ルイ・アガシ

Louis Agassiz, 1807-1873

☆ ルイ・アガシ Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (/ˈɡəsi/ AG-ə-see; French: [aɡ]) FRS (For) FRSE (1807年5月28日 - 1873年12月14日) はスイス生まれのアメリカの生物学者、地質学者で、地球の自然史の研究者として知られている。幼少期をスイスで過ごし、エアランゲンで博士号を、ミュンヘンで医学の学位を取得。パリでジョルジュ・キュヴィエとアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトに 師事した後、ヌーシャテル大学の自然史教授に就任。ハーバード大学を訪問した後、1847年にアメリカに移住。その後、ハーバード大学で動物学と地質学の 教授となり、ローレンス科学学校の校長を務め、比較動物学博物館を設立した。人間、動物、植物の多元論(polygenism)に関する彼の理論は、暗黙のうちに科学的人種差別を支持していると批判されている。

| Jean Louis Rodolphe Agassiz (/ˈæɡəsi/

AG-ə-see; French: [aɡasi]) FRS (For) FRSE (May 28, 1807 – December 14,

1873) was a Swiss-born American biologist and geologist who is

recognized as a scholar of Earth's natural history. Spending his early life in Switzerland, he received a PhD at Erlangen and a medical degree in Munich. After studying with Georges Cuvier and Alexander von Humboldt in Paris, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel. He emigrated to the United States in 1847 after visiting Harvard University. He went on to become professor of zoology and geology at Harvard, to head its Lawrence Scientific School, and to found its Museum of Comparative Zoology. Agassiz is known for observational data gathering and analysis. He made institutional and scientific contributions to zoology, geology, and related areas, including multivolume research books running to thousands of pages. He is particularly known for his contributions to ichthyological classification, including of extinct species such as megalodon, and to the study of historical geology, including the founding of glaciology. His theories on human, animal and plant polygenism have been criticised as implicitly supporting scientific racism. |

Jean Louis Rodolphe

Agassiz (/ˈɡəsi/ AG-ə-see; French: [aɡ]) FRS (For) FRSE (1807年5月28日 -

1873年12月14日) はスイス生まれのアメリカの生物学者、地質学者で、地球の自然史の研究者として知られている。 幼少期をスイスで過ごし、エアランゲンで博士号を、ミュンヘンで医学の学位を取得。パリでジョルジュ・キュヴィエとアレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトに 師事した後、ヌーシャテル大学の自然史教授に就任。ハーバード大学を訪問した後、1847年にアメリカに移住。その後、ハーバード大学で動物学と地質学の 教授となり、ローレンス科学学校の校長を務め、比較動物学博物館を設立した。 アガシは観察データの収集と分析で知られる。彼は動物学、地質学、および関連分野に組織的かつ科学的な貢献をし、その中には数千ページに及ぶ多巻の研究書 も含まれる。特に、メガロドンなどの絶滅種を含む魚類学の分類や、氷河学の創始を含む歴史的地質学の研究に貢献したことで知られている。 人間、動物、植物の多元論(polygenism)に関する彼の理論は、暗黙のうちに科学的人種差別を支持していると批判されている。 |

| Early life Further information: Agassiz family Louis Agassiz was born in the village of Môtier (fr) (now part of Haut-Vully which merged into Mont-Vully in 2016) in the Swiss Canton of Fribourg.[2] He was the son of a pastor,[3] Louis Rudolphe and his wife, Rose Mayor. His father was a Protestant clergyman, as had been his progenitors for six generations, and his mother was the daughter of a physician and an intellectual in her own right, who had assisted her husband in the education of her boys.[2] He was educated at home[2] until he spent four years at secondary school in Bienne, which he entered in 1818 and completed his elementary studies in Lausanne. Agassiz studied at the Universities of Zürich, Heidelberg and Munich. At the last one, he extended his knowledge of natural history, especially of botany. In 1829, he received the degree of doctor of philosophy at Erlangen and, in 1830, that of doctor of medicine at Munich.[4] Moving to Paris, he came under the tutelage of Alexander von Humboldt and later received his financial benevolence.[5] Humboldt and Georges Cuvier launched him on his careers of respectively geology and zoology.[6] Ichthyology soon became a focus of Agassiz's life's work.[6] |

生い立ち さらに詳しい情報 アガシ家 ルイ・アガシは、スイスのフリブール州にあるモティエ村(現在はオー・ヴュリーの一部で、2016年にモン・ヴュリーに合併)に生まれた[2]。 牧師のルイ・ルドルフ[3]とその妻ローズ・マヨールの息子であった。 父親は6代続くプロテスタントの聖職者であり、母親は医師の娘で、夫の息子たちの教育を援助した知識人であった[2]。1818年に入学したビエンヌの中 等学校で4年間を過ごし、ローザンヌで初等教育を修了するまで、家庭で教育を受けた[2]。アガシはチューリッヒ大学、ハイデルベルク大学、ミュンヘン大 学で学んだ。最後の大学では、博物学、特に植物学の知識を深めた。1829年、エアランゲンで哲学博士の学位を、1830年にはミュンヘンで医学博士の学 位を取得した[4]。パリに移り、アレクサンダー・フォン・フンボルトの薫陶を受け、後に彼の経済的援助を受けることになる[5]。フンボルトとジョル ジュ・キュヴィエによって、それぞれ地質学と動物学の道に進むことになる。 魚類学はすぐにアガシのライフワークの中心となった[6]。 |

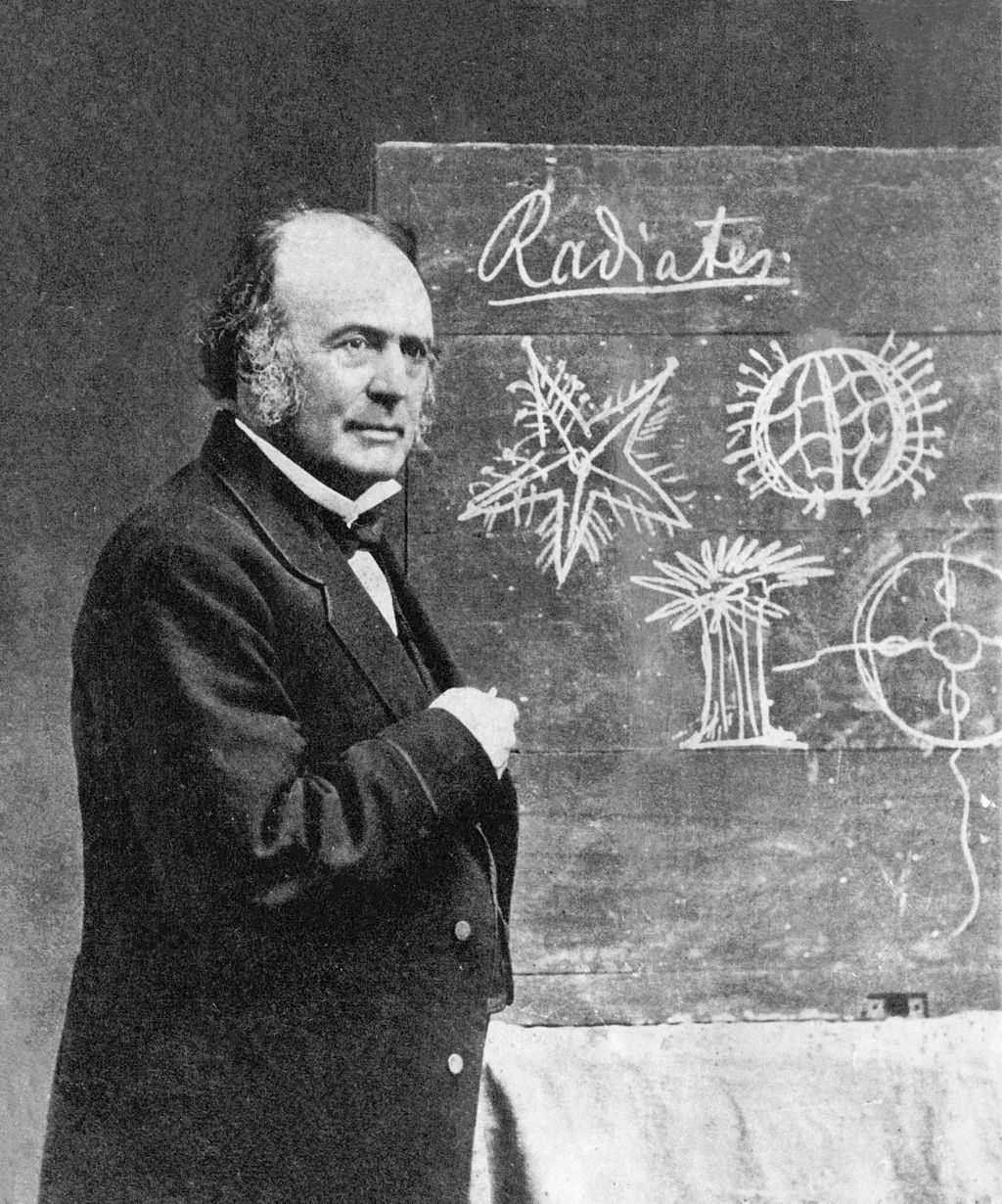

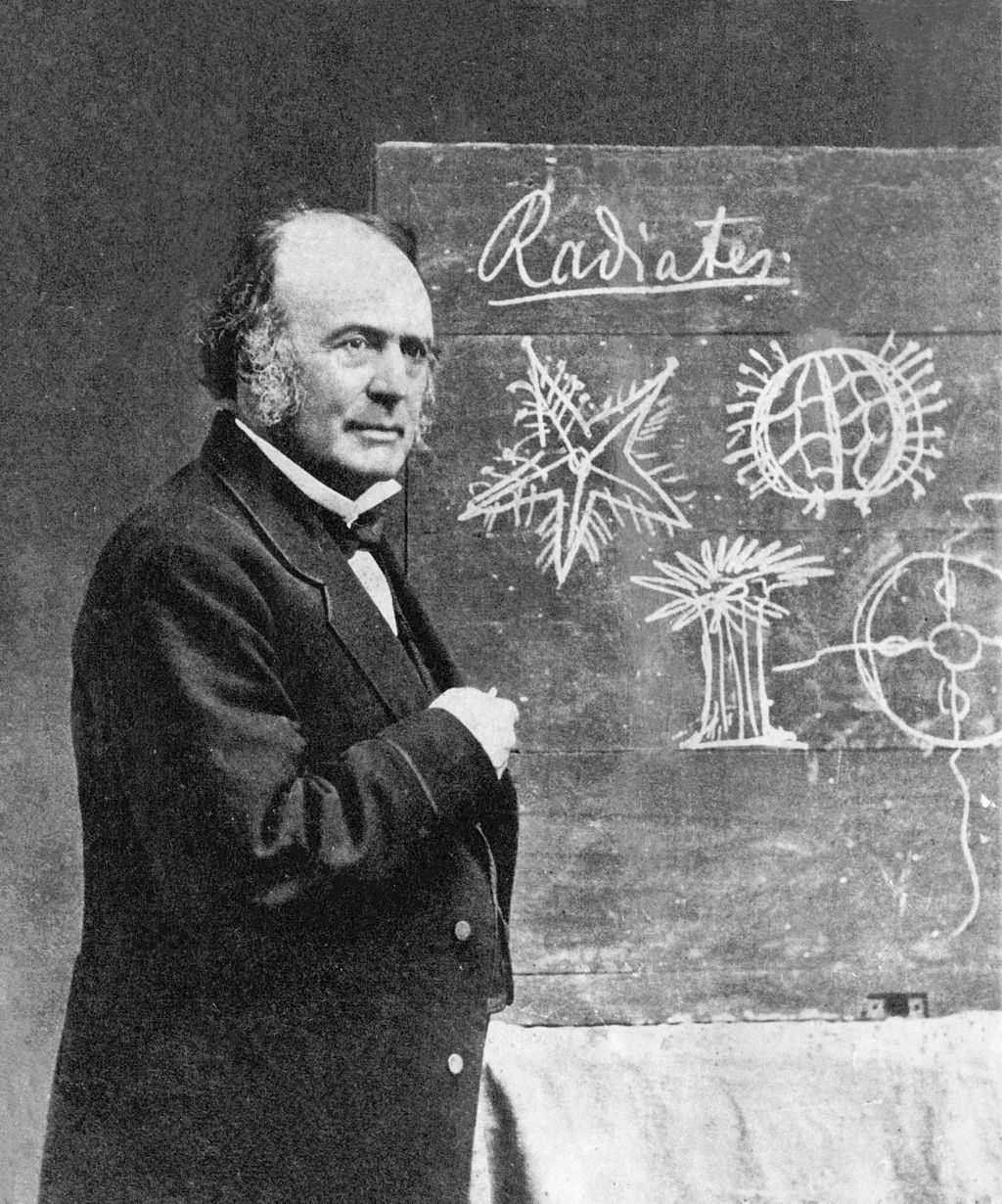

Early work Agassiz in 1870 In 1819 to 1820, the German biologists Johann Baptist von Spix and Carl Friedrich Philipp von Martius undertook an expedition to Brazil. They returned home to Europe with many natural objects, including an important collection of the freshwater fish of Brazil, especially of the Amazon River. Spix, who died in 1826, likely from a tropical disease, did not live long enough to work out the history of those fish, and Martius selected Agassiz for this project. Agassiz threw himself into the work with an enthusiasm that would go on to characterize the rest of his life's work. The task of describing the Brazilian fish was completed and published in 1829. It was followed by research into the history of fish found in Lake Neuchâtel. Enlarging his plans, he in 1830 issued a prospectus of a History of the Freshwater Fish of Central Europe. In 1839, however, the first part of the publication appeared, and it was completed in 1842.[4] In November 1832, Agassiz was appointed professor of natural history at the University of Neuchâtel, at a salary of about US$400 and declined brilliant offers in Paris because of the leisure for private study that that position afforded him.[7] The fossil fish in the rock of the surrounding region, the slates of Glarus and the limestones of Monte Bolca, soon attracted his attention. At the time, very little had been accomplished in their scientific study. Agassiz as early as 1829, planned the publication of a work. More than any other, it would lay the foundation of his worldwide fame. Five volumes of his Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (Research on Fossil Fish) were published from 1833 to 1843. They were magnificently illustrated, chiefly by Joseph Dinkel.[8] In gathering materials for that work, Agassiz visited the principal museums in Europe. Meeting Cuvier in Paris, he received much encouragement and assistance from him.[4] In 1833, he married Cecile Braun, the sister of his friend Alexander Braun and established his household at Neuchâtel. Trained to scientific drawing by her brothers, his wife was of the greatest assistance to Agassiz, with some of the most beautiful plates in fossil and freshwater fishes being drawn by her.[7]  With Benjamin Peirce Agassiz found that his palaeontological analyses required a new ichthyological classification. The fossils that he examined rarely showed any traces of the soft tissues of fish but instead, consisted chiefly of the teeth, scales, and fins, with the bones being perfectly preserved in comparatively few instances. He therefore adopted a classification that divided fish into four groups (ganoids, placoids, cycloids, and ctenoids), based on the nature of the scales and other dermal appendages. That did much to improve fish taxonomy, but Agassiz's classification has since been superseded.[4] With Louis de Coulon, both father and son, he founded the Societé des Sciences Naturelles, of which he was the first secretary and in conjunction with the Coulons also arranged a provisional museum of natural history in the orphan's home.[7] Agassiz needed financial support to continue his work. The British Association and the Earl of Ellesmere, then Lord Francis Egerton, stepped in to help. The 1290 original drawings made for the work were purchased by the Earl and presented by him to the Geological Society of London. In 1836, the Wollaston Medal was awarded to Agassiz by the council of that society for his work on fossil ichthyology. In 1838, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Society. Meanwhile, invertebrate animals engaged his attention. In 1837, he issued the "Prodrome" of a monograph on the recent and fossil Echinodermata, the first part of which appeared in 1838; in 1839–1840, he published two quarto volumes on the fossil echinoderms of Switzerland; and in 1840–1845, he issued his Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (Critical Studies on Fossil Mollusks).[4] Before Agassiz's first visit to England in 1834, Hugh Miller and other geologists had brought to light the remarkable fossil fish of the Old Red Sandstone of the northeast of Scotland. The strange forms of Pterichthys, Coccosteus, and other genera were then made known to geologists for the first time. They were of intense interest to Agassiz and formed the subject of a monograph by him published in 1844–1(45: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie (Monograph on Fossil Fish of the Old Red Sandstone, or Devonian System of the British Isles and of Russia).[4] In the early stages of his career in Neuchatel, Agassiz also made a name for himself as a man who could run a scientific department well. Under his care, the University of Neuchâtel soon became a leading institution for scientific inquiry.[citation needed]  Portrait photograph by John Adams Whipple, circa 1865 In 1842 to 1846, Agassiz issued his Nomenclator Zoologicus, a classification list with references of all names used in zoological genera and groups. He was elected as a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1843.[9] |

初期の仕事 1870年のアガシ 1819年から1820年にかけて、ドイツの生物学者ヨハン・バプティスト・フォン・スピクスとカール・フリードリッヒ・フィリップ・フォン・マルティウ スがブラジルに遠征した。彼らは、ブラジル、特にアマゾン川の淡水魚の重要なコレクションを含む、多くの自然物を携えてヨーロッパに帰国した。スピックス は1826年に熱帯病で亡くなったが、それらの魚の歴史を解明するほど長くは生きられなかったため、マルティウスはこのプロジェクトにアガシを選んだ。 アガシは、その後の彼のライフワークを特徴づけることになる熱意をもって、この仕事に打ち込んだ。ブラジルの魚の記述は1829年に完成し、出版された。 その後、ヌーシャテル湖で発見された魚の歴史に関する研究が続いた。1830年、彼は計画を拡大し、『中央ヨーロッパの淡水魚の歴史』の趣意書を発表し た。しかし、1839年に出版物の最初の部分が出版され、1842年に完成した[4]。 1832年11月、アガシはヌーシャテル大学の自然史教授に任命された。当時、これらの化石魚類の科学的研究はほとんど行われていなかった。アガシは 1829年の時点で、ある著作の出版を計画していた。それは彼の世界的な名声の礎となった。1833年から1843年にかけて、全5巻の『化石魚類研究』 (Recherches sur les poissons fossiles)が出版された。この著作のための資料を集めるために、アガシはヨーロッパの主要な博物館を訪れた。パリでキュヴィエと出会い、彼から多 くの励ましと援助を受けた[4]。 1833年、友人アレクサンダー・ブラウンの妹セシル・ブラウンと結婚し、ヌーシャテルに居を構える。兄弟から科学的なデッサンの手ほどきを受けた妻は、アガシの最大の助けとなり、化石や淡水魚の最も美しいプレートのいくつかは妻によって描かれた[7]。  ベンジャミン・パース(数学者)とともに アガシは、古生物学的分析に新しい魚類学的分類が必要であることに気づいた。彼が調査した化石には、魚類の軟部組織の痕跡はほとんど見られず、歯、うろ こ、ひれが主で、骨が完全に保存されている例は比較的少なかった。そこで彼は、鱗やその他の皮膚付属物の性質に基づいて、魚を4つのグループ(ガノイド、 プラコイド、サイクロイド、クテノイド)に分ける分類を採用した。この分類は魚類の分類学の改善に大きく貢献したが、アガシズの分類はその後、取って代わ られた[4]。 アガシはルイ・ド・クーロン父子とともに自然科学協会を設立し、初代事務局長を務め、クーロン夫妻とともに孤児院に仮の自然史博物館を設置した[7]。英 国協会とエレスミア伯爵(当時はフランシス・エガートン卿)が支援に乗り出した。作品のために描かれた1290枚の原画は伯爵によって購入され、ロンドン の地質学会に贈られた。1836年、アガシは魚類化石の研究に対して、同協会の評議会からウォラストン・メダルを授与された。1838年には王立協会の外 国人会員に選ばれた。一方、無脊椎動物にも関心を持った。1837年には、最近および化石の棘皮動物に関するモノグラフの「プロドローム」を発表し、その 最初の部分は1838年に出版された。1839年から1840年にかけては、スイスの化石の棘皮動物に関する四つ切の2巻を出版し、1840年から 1845年にかけては、『化石の軟体動物に関する批判的研究』(Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles)を出版した[4]。 1834年にアガシが初めてイギリスを訪れる前に、ヒュー・ミラーをはじめとする地質学者たちが、スコットランド北東部のオールド・レッド・サンドストー ンに生息する驚くべき魚類の化石を発見していた。プテリクティス(Pterichthys)属、コッコステウス(Coccosteus)属、その他の属の 奇妙な形態は、そのとき初めて地質学者に知られることになった。それらはアガシの強い関心を引き、1844-1年に出版された彼のモノグラフの主題となっ た(45: Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Grès Rouge, ou Système Dévonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Îles Britanniques et de Russie)。 [4] ヌーシャテルでのキャリアの初期には、アガシは科学部門をうまく運営できる人物としても名を馳せた。彼のもとで、ヌーシャテル大学はすぐに科学的探求のた めの主要な機関となった[要出典]。  ジョン・アダムス・ウィップルによる肖像写真、1865年頃 1842年から1846年にかけて、アガシは動物学上の属名や群名で使用されるすべての名称の参考文献を記載した分類表『Nomenclator Zoologicus』を刊行した。 1843年にはアメリカ哲学協会の会員に選出された[9]。 |

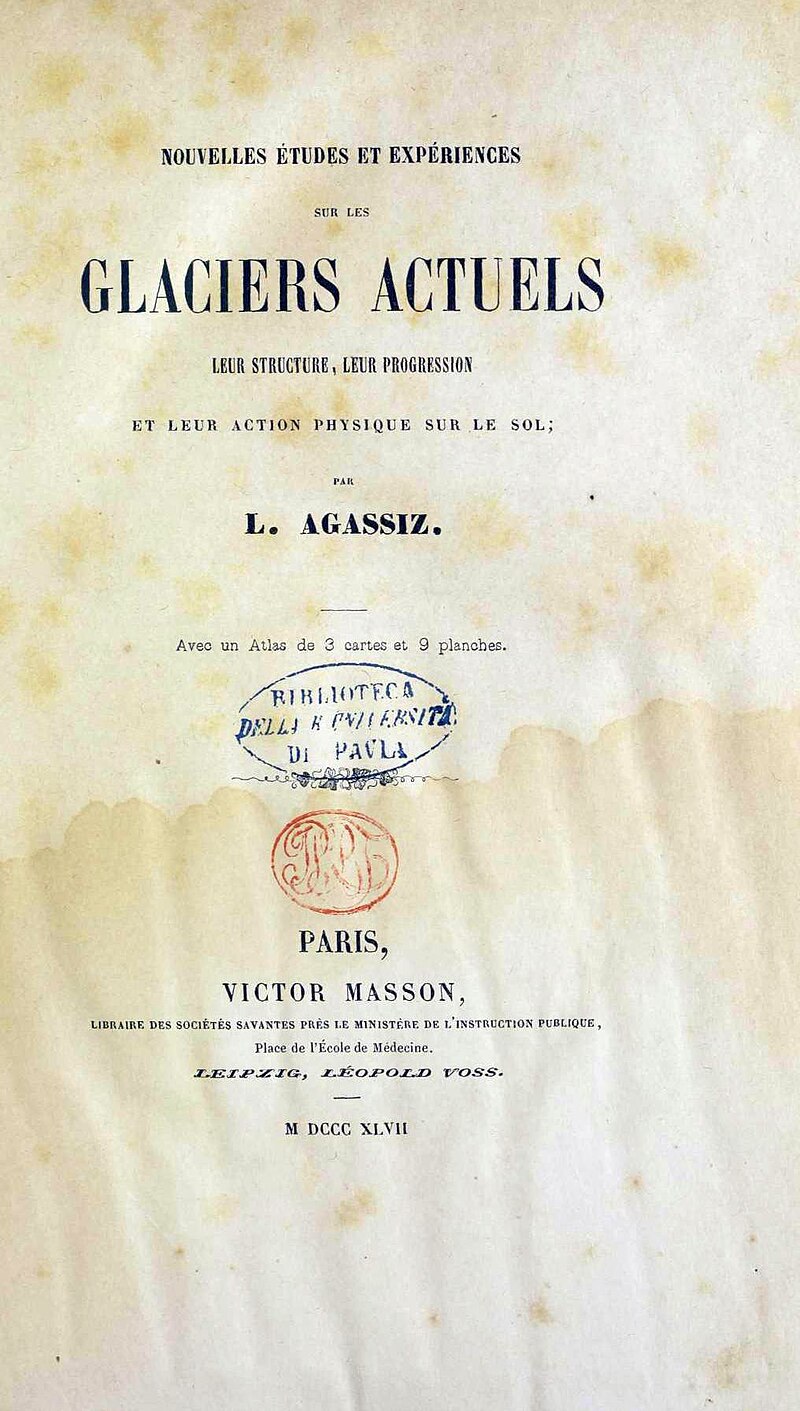

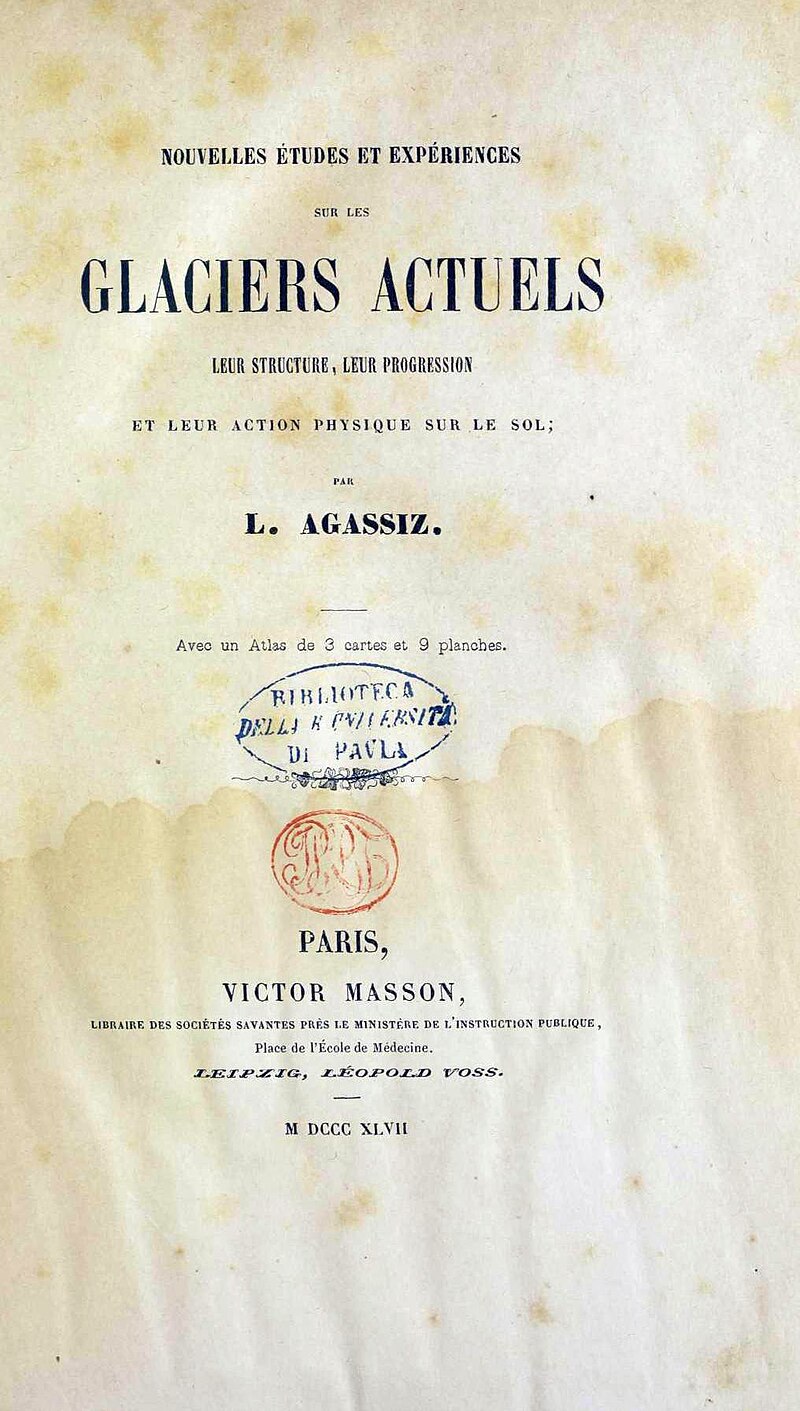

Ice age  Nouvelles études et expériences sur les glaciers actuels, 1847 The man-sized iron auger that was used by Agassiz to drill up to 7.5 m deep into the Unteraar Glacier to take its temperature (Swiss Alpine Museum, Bern) The vacation of 1836 was spent by Agassiz and his wife in the little village of Bex, where he met Jean de Charpentier and Ignaz Venetz. Their recently announced glacial theories had startled the scientific world, and Agassiz returned to Neuchâtel as an enthusiastic convert.[10] In 1837, Agassiz proposed that the Earth had been subjected to a past ice age.[11] He presented the theory to the Helvetic Society that ancient glaciers flowed outward from the Alps, and even larger glaciers had covered the plains and mountains of Europe, Asia, and North America and smothered the entire Northern Hemisphere in a prolonged ice age. In the same year, he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Before that proposal, Goethe, de Saussure, Ignaz Venetz, Jean de Charpentier, Karl Friedrich Schimper, and others had studied the glaciers of the Alps, and Goethe,[12] Charpentier, and Schimper[11] had even concluded that the erratic blocks of alpine rocks scattered over the slopes and summits of the Jura Mountains had been moved there by glaciers. Those ideas attracted the attention of Agassiz, and he discussed them with Charpentier and Schimper, whom he accompanied on successive trips to the Alps. Agassiz even had a hut constructed upon one of the Aar Glaciers and for a time made it his home to investigate the structure and movements of the ice.[4] Agassiz visited England, and with William Buckland, the only English naturalist who shared his ideas, made a tour of the British Isles in search of glacial phenomena, and became satisfied that his theory of an ice age was correct.[10] In 1840, Agassiz published a two-volume work, Études sur les glaciers ("Studies on Glaciers").[13] In it, he discussed the movements of the glaciers, their moraines, and their influence in grooving and rounding the rocks and in producing the striations and roches moutonnées seen in Alpine-style landscapes. He accepted Charpentier and Schimper's idea that some of the alpine glaciers had extended across the wide plains and valleys of the Aar and Rhône, but he went further by concluding that in the recent past, Switzerland had been covered with one vast sheet of ice originating in the higher Alps and extending over the valley of northwestern Switzerland to the southern slopes of the Jura. The publication of the work gave fresh impetus to the study of glacial phenomena in all parts of the world.[14] Familiar then with recent glaciation, Agassiz and the English geologist William Buckland visited the mountains of Scotland in 1840. There, they found clear evidence in different locations of glacial action. The discovery was announced to the Geological Society of London in successive communications. The mountainous districts of England, Wales, and Ireland were understood to have been centres for the dispersion of glacial debris. Agassiz remarked "that great sheets of ice, resembling those now existing in Greenland, once covered all the countries in which unstratified gravel (boulder drift) is found; that this gravel was in general produced by the trituration of the sheets of ice upon the subjacent surface, etc."[15] In his later years, Agassiz applied his glacial theories to the geology of the Brazilian tropics, including the Amazon. Agassiz began with a working hypothesis which could be tested by the results of fieldwork to find either inconclusive, or conclusively supporting or refuting evidence. A hypothesis that can be conclusively refuted is better than a hypothesis that is difficult to test. Agassiz had a close association with his student and field assistant, the geologist Charles Hartt who eventually refuted Agassiz's theories about the Amazon based on his fieldwork there. Instead of evidence for any glacial processes, he found chemically weathered sediments from marine and tropical fluvial, not glacial, processes, a finding that later geologists confirmed.[16] Agassiz hypothesis that the Amazon was affected by the Last Glacial Maximum was correct, although the mechanism causing the effect was non-glacial. The Amazon rainforest was split into two large blocks by extensive savanna during the LGM. |

氷河期  氷河に関する新たな研究と実験、1847年 アガシがウンテラール氷河の温度を測定するために深さ7.5mまで掘削するために使用した人大の鉄製オーガー(スイス・アルプス博物館、ベルン) 1836年の休暇は、アガシとその妻はベックスという小さな村で過ごし、そこでジャン・ド・シャルパンティエとイグナツ・ヴェネツに出会った。1837 年、アガシは、地球が過去に氷河期を迎えていたという説を唱え、ヘルヴェティア協会で、古代の氷河はアルプス山脈から流れ出し、さらに大きな氷河がヨー ロッパ、アジア、北アメリカの平原や山々を覆い、北半球全体を氷河期に覆い尽くしたという説を発表した[11]。同年、ゲーテはスウェーデン王立科学アカ デミーの外国人会員に選ばれた。この提案以前に、ゲーテ、ド・ソシュール、イグナツ・ヴェネッツ、ジャン・ド・シャルパンティエ、カール・フリードリッ ヒ・シンパーらがアルプスの氷河を研究しており、ゲーテ、[12] シャルパンティエ、シンパー[11]は、ジュラ山脈の斜面や山頂に散在する不規則な高山岩の塊は氷河によって移動させられたと結論付けていた。これらの考 えはアガシの関心を引き、アルプスへの連続旅行に同行したシャルパンティエやシンパーと議論した。アガシはアール氷河のひとつに小屋を建て、一時期そこを 住まいとして氷の構造と動きを調査した[4]。 アガシはイギリスを訪れ、彼の考えに共感した唯一のイギリス人博物学者であるウィリアム・バックランドとともに、氷河現象を求めてイギリス諸島を巡り、彼 の氷河期説が正しいことを確信した[10]。 [1840年、アガシは2巻からなる著作『氷河の研究』(Études sur les glaciers)を出版した[13]。その中で彼は、氷河の動きとそのモレーン、そして岩に溝を作ったり丸みを帯びさせたり、アルプス風の景観に見られ る縞模様やロッシュ・ムートネを作り出す氷河の影響について論じた。シャルパンティエとシンパーのアルプス氷河の一部は、アール川とローヌ川の広い平原と 谷を横切って広がっていたという説を受け入れたが、彼はさらに、最近のスイスは、アルプス山脈の高地に端を発し、スイス北西部の谷からジュラ山脈の南斜面 にかけて広がる広大な氷に覆われていたと結論づけた。この著作の出版は、世界各地の氷河現象の研究に新たな弾みをつけた[14]。 アガシとイギリスの地質学者ウィリアム・バックランドは、1840年にスコットランドの山々を訪れた。そこで彼らは、氷河作用の明確な証拠をさまざまな場 所で発見した。この発見は、ロンドンの地質学会に相次いで発表された。イングランド、ウェールズ、アイルランドの山岳地帯は、氷河の残骸が拡散する中心地 であったと理解された。アガシは、「現在グリーンランドにあるような大きな氷床が、かつて、層状化していない礫(転石流)が発見されるすべての国を覆って いたこと、この礫は一般に、氷床が隣接する表面で三畳化することによって生成されたこと、など」と述べた[15]。 晩年、アガシは氷河の理論をアマゾンを含むブラジルの熱帯地域の地質学に応用した。アガシは、まず作業仮説を立て、それをフィールドワークの結果によって 検証し、結論の出ない、あるいは決定的な裏付けや反論となる証拠を見つけることから始めた。決定的な反論ができる仮説は、検証が難しい仮説よりも優れてい る。アガシは、彼の教え子でありフィールド・アシスタントでもあった地質学者チャールズ・ハートと親交があった。彼は最終的に、アマゾンでのフィールド ワークに基づいて、アガシのアマゾンに関する理論に反論した。アガシは、アマゾンが最終氷期最盛期の影響を受けたという仮説は正しかったが、その影響を引 き起こしたメカニズムは非氷期的なものであった。アマゾンの熱帯雨林は、最終氷期最盛期にサバンナによって2つの大きなブロックに分割された。 |

| United States With the aid of a grant of money from the king of Prussia, Agassiz crossed the Atlantic in the autumn of 1846 to investigate the natural history and geology of North America and to deliver a course of lectures on "The Plan of Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom"[17] by invitation from John Amory Lowell, at the Lowell Institute in Boston, Massachusetts. The financial offers that were presented to him in the United States induced him to settle there, where he remained to the end of his life.[15] He was elected a foreign honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1846.[18] In 1846, still married to Cecilie, who remained with their three children in Switzerland, Agassiz met Elizabeth Cabot Cary at a dinner. The two developed a romantic attachment, and when his wife died in 1848, they made plans to marry. The ceremony took place on April 25, 1850, in Boston, Massachusetts at King's Chapel. Agassiz brought his children to live with them, and Elizabeth raised and developed close relationships with her step-children. She had no children of her own.[19] Agassiz had a mostly cordial relationship with the Harvard botanist Asa Gray despite their disagreements.[20] Agassiz believed each human race had been separately created,[21] but Gray, a supporter of Charles Darwin, believed in the shared evolutionary ancestry of all humans.[22] In addition, Agassiz was a member of the Scientific Lazzaroni, a group of mostly physical scientists who wanted American academia to mimic the more autocratic academic structures of European universities, but Gray was a staunch opponent of that group. Agassiz's engagement for the Lowell Institute lectures precipitated the establishment in 1847 of the Lawrence Scientific School at Harvard University, with Agassiz as its head.[23] Harvard appointed him professor of zoology and geology, and he founded the Museum of Comparative Zoology there in 1859 and served as its first director until his death in 1873. During his tenure at Harvard, Agassiz studied the effect of the last ice age in North America.[citation needed] In August 1857, Agassiz was offered the chair of palaeontology in the Museum of Natural History, Paris, which he refused. He was later decorated with the Cross of the Legion of Honor.[24] Agassiz continued his lectures for the Lowell Institute. In succeeding years, he gave lectures on "Ichthyology" (1847–1848), "Comparative Embryology" (1848–1849), "Functions of Life in Lower Animals" (1850–1851), "Natural History" (1853–1854), "Methods of Study in Natural History" (1861–1862), "Glaciers and the Ice Period" (1864–1865), "Brazil" (1866–1867), and "Deep Sea Dredging" (1869–1870).[25] In 1850, he had married Elizabeth Cabot Cary, who later wrote introductory books about natural history and a lengthy biography of her husband after he had died.[26] Agassiz served as a nonresident lecturer at Cornell University while he was also on faculty at Harvard.[27] In 1852, he accepted a medical professorship of comparative anatomy at Charlestown, Massachusetts, but he resigned in two years.[15] From then on, Agassiz's scientific studies dropped off, but he became one of the best-known scientists in the world. By 1857, Agassiz was so well-loved that his friend Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote "The Fiftieth Birthday of Agassiz" in his honor and read it at a dinner given for Agassiz by the Saturday Club in Cambridge.[15] Agassiz's own writing continued with four (of a planned 10) volumes of Natural History of the United States, published from 1857 to 1862. He also published a catalog of papers in his field, Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae, in four volumes between 1848 and 1854.[28][29][30][31] Stricken by ill health in the 1860s, Agassiz resolved to return to the field for relaxation and to resume his studies of Brazilian fish. In April 1865, he led the Thayer Expedition to Brazil. While there, he commissioned two photographers, Augusto Stahl and Georges Leuzinger, to accompany the expedition and produce somatological images of Indigenous people and enslaved Africans and Black people.[32] After his return in August 1866, an account of the expedition, A Journey in Brazil,[33] was published in 1868. In December 1871, he made a second eight-month excursion, known as the Hassler expedition under the command of Commander Philip Carrigan Johnson (the brother of Eastman Johnson) and visited South America on its southern Atlantic and Pacific Seaboards. The ship explored the Magellan Strait, which drew the praise of Charles Darwin.[34] Following the establishment of the first U.S. Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals in New York City in 1866, Agassiz was called on to help settle disputes about animal behavior. He deemed the way turtles were shipped caused them suffering, while P.T. Barnum argued with Agassiz' support that his snakes would eat only live animals.[35] His second wife, Elizabeth Cary Agassiz, assisted him in preparing his A Journey in Brazil. Along with her stepson, Alexander Agassiz, she wrote Seaside Studies in Natural History and Marine Animals of Massachusetts.[24] Elizabeth wrote at the Strait that "the Hassler pursued her course, past a seemingly endless panorama of mountains and forests rising into the pale regions of snow and ice, where lay glaciers in which every rift and crevasse, as well as the many cascades flowing down to join the waters beneath, could be counted as she steamed by them.... These were weeks of exquisite delight to Agassiz. The vessel often skirted the shore so closely that its geology could be studied from the deck."[36 |

アメリカ 1846年秋、プロイセン国王からの資金援助により、アガシは大西洋を渡り、北アメリカの自然史と地質学を調査し、マサチューセッツ州ボストンのローウェ ル研究所で、ジョン・エイモリー・ローウェルの招きにより、「動物界に示された天地創造の計画」[17]に関する講義を行った。1846年にはアメリカ芸 術科学アカデミーの外国人名誉会員に選出された[18]。 1846年、まだセシリーと結婚していたアガシは、3人の子供を連れてスイスに滞在していた。2人は恋愛関係に発展し、1848年に妻が亡くなると、2人 は結婚する計画を立てた。挙式は1850年4月25日、マサチューセッツ州ボストンのキングス・チャペルで行われた。アガシは子供たちを連れてきて一緒に 暮らし、エリザベスは継子たちを育て、親密な関係を築いた。エリザベスには自分の子供はいなかった[19]。 アガシはハーバード大学の植物学者アサ・グレイと、意見の相違はあったものの、ほぼ友好的な関係にあった[20]。アガシは人類はそれぞれ別々に創造され たと信じていたが[21]、チャールズ・ダーウィンの支持者であったグレイは、全人類が共通の進化的祖先を持っていると信じていた[22]。 アガシはローウェル研究所の講義に参加したことがきっかけとなり、1847年、ハーバード大学にアガシを校長とするローレンス科学学校が設立された [23]。ハーバード大学では動物学と地質学の教授に任命され、1859年には同大学に比較動物学博物館を設立し、1873年に亡くなるまで初代館長を務 めた。1857年8月、アガシはパリ自然史博物館の古生物学の講座のオファーを受けたが、これを断った。後にレジオン・ドヌール勲章を授与された [24]。 アガシズはローウェル研究所で講義を続けた。その後、「魚類学」(1847年-1848年)、「比較発生学」(1848年-1849年)、「下等動物の生 命機能」(1850年-1851年)、「自然史」(1853年-1854年)、「自然史研究の方法」(1861年-1862年)、「氷河と氷河期」 (1864年-1865年)、「ブラジル」(1866年-1867年)、「深海の浚渫」(1869年-1870年)の講義を行った。 [25]1850年、彼はエリザベス・カボット・カリーと結婚し、後に自然史に関する入門書や、夫の死後に夫の長大な伝記を執筆した[26]。 1852年、アガシはマサチューセッツ州チャールスタウンで比較解剖学の医学教授の職を得たが、2年で辞職した[15]。1857年までにアガシは非常に 愛されるようになり、友人のヘンリー・ワズワース・ロングフェローはアガシに敬意を表して "The Fifieth Birthday of Agassiz "を書き、ケンブリッジのサタデークラブがアガシのために開いた晩餐会で朗読した[15]。アガシ自身の執筆は続き、1857年から1862年にかけて 『アメリカの自然史』4巻(全10巻の予定)が出版された。また、1848年から1854年にかけて、彼の専門分野の論文目録 『Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae』全4巻を出版した[28][29][30][31]。 1860年代に体調を崩したアガシは、リラクゼーションのためにフィールドに戻り、ブラジルの魚の研究を再開することを決意した。1865年4月、彼はセ イヤー探検隊を率いてブラジルを訪れた。現地では、アウグスト・スタールとジョルジュ・ロイジンガーという2人の写真家に同行を依頼し、先住民や奴隷にさ れたアフリカ人、黒人の身体学的な写真を撮影した[32]。1866年8月に帰国後、1868年に探検の記録『A Journey in Brazil』[33]が出版された。1871年12月、彼はフィリップ・キャリガン・ジョンソン中佐(イーストマン・ジョンソンの弟)の指揮の下、ハス ラー探検隊として知られる2度目の8ヶ月の遠征を行い、南アメリカの南大西洋と太平洋沿岸を訪れた。この船はマゼラン海峡を探検し、チャールズ・ダーウィ ンの賞賛を浴びた[34]。 1866年にニューヨークで最初の米国動物虐待防止協会が設立されると、アガシは動物の行動に関する論争を解決するために呼ばれた。彼はカメの出荷方法が カメを苦しめているとみなし、一方P.T.バーナムは、彼のヘビは生きた動物しか食べないとアガシの支持のもとに主張した[35]。 2番目の妻であるエリザベス・ケーリー・アガシは、『ブラジルの旅』の準備のためにアガシを援助した。エリザベスは海峡で、「ハスラー号は、雪と氷の淡い 地域にそびえ立つ山々と森林の果てしなく続くかのようなパノラマを通り過ぎていった。この数週間はアガシにとって至上の喜びだった。この数週間はアガシに とって極上の喜びであった。船はしばしば海岸の近くを通り、デッキからその地質を調べることができた」[36 |

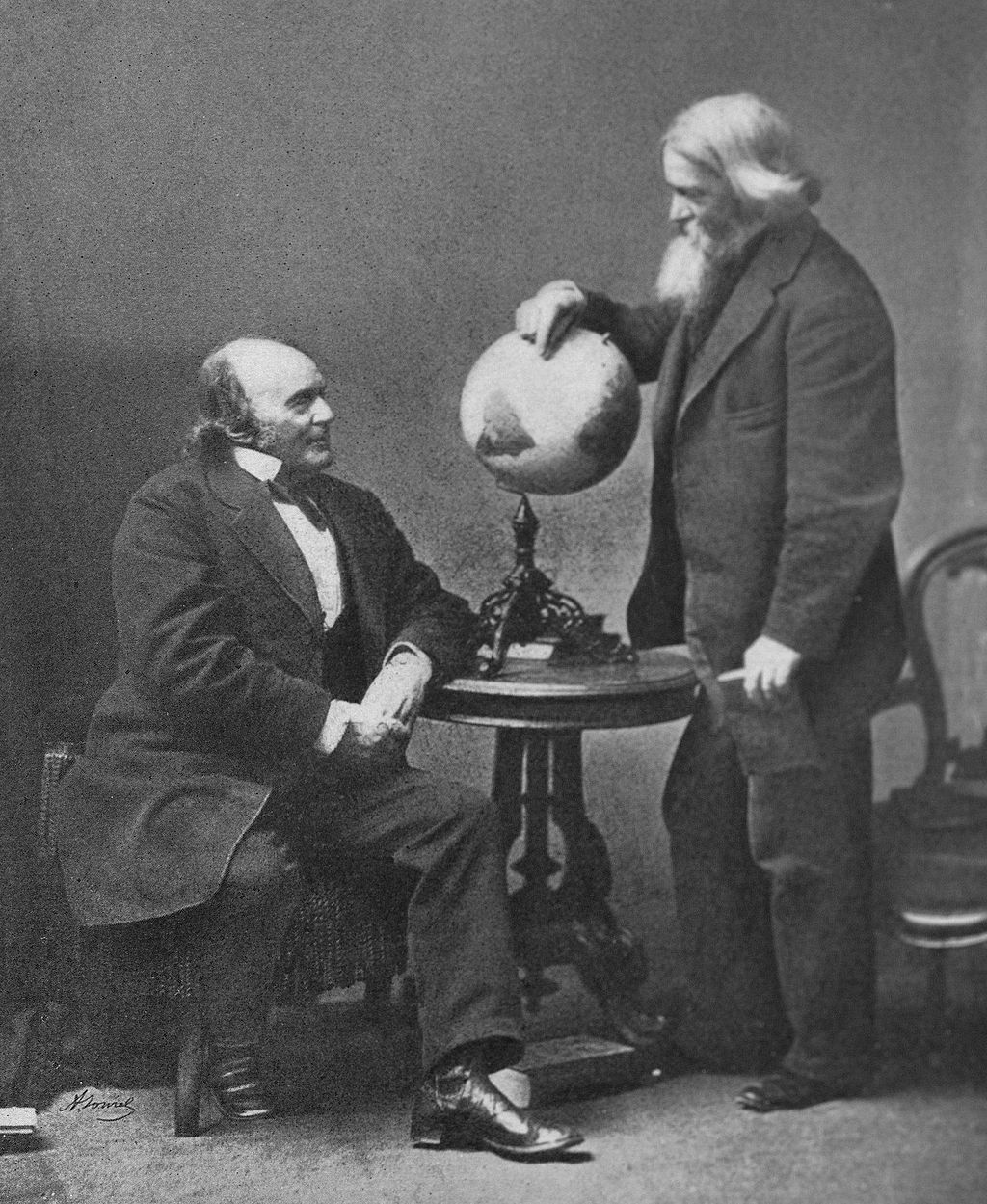

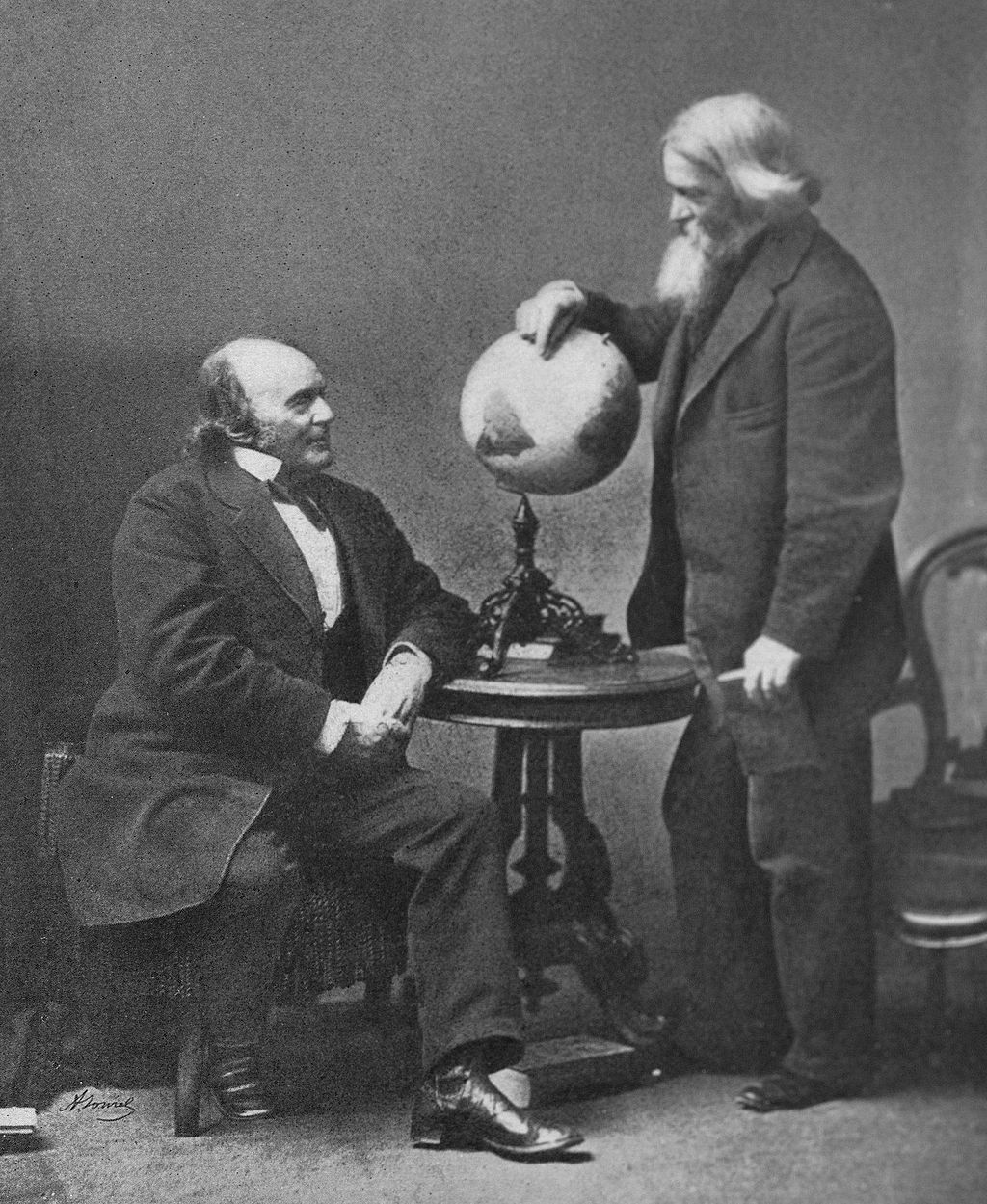

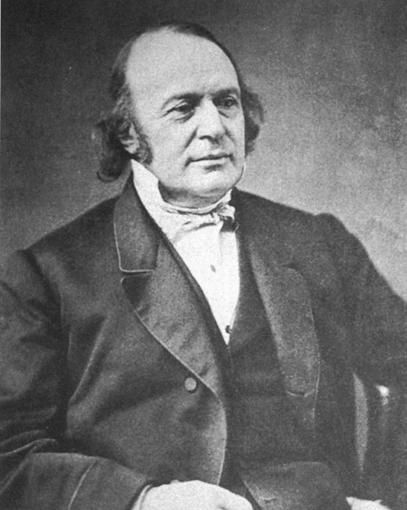

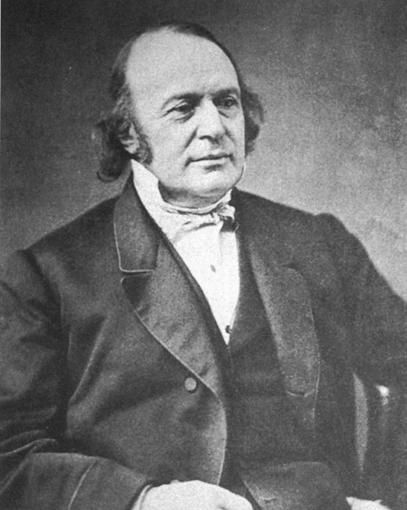

Family Agassiz in middle age From his first marriage to Cecilie Braun, Agassiz had two daughters, Ida and Pauline, and a son, Alexander.[37] In 1863, Agassiz's daughter Ida married Henry Lee Higginson, who later founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra and was a benefactor to Harvard and other schools. On November 30, 1860, Agassiz's daughter Pauline was married to Quincy Adams Shaw (1825–1908), a wealthy Boston merchant and later a benefactor to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[38] Pauline Agassiz Shaw later became a prominent educator, suffragist, and philanthropist.[39] Later life In the last years of his life, Agassiz worked to establish a permanent school in which zoological science could be pursued amid the living subjects of its study. In 1873, the private philanthropist John Anderson gave Agassiz the island of Penikese, in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts (south of New Bedford), and presented him with $50,000 to endow it permanently as a practical school of natural science that would be especially devoted to the study of marine zoology.[15] The school collapsed soon after Agassiz's death but is considered to be a precursor of the nearby Woods Hole Marine Biological Laboratory.[40] Agassiz had a profound influence on the American branches of his two fields and taught many future scientists who would go on to prominence, including Alpheus Hyatt, David Starr Jordan, Joel Asaph Allen, Joseph Le Conte, Ernest Ingersoll, William James, Charles Sanders Peirce, Nathaniel Shaler, Samuel Hubbard Scudder, Alpheus Packard, and his son Alexander Emanuel Agassiz. He had a profound impact on the paleontologist Charles Doolittle Walcott and the natural scientist Edward S. Morse. Agassiz had a reputation for being a demanding teacher. He would allegedly "lock a student up in a room full of turtle-shells, or lobster-shells, or oyster-shells, without a book or a word to help him, and not let him out till he had discovered all the truths which the objects contained."[41] Two of Agassiz's most prominent students detailed their personal experiences under his tutelage: Scudder, in a short magazine article for Every Saturday,[42] and Shaler, in his Autobiography.[43] Those and other recollections were collected and published by Lane Cooper in 1917,[44] which Ezra Pound would draw on for his anecdote of Agassiz and the sunfish.[45] In the early 1840s, Agassiz named two fossil fish species after Mary Anning (Acrodus anningiae and Belenostomus anningiae) and another after her friend, Elizabeth Philpot. Anning was a paleontologist known around the world for important finds, but because of her gender, she was often not formally recognized for her work. Agassiz was grateful for the help that the women gave him in examining fossil fish specimens during his visit to Lyme Regis in 1834.[46] Agassiz died in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1873 and was buried on the Bellwort Path at Mount Auburn Cemetery,[47] joined later by his wife. His monument is a boulder from a glacial moraine of the Aar near the site of the old Hôtel des Neuchâtelois, not far from the spot where his hut once stood. His grave is sheltered by pine trees from his old home in Switzerland.[15] |

家族 中年のアガシ セシリエ・ブラウンとの最初の結婚で、アガシはアイダとポーリーンの2人の娘と息子のアレクサンダーをもうけた[37]。1863年、娘のアイダは後にボ ストン交響楽団を創設し、ハーバード大学やその他の学校の後援者となるヘンリー・リー・ヒギンソンと結婚。1860年11月30日、アガシズの娘ポーリー ンは、ボストンの裕福な商人であり、後にボストン美術館の後援者となるクインシー・アダムス・ショー(1825-1908)と結婚した[38]。 晩年 晩年、アガシズは、生きた研究対象の中で動物学が学べる恒久的な学校の設立に取り組んだ。1873年、民間の慈善家ジョン・アンダーソンは、マサチュー セッツ州バザーズ湾(ニューベッドフォードの南)にあるペニケーゼ島をアガシに与え、特に海洋動物学の研究に専念する自然科学の実践的な学校として恒久的 に寄附するために5万ドルを贈った[15]。この学校はアガシの死後すぐに崩壊したが、近くにあるウッズホール海洋生物学研究所の前身と考えられている [40]。 アガシはアメリカの2つの分野に多大な影響を与え、アルフェウス・ハイアット、デイヴィッド・スター・ジョーダン、ジョエル・アサフ・アレン、ジョセフ・ ル・コント、アーネスト・インガソール、ウィリアム・ジェイムズ、チャールズ・サンダース・ペアーズ、ナサニエル・シャラー、サミュエル・ハバード・スカ ダー、アルフェウス・パッカード、そして息子のアレクサンダー・エマニュエル・アガシなど、後に著名になる多くの科学者を教えた。古生物学者のチャール ズ・ドリトル・ウォルコットや自然科学者のエドワード・S・モースに多大な影響を与えた。アガシは厳しい教師として評判だった。彼は「生徒を亀の甲羅、ロ ブスターの甲羅、牡蠣の甲羅でいっぱいの部屋に閉じ込め、本も助けの言葉も与えず、その中に含まれる真理をすべて発見するまで外に出さなかった」と言われ ている[41]: これらの回想やその他の回想は1917年にレーン・クーパーによって収集・出版され[44]、エズラ・パウンドがアガシとマンボウの逸話に引用することに なる[45]。 1840年代初頭、アガシは2種の化石魚類をメアリー・アニングにちなんで(Acrodus anningiaeとBelenostomus anningiae)、もう1種を彼女の友人エリザベス・フィルポットにちなんで命名した。アニングは重要な発見で世界中に知られた古生物学者であった が、その性別ゆえに、しばしば正式にその業績が認められることはなかった。アガシは、1834年にライム・レジスを訪れた際、彼女たちが魚の化石の標本を 調べてくれたことに感謝していた[46]。 アガシは1873年にマサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで死去し、マウント・オーバーン墓地のベルワート・パス沿いに埋葬された[47]。彼の記念碑は、か つて彼の小屋があった場所からそう遠くない、ヌーシャテロワの旧オテルの近くにあるアール川の氷河堆石である。彼の墓は、スイスの古里の松の木に守られて いる[15]。 |

| Legacy The Cambridge elementary school north of Harvard University was named in his honor, and the surrounding neighborhood became known as "Agassiz" as a result. The school's name was changed to the Maria L. Baldwin School on May 21, 2002, because of concerns about Agassiz's involvement in scientific racism and to honor Maria Louise Baldwin, the African-American principal of the school, who served from 1889 to 1922.[48][49] The neighborhood, however, continued to be known as Agassiz.[50] c. 2009, neighborhood residents decided to rename the neighborhood's community council as the "Agassiz-Baldwin Community".[51] Then, in July 2021, culminating a two-year effort on the part of neighborhood residents, the Cambridge City Council voted unanimously to change the name to the Baldwin Neighborhood.[52] An elementary school, the Agassiz Elementary School in Minneapolis, Minnesota, existed from 1922 to 1981.[53] Geological tributes  Agassiz's grave, Mount Auburn Cemetery, Cambridge, Massachusetts, is a boulder from the moraine of the Aar Glaciers, near where he once lived. An ancient glacial lake that formed in central North America, Lake Agassiz, is named after him, as are Mount Agassiz in California's Palisades, Mount Agassiz in the Uinta Mountains of Utah, Agassiz Peak in Arizona, Agassiz Rock in Massachusetts, and the Agassizhorn in the Bernese Alps in his native Switzerland. Agassiz Glacier in Montana, Agassiz Creek in Glacier National Park, Agassiz Glacier in the Saint Elias Mountains of Alaska, and Mount Agassiz in the White Mountains of New Hampshire also bear his name. A crater on Mars, Crater Agassiz,[54] and a promontorium on the moon are also named in his honor. Cape Agassiz, a headland situated in Palmer Land, Antarctica, is named in his honor. A main-belt asteroid, 2267 Agassiz, is also named in association with him. Biological tributes Several animal species are named in honor of him, including Agassiz's dwarf cichlid Apistogramma agassizii Steindachner, 1875; Agassiz's perchlet, also known as Agassiz's glass fish; and the olive perchlet Ambassis agassizii Steindachner, 1866; The Spring Cavefish Forbesichthys agassizii (Putnam, 1872); the catfish Corydoras agassizii Steindachner, 1876; the Rio Skate Rioraja agassizii (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1841); The South American fish Leporinus agassizii [55] the Snailfish Liparis agassizii Putnam, 1874; a sea snail, Borsonella agassizii (Dall, 1908); a species of crab Eucratodes agassizii A. Milne Edwards, 1880; Isocapnia agassizi Ricker, 1943 (a stonefly); Publius agassizi (Kaup, 1871) (a passalid beetle); Xylocrius agassizi (LeConte, 1861) (a longhorn beetle); Exoprosopa agassizii Loew, 1869 (a bee fly); Chelonia agassizii Bocourt, 1868 (Galápagos green turtle);[56] Philodryas agassizii (Jan, 1863) (a South American snake);[56] and the most well-known, Gopherus agassizii (Cooper, 1863) (the desert tortoise).[56] In 2020, a new genus of pycnodont fish (Actinopterygii, Pycnodontiformes) named Agassazilia erfoundina (Cooper and Martill, 2020) from the Moroccan Kem Kem Group was named in honor of Agassiz, who first identified the group in the 1830s. Tribute awards In 2005, the European Geosciences Union Division on Cryospheric Sciences established the Louis Agassiz Medal, awarded to individuals in recognition of their outstanding scientific contribution to the study of the cryosphere on Earth or elsewhere in the solar system.[57] Agassiz took part in a monthly gathering called the Saturday Club at the Parker House, a meeting of Boston writers and intellectuals. He was therefore mentioned in a stanza of the Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. poem "At the Saturday Club:" There, at the table's further end I see In his old place our Poet's vis-à-vis, The great PROFESSOR, strong, broad-shouldered, square, In life's rich noontide, joyous, debonair ... How will her realm be darkened, losing thee, Her darling, whom we call our AGASSIZ! |

遺産 ハーバード大学の北にあるケンブリッジの小学校は、アガシにちなんで命名された。アガシが科学的人種差別に関与していたことを懸念し、1889年から 1922年まで同校の校長を務めたアフリカ系アメリカ人のマリア・ルイーズ・ボールドウィンに敬意を表して、2002年5月21日に校名がマリア・L・ ボールドウィン・スクールに変更された[48][49]。 2009年、近隣住民は近隣のコミュニティ協議会の名称を「アガシズ・ボールドウィン・コミュ ニティ」に変更することを決定した[51]。そして2021年7月、近隣住民側の2年間にわたる努力の集大成として、ケンブリッジ市議会は全会一致で名称 をボールドウィン・ネイバーフッドに変更することを決議した[52]。ミネソタ州ミネアポリスにある小学校、アガシズ小学校は1922年から1981年ま で存在した[53]。 地質学的オマージュ  マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジのマウント・オーバーン墓地にあるアガシズの墓は、彼がかつて住んでいた場所の近くにあるアール氷河のモレーンの巨石である。 北アメリカ中央部に形成された古代氷河湖アガシ湖は、彼の名にちなんで名づけられた。カリフォルニア州パリセーズのアガシ山、ユタ州ユインタ山脈のアガシ 山、アリゾナ州のアガシ・ピーク、マサチューセッツ州のアガシ・ロック、そして彼の母国スイスのベルナー・アルプスのアガシ・ホルンもアガシにちなんで名 づけられた。モンタナのアガシ氷河、グレイシャー国立公園のアガシ・クリーク、アラスカのセント・エリアス山脈のアガシ氷河、ニューハンプシャーのホワイ ト・マウンテンのアガシ山も彼の名を冠している。火星のクレーター、クレーター・アガシ[54]や月の岬にも彼の名前がつけられている。南極大陸のパー マーランドにある岬、ケープ・アガシは彼にちなんで名付けられた。主ベルト小惑星の2267 Agassizも彼にちなんで命名された。 生物学的オマージュ アガシにちなんで命名された動物種もいくつかある。 アガシズ・ドワーフ・シクリッド Apistogramma agassizii Steindachner, 1875; Agassiz's perchlet、別名Agassiz's glass fish; and the olive perchlet Ambassis agassizii Steindachner, 1866; スプリング・ケーブフィッシュ Forbesichthys agassizii (Putnam, 1872); ナマズ Corydoras agassizii Steindachner, 1876; Rio Skate Rioraja agassizii (J. P. Müller & Henle, 1841); 南米の魚Leporinus agassizii [55]. the Snailfish Liparis agassizii Putnam, 1874; ウミタニシ Borsonella agassizii (Dall, 1908); カニの一種 Eucratodes agassizii A. Milne Edwards, 1880; Isocapnia agassizi Ricker, 1943(石蜻蛉の一種); Publius agassizi (Kaup, 1871) (カミキリムシの一種); Xylocrius agassizi (LeConte, 1861) (カミキリムシ); Exoprosopa agassizii Loew, 1869(ハナアブ); Chelonia agassizii Bocourt, 1868(ガラパゴスゾウガメ);[56]。 Philodryas agassizii(Jan, 1863)(南米のヘビ);[56]。 そして最もよく知られているのが Gopherus agassizii (Cooper, 1863)(砂漠のカメ)[56]。 2020年、モロッコのケムケム層群に生息するピクノドン魚類(Actinopterygii, Pycnodontiformes)の新属名Agassazilia erfoundina(Cooper and Martill, 2020)が、1830年代にこのグループを初めて同定したアガシにちなんで命名された。 トリビュート賞 2005年、欧州地球惑星科学連合(European Geosciences Union Division on Cryospheric Sciences)は、地球上または太陽系内の他の場所における雪氷圏の研究に対する卓越した科学的貢献を称え、個人に授与されるルイ・アガシ・メダルを 設立した[57]。 アガシは、ボストンの作家や知識人が集まるパーカー・ハウスのサタデー・クラブと呼ばれる集まりに毎月参加していた。そのため、オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズ・シニアの詩 "At the Saturday Club "の一節に、アガシが登場する。 テーブルの奥に見えるのは 我らが詩人の、その昔からの居場所を、 偉大な教授、力強く、肩幅が広く、四角い、 人生の豊かな昼下がりに、陽気に、蕩けるように ... あなたを失って、彼女の領域はどのように暗くなるのだろう、 我らがアガシズと呼ぶ、彼女の最愛の人を! |

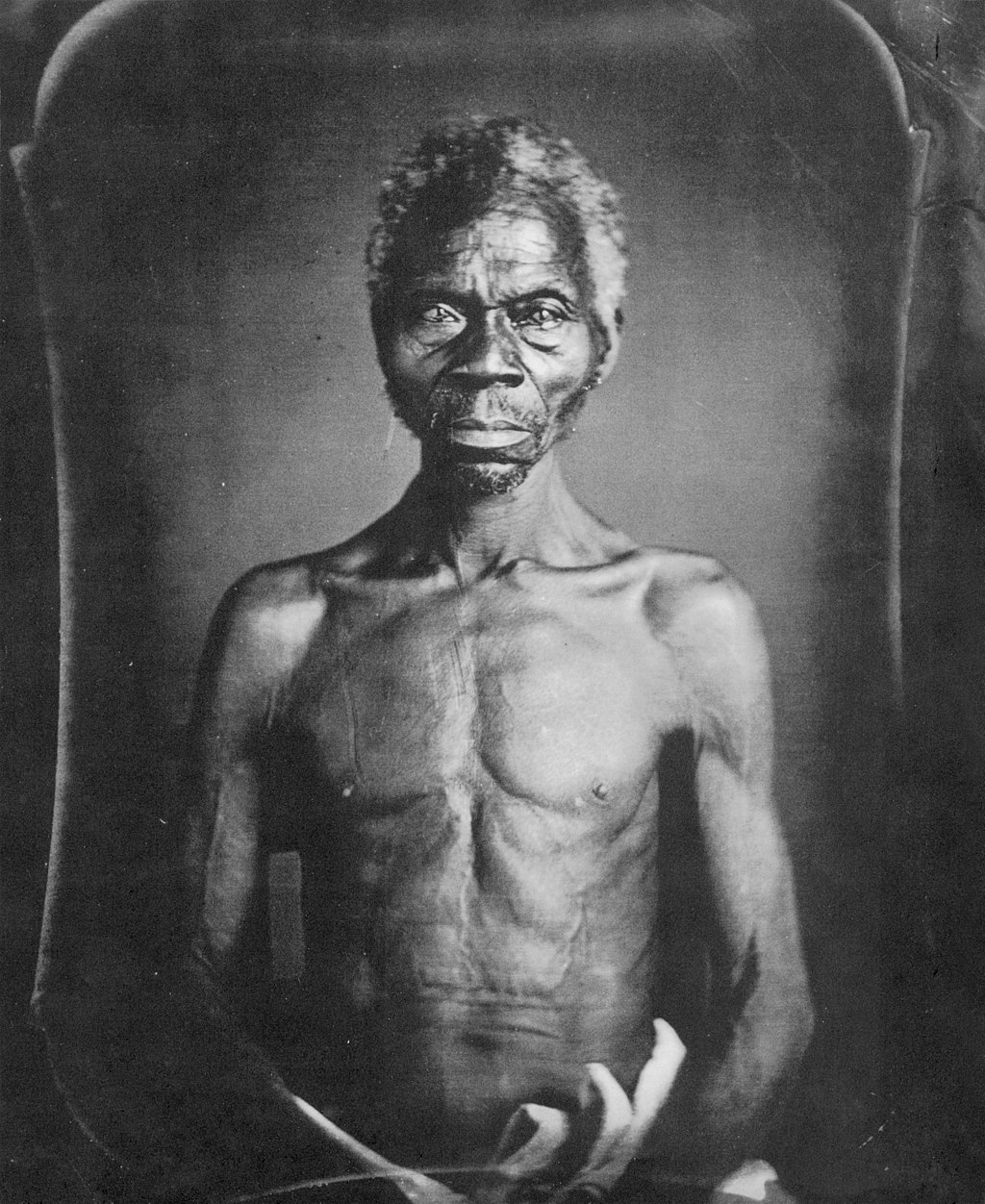

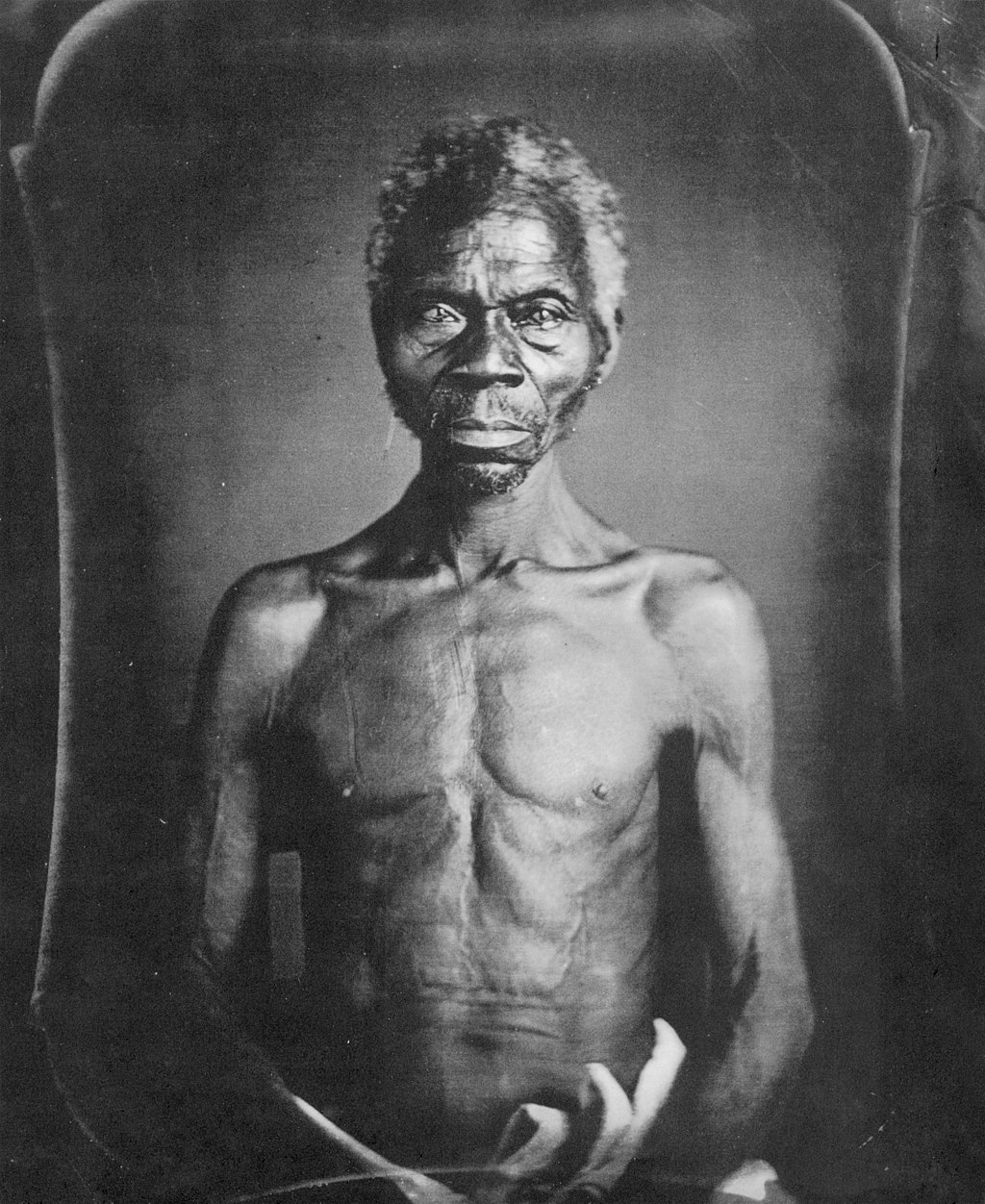

Daguerreotypes of Renty and Delia Taylor https://www.americanheritage.com/faces-slavery-historical-find Renty Taylor and more pictures. In 1850, Agassiz commissioned daguerreotypes, which were described as "haunting and voyeuristic" of the enslaved Renty Taylor and Taylor's daughter, Delia, to further his arguments about black inferiority.[58] They are the earliest known photographs of enslaved persons.[59][60][58][61] Agassiz left the images to Harvard, and they remained in the Peabody Museum's attic until 1976, when they were rediscovered by Ellie Reichlin, a former staff member.[62][63] The 15 daguerrotypes were in a case with the embossing "J. T. Zealy, Photographer, Columbia," with several handwritten labels, which helped in later identification.[63] Reichlin spent months doing research to try to identify the people in the photos, but Harvard University did not make efforts to contact the families and licensed the photos for use.[63][64] In 2011, Tamara Lanier wrote a letter to the president of Harvard that identified herself as a direct descendant of the Taylors and asked the university to turn over the photos to her.[64][65] In 2019, Taylor's descendants sued Harvard for the return of the images and unspecified damages.[66] The lawsuit was supported by 43 living descendants of Agassiz, who wrote in a letter of support, "For Harvard to give the daguerreotypes to Ms. Lanier and her family would begin to make amends for its use of the photos as exhibits for the white supremacist theory Agassiz espoused." Everyone must evaluate fully "his role in promoting a pseudoscientific justification for white supremacy."[59] [58]"Who Should Own Photos of Slaves? The Descendants, not Harvard, a Lawsuit Says". The New York Times. March 20, 2019. [59]Moser, Erica. "Descendants of racist scientist back Norwich woman in fight over slave images". theday.com. The Day. [60]Browning, Kellen. "Descendants of slave, white supremacist join forces on Harvard's campus to demand school hand over 'family photos'".www.bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. [61]"The World Is Watching: Woman Suing Harvard for Photos of Enslaved Ancestors Says History Is At Stake". Democracy Now!. March 29, 2019. [62]Sehgal, Parul (October 2, 2020). "The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. [63] "Faces of Slavery: A Historical Find". American Heritage magazine. June 1977. [64]"Woman who claims descent sues Harvard over refusal to return photos of enslaved man from 1850". St. Louis American. March 22, 2019. [65]"Harvard 'Shamelessly' Profits From Photos Of Slaves, Lawsuit Claims". March 20, 2019. [66]Tony Marco, Ray Sanchez and (March 20, 2019). "The descendants of slaves want Harvard to stop using iconic photos of their relatives". /www.cnn.com. CNN. - Ilisa Barbash , Molly Rogers et al., 2020. To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes. New York:Aperture. |

レンティ・テイラーとデリア・テイラーのダゲレオタイプ レンティ・テイラー https://www.americanheritage.com/faces-slavery-historical-find 1850年、アガシは黒人の劣等性についての議論を深めるために、奴隷であったレンティ・テイラーとテイラーの娘デリアのダゲレオタイプを依頼した。 これは奴隷にされた人物の写真としては最古のものである[59][60][58][61]。アガシはこの画像をハーバード大学に残し、1976年に元ス タッフのエリー・ライヒリンによって再発見されるまで、ピーボディ博物館の屋根裏部屋に保管されていた。 [62][63]。15枚のダゲロタイプは、「J. T. Zealy, Photographer, Columbia」というエンボスの入ったケースに入っており、手書きのラベルが数枚貼られていたため、後の身元確認に役立った[63]。 ライヒリンは、写真に写っている人物を特定するために数カ月かけて調査を行ったが、ハーバード大学は遺族と連絡を取る努力をせず、写真の使用許諾を得な かった[63][64]。 2011年、タマラ・ラニエはハーバード大学の学長に手紙を書き、自分がテイラー家の直系の子孫であることを明らかにし、写真を引き渡すよう大学に求めた[64][65]。 2019年、テイラーの子孫は画像の返還と不特定の損害賠償を求めてハーバード大学を提訴した[66]。 この訴訟を支持したのはアガシズの存命中の子孫43人で、彼らは支持の手紙の中で、"ハーバード大学がラニアー女史とその家族にダゲレオタイプを渡すこと は、アガシズが信奉した白人至上主義理論のための展示品として写真を使用したことに対する償いを始めることになる "と書いている。誰もが「白人至上主義を疑似科学的に正当化することを推進した彼の役割」を十分に評価しなければならない[59]。 ▲はフリーアクセスが難しい制限サイト [58]"Who Should Own Photos of Slaves? The Descendants, not Harvard, a Lawsuit Says". The New York Times. March 20, 2019. ▲ [59]Moser, Erica. "Descendants of racist scientist back Norwich woman in fight over slave images". theday.com. The Day. ▲ [60]Browning, Kellen. "Descendants of slave, white supremacist join forces on Harvard's campus to demand school hand over 'family photos'".www.bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe. ▲ [61]"The World Is Watching: Woman Suing Harvard for Photos of Enslaved Ancestors Says History Is At Stake". Democracy Now!. March 29, 2019. [62]Sehgal, Parul (October 2, 2020). "The First Photos of Enslaved People Raise Many Questions About the Ethics of Viewing". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.▲ [63] "Faces of Slavery: A Historical Find". American Heritage magazine. June 1977. [64]"Woman who claims descent sues Harvard over refusal to return photos of enslaved man from 1850". St. Louis American. March 22, 2019. [65]"Harvard 'Shamelessly' Profits From Photos Of Slaves, Lawsuit Claims". March 20, 2019. [66]Tony Marco, Ray Sanchez and (March 20, 2019). "The descendants of slaves want Harvard to stop using iconic photos of their relatives". /www.cnn.com. CNN. - Ilisa Barbash , Molly Rogers et al., 2020. To Make Their Own Way in the World: The Enduring Legacy of the Zealy Daguerreotypes. New York:Aperture. |

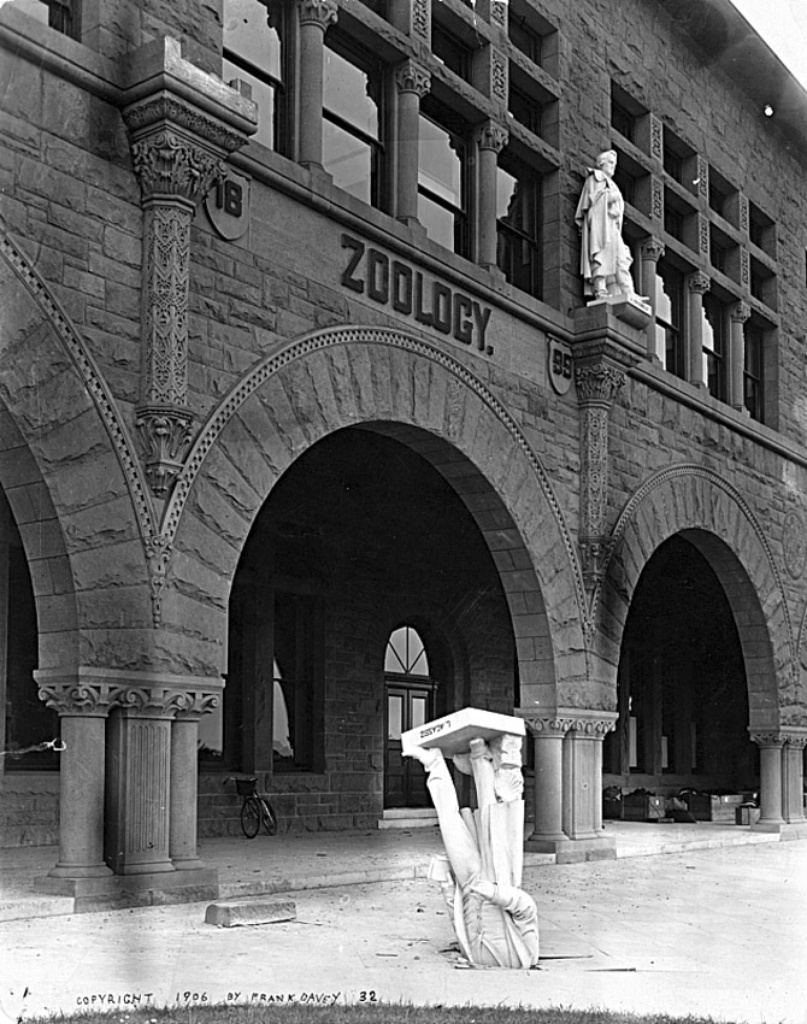

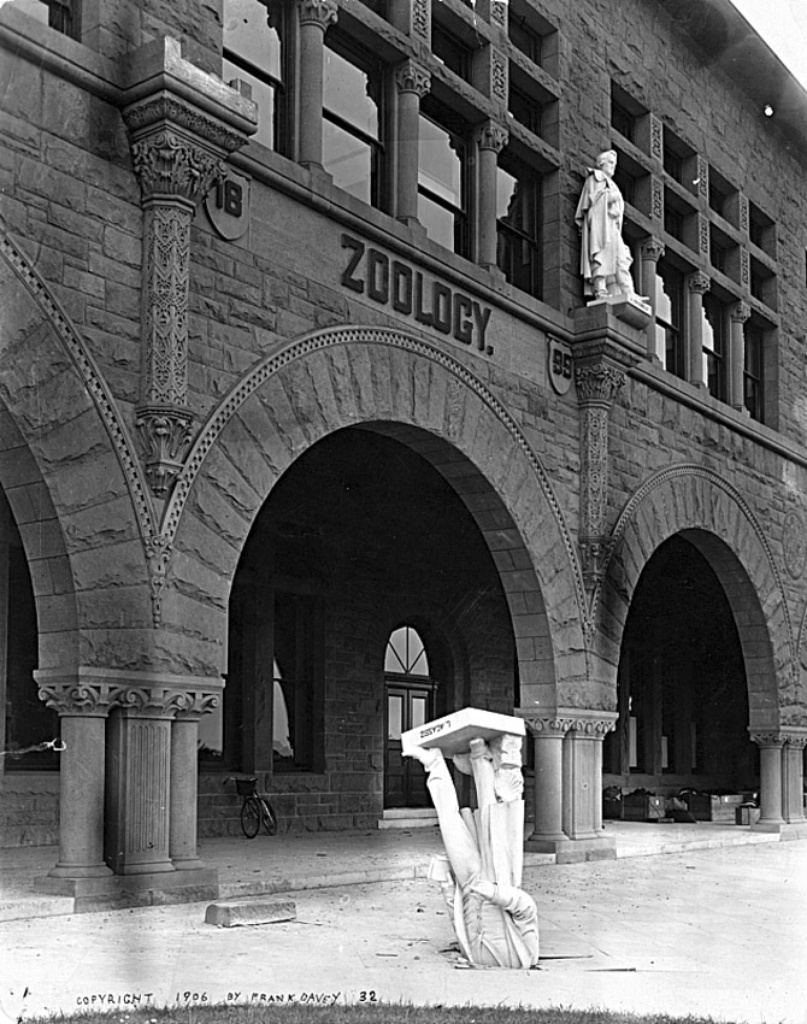

Polygenism and racism After the 1906 San Francisco earthquake toppled Agassiz's statue from the façade of Stanford's zoology building, Stanford President David Starr Jordan wrote, "Somebody—Dr. Angell, perhaps—remarked that 'Agassiz was great in the abstract but not in the concrete.'"[67] Agassiz was a well-known natural scientist of his generation in America.[68] In addition to being a natural scientist, Agassiz wrote prolifically in the field of scientific polygenism after he came to the United States. Upon arriving in Boston in 1846, Agassiz spent a few months acquainting himself with the northeast region of the United States.[69] He spent much of his time with Samuel George Morton, a famous American anthropologist at the time who became well known by analyzing fossils brought back by Lewis and Clark.[70] One of Morton’s personal projects involved studying cranial capacity of human skulls from around the world. Morton aimed to use craniometry to prove that white people were biologically superior to other races. His work "Crania Aegyptiaca" claimed to support the polygenism belief that the races were created separately and each had their own unique attributes.[71] Morton relied on other scientists to send him skulls along with information about where they were acquired. Factors that can affect cranial capacity, such as body size and gender, were not taken into consideration by Morton.[70] He made questionable judgment calls such as dismissing Hindu skull calculations from his Caucasian cranial measurements because they brought the overall average down. Oppositely, he included Peruvian skull measurements alongside Native American calculations even though the Peruvian numbers lowered the average score. Despite Morton's unsound methods, his published work on cranial capacities across races was deemed authoritative in the United States and Europe. Morton is a primary influence on Agassiz's belief in polygenism.[70] John Amory Lowell invited Agassiz to present twelve lectures in December 1846 on three subjects titled "The Plan of Creation as shown in the Animal Kingdom, Ichthyology, and Comparative Embryology” as a part of the Lowell Lecture series. These lectures were widely attended with up to 5,000 people in attendance on some nights.[72] It was during these lectures that Agassiz announced for the first time that black and white people had different origins but were part of the same species.[70] Agassiz repeated this lecture 10 months later to the Charleston Literary Club but changed his original stance, claiming that black people were physiologically and anatomically a distinct species.[70] Agassiz believed that humans did not descend from one single common ancestor. He believed that like plants and animals, various regions have differentiated species of humans.[69] He considered this hypothesis testable, and matched to the available evidence. He also indicated that there were obvious geographical barriers that were the likely cause of speciation. Stephen Jay Gould asserted that Agassiz's observations sprang from racist bias, in particular from his revulsion on first encountering African-Americans in the United States.[73] Referencing letters written by Agassiz, Gould compares Agassiz' public display of dispassionate objectivity to his private correspondence, in which he describes "the production of half breeds" as "a sin against nature..." Describing the interbreeding of white and black people, he warns, "We have already had to struggle, in our progress, against the influence of universal equality... but how shall we eradicate the stigma of a lower race when its blood has once been allowed to flow freely into our children." In contrast, others have asserted that, despite favoring polygenism, Agassiz rejected racism and believed in a spiritualized human unity. However, in the same article, Agassiz asks the reader to consider the hierarchy of races, mentioning "The indomitable, courageous, proud Indian, — in how very different a light he stands by the side of the submissive, obsequious, imitative negro, or by the side of the tricky, cunning, and cowardly Mongolian! Are not these facts indications that the different races do not rank upon one level in nature?" Agassiz never supported slavery and claimed his views on polygenism had nothing to do with politics.[70] His views on polygenism have been claimed to have emboldened proponents of slavery. Accusations of racism against Agassiz have prompted the renaming of landmarks, schoolhouses, and other institutions (which abound in Massachusetts) that bear his name. Opinions about those moves are often mixed, given his extensive scientific legacy in other areas, and uncertainty about his actual racial beliefs. In 2007, the Swiss government acknowledged his "racist thinking", but declined to rename the Agassizhorn summit. In 2017, the Swiss Alpine Club declined to revoke Agassiz's status as a member of honor, which he received in 1865 for his scientific work, because the club considered that status to have lapsed on Agassiz's death. In 2020, the Stanford Department of Psychology asked for a statue of Louis Agassiz to be removed from the front façade of its building. In 2021, Chicago Public Schools announced they would remove Agassiz's name from an elementary school and rename it for the abolitionist and political activist, Harriet Tubman. In 2022, The Trustees of Reservations renamed Agassiz Rock as The Monoliths.[74] |

ポリジェニズムと人種差別 1906年のサンフランシスコ地震でスタンフォード大学の動物学の建物のファサードからアガシズの銅像が倒された後、スタンフォード大学のデイヴィッド・ スター・ジョーダン学長は、「誰か アンゲル博士 は、『アガシズは抽象的には偉大であったが、具体的には偉大ではなかった』と記している」と書いている [67]。 自然科学者であることに加え、アガシは渡米後、科学的多遺伝主義の分野で多くの著作を残した。 1846年にボストンに到着したアガシは、アメリカ北東部を知るために数ヶ月を過ごした[69]。彼は、ルイスとクラークが持ち帰った化石の分析によって 有名になった、当時有名なアメリカの人類学者であったサミュエル・ジョージ・モートンと共に多くの時間を過ごした[70]。モートンは頭蓋計測を利用し て、白人が他の人種よりも生物学的に優れていることを証明することを目指していた。彼の著作 "Crania Aegyptiaca "は、人種は別々に創造され、それぞれが独自の属性を持っているという多遺伝主義の信念を支持すると主張した[71]。 モートンは、他の科学者が頭蓋骨をどこで入手したかという情報とともに送ってくれることを頼りにしていた。体格や性別など、頭蓋の容量に影響を与えうる要 因は、モートンによって考慮されなかった[70]。 彼は、全体的な平均値を下げるという理由で、コーカソイドの頭蓋測定からヒンズー教の頭蓋骨の計算を除外するなど、疑わしい判断を下した。反対に、ペルー の数値が平均点を下げたにもかかわらず、彼はネイティブ・アメリカンの計算と一緒にペルーの頭蓋骨の測定値を含めた。モートンの不健全な方法にもかかわら ず、彼が発表した人種間の頭蓋骨の能力に関する研究は、米国とヨーロッパで権威あるものとみなされた。モートンは、アガシが多遺伝子主義を信じるように なった主な原因である[70]。 ジョン・エイモリー・ローウェルは、1846年12月にアガシを招き、ローウェル講義シリーズの一環として、「動物界に示される天地創造の計画、魚類学、 比較発生学」と題した3つのテーマで12回の講義を行った。これらの講義は広く聴衆を集め、夜には5,000人もの聴衆が集まったこともあった[72]。 アガシズはこの講義の中で、黒人と白人は異なる起源を持つが、同じ種の一部であると初めて発表した[70]。アガシズは10ヶ月後、チャールストン文芸ク ラブでこの講義を繰り返したが、当初の姿勢を変え、黒人は生理学的にも解剖学的にも異なる種であると主張した[70]。 アガシは、人類は単一の共通の祖先の子孫ではないと信じていた。彼はこの仮説を検証可能であり、利用可能な証拠と一致すると考えた[69]。彼はまた、種分化の原因と思われる明らかな地理的障壁が存在すると指摘した。 スティーヴン・ジェイ・グールドは、アガシズの観察は人種差別的な偏見、特にアメリカで初めてアフリカ系アメリカ人に遭遇したときの反発から生まれたと主 張した。白人と黒人の交配について、彼はこう警告している。"われわれはすでに進歩の過程で、普遍的平等の影響と闘わなければならなかった......し かし、いったんその血がわれわれの子供たちに自由に流れ込むことを許されてしまったら、どのようにして下等人種の汚名を拭い去ろうか"。これとは対照的 に、アガシは多系統主義を支持しながらも人種差別を否定し、精神化された人間の統一を信じていたと主張する者もいる。しかし、アガシは同じ論文の中で、 「不屈で、勇気があり、誇り高いインディアンは、従順で、卑屈で、模倣的なニグロや、ずるがしこくて、臆病なモンゴル人と比べて、どれほど異なる存在であ ろうか!これらの事実は、異なる種族が自然界において同じレベルにないことを示しているのではないだろうか? アガシは奴隷制を支持したことはなく、彼の多遺伝子主義に関する見解は政治とは無関係であると主張した[70]。彼の多遺伝子主義に関する見解は奴隷制支持者を勇気づけたと主張されている。 アガシに対する人種差別の非難は、彼の名を冠したランドマーク、校舎、その他の施設(マサチューセッツ州に多い)の改名を促した。アガシが他の分野で残し た広範な科学的遺産や、実際の人種的信条についての不確かさを考慮すると、こうした動きに対する意見はしばしば複雑である。2007年、スイス政府は彼の 「人種差別主義的思考」を認めたが、アガシホルン山頂の名称変更を拒否した。2017年、スイス山岳クラブは、アガシが1865年にその科学的業績に対し て授与された名誉会員の資格を、アガシの死によって失効したとみなし、取り消すことを拒否した。2020年、スタンフォード大学心理学部がルイ・アガシズ の銅像を建物の正面ファサードから撤去するよう要請。2021年、シカゴ公立学校は小学校からアガシズの名前を削除し、奴隷廃止運動家で政治活動家のハリ エット・タブマンの名前に改名すると発表。2022年、トラスティーズ・オブ・レザベーションズはアガシズ・ロックをモノリスと改名した[74]。 |

| Recherches sur les poissons fossiles (1833–1843) History of the Freshwater Fishes of Central Europe (1839–1842) Études sur les glaciers (1840) Études critiques sur les mollusques fossiles (1840–1845) Nomenclator Zoologicus (1842–1846) Monographie des poissons fossiles du Vieux Gres Rouge, ou Systeme Devonien (Old Red Sandstone) des Iles Britanniques et de Russie (1844–1845) Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae (1848) (with A. A. Gould) Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges (Boston, 1848) Lake Superior: Its Physical Character, Vegetation and Animals, compared with those of other and similar regions (Boston: Gould, Kendall and Lincoln, 1850) Contributions to the Natural History of the United States of America (Boston: Little, Brown, and Co., 1857–1862) Geological Sketches (Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1866) A Journey in Brazil (1868) De l'espèce et de la classification en zoologie [Essay on classification] (Trans. Felix Vogeli. Paris: Bailière, 1869) Geological Sketches (Second Series) (Boston: J.R. Osgood, 1876) Essay on Classification, by Louis Agassiz (1962, Cambridge) |

化石魚類の研究(1833年~1843年) 中央ヨーロッパの淡水魚類の歴史(1839年~1842年) 氷河の研究(1840年) 化石軟体動物に関する批判的研究(1840年~1845年) 動物学命名法(1842年~1846年) 英国およびロシアのオールド・レッド・サンドストーン(Old Red Sandstone)またはデボン紀(Systeme Devonien)の魚類化石に関するモノグラフ(1844年~1845年) 動物学および地質学の書誌(Bibliographia Zoologiae et Geologiae)(1848年) (A. A. ゴールドと共著)学校および大学向け動物学の基礎(Principles of Zoology for the use of Schools and Colleges)(ボストン、1848年) スーペリア湖:その物理的特徴、植生、動物相、および他の類似地域との比較(ボストン:グールド、ケンドール、リンカーン、1850年) アメリカ合衆国の自然史への貢献(ボストン:リトル、ブラウン、アンド、カンパニー、1857年~1862年) 地質スケッチ(ボストン、ティックナー&フィールズ、1866年) ブラジル旅行記(1868年) 動物学における種と分類について[分類に関するエッセイ](フェリックス・ヴォゲリ訳、パリ、バイリエール、1869年) 地質スケッチ(第二シリーズ)(ボストン:J.R.オズグッド、1876年) 分類に関するエッセイ、ルイ・アガシ著(1962年、ケンブリッジ) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Agassiz |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆