マヤ文字・マヤ記法

Maya script

Maya

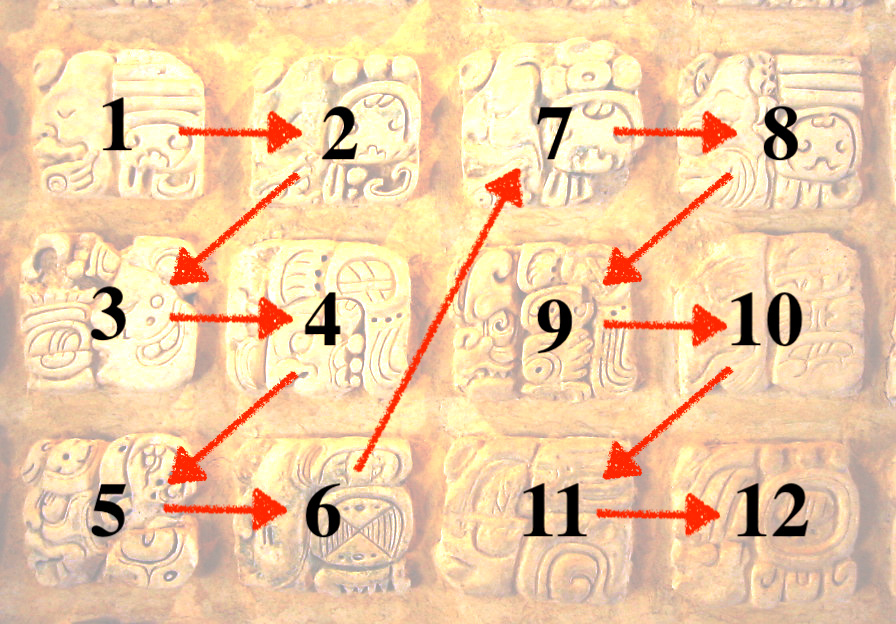

stucco glyphs diplayed in the museum at Palenque, Mexico.

☆ マ ヤ文字は、マヤグリフとも呼ばれ、歴史的にはメソアメリカのマヤ文明 の先住民の文字体系であり、メソアメリカの文字体系の中で唯一解読が進んでいる。マヤ文字は、16世紀から17世紀にかけてスペインがマヤを征服するま で、メソアメリカ全域で使用され続けた。現代のマヤ語は、マヤ文字ではなくラテンアルファベットを使用してほぼ完全に書かれている。 マヤ文字は音節グリフで補完されたロゴグラムを使用している。

| Maya script, also

known as Maya glyphs, is

historically the native writing system of the

Maya civilization of Mesoamerica and is the only Mesoamerican writing

system that has been substantially deciphered. The earliest

inscriptions found which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century

BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala.[1][2] Maya writing was in continuous use

throughout Mesoamerica until the Spanish conquest of the Maya in the

16th and 17th centuries. Though modern Mayan languages are almost

entirely written using the Latin alphabet rather than Maya script,[3]

there have been recent developments encouraging a revival of the Maya

glyph system.[citation needed] Maya writing used logograms complemented with a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Maya writing was called "hieroglyphics" or hieroglyphs by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who found its general appearance reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, although the two systems are unrelated. |

マヤ文字は、マヤグリフとも呼ばれ、歴史的にはメソアメリカのマヤ文明

の先住民の文字体系であり、メソアメリカの文字体系の中で唯一解読が進んでいる。マヤ文字は、16世紀から17世紀にかけてスペインがマヤを征服するま

で、メソアメリカ全域で使用され続けた。現代のマヤ語は、マヤ文字ではなくラテンアルファベットを使用してほぼ完全に書かれているが[3]、マヤのグリ

フシステムの復活を奨励する最近の開発があった[要出典]。 マヤ文字は音節グリフで補完されたロゴグラムを使用しており、その機能は現代の日本語の文字にやや似ている。マヤの文字は、その一般的な外観がエジプトの 象形文字を連想させることを発見した18世紀と19世紀の初期のヨーロッパの探検家によって 「象形文字 」または象形文字と呼ばれたが、2つのシステムは無関係である。 |

| Languages Evidence suggests that codices and other classic texts were written by scribes—usually members of the Maya priesthood—in Classic Maya, a literary form of the extinct Chʼoltiʼ language.[4][5] It is possible that the Maya elite spoke this language as a lingua franca over the entire Maya-speaking area, but texts were also written in other Mayan languages of the Petén and Yucatán, especially Yucatec. There is also some evidence that the script may have been occasionally used to write Mayan languages of the Guatemalan Highlands.[5] However, if other languages were written, they may have been written by Chʼoltiʼ scribes, and therefore have Chʼoltiʼ elements. |

言語 写本やその他の古典的なテキストは、通常マヤの神職のメンバーである書記によって、絶滅したChʼoltiʼ言語の文学形式である古典マヤ語で書かれたこ とを示唆する証拠がある。マヤのエリートたちは、マヤ語圏全体の共通語としてこの言語を話していた可能性があるが、テキストはペテンやユカタンの他のマヤ 語、特にユカテク語でも書かれていた。また、グアテマラ高地のマヤ諸語を書くためにこの文字が時折使われたかもしれないという証拠もある。しかし、もし他 の言語が書かれたのであれば、それはChʼoltiʼの書記によって書かれた可能性があり、したがってChʼoltiʼの要素を持っている。 |

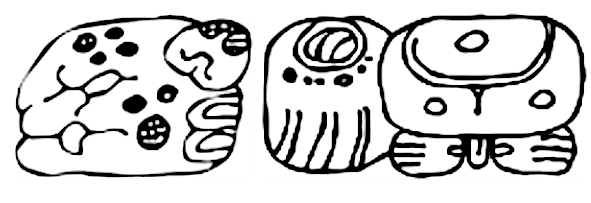

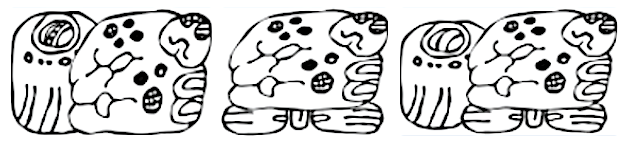

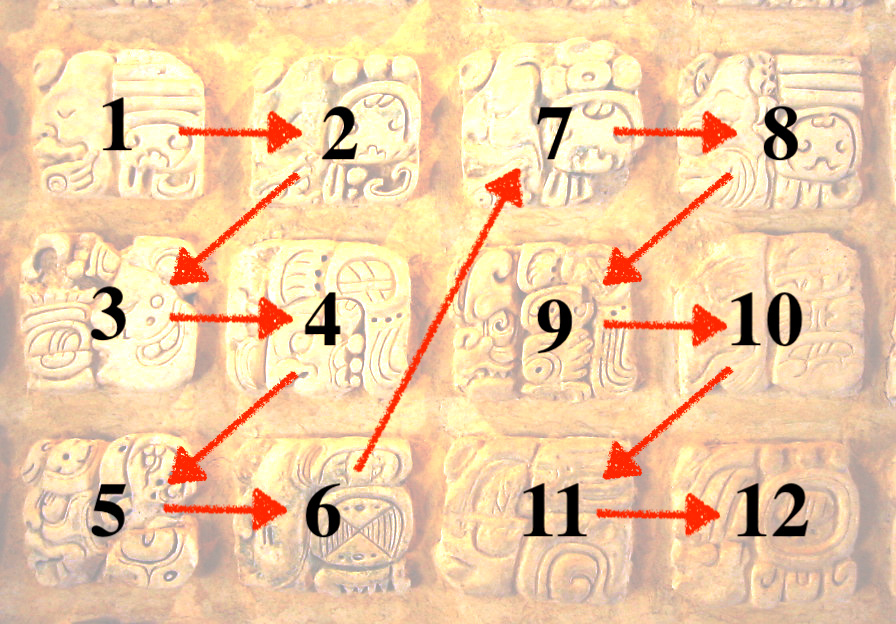

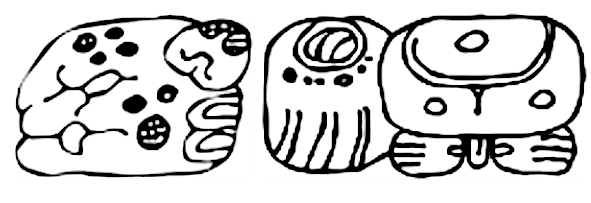

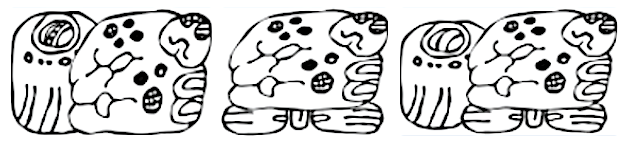

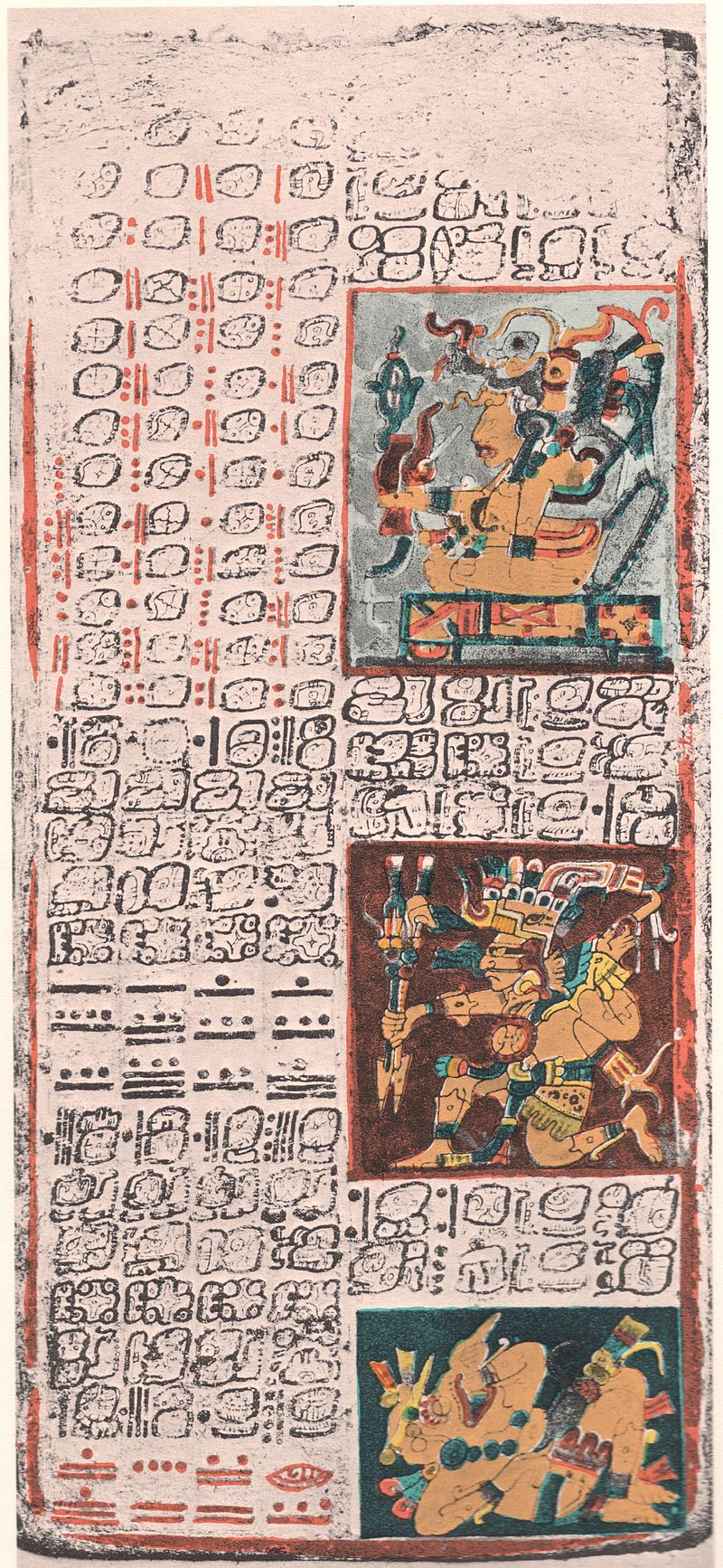

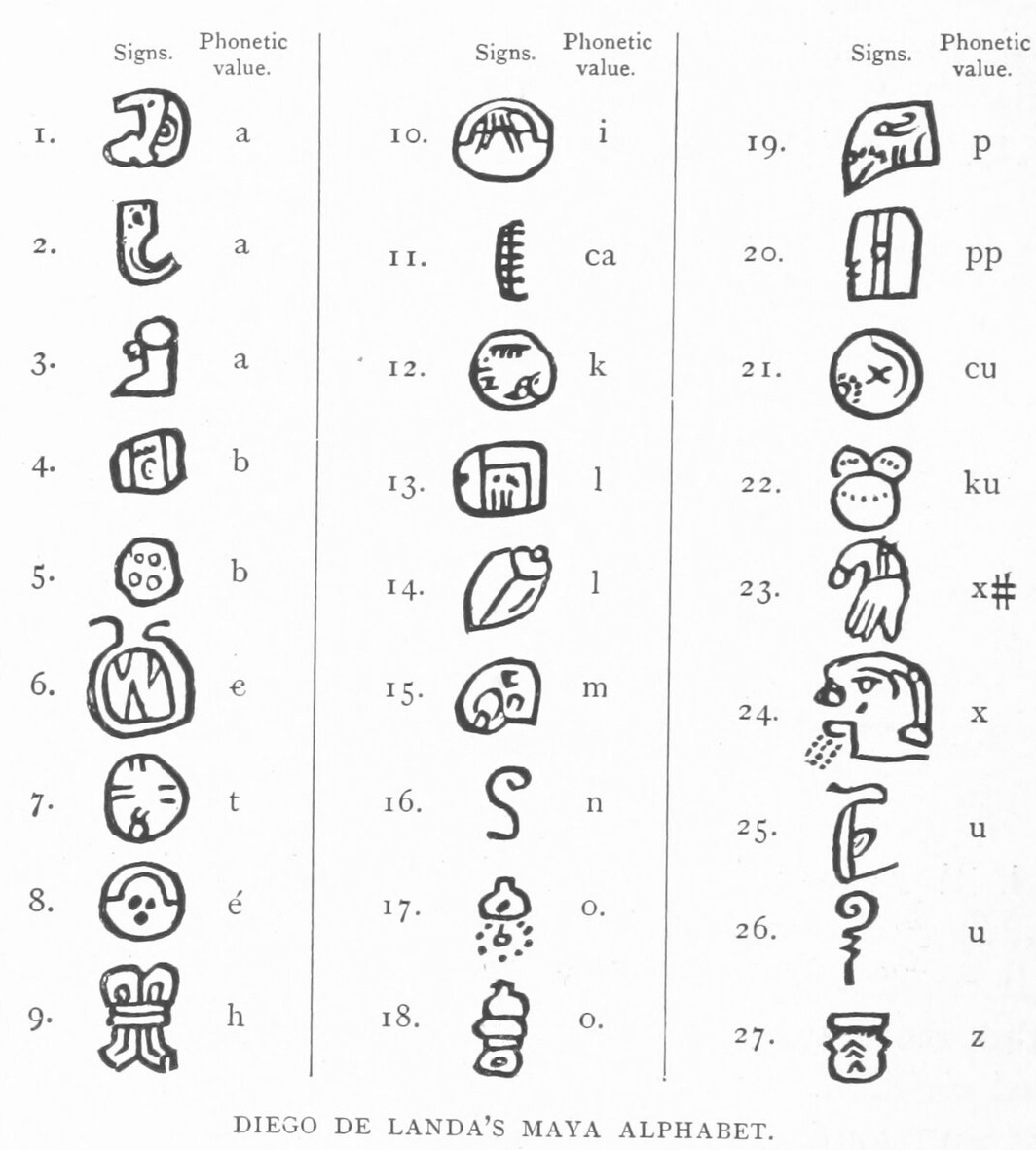

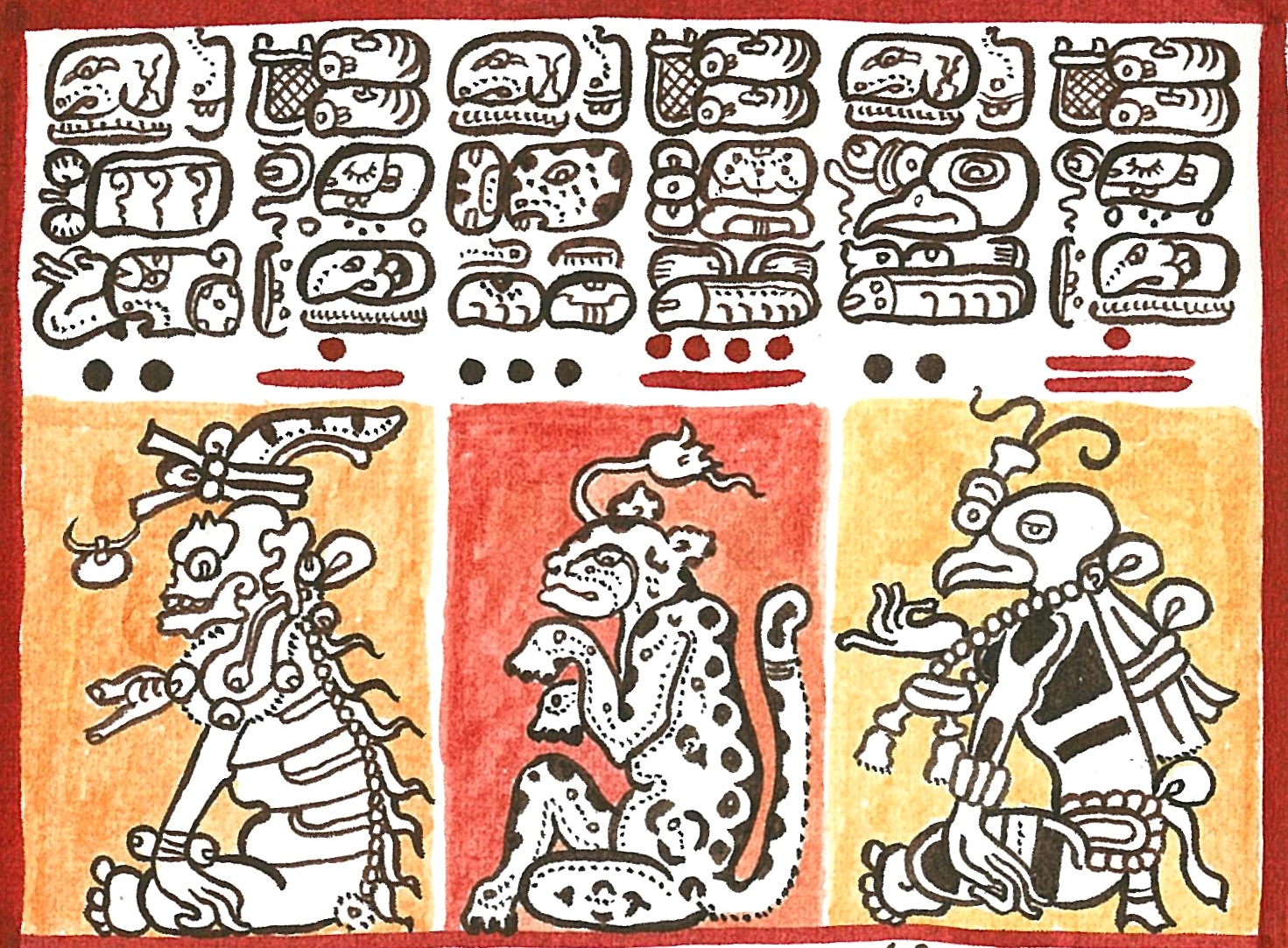

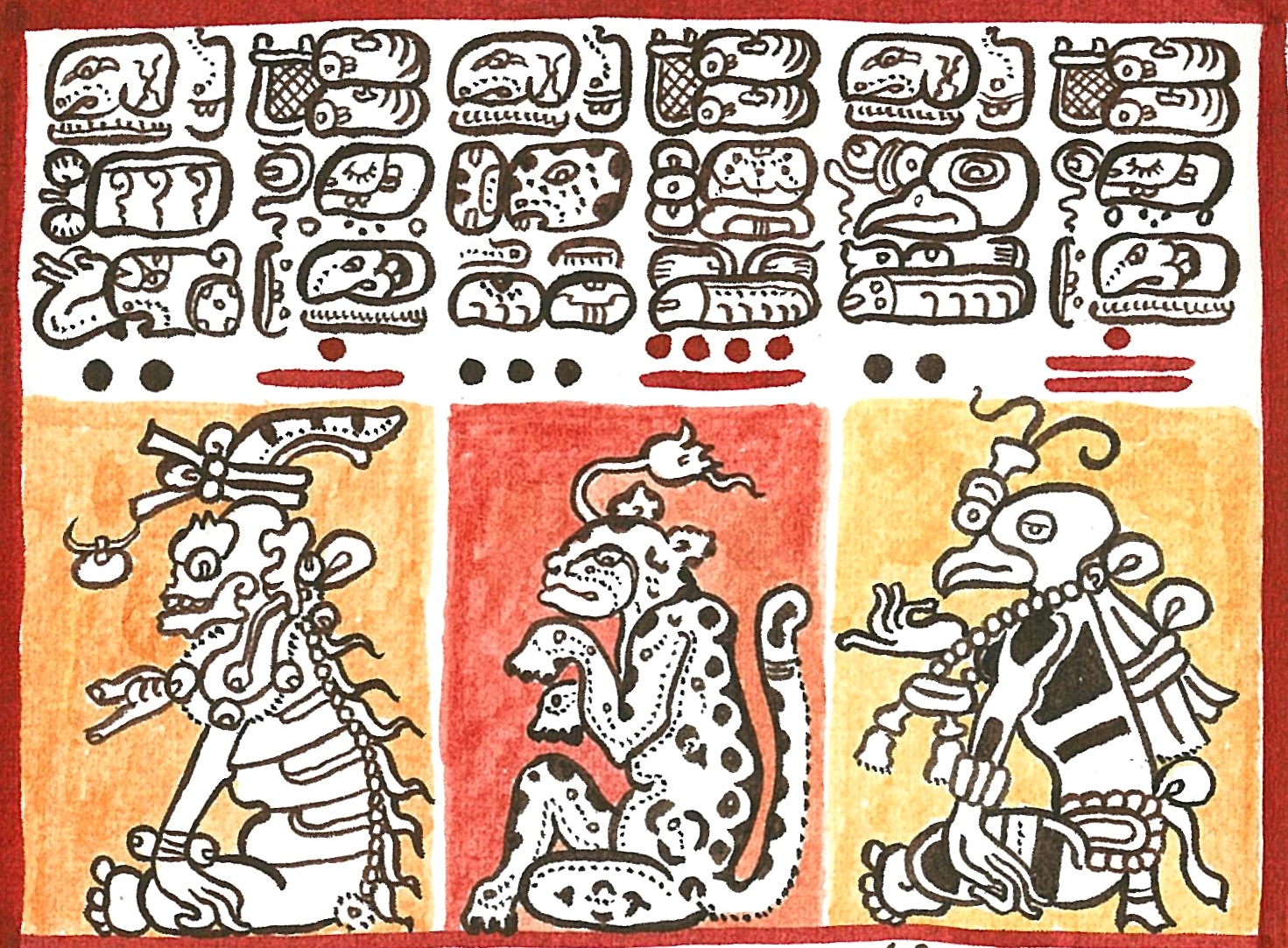

Structure Two different ways of writing the word bʼalam 'jaguar' in the Maya script – first, as a logogram representing the entire word with the single glyph bʼalam, and then, phonetically using the three syllable signs bʼa, la, and ma  Three ways to write bʼalam using combinations of the logogram with the syllabic signs as phonetic complements. From left to right: bʼa-bʼalam, bʼalam-ma, and bʼa-bʼalam-ma   Maya inscriptions were most often written in columns two glyphs wide, with each successive pair of columns read left to right, top to bottom Mayan writing consisted of a relatively elaborate and complex set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls and bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, and molded in stucco. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has rarely survived. As of 2008, the sound of about 80% of Maya writing could be read and the meaning of about 60% could be understood with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure.[6] Maya texts were usually written in blocks arranged in columns two blocks wide, with each block corresponding to a noun or verb phrase. The blocks within the columns were read left to right, top to bottom, and would be repeated until there were no more columns left. Within a block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right (similar to Korean Hangul syllabic blocks). Glyphs were sometimes conflated into ligatures, where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. In place of the standard block configuration, Maya was also sometimes written in a single row or column, or in an 'L' or 'T' shape. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed. The Maya script was a logosyllabic system with some syllabogrammatic elements. Individual glyphs or symbols could represent either a morpheme or a syllable, and the same glyph could often be used for both. Because of these dual readings, it is customary to write logographic readings in all caps and phonetic readings in italics or bold. For example, a calendaric glyph can be read as the morpheme manikʼ or as the syllable chi. Glyphs used as syllabograms were originally logograms for single-syllable words, usually those that ended in a vowel or in a weak consonant such as y, w, h, or glottal stop. For example, the logogram for 'fish fin'—found in two forms, as a fish fin and as a fish with prominent fins—was read as [kah] and came to represent the syllable ka. These syllabic glyphs performed two primary functions: as phonetic complements to disambiguate logograms which had more than one reading (similar to ancient Egyptian and modern Japanese furigana); and to write grammatical elements such as verbal inflections which did not have dedicated logograms (similar to Japanese okurigana). For example, bʼalam 'jaguar' could be written as a single logogram, bʼalam; a logogram with syllable additions, as ba-bʼalam, or bʼalam-ma, or bʼa-bʼalam-ma; or written completely phonetically with syllabograms as bʼa-la-ma. In addition, some syllable glyphs were homophones, such as the six different glyphs used to write the very common third person pronoun u-. Harmonic and disharmonic echo vowels  Yucatec Maya writing in the Dresden Codex, c. 11–12th century, Chichen Itza Phonetic glyphs stood for simple consonant-vowel (CV) or vowel-only (V) syllables. However, Mayan phonotactics is slightly more complicated than this. Most Mayan words end with consonants, and there may be sequences of two consonants within a word as well, as in xolteʼ ([ʃolteʔ] 'scepter') which is CVCCVC. When these final consonants were sonorants (l, m, n) or gutturals (j, h, ʼ) they were sometimes ignored ("underspelled"). More often, final consonants were written, which meant that an extra vowel was written as well. This was typically an "echo" vowel that repeated the vowel of the previous syllable. For example, the word [kah] 'fish fin' would be underspelled ka or written in full as ka-ha. However, there are many cases where some other vowel was used, and the orthographic rules for this are only partially understood; this is largely due to the difficulty in ascertaining whether this vowel may be due to an underspelled suffix. Lacadena & Wichmann (2004) proposed the following conventions: A CVC syllable was written CV-CV, where the two vowels (V) were the same: yo-po [yop] 'leaf' A syllable with a long vowel (CVVC) was written CV-Ci, unless the long vowel was [i], in which case it was written CiCa: ba-ki [baak] 'captive', yi-tzi-na [yihtziin] 'younger brother' A syllable with a glottalized vowel (CVʼC or CVʼVC) was written with a final a if the vowel was [e, o, u], or with a final u if the vowel was [a] or [i]: hu-na [huʼn] 'paper', ba-tzʼu [baʼtsʼ] 'howler monkey'. Preconsonantal [h] is not indicated. In short, if the vowels are the same (harmonic), a simple vowel is intended. If the vowels are not the same (disharmonic), either two syllables are intended (likely underspelled), or else a single syllable with a long vowel (if V1 = [a e? o u] and V2 = [i], or else if V1 = [i] and V2 = [a]) or with a glottalized vowel (if V1 = [e? o u] and V2 = [a], or else if V1 = [a i] and V2 = [u]). The long-vowel reading of [Ce-Ci] is still uncertain, and there is a possibility that [Ce-Cu] represents a glottalized vowel (if it is not simply an underspelling for [CeCuC]), so it may be that the disharmonies form natural classes: [i] for long non-front vowels, otherwise [a] to keep it disharmonic; [u] for glottalized non-back vowels, otherwise [a]. A more complex spelling is ha-o-bo ko-ko-no-ma for [haʼoʼb kohknoʼm] 'they are the guardians'.[a] A minimal set is, ba-ka [bak] ba-ki [baak] ba-ku [baʼk] = [baʼak] ba-ke [baakel] (underspelled) ba-ke-le [baakel] |

構造 bʼalam「ジャガー」という単語をマヤ文字で書く2つの異なる方法-まず、単語全体を単一のグリフbʼalamで表すロゴグラムとして、次に、3つの 音節記号bʼa、la、maを使って音声的に書く。  音素補語としての音節記号とロゴグラムの組み合わせによるbʼalamの3つの書き方。左からbʼa-bʼalam、bʼalam-ma、bʼa- bʼalam-ma。   マヤの碑文は2グリフ幅の列で書かれることが多く、各列の連続するペアは左から右、上から下へと読まれる。 マヤの文字は比較的精巧で複雑なグリフで構成され、陶器、壁、樹皮紙のコーディスに手間を惜しまず描かれ、木や石に彫られ、漆喰で成形された。彫刻や成形 されたグリフには絵が描かれたが、絵の具が残っていることはほとんどない。2008年現在、マヤの文字の約80%の音は読むことができ、約60%の意味は 程度の差こそあれ、その構造を包括的に理解するのに十分な程度に理解することができる[6]。 マヤのテキストは通常、2ブロック幅の列に配置されたブロックで書かれており、各ブロックは名詞または動詞句に対応しています。列内のブロックは左から右 へ、上から下へと読まれ、列がなくなるまで繰り返された。ブロックの中では、グリフは上から下へ、左から右へと並べられた(韓国語のハングル音節ブロック に似ている)。グリフは時に合字になり、1つのグリフの要素が2つ目のグリフの一部を置き換えることもあった。標準的なブロックの代わりに、Maya は 1 行または 1 列で書かれたり、'L' や 'T' の形で書かれたりすることもあった。このようなバリエーションは、刻まれる面によりよく適合する場合に、最も頻繁に現れた。 マヤ文字はロゴス音節系で、音節文字的な要素もある。個々のグリフや記号は形態素か音節のどちらかを表すことができ、同じグリフが両方に使われること もしばしばあった。このような二重の読み方があるため、対義語的な読み方はすべて大文字で、音韻的な読み方はイタリック体や太字で書くのが通例である。例 えば、暦のグリフは形態素 manikʼ としても音節 chi としても読める。 音節文字として使われるグリフは、もともとは単音節の単語、たいていは母音で終わるもの、または y、w、h、声門停止などの弱い子音で終わるもののためのロゴグラムであった。例えば、「魚のヒレ」のロゴグラムは、魚のヒレとヒレの目立つ魚の2つの形 があり、[kah]と読まれ、音節のkaを表すようになった。これらの音節グリフは主に2つの機能を果たしていた。1つは、複数の読み方を持つロゴグラム を曖昧にするための音声補語として(古代エジプト語や現代日本語のふりがなのようなもの)、もう1つは、専用のロゴグラムを持たない動詞の屈折などの文法 要素を書くためのもの(日本語の送り仮名のようなもの)である。例えば、bʼalam「ジャガー」は、bʼalamという単一のロゴグラム、ba- bʼalam、bʼalam-ma、bʼa-bʼalam-maという音節を加えたロゴグラム、bʼa-la-maという音節文字で完全に音声的に書くこ とができる。 さらに、いくつかの音節のグリフは、非常に一般的な三人称代名詞u-を書くのに使われる6つの異なるグリフのように、同音異義語であった。 調和母音と非調和エコー母音  ドレスデン写本のユカテク・マヤ文字、11~12世紀頃、チチェン・イッツァ 音韻グリフは単純な子音-母音(CV)または母音のみ(V)の音節を表す。しかし、マヤの音韻はこれよりも少し複雑である。マヤ語のほとんどの単語は子音 で終わり、xolteʼ ([ʃolteʔ] 'scepter')のように単語内に2つの子音が連続することもあり、これはCVCCVCである。これらの最終子音がソノラント(l、m、n)または露 頭(j、h、ʼ)である場合、無視されることもあった(「アンダースペル」)。最終子音が書かれることで、母音も追加で書かれることがよくあった。これは 通常、前の音節の母音を繰り返す「エコー」母音であった。例えば、[kah]「魚のヒレ」という単語は、アンダースペルでkaと書かれるか、フル でka-haと書かれる。これは、この母音がアンダースペルの接尾辞によるものかどうかを判断するのが難しいことが主な原因である。 Lacadena & Wichmann (2004)は次のような規則を提案した: CVC音節はCV-CVと表記され、2つの母音(V)は同じである。 長母音(CVVC)を持つ音節はCV-Ciと表記されますが、長母音が[i]の場合はCiCaと表記される: ba-ki [baak] 'captive', yi-tzi-na [yihtziin] 'younger brother' 声門化母音(CVʼCまたはCVʼVC)を持つ音節は、母音が[e, o, u]の場合は最後のaで、母音が[a]または[i]の場合は最後のuで書かれました:hu-na [huʼn] 'paper', ba-tzʼu [baʼtsʼ] 'howler monkey'。 前子音[h]は示されない。 要するに、母音が同じ(調和的)であれば、単純母音が意図されている。母音が同じでない場合(非調和)、2つの音節が 意図されるか(アンダースペルである可能性が高い)、長母音(V1 = [a e? o u]でV2 = [i]の場合、またはV1 = [i]でV2 = [a]の場合)、または声門化母音(V1 = [e? o u]でV2 = [a]の場合、またはV1 = [a i]でV2 = [u]の場合)を持つ1つの音節が意図されます。Ce-Ci]の長母音読みはまだ不確かであり、[Ce-Cu]が声門化母音を表す可能性もある(単に [CeCuC]のアンダースペルでない場合): [i]は長い非前頭母音を表し、そうでなければ[a]で非調和を保ち、[u]は声門化した非後頭母音を表し、そうでなければ[a]となる。 より複雑な綴りは、[haʼoʼb kohknoʼm]のha-o-bo ko-ko-no-maである、 ba-ka [bak] ba-ki [baak] バ・ク【baʼk】=【baʼak ba-ke[baakel](アンダースペル) バ・ケ・ル [baakel] |

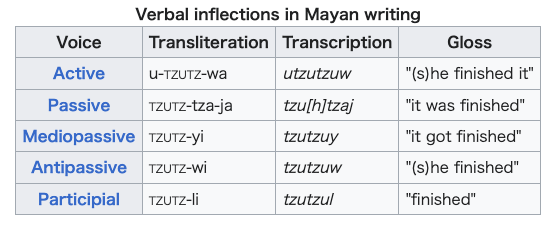

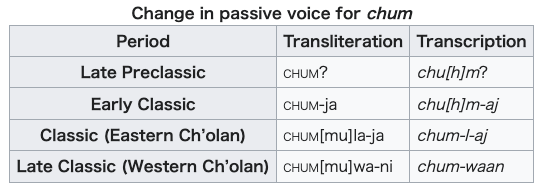

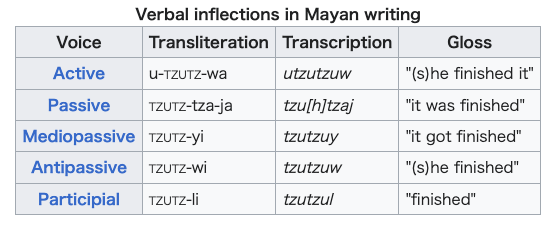

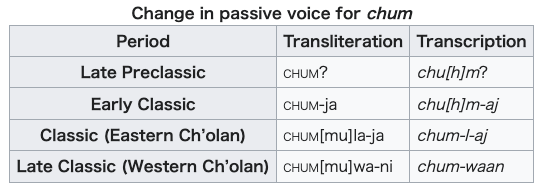

| Verbal inflections Despite depending on consonants which were frequently not written, the Mayan voice system was reliably indicated. For instance, the paradigm for a transitive verb with a CVC root is as follows:[7]  The active suffix did not participate in the harmonic/disharmonic system seen in roots, but rather was always -wa. However, the language changed over 1500 years, and there were dialectal differences as well, which are reflected in the script, as seen next for the verb "(s)he sat" (⟨h⟩ is an infix in the root chum for the passive voice):[8]  |

動詞の屈折 マヤの音声システムは、しばしば文字で表記されない子音に依存していたにもかかわらず、確実に表記されていた。例えば、CVC語根を持つ他動詞のパラ ダイムは以下の通りである[7]。  能動接尾辞は、語根に見られる和声/異和声のシステムには参加せず、常に-waであった。 しかし、言語は1500年の間に変化し、方言の違いもあり、それは次の「(s)he sat」(ɾh⟩は受動態を表すchum語根の接尾辞)のように文字に反映されている[8]。  |

Emblem glyphs Tikal or "Mutal" Emblem Glyph, Stela 26 in Tikal's Litoteca Museum  An inscription in Maya glyphs from the site of Naranjo, relating to the reign of king Itzamnaaj Kʼawil, 784–810 An "emblem glyph" is a kind of royal title. It consists of a place name followed by the word ajaw, a Classic Maya term for "lord" with an unclear but well-attested etymology.[9] Sometimes the title is introduced by an adjective kʼuhul ("holy, divine" or "sacred"), resulting in the construction "holy [placename] lord". However, an "emblem glyph" is not a "glyph" at all: it can be spelled with any number of syllabic or logographic signs and several alternative spellings are attested for the words kʼuhul and ajaw, which form the stable core of the title. "Emblem glyph" simply reflects the time when Mayanists could not read Classic Maya inscriptions and used a term to isolate specific recurring structural components of the written narratives, and other remaining examples of Maya orthography. This title was identified in 1958 by Heinrich Berlin, who coined the term "emblem glyph".[10] Berlin noticed that the "emblem glyphs" consisted of a larger "main sign" and two smaller signs now read as kʼuhul ajaw. Berlin also noticed that while the smaller elements remained relatively constant, the main sign changed from site to site. Berlin proposed that the main signs identified individual cities, their ruling dynasties, or the territories they controlled. Subsequently, Marcus (1976) argued that the "emblem glyphs" referred to archaeological sites, or more so the prominence and standing of the site, broken down in a 5-tiered hierarchy of asymmetrical distribution. Marcus' research assumed that the emblem glyphs were distributed in a pattern of relative site importance depending on broadness of distribution, roughly broken down as follows: Primary regional centers (capitals) (Tikal, Calakmul, and other "superpowers") were generally first in the region to acquire a unique emblem glyph(s). Texts referring to other primary regional centers occur in the texts of these "capitals", and dependencies exist which use the primary center's glyph. Secondary centers (Altun Ha, Lubaantun, Xunantunich, and other mid-sized cities) had their own glyphs but are only rarely mentioned in texts found in the primary regional center, while repeatedly mentioning the regional center in their own texts. Tertiary centers (towns) had no glyphs of their own, but have texts mentioning the primary regional centers and perhaps secondary regional centers on occasion. These were followed by the villages with no emblem glyphs and no texts mentioning the larger centers, and hamlets with little evidence of texts at all.[11] This model was largely unchallenged for over a decade until Mathews and Justeson,[12] as well as Houston,[13] argued once again that the "emblem glyphs" were the titles of Maya rulers with some geographical association. The debate on the nature of "emblem glyphs" received a new spin in Stuart & Houston (1994). The authors demonstrated that there were many place-names-proper, some real, some mythological, mentioned in the hieroglyphic inscriptions. Some of these place names also appeared in the "emblem glyphs", some were attested in the "titles of origin" (expressions like "a person from Lubaantun"), but some were not incorporated in personal titles at all. Moreover, the authors also highlighted the cases when the "titles of origin" and the "emblem glyphs" did not overlap, building upon Houston's earlier research.[14] Houston noticed that the establishment and spread of the Tikal-originated dynasty in the Petexbatun region was accompanied by the proliferation of rulers using the Tikal "emblem glyph" placing political and dynastic ascendancy above the current seats of rulership.[15] Recent investigations also emphasize the use of emblem glyphs as an emic identifier to shape socio-political self-identity.[16] |

エンブレム・グリフ ティカルまたは 「ムタル 」エンブレムグリフ、ティカル・リトテカ博物館のステラ26  ナランホ遺跡から出土したマヤのグリフによる碑文で、イツァムナアジ・カウィル王(784-810年)の治世に関するもの。 エンブレム・グリフ "とは、王家の称号の一種である。地名に続き、語源は不明だがよく証明されている古典マヤ語で「領主」を意味する単語アジャウが続く[9]。この称号に形 容詞kʼuhul(「聖なる、神聖な」または「神聖な」)が導入されることもあり、「聖なる(地名)領主」という構文になる。しかし、「emblem glyph 」は 「glyph 」ではない。「emblem glyph 」は任意の数の音節記号または記号で綴ることができ、タイトルの安定した核を形成するkʼuhulとajawの単語にはいくつかの別の綴りが証明されてい る。「エンブレムグリフ 」は、マヤ学者が古典マヤの碑文を読めなかった時代を反映したもので、書かれた物語の特定の繰り返し構造的構成要素や、マヤの正書法の他の残存例を分離す るために使われた用語です。 この呼称は1958年にハインリッヒ・バーリン(Heinrich Berlin)によって特定され、彼は「エンブレム・グリフ(emblem glyph)」という用語を作り出しました[10]。バーリンは「エンブレム・グリフ」が大きな「主符号」と、現在ではkʼuhul ajawと読まれる2つの小さな符号から構成されていることに気づきました。バーリンはまた、小さな要素は比較的一定している一方で、主符号は遺跡ごとに 変化していることにも気づいた。バーリンは、メイン・サインは個々の都市、その支配王朝、または彼らが支配する領土を特定するものだと提唱した。その後、 マーカス(1976)は、「エンブレム・グリフ」は遺跡を指し示すものであり、より詳細には、非対称に分布する5段階の階層に分けられた遺跡の卓越性と地 位を指すものであると主張した。マーカスの研究では、エンブレム・グリフは分布の広さに応じて遺跡の相対的な重要性を示すパターンで分布しており、大まか に以下のように分類されると仮定した: 一次的な地域中心地(首都)(ティカル、カラクムル、その他の「超大国」)は、一般的にその地域で最初に固有のエンブレムグリフを獲得した。これらの 「首都 」のテキストには、他の一次的な地域センターに言及するテキストがあり、一次的なセンターのグリフを使用する依存関係が存在する。二次中心地(アルトゥ ン・ハ、ルバントゥン、スナントゥニッチ、その他の中規模都市)は独自のグリフを持つが、一次中心地のテキストで言及されることは稀である。第三次中心地 (町)には独自のグリフはないが、第一次地域中心地やおそらく第二次地域中心地について言及した文章が時々ある。このモデルは、Mathewsと Justeson[12]、そしてHouston[13]が、「エンブレム・グリフ」は何らかの地理的関連性を持つマヤの支配者の称号であると再び主張す るまで、10年以上ほとんど議論の余地がなかった。 エンブレム・グリフ」の性質に関する議論は、Stuart & Houston (1994)で新たな展開を見せた。著者らは、ヒエログリフ碑文には、実在の地名や神話上の地名が数多く記されていることを明らかにした。これらの地名の いくつかは「エンブレム・グリフ」にも登場し、いくつかは「出身地称号」(「ルバントゥン出身者」のような表現)の中で証明されたが、いくつかは個人の称 号にはまったく含まれていなかった。さらに著者らは、ヒューストンの先行研究を踏まえて、「出身地の称号」と「紋章字体」が重ならない場合にも注目した。 [14]ヒューストンは、ペテクスバトゥン地域におけるティカルを起源とする王朝の確立と普及が、現在の支配権の座の上に政治的・王朝的な優位を置くティ カルの「紋章グリフ」を使用する支配者の急増を伴っていたことに注目した[15]。 最近の調査でも、社会的・政治的な自己同一性を形成するための象徴的な識別子としての紋章グリフの使用が強調されている[16]。 |

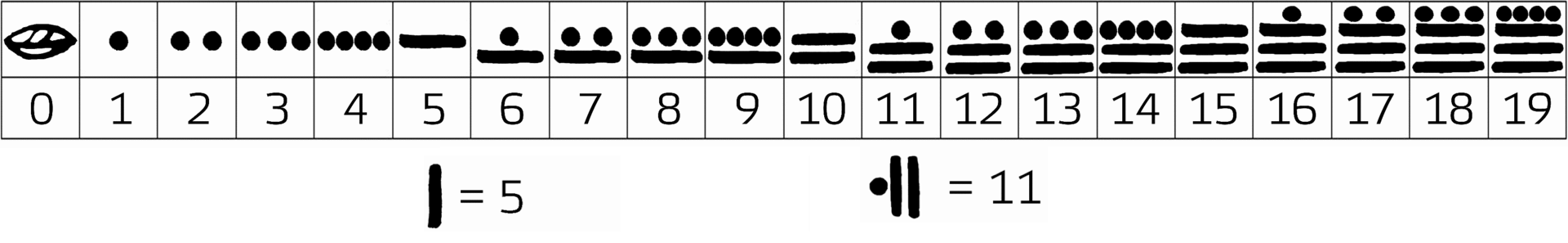

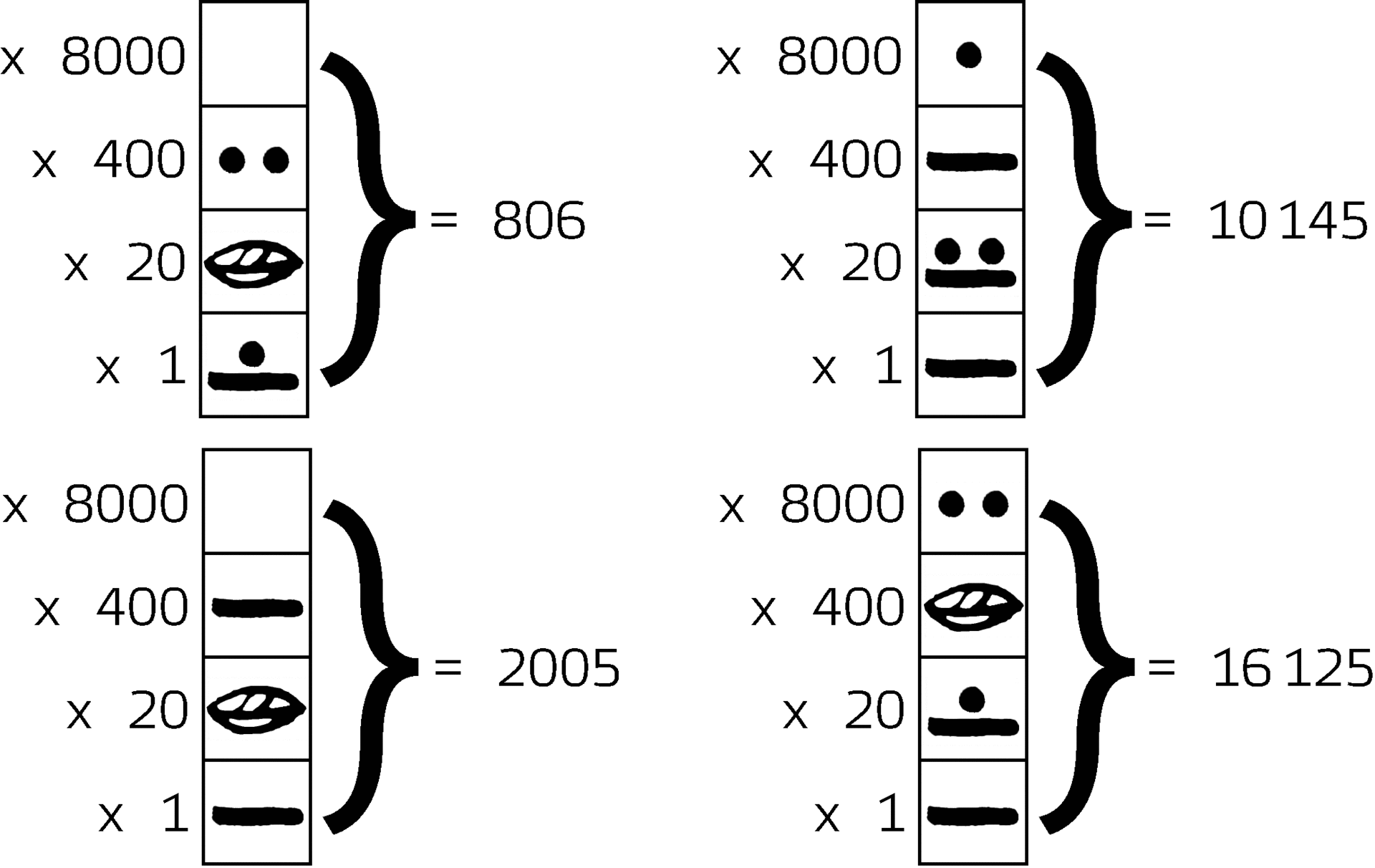

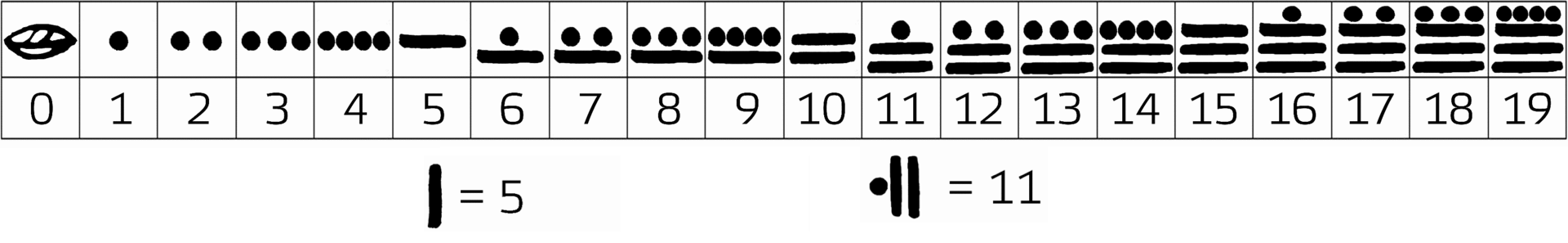

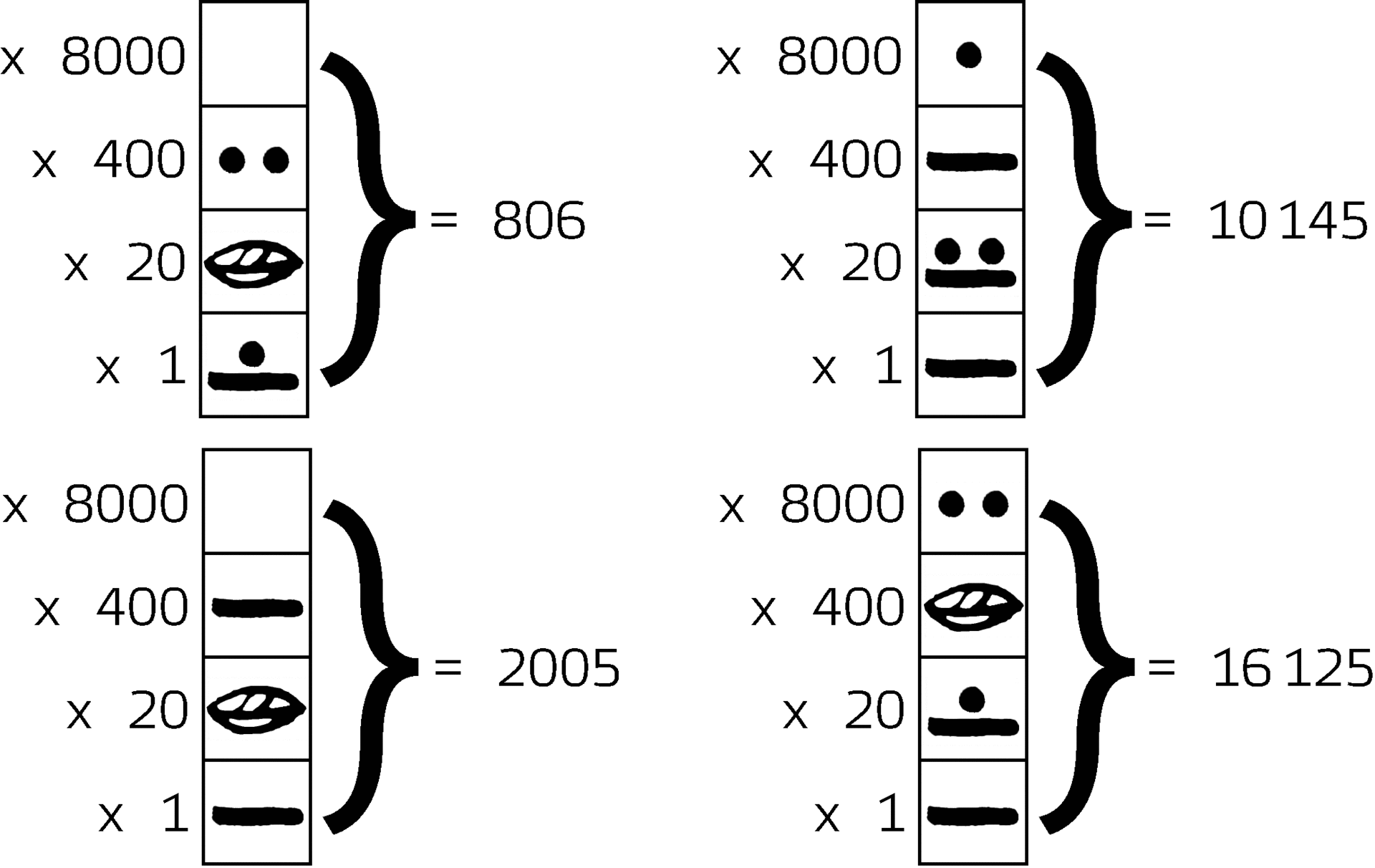

| Numerical system Main article: Maya numerals  List of Maya numerals from 0 to 19 with underneath two vertically oriented examples The Mayas used a positional base-twenty (vigesimal) numerical system which only included whole numbers. For simple counting operations, a bar and dot notation was used. The dot represents 1 and the bar represents 5. A shell was used to represent zero. Numbers from 6 to 19 are formed combining bars and dots, and can be written horizontally or vertically. Numbers over 19 are written vertically and read from the bottom to the top as powers of 20. The bottom number represents numbers from 0 to 20, so the symbol shown does not need to be multiplied. The second line from the bottom represents the amount of 20s there are, so that number is multiplied by 20. The third line from the bottom represents the amount of 400s, so it is multiplied by 400; the fourth by 8000; the fifth by 160,000, etc. Each successive line is an additional power of twenty (similar to how in Arabic numerals, additional powers of 10 are added to the left of the first digit). This positional system allows the calculation of large figures, necessary for chronology and astronomy.[17]  These four examples show how the value of Maya numerals can be calculated. |

数値システム 主な記事 マヤ数字  マヤの0から19までの数字のリストと、その下にある2つの縦書きの例 マヤでは、整数のみを含む20進数法を用いていた。簡単な計数操作には、棒と点の表記法が用いられた。点は1を表し、棒は5を表す。シェルはゼロを表すの に使われた。6から19までの数字は、棒と点を組み合わせて形成され、横書きにも縦書きにもできる。 19以上の数字は縦書きで、下から上へ20の累乗として読む。一番下の数字は0から20までの数字を表すので、表示されている記号は掛け算の必要はない。 下から2行目は20の数を表すので、その数に20を掛ける。下から3番目の行は400の数を表すので、400倍、4番目は8000倍、5番目は16万倍な どである。連続する各行は、さらに20の累乗となる(アラビア数字で、最初の桁の左側に10の累乗が追加されるのと同様である)。この位置システムは、年 表や天文学に必要な大きな数字の計算を可能にする[17]。  これらの4つの例は、マヤ数字の値がどのように計算できるかを示している。 |

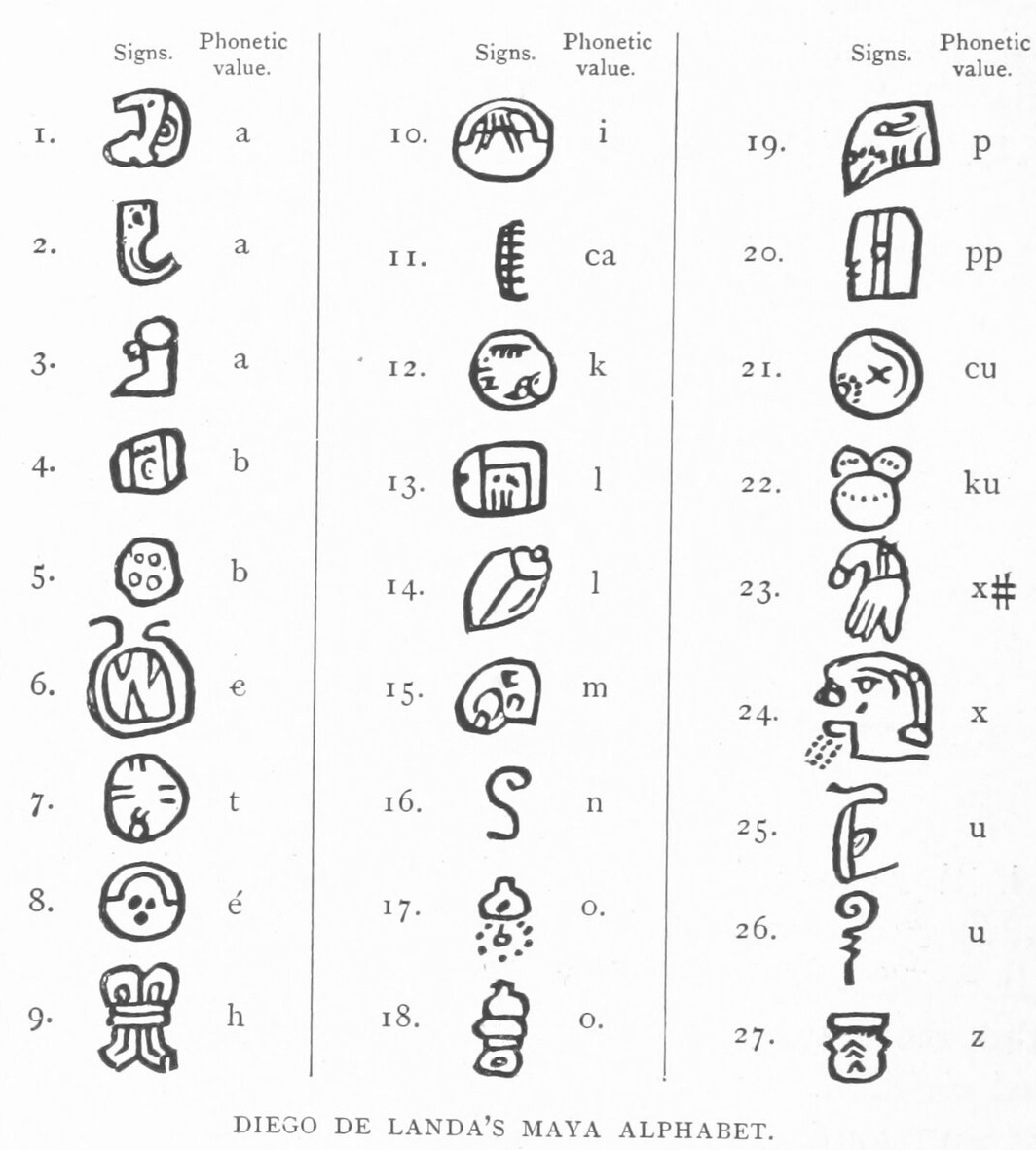

| History It was until recently thought that the Maya may have adopted writing from the Olmec or Epi-Olmec culture, who used the Isthmian script. However, murals excavated in 2005 have pushed back the origin of Maya writing by several centuries, and it now seems possible that the Maya were the ones who invented writing in Mesoamerica.[18] Scholarly consensus is that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in Mesoamerica.[19] Before the arrival of Spanish conquistadors, the Aztecs destroyed many Mayan works and sought to depict themselves as the true rulers through a fake history and newly written texts.[20] Knowledge of the Maya writing system continued into the early colonial era and reportedly[by whom?] a few of the early Spanish priests who went to Yucatán learned it. However, as part of his campaign to eradicate pagan rites, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered the collection and destruction of written Maya works, and a sizable number of Maya codices were destroyed. Later, seeking to use their native language to convert the Maya to Christianity, he derived what he believed to be a Maya "alphabet" (the so-called de Landa alphabet). Although the Maya did not actually write alphabetically, nevertheless he recorded a glossary of Maya sounds and related symbols, which was long dismissed as nonsense (for instance, by leading Mayanist J. E. S. Thompson in his 1950 book Maya Hieroglyphic Writing)[21] but eventually became a key resource in deciphering the Maya script. The difficulty was that there was no simple correspondence between the two systems, and the names of the letters of the Spanish alphabet meant nothing to Landa's Maya scribe, so Landa ended up asking things like write "ha": "hache–a", and glossed a part of the result as "H," which, in reality, was written as a-che-a in Maya glyphs.  Diego de Landa's Maya alphabet was an early attempt at decipherment. Landa was also involved in creating an orthography, or a system of writing, for the Yukatek Maya language using the Latin alphabet. This was the first Latin orthography for any of the Mayan languages,[citation needed] which number around thirty. For many years, only three Maya codices were known to have survived the conquistadors; this was expanded with the 2015 authentication of the Grolier Codex as the fourth.[22] Most surviving texts are found on pottery recovered from Maya tombs, or from monuments and stelae erected in sites which were abandoned or buried before the arrival of the Spanish. Knowledge of the writing system was lost, probably by the end of the 16th century. Renewed interest in it was sparked by published accounts of ruined Maya sites in the 19th century.[22] |

歴史 最近まで、マヤはイスティミア文字を使用していたオルメカまたはエピ・オルメカ文化から文字を取り入れたのではないかと考えられていた。しかし、2005 年に発掘された壁画によって、マヤの文字の起源は数世紀遡ることになり、現在では、マヤがメソアメリカで文字を発明した可能性があると考えられている [18]。学者のコンセンサスでは、マヤはメソアメリカで唯一の完全な文字体系を開発したとされている[19]。 スペインのコンキスタドールが到着する前に、アステカは多くのマヤの著作物を破壊し、偽の歴史と新しく書かれたテキストを通して自分たちが真の支配者であ ると描こうとした[20]。しかし、ディエゴ・デ・ランダ司教は異教の儀式を根絶するキャンペーンの一環として、マヤの文字著作物の収集と破壊を命じ、か なりの数のマヤの写本が破壊された。その後、マヤをキリスト教に改宗させるために彼らの母国語を使おうとした彼は、マヤの「アルファベット」と思われるも の(いわゆるデ・ランダ・アルファベット)を導き出した。マヤは実際にはアルファベットを書かなかったが、それにもかかわらず彼はマヤの音と関連する記号 の用語集を記録した。この用語集は長い間ナンセンスなものとして否定されていたが(例えば、マヤ研究の第一人者であるJ. E. S. Thompsonが1950年に出版した『Maya Hieroglyphic Writing』)[21]、やがてマヤ文字を解読する上で重要な資料となった。困難だったのは、2つの文字体系の間に単純な対応関係がなかったことで、 スペイン語のアルファベットの名前はランダのマヤ書記にとっては何の意味も持たなかった: そして、その結果の一部を 「H 」とし、実際にはマヤのグリフでは 「a-che-a 」と書かれていた。  ディエゴ・デ・ランダのマヤ・アルファベットは、解読の初期の試みであった。 ランダはまた、ラテンアルファベットを用いたユカテク・マヤ語の正書法(文字体系)の作成にも携わった。この正書法は、約30種あるマヤ諸語[要出典]に とって最初のラテン正書法であった。 長年にわたり、唯一の3つのマヤ写本は、征服者を生き残ったことが知られていたが、これは4番目としてグロリア写本の2015年の認証で拡大された [22]。現存するテキストのほとんどは、マヤの墓から回収された陶器、またはスペイン人の到着前に放棄されたか、埋葬されたサイトに建てられたモニュメ ントやステラから発見されている。 文字システムの知識は、おそらく16世紀の終わりまでに失われた。19世紀に出版された廃墟となったマヤの遺跡の記録によって、文字への関心が再び高まっ た[22]。 |

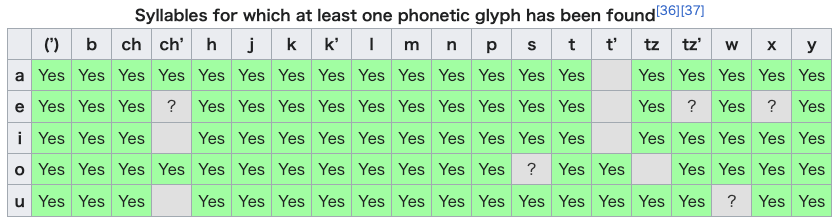

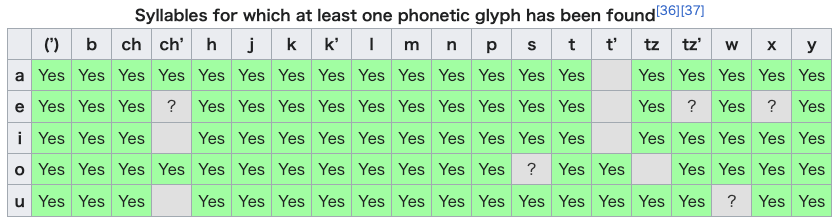

Decipherment Monument to Yuri Knorozov in Mérida, Yucatán Deciphering Maya writing has proven a long and laborious process. 19th-century and early 20th-century investigators managed to decode the Maya numbers[23] and portions of the texts related to astronomy and the Maya calendar, but understanding of most of the rest long eluded scholars. In the 1930s, Benjamin Whorf wrote a number of published and unpublished essays, proposing to identify phonetic elements within the writing system. Although some specifics of his decipherment claims were later shown to be incorrect, the central argument of his work, that Maya hieroglyphs were phonetic (or more specifically, syllabic), was later supported by the work of Yuri Knorozov (1922–1999), who played a major role in deciphering Maya writing.[24] Napoleon Cordy also made some notable contributions in the 1930s and 1940s to the early study and decipherment of Maya script. Including "Examples of Phonetic Construction in Maya Hieroglyphs", in 1946.[25] In 1952 Knorozov published the paper "Ancient Writing of Central America", arguing that the so-called "de Landa alphabet" contained in Bishop Diego de Landa's manuscript Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán was made of syllabic, rather than alphabetic symbols. He further improved his decipherment technique in his 1963 monograph "The Writing of the Maya Indians"[26] and published translations of Maya manuscripts in his 1975 work "Maya Hieroglyphic Manuscripts". In the 1960s, progress revealed the dynastic records of Maya rulers. Since the early 1980s scholars have demonstrated that most of the previously unknown symbols form a syllabary, and progress in reading the Maya writing has advanced rapidly since. As Knorozov's early essays contained several older readings already published in the late 19th century by Cyrus Thomas,[27] and the Soviet editors added propagandistic claims[28] to the effect that Knorozov was using a peculiarly "Marxist-Leninist" approach to decipherment,[28] many Western Mayanists simply dismissed Knorozov's work. However, in the 1960s, more came to see the syllabic approach as potentially fruitful, and possible phonetic readings for symbols whose general meaning was understood from context began to develop. Prominent older epigrapher J. Eric S. Thompson was one of the last major opponents of Knorozov and the syllabic approach. Thompson's disagreements are sometimes said to have held back advances in decipherment.[29] For example, Coe (1992, p. 164) says "the major reason was that almost the entire Mayanist field was in willing thrall to one very dominant scholar, Eric Thompson". G. Ershova, a student of Knorozov's, stated that reception of Knorozov's work was delayed only by authority of Thompson, and thus has nothing to do with Marxism – "But he (Knorozov) did not even suspect what a storm of hatred his success had caused in the head of the American school of Mayan studies, Eric Thompson. And the Cold War was absolutely nothing to do with it. An Englishman by birth, Eric Thompson, after learning about the results of the work of a young Soviet scientist, immediately realized 'who got the victory'."[30]  Maya glyphs at National Museum of Anthropology (Mexico)  Detail of the Dresden Codex (modern reproduction) In 1959, examining what she called "a peculiar pattern of dates" on stone monument inscriptions at the Classic Maya site of Piedras Negras, Russian-American scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff determined that these represented events in the lifespan of an individual, rather than relating to religion, astronomy, or prophecy, as held by the "old school" exemplified by Thompson. This proved to be true of many Maya inscriptions, and revealed the Maya epigraphic record to be one relating actual histories of ruling individuals: dynastic histories similar in nature to those recorded in other human cultures throughout the world. Suddenly, the Maya entered written history.[31] Although it was then clear what was on many Maya inscriptions, they still could not literally be read. However, further progress was made during the 1960s and 1970s, using a multitude of approaches including pattern analysis, de Landa's "alphabet", Knorozov's breakthroughs, and others. In the story of Maya decipherment, the work of archaeologists, art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and anthropologists cannot be separated. All contributed to a process that was truly and essentially multidisciplinary. Key figures included David Kelley, Ian Graham, Gilette Griffin, and Michael Coe. A new wave of breakthroughs occurred in the early 1970s, in particular at the first Mesa Redonda de Palenque, a scholarly conference organized by Merle Greene Robertson at the Maya site of Palenque and held in December, 1973. A working group consisting of Linda Schele, then a studio artist and art instructor, Floyd Lounsbury, a linguist from Yale, and Peter Mathews, then an undergraduate student of David Kelley's at the University of Calgary (whom Kelley sent because he could not attend). In one afternoon they reconstructed most of the dynastic list of Palenque, building on the earlier work of Heinrich Berlin.[32][3] By identifying a sign as an important royal title (now read as the recurring name Kʼinich), the group was able to identify and "read" the life histories (from birth, to accession to the throne, to death) of six kings of Palenque.[33][3] Palenque was the focus of much epigraphic work through the late 1970s, but linguistic decipherment of texts remained very limited. From that point, progress proceeded rapidly. Scholars such as J. Kathryn Josserand, Nick Hopkins and others published findings that helped to construct a Mayan vocabulary.[34] The "old school" continued to resist the results of the new scholarship for some time. A decisive event which helped to turn the tide in favor of the new approach occurred in 1986, at an exhibition entitled "The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art", organized by InterCultura and the Kimbell Art Museum and curated by Schele and by Yale art historian Mary Miller. This exhibition and its attendant catalogue—and international publicity—revealed to a wide audience the new world which had latterly been opened up by progress in decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. Not only could a real history of ancient America now be read and understood, but the light it shed on the material remains of the Maya showed them to be real, recognisable individuals. They stood revealed as a people with a history like that of all other human societies: full of wars, dynastic struggles, shifting political alliances, complex religious and artistic systems, expressions of personal property and ownership and the like. Moreover, the new interpretation, as the exhibition demonstrated, made sense out of many works of art whose meaning had been unclear and showed how the material culture of the Maya represented a fully integrated cultural system and world-view. Gone was the old Thompson view of the Maya as peaceable astronomers without conflict or other attributes characteristic of most human societies. However, three years later, in 1989, supporters who continued to resist the modern decipherment interpretation made their last argument against it. This occurred at a conference at Dumbarton Oaks. It did not directly attack the methodology or results of decipherment, but instead contended that the ancient Maya texts had indeed been read but were "epiphenomenal". This argument was extended from a populist perspective to say that the deciphered texts tell only about the concerns and beliefs of the society's elite, and not about the ordinary Maya. In opposition to this idea, Michael Coe described "epiphenomenal" as "a ten penny word meaning that Maya writing is only of marginal application since it is secondary to those more primary institutions—economics and society—so well studied by the dirt archaeologists."[35] Linda Schele noted following the conference that this is like saying that the inscriptions of ancient Egypt—or the writings of Greek philosophers or historians—do not reveal anything important about their cultures. Most written documents in most cultures tell us about the elite, because in most cultures in the past, they were the ones who could write (or could have things written down by scribes or inscribed on monuments).[citation needed] Over 90 percent of the Maya texts can now be read with reasonable accuracy.[3] As of 2020, at least one phonetic glyph was known for each of the syllables marked green in this chart. /tʼ/ is rare. /pʼ/ is not found, and is thought to have been a later innovation in the Ch'olan and Yucatecan languages.  |

解読 ユカタン州メリダにあるユーリ・クノロゾフの記念碑 マヤ文字の解読は、長く骨の折れる作業であることが証明されている。19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけての研究者たちは、マヤの数字[23]や、天文学やマ ヤ暦に関連するテキストの一部を解読することに成功しましたが、それ以外の大部分については、長い間学者たちの理解を得ることができなかった。 1930年代、ベンジャミン・ウォーフは多くの出版物や未発表のエッセイを執筆し、文字体系の中の音声的要素を特定することを提案した。彼の解読の主張の いくつかは後に誤りであることが明らかになったが、マヤの象形文字が表音文字(より具体的には音節文字)であるという彼の研究の中心的な主張は、後に マヤ文字の解読に大きな役割を果たしたユーリ・クノロゾフ(Yuri Knorozov, 1922-1999)の研究によって支持された。 1946年には 「Examples of Phonetic Construction in Maya Hieroglyphs 」を発表している[25]。1952年にはクノロゾフが 「Ancient Writing of Central America 」という論文を発表し、ディエゴ・デ・ランダ司教の手稿Relación de las Cosas de Yucatánに含まれるいわゆる 「デ・ランダ・アルファベット 」はアルファベットではなく音節記号で構成されていると主張した。彼は1963年の単行本『マヤ・インディオの文字』[26]で解読技術をさらに向上さ せ、1975年の著作『マヤ・ヒエログリフ手稿』ではマヤ手稿の翻訳を発表した。1960年代には、マヤの支配者の王朝記録が明らかになった。1980年 代初頭からは、これまで知られていなかった記号のほとんどが音節を形成していることが明らかになり、マヤ文字の読み方は急速に進歩した。 クノロゾフの初期のエッセイには、サイラス・トーマスによって19世紀後半にすでに発表された古い読み方がいくつか含まれており[27]、ソ連の編集者は クノロゾフが解読に独特の「マルクス・レーニン主義的」アプローチを用いているという宣伝的な主張[28]を加えたため、多くの西洋のマヤ研究者はクノロ ゾフの研究を単に否定した[28]。しかし、1960年代になると、音節論的なアプローチを実りあるものと考える者が増え、文脈から一般的な意味が理解で きる記号の音読みの可能性が発展し始めた。著名な古代のエピグラファーであるJ.エリック・S.トンプソンは、クノロゾフとシラビア・アプローチの最後の 主要な反対者の一人であった。例えば、Coe (1992, p. 164)は、「その大きな理由は、マヤの研究分野全体が、エリック・トンプソンという一人の非常に支配的な学者の意のままに操られていたからである」と述 べている。クノロゾフの教え子であるG.エルショヴァは、クノロゾフの研究の受容はトンプソンの権威によってのみ遅れたのであり、したがってマルクス主義 とは何の関係もない、と述べている-「しかし、彼(クノロゾフ)は、自分の成功がアメリカのマヤ研究学派の長であるエリック・トンプソンに憎悪の嵐を引き 起こしたことを疑うことさえしなかった。冷戦は全く関係ない。生粋のイギリス人であるエリック・トンプソンは、ソ連の若い科学者の研究成果を知った後、す ぐに『勝利を手にしたのは誰か』を悟った」[30]。  国立人類学博物館(メキシコ)にあるマヤのグリフ。  ドレスデン写本の詳細(現代の複製品) 1959年、ロシア系アメリカ人の学者タチアナ・プロスコウリアコフは、古典期マヤのピエドラス・ネグラス遺跡の石碑に刻まれた「特異な日付パターン」を 調査し、トンプソンに代表される「旧派」が主張するような宗教、天文学、予言に関するものではなく、個人の生涯における出来事を表していると断定した。こ のことは、マヤの碑文の多くに当てはまることが証明され、マヤの碑文記録が、支配する個人の実際の歴史に関連するものであることが明らかになった。突然、 マヤは文字による歴史に参入したのである[31]。 多くのマヤの碑文に何が記されているかは明らかであったが、文字どおり読むことはできなかった。しかし、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、パターン 分析、デ・ランダの「アルファベット」、クノロゾフのブレークスルーなど、多くのアプローチを用いて、さらなる進歩がなされた。マヤの解読を語る上で、考 古学者、美術史家、叙事詩学者、言語学者、人類学者の仕事を切り離すことはできない。すべての人が、真に本質的に学際的なプロセスに貢献したのである。主 要人物としては、デイヴィッド・ケリー、イアン・グラハム、ジレット・グリフィン、マイケル・コーらが挙げられる。 1970年代初頭、特に1973年12月にパレンケのマヤ遺跡でマール・グリーン・ロバートソンが主催した学術会議、第1回メサ・レドンダ・デ・パレンケ で新たな飛躍の波が起こった。当時スタジオ・アーティストで美術講師だったリンダ・シェール(Linda Schele)、イェール大学の言語学者フロイド・ラウンズベリー(Floyd Lounsbury)、カルガリー大学のデビッド・ケリー(David Kelley)の学部生だったピーター・マシューズ(Peter Mathews)で構成されたワーキング・グループ(Kelleyは出席できなかったので派遣された)。ハインリッヒ・ベルリンの先行研究を基に、午後1 時でパレンケの王朝リストのほとんどを再構築した[32][3]。重要な王位(現在はKʼinichと読み替えられる)を示す記号を特定することで、グ ループはパレンケの6人の王の生活史(誕生から即位、死まで)を特定し、「読み取る」ことができた。 [33][3]パレンケは1970年代後半まで多くの碑文研究の焦点であったが、テキストの言語学的解読は非常に限られたものであった。 そこから急速に進展した。J. Kathryn Josserand、Nick Hopkinsなどの学者が、マヤ語の語彙を構築するのに役立つ発見を発表した[34]。1986年、「王たちの血」と題された展覧会が開催された: InterCulturaとキンベル美術館が主催し、シェールとイェール大学の美術史家メアリー・ミラーがキュレーションを担当した展覧会である。この展 覧会とそれに付随するカタログは、マヤのヒエログリフ解読の進展によって開かれた新たな世界を、多くの人々に知らしめた。古代アメリカの真の歴史が読み解 かれるようになっただけでなく、マヤの物質的な遺跡に光が当てられたことで、彼らが実在し、認識可能な個人であることが示された。戦争、王朝の闘争、政治 的同盟関係の変化、複雑な宗教的・芸術的システム、個人の財産や所有権の表現など、他のすべての人類社会と同じような歴史を持つ民族であることが明らかに なったのだ。さらに、展覧会で示された新しい解釈は、これまで意味が不明だった多くの美術品の意味を明らかにし、マヤの物質文化が完全に統合された文化シ ステムと世界観を表していることを示した。マヤは平和的な天文学者であり、争いや他の多くの人間社会に特徴的な属性とは無縁であったという古いトンプソン の見方は消えたのである。 しかし、その3年後の1989年、近代解読解釈に抵抗を続ける支持者たちが、最後の反論を行った。ダンバートン・オークスでの会議でのことである。それ は、解読の方法論や結果を直接攻撃するものではなく、古代マヤのテキストは確かに読まれていたが、「エピフェノメンタル」なものであったという主張であっ た。この主張は大衆主義的な観点から拡張され、解読されたテキストは社会のエリートの関心事や信念についてのみ語っており、一般的なマヤについては語って いないとした。この考え方に反対して、マイケル・コーは「エピフェノメナル(epiphenomenal)」を「マヤの文字は、土と埃にまみれた考古学者 によってよく 研究されている、より主要な制度-経済や社会-にとって二次的なものであるため、ほんのわずかな用途しかないという意味の小銭のような言葉」と表現し た[35]。 リンダ・シェレは会議の後、これは古代エジプトの碑文やギリシャの哲学者や歴史家の文章からは、その文化について重要なことは何もわからないと言っている ようなものだと指摘した。というのも、過去のほとんどの文化において、文字を書くことができた(あるいは書記によって書き留められたり、石碑に刻まれたり した)のはエリートたちだったからだ。 現在ではマヤのテキストの90パーセント以上が妥当な精度で読むことができる[3] 2020年現在、このチャートで緑色でマークされた音節のそれぞれについて、少なくとも1つの音声グリフが知られている。/tʼ/はまれである。/pʼ/ は見つかっておらず、チョラン語やユカテカ語の後世の革新であると考えられている。  |

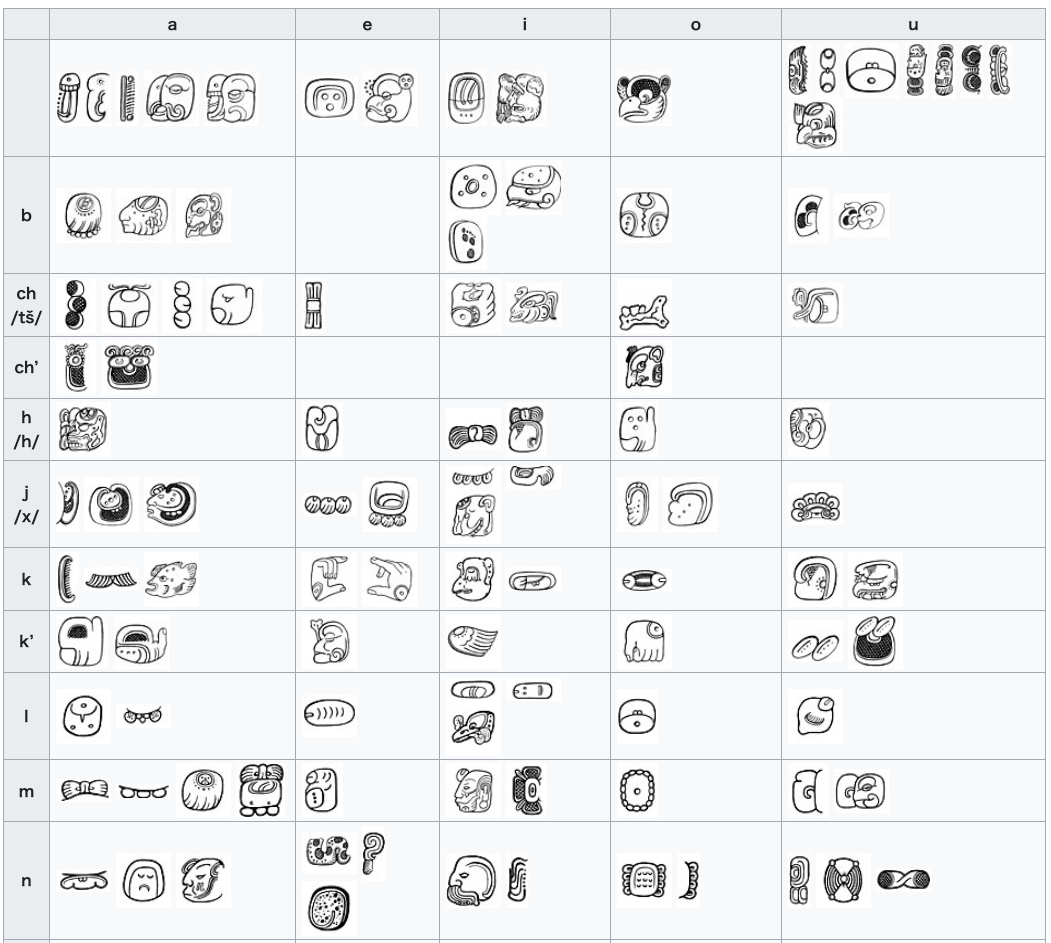

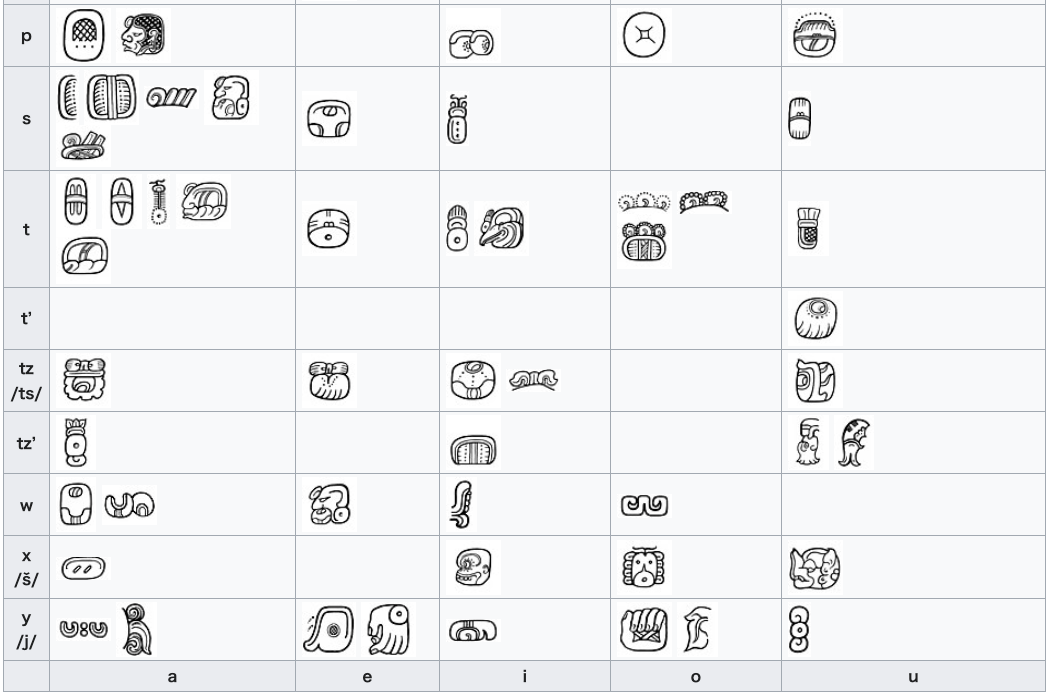

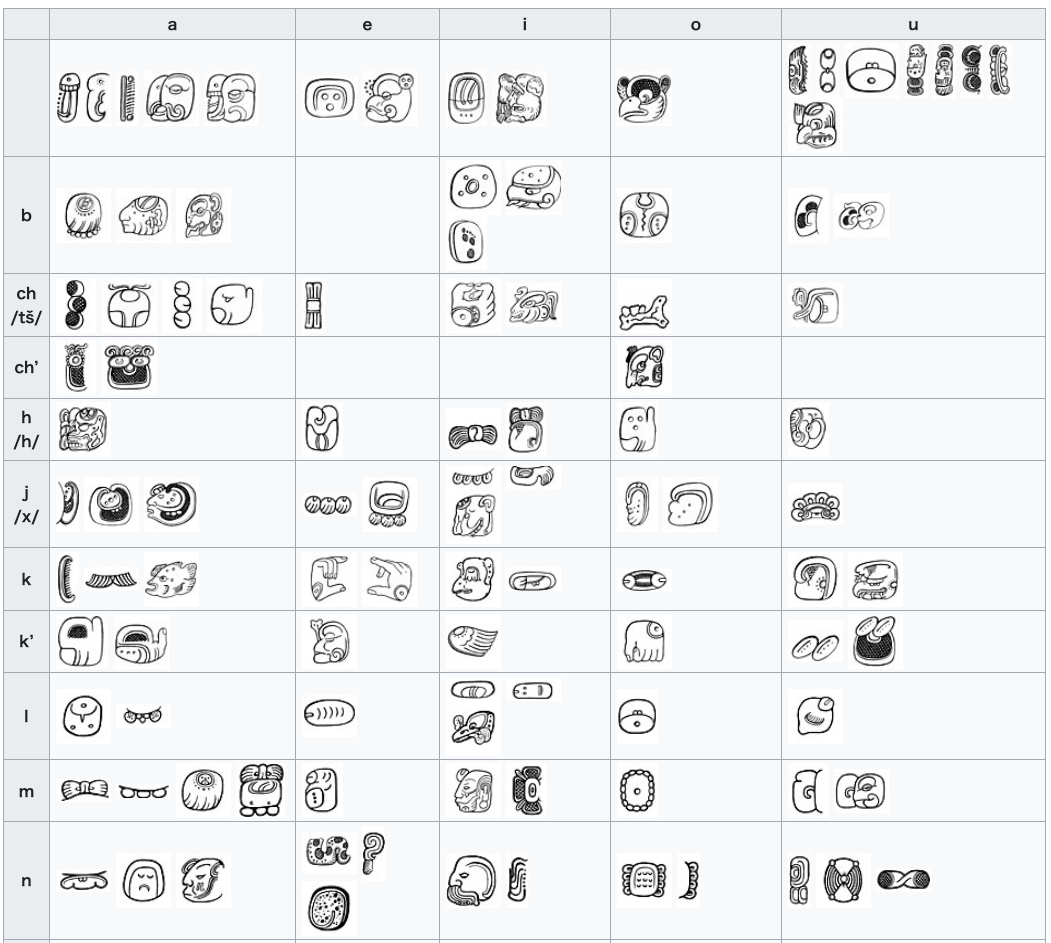

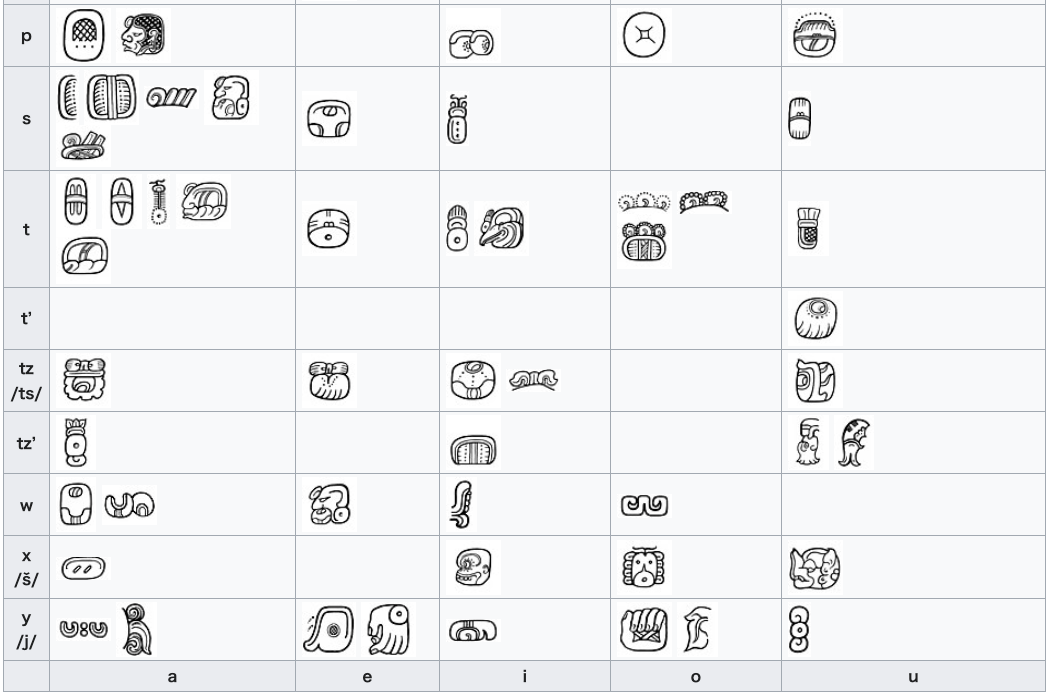

| Syllables Syllables are in the form of consonant + vowel. The top line contains individual vowels. In the left column are the consonants with their pronunciation instructions. The apostrophe ' represents the glottal stop. There are different variations of the same character in the table cell. Blank cells are bytes whose characters are not yet known.[38]   |

シラブル 音節は子音+母音の形である。一番上の行には個々の母音が記載されている。左の列は子音とその発音記号である。アポストロフィ「」は声門停止を表す。表の セルには同じ文字でもさまざまなバリエーションがある。空白のセルは、文字がまだ知られていないバイトである[38]。   |

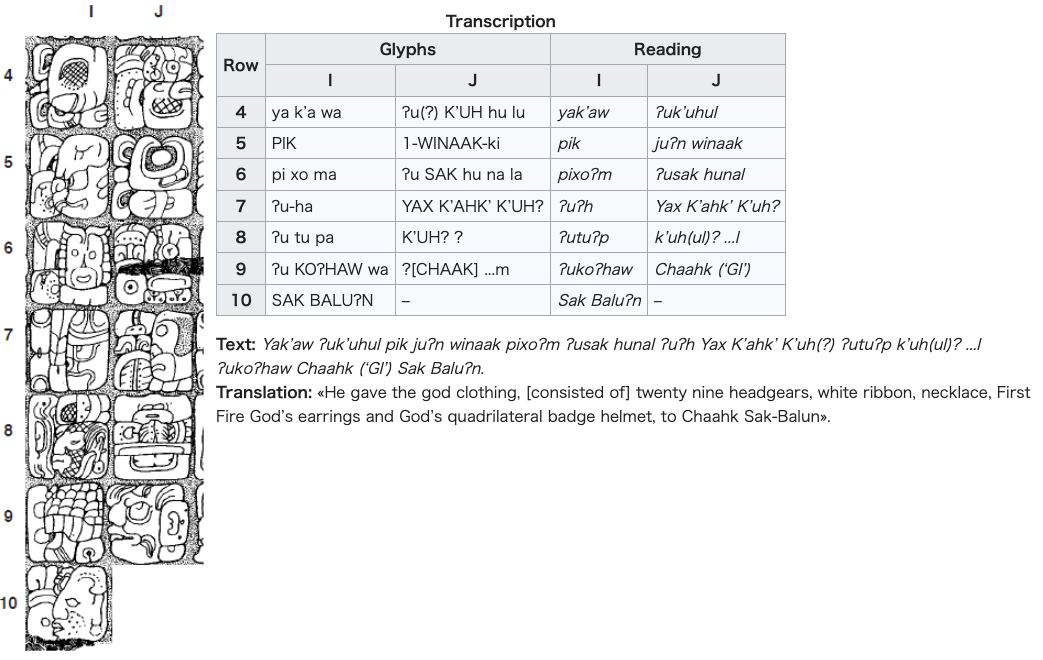

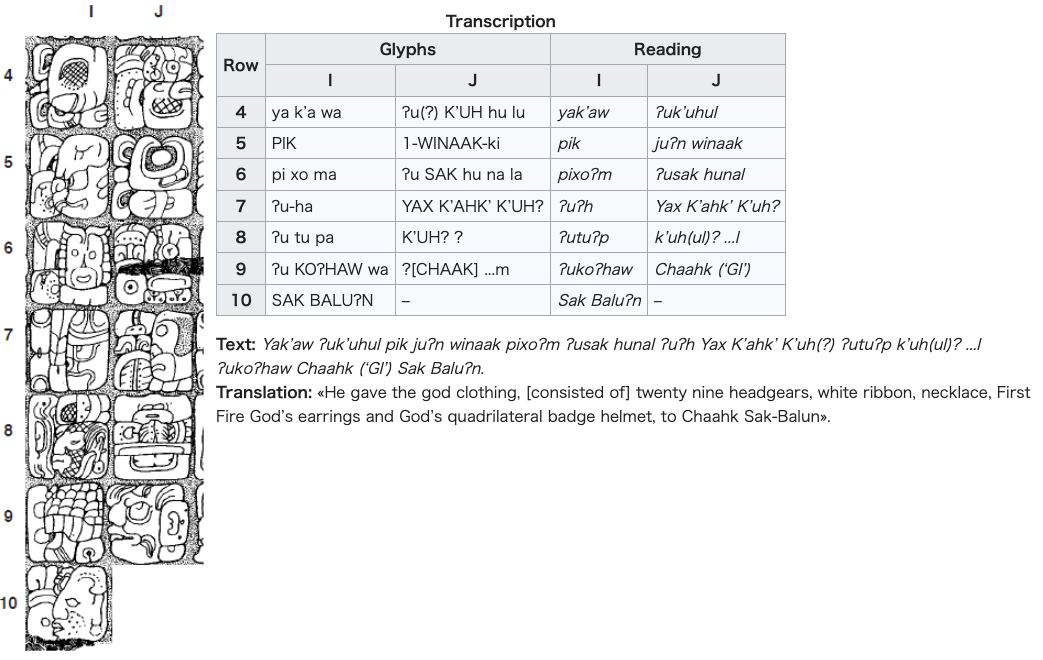

| Example Tomb of Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal: Text: Yak’aw ʔuk’uhul pik juʔn winaak pixoʔm ʔusak hunal ʔuʔh Yax K’ahk’ K’uh(?) ʔutuʔp k’uh(ul)? ...l ʔukoʔhaw Chaahk (‘GI’) Sak Baluʔn. Translation: «He gave the god clothing, [consisted of] twenty nine headgears, white ribbon, necklace, First Fire God’s earrings and God’s quadrilateral badge helmet, to Chaahk Sak-Balun».  |

例 K'inich Janaab' Pakalの墓: テキスト Yak'aw ʔ uk'uhul pik ju294n winaak pixoʔ m ʔusak hunal ʔ Yax K'ahk' K'uh(?) k'uh(ul)? ...l ʔukoʔ Chaahk ('GI') Sak Baluʔn. 直訳すると 「彼はチャアク・サク・バルンに、29の頭飾り、白いリボン、ネックレス、最初の火の神のイヤリング、神の四角形のバッジのヘルメットからなる神服を与え た」。  |

| Revival In recent times, there has been an increased interest in reviving usage of the script. Various works have recently been both transliterated and created into the script, notably the transcription of the Popol Vuh in 2018, a record of Kʼicheʼ religion. Another example is the sculpting and writing of a modern stele placed at Iximche in 2012, describing the full historical record of the site dating back to the beginning of the Mayan long count.[39] The 2014 poem "Cigarra", by Martín Gómez Ramírez, was written entirely in Tzeltal using the script.[40] |

復活 最近、この文字の復活に関心が高まっている。2018年にはKʼicheʼ宗教の記録であるPopol Vuhの転写が行われた。他の例としては、2012年にイクシムチェに設置された近代的な石碑の彫刻と筆記があり、マヤの長計の始まりまで遡るこの遺跡の 歴史的な全記録が記述されている[39]。2014年のマルティン・ゴメス・ラミレスの詩 「Cigarra 」は、この文字を使ってすべてツェルト文字で書かれている[40]。 |

| Computer encoding The Maya script can be represented as a custom downloadable primer's font [41] but has yet to be formally introduced into Unicode standards. With the renewed usage of Maya writing, digital encoding of the script has been of recent interest.[42] A range of code points (U+15500–U+159FF) has been tentatively allocated for Unicode, but no detailed encoding proposal has been submitted yet.[43] The Script Encoding Initiative project of the University of California, Berkeley, was awarded a grant in June 2016 to create a proposal to the Unicode Consortium for layout and presentation mechanisms in Unicode text. It was expected to be completed in 2017,[44] but as of 2023, they have not completed this project.[45] The goal of encoding Maya hieroglyphs in Unicode is to facilitate the modern use of the script. For representing the degree of flexibility and variation of classical Maya, the expressiveness of Unicode is insufficient (e.g., with regard to the representation of infixes, i.e., signs inserted into other signs), so, for philological applications, different technologies are required.[46] The Mayan numerals, with values 0–1910 creating a base-20 system, are encoded in block Mayan Numerals. |

コンピュータによるエンコーディング マヤ文字は、ダウンロード可能な入門者向けのカスタムフォント[41]として表現することができるが、Unicode標準にはまだ正式に導入されていな い。マヤ文字の再利用に伴い、この文字のデジタルエンコーディングが最近注目されている[42]。Unicodeにはコードポイントの範囲(U+ 15500-U+159FF)が暫定的に割り当てられているが、詳細なエンコーディング提案はまだ提出されていない[43]。カリフォルニア大学バーク レー校のScript Encoding Initiativeプロジェクトは、Unicodeテキストのレイアウトと表示メカニズムに関するUnicodeコンソーシアムへの提案を作成するため の助成金を2016年6月に授与された。2017年に完了する予定であったが[44]、2023年現在、このプロジェクトは完了していない[45]。 マヤのヒエログリフをUnicodeでエンコードする目的は、スクリプトの現代的な使用を容易にすることです。古典的なマヤの柔軟性と多様性の程度を表現 するには、Unicodeの表現力は不十分であり(例えば、接尾辞、すなわち他の符号の中に挿入される符号の表現に関して)、言語学的な応用のためには、 別の技術が必要である[46]。 マヤの数字は、0~1910の値で20進法になっており、マヤ数字ブロックにエンコードされている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maya_script |

★マ ヤ文字解読 / マイケル・D. コウ著 ; 武井摩利, 徳江佐和子訳, 創元社 , 2003/ Breaking the Maya code

4 冊の絵文書、1,000年の沈黙を守る石碑の記号、450年前、スペイン人神父が書き残した謎めいた手稿…わずかな手がかりから、いったいだれが古代マヤ の暗号を読み解くのか。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆