第二バチカン公会議

Second

Vatican Council, Concilium

Oecumenicum Vaticanum Secundum

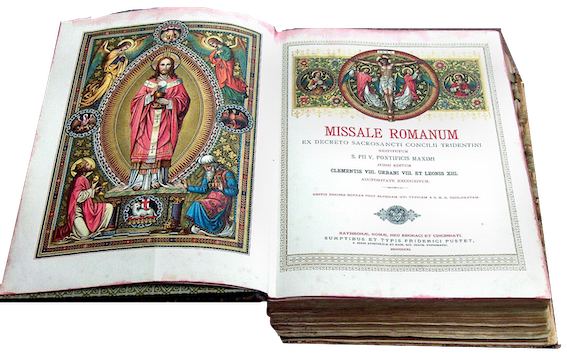

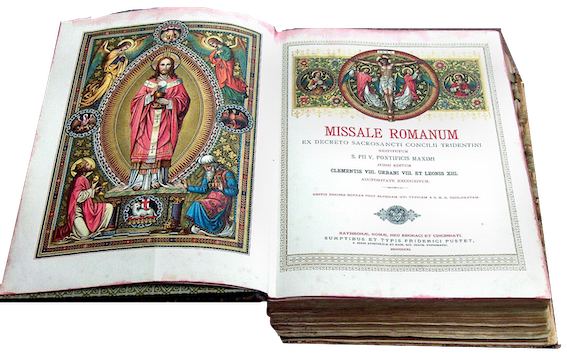

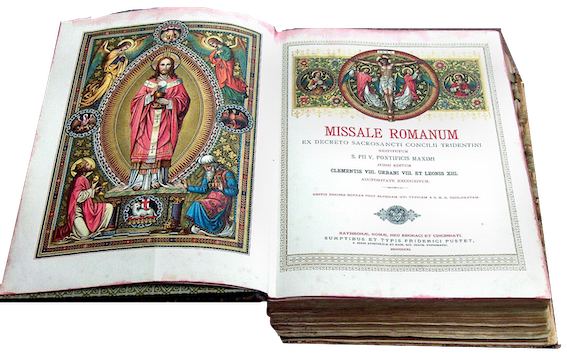

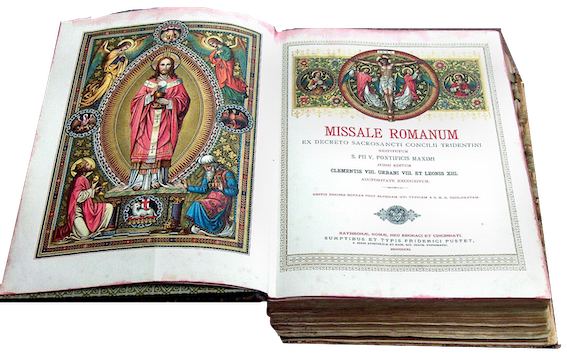

ロー マ・ミサ典礼書の1884年版からの復刻版(1911年)

☆第 二バチカン公会議、通称第二バチカン公会議は、カトリック教会の第 21回エキュメニカル公会議である。公会議は、1962年から1965年までの4年間の各秋に、バチカン市国のサン・ピエトロ大聖堂で、8週間から12週 間の会期で4回開かれた。この公会議が扱った問題の範囲と種類の多さから、公会議はのちのローマ・カトリック教会に大きな影響を与えている(→同会議のスケジュールは「第二バチカン公会議のスケジュール」にある)。

☆

第二バチカン公会議の意義はおよそ以下のようにまとめられよう:1. 神の民としての教会/

2. 教会とその一致の中心としての聖体/

3. 理論と実践における聖書の優位性/

4. 多様性の有益な性質:教会的多様性("教会 "の共同体としての教会)、典礼的多様性、神学的多様性("啓示された真理の神学的精緻化においても "多様であること)/

5. 他のキリスト教徒は教会と[不完全な]交わりをしていると理解される。/

6. 正義と平和という世俗的な人間的価値への関心。(→「解放の神学」「宗教と音楽性」「カリスマ運動」「宗教的多元主義」)

☆

「第二バチカン公会議の基準によって典礼の刷新における改革は真に教会のため

に確実に役立つものとして要求されているものでなければ行わないように、また、すでに

存在している形態から、新しい形態がいわば有機的に生じるように慎重に配慮するこ

とが定められている。この基準は、ローマ典礼様式自体のインカルチュレーション(=文化化、引用者)を果

たすためにふさわしいものでなければならない。さらにインカルチュレーションは、

性急さと不注意によって正当の典礼の伝統が損なわれないように、相応の時間を必要とする。/

最後にインカルチュレーションの要求は決して新しい典礼様式を作り出そうとする

ものではない。それは、ミサ典礼書に導入された適応、あるいは他の典礼書と調和した適

応が、ローマ典礼固有の特質と矛盾しないような方法で、与えられた文化の必要にこ

たえようとするものである」。——カトリック中央協議会『ローマ・ミサ典礼書の総則(暫定版)』カトリック中央協議会、p.84.、2004年4月8日 https://www.cbcj.catholic.jp/wp-content/uploads/2004/05/sosoku2.pdf

| ★The Second

Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the Second

Vatican Council, or Vatican II, was the 21st ecumenical council of the

Catholic Church. The council met in Saint Peter's Basilica in Vatican

City for four periods (or sessions), each lasting between 8 and 12

weeks, in the autumn of each of the four years 1962 to 1965.

Preparation for the council took three years, from the summer of 1959

to the autumn of 1962. The council was opened on 11 October 1962 by

John XXIII (pope during the preparation and the first session), and was

closed on 8 December 1965 by Paul VI (pope during the last three

sessions, after the death of John XXIII on 3 June 1963). Pope John XXIII called the council because he felt the Church needed "updating" (in Italian: aggiornamento). In order to better connect with people in an increasingly secularized world, some of the Church's practices and teachings needed to be improved and presented in a more understandable and relevant way.[citation needed] Many Council participants were sympathetic to this, while others saw little need for change and resisted. Support for aggiornamento won out over resistance to change, and as a result the sixteen magisterial documents produced by the council proposed significant developments in doctrine and practice: an extensive reform of the liturgy; a renewed theology of the Church, of revelation and of the laity; and new approaches to relations between the Church and the world, to ecumenism, to non-Christian religions, and to religious freedom.[citation needed] The council had a significant impact on the Church, due to the scope and variety of issues it addressed.[2] |

第二バチカン公会議、通称第二バチカン公会議は、カトリック教会の第

21回エキュメニカル公会議である。公会議は、1962年から1965年までの4年間の各秋に、バチカン市国のサン・ピエトロ大聖堂で、8週間から12週

間の会期で4回開かれた。公会議の準備には1959年夏から1962年秋までの3年間を要した。公会議は1962年10月11日にヨハネ23世(準備期間

と第1会期の教皇)によって開会され、1965年12月8日にパウロ6世(1963年6月3日のヨハネ23世の死後、最後の3会期の教皇)によって閉会さ

れた。 教皇ヨハネ23世が公会議を招集したのは、教会に「刷新」(イタリア語でaggiornamento)が必要だと感じたからである。世俗化が進む世界の人 々とより良い関係を築くためには、教会の実践や教えの一部を改善し、より理解しやすく適切な方法で示す必要があった。その結果、公会議が作成した16の公 文書は、教義と実践における重要な発展を提案した。すなわち、典礼の広範な改革、教会、啓示、信徒に関する新たな神学、教会と世界との関係、エキュメニズ ム、非キリスト教諸宗教、信教の自由に対する新たなアプローチなどである[要出典]。 公会議が扱った問題の範囲と種類の多さから、公会議は教会に大きな影響 を与えた[2]。 |

| Background Biblical movement Pope Pius XII's 1943 encyclical Divino afflante spiritu[3] gave a renewed impetus to Catholic Bible studies and encouraged the production of new Bible translations from the original languages. This led to a pastoral attempt to get ordinary Catholics to re-discover the Bible, to read it, to make it a source of their spiritual life. This found a response in very limited circles. By 1960, the movement was still in its infancy.[4][5] Ressourcement and Nouvelle théologie Main article: Nouvelle théologie By the 1930s, mainstream theology based on neo-scholasticism and papal encyclicals was being rejected by some theologians as dry and uninspiring. Thus was born the movement called ressourcement, the return to the sources: basing theology directly on the Bible and the Church Fathers. Some theologians also began to discuss new topics, such as the historical dimension of theology, the theology of work, ecumenism, the theology of the laity and the theology of "earthly realities".[6] All these writings in a new style came to be called "la nouvelle théologie", and they soon attracted Rome's attention. The reaction came in 1950. That year Pius XII published Humani generis, an encyclical "concerning some false opinions threatening to undermine the foundations of Catholic doctrine". Without citing specific individuals, he criticized those who advocated new schools of theology. Everyone understood the encyclical was directly against the nouvelle théologie as well as developments in ecumenism and Bible studies. Some of these works were placed on the Index of Prohibited Books, and some of the authors were forbidden to teach or to publish. Those who suffered most were the Henri de Lubac SJ and Yves Congar OP, who were unable to teach or publish until the death of Pius XII in 1958. By the early 1960s, other theologians under suspicion included Karl Rahner SJ and the young Hans Küng.[citation needed] In addition, there was the unfinished business of the First Vatican Council (1869–70). When it had been cut short by the Italian Army's entry into Rome at the end of Italian unification, the only topics that had been completed were the theology of the papacy and the relationship of faith and reason, while the theology of the episcopate and of the laity were left unaddressed.[7][8] At the same time, the world's bishops were facing challenges driven by political, social, economic, and technological change. Some of these bishops were seeking new ways of addressing those challenges. So, when Pope John announced that he would convene a General Council of the Church, many wondered if he wanted to break down the "fortress Church" mentality and make room for these tentative movements for renewal that had been developing over the previous few decades.[citation needed] |

背景 聖書運動 教皇ピオ12世の1943年の回勅『Divino afflante spiritu』[3]は、カトリックの聖書研究に新たな推進力を与え、原語からの新しい聖書翻訳の作成を奨励した。これは、一般のカトリック信者に聖書 を再発見させ、聖書を読ませ、聖書を霊的生活の源泉とさせようとする司牧的試みにつながった。この試みは、ごく限られた界隈で反響を呼んだ。1960年ま で、この運動はまだ初期段階にあった[4][5]。 ルソースマンとヌーヴェル・テオロギー 主な記事 ヌーヴェル・テオロギー 1930年代までに、新スコラ学やローマ教皇の回勅に基づく主流の神学は、一部の神学者たちによって、乾いて刺激に欠けるものとして否定されるようになっ ていた。こうして、神学を聖書と教父に直接基づかせるという、原典回帰(resourcement)と呼ばれる運動が生まれた。一部の神学者たちはまた、 神学の歴史的次元、仕事の神学、エキュメニズム、信徒の神学、「地上の現実」の神学など、新しいテーマを論じ始めた。 その反動は1950年に起こった。この年、ピウス12世は回勅『Humani generis』を発表した。特定の個人を挙げることなく、新しい神学学派を提唱する人々を批判した。この回勅は、エキュメニズムや聖書研究の発展と同様 に、ヌーヴェル・テオロギーに真っ向から反対するものだと誰もが理解していた。これらの著作のいくつかは禁書目録に掲載され、著者の何人かは教壇に立つこ とも出版することも禁じられた。最も苦しんだのはアンリ・ド・リュバックSJとイヴ・コンガールOPで、彼らは1958年にピオ12世が亡くなるまで、教 えることも出版することもできなかった。1960年代初頭までには、カール・ラーナーSJや若きハンス・キュングなど、他の神学者たちも疑いをかけられて いた[要出典]。 さらに、第一バチカン公会議(1869-70年)の未完の仕事があった。イタリア統一の終わりにイタリア軍のローマ進駐によって中断されたとき、完了して いたテーマは教皇庁の神学と信仰と理性の関係だけであり、司教座の神学と信徒の神学は未解決のまま残されていた[7][8]。 同時に、世界の司教たちは、政治的、社会的、経済的、技術的な変化による課題に直面していた。これらの司教の中には、それらの課題に取り組む新たな方法を 模索している者もいました。そのため、教皇ヨハネが教会総会を招集すると発表したとき、多くの人々は、教皇ヨハネが「要塞教会」の考え方を打破し、過去数 十年にわたって発展してきたこれらの暫定的な刷新の動きを受け入れる余地を作りたいと考えているのではないかと考えた[要出典]。 |

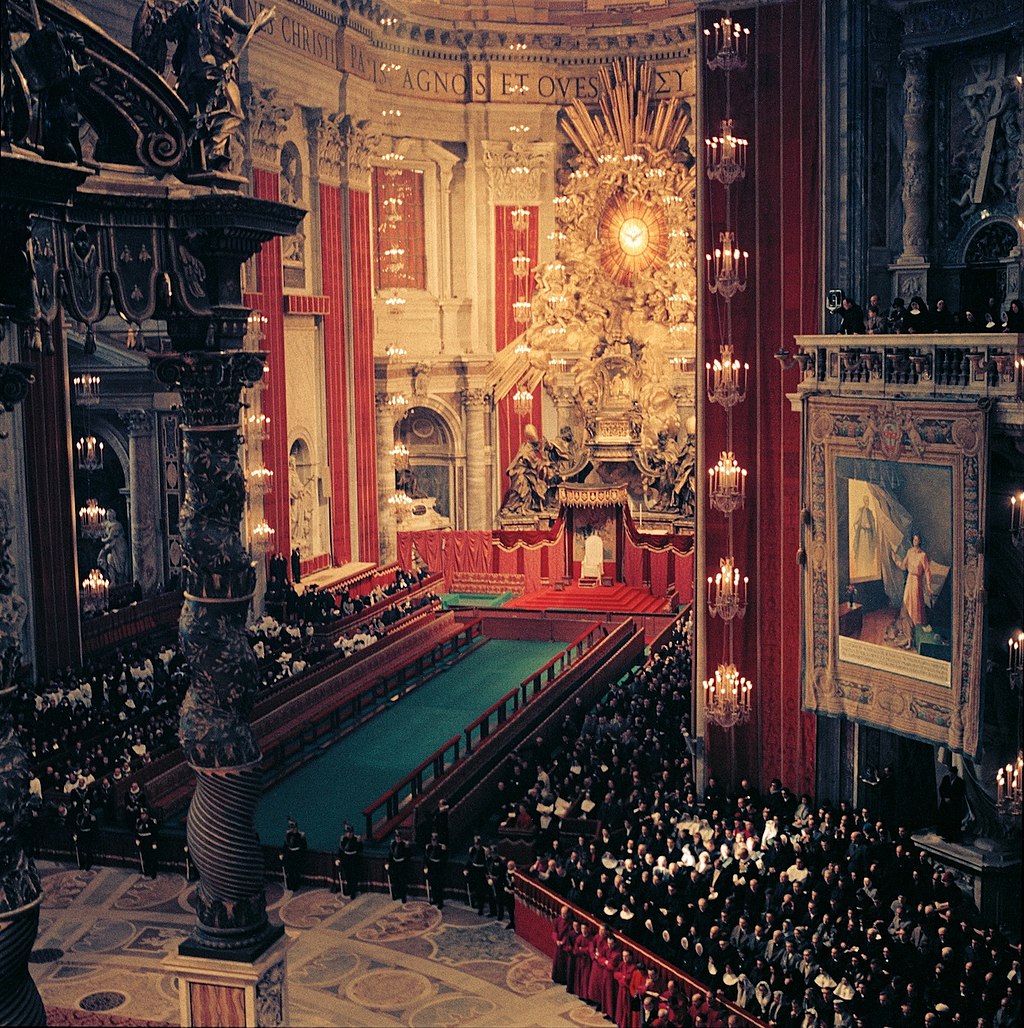

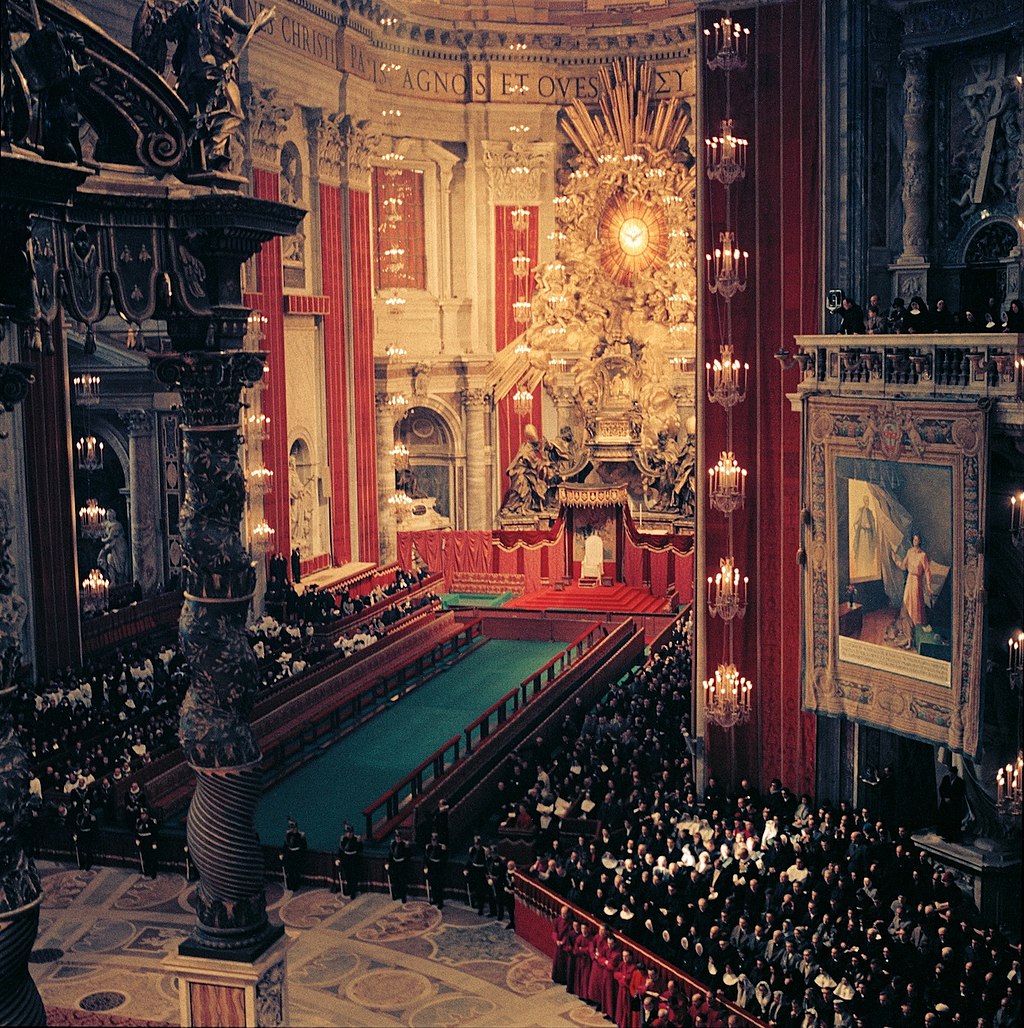

Beginnings Before a papal Mass at the council; area between papal altar and apse/cathedra altar, in front of it the seat of the pope. Announcement and expectations John XXIII gave notice of his intention to convene an ecumenical council on 25 January 1959, less than three months after his election in October 1958.[9] His announcement in the chapter hall of the Benedictine monastery attached to the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls in Rome came as a surprise to the cardinals present.[10][11] He had tested the idea only ten days before with one of them, his Cardinal Secretary of State Domenico Tardini, who gave enthusiastic support to the idea.[12] Although the pope later said the idea came to him in a flash in his conversation with Tardini, two cardinals had earlier attempted to interest him in the idea. They were two of the most conservative, Ernesto Ruffini and Alfredo Ottaviani, who had already in 1948 proposed the idea to Pius XII and who put it before John XXIII on 27 October 1958.[13] Over the course of the next 3 years, the Pope would make many statements describing the results he expected from the council. They formed something like 3 concentric circles:[14] 1. For the Catholic Church, he expected a renewal which he described variously as a "new Pentecost", a "new Springtime", a new "blossoming", "a rejuvenation with greater vigour of the Body of Christ that is the Church".[15] This would be achieved by the "updating" (aggiornamento) or "adapting" of Church practices to new circumstances[16] and a restatement of her beliefs in a way that would connect with modern man.[17] 2. Within the wider Christian family, he sought progress toward reunion of all Christians.[18] 3. For the whole human family, he expected the council to contribute toward resolving major social and economic problems, such as war, hunger, underdevelopment.[19] Two less solemn statements are attributed to John XXIII about the purpose of the council. One is about opening the windows of the Church to let in some fresh air;[20] the other about shaking off the imperial dust accumulated on the throne of St. Peter. They have been repeated over and over, usually without any indication of source. The source for the second statement is Cardinal Léger of Montréal, as reported by Congar.[21] As for the first statement, it has been repeated so many times that it may be impossible to find out if and when the Pope said it. Once the officials of the Curia had recovered from their shock at the Pope's announcement of a Council, they realized that it could be the culmination of the Church's program of resistance to Protestantism, the Enlightenment and all the other errors of the modern world. It was the providential opportunity to give the stamp of conciliar infallibility to the teachings of the most recent popes and to the Curia's vision of the role of the Church in the modern world, provided the Pope could be convinced to forget about aggiornamento.[22] On the other side were those theologians and bishops who had been working towards a new way of doing things, some of whom had been silenced and humiliated by the Curia in the 1940s and 1950s. For them, the council came as a "divine surprise",[23] the opportunity to convince the bishops of the world to turn away from a fortress-like defensive attitude to the modern world and set off in a new direction towards a renewed theology of the Church and of the laity, ecumenism and the reform of the liturgy. [24] So, soon after the Pope's announcement, the stage was set for a confrontation between two programs: continuing the resistance to the modern world or taking seriously the Pope's call for renewal. The council was officially summoned by the apostolic constitution Humanae Salutis on 25 December 1961.[25][26] Preparation  Pope John XXIII Preparation for the council took over three years, from the summer of 1959 to the autumn of 1962. The first year was known officially as the "antepreparatory period". On 17 May 1959, Pope John appointed an Antepreparatory Commission to conduct a vast consultation of the Catholic world concerning topics to be examined at the council. Three groups of people were consulted: the bishops of the world, the Catholic universities and faculties of theology, and the departments of the Curia. By the following summer, 2,049 individuals and institutions had replied with 9,438 individual vota ("wishes"). Some were typical of past ways of doing things, asking for new dogmatic definitions or condemnations of errors. Others were in the spirit of aggiornamento, asking for reforms and new ways of doing things.  The next two years (known officially as the "preparatory period") were occupied with preparing the drafts, called schemas, that would be submitted to the bishops for discussion at the council. On 5 June 1960, ten Preparatory Commissions were created, to which a total of 871 bishops and experts were appointed.[27] Each preparatory commission had the same area of responsibility as one of the main departments of the Curia and was chaired by the cardinal who headed that department. From the 9,438 proposals, a list of topics was created, and these topics were parcelled out to these commissions according to their area of competence. The total number of schemas was 70. As most of these preparatory bodies were predominantly conservative, the schemas they produced showed only modest signs of updating. The schemas drafted by the preparatory commission for theology, dominated by officials of the Holy Office (the curial department for theological orthodoxy) showed no signs of aggiornamento at all. The two notable exceptions were the preparatory commission for liturgy and the Secretariat for Christian unity, whose schemas were very much in the spirit of renewal. In addition to these specialist commissions and secretariats, there was a Central Preparatory Commission, to which all the schemas had to be submitted for final approval. It was a large body of 108 members from 57 countries,[27] including two thirds of the cardinals. As a result of its work, 22 schemas were eliminated from the conciliar agenda, mainly because they could be dealt with during a planned revision of the 1917 Code of Canon Law after the council, and a number of schemas were consolidated and merged, with the result that the total number of schemas was whittled down from 70 to 22. Organization Paragraph numbers in this section refer to the Council Regulations published in the motu proprio Appropinquante concilio, of 6 August 1962.[28] Council Fathers (§1). All the bishops of the world, as well as the heads of the main religious orders of men, were entitled to be "Council Fathers", that is, full participants with the right to speak and vote. Their number was about 2,900, though some 500 of them would be unable to attend, either for reasons of health or old age, or because the Communist authorities of their country would not let them travel. The Council Fathers in attendance represented 79 countries: 38% were from Europe, 31% from the Americas, 20% from Asia & Oceania, and 10% from Africa. (At Vatican I a century earlier there were 737 Council Fathers, mostly from Europe[29]). At Vatican II, some 250 bishops were native-born Asians and Africans, whereas at Vatican I, there were none at all. General Congregations (§3, 20, 33, 38–39, 52–63). The Council Fathers met in daily sittings — known as General Congregations — to discuss the schemas and vote on them. These sittings took place in St. Peter's Basilica every morning until 12:30 Monday to Saturday (except Thursday). The average daily attendance was about 2,200. Stands with tiers of seats for all the Council Fathers had been built on both sides of the central nave of St. Peter's. During the first session, a council of presidents, of 10 cardinals,[30] was responsible for presiding over the general assemblies, its members taking turns chairing each day's sitting (§4). During the later sessions, this task belonged to a council of 4 Moderators.[28] All votes required a two-thirds majority. For each schema, after a preliminary discussion there was a vote whether it was considered acceptable in principle, or rejected. If acceptable, debate continued with votes on individual chapters and paragraphs. Bishops could submit amendments, which were then written into the schema if they were requested by many bishops. Votes continued in this way until wide agreement was reached, after which there was a final vote on a document. This was followed some days later by a public session where the Pope promulgated the document as the official teaching of the council, following another, ceremonial, vote of the Council Fathers. There was an unwritten rule that, in order to be considered official Church teaching, a document had to receive an overwhelming majority of votes, somewhere in the area of 90%. This led to many compromises, as well as formulations that were broad enough to be acceptable by people on either side of an issue.[28] All General Congregations were closed to the public. Council Fathers were under an obligation not to reveal anything that went on in the daily sittings (§26).[28] Secrecy soon broke down, and much information about the daily General Congregations was leaked to the press. The Pope did not attend General Congregations, but followed the deliberations on closed-circuit television. Public Sessions (§2, 44–51). These were similar to General Congregations, except that they were open to the press and television, and the Pope was present. There were 10 public sessions in the course of the council: the opening day of each of the council's four periods, 5 days when the Pope promulgated Council documents, and the final day of the council.[31] Commissions (§5-6, 64–70). Much of the detailed work of the council was done in these commissions.[32][33][34][35][36] Like the preparatory commissions during the preparatory period, they were 10 in number, each covering the same area of Church life as a particular curial department and chaired by the cardinal who headed that department:[37] Commission on the Doctrine of Faith and Morals: president Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani; Commission on Bishops and the Governance of Dioceses: president Cardinal Paolo Marella; Commission on the Eastern Churches: president Cardinal Amleto Giovanni Cicognani; Commission on the Discipline of the Sacraments: president Cardinal Benedetto Aloisi Masella; Commission for the Discipline of the Clergy and the Christian People: president Cardinal Pietro Ciriaci; Commission for Religious: president Cardinal Ildebrando Antoniutti; Commission on the Sacred Liturgy: president Cardinal Arcadio Larraona; Commission for the Missions: president Cardinal Gregorio Pietro XV Agagianian; Commission on Seminaries, Studies, and Catholic Education: president Cardinal Giuseppe Pizzardo; Commission for the Lay Apostolate and for the Media: president Cardinal Fernando Cento. Each commission included 25 Council Fathers (16 elected by the council and 9 appointed by the Pope) as well as consultors (official periti appointed by the pope). In addition, the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity, appointed during the preparatory period, continued to exist under its president Cardinal Augustin Bea throughout the 4 years of the council, with the same powers as a commission. The commissions were tasked with revising the schemas as Council Fathers submitted amendments. They met in the afternoons or evenings. Procedure was more informal than in the general assemblies: there was spontaneous debate, sometimes heated, and Latin was not the only language used. Like the General Congregations, they were closed to the public and subject to the same rules of secrecy. Official Periti (§9-10). These experts in theology, canon law and other areas were appointed by the Pope to advise the Council Fathers, and were assigned as consultors to the commissions, where they played an important part in re-writing the council documents. At the beginning of the council, there were 224 official periti, but their number would eventually rise to 480. They could attend the debates in the General Congregations, but could not speak. The theologians who had been silenced during the 1940s and 1950s, such as Yves Congar and Henri de Lubac, and some theologians who were under suspicion in Roman circles at the beginning of the 1960s, such as Karl Rahner and Hans Küng, were appointed periti because of their expertise. Their appointment served to vindicate their ideas and gave them a platform from which they could work to further their views.[38] Private Periti (§11). Each bishop was allowed to bring along a personal theological adviser of his choice. Known as "private periti", they were not official Council participants and could not attend General Congregations or commission meetings. But like the official periti, they gave informal talks to groups of bishops, bringing them up to date on developments in their particular area of expertise. Karl Rahner, Joseph Ratzinger and Hans Küng first went to the council as some bishop's personal theologian, and were later appointed official periti. Some notable theologians, such as Edward Schillebeeckx, remained private periti for the whole duration of the council. Observers (§18) . An important innovation was the invitation by Pope John to Orthodox and Protestant Churches to send observers to the council. Eventually 21 denominations or bodies such as the World Council of Churches were represented.[39][29][40][a] The observers were entitled to sit in on all general assemblies (but not the commissions) and they mingled with the Council Fathers during the breaks and let them know their reactions to speeches or to schemas. Their presence helped to break down centuries of mistrust. Lay auditors. While not provided for in the Official Regulations, a small number of lay people were invited to attend as "auditors" beginning with the Second Session. While not allowed to take part in debate, a few of them were asked to address the council about their concerns as lay people. The first auditors were all male, but beginning with the third session, a number of women were also appointed.  A Catholic priest celebrating Tridentine Mass, the form of the Mass prevalent before the council, showing the chalice after the consecration. Main players In the very first weeks of the council proceedings, it became clear to the participants that there were two "tendencies" among the Council Fathers, those who were supporters of aggiornamento and renewal, and those who were not.[42][43] The two tendencies had already appeared in the deliberations of the Central Preparatory Commission before the opening of the council.[44] In addition to popes John XXIII and Paul VI, these were the prominent actors at the council: Prominent Conservative Bishops at the Council[45] Cardinal Alfredo Ottaviani: secretary of the Holy Office Cardinal Michael Browne OP: professor at the Angelicum and consultor for the Holy Office. Cardinal Giuseppe Siri: archbishop of Genoa, president of the Italian Bishops' Conference. Cardinal Ernesto Ruffini: archbishop of Palermo. Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre CSSp: superior-general of the Congregation of the Holy Spirit; at the council, he acted as the president of the Coetus Internationalis Patrum ("International Group of Fathers"), the bloc of conservative Council Fathers Prominent Reform-minded Bishops at the Council[46] Cardinal Augustin Bea SJ: president of the Secretariat for Promoting Christian Unity Patriarch Maximos IV Sayegh: patriarch of the Melkite Greek Catholic Church Cardinal Achille Liénart: bishop of Lille (France), the senior French bishop Cardinal Josef Frings: archbishop of Cologne (Germany), the senior German bishop Cardinal Bernardus Alfrink: archbishop of Utrecht (Netherlands), the senior Dutch bishop Cardinal Leo Jozef Suenens: archbishop of Mechelen-Brussels (Belgium), the senior Belgian bishop Cardinal Franz König, archbishop of Vienna (Austria), the senior Austrian bishop Cardinal Giacomo Lercaro: archbishop of Bologna (Italy) Cardinal Paul-Émile Léger: archbishop of Montreal (Canada) Cardinal Julius Döpfner: archbishop of Munich and Freising (Germany) Prominent reform-minded theologians at the Council[47] Marie-Dominique Chenu OP: private peritus Henri de Lubac SJ: official peritus Yves Congar OP: official peritus Karl Rahner SJ: official peritus John Courtney Murray SJ: official peritus Bernhard Häring CSsR: official peritus Edward Schillebeeckx OP: private peritus Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI): official peritus Hans Küng: official peritus |

始まり 公会議での法王ミサの前。法王祭壇と後陣/カテドラ祭壇の間のエリア、その前に法王の席がある。 発表と期待 ヨハネ23世は、1958年10月の選出から3ヵ月も経たない1959年1月25日にエキュメニカル公会議を招集する意向を表明した[9]。ローマの城壁 外の聖パウロ大聖堂に付属するベネディクト会修道院の講堂での発表は、出席していた枢機卿たちにとって驚きであった[10][11]。 教皇はわずか10日前に、そのうちの一人である国務長官ドメニコ・タルディーニ枢機卿とこのアイデアを試したばかりで、彼はこのアイデアに熱狂的な支持を 示した[12]。後に教皇は、このアイデアはタルディーニとの会話の中でふと思いついたと語ったが、それ以前に2人の枢機卿が教皇にこのアイデアに関心を 持たせようとしていた。エルネスト・ルッフィーニとアルフレード・オッタヴィアーニという最も保守的な2人の枢機卿で、彼らは1948年にすでにピウス 12世にこのアイデアを提案しており、1958年10月27日にヨハネ23世にこのアイデアを提出した[13]。 その後3年間、教皇は公会議から期待される結果について多くの声明を発表した。それらは3つの同心円のようなものを形成していた[14]。 1. カトリック教会に対しては、「新たな聖霊降臨」、「新たな春」、「開花」、「教会であるキリストのからだのより大きな活力による若返り」[15]などとさ まざまに表現した刷新を期待した[15]。これは、教会の実践を新たな状況に「更新」(aggiornamento)または「適応」させ[16]、現代人 とつながるような形で教会の信条を再表明することによって達成されるであろう[17]。 2. より広いキリスト教家族の中で、彼はすべてのキリスト教徒の再統一に向けた進歩を求めた[18]。 3. 全人類家族のために、彼は公会議が戦争、飢餓、低開発などの主要な社会的・経済的問題の解決に貢献することを期待した[19]。 公会議の目的について、ヨハネ23世はそれほど厳粛ではない2つの発言をしている。ひとつは、教会の窓を開けて新鮮な空気を取り入れること[20]、もう ひとつは、サン・ピエトロの玉座に積もった帝国の埃を振り払うことである。これらは何度も何度も繰り返されてきたが、たいていの場合、出典が明らかにされ ることはなかった。 二つ目の発言の出典は、コンガールによって報告されたモントリオールのレジェ枢機卿である[21]。一つ目の発言に関しては、あまりにも何度も繰り返され てきたため、教皇がいつ発言したのかを知ることは不可能かもしれない。 教皇の公会議開催宣言に対する衝撃から立ち直った教皇庁幹部は、公会議がプロテスタンティズム、啓蒙主義、その他現代世界のあらゆる誤りに対する教会の抵 抗プログラムの集大成となりうることを理解した。それは、直近の教皇の教えと、現代世界における教会の役割に関する教皇庁のビジョンに、教皇が aggiornamentoを忘れるように説得されることを条件として、信徒的無謬性の刻印を与える摂理的な機会であった[22]。 もう一方の側には、1940年代と1950年代に教皇庁によって沈黙させられ、屈辱を受けた神学者や司教たちがいた。彼らにとって公会議は「神の驚き」で あり[23]、世界の司教たちに、現代世界に対する要塞のような防御的な態度から目を背け、教会と信徒の新たな神学、エキュメニズム、典礼の改革へと向か う新たな方向へと出発するよう説得する機会であった。[24] つまり、教皇の発表の直後から、現代世界に対する抵抗を続けるか、教皇の刷新の呼びかけを真摯に受け止めるかという2つのプログラムの対決の舞台が用意さ れたのである。 公会議は、1961年12月25日に使徒憲章『Humanae Salutis』によって正式に召集された[25][26]。 準備  教皇ヨハネ23世 公会議の準備は、1959年の夏から1962年の秋まで、3年以上にわたって行われた。 最初の1年間は、公式には「前準備期間」として知られていた。1959年5月17日、教皇ヨハネは前準備委員会を任命し、公会議で検討されるテーマについ てカトリック世界からの膨大な諮問を行った。協議の対象となったのは、世界の司教、カトリックの大学や神学部、教皇庁の部局の3つのグループであった。翌 年の夏までに、2,049の個人と機関から9,438の個人的な要望が寄せられた。その中には、新しい教義上の定義や誤りの非難を求める、これまでの典型 的なやり方もあった。また、アジョルナメントの精神に則り、改革や新しいやり方を求めるものもあった。  次の2年間(公式には「準備期間」と呼ばれる)は、公会議で討議するために司教団に提出される「スキーマ」と呼ばれる草案の準備に費やされた。1960年 6月5日、10の準備委員会が設置され、合計871人の司教と専門家が任命された[27]。各準備委員会は、教皇庁の主要部門のひとつと同じ責任範囲を持 ち、その部門を率いる枢機卿が委員長を務めた。9,438の提案の中からトピックのリストが作成され、これらのトピックは、それぞれの担当分野に従って、 これらの委員会に分割された。 スキーマの総数は70。これらの準備委員会のほとんどは保守的な組織であったため、彼らが作成したスキーマはささやかな更新の兆ししか示さなかった。神学 準備委員会が起草したスキーマは、聖職者庁(神学的正統性のための司祭部門)の職員が大半を占め、アジョルナメントの兆候はまったく見られなかった。2つ の顕著な例外は、典礼準備委員会とキリスト教一致事務局であり、そのスキーマは非常に刷新の精神に満ちていた。 これらの専門委員会と事務局に加えて、すべてのスキーマを最終承認のために提出しなければならない中央準備委員会があった。中央準備委員会は、57カ国か ら108名の委員を擁する大規模な組織であり[27]、その中には枢機卿の3分の2も含まれていた。その結果、主に公会議後に予定されていた1917年の 『カノン法典』の改訂の際に扱えるという理由で、22のスキーマが公会議の議題から削除され、多くのスキーマが統合・合併された。 組織 このセクションの段落番号は、1962年8月6日付のモツ・プロプリオ『Appropinquante concilio』で発表された公会議規則を参照している[28]。 公会議教父 (§1). 全世界の司教と主要な男子修道会の長には、「公会議議長」、すなわち発言権と投票権を持つ完全な参加者となる権利が与えられた。その数は約2,900人で あったが、そのうち約500人は健康上の理由や高齢のため、あるいは自国の共産党当局が渡航を許可しなかったために出席できなかった。出席した教父たちは 79カ国を代表していた: 38%がヨーロッパから、31%がアメリカ大陸から、20%がアジア・オセアニアから、そして10%がアフリカからだった。(その1世紀前の第1バチカン 公会議では、737名の公会議教父が出席しており、そのほとんどがヨーロッパ出身であった[29])。第二バチカン公会議では、約250人の司教が生粋の アジア人とアフリカ人であったが、第一バチカン公会議では全くいなかった。 総会(§3, 20, 33, 38-39, 52-63)。公会議の教父たちは、スキーマを討議し、議決するために、総会と呼ばれる会合に毎日出席した。総会は月曜日から土曜日(木曜日を除く)の毎 朝12時30分までサンピエトロ大聖堂で開かれた。1日の平均出席者は約2,200人だった。サン・ピエトロ大聖堂の中央身廊の両側には、すべての公会議 教父が座ることのできる席が設けられた。最初の会期中は、10人の枢機卿からなる議長会[30]が総会の議長を務め、そのメンバーが交代で各日の会議の議 長を務めた(§4)。後の会期では、この任務は4人の司会者からなる評議会に属した[28]。 すべての議決には3分の2以上の賛成が必要であった。各スキーマについて、予備的な議論の後、それが原則的に受け入れられるとみなされるか、拒否されるか の投票が行われた。もし容認されれば、個々の章や段落についての投票が行われ、討議が続けられた。ビショップは修正案を提出することができ、多くのビ ショップの要求があれば、修正案はシェーマに書き込まれた。このようにして、大方の合意が得られるまで投票は続けられ、その後、文書の最終投票が行われ た。数日後、公会議が開かれ、教皇が公会議の公式教書として文書を公布した。教会の公式の教えとみなされるためには、ある文書が90%前後の圧倒的多数の 票を得なければならないという不文律があった。このため、多くの妥協案が生まれ、また、ある問題のどちらの立場の人々にも受け入れられるような広範な定式 化が行われた[28]。 すべての総会は非公開であった。公会議の教父たちは、毎日の会議で行われていることを何一つ明らかにしない義務を負っていた(第26条)[28]。秘密主 義はすぐに崩壊し、毎日の総会に関する多くの情報がマスコミに漏れるようになった。 教皇は総会に出席せず、閉回路テレビで審議を見守った。 公会(§2、44-51)。報道陣やテレビに公開され、教皇も出席したことを除けば、総会と同様のものであった。公会議は、公会議の4つの期間のそれぞれ の初日、教皇が公会議文書を公布した5日間、公会議の最終日の計10回行われた[31]。 委員会(§5-6、64-70)。公会議の詳細な作業の多くは、これらの委員会で行われた[32][33][34][35][36]。準備期間中の準備委 員会と同様、委員会は10個あり、それぞれが特定の司教部門と同じ教会生活の領域をカバーし、その部門を率いる枢機卿が委員長を務めた[37]。 信仰と道徳の教義に関する委員会:委員長アルフレード・オッタヴィアーニ枢機卿; 司教と教区の統治に関する委員会:委員長パオロ・マレッラ枢機卿; 東方教会委員会:委員長 アムレート・ジョヴァンニ・チコニャーニ枢機卿 秘跡の規律委員会:委員長ベネデット・アロイージ・マゼッラ枢機卿 聖職者とキリスト者の規律委員会:委員長ピエトロ・チリアッチ枢機卿 修道者委員会:委員長 イルデブランド・アントニウッティ枢機卿 典礼委員会:委員長 アルカディオ・ララオナ枢機卿 宣教委員会:委員長 グレゴリオ・ピエトロ15世アガジアン枢機卿 神学校・研究・カトリック教育委員会:委員長 ジュゼッペ・ピッツァルド枢機卿 信徒使徒職およびメディア委員会:委員長フェルナンド・チェント枢機卿。 各委員会には、25人の評議会教父(評議会によって選出された16人と教皇によって任命された9人)とコンサルタント(教皇によって任命された公式のペリ ティ)が含まれていた。さらに、準備期間中に任命されたキリスト教一致推進事務局は、公会議の4年間を通じて、委員会と同じ権限を持ち、その会長であるア ウグスティン・ベア枢機卿の下に存続した。委員会は、公会議教父たちが修正案を提出するたびに、スキーマを修正する任務を負った。委員会は午後か夜に開か れた。手続きは総会よりも非公式で、自発的な討論が行われ、時には白熱し、使用される言語はラテン語だけではなかった。総会と同様、非公開で、秘密厳守の 規則が適用された。 公式ペリティ(§9-10)。神学、典礼法、その他の分野の専門家たちは、教皇によって公会議教父たちに助言を与えるために任命され、委員会の相談役とし て任命され、公会議文書の再執筆に重要な役割を果たした。公会議当初、公式ペリチは224名であったが、最終的には480名に増加した。彼らは総会での討 論に出席することはできたが、発言することはできなかった。イヴ・コンガールやアンリ・ド・リュバックなど、1940年代から1950年代にかけて沈黙を 守っていた神学者たちや、カール・ラーナーやハンス・キュングなど、1960年代初頭にローマ教皇庁内で疑惑の目を向けられていた神学者たちは、その専門 性の高さからペリティに任命された。彼らの任命は、彼らの考えを正当化する役割を果たし、彼らの意見をさらに推進するために活動できるプラットフォームを 与えた[38]。 私的ペリティ(§11)。各司教は、自ら選んだ個人的な神学顧問を同伴することを許された。私的ペリティ」と呼ばれる彼らは、公式の評議会参加者ではな く、総会や委員会会議にも出席できなかった。しかし、公式ペリティと同様、彼らは司教団に非公式な講演を行い、特定の専門分野の進展について最新情報を提 供した。カール・ラーナー、ヨゼフ・ラッツィンガー、ハンス・キュングは、まず司教の個人的な神学者として公会議に出席し、後に公式ペリティに任命され た。エドワード・シルベクスのような著名な神学者は、公会議期間中、私的なペリティのままであった。 オブザーバー (§18) . 重要な革新は、教皇ヨハネが正教会とプロテスタント教会に公会議へのオブザーバー派遣を呼びかけたことであった。最終的に21の教派、あるいは世界教会協 議会のような団体が代表として参加した[39][29][40][a]。オブザーバーはすべての総会(ただし委員会は除く)に傍聴する権利を与えられ、休 憩時間には公会議の教父たちと交流し、演説やスキーマに対する自分たちの反応を知らせた。彼らの存在は、何世紀にもわたる不信感の解消に役立った。 信徒の監査役 公式規則には規定されていなかったが、第2会期から、少数の信徒が「監査役」として招かれた。討論に参加することは許されなかったが、そのうちの数人は、 信徒としての懸念について評議会で演説するよう求められた。最初の監査役は全員男性だったが、第3会期からは女性も多数任命された。  カトリックの司祭が、公会議前に普及していたミサの形式であるトリデンテ・ミサを行い、聖別後の聖杯を示す。 主な参加者 公会議が始まった最初の数週間で、公会議教父たちの間には、アジョルメントと刷新を支持する人々とそうでない人々という2つの「傾向」があることが参加者 たちの間で明らかになった[42][43]。この2つの傾向は、公会議開会前の中央準備委員会の審議の中ですでに現れていた[44]。 教皇ヨハネ23世とパウロ6世に加えて、これらは公会議における著名なアクターであった: 公会議における著名な保守派司教たち[45]。 アルフレード・オッタヴィアーニ枢機卿:聖庁長官 マイケル・ブラウン枢機卿(OP):アンジェリカム教授、聖庁顧問官 ジュゼッペ・シリ枢機卿:ジェノヴァ大司教、イタリア司教会議議長 エルネスト・ルッフィーニ枢機卿:パレルモ大司教。 マルセル・ルフェーヴル大司教(CSSp):聖霊会総長。公会議では、保守的な公会議教父のブロックであるCoetus Internationalis Patrum(「国際教父グループ」)の議長を務める。 公会議における改革派の著名な司教たち[46]。 アウグスティン・ベアSJ枢機卿:キリスト教一致推進事務局議長 マクシモス4世セーグ総主教:メルキト・ギリシャ・カトリック教会総主教 アキル・リエナール枢機卿:リール(フランス)司教、フランス上級司教 ヨゼフ・フリングス枢機卿:ケルン(ドイツ)大司教、ドイツの上級司教 ベルナルドゥス・アルフリンク枢機卿:ユトレヒト(オランダ)大司教、オランダの上級司教 レオ・ヨゼフ・スエネンス枢機卿:メヘレン=ブリュッセル(ベルギー)大司教、ベルギー上級司教 フランツ・ケーニヒ枢機卿:ウィーン(オーストリア)大司教、オーストリアの上級司教 ジャコモ・レルカロ枢機卿:ボローニャ(イタリア)大司教 ポール=エミール・レジェ枢機卿:モントリオール(カナダ)大司教 ユリウス・デプフナー枢機卿:ミュンヘンとフライジングの大司教(ドイツ) 公会議において改革を志向した著名な神学者たち[47]。 マリー=ドミニク・シュニュOP:私的ペリトゥス アンリ・ド・リュバックSJ: 公式信任状 イヴ・コンガールOP: 公式信任状 カール・ラーナーSJ:公式peritus ジョン・コートニー・マーレイSJ: 公式功労者 Bernhard Häring CSsR: 公式peritus エドワード・シレベックスOP:私的就任 ヨゼフ・ラッツィンガー(後のローマ教皇ベネディクト16世):公式功労者 ハンス・キュング:公式役職 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Second_Vatican_Council |

|

| Documents of the council Vatican II's teaching is contained in sixteen documents: 4 constitutions, 9 decrees and 3 declarations. While the constitutions are clearly the documents of highest importance, "the distinction between decrees and declarations, no matter what it originally meant, has become meaningless".[193] For each document, approval of the final text was followed a few days later by the pope's promulgation of the document as the Church's official teaching. On the day of promulgation, there was a second vote of approval by the Council Fathers: it was "basically ceremonial"[114] since the document's final text had already been approved a few days earlier. It is this earlier vote that best indicates the degree of support for, or opposition to, the document. Most documents were approved by overwhelming margins. In only 6 cases were the negative votes in the triple digits. In 3 of these cases (Church and Modern World, Non-Christian Religions and Religious Freedom), 10% to 12% of the Fathers rejected the document on theological grounds. In 2 other cases (Media and Christian Education), the negative votes mostly expressed disappointment in a bland text, rather than opposition.  Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy Main article: Sacrosanctum Concilium  The abolition of Friday of Sorrows of the Virgin Mary is an example of changes in the Liturgical Calendar after the council. The Virgin of Hope of Macarena, Spain. Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, was the blueprint for an extensive reform of the Western liturgy. Chapter 1 of the Constitution set out principles to guide this reform:[218] The Paschal mystery of Christ's death and resurrection is made present to us through the liturgy, which is a communal celebration and not just the action of the priest (SC 7). Each person present participates in it according to his/her role (SC 28, 29). Christ is present to us not only under the appearance of bread and wine, but also in the Word of God, in the person of the priest and in the gathered assembly (SC 7). "The liturgy is the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the font from which all her power flows" (SC 10). "In the restoration and promotion of the sacred liturgy, [...] full and active participation by all the people is the aim to be considered before all else" (SC 14). In order to be better understood, the rites should be simplified and a limited use of the vernacular is permitted, but the use of Latin is to be preserved (SC 36). There needs to be more reading from holy scripture, and it is to be more varied and suitable (SC 35). A certain degree of local adaptation is permissible (SC 37-40). Chapter 2: Mass.[219] The Eucharist is both the sacrifice of Christ's body and blood and a paschal banquet (SC 47). In addition to repeating the need for active participation (SC 47), simplification of the rites (SC 50) and a greater variety of Scripture readings (SC 51), the chapter decrees that certain practices that had disappeared, such as the prayer of the faithful (SC 53), concelebration (SC 57), and communion under both kinds for the laity (SC 55), are to be restored under certain conditions, and that the homily should be a commentary on the Scripture readings (SC 52). Chapter 3: Sacraments.[220] The rite of each sacrament is to be simplified in order to make its meaning clear (SC 62); the catechumenate is to be restored for adult baptism (SC 64); the link between confirmation and baptism is to be made clear (SC 71); the sacrament then called extreme unction is to become a sacrament for those who are seriously ill (anointing of the sick) and not just of those who are on the point of death (SC 73-5); funerals are to focus on the hope of the resurrection and not on mourning (SC 81), and local cultural practices may be included in the celebration of some sacraments such as weddings (SC 63). Chapters 4 to 7[221] provide that the divine office (now called Liturgy of the Hours) is to be adapted to modern conditions by reducing its length for those in active ministry (SC 97), that the calendar is to be revised to give Sunday and the mysteries of Christ priority over saints' days (SC 108), and that, while traditional music forms such as Gregorian chant (SC 116) and organ music (SC 120) are to be preserved, congregational singing is to be encouraged (SC 114) and the use of other instruments is permissible (SC 120). The Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy launched the most extensive revision of the liturgy in the history of the Church.[40] The invitation for more active, conscious participation of the laity through Mass in the vernacular did not stop with the constitution on the liturgy. It was taken up by the later documents of the council that called for a more active participation of the laity in the life of the Church.[222] Pope Francis referred to a turn away from clericalism toward a new age of the laity.[223] Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Main article: Lumen gentium See also: Ecclesiology (Catholic Church) The Dogmatic Constitution on the Church Lumen gentium ("Light of the Nations") gave direction to several of the documents that followed it, including those on Ecumenism, on Non-Christian Religions, on Religious Freedom, and on The Church in the Modern World (see below). According to Paul VI, "the most characteristic and ultimate purpose of the teachings of the Council" is the universal call to holiness. John Paul II calls this "an intrinsic and essential aspect of [the council Fathers'] teaching on the Church",[224] where "all the faithful of Christ of whatever rank or status, are called to the fullness of the Christian life and to the perfection of charity" (Lumen gentium, 40). Francis, in his apostolic letter Evangelii Gaudium (17) which laid out the programmatic for his pontificate, said that "on the basis of the teaching of the Dogmatic Constitution Lumen Gentium" he would discuss the entire People of God which evangelizes, missionary outreach, the inclusion of the poor in society, and peace and dialogue within society. Francis has also followed the call of the council for a more collegial style of leadership, through synods of bishops and through his personal use of a worldwide advisory council of eight cardinals.[225][226]  The Second Vatican Council encouraged the scriptural reading of the Bible rather than relying solely on devotional writings, booklets and the lives of the Catholic saints, as had the Council of Trent and the First Vatican Council. A most contentious conclusion that seems to follow from the Bishops' teaching in the decree is that while "in some sense other Christian communities are institutionally defective," these communities can "in some cases be more effective as vehicles of grace."[227] Belgian Bishop Emil de Smedt, commenting on institutional defects that had crept into the Catholic church, "contrasted the hierarchical model of the church that embodied the triad of 'clericalism, legalism, and triumphalism' with one that emphasized the 'people of God', filled with the gifts of the Holy Spirit and radically equal in grace," that was extolled in Lumen Gentium.[228] Dogmatic Constitution on Divine Revelation Main article: Dei verbum The council's document Dei Verbum ("The Word of God") states the principle active in the other council documents that "The study of the sacred page is, as it were, the soul of sacred theology".[229] It is said of Dei Verbum that "arguably it is the most seminal of all the conciliar documents," with the fruits of a return to the Bible as the foundation of Christian life and teaching, evident in the other council documents.[230] Joseph Ratzinger, who would become Benedict XVI, said of the emphasis on the Bible in the council that prior to Vatican II the theology manuals continued to confuse "propositions about revelation with the content of revelation. It represented not abiding truths of faith, but rather the peculiar characteristics of post-Reformation polemic."[231] In spite of the guarded approval of biblical scholarship under Pius XII, scholars suspected of Modernism were silenced right up to Vatican II.[232] The council brought a definitive end to the Counter-Reformation and, in a spirit of aggiornamento, reached back "behind St. Thomas himself and the Fathers, to the biblical theology which governs the first two chapters of the Constitution on the Church."[233] "The documents of the Second Vatican Council are shot through with the language of the Bible. ...The church's historical journey away from its earlier focus upon these sources was reversed at Vatican II." For instance, the council's document on the liturgy called for a broader use of liturgical texts, which would now be in the vernacular, along with more enlightened preaching on the Bible explaining "the love affair between God and humankind".[234] The translation of liturgical texts into vernacular languages, the allowance of communion under both kinds for the laity, and the expansion of Scripture readings during the Mass was resonant with the sensibilities of other Christian denominations, thus making the Second Vatican Council "a milestone for Catholic, Protestants, [and] the Orthodox".[40] Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World Main article: Gaudium et Spes This document, named for its first words Gaudium et Spes ("Joy and Hope"), built on Lumen Gentium's understanding of the Church as the "pilgrim people of God" and as "communion", aware of the long history of the Church's teaching and in touch with what it calls the "signs of the times". It reflects the understanding that Baptism confers on all the task that Jesus entrusted to the Church, to be on mission to the world in ways that the present age can understand, in cooperation with the ongoing work of the Spirit. Decrees and declarations on the Church as People of God These seven documents apply the teaching contained in the Constitution on the Church Lumen gentium to the various categories of people in the Church – bishops, priests, religious, laity, Eastern Catholics – and to Christian education. The Pastoral Office of Bishops – The decree Christus Dominus ("Christ the Lord", 1965) deals with practical matters concerning bishops and dioceses, on the basis of the theology of the episcopate found in chapter 3 of Lumen gentium, including collegiality. It deals with the 3 levels where a bishop exercises his ministry: the universal Church, his own diocese and the national or regional level.[235] The universal Church (CD 4-10). Since the doctrine of collegiality holds that bishops share with the pope the governance of the universal Church, the decree proposes that there be a council of bishops from around the world to assist the pope in this governance. (It would later be called the Synod of bishops.) And since the true purpose of the Roman Curia is to serve the bishops, it needs to be reorganized and become more international.[235] The diocese (CD 11-35). The decree gives a job description of the bishop in his ministry as teacher, sanctifier and shepherd. It discusses his relationship to the main office-holders in the diocese, and deals with such practical matters as the need to redraw diocesan boundaries as a result of shifts in population.[236] The national or regional level (CD 36-44). The decree stresses the need for an intermediate level between the universal Church and the individual diocese: this is the national (or regional) episcopal conference, an institution that did not exist in all countries at the time.[237] The Ministry and Life of Priests – The decree Presbyterorum ordinis ("The order of priests", 1965) describes priests as "father and teacher" but also "brothers among brothers with all those who have been reborn at the baptismal font." Priests must "promote the dignity" of the laity, "willingly listen" to them, acknowledge and diligently foster "exalted charisms of the laity", and "entrust to the laity duties in the service of the Church, allowing them freedom and room for action." Also, the human and spiritual needs of priests are discussed in detail. Priestly Training – The decree Optatam totius ("Desired [renewal] of the whole [Church]", 1965) seeks to adapt the training of priests to modern conditions. While some of the points made in the decree are quite traditional, such as the insistence that seminaries remain the main place for priestly training, there are interesting proposals for adaptation to new conditions. The first is that instead of having the program of formation set for the whole Catholic world by the Congregation for Seminaries and Universities in Rome, the bishops of each country may devise a program that is adapted to the needs of their particular country (though it still needs Rome's approval). Another is that training for the priesthood has to integrate 3 dimensions: spiritual, intellectual and pastoral.[238] Spiritual formation aims to produce a mature minister, and to this end may call on the resources of psychology. There are many proposals for improving intellectual formation: the use of modern teaching methods; a better integration of philosophy and theology; the centrality of Scripture in theological studies; knowledge of other religions. Pastoral formation should be present throughout the course of studies and should include practical experience of ministry. Finally, there should be ongoing formation after ordination.[239]  pre-Vatican II habit The Adaptation and Renewal of Religious Life – The decree Perfectae Caritatis ("Of perfect charity", 1965) deals with the adaptation of religious life to modern conditions. The decree presupposes the theology of the religious life found in chapter 6 of the Constitution on the Church (Lumen Gentium), to which it adds guidelines for renewal. The two basic principles that should guide this renewal are: "the constant return [...] to the original spirit of the institutes and their adaptation to the changed conditions of our time" (PC 2).[240] The decree deals mainly with religious orders, also known as religious institutes (whose members take vows and live a communal life), but touches also societies of common life (whose members take no vows but live a communal life) and secular institutes (whose members take vows but do not share a communal life).[241] The decree restates well-known views on the religious life, such as the consecrated life as a life of following Christ, the importance of the three vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and the importance of charity in the life of an order.[242] To these it adds a call for every order, whether contemplative or active, to renew itself, as well as specific proposals for adaptation to new conditions, such as the simplification of the religious habit, the importance of education for members of all religious orders (and not just priests), and the need for poverty not just for individual members but for each order as a whole.[243] The Apostolate of the Laity – The decree Apostolicam actuositatem ("Apostolic Activity", 1965) declares that the apostolate of the laity is "not only to bring the message and grace of Christ to men but also to penetrate and perfect the temporal order with the spirit of the Gospel", in every field of life, together or through various groups, with respectful cooperation with the Church's hierarchy. The Eastern Catholic Churches – The decree Orientalium Ecclesiarum ("Of the Eastern Churches", 1964) deals with the Eastern Catholic Churches, those communities that are in full union with Rome, but have their own distinctive liturgy, customs (such as married priests) and forms of organization (patriarchs and synods).[244] The decree states that they are not simply different rites (as they were commonly called previously) but are sui iuris particular Churches along with the much larger Latin Church, and with the same rights as the Latin Church, including the right to govern themselves according to their traditional organizational practices.[245] The decree affirms certain practices typical of the Eastern Churches, such as the administration of confirmation by priests, as well as the possibility of satisfying Sunday obligation by taking part in the Canonical Hours. It also provides guidelines concerning common worship and shared communion between Eastern Catholics and members of the Eastern Orthodox Church.[246] Christian Education – The declaration Gravissimum educationis ("Extreme [importance] of education", 1965)[247] discusses the importance of education (GE 1), of Christian education (GE 2-7), of Catholic schools (GE 8-9) and of Catholic colleges and universities (GE 10-12). Most everything in the declaration had been said many times before: the Church has the right to establish Catholic schools; parents have the right to choose the education they want for their children, governments have a duty to fund Catholic schools; and Catholics have a duty to support Catholic schools.[248] Many observers found the declaration disappointing: "Even at the last minute, dissatisfaction with the text was widespread and wide-ranging".[249] It was called "probably the most inferior document produced by the Council".[250] But as it was late in the 4th session when everyone was under pressure to bring the council's business to a close, most bishops chose to vote for the text, though close to 9% rejected it. |

公会議文書 第二バチカン公会議の教えは16の文書に含まれている: 4つの憲法、9つの教令、3つの宣言である。憲法が最も重要な文書であることは明らかだが、「政令と宣言の区別は、それが本来どのような意味を持つもので あったとしても、無意味なものとなった」[193]。 それぞれの文書について、最終文書の承認に続いて、数日後に教皇がその文書を教会の公式教書として公布した。公布の日、公会議教父たちによる2回目の承認 投票が行われたが、それは「基本的に儀式的」なものであった[114]。文書に対する支持や反対の度合いを最もよく示すのは、この先の投票である。ほとん どの文書は圧倒的な差で承認された。反対票が3桁に達したのは6件だけだった。このうち3件(教会と現代世界、非キリスト教諸宗教、信教の自由)では、神 学的な理由から教父の10%から12%が文書を否決した。他の2つのケース(メディアとキリスト教教育)では、反対票のほとんどは、反対というよりも、当 たり障りのない文章に対する失望を表していた。 神聖典礼に関する憲法  主な記事 サクロサンクトゥム・コンシリウム  聖母マリアの悲しみの金曜日の廃止は、公会議後の典礼暦の変更の一例である。スペイン、マカレナの希望の聖母。 サクロサンクチュアム・コンシリウム(聖礼典に関する憲法)は、西洋典礼の大規模な改革の青写真であった。 憲法の第1章は、この改革の指針となる原則を次のように定めている[218]。 キリストの死と復活の秘義は、典礼を通して私たちに現される。典礼は共同体の祝典であり、司祭の行為にとどまらない(SC 7)。典礼は司祭だけの行為ではなく、共同体の祝典である(SC 7)。 キリストは、パンとぶどう酒の姿の下だけでなく、神のことばの中にも、司祭の人格の中にも、集まった集会の中にも、私たちに現存しておられるのです(SC 7)。 「典礼は教会の活動を方向づける頂点であり、同時に教会のすべての力が流れ出る泉である"(SC 10)。 「聖なる典礼の回復と推進においては、......すべての民衆の完全かつ積極的な参加が何よりも優先して考慮されるべき目的である"(SC 14)。 よりよく理解されるために、儀式は簡略化されるべきであり、方言の限定的な使用は許されるが、ラテン語の使用は守られるべきである(SC 36)。 聖典の朗読を増やす必要があり、それはより多様で適切なものでなければならない(SC 35)。 ある程度の地域的適応は許される(SC 37-40)。 第2章 ミサ[219] 聖体は、キリストのからだと血のいけにえであると同時に、牧会の宴である(SC 47)。この章では、積極的な参加(SC 47)、儀式の簡略化(SC 50)、聖句の朗読の多様化(SC 51)の必要性を繰り返すとともに、信徒の祈り(SC 53)、聖体拝領(SC 57)、信徒のための両儀式による聖体拝領(SC 55)など、消滅していた特定の慣習を一定の条件の下で復活させること、また、説教は聖句の朗読の解説であるべきであること(SC 52)を命じている。 第3章 秘跡 [220] 各秘跡の儀式は、その意味を明確にするために簡略化されること(SC 62)、成人の洗礼のためにカテキューメネートが復活すること(SC 64)、堅信と洗礼の関連性が明確にされること(SC 71); 当時は極度の不浄と呼ばれていた秘跡は、死に瀕している人のためだけでなく、重病人のための秘跡(病者の塗油)となること(SC 73-5)、葬儀は喪に服すのではなく、復活の希望に焦点を当てること(SC 81)、結婚式などいくつかの秘跡の祝いに地元の文化的慣習を含めることができること(SC 63)。 第4章から第7章[221]までは、聖務(現在は時祷の典礼と呼ばれる)を、現役の聖職者のためにその長さを短縮することによって現代の状況に適合させる こと(SC 97)、聖人の日よりも日曜日とキリストの秘義を優先するように暦を改訂すること(SC 108)、グレゴリオ聖歌(SC 116)やオルガン音楽(SC 120)といった伝統的な音楽形式を維持する一方で、会衆唱歌を奨励し(SC 114)、他の楽器の使用を許容すること(SC 120)などが規定されている。 聖礼典に関する憲法は、教会史上最も大規模な典礼の改訂を開始した[40]。 方言によるミサを通して、信徒がより積極的かつ意識的に参加するようにという呼びかけは、典礼に関する憲法にとどまらなかった。教皇フランシスコは、聖職 者主義から信徒の新時代への転換に言及した[222]。 教会に関する教義憲章 主な記事 ルーメン・ゲンチウム 以下も参照: 教会論(カトリック教会) ルーメン・ゲンチウム教会教義憲章(「諸国民の光」)は、エキュメニズム、非キリスト教諸宗教、信教の自由、現代世界における教会(下記参照)など、それ に続くいくつかの文書に方向性を与えた。パウロ6世によれば、「公会議の教えの最も特徴的で究極的な目的」は、聖性への普遍的な呼びかけである。ヨハネ・ パウロ二世はこれを「公会議教父たちの教会に関する教えの本質的かつ本質的な側面」[224]と呼び、「キリストに仕えるすべての信徒は、身分や地位の如 何を問わず、キリスト教的生活の充足と慈善の完成へと召されている」(『ルーメン・ゲンティウム』40)と述べている。フランシスコは、教皇職のプログラ ムを示した使徒的書簡『エヴァンゲリイ・ガウディウム』(17)の中で、「教義憲章『ルーメン・ゲンチウム』の教えに基づいて」、伝道する神の民全体、宣 教活動、貧しい人々の社会への包摂、社会内の平和と対話について論じると述べている。フランシスコはまた、司教会議を通じて、また8人の枢機卿からなる世 界的な諮問評議会を個人的に利用することを通じて、より合議制的なリーダーシップのスタイルを求める公会議の呼びかけに従った[225][226]。  第二バチカン公会議は、トレント公会議や第一バチカン公会議と同様に、献身的な文章や小冊子、カトリック聖人の生涯だけに頼るのではなく、聖書を聖典的に 読むことを奨励した。 この教令における司教団の教えから導き出される最も論争的な結論は、「ある意味で他のキリスト教共同体は制度的に欠陥がある」としながらも、これらの共同 体は「場合によっては恵みの乗り物としてより効果的でありうる」というものである。 227] ベルギーのエミール・デ・スメド司教は、カトリック教会に忍び込んだ制度的欠陥についてコメントし、「『聖職者主義、律法主義、勝利主義』の三位一体を体 現する教会の階層的モデルと、『ルーメン・ゲンチウム』で称賛された、聖霊の賜物に満たされ、恵みにおいて根本的に平等である『神の民』を強調するものと を対比させた」[228]。 神の啓示に関する教義憲章 主な記事 神の啓示に関する教義憲章 公会議の文書『神の言葉』(Dei Verbum)は、「聖なるページの研究は、いわば聖なる神学の魂である」という他の公会議文書で積極的に用いられている原則を述べている[229]。 [後にベネディクト16世となるヨゼフ・ラッツィンガーは、公会議における聖書の強調について、第二バチカン公会議以前の神学書は「啓示に関する命題と啓 示の内容」を混同し続けていたと述べている。ピウス12世のもとで聖書学が慎重に承認されていたにもかかわらず、第二バチカン公会議の直前まで、モダニズ ムを疑う学者たちは沈黙を守っていた。 [232]公会議は反宗教改革に決定的な終止符を打ち、アジョルナメントの精神で、「聖トマス自身と教父たちの背後、教会憲法の最初の2章を支配する聖書 神学にまで」さかのぼった[233]。......教会の歴史的な旅路は、第二バチカン公会議において、これらの資料に対する以前の焦点から逆転したので ある"[233]。例えば、典礼に関する公会議の文書は、「神と人類との間の愛の関係」を説明する聖書についてのより啓蒙的な説教とともに、典礼文をより 広く使用することを求めた。 [234]典礼文の現地語への翻訳、信徒に対する両方の聖体拝領の許可、ミサ中の聖書朗読の拡大は、他のキリスト教宗派の感覚と共鳴するものであったた め、第二バチカン公会議は「カトリック、プロテスタント、そして正教会にとって画期的な出来事」となった[40]。 現代世界における教会に関する司牧憲章 主な記事 ガウディウムと勧告 この文書は、その最初の言葉『喜びと希望』(Gaudium et Spes)にちなんで名づけられたもので、『ルーメン・ゲンティウム』の「神の巡礼の民」としての、また「交わり」としての教会の理解を基礎とし、教会の 教えの長い歴史を認識し、「時代のしるし」と呼ばれるものに触れている。それは、洗礼によって、イエスが教会に託された任務、すなわち、聖霊の継続的な働 きと協力しながら、現代が理解できるような方法で世界に宣教することが、すべての人に与えられているという理解を反映したものである。 神の民としての教会に関する教令と宣言 これらの7つの文書は、『教会憲章』(Lumen gentium)に含まれる教えを、司教、司祭、修道者、信徒、東方カトリック信徒など、教会のさまざまなカテゴリーに属する人々とキリスト教教育に適用 しています。 司教の司牧職 - 『主なるキリスト』(Christus Dominus、1965年)という教令は、『ルーメン・ゲンチウム』第3章にある司教職の神学に基づいて、合議制を含め、司教と教区に関する実際的な事 柄を扱っている。このCDは、司教がその職責を行使する3つのレベル、すなわち、普遍教会、自らの教区、国または地域のレベルを扱っている[235]。 普遍教会(CD 4-10)。合議制の教義では、司教は教皇と普遍教会の統治を分かち合うとされているため、この教令は、この統治において教皇を補佐するために、世界中の 司教からなる評議会を設置することを提案している。(ローマ教皇庁の真の目的は司教たちに奉仕することであるため、教皇庁は再編成され、より国際的になる 必要がある[235]。 教区(CD 11-35)。この教令は、教師、聖化者、羊飼いとしての司教の職務を説明している。司教と教区内の主な役職者との関係を論じ、人口の移動に伴う教区境界 の引き直しの必要性などの実際的な事柄を扱っている[236]。 国または地域レベル(CD 36-44)。勅令は、普遍教会と個々の教区の間に中間的なレベルの必要性を強調している。これは、当時すべての国に存在しなかった制度である全国(また は地域)司教会議である[237]。 司祭の職務と生活 - 『司祭の位階』(Presbyterorum ordinis、1965年)という教令は、司祭を「父であり教師」であると同時に、「洗礼盤で生まれ変わったすべての人々との兄弟の中の兄弟」であると している。司祭は信徒の "尊厳を促進し"、信徒の声に "喜んで耳を傾け"、信徒の "高貴なカリスマ "を認め、熱心に育て、"信徒に教会の奉仕の任務を委ね、信徒の自由と行動の余地を認めなければならない"。また、司祭の人間的・霊的ニーズについても詳 しく述べられている。 司祭養成-『オプタタム・トティウス』(『教会全体の望ましい(刷新)』、1965年)という教令は、司祭養成を現代の状況に適合させようとしている。こ の教令の中には、神学校が司祭養成の主要な場であり続けるという主張など、極めて伝統的な指摘もあるが、新しい状況に適応するための興味深い提案もある。 ひとつは、ローマの神学校・大学修道会がカトリック世界全体の養成プログラムを決める代わりに、各国の司教がそれぞれの国のニーズに合わせたプログラムを 考案してもよいというものだ(ただし、ローマの承認は必要)。もう一つは、司祭職の養成は、霊的、知的、司牧的という3つの側面を統合しなければならない ということである[238]。 霊的養成は、成熟した聖職者を生み出すことを目的とし、そのために心理学の力を借りることができる。知的養成を改善するために、現代的な教授法の使用、哲 学と神学のよりよい統合、神学研究における聖書の中心性、他宗教の知識など、多くの提案がある。牧会的形成は、研究課程全体を通じて行われるべきであり、 聖職の実践的経験を含むべきである。最後に、司祭叙階後も継続的な養成がなされるべきである[239]。  第二バチカン公会議以前の習慣 修道生活の適応と刷新-『完全なる慈愛』(Perfectae Caritatis、1965年)という教令は、修道生活を現代の状況に適応させることを扱っている。この教令は『教会憲章』(Lumen Gentium)第6章にある修道生活の神学を前提とし、それに刷新のための指針を加えている。この刷新の指針となるべき2つの基本原則は次の通りです: 「この教令は、主に修道会(修道誓願を立てて共同生活を営む修道会)を対象としているが、共同生活会(修道誓願を立てずに共同生活を営む修道会)や世俗的 修道会(修道誓願を立てて共同生活を営まない修道会)も対象としている[241]。 この教令は、キリストに従う生活としての奉献生活、清貧・貞潔・従順の3つの誓願の重要性、修道会の生活における慈善の重要性など、修道生活に関するよく 知られた見解を再掲している。 [242] これらに、観想的であれ活動的であれ、すべての修道会が自らを刷新するよう呼びかけるとともに、修道生活の簡素化、(司祭だけでなく)すべての修道会の会 員に対する教育の重要性、個々の会員だけでなく、各修道会全体としての清貧の必要性など、新しい状況に適応するための具体的な提案を加えている [243]。 信徒の使徒職 - 1965年の勅令Apostolicam actuositatemは、信徒の使徒職は「キリストのメッセージと恵みを人々にもたらすだけでなく、福音の精神をもって現世の秩序を貫き、完成させる こと」であると宣言している。 東方カトリック教会 - 『東方教会憲章』(Orientalium Ecclesiarum、1964年)は、東方カトリック教会、すなわち、ローマと完全な同盟関係にありながら、独自の典礼、慣習(既婚司祭など)、組織 形態(総主教と会堂)を持つ共同体について述べている。 [244]この教令は、これらの共同体は(以前一般的に呼ばれていたように)単に異なる儀式を行うものではなく、はるかに大規模なラテン教会と並ぶ特別な 教会であり、伝統的な組織慣行に従って自らを統治する権利を含め、ラテン教会と同じ権利を有すると述べている[245]。この教令は、司祭による堅信礼の 執行や、典礼時間への参加によって日曜日の義務を満たす可能性など、東方教会に典型的な特定の慣行を肯定している。また、東方カトリック信者と東方正教会 信者の間の共通の礼拝と共通の交わりに関する指針も示している[246]。 キリスト教教育 - 宣言Gravissimum educationis("Extreme [importance] of education"、1965年)[247]は、教育の重要性(GE 1)、キリスト教教育の重要性(GE 2-7)、カトリック学校の重要性(GE 8-9)、カトリック大学の重要性(GE 10-12)を論じている。教会にはカトリック学校を設立する権利があり、親には子どもに望む教育を選択する権利があり、政府にはカトリック学校に資金を 提供する義務があり、カトリック教徒にはカトリック学校を支援する義務がある[248]。 多くのオブザーバーは、この宣言に失望した: 「249]この宣言は、「公会議が作成した文書の中で、おそらく最も劣ったもの」[250]と呼ばれたが、第4会期の終盤で、誰もが公会議の議事を終了さ せなければならないというプレッシャーにさらされていたため、9%近くが拒否したものの、ほとんどの司教はこの宣言に賛成票を投じた。 |

| Decrees and declarations on the

Church in the world These 5 documents deal with the Church in its relationship with the surrounding world: other religious groups – non-Catholic Christians, non-Christians – missionary outreach, religious freedom, and the media. Three of them – on ecumenism, non-Christian religions and religious freedom – were important advances in the Church's teaching. Mission Activity – The decree Ad gentes ("To the Nations", 1965) treats evangelization as the fundamental mission of the Catholic Church, "to bring good news to the poor." It includes sections on training missionaries and on forming communities. Ecumenism – The decree Unitatis redintegratio ("Restoration of Unity", 1964) opens with the statement: "The restoration of unity among all Christians is one of the principal concerns of the Second Vatican Council." This was a reversal of the Church's previous position, one of hostility or, at best, indifference to the ecumenical movement, because the Church claimed the only way unity would come about was if the non-Catholics returned to the true Church.[251] The text produced by the Secretariat for Christian Unity said many things Catholics had not heard before: Instead of showing hostility or indifference to the ecumenical movement, a movement which originated among Protestant and Orthodox Christians,[252][253] the decree states it was fostered by the Holy Spirit. Instead of repeating the previous prohibition on Catholics taking part in ecumenical activities, the decree states that a concern for unity is an obligation for all Catholics.[254] Instead of claiming that disunity is the fault of non-Catholic Christians, the decree states that the Catholic Church must accept its share of the blame and ask for forgiveness.[255] Instead of claiming that the Catholic Church is in no need of reform, the decree states that all Christians, including Catholics, must examine their own faithfulness to Christ's will, and undertake whatever internal reforms are called for. Ecumenism requires a new attitude, a "change of heart" (UR 7), an interior conversion, on the part of Catholics.[256] Instead of claiming that only the Catholic Church has the means of salvation, the decree states that non-Catholic Christians have many of the elements of the true Church and, thanks to these, they can achieve salvation. All baptized are members of Christ's body. Catholics must get rid of false images of non-Catholics and come to appreciate the riches of their traditions.[255] Theological experts from both sides should enter into dialogue, in which each side sets out clearly its understanding of the Gospel. It should be remembered there is a hierarchy of truths, that not all teachings are equally central to the faith.[257] Christians of various traditions should pray together, though intercommunion is still not possible,[256] and undertake actions for the common good of humanity.[257] The last chapter addresses the situation of the Eastern Orthodox and of Protestants. The Orthodox are very close to the Catholic Church: they have valid sacraments and a valid priesthood, and though their customs and liturgical practices are different, this is not an obstacle to unity. Protestants comprise many denominations and their closeness to the Catholic Church varies according to the denomination; however all of them share with Catholics the belief in Jesus as saviour, the Bible, baptism, worship and the effort to lead a moral life.[258] This new way of considering the issue of Church unity met with great approval at the council and was adopted with very few dissenting voices.[259] Relation of the Church to Non-Christian Religions – The declaration Nostra aetate ("In our time", 1965), the shortest of Vatican II's documents, is a brief commentary on non-Christian religions, with a special section on the Jews. Pope John wanted the council to condemn antisemitism, including any Catholic teaching that might encourage antisemitism. It was felt the way to avoid stirring up trouble in the Middle East was to include the passage on the Jews within a broader document about non-Christian religions.[260] Avoiding argument or criticism, the declaration points out some positive features of Hinduism, Buddhism and Islam. "The Catholic Church rejects nothing of what is holy and true in these religions"; they often "reflect a ray of that truth which enlightens all men and women" (NA 2).[261] As for the Jews, the declaration says they are very dear to God: "God does not take back the gifts he bestowed or the choice he made" (NA 4). Jews are not rejected or cursed by God because of the death of Jesus: neither all Jews then, nor any Jew today, can be blamed for the death of Jesus. The Church deplores all hatred and antisemitism. And the declaration ends with a condemnation of all forms of discrimination based on religion or ethnicity.[262] In [the Declaration], a Council for the first time in history acknowledges the search for the absolute by other men and by whole races and peoples, and honours the truth and holiness in other religions as the work of the one living God. [...] Furthermore, in it the Church gives glory to God for his enduring faithfulness towards his chosen people, the Jews.[263] Better Jewish-Catholic relations have been emphasized since the council.[264][265] See also: Christian–Jewish reconciliation and Relations between Catholicism and Judaism Religious Freedom – The declaration Dignitatis humanae ("Of the Dignity of the Human Person", 1965), "on the right of the person and of communities to social and civil freedom in matters religious", is the most striking instance of the council's staking out a new position. Traditional Catholic teaching rejected freedom of religion as a basic human right.[266] The argument: only Catholics have the truth and so they alone are entitled to freedom of belief and of practice. All other religions are in error and, since "error has no rights", other religions have no right to freedom of belief and practice, and Catholic states have the right to suppress them. While it may be prudent to tolerate the existence of other religions in order to avoid civil unrest, this is merely a favour extended to them, not a matter of right. This double standard became increasingly intolerable to many Catholics. Furthermore, Protestants would not believe in the sincerity of Catholics' involvement in ecumenism, if they continued to support this double standard.[267] Pope John's last encyclical, Pacem in terris (April 1963), listed freedom of religion among the basic human rights – the first papal document to support freedom of religion – and he wanted Vatican II to address the issue. Dignitatis humanae broke with the traditional position and asserted that every human being was entitled to religious freedom. The argument: belief cannot be coerced. Since the Church wants people's religious belief to be genuine, people must be left free to see the truth of what is preached. The declaration also appealed to revelation: Jesus did not coerce people to accept his teaching, but invited them to believe, and so did his immediate followers.[268] Most Council Fathers supported this position, but 11% of them rejected it on the day of the final vote. If this position was true, they said, then the Church's previous teaching was wrong, and this was a conclusion they could not accept. The council's position on religious freedom raised in an acute way the issue of the development of doctrine: how can later teachings develop out of earlier ones? And how to tell whether a new position is a legitimate development of previous teaching or is heresy?[269] The Means of Social Communication – The decree Inter mirifica ("Among the wonderful [discoveries]", 1963) addresses issues concerning the press, cinema, television, and other media of communication. Chapter 1 is concerned with the dangers presented by the media, and insists that media producers should ensure that the media offer moral content, that media consumers should avoid media whose content is not moral, and that parents should supervise their children's media consumption. Chapter 2 discusses the usefulness of the media for the Church's mission: Catholic press and cinema should be promoted, and suitable persons within the Church should be trained in the use of the media.[270] "The text [is] generally considered to be one of the weakest of the Council."[271] Rather than improve it, most Council Fathers preferred approving it as is and moving on to more important matters. Some 25% of the Council Fathers voted against it to express their disappointment. |

世界における教会に関する声明と宣言 これらの5つの文書は、教会と周囲の世界との関係、すなわち、他の宗教団体、非カトリックのキリスト教徒、非キリスト教徒、宣教活動、信教の自由、メディ アについて扱っている。そのうちの3つ(エキュメニズム、非キリスト教諸宗教、信教の自由に関するもの)は、教会の教えにおける重要な進歩であった。 宣教活動 - 『Ad gentes』(「諸国民へ」、1965年)は、福音宣教をカトリック教会の基本的な使命として扱っている。宣教師の養成や共同体の形成に関する項目も含 まれている。 エキュメニズム - 「一致の回復(Unitatis redintegratio)」(1964年)という教令の冒頭にはこう書かれている: 「すべてのキリスト者の間の一致の回復は、第二バチカン公会議の主要な関心事の一つである。これは、エキュメニカルな動きに対して敵意を持っているか、せ いぜい無関心であった教会の以前の立場を覆すものであった: プロテスタントと正教会の間で生まれた運動であるエキュメニカル運動に敵意や無関心を示す代わりに[252][253]、政令はそれが聖霊によって育成さ れたと述べている。カトリック信者がエキュメニカルな活動に参加することに対する以前の禁止を繰り返す代わりに、教令は一致への関心がすべてのカトリック 信者の義務であると述べている[254]。 カトリック教会は改革の必要がないと主張する代わりに、カトリックを含むすべてのキリスト教徒は、キリストの御心に対する自らの忠実さを吟味し、必要とさ れる内部改革に取り組まなければならないと述べている[255]。エキュメニズムは、カトリック信者の側に新しい態度、「心の変化」(UR 7)、内的転換を要求する[256]。 カトリック教会だけが救いの手段を持っていると主張する代わりに、教令は、非カトリックのキリスト教徒も真の教会の多くの要素を持っており、これらのおか げで救いを得ることができると述べている。洗礼を受けた者はすべてキリストの体の一員である。カトリック信者は、非カトリック信者に対する誤ったイメージ を捨て去り、彼らの伝統の豊かさを認めるようにならなければならない[255]。 双方の神学専門家が対話に入り、その中でそれぞれの福音理解を明確に示すべきである。真理には階層があり、すべての教えが等しく信仰の中心であるわけでは ないことを忘れてはならない[257]。さまざまな伝統のキリスト教徒は、相互の交わりはまだ不可能だが[256]、ともに祈り、人類共通の善のために行 動を起こすべきである[257]。 最後の章は、東方正教会とプロテスタントの状況を取り上げている。正教会はカトリック教会に非常に近い存在であり、有効な秘跡と有効な司祭職を持ち、習慣 や典礼は異なるが、それは一致の障害にはなっていない。プロテスタントは多くの教派から構成されており、カトリック教会との親密さは教派によって異なる が、救世主としてのイエスへの信仰、聖書、洗礼、礼拝、道徳的な生活を送る努力はカトリックと共通している[258]。 教会一致の問題を考察するこの新しい方法は、公会議で大きな賛同を得、反対意見はほとんどなく採択された[259]。 教会と非キリスト教諸宗教との関係 - 第二バチカン公会議文書の中で最も短い宣言『ノストラ・アエターテ』(「私たちの時代に」、1965年)は、非キリスト教諸宗教についての簡潔な解説であ り、ユダヤ人についての特別なセクションがある。教皇ヨハネは、反ユダヤ主義を助長するようなカトリックの教えも含めて、公会議が反ユダヤ主義を非難する ことを望んだ。中東でのトラブルを引き起こさないためには、非キリスト教的宗教に関するより広範な文書の中にユダヤ人に関する一節を含めることが必要だと 考えられた[260]。 議論や批判を避け、宣言はヒンドゥー教、仏教、イスラム教の肯定的な特徴を指摘している。「カトリック教会は、これらの宗教の中にある聖なるもの、真実な ものを何一つ否定しない」、それらはしばしば「すべての男女を啓発する真理の一筋を反映している」(NA 2)[261]。 ユダヤ人については、彼らは神にとって非常に大切な存在であると宣言している: 「神はお与えになった賜物やお選びになったものをお戻しになることはない」(NA 4)。イエスの死のためにユダヤ人が神に拒絶されたり呪われたりすることはない。当時のすべてのユダヤ人も、今日のユダヤ人も、イエスの死について非難さ れることはない。教会はすべての憎悪と反ユダヤ主義を非難する。そして宣言は、宗教や民族に基づくあらゆる形態の差別を非難することで締めくくられている [262]。 宣言]の中で、公会議は歴史上初めて、他の人々や全人種や民族による絶対的なものの探求を認め、他の宗教における真理と聖性を唯一の生ける神の御業として 尊ぶ。[さらに、教会はその中で、選ばれた民であるユダヤ人に対する神の永続的な誠実さに栄光を帰するのである[263]。 公会議以来、ユダヤ人とカトリックのより良い関係が強調されている[264][265]。 以下も参照: キリスト教とユダヤ教の和解とカトリックとユダヤ教の関係 信教の自由 - 1965年に発表された『人間の尊厳』(Dignitatis humanae)は、「宗教的な事柄における社会的・市民的自由に対する個人と共同体の権利に関する」宣言であり、公会議が新しい立場を打ち出した最も顕 著な例である。 伝統的なカトリックの教えは、基本的人権としての信教の自由を否定していた[266]。他の宗教はすべて誤りであり、「誤りは権利を持たない」ので、他の 宗教には信仰と実践の自由を得る権利はなく、カトリック国家にはそれらを抑圧する権利がある。内乱を避けるために他宗教の存在を容認することは賢明かもし れないが、それは単なる好意に過ぎず、権利の問題ではない。このダブルスタンダードは、多くのカトリック教徒にとって次第に耐え難いものとなっていった。 さらに、プロテスタントは、この二重基準を支持し続けるのであれば、カトリックのエキュメニズムへの関与の誠意を信じることはできないだろう[267]。 教皇ヨハネの最後の回勅『Pacem in terris』(1963年4月)は、基本的人権の中に信教の自由を挙げており、信教の自由を支持する最初の教皇文書であった。 Dignitatis humanae』は従来の立場を打ち破り、すべての人間に信教の自由が与えられると主張した。その主張とは、信仰を強制することはできないというものだ。 教会は人々の信仰が本物であることを望んでいるのだから、人々は説かれていることの真理を見抜く自由を与えられなければならない。宣言はまた、啓示に訴え た: イエスは自分の教えを受け入れるよう人々に強要せず、信じるよう招き入れ、またイエスの直属の信者たちもそうであった[268]。 ほとんどの公会議教父はこの立場を支持したが、最終投票の日には11%の教父がこの立場を拒否した。もしこの立場が真実であれば、教会のこれまでの教えは 間違っていることになり、これは受け入れることのできない結論であったという。信教の自由に関する公会議の見解は、教義の発展という問題を鋭く提起した。 また、新しい立場が以前の教えの正当な発展であるのか、それとも異端であるのかをどのようにして見分けることができるのだろうか[269]。 社会的コミュニケーションの手段-『Inter mirifica』(「すばらしい発見の中で」、1963年)は、報道、映画、テレビ、その他のコミュニケーション・メディアに関する問題を扱っている。 第1章では、メディアがもたらす危険について述べ、メディア製作者はメディアが道徳的な内容を提供するようにし、メディア消費者は道徳的でない内容のメ ディアを避けるようにし、親は子どものメディア消費を監督すべきだと主張している。第2章では、教会の使命に対するメディアの有用性について論じている: カトリックの報道と映画は促進されるべきであり、教会内の適切な人物はメディアの使用について訓練されるべきである[270]。 「一般に、この文書は公会議の中で最も弱いものの一つと考えられている。25%の公会議教父は、失望を表明するために反対票を投じた。 |

| Impact

of Vatican II Vatican II was a record-breaking event Vatican II's features "are so extraordinary [...] that they set the council apart from its predecessors almost as a different kind of entity":[272] Its proportions were massive. “It was not the biggest gathering in the sense of number of people assembled at a given moment. But it was the biggest meeting, that is, a gathering with an agenda on which the sustained participation of all parties was required and which resulted in actual decisions. It was a gathering the likes of which had never been seen before”.[273] Its breadth was international. It was the first ecumenical council to be truly “ecumenical” (“world-wide”) since it was the first to be attended by bishops originating from all parts of the world, including some 250 native Asian and African bishops. (At Vatican I a century earlier, Asia and Africa were represented by European missionaries.) The scope and variety of issues it addressed was unprecedented: The topics discussed ranged from the most fundamental theological issues (such as the nature of the Church or the nature of Revelation) to eminently practical ones (such as nuns' habits and music in the liturgy), including topics no general Council had addressed before, such as collaboration of the Catholic Church with the concerns of the secular world and the Church's relation to non-Christian religions.[274] Its style was novel. It inaugurated a new style of conciliar teaching, a style that was called “pastoral” as it avoided anathemas and condemnations. Information could be transmitted almost immediately. It was the first general council in the era of mass-circulation newspapers, radio and television. As a result, information (and reactions) could be reported immediately, something beyond the realm of possibility at other ecumenical councils. Importance of Vatican II Its impact on the Church was huge: "It was the most important religious event of the twentieth century"[275] “The Second Vatican Council was the most significant event in the history of Catholicism since the Protestant Reformation”.[276] “Vatican II was the single most important event for Catholicism in four centuries, since the Council of Trent”.[277] "The sixteen documents of the Second Vatican Council are the most important texts produced by the Catholic Church in the past four hundred years"[278] In declaring the period from October 2012 to the end of November 2013 to be a "Year of Faith" to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the beginning of Vatican II, pope Benedict XVI wanted it to be a good opportunity to help people understand that the texts bequeathed by the Council Fathers, in the words of John Paul II, "have lost nothing of their value or brilliance". They need to be read correctly, to be widely known and taken to heart as important and normative texts of the Magisterium, within the Church's Tradition. ...I feel more than ever in duty bound to point to the Council as the great grace bestowed on the Church in the twentieth century: there we find a sure compass by which to take our bearings in the century now beginning.[279] Key Developments due to Vatican II According to theologian Adrian Hastings, the key theological and practical developments due to Vatican II are of 3 kinds:[280] 1. New general orientations and basic themes found throughout the documents: The Church defined as People of God The Eucharist as centre of the Church and its unity The primacy of Scripture in theory and in practice The beneficial nature of diversity: ecclesial (the Church as a communion of “churches”), liturgical, and theological (diversity “even in the theological elaborations of revealed truth”) Other Christians understood as being in [imperfect] communion with the Church The concern for secular human values, with justice and peace. 2. Specific texts that contain a recognizable shift from pre-conciliar teaching: The text on the collegiality of bishops (Lumen Gentium 22) The statement that the unique Church of Christ “subsists” in the Catholic Church (Lumen Gentium 8) The statement that “the Churches of the East, as much as those of the West, fully enjoy the right to rule themselves” (Orientalium Ecclesiarum 5 and Unitatis Redintegratio 16) The recognition and commendation of the ministry of married priests in the Eastern Churches (Presbyterorum Ordinis 16) The recognition that every person has the right to religious freedom (Dignitatis humanae 2) The condemnation of anti-Semitism (Nostra aetate 4) The condemnation of mass destruction in war (Gaudium et spes 80) The statement that “parents themselves should ultimately make the judgment” as to the size of their family (Gaudium et Spes 50). 3. Practical decisions requiring new institutions or new behaviour: The use of the vernacular in the liturgy The restoration of communion under both kinds for the laity The restoration of concelebration The restoration of the diaconate as a permanent order open to married men The [limited] possibility of sharing in the worship (including communion) of a Church other than one’s own The instruction to establish national or regional Episcopal Conferences with authority and responsibilities The recommendation to establish an agency of the universal Church to “foster progress in needy regions and social justice on the international scene”. Some changes resulting from Vatican II Main article: Post Vatican II history of the Catholic Church The council addressed relations between the Catholic Church and the modern world.[281] Several changes resulting from the council include the renewal of consecrated life with a revised charism, ecumenical efforts with other Christian denominations, interfaith dialogue with other religions, and the universal call to holiness, which according to Paul VI was "the most characteristic and ultimate purpose of the teachings of the Council".[282] According to Pope Benedict XVI, the most important and essential message of the council was "the Paschal Mystery as the center of what it is to be Christian and therefore of the Christian life, the Christian year, the Christian seasons".[283] Other changes that followed the council included the widespread use of vernacular languages in the Mass instead of Latin, the allowance of communion under both kinds for the laity, the subtle disuse of ornate clerical regalia, the revision of Eucharistic (liturgical) prayers, the abbreviation of the liturgical calendar, the ability to celebrate the Mass versus populum (with the officiant facing the congregation), as well as ad orientem (facing the "East" and the Crucifix), and modern aesthetic changes encompassing contemporary Catholic liturgical music and artwork.[40] With many of these changes resonating with the perspectives of other Christian denominations who sent observers to the Second Vatican Council, it was an ecumenical "milestone for Catholics, Protestants, [and] the Orthodox".[40] These changes, while praised by many faithful Catholics,[284] remain divisive among those identifying as traditionalist Catholics.[285][b] Dignitatis humanae, authored largely by United States theologian John Courtney Murray, challenged the council fathers to find "reasons for religious freedom" in which they believed,[286]: 8 and drew from scripture scholar John L. McKenzie the comment: "The Church can survive the disorder of development better than she can stand the living death of organized immobility."[286]: 106 As a result of the reforms of Vatican II, on 15 August 1972 Paul issued the motu proprio Ministeria Quaedam which in effect suppressed the minor orders and replaced them with two instituted ministries, those of lector and acolyte. A major difference was: "Ministries may be assigned to lay Christians; hence they are no longer to be considered as reserved to candidates for the sacrament of orders."[287] Vatican II and the pontificate of Pope Francis Main article: Theology of Pope Francis § Vatican II revisited It has been suggested that the pontificate of Francis will be looked upon as the "decisive moment in the history of the church in which the full force of the Second Vatican Council's reformist vision was finally realized."[288]: 178 |

第

二バチカン公会議のインパクト 第二バチカン公会議は記録的な出来事だった 第二バチカン公会議の特徴は、「非常に非凡であり、......公会議をその前任者たちからほとんど別種の存在として引き離すものであった」[272]。 その規模は巨大であった。「ある瞬間に集まった人々の数という意味では、最大の集会ではなかった。しかし、最大規模の会合、つまり、すべての関係者の持続 的な参加が必要とされ、実際の決定がなされた議題のある会合であった。それは、かつてなかったような集まりだった」[273]。 その広がりは国際的であった。アジアやアフリカ出身の司教約250人を含む世界各地の司教が出席した最初のエキュメニカル公会議であったため、真に「エ キュメニカル」(「世界的」)な公会議であった。(その100年前の第1バチカン公会議では、アジアとアフリカの代表はヨーロッパの宣教師たちだった)。 バチカン第1バチカン公会議では、アジアとアフリカはヨーロッパの宣教師たちによって代表された: 議論されたトピックは、最も基本的な神学的な問題(教会の性質や啓示の性質など)から、きわめて実際的な問題(修道女の習慣や典礼における音楽など)まで 多岐にわたり、世俗世界の関心事とカトリック教会の協力や、キリスト教以外の宗教と教会の関係など、それまでの公会議では取り上げられなかったトピックも 含まれていた[274]。 そのスタイルは斬新であった。この公会議は、新しいスタイルの公会議の教えを開始した。このスタイルは、アナテマや非難を避けることから「司牧的」と呼ば れた。 情報はほとんど即座に伝達された。新聞、ラジオ、テレビが大量に流通する時代になって初めての総会だった。その結果、他のエキュメニカル公会議では考えら れなかったような情報(および反応)が即座に報告された。 第二バチカン公会議の重要性 第2バチカン公会議が教会に与えた影響は非常に大きかった: 「それは20世紀で最も重要な宗教的出来事であった」[275]。 「第二バチカン公会議は、プロテスタントの宗教改革以来、カトリックの歴史において最も重要な出来事であった」[276]。 「第二バチカン公会議は、カトリックにとってトレント公会議以来4世紀で最も重要な出来事であった」[277]。 「第二バチカン公会議の16の文書は、過去400年間にカトリック教会が作成した最も重要な文書である」[278]。 教皇ベネディクト16世は、2012年10月から2013年11月末までの期間を、第二バチカン公会議開始50周年を記念する「信仰年」とすることを宣言 し、次のように望んだ。 ヨハネ・パウロ二世の言葉を借りれば、公会議教父たちによって遺された教典は、「その価値も輝きも何一つ失っていない」ことを人々に理解してもらう良い機 会である。公会議の教父たちが遺したテキストは、ヨハネ・パウロ二世の言葉を借りれば、「その価値や輝きを失ってはいない」のである。......私は、 20世紀の教会に与えられた偉大な恵みとして公会議を指し示す義務があることをこれまで以上に感じています。 第二バチカン公会議による主要な発展 神学者エイドリアン・ヘイスティングスによれば、第二バチカン公会議による神学的・実践的発展の鍵は次の3つである[280]。 1. 文書全体に見られる新しい一般的方向性と基本的テーマ: 神の民としての教会 教会とその一致の中心としての聖体 理論と実践における聖書の優位性 多様性の有益な性質:教会的多様性("教会 "の共同体としての教会)、典礼的多様性、神学的多様性("啓示された真理の神学的精緻化においても "多様であること) 他のキリスト教徒は教会と[不完全な]交わりをしていると理解される。 正義と平和という世俗的な人間的価値への関心。 2. 前教会の教えからの明白な転換を含む特定のテキスト: 司教の合議制に関するテキスト(Lumen Gentium 22) キリストの唯一の教会がカトリック教会の中に "存在する "という声明(ルーメン・ゲンチウム8章) 東方諸教会も西方諸教会と同様に、自らを統治する権利を完全に享受している」という声明(Orientalium Ecclesiarum 5 and Unitatis Redintegratio 16) 東方諸教会における既婚司祭の宣教の承認と称賛(Presbyterorum Ordinis 16) すべての人が信教の自由に対する権利を有するという認識(Dignitatis humanae 2) 反ユダヤ主義の非難(Nostra aetate 4) 戦争における大量破壊行為の非難(Gaudium et spes 80) 家族の人数について「最終的には親自身が判断すべきである」という声明(Gaudium et Spes 50) 3. 新しい制度や新しい行動を必要とする実際的な決定: 典礼における方言の使用 信徒のための両聖体拝領の復活 聖体拝領の復活 既婚男性に開かれた永続的な修道会としての助祭職の復活 自分の教会以外の教会の礼拝(聖体拝領を含む)に参加する[限定的な]可能性 権限と責任を持つ全国または地域の司教協議会の設立指示 恵まれない地域の発展と国際的な社会正義を促進する "ための普遍的な教会の機関を設立するようにという勧告。 第二バチカン公会議によるいくつかの変更 主な記事 第二バチカン公会議後のカトリック教会の歴史 公会議は、カトリック教会と現代世界との関係に取り組んだ[281]。公会議からもたらされたいくつかの変化には、改訂されたカリスマによる奉献生活の刷 新、他のキリスト教教派とのエキュメニカルな取り組み、他の宗教との宗教間対話、パウロ6世によれば「公会議の教えの最も特徴的で究極的な目的」であった 聖性への普遍的な呼びかけなどがある[282]。 教皇ベネディクト16世によれば、公会議の最も重要で本質的なメッセージは、「キリスト者であること、したがってキリスト者の生活、キリスト者の年、キリ スト者の季節の中心としての牧会の神秘」であった。 [283] 公会議後のその他の変化には、ミサにおけるラテン語に代わる方言の普及、信徒に対する両方の聖体拝領の許可、華麗な聖職者の礼服の微妙な不使用、聖体(典 礼)の祈りの改訂などがある、 典礼暦の省略、ミサを対民衆的(司式者が会衆の方を向いて)に、またアド・オリエンテム(「東方」と十字架の方を向いて)に祝う能力、現代のカトリック典 礼音楽や芸術作品を包含する現代的な美的変化などである。 [40]これらの変更の多くは、第二バチカン公会議にオブザーバーを派遣した他のキリスト教宗派の視点と共鳴するものであり、それはエキュメニカルな「カ トリック、プロテスタント、[そして]正教会のためのマイルストーン」であった[40]。これらの変更は、多くの忠実なカトリック信者によって賞賛される 一方で[284]、伝統主義的なカトリック信者として識別される人々の間では分裂したままである[285][b]。 米国の神学者ジョン・コートニー・マーレイによって主に執筆された『人間の尊厳』(Dignitatis humanae)は、公会議の教父たちが信じている「信教の自由の理由」を見つけるよう挑戦し[286]: 8、聖典学者ジョン・L・マッケンジーから次のようなコメントを引き出した: 「教会は、組織化された不動の生ける死に耐えるよりも、発展の無秩序に耐えることができる」[286]: 106 第二バチカン公会議の改革の結果、1972年8月15日、パウロは「Ministeria Quaedam」という教令を発布した。大きな違いは次の通りである: 「従って、これらの奉仕職は、もはや修道会の秘跡の候補者にのみ許されたものとはみなされない。 第二バチカン公会議とフランシスコ教皇の教皇職 主な記事 教皇フランシスコの神学 § 第二バチカン公会議再訪 フランシスコの教皇職は、「第二バチカン公会議の改革主義的ビジョンの全力が最終的に実現された、教会史における決定的瞬間」と見なされるだろうと示唆さ れている[288]: 178 |

Controversies An illustrated 1911

Roman Missal reprint from its 1884 edition An illustrated 1911