Knowledge

The

owl of Athena, a symbol of knowledge in the Western world

☆知識(Knowledge)とは、事実に対する認識、個人や状況に対する精通、または実用的な技能である。事実に対する知識は命題的知識とも呼ばれ、正当性によって意見や推測とは区別される真の信念で あると特徴づけられることが多い。 命題的知識が真の信念の一形態であるという点については哲学者の間で広く同意されているが、多くの論争は正当性に焦点を当てている。これには、正当性をど のように理解するか、それが本当に必要なのか、それ以外に必要なものがあるのかといった疑問が含まれる。これらの論争は、ゲッティエ・ケースと呼ばれる一 連の思考実験により、代替的な定義が提起されたことで、20世紀後半に激化した。 知識はさまざまな方法で生み出される。経験的知識の主な源泉は知覚であり、知覚には外界を知るための感覚の使用が含まれる。内省によって、人は自身の内的 な精神状態や過程について知ることができる。その他の知識の源泉には、記憶、合理的直観、推論、証言などがある。

★基礎づけ主義(foundationalism)によれば、これらの源泉の一

部は、他の精神状態に依存することなく信念を正当化できるという点で基本的である。首尾一貫説(真理の整合説)の支持者たちはこの主張を否定し、知識を得るためには、信念

を持つ者の精神状態すべてに十分な首尾一貫性がなければならないと主張する。無限主義によれば、信念の無限連鎖が必要である。

知識を研究する主な学問分野は認識論であり、人々が何をどのようにして知るのか、また何かを知るとはどういうことなのかを研究する。認識論では、知識の価

値や、知識の可能性を問う哲学的な懐疑論の論文についても論じられる。知識は、再現可能な実験、観察、測定に基づく科学的手法を用いて知識の獲得を目指す

科学など、多くの分野に関連している。さまざまな宗教では、人間は知識を求めるべきであり、神や神聖な存在が知識の源であるとされている。知識人類学で

は、知識が異なる文化においてどのように獲得され、蓄積され、検索され、伝達されるかを研究する。知識社会学では、知識がどのような社会歴史的状況で生

じ、どのような社会学的帰結をもたらすかを研究する。知識史では、異なる分野における知識が歴史の中でどのように発展し、進化してきたかを研究する。

| Knowledge is an

awareness of facts, a familiarity with individuals and situations, or a

practical skill. Knowledge of facts, also called propositional

knowledge, is often characterized as true belief that is distinct from

opinion or guesswork by virtue of justification. While there is wide

agreement among philosophers that propositional knowledge is a form of

true belief, many controversies focus on justification. This includes

questions like how to understand justification, whether it is needed at

all, and whether something else besides it is needed. These

controversies intensified in the latter half of the 20th century due to

a series of thought experiments called Gettier cases that provoked

alternative definitions. Knowledge can be produced in many ways. The main source of empirical knowledge is perception, which involves the usage of the senses to learn about the external world. Introspection allows people to learn about their internal mental states and processes. Other sources of knowledge include memory, rational intuition, inference, and testimony.[a] According to foundationalism, some of these sources are basic in that they can justify beliefs, without depending on other mental states. Coherentists reject this claim and contend that a sufficient degree of coherence among all the mental states of the believer is necessary for knowledge. According to infinitism, an infinite chain of beliefs is needed. The main discipline investigating knowledge is epistemology, which studies what people know, how they come to know it, and what it means to know something. It discusses the value of knowledge and the thesis of philosophical skepticism, which questions the possibility of knowledge. Knowledge is relevant to many fields like the sciences, which aim to acquire knowledge using the scientific method based on repeatable experimentation, observation, and measurement. Various religions hold that humans should seek knowledge and that God or the divine is the source of knowledge. The anthropology of knowledge studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated in different cultures. The sociology of knowledge examines under what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, and what sociological consequences it has. The history of knowledge investigates how knowledge in different fields has developed, and evolved, in the course of history. |

知識とは、事実に対する認識、個人や状況に対する精通、または実用的な

技能である。事実に対する知識は命題的知識とも呼ばれ、正当性によって意見や推測とは区別される真の信念であると特徴づけられることが多い。命題的知識が

真の信念の一形態であるという点については哲学者の間で広く同意されているが、多くの論争は正当性に焦点を当てている。これには、正当性をどのように理解

するか、それが本当に必要なのか、それ以外に必要なものがあるのかといった疑問が含まれる。これらの論争は、ゲッティエ・ケースと呼ばれる一連の思考実験

により、代替的な定義が提起されたことで、20世紀後半に激化した。 知識はさまざまな方法で生み出される。経験的知識の主な源泉は知覚であり、知覚には外界を知るための感覚の使用が含まれる。内省によって、人は自身の内的 な精神状態や過程について知ることができる。その他の知識の源泉には、記憶、合理的直観、推論、証言などがある。[a] 基礎づけ主義(foundationalism)によれば、これらの源泉の一部は、他の精神状態に依存することなく信念を正当化できるという点で基本的である。首尾一貫説の支持者たちはこの主張 を否定し、知識を得るためには、信念を持つ者の精神状態すべてに十分な首尾一貫性がなければならないと主張する。無限主義によれば、信念の無限連鎖が必要 である。 知識を研究する主な学問分野は認識論であり、人々が何をどのようにして知るのか、また何かを知るとはどういうことなのかを研究する。認識論では、知識の価 値や、知識の可能性を問う哲学的な懐疑論の論文についても論じられる。知識は、再現可能な実験、観察、測定に基づく科学的手法を用いて知識の獲得を目指す 科学など、多くの分野に関連している。さまざまな宗教では、人間は知識を求めるべきであり、神や神聖な存在が知識の源であるとされている。知識人類学で は、知識が異なる文化においてどのように獲得され、蓄積され、検索され、伝達されるかを研究する。知識社会学では、知識がどのような社会歴史的状況で生 じ、どのような社会学的帰結をもたらすかを研究する。知識史では、異なる分野における知識が歴史の中でどのように発展し、進化してきたかを研究する。 |

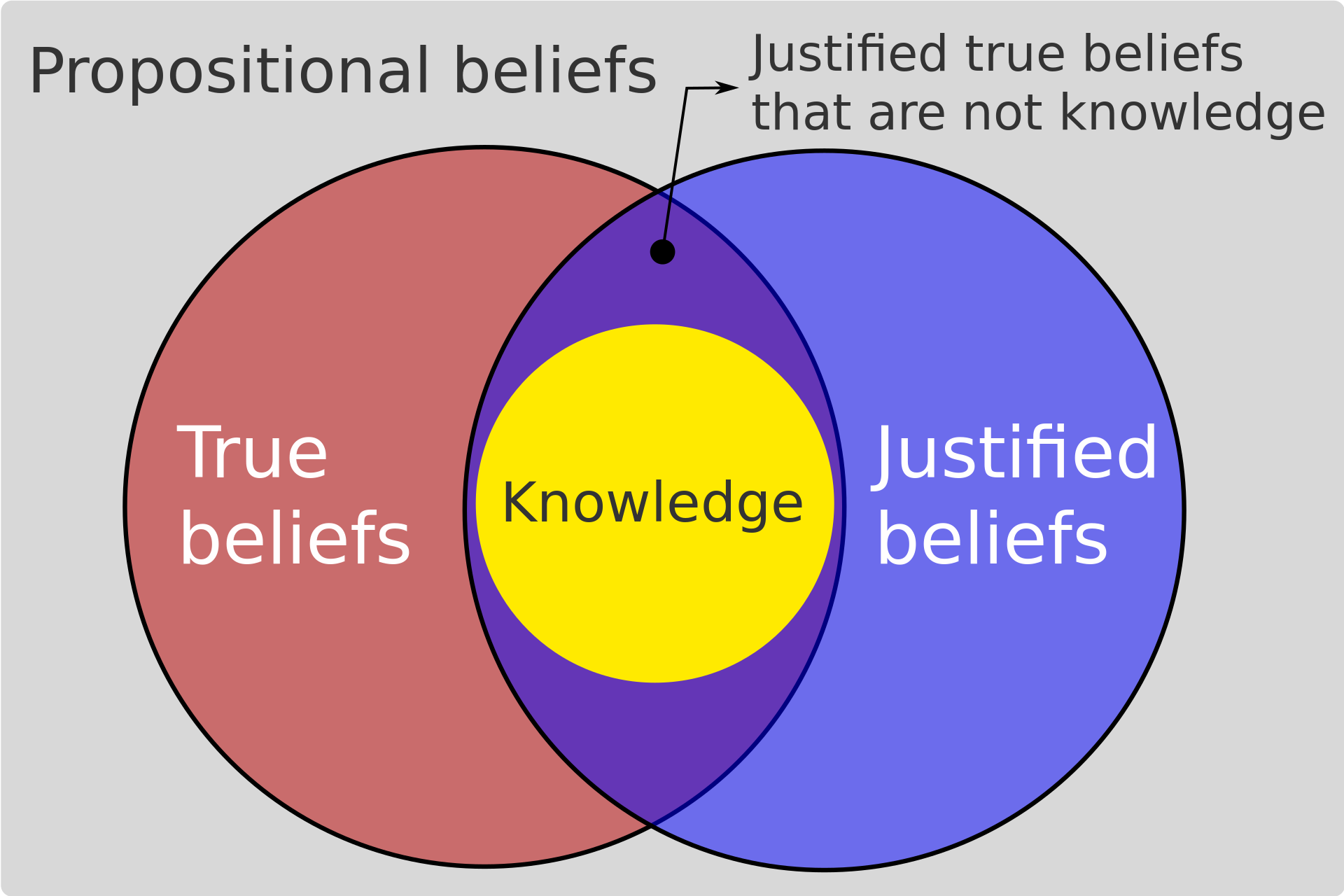

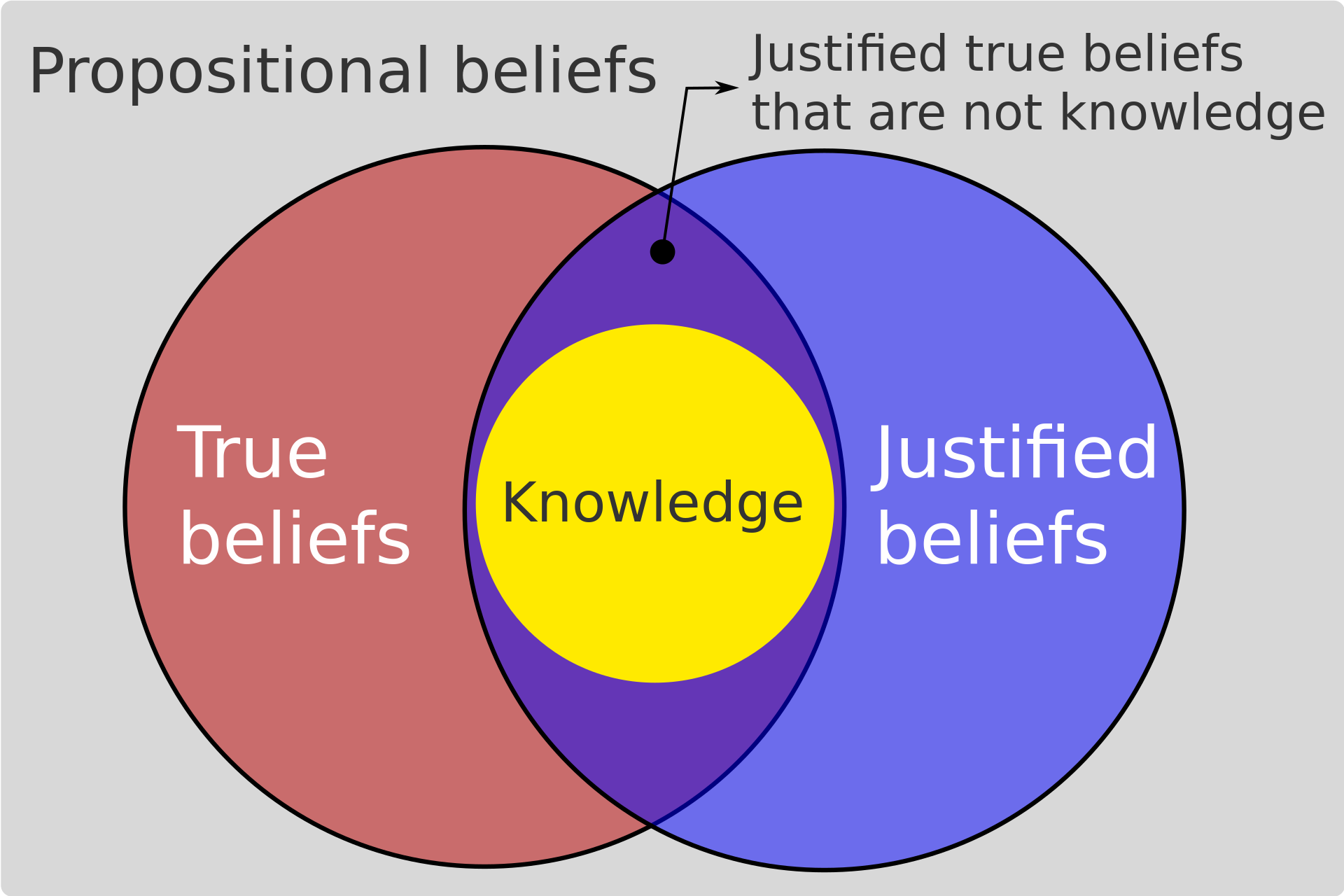

| Definitions Main article: Definitions of knowledge Knowledge is a form of familiarity, awareness, understanding, or acquaintance. It often involves the possession of information learned through experience[1] and can be understood as a cognitive success or an epistemic contact with reality, like making a discovery.[2] Many academic definitions focus on propositional knowledge in the form of believing certain facts, as in "I know that Dave is at home".[3] Other types of knowledge include knowledge-how in the form of practical competence, as in "she knows how to swim", and knowledge by acquaintance as a familiarity with the known object based on previous direct experience, like knowing someone personally.[4] Knowledge is often understood as a state of an individual person, but it can also refer to a characteristic of a group of people as group knowledge, social knowledge, or collective knowledge.[5] Some social sciences understand knowledge as a broad social phenomenon that is similar to culture.[6] The term may further denote knowledge stored in documents like the "knowledge housed in the library"[7] or the knowledge base of an expert system.[8] Knowledge is closely related to intelligence, but intelligence is more about the ability to acquire, process, and apply information, while knowledge concerns information and skills that a person already possesses.[9] The word knowledge has its roots in the 12th-century Old English word cnawan, which comes from the Old High German word gecnawan.[10] The English word includes various meanings that some other languages distinguish using several words.[11] In ancient Greek, for example, four important terms for knowledge were used: epistēmē (unchanging theoretical knowledge), technē (expert technical knowledge), mētis (strategic knowledge), and gnōsis (personal intellectual knowledge).[12] The main discipline studying knowledge is called epistemology or the theory of knowledge. It examines the nature of knowledge and justification, how knowledge arises, and what value it has. Further topics include the different types of knowledge and the limits of what can be known.[13] Despite agreements about the general characteristics of knowledge, its exact definition is disputed. Some definitions only focus on the most salient features of knowledge to give a practically useful characterization.[14] Another approach, termed analysis of knowledge, tries to provide a theoretically precise definition by listing the conditions that are individually necessary and jointly sufficient,[15] similar to how chemists analyze a sample by seeking a list of all the chemical elements composing it.[16] According to a different view, knowledge is a unique state that cannot be analyzed in terms of other phenomena.[17] Some scholars base their definition on abstract intuitions while others focus on concrete cases[18] or rely on how the term is used in ordinary language.[19] There is also disagreement about whether knowledge is a rare phenomenon that requires high standards or a common phenomenon found in many everyday situations.[20] Analysis of knowledge See also: Belief § Justified true belief, and Definitions of knowledge § Justified true belief  Venn diagram of justified true belief The definition of knowledge as justified true belief is often discussed in the academic literature. An often-discussed definition characterizes knowledge as justified true belief. This definition identifies three essential features: it is (1) a belief that is (2) true and (3) justified.[21][b] Truth is a widely accepted feature of knowledge. It implies that, while it may be possible to believe something false, one cannot know something false.[23][c] That knowledge is a form of belief implies that one cannot know something if one does not believe it. Some everyday expressions seem to violate this principle, like the claim that "I do not believe it, I know it!" But the point of such expressions is usually to emphasize one's confidence rather than denying that a belief is involved.[25] The main controversy surrounding this definition concerns its third feature: justification.[26] This component is often included because of the impression that some true beliefs are not forms of knowledge, such as beliefs based on superstition, lucky guesses, or erroneous reasoning. For example, a person who guesses that a coin flip will land heads usually does not know that even if their belief turns out to be true. This indicates that there is more to knowledge than just being right about something.[27] These cases are excluded by requiring that beliefs have justification for them to count as knowledge.[28] Some philosophers hold that a belief is justified if it is based on evidence, which can take the form of mental states like experience, memory, and other beliefs. Others state that beliefs are justified if they are produced by reliable processes, like sensory perception or logical reasoning.[29]  Venn diagram of justified true belief that does not amount to knowledge The Gettier problem is grounded in the idea that some justified true beliefs do not amount to knowledge. The definition of knowledge as justified true belief came under severe criticism in the 20th century, when epistemologist Edmund Gettier formulated a series of counterexamples.[30] They purport to present concrete cases of justified true beliefs that fail to constitute knowledge. The reason for their failure is usually a form of epistemic luck: the beliefs are justified but their justification is not relevant to the truth.[31] In a well-known example, someone drives along a country road with many barn facades and only one real barn. The person is not aware of this, stops in front of the real barn by a lucky coincidence, and forms the justified true belief that they are in front of a barn. This example aims to establish that the person does not know that they are in front of a real barn, since they would not have been able to tell the difference.[32] This means that it is a lucky coincidence that this justified belief is also true.[33] According to some philosophers, these counterexamples show that justification is not required for knowledge[34] and that knowledge should instead be characterized in terms of reliability or the manifestation of cognitive virtues. Another approach defines knowledge in regard to the function it plays in cognitive processes as that which provides reasons for thinking or doing something.[35] A different response accepts justification as an aspect of knowledge and include additional criteria.[36] Many candidates have been suggested, like the requirements that the justified true belief does not depend on any false beliefs, that no defeaters[d] are present, or that the person would not have the belief if it was false.[38] Another view states that beliefs have to be infallible to amount to knowledge.[39] A further approach, associated with pragmatism, focuses on the aspect of inquiry and characterizes knowledge in terms of what works as a practice that aims to produce habits of action.[40] There is still very little consensus in the academic discourse as to which of the proposed modifications or reconceptualizations is correct, and there are various alternative definitions of knowledge.[41] |

定義 詳細は「知識の定義」を参照 知識とは、精通、認識、理解、または知人の一形態である。 経験を通じて学んだ情報の所有を伴うことが多く[1]、発見を行うような現実に対する認識上の成功または認識上の接触として理解することができる。[2] 多くの学術的な定義は、特定の事実を信じるという命題の知識に焦点を当てている。例えば、「私は 「というように、特定の事実を信じることによる命題的知識に焦点を当てている。[3] その他の知識の種類には、「彼女は泳ぎ方を知っている」というように、実践的な能力の形をとる知識-ハウや、個人的に誰かを知っているというように、以前 の直接的な経験に基づく既知の対象への精通という知人による知識がある。[4] 知識はしばしば個人の状態として理解されるが、集団の知識、社会の知識、集合的知識として、人々の集団の特徴を指すこともある。[5] 社会科学の一部では、知識を文化に類似した広範な社会現象として理解している。[6] この用語はさらに、 「図書館に収蔵された知識」[7]やエキスパートシステムの知識ベース[8]のように、文書に保存された知識を指す場合もある。知識は知能と密接に関連し ているが、知能は情報を取得、処理、応用する能力を意味するのに対し、知識は人がすでに所有している情報やスキルを意味する。 知識という言葉は、12世紀の古英語のcnawanという語に由来しており、これはさらに古高ドイツ語のgecnawanという語に由来している。 [10] 英語の「知識」という言葉には、他の言語では複数の語で区別されているさまざまな意味が含まれている。[11] 例えば、古代ギリシャ語では、 知識を表す重要な用語として、エピステーメー(不変の理論的知識)、テクネー(専門的技術的知識)、メーテース(戦略的知識)、グノーシス(個人的知的知 識)の4つが使用されていた。[12] 知識を研究する主な学問分野は、認識論または知識論と呼ばれる。知識の性質や正当性、知識がどのように生じるか、また知識が持つ価値について研究する。さ らに、知識のさまざまな種類や、知ることのできる限界についても研究対象となる。[13] 知識の一般的な特徴については合意があるものの、その厳密な定義については議論がある。 実用的な有用性を備えた特徴を付与するために、知識の最も顕著な特徴のみに焦点を当てる定義もある。[14] 知識の分析と呼ばれる別のアプローチでは、個別に必要とされる条件と共同で十分な条件を列挙することで、理論的に厳密な定義を提供しようとしている。 [15] これは、化学者がサンプルを分析する際に、それを構成するすべての化学元素のリストを求める方法に似ている。[16] 別の見解によると、 知識は、他の現象の観点から分析できない独特な状態であるという見解もある。[17] ある学者は抽象的な直観に基づいて定義を導き出し、また別の学者は具体的な事例に焦点を当てたり[18] 、日常言語における用語の用法に依拠したりしている。[19] また、知識は高い基準を必要とする稀な現象であるか、あるいは日常の多くの場面で見られる一般的な現象であるかについても意見が分かれている。[20] 知識の分析 参照:信念 § 正当化された真の信念、知識の定義 § 正当化された真の信念  正当化された真の信念のベン図 正当化された真の信念としての知識の定義は、学術文献でしばしば議論されている。 よく議論される定義では、知識を正当化された真の信念と特徴づけている。この定義では、3つの本質的な特徴を特定している。すなわち、(1)信念であり、 (2)真実であり、(3)正当化されていることである。[21][b]真実は、広く受け入れられている知識の特徴である。それは、偽りのことを信じること が可能であるかもしれない一方で、偽りのことを知ることはできないということを意味する。[23][c] 知識が信念の一形態であるということは、それを信じていないのであれば、何かを知ることはできないということを意味する。「私はそれを信じていない、私は それを知っている!」という主張のように、この原則に反しているように見える日常的な表現もある。しかし、このような表現のポイントは、信念が関わってい ることを否定するよりも、むしろ自信を強調することにある場合が多い。[25] この定義を巡る主な論争は、その第3の特徴である「正当化」に関するものである。[26] この要素は、迷信や当てずっぽう、誤った推論に基づく信念など、真実の信念の中には知識の形態ではないものもあるという印象から、しばしば含まれる。例え ば、コイン投げで表が出るだろうと推測する人は、その推測が真実であることが判明しても、通常はそれを知らない。これは、知識とは単に何かについて正しい というだけではないことを示している。[27] 信念が知識として数えられるためには、それらに正当性があることが必要であるため、このようなケースは除外される。[28] 信念は、経験、記憶、その他の信念のような心的状態の形を取ることができる証拠に基づいている場合、正当であると主張する哲学者もいる。また、信念は、感 覚知覚や論理的推論のような信頼性の高いプロセスによって生み出された場合、正当であると主張する者もいる。[29]  知識に値しない正当化された真信念のベン図 ゲッティエ問題は、正当化された真信念の中には知識に値しないものがあるという考えに基づいている。 知識を正当化された真信念と定義することには、20世紀にエドマンド・ゲッティエが反例をいくつか提示したことで、厳しい批判が寄せられた。[30] それらの反例は、知識を構成しない正当化された真信念の具体的な事例を示すことを目的としている。その失敗の理由は、通常、認識上の運によるものである。 信念は正当化されているが、その正当化は真実とは関係がないのである。[31] よく知られた例として、納屋の正面が多数並ぶ田舎道を走っていると、本物の納屋が1軒だけあるというものがある。その人はそのことに気づいておらず、幸運 な偶然によって本物の納屋の前で車を停め、納屋の正面の前にいるという正当化された真の信念を形成する。この例は、その人物が本物の納屋の前にいることを 知らないことを証明しようとしている。なぜなら、その人物は違いを見分けることができないからだ。[32] つまり、この正当な信念が真実であることは、単なる幸運な偶然であるということだ。[33] 一部の哲学者によると、これらの反例は、正当化が知識に必要ではないことを示している。[34] また、知識はむしろ信頼性や認識の美徳の顕現という観点から特徴づけられるべきである。別のアプローチでは、知識を認知プロセスにおける機能として定義 し、思考や行動の理由を提供するものとしている。[35] 別の見解では、正当化を知識の一側面として認め、追加の基準を含めている。[36] 多くの候補が提案されており、例えば、正当化された真の信念は、いかなる誤った信念にも依存しないこと、反証[d]が存在しないこと、あるいは、その信念 が誤りである場合にはその信念を持たないこと、などである。[38] 別の見解では、信念が知識に値するには、誤りのないものでなければならないとしている。[39] プラグマティズムに関連するさらなるアプローチでは、探究の側面に焦点を当て、行動の習慣を生み出すことを目的とした実践として機能するものという観点か ら知識を特徴づけている。[40] 学術的な議論においては、提案された修正や再概念化のどれが正しいかについては、まだほとんどコンセンサスが得られておらず、知識の定義についてもさまざ まな代替案がある。[41] |

| Types A common distinction among types of knowledge is between propositional knowledge, or knowledge-that, and non-propositional knowledge in the form of practical skills or acquaintance.[42][e] Other distinctions focus on how the knowledge is acquired and on the content of the known information.[44] Propositional Main article: Declarative knowledge  Photo of the Totius Latinitatis Lexicon by Egidio Forcellini, a multi-volume Latin dictionary Declarative knowledge can be stored in books. Propositional knowledge, also referred to as declarative and descriptive knowledge, is a form of theoretical knowledge about facts, like knowing that "2 + 2 = 4". It is the paradigmatic type of knowledge in analytic philosophy.[45] Propositional knowledge is propositional in the sense that it involves a relation to a proposition. Since propositions are often expressed through that-clauses, it is also referred to as knowledge-that, as in "Akari knows that kangaroos hop".[46] In this case, Akari stands in the relation of knowing to the proposition "kangaroos hop". Closely related types of knowledge are know-wh, for example, knowing who is coming to dinner and knowing why they are coming.[47] These expressions are normally understood as types of propositional knowledge since they can be paraphrased using a that-clause.[48][f] Propositional knowledge takes the form of mental representations involving concepts, ideas, theories, and general rules. These representations connect the knower to certain parts of reality by showing what they are like. They are often context-independent, meaning that they are not restricted to a specific use or purpose.[50] Propositional knowledge encompasses both knowledge of specific facts, like that the atomic mass of gold is 196.97 u, and generalities, like that the color of leaves of some trees changes in autumn.[51] Because of the dependence on mental representations, it is often held that the capacity for propositional knowledge is exclusive to relatively sophisticated creatures, such as humans. This is based on the claim that advanced intellectual capacities are needed to believe a proposition that expresses what the world is like.[52] Non-propositional  Photograph of someone riding a bicycle Knowing how to ride a bicycle is one form of non-propositional knowledge. Non-propositional knowledge is knowledge in which no essential relation to a proposition is involved. The two most well-known forms are knowledge-how (know-how or procedural knowledge) and knowledge by acquaintance.[53] To possess knowledge-how means to have some form of practical ability, skill, or competence,[54] like knowing how to ride a bicycle or knowing how to swim. Some of the abilities responsible for knowledge-how involve forms of knowledge-that, as in knowing how to prove a mathematical theorem, but this is not generally the case.[55] Some types of knowledge-how do not require a highly developed mind, in contrast to propositional knowledge, and are more common in the animal kingdom. For example, an ant knows how to walk even though it presumably lacks a mind sufficiently developed to represent the corresponding proposition.[52][g] Knowledge by acquaintance is familiarity with something that results from direct experiential contact.[57] The object of knowledge can be a person, a thing, or a place. For example, by eating chocolate, one becomes acquainted with the taste of chocolate, and visiting Lake Taupō leads to the formation of knowledge by acquaintance of Lake Taupō. In these cases, the person forms non-inferential knowledge based on first-hand experience without necessarily acquiring factual information about the object. By contrast, it is also possible to indirectly learn a lot of propositional knowledge about chocolate or Lake Taupō by reading books without having the direct experiential contact required for knowledge by acquaintance.[58] The concept of knowledge by acquaintance was first introduced by Bertrand Russell. He holds that knowledge by acquaintance is more basic than propositional knowledge since to understand a proposition, one has to be acquainted with its constituents.[59] A priori and a posteriori Main article: A priori and a posteriori The distinction between a priori and a posteriori knowledge depends on the role of experience in the processes of formation and justification.[60] To know something a posteriori means to know it based on experience.[61] For example, by seeing that it rains outside or hearing that the baby is crying, one acquires a posteriori knowledge of these facts.[62] A priori knowledge is possible without any experience to justify or support the known proposition.[63] Mathematical knowledge, such as that 2 + 2 = 4, is traditionally taken to be a priori knowledge since no empirical investigation is necessary to confirm this fact. In this regard, a posteriori knowledge is empirical knowledge while a priori knowledge is non-empirical knowledge.[64] The relevant experience in question is primarily identified with sensory experience. Some non-sensory experiences, like memory and introspection, are often included as well. Some conscious phenomena are excluded from the relevant experience, like rational insight. For example, conscious thought processes may be required to arrive at a priori knowledge regarding the solution of mathematical problems, like when performing mental arithmetic to multiply two numbers.[65] The same is the case for the experience needed to learn the words through which the claim is expressed. For example, knowing that "all bachelors are unmarried" is a priori knowledge because no sensory experience is necessary to confirm this fact even though experience was needed to learn the meanings of the words "bachelor" and "unmarried".[66] It is difficult to explain how a priori knowledge is possible and some empiricists deny it exists. It is usually seen as unproblematic that one can come to know things through experience, but it is not clear how knowledge is possible without experience. One of the earliest solutions to this problem comes from Plato, who argues that the soul already possesses the knowledge and just needs to recollect, or remember, it to access it again.[67] A similar explanation is given by Descartes, who holds that a priori knowledge exists as innate knowledge present in the mind of each human.[68] A further approach posits a special mental faculty responsible for this type of knowledge, often referred to as rational intuition or rational insight.[69] Others Various other types of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature. In philosophy, "self-knowledge" refers to a person's knowledge of their own sensations, thoughts, beliefs, and other mental states. A common view is that self-knowledge is more direct than knowledge of the external world, which relies on the interpretation of sense data. Because of this, it is traditionally claimed that self-knowledge is indubitable, like the claim that a person cannot be wrong about whether they are in pain. However, this position is not universally accepted in the contemporary discourse and an alternative view states that self-knowledge also depends on interpretations that could be false.[70] In a slightly different sense, self-knowledge can also refer to knowledge of the self as a persisting entity with certain personality traits, preferences, physical attributes, relationships, goals, and social identities.[71][h] Metaknowledge is knowledge about knowledge. It can arise in the form of self-knowledge but includes other types as well, such as knowing what someone else knows or what information is contained in a scientific article. Other aspects of metaknowledge include knowing how knowledge can be acquired, stored, distributed, and used.[73] Common knowledge is knowledge that is publicly known and shared by most individuals within a community. It establishes a common ground for communication, understanding, social cohesion, and cooperation.[74] General knowledge encompasses common knowledge but also includes knowledge that many people have been exposed to but may not be able to immediately recall.[75] Common knowledge contrasts with domain knowledge or specialized knowledge, which belongs to a specific domain and is only possessed by experts.[76] Situated knowledge is knowledge specific to a particular situation.[77] It is closely related to practical or tacit knowledge, which is learned and applied in specific circumstances. This especially concerns certain forms of acquiring knowledge, such as trial and error or learning from experience.[78] In this regard, situated knowledge usually lacks a more explicit structure and is not articulated in terms of universal ideas.[79] The term is often used in feminism and postmodernism to argue that many forms of knowledge are not absolute but depend on the concrete historical, cultural, and linguistic context.[77] Explicit knowledge is knowledge that can be fully articulated, shared, and explained, like the knowledge of historical dates and mathematical formulas. It can be acquired through traditional learning methods, such as reading books and attending lectures. It contrasts with tacit knowledge, which is not easily articulated or explained to others, like the ability to recognize someone's face and the practical expertise of a master craftsman. Tacit knowledge is often learned through first-hand experience or direct practice.[80] Cognitive load theory distinguishes between biologically primary and secondary knowledge. Biologically primary knowledge is knowledge that humans have as part of their evolutionary heritage, such as knowing how to recognize faces and speech and many general problem-solving capacities. Biologically secondary knowledge is knowledge acquired because of specific social and cultural circumstances, such as knowing how to read and write.[81] Knowledge can be occurrent or dispositional. Occurrent knowledge is knowledge that is actively involved in cognitive processes. Dispositional knowledge, by contrast, lies dormant in the back of a person's mind and is given by the mere ability to access the relevant information. For example, if a person knows that cats have whiskers then this knowledge is dispositional most of the time and becomes occurrent while they are thinking about it.[82] Many forms of Eastern spirituality and religion distinguish between higher and lower knowledge. They are also referred to as para vidya and apara vidya in Hinduism or the two truths doctrine in Buddhism. Lower knowledge is based on the senses and the intellect. It encompasses both mundane or conventional truths as well as discoveries of the empirical sciences.[83] Higher knowledge is understood as knowledge of God, the absolute, the true self, or the ultimate reality. It belongs neither to the external world of physical objects nor to the internal world of the experience of emotions and concepts. Many spiritual teachings stress the importance of higher knowledge to progress on the spiritual path and to see reality as it truly is beyond the veil of appearances.[84] |

種類 知識の種類を区別する一般的な方法として、命題的知識(または「~である」という知識)と、実践的なスキルや人脈といった命題的ではない知識を区別する方 法がある。[42][e] その他の区別では、知識の習得方法や、既知の情報の中身に焦点を当てる。[44] 命題 詳細は「宣言的知識」を参照  エジディオ・フォルチェリーニによる『ラテン語大辞典』の写真。 宣言的知識( Declarative knowledge)は書籍に保存することができる。 命題的知識は、宣言的知識や記述的知識とも呼ばれ、「2 + 2 = 4」という事実を知っているような、事実に関する理論的知識の一形態である。分析哲学における典型的な知識である。命題知識は命題的な意味で命題との関係 を含む。命題はしばしばthat節で表現されるため、「Akari knows that kangaroos hop」(あかりはカンガルーが跳ねることを知っている)のように、知識-thatとも呼ばれる。この場合、あかりは命題「カンガルーが跳ねる」を知って いるという関係にある。これと密接に関連する知識の種類として、例えば「誰が夕食に来るのか」や「なぜ彼らが来るのか」を知るというknow-whがあ る。[47] これらの表現は通常、that節を用いて言い換えられるため、命題的知識の一種として理解される。[48][f] 命題的知識は、概念、アイデア、理論、一般的な規則を含む心的表象の形式を取る。これらの表象は、それらがどのようなものであるかを示し、知る者を現実の 特定の部分と結びつける。それらはしばしば文脈に依存しないものであり、特定の用途や目的に制限されないことを意味する。[50] 命題的知識は、金の原子量が196.97uであるというような特定の事実に関する知識と、 また、秋になると木々の葉の色が変わるというような一般論も含まれる。[51] 心的表象に依存しているため、命題的知識の能力は人間のような比較的高度な生物にのみ備わっているとされることが多い。これは、世界がどのようなものであ るかを表現する命題を信じるためには高度な知的能力が必要であるという主張に基づいている。[52] 命題的でない知識  自転車に乗っている人の写真 自転車に乗る方法を知っていることは命題ではない知識の一形態である。 命題ではない知識とは、命題との本質的な関係が関与しない知識である。最もよく知られている2つの形態は、知識-how(ノウハウまたは手続き的知識) と、知識-by acquaintance(知識-by acquaintance)である。[53] 知識-howを持つとは、何らかの実践的な能力、スキル、または能力を持つことを意味する。[54] 例えば、自転車や水泳の方法を知っていることなどである。知識-howを担う能力の中には、数学の定理の証明方法を知るような知識-thatの形式を含む ものもあるが、これは一般的ではない。[55] 知識-howのいくつかの種類は命題的知識とは対照的に高度な精神を必要とせず、動物界ではより一般的である。例えば、アリは対応する命題を表現するのに 十分なほど高度な精神を持っていないと推定されるにもかかわらず、歩く方法を知っている。[52][g] 知識の獲得は、直接的な経験的な接触の結果として、何かについて精通することである。[57] 知識の対象は、人、物、場所である。例えば、チョコレートを食べることによって、人はチョコレートの味に精通し、タウポ湖を訪れることによって、タウポ湖 についての知識を獲得することになる。これらの場合、人は対象についての事実情報を必ずしも獲得することなく、直接的な経験に基づいて非推論的な知識を形 成する。これに対して、知人による知識を得るために必要な直接的な経験的接触を伴わずに、本を読むことによってチョコレートやタウポ湖に関する命題的知識 を間接的に多く学ぶことも可能である。[58] 知人による知識の概念は、バートランド・ラッセルによって初めて導入された。ラッセルは、命題を理解するためにはその構成要素を知っていなければならない ため、命題的知識よりも知人による知識の方がより基本的であると主張している。[59] 先験的知識と後天的知識 詳細は「先験的知識と後天的知識」を参照 先験的知識と後天的知識の区別は、形成と正当化のプロセスにおける経験の役割に依存する。[60] 後天的に何かを知るということは、経験に基づいてそれを知ることを意味する。[61] 例えば、外が雨であることや赤ん坊が泣いていることを知ることによって、人は これらの事実の後天的知識を得る。[62] 既知の命題を正当化または支持する経験が一切なくても、先天的知識は可能である。[63] 2 + 2 = 4 といった数学的知識は、この事実を確認するために経験的な調査が必要ないため、伝統的に先天的知識とみなされてきた。この点において、後天的知識は経験的 知識であり、先天的知識は非経験的知識である。[64] 関連する経験とは、主に感覚経験を指す。記憶や内省のような感覚以外の経験も、しばしば含まれる。合理的な洞察力のような意識的な現象は、関連経験から除 外される。例えば、数学の問題の解決に関する先験的な知識に到達するには、2つの数字を掛け合わせる暗算を行う場合のように、意識的な思考プロセスが必要 となる場合がある。[65] 特許請求の範囲に表現された文言を学習する際に必要な経験も同様である。例えば、「独身者はすべて未婚である」という事実は、感覚経験がなくても確認でき るため、先験的知識である。「独身者」や「未婚」という言葉の意味を学ぶには経験が必要であるが、[66] 先験的知識がどのように可能なのかを説明するのは難しく、経験論者のなかには、それが存在することを否定する者もいる。通常、経験を通じて物事を認識でき ることは問題ないと見なされているが、経験なしに知識がどのように可能なのかは明確ではない。この問題に対する最も初期の解決策のひとつは、プラトンによ るもので、魂はすでに知識を所有しており、それを再び利用するには、想起、つまり思い出すだけでよいと主張している。[67] デカルトも同様の説明を行っており、先験的知識は、人間一人一人の心に存在する生得的な知識として存在していると主張している。[68] さらに、この種の知識を司る特別な精神能力を仮定するアプローチもあり、これはしばしば「理性的直観」または「理性的洞察」と呼ばれる。[69] その他 学術文献では、この他にもさまざまな種類の知識が論じられている。哲学では、「自己認識」とは、感覚、思考、信念、その他の精神状態に関する個人の知識を 指す。一般的な見解では、自己認識は感覚データの解釈に依存する外界の知識よりも直接的である。このため、自己認識は疑う余地のないものであると伝統的に 主張されてきた。例えば、人が痛みを感じているかどうかについて、その人が間違っているはずがないという主張のようなものである。しかし、この立場は現代 の議論では必ずしも受け入れられておらず、自己認識も誤った解釈に左右されるという別の見解もある。[70] 少し異なる意味では、自己認識は、特定の性格特性、好み、身体的特徴、人間関係、目標、社会的アイデンティティを持つ永続的な存在としての自己に関する知 識を指すこともある。[71][h] メタ知識とは、知識に関する知識である。自己知識の形をとることもあるが、他者が何を知っているか、あるいは科学論文にどのような情報が含まれているかを 知るといった、他のタイプのものも含む。メタ知識の他の側面には、知識がどのように獲得、保存、配布、使用されるかを知ることも含まれる。 共通知識とは、一般に知られ、コミュニティ内のほとんどの個人によって共有されている知識である。これは、コミュニケーション、理解、社会的な結束、協力 のための共通基盤を確立する。一般的な知識は、共通知識を包含するが、多くの人が触れたことはあるが、即座に思い出すことができない知識も含む。 状況依存知識とは、特定の状況に特有の知識である。[77] それは、特定の状況で学習され適用される実践的または暗黙的な知識と密接に関連している。これは特に、試行錯誤や経験からの学習といった、ある種の知識の 習得方法に関係している。この点において、状況依存型知識は通常、より明確な構造を欠き、普遍的な概念で明確に表現されることはない。この用語は、多くの 知識の形態は絶対的なものではなく、具体的な歴史的、文化的、言語的文脈に依存しているという主張を展開するために、フェミニズムやポストモダニズムにお いてしばしば使用される。 明示的知識とは、歴史上の出来事や数学の公式のような、完全に明確化され、共有され、説明できる知識である。それは、書籍を読んだり講義を受けたりすると いった伝統的な学習方法を通じて習得できる。それとは対照的に、他者に明確化したり説明したりすることが容易ではない知識を暗黙知という。暗黙知は、誰か の顔を認識する能力や熟練した職人の実践的な専門知識のようなものである。暗黙知は、多くの場合、直接的な経験や直接的な実践を通じて習得される。 認知的負荷理論では、生物学的に一次的知識と二次的知識を区別している。生物学的に一次的知識とは、人間が進化の過程で受け継いできた知識であり、例え ば、顔や話し声を認識する方法や、多くの一般的な問題解決能力などである。生物学的に二次的知識とは、特定の社会的・文化的状況によって獲得された知識で あり、例えば、読み書きの方法などである。 知識は、随伴的または素質的である。随伴的知識とは、認知プロセスに能動的に関わる知識である。これに対し、素質的知識は、人の心の奥底に眠っており、関 連情報にアクセスする能力によって得られる。例えば、人が猫にひげがあることを知っている場合、この知識はほとんどの場合、素質的であるが、猫について考 えている間は随伴的となる。 東洋の精神性や宗教の多くの形態では、高次知識と低次知識を区別している。これらはヒンドゥー教ではパラ・ヴィディヤとアパラ・ヴィディヤ、仏教では二諦 教義とも呼ばれる。低次知識は感覚と知性に基づいている。それは世俗的な真理や経験科学の知見の両方を包含している。[83] 高等知識は、神、絶対者、真我、究極の現実についての知識と理解されている。それは、物理的な物体が存在する外界にも、感情や概念の経験が存在する内界に も属さない。多くの精神的な教えは、精神の道を進歩させ、外見のヴェールを越えた真実の現実を見るために、高等知識の重要性を強調している。[84] |

Sources Photos of the five senses Perception relies on the senses to acquire knowledge. Sources of knowledge are ways in which people come to know things. They can be understood as cognitive capacities that are exercised when a person acquires new knowledge.[85] Various sources of knowledge are discussed in the academic literature, often in terms of the mental faculties responsible. They include perception, introspection, memory, inference, and testimony. However, not everyone agrees that all of them actually lead to knowledge. Usually, perception or observation, i.e. using one of the senses, is identified as the most important source of empirical knowledge.[86] Knowing that a baby is sleeping is observational knowledge if it was caused by a perception of the snoring baby. However, this would not be the case if one learned about this fact through a telephone conversation with one's spouse. Perception comes in different modalities, including vision, sound, touch, smell, and taste, which correspond to different physical stimuli.[87] It is an active process in which sensory signals are selected, organized, and interpreted to form a representation of the environment. This leads in some cases to illusions that misrepresent certain aspects of reality, like the Müller-Lyer illusion and the Ponzo illusion.[88] Introspection is often seen in analogy to perception as a source of knowledge, not of external physical objects, but of internal mental states. A traditionally common view is that introspection has a special epistemic status by being infallible. According to this position, it is not possible to be mistaken about introspective facts, like whether one is in pain, because there is no difference between appearance and reality. However, this claim has been contested in the contemporary discourse and critics argue that it may be possible, for example, to mistake an unpleasant itch for a pain or to confuse the experience of a slight ellipse for the experience of a circle.[89] Perceptual and introspective knowledge often act as a form of fundamental or basic knowledge. According to some empiricists, they are the only sources of basic knowledge and provide the foundation for all other knowledge.[90] Memory differs from perception and introspection in that it is not as independent or basic as they are since it depends on other previous experiences.[91] The faculty of memory retains knowledge acquired in the past and makes it accessible in the present, as when remembering a past event or a friend's phone number.[92] It is generally seen as a reliable source of knowledge. However, it can be deceptive at times nonetheless, either because the original experience was unreliable or because the memory degraded and does not accurately represent the original experience anymore.[93][i] Knowledge based on perception, introspection, and memory may give rise to inferential knowledge, which comes about when reasoning is applied to draw inferences from other known facts.[95] For example, the perceptual knowledge of a Czech stamp on a postcard may give rise to the inferential knowledge that one's friend is visiting the Czech Republic. This type of knowledge depends on other sources of knowledge responsible for the premises. Some rationalists argue for rational intuition as a further source of knowledge that does not rely on observation and introspection. They hold for example that some beliefs, like the mathematical belief that 2 + 2 = 4, are justified through pure reason alone.[96]  Photograph of a person giving testimony Knowledge by testimony relies on statements given by other people, like the testimony given at a trial. Testimony is often included as an additional source of knowledge that, unlike the other sources, is not tied to one specific cognitive faculty. Instead, it is based on the idea that one person can come to know a fact because another person talks about this fact. Testimony can happen in numerous ways, like regular speech, a letter, a newspaper, or a blog. The problem of testimony consists in clarifying why and under what circumstances testimony can lead to knowledge. A common response is that it depends on the reliability of the person pronouncing the testimony: only testimony from reliable sources can lead to knowledge.[97] |

出典 五感の写真 知覚は知識を得るために感覚に依存する。 知識の源泉は、人々が物事を知る方法である。それは、人が新しい知識を得る際に発揮される認知能力として理解することができる。[85] さまざまな知識の源泉は学術文献で議論されており、しばしば責任を負う精神能力の観点から論じられる。それらには知覚、内省、記憶、推論、証言が含まれ る。しかし、それらすべてが実際に知識につながるという点については、誰もが同意しているわけではない。通常、知覚または観察、すなわち感覚の1つを用い ることが、経験的知識の最も重要な源であるとみなされている。[86] 赤ん坊が寝ていることを知っているということは、赤ん坊のいびきを感知したことによる観察的知識である。しかし、配偶者との電話での会話を通じてこの事実 を知った場合は、そうではない。知覚には視覚、聴覚、触覚、嗅覚、味覚など、さまざまな様態があり、それぞれ異なる物理的刺激に対応している。[87] 知覚は、感覚信号が選択、整理、解釈され、環境の表現が形成される能動的なプロセスである。これにより、ミュラー・リヤー錯視やポンゾ錯視のように、現実 の特定の側面を誤って表現する錯覚が生じる場合がある。[88] 内省は、外部の物理的な対象ではなく、内部の精神状態に関する知識の源として、知覚と類似していると見られることが多い。伝統的に一般的な見解は、内省は 誤りがないという点で特別な認識論的地位を持つというものである。この立場によれば、外見と現実との間に違いがないため、痛みを感じているかどうかといっ た内省的事実について誤ることはあり得ない。しかし、この主張は現代の議論では異論があり、批判派は、例えば不快なかゆみを痛みと間違えたり、わずかに楕 円形に歪んだ視界を円形と混同したりすることはあり得る、と主張している。[89] 知覚と内省による知識は、しばしば根本的または基本的な知識の一形態として機能する。経験論者の中には、それらが唯一の基本的な知識の源であり、他のすべ ての知識の基盤を提供している、と主張する者もいる。[90] 記憶は、他の過去の経験に依存しているため、知覚や内省ほど独立したものでも基本的なものでもないという点で、それらとは異なる。記憶の能力は、過去の出 来事や友人の電話番号を思い出すように、過去に獲得した知識を保持し、現在において利用できるようにする。しかし、それでもなお、記憶は時に人を欺くこと がある。それは、もとの経験が信頼できないものだったか、記憶が劣化してしまい、もとの経験を正確に表さなくなったためである。[93][i] 知覚、内省、記憶に基づく知識は、推論が適用され、他の既知の事実から推論が導かれる際に生じる推論的知識を生み出す可能性がある。例えば、葉書に貼られ たチェコの切手の知覚的知識は、友人がチェコ共和国を訪れているという推論的知識を生み出す可能性がある。この種の知識は、前提を導く他の知識源に依存し ている。合理主義者の一部は、観察や内省に頼らないさらなる知識の源泉として、合理的直観を主張している。例えば、2 + 2 = 4 という数学的な信念のように、純粋理性のみによって正当化される信念もあると主張している。  証言する人物の写真 証言による知識は、裁判での証言のように、他の人々による発言に依存している。 証言は、他の情報源とは異なり、特定の認知能力に結びつかない知識の追加情報源として、しばしば含まれる。その代わり、ある人物が事実を知るに至ったの は、他の人物がその事実について語ったからだという考えに基づいている。証言は、通常の会話、手紙、新聞、ブログなど、さまざまな方法でなされる。証言の 問題は、証言がどのような状況で、なぜ知識につながるのかを明確にすることである。一般的な回答は、証言を述べる人物の信頼性によるというものである。信 頼できる情報源からの証言のみが知識につながる。[97] |

| Limits The problem of the limits of knowledge concerns the question of which facts are unknowable.[98] These limits constitute a form of inevitable ignorance that can affect both what is knowable about the external world as well as what one can know about oneself and about what is good.[99] Some limits of knowledge only apply to particular people in specific situations while others pertain to humanity at large.[100] A fact is unknowable to a person if this person lacks access to the relevant information, like facts in the past that did not leave any significant traces. For example, it may be unknowable to people today what Caesar's breakfast was the day he was assassinated but it was knowable to him and some contemporaries.[101] Another factor restricting knowledge is given by the limitations of the human cognitive faculties. Some people may lack the cognitive ability to understand highly abstract mathematical truths and some facts cannot be known by any human because they are too complex for the human mind to conceive.[102] A further limit of knowledge arises due to certain logical paradoxes. For instance, there are some ideas that will never occur to anyone. It is not possible to know them because if a person knew about such an idea then this idea would have occurred at least to them.[103][j] There are many disputes about what can or cannot be known in certain fields. Religious skepticism is the view that beliefs about God or other religious doctrines do not amount to knowledge.[105] Moral skepticism encompasses a variety of views, including the claim that moral knowledge is impossible, meaning that one cannot know what is morally good or whether a certain behavior is morally right.[106] An influential theory about the limits of metaphysical knowledge was proposed by Immanuel Kant. For him, knowledge is restricted to the field of appearances and does not reach the things in themselves, which exist independently of humans and lie beyond the realm of appearances. Based on the observation that metaphysics aims to characterize the things in themselves, he concludes that no metaphysical knowledge is possible, like knowing whether the world has a beginning or is infinite.[107] There are also limits to knowledge in the empirical sciences, such as the uncertainty principle, which states that it is impossible to know the exact magnitudes of certain certain pairs of physical properties, like the position and momentum of a particle, at the same time.[108] Other examples are physical systems studied by chaos theory, for which it is not practically possible to predict how they will behave since they are so sensitive to initial conditions that even the slightest of variations may produce a completely different behavior. This phenomenon is known as the butterfly effect.[109]  Bust of Pyrrho of Elis Pyrrho was one of the first philosophical skeptics. The strongest position about the limits of knowledge is radical or global skepticism, which holds that humans lack any form of knowledge or that knowledge is impossible. For example, the dream argument states that perceptual experience is not a source of knowledge since dreaming provides unreliable information and a person could be dreaming without knowing it. Because of this inability to discriminate between dream and perception, it is argued that there is no perceptual knowledge of the external world.[110][k] This thought experiment is based on the problem of underdetermination, which arises when the available evidence is not sufficient to make a rational decision between competing theories. In such cases, a person is not justified in believing one theory rather than the other. If this is always the case then global skepticism follows.[111] Another skeptical argument assumes that knowledge requires absolute certainty and aims to show that all human cognition is fallible since it fails to meet this standard.[112] An influential argument against radical skepticism states that radical skepticism is self-contradictory since denying the existence of knowledge is itself a knowledge-claim.[113] Other arguments rely on common sense[114] or deny that infallibility is required for knowledge.[115] Very few philosophers have explicitly defended radical skepticism but this position has been influential nonetheless, usually in a negative sense: many see it as a serious challenge to any epistemological theory and often try to show how their preferred theory overcomes it.[116] Another form of philosophical skepticism advocates the suspension of judgment as a form of attaining tranquility while remaining humble and open-minded.[117] A less radical limit of knowledge is identified by falliblists, who argue that the possibility of error can never be fully excluded. This means that even the best-researched scientific theories and the most fundamental commonsense views could still be subject to error. Further research may reduce the possibility of being wrong, but it can never fully exclude it. Some fallibilists reach the skeptical conclusion from this observation that there is no knowledge but the more common view is that knowledge exists but is fallible.[118] Pragmatists argue that one consequence of fallibilism is that inquiry should not aim for truth or absolute certainty but for well-supported and justified beliefs while remaining open to the possibility that one's beliefs may need to be revised later.[119] |

限界 知識の限界の問題は、どの事実が知り得ないものであるかという問題に関係している。[98] これらの限界は、外部世界について知り得るものだけでなく、自分自身について、また何が善であるかについて知り得るものにも影響を及ぼす、避けられない無 知の一形態である。[99 知識の限界は、特定の状況下にある特定の人々だけに当てはまる場合もあれば、人類全体に関わる場合もある。例えば、シーザーが暗殺された日の朝食が何で あったかは、現代人にとっては知ることができないかもしれないが、シーザーや同時代人にとっては知ることができた。[101] 知識を制限するもう一つの要因は、人間の認識能力の限界である。一部の人々は、高度に抽象的な数学的真理を理解する認識能力に欠けているかもしれないし、 人間の精神では理解できないほど複雑であるため、一部の事実はいかなる人間にも知ることができないかもしれない。[102] 知識の限界は、特定の論理的なパラドックスによっても生じる。例えば、誰にも思い浮かばないような考え方がある。そのような考え方を知っている人がいると すれば、その考え方は少なくともその人には思い浮かんだはずであるため、それを知ることは不可能である。[103][j] 特定の分野において、何が知ることができ、何ができないかについては、多くの論争がある。宗教的懐疑論とは、神やその他の宗教的教義に関する信念は知識に 値しないという見解である。[105] 道徳的懐疑論は、道徳的知識は不可能であるという主張を含め、さまざまな見解を包含する。つまり、何が道徳的に善であるか、ある特定の行動が道徳的に正し いかどうかを知ることはできないという意味である。[106] 形而上学的知識の限界に関する有力な理論は、イマヌエル・カントによって提唱された。彼によれば、知識は外見の領域に限られ、人間とは独立して存在し、外 見の領域を超えたところにある事物そのものには及ばない。形而上学は事物そのものを特徴づけることを目的としているという観察に基づき、彼は、世界に始ま りがあるのか、それとも無限なのかを知るような形而上学的な知識は不可能であると結論づけている。 また、経験科学における知識にも限界があり、例えば不確定性原理では、粒子の位置と運動量のような、ある特定の物理的特性の組合せについて、その正確な大 きさを同時に知ることは不可能であるとされている。[108] その他の例としては、カオス理論で研究されている物理システムがある。初期条件に非常に敏感であるため、わずかな変化でも全く異なる挙動を引き起こす可能 性があるため、それらの挙動を予測することは実際上不可能である。この現象はバタフライ効果として知られている。[109]  エリスのピュロン胸像 ピュロンは初期の哲学的懐疑論者の一人であった。 知識の限界に関する最も強い立場は、根本的懐疑論または全体的懐疑論であり、人間はあらゆる種類の知識を欠いている、あるいは知識は不可能であると主張す る。例えば、夢判断は、夢は信頼できない情報を提供し、人はそれを知らずに夢を見ている可能性があるため、知覚経験は知識の源ではないと主張する。夢と知 覚を区別できないため、外部世界についての知覚的知識は存在しないという主張もある。[110][k] この思考実験は、競合する理論のどちらかを選択するのに合理的な判断を下すのに十分な証拠が得られない場合に生じる、過少決定の問題に基づいている。その ような場合、人はどちらかの理論を信じることに正当性を見いだせない。これが常に当てはまる場合、世界懐疑論が導かれる。[111] 別の懐疑論の主張では、知識には絶対的な確実性が求められるとし、この基準を満たさないため、人間の認識はすべて誤りを犯しうるとする。[112] 根本的懐疑論に対する有力な反論は、知識の存在を否定することはそれ自体が知識の主張であるため、根本的懐疑論は自己矛盾しているというものである。 [113] その他の反論は、常識に依拠するもの[114]や、知識に絶対的な誤りのなさは必要ないとするものもある。[115] 根本的懐疑論を明確に擁護する哲学者はほとんどいないが、 この立場は、否定的な意味で影響力を持ち続けている。多くの人々は、この立場を認識論的理論に対する深刻な挑戦と見なし、自分たちが支持する理論がそれを どのように克服するかを示そうとする。[116] 哲学的な懐疑論の別の形態は、謙虚で偏見のない姿勢を保ちつつ、静けさを手に入れるための判断保留を提唱している。[117] 知識の限界について、より穏健な立場をとるのが、誤謬の可能性を完全に排除することはできないと主張するファリブルリストである。つまり、最も綿密に研究 された科学的理論や最も基本的な常識的な見解でさえ、誤りを含む可能性があるということである。さらなる研究によって誤りの可能性は低くなるかもしれない が、完全に排除することはできない。この観察から、懐疑論的な結論に達する懐疑論者もいるが、一般的な見解は、知識は存在するが、誤りを犯す可能性がある というものである。[118] プラグマティストは、懐疑論の帰結のひとつとして、探究は真実や絶対的な確実性を目的とするのではなく、根拠がしっかりしていて正当化された信念を目的と すべきであり、その信念が後に修正される必要がある可能性を残しておくべきであると主張する。[119] |

| Structure The structure of knowledge is the way in which the mental states of a person need to be related to each other for knowledge to arise.[120] A common view is that a person has to have good reasons for holding a belief if this belief is to amount to knowledge. When the belief is challenged, the person may justify it by referring to their reason for holding it. In many cases, this reason depends itself on another belief that may as well be challenged. An example is a person who believes that Ford cars are cheaper than BMWs. When their belief is challenged, they may justify it by claiming that they heard it from a reliable source. This justification depends on the assumption that their source is reliable, which may itself be challenged. The same may apply to any subsequent reason they cite.[121] This threatens to lead to an infinite regress since the epistemic status at each step depends on the epistemic status of the previous step.[122] Theories of the structure of knowledge offer responses for how to solve this problem.[121]  Diagram showing the differences between foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism Foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism are theories of the structure of knowledge. The black arrows symbolize how one belief supports another belief. Three traditional theories are foundationalism, coherentism, and infinitism. Foundationalists and coherentists deny the existence of an infinite regress, in contrast to infinitists.[121] According to foundationalists, some basic reasons have their epistemic status independent of other reasons and thereby constitute the endpoint of the regress.[123] Some foundationalists hold that certain sources of knowledge, like perception, provide basic reasons. Another view is that this role is played by certain self-evident truths, like the knowledge of one's own existence and the content of one's ideas.[124] The view that basic reasons exist is not universally accepted. One criticism states that there should be a reason why some reasons are basic while others are not. According to this view, the putative basic reasons are not actually basic since their status would depend on other reasons. Another criticism is based on hermeneutics and argues that all understanding is circular and requires interpretation, which implies that knowledge does not need a secure foundation.[125] Coherentists and infinitists avoid these problems by denying the contrast between basic and non-basic reasons. Coherentists argue that there is only a finite number of reasons, which mutually support and justify one another. This is based on the intuition that beliefs do not exist in isolation but form a complex web of interconnected ideas that is justified by its coherence rather than by a few privileged foundational beliefs.[126] One difficulty for this view is how to demonstrate that it does not involve the fallacy of circular reasoning.[127] If two beliefs mutually support each other then a person has a reason for accepting one belief if they already have the other. However, mutual support alone is not a good reason for newly accepting both beliefs at once. A closely related issue is that there can be distinct sets of coherent beliefs. Coherentists face the problem of explaining why someone should accept one coherent set rather than another.[126] For infinitists, in contrast to foundationalists and coherentists, there is an infinite number of reasons. This view embraces the idea that there is a regress since each reason depends on another reason. One difficulty for this view is that the human mind is limited and may not be able to possess an infinite number of reasons. This raises the question of whether, according to infinitism, human knowledge is possible at all.[128] |

構造 知識の構造とは、知識が生じるために、人の精神状態が互いに関連付けられる必要がある方法である。[120] 一般的な見解では、ある信念が知識に値するものであるためには、その信念を保持するに足る十分な理由がなければならない。その信念が疑われた場合、その人 はそれを保持する理由を挙げてそれを正当化するかもしれない。多くの場合、この理由は、それ自体が疑われる可能性のある別の信念に依存している。例えば、 フォード車はBMWよりも安いと信じている人がいる。その信念が疑われた場合、その人は信頼できる情報源から聞いたと主張することで、それを正当化するか もしれない。この正当化は、その情報源が信頼できるという前提に依存しており、その前提自体が疑われる可能性がある。同じことが、その後に挙げられる理由 にも当てはまる可能性がある。[121] これは、各段階における認識の状態が、前の段階における認識の状態に依存しているため、無限後退につながる恐れがある。[122] 知識の構造に関する理論は、この問題の解決策を提供している。[121]  基礎主義(あるいは基礎づけ主義)、首尾一貫説、無限後退説の違いを示す図 基礎主義、首尾一貫説、無限後退説は、知識の構造に関する理論である。黒い矢印は、ある信念が別の信念を支える様子を象徴している。 伝統的な理論には、基礎主義、首尾一貫説、無限後退説の3つがある。基礎主義者と首尾一貫説者は無限後退の存在を否定するが、無限後退説者とは対照的であ る。[121] 基礎主義者によると、いくつかの基本的な理由は他の理由とは独立した認識上の地位を持ち、それによって後退の終点となる。[123] 基礎主義者の一部は、知覚のような知識の源が基本的な理由を提供すると主張する。別の見解では、この役割は、自己の存在の認識や観念の内容といった、ある 種の自明の真理によって果たされるというものである。[124] 基本的な理由が存在するという見解は、普遍的に受け入れられているわけではない。ある批判では、ある理由が基本的なものである一方で、他の理由がそうでは ない理由があるはずだという。この見解によると、仮説上の基本的な理由は、その地位が他の理由に依存しているため、実際には基本的なものではない。もう一 つの批判は解釈学に基づくもので、すべての理解は循環的であり、解釈を必要とするというもので、これは知識に確固とした基盤は必要ないことを意味する。 首尾一貫説と無限説の支持者たちは、基本的な理由とそうでない理由の対比を否定することで、これらの問題を回避している。首尾一貫説の支持者たちは、理由 の数は限られており、それらは相互に支持し、正当化し合っていると主張する。これは、信念は孤立して存在するのではなく、相互に結びついた複雑な考えの網 目構造を形成しており、その正当性は少数の特権的な基礎的信念によってではなく、その首尾一貫性によって裏付けられるという直観に基づいている。 [126] この見解の難点のひとつは、循環論法の誤謬を含まないことをどのようにして証明するかである。[127] 2つの信念が相互に支持し合っている場合、人はもう一方の信念をすでに持っているのであれば、その信念を受け入れる理由がある。しかし、相互支持だけで は、同時に両方の信念を受け入れることの十分な理由にはならない。密接に関連する問題として、首尾一貫した信念の明確な集合が存在しうるということがあ る。首尾一貫説の信奉者は、ある首尾一貫した信念の集合を、別の集合ではなく受け入れるべき理由を説明しなければならないという問題に直面する。 [126] 基礎論者や首尾一貫説の信奉者とは対照的に、無限論者にとっては、理由の数は無限にある。この見解は、各々の理由が別の理由に依存しているため、後退が起 こるという考え方を包含している。この見解の難点のひとつは、人間の心には限界があり、無限の理由を所有することはできないかもしれないということであ る。このことは、無限論によれば人間の知識は可能であるのかという疑問を提起する。[128] |

Value Sculpture showing a torch being passed form one person to another Los portadores de la antorcha (The Torch-Bearers) – sculpture by Anna Hyatt Huntington symbolizing the transmission of knowledge from one generation to the next (Ciudad Universitaria, Madrid, Spain) Knowledge may be valuable either because it is useful or because it is good in itself. Knowledge can be useful by helping a person achieve their goals. For example, if one knows the answers to questions in an exam one is able to pass that exam or by knowing which horse is the fastest, one can earn money from bets. In these cases, knowledge has instrumental value.[129] Not all forms of knowledge are useful and many beliefs about trivial matters have no instrumental value. This concerns, for example, knowing how many grains of sand are on a specific beach or memorizing phone numbers one never intends to call. In a few cases, knowledge may even have a negative value. For example, if a person's life depends on gathering the courage to jump over a ravine, then having a true belief about the involved dangers may hinder them from doing so.[130]  Photo of early childhood education in Ziway, Ethiopia The value of knowledge plays a key role in education for deciding which knowledge to pass on to the students. Besides having instrumental value, knowledge may also have intrinsic value. This means that some forms of knowledge are good in themselves even if they do not provide any practical benefits. According to philosopher Duncan Pritchard, this applies to forms of knowledge linked to wisdom.[131] It is controversial whether all knowledge has intrinsic value, including knowledge about trivial facts like knowing whether the biggest apple tree had an even number of leaves yesterday morning. One view in favor of the intrinsic value of knowledge states that having no belief about a matter is a neutral state and knowledge is always better than this neutral state, even if the value difference is only minimal.[132] A more specific issue in epistemology concerns the question of whether or why knowledge is more valuable than mere true belief.[133] There is wide agreement that knowledge is usually good in some sense but the thesis that knowledge is better than true belief is controversial. An early discussion of this problem is found in Plato's Meno in relation to the claim that both knowledge and true belief can successfully guide action and, therefore, have apparently the same value. For example, it seems that mere true belief is as effective as knowledge when trying to find the way to Larissa.[134] According to Plato, knowledge is better because it is more stable.[135] Another suggestion is that knowledge gets its additional value from justification. One difficulty for this view is that while justification makes it more probable that a belief is true, it is not clear what additional value it provides in comparison to an unjustified belief that is already true.[136] The problem of the value of knowledge is often discussed in relation to reliabilism and virtue epistemology.[137] Reliabilism can be defined as the thesis that knowledge is reliably formed true belief. This view has difficulties in explaining why knowledge is valuable or how a reliable belief-forming process adds additional value.[138] According to an analogy by philosopher Linda Zagzebski, a cup of coffee made by a reliable coffee machine has the same value as an equally good cup of coffee made by an unreliable coffee machine.[139] This difficulty in solving the value problem is sometimes used as an argument against reliabilism.[140] Virtue epistemology, by contrast, offers a unique solution to the value problem. Virtue epistemologists see knowledge as the manifestation of cognitive virtues. They hold that knowledge has additional value due to its association with virtue. This is based on the idea that cognitive success in the form of the manifestation of virtues is inherently valuable independent of whether the resulting states are instrumentally useful.[141] Acquiring and transmitting knowledge often comes with certain costs, such as the material resources required to obtain new information and the time and energy needed to understand it. For this reason, an awareness of the value of knowledge is crucial to many fields that have to make decisions about whether to seek knowledge about a specific matter. On a political level, this concerns the problem of identifying the most promising research programs to allocate funds.[142] Similar concerns affect businesses, where stakeholders have to decide whether the cost of acquiring knowledge is justified by the economic benefits that this knowledge may provide, and the military, which relies on intelligence to identify and prevent threats.[143] In the field of education, the value of knowledge can be used to choose which knowledge should be passed on to the students.[144] |

価値 トーチが一人から別の人へと渡される様子を表した彫刻 Los portadores de la antorcha (The Torch-Bearers)(聖火ランナー) - 世代から世代へと知識が受け継がれていくことを象徴する、アンナ・ハイアット・ハンティントンによる彫刻(スペイン、マドリードのシウダ・ウニベルシタリ ア) 知識は、それが役立つから、あるいはそれ自体が価値があるから、どちらかの理由で価値があると言える。知識は、人が目標を達成するのを助けることで役立 つ。例えば、試験の問題の答えを知っていればその試験に合格できるし、どの馬が最も速いのかを知っていれば賭けで金を稼ぐことができる。このような場合、 知識は道具としての価値がある。[129] 知識のすべての形態が役立つわけではなく、些細な事柄に関する多くの信念には道具としての価値がない。これは例えば、特定の浜辺にある砂の粒の数を数えた り、電話をかける予定のない電話番号を暗記したりすることなどである。ごくまれに、知識が負の価値を持つ場合もある。例えば、渓谷を飛び越える勇気を出す ことがその人の命に関わる場合、その危険性について真に信じていることが、それを妨げる可能性がある。  エチオピアのズワイにおける幼児教育の写真 知識の価値は、学生にどの知識を伝えるかを決定する上で、教育において重要な役割を果たす。 道具的価値を持つだけでなく、知識には本質的価値もある。これは、実用的な利益をもたらさないとしても、知識のいくつかの形態はそれ自体が価値を持つこと を意味する。哲学者ダンカン・プリチャードによると、これは知恵と結びついた知識の形態に当てはまるという。[131] 最大級のリンゴの木の葉の数が昨日の朝偶数だったか知っているといった些細な事実に関する知識を含め、すべての知識に本質的な価値があるかどうかについて は議論がある。知識の本質的な価値を支持する見解のひとつは、ある事柄について信念を持たないことは中立的な状態であり、価値の差がわずかであっても、知 識は常にこの中立的な状態よりも優れているというものである。[132] 認識論におけるより具体的な問題は、知識が単なる真の信念よりも価値があるのか、またその理由は何なのかという疑問である。[133] 知識は通常、ある意味で良いものであるという点については広く同意されているが、知識が真の信念よりも優れているという主張については議論の余地がある。 この問題に関する初期の議論は、知識と真の信念の両方が行動をうまく導くことができるという主張に関連して、プラトンの『メノン』に見られる。例えば、ラ リッサへの道を見つけようとする場合、単なる真の信念は知識と同様に有効であると思われる。[134] プラトンによれば、知識の方が優れているのは、より安定しているからである。[135] 別の見解では、知識は正当性によって付加価値を得るという。この見解の難点のひとつは、正当化によって信念が真である可能性が高まるとはいえ、すでに真で ある正当化されていない信念と比較して、それがどのような付加価値をもたらすのかが明確ではないことである。 知識の価値の問題は、信頼主義と徳に基づく認識論に関連してしばしば議論される。信頼主義は、知識は信頼性の高い真の信念として形成されるという命題とし て定義できる。この見解は、知識がなぜ価値があるのか、あるいは信頼性の高い信念形成プロセスがどのように付加価値をもたらすのかを説明するのが難しい。 哲学者リンダ・ザグゼブスキの例え話によると、信頼性の高いコーヒーメーカーで入れたコーヒーは、 信頼性の低いコーヒーメーカーで入れた同等の美味しいコーヒーと同じ価値を持つ。[139] この価値問題の解決の難しさは、信頼主義に対する反論として用いられることがある。[140] これに対して、徳に基づく認識論は、価値問題に対する独自の解決策を提示している。徳に基づく認識論者は、知識を認識上の徳の現れと見なしている。彼ら は、知識には徳との関連性によって付加価値があると考えている。これは、徳の顕現という形での認識上の成功は、その結果生じる状態が道具的に有用であるか どうかとは無関係に、本質的に価値があるという考えに基づいている。 知識の獲得や伝達には、新しい情報を得るために必要な物的資源や、それを理解するために必要な時間や労力といった、一定のコストが伴うことが多い。このた め、特定の事柄に関する知識を求めるべきかどうかを決定しなければならない多くの分野において、知識の価値に対する認識は極めて重要である。政治レベルで は、これは資金を配分する最も有望な研究プログラムを特定する問題に関係する。[142] 類似の懸念は、知識の獲得コストがその知識がもたらす経済的利益によって正当化されるかどうかを利害関係者が決定しなければならない企業や、脅威を特定し 防止するために情報に依存する軍事分野にも影響する。[143] 教育分野では、知識の価値は学生に伝達すべき知識を選択するために利用できる。[144] |

| Science Main article: Philosophy of science The scientific approach is usually regarded as an exemplary process of how to gain knowledge about empirical facts.[145] Scientific knowledge includes mundane knowledge about easily observable facts, for example, chemical knowledge that certain reactants become hot when mixed together. It also encompasses knowledge of less tangible issues, like claims about the behavior of genes, neutrinos, and black holes.[146] A key aspect of most forms of science is that they seek natural laws that explain empirical observations.[145] Scientific knowledge is discovered and tested using the scientific method.[l] This method aims to arrive at reliable knowledge by formulating the problem in a clear way and by ensuring that the evidence used to support or refute a specific theory is public, reliable, and replicable. This way, other researchers can repeat the experiments and observations in the initial study to confirm or disconfirm it.[148] The scientific method is often analyzed as a series of steps that begins with regular observation and data collection. Based on these insights, scientists then try to find a hypothesis that explains the observations. The hypothesis is then tested using a controlled experiment to compare whether predictions based on the hypothesis match the observed results. As a last step, the results are interpreted and a conclusion is reached whether and to what degree the findings confirm or disconfirm the hypothesis.[149] The empirical sciences are usually divided into natural and social sciences. The natural sciences, like physics, biology, and chemistry, focus on quantitative research methods to arrive at knowledge about natural phenomena.[150] Quantitative research happens by making precise numerical measurements and the natural sciences often rely on advanced technological instruments to perform these measurements and to setup experiments. Another common feature of their approach is to use mathematical tools to analyze the measured data and formulate exact and general laws to describe the observed phenomena.[151] The social sciences, like sociology, anthropology, and communication studies, examine social phenomena on the level of human behavior, relationships, and society at large.[152] While they also make use of quantitative research, they usually give more emphasis to qualitative methods. Qualitative research gathers non-numerical data, often with the goal of arriving at a deeper understanding of the meaning and interpretation of social phenomena from the perspective of those involved.[153] This approach can take various forms, such as interviews, focus groups, and case studies.[154] Mixed-method research combines quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the same phenomena from a variety of perspectives to get a more comprehensive understanding.[155] The progress of scientific knowledge is traditionally seen as a gradual and continuous process in which the existing body of knowledge is increased at each step. This view has been challenged by some philosophers of science, such as Thomas Kuhn, who holds that between phases of incremental progress, there are so-called scientific revolutions in which a paradigm shift occurs. According to this view, some basic assumptions are changed due to the paradigm shift, resulting in a radically new perspective on the body of scientific knowledge that is incommensurable with the previous outlook.[156][m] Scientism refers to a group of views that privilege the sciences and the scientific method over other forms of inquiry and knowledge acquisition. In its strongest formulation, it is the claim that there is no other knowledge besides scientific knowledge.[158] A common critique of scientism, made by philosophers such as Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Feyerabend, is that the fixed requirement of following the scientific method is too rigid and results in a misleading picture of reality by excluding various relevant phenomena from the scope of knowledge.[159] |

科学 詳細は「科学哲学」を参照 科学的手法は通常、経験的事実に関する知識を得るための模範的なプロセスとみなされている。[145] 科学的な知識には、例えば、ある種の反応物が混ぜ合わされると熱くなるという化学的知識のように、容易に観察可能な事実に関する日常的な知識が含まれる。 また、遺伝子、ニュートリノ、ブラックホールの挙動に関する主張のような、より捉えどころのない問題に関する知識も含まれる。[146] ほとんどの科学の主要な特徴は、経験的観察を説明する自然法則を求めることである。[145] 科学的知識は科学的手法を用いて発見され、検証される。[l] この手法は、問題を明確に定式化し、特定の理論を支持または反証する証拠が公開され、信頼でき、再現可能であることを保証することで、信頼できる知識を導 き出すことを目的としている。これにより、他の研究者が最初の研究における実験や観察を繰り返し、それを確認または反証することが可能となる。[148] 科学的手法は、通常、定期的な観察とデータ収集から始まる一連のステップとして分析される。これらの洞察に基づいて、科学者は観察結果を説明する仮説を見 つけようとする。仮説は、仮説に基づく予測が観察結果と一致するかどうかを比較する管理された実験によって検証される。最後のステップとして、結果が解釈 され、発見が仮説をどの程度まで確認または否定するものであるかについて結論が導かれる。[149] 経験科学は通常、自然科学と社会科学に分けられる。自然科学、例えば物理学、生物学、化学などは、自然現象に関する知識を得るために量的研究法に重点を置 いている。[150] 量的研究は精密な数値測定を行うことで行われ、自然科学はしばしば、これらの測定や実験の設定を行うために高度な技術機器に頼っている。 また、測定したデータを分析し、観察された現象を説明する厳密かつ一般的な法則を定式化するために数学的手法を用いることも、そのアプローチにおけるもう 一つの共通の特徴である。[151] 社会学、人類学、コミュニケーション学などの社会科学は、人間の行動、関係性、社会全般のレベルで社会現象を調査する。[152] 社会科学も定量的な研究を利用するが、通常は定性的な手法をより重視する。定性的研究では、数値化できないデータを収集し、しばしば、当事者の視点から社 会現象の意味や解釈をより深く理解することを目的としている。[153] このアプローチには、インタビュー、フォーカスグループ、ケーススタディなど、さまざまな形態がある。[154] 混合研究法では、定量的および定性的な方法を組み合わせて、同じ現象をさまざまな視点から調査し、より包括的な理解を得る。[155] 科学知識の進歩は、従来、段階的に連続するプロセスと見なされており、そのプロセスにおいて、既存の知識体系が各段階で増大していく。この見解は、トーマ ス・クーンなどの科学哲学者たちによって疑問視されている。クーンは、増大する進歩の段階の間には、パラダイムシフトが起こるいわゆる科学革命がある、と 主張している。この見解によると、パラダイムシフトによっていくつかの基本的な前提が変化し、科学知識の体系に対する根本的に新しい視点がもたらされ、そ れは以前の見解とは比較にならないほどである。[156][m] 科学主義とは、科学と科学的手法を他の調査や知識の獲得よりも優先する一連の見解を指す。最も強い表現では、科学的知識以外の知識は存在しないという主張 である。[158] ハンス=ゲオルク・ガダマーやポール・フェイヤーアーベントなどの哲学者による科学主義に対する一般的な批判は、科学的知識の固定的な要件に従うことがあ まりにも厳格であり、さまざまな関連現象を知識の範囲から除外することで、現実を誤解させるような見解をもたらしているというものである。[159] |

| History Main article: History of knowledge The history of knowledge is the field of inquiry that studies how knowledge in different fields has developed and evolved in the course of history. It is closely related to the history of science, but covers a wider area that includes knowledge from fields like philosophy, mathematics, education, literature, art, and religion. It further covers practical knowledge of specific crafts, medicine, and everyday practices. It investigates not only how knowledge is created and employed, but also how it is disseminated and preserved.[160] Before the ancient period, knowledge about social conduct and survival skills was passed down orally and in the form of customs from one generation to the next.[161] The ancient period saw the rise of major civilizations starting about 3000 BCE in Mesopotamia, Egypt, India, and China. The invention of writing in this period significantly increased the amount of stable knowledge within society since it could be stored and shared without being limited by imperfect human memory.[162] During this time, the first developments in scientific fields like mathematics, astronomy, and medicine were made. They were later formalized and greatly expanded by the ancient Greeks starting in the 6th century BCE. Other ancient advancements concerned knowledge in the fields of agriculture, law, and politics.[163]  Photo of a replica of the printing press created by Johannes Gutenberg The invention of the printing press in the 15th century greatly expanded access to written materials. In the medieval period, religious knowledge was a central concern, and religious institutions, like the Catholic Church in Europe, influenced intellectual activity.[164] Jewish communities set up yeshivas as centers for studying religious texts and Jewish law.[165] In the Muslim world, madrasa schools were established and focused on Islamic law and Islamic philosophy.[166] Many intellectual achievements of the ancient period were preserved, refined, and expanded during the Islamic Golden Age from the 8th to 13th centuries.[167] Centers of higher learning were established in this period in various regions, like Al-Qarawiyyin University in Morocco,[168] the Al-Azhar University in Egypt,[169] the House of Wisdom in Iraq,[170] and the first universities in Europe.[171] This period also saw the formation of guilds, which preserved and advanced technical and craft knowledge.[172] In the Renaissance period, starting in the 14th century, there was a renewed interest in the humanities and sciences.[173] The printing press was invented in the 15th century and significantly increased the availability of written media and general literacy of the population.[174] These developments served as the foundation of the Scientific Revolution in the Age of Enlightenment starting in the 16th and 17th centuries. It led to an explosion of knowledge in fields such as physics, chemistry, biology, and the social sciences.[175] The technological advancements that accompanied this development made possible the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries.[176] In the 20th century, the development of computers and the Internet led to a vast expansion of knowledge by revolutionizing how knowledge is stored, shared, and created.[177][n] |

歴史 詳細は「知識の歴史」を参照 知識の歴史とは、異なる分野における知識が歴史の中でどのように発展し、進化してきたかを研究する学問分野である。科学史と密接に関連しているが、哲学、 数学、教育、文学、芸術、宗教などの分野からの知識を含むより広い領域をカバーしている。さらに、特定の工芸、医学、日常的な実践に関する実用的な知識も カバーしている。知識がどのように創造され、活用されるかだけでなく、それがどのように普及し、保存されるかも調査する。[160] 古代以前においては、社会的な行動や生存技術に関する知識は、口頭や慣習という形で世代から世代へと受け継がれていた。[161] 古代においては、メソポタミア、エジプト、インド、中国において、紀元前3000年頃に始まる主要な文明の勃興が見られた。この時代に文字が発明されたこ とで、不完全な人間の記憶力に左右されることなく知識を保存し共有することが可能となり、社会における安定した知識の量が大幅に増加した。[162] この時代には、数学、天文学、医学といった科学分野における最初の進歩が遂げられた。 これらは後に、紀元前6世紀に古代ギリシア人によって体系化され、大幅に拡大された。 その他の古代の進歩は、農業、法律、政治の分野における知識に関するものであった。[163]  ヨハネス・グーテンベルクが製作した印刷機のレプリカの写真 15世紀に印刷機が発明されたことにより、書物へのアクセスが大幅に拡大した。 中世では宗教的知識が中心的な関心事であり、ヨーロッパのカトリック教会のような宗教的機関が知的活動に影響を与えていた。[164] ユダヤ人社会では、宗教的テキストやユダヤ法を研究する中心地としてイェシバが設立された。[165] イスラム世界ではマドラサが設立され、イスラム法とイスラム哲学に重点が置かれた。[166] 古代の多くの知的業績は、8世紀から13世紀にかけてのイスラム黄金時代に保存、洗練、拡大された。 世紀から13世紀にかけてのイスラム黄金時代に、古代の多くの知的業績が保存され、洗練され、拡大された。 14世紀に始まるルネサンス期には、人文科学や自然科学への関心が再び高まった。[173] 15世紀には印刷機が発明され、書物の入手が容易になり、一般の人々の識字率が大幅に向上した。[174] これらの発展は、16世紀から17世紀にかけて始まる啓蒙時代の科学革命の基礎となった。これにより、物理学、化学、生物学、社会科学などの分野で知識が 爆発的に増大した。[175] この発展に伴う技術の進歩により、18世紀と19世紀に産業革命が可能となった。[176] 20世紀には、コンピュータとインターネットの発展により、知識の保存、共有、創造の方法が革命的に変化し、知識が大幅に拡大した。[177][n] |

| In various disciplines Religion See also: Desacralization of knowledge and Resacralization of knowledge Knowledge plays a central role in many religions. Knowledge claims about the existence of God or religious doctrines about how each one should live their lives are found in almost every culture.[179] However, such knowledge claims are often controversial and are commonly rejected by religious skeptics and atheists.[180] The epistemology of religion is the field of inquiry studying whether belief in God and in other religious doctrines is rational and amounts to knowledge.[181] One important view in this field is evidentialism, which states that belief in religious doctrines is justified if it is supported by sufficient evidence. Suggested examples of evidence for religious doctrines include religious experiences such as direct contact with the divine or inner testimony when hearing God's voice.[182] Evidentialists often reject that belief in religious doctrines amounts to knowledge based on the claim that there is not sufficient evidence.[183] A famous saying in this regard is due to Bertrand Russell. When asked how he would justify his lack of belief in God when facing his judgment after death, he replied "Not enough evidence, God! Not enough evidence."[184] However, religious teachings about the existence and nature of God are not always seen as knowledge claims by their defenders. Some explicitly state that the proper attitude towards such doctrines is not knowledge but faith. This is often combined with the assumption that these doctrines are true but cannot be fully understood by reason or verified through rational inquiry. For this reason, it is claimed that one should accept them even though they do not amount to knowledge.[180] Such a view is reflected in a famous saying by Immanuel Kant where he claims that he "had to deny knowledge in order to make room for faith."[185] Distinct religions often differ from each other concerning the doctrines they proclaim as well as their understanding of the role of knowledge in religious practice.[186] In both the Jewish and the Christian traditions, knowledge plays a role in the fall of man, in which Adam and Eve were expelled from the Garden of Eden. Responsible for this fall was that they ignored God's command and ate from the tree of knowledge, which gave them the knowledge of good and evil. This is seen as a rebellion against God since this knowledge belongs to God and it is not for humans to decide what is right or wrong.[187] In the Christian literature, knowledge is seen as one of the seven gifts of the Holy Spirit.[188] In Islam, "the Knowing" (al-ʿAlīm) is one of the 99 names reflecting distinct attributes of God. The Qur'an asserts that knowledge comes from Allah and the acquisition of knowledge is encouraged in the teachings of Muhammad.[189]  Oil painting showing Saraswati Saraswati is the goddess of knowledge and the arts in Hinduism. In Buddhism, knowledge that leads to liberation is called vijjā. It contrasts with avijjā or ignorance, which is understood as the root of all suffering. This is often explained in relation to the claim that humans suffer because they crave things that are impermanent. The ignorance of the impermanent nature of things is seen as the factor responsible for this craving.[190] The central goal of Buddhist practice is to stop suffering. This aim is to be achieved by understanding and practicing the teaching known as the Four Noble Truths and thereby overcoming ignorance.[191] Knowledge plays a key role in the classical path of Hinduism known as jñāna yoga or "path of knowledge". It aims to achieve oneness with the divine by fostering an understanding of the self and its relation to Brahman or ultimate reality.[192] Anthropology The anthropology of knowledge is a multi-disciplinary field of inquiry.[193] It studies how knowledge is acquired, stored, retrieved, and communicated.[194] Special interest is given to how knowledge is reproduced and changes in relation to social and cultural circumstances.[195] In this context, the term knowledge is used in a very broad sense, roughly equivalent to terms like understanding and culture.[196] This means that the forms and reproduction of understanding are studied irrespective of their truth value. In epistemology, by contrast, knowledge is usually restricted to forms of true belief. The main focus in anthropology is on empirical observations of how people ascribe truth values to meaning contents, like when affirming an assertion, even if these contents are false.[195] This also includes practical components: knowledge is what is employed when interpreting and acting on the world and involves diverse phenomena, such as feelings, embodied skills, information, and concepts. It is used to understand and anticipate events to prepare and react accordingly.[197] The reproduction of knowledge and its changes often happen through some form of communication used to transfer knowledge.[198] This includes face-to-face discussions and online communications as well as seminars and rituals. An important role in this context falls to institutions, like university departments or scientific journals in the academic context.[195] Anthropologists of knowledge understand traditions as knowledge that has been reproduced within a society or geographic region over several generations. They are interested in how this reproduction is affected by external influences. For example, societies tend to interpret knowledge claims found in other societies and incorporate them in a modified form.[199] Within a society, people belonging to the same social group usually understand things and organize knowledge in similar ways to one another. In this regard, social identities play a significant role: people who associate themselves with similar identities, like age-influenced, professional, religious, and ethnic identities, tend to embody similar forms of knowledge. Such identities concern both how a person sees themselves, for example, in terms of the ideals they pursue, as well as how other people see them, such as the expectations they have toward the person.[200] Sociology Main article: Sociology of knowledge The sociology of knowledge is the subfield of sociology that studies how thought and society are related to each other.[201] Like the anthropology of knowledge, it understands "knowledge" in a wide sense that encompasses philosophical and political ideas, religious and ideological doctrines, folklore, law, and technology. The sociology of knowledge studies in what sociohistorical circumstances knowledge arises, what consequences it has, and on what existential conditions it depends. The examined conditions include physical, demographic, economic, and sociocultural factors. For instance, philosopher Karl Marx claimed that the dominant ideology in a society is a product of and changes with the underlying socioeconomic conditions.[201] Another example is found in forms of decolonial scholarship that claim that colonial powers are responsible for the hegemony of Western knowledge systems. They seek a decolonization of knowledge to undermine this hegemony.[202] A related issue concerns the link between knowledge and power, in particular, the extent to which knowledge is power. The philosopher Michel Foucault explored this issue and examined how knowledge and the institutions responsible for it control people through what he termed biopower by shaping societal norms, values, and regulatory mechanisms in fields like psychiatry, medicine, and the penal system.[203] A central subfield is the sociology of scientific knowledge, which investigates the social factors involved in the production and validation of scientific knowledge. This encompasses examining the impact of the distribution of resources and rewards on the scientific process, which leads some areas of research to flourish while others languish. Further topics focus on selection processes, such as how academic journals decide whether to publish an article and how academic institutions recruit researchers, and the general values and norms characteristic of the scientific profession.[204] Others Formal epistemology studies knowledge using formal tools found in mathematics and logic.[205] An important issue in this field concerns the epistemic principles of knowledge. These are rules governing how knowledge and related states behave and in what relations they stand to each other. The transparency principle, also referred to as the luminosity of knowledge, states that it is impossible for someone to know something without knowing that they know it.[o][206] According to the conjunction principle, if a person has justified beliefs in two separate propositions, then they are also justified in believing the conjunction of these two propositions. In this regard, if Bob has a justified belief that dogs are animals and another justified belief that cats are animals, then he is justified to believe the conjunction that both dogs and cats are animals. Other commonly discussed principles are the closure principle and the evidence transfer principle.[207] Knowledge management is the process of creating, gathering, storing, and sharing knowledge. It involves the management of information assets that can take the form of documents, databases, policies, and procedures. It is of particular interest in the field of business and organizational development, as it directly impacts decision-making and strategic planning. Knowledge management efforts are often employed to increase operational efficiency in attempts to gain a competitive advantage.[208] Key processes in the field of knowledge management are knowledge creation, knowledge storage, knowledge sharing, and knowledge application. Knowledge creation is the first step and involves the production of new information. Knowledge storage can happen through media like books, audio recordings, film, and digital databases. Secure storage facilitates knowledge sharing, which involves the transmission of information from one person to another. For the knowledge to be beneficial, it has to be put into practice, meaning that its insights should be used to either improve existing practices or implement new ones.[209] Knowledge representation is the process of storing organized information, which may happen using various forms of media and also includes information stored in the mind.[210] It plays a key role in the artificial intelligence, where the term is used for the field of inquiry that studies how computer systems can efficiently represent information. This field investigates how different data structures and interpretative procedures can be combined to achieve this goal and which formal languages can be used to express knowledge items. Some efforts in this field are directed at developing general languages and systems that can be employed in a great variety of domains while others focus on an optimized representation method within one specific domain. Knowledge representation is closely linked to automatic reasoning because the purpose of knowledge representation formalisms is usually to construct a knowledge base from which inferences are drawn.[211] Influential knowledge base formalisms include logic-based systems, rule-based systems, semantic networks, and frames. Logic-based systems rely on formal languages employed in logic to represent knowledge. They use linguistic devices like individual terms, predicates, and quantifiers. For rule-based systems, each unit of information is expressed using a conditional production rule of the form "if A then B". Semantic nets model knowledge as a graph consisting of vertices to represent facts or concepts and edges to represent the relations between them. Frames provide complex taxonomies to group items into classes, subclasses, and instances.[212] Pedagogy is the study of teaching methods or the art of teaching.[p] It explores how learning takes place and which techniques teachers may employ to transmit knowledge to students and improve their learning experience while keeping them motivated.[214] There is a great variety of teaching methods and the most effective approach often depends on factors like the subject matter and the age and proficiency level of the learner.[215] In teacher-centered education, the teacher acts as the authority figure imparting information and directing the learning process. Student-centered approaches give a more active role to students with the teacher acting as a coach to facilitate the process.[216] Further methodological considerations encompass the difference between group work and individual learning and the use of instructional media and other forms of educational technology.[217] |