ミサ曲

Mass (music)

Manuscript

page with the five-voice "Kyrie" of the Missa Virgo Parens Christi by

Jacques Barbireau (ca.1420-1491).

☆ ミサ曲(ラテン語: missa)は、キリスト教の聖体礼儀(主にカトリック教会、聖公会、ルーテル教)の不変の部分を設定する神聖な楽曲の形式であり、ミサとして知られてい る。 ほとんどのミサは、カトリック教会のローマ典礼の聖なる言語であるラテン語で書かれた典礼であるが、長い間方言礼拝が主流であった非カトリック諸国の言語 で書かれたものも相当数ある。例えば、第二バチカン公会議以降、 米国向けに英語で書かれたミサが数多くあり、英国教会向けのミサ(しばしば「聖体拝領」と 呼ばれる)もある。

| The

Mass (Latin: missa) is a form of sacred musical composition that

sets

the invariable portions of the Christian Eucharistic liturgy

(principally that of the Catholic Church, the Anglican Communion, and

Lutheranism), known as the Mass. Most Masses are settings of the liturgy in Latin, the sacred language of the Catholic Church's Roman Rite, but there are a significant number written in the languages of non-Catholic countries where vernacular worship has long been the norm. For example, there have been many Masses written in English for a United States context since the Second Vatican Council, and others (often called "communion services") for the Church of England. Masses can be a cappella, that is, without an independent accompaniment, or they can be accompanied by instrumental obbligatos up to and including a full orchestra. Many masses, especially later ones, were never intended to be performed during the celebration of an actual |

ミサ曲(ラテン語:

missa)は、キリスト教の聖体礼儀(主にカトリック教会、聖公会、ルーテル教)の不変の部分を設定する神聖な楽曲の形式であり、ミサとして知られてい

る。 ほとんどのミサは、カトリック教会のローマ典礼の聖なる言語であるラテン語で書かれた典礼であるが、長い間方言礼拝が主流であった非カトリック諸国の言語 で書かれたものも相当数ある。例えば、第二バチカン公会議以降、米国向けに英語で書かれたミサが数多くあり、英国教会向けのミサ(しばしば「聖体拝領」と 呼ばれる)もある。 ミサ曲はアカペラ、つまり独立した伴奏を伴わないこともあれば、フルオーケストラを含む器楽のオブリガートを伴うこともある。多くのミサ曲、特に後期のミ サ曲は、実際の祝典の中で演奏されることを意図していない。 |

Manuscript page with the

five-voice "Kyrie" of the Missa Virgo Parens Christi by Jacques

Barbireau (ca.1420-1491). Early 16th century manuscript (Capp. Sist.

160 fols. 2 verso-3 recto music25 NB.06), now held in the Vatican,

probably produced at the court of Margaret of Austria in Flanders,

dedicated as a gift to Pope Leo X (whose coat of arms is pictured in

the middle of the right-hand page.) Manuscript page with the

five-voice "Kyrie" of the Missa Virgo Parens Christi by Jacques

Barbireau (ca.1420-1491). Early 16th century manuscript (Capp. Sist.

160 fols. 2 verso-3 recto music25 NB.06), now held in the Vatican,

probably produced at the court of Margaret of Austria in Flanders,

dedicated as a gift to Pope Leo X (whose coat of arms is pictured in

the middle of the right-hand page.) |

ジャック・バルビロー(Jacques

Barbireau,

ca.1420-1491)によるミサ「ヴィルゴ・パレンス・クリスティ(Missa Virgo Parens

Christi)」の5声の「キリエ(Kyrie)」の写本ページ。16世紀初頭の写本(Capp. Sist. 160 fols. 2

verso-3 recto music25

NB.06)で、現在はヴァチカンに所蔵されているが、おそらくフランドルのオーストリア王マルガレットの宮廷で制作され、教皇レオ10世(右ページ中央

に紋章が描かれている)への贈り物として捧げられた。 ジャック・バルビロー(Jacques

Barbireau,

ca.1420-1491)によるミサ「ヴィルゴ・パレンス・クリスティ(Missa Virgo Parens

Christi)」の5声の「キリエ(Kyrie)」の写本ページ。16世紀初頭の写本(Capp. Sist. 160 fols. 2

verso-3 recto music25

NB.06)で、現在はヴァチカンに所蔵されているが、おそらくフランドルのオーストリア王マルガレットの宮廷で制作され、教皇レオ10世(右ページ中央

に紋章が描かれている)への贈り物として捧げられた。 |

| History Middle Ages The earliest musical settings of the mass are Gregorian chant. The different portions of the Ordinary came into the liturgy at different times, with the Kyrie probably being first (perhaps as early as the 7th century) and the Credo being last (it did not become part of the Roman mass until 1014).[1] In the early 14th century, composers began writing polyphonic versions of the sections of the Ordinary. The reason for this surge in interest is not known, but it has been suggested that there was a shortage of new music since composers were increasingly attracted to secular music, and overall interest in writing sacred music had entered a period of decline.[2] The non-changing part of the mass, the Ordinary, then would have music which was available for performance all the time. Two manuscripts from the 14th century, the Ivrea Codex and the Apt Codex, are the primary sources for polyphonic settings of the Ordinary. Stylistically, these settings are similar to both motets and secular music of the time, with a three-voice texture dominated by the highest part. Most of this music was written or assembled at the papal court at Avignon. Several anonymous complete masses from the 14th century survive, including the Tournai Mass; however, discrepancies in style indicate that the movements of these masses were written by several composers and later compiled by scribes into a single set. The first complete mass we know of whose composer can be identified was the Messe de Nostre Dame (Mass of Our Lady) by Guillaume de Machaut in the 14th century. Renaissance The musical setting of the Ordinary of the mass was the principal large-scale form of the Renaissance. The earliest complete settings date from the 14th century, with the most famous example being the Messe de Nostre Dame of Guillaume de Machaut. Individual movements of the mass, and especially pairs of movements (such as Gloria–Credo pairs, or Sanctus–Agnus pairs), were commonly composed during the 14th and early 15th centuries. Complete masses by a single composer were the norm by the middle of the 15th century, and the form of the mass, with the possibilities for large-scale structure inherent in its multiple movement format, was the main focus of composers within the area of sacred music; it was not to be eclipsed until the motet and related forms became more popular in the first decades of the 16th century. Most 15th-century masses were based on a cantus firmus, usually from a Gregorian chant, and most commonly put in the tenor voice. The cantus firmus sometimes appeared simultaneously in other voices, using a variety of contrapuntal techniques. Later in the century, composers such as Guillaume Dufay, Johannes Ockeghem, and Jacob Obrecht, used secular tunes for cantus firmi. This practice was accepted with little controversy until prohibited by the Council of Trent in 1562. In particular, the song L'homme armé has a long history with composers; more than 40 separate mass settings exist. Other techniques for organizing the cyclic mass evolved by the beginning of the 16th century, including the paraphrase technique, in which the cantus firmus was elaborated and ornamented, and the parody technique, in which several voices of a polyphonic source, not just one, were incorporated into the texture of the mass. Paraphrase and parody supplanted cantus firmus as the techniques of choice in the 16th century: Palestrina alone wrote 51 parody masses. Yet another technique used to organize the multiple movements of a mass was canon. The earliest masses based entirely on canon are Johannes Ockeghem's Missa prolationum, in which each movement is a prolation canon on a freely-composed tune, and the Missa L'homme armé of Guillaume Faugues, which is also entirely canonic but also uses the famous tune L'homme armé throughout. Pierre de La Rue wrote four separate canonic masses based on plainchant, and one of Josquin des Prez's mature masses, the Missa Ad fugam, is entirely canonic and free of borrowed material.[3] The Missa sine nomine, literally "Mass without a name", refers to a mass written on freely composed material. Sometimes these masses were named for other things, such as Palestrina's famous Missa Papae Marcelli, the Mass of Pope Marcellus, and many times they were canonic masses, as in Josquin's Missa sine nomine. Many famous and influential masses were composed by Josquin des Prez, the single most influential composer of the middle Renaissance. At the end of the 16th century, prominent representatives of a cappella choral counterpoint included the Englishman William Byrd, the Castilian Tomás Luis de Victoria and the Roman Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina, whose Missa Papae Marcelli is sometimes credited with saving polyphony from the censure of the Council of Trent. By the time of Palestrina, however, most composers outside of Rome were using other forms for their primary creative outlet for expression in the realm of sacred music, principally the motet and the madrigale spirituale; composers such as the members of the Venetian School preferred the possibilities inherent in the new forms. Other composers, such as Orlande de Lassus, working in Munich and comfortably distant from the conservative influence of the Council of Trent, continued to write parody masses on secular songs. Monteverdi composed masses in stile antico, the Missa in illo tempore was published in 1610, one Messa a 4 da cappella in 1641 as part of Selva morale e spirituale along with single movements of the mass in stile concertato, another Messa a 4 da cappella was published after his death, in 1650. Antoine Brumel composed a Missa Et ecce terrae motus with the employment of twelve voices, Stefano Bernardi created masses for double choir for the balconies of the Salzburg Cathedral, such as the 1630 Missa primi toni octo vocum, when he was music director of the new building. Baroque to Romantic (Catholic and Lutheran traditions) The early Baroque era initiated stylistic changes which led to increasing disparity between masses written entirely in the traditional polyphonic manner (stile antico), whose principal advancements were the use of the basso continuo and the gradual adoption of a wider harmonic vocabulary, and the mass in modern style with solo voices and instrumental obbligatos. The Lutheran Michael Praetorius composed a mass for double choir in the old style, which he published in 1611 in the collection of church music for the mass in Latin, Missodia Sionia. Composers such as Henri Dumont (1610–1684) continued to compose plainsong settings, distinct from and more elaborate than the earlier Gregorian chants.[4] A further disparity arose between the festive missa solemnis and the missa brevis, a more compact setting. Composers like Johann Joseph Fux in the 18th century continued to cultivate the stile antico mass, which was suitable for use on weekdays and at times when orchestral masses were not practical or appropriate, and in 19th-century Germany the Cecilian movement kept the tradition alive. František Brixi, who worked at the Prague Cathedral, wrote his Missa aulica, a missa brevis in C, for four voices, trumpets, violin and continuo, "cantabile" but solo voices just singing short passages within chorale movements. The Italian style cultivated orchestral masses including soloists, chorus and obbligato instruments. It spread to the German-speaking Catholic countries north of the Alps, using instruments for color and creating dialogues between solo voices and chorus that was to become characteristic of the 18th-century Viennese style. The so-called "Neapolitan" or "cantata" mass style also had much influence on 18th-century mass composition, with its short sections set as self-contained solo arias and choruses in a variety of styles.[5] The 18th-century Viennese mass combines operatic elements from the cantata mass with a trend in the symphony and concerto to organize choral movements. The large scale masses of the first half of the century still have Glorias and Credos divided into many movements, unlike smaller masses for ordinary churches. Many of Mozart's masses are in missa brevis form, as are some of Haydn's early ones. Later masses, especially of Haydn, are of symphonic structure, with long sections divided into fewer movements, organized like a symphony, with soloists used as an ensemble rather than as individuals. The distinction between concert masses and those intended for liturgical use also came into play as the 19th century progressed.[5] After the Renaissance, the mass tended not to be the central genre for any one composer, yet among the most famous works of the Baroque, Classical, and Romantic periods are settings of the Ordinary of the Mass. Many of the famous masses of the Romantic era were Requiems, one of the most famous, A German Requiem by Brahms, being the composer's own selection of biblical texts rather than a setting of a standard liturgy. 20th and 21st century By the end of the 19th century, composers were combining modern elements with the characteristics of Renaissance polyphony and plainchant, which continued to influence 20th-century composers, possibly fueled by the motu proprio Tra le sollecitudini (1903) of Pope Pius X. The revival of choral celebration of Holy Communion in the Anglican Church in the late 19th century marked the beginning several liturgical settings of mass texts in English, particularly for choir and organ.[6] The movement for liturgical reform has resulted in revised forms of the mass, making it more functional by using a variety of accessible styles, popular or ethnic, and using new methods such as refrain and response to encourage congregational involvement.[6] Nevertheless, the mass in its musical incarnation continues to thrive beyond the walls of the church, as is evident in many of the 21st-century masses listed here which were composed for concert performance rather than in service of the Roman Rite.[citation needed] Musical reforms of Pius X Pope Pius X initiated many regulations reforming the liturgical music of the mass in the early 20th century. He felt that some of the masses composed by the famous post-Renaissance composers were too long and often more appropriate for a theatrical rather than a church setting. He advocated primarily Gregorian plainchant and polyphony. He was primarily influenced by the work of the Abbey of Solesmes. Some of the rules he put forth include the following:[7] That any mass be composed in an integrated fashion, not by assembling different compositions for different parts. That all percussive instruments should be forbidden. That the piano be explicitly forbidden. That the centuries' old practice of alternatim between choir and organ be concluded immediately. That women must not be present in the choir. These regulations carry little if any weight today, especially after the changes of the Second Vatican Council. Quite recently, Pope Benedict XVI has encouraged a return to chant as the primary music of the liturgy, as this is explicitly mentioned in the documents of the Second Vatican Council, specifically Sacrosanctum Concilium 116.[8] |

歴史 中世 ミサの最も古い音楽はグレゴリオ聖歌である。普通歌のさまざまな部分が典礼に取り入れられた時期はそれぞれ異なり、おそらくキリエが最初(おそらく7世紀 ごろ)で、クレドが最後(ローマ・ミサの一部となったのは1014年)であった[1]。 14世紀初頭には、作曲家たちが普通曲の各セクションのポリフォニック版を書き始めた。このような関心の高まりの理由は定かではないが、作曲家たちが世俗 音楽にますます惹かれるようになり、聖楽の作曲に対する全体的な関心が衰退期に入っていたため、新しい音楽が不足していたことが示唆されている[2]。 14世紀の2つの写本、イヴレア写本(Ivrea Codex)とアプト写本(Apt Codex)は、普通部のポリフォニック・セッティングの主要な資料である。様式的には、当時のモテットや世俗音楽と類似しており、3声のテクスチュアが 最高部を支配している。これらの曲のほとんどは、アヴィニョンの法王庁で書かれたか、あるいは集められたものである。 14世紀に書かれたミサ曲は、トゥルネーのミサ曲をはじめ、いくつかの匿名のミサ曲全集が残されているが、スタイルの相違から、これらのミサ曲の楽章は複 数の作曲家によって書かれ、後に書記によって1つのセットにまとめられたと考えられている。作曲者が特定できる最初のミサ曲は、14世紀のギョーム・ド・ マショーによる「聖母のミサ」(Messe de Nostre Dame)である。 ルネサンス ミサ典礼の楽典は、ルネサンス期の主要な大規模形式であった。最も古い ものは14世紀のもので、ギョーム・ド・マショー(Guillaume de Machaut)の「ノストル・ダム(Messe de Nostre Dame)」が有名である。ミサ曲の個々の楽章、特に楽章のペア(グローリアとクレドのペアやサンクトゥスとアグヌスのペアなど)は、14世紀か ら15世 紀初頭にかけてよく作曲された。15世紀半ばには、一人の作曲家によるミサ曲全集が主流となり、ミサ曲の形式は、その複数の楽章からなる形式に内在する大 規模な構成の可能性とともに、聖楽分野の作曲家たちの主な焦点となった。 15世紀のミサ曲のほとんどは、カントゥス・ファルムス(通常はグレゴリオ聖歌のカントゥス・ファルムス)に基づいており、テノール声で歌われるのが一般 的であった。カントゥス・ファルモゥスは、様々なコントラプンタルの技法を用いて、他の声部で同時に現れることもあった。世紀後半には、ギヨーム・デュ ファイ、ヨハネス・オッケヘム、ヤコブ・オブレヒトといった作曲家たちが、カントゥス・ファルミに世俗の曲を用いた。1562年にトレント公会議によって 禁止されるまで、この慣習はほとんど論争なく受け入れられていた。特にL'homme arméは作曲家たちの間で長い歴史を持ち、40以上のミサ曲が存在する。 16世紀初頭には、カントゥス・ファルムスを精巧に装飾するパラフレーズ技法や、ポリフォニックな音源の1声だけでなく複数の声部をミサのテクスチュアに 取り入れるパロディ技法など、循環ミサを構成する他の技法も発展した。パラフレーズとパロディは、16世紀にはカントゥス・ファルムスに取って代わる技法 となった: パレストリーナだけでも51曲のパロディ・ミサを作曲している。 パレストリーナだけでも51のパロディ・ミサ曲を書いている。ミサ曲の複数の楽章を構成するために使われたもうひとつの技法がカノンである。カノンに基づ く最も初期のミサ曲は、ヨハネス・オッケヘムの『ミサ・プロラショナム』(Missa prolationum)で、各楽章は自由に作曲された曲によるプロラショナルのカノンであり、ギョーム・フォーグの『ミサ・アルメ』(Missa L'homme armé)もカノンに基づくものだが、有名な曲『アルメ』(L'homme armé)を全曲に用いている。ピエール・ド・ラ・リューは、平叙歌に基づく4つの独立したカノン的ミサ曲を書き、ジョスカン・デ・プレの成熟したミサ曲 のひとつである『ミサ・アド・フーガム』は、完全にカノン的で、借用物はない[3]。 ミサ・シネ・ノミネ(Missa sine nomine)は、文字通り「名前のないミサ曲」で、自由に作曲された素材を使って書かれたミサ曲を指す。パレストリーナの有名なミサ曲「教皇マルセルス のミサ」(Missa Papae Marcelli)のように、これらのミサ曲に別の名前が付けられることもあれば、ジョスカンのミサ曲「ミサ・シネ・ノミネ」(Missa sine nomine)のように典雅なミサ曲であることも多い。 中世ルネサンスで最も影響力のあった作曲家ジョスカン・デ・プレは、多くの有名で影響力のあるミサ曲を作曲した。16世紀末、アカペラの対位法を代表する 作曲家として、イギリス人のウィリアム・バード、カスティーリャ人のトマス・ルイス・デ・ヴィクトリア、ローマ人のジョヴァンニ・ピエルルイージ・ダ・パ レストリーナが挙げられる。しかし、パレストリーナの時代には、ローマ以外のほとんどの作曲家たちは、モテットやマドリガーレ・スピリチュアルを中心に、 聖楽の領域における創作の主要な表現手段として他の形式を用いるようになっていた。オルランド・ド・ラッススのように、トレント公会議の保守的な影響から 距離を置いてミュンヘンで活動していた作曲家たちは、世俗の歌曲をパロディ化したミサ曲を書き続けた。モンテヴェルディはアンコ調のミサ曲を作曲し、 1610年には「Missa in illo tempore」が、1641年には「Selva morale e spirituale」の一部として「Messa a 4 da cappella」が、コンチェルト調のミサ曲の単一楽章とともに出版された。 アントワーヌ・ブリュメルは、12声部を用いたミサEt ecce terrae motusを作曲し、ステファノ・ベルナルディは、ザルツブルク大聖堂のバルコニーのための二重合唱のためのミサ曲を創作した。 バロックからロマン派へ(カトリックとルター派の伝統) バロック時代初期には、伝統的なポリフォニックな手法(スティレ・アンティコ)で書かれたミサ曲と、独唱と楽器のオブリガートによる近代的なスタイルのミ サ曲との間に、ますます大きな格差が生じるようになった。ルター派のミヒャエル・プレトリウスは、1611年にラテン語のミサ曲集『Missodia Sionia』に掲載された、古いスタイルの二重合唱のためのミサ曲を作曲した。アンリ・デュモン(Henri Dumont, 1610-1684)のような作曲家たちは、初期のグレゴリオ聖歌とは異なる、より精巧な平聖歌を作曲し続けた[4]。 さらに、祝祭的なミサ・ソレムニスと、よりコンパクトなミサ・ブレヴィスとの間に格差が生じた。18世紀のヨハン・ヨーゼフ・フックスのような作曲家たち は、平日やオーケストラ・ミサが実用的でない時や適切でない時に適したスティレ・アンティコのミサ曲を作り続け、19世紀のドイツではセシリア運動がその 伝統を守り続けた。プラハ大聖堂に勤務していたフランティシェク・ブリクシは、4声、トランペット、ヴァイオリンと通奏低音のためのミサ・アウリカ (Missa aulica)をハ調で作曲した。イタリア様式は、ソリスト、合唱、オブリガート楽器を含むオーケストラ・ミサを発展させた。アルプス以北のドイツ語圏の カトリック諸国に広まり、色彩のために楽器を用い、独唱と合唱の対話が生まれた。いわゆる「ナポリ風」あるいは「カンタータ」と呼ばれるミサ曲のスタイル も、18世紀のミサ曲に大きな影響を与えた。 18世紀のウィーンのミサ曲は、カンタータ・ミサ曲のオペラ的な要素と、交響曲や協奏曲の合唱楽章を組織する傾向を組み合わせたものである。世紀前半の大 規模なミサ曲は、一般教会用の小規模なミサ曲とは異なり、多くの楽章に分割されたグローリアとクレドを持っている。モーツァルトのミサ曲の多くはミサ・ブ レヴィス形式であり、ハイドンの初期のミサ曲も同様である。後期のミサ曲、特にハイドンのミサ曲は、交響曲のような構造で、長い部分がより少ない楽章に分 割され、交響曲のように編成され、ソリストは個人ではなくアンサンブルとして使われる。演奏会用ミサ曲と典礼用ミサ曲の区別は、19世紀が進むにつれて行 われるようになった[5]。 ルネサンス以降、ミサ曲はどの作曲家にとっても中心的なジャンルではなくなる傾向があったが、バロック、古典派、ロマン派の最も有名な作品の中には、ミサ 曲の「普通曲」の設定がある。ロマン派の有名なミサ曲の多くはレクイエムであり、最も有名なブラームスの「ドイツ・レクイエム」は、標準的な典礼の設定で はなく、聖書のテキストを作曲者自身が選んだものである。 20世紀と21世紀 19世紀末には、作曲家たちは近代的な要素とルネサンス時代のポリフォニーやプレーンチャントの特徴を融合させるようになった。 [6]典礼改革の動きは、ミサの改訂をもたらし、ポピュラーまたは民族的な様々な親しみやすい様式を用いることによって、ミサをより機能的なものにし、信 徒の参加を促すためにリフレインやレスポンスなどの新しい方法を用いた[6]。それにもかかわらず、ここに挙げた21世紀のミサの多くがローマ典礼の奉仕 のためではなく、コンサート演奏のために作曲されたことからも明らかなように、ミサはその音楽的化身として教会の壁を越えて繁栄し続けている[要出典]。 ピウス10世の音楽改革 教皇ピウス10世は、20世紀初頭にミサの典礼音楽を改革する多くの規則を制定した。ピウス10世は、ルネサンス以後の有名な作曲家たちが作曲したミサ曲 は長すぎ、教会というよりむしろ劇場にふさわしいと考えた。彼は主にグレゴリオ平叙歌とポリフォニーを提唱した。彼は主にソレスム修道院の作品に影響を受 けた。彼が打ち出した規則には次のようなものがある[7]。 あらゆるミサ曲は、パートごとに異なる曲を組み合わせるのではなく、統合された形で作曲されること。 すべての打楽器を禁止すること。 ピアノを明確に禁止すること。 聖歌隊とオルガンが交互に演奏するという、何世紀にもわたって行われてきた慣習を直ちに廃止すること。 合唱団に女性は入ってはならない。 これらの規定は、特に第二バチカン公会議による変更後の今日、ほとんど重みを持たない。ごく最近、教皇ベネディクト16世は、典礼の主要な音楽として聖歌 への回帰を奨励している。これは、第二バチカン公会議の文書、特にサクロサンクトゥム・コンシリウム116に明確に言及されているからである[8]。 |

| Major works Post-Renaissance Messa Concertata by Cavalli (1656) Mass for double choir, from Missodia Sionia, by Michael Praetorius (1611) 12 masses by Marc-Antoine Charpentier (including 3 Requiem + H.12, H.311), H.1, H.2, H.3, H.4, H.5, H.6, H.7, H.8, H.9, H.10, H.11, H.513. Missa Scala Aretina by Francesc Valls (Barcelona, 1702) Mass in B minor and four Missae by Johann Sebastian Bach High Masses by Jan Dismas Zelenka Requiem by Jean Gilles Mass for double choir and double orchestra by Henri Desmarets Requiem by André Campra 1723 Requiem by François-Joseph Gossec 1760 18 masses by W. A. Mozart, including the Great Mass in C minor (1782) and Requiem (1791) 14 masses by Joseph Haydn, including Nelson Mass and Mass in Time of War Mass in C major and Missa Solemnis in D major by Ludwig van Beethoven Mass in G major and 5 others by Franz Schubert Missa Choralis and Hungarian Coronation Mass by Franz Liszt Requiem by Hector Berlioz (1837) A German Requiem by Johannes Brahms (1868) Mass in D minor, Mass in E minor and Mass in F minor by Anton Bruckner Requiem by Camille Saint-Saëns 1878 St. Cecilia Mass and 13 others by Charles Gounod Messa by Giacomo Puccini Petite messe solennelle (1863) by Gioachino Rossini Mass in D minor, op. 10 (1866) by John Knowles Paine Requiem by Gabriel Fauré Requiem by Giuseppe Verdi Mass in E♭, Op. 5 (1886) by Amy Beach Requiem in B-flat minor (1890) by Antonín Dvořák Mass in D major, Op. 86 (1887) by Antonín Dvořák Mass in D by Ethel Smyth (1891) 20th century Requiem Mass by Herbert Howells Requiem by Maurice Duruflé Mass in G by Francis Poulenc Messe Solennelle by Jean Langlais Glagolitic Mass (1926) by Leoš Janáček Messe modale en septuor (1938) for soprano, alto, flute and string quartet by Jehan Alain Mass in G minor by Ralph Vaughan Williams Mass, Op. 130 (1945) for choir and brass by Joseph Jongen Requiem by Bruno Maderna (1946) Mass by Igor Stravinsky Mass by Leonard Bernstein[9] Bộ lễ Seraphim (1960) by Paul Nguyễn Văn Hoà War Requiem (1962) by Benjamin Britten Mass for mixed chorus (1963) by Paul Hindemith Requiem, for soprano and mezzo-soprano solo, mixed chorus and orchestra (1963–65) by György Ligeti Missa supra Parsifal (1985) by Dimitri Aguero[10] Requiem (1990), Mass of the Children (2004), and Gloria by John Rutter Requiem by Andrew Lloyd Webber Mass in F minor by The Electric Prunes Mass by David Maslanka Mass Of The Sea, Op. 47 by Paul Patterson Berliner Messe and Missa Syllabica by Arvo Pärt Mass by Frank Martin A Symphonic Mass by George Lloyd Missa Laudate Pueri by Bertold Hummel[11] At Grace Cathedral, jazz mass by Vince Guaraldi Mass To Hope by Dave Brubeck Misa Criolla by Ariel Ramírez Misa by Rodrigo Prats New Plainsong Mass by David Hurd Mass in Honor of St. Cecilia by Lou Harrison African Sanctus by David Fanshawe Polish Requiem by Krzysztof Penderecki Missa Luba by Guido Haazen "Misatango" o "Misa a Buenos Aires" by Martín Palmieri (1996) 21st century Missa Latina: pro Pace by Roberto Sierra Missa pro Pace (Mass for Peace) by Kentaro Sato The Armed Man: A Mass for Peace by Karl Jenkins Son of God Mass by James Whitbourn Missa Carolae (Mass from Christmas Carols) by James Whitbourn Bright Mass with Canons by Nico Muhly Misa Flamenca by Paco Peña Mass (2000) by James MacMillan Misa de San Isidro (2001) by Dieter Lehnhoff Requiem (2001–2002) by Christopher Rouse Missa Brevis by Douglas Knehans Missa Concertante (2008) by Marcus Paus Messe brève: "Acclamez le Seigneur!", in French for choir and organ ( 2011) by Jean Huot;[12] Street Requiem (for those who have died on the street) for choir and orchestra by Kathleen McGuire, Jonathon Welch and Andy Payne (2014) [13] Messe de la Miséricorde divine, in French for choir and organ (2015) by Jean Huot;[14] Missa Papae Francisci (2015) by Ennio Morricone[15] Mass of Innocence and Experience for SATB and organ (2006) by Stephen Hough Missa Mirabilis for SATB and organ or orchestra (2007) by Stephen Hough Sunrise Mass for SATB and strings by Ola Gjeilo Mass in Blue (2003) by Will Todd (Jazz/Blues style) Jazz Missa Brevis (2015) by Will Todd (Jazz style) |

主要作品 ルネサンス後期 カヴァッリ『コンチェルタータ・ミサ』(1656年) ミヒャエル・プレトリウス『ミソディア・シオニア』より二重合唱ミサ(1611年) マルク=アントワーヌ・シャルパンティエの12のミサ曲(3つのレクイエム、H.12、H.311を含む)、H.1、H.2、H.3、H.4、H.5、H.6、H.7、H.8、H.9、H.10、H.11、H.513。 フランセスク・ヴァルス作曲「ミサ・スカラ・アレティーナ」(1702年、バルセロナ) ヨハン・セバスチャン・バッハ作曲「ロ短調ミサ」および4つのミサ ヤン・ディスマス・ゼレンカ作曲「高ミサ ジャン・ジル作曲「レクイエム アンリ・デスマレ作曲「二重合唱と二重オーケストラのためのミサ アンドレ・カンプラ作曲「レクイエム」(1723年 フランソワ=ジョセフ・ゴセックのレクイエム(1760年 W. A. モーツァルトの18のミサ曲、C 短調のミサ曲(1782年)およびレクイエム(1791年)を含む ヨーゼフ・ハイドンの14のミサ曲、ネルソンミサおよび戦時ミサを含む ルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンのハ長調のミサ曲およびニ長調のミサ・ソレムニス フランツ・シューベルトのト長調のミサ曲およびその他5曲 フランツ・リストのミサ・コラリスとハンガリー戴冠ミサ エクトール・ベルリオーズのレクイエム(1837年) ヨハネス・ブラームスのドイツレクイエム(1868年) アントン・ブルックナーのニ短調ミサ、ホ短調ミサ、ヘ短調ミサ カミーユ・サン=サーンスのレクイエム(1878年) シャルル・グノーの聖セシリアミサとその他13曲 ジャコモ・プッチーニのミサ ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニの小さな荘厳ミサ(1863年) ジョン・ノウルズ・ペインのニ短調ミサ曲作品10(1866年) ガブリエル・フォーレのレクイエム ジュゼッペ・ヴェルディのレクイエム エイミー・ビーチの変ホ長調ミサ曲作品5(1886年) ドヴォルザークの変ロ短調レクイエム(1890年) ドヴォルザークのニ長調ミサ曲作品86(1887年) エセル・スミスのニ長調ミサ曲(1891年) 20世紀 ハーバート・ハウエルズのレクイエムミサ モーリス・デュリュフレのレクイエム フランシス・プーランクのト長調ミサ曲 ジャン・ラングレの荘厳ミサ曲 レオシュ・ヤナーチェクのグラゴリツァ語ミサ曲(1926年) ジェハン・アランのソプラノ、アルト、フルート、弦楽四重奏のためのモードミサ曲(1938年) ラルフ・ヴォーン・ウィリアムズのト短調ミサ曲 ジョゼフ・ジョンゲンの合唱と金管楽器のためのミサ曲作品130(1945年) ブルーノ・マデルナ『レクイエム』(1946年) イゴール・ストラヴィンスキー『ミサ曲』 レナード・バーンスタイン『ミサ曲』[9] ポール・グエン・ヴァン・ホア『セラフィム祭典』(1960年) ベンジャミン・ブリテン『戦争レクイエム』(1962年) パウル・ヒンデミット『混声合唱のためのミサ曲』(1963年) リゲティのソプラノとメゾソプラノの独唱、混声合唱、オーケストラのためのレクイエム(1963年~1965年 ディミトリ・アグエロのミサ・スパ・パルジファル(1985年 ジョン・ラッターのレクイエム(1990年)、子供たちのミサ(2004年)、グロリア アンドルー・ロイド・ウェバーのレクイエム エレクトリック・プルーンズによる F 短調ミサ デイヴィッド・マスランカによるミサ ポール・パターソンによる海のミサ、作品 47 アルヴォ・ペルトによるベルリンのミサとミサ・シラビカ フランク・マーティンによるミサ ジョージ・ロイドによる交響曲ミサ ベルトルト・フンメルによるミサ・ラウダテ・プエリ[11] グレース大聖堂での、ヴィンス・ガラルディによるジャズミサ デイヴ・ブルーベックの「希望へのミサ アリエル・ラミレスの「ミサ・クリオージャ ロドリゴ・プラッツの「ミサ デイヴィッド・ハードの「ニュー・プレインソング・ミサ ルー・ハリソンの「聖セシリアを称えるミサ デイヴィッド・ファンショーの「アフリカの聖歌 クシシュトフ・ペンデレツキの「ポーランドのレクイエム グイド・ハーゼンの「ミサ・ルバ マルティン・パルミエリの「ミサタンゴ」または「ミサ・ア・ブエノスアイレス (1996) 21世紀 ミサ・ラティーナ:プロ・ペース(平和のためのミサ) ロベルト・シエラ ミサ・プロ・ペース(平和のためのミサ) 佐藤健太郎 武装した男:平和のためのミサ カール・ジェンキンズ 神の子ミサ ジェームズ・ウィットボーン ミサ・カロラエ(クリスマスキャロルのミサ) ジェームズ・ウィットボーン ブライト・ミサ・ウィズ・キャノンズ ニコ・ムリー ミサ・フラメンカ パコ・ペーニャ ジェームズ・マクミランのミサ(2000年 ディーター・レーンホフのミサ・デ・サン・イシドロ(2001年 クリストファー・ラウスのレクイエム(2001年~2002年 ダグラス・クネハンスのミサ・ブレヴィス マーカス・パウスのミサ・コンチェルタンテ(2008年 ジャン・ウー作『短いミサ曲:「主を賛美せよ!」』(2011年、フランス語、合唱とオルガンのための)[12] キャスリーン・マクガイア、ジョナサン・ウェルチ、アンディ・ペイン共作『ストリート・レクイエム(路上で亡くなった者たちのための)』(2014年、合唱とオーケストラのための) [13] ジャン・ウー作『神の慈悲のミサ』(フランス語、合唱とオルガン用、2015年);[14] エンニオ・モリコーネ作『教皇フランシスコのミサ』(2015年)[15] スティーヴン・ホウ作『無垢と経験のミサ』(SATBとオルガン用、2006年) スティーヴン・ホウグ作曲『驚異のミサ』(SATBとオルガンまたはオーケストラ用、2007年) オラ・イェイロ作曲『日の出ミサ』(SATBと弦楽合奏用) ウィル・トッド作曲『青のミサ』(ジャズ/ブルース様式、2003年) ウィル・トッド作曲『ジャズ・ミサ・ブレヴィス』(ジャズ様式、2015年) |

| Masses written for the Anglican

liturgy These are more often known as 'Communion Services', and differ not only in that they are settings of English words,[9] but also, as mentioned above, in that the Gloria usually forms the last movement. Sometimes the Kyrie movement takes the form of sung responses to the Ten Commandments, 1 to 9 being followed by the words 'Lord have mercy upon us and incline our hearts to keep this law', and the tenth by 'Lord have mercy upon us and write all these thy laws in our hearts, we beseech thee'. Since the texts of the 'Benedictus qui venit' and the 'Agnus Dei' do not actually feature in the liturgy of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, these movements are often missing from some of the earlier Anglican settings. Charles Villiers Stanford composed a Benedictus and Agnus in the key of F major which was published separately to complete his service in C. With reforms in the Anglican liturgy, the movements are now usually sung in the same order that they are in the Roman Catholic rite. Choral settings of the Creed, the most substantial movement, are nowadays rarely performed in Anglican cathedrals.[citation needed] Well known Anglican settings of the mass, which may be found in the repertoire of many English cathedrals are: Darke in F Darke in E Darke in A minor Ireland in C Stanford in C & F Stanford in B flat Stanford in A Sumsion in F Oldroyd, Mass of the Quiet Hour Jackson in G Howells, Collegium Regale Leighton in D Harwood in A flat Wood in the Phrygian mode |

英国国教会の典礼用に書かれたミサ曲 これらはより一般的に「聖餐式」として知られており、英語の歌詞を用いた編曲である点[9]だけでなく、前述の通り、通常はグロリアが最終楽章を構成する 点でも異なる。時にはキリエの楽章が十戒への応答歌の形を取る。1から9の戒めには「主よ、私たちに憐れみを与え、この律法を守るよう私たちの心を傾けて ください」という言葉が続き、10番目の戒めには「主よ、私たちに憐れみを与え、これらのあなたの律法を私たちの心に書き記してください、私たちは懇願し ます」という言葉が続く。『ベネディクトゥス・クイ・ヴェニト』と『アグヌス・デイ』のテキストは、1662年版『共通祈祷書』の典礼には実際に出てこな いため、これらの楽章は初期の英国国教会の編曲ではしばしば省略される。チャールズ・ヴィリアーズ・スタンフォードは、自身のC調の礼拝曲集を完成させる ため、F長調のベネディクトゥスとアグヌスを別冊で出版した。 英国国教会の典礼改革により、現在ではこれらの楽章は通常、ローマ・カトリックの典礼と同じ順序で歌われる。信条(クレド)の合唱編曲は最も大規模な楽章 だが、現代の英国国教会大聖堂ではほとんど演奏されない。[出典が必要] 多くの英国の大聖堂で演奏される、よく知られた英国国教会のミサ曲は以下の通りである: ダーク(F調) ダーク(E調) ダーク(A短調) アイルランド(C調) スタンフォード(C調及びF調) スタンフォード(Bフラット調) スタンフォード(A調) サムシオン(F調) オールドロイド『静寂の時のミサ』 ジャクソン(G調) ハウエルズ『コレギウム・レガレ』 レイトン(D調) ハーウッド(Aフラット調) ウッド(フリジアン調) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_(music) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mass_(music) | |

| Alternatim refers

to a technique of liturgical musical performance, especially in

relationship to the Organ Mass, but also to the Hymns, Magnificat and

Salve regina traditionally incorporated into the Vespers and other

liturgies of the Catholic Church. A specific part of the ordinary of

the Mass (such as the Kyrie and the Gloria) would be divided into

versets. Each verset would be performed antiphonally by two groups of

singers, giving rise to polyphonic settings of half of the text. One of

these groups may alternatively have consisted of a soloist, a group of

instruments, or organ. The missing even- or odd-numbered verses were

supplied by plainchant or, perhaps more commonly (to judge by the organ

masses of Hans Buchner), by improvisations on the organ.[1] The verso

became a particularly prevalent genre in Renaissance and Baroque organ

music, both Italian and Iberian, and most of the French classical organ

literature consists of alternatim versets. A large amount of musical repertoire was specifically written for alternatim performance, with Heinrich Isaac and Charles Justin (1830–1873) as notable composers. Alternatim performance of the Mass was common throughout Europe in the seventeenth, eighteenth, and nineteenth centuries. A similar tradition of alternatim performance existed for example also for Magnificat compositions. Documentation in England is rather slight. The organ involved seems to have been a man-portable instrument, of 1 or so speaking ranks. There is no evidence for the use, in alternatim, of the larger "standing" (on a loft or platform) organ of the English Cathedral. In the Catholic church, the practice was banned by Pope Pius X in his 1903 Motu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini.[2] The practice did, however, inform the works of Olivier Messiaen, who wrote pseudo-versets for his many liturgical organ works, especially his Messe de la Pentecôte (1950). |

オルタナティム(Alternatim)

とは、典礼音楽の演奏技法のひとつで、特にオルガン・ミサに関係するものだが、カトリック教会のヴェスペルやその他の典礼に伝統的に取り入れられている賛

美歌、マニフィカト、サルヴェ・レジーナも含まれる。ミサ典礼の特定の部分(キリエやグローリアなど)は、ヴァーセットに分けられる。それぞれのヴァー

セットは、2つの歌い手グループによって対位法的に演奏され、テキストの半分をポリフォニックに歌うことになる。これらのグループのうち1つは、ソリス

ト、楽器のグループ、またはオルガンで構成されていたかもしれない。ヴェルソは、ルネサンスとバロックのオルガン音楽(イタリアとイベリア)において、特

によく使われたジャンルであり、フランス古典オルガンの文献のほとんどは、オルタンタイム・ヴェルセットで構成されている。 オルタナティムのために書かれたレパートリーも多く、ハインリヒ・イサークやシャルル・ユスティン(1830-1873)はその代表的な作曲家である。ミ サ曲のオルタナティム演奏は、17、18、19世紀のヨーロッパ全土で一般的だった。例えば、マニフィカトの作曲にも同様の伝統があった。 イギリスでの資料は少ない。関係するオルガンは、人が持ち運び可能な楽器で、1つほどのスピーキング・ランクだったと思われる。イギリスの大聖堂で、より 大きな「スタンディング」(ロフトや台の上)のオルガンがオルタナティムで使われた形跡はない。 カトリック教会では、教皇ピウス10世が1903年のMotu proprio Tra le Sollecitudini[2]でこの慣習を禁止した。しかし、この慣習はオリヴィエ・メシアンの作品に影響を与え、彼は多くの典礼オルガン作品、特に 彼のMesse de la Pentecôte(1950年)のために擬似ヴァーセットを書いた |

++++

| ミサ曲(ミサきょく)は、カトリック教会のミサ(感謝の祭儀)に伴う声楽曲。 カトリック教会においては、聖体拝領を伴うミサは、教会の典礼儀式の中で最も重要なものである。典礼文の歌唱は、東西分裂前に発する伝統を有する(ただ し、こんにちの東方教会の奉神礼で用いられる形式・祈祷文は、西方教会各教派のものとは大きく異なる)。正教会の聖体礼儀に対して「ミサ」の語が誤用され る場合があるが、正教会自身が「ミサ」との呼称を聖体礼儀に対して用いる事はない[1]。 ミサの典礼文には、固有文(proprium)と通常文(ordinarium)があり、固有文はミサの行われる日によって扱われる文が異なるが、ミサ曲 は基本的に通常文をテキストとしているため、作曲された時代背景が異なっても、歌詞そのものは一定である。 西方教会においてはグレゴリウス1世の頃より典礼の形式が整備され、最初期のミサにおいては、典礼文はグレゴリオ聖歌や単声による朗唱方式によって歌われ た。 これらが音楽的な基盤となり、多声によるミサ曲が書かれるようになった。複数の音楽家がミサの各章ごとに付曲していたが、のちに一人の音楽家が全曲を扱う ようになった。全曲を通じて一人の音楽家によって作曲されたミサ曲は、14世紀、ギヨーム・ド・マショーの『ノートルダム・ミサ曲』が最初のものといわれ る。さらに、声楽に加えて器楽も付加されるようになり、大規模化された。19世紀、ベートーヴェンの頃には、宗教音楽の域を超えた演奏会用の作品としての 位置づけも持つようになった。 現代では、ルネサンス期のものとして、ギヨーム・デュファイ、ヨハネス・オケゲム、ジョスカン・デ・プレ、ジョヴァンニ・ダ・パレストリーナなど、バロッ ク期では、マルカントワーヌ・シャルパンティエの作品や、ヨハン・ゼバスティアン・バッハのロ短調のミサ曲、古典派では、ヴォルフガング・アマデウス・ モーツァルトの作品やルートヴィヒ・ヴァン・ベートーヴェンのミサ・ソレムニス、ロマン派ではルイジ・ケルビーニ、ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニ、フランツ・ シューベルト、アントン・ブルックナーの作品などが有名である。また、日本の作曲家の作品としては、三枝成彰や佐藤賢太郎のものが挙げられる。 |

|

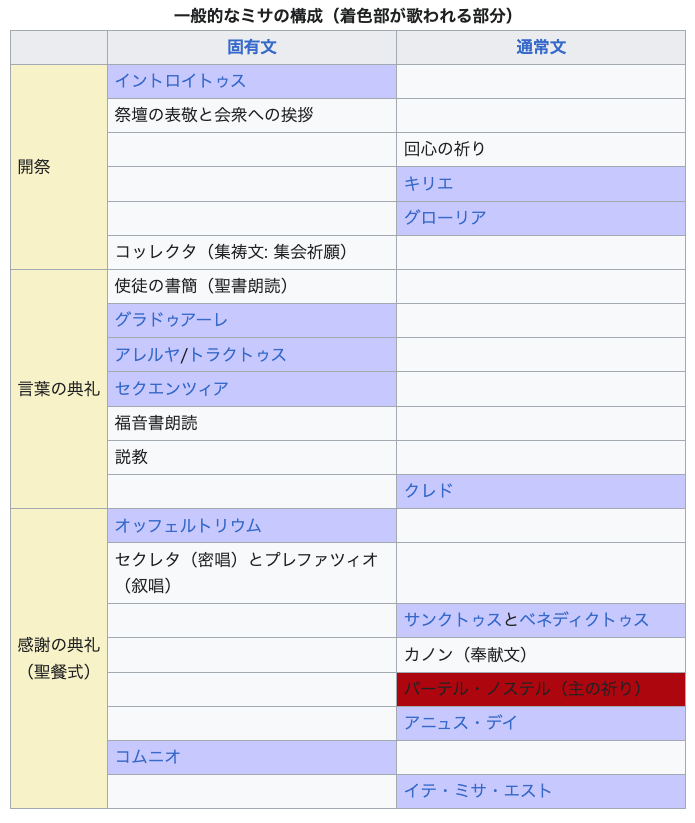

一般的な

ミサの構成(着色部が歌われる箇所):図をクリックすると単体で拡大します。 |

|

| ミサ曲の構成 ミサ曲の基本的な構成要素は、一般的に、『キリエ』(求憐誦)、『グローリア』(栄光頌、天には神に栄光)、『クレド』(信経、信仰宣言)、『サンクトゥ ス』(三聖頌、感謝の賛歌)、『アニュス・デイ』(神羔頌、神の小羊)の5曲である。これらはみな通常文といい、どのような場合にも必ず同じ典礼文を用い る。これら5曲をすべて備えたものを通作ミサ曲と呼ぶ[2]。これに対し、『クレド』(信経、信仰宣言)を含まないものをミサ・ブレヴィス(小ミサ)と呼 ぶ[2]。ルーテル派では『キリエ』と『グローリア』のみで構成されるものをミサ・ブレヴィスとした[2]。中世では、この他に『イテ・ミサ・エスト』 (終わりの言葉、ミサの散会)も作曲された例があるが(例えばギョーム・ド・マショー)、一般には『キリエ』の旋律を当てはめていた。 ミサで歌われるものには、この基本要素に、入祭唱(イントロイトゥス)、昇階唱(グラドゥアーレ)、アレルヤ唱、続唱(セクエンツィア)、奉献唱(オッ フェルトリウム)、聖体拝領誦(コンムニオ)などの固有文が加わる。固有文は、例えば祭日や死者ミサなど、時と場合によってその構成が異なる(死者ミサに ついてはレクイエムの項を参照)。ミサ曲の作曲は、どのミサでも歌われる通常文に対して行われるのが普通で、固有文はグレゴリオ聖歌を使用する場合が多 い。年間に用いられる全ての固有文(ただしオッフェルトリウムを除く)に作曲した例はハインリヒ・イザークの3巻の「コラーリス・コンスタンティヌス」 (未完/ゼンフル補筆)が存在するのみである。続唱は中世後期からルネサンス期初頭にかけて発達したが、1545年から1563年にかけて開かれたトリエ ント公会議で大幅に整理された。 |

|

| 通常文(ordinarium) 通常文の全文(キリエはギリシア語、ほかは、ラテン語による)と、その概要は次のとおり。 キリエ (Kyrie) Kyrie eleison. Christe eleison. Kyrie eleison. 「キリエ」は「主よ憐れみたまえ」という意味のギリシャ語 "Κυριε ελεησον" から来ている。キリエ参照。 グローリア (Gloria) 「グロリア・イン・エクチェルシス・デオ」も参照 Gloria in excelsis Deo. Et in terra pax hominibus bonae voluntatis. Laudamus te. Benedicimus te. Adoramus te. Glorificamus te. Gratias agimus tibi propter magnam gloriam tuam. Domine deus, rex caelestis, deus pater omnipotens. Domine fili unigenite, Jesu Christe. Domine deus, agnus dei, filius patris. Qui tollis peccata mundi, miserere nobis. Qui tollis peccata mundi, suscipe deprecationem nostram. Qui sedes ad dexteram patris, miserere nobis. Quoniam tu solus sanctus, Tu solus dominus. Tu solus altissimus, Jesu Christe. Cum Sancto spiritu, in gloria dei patris, Amen. 「グローリア」はラテン語の「栄光」。神の栄光を称える賛歌。冒頭文は『ルカによる福音書』の「天には神に栄光、地には善意の人々に平安」から取られる。 これに神とキリストへの讃美と嘆願が続き、「汝は独り聖なり、父の独生の子、世の罪を贖う小羊、イエス・キリストよ。聖霊とともに父の栄光にありて。アー メン」と結ばれる。典礼文の起源は東方教会にある(早課の大栄頌)。なお、ヴィヴァルディやプーランクなど、「グローリア」のみを独立した作品として作曲 した例もある。 四旬節、待降節のミサ及びレクイエムでは省略される。 クレド (Credo) Credo in unum deum, patrem omnipotentem. Factorem caeli et terrae, visibilium omnium et invisibilium, Et in unum dominum. Jesum Christum filium dei unigenitum. Et ex patre natum ante omnia saecula. Deum de deo, lumen de lumine, deum verum de deo vero. Genitum, non factum, consubstantialem patri: per quem omnia facta sunt. Qui propter nos homines, et propter nostram salutem descendit de caelis. Et incarnatus est de spiritu sancto ex Maria virgine: et homo factus est. Crucifixus etiam pro nobis sub Pontio Pilato: passus, et sepultus est. Et resurrexit tertia die, secundum scripturas. Et ascendit in caelum: sedet ad dexteram patris. Et iterum venturus est cum gloria judicare vivos et mortuos: cujus regni non erit finis. Et in spiritum sancutum dominum, et vivificantem: qui ex patre, filioque procedit. Qui cum patre, et filio simul adoratur, et conglorificatur: qui locutus est per prophetas. Et unam, sanctam, catholicam et apostolicam ecclesiam. Confiteor unum baptisma in remissionem peccatorum. Et exspecto resurrectionem mortuorum. Et vitam venturi saecli. Amen. 「クレド」はラテン語で「信じる」。信仰宣言あるいは信条告白といわれる賛歌。ニカイア・コンスタンティノポリス信条(上掲文。日本語訳は項目を参照)の ほか、使徒信条などが用いられる。レクイエムでは省略される。 サンクトゥス (Sanctus) Sanctus, sanctus, sanctus, dominus deus sabaoth. Pleni sunt caeli et terra gloria tua. Hosanna in excelsis. 「サンクトゥス」は、ラテン語で「聖なる」。「聖なるかな、聖なるかな、聖なるかな、万軍の主よ。天と地はあなたの光栄にあまねく満ち渡る。天のいと高き ところにホザンナ」。神への感謝を捧げ、その栄光を称える賛歌。 「聖三祝文#セラフィムの歌」も参照 東方教会に起源をもつ祈祷で、典礼文はイザヤ書から取られる。冒頭でサンクトゥスを三回唱えるので、和訳では「三聖頌」とも言う。ちなみにHosanna (ホサンナ)はヘブライ語の音訳で、原義は「救いたまえと(我らは)祈る」。 ベネディクトゥス (Benedictus) Benedictus qui venit in nomine domini. Hosanna in excelsis. 短い賛歌で、普通「サンクトゥス」と併せて一つの曲にまとめられる事が多い。マタイ福音書21:9から採られる。 意味はラテン語で「祝福があるように」 アニュス・デイ (Agnus Dei) Agnus dei, qui tollis peccata mundi miserere nobis. Agnus dei, qui tollis peccata mundi dona nobis pacem. 「アニュス・デイ」はラテン語で「神の小羊」。平和を祈る賛歌。ヨハネ福音書1:29に基づき、これを拡充したもの。 イテ・ミサ・エスト (Ite Missa Est) Ite missa est Deo gratias ミサの解散のための言葉。中世からルネッサンス初頭にかけて作曲された例がある。また、中世フランス(サン・マルシャル楽派、カリクストゥス写本、ノート ルダム楽派など)に特徴的であるが「ベネディカムス・ドミノ」が代わりに歌われる事が多かったようである。それ以外はハンガリーの作曲家、コダーイが「ミ サ・ブレヴィス」において作曲している。 固有文 (proprium) 固有文については、ミサの目的によってテキストが異なるため、その概要について記述するのに留める。ルネッサンス期までは作曲依頼されたミサ曲の目的に合 わせて新たに作曲された例もわずかに見られるが、この場合そのミサ曲は年間を通して一度しか演奏される機会が無いことになるため、ミサ曲とは分離して単独 の曲として作曲される例が多い。特にオッフェルトリウムの作曲はモーツァルトの頃まで行われている。 イントロイトゥス (Introitus) ミサの開始で歌われ、そのミサの目的が紹介される。和訳では「入祭唱」。現行典礼の「第一朗読」および「答唱詩篇」にあたり、アンティフォナと詩篇唱とド クソロジア(小栄光唱)、すなわちアンティフォナ-詩篇唱-ドクソロジア-アンティフォナ形式で歌われる。降誕節(主の降誕)の日中のミサの例では、アン ティフォナでは『旧約聖書』「イザヤ書」9:6から採られた歌詞(Puer natus est......)が「おさな子われらに生まれ、み子われらに与えられぬ。その肩に権威おび、その名大いなる御計画の使いと呼ばれん」と歌われ、詩篇唱 では『旧約聖書』「詩篇」97:1からとられた歌詞(Cantate Domino......)が「主に向かいて新しき歌うたえ、主、不思議なるわざなさりしゆえ」と歌われる。グレゴリオ聖歌の場合、旋律は第七旋法で書か れ、喜びにわき上がるような動きが印象的である。 グラドゥアーレ (Graduale) ミサの前半「言葉の儀」において、「使徒の書簡」朗読の後に歌われる。名前の由来は幾つかあるが、いずれの説も祭壇の階段(グラドゥス)に関係する。和訳 では「昇階唱」。レスポンソリウム形式で歌われる。降誕節の日中のミサの例では、詩篇97:3、4からとられた歌詞が「地上のすべての国々はわれらが神の 救いを見たり。すべての地よ、神をたたえよ。主はその救いを知らせ、民の目の前にその正義を示したまえり」と歌われる。グレゴリオ聖歌の場合、旋律は第五 旋法で書かれ、歌詞の母音をのばすメリスマが目立つ(昇階曲参照)。 アレルヤ (Alleluia) もしくはアレルイア。ヘブライ語が語源で非常に古い起源をもつ。レスポンソリウム形式で歌われる。賛嘆の歌なので、待降節、レクイエム、四旬節には歌われ ず、代わりに次のトラクトゥスが歌われる。和訳では「アレルヤ唱」。 トラクトゥス (Tractus) 待降節、レクイエム、四旬節のミサにおいて、アレルヤ唱の代わりに歌われる。和訳では「詠唱」。 セクエンツィア (Sequentia) 中世後期からルネッサンスにかけて、アレルヤ唱の説明文的な役割として派生し、アレルヤ唱に続いて歌われるようになった。和訳では「続唱」。セクエンツィ アはその後ミサのあちこちに挿入されるようにもなった。トリエント公会議に於いて4曲を残して全て禁止された(後に1曲が追加公認)。レクイエムのセクエ ンツィアであるディエス・イーレはその残されたものの一つ(セクエンツィア参照)。 オッフェルトリウム (Offertorium) ミサの後半「聖餐式」の始めに最後の晩餐を再現するため葡萄酒と種なしパンを祭壇に捧げるが、この間に歌われる。アンティフォナ形式。和訳では「奉献 唱」。 コンムニオ (Communio) 「聖餐式」の最後の「聖体拝領(キリストの血と肉の象徴である葡萄酒と種なしパンを信者に配る儀式)」の直前に歌われる。和訳では「聖体拝領唱」 |

|

| レクイエムとの違い ミサ曲の特殊な形としてレクイエムがある。レクイエムは、「死者のためのミサ曲」あるいは「鎮魂ミサ曲」などと訳され、死者ミサの入祭唱の冒頭句から取ら れた名称である。通常のミサ曲と典礼文に若干の違いがある。まず通常は教会暦にしたがって通常文(たとえばミサ開始の典礼文である入祭唱)が割り振られる 箇所でも、レクイエムでは、入祭唱をはじめとして固有文や儀式に関連する聖歌などが含まれる。また通常のミサで用いる『グローリア』や『クレド』が用いら れず、他の通常文も語句が変更される場合などがある。 |

|

| 第2バチカン公会議以降のミサ曲 1962年から65年にかけて開かれた第2バチカン公会議では、その典礼改革に於いてミサをラテン語ではなく各国の言語に訳したもので執り行うことが許可 された。また、上記で解説されている固有文にも、第2バチカン公会議で変更・廃止され、現代の一般的な典礼では用いられない部分がある。 ミサ曲においてもこれをうけて、例えばアルゼンチンのアリエル・ラミレスによる「ミサ・クリオージャ」(南米大陸のミサ)のように自国の言語によるものが 作曲され始めている。日本においては高田三郎による『やまとのささげうた』や『ミサ賛歌 I』、その弟子である新垣壬敏の『神の母聖マリア』、サレジオ会の司祭である伏木幹育によるものなど、「典礼聖歌」におさめられたミサ曲がある。 これらのミサ曲は、歌唱の訓練を受けた聖歌隊が歌うためではなく、ミサの参加者である会衆が皆で歌えることを目的としており、演奏会用に作曲された作品群 とは趣を異にする。とはいえ、ミサ曲としての構成は同じであり、多くは「Kyrie」「Gloria」「Sanctus(Benedictusも含む)」 「Agnus Dei」の4曲、もしくは「Gloria」を除いたもの、「Credo」が加えられたものなどが存在する。 https://x.gd/6631i |

Machaut - Messe de Notre Dame (abbaye de Thoronet, Ens. G. Binchois, dir. D. Vellard).av

ARIEL

RAMIREZ: "Misa Criolla" - Gloria & Agnus Dei

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆