クワクワカワク

Kwakwaka'wakw

Crooked

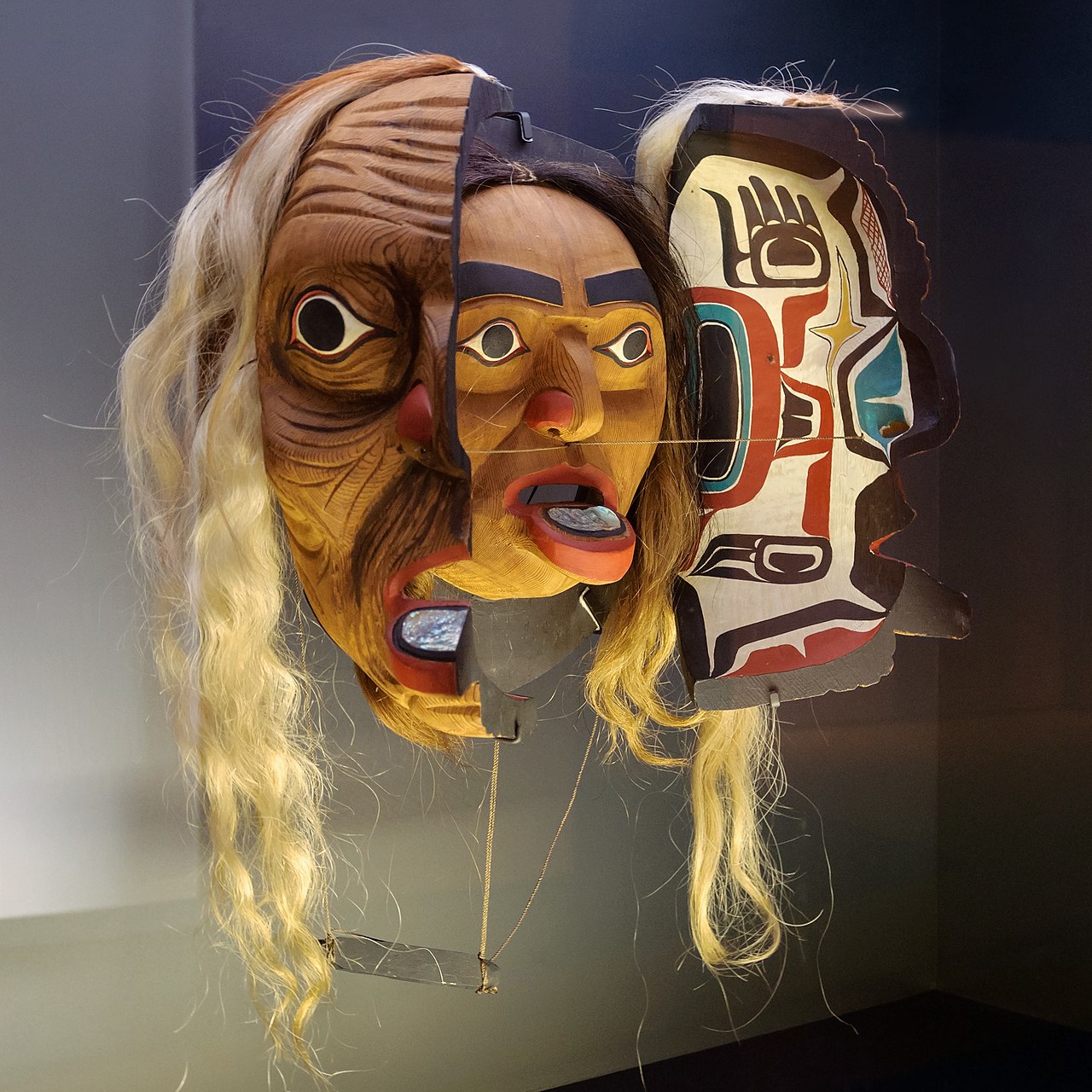

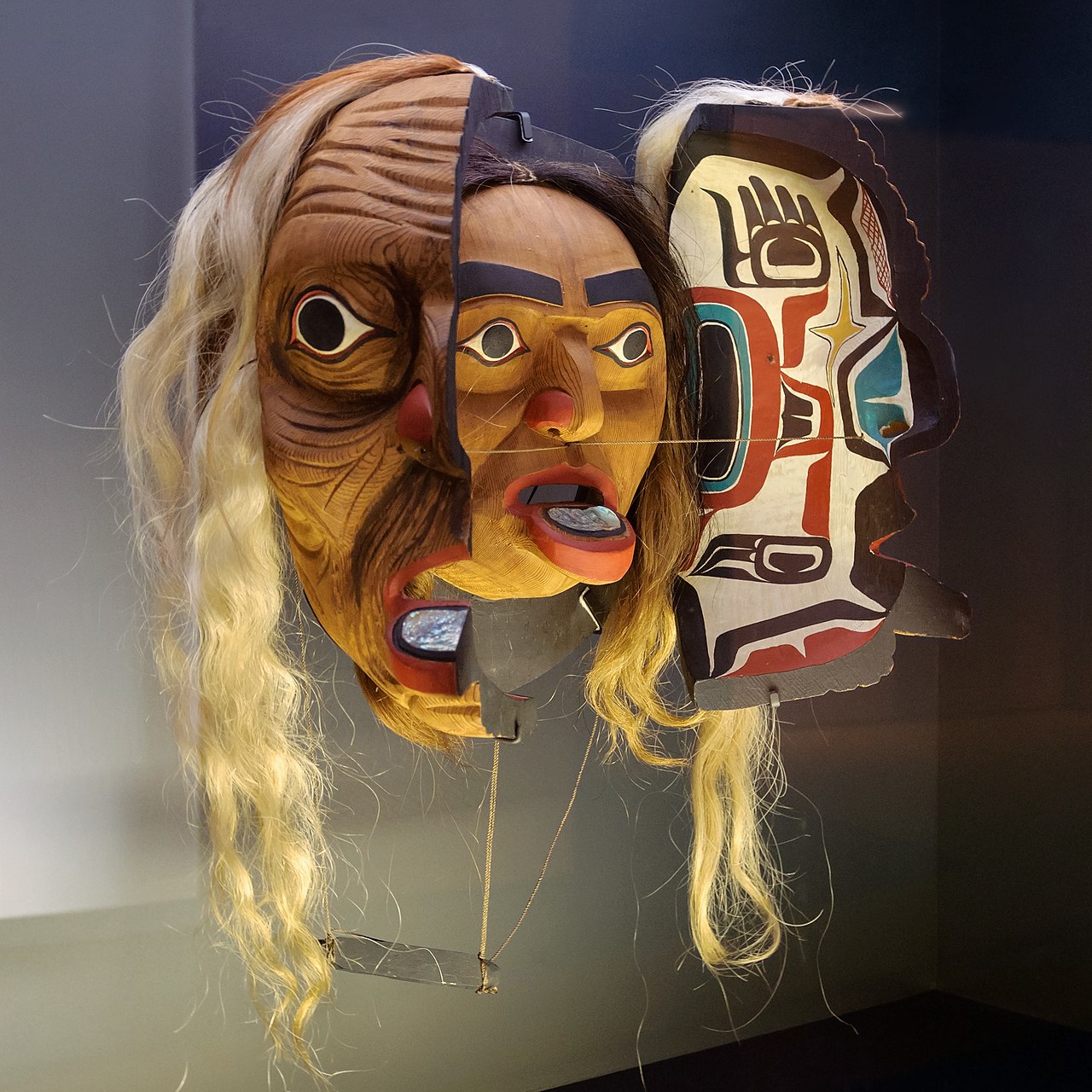

Beak of Heaven Mask, Kawakwaka'wakw, British Columbia/ https://sogdatacentre.ca/people/first-nations/

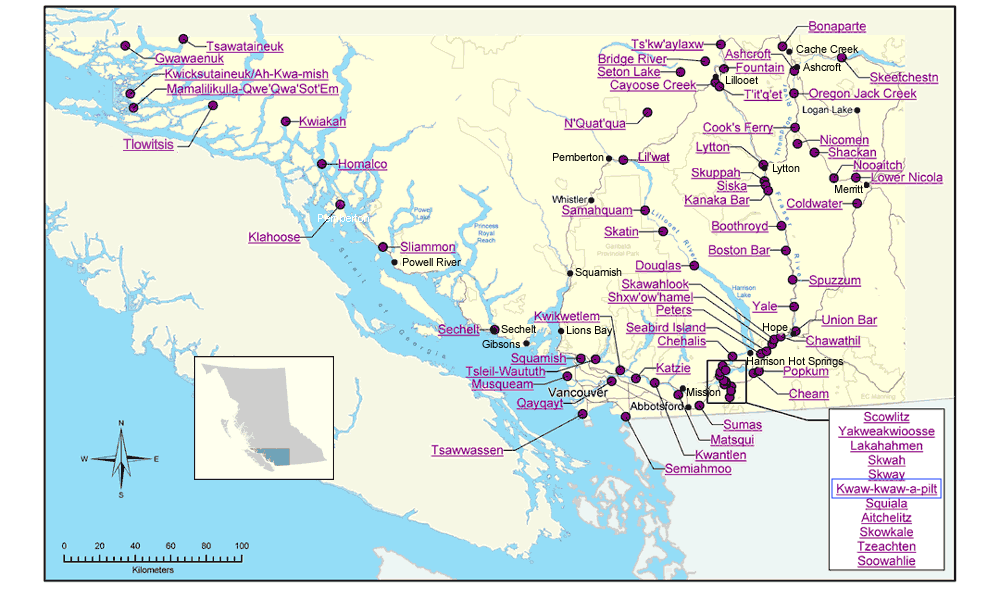

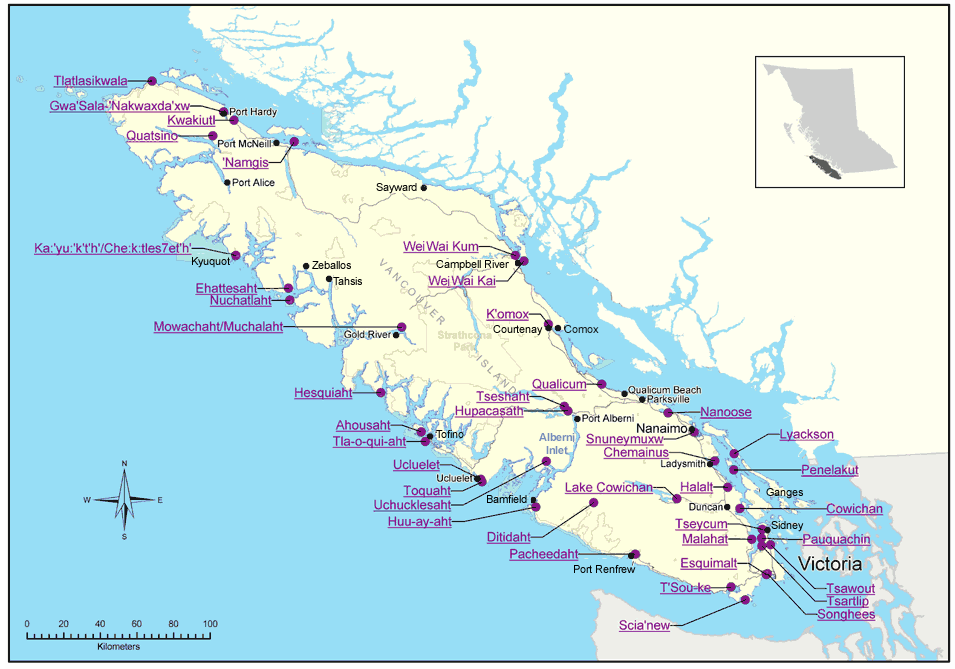

☆ クワクワカワク(the Kwakwa̱ka̱'wakw)は、太平洋岸北西部の先住民族のひとつである。2016年の国勢調査による現在の人口は3,665人である。ほとんどがバンクーバー島北部、ディスカバ リー諸島を含む近隣の小さな島々、そして隣接するブリティッシュ・コロンビア本土の伝統的な領土に住んでいる。一部はビクトリアやバンクーバーなどの都市 部にも居住している。彼らは13のバンド政府に政治的に組織されている。

| The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw

(IPA: [ˈkʷakʷəkʲəʔwakʷ]), also known as the Kwakiutl[2][3]

(/ˈkwɑːkjʊtəl/; "Kwakʼwala-speaking peoples"),[4][5] are one of the

indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast. Their current

population, according to a 2016 census, is 3,665. Most live in their

traditional territory on northern Vancouver Island, nearby smaller

islands including the Discovery Islands, and the adjacent British

Columbia mainland. Some also live outside their homelands in urban

areas such as Victoria and Vancouver. They are politically organized

into 13 band governments. Their language, now spoken by only 3.1% of the population, consists of four dialects of what is commonly referred to as Kwakʼwala. These dialects are Kwak̓wala, ʼNak̓wala, G̱uc̓ala and T̓łat̓łasik̓wala.[6]  |

ク

ワクワ̱カ̱ワク(IPA: [ˈkʷakʷəkʷ)[2][3] (/ˈkʷ)[4][5]

は、太平洋岸北西部の先住民族のひとつである。2016年の国勢調査による現在の人口は3,665人である。ほとんどがバンクーバー島北部、ディスカバ

リー諸島を含む近隣の小さな島々、そして隣接するブリティッシュ・コロンビア本土の伝統的な領土に住んでいる。一部はビクトリアやバンクーバーなどの都市

部にも居住している。彼らは13のバンド政府に政治的に組織されている。 現在では人口の3.1%しか話されていない彼らの言語は、一般的にKwakʼwalaと呼ばれる4つの方言から構成されている。これらの方言はKwak̓wala、ʼNak̓wala、Gn_331↩uc̓wala、T̓łat̓wasik̓walaである[6]。  |

Name Wawaditʼla, also known as Mungo Martin House, a Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw "big house", with totem pole. Built by Chief Mungo Martin in 1953. Located at Thunderbird Park in Victoria, British Columbia.[7] The name Kwakiutl derives from Kwaguʼł—the name of a single community of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw located at Fort Rupert. The anthropologist Franz Boas had done most of his anthropological work in this area and popularized the term for both this nation and the collective as a whole. The term became misapplied to mean all the nations who spoke Kwakʼwala, as well as three other Indigenous peoples whose language is a part of the Wakashan linguistic group, but whose language is not Kwakʼwala. These peoples, incorrectly known as the Northern Kwakiutl, were the Haisla, Wuikinuxv, and Heiltsuk. Many people who others call "Kwakiutl" consider that name a misnomer. They prefer the name Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, which means "Kwakʼwala-speaking-peoples".[8] One exception is the Laich-kwil-tach at Campbell River—they are known as the Southern Kwakiutl, and their council is the Kwakiutl District Council. |

名称 Wawaditʼla、別名Mungo Martin House、Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの「大きな家」で、トーテムポールがある。1953年にマンゴ・マーティン酋長によって建てられた。ブリティッ シュ・コロンビア州ビクトリアのサンダーバード・パークにある[7]。 クワキウトルという名前は、フォート・ルパートにあったクワクワ̱カ̱ワクワの単一コミュニティの名前であるクワグ̱ウに由来する。人類学者フランツ・ ボースは人類学的研究のほとんどをこの地域で行い、この民族と集団全体を指す言葉として広めた。この言葉は、Kwakʼwalaを話すすべての民族と、 Wakashan言語グループの一部ではあるがKwakʼwalaではない言語を話す他の3つの先住民族を意味する言葉として誤用されるようになった。こ れらの民族は誤ってノーザン・クワキウトルと呼ばれ、ヘイスラ族、ウイキヌクスフ族、ハイルツク族である。 他の人々が "クワキウトル "と呼ぶ人々の多くは、その呼び名が誤りであると考えている。彼らは「クワクワラ語を話す民族」を意味するKwakwa̱ka̱wakwという名称を好ん でいる[8]。キャンベル・リバーのLaich-kwil-tachは例外で、彼らは南クワキウトル族として知られており、彼らの評議会はクワキウトル地 区評議会(Kwakiutl District Council)である。 |

| History Grave Marker, Gwaʼsa̱la Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw (Native American), late 19th century, Brooklyn Museum. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw oral history says their ancestors (ʼnaʼmima) came in the forms of animals by way of land, sea, or underground. When one of these ancestral animals arrived at a given spot, it discarded its animal appearance and became human. Animals that figure in these origin myths include the Thunderbird, his brother Kolas, the seagull, orca, grizzly bear, or chief ghost. Some ancestors have human origins and are said to come from distant places.[9] Historically, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw economy was based primarily on fishing, with the men also engaging in some hunting, and the women gathering wild fruits and berries. Ornate weaving and woodwork were important crafts, and wealth, defined by slaves and material goods, was prominently displayed and traded at potlatch ceremonies. These customs were the subject of extensive study by the anthropologist Franz Boas. In contrast to most non-native societies, wealth and status were not determined by how much you had, but by how much you had to give away. This act of giving away your wealth was one of the main acts in a potlatch. The first documented contact with Europeans was with Captain George Vancouver in 1792. Disease, which developed as a result of direct contact with European settlers along the West Coast of Canada, drastically reduced the Indigenous Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population during the late 19th-early 20th century. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw population dropped by 75% between 1830 and 1880.[10] The 1862 Pacific Northwest smallpox epidemic alone killed over half of the people. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw dancers from Vancouver Island performed at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago.[11] An account of experiences of two founders of early residential schools for Aboriginal children was published in 2006 by the University of British Columbia Press. Good Intentions Gone Awry – Emma Crosby and the Methodist Mission On the Northwest Coast[12] by Jan Hare and Jean Barman contains the letters and account of the life of the wife of Thomas Crosby the first missionary in Lax Kwʼalaams (Port Simpson). This covers the period from 1870 to the turn of the 20th century. A second book was published in 2005 by the University of Calgary Press, The Letters of Margaret Butcher – Missionary Imperialism on the North Pacific Coast[13] edited by Mary-Ellen Kelm. It picks up the story from 1916 to 1919 in Kitamaat Village and details of Butcher's experiences among the Haisla people. A review article entitled Mothers of a Native Hell[14] about these two books was published in the British Columbia online news magazine The Tyee in 2007. Restoring their ties to their land, culture and rights, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw have undertaken much in bringing back their customs, beliefs and language. Potlatches occur more frequently as families reconnect to their birthright, and the community uses language programs, classes and social events to restore the language. Artists in the 19th and 20th centuries, such as Mungo Martin, Ellen Neel and Willie Seaweed have taken efforts to revive Kwakwakaʼwakw art and culture. Divisions Each Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nation has its own clans, chiefs, history, culture and peoples, but remain collectively similar to the rest of the Kwak̓wala-Speaking nations.  |

歴史 墓標、Gwaʼsa̱la Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw(ネイティブ・アメリカン)、19世紀後半、ブルックリン博物館。 Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwのオーラルヒストリーによると、彼らの祖先(ʼnaʼmima)は陸、海、地下を通り、動物の姿をしてやってきたという。こ れらの祖先の動物のひとつがある場所に到着すると、動物の姿を捨てて人間になったという。これらの起源神話に登場する動物には、サンダーバード、その兄弟 コラス、カモメ、シャチ、グリズリーベア、幽霊の長などがいる。一部の祖先は人間に起源を持ち、遠い場所からやってきたと言われている[9]。 歴史的に、クワクワ族の経済は主に漁業に基づいており、男性は狩猟にも従事し、女性は野生の果物やベリーを採集していた。華麗な織物や木工細工は重要な工 芸品であり、奴隷や物資によって定義される富はポトラッチの儀式で盛んに展示され、取引された。これらの習慣は、人類学者フランツ・ボースによる広範な研 究の対象となった。ほとんどの非ネイティブ社会とは対照的に、富と地位はどれだけ持っているかではなく、どれだけ手放さなければならないかによって決定さ れた。この富を与えるという行為は、ポトラッチにおける主要な行為のひとつであった。 記録に残るヨーロッパ人との最初の接触は、1792年のジョージ・バンクーバー船長である。カナダ西海岸でヨーロッパ人入植者と直接接触した結果発症した 病気が、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて先住民クワクワ族の人口を激減させた。Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの人口は1830年から1880年の間 に75%減少した[10]。1862年の太平洋岸北西部での天然痘の流行だけで半数以上が死亡した。 1893年にシカゴで開催されたコロンブス万国博覧会では、バンクーバー島のクワクワクワ族のダンサーがパフォーマンスを披露した[11]。 アボリジニの子供たちのための初期のレジデンシャル・スクールの創設者2人の体験談が、2006年にブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学出版局から出版され た。Jan HareとJean Barmanによる『Good Intentions Gone Awry - Emma Crosby and the Methodist Mission On the Northwest Coast』[12]には、Lax Kwʼalaams(ポート・シンプソン)で最初の宣教師となったThomas Crosbyの妻の手紙と生涯の記録が収められている。これは1870年から20世紀初頭までをカバーしている。 2005年にはカルガリー大学出版局から、メアリー=エレン・ケルム編『The Letters of Margaret Butcher - Missionary Imperialism on the North Pacific Coast』[13]という2冊目の本が出版された。本書は1916年から1919年にかけてのキタマアト村での物語と、ブッチャーのヘイスラ族での体験 の詳細を取り上げている。 この2冊の本についての『Mothers of a Native Hell』[14]と題されたレビュー記事が、2007年にブリティッシュ・コロンビア州のオンライン・ニュース誌『The Tyee』に掲載された。 自分たちの土地、文化、権利との結びつきを取り戻したクワクワ族は、自分たちの習慣、信仰、言語を取り戻すために多くのことに取り組んできた。ポトラッチ は家族が自分たちの生得権に再びつながるために頻繁に開催され、コミュニティは言語プログラム、クラス、社交イベントを使って言語を回復している。マン ゴ・マーティン、エレン・ニール、ウィリー・シーウィードなど、19世紀から20世紀にかけて活躍した芸術家たちは、クワクワクワクワの芸術と文化を復興 させるために尽力した。 ディビジョン それぞれのクワクワクワ族は独自の氏族、酋長、歴史、文化、民族を持つが、他のクワクワ語を話す民族と似ている。  |

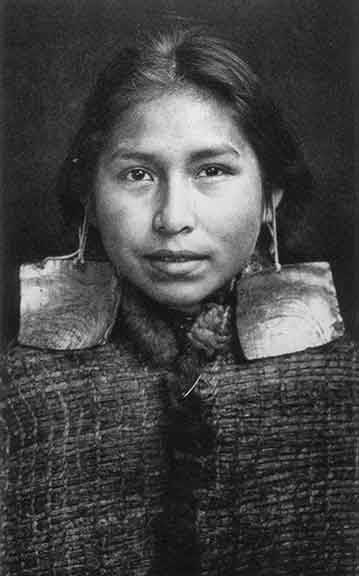

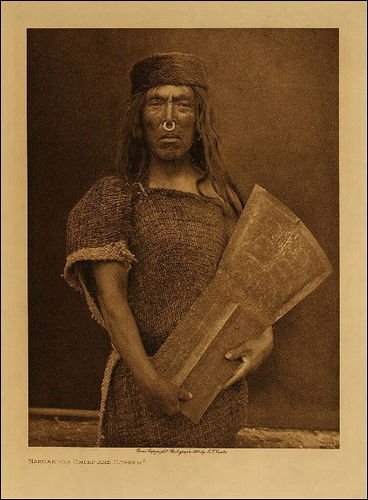

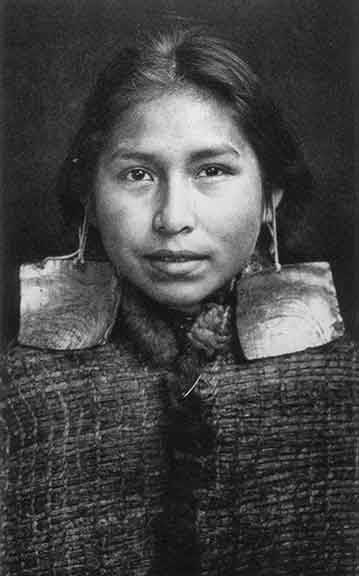

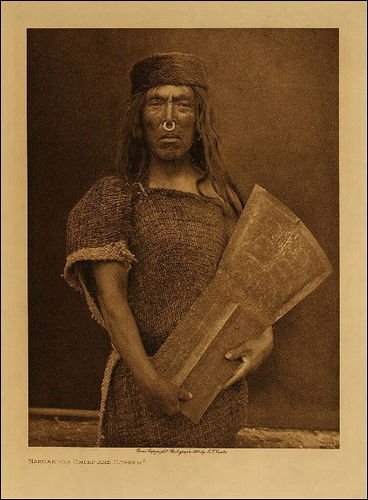

Society Dzawa̱da̱ʼenux̱w[17] girl, Margaret Frank (née Wilson)[18] wearing abalone shell earrings, a sign of nobility and worn only by members of this class.[19] Kinship Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw kinship is based on a bilinear structure, with loose characteristics of a patrilineal culture. It has large extended families and interconnected community life. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are made up of numerous communities or bands. Within those communities they are organized into extended family units or naʼmima, which means 'of one kind'. Each naʼmima had positions that carried particular responsibilities and privileges. Each community had around four naʼmima, although some had more, some had less. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw follow their genealogy back to their ancestral roots. A head chief who, through primogeniture, could trace his origins to that naʼmima's ancestors delineated the roles throughout the rest of his family. Every clan had several sub-chiefs, who gained their titles and position through their own family's primogeniture. These chiefs organized their people to harvest the communal lands that belonged to their family. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw society was organized into four classes: the nobility, attained through birthright and connection in lineage to ancestors, the aristocracy who attained status through connection to wealth, resources or spiritual powers displayed or distributed in the potlatch, commoners, and slaves. On the nobility class, "the noble was recognized as the literal conduit between the social and spiritual domains, birthright alone was not enough to secure rank: only individuals displaying the correct moral behavior [sic] throughout their life course could maintain ranking status."[20] Property As in other Northwest Coast peoples, the concept of property was well developed and important to daily life. Territorial property such as hunting or fishing grounds was inherited, and from these properties material wealth was collected and stored.[21] Economy A trade and barter subsistence economy formed the early stages of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw economy. Trade was carried out between internal Kwakwakaʼwakw nations, as well as surrounding Indigenous nations such as the Tsimshian, Tlingit, the Nuu-chah-nulth and Coast Salish peoples.  Man with copper piece, hammered in the characteristic "T" shape. Photo taken by Edward S. Curtis. Over time, the potlatch tradition created a demand for stored surpluses, as such a display of wealth had social implications. By the time of European colonialism, it was noted that wool blankets had become a form of common currency. In the potlatch tradition, hosts of the potlatch were expected to provide enough gifts for all the guests invited.[22] This practice created a system of loan and interest, using wool blankets as currency.[23] As with other Pacific Northwest nations, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw highly valued copper in their economy and used it for ornament and precious goods.[23] Scholars have proposed that prior to trade with Europeans, the people acquired copper from natural copper veins along riverbeds, but this has not been proven. Contact with European settlers, particularly through the Hudson's Bay Company, brought an influx of copper to their territories. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw nations also were aware of silver and gold, and crafted intricate bracelets and jewellery from hammered coins traded from European settlers.[24] Copper was given a special value amongst the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, most likely for its ceremonial purposes. This copper was beaten into sheets or plates, and then painted with mythological figures.[23] The sheets were used for decorating wooden carvings or kept for the sake of prestige. Individual pieces of copper were sometimes given names based on their value.[23] The value of any given piece was defined by the number of wool blankets last traded for them. In this system, it was considered prestigious for a buyer to purchase the same piece of copper at a higher price than it was previously sold, in their version of an art market.[23] During potlatch, copper pieces would be brought out, and bids were placed on them by rival chiefs. The highest bidder would have the honour of buying said copper piece.[23] If a host still held a surplus of copper after throwing an expensive potlatch, he was considered a wealthy and important man.[23] Highly ranked members of the communities often have the Kwakʼwala word for "copper" as part of their names.[23] Copper's importance as an indicator of status also led to its use in a Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shaming ritual. The copper cutting ceremony involved breaking copper plaques. The act represents a challenge; if the target cannot break a plaque of equal or greater value, he or she is shamed. The ceremony, which had not been performed since the 1950s, was revived by chief Beau Dick in 2013, as part of the Idle No More movement. He performed a copper cutting ritual on the lawn of the British Columbia Legislature on February 10, 2013, to ritually shame the Stephen Harper government.[25] |

社会 Dzawa̱da̱̱w[17]の少女、マーガレット・フランク(旧姓ウィルソン)[18]は、貴族の証であり、この階級の者だけが身につけるアワビの貝殻のイヤリングをつけていた[19]。 親族関係 Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの親族関係は、父系文化の緩やかな特徴を持つ二系統構造に基づいている。大家族を持ち、相互に結びついた共同生活を営んでい る。Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は多数のコミュニティやバンドで構成されている。それらのコミュニティの中で、彼らは拡大家族単位、つまり「一種類 の」という意味のnaʼmimaに組織されている。それぞれのnaʼmimaには、特定の責任と特権を担う役職があった。各コミュニティにはおよそ4人の naʼmimaがいたが、もっと多い人もいれば少ない人もいた。 Kwakwa̱ka̱̱wakwは祖先のルーツまで系譜をたどる。先祖代々、そのnaʼmimaの祖先まで遡ることができる首長が、他の一族全体の役割を 明確にした。どの氏族にも何人かのサブチーフがおり、彼らは一族の先祖代々続く血筋によって称号と地位を得ていた。これらの酋長は、一族に属する共同所有 地を収穫するために民衆を組織した。 クワクワ̱カ̱ワクフ族の社会は4つの階級で組織されていた:生得権と祖先との血縁によって得られる貴族、ポトラッチで示されたり分配されたりする富や資 源、精神的な力とのつながりによって地位を得る貴族、平民、奴隷。貴族階級では、「貴族は社会的領域と精神的領域の間の文字通りのパイプ役として認識さ れ、生得権だけでは位階を確保するのに十分ではなかった:生涯を通じて正しい道徳的行動[中略]を示す個人だけが位階を維持することができた」[20]。 財産 他の北西海岸の民族と同様に、財産の概念は発達しており、日常生活にとって重要であった。狩猟場や漁場などの領土財産は相続され、これらの財産から物質的な富が集められ、蓄えられた[21]。 経済 交易と物々交換の自給自足経済がクワクワ̱カ̱ワクワ経済の初期段階を形成していた。交易はクワクワクワクワの内部だけでなく、ツィムシャン族、トリンギット族、ヌウ・チャ・ヌルス族、コースト・サリッシュ族といった周辺の先住民族との間でも行われていた。  特徴的な "T "の形に打ち出された銅片を持つ男。エドワード・S・カーティス撮影。 時が経つにつれ、ポトラッチの伝統は余剰品を貯蔵する需要を生み出した。ヨーロッパの植民地支配の時代には、ウールの毛布が一種の共通通貨になっていた。 ポトラッチの伝統では、ポトラッチのホストは招待されたゲスト全員に十分な贈り物を用意することが期待されていた[22]。この慣習は、ウールブランケッ トを通貨として使用する貸借と利息のシステムを生み出した[23]。 他の太平洋岸北西部の国々と同様に、クワクワ族はその経済において銅を非常に重要視しており、装飾品や貴重品に使用していた[23]。ヨーロッパ人入植 者、特にハドソンズ・ベイ・カンパニーとの接触は、彼らの領土に銅の流入をもたらした。Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は銀や金も知っており、ヨーロッパ 人入植者から取引されたコインをハンマーで叩いて複雑なブレスレットやジュエリーを作っていた[24]。銅はKwakwa̱ka̱wakw族の間で特別な 価値を与えられていたが、それはおそらく儀式用であった。この銅は叩いて板やプレートにされ、神話の人物像が描かれた[23]。板は木彫りの装飾に使われ たり、威信のために保管された。 個々の銅片には、その価値に基づいて名前が付けられることもあった[23]。どの銅片の価値も、最後に取引された毛布の枚数によって定義された。このシス テムでは、買い手は同じ銅片を以前売られたときよりも高い値段で購入することが名声につながると考えられていた。ポトラッチでは銅片が持ち出され、ライバ ルの首長たちによって入札が行われた。もしホストが高価なポトラッチをした後でもまだ銅の余剰を持っていれば、彼は裕福で重要な人物であるとみなされた [23]。コミュニティの高位のメンバーは、しばしば名前の一部として「銅」を意味するKwakʼwala語を持つ[23]。 地位の指標としての銅の重要性は、Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの辱めの儀式にも使われるようになった。銅を切る儀式では、銅板を割る。この行為は挑戦を 意味し、もし対象者が同等かそれ以上の価値のあるプレートを壊すことができなければ、その人は辱めを受けることになる。1950年代以来行われていなかっ たこの儀式は、2013年にボー・ディック酋長によってアイドル・ノー・モア運動の一環として復活した。彼は2013年2月10日、ブリティッシュ・コロ ンビア州議会の芝生で銅を切る儀式を行い、スティーブン・ハーパー政権を儀式的に辱めた[25]。 |

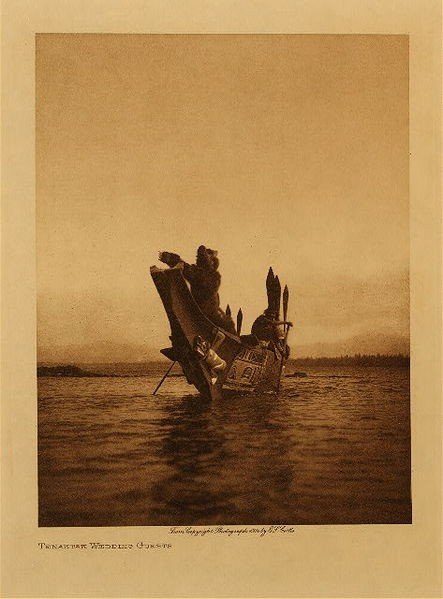

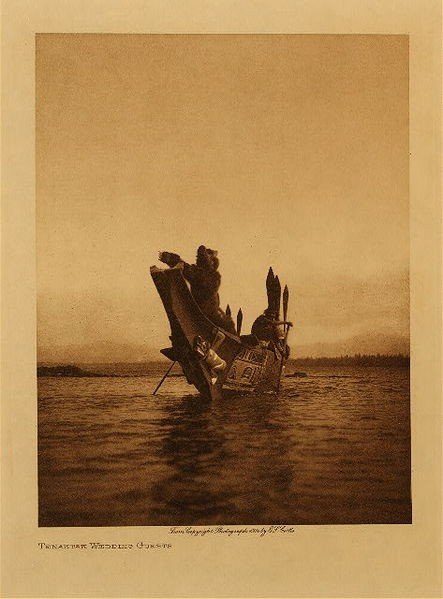

Culture Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw canoe welcoming with masks and traditional dug out cedar canoes. On bow is dancer in Bear regalia. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are a highly stratified bilineal culture of the Pacific Northwest. They are many separate nations, each with its own history, culture and governance. The Nations commonly each had a head chief, who acted as the leader of the nation, with numerous hereditary clan or family chiefs below him. In some of the nations, there also existed Eagle Chiefs, but this was a separate society within the main society and applied to the potlatching only. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw are one of the few bilineal cultures. Traditionally the rights of the family would be passed down through the paternal side, but in rare occasions, the rights could pass on the maternal side of their family also. Within the pre-colonization times, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw were organized into three classes: nobles, commoners, and slaves. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw shared many cultural and political alliances with numerous neighbours in the area, including the Nuu-chah-nulth, Heiltsuk, Wuikinuxv and some Coast Salish. Language The Kwakʼwala language is a part of the Wakashan language group. Word lists and some documentation of Kwakʼwala were created from the early period of contact with Europeans in the 18th century, but a systematic attempt to record the language did not occur before the work of Franz Boas in the late 19th and early 20th century. The use of Kwakʼwala declined significantly in the 19th and 20th centuries, mainly due to the assimilationist policies of the Canadian government. Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw children were forced to attend residential schools, which enforced English use and discouraged other languages. Although Kwakʼwala and Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw culture have been well-studied by linguists and anthropologists, these efforts did not reverse the trends leading to language loss. According to Guy Buchholtzer, "The anthropological discourse had too often become a long monologue, in which the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw had nothing to say."[26] As a result of these pressures, there are relatively few Kwakʼwala speakers today. Most remaining speakers are past the age of child-rearing, which is considered a crucial stage for language transmission. As with many other Indigenous languages, there are significant barriers to language revitalization.[27] Another barrier separating new learners from the native speaker is the presence of four separate orthographies; the young are taught Uʼmista or NAPA, while the older generations generally use Boaz, developed by the American anthropologist Franz Boas. A number of revitalization efforts are underway. A 2005 proposal to build a Kwakwakaʼwakw First Nations Centre for Language Culture has gained wide support.[28] A review of revitalization efforts in the 1990s showed that the potential to fully revitalize Kwakʼwala still remained, but serious hurdles also existed.[29] Arts  "Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw transformation mask". In the old times, the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw believed that art symbolized a common underlying element shared by all species.[30] Kwakwakaʼwakw arts consist of a diverse range of crafts, including totems, masks, textiles, jewellery and carved objects, ranging in size from transformation masks to 40 ft (12 m) tall totem poles. Cedar wood was the preferred medium for sculpting and carving projects as it was readily available in the native Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw regions. Totems were carved with bold cuts, a relative degree of realism, and an emphatic use of paints. Masks make up a large portion of Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw art, as masks are important in the portrayal of the characters central to Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw dance ceremonies. Woven textiles included the Chilkat blanket, dance aprons and button cloaks, each patterned with Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw designs. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw used a variety of objects for jewellery, including ivory, bone, abalone shell, copper, silver and more. Adornments were frequently found on the clothes of important persons. Music Kwakwakaʼwakw music is the ancient art of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw peoples. The music is an ancient art form, stretching back thousands of years. The music is used primarily for ceremony and ritual, and is based on percussive instrumentation, especially log, box, and hide drums, as well as rattles and whistles. The four-day Klasila festival is an important cultural display of song and dance and masks; it occurs just before the advent of the tsetseka, or winter. Ceremonies and events Potlatch  Showing of masks at Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw potlatch.  Speaker Figure, 19th century, Brooklyn Museum, the figure represents a speaker at a potlatch. An orator standing behind the figure would have spoken through its mouth, announcing the names of arriving guests. The potlatch culture of the Northwest is well known and widely studied. It is still practised among the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw, as is the lavish artwork for which they and their neighbours are so renowned. The phenomenon of the potlatch, and the vibrant societies and cultures associated with it, can be found in Chiefly Feasts: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch, which details the incredible artwork and legendary material that go with the other aspects of the potlatch, and gives a glimpse into the high politics and great wealth and power of the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw chiefs. When the Canadian government was focused on assimilation of First Nations, it made the potlatch a target of activities to be suppressed. Missionary William Duncan wrote in 1875 that the potlatch was "by far the most formidable of all obstacles in the way of Indians becoming Christians, or even civilized".[31] In 1885, the Indian Act was revised to include clauses banning the potlatch and making it illegal to practise. The official legislation read, Every Indian or other person who engages in or assists in celebrating the Indian festival known as the "Potlatch" or the Indian dance known as the "Tamanawas" is guilty of a misdemeanour, and shall be liable to imprisonment for a term not more than six nor less than two months in a jail or other place of confinement; and, any Indian or other person who encourages, either directly or indirectly an Indian or Indians to get up such a festival or dance, or to celebrate the same, or who shall assist in the celebration of same is guilty of a like offence, and shall be liable to the same punishment. Oʼwax̱a̱laga̱lis, Chief of the Kwaguʼł "Fort Rupert Tribes", said to anthropologist Franz Boas on October 7, 1886, when he arrived to study their culture: We want to know whether you have come to stop our dances and feasts, as the missionaries and agents who live among our neighbors [sic] try to do. We do not want to have anyone here who will interfere with our customs. We were told that a man-of-war would come if we should continue to do as our grandfathers and great-grandfathers have done. But we do not mind such words. Is this the white man's land? We are told it is the Queen's land, but no! It is mine. Where was the Queen when our God gave this land to my grandfather and told him, "This will be thine"? My father owned the land and was a mighty Chief; now it is mine. And when your man-of-war comes, let him destroy our houses. Do you see yon trees? Do you see yon woods? We shall cut them down and build new houses and live as our fathers did. We will dance when our laws command us to dance, and we will feast when our hearts desire to feast. Do we ask the white man, "Do as the Indian does"? It is a strict law that bids us dance. It is a strict law that bids us distribute our property among our friends and neighbors. It is a good law. Let the white man observe his law; we shall observe ours. And now, if you come to forbid us dance, be gone. If not, you will be welcome to us. Eventually the Act was amended, expanded to prohibit guests from participating in the potlatch ceremony. The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw were too numerous to police, and the government could not enforce the law. Duncan Campbell Scott convinced Parliament to change the offence from criminal to summary, which meant "the agents, as justice of the peace, could try a case, convict, and sentence".[32] Sustaining the customs and culture of their ancestors, in the 21st century the Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw openly hold potlatches to commit to the revival of their ancestors' ways. The frequency of potlatches has increased as occur frequently and increasingly more over the years as families reclaim their birthright. Housing and shelter The Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw built their houses from cedar planks, which are highly water resistant. They were very large, anywhere from 50 to 100 ft (15 to 30 m) long. The houses could hold about 50 people, usually families from the same clan. At the entrance, there was usually a totem pole carved with different animals, mythological figures and family crests. Clothing and regalia In summer, men wore no clothing except jewelry. In the winter, they usually rubbed fat on themselves to keep warm. In battle the men wore red cedar armor and helmets, and breech clouts made from cedar. During ceremonies they wore circles of cedar bark on their ankles as well as cedar breech clouts. The women wore skirts of softened cedar, and a cedar or wool blanket on top during the winter. Transportation  A Kwakwakaʼwakw canoe Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw transportation was similar to that of other coastal people. Being an ocean and coastal people, they travelled mainly by canoe. Cedar dugout canoes, each made from one log, would be carved for use by individuals, families and communities. Sizes varied from ocean-going canoes, for long sea-worthy travel in trade missions, to smaller local canoes for inter-village travel. Some boats had buffalo fur inside to keep protection from the cold winters. |

文化 クワクワ̱カ̱カヌーが仮面と伝統的な杉のカヌーで歓迎する。船首には熊の衣装をまとったダンサーがいる。 Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は、太平洋岸北西部の高度に階層化されたバイライン文化である。彼らは多くの独立した国家であり、それぞれが独自の歴史、 文化、統治を持っている。各民族には通常、国のリーダーとして機能する首長がおり、その下に多数の世襲的な氏族や家族の首長がいた。いくつかの国にはイー グル・チーフも存在したが、これはメイン・ソサエティ内の別個のソサエティであり、ポトラッチにのみ適用された。 Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は数少ない二系統の文化である。伝統的に一族の権利は父方を通じて受け継がれるが、稀に母方にも受け継がれることがある。 植民地化以前の時代、クワクワ族は貴族、平民、奴隷の3つの階級に分かれていた。Kwakwa̱ka̱̱wakwはNuu-chah-nulth、 Heiltsuk、Wuikinuxv、Coast Salishの一部など、この地域の多くの近隣住民と文化的、政治的に多くの同盟を結んでいた。 言語 Kwakʼwala言語はWakashan言語グループの一部である。Kwakʼwalaの単語リストやいくつかの記録は、18世紀にヨーロッパ人と接触 した初期から作成されているが、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのFranz Boasの研究以前には、この言語を体系的に記録する試みはなかった。クワクワ語の使用は19世紀から20世紀にかけて著しく減少したが、これは主にカナ ダ政府の同化政策によるものであった。Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの子どもたちは強制的に居住学校に通わされ、英語の使用を強制され、他の言語は奨励さ れなかった。クワクワラとクワクワ文化は言語学者や人類学者によってよく研究されてきたが、こうした努力は言語喪失の傾向を覆すものではなかった。ガイ・ ブッフホルツァーによれば、「人類学の言説はあまりにもしばしば長い独白になっており、その中でクワクワ族は何も語ることができなかった」[26]。 こうした圧力の結果、現在ではクワクワ語を話す人は比較的少なくなっている。残っている話者のほとんどは、言語継承にとって重要な段階とされる子育ての年 齢を過ぎている。他の多くの先住民言語と同様、言語活性化には大きな障壁がある[27]。新しい学習者と母語話者を隔てるもう一つの障壁は、4つの別々の 正書法が存在することである。若い世代はUʼmistaかNAPAを教えられ、年配の世代は一般的にアメリカの人類学者フランツ・ボースが開発した Boazを使う。 現在、多くの活性化の取り組みが行われている。2005年に提案されたKwakwakaʼwakw First Nations Centre for Language Cultureの建設は幅広い支持を得ている[28]。1990年代の再活性化の取り組みを見直すと、Kwakʼwalaを完全に再活性化する可能性はま だ残っているが、深刻なハードルも存在することがわかった[29]。 芸術  「クワクワ̱カ̱の変身マスク」。 昔、クワクワ̱カ̱ワクフは、芸術はすべての種族に共通する根底にある要素を象徴していると信じていた[30]。 Kwakwakaʼwakwの芸術は、トーテム、マスク、織物、宝飾品、彫刻品など多様な工芸品で構成され、変身マスクから高さ40フィート(12メート ル)のトーテムポールまで様々な大きさがある。杉材は先住民クワクワ̱カ̱ワクワ地域で容易に入手できるため、彫刻や彫り物の材料として好まれた。トーテ ムには大胆なカットが施され、比較的写実的で、絵の具が強調されて使われた。仮面はクワクワ族のダンス儀式の中心的なキャラクターを描くのに重要であるた め、クワクワ族の芸術の大部分を占めている。織物にはチルカット・ブランケット、ダンス・エプロン、ボタン・マントなどがあり、それぞれにクワクワ̱カ̱ ワクワのデザインが施されている。Kwakwa̱ka̱̱wakw族は象牙、骨、アワビの貝殻、銅、銀など、さまざまなものをジュエリーに使った。装飾品 は重要人物の衣服によく見られた。 音楽 Kwakwakaʼwakw音楽はKwakwa̱ka̱wakw族の古代の芸術である。音楽は数千年前にさかのぼる古代の芸術である。音楽は主に儀式や儀 礼のために使われ、パーカッシブな楽器、特に丸太太鼓、箱太鼓、皮太鼓、ガラガラや笛をベースにしている。4日間にわたって行われるクラシラ祭は、歌と踊 りと仮面が披露される重要な文化的行事で、ツェツェカ(冬)が訪れる直前に行われる。 儀式と行事 ポトラッチ  Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwのポトラッチで仮面を披露する。  スピーカー・フィギュア、19世紀、ブルックリン博物館、このフィギュアはポトラッチでの演説者を表している。フィギュアの後ろに立つ弁士が口を通して話し、到着した客の名前を告げたのだろう。 北西部のポトラッチ文化はよく知られ、広く研究されている。クワクワ族の間では今でもポトラッチが行われており、彼らや近隣住民の間で有名な豪華なアート ワークもそのひとつである。ポトラッチという現象、そしてそれにまつわる活気ある社会と文化については、『Chiefly Feasts(酋長の祝宴)』を参照されたい: The Enduring Kwakiutl Potlatch』には、ポトラッチの他の側面に付随する驚くべき芸術作品や伝説的な資料が詳しく紹介されており、クワクワ族の酋長たちの高度な政治や巨 万の富と権力を垣間見ることができる。 カナダ政府がファースト・ネーションの同化に力を入れていた頃、ポトラッチは弾圧すべき活動の対象とされた。ウィリアム・ダンカン宣教師は1875年に、 ポトラッチは「インディアンがクリスチャンに、あるいは文明人になることを妨げるあらゆる障害の中で、圧倒的に最も手ごわいものである」と書いている [31]。 1885年、インディアン法が改正され、ポトラッチを禁止し、違法とする条項が盛り込まれた。正式な法律にはこうある、 ポトラッチ」として知られるインディアンの祭り、または「タマナワス」として知られるインディアンの踊りに従事する、またはそれを援助するすべてのイン ディアンまたはその他の者は、軽罪に問われ、6ヶ月以上2ヶ月以下の期間、拘置所またはその他の監禁場所に収監される; また、インディアンまたはその他の者が、直接的または間接的に、インディアンまたはその他の者に、そのような祭りや踊りを催すこと、またはそれを祝うこと を奨励すること、またはそれを援助することも、同様の罪となり、同様の処罰を受ける。 Oʼwax̱a̱laga̱の酋長であるクワグ̱ラガ̱リスは、1886年10月7日、人類学者フランツ・ボースが彼らの文化を研究するためにやってきたとき、こう言った: 私たちの隣人[中略]に住む宣教師や斡旋業者がしようとするように、あなたが私たちの踊りや宴会を止めに来たのかどうか知りたい。私たちは、私たちの習慣 に干渉するような人物をここに入れたくない。私たちの祖父や曾祖父たちがしてきたようなことを続けるなら、戦争が起こると言われた。だが、そんな言葉は気 にしない。ここは白人の土地なのか?女王の土地だと言われているが、違う! 私の土地だ。 私たちの神が祖父にこの土地を与え、「これは汝のものである」と告げたとき、女王はどこにいたのだろう?私の父はこの土地を所有し、強大な酋長だった。そ して、あなた方の操船兵が来たら、私たちの家を破壊させればいい。木が見えるか?森が見えるか?我々はそれらを切り倒し、新しい家を建てて、我々の父祖が したように暮らそう。 われわれは、掟がわれわれに踊れと命じれば踊り、われわれの心が宴会を望むならば宴会をする。白人に「インディアンのようにしろ」と言うのか?われわれに ダンスを命じるのは厳格な掟である。我々の財産を友人や隣人に分配することを命じる厳しい法律だ。良い掟だ。白人には白人の掟を守らせ、われわれにはわれ われの掟を守らせよう。そして今、われわれのダンスを禁じに来たのなら、立ち去れ。そうでないなら、歓迎する。 やがてこの法律は改正され、ポトラッチの儀式にゲストが参加することを禁止するようになった。Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は数が多すぎて取り締まるこ とができず、政府も法律を施行できなかった。ダンカン・キャンベル・スコットは議会を説得し、犯罪を刑事から略式に変更した。これは「平和の正義を司る捜 査官が裁判を行い、有罪判決を下し、判決を下すことができる」ことを意味した[32]。 先祖代々の習慣と文化を維持するクワクワ族は、21世紀になってもポトラッチを公然と開催し、先祖代々のやり方の復活を誓っている。ポトラッチの開催頻度は、家族が自分たちの生得権を取り戻すにつれて年々増加し、頻繁に開催されるようになっている。 住居とシェルター Kwakwa̱ka̱wakw族は耐水性の高い杉板で家を建てた。家屋の長さは50~100フィート(15~30メートル)と非常に大きかった。家屋には 50人ほどが住むことができ、たいていは同じ一族の家族だった。入り口には通常、さまざまな動物や神話の人物、家紋が彫られたトーテムポールがあった。 衣服とレガリア 夏、男性は宝石以外の衣服を身につけなかった。冬は暖をとるために脂肪を身につけた。戦闘時にはレッドシダーの鎧と兜を着用し、ブリーチ・クラウトはシ ダー製だった。儀式の際には、足首にスギの樹皮の輪をつけ、スギのブリーチ・クラウトを履いた。女性は柔らかくしたスギのスカートをはき、冬はその上にス ギかウールの毛布を羽織った。 交通手段  クワクワクワクワのカヌー Kwakwa̱ka̱wakwの交通手段は他の沿岸民族と似ていた。海と沿岸の民である彼らは、主にカヌーで移動した。一本の丸太から作られる杉の掘っ立 て小屋のカヌーは、個人や家族、コミュニティが使うために彫られた。その大きさは、通商使節団が長い航海をするための外洋用のカヌーから、集落間の移動用 の小型のローカル・カヌーまでさまざまだった。中には、寒い冬から身を守るためにバッファローの毛皮を内張りにしたボートもあった。 |

| Notable Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw Alfred Scow (1927-2013), first Aboriginal person to graduate from a BC law school, the first Aboriginal lawyer called to the BC bar and the first Aboriginal legally trained judge appointed to the BC Provincial Court Sonny Assu (b. 1975), interdisciplinary artist Joe Peters Jr., artist, woodcarver Beau Dick, artist, woodcarver Gord Hill, artist, author and Indigenous rights activist Calvin Hunt (b. 1956), artist Henry Hunt (1923-1985), artist Richard Hunt (b. 1951), artist Tony Hunt Sr. (1942-2017), artist Charles Joseph, carver from Maʼamtaglia-Tlowitsis tribe[33][34] Mungo Martin, woodcarver David Neel, artist, writer Ellen Neel, woodcarver Marianne Nicolson (b. 1969), artist, academic Spencer O'Brien (b. 1988), snowboarder Joe Peters Jr. artist, woodcarver (b.1960-1994) Quesalid, medicine man, writer Willie Seaweed, woodcarver James Sewid, writer Jody Wilson-Raybould, politician |

著名なクワクワ族 アルフレッド・スコウ(1927-2013):アボリジニとして初めてBC州のロースクールを卒業、アボリジニとして初めてBC州の法曹界に召集された弁護士、アボリジニとして初めてBC州裁判所に任命された法的訓練を受けた裁判官 ソニー・アスー(1975年生)、学際的アーティスト ジョー・ピーターズ・ジュニア(Joe Peters Jr. ボー・ディック(アーティスト、木彫作家 ゴード・ヒル(アーティスト、作家、先住民権利活動家 カルヴィン・ハント(1956年生)、アーティスト ヘンリー・ハント(1923-1985)、アーティスト リチャード・ハント(1951年生)、アーティスト トニー・ハント・シニア(1942-2017)、アーティスト チャールズ・ジョセフ、Maʼamtaglia-Tlowitsis部族の彫刻家[33][34]。 マンゴ・マーティン、木彫り職人 デヴィッド・ニール、アーティスト、作家 エレン・ニール、木彫家 マリアンヌ・ニコルソン(1969年生)、アーティスト、学者 スペンサー・オブライエン(1988年生)、スノーボーダー ジョー・ピーターズ・ジュニア(Joe Peters Jr.) ケサリード、メディスンマン、作家 ウィリー・シーウィード(木彫家 ジェームズ・セウィッド(作家 ジョディ・ウィルソン=レイボールド、政治家 |

| Kwakiutl (statue) In the Land of the Head Hunters Sisiutl Dances of the Kwakiutl I Heard the Owl Call My Name |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kwakwaka%CA%BCwakw |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆