ルイス・キャロル

Lewis Carroll, 1832-1898

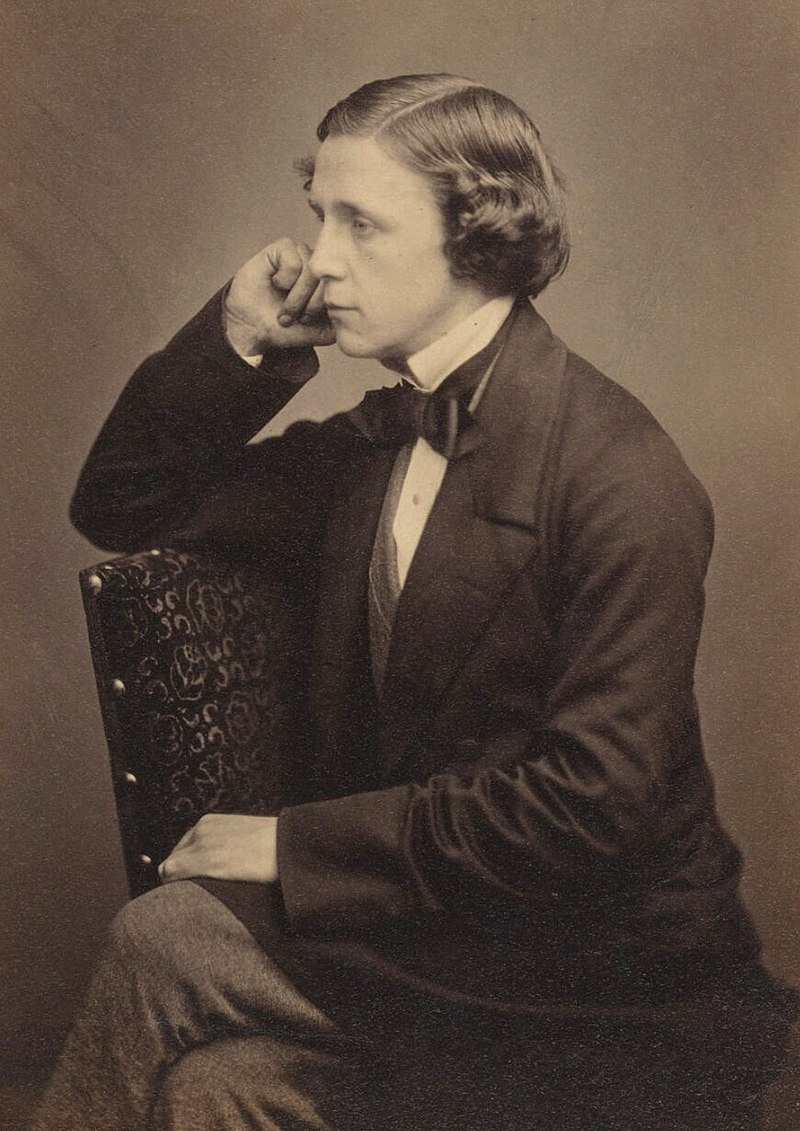

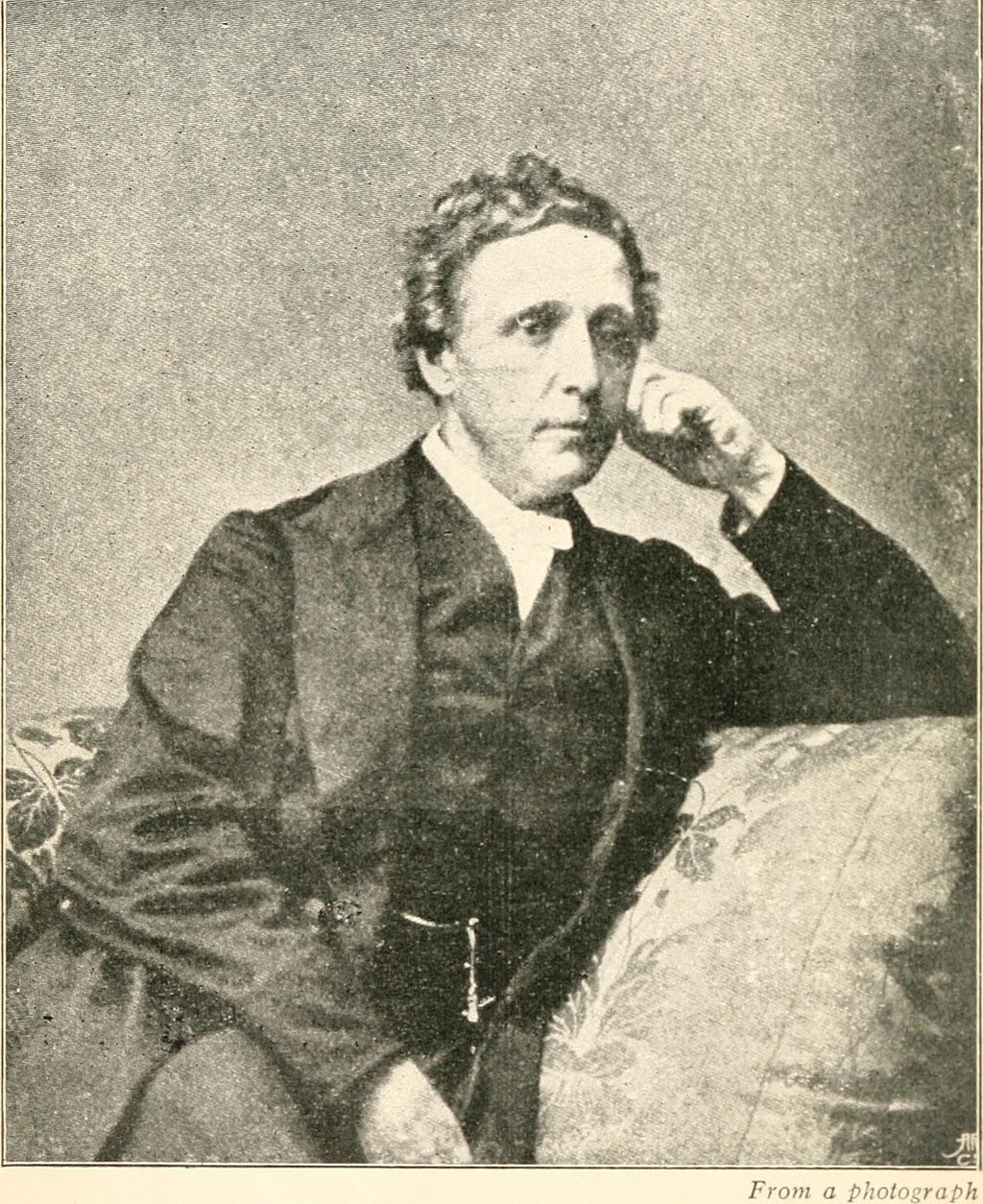

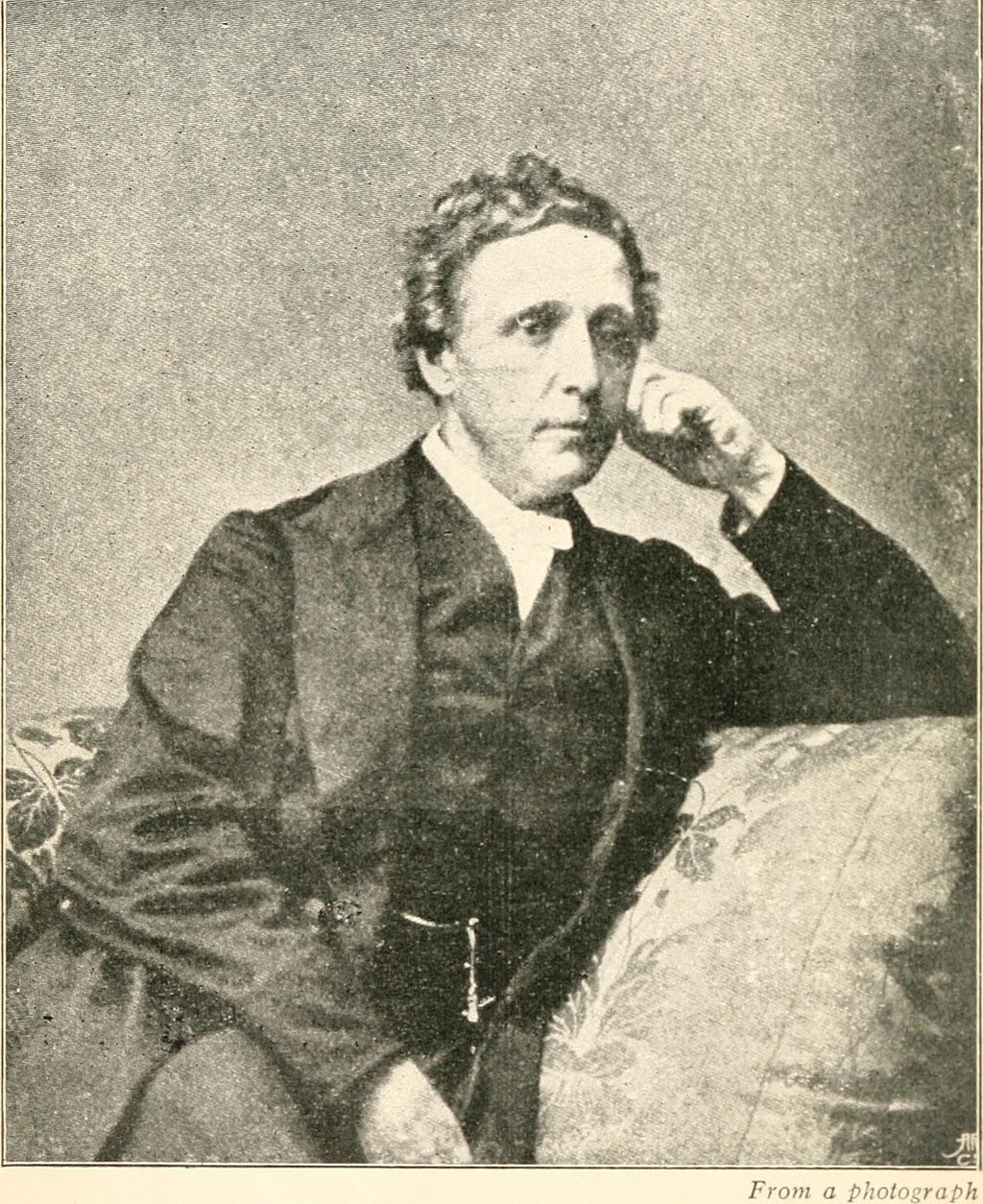

Carroll

in 1857

☆ チャールズ・ラトウィッジ・ドジソン(/ˈlʌtwɪdʒ ˈdɒdsən/ LUT-wij DOD-sən、1832年1月27日 - 1898年1月14日)は、ペンネームのルイス・キャロル(Lewis Carroll)の名で知られる、イギリスの作家、詩人、数学者、写真家である。彼の最も有名な作品は『不思議の国のアリス』(1865年)とその続編 『鏡の国のアリス』(1871年)である。彼は言葉遊び、論理、空想に長けていたことで知られている。彼の詩『ジャバウォーキー』(1871年)と『ス ナーク狩り』(1876年)は、文学上のナンセンスに分類されている。 キャロルは英国国教会の高教会派の家庭に生まれ、オックスフォードのクライストチャーチと長年にわたる関係を築き、学者や教師として人生のほとんどをそこ で過ごした。ヘンリー・リデル(クライストチャーチ学長)の娘であるアリス・リデルは、『不思議の国のアリス』のインスピレーションの源として広く知られ ているが、キャロルはこれを常に否定していた。 パズル好きだったキャロルは、1879年から1881年にかけて『ヴァニティ・フェア』誌の週刊コラムで発表した「ダブルッツ」と名付けた「ワードラダー パズル」を考案した。1982年には、ウェストミンスター寺院の詩人コーナーにキャロルを記念する石碑が建立された。彼の作品の普及と普及を目的とした団 体は、世界の多くの地域に存在する。

| Charles Lutwidge

Dodgson (/ˈlʌtwɪdʒ ˈdɒdsən/ LUT-wij DOD-sən; 27 January 1832 – 14

January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an

English author, poet, mathematician and photographer. His most notable

works are Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and its sequel

Through the Looking-Glass (1871). He was noted for his facility with

word play, logic, and fantasy. His poems Jabberwocky (1871) and The

Hunting of the Snark (1876) are classified in the genre of literary

nonsense. Carroll came from a family of high-church Anglicans, and developed a long relationship with Christ Church, Oxford, where he lived for most of his life as a scholar and teacher. Alice Liddell – a daughter of Henry Liddell, the Dean of Christ Church – is widely identified as the original inspiration for Alice in Wonderland, though Carroll always denied this. An avid puzzler, Carroll created the word ladder puzzle (which he then called "Doublets"), which he published in his weekly column for Vanity Fair magazine between 1879 and 1881. In 1982 a memorial stone to Carroll was unveiled at Poets' Corner in Westminster Abbey. There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works.[1][2] |

チャールズ・ラトウィッジ・ドジソン(/ˈlʌtwɪdʒ

ˈdɒdsən/ LUT-wij DOD-sən、1832年1月27日 - 1898年1月14日)は、ペンネームのルイス・キャロル(Lewis

Carroll)の名で知られる、イギリスの作家、詩人、数学者、写真家である。彼の最も有名な作品は『不思議の国のアリス』(1865年)とその続編

『鏡の国のアリス』(1871年)である。彼は言葉遊び、論理、空想に長けていたことで知られている。彼の詩『ジャバウォーキー』(1871年)と『ス

ナーク狩り』(1876年)は、文学上のナンセンスに分類されている。 キャロルは英国国教会の高教会派の家庭に生まれ、オックスフォードのクライストチャーチと長年にわたる関係を築き、学者や教師として人生のほとんどをそこ で過ごした。 ヘンリー・リデル(クライストチャーチ学長)の娘であるアリス・リデルは、『不思議の国のアリス』のインスピレーションの源として広く知られているが、 キャロルはこれを常に否定していた。 パズル好きだったキャロルは、1879年から1881年にかけて『ヴァニティ・フェア』誌の週刊コラムで発表した「ダブルッツ」と名付けた「ワードラダー パズル」を考案した。1982年には、ウェストミンスター寺院の詩人コーナーにキャロルを記念する石碑が建立された。彼の作品の普及と普及を目的とした団 体は、世界の多くの地域に存在する[1][2]。 |

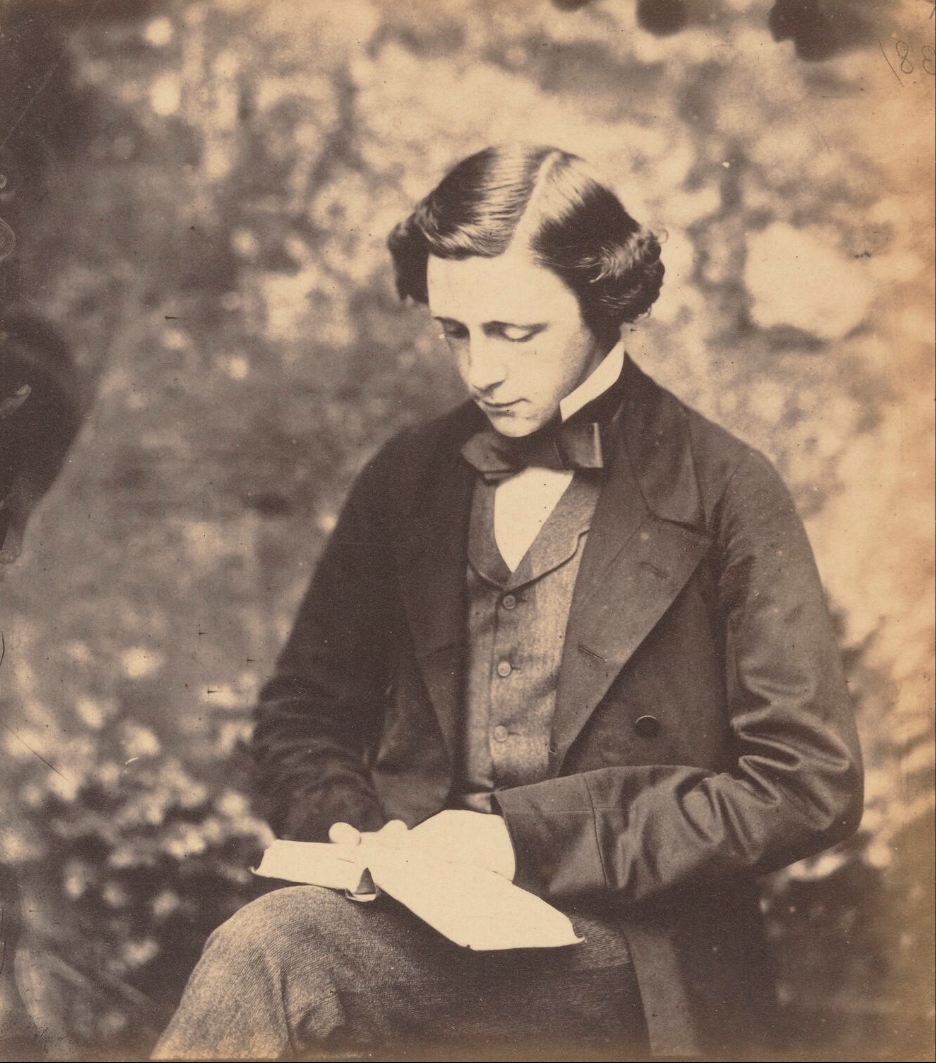

| Early life Dodgson's family was predominantly northern English, conservative, and high-church Anglican. Most of his male ancestors were army officers or Anglican clergymen. His great-grandfather, Charles Dodgson, had risen through the ranks of the church to become the Bishop of Elphin in rural Ireland.[3] His paternal grandfather, also named Charles, was an army captain who was killed in action in Ireland in 1803, when his two sons were hardly more than babies.[4] The older of these sons, yet another Charles Dodgson, was Carroll's father. He went to Westminster School and then to Christ Church, Oxford.[5] He reverted to the other family tradition and took holy orders. He was mathematically gifted and won a double first degree, which could have been the prelude to a brilliant academic career. Instead, he became a country parson.[6][7] Dodgson was born on 27 January 1832 at All Saints' Vicarage in Daresbury, Cheshire,[8] the oldest boy and the third oldest of 11 children. When he was 11, his father was given the living of Croft-on-Tees, Yorkshire, and the whole family moved to the spacious rectory. This remained their home for the next 25 years. Charles' father was an active and highly conservative cleric of the Church of England who later became the Archdeacon of Richmond[9] and involved himself, sometimes influentially, in the intense religious disputes that were dividing the church. He was high-church, inclining toward Anglo-Catholicism, an admirer of John Henry Newman and the Tractarian movement, and did his best to instil such views in his children. However, Charles developed an ambivalent relationship with his father's values and with the Church of England as a whole.[10] During his early youth, Dodgson was educated at home. His "reading lists" preserved in the family archives testify to a precocious intellect: at the age of seven, he was reading books such as The Pilgrim's Progress. He also spoke with a stammer – a condition shared by most of his siblings[11] – that often inhibited his social life throughout his years. At the age of twelve he was sent to Richmond Grammar School (now part of Richmond School) in Richmond, North Yorkshire.  Photographic portrait of Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (Lewis Carroll), seated and holding a book Lewis Carroll self-portrait c. 1856, aged 24 at that time In 1846, Dodgson entered Rugby School, where he was evidently unhappy, as he wrote some years after leaving: "I cannot say ... that any earthly considerations would induce me to go through my three years again ... I can honestly say that if I could have been ... secure from annoyance at night, the hardships of the daily life would have been comparative trifles to bear."[12] He did not claim he suffered from bullying, but cited little boys as the main targets of older bullies at Rugby.[13] Stuart Dodgson Collingwood, Dodgson's nephew, wrote that "even though it is hard for those who have only known him as the gentle and retiring don to believe it, it is nevertheless true that long after he left school, his name was remembered as that of a boy who knew well how to use his fists in defence of a righteous cause", which is the protection of the smaller boys.[13] Scholastically, though, he excelled with apparent ease. "I have not had a more promising boy at his age since I came to Rugby", observed mathematics master R. B. Mayor.[14] Francis Walkingame's The Tutor's Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic – the mathematics textbook that the young Dodgson used – still survives and it contained an inscription in Latin, which translates to: "This book belongs to Charles Lutwidge Dodgson: hands off!"[15] Some pages also included annotations such as the one found on p. 129, where he wrote "Not a fair question in decimals" next to a question.[16] He left Rugby at the end of 1849 and matriculated at the University of Oxford in May 1850 as a member of his father's old college, Christ Church.[17] After waiting for rooms in college to become available, he went into residence in January 1851.[18] He had been at Oxford only two days when he received a summons home. His mother had died of "inflammation of the brain" – perhaps meningitis or a stroke – at the age of 47.[18] His early academic career veered between high promise and irresistible distraction. He did not always work hard, but was exceptionally gifted, and achievement came easily to him. In 1852, he obtained first-class honours in Mathematics Moderations and was soon afterwards nominated to a Studentship by his father's old friend Canon Edward Pusey.[19][20] In 1854, he obtained first-class honours in the Final Honours School of Mathematics, standing first on the list, and thus graduated as Bachelor of Arts.[21][22] He remained at Christ Church studying and teaching, but the next year he failed an important scholarship exam through his self-confessed inability to apply himself to study.[23][24] Even so, his talent as a mathematician won him the Christ Church Mathematical Lectureship in 1855,[25] which he continued to hold for the next 26 years.[26] Despite early unhappiness, Dodgson remained at Christ Church, in various capacities, until his death, including that of Sub-Librarian of the Christ Church library, where his office was close to the Deanery, where Alice Liddell lived.[27] |

幼少期[編集] ドジソンの家族は主に北部イングランド出身で、保守的で、英国国教会の高位聖職者であった。彼の男性の先祖のほとんどは軍人または英国国教会の聖職者で あった。彼の曽祖父チャールズ・ドジソンは、アイルランドの田舎にあるエルフィン教区の司教にまで出世した人物だった[3]。父方の祖父もチャールズとい う名前で、軍の大尉だったが、1803年にアイルランドで戦死した。彼の二人の息子はまだ赤ん坊だった[4]。この息子たちの兄、同じくチャールズ・ドジ ソンはキャロルの父親だった。彼はウェストミンスター・スクール、そしてオックスフォードのクライストチャーチに進学した[5]。彼は家族の伝統に従い聖 職に就いた。彼は数学に才能があり、優秀な学業キャリアの序章となる可能性があったダブルファーストディグリー(2つの学位)を取得した。しかし、彼は田 舎の牧師となった[6][7]。 ドジソンは1832年1月27日、チェシャー州ダレスベリーにあるオールセインツ・ヴィカーレッジで生まれた[8]。11人兄弟の末っ子で、長男だった。 11歳のとき、父親がヨークシャー州クロフト・オン・ティーズの牧師職に就き、家族全員で広い牧師館に引っ越した。この牧師館はその後25年間、彼らの家 となった。チャールズの父親は、英国国教会の活動的で非常に保守的な聖職者であり、後にリッチモンド大司教[9]となった。彼は、教会を二分する激しい宗 教論争に、時には大きな影響力をもって関わっていた。彼はハイチャーチ派であり、アングロ・カトリック主義に傾倒し、ジョン・ヘンリー・ニューマンとトラ クティアニズム運動の崇拝者であり、子供たちにそのような考え方を植え付けることに全力を尽くしていた。しかし、チャールズは父の価値観や英国国教会全体 に対して、複雑な感情を抱くようになった[10]。 幼少期、ドジソンは家庭で教育を受けた。 家族文書に保存されている「読書リスト」は、彼の早熟な知性を証明している。7歳の時には『天路歴程』などの本を読んでいた。また、兄弟の多くにみられた [11]どもりがあり、それが長年にわたって彼の社会生活を妨げる要因となった。12歳のとき、彼はノースヨークシャー州リッチモンドのリッチモンドグラ マースクール(現在はリッチモンドスクールの一部)に入学した。  1856年頃のルイス・キャロルの自画像。当時24歳。 1846年、ドジソンはラグビー校に入学したが、明らかに不満足だったようで、退学後数年してこう書いている。「... 3年間をもう一度やり直すようなことは、この世のどんな理由があっても考えられない... 正直に言えば、もし夜間の迷惑行為から守られることができたら、日々の生活の苦難は耐えるに値しない些細なことだっただろう」[12]。彼はいじめを受け たと主張したわけではないが、ラグビーでは年上のいじめっ子の主な標的は小さな男の子だったと述べた[13]。スチュアート・ドジソン・コリングウッド (Stuart Dodgson Collingwood)、ドジソンの甥は、次のように書いている。 ドジソンの甥であるスチュアート・ドジソン・コリングウッドは、「彼を知っている人にとっては信じられないかもしれないが、彼が学校を卒業してかなり経っ た後でも、正義のために拳をうまく使う少年の名前として彼の名前が記憶されていたのは事実である」と書いている。 しかし、学業面では彼は明らかに優れており、「私がラグビーに来た以来、彼の年齢でこれほど有望な生徒は見たことがない」と数学の教師R.B.メイヤーは 述べていた[14]。フランシス・ウォーキンゲムの『The Tutor's Assistant; Being a Compendium of Arithmetic』は、若いドジソンが使用していた数学の教科書であり、現在も現存している。この本にはラテン語で次のような碑文が刻まれていた。 「この本はチャールズ・ラトウィッジ・ドジソンに属する。手を出すな!」[15] いくつかのページには、129ページに見られるような注釈も書かれており、質問の横に「小数では公平な質問ではない」と書かれていた[16]。 彼は1849年末にラグビー校を退学し、1850年5月に父の母校であるオックスフォード大学クライスト・チャーチ・カレッジに入学した[17]。大学内 の空室が出るのを待った後、1851年1月に寮に入った[18]。オックスフォードに来てわずか2日目に、彼は故郷への召還状を受け取った。彼の母親は、 おそらく髄膜炎か脳卒中による「脳炎」で、47歳のときに亡くなった[18]。 彼の初期の学業は、将来への期待と抗いがたい気晴らしの間で揺れ動いていた。彼は常に努力していたわけではないが、並外れた才能に恵まれており、成果は簡 単に得られた。1852年、彼は数学中級で優等第一級を取得し、その後まもなく、父の旧友であるエドワード・プージー大主教から奨学金を受ける学生に指名 された[19][20]。1854年、彼は数学最終優等学校で優等第一級を取得し、首席で卒業した 文学士として卒業した[21][22]。彼はその後もクライストチャーチで学び、教鞭を執っていたが、翌年、勉強に打ちこむ自信がないことを理由に、重要 な奨学金試験に不合格となった[23][24]。それでも、数学者としての才能が認められ、1855年にクライストチャーチ数学講座の職に就いた[2 5] 彼はその後26年間その地位に就き続けた[26]。初期の不幸にもかかわらず、ドジソンは、アリス・リデルが住んでいたディーンリーに近い、クライスト チャーチ図書館の副司書を含むさまざまな役職に就き、生涯を終えるまでクライストチャーチにとどまった[27]。 |

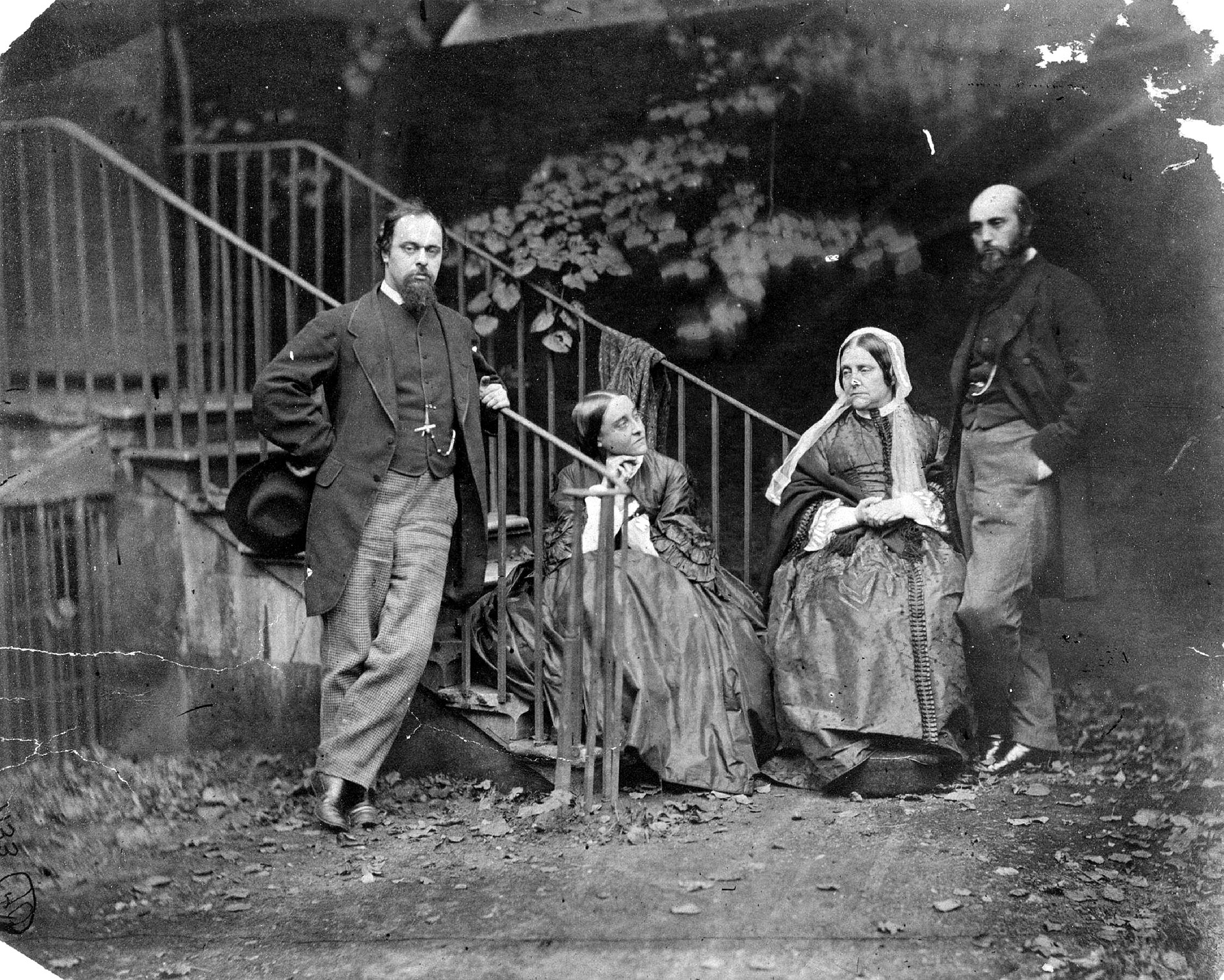

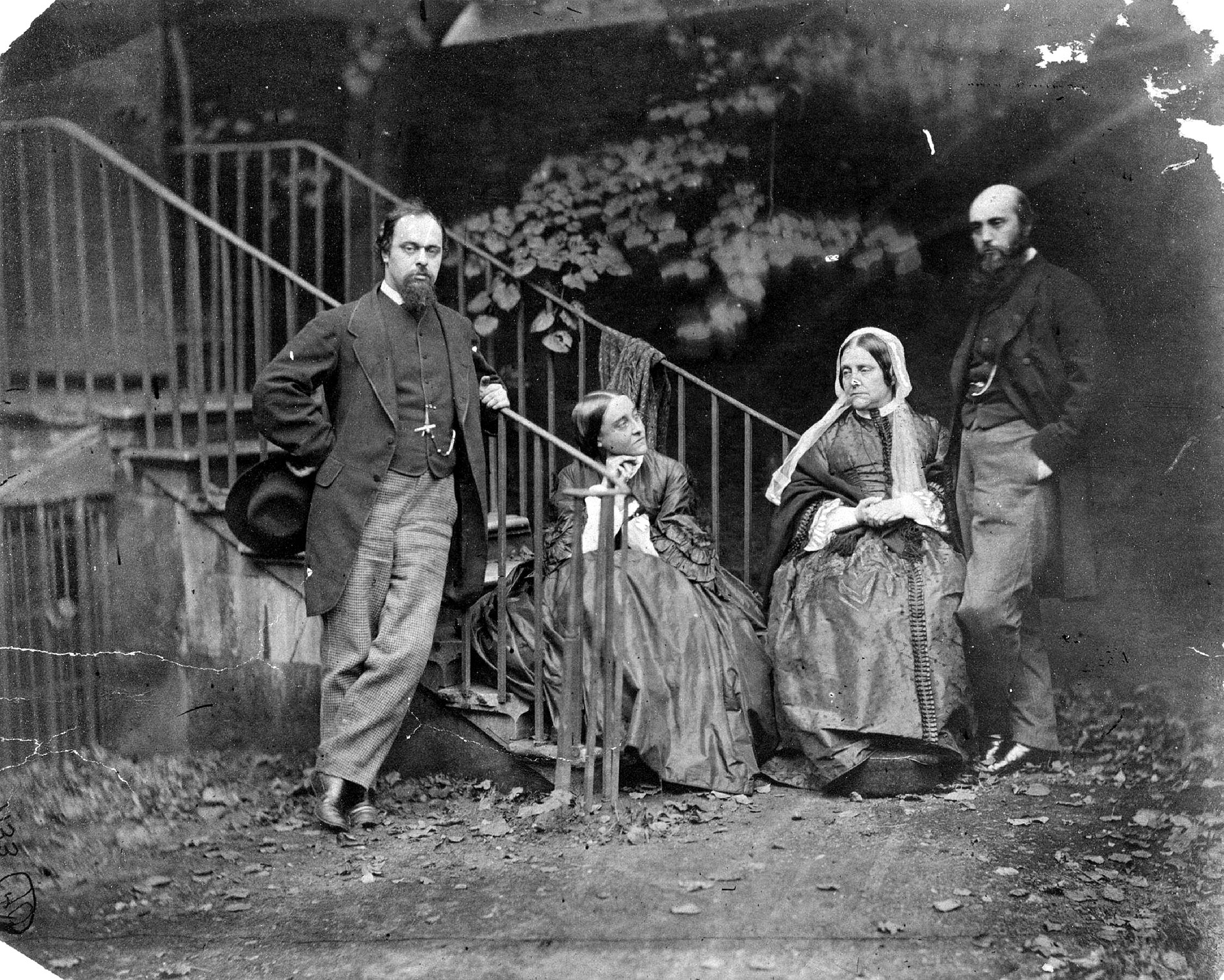

| Character and appearance Health problems 1863 photograph of Carroll by Oscar G. Rejlander The young adult Charles Dodgson was about 6 feet (1.83 m) tall and slender, and he had curly brown hair and blue or grey eyes (depending on the account). He was described in later life as somewhat asymmetrical, and as carrying himself rather stiffly and awkwardly, although this might be on account of a knee injury sustained in middle age. As a very young child, he suffered a fever that left him deaf in one ear. At the age of 17, he suffered a severe attack of whooping cough, which was probably responsible for his chronically weak chest in later life. In early childhood, he acquired a stammer, which he referred to as his "hesitation"; it remained throughout his life.[27] The stammer has always been a significant part of the image of Dodgson. While one apocryphal story says that he stammered only in adult company and was free and fluent with children, there is no evidence to support this idea.[28] Many children of his acquaintance remembered the stammer, while many adults failed to notice it. Dodgson himself seems to have been far more acutely aware of it than most people whom he met; it is said that he caricatured himself as the Dodo in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, referring to his difficulty in pronouncing his last name, but this is one of the many supposed facts often repeated for which no first-hand evidence remains. He did indeed refer to himself as a dodo, but whether or not this reference was to his stammer is simply speculation.[27] Dodgson's stammer did trouble him, but it was never so debilitating that it prevented him from applying his other personal qualities to do well in society. He lived in a time when people commonly devised their own amusements and when singing and recitation were required social skills, and the young Dodgson was well equipped to be an engaging entertainer. He could reportedly sing at a passable level and was not afraid to do so before an audience. He was also adept at mimicry and storytelling, and reputedly quite good at charades.[27] Social connections In the interim between his early published writings and the success of the Alice books, Dodgson began to move in the pre-Raphaelite social circle. He first met John Ruskin in 1857 and became friendly with him. Around 1863, he developed a close relationship with Dante Gabriel Rossetti and his family. He would often take pictures of the family in the garden of the Rossetti's house in Chelsea, London. He also knew William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, and Arthur Hughes, among other artists. He knew fairy-tale author George MacDonald well – it was the enthusiastic reception of Alice by the young MacDonald children that persuaded him to submit the work for publication.[27][29] Politics, religion, and philosophy In broad terms, Dodgson has traditionally been regarded as politically, religiously, and personally conservative. Martin Gardner labels Dodgson as a Tory who was "awed by lords and inclined to be snobbish towards inferiors".[30] William Tuckwell, in his Reminiscences of Oxford (1900), regarded him as "austere, shy, precise, absorbed in mathematical reverie, watchfully tenacious of his dignity, stiffly conservative in political, theological, social theory, his life mapped out in squares like Alice's landscape".[31] Dodgson was ordained a deacon in the Church of England on 22 December 1861. In The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll, the editor states that "his Diary is full of such modest depreciations of himself and his work, interspersed with earnest prayers (too sacred and private to be reproduced here) that God would forgive him the past, and help him to perform His holy will in the future."[32] When a friend asked him about his religious views, Dodgson wrote in response that he was a member of the Church of England, but "doubt[ed] if he was fully a 'High Churchman'". He added: I believe that when you and I come to lie down for the last time, if only we can keep firm hold of the great truths Christ taught us—our own utter worthlessness and His infinite worth; and that He has brought us back to our one Father, and made us His brethren, and so brethren to one another—we shall have all we need to guide us through the shadows. Most assuredly I accept to the full the doctrines you refer to—that Christ died to save us, that we have no other way of salvation open to us but through His death, and that it is by faith in Him, and through no merit of ours, that we are reconciled to God; and most assuredly I can cordially say, "I owe all to Him who loved me, and died on the Cross of Calvary." — Carroll (1897)[33] Dodgson also expressed interest in other fields. He was an early member of the Society for Psychical Research, and one of his letters suggests that he accepted as real what was then called "thought reading".[34] Dodgson wrote some studies of various philosophical arguments. In 1895, he developed a philosophical regressus-argument on deductive reasoning in his article "What the Tortoise Said to Achilles", which appeared in one of the early volumes of Mind.[35] The article was reprinted in the same journal a hundred years later in 1995, with a subsequent article by Simon Blackburn titled "Practical Tortoise Raising".[36] |

性格と外見[編集] 健康問題[編集] オスカー・G・レイランダーによる1863年のキャロルの写真 青年期のチャールズ・ドジソンは、身長約183センチメートルで細身、茶色の巻き毛と青または灰色の目(記述による)をしていた。晩年、彼はやや非対称 で、ぎこちなく不格好に歩く人だと評されたが、これは中年期に負った膝の怪我によるものかもしれない。幼い頃、彼は熱病にかかり、片耳が聞こえなくなっ た。17歳の時、彼は百日咳にひどくかかり、それが後の人生で慢性的に胸が弱かった原因となったと思われる。幼少期に吃音症になり、それを「ためらい」と 呼んでいたが、それは生涯続いた[27]。 どもりは常にドジソンのイメージの重要な部分を占めていた。ある逸話では、彼は大人たちの前ではどもり、子供たちとは自由に流暢に話していたとされている が、この説を裏付ける証拠はない[28]。彼の知り合いの子供たちの多くはどもりを覚えていたが、多くの大人はそれに気づかなかった。ドジソン自身は、出 会った多くの人々よりもはるかに強くそのことを自覚していたようである。彼は『不思議の国のアリス』の中で、自分の名字の発音が難しいことを理由に、自分 をドードーと風刺したと言われているが、これは多くの推測事実の1つであり、直接的な証拠は残っていない。彼は確かに自分自身をドードーと呼んでいたが、 この呼び名が吃音に関連していたかどうかは単なる憶測にすぎない[27]。 ドジソンは吃音に悩まされていたが、それが彼の他の優れた資質を社会で生かすのを妨げるほど深刻な障害になったことはなかった。当時、人々は娯楽を自ら考 案するのが一般的であり、歌や朗読は社交術として求められていた。若いドジソンは魅力的なエンターテイナーになる素質を備えていた。彼は歌がそこそこ上手 で、人前で歌うことを恐れていなかったと伝えられている。また、物まねや物語作りにも長けており、ジェスチャーゲームも得意だったという。 社会的つながり[編集] 初期の著作が発表されてから『不思議の国のアリス』が成功を収めるまでの間、ドジソンはラファエル前派の社交界で活動し始めた。 1857年にジョン・ラスキンと初めて出会い、親しくなった。 1863年頃、ダンテ・ガブリエル・ロセッティとその家族と親しい関係を築いた。 ロセッティ一家が住んでいたロンドンのチェルシーにある家の庭で、しばしば彼らの写真を撮っていた。彼はウィリアム・ホルマン・ハント、ジョン・エヴァ レット・ミレイ、アーサー・ヒューズなど、他の芸術家たちとも知り合いだった。童話作家ジョージ・マクドナルドとも親しく、マクドナルドの子供たちが『不 思議の国のアリス』を熱狂的に読んだことが、出版を決意するきっかけとなった[27][29]。 政治、宗教、哲学[編集] 大まかに言えば、ドジソンは伝統的に政治的にも宗教的にも個人的にも保守的であると見なされてきた。マーティン・ガードナーはドジソンを「貴族に畏敬の念 を抱き、目下の人に対して見下す傾向がある」保守党員と評している[30]。ウィリアム・タックウェルは『オックスフォードの思い出』(1900年)の中 で、ドジソンを「厳格で内気、几帳面で、数学的な空想に没頭し、 厳格で内気、几帳面で、数学的な空想に没頭し、威厳を保ち、政治、神学、社会理論において頑固に保守的であり、彼の生涯はアリスが描いた風景のように四角 形で区切られていた」[31]。ドジソンは1861年12月22日に英国国教会の助祭に叙階された。『ルイス・キャロルの生涯と書簡』の編集者は、「彼の 日記には、自分自身と自分の作品に対する謙虚な評価が数多く書かれており、神が過去の自分を許し、将来、神聖な御心を行うのを助けてくれるようにという切 実な祈り(神聖かつ個人的な内容のため、ここに転載できない)が散りばめられている」と記している[32]。将来、神聖な御心を行えるよう助けてほしい」 と記している[32]。友人の宗教観について尋ねられたドジソンは、自分は英国国教会の信者だが、「自分が完全に『高位聖職者』であるかどうか疑わしい」 と書いた。彼はさらにこう付け加えた。 あなたと私が最後に横たわる時が来たら、キリストが私たちに教えてくれた偉大な真理、すなわち私たち自身の無価値さとキリストの無限の価値をしっかりと心 に留めていられれば、そして、キリストが私たちを唯一の父のもとに戻し、私たちを兄弟とし、そして兄弟同士としてくださったなら、私たちは闇の中を導くた めに必要なものすべてを手に入れることができると私は信じている。私があなたがおっしゃる教義を完全に受け入れることは疑いありません。すなわち、キリス トは私たちを救うために死なれ、私たちにはキリストの死を通してしか救いの道が開かれておらず、神と和解できるのはキリストへの信仰によるものであり、私 たちの功績によるものではないということです。そして、私は心からこう言うことができます。「私を愛し、カルヴァリーの十字架で死んでくださった方に、私 はすべてを負っています。」 — キャロル(1897年)[33] ドジソンは他の分野にも興味を示していた。彼は超常現象研究協会の初期の会員であり、彼の手紙の1つには、当時「心読」と呼ばれていたものを真実として受 け入れていたことが示唆されている[34]。ドジソンはさまざまな哲学的議論に関する研究論文をいくつか執筆した。1895年、彼は『マインド』誌の初期 の号に掲載された「亀がアキレスに言ったこと」という論文で、演繹的推論に関する哲学的回帰論を展開した[35]。この論文は、100年後の1995年に 同じ雑誌に再掲載され、サイモン・ブラックバーンの「実践的亀の飼育」という論文がそれに続いた[36]。 |

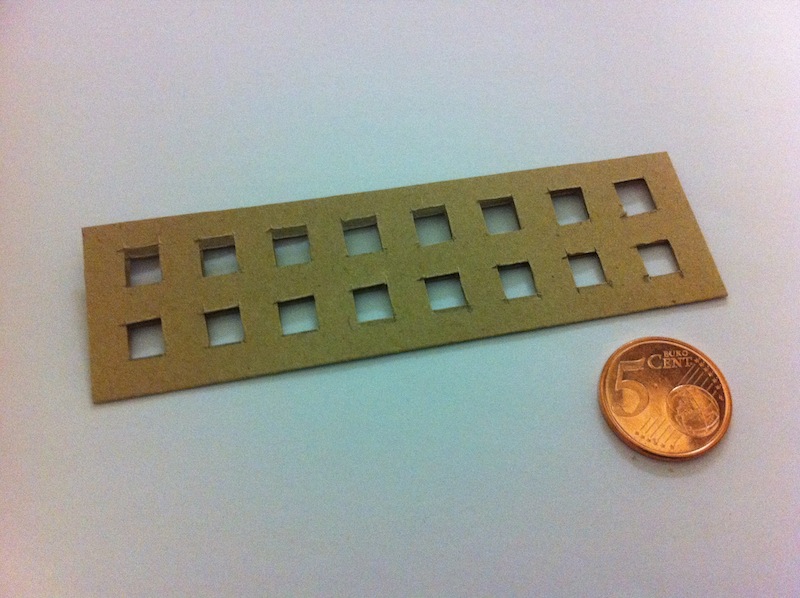

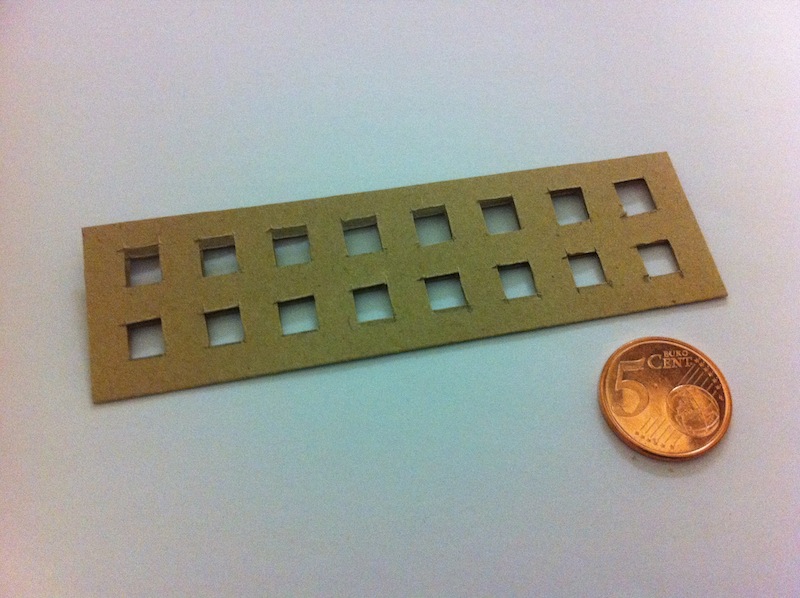

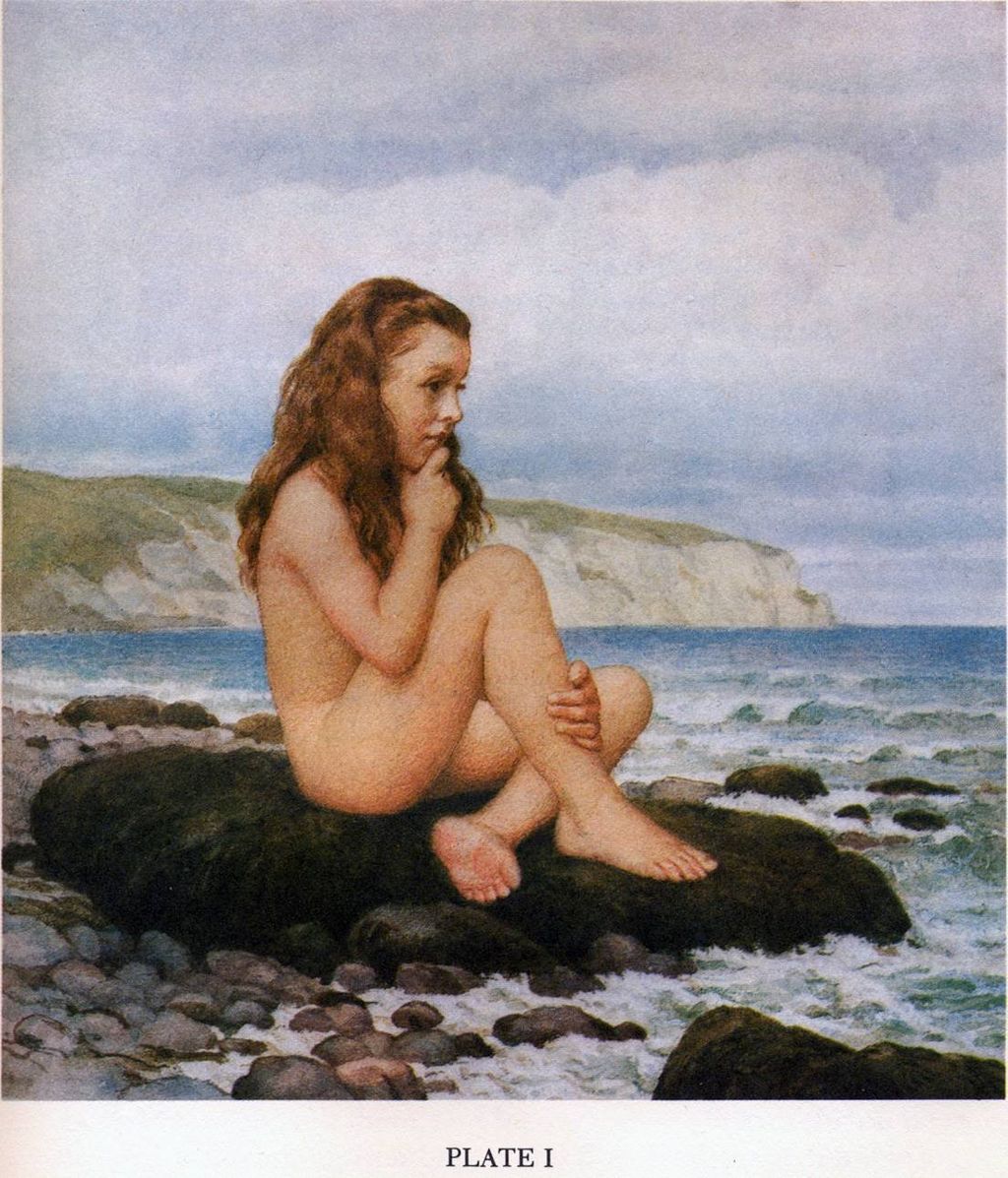

| Artistic activities Head and shoulders drawing of a girl (Alice) holding a key One of Carroll's own illustrations Literature From a young age, Dodgson wrote poetry and short stories, contributing heavily to the family magazine Mischmasch and later sending them to various magazines, enjoying moderate success. Between 1854 and 1856, his work appeared in the national publications The Comic Times and The Train, as well as smaller magazines such as the Whitby Gazette and the Oxford Critic. Most of this output was humorous, sometimes satirical, but his standards and ambitions were exacting. "I do not think I have yet written anything worthy of real publication (in which I do not include the Whitby Gazette or the Oxonian Advertiser), but I do not despair of doing so someday," he wrote in July 1855.[27] Sometime after 1850, he did write puppet plays for his siblings' entertainment, of which one has survived: La Guida di Bragia.[37] In March 1856, he published his first piece of work under the name that would make him famous. A romantic poem called "Solitude" appeared in The Train under the authorship of "Lewis Carroll". This pseudonym was a play on his real name: Lewis was the anglicised form of Ludovicus, which was the Latin for Lutwidge, and Carroll an Irish surname similar to the Latin name Carolus, from which comes the name Charles.[7] The transition went as follows: "Charles Lutwidge" translated into Latin as "Carolus Ludovicus". This was then translated back into English as "Carroll Lewis" and then reversed to make "Lewis Carroll".[38] This pseudonym was chosen by editor Edmund Yates from a list of four submitted by Dodgson, the others being Edgar Cuthwellis, Edgar U. C. Westhill, and Louis Carroll.[39] Alice books  Illustration of Alice holding a Flamingo, standing with one foot on a curled-up hedgehog with another hedgehog walking away "The chief difficulty Alice found at first was in managing her flamingo". Illustration by John Tenniel, 1865. Illustration of a child with a sword facing a fearsome winged dragon in a forest The Jabberwock, as illustrated by John Tenniel for Lewis Carroll's Through the Looking-Glass, including the poem "Jabberwocky" In 1856, Dean Henry Liddell arrived at Christ Church at Oxford University, bringing with him his young family, all of whom would figure largely in Dodgson's life over the following years, and would greatly influence his writing career. Dodgson became close friends with Liddell's wife, Lorina, and their children, particularly the three sisters Lorina, Edith, and Alice Liddell. He was widely assumed for many years to have derived his own "Alice" from Alice Liddell; the acrostic poem at the end of Through the Looking-Glass spells out her name in full, and there are also many superficial references to her hidden in the text of both books. It has been noted that Dodgson himself repeatedly denied in later life that his "little heroine" was based on any real child,[40][41] and he frequently dedicated his works to girls of his acquaintance, adding their names in acrostic poems at the beginning of the text. Gertrude Chataway's name appears in this form at the beginning of The Hunting of the Snark, and it is not suggested that this means that any of the characters in the narrative are based on her.[41] Information is scarce (Dodgson's diaries for the years 1858–1862 are missing), but it seems clear that his friendship with the Liddell family was an important part of his life in the late 1850s, and he grew into the habit of taking the children on rowing trips (first the boy, Harry, and later the three girls) accompanied by an adult friend[42] to nearby Nuneham Courtenay or Godstow.[43] It was on one such expedition on 4 July 1862 that Dodgson invented the outline of the story that eventually became his first and greatest commercial success. He told the story to Alice Liddell and she begged him to write it down, and Dodgson eventually (after much delay) presented her with a handwritten, illustrated manuscript entitled Alice's Adventures Under Ground in November 1864.[43] Before this, the family of friend and mentor George MacDonald read Dodgson's incomplete manuscript, and the enthusiasm of the MacDonald children encouraged Dodgson to seek publication. In 1863, he had taken the unfinished manuscript to Macmillan the publisher, who liked it immediately. After the possible alternative titles were rejected – Alice Among the Fairies and Alice's Golden Hour – the work was finally published as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland in 1865 under the Lewis Carroll pen-name, which Dodgson had first used some nine years earlier.[29] The illustrations this time were by Sir John Tenniel; Dodgson evidently thought that a published book would need the skills of a professional artist. Annotated versions provide insights into many of the ideas and hidden meanings that are prevalent in these books.[44][45] Critical literature has often proposed Freudian interpretations of the book as "a descent into the dark world of the subconscious", as well as seeing it as a satire upon contemporary mathematical advances.[46][47] The overwhelming commercial success of the first Alice book changed Dodgson's life in many ways.[48][49][50] The fame of his alter ego "Lewis Carroll" soon spread around the world. He was inundated with fan mail and with sometimes unwanted attention. Indeed, according to one popular story, Queen Victoria herself enjoyed Alice in Wonderland so much that she commanded that he dedicate his next book to her, and was accordingly presented with his next work, a scholarly mathematical volume entitled An Elementary Treatise on Determinants.[51][52] Dodgson himself vehemently denied this story, commenting "... It is utterly false in every particular: nothing even resembling it has occurred";[52][53] and it is unlikely for other reasons. As T. B. Strong comments in a Times article, "It would have been clean contrary to all his practice to identify [the] author of Alice with the author of his mathematical works".[54][55] He also began earning quite substantial sums of money but continued with his seemingly disliked post at Christ Church.[29] Late in 1871, he published the sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There. (The title page of the first edition erroneously gives "1872" as the date of publication.[56]) Its somewhat darker mood possibly reflects changes in Dodgson's life. His father's death in 1868 plunged him into a depression that lasted some years.[29] The Hunting of the Snark In 1876, Dodgson produced his next great work, The Hunting of the Snark, a fantastical "nonsense" poem, with illustrations by Henry Holiday, exploring the adventures of a bizarre crew of nine tradesmen and one beaver, who set off to find the snark. It received largely mixed reviews from Carroll's contemporary reviewers,[57] but was enormously popular with the public, having been reprinted seventeen times between 1876 and 1908,[58] and has seen various adaptations into musicals, opera, theatre, plays and music.[59] Painter Dante Gabriel Rossetti reputedly became convinced that the poem was about him.[29] Sylvie and Bruno In 1895, 30 years after the publication of his masterpieces, Carroll attempted a comeback, producing a two-volume tale of the fairy siblings Sylvie and Bruno. Carroll entwines two plots set in two alternative worlds, one set in rural England and the other in the fairytale kingdoms of Elfland, Outland, and others. The fairytale world satirizes English society and, more specifically, the world of academia. Sylvie and Bruno came out in two volumes and is considered a lesser work, although it has remained in print for over a century. Photography (1856–1880)  Photo of Alice Liddell taken by Lewis Carroll (1858) In 1856, Dodgson took up the new art form of photography under the influence first of his uncle Skeffington Lutwidge, and later of his Oxford friend Reginald Southey.[60] He soon excelled at the art and became a well-known gentleman-photographer, and he seems even to have toyed with the idea of making a living out of it in his very early years.[29] A study by Roger Taylor and Edward Wakeling exhaustively lists every surviving print, and Taylor calculates that just over half of Dodgson's surviving work depicts young girls. Thirty surviving photographs depict nude or semi-nude children.[61] About 60% of Dodgson's original photographic portfolio was deliberately destroyed.[62] Dodgson also made many studies of men, women, boys, and landscapes; his subjects also include skeletons, dolls, dogs, statues, paintings, and trees.[63]  The Rossetti Family, by Lewis Carroll (1863). L-R: Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Christina Rossetti, Frances Polidori and William Michael Rossetti His pictures of children were taken with a parent in attendance [disputed – discuss] and many of the pictures were taken in the Liddell garden because natural sunlight was required for good exposures.[42] Dodgson also found photography to be a useful entrée into higher social circles.[64] During the most productive part of his career, he made portraits of notable sitters such as John Everett Millais, Ellen Terry, Maggie Spearman, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Julia Margaret Cameron, Michael Faraday, Lord Salisbury, and Alfred Tennyson.[65][29] By the time that Dodgson abruptly ceased photography (1880, after 24 years), he had established his own studio on the roof of Tom Quad, created around 3,000 images, and become an amateur master of the medium, though fewer than 1,000 images have survived time and deliberate destruction. He stopped taking photographs because keeping his studio working was too time-consuming.[66] He used the wet collodion process; commercial photographers who started using the dry-plate process in the 1870s took pictures more quickly.[67] He often altered his photographs through blurring techniques or by painting over them, a practice new to the nineteenth century. He exerted his agency of this craft by literally rewriting the text created by the image to produce a new dialogue about childhood. However, popular taste changed with the advent of Modernism, affecting the types of photographs that he produced.[68] Inventions To promote letter writing, Dodgson invented "The Wonderland Postage-Stamp Case" in 1889. This was a cloth-backed folder with twelve slots, two marked for inserting the most commonly used penny stamp, and one each for the other current denominations up to one shilling. The folder was then put into a slipcase decorated with a picture of Alice on the front and the Cheshire Cat on the back. It intended to organize stamps wherever one stored their writing implements; Carroll expressly notes in Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing it is not intended to be carried in a pocket or purse, as the most common individual stamps could easily be carried on their own. The pack included a copy of a pamphlet version of this lecture.[69][70]  Reconstructed nyctograph, with scale demonstrated by a 5 euro cent Another invention was a writing tablet called the nyctograph that allowed note-taking in the dark, thus eliminating the need to get out of bed and strike a light when one woke with an idea. The device consisted of a gridded card with sixteen squares and a system of symbols representing an alphabet of Dodgson's design, using letter shapes similar to the Graffiti writing system on a Palm device.[71] He also devised a number of games, including an early version of what today is known as Scrabble. Devised sometime in 1878, he invented the "doublet" (see word ladder), a form of brain-teaser that is still popular today, changing one word into another by altering one letter at a time, each successive change always resulting in a genuine word.[72] For instance, CAT is transformed into DOG by the following steps: CAT, COT, DOT, DOG.[29] It first appeared in the 29 March 1879 issue of Vanity Fair, with Carroll writing a weekly column for the magazine for two years; the final column dated 9 April 1881.[73] The games and puzzles of Lewis Carroll were the subject of Martin Gardner's March 1960 Mathematical Games column in Scientific American. Other items include a rule for finding the day of the week for any date; a means for justifying right margins on a typewriter; a steering device for a velociman (a type of tricycle); fairer elimination rules for tennis tournaments; a new sort of postal money order; rules for reckoning postage; rules for a win in betting; rules for dividing a number by various divisors; a cardboard scale for the Senior Common Room at Christ Church which, held next to a glass, ensured the right amount of liqueur for the price paid; a double-sided adhesive strip to fasten envelopes or mount things in books; a device for helping a bedridden invalid to read from a book placed sideways; and at least two ciphers for cryptography.[29] He also proposed alternative systems of parliamentary representation. He proposed the so-called Dodgson's method, using the Condorcet method.[74] In 1884, he proposed a proportional representation system based on multi-member districts, each voter casting only a single vote, quotas as minimum requirements to take seats, and votes transferable by candidates through what is now called Liquid democracy.[75] Mathematical work  A posthumous portrait of Lewis Carroll by Hubert von Herkomer, based on photographs. This painting now hangs in the Great Hall of Christ Church, Oxford. Within the academic discipline of mathematics, Dodgson worked primarily in the fields of geometry, linear and matrix algebra, mathematical logic, and recreational mathematics, producing nearly a dozen books under his real name. Dodgson also developed new ideas in linear algebra (e.g., the first printed proof of the Rouché–Capelli theorem),[76][77] probability, and the study of elections (e.g., Dodgson's method) and committees; some of this work was not published until well after his death. His occupation as Mathematical Lecturer at Christ Church gave him some financial security.[78] Mathematical logic His work in the field of mathematical logic attracted renewed interest in the late 20th century. Martin Gardner's book on logic machines and diagrams and William Warren Bartley's posthumous publication of the second part of Dodgson's symbolic logic book have sparked a reevaluation of Dodgson's contributions to symbolic logic.[79][80][81] It is recognized that in his Symbolic Logic Part II, Dodgson introduced the Method of Trees, the earliest modern use of a truth tree.[82] Algebra Robbins' and Rumsey's investigation[83] of Dodgson condensation, a method of evaluating determinants, led them to the alternating sign matrix conjecture, now a theorem. Recreational mathematics The discovery in the 1990s of additional ciphers that Dodgson had constructed, in addition to his "Memoria Technica", showed that he had employed sophisticated mathematical ideas in their creation.[84] |

芸術活動 鍵を持った少女(アリス)の頭と肩を描いた絵 キャロルの自作のイラストのひとつ。 文学 ドジソンは幼い頃から詩や短編小説を書き、家族の雑誌『Mischmasch』に投稿し、後にさまざまな雑誌にも投稿して、それなりの成功を収めた。 1854年から1856年にかけて、彼の作品は全国誌『The Comic Times』や『The Train』、小規模な雑誌『Whitby Gazette』や『Oxford Critic』に掲載された。これらの作品のほとんどはユーモアがあり、時には風刺的だったが、彼の基準と野心は厳しかった。「私はまだ、本格的な出版に 値するものを書いたことがないと思う(『ウィットビー・ガゼット』や『オックスフォード・クリティック』は含まない)。しかし、いつかそうできると絶望は していない」と彼は1855年7月に書いている[27]。1850年以降、彼は兄弟を楽しませるために人形劇を書いており、そのうちの1つ『ブラギアの導 き手』は現存している[37]。 1856年3月、彼は後に有名になるペンネームで最初の作品を出版した。 「孤独」という題のロマンチックな詩が『The Train』誌に「ルイス・キャロル」のペンネームで掲載された。このペンネームは、彼の本名をもじったものだった。ルイスはラテン語でルトウィッジを意 味するルドヴィクスを英語化したものであり、キャロルはラテン語のカロルスに似たアイルランド系の姓で、そこからチャールズという名前が生まれた[7]。 その経緯はこうである。「チャールズ・ルドウィッジ」はラテン語で「カロルス・ルドヴィクス」と訳された。そして、これを英語に訳し直すと「キャロル・ル イス」となり、さらに逆から訳すと「ルイス・キャロル」となる[38]。このペンネームは、ドジソンが提出した4つの候補から、編集者のエドマンド・ イェーツが選んだものである。他の候補は、エドガー・カスウェルイス、エドガー・U.C.ウェストヒル、ルイ・キャロルであった[39]。 『不思議の国のアリス』シリーズ  フラミンゴを抱え、丸まったハリネズミの上に片足を乗せ、もう1匹のハリネズミが離れていくアリスのイラスト 「アリスが最初に直面した最大の難関は、フラミンゴの世話をすることだった」。ジョン・テニエル作、1865年。  森の中で恐ろしい翼竜に剣を持った子供が立ち向かうイラスト ルイス・キャロルの『鏡の国のアリス』のためにジョン・テニエルが描いたジャバウォーキー。詩「ジャバウォーキー」を含む。 1856年、ヘンリー・リデル学長がオックスフォード大学のクライストチャーチに到着した。彼は若い家族を連れて来ており、その家族は皆、その後数年にわ たってドジソンの人生に大きな影響を与え、彼の作家としてのキャリアにも多大な影響を与えた。ドジソンはリデル学長の妻ロリーナ、そして子供たち、特にロ リーナ、エディス、アリス・リデルの3姉妹と親しい友人となった。彼は長年、自身の『不思議の国のアリス』をアリス・リデルから着想したと広く考えられて いた。鏡の国のアリス』の最後の頭字詩には彼女の名前が完全に綴られており、また、両方の本の本文には彼女に関する表面的な言及が数多く隠されている。ド ジソン自身は晩年、「小さなヒロイン」が実在の子供に基づいていることを繰り返し否定していたことが指摘されている[40][41]。また、彼は自分の作 品を知り合いの少女たちに捧げることがよくあり、文章の冒頭で頭文字詩に彼女たちの名前を付け加えていた。『スナーク狩り』の冒頭には、ゲルトルード・ チャタウェイの名前がこのような形で登場しているが、このことが物語の登場人物の誰かをモデルとしていることを意味しているわけではない[41]。 情報は乏しいが(1858年から1862年までのドジソンの日記は紛失している)、リデル家との友情が1850年代後半の彼の生活において重要な役割を果 たしていたことは明らかである。 1850年代後半、リデル家との友情は彼の生活において重要な部分を占めていたことは明らかであり、彼は子供たちを(最初は男の子のハリー、後に3人の女 の子)を近くのヌネハム・コートニーやゴドストウに連れて行く習慣を身につけた[42]。 1862年7月4日、そのような遠征の1つで、ドジソンは最終的に彼の最初の、そして最大の商業的成功となる物語のアウトラインを考案した。彼はその物語 をアリス・リデルに話し、彼女はそれを書き留めてほしいと懇願した。そしてドジソンは(多くの遅れの後)、1864年11月に『地底の国のアリス』と題さ れた手書きのイラスト入り原稿を彼女に贈った[43]。 それ以前に、友人であり師でもあったジョージ・マクドナルドの家族はドジソンの未完成の原稿を読んでいた。マクドナルド家の子供たちの熱意がドジソンに出 版を勧めた。1863年、彼は未完成の原稿を出版社のマクミランに持ち込んだ。マクミランはすぐにその原稿を気に入った。『妖精たちのいるアリス』や『ア リス黄金の時間』といった候補タイトルが却下された後、この作品は最終的に1865年に『不思議の国のアリス』というタイトルで出版された。このペンネー ムは、ドジソンが9年ほど前に初めて使用したものであった[29]。このときの挿絵はサー・ジョン・テニエルによるものであった。ドジソンは明らかに、出 版される本にはプロの画家の技術が必要だと考えていた。注釈付きバージョンでは、これらの本に広く見られる多くのアイデアや隠された意味について洞察する ことができる[44][45]。批評的な文献では、この本を「潜在意識の暗い世界への下降」としてフロイト的な解釈をすることが多いほか、現代の数学的進 歩に対する風刺として捉えることもある[46][47]。 『不思議の国のアリス』の圧倒的な商業的成功は、ドジソンの人生にさまざまな変化をもたらした[48][49][50]。彼の分身である「ルイス・キャロ ル」の名声は、たちまち世界中に広まった。ドジソンはファンレターや、時には望ましくない注目を浴びるようになった。実際、ある有名な話によると、ヴィク トリア女王自身が『不思議の国のアリス』を非常に気に入っており、次の本を女王に捧げるよう命じたため、次の作品として『行列式に関する初歩的論文』とい う学術的な数学の著作が贈られたという。[51][52]ドジソン自身はこの話を強く否定し、「... あらゆる点で完全に間違っている。それに似たことは何も起こっていない」とコメントしている。[52][53]また、他の理由からもあり得ない話である。 T. B. ストロングはタイムズ紙の記事で、「アリス』の作者を、彼の数学作品の作者と同一人物であると考えるのは、これまでの彼の行動とは正反対の考えだ」とコメ ントしている[54][55]。また、彼はかなりの額の収入を得るようになったが、嫌々ながらクライストチャーチの教職を続けていた[29]。 1871年の終わり頃、彼は続編『鏡の国のアリス』と『アリスが見つけたもの』を出版した。 (初版のタイトルページには誤って出版日が「1872年」と記載されている[56])。この作品のやや暗い雰囲気は、ドジソンの生活の変化を反映している のかもしれない。1868年に父親が亡くなり、彼は数年にわたるうつ病に苦しんだ[29]。 『スナーク狩り』 1876年、ドジソンは次の大作『スナーク狩り』を制作した。ヘンリー・ホリデイによる幻想的な「ナンセンス」詩で、9人の商人1匹のビーバーという奇妙 な乗組員がスナークを探しに出かける冒険を描いている。キャロルの同時代の批評家からは賛否両論の評価を受けたが[57]、1876年から1908年にか けて17回も再版されるなど、一般読者には絶大な人気を博した[58]。また、ミュージカル、オペラ、演劇、劇、音楽など、さまざまな形で脚色された [59]。画家のダンテ・ガブリエル・ロセッティは、この詩が自分のことを歌ったものだと確信したと言われている[29]。 シルヴィとブルーノ 1895年、傑作の出版から30年後、キャロルはカムバックを試み、妖精の兄妹シルヴィーとブルーノの2巻からなる物語を制作した。キャロルは、イギリス の田舎と妖精の国エルフランド、アウトランド、その他の2つの異なる世界を舞台にした2つのプロットを織り交ぜている。この童話の世界は、イギリス社会、 より具体的には学術の世界を風刺している。『シルヴィとブルーノ』は上下2巻で出版され、あまり評価されていないが、100年以上も版を重ねている。 写真(1856年~1880年)  ルイス・キャロルが撮影したアリス・リデルの写真(1858年) 1856年、ドジソンは叔父のスケフィントン・ラトウィッジ、そして後にオックスフォード大学の友人レジナルド・サウシーの影響を受けて、写真という新し い芸術形式を取り入れた。[60] 彼はすぐにその芸術に秀で、有名な紳士写真家となった。また、彼は非常に早い時期から、写真で生計を立てるというアイデアを弄んでいたようだ。 ロジャー・テイラーとエドワード・ウェケリングの研究では、現存するすべてのプリントが網羅的にリストアップされており、テイラーはドジソンの現存する作 品の半分強が少女を描写していると計算している。現存する30枚の写真には、裸または半裸の子供たちが写っている[61]。ドジソンのオリジナルの写真 ポートフォリオの約60%は意図的に破棄された[62]。ドジソンはまた、男性、女性、少年、風景の多くの研究も行った。被写体には、骨格、人形、犬、彫 像、絵画、樹木なども含まれる[63]。  ルイス・キャロル作『ロセッティ一家』(1863年)。左からダンテ・ガブリエル・ロセッティ、クリスティーナ・ロセッティ、フランシス・ポリドリ、ウィ リアム・マイケル・ロセッティ 彼の子供たちの写真は、親立ち会いのもとで撮影された[議論の余地あり。議論する]。また、多くの写真はリデル家の庭で撮影された。なぜなら、自然な太陽 光が良好な露出に必要だったからだ[42]。 ドジソンは、写真撮影が上流社会への有効な入り口であることも発見した[64]。キャリアで最も多作だった時期、彼はジョン・エヴァレット・ミレイ、エレ ン・テリー、マギー・スピアマン、ダンテ・ガブリエル・ロセッティ、ジュリア・マーガレット・キャメロン、マイケル・ファラデー、ソールズベリー卿、アル フレッド・テニスンといった著名人の肖像画を撮影した[65][29]。 ドジソンが突然写真撮影をやめたとき(1880年、24年後)、彼はトム・クワッドの屋上に自分のスタジオを構え、約3,000枚の写真を制作し、アマ チュア写真家の第一人者となっていた。しかし、意図的な破壊や時間の経過により、現存する写真は1,000枚に満たない。彼はスタジオを維持することがあ まりにも時間のかかる作業であったため、写真を撮影することをやめた[66]。彼は湿板コロジオン法を使用していたが、1870年代に乾板法を使い始めた 商業写真家は、より迅速に写真を撮影することができた[67]。彼はしばしば、ぼかし技法や写真に絵を描くことで写真を加工したが、これは19世紀には新 しい手法であった。彼は、この技術を用いて、文字通りイメージが作り出すテキストを書き換えることで、子供時代についての新たな対話を生み出していた。し かし、モダニズムの到来とともに大衆の好みが変わり、彼が制作する写真のタイプにも影響を与えた[68]。 発明 手紙を書くことを奨励するために、ドジソンは1889年に「不思議の国の切手ケース」を発明した。これは、布製の表紙に12個のポケットが付いたフォル ダーで、2つのポケットには最も一般的に使用される1ペニー切手を、他のポケットには1シリングまでの他の現行の額面の切手を入れるようになっていた。 フォルダーは、表にアリス、裏にチェシャ猫の絵が描かれたスリップケースに収められた。これは、筆記用具を収納する場所であればどこでも切手を整理できる ように意図されていた。キャロルは『手紙の書き方に関する8つか9つの賢明な言葉』の中で、最も一般的な個人用の切手は簡単に持ち運べるため、ポケットや 財布に入れて持ち運ぶためのものではないと明確に述べている。このパックには、この講演のパンフレット版が1部含まれていた。  5ユーロセント硬貨でスケールが示された、復元されたニクトグラフ もう一つの発明は、暗闇でもメモを取れるようにした「ナイトグラフ」と呼ばれる筆記用タブレットである。これにより、アイデアが浮かんだときにベッドから 起きて明かりを点ける必要がなくなった。この装置は、16個の正方形が描かれたグリッド状のカードと、ドジソンが考案したアルファベットを表す記号システ ムで構成されていた。この記号システムは、Palmデバイス上のGraffiti筆記システムに似た文字の形を使用していた[71]。 また、彼は今日「Scrabble」として知られるゲームの初期バージョンを含む、数多くのゲームを考案した。1878年のある時、彼は 「doublet」(「word ladder」を参照)を考案した。これは、今でも人気のある頭の体操の一種で、1文字ずつを変えて別の単語を作り、その変化のたびに必ず本物の単語にな るというものだ。CAT、COT、DOT、DOG[29]。1879年3月29日号の『ヴァニティ・フェア』誌に初めて掲載され、キャロルは2年間同誌に 毎週コラムを執筆した。最終回は1881年4月9日付[73]。ルイス・キャロルのゲームやパズルは、1960年3月の『サイエンティフィック・アメリカ ン』誌のマーティン・ガードナーの「Mathematical Games」コラムで取り上げられた。 その他の項目には、任意の日にちに対応する曜日を求めるためのルール、タイプライターの右余白を揃えるための方法、ベロシマン(三輪車の一種)の操縦装 置、テニス大会におけるより公平な敗者決定ルール、新しいタイプの郵便為替、郵便料金の計算方法、賭け事の勝敗のルール、さまざまな約数による数の割り算 のルール、 また、グラスに添えておくことで、支払った金額に見合った量のリキュールを確実に提供できる、クライストチャーチ大学のシニア・コモンルーム用の厚紙製計 量器、封筒を固定したり本に物を挟んだりするための両面テープ、寝たきりの病人でも横向きに置いた本を読めるようにする器具、暗号化の少なくとも2つの方 式なども考案した[29]。 彼はまた、議会における代議制の代替システムも提案した。コンドルセの方法を応用した、いわゆるドジソン方式を提案した[74]。1884年には、小選挙 区制に基づく比例代表制を提案した。この制度では、有権者は一人一票を投じ、議席を獲得するための最低必要数としてクオータが定められ、現在リキッド・デ モクラシーと呼ばれる方法で候補者が票を移譲できる[75]。 数学的な業績  写真をもとにヒューバート・フォン・ヘルコマールが描いたルイス・キャロルの遺作。この絵は現在、オックスフォードのクライストチャーチにある大広間に飾 られている。 数学の学術分野において、ドジソンは主に幾何学、線形代数、行列代数、数理論理学、娯楽数学の分野で活躍し、本名では10冊近くの著書を残した。ドジソン は、線形代数(例えば、ルーシェ=カペッリ定理の最初の印刷された証明)[76][77]、確率、選挙(例えば、ドジソンの方法)や委員会の調査における 新しいアイデアも開発し、これらの研究の一部は、彼の死後かなり経ってから出版された。 クライストチャーチで数学講師として働いていたことで、彼はある程度の経済的な安定を得ることができた[78]。 数理論理学 20世紀後半、ドジソンの数理論理学分野における業績が再び注目を集めるようになった。マーティン・ガードナーによる論理機械と図に関する著書、および ウィリアム・ウォーレン・バートリーによるドジソンの記号論理学書の後半部分の死後出版により、ドジソンの記号論理学への貢献が見直されるきっかけとなっ た[79][80][81]。ドジソンが『記号論理学』第2部で「木の方法」を紹介し、真理の木を初めて現代的に用いたことが認められている[82]。 代数学 ロビンスとラムゼイによるドジソンの凝縮法(行列式の評価法)の研究[83]は、現在定理となっている交代符号行列の予想につながった。 レクリエーション数学 1990年代にドジソンが作成した「メモリア・テクニカ」に加えて、さらに別の暗号が発見されたことにより、それらの作成に高度な数学的アイデアが用いら れていたことが明らかになった[84]。 |

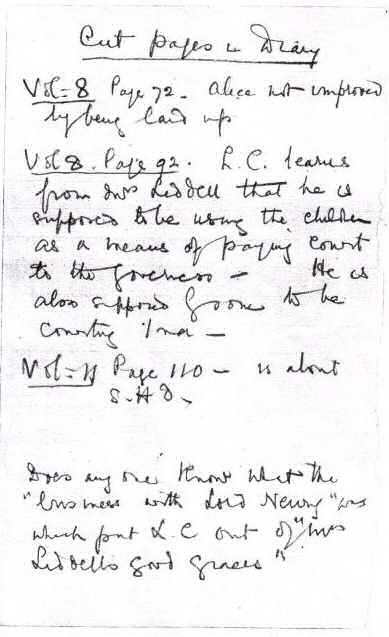

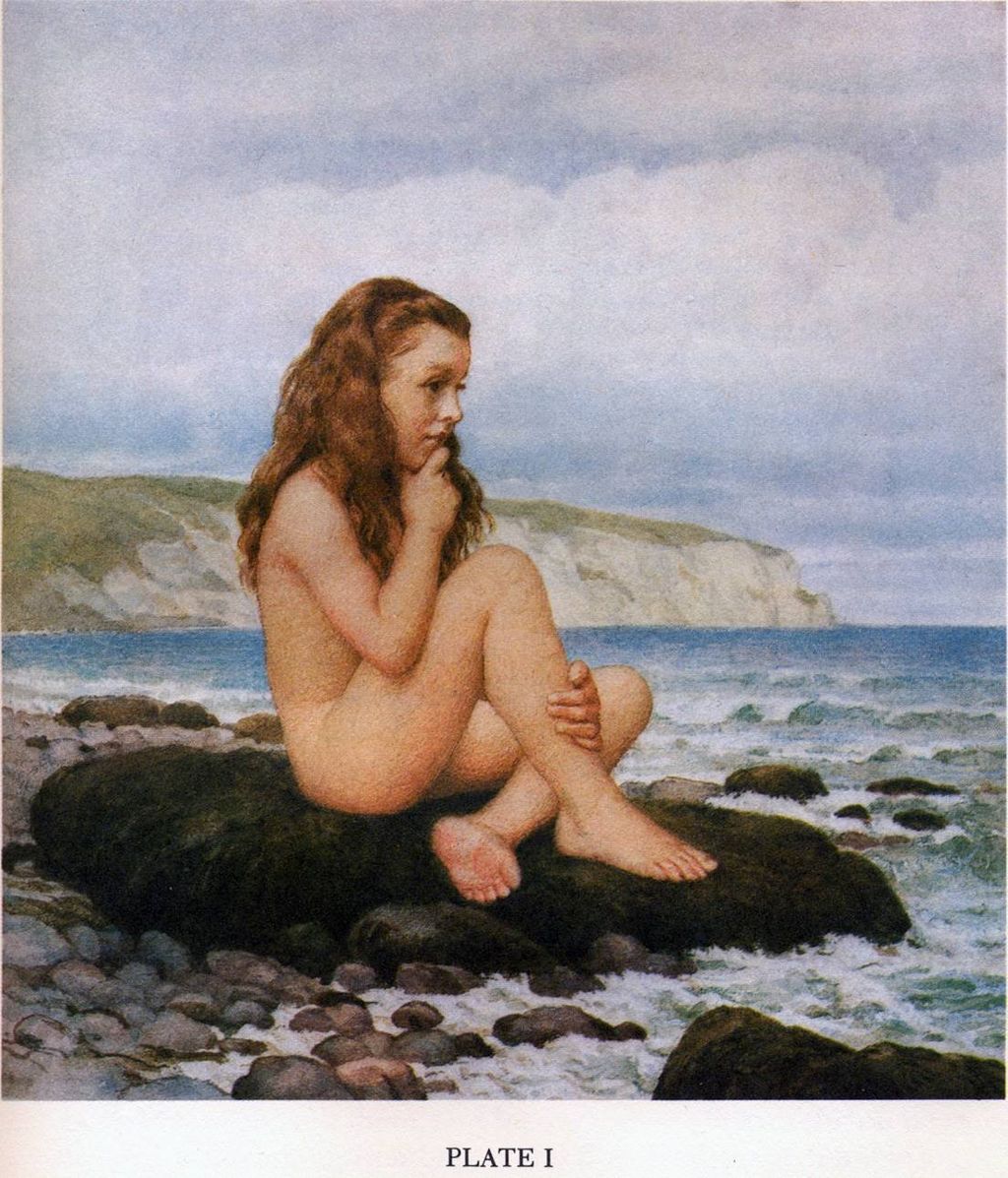

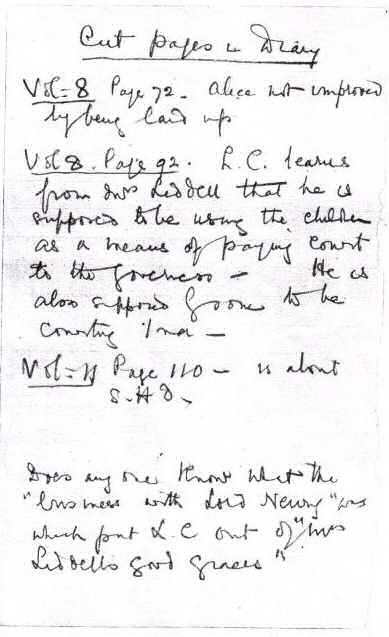

| Correspondence Dodgson wrote and received as many as 98,721 letters, according to a special letter register which he devised. He documented his advice about how to write more satisfying letters in a missive entitled "Eight or Nine Wise Words about Letter-Writing", published in 1890.[85] Later life  Lewis Carroll in later life Dodgson's existence remained little changed over the last twenty years of his life, despite his growing wealth and fame. He continued to teach at Christ Church until 1881 and remained in residence there until his death. Public appearances included attending the West End musical Alice in Wonderland (the first major live production of his Alice books) at the Prince of Wales Theatre on 30 December 1886.[86] The two volumes of his last novel, Sylvie and Bruno, were published in 1889 and 1893, but the intricacy of this work was apparently not appreciated by contemporary readers; it achieved nothing like the success of the Alice books, with disappointing reviews and sales of only 13,000 copies.[87][88] The only known occasion on which he travelled abroad was a trip to Russia in 1867 as an ecclesiastic, together with the Reverend Henry Liddon. He recounts the travel in his "Russian Journal", which was first commercially published in 1935.[89] On his way to Russia and back, he also saw different cities in Belgium, Germany, partitioned Poland and Lithuania, and France. In his early sixties, Dodgson increasingly suffered from synovitis which eventually prevented him walking and sometimes left him bed-ridden for months.[90] Death  The grave of Lewis Carroll at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford Dodgson died of pneumonia following influenza on 14 January 1898 at his sisters' home, "The Chestnuts", in Guildford in the county of Surrey, just four days before the death of Henry Liddell. He was two weeks away from turning 66 years old. His funeral was held at the nearby St Mary's Church.[91] His body was buried at the Mount Cemetery in Guildford.[29] He is commemorated at All Saints' Church, Daresbury, in its stained glass windows depicting characters from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, erected in 1935.[92] Controversies and mysteries The Secret World of Lewis Carroll (2015) BBC documentary A BBC documentary from 2015, The Secret World of Lewis Carroll,[93] critically examined Dodgson's relationship with Alice Liddell and her sisters. It explored the possibility that Dodgson's rift with the Liddell family (and his temporary suspension from the college) might have been caused by improper relations with their children, including Alice. The research for the documentary found a "disturbing" full frontal nude of Alice's adolescent sister Lorina during filming,[94] and speculated on the "likelihood" of Dodgson taking the photo. However, it was later revealed the timeline for this research had more than met the eye. The photo currently exists in the archives of the Musée Cantini in Marseille, and was attributed to Dodgson by a currently unknown hand.[95] It was subsequently revealed in early 2015 by the Carroll scholar Edward Wakeling that the photo first appeared in the 1970s, when it was owned by Parisian photo collectors. The provenance of the photo's link to Dodgson could be questioned. It was left to the Musée de Cantini. There was no link to Dodgson, and no link to the Liddell family.[96] This was not explained in the documentary. The documentary raised suspicions about Dodgson being a "repressed paedophile",[93] as one of the interviewees, Will Self, put it. This aspect was leaked to The Telegraph a week in advance.[97] When reviewing the documentary, papers sought to link the 19th-century Carroll with 21st-century sexual conduct revelations about recent paedophiles.[98] This attempted link could be considered an act of scapegoating inspired by the media's reactions to the UK's early 2010 Yewtree investigations. When problems about the documentary's conduct and research surfaced, The Times and The Telegraph reported it.[99][100] The material in the documentary has come under intense scrutiny by Carroll scholars, including those such as Jenny Woolf and Edward Wakeling, who appeared in it. Woolf claimed that she was not told of the use of the alleged photo until editing of the documentary was underway.[101] Edward Wakeling's paper/review "Eight or nine wise words on documentary making" [1] appeared in March 2015 as part of the Lewis Carroll society newsletter Bandersnatch. Wakeling also echoed Woolf's assertions that he was not given time to talk about the alleged photo. Wakeling claimed, "The documentary knew I could authenticate [the photo] or not, but they chose to keep it from me as they anticipated my response." Wakeling further criticises in his paper the Cantini photo's authenticity, the BBC's failure to tell participants of the found photo, and several factual errors.[96] Wakeling draws attention to the irregular "trimmed" nature of the photo itself, and no trace of Dodgson's writing. The inscription on the back of the photo, attributed "lewis Carroll" in pencil, "is an unknown hand... so it could have been written by anybody". The photo negative is also missing the personal catalogue number that Dodgson meticulously catalogued his photos under. "[Dodgson's] usual practice was to add a number on the back of any prints which he had developed". Wakeling also points out that Dodgson never made "full frontal studies...particularly a girl as mature as this.. There's no way the Liddells would have allowed a picture of this kind to have been taken."[96] It is currently unknown whether this photo is by Dodgson, nor who wrote the pencil inscription on the back of it and for what reason. The photo was not included in Wakeling's catalogue raisonné of Dodgson's complete surviving photographs [102] and has remained unused by other subsequent documentaries on Dodgson.[103] The BBC Trust later ruled that the documentary could not be shown on UK TV in its current form again, as the BBC failed to tell participants of the photo's appearance during filming or give them time to fully react to it.[100][99] Speculation of sexual conduct by scholars (1940s onwards) Late twentieth-century biographers have speculated that Dodgson's interest in children might have had an "erotic" element, including Morton N. Cohen in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1995),[104] Donald Thomas in his Lewis Carroll: A Portrait with Background (1995), and Michael Bakewell in his Lewis Carroll: A Biography (1996). Cohen, in particular, speculates that Dodgson's "sexual energies sought unconventional outlets", and further writes: We cannot know to what extent sexual urges lay behind Charles's preference for drawing and photographing children in the nude. He contended the preference was entirely aesthetic. But given his emotional attachment to children as well as his aesthetic appreciation of their forms, his assertion that his interest was strictly artistic is naïve. He probably felt more than he dared acknowledge, even to himself.[105]  Lewis Carroll photograph of Beatrice Hatch, colourised on Carroll’s instructions Cohen goes on to note that Dodgson "apparently convinced many of his friends that his attachment to the nude female child form was free of any eroticism", but adds that "later generations look beneath the surface" (p. 229). He argues that Dodgson may have wanted to marry the 11-year-old Alice Liddell and that this was the cause of the unexplained "break" with the family in June 1863,[29] an event for which other explanations are offered. Biographers Derek Hudson and Roger Lancelyn Green stop short of identifying Dodgson as a paedophile (Green also edited Dodgson's diaries and papers), but they concur that he had a passion for small female children and next to no interest in the adult world. [citation needed] Catherine Robson refers to Carroll as "the Victorian era's most famous (or infamous) girl lover".[106] Several other writers and scholars have challenged the evidential basis for Cohen's and others' views about Dodgson's potential exploitative behavior. Hugues Lebailly has endeavoured to set Dodgson's child photography within the "Victorian Child Cult", which perceived child nudity as essentially an expression of innocence.[107] He claims that Dodgson's diaries contained numerous entries that reveal an appreciation for adult women, as well as their appearance in art and theater, even "vulgar" entertainment. Dodgson's nieces removed such references from early manuscripts of Dodgson's diaries, but kept references to children, because such appreciation was not controversial at the time. Lebailly claims that studies of child nudes were mainstream and fashionable in Dodgson's time and that most photographers made them as a matter of course, including Oscar Gustave Rejlander and Julia Margaret Cameron. Lebailly continues that child nudes even appeared on Victorian Christmas cards, implying a very different social and aesthetic assessment of such material. Lebailly concludes that it has been an error of Dodgson's biographers to view his child-photography with 20th- or 21st-century eyes, and to have presented it as some form of personal idiosyncrasy, when it was a response to a prevalent aesthetic and philosophical movement of the time. Karoline Leach's reappraisal of Dodgson focused in particular on his controversial interest in nude children. She argues that the allegations of paedophilia rose initially from a misunderstanding of Victorian morals, as well as the mistaken idea – fostered by Dodgson's various biographers – that he had no interest in adult women. She termed the traditional image of Dodgson "the Carroll Myth". She drew attention to the large amounts of evidence in his diaries and letters that he was also keenly interested in adult women, married and single, and enjoyed several relationships with them that would have been considered scandalous by the social standards of his time. She also pointed to the fact that many of those whom he described as "child-friends" were girls in their late teens and even twenties.[108] She argues that suggestions of paedophilia emerged only many years after his death, when his well-meaning family had suppressed all evidence of his relationships with women in an effort to preserve his reputation, thus giving a false impression of a man interested only in little girls. Similarly, Leach points to a 1932 biography by Langford Reed as the source of the dubious claim that many of Carroll's female friendships ended when the girls reached the age of 14.[109] In addition to the biographical works that have discussed Dodgson's alleged sexual misconduct of children, there are modern artistic interpretations of his life and work that do so as well – in particular, Dennis Potter in his play Alice and his screenplay for the motion picture Dreamchild, and Robert Wilson in his musical Alice. Ordination Dodgson had been groomed for the ordained ministry in the Church of England from a very early age, and was expected to be ordained within four years of obtaining his master's degree as a condition of his residency at Christ Church. He delayed the process for some time but was eventually ordained as a deacon on 22 December 1861, but when the time came a year later to be ordained as a priest, Dodgson appealed to the dean for permission not to proceed. This was against college rules and, initially, Dean Liddell told him that he would have to consult the college ruling body, which would almost certainly have resulted in his being expelled. For unknown reasons, Liddell changed his mind overnight and permitted him to remain at the college in defiance of the rules.[110] Dodgson never became a priest, unique amongst senior students of his time. There is currently no conclusive evidence about why Dodgson rejected the priesthood. Some have suggested that his stammer made him reluctant to take the step because he was afraid of having to preach.[111] Wilson quotes letters by Dodgson describing difficulty in reading lessons and prayers rather than preaching in his own words.[112] However Dodgson did indeed preach in later life, even though not in priest's orders, so it seems unlikely that his impediment was a major factor affecting his choice. Wilson also points out that the Bishop of Oxford, Samuel Wilberforce, who ordained Dodgson, had strong views against clergy going to the theatre, one of Dodgson's great interests. He was interested in minority forms of Christianity (he was an admirer of F. D. Maurice) and "alternative" religions (theosophy).[113] Dodgson became deeply troubled by an unexplained sense of sin and guilt at this time (the early 1860s), and frequently expressed the view in his diaries that he was a "vile and worthless" sinner, unworthy of the priesthood, and this sense of sin and unworthiness may well have informed his decision to abandon being ordained to the priesthood.[114] Missing diaries At least four complete volumes and around seven pages of text are missing from Dodgson's 13 diaries.[115] The loss of the volumes remains unexplained; the pages have been removed by an unknown hand. Most scholars assume that the diary material was removed by family members in the interests of preserving the family name, but this has not been proven.[116] Except for one page, material is missing from his diaries for the period between 1853 and 1863 (when Dodgson was 21–31 years old).[117][118] During this period, Dodgson began experiencing great mental and spiritual anguish and confessing to an overwhelming sense of his own sin. This was also the period of time when he composed his extensive love poetry, leading to speculation that the poems were autobiographical.[119][120] Many theories have been put forward to explain the missing material. A popular explanation for one missing page (27 June 1863) is that it might have been torn out to conceal a proposal of marriage on that day by Dodgson to the 11-year-old Alice Liddell. However, there has never been any evidence to suggest this, and a paper suggests evidence to the contrary which was discovered by Karoline Leach in the Dodgson family archive in 1996.[121][better source needed]  The "cut pages in diary" document, in the Dodgson family archive in Woking This paper is known as the "cut pages in diary" document. Carroll's nephew Philip Dodgson Jacques reports that he wrote it well after Carroll's death, based on information from his aunts, who destroyed two diary pages, including the one for 27 June 1863. Jacques did not see the pages himself.[122] The summary for 27 June states that Mrs. Liddell told Dodgson there was gossip circulating about him and the Liddell family's governess, as well as about his relationship with "Ina", presumably Alice's older sister Lorina Liddell. The "break" with the Liddell family that occurred soon after was presumably in response to this gossip.[123][121] Without evidence, Leach suggests an alternative interpretation; Lorina was also the name of Alice Liddell's mother. What is deemed most crucial and surprising is the document seems to imply that Dodgson's break with the family was not connected with Alice at all. Until a primary source is discovered, the events of 27 June 1863 will remain in doubt; however, a 1930 letter from the younger Lorina Liddell to Alice may shed light on the matter. Reporting an interview with an early Dodgson biographer, she wrote: I said his manner became too affectionate to you as you grew older, and that mother spoke to him about it, and that offended him so he ceased coming to visit us again – as one had to find some reason for all intercourse ceasing . . . Mr. D used to take you on his knee . . . I did not say that.[124] Migraine and epilepsy In his diary from 1880, Dodgson recorded experiencing his first episode of migraine with aura, describing very accurately the process of "moving fortifications" that are a manifestation of the aura stage of the syndrome.[125] There is no clear evidence to show whether this was his first experience of migraine per se or he previously had the far more common form of migraine without aura, although the latter seems most likely, given the fact that migraine most commonly develops in the teens or early adulthood. Another form of migraine aura called Alice in Wonderland syndrome has been named after Dodgson's book of the same name and its titular character, because its manifestation can resemble the sudden size-changes in the book. It is also known as micropsia and macropsia, a brain condition affecting the way that objects are perceived by the mind. For example, an affected person may look at a larger object such as a basketball and perceive it as having the size of a golf ball. Some authors have suggested that Dodgson experienced this type of aura and used it as an inspiration in his work, but there is no evidence that he did.[126][127] Dodgson also had two attacks in which he lost consciousness. He was diagnosed by a Dr Morshead, Dr Brooks, and Dr Stedman, and they believed the attack and a consequent attack to be an "epileptiform" seizure (initially thought to be fainting, but Brooks changed his mind). Some have concluded from this that he had this condition for his entire life, but there is no evidence of this in his diaries beyond the diagnosis of the two attacks already mentioned.[125] Some authors, Sadi Ranson in particular, have suggested that Carroll had temporal lobe epilepsy in which consciousness is not always completely lost but altered, and in which the symptoms mimic many of the same experiences as Alice in Wonderland. Carroll had at least one incident in which he suffered full loss of consciousness and awoke with a bloody nose, which he recorded in his diary and noted that the episode left him not feeling himself for "quite sometime afterward". This attack was diagnosed as possibly "epileptiform", and Carroll himself later wrote of his "seizures" in the same diary. Most of the standard diagnostic tests of today were not available in the nineteenth century. Yvonne Hart, consultant neurologist at the John Radcliffe Hospital, Oxford, considered Dodgson's symptoms. Her conclusion, quoted in Jenny Woolf's 2010 The Mystery of Lewis Carroll, is that Dodgson very likely had migraine and may have had epilepsy, but she emphasises that she would have considerable doubt about making a diagnosis of epilepsy without further information.[128] |

手紙 ドジソンが考案した特別な手紙登録簿によると、彼は98,721通もの手紙を書き、また受け取っていた。彼は、より満足のいく手紙の書き方に関するアドバ イスを、1890年に出版された『手紙の書き方に関する8、9の賢明な言葉』という書簡に記している[85]。 晩年  晩年のルイス・キャロル ドジソンの生活は、彼の富と名声が増大するにもかかわらず、人生最後の20年間ほとんど変化しなかった。彼は1881年までクライストチャーチで教え続 け、死ぬまでそこに住んでいた。公の場に姿を見せたのは、1886年12月30日にプリンス・オブ・ウェールズ劇場で上演されたミュージカル『不思議の国 のアリス』(彼の『不思議の国のアリス』の初の大型ライブ公演)を観劇したことなどである[86]。彼の最後の小説『シルヴィーとブルーノ』上下巻は、 1889年と1893年に出版されたが、この作品の複雑さは当時の読者には理解されなかったようで、アリス・シリーズのような成功を収めることはなく、評 価も低く、販売部数は1万3千部に留まった[87][88]。 彼が海外へ旅行した唯一の記録として知られているのは、1867年にヘンリー・リドン牧師とともに聖職者としてロシアへ旅行した時のことである。彼はこの 旅行について『ロシア日記』に記しており、この日記は1935年に初めて商業出版された[89]。ロシアへの往復の途中、彼はベルギー、ドイツ、分割され たポーランドとリトアニア、フランスのさまざまな都市も訪れた。 60代前半、ドジソンは滑膜炎を患い、やがて歩くことができなくなり、時には数か月間寝たきりになることもあった[90]。 死  ギルフォードのマウント墓地にあるルイス・キャロルの墓 ドジソンは、1898年1月14日、サリー州ギルフォードにある姉の自宅「チェスナッツ」で、インフルエンザに続いて肺炎で死去した。ヘンリー・リデルが 亡くなるわずか4日前のことであった。彼は66歳になる2週間前のことであった。葬儀は近くのセントメアリー教会で行われた[91]。彼の遺体はギル フォードのマウント墓地に埋葬された[29]。 彼は、1935年に建てられた、不思議の国のアリスに登場するキャラクターが描かれたステンドグラスの窓がある、ダーズベリーにあるオールセインツ教会で 追悼されている[92]。 論争と謎 ルイス・キャロルの秘密の世界』(2015年)BBCドキュメンタリー 2015年にBBCが制作したドキュメンタリー『The Secret World of Lewis Carroll』[93]は、ドジソンとリデル姉妹の関係について批判的に検証した。 ドジソンとリデル家との確執(および大学の一時停学)は、アリスを含む子供たちとの不適切な関係が原因だった可能性を探った。ドキュメンタリー制作のため の調査で、撮影中にアリス・リデルの思春期の妹ロリーナの「不穏な」全裸が発見され、ドジソンが撮影した「可能性」が推測された。しかし、この調査のタイ ムラインには、目に見える以上のものがあったことが後に明らかになった。この写真は現在、マルセイユのカンティーニ美術館のアーカイブに存在しており、ド ジソンによるものと現在不明の手によってされている[95]。その後、2015年初頭にキャロル研究家のエドワード・ウェケリングによって、この写真は 1970年代にパリの写真コレクターが所有していたときに初めて現れたことが明らかになった。この写真のドジソンとのつながりの由来は疑われる可能性があ る。それはカンティーニ美術館に委ねられていた。ドジソンとの関連もリデル家との関連もなかった[96]。ドキュメンタリーではこの点について説明されな かった。ドキュメンタリーでは、インタビューを受けたウィル・セルフが「ドジソンは抑圧された小児性愛者」[93]であるとの疑念を呈した。この側面は、 1週間前にテレグラフ紙にリークされていた[97]。ドキュメンタリーを検証する際、新聞各紙は19世紀のキャロルと、最近の小児性愛者に関する21世紀 の性的行為の暴露とを結び付けようとした[98]。この結び付けの試みは、2010年初頭のイギリスのユーツリー調査に対するメディアの反応に触発された スケープゴート行為と見なすことができる。ドキュメンタリーの制作や調査に関する問題が表面化した際、タイムズ紙とテレグラフ紙がそれを報じた[99] [100]。 ドキュメンタリーに登場するジェニー・ウルフやエドワード・ウェケリングを含むキャロル研究家たちから、このドキュメンタリーの内容が厳しく吟味された。 ウルフは、ドキュメンタリーの編集作業が始まるまで、問題の写真の使われ方について知らされていなかったと主張している[101]。エドワード・ウェケリ ングの論文/レビュー「ドキュメンタリー制作に関する8つか9つの賢明な言葉」[1]は、2015年3月にルイス・キャロル協会ニュースレター『バンダー スナッチ』に掲載された。また、ワケリングは、その写真について話す時間が与えられなかったというウォルフの主張に同意している。ワケリングは、「ドキュ メンタリーは私がその写真を証明できるかどうかを知っていたが、私の反応を予想して、それを私に知らせないことを選んだ」と主張している。 Wakelingはさらに、論文の中でカンティーニ写真の信憑性、BBCが発見写真の参加者にその事実を伝えなかったこと、いくつかの事実誤認を批判して いる[96]。 Wakelingは、写真の不規則な「トリミング」された性質と、ドジソンの筆跡の痕跡がないことに注目している。写真の背面に鉛筆で「ルイス・キャロ ル」と書かれた碑文は、「誰かの手によるもので、ドジソン以外の誰かの筆跡である可能性がある」という。写真のネガには、ドジソンが自分の写真を丹念に整 理した際の個人的なカタログ番号も欠落している。「ドジソンは、現像したプリントの裏に番号を付けるのが常だった」[96]。また、ウェケリングは、ドジ ソンが「正面からの完全な研究、特にこれほど成熟した少女を正面から研究したことは一度もない」と指摘している。リデル夫妻がこのような写真を許可するは ずがない」[96]。この写真がドジソンによるものなのか、また、裏面に鉛筆で書かれた署名は誰によるものなのか、そして、どのような理由で書かれたのか は、現在不明である。この写真は、ドジソンの現存する写真の完全なカタログレゾネであるウェケリングの『Catalogue raisonné of Dodgson's complete surviving photographs』[102]には含まれておらず、ドジソンに関するその後のドキュメンタリーでも使用されていない[103]。 BBCトラストは後に、BBCが撮影中に写真の登場を参加者に伝えず、また参加者がその写真に十分に反応する時間を設けなかったとして、ドキュメンタリー を現在の形で再び英国のテレビで放映することはできないと裁定した[100][99]。 学者による性的行為の憶測(1940年代以降) 20世紀後半の伝記作家たちは、ドジソンの子供たちへの興味には「エロティック」な要素があったのではないかと推測している。その中には、モートン・N・ コーエン著『ルイス・キャロル伝』(1995年)、[104]ドナルド・トーマス著『ルイス・キャロル伝』(1995年)、マイケル・ベイクウェル著『ル イス・キャロル伝』(1996年)などが含まれる。特にコーエンは、ドジソンの「性的エネルギーは型にはまらない出口を求めていた」と推測し、さらにこう 書いている。 チャールズが裸の子供たちを絵に描いたり写真を撮ったりすることを好む背景には、どの程度の性的衝動があるかはわからない。彼はその嗜好は完全に美的であ ると主張した。しかし、子供たちへの感情的な愛着と、子供たちの姿に対する美的評価の両方を考慮すると、彼の興味は純粋に芸術的なものであるという主張は 甘すぎる。おそらく彼は、自分自身に対しても、認める勇気がない以上に感じていたのだろう。  ルイス・キャロルのベアトリス・ハッチの写真。キャロルの指示によりカラー化されている コーエンは、ドジソンが「自分の裸の女児への執着にエロティシズムはまったく含まれていないと、多くの友人たちを説得したらしい」と記した上で、「後世の 世代は表面の下にあるものを見ている」(229ページ)と付け加えている。彼は、ドジソンは11歳の少女アリス・リデルと結婚したかったのではないか、そ れが1863年6月の家族との不可解な「決別」の原因だったのではないかと主張している[29]。伝記作家のデレク・ハドソンとロジャー・ランセリン・グ リーンは、ドジソンを小児性愛者と断定することは控えているが(グリーンはドジソンの日記や論文の編集も手がけた)、ドジソンが幼い女の子に情熱を傾け、 大人の世界にはほとんど興味を示さなかったという点では一致している。 [citation needed] キャサリン・ロブソンはキャロルを「ヴィクトリア朝時代で最も有名な(あるいは悪名高い)少女愛好家」と呼んでいる[106]。 ドジソンの潜在的な搾取的行動に関するコーエンや他の人々の見解の証拠的根拠について、他の作家や学者数人が異議を唱えている。ヒュー・ルベイリーは、ド ジソンの子供の写真撮影を、子供のヌードを本質的に無邪気さの表現と捉える「ヴィクトリア朝の子供崇拝」の文脈に位置づける試みをしている[107]。彼 は、ドジソンの日記には、大人の女性に対する評価や、芸術や演劇、さらには「下品」な娯楽における女性の姿に関する記述が多数含まれていると主張してい る。ドジソンの姪たちは、ドジソンの日記の初期の草稿からそのような言及を削除したが、子供たちへの言及は残した。なぜなら、そのような評価は当時物議を 醸すようなものではなかったからだ。レベイリーは、ドジソンの時代には子供のヌード写真は主流であり、流行していたと主張し、オスカー・グスタフ・レイラ ンダーやジュリア・マーガレット・キャメロンを含むほとんどの写真家が当然のように子供のヌード写真を撮っていたと主張している。レベイリーはさらに、 ヴィクトリア朝のクリスマスカードにも子供のヌードが使われていたと付け加え、このような素材に対する社会的・美的評価が当時とは大きく異なっていたこと を示唆している。レベイリーは、ドジソンの子供写真について、20世紀や21世紀の価値観で捉え、一種の個人的な癖として紹介するのは誤りであると結論づ けている。 キャロライン・リーチは、ドジソンの再評価にあたり、特に彼の子供ヌードに対する物議を醸す興味に注目した。彼女は、小児性愛疑惑は、ビクトリア朝の道徳 に対する誤解、そしてドジソンの伝記作家たちが広めた、ドジソンが成人女性に興味を持たないという誤った考えから生じたと主張している。彼女は、ドジソン の伝統的なイメージを「キャロル神話」と呼んだ。彼女は、彼の日記や手紙に、彼が既婚・未婚を問わず大人の女性にも強い関心を抱き、当時の社会基準からす ればスキャンダルとみなされるような複数の関係を楽しんでいたという証拠が多数あることに注目した。また、リーチの「子供時代の友人」として描写された人 物たちの多くが、10代後半から20代前半の少女であった事実も指摘している[108]。リーチの主張によると、彼が小児性愛者であったという噂が広まっ たのは、彼の死後、彼の家族が良い印象を保とうとして、彼と女性たちとの関係を示す証拠をすべて隠蔽してからずっと後のことだった。同様に、リーチは、 キャロルの女性との友情の多くが、その女性たちが14歳になった時点で終わってしまったという疑わしい主張の根拠として、1932年にラングフォード・ リードが書いた伝記を挙げている[109]。 ドジソンの子供に対する性的虐待疑惑について論じた伝記作品に加え、彼の生涯と作品について同様の解釈をした現代的な芸術作品もある。特に、デニス・ポッ ターの戯曲『アリス』と映画『ドリームチャイルド』の脚本、ロバート・ウィルソンのミュージカル『アリス』などが挙げられる。 叙勲 ドジソンは幼い頃から英国国教会の聖職者になるための教育を受けており、クライストチャーチに居住する条件として修士号取得から4年以内に聖職に就くこと が期待されていた。彼はしばらくそのプロセスを遅らせたが、最終的に1861年12月22日に助祭として叙階された。しかし、1年後に司祭として叙階され る時期が来たとき、ドジソンは司祭叙階を保留する許可を学部長に求めた。これは大学の規則に反するもので、当初、リデル学部長は、大学の決定機関に相談し なければならないと彼に告げた。その結果、ほぼ確実に彼は退学処分となっただろう。理由は不明だが、リデルは一夜にして考えを変え、規則に背いてカレッジ に留まることを許可した[110]。ドジソンは結局司祭にはならず、同世代の学生の中では異例の存在となった。 ドジソンが聖職を拒否した理由について、決定的な証拠は今のところない。吃音のために説教することを恐れて、その一歩を踏み出せなかったという説もある [111]。ウィルソンは、ドジソンが説教ではなく、聖書や祈りの朗読に苦労していたことを示す手紙を引用している[112]。しかし、ドジソンは司祭の 叙任式には参加しなかったものの、晩年になって実際に説教を行っている。そのため、吃音がドジソンの選択に大きな影響を与えたとは考えにくい。ウィルソン はまた、ドジソンに叙階したオックスフォード大司教サミュエル・ウィルバーフォースが、聖職者が劇場に行くことに強い反対の立場を取っていたことを指摘し ている。彼はキリスト教の少数派(彼はF.D.モーリスを賞賛していた)や「代替」宗教(神智学)に興味を持っていた[113]。ドジソンはこの頃 (1860年代初頭)、説明のつかない罪悪感と罪の意識に深く悩まされていた。 1860年代前半)、そして頻繁に日記に「自分は下劣で価値のない罪人であり、聖職に就く資格はない」と記していた。この罪の意識と無価値感が、聖職に就 くことを諦める決断を下すきっかけとなった可能性もある[114]。 日記の紛失 ドジソンの13冊の日記のうち、少なくとも4冊分の完全な内容と、約7ページ分のテキストが失われている[115]。ページの紛失についてはいまだに説明 されておらず、ページは不明の手によって削除された。ほとんどの学者は、日記の記述が家族の名前を守るために家族によって削除されたと推測しているが、こ れは証明されていない[116]。1ページを除いて、1853年から1863年(ドジソンが21歳から31歳)までの日記の記述が失われている[117] [118]。1863年(ドジソンが21歳から31歳の間)の期間である。[117][118] この期間、ドジソンは精神的に大きな苦悩を経験し、自身の罪に対する圧倒的な感覚を告白し始めた。また、この時期は彼が膨大な愛の詩を綴っていた時期でも あり、これらの詩は自伝的であるとの憶測を呼んだ[119][120]。 欠落したページを説明する多くの説が提示されている。1863年6月27日の1ページが欠落している理由として、ドジソンが11歳のアリス・リデルに求婚 したその日に、求婚の事実を隠すために破り捨てたのではないかという説が一般的である。しかし、これを示唆する証拠はこれまで一度も発見されておらず、 1996年にドジソン家のアーカイブでキャロライン・リーチが発見した、これとは反対の証拠を示唆する論文がある[121][より確かな情報源が必要]。  ワーキングにあるドジソン家のアーカイブに「日記の切り抜き」文書がある この論文は「日記の切り取られたページ」として知られている。キャロルの甥のフィリップ・ドジソン・ジャックは、キャロルの死後かなり経ってから、キャロ ルの叔母たちから得た情報に基づいてこれを書いたと報告している。叔母たちは、1863年6月27日を含む日記のページ2枚を破棄していた。ジャックは ページを直接目にしたわけではない[122]。6月27日の要約には、リデル夫人がドジソンに、彼とリデル家の家庭教師、そしておそらくアリスのお姉さん であるロリーナ・リデルとの噂が流れていると伝えたことが記されている。リデル家との「決別」は、おそらくこの噂に対する反応だったと思われる[123] [121]。証拠はないが、リーチは別の解釈を示唆している。ロリーナはアリス・リデルの母親の名前でもある。最も重要で驚くべきことは、この文書が、ド ジソンとリデル家の決別はアリスとはまったく無関係だったことを示唆しているように見えることだ。一次資料が発見されるまでは、1863年6月27日の出 来事は疑わしいままとなるが、1930年にロリーナ・リデルがアリスに送った手紙が、この問題について新たな光を当てるかもしれない。初期のドジソン伝記 作家とのインタビューについて、彼女は次のように書いている。 私は、あなたが年を重ねるにつれ、彼の態度があなたに対して愛情深くなりすぎたこと、そして、それについてお母さんが彼に話したこと、そして、それが彼を 怒らせたので、彼は二度と私たちを訪ねて来なくなったこと、そして、すべての交流が途絶えるには何らかの理由を見つけなければならないことについて述べ た。D氏は、あなたを膝に乗せていた。私は、そのことは言わなかった。 偏頭痛とてんかん 1880年の日記に、ドジソンは初めて前兆のある片頭痛を経験したと記録している。前兆段階の「動く要塞」のプロセスを非常に正確に描写している。これが 彼の初めての片頭痛の経験であったのか、それともそれ以前に前兆のない、より一般的なタイプの片頭痛を経験していたのかは明らかではない。しかし、片頭痛 は10代から20代前半に最も発症しやすいことを考えると、後者の可能性の方が高いと思われる。「不思議の国のアリス症候群」と呼ばれる片頭痛の前兆のも う一つのタイプは、ドジソンの同名の小説とその主人公の名前から名付けられた。その症状は、小説の中で突然サイズが変わることに似ているためである。ま た、この症状は「微小視症」や「巨大視症」とも呼ばれ、物体の知覚に影響を及ぼす脳の状態である。例えば、この症状を持つ人は、バスケットボールなどの大 きな物体をゴルフボールの大きさだと認識してしまうことがある。ドジソンがこのタイプのオーラを経験し、それを作品のインスピレーションとして活用してい たと示唆する作家もいるが、それを裏付ける証拠はない[126][127]。 ドジソンは意識を失う発作を2度起こしている。彼はモースヘッド医師、ブルックス医師、ステッドマン医師に診断され、発作とその後の発作は「てんかん様」 発作であると考えられた(最初は失神と思われたが、ブルックスは考えを変えた)。このことから、彼は生涯にわたってこの症状を抱えていたと結論づける者も いるが、すでに述べた2回の発作の診断以上のことは日記には書かれていない[125]。特にサディ・ランソンをはじめとする一部の作家は、キャロルは必ず しも完全に意識を失うわけではないが、意識が変化し、その症状が『不思議の国のアリス』の多くの体験と類似している側頭葉てんかんであったと示唆してい る。キャロルは少なくとも1度、意識を完全に失い、鼻血を出して目を覚ましたことがあった。彼はその出来事を日記に記録し、「その後しばらくの間」自分が 自分ではないような気分が続いたと記している。この発作は「てんかん様」と診断され、キャロル自身も後に同じ日記に「発作」について書いている。 19世紀には、今日の標準的な診断テストのほとんどは存在していなかった。オックスフォードのジョン・ラドクリフ病院の神経科医であるイボンヌ・ハート は、ドジソンの症状について考察した。彼女の結論は、ジェニー・ウルフの2010年の著書『ルイス・キャロルの謎』で引用されているが、ドジソンは片頭痛 を患っていた可能性が非常に高く、てんかんを患っていた可能性もあるが、さらなる情報がない限り、てんかんの診断を下すことにはかなりの疑問が残ると強調 している[128]。 |

Legacy Lewis Carroll memorial window (Mad Hatter, Dormouse and March Hare pictured) at All Saints' Church, Daresbury, Cheshire There are societies in many parts of the world dedicated to the enjoyment and promotion of his works and the investigation of his life.[129] Copenhagen Street in Islington, north London is the location of the Lewis Carroll Children's Library.[130] In 1982, his great-nephew unveiled a memorial stone to him in Poets' Corner, Westminster Abbey.[131] In January 1994, an asteroid, 6984 Lewiscarroll, was discovered and named after Carroll. The Lewis Carroll Centenary Wood near his birthplace in Daresbury opened in 2000.[132] As Carroll was born in All Saints' Vicarage, he is commemorated at All Saints' Church, Daresbury by stained glass windows depicting characters from Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. The Lewis Carroll Centre, attached to the church, was opened in March 2012.[133] |

遺産[編集] チェシャー州ダレスベリーにあるオールセインツ教会にあるルイス・キャロルの記念窓(マッドハッター、ヤマネ、マーチ・ヘアが描かれている 彼の作品を楽しんだり、普及させたり、彼の人生を調査したりする団体が世界の多くの地域に存在する[129]。 ロンドン北部イズリントンのコペンハーゲン・ストリートには、ルイス・キャロル児童図書館がある[130]。 1982年、彼の曾孫がウェストミンスター寺院の詩人コーナーに彼を記念する石碑を建立した[131]。1994年1月、小惑星6984ルイス・キャロル が発見され、キャロルにちなんで命名された。2000年には、彼の生誕地ダーズベリー近郊にルイス・キャロル生誕100周年記念の森がオープンした [132]。 キャロルはオールセインツ・ヴィカーレッジで生まれたため、ダーズベリーにあるオールセインツ教会では、『不思議の国のアリス』の登場人物が描かれたステ ンドグラスで彼を記念している。教会に併設されたルイス・キャロル・センターは、2012年3月にオープンした[133]。 |

| Literary works La Guida di Bragia, a Ballad Opera for the Marionette Theatre (around 1850) "Miss Jones", comic song (1862)[134] Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1865) Phantasmagoria and Other Poems (1869) Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There (includes "Jabberwocky" and "The Walrus and the Carpenter") (1871) The Hunting of the Snark (1876) Rhyme? And Reason? (1883) – shares some contents with the 1869 collection, including the long poem "Phantasmagoria" A Tangled Tale (1885) Sylvie and Bruno (1889) The Nursery "Alice" (1890) Sylvie and Bruno Concluded (1893) Pillow Problems (1893) What the Tortoise Said to Achilles (1895) Three Sunsets and Other Poems (1898) The Manlet (1903)[135] Mathematical works A Syllabus of Plane Algebraic Geometry (1860) The Fifth Book of Euclid Treated Algebraically (1858 and 1868) An Elementary Treatise on Determinants, With Their Application to Simultaneous Linear Equations and Algebraic Equations Euclid and his Modern Rivals (1879), both literary and mathematical in style Symbolic Logic Part I Symbolic Logic Part II (published posthumously) The Alphabet Cipher (1868) The Game of Logic (1887) Curiosa Mathematica I (1888) Curiosa Mathematica II (1892) A discussion of the various methods of procedure in conducting elections (1873), Suggestions as to the best method of taking votes, where more than two issues are to be voted on (1874), A method of taking votes on more than two issues (1876), collected as The Theory of Committees and Elections, edited, analysed, and published in 1958 by Duncan Black Other works Some Popular Fallacies about Vivisection Eight or Nine Wise Words About Letter-Writing (1890) Notes by an Oxford Chiel (1865–74) The Principles of Parliamentary Representation (1884) |

文学作品[編集] 「ブラギアの案内」:マリオネット劇のためのバラッドオペラ(1850年頃) 「ミス・ジョーンズ」、喜歌劇(1862年)[134] 『不思議の国のアリス』(1865年) 『ファンタスマゴリアとその他の詩』(1869年) 鏡の国のアリス』(「ジャバウォーキー」と「セイウチと大工」を含む)(1871年) スナーク狩り』(1876年) Rhyme? And Reason? (1883) – 1869年のコレクションと内容が一部重なり、長編詩「Phantasmagoria」などが含まれる 『A Tangled Tale』(1885年) シルヴィーとブルーノ』(1889年) 「アリス」の子供部屋(1890年) シルヴィとブルーノ完結篇(1893年) 枕の問題(1893年) 亀がアキレスに言ったこと(1895年) 『3つの夕日とその他の詩』(1898年) The Manlet(1903年)[135] 数学作品[編集] 平面代数幾何学概論』(1860年) ユークリッドの第五書(1858年および1868年)を代数的に扱ったもの 決定係数に関する初歩的論文、連立一次方程式および代数方程式への応用 『ユークリッドと彼の近代のライバルたち』(1879年)は、文学的かつ数学的なスタイルで書かれている。 記号論理学 第1部 記号論理学 第2部(死後出版) アルファベット暗号(1868年) 論理のゲーム(1887年) 『数学の珍品』第1巻(1888年) 『数学の珍品』第2巻(1892年) 選挙実施におけるさまざまな手続き方法についての考察(1873年)、2つ以上の案件について投票を行う場合の最良の方法に関する提案(1874年)、2 つ以上の案件について投票を行う方法(1876年)、『委員会と選挙の理論』としてまとめられ、1958年にダンカン・ブラックが編集、分析、出版 その他の著作[編集] 生体解剖に関するいくつかの一般的な誤解 手紙の書き方に関する8つか9つの賢明な言葉(1890年) オックスフォードの学生によるノート(1865年~1874年) 議会代表の原則(1884年) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lewis_Carroll |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆