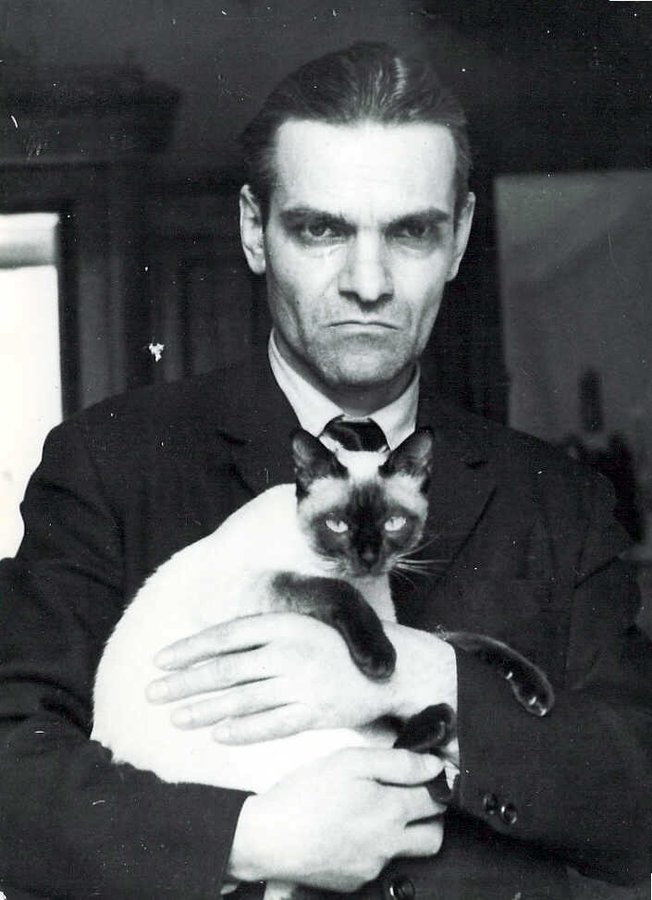

ユーリ・クノロゾフ

Yuri Knorozov, 1922-1999

Knorozov

with his Siamese cat Asya in the 1980s

☆ ユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィチ・クノロゾフ(ロシア語: Ю́рий Валенти́нович Кноро́зов、1922年11月19日 - 1999年3月31日)は、ソビエトおよびウクライナの言語学者、エピグラファー、民族学者。ソビエトのマヤ研究学派の創始者であり、音節記号の存在を特 定したことは、メソアメリカの先コロンビア期のマヤ文明で使用されていた文字体系であるマヤ文字の解読に不可欠な一歩となった。

| Yuri Valentinovich

Knorozov (Russian: Ю́рий Валенти́нович Кноро́зов; 19 November 1922 – 31

March 1999) was a Soviet and Ukrainian linguist,[3] epigrapher, and

ethnographer. He became the founder of the Soviet school of Mayan

studies, and his identification of the existence of syllabic signs

proved an essential step forward in the eventual decipherment of the

Mayan script, the writing system used by the pre-Columbian Maya

civilization of Mesoamerica.[4] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuri_Knorozov |

ユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィチ・クノロゾフ(ロシア語: Ю́рий

Валенти́нович Кноро́зов、1922年11月19日 -

1999年3月31日)は、ソビエトおよびウクライナの言語学者、[3]エピグラファー、民族学者。ソビエトのマヤ研究学派の創始者であり、音節記号の存

在を特定したことは、メソアメリカの先コロンビア期のマヤ文明で使用されていた文字体系であるマ

ヤ文字の解読に不可欠な一歩となった[4]。 |

| Early life Knorozov was born in the village of Yuzhny near Kharkov, at that time the capital of the newly formed Ukrainian SSR.[5] His parents were Russian intellectuals, and his paternal grandmother Maria Sakhavyan had been a stage actress of national repute in Armenia.[6][7] At school, the young Yuri was a difficult and somewhat eccentric student, who made indifferent progress in a number of subjects and was almost expelled for poor and willful behavior. Aged 5, he sustained a heavy injury to his head that nearly left him blind.[8] However, it became clear that he was academically bright with an inquisitive temperament; he was an accomplished violinist, wrote romantic poetry and could draw with accuracy and attention to detail.[9] His scores were excellent for all subjects, except for Ukrainian language.[8] In 1940 at the age of 17, Knorozov left Kharkiv for Moscow where he commenced undergraduate studies in the newly created Department of Ethnology[10] at Moscow State University's department of History. He initially specialised in Egyptology.[11][12] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuri_Knorozov |

生い立ち 両親はロシアの知識人で、父方の祖母マリア・サハヴィアンはアルメニアで国民的な人気を誇る舞台女優であった[6][7]。 学校では、幼いユーリは気難しく、やや風変わりな生徒であった。5歳のとき、彼は頭部に大怪我を負い、失明寸前まで追い込まれた[8]。しかし、彼は学業 優秀で好奇心旺盛な気質であることが明らかになった。彼は優れたヴァイオリニストであり、ロマンチックな詩を書き、正確で細部まで注意を払った絵を描くこ とができた[9]。 1940年、17歳のクノロゾフはハリコフからモスクワに向かい、モスクワ大学歴史学部に新設された民族学[10]学部で学び始める。当初はエジプト学を 専門としていた[11][12]。 |

Military service and the "Berlin

Affair" Inner courtyard of the Preußische Staatsbibliothek (2005) Knorozov's study plans were soon interrupted by the outbreak of World War II hostilities along the Eastern Front in mid-1941. Due to his poor health, Knorozov was unfit for regular military service in the Soviet Army; however, he and his family spent most of 1941–1943 years on the German-occupied territories, where he could be forced to join the German army support units. Knorozov managed to avoid that by moving from village to village, where he earned his living as a school teacher.[13] In 1943, Knorozov survived an outbreak of typhus, and in September of that year managed to escape with his family to Moscow.[14] There he resumed his Egyptology studies, at the Moscow State University.[15] In 1944, he was unexpectedly recalled for a military service, but his father, who was a colonel in the Soviet Army, arranged for him a job as a telephone operator in an artillery unit stationed near Moscow.[16] According to a popular legend, Knorozov and his unit supported the push of the Red Army vanguard into Berlin. There, Knorozov is supposed to have by chance retrieved a book which would spark his later interest in and association with deciphering the Maya script.[17] The legend has been much reproduced, particularly following the 1992 publication of Michael D. Coe's Breaking the Maya Code.[18] Supposedly, when stationed in Berlin, Knorozov came across the National Library while it was ablaze. Somehow he managed to retrieve from the fire a book, which remarkably enough turned out to be a rare edition[18][19] containing reproductions of the three Maya codices which were then known as the Dresden, Madrid, and Paris codices.[20] Knorozov is said to have taken this book back with him to Moscow at the end of the war, where its examination would form the basis for his later pioneering research into the Maya script. Although many details of Knorozov's life during the war remained unclear, his student Galina Ershova could not find any evidence that he traveled outside of Moscow Oblast in 1943–1945.[8] Knorozov himself, in an interview conducted a year before his death, denied the Berlin legend.[19][17] As he explained to the Mayanist epigrapher Harri Kettunen:[17] "Unfortunately it was a misunderstanding: I told about it [finding books in a library in Berlin] to my colleague Michael Coe, but he didn't get it right. There wasn't any fire in the library. And the books that were in the library, were in boxes to be sent somewhere else. The Germans had packed them, and since they didn't have time to move them anywhere, the boxes were taken to Moscow." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuri_Knorozov |

兵役と 「ベルリン事件」 ドイツ国立図書館の中庭(2005年) クノロゾフの研究計画は、1941年半ばの第二次世界大戦の東部戦線での戦闘開始によって中断された。健康状態が悪かったため、クノロゾフはソ連軍の正規 兵役に就くことができなかった。しかし、彼と彼の家族は1941年から1943年の大半をドイツ占領地で過ごした。1943年、クノロゾフはチフスの流行 から生き延び、その年の9月に家族とともにモスクワに逃れることに成功した[14]。 [1944年、クノロゾフは予期せず兵役に召集されたが、ソ連陸軍大佐であった父の計らいで、モスクワ近郊に駐屯する砲兵部隊の電話交換手として働くこと になった[16]。 人々に膾炙されている話によると、クノロゾフと彼の部隊は、赤軍の前衛 がベルリンに押し寄せるのを支援した。この伝説は、特に1992年に出版されたマイケル・D・コーの『Breaking the Maya Code(マヤの暗号を解く)』以降、再現されている。おそらく、ベルリンに駐在していたクノロゾフは、炎上中の国立図書館に出くわした。その本は、当時 ドレスデン、マドリード、パリの写本として知られていた3つのマヤ写本の複製を収録した貴重なものだった。クノロゾフはこの本を終戦時にモスクワに持ち 帰ったと言われている。この本を調査したことが、後のマヤ文字の先駆的研究の基礎となった。 戦時中のクノロゾフの生活については多くの詳細が不明なままであったが、彼の学生であったガリーナ・エルショヴァは、1943年から1945年にかけて彼 がモスクワ州外を旅行したという証拠を見つけることができなかった[8]。 クノロゾフ自身は、亡くなる前年に行われたインタビューで、ベルリンの伝説を否定している[19][17]。 マヤのエピグラファーであるハッリ・ケトゥネンに次のように説明している[17]。 「残念ながら誤解でした: 私はそのこと(ベルリンの図書館で本を見つけたこと)を同僚のマイケル・コーに話したが、彼は正しく理解していなかった。図書館に火はなかった。図書館に あった本は、どこかに送るための箱に入っていたんだ。ドイツ軍はそれらを梱包し、どこにも移動させる時間がなかったため、箱はモスクワに運ばれた」 |

| Resumption of studies Any possible system made by a man can be solved or cracked by a man.[19] [19]. Kettunen, Harri J. (1998). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I". Revista Xaman. 3/1998. Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. Archived from the original (online publication) In the autumn of 1945 after World War II, Knorozov returned to Moscow State University to complete his undergraduate courses at the department of Ethnography. He resumed his research into Egyptology, and also undertook comparative cultural studies in other fields such as Sinology. He displayed a particular interest and aptitude for the study of ancient languages and writing systems, especially hieroglyphs, and he also read medieval Japanese and Arabic literature.[9] According to his roommate, Sevʹyan I. Vainshtein, Knorozov was entirely devoting himself to science. After receiving a scholarship, he would spend it on books, surviving on meager food until the next scholarship.[21] While still an undergraduate at MSU, Knorozov found work at the N.N. Miklukho-Maklai Institute of Ethnology and Anthropology[22] (or IEA), part of the prestigious Academy of Sciences of the USSR. Knorozov's later research findings would be published by the IEA under its imprint. As part of his ethnographic curriculum Knorozov spent several months as a member of a field expedition to the Central Asian Soviet republics of the Uzbek and Turkmen SSRs (what had formerly been the Khorezm PSR, and would much later become the independent nations of Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan following the 1991 breakup of the Soviet Union). On this expedition his ostensible focus was to study the effects of Russian expansionary activities and modern developments upon nomadic ethnic groups, of what was a far-flung frontier world of the Soviet state.[23] At this point the focus of his research had not yet been drawn on the Maya script. This would change in 1947, when at the instigation of his professor, Knorozov wrote his dissertation on the "de Landa alphabet", a record produced by the 16th century Spanish Bishop Diego de Landa in which he claimed to have transliterated the Spanish alphabet into corresponding Maya hieroglyphs. De Landa, who during his posting to Yucatán had overseen the destruction of all the codices from the Maya civilization he could find, reproduced his alphabet in a work (Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán) intended to justify his actions once he had been placed on trial when recalled to Spain. The original document had disappeared, and this work was unknown until 1860s when an abridged copy was discovered in the archives of the Spanish Royal Academy by the French scholar, Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg.[24] Since de Landa's "alphabet" seemed to be contradictory and unclear (e.g., multiple variations were given for some of the letters, and some of the symbols were not known in the surviving inscriptions), previous attempts to use this as a key for deciphering the Maya writing system had not been successful.[8] |

研究の再開 「人間によって作られたどんな可能性のあるシステムも、人間によって解 決されたり、解読されたりすることがある」[19]。 [19]. Kettunen, Harri J. (1998). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I". Revista Xaman. 3/1998. Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. Archived from the original (online publication) 第二次世界大戦後の1945年秋、クノロゾフはモスクワ大学に戻り、民族学部の学部課程を修了した。彼はエジプト学の研究を再開し、中国学など他の分野の 比較文化研究も行った。ルームメイトのセヴリヤン・I・ヴァインシュテインによると、クノロゾフは完全に科学に打ち込んでいた。奨学金をもらうと、次の奨 学金がもらえるまでその奨学金を本に費やし、わずかな食費でしのいでいた[21]。 まだMSUの学部生であったクノロゾフは、ソビエト連邦の権威ある科学アカデミーの一部であるN.N.ミクルーホ・マクライ民族学・人類学研究所[22] (またはIEA)に就職した。クノロゾフの後の研究成果は、IEAから出版されることになる。 クノロゾフは民族誌学のカリキュラムの一環として、中央アジアのソビエト連邦ウズベキスタン共和国とトルクメン共和国(以前はホレズム特別共和国だった が、1991年のソビエト連邦解体後、ウズベキスタンとトルクメニスタンが独立することになる)に数ヶ月間、実地調査を行った。この遠征で彼の表向きの焦 点は、ソビエト国家の遠く離れた辺境世界であった遊牧民族集団にロシアの拡張活動と現代の発展が与えた影響を研究することであった[23]。 この時点では、彼の研究の焦点はまだマヤ文字には当てられていなかった。1947年、クノロゾフは教授の勧めで「デ・ランダ・アルファベット」についての 論文を書いた。デ・ランダはユカタンに赴任中、マヤ文明の写本をすべて破壊するよう監督していたが、スペインに呼び戻された際に裁判にかけられ、その行為 を正当化するために、自分のアルファベットを作品(Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán)に再現した。原本は消失しており、この著作は1860年代にフランスの学者シャルル・エティエンヌ・ブラッスール・ド・ブルブールによっ てスペイン王立アカデミーのアーカイブから要約されたコピーが発見されるまで知られていなかった[24]。 デ・ランダの 「アルファベット 」は矛盾しており、不明瞭であったため(例えば、いくつかの文字には複数のバリエーションが与えられており、いくつかの記号は現存する碑文では知られてい なかった)、これをマヤの文字体系を解読する鍵として使おうとする以前の試みは成功していなかった[8]。 |

| [19].

Kettunen, Harri J.

(1998). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with

Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I". Revista Xaman. 3/1998.

Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. Archived from the

original (online publication) Harri J. Kettunen Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I St. Petersburg is located 87 miles from the Finnish eastern border, and six hours by train from my home town Helsinki. St. Petersburg also accommodates the key figure in the modern decipherment of the Ancient Maya script, Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov. Living in the neighborhood, I thought of paying this Russian Champollion a visit. The following is the outcome of that sojourn. Born in a village near Kharkov, Ukraine, some 400 miles south of Moscow, in the year 1922, Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov entered the world of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics led by Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov a.k.a. Lenin, who soon died and was replaced by one Iosif Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili a.k.a. Stalin. Serving in the Soviet forces as an artillery spotter during the Great Patriotic War from 1943 until 1945, Knorozov was also one of the soldiers to enter the capital of the Thousand Year Reich, Berlin. There he, among other comrades, visited the National Library, where they ran into boxes full of books waiting in vain to be sent somewhere else in Germany as ordered by the "fascist command", as Dr. Knorozov put it. The boxes were eventually sent to Moscow, where Knorozov continued his studies and research after the war (he already had joined in at the University at the age of 17, when he was, among other things preoccupied with Egyptology). In one of the boxes they found a reproduction of the three then known Maya codices: Códices mayas by J. Antonio and Carlos A. Villacorta (1930). The initiative for studying the Maya script came from Knorozov's professor Sergei Aleksandrovich Tokarev, who suggested that he should read the 1945 article in Ethnos by a German Paul Schellhas, entitled: "Die Entzifferung der Mayahieroglyphen: ein unlösbares Problem?" Knorozov's viewpoint was at that time, and still is, that "any possible system made by a man can be solved or cracked by a man". Soon after the war Knorozov finished his studies at the University of Moscow and was driven to search for a job: "After the war there was not really a place to go, the situation was similar to the conditions now: there simply was not too many posts available.". However, the Museum of Ethnography in (at that time) Leningrad, lacked working force, so Knorozov moved to the former capital of Russia, the whilom town of Landskrona and Nyenskans of the Swedish Empire. By the early 1950's, Knorozov had accomplished to get acquainted with the Maya glyphs from the research done by other scholars in the past decades. He also studied Diego de Landa's work on the Maya Relación de las cosas de Yucatán (ca. 1566), which was to be the topic for his doctoral dissertation (Diego de Landa: Soobshchenie o delakh v Yukatani, 1566), and used the "Landa alphabet" as a point of departure for cracking the system (for more detailed account of the Knorozovian method see "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An Interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part II"; in Revista Xaman 4/98 (forthcoming) or "Landan 'aakkoset' ja mayahieroglyfitutkimus" in Kertomus Jukatanin asioista, LIKE, Helsinki 1997). The article entitled "Drevniaia Pis'mennost Tsentral'noi Ameriki" ("Ancient Writing of Central America") was published in the Sovietskaya Etnografiya in October 1952, and soon caused the "Establishment" to quake. However, The "Establishment", led by John Eric Sydney Thompson, did not collapse for another twenty years. The reason for this was mostly political, and can be further studied in Michael Coe's superb Breaking the Maya Code (Thames & Hudson 1992). Knorozov sums up: "He [Thompson] dominated and nobody objected to him. It was like with Marx: you couldn't oppose. The same goes [went] with Thompson.". Knorozov's endeavors in the field of ethnology and linguistics, and his revolutionary breakthrough in Maya epigraphy and life-long dedication to the Maya studies have not, however, financially paid off: the roughly 20 square meter apartment in the suburbs of St. Petersburg was so cold (in early February) that he had to wear an overcoat and a beret inside the house to keep warm. When he regretted that we (I and the interpreter) had to carry out the interview in such cold conditions, I thought of comforting him with a comment that it does not matter since it is always cold in Finland (which, of course, is not true), and he replied: "Yes, but it is supposed to be cold in Finland.". Knorozov did not seem to mind the circumstances, or at least did not say he did. The only complaint was aimed at the papers and books on the floor and a missing desk: "The papers used to be on the table, but it was taken away.". Otherwise, the room was full of books - predominantly on Maya related topics - and most of them piled up on a book-shelf constructed out of plank. Books and articles on Maya covering the majority of the material in Knorozov's house led to the aforethought question: whether the Maya research has been a favorite topic of his or merely a field among others. Knorozov replied: "Truly a field among others. My interest has always been in traveling: I have traveled from one place to another. I started with taking an interest in the Middle-Asia, where I have participated in numerous excavations. Also, I have directed an expedition in the Kurile Islands for ten years. After that I had to [NB] go to Mexico.". When asking about the visit to Mexico, and whether it was an interesting experience, Knorozov replied: "As a matter of fact, no: I think back it with horror. There I was attacked by a German woman, and not any woman but a millionaire woman, who took me for a famous scientist and wanted to make a film about me, which she would then sell to Russia. We all have various conceptions. This way she managed to keep one third of my group occupied with the film-making. I tried to convince her to make the film at one go, but it did not happen. I thought they will keep on shooting for as long as I live, and possibly thereafter as well. One big joke the whole trip.". ---------- The second part of "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov" will be released in Revista Xaman's April edition. The interview took place in the city of St. Petersburg on the 7th of February 1998. Interpreter on-site: Jorma Turpeinen, a prominent authority of Russian language and culture. https://web.archive.org/web/20050331005946/http://www.helsinki.fi/hum/ibero/xaman/articulos/9803/9803_hk.html |

[19].

Kettunen, Harri J.

(1998). "Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An interview with

Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part I". Revista Xaman. 3/1998.

Helsinki: Ibero-American Center, Helsinki University. Archived from the

original (online publication) ハッリ・J・ケトゥネン サンクトペテルブルクの歴史:ユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィッチ・クノロゾフ博士へのインタビュー 前編 サンクトペテルブルクはフィンランドの東部国境から87マイル、私の故郷ヘルシンキから電車で6時間のところにある。サンクトペテルブルクには、古代マヤ 文字解読のキーパーソンであるユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィッチ・クノロゾフ博士が住んでいる。近所に住む私は、このロシアのシャンポリオンを訪ねてみよう と思った。以下はその訪問の結果である。 ユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィッチ・クノロゾフは1922年、モスクワから南へ400マイルほど離れたウクライナのハリコフ近郊の村に生まれ、レーニンこと ウラジーミル・イリヤノヴィチ・ウリヤノフ率いるソビエト社会主義共和国連邦の世界に入った。 1943年から1945年までの大祖国戦争中、ソ連軍に砲兵監視員として従軍していたクノロゾフは、千年帝国の首都ベルリンに入城した兵士の一人でもあっ た。クノロゾフ博士が言うところの「ファシスト司令部」の命令で、ドイツ国内のどこかに送られるのを待っていた本が詰まった箱の中に無駄に出くわした。 その箱は最終的にモスクワに送られ、クノロゾフは戦後もそこで勉学と研究を続けた(彼はすでに17歳で大学に入り、エジプト学に夢中になっていた)。その 箱のひとつから、当時知られていた3つのマヤ写本の複製が見つかった: J.アントニオとカルロス・A.ビジャコルタによるCódices mayas(1930年)である。 マヤ文字を研究するきっかけとなったのは、クノロゾフの教授であったセルゲイ・アレクサンドロヴィチ・トカレフが、1945年にエスノス誌に掲載されたド イツ人パウル・シェルハスの論文 「Die Entzifferung der Mayahieroglyphen: ein unlösbares Problem? 」を読むように勧めたことだった。クノロゾフの視点は、当時も今も、「人間が作った可能性のあるシステムは、人間によって解決されたり、解読されたりする 可能性がある」というものである。 戦後まもなく、クノロゾフはモスクワ大学での学業を終え、職探しに駆り立てられた: 「戦後は行くところがなく、今と同じような状況だった。しかし、レニングラード(当時)の民族学博物館では労働力が不足していたため、クノロゾフはロシア の旧首都、スウェーデン帝国のランスクローナとニェンスカンスに移り住んだ。 1950年代初頭までに、クノロゾフは過去数十年間に他の学者によって行われた研究からマヤのグリフに精通することを成し遂げた。また、博士論文 (Diego de Landa: Soobshchenie o delakh v Yukatani, 1566)のテーマとなったディエゴ・デ・ランダ(Diego de Landa)の「Relación de las cosas de Yucatán」(1566年頃)の研究を行い、「ランダ文字」を解読の出発点とした。Revista Xaman 4/98(近刊)所収の 「Relación de las cosas de San Petersburgo: An Interview with Dr. Yuri Valentinovich Knorozov, Part II」、またはKertomus Jukatanin asioista, LIKE, Helsinki 1997所収の 「Landan 『aakkoset』 ja mayahieroglyfitutkimus 」を参照)。 Drevniaia Pis'mennost Tsentral'noi Ameriki」(「中央アメリカの古代文字」)と題する論文は、1952年10月にSovietskaya Etnografiya誌に発表され、すぐに「エスタブリッシュメント」を震え上がらせた。しかし、ジョン・エリック・シドニー・トンプソン率いる「エス タブリッシュメント」は、その後20年間は崩壊しなかった。その理由のほとんどは政治的なものであり、マイケル・コーの『マヤの暗号を解く』(テムズ&ハ ドソン 1992年)に詳しく書かれている。クノロゾフは要約する: 「彼(トンプソン)が支配し、誰も彼に反対しなかった。マルクスと同じで、反対することはできなかった。トンプソンも同じだった」。 民族学と言語学の分野でのクノロゾフの努力、マヤの碑文学での革命的な躍進、マヤ研究への生涯をかけた献身は、しかし、経済的には報われなかった。サンク トペテルブルグ郊外にある約20平方メートルのアパートは(2月初旬)とても寒く、彼は暖をとるために家の中でオーバーコートとベレー帽をかぶらなければ ならなかった。私たち(私と通訳)がこんな寒い中でインタビューをしなければならなかったことを残念がる彼に、「フィンランドはいつも寒いから関係ない」 と慰めようと思ったが(もちろんそんなことはない)、彼はこう答えた: 「でも、フィンランドは寒いはずだよ」。 クノロゾフはその状況を気にしていないようで、少なくとも気にしているとは言わなかった。唯一の不満は、床に置かれた書類と本、そして机がないことだっ た: 「以前は机の上に書類があったのですが、持ち去られてしまいました」。それ以外は、部屋は本でいっぱいで、主にマヤ関連の本が多く、そのほとんどは板で作 られた本棚に積まれていた。 クノロゾフ氏の家にある資料の大半はマヤに関する本や論文で占められていることから、「マヤ研究は彼の好きなテーマなのか、それとも他の分野の一つに過ぎ ないのか」という疑問が浮かんだ。クノロゾフは答えた: 「まさに、他の分野のひとつです。私の興味は常に旅にあります: あちこちを旅してきました。中アジアに興味を持ったのが始まりで、数多くの発掘調査に参加しました。また、千島列島の探検隊を10年間指揮したこともあり ます。その後、メキシコに行くことになりました」。 メキシコ訪問は興味深い経験だったかと尋ねると、クノロゾフはこう答えた: 「実のところ、そんなことはありません。そこで私はドイツ人女性、それもただの女性ではなく大富豪の女性に襲われた。その女性は私を有名な科学者と勘違い し、私についての映画を作り、それをロシアに売り込もうとしていた。私たちは皆、さまざまな観念を持っている。こうして彼女は、私のグループの3分の1を 映画作りのために忙殺することに成功した。私は彼女に一気に映画を撮るよう説得しようとしたが、そうはならなかった。私が生きている限り、そしておそらく その後も、彼らは撮影を続けるだろうと思った。旅の間中、ひとつの大きなジョークだった」。 ---------- サンクトペテルブルクでの出来事:ユーリ・ヴァレンティノヴィッチ・クノロゾフ博士へのインタビュー」の後編が、『Revista Xaman』4月号に掲載される。 インタビューは1998年2月7日、サンクトペテルブルク市内で行われた。 通訳は現地で: ロシア語とロシア文化の権威、ヨルマ・トゥルペイネン氏。 出典:https://web.archive.org/web/20050331005946/http: //www.helsinki.fi/hum/ibero/xaman/articulos/9803/9803_hk.html |

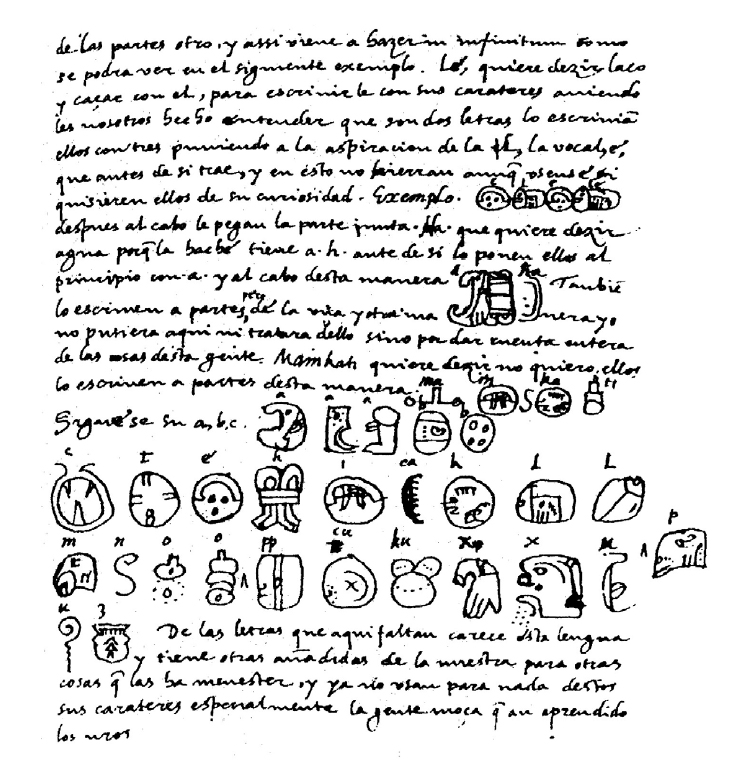

Key research Page from Diego de Landa's Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán (1853 edition by Brasseur de Bourbourg), containing description of the de Landa alphabet which Knorozov relied upon for his breakthrough. In 1952, the then 30-year-old Knorozov published a paper which was later to prove to be a seminal work in the field (Drevnyaya pis’mennost’ Tsentral’noy Ameriki, or "Ancient Writing of Central America".) The general thesis of this paper put forward the observation that early scripts such as ancient Egyptian and Cuneiform which were generally or formerly thought to be predominantly logographic or even purely ideographic in nature, in fact contained a significant phonetic component. That is to say, rather than the symbols representing only or mainly whole words or concepts, many symbols in fact represented the sound elements of the language in which they were written, and had alphabetic or syllabic elements as well, which if understood could further their decipherment.[2] By this time, this was largely known and accepted for several of these, such as Egyptian hieroglyphs (the decipherment of which was famously commenced by Jean-François Champollion in 1822 using the tri-lingual Rosetta Stone artefact); however the prevailing view was that Mayan did not have such features. Knorozov's studies in comparative linguistics drew him to the conclusion that the Mayan script should be no different from the others, and that purely logographic or ideographic scripts did not exist.[8] Knorozov's key insight was to treat the Maya glyphs represented in de Landa's alphabet not as an alphabet, but rather as a syllabary. He was perhaps not the first to propose a syllabic basis for the script, but his arguments and evidence were the most compelling to date. He maintained that when de Landa had commanded of his informant to write the equivalent of the Spanish letter "b" (for example), the Maya scribe actually produced the glyph which corresponded to the syllable, /be/, as spoken by de Landa. Knorozov did not actually put forward many new transcriptions based on his analysis; nevertheless, he maintained that this approach was the key to understanding the script. In effect, the de Landa "alphabet" was to become almost the "Rosetta stone" of Mayan decipherment.[8] A further critical principle put forward by Knorozov was that of synharmony. According to this, Mayan words or syllables which had the form consonant-vowel-consonant (CVC) were often to be represented by two glyphs, each representing a CV-syllable (i.e., CV-CV). In the reading, the vowel of the second was meant to be ignored, leaving the reading (CVC) as intended. The principle also stated that when choosing the second CV glyph, it would be one with an echo vowel that matched the vowel of the first glyph syllable. Later analysis has proved this to be largely correct.[8] |

研究の鍵 ディエゴ・デ・ランダの『ユカタンの歴史』(1853年、ブラッスール・ド・ブールブール版)の1ページ。クノロゾフが突破口を開くために依拠したデ・ラ ンダ・アルファベットの記述がある。 1952年、当時30歳だったクノロゾフは、後にこの分野の代表的な著作となる論文を発表した(Drevnyaya pis'mennost' Tsentral'noy Ameriki、「中央アメリカの古代文字」)。この論文の一般的な論旨は、古代エジプト文字や楔形文字のような初期の文字は、一般的に、あるいは以前 は、その性質上、主に記号的、あるいは純粋に表意文字的であると考えられていたが、実際には重要な表音文字的要素を含んでいた、という観察である。つま り、記号は主に単語や概念全体を表すというよりも、多くの記号は実際にその言語の音の要素を表し、アルファベットや音節の要素も持っていたのである。 [2]この頃までに、エジプトのヒエログリフ(1822年にジャン=フランソワ・シャンポリオンが3ヶ国語のロゼッタ・ストーンを用いて解読を開始したこ とで有名)など、いくつかのヒエログリフについては、このことが広く知られ、受け入れられていたが、マヤ語にはそのような特徴はないというのが一般的な見 解であった。クノロゾフは比較言語学の研究により、マヤ文字も他の文字と変わらないはずであり、純粋な記号文字や表意文字は存在しないという結論に達した [8]。 クノロゾフの重要な洞察は、デ・ランダのアルファベットに表されたマヤのグリフをアルファベットとしてではなく、むしろ音節文字として扱うことであった。 デ・ランダのアルファベットをアルファベットとしてではなく、むしろ音節文字として扱ったのである。音節文字の基礎を提唱したのはおそらく彼が最初ではな かったが、その論拠と証拠は今日までで最も説得力のあるものだった。彼は、デ・ランダが情報提供者にスペイン語の 「b 」に相当する文字を書くように命じたとき(たとえば)、マヤの書記はデ・ランダが話した音節「/be/」に対応するグリフを実際に作成したと主張した。ク ノロゾフは実際には、彼の分析に基づいて多くの新しい転写を提唱したわけではなかったが、それにもかかわらず、彼はこのアプローチが文字を理解する鍵であ ると主張した。事実上、デ・ランダの「アルファベット」はマヤの解読におけるほぼ「ロゼッタストーン」となった[8]。 クノロゾフによって提唱されたさらに重要な原則は、シンハーモニーであった。これによると、子音-母音-子音(CVC)の形を持つマヤの単語や音節は、し ばしば2つのグリフで表され、それぞれがCV-音節を表す(すなわち、CV-CV)。読みでは、2番目の母音は無視され、(CVC)という読みが意図され たままになる。また、この原則では、2番目のCVグリフを選択する際には、最初のグリフの音節の母音と一致するエコー母音を持つグリフを選択することに なっていました。後の分析により、これはほぼ正しいことが証明されている[8]。 |

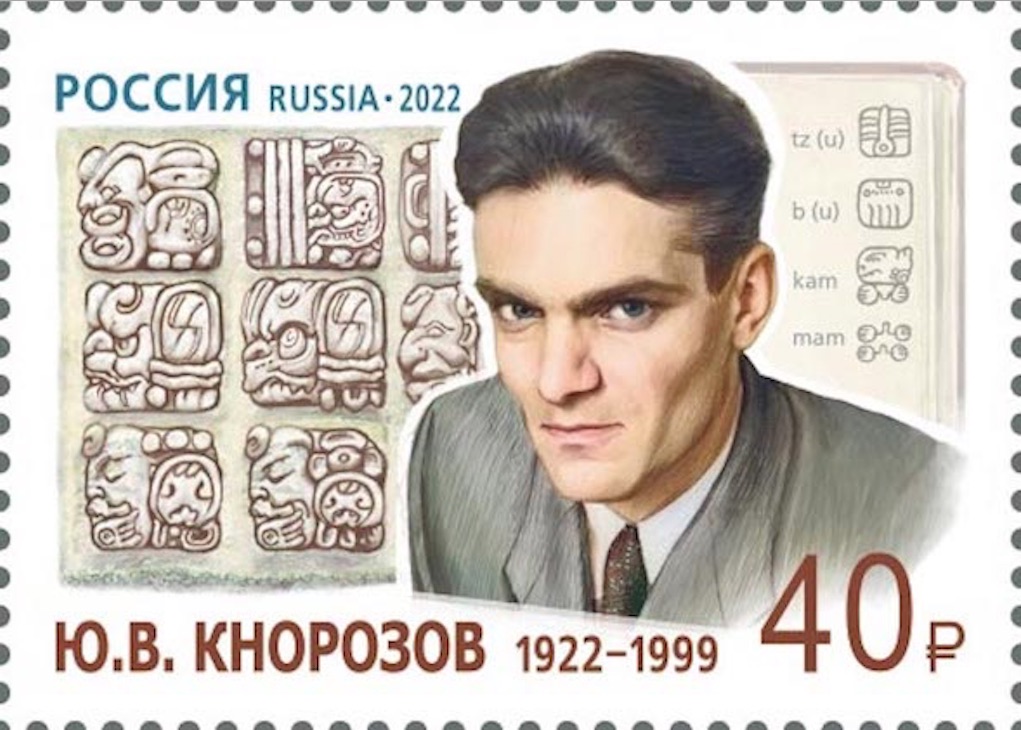

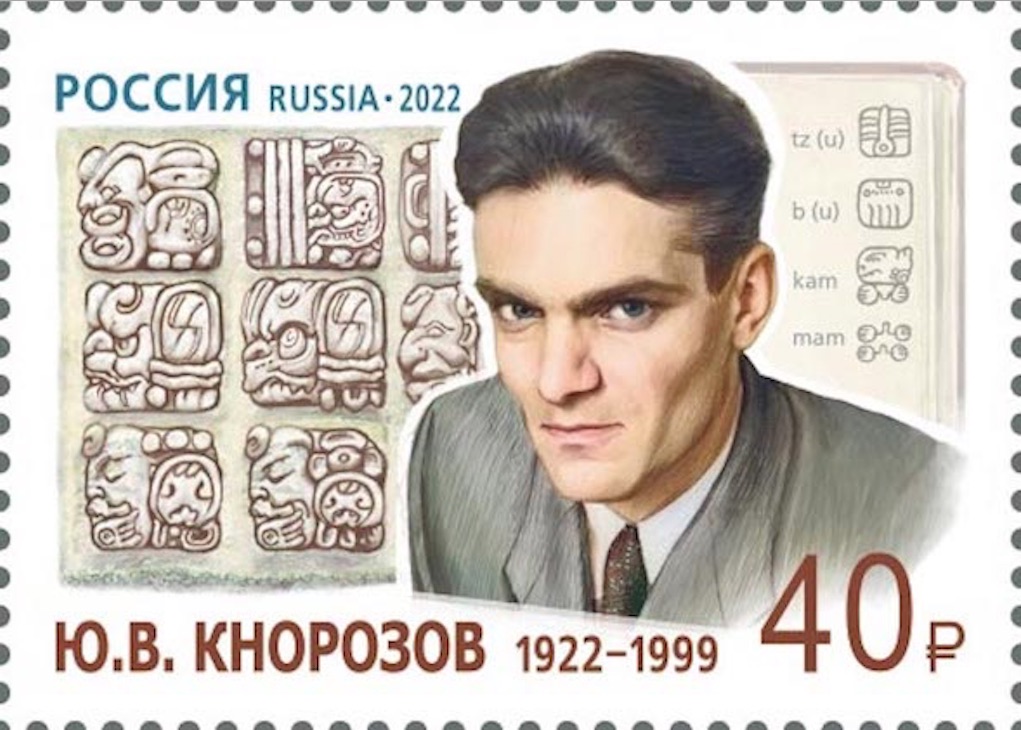

Critical reactions to his work Knorozov on a 2022 stamp of Russia Upon the publication of this work from a then hardly known scholar, Knorozov and his thesis came under some severe and at times dismissive criticism. J. Eric S. Thompson, the noted British scholar regarded by most as the leading Mayanist of his day, led the attack. Thompson's views at that time were solidly anti-phonetic, and his own large body of detailed research had already fleshed-out a view that the Maya inscriptions did not record their actual history, and that the glyphs were founded on ideographic principles. His view was the prevailing one in the field, and many other scholars followed suit.[8] According to Michael Coe, "during Thompson's lifetime, it was a rare Maya scholar who dared to contradict" him on the value of Knorozov's contributions or on most other questions. As a result, decipherment of Maya scripts took much longer than their Egyptian or Hittite counterparts and could only take off after Thompson's demise in 1975.[18] The situation was further complicated by Knorozov's paper appearing during the height of the Cold War, and many were able to dismiss his paper as being founded on misguided Marxist-Leninist ideology and polemic. Indeed, in keeping with the mandatory practices of the time, Knorozov's paper was prefaced by a foreword written by the journal's editor which contained digressions and propagandist comments extolling the State-sponsored approach by which Knorozov had succeeded where Western scholarship had failed. However, despite claims to the contrary by several of Knorozov's detractors, Knorozov himself never did include such polemic in his writings.[8] |

彼の作品に対する批評家の反応 ロシアの2022年切手に描かれたクノロゾフ 当時はまだほとんど知られていなかったクノロゾフがこの論文を発表すると、クノロゾフと彼の論文は厳しい、時には否定的な批判にさらされた。J.エリッ ク・S.トンプソンは、当時のマヤ研究者の第一人者として知られる著名なイギリス人学者である。当時のトンプソンの見解は強固な反フォネティックであり、 彼自身の膨大な詳細な研究によって、マヤの碑文は実際の歴史を記録しておらず、グリフは表意文字の原理に基づいているという見解がすでに具体化されてい た。彼の見解はこの分野では一般的なものであり、他の多くの学者もそれに倣った[8]。 マイケル・コーによれば、「トンプソンが存命中、クノロゾフの貢献の価値や他のほとんどの疑問について、あえて彼に反論したマヤ学者はまれだった」。その 結果、マヤ文字の解読はエジプト文字やヒッタイト文字よりもはるかに時間がかかり、1975年にトンプソンが死去して初めて軌道に乗ることができた [18]。 クノロゾフの論文は冷戦の真っ只中に発表されたため、状況はさらに複雑になり、多くの人が彼の論文を誤ったマルクス・レーニン主義のイデオロギーと極論に 基づいているとして退けることができた。実際、クノロゾフの論文の前書きには、当時の慣例に従って、雑誌の編集者が書いた序文があり、そこには、クノロゾ フが西洋の学問が失敗したところを成功させた、国家が後援したアプローチを称賛する余談や宣伝的なコメントが含まれていた。しかし、クノロゾフを非難する 何人かの人々によって反対の主張がなされたにもかかわらず、クノロゾフ自身は自分の著作にそのような極論を含めることはなかった[8]。 |

| Progress of decipherment Knorozov further improved his decipherment technique in his 1963 monograph "The Writing of the Maya Indians"[2][9] and published translations of Mayan manuscripts in his 1975 work "Maya Hieroglyphic Manuscripts".[25] During the 1960s, other Mayanists and researchers began to expand upon Knorozov's ideas. Their further field-work and examination of the extant inscriptions began to indicate that actual Maya history was recorded in the stelae inscriptions, and not just calendric and astronomical information. The Russian-born but American-resident scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoff was foremost in this work, eventually convincing Thompson and other doubters that historical events were recorded in the script.[26] Other early supporters of the phonetic approach championed by Knorozov included Michael D. Coe and David Kelley, and whilst initially they were in a clear minority, more and more supporters came to this view as further evidence and research progressed.[18] Through the rest of the decade and into the next, Proskouriakoff and others continued to develop the theme, and using Knorozov's results and other approaches began to piece together some decipherments of the script. A major breakthrough came during the first round table or Mesa Redonda conference at the Maya site of Palenque in 1973, when using the syllabic approach those present (mostly) deciphered what turned out to be a list of former rulers of that particular Maya city-state.[27] Subsequent decades saw many further such advances, to the point now where quite a significant portion of the surviving inscriptions can be read. Most Mayanists and accounts of the decipherment history apportion much of the credit to the impetus and insight provided by Knorozov's contributions, to a man who had been able to make important contributions to the understanding of this distant, ancient civilisation. In retrospect, Prof. Coe writes that "Yuri Knorozov, a man who was far removed from the Western scientific establishment and who, prior to the late 1980s, never saw a Mayan ruin nor touch[ed] a real Mayan inscription, had nevertheless, against all odds, "made possible the modern decipherment of Maya hieroglyphic writing."[18] |

解読の進展 クノロゾフは1963年の単行本『マヤ・インディオの文字』[2][9]で解読技術をさらに向上させ、1975年の著作『マヤ・ヒエログリフ手稿』ではマ ヤの手稿の翻訳を発表した[25]。 1960年代には、他のマヤ研究者や研究者がクノロゾフの考えを発展させ始めた。彼らのフィールドワークと現存する碑文の調査によって、ステラ碑文には暦 や天文情報だけでなく、実際のマヤの歴史が記録されていることが明らかになり始めた。ロシア出身でアメリカ在住の学者タチアナ・プロスコウリアコフはこの 研究の第一人者であり、最終的にはトンプソンや他の疑念を抱いていた人々を、歴史的出来事が文字に記録されていると説得した[26]。 クノロゾフが提唱した音声学的アプローチの初期の支持者には、他にもマイケル・D・コーやデヴィッド・ケリーがおり、当初は明らかに少数派であったが、さ らなる証拠や研究が進むにつれて、この見解を支持する者が増えていった[18]。 残りの10年間と次の10年間を通じて、プロスコリアコフと他の研究者たちはこのテーマを発展させ続け、クノロゾフの成果と他のアプローチを使って、文字 の解読をいくつかまとめ始めた。1973年、パレンケのマヤ遺跡で開催された第1回円卓会議(メサ・レドンダ会議)で大きな突破口が開かれ、出席者(ほと んど)が音節法を用いて、その特定のマヤ都市国家の元支配者のリストであることが判明した。 その後数十年の間に、このような進歩が何度も見られ、今では現存する碑文のかなりの部分が読めるようになっている。ほとんどのマヤ研究者や解読の歴史に関 する記述は、クノロゾフの貢献によってもたらされた推進力と洞察力によって、この遠い古代文明の理解に重要な貢献ができたと評価している。振り返って、 コー教授は、「ユーリ・クノロゾフは、西洋の科学体制からかけ離れ、1980年代後半以前は、マヤの遺跡を見たこともなく、本物のマヤの碑文に触れたこと もなかったが、それにもかかわらず、あらゆる困難を乗り越えて、マヤの象形文字の現代的解読を可能にした」と書いている[18]。 |

| Later life Knorozov had presented his work in 1956 at the International Congress of Americanists in Copenhagen, but in the ensuing years he was not able to travel abroad at all. After diplomatic relations between Guatemala and the Soviet Union were restored in 1990, Knorozov was invited by President Vinicio Cerezo to visit Guatemala. President Cerezo awarded Knorozov the Order of the Quetzal and Knorozov visited several of the major Mayan archaeological sites, including Tikal. The government of Mexico awarded Knorozov the Order of the Aztec Eagle, the highest decoration awarded by the Mexican state to non-citizens, in a ceremony at the Mexican Embassy in Moscow on 30 November 1994. While receiving the award, he said in Spanish Mi corazón siempre es mexicano (My heart always remains with Mexico).[8] Knorozov had broad interests in, and contributed to, other investigative fields such as archaeology, semiotics, human migration to the Americas, and the evolution of the mind. However, it is his contributions to the field of Maya studies for which he is best remembered.[8] In his very last years, Knorozov is also known to have pointed to a place in the United States as the likely location of Chicomoztoc, the ancestral land from which—according to ancient documents and accounts considered mythical by a sizable number of scholars—indigenous peoples now living in Mexico are said to have come.[28] Knorozov died in Saint Petersburg on 31 March 1999, of pneumonia in the corridors of a city hospital.[29] He was survived by his daughter Ekaterina and granddaughter Anna.[30] |

その後の人生 クノロゾフは1956年にコペンハーゲンで開催された国際アメリカニスト会議で研究発表を行ったが、その後数年間はまったく海外に出ることができなかっ た。1990年にグアテマラとソビエト連邦の国交が回復すると、クノロゾフはビニシオ・セレーゾ大統領の招きでグアテマラを訪れた。セレーゾ大統領はクノ ロゾフにケツァール勲章を授与し、クノロゾフはティカルを含む主要なマヤ遺跡のいくつかを訪れた。1994年11月30日、モスクワのメキシコ大使館で行 われた式典で、メキシコ政府はクノロゾフに、メキシコ国家が国民以外に授与する最高位の勲章であるアステカ・イーグル勲章を授与した。勲章を授与された 際、彼はスペイン語で「私の心はいつもメキシコにあります」と述べた[8]。 クノロゾフは、考古学、記号論、アメリカ大陸への人類の移動、心の進化など、他の調査分野にも広く関心を持ち、貢献した。しかし、最もよく知られているの はマヤ研究の分野への貢献である[8]。 また、クノロゾフは晩年、チコモズトック(現在メキシコに居住する先住民族が起源とされる古文書や、かなりの数の学者によって神話的とされる記述によれ ば、その祖先の土地)が存在する可能性が高い場所として、アメリカのある場所を指摘したことでも知られている[28]。 クノロゾフは1999年3月31日、肺炎のため市内の病院の廊下でサンクトペテルブルグにて死去した[29]。娘のエカテリーナと孫娘のアンナが遺族であ る[30]。 |

| List of publications An incomplete listing of Knorozov's papers, conference reports and other publications, divided by subject area and type. Note that several of those listed are re-editions and/or translations of earlier papers.[31][12][18] Knorozov listed his cat Asya as a co-author on his work, but the editors always removed her. He always used the photo with Asya (above) as his author photo, and got annoyed when editors cropped her out.[32] Maya-related Conference papers "A brief summary of the studies of the ancient Maya hieroglyphic writing in the Soviet Union". Reports of the Soviet Delegations at the 10th International Congress of Historical Science in Rome (Authorized English translation ed.). Moscow: Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1955. "Краткие итоги изучения древней письменности майя в Советском Союзе". Proceedings of the International Congress of Historical Sciences (Rome, 1955). Rome. 1956. pp. 343–364. "New data on the Maya written language". Proc. 32nd International Congress of Americanists, (Copenhagen, 1956). Copenhagen. 1958. pp. 467–475. "La lengua de los textos jeroglíficos mayas". Proceedings of the International Congress of Americanists (33rd session, San José, 1958). San José, Costa Rica. 1959. pp. 573–579. "Le Panthéon des anciens Maya". Proceedings of the International Congress of Anthropological and Ethnological Sciences (7th session, Moscow, 1964). Moscow. 1970. pp. 126–232. Journal articles "Древняя письменность Центральной Америки (Ancient Writings of Central America)". Soviet Ethnography. 3 (2): 100–118. 1952. "Письменность древних майя: (опыт расшифровки) (Written Language of the Ancient Maya)" (PDF). Soviet Ethnography. 1: 94–125. 1955. Knorozov, Y. V. (1956). "New data on the Maya written language". Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris. 45: 209–217. doi:10.3406/jsa.1956.961. "Estudio de los jeroglíficos mayas en la U.R.S.S." [The Study of Maya hieroglyphics in the USSR]. Khana, Revista municipal de artes y letras (La Paz, Bolivia). 2 (17–18): 183–189. 1958. Knorozov, Y. V.; Coe, Sophie D. (1958). "The problem of the study of the Maya hieroglyphic writing". American Antiquity. 23 (3): 284–291. doi:10.2307/276310. JSTOR 276310. S2CID 163305055. Knorozov, Youri V.; Alexander, Sidney (1962). "Problem of deciphering Mayan writing". Diogènes (Montreal). 10 (40): 122–128. doi:10.1177/039219216201004007. S2CID 143041913. Knorozov, Iu. V. (1963). "Machine decipherment of Maya script". Soviet Anthropology and Archeology. 1 (3): 43–50. doi:10.2753/aae1061-1959010343. Knorozov, Yuri (1963). "Aplicación de las matematicas al estudio lingüistico" [Application of mathematics to linguistic studies]. Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 3: 169–185. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1963.3.686. Knorozov, Yuri (1965). "Principios para descifrar los escritos mayas" [Principles for deciphering Maya writing]. Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 5: 153–188. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1965.5.667. Knorozov, Yuri V. (1968). "Investigación formal de los textos jeroglíficos mayas" [Formal investigations of Maya hieroglyphic texts]. Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 7: 153–188. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1968.7.694. "Заметки о календаре майя: 365-дневный год". Soviet Ethnography. 1: 70–80. 1973. "Notas sobre el calendario maya; el monumento E de Tres Zapotes". América Latina; Estudios de Científicos Soviéticos. 3: 125–140. 1974. "Acerca de las relaciones precolombinas entre América y el Viejo Mundo". América Latina; Estudios de Científicos Soviéticos. 1: 84–98. 1986. Books La antigua escritura de los pueblos de America Central. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Popular. 1954. Система письма древних майя. Moscow: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1955. "Сообщение о делах в Юкатане" Диего де Ланда как историко-этнографический источник. Moscow: Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1956. (Knorozov's doctoral dissertation) Письменность индейцев майя. Moscow-Leningrad: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1963. Tatiana Proskouriakoff, ed. (1967). "The Writing of the Maya Indians". Russian Translation Series 4. Sophie Coe (trans.). Cambridge MA.: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. ISBN 0894121820. Иероглифические рукописи майя. Leningrad: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. 1975. Maya Hieroglyphic Codices. Sophie Coe (trans.). Albany NY.: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies. 1982. ISBN 0942041070. "Compendio Xcaret de la escritura jeroglifica maya descifrada por Yuri V. Knorosov". Promotora Xcaret. Mexico City: Universidad de Quintana Roo. 1999. Stephen Houston; Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos; David Stuart, eds. (2001). "New data on the Maya written language". The Decipherment of Ancient Maya Writing. Norman OK.: University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 144–152. ISBN 9780806132044. Others "Preliminary Report on the Study of the Written Language of Easter Island". Journal of the Polynesian Society. 66 (1): 5–17. 1957. (on the Rongorongo script, with N.A. Butinov) Yuri Knorozov, ed. (1965). Predvaritel'noe soobshchenie ob issledovanii protoindiyskih tekstov. Moscow: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. (Collated results of a research team under Knorozov investigating the Harappan script, with the use of computers) "Protoindiyskie nadpisi (k probleme deshifrovki)". Sovetskaya Etnografiya. 5 (2): 47–71. 1981. (on the Harappan script of the Indus Valley civilization) |

出版物一覧 ノロゾフの論文、学会報告その他の出版物を主題分野と種類別に分類した不完全なリストである。記載されているもののいくつかは、以前の論文の再版および/ または翻訳であることに留意せよ。[31][12][18] ノロゾフは自身の著作において猫のアシャを共著者として記載したが、編集者は常に彼女を除外した。彼は常にアシャとの写真(上記)を著者写真として使用 し、編集者が彼女を切り取ることに苛立っていた。[32] マヤ関連 学会発表 「ソビエト連邦における古代マヤ象形文字研究の概略」。ローマ開催第10回国際歴史科学会議におけるソ連代表団報告(公認英訳版)。モスクワ:ソ連科学ア カデミー。1955年。 「ソ連における古代マヤ文字研究の概略」。国際歴史科学会議議事録(ローマ、1955年)。ローマ。1956年。343–364頁。 「マヤ文字に関する新資料」。第32回アメリカ研究国際会議議事録(コペンハーゲン、1956年)。コペンハーゲン。1958年。467–475頁。 「マヤ象形文字テキストの言語」。アメリカ研究国際会議議事録(第33回、サンホセ、1958年)。サンホセ、コスタリカ。1959年。573–579 頁。 「古代マヤ人のパンテオン」。人類学・民族学国際会議議事録(第7回、モスクワ、1964年)。モスクワ。1970年。126–232頁。 学術論文 「中央アメリカの古代文字(Древняя письменность Центральной Америки)」。ソビエト民族誌学。3巻2号:100–118頁。1952年。 「古代マヤの文字(Письменность древних майя: (опыт расшифровки))」(PDF)。ソビエト民族誌. 1: 94–125. 1955. Knorozov, Y. V. (1956). 「マヤ文字に関する新たな資料」. Journal de la Société des Américanistes de Paris. 45: 209–217. doi:10.3406/jsa.1956.961. 「ソ連におけるマヤ象形文字の研究」. 『カナ』市芸術文学誌(ボリビア、ラパス). 2 (17–18): 183–189. 1958. クノロゾフ, Y. V.; Coe, Sophie D. (1958). 「マヤ象形文字の研究の問題」 American Antiquity. 23 (3): 284–291. doi:10.2307/276310. JSTOR 276310. S2CID 163305055. Knorozov, Youri V.; Alexander, Sidney (1962). 「マヤ文字の解読の問題」. Diogènes (モントリオール). 10 (40): 122–128. doi:10.1177/039219216201004007. S2CID 143041913。 Knorozov, Iu. V. (1963). 「マヤ文字の機械的解読」. Soviet Anthropology and Archeology. 1 (3): 43–50. doi:10.2753/aae1061-1959010343. Knorozov, Yuri (1963). 「言語学研究への数学の応用」. Estudios de Cultura Maya (メキシコシティ). 3: 169–185. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1963.3.686. Knorozov, Yuri (1965). 「Principios para descifrar los escritos mayas」 [マヤ文字解読の原理]. Estudios de Cultura Maya (Mexico City). 5: 153–188. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1965.5.667. Knorozov, Yuri V. (1968). 「Investigación formal de los textos jeroglíficos mayas」 [マヤ象形文字テキストの形式的調査]. Estudios de Cultura Maya (メキシコシティ). 7: 153–188. doi:10.19130/iifl.ecm.1968.7.694. 「マヤ暦に関する覚書:365日暦」『ソビエト民族誌学』1: 70–80. 1973. 「マヤ暦に関する覚書:トレス・サポテスE碑文」『ラテンアメリカ:ソビエト科学者研究』3: 125–140. 1974. 「アメリカ大陸と旧世界とのコロンブス以前の関係について」。『ラテンアメリカ:ソ連科学者研究』1: 84–98頁。1986年。 書籍 『中央アメリカ諸民族の古代文字』。メキシコシティ:国民文化基金。1954年。 古代マヤ文字体系。モスクワ:ソ連科学アカデミー民族学研究所。1955年。 「ユカタン事情報告」ディエゴ・デ・ランダの歴史民族学的資料としての価値。モスクワ:ソ連科学アカデミー。1956年。(クロゾフ博士論文) マヤ族の文字体系。モスクワ・レニングラード:ソ連科学アカデミー民族学研究所。1963年。 タチアナ・プロスクリアコフ編(1967年)。『マヤ族の文字』。ロシア翻訳シリーズ4。ソフィー・コー訳。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:ピーボディ 考古学民族学博物館。ISBN 0894121820。 マヤの象形文字写本。レニングラード:ソ連科学アカデミー民族学研究所。1975年。 マヤ象形文字写本。ソフィー・コー訳。ニューヨーク州オールバニ:メソアメリカ研究所。1982年。ISBN 0942041070。 「Compendio Xcaret de la escritura jeroglifica maya descifrada por Yuri V. Knorosov」。Promotora Xcaret。メキシコシティ:Universidad de Quintana Roo。1999年。 Stephen Houston; Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos; David Stuart, eds. (2001). 「マヤの文字言語に関する新たなデータ」。『古代マヤ文字の解読』。ノーマン、オクラホマ州:オクラホマ大学出版局。144-152 ページ。ISBN 9780806132044。 その他 「イースター島の文字言語に関する研究に関する予備報告」。『ポリネシア協会誌』。66 (1): 5–17. 1957. (ロンゴロンゴ文字について、N.A. ブティノフと共著) ユーリ・クノロゾフ編 (1965). Predvaritel'noe soobshchenie ob issledovanii protoindiyskih tekstov. モスクワ: Institut Etnografii, Akademiya Nauk SSSR. (クノロゾフ率いる研究チームによるハラッパー文字調査の成果をコンピュータを用いて整理したもの) 「プロトインド文字(解読問題について)」。『ソビエト民族学』5巻2号:47–71頁。1981年。(インダス文明のハラッパー文字に関する論文) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuri_Knorozov |

ユー リ・クロノゾフ・アルバム

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆