形而上学

Metaphysics

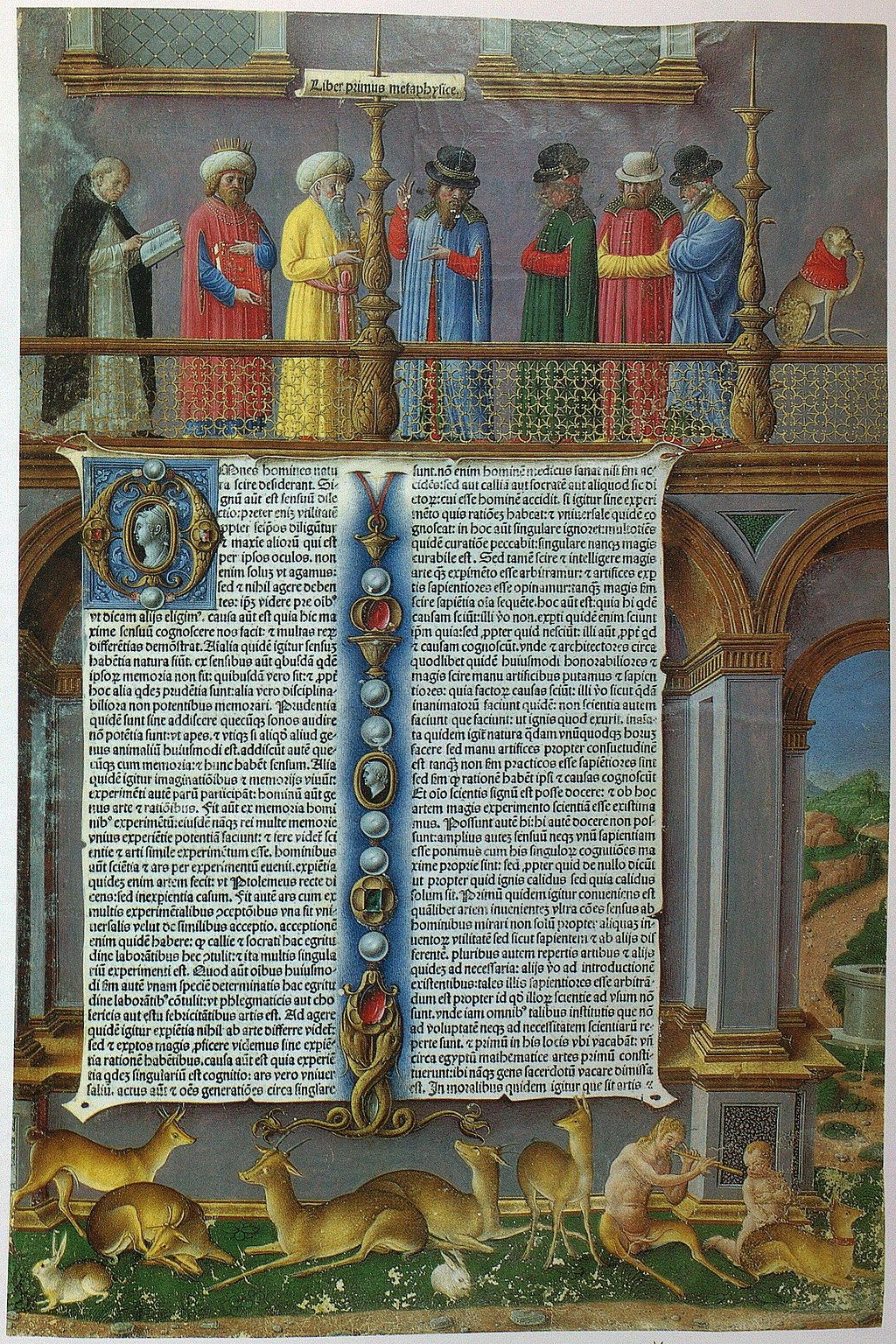

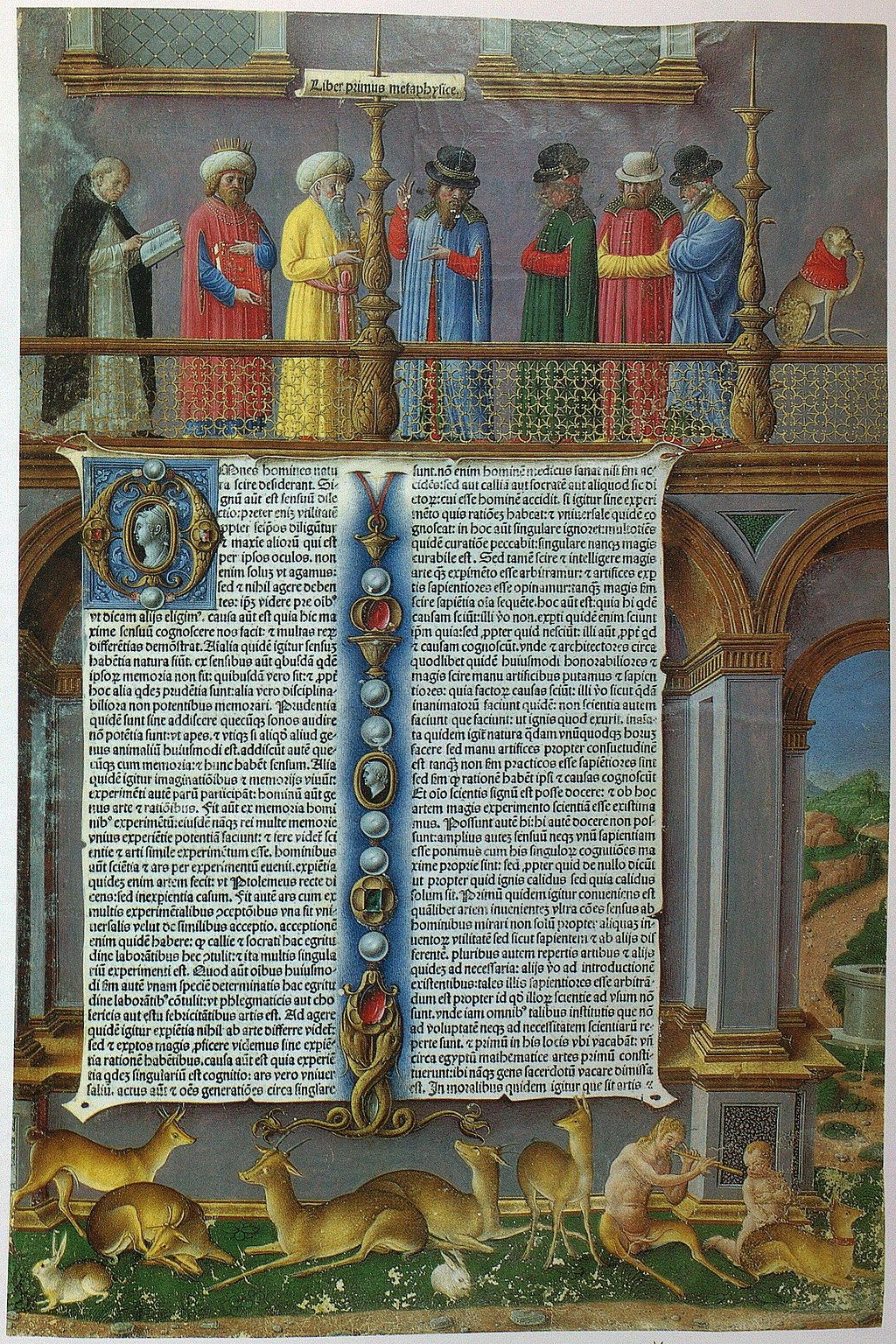

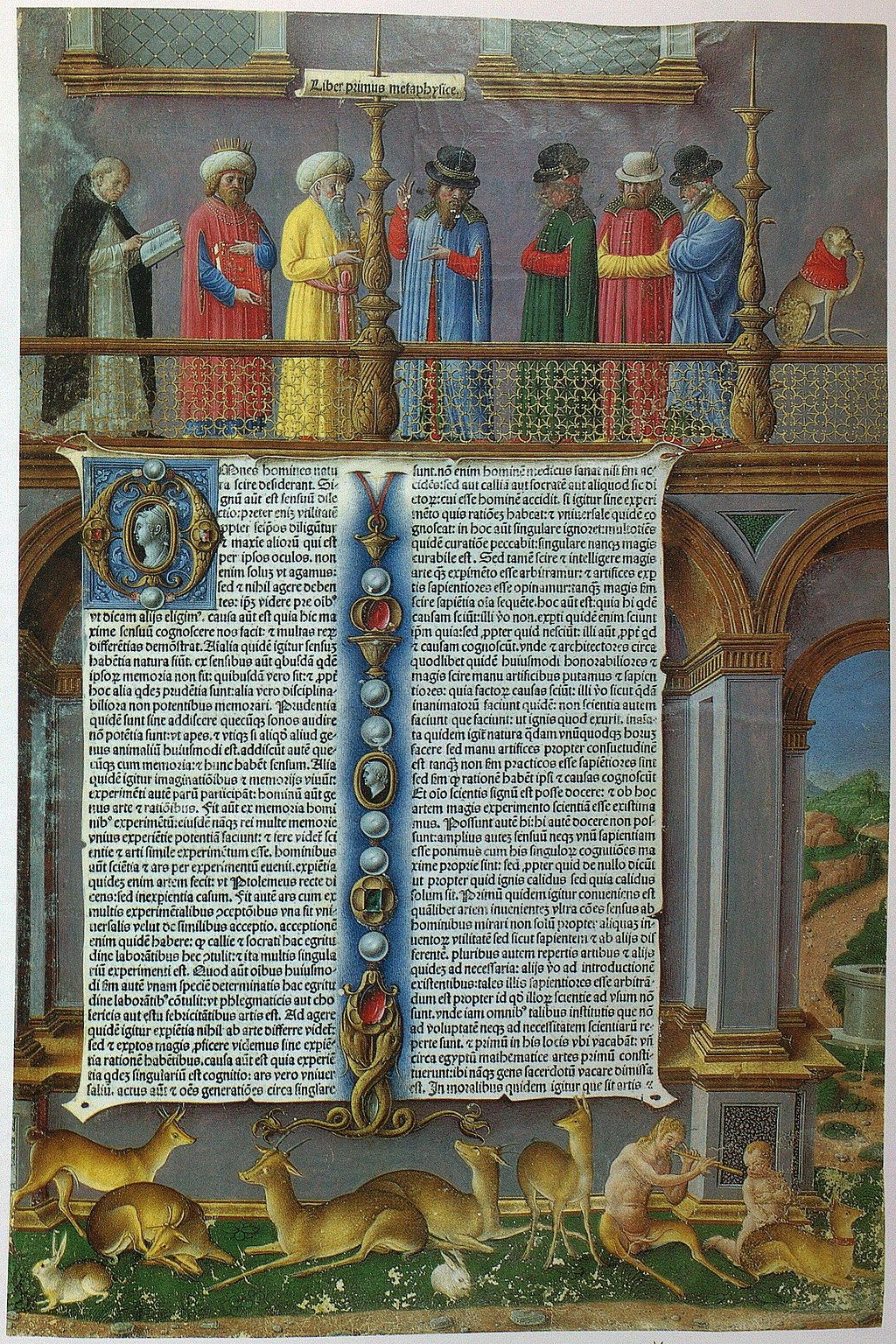

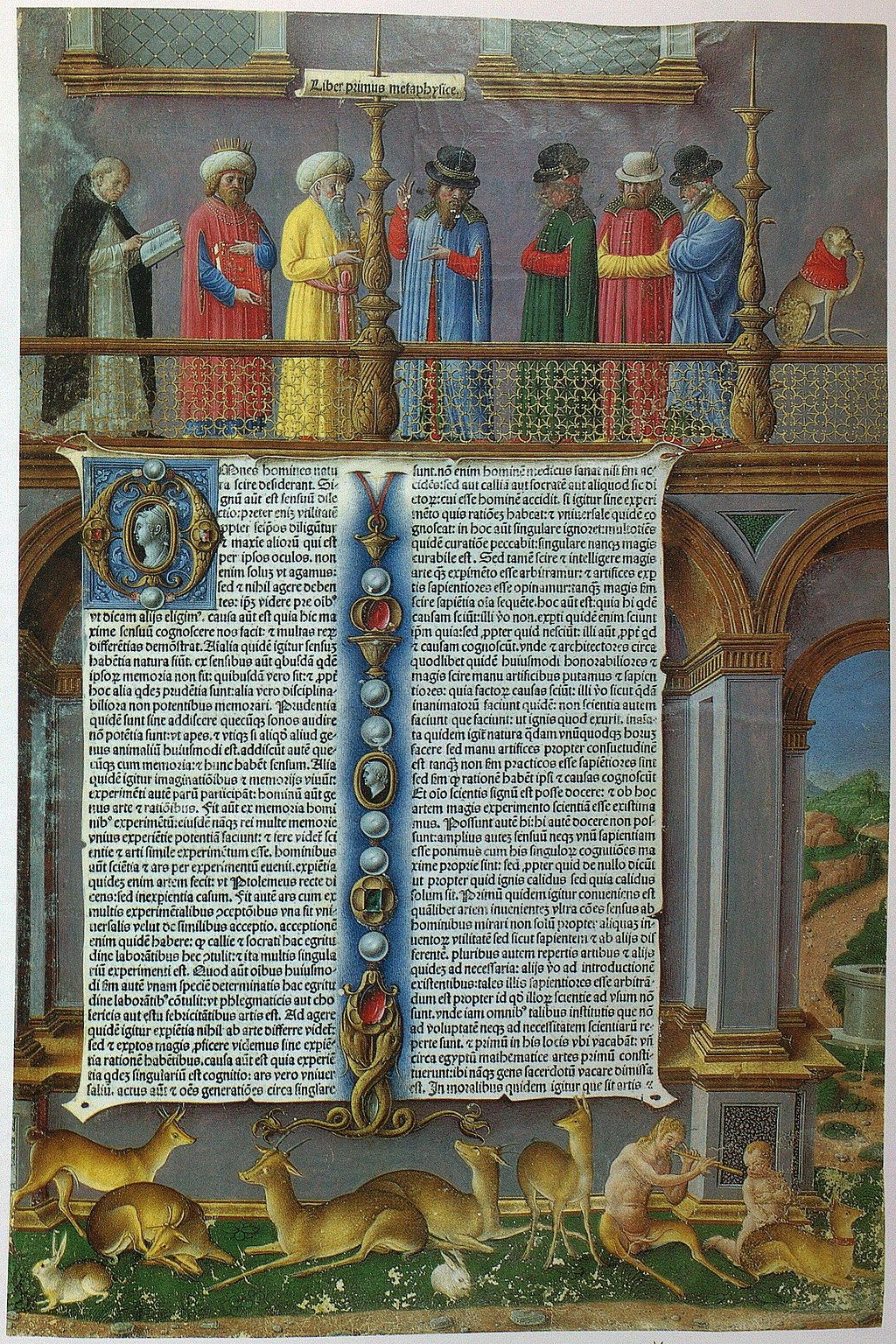

The beginning of Aristotle's Metaphysics, one of the foundational texts of the discipline/

Immanuel Kant conceived metaphysics from the perspective of critical

philosophy as the study of the principles underlying all human thought

and experience.

☆ 形而上学(Metaphysics)は、現実の基本的構造を考察する哲学の一分野である。形而上学はしばしば第一哲学と呼ばれ、他の哲学的探究よりも根本的であることを意味する。形 而上学は伝統的に、世界の心に依存しない特徴を研究する学問とみなされてきたが、現代の理論家の中には、人間の思考や経験の根底にある概念スキームを探求 する学問と理解する者もいる。形而上学の起源は古代にあり、古代インドのウパニシャッド、古代中国の道教、古代ギリシャのソクラテス以前の哲学に見られるような、現実と宇宙の本質につ いての思索があった。続く西洋の中世では、古代ギリシアの哲学者プラトンやアリストテレスによって形作られた普遍の本質が議論された。近代になると、さま ざまな包括的形而上学体系が登場し、その多くが観念論を取り入れた。20世紀から現代にかけて、「観念論への反乱」が起こり、形而上学は一度は無意味とさ れたが、それ以前の理論に対するさまざまな批判や形而上学的探究への新たなアプローチによって復活した。

★概説

| Metaphysics

is the branch of philosophy that examines the basic structure of

reality. It is often characterized as first philosophy, implying that

it is more fundamental than other forms of philosophical inquiry.

Metaphysics is traditionally seen as the study of mind-independent

features of the world, but some modern theorists understand it as an

inquiry into the conceptual schemes that underlie human thought and

experience. Many general and abstract topics belong to the subject of metaphysics. It investigates the nature of existence, the features all entities have in common, and their division into categories of being. An influential contrast is between particulars, which are individual unique entities, like a specific apple, and universals, which are general repeatable entities that characterize particulars, like the color red. Modal metaphysics examines what it means for something to be possible or necessary. The nature of space, time, and change is also discussed by metaphysicians. A closely related issue concerns the essence of causality and its relation to the laws of nature. Other topics include how mind and matter are related, whether everything in the world is predetermined, and whether there is free will. Metaphysicians employ various methods to conduct their inquiry. Traditionally, they rely on rational intuitions and abstract reasoning but have more recently also included empirical approaches associated with scientific theories. Due to the abstract nature of its topic, metaphysics has received criticisms questioning the reliability of its methods and the meaningfulness of its theories. Metaphysics is relevant to many fields of inquiry that often implicitly rely on metaphysical concepts and assumptions. The origin of metaphysics lies in antiquity with speculations about the nature of reality and the universe, like those found in the Upanishads in ancient India, Daoism in ancient China, and pre-Socratic philosophy in ancient Greece. The subsequent medieval period in the West discussed the nature of universals as shaped by ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle. The modern period saw the emergence of various comprehensive systems of metaphysics, many of which embraced idealism. In the 20th century and contemporary period, a "revolt against idealism" was started, and metaphysics was once declared meaningless, then revived with various criticisms of earlier theories and new approaches to metaphysical inquiry. |

形

而上学は、現実の基本的構造を考察する哲学の一分野である。形而上学はしばしば第一哲学と呼ばれ、他の哲学的探究よりも根本的であることを意味する。形而

上学は伝統的に、世界の心に依存しない特徴を研究する学問とみなされてきたが、現代の理論家の中には、人間の思考や経験の根底にある概念スキームを探求す

る学問と理解する者もいる。 形而上学には多くの一般的で抽象的なテーマが含まれる。形而上学は、存在の本質、すべての実体が共通に持つ特徴、存在のカテゴリーへの分割について研究す る。影響力のある対比は、特定のリンゴのような個々のユニークな存在である特殊と、赤い色のような特殊を特徴づける一般的な反復可能な存在である普遍であ る。様相形而上学は、何かが可能である、あるいは必要であるということが何を意味するのかを考察する。空間、時間、変化の本質も形而上学者によって議論さ れる。密接に関連する問題として、因果性の本質と自然法則との関係がある。その他にも、心と物質がどのように関係しているのか、世界のすべてはあらかじめ 決められているのか、自由意志はあるのか、といったテーマがある。 形而上学者は様々な方法を用いて研究を行う。伝統的には理性的な直観と抽象的な推論に頼るが、最近では科学理論に関連した経験的なアプローチも含まれるよ うになった。形而上学はそのテーマが抽象的であるため、その方法の信頼性や理論の意味を問う批判を受けてきた。形而上学は、しばしば暗黙のうちに形而上学 的な概念や仮定に依存している多くの探究分野に関連している。 形而上学の起源は古代にあり、古代インドのウパニシャッド、古代中国の道教、古代ギリシャのソクラテス以前の哲学に見られるような、現実と宇宙の本質につ いての思索があった。続く西洋の中世では、古代ギリシアの哲学者プラトンやアリストテレスによって形作られた普遍の本質が議論された。近代になると、さま ざまな包括的形而上学体系が登場し、その多くが観念論を取り入れた。20世紀から現代にかけて、「観念論への反乱」が起こり、形而上学は一度は無意味とさ れたが、それ以前の理論に対するさまざまな批判や形而上学的探究への新たなアプローチによって復活した。 |

The beginning of Aristotle's Metaphysics, one of the foundational texts of the discipline |

アリストテレスの『形而上学』の冒頭部分。 |

| Definition Metaphysics is the study of the most general features of reality, including existence, objects and their properties, possibility and necessity, space and time, change, causation, and the relation between matter and mind. It is one of the oldest branches of philosophy.[1] The precise nature of metaphysics is disputed and its characterization has changed in the course of history. Some approaches see metaphysics as a unified field and give a wide-sweeping definition by understanding it as the study of "fundamental questions about the nature of reality" or as an inquiry into the essences of things. Another approach doubts that the different areas of metaphysics share a set of underlying features and provides instead a fine-grained characterization by listing all the main topics investigated by metaphysicians.[2] Some definitions are descriptive by providing an account of what metaphysicians do while others are normative and prescribe what metaphysicians ought to do.[3] Two historically influential definitions in ancient and medieval philosophy understand metaphysics as the science of the first causes and as the study of being qua being, that is, the topic of what all beings have in common and to what fundamental categories they belong. In the modern period, the scope of metaphysics was extended to cover topics such as the distinction between mind and body and free will.[4] Some philosophers follow Aristotle in describing metaphysics as "first philosophy", implying that it is the most basic inquiry while all other branches of philosophy depend on it in some way.[5][a]  Painting of Immanuel Kant Immanuel Kant conceived critical metaphysics as the study of the principles underlying all human thought and experience. Metaphysics is traditionally understood as a study of mind-independent features of reality. Starting with Immanuel Kant's critical philosophy, an alternative conception gained prominence that focuses on conceptual schemes rather than external reality. Kant distinguishes transcendent metaphysics, which aims to describe the objective features of reality beyond sense experience, from critical metaphysics, which outlines the aspects and principles underlying all human thought and experience.[7] Regarding the analysis of conceptual schemes, philosopher P. F. Strawson contrasts descriptive metaphysics, which articulates conceptual schemes commonly used to understand the world, with revisionary metaphysics, which aims to produce better conceptual schemes.[8] Metaphysics differs from the individual sciences by studying very general and abstract aspects of reality. The individual sciences, by contrast, examine more specific and concrete features and restrict themselves to certain classes of entities, such as the focus on physical things in physics, living entities in biology, and cultures in anthropology.[9] It is disputed to what extent this contrast is a strict dichotomy rather than a gradual continuum.[10] Philosophers engaged in metaphysics are called metaphysicians or metaphysicists.[11] Outside the academic discourse, the term metaphysics is sometimes used in a different sense for the study of occult and paranormal phenomena, like metaphysical healing, auras, and the power of pyramids.[12] |

定義 形而上学とは、存在、対象とその性質、可能性と必然性、空間と時間、変化、因果関係、物質と心の関係など、現実の最も一般的な特徴を研究する学問である。哲学の最も古い学問分野のひとつである[1]。 形而上学の正確な性質については議論があり、その特徴は歴史の過程で変化してきた。形而上学を統一的な分野とみなし、「現実の本質に関する根本的な疑問」 の研究、あるいは「事物の本質に関する探究」と理解することで、広範な定義を与えるアプローチもある。別のアプローチでは、形而上学のさまざまな領域が一 連の基本的な特徴を共有していることに疑問を呈し、代わりに形而上学者によって研究されるすべての主要なトピックを列挙することによって、きめ細かな特徴 付けを行う[2]。ある定義は、形而上学者が行うことの説明を提供することによって記述的なものであり、別の定義は規範的なものであり、形而上学者が行う べきことを規定するものである[3]。 古代と中世の哲学において歴史的に影響力のある2つの定義は、形而上学を第一原因の科学として、また存在することについての研究、すなわち、すべての存在 が共通に持つもの、そしてそれらがどのような基本的なカテゴリーに属するかというテーマとして理解している。アリストテレスに倣って形而上学を「第一哲 学」と表現する哲学者もいるが、これは形而上学が最も基本的な学問であり、他のすべての哲学分野が何らかの形で形而上学に依存していることを示唆している [5][a]。  イマヌエル・カントの絵画 イマヌエル・カントは、批判的形而上学をすべての人間の思考と経験の根底にある原理の研究であると考えた。 形而上学は伝統的に、現実の心に依存しない特徴の研究として理解されてきた。イマヌエル・カントの批判哲学を皮切りに、外的現実ではなく概念的スキームに 焦点を当てた別の概念が注目されるようになった。カントは、感覚的経験を超えた現実の客観的特徴を記述することを目的とする超越的形而上学と、すべての人 間の思考と経験の根底にある側面と原理を概説する批判的形而上学を区別している[7]。概念スキームの分析に関して、哲学者のP.F.ストローソンは、世 界を理解するために一般的に用いられる概念スキームを明確にする記述的形而上学と、より優れた概念スキームを生み出すことを目的とする修正的形而上学を対 比している[8]。 形而上学は、現実の非常に一般的で抽象的な側面を研究することによって、個々の科学とは異なる。これとは対照的に、個別科学はより具体的で具体的な特徴を 研究し、物理学では物理的なもの、生物学では生物的なもの、人類学では文化に焦点を当てるなど、ある種の実体に限定している。 形而上学に従事する哲学者は形而上学者または形而上学者と呼ばれる[11]。学術的な言説の外では、形而上学という用語は、形而上ヒーリング、オーラ、ピラミッドの力のようなオカルトや超常現象の研究に対して別の意味で使われることもある[12]。 |

|

Etymology The word metaphysics has its origin in the ancient Greek words metá (μετά, meaning after, above, and beyond) and phusiká (φυσικά) as a short form of ta metá ta phusiká: that is, what comes after the physics. This is frequently interpreted in the sense that metaphysics discusses topics that, due to their generality and comprehensiveness, lie beyond the realm of physics and its focus on empirical observation. However, it is often suggested that metaphysics got its name by a historical accident when Aristotle's book on this subject was published.[13] Aristotle did not use the term metaphysics but his editor (likely Andronicus of Rhodes) may have coined it for its title to indicate that this book should be studied after Aristotle's book published on physics: literally after physics. The term entered the English language through the Latin word metaphysica.[13] Branches The nature of metaphysics can also be characterized in relation to its main branches. An influential division from early modern philosophy distinguishes between general and special or specific metaphysics.[14] General metaphysics, also called ontology,[b] takes the widest perspective and studies the most fundamental aspects of being. It investigates the features that all entities have in common and how entities can be divided into different categories. Categories are the most general kinds, such as substance, property, relation, and fact.[16] Ontologists research which categories there are, how they depend on one another, and how they form a system of categories that provides an encompassing classification of all entities.[17] Special metaphysics considers being from more narrow perspectives and is divided into subdisciplines based on the perspective they take. Metaphysical cosmology examines changeable things and investigates how they are connected to form a world as a totality of entities extending through space and time.[18] Rational psychology restricts itself to exploring metaphysical foundations and problems concerning the mind, such as its relation to matter and the freedom of the will. Natural theology studies the divine and its role as the first cause.[18] The scope of special metaphysics overlaps with other philosophical disciplines and it is often not clear whether a topic belongs to it rather than to disciplines like philosophy of mind and theology.[19] Applied metaphysics is a young subdiscipline. It belongs to applied philosophy and studies the applications of metaphysics, both within philosophy and other fields of inquiry. In ethics and philosophy of religion, it concerns topics like the ontological foundation of moral claims and religious doctrines.[20] Applications outside philosophy include the use of ontologies in artificial intelligence, economics, and sociology to classify entities[21] as well as questions in psychiatry and medicine about the metaphysical status of diseases.[22] Meta-metaphysics[c] is the metatheory of metaphysics and investigates the nature and methods of metaphysics. It also examines how metaphysics differs from other philosophical and scientific disciplines and how it is relevant to them. While the discussions of its topics have a long history in metaphysics, it has only recently developed into a systematic field of inquiry.[24] |

語源 形而上学(metaphysics)の語源は、古代ギリシア語のmetá(μετά、後、上、超越を意味する)とphusiká(φυσικά)であり、 ta metá ta phusikáの短縮形である。これは、形而上学は、その一般性と包括性から、物理学とその経験的観察に焦点を当てた領域を超えたトピックを論じていると いう意味で解釈されることが多い。アリストテレスは形而上学という言葉を使っていないが、彼の編集者(おそらくロードス島のアンドロニコス)が、この本は アリストテレスが物理学について出版した本の後に研究されるべきものであることを示すために、文字通り物理学の後にという意味の造語をタイトルに使ったの だろう。この言葉は、ラテン語のmetaphysicaを通じて英語に入った[13]。 枝分かれ 形而上学の性質は、その主要な枝との関係においても特徴づけることができる。一般形而上学は存在論とも呼ばれ[b]、最も広い視野を持ち、存在の最も根本 的な側面を研究する。一般形而上学は、すべての実体が共通して持っている特徴や、実体がどのように異なるカテゴリーに分けられるかを研究する。カテゴリー とは、実体、性質、関係、事実といった最も一般的な種類のことである[16]。存在論者は、どのようなカテゴリーが存在するのか、それらがどのように互い に依存し合っているのか、そしてそれらがすべての実体を包括的に分類するカテゴリーの体系をどのように形成しているのかを研究する[17]。 特殊形而上学は、より狭い視点から存在を考察し、その視点に基づいて下位の学問に分かれている。形而上学的宇宙論は、変化しうる事物を検討し、それらがど のように結びついて、空間と時間を通じて広がる実体の全体としての世界を形成しているかを研究する[18]。自然神学は神とその第一原因としての役割を研 究している[18]。特殊形而上学の範囲は他の哲学分野と重複しており、あるトピックが心の哲学や神学のような学問分野ではなく、特殊形而上学に属するか どうかが明確でないことが多い[19]。 応用形而上学は若い学問分野である。応用哲学に属し、哲学内や他の探究分野での形而上学の応用を研究する。倫理学や宗教哲学においては、道徳的主張や宗教 的教義の存在論的基盤のようなトピックに関係している[20]。哲学以外の分野での応用としては、人工知能、経済学、社会学における実体を分類するための オントロジーの使用[21]や、精神医学や医学における病気の形而上学的地位に関する疑問がある[22]。 メタ形而上学[c]は形而上学のメタ理論であり、形而上学の性質と方法を研究している。また、形而上学が他の哲学的・科学的学問分野とどのように異なり、 どのようにそれらと関連するのかを検討する。そのテーマの議論は形而上学において長い歴史を持っているが、体系的な研究分野として発展したのはごく最近の ことである[24]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics |

★形而上学に関する伝統的なトピックス

|

Existence and categories of being Main articles: Existence and Theory of categories Metaphysicians often see existence or being as one of the most basic and general concepts.[25] To exist means to form part of reality and existence marks the difference between real entities and imaginary ones.[26] According to the orthodox view, existence is a second-order property or a property of properties: if an entity exists then its properties are instantiated.[27] A different position states that existence is a first-order property, meaning that it is similar to other properties of entities, such as shape or size.[28] It is controversial whether all entities have this property. According to Alexius Meinong, there are nonexistent objects, including merely possible objects like Santa Claus and Pegasus.[29][d] A related question is whether existence is the same for all entities or whether there are different modes or degrees of existence.[30] For instance, Plato held that Platonic forms, which are perfect and immutable ideas, have a higher degree of existence than matter, which is only able to imperfectly mirror Platonic forms.[31] Another key concern in metaphysics is the division of entities into different groups based on underlying features they have in common. Theories of categories provide a system of the most fundamental kinds or the highest genera of being by establishing a comprehensive inventory of everything.[32] One of the earliest theories of categories was provided by Aristotle, who proposed a system of 10 categories. Substances (e.g. man and horse), are the most important category since all other categories like quantity (e.g. four), quality (e.g. white), and place (e.g. in Athens) are said of substances and depend on them.[33] Kant understood categories as fundamental principles underlying human understanding and developed a system of 12 categories, which are divided into the four classes quantity, quality, relation, and modality.[34] More recent theories of categories were proposed by C. S. Peirce, Edmund Husserl, Samuel Alexander, Roderick Chisholm, and E. J. Lowe.[35] Many philosophers rely on the contrast between concrete and abstract objects. According to a common view, concrete objects, like rocks, trees, and human beings, exist in space and time, undergo changes, and impact each other as cause and effect, while abstract objects, like numbers and sets, exist outside space and time, are immutable, and do not enter into causal relations.[36] |

存在と存在のカテゴリー 主な記事 存在とカテゴリーの理論 形而上学者はしばしば「存在」または「存在」を最も基本的で一般的な概念の一つと見なす[25]。正統的な見解によれば、存在は二次的な性質または性質の 性質であり、実体が存在すればその性質はインスタンス化される[27]。アレクシウス・マイノングによれば、サンタクロースやペガサスのような単に可能性 のある対象を含む非存在の対象が存在する[29][29][d]。関連する問題は、存在はすべての実体にとって同じなのか、それとも存在の異なる様式や程 度が存在するのかということである[30]。例えばプラトンは、完全で不変のイデアであるプラトン的形式は、プラトン的形式を不完全に映し出すことしかで きない物質よりも高い存在の程度を持つとした[31]。 形而上学におけるもう一つの重要な関心事は、実体が共通して持つ根本的な特徴に基づいて、実体を異なるグループに分けることである。カテゴリーの理論は、 あらゆるものの包括的な目録を確立することによって、存在の最も基本的な種類または最も高い属性の体系を提供する[32]。最も初期のカテゴリーの理論の 一つはアリストテレスによって提供され、彼は10のカテゴリーの体系を提案した。物質(例えば人間と馬)は最も重要なカテゴリーであり、量(例えば4 つ)、質(例えば白)、場所(例えばアテネ)のような他のすべてのカテゴリーは物質について言われ、それらに依存しているからである[33]。 [34]より最近のカテゴリーの理論は、C.S.パース、エドモンド・フッサール、サミュエル・アレクサンダー、ロデリック・チショルム、E.J.ロウに よって提案された[35]。一般的な見解によれば、具体的な対象は岩や木や人間のように空間と時間の中に存在し、変化を受け、因果関係として互いに影響し 合うが、抽象的な対象は数や集合のように空間と時間の外に存在し、不変であり、因果関係には入らない[36]。 |

| Particulars Particulars are individual entities and include both concrete objects, like Aristotle, the Eiffel Tower, or a specific apple, and abstract objects, like the number 2 or a specific set in mathematics. Also called individuals,[e] they are unique, non-repeatable entities and contrast with universals, like the color red, which can at the same time exist in several places and characterize several particulars.[38] A widely held view is that particulars instantiate universals but are not themselves instantiated by something else, meaning that they exist in themselves while universals exist in something else. Substratum theory analyzes particulars as a substratum, also called bare particular, together with various properties. The substratum confers individuality to the particular while the properties express its qualitative features or what it is like. This approach is rejected by bundle theorists, who state that particulars are only bundles of properties without an underlying substratum. Some bundle theorists include in the bundle an individual essence, called haecceity, to ensure that each bundle is unique. Another proposal for concrete particulars is that they are individuated by their space-time location.[39] Concrete particulars encountered in everyday life, like rocks, tables, and organisms, are complex entities composed of various parts. For example, a table is made up of a tabletop and legs, each of which is itself made up of countless particles. The relation between parts and wholes is studied by mereology.[40] The problem of the many is about which groups of entities form mereological wholes, for instance, whether a dust particle on the tabletop forms part of the table. According to mereological universalists, every collection of entities forms a whole, meaning that the parts of the table without the dust particle form one whole while they together with it form a second whole. Mereological moderatists hold that certain conditions have to be fulfilled for a group of entities to compose a whole, for example, that the entities touch one another. Mereological nihilists reject the idea that there are any wholes. They deny that, strictly speaking, there is a table and talk instead of particles that are arranged table-wise.[41] A related mereological problem is whether there are simple entities that have no parts, as atomists claim, or not, as continuum theorists contend.[42] |

部分体 個別的なものは個々の実体であり、アリストテレス、エッフェル塔、特定のリンゴのような具体的な対象と、数2や数学における特定の集合のような抽象的な対 象の両方を含む。個体とも呼ばれ[e]、ユニークで反復不可能な実体であり、同時に複数の場所に存在し、複数の特殊体を特徴づけることができる赤という色 のような普遍体とは対照的である[38]。広く受け入れられている見解は、特殊体は普遍体をインスタンス化するが、それ自体は他の何かによってインスタン ス化されることはなく、普遍体が他の何かの中に存在するのに対して、特殊体はそれ自身の中に存在するということである。基層理論では、特殊は基層として分 析され、さまざまな性質とともに裸の特殊とも呼ばれる。基層は特殊に個性を与え、性質は特殊の質的特徴や特殊がどのようなものであるかを表す。このアプ ローチは束論者によって否定される。束論者は、基層を持たない特殊は特性の束に過ぎないとする。束の理論家の中には、それぞれの束がユニークであることを 保証するために、束の中にヘセシティと呼ばれる個々の本質を含める人もいる。具体的特殊性に関するもう一つの提案は、具体的特殊性は時空間的な位置によっ て個別化されるというものである[39]。 岩石、テーブル、生物など、日常生活で遭遇する具体的な特殊性は、さまざまな部分から構成される複雑な実体である。例えば、テーブルは天板と脚で構成され ており、そのそれぞれが無数の粒子で構成されている。部分と全体との関係は唯物論によって研究される[40]。例えば、テーブルの天板の上にある塵の粒子 がテーブルの一部を形成しているかどうかというように、どのような実体のグループが唯物論的な全体を形成しているかということが唯物論の問題である。つま り、塵を含まないテーブルの部分は一つの全体を形成し、塵を含むテーブルは第二の全体を形成するということである。唯物論的中庸論者は、実体の集まりが全 体を構成するためには、ある条件が満たされなければならないと主張する。実在論的虚無主義者は、全体が存在するという考えを否定する。彼らは厳密に言え ば、テーブルが存在し、テーブル状に配置された粒子の代わりに話すことを否定する[41]。関連する唯物論的問題は、原子論者が主張するように部分を持た ない単純な実体が存在するのか、連続体論者が主張するように存在しないのかということである[42]。 |

|

Universals Main article: Universal (metaphysics) Universals are general entities, encompassing both properties and relations, that express what particulars are like and how they resemble one another. They are repeatable, meaning that they are not limited to a unique existent but can be instantiated by different particulars at the same time. For example, the particulars Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi instantiate the universal humanity, similar to how a strawberry and a ruby instantiate the universal red.[43] A topic discussed since ancient philosophy, the problem of universals consists in the challenge of characterizing the ontological status of universals.[44] Realists argue that universals are real, mind-independent entities that exist in addition to particulars. According to Platonic realists, universals exist also independently of particulars, which implies that the universal red would continue to exist even if there were no red things. A more moderate form of realism, inspired by Aristotle, states that universals depend on particulars, meaning that they are only real if they are instantiated. Nominalists reject the idea that universals exist in either form. For them, the world is composed exclusively of particulars. The position of conceptualists constitutes a middle ground: they state that universals exist, but only as concepts in the mind used to order experience by classifying entities.[45] Natural and social kinds are often understood as special types of universals. Entities belonging to the same natural kind share certain fundamental features characteristic of the structure of the natural world. In this regard, natural kinds are not an artificially made-up classification but are discovered,[f] usually by the natural sciences, and include kinds like electrons, H2O, and tigers. Scientific realists and anti-realists are in disagreement about whether natural kinds exist.[47] Social kinds are studied by social metaphysics and characterized as useful social constructions that, while not purely fictional, fail to reflect the fundamental structure of mind-independent reality.[48] Uncontroversial examples include money or baseball.[49] |

普遍 主な記事 普遍(形而上学) 普遍とは、性質と関係の両方を包含する一般的な実体であり、特定のものがどのようなものであり、それらが互いにどのように似ているかを表現するものであ る。普遍は反復可能であり、一意的な存在に限定されず、異なる特殊によって同時にインスタンス化されうる。例えば、ネルソン・マンデラとマハトマ・ガン ジーという特殊性は、イチゴとルビーが普遍的な赤をインスタンス化するのと同じように、普遍的な人類をインスタンス化する[43]。 古代哲学から議論されている普遍の問題は、普遍の存在論的地位を特徴づけるという課題からなる[44]。実在論者は、普遍は実在であり、特殊に加えて存在 する心とは独立した存在であると主張する。プラトン的実在論者によれば、普遍的なものは特殊的なものからも独立して存在し、普遍的な赤は赤いものがなかっ たとしても存在し続けるということになる。アリストテレスに触発された、より穏健な実在論は、普遍は特殊に依存する、つまり、普遍はインスタンス化されて 初めて実在するとする。名辞論者は、普遍がどちらの形でも存在するという考えを否定する。彼らにとって世界は特殊なものだけで構成されている。概念論者の 立場はその中間をなすものであり、彼らは普遍は存在するが、それは実体を分類することによって経験を秩序づけるために用いられる心の中の概念としてのみ存 在すると述べている[45]。 自然的種類と社会的種類はしばしば普遍の特別な種類として理解される。同じ自然類に属する存在は、自然界の構造に特徴的なある基本的特徴を共有している。 この点で、自然類は人為的に作り上げられた分類ではなく、通常は自然科学によって発見されるものであり[f]、電子、H2O、トラなどの類が含まれる。科 学的実在論者と反実在論者は、自然的類型が存在するかどうかについて意見が対立している[47]。社会的類型は社会形而上学によって研究され、純粋なフィ クションではないものの、心に依存しない現実の基本的構造を反映していない有用な社会的構築物として特徴づけられる[48]。 |

|

Possibility and necessity The concepts of possibility and necessity convey what can or must be the case, expressed in statements like "it is possible to find a cure for cancer" and "it is necessary that two plus two equals four". They belong to modal metaphysics, which investigates the metaphysical principles underlying them, in particular, why it is the case that some modal statements are true while others are false.[50][g] Some metaphysicians hold that modality is a fundamental aspect of reality, meaning that besides facts about what is the case, there are additional facts about what could or must be the case.[52] A different view argues that modal truths are not about an independent aspect of reality but can be reduced to non-modal characteristics, for example, to facts about what properties or linguistic descriptions are compatible with each other or to fictional statements.[53] Borrowing a term from German philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's theodicy, many metaphysicians use the concept of possible worlds to analyze the meaning and ontological ramifications of modal statements. A possible world is a complete and consistent way of how things could have been.[54] For example, the dinosaurs were wiped out in the actual world but there are possible worlds in which they are still alive.[55] According to possible world semantics, a statement is possibly true if it is true in at least one possible world while it is necessarily true if it is true in all possible worlds.[56] Modal realists argue that possible worlds exist as concrete entities in the same sense as the actual world, with the main difference being that the actual world is the world we live in while other possible worlds are inhabited by counterparts. This view is controversial and various alternatives have been suggested, for example, that possible worlds only exist as abstract objects or that they are similar to stories told in works of fiction.[57] |

可能性と必然性 可能性と必然性の概念は、「癌の治療法を見つけることは可能である」や「2+2=4であることは必然である」のような文で表現されるように、何が起こりう るか、あるいは何が起こらなければならないかを伝えるものである。形而上学者の中には、様相が現実の基本的な側面であり、何が事実であるかについての事実 のほかに、何が事実でありうるか、あるいは何が事実でなければならないかについての追加的な事実が存在することを意味する、と主張する者もいる[50] [g]。 [52]異なる見解では、様相真理は現実の独立した側面に関するものではなく、例えば、どのような性質や言語的記述が互いに適合するかについての事実や虚 構の記述など、様相以外の特徴に還元することができると主張している[53]。 ドイツの哲学者ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツの神義論から用語を借りて、多くの形而上学者は可能世界の概念を用いて、様相言明の意味と存在 論的な影響を分析している。例えば、恐竜は現実の世界では絶滅したが、恐竜がまだ生きている可能世界が存在する。 [56]様相実在論者は、可能世界は現実世界と同じ意味で具体的な実体として存在すると主張するが、主な違いは、現実世界が私たちの住む世界であるのに対 して、他の可能世界には対偶が住んでいるということである。この見解は議論の余地があり、様々な代替案が提案されている。例えば、可能世界は抽象的なオブ ジェクトとしてのみ存在するとか、フィクション作品で語られる物語に似ているといったものである[57]。 |

|

Space, time, and change Main article: Philosophy of space and time Space and time are dimensions that entities occupy. Spacetime realists state that space and time are fundamental aspects of reality and exist independently of the human mind. This view is rejected by spacetime idealists, who hold that space and time are constructions of the human mind in its attempt to organize and make sense of reality.[58] Spacetime absolutism or substantivalism understands spacetime as a distinct object, with some metaphysicians conceptualizing it as a box that contains all other entities within it. Spacetime relationism, by contrast, sees spacetime not as an object but as relations between objects, such as the spatial relation of being next to and the temporal relation of coming before.[59] In the metaphysics of time, an important contrast is between the A-series and the B-series. According to the A-series theory, the flow of time is real, meaning that events are categorized into the past, present, and future. The present keeps moving forward in time and events that are in the present now will change their status and lie in the past later. From the perspective of the B-series theory, time is static and events are ordered by the temporal relations earlier-than and later-than without any essential difference between past, present, and future.[60] Eternalism holds that past, present, and future are equally real while according to presentists, only entities in the present exist.[61] Material objects persist through time and change in the process, like a tree that grows or loses leaves.[62] The main ways of conceptualizing persistence through time are endurantism and perdurantism. According to endurantism, material objects are three-dimensional entities that are wholly present at each moment. As they change, they gain or lose properties but remain the same otherwise. Perdurantists see material objects as four-dimensional entities that extend through time and are made up of different temporal parts. At each moment, only one part of the object is present but not the object as a whole. Change means that an earlier part is qualitatively different from a later part. For example, if a banana ripens then there is an unripe part followed by a ripe part.[63] |

空間、時間、変化 主な記事 空間と時間の哲学 空間と時間は実体が占める次元である。時空実在論者は、空間と時間は現実の基本的な側面であり、人間の心とは無関係に存在すると述べる。この見解は時空間 観念論者によって否定され、空間と時間は現実を整理し理解しようとする人間の心が作り出したものであるとする[58]。時空間絶対主義または実体主義は時 空間を別個の物体として理解し、一部の形而上学者は時空間をその中に他のすべての実体を含む箱として概念化している。対照的に時空関係論は、時空を物体と してではなく、隣にあるという空間的関係や前に来るという時間的関係のような物体間の関係として捉える[59]。 時間の形而上学において、重要な対比はA系列とB系列である。A系列理論によれば、時間の流れは現実であり、出来事は過去、現在、未来に分類される。現在 は時間的に前進し続け、今現在にある出来事は、後にその地位を変えて過去に横たわる。B系列説の観点からすると、時間は静的であり、出来事は過去、現在、 未来の間に本質的な違いはなく、時間的な関係であるearlier-thanとlater-thanによって秩序づけられている[60]。永遠主義は過 去、現在、未来が等しく実在するとする一方で、現在主義者によれば、現在に存在する実体のみが実在するとする[61]。 物質的対象は時間を通じて持続し、その過程で木が成長したり葉を落としたりするように変化する[62]。時間を通じて持続することを概念化する主な方法は 持久主義と永続主義である。永続主義によれば、物質的対象は3次元の実体であり、それぞれの瞬間に完全に存在している。変化するにつれて、それらは特性を 得たり失ったりするが、それ以外は同じである。パーデュラント派は、物質的対象物を、時間を通じて拡張し、異なる時間的部分から構成される4次元の実体で あるとみなす。それぞれの瞬間において、物体の一部分だけが存在し、全体としては存在しない。変化とは、以前の部分が後の部分と質的に異なることを意味す る。例えば、バナナが熟すと、未熟な部分の後に熟した部分が存在する[63]。 |

|

Causality Main article: Causality Causality is the relation between cause and effect whereby one entity produces or affects another entity.[64] For instance, if a person bumps a glass and spills its contents then the bump is the cause and the spill is the effect.[65] Besides the single-case causation between particulars in this example, there is also general-case causation expressed in general statements such as "smoking causes cancer".[66] The term agent causation is used if people and their actions cause something.[67] Causation is usually interpreted deterministically, meaning that a cause always brings about its effect. This view is rejected by probabilistic theories, which claim that the cause merely increases the probability that the effect occurs. This view can be used to explain that smoking causes cancer even though this is not true in every single case.[68] The regularity theory of causation, inspired by David Hume's philosophy, states that causation is nothing but a constant conjunction in which the mind apprehends that one phenomenon, like putting one's hand in a fire, is always followed by another phenomenon, like a feeling of pain.[69] According to nomic regularity theories, the regularities take the forms of laws of nature studied by science.[70] Counterfactual theories focus not on regularities but on how effects depend on their causes. They state that effects owe their existence to the cause and would not be present without them.[71] According to primitivism, causation is a basic concept that cannot be analyzed in terms of non-causal concepts, such as regularities or dependence relations. One form of primitivism identifies causal powers inherent in entities as the underlying mechanism.[72] Eliminativists reject the above theories by holding that there is no causation.[73] |

因果性 主な記事 因果性 因果性とは原因と結果の間の関係であり、それによってある実体が別の実体を生み出したり、別の実体に影響を与えたりする。 [この例のような特殊なものの間の単一的な因果関係の他に、「喫煙が癌を引き起こす」というような一般的な記述で表現される一般的な因果関係もある [66]。因果関係という用語は、人やその行動が何かを引き起こす場合に使用される[67]。この見解は確率論的理論によって否定され、原因は単に結果が 生じる確率を増加させるだけであると主張する。この見解は、喫煙が癌を引き起こすことを説明するために使用される。 デイヴィッド・ヒュームの哲学に触発された因果関係の規則性理論は、因果関係とは、火の中に手を入れるというようなある現象が、痛みを感じるというような 別の現象に常に続くということを心が理解する一定の連関に過ぎないと述べている[69]。規則性理論によれば、規則性は科学によって研究される自然の法則 の形をとる[70]。原始主義によれば、因果関係は、規則性や依存関係といった非因果的な概念では分析できない基本的な概念である。原始主義の一形態は、 根底にあるメカニズムとして実体に内在する因果力を同定している[72]。排除主義者は因果関係は存在しないとすることで、上記の理論を否定している [73]。 |

|

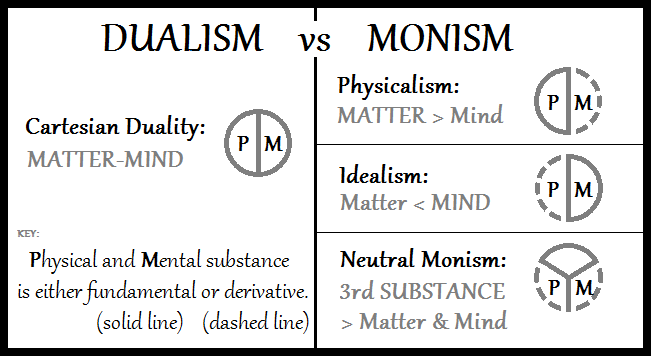

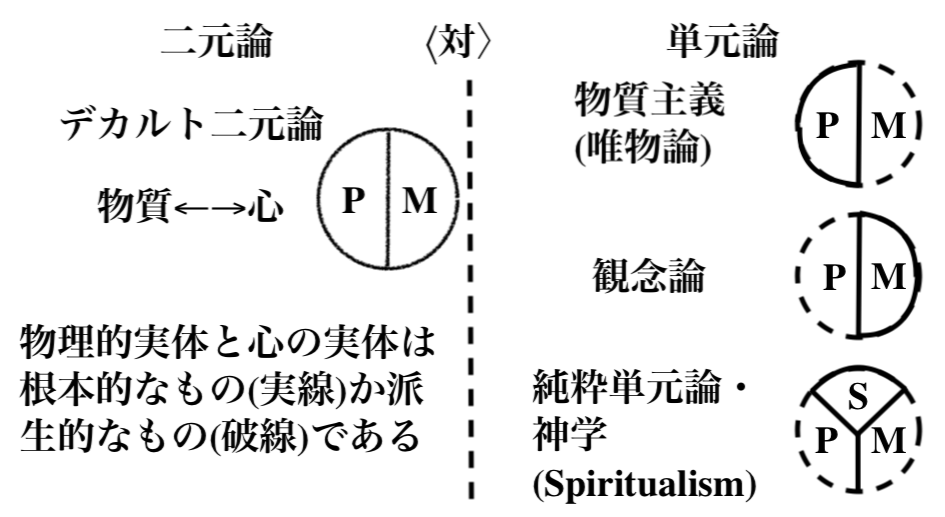

Mind and free will Main articles: Mind and Free will  Diagram of approaches to the mind–body problem Different approaches toward resolving the mind–body problem Mind encompasses phenomena like thinking, perceiving, feeling, and desiring as well as the underlying faculties responsible for these phenomena.[74] The mind–body problem is the challenge of clarifying the relation between physical and mental phenomena. According to Cartesian dualism, minds and bodies are distinct substances. They causally interact with each other in various ways but can, at least in principle, exist on their own.[75] This view is rejected by monists, who argue that reality is made up of only one kind. According to idealism, everything is mental, including physical objects, which may be understood as ideas or perceptions of conscious minds. Materialists, by contrast, state that all reality is at its core material. Some deny that mind exists but the more common approach is to explain mind in terms of certain aspects of matter, such as brain states, behavioral dispositions, or functional roles.[76] Neutral monists argue that reality is fundamentally neither material nor mental and suggest that matter and mind are both derivative phenomena.[77] A key aspect of the mind–body problem is the hard problem of consciousness, which concerns the question of how physical systems like brains can produce phenomenal consciousness.[78] The status of free will as the ability of a person to choose their actions is a central aspect of the mind–body problem.[79] Metaphysicians are interested in the relation between free will and causal determinism, the view that everything in the universe, including human behavior, is determined by preceding events and laws of nature. It is controversial whether causal determinism is true, and, if so, whether this would imply that there is no free will. According to incompatibilism, free will cannot exist in a deterministic world since there is no true choice or control if everything is determined.[h] Hard determinists infer from this observation that there is no free will while libertarians conclude that determinism must be false. Compatibilists take a third approach by arguing that determinism and free will do not exclude each other, for instance, because a person can still act in tune with their motivation and choices even if they are determined by other forces. Free will plays a key role in ethics regarding the moral responsibility people have for what they do.[81] |

心と自由意志 主な記事 心と自由意志  心身問題に対するアプローチの図 心身問題の解決に向けた様々なアプローチ 心とは、考える、知覚する、感じる、欲望するといった現象と、これらの現象を引き起こす根本的な能力を含む[74]。デカルトの二元論によれば、心と身体 は別個の物質である。この見解は一元論者によって否定され、現実はただ一種類のものから構成されていると主張する[75]。観念論によれば、物理的な物体 を含め、すべては精神的なものであり、それは意識的な精神の観念や知覚として理解することができる。これに対して唯物論者は、すべての現実の核心は物質で あるとする。心の存在を否定する者もいるが、より一般的なアプローチは、脳の状態、行動的性質、機能的役割といった物質の特定の側面から心を説明すること である[76]。中立的な一元論者は、現実は基本的に物質的でも精神的でもないと主張し、物質と心はどちらも派生的な現象であると示唆している[77]。 心身問題の重要な側面は意識のハード・プロブレムであり、脳のような物理的システムがどのようにして現象的な意識を生み出すことができるのかという問題に 関係している[78]。 形而上学者は自由意志と因果的決定論(人間の行動を含む宇宙のすべては先行する出来事や自然の法則によって決定されるという考え方)との関係に興味を持っ ている。因果的決定論が正しいかどうか、もしそうなら自由意志がないことを意味するかどうかについては議論がある。非適合主義によれば、すべてが決定され ているのであれば、真の選択もコントロールも存在しないので、決定論的世界には自由意志は存在し得ない[h]。ハード決定論者はこの観察から自由意志は存 在しないと推論し、自由主義者は決定論は偽でなければならないと結論付ける。コンパティビリストは第三のアプローチを取り、決定論と自由意志はお互いを排 除するものではないと主張する。自由意志は倫理学において、人が自分の行為に対して持つ道徳的責任に関して重要な役割を果たしている[81]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics |

★

| Others Identity is a relation that every entity has to itself as a form of sameness. It refers to numerical identity when the very same entity is involved, as in the statement "the morning star is the evening star" (both are the planet Venus). In a slightly different sense, it encompasses qualitative identity, also called exact similarity and indiscernibility, which is the case when two distinct entities are exactly alike, such as perfect identical twins.[82] The principle of the indiscernibility of identicals is widely accepted and holds that numerically identical entities exactly resemble one another. The converse principle, known as identity of indiscernibles or Leibniz's Law, is more controversial and states that two entities are numerically identical if they exactly resemble one another.[83] Another distinction is between synchronic and diachronic identity. Synchronic identity relates an entity to itself at the same time while diachronic identity is about the same entity at different times, as in statements like "the table I bought last year is the same as the table in my dining room now".[84] Personal identity is a related topic in metaphysics that uses the term identity in a slightly different sense and concerns questions like what personhood is or what makes someone a person.[85] Various contemporary metaphysicians rely on the concepts of truth, truth-bearer, and truthmaker to conduct their inquiry.[86] Truth is a property of being in accord with reality. Truth-bearers are entities that can be true or false, such as linguistic statements and mental representations. A truthmaker of a statement is the entity whose existence makes the statement true.[87] For example, the statement "a tomato is red" is true because there exists a red tomato as its truthmaker.[88] Based on this observation, it is possible to pursue metaphysical research by asking what the truthmakers of statements are, with different areas of metaphysics being dedicated to different types of statements. According to this view, modal metaphysics asks what makes statements about what is possible and necessary true while the metaphysics of time is interested in the truthmakers of temporal statements about the past, present, and future.[89] |

その他 同一性とは、あらゆる実体が同一性の一形態としてそれ自身に対して持つ関係である。朝の星は宵の明星である」(どちらも金星である)という文のように、 まったく同じ実体が関係する場合には、数的同一性を指す。少し異なる意味では、質的同一性を包含し、正確な類似性や無分別性とも呼ばれ、完全な一卵性双生 児のように2つの異なる実体が完全に似ている場合を指す[82]。ライプニッツの法則として知られる逆原則はより論争的であり、2つの実体が互いに完全に 類似している場合は数値的に同一であると述べている[83]。通時的同一性は、「去年買ったテーブルは、今私のダイニングルームにあるテーブルと同じであ る」というような記述のように、異なる時間における同じ実体に関するものであるのに対し、共時的同一性は、同じ実体を同じ時間におけるそれ自体に関連付け るものである[84]。 現代のさまざまな形而上学者は、真理、真理を担う者、真理をつくる者という概念に依拠して探究を行っている[86]。真理を伝える者とは、言語的言明や心 的表象など、真であることもあれば偽であることもある実体である。例えば、「トマトは赤い」という文が真であるのは、その真理を作るものとして赤いトマト が存在するからである[88]。この観察に基づけば、文の真理を作るものが何であるかを問うことによって形而上学的研究を進めることが可能であり、形而上 学の異なる領域は異なるタイプの文に特化している。この見解によれば、様相形而上学は、何が可能で何が必要であるかについての記述を真にするのかを問うも のであり、時間の形而上学は、過去、現在、未来についての時間的記述の真理決定者に関心を持つものである[89]。 |

| Methodology Metaphysicians employ a variety of methods to arrive at metaphysical theories and formulate arguments for and against them.[90] Traditionally, a priori methods are the dominant approach. They rely on rational intuition and abstract reasoning from general principles rather than sensory experience. A posteriori approaches, by contrast, ground metaphysical theories in empirical observations and scientific theories.[91] Some metaphysicians use perspectives from fields such as physics, psychology, linguistics, and history to conduct their inquiry.[92] The two approaches are not exclusive and it is possible to combine elements from both.[93] Which method a metaphysician employs often depends on their conception of the nature of metaphysics, for example, whether they see it as an inquiry into the mind-independent structure of reality, as metaphysical realists claim, or the principles underlying thought and experience, as some metaphysical anti-realists contend.[94] A priori approaches often rely on intuitions, that is, non-inferential impressions about the correctness of specific claims or general principles.[95] For example, arguments for the A-theory of time, which states that time flows from the past through the present and into the future, often rely on pre-theoretical intuitions associated with the sense of the passage of time.[96] Some approaches use intuitions to establish a small set of self-evident fundamental principles, known as axioms, and employ deductive reasoning to build complex metaphysical systems by drawing conclusions from these axioms.[97] Intuition-based approaches can be combined with thought experiments, which help evoke and clarify intuitions by linking them to imagined situations while using counterfactual thinking to assess the possible consequences of these situations.[98] To explore the relation between matter and consciousness, some theorists compare humans to philosophical zombies, that is, hypothetical creatures identical to humans but without conscious experience.[99] A related method relies on commonly accepted beliefs instead of intuitions to formulate arguments and theories. The common-sense approach is often used to criticize metaphysical theories that deviate a lot from how the average person thinks about an issue. For example, common-sense philosophers have argued that mereological nihilism is false since it implies that commonly accepted things, like tables, do not exist.[100] Conceptual analysis, a method particularly prominent in analytic philosophy, aims to decompose metaphysical concepts into component parts to clarify their meaning and identify essential relations.[101] In phenomenology, the method of eidetic variation is used to investigate essential structures underlying phenomena. To study the essential features of any kind of object, it proceeds by imagining this object and varying its features to identify which ones are essential and cannot be changed.[102] The transcendental method is a further approach and examines the metaphysical structure of reality by observing what entities there are and studying the conditions of possibility without which these entities could not exist.[103] Some approaches give less importance to a priori reasoning and see metaphysics instead as a practice continuous with the empirical sciences that generalizes their insights while making their underlying assumptions explicit. This approach is known as naturalized metaphysics and is closely associated with the work of Willard Van Orman Quine.[104] He relies on the idea that true sentences from the sciences and other fields have ontological commitments, that is, they imply that certain entities exist.[105] For example, if the sentence "some electrons are bonded to protons" is true then it can be used to justify that electrons and protons exist.[106] Quine used this insight to argue that one can learn about metaphysics by closely analyzing[i] scientific claims to understand what kind of metaphysical picture of the world they presuppose.[108] In addition to methods of conducting metaphysical inquiry, there are various methodological principles used to decide between competing theories by comparing their theoretical virtues. Ockham's Razor is a well-known principle that gives preference to simple theories, in particular, to theories that assume that few entities exist. Other principles consider explanatory power, theoretical usefulness, and proximity to established beliefs.[109] |

方法論 形而上学者は、形而上学的理論に到達し、それに対する賛否を論証するために様々な方法を用いる[90]。先験的な方法は、感覚的な経験よりもむしろ一般的 な原理からの合理的な直観と抽象的な推論に依存している。これとは対照的に、事後的アプローチは、形而上学的理論を経験的観察や科学的理論に基づかせる [91]。 形而上学者の中には、物理学、心理学、言語学、歴史学などの分野からの視点を用いて探求を行う者もいる[92]。 [例えば、形而上学的実在論者が主張するように、形而上学を現実の精神に依存しない構造に対する探究とみなすか、形而上学的反実在論者が主張するように、 思考と経験の根底にある原理に対する探究とみなすかである[94]。 アプリオリなアプローチはしばしば直観、つまり特定の主張や一般的な原理の正しさについての非推論的な印象に依拠している[95]。例えば、時間は過去か ら現在を経て未来へと流れるという時間のA理論に対する議論は、しばしば時間の経過の感覚に関連する理論以前の直観に依拠している。 [96]いくつかのアプローチは、公理として知られる自明な基本原理の小さなセットを確立するために直観を使用し、これらの公理から結論を引き出すことに よって複雑な形而上学的体系を構築するために演繹的推論を採用している。 [直観に基づくアプローチは、思考実験と組み合わせることができる。思考実験は、直観を想像される状況に結びつけながら、反事実的思考を用いてこれらの状 況から起こりうる結果を評価することで、直観を喚起し明確にするのに役立つ[98]。物質と意識の関係を探求するために、人間を哲学的ゾンビ、つまり人間 と同じであるが意識的経験を持たない仮想的な生き物と比較する理論家もいる[99]。常識的アプローチは、ある問題についての一般人の考え方から大きく逸 脱した形而上学的理論を批判するためによく用いられる。例えば、常識的な哲学者たちは、テーブルのような一般的に受け入れられているものは存在しないとい うことを意味しているため、唯物論的ニヒリズムは誤りであると主張している[100]。 分析哲学において特に顕著な方法である概念分析は、形而上学的概念を構成要素に分解してその意味を明らかにし、本質的な関係を特定することを目的としてい る[101]。超越論的方法はさらなるアプローチであり、どのような実体が存在するかを観察し、これらの実体が存在することができない可能性の条件を研究 することによって、現実の形而上学的構造を検討する[103]。 先験的な推論をあまり重要視せず、代わりに形而上学を経験科学と連続した実践としてとらえ、その根底にある仮定を明示しながらその洞察を一般化するアプ ローチもある。このアプローチは自然化された形而上学として知られており、ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クインの仕事と密接に関連している[104]。 彼は科学や他の分野からの真の文章は存在論的なコミットメントを持っている、つまり特定の実体が存在することを暗示しているという考えに依拠している。 [例えば、「いくつかの電子は陽子と結合している」という文が真であるならば、それは電子と陽子が存在することを正当化するために使用することができる [106]。クワインはこの洞察を用いて、科学的主張を綿密に分析することによって形而上学を学ぶことができると主張し、科学的主張がどのような形而上学 的な世界像を前提としているのかを理解した[108]。 形而上学的な探究を行う方法に加えて、理論的な美点を比較することによって競合する理論間を決定するために使用される様々な方法論的原則がある。オッカム の剃刀」はよく知られた原理であり、単純な理論、特に実体がほとんど存在しないと仮定する理論を優先する。その他の原則は、説明力、理論的有用性、確立さ れた信念への近さを考慮するものである[109]。 |

Criticism David Hume criticized metaphysicians for trying to arrive at knowledge outside the field of sensory experience. Despite its status as one of the main branches of philosophy, metaphysics has received numerous criticisms putting into question its status as a legitimate field of inquiry.[110] One type of criticism states that metaphysical inquiry is impossible because humans do not have the cognitive capacities needed to access the ultimate nature of reality.[111] This line of thought leads to a form of skepticism about the possibility of metaphysical knowledge. It is often followed by empiricists like Hume, who argue that there is no good source of metaphysical knowledge since metaphysics lies outside the field of empirical knowledge and relies on dubious intuitions about the realm beyond sensory experience. A closely related concern about the unreliability of metaphysical theorizing is that there are deep and lasting disagreements about metaphysical issues, indicating a lack of overall progress.[112] Another criticism holds that the problem lies not with human cognitive abilities but with metaphysical statements themselves, which are claimed to be neither true nor false but meaningless. According to logical positivists, for instance, the meaning of a statement is given by the procedure used to verify it, usually in terms of the observations that would confirm it. Based on this controversial assumption, they argue that metaphysical statements are meaningless since they do not make predictions about experience.[113] A slightly weaker position allows metaphysical statements to have meaning while holding that metaphysical disagreements are merely verbal disputes about different ways to describe the world. According to this view, the disagreement in the metaphysics of composition about whether there are tables or only particles arranged table-wise is a trivial debate about linguistic preferences without any substantive consequences for the nature of reality.[114] The position that metaphysical disputes have no meaning or no significant point is called metaphysical or ontological deflationism.[115] This view is opposed by serious metaphysicians, who contend that metaphysical disputes are about substantial features of the underlying structure of reality.[116] A closely related debate between ontological realists and anti-realists concerns the question of whether there are any objective facts that determine which metaphysical theories are true.[117] A different criticism, formulated by pragmatists, sees the fault of metaphysics not in its cognitive ambitions or the meaninglessness of its statements, but in its practical irrelevance and lack of usefulness.[118] It is questionable to what extent the criticisms of metaphysics affect the discipline as a whole or only certain issues or approaches in it. For example, it could be the case that certain metaphysical disputes are merely verbal while others are substantive.[119] |

批評 デイヴィッド・ヒュームは、形而上学者が感覚的経験の領域外の知識に到達しようとしていることを批判した。 形而上学は哲学の主要な一分野であるにもかかわらず、その正当な探究分野としての地位を疑問視する多くの批判を受けてきた[110]。ある種の批判は、人 間には現実の究極的な本質にアクセスするのに必要な認識能力がないため、形而上学的な探究は不可能であるとする[111]。ヒュームのような経験主義者 は、形而上学は経験的知識の分野の外にあり、感覚的経験を超えた領域に関する疑わしい直観に依存しているため、形而上学的知識の良い情報源は存在しないと 主張する。形而上学的理論化の信頼性の低さに関する密接に関連した懸念は、形而上学的問題に関して深く永続的な意見の相違があり、全体的な進歩の欠如を示 しているということである[112]。 もう一つの批判は、問題は人間の認識能力にあるのではなく、真でも偽でもなく無意味であると主張される形而上学的言明そのものにあるというものである。例 えば、論理実証主義者によれば、ある言明の意味は、それを検証するために使用される手順によって、通常はそれを確認するような観察によって与えられる。こ の論争の的となる仮定に基づいて、彼らは形而上学的言明は経験についての予測を行わないので無意味であると主張する[113]。 少し弱い立場は、形而上学的な意見の相違は世界を記述する異なる方法についての言葉による論争に過ぎないとしながらも、形而上学的な記述に意味があること を認めている。この見解によれば、組成の形而上学における、テーブルが存在するのか、テーブル状に並べられた粒子だけが存在するのかについての意見の相違 は、現実の性質に対する実質的な影響を伴わない、言語的嗜好に関する些細な議論である[114]。形而上学的論争には意味がない、あるいは重要な論点がな いという立場は、形而上学的または存在論的デフレーション主義と呼ばれている[115]。この見解は、形而上学的論争は現実の根本的な構造の実質的な特徴 に関するものであると主張する、真面目な形而上学者によって反対されている。 [116] 存在論的実在論者と反実在論者の間の密接に関連した議論は、どの形而上学的理論が真であるかを決定する客観的事実が存在するかどうかという問題に関係して いる[117]。プラグマティストによって定式化された別の批判は、形而上学の欠点をその認識的野心やその言明の無意味さにではなく、その実際的な無関連 性と有用性の欠如にあると見ている[118]。 形而上学に対する批判が学問分野全体にどの程度影響を及ぼしているのか、あるいはその中の特定の問題やアプローチのみに影響を及ぼしているのかは疑問であ る。例えば、ある形而上学的な論争が単に言葉上のものであるのに対して、他の論争が本質的なものであるということもあり得る[119]。 |

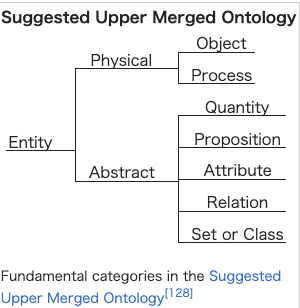

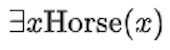

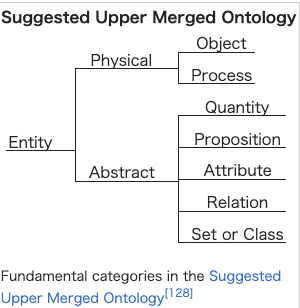

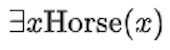

| elation to other disciplines Metaphysics is related to many fields of inquiry by investigating their basic concepts and relation to the fundamental structure of reality. For example, scientists often rely on concepts such as law of nature, causation, necessity, and spacetime to formulate their theories and predict or explain the outcomes of experiments.[120] While the main focus of scientists is on the application of these concepts to specific situations, metaphysics examines their general nature and how they depend on each other. Physicists formulate specific laws of nature, like laws of gravitation and thermodynamics, to describe how physical systems behave under various conditions. Metaphysicians, by contrast, ask what all laws of nature have in common, for example, whether they merely describe contingent regularities or express necessary relations.[121] At the same time, new scientific findings have also influenced existing and inspired new metaphysical theories. Einstein's theory of relativity, for instance, prompted various metaphysicians to conceive space and time as a unified dimension rather than as independent dimensions.[122] Empirically focused metaphysicians often rely on scientific theories to ground their theories about the nature of reality in empirical observations.[123] Similar issues pertain to the social sciences where metaphysicians investigate their basic concepts and analyze their metaphysical implications. This includes questions like whether social facts arise from non-social facts, whether social groups and institutions have mind-independent existence, and how they persist through time.[124] Metaphysical assumptions and topics in psychology and psychiatry include the questions about the relation between body and mind, whether the nature of the human mind is historically fixed, and what the metaphysical status of diseases is.[125] Metaphysics is similar to both physical cosmology and theology in its interest in the first causes and the universe as a whole. Key differences are that metaphysics relies on rational inquiry while physical cosmology gives more weight to empirical observations and theology is additionally based on divine revelation and faith-based doctrines.[126] Historically, cosmology and theology were considered subfields of metaphysics.[127] Suggested Upper Merged Ontology  Fundamental categories in the Suggested Upper Merged Ontology[128] Metaphysics in the form of ontology plays a central role in computer science to classify objects and formally represent information about them. Unlike metaphysicians, computer scientists are usually not interested in providing a single all-encompassing characterization of reality as a whole but instead employ many different ontologies, each one concerned only with a limited domain of entities.[129] For example, a college database may use an ontology with categories such as person, teacher, student, and exam to represent information about academic activities.[130] Ontologies provide standards or conceptualizations for encoding and storing information in a structured way, which makes it possible to use and transform the information by computational processes for a variety of purposes.[131] Some knowledge bases integrate information belonging to various domains, which brings with it the problem of handling data that was formulated using different ontologies. They do so by providing an upper ontology that defines concepts on a higher level of abstraction to apply to all domains. Influential upper ontologies include Suggested Upper Merged Ontology and Basic Formal Ontology.[132] Logic as the study of correct reasoning[133] is often used by metaphysicians as a tool to engage in their inquiry and express insights using precise logical formulas.[134] Another relation between the two fields concerns the metaphysical assumptions associated with logical systems. Many logical systems like first-order logic rely on existential quantifiers to express existential statements. For instance, in the logical formula  Horsethe existential quantifier is applied to the predicate  to express that there are horses. Following Quine, various metaphysicians assume that existential quantifiers carry ontological commitments, meaning that existential statements imply that the entities over which one quantifies form part of reality.[135] |

他の学問分野との関係 形而上学は、その基本概念と現実の基本構造との関係を調査することによって、多くの探究分野と関連している。例えば、科学者はしばしば、自然法則、因果関 係、必然性、時空などの概念に依拠して理論を構築し、実験結果を予測したり説明したりする[120]。科学者がこれらの概念を特定の状況に適用することに 主眼を置いているのに対し、形而上学はこれらの概念の一般的な性質や、それらが互いにどのように依存しているかを検討する。物理学者は、重力法則や熱力学 の法則のような特定の自然法則を定式化し、物理システムが様々な条件下でどのように振る舞うかを記述する。これとは対照的に形而上学者は、すべての自然法 則に共通するものは何か、例えばそれらは単に偶発的な規則性を記述しているのか、それとも必要な関係を表現しているのかを問う[121]。例えば、アイン シュタインの相対性理論は、様々な形而上学者に、空間と時間を独立した次元としてではなく、統一された次元として考えるように促した[122]。経験重視 の形而上学者は、現実の本質に関する理論を経験的観察に基づかせるために、しばしば科学理論に依存している[123]。 同様の問題は、形而上学者がその基本概念を調査し、その形而上学的な意味を分析する社会科学にも関係している。これには、社会的事実は非社会的事実から生 じるのか、社会集団や社会制度は心に依存しない存在であるのか、時間を通じてどのように持続するのかといった疑問が含まれる[124]。心理学や精神医学 における形而上学的な仮定やトピックには、身体と心の関係についての疑問、人間の心の性質は歴史的に固定されているのか、病気の形而上学的な地位とは何か といったものが含まれる[125]。 形而上学は、第一原因や宇宙全体への関心において、物理学的宇宙論や神学と類似している。主な違いは、形而上学が合理的な探究に依拠するのに対して、物理学的宇宙論は経験的観察をより重視し、神学はさらに神の啓示と信仰に基づく教義に基づいていることである[126]。 統合された上位存在論の提案  提案された上位統合オントロジー[128]における基本カテゴリー オントロジーという形の形而上学は、オブジェクトを分類し、それらに関する情報を正式に表現するために、コンピュータサイエンスにおいて中心的な役割を果 たす。形而上学者とは異なり、コンピュータ科学者は通常、全体として現実の単一の包括的な特徴付けを提供することに興味を持たず、その代わりに多くの異な るオントロジーを採用し、それぞれがエンティティの限定されたドメインにのみ関係している[129]。 [オントロジーは、構造化された方法で情報を符号化し、格納するための標準または概念化を提供し、さまざまな目的のために計算処理によって情報を使用し、 変換することを可能にする[131]。さまざまなドメインに属する情報を統合する知識ベースもあるが、これは異なるオントロジーを使用して定式化された データを扱うという問題をもたらす。そのため、すべてのドメインに適用できるように、より抽象度の高い概念を定義する上位オントロジーを提供することで対 応している。影響力のある上位オントロジーには、Suggested Upper Merged OntologyやBasic Formal Ontologyなどがある[132]。 正しい推論[133]の学問としての論理学は、形而上学者によって、その探究に従事し、正確な論理式を使って洞察を表現するためのツールとしてしばしば使 用される[134]。一階論理のような多くの論理システムは、実存的な記述を表現するために実存的量化子に依存している。例えば  は述語に適用される。は述語 (Horce)  に対して存在量化詞∃{displaystyle {text{Horse}}} を適用し、馬が存在することを表現する。クワインに続いて、様々な形而上学者が、存在量化詞は存在論的なコミットメントを持つと仮定している。 |

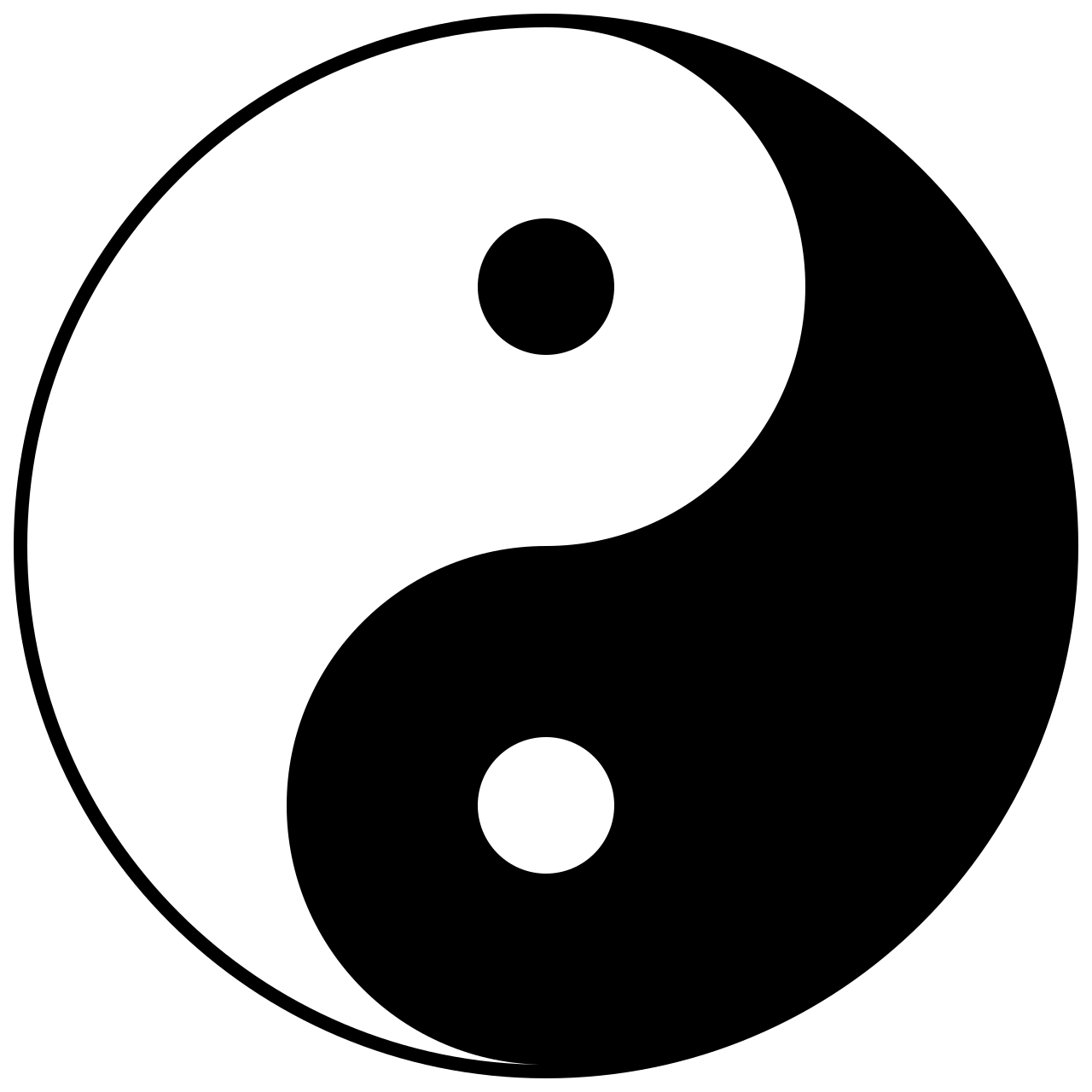

| History Main article: History of metaphysics  Symbol of yin and yang The taijitu symbol shows yin and yang, which are concepts of two correlated forces used in Chinese metaphysics to explore the nature and patterns of existence.[136] The history of metaphysics examines how the inquiry into the basic structure of reality has evolved in the course of history. Metaphysics has its origin in speculations about the nature and origin of the cosmos that go back to ancient civilizations.[137] In ancient India starting in the 7th century BCE, the Upanishads were written as religious and philosophical texts that examine how ultimate reality constitutes the ground of all being. They further explore the nature of the self and how it can reach liberation by understanding ultimate reality.[138] This period also saw the emergence of Buddhism in the 6th century BCE,[j] which denies the existence of an independent self and understands the world as a cyclic process.[140] At about the same time[k] in ancient China, the school of Daoism was formed and explored the natural order of the universe, known as Dao, and how it is characterized by the interplay of yin and yang as two correlated forces.[142] In ancient Greece, metaphysics emerged in the 6th century BCE with the pre-Socratic philosophers, who gave rational explanations of the whole cosmos by examining the first principles from which everything arises.[143] Following them, Plato (427–347 BCE) formulated his theory of forms, which states that eternal forms or ideas possess the highest kind of reality while the material world is only an imperfect reflection of them.[144] Aristotle (384–322 BCE) accepted Plato's idea that there are universal forms but held that they cannot exist on their own but depend on matter. He also proposed a system of categories and developed a comprehensive framework of the natural world through his theory of the four causes.[145] Starting in the 4th century BCE, Hellenistic philosophy explored the rational order underlying the cosmos and the idea that it is made up of indivisible atoms.[146] Neoplatonism emerged towards the end of the ancient period in the 3rd century CE and introduced the idea of "the One" as a transcendent and ineffable entity that is the source of all of creation.[147] Meanwhile, in Indian Buddhism, the Madhyamaka school developed the idea that all phenomena are inherently empty without a permanent essence while the consciousness-only doctrine of the Yogācāra school stated that experienced objects are mere transformations of consciousness that do not reflect external reality.[148] The Hindu school of Samkhya philosophy[l] introduced a metaphysical dualism with pure consciousness and matter as its fundamental categories.[149] In China, the school of Xuanxue explored metaphysical problems such as the contrast between being and non-being.[150] Illustration of Boethius  Boethius's theory of universals influenced many subsequent metaphysicians. Medieval Western philosophy was strongly influenced by ancient Greek philosophy. Boethius (477–524 CE) attempted to harmonize Plato's and Aristotle's theories of universals by stating that universals can exist both in matter and mind. His theory inspired the philosophies of nominalism and conceptualism, as in the thought of Peter Abelard (1079–1142 CE).[151] Thomas Aquinas (1224–1274 CE) understood metaphysics as the discipline that investigates the different meanings of being, such as the contrast between substance and accident, and principles applying to all beings, such as the principle of identity.[152] William of Ockham (1285–1347 CE) proposed the methodological principles of Ockham's razor as a tool to decide between competing metaphysical theories.[153] Arabic–Persian philosophy, which had its prime period from the early 9th century CE to the late 12th century CE, employed many ideas of the ancient Greek philosophers to interpret and clarify the teachings of the Quran.[154] Avicenna (980–1037 CE) developed a comprehensive philosophical system that examined the contrast between existence and essence and distinguished between contingent and necessary existence.[155] Medieval India saw the emergence of the monist school of Advaita Vedanta in the 8th century CE, which holds that everything is one and that the idea of many entities existing independently is an illusion.[156] In China, Neo-Confucianism arose in the 9th century CE and explored the concept of li as the rational principle that is the ground of being and reflects the order of the universe.[157] In the early modern period, René Descartes (1596–1650) developed a substance dualism according to which body and mind exist as independent entities that causally interact.[158] This idea was rejected by Baruch Spinoza (1632–1677), who formulated a monist philosophy according to which there is only one substance that has both physical and mental attributes developing side-by-side without interacting.[159] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) introduced the concept of possible worlds and articulated a metaphysical system, known as monadology, that understands the universe as a collection of simple substances that are synchronized without causally interacting with one another.[160] Christian Wolff (1679–1754), conceptualized the scope of metaphysics by introducing the distinction between general and special metaphysics.[161] According to the idealism of George Berkeley (1685–1753), everything is mental, including material objects, which are ideas perceived by the mind.[162] David Hume (1711–1776) made various contributions to metaphysics, including the regularity theory of causation and the idea that there are no necessary connections between distinct entities. At the same time, his empiricist outlook led him to formulate a stark criticism of metaphysical theories that aim to arrive at ultimate principles inaccessible to sensory experience.[163] This skeptical outlook was embraced by Immanuel Kant (1724–1804). He tried to reconceptualize metaphysics as a critical inquiry into the basic principles and categories of thought and understanding rather than seeing it as an attempt to comprehend mind-independent reality.[164] Many developments in the later modern period were shaped by Kant's philosophy. German idealists employed his idealistic outlook in their attempt to find a unifying principle as the foundation of all reality.[165] Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770–1831) developed a comprehensive system of philosophy that examines how absolute spirit manifests itself.[166] He inspired the British idealism of Francis Herbert Bradley (1846–1924), who interpreted absolute spirit as the all-inclusive totality of being.[167] Arthur Schopenhauer (1788–1860) was a strong critic of German idealism and articulated a different metaphysical vision that takes a blind and irrational will as the underlying principle of reality.[168] Pragmatists like C. S. Peirce (1839–1914) and John Dewey (1859–1952) conceived metaphysics as an observational science of the most general features of reality and experience.[169]  Alfred North Whitehead articulated the foundations of process philosophy in his work Process and Reality. At the turn of the 20th century in analytic philosophy, philosophers like Bertrand Russell (1872–1970) and George Edward Moore's (1873–1958) led a "revolt against idealism".[170] Logical atomists, like Russell and the early Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), conceived the world as a multitude of atomic facts, which inspired later metaphysicians such as D. M. Armstrong (1926–2014).[171] Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) developed process metaphysics as an attempt to provide a holistic description of both the objective and the subjective worlds.[172] Rudolf Carnap (1891–1970) and other logical positivists formulated a wide-ranging criticism of metaphysical statements by holding that they are meaningless since there is no way to verify them.[173] Other criticisms of traditional metaphysics identified misunderstandings of ordinary language as the source of many traditional metaphysical problems or challenged complex metaphysical deductions by relying on common sense.[174] The decline of logical positivism saw a revival of metaphysical theorizing.[175] Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000) tried to naturalize metaphysics by connecting it to the empirical sciences. His student David Lewis (1941–2001) employed the concept of possible worlds to formulate his modal realism.[176] Saul Kripke (1940–2022) helped revive discussions of identity and essentialism, and distinguished necessity as a metaphysical notion from the epistemic notion of a priori.[177] In continental philosophy, Edmund Husserl (1859–1938) engaged in ontology through a phenomenological description of experience while his student Martin Heidegger (1889–1976) developed fundamental ontology as an attempt to clarify the meaning of being.[178] Heidegger's philosophy inspired general criticisms of metaphysics by postmodern thinkers like Jacques Derrida (1930–2004).[179] |

沿革 主な記事 形而上学の歴史  陰陽のシンボル 太極図のシンボルは陰と陽を示しており、これは中国の形而上学において存在の本質とパターンを探求するために用いられる、相関する2つの力の概念である[136]。 形而上学の歴史は、現実の基本構造に対する探究が歴史の中でどのように発展してきたかを検証するものである。形而上学は、古代文明に遡る宇宙の本質と起源 に関する思索にその起源を持つ[137]。紀元前7世紀に始まる古代インドでは、ウパニシャッドが宗教的・哲学的なテキストとして書かれ、究極的な実在が いかにしてすべての存在の根底を構成しているかを検証している。ほぼ同時期に[k]、古代中国では道教の学派が形成され、道として知られる宇宙の自然の秩 序と、それがどのように二つの相関する力としての陰と陽の相互作用によって特徴付けられるかを探求した[142]。 古代ギリシアでは、形而上学は紀元前6世紀にソクラテス以前の哲学者たちによって出現し、彼らはすべてのものが生じる第一原理を考察することによって宇宙 全体の合理的な説明を与えた。 [143]プラトン(前427-前347)は彼らに続いて形相論を唱え、永遠の形相やイデアは最高の実在性を持っているが、物質世界はそれらの不完全な反 映に過ぎないとした[144]。アリストテレス(前384-前322)は普遍的な形相が存在するというプラトンの考えを受け入れたが、それらは単独では存 在できず物質に依存しているとした。紀元前4世紀に始まったヘレニズム哲学は、宇宙の根底にある合理的な秩序と、それが不可分な原子で構成されているとい う考えを探求した[146]。紀元前3世紀の古代末期に新プラトン主義が登場し、すべての創造の源である超越的で不可解な存在としての「唯一」の考えを導 入した[147]。 一方、インド仏教では、マディヤマカ学派が、すべての現象は永続的な本質を持たず本質的に空であるという考えを発展させ、一方、ヨーガーカーラ学派の意識のみの教義は、経験された対象は外的現実を反映しない意識の単なる変容であると述べていた[148]。 ボエティウスの図解  ボエティウスの普遍論はその後の多くの形而上学者に影響を与えた。 中世の西洋哲学は古代ギリシア哲学の影響を強く受けていた。ボエティウス(CE477-524)は、普遍は物質と心の両方に存在しうると述べることで、プ ラトンとアリストテレスの普遍論を調和させようとした。彼の理論は、ピーター・アベラール(Peter Abelard, 1079-1142 CE)の思想のように、名辞論と概念論の哲学に影響を与えた[151]。トマス・アクィナス(Thomas Aquinas, 1224-1274 CE)は形而上学を、物質と偶然の対比のような存在のさまざまな意味や、同一性の原理のようなすべての存在に適用される原理を研究する学問であると理解し ていた。 [152] オッカムのウィリアム(William of Ockham, 1285-1347 CE)は、競合する形而上学的理論を決定するための道具として、オッカムの剃刀の方法原理を提唱した[153]。 9世紀初頭から12世紀後半にかけて最盛期を迎えたアラビア・ペルシャ哲学は、コーランの教えを解釈し、明確にするために古代ギリシャ哲学者の多くの考え 方を採用した。 [154]アヴィセンナ(980-1037年)は、存在と本質の対比を考察し、偶発的存在と必要的存在を区別する包括的な哲学体系を構築した。 [155]中世インドでは、8世紀にアドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタの一元論学派が出現し、万物は一つであり、独立して存在する多くの実体という考えは幻想 であるとした[156]。中国では、9世紀に新儒教が発生し、存在の根拠であり宇宙の秩序を反映する合理的原理としての「理」の概念を探求した [157]。 この考えはバルーク・スピノザ(1632-1677)によって否定され、肉体的属性と精神的属性の両方を持ち、相互作用することなく並行して発展する唯一 の物質が存在するという一元論的な哲学を打ち立てた[159]。 [ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツ(Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, 1646-1716)は可能世界の概念を導入し、宇宙を互いに因果的に相互作用することなく同期している単純な物質の集合体として理解する、単子論として 知られる形而上学的体系を明確にした。 [ジョージ・バークレー(1685-1753)の観念論によれば、すべては心的なものであり、心によって知覚される観念である物質的対象もそのひとつであ る[162]。デイヴィッド・ヒューム(1711-1776)は、因果関係の規則性理論や、異なる実体間には必然的な結びつきは存在しないという考え方な ど、形而上学にさまざまな貢献をした。同時に、彼の経験主義的な考え方は、感覚的な経験にアクセスできない究極的な原理に到達することを目的とする形而上 学的な理論に対する厳しい批判を打ち立てることになった[163]。彼は形而上学を、心に依存しない現実を理解する試みとみなすのではなく、思考と理解の 基本原理とカテゴリーに対する批判的探究として再認識しようとした[164]。 後期近代における多くの発展はカントの哲学によって形成された。ゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲル(Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831)は、絶対精神がどのようにそれ自身を現すかを考察する包括的な哲学体系を構築した[166]。 彼は絶対精神を存在のすべてを包括する全体性として解釈したフランシス・ハーバート・ブラッドリー(Francis Herbert Bradley, 1846-1924)のイギリス観念論に影響を与えた。 [167]アルトゥール・ショーペンハウアー(1788-1860)はドイツ観念論を強く批判し、盲目的で非合理的な意志を現実の根本原理とする異なる形 而上学的ヴィジョンを明確にした[168]。C・S・パース(1839-1914)やジョン・デューイ(1859-1952)のようなプラグマティストは 形而上学を現実と経験の最も一般的な特徴の観察科学として考えた[169]。  アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドは、その著作『過程と現実』において、過程哲学の基礎を明確にした。 20世紀に入ると、分析哲学において、バートランド・ラッセル(1872-1970)やジョージ・エドワード・ムーア(1873-1958)のような哲学 者たちが「観念論への反乱」を起こした[170]。ラッセルや初期のルートヴィヒ・ウィトゲンシュタイン(1889-1951)のような論理的原子論者た ちは、世界を多数の原子的事実として考え、後の形而上学者であるD. アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッド(1861-1947)は、客観的世界と主観的世界の両方の全体的な記述を提供する試みとして、過程形而上学を発展 させた[172]。 ルドルフ・カルナップ(Rudolf Carnap, 1891-1970)をはじめとする論理実証主義者たちは、形而上学的な言明は検証する方法がないため無意味であるとすることで、形而上学的な言明に対す る広範な批判を展開していた[173]。 伝統的な形而上学に対する他の批判は、伝統的な形而上学的問題の多くの原因として通常の言語の誤解を特定したり、常識に依拠することで複雑な形而上学的演 繹に異議を唱えたりしていた[174]。 ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン(1908-2000)は形而上学を経験科学と結びつけることによって自然化しようとした。彼の弟子であるデイ ヴィッド・ルイス(David Lewis, 1941-2001)は可能世界の概念を用いて彼の様相実在論を定式化していた[176]。ソール・クリプキ(Saul Kripke, 1940-2022)は同一性と本質論の議論を復活させることに貢献し、形而上学的概念としての必然性をアプリオリの認識論的概念から区別していた [177]。 大陸哲学においては、エドムント・フッサール(Edmund Husserl, 1859-1938)が経験の現象学的記述を通じて存在論に取り組む一方で、彼の弟子であるマルティン・ハイデガー(Martin Heidegger, 1889-1976)は存在の意味を明らかにする試みとして基本的存在論を展開していた[178]。ハイデガーの哲学は、ジャック・デリダ (Jacques Derrida, 1930-2004)のようなポストモダンの思想家たちによる形而上学に対する一般的な批判に影響を与えていた[179]。 |

| Computational metaphysics Doctor of Metaphysics Enrico Berti's classification of metaphysics Feminist metaphysics Fundamental question of metaphysics List of metaphysicians Metaphysical grounding |

計算形而上学 形而上学博士 エンリコ・ベルティの形而上学の分類 フェミニスト形而上学 形而上学の根本問題 形而上学者のリスト 形而上学的根拠 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Metaphysics |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆