心身相関と心身問題

Mind–body problem;

Mind–body relationship

☆心

身の関係、別名「心身のつながり」とは、私たちの精神的・感情的な状態と身体の健康との複雑な相互作用を指す。これは、私たちの思考、感情、態度などが、

身体の健康に大きな影響を与える、またその逆も同様である、という理解です。このつながりは単なる哲学的な考えではなく、脳と体がどのようにコミュニケー

ションを取り、互いに影響し合っているかを実証する科学的証拠によって裏付けられている。

| The mind-body

relationship, also known as the mind-body connection, refers to the

complex interplay between our mental and emotional states and our

physical health. It's the understanding that our thoughts, feelings,

and attitudes can significantly influence our physical well-being and

vice versa. This connection is not just a philosophical idea but is

supported by scientific evidence demonstrating how the brain and body

communicate and affect each other. |

心

身の関係、別名「心身のつながり」とは、私たちの精神的・感情的な状態と身体の健康との複雑な相互作用を指す。これは、私たちの思考、感情、態度などが、

身体の健康に大きな影響を与える、またその逆も同様である、という理解です。このつながりは単なる哲学的な考えではなく、脳と体がどのようにコミュニケー

ションを取り、互いに影響し合っているかを実証する科学的証拠によって裏付けられている。 |

| Intertwined systems: The mind and body are not separate entities but rather interconnected systems that influence each other. |

相互に関連したシステム: 心と体は別々の存在ではなく、互いに影響し合う相互に関連したシステムである |

| Communication pathways: Neural pathways, neurotransmitters, hormones, and other biochemicals facilitate communication between the brain and the body, affecting everything from breathing and digestion to emotions and movement. |

コミュニケーション経路: 神経経路、神経伝達物質、ホルモン、その他の生化学物質は、脳と体の間のコミュニケーションを促進し、呼吸や消化から感情や運動に至るまで、あらゆることに影響を与えている。 |

| Impact on health: The mind-body connection plays a crucial role in both physical and mental health, with emotional states like stress, anxiety, and depression having a demonstrable impact on physical symptoms and vice versa. |

健康への影響: 心身のつながりは、身体的および精神的健康の両方に重要な役割を果たしており、ストレス、不安、うつ病などの感情状態は身体的症状に明らかな影響を与え、その逆も同様です。 |

| Holistic approach: Understanding the mind-body connection is essential for a holistic approach to healthcare, recognizing that addressing both mental and physical well-being is crucial for overall health. |

総合的なアプローチ: 心身のつながりを理解することは、総合的なヘルスケアアプローチに不可欠であり、精神的および肉体的な健康の両方に対処することが、全体的な健康にとって非常に重要であることを認識しています。 |

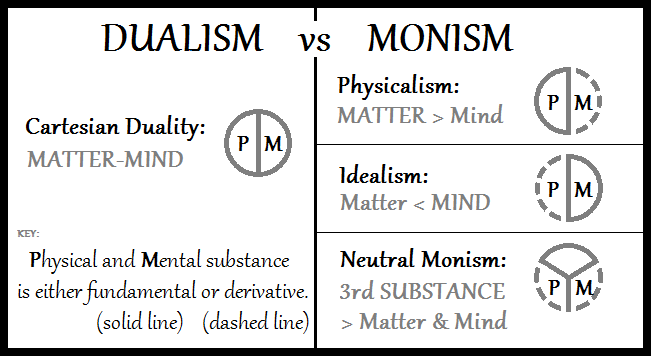

| Examples: Feeling butterflies in your stomach when nervous or experiencing muscle tension when stressed are examples of the mind-body connection in action. Examples of the mind-body connection: Stress and physical symptoms: High levels of stress can lead to physical symptoms like headaches, digestive issues, sleep problems, and increased blood pressure. Positive thinking and physical health: Studies suggest that positive thinking and optimism may be linked to a lower risk of heart disease and increased longevity. Mindfulness and physical well-being: Practices like mindfulness can help regulate emotions and potentially reduce physical symptoms associated with stress and anxiety. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT): CBT is a therapy that explores the connection between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, demonstrating how changing negative thought patterns can positively impact physical health. Mind-Body Relationship In Psychology: Dualism vs Monism In essence, the mind-body relationship highlights the powerful influence our mental and emotional states have on our physical health and the importance of a holistic approach to well-being. |

事例: 緊張したときに胃がドキドキしたり、ストレスを感じたときに筋肉が緊張したりすることは、心身のつながりが働いている例です。 心身のつながりの例: ストレスと身体的症状: 高いストレスは、頭痛、消化器系の問題、睡眠障害、血圧の上昇などの身体的症状を引き起こすことがある。 前向きな思考と身体の健康: 研究によると、前向きな思考や楽観的な性格は、心臓疾患のリスク低下や長寿につながると考えられている。 マインドフルネスと身体の健康: マインドフルネスなどの実践は、感情のコントロールに役立ち、ストレスや不安に伴う身体的症状を軽減する可能性がある。 認知行動療法(CBT): CBT は、思考、感情、行動の関連性を探求し、ネガティブな思考パターンを変えることで身体の健康に良い影響を与えることを実証する療法だ。 心理学における心と体の関係:二元論対一元論 本質的に、心と体の関係は、私たちの精神的および感情的な状態が身体の健康に与える強力な影響、そしてウェルビーイングに対する総合的なアプローチの重要性を強調している。 |

| Google - AI |

|

☆心身問題(Mind–body problem)

Illustration

of mind–body dualism by René Descartes. Inputs are passed by the

sensory organs to the pineal gland, and from there to the immaterial

spirit.

| The mind–body

problem is a philosophical problem concerning the relationship between

thought and consciousness in the human mind and body.[1][2] It

addresses the nature of consciousness, mental states, and their

relation to the physical brain and nervous system. The problem centers

on understanding how immaterial thoughts and feelings can interact with

the material world, or whether they are ultimately physical phenomena. This problem has been a central issue in philosophy of mind since the 17th century, particularly following René Descartes' formulation of dualism, which proposes that mind and body are fundamentally distinct substances. Other major philosophical positions include monism, which encompasses physicalism (everything is ultimately physical) and idealism (everything is ultimately mental). More recent approaches include functionalism, property dualism, and various non-reductive theories. The mind-body problem raises fundamental questions about causation between mental and physical events, the nature of consciousness, personal identity, and free will. It remains significant in both philosophy and science, influencing fields such as cognitive science, neuroscience, psychology, and artificial intelligence. In general, the existence of these mind–body connections seems unproblematic. Issues arise, however, when attempting to interpret these relations from a metaphysical or scientific perspective. Such reflections raise a number of questions, including: Are the mind and body two distinct entities, or a single entity? If the mind and body are two distinct entities, do the two of them causally interact? Is it possible for these two distinct entities to causally interact? What is the nature of this interaction? Can this interaction ever be an object of empirical study? If the mind and body are a single entity, then are mental events explicable in terms of physical events, or vice versa? Is the relation between mental and physical events something that arises de novo at a certain point in development? These and other questions that discuss the relation between mind and body are questions that all fall under the banner of the 'mind–body problem'. |

心身問題とは、人間の心と身体における思考と意識の関係に関する哲学的

問題である[1][2]。意識、精神状態、物理的な脳や神経系との関係の本質を扱う。この問題の中心は、非物質的な思考や感情が物質世界とどのように相互

作用しうるのか、あるいはそれらが究極的に物理的な現象なのかどうかを理解することにある。 この問題は、特にルネ・デカルトが二元論を提唱し、心と身体は根本的に異なる物質であると提唱したことから、17世紀以来、心の哲学における中心的な課題 となっている。他の主要な哲学的立場には、物理主義(すべては究極的に物理的である)と観念論(すべては究極的に精神的である)を包含する一元論がある。 最近のアプローチとしては、機能主義、性質二元論、様々な非還元的理論などがある。 心身問題は、精神的事象と物理的事象の因果関係、意識の本質、人格の同一性、自由意志について根本的な問題を提起している。哲学と科学の両分野で重要な位置を占めており、認知科学、神経科学、心理学、人工知能などの分野に影響を与えている。 一般的に、こうした心と身体のつながりの存在は問題ないように思われる。しかし、これらの関係を形而上学的あるいは科学的観点から解釈しようとすると、問題が生じる。このような考察は、以下のような多くの問題を提起する: 心と身体は2つの異なる存在なのか、それとも1つの存在なのか。 もし心と身体が2つの異なる実体であるならば、その2つは因果的に相互作用するのだろうか? この2つの異なる実体が因果的に相互作用することは可能なのか? この相互作用はどのような性質を持つのか。 この相互作用を経験的研究の対象とすることはできるのか? もし精神と肉体が一体であるならば、精神的な出来事は肉体的な出来事で説明できるのか、あるいはその逆なのか。 精神的事象と身体的事象の関係は、発達のある時点で自然に生じるものなのだろうか? このような、心と身体の関係を論じるその他の疑問は、すべて「心身問題」の旗印の下にある疑問である。 |

| Mind–body interaction and mental causation Philosophers David L. Robb and John F. Heil introduce mental causation in terms of the mind–body problem of interaction: Mind–body interaction has a central place in our pretheoretic conception of agency. Indeed, mental causation often figures explicitly in formulations of the mind–body problem. Some philosophers insist that the very notion of psychological explanation turns on the intelligibility of mental causation. If your mind and its states, such as your beliefs and desires, were causally isolated from your bodily behavior, then what goes on in your mind could not explain what you do. If psychological explanation goes, so do the closely related notions of agency and moral responsibility. Clearly, a good deal rides on a satisfactory solution to the problem of mental causation [and] there is more than one way in which puzzles about the mind's "causal relevance" to behavior (and to the physical world more generally) can arise. [René Descartes] set the agenda for subsequent discussions of the mind–body relation. According to Descartes, minds and bodies are distinct kinds of "substance". Bodies, he held, are spatially extended substances, incapable of feeling or thought; minds, in contrast, are unextended, thinking, feeling substances. If minds and bodies are radically different kinds of substance, however, it is not easy to see how they "could" causally interact. Princess Elizabeth of Bohemia puts it forcefully to him in a 1643 letter: how the human soul can determine the movement of the animal spirits in the body so as to perform voluntary acts—being as it is merely a conscious substance. For the determination of movement seems always to come about from the moving body's being propelled—to depend on the kind of impulse it gets from what sets it in motion, or again, on the nature and shape of this latter thing's surface. Now the first two conditions involve contact, and the third involves that the impelling thing has extension; but you utterly exclude extension from your notion of soul, and contact seems to me incompatible with a thing's being immaterial... Elizabeth is expressing the prevailing mechanistic view as to how causation of bodies works. Causal relations countenanced by contemporary physics can take several forms, not all of which are of the push–pull variety.[3] — David Robb and John Heil, "Mental Causation" in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Contemporary neurophilosopher Georg Northoff suggests that mental causation is compatible with classical formal and final causality.[4] Biologist, theoretical neuroscientist and philosopher, Walter J. Freeman, suggests that explaining mind–body interaction in terms of "circular causation" is more relevant than linear causation.[5] In neuroscience, much has been learned about correlations between brain activity and subjective, conscious experiences. Many suggest that neuroscience will ultimately explain consciousness: "...consciousness is a biological process that will eventually be explained in terms of molecular signaling pathways used by interacting populations of nerve cells..."[6] However, this view has been criticized because consciousness has yet to be shown to be a process,[7] and the "hard problem" of relating consciousness directly to brain activity remains elusive.[8] Cognitive science today gets increasingly interested in the embodiment of human perception, thinking, and action. Abstract information processing models are no longer accepted as satisfactory accounts of the human mind. Interest has shifted to interactions between the material human body and its surroundings and to the way in which such interactions shape the mind. Proponents of this approach have expressed the hope that it will ultimately dissolve the Cartesian divide between the immaterial mind and the material existence of human beings (Damasio, 1994; Gallagher, 2005). A topic that seems particularly promising for providing a bridge across the mind–body cleavage is the study of bodily actions, which are neither reflexive reactions to external stimuli nor indications of mental states, which have only arbitrary relationships to the motor features of the action (e.g., pressing a button for making a choice response). The shape, timing, and effects of such actions are inseparable from their meaning. One might say that they are loaded with mental content, which cannot be appreciated other than by studying their material features. Imitation, communicative gesturing, and tool use are examples of these kinds of actions.[9] — Georg Goldenberg, "How the Mind Moves the Body: Lessons From Apraxia" in Oxford Handbook of Human Action Since 1927, at the Solvay Conference in Austria, European physicists of the late 19th and early 20th centuries realized that the interpretations of their experiments with light and electricity required a different theory to explain why light behaves both as a wave and particle. The implications were profound. The usual empirical model of explaining natural phenomena could not account for this duality of matter and non-matter. In a significant way, this has brought back the conversation on the mind–body duality.[10][page needed] |

心身相互作用と精神的因果関係 哲学者のデイヴィッド・L・ロブとジョン・F・ハイルは、精神的因果関係を心身相互作用問題の観点から紹介している: 心と身体の相互作用は、われわれの前理論的なエージェンシーの概念において中心的な位置を占めている。実際、精神的因果関係はしばしば心身問題の定式化に おいて明示的に登場する。哲学者の中には、心理学的説明の概念そのものが、精神的因果関係の理解可能性にかかっていると主張する者もいる。もしあなたの心 やその状態(信念や欲望など)が、あなたの身体的行動から因果的に切り離されているとしたら、あなたの心で起こっていることが、あなたの行動を説明するこ とはできない。心理学的な説明が成り立たなくなれば、密接に関連する主体性や道徳的責任という概念も成り立たなくなる。明らかに、心の因果関係の問題に対 する満足のいく解決策には、多くのことがかかっている[そして]行動(そしてより一般的には物理的世界)に対する心の「因果的関連性」についての不可解さ が生じる可能性がある。 [ルネ・デカルトは、その後の心身関係に関する議論のアジェンダを設定した。デカルトによれば、心と身体は別種の「物質」である。デカルトは、身体は空間 的に拡張された物質であり、感情や思考を持つことができないとした。しかし、もし心と身体が根本的に異なる種類の物質であるならば、それらが因果的に相互 作用する「可能性がある」ことを理解するのは容易ではない。ボヘミアのエリザベス王女は、1643年の手紙の中で、次のように力説している: 人間の魂が、身体の中の動物霊の動きをどのように決定し、自発的な行為を行うことができるのか。動きの決定は、常に、動く身体が推進されることから生じる ように思われる。つまり、身体を動かすものから受ける衝動の種類に依存するか、あるいは、後者のものの表面の性質と形状に依存するのである。最初の2つの 条件には接触が含まれ、3つ目の条件には、推進するものが伸長性を持っていることが含まれる。しかし、あなたは魂の概念から伸長性を完全に排除している。 エリザベスは、身体の因果関係がどのように働くかについて、一般的な機械論的見解を述べている。現代の物理学が認める因果関係にはいくつかの形態があり、そのすべてがプッシュ・プルのようなものではない[3]。 - デイヴィッド・ロブとジョン・ハイル、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』所収の「精神的因果」。 現代の神経哲学者であるゲオルク・ノースフは、精神的因果関係は古典的な形式的因果関係や最終的因果関係と両立することを示唆している[4]。 生物学者であり、理論的神経科学者であり、哲学者でもあるウォルター・J・フリーマンは、心と身体の相互作用を「循環的因果関係」の観点から説明することは、直線的因果関係よりも適切であると示唆している[5]。 神経科学では、脳の活動と主観的な意識体験との相関関係について多くのことが分かってきた。神経科学が最終的に意識を説明することを示唆する人も多い: 「意識は生物学的プロセスであり、最終的には相互作用する神経細胞集団が使用する分子シグナル伝達経路の観点から説明されるだろう」[6]。 認知科学は今日、人間の知覚、思考、行動の具現化にますます関心を寄せている。抽象的な情報処理モデルは、もはや人間の心について満足のいく説明としては 受け入れられていない。関心は、物質的な人間の身体とその周囲の環境との相互作用、そしてそのような相互作用が心を形成する方法に移っている。このアプ ローチの支持者たちは、非物質的な心と人間の物質的存在との間にあるデカルト主義的な隔たりを最終的に解消することに期待を表明している (Damasio, 1994; Gallagher, 2005)。心と身体の分断を越える架け橋として個別主義的に有望視されているのが、身体動作の研究である。身体動作は、外部刺激に対する反省的反応でも なければ、精神状態を示すものでもなく、動作の運動的特徴(例えば、選択反応を行うためにボタンを押す)とは恣意的な関係しか持たない。このような行動の 形、タイミング、効果は、その意味と不可分である。そのような行為には、物質的な特徴を研究しなければ理解できないような、精神的な内容が含まれていると 言えるかもしれない。模倣、コミュニケーション的身振り、道具の使用などは、この種の行動の例である[9]。 - ゲオルク・ゴールデンベルク「心はいかに身体を動かすか: 失行からの教訓」(『オックスフォード・ハンドブック・オブ・ヒューマン・アクション』所収 1927年にオーストリアで開催されたソルベイ会議以来、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのヨーロッパの物理学者たちは、光と電気に関する実験の解釈 には、なぜ光が波動としても粒子としても振る舞うのかを説明する異なる理論が必要であることに気づいた。その意味は深遠であった。自然現象を説明する通常 の経験モデルでは、この物質と非物質の二元性を説明できなかったのである。重要な意味で、これは心と体の二元性についての会話を復活させた[10][要 ページ]。 |

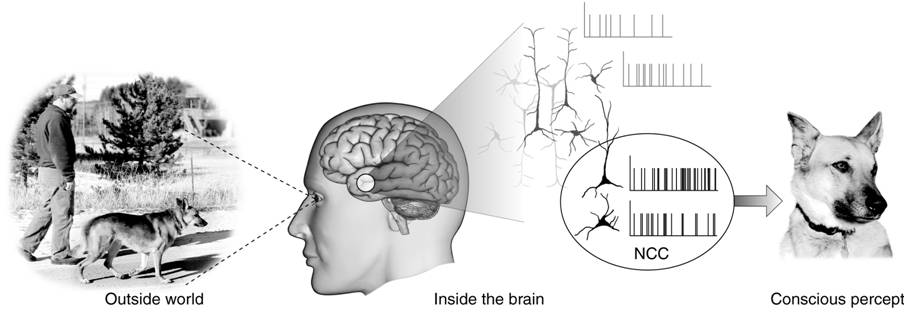

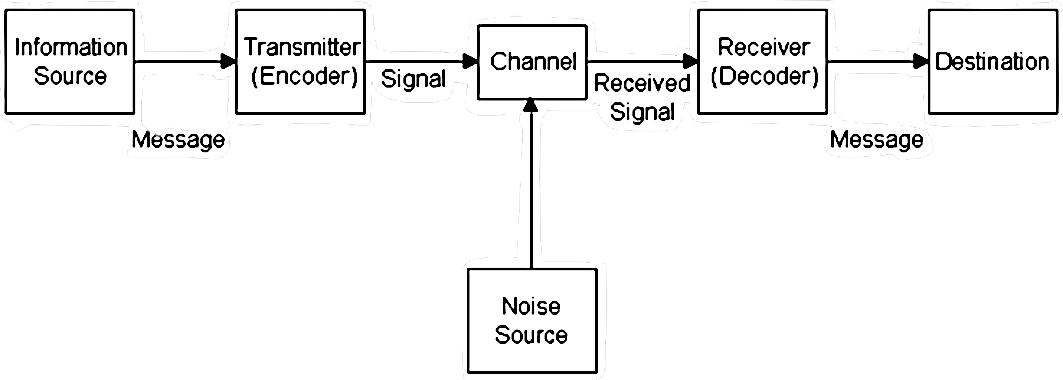

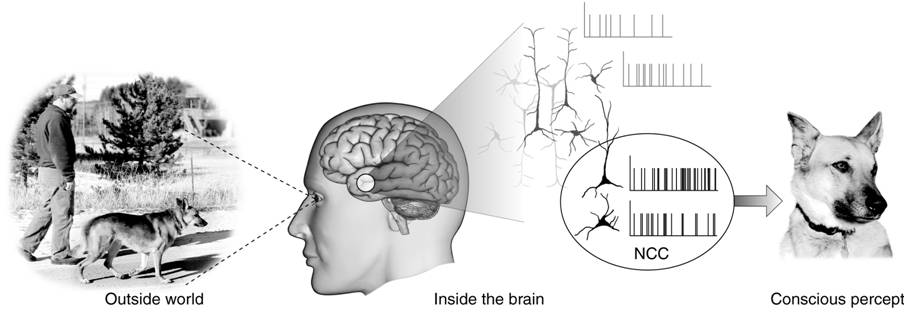

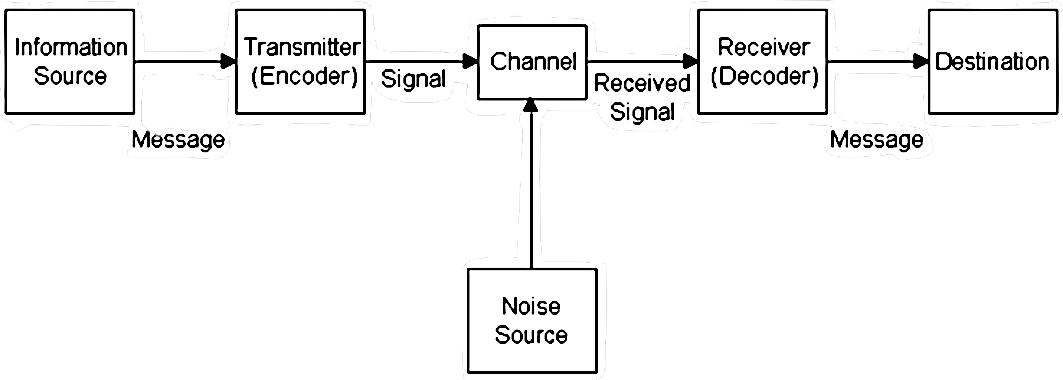

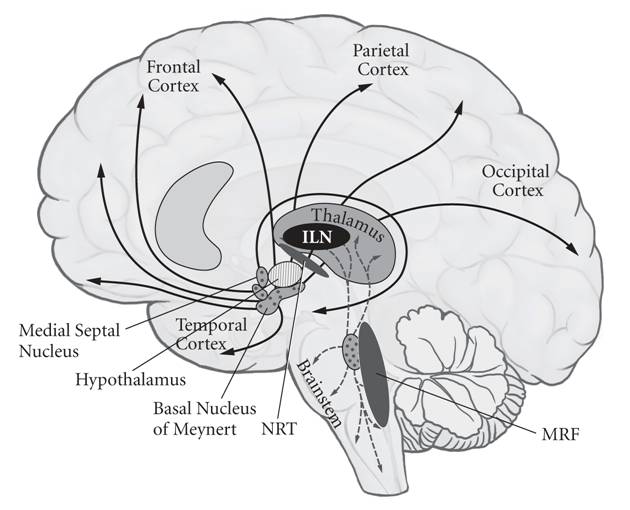

| Neural correlates Main article: Neural correlates of consciousness   The neuronal correlates of consciousness constitute the smallest set of neural events and structures sufficient for a given conscious percept or explicit memory. This case involves synchronized action potentials in neocortical pyramidal neurons.[11] The neural correlates of consciousness "are the smallest set of brain mechanisms and events sufficient for some specific conscious feeling, as elemental as the color red or as complex as the sensual, mysterious, and primeval sensation evoked when looking at [a] jungle scene..."[12] Neuroscientists use empirical approaches to discover neural correlates of subjective phenomena.[13] |

神経相関 主な記事 意識の神経相関   (シャノンウィーバーのコミュニケーション伝達の図は池田が加筆している) 意識の神経相関は、与えられた意識的知覚や明示的記憶に十分な神経事象と神経構造の最小セットを構成する。この場合、大脳新皮質の錐体ニューロンにおける同期活動電位が関係している[11]。 意識の神経相関は、「赤という色のような要素的なものから、ジャングルの光景を見たときに呼び起こされる感覚的で神秘的で原始的な感覚のような複雑なものまで、ある特定の意識的な感覚に十分な脳のメカニズムと事象の最小集合である」[12][13]。 |

| Neurobiology and neurophilosophy Main articles: Neurobiology and Neurophilosophy A science of consciousness must explain the exact relationship between subjective conscious mental states and brain states formed by electrochemical interactions in the body, the so-called hard problem of consciousness.[14] Neurobiology studies the connection scientifically, as do neuropsychology and neuropsychiatry. Neurophilosophy is the interdisciplinary study of neuroscience and philosophy of mind. In this pursuit, neurophilosophers, such as Patricia Churchland,[15][16] Paul Churchland[17] and Daniel Dennett,[18][19] have focused primarily on the body rather than the mind. In this context, neuronal correlates may be viewed as causing consciousness, where consciousness can be thought of as an undefined property that depends upon this complex, adaptive, and highly interconnected biological system.[20] However, it's unknown if discovering and characterizing neural correlates may eventually provide a theory of consciousness that can explain the first-person experience of these "systems", and determine whether other systems of equal complexity lack such features. The massive parallelism of neural networks allows redundant populations of neurons to mediate the same or similar percepts. Nonetheless, it is assumed that every subjective state will have associated neural correlates, which can be manipulated to artificially inhibit or induce the subject's experience of that conscious state. The growing ability of neuroscientists to manipulate neurons using methods from molecular biology in combination with optical tools[21] was achieved by the development of behavioral and organic models that are amenable to large-scale genomic analysis and manipulation. Non-human analysis such as this, in combination with imaging of the human brain, have contributed to a robust and increasingly predictive theoretical framework. |

神経生物学と神経哲学 主な記事 神経生物学と神経哲学 意識の科学は、主体的な意識的精神状態と、体内の電気化学的相互作用によって形成される脳の状態との間の正確な関係を説明しなければならない、いわゆる意 識の難問である[14]。神経生物学は、神経心理学や神経精神医学と同様に、この関係を科学的に研究している。神経哲学は、神経科学と心の哲学の学際的研 究である。この追求において、パトリシア・チャーチランド[15][16]、ポール・チャーチランド[17]、ダニエル・デネット[18][19]などの 神経哲学者は、主に心よりも身体に焦点を当ててきた。この文脈では、神経相関は意識を引き起こすとみなすことができ、意識はこの複雑で、適応的で、高度に 相互接続された生物学的システムに依存する未定義の性質と考えることができる[20]。しかし、神経相関を発見し、特徴付けることが、最終的にこれらの 「システム」の一人称の経験を説明できる意識の理論を提供し、同等の複雑性を持つ他のシステムがそのような特徴を欠いているかどうかを決定できるかどうか は不明である。 神経ネットワークの大規模な並列性により、ニューロンの冗長な集団が同一または類似の知覚を媒介することができる。それにもかかわらず、すべての主観的状 態には関連する神経相関があると仮定され、それを操作することで、その意識状態の経験を人為的に抑制したり誘発したりすることができる。神経科学者が、分 子生物学的手法と光学ツール[21]を組み合わせてニューロンを操作する能力を高めているのは、大規模なゲノム解析や操作が可能な行動モデルや器質モデル が開発されたからである。このような非ヒト分析が、ヒトの脳のイメージングと組み合わされることで、強固でますます予測可能な理論的枠組みに貢献してい る。 |

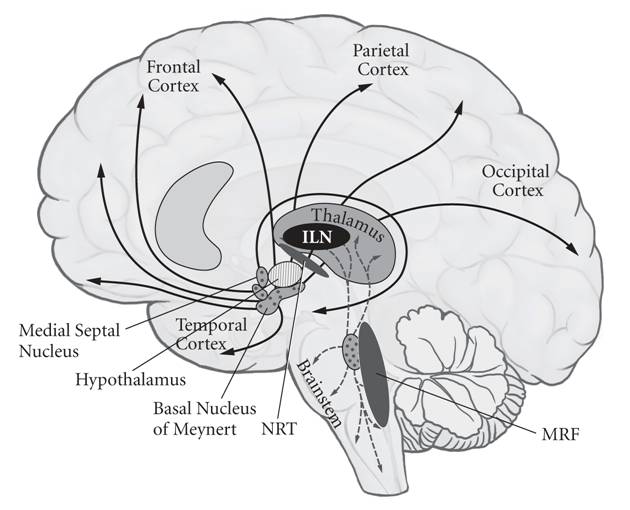

Arousal and content Midline structures in the brainstem and thalamus necessary to regulate the level of brain arousal. Small, bilateral lesions in many of these nuclei cause a global loss of consciousness.[22] There are two common but distinct dimensions of the term consciousness,[23] one involving arousal and states of consciousness and the other involving content of consciousness and conscious states. To be conscious of something, the brain must be in a relatively high state of arousal (sometimes called vigilance), whether awake or in REM sleep. Brain arousal level fluctuates in a circadian rhythm but these natural cycles may be influenced by lack of sleep, alcohol and other drugs, physical exertion, etc. Arousal can be measured behaviorally by the signal amplitude required to trigger a given reaction (for example, the sound level that causes a subject to turn and look toward the source). High arousal states involve conscious states that feature specific perceptual content, planning and recollection or even fantasy. Clinicians use scoring systems such as the Glasgow Coma Scale to assess the level of arousal in patients with impaired states of consciousness such as the comatose state, the persistent vegetative state, and the minimally conscious state. Here, "state" refers to different amounts of externalized, physical consciousness: ranging from a total absence in coma, persistent vegetative state and general anesthesia, to a fluctuating, minimally conscious state, such as sleep walking and epileptic seizure.[24] Many nuclei with distinct chemical signatures in the thalamus, midbrain and pons must function for a subject to be in a sufficient state of brain arousal to experience anything at all. These nuclei therefore belong to the enabling factors for consciousness. Conversely it is likely that the specific content of any particular conscious sensation is mediated by particular neurons in the cortex and their associated satellite structures, including the amygdala, thalamus, claustrum and the basal ganglia. |

覚醒と内容 脳の覚醒レベルを調節するのに必要な脳幹と視床の正中線構造。これらの核の多くに小さな両側性の病変があると、全体的な意識消失が起こる[22]。 意識という用語には、覚醒と意識状態に関わるものと、意識内容と意識状態に関わるものという、2つの共通するが異なる次元がある[23]。何かを意識する ためには、脳は覚醒状態であれレム睡眠状態であれ、比較的高い覚醒状態(警戒と呼ばれることもある)になければならない。脳の覚醒レベルは概日リズムで変 動するが、こうした自然なサイクルは、睡眠不足、アルコールなどの薬物、肉体的労作などによって影響を受けることがある。覚醒度は、ある反応を引き起こす のに必要な信号振幅によって行動学的に測定することができる(例えば、被験者が振り返って音源の方を見るようになる音レベル)。高覚醒状態には、特定の知 覚内容、計画、回想、あるいは空想などを特徴とする意識状態が含まれる。臨床医は、昏睡状態、遷延性植物状態、最小意識状態などの意識障害状態にある患者 の覚醒レベルを評価するために、グラスゴー昏睡スケールなどの採点システムを使用している。ここで「状態」とは、外在化した身体的意識の異なる量を指す: 昏睡、持続性植物状態、全身麻酔における完全な欠如から、睡眠時遊行やてんかん発作のような変動する最小意識状態までである[24]。 主体が何かを経験するのに十分な脳の覚醒状態にあるためには、視床、中脳、大脳皮質にある、明確な化学的シグネチャーを持つ多くの核が機能しなければなら ない。したがって、これらの核は意識を可能にする要因に属する。逆に言えば、特定の意識的な感覚の具体的な内容は、大脳皮質とそれに関連する扁桃体、視 床、脳梁、大脳基底核などの衛星構造にある特定のニューロンによって媒介されていると考えられる。 |

Theoretical frameworks Different approaches toward resolving the mind–body problem A variety of approaches have been proposed. Most are either dualist or monist. Dualism maintains a rigid distinction between the realms of mind and matter. Monism maintains that there is only one unifying reality as in neutral or substance or essence, in terms of which everything can be explained. Each of these categories contains numerous variants. The two main forms of dualism are substance dualism, which holds that the mind is formed of a distinct type of substance not governed by the laws of physics, and property dualism, which holds that mental properties involving conscious experience are fundamental properties, alongside the fundamental properties identified by a completed physics. The three main forms of monism are physicalism, which holds that the mind consists of matter organized in a particular way; idealism, which holds that only thought truly exists and matter is merely a representation of mental processes; and neutral monism, which holds that both mind and matter are aspects of a distinct essence that is itself identical to neither of them. Psychophysical parallelism is a third possible alternative regarding the relation between mind and body, between interaction (dualism) and one-sided action (monism).[25] Several philosophical perspectives that have sought to escape the problem by rejecting the mind–body dichotomy have been developed. The historical materialism of Karl Marx and subsequent writers, itself a form of physicalism, held that consciousness was engendered by the material contingencies of one's environment.[26] An explicit rejection of the dichotomy is found in French structuralism, and is a position that generally characterized post-war Continental philosophy.[27] An ancient model of the mind known as the Five-Aggregate Model, described in the Buddhist teachings, explains the mind as continuously changing sense impressions and mental phenomena.[28] Considering this model, it is possible to understand that it is the constantly changing sense impressions and mental phenomena (i.e., the mind) that experience/analyze all external phenomena in the world as well as all internal phenomena including the body anatomy, the nervous system as well as the organ brain. This conceptualization leads to two levels of analyses: (i) analyses conducted from a third-person perspective on how the brain works, and (ii) analyzing the moment-to-moment manifestation of an individual's mind-stream (analyses conducted from a first-person perspective). Considering the latter, the manifestation of the mind-stream is described as happening in every person all the time, even in a scientist who analyzes various phenomena in the world, including analyzing and hypothesizing about the organ brain.[28] Christian List argues that Benj Hellie's vertiginous question, i.e. why an individual exists as themselves and not as someone else, and the existence of first-personal facts, is evidence against physicalism. However, according to List, this is also evidence against other third-personal metaphysical pictures, including standard versions of dualism.[29] List also argues that the vertiginous question implies a "quadrilemma" for theories of consciousness. He claims that at most three of the following metaphysical claims can be true: 'first-person realism', 'non-solipsism', 'non-fragmentation', and 'one world' – and thus one of these four must be rejected.[30] List has proposed a model he calls the "many-worlds theory of consciousness" in order to reconcile the subjective nature of consciousness without lapsing into solipsism.[31] |

理論的枠組み 心身問題の解決に向けた異なるアプローチ さまざまなアプローチが提案されている。そのほとんどは二元論か一元論である。二元論は心と物質の領域を厳密に区別する。一元論は、中立的、物質的、本質的というように、ただ一つの統一的な実在があり、それに基づいてすべてが説明できると主張する。 これらのカテゴリーには、それぞれ数多くの変種がある。二元論の2つの主な形式は物質二元論で、心は物理法則に支配されない別個のタイプの物質で形成され ているとするものであり、性質二元論では、完成された物理学によって特定される基本的性質と並んで、意識的経験に関わる精神的性質が基本的性質であるとす るものである。一元論の3つの主な形態は、心は個別主義的に組織化された物質から構成されるとする物理主義、思考のみが真に存在し、物質は精神過程の表象 に過ぎないとする観念論、そして心と物質の両方が、そのどちらとも同一ではない別個の本質の側面であるとする中立的一元論である。精神物理学的平行主義 は、精神と身体の関係に関して、相互作用(二元論)と一方的作用(一元論)の間にある第三の可能な選択肢である[25]。 心身二元論を否定することによってこの問題から逃れようとする哲学的視点がいくつか開発されてきた。カール・マルクスとそれに続く作家たちの史的唯物論 は、それ自体物理主義の一形態であり、意識は環境の物質的偶発性によって生み出されるとした[26]。二項対立の明確な否定はフランス構造主義に見られ、 戦後の大陸哲学を一般的に特徴づける立場である[27]。 このモデルを考慮すると、世界のあらゆる外的現象や、身体の解剖学的構造、神経系、器官である脳を含むあらゆる内的現象を経験/分析するのは、絶えず変化 する感覚的印象と心的現象(すなわち心)であると理解することができる。この概念化は、(i)脳がどのように機能するかという三人称視点からの分析、 (ii)個人の心の流れの瞬間瞬間の現れ方の分析(一人称視点からの分析)という2つのレベルの分析につながる。後者について考えると、マインド・スト リームの顕現は、臓器である脳についての分析や仮説を含め、世の中の様々な現象を分析する科学者であっても、すべての人格の中で常に起こっていると説明さ れている[28]。 クリスチャン・リストは、ベンジー・ヘリーの暈のような問い、すなわち、なぜ人格が他の誰かとしてではなく自分自身として存在するのか、一人称的事実の存 在は、物理主義に対する証拠であると主張している。しかしリストによれば、これは標準的な二元論を含む他の三人称的な形而上学的図式に対する証拠でもあ る。一人称実在論」、「非ソリュプシス主義」、「非断片化」、「一つの世界」という形而上学的主張のうち、真である可能性があるのはせいぜい三つであり、 したがってこれら四つのうちの一つは否定されなければならないと主張している[30]。リストはソリュプシス主義に陥ることなく意識の主体性を調和させる ために、「意識の多世界理論」と呼ぶモデルを提唱している[31]。 |

| Dualism The following is a very brief account of some contributions to the mind–body problem. Interactionism Main article: Interactionism (philosophy of mind) The viewpoint of interactionism suggests that the mind and body are two separate substances, but that each can affect the other.[32] This interaction between the mind and body was first put forward by the philosopher René Descartes. Descartes believed that the mind was non-physical and permeated the entire body, but that the mind and body interacted via the pineal gland.[33][34] This theory has changed throughout the years, and in the 20th century its main adherents were the philosopher of science Karl Popper and the neurophysiologist John Carew Eccles.[35][36] A more recent and popular version of Interactionism is the viewpoint of emergentism.[32] This perspective states that mental states are a result of the brain states, and that the mental events can then influence the brain, resulting in a two way communication between the mind and body.[32] The absence of an empirically identifiable meeting point between the non-physical mind (if there is such a thing) and its physical extension (if there is such a thing) has been raised as a criticism of interactionalist dualism. This criticism has led many modern philosophers of mind to maintain that the mind is not something separate from the body.[37] These approaches have been particularly influential in the sciences, particularly in the fields of sociobiology, computer science, evolutionary psychology, and the neurosciences.[38][39][40][41] Avshalom Elitzur has defended interactionism and has described himself as a "reluctant dualist". One argument Elitzur makes in favor of dualism is an argument from bafflement. According to Elitzur, a conscious being can conceive of a P-zombie version of his/herself. However, a P-zombie cannot conceive of a version of itself that lacks corresponding qualia.[42] |

二元論 以下は、心身問題に対するいくつかの貢献についてのごく簡単な説明である。 相互作用論 主な記事 相互作用論(心の哲学) 相互作用主義の視点は、心と身体は2つの別々の物質であるが、それぞれが他方に影響を与えることができると示唆している[32]。デカルトは、心は非物理 的なものであり、身体全体に浸透しているが、心と身体は松果体を介して相互作用していると考えていた[33][34]。この理論は長い年月をかけて変化 し、20世紀には科学哲学者のカール・ポパーと神経生理学者のジョン・カリュー・エクルズが主な支持者となった。[35][36]相互作用論のより最近の 一般的なバージョンは、創発主義という視点である[32]。この視点は、心的状態は脳の状態の結果であり、心的事象が脳に影響を与え、その結果、心と身体 の間で双方向のコミュニケーションが生じると述べている[32]。 非物理的な心(そのようなものがあるとすれば)とその物理的な拡張(そのようなものがあるとすれば)の間に経験的に識別可能な会合点が存在しないことは、 相互作用論的二元論の批判として提起されてきた。この批判によって、現代の多くの心の哲学者たちは、心は身体から切り離されたものではないと主張している [37]。こうしたアプローチは、特に社会生物学、コンピュータ科学、進化心理学、神経科学などの科学分野において大きな影響力を持っている[38] [39][40][41]。 Avshalom Elitzurは相互作用論を擁護し、自らを「消極的な二元論者」であると述べている。エリッツアーが二元論を支持する論拠の一つに困惑からの議論があ る。エリッツァーによると、意識のある人は自分のP-ゾンビを考えることができる。しかし、P-ゾンビは対応するクオリアを持たない自分自身のバージョン を考えることができない[42]。 |

| Epiphenomenalism Main article: Epiphenomenalism The viewpoint of epiphenomenalism suggests that the physical brain can cause mental events in the mind, but that the mind cannot interact with the brain at all; stating that mental occurrences are simply a side effect of the brain's processes.[32] This viewpoint explains that while one's body may react to them feeling joy, fear, or sadness, that the emotion does not cause the physical response. Rather, it explains that joy, fear, sadness, and all bodily reactions are caused by chemicals and their interaction with the body.[43] |

エピフェノメナリズム 主な記事 エピフェノメナリズム エピフェノメナリズムの視点は、物理的な脳が心の中で精神的な出来事を引き起こすことはできるが、心は脳とまったく相互作用することはできないと示唆して いる。この視点は、喜び、恐れ、悲しみを感じて身体が反応することはあっても、感情が身体的な反応を引き起こすことはないと説明する[32]。むしろ、喜 び、恐れ、悲しみ、そしてすべての身体的反応は、化学物質と身体との相互作用によって引き起こされると説明している[43]。 |

| Psychophysical parallelism Main article: Psychophysical parallelism The viewpoint of psychophysical parallelism suggests that the mind and body are entirely independent from one another. Furthermore, this viewpoint states that both mental and physical stimuli and reactions are experienced simultaneously by both the mind and body, however, there is no interaction nor communication between the two.[32][44] |

心理物理学的平行移動 主な記事 精神物理学的平行論 精神物理学的平行主義とは、精神と身体は互いに完全に独立しているという考え方である。さらにこの視点は、精神的刺激と身体的反応の両方が心と身体の両方によって同時に経験されるが、両者の間には相互作用もコミュニケーションも存在しないと述べている[32][44]。 |

| Double aspectism Main article: Double aspectism Double aspectism is an extension of psychophysical parallelism which also suggests that the mind and body cannot interact, nor can they be separated.[32] Baruch Spinoza and Gustav Fechner were two of the notable users of double aspectism, however, Fechner later expanded upon it to form the branch of psychophysics in an attempt to prove the relationship of the mind and body.[45] |

ダブルアスペクト主義 主な記事 二重アスペクト主義 二重アスペクト論は精神物理学的平行論の延長であり、精神と肉体は相互作用することも分離することもできないことを示唆している[32]。バルーク・スピ ノザとグスタフ・フェヒナーは二重アスペクト論の著名な使用者の一人であったが、フェヒナーは後に精神と肉体の関係を証明しようとして精神物理学の一分野 を形成するためにそれを拡張した[45]。 |

| Pre-established harmony The viewpoint of pre-established harmony is another offshoot of psychophysical parallelism which suggests that mental events and bodily events are separate and distinct, but that they are both coordinated by an external agent: an example of such an agent could be God.[32] A notable adherent to the idea of pre-established harmony is Gottfried Wilhelm von Leibniz in his theory of Monadology.[46] His explanation of pre-established harmony relied heavily upon God as the external agent who coordinated the mental and bodily events of all things in the beginning.[47] Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz's theory of pre-established harmony (French: harmonie préétablie) is a philosophical theory about causation under which every "substance" affects only itself, but all the substances (both bodies and minds) in the world nevertheless seem to causally interact with each other because they have been programmed by God in advance to "harmonize" with each other. Leibniz's term for these substances was "monads", which he described in a popular work (Monadology §7) as "windowless". The concept of pre-established harmony can be understood by considering an event with both seemingly mental and physical aspects. For example, consider saying 'ouch' after stubbing one's toe. There are two general ways to describe this event: in terms of mental events (where the conscious sensation of pain caused one to say 'ouch') and in terms of physical events (where neural firings in one's toe, carried to the brain, are what caused one to say 'ouch'). The main task of the mind–body problem is figuring out how these mental events (the feeling of pain) and physical events (the nerve firings) relate. Leibniz's pre-established harmony attempts to answer this puzzle, by saying that mental and physical events are not genuinely related in any causal sense, but only seem to interact due to psycho-physical fine-tuning. Leibniz's theory is best known as a solution to the mind–body problem of how mind can interact with the body. Leibniz rejected the idea of physical bodies affecting each other, and explained all physical causation in this way. Under pre-established harmony, the preprogramming of each mind must be extremely complex, since only it causes its own thoughts or actions, for as long as it exists. To appear to interact, each substance's "program" must contain a description of either the entire universe, or of how the object behaves at all times during all interactions that appear to occur. An example: An apple falls on Alice's head, apparently causing the experience of pain in her mind. In fact, the apple does not cause the pain—the pain is caused by some previous state of Alice's mind. If Alice then seems to shake her hand in anger, it is not actually her mind that causes this, but some previous state of her hand. Note that if a mind behaves as a windowless monad, there is no need for any other object to exist to create that mind's sense perceptions, leading to a solipsistic universe that consists only of that mind. Leibniz seems to admit this in his Discourse on Metaphysics, section 14. However, he claims that his principle of harmony, according to which God creates the best and most harmonious world possible, dictates that the perceptions (internal states) of each monad "expresses" the world in its entirety, and the world expressed by the monad actually exists. Although Leibniz says that each monad is "windowless", he also claims that it functions as a "mirror" of the entire created universe. On occasion, Leibniz styled himself as "the author of the system of pre-established harmony".[48] Immanuel Kant's professor Martin Knutzen regarded pre-established harmony as "the pillow for the lazy mind".[49] In his sixth Metaphysical Meditation, Descartes talked about a "coordinated disposition of created things set up by God", shortly after having identified "nature in its general aspect" with God himself. His conception of the relationship between God and his normative nature actualized in the existing world recalls both the pre-established harmony of Leibniz and the Deus sive Natura of Baruch Spinoza.[50] |

あらかじめ確立された調和 この考え方は、精神的な出来事と身体的な出来事は別個のものであるが、両者は外部の主体によって調整されていると示唆するものである。 ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツの既成調和論(フランス語:harmonie prétablie)は因果関係についての哲学的理論であり、あらゆる「物質」はそれ自体にしか影響を及ぼさないが、それにもかかわらず世界のすべての物 質(身体と精神の両方)は因果的に相互作用しているように見えるというものである。ライプニッツはこのような物質を「モナド」と呼び、一般的な著作(『モ ナド論』§7)では「窓のない」と表現した。 あらかじめ確立された調和という概念は、一見精神的な側面と物理的な側面の両方を持つ事象を考えることで理解できる。例えば、足の指を踏んづけた後に「痛 い」と言うことを考えてみよう。この出来事を説明する一般的な方法は2つある。精神的な出来事(痛みという意識的な感覚が「痛い」と言わせた)という観点 と、身体的な出来事(足の指の神経が発火し、それが脳に伝わったことが「痛い」と言わせた)という観点である。心身の問題の主な課題は、これらの心的事象 (痛みを感じること)と物理的事象(神経の発火)がどのように関連しているかを解明することである。ライプニッツの既成調和は、このパズルに答えようとす るもので、精神的事象と物理的事象は、因果的な意味で純粋に関連しているのではなく、精神物理的微調整によって相互作用しているように見えるだけだと言 う。 ライプニッツの理論は、心が身体とどのように相互作用するかという心身問題の解決策として最もよく知られている。ライプニッツは、肉体が互いに影響し合うという考え方を否定し、すべての物理的因果関係をこのように説明した。 あらかじめ確立された調和のもとでは、存在する限り、心だけが自らの思考や行動を引き起こすのだから、それぞれの心の事前プログラミングは極めて複雑でな ければならない。相互作用しているように見えるためには、各物質の「プログラム」には、宇宙全体か、あるいは、相互作用が起こっているように見える間、そ の物体が常にどのように振る舞うかについての記述が含まれていなければならない。 例を挙げよう: あるリンゴがアリスの頭の上に落ちてきて、アリスの心の中に痛みを引き起こしたように見える。実は、リンゴが痛みを引き起こしているのではなく、アリスの 心の以前の状態によって痛みが引き起こされているのだ。アリスが怒って手を振るように見えたとしても、それは実はアリスの心ではなく、アリスの手の以前の 状態によって引き起こされるのだ。 もし心が窓のないモナドとして振る舞うなら、その心の感覚を作り出すために他の物体が存在する必要はなく、その心だけで構成される独我論的な宇宙が生まれ ることに注意しよう。ライプニッツは『形而上学言説』第14節でこのことを認めているようだ。しかしライプニッツは、神が可能な限り最良で調和のとれた世 界を創造するという彼の調和の原理に従って、各モナドの知覚(内的状態)は世界を「表現」するものであり、モナドによって表現された世界は実際に存在する と主張している。ライプニッツは、各モナドは「窓がない」としながらも、創造された宇宙全体の「鏡」として機能しているとも主張している。 ライプニッツは自らを「あらかじめ確立された調和の体系の作者」と称することもあった[48]。 イマヌエル・カントの教授であったマルティン・クヌッツェンは、あらかじめ確立された調和を「怠惰な心の枕」とみなしていた[49]。 デカルトは第6の形而上学的瞑想において、「一般的な側面における自然」を神自身と同一視した直後に、「神によって設定された被造物の調整された性質」に ついて語った。現存する世界において現実化された神とその規範的自然との関係についての彼の概念は、ライプニッツのあらかじめ確立された調和とバルーク・ スピノザのDeus sive Naturaの両方を想起させる[50]。 |

| Occasionalism Main article: Occasionalism The viewpoint of Occasionalism is another offshoot of psychophysical parallelism, however, the major difference is that the mind and body have some indirect interaction. Occasionalism suggests that the mind and body are separate and distinct, but that they interact through divine intervention.[32] Nicolas Malebranche was one of the main contributors to this idea, using it as a way to address his disagreements with Descartes' view of the mind–body problem.[51] In Malebranche's occasionalism, he viewed thoughts as a wish for the body to move, which was then fulfilled by God causing the body to act.[51] |

オケージョナリズム 主な記事 オカジョナリズム オカシオナリズムの視点は、精神物理学的並行論のもう一つの分派であるが、大きな違いは、心と身体は間接的な相互作用を持っているという点である。ニコ ラ・マルブランシュはこの思想の主要な貢献者の一人であり、デカルトの心身問題に対する見解との不一致に対処する方法としてこの思想を用いていた [51]。マルブランシュの機会主義では、思考を身体が動くことへの願いとみなし、その願いは神が身体を行動させることによって叶えられるとした [51]。 |

| Historical background The problem was popularized by René Descartes in the 17th century, which resulted in Cartesian dualism, also by pre-Aristotelian philosophers,[52][53] in Avicennian philosophy,[54] and in earlier Asian traditions. The Buddha See also: Gautama Buddha, Buddhism and the body, and Pratītyasamutpāda The Buddha (480–400 B.C.E), founder of Buddhism, described the mind and the body as depending on each other in a way that two sheaves of reeds were to stand leaning against one another[55] and taught that the world consists of mind and matter which work together, interdependently. Buddhist teachings describe the mind as manifesting from moment to moment, one thought moment at a time as a fast flowing stream.[28] The components that make up the mind are known as the five aggregates (i.e., material form, feelings, perception, volition, and sensory consciousness), which arise and pass away continuously. The arising and passing of these aggregates in the present moment is described as being influenced by five causal laws: biological laws, psychological laws, physical laws, volitional laws, and universal laws.[28] The Buddhist practice of mindfulness involves attending to this constantly changing mind-stream. Ultimately, the Buddha's philosophy is that both mind and forms are conditionally arising qualities of an ever-changing universe in which, when nirvāna is attained, all phenomenal experience ceases to exist.[56] According to the anattā doctrine of the Buddha, the conceptual self is a mere mental construct of an individual entity and is basically an impermanent illusion, sustained by form, sensation, perception, thought and consciousness.[57] The Buddha argued that mentally clinging to any views will result in delusion and stress,[58] since, according to the Buddha, a real self (conceptual self, being the basis of standpoints and views) cannot be found when the mind has clarity. |

歴史的背景 この問題は17世紀にルネ・デカルトによって一般化され、デカルト主義的な二元論を生み出したが、アリストテレス以前の哲学者たち[52][53]、アヴィケニア哲学[54]、そしてそれ以前のアジアの伝統においても同様であった。 ブッダ 以下も参照: ゴータマ・ブッダ、仏教と身体、プラティヤサムットパーダも参照のこと。 仏教の開祖であるブッダ(B.C.E.480-400)は、2本の葦の束が互いに寄り添って立っているように、心と身体は互いに依存していると説明し [55]、世界は相互に依存しながら共に働く心と物質で構成されていると説いた。仏教の教えでは、心は瞬間から瞬間へと現れ、一度に一つの思考の瞬間が速 い流れのように現れると表現している[28]。心を構成する要素は五つの集合体(すなわち、物質的な形、感情、知覚、意志、感覚意識)として知られてお り、これらは絶え間なく生じては消えていく。今この瞬間におけるこれらの集合体の発生と消滅は、5つの因果律(生物学的法則、心理学的法則、物理学的法 則、意志的法則、普遍的法則)の影響を受けていると説明されている[28]。仏教のマインドフルネスの実践には、この絶えず変化する心の流れに注意を向け ることが含まれる。 最終的に、釈迦の哲学は、心も形も、常に変化する宇宙の条件付きで生じる性質であり、涅槃に到達すると、すべての現象的経験は存在しなくなるというもので ある[56]。釈迦の無我の教義によれば、概念的な自己は、個々の実体の単なる精神的構成物であり、基本的に無常な幻影であり、形、感覚、知覚、思考、意 識によって支えられている。[ブッダによれば、心が明晰であるとき、本当の自己(立場と見解の基礎である概念的自己)を見出すことはできないからである。 |

| Plato See also: Plato and Theory of forms Plato (429–347 B.C.E.) believed that the material world is a shadow of a higher reality that consists of concepts he called Forms. According to Plato, objects in our everyday world "participate in" these Forms, which confer identity and meaning to material objects. For example, a circle drawn in the sand would be a circle only because it participates in the concept of an ideal circle that exists somewhere in the world of Forms. He argued that, as the body is from the material world, the soul is from the world of Forms and is thus immortal. He believed the soul was temporarily united with the body and would only be separated at death, when it, if pure, would return to the world of Forms; otherwise, reincarnation follows. Since the soul does not exist in time and space, as the body does, it can access universal truths. For Plato, ideas (or Forms) are the true reality, and are experienced by the soul. The body is for Plato empty in that it cannot access the abstract reality of the world; it can only experience shadows. This is determined by Plato's essentially rationalistic epistemology.[59] |

プラトン も参照のこと: プラトン、形相論 プラトン(紀元前429~347年)は、物質世界は、彼が「形相」と呼ぶ概念からなる高次の現実の影であると考えた。プラトンによれば、私たちの日常世界 にある物体は、この形相に「参加」しており、形相が物質的な物体に同一性と意味を与えている。例えば、砂に描かれた円は、形相の世界のどこかに存在する理 想的な円という概念に参加しているからこそ、円なのである。肉体が物質界のものであるように、魂は形相界のものであり、したがって不滅であると主張した。 魂は一時的に肉体と一体化し、純粋であれば形相の世界に戻り、そうでなければ輪廻転生する。魂は肉体のように時間と空間の中に存在しないので、普遍的な真 理にアクセスすることができる。プラトンにとって、イデア(あるいは形相)こそが真の現実であり、魂によって経験される。肉体はプラトンにとって空虚であ り、世界の抽象的な現実にアクセスすることはできない。これはプラトンの本質的に合理主義的な認識論によって決定される[59]。 |

| Aristotle Main article: Hylomorphism § Body–soul hylomorphism For Aristotle (384–322 BC) mind is a faculty of the soul.[60][61] Regarding the soul, he said: It is not necessary to ask whether soul and body are one, just as it is not necessary to ask whether the wax and its shape are one, nor generally whether the matter of each thing and that of which it is the matter are one. For even if one and being are spoken of in several ways, what is properly so spoken of is the actuality. — De Anima ii 1, 412b6–9 In the end, Aristotle saw the relation between soul and body as uncomplicated, in the same way that it is uncomplicated that a cubical shape is a property of a toy building block. The soul is a property exhibited by the body, one among many. Moreover, Aristotle proposed that when the body perishes, so does the soul, just as the shape of a building block disappears with destruction of the block.[62] Medieval Aristotelianism Working in the Aristotelian-influenced tradition of Thomism, Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274), like Aristotle, believed that the mind and the body are one, like a seal and wax; therefore, it is pointless to ask whether or not they are one. However, (referring to "mind" as "the soul") he asserted that the soul persists after the death of the body in spite of their unity, calling the soul "this particular thing". Since his view was primarily theological rather than philosophical, it is impossible to fit it neatly within either the category of physicalism or dualism.[63] |

アリストテレス 主な記事 同形論 § 肉体と魂の同形論 アリストテレス(前384-前322年)にとって、心は魂の能力である[60][61]: 魂と身体が一つであるかどうかを問う必要はない。ちょうど、蝋とその形が一つであるかどうかを問う必要がないように、また一般に、それぞれの事物の物質と それが物質であるものが一つであるかどうかを問う必要もない。というのも、一つであることと存在することがいくつかの仕方で語られるとしても、正しくそう 語られるのは実在性だからである。 - デ・アニマ II 1, 412b6-9 結局のところ、アリストテレスは魂と身体との関係を、立方体の形がおもちゃの積み木の性質であることが単純でないのと同じように、単純でないと考えた。魂 は身体が示す性質であり、数ある性質のうちのひとつなのだ。さらにアリストテレスは、積み木の形が積み木の破壊とともに消滅するように、身体が消滅すると きには魂も消滅すると提唱した[62]。 中世のアリストテレス主義 トマス・アクィナス(1225-1274)は、アリストテレスの影響を受けたトミズムの伝統の中で活動し、アリストテレスと同様に、心と身体は印鑑と蝋の ように一体であり、従って両者が一体であるかどうかを問うことは無意味であると考えた。しかし(「心」を「魂」と呼ぶ)彼は、魂は肉体の死後も一体である にもかかわらず存続すると主張し、魂を「この個別主義」と呼んだ。彼の見解は哲学的というよりも主に神学的であったため、物理主義や二元論の範疇にきれい に収めることは不可能である[63]。 |

| Influences of Eastern monotheistic religions Main articles: Dualistic cosmology and Gnosticism In religious philosophy of Eastern monotheism, dualism denotes a binary opposition of an idea that contains two essential parts. The first formal concept of a "mind–body" split may be found in the divinity–secularity dualism of the ancient Persian religion of Zoroastrianism around the mid-fifth century BC. Gnosticism is a modern name for a variety of ancient dualistic ideas inspired by Judaism popular in the first and second century AD. These ideas later seem to have been incorporated into Galen's "tripartite soul" [64] that led into both the Christian sentiments[65] expressed in the later Augustinian theodicy and Avicenna's Platonism in Islamic Philosophy. |

東方一神教の影響 主な記事 二元論的宇宙論とグノーシス主義 東洋の一神教の宗教哲学では、二元論は2つの本質的な部分を含む思想の二元的対立を示す。心と体」の分裂という最初の正式な概念は、紀元前5世紀半ばごろ の古代ペルシアの宗教ゾロアスター教の神性と世俗の二元論に見られる。グノーシス主義とは、紀元1~2世紀に流行しあcたユダヤ教に触発された古代の様々 な二元論的思想の現代的名称である。これらの思想は後にガレンの「三位一体の魂」[64]に取り入れられ、後のアウグスティヌスの神義論で表現されたキリ スト教的感情[65]やイスラム哲学におけるアヴィセンナのプラトン主義へとつながっていったようである。 |

| Descartes Main article: René Descartes René Descartes (1596–1650) believed that mind exerted control over the brain via the pineal gland: My view is that this gland is the principal seat of the soul, and the place in which all our thoughts are formed.[66] — René Descartes, Treatise of Man [The] mechanism of our body is so constructed that simply by this gland's being moved in any way by the soul or by any other cause, it drives the surrounding spirits towards the pores of the brain, which direct them through the nerves to the muscles; and in this way the gland makes the spirits move the limbs.[67] — René Descartes, Passions of the Soul His posited relation between mind and body is called Cartesian dualism or substance dualism. He held that mind was distinct from matter, but could influence matter. How such an interaction could be exerted remains a contentious issue. |

デカルト 主な記事 ルネ・デカルト ルネ・デカルト(1596-1650)は、心は松果体を介して脳を支配していると考えていた: 私の考えでは、この腺は魂の主要な座であり、すべての思考が形成される場所である。 - ルネ・デカルト『人間論 [われわれの身体の機構は、この腺が魂によって、あるいはその他の原因によって何らかの形で動かされるだけで、周囲の霊魂を脳の孔のほうに向かわせ、その孔が神経を通じて霊魂を筋肉に向かわせるようにできている[67]。 - ルネ・デカルト『魂の情熱 デカルトが提唱した精神と肉体の関係は、デカルト二元論あるいは物質二元論と呼ばれている。デカルトは、心は物質とは異なるが、物質に影響を与えることができると考えた。そのような相互作用がどのように発揮されうるかについては、論争が続いている。 |

| Kant Main article: Immanuel Kant For Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) beyond mind and matter there exists a world of a priori forms, which are seen as necessary preconditions for understanding. Some of these forms, space and time being examples, today seem to be pre-programmed in the brain. ...whatever it is that impinges on us from the mind-independent world does not come located in a spatial or a temporal matrix,...The mind has two pure forms of intuition built into it to allow it to... organize this 'manifold of raw intuition'.[68] — Andrew Brook, Kant's view of the mind and consciousness of self: Transcendental aesthetic Kant views the mind–body interaction as taking place through forces that may be of different kinds for mind and body.[69] |

カント 主な記事 イマヌエル・カント イマヌエル・カント(1724-1804)にとって、心と物質の向こう側にはア・プリオリに形づくられた世界が存在する。空間と時間がその例であるが、これらの形態のいくつかは、今日、脳にあらかじめプログラムされているようである。 ...心に依存しない世界からわれわれに迫ってくるものは何であれ、空間的あるいは時間的なマトリックスに位置づけられるものではない。...心には、この「生の直観の多様体」を整理できるようにするために、二つの純粋な直観の形式が組み込まれている[68]。 - アンドリュー・ブルック『カントの心観と自己意識 超越論的美学 カントは心と身体の相互作用を、心と身体にとって異なる種類であるかもしれない力を通じて起こるものとして捉えている[69]。 |

| Huxley Main article: Thomas Henry Huxley For Thomas Henry Huxley (1825–1895) the conscious mind was a by-product of the brain that has no influence upon the brain, a so-called epiphenomenon. On the epiphenomenalist view, mental events play no causal role. Huxley, who held the view, compared mental events to a steam whistle that contributes nothing to the work of a locomotive.[70] — William Robinson, Epiphenomenalism |

ハクスリー 主な記事 トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー トーマス・ヘンリー・ハクスリー(1825-1895)にとって、意識は脳の副産物であり、脳には何の影響も及ぼさない、いわゆるエピフェノメノンであった。 エピフェノメノン主義者の見解では、精神的な出来事は因果的な役割を果たさない。この考え方を持つハクスリーは、心的事象を機関車の仕事に何も貢献しない汽笛に例えている[70]。 - ウィリアム・ロビンソン『エピフェノメナリズム |

| Whitehead Main article: Alfred North Whitehead Alfred North Whitehead advocated a sophisticated form of panpsychism that has been called by David Ray Griffin panexperientialism.[71] |

ホワイトヘッド 主な記事 アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッド アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドは、デイヴィッド・レイ・グリフィンによってパネクスペリエンタリズムと呼ばれる洗練された形の汎心論を提唱した[71]。 |

| Popper Main article: Karl Popper For Karl Popper (1902–1994) there are three aspects of the mind–body problem: the worlds of matter, mind, and of the creations of the mind, such as mathematics. In his view, the third-world creations of the mind could be interpreted by the second-world mind and used to affect the first-world of matter. An example might be radio, an example of the interpretation of the third-world (Maxwell's electromagnetic theory) by the second-world mind to suggest modifications of the external first world. The body–mind problem is the question of whether and how our thought processes in World 2 are bound up with brain events in World 1. ...I would argue that the first and oldest of these attempted solutions is the only one that deserves to be taken seriously [namely]: World 2 and World 1 interact, so that when someone reads a book or listens to a lecture, brain events occur that act upon the World 2 of the reader's or listener's thoughts; and conversely, when a mathematician follows a proof, his World 2 acts upon his brain and thus upon World 1. This, then, is the thesis of body–mind interaction.[72] — Karl Popper, Notes of a realist on the body–mind problem |

ポッパー 主な記事 カール・ポパー カール・ポパー(1902-1994)にとって、心身問題には3つの側面がある:物質、心、そして数学のような心の創造物の世界である。彼の考えでは、第 三世界の心の創造物は、第二世界の心によって解釈され、第一世界の物質に影響を与えるために使われる可能性がある。その例としてラジオが挙げられるが、こ れは第三の世界(マクスウェルの電磁気理論)を第二の世界の心が解釈し、外的な第一の世界の修正を示唆した例である。 身体と心の問題とは、第2世界における我々の思考プロセスが、第1世界における脳の出来事とどのように結びついているのかという問題である: つまり、誰かが本を読んだり講義を聞いたりするとき、読者や聴衆の思考の世界2に作用する脳の出来事が起こり、逆に数学者が証明に従うとき、彼の世界2は 彼の脳に作用し、その結果世界1に作用する。そして逆に、数学者が証明に従うとき、彼の世界2は彼の脳に作用し、その結果世界1に作用する。これが身体と 心の相互作用のテーゼである[72]。 - カール・ポパー『身体と心の問題に関する現実主義者のノート |

| Ryle Main article: Gilbert Ryle With his 1949 book, The Concept of Mind, Gilbert Ryle "was seen to have put the final nail in the coffin of Cartesian dualism".[73] In the chapter "Descartes' Myth," Ryle introduces "the dogma of the Ghost in the machine" to describe the philosophical concept of the mind as an entity separate from the body: I hope to prove that it is entirely false, and false not in detail but in principle. It is not merely an assemblage of particular mistakes. It is one big mistake and a mistake of a special kind. It is, namely, a category mistake. |

ライル 主な記事 ギルバート・ライル 1949年の著書『心の概念』によって、ギルバート・ライルは「デカルト主義的二元論の棺桶に最後の釘を刺したと見なされた」[73]。 デカルトの神話」の章において、ライルは「機械の中の幽霊の教義」を紹介し、身体から切り離された実体としての心の哲学的概念を説明している: 私はそれが全くの誤りであり、細部においてではなく原理において誤りであることを証明したい。それは単なる個別主義の集合体ではない。それは一つの大きな間違いであり、特別な種類の間違いである。それはすなわち、カテゴリーの間違いである。 |

| Searle Main article: John Searle For John Searle (b. 1932) the mind–body problem is a false dichotomy; that is, mind is a perfectly ordinary aspect of the brain. Searle proposed biological naturalism in 1980. According to Searle then, there is no more a mind–body problem than there is a macro–micro economics problem. They are different levels of description of the same set of phenomena. [...] But Searle is careful to maintain that the mental – the domain of qualitative experience and understanding – is autonomous and has no counterpart on the microlevel; any redescription of these macroscopic features amounts to a kind of evisceration, ...[74] — Joshua Rust, John Searle |

サール 主な記事 ジョン・サール ジョン・サール(1932年生まれ)にとって、心と身体の問題は誤った二分法である。サールは1980年に生物学的自然主義を提唱した。 サールによれば、心身の問題は、マクロ経済学とミクロ経済学の問題と同じである。それらは同じ現象の異なるレベルの記述である。[しかしサールは、心的な もの(質的な経験と理解の領域)は自律的なものであり、ミクロなレベルには対応するものがないことを注意深く主張している。] - ジョシュア・ラスト、ジョン・サール |

| Binding problem Bodymind Chinese room Cognitive closure (philosophy) Cognitive neuroscience Connectionism Consciousness in animals Downward causation Descartes' Error Embodied cognition Existentialism Explanatory gap Free will Ideasthesia Namarupa (Buddhist concept) Neuroscience of free will Philosophical zombie Philosophy of artificial intelligence Pluralism Problem of mental causation Problem of other minds Qualia Reductionism Sacred–profane dichotomy Sentience Strange loop (self-reflective thoughts) The Mind's I (book on the subject) Turing test Vertiginous question William H. Poteat |

バインディングの問題 ボディマインド 中国の部屋 認知的閉鎖(哲学) 認知神経科学 コネクショニズム 動物における意識 下向きの因果関係 デカルトの誤り 身体化された認知 実存主義 説明のギャップ 自由意志 イデアステシア ナマルパ(仏教の概念) 自由意志の脳科学 哲学的ゾンビ 人工知能の哲学 多元主義 精神的因果関係の問題 他の心の問題 クオリア 還元主義 聖と俗の二分法 感覚 奇妙なループ(自己反省的思考) 心の私」(主体性に関する本) チューリングテスト 垂直的な問い ウィリアム・H・ポティート |

| Bunge, Mario (2014). The Mind–Body Problem: A Psychobiological Approach. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-5012-3. Feigl, Herbert (1958). "The 'Mental' and the 'Physical'". In Feigl, Herbert; Scriven, Michael; Maxwell, Grover (eds.). Concepts, Theories, and the Mind–Body Problem. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science. Vol. 2. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 370–457. Gendlin, E. T. (2012a). "Line by Line translation on Aristotle's De Anima, Books I and II" (PDF). Gendlin, E. T. (2012b). "Line by Line translation on Aristotle's De Anima, Book III" (PDF). Hicks, R. D. (1907). Aristotle, De Anima. Cambridge University Press. Kim, J. (1995). "Mind–Body Problem", Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Ted Honderich (ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. Jaegwon Kim (2010). Essays in the Metaphysics of Mind. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-162506-0. Massimini, M.; Tononi, G. (2018). Sizing up Consciousness: Towards an Objective Measure of the Capacity for Experience. Oxford University Press. Turner, Bryan S. (1996). The Body and Society: Exploration in Social Theory. |

Bunge, Mario (2014). 心と体の問題:心理生物学的アプローチ. Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4831-5012-3. Feigl, Herbert (1958). 精神』と『肉体』」。Feigl, Herbert; Scriven, Michael; Maxwell, Grover (eds.). 概念、理論、そして心身問題. Minnesota Studies in the Philosophy of Science. ミネアポリス: ミネソタ大学出版局. 370-457. Gendlin, E. T. (2012a). 「Line by Line translation on Aristotle's De Anima, Books I and II」 (PDF). Gendlin, E. T. (2012b). アリストテレス『デ・アニマ』第III巻の行訳" (PDF). Hicks, R. D. (1907). Aristotle, De Anima. Cambridge University Press. Kim, J. (1995). 「Mind-Body Problem", Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Ted Honderich (ed.). オックスフォード: Oxford University Press. Jaegwon Kim (2010). Essays in the Metaphysics of Mind. オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-162506-0. Massimini, M.; Tononi, G. (2018). Sizing up Consciousness: Towards an Objective Measure of the Capacity for Experience. オックスフォード大学出版局。 Turner, Bryan S. (1996). 身体と社会: 社会理論の探究. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mind%E2%80%93body_problem |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099