マルチチュード

Multitude in philosophy

☆

マルチチュード(multitude)とは哲学用語で、存在するという事実を共有し

ていること以外、他の明確なカテゴリーに分類されない人々の集団を指

す。この言葉には古くからのテキストと哲学の歴史がある。ニッコロ・マキアヴェッリは特にこの言葉を使い、トマス・ホッブズとバルーク・スピノザは、哲学

において、またそれぞれの歴史的・知的文脈に関わる際に、より専門的にこの言葉を用いた。後世の哲学者や理論家たちは、しばしばスピノザから明確に引用し

ながら、この言葉を復活させた。特にマイケル・ハートとアントニオ・ネグリの作品では、個人が制度に立ち向かうという、根本的に民主的あるいは革命的な概

念となった。

| Multitude

is a philosophical term for a group of people not classed under any

other distinct category, except for their shared fact of existence. It

has an ancient textual and philosophical history. Niccolò Machiavelli

notably used it, and both Thomas Hobbes and Baruch Spinoza deployed it

more technically in philosophy and in engaging with their respective

historical or intellectual contexts. Later philosophers and theorists

revived it, often explicitly from Spinoza. In the work of Michael Hardt

and Antonio Negri, among others, it became a radically democratic or

revolutionary concept whereby individuals stand against institutions. |

マルチチュード(multitude)とは哲学用語で、存在するという

事実を共有していること以外、他の明確なカテゴリーに分類されない人々の集団を指す。この言葉には古くからのテキストと哲学の歴史がある。ニッコロ・マキ

アヴェッリは特にこの言葉を使い、トマス・ホッブズとバルーク・スピノザは、哲学において、またそれぞれの歴史的・知的文脈に関わる際に、より専門的にこ

の言葉を用いた。後世の哲学者や理論家たちは、しばしばスピノザから明確に引用しながら、この言葉を復活させた。特にマイケル・ハートとアントニオ・ネグ

リの作品では、個人が制度に立ち向かうという、根本的に民主的あるいは革命的な概念となった。 |

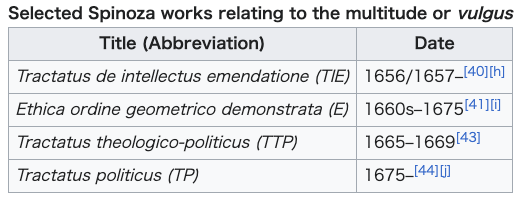

| Canonic literature and philosophy As a term in general and philosophical use, multitude appears in texts from antiquity, including ancient philosophy. For example, it appears in the Bible as well as in texts attributed to Thucydides, Plato (e.g., Euthyphro), Aristotle, Polybius, and Cicero. It also appears in medieval philosophy texts, for example, in the works of Averroes. The term first entered into the lexicon of early modern philosophy when it was used by thinkers like Machiavelli, Hobbes (in De Cive), and Spinoza (especially in the Tractatus Politicus or TP). Machiavelli[citation needed] and Spinoza wrote about the multitude with vacillating admiration and contempt.[1] Spinoza wrote about it in a historical context of war and civil instability, which informed and motivated his work.[2] |

正典となる文献と哲学 一般的・哲学的に使われる用語として、マルチチュードは古代哲学を含む古代のテキストに登場する。例えば、聖書や、トゥキュディデス、プラトン(エウテュ フロなど)、アリストテレス、ポリュビオス、キケロの著作に登場する。また、中世の哲学書、例えばアヴェロエスの著作にも登場する。 この用語が近世哲学の辞書に初めて登場したのは、マキアヴェッリ、ホッブズ(『デ・シーヴ』)、スピノザ(特に『政治学綱要』または『TP』)といった思 想家によって使われたときである。マキアヴェッリ[要出典]とスピノザはマルチチュードについて、揺れ動く称賛と軽蔑の念を込めて書いている[1]。スピ ノザは戦争と市民の不安定さという歴史的背景の中でマルチチュードについて書いており、それが彼の著作に影響を与え、彼の著作の動機づけとなった[2]。 |

| Hobbes For Hobbes, the multitude was a rabble that needed to enact a social contract with a monarch or sovereign, thus making them a people. Until then, such individuals retained the capacity for political self-determination. |

ホッブズ ホッブズにとってマルチチュードは、君主や君主と社会契約を結び、国民となる必要のある有象無象であった。それまでは、そのような個人は政治的自己決定能 力を保持していた。 |

| Spinoza In Spinoza's political philosophy, multitude ("multitudo" or "veelheid")[3] is a key concept that is essential to his systematic œuvre in its historical context.[4] Spinoza apparently derived the term from engaging with Hobbes, for whom it was also a technical term, but with whom he differed.[5] It appears primarily in his mature political philosophy in the TP, though there are several connotatively negative instances in the Tractatus Theologico-Politicus (TTP).[6][a] In the TP, multitude more technically (and without the same degree of negative connotation) referred to a great aggregate of people, whether or not politically organized, who are often led more by affect than reason, too often by "common affect" but at best "as if by one mind" as in a "union of minds".[8] For Curley, the main thesis of Spinoza's moral and political philosophy is that what is most useful to us is "living in a community with other people, and binding ourselves to our fellow citizens ... 'to make us one people'".[9][b] But to do so rationally and virtuously is a supreme challenge.[10][c] The individual's task in the Ethics—to overcome bondage to the passions—became the task of the entire community in Spinoza's political philosophy.[10] "Multitude" followed Spinoza's somewhat distinct but comparable use of "vulgus" or "crowd" in earlier works.[12][d] In the TP, "vulgus" is largely replaced by multitude, "plebs" ("ordinary people" or "plebeians"), or populus ("people").[13][e] It has been translated with negative connotations as "the mob", "the rabble", or "the vulgar", but Curley advised against these translations with the exception of "the mob" in some political contexts.[3] Curley wrote that Spinoza often applied the term not only to people whose capacity and views he considered unreliable, but also in contrast to philosophers.[3] However, Spinoza also occasionally wrote of a "vulgus of philosophers".[3] Curley generally translated vulgus as "the common people".[15] |

スピノザ スピノザの政治哲学において、マルチチュード(「multitudo 」または 「veelheid」)[3]は、歴史的文脈における彼の体系的な作品に不可欠な重要な概念である[4]。スピノザは、この用語を、専門用語でもあった が、彼とは異なっていたホッブズとの関わりから得たようである[5]。 TPでは、マルチチュードはより厳密には(そして同じ程度の否定的な意味合いを持たずに)、政治的に組織化されているか否かにかかわらず、しばしば理性よ りも感情によって導かれ、あまりにしばしば「共通の感情」によって導かれるが、せいぜい「心の結合」のように「あたかも一つの心によって」導かれる人々の 大きな集合体を指していた。 [8]カーリーにとってスピノザの道徳哲学と政治哲学の主要なテーゼは、私たちにとって最も有益なことは「他の人々と共同体の中で生活し、私たちの仲間で ある市民と私たち自身を結びつけること......『私たちを一つの国民にすること』」であるということである[9][b]。しかし、それを合理的かつ美 徳的に行うことは至難の業である[10][c]。 倫理学における個人の課題である情念への束縛を克服することは、スピノザの政治哲学においては共同体全体の課題となった[10]。 「マルチチュード」はスピノザが以前の著作において「ヴァルガス」や「群衆」を使用していたことに続くものであった[12][d]。TPにおいては、 「ヴァルガス」はマルチチュード、「プレブス」(「普通の人々」または「プレベ人」)、またはポピュラス(「人々」)に置き換えられている。 [13][e]「暴徒」、「徒党」、「低俗な」といった否定的な意味合いで訳されてきたが、カーリーは一部の政治的文脈における「暴徒」を除き、これらの 訳語に反対するよう忠告した[3]。 [しかし、カーリーは一般的にvulgusを「庶民」と訳している[15]。 |

| Spinoza's interpreters Spinoza's concept of the multitude is distinct from its later, radically democratic or even revolutionary interpretation by Hardt and Negri, which forms a counterweight to Spinoza's more negative dispositions toward the "vulgus".[16] Moreso on the Right, Leo Strauss emphasized Spinoza's fear of the masses in his more general understanding of political philosophy as a manual for the elite.[17] Indeed, Spinoza asked unprepared commoners not to read his TTP, arguing that it would exceed their limitations and be misinterpreted (though he is arguably most positive about democracy in this work).[18] Strauss's orientation may be seen in some secondary literature on Spinoza, including that of Raia Prokhovnik, Alexandre Matheron, Steven B. Smith, and Étienne Balibar (to some extent).[17] Matheron, Prokhovnik, and Smith argued that Spinoza ultimately rejected democracy in the TP.[17] Matheron and Prokhovnik argued that he may have endorsed aristocracy as the best possibility, given the antinomy (or at least the unresolved tension) he identified between democracy and reason.[12] Smith identified this aristocracy as a philosophical clerisy.[12] Ericka Tucker cast doubt on this interpretation.[f] Curley cautioned that "many" or "probably most" contemporary Spinoza scholars reject Strauss's views.[28] Balibar was more nuanced.[12] He merely agreed that Spinoza expressed fear of the labile masses.[12] But Balibar proposed that Spinoza's pro-democratic arguments, though marred, nonetheless stood.[12] Tucker acknowledged substantial evidence throughout Spinoza's work supporting broad consensus about his fears, but she cautioned that Spinoza's attitude toward the multitude was complex and vacillating, as well as deeply connected with his views on democracy.[12] She proposed that Spinoza ultimately developed a theory of the multitude as something to be understood, not feared, in order to sustain institutions, peace, and prosperity within democratic states.[29] |

スピノザの解釈者たち スピノザのマルチチュード概念は、ハートとネグリによる、後の、根本的に民主的な、あるいは革命的な解釈とは一線を画すものであり、スピノザの「バルグー ス」に対するより否定的な気質に対抗するものを形成している。 [16] 右派の中でも特にレオ・シュトラウスは、政治哲学をエリートのためのマニュアルとしてより一般的に理解する中で、スピノザが大衆を恐れていることを強調し ていた[17]。実際、スピノザは準備の整っていない平民に対して、それが彼らの限界を超え、誤解されるとして、彼のTTPを読まないように求めていた (しかし、彼はこの著作の中で民主主義について最も肯定的であることは間違いない)[18]。 シュトラウスの方向性は、ライア・プロホヴニク、アレクサンドル・マサロン、スティーヴン・B・スミス、エティエンヌ・バリバール(ある程度)[17]を 含むスピノザに関するいくつかの二次文献に見ることができる。マサロン、プロホヴニク、スミスは、スピノザはTPにおいて最終的に民主主義を否定している と主張していた。 [17]マザロンとプロホフニクは、彼が民主主義と理性との間に見出したアンチノミー(あるいは少なくとも未解決の緊張関係)を考慮すると、彼は最良の可 能性として貴族制を支持した可能性があると主張していた[12]。スミスはこの貴族制を哲学的な聖職者と見なしていた[12]。エリカ・タッカーはこの解 釈に疑問を投げかけていた[f]。 バリバールはより微妙なニュアンスをもっていた[12]。 彼はスピノザが不安定な大衆に対する恐怖を表明していたことに同意していただけであった[12]。 しかしバリバールは、スピノザの民主主義的な主張は、傷ついてはいたものの、それでも成り立っていたと提唱していた[12]。 タッカーはスピノザの著作全体を通して、彼の恐怖に関する広範なコンセンサスを支持する実質的な証拠を認めていたが、スピノザのマルチチュードに対する態 度は複雑で揺れ動くものであり、また彼の民主主義に対する見解と深く結びついていることに注意を促していた[12]。 彼女はスピノザが最終的に民主主義国家の中で制度、平和、繁栄を維持するために、恐怖ではなく理解されるべきものとしてマルチチュードの理論を発展させた と提唱していた[29]。 |

| Spinoza's historical context Spinoza's concerns were animated by civil instability in the Dutch Republic, specifically during the First Stadtholderless Period and in the aftermath of the Rampjaar.[30] A bona fide, if strained, period of "new freedom" and tolerance was disrupted by riots and war, including the Anglo-Dutch Wars and Franco-Dutch War.[31] This culminated in the lynching of the De Witt brothers of the Loevestein faction, against whom the Calvinists of the Dutch Reformed Church and Orangists were allied.[30] Spinoza was convinced that Calvinist ministers deliberately fomented moral panics among their congregations.[32] He wrote to Henry Oldenburg in 1665 that he worked to counter the "prejudices of theologians", citing them as "the main obstacles to ... philosoph[izing]".[33] Thus he sought to "expos[e] such prejudices and remov[e] them from the minds of sensible people".[34] He aimed to "vindicate completely" the freedom to philosophize, "for here it is in every way suppressed by the excessive authority and egotism of the preachers".[35][g] |

スピノザの歴史的背景 スピノザの関心は、オランダ共和国の市民的不安定、特に第一次シュタットホルダー不在時代とランパイヤールの余波の中にあった。 [これは、オランダ改革派教会のカルヴァン派とオランジュ派が同盟していたローヴェシュタイン派のデ・ヴィット兄弟のリンチで頂点に達した[30]。 スピノザは、カルヴァン派の牧師たちが意図的に信徒たちの間で道徳的パニックを煽っていると確信していた[32]。 彼は1665年にヘンリー・オルデンブルクに宛てて、「神学者たちの偏見」に対抗するために働いていると書き、「哲学することの......主な障害」と して挙げている[33]。 [33]こうして彼は「そのような偏見を暴露し、良識ある人々の心から取り除く」ことを目指した[34]。彼は哲学する自由を「完全に擁護する」ことを目 指したが、「ここでは説教者たちの過剰な権威とエゴイズムによってあらゆる方法で抑圧されているからである」[35][g]。 |

Spinoza's works Young Spinoza hoped for the improvement of common people in the Tractatus de Intellectus Emendatione (TIE), who he referred to as the "vulgus" before better theorizing the "multitude" in the TP.[45] His attitudes changed over time, as may be seen in his work.[46] These complex changes reflected both the logical refinement of his thought and the developing events of his historical context.[46] In mid-1660s Amsterdam, Spinoza became fearful amid civil instability, including riots, throughout the United Provinces. In attending to politics, his fear arguably settled into resignation as he began to consider the situation in terms of the role of the multitude.[46] He sought to understand the affects (or the confused ideas) of the people.[46] His aim was to help establish peaceful governance and to help the state develop more stable institutions.[46] Spinoza used "vulgus" in a distinctly slighting way in the Ethics and TTP,[47] among other texts. He wrote in the Ethics that the "vulgus" is "terrifying if unafraid", showing a concern for crowd psychology.[48][k] Balibar, Warren Montag, Justin Steinberg, and Tucker read Spinoza as deliberately ambiguous here, referring to the fear of the masses as that which they felt and inspired.[50] |

スピノザの作品 若きスピノザは『知性改善論』(TIE)において庶民の改善を願っており、TPにおいて「マルチチュード」をより理論化する前に、彼は庶民を「バルガス」 と呼んでいた[45]。彼の著作に見られるように、彼の態度は時とともに変化していった[46]。 こうした複雑な変化は、彼の思想の論理的洗練と、彼の歴史的背景の発展する出来事の両方を反映していた[46]。 1660年代半ばのアムステルダムで、スピノザは連合州全体の暴動を含む市民の不安定さの中で恐怖を抱くようになった。政治に携わる中で、彼の恐怖は、マ ルチチュードの役割という観点から状況を考察し始めたことで間違いなく諦観へと落ち着いた[46]。 彼は民衆の影響(あるいは混乱した考え)を理解しようと努めた[46]。彼の目的は、平和的な統治を確立し、国家がより安定した制度を発展させるのを助け ることであった[46]。 スピノザは『倫理学』や『TTP』[47]などのテクストの中で「バルガス」を明らかに軽蔑的な意味で用いていた。彼は『倫理学』において「ヴァルグス」 は「恐れないとすれば恐ろしい」と書いており、群衆心理に対する関心を示していた[48][k]。バリバール、ウォーレン・モンターグ、ジャスティン・ス タインバーグ、タッカーはスピノザをここでは意図的に曖昧にしており、大衆の恐怖を彼らが感じ、鼓舞するものとして言及していると読んでいた[50]。 |

| Tractatus de intellectus

emendatione (TIE) In the TIE, Spinoza expressed concern and hope for the vulgus.[51] He sought to identify the path to the good life, or eudaimonia.[51] He considered the immediate or ostentatious materialistic concerns of the vulgus[52] and recommended the pursuit of knowledge and love of God, "the end for which I [myself] strive".[53] He regarded the vulgus more with concern than disapproval, and he held out the hope that "many should acquire [this view] along with me".[53] He argued that the improvement of education, medicine, and social order would be not only virtuous, but also instrumental in raising the vulgus to higher things and better capabilities.[53] |

知性改善論(TIE TIE では、スピノザはヴルガスに対する懸念と希望を表明している[51]。彼は、良い人生、すなわちユーダイモニアへの道を見出そうとした[51]。彼は、ヴ ルガスの当面の、あるいは見栄を張った物質的な関心事[52] を考察し、知識の追求と「私[自身] が努力する目的」である神への愛を勧めた。 [53] 彼は、大衆を非難するよりも懸念の目で見ており、「多くの人々が私と共にこの見解を獲得する」ことを希望していた。[53] 彼は、教育、医療、社会秩序の改善は、徳のある行為であるだけでなく、大衆をより高いものへと引き上げ、より良い能力を与えるための手段となるだろうと主 張した。[53] |

| Tractatus theologico-politicus

(TTP) Spinoza paused work on the Ethics to begin the TTP.[54] In writing the TTP, Spinoza had become fearful of the vulgus amid riots and civil instability, as well as wars.[31] These events were marked by political factionalism and culminated in the Rampjaar.[31] Spinoza was specifically concerned about the excessive role of religion in politics and the threat to philosophy or freedom of thought.[55] Democracy was the "most natural" and "best" form of state in Spinoza's TTP.[56] He argued that it was the kind of civitas most likely to result in freedom and peace, which he elevated as the chief aims of the state.[57] Tucker noted that democracy requires "the people, the masses, the vulgus".[46] Many thus observed as an apparent tension in Spinoza's political philosophy that the vulgus must give rise to the "best" state.[46] |

神学・政治論(TTP) スピノザは『倫理学』の執筆を中断し、『TTP』の執筆を開始した。[54] 『TTP』を執筆する中で、スピノザは暴動や内乱、戦争などにより、一般大衆に対して恐怖を抱くようになった。[31] これらの出来事は政治的派閥争いに特徴付けられ、ランピアール(Rampjaar)で頂点に達した。[31] スピノザは、政治における宗教の過剰な役割と、哲学や思想の自由に対する脅威について特に懸念を抱いていた。[55] スピノザの『TTP』において、民主主義は「最も自然」で「最良」の国家形態だった。[56] 彼は、民主主義が自由と平和をもたらす最も可能性の高い市民社会形態であり、国家の主要な目的としてこれらを掲げた。 [57] ターカーは、民主主義には「人民、大衆、ヴルグス」が必要だと指摘した。[46] そのため、多くの研究者は、スピンノザの政治哲学に、ヴルグスが「最良の」国家を生み出す必要があるという明らかな矛盾があると指摘した。[46] |

| Tractatus politicus (TP) Spinoza's mature political theory in the TP made reference to his theories of affects and power from the Ethics.[46] "Multitude" became a properly technical term in the TP, and Spinoza sought to frame a path by which the multitude (like individuals in the Ethics) could be ruled less by fear.[46] Whereas in the TTP democracy was the "freest" or "most natural" government, in the TP it became the "most absolute" or "best" because it best preserved natural rights and had the most power of any civitas.[58] However, the purpose of the state was no longer freedom, but rather prosperity and stability, requiring absolute power.[59] Thus many twentieth-century commentators felt Spinoza effectively abandoned democracy.[51] Tucker and others instead saw Spinoza as developing his theories of affects, power, and the multitude.[51] In Spinoza's typical, semantically revisionist sense, argued J. Steinberg, this "absolute" power was simply that of a sovereign as in principle greater than that of the church, as defined in relation to (and sometimes constrained by) that of the multitude, and as necessarily limited or finite in an immanent and naturalistic sense (i.e., in the same way as "Deus ..." is rendered "... sive Natura" in the Ethics, though Spinoza specifically clarified that "Kings are not Gods, but men").[60] For Spinoza, the multitude's power simply arose from that of individuals in their aggregation and organization.[61] He argued that natural right was coextensive with power and drew relations between the individual and the sovereign, and between the multitude and the entire state.[62] In Spinoza's account, the multitude's power was determined not only by its individuals in number, but also by their mode of agreement.[63] Passive affects like fear and less adequate ideas were disempowering. Active affects like joy united the multitude, and along with more adequate ideas were more empowering.[63] To empower more of the multitude, Spinoza recommended democracy, however broadly conceived, as the best form of government.[63] He proposed large, deliberative, popular councils for its institutions, postulating their epistemic advantage.[63] |

Tractatus politicus (TP) TP に記されたスピノザの成熟した政治理論は、Ethics における感情と権力に関する理論を参照している[46]。「マルチチュード」は TP において適切な専門用語となり、スピノザは、マルチチュード(Ethics における個人と同様)が恐怖によって支配されるのを軽減する道筋を模索した[46]。 『政治論』では民主主義が「最も自由な」または「最も自然な」政府形態であったのに対し、『政治論』では、自然権を最もよく保護し、あらゆる市民社会 (civitas)の中で最も権力を持つため、「最も絶対的な」または「最良の」政府形態となった。[58] しかし、国家の目的はもはや自由ではなく、繁栄と安定であり、そのためには絶対的な権力が必要となった。[59] そのため、20世紀の多くの評論家は、スピノザが民主主義を事実上放棄したと感じた。[51] 一方、タッカーらは、スピノザは感情、権力、マルチチュードに関する理論を展開したと捉えた[51]。J. スタインバーグは、スピノザの典型的な意味論的修正主義的意味において、この「絶対的」権力は、マルチチュードに対して(そして時にはマルチチュードに よって制約される)原則的にマルチチュードよりも大きな、そして必然的に限定的または有限である、教会と同じ [60] スピノザにとって、マルチチュードの権力は、単に、その集合体および組織における個人の権力から生じ、内在的かつ自然主義的な意味で必然的に限定的または 有限である(すなわち、『倫理学』で「Deus ...」が「... sive Natura」と表現されているのと同じように、ただしスピノザは「王は神ではなく、人間である」と明確に述べている)。 [60] スピノザにとって、マルチチュードの権力は、単に、その集合体および組織における個々人の権力から生じるものでした[61]。彼は、自然権は権力と同範囲 であり、個人と主権者、およびマルチチュードと国家全体との関係を明らかにしました[62]。 スピノザの説明では、マルチチュードの力は、その個体の数だけでなく、その合意の様式によっても決定される[63]。恐怖や不十分な観念のような受動的な 感情は、力を奪う。喜びのような能動的な感情はマルチチュードを団結させ、より適切な考えとともに、より力を与えた[63]。マルチチュードにより多くの 力を与えるため、スピノザは、広く解釈される民主主義を最良の政治体制として推奨した[63]。彼は、その制度として、大規模で審議的な民衆議会を提案 し、その認識上の優位性を主張した[63]。 |

| Twentieth-century philosophy Recently the term has returned to prominence as a new model of resistance against global systems of power. Hardt and Negri describe it as such in Empire (2000), expanding upon this description in Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire (2004). Other theorists to use the term include those associated with Autonomism, like Sylvère Lotringer and Paolo Virno. Still others are connected with the eponymous French journal Multitudes, including Laurent Bove [fr] and Pierre-François Moreau [fr]. Hardt and Negri Negri describes the multitude in his The Savage Anomaly as an unmediated, revolutionary, immanent, and positive collective social subject which can found a "nonmystified" form of democracy (p. 194). In his more recent writings with Michael Hardt, however, he does not so much offer a direct definition, but presents the concept through a series of mediations. In Empire it is mediated by the concept of Empire (the new global constitution that Negri and Hardt describe as a copy of Polybius's description of Roman government): New figures of struggle and new subjectivities are produced in the conjecture of events, in the universal nomadism ... . They are not posed merely against the imperial system—they are not simply negative forces. They also express, nourish, and develop positively their own constituent projects. ... This constituent aspect of the movement of the multitude, in its myriad faces, is really the positive terrain of the historical construction of Empire, ... an antagonistic and creative positivity. The deterritorializing power of the multitude is the productive force that sustains Empire and at the same time the force that calls for and makes necessary its destruction.[64] They were vague as to this "positive" or "constituent" aspect of the multitude:[65] Certainly, there must be a moment when reappropriation [of wealth from capital] and self-organization [of the multitude] reach a threshold and configure a real event. This is when the political is really affirmed—when the genesis is complete and self-valorization, the cooperative convergence of subjects, and the proletarian management of production become a constituent power. ... We do not have any models to offer for this event. Only the multitude through its practical experimentation will offer the models and determine when and how the possible becomes real.[66] In their sequel Multitude: War and Democracy in the Age of Empire they still refrain from a clear definition of the concept but approach the concept through mediation of a host of "contemporary" phenomena, most importantly the new type of postmodern war they postulate and the history of post-WWII resistance movements. It remains a rather vague concept which is assigned a revolutionary potential without much theoretical substantiation apart from a generic potential of love. Criticism In the Introduction to Virno's A Grammar of the Multitude, Lotringer criticized Hardt's and Negri's use of the concept for its ostensible return to dialectical dualism. |

20 世紀の哲学 最近、この用語は、グローバルな権力システムに対する新たな抵抗モデルとして再び注目されている。ハートとネグリは、著書『エンパイア』(2000 年)でこの用語をこのように説明し、著書『マルチチュード:帝国時代の戦争と民主主義』(2004 年)でさらに詳しく述べている。この用語を使用している他の理論家としては、シルヴェール・ロトリンガーやパオロ・ヴィルノなど、オートノミズムに関連す る人物たちが挙げられる。さらに、ローラン・ボヴェ [fr] やピエール・フランソワ・モロー [fr] など、同名のフランス語誌『Multitudes』に関係する理論家たちもこの用語を使っている。 ハートとネグリ ネグリは『野蛮な異常』の中で、マルチチュードを「非神秘化された」民主主義の形を築くことができる、仲介のない、革命的で、内在的で、ポジティブな集団 的社会主体として説明している(194 ページ)。しかし、マイケル・ハートとの最近の著作では、直接的な定義を提示するよりも、一連の媒介を通じてこの概念を紹介している。『エンパイア』で は、この概念は「エンパイア」という概念(ネグリとハートがポリュビオスのローマ政府の説明の模倣と表現する新しい世界憲法)によって媒介されている。 新しい闘争の形態と新しい主観性は、出来事の推測、普遍的なノマド主義の中で生み出される...。それらは、単に帝国体制に対抗するものではなく、単なる 否定的な力ではない。それらはまた、自らの構成的なプロジェクトを肯定的に表現、育成、発展させる...。マルチチュードの動きのこの構成的な側面は、そ の無数の顔の中で、まさに帝国の歴史的構築の肯定的な領域であり...、敵対的かつ創造的な肯定性である。マルチチュードの脱領域化力は、帝国を支える生 産力であると同時に、その破壊を要求し、必要とする力でもある。[64] 彼らは、マルチチュードのこの「ポジティブな」または「構成的な」側面について曖昧だった。[65] 確かに、[資本からの富の]再獲得と[マルチチュードの]自己組織化が、あるしきい値に達して現実の出来事となる瞬間があるはずだ。それは、政治が真に肯 定される瞬間、つまり、生成が完了し、自己評価、主体の協力的な収斂、そして生産のプロレタリア的経営が構成力となる瞬間だ。... 私たちは、この出来事について、いかなるモデルも提示できない。そのモデルを提供し、可能性が現実になる時期と方法を決定するのは、実践的な実験を通じて のマルチチュードだけだ[66]。 続編『マルチチュード:帝国時代の戦争と民主主義』でも、彼らはこの概念の明確な定義を避け、多くの「現代的」現象、とりわけ彼らが提唱する新しいタイプ のポストモダン戦争と、第二次世界大戦後の抵抗運動の歴史を媒介としてこの概念にアプローチしている。この概念は、愛という一般的な可能性以外には、理論 的な根拠があまりないまま、革命的な可能性を付与された、かなり曖昧なままの概念のままです。 批判 ヴィルノの『マルチチュードの文法』の序文で、ロトリンガーは、ハートとネグリがこの概念を使用していることを、弁証法的二元論への表向きの回帰として批 判しています。 |

| Commoner Crowd psychology Feeding the multitude Global citizens movement Hoi polloi Mass movement Mass society People |

コモン 群衆心理 マルチチュードに食糧を供給する グローバル市民運動 ホイ・ポイ 大衆運動 大衆社会 人々(人民) |

| Bibliography Primary texts (with commentary) Spinoza, Baruch. 1985. Vol. I, The Collected Works of Spinoza, ed. and trans. Edwin Curley. Second printing with corrections, 1988. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-07222-7 (hbk). Spinoza, Baruch. 2016. Vol. II, The Collected Works of Spinoza, ed. and trans. Edwin Curley. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-16763-3 (hbk). Other texts Balibar, Etienne. 1994. Masses, Classes, Ideas: Studies on Politics and Philosophy Before and After Marx, trans. James Swenson. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-41-590601-2 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-41-590602-9 (pbk). Campos, Andre Santos, ed and intro. 2015. Spinoza: Basic Concepts. Exeter: Imprint Academic. ISBN 978-1-84-540791-9 (hbk). Montag, Warren. 1999. Bodies, Masses, Power: Spinoza and His Contemporaries. London and New York: Verso Books. ISBN 978-0-521-85339-2 (hbk). Tucker, Ericka. 2015. "Multitude". Spinoza: Basic Concepts, ed. and intro. Andre Santos Campos, 129–141. Exeter: Imprint Academic. ISBN 978-1-84-540791-9 (hbk). Steinberg, Diane. 2009. "Knowledge in Spinoza's Ethics". The Cambridge Companion to Spinoza's Ethics, ed. Olli Koistinen [fi], intro. Olli Koistinen and Valtteri Viljanen, 140–166. The Cambridge Companions to Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Digitally republished in 2010. ISBN 978-0-521-85339-2 (hbk). ISBN 978-0-521-61860-1 (pbk). Steinberg, Justin. 2018. "Spinoza and Political Absolutism". Spinoza's Political Treatise: A Critical Guide, eds. and intro. Yitzhak Y. Melamed and Hasana Sharp, 179–189. Cambridge Critical Guides. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-17058-2 (hbk). Steinberg, Justin. 2009. "Spinoza on Civil Liberation". Journal of the History of Philosophy. 47(1):35–58. Johns Hopkins University Press. doi:10.1353/hph.0.0082. van Bunge, Wiep, Henri Krop [nl], Piet Steenbakkers, and Jeroen van de Ven, eds. 2024. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Spinoza, 2nd ed. London, New York, and Dublin: Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-1-3502-5642-2 (hbk). ISBN 978-1-3502-5644-6 (ebk). ISBN 978-1-3502-5643-9 (ePDF). |

参考文献 主要文献(解説付き スピノザ、バルーク。1985年。第1巻、『スピノザ全集』、エドウィン・カーリー編・訳。1988年、修正再版。プリンストン:プリンストン大学出版 局。ISBN 978-0-691-07222-7(ハードカバー)。 スピノザ、バルーク。2016年。第2巻、『スピノザ全集』、エドウィン・カーリー編・訳。プリンストンおよびオックスフォード:プリンストン大学出版 局。ISBN 978-0-691-16763-3 (hbk)。 その他の文献 バリバル、エティエンヌ。1994年。『マス、クラス、アイデア:マルクス以前と以後の政治と哲学の研究』、ジェームズ・スウェンソン訳。ロンドンと ニューヨーク:ルートレッジ。ISBN 978-0-41-590601-2 (hbk)。ISBN 978-0-41-590602-9 (pbk)。 カンポス、アンドレ・サントス、編および序文。2015. 『スピノザ:基本概念』。エクセター:Imprint Academic。ISBN 978-1-84-540791-9 (hbk)。 モンタグ、ウォーレン。1999 年。『身体、大衆、権力:スピノザとその同時代人たち』。ロンドンおよびニューヨーク:Verso Books。ISBN 978-0-521-85339-2 (hbk)。 タッカー、エリカ。2015 年。「マルチチュード」。『スピノザ:基本概念』、編および序文。アンドレ・サントス・カンポス, 129–141. エクセター: インプリント・アカデミック. ISBN 978-1-84-540791-9 (hbk). スタインバーグ, ダイアン. 2009. 「スピノザの倫理学における知識」. 『スピノザの倫理学 カムブリッジ・コンパニオン』, オッリ・コイスティネン [fi] 編, 序文. オッリ・コイスティネンとヴァルッテリ・ヴィルヤネン、140–166。ケンブリッジ哲学ガイド。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。2010年にデ ジタル再版。ISBN 978-0-521-85339-2(ハードカバー)。ISBN 978-0-521-61860-1(ペーパーバック)。 スタインバーグ、ジャスティン。2018。「スピノザと政治的絶対主義」。『スピノザの政治論:批判的ガイド』、編者および序文:イザック・Y・メラメド とハサナ・シャープ、179–189。ケンブリッジ・クリティカル・ガイド。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-1-107-17058-2 (hbk)。 スタインバーグ、ジャスティン。2009. 「スピノザの市民的解放」. 『哲学史ジャーナル』. 47(1):35–58. ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学出版局. doi:10.1353/hph.0.0082. ファン・ブンゲ, ウィープ, ヘンリ・クロップ [nl], ピエト・ステーンバッカース, ジェロエン・ファン・デ・ヴェン, 編. 2024. 『ブルームズベリー・ハンドブック・オブ・スピノザ』第2版。ロンドン、ニューヨーク、ダブリン:ブルームズベリー・アカデミック。ISBN 978-1-3502-5642-2 (hbk)。ISBN 978-1-3502-5644-6 (ebk)。ISBN 978-1-3502-5643-9 (ePDF)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multitude_(philosophy) |

Nobody

| The Bus Fight in 4K HDR - このシーンの教訓は主人公が全然 "Nobody"じゃない身体能力の持ち主ということだ

『Nobody』 は、イリヤ・ナイシュラー監督、デレク・コルスタッド脚本による2021年のアメリカ映画。ボブ・オデンカークが、家族と復讐に燃える犯罪組織のボスに狙 われたことで、元暗殺者の生活に戻ることになる穏やかな家庭人の男を演じる。コニー・ニールセン、RZA、アレクセイ・セレブリャコフ、クリストファー・ ロイドが共演する。オデンキルクとデビッド・リーチが製作総指揮を務めている。ユニバーサル・ピクチャーズは、2021年3月26日に米国で、2021年 6月9日に英国で『ノーバディ』を劇場公開した。この映画は、1,600万ドルの製作費に対して5,700万ドルの興行収入を記録し、アクションシーンや オデンカークの演技を称賛する批評家から、概ね好評を博した。続編『ノーバディ 2』は、2025年8月15日に公開予定だ。

★平 民(へいみん)は、一般の人、庶民、大衆とも呼ばれ、かつては、社会や国家において、特に王族、貴族、貴族階級に属さない、社会的地位のない一般の人々 を指していた。文化や時代によっては、他の高位の人(聖職者など)が、それ自体でより高い社会的地位を有していた場合や、貴族の出身でない場合は平民とみ なされていた場合もある。この階級は、イングランドおよびウェールズの土地法に古くからある、共有地に対する財産権を有する人々の法的階級と重なってい る。特定の共有地に対する権利を有する平民は、通常、一般市民ではなく、その共有地の隣人である。君主制の用語では、貴族や貴族もこの用語に含まれる。

| A commoner, also known

as the common man, commoners, the common people or the masses, was in

earlier use an ordinary person in a community or nation who did not

have any significant social status, especially a member of neither

royalty, nobility, nor any part of the aristocracy. Depending on

culture and period, other elevated persons (such members of clergy) may

have had higher social status in their own right, or were regarded as

commoners if lacking an aristocratic background. This class overlaps with the legal class of people who have a property interest in common land, a longstanding feature of land law in England and Wales. Commoners who have rights for a particular common are typically neighbors, not the public in general. In monarchist terminology, aristocracy and nobility are included in the term. |

平民(へいみん)は、一般の人、庶民、大衆とも呼ばれ、かつては、社会

や国家において、特に王族、貴族、貴族階級に属さない、社会的地位のない一般の人々を指していた。文化や時代によっては、他の高位の人(聖職者など)が、

それ自体でより高い社会的地位を有していた場合や、貴族の出身でない場合は平民とみなされていた場合もある。 この階級は、イングランドおよびウェールズの土地法に古くからある、共有地に対する財産権を有する人々の法的階級と重なっている。特定の共有地に対する権 利を有する平民は、通常、一般市民ではなく、その共有地の隣人である。 君主制の用語では、貴族や貴族もこの用語に含まれる。 |

| History Various sovereign states throughout history have governed, or claimed to govern, in the name of the common people. In Europe, a distinct concept analogous to common people arose in the Classical civilization of ancient Rome around the 6th century BC, with the social division into patricians (nobles) and plebeians (commoners). The division may have been instituted by Servius Tullius, as an alternative to the previous clan-based divisions that had been responsible for internecine conflict.[1] The ancient Greeks generally had no concept of class and their leading social divisions were simply non-Greeks, free-Greeks and slaves.[2] The early organization of Ancient Athens was something of an exception with certain official roles like archons, magistrates and treasurers being reserved for only the wealthiest citizens – these class-like divisions were weakened by the democratic reforms of Cleisthenes who created new horizontal social divisions in contrasting fashion to the vertical ones thought to have been created by Tullius.[3] Both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire used the Latin term Senatus Populusque Romanus, (the Senate and People of Rome). This term was fixed to Roman legionary standards, and even after the Roman Emperors achieved a state of total personal autocracy, they continued to wield their power in the name of the Senate and People of Rome.  A Medieval French manuscript illustration depicting the three estates: clergy (oratores), nobles (bellatores), and commoners (laboratores). With the growth of Christianity in the 4th century AD, a new world view arose that underpinned European thinking on social division until at least early modern times.[1] Saint Augustine postulated that social division was a result of the Fall of Man.[1] The three leading divisions were considered to be the priesthood (clergy), the nobility, and the common people. Sometimes this was expressed as "those who prayed", "those who fought" and "those who worked". The Latin terms for the three classes – oratores, bellatores and laboratores – are often found even in modern textbooks, and have been used in sources since the 9th century.[4] This threefold division was formalized in the estate system of social stratification, where again commoners were the bulk of the population who are neither members of the nobility nor of the clergy.[5] They were the third of the Three Estates of the Realm in medieval Europe, consisting of peasants and artisans. Social mobility for commoners was limited throughout the Middle Ages. Generally, the serfs were unable to enter the group of the bellatores. Commoners could sometimes secure entry for their children into the oratores class; usually they would serve as rural parish priests. In some cases they received education from the clergy and ascended to senior administrative positions; in some cases nobles welcomed such advancement as former commoners were more likely to be neutral in dynastic feuds. There were cases of serfs becoming clerics in the Holy Roman Empire,[6] though from the Carolingian era, clergy were generally recruited from the nobility.[7] Of the two thousand bishops serving from the 8th to the 15th century, just five came from the peasantry.[8] The social and political order of medieval Europe was relatively stable until the development of the mobile cannon in the 15th century. Up until that time a noble with a small force could hold their castle or walled town for years even against large armies - and so they were rarely disposed.[9] Once effective cannons were available, walls were of far less defensive value and rulers needed expensive field armies to keep control of a territory. This encouraged the formation of princely and kingly states, which needed to tax the common people much more heavily to pay for the expensive weapons and armies required to provide security in the new age. Up until the late 15th century, surviving medieval treaties on government were concerned with advising rulers on how to serve the common good: Assize of Bread is an example of medieval law specifically drawn up in the interests of the common people.[9] But then works by Philippe de Commines, Niccolò Machiavelli, and later Cardinal Richelieu began advising rulers to consider their own interests and that of the state ahead of what was "good", with Richelieu explicitly saying the state is above morality in doctrines such as Raison d'Etat.[9] This change of orientation among the nobles left the common people less content with their place in society. A similar trend occurred regarding the clergy, where many priests began to abuse the great power they had due to the sacrament of contrition. The Reformation was a movement that aimed to correct this, but even afterwards the common people's trust in the clergy continued to decline – priests were often seen as greedy and lacking in true faith. An early major social upheaval driven in part by the common people's mistrust of both the nobility and clergy occurred in Great Britain with the English Revolution of 1642. After the forces of Oliver Cromwell triumphed, movements like the Levellers rose to prominence demanding equality for all. When the general council of Cromwell's army met to decide on a new order at the Putney Debates of 1647, one of the commanders, Colonel Thomas Rainsborough, requested that political power be given to the common people. According to historian Roger Osbourne, the Colonel's speech was the first time a prominent person spoke in favor of universal male suffrage, but it was not to be granted until 1918. After much debate it was decided that only those with considerable property would be allowed to vote, and so after the revolution political power in England remained largely controlled by the nobles, with at first only a few of the most wealthy or well-connected common people sitting in Parliament.[3] The rise of the bourgeoisie during the Late Middle Ages, had seen an intermediate class of wealthy commoners develop, which ultimately gave rise to the modern middle classes. Middle-class people and upper bourgeoisie could still be called commoners until after World War I. For example, Pitt the Elder was often called The Great Commoner in England, and this appellation was later used for the 20th-century American anti-elitist campaigner William Jennings Bryan. The interests of the middle class were not always aligned with their fellow commoners of the working class. According to social historian Karl Polanyi, Britain's middle class in 19th-century Britain turned against their fellow commoners by seizing political power from the British upper class via the Reform Act 1832. The emergence of the Industrial Revolution had caused severe economic distress to a large number of working class commoners, leaving many of them with no means to learn a living as the traditional system of tenant farming was replaced with large-scale agriculture run by a small number of individuals. The upper class had responded to their plight by establishing institutions such as workhouses, where unemployed lower-class Britons could find a source of employment, and outdoor relief, where monetary and other forms of assistance were given to both the unemployed and those on low income without them needing to enter a workhouse to receive it.[10] Though initial middle class opposition to the Poor Law reform of William Pitt the Younger had prevented the emergence of a coherent and generous nationwide provision, the resulting Speenhamland system did generally manage to prevent working class commoners from starvation. In 1834, outdoor relief was abolished and workhouses were deliberately made into places so unappealing that many often preferred to starve rather than enter them. For Polanyi this related to the economic doctrine prevalent at the time which held that only the spur of hunger could make workers flexible enough for the proper functioning of the free market. By the end of the 19th century, at least in mainland Britain, economic progress has been sufficient that even the working class were generally able to earn a good living, and as such working and middle class interests began to converge, lessening the division within the ranks of common people. Polanyi notes that in Continental Europe, middle and working class interests did not diverge anywhere near as markedly as they had in Britain.[10] |

歴史 歴史上、さまざまな主権国家が、一般大衆の名の下に統治を行ってきた、あるいは統治を主張してきた。ヨーロッパでは、紀元前6世紀頃の古代ローマ古典文明 において、一般大衆に相当する概念が明確に生まれ、社会は貴族(パトリキ)と平民(プレブス)に分けられた。この区分は、以前の氏族に基づく区分が内紛の 原因となっていたため、セルウィウス・トゥッリウスによって導入された可能性がある。[1] 古代ギリシャ人は一般的に階級概念を持たず、主要な社会区分は非ギリシャ人、自由ギリシャ人、奴隷の3つだけだった。 [2] 古代アテネの初期の組織は例外で、アルコン、裁判官、財務官などの特定の公的役職は最も裕福な市民に限定されていた。これらの階級的な区分は、トゥッリウ スが創設した垂直的な区分とは対照的な新しい水平的な社会区分を創設したクレイステネスの民主的改革によって弱体化した。[3] ローマ共和国とローマ帝国は、ラテン語の「Senatus Populusque Romanus」(ローマ元老院とローマ人民)という用語を使用していた。この用語は、ローマ軍団の旗に刻まれ、ローマ皇帝が完全な個人独裁体制を確立し た後も、皇帝は元老院とローマ人民の名の下に権力を振るい続けた。  中世フランスの写本に描かれた三つの身分:聖職者(オラトーレス)、貴族(ベラトーレス)、平民(ラボーラトーレス)。 4世紀にキリスト教が広まるにつれ、少なくとも近世初期までヨーロッパの社会分化に関する考え方の基盤となった新たな世界観が生まれた。[1] 聖アウグスティヌスは、社会分化は人間の堕落の結果であると主張した。[1] 主要な三つの分化は、聖職者(聖職者)、貴族、平民とされた。これらは「祈る者」「戦う者」「働く者」と表現されることもあった。3つの階級のラテン語表 現である「オラトーレス」「ベラトーレス」「ラボーラトーレス」は、現代の教科書でもよく見られ、9世紀以降の資料でも使用されてきた。 [4] この三つの区分は、社会階層の身分制度として正式に確立され、再び平民は貴族や聖職者ではない大多数の住民を構成した。[5] 彼らは中世ヨーロッパの「三身分」の第三身分であり、農民と職人から成っていた。 中世を通じて、平民の社会的移動は制限されていた。一般に、農奴はベラトーレスの階級に入ることはできなかった。平民は、子供をオラトーレスの階級に入れ ることを時々確保できたが、通常は農村部の教区神父として仕えた。一部のケースでは、聖職者から教育を受け、上級行政職に昇進した者もいた。また、一部の 貴族は、前平民は王族間の争いにおいて中立的である可能性が高いため、このような昇進を歓迎した。神聖ローマ帝国では農奴が聖職者になるケースもあった [6]が、カロリング朝以降、聖職者は一般に貴族から採用されるようになった[7]。8世紀から15世紀にかけて務めた2,000人の司教のうち、農民出 身はわずか5人だった[8]。 中世ヨーロッパの社会・政治秩序は、15世紀に移動式大砲が開発されるまで比較的安定していた。その時代まで、小規模な軍隊を率いる貴族は、大規模な軍隊 に対しても城や城壁都市を数年守ることができ、そのため彼らはほとんど追放されなかった[9]。効果的な大砲が利用可能になると、城壁の防御価値は大幅に 低下し、統治者は領土を支配するために高価な野戦軍を必要とするようになった。これにより、領主や王の国家が形成され、新たな時代における安全保障のため に必要な高価な武器や軍隊の費用を賄うため、一般市民への課税が大幅に強化された。15世紀後半まで、中世の政府に関する残存する条約は、統治者が公共の 利益に奉仕する方法について助言する内容だった: 「パンの価格規制法」は、一般市民の利益のために制定された中世の法律の例だ。[9] しかし、フィリップ・ド・コミヌス、ニコロ・マキャヴェッリ、そして後のリシュリュー枢機卿の著作は、統治者に「善」よりも自分と国家の利益を優先するよ う助言し、リシュリューは「国家の理性」などの教義で、国家は道徳の上に立つと明言した。 [9] 貴族たちのこの方向転換は、一般市民が社会における自身の立場に不満を抱くようになった。同様の傾向は聖職者にも見られ、多くの神父が懺悔の秘跡による大 きな権力を濫用するようになった。宗教改革はこれを是正する運動だったが、その後も一般市民の聖職者への信頼は低下し続けた——神父は貪欲で真の信仰に欠 ける存在と見なされることが多かった。貴族と聖職者に対する一般市民の不信感に一部起因する最初の主要な社会変動は、1642年のイギリス革命で起こっ た。オリバー・クロムウェル率いる勢力が勝利した後、レヴェラーズのような運動が台頭し、すべての人の平等を要求した。1647年にパトニー討論会で、ク ロムウェルの軍隊の総会議が新しい秩序を決定するために開催されたとき、指揮官の一人であるトーマス・レインズボロー大佐は、政治権力を庶民に与えるよう 要求した。歴史家のロジャー・オズボーンによると、大佐の演説は、著名人が普遍的な男子選挙権を支持して発言したのは初めてのことだったが、それが実現し たのは1918年のことだった。激しい議論の末、投票権は財産を相当に持つ者に限られることになり、革命後もイギリスの政治権力は主に貴族が掌握し、当初 は最も富裕または有力な一般市民のほんの一握りだけが議会に議席を占めた。[3] 中世後期にブルジョアジーが台頭する中で、富裕な一般市民の中間階級が形成され、これが現代の中間階級へと発展した。中流階級と上流ブルジョアジーは、第 一次世界大戦後まで一般市民と呼ばれていた。例えば、ピット長老はイギリスで「偉大な一般市民」と呼ばれ、この呼称は20世紀のアメリカの反エリート主義 活動家ウィリアム・ジェニングス・ブライアンにも用いられた。中流階級の利益は、労働者階級の一般市民の利益と常に一致していたわけではなかった。 社会史家のカール・ポラニーによると、19世紀のイギリスの中間階級は、1832年の改革法を通じてイギリスの上流階級から政治権力を奪取し、同時代の平 民階級と対立した。産業革命の台頭は、多くの労働者階級のコモンズに深刻な経済的苦境をもたらし、伝統的な小作農制度が少数の個人によって運営される大規 模農業に置き換えられたため、多くの人が生計を立てる手段を失った。上流階級は、失業した下層階級のイギリス人が雇用を見つけるための施設である救貧院 や、失業者と低所得者に対して救貧院に入らなくても金銭的な支援やその他の援助を提供する屋外救済制度を設立することで、彼らの苦境に対応した。[10] ウィリアム・ピット・ザ・ヤングの貧困法改革に対する初期の中間階級の反対により、全国的な一貫した寛大な支援制度の確立は阻まれたが、その結果生まれた スピーンハムランド制度は、一般に労働者階級の庶民が飢餓に陥ることを防ぐ役割を果たした。1834年、屋外救済は廃止され、救貧院は意図的に不快な場所 に変えられ、多くの人が飢え死を選ぶほどになった。ポラニーは、これは当時の経済学の教義と関連していると指摘している。その教義は、飢餓の刺激だけが労 働者を自由市場が適切に機能するために必要な柔軟性にさせるというものであった。19世紀末までに、少なくともイギリス本土では経済的進歩が十分に進み、 労働者階級も一般的に十分な生計を立てられるようになったため、労働者階級と中流階級の利益が一致し始め、一般市民の間の分断が緩和された。ポラニーは、 大陸ヨーロッパでは、中流階級と労働者階級の利益がイギリスほど明確に分裂しなかったと指摘している。[10] |

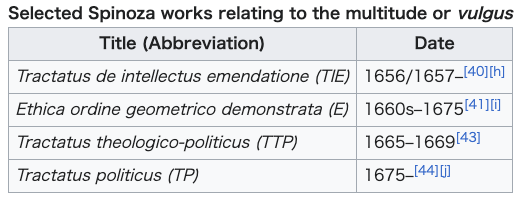

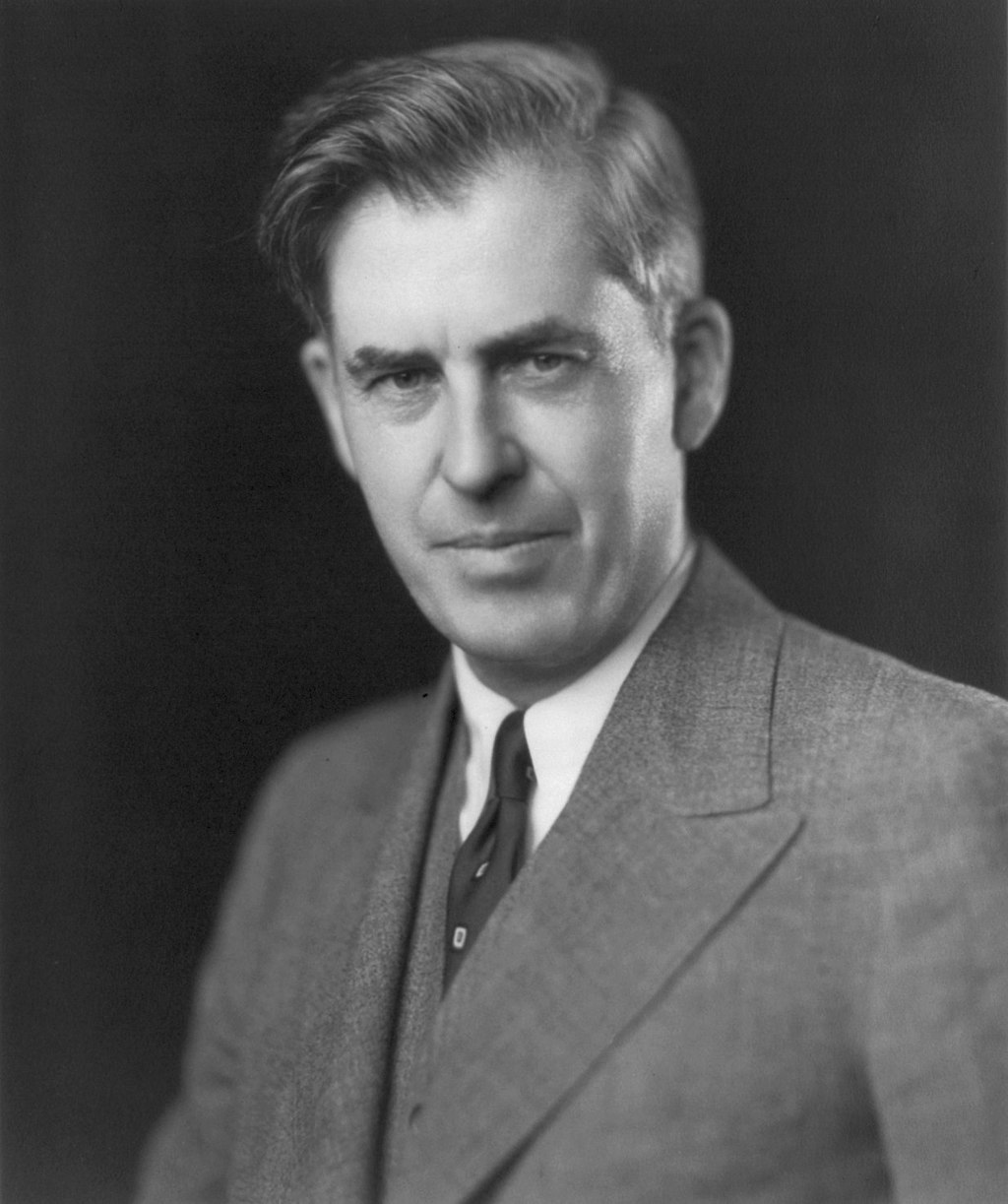

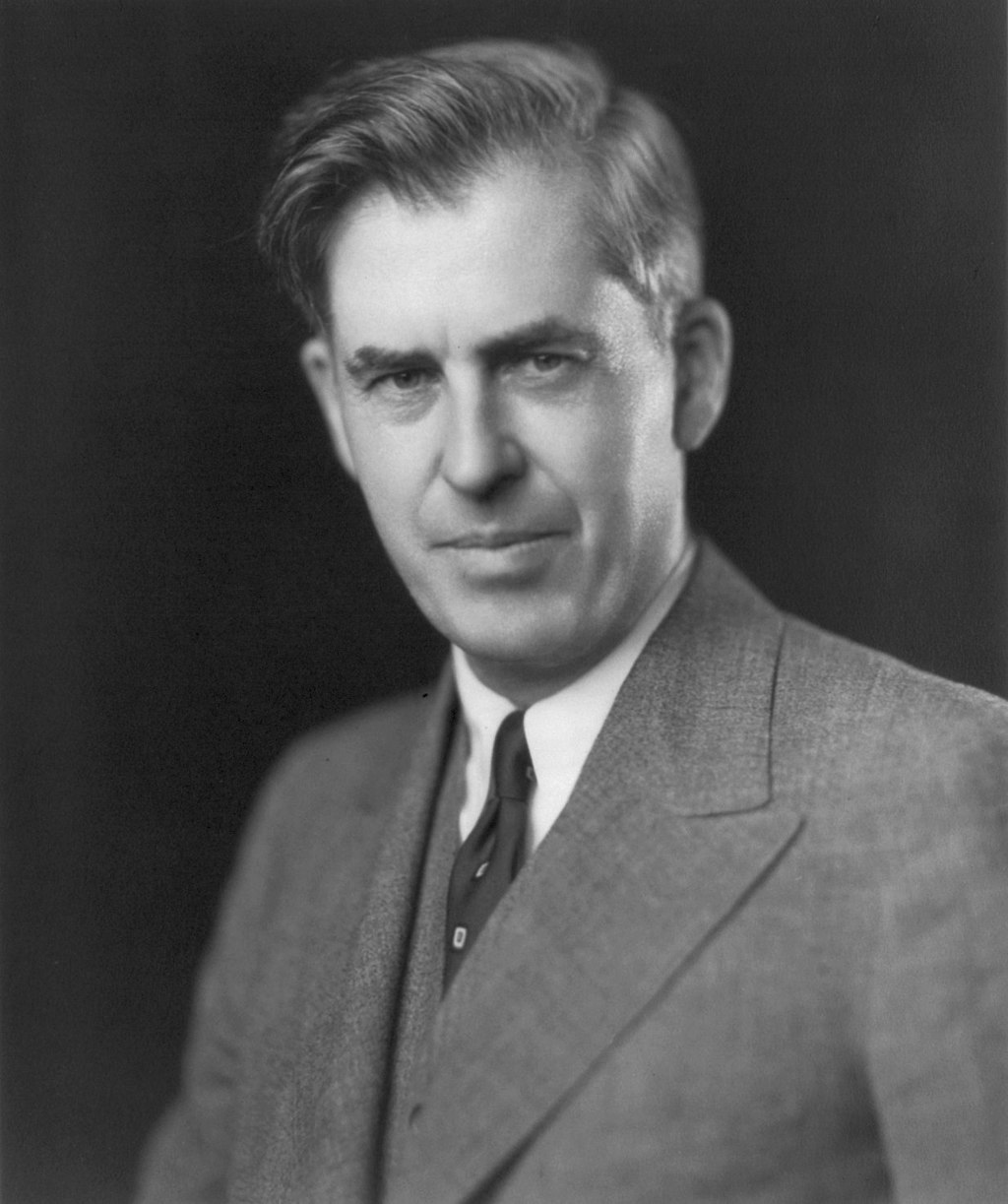

Trifold division breakdown US Vice President Henry A. Wallace proclaimed the "arrival of the century of the common man" in a 1942 speech broadcast nationwide in the United States. After the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars along with industrialization, the division in three estates – nobility, clergy and commoners – had become somewhat outdated. The term "common people" continued to be used, but now in a more general sense to refer to regular people as opposed to the privileged elite. Communist theory divided society into capitalists on one hand, and the proletariat or the masses on the other. In Marxism, the people are considered to be the creator of history.[citation needed] By using the word "people", Marx did not gloss over the class differences, but united certain elements, capable of completing the revolution. The Intelligentsia's sympathy for the common people gained strength in the 19th century in many countries. For example, in Imperial Russia a big part of the intelligentsia was striving for its emancipation. Several great writers (Nekrasov, Herzen, Tolstoy etc.) wrote about sufferings of the common people. Organizations, parties and movements arose, proclaiming the liberation of the people. These included among others: "People's Reprisal", "People’s Will", "Party of Popular Freedom" and the "People's Socialist Party". In the United States, a famous 1942 speech by vice president Henry A. Wallace proclaimed the arrival of the "century of the common man" saying that all over the world the "common people" were on the march, specifically referring to Chinese, Indians, Russians, and as well as Americans.[11] Wallace's speech would later inspire the widely reproduced popular work Fanfare for the Common Man by Aaron Copland.[12] In 1948, US President Harry S. Truman made a speech saying there needs to be a government "that will work in the interests of the common people and not in the interests of the men who have all the money."[13] |

三部構成の分解 1942年、ヘンリー・A・ウォレス米国副大統領は、全米で放送された演説で「平民の世紀の到来」を宣言した。 フランス革命とナポレオン戦争、そして工業化を経て、貴族、聖職者、平民の三つの身分制度は時代遅れになっていった。しかし、「一般市民」という用語は引 き続き使用され、特権的なエリート層に対して、一般の人々を指すより一般的な意味合いで使われるようになった。 共産主義理論は、社会を資本家とプロレタリアート(大衆)に二分した。マルクス主義では、人民は歴史の創造者であるとみなされている。マルクスは「人民」 という言葉を使用することで、階級差を美化したのではなく、革命を成し遂げることができる特定の要素を統合した。19 世紀、多くの国々で、知識層による庶民への共感が高まった。例えば、帝政ロシアでは、インテリゲンツィアの大部分が自らの解放を追求していた。ネクラソ フ、ヘルツェン、トルストイなど、多くの偉大な作家が一般大衆の苦悩を描いた。組織、政党、運動が次々と誕生し、人民の解放を掲げた。その中には「人民の 報復」「人民の意志」「人民の自由党」「人民社会党」などが含まれていた。 米国では、1942年にヘンリー・A・ウォレス副大統領が、世界中で「庶民」が台頭しており、特に中国人、インディアン、ロシア人、そしてアメリカ人を指 して、「庶民の世紀」の到来を宣言した有名な演説を行った。 [11] ウォレスの演説は、後にアーロン・コープランドの広く知られる作品『一般市民のためのファンファーレ』にインスピレーションを与えた。[12] 1948年、アメリカ合衆国大統領ハリー・S・トルーマンは、次のように述べた。「一般市民の利益のために働き、金持ちの利益のために働かない政府が必要 だ。」[13] |

| Social divisions in non-Western

civilizations Comparative historian Oswald Spengler found the social separation into nobility, priests and commoners to occur again and again in the various civilizations that he surveyed (although the division may not exist for pre-civilized society).[14] As an example, in the Babylonian civilization, the Code of Hammurabi made provision for punishments to be harsher for harming a noble than a commoner.[15] |

非西洋文明における社会的分断 比較歴史学者のオズワルド・シュペングラーは、彼が調査したさまざまな文明において、貴族、僧侶、平民への社会的分断が繰り返し発生していることを発見し た(ただし、文明以前の社会ではこの分断が存在しない可能性もある)。[14] 例えば、バビロニア文明では、ハムラビ法典において、貴族を傷つけた場合の罰則が平民を傷つけた場合よりも厳しく定められていた。[15] |

| Aam Aadmi – Hindustani

colloquial expression Battler (underdog) – Australian term for working-class hard worker British subject – Legal term that has evolved over time Demagogue – Politician or orator who panders to fears and emotions of the public Deme – Administrative unit in ancient Athens Dominant ideology – Concept in Marxist philosophy Folk Hoi polloi – Expression from Greek that means "the many" Normality (behavior) – Behavior that can be normal for an individual with the most common behavior for that person NPC (meme) – Insult that implies a person lacks critical thinking Ochlocracy – Democracy spoiled by demagoguery and the rule of passion over reason List of peasant revolts Plain folks – Logical fallacy Populism – Political philosophy Republicanism – Political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic The Common Man – Comic character created by R. K. Laxman Tyranny of the majority – Inherent oppressive potential of simple majority rule Qara bodun – Term given to common people of early Turks Rayah – Name given to common people by Ottomans |

アアム・アドミ – ヒンディー語の方言表現 バトラー(弱者) – オーストラリアで労働者階級の勤勉な労働者を指す用語 英国臣民 – 時代とともに変化してきた法的用語 デマゴーグ – 国民の恐怖や感情に迎合する政治家や演説家 デメ – 古代アテネの行政単位 支配的イデオロギー – マルクス主義哲学の概念 フォーク ホイ・ポロイ – ギリシャ語で「大衆」を意味する表現 正常性(行動) – その人物にとって最も一般的な行動であり、その人物にとって正常であると考えられる行動 NPC(ミーム) – 批判的思考が欠如していることをほのめかす侮辱 オクロクラシー – デマゴーグと理性よりも感情が優先される民主主義 農民反乱のリスト 平民 – 論理的誤謬 ポピュリズム – 政治哲学 共和主義 – 共和制国家における市民権を中核とする政治思想 ザ・コモン・マン – R. K. ラクマンが創作した漫画のキャラクター 多数派の専制 – 単純多数決の統治に内在する抑圧的な可能性 カラ・ボドゥン – 初期のトルコ人の一般市民を指す用語 ラヤ – オットマン帝国が一般市民に与えた名称 |

| Further reading The common people: a history from the Norman Conquest to the present J. F. C. Harrison Fontana Press (1989) The concept of class: a historical introduction Peter Calvert Palgrave Macmillan (1985) |

さらに読む 一般大衆:ノルマン征服から現在までの歴史 J. F. C. ハリソン フォンタナ・プレス (1989) 階級概念:歴史的紹介 ピーター・カルバート パルグレイブ・マクミラン (1985) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Commoner |

★ 英語表現「the hoi polloi」(/ˌhɔɪ pəˈlɔɪ/;古代ギリシャ語の「οἱ πολλοί」(hoi polloí)から)は、古代ギリシャ語から借用されたもので、その意味は「多くの人々」または、最も厳密な意味では「人々」である。英語では、一般大衆 を意味する否定的な意味合いが与えられている。[1] 「hoi polloi」の同義語には、「the plebs」(plebeians)、 「the rabble」、「the masses」、「the great unwashed」、「the riffraff」、 「the proles」(proletarians)などがある。[2] この用語は、少なくとも1950年代以降、オーストラリア、北アメリカ、スコットランドを含むいくつかの英語圏の国や地域で、中流階級や低所得層の人々が エリートを蔑称する意味で広く口語的に使用されている。[1][3] この表現は、トゥキディデスの『ペロポネソス戦争史』で言及されているペリクレスの葬送演説を通じて、英語学者たちに知られたと考えられている。ペリクレ スは、アテネの民主主義を称賛する際に、この表現を肯定的な意味で用い、対比として「hoi oligoi」(ギリシャ語: οἱ ὀλίγοι;オリガルキーも参照)を用いている。[4] 現在の英語での使用は、19世紀初頭に起源を持つ。この時代、ギリシャ語とラテン語に精通していることが、教養のある人間として認められるための条件とさ れていた。[5][6] この表現は、元々はギリシャ文字で書かれていた。[7][8][9] これらの言語の知識は、同様の教育を受けていない「hoi polloi」と、その表現を使用する者を区別する役割を果たしていた。[7]

★★「人民(the people)」という用語は、政治体制における大衆または一般大衆を指す[1]。そのため、これは人権法、国際法、憲法上の概念であり、特に人民主権の 主張に使用される。対照的に、「国民」とは、全体として考えられる複数の人格を指す。政治や法律で使用される「人びと(a people)」という用語は、民族や国民という集団またはコミュニティを指す[1]。

| The English

expression the hoi polloi (/ˌhɔɪ pəˈlɔɪ/; from Ancient Greek οἱ πολλοί

(hoi polloí) 'the many') was borrowed from Ancient Greek, where it

means "the many" or, in the strictest sense, "the people". In English,

it has been given a negative connotation to signify the common

people.[1] Synonyms for hoi polloi include "the plebs" (plebeians),

"the rabble", "the masses", "the great unwashed", "the riffraff", and

"the proles" (proletarians).[2] There is also widespread spoken use of the term in the opposite sense to refer denigratingly to elites that is common among middle-class and lower income people in several English-speaking countries and regions, including at least Australia, North America, and Scotland since at least the 1950s.[1][3] The phrase probably became known to English scholars through Pericles' Funeral Oration, as mentioned in Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War. Pericles uses it in a positive way when praising the Athenian democracy, contrasting it with hoi oligoi, "the few" (Greek: οἱ ὀλίγοι; see also oligarchy).[4] Its current English usage originated in the early 19th century, a time when it was generally accepted that one must be familiar with Greek and Latin in order to be considered well educated.[5][6] The phrase was originally written in Greek letters.[7][8][9] Knowledge of these languages served to set apart the speaker from hoi polloi in question, who were not similarly educated.[7] |

英語表現「the hoi polloi」(/ˌhɔɪ

pəˈlɔɪ/;古代ギリシャ語の「οἱ πολλοί」(hoi

polloí)から)は、古代ギリシャ語から借用されたもので、その意味は「多くの人々」または、最も厳密な意味では「人々」である。英語では、一般大衆を

意味する否定的な意味合いが与えられている。[1] 「hoi polloi」の同義語には、「the plebs」(plebeians)、

「the rabble」、「the masses」、「the great unwashed」、「the riffraff」、 「the

proles」(proletarians)などがある。[2] この用語は、少なくとも1950年代以降、オーストラリア、北アメリカ、スコットランドを含むいくつかの英語圏の国や地域で、中流階級や低所得層の人々が エリートを蔑称する意味で広く口語的に使用されている。[1][3] この表現は、トゥキディデスの『ペロポネソス戦争史』で言及されているペリクレスの葬送演説を通じて、英語学者たちに知られたと考えられている。ペリクレ スは、アテネの民主主義を称賛する際に、この表現を肯定的な意味で用い、対比として「hoi oligoi」(ギリシャ語: οἱ ὀλίγοι;オリガルキーも参照)を用いている。[4] 現在の英語での使用は、19世紀初頭に起源を持つ。この時代、ギリシャ語とラテン語に精通していることが、教養のある人間として認められるための条件とさ れていた。[5][6] この表現は、元々はギリシャ文字で書かれていた。[7][8][9] これらの言語の知識は、同様の教育を受けていない「hoi polloi」と、その表現を使用する者を区別する役割を果たしていた。[7] |

| Pronunciation The term is of course pronounced very differently in English, Ancient Greek, and Modern Greek: English educated speakers pronounce it /ðə ˌhɔɪ pəˈlɔɪ/, but use in the opposite sense of "elites" usually has initial stress on "polloi".[10][1] Ancient Greek had phonemic consonant length, or gemination. Speakers would have pronounced it [hoi polloi˨˦] with the double-λ being geminated. Modern Greek speakers pronounce it [i poˈli] since in Modern Greek there is no voiceless glottal /h/ phoneme and οι is pronounced [i] (all Ancient Greek diphthongs are now pronounced as monophthongs). Greek Cypriots still pronounce the double-λ ([i polˈli]).[11] |

発音 この用語は、もちろん英語、古代ギリシャ語、現代ギリシャ語ではまったく異なる発音になります。 英語教育を受けた話者は /ðə ˌhɔɪ pəˈlɔɪ/ と発音しますが、「エリート」の反対の意味で使用する場合は、通常「polloi」に最初のアクセントが置かれます。[10][1] 古代ギリシャ語には音素的な子音の長さ、つまり子音の二重化があった。話者は [hoi polloi˨˦] と発音し、二重の λ が二重化されていた。 現代ギリシャ語話者は、現代ギリシャ語には無声の喉頭音 /h/ の音素がなく、οι は [i] と発音されるため、[i poˈli] と発音する。ギリシャ系キプロス人は、二重の λ ([i polˈli]) と発音する。[11] |

| Usage Some linguists argue that, given that hoi is a definite article, the phrase "the hoi polloi" is redundant, akin to saying "the the masses". Others argue that this is inconsistent with other English loanwords.[12] The word "alcohol", for instance, derives from the Arabic al-kuhl, al being an article, yet "the alcohol" is universally accepted as good grammar.[13] |

用法 一部の言語学者は、hoi は定冠詞であるため、「the hoi polloi」という表現は「the the masses」と言うのと同じで冗長であると主張している。一方、これは他の英語借用語と矛盾すると主張する者もいる[12]。「アルコール」という単語 は、アラビア語の al-kuhl に由来し、al は定冠詞であるが、「the alcohol」は普遍的に文法的に正しいと認められている[13]。 |

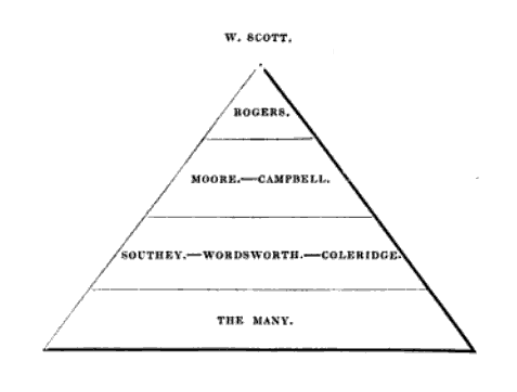

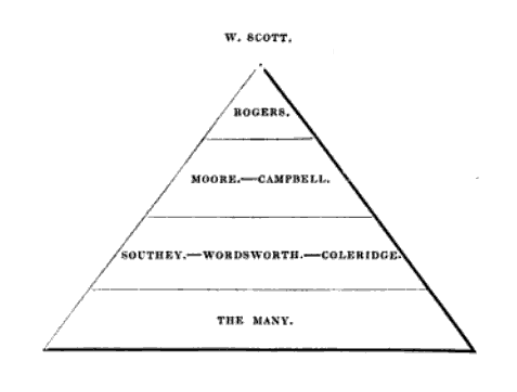

| Appearances in the nineteenth century See also: Macaronic verse There have been numerous uses of the term in English literature. James Fenimore Cooper, author of The Last of the Mohicans, is often credited with making the first recorded usage of the term in English.[14][15] The first recorded use by Cooper occurs in his 1837 work Gleanings in Europe where he writes "After which the oi polloi are enrolled as they can find interest."[16]  Diagram of Lord Byron's view of the hoi polloi, as arranged in his journals, ranked as "the many" beneath a handful of his personal contacts Lord Byron had, in fact, previously used the term in his letters and journal. In one journal entry, dated 24 November 1813, Byron writes: I have not answered W. Scott's last letter,—but I will. I regret to hear from others, that he has lately been unfortunate in pecuniary involvements. He is undoubtedly the Monarch of Parnassus, and the most English of bards. I should place Rogers next in the living list (I value him more as the last of the best school) —Moore and Campbell both third—Southey and Wordsworth and Coleridge—the rest, οι πολλοί [hoi polloi in Greek].[17][18] Byron also wrote an 1821 entry in his journal "... one or two others, with myself, put on masks, and went on the stage with the 'oi polloi."[19] In Confessions of an English Opium-Eater, Thomas De Quincey uses the term during a passage discussing which of the English classes is most proud, noting "... the children of bishops carry about with them an austere and repulsive air, indicative of claims not generally acknowledged, a sort of noli me tangere manner, nervously apprehensive of too familiar approach, and shrinking with the sensitiveness of a gouty man from all contact with the οι πολλοι."[20] While Charles Darwin was at the University of Cambridge from 1828 to 1831, undergraduates used the term "hoi polloi" or "Poll" for those reading for an ordinary degree, the "pass degree".[21] At that time only capable mathematicians would take the Tripos or honours degree. In his autobiography written in the 1870s, Darwin recalled that "By answering well the examination questions in Paley, by doing Euclid well, and by not failing miserably in Classics, I gained a good place among the οἱ πολλοί, or crowd of men who do not go in for honours."[22] W. S. Gilbert used the term in 1882 when he wrote the libretto of the comic opera Iolanthe. In Act I, the following exchange occurs between a group of disgruntled fairies who are arranging to elevate a lowly shepherd to the peerage, and members of the House of Lords who will not hear of such a thing: PEERS: Our lordly style You shall not quench With base canaille! FAIRIES: (That word is French.) PEERS: Distinction ebbs Before a herd Of vulgar plebs! FAIRIES: (A Latin word.) PEERS: 'Twould fill with joy, And madness stark The hoi polloi! FAIRIES: (A Greek remark.) Gilbert's parallel use of canaille, plebs (plebeians), and hoi polloi makes it clear that the term is derogatory of the lower classes. In many versions of the vocal score, it is written as "οἱ πολλοί", likely confusing generations of amateur choristers who couldn't read Greek. John Dryden used the phrase in his Essay of Dramatick Poesie, published in 1668. Dryden spells the phrase with Greek letters, but the rest of the sentence is in English (and he does precede it with "the").[citation needed] |

19世紀における登場 参照:マカロニック詩 英語文学において、この用語は数多くの使用例がある。ジェームズ・フェニモア・クーパー(『モヒカン族の最後』の著者)は、英語でこの用語を初めて記録し た人物としてよく知られている。[14][15] クーパーによる最初の記録された使用例は、1837年の著作『ヨーロッパの断片』において、「その後、オイ・ポイ・ポイは興味がある限り登録される」と書 かれている。[16]  バイロン卿の日記に記された、彼の個人的な知人であるごく少数の人々よりも下位にランク付けされた「大衆」に対するバイロン卿の見解の図。 バイロンは実際、この用語を以前の手紙や日記でも使用していた。1813年11月24日の日記のエントリーで、バイロンは次のように書いている: W・スコットの最後の手紙には答えていないが、答えるつもりだ。他の人から、彼が最近金銭的なトラブルに巻き込まれたと聞いて残念だ。彼は間違いなくパル ナッソスの王であり、最もイギリス的な詩人だ。生きている詩人の中で、私はロジャースを次に置く(私は彼を最高の流派の最後の詩人としてより高く評価して いる)——ムーアとキャンベルは共に3位——サウスリーとワーズワースとコリッジ——残りは、οι πολλοί [hoi polloi(ギリシャ語で「大衆」の意)]。[17][18] バイロンも1821年の日記に「私を含む1、2人と『オイ・ポイロイ』と共に仮面をつけて舞台に上がった」と記している。[19] トマス・デ・クインシーは『イギリス人アヘン中毒者の告白』で、イギリスの階級のうち最も誇り高いのはどれかについて論じる際にこの用語を使用し、「司教 の子どもたちは、一般に認められていない主張を示すような厳格で不快な態度を漂わせ、神経質に親しみを拒み、痛風患者のように敏感に接触を避け、oi polloi から身を引く」と記している。 [20] チャールズ・ダーウィンが1828年から1831年までケンブリッジ大学に在籍していた頃、学部生たちは「ホイ・ポイ・ロイ」または「ポール」という用語 を、通常の学位である「パス・ディグリー」を取得する学生を指す言葉として使っていた。[21] 当時、トリポスまたは優等学位を取得するのは、優秀な数学者だけだった。1870年代に執筆した自伝で、ダーウィンは「ペイリーの試験問題に正しく答え、 ユークリッドをうまくこなし、古典で惨敗しなかったことで、私はοἱ πολλοί、つまり栄誉を求めない人々の群れの中で良い地位を得た」と回想している。[22] W. S. ギルバートは、1882年に喜劇オペラ『イオランテ』の台本を書く際にこの用語を使用しました。第1幕で、低位の羊飼いを貴族に昇格させようと画策する不 満を抱えた妖精たちのグループと、そのようなことを聞き入れない貴族院の議員たちとの間で、次のような会話が交わされます: 貴族たち:我々の高貴な風格 お前たちは消すことはできない 卑しい群衆よ! 妖精たち:(その言葉はフランス語だ。 貴族たち:区別は 下品な民衆の群畜の前に 失われてしまう! 妖精たち:(ラテン語だ。 貴族たち:それは 民衆を 狂喜と狂乱で満たすだろう! 妖精たち:(ギリシャ語だ。 ギルバートが「canaille」「plebs(平民)」、「hoi polloi」を並列に使用していることは、この用語が下層階級に対する蔑称であることを明確にしている。多くの声楽スコアでは「οἱ πολλοί」と表記されており、ギリシャ語を読めないアマチュア合唱団員を混乱させてきた。 ジョン・ドライデンは、1668年に発表された『劇詩論』でこのフレーズを使用している。ドライデンはフレーズをギリシャ文字で表記しているが、文の残りは英語で書かれている(また、その前に「the」を付けている)。[出典が必要] |

| Appearances in the twentieth century The term has appeared in several films and radio programs. For example, one of the earliest short films from the Three Stooges, Hoi Polloi (1935), opens in an exclusive restaurant where two wealthy gentlemen are arguing whether heredity or environment is more important in shaping character.[23] They make a bet and pick on nearby trashmen (the Stooges) to prove their theory. At the conclusion of three months in training, the Stooges attend a dinner party, where they thoroughly embarrass the professors. The University of Dayton's Don Morlan says, "The theme in these shorts of the Stooges against the rich is bringing the rich down to their level and shaking their heads." A typical Stooges joke from the film is when someone addresses them as "gentlemen", and they look over their shoulders to see who is being addressed.[24] The Three Stooges turn the tables on their hosts by calling them "hoi polloi" at the end. The term continues to be used in contemporary writing. In his 1983 introduction to Robert Anton Wilson's Prometheus Rising, Israel Regardie writes, "Once I was even so presumptuous as to warn (Wilson) in a letter that his humor was much too good to waste on hoi polloi who generally speaking would not understand it and might even resent it."[25] The term "hoi polloi" was used in a dramatic scene in the film Dead Poets Society (1989). Professor Keating speaks negatively about the use of the article "the" in front of the phrase.[26] The term was also used in the comedy film Caddyshack (1980). In a rare moment of cleverness, Spaulding Smails greets Danny Noonan as he arrives for the christening of The Flying Wasp, the boat belonging to Judge Elihu Smails (Spaulding's grandfather), with "Ahoy, polloi! Where did you come from, a scotch ad?" This is particularly ironic, because Danny has just finished mowing the Judge's lawn, and arrives overdressed, wearing a sailboat captain's outfit (as the girl seated next to him points out, Danny "looks like Dick Cavett").[17] In the song "Risingson" on Massive Attack's Mezzanine album, the singer apparently appeals to his company to leave the club they're in, deriding the common persons' infatuation with them, and implying that he's about to slide into antisocial behaviour: Toy-like people make me boy-like (...) And everything you got, hoi polloi like Now you're lost and you're lethal And now's about the time you gotta leave all These good people...dream on.[27] The term was used in a first-series episode (The New Vicar, aired 5 November 1990) of the British sitcom Keeping Up Appearances. The main character, Hyacinth Bucket, gets into a telephone argument with a bakery employee. When the employee abruptly hangs up in frustration, Hyacinth disparagingly refers to him as "hoi polloi". This is in keeping with her character; she looks down upon those she considers to be of lesser social standing, including working-class people.[28] Hoi Polloi was used in Larry Marder's Tales of the Beanworld to name the unusual group of creatures that lived beneath the Beanworld.[29] |

20世紀における登場 この用語は、いくつかの映画やラジオ番組で登場している。例えば、スリー・ストゥージーズの初期の短編映画『ホイ・ポロイ』(1935年)は、高級レスト ランで2人の裕福な紳士が、性格形成において遺伝と環境のどちらが重要か議論するシーンから始まる。[23] 彼らは賭けをし、近くのゴミ収集人(ストゥージーズ)を標的にして自分の理論を証明しようとする。3か月の訓練を終えたストゥージーズは、ディナーパー ティーに出席し、教授たちを完全に恥をかかせる。 デイトン大学のドン・モランは、「これらの短編におけるスリー・ストーリーズ対富裕層のテーマは、富裕層を彼らのレベルまで引きずり下ろし、首を振ること にあります」と述べています。映画における典型的なスリー・ストーリーズのジョークは、誰かが彼らを「紳士たち」と呼ぶと、彼らは後ろを振り返って誰が呼 ばれたのかを確認するシーンです。[24] スリー・ストーリーズは、最後にホストたちに対して「ホイ・ポイロイ」と呼び返すことで、立場を逆転させます。 この用語は現代の著作でも使用されている。イスラエル・レガディは1983年にロバート・アントン・ウィルソンの『プロメテウス・ライジング』の序文で、 「私はかつて、ウィルソンに手紙で、彼のユーモアは一般の人々には理解できず、むしろ反感を買う可能性があるため、無駄にすべきではないと警告するほど傲 慢だった」と書いている。[25] 「ホイ・ポイロイ」という用語は、映画『デッド・ポエツ・ソサエティ』(1989年)の劇的なシーンでも使われた。キートン教授は、このフレーズの前に冠詞「the」を使うことについて否定的に語っている。[26] この用語は、コメディ映画『キャディシャック』(1980年)でも使用されています。スパルディング・スメールズは、エリユー・スメールズ判事(スパル ディングの祖父)の所有するボート「ザ・フライング・ワスプ」の命名式にダニー・ヌーナンが到着した際、珍しい機知に富んだ挨拶をします。「アホイ、ポイ ロイ!どこから来たんだ、スコッチの広告か?」と挨拶する。これは、ダニーが裁判官の芝生を刈ったばかりで、セーリングの船長の衣装を身に着けて、着飾り すぎて到着したばかりだったため、特に皮肉な表現となっている(隣に座っていた少女が、ダニーは「ディック・キャヴェットみたい」と指摘している)。 マッシヴ・アタックのアルバム「メザニン」収録の曲「ライジングソン」では、歌手は、彼らに夢中になっている一般大衆を嘲笑し、反社会的な行動に走ろうとしていることをほのめかしながら、仲間たちにクラブから出るよう呼びかけているようです。 おもちゃのような人々は、私を子供のようにさせる(...) そして、あなたが持っているものはすべて、大衆のようなもの 今、あなたは迷い、危険だ そして今こそ、すべてを捨てて去る時だ これらの良い人々…夢を見続けろ。[27] この用語は、イギリスのシットコム『Keeping Up Appearances』の第1シリーズ(1990年11月5日放送の「The New Vicar」)で使用されました。主人公のハイアシンサ・バケットは、ベーカリーの従業員と電話で口論になります。従業員がイライラして突然電話を切る と、ハイアシンサは彼を「ホイ・ポイ・ロイ」と軽蔑的に呼ぶ。これは彼女の性格に一致している。彼女は、労働者階級を含む、自分より社会的地位が低いと考 える人々を見下している。[28] ホイ・ポイ・ロイは、ラリー・マーダーの『Tales of the Beanworld』で、ビーンワールドの下に住む不思議な生物の集団の名前として使われた。[29] |

| Appearances in the twenty-first century The August 14, 2001 episode of CNN's Larry King Live program included a discussion about whether the sport of polo was an appropriate part of the image of the British Royal Family. Joining King on the program were Robert Lacey and Kitty Kelley. Their discussions focused on Prince Charles and his son Prince William: Lacey said, "There is another risk that I see in polo. Polo is a very nouveau riche, I think, rather vulgar game. I can say that having played it myself, and I don't think it does Prince Charles's image, or, I dare say, this is probably arrogant of me, his spirit any good. I don't think it is a good thing for him to be involved in. I also, I'm afraid, don't think [polo] is a good thing for [Charles] to be encouraging his sons to get involved in. It is a very "playboy" set. I think the whole polo syndrome is something that the royal family would do very well to get uninvolved with as soon as possible. King turned the question to Kelley, saying, "Kitty, it is kind of hoi polloi, although it is an incredible sport in which, I have been told, that the horse is 80 percent of the game, the rider 20 percent. But it is a great sport to watch. But it is hoi polloi isn't it?" To which Kelley replied, "Yes, I do agree with Robert. The time is come and gone for the royals to be involved with polo. I mean it is – it just increases that dissipated aristo-image that they have, and it is too bad to encourage someone like Prince William to get involved."[30] The term appears in the 2003 Broadway musical Wicked, where it is used by the characters Elphaba and Glinda to refer to the many inhabitants of the Emerald City: "... I wanna be in this hoi polloi ..."[31] Jack Cafferty, a CNN anchorman, was caught misusing the term. On 9 December 2004 he retracted his statement, saying "And hoi-polloi refers to common people, not those rich morons that are evicting those two red-tail hawks (ph) from that fifth Avenue co-op. I misused the word hoi-polloi. And for that I humbly apologize."[32] New media and new inventions have also been described as being by or for the hoi polloi. Bob Garfield, co-host of NPR's On the Media program, 8 November 2005, used the phrase in reference to changing practices in the media, especially Wikipedia, "The people in the encyclopedia business, I understand, tend to sniff at the wiki process as being the product of the mere hoi polloi."[33] In "Sunk Costs" (season 3 episode 3) of Better Call Saul, Jimmy has been arrested and the DDA (Oakley) teases him "getting fingerprinted with the hoi polloi".[34] |

21世紀におけるポロのイメージ 2001年8月14日に放送されたCNNの番組「ラリー・キング・ライブ」では、ポロが英国王室のイメージにふさわしいスポーツかどうかについて議論が行 われた。キングと共に番組に出演したのは、ロバート・レイシーとキティ・ケリーだった。彼らの議論は、チャールズ皇太子とその息子ウィリアム王子に焦点を 当てたものだった: レイシーは次のように述べました。「ポロにはもう一つのリスクがあると思います。ポロは、非常に新富層向けの、やや下品なスポーツだと思います。私自身も プレーしたことがあるので言えますが、チャールズ皇太子のイメージ、あるいは、これはおそらく傲慢な発言かもしれませんが、彼の精神にとって良いものとは 思えません。彼にとって関与するべきものではないと思う。また、残念ながら、チャールズが息子たちにポロを奨励することも良いことではないと思う。それは 非常に『プレイボーイ』的な世界だ。ポロ症候群は、王室が可能な限り早く関与を断つべきものだと考える。」 キングは質問をケリーに向け、「キティ、それは少し庶民的だけど、素晴らしいスポーツだと聞いている。馬が80%、騎手が20%を占めるゲームだと。でも観るには素晴らしいスポーツだ。でも庶民的だよね?」 ケリーは「はい、ロバートに同意する。王室がポロに関与する時代は終わった。つまり、それは彼らが持つ散漫な貴族のイメージを強化するだけで、ウィリアム王子のような人物が関与することを奨励するのは残念だ」と答えた。[30] この用語は、2003年のブロードウェイミュージカル『ウィキッド』で、エルファバとグリンダがエメラルドシティの多くの住民を指して使用している。「...私はこのホイ・ポイ・ロイの一員になりたい...」[31] CNNのアンカーマン、ジャック・カフティは、この用語を誤用したことが発覚した。2004年12月9日、彼は発言を撤回し、「ホイ・ポイロイとは一般市 民を指すもので、5番街のコーポラティブ住宅から2羽の赤尾のハヤブサ(ph)を追い出しているあの金持ちの馬鹿者たちではない。ホイ・ポイロイという言 葉を誤用した。その点について、心から謝罪する」と述べた。[32] 新メディアや新発明も、ホイ・ポイロイによるもの、またはそのためのものとして描写されている。NPRの『On the Media』番組の共同司会者ボブ・ガーフィールドは、2005年11月8日、メディアの変革、特にウィキペディアを指して「百科事典業界の人々は、ウィ キプロセスを『単なるホイ・ポイロイの産物』と軽蔑する傾向がある」と述べた。[33] 『ベター・コール・ソウル』のシーズン3エピソード3「サンク・コスト」で、ジミーが逮捕され、DDA(オークリー)が「一般大衆と一緒に指紋を取られるんだ」とからかう。[34] |

| Polyarchy Criticism of democracy – Critiques of democratic political systems Dominant ideology – Concept in Marxist philosophy Doxa – Greek word meaning common belief or popular opinion NPC (meme) – Insult that implies a person lacks critical thinking Tragedy of the commons – Self-interests causing depletion of a shared resource Tyranny of the majority – Inherent oppressive potential of simple majority rule Vox populi – Latin phrase meaning "voice of the people" |

多頭政治 民主主義の批判 – 民主的な政治体制に対する批判 支配的イデオロギー – マルクス主義哲学の概念 ドクサ – 一般的な信念や大衆の意見を表すギリシャ語 NPC (ミーム) – 批判的思考能力に欠ける人格を侮辱する言葉 コモンズの悲劇 – 共有資源の枯渇を引き起こす自己利益 多数決の専制 – 単純多数決の制度に内在する抑圧の可能性 ヴォックス・ポピュリ – 「民衆の声」を意味するラテン語 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hoi_polloi | |

| The term "the people" refers to the public or common mass of people of a polity.[1] As such it is a concept of human rights law, international law as well as constitutional law, particularly used for claims of popular sovereignty. In contrast, a people is any plurality of persons considered as a whole. Used in politics and law, the term "a people" refers to the collective or community of an ethnic group or nation.[1] | 「人民(the

people)」という用語は、政治体制における大衆または一般大衆を指す[1]。そのため、これは人権法、国際法、憲法上の概念であり、特に人民主権の

主張に使用される。対照的に、「国民」とは、全体として考えられる複数の人格を指す。政治や法律で使用される「人びと(a

people)」という用語は、民族や国民という集団またはコミュニティを指す[1]。 |

| Concepts Legal See also: Popular sovereignty  Liberty Leading the People, 1830 by Eugène Delacroix Chapter One, Article One of the Charter of the United Nations states that "peoples" have the right to self-determination.[2] Though the mere status as peoples and the right to self-determination, as for example in the case of Indigenous peoples (peoples, as in all groups of indigenous people, not merely all indigenous persons as in indigenous people),[clarification needed] does not automatically provide for independent sovereignty and therefore secession.[3][4] Indeed, judge Ivor Jennings identified the inherent problems in the right of "peoples" to self-determination, as it requires pre-defining a said "people".[5] Constitutional Both the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire used the Latin term Senatus Populusque Romanus, (the Senate and People of Rome). This term was fixed abbreviated (SPQR) to Roman legionary standards, and even after the Roman Emperors achieved a state of total personal autocracy, they continued to wield their power in the name of the Senate and People of Rome. The term People's Republic, used since late modernity, is a name used by states, which particularly identify constitutionally with a form of socialism. Judicial In criminal law, in certain jurisdictions, criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the People. Several U.S. states, including California, Illinois, and New York, use this style.[6] Citations outside the jurisdictions in question usually substitute the name of the state for the words "the People" in the case captions.[7] Four states — Massachusetts, Virginia, Pennsylvania, and Kentucky — refer to themselves as the Commonwealth in case captions and legal process. Other states, such as Indiana, typically refer to themselves as the State in case captions and legal process. Outside the United States, criminal trials in Ireland and the Philippines are prosecuted in the name of the people of their respective states. The political theory underlying this format is that criminal prosecutions are brought in the name of the sovereign; thus, in these U.S. states, the "people" are judged to be the sovereign, even as in the United Kingdom and other dependencies of the British Crown, criminal prosecutions are typically brought in the name of the Crown. "The people" identifies the entire body of the citizens of a jurisdiction invested with political power or gathered for political purposes.[8] |

概念 法律 関連項目:人民主権  1830年、ウジェーヌ・ドラクロワ作「自由を導く女神」 国連憲章第 1 章第 1 条は、「人民」は自決の権利を有すると定めている[2]。しかし、先住民(先住民とは、先住民であるすべての集団を指し、先住民である個人を指すわけでは ない)の場合のように、単に「人民」であるということ、および自決の権利を有するという事実だけでは、自動的に独立主権、ひいては分離独立が認められるわ けではない。 [3][4] 実際、アイヴァー・ジェニングス裁判官は、「人民」の自決権には、その「人民」を事前に定義しておく必要があるという本質的な問題があると指摘している。 [5] 憲法 ローマ共和国とローマ帝国は、いずれもラテン語の「Senatus Populusque Romanus」(ローマ元老院と人民)という用語を使用していた。この用語は、ローマ軍団の基準により略語(SPQR)として固定され、ローマ皇帝が完 全な個人独裁の状態を達成した後も、彼らはローマ元老院および人民の名の下に権力を振るい続けた。 近代後期から使用されている「人民共和国」という用語は、特に憲法上、社会主義の一形態を標榜する国家によって使用される名称だ。 司法 刑法では、特定の法域において、刑事訴追は人民の名において行われる。カリフォルニア州、イリノイ州、ニューヨーク州など、いくつかの米国の州ではこの形 式が採用されている。[6] 当該法域以外の引用では、通常、事件名には「人民」という単語の代わりに州名が代用される。[7] マサチューセッツ州、バージニア州、ペンシルベニア州、ケンタッキー州の 4 州は、事件名および法的手続きにおいて、自らを「連邦」と呼んでいる。インディアナ州などの他の州では、通常、事件名や法的手続きでは、州を「州」と表記 している。米国以外では、アイルランドとフィリピンでは、刑事裁判はそれぞれの州の人民の名において行われている。 この形式の根底にある政治理論は、刑事訴追は主権者の名において行われるというものです。したがって、これらの米国州では、「人民」が主権者とみなされま すが、英国および英国王室の他の属領では、刑事訴追は通常、王冠の名において行われます。「人民」とは、政治権力を付与された、あるいは政治的目的のため に集まった、ある管轄区域の市民全体を指します[8]。 |

| Civitas Clan Collective Community Kinship Tribe List of contemporary ethnic groups List of indigenous peoples Volk National identity Nationality Public Republic Republicanism Democracy People's republic Populism The People, in a series of 1950s science fiction stories by Zenna Henderson |

市民 氏族 集団 コミュニティ 親族 部族 現代民族一覧 先住民族一覧 フォルク 国民的アイデンティティ 国籍 公共 共和国 共和主義 民主主義 人民共和国 ポピュリズム 1950年代のゼナ・ヘンダーソンによる一連のSF小説に登場する「人民」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/People |

|

★

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

cc

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆