マリアニスモ

Marianismo

Marianismo

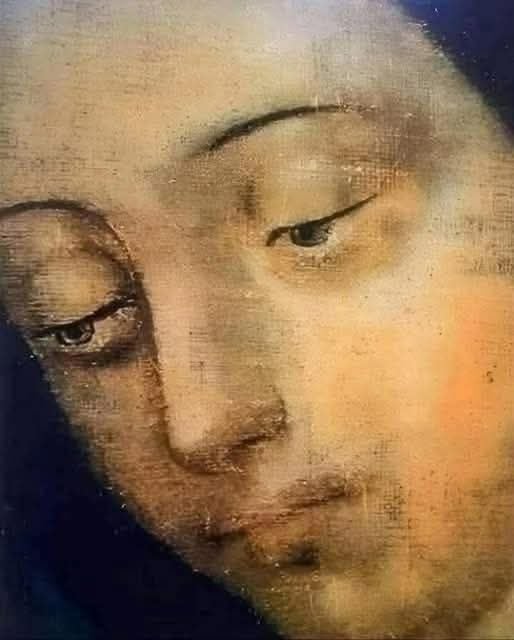

derives from Roman Catholic and Hispanic American beliefs about Mary,

mother of Jesus, providing a supposed ideal of true femininity as the

"absolute role model" for adult and young Hispanic/Latina women.

☆ マリアニスモは、メキシコにおけるローマ・カトリックの中心的人物であるグアダルーペの聖母マリアへの信心から派生した特徴を持つ、真の女性らしさの理想 を意味するヒスパニック系の用語である。これは、ヒスパニック系アメリカ人の民俗文化における女性の性別役割の基準を定義するものであり、マチズモとロー マ・カトリックと密接に結びついている。 マリアニスモは、ヒスパニック系/ラテン系の女性の間で、対人関係における調和、内面の強さ、自己犠牲、家族、貞操、道徳といった女性的な美徳を崇拝する ことに重点を置いている。[1][2][3] ヒスパニック系アメリカ文化におけるマリアニスモが持つ女性性役割に関する理想には、女性的な受動性、性的純潔、自己抑制なども含まれる。[1][2] [3][4] 政治学者のエブリン・スティーブンスは次のように述べている。「女性は半神であり、道徳的に男性よりも優れ、精神的に男性よりも強いと教えている」[5] [6]

| Marianismo is a

Hispanic term that describes an ideal of true femininity with

characteristics derived from the devotional cult of St. Mary of

Guadalupe, a central figure of Roman Catholicism in Mexico. It defines

standards for the female gender role in Hispanic American folk

cultures, and is strictly intertwined with machismo and Roman

Catholicism.[1] Marianismo revolves around the veneration for feminine virtues like interpersonal harmony, inner strength, self-sacrifice, family, chastity, and morality among Hispanic/Latina women.[1][2][3] More ideals regarding the female gender role held within marianismo in Hispanic American culture include those of feminine passivity, sexual purity, and self-silencing.[1][2][3][4] Evelyn Stevens, political scientist, states: "[I]t teaches that women are semi-divine, morally superior to and spiritually stronger than men."[5][6] |

マリアニスモは、メキシコにおけるローマ・カトリックの中心的人物であ

るグアダルーペの聖母マリアへの信心から派生した特徴を持つ、真の女性らしさの理想を意味するヒスパニック系の用語である。これは、ヒスパニック系アメリ

カ人の民俗文化における女性の性別役割の基準を定義するものであり、マチズモとローマ・カトリックと密接に結びついている。 マリアニスモは、ヒスパニック系/ラテン系の女性の間で、対人関係における調和、内面の強さ、自己犠牲、家族、貞操、道徳といった女性的な美徳を崇拝する ことに重点を置いている。[1][2][3] ヒスパニック系アメリカ文化におけるマリアニスモが持つ女性性役割に関する理想には、女性的な受動性、性的純潔、自己抑制なども含まれる。[1][2] [3][4] 政治学者のエブリン・スティーブンスは次のように述べている。「女性は半神であり、道徳的に男性よりも優れ、精神的に男性よりも強いと教えている」[5] [6] |

| Origin of term "Marianismo" originally referred to a devotion towards the Virgin Mary (Spanish: María). The term was first used by political scientist Evelyn Stevens in her 1973 essay "Marianismo: The Other Face of Machismo". It was coined as a female counterpart to machismo, the hispanic ideal of masculinity. Marianismo is the supposed ideal of true femininity that women are supposed to live up to – i.e. being modest, virtuous, and sexually abstinent until marriage – and then being faithful and subordinate to their husbands. Although Stevens was the first to use the term, the concept probably originated at the same as machismo, during the time of the Spanish colonization of the Americas.[7] In their book The Maria Paradox: How Latinas Can Merge Old World Traditions with New World Self-esteem (1996, G. P. Putnam), Rosa Maria Gil and Carmen Inoa Vazquez credit Stevens with introducing the concept of marianismo, citing the "ground-breaking essay written by Evelyn P. Stevens in 1973". They also discuss use of the term by academicians such as Sally E. Romero, Julia M. Ramos-McKay, Lillian Comas-Díaz, and Luis Romero. In their book, Gil and Vazquez use it as applicable across a variety of Hispanic cultures.[8] |

「マリアニスモ」という用語の起源 「マリアニスモ」という用語は、もともと聖母マリア(スペイン語:マリア)への信仰を指していた。この用語は、政治学者のエブリン・スティーブンスが 1973年の論文「マリアニスモ:マチズモのもう一つの側面」で初めて使用した。これは、ヒスパニックの理想とする男らしさであるマチズモの女性版として 作られた造語である。マリアニスモとは、女性が理想とされるべき真の女性らしさのことであり、すなわち、慎み深く、貞淑で、結婚までは性的に禁欲的であ り、その後は夫に誠実で従順であることである。スティーブンスがこの用語を初めて使用したが、この概念はおそらくマチズモと同時期に、スペインによるアメ リカ大陸の植民地化の時代に生まれたものである。 ロサ・マリア・ギルとカルメン・イノア・バスケスは、著書『マリアのパラドックス:ラテン系女性が旧世界の伝統と新世界の自尊心を融合させる方法』 (1996年、G. P. パトナム)の中で、スティーブンスが「マリアニスモ」という概念を導入したと評価し、「1973年にイヴリン・P・スティーブンスが執筆した画期的なエッ セイ」を引用している。また、サリー・E・ロメロ、ジュリア・M・ラモス=マッケイ、リリアン・コマス=ディアス、ルイス・ロメロなどの学者による用語の 使用についても論じている。ギルとバスケスは著書の中で、この用語をさまざまなヒスパニック文化に適用している。[8] |

| Evelyn Stevens' Contributions In her essay, Stevens defines Marianismo as "the cult of female spiritual superiority, which teaches that women are semidivine, morally superior to and spiritually stronger than men." She explains the characteristics of machismo: "exaggerated aggressiveness in intransigence in male-to-male interpersonal relationships and arrogance and sexual aggression in male-to-female relationships." Stevens argues that marianismo and machismo are complements, and that one cannot exist without the other.[5] |

エブリン・スティーブンスの貢献 彼女の論文で、スティーブンスはマリアニスモを「女性が半神であり、道徳的にも精神的にも男性よりも優れていると教える、女性の精神的な優越性を崇拝する もの」と定義している。また、マチスモの特徴を「男性同士の関係における強情さや、男性と女性の関係における傲慢さや性的な攻撃性」と説明している。ス ティーブンスは、マリアニスモとマチスモは補完関係にあり、一方が存在するには他方が不可欠であると主張している。[5] |

| Origin of Marianismo Stevens believes that marianismo is rooted in the awe and worship of female bodies, particularly in the context of pregnancy, exemplified by early cultures. She discusses the various versions of holy Mother figures found through the world, such as Ninhursaga, Mah, Ninmah, Innana, Ishtar, Astarte, Nintu, and Aruru. In many of these goddess' myths, there are stories of the young male figure in their lives, be it a son or lover, disappearing. The response of the goddesses is typically grief, and as she grieves the earth is barren. Stevens argues that this may be an allegory or explanation of the seasons. Stevens points out that the monotheistic structure of Christianity did not produce a woman-figure to venerate, especially in early Christianity, which was deeply rooted in Hebrew beliefs.[5] Around 431 AD, people began to exalt the popular figure of Mary, Mother of Jesus. As veneration of her grew, so did concern from Protestant leaders, who believed people were practicing Mariolatry. When Spanish colonists brought Catholicism to what is now modern-day Mexico, a Native American man, who took the name Juan Diego, is said to have seen a vision of the "Most Holy Mother of God" on a mound in Tepeyac, north of what is now Mexico City. Before Christianity was introduced to the continent, Native Americans in the region believed the mound to be sacred to the Aztec goddess Tonantzin, or "Our Mother". The vision Diego saw was eventually named "Our Lady of Guadalupe" and made patroness of Mexico by Pope Benedict XIV in 1756. Our Lady of Guadalupe quickly gained prestige in Hispanic America. Father Hidalgo lead rebels with the famous Grito de Dolores in 1810: "¡Viva Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, muera el mal gobierno, mueran los gachupines!" (transl. "Long live our Lady of Guadalupe, down with bad government, down with the spurred ones" (or Spanish Mexicans)) [9] |

マリアニスモの起源 スティーブンスは、マリアニスモは、特に妊娠という文脈における女性身体への畏敬と崇拝に根ざしていると考える。彼女は、ニンフルサガ、マハ、ニンマ、イ ナンナ、イシュタル、アスタルテ、ニントゥ、アルルなど、世界中で見られる聖なる母のさまざまなバージョンについて論じている。これらの女神の神話の多く には、息子や恋人のような若い男性の存在が人生から消えるというストーリーがある。女神の反応は通常悲しみであり、女神が悲しむと大地は不毛となる。ス ティーブンスは、これは季節の寓話または説明である可能性があると主張している。スティーブンスは、キリスト教の一神教的な構造は、特にヘブライ人の信仰 に深く根ざしていた初期のキリスト教においては、崇拝するに値する女性像を生み出さなかったと指摘している。西暦431年頃、人々はイエスの母マリアとい う人気のある人物を崇拝し始めた。彼女への崇敬が高まるにつれ、プロテスタントの指導者たちも懸念を示すようになった。彼らは、人々がマリア崇拝を行って いると信じていた。 スペイン人入植者が現在のメキシコにカトリックをもたらした際、フアン・ディエゴという名を名乗ったアメリカ先住民が、現在のメキシコシティの北にあるテ ペヤックの丘で「神の最も聖なる母」の幻を見たと言われている。キリスト教が大陸に伝わる以前から、この地域のネイティブアメリカンは、その塚をアステカ の女神トナンツィン、すなわち「我らが母」の聖地であると信じていた。ディエゴが目にしたビジョンは最終的に「グアダルーペの聖母」と名付けられ、 1756年にローマ教皇ベネディクト14世によってメキシコの守護聖人となった。グアダルーペの聖母は、ヒスパニック系アメリカで急速にその威信を高めて いった。1810年、ヒダルゴ神父は「グアダルーペの聖母万歳!悪政は滅びろ!スペイン人メキシコ人は死ね!」という有名な叫び声をあげて反乱軍を率い た。(訳:「グアダルーペの聖母万歳!悪政は滅びろ!スペイン人メキシコ人は死ね」)[9] |

| Marianismo in Mexican National Identity During the Porfiriato, marianismo was promoted by women to encourage the value in the traditional social roles relegated for women. Writers such as Laureana Wright de Kleinhans published articles that argued women were important agents to the nation's integrity by taking care of domestic duties with special emphasis on raising children. In La Reforma, marianismo was the primary rhetoric used to promote women's education for the purpose of teaching children to cultivate the right virtues and above all, be contributing members of society. [10] The rhetoric's emphasis on educating women for the betterment of the nation bears significant similarities to Republican Motherhood. |

メキシコの国民的アイデンティティにおけるマリアニスモ ポルフィリオ政権時代、マリアニスモは女性たちによって推進され、女性に押し付けられていた伝統的な社会的役割の価値を認めさせることを目指した。作家の ラウレアナ・ライト・デ・クラインハンス(Laureana Wright de Kleinhans)などは、女性が家庭内の仕事をこなし、特に子育てに重点を置くことで、国民の統合にとって重要な存在であると主張する記事を出版し た。ラ・レフォルマ紙では、マリアニスモが、子供たちに正しい徳を教え、何よりも社会に貢献する一員となるよう、女性教育を推進する主なレトリックとして 使用されていた。[10] 女性教育を国民の向上のために重視するというレトリックは、共和母性主義と多くの類似点がある。 |

| Effects on women In marianismo, Stevens argues, it is the bad woman who enjoys premarital sex, whereas the good woman only experiences it as a marriage requirement. Many women confess of sex with their husbands to their priests by referring to the act as "le hice el servicio" (or "I did him the service"). The belief system also believes that women should grieve heavily over family, encouraging women not to show any happiness or participate in anything that may bring them joy. Some have gained social prestige by mourning in these ways until they too die. [5] She also states in her argument that the characteristics of the ideal woman are the same throughout the culture when she claims that "popular acceptance of a stereotype of the ideal woman [is] ubiquitous in every social class. There is near universal agreement on what a 'real woman' is like and how she should act".[7] However, she argues that most indigenous communities do not share the marianismo-machismo dichotomy. Marianismo dictates the ideologies imposed on the day-to-day lives of Hispanic American women. Stevens believes that marianismo will not disappear anytime soon because Hispanic American women still cling to the role. She points out that men follow machismo because they are taught to by their mothers, aunts, and grandmothers. She also says that women encourage marianismo in each other because of the potential shame they could face for not fitting into its standards. Stevens believes many women find comfort in their personal and historical identities by partaking in this system.[5] |

女性への影響 スティーブンスは、マリアニスモにおいては、婚前交渉を楽しむのは悪い女性であり、良い女性は結婚の要件としてそれを受け入れるだけだと主張している。多 くの女性は、司祭に対して「le hice el servicio」(または「私は彼に奉仕した」)という表現を使って、夫との性交渉について告白している。この信念体系では、女性は家族のために深く悲 しむべきであり、女性は一切の幸福を表に出さず、喜びをもたらす可能性のあるものには一切参加すべきではないとされている。中には、自分も死ぬまでそうし て喪に服すことで社会的威信を得る者もいる。[5] また、彼女は「理想の女性像に対する一般の受け入れは、あらゆる社会階級に共通して見られる」と主張し、理想の女性像の特徴は文化を問わず同じであると論 じている。真の女性とはどのようなもので、どのように行動すべきかについては、ほぼ普遍的な合意がある」と主張している。[7] しかし、彼女は、ほとんどの先住民コミュニティでは、マリアニスモとマチスモの二元論は共有されていないと主張している。 マリアニスモは、ヒスパニック系アメリカ人女性の日常生活に押し付けられたイデオロギーである。スティーブンスは、ヒスパニック系アメリカ人女性が今でも その役割に固執しているため、マリアニスモはすぐに消えることはないだろうと考えている。彼女は、男性がマチスモに従うのは、母親や叔母、祖母からそう教 えられているからだと指摘する。また、女性たちは、マリアニスモの基準に適合しないことで恥をかく可能性があるため、互いにマリアニスモを推奨し合うと彼 女は言う。スティーブンスは、多くの女性がこのシステムに参加することで、個人的なアイデンティティと歴史的なアイデンティティに安らぎを見出していると 考えている。[5] |

| Critique of Stevens Evelyn Stevens' essay was very significant to this area of study. However, since its publication, her argument has been debated by other researchers and critics. Although her argument addresses marianismo in Hispanic America at large, many of the sources she uses mainly focus on Mexican culture, thus severely limiting her frame of reference. Also, she is criticized for implying that, despite other differences among various socio-economic classes, the ideal woman's characteristics are ultimately the same across social classes. Her critics claim Stevens ignores socio-economic factors, saying "her description of women as altruistic, selfless, passive, [and] morally pure" is inadequate.[11] There have been some responses in the literature to the concept of marianismo that assert that its model of/for women's behavior is very class-based. In other words, the idea that men do all the hard work, while women remain idle, on a pedestal is something that rarely exists for the lowest classes. As Gil and Vazquez remind us, "most of her [Stevens's] data came from middle class Mexican women".[8] Researcher Gloria González-López says heterosexual norms are created, maintained, and changed in different national locations.[12] González-López goes so far as to say: Marianismo has done damage to our understanding of gender relations and inequalities among Latin American and U.S Latina women...Now discredited, marianismo was originally an attempt to examine women's gender identities and relationships within the context of inequality, by developing a model based on a religious icon (María), the quintessential expression of submissiveness and spiritual authority. This notion of Latin American women is grounded in a culturalist essentialism that does far more than spread misinformed ideas: it ultimately promotes gender inequality. Both marianismo and machismo have created clichéd archetypes, fictitious and cartoonesque representations of women and men of Latin American origin."[citation needed] |

スティーブンスの批評 Evelyn Stevensの論文は、この研究分野にとって非常に意義深いものであった。しかし、発表以来、彼女の主張は他の研究者や批評家によって議論されてきた。 彼女の主張はラテンアメリカにおけるマリアニスモ全般を対象としているが、彼女が使用した資料の多くは主にメキシコ文化に焦点を当てており、そのため彼女 の参照枠は著しく限定されている。また、彼女は、様々な社会経済階級の間には他にも異なる点があるにもかかわらず、理想的な女性の特性は社会階級を問わず 最終的には同じであると暗示しているとして批判されている。彼女の批判者たちは、スティーブンスが社会経済的要因を無視していると主張し、「利他的、無私 無欲、受動的、道徳的に純粋な女性像」は不適切であると述べている。[11] マリアニスモの概念に対する文献上の反応としては、女性の行動のモデルは階級に基づくものであると主張するものもある。言い換えれば、男性がすべての重労 働をこなし、女性は高みから何もしないという考え方は、最下層階級にはほとんど存在しない。ギルとバスケスが指摘しているように、「彼女(スティーブン ス)のデータのほとんどは、メキシコの中流階級の女性から得られたもの」である。[8] 研究者のグロリア・ゴンザレス=ロペスは、異性愛の規範は異なる国民の間で形成され、維持され、変化すると述べている。[12] ゴンザレス=ロペスはさらに、次のように述べている。 マリアニスモは、ラテンアメリカおよび米国のラテン系女性たちの間のジェンダー関係や不平等に対する我々の理解にダメージを与えてきた。今では信用を失っ ているマリアニスモは、もともとは、服従と精神的な権威の典型的な表現である宗教的な象徴(マリア)に基づくモデルを開発することで、不平等という文脈に おける女性のジェンダー・アイデンティティと関係を調査しようとする試みであった。ラテンアメリカ女性に関するこの概念は、誤った考えを広める以上の影響 を及ぼす文化本質主義に基づいている。それは最終的に男女間の不平等を助長する。マリアニスモとマチスモの両方が、ラテンアメリカ出身の女性と男性の型に はまった典型的な、架空の漫画のような表現を生み出した。 |

| Ten Commandments of Marianismo Therapists Rosa Maria Gil and Carmen Inoa Vasquez, present the beliefs they observed many of their patients holding as intrinsic to marianismo: "Don't forget the place of the woman; don't give up your traditions; don't be an old maid, independent, or have your own opinions; don't put your needs first; don't wish anything but to be a housewife; don't forget sex is to make babies, not pleasure; don't be unhappy with your man, no matter what he does to you; don't ask for help outside of your husband; don't discuss your personal problems outside the house; and don't change."[13] |

マリアニスモの10の戒律 セラピストのロサ・マリア・ギルとカルメン・イノア・バスケスは、多くの患者がマリアニスモの本質的要素として抱いている信念を次のように紹介している。 「女性の立場を忘れてはいけない。伝統を捨ててはいけない。おばさんになってはいけないし、自立し、自分の意見を持つべきだ。自分のニーズを最優先にして はいけない。専業主婦になることだけを望んではいけない。セックスは快楽のためではなく、赤ちゃんを作るためのものだということを忘れないこと。夫がどん なことをしても、彼に対して不満を抱かないこと。夫以外の助けを求めないこと。個人的な問題を外で議論しないこと。そして、変わらないこと。」[13] |

| Five Pillars Other researchers identify "five pillars" of Marianismo, or specific beliefs that "good women" must adhere to.[14][15] Familismo Familismo is an individual's strong identification with and attachment to family, both nuclear and extended.[14] To ascribe to this belief, Hispanic women function as the source of strength of families by maintaining their overall happiness, health, and unity.[14][16] In order to maintain their families' reputations, Hispanic women are discouraged from sharing what is considered "family issues" with others.[15] This belief causes many women who are abused by their partners to not report their experiences to law enforcement.[17] Instead, they may talk about the abuse with family and friends. However, this disclosure to friends and family is linked to increased risk of future assault of Hispanic women.[18] Therefore, adherence to traditional values of keeping matters regarding abuse within one's family discourage reporting and may have serious health implications for those experiencing abuse.[15] The concept of family is considered so important to marianismo women that those who attempt to intervene in situations of partner violence in marianismos are encouraged to view autonomy and independence as very westernized concepts, and are told to instead focus on listening and aiding women in the goals they create to avoid violence, in order to avoid alienating the women.[19] Many of the goals stated by those interviewed were, rather than leaving a relationship with an abusive husband, to stop the violence, improve relationships with their partners, help their partners learn to be more supportive husbands and fathers.[20] Men and women in Hispanic cultures are expected to value their families, though the ways to express the value vary based on gender proscriptions. While men are expected to provide financial resources, protection, and leadership,[21] women are told to provide emotionally and physically in part by raising children and doing domestic work within their homes.[14] |

5つの柱 他の研究者は、マリアニスモの「5つの柱」、すなわち「善良な女性」が固守すべき特定の信念を特定している。[14][15] ファミリスモ ファミリスモとは、核家族および拡大家族の両方において、個人と家族との強い同一性および結びつきを意味する。[14] この信念によると、ヒスパニック系の女性は、家族全体の幸福、保健、団結を維持することで、家族の強さの源として機能する。[14][16] 家族の評判を維持するために、ヒスパニック系の女性は「家族の問題」と見なされることを他人と共有することをためらう。 [15] この信念により、パートナーから虐待を受けている多くの女性が、その経験を警察に報告しないという結果になっている。[17] その代わり、彼女たちは家族や友人たちに虐待について話すことがある。しかし、友人や家族に打ち明けることは、ヒスパニック系女性が将来さらに虐待を受け るリスクを高めることにつながっている。[18] そのため、虐待に関する問題を家族内で解決するという伝統的価値観に固執することは、被害届の提出を妨げ、虐待を受けている人々にとって深刻な保健上の影 響を及ぼす可能性がある。[15] マリアニスモの女性にとって家族の概念は非常に重要であるため、マリアニスモにおけるパートナーからの暴力の状況に介入しようとする人々は、自立や独立と いう概念は極めて西洋化された概念であると見なされ、代わりに女性が暴力を回避するための目標を聞き、支援することに焦点を当てるよう勧められる。 [19] インタビューを受けた人々が挙げた目標の多くは、虐待的な夫との関係を解消するのではなく、暴力を止め、パートナーとの関係を改善し、パートナーがより良 い夫や父親になるよう手助けすることだった。[20] ヒスパニック文化圏の男女は、家族を大切にすることを期待されているが、その価値の表現方法は性別による規範によって異なる。男性は経済的な支援、保護、 リーダーシップを発揮することが期待されているが、[21] 一方で女性は、家庭内で子供を育てたり家事をしたりすることで、情緒的にも身体的にも貢献することが求められている。[14] |

| Chastity Virginity is viewed as an important feature, and by abstaining from premarital sex, women prevent shame from coming upon themselves and their families.[14] Often, sex is associated with feelings of guilt and sadness in marianismo-abiding girls and women.[22][13] This is because sex is often framed in a dichotomy of either being for procreation or eroticism.[13] Women are expected to be non-sexual and virginally pure. This means that women should strive for monogamy, sexual desire in long-term, committed (ideally married) relationships only, and should limit their exploration of their sexual identities only in heterosexual relationships.[23] This often leads to an interpretation that women should remain with their partner for the rest of their lives, even if they are abused.[24] Women are also expected to be passive in sexual encounters, which is linked to lower condom usage and therefore higher risk of STIs, especially HIV/AIDS.[15][25][26] Women are expected to learn how to have sex from their husbands, and if a woman shows too much interest or assertiveness, she is sometimes treated as "suspect".[13] |

貞操 処女性は重要な特徴と見なされており、婚前交渉を控えることで、女性は自分自身や家族に恥が及ぶのを防ぐことができる。[14] マリアニスモを信奉する少女や女性にとって、セックスは罪悪感や悲しみと結びついていることが多い。[22][13] これは、セックスが生殖のためか、あるいはエロティシズムのためかという二分法で捉えられることが多いからである。[13] 女性は非性的で処女性を保ったままでいることが期待される。つまり、女性は一夫一婦制を求め、性的欲求は長期的な関係を築いた相手(理想的には結婚相手) との間のみに限定し、性的アイデンティティの探求も異性愛関係においてのみ行うべきであるとされる。[23] これはしばしば、たとえ虐待を受けても、女性は生涯パートナーと添い遂げるべきであるという解釈につながる。[24] また、女性は性的な場面では受動的であることが期待されており、これはコンドームの使用率の低下につながり、その結果、性感染症、特にHIV/エイズのリ スクが高くなる。[15][25][26] 女性は夫からセックスのやり方を学ぶことが期待されており、女性が関心や積極性を示しすぎると、「疑わしい」と見なされることもある。[13] |

| Respeto Respeto ("respect") is the obedience, duty, and deference an individual adheres to in their position of a hierarchical structure.[14] This maintains the common Hispanic family structure, and provides individuals with a standard to how they respond to interpersonal situations.[27] There is a golden rule, no faltarle el respeto, which tells individuals not to speak against those who are higher up in the hierarchy.[27] |

尊敬 尊敬(「尊敬」)とは、個人が階層構造の中で従う服従、義務、敬意である。[14] これは一般的なヒスパニック系の家族構造を維持し、個人が対人関係の状況にどう対応するかの基準を提供する。[27] そこには黄金律、no faltarle el respeto(尊敬を欠かさない)があり、個人が階層の上位者に逆らってはならないと教えている。[27] |

| Self-silencing According to marianismo, Hispanic women should withhold personal thoughts and needs in order to avoid disagreement.[2][3][4][15] Adherence to this belief is linked with significantly higher rates of psychological distress, depression, and anxiety in Hispanic women and young girls.[2][3][4][28] It also influences women to stay in violent interpersonal relationships.[3][15][26] Many Hispanic women perceive that "keeping things inside" causes their depression.[29] |

自己抑制 マリアニスモによると、ヒスパニック系の女性は、意見の相違を避けるために、個人的な考えや欲求を抑制すべきである。 [2][3][4][15] この信念に固執することは、ヒスパニック系の女性や少女の心理的苦痛、うつ病、不安の割合が著しく高くなることと関連している。[2][3][4] [28] また、この信念は女性が暴力的な対人関係を続けることにも影響している。[3][15][26] 多くのヒスパニック系の女性は、「心に抱え込む」ことがうつ病の原因となっていると認識している。[29] |

| Simpatía Simpatía is a value of peace keeping and "kindness" that calls for women to avoid disagreements and assertiveness to keep relationships harmonious.[15][30] |

Simpatía(シンパティア;親切、共感、シンパシー) Simpatíaは、平和維持の価値であり、「親切」を意味する。女性に対して、争いを避け、自己主張することで人間関係を円満に保つことを呼びかけている。[15][30] |

| Spiritual This pillar focuses on the perceived ability, and therefore responsibility, given to women to lead their families in spiritual growth and religious practice.[15] This pillar is considered to be very important to perceived "good mothers".[30] Higher endorsement of spiritual responsibility of women and mothers is linked to anger, hostility, and anxiety in women.[2] |

スピリチュアル この柱は、女性が家族の精神的な成長と宗教的実践を導くために与えられた能力と責任に焦点を当てている。[15] この柱は、良き母親にとって非常に重要であると考えられている。[30] 女性と母親のスピリチュアルな責任に対する高い支持は、女性における怒り、敵意、不安と関連している。[2] |

| In the media Very few studies on the role of marianismo in the media have been conducted. However, in more recent years, researchers are beginning to explore this cultural phenomenon. Researchers Jorge Villegas, Jennifer Lemanski and Carlos Valdez conducted a study on the portrayal of women in Mexican television commercials. Often women are portrayed as either those who adhere to the feminine ideal, and those who do not. These women are then categorized as good women and bad women, respectively. These "good women" are seen as nurturing, family-oriented, soft-spoken, even-tempered and sexually naïve, whereas the "bad women" are often the sexual targets of men. Another dichotomy presented by this study is dependent women versus independent women. The researchers found that "dependent women tended to display characteristics perceived as positive in marianismo (helpful, rewarded by their family) whereas independent women were more sexualized".[31] A similar study by Rocío Rivadeneyra examined the gender portrayals in telenovelas. Her research found that in comparison to their male counterparts, women were seen as spending more time with children and were either homemakers or unemployed.[32] Both studies, however, noted that women and men were portrayed with equal frequency in the media. A study of commercials on Mexico's national TV found a disparity in the ways women are depicted based on whether they are dependent on another person to have their role (mothers/wives) or independent (single women/employees). The study found that independent women are objectified and sexualized more than dependent women, by wearing significantly more torn clothing to expose the torso and explicit/implicit nudity. Though, both independent and dependent women are more sexualized than men, by wearing more tight-fitting clothes, low-cut/unbuttoned shirts to show cleavage, and nudity. Independent women's motivations for taking actions were significantly more for the approval of men and for social advancement than dependent women.[33][34] In addition, in these commercials, dependent women are viewed in stereotypical feminine settings, significantly more often in homes and restaurants and less in stores and occupational settings than men. Dependent women are found in homes and outdoors significantly more than independent women who are seen in workplaces more often. Also, women were shown significantly more often as both the givers and receivers of advice and the receivers of help, with men most commonly giving help to others. Commercials reflect cultural views, and these may show understandings on women's expected roles.[33][35] Portrayals of women as traditional has a real effect on what women and girls can perceive themselves doing and becoming.[36] |

メディアにおける マリアニスモの役割に関する研究はほとんど行われていない。しかし、近年になってようやく、この文化的現象の研究が始まっている。研究者Jorge Villegas、Jennifer Lemanski、Carlos Valdezは、メキシコのテレビコマーシャルにおける女性の描写に関する研究を行った。女性は、しばしば「女性らしさの理想像」に忠実な女性とそうでな い女性として描かれる。そして、それぞれ「良い女性」と「悪い女性」として分類される。「良い女性」は、家庭的な、物静かな、温厚な、性的に純粋な女性と して描かれる。一方、「悪い女性」は、男性の性的対象として描かれることが多い。この研究で提示されたもう一つの二分法は、依存的な女性と自立した女性で ある。研究者は、「依存的な女性はマリアニスモ(家族に役立つ、家族から報われる)でポジティブと認識される特徴を示す傾向があるのに対し、自立した女性 はより性的である」ことを発見した。[31] ロシオ・リバデネラによる同様の研究では、テレノベラにおけるジェンダー描写を調査した。彼女の研究では、男性と比較して、女性は子供とより多くの時間を 過ごしていると見られており、専業主婦か無職であることが分かった。[32] しかし、どちらの研究でも、メディアでは女性と男性が同等の頻度で描かれていることが指摘されている。 メキシコの国営テレビのコマーシャルに関する研究では、女性が描かれる方法には、役割(母親/妻)を他の人格に依存しているか、自立しているか(独身女性 /従業員)によって違いがあることが分かった。この調査では、自立した女性は、胴体を露出する破れた服や露骨な、あるいは暗示的なヌードを身にまとうこと が多く、依存的な女性よりも対象化され、性的に描写されることが分かった。ただし、自立した女性も依存的な女性も、体にフィットした服や胸の谷間を見せる 胸元の開いたシャツ、ヌードを身にまとうことが多く、男性よりも性的に描写されることが多い。自立した女性の行動の動機は、男性の承認や社会的な地位向上 を求めるものであり、依存的な女性よりもはるかに多い。[33][34] さらに、これらのコマーシャルでは、依存的な女性はステレオタイプ的な女性的な環境で描かれており、家庭やレストランで描かれることが男性よりもはるかに 多く、店舗や職場では描かれることが少ない。依存的な女性は家庭や屋外で描かれることが自立的な女性よりもはるかに多く、自立的な女性は職場での場面で描 かれることが多い。また、女性はアドバイスを与える側、受ける側、助けを求める側として、男性が他者に手を差し伸べる場面よりもはるかに多く描かれてい る。コマーシャルは文化的な見方を反映しており、そこには女性に期待される役割についての理解が示されている可能性がある。[33][35] 女性を伝統的な存在として描くことは、女性や少女が自分自身について、また自分たちが何者になり得るかについて、現実的な影響を及ぼす。[36] |

| Criticisms Marianismo presents a foundation for normal female behavior within Hispanic countries. Under Marianismo, women are expected to present behavior that shows compliance to male dominance, strong ties to morality (especially relating to the Virgin Mary), and willing to give up everything for the name of family.[37] Like machismo, Marianismo sets up a list of rules that promotes how one needs to be when interacting with society, strongly encouraging a gap between the genders by reinforcing these beliefs in various ways throughout society. Hispanic people who are exposed to the constructs of Marianismo and Machismo are predisposed to behaviors normative within the Hispanic cultures of what constitutes being a man and a woman. Expectations of behavior begin to be evident before birth with these social constructs, liberating and constricting both genders to fit inside a bubble deemed appropriate by Hispanic cultural values.[14] Men are viewed as providers and decision-makers for their family, while women are to provide emotional support to their families only.[14] Marianismo also plays a role in gender roles that may lead to increased incidence of gender-based violence in Latin American countries, which can portray women as submissive, and extensions of men who dominate them.[38] This can result in women being victims of gender-based violence, especially intimate-partner violence* which is often defended by the belief that a woman’s husband has the right to use physical or emotional abuse against her.[38] Furthermore, Femicide in Latin America is an issue that has been prevalent for many years throughout the region. Gender roles, and the concept of marianismo shape attitudes towards women, thus determining how they are treated in society.[38] Hispanic women's experiences in life both hinder and improve due to Marianismo. They are more likely to exhibit higher levels for pessimistic views in life and developing depression. Yet, they are also less likely to attempt unsafe behavior, such as underage drinking and substance abuse.[39] Restrictions placed on their expected behaviors instills women to remain quiet about their issues. If efforts build to push away from the social constructs behind Marianismo, criticisms appear from the outside community. Even without going against the norm, stereotypes of Hispanic women are conjured up, similar to men under Machismo. They are viewed as "exotic", implying they are secretly sexually passionate wanting to branch out from that ideology, or prefer to divulge in dangerous activities to make up for this “innocent” life they’ve been confined in, much like the archetype of the "sexy librarian". Furthermore, women can ostracize the woman fighting against the norm, claiming she is going against her culture and faith by her challenges towards Marianismo[39] In Hispanic countries, a woman who presents herself in society without a man is frowned upon, as a man is the basis of family life and having a positive association within the community.[37] Machismo promotes aggression, dominance and entitlement – characteristics that can be applied when focusing on interpersonal violence.[40] When applying interpersonal violence, Hispanic women deal with the abuse from IPV from fear of losing their husbands, their children’s father and social status of admitting abuse to the outside world.[37] Marianismo promotes women to be self-sacrificing, leading for them to accept abuse continually and remain quiet from fear of losing their livelihood and dependency from their husbands. Given these characteristics, men remain dominant and exert their power over their partner, continuing the cultural establishment of patriarchy within Hispanic cultures.[37] Studies conducted on marianismo have concluded that Hispanic women who ascribe to this particular female gender role are more likely to engage in high-risk sexual behaviors, gender-based violence, and experience negative mental health outcomes.[1] Jane F. Collier demonstrated that access to economic opportunity is a factor in determining to what extent Hispanic women may choose to conform to traditional notions of marianismo, and to what degree they are inclined to adapt them to new circumstances. As early as 1997, Dr. Rosa Gil and Dr. Carmen Inoa-Vazquez made reference to Nuevo Marianismo, which is to embrace the marianismo ideal of being nurturing and caring, yet breaking away from the barriers those characteristics previously presented. Coined in 1973, researcher Gloria González-López says that marianismo, as a theoretical category, is not only culturally chauvinist but elitist as well.[citation needed] |

批判 マリアニスモは、ラテンアメリカ諸国における女性の正常な行動の基礎を提示している。マリアニスモの下では、女性は男性優位に従順であること、道徳(特に 聖母マリアに関連する)に強く結びついていること、そして家族の名のもとにすべてを捧げることを示す行動が期待される。[37] マチスモと同様に、マリアニスモは社会と関わる際に必要とされる行動を促す一連の規則を定めている。マリアニスモとマチスモの概念に触れたヒスパニック系 の人々は、ヒスパニック文化における男女のあり方として標準的な行動をとる傾向がある。こうした社会構造により、出生前から行動に対する期待が明らかにな り、ヒスパニック文化の価値観が適切と考える枠内に収まるよう、男女両方を解放したり、束縛したりする。[14] 男性は家族の提供者であり、意思決定者とみなされるが、女性は家族に感情的なサポートを提供するだけである。[14] マリアニスモは、ラテンアメリカ諸国におけるジェンダーに基づく暴力の発生率を高める可能性があるジェンダーの役割にも影響を与えている。このため、女性 は従順で、男性に従属する存在として描かれることがある。[38] その結果、女性はジェンダーに基づく暴力、特にパートナーからの暴力の被害者となることがある。パートナーからの暴力は、しばしば「夫には妻に対して身体 的・精神的虐待を行う権利がある」という考え方によって正当化される。 [38] さらに、ラテンアメリカにおける女性殺害は、長年にわたり地域全体で蔓延している問題である。性別による役割やマリアニスモの概念が女性に対する態度を形 成し、それによって社会における女性の扱いが決定される。[38] ヒスパニック系女性の人生経験は、マリアニスモによって妨げられることもあれば、改善されることもある。彼女たちは人生に対して悲観的な見方を示し、うつ 病を発症する可能性が高い。しかし、未成年者の飲酒や薬物乱用などの危険な行動に走る可能性は低い。[39] 期待される行動に制限が課せられることで、女性たちは自分の抱える問題について口をつぐむようになる。マリアニスモの背景にある社会構造から離れようとす る取り組みが行われると、外部のコミュニティから批判が寄せられる。社会通念に背かずとも、マチスモの男性と同様に、ヒスパニック系女性に対するステレオ タイプが思い起こされる。彼女たちは「エキゾチック」と見なされ、その思想から抜け出したいと密かに性的に情熱的であったり、あるいは、閉じ込められた 「無垢」な生活を補うために危険な活動に身を投じたりする、というような意味合いが含まれている。これは「セクシーな司書」の典型的なイメージとよく似て いる。さらに、女性は、マリアニスモ(マリア信仰)に立ち向かう女性を、文化や信仰に反するとして排斥する可能性もある[39]。 ヒスパニック系諸国では、男性のいない社会で自己主張する女性は、家族生活の基盤であり、地域社会で肯定的な関係を築く存在である男性が重視されるため、 嫌悪の対象となる[37]。マチスモは、攻撃性、支配性、権利主張を助長する。これらは、対人暴力に焦点を当てた場合の特徴である。 [40] ヒスパニック系の女性が対人暴力を振るう場合、夫や子供の父親、社会的な地位を失うことを恐れて、家庭内暴力による虐待を外部に認めないことが多い。 [37] マリアニスモは女性に自己犠牲を促し、虐待を受け続けても黙っていることを受け入れさせ、生計手段や夫からの依存を失うことを恐れさせる。こうした特徴が あるため、男性は支配的な立場を維持し、パートナーに対して権力をふるい、ヒスパニック文化における家父長制の文化的確立を継続している。 マリアニスモに関する研究では、この特定の女性性別役割に帰属するヒスパニック系女性は、リスクの高い性的行動や性別に基づく暴力に関与しやすく、精神保健上の悪影響を経験する可能性が高いという結論に達している。 ジェーン・F・コリアーは、ヒスパニック系女性が伝統的なマリアニスモの概念にどの程度従うか、また、それを新しい状況にどの程度適応させるかについて は、経済的な機会にアクセスできるかどうかが要因であることを示した。1997年には早くも、ロサ・ギル博士とカルメン・イノア=バスケス博士が、マリア ニスモの理想である「育むこと」や「思いやり」を受け入れながらも、それらの特性がもたらす障壁から脱却するという「ヌエボ・マリアニスモ」について言及 している。1973年に造語された「マリアニスモ」は、理論上のカテゴリーとして、文化的排外主義であるだけでなく、エリート主義でもあると、研究者のグ ロリア・ゴンサレス=ロペスは述べている。[要出典] |

| HIV crisis According to Marianismo beliefs, women are expected to be naïve about sex, which means that many girls and women are not taught about the spread of HIV/AIDS.[25] As a result women know very little about sex, including the homosexual extramarital affairs of their husbands.[25] Many husbands have homosexual relations as a way to prove their machismo. Most women in Hispanic American cultures with HIV contracted it from their sole sex partner, their husband.[41] Regardless of the sexual monogamy associated with Marianismo purity a woman adheres to, her status as HIV-positive threatens the identity she wants to associate with.[25] Women often stay silent about their status out of fear of being ostracized by family. Women are often blamed for their husbands' contractions of and death from HIV.[25] Women who are HIV-positive have the risk of their children being taken away from them, because their families often see them as too sick and dirty to care for them.[25] Women often lose status if they are seen to be associating with people who are HIV-positive, because people with HIV are often associated with sexual deviancy and impurity.[42] |

HIVの危機 マリアニスモの信仰によると、女性は性に対して純粋であることが期待されており、そのため、多くの少女や女性はHIV/AIDSの感染について教えられて いない。[25] その結果、女性たちは、夫の同性愛や婚外交渉を含む性についてほとんど知らない。[25] 多くの夫は、マチスモを証明する方法として、同性愛関係を持っている。HIVに感染したヒスパニック系アメリカ人の大半の女性は、唯一の性パートナーであ る夫から感染している。[41] 女性がマリアニスモの純潔性に関連する一夫一婦制を遵守しているかどうかに関わらず、HIV陽性であるという事実が、女性が自らと関連付けたいアイデン ティティを脅かすことになる。[25] 女性は家族から疎外されることを恐れて、自分の感染状態について黙っていることが多い。女性は、夫がHIVに感染し、死亡した場合に非難されることが多 い。[25] HIV陽性の女性は、家族が彼女たちを看病するにはあまりにも病気で不潔であると見なすことが多いため、子供たちを奪われる危険性がある。[25] HIV陽性の人々と付き合っていると見なされると、女性は地位を失うことが多い。なぜなら、HIV感染者はしばしば性的逸脱や不純と関連付けられるからで ある。[42] |

| Feminist criticism Some feminists criticize the concept of marianismo, suggesting that it simply legitimizes the social conditions of women in Hispanic America by making it seem valid and normal. They also note that marianismo is often presented as everything machismo is not; therefore femaleness is put into "the realm of passivity, chastity, and self-sacrifice".[43] They argue marianismo suggests that if a woman has a job outside of the home, her virtues and her husband's machismo are put into question. |

フェミニスト批評 一部のフェミニストは、マリアニスモの概念を批判し、それが単にラテンアメリカ系アメリカ女性の社会的状況を正当かつ正常であるかのように見せかけ、それ を合法化していると指摘している。また、マリアニスモはマチスモの否定するものとして提示されることが多く、そのため女性らしさは「受動性、貞操、自己犠 牲の領域」に置かれると指摘している。[43] 彼らは、マリアニスモは、女性が外で仕事を持つ場合、その女性の美徳や夫のマチスモが疑問視されることを示唆していると主張している。 |

| Ambivalent Sexism Theory According to Ambivalent Sexism Theory, sexism and women's low status in terms of autonomy and safety is maintained through two types of sexism, hostile and benevolent. Hostile sexism being the belief that women inherently have negative features, and benevolent sexism often being the belief that women have inherently delicate features that causes the need for protection.[44] Marianismo and ambivalent sexism share similar traits, including the fact that women are given respect, high status, and protection if they conform to gendered expectations.[45] Marianismo thus functions as a risk factor and a protective factor.[46] |

アンビヴァレント・セクシズム理論 アンビヴァレント・セクシズム理論によると、性差別と女性の地位の低さは、敵対的性差別と慈悲深い性差別の2つの性差別によって維持されている。敵対的性 差別とは、女性には本質的にネガティブな特徴があるという考え方であり、好意的性差別とは、女性には本質的に繊細な特徴があり、保護が必要だという考え方 であることが多い。[44] マリアニスモとアンビバレント・セクシズムは、女性がジェンダーによる期待に適合していれば尊敬や高い地位、保護が与えられるという点を含め、類似した特 徴がある。[45] したがって、マリアニスモはリスク要因と保護要因として機能する。[46] |

| Modern Marianismo Hispanic and Latina women in the United States find themselves attempting to merge two cultures. "Latinas today are demonstrating ... "Modern Marianismo" (Gil & Vazquez (1997) referred to as "Nuevo Marianismo") which is to embrace the Marianismo Ideal (of being nurturing and caring), yet breaking away from the barriers those characteristics previously presented (for Latinas)."[47] Damary Bonilla-Rodríguez says that values such as: Familia, Amor y Pasión (Family, Love and Passion) have allowed [her] people to overcome adversity across centuries, and highlighting successful Latinas such as Justice Sonia Sotomayor, Secretary Hilda Solis, and others is essential to connecting Latino cultural values with mainstream American values.[47] Such change is not unique to the United States. In Andalusia, with exposure to more modern models in Spanish TV and advertising, in one generation the focus shifted from traditional norms of expected behavior with the realization that "inequalities in income and lifestyle among villagers no longer appeared to rest on inheritance, but on urban, salaried jobs people obtained."[48] |

現代のマリアニスモ 米国のヒスパニック系およびラテン系の女性は、2つの文化を融合させようとしている。「現代のラテン系女性は...」と主張している。「モダン・マリアニ スモ」(Gil & Vazquez (1997)は「ヌエボ・マリアニスモ」とも呼ばれる)は、マリアニスモの理想(育むこと、思いやりを持つこと)を受け入れながらも、それらの特性が以前 ラテン系女性に課していた障壁から脱却しようとするものである。」[47] ダマリー・ボニーヤ=ロドリゲスは、 ファミリア、アモール・イ・パシオン(家族、愛、情熱)といった価値観が、何世紀にもわたって人々が逆境を乗り越えることを可能にしてきた。ソニア・ソト マイヨール判事やヒルダ・ソリス長官など成功したラテン系女性を強調することは、ラテン系の文化的価値観とアメリカ主流の価値観を結びつけるために不可欠 である。 このような変化は米国に限ったことではない。アンダルシアでは、スペインのテレビや広告でより現代的なモデルを目にするようになり、ある世代では、伝統的 な行動規範に重点が置かれていたのが、「村人の間の収入や生活様式の格差は、もはや相続によるものではなく、都市部の給与所得の仕事に就くことによるもの と思われる」という認識へと変化した。[48] |

| Barefoot and pregnant Feminine psychology Feminism Good Wife, Wise Mother Kinder, Küche, Kirche Machismo María Clara Marian devotion New feminism Sexism Yamato nadeshiko Violence against women in Mexico |

裸足と妊娠 女性心理学 フェミニズム 良妻賢母 キッチン、子供部屋、教会 マチスモ マリア・クララ マリア信仰 新しいフェミニズム 性差別 大和撫子 メキシコにおける女性に対する暴力 |

| Stevens Evelyn P.; 1973.

:Marianismo:The Other Face of Machismo in Latin America; in: Pescatelo

Ann; Female and Male in Latin America, University of Pittsburgh Press,

1973. Villegas, Jorge, Jennifer Lemanski, and Carlos Valdéz. "Marianismo And Machismo: The Portrayal Of Females In Mexican TV Commercials." Journal of International Consumer Marketing 22.4 (2010): 327–346. Rivadeneyra, Rocío. "Gender And Race Portrayals On Spanish-Language Television." Sex Roles 65.3/4 (2011): 208–222. Montoya, Rosario, Lessie Jo Frazier, and Janise Hurtig. Gender's Place : Feminist Anthropologies Of Latin America / Edited By Rosario Montoya, Lessie Jo Frazier, And Janise Hurtig. n.p.: New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. De La Torre, Miguel A. Hispanic American Religious Cultures. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2009. |

Stevens Evelyn P.; 1973.

:Marianismo:The Other Face of Machismo in Latin America; in: Pescatelo

Ann; Female and Male in Latin America, University of Pittsburgh Press,

1973. Villegas, Jorge, Jennifer Lemanski, and Carlos Valdéz. "Marianismo And Machismo: The Portrayal Of Females In Mexican TV Commercials.」 Journal of International Consumer Marketing 22.4 (2010): 327–346. Rivadeneyra, Rocío. 「Gender And Race Portrayals On Spanish-Language Television.」 Sex Roles 65.3/4 (2011): 208–222. モントヤ、ロザリオ、レッシー・ジョ・フレイジャー、ジャニス・ハーティグ。Gender's Place : Feminist Anthropologies Of Latin America / Edited By Rosario Montoya, Lessie Jo Frazier, And Janise Hurtig. n.p.: New York : Palgrave Macmillan, 2002. デ・ラ・トーレ、ミゲル・A. Hispanic American Religious Cultures. Santa Barbara, Calif: ABC-CLIO, 2009. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marianismo |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆