マプーチェ

Mapuche

Minister

Osorio delivers land to the Mapuche Community Lorenzo Quintrileo of

Tirúa

▲

▲| The Mapuche

(/məˈpuːtʃi/ mə-POO-chee,[3] Mapuche and Spanish: [maˈputʃe]) are a

group of indigenous inhabitants of south-central Chile and southwestern

Argentina, including parts of Patagonia. The collective term refers to

a wide-ranging ethnicity composed of various groups who share a common

social, religious, and economic structure, as well as a common

linguistic heritage as Mapudungun speakers. Their homelands once

extended from Choapa Valley to the Chiloé Archipelago and later spread

eastward to Puelmapu,[clarification needed] a land comprising part of

the Argentine pampa and Patagonia. Today the collective group makes up

over 80% of the indigenous peoples in Chile and about 9% of the total

Chilean population. The Mapuche are concentrated in the Araucanía

region. Many have migrated from rural areas to the cities of Santiago

and Buenos Aires for economic opportunities, more than 92% of the

Mapuches are from Chile. The Mapuche traditional economy is based on agriculture; their traditional social organization consists of extended families, under the direction of a lonko or chief. In times of war, the Mapuche would unite in larger groupings and elect a toki (meaning "axe" or "axe-bearer") to lead them. Mapuche material culture is known for its textiles and silverwork. At the time of Spanish arrival, the Picunche inhabited the valleys between the Choapa and Itata, Araucanian Mapuche inhabited the valleys between the Itata and Toltén rivers, south of there, the Huilliche and the Cunco lived as far south as the Chiloé Archipelago. In the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries, Mapuche groups migrated eastward into the Andes and Pampas, conquering, fusing and establishing relationships with the Poya and Pehuenche. At about the same time, ethnic groups of the Pampa regions, the Puelche, Ranquel, and northern Aonikenk, made contact with Mapuche groups. The Tehuelche adopted the Mapuche language and some of their culture, in what came to be called Araucanization, during which Patagonia came under effective Mapuche suzerainty. Mapuche in the Spanish-ruled areas, especially the Picunche, mingled with the Spanish during the colonial period, forming a mestizo population that lost its indigenous identity. But Mapuche society in Araucanía and Patagonia remained independent until the late nineteenth century, when Chile occupied Araucanía and Argentina conquered Puelmapu. Since then the Mapuche have become subjects, and later nationals and citizens of the respective states. Today, many Mapuche and Chilean communities are engaged in the so-called Mapuche conflict over land and indigenous rights in both Argentina and Chile.  Ancient Mapuche flag according to descriptions given by chroniclers. It contains an eight-pointed star on a blue background. |

マプチェ(/məˈpu↪Lt_i/

mə-POO-chee、[3] Mapuche、スペイン語: [maˈputl_283e]

)は、パタゴニアの一部を含むチリ中南部とアルゼンチン南西部の先住民族である。この総称は、社会的、宗教的、経済的構造を共有し、マプドゥングン語話者

としての言語的遺産を共有するさまざまな集団からなる広範な民族を指す。彼らの祖国はかつてチョアパ渓谷からチロエ群島まで広がり、その後東に向かい、ア

ルゼンチンのパンパとパタゴニアの一部を構成するプエルマプ[要出典]まで広がった。今日、この集団はチリの先住民の80%以上を占め、チリの全人口の約

9%を占めている。マプチェはアラウカニア地方に集中している。多くは経済的機会を求めて農村部からサンティアゴやブエノスアイレスの都市部に移住してお

り、マプチェの92%以上がチリ出身者である。 マプチェの伝統的な経済基盤は農業であり、伝統的な社会組織は、ロンコ(首長)の指揮のもと、拡大家族で構成されている。マプチェの伝統的な社会組織は、 ロンコ(首長)の指揮のもと、大家族で構成され、戦争時には、より大きな集団で団結し、トキ(「斧」または「斧持ち」を意味する)を選出した。マプチェの 物質文化は織物と銀細工で知られている。 スペイン人到着当時、ピクンチェ族はチョアパ川とイタタ川の間の渓谷に、アラウカン・マプチェ族はイタタ川とトルテン川の間の渓谷に、その南にはヒュイリ チェ族とクンコ族がチロエ群島まで住んでいた。17世紀、18世紀、19世紀には、マプチェのグループはアンデスやパンパへと東に移動し、ポヤやペウェン チェを征服し、融合し、関係を築いた。ほぼ同時期に、パンパ地方の民族、プエルチェ族、ランケル族、北アオニケンク族がマプチェ族と接触した。テフエル チェ族はマプチェ語とその文化の一部を取り入れ、アラウカナイズと呼ばれるようになり、その間にパタゴニアは実質的なマプチェの宗主国となった。 スペイン統治地域のマプチェ、特にピクンチェ族は植民地時代にスペイン人と混血し、先住民のアイデンティティを失ったメスティーソ集団を形成した。しかし アラウカニアとパタゴニアのマプチェ社会は、チリがアラウカニアを占領し、アルゼンチンがプエルマプを征服する19世紀後半まで独立を保っていた。それ以 来、マプチェはそれぞれの国家の臣民となり、後に国民となった。今日、多くのマプチェとチリのコミュニティは、アルゼンチンとチリの両国で土地と先住民族 の権利をめぐるいわゆるマプチェ紛争に巻き込まれている。  年代記編者による記述に基づく古代のマプチェ族の旗。青地に8つの突起のある星が描かれている。 |

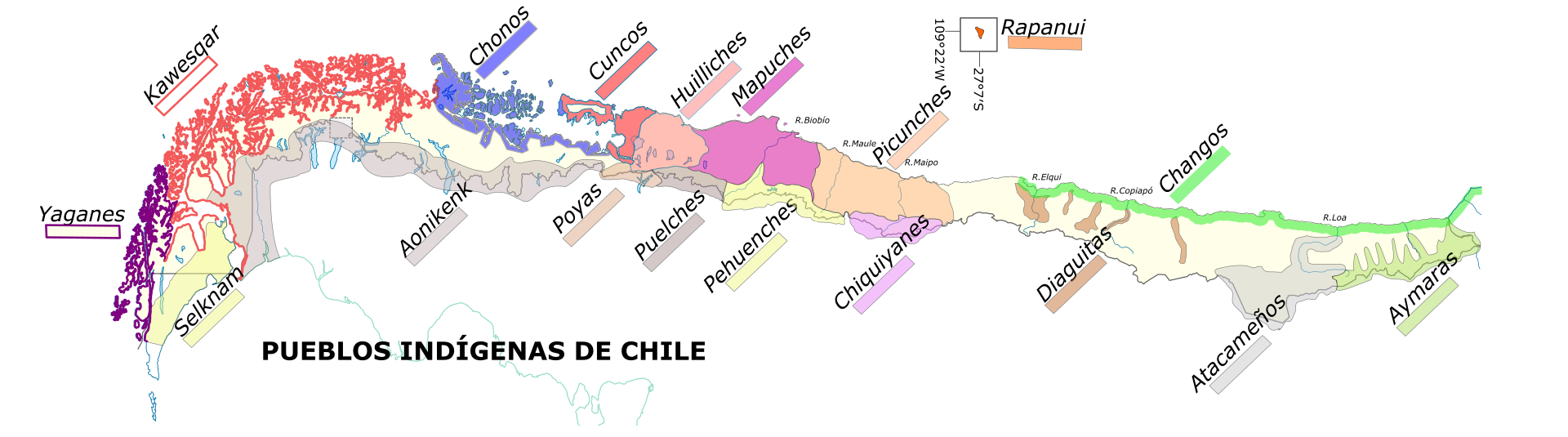

Etymology Euler diagram of Mapuche ethnicities. Historical denominations no longer in use are shown with white fields. Groups that adopted Mapuche language and culture or that have partial Mapuche descent are shown in the periphery of the main magenta-colored field. Historically, the Spanish colonizers of South America referred to the Mapuche people as Araucanians (/ˌærɔːˈkeɪniənz/ ARR-aw-KAY-nee-ənz;[4] Spanish: araucanos). This term is now considered pejorative[5] by some people. For others, the importance of the term Araucanian lies in the universality of the epic work La Araucana,[6] written by Alonso de Ercilla, and the feats of that people in their long and interminable war against the Spanish Empire. The name is probably derived from the placename rag ko (Spanish Arauco), meaning "clayey water".[7][8] The Quechua word awqa, meaning "rebel, enemy", is probably not the root of araucano.[7] Scholars believe that the various Mapuche groups (Moluche, Huilliche, Picunche, etc.) called themselves Reche during the early Spanish colonial period, due to what they referred to as their pure native blood, derived from re meaning "pure" and che meaning "people".[9] The name Mapuche is used both to refer collectively to the Picunche, Huilliche, and Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía, at other times, exclusively to the Moluche or Nguluche from Araucanía. However, Mapuche is a relatively recent endonym meaning "People of the Earth" or "Children of the Land", with mapu meaning "earth" or "land", and che meaning "person". It is preferred as a term when referring to the people after the Arauco War.[10] The Mapuche identify by the geography of their territories, such as: Pwelche or Puelche: "people of the east" occupied Pwel mapu or Puel mapu, the eastern lands (Pampa and Patagonia of Argentina). Pikunche or Picunche: "people of the north" occupied Pikun-mapu, the "northern lands". Williche or Huilliche: "people of the south" occupied Willi mapu, the "southern lands". Pewenche or Pehuenche: "people of the pewen/pehuen" occupied Pewen mapu, "the land of the pewen (Araucaria araucana) tree". Lafkenche: "people of the sea" occupied Lafken mapu, "the land of the sea"; also known as Coastal Mapuche. Nagche: "people of the plains" occupied Nag mapu, "the land of the plains" (located in sectors of the Cordillera de Nahuelbuta and the low zones bordering it). Its epic and literary name is Araucanians and its old autochthonous name is Reche.[11] The ancient Mapuche Toqui ("axe-bearer") like Lef-Traru ("swift hawk", better known as Lautaro), Kallfülikan ("blue quartz stone", better known as Caupolicán – "polished flint") or Pelontraru ("Shining Caracara", better known as Pelantaro) were Nagche. Wenteche: "people of the valleys" occupied Wente mapu, "the land of the valleys".[12] |

語源 マプチェ民族のオイラー図。現在は使用されていない歴史的な集団は白地で示されている。マプーチェの言語と文化を取り入れたグループや、部分的にマプー チェの血を引くグループは、メインとなるマゼンタ色のフィールドの周辺に示されている。 歴史的に、南米を植民地化したスペイン人はマプチェの人々をアラウカニアン(/ˌærɔːˈkeɪniənz/ ARR-aw-KAY-nee-ənz; [4] Spanish: araucanos)と呼んでいた。この言葉は現在、一部の人々によって蔑称とみなされている[5]。他の人々にとっては、アラウカニアンという言葉の重 要性は、アロンソ・デ・エルシーリャによって書かれた叙事詩『ラ・アラウカナ』[6]の普遍性と、スペイン帝国との長く果てしない戦争におけるこの民族の 偉業にある。この名前はおそらく「粘土質の水」を意味する地名rag ko(スペイン語Arauco)に由来する[7][8]。ケチュア語で「反逆者、敵」を意味するawqaは、おそらくarucanoの語源ではないだろう [7]。 学者たちは、スペインの植民地時代初期に様々なマプチェのグループ(モルーチェ、ヒュイリチェ、ピクンチェなど)が自分たちをレチェと呼んでいたのは、彼 らが純粋な土着の血と呼んでいたためだと考えている。 マプチェという名称は、ピクンチェ、ヒュイリチェ、アラウカニアのモルーチェまたはングルーチェを総称する場合にも、アラウカニアのモルーチェまたはング ルーチェのみを指す場合にも使われる。しかし、マプチェは「大地の民」または「大地の子」を意味する比較的最近の呼称であり、マプは「大地」または「土 地」、チェは「人」を意味する。アラウコ戦争後の人々を指す言葉として好まれている[10]。 マプチェは、自分たちの領土の地理によって、次のように識別する: プエルチェまたはプエルチェである: プウェルチェ(Pwelche)またはプエルチェ(Puelche):プウェル・マプ(Pwel mapu)またはプエル・マプ(Puel mapu)、東の土地(アルゼンチンのパンパとパタゴニア)を占める「東の人々」。 ピクンチェまたはピクンチェ: 「北の人々 「はピクンマプ、」北の土地 "を占領した。 ウィリチェまたはホイリチェ:「南の人々」はウィリ・マプ、「南の土地」を占領した。 PewencheまたはPehuenche: 「ピウェン(アラウカリア・アラウカナ)の木の土地」であるピウェン・マプを占領した。 Lafkenche: 「海の民 「はLafken mapu、」海の土地 "を占領した。 海岸マプチェとも呼ばれる: 「平原の民 "はナグ・マプ(平原の土地)(ナウエルブタ山脈とそれに接する低地帯に位置する)を占領した。古代マプチェのトキ(「斧を持つ者」)は、レフ=トラル (「迅速な鷹」、ラウタロとして知られる)、カルフュリカン(「青い石英石」、カウポリカンとして知られる)、ペロントラル(「輝くカラカラ」、ペランタ ロとして知られる)であった。 ウェンテチェ:「渓谷の人々」はウェンテ・マプ、「渓谷の土地」を占領していた[12]。 |

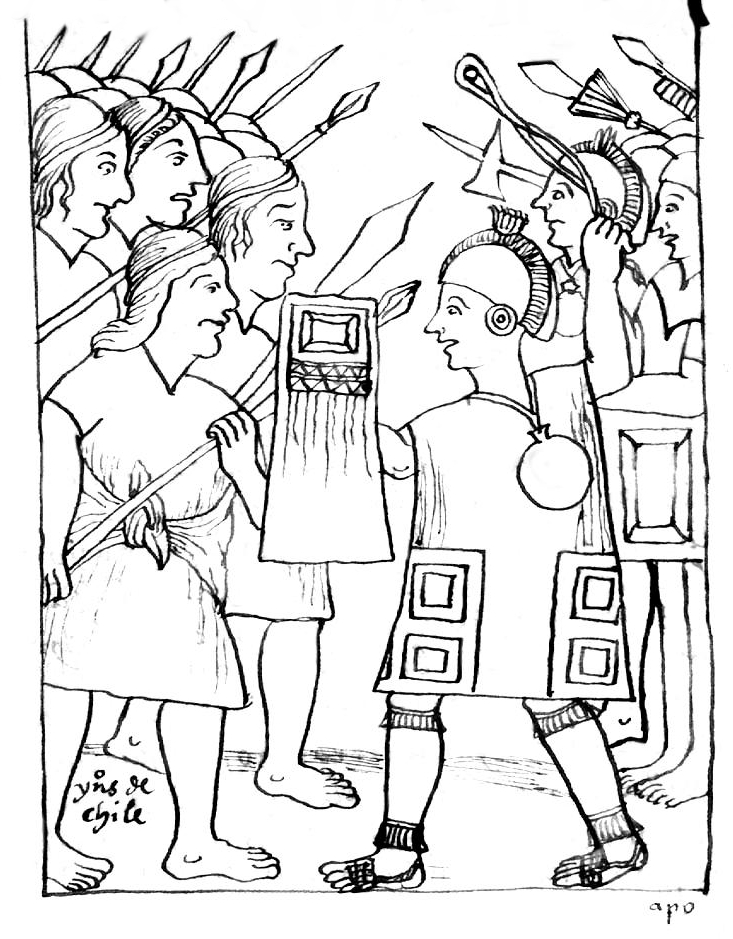

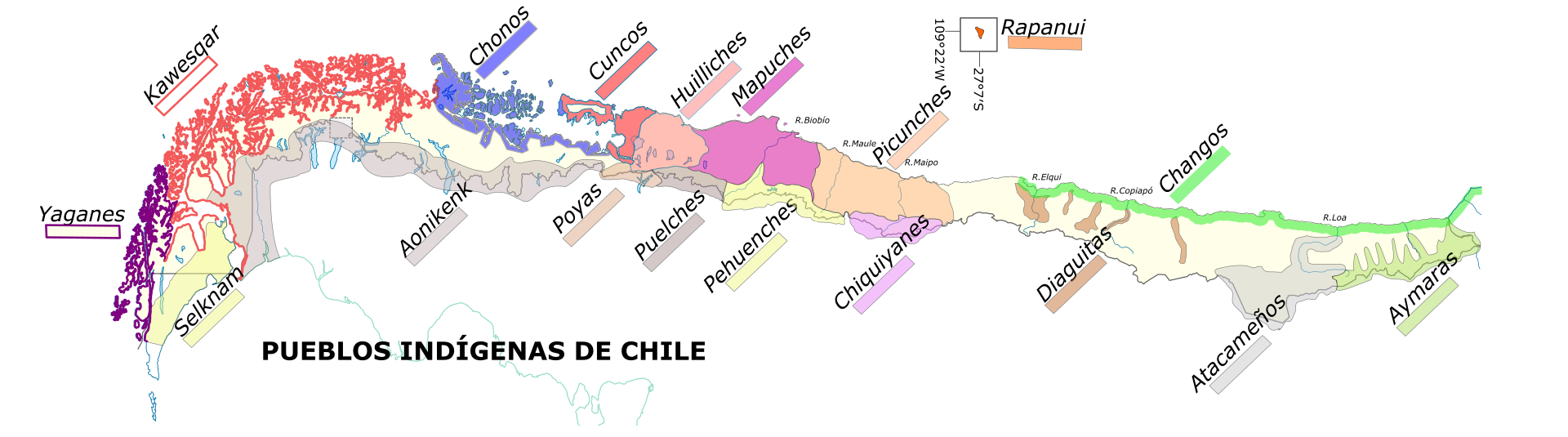

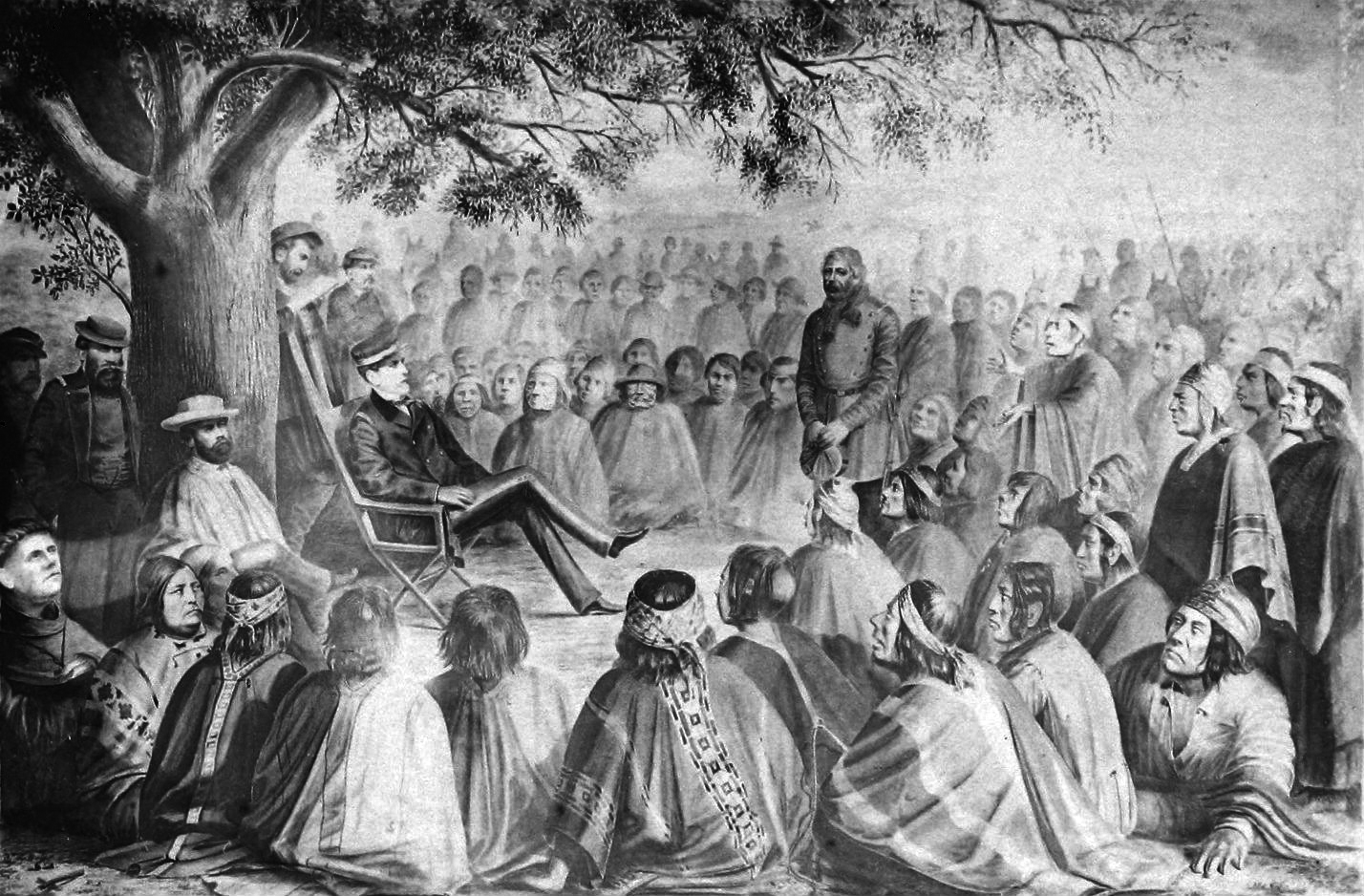

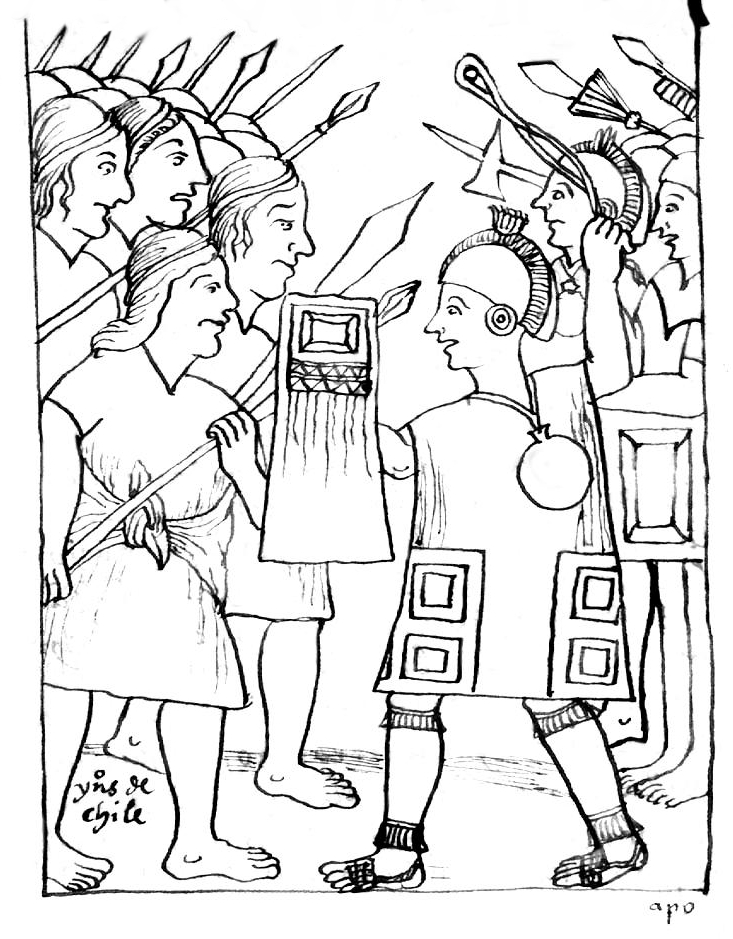

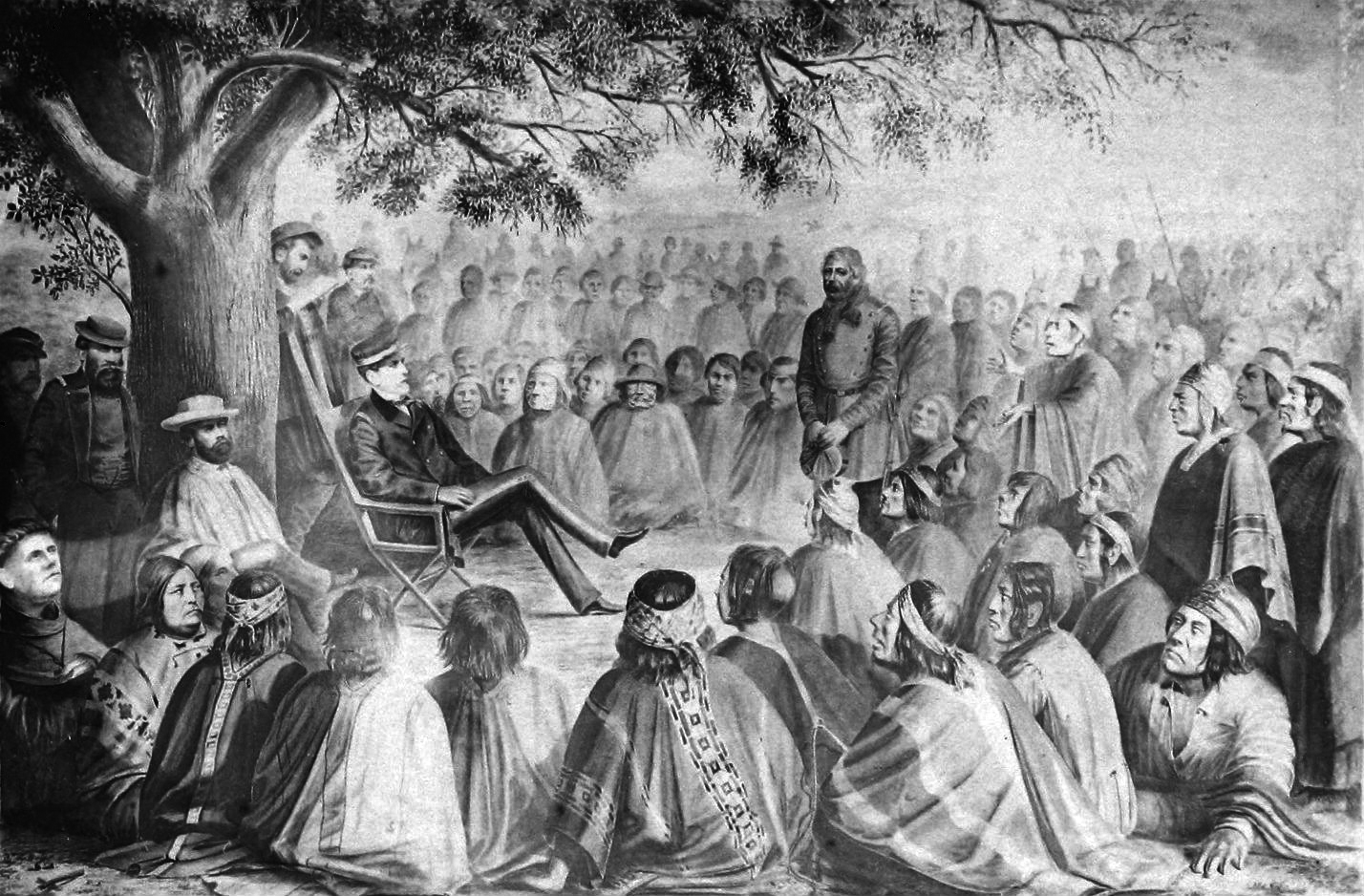

| History Main article: Mapuche history  Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala's picture of the confrontation between the Mapuches (left) and the Incas (right) Pre-Columbian period See also: Origin of the Mapuche and Incas in Central Chile Archaeological finds have shown that Mapuche culture existed in Chile and Argentina as early as 600 to 500 BC.[13] Genetically the Mapuche differ from the adjacent indigenous peoples of Patagonia.[14] This suggests a "different origin or long-lasting separation of Mapuche and Patagonian populations".[14] Troops of the Inca Empire are reported to have reached the Maule River and had a battle with the Mapuche between the Maule and the Itata Rivers there.[15] The southern border of the Inca Empire is believed by most modern scholars to have been situated between Santiago and the Maipo River, or somewhere between Santiago and the Maule River.[16] Thus the bulk of the Mapuche escaped Inca rule. Through their contact with Incan invaders Mapuches would have for the first time met people with state organizations. Their contact with the Incas gave them a collective awareness distinguishing between them and the invaders and uniting them into loose geo-political units despite their lack of state organization.[17] At the time of the arrival of the first Spaniards to Chile, the largest indigenous population concentration was in the area spanning from the Itata River to Chiloé Island – that is the Mapuche heartland.[18] The Mapuche population between Itata River and Reloncaví Sound has been estimated at 705,000–900,000 in the mid-sixteenth century by historian José Bengoa.[19][note 1]  Distribution of pre-Hispanic people of Chile Arauco War Main article: Arauco War The Spanish expansion into Mapuche territory was an offshoot of the conquest of Peru.[20] In 1536, Diego de Almagro set out to conquer Chile, after crossing the Itata River they were intercepted by a numerous contingent of Araucanian Mapuche armed with many bows and pikes in the Battle of Reynogüelén. Discouraged by the ferocity of the Mapuches, and the apparent lack of gold and silver in these lands, Almagro decided its full retreat the following year to Peru. In 1541, Pedro de Valdivia reached Chile from Cuzco and founded Santiago.[21] The northern Mapuche tribes, known as Picunches had recently gained independence from Inca rule, being commanded by Michimalonco, who had defeated the Inca governor Quilicanta. It would be the same Michimalonco who would lead the Picunche resistance against the Spanish between 1541 and 1545. His most famous stain is the Destruction of Santiago.[22]  Painting El joven Lautaro of Pedro Subercaseaux, shows the military genius and expertise of his people. In 1550, Pedro de Valdivia, who aimed to control all of Chile to the Straits of Magellan, campaigned in south-central Chile to conquer more Mapuche territory.[23] Between 1550 and 1553, the Spanish founded several cities[note 2] in Mapuche lands including Concepción, Valdivia, Imperial, Villarrica, and Angol.[23] The Spanish also established the forts of Arauco, Purén, and Tucapel.[23] Further efforts by the Spanish to gain more territory engaged them in the Arauco War against the Mapuche, a sporadic conflict that lasted nearly 350 years. Hostility towards the conquerors was compounded by the lack of a tradition of forced labor akin to the Inca mit'a among the Mapuche, who largely refused to serve the Spanish.[25] From their establishment in 1550 to 1598, the Mapuche frequently laid siege to Spanish settlements in Araucanía.[24] In 1553, the Mapuches held a council at which they resolved to make war. They chose as their "toqui" (wartime chief) an strong man called Caupolicán and as his vice toqui Lautaro, because he had served as an auxiliary to the Spanish cavalry; he created the first Mapuche cavalry corps. With six thousand warriors under his command, Lautaro attacked the fort at Tucapel. The Spanish garrison was unable to withstand the assault and retreated to Purén. Lautaro seized and burned the fort and prepared his army certain that the Spaniards would attempt to retake Tucapel. Valdivia mounted a counter-attack, but he was quickly surrounded. He and his army was massacred by the Mapuches in the Battle of Tucapel. [26] In 1554 Lautaro went to destroy Concepción where in the Battle of Marihueñu he defeated Governor Villagra and devastated the city. In 1555 Lautaro went to the city of Angol and destroyed it, he also returned to Concepción, rebuilt by the Spanish and destroyed it again. In 1557 Lautaro headed with his army to destroy Santiago, fighting numerous battles with the Spanish along the way, but he and his army were devastated in the Battle of Mataquito. From 1558 to 1598 war was mostly a low-intensity conflict.[27] Mapuche numbers decreased significantly following contact with the Spanish invaders; wars and epidemics decimated the population.[22] Others died in Spanish-owned gold mines.[25]  Caupolican by Nicanor Plaza In 1598 a party of warriors from Purén led by Pelantaro, who were returning south from a raid in the Chillán area, ambushed Governor Martín García Óñez de Loyola and his troops[28] while they rested without taking any precautions against attack. Almost all the Spaniards died, save a cleric named Bartolomé Pérez, who was taken prisoner, and a soldier named Bernardo de Pereda. The Mapuche then initiated a general uprising that destroyed all the cities in their homeland south of the Biobío River. In the years following the Battle of Curalaba, a general uprising developed among the Mapuches and Huilliches led to the Destruction of the Seven Cities. The Spanish cities of Angol, Imperial, Osorno, Santa Cruz de Oñez, Valdivia, and Villarrica were either destroyed or abandoned.[29] The city of Castro was taken by a Dutch-Mapuche alliance in 1599, but reconquered by the Spanish in 1600. Only Chillán and Concepción resisted Mapuche sieges and raids.[30] Except for the Chiloé Archipelago, all Chilean territory south of the Bíobío River was freed from Spanish rule.[29] In this period the Mapuche Nation crossed the Andes to conquer the present Argentine provinces of Chubut, Neuquen, La Pampa, and Río Negro.[citation needed] Incorporation into Chile and Argentina Further information: Occupation of Araucanía and Conquest of the Desert  Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez in meeting with the main lonkos of Araucania in 1869 In the nineteenth century, Argentina and Chile experienced a fast territorial expansion. Argentina established a colony at the Falkland Islands in 1820, settled Chubut with Welsh immigrants in 1865 and conquered Formosa, Misiones and Chaco from Paraguay in 1870. Later Argentina would also annex the Puna de Atacama in 1898. Chile on the other hand, established a colony at the Strait of Magellan in 1843, settled Valdivia, Osorno, and Llanquihue with German immigrants, and conquered land from Peru and Bolivia.[31][32] Later Chile would also annex Easter Island.[33] In this context, Wallmapu began to be conquered by Argentina and Chile due to two reasons. First, the Argentinean and Chilean states aimed for territorial continuity,[34] and second it remained the sole place for Argentinean livestock to expand and Chilean agriculture to expand.[35] Between 1861 and 1879 Argentina and Chile incorporated several Mapuche territories in Wallmapu. In January 1881, having Chile decisively defeated Peru in the battles of Chorrillos and Miraflores, Chile and Argentina resumed the conquest of Wallmapu.[36][37][38] Historian Ward Churchill has claimed that the Mapuche population dropped from a total of half a million to 25,000 within a generation as a result of the occupation and its associated famine and disease.[39] The conquest of Wallmapu caused numerous Mapuches to be displaced and forced to roam in search of shelter and food.[40] Scholar Pablo Miramán claims the introduction of state education during the Occupation of Wallmapu had detrimental effects on traditional Mapuche education.[41]  Ancient flag of the Mapuche on the Arauco War. In the years following the occupation the economy of Araucanía changed from being based on sheep and cattle herding to one based on agriculture and wood extraction.[42] About 70% of the Mapuche Territory (Wallmapu) left in the hands of Argentina, the loss of land by Mapuches following the occupation caused severe erosion since Mapuches continued to practice a massive livestock herding in limited areas.[43] |

沿革 主な記事 マプチェの歴史  フェリペ・グアマン・ポマ・デ・アヤラが描いたマプチェ族(左)とインカ族(右)の対立図 先コロンビア時代 こちらも参照のこと: チリ中央部におけるマプチェ族とインカ族の起源 考古学的発見から、マプーチェ文化が紀元前600年から500年頃にはチリとアルゼンチンに存在していたことが判明している[13]。遺伝学的にマプー チェは隣接するパタゴニアの先住民族とは異なる[14]。このことは「マプーチェとパタゴニアの集団の起源が異なるか、長く分離していた」ことを示唆して いる[14]。 インカ帝国の軍隊はマウレ川に到達し、そこのマウレ川とイタタ川の間でマプチェ族と戦闘を行ったと報告されている[15]。インカ帝国の南の境界線はサン ティアゴとマイポ川の間、またはサンティアゴとマウレ川の間のどこかに位置していたと、ほとんどの現代学者は信じている[16]。インカの侵略者との接触 を通じて、マプチェは初めて国家組織を持つ人々と出会ったのである。インカとの接触は、彼らに侵略者と区別する集団意識を与え、国家組織を持たないにもか かわらず、彼らを緩やかな地政学的単位に統合した[17]。 最初のスペイン人がチリに到着した当時、先住民の人口が最も集中していたのはイタタ川からチロエ島にかけての地域であり、マプーチェの中心地であった [18]。イタタ川とレロンカビ海峡の間のマプーチェの人口は、歴史家ホセ・ベンゴアによって16世紀半ばには705,000~90万人と推定されている [19][注釈 1]。  チリの先スペイン人の分布 アラウコ戦争 主な記事 アラウコ戦争 1536年、ディエゴ・デ・アルマグロはチリ征服に出発したが、イタタ川を渡った後、レイノグエレンの戦いで弓と矛で武装したアラウカ族マプチェの大軍に 迎撃された。マプチェ族の獰猛さと、この地に金銀がないことに落胆したアルマグロは、翌年ペルーへの撤退を決定した。1541年、ペドロ・デ・バルディビ アがクスコからチリに到達し、サンティアゴを建国した[21]。ピクンチェスとして知られる北部マプチェ族は、インカの総督キリカンタを倒したミチマロン コに指揮され、インカの支配から独立したばかりであった。1541年から1545年にかけて、スペインに対するピクンチェ族の抵抗を指揮したのもミチマロ ンコだった。彼の最も有名なステインは『サンティアゴの破壊』である[22]。  ペドロ・スベルカソーのEl joven Lautaroの絵は、彼の民族の軍事的才能と専門知識を示している。 1550年、マゼラン海峡までのチリ全土の支配を目指したペドロ・デ・バルディビアは、より多くのマプーチェの領土を征服するためにチリ中南部で作戦を 行った[23]。1550年から1553年にかけて、スペインはマプーチェの土地にコンセプシオン、バルディビア、インペリアル、ビジャリカ、アンゴルな どいくつかの都市[注 2]を建設した。 [23]スペイン人はまた、アラウコ、プレン、トゥカペルの砦を築いた。[23]スペイン人はさらに多くの領土を得るために、マプチェ族とのアラウコ戦争 に参戦した。征服者に対する敵意は、マプチェ族にはインカのミタのような強制労働の伝統がなかったために、スペイン人に仕えることをほとんど拒否していた ことによって、さらに悪化した[25]。 1550年の設立から1598年まで、マプチェは頻繁にアラウカニアのスペイン人入植地を包囲した[24]。彼らはカウポリカンと呼ばれる屈強な男を「ト キ」(戦時の長)に選び、スペイン騎兵隊の補助兵として働いていたラウタロを副トキに選んだ。ラウタロは6000人の戦士を率いてトゥカペルの砦を攻撃し た。スペインの守備隊はこの攻撃に耐えることができず、プレンに退却した。ラウタロは砦を奪って焼き払い、スペイン軍がトゥカペルを奪還することを確信し て軍備を整えた。バルディビアは反撃を開始したが、すぐに包囲された。バルディビアは反撃を開始したが、すぐに包囲され、バルディビアとその軍はトゥカペ ルの戦いでマプチェ族に虐殺された。[26] 1554年、ラウタロはコンセプシオンを破壊しに行き、マリフエニュの戦いでビジャグラ総督を破り、町を荒廃させた。1555年、ラウタロはアンゴル市を 破壊し、スペイン人によって再建されたコンセプシオンにも戻り、再び破壊した。1557年、ラウタロは軍隊を率いてサンティアゴを破壊するために向かい、 途中スペイン軍と何度も戦ったが、彼と彼の軍隊はマタキートの戦いで壊滅的な打撃を受けた。 1558年から1598年まで、戦争はほとんど低強度の紛争であった[27]。マプチェの数はスペイン人侵略者との接触により著しく減少し、戦争や伝染病 が人口を減少させた[22]。 また、スペイン所有の金鉱で死亡する者もいた[25]。  ニカノール・プラザ作カウポリカン 1598年、ペランタロ率いるプレン出身の戦士の一団が、チラン地区での襲撃から南へ戻る途中、マルティン・ガルシア・オニェス・デ・ロヨラ総督とその軍 隊を待ち伏せした[28]。捕虜となったバルトロメ・ペレスという聖職者とベルナルド・デ・ペレーダという兵士を除いて、スペイン人はほとんど全員死亡し た。その後、マプチェ族は反乱を起こし、ビオビオ川以南のすべての都市を破壊した。 クラーラバの戦いから数年後、マプチェとヒュイリチェの間で蜂起が起こり、7つの都市が破壊された。アンゴル、インペリアル、オソルノ、サンタ・クルス・ デ・オニェス、バルディビア、ビジャリカのスペインの都市は破壊されるか放棄された[29]。カストロの都市は1599年にオランダとマプチェの同盟に よって奪われたが、1600年にスペインによって再征服された。チロエ群島を除き、ビオビオ川以南のチリ領土はスペインの支配から解放された[29]。こ の時代、マプチェ国民はアンデス山脈を越え、現在のアルゼンチン、チュブト州、ネウケン州、ラ・パンパ州、リオ・ネグロ州を征服した[要出典]。 チリとアルゼンチンへの編入 さらに詳しい情報 アラウカニアの占領と砂漠の征服  1869年、アラウカニアの主要ロンコスと会談するコルネリオ・サーベドラ・ロドリゲス。 19世紀、アルゼンチンとチリは急速な領土拡大を経験した。アルゼンチンは1820年にフォークランド諸島に植民地を設立し、1865年にはウェールズか らの移民を受け入れてチュブトを開拓し、1870年にはパラグアイからフォルモサ、ミシオネス、チャコを征服した。その後、アルゼンチンは1898年にプ ナ・デ・アタカマを併合する。一方チリは、1843年にマゼラン海峡に植民地を設立し、バルディビア、オソルノ、ランキフエをドイツ系移民で開拓し、ペ ルーとボリビアから土地を征服した[31][32]。後にチリはイースター島も併合することになる[33]。このような状況の中で、ワルマプは2つの理由 からアルゼンチンとチリに征服され始めた。第一に、アルゼンチンとチリの国家は領土の連続性を目指しており[34]、第二に、アルゼンチンの家畜とチリの 農業が拡大するための唯一の場所であった[35]。 1861年から1879年にかけて、アルゼンチンとチリはいくつかのマプチェの領土をワルマプに編入した。1881年1月、チョリリョスとミラフローレス の戦いでチリがペルーに決定的な勝利を収めると、チリとアルゼンチンはワルマプの征服を再開した[36][37][38]。 歴史家のウォード・チャーチルは、占領とそれに伴う飢饉と病気の結果、マプーチェの人口は1世代で50万人から2万5千人に減少したと主張している [39]。 ワルマプの征服によって、多くのマプーチェが避難民となり、避難所と食料を求めて放浪することを余儀なくされた[40]。 学者のパブロ・ミラマンは、ワルマプ占領中に国家教育が導入されたことで、伝統的なマプーチェの教育に悪影響を及ぼしたと主張している[41]。  アラウコ戦争時のマプチェの古代旗。 占領後の数年間、アラウカニアの経済は羊と牛の牧畜を中心としたものから農業と木材採取を中心としたものへと変化した[42]。マプーチェ領土(ワルマ プ)の約70%がアルゼンチンの手に残されたが、マプーチェは限られた地域で大規模な家畜牧畜を続けていたため、占領後のマプーチェによる土地の喪失は深 刻な浸食を引き起こした[43]。 |

| Modern conflict Main article: Mapuche conflict See also: Ralco Hydroelectric Plant Land disputes and violent confrontations continue in some Mapuche areas, particularly in the northern sections of the Araucanía region between and around Traiguén and Lumaco. In 2003, the Commission for Historical Truth and New Treatments issued a report to defuse tensions calling for drastic changes in Chile's treatment of its indigenous people, more than 80% of whom are Mapuche. The recommendations included the formal recognition of political and "territorial" rights for indigenous peoples, as well as efforts to promote their cultural identities.[citation needed] Though Japanese and Swiss interests are active in the economy of Araucanía (Ngulu Mapu), the two chief forestry companies are Chilean-owned.[citation needed] In the past, the firms have planted hundreds of thousands of hectares with non-native species such as Monterey pine, Douglas firs, and eucalyptus trees, sometimes replacing native Valdivian forests, although such substitution and replacement is now[when?] forgotten.[citation needed] Chile exports wood to the United States, almost all of which comes from this southern region, with an annual value of around $600 million. Stand.earth, a conservation group, has led an international campaign for preservation, resulting in the Home Depot chain and other leading wood importers agreeing to revise their purchasing policies to "provide for the protection of native forests in Chile". Some Mapuche leaders want stronger protections for the forests.[citation needed] In recent years[when?], the crimes committed by Mapuche armed insurgents have been prosecuted under counter-terrorism legislation, originally introduced by the military dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet to control political dissidents. The law allows prosecutors to withhold evidence from the defense for up to six months and to conceal the identity of witnesses, who may give evidence in court behind screens. Insurgent groups, such as the Coordinadora Arauco Malleco, use multiple tactics with the more extreme occurrences such as the burning of homes, churches, vehicles, structures, and pastures, which at times included causing deaths and threats to specific targets. As of 2005, protesters from Mapuche communities have used these tactics against properties of both multinational forestry corporations and private individuals.[44][45] In 2010 the Mapuche launched many hunger strikes in attempts to effect change in the anti-terrorism legislation.[46] As of 2019, the Chilean government committed human rights abuses against the Mapuche based on Israeli military techniques and surveillance according to the French website Orin21.[47] Oil exploitation and fracking in the Vaca Muerta site in Neuquen, one of the biggest shale-oil and shale-gas deposits in the world, has produced waste dumps of sludge waste, polluting the environment close to the town of Añelo, which is about 1,200km south of Buenos Aires. In 2018, the Mapuche were suing Exxon, French company TotalEnergies and Pan American Energy.[48] |

現代の紛争 主な記事 マプチェ紛争 こちらも参照のこと: ラルコ水力発電所 マプチェの一部地域、特にアラウカニア地方北部のトライゲンとルマコ周辺では、土地紛争や暴力的な対立が続いている。2003年、歴史的真実と新たな処遇 のための委員会は、緊張を和らげるために、チリの先住民族(その80%以上がマプチェ族)に対する扱いを抜本的に変えるよう求める報告書を発表した。その 勧告には、先住民族の政治的権利と「領土」権の正式な承認、および彼らの文化的アイデンティティを促進するための努力が含まれていた[要出典]。 アラウカニア(Ngulu Mapu)の経済には日本やスイスの利権が絡んでいるが、2つの主要な林業会社はチリ資本である[要出典]。過去には、これらの会社はモントレーパイン、 ダグラスファー、ユーカリなどの外来種を何十万ヘクタールも植林し、時にはバルディブの原生林を置き換えてきた。 チリは米国に木材を輸出しているが、そのほとんどがこの南部地域産で、年間輸出額は約6億ドルにのぼる。自然保護団体Stand.earthは、保護を求 める国際的なキャンペーンを主導し、その結果、ホーム・デポ・チェーンをはじめとする大手木材輸入業者は、「チリの原生林の保護を提供する」ために購入方 針を改定することに同意した。マプチェの指導者の中には、森林の保護強化を望む者もいる[要出典]。 近年[いつ?]、マプチェの武装反乱軍が犯した犯罪は、もともとアウグスト・ピノチェトの軍事独裁政権が政治的反体制派を取り締まるために導入したテロ対 策法に基づいて起訴されている。この法律では、検察は弁護側に対して最大6ヶ月間証拠を隠し、証人の身元を隠すことができる。アラウコ・マレコ組織 (Coordinadora Arauco Malleco)のような反乱グループは、家屋、教会、車両、建造物、牧草地などを焼き払うなど、より過激な戦術を多用し、時には特定のターゲットに死者 や脅迫者を出すこともある。2005年現在、マプーチェのコミュニティからの抗議者たちは、多国籍林業企業や私人の財産に対してこれらの戦術を使用してい る[44][45]。 2019年現在、フランスのウェブサイトOrin21によれば、チリ政府はイスラエルの軍事技術や監視に基づき、マプーチェに対して人権侵害を行っている [47]。 世界最大級のシェールオイル・シェールガス鉱床であるネウケンのヴァカ・ムエルタ遺跡での石油採掘と水圧破砕は、汚泥廃棄物のゴミ捨て場を生み出し、ブエ ノスアイレスの南約1,200kmにあるアニェロの町の近くの環境を汚染している。2018年、マプチェ族はエクソン社、フランスのトタルエナジーズ社、 パン・アメリカン・エナジー社を訴えていた[48]。 |

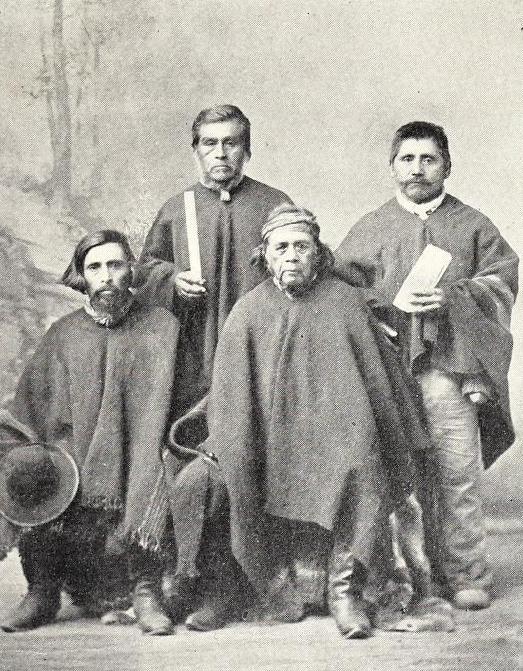

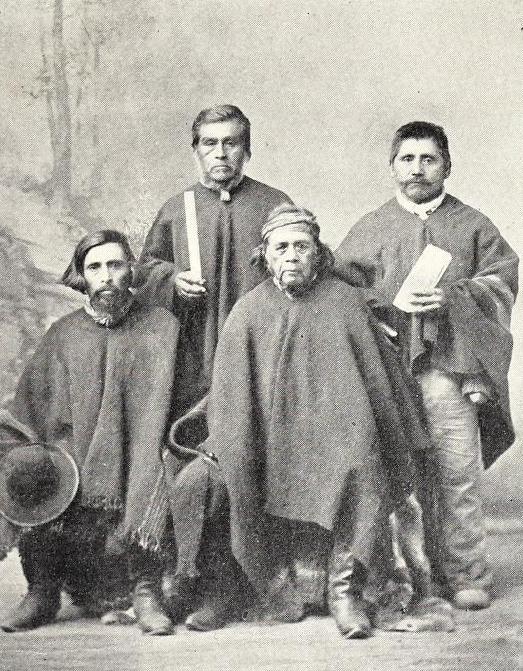

| Culture At the time of the arrival of Europeans, the Mapuche organized and constructed a network of forts and defensive buildings. Ancient Mapuche also built ceremonial constructions such as some earthwork mounds discovered near Purén.[49] Mapuche quickly adopted iron metal-working (Picunches already worked copper[50]) Mapuche learned horse riding and the use of cavalry in war from the Spaniards, along with the cultivation of wheat and sheep. In the 300-year co-existence between the Spanish colonies and the relatively well-delineated autonomous Mapuche regions, the Mapuche also developed a strong tradition of trading with Spaniards, Argentines, and Chileans. Such trade lies at the heart of the Mapuche silver-working tradition, for Mapuche wrought their jewelry from the large and widely dispersed quantity of Spanish, Argentine, and Chilean silver coins. Mapuche also made headdresses with coins, which were called trarilonko, etc. Mapuche languages Main article: Mapudungun  Familia Mapuche, by Claudio Gay, 1848. Mapuche languages are spoken in Chile and Argentina. The two living branches are Huilliche and Mapudungun. Although not genetically related, lexical influence has been discerned from Quechua. Linguists estimate that only about 200,000 full-fluency speakers remain in Chile. The language receives only token support in the educational system. In recent years, it has started to be taught in rural schools of Bío-Bío, Araucanía, and Los Lagos Regions. Mapuche speakers of Chilean Spanish who also speak Mapudungun tend to use more impersonal pronouns when speaking Spanish.[51] Cosmology and beliefs Main article: Mapuche religion  A council of Araucanian philosophers, 1904 Central to Mapuche cosmology is the idea of a creator called ngenechen, who is embodied in four components: an older man (fucha/futra/cha chau), an older woman (kude/kuse), a young man, and a young woman. They believe in worlds known as the Wenu Mapu and Minche Mapu. Also, Mapuche cosmology is informed by complex notions of spirits that coexist with humans and animals in the natural world, and daily circumstances can dictate spiritual practices.[52] The most well-known Mapuche ritual ceremony is the Ngillatun, which loosely translates as "to pray" or "general prayer". These ceremonies are often major communal events that are of extreme spiritual and social importance. Many other ceremonies are practiced, and not all are for public or communal participation but are sometimes limited to family. The main groups of deities and/or spirits in Mapuche mythology are the Pillan and Wangulen (ancestral spirits), the Ngen (spirits in nature), and the wekufe (evil spirits). Central to Mapuche belief is the role of the machi (shaman). It is usually filled by a woman, following an apprenticeship with an older machi, and has many of the characteristics typical of shamans. The machi performs ceremonies for curing diseases, warding off evil, influencing weather, harvests, social interactions, and dreamwork. Machis often have extensive knowledge of regional medicinal herbs. As biodiversity in the Chilean countryside has declined due to commercial agriculture and forestry, the dissemination of such knowledge has also declined, but the Mapuche people are reviving it in their communities. Machis have an extensive knowledge of sacred stones and sacred animals.  The daughter of lonko Quilapán Like many cultures, the Mapuche have a deluge myth (epeu) of a major flood in which the world is destroyed and recreated. The myth involves two opposing forces: Kai Kai (water, which brings death through floods) and Tren Tren (dry earth, which brings sunshine). In the deluge almost all humanity is drowned; the few not drowned survive through cannibalism. At last, only one couple is left. A machi tells them that they must give their only child to the waters, which they do, and this restores order to the world. Part of the Mapuche ritual is prayer and animal sacrifice, required to maintain the cosmic balance. This belief has continued to current times. In 1960, for example, a machi sacrificed a young boy, throwing him into the water after an earthquake and a tsunami.[53][54][55] The Mapuche have incorporated the remembered history of their long independence and resistance from 1540 (Spanish and then Chileans and Argentines) and of the treaty with the Chilean and Argentine governments in the 1870s. Memories, stories, and beliefs, often very local and particularized, are a significant part of the Mapuche traditional culture. To varying degrees, this history of resistance continues to this day amongst the Mapuche. At the same time, a large majority of Mapuche in Chile identify with the state as Chilean, similar to a large majority in Argentina identifying as Argentines.[citation needed] Ethnobotany Main article: Paleoethnobotany of the Mapuche  Height of a chemamull (Mapuche funeral statue) compared to a person. Ceremonies and traditions We Tripantu is the Mapuche New Year celebration. Textiles Main article: Mapuche textiles  Traditional Mapuche poncho exhibited in Museo Artesanía Chilena. One of the best-known arts of the Mapuche is their textiles. The oldest data on textiles in the southernmost areas of the American continent (southern Chile and Argentina today) are found in some archaeological excavations, such as those of Pitrén Cemetery near the city of Temuco, and the Alboyanco site in the Biobío Region, both of Chile; and the Rebolledo Arriba Cemetery in Neuquén Province (Argentina). researchers have found evidence of fabrics made with complex techniques and designs, dated between AD 1300–1350.[56] The Mapuche women were responsible for spinning and weaving. Knowledge of both weaving techniques and textile patterns particular to the locality was usually transmitted within the family, with mothers, grandmothers, and aunts teaching a girl the skills they had learned from their elders. Women who excelled in the textile arts were highly honored for their accomplishments and contributed economically and culturally to their kinship group. A measure of the importance of weaving is evident in the expectation that a man gives a larger dowry for a bride who was an accomplished weaver.[57] In addition, the Mapuche used their textiles as an important surplus and an exchange trading good. Numerous sixteenth-century accounts describe their bartering the textiles with other indigenous peoples, and with colonists in newly developed settlements. Such trading enabled the Mapuche to obtain those goods that they did not produce or held in high esteem, such as horses. Tissue volumes made by Aboriginal women and marketed in the Araucanía and the north of Patagonia Argentina were considerable and constituted a vital economic resource for indigenous families.[58] The production of fabrics in the time before European settlement was intended for uses beyond domestic consumption.[59] At present, the fabrics woven by the Mapuche continue to be used for domestic purposes, as well as for gift, sale, or barter. Most Mapuche women and their families now wear garments with foreign designs and tailored with materials of industrial origin, but they continue to weave ponchos, blankets, bands, and belts for regular use. Many of the fabrics are woven for trade, and in many cases, are an important source of income for families.[60] Glazed pots are used to dye the wool.[61][unreliable source?] Many Mapuche women continue to weave fabrics according to the customs of their ancestors and transmit their knowledge in the same way: within domestic life, from mother to daughter, and from grandmothers to granddaughters. This form of learning is based on gestural imitation, and only rarely, and when strictly necessary, the apprentice receives explicit instructions or help from their instructors. Knowledge is transmitted as the fabric is woven, the weaving and transmission of knowledge go together.[57] Clava hand-club  Monument in the form of a gigantic clava mere okewa, located in Avenida Presidente Eduardo Frei Montalva, Cañete, Chile There is a traditional stone hand club used by the Mapuche which has been called a clava (Spanish for club). It has a long flat body. Another name is clava mere okewa; in Spanish, it may also be called a clava cefalomorfa. It has some ritual importance as a special sign of distinction carried by tribal chiefs. Many kinds of clubs are known. This is an object associated with masculine power. It consists of a disk with an attached handle; the edge of the disc usually has a semicircular recess. In many cases, the face portrayed on the disc carries incised designs. The handle is cylindrical, generally with a larger diameter at its connection to the disk.[62][63] Silverwork Main article: Mapuche silverwork  Drawing of a trapelacucha, a silver finery piece. In the later half of the eighteenth century, Mapuche silversmiths began to produce large amounts of silver finery.[64] The surge of silversmithing activity may be related to the 1726 parliament of Negrete that decreased hostilities between Spaniards and Mapuches and allowed trade to increase between colonial Chile and the free Mapuches.[64] In this context of increasing trade Mapuches began in the late eighteenth century to accept payments in silver coins for their products, usually cattle or horses.[64] These coins and silver coins obtained in political negotiations served as raw material for Mapuche metalsmiths (Mapudungun: rüxafe).[64][65][66] Old Mapuche silver pendants often included unmelted silver coins, something that has helped modern researchers to date the objects.[65] The bulk of the Spanish silver coins originated from mining in Potosí in Upper Peru.[66] The great diversity in silver finery designs is because designs were made to be identified with different reynma (families), lof mapu (lands) as well as specific lonkos and machis.[67] Mapuche silver finery was also subject to changes in fashion albeit designs associated with philosophical and spiritual concepts have not undergone major changes.[67] In the late eighteenth century and early nineteenth century, Mapuche silversmithing activity and artistic diversity reached its climax.[68] All important Mapuche chiefs of the nineteenth century are supposed to have had at least one silversmith.[64] By 1984 Mapuche scholar Carlos Aldunate noted that there were no silversmiths alive among contemporary Mapuches.[64] Literature The Mapuche culture of the sixteenth century had an oral tradition and lacked a writing system. Since that time, a writing system for Mapudungun was developed, and Mapuche writings in both Spanish and Mapudungun have flourished.[69] Contemporary Mapuche literature can be said to be composed of an oral tradition and Spanish-Mapudungun bilingual writings.[69] Notable Mapuche poets include Sebastián Queupul, Pedro Alonzo, Elicura Chihuailaf, and Leonel Lienlaf.[69] Cogender views Among the Mapuche in La Araucanía, in addition to heterosexual female machi shamanesses, there are homosexual male machi weye shamans, who wear female clothing.[70][71][72] These machi weye were first described in Spanish in a chronicle of 1673.[73] Among the Mapuche, "the spirits are interested in machi's gendered discourses and performances, not in the sex under the machi's clothes".[74] In attracting the filew (possessing spirit), "Both male and female machi become spiritual brides who seduce and call their filew – at once husband and master – to possess their heads ... The ritual transvestism of male machi ... draws attention to the relational gender categories of spirit husband and machi wife as a couple (kurewen)."[75] As concerning "co-gendered identities"[76] of "machi as co-gender specialists",[77] it has been speculated that "female berdaches" may have formerly existed among the Mapuche.[78] |

文化 ヨーロッパ人が到着した頃、マプチェは砦や防衛のための建物のネットワークを組織し、建設した。古代マプチェは、プレン近郊で発見されたいくつかの土塁の ような儀式用の建造物も建設した[49]。マプチェは、鉄の金属加工をすぐに取り入れた(ピクンチェスはすでに銅を加工していた[50])。 スペインの植民地と比較的明確なマプチェの自治地域との300年にわたる共存の中で、マプチェはスペイン人、アルゼンチン人、チリ人との交易の強い伝統も 築いた。このような交易は、マプーチェの銀細工の伝統の中核をなすものであり、マプーチェは、スペイン、アルゼンチン、チリの銀貨を大量かつ広範囲に散布 して宝飾品を作った。マプチェはまた、トラリロンコなどと呼ばれるコインを使った頭飾りも作っていた。 マプチェの言語 主な言語 マプドゥングン語  クラウディオ・ゲイ作『マプチェの家族』1848年 マプチェ語はチリとアルゼンチンで話されている。現存する2つの分派はヒュイリチェ語とマプドゥングン語である。遺伝的な関連はないが、語彙的にはケチュ ア語の影響が見られる。言語学者の推定によると、チリには20万人ほどしか完全な流暢語を話す人が残っていないという。この言語は、教育制度では形だけの 支援しか受けていない。近年、ビオビオ州、アラウカニア州、ロスラゴス州の農村部の学校で教え始めている。 マプトゥングン語も話すマプチェ人は、スペイン語を話すときに非人称代名詞を使う傾向がある[51]。 宇宙観と信仰 主な記事 マプチェの宗教  1904年、アラウカの哲学者会議 マプチェの宇宙観の中心はヌゲネチェンと呼ばれる創造主の考え方であり、ヌゲネチェンは年上の男性(フチャ/フトラ/チャ・チャウ)、年上の女性(クデ/ クセ)、若い男性、若い女性の4つの要素で具現化される。彼らはウェヌ・マプとミンチェ・マプとして知られる世界を信じている。また、マプーチェの宇宙観 は、自然界で人間や動物と共存する精霊の複雑な概念によってもたらされており、日々の状況が精神的な修行を左右することもある[52]。 最もよく知られているマプチェの儀式はンギラトゥンであり、ンギラトゥンは 「祈る 」または 「一般的な祈り 」と大まかに訳されている。これらの儀式は、精神的・社会的に極めて重要な共同体の主要行事であることが多い。その他にも多くの儀式が行われており、すべ てが公の場や共同体の参加するものではなく、家族に限定されることもある。 マプチェ神話に登場する神々や精霊の主なグループは、ピランとワングレン(祖先の精霊)、ンゲン(自然界の精霊)、ウェクフェ(悪霊)である。 マプチェの信仰の中心はマチ(シャーマン)の役割である。通常、年上のマチに弟子入りした女性がその役割を担い、シャーマンの典型的な特徴を多く備えてい る。マチは病気を治す儀式、魔除けの儀式、天候や収穫に影響を与える儀式、社会的交流、ドリームワークなどを行う。マチは多くの場合、地域の薬草について 幅広い知識を持っている。チリの田舎の生物多様性が商業的農業や林業によって減少するにつれ、そのような知識の普及もまた減少してきたが、マプチェの人々 は自分たちのコミュニティでそれを復活させている。マチ族は聖なる石や聖なる動物について幅広い知識を持っている。  ロンコ・キラパンの娘 多くの文化と同じように、マプチェにも大洪水の神話がある。この神話には2つの対立する力が関わっている: カイカイ(洪水によって死をもたらす水)とトレン・トレン(太陽の光をもたらす乾いた大地)である。大洪水ではほとんどすべての人類が溺死し、溺死しな かった少数の人々は共食いによって生き延びる。そしてついに、一組の夫婦だけが残された。マチが彼らに、たった一人の子供を水に捧げなければならないと告 げ、彼らはそれを実行し、世界の秩序が回復する。 マプチェの儀式の一部には、宇宙のバランスを保つために必要な祈りと動物の生贄がある。この信仰は現代まで続いている。例えば1960年には、地震と津波 の後にマチが少年を生け贄として水に投げ入れた[53][54][55]。 マプチェは、1540年からの長い独立と抵抗(スペイン人、その後チリ人、アルゼンチン人)、そして1870年代のチリ政府、アルゼンチン政府との条約に ついて記憶された歴史を取り入れている。記憶、物語、信仰は、しばしば非常にローカルで特殊なものであるが、マプチェの伝統文化の重要な一部である。程度 の差こそあれ、この抵抗の歴史はマプチェの間で今日まで続いている。同時に、チリのマプチェの大多数はチリ人として国家を認識しており、アルゼンチンの大 多数がアルゼンチン人として認識しているのと似ている[要出典]。 民族植物学 主な記事 マプチェの古植物学  ケマムル(マプチェの葬儀像)の高さを人と比較したもの。 儀式と伝統 We Tripantuはマプチェの新年のお祝いである。 織物 主な記事 マプチェの織物  Museo Artesanía Chilenaに展示されているマプチェの伝統的なポンチョ。 マプチェの最もよく知られた芸術のひとつが織物である。アメリカ大陸最南端(現在のチリ南部とアルゼンチン)の織物に関する最古の資料は、チリのテムコ市 近郊のピトレン墓地やビオビオ地方のアルボヤンコ遺跡、アルゼンチンのネウケン州のレボレド・アリバ墓地などの考古学的発掘調査で見つかっている。 マプチェの女性たちは紡績と織りを担当していた。その土地特有の織物技法と織物模様の知識は、通常家族内で伝達され、母親、祖母、叔母が年長者から学んだ 技術を少女に教えていた。織物芸術に秀でた女性は、その功績を高く評価され、親族集団に経済的・文化的に貢献した。織物の重要性を示す指標は、織物の上手 な花嫁には男性がより多くの持参金を与えるという期待に表れている[57]。 さらに、マプチェは織物を重要な余剰品や交換交易品として利用していた。16世紀の数多くの記録には、彼らが他の先住民や新しく開発された入植地の植民者 と織物を物々交換していたことが記されている。このような取引によって、マプチェ族は馬のような、自分たちが生産していない、あるいは高く評価されていな い商品を手に入れることができたのである。アボリジニの女性たちによって作られ、アラウカニアとパタゴニア・アルゼンチン北部で販売されたティッシュの量 は相当なもので、先住民の家族にとって不可欠な経済資源であった[58]。 現在、マプチェが織った織物は、贈答用、販売用、物々交換用だけでなく、家庭用としても使用され続けている。現在、マプチェの女性とその家族のほとんど は、外国のデザインで、工業製品由来の素材で仕立てられた衣服を身に着けているが、ポンチョ、毛布、バンド、ベルトなどは普段使いに織り続けられている。 多くの織物は交易用に織られ、多くの場合、家族の重要な収入源となっている[60]。多くのマプーチェ女性は、祖先の習慣に従って織物を織り続け、同じ方 法で知識を伝えている。このような学習形態は身振り手振りの模倣に基づくもので、弟子が指導者から明確な指示や助けを受けるのはごく稀で、厳密に必要な場 合に限られる。知識は、織物が織られるように伝達され、織物と知識の伝達は一体である[57]。 クラヴァ・ハンドクラブ  チリ、カニェテのプレジデンテ・エドゥアルド・フレイ・モンタルバ通りにある、巨大なクラヴァの形をしたモニュメント。 マプチェ族が使う伝統的な石の手棍棒があり、クラバ(スペイン語で棍棒の意)と呼ばれている。平たい長い胴体をしている。スペイン語ではクラバ・セファロ モルファと呼ばれることもある。スペイン語ではクラバ・セファロモルファと呼ばれることもある。部族の長が持つ特別な区別の印として、儀式的に重要な意味 を持っている。多くの種類の棍棒が知られている。 これは男性的な力に関連するものである。円盤の縁に半円形の凹みがあるのが普通である。円盤の縁には半円形の凹みがあるのが普通で、多くの場合、円盤に描 かれた顔には切り込みがある。柄は円筒形で、一般に円盤との接続部の直径が大きい[62][63]。 銀細工 主な記事 マプチェの銀細工  トラペラクーチャ(銀製の装飾品)の図面。 18世紀後半、マプチェの銀細工職人は大量の銀細工を生産し始めた[64]。銀細工の急増は、スペイン人とマプチェの間の敵対関係を減少させ、植民地チリ と自由マプチェの間の貿易の増加を可能にした1726年のネグレテ議会[64]に関連している可能性がある。 [64]これらの銀貨や政治的交渉で得た銀貨は、マプチェの金属細工職人(Mapudungun: rüxafe)の原材料となった[64][65][66]。古いマプチェの銀製ペンダントには、しばしば未溶解の銀貨が含まれていた。 マプーチェの銀製のデザインは、哲学的・精神的概念に関連するデザインは大きな変化を遂げなかったものの、ファッションの変化にも左右された[67]。 18世紀後半から19世紀初頭にかけて、マプチェの銀細工の活動と芸術の多様性は最高潮に達した[68]。 19世紀のすべての重要なマプチェの首長には、少なくとも一人の銀細工師がいたと考えられている[64]。 1984年までに、マプチェの学者であるカルロス・アルドゥナーテは、現代のマプチェには生きている銀細工師はいないと指摘した[64]。 文学 16世紀のマプチェ文化は口承によるもので、文字を持たなかった。16世紀のマプチェ文化は口承の伝統があり、文字がなかったが、マプドゥングン語の文字 が開発され、スペイン語とマプドゥングン語の両方で書かれたマプチェ語文学が盛んになった。 コジェンダー観 ラ・アラウカニアのマプチェの間では、異性愛者の女性マチ・シャーマネスに加えて、同性愛者の男性マチ・ウェアイ・シャーマネスが存在し、彼らは女性の服 を着ている[70][71][72]。 [73] マプチェの間では、「精霊はマチの衣服の下の性ではなく、マチのジェンダー化された言説やパフォーマンスに興味を持つ」[74] 。男性マチの儀式的な女装は......精霊の夫とマチの妻というカップル(クレウェン)としての関係的なジェンダーのカテゴリーに注意を喚起する」 [75][76]。「同性の専門家としてのマチ 」という「同性間のアイデンティティ」[77]に関しては、かつてマプチェの間に「女性のベルダハ」が存在していたのではないかと推測されている [78]。 |

| Mapuche, Chileans and the

Chilean state Following the independence of Chile in the 1810s, the Mapuche began to be perceived as Chilean by other Chileans, contrasting with previous perceptions of them as a separate people or nation.[79] However, not everybody agreed; 19th-century Argentine writer and president Domingo Faustino Sarmiento presented his view of the Mapuche-Chile relation by stating:[80] Between two Chilean provinces (Concepción and Valdivia) there is a piece of land that is not a province, its language is different, it is inhabited by other people and it can still be said that it is not part of Chile. Yes, Chile is the name of the country over where its flag waves and its laws are obeyed. Civilizing mission discourses and scientific racism  Painting by Raymond Monvoisin showing Elisa Bravo who was said to have survived the 1849 wreck of Joven Daniel to be then kidnapped by Mapuches. The events surrounding the wreck of Joven Daniel at the coast of Araucanía in 1849 are considered an "inflection point" or "point of no return" in the relations between Mapuches and the Chilean state.[81] It cemented views of Mapuches as brutal barbarians and showed in the view of many that Chilean authorities' earlier goodwill was naive.[81][82] There are various recorded instances in the nineteenth century when Mapuches were the subject of civilizing mission discourses by elements of the Chilean government and military. For example, Cornelio Saavedra Rodríguez called in 1861 for Mapuches to submit to Chilean state authority and "enter into reduction and civilization".[83] When the Mapuches were finally defeated in 1883 President Domingo Santa María declared:[84] The country has with satisfaction seen the problem of the reduction of the whole Araucanía solved. This event, so important to our social and political life, and so significant for the future of the republic, has ended, happily and with costly and painful sacrifices. Today the whole Araucanía is subjugated, more than to the material forces, to the moral and civilizing force of the republic ... The Chilean race, as everybody knows, is a mestizo race made of Spanish conquistadors and the Araucanian ... — Nicolás Palacios in La raza chilena, p. 34. After the War of the Pacific (1879–1883) there was a rise of racial and national superiority ideas among the Chilean ruling class.[85] It was in this context that Chilean physician Nicolás Palacios hailed the Mapuche "race" arguing from a scientific racist and nationalist point of view. He considered the Mapuche superior to other tribes and the Chilean mestizo a blend of Mapuches and Visigothic elements from Spain.[86] The writings of Palacios became later influential among Chilean Nazis.[87] As a result of the Occupation of Araucanía (1861–1883) and the War of the Pacific, Chile had incorporated territories with new indigenous populations. Mapuches obtained relatively favourable views as "primordial" Chileans contrasting with other indigenous peoples like the Aymara who were perceived as "foreign elements".[88] Contemporary attitudes Since some four years ago a History of the Civilization in Araucanía has been published in the said Anales in which our indigenous ancestors are treated like savages, cruel, depraved, lacking morals, lacking warrior skills ... — Nicolás Palacios, La raza chilena, p. 62. Contemporary attitudes towards Mapuches on the part of non-indigenous people in Chile are highly individual and heterogeneous. Nevertheless, a considerable part of the non-indigenous people in Chile have a prejudiced and discriminatory attitude towards Mapuche. In a 2003 study, it was found that among the sample, 41% of people over 60 years old, 35% of people of low socioeconomic standing, 35% of the supporters of right-wing parties, 36% of Protestants, and 26% of Catholics were prejudiced against indigenous peoples in Chile. In contrast, only 8% of those who attended university, 16% of supporters of left-wing parties, and 19% of people aged 18–29 were prejudiced.[89] Specific prejudices about the Mapuche are that the Mapuches are lazy and alcoholic; to some lesser degree, Mapuche are sometimes judged antiquated and dirty.[90] In the 20th century, many Mapuche women migrated to large cities to work as domestic workers (Spanish: nanas mapuches). In Santiago, many of these women settled in Cerro Navia and La Pintana.[91] Sociologist Éric Fassin has called the occurrence of Mapuche domestic workers a continuation of colonial relations of servitude.[92]  Wenufoye flag created in 1992 by the indigenist organization "Consejo de Todas las Tierras". Historian Gonzalo Vial claimed that the Republic of Chile owes a "historical debt" to the Mapuche. The Coordinadora Arauco-Malleco claims to have the goal of a "national liberation" of Mapuche, with their regaining sovereignty over their lands.[79] Reportedly there is a tendency among female Mapuche activists to reject feminism as they consider their struggle to go beyond gender.[91] |

マプチェ、チリ人、チリ国家 1810年代にチリが独立した後、マプチェは他のチリ人からチリ人として認識されるようになり、それまで別の民族や国民として認識されていたのとは対照的 であった[79]。しかし、すべての人が同意していたわけではなく、19世紀のアルゼンチンの作家であり大統領であったドミンゴ・ファウスティーノ・サル ミエントは、マプチェとチリの関係について次のような見解を示している[80]。  チリの2つの州(コンセプシオンとバルディビア)の間には、州ではない土地があり、言語も異なり、他の人々が住んでいる。そう、チリは国旗が掲げられ、法 律が守られている国の名前なのだ。 文明化ミッションの言説と科学的人種差別 レイモン・モンヴォワザンが描いた、1849年の難破船ジョベン・ダニエル号から生還し、マプチェ族に誘拐されたとされるエリサ・ブラボの絵。 1849年にアラウカニア海岸で起きた難破船ホヴェン・ダニエルをめぐる出来事は、マプーチェとチリ国家との関係における「変曲点」あるいは「戻れない地 点」と考えられている[81]。マプーチェは残忍な野蛮人であるという見方が定着し、チリ当局のそれまでの好意が甘かったことが多くの人々に示された [81][82]。 19世紀には、マプチェがチリ政府や軍の一部による文明化ミッションの言説の対象となった様々な事例が記録されている。例えば、コルネリオ・サーベドラ・ ロドリゲスは1861年にマプチェ族がチリの国家権力に服従し、「削減と文明に入る」よう呼びかけた[83]。 1883年にマプチェ族が最終的に敗北したとき、ドミンゴ・サンタ・マリア大統領は次のように宣言した[84]。 国は、アラウカニア全土の縮小という問題が解決されたのを満足げに見た。われわれの社会的、政治的生活にとって、また共和国の将来にとって非常に重要なこ の出来事は、高価で苦しい犠牲の上に、幸福な形で終結した。今日、アラウカニア全土は、物質的な力以上に、共和国の道徳的・文明的な力に服従してい る......。 チリ人は、誰もが知っているように、スペインのコンキスタドールとアラウカニア人の混血である。 - ニコラス・パラシオスのLa raza chilena, p. 34. 太平洋戦争(1879年-1883年)後、チリの支配階級の間で人種的・国民的優越思想が台頭した[85]。このような状況の中で、チリの医師ニコラス・ パラシオスは科学的人種差別主義的・民族主義的観点からマプーチェ「民族」を称賛した。彼はマプーチェ族を他の部族よりも優れていると考え、チリのメス ティーソはマプーチェ族とスペインからの西ゴート族の要素が混ざったものだと考えた[86]。パラシオスの著作は後にチリのナチスの間で影響力を持つよう になった[87]。 アラウカニア占領(1861年-1883年)と太平洋戦争の結果、チリは新たな先住民族を含む領土を編入した。マプチェは「原初の」チリ人として比較的好 意的な見方を得ており、「外来の要素」として認識されていたアイマラ族などの他の先住民族とは対照的であった[88]。 現代の態度 4年ほど前から、アラウカニアにおける文明の歴史が『Anales』誌に掲載されるようになった。 - ニコラス・パラシオス, La raza chilena, p. 62. チリの非先住民の側におけるマプーチェに対する現代の態度は、非常に個人的で異質なものである。とはいえ、チリの非先住民のかなりの部分は、マプーチェに 対して偏見と差別的な態度を持っている。2003年の調査では、サンプルのうち60歳以上の41%、社会経済的地位の低い35%、右派政党支持者の 35%、プロテスタントの36%、カトリックの26%がチリの先住民に対して偏見を持っていることがわかった。一方、大学に通っている人の8%、左翼政党 支持者の16%、18~29歳の19%のみが偏見を抱いていた[89]。マプーチェに対する具体的な偏見としては、マプーチェは怠け者でアルコール依存症 であるというものがあり、程度は低いが、マプーチェは時代遅れで汚いと判断されることもある[90]。 20世紀には、多くのマプチェ女性が家事労働者(スペイン語でnanas mapuches)として働くために大都市に移住した。社会学者のエリック・ファッサンは、マプチェの家事労働者の発生を植民地時代の隷属関係の継続と呼 んでいる[92]。  ウェヌフォエの旗は1992年に先住民組織「コンセホ・デ・トダス・ラス・ティエラス」によって作られた。 歴史家ゴンサロ・ヴィアルは、チリ共和国はマプチェに対して「歴史的負債」を負っていると主張した。Coordinadora Arauco-Mallecoは、マプーチェの「国民解放」を目標に掲げ、彼らの土地に対する主権を取り戻すことを主張している[79]。伝えられるとこ ろによると、女性マプーチェ活動家の間では、自分たちの闘いは性別を超えたものであると考え、フェミニズムを拒否する傾向がある[91]。 |

Mapuches and the Argentine state Flag of Argentinian Tehuelche-Mapuche 19th-century Argentine authorities aiming to incorporate the Pampas and Patagonia into national territory recognized the Puelmapu Mapuche's strong connections with Chile. This gave Chile a certain influence over the Pampas. Argentine authorities feared that in an eventual war with Chile over Patagonia, Mapuches would align themselves with Chile.[93] In this context, Estanislao Zeballos published the work La Conquista de quince mil leguas (The Fifteen Thousand League Conquest) in 1878, which had been commissioned by the Argentine Ministry of War. In La Conquista de quince mil leguas Mapuches were presented as Chileans who were bound to return to Chile.[94] Mapuches were thus indirectly considered foreign enemies.[94] Such a notion fitted well with the expansionist designs of Nicolás Avellaneda and Julio Argentino Roca for Puelmapu.[94] The notion of Mapuches as Chileans is however an anachronism as Mapuches precede the formation of the modern state of Chile.[94] By 1920 Argentine Nacionalismo revived the idea of Mapuches being Chileans, in strong contrast with 20th-century scholars based in Chile such as Ricardo E. Latcham and Francisco Antonio Encina who advanced a theory that Mapuches originated east of the Andes before penetrating what came to be Chile.[13][94] As late as 2017 Argentine historian Roberto E. Porcel wrote in a communiqué to the National Academy of History that those who often claim to be Mapuches in Argentina would be rather Mestizos, emboldened by European-descent supporters, who "lack any right for their claims and violence, not only for NOT being most of them Araucanians [sic], but also because they [the Araucanians] do not rank among our indigenous peoples".[95] |

マプチェ族とアルゼンチン国家 Flag of Argentinian Tehuelche-Mapuche国旗 19世紀のアルゼンチン当局は、パンパとパタゴニアを国民領土に編入することを目指し、プエルマプチェとチリとの強い結びつきを認めた。これによりチリは パンパに一定の影響力を持つようになった。アルゼンチン当局は、パタゴニアをめぐる最終的なチリとの戦争において、マプーチェがチリに味方することを恐れ た[93]。このような状況の中で、エスタニスラオ・ゼバロスは、1878年にアルゼンチン陸軍省の依頼で『La Conquista de quince mil leguas(1万5千リーグ征服)』を出版した。La Conquista de quince mil leguas』では、マプーチェはチリに戻るべきチリ人として描かれていた[94]。そのため、マプーチェは間接的に外敵と見なされていた[94]。この ような概念は、ニコラス・アベラネダとフリオ・アルヘンティーノ・ロカによるプエルマプの拡張主義的な計画とよく合致していた[94]。しかし、マプー チェをチリ人と見なすのは時代錯誤であり、マプーチェは近代チリ国家の形成に先行していた。 [1920年までにアルゼンチンのナシオナリズムはマプーチェがチリ人であるという考えを復活させ、リカルド・E・ラッチャムやフランシスコ・アントニ オ・エンシナのようなチリを拠点とする20世紀の学者が、マプーチェはアンデス山脈の東に起源を持ち、その後チリに侵入したという説を唱えたのとは対照的 であった[13][94]。 2017年の時点で、アルゼンチンの歴史家ロベルト・E・ポルセルは国民歴史アカデミーのコミュニケの中で、アルゼンチンでしばしばマプーチェ族であると 主張する人々は、むしろヨーロッパ系の支持者によって強化されたメスチソ族であり、彼らは「彼らの主張と暴力には何の権利もなく、彼らのほとんどがアラウ カ人(中略)でないだけでなく、彼ら(アラウカ人)は私たちの先住民族の中にランクされていないからである」と書いている[95]。 |

| Modern politics In the 2017 Chilean general election, the first two Mapuche women were elected to the Chilean Congress; Aracely Leuquén Uribe from National Renewal and Emilia Nuyado from the Socialist Party.[96] |

現代の政治 2017年のチリ総選挙では、国民刷新党からアラセリー・ロイケン・ウリベ、社会党からエミリア・ヌヤドの2人のマプーチェ女性が初めてチリ下院議員に選 出された[96]。 |

| In popular culture In 2012, renowned Mapuche weaver Anita Paillamil collaborated with Chilean artist Guillermo Bert to create "Encoded Textiles," an exhibit that combined traditional mapuche textile weaving with QR Code designs.[97] The 2020 Chilean-Brazilian animated film Nahuel and the Magic Book features major characters, Fresia and Huenchur who represent her clothing attire and her tribe. The 4X video game Civilization VI features the Mapuche as a playable civilization (added in the Rise and Fall expansion). Their leader is Lautaro, a young Mapuche toqui known for leading the indigenous resistance against Spanish conquest in Chile and developing the tactics that would continue to be employed by the Mapuche during the long-running ArauIsab. The novel "Inés of My Soul" by Isabel Allende features the conquest of Chile by Pedro Valdivia, and a large part of the book deals with the Mapuche Conflict. The plot of the 2021 Chilean thriller film "Immersion" is a power struggle between a vacationing family and three Mapuche men. The 2023 film "Sayen" depicts Mapuche villagers resisting an international mining company seeking to exploit cobalt. In 2024 expansion pack Trial of Allegiance for grand-strategy video game Hearts of Iron IV the player may play as Chile and with respective focus trees, either restore the kingdom of Araucania and Patagonia, with recognized Mapuche minority or have Mapuche coup and liberate the Native Americans from both North and South American continents. |

ポピュラーカルチャー 2012年、有名なマプチェの織物職人であるアニタ・パイヤミルは、チリのアーティストであるギジェルモ・ベルトと共同で、伝統的なマプチェの織物とQR コードのデザインを組み合わせた展示「Encoded Textiles」を制作した[97]。 2020年のチリとブラジルのアニメ映画『Nahuel and the Magic Book』には、彼女の服装と部族を象徴する主要キャラクター、フレシアとフエンチュールが登場する。 4Xゲーム『シヴィライゼーション VI』では、マプチェ族がプレイアブル文明として登場する(拡張版『ライズ・アンド・フォール』で追加)。彼らのリーダーはラウタロで、チリでスペインの 征服に対する先住民の抵抗を指揮し、長期にわたるアラウイサブ戦争でマプチェ族が採用し続ける戦術を開発したことで知られる若いマプチェ・トキである。 イサベル・アジェンデの小説『わが魂のイネス』には、ペドロ・バルディビアによるチリ征服が登場し、その大部分でマプチェ紛争が扱われている。 2021年のチリのスリラー映画 「Immersion 」のプロットは、休暇を過ごす家族と3人のマプチェの男たちの権力闘争である。 2023年の映画 「Sayen 」は、コバルトを採掘しようとする国際鉱山会社に抵抗するマプチェの村人たちを描いている。 グランドストラテジーゲーム『Hearts of Iron IV(ハーツ・オブ・アイアンIV)』の2024年拡張パック『Trial of Allegiance(忠誠の試練)』では、プレイヤーはチリとしてプレイし、それぞれのフォーカスツリーで、少数民族マプチェを公認したアラウカニア王 国とパタゴニア王国を回復させるか、マプチェにクーデターを起こさせ、南北両大陸のネイティブ・アメリカンを解放することができる。 |

| Guaraní people Flag of the Mapuches Guñelve Wekufe Pillan |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mapuche |

Distribution of pre-Hispanic people of Chile

|

☆ マプチェ族(マプチェぞく、Mapuche、マプーチェ族とも表記される)は、チリ中南 部からアルゼンチン南部に住むアメリカ先住民。民族名は、彼らが話 すマプチェ語で「大地」(Mapu)に生きる「人々」(Che)を意味する[2]。マプチェ族は、南アメリカ南部を支配し、インカ帝国やスペインの侵略に 対し長く抵抗を続けた民族として知られており、コンキスタドールが南アメリカ大陸に足を踏み入れてから500年余り、各国で先住民の同化が進む中、マプ チェ族は支配にあらがい、同化を拒み続け、「抵抗する民」として名をはせてきた[1]。 彼らは生計を牧畜と農業に依存し[1]、ロンコ(Lonko)と呼ばれる首長のもとで血縁関係を単位とした社会を構成していた。戦争のときには「トキ」 (toqui「斧を持つ者」の意)というリーダーを選出し、その下に連合してより大きな集団を形成することもあった。 ★16

世紀以降南アメリカに進出したスペイン人の報告では、彼らはアラウカノ族 (Araucanos) またはアラウコ(アラウカーノ)語族

(Araukanians)

と呼ばれていたが、現在では軽蔑的な言葉としてこれは忌避され、チリやアルゼンチンではもっぱら「マプチェ族」の表現が用いられており、彼ら自身もこれを

歓迎している。araucanoの語源は、一般に信じられているケチュア語で「反逆者」を意味するaraucoではなく、マプチェ語で「泥の水」の意であ

る地名Araucoから来ていると言われる[3][4]。

マプチェ族は共通の社会構成、宗教、経済構造、言語的遺産を引き継いだ数多いグループからなる広い地域に住む民族である。その影響はアコンカグア川とアル

ゼンチンのラ・パンパ州に挟まれた地区全域に及んだ。チリ中部の山峡地域に住み、スペイン人からはインカ帝国の一部とみなされたピクンチェ族(スペイン語

版)や、ウイジチェ族(スペイン語版)、クンコ族も同じ一派と考えられている[5]。マプチェ族は、ウイジチェ族・ラフケンチェ族およびペウンチェ族と同

様にイタタ川とトルテン川の間にある谷に住んでいた。これは、「マプチェ族」をラ・アラウカニア州に居留した部族に限定した狭義でも、ピクンチェ・ウイジ

チェなど諸族を含みアラウカーノ語族とした広義でも当てはまる。フェルディナンド・マゼランによってパタゴン族と呼ばれた北部のAonikenk族(英語

版)は、マプチェ族と交流を持ち言語や文化への影響を受けたラ・パンパ地域のテウェルチェ族に属する少数部族とされている。このようなマプチェ族の言語や

文化が南アメリカ西部の諸族へ影響を及ぼす過程はスペインの進出後も継続し、この一連の伝播をアラウカナイゼーションと呼ぶ。

チリの統計によると、チリのマプチェ族はほとんどが土着の家系ではなくなっている一方で、60%を越える一般のチリ人は、彼ら自身は認めない傾向にある

が、様々な比率ながらアメリカ先住民族との混血である。2002年のチリの国勢調査では、マプチェ族の人口は604,349人である。[要出典]チリの人

口に占めるマプチェ族の割合は約9%であり、アルゼンチンに至っては先住民全体でも約3%にすぎない[1]。アルゼンチン側では約300,000人がアン

デス山脈に居住している。マプチェ族の多くは先祖伝来の土地を失い、サンティアゴ・デ・チレなどの大都市で、恵まれない環境の中で生活している(チリの人

口統計を参照)。 ス ペイン人に立ち向かったマプーチェ人の英雄ラウタロ(部分) ス

ペイン人に立ち向かったマプーチェ人の英雄ラウタロ(全体像)

■ 歴史への登場とアラウコ戦争 マ

プチェ族の名が歴史に記されるのは、新大陸発見以降のスペイン進出に始まる。それ以前のマプチェ族は、大規模な連合こそ形成されなかったが、長年のインカ

帝国の侵略に耐え、これを跳ね除けて来た(マウレの戦い(英語版))。コンキスタドール(征服者)のディエゴ・デ・アルマグロとのレイノウェレンの戦い

(スペイン語版、英語版))、さらにラウタロやカウポリカン(スペイン語版、英語版)やコロコロといった優秀な指導者の登場により、16世紀に現れた新た

な侵略者・スペインに対しても300年以上闘い続けた。侵略初期に奪われた土地を取り戻し、19世紀後半まで自治を維持した例もある。ビオビオ川はマプ

チェ抵抗の地として知られ、彼らは自然の地形を利用してスペインへの反抗を続けた。この間、しばしば交易や外交的な交渉が取り交わされるなど、マプチェと

スペインの関係は必ずしも膠着的な戦闘状態にあったわけではない。それでも、アラウコ戦争(en)と呼ばれる長期にわたる対立はアロンソ・デ・エルシー

ジャ(en)の叙事詩『ラ・アラウカーナ(en)』に残され、その記憶は消えることは無い。

チリがスペイン王国から分離独立した際、一部に協力的な者もいたが、ほとんどのマプチェ族は無関心か、もしくはその出来事そのものを知らなかった。この認

識不足は、入植者たちがもたらすマプチェに与える脅威についてあまり深刻に考えておらず、過去からこの土地で受け継いできた暮らしが変わる可能性を想像だ

にしていなかったことを証明している。事実、チリ独立後もマプチェ族はビオビオ川北岸に住む用心深い植民者たちと、時に衝突を起こすこともあったが、おお

むね問題なく共存し交易を行っていた。だが、チリ政府は膨張する経済を支える資本を獲得するためにも、アラウカニアを支配下に置く準備を進めていた。 ■ アラウカニア制圧作戦 ア ラウカニア・パタゴニア王国 詳細は「en:Malón」、「荒野の征服作戦(英語版)」、「アラウカニア制圧作戦」、および「砂漠の征服作戦(英語版)」を参照 |

フ ランス人弁護士兼冒険家のオルリ・アントワーヌ・ド・トゥナンが「アラウカニアの王」と称し、マプチェ族の土地を中心に独立国家アラウカニア・パタゴニア 王国(1860年 - 1862年)の建国を宣言したが、他国からの承認を得られるはずもなく、かえってチリ側に非合法国家の打倒という口実を与えてしまった。アラウカニア・パ タゴニア王国はリーダー不在で瓦解し[1]、チリ政府はマプチェ族の土地を圧迫し、1880年代半ばから後半にかけてこれを占拠した。これは「アラウカニ ア制圧作戦」と呼ばれる。この征服の背景には、元々チリにとってマプチェの土地は自国のものだという1800年代後半の思想が根底にあり、さらにチリ人の 人口増加がもたらす経済活動がマプチェとの境界線を圧迫し始めた点がある。さらに、当時ボリビア・ペルー連合に対する南米の太平洋戦争の渦中にあったチリ は、戦勝のために大規模な常設陸軍の整備やライフル銃を始めとした近代兵器の自国内製造を実現していた。太平洋戦争終結とともにこれらの兵力はマプチェと の戦闘に投入された。さらに通信網の整備などもあり、マプチェ族は地理的に南北双方から、さらなる軍事力によって押さえつけられた。 激しい戦闘と外交交渉とを織り交ぜながら、チリ政府はマプチェ族の首長たちから彼らの土地をチリに併呑する同意を取り付け、条約を締結した。これには、マ プチェ側にとって拒みがたい事情があった。長引く戦争の影響から飢餓と病気が蔓延し、ある報告によればかつては50万の人口を誇ったマプチェ族は 25,000人まで著しい減少を見せていた[6]。この数字の推移には意図的な誇張が紛れ込んでいるとの主張もある。しかしながら、占領下に置かれたマプ チェ族のかなりの比率が抑留され、農業や交易で成り立っていた彼らの経済活動はほとんどの地域で破壊され、彼らが所有していた大量の銀や宝石類を含む動産 や不動産などの財産がチリ政府の国庫に納められるために没収され、さらに、アメリカ合衆国の「強制移住法」と同じような「reducciones」と呼ば れる一連の制度で縛られるに至り、人口減少数の信憑性云々に関係なくその末路は同じようなものだったと言えた。彼らは、追いやられ略奪され、極度の貧困に 晒される結果となった。 ■ 現代 マプチェ族の旗 現 在、マプチェ族の子孫はチリとアルゼンチンに跨る地域に多く居住し、ラ・アラウカニア州の住民のうち80%を占め、ロス・ラゴス州、ビオビオ州およびマウ レ州でも人口比率が高い。伝統を継承し農業を中心とした生活を続けている者もいるが、大多数がより良い収入を求めて都市部へ移り棲みつつある。しかしなが ら、彼らはさまざまな差別の対象にあり、経済面や公的な面で不遇な状態にある[7]。 マプチェ族が特に多いラ・アラウカニア州では、国軍の駐留に抵抗したため、ピノチェト政権時代には多くの先住民が非業の死を遂げ、1990年の民主化で政 府との対話が始まったが頓挫し、土地や水の権利を求めるデモや占拠が各地で続いている[1]。近年では彼らの先住する土地を開発する林業系大企業[8]に も向けられ、地権争いなどに端を発した暴力の応報が続き、特にラ・アラウカニア州北部のTraiguén区やルマコ区に挟まれた歴史的に激しい紛争が続い た地区で頻発している。そのため、彼ら反抗組織のリーダーやマプチェ族の政治活動には、近年になってもピノチェト政権時の対テロリズム法が取り締まりや起 訴に適用されている。その法律では検察は6ヶ月間証拠の提出を拒むことができ、また裁判において喚問した証人をスクリーンの向こうから証言させて匿名のま まにすることが可能になる。ピノチェト政権時の対テロリズム法をマプチェ族に適用して厳罰化したが、服役囚はハンガー・ストライキを起こし、国連に仲介を 求めてサンティアゴの国連施設に立てこもったグループもいる[1]。 チリ人が「Araucanía」、マプチェ族が「Ngulu Mapu」と呼ぶチリ人の林業会社が所有するふたつの地域の森林資源に対して日本とスイスが利権確保に動いた際、マプチェ族はこれらラジアータパイン(モ ントレーマツ)やユーカリなどの森林は本来彼らが植樹し大量の水と肥料を与えて育てたもので、資源の権利は彼らに帰すと主張した。また、チリから年間約6 億ドルにのぼる木材を輸入するアメリカでは、そのほとんどが南部地域で伐採されていることから、熱帯保護キャンペーン団体Forest Ethicsが先導し、ホームデポなど主要な輸入業者から「チリの原生林を保護する」木材の購買方針へ変更する同意を取り付けるなどの動きもある。しか し、マプチェ族首長の中にはこれでも不充分との声があり、一部の団体はUNPOに参加して国際的な関心や所有地の権利や文化の保護を訴える活動を行ってい る。これらを受け、チリ政府もマプチェ族を受益者とし資源開発と彼らの生活水準向上を両立させることを目的とした「先住民コミュニティ管理プロジェクト」 を2003年から実施している[9]。 近年、チリ政府はマプチェ族の待遇を改善するいくつかの施策を試しつつある。例えば、テムコ市では小学校にマプチェ語や文化の授業を加える試みが行なわれ ている。また、政府の特務機関である委員会(the Commission for Historical Truth and New Treatment)は2003年にレポートを提出し、80%以上がマプチェ族によって占められる先住民族について彼らへの政策を大胆に改善すべきとの見 解を纏めた。その中では、文化的アイデンティティの促進以外にも、政治そして「領土」に関する権利についても公的にこれを認めるべきとの内容を含んでい る。 ★

文化 伝 統的なマプチェ族のポンチョ 技 術・工芸 ヨーロッパ人が南アメリカに進出した頃には、マプチェ族は塹壕と複雑な防御砦のネットワークを建築するに充分な技術を備えていた。また、金属加工や乗馬技 術を素早く自分たちのものとし、小麦栽培や羊の飼育も取り入れた。スペインからの植民地と、相対的に良く自治管理されたマプチェの居住地は300年にわ たって共存し、両者の間には強い交易関係が生まれた。マプチェ族が伝統的に持っていた銀細工の技術は広く流通したチリやスペインの硬貨の質を支え、また宝 石類やヘッドバンドなどもその精巧さが高く評価されていた。近年では、彼らの文化を伝える機織や手工芸品が観光みやげなどになり、現金収入の一手段とも なっている[10]。 言語 マプチェ族の言語は、アラウコ語族の代表的言語であるマプチェ語(マプチェ・ドゥングン=「マプチェ人の舌」の意味)を用いている。これは、北アメリカ先 住民族言語にも見られる複雑な動詞語幹を特徴とする。一方で文字を持たず、神話などはもっぱら口頭で伝承されて来た[11]。大別すると二つの系統があ り、ウイジチェ語系とマプチェ語系に分けられる。言語学的には直接関連していないが、いくつかの語彙にケチュア語からの影響が識別されている。 マプチェ語は現在、チリとアルゼンチンの一部地域で用いられているが、流暢に喋ることができる人口はチリ国内に約200,000人にとどまる。教育現場で のマプチェ語学習はビオビオ州、ラ・アラウカニア州、ロス・ラゴス州で実施されている。 マプチェ族のうち、マプチェ語を話せる者は20%しかいない[1]。 神話と信仰 マプチェ族の信仰はマチ(en)と呼ばれる祈祷師が執り行う儀式を中心とした自然崇拝に分類される。彼らの信仰では、伝承『Trentren Vilu y Caicai Vilu』が重要な位置を占める。さらにNgenやPillanなどをはじめとする自然崇拝に基づいた霊的存在が信奉されている。マチはシャーマニズム的 な特徴を持ち、通常は女性が担いつつ、年長の者が後進を指導する。マチは多様な薬草などや科学的な知識を広く持ち、病気治療(マチトゥン)や悪霊払い、ま たは雨乞い(ギジャトゥン)や豊作についての儀式や社会的な交流などを執り行う。 また、1540年代から続いたスペインやチリに対する独立や抵抗と、1870年代にチリによって征服された歴史もマプチェ族の信仰において重要な位置を占 めている。これらの記憶や物語・信念などは時に局地的なものだったりかなり特殊なものに変化している場合もある。しかし、チリに生きる多くのマプチェ族が 自分をチリ人だと、アルゼンチンに生きる彼らが自分をアルゼンチン人だと受け取っている現在においても、その反抗の歴史は消えること無く未だに息づき、チ リの文化に多大な影響を与えている。 音楽 マプチェ族では、音楽は儀式の一環として演奏される。木製の笛ピフィルカ(Pifilca)、角のホルン・トゥルトゥルカ(Trutruka)、片面太鼓 クルトゥルン(Kultrun)、口琴トロンペ(Trompe)など固有の楽器を用い、列になって演奏しながら祭壇を廻る。この他にも、語り調の歌も伝 わっている[12][13][14]。 現代にマプチェ音楽を伝えるミュージシャンとしては、アルゼンチンのベアトリス・ピチ・マレンなどが活躍している[15]。

|

****

★「1970年代のプロテスタント 福音主義者との対立の後は、カソリックも福音主義傾向をつよめる。ヨハネ・パウロ2世は、1987年チリ のテムコで、マプーチェ先住民を前に、彼らの文化的アイデンティティを擁護するのは、教会の権利というよりも義務だと断言(p.145)」——インディヘニスモ入門(アンリ・ファーヴル『イン ディヘニスモ:ラテンアメリカ先住民擁護運動の歴史』染田秀藤訳、文庫クセジュ、白水社、2002 年★Mapuche religion

The

Kultrul

| Mapuche religion

is

the traditional Native American religion of the Mapuche people. It is

practiced primarily in south-central Chile and southwest Argentina. The

tradition has no formal leadership or organizational structure and

displays much internal variation. Mapuche theology incorporates a range of deities and spirits. One of the most prominent deities is Ngünechen, sometimes equated with the Christian God. Communal prayer ceremonies are termed ngillatun and involve the provision of offerings and animal sacrifice. Ritual specialists, called machi, are responsible for contacting the spirits and overseeing healing rituals. These myths tell of the creation of the world and the various deities and spirits that reside in it. In 1883 the Chilean military defeated the Mapuche and began to restrict them to reservations. Chilean efforts were then made to convert the Mapuche to Catholicism. From the 1990s, Mapuche religion underwent a revitalisation, with greater visibility and efforts to use it to encourage tourism. |

マプチェ族の宗教は、マプチェ族の伝統的なネイティブアメリカン宗教で

ある。主にチリの中南部とアルゼンチンの南西部で信仰されている。この伝統には、正式な指導者や組織構造はなく、内部には多くのバリエーションがある。 マプチェの神学には、さまざまな神々や精霊が取り入れられている。最も著名な神のひとつに、キリスト教の神と同一視されることもあるNgünechenが ある。共同体の祈りの儀式はngillatunと呼ばれ、供物の提供や動物の生け贄を伴う。儀式の専門家であるマチと呼ばれる人々は、精霊との交信や癒し の儀式の監督を担当する。これらの神話は、世界の創造と、そこに存在するさまざまな神々や精霊について語っている。 1883年、チリ軍がマプチェ族を打ち負かし、彼らを居留地に制限し始めた。その後、チリはマプチェ族をカトリックに改宗させる努力をした。1990年代 から、マプチェ族の宗教は活性化し、より注目を集めるようになり、観光促進に役立てようとする動きも出てきた。 |

| Definitions and terminology Mapuche religion is not institutional.[1] In Latin America, traditional religions are rarely pure, unadulterated continuations from the traditions that existed prior to European contact.[2] In order to describe the beliefs of the Mapuche people, it is important to note that there are no written records about their ancient legends and myths from before the Spanish arrival, since their religious beliefs were passed down orally. Their beliefs are not necessarily homogenous; among different ethnic groups, and the families, villages, and territorial groups within those ethnic groups, there are variations and differences and discrepancies in these beliefs. Likewise, it is important to understand that many of the Mapuche beliefs have been integrated into the myths and legends of Chilean folklore, and to a lesser extent, folklore in some areas of Argentina. Many of these beliefs have been altered and influenced by Christianity, due largely to the evangelization done by Spanish missionaries.[3][4][5] This happened chiefly through the syncretism of these beliefs and also through misinterpretation or adaptation within both Chilean and Argentine societies. This syncretism has brought about several variations and differences of these core beliefs as they have become assimilated within Chilean, Argentine and even Mapuche culture. Today, these cultural values, beliefs and practices are still taught in some places with an aim to preserve different aspects of this indigenous Mapuche culture.[6] |

定義と用語 マプチェ族の宗教は制度化されていない。[1] ラテンアメリカでは、伝統宗教がヨーロッパ人との接触以前から存在した伝統の純粋な、混じりけのない継続であることはまれである。[2] マプチェ族の信仰を説明するには、スペイン人が到来する以前の古代の伝説や神話に関する書面による記録が存在しないことに留意することが重要である。彼ら の信仰は必ずしも均質ではなく、異なる民族グループ間、およびそれらの民族グループ内の家族、村、地域グループの間で、これらの信仰には相違や矛盾が見ら れる。同様に、マプチェ族の信仰の多くはチリの民話の神話や伝説に組み込まれており、また、アルゼンチンの一部の地域の民話にも少なからず組み込まれてい ることを理解することが重要である。これらの信仰の多くは、スペイン人宣教師による布教活動が主な原因となって、キリスト教の影響を受け、変化してきた。 [3][4][5] これは主に、これらの信仰の習合や、チリおよびアルゼンチン社会における誤った解釈や適応によって生じた。このシンクレティズム(混交)により、これらの コアな信念にはいくつかのバリエーションや相違が生じ、チリ、アルゼンチン、さらにはマプチェ族の文化に同化されていった。今日、これらの文化的価値観、 信念、慣習は、マプチェ族の土着文化のさまざまな側面を保存することを目的として、一部の地域では今もなお教えられている。[6] |

| Beliefs Theology Mapuche traditional religion features a pantheon of gods and goddesses.[7] The Meli Küyen are the four moon spirits; the Meli Wangülen are the four spirits of the stars.[8] The wenu püllüam are ancestral spirits in the sky.[8] Ngünechen is also known as Chaw Dios (Old Man God) and Ñuke Dios (Old Woman God).[9] Ngünechen first appeared in Mapuche religion during the 19th century; it has been argued that the introduction of this deity was a response to the Chilean national hierarchies.[8] The root of this divinity's name, genche, first appeared in 1601 to describe a Spanish landowner.[8] Many Mapuche equate Ngünechen with the Christian God, although other Mapuche traditionalists stress they are different.[10] The ngen are nature spirits.[8] They populate the earth and are in turn prayed to by other spirits.[9] These ngen are the owners of particular environments and can capture, possess, and punish those who enter their realms without permission.[11] The foki spirits are intermediaries between the forest and humanity, connecting the two through the rainbow.[12] Like humans, the foki engage in prayer.[12] Both the deities and other spirits are thought to have both good and bad sides.[9] The gods and spirits can grant wealth, good harvests, and fertility if propitiated with offerings.[13] If people fail to provide offerings, or if they transgress norms called admapu, Machuche traditionalists believe that the deities and spirits can punish people with illness, scarcity, or infertility.[14] Various wekufe spirits kill humans. The sumpall is a blond mermaid who seduces men into the river, where it kills them and steals their soul.[15] The witranalwe takes the form of a thin Spaniard on a horse; his wife is the small, luminescent añchümalleñ, who sucks people's blood.[15] The Punkure and Punfüta are spouses who seduce their victims in their dreams to drain their life energy.[16] Sun and moon worship among the Mapuche have parallels among the Central Andean peoples and the Inca religion.[17] Indeed, in among Mapuches as well as Central Andean peoples the moon (Mama Killa, Cuyen in Mapudungun) and the sun (Inti, Antu in Mapudungun) are spouses.[17] Mapuche, Quechua and Aymara words for the sun and the moon appear to be a borrowing from Puquina language.[18] Thus the parallels in cosmology may be traced back to the days of the Tiwanaku Empire in which Puquina is thought to have been an important language.[18] |

信仰 神学 マプチェ族の伝統宗教では、神々と女神の神々が崇められている。[7] メリ・クイエンは4つの月の精霊であり、メリ・ワンギュレンは4つの星の精霊である。[8] ウェヌ・プルヤムは空の祖先の精霊である。[8] Ngünechenは、Chaw Dios(老神)およびÑuke Dios(老女神)としても知られている。[9] Ngünechenは19世紀にマプチェ族の宗教に初めて登場した。この神の導入はチリの国民階層への対応であったという主張もある。。この神の名の語源 であるゲンチェは、1601年にスペインの地主を指して初めて登場した。[8] 多くのマプチェ族は、グネチェンをキリスト教の神と同一視しているが、他のマプチェ族の伝統主義者は、両者は異なるものであると強調している。[10] ンゲンは自然の精霊である。[8] 彼らは地球に存在し、他の精霊たちから祈りを捧げられている。[9] これらのンゲンは特定の環境の所有者であり、許可なくその領域に侵入した者を捕らえ、憑依し、罰することができる。[11] フォキの精霊は、森と人間社会の仲介者であり、虹を通じて両者を結びつける。[12] 人間と同様に、フォキは祈りを捧げる。[12] 神々やその他の精霊には、善と悪の両方の側面があると考えられている。[9] 神々や精霊は、供物を捧げて鎮めれば、富や豊作、豊饒を与えることができる。[13] 人々が供物を捧げなかったり、アドマプと呼ばれる規範に違反した場合、マチュチェの伝統主義者は、神々や精霊が病や飢饉、不妊によって人々を罰すると信じ ている。[14] さまざまなウェクフェの精霊が人間を殺す。スンパールはブロンドのマーメイドで、男たちを川に誘い込み、そこで彼らを殺して魂を奪う。[15] ウィトラナルウェは馬に乗った痩せたスペイン人の姿をしている。彼の妻は小さく発光するアンチュマルエンで、人の血を吸う。[15] プンクレとプンフータは、夢の中で犠牲者を誘惑し、生命エネルギーを奪う。[16] マプチェ族の太陽と月の崇拝は、中央アンデス民族やインカの宗教と類似している。実際、マプチェ族や中央アンデス民族の間では、月(ママ・キラ、マプドゥ ングン語ではクエン)と太陽(インティ、マプドゥングン語ではアントゥ)は配偶者である 。マプチェ族、ケチュア族、アイマラ族の言葉で太陽と月を表す言葉は、プキナ語からの借用語であるようだ。[18] したがって、宇宙論における類似性は、プキナ語が重要な言語であったと考えられているティワナク帝国の時代まで遡ることができるかもしれない。[18] |

| Cosmology In Mapuche traditional belief, the cosmos consists of three vertical planes, each of which comprises a different force that remains in conflict with the other two.[9] The upper realm is termed the wenu mapu and is associated with goodness, purity, and the forces of creation. Located in the sky and containing the sun and the moon, it is the home of the gods and the ancestral spirits.[9] It is associated with the colors white, yellow, and blue.[9] The earth is called mapu and it is here that the struggle between good and evil takes place.[9] Mapu is associated with the colors green and blood red.[9] The underworld beneath mapu is termed munche mapu, a realm associated with evil, death, destruction, and pollution.[9] It is also associated with volcanic eruptions, whirlwinds, and cemeteries, as well as the colors bright red and opaque black.[9] It is in munche mapu that the wekufe spirits live.[9] The word Wallmapu originally meaned "Universe"[19] as well as "set of surrounding lands". |

宇宙論 マプチェ族の伝統的な信仰では、宇宙は3つの垂直の平面から成り、それぞれが異なる力を持ち、他の2つと対立し続けているとされる。[9] 上の領域はウェヌ・マプと呼ばれ、善良さ、純粋さ、創造の力と関連付けられている。天に位置し、太陽と月を包含するこの領域は、神々と先祖の霊の住処であ る。[9] 白色、黄色、青色の色と関連付けられている。[9] 大地は「mapu」と呼ばれ、善と悪の闘争が繰り広げられる場所である。[9] 「mapu」は緑色と血のような赤色と関連付けられている。[9] 「mapu」の下にある冥界は「munche mapu」と呼ばれ、悪、死、 破壊、汚染と関連付けられている。[9] また、火山噴火、つむじ風、墓地、鮮やかな赤色と不透明な黒色とも関連付けられている。[9] ウェクフェの精霊はムンチェ・マプに住んでいる。[9] ウォルマプという言葉は、もともと「宇宙」[19] および「周辺の土地の集合」を意味していた。 |

| Soul and the ancestors Mapuche traditional religion teaches that humans, other animals, and natural phenomena all have a trata, or body, as well as a distinct spiritual essence.[11] The living soul is called a püllü, while humans also have a soul that survives bodily death, the am.[9] According to the traditional belief, Mapuche people fear that their spirit can be captured and manipulated by a wekufe spirit or a witch;[11] spirits of the dead can for instance be captured and polluted by witches unless they are appropriately dispatched to the afterlife.[20] The spirits of the dead can reside in an eternal shadow realm.[21] The continuing relationship of mutual dependence between the living and their ancestors is an important facet of Mapuche traditional religion.[22] Propitiating these ancestors is thus a key ritual among Mapuche traditionalists.[22] If ancestral spirits do not feel they are being acknowledged they may return to the land of the living to remind their descendants of their obligations.[20] There are differing views among scholars if ancestors play a significant role in the Mapuche religion.[23] Libations of wine or chicha are regularly poured for the ancestors.[7] |

魂と先祖 マプチェ族の伝統宗教では、人間、その他の動物、自然現象にはすべてトラタ(体)があり、それぞれに固有の精神的な本質があるとしている。[11] 生きた魂はプリュと呼ばれ、人間には肉体的な死を越えて存続する魂、アムもある。[9] 伝統的な信仰によると、マプチェ族の人々は、自分たちの魂がウェクフェの魂や魔女に捕らえられ、操られることを恐れている。[11] 死者の魂は、適切に死後の世界に送られない限り、例えば魔女に捕らえられ、汚染される可能性がある。[20] 死者の霊魂は永遠の影の世界に存在しうる。[21] 生者と祖先との相互依存の関係が継続することは、マプチェ族の伝統宗教の重要な側面である。[22] したがって、これらの祖先を鎮めることは、マプチェ族の伝統主義者にとって重要な儀式である。[22] 祖先の霊が認められていないと感じた場合、彼らは生者の世界に戻り、子孫に彼らの義務を思い出させることがある。[20] マプチェ族の宗教において先祖が重要な役割を果たしているかどうかについては、学者の間でも見解が分かれている。[23] 先祖のために、ワインやチチャ(chicha)を定期的に供える。[7] |

| Morality and ethics In traditional Mapuche culture, the transgression of social norms or the failure to fulfil commitments to kin, ancestors, and gods, can result in individual and social illness as well as social chaos. [24] Rural Mapuche women often place great emphasis on modesty.[25] |

道徳と倫理 伝統的なマプチェ文化では、社会規範の侵害や、親族、先祖、神々に対する約束の不履行は、個人や社会の病、さらには社会の混乱を招く可能性がある。 [24] マプチェの農村部の女性は、謙虚さを非常に重視することが多い。 [25] |

| Practices Prayers are called ngillatunes.[12] The prayers of the machi are usually in their native Mapudungu language, although rituals and other situations will often see them use both Mapudungu and Spanish.[26] There are often taboos on photographing traditional rituals.[27] |

宗教実践 祈りはンギラトゥネス(ngillatunes)と呼ばれる。[12] マプチェ族の祈りは通常、彼らの母国語であるマプチェ語であるが、儀式やその他の状況ではマプチェ語とスペイン語の両方が使われることが多い。[26] 伝統的な儀式の写真撮影にはタブーが伴うことが多い。[27] |

Machi Three machis photographed in 1900 A key ritual specialist in Mapuche traditional religion is the machi; various anthropologists describe the machi as shamans.[28] The machi are believed to obtain their powers from various natural and ancestral spirits, as well as from Ngünechen.[9] They also draw on the power of special locations, such as waterfalls, lakes, volcanoes, and the rock.[8] They embody and travel with a spirit called a machi püllü as well as having an ancestral spirit of all the machi, the filew.[9] Mapuche traditionalists believe that the machi are capable of using their powers for either good or evil,[29] thus existing on a spectrum of good to bad.[13] Mapuche traditionalists believe that the spirits call certain individuals to become machi, sending them dreams (pewma) and visions (perimontum).[30] The spirits may inflict an illness on the person, the machikutran, which can include boils, fever, foaming at the mouth, insomnia, partial blindness, and partial paralysis.[31] The machikutran is only alleviated by their initiation as a machi through the machiluwün ritual.[32] As the spirits are insistent, it is thought difficult for a person to resist them, although some people do.[30] Through visions and dreams, the spirits reveal the use of herbs to the prospective machi and then give them their ritual tools for healing, such as the drum and their spirit animals.[33] Machis may experience their initiation through various ways. They may inherit their machi spirit from a deceased machi from their material family; experience direct initiation in the midst of a powerful natural event like an earthquake or lightning; or they may experience a vision called the perimontum in which a spirit appears before them.[34] Those who have gained initiation through the latter two methods are considered more powerful although also more morally ambiguous.[35] During possession, the spirit mounts the machi's head, a process called the longkoluupan.[36] Machi may have sexual relationships or remain celibate;[25] in Chilean culture they are stereotyped as homosexuals.[37]However, it is important to understand that machis use gender constructs that may not align with Chilean culture. Machis have a complex construction of gender within their beliefs and as a result their religious practice is shaped by gendered relationships that are usually not defined by the sex of the machi.[38] As a machi the goal is to reach wholeness. Wholeness is "the melding of all the world's experience and knowledge." [39]In Mapuche cosmovision, Ngünechen is the main deity and it is fourfold, it is composed by Old Man, Old Woman, Young Man, and Young Woman[38].The deity represents wholeness, and provides machis knowledge. Ngünechen manifests through nature elements that provide machisenergy, they can be either feminine and masculine (i.e., waterfalls and lakes are feminine as they represent fertility and lightning, volcanoes are considered masculine)[39] and at the same time they have different age dimensions. All of these components are what provide machis the power to heal and maintain the cosmological balance, and these have to be drawn in a need based model, therefore machis are forced to perform the different personas of Ngünechen who are gendered in their nature, regardless of the machi's sex.[38] Some find the burden too much and cease to be machi.[40] The machi has to periodically renew their powers through the ngeykurewen rituals or they will become ill.[32] After the ngeykurewen, many machis place their old rewe into a river to decay, replacing it with a new one; other machis believe that their rewe should only be deposited in a river after their deaths.[41] Some machi use hallucinogens during their rituals, namely palo de bruja or seeds of the miyaya or chamico, although other machis are critical of this practice.[41] |

マチ 1900年に撮影された3人のマチ マプチェ族の伝統宗教における重要な儀式の専門家はマチであり、さまざまな人類学者がマチをシャーマンであると説明している。[28] マチは、自然界や先祖の霊、そしてニュチェンから力を得ていると信じられている。[9] また、滝や湖、火山、岩などの特別な場所の力も利用している。。彼らはマチ・プルユと呼ばれる霊を具現化し、ともに旅をする。また、すべてのマチの祖先の 霊であるフィレウも持つ。 マプチェ族の伝統主義者は、霊が特定の個人をマチになるよう呼び、夢(プエマ)や幻視(ペリモンタム)を見せる、と信じている。[30] 霊はマチクトランと呼ばれる人物に病気を引き起こすことがあり、その症状には、腫れ物、発熱、口内炎、不眠症、部分的な失明、部分的な麻痺などがある。 [31] マチクトランは、 マチルウン儀式によってマチとして入門することで、初めて緩和される。[32] 精霊の強迫は執拗であるため、それに抵抗するのは難しいと考えられているが、一部の人々は抵抗している。[30] 精霊はビジョンや夢を通じて、マチとなる見込みのある人物に薬草の使い方を示し、ドラムや精霊の動物などの治療用の儀式道具を与える。[33] マチは、さまざまな方法でイニシエーションを経験することがある。彼らは、物質的な家族の一員である亡くなったマチからマチ・スピリットを受け継ぐことも ある。地震や雷などの強力な自然現象の最中に直接的なイニシエーションを経験することもある。あるいは、ペリモンタムと呼ばれるビジョンを経験し、その中 でスピリットが目の前に現れることもある 。[34] 後者の2つの方法でイニシエーションを受けた者は、より強力であると考えられているが、道徳的には曖昧であるともされる。[35] 憑依の際、霊はマチの頭に乗り移る。この過程は「ロンコル・ウパン」と呼ばれる。[36] マチは性的関係を持つこともあれば、独身のままでいることもある。[25]チリの文化では、彼らは同性愛者としてステレオタイプ化されている。[37]し かし、マチがチリの文化と一致しないジェンダーの概念を使用していることを理解することが重要である。マチは、彼らの信念の中でジェンダーを複雑に構築し ており、その結果、彼らの宗教的実践は、通常マチの性別によって定義されないジェンダー関係によって形作られている。[38] マチとして、その目標は完全性を得ることである。完全性とは「世界のあらゆる経験と知識の融合」である。[39] マプチェ族の宇宙観では、ヌネチェンが主要な神であり、それは4つの要素から成り、老人、老女、若者、そして若い女性によって構成されている。[38] この神は完全性を象徴し、マチに知識を与える。Ngünechenは、マチスにエネルギーを与える自然の要素を通じて顕現する。それらは女性的または男性 的である(すなわち、滝や湖は豊穣と雷を象徴する女性的なものであり、火山は男性的なものと考えられている)[39]。同時に、それらは異なる年齢の次元 を持つ。これらの要素すべてが、マチに癒しと宇宙論的バランスを維持する力を与えるものであり、それらは必要に基づくモデルで描かれなければならない。し たがって、マチは、その性別に関係なく、性別を持つニュエチェンの異なるペルソナを演じざるを得ない。 負担が大きすぎてマチでいられなくなる人もいる。[40] マチは、ンゲイクレウェンの儀式を通じて定期的に力を更新しなければならない。さもなければ病気になる。[32] ンゲイクレウェンの後、多くのマチは古いリウェを川に流して腐らせ、新しいリウェと取り替える。。他のマチでは、死後に初めて川にリウェを沈めるべきだと 考えられている。[41] 儀式の際に幻覚剤を使用するマチもある。具体的には、パロ・デ・ブルハやミヤヤまたはチャミコの種子などである。ただし、他のマチでは、この慣習を批判す る声もある。[41] |

Rewe A machi on their rewe At their home, machis will have a timber pole called a rewe ("the purest"), alternatively referred to as the foye or canelo.[42] This usually consists of the trunk of a laurel or oak tree, into which steps have been notched.[43] Branches of klon, triwe, foye, or coligüe will often be tied to the side.[44] The rewe represents the axis mundi of the world, a nexus between the human and spirit worlds, and is positioned to face east.[42] The filew is believed to live in the rewe;[43] kopiwe flowers, food, drink, and herbal remedies, all things regarded as female, are placed on or around the rewe to feed the rewe, while knives, volcanic rocks, and chueca sticks, all things thought male, are places atop the rewe and on its steps to protect the filew from evil spirits.[44] It is on this pole that the machi travels to other worlds while in a trance state;[43] during rituals, the machis ascend the steps on the rewe to inform their audience that they have entered their visionary flight.[41] Some machis put a llang llang, a rainbow-shaped arch made from vines, above the rewe; it represents their connection with forest spirits.[45] The machi uses a shallow drum called a kultrun. This consists of a laurel or oak bowl with goatskin stretched across it, and is often conceptualised as a womb.[46] Often, four items are placed inside the drum; two of these are regarded as male and may include darts, bullets, foye leaves, charcoal or volcanic rocks, while the other two are regarded as female and can include maize, seeds, wool, or kopiwe flowers.[42] The goatskin will be decorated with a painted cross, representing the meli witran mapu, or fourfold division of the world.[42] |

Rewe A machi on their rewe 彼らの家では、マチはrew(「最も純粋な」)と呼ばれる木材の棒を持つ。これは、フォエまたはカネロとも呼ばれる。[42] これは通常、月桂樹または樫の木の幹からなり、そこに階段状の切り込みが入れられている。[43] クロン、トリウィ、フォイ、コリグエなどの枝がしばしば側面に結び付けられる。[44] ルエは世界のアクシス・ムンディ(世界の軸)であり、人間界と精霊界の接点であり、東を向くように置かれる。[42] フィレウェは、レウェの中に住んでいると信じられている。[43] コピウェの花、食べ物、飲み物、薬草など、女性とみなされるものはすべて、レウェに食べさせるために、レウェの上またはその周辺に置かれる。一方、ナイ フ、火山岩、チュエカの棒など、男性とみなされるものはすべて、悪霊からフィレウェを守るために、レウェの上部や階段に置かれる。[44] マチがトランス状態の際に他の世界へと旅立つのはこのポール上である。[43] 儀式の間、マチは彼らが幻視の旅に入ったことを観衆に知らせるために、このポールを登る。[41] いくつかのマチは、つるでできた虹の形をしたアーチである「llang llang」をこのポールの上に置く。これは彼らの森の精霊とのつながりを象徴している。[45] マチはクルトゥランと呼ばれる浅い太鼓を使用する。これは月桂樹または樫の木のボウルにヤギの皮を張ったもので、子宮として考えられることが多い。 [46] 太鼓の中には4つの品目が置かれることが多い。そのうちの2つは男性と見なされ、ダーツ、弾丸、フォイエの葉、木炭、火山岩などが含まれることがある 一方、他の2つは女性とみなされ、トウモロコシ、種子、羊毛、コピウェの花などを入れることができる。[42] ゴートスキンには、メル・ウィトラン・マプ(meli witran mapu)または世界の4分割を表す十字架が描かれる。[42] |