.[3][4] Through them, he met Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg;[5] along with Burroughs himself, these writers would become the core figures of the Beat generation.[6] While in New York, Burroughs became addicted to opioids, and increasingly committed crimes as the cost of his addiction exceeded his allowance.[7][8] Carr fatally stabbed Kammerer in 1944.[9] Burroughs and Kerouac were briefly arrested for not reporting the homicide,[10] then co-wrote a novel inspired by the event called And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks, which they were unable to get published.[11] The novel was eventually published in 2008.[12] In 1945, Burroughs met Joan Vollmer,[13] who would become his common-law wife.[14] In October 1946, Burroughs and Vollmer left New York for Texas,[15] where they had a child.[16] They later moved to Mexico City in October 1949, partly to avoid legal risks around Burroughs' drug use.[17] Carr visited Burroughs in August 1950 and suggested he write a book about his experiences.[18] Burroughs began writing Junkie while he was using heroin. By February 1951, he had quit heroin, but continued to smoke opium, which he believed carried minimal risk of addiction.[19] Although Burroughs' preface to the novel refers to his addiction in the past tense, he remained dependent on opioids like methadone for the rest of his life.[20] Over the summer of 1951, Burroughs traveled to Ecuador with his friend Lewis Marker, hoping to start a romantic relationship. This experience would become the foundation of Burroughs' second novel Queer.[21] Back in Mexico City, on September 6, 1951, Burroughs fatally shot Vollmer; he had attempted to shoot a glass balanced on her head while drunk.[22] Although he had already written the first draft of Junkie, he would later state that he would not have become a writer if not for her death.[23] |

生い立ち ウィリアム・S・バロウズは、バロウズ・コーポレーションを設立したウィリアム・スワード・バロウズ1世の孫である。バロウズの家庭は経済的に余裕があ り、生涯のほとんどを小遣いをもらって過ごした[1][2]。1942年に陸軍に志願したが、精神不安定を理由に除隊。1943年9月、友人のルシアン・ カーとデヴィッド・カメラーを追ってニューヨークに移り住む[3][4]。彼らを通じてジャック・ケルアックとアレン・ギンズバーグに出会い[5]、バロ ウズ自身とともにビート世代の中心人物となる。 ニューヨーク滞在中、バロウズはオピオイド中毒になり、その代償が小遣いを上回ったため、次第に犯罪を犯すようになる[7][8]。 カーは1944年にカメラーを致命的に刺した[9]。バロウズとケルアックはこの殺人を報告しなかったために一時的に逮捕され[10]、その後この出来事 にインスパイアされた小説『そしてカバは水槽で茹でられた(And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks)』を共同執筆したが、出版には至らなかった[11]。この小説は最終的に2008年に出版された[12]。 1945年、バロウズは内縁の妻となるジョーン・ヴォルマーと出会う[13]。1946年10月、バロウズとヴォルマーはニューヨークからテキサスに向かい、そこで子供をもうけた[15]。 カーは1950年8月にバロウズを訪ね、自分の経験について本を書くよう勧めた[18]。バロウズはヘロインを使用しながら『ジャンキー』の執筆を始め た。1951年2月までに、彼はヘロインをやめたが、中毒の危険性が少ないと信じていたアヘンを吸い続けた[19]。バロウズはこの小説の序文で自分の中 毒について過去形で言及しているが、彼はメタドンのようなオピオイドに一生依存し続けた[20]。 1951年の夏、バロウズは友人のルイス・マーカーとエクアドルを訪れ、恋愛関係を始めようとした。1951年9月6日、メキシコ・シティに戻ったバロウ ズはヴォルマーを射殺した。ヴォルマーは酒に酔っていたため、彼女の頭の上にバランスよく置かれたグラスを撃とうとしたのだった。 |

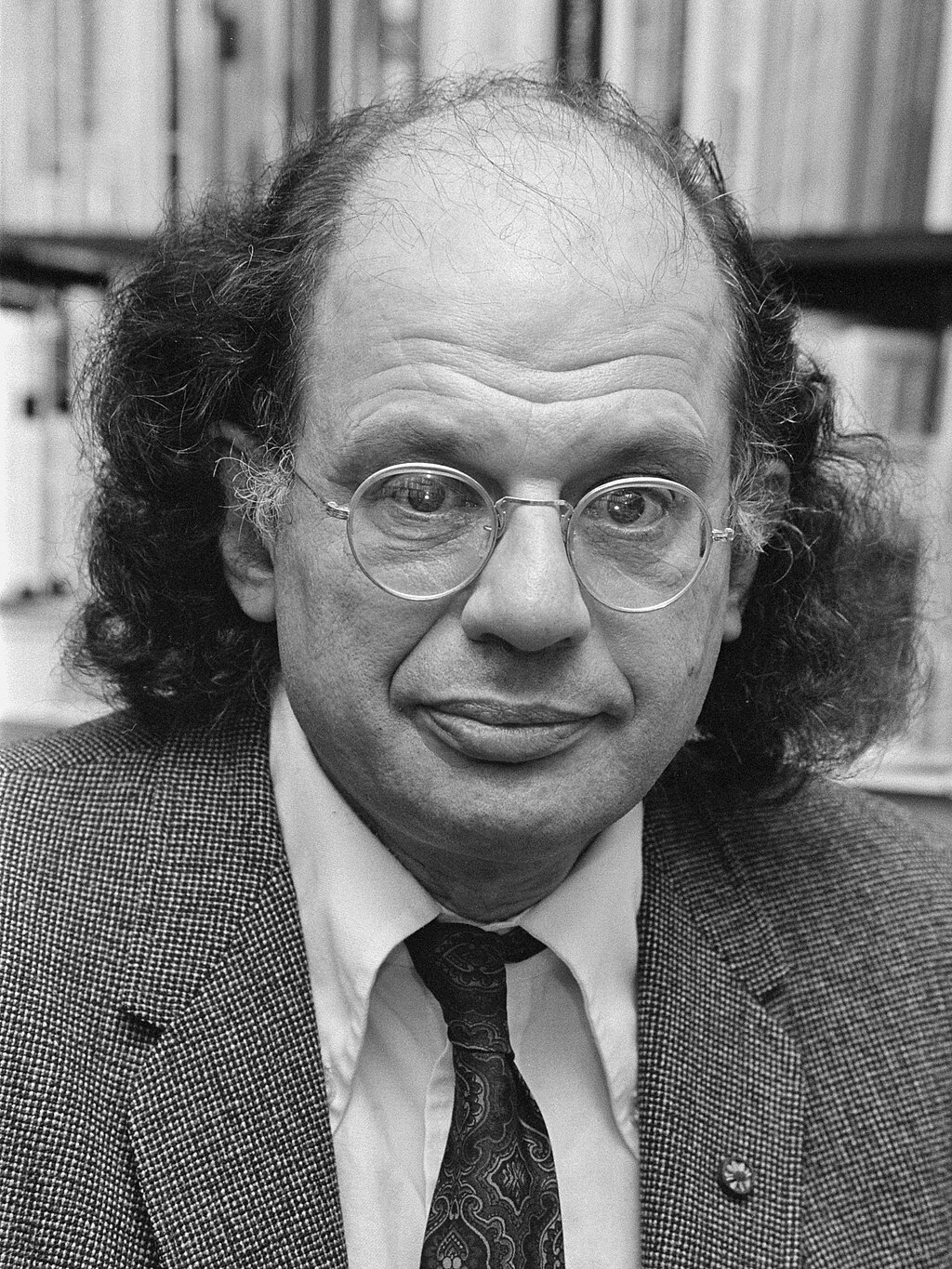

Publication Allen Ginsberg (pictured in 1979) used his literary connections to get Junkie published through Ace Books. He later criticized the terms of publication as "ridiculous". Burroughs mailed chapters of Junkie to Allen Ginsberg as he wrote.[24] In his preface to the 1977 edition, Ginsberg claims that he and Burroughs collaboratively assembled the novel from these letters. He also notes that they continued this practice for Burroughs' subsequent novels Queer and Naked Lunch.[25] Oliver Harris, a scholar and editor of Burroughs' works, disputes this story. He argues that Burroughs wrote most of the novel before sharing it with Ginsberg, and that the book "shows no signs of an interpersonal epistolary aesthetic."[26] Burroughs finished his initial manuscript by January 1, 1951.[14] In April 1952, Ginsberg began the process of getting it published.[27] Ginsberg sent copies of Junkie and Jack Kerouac's On the Road to his acquaintance Carl Solomon, whose uncle A. A. Wyn owned Ace Books. Solomon and Wyn rejected On The Road, but agreed to publish Junkie.[28] Ginsberg later regretted signing a "ridiculous" contract with Ace Books, which he felt substantially underpaid Burroughs for the book's success.[29] Burroughs' manuscript was originally titled Junk. Ace Books renamed it to Junkie, out of a concern that Junk would imply the book itself was poor quality, and added the subtitle Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict.[30] Ace Books took advantage of Burroughs' provocative subject by creating what Harris calls an "especially lurid and voyeuristic" book cover,[31] but also censored the book's language, removed passages, and added editors' notes and disclaimers.[32] To avoid appearing to endorse recreational drug use, Wyn bundled Junkie with a reprint of Narcotics Agent, a 1941 book by Maurice Helbrant chronicling his work in the Federal Bureau of Narcotics.[28] The publisher also asked Burroughs to include a prologue about his upbringing, to make it clear he did not come from a family of addicts and criminals.[33] Burroughs originally named the protagonist "William Dennison." This name had previously been used for Burroughs' analogs in two romans à clef: Jack Kerouac's first published novel The Town and the City, and Kerouac and Burroughs' unpublished collaboration And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks.[34] Burroughs later renamed the protagonist "William Lee", after his mother's maiden name.[30] Before the novel was published, Ace Books asked Burroughs to add 40 more pages. Burroughs incorporated material he had intended for his follow-up novel Queer, which was written in the third-person. Although Burroughs edited these sections to match Junkie's first-person narration, this approach led to incongruities in the final text.[35] Burroughs assembled the combined version by cutting up the original manuscripts and pasting them back together, a technique he would push much farther in his later books.[36] |

出版 アレン・ギンズバーグ(1979年当時の写真)は、その文学的コネクションを利用して『ジャンキー』をエース・ブックスから出版させた。彼は後に、その出版条件を「馬鹿げている」と批判した。 1977年版の序文で、ギンズバーグはバロウズと共同でこれらの手紙から小説を組み立てたと主張している。彼はまた、バロウズのその後の小説『クィア』や 『裸のランチ』でもこのやり方を続けたと記している[25]。バロウズ作品の研究者であり編集者でもあるオリヴァー・ハリスは、この話に異議を唱えてい る。彼は、バロウズはこの小説のほとんどをギンズバーグと共有する前に書いており、この本には「対人エピストリーの美学の兆候は見られない」と主張してい る[26]。 バロウズは1951年1月1日までに最初の原稿を書き上げた[14]。1952年4月、ギンズバーグはそれを出版するためのプロセスを開始した[27]。 ギンズバーグは『ジャンキー』とジャック・ケルアックの『オン・ザ・ロード』のコピーを、叔父のA・A・ウィンがエース・ブックスを経営していた知人の カール・ソロモンに送った。ソロモンとウィンは『オン・ザ・ロード』を拒絶したが、『ジャンキー』の出版には同意した[28]。後にギンズバーグはエー ス・ブックスとの「ばかげた」契約にサインしたことを後悔しており、彼はこの本の成功に対してバロウズへの報酬が大幅に不足していると感じていた [29]。 バロウズの原稿の原題は『Junk』だった。エース・ブックスは、『ジャンク』が本そのものの質を低下させることを懸念して『ジャンキー』と改題し、 『Confessions of an Unredeemed Drug Addict』という副題を付けた[30]。エース・ブックスは、ハリスが「特に薄気味悪く、覗き見趣味的な」表紙を作ることで、バロウズの挑発的な題材 を利用した[31]。[32]娯楽的な薬物使用を推奨しているように見えるのを避けるため、ウィンは『ジャンキー』をモーリス・ヘルブラントが1941年 に出版した『麻薬捜査官』の再版と同梱した。出版社はまた、バロウズが中毒者や犯罪者の家族の出身ではないことを明らかにするため、自身の生い立ちについ てのプロローグを含めるよう要請した[33]。 バロウズは当初、主人公を 「ウィリアム・デニソン 」と名付けた。この名前は以前、2つのロマン・ア・クレフでバロウズの類似作に使われていた: ジャック・ケルアックの最初に出版された小説『The Town and the City』と、ケルアックとバロウズの未発表の合作『And the Hippos Were Boiled in Their Tanks』である[34]。後にバロウズは主人公を母親の旧姓にちなんで「ウィリアム・リー」と改名した[30]。 この小説が出版される前に、エース・ブックスはバロウズに40ページ追加するよう依頼した。バロウズは、三人称で書かれた次の小説『クィア』のために意図 していた素材を取り入れた。バロウズは、ジャンキーの一人称の語りに合うようにこれらの部分を編集したが、このアプローチは最終的なテキストに不調和をも たらした[35]。 |

| Later Editions In the 1970s, Burroughs successfully sued Ace Books for breach of contract, arguing that he had never received sufficient royalties. The court reverted the novel's publishing rights, and James Grauerholz edited a new edition that Burroughs personally approved. This edition was published by Penguin Books in 1977. It restored material that had previously been censored by Ace Books and changed the title to Junky, with no subtitle.[37] In 2003, for the books's 50th anniversary, Penguin reissued the book as Junky: The Definitive Text of "Junk". This release included previously unpublished material from Allen Ginsberg's archives, in which Lee builds an "orgone accumulator" based on the writings of Wilhelm Reich. Burroughs had omitted this chapter in part to avoid being seen as a "lunatic".[38] |

その後のエディション 1970年代、バロウズは十分な印税を受け取っていないとして、エース・ブックスを契約違反で訴えることに成功した。裁判所は小説の出版権を差し戻し、 ジェームズ・グラウアホルツがバロウズが人格的に承認した新版を編集した。この版は1977年にペンギン・ブックスから出版された。この版では、エース・ ブックスによって検閲されていた内容が元に戻され、サブタイトルのない『ジャンキー』というタイトルに変更された[37]。 2003年、この本の50周年を記念して、ペンギンは『Junky: The Definitive Text of 「Junk」』として再発行した。このリリースには、アレン・ギンズバーグのアーカイヴから未発表の資料が収録されており、その中でリーはヴィルヘルム・ ライヒの著作に基づいて「オルゴン・アキュムレーター」を作っている。バロウズは「狂人」と見られるのを避けるため、この章を一部省略していた[38]。 |

| Style and themes Junkie is sometimes considered an autobiographical memoir, in which William Lee is a stand-in for Burroughs himself.[39][20] Others, including Beat scholar Jennie Skerl, interpret the book as a novel and William Lee as a fictionalized caricature.[40] William Stull considers the novel a Bildungsroman similar to The Catcher in the Rye,[41] while Oliver Harris argues that "the last genre to which Junkie belongs is that of the Künstlerroman."[42] Burroughs' writing style is dry and direct. His narrative voice is often compared to Dashiell Hammett's.[43][44][45][46] Jack Kerouac favorably compared him to Ernest Hemingway.[28] Oliver Harris notes that Burroughs' deadpan narration is often subtly ironic, as in Lee's observation that "You need a good bedside manner with doctors or you will get nowhere".[47] The narration is interspersed with journalistic asides, which document various drugs, addiction treatments, laws, police procedures, and slang.[48] In particular, Burroughs criticizes specific provisions in New York's public health laws and the federal Harrison Narcotics Tax Act.[49] The narration frequently changes focus, reflecting Lee's nervousness and paranoia.[50] The book is written in the first-person, but it rarely explores Lee's psychology or motivations.[51] Lee routinely breaks the law and commits acts of cruelty, but his actions are described in straightforward prose without excuses or explicit value judgments.[45] While the novel does not condemn or justify Lee's actions, it does criticize overzealous law enforcement,[45] doctors who try to control their patients,[52] and anti-drug legislation aimed at "penalizing a state of being".[53] Burroughs emphasizes the negative aspects of addiction and the pain of withdrawal, only briefly mentioning the pleasurable effects of drugs.[54] Despite its pervasive criticism of power dynamics, the novel does not emphasize the control drug dealers have over their customers.[55] The novel describes opioid addicts with grotesque and dehumanizing language, such as comparing them to wooden puppets and deep-sea creatures. Lee claims that opioids reshape drug users on a cellular level, and that severe addicts are not recognizably human. Burroughs later expands on this motif in his follow-up novel Naked Lunch, in which heroin addicts metamorphose into surreal monsters.[39] The book describes surreal hallucinations, such as giant insects swarming over New York and people transforming into crustaceans and plants. These sections have also been seen as precursors to Burroughs' later works.[56] The novel is structured around cycles of addiction and withdrawal, which become progressively more severe as Lee moves further South. The book ends with no clear resolution: Lee starts another cycle by heading South from Mexico City to find a new addictive substance, yage.[33][57] The novel also follows the rise of police surveillance and decline of hipster subculture. As the police crack down on drugs, the community becomes increasingly paranoid and isolated. They no longer trust obscure jargon or their fellow addicts to protect them.[58] |

スタイルとテーマ 『ジャンキー』は、ウィリアム・リーがバロウズ自身の代役である自伝的回顧録とみなされることもある[39][20]。また、ビート研究家のジェニー・ス ケールをはじめ、この本を小説、ウィリアム・リーをフィクションの戯画と解釈する者もいる[40]。 ウィリアム・スタルは、この小説を『ライ麦畑でつかまえて』に似たビルドゥングスロマンとみなし[41]、オリヴァー・ハリスは「『ジャンキー』が属する 最後のジャンルはキュンストラーロマンである」と論じている[42]。 バロウズの文体はドライで直接的である。彼の語り口はしばしばダシール・ハメットの語り口と比較される[43][44][45][46]。ジャック・ケル アックは彼をアーネスト・ヘミングウェイと好意的に比較している[28]。オリヴァー・ハリスは、バロウズの無表情な語り口はしばしば微妙に皮肉であると 指摘する。[47]ナレーションにはジャーナリスティックな余談が散りばめられており、様々な薬物、中毒治療、法律、警察の手続き、スラングなどを記録し ている[48]。特にバロウズはニューヨークの公衆衛生法や連邦のハリソン麻薬税法における特定の条項を批判している[49]。ナレーションは頻繁に焦点 を変え、リーの神経質さと偏執狂を反映している[50]。 本書は一人称で書かれているが、リーの心理や動機を探ることはほとんどない[51]。リーは日常的に法を犯し、残酷な行為を行うが、彼の行動は言い訳や明 確な価値判断なしに、端的な散文で描写されている[45]。小説はリーの行動を非難したり正当化したりはしないが、行き過ぎた法執行機関[45]、患者を コントロールしようとする医師[52]、「存在の状態を罰する」ことを目的とした反ドラッグ法を批判している[53]。[バロウズは中毒の否定的な側面と 禁断症状の苦痛を強調し、薬物の快楽的な効果については少ししか触れていない。 この小説は、オピオイド中毒者を木の人形や深海生物に例えるなど、グロテスクで非人間的な表現で描写している。リーは、オピオイドは薬物使用者を細胞レベ ルで再形成し、重度の中毒者は人間とは認識できないと主張している。バロウズは後に、ヘロイン中毒者が超現実的な怪物に変身する『裸のランチ』の続編で、 このモチーフを発展させている。これらの部分は、バロウズの後の作品の前兆ともみなされている[56]。 この小説は、中毒と禁断症状のサイクルを中心に構成されており、リーがさらに南へ進むにつれて、そのサイクルは徐々に深刻になっていく。本書は明確な解決 策を持たずに終わる: リーは新たな中毒性物質であるヤゲを見つけるためにメキシコシティから南へ向かうことで、別のサイクルを始める。警察がドラッグを取り締まるにつれ、コ ミュニティはますます偏執的になり、孤立していく。彼らはもはや、自分たちを守ってくれる曖昧な専門用語や中毒者仲間を信用していない[58]。 |

| Sexuality Lee describes heroin as "short-circuit[ing]" sexual desires, and withdrawal as a chance for those desires to reawaken. In one scene, Lee experiences a spontaneous orgasm while in jail, unable to satisfy his addiction.[59] Although the novel rarely mentions his sexuality, Lee is gay, as was Burroughs himself.[60] When Lee does seek out sexual encounters, he asserts his masculinity, derides gay bars, and expresses revulsion toward effeminate men, whom he lambasts as "ventriloquists’ dummies who have moved in and taken over the ventriloquist". In Burroughs' follow-up novel Queer, Lee's sexual frustrations and anxieties receive much more focus. Burroughs' preface to Queer suggests that, in Junkie, Lee's sexuality was "held in check by junk".[61][62][63] |

セクシュアリティ リーは、ヘロインは性的欲望を「ショートさせる」ものであり、禁断症状はその欲望が再び目覚めるチャンスであると述べている。小説の中でリーが自身のセク シュアリティについて言及することはほとんどないが、バロウズ自身と同様、リーはゲイである[60]。 リーが性的な出会いを求めるとき、彼は自分の男らしさを主張し、ゲイバーを嘲笑し、女々しい男たちに嫌悪感を示す。バロウズの次作『クィア』では、リーの 性的欲求不満と不安がよりクローズアップされる。バロウズは『クィア』の序文で、『ジャンキー』ではリーのセクシュアリティが「ガラクタによって抑制され ていた」ことを示唆している[61][62][63]。 |

| Omissions Despite their influence on Burroughs' writing, the novel does not mention Allen Ginsberg or Jack Kerouac. In contrast, contemporary works by Kerouac and Ginsberg prominently featured Burroughs.[47] Lee's wife abruptly disappears from the story during the Mexico City section. In reality, Burroughs fatally shot Joan Vollmer; he was allowed to leave Mexico after the courts ruled the shooting an accident, not a homicide. A. A. Wyn asked Burroughs to add additional material explaining her character's disappearance, but he refused to write about the shooting. Instead, he suggested they remove all references to her from the book, and offered to invent a fictional car accident if Wyn insisted that she had to die. Wyn relented and published the book with no explanation for her absence, besides a brief reference to Lee and his wife being separated.[64] |

省略 バロウズの執筆に影響を与えたにもかかわらず、この小説はアレン・ギンズバーグやジャック・ケルアックについて触れていない。対照的に、ケルアックとギンズバーグの現代作品はバロウズを大きく取り上げている[47]。 リーの妻はメキシコシティ編で突然物語から姿を消す。実際には、バロウズはジョーン・ヴォルマーを射殺したのだが、裁判所がこの射殺を殺人ではなく事故と 判断したため、彼はメキシコからの出国を許された。A.A.ウィンはバロウズに、彼女の失踪を説明する追加資料を加えるよう求めたが、彼は銃撃について書 くことを拒否した。その代わり、彼は本から彼女に関する記述をすべて削除するよう提案し、もしウィンが彼女を死なせなければならないと主張するなら、架空 の交通事故を創作すると申し出た。ウィンは譲歩し、リーと彼の妻が別居中であるという短い言及のほかに、彼女の不在について何の説明もないまま本を出版し た[64]。 |

| Reception Ace Books printed 150,000 copies of Junkie,[65] and the novel sold 113,000 copies in its first year. Despite this commercial success, it was not professionally reviewed or analyzed when first released.[28] In retrospect, Tony Tanner considers the novel a foundation for Burroughs' later experimentalism. He notes that "Later, [Burroughs] made the business of drug addiction into a vast encompassing metaphor; in this book he looks at it, with a remarkable cool lucidity, simply as the dominant fact of his life."[66] Mario Vargas Llosa wrote that while he did not care for Burroughs's subsequent experimental fiction, he admired the more straightforward Junkie as "an accurate description of what I believe to be the literary vocation".[67] Carlo Gébler found the novel riveting and felt it exemplified Burroughs' unflinching writing style, saying that "in a world where writers more and more want their readers to believe they are nice people, Burroughs was a rare example of real authorial honesty". He called Junkie "the only book I know that doesn't glamorize heroin".[68] Beat scholar Jennie Skerl considers the novel a more successful portrait of hipster subculture than Norman Mailer's essay The White Negro. She notes that Burroughs displays a deeper familiarity with the subculture's slang, and correctly identifies that drug use is central to the hipster worldview.[69] Norman Mailer himself considered Junkie a well-written potboiler.[70] Will Self argues that the novel fails to insightfully analyze addiction, in part because Burroughs was deluded about his own relationship with drugs. However, he considers it an enduring portrayal of alienation.[20] Burroughs himself later criticized the novel. In 1965, he commented "I don't feel the results were at all spectacular. Junky is not much of a book, actually. I knew very little about writing at that time."[71] |

Reception Ace Books printed 150,000 copies of Junkie,[65] and the novel sold 113,000 copies in its first year. Despite this commercial success, it was not professionally reviewed or analyzed when first released.[28] In retrospect, Tony Tanner considers the novel a foundation for Burroughs' later experimentalism. He notes that "Later, [Burroughs] made the business of drug addiction into a vast encompassing metaphor; in this book he looks at it, with a remarkable cool lucidity, simply as the dominant fact of his life."[66] Mario Vargas Llosa wrote that while he did not care for Burroughs's subsequent experimental fiction, he admired the more straightforward Junkie as "an accurate description of what I believe to be the literary vocation".[67] Carlo Gébler found the novel riveting and felt it exemplified Burroughs' unflinching writing style, saying that "in a world where writers more and more want their readers to believe they are nice people, Burroughs was a rare example of real authorial honesty". He called Junkie "the only book I know that doesn't glamorize heroin".[68] Beat scholar Jennie Skerl considers the novel a more successful portrait of hipster subculture than Norman Mailer's essay The White Negro. She notes that Burroughs displays a deeper familiarity with the subculture's slang, and correctly identifies that drug use is central to the hipster worldview.[69] Norman Mailer himself considered Junkie a well-written potboiler.[70] Will Self argues that the novel fails to insightfully analyze addiction, in part because Burroughs was deluded about his own relationship with drugs. However, he considers it an enduring portrayal of alienation.[20] Burroughs himself later criticized the novel. In 1965, he commented "I don't feel the results were at all spectacular. Junky is not much of a book, actually. I knew very little about writing at that time."[71] |

| Notes The original Ace Books edition is credited to the pen name William Lee. More recent editions are credited to William S. Burroughs, but the narrative still refers to William Lee. |

注釈 オリジナルのエース・ブックス版では、ウィリアム・リーというペンネームでクレジットされている。最近の版ではウィリアム・S・バロウズとクレジットされているが、物語ではウィリアム・リーと表記されている。 |

| Bibliography Burroughs, William S.; Harris, Oliver (2003). Junky: The Definitive Text of "Junk". New York, NY: Grove. ISBN 978-0-8021-2042-7. Foster, Edward Halsey (1992). Understanding the Beats. Columbia, S.C: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-798-4. Harris, Oliver (2003). William Burroughs and the Secret of Fascination. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2484-9. Miles, Barry (2014). Call Me Burroughs: A Life (First ed.). New York: Twelve. ISBN 9781455511938. Murphy, Timothy S. (1997). Wising up the Marks: The Amodern William Burroughs. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520209510. Retrieved July 17, 2023. Newhouse, Thomas (2000). The Beat Generation and the Popular Novel in the United States: 1945-1970. Jefferson (N.C.): McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0841-3. Russell, Jamie (2001). Queer Burroughs. Basingstoke New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23868-1. Skerl, Jennie (1985). William S. Burroughs. Boston: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-7438-6. Sterritt, David (2013). The Beats: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979677-9. |

書誌 バロウズ, ウィリアム・S.; ハリス, オリバー (2003). Junky: The Definitive Text of 「Junk」. ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: Grove. ISBN 978-0-8021-2042-7. Foster, Edward Halsey (1992). Understanding the Beats. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 0-87249-798-4. Harris, Oliver (2003). William Burroughs and the Secret of Fascination. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-8093-2484-9. Miles, Barry (2014). Call Me Burroughs: A Life (First ed.). New York: Twelve. ISBN 9781455511938. Murphy, Timothy S. (1997). Wising up the Marks: The Amodern William Burroughs. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520209510. 2023年7月17日取得。 Newhouse, Thomas (2000). The Beat Generation and the Popular Novel in the United States: 1945-1970. Jefferson (N.C.): McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-0841-3. Russell, Jamie (2001). Queer Burroughs. Basingstoke New York: Palgrave. ISBN 0-312-23868-1. Skerl, Jennie (1985). William S. Burroughs. ボストン: Twayne. ISBN 0-8057-7438-6. Sterritt, David (2013). The Beats: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-979677-9. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Junkie_(novel) |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆