中世音楽

Medieval music

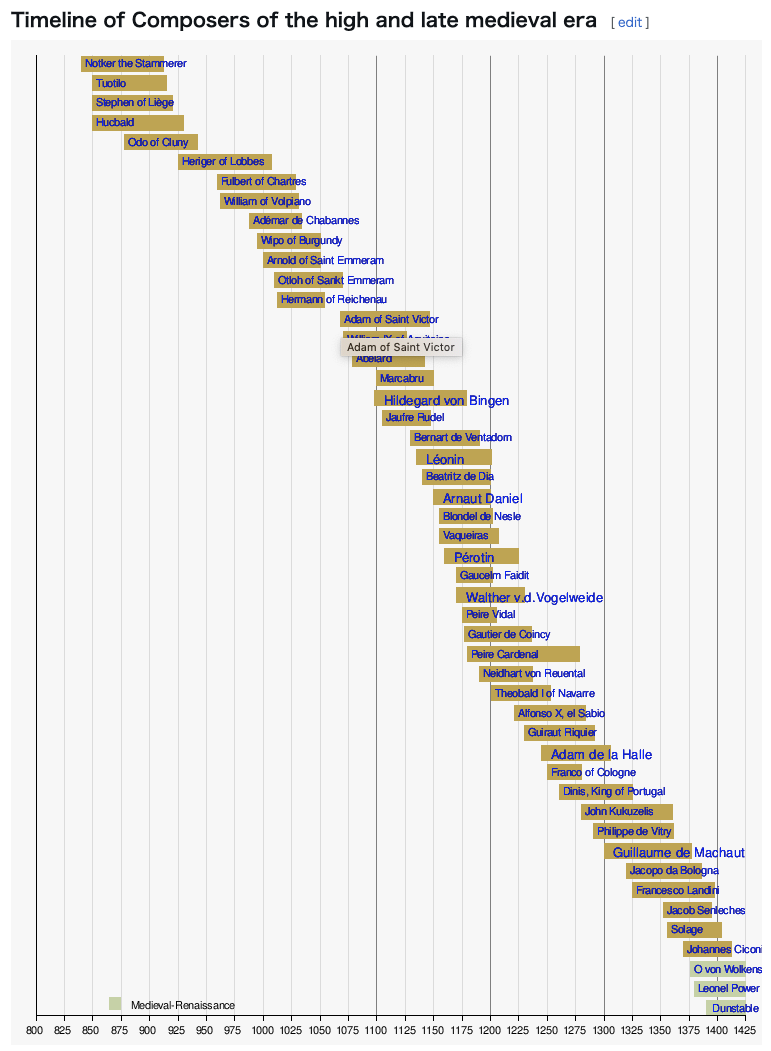

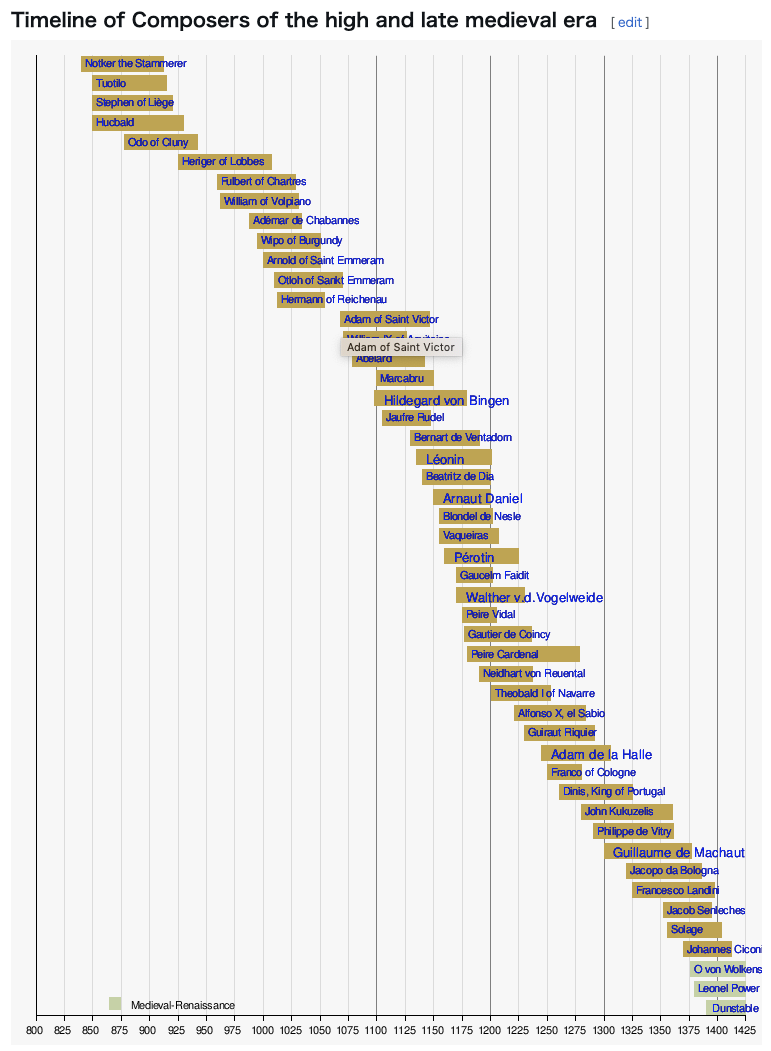

☆ 中世音楽とは、西ヨーロッパの中世(6世紀頃から15世紀頃まで)の宗教音楽と世俗音楽を指す。西洋クラシック音楽の最初の、そして最も長い主要な時代で あり、ルネサンス音楽に続く。この2つの時代は、一般的に初期音楽と呼ばれ、共通実践期に先行する。中世の伝統的な区分に従い、中世音楽は初期(500年 ~1000年)、盛期(1000年~1300年)、後期(1300年~1400年)に区分される。 中世音楽には、教会で使用される典礼音楽、その他の宗教音楽、世俗音楽や非宗教音楽が含まれる。中世音楽の多くはグレゴリオ聖歌のような純粋な声楽であ る。その他の音楽は楽器のみ、あるいは声楽と器楽の両方(通常は器楽が声楽を伴奏する)で演奏される。 中世には、音楽のアイデアをより簡単に記録し、伝達することを可能にする楽譜のシステムが作成され、適応された。楽譜は口承伝統と共存し、それを補完する ものであった。

King

David and musicians from Olomouc Bible, folio 276R, color enhanced/

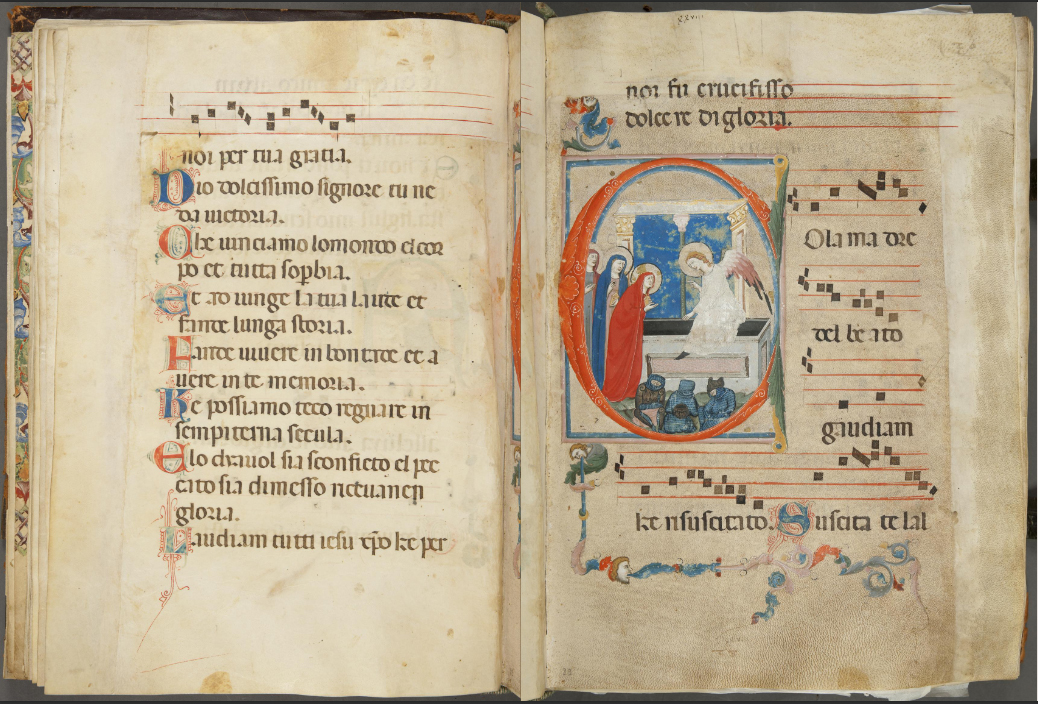

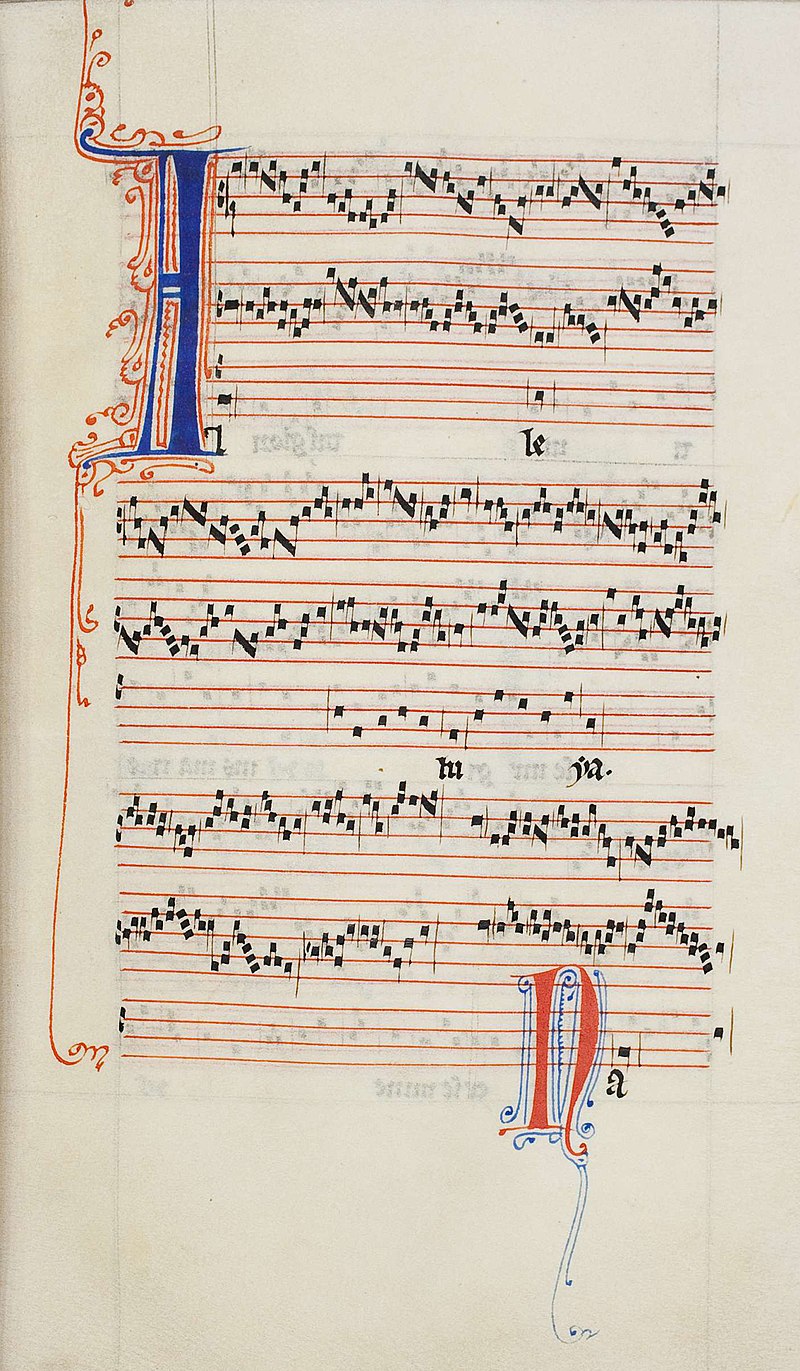

Laudario Magliabechiano (Ms Banco Rari 18), lauda Co[n] la madre del

beato

| Medieval music

encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the

Middle Ages,[1] from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the

first and longest major era of Western classical music and is followed

by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists

generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period.

Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music

can be divided into Early (500–1000), High (1000–1300), and Late

(1300–1400) medieval music. Medieval music includes liturgical music used for the church, other sacred music, and secular or non-religious music. Much medieval music is purely vocal music, such as Gregorian chant. Other music used only instruments or both voices and instruments (typically with the instruments accompanying the voices). The medieval period saw the creation and adaptation of systems of music notation which enabled creators to document and transmit musical ideas more easily, although notation coexisted with and complemented oral tradition. |

中世音楽とは、西ヨーロッパの中世(6世紀頃から15世紀頃まで)の宗

教音楽と世俗音楽を指す。西洋クラシック音楽の最初の、そして最も長い主要な時代であり、ルネサンス音楽に続く。この2つの時代は、一般的に初期音楽と呼

ばれ、共通実践期に先行する。中世の伝統的な区分に従い、中世音楽は初期(500年~1000年)、盛期(1000年~1300年)、後期(1300年

~1400年)に区分される。 中世音楽には、教会で使用される典礼音楽、その他の宗教音楽、世俗音楽や非宗教音楽が含まれる。中世音楽の多くはグレゴリオ聖歌のような純粋な声楽であ る。その他の音楽は楽器のみ、あるいは声楽と器楽の両方(通常は器楽が声楽を伴奏する)で演奏される。 中世には、音楽のアイデアをより簡単に記録し、伝達することを可能にする楽譜のシステムが作成され、適応された。楽譜は口承伝統と共存し、それを補完する ものであった。 |

| Overview Genres Further information: Gregorian chant, Ars nova, Organum, Motet, Madrigal (Trecento), Canon (music), and Ballata Medieval music was created for a number of different uses and contexts, resulting in different music genres. Liturgical as well as more general sacred contexts were important, but secular types emerged as well, including love songs and dances. During the earlier medieval period, liturgical music was monophonic chant; Gregorian chant became the dominant style. Polyphonic genres, in which multiple independent melodic lines are performed simultaneously, began to develop during the high medieval era, becoming prevalent by the later 13th and early 14th century. The development of polyphonic forms is often associated with the Ars antiqua style associated with Notre-Dame de Paris, but improvised polyphony around chant lines predated this.[2] Organum, for example, elaborated on a chant melody by creating one or more accompanying lines. The accompanying line could be as simple as a second line sung in parallel intervals to the original chant (often a perfect fifth or perfect fourth away from the main melody). The principles of this kind of organum date back at least to an anonymous 9th century tract, the Musica enchiriadis, which describes the tradition of duplicating a preexisting plainchant in parallel motion at the interval of an octave, a fifth or a fourth.[3] Some of the earliest written examples are in a style known as Aquitanian polyphony, but the largest body of surviving organum comes from the Notre-Dame school. This loose collection of repertory is often called the Magnus Liber Organi (Great Book of Organum).[4] Related polyphonic genres included the motet and clausula genres, both also often built on an original segment of plainchant or as an elaboration on an organum passage.[5] While most early motets were sacred and may have been liturgical (designed for use in a church service), by the end of the thirteenth century the genre had expanded to include secular topics, such as political satire and courtly love, and French as well as Latin texts. They also included from one to three upper voices, each with its own text.[6] In Italy, the secular genre of the Madrigal became popular. Similar to the polyphonic character of the motet, madrigals featured greater fluidity and motion in the leading melody. The madrigal form also gave rise to polyphonic canons (songs in which multiple singers sing the same melody, but starting at different times), especially in Italy where they were called caccie. These were three-part secular pieces, which featured the two higher voices in canon, with an underlying instrumental long-note accompaniment.[7] In the late middle ages, some purely instrumental music also began to be notated, though this remained rare. Dance music makes up most of the surviving instrumental music, and includes types such as the estampie, ductia, and nota.[8] |

概要 ジャンル 詳細情報:グレゴリオ聖歌、アルス・ノヴァ、オルガヌム、モテット、マドリガーレ(14世紀)、カノン(音楽)、バラータ 中世音楽は、さまざまな用途や状況に合わせて作られ、異なるジャンルの音楽を生み出した。典礼用やより一般的な宗教的な状況は重要であったが、世俗的なも のも現れ、愛の歌や舞曲なども含まれた。初期の中世では、典礼音楽は単旋律の聖歌であり、グレゴリオ聖歌が支配的なスタイルとなった。複数の独立した旋律 線が同時に演奏される多旋律のジャンルは、盛期中世の時代に発展し始め、13世紀後半から14世紀前半にかけて広く普及した。ポリフォニー形式の発展は、 ノートルダム大聖堂と関連付けられるアルス・アンティクァ様式と関連付けられることが多いが、聖歌の旋律を基にした即興のポリフォニーはこれより以前から 存在していた。 例えばオルガヌムは、聖歌の旋律を基に、1つまたは複数の伴奏旋律を創作することで発展した。伴奏旋律は、元の聖歌と平行する音程(主旋律から完全5度ま たは完全4度離れた音程であることが多い)で歌われる2番目の旋律のように、単純なものでもよい。このオルガヌムの原理は、少なくとも9世紀の匿名の著作 『ムジカ・エンキリアディス(Musica enchiriadis)』にまで遡ることができる。この著作では、既存のプレーンチャントをオクターブ、5度、または4度の平行移動で複製する伝統につ いて説明している。[3] 最も初期に書かれた例のいくつかは、アキテーヌ多声音楽として知られる様式であるが、現存するオルガヌムの大部分はノートルダム楽派に由来する。この緩や かなレパートリーの集合は、しばしば「マグヌス・リベル・オルガヌム(Magnus Liber Organi)」(オルガヌムの大著)と呼ばれる。[4] ポリフォニーの関連ジャンルにはモテットとクラウズラのジャンルがあり、いずれもプレインチャントのオリジナルセグメントを基に、あるいはオルガヌムの パッセージをさらに発展させたものとして作られることが多かった。[5] 初期のモテットのほとんどは宗教的なもので、典礼用(教会の礼拝で使用するために作られた)であったが、13世紀末には、政治風刺や宮廷恋愛といった世俗 的な主題や、ラテン語だけでなくフランス語のテキストも含まれるようになった。また、1声から3声の上声部が含まれ、それぞれ独自の歌詞が付けられてい た。 イタリアでは世俗的なマドリガルが人気を博した。モテットの多声音楽の性格に似たマドリガルは、主旋律にさらに流動性と動きが加わった。マドリガルの形式 は、多声音楽のカノン(複数の歌手が同じ旋律を歌うが、異なるタイミングで開始する楽曲)を生み出した。特にイタリアでは、カノンは「カッチェ」と呼ばれ た。これらは世俗的な3部構成の楽曲で、2つの高い声部がカノンで歌い、その下に楽器による長い音符の伴奏が続く。 中世後期には、純粋な器楽曲も記譜されるようになったが、これはまれであった。舞曲は、現存する器楽曲のほとんどを占めており、エステピー、ダクティア、ノータなどの種類がある。 |

| Instruments Further information: List of medieval musical instruments  A creature plays the vielle in the margins of the Hours of Charles the Noble, a book which contains 180 depictions of medieval instruments, probably more than any other book of hours. Many instruments used to perform medieval music still exist in the 21st century, but in different and typically more technologically developed forms.[9] The flute was made of wood in the medieval era rather than silver or other metal, and could be made as a side-blown or end-blown instrument. While modern orchestral flutes are usually made of metal and have complex key mechanisms and airtight pads, medieval flutes had holes that the performer had to cover with the fingers (as with the recorder). The recorder was made of wood during the medieval era, and despite the fact that in the 21st century it may be made of synthetic materials such as plastic, it has more or less retained its past form. The gemshorn is similar to the recorder as it has finger holes on its front, though it is actually a member of the ocarina family. One of the flute's predecessors, the pan flute, was popular in medieval times, and is possibly of Hellenic origin. This instrument's pipes were made of wood, and were graduated in length to produce different pitches.[citation needed] |

楽器 詳細情報:中世の楽器の一覧  シャルルマーニュの時祷書(Hours of Charles the Noble)の余白にヴィエル(vielle)を演奏する生き物。この本には、おそらく他のどの時祷書よりも多い180種類もの中世の楽器が描かれている。 中世音楽の演奏に使われた楽器の多くは21世紀の現在でも存在しているが、異なる、より技術的に進化した形態となっている。[9] フルートは中世では銀やその他の金属ではなく木製で、サイド・ブロー式またはエンド・ブロー式の楽器として作られた。現代のオーケストラで使用されるフ ルートは通常金属製で、複雑なキイの仕組みと気密パッドを備えているが、中世のフルートには演奏者が指でふさぐ穴(リコーダーと同様)があった。リコー ダーは中世時代には木製で、21世紀の現代ではプラスチックなどの合成素材で製造されているが、その形状はほぼ昔のままのものとなっている。ジェムショー ンは、前面に指穴がある点でリコーダーに似ているが、実際にはオカリナの仲間である。フルートの先駆けのひとつであるパンフルートは、中世に人気があり、 おそらくヘレニズム時代に起源を持つ。この楽器のパイプは木製で、異なる音程を生み出すために長さが段階的に異なっていた。[要出典] |

David playing the harp, accompanied by plucked fiddle and clappers/cymbals. Circa 795, Germany or France. Medieval music used many plucked string instruments like the lute, a fretted instrument with a pear-shaped hollow body which is the predecessor to the modern guitar. Other plucked stringed instruments included the mandore, gittern, citole and psaltery. The dulcimers, similar in structure to the psaltery and zither, were originally plucked, but musicians began to strike the dulcimer with hammers in the 14th century after the arrival of new metal technology that made metal strings possible.[citation needed] The bowed lyra of the Byzantine Empire was the first recorded European bowed string instrument. Like the modern violin, a performer produced sound by moving a bow with tensioned hair over tensioned strings. The Persian geographer Ibn Khurradadhbih of the 9th century (d. 911) cited the Byzantine lyra, in his lexicographical discussion of instruments as a bowed instrument equivalent to the Arab rabāb and typical instrument of the Byzantines along with the urghun (organ),[10][failed verification] shilyani (probably a type of harp or lyre) and the salandj (probably a bagpipe).[11] The hurdy-gurdy was (and still is) a mechanical violin using a rosined wooden wheel attached to a crank to "bow" its strings. Instruments without sound boxes like the jew's harp were also popular. Early versions of the pipe organ, fiddle (or vielle), and a precursor to the modern trombone (called the sackbut) were used.[citation needed] |

ハープを演奏するダヴィデ、爪弾きバイオリンと拍子木/シンバルの伴奏付き。 795年頃、ドイツまたはフランス。 中世の音楽では、リュートのような多くの爪弾き弦楽器が使用されていた。リュートは、洋ナシ形の空洞ボディを持つフレット楽器で、現代のギターの先駆けで ある。 その他の爪弾き弦楽器には、マンドール、ギターン、シトーレ、サルタリーなどがある。ダルシマーは、プサルテリーやツィターと似た構造で、もともとは弾奏 されていたが、金属弦の製造を可能にする新しい金属技術が14世紀に登場してからは、ダルシマーをハンマーで叩く奏法も行われるようになった。 ビザンティン帝国の弓奏リラは、ヨーロッパで最初に記録された弓奏弦楽器である。現代のヴァイオリンと同様に、演奏者は張られた弦の上を毛皮の弓を動かし て音を出す。9世紀のペルシアの地理学者イブン・ハルワードビー(911年没)は、楽器の語源学的な議論の中で、ビザンティン・リラを挙げ、アラブのラ バーブと並ぶ弓奏楽器であり、ビザンティン帝国の典型的な楽器であると述べている。また、ウルグン(オルガン)、シリアニ(おそらくハープまたはリラの一 種)、サランドゥ(おそらくバグパイプ)も挙げている。バグパイプ)があった。[11]ハーディガーディは(そして今でも)弦を「弓で弾く」ために、ロジ ンを塗った木製の車輪をクランクに取り付けた機械仕掛けのバイオリンであった。口琴のような共鳴箱のない楽器も人気があった。初期のパイプオルガン、フィ ドル(またはヴィエル)、そして現代のトロンボーンの先駆けとなる楽器(サックバットと呼ばれる)が使われていた。[要出典] |

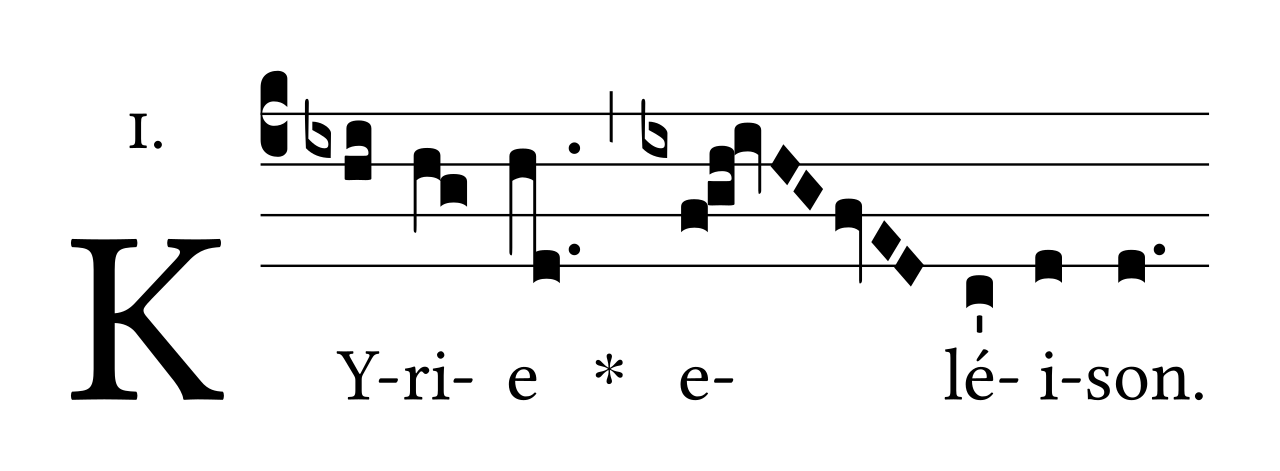

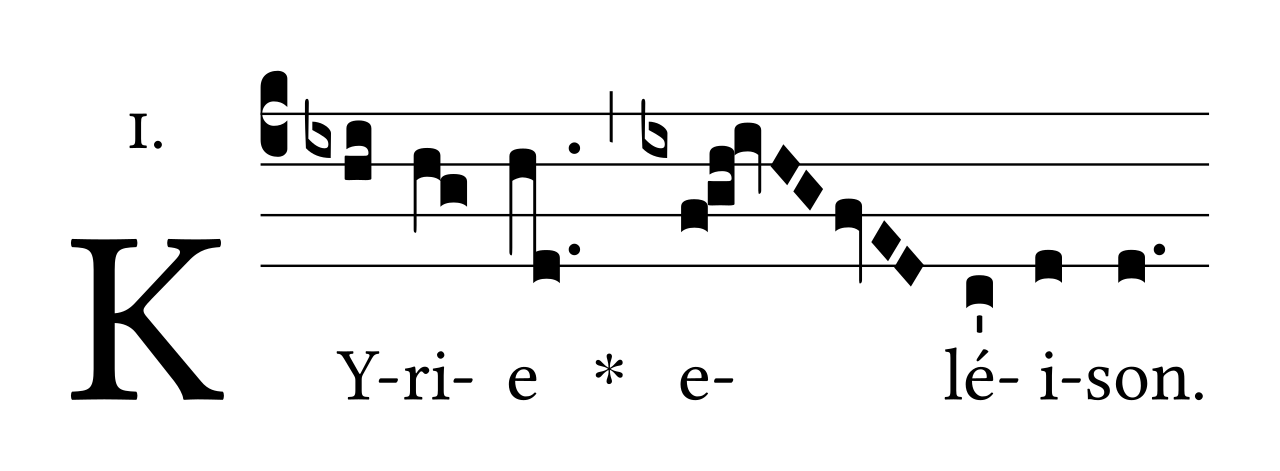

| Notation During the medieval period the foundation was laid for the notational and theoretical practices that would shape Western music into the norms that developed during the common practice era. The most obvious of these is the development of a comprehensive music notational system; however the theoretical advances, particularly in regard to rhythm and polyphony, are equally important to the development of Western music.  A sample of Kýrie Eléison XI (Orbis Factor) from the Liber Usualis. The modern "neumes" on the staff above the text indicate the pitches of the melody. Listen to it interpreted. The earliest medieval music did not have any kind of notational system. The tunes were primarily monophonic (a single melody without accompaniment) and transmitted by oral tradition.[12] As Rome tried to centralize the various liturgies and establish the Roman rite as the primary church tradition the need to transmit these chant melodies across vast distances effectively was equally glaring.[13] So long as music could only be taught to people "by ear," it limited the ability of the church to get different regions to sing the same melodies, since each new person would have to spend time with a person who already knew a song and learn it "by ear." The first step to fix this problem came with the introduction of various signs written above the chant texts to indicate direction of pitch movement, called neumes.[12] The origin of neumes is unclear and subject to some debate; however, most scholars agree that their closest ancestors are the classic Greek and Roman grammatical signs that indicated important points of declamation by recording the rise and fall of the voice.[14] The two basic signs of the classical grammarians were the acutus, /, indicating a raising of the voice, and the gravis, \, indicating a lowering of the voice. A singer reading a chant text with neume markings would be able to get a general sense of whether the melody line went up in pitch, stayed the same, or went down in pitch. Since trained singers knew the chant repertoire well, written neume markings above the text served as a reminder of the melody but did not specify the actual intervals.[15] However, a singer reading a chant text with neume markings would not be able to sight read a song which he or she had never heard sung before; these pieces would not be possible to interpret accurately today without later versions in more precise notation systems.[16] These neumes eventually evolved into the basic symbols for neumatic notation, the virga (or "rod") which indicates a higher note and still looked like the acutus from which it came; and the punctum (or "dot") which indicates a lower note and, as the name suggests, reduced the gravis symbol to a point.[14] Thus the acutus and the gravis could be combined to represent graphical vocal inflections on the syllable.[14] This kind of notation seems to have developed no earlier than the eighth century, but by the ninth it was firmly established as the primary method of musical notation.[17] The basic notation of the virga and the punctum remained the symbols for individual notes, but other neumes soon developed which showed several notes joined. These new neumes—called ligatures—are essentially combinations of the two original signs.[18] The first music notation was the use of dots over the lyrics to a chant, with some dots being higher or lower, giving the reader a general sense of the direction of the melody. However, this form of notation only served as a memory aid for a singer who already knew the melody.[19] This basic neumatic notation could only specify the number of notes and whether they moved up or down. There was no way to indicate exact pitch, any rhythm, or even the starting note. These limitations are further indication that the neumes were developed as tools to support the practice of oral tradition, rather than to supplant it. However, even though it started as a mere memory aid, the worth of having more specific notation soon became evident.[17] The next development in musical notation was "heighted neumes", in which neumes were carefully placed at different heights in relation to each other. This allowed the neumes to give a rough indication of the size of a given interval as well as the direction. This quickly led to one or two lines, each representing a particular note, being placed on the music with all of the neumes relating to the earlier ones. At first, these lines had no particular meaning and instead had a letter placed at the beginning indicating which note was represented. However, the lines indicating middle C and the F a fifth below slowly became most common. Having been at first merely scratched on the parchment, the lines now were drawn in two different colored inks: usually red for F, and yellow or green for C. This was the beginning of the musical staff.[20] The completion of the four-line staff is usually credited to Guido d'Arezzo (c. 1000–1050), one of the most important musical theorists of the Middle Ages. While older sources attribute the development of the staff to Guido, some modern scholars suggest that he acted more as a codifier of a system that was already being developed. Either way, this new notation allowed a singer to learn pieces completely unknown to him in a much shorter amount of time.[13][21] However, even though chant notation had progressed in many ways, one fundamental problem remained: rhythm. The neumatic notational system, even in its fully developed state, did not clearly define any kind of rhythm for the singing of notes.[22] |

表記 中世の時代に、西洋音楽の表記法と理論の基礎が確立され、それが共通実践時代に発展した規範となった。最も明白な例は、包括的な音楽表記法の発展である。しかし、理論面での進歩、特にリズムとポリフォニーに関するものは、西洋音楽の発展に同様に重要である。  Liber Usualis(通常使われる本)からの「キリエ・エレイソン XI(Orbis Factor)」の一例。テキストの上の五線譜に書かれた現代の「ヌース」は、旋律の音高を示している。演奏を聴く。 中世初期の音楽には、いかなる種類の記譜法も存在しなかった。曲は主に単旋律(伴奏のない単一の旋律)であり、口頭伝承によって伝えられていた。[12] ローマがさまざまな典礼を中央集権化し、ローマ式典礼を主要な教会の伝統として確立しようとしたため、これらの聖歌の旋律を広大な距離を越えて効果的に伝 える必要性も同様に顕著であった。[13] 音楽が「耳で」しか教えられない限り、異なる地域で同じ旋律を歌うように教会が指示する能力は限られていた。なぜなら、 その都度、すでに曲を知っている人格と時間を過ごし、耳で覚える必要があった。この問題を解決する第一歩は、旋律のテキストの上に、音程の変化の方向を示 すさまざまな記号を導入したことだった。 ネウマの起源は不明であり、議論の余地があるが、ほとんどの学者は、ネウマの最も近い祖先は、声の高まりと落ち込みを記録することで朗唱の重要なポイント を示す古典ギリシャ・ローマの文法記号であることに同意している。[14] 古典文法学者の2つの基本記号は、声を上げることを示すアクタス(/)と、声を下げることを示すグラヴィス(\,)であった。ネウム記号付きの聖歌のテキ ストを読む歌手は、旋律が上昇しているのか、同じ高さなのか、下降しているのかを大まかに把握することができる。訓練を受けた歌手は聖歌のレパートリーを 熟知していたため、テキストの上に書かれたネウム記号は旋律を思い出す手掛かりにはなったが、実際の音程を特定するものではなかった。[15] しかし、ネウム記号付きの聖歌テキストを読む歌手は、歌ったことがない曲を初見で歌うことはできなかった。このような楽曲は、より正確な記譜法による後世 のバージョンがなければ、今日では正確に解釈することは不可能である。[16] これらのネウマ記号は、最終的にネウマ記譜法の基本記号へと発展し、より高い音を示すvirga(「棒」)は、その起源であるacutus(「鋭音符」) に似た形を残し、より低い音を示すpunctum(「点」)は、その名の通り、gravis(「嬰音符」)を点に縮小した形となった。[14] このように、acutusとgravisを組み合わせることで、音節上の声楽的抑揚を表すことができた。[14] この種の 表記法は8世紀以前には発達しなかったようだが、9世紀には音楽表記法の主要な方法として確立された。[17] ヴィルガとプンクタムの基本的な表記法は、個々の音符の記号として残ったが、すぐに複数の音符を結合して示す他のネウマ記号も開発された。これらの新しい ネウマ記号は、リガチャーと呼ばれ、基本的に2つの元の記号の組み合わせである。[18] 最初の楽譜は、聖歌の歌詞の上に点(ドット)を置くというもので、いくつかの点には上下の区別があり、旋律の方向性を大まかに示すものであった。しかし、 この楽譜はすでに旋律を知っている歌手のための記憶の手助けにしかならなかった。[19] この基本的なネウマ譜では、音符の数と上下の移動のみを指定することができた。正確な音程やリズム、あるいは開始音を示す方法もなかった。こうした限界 は、ネウマ譜が口伝の実践を補うためのツールとして開発されたものであり、口伝に取って代わるものではないことを示すさらなる証拠である。しかし、単なる 記憶補助として始まったものであっても、より具体的な記譜法を持つことの価値はすぐに明らかになった。 [17] 音楽記譜法における次の発展は、「高さ付きネウマ譜」であり、ネウマ譜は互いに関連して異なる高さに慎重に配置された。これにより、ネウムは特定の音程の 大きさや方向を大まかに示すことができるようになった。 これにより、特定の音符を表す1本または2本の線が、それ以前のネウムすべてに関連して楽譜上に配置されるようになった。 当初、これらの線には特に意味はなく、どの音符を表しているかを示す文字が先頭に置かれていた。 しかし、中央のドと5度下のファを表す線が徐々に一般的になっていった。当初は羊皮紙に単に引っ掻いて描かれていた線は、今では異なる2色のインクで描か れるようになった。通常、Fは赤、Cは黄色または緑で描かれた。これが五線譜の始まりである。[20] 4線譜の完成は、中世で最も重要な音楽理論家の一人であるグイード・ダレッツォ(1000年頃 - 1050年)によるものとされることが多い。古い資料では、五線譜の発展をグイドに帰しているが、一部の現代の学者は、グイドはすでに開発されていたシス テムの体系化に貢献したに過ぎないとしている。いずれにしても、この新しい記譜法により、歌手はまったく知らない曲でも、より短期間で習得することが可能 になった。[13][21] しかし、聖歌の記譜法は多くの点で進歩したとはいえ、根本的な問題が1つ残されていた。それは、リズムである。ネウマ記譜法は、完全に発展した状態であっ ても、音符の歌い方について、あらゆる種類のリズムを明確に定義することはできなかった。[22] |

| Music theory See also: List of medieval music theorists The music theory of the medieval period saw several advances over previous practice both in regard to tonal material, texture, and rhythm. |

音楽理論 関連項目:中世音楽理論家の一覧 中世の音楽理論は、調性素材、テクスチャ、リズムの観点において、それまでの慣習をいくつか上回る進歩を遂げた。 |

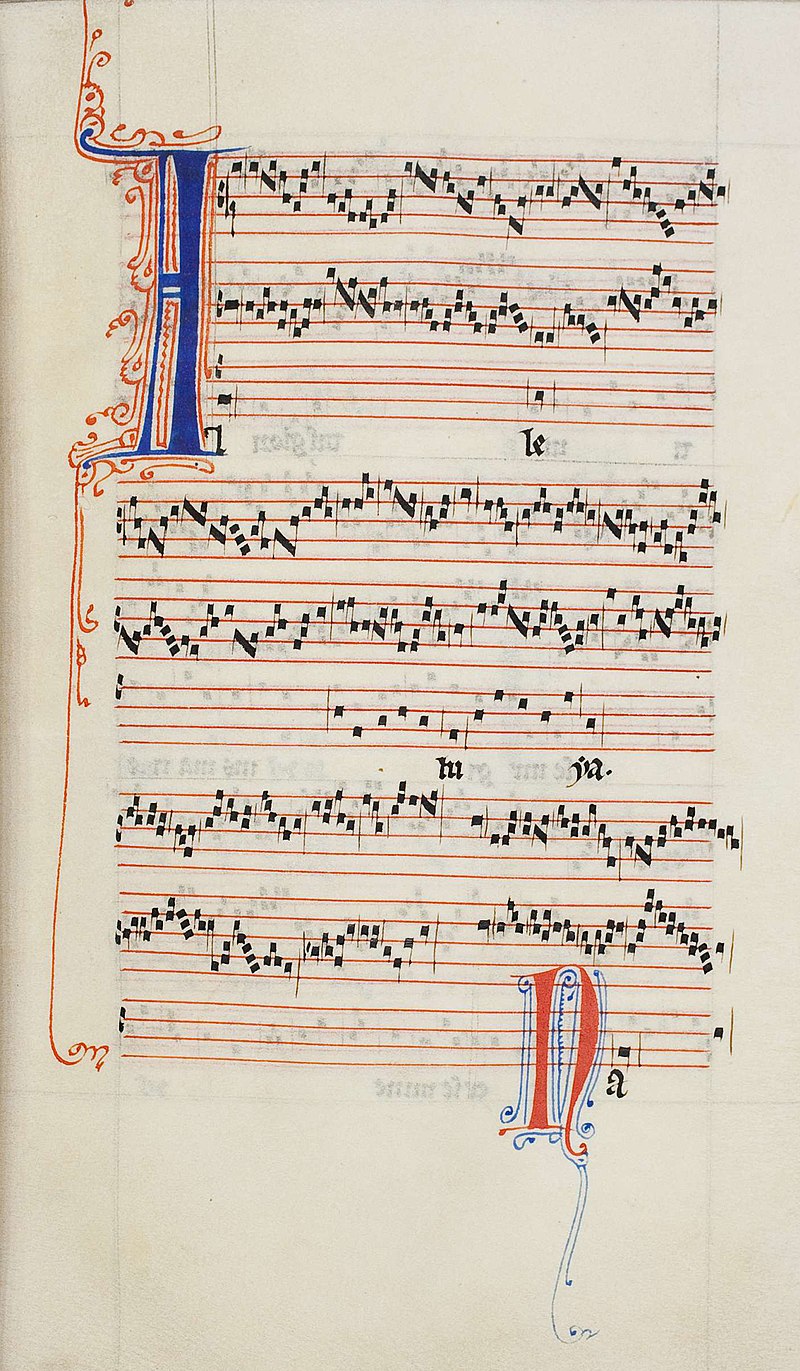

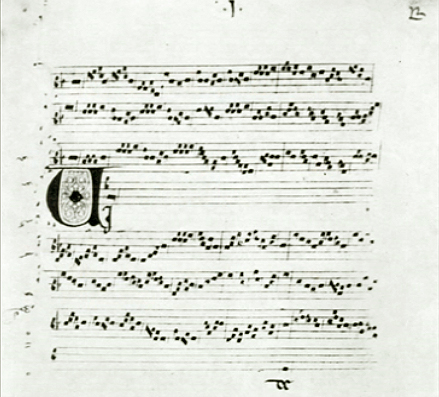

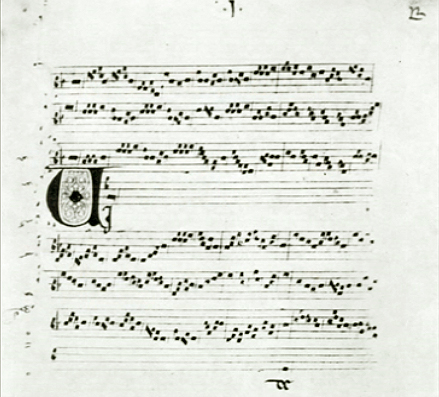

Rhythm Pérotin, "Alleluia nativitas", in the third rhythmic mode. Concerning rhythm, this period had several dramatic changes in both its conception and notation. During the early medieval period there was no method to notate rhythm, and thus the rhythmical practice of this early music is subject to debate among scholars.[22] The first kind of written rhythmic system developed during the 13th century and was based on a series of modes. This rhythmic plan was codified by the music theorist Johannes de Garlandia, author of the De Mensurabili Musica (c. 1250), the treatise which defined and most completely elucidated these rhythmic modes.[23] In his treatise Johannes de Garlandia describes six species of mode, or six different ways in which longs and breves can be arranged. Each mode establishes a rhythmic pattern in beats (or tempora) within a common unit of three tempora (a perfectio) that is repeated again and again. Furthermore, notation without text is based on chains of ligatures (the characteristic notations by which groups of notes are bound to one another). The rhythmic mode can generally be determined by the patterns of ligatures used.[24] Once a rhythmic mode had been assigned to a melodic line, there was generally little deviation from that mode, although rhythmic adjustments could be indicated by changes in the expected pattern of ligatures, even to the extent of changing to another rhythmic mode.[25] The next step forward concerning rhythm came from the German theorist Franco of Cologne. In his treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis ("The Art of Mensurable Music"), written around 1280, he describes a system of notation in which differently shaped notes have entirely different rhythmic values. This is a striking change from the earlier system of de Garlandia. Whereas before the length of the individual note could only be gathered from the mode itself, this new inverted relationship made the mode dependent upon—and determined by—the individual notes or figurae that have incontrovertible durational values,[26] an innovation which had a massive impact on the subsequent history of European music. Most of the surviving notated music of the 13th century uses the rhythmic modes as defined by Garlandia. The step in the evolution of rhythm came after the turn of the 13th century with the development of the Ars Nova style. The theorist who is most well recognized in regard to this new style is Philippe de Vitry, famous for writing the Ars Nova ("New Art") treatise around 1320. This treatise on music gave its name to the style of this entire era.[27] In some ways the modern system of rhythmic notation began with Vitry, who completely broke free from the older idea of the rhythmic modes. The notational predecessors of modern time meters also originate in the Ars Nova. This new style was clearly built upon the work of Franco of Cologne. In Franco's system, the relationship between a breve and a semibreves (that is, half breves) was equivalent to that between a breve and a long: and, since for him modus was always perfect (grouped in threes), the tempus or beat was also inherently perfect and therefore contained three semibreves. Sometimes the context of the mode would require a group of only two semibreves, however, these two semibreves would always be one of normal length and one of double length, thereby taking the same space of time, and thus preserving the perfect subdivision of the tempus.[28] This ternary division held for all note values. In contrast, the Ars Nova period introduced two important changes: the first was an even smaller subdivision of notes (semibreves, could now be divided into minim), and the second was the development of "mensuration." Mensurations could be combined in various manners to produce metrical groupings. These groupings of mensurations are the precursors of simple and compound meter.[29] By the time of Ars Nova, the perfect division of the tempus was not the only option as duple divisions became more accepted. For Vitry the breve could be divided, for an entire composition, or section of one, into groups of two or three smaller semibreves. This way, the tempus (the term that came to denote the division of the breve) could be either "perfect" (tempus perfectum), with ternary subdivision, or "imperfect" (tempus imperfectum), with binary subdivision.[30] In a similar fashion, the semibreve's division (termed prolation) could be divided into three minima (prolatio perfectus or major prolation) or two minima (prolatio imperfectus or minor prolation) and, at the higher level, the longs division (called modus) could be three or two breves (modus perfectus or perfect mode, or modus imperfectus or imperfect mode respectively).[31][32] Vitry took this a step further by indicating the proper division of a given piece at the beginning through the use of a "mensuration sign", equivalent to our modern "time signature".[33] Tempus perfectum was indicated by a circle, while tempus imperfectum was denoted by a half-circle[33] (the current symbol common time, used as an alternative for the 4 4 time signature, is actually a holdover of this symbol, not a letter C as an abbreviation for "common time", as popularly believed). While many of these innovations are ascribed to Vitry, and somewhat present in the Ars Nova treatise, it was a contemporary—and personal acquaintance—of de Vitry, named Johannes de Muris (or Jehan des Mars) who offered the most comprehensive and systematic treatment of the new mensural innovations of the Ars Nova[29] (for a brief explanation of the mensural notation in general, see the article Renaissance music). Many scholars, citing a lack of positive attributory evidence, now consider "Vitry's" treatise to be anonymous, but this does not diminish its importance for the history of rhythmic notation. However, this makes the first definitely identifiable scholar to accept and explain the mensural system to be de Muris, who can be said to have done for it what Garlandia did for the rhythmic modes. For the duration of the medieval period, most music would be composed primarily in perfect tempus, with special effects created by sections of imperfect tempus; there is a great current controversy among musicologists as to whether such sections were performed with a breve of equal length or whether it changed, and if so, at what proportion. This Ars Nova style remained the primary rhythmical system until the highly syncopated works of the Ars subtilior at the end of the 14th century, characterized by extremes of notational and rhythmic complexity.[34] This sub-genera pushed the rhythmic freedom provided by Ars Nova to its limits, with some compositions having different voices written in different mensurations simultaneously. The rhythmic complexity that was realized in this music is comparable to that in the 20th century.[35] |

リズム ペロータン作曲「アレルヤ・ナティヴィタス」、第3のリズムモード。 リズムに関しては、この時代にはその概念と記譜法の両面で劇的な変化がいくつかあった。中世初期にはリズムを記譜する方法がなかったため、初期音楽のリズ ムの実践については学者の間でも議論の余地がある。[22] 最初の種類の書面によるリズム体系は13世紀に開発され、一連のモードに基づいている。このリズム計画は、音楽理論家ヨハネス・デ・ガランディア(De Mensurabili Musica(c. 1250年)の著者)によって体系化された。この論文は、これらのリズムモードを定義し、最も完全に解明したものである。[23] ヨハネス・デ・ガランディアは、論文の中で6種類のモード、すなわち、ロングとブリーフを配置する6つの異なる方法を説明している。各モードは、3拍子 (パーフェクトゥス)という共通単位の中で繰り返される拍子(またはテンポ)のリズムパターンを確立する。さらに、テキストのない楽譜は、連結記号(音符 のグループを互いに結合する独特の表記法)の連鎖に基づいている。 一般的に、使用されるリガチャーのパターンによってリズムの様式を決定することができる。[24] メロディラインに一度リズム様式が割り当てられると、通常はその様式から逸脱することはほとんどないが、リガチャーの予想されるパターンが変化することに よって、別のリズム様式に変更される場合もある。[25] リズムに関する次の進歩は、ケルンのドイツ人理論家フランコによるものである。1280年頃に書かれた論文『アルス・カントゥス・メンスラビリス』(「計 量音楽の芸術」)の中で、彼は異なる形状の音符がまったく異なるリズム的価値を持つという表記法の体系を説明している。これは、それ以前のデ・ガーラン ディアのシステムから著しい変化である。それまでは、個々の音符の長さは様式そのものからしか知ることができなかったが、この新しい逆転した関係により、 様式は、議論の余地のない持続的価値を持つ個々の音符または音型に依存し、それらによって決定されるようになった。この革新は、その後のヨーロッパ音楽の 歴史に大きな影響を与えた。現存する13世紀の楽譜のほとんどは、ガルデラーニアが定義したリズム・モードを使用している。13世紀の変わり目に、アル ス・ノヴァ様式の発展とともに、リズムの進化における新たな段階が訪れた。 この新しい様式に関して最もよく知られている理論家は、1320年頃に『アルス・ノヴァ(新芸術)』という論文を著したことで有名なフィリップ・ド・ヴィ トリである。この音楽に関する論文は、この時代の様式全体にその名を残している。[27] ある意味では、ヴィトリは、古いリズム・モードの概念から完全に脱却した人物であり、現代のリズム表記法の始まりであった。現代の拍子記号の記譜法の先駆 者も、アルス・ノヴァに起源を持つ。この新しいスタイルは明らかにケルンのフランコの作品を基にしている。フランコのシステムでは、ブリーベとセミブリー ベ(つまり半分のブリーベ)の関係は、ブリーベとロングの関係と同等であった。また、彼にとってモードは常に完全(3つずつでグループ化)であったため、 テンポまたは拍も本質的に完全であり、したがって3つのセミブリーベを含んでいた。しかし、モードの文脈によっては、2つのセミブレフのみのグループが必 要になることもあった。しかし、この2つのセミブレフは常に通常の長さと2倍の長さのものが1つずつであり、同じ時間的長さを占めるため、テンポスの完璧 な細分化が保たれる。[28] この3分割はすべての音符の値に適用された。それに対し、アルス・ノヴァの時代には、2つの重要な変化がもたらされた。1つ目は、音符のさらに細かい分割 (セミブレヴェがミニムに分割できるようになった)であり、2つ目は「 Mensuration(測地学)」の発展である。 さまざまな方法で組み合わせることにより、拍のグループを作ることができる。 これらの拍のグループは、単純拍子や複合拍子の先駆けである。[29] アルス・ノヴァの時代には、二拍子の分割がより受け入れられるようになったため、テンポの完全な分割が唯一の選択肢ではなくなった。ヴィトリにとって、ブ リーヴェは、楽曲全体またはその一部を、2つまたは3つのより小さなセミブリーヴェのグループに分割することができた。このようにして、テンポス(ブリー ベの分割を表す用語)は、3分割の「完全な」(テンポス・パーフェクトゥム)か、2分割の「不完全な」(テンポス・インパーフェクトゥム)となる。同様 に、セミブリーベの分割(プロラティオ)は、3分割(プロラティオ・パーフェクトゥムまたはメジャー・プロラティオ)か、2分割(プロラティオ・インパー フェクトゥムまたはマイナー・プロラティオ)となる。、より高いレベルでは、長音符の分割(モード)はそれぞれ3つまたは2つのブレッフェ(モード・パー フェクトゥスまたはパーフェクト・モード、またはモード・インパーフェクトゥスまたはインパーフェクト・モード)となる可能性がある。[31][32] ヴィトリはさらに一歩進んで、現代の「拍子記号」に相当する「測度記号」の使用により、楽曲の冒頭における適切な分割を示すことを示唆した。[33] 完全な時間(tempus perfectum)は円で示され、不完全な時間(tempus imperfectum)は半円で示された[33](現在の記号である共通時間の記号は、4/4拍子記号の代替として使用されているが、 これは実際にはこの記号の名残であり、「共通時間」の省略形としてCが使われているわけではない。一般的に信じられているように)。これらの革新の多くは ヴィトリに帰せられ、アルス・ノヴァ論文にも多少言及されているが、アルス・ノヴァの新しい拍子記号の革新について最も包括的かつ体系的な説明を提供した のは、ヴィトリの同時代人で、人格的にも知人であったヨハネス・ド・ムリス(またはジャン・ド・マルス)であった[29](拍子記号全般についての簡単な 説明は、ルネサンス音楽の記事を参照)。多くの学者は、確実な帰属を示す証拠がないことを理由に、現在では「ヴィトリ」の論文を匿名のものとみなしている が、これはリズム表記の歴史におけるその重要性を損なうものではない。しかし、このことから、メンスラ・システムを最初に明確に受け入れ、説明した学者は ド・ムリスであることが明らかになる。彼は、リズム・モードに関してガルランディアが成し遂げたことを、メンスラ・システムに関して成し遂げたと言える。 中世の時代を通じて、ほとんどの音楽は主にパーフェクト・テンポスで作曲され、不完全テンポスのセクションによって特殊効果が作り出されていた。このよう なセクションが等しい長さのブリーベで演奏されたのか、それとも変化したのか、また変化した場合はどのような割合で変化したのかについて、音楽学者の間で は現在も大きな論争が続いている。このアルス・ノヴァ様式は、14世紀末にアルス・スブティリオールが高度なシンコペーションを用いた作品を生み出すま で、主要なリズム体系であり続けた。アルス・スブティリオールは、記譜法とリズムの極端な複雑さによって特徴づけられる。[34] この亜ジャンルは、アルス・ノヴァが提供したリズムの自由を限界まで押し進めた。一部の楽曲では、異なる声部が異なる拍子で同時に書かれていた。この音楽 で実現されたリズムの複雑さは、20世紀のそれに匹敵するものである。[35] |

Polyphony Pérotin's Viderunt omnes, c. 13th century. Of equal importance to the overall history of western music theory were the textural changes that came with the advent of polyphony. This practice shaped western music into the harmonically dominated music that we know today.[36] The first accounts of this textural development were found in two anonymous yet widely circulated treatises on music, the Musica and the Scolica enchiriadis. These texts are dated to sometime within the last half of the ninth century.[37] The treatises describe a technique that seemed already to be well established in practice.[37] This early polyphony is based on three simple and three compound intervals. The first group comprises fourths, fifths, and octaves; while the second group has octave-plus-fourths, octave-plus-fifths, and double octaves.[37] This new practice is given the name organum by the author of the treatises.[37] Organum can further be classified depending on the time period in which it was written. The early organum as described in the enchiriadis can be termed "strict organum" [38] Strict organum can, in turn, be subdivided into two types: diapente (organum at the interval of a fifth) and diatesseron (organum at the interval of a fourth).[38] However, both of these kinds of strict organum had problems with the musical rules of the time. If either of them paralleled an original chant for too long (depending on the mode) a tritone would result.[39] This problem was somewhat overcome with the use of a second type of organum. This second style of organum was called "free organum". Its distinguishing factor is that the parts did not have to move only in parallel motion, but could also move in oblique, or contrary motion. This made it much easier to avoid the dreaded tritone.[40] The final style of organum that developed was known as "melismatic organum", which was a rather dramatic departure from the rest of the polyphonic music up to this point. This new style was not note against note, but was rather one sustained line accompanied by a florid melismatic line.[41] This final kind of organum was also incorporated by the most famous polyphonic composer of this time—Léonin. He united this style with measured discant passages, which used the rhythmic modes to create the pinnacle of organum composition.[41] This final stage of organum is sometimes referred to as Notre Dame school of polyphony, since that was where Léonin (and his student Pérotin) were stationed. Furthermore, this kind of polyphony influenced all subsequent styles, with the later polyphonic genera of motets starting as a trope of existing Notre Dame organums. Another important element of medieval music theory was the system by which pitches were arranged and understood. During the Middle Ages, this systematic arrangement of a series of whole steps and half steps, what we now call a scale, was known as a mode.[citation needed] The modal system worked like the scales of today, insomuch that it provided the rules and material for melodic writing.[42] The eight church modes are: Dorian, Hypodorian, Phrygian, Hypophrygian, Lydian, Hypolydian, Mixolydian, and Hypomixolydian.[43] Much of the information concerning these modes, as well as the practical application of them, was codified in the 11th century by the theorist Johannes Afflighemensis. In his work he describes three defining elements to each mode: the final (or finalis), the reciting tone (tenor or confinalis), and the range (or ambitus). The finalis is the tone that serves as the focal point for the mode and, as the name suggests, is almost always used as the final tone. The reciting tone is the tone that serves as the primary focal point in the melody (particularly internally). It is generally also the tone most often repeated in the piece, and finally the range delimits the upper and lower tones for a given mode.[44] The eight modes can be further divided into four categories based on their final (finalis). Medieval theorists called these pairs maneriae and labeled them according to the Greek ordinal numbers. Those modes that have d, e, f, and g as their final are put into the groups protus, deuterus, tritus, and tetrardus respectively.[45] These can then be divided further based on whether the mode is "authentic" or "plagal." These distinctions deal with the range of the mode in relation to the final. The authentic modes have a range that is about an octave (one tone above or below is allowed) and start on the final, whereas the plagal modes, while still covering about an octave, start a perfect fourth below the authentic.[46] Another interesting aspect of the modal system is the use of "Musica ficta" which allows pitches to be altered (changing B♮ to B♭ for example) in certain contexts regardless of the mode.[47] These changes have several uses, but one that seems particularly common is to avoid melodic difficulties caused by the tritone.[48] These ecclesiastical modes, although they have Greek names, have little relationship to the modes as set out by Greek theorists. Rather, most of the terminology seems to be a misappropriation on the part of the medieval theorists[43] Although the church modes have no relation to the ancient Greek modes, the overabundance of Greek terminology does point to an interesting possible origin in the liturgical melodies of the Byzantine tradition. This system is called octoechos and is also divided into eight categories, called echoi.[49] For specific medieval music theorists, see also: Isidore of Seville, Aurelian of Réôme, Odo of Cluny, Guido of Arezzo, Hermannus Contractus, Johannes Cotto (Johannes Afflighemensis), Johannes de Muris, Franco of Cologne, Johannes de Garlandia (Johannes Gallicus), Anonymous IV, Marchetto da Padova (Marchettus of Padua), Jacques of Liège, Johannes de Grocheo, Petrus de Cruce (Pierre de la Croix), and Philippe de Vitry. |

ポリフォニー ペロタン著『Viderunt omnes』、13世紀頃。 西洋音楽理論の全体的な歴史と同様に重要なのは、ポリフォニーの出現に伴う音質変化であった。この慣習により、西洋音楽は今日私たちが知るような和声が支 配的な音楽へと形作られた。[36] この音質の発展に関する最初の記述は、匿名で広く流布された音楽に関する2つの論文、MusicaとScolica enchiriadisに見られる。これらのテキストは9世紀後半のどこかの時期に書かれたものである。[37] これらの論文では、すでに実践において確立されていたと思われる技法が説明されている。[37] この初期のポリフォニーは、3つの単純な音程と3つの複合音程に基づいている。最初のグループは4度、5度、8度で構成され、2番目のグループは8度プラ ス4度、8度プラス5度、2倍の8度である。[37] この新しい手法は、論文の著者が「オルガヌム」と名付けた。オルガヌムは、それが書かれた時代によってさらに分類することができる。エンキリアディスで説 明されている初期のオルガヌムは「厳格なオルガヌム」と呼ばれている。[38] 厳格なオルガヌムはさらに2つのタイプに細分化される。すなわち、ディアペンテ(オルガヌムの音程が5度の場合)とディアテッソン(オルガヌムの音程が4 度の場合)である。[38] しかし、これらの厳格なオルガヌムのどちらも、当時の音楽の規則に問題があった。どちらかのオルガヌムが元の聖歌と長すぎる期間平行すると(旋法によって 異なるが)全音音程が生じる。 この問題は、オルガヌムの2番目のタイプを使用することでいくらか克服された。オルガヌムの2番目のスタイルは「自由オルガヌム」と呼ばれた。その特徴 は、各パートが平行移動のみでなく、斜めや逆方向にも移動できることである。これにより、恐ろしい三全音を回避することがはるかに容易になった。[40] オルガヌムの最終的なスタイルは「旋律唱オルガヌム」として知られ、それまでのポリフォニー音楽から劇的に離れたものとなった。この新しいスタイルは、音 と音を対比させるものではなく、むしろ、華麗な旋律を伴う持続的な旋律であった。[41] このオルガヌムの最終的なスタイルは、この時代の最も有名なポリフォニー作曲家レオナンも取り入れた。彼は、このスタイルを、リズム・モードを使用してオ ルガヌム作曲の頂点を極めた、正確なディスカント・パッセージと融合させた。[41] このオルガヌムの最終段階は、レオナン(および彼の弟子ペロタン)が活躍した場所であったことから、ノートルダム楽派と呼ばれることもある。さらに、この 種のポリフォニーは、その後のすべてのスタイルに影響を与え、モテットという後のポリフォニーのジャンルは、ノートルダムのオルガヌムのトロペとして始 まった。 中世音楽理論のもう一つの重要な要素は、音程の配列と理解の体系であった。中世では、半音階と全音階の体系的な配列、すなわち、現在では音階と呼ばれるも のは、モードとして知られていた。[要出典] モードの体系は、現代の音階と同様に機能し、旋律の作曲のための規則と素材を提供していた。[42] 8つの教会モードは以下の通りである。ドリアン、ハイポドリアン、フリジアン、ハイポフリジアン、リディアン、ハイポリディアン、ミクソリディアン、ハイ ポミクソリディアンである。彼の著作では、各旋法を定義する3つの要素、すなわち最終音(または finalis)、旋律音(または confinalis)、音域(または ambitus)について説明している。 finalis は旋法の中心となる音であり、その名称が示すように、ほとんどの場合、最終音として使用される。 旋律音(または reciting tone)は旋律の中心となる音(特に内部)である。一般的に、楽曲の中で最も頻繁に繰り返される音程でもあり、最終的には、あるモードの上限と下限の音 程の範囲を決定する。[44] 8つのモードは、最終音(finalis)に基づいて、さらに4つのカテゴリーに分類することができる。 中世の理論家たちは、これらのペアを「マネリア」と呼び、ギリシャ語の序数に従ってラベル付けした。終止音が d、e、f、g のモードは、それぞれ protus、deuterus、tritus、tetrardus のグループに分類される。[45] これらのモードは、さらに「オーセンティック」か「プラガール」かによって分類される。これらの区別は、終止音との関係におけるモードの範囲を扱う。純正 旋法は約1オクターブの範囲(上下1音まで許容)で最終音から開始するのに対し、複旋法はやはり約1オクターブの範囲ではあるが、純正旋法の完全4度下の 音から開始する。[46] 旋法システムにおけるもう一つの興味深い側面は、「ムジカ・フィクタ」の使用である。これは、旋法に関係なく、特定の文脈において音程を変更することを可 能にする(例えば、B♮をB♭に変更する)。[47] これらの変化にはいくつかの用途があるが、特に一般的なのは、三全音程による旋律上の困難を回避することである。 これらの教会旋法はギリシャ語の名称を持つが、ギリシャの理論家が定めた旋法とはほとんど関係がない。むしろ、その用語のほとんどは中世の理論家による誤 用であると思われる。[43] 教会旋法は古代ギリシャの旋法とは何の関係もないが、ギリシャ語の用語が過剰に使用されていることは、ビザンチン典礼聖歌の旋律に興味深い起源がある可能 性を示唆している。このシステムはオクトエコスと呼ばれ、エコーイと呼ばれる8つのカテゴリーに分けられている。[49] 中世の音楽理論家については、以下を参照のこと。セビリアのイシドール、レオームのアウレリアヌス、クリュニーのオド、アレッツォのグイード、ヘルマン・ フォン・コントラクトゥス、ヨハネス・コット(ヨハネス・アフルゲメンシス)、ヨハネス・デ・ムリス、ケルンのフランコ、ヨハネス・デ・ガルランディア (ヨハネス・ガッルィクス)、匿名4世、マルケット・ダ・パドヴァ(マルケッタス・パドヴァ)、リエージュのジャック、ヨハネス・デ・グロシェオ、ペトル ス・デ・クルーチェ(ピエール・ド・ラ・クルー)、フィリップ ヴィトリ。 |

| Early medieval music (500–1000) Further information: Early Middle Ages See also: List of medieval composers § (5th century) Early Middle Ages Early chant traditions Main article: Plainsong See also: Gregorian chant  Hildegard of Bingen, one of the best-known composers of sacred monophony Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred (single, unaccompanied melody) form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian church. Chant developed separately in several European centres. Although the most important were Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan, and Ireland, there were others as well. These styles were all developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating the Mass there. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used and shows the influence of North African music. The Mozarabic liturgy even survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and this music was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. In Milan, Ambrosian chant, named after St. Ambrose, was the standard, while Beneventan chant developed around Benevento, another Italian liturgical center. Gallican chant was used in Gaul, and Celtic chant in Ireland and Great Britain. The reigning Carolingian dynasty wanted to standardize the Mass and chant across its Frankish Empire. At this time, Rome was the religious centre of western Europe, and northern Gaul and Rhineland (most notably the city of Aachen) was the political centre. The standardization effort consisted mainly of combining the two – Roman and Gallican – regional liturgies. Charlemagne (742–814) sent trained singers throughout the Empire to teach this new form of chant.[50] This body of chant became known as Gregorian Chant, named after Pope Gregory I. Gregorian chant was said to be collected and codified during his papacy or even composed by himself, inspired by the Holy Spirit in the form of a dove. However, that is only a popular legend that was spread by the Carolingians who wanted to legitimize their liturgy unification efforts. Gregorian chant certainly didn't exist at that time. It is possible, nevertheless, that Gregory's papacy really may have contributed to collecting and codifying the Roman chant of the time which then, in the 9th and 10th centuries, formed – alongside the Gallican chant – one of the two roots of the Gregorian chant.[51][52] By the 12th and 13th centuries, Gregorian chant had superseded all the other Western chant traditions, with the exception of the Ambrosian chant in Milan and the Mozarabic chant in a few specially designated Spanish chapels. Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) was one of the earliest known female composers. She wrote many monophonic works for the Catholic Church, almost all of them for female voices. |

初期中世音楽(500年~1000年) 詳細情報:初期中世 関連項目:中世の作曲家一覧 §(5世紀)初期中世 初期の聖歌の伝統 詳細は「定旋律」を参照 関連項目:グレゴリオ聖歌  ヒルデガルト・フォン・ビンゲン、宗教的単旋律音楽の作曲家として最もよく知られている人物の一人 聖歌(またはプレインソング)は、単旋律の宗教音楽(単旋律の無伴奏旋律)であり、キリスト教教会で知られている最も古い音楽である。聖歌はヨーロッパの いくつかの中心地で別々に発展した。最も重要なのはローマ、ヒスパニア、ガウル、ミラノ、アイルランドであったが、他にもあった。これらの様式はすべて、 そこでミサを祝う際に使用される地域固有の典礼を支えるために発展した。各地域は独自の聖歌と祝祭の規則を発展させた。スペインとポルトガルではモサラベ 聖歌が用いられ、北アフリカ音楽の影響が見られる。モサラベ聖歌はイスラム教徒の支配下でも生き残ったが、これは孤立した流れであり、後に典礼全体に統一 性を強制する試みとして、この音楽は弾圧された。ミラノでは聖アンブロジオにちなんで名づけられたアンブロジオ聖歌が標準とされ、一方、イタリアのもう一 つの典礼の中心地であるベネヴェント周辺ではベネヴェンタン聖歌が発展した。ガリア聖歌はガリアで、ケルト聖歌はアイルランドとイギリスで使用されてい た。 カロリング朝の王族は、フランク王国のミサと聖歌を標準化しようとしていた。当時、ローマは西ヨーロッパの宗教的中心地であり、北ガリアとラインラント (特にアーヘン)は政治的中心地であった。標準化の取り組みは主に、ローマ式とガリア式の2つの地域典礼を統合することから成っていた。シャルルマーニュ (742年-814年)は、帝国全土に訓練された歌手を派遣し、この新しい聖歌の形式を教えた。[50] この聖歌の体系は、教皇グレゴリウス1世にちなんでグレゴリオ聖歌と呼ばれるようになった。グレゴリオ聖歌は、教皇在任中に収集・体系化された、あるいは 教皇自身が聖霊の導きを受けて鳩の姿で作曲したと言われている。しかし、それはカロリング朝の人々が典礼の統一化を正当化するために広めた俗説に過ぎな い。グレゴリオ聖歌は当時、確かに存在していなかった。しかし、グレゴリーの教皇在位が、当時のローマ聖歌の収集と体系化に貢献した可能性はあり、それが 9世紀と10世紀に、ガリア聖歌と並んでグレゴリオ聖歌の2つのルーツの1つを形成した可能性もある。[51][52] 12世紀と13世紀までに、グレゴリオ聖歌は、ミラノのアンブロシアン聖歌と ミラノのアンブロシアン聖歌と、スペインのいくつかの特別に指定された礼拝堂で歌われるモサラベ聖歌を除いては。ヒルデガルト・フォン・ビンゲン (1098年 - 1179年)は、最も初期に知られるようになった女性作曲家の一人である。彼女はカトリック教会のために多くの単旋律作品を書き、そのほとんどは女性の声 楽のために書かれた。 |

| Early polyphony: organum Main article: Organum Around the end of the 9th century, singers in monasteries such as St. Gall in Switzerland began experimenting with adding another part to the chant, generally a voice in parallel motion, singing mostly in perfect fourths or fifths above the original tune (see interval). This development is called organum and represents the beginnings of counterpoint and, ultimately, harmony.[53] Over the next several centuries, organum developed in several ways. The most significant of these developments was the creation of "florid organum" around 1100, sometimes known as the school of St. Martial (named after a monastery in south-central France, which contains the best-preserved manuscript of this repertory). In "florid organum" the original tune would be sung in long notes while an accompanying voice would sing many notes to each one of the original, often in a highly elaborate fashion, all the while emphasizing the perfect consonances (fourths, fifths and octaves), as in the earlier organa. Later developments of organum occurred in England, where the interval of the third was particularly favoured, and where organa were likely improvised against an existing chant melody, and at Notre Dame in Paris, which was to be the centre of musical creative activity throughout the thirteenth century. Much of the music from the early medieval period is anonymous. Some of the names may have been poets and lyric writers, and the tunes for which they wrote words may have been composed by others. Attribution of monophonic music of the medieval period is not always reliable. Surviving manuscripts from this period include the Musica Enchiriadis, Codex Calixtinus of Santiago de Compostela, the Magnus Liber, and the Winchester Troper. For information about specific composers or poets writing during the early medieval period, see Pope Gregory I, St. Godric, Hildegard of Bingen, Hucbald, Notker Balbulus, Odo of Arezzo, Odo of Cluny, and Tutilo. |

初期のポリフォニー:オルガヌム 詳細は「オルガヌム」を参照 9世紀末頃、スイスのサンクトガレン修道院などの修道院の歌手たちは、聖歌に別のパートを加える試みを始めた。通常は平行移動する声部で、元の旋律の完全 4度または完全5度上の音程で歌うことが多かった(音程を参照)。この発展はオルガヌムと呼ばれ、対位法、そして最終的には和声の始まりを象徴するもので ある。[53] その後数世紀にわたって、オルガヌムはいくつかの方法で発展した。 これらの発展の中で最も重要なものは、1100年頃に「フローリド・オルガヌム」が創作されたことである。この音楽は、セント・マーシャル派(このレパー トリーの最も保存状態の良い写本が保管されている、フランス中南部の修道院にちなんで名付けられた)として知られることもある。「フローリド・オルガヌ ム」では、オリジナルの旋律は長い音で歌われ、伴奏の声部はオリジナルの旋律の1音につき多くの音を、しばしば非常に凝った方法で歌い、初期のオルガヌム と同様に完全な協和音(4度、5度、8度)を強調する。オルガヌムの後の発展は、特に第3音程が好まれたイングランドで起こり、オルガヌムは既存の聖歌の 旋律に合わせて即興で演奏されたと考えられている。また、13世紀を通じて音楽の創造活動の中心地となったパリのノートルダム大聖堂でも、オルガヌムが発 展した。 初期中世の音楽の多くは作者不明である。作者として名が挙げられている人物の中には詩人や作詞家もいたが、彼らが歌詞を書いた曲は他の作曲家によるもの だった可能性もある。中世の単旋律音楽の作曲者名は必ずしも信頼できるものではない。この時代に現存する写本には、Musica Enchiriadis、サンティアゴ・デ・コンポステーラのカリクスティヌス写本、Magnus Liber、ウィンチェスター・ローパーなどがある。初期中世の特定の作曲家や詩人に関する情報については、グレゴリウス1世、聖ゴドリック、ヒルデガル ト・フォン・ビンゲン、フクバルト、ノットケル・バルブュラス、アレッツォのオド、クリュニーのオド、トゥティロを参照のこと。 |

| Liturgical drama Main article: Liturgical drama Another musical tradition of Europe originating during the early Middle Ages was the liturgical drama. Liturgical drama developed possibly in the 10th century from the tropes—poetic embellishments of the liturgical texts. One of the tropes, the so-called Quem Quaeritis, belonging to the liturgy of Easter morning, developed into a short play around the year 950.[54] The oldest surviving written source is the Winchester Troper. Around the year 1000 it was sung widely in Northern Europe.[55][failed verification] Shortly,[clarification needed] a similar Christmas play was developed, musically and textually following the Easter one, and other plays followed. There is a controversy among musicologists as to the instrumental accompaniment of such plays, given that the stage directions, very elaborate and precise in other respects, do not request any participation of instruments.[citation needed] These dramas were performed by monks, nuns and priests.[citation needed] In contrast to secular plays, which were spoken, the liturgical drama was always sung.[citation needed] Many have been preserved sufficiently to allow modern reconstruction and performance (for example the Play of Daniel, which has been recently recorded at least ten times). |

典礼劇 詳細は「典礼劇」を参照 ヨーロッパの音楽のもう一つの伝統は、初期の中世に始まった典礼劇である。 典礼劇は、おそらく10世紀に典礼のテキストの詩的な装飾であるトロプスから発展した。そのトロペのひとつである「クエム・クァエリス」(いわゆる「キ ム・クァエリス」)は、復活祭の朝の典礼に属するもので、950年頃には短い劇へと発展した。[54] 現存する最古の文書資料は「ウィンチェスター・トロパー」である。1000年頃には、北欧で広く歌われていた。[55][検証失敗] まもなく、音楽的にもテキスト的にも復活祭の劇に倣った同様のクリスマス劇が作られ、その後も他の劇が作られた。 このような劇の楽器伴奏については音楽学者の間で論争がある。舞台演出は、他の点では非常に精巧かつ正確であるが、楽器の参加は一切要求されていないから だ。[要出典] これらの劇は修道士、修道女、司祭によって演じられた。[要出典] 世俗劇が会話劇であるのに対し、典礼劇は常に歌われるものだった。[要出典] 現代の再構成と上演を可能にするほど十分に保存されているものも多い(例えば『ダニエル書』は 最近少なくとも10回は録音されている) |

| High medieval music (1000–1300) Further information: High Middle Ages See also: List of medieval composers § (1000) High Middle Ages Goliards Main article: Goliards The Goliards were itinerant poet-musicians of Europe from the tenth to the middle of the thirteenth century. Most were scholars or ecclesiastics, and they wrote and sang in Latin. Although many of the poems have survived, very little of the music has. They were possibly influential—even decisively so—on the troubadour-trouvère tradition which was to follow. Most of their poetry is secular and, while some of the songs celebrate religious ideals, others are frankly profane, dealing with drunkenness, debauchery and lechery. One of the most important extant sources of Goliards chansons is the Carmina Burana.[56] |

中世後期の音楽(1000年-1300年) 詳細情報:中世後期 関連項目:中世の作曲家一覧 §(1000年)中世後期 ゴリアード 詳細は「ゴリアード」を参照 ゴリアードは、10世紀から13世紀中頃にかけてヨーロッパを放浪した詩人兼音楽家であった。その多くは学者や聖職者であり、ラテン語で詩を書き歌を歌っ た。多くの詩が現存しているが、音楽はほとんど残っていない。彼らは、後に続くトルバドゥールとトルヴェールの伝統に、おそらくは決定的な影響を与えた。 彼らの詩のほとんどは世俗的なもので、宗教的理想を称える歌もある一方で、酩酊、放蕩、好色を扱った、あからさまに不敬な歌もある。ゴリアードのシャンソ ンの現存する最も重要な資料のひとつは、カルミナ・ブラーナである。 |

| Ars antiqua Main article: Ars antiqua  Men playing the organistrum, from the Ourense Cathedral, Spain, 12th century The flowering of the Notre Dame school of polyphony from around 1150 to 1250 corresponded to the equally impressive achievements in Gothic architecture: indeed the centre of activity was at the cathedral of Notre Dame itself. Sometimes the music of this period is called the Parisian school, or Parisian organum, and represents the beginning of what is conventionally known as Ars antiqua. This was the period in which rhythmic notation first appeared in western music, mainly a context-based method of rhythmic notation known as the rhythmic modes. This was also the period in which concepts of formal structure developed which were attentive to proportion, texture, and architectural effect. Composers of the period alternated florid and discant organum (more note-against-note, as opposed to the succession of many-note melismas against long-held notes found in the florid type), and created several new musical forms: clausulae, which were melismatic sections of organa extracted and fitted with new words and further musical elaboration; conductus, which were songs for one or more voices to be sung rhythmically, most likely in a procession of some sort; and tropes, which were additions of new words and sometimes new music to sections of older chant. All of these genres save one were based upon chant; that is, one of the voices, (usually three, though sometimes four) nearly always the lowest (the tenor at this point) sang a chant melody, though with freely composed note-lengths, over which the other voices sang organum. The exception to this method was the conductus, a two-voice composition that was freely composed in its entirety.[citation needed] The motet, one of the most important musical forms of the high Middle Ages and Renaissance, developed initially during the Notre Dame period out of the clausula, especially the form using multiple voices as elaborated by Pérotin, who paved the way for this particularly by replacing many of his predecessor (as canon of the cathedral) Léonin's lengthy florid clausulae with substitutes in a discant style. Gradually, there came to be entire books of these substitutes, available to be fitted in and out of the various chants. Since, in fact, there were more than can possibly have been used in context, it is probable that the clausulae came to be performed independently, either in other parts of the mass, or in private devotions. The clausula, thus practised, became the motet when troped with non-liturgical words, and this further developed into a form of great elaboration, sophistication and subtlety in the fourteenth century, the period of Ars nova. Surviving manuscripts from this era include the Montpellier Codex, Bamberg Codex, and Las Huelgas Codex. Composers of this time include Léonin, Pérotin, W. de Wycombe, Adam de St. Victor, and Petrus de Cruce (Pierre de la Croix). Petrus is credited with the innovation of writing more than three semibreves to fit the length of a breve. Coming before the innovation of imperfect tempus, this practice inaugurated the era of what are now called "Petronian" motets. These late 13th-century works are in three to four parts and have multiple texts sung simultaneously. Originally, the tenor line (from the Latin tenere, "to hold") held a preexisting liturgical chant line in the original Latin, while the text of the one, two, or even three voices above, called the voces organales, provided commentary on the liturgical subject either in Latin or in the vernacular French. The rhythmic values of the voces organales decreased as the parts multiplied, with the duplum (the part above the tenor) having smaller rhythmic values than the tenor, the triplum (the line above the duplum) having smaller rhythmic values than the duplum, and so on. As time went by, the texts of the voces organales became increasingly secular in nature and had less and less overt connection to the liturgical text in the tenor line.[57] The increasing rhythmic complexity seen in Petronian motets would be a fundamental characteristic of the 14th century, though music in France, Italy, and England would take quite different paths during that time.[citation needed] |

アルス・アンティクァ 詳細は「アルス・アンティクァ」を参照  オルガンストラムを演奏する男性たち、スペイン、オウレンセ大聖堂、12世紀 1150年頃から1250年頃にかけてのノートルダム楽派のポリフォニーの全盛期は、ゴシック建築の同様に素晴らしい成果と一致していた。実際、活動の中 心はノートルダム大聖堂そのものにあった。この時代の音楽は、パリ楽派、またはパリ・オルガヌムと呼ばれ、通例アルス・アンティクァとして知られるものの 始まりを象徴している。この時代は、西洋音楽において初めてリズム記譜法が登場した時代であり、主にコンテクストに基づくリズム記譜法として知られるリズ ム・モードが用いられた。 また、この時代は、比率、テクスチャ、建築効果に配慮した形式構造の概念が発展した時代でもあった。この時代の作曲家たちは、華麗なオルガヌム(多くの音 符のメロディが長音符に対して連続する華麗なタイプのものとは対照的に、音符と音符が交互に並ぶもの)と、新しい音楽形式であるクラウズラ(オルガヌムの メロディ部分を抜き出し、新しい言葉とさらに音楽的な工夫を加えたもの)、コンダクトゥス(1つまたは複数の声部で歌われる歌で、おそらく何らかの行列の 中でリズムに合わせて歌われるもの)、トロプス(古い聖歌のセクションに新しい言葉や、時には新しい音楽を追加したもの)を交互に用いた。。トロプスは、 古い聖歌の節に新しい言葉や時には新しい音楽を付け加えたものである。これらのジャンルのうち、1つを除いてはすべて聖歌を基盤としていた。すなわち、1 つの声部(通常は3つ、時には4つ)が、ほぼ常に最も低い音(この時点ではテノール)で聖歌の旋律を歌うが、音の長さは自由に作曲され、他の声部はオルガ ヌムを歌う。この方法の例外はコンダクトゥスで、2声部構成で全体が自由に作曲される。 モテットは、中世後期とルネサンス期における最も重要な音楽形式のひとつであり、ノートルダム時代にクラウズラから発展した。特にペロタンが発展させた、 複数の声部を使用する形式が発展した。ペロタンは、前任者(大聖堂のカノンであるレオニヌスの長い華麗なクラウズラ)の多くを、ディスキャントスタイルの 代替物に置き換えることで、この発展に道筋をつけた。徐々に、こうした代用句をまとめた本が出版されるようになり、さまざまな聖歌に挿入したり、差し替え たりすることが可能になった。実際には、文脈上使用される可能性がある以上に多くの代用句が存在していたため、代用句はミサの他の部分や個人的な祈りにお いて、独立して演奏されるようになったと考えられる。このようにして実践されたクラウズラは、典礼用語以外の言葉が付け加えられたことでモテットとなり、 さらに14世紀のアルス・ノヴァの時代に、非常に精巧で洗練された、繊細な形式へと発展した。この時代の現存する写本には、モンペリエ写本、バンベルク写 本、ラス・ウエルガス写本などがある。 この時代の作曲家には、レオナン、ペロタン、W. ド・ワイコム、アダム・ド・サン・ヴィクトール、ペトルス・デ・クルーチェ(ピエール・ド・ラ・クロワ)などがいる。ペトルスは、ブリーヴェの長さに合う ように3つ以上のセミブレヴェを書くという革新を行ったことで知られている。不完全時制の革新に先立つこの慣習は、現在「ペトルス様式」と呼ばれるモテッ トの時代の幕開けとなった。13世紀後半のこれらの作品は3部または4部構成で、複数のテキストが同時に歌われる。もともと、テノール・ライン(ラテン語 の「保持する」を意味するtenereに由来)には、元々の典礼聖歌の旋律がラテン語で歌われていた。一方、1つ、2つ、あるいは3つの声部(ボーチェ ス・オルガナレス)のテキストは、典礼の主題についてラテン語またはフランス語で解説するものであった。声部の数が増加するにつれ、ボカス・オルガナレス のリズムの価値は減少した。デュプラム(テノールより上の声部)のリズムの価値はテノールより小さくなり、トリプラム(デュプラムより上の声部)のリズム の価値はデュプラムより小さくなり、以下同様である。時代が下るにつれ、ヴォーチェス・オルガネスのテキストは次第に世俗的な性質を帯びるようになり、テ ノール・ラインの典礼用テキストとの明白な関連性は薄れていった。 ペトロニアン・モテットに見られるリズムの複雑性は、14世紀の音楽の根本的な特徴となるが、フランス、イタリア、イングランドの音楽は、この時代に全く異なる道を歩むことになる。 |

Cantigas de Santa Maria Christian and Muslim playing lutes in a miniature from Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X Main article: Cantigas de Santa Maria The Cantigas de Santa Maria ("Canticles of St. Mary") are 420 poems with musical notation, written in Galician-Portuguese during the reign of Alfonso X The Wise (1221–1284).[58] The manuscript was probably compiled from 1270 to 1280, and is highly decorated, with an illumination every 10 poems.[59] The illuminations often depict musicians making the manuscript a particularly important source of medieval music iconography.[58] Though the Cantigas are often attributed to Alfonso, it remains unclear as to whether he was a composer himself, or perhaps a compiler;[59] Alfonso is known to regularly invited musicians and poets to court whom were undoubtedly involved in the Cantigas production.[60] It is one of the largest collections of monophonic (solo) songs from the Middle Ages and is characterized by the mention of the Virgin Mary in every song, while every tenth song is a hymn. The manuscripts have survived in four codices: two at El Escorial, one at Madrid's National Library, and one in Florence, Italy. Some have colored miniatures showing pairs of musicians playing a wide variety of instruments. |

サンタ・マリアの歌(カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリア) キリスト教徒とイスラム教徒がサンタ・マリアの歌のミニチュアでリュートを演奏する 詳細は「サンタ・マリアの歌」を参照 カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリア(「聖母マリアの歌」)は、賢王アルフォンソ10世(在位:1221年 - 1284年)の統治時代にガリシア・ポルトガル語で書かれた、楽譜付きの420編の詩である。[58] この写本は、おそらく1270年から1280年の間に編纂されたもので、10編ごとに挿絵が施され、非常に装飾が凝っている。[59] 挿絵には、しばしば楽譜を手にした音楽家たちが描かれており、 中世音楽の図像学において特に重要な資料となっている。[58] カンティガスはしばしばアルフォンソの作品とされるが、彼自身が作曲家であったのか、あるいは編纂者であったのかは不明である。[59] アルフォンソは定期的に音楽家や詩人を宮廷に招いており、彼らがカンティガスの制作に間違いなく関与していたことが知られている。[60] これは中世におけるモノフォニー(独唱)の歌の最大のコレクションのひとつであり、すべての歌に聖母マリアについて言及されているのが特徴である。また、 10曲に1曲は賛美歌である。写本は4つの写本に現存している。2つはエル・エスコリアル修道院に、1つはマドリード国立図書館に、そして1つはイタリア のフィレンツェにある。中には、さまざまな楽器を演奏する音楽家たちのペアを描いた彩色の挿絵が含まれているものもある。 |

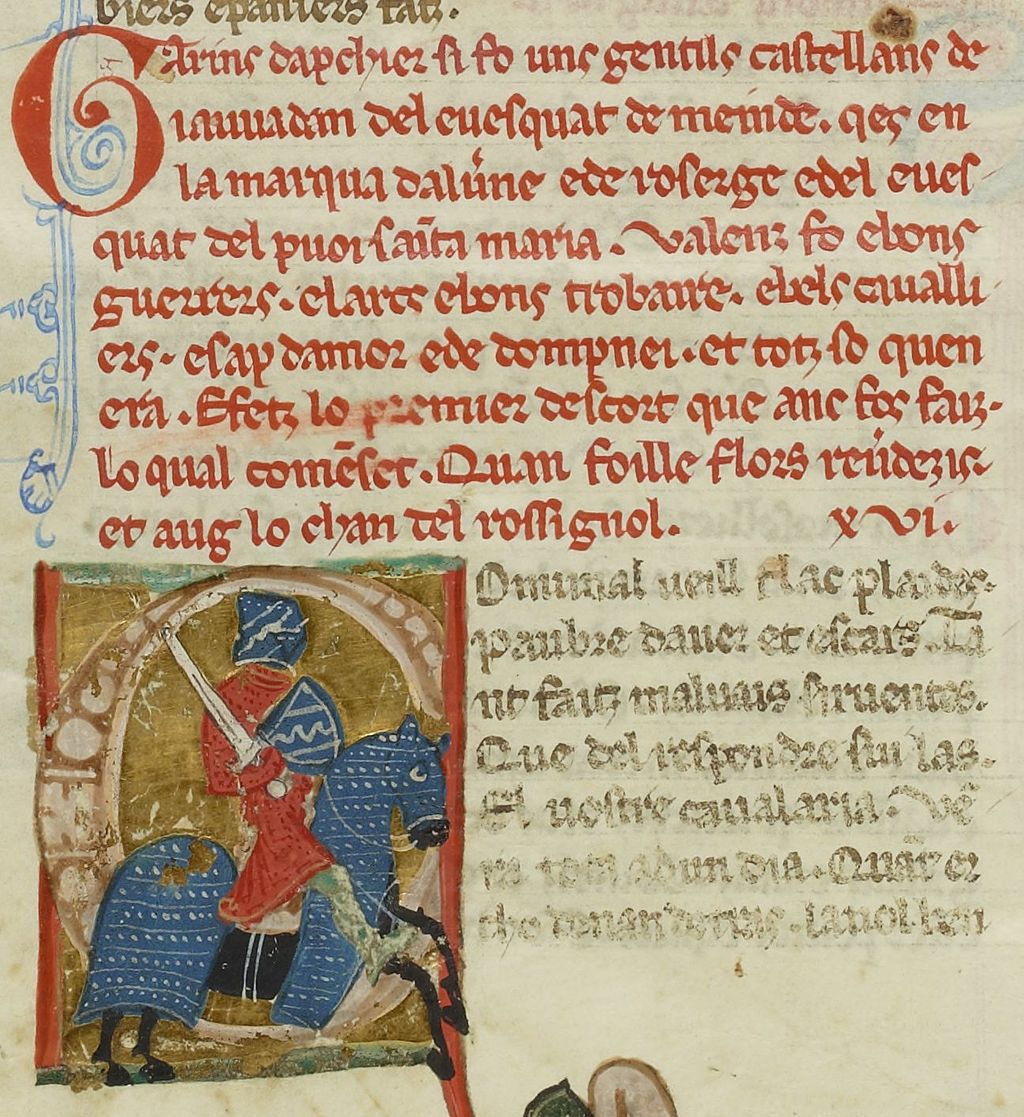

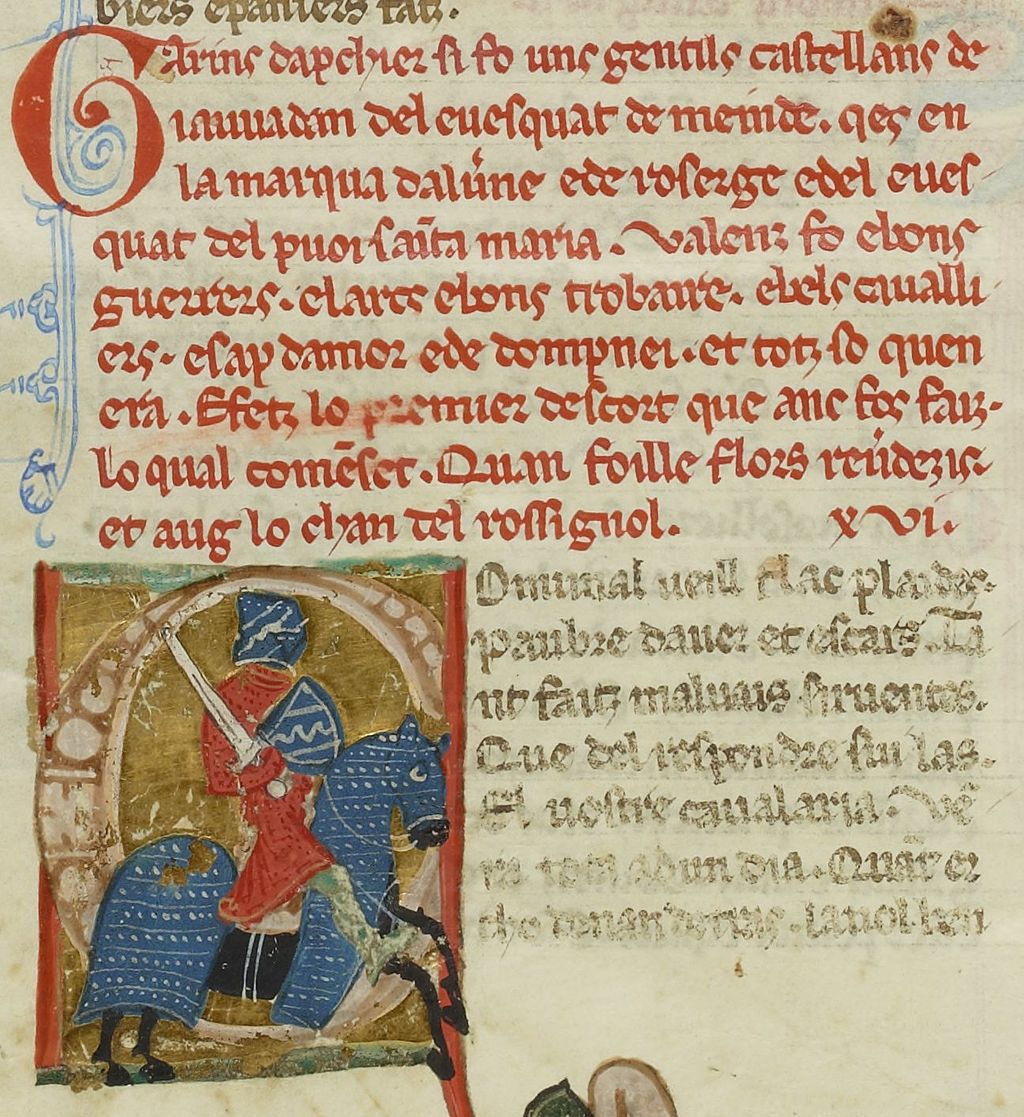

| Troubadours and trouvères Main articles: Troubadour and Trouvère See also: List of troubadours and trobairitz and List of trouvères  Garin d'Apchier in a medieval manuscript, 13th century The music of the troubadours and trouvères was a vernacular tradition of monophonic secular song, probably accompanied by instruments, sung by professional, occasionally itinerant, musicians who were as skilled as poets as they were singers and instrumentalists. The language of the troubadours was Occitan (also known as the langue d'oc, or Provençal); the language of the trouvères was Old French (also known as langue d'oïl). The period of the troubadours corresponded to the flowering of cultural life in Provence which lasted through the twelfth century and into the first decade of the thirteenth. Typical subjects of troubadour song were war, chivalry and courtly love—the love of an idealized woman from afar. The period of the troubadours wound down after the Albigensian Crusade, the fierce campaign by Pope Innocent III to eliminate the Cathar heresy (and northern barons' desire to appropriate the wealth of the south). Surviving troubadours went either to Portugal, Spain, northern Italy or northern France (where the trouvère tradition lived on), where their skills and techniques contributed to the later developments of secular musical culture in those places.[50] The trouvères and troubadours shared similar musical styles, but the trouvères were generally noblemen.[50] The music of the trouvères was similar to that of the troubadours, but was able to survive into the thirteenth century unaffected by the Albigensian Crusade. Most of the more than two thousand surviving trouvère songs include music, and show a sophistication as great as that of the poetry it accompanies.[61] |

トルバドゥールとトルヴェール 主な記事:トルバドゥールとトルヴェール 関連項目:トルバドゥールとトロバイルの一覧、トルヴェールの一覧  ガリン・ダプシエ、13世紀の中世写本より トルバドゥールとトルヴェールの音楽は、おそらく楽器の伴奏付きの、単旋律の世俗歌の郷土の伝統であり、プロの音楽家によって歌われた。彼らは、詩人とし て、また歌手や楽器奏者としても同様に熟練していた。トルバドゥールが用いた言語はオック語(オック語、またはプロヴァンス語とも呼ばれる)であり、トル ヴェールが用いた言語は古フランス語(オワ語とも呼ばれる)であった。トルバドゥールの時代は、12世紀から13世紀の最初の10年まで続いたプロヴァン スの文化の繁栄期と重なっていた。トルバドゥールの歌の典型的な主題は、戦争、騎士道、宮廷恋愛(理想化された女性を遠くから愛する)であった。アルビ ジョア十字軍の遠征後、教皇インノケンティウス3世によるカタル派異端の根絶(および北部諸侯の南の富の独占)を目的とした激しいキャンペーンにより、ト ルバドゥールの時代は終焉を迎えた。生き残ったトルバドゥールたちはポルトガル、スペイン、北イタリア、あるいは北フランス(トルヴェール派の伝統が生き 残った)へと去り、彼らの技術や技法は、それらの場所における世俗音楽文化の後の発展に貢献した。 トルヴェール人とトルバドゥール人は類似した音楽スタイルを共有していたが、トルヴェール人は概して貴族階級であった。トルヴェール人の音楽はトルバ ドゥール人の音楽と類似していたが、アルビジョア十字軍の影響を受けずに13世紀まで生き残ることができた。2000曲以上が現存するトルヴェール人の歌 のほとんどは音楽を含み、詩の洗練度に匹敵するほどの高度な音楽性を示している。 |

| Minnesänger and Meistersinger Main articles: Minnesang and Meistersinger See also: List of Minnesänger  Portrait of Walther von der Vogelweide The Minnesänger tradition was the Germanic counterpart to the activity of the troubadours and trouvères to the west. Unfortunately, few sources survive from the time; the sources of Minnesang are mostly from two or three centuries after the peak of the movement, leading to some controversy over the accuracy of these sources.[62] Among the Minnesängers with surviving music are Wolfram von Eschenbach, Walther von der Vogelweide, and Niedhart von Reuenthal. A Meistersinger (German for "master singer") was a member of a German guild for lyric poetry, composition and unaccompanied art song of the 14th, 15th and 16th centuries. The Meistersingers were drawn from middle class males for the most part. Konrad von Würzburg, Reinmar von Zweter, and Heinrich Frauenlob. Frauenlob allegedly established the earliest Meistersinger school at Mainz, early in the 14th century. The schools originated first in the upper Rhine district, then spread elsewhere. |

ミンネゼンガーとマイスタージンガー 主な記事:ミンネゼンガーとマイスタージンガー 関連項目:ミンネゼンガーの一覧  ヴァルター・フォン・デア・フォーゲルヴァイデの肖像 ミンネゼンガーの伝統は、西のトルバドゥールやトルヴェールの活動に対するゲルマン的な対応であった。残念ながら、当時の資料はほとんど残っていない。ミ ンネザングの資料は、その運動の最盛期から2、3世紀後のものがほとんどであり、それらの資料の正確性については議論の余地がある。[62] 音楽が残っているミンネザングの歌人には、ヴォルフラム・フォン・エッシェンバッハ、ヴァルター・フォン・デア・フォーゲルヴァイデ、ニードハルト・フォ ン・ロイエンタールなどがいる。 マイスタージンガー(ドイツ語で「マスターシンガー」の意)は、14世紀、15世紀、16世紀のドイツの叙情詩、作曲、無伴奏歌曲のギルドのメンバーで あった。 マイスタージンガーは主に中流階級の男性から選ばれていた。コンラート・フォン・ヴュルツブルク、ラインマル・フォン・ツヴェーテル、ハインリヒ・フラウ エンロプ。フラウエンロプは14世紀初頭にマインツで最も古いマイスタージンガー派を創設したとされる。この派はまずライン川上流地域で生まれ、その後、 他の地域にも広がった。 |

| Trovadorismo Main article: Galician-Portuguese lyric In the Middle Ages, Galician-Portuguese was the language used in nearly all of Iberia for lyric poetry.[63] From this language derive both modern Galician and Portuguese. The Galician-Portuguese school, which was influenced to some extent (mainly in certain formal aspects) by the Occitan troubadours, is first documented at the end of the twelfth century and lasted until the middle of the fourteenth. The earliest extant composition in this school is usually agreed to be Ora faz ost' o senhor de Navarra by the Portuguese João Soares de Paiva, usually dated just before or after 1200. The troubadours of the movement, not to be confused with the Occitan troubadours (who frequented courts in nearby León and Castile), wrote almost entirely cantigas. Beginning probably around the middle of the thirteenth century, these songs, known also as cantares or trovas, began to be compiled in collections known as cancioneiros (songbooks). Three such anthologies are known: the Cancioneiro da Ajuda, the Cancioneiro Colocci-Brancuti (or Cancioneiro da Biblioteca Nacional de Lisboa), and the Cancioneiro da Vaticana. In addition to these there is the priceless collection of over 400 Galician-Portuguese cantigas in the Cantigas de Santa Maria, which tradition attributes to Alfonso X. The Galician-Portuguese cantigas can be divided into three basic genres: male-voiced love poetry, called cantigas de amor (or cantigas d'amor, in Galician-Portuguese spelling) female-voiced love poetry, called cantigas de amigo (or cantigas d'amigo); and poetry of insult and mockery called cantigas de escárnio e maldizer (or cantigas d'escarnho e de mal dizer). All three are lyric genres in the technical sense that they were strophic songs with either musical accompaniment or introduction on a stringed instrument. But all three genres also have dramatic elements, leading early scholars to characterize them as lyric-dramatic. The origins of the cantigas d'amor are usually traced to Provençal and Old French lyric poetry, but formally and rhetorically they are quite different. The cantigas d'amigo are probably rooted in a native song tradition,[64] though this view has been contested. The cantigas d'escarnho e maldizer may also (according to Lang) have deep local roots. The latter two genres (totalling around 900 texts) make the Galician-Portuguese lyric unique in the entire panorama of medieval Romance poetry. |

トルバドゥール 詳細は「ガリシア・ポルトガル語の歌詞」を参照 中世において、ガリシア・ポルトガル語はイベリア半島の大半で叙情詩の言語として使用されていた。ガリシア・ポルトガル語の学校は、オック語のトルバ ドゥールたちから(主に特定の形式的な側面において)ある程度影響を受けており、12世紀末に初めて記録され、14世紀半ばまで続いた。 この学校における現存する最古の作品は、通常、ポルトガルのジョアン・ソアレス・デ・パイヴァによる『Ora faz ost' o senhor de Navarra』(1200年直前の、あるいは直後の年号)であると一般的に認められている。この運動のトルバドゥールたちは、近隣のレオンやカスティー リャの宮廷に出入りしていたオック語のトルバドゥールたちと混同されるべきではないが、ほぼ完全にカンティガスを書いた。おそらく13世紀半ば頃から、カ ンタレスやトロヴァスとしても知られるこれらの歌は、カンシオーニロス(歌集)としてまとめられるようになった。このようなアンソロジーとして知られてい るのは、カンシオーネイロ・ダ・アジュダ、カンシオーネイロ・コロッチ・ブランクーティ(またはカンシオーネイロ・ダ・ベラチカ・ナシオナル・デ・リスボ ア)、カンシオーネイロ・ダ・ヴァチカーナの3つである。これらに加えて、アルフォンソ10世の作品とされる400以上のガリシア・ポルトガル語カンティ ガスを集めた貴重なコレクション、カンティガス・デ・サンタ・マリアがある。 ガリシア・ポルトガル語のカンティガスは、大きく3つのジャンルに分けられる。男性の声による愛の詩であるカンティガス・デ・アモール(またはガリシア・ ポルトガル語の綴りではカンティガス・ド・アモール)、女性の声による愛の詩であるカンティガス・デ・アミーゴ(またはカンティガス・ド・アミーゴ)、そ して侮辱と嘲笑の詩であるカンティガス・デ・エスカルニオ・イ・マルディゼール(またはカンティガス・ド・エスカルニオ・イ・ド・マルディゼール)であ る。3つとも、弦楽器の伴奏や導入部が付いた、節のある歌であるという意味で、技術的には抒情詩のジャンルである。しかし、3つのジャンルにはいずれも劇 的な要素があり、初期の学者たちはこれを「抒情劇」と特徴づけた。 カンティガス・ダモール(愛の歌)の起源は、通常、プロヴァンスや古フランス語の抒情詩にさかのぼるとされるが、形式や修辞法はかなり異なる。カンティガ ス・ダ・アミーゴは、おそらく土着の歌の伝統に根ざしているが、この見解には異論もある。カンティガス・デスカルニョ・イ・マウヂゼーも(ラングによる と)、深い土着のルーツを持っている可能性がある。後者の2つのジャンル(合計で約900のテキスト)は、ガリシア・ポルトガル語の叙情詩を中世ロマンス 詩の全体像の中で独特なものとしている。 |

| Troubadours with surviving melodies Aimeric de Belenoi Aimeric de Peguilhan Airas Nunes Albertet de Sestaro Arnaut Daniel Arnaut de Maruoill Beatritz de Dia Berenguier de Palazol Bernart de Ventadorn Bertran de Born Blacasset Cadenet Daude de Pradas Denis of Portugal Folquet de Marselha Gaucelm Faidit Gui d'Ussel Guilhem Ademar Guilhem Augier Novella Guilhem Magret Guilhem de Saint Leidier Guiraut de Bornelh Guiraut d'Espanha Guiraut Riquier Jaufre Rudel João Soares de Paiva João Zorro Jordan Bonel Marcabru Martín Codax Monge de Montaudon Peire d'Alvernhe Peire Cardenal Peire Raimon de Tolosa Peire Vidal Peirol Perdigon Pistoleta Pons d'Ortaffa Pons de Capduoill Raimbaut d'Aurenga Raimbaut de Vaqueiras Raimon Jordan Raimon de Miraval Rigaut de Berbezilh Uc Brunet Uc de Saint Circ William IX of Aquitaine |

旋律が残っているトルバドゥールたち エメリック・ド・ベレノワ エメリック・ド・ペギルハン アイラス・ヌネス アルベルト・ド・セスタロ アルノー・ダニエル アルノー・ド・マルイユ ベアトリス・ド・ディア ベレンギエ・ド・パラスル ベルナル・ド・ヴェンタドール ベルトラン・ド・ボルン ブラカセット カデネ ドード・ド・プラダス ポルトガルのドニ フォルケ・ド・マルセイユ ガウセルム・ファイディット ギ・ド・ウセル ギレム・アデマール ギレム・オジエ・ノヴェラ ギレム・マグレー ギレム・ド・サン・レディエ ギラウ・ド・ボルネル ギラウ・デ・エスパーニャ ギラウ・リキエ ジョフレ・ルデル ジョアン・ソアレス・デ・パイヴァ ジョアン・ゾロ ジョーダン・ボネル マルカブル マルティン・コダックス モンジュ・ド・モントードン ペイレ・ダルベルヌ ペイレ・カルデナル ペイレ・ライモン・ド・トロサ ペイレ・ヴィダル ペイロール ペルディゴン ピストレータ ポン・ダルタッファ ポン・ド・カプドゥーユ ランボー・ダルエンガ ランボー・ド・ヴァケイラス ライモン・ジョーダン ライモン・ド・ミラヴァル リゴー・ド・ベルベシル ユック・ブリュネ ユック・ド・サン・シルク ウィリアム9世(アキテーヌ王 |

|

|

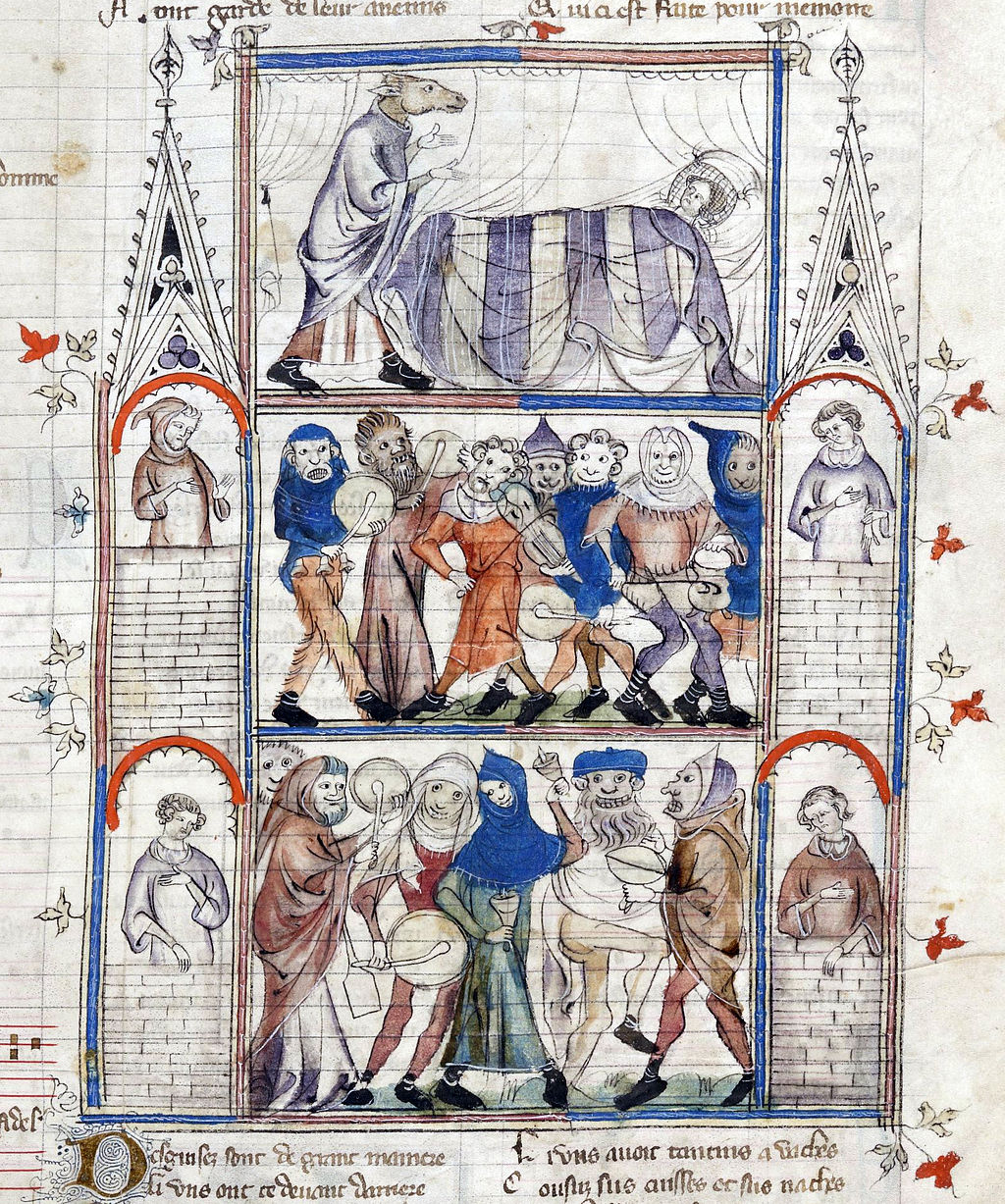

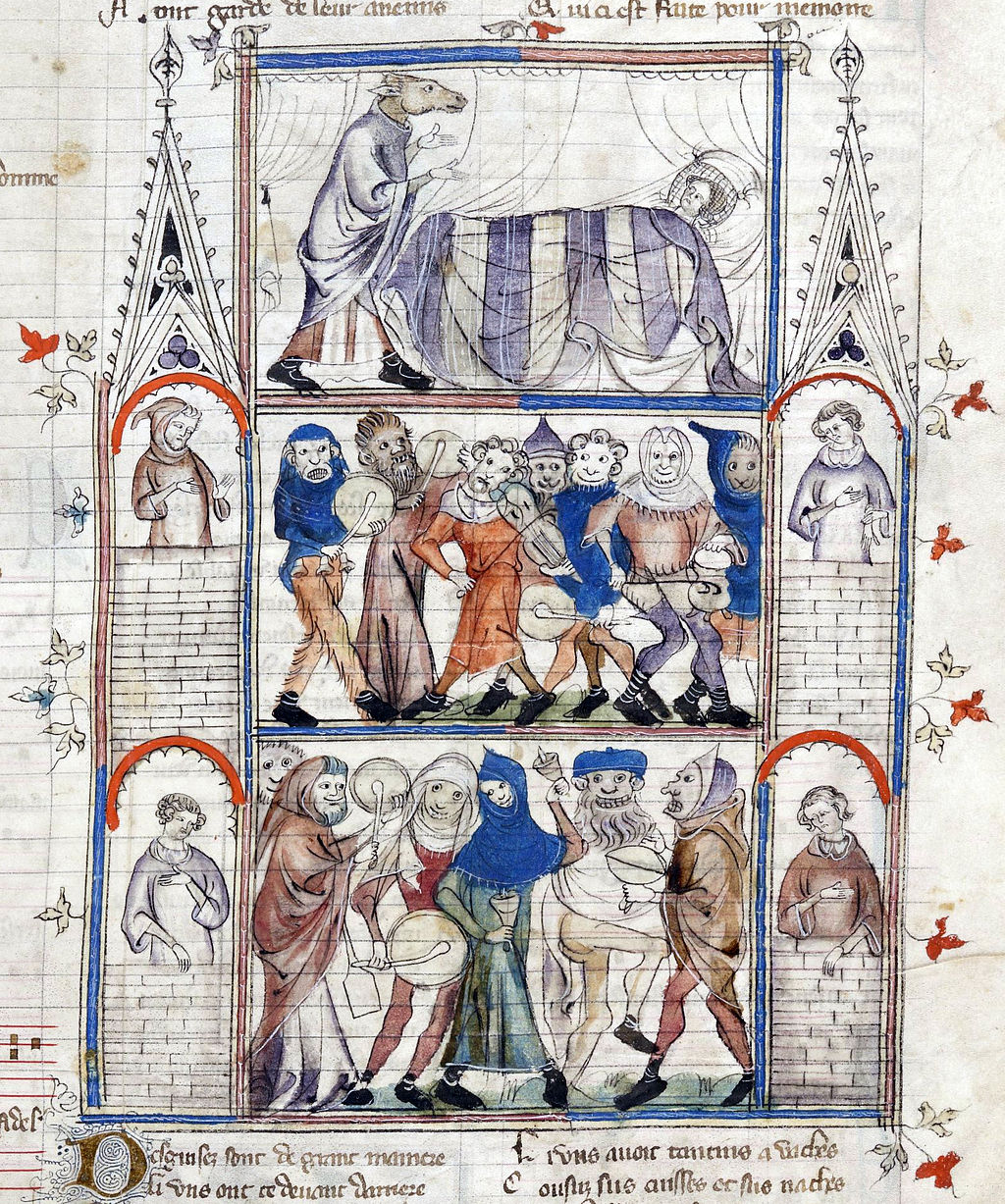

| Late medieval music (1300–1400) Further information: Late Middle Ages See also: List of medieval composers § (1250) Late Middle Ages France: Ars nova This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Ars nova  In this illustration from the satirical collection of music and poetry Roman de Fauvel, the horse Fauvel is about to join Vainglory in the bridal bed and the people form a charivari in protest. The beginning of the Ars nova is one of the few clear chronological divisions in medieval music, since it corresponds to the publication of the Roman de Fauvel, a huge compilation of poetry and music, in 1310 and 1314. The Roman de Fauvel is a satire on abuses in the medieval church, and is filled with medieval motets, lais, rondeaux and other new secular forms. While most of the music is anonymous, it contains several pieces by Philippe de Vitry, one of the first composers of the isorhythmic motet, a development which distinguishes the fourteenth century. The isorhythmic motet was perfected by Guillaume de Machaut, the finest composer of the time. During the Ars nova era, secular music acquired a polyphonic sophistication formerly found only in sacred music, a development not surprising considering the secular character of the early Renaissance (while this music is typically considered "medieval", the social forces that produced it were responsible for the beginning of the literary and artistic Renaissance in Italy—the distinction between Middle Ages and Renaissance is a blurry one, especially considering arts as different as music and painting). The term "Ars nova" (new art, or new technique) was coined by Philippe de Vitry in his treatise of that name (probably written in 1322), in order to distinguish the practice from the music of the immediately preceding age. The dominant secular genre of the Ars Nova was the chanson, as it would continue to be in France for another two centuries. These chansons were composed in musical forms corresponding to the poetry they set,[65] which were in the so-called formes fixes of rondeau, ballade, and virelai. These forms significantly affected the development of musical structure in ways that are felt even today; for example, the ouvert-clos rhyme-scheme shared by all three demanded a musical realization which contributed directly to the modern notion of antecedent and consequent phrases. It was in this period, too, in which began the long tradition of setting the mass ordinary. This tradition started around mid-century with isolated or paired settings of Kyries, Glorias, etc., but Machaut composed what is thought to be the first complete mass conceived as one composition. The sound world of Ars Nova music is very much one of linear primacy and rhythmic complexity. "Resting" intervals are the fifth and octave, with thirds and sixths considered dissonances. Leaps of more than a sixth in individual voices are not uncommon, leading to speculation of instrumental participation at least in secular performance. Surviving French manuscripts include the Ivrea Codex and the Apt Codex. For information about specific French composers writing in late medieval era, see Jehan de Lescurel, Philippe de Vitry, Guillaume de Machaut, Borlet, Solage, and François Andrieu. |

後期中世音楽(1300年-1400年) さらに詳しい情報: 後期中世 関連項目: 中世の作曲家一覧 § (1250) 後期中世 フランス:アルス・ノヴァ この節には出典が全く示されていない。信頼できる情報源を追加してこの節を改善するのを手伝ってほしい。出典の明記されていない内容は、異議を申し立てら れ、削除される可能性がある。 (2017年5月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 詳細は「アルス・ノヴァ」を参照  風刺的な音楽と詩のコレクション『ローマン・ド・フォーヴェル』の挿絵では、馬のフォーヴェルがヴァングロアの寝室に乗り込もうとしており、人々は抗議のためにチャリジャリーを形成している。 アルス・ノヴァの始まりは、1310年と1314年に詩と音楽の膨大な集成である『ローマン・ド・フォーヴェル』が出版されたことに一致するため、中世音 楽における数少ない明確な年代区分のひとつである。『ローマン・ド・フォーヴェル』は中世教会の腐敗を風刺した作品であり、中世のモテット、レ、ロン ドー、その他の新しい世俗的な形式で満たされている。ほとんどの音楽は匿名作曲であるが、イソリズム・モテットの最初の作曲家の一人であるフィリップ・ ド・ヴィトリの作品もいくつか含まれている。イソリズム・モテットは、同時代の最も優れた作曲家であるギョーム・ド・マショーによって完成された。 アルス・ノヴァの時代には、世俗音楽はそれまで宗教音楽にしか見られなかったポリフォニーの洗練さを獲得した。これは、初期ルネサンスの世俗的性格を考慮 すると驚くことではない(この音楽は一般的に「中世」とみなされているが、それを生み出した社会的勢力がイタリアにおける文学的・芸術的ルネサンスの始ま りを担ったのである。中世とルネサンスの区別は、特に音楽と絵画という異なる芸術を考慮すると、曖昧である)。「アルス・ノヴァ(新しい芸術、または新し い技法)」という用語は、直前の時代の音楽と区別するために、フィリップ・ド・ヴィトリが同名の論文(おそらく1322年に執筆)で作り出したものであ る。 アルス・ノヴァの支配的な世俗的なジャンルはシャンソンであり、フランスではその後2世紀にわたってシャンソンが主流であった。これらのシャンソンは、そ れらが用いた詩に対応する音楽形式で作曲された。これらの形式は、今日でも感じられるような形で音楽構造の発展に大きな影響を与えた。例えば、3つすべて に共通するオーヴェール・クロ韻律は、音楽的実現を必要とし、それは先行フレーズと後続フレーズという現代的な概念に直接貢献した。ミサ曲の通常唱の長い 伝統も、この時代に始まった。この伝統は世紀半ば頃にキリエやグロリアなどの単独またはペアでの作曲から始まったが、マショーは、ひとつの作品として構想 された最初のミサ曲と考えられている作品を作曲した。アルス・ノヴァ音楽の音の世界は、線的な優位性とリズムの複雑性を非常に強く感じさせる。「休符」と なる音程は5度とオクターブであり、3度と6度は不協和音とみなされる。個々の声部における6度以上の跳躍は珍しくなく、世俗的な演奏では少なくとも楽器 の参加があったのではないかと考えられている。現存するフランス語の写本には、イヴレア写本とアプト写本がある。 後期中世に活躍したフランスの作曲家については、ジャン・ド・レスキュレル、フィリップ・ド・ヴィトリ、ギヨーム・ド・マショー、ボルレ、ソラージュ、フランソワ・アンドリューを参照のこと。 |

| Italy: Trecento This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Music of the Trecento Most of the music of Ars nova was French in origin; however, the term is often loosely applied to all of the music of the fourteenth century, especially to include the secular music in Italy. There this period was often referred to as Trecento. Italian music has always been known for its lyrical or melodic character, and this goes back to the 14th century in many respects. Italian secular music of this time (what little surviving liturgical music there is, is similar to the French except for somewhat different notation) featured what has been called the cantalina style, with a florid top voice supported by two (or even one; a fair amount of Italian Trecento music is for only two voices) that are more regular and slower moving. This type of texture remained a feature of Italian music in the popular 15th and 16th century secular genres as well, and was an important influence on the eventual development of the trio texture that revolutionized music in the 17th. There were three main forms for secular works in the Trecento. One was the madrigal, not the same as that of 150–250 years later, but with a verse/refrain-like form. Three-line stanzas, each with different words, alternated with a two-line ritornello, with the same text at each appearance. Perhaps we can see the seeds of the subsequent late-Renaissance and Baroque ritornello in this device; it too returns again and again, recognizable each time, in contrast with its surrounding disparate sections. Another form, the caccia ("chase,") was written for two voices in a canon at the unison. Sometimes, this form also featured a ritornello, which was occasionally also in a canonic style. Usually, the name of this genre provided a double meaning, since the texts of caccia were primarily about hunts and related outdoor activities, or at least action-filled scenes; second meaning was that a voice caccia (follows, run after) the preceding one. The third main form was the ballata, which was roughly equivalent to the French virelai. Surviving Italian manuscripts include the Squarcialupi Codex and the Rossi Codex. For information about specific Italian composers writing in the late medieval era, see Francesco Landini, Gherardello da Firenze, Andrea da Firenze, Lorenzo da Firenze, Giovanni da Firenze (aka Giovanni da Cascia), Bartolino da Padova, Jacopo da Bologna, Donato da Cascia, Lorenzo Masini, Niccolò da Perugia, and Maestro Piero. |

イタリア:14世紀 この節には出典が全く示されていない。信頼できる情報源を追加してこの節を改善するのを手伝ってほしい。未出典の資料は、異議を申し立てられ、削除される可能性がある。 (2017年5月) (このメッセージの削除方法とタイミングについてはこちらをご覧ください) 詳細は「14世紀の音楽」を参照 アルス・ノヴァの音楽のほとんどはフランス起源であったが、この用語は14世紀の音楽すべてに、特にイタリアの世俗音楽を含めるために、しばしば曖昧に適 用される。この時代はイタリアではトレチェントと呼ばれていた。イタリア音楽は常に叙情的または旋律的な性格で知られており、これは多くの点で14世紀ま で遡る。この時代のイタリア世俗音楽(わずかに残っている典礼音楽は、表記法が若干異なる以外はフランス音楽と類似している)は、カンタリーナ様式と呼ば れるスタイルが特徴的であり、華やかな高音部を2声(あるいは1声、イタリアの14世紀音楽の多くは2声のみ)が、より規則的でゆっくりとした動きで支え る。このテクスチャは、15世紀から16世紀の世俗的なジャンルのイタリア音楽にも見られる特徴であり、17世紀の音楽に革命をもたらしたトリオ・テクス チャの最終的な発展に重要な影響を与えた。 14世紀の世俗的作品には主に3つの形式があった。1つはマドリガーレで、150年から250年後に誕生したものとは異なるが、詩節/リフレインのような 形式であった。異なる言葉で書かれた3行のスタンザと、同じテキストが繰り返される2行のリトルネロが交互に繰り返される。おそらく、この手法には、その 後のルネサンス後期やバロックのリトルネロの萌芽を見ることができるだろう。周囲の異なるセクションとは対照的に、リトルネロは何度も繰り返され、その都 度認識できる。もう一つの形式であるカッチャ(「追跡」)は、ユニゾンで2つの声部がカノンで書かれている。この形式にもリトルネロが用いられることがあ り、それは時にカノン形式でもあった。通常、このジャンルの名称には二重の意味が込められていた。カッチャの歌詞は主に狩猟や屋外での活動、あるいは少な くとも活気のある場面についてのものであり、第二の意味は、声部が先行する声部を追いかける(追い駆ける)という意味である。第三の主要な形式はバラータ で、これはフランス語のヴィルレーにほぼ相当する。 現存するイタリアの写本には、スクアルチャルーピ写本とロッシ写本がある。 中世後期に活躍したイタリアの作曲家については、フランチェスコ・ランディーニ、ジェラルデッロ・ダ・フィレンツェ、アンドレア・ダ・フィレンツェ、ロレ ンツォ・ダ・フィレンツェ、ジョヴァンニ・ダ・フィレンツェ(別名ジョヴァンニ・ダ・カッシャ)、バルトロリーノ・ダ・パドヴァ、ヤコポ・ダ・ボロー ニャ、ドナート・ダ・カッシャ、ロレンツォ・マジーニ、ニコロ・ダ・ペルージャ、マエストロ・ピエロなどがある。 |

| Germany: Geisslerlieder This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Geisslerlieder The Geisslerlieder were the songs of wandering bands of flagellants, who sought to appease the wrath of an angry God by penitential music accompanied by mortification of their bodies. There were two separate periods of activity of Geisslerlied: one around the middle of the thirteenth century, from which, unfortunately, no music survives (although numerous lyrics do); and another from 1349, for which both words and music survive intact due to the attention of a single priest who wrote about the movement and recorded its music. This second period corresponds to the spread of the Black Death in Europe, and documents one of the most terrible events in European history. Both periods of Geisslerlied activity were mainly in Germany. |

ドイツ:Geisslerlieder この節には出典が全く示されていない。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。出典のない項目は、削除されることがあります。 (2017年5月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 詳細は「Geisslerlieder」を参照 Geisslerliederは、鞭打ちを行う苦行者たちの放浪集団の歌であり、苦行を伴う悔悛の音楽によって怒れる神の怒りを鎮めようとした。ゲイス ラーリートの活動期間は2回に分かれており、1回目は13世紀半ば頃のもので、残念ながら音楽は残っていない(歌詞は多数残っている)。2回目は1349 年のもので、この時期には、この運動について書き、音楽を記録した1人の司祭の関心により、歌詞と音楽の両方がそのまま残っている。この第2期は、ヨー ロッパにおけるペストの流行と重なっており、ヨーロッパ史上最も恐ろしい出来事のひとつを記録している。ゲイスラーリートの活動は、いずれも主にドイツで 行われた。 |

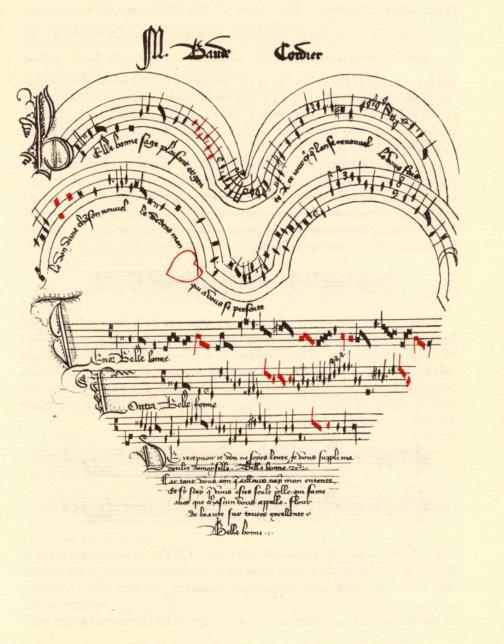

| Ars subtilior This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2017) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Ars subtilior  The chanson Belle, bonne, sage by Baude Cordier, an Ars subtilior piece included in the Chantilly Codex As often seen at the end of any musical era, the end of the medieval era is marked by a highly manneristic style known as Ars subtilior. In some ways, this was an attempt to meld the French and Italian styles. This music was highly stylized, with a rhythmic complexity that was not matched until the 20th century. In fact, not only was the rhythmic complexity of this repertoire largely unmatched for five and a half centuries, with extreme syncopations, mensural trickery, and even examples of augenmusik (such as a chanson by Baude Cordier written out in manuscript in the shape of a heart), but also its melodic material was quite complex as well, particularly in its interaction with the rhythmic structures. Already discussed under Ars Nova has been the practice of isorhythm, which continued to develop through late-century and in fact did not achieve its highest degree of sophistication until early in the 15th century. Instead of using isorhythmic techniques in one or two voices, or trading them among voices, some works came to feature a pervading isorhythmic texture which rivals the integral serialism of the 20th century in its systematic ordering of rhythmic and tonal elements. The term "mannerism" was applied by later scholars, as it often is, in response to an impression of sophistication being practised for its own sake, a malady which some authors have felt infected the Ars subtilior. One of the most important extant sources of Ars Subtilior chansons is the Chantilly Codex. For information about specific composers writing music in Ars subtilior style, see Anthonello de Caserta, Philippus de Caserta (aka Philipoctus de Caserta), Johannes Ciconia, Matteo da Perugia, Lorenzo da Firenze, Grimace, Jacob Senleches, and Baude Cordier. |

アルス・スブティオリ この節には出典が全く示されていない。信頼できる情報源を追加してこの節の改善にご協力ください。出典の明記されていない内容は、異議申し立てを受けた 後、削除される場合があります。 (2017年5月) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 詳細は「アルス・スブティオリ」を参照  ボー・コルディエ作曲のシャンソン『美しく、優雅で、賢い』はアルス・スブティリオルの作品であり、シャンティイ写本に収録されている 音楽の時代の終わりにはよく見られることだが、中世の終わりはアルス・スブティリオルとして知られる非常にマニエリスム的な様式によって特徴づけられてい る。ある意味では、これはフランスとイタリアの様式を融合しようとする試みであった。この音楽は高度に様式化されており、20世紀まで匹敵するもののない リズムの複雑さを持っていた。実際、このレパートリーの複雑なリズムは、5世紀半の間、ほとんど比類のないものであり、極端なシンコペーション、拍子によ るトリック、オーゲンムジーク(例えば、ボード・コルディエのシャンソンは、ハートの形をした原稿用紙に書かれている)の例さえもあった。また、その旋律 素材も、特にリズム構造との相互作用において、非常に複雑であった。アルス・ノヴァの項で既に述べたように、イソリズムの手法が用いられるようになったの は15世紀後半からで、実際、その洗練度が最高度に達したのは15世紀初頭になってからであった。1つか2つの声部でイソリズムの技法を用いたり、声部間 でそれらを交換したりするのではなく、いくつかの作品では、リズムや音色の要素を体系的に整理するという点で20世紀の総合的な系列主義に匹敵する、イソ リズムのテクスチャが全体に広がるようになった。「マニエリスム」という用語は、しばしばそうであるように、洗練された印象が自己目的化されているという 印象から、後の学者によって適用された。この病は、アルス・スブティリオールに感染していると感じた作家もいる。 アルス・スブティリオのシャンソンに関する現存する最も重要な資料のひとつがシャンティイ写本である。アルス・スブティリオ様式で作曲した特定の作曲家に 関する情報は、アントネッロ・デ・カゼルタ、フィリッポ・デ・カゼルタ(別名フィリポクトゥス・デ・カゼルタ)、ヨハネス・シコニア、マッテオ・ダ・ペ ルージャ、ロレンツォ・ダ・フィレンツェ、グリマース、ヤコブ・センレシュ、ボード・コルディエを参照のこと。 |