Society

社会

Society

解説:池田光穂

■ 社会(society)の定義

オッ クスフォード英語辞典(OED)の「社会 (society)」の最初の定義はこのように書いてある。

Association

with

one's fellow men, esp. in a friendly or intimate manner; companionship

or fellowship. Also rarely of animals (quot. 1774).

【翻 訳】ある人の仲間と共にある、とりわけ友好的 な いしは親密な流儀での、連合(アソシーエション)のこと。仲間付き合い、親睦的結社。時には(人間以外の)動物にもみられる。[以上の用例は 1774年の下記]。

1774

Goldsm. Nat.

Hist. (1776) V. 153 As Nature has formed the rapacious class for war,

so she seems equally to have fitted these for peace, rest, and society.

【翻 訳】1776年に出版されたオリバー・ゴール ド スミス(Oliver Goldsmith, 1730-1774)『地球と生きている自然に関する歴史(An History of the Earth and Animated Nature)』5巻153ページからの用例:「自然は闘争のための強欲な階級を造ったがゆえに、自然は同様に、平和と休息と社会のための階級をも併せて もつようになった」。

OED はそれよりも140年ほど古い用例を示してい るが、この現代的用法の起源は18世紀後半の博物学者ゴールドスミスのものに依拠させている。

さ て、ではこのことは、何を意味するのだろうか? 私の考えでは、社会というものの用例は、啓蒙主義にもとづく市民社会の登場と深い関係があるのではないかということである。これは古い用法では、社会の語 源となったラテン語の形容詞 socius(主格・男性形)——意味は分有している・加盟している・家族親族である・連盟している——の用法の対象の範囲が狭かったの対して、国家を構 成するメンバーである市民の啓蒙時代における「急速な拡張」のせいで、社会というものの定義が想定する範囲がきわめて大きなものになったということに他な らない。すなわち、現代の我々の社会が想像する一番大きな集団は、まさに市民社会(civil society)そのものなのである。

市

民社会の確立は、あるいはそのような権利主張が公

共のものになる根拠は、市民からの代表者が政治権力を司る民主主義(democracy)——人民による権力掌握(demos+cracia)——という

考え方が確立しつつあったということである。この最たる力の行使の結果がブルジョア革命である。

今 日における社会の概念は、市民による共同性を前提 にしているが、それが古代から引き継いだ親密性の範疇=親密圏(intimate sphere)と公共性の範疇=公共圏(public sphere)との重なりや、時代的取り扱いについては、さまざまな議論がある。

他 方、別の観点から考える必要もある。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは『自由論』(On Liberty, 1859)のなかで、「自分自身に対して、自分の身体と心に対して、人はみな主権をもっている(Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign)」と主張する。(→CHAPTER I.[22])

The object of this Essay is to assert one very simple principle, as entitled to govern absolutely the dealings of society with the individual in the way of compulsion and control, whether the means used be physical force in the form of legal penalties, or the moral coercion of public opinion. That principle is, that the sole end for which mankind are warranted, individually or collectively, in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number, is self-protection. That the only purpose for which power can be rightfully exercised over any member of a civilized community, against his will, is to prevent harm to others. His own good, either physical or moral, is not a sufficient warrant. He cannot rightfully be compelled to do or forbear because it will be better for him to do so, because it will make him happier, because, in the opinions of others, to do so would be wise, or even right. These are good reasons for remonstrating with him, or reasoning with him, or persuading him, or entreating him, but not for compelling him, or visiting him with any evil in case he do otherwise. To justify that, the conduct from which it is desired to deter him, must be calculated to produce evil to some one else. The only part of the conduct of any one, for which he is amenable to society, is that which concerns others. In the part which merely concerns himself, his independence is, of right, absolute. Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign. - On Liberty by John Stuart Mill, Chapter 1: Introductory.

こ

のエッセイの目的は、非常に単純な1つの原則を主張することである。それは、強制と管理の方法で社会が個人に対処することを絶対的に支配する権利があると

いうもので、その手段が法的な罰則という形の物理的な力であれ、世論による道徳的な強制であれ、どちらでも構わない。その原則とは、人類が個人的にも集団

的にも、その中の誰かの行動の自由に干渉することが正当化される唯一の目的は、自己防衛であるということだ。文明社会の構成員に対して、その意思に反して

権力を正当に行使できる唯一の目的は、他者への危害を防止することである。彼自身の物理的または道徳的な利益は、十分な保証にはならない。彼は、そうする

ことが彼のためになるから、彼を幸せにするから、他人の意見ではそうすることが賢明であるから、あるいは正しいからといって、そうすることや我慢すること

を正当に強制されることはない。これらは、その人を諌めたり、理屈を言ったり、説得したり、懇願したりするための正当な理由であって、その人を強制した

り、そうしない場合に悪事を働いたりするための理由ではない。それを正当化するためには、彼を抑止しようとする行為が、他の誰かに悪をもたらすように計算

されていなければならない。誰かの行動のうち、社会に従順な部分は、他人に関わる部分だけである。たんに自分自身に関わる部分では、彼の独立性は当然なが

ら絶対的なものだ。自分自身に対して、自分の身体と心に対して、個人は主権を持っているのである

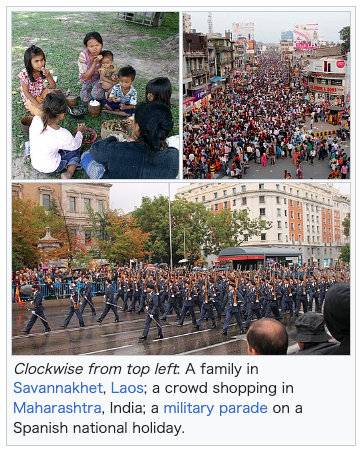

★社会(society)——写真:左上から時計回り:ラオスのサワンナケートに住む家族、インドのマハーラーシュトラ州で買い物をする人々、スペインの国民の祝日に行われる軍事パレード。

| A society

(/səˈsaɪəti/) is a group of individuals involved in persistent social

interaction or a large social group sharing the same spatial or social

territory, typically subject to the same political authority and

dominant cultural expectations. Societies are characterized by patterns

of relationships (social relations) between individuals who share a

distinctive culture and institutions; a given society may be described

as the sum total of such relationships among its constituent members. Human social structures are complex and highly cooperative, featuring the specialization of labor via social roles. Societies construct roles and other patterns of behavior by deeming certain actions or concepts acceptable or unacceptable—these expectations around behavior within a given society are known as societal norms. So far as it is collaborative, a society can enable its members to benefit in ways that would otherwise be difficult on an individual basis. Societies vary based on level of technology and type of economic activity. Larger societies with larger food surpluses often exhibit stratification or dominance patterns. Societies can have many different forms of government, various ways of understanding kinship, and different gender roles. Human behavior varies immensely between different societies; humans shape society, but society in turn shapes human beings. |

社会

(/səˈsaɪəti/)とは、持続的な社会的相互作用に関わる個人の集団、または同じ空間的または社会的領域を共有する大規模な社会的集団を指し、通

常は同じ政治的権威と支配的な文化的期待に服従している。社会は、独自の文化と制度を共有する個人間の関係パターン(社会的関係)によって特徴付けられ

る。特定の社会は、その構成員間のそのような関係の総和として記述することができる。 人間の社会構造は複雑で高度に協力的であり、社会的役割による労働の分業が特徴的だ。社会は、特定の行動や概念を許容または不許容とみなすことで、役割や その他の行動パターンを構築する。特定の社会における行動に関するこれらの期待は、社会的規範として知られている。協力的である限り、社会は、その構成員 が個人では困難な方法で利益を得ることを可能にする。 社会は、技術レベルや経済活動のタイプによって異なる。食糧の余剰が多い大規模な社会では、階層化や支配構造が見られることが多い。社会には、さまざまな 形態の政府、さまざまな親族関係、さまざまな性別役割がある。人間の行動は、社会によって大きく異なる。人間は社会を形成するが、社会も人間を形成する。 |

| Etymology and usage The term "society" often refers to a large group of people in an ordered community, in a country or several similar countries, or the 'state of being with other people', e.g. "they lived in medieval society."[1] The term dates back to at least 1513 and comes from the 12th-century French societe (modern French société) meaning 'company'.[2] Societe was in turn derived from the Latin word societas ('fellowship,' 'alliance', 'association'), which in turn was derived from the noun socius ("comrade, friend, ally").[2] |

語源と用法 「社会」という用語は、多くの場合、ある国または複数の類似の国の、秩序あるコミュニティにおける大規模な集団、あるいは「他の人々と共にある状態」を指 す。「彼らは中世の社会で暮らしていた。」[1] この用語は少なくとも1513年に遡り、12世紀のフランス語「societe」(現代フランス語「société」)に由来し、「会社」を意味する。 [2] 「societe」は、ラテン語の「societas」(「同胞団」、「同盟」、「協会」)に由来し、さらに「socius」(「同志」、「友人」、「同 盟者」)という名詞に由来する。[2] |

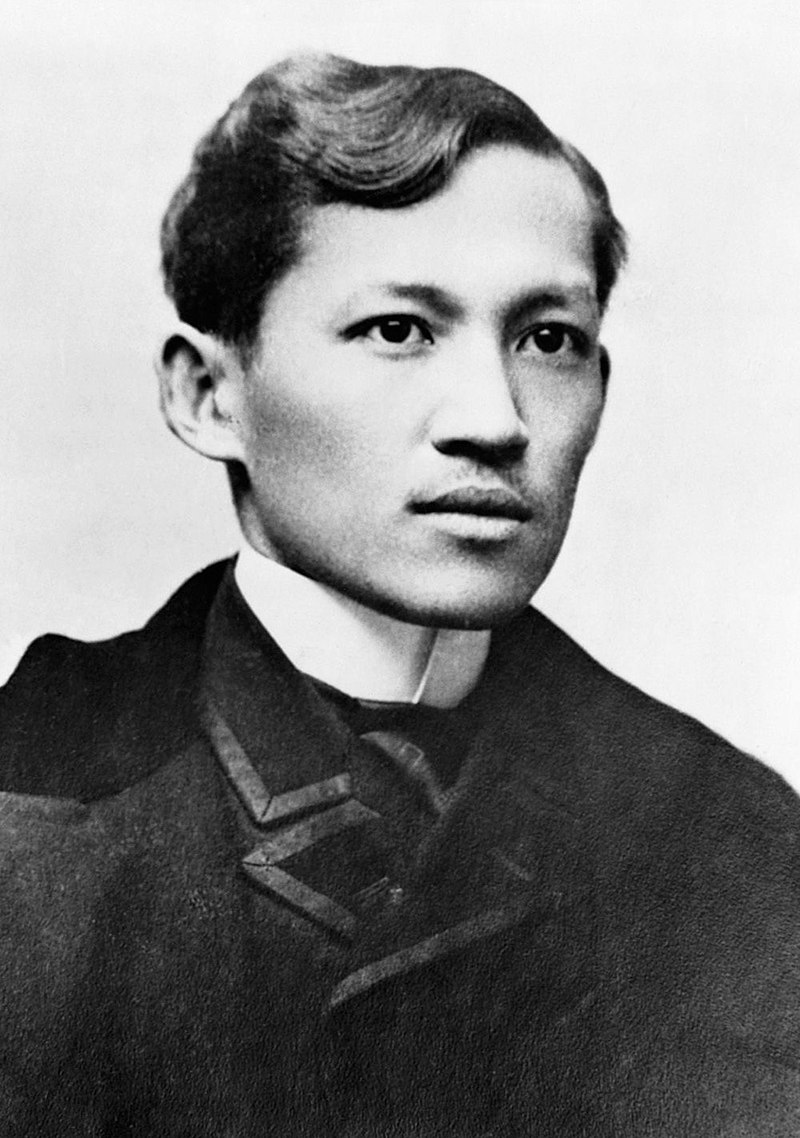

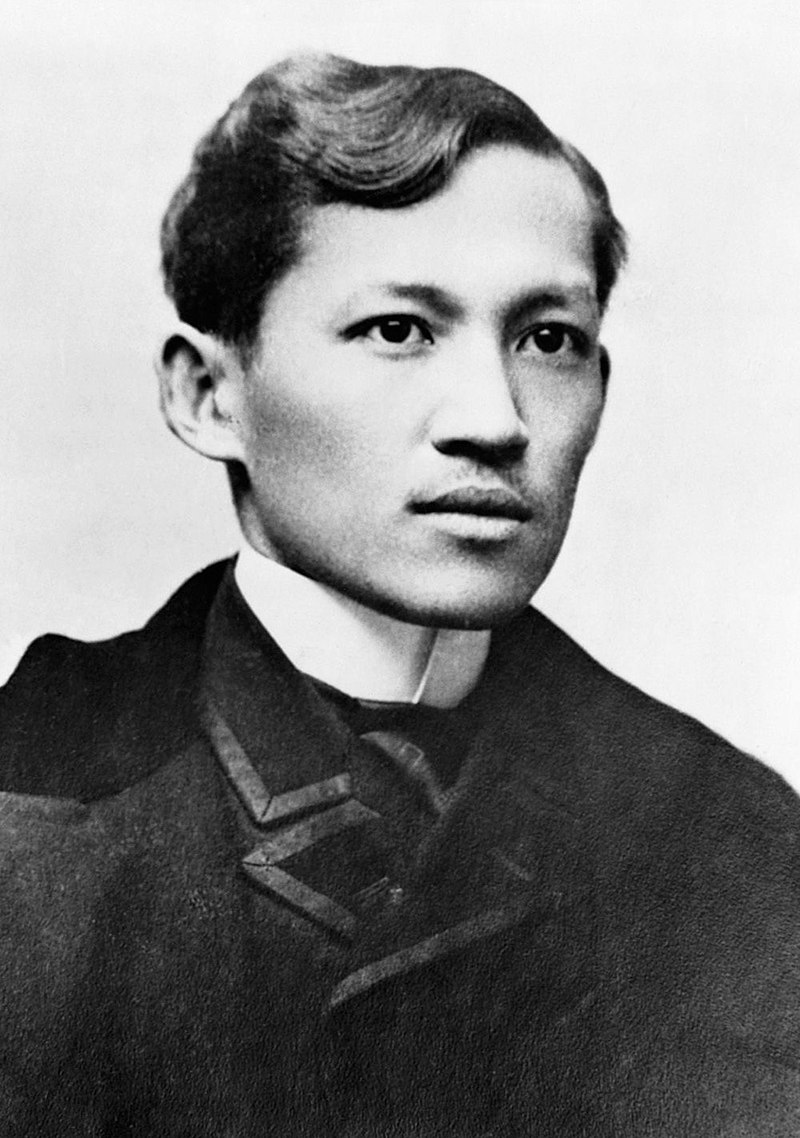

| Conceptions In biology Further information: Sociality  Multiple black ants surrounding and crawling on a dead mantis Ant social ethology: Ants are eusocial insects. The social group enables its members to benefit in ways that would not otherwise be possible on an individual basis. Humans, along with their closest relatives bonobos and chimpanzees, are highly social animals. This biological context suggests that the underlying sociability required for the formation of societies is hardwired into human nature.[3] Human society features high degrees of cooperation, and differs in important ways from groups of chimps and bonobos, including the parental role of males,[4][5] the use of language to communicate,[3] the specialization of labor,[6] and the tendency to build "nests" (multigenerational camps, town, or cities).[6] Some biologists, including entomologist E.O. Wilson, categorize humans as eusocial, placing humans with ants in the highest level of sociability on the spectrum of animal ethology, although others disagree.[6] Social group living may have evolved in humans due to group selection in physical environments that made survival difficult.[7] In sociology Further information: Sociology In Western sociology, there are three dominant paradigms for understanding society: functionalism (also known as structural functionalism), conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism.[8] Functionalism According to the functionalist school of thought, individuals in society work together like organs in the body to create emergent behavior, sometimes referred to as collective consciousness.[9] 19th century sociologists Auguste Comte and Émile Durkheim, for example, believed that society constitutes a separate "level" of reality, distinct from both biological and inorganic matter. Explanations of social phenomena had therefore to be constructed within this level, individuals being merely transient occupants of comparatively stable social roles.[10] Conflict theory Conflict theorists take the opposite view, and posit that individuals and social groups or social classes within society interact on the basis of conflict rather than agreement. One prominent conflict theorist is Karl Marx who conceived of society as operating on an economic "base" with a "superstructure" of government, family, religion and culture. Marx argues that the economic base determines the superstructure, and that throughout history, societal change has been driven by conflict between laborers and those who own the means of production.[11] Symbolic interactionism Symbolic interactionism is a microsociological theory that focuses on individuals and how the individual relates to society.[12] Symbolic interactionists study humans' use of shared language to create common symbols and meanings,[13] and use this frame of reference to understand how individuals interact to create symbolic worlds, and in turn, how these worlds shape individual behaviors.[14] In the latter half of the 20th century, theorists began to view society as socially constructed.[15] In this vein, sociologist Peter L. Berger describes society as "dialectic": Society is created by humans, but this creation turns in turn creates or molds humans.[16] Non-Western views  Black and white portrait of José Rizal José Rizal, a theorist of colonial societies The sociologic emphasis placed on functionalism, conflict theory, and symbolic interactionism, has been criticized as Eurocentric.[17] The Malaysian sociologist Syed Farid al-Attas, for example, argues that Western thinkers are particularly interested in the implications of modernity, and that their analysis of non-Western cultures is therefore limited in scope.[17] As examples of nonwestern thinkers who took a systematic approach to understanding society, al-Attas mentions Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) and José Rizal (1861–1896).[17] Khaldun, an Arab living in the 14th century, understood society, along with the rest of the universe, as having "meaningful configuration", with its perceived randomness attributable to hidden causes. Khaldun conceptualized social structures as having two fundamental forms: nomadic and sedentary. Nomadic life has high social cohesion (asabijja), which Khaldun argued arose from kinship, shared customs, and a shared need for defense. Sedentary life, in Khaldun's view, was marked by secularization, decreased social cohesion, and increased interest in luxury.[18] Rizal was a Filipino nationalist living toward the end of the Spanish Colonial Period who theorized about colonial societies. Rizal argued that indolence, which the Spanish used to justify their colonial occupation, was instead caused by the colonial occupation. Rizal compared the pre-colonial era, when the Filipinos controlled trade routes and had higher economic activity, to the period of colonial rule, and argued that exploitation, economic disorder, and colonial policies that discouraged farming led to a decreased interest in work.[19] |

概念 生物学 詳細情報:社会性  死んだカマキリを取り囲み、這い回る複数の黒いアリ アリの社会行動学:アリは真社会性昆虫です。社会集団は、その構成員が個人では不可能な方法で利益を得ることを可能にします。 人間とその最も近い親戚であるボノボやチンパンジーは、高度に社会的な動物です。この生物学的背景から、社会形成に必要な基本的な社会性は、人間の本性に 組み込まれていると推測される[3]。人間社会は高度な協力関係によって特徴づけられ、チンパンジーやボノボの群れとは、男性の親としての役割[4] [5]、コミュニケーションのための言語の使用[3]、分業[6]、「巣」(多世代が暮らすキャンプ、町、都市)を構築する傾向など、重要な点で異なって いる。 [6] [6] 一部の生物学者、昆虫学者のE.O.ウィルソンを含む、は人間を真社会性生物に分類し、動物行動学の社会性スペクトルにおいて人間をアリと共に最高位の位 置に置いているが、他の研究者はこれに反対している。[6] 社会的集団生活は、生存が困難な物理的環境における集団選択の結果、人間に進化した可能性がある。[7] 社会学 西洋社会学では、社会を理解するための3つの主要なパラダイムがある:機能主義(構造機能主義とも呼ばれる)、対立理論、象徴相互作用論。[8] 機能主義 機能主義の学派によると、社会を構成する個人は、身体の器官のように連携して、集団意識と呼ばれる新たな行動を生み出している[9]。例えば、19 世紀の社会学者、オーギュスト・コントとエミール・デュルケームは、社会は生物や無機物とは別の、独立した「現実の層」を構成していると信じていた。した がって、社会現象の説明は、このレベルの中で構築されなければならず、個人は比較的安定した社会的役割の一時的な担い手に過ぎないと考えられた。[10] 紛争理論 紛争理論者は反対の見解を取り、社会内の個人や社会集団、社会階級は、合意ではなく紛争に基づいて相互作用すると主張する。紛争理論の代表的な人物はカー ル・マルクスで、彼は社会を経済的な「基盤」と、政府、家族、宗教、文化などの「上層構造」から成るものとして捉えた。マルクスは、経済基盤が上層構造を 決定し、歴史を通じて、社会の変化は労働者と生産手段の所有者との間の紛争によって推進されてきたと主張している。[11] 象徴相互作用論 象徴的相互作用論は、個人と社会との関係に焦点を当てたマイクロ社会学理論だ。[12] 象徴的相互作用論者は、人間が共有する言語を用いて共通の象徴や意味を創造するプロセスを研究し、[13] この枠組みを用いて、個人が相互作用して象徴的な世界を創造し、その世界が個人の行動を形作る仕組みを理解しようとする。[14] 20世紀後半、理論家たちは社会を社会的に構築されたものと捉えるようになった。[15] この流れを受けて、社会学者ピーター・L・バーガーは社会を「弁証法的」と表現している。社会は人間によって創造されるが、この創造は逆に人間を創造したり形作ったりする。[16] 非西洋的見解  ホセ・リサールの白黒肖像画 植民地社会理論家、ホセ・リサル 機能主義、紛争理論、象徴的相互作用論に重点を置いた社会学は、ヨーロッパ中心主義であると批判されてきた[17]。例えば、マレーシアの社会学者サイー ド・ファリド・アル・アッタスは、西洋の思想家は現代性の意味合いに特に興味があり、そのため、非西洋文化の分析の範囲が限定的であると主張している。 [17] 社会を理解するための体系的なアプローチを採用した非西洋の思想家として、アル=アッタスはイブン・ハルドゥーン(1332–1406)とホセ・リサール (1861–1896)を挙げている。[17] 14世紀に生きたアラブ人であるイブン・ハルドゥーンは、社会を宇宙の他の部分と同様に「意味のある構成」を持つものと捉え、そのランダムさは隠れた原因 に起因すると考えた。ハルドゥーンは、社会構造を遊牧型と定住型の2つの根本的な形態に分類した。遊牧生活は社会的結束(アサビジャ)が高く、これは親族 関係、共通の慣習、防衛の必要性から生じるとカルドゥーンは主張した。定住生活は、カルドゥーンの見解では、世俗化、社会的結束の低下、贅沢への関心の高 まりを特徴としていた[18]。リサールは、スペイン植民地時代末期に活躍したフィリピン人ナショナリストで、植民地社会について理論を唱えた人物だ。リ ザルは、スペインが植民地支配を正当化するために用いた「怠惰」は、むしろ植民地支配自体が原因だと主張した。リザルは、フィリピン人が貿易路を支配し経 済活動が活発だった植民地支配前の時代と、植民地支配下の時代を比較し、搾取、経済的混乱、農業を抑制する植民地政策が労働への関心の低下をもたらしたと 主張した。[19] |

| Types Sociologists tend to classify societies based on their level of technology, and place societies in three broad categories: pre-industrial, industrial, and postindustrial.[20] Subdivisions of these categories vary, and classifications are often based on level of technology, communication, and economy. One example of such a classification comes from sociologist Gerhard Lenski who lists: (1) hunting and gathering; (2) horticultural; (3) agricultural; and (4) industrial; as well as specialized societies (e.g., fishing or herding).[21] Some cultures have developed over time toward more complex forms of organization and control. This cultural evolution has a profound effect on patterns of community. Hunter-gatherer tribes have, at times, settled around seasonal food stocks to become agrarian villages. Villages have grown to become towns and cities. Cities have turned into city-states and nation-states. However, these processes are not unidirectional.[22] Pre-industrial Main article: Pre-industrial society In a pre-industrial society, food production, which is carried out through the use of human and animal labor, is the main economic activity. These societies can be subdivided according to their level of technology and their method of producing food. These subdivisions are hunting and gathering, pastoral, horticultural, and agrarian.[21] Hunting and gathering Main article: Hunter-gatherer  refer to caption San people in Botswana start a fire by hand. The main form of food production in hunter-gatherer societies is the daily collection of wild plants and the hunting of wild animals. Hunter-gatherers move around constantly in search of food.[23] As a result, they do not build permanent villages or create a wide variety of artifacts. The need for mobility also limits the size of these societies, and they usually only form small groups such as bands and tribes,[24] usually with fewer than 50 people per community.[25][24] Bands and tribes are relatively egalitarian, and decisions are reached through consensus. There are no formal political offices containing real power in band societies, rather a chief is merely a person of influence, and leadership is based on personal qualities.[26] The family forms the main social unit, with most members being related by birth or marriage.[27] The anthropologist Marshall Sahlins described hunter-gatherers as the "original affluent society" due to their extended leisure time: Sahlins estimated that adults in hunter gatherer societies work three to five hours per day.[28][29] This perspective has been challenged by other researchers, who have pointed out high mortality rates and perennial warfare in hunter-gatherer societies.[30][31][32] Proponents of Sahlins' view argue that the general well-being of humans in hunter gatherer societies challenges the purported relationship between technological advancement and human progress.[33][34] |

種類 社会学者たちは、社会の技術を基準として社会を分類し、大きく3つのカテゴリーに分類する傾向がある:産業革命以前、産業革命、産業革命後[20]。 これらのカテゴリーの細分化はさまざまで、分類は多くの場合、技術、通信、経済のレベルに基づいて行われます。このような分類の一例として、社会学者ゲル ハルト・レンスキーが挙げているものがあります。彼は、 (1) 狩猟採集、(2) 園芸、(3) 農業、(4) 工業、そして専門社会(漁業や牧畜など)に分類しています[21]。 一部の文化は、時間の経過とともに、より複雑な組織や統制の形態へと発展してきた。この文化の進化は、コミュニティのパターンに大きな影響を与えている。 狩猟採集民の部族は、季節ごとに食糧の貯蔵場所周辺に定住し、農耕村落を形成する場合もある。村落は町や都市へと成長し、都市は都市国家や国民国家へと変 化した。しかし、これらの過程は一方向的なものではない[22]。 産業革命以前 主な記事:産業革命以前 産業革命以前の社会では、人間と動物の労働力を用いた食料生産が主な経済活動だった。これらの社会は、技術レベルと食料生産の方法に応じて、狩猟採集、牧畜、園芸、農業に分類される。[21] 狩猟採集 メイン記事:狩猟採集  キャプションを参照 ボツワナのサン族は、手を使って火を起こしている。 狩猟採集社会における食糧生産の主な形態は、野生の植物を毎日採集し、野生動物を狩ることだ。狩猟採集民は、食糧を求めて絶えず移動している。その結果、 彼らは恒久的な村を築いたり、多種多様な工芸品を作ったりすることはない。移動の必要性により、これらの社会の規模も制限され、通常は、バンドや部族など の小規模な集団しか形成されません[24]、通常、1つのコミュニティの人口は50人未満です[25][24]。バンドや部族は比較的平等主義であり、決 定は合意によって行われます。バンド社会には、実際の権力を持つ正式な政治機関は存在せず、首長は単に影響力のある人物であり、リーダーシップは個人の資 質に基づいて決定される[26]。家族は社会の基本単位であり、そのほとんどのメンバーは血縁または婚姻関係にある[27]。 人類学者のマーシャル・サリンズは、狩猟採集民を「原始的な豊か社会」と表現した。これは、彼らが持つ長い余暇時間に基づいている。サリンズは、狩猟採集 民社会の成人は1日あたり3~5時間しか働いていないと推定した[28][29]。この見解は、狩猟採集民社会における高い死亡率と恒常的な戦争を指摘す る他の研究者によって批判されている。 [30][31][32] サリンズの主張を支持する研究者は、狩猟採集社会における人間の一般的な福祉が、技術的進歩と人間の発展との間のとされる関係に疑問を投げかけていると主 張している。[33][34] |

| Pastoral Main article: Pastoral society  refer to caption Maasai men perform adumu, the traditional jumping dance. Rather than searching for food on a daily basis, members of a pastoral society rely on domesticated herd animals to meet their food needs. Pastoralists typically live a nomadic life, moving their herds from one pasture to another.[35] Community size in pastoral societies is similar to hunter-gatherers (about 50 individuals), but unlike hunter gatherers, pastoral societies usually consist of multiple communities—the average pastoral society contains thousands of people. This is because pastoral groups tend to live in open areas where movement is easy, which enables political integration.[36] Pastoral societies tend to create a food surplus, and have specialized labor[20] and high levels of inequality.[36] |

牧畜 主な記事:牧畜社会  キャプションを参照 マサイ族の男性が、伝統的な跳躍舞踊「アドゥム」を披露している。 牧畜社会では、メンバーは毎日食糧を探すのではなく、家畜の群畜に食糧を依存している。牧畜民は通常、牧草地から牧草地へと移動しながら遊牧生活を送って いる[35]。牧畜社会のコミュニティの規模は、狩猟採集民(約 50 人)と似ているが、狩猟採集民とは異なり、牧畜社会は通常、複数のコミュニティで構成されており、平均的な牧畜社会には数千人の人民が暮らしている。これ は、遊牧民の集団が移動が容易な開けた地域に住む傾向があり、政治的統合を可能にするためだ。[36] 遊牧社会は食料の余剰を生み出し、専門分業[20] と高い不平等水準[36] を有する傾向がある。 |

| Horticultural Further information: Horticulture and Subsistence pattern Fruits and vegetables grown in garden plots, that have been cleared from the jungle or forest, provide the main source of food in a horticultural society. These societies have a similar level of technology and complexity to pastoral societies.[37] Along with pastoral societies, horticultural societies emerged about 10,000 years ago, after technological changes of the Agricultural Revolution made it possible to cultivate crops and raise animals.[37] Horticulturists use human labor and simple tools to cultivate the land for one or more seasons. When the land becomes barren, horticulturists clear a new plot and leave the old plot to revert to its natural state. They may return to the original land several years later and begin the process again. By rotating their garden plots, horticulturists can stay in one area for a long period of time. This allows them to build permanent or semi-permanent villages.[38] As with pastoral societies, surplus food leads to a more complex division of labor. Specialized roles in horticultural societies include craftspeople, shamans (religious leaders), and traders.[38] This role specialization allows horticultural societies to create a variety of artifacts. Scarce, defensible resources can lead to wealth inequalities in horticultural political systems.[39] |

園芸 詳細情報:園芸と自給自足パターン ジャングルや森林から開墾された庭の畑で栽培される果物や野菜は、園芸社会における主要な食料源を提供する。これらの社会は、牧畜社会と類似した技術水準 と複雑さを有している。[37] 牧畜社会と共に、園芸社会は農業革命の技術的変化により作物の栽培と家畜の飼育が可能になった約1万年前に出現した。[37] 園芸家は、人間の労働力と単純な道具を用いて、1シーズンまたは複数のシーズンにわたって土地を耕作する。土地が不毛になると、園芸農家は新しい土地を開 墾し、古い土地を自然の状態に戻す。数年後、元の土地に戻り、プロセスを再び始めることもある。畑の場所を輪作することで、園芸農家は同じ地域に長期滞在 できる。これにより、永久的または半永久的な村を建設することが可能になる。[38] 牧畜社会と同様に、余剰食料はより複雑な分業をもたらす。園芸社会における専門的な役割には、職人、シャーマン(宗教的指導者)、商人などが含まれる。 [38] この役割分業により、園芸社会は多様な人工物を創造することができる。希少で防衛可能な資源は、園芸政治システムにおいて富の格差を引き起こす可能性があ る。[39] |

| Agrarian Main article: Agrarian society  Painting of farmers, with one plouging with two oxen Ploughing with oxen in the 15th century Agrarian societies use agricultural technological advances to cultivate crops over a large area. Lenski differentiates between horticultural and agrarian societies by the use of the plow.[40] Larger food supplies due to improved technology mean agrarian communities are larger than horticultural communities. A greater food surplus results in towns that become centers of trade. Economic trade in turn leads to increased specialization, including a ruling class, as well as educators, craftspeople, merchants, and religious figures, who do not directly participate in the production of food.[41] Agrarian societies are especially noted for their extremes of social classes and rigid social mobility.[42] As land is the major source of wealth, social hierarchy develops based on landownership and not labor. The system of stratification is characterized by three coinciding contrasts: governing class versus the masses, urban minority versus peasant majority, and literate minority versus illiterate majority. This results in two distinct subcultures; the urban elite versus the peasant masses. Moreover, this means cultural differences within agrarian societies are greater than differences between them.[43] The landowning strata typically combine government, religious, and military institutions to justify and enforce their ownership, and support elaborate patterns of consumption, slavery, serfdom, or peonage is commonly the lot of the primary producer. Rulers of agrarian societies often do not manage their empire for the common good or in the name of the public interest, but as property they own.[44] Caste systems, as historically found in South Asia, are associated with agrarian societies, where lifelong agricultural routines depend upon a rigid sense of duty and discipline. The scholar Donald Brown suggests that an emphasis in the modern West on personal liberties and freedoms was in large part a reaction to the steep and rigid stratification of agrarian societies.[45] |

農業 主な記事:農業社会  農民の絵、2頭の牛で耕す農民 15世紀の牛による耕作 農業社会は、農業技術の進歩を利用して広大な土地で作物を栽培する。レンズキは、耕作の有無によって園芸社会と農業社会を区別している[40]。技術の進 歩による食糧供給量の増加により、農業社会は園芸社会よりも規模が大きくなる。食料の余剰が増加すると、町が交易の中心地となる。経済的な交易はさらに専 門分化を促進し、支配階級、教育者、職人、商人、宗教者など、食料の生産に直接参加しない層が生まれる。[41] 農業社会は、社会的階級の極端な格差と rigid な社会的流動性の低さで特に知られている。[42] 土地が主要な財源であるため、社会的階層は労働ではなく土地所有に基づいて形成される。階層化システムは、3つの対立する特徴で特徴付けられる:支配階級 対大衆、都市の少数派対農民の多数派、識字少数派対非識字多数派。これにより、都市のエリート対農民の大衆という2つの異なるサブカルチャーが生まれる。 さらに、これは、農業社会内の文化の違いが、農業社会間の違いよりも大きいことを意味する。[43] 土地所有層は通常、その所有権を正当化し、行使するために、政府、宗教、軍事機関を統合し、精巧な消費パターン、奴隷制度、農奴制度、または小作人制度を 支持することが一般的で、一次生産者はその恩恵を受けることが多い。農業社会の支配者は、帝国を共通の利益や公共の利益のために管理するのではなく、自分 たちが所有する財産として管理する。[44] 南アジアで歴史的に見られるカースト制度は、農業社会と関連しており、生涯にわたる農業のルーティンは、厳格な義務感と規律に依存している。学者ドナル ド・ブラウンは、現代西洋における個人の自由と権利の重視は、農業社会の厳格で硬直した階層構造に対する反動であるとの見解を示している[45]。 |

| Industrial Main article: Industrial society  An industrial train Industrial transportation, including trains, can stabilize the economy, leading to population growth. Industrial societies, which emerged in the 18th century in the Industrial Revolution, rely heavily on machines powered by external sources for the mass production of goods.[46][47] Whereas in pre-industrial societies the majority of labor takes place in primary industries focused on extracting raw materials (farming, fishing, mining, etc.), in industrial societies, labor is mostly focused on processing raw materials into finished products.[48] Present-day societies vary in their degree of industrialization, with some using mostly newer energy sources (e.g. coal, oil, and nuclear energy), and others continuing to rely on human and animal power.[49] Industrialization is associated with population booms and the growth of cities. Increased productivity, as well as the stability caused by improved transportation, leads to decreased mortality and resulting population growth.[50] Centralized production of goods in factories and a decreased need for agricultural labor leads to urbanization.[47][51] Industrial societies are often capitalist, and have high degrees of inequality along with high social mobility, as businesspeople use the market to amass large amounts of wealth.[47] Working conditions in factories are generally restrictive and harsh.[52] Workers, who have common interests, may organize into labor unions to advance those interests.[53] On the whole, industrial societies are marked by the increased power of human beings. Technological advancements mean that industrial societies have increased potential for deadly warfare. Governments use information technologies to exert greater control over the populace. Industrial societies also have an increased environmental impact.[54] |

産業 主な記事:産業社会  産業用列車 列車を含む産業輸送は、経済を安定させ、人口増加につながる。 18世紀の産業革命で出現した産業社会は、外部からエネルギーを供給される機械に依存して製品の大量生産を行う。[46][47] 産業革命以前の社会では、労働の大部分は原材料の採掘(農業、漁業、鉱業など)に焦点を当てた一次産業で行われていたが、産業社会では、労働は主に原材料 を加工して完成品に加工する工程に集中している。 [48] 現代の社会は工業化の程度が異なり、主に新しいエネルギー源(石炭、石油、原子力など)を使用する社会もあれば、人間や動物の力に依存し続ける社会もあ る。[49] 工業化は人口爆発と都市の拡大と関連している。生産性の向上と、交通手段の改善による安定性は、死亡率の低下とそれに伴う人口増加をもたらす。[50] 工場での製品の集中生産と農業労働力の減少は、都市化を促進する。[47][51] 工業社会はしばしば資本主義であり、市場を利用して莫大な富を蓄積する事業家により、高い不平等と高い社会流動性を特徴とする。 [47] 工場の労働条件は一般的に厳しく過酷だ。[52] 共通の利益を持つ労働者は、その利益を追求するために労働組合を結成することがある。[53] 全体として、産業社会は人間の力の増大が特徴だ。技術進歩により、産業社会は致命的な戦争の可能性が高まっている。政府は情報技術を利用して国民に対する支配を強化している。産業社会はまた、環境への影響も増大している。[54] |

| Post-industrial Main article: Post-industrial society See also: Information revolution Post-industrial societies are societies dominated by information and services, rather than the production of goods.[55] Advanced industrial societies see a shift toward an increase in service sectors, over manufacturing. Service industries include education, health and finance.[56] Information Main article: Information society  Many people gathered in a large meeting room World Summit on the Information Society, Geneva An information society is a society where the usage, creation, distribution, manipulation and integration of information is a significant activity.[57] Proponents of the idea that modern-day global society is an information society posit that information technologies are impacting most important forms of social organization, including education, economy, health, government, warfare, and levels of democracy.[58] Although the concept of information society has been discussed since the 1930s, in the present day, it is almost always applied to ways that information technologies impact society and culture. It therefore covers the effects of computers and telecommunications on the home, the workplace, schools, government, and various communities and organizations, as well as the emergence of new social forms in cyberspace.[59] Knowledge Main article: Knowledge society  Three people working on computers in a control room The Seoul Cyworld control room As the access to electronic information resources increased at the beginning of the 21st century, special attention was extended from the information society to the knowledge society. A knowledge society generates, shares, and makes available to all members of the society knowledge that may be used to improve the human condition.[60] A knowledge society differs from an information society in that it transforms information into resources that allow society to take effective action, rather than only creating and disseminating raw data.[61] |

ポスト産業 主な記事:ポスト産業社会 関連項目:情報革命 ポスト産業社会とは、商品の生産よりも情報およびサービスが支配的な社会のことである[55]。先進工業社会では、製造業からサービス業への移行が進んでいる。サービス業には、教育、保健、金融などが含まれる[56]。 情報 主な記事:情報社会  大きな会議室に多くの人々が集まった様子 情報社会世界サミット、ジュネーブ 情報社会とは、情報の利用、作成、流通、操作、統合が重要な活動となっている社会のことです。[57] 現代のグローバル社会は情報社会であるという考えの支持者は、情報技術が、教育、経済、保健、政府、戦争、民主主義のレベルなど、社会組織の最も重要な形 態に影響を与えていると主張しています。 [58] 情報社会の概念は1930年代から議論されてきたが、現在では、情報技術が社会や文化に与える影響を指す場合がほとんどだ。したがって、家庭、職場、学 校、政府、さまざまなコミュニティや組織におけるコンピュータや通信の影響、およびサイバースペースにおける新しい社会形態の出現も含まれる。[59] 知識 メイン記事:知識社会  コントロールルームでコンピューターを操作する 3 人の人民 ソウルサイワールドのコントロールルーム 21 世紀初頭、電子情報資源へのアクセスが拡大するにつれて、情報社会から知識社会へと注目が移った。知識社会とは、人間の生活向上に役立つ知識を生み出し、 それを社会の構成員全員が共有し、利用できるようにする社会のことだ。[60] 知識社会は、生データを作成・普及するだけでなく、その情報を社会が効果的な行動を取るための資源に変換するという点で、情報社会とは異なる。[61] |

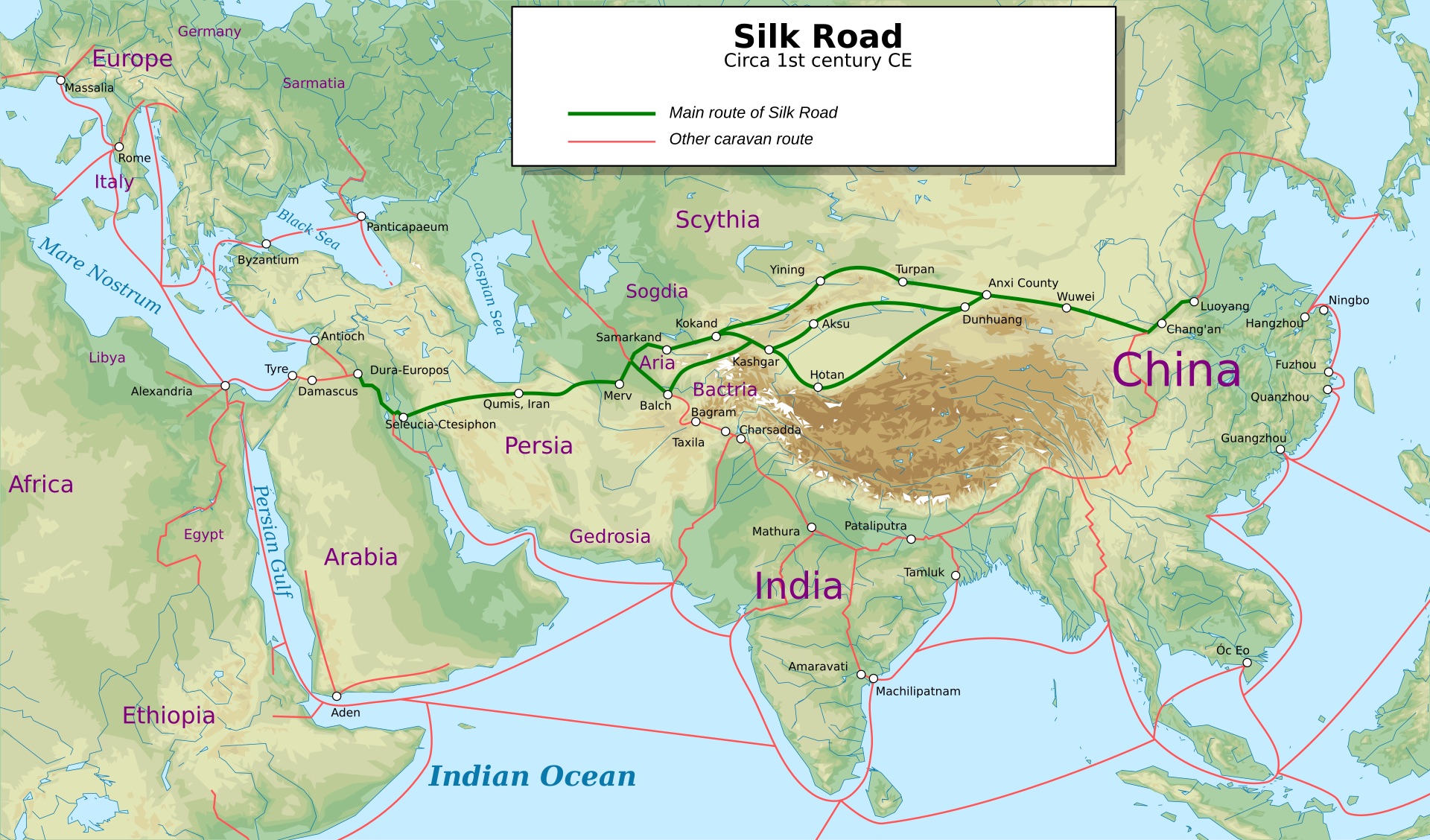

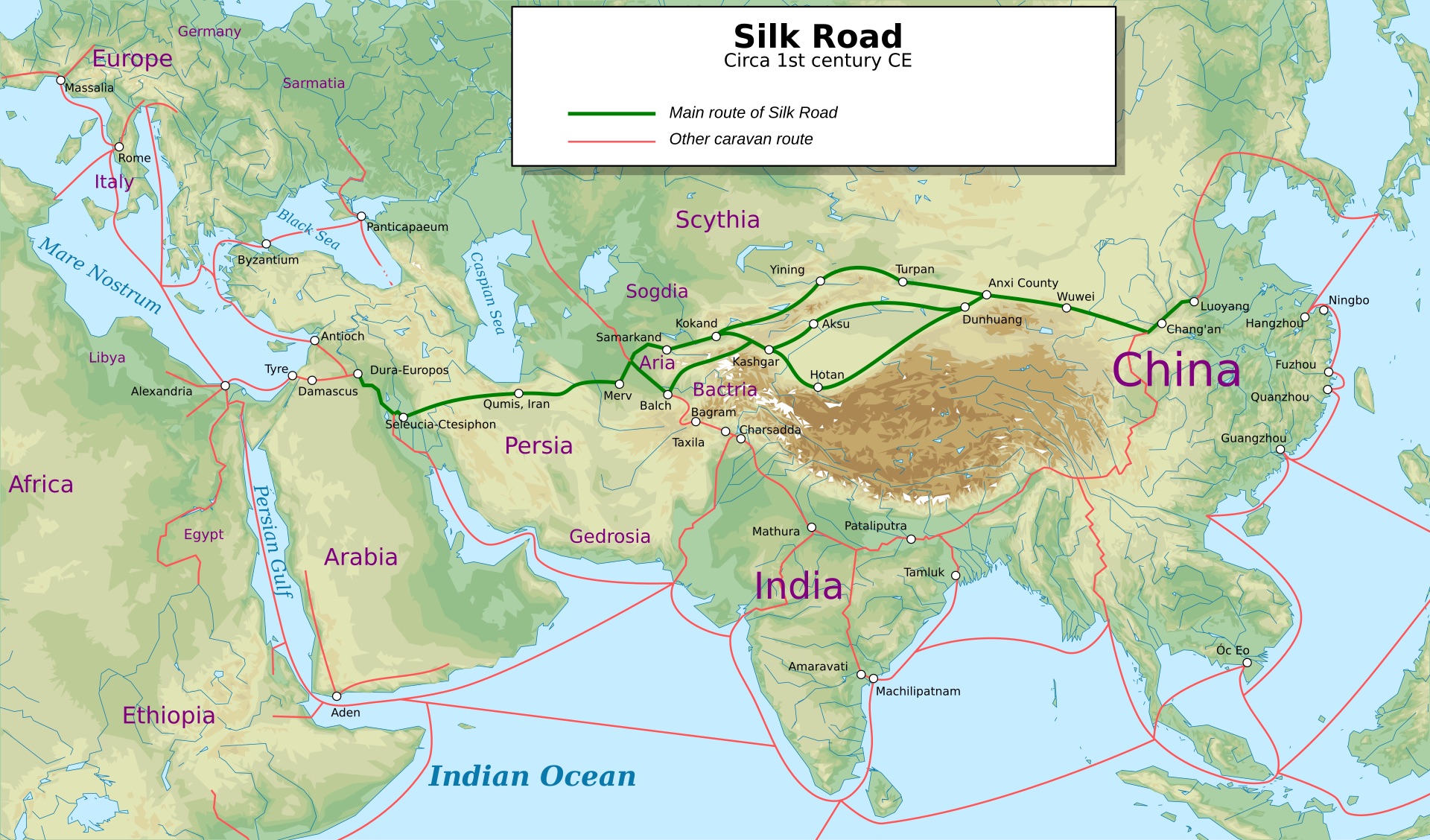

| Characteristics Norms and roles Social norms are shared standards of acceptable behavior by groups.[62][63] Social norms, which can both be informal understandings that govern the behavior of members of a society, as well as be codified into rules and laws,[64] are powerful drivers of human behavior.[65] Social roles are norms, duties, and patterns of behavior that relate to an individual's social status.[66] In functionalist thought, individuals form the structure of society by occupying social roles.[10] According to symbolic interactionism, individuals use symbols to navigate and communicate roles.[67] Erving Goffman used the metaphor of a theater to develop the dramaturgical lens, which argues that roles provide scripts that govern social interactions.[67] Gender and kinship Main articles: Gender, Gender role, and Kinship  refer to caption Egyptian family riding on a donkey-drawn cart in 2019. Familial relationships are one of the most important organizing principles in many societies. The division of humans into male and female gender roles has been marked culturally by a corresponding division of norms, practices, dress, behavior, rights, duties, privileges, status, and power. Some argue that gender roles arise naturally from sex differences, which lead to a division of labor where women take on reproductive labor and other domestic roles.[68] Gender roles have varied historically, and challenges to predominant gender norms have recurred in many societies.[69][70] All human societies organize, recognize and classify types of social relationships based on relations between parents, children and other descendants (consanguinity), and relations through marriage (affinity). There is also a third type of familial relationship applied to godparents or adoptive children (fictive). These culturally defined relationships are referred to as kinship. In many societies, it is one of the most important social organizing principles and plays a role in transmitting status and inheritance.[71] All societies have rules of incest taboo, according to which marriage between certain kinds of kin relations are prohibited; and some societies also have rules of preferential marriage with certain other kin relations.[72] Ethnicity Main article: Ethnicity Human ethnic groups are a social category that identify together as a group based on shared attributes that distinguish them from other groups. These shared attributes can be a common set of traditions, ancestry, language, history, society, culture, nation, religion, or social treatment within their residing area.[73][74] There is no generally accepted definition of what constitutes an ethnic group,[75] and humans have evolved the ability to change affiliation with social groups relatively easily, including leaving groups with previously strong alliances, if doing so is seen as providing personal advantages.[76] Ethnicity is separate from the concept of race, which is based on physical characteristics, although both are socially constructed.[77] Assigning ethnicity to a certain population is complicated, as even within common ethnic designations there can be a diverse range of subgroups, and the makeup of these ethnic groups can change over time at both the collective and individual level.[78] Ethnic groupings can play a powerful role in the social identity and solidarity of ethnopolitical units. Ethnic identity has been closely tied to the rise of the nation state as the predominant form of political organization in the 19th and 20th centuries.[79][80][81] Government and politics Main articles: Government and Politics  refer to caption The United Nations headquarters in New York City, which houses one of the world's largest political organizations Governments create laws and policies that affect the people that they govern. There have been many forms of government throughout human history, with various ways of allocating power, and with different levels and means of control over the population.[82] In early history, distribution of political power was determined by the availability of fresh water, fertile soil, and temperate climate of different locations.[83] As farming populations gathered in larger and denser communities, interactions between different groups increased, leading to the further development of governance within and between communities.[84] As of 2022, according to The Economist, 43% of national governments were democracies, 35% autocracies, and 22% containing elements of both.[85] Many countries have formed international political organizations and alliances, the largest being the United Nations with 193 member states.[86][87] Trade and economics Main articles: Trade and Economics  A map depicting the Silk Road and relevant trade routes Long-distance spice trade routes along the Silk Road (green) and other routes (red) circa 1st century AD Trade, the voluntary exchange of goods and services, has long been an aspect of human societies, and it is seen as a characteristic that differentiates humans from other animals.[88] Trade has even been cited as a practice that gave Homo sapiens a major advantage over other hominids; evidence suggests early H. sapiens made use of long-distance trade routes to exchange goods and ideas, leading to cultural explosions and providing additional food sources when hunting was sparse. Such trade networks did not exist for the now-extinct Neanderthals.[88][89] Early trade involved materials for creating tools, like obsidian, exchanged over short distances.[90] In contrast, throughout antiquity and the medieval period, some of the most influential long-distance routes carried food and luxury goods, such as the spice trade.[91] Early human economies were more likely to be based around gift giving than a bartering system.[92] Early money consisted of commodities; the oldest being in the form of cattle and the most widely used being cowrie shells.[93][94] Money has since evolved into governmental issued coins, paper and electronic money.[95][96] Human study of economics is a social science that looks at how societies distribute scarce resources among different people.[97] There are massive inequalities in the division of wealth among humans; as of 2018 in China, Europe, and the United States, the richest tenth of humans hold more than seven-tenths of those regions' total wealth.[98] |

特徴 規範と役割 社会的規範とは、集団が共有する許容される行動の基準です。[62][63] 社会的規範は、社会の構成員の行動を規制する非公式な理解である場合もあれば、規則や法律として成文化されている場合もあり[64]、人間の行動を強力に駆動する要因です。[65] 社会的役割とは、個人の社会的地位に関連する規範、義務、行動パターンです。[66] 機能主義的思考では、個人は社会的役割を占めることで社会の構造を形成しています。[10] 象徴的相互作用論によると、個人は象徴を用いて役割をナビゲートし、コミュニケーションを取っています。[67] アーヴィング・ゴフマンは、演劇の隠喩を用いて、役割は社会的相互作用を支配する台本を提供する、というドラマツルギー的レンズを開発しました。[67] 性別と親族関係 主な記事:性別、性別役割、親族関係  キャプションを参照 2019年にロバの引く荷車に乗るエジプトの家族。家族関係は、多くの社会において最も重要な組織原理の一つだ。 人間を男性と女性の性別役割に区分することは、規範、慣習、服装、行動、権利、義務、特権、地位、権力などの対応する区分によって文化的に特徴づけられて きた。性別役割は、性差から自然に生じ、女性が生殖労働やその他の家事役割を担うという分業につながる、と主張する人もいる。[68] 性別役割は歴史的に変化しており、多くの社会で、支配的な性別規範に対する挑戦が繰り返されてきた。[69][70] すべての社会は、親と子および他の子孫(血縁)との関係、および婚姻を通じた関係(姻族)に基づいて、社会的関係のタイプを組織化し、認識し、分類してい る。また、養親や養子に適用される第三の家族関係(擬親族)も存在する。これらの文化的に定義された関係は、血縁関係と呼ばれます。多くの社会において、 これは最も重要な社会的組織原理の一つであり、地位や相続の伝達に役割を果たしています。[71] すべての社会には、特定の種類の血縁関係間の結婚を禁止する近親相姦のタブーの規則があり、一部の社会では、特定の他の血縁関係との優先的な結婚の規則も あります。[72] 民族 メイン記事:民族 人間の民族集団は、他の集団と区別する共有属性に基づいて、集団として自己を認識する社会的カテゴリーだ。これらの共通属性は、伝統、祖先、言語、歴史、 社会、文化、国民性、宗教、居住地域における社会的待遇など、さまざまなものがあります[73][74]。民族を構成する要素について、一般的に受け入れ られている定義はありません[75]。人間は、個人的な利益になると判断した場合、これまで強い絆で結ばれていた集団から離れるなど、社会集団への所属を 比較的容易に変更する能力を進化させてきました。 [76] 民族性は、身体的特徴に基づく人種という概念とは別のものであり、どちらも社会的に構築されたものである。[77] 特定の集団に民族性を割り当てることは複雑だ。なぜなら、一般的な民族の呼称の中でも、多様なサブグループが存在し、これらの民族グループの構成は、集団 レベルでも個人レベルでも、時間の経過とともに変化する場合があるからだ。[78] 民族グループは、民族政治単位の社会的アイデンティティと連帯感において強力な役割を果たすことがある。民族のアイデンティティは、19 世紀から 20 世紀にかけて、政治組織の主な形態として国家が台頭してきたことと密接に関連している。[79][80][81] 政府と政治 主な記事:政府と政治  キャプションを参照 世界最大の政治組織の一つである国連本部(ニューヨーク市) 政府は、統治する国民に影響を与える法律や政策を制定する。人類の歴史を通じて、権力の配分方法、国民に対する統制のレベルや手段が異なる、さまざまな形 態の政府が存在してきた[82]。初期の歴史では、政治権力の分配は、各地域の淡水、肥沃な土壌、温暖な気候などの条件によって決定されていた[83]。 農業人口がより大規模で密集したコミュニティに集まるにつれて、異なるグループ間の交流が増加し、コミュニティ内およびコミュニティ間の統治がさらに発展 した[84]。 2022年現在、エコノミスト誌によると、各国政府の43%は民主主義、35%は独裁政治、22%は両方の要素を含む政治体制となっている[85]。多くの国が国際政治組織や同盟を結成しており、その最大のものは193カ国が加盟する国際連合である[86][87]。 貿易と経済 主な記事:貿易と経済  シルクロードと関連する貿易ルートを示す地図 シルクロード(緑)とその他のルート(赤)沿いの長距離香辛料貿易ルート(紀元1世紀頃) 貿易、すなわち商品やサービスの自発的な交換は、人類社会の長年の特徴であり、人間を他の動物と区別する特徴の一つと見なされています。[88] 貿易は、ホモ・サピエンスが他のホミニッドに対して大きな優位性を獲得した要因の一つとして指摘されています。証拠によると、早期のホモ・サピエンスは長 距離貿易ルートを利用して商品やアイデアを交換し、文化の爆発的発展を促し、狩猟が不十分な時期に追加の食料源を確保しました。現在絶滅したネアンデル タール人には、このような貿易ネットワークは存在しなかった。[88][89] 初期の貿易は、短距離で交換される工具の材料(例えば黒曜石)が中心だった。[90] 一方、古代から中世にかけては、スパイス貿易など、食料や高級品輸送を目的とした最も影響力のある長距離貿易ルートが存在した。[91] 初期の人間の経済は、物々交換システムよりも贈り物交換に依存していた可能性が高い。[92] 初期の貨幣は商品であり、最も古いものは家畜の形で、最も広く使用されたものはカウリ貝だった。[93][94] 貨幣はその後、政府が発行する硬貨、紙幣、電子貨幣へと進化した。 [95][96] 経済学は、社会が希少な資源をさまざまな人民にどのように分配するかを研究する社会科学です。[97] 人間間の富の分配には大きな不平等があります。2018 年の時点で、中国、ヨーロッパ、米国では、最富裕層 10% がこれらの地域の総富の 70% 以上を占めています。[98] |

| Conflict See also: War and Violence  refer to caption Napoleon's retreat after his failed invasion of Russia in 1812 (oil painting by Adolph Northen, 1851) The willingness of humans to kill other members of their species en masse through organized conflict (i.e. war) has long been the subject of debate. One school of thought is that war evolved as a means to eliminate competitors, and that violence is an innate human characteristic. Humans commit violence against other humans at a rate comparable to other primates (although humans kill adults at a relatively high rate and have a relatively low rate of infanticide).[99] Another school of thought suggests that war is a relatively recent phenomenon and appeared due to changing social conditions.[100] While not settled, the current evidence suggests warlike behavior only became common about 10,000 years ago, and in many regions even more recently.[100] Phylogenetic analysis predicts 2% of human deaths to be caused by homicide, which approximately matches the rate of homicide in band societies.[101] However, rates of violence vary widely according to societal norms,[101][102] and rates of homicide in societies that have legal systems and strong cultural attitudes against violence stand at about 0.01%.[102] |

紛争 関連項目:戦争と暴力 キャプションを参照  1812年のロシア侵攻に失敗した後のナポレオンの撤退(アドルフ・ノーセンの油絵、1851年) 組織的な紛争(すなわち戦争)を通じて、同種の他のメンバーを大量に殺す人間の傾向は、長い間議論の対象となってきた。ある学派は、戦争は競争相手を排除 する手段として進化したものであり、暴力は人間にとって生来の特性であると主張している。人間は、他の霊長類と同等の割合で、他の人間に対して暴力を振る う(ただし、人間は成人の殺害割合が比較的高く、幼児殺しの割合は比較的低い)。[99] 別の学派は、戦争は比較的最近の現象であり、社会条件の変化により出現したと主張している。[100] 確定的な結論は出ていないが、現在の証拠は、戦争的な行動が約1万年前から一般的になり、多くの地域ではさらに最近になって出現した可能性を示している。[100] 系統発生分析は、人間の死亡の2%が殺人によるものだと予測しており、これはバンド社会における殺人率とほぼ一致している。[101] しかし、暴力の率は社会的規範によって大きく異なり、[101][102] 法的システムと暴力に対する強い文化的態度を有する社会における殺人率は約0.01%である。[102] |

| Consumerism Group cohesiveness High society Learned society Mass society Open society Outline of community Outline of culture Outline of religion Outline of society Professional association Reciprocal altruism Secret society Sociobiology Social action Social capital Social contract Social order Social system Societal collapse Structure and agency |

消費主義 集団の結束力 上流社会 知識層 大衆社会 開かれた社会 コミュニティの概要 文化の概要 宗教の概要 社会の概要 専門家団体 相互利他主義 秘密結社 社会生物学 社会的行動 社会資本 社会契約 社会秩序 社会システム 社会の崩壊 構造と主体 |

| Sources Brown, Donald E. (1988). Hierarchy, History, and Human Nature: The Social Origins of Historical Consciousness. University of Arizona Press. ISBN 0-8165-1060-1. LCCN 88015287. OCLC 17954611. Conerly, Tanja; Holmes, Kathleen; Tamang, Asha Lal (2021). Introduction to Sociology (PDF) (3rd ed.). Houston, TX: OpenStax. ISBN 978-1-711493-98-5. OCLC 1269073174. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 October 2022. Retrieved 9 January 2024. Lenski, Gerhard E.; Lenski, Jean (1974). Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-037172-9. LCCN 73008956. OCLC 650644. Lenski, Gerhard E.; Lenski, Jean (1987). Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (5th ed.). McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-037181-4. LCCN 86010586. OCLC 13703170. Nolan, Patrick; Lenski, Gerhard Emmanuel (2009). Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (Rev. and Updated 11th ed.). Boulder: Paradigm Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59451-578-1. LCCN 2008026843. OCLC 226355644. Further reading Bicchieri, Cristina; Muldoon, Ryan; Sontuoso, Alessandro (24 September 2018). "Social Norms". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2018 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. ISSN 1095-5054. LCCN sn97004494. OCLC 37550526. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 12 January 2024. Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter J. (12 November 2009). "Culture and the evolution of human cooperation". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1533): 3281–3288. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0134. LCCN 86645785. OCLC 1403239. PMC 2781880. PMID 19805434. Calhoun, Craig, ed. (2002). Dictionary of the Social Sciences. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512371-9. LCCN 00068151. OCLC 45505995. Clutton-Brock, T.; West, S.; Ratnieks, F.; Foley, R. (12 November 2009). "The evolution of society". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 364 (1533): 3127–3133. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0207. LCCN 86645785. OCLC 1403239. PMC 2781882. PMID 19805421. Griffen, Leonid (2021). "The Society as a Superorganism" (PDF). The Scientific Heritage. 5 (67): 51–60. ISSN 9215-0365. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 September 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2024. Jenkins, Richard (2002). Foundations of Sociology: Towards a Better Understanding of the Human World. London, UK: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 978-0-333-96050-9. LCCN 2002071539. OCLC 49859950. Lenski, Gerhard (1966). "Agrarian Societies [Parts I & II]". Power and Privilege: A Theory of Social Stratification. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 189–296. ISBN 0-07-037165-2. LCCN 65028594. OCLC 262063. Postone, Moishe (1993). Time, Labour, and Social Domination: A Reinterpretation of Marx's Critical Theory. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56540-0. LCCN 92035758. OCLC 26853972. Rummel, Ruldolph Joseph (1976). "The State, Political System and Society". Understanding Conflict and War, Vol. 2: The Conflict Helix. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-470-15123-5. LCCN 74078565. OCLC 59238703. Archived from the original on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 12 January 2024. Williams, Raymond (1976). Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London, UK: Fontana/Croom Helm. ISBN 0-85664-289-4. LCCN 76377757. OCLC 2176518. |

出典 ブラウン、ドナルド・E.(1988)。『階層、歴史、そして人間性:歴史意識の社会的起源』。アリゾナ大学出版局。ISBN 0-8165-1060-1。LCCN 88015287。OCLC 17954611。 コナーリー、タンジャ;ホームズ、キャスリーン;タマン、アシャ・ラル(2021)。『社会学入門』(PDF)(第3版)。テキサス州ヒューストン: OpenStax。ISBN 978-1-711493-98-5。OCLC 1269073174。2022年10月9日にオリジナルからアーカイブ(PDF)。2024年1月9日に取得。 Lenski, Gerhard E.; Lenski, Jean (1974). Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (第2版). New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc. ISBN 978-0-07-037172-9. LCCN 73008956. OCLC 650644. Lenski, Gerhard E.; Lenski, Jean (1987). Human Societies: An Introduction to Macrosociology (第5版). McGraw-Hill Book Company. ISBN 0-07-037181-4. LCCN 86010586. OCLC 13703170. ノーラン、パトリック;レンスキー、ゲルハルト・エマニュエル(2009)。『人間社会:マクロ社会学入門』(改訂・更新第 11 版)。ボルダー:パラダイム・パブリッシャーズ。ISBN 978-1-59451-578-1。LCCN 2008026843。OCLC 226355644。 さらに読む Bicchieri, Cristina; Muldoon, Ryan; Sontuoso, Alessandro (2018年9月24日). 「社会規範」. Zalta, Edward N. (編). 『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』(2018年冬版). メタフィジックス研究ラボ、スタンフォード大学. ISSN 1095-5054. LCCN sn97004494. OCLC 37550526。2020年3月22日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2024年1月12日に取得。 Boyd, Robert; Richerson, Peter J. (2009年11月12日). 「文化と人間の協力の進化」. 王立協会哲学論文集B:生物科学. 364 (1533): 3281–3288. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0134. LCCN 86645785. OCLC 1403239. PMC 2781880. PMID 19805434. カルホーン、クレイグ(編) (2002). 社会科学辞典. ニューヨーク, NY: オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 0-19-512371-9. LCCN 00068151. OCLC 45505995. Clutton-Brock, T.; West, S.; Ratnieks, F.; Foley, R. (2009年11月12日). 「社会の進化」. 王立協会哲学論文集B:生物科学. 364 (1533): 3127–3133. doi:10.1098/rstb.2009.0207. LCCN 86645785. OCLC 1403239. PMC 2781882. PMID 19805421. グリフィン、レオニード (2021). 「超有機体としての社会」 (PDF). The Scientific Heritage. 5 (67): 51–60. ISSN 9215-0365. 2021年9月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ (PDF). 2024年1月12日に取得。 ジェンキンス、リチャード (2002). 社会学の基礎:人間世界へのより良い理解に向けて. ロンドン, イギリス: パルグレイブ・マクミラン. ISBN 978-0-333-96050-9. LCCN 2002071539. OCLC 49859950. レンズキー, ゲルハルト (1966). 「農業社会 [第1部および第2部]」. 『権力と特権: 社会階層の理論』. マクグロー・ヒル・ブック・カンパニー. pp. 189–296. ISBN 0-07-037165-2. LCCN 65028594. OCLC 262063. ポストーン、モイシェ(1993)。『時間、労働、社会支配:マルクスの批判理論の再解釈』。イギリス:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-56540-0。LCCN 92035758。OCLC 26853972。 ルメル、ルドルフ・ジョセフ (1976). 「国家、政治体制、社会」. 『紛争と戦争を理解する』第 2 巻:紛争の螺旋. SAGE Publications. ISBN 978-0-470-15123-5. LCCN 74078565. OCLC 59238703. 2022年3月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2024年1月12日に取得。 Williams, Raymond (1976). Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society. London, UK: Fontana/Croom Helm. ISBN 0-85664-289-4. LCCN 76377757. OCLC 2176518. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Society |

リンク

●群れ=社会システムの5つの長所と短所 (ケリー 1999:43-47)https://kk.org/mt-files/books-mt/ooc-mf.pdf

| 群れ=社会システムの長所 | 群れ=社会システムの短所 |

| 1. 適応できる 適応性—あらかじめ決められた刺激に反応する時計仕掛けのシステムを構築することは可能だ。しかし、新しい刺激や狭い範囲を超えた変化に適応できるシステ ムを構築するには、群れ、すなわち集合知が必要である。多くの部分からなる全体のみが、部分が死滅したり、新しい刺激に適合するように変化したりしても、 全体を維持できる。 Adaptable—It is possible to build a clockwork system that can adjust to predetermined stimuli. But constructing a system that can adjust to new stimuli, or to change beyond a narrow range, requires a swarm—a hive mind. Only a whole containing many parts can allow a whole to persist while the parts die off or change to fit the new stimuli. |

6. 最適化できない 最適ではない—群れシステムは冗長で中央管理されていないため、非効率的である。資源は行き当たりばったりで割り当てられ、常に無駄な努力が繰り返され る。カエルがたった数匹の子供のために何千もの卵を産むのは、何という無駄だろう!自由市場経済における価格のような突発的な統制は、群れシステムが存在 したならば、非効率性を抑える傾向があるが、線形システムのように非効率性を完全に排除することはできない。 Nonoptimal—Because they are redundant and have no central control, swarm systems are inefficient. Resources are allotted higgledy-piggledy, and duplication of effort is always rampant. What a waste for a frog to lay so many thousands of eggs for just a couple of juvenile offspring! Emergent controls such as prices in free-market economy— a swarm if there ever was one—tend to dampen inefficiency, but never eliminate it as a linear system can. |

| 2. 進化できる 進化可能—適応の焦点をシステムの一部分から別の部分へと時間とともに移行できるシステム(身体から遺伝子へ、あるいは個体から個体群へ)は、群れを基盤 とするものでなければならない。非集団システムは(生物学的な意味で)進化できない。 Evolvable—Systems that can shift the locus of adaptation over time from one part of the system to another (from the body to the genes or from one individual to a population) must be swarm based. Noncollective systems cannot evolve (in the biological sense). |

7. コントロールできない 非制御可能—担当する権限がない。群れを導くことは、羊飼いが羊の群れを導くように、重要な支点に力を加え、システムの自然な傾向を新しい目的に転換する ことによってのみ可能である(羊がオオカミを恐れることを利用して、羊を追いたい犬を使って羊を集める)。経済は外から制御することはできず、内部からわ ずかに調整することしかできない。夢を見ることを妨げることはできないが、夢が実を結ぶ前に摘み取ることならできる。 「創発」という言葉がどこに登場しても、そこには人間のコントロールが消えている。 Noncontrollable—There is no authority in charge. Guiding a swarm system can only be done as a shepherd would drive a herd: by applying force at crucial leverage points, and by subverting the natural tendencies of the system to new ends (use the sheep’s fear of wolves to gather them with a dog that wants to chase sheep). An economy can’t be controlled from the outside; it can only be slightly tweaked from within. A mind cannot be prevented from dreaming, it can only be plucked when it produces fruit. Wherever the word “emergent” appears, there disappears human control. |

| 3. レジリエント 回復力—集合システムは多数の並列処理に基づいて構築されているため、冗長性がある。 個々の要素は重要ではない。 小さな障害は騒ぎの中で見過ごされる。大きな障害は、階層構造で次のレベルでの小さな障害に留まることで抑制される Resilient—Because collective systems are built upon multitudes in parallel, there is redundancy. Individuals don’t count. Small failures are lost in the hubbub. Big failures are held in check by becoming merely small failures at the next highest level on a hierarchy |

8. 予測できない 予測不可能—群集システムの複雑さは、予測不可能な方向に群れを導く。現在、数学的群集モデルを開発している研究者クリス・ラングトンは、「生物学の歴史 は、予想外の出来事についてである」と語る。 「創発」という言葉には暗い側面もある。ビデオゲームにおける創発的な新機能は非常に楽しいが、航空交通管制システムにおける創発的な新機能は国家的な緊 急事態を招くだろう。 Nonpredictable—The complexity of a swarm system bends it in unforeseeable ways. “The history of biology is about the unexpected,” says Chris Langton, a researcher now developing mathematical swarm models. The word emergent has its dark side. Emergent novelty in a video game is tremendous fun; emergent novelty in our airplane traffic-control system would be a national emergency. |

| 4. 限界がない 無限大— 従来の線形システムには、例えば PA マイクのけたたましい雑音のような正のフィードバックループが存在し得る。しかし、群れシステムでは、正のフィードバックは秩序の増大につながる可能性が ある。新しい構造を初期状態の限界を超えて徐々に拡張することで、群れはさらなる構造を構築するための足場を構築することができる。自発的な秩序は、より 大きな秩序の創造に役立つ。生命はさらなる生命を生み出し、富はさらなる富を生み出し、情報はさらなる情報を生み出す。そして、それらはすべて、もとのゆ りかごを破壊する。そして、限界は見えない Boundless—Plain old linear systems can sport positive feedback loops—the screeching disordered noise of PA microphone, for example. But in swarm systems, positive feedback can lead to increasing order. By incrementally extending new structure beyond the bounds of its initial state, a swarm can build its own scaffolding to build further structure. Spontaneous order helps create more order. Life begets more life, wealth creates more wealth, information breeds more information, all bursting the original cradle. And with no bounds in sight. |

9. 理解できない 不可解—私たちが知る限り、因果関係は時計仕掛けのようなものです。 私たちが理解できる連続的な時計仕掛けのシステムは、非線形ウェブシステムは純粋な謎です。 後者は、自ら作り出した逆説的な論理に溺れています。 A が B を引き起こし、B が A を引き起こします。 群集システムは、交差する論理の海です。A は間接的に他のすべてを引き起こし、他のすべては間接的に A を引き起こします。私はこれを水平または横方向の因果関係と呼んでいます。真の要因(より正確には、真の要因の比率)の功績は、特定の事象の引き金となる ものが本質的に不明である限り、ウェブを通じて水平方向に広がる。物事は起こる。トマトの細胞がどのように機能するか正確に知る必要はなく、トマトを育 て、食べ、改良することができる。大規模な計算集団システムがどのように機能するか正確に知る必要はなく、構築し、使用し、改良することができる。しか し、システムを理解しているか否かにかかわらず、私たちはシステムに対して責任を負っているため、理解することは間違いなく役立つ。. Nonunderstandable—As far as we know, causality is like clockwork. Sequential clockwork systems we understand; nonlinear web systems are unadulterated mysteries. The latter drown in their self-made paradoxical logic. A causes B, B causes A. Swarm systems are oceans of intersecting logic: A indirectly causes everything else and everything else indirectly causes A. I call this lateral or horizontal causality. The credit for the true cause (or more precisely the true proportional mix of causes) will spread horizontally through the web until the trigger of a particular event is essentially unknowable. Stuff happens. We don’t need to know exactly how a tomato cell works to be able to grow, eat, or even improve tomatoes. We don’t need to know exactly how a massive computational collective system works to be able to build one, use it, and make it better. But whether we understand a system or not, we are responsible for it, so understanding would sure help. |

| 5. 新しいものを生み出す 新奇性—群れシステムは3つの理由から新奇性を生み出す。 (1) 群れシステムは「初期条件に敏感」である。これは、効果の大きさは原因の大きさと比例しないことを科学的に簡潔に表現したものである。 (2) 群れシステムは、相互に関連し合う多数の個体の指数関数的な組み合わせに無数の新奇な可能性を秘めている。 (3) 群れシステムは個体を考慮しないため、個々の差異や不完全性を許容できる。遺伝性を持つ群集システムでは、個体差や不完全性により、絶え間ない新しさ、つ まり進化がもたらされる。 Novelty—Swarm systems generate novelty for three reasons: (1) They are “sensitive to initial conditions”—a scientific shorthand for saying that the size of the effect is not proportional to the size of the cause—so they can make a surprising mountain out of a molehill. (2) They hide countless novel possibilities in the exponential combinations of many interlinked individuals. (3) They don’t reckon individuals, so therefore individual variation and imperfection can be allowed. In swarm systems with heritability, individual variation and imperfection will lead to perpetual novelty, or what we call evolution. |

10. 時間がかかる 即時ではない。火を灯し、蒸気を発生させ、スイッチを入れると、線形システムは起動する。あなたのために準備が整う。システムが停止した場合は、再起動す る。単純な集合システムは簡単に起動できる。しかし、複雑な階層構造を持つ群集システムは起動に時間がかかる。複雑であればあるほど、ウォームアップに時 間がかかる。各階層で落ち着く必要がある。横方向の要因が激しく動き回り、落ち着く必要がある。100万もの自律エージェントが互いに認識し合う必要があ る。これが人間にとって最も学ぶのが難しい教訓になるだろう。つまり、有機的な複雑さには有機的な時間が必要だということだ。 Nonimmediate—Light a fire, build up the steam, turn on a switch, and a linear system awakens. It’s ready to serve you. If it stalls, restart it. Simple collective systems can be awakened simply. But complex swarm systems with rich hierarchies take time to boot up. The more complex, the longer it takes to warm up. Each hierarchical layer has to settle down; lateral causes have to slosh around and come to rest; a million autonomous agents have to acquaint themselves. I think this will be the hardest lesson for humans to learn: that organic complexity will entail organic time. |

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

![]()

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆