ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ

Michel de Montaigne, 1533-1592

1570年ごろのモンテーニュ

☆ ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュは、フランス・ルネサンス期を代表する哲学者の一人である。文学のジャンルとしてエッセイを普及させたことで知られる。彼の作 品は、何気ない逸話や自伝を知的洞察と融合させていることで知られている。モンテーニュは多くの西洋の作家に直接的な影響を与えた。彼の膨大なエッ セイ集には、これまでに書かれた中で最も影響力のあるエッセイのいくつかが収められている。生前、モンテーニュは作家としてよりも政治家として賞賛された。彼のエッセイには、逸話や個人的な考察に脱線する傾向があり、それは革新的というよりもむ しろ、正しいスタイルを損なうものと見なされ、また、「私自身が私の本の主題である」という彼の宣言は、同時代の人々から独りよがりと見なされた。しか し、やがてモンテーニュは、おそらく同時代のどの作家よりも、当時生まれ始めた自由闊達な懐疑の精神を体現した人物として認識されるようになった。彼の懐 疑的な発言で最も有名なのは、「Que sçay-je? (中フランス語で 「What do I know?」、現代フランス語では 「Que sais-je? 」と表記される)。

| Michel Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne

(/mɒnˈteɪn/ mon-TAYN;[4] French: [miʃɛl ekɛm də mɔ̃tɛɲ]; 28 February

1533 – 13 September 1592[5]), commonly known as Michel de Montaigne,

was one of the most significant philosophers of the French Renaissance.

He is known for popularizing the essay as a literary genre. His work is

noted for its merging of casual anecdotes[6] and autobiography with

intellectual insight. Montaigne had a direct influence on numerous

Western writers; his massive volume Essais contains some of the most

influential essays ever written. During his lifetime, Montaigne was admired more as a statesman than as an author. The tendency in his essays to digress into anecdotes and personal ruminations was seen as detrimental to proper style rather than as an innovation, and his declaration that "I am myself the matter of my book" was viewed by his contemporaries as self-indulgent. In time, however, Montaigne came to be recognized as embodying, perhaps better than any other author of his time, the spirit of freely entertaining doubt that began to emerge at that time. He is most famously known for his skeptical remark, ''Que sçay-je?" ("What do I know?", in Middle French; now rendered as "Que sais-je?" in modern French). |

Michel

Eyquem, Seigneur de Montaigne (/mɒteɪ/ mon-TAYN;[4] French: [miɒ də

mɔ̃ɛ; [miɒ də mɔ̃ɛ], 1533年2月28日 -

1592年9月13日[5])、通称ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュは、フランス・ルネサンス期を代表する哲学者の一人である。文学のジャンルとしてエッセイ

を普及させたことで知られる。彼の作品は、何気ない逸話[6]や自伝を知的洞察と融合させていることで知られている。モンテーニュは多くの西洋の作家に直

接的な影響を与えた。彼の膨大なエッセイ集には、これまでに書かれた中で最も影響力のあるエッセイのいくつかが収められている。 生前、モンテーニュは作家としてよりも政治家として賞賛された。彼のエッセイには、逸話や個人的な考察に脱線する傾向があり、それは革新的というよりもむ しろ、正しいスタイルを損なうものと見なされ、また、「私自身が私の本の主題である」という彼の宣言は、同時代の人々から独りよがりと見なされた。しか し、やがてモンテーニュは、おそらく同時代のどの作家よりも、当時生まれ始めた自由闊達な懐疑の精神を体現した人物として認識されるようになった。彼の懐 疑的な発言で最も有名なのは、「Que sçay-je? (中フランス語で 「What do I know?」、現代フランス語では 「Que sais-je? 」と表記される)。 |

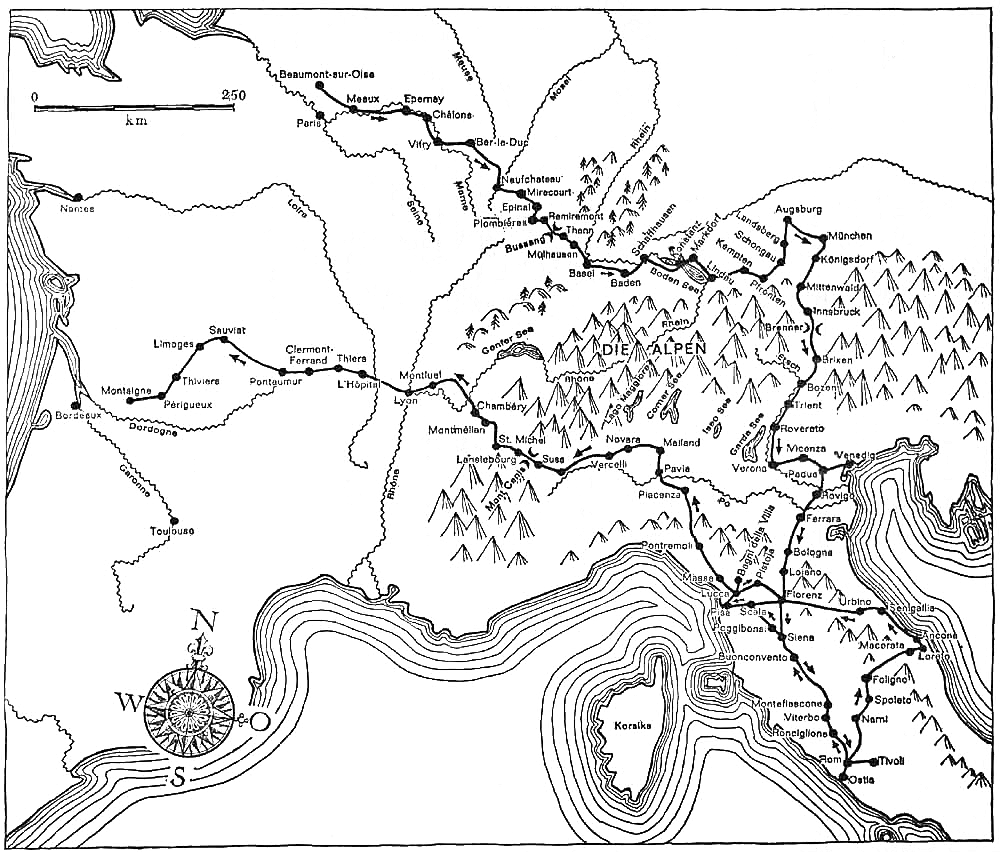

| Biography Family, childhood and education Montaigne was born in the Aquitaine region of France, on the family estate Château de Montaigne in a town now called Saint-Michel-de-Montaigne, close to Bordeaux. The family was very wealthy. His great-grandfather, Ramon Felipe Eyquem, had made a fortune as a herring merchant - and had bought the estate in 1477, thus becoming the Lord of Montaigne. His father, Pierre Eyquem, Seigneur of Montaigne, was a French Catholic soldier in Italy for a time, and had also been the mayor of Bordeaux.[5] Although there were several families bearing the patronym "Eyquem" in Guyenne, his father's family is thought to have had some degree of Marrano (Spanish and Portuguese Jewish) origins,[7] while his mother, Antoinette López de Villanueva, was a convert to Protestantism.[8] His maternal grandfather, Pedro López,[9] from Zaragoza, was from a wealthy Marrano (Sephardic Jewish) family, that had converted to Catholicism.[10][11][12][13] His maternal grandmother, Honorette Dupuy, was from a Catholic family in Gascony, France.[14] During a great part of Montaigne's life his mother lived near him, and even survived him; but she is mentioned only twice in his essays. Montaigne's relationship with his father however is frequently reflected upon and discussed in his essays.[10] Montaigne's education began in early childhood, and followed a pedagogical plan, that his father had developed, refined by the advice of the latter's humanist friends. Soon after his birth Montaigne was brought to a small cottage, where he lived the first three years of life in the sole company of a peasant family, in order to, according to the elder Montaigne, "draw the boy close to the people, and to the life conditions of the people, who need our help".[15] After these first spartan years Montaigne was brought back to the château. Another objective was for Latin to become his first language. The intellectual education of Montaigne was assigned to a German tutor (a doctor named Horstanus, who could not speak French). His father hired only servants who could speak Latin, and they also were given strict orders always to speak to the boy in Latin. The same rule applied to his mother, father, and servants, who were obliged to use only Latin words he employed; and thus they acquired a knowledge of the very language his tutor taught him. Montaigne's Latin education was accompanied by constant intellectual and spiritual stimulation. He was familiarized with Greek by a pedagogical method that employed games, conversation, and exercises of solitary meditation, rather than the more traditional books.[16] The atmosphere of the boy's upbringing engendered in him a spirit of "liberty and delight" - that he would later describe as making him "relish...duty by an unforced will, and of my own voluntary motion...without any severity or constraint". His father had a musician wake him every morning, playing one instrument or another;[17] and an epinettier (with a zither) was the constant companion to Montaigne and his tutor, playing tunes to alleviate boredom and tiredness. Around the year 1539 Montaigne was sent to study at a highly regarded boarding school in Bordeaux, the College of Guienne, then under the direction of the greatest Latin scholar of the era, George Buchanan, where he mastered the whole curriculum by his thirteenth year. He finished the first phase of his educational studies at the College of Guienne in 1546.[18] He then began his study of law (his alma mater remains unknown, since there are no certainties about his activity from 1546 to 1557)[19] and entered a career in the local legal system. Career and marriage  Portrait of Montaigne c. 1565, by an anonymous artist Montaigne was a counselor of the Court des Aides of Périgueux, and in 1557 he was appointed counselor of the Parlement in Bordeaux, a high court. From 1561 to 1563 he was courtier at the court of Charles IX, and he was present with the king at the siege of Rouen (1562). He was awarded the highest honour of the French nobility, the collar of the Order of Saint Michael.[20] While serving at the Bordeaux Parlement, he became a very close friend of the humanist poet Étienne de La Boétie, whose death in 1563 deeply affected Montaigne. It has been suggested by Donald M. Frame - in his introduction to The Complete Essays of Montaigne - that because of Montaigne's "imperious need to communicate", after losing Étienne, he began the Essais as a new "means of communication", and that "the reader takes the place of the dead friend".[21] Montaigne married Françoise de la Cassaigne in 1565, probably in an arranged marriage. She was the daughter and niece of wealthy merchants of Toulouse and Bordeaux. They had six daughters, but only the second-born, Léonor, survived infancy.[22] He wrote very little about the relationship with his wife, and little is known about their marriage. Of his daughter Léonor he wrote: "All my children die at nurse; but Léonore, our only daughter, who has escaped this misfortune, has reached the age of six and more, without having been punished, the indulgence of her mother aiding, except in words, and those very gentle ones."[23] His daughter married François de la Tour and later Charles de Gamaches. She had a daughter by each.[24] Writing Following the petition of his father, Montaigne started to work on the first translation of the Catalan monk Raymond Sebond's Theologia naturalis, which he published a year after his father's death in 1568 (in 1595 Sebond's Prologue was put on the Index Librorum Prohibitorum because of its declaration that the Bible is not the only source of revealed truth). Montaigne also published a posthumous edition of the works of his friend, Boétie.[25] In 1570 he moved back to the family estate, the Château de Montaigne, which he had inherited. He thus became the Lord of Montaigne. Around this time he was seriously injured in a riding accident on the grounds of the château when one of his mounted companions collided with him at speed, throwing Montaigne from his horse and briefly knocking him unconscious.[26] It took weeks or months for him to recover, and this close brush with death apparently affected him greatly, as he discussed it at length in his writings over the following years. Not long after the accident he relinquished his magistracy in Bordeaux, his first child was born (and died a few months later), and by 1571 he had retired from public life completely, to the tower of the château – his so-called "citadel" – where he almost totally isolated himself from every social and family affair. Locked up in his library, which contained a collection of some 1,500 volumes, he began work on the writings that would later be compiled into his Essais ("Essays"), first published in 1580. On the day of his 38th birthday, as he entered this almost ten-year period of self-imposed reclusion, he had the following inscription placed on the crown of the bookshelves of his working chamber: In the year of Christ 1571, at the age of thirty-eight, on the last day of February, his birthday, Michael de Montaigne, long weary of the servitude of the court and of public employments, while still entire, retired to the bosom of the learned virgins, where in calm and freedom from all cares he will spend what little remains of his life, now more than half run out. If the fates permit, he will complete this abode, this sweet ancestral retreat; and he has consecrated it to his freedom, tranquility, and leisure.[27] Château de Montaigne, a house built on the land once owned by Montaigne's family. His original family home no longer exists, although the tower in which he wrote still stands.  The Tour de Montaigne (Montaigne's tower), where Montaigne's library was located, remains mostly unchanged since the sixteenth century. Travels  Portrait of Michel de Montaigne around 1578 by Dumonstier During this time of the Wars of Religion in France, Montaigne, a Roman Catholic,[28] acted as a moderating force,[29] respected both by the Catholic King Henry III and the Protestant Henry of Navarre, who later converted to Catholicism. In 1578 Montaigne, whose health had always been excellent, started suffering from painful kidney stones, a tendency he inherited from his father's family. Throughout this illness he would have nothing to do with doctors or drugs.[5] From 1580 to 1581 Montaigne traveled in France, Germany, Austria, Switzerland, and Italy, partly in search of a cure, establishing himself at Bagni di Lucca, where he took the waters. His journey was also a pilgrimage to the Holy House of Loreto, to which he presented a silver relief (depicting him, his wife, and their daughter, kneeling before the Madonna) considering himself fortunate that it should be hung on a wall within the shrine.[30] He kept a journal, recording regional differences and customs[31] - and a variety of personal episodes, including the dimensions of the stones he succeeded in expelling. This was published much later, in 1774, after its discovery in a trunk, that is displayed in his tower.[32] During a visit to the Vatican that Montaigne described in his travel journal, the Essais were examined by Sisto Fabri, who served as Master of the Sacred Palace under Pope Gregory XIII. After Fabri examined Montaigne's Essais, the text was returned to him on 20 March 1581. Montaigne had apologized for references to the pagan notion of "fortuna", as well as for writing favorably of Julian the Apostate and of heretical poets, and was released to follow his own conscience in making emendations to the text.[33] Later career  Journey to Italy by Michel de Montaigne 1580–1581  Portrait of 1587 by Étienne Martellange While in the city of Lucca in 1581 he learned that, like his father before him, he had been elected mayor of Bordeaux. He thus returned and served as mayor. He was re-elected in 1583 and served until 1585, again moderating between Catholics and Protestants. The plague broke out in Bordeaux toward the end of his second term in office, in 1585. In 1586 the plague and the French Wars of Religion prompted him to leave his château for two years.[5] Montaigne continued to extend, revise, and oversee the publication of the Essais. In 1588 he wrote its third book - and also met Marie de Gournay, an author, who admired his work, and later edited and published it. Montaigne later referred to her as his adopted daughter.[5] When King Henry III was assassinated in 1589, Montaigne, despite his aversion to the cause of The Reformation, was anxious to promote a compromise, that would end the bloodshed, and gave his support to Henry of Navarre, who would go on to become King Henry IV. Montaigne's position associated him with the politiques, the establishment movement that prioritised peace, national unity, and royal authority over religious allegiance.[34] Death  Portrait of Montaigne circa 1590 by an anonymous artist Montaigne died of quinsy at the age of 59 in 1592 at the Château de Montaigne. In his case the disease "brought about paralysis of the tongue",[35] especially difficult for one who once said: "the most fruitful and natural play of the mind is conversation. I find it sweeter than any other action in life; and if I were forced to choose, I think I would rather lose my sight than my hearing and voice."[36] Remaining in possession of all his other faculties, he requested Mass, and died during the celebration of that Mass.[37] He was buried nearby. Later his remains were moved to the church of Saint Antoine at Bordeaux. The church no longer exists. It became the Convent des Feuillants, which also has disappeared.[38] |

バイオグラフィー(生涯・伝記) 家族、子供時代、教育 モンテーニュはフランスのアキテーヌ地方、現在はボルドーに近いサン=ミシェル=ド=モンテーニュと呼ばれる町のモンテーニュ城で生まれた。一族は非常に 裕福だった。彼の曽祖父ラモン・フェリペ・アイケムはニシン商人として財を成し、1477年にこの領地を購入してモンテーニュ領主となった。彼の父である モンテーニュ領主ピエール・アイケムは、一時期イタリアで活躍したフランス・カトリックの軍人であり、ボルドー市長も務めていた[5]。 ガイエンヌには「エイケム」の姓を持つ家系がいくつかあったが、父の家系はマラーノ(スペインとポルトガルのユダヤ人)を起源とすると考えられており [7]、母のアントワネット・ロペス・デ・ヴィラヌエバはプロテスタントへの改宗者であった[8]。 [母方の祖父ペドロ・ロペスはサラゴサ出身で[9]、裕福なマラノ(セファルディ系ユダヤ人)の家系で、カトリックに改宗していた[10][11] [12][13]。 母方の祖母オノレット・デュピュイはフランスのガスコーニュ地方のカトリックの家系だった[14]。 モンテーニュの生涯の大部分において、母親はモンテーニュの近くに住んでおり、モンテーニュと死別している。しかし、モンテーニュと父との関係は、彼のエッセイの中で頻繁に考察され、議論されている[10]。 モンテーニュの教育は幼年期から始まり、父親が考案した教育学的計画に沿って、父親の人文主義者の友人の助言によって洗練されていった。長男のモンテーニュによれば、「少年を人々に近づけ、我々の助けを必要としている人々の生活状況に近づける」ためであった[15]。 もう一つの目的は、ラテン語を第一外国語にすることだった。モンテーニュの知的教育はドイツ人の家庭教師(ホルスタヌスという名の医者でフランス語は話せ なかった)に任された。父親はラテン語を話せる使用人だけを雇い、使用人も常にラテン語で少年に話しかけるよう厳命された。母親、父親、使用人も同じよう に、彼が使うラテン語の単語だけを使うように命じられ、家庭教師が教えたラテン語の知識を身につけた。モンテーニュのラテン語教育は、常に知的、精神的な 刺激を伴っていた。彼は、伝統的な書物ではなく、ゲームや会話、孤独な瞑想の練習を用いた教育法によってギリシア語に親しんだ[16]。 そのような雰囲気の中で育った少年は、「自由と歓喜」の精神を育み、それは後に「強制されない意志によって、自分自身の自発的な動きによって...... いかなる厳しさも束縛もなく......義務を......喜ぶ」ようになったと述べている。父親は毎朝音楽家を起こし、楽器を演奏させ[17]、エピネ チエ(琴を持つ)がモンテーニュと家庭教師に付き添い、退屈と疲れを癒すために曲を演奏していた。 1539年頃、モンテーニュはボルドーにある評価の高い全寮制の学校、ギエンヌ・カレッジで学ぶことになった。1546年、ギエンヌ・カレッジでの教育研 究の第一段階を修了し[18]、法学を学び始め(1546年から1557年までの活動については定かでないため、母校は不明)[19]、地元の法曹界に入 る。 キャリアと結婚  1565年頃のモンテーニュの肖像画(作者不詳) 1557年、ボルドーの高等法院(パルマン)の顧問に任命される。1561年から1563年までシャルル9世の宮廷廷臣を務め、ルーアン包囲戦(1562年)には王とともに立ち会った。フランス貴族の最高の栄誉である聖ミカエル勲章の襟章を授与された[20]。 ボルドー高等法院に在職中、人文主義者の詩人エティエンヌ・ド・ラ・ボエティの親友となり、1563年の彼の死はモンテーニュに深い影響を与えた。ドナル ド・M・フレームは、『モンテーニュ随筆全集』の序文で、エティエンヌを失ったモンテーニュの「不断のコミュニケーションの必要性」のために、新たな「コ ミュニケーションの手段」としてエッセを書き始め、「読者が死んだ友人の代わりになった」と述べている[21]。 モンテーニュは1565年にフランソワーズ・ド・ラ・カセーニュと結婚した。彼女はトゥールーズとボルドーの裕福な商人の娘と姪であった。二人の間には6 人の娘がいたが、幼児期を生き延びたのは次女のレオノールだけであった[22]。娘のレオノールについては、「私の子供たちは皆、乳飲み子で死んでしまう が、この不幸を免れた一人娘のレオノールは、罰せられることもなく、6歳以上になった。それぞれの間に娘をもうけた[24]。 執筆 父の請願を受けて、モンテーニュはカタロニア人修道士レイモン・セボンドの『自然神学』(Theologia naturalis)の最初の翻訳に取りかかった。モンテーニュはまた、友人ボエティの著作の遺稿集を出版した[25]。 1570年、モンテーニュは家督を相続したモンテーニュ城に戻る。こうしてモンテーニュ領主となる。この頃、モンテーニュはシャトーの敷地内で乗馬中の仲 間と衝突し、馬から投げ出され、意識不明の重傷を負った[26]。事故から間もなくボルドーでの司政職を辞し、最初の子供が生まれ(数ヶ月後に死去)、 1571年までには公の生活から完全に引退し、いわゆる「城塞」と呼ばれる城の塔に閉じこもり、あらゆる社会的、家庭的事件からほぼ完全に隔離された。 1,500冊もの蔵書がある書斎に閉じこもり、後に1580年に出版された『エッセイ』にまとめられる文章を書き始めた。38歳の誕生日を迎え、10年近 い隠遁生活に入った彼は、仕事部屋の本棚の王冠に次のような碑文を刻んだ: キリストの年1571年、38歳、誕生日である2月末日、ミヒャエル・ド・モンテーニュは、宮廷の隷属と公的な仕事に長い間疲れていたが、まだ完全なま ま、学問のある処女の懐に引きこもり、あらゆる心配事から解放され、平静のうちに、あらゆる心配事から解放されて、残り少ない人生の半分以上を過ごす。運 命が許せば、彼はこの住まい、この甘美な先祖伝来の隠れ家を完成させるだろう。 モンテーニュ城、かつてモンテーニュの家族が所有していた土地に建てられた邸宅。モンテーニュが執筆した塔は残っているが、元の実家は現存していない。 シャトー・ド・モンテーニュ、かつてモンテーニュの家族が所有していた土地に建てられた邸宅。モンテーニュが執筆した塔は残っているが、元の実家は現存していない。  モンテーニュの書斎があったトゥール・ド・モンテーニュ(モンテーニュの塔)は、16世紀からほとんど変わっていない。 旅行記  1578年頃のミシェル・ド・モンテーニュの肖像(デュモンティエ作) フランスにおける宗教戦争の最中、ローマ・カトリック教徒であったモンテーニュは穏健派として活動し[28]、カトリック国王アンリ3世とプロテスタント国王ナバラのアンリの両方から尊敬された[29]。 1578年、常に健康であったモンテーニュは、父の家系から受け継いだ腎臓結石の痛みに悩まされるようになる。1580年から1581年にかけて、モン テーニュは治療法を求めて、フランス、ドイツ、オーストリア、スイス、イタリアを旅し、バーニ・ディ・ルッカに身を置いて水を得た。彼の旅はロレートの聖 堂への巡礼でもあり、聖堂の壁に飾られることを幸運に思い、銀のレリーフ(聖母の前に跪くモンテーニュとその妻、娘を描いたもの)を奉納した[30]。こ れは、彼の塔に展示されているトランクから発見された後、1774年に出版された[32]。 モンテーニュが旅行記に記したバチカン訪問の際、エッセは教皇グレゴリウス13世のもとで聖宮司を務めたシスト・ファブリによって調査された。ファブリが モンテーニュのエッセを検閲した後、1581年3月20日にモンテーニュに返却された。モンテーニュは、異教徒の「フォルトゥーナ」という概念への言及 や、背教者ユリアヌスや異端の詩人について好意的に書いたことを謝罪し、自分の良心に従って本文を修正することを許された[33]。 その後の経歴  1580年~1581年、ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ作『イタリアへの旅  エティエンヌ・マルトランジュによる1587年の肖像画 1581年、ルッカに滞在していたモンテーニュは、父がボルドー市長に当選したことを知る。こうして彼はボルドーに戻り、市長を務めた。1583年に再選 され、1585年まで務め、再びカトリックとプロテスタントの間を調停した。2期目の任期が終わる1585年、ボルドーでペストが発生。1586年、ペス トとフランス宗教戦争により、モンテーニュは2年間城を離れることになる[5]。 モンテーニュはエッセの増補、改訂、出版の監督を続けた。1588年、モンテーニュはエセー第三巻を執筆し、また作家のマリー・ド・グルネーに出会い、彼女はモンテーニュの作品を賞賛し、後に編集・出版した。モンテーニュは後に彼女を養女と呼んだ[5]。 1589年に国王アンリ3世が暗殺されたとき、モンテーニュは宗教改革の大義を嫌っていたにもかかわらず、流血を終わらせる妥協案を推進することに熱心 で、後に国王アンリ4世となるナバラのアンリを支持した。モンテーニュの立場は、宗教的忠誠よりも平和、国民の団結、王権を優先するポリティク派と結びつ いていた[34]。 死  1590年頃のモンテーニュの肖像画(作者不詳) モンテーニュは1592年、59歳の時にクインシーでモンテーニュ城で亡くなった。彼の場合、この病気は「舌の麻痺をもたらした」[35]: 「心の最も実り豊かで自然な遊びは会話である。もし選ばなければならないとしたら、聴覚と声を失うくらいなら、視力を失う方がましだと思う」[36]。他 のすべての能力は保たれていたが、ミサを求め、そのミサの最中に亡くなった[37]。 近くに埋葬された。後に遺骸はボルドーのサン・アントワーヌ教会に移された。この教会は現存しない。そこはフォイヤン修道院となったが、それも消滅した[38]。 |

| Essais Main article: Essays (Montaigne) His humanism finds expression in his Essais, a collection of a large number of short subjective essays on various topics published in 1580 that were inspired by his studies in the classics, especially by the works of Plutarch and Lucretius.[39] Montaigne's stated goal was to describe humans, and especially himself, with utter frankness. Inspired by his consideration of the lives and ideals of the leading figures of his age, he finds the great variety and volatility of human nature to be its most basic features. He describes his own poor memory, his ability to solve problems and mediate conflicts without truly getting emotionally involved, his disdain for the human pursuit of lasting fame, and his attempts to detach himself from worldly things to prepare for his timely death. He writes about his disgust with the religious conflicts of his time. He believed that humans are not able to attain true certainty. The longest of his essays, Apology for Raymond Sebond, marking his adoption of Pyrrhonism,[40] contains his famous motto, "What do I know?" Montaigne considered marriage necessary for the raising of children but disliked strong feelings of passionate love because he saw them as detrimental to freedom. In education, he favored concrete examples and experience over the teaching of abstract knowledge intended to be accepted uncritically. His essay "On the Education of Children" is dedicated to Diana of Foix. The Essais exercised an important influence on both French and English literature, in thought and style.[41] Francis Bacon's Essays, published over a decade later, first in 1597, usually are presumed to be directly influenced by Montaigne's collection, and Montaigne is cited by Bacon alongside other classical sources in later essays.[42] Montaigne's influence on psychology Although not a scientist, Montaigne made observations on topics in psychology.[43] In his essays, he developed and explained his observations of these themes. His thoughts and ideas covered subjects such as thought, motivation, fear, happiness, child education, experience, and human action. Montaigne's ideas have influenced psychology and are a part of its rich history. Child education Child education was among the psychological topics that he wrote about.[43] His essays On the Education of Children, On Pedantry, and On Experience explain the views he had on child education.[44]: 61 : 62 : 70 Some of his views on child education are still relevant today.[45] Montaigne's views on the education of children were opposed to the common educational practices of his day.[44]: 63 : 67 He found fault both with what was taught and how it was taught.[44]: 62 Much of education during Montaigne's time focused on reading the classics and learning through books.[44]: 67 Montaigne disagreed with learning strictly through books. He believed it was necessary to educate children in a variety of ways. He also disagreed with the way information was being presented to students. It was being presented in a way that encouraged students to take the information that was taught to them as absolute truth. Students were denied the chance to question the information; but Montaigne, in general, took the position that to learn truly, a student had to take the information and make it their own: Let the tutor make his charge pass everything through a sieve and lodge nothing in his head on mere authority and trust: let not Aristotle's principles be principles to him any more than those of the Stoics or Epicureans. Let this variety of ideas be set before him; he will choose if he can; if not, he will remain in doubt. Only the fools are certain and assured. "For doubting pleases me no less than knowing." [Dante]. For if he embraces Xenophon's and Plato's opinions by his own reasoning, they will no longer be theirs, they will be his. He who follows another follows nothing. He finds nothing; indeed he seeks nothing. "We are not under a king; let each one claim his own freedom." [Seneca]. . . . He must imbibe their way of thinking, not learn their precepts. And let him boldly forget, if he wants, where he got them, but let him know how to make them his own. Truth and reason are common to everyone, and no more belong to the man who first spoke them than to the man who says them later. It is no more according to Plato than according to me, since he and I see it in the same way. The bees plunder the flowers here and there, but afterward they make of them honey, which is all and purely their own, and no longer thyme and marjoram.[46][47] At the foundation, Montaigne believed that the selection of a good tutor was important for the student to become well educated.[44]: 66 Education by a tutor was to be conducted at the pace of the student.[44]: 67 He believed that a tutor should be in dialogue with the student, letting the student speak first. The tutor also should allow for discussions and debates to be had. Such a dialogue was intended to create an environment in which students would teach themselves. They would be able to realize their mistakes and make corrections to them as necessary.[citation needed] Individualized learning was integral to his theory of child education. He argued that the student combines information already known with what is learned and forms a unique perspective on the newly learned information.[48]: 356 Montaigne also thought that tutors should encourage the natural curiosity of students and allow them to question things.[44]: 68 He postulated that successful students were those who were encouraged to question new information and study it for themselves, rather than simply accepting what they had heard from the authorities on any given topic. Montaigne believed that a child's curiosity could serve as an important teaching tool when the child is allowed to explore the things that the child is curious about.[citation needed] Experience also was a key element to learning for Montaigne. Tutors needed to teach students through experience rather than through the mere memorization of information often practised in book learning.[44]: 62 : 67 He argued that students would become passive adults, blindly obeying and lacking the ability to think on their own.[48]: 354 Nothing of importance would be retained and no abilities would be learned.[44]: 62 He believed that learning through experience was superior to learning through the use of books.[45] For this reason he encouraged tutors to educate their students through practice, travel, and human interaction. In doing so, he argued that students would become active learners, who could claim knowledge for themselves.[citation needed] Montaigne's views on child education continue to have an influence in the present. Variations of Montaigne's ideas on education are incorporated into modern learning in some ways. He argued against the popular way of teaching in his day, encouraging individualized learning. He believed in the importance of experience, over book learning and memorization. Ultimately, Montaigne postulated that the point of education was to teach a student how to have a successful life by practising an active and socially interactive lifestyle.[48]: 355 |

エッセ 主な記事 エッセイ(モンテーニュ) モンテーニュのヒューマニズムは、1580年に出版された、古典、特にプルタークとルクレティウスの著作に触発された、様々なテーマに関する多数の短い主観的なエッセイを集めた『エッセー』に表現されている[39]。 同時代を代表する人物の人生と理想を考察することに触発された彼は、人間の本性の最も基本的な特徴として、その大きな多様性と不安定性を見出す。彼は、自 身の記憶力のなさ、感情的になることなく問題を解決し対立を調停する能力、永続的な名声を追い求める人間への軽蔑、時宜を得た死に備えるために世俗的なも のから自分を切り離そうとする試みについて述べている。彼は、同時代の宗教的対立に対する嫌悪感について書いている。彼は、人間は真の確信を得ることはで きないと信じていた。彼の随筆の中で最も長い『レイモン・セボンドへの弁明』は、ピュロニズム[40]を採用したことを示すもので、有名なモットーである 「What do I know? 」を含んでいる。 モンテーニュは、子育てのために結婚は必要だと考えたが、情熱的な愛の強い感情は自由を損なうと考え嫌った。教育においては、無批判に受け入れることを意 図した抽象的な知識を教えるよりも、具体的な事例や経験を重視した。エッセイ『子供の教育について』はフォワ家のディアナに捧げられている。 フランシス・ベーコンの『エッセイ』は、その10年後、1597年に出版されたが、通常、モンテーニュのエッセイ集から直接影響を受けたと推測され、ベーコンは後のエッセイで、他の古典的な資料とともにモンテーニュを引用している[42]。 心理学におけるモンテーニュの影響 科学者ではなかったが、モンテーニュは心理学のテーマを観察していた[43]。彼の考えや思想は、思考、動機づけ、恐怖、幸福、子供の教育、経験、人間の行動といったテーマを扱っていた。モンテーニュの思想は心理学に影響を与え、その豊かな歴史の一部となっている。 児童教育 児童教育はモンテーニュが執筆した心理学的テーマの一つである[43]。彼のエッセイ『子供の教育について』、『ペダントリーについて』、『経験について』は、彼が児童教育に対して持っていた見解を説明している[44]。 モンテーニュの子供の教育についての見解は、当時の一般的な教育実践に反対するものであった[44]: 63 : 67 モンテーニュは、何を教えるか、どのように教えるかの両方に欠点を見出していた[44]: 62 モンテーニュの時代の教育の多くは、古典を読み、書物を通して学ぶことに重点を置いていた[44]: 67 モンテーニュは、書物を通して厳密に学ぶことに反対であった。彼は様々な方法で子供たちを教育する必要があると考えていた。モンテーニュはまた、生徒に対 する情報の提示の仕方にも反対であった。生徒が教えられた情報を絶対的な真実として受け止めるように仕向けたのである。しかし、モンテーニュは一般的に、 真に学ぶためには、生徒が情報を自分のものにしなければならないという立場をとっていた: アリストテレスの原理を、ストア派やエピクロス派の原理と同じように、生徒の原理とさせてはならない。アリストテレスの原理を、ストア派やエピクロス派の 原理と同じように、彼にとっての原理にしてはならない。愚か者だけが確信し、確信する。「疑うことは、知ることに劣らず私を喜ばせる。[ダンテ] クセノフォンやプラトンの意見を自分の理性で受け入れるなら、それはもはや彼らのものではなく、彼のものである。他者に従う者は何も従わない。彼は何も見 出さない。「われわれは王の下にいるのではない。[セネカ] . . . 彼は彼らの戒律を学ぶのではなく、彼らの考え方を身につけなければならない。そして、彼が望むなら、どこでそれを得たかは大胆に忘れさせよ。真理と理性は 万人に共通するものであり、後からそれを言う人よりも、最初にそれを口にした人のものである。プラトンも私も同じように見ているのだから。ミツバチはあち こちの花を略奪するが、その後、それらの花から蜂蜜を作る。それはすべて、純粋に彼ら自身のものであり、もはやタイムやマジョラムではない。 44]: 66 家庭教師による教育は生徒のペースに合わせて行われるべきであった。家庭教師はまた、議論や討論ができるようにすべきである。このような対話は、生徒が自 分自身を教える環境を作ることを意図していた。生徒たちは自分の間違いに気づき、必要に応じてそれを修正することができるだろう。 個別学習は、彼の児童教育理論に不可欠であった。モンテーニュは、生徒がすでに知っている情報と新たに学んだ情報とを組み合わせ、新たに学んだ情報に対し て独自の視点を形成すると主張した[48]: 356 モンテーニュはまた、家庭教師は生徒の自然な好奇心を奨励し、生徒が物事に疑問を持つようにすべきであると考えた[44]: 68 モンテーニュは、成功する生徒とは、与えられた話題について権威者から聞いたことを単に受け入れるのではなく、新しい情報に疑問を持ち、自分自身で研究す るよう奨励された生徒であると仮定した。モンテーニュは、子供の好奇心が重要な教材になると考えた。 経験もまた、モンテーニュにとって学習の重要な要素であった。家庭教師は、書籍学習でよく行われる単なる情報の暗記ではなく、経験を通じて生徒を教える必 要があった[44]: 62 : 67 彼は、生徒が受動的な大人になり、盲目的に従順になり、自分で考える能力を欠いてしまうと主張した[48]: 354 重要なことは何一つ保持されず、能力も身につかない[44]: 62 彼は、経験を通じて学ぶことは、書物による学習よりも優れていると信じていた[45]。そうすることで、彼は生徒が能動的な学習者となり、自分自身で知識 を主張できるようになると主張した[要出典]。 モンテーニュの児童教育に対する見解は、現在も影響を与え続けている。教育に関するモンテーニュの考え方のバリエーションは、いくつかの方法で現代の学習 に取り入れられている。モンテーニュは、当時の一般的な教育方法に反対し、個人学習を奨励した。彼は、書物による学習や暗記よりも経験の重要性を信じてい た。最終的に、モンテーニュは、教育の要点は、生徒が活動的で社会的に相互作用的なライフスタイルを実践することによって、成功した人生を送る方法を教え ることであると仮定した[48]: 355 |

| Related writers and influence Thinkers exploring ideas similar to Montaigne include Erasmus, Thomas More, John Fisher, and Guillaume Budé, who all worked about fifty years before Montaigne.[49] Many of Montaigne's Latin quotations are from Erasmus' Adagia, and most critically, all of his quotations from Socrates. Plutarch remains perhaps Montaigne's strongest influence, in terms of substance and style.[50] Montaigne's quotations from Plutarch in the Essays number more than 500.[51] Ever since Edward Capell first made the suggestion in 1780, scholars have suggested Montaigne to be an influence on Shakespeare.[52] The latter would have had access to John Florio's translation of Montaigne's Essais, published in English in 1603, and a scene in The Tempest "follows the wording of Florio [translating Of Cannibals] so closely that his indebtedness is unmistakable".[53] Most parallels between the two may be explained, however, as commonplaces:[52] as similarities with writers in other nations to the works of Cervantes and Shakespeare could be due simply to their own study of Latin moral and philosophical writers such as Seneca the Younger, Horace, Ovid, and Virgil. Much of Blaise Pascal's skepticism in his Pensées has been attributed traditionally to his reading Montaigne.[54] The English essayist William Hazlitt expressed boundless admiration for Montaigne, exclaiming that "he was the first who had the courage to say as an author what he felt as a man. ... He was neither a pedant nor a bigot. ... In treating of men and manners, he spoke of them as he found them, not according to preconceived notions and abstract dogmas".[55] Beginning most overtly with the essays in the "familiar" style in his own Table-Talk, Hazlitt tried to follow Montaigne's example.[56] Ralph Waldo Emerson chose "Montaigne; or, the Skeptic" as a subject of one of his series of lectures entitled, Representative Men, alongside other subjects such as Shakespeare and Plato. In "The Skeptic" Emerson writes of his experience reading Montaigne, "It seemed to me as if I had myself written the book, in some former life, so sincerely it spoke to my thought and experience." Friedrich Nietzsche judged of Montaigne: "That such a man wrote has truly augmented the joy of living on this Earth".[57] Sainte-Beuve advises us that "to restore lucidity and proportion to our judgments, let us read every evening a page of Montaigne."[58] Stefan Zweig drew inspiration from one of Montaigne's quotes to give the title to one of his autobiographical novels, "A Conscience Against Violence."[59] The American philosopher Eric Hoffer employed Montaigne both stylistically and in thought. In Hoffer's memoir, Truth Imagined, he said of Montaigne, "He was writing about me. He knew my innermost thoughts." The British novelist John Cowper Powys expressed his admiration for Montaigne's philosophy in his books, Suspended Judgements (1916)[60] and The Pleasures of Literature (1938). Judith N. Shklar introduces her book Ordinary Vices (1984), "It is only if we step outside the divinely ruled moral universe that we can really put our minds to the common ills we inflict upon one another each day. That is what Montaigne did and that is why he is the hero of this book. In spirit he is on every one of its pages..." Twentieth-century literary critic Erich Auerbach called Montaigne the first modern man. "Among all his contemporaries", writes Auerbach (Mimesis, Chapter 12), "he had the clearest conception of the problem of man's self-orientation; that is, the task of making oneself at home in existence without fixed points of support".[61] Discovery of remains The Musée d'Aquitaine announced on 20 November 2019 that the human remains, which had been found in the basement of the museum a year earlier, might belong to Montaigne.[62] Investigation of the remains, postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic, resumed in September 2020.[63] Commemoration The birthdate of Montaigne served as the basis to establish National Essay Day in the United States. The humanities branch of the University of Bordeaux is named after him: Université Michel de Montaigne Bordeaux 3.[64] |

関連作家と影響 エラスムス、トマス・モア、ジョン・フィッシャー、ギヨーム・ブデなど、モンテーニュより50年ほど前に活躍した思想家がいる[49]。プルタークからの引用は500を超える[51]。 1780年にエドワード・カペルがこの提案を初めて行って以来、学者たちはモンテーニュがシェイクスピアに影響を与えたと示唆している[52]。 シェイクスピアは1603年に英語で出版されたジョン・フローリオによるモンテーニュのエッセイの翻訳を入手していたはずであり、『テンペスト』の一場面 は「フローリオ(『食人族』の翻訳)の表現に忠実に従っており、彼の恩義は紛れもないものである」[53]。 [セルバンテスやシェイクスピアの作品と他国の作家との類似性は、単に彼らがセネカ、ホレス、オヴィッド、ヴァージルといったラテン語の道徳的・哲学的作 家を研究していたことに起因しているのかもしれない。 ブレーズ・パスカルが『ペンセー』において懐疑主義を唱えたのは、伝統的にモンテーニュを読んだからだとされてきた[54]。 イギリスのエッセイスト、ウィリアム・ハズリットはモンテーニュに限りない賞賛を表し、「彼は人間として感じたことを作家として言う勇気を持った最初の人 である。彼は衒学者でも偏屈者でもなかった。... 人間や風俗について語るとき、彼は先入観や抽象的な教義に従うのではなく、自分が見出したままに語った」[55]。ハズリットは自身の『テーブル・トー ク』の「親しみやすい」文体によるエッセイで最もあからさまに始めて、モンテーニュに倣おうとした[56]。 ラルフ・ウォルドー・エマーソンは、シェイクスピアやプラトンといった他の題材と並んで、「代表的な人物」と題された一連の講義の題材として「モンテー ニュ、あるいは懐疑論者」を選んだ。エマーソンは『懐疑論者』の中で、モンテーニュを読んだときの感想をこう書いている。フリードリヒ・ニーチェはモン テーニュをこう評した: フリードリヒ・ニーチェはモンテーニュをこう評した。「このような人物が書いたことは、この地上に生きる喜びを真に増大させた」[57] サント=ブーヴは、「私たちの判断に明晰さと均整を取り戻すために、毎晩モンテーニュの1ページを読もう」とアドバイスしている[58] ステファン・ツヴァイクは、モンテーニュの名言からインスピレーションを得て、自伝的小説のひとつ『暴力に対する良心』のタイトルをつけた[59]。 アメリカの哲学者エリック・ホッファーは、文体的にも思想的にもモンテーニュを用いた。ホッファーは回顧録『Truth Imagined』の中で、モンテーニュについてこう語っている。彼は私の内心を知っていた。イギリスの小説家ジョン・カウパー・パウイスは、著書 『Suspended Judgements』(1916年)[60]と『The Pleasures of Literature』(1938年)の中で、モンテーニュの哲学への賞賛を表明している。ジュディス・N・シュクラーはその著書『Ordinary Vices』(1984年)を紹介し、「私たちが日々互いに与え合っている一般的な悪に真摯に向き合うことができるのは、神の支配する道徳的宇宙の外に一 歩踏み出したときだけである」と述べている。それがモンテーニュのやったことであり、彼が本書の主人公である理由である。その精神は、この本のすべての ページにある......」。 20世紀の文芸評論家エーリッヒ・アウエルバッハは、モンテーニュを最初の近代人と呼んだ。同時代のすべての作家の中で」、アウエルバッハは書いている (『ミメーシス』第12章)、「彼は人間の自己志向の問題、つまり固定した支えのない存在の中で自分自身をくつろがせるという仕事について、最も明確な概 念を持っていた」[61]。 遺骨の発見 アキテーヌ美術館は2019年11月20日、1年前に同美術館の地下で発見された人骨がモンテーニュのものである可能性があると発表した[62]。 COVID-19の流行により延期されていた遺骨の調査は2020年9月に再開された[63]。 記念 モンテーニュの生誕日は、米国で「全国エッセイの日」を制定する根拠となった。 ボルドー大学の人文学部はモンテーニュにちなんで命名された: ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュ・ボルドー第3大学[64]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Michel_de_Montaigne |

|

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆