喰人種宣言

Manifesto Antropófago,

1928

A

Tapuya woman with human body parts" by Albert Eckhout.[4]- 1641.

☆人喰い宣言=喰人種宣言(ポルトガル語: Manifesto Antropófago)

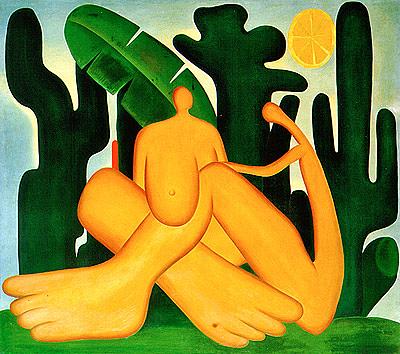

は、1928年にブラジルの詩人であり論争家であるオズワルド・デ・アンドラーデによって発表されたエッセイである。彼はブラジル近代主義の文化運動にお

ける中心人物であり、雑誌『人喰い宣言』への寄稿者でもあった。この著作は、オスワルド・デ・アンドラーデの妻でありモダニスト画家であるタルシーラ・

ド・アマラルの絵画『アバポル』に触発されたものである[1]。1991年にレスリー・バリーによって英語に翻訳された[2]。

| The Anthropophagic Manifesto (Portuguese: Manifesto Antropófago),

also variously translated as the Cannibal Manifesto or the Cannibalist

Manifesto, is an essay published in 1928 by the Brazilian poet and

polemicist Oswald de Andrade, a key figure in the cultural movement of

Brazilian Modernism and contributor to the publication Revista de

Antropofagia. It was inspired by "Abaporu," a painting by Tarsila do

Amaral, modernist artist and wife of Oswald de Andrade.[1] The essay

was translated to English in 1991 by Leslie Bary.[2] |

人

喰い宣言(ポルトガル語: Manifesto

Antropófago)は、1928年にブラジルの詩人であり論争家であるオズワルド・デ・アンドラーデによって発表されたエッセイである。彼はブラジ

ル近代主義の文化運動における中心人物であり、雑誌『人喰い宣言』への寄稿者でもあった。この著作は、オスワルド・デ・アンドラーデの妻でありモダニスト

画家であるタルシーラ・ド・アマラルの絵画『アバポル』に触発されたものである[1]。1991年にレスリー・バリーによって英語に翻訳された[2]。 |

Content The Grupo dos Cinco, a modernist art collective that upheld the principles of the Modern Art Week of 1922.[3]  "A Tapuya woman with human body parts" by Albert Eckhout.[4] Written in poetic prose in the modernist style of Une Saison en Enfer by Rimbaud, the Manifesto Antropófago is more directly political than Oswald's previous manifesto, Manifesto Pau-Brasil, which was created in the interest of propagating a Brazilian poetry for export. The "Manifesto" has often been interpreted as an essay in which the main argument proposes that Brazil's history of "cannibalizing" other cultures is its greatest strength, while playing on the modernists' primitivist interest in cannibalism as an alleged tribal rite. Cannibalism becomes a way for Brazil to assert itself against European post-colonial cultural domination.[5] One of the Manifesto's iconic lines, written in English in the original, is "Tupi or not Tupi, that is the question." The line is simultaneously a celebration of the Tupi, who practiced certain forms of ritual cannibalism (as detailed in the 16th century writings of André Thévet, Hans Staden, and Jean de Léry), and a metaphorical instance of cannibalism: it eats Shakespeare. On the other hand, some critics argue that Antropofagia as a movement was too heterogeneous for overarching arguments to be extracted from it, and that often it had little to do with a post-colonial cultural politics.[6] |

内容 グルーポ・ドス・シンコは、1922年の現代美術週間の理念を支持したモダニズム芸術家集団である。[3]  アルベルト・エックハウト作「人体の一部を持つタプヤ族の女性」(1641) [4] ランボーの『地獄の一季』を模した詩的散文で書かれた『人食宣言』は、ブラジル詩の輸出を目的としたオズワルドの前作『パウ・ブラジル宣言』よりも直接的 に政治的だ。この「宣言」はしばしば、ブラジルが他文化を「食人」してきた歴史こそが最大の強みだと主張する論考と解釈されてきた。同時に、モダニストた ちが部族の儀式として食人行為に関心を寄せていた原始主義的傾向を巧みに利用している。食人行為は、ヨーロッパのポストコロニアル的文化的支配に対してブ ラジルが自己を主張する手段となるのだ。 マニフェストの象徴的な一節「トゥピか、トゥピでないか、それが問題だ」は、原典では英語で記されている。この一節は、特定の儀礼カニバリズムを実践した トゥピ族(16世紀のアンドレ・テヴェ、ハンス・シュターデン、ジャン・ド・レリーの記述に詳述)への賛美であると同時に、隠喩的なカニバリズムの事例で もある。すなわちシェイクスピアを食らうという行為だ。一方で、一部の批評家は、運動としてのアントロポファジアは異質性が強すぎて包括的な主張を導き出 せず、ポストコロニアルな文化政治とはほとんど無関係だったと論じている。[6] |

| Influences In the 1960s, introduced to the work of Oswald de Andrade by concrete poet Augusto de Campos, both visual artist Hélio Oiticica and musician Caetano Veloso saw the Manifesto as a major artistic influence on the Tropicália movement. Veloso has stated, "the idea of cultural cannibalism fit us, the tropicalists, like a glove. We were ‘eating’ the Beatles and Jimi Hendrix."[7] On the 1968 album Tropicalia: ou Panis et Circensis, Gilberto Gil and Torquato Neto explicitly refer to the Manifesto in the song "Geléia geral" in the lyric "a alegria é a prova dos nove" (happiness is the proof of nines), which they follow with "e a tristeza é teu porto seguro" (and sadness is your safe harbor). In 1990, Brazilian visual artist Antonio Peticov created a mural in honour of what would have been Andrade's 100th birthday. Momento Antropofágico com Oswald de Andrade was installed in the São Paulo Metro's Republica station. It was inspired by three of Andrade's works: O Perfeito Cozinheiro das Almas deste Mundo, Manifesto Antropofágico, and O Homem do Povo.[8][9] |

影響 1960年代、具体詩人アウグスト・デ・カンポスを通じてオズワルド・デ・アンドラーデの著作を知った視覚芸術家エリオ・オイティシカと音楽家カエター ノ・ヴェローゾは、このマニフェストがトロピカリア運動に大きな芸術的影響を与えたと認識した。ヴェローゾは「文化的なカニバリズムという概念は、我々ト ロピカリストにぴったりだった。我々はビートルズやジミ・ヘンドリックスを『食っていた』のだ」と述べている。[7] 1968年のアルバム『トロピカリア:オウ・パニス・エト・チルケンシス』において、ジルベルト・ジルとトルカート・ネートは楽曲「ジェレイア・ジェラ ル」の歌詞で宣言を明示的に引用している。「喜びは九の証明だ」という一節に続き、「そして悲しみは君の安全な港だ」と歌っている。 1990年、ブラジルの視覚芸術家アントニオ・ペティコフは、アンドラーデの生誕100周年を記念して壁画を制作した。『オズワルド・デ・アンドラーデに よる人食いの瞬間』はサンパウロ地下鉄レプブリカ駅に設置された。この作品はアンドラーデの3作品『この世の魂の完璧な料理人』『人食いの宣言』『民衆の 男』に着想を得ている。[8][9] |

| Literature of Brazil Tropicália |

ブラジルの文学 トロピカリア |

| References 1. "Tarsila do Amaral: Inventing Modern Art in Brazil | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art. Retrieved 18 August 2020. 2. Andrade, Oswald de (1991). "Cannibalist Manifesto". Latin American Literary Review. 19 (38). Translated by Leslie Bary. Pittsburgh: Dept. of Modern Languages, Carnegie-Mellon University: 38–47. JSTOR 20119601. Retrieved 22 July 2015. Gearini, Victória (26 February 2020). "Aventuras na História · Grupo dos Cinco: os precursores do Modernismo no Brasil". Aventuras na História (in Brazilian Portuguese). Retrieved 18 August 2020. 3. "Albert Eckhout, Series of eight figures (article)". Khan Academy. Retrieved 18 August 2020. 4. Garcia, Luis Fellipe (2020). "Oswald de Andrade / Anthropophagy". ODIP: The Online Dictionary of Intercultural Philosophy. Thorsten Botz-Bornstein (ed.). Retrieved 13 June 2020. 5. Jauregui, Carlos, A. (2012). McKee Irwin & Szurmuk, Robert & Mónica (ed.). Dictionary of Latin American Cultural Studies. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. pp. 22–28. 6. Dunn, Christopher. Brutality garden : Tropicália and the emergence of a Brazilian counterculture. Chapel Hill, NC. ISBN 978-1-4696-1571-4. OCLC 862077082. 7. "Editorial - Underground collection: works of art in São Paulo subway". SP-Arte (in Brazilian Portuguese). 24 January 2020. Retrieved 18 August 2021. 8. "Livro Digital" (PDF). Arte no Metrô (in Brazilian Portuguese). p. 31. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 June 2019. |

参考文献 1. 「タルシラ・ド・アマラル:ブラジルにおける現代美術の創始|MoMA」. ニューヨーク近代美術館. 2020年8月18日閲覧. 2. アンドラーデ, オズワルド・デ (1991). 「カニバリズム宣言」. 『ラテンアメリカ文学評論』. 19巻 (38号). レスリー・バリー訳。ピッツバーグ:カーネギーメロン大学現代言語学科:38–47頁。JSTOR 20119601。2015年7月22日閲覧。 Aventuras na História(ブラジルポルトガル語)。2020年8月18日閲覧。 3. 「アルバート・エックハウト、8体の像の連作(記事)」。カーン・アカデミー。2020年8月18日閲覧。 4. Garcia, Luis Fellipe (2020). 「オズワルド・デ・アンドラーデ/人食主義」。ODIP: 異文化哲学オンライン辞典。トーステン・ボッツ=ボルンシュタイン(編)。2020年6月13日閲覧。 5. ハウレギ、カルロス・A.(2012)。マッキー・アーウィン&シュルムク、ロバート&モニカ(編)。『ラテンアメリカ文化研究辞典』。ゲインズビル:フロリダ大学出版局。pp. 22–28。 6. ダン、クリストファー。『残虐の園:トロピカリアとブラジル反文化の台頭』。ノースカロライナ州チャペルヒル。ISBN 978-1-4696-1571-4。OCLC 862077082。 7. 「編集部 - アンダーグラウンド・コレクション:サンパウロ地下鉄の芸術作品」. SP-Arte(ブラジルポルトガル語). 2020年1月24日. 2021年8月18日閲覧. 8. 「デジタル書籍」 (PDF). Arte no Metrô(ブラジルポルトガル語). p. 31. 2019年6月17日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manifesto_Antrop%C3%B3fago |

|

Pintura de Tarsila do Amaral de 1929 |

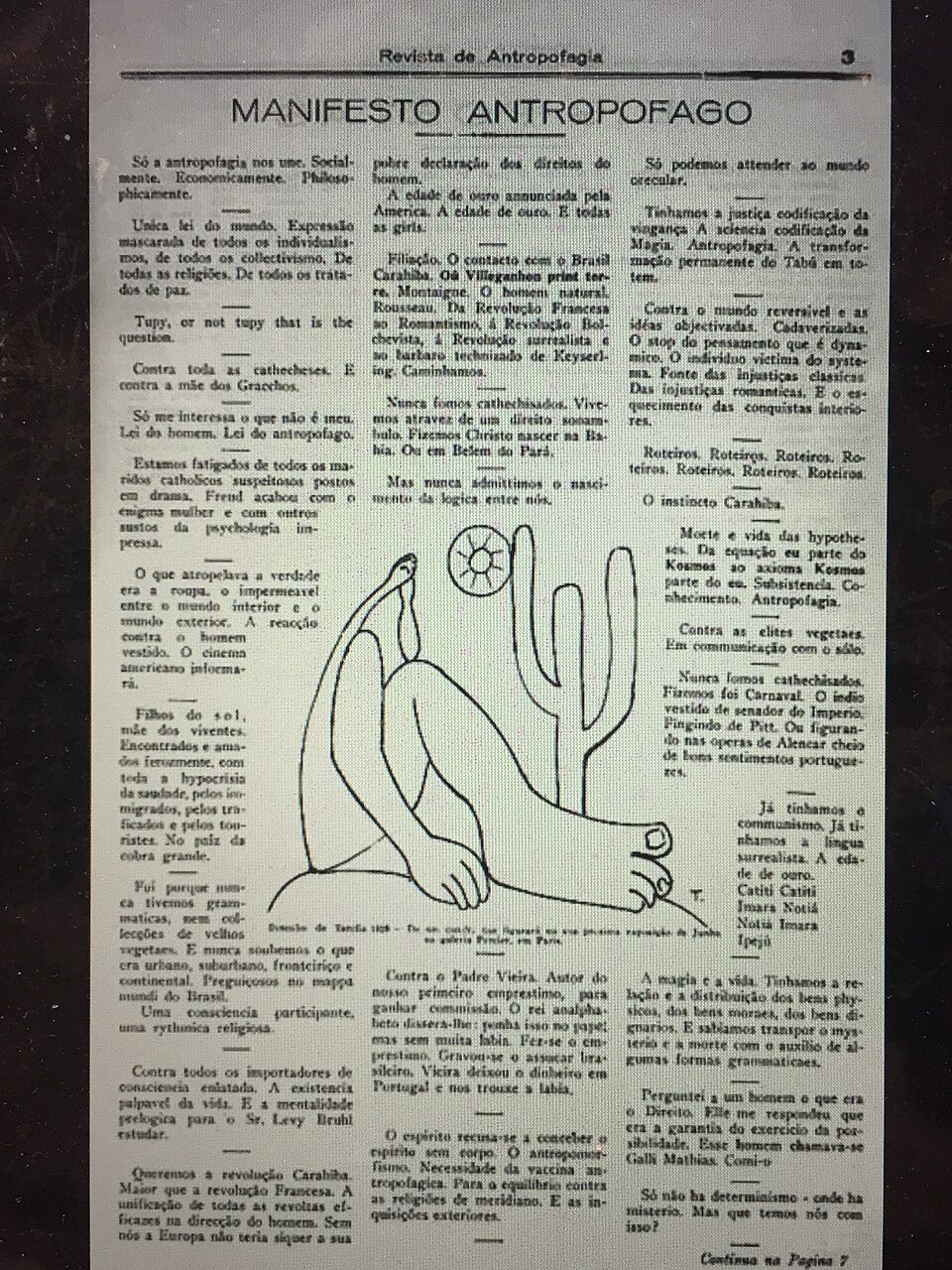

Publicação original do "Manifesto Antropófago" na Revista de Antropofagia de Oswald de Andrade em 1928. A imagem ao centro é um desenho de contorno da artista brasileira Tarsila do Amaral de sua pintura de 1928 "Abaporu". 1928年にオズワルド・デ・アンドラーデが『人食いの雑誌』に発表した「人食いのマニフェスト」のオリジナル版。中央の画像は、ブラジル人アーティスト、タルシーラ・ド・アマラルが1928年に描いた絵画「アバポル」の輪郭画だ。 |

| Macunaíma Main article: Macunaíma (novel)  Photograph of a yellow house on a street corner Andrade's house in Rua Lopes Chaves, São Paulo, where he describes himself "crouched at my desk" in a 1927 poem.[25] At the same time, Andrade was developing an extensive familiarity with the dialects and cultures of large parts of Brazil. He started to apply to prose fiction the speech-patterned technique he had developed in writing the poems of Hallucinated city. He wrote two novels during this period using these techniques: the first, Love, Intransitive Verb, was largely a formal experiment.;[26] the second, written shortly after and published in 1928, was Macunaíma, a novel about a man ("The hero without a character" is the subtitle of the novel) from an indigenous tribe who comes to São Paulo, learns its languages—both of them, the novel says: Portuguese and Brazilian—and returns.[27] The style of the novel is composite, mixing vivid descriptions of both jungle and city with abrupt turns toward fantasy, the style that would later be called magical realism. Linguistically, too, the novel is composite; as the rural hero comes into contact with his urban environment, the novel reflects the meeting of languages.[28] Relying heavily on the primitivism that Andrade learned from the European modernists, the novel lingers over possible indigenous cannibalism even as it explores Macunaíma's immersion in urban life. Critic Kimberle S. López has argued that cannibalism is the novel's driving thematic force: the eating of cultures by other cultures.[29] Formally, Macunaíma is an ecstatic blend of dialects and of the urban and rural rhythms that Andrade was collecting in his research. It contains an entirely new style of prose—deeply musical, frankly poetic, and full of gods and almost-gods, yet containing considerable narrative momentum. At the same time, the novel as a whole is pessimistic. It ends with Macunaíma's willful destruction of his own village; despite the euphoria of the collision, the meeting of cultures the novel documents is inevitably catastrophic. As Severino João Albuquerque has demonstrated, the novel presents "construction and destruction" as inseparable. It is a novel of both power (Macunaíma has all kinds of strange powers) and alienation.[30] Even as Macunaíma changed the nature of Brazilian literature in an instant—Albuquerque calls it "the cornerstone text of Brazilian Modernism"—the inner conflict in the novel was a strong part of its influence.[30] Modernismo, as Andrade depicted it, was formally tied to the innovations of recent European literature and based on the productive meeting of cultural forces in Brazil's diverse population; but it was fiercely nationalistic, based in large part on distinguishing Brazil's culture from the world and on documenting the damage caused by the lingering effects of colonial rule. At the same time, the complex inner life of its hero suggests themes little explored in earlier Brazilian literature, which critics have taken to refer back to Andrade himself. While Macunaíma is not autobiographical in the strict sense, it clearly reflects and refracts Andrade's own life. Andrade was a mulatto; his parents were landowners but were in no sense a part of Brazil's Portuguese pseudo-aristocracy. Some critics have paralleled Andrade's race and family background to the interaction between categories of his character Macunaíma.[31] Macunaíma's body itself is a composite: his skin is darker than that of his fellow tribesmen, and at one point in the novel, he has an adult's body and a child's head. He himself is a wanderer, never belonging to any one place. Other critics have argued for similar analogues between Andrade's sexuality and Macunaíma's complex status.[18] Though Andrade was not openly homosexual, and there is no direct evidence of his sexual practices, many of his friends have reported after his death that he was clearly interested in men (the subject is only reluctantly discussed in Brazil).[32] It was over a pseudonymous accusation of effeminacy that Andrade broke with Oswald de Andrade in 1929.[18] Macunaíma prefers women, but his constant state of belonging and not belonging is associated with sex. The character is sexually precocious, starting his romantic adventures at the age of six, and his particular form of eroticism seems always to lead to destruction of one kind or another. Inevitably, Macunaíma's polemicism and sheer strangeness have become less obvious as it has grown ensconced in mainstream Brazilian culture and education. Once regarded by academic critics as an awkwardly constructed work of more historical than literary importance, the novel has come to be recognized as a modernist masterpiece whose difficulties are part of its aesthetic.[33] Andrade is a national cultural icon; his face has appeared on the Brazilian currency. A film of Macunaíma was made in 1969, by Brazilian director Joaquim Pedro de Andrade, updating Andrade's story to the 1960s and shifting it to Rio de Janeiro; the film was rereleased internationally in 2009.[34] |

マクナイマ メイン記事: マクーナイマ (小説)  Capa da primeira edição de Macunaíma 同時に、アンドラーデ(アンドラージ)はブラジル広域の方言や文化に精通していった。彼は詩集『幻覚の都市』で培った言語パターン技法を散文小説に応用し 始めた。この時期にこの技法を用いた二つの小説を執筆した。最初の『愛、自動詞』は主に形式的な実験作であった。[26] その後間もなく執筆され1928年に出版された第二作は『マクナイマ』であり、これはサンパウロにやって来てその言語(小説によれば二言語、すなわち ポルトガル語とブラジル語——を習得し、帰還する。[27] この小説の文体は複合的で、ジャングルと都市の鮮やかな描写が、後に呪術的リアリズムと呼ばれることになる幻想への急転と混ざり合っている。 言語的にも、この小説は複合的である。田舎の主人公が都会という環境と接触するにつれて、小説は言語の出会いをも反映している。[28] アンドラーデがヨーロッパのモダニストたちから学んだプリミティヴィズムに大きく依存し、この小説は、マクーナイマが都会生活に没入していく様子を探求し ながらも、先住民による人食いの可能性について長く立ち止まっている。批評家キンバーレ・S・ロペスは、食人行為こそが小説の主題を駆動する力であると論 じている。すなわち、ある文化が別の文化を「食う」という行為である。[29] 形式的には、マクーナイマは、アンドラーデが研究で収集した方言や都市と農村のリズムが恍惚と融合した作品である。そこには全く新しい散文様式が存在する ——深く音楽的で、率直に詩的であり、神々や神に近い存在に満ちながらも、かなりの物語的推進力を備えている。 同時に、小説全体は悲観的である。マクーナイマが自らの村を故意に破壊する場面で幕を閉じる。衝突の陶酔感にもかかわらず、小説が描く文化の邂逅は必然的 に破滅的である。 セヴェリーノ・ジョアン・アルブケルケが指摘したように、この小説は「構築と破壊」を不可分なものとして提示している。それは力(マクナイマはあらゆる奇 妙な力を持つ)と疎外の両方を描く小説である。[30] 『マクナイマ』が瞬時にブラジル文学の本質を変えた一方で——アルブケルケはこれを「ブラジル・モダニズムの礎となる作品」と呼ぶ——小説内の葛藤こそが その影響力の核心であった。 モダニズモは、アンドラーデが描いたように、形式的には近年のヨーロッパ文学の革新と結びつき、ブラジルの人口多様性における文化的力の生産的邂逅に基づ いていた。しかしそれは激しくナショナリストであり、その基盤の大部分は、ブラジルの文化を世界から区別することと、植民地支配の残存効果がもたらした損 害を記録することにあった。 同時に、その主人公の複雑な内面は、従来のブラジル文学ではほとんど探求されてこなかったテーマを示唆しており、批評家たちはこれをアンドラーデ自身への 言及と見なしている。マクーナイマは厳密な意味での自伝的作品ではないが、明らかにアンドラーデ自身の生涯を反映し、屈折させている。 アンドラーデはムラートであり、両親は地主であったが、ブラジルのポルトガル系の擬似貴族階級には決して属していなかった。批評家の中には、アンドラーデ の人種・家族的背景を、彼の創作したマクーナイマという人物のカテゴリー間の相互作用に重ね合わせる者もいる。[31] マクナイマの身体そのものが複合体である。彼の肌は部族の仲間たちよりも黒く、小説のある場面では、大人の身体に子供の頭を持つ姿で登場する。 彼自身は放浪者であり、決してどこにも属していない。 他の批評家たちは、アンドラーデのセクシュアリティとマクナイマの複雑な立場との間に、同様の類似性を主張している。[18] アンドラーデは公然と同性愛者ではなかったし、彼の性的慣行に関する直接的な証拠も存在しないが、彼の友人たちの多くは、彼の死後、彼が明らかに男性に興 味を持っていたと報告している(この話題はブラジルではしぶしぶしか議論されない)。[32] 1929年、アンドラーデはオズワルド・デ・アンドラーデとの決裂に至った。そのきっかけは、女々しさを非難する匿名の手紙であった。[18] マクナイマは女性を好むが、彼の絶え間ない「属しているようで属していない」状態は性に関連している。このキャラクターは性的早熟で、6歳で恋愛の冒険を 始め、彼の独特のエロティシズムは常に何らかの破壊へとつながるようだ。 必然的に、『マクーナイマ』の論争性と純粋な奇妙さは、ブラジル文化と教育の主流に定着するにつれ、その存在感が薄れていった。 かつては、学術的な批評家たちから、文学的価値よりも歴史的価値の方が大きい、構成のぎこちない作品と見なされていたこの小説は、その難解さがその美的特 徴の一部である、モダニズムの傑作として認識されるようになった。[33] アランデは、国民的文化の象徴であり、彼の顔はブラジルの通貨にも登場している。 1969年には、ブラジルの映画監督ジョアキン・ペドロ・デ・アンドラーデによって『マクナイマ』の映画化が行われ、アンドラーデの物語を1960年代に 更新し、舞台をリオデジャネイロに移した。この映画は2009年に国際的に再公開された。[34] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/M%C3%A1rio_de_Andrade |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099