ミュゼ・ド・ロムとポール・リヴェ

Musée de l'Homme and Paul Rivet

☆ フランス・パリにある人類学博物館である。1937年、ポール・リヴェによって国際現代美術・技術博覧会のために設立された。1878年に設立されたトロカデロ民族学博物館(Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro) の流れを汲む。人間博物館は、各省庁の管轄下にある研究センターで、CNRSのいくつかの組織をグループ化している。人間博物館は、国立自然史博物館の7 つの部門のひとつである。人間博物館は、16区にあるシャイヨー宮のパッシー棟の大部分を占めている。コレクションの大部分はケ・ブランリー美術館に移さ れた。

| The Musée de l'Homme

(French, "Museum of Mankind" or "Museum of Humanity") is an

anthropology museum in Paris, France. It was established in 1937 by

Paul Rivet for the 1937 Exposition Internationale des Arts et

Techniques dans la Vie Moderne. It is the descendant of the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro,

founded in 1878. The Musée de l'Homme is a research center under the

authority of various ministries, and it groups several entities from

the CNRS. The Musée de l'Homme is one of the seven departments of the

Muséum national d'histoire naturelle. The Musée de l'Homme occupies

most of the Passy wing of the Palais de Chaillot in the 16th

arrondissement. The vast majority of its collection was transferred to

the Quai Branly museum.[1] |

フランス・パリにある人類学博物館である。1937年、ポール・リヴェによって国際現代美術・技術博覧会のために設立された。1878年に設立されたトロカデロ民族学博物館(Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro)

の流れを汲む。人間博物館は、各省庁の管轄下にある研究センターで、CNRSのいくつかの組織をグループ化している。人間博物館は、国立自然史博物館の7

つの部門のひとつである。人間博物館は、16区にあるシャイヨー宮のパッシー棟の大部分を占めている。コレクションの大部分はケ・ブランリー美術館に移さ

れた[1]。 |

| History Earlier Collections The Musée de l'Homme has inherited items from historical collections created as early as the 16th century, from cabinets of curiosities, and the Royal Cabinet. These collections were enriched during the 19th century, and are still added to today. The aim is to gather in one site everything which defines the human being: in terms of evolution (prehistory), of unity and diversity (anthropology), and of cultural and social expression (ethnology). The majority of the "ethnographic exhibition" from the Musée de l'Armée of the Invalides, as it was then called, is composed of dummies representing people from French colonies, along with weapons and equipment. This material was transferred to the museum in 1910 and 1917.[2] Photos of the Moroccan population, taken by Clérambault, were also displayed there. As the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro (Trocadéro Museum of Ethnography) (1882–1928) The Musée de l'Homme is the direct descendant of the Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro, which was founded in the Trocadéro Palace in 1828. Transformation into the Musée de l'Homme (1928–36) In 1928, Paul Rivet became the new director of the Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro. He oversaw a major modernization and reorganization project, and had the museum linked to the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle.[3] In 1935, the Trocadéro Palace was demolished and replaced by the Palais de Chaillot, built for the 1937 World's Fair. The museum reopened in the Palais as the Musée de l'Homme. Disruption and Resistance (1937–1945) Several members of the Musée de l'Homme, including its founder Paul Rivet, formed a resistance group during the German occupation of Paris in World War II. When Nazi tanks rolled into the city on 14 June 1940, Rivet had a French translation of Rudyard's Kipling poem If tacked to the museum's door in a gesture of defiance.[4] Refurbishment (1996–2015) In 1996, French President Jacques Chirac announced plans to create a new museum that would combine key collections from the Musée de l'Homme and Musée national des Arts d'Afrique et d'Océanie. Curators at the Musée de l'Homme fought vigorously to retain the collections at their museum, but were unsuccessful.[5] These collections went to the new museum, the Musée du quai Branly, which opened in 2006. In 2008, the French government committed to the refurbishment of the Musée de l’Homme.[6] The museum was closed for renovations in 2009, and reopened in October 2015.The total amount of money appropriated for the renovation process was 52 million Euros.[7] |

歴史 初期のコレクション 人間博物館には、16世紀以前に作られた歴史的コレクション、珍品棚、王室内閣のコレクションが受け継がれている。これらのコレクションは19世紀に充実 し、今日もなお追加されている。その目的は、進化(先史学)、単一性と多様性(人類学)、文化的・社会的表現(民族学)の観点から、人間を定義するあらゆ るものを一箇所に集めることである。 アンヴァリッド陸軍博物館(当時はそう呼ばれていた)の「民族学展示」の大部分は、フランスの植民地の人々を模したダミーと武器や装備品で構成されてい る。この資料は1910年と1917年に博物館に移され、クレランボーが撮影したモロッコの人々の写真も展示された[2]。 トロカデロ民族学博物館(Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro) (1882-1928) として 1828年にトロカデロ宮殿内に設立されたトロカデロ民族学博物館の直系である。 人間博物館への変貌(1928-36年) 1928年、ポール・リヴェがトロカデロ民族学博物館の新館長に就任した。彼は大規模な近代化と再編成プロジェクトを監督し、博物館を国立自然史博物館と統合させた[3]。 1935年、トロカデロ宮殿は取り壊され、1937年の万国博覧会のために建設されたシャイヨー宮に建て替えられた。博物館はシャイヨー宮で人間博物館として再オープンした。 混乱と抵抗(1937年-1945年) 創設者のポール・リヴェを含む人間博物館のメンバー数名は、第二次世界大戦中、ドイツ軍によるパリ占領下でレジスタンス・グループを結成した。1940年 6月14日、ナチスの戦車がパリに進入した際、リヴェはラドヤード・キップリングの詩『if』のフランス語訳を美術館のドアに貼らせ、反抗の意思を示した [4]。 改装(1996年~2015年) 1996年、フランスのジャック・シラク大統領は、人間美術館とアフリカ・オセアニア国立美術館の主要コレクションを統合した新しい美術館を創設する計画を発表した。これらのコレクションは、2006年に開館した新美術館、ケ・ブランリー美術館に移された[5]。 2008年、フランス政府はケ・ブランリー美術館の改修を約束した[6]。2009年、美術館は改修のために閉鎖され、2015年10月に再オープンした。改修プロセスのために計上された総額は5200万ユーロだった[7]。 |

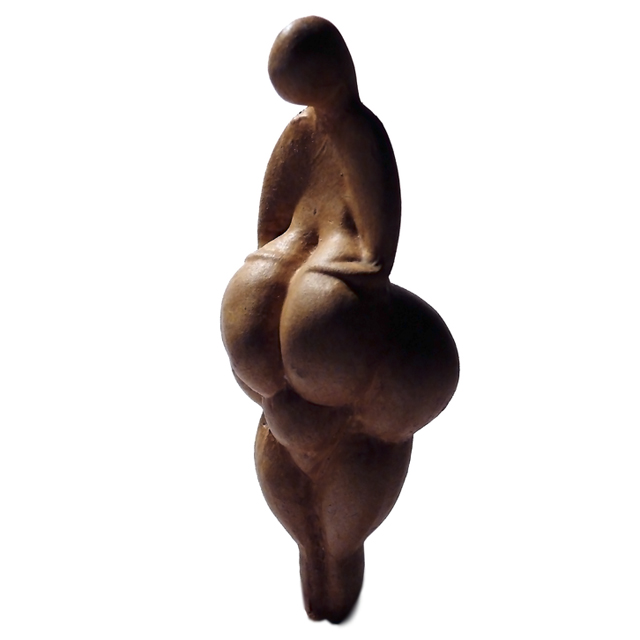

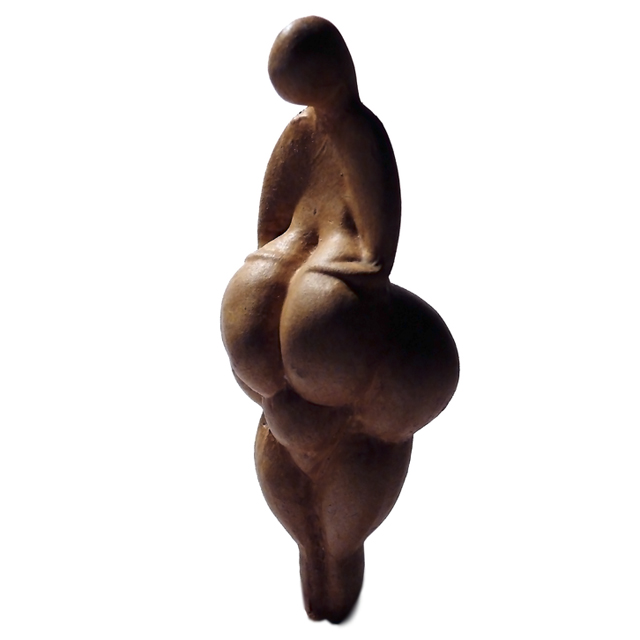

Mission Venus of Lespugue (replica), from the Musée de l'Homme The museum's original purpose was to gather in one place all that can define humanity: its evolution, its unity and its variety, and its cultural and social expression. The removal of the Musée de l'Homme's ethnographic collections to the new Musée du quai Branly and MUCEM broke with its original mission. This change aroused many debates concerning the curatorial choices of the new structure. The permanent exhibition of the Musée de l'Homme counted more than 15,000 artifacts, reflecting artistic, technical and cultural treasures from five continents. Quai Branly, however, holds only 3500 artifacts, presented without cultural contextualization, chosen for their aesthetic qualities and their "exotic" origins (Africa, Oceania, Americas) and not on educational value. European ethnographical collections are going to be exhibited at MUCEM, and critics believe it is creating an unjustified discontinuity between human cultures. This situation led the Musée de l'Homme to review its mission. In 2015 it reaffirmed Paul Rivet's original vision for a laboratory museum.[8] Combining biological, social and cultural approaches, the museum today focuses on the evolution of humans and human societies in keeping with Rivet's view that "Humanity is one and indivisible, not only in space, but also in time."[8] |

ミッション レスプゲのヴィーナス(レプリカ)、人間博物館より 博物館の本来の目的は、人類を定義しうるすべてのもの、すなわち、その進化、統一性、多様性、文化的・社会的表現などを一箇所に集めることであった。 しかし、ケ・ブランリー美術館とMUCEMに移管された人間博物館の民族誌コレクションは、その本来の使命とはかけ離れたものであった。この変更は、新館 の学芸員の選択に関して多くの議論を引き起こした。人間博物館の常設展示は、5大陸の芸術的、技術的、文化的な宝物を反映した15,000点以上の工芸品 を数えた。しかし、ケ・ブランリー美術館が所蔵するのは、文化的な背景を説明することなく、美的品質と「エキゾチック」な起源(アフリカ、オセアニア、ア メリカ大陸)のために選ばれた、教育的価値のない3500点にすぎない。ヨーロッパの民族学的コレクションがMUCEMに展示されることになり、人類文化 の間に不当な不連続性を生み出していると批判されている。 このような状況から、人間博物館はその使命を見直すことになった。生物学的、社会学的、文化学的なアプローチを組み合わせ、「人類は空間的にも時間的にも一つであり、不可分である」というリヴェの見解に沿って、今日、人類と人類社会の進化に焦点を当てている[8]。 |

| Notable directors and staff scientists René-Yves Creston, director of the Arctic section in the 1930s Maurice Leenhardt André Leroi-Gourhan Paul Rivet Jacques Soustelle (vice-president in 1938) Claude Lévi-Strauss (interim director 1949–1950) Germaine Dieterlen (Comité du film ethnographique) Jean Rouch (Comité du film ethnographique) Henri Victor Vallois Zeev Gourarier (Director 2003–2007) |

著名な所長とスタッフ科学者 ルネ=イヴ・クレストン、1930年代の北極セクション責任者 モーリス・リーンハルト アンドレ・レロワ・グーラン ポール・リヴェ ジャック・スステル(1938年副会長) クロード・レヴィ=ストロース(1949-1950年暫定会長) ジェルメーヌ・ディーターレン(民族写真映画委員会) ジャン・ルーシュ(民族写真映画委員会) アンリ・ヴィクトール・ヴァロワ ゼフ・グーラリエ(2003-2007年ディレクター) |

| Notable holdings A crystal skull The skull of René Descartes, scientist, mathematician, physicist, and philosopher The skull of Suleiman al-Halabi (1777–1800), who, in 1800, assassinated Jean-Baptiste Kléber in Egypt Mapa pintado en papel europeo y aforrado en el indiano, a Mesoamerican pictorial document Former holdings The body of Khoikhoi woman Saartjie Baartman (displayed until 1974; repatriated in 2002) Skulls of 24 Algerian fighters who resisted French rule in the 19th century and were beheaded (repatriated in 2020)[9][10][11] |

注目すべき所有物 水晶の頭蓋骨 ルネ・デカルト(科学者、数学者、物理学者、哲学者)の頭骨 1800年にエジプトでジャン=バティスト・クレベールを暗殺したスレイマン・アル=ハラビ(1777-1800)の頭骨 ヨーロッパ紙に描かれ、インド紙に貼られた地図。 旧所蔵品 コイコイ族の女性、サートジー・バートマンの遺体(1974年まで展示、2002年に本国へ移送された) 19世紀にフランスの支配に抵抗し、斬首された24人のアルジェリア人戦士の頭蓋骨(2020年に本国へ送還)[9][10][11]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C3%A9e_de_l%27Homme |

|

Paul Rivet was born in Wasigny, Ardennes in 1876. He attended local schools and university, studying to be a physician. Paul Rivet was born in Wasigny, Ardennes in 1876. He attended local schools and university, studying to be a physician.Career Trained as a physician, in 1901 he took part in the Second French Geodesic Mission for survey measurements of the length of a meridian arc to Ecuador. He remained for five years in South America, where he was mentored by Federico González Suárez, an Ecuadorian bishop, historian and archaeologist. Rivet became interested in the indigenous peoples, beginning an ethnographic study of the Huaorani people of the Ecuadorian Amazon, then known as the Jívaro. While in Ecuador he collected specimens of amphibians and reptiles.[1] Returning to France, Rivet went to work with the Muséum national d'histoire naturelle, directed by René Verneau. He published several papers on his Ecuadorian research, before publishing an extended volume co-authored with René Verneau, titled Ancient Ethnography of Ecuador (1921-1922). In 1926, Rivet participated in founding the Institut d'ethnologie in Paris, together with Marcel Mauss and Lucien Lévy-Bruhl. They intended it as a collaboration among the fields of philosophy, ethnology and sociology. He taught many French ethnologists, including George Devereux. In 1928, he succeeded René Verneau as director of the National Museum of Natural History. He continued to develop institutions for the study of mankind. In 1937, he founded the Musée de l'Homme in Paris, which became renowned for its ethnographic research and collections. In 1942, following Nazi occupation of Paris, Rivet was ousted from his position at the museum. He went to the US where Franz Boas tried to help him along with other academicians displaced by the Nazis. On knowing that the Germans were failing to scientifically prove racial difference and superiority, Boas said, "We should never stop repeating the idea that racism is a monstrous error and an imprudent lie." This exchange took place at a luncheon organised by Boas at the Columbia Faculty Club in honour of Rivet.[2] Beginning his stint in Columbia University from 1942, Rivet founded the Anthropological Institute and Museum. Returning to Paris in 1945, he continued teaching while carrying on his research. His linguistic research introduced several new perspectives on the Aymara and Quechua languages of South America. Politics Rivet also became involved in politics, alarmed at the rise of fascism in Europe during the 1930s. During the 6 February 1934 crisis, he was one of the founders of the Comité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistes, an antifascist organization created in the wake of massive riots in Paris. Rivet was a leader in the French Resistance to Nazi occupation. He narrowly escaped arrest and execution by the Nazis. Several of his colleagues, including Anatole Lewitsky and Boris Vilde were shot. Linguistic classification Further information: Classification of indigenous languages of the Americas Rivet is well known for his classification of South American languages. He proposed 77 language families and about 1240 languages and dialects.[3] Much of his work on language classification was later incorporated by John Alden Mason and his former student Čestmír Loukotka.[4] Migration theory Rivet's theory asserts that Asia was the origin of the Indigenous people of the Americas. However, he also suggested that migrations to South America were made from Australia some 6,000 years before, and from Melanesia somewhat later. Les Origines de l'Homme Américain ("The Origins of the American Man") was published in 1943, and contains linguistic and anthropological arguments to support his thesis. Honors Rivet is commemorated in the scientific names of the South American snake Leptophis riveti[1] and frog Pristimantis riveti.[5] Books with René Verneau, 1921-1922. Ancient Ethnography of Ecuador. 1923. L'orfèvrerie du Chiriquí et de Colombie. Paris: Société des Américanistes de Paris. 1923. L'orfèvrerie précolombienne des Antilles, des Guyanes, et du Vénézuéla, dans ses rapports avec l'orfèvrerie et la métallurgie des autres régions américaines. Paris: Au siège de la société des Américanistes de Paris. 1943. Los origenes del hombre Americano. México: Cuadernos amerícanos. 1960. Maya cities: Ancient cities and temples. London: Elek Books. with Freund, Gisèle, 1954. Mexique précolombien. Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et calendes. |

ポール・リヴェは1876年、アルデンヌ地方のワシニーに生まれた。地元の学校と大学に通い、医師を目指した。 ポール・リヴェは1876年、アルデンヌ地方のワシニーに生まれた。地元の学校と大学に通い、医師を目指した。経歴 医師としての訓練を受け、1901年、子午線円弧の長さを測定するためにエクアドルに派遣された第2次フランス測地使節団に参加した。南米に5年間滞在 し、エクアドルの司教、歴史家、考古学者であるフェデリコ・ゴンサレス・スアレスの指導を受けた。リヴェットは先住民族に興味を持ち、当時ジバロ族として 知られていたエクアドル・アマゾンのフアオラニ族の民族誌的研究を始めた。エクアドル滞在中、両生類や爬虫類の標本を収集した[1]。フランスに戻ったリ ヴェは、ルネ・ヴェルノーが館長を務める国立自然史博物館で働くことになった。 ルネ・ヴェルノーとの共著『エクアドルの古代民族誌』(1921-1922年)を出版する前に、エクアドルでの研究についていくつかの論文を発表した。 1926年、リヴェはマルセル・モース、ルシアン・レヴィ=ブリュールとともにパリ民族学研究所の設立に参加した。彼らは哲学、民族学、社会学の各分野の 共同研究を意図していた。彼はジョージ・デヴリューを含む多くのフランス人民族学者を教えた。1928年、ルネ・ヴェルノーの後任として国立自然史博物館 の館長に就任した。 その後も、人類研究のための機関を発展させた。1937年、パリに人間博物館を設立し、その民族学的研究とコレクションで有名になった。 1942年、ナチスによるパリ占領に伴い、リヴェは博物館の職を追われた。彼はアメリカに渡り、フランツ・ボアスがナチスに追われた他の学者たちとともに 彼を助けようとした。ドイツ人が人種的差異と優越性を科学的に証明することに失敗していることを知ったボアスは、「人種差別はとんでもない誤りであり、軽 率な嘘であるという考えを繰り返すことを決して止めるべきではない」と言った。このやりとりは、ボアスがコロンビア大学ファカルティ・クラブでリヴェを記 念して企画した昼食会で行われた[2]。1942年からコロンビア大学に勤務したリヴェは、人類学研究所と人類学博物館を設立した。 1945年にパリに戻り、研究を続けながら教鞭をとった。彼の言語学的研究は、南米のアイマラ語とケチュア語についていくつかの新しい視点を導入した。 政治 リヴェットは、1930年代のヨーロッパにおけるファシズムの台頭を憂慮し、政治にも関わるようになった。1934年2月6日の危機の際には、パリでの大 規模な暴動をきっかけに創設された反ファシズム組織、Commité de vigilance des intellectuels antifascistesの創設者の一人となった。リヴェは、ナチスの占領に対するフランスのレジスタンスのリーダーだった。彼は辛うじてナチスによる 逮捕と処刑を免れた。アナトール・ルヴィツキーやボリス・ヴィルデを含む数人の同僚が銃殺された。 言語分類 さらに詳しい情報 アメリカ大陸の先住民言語の分類 リヴェットは南米の言語を分類したことで知られている。彼は77の語族と約1240の言語と方言を提唱した[3]。言語分類に関する彼の研究の多くは、後にジョン・オールデン・メイソンと彼の元教え子チェスミール・ルーコトカによって取り入れられた[4]。 移動理論 リヴェットの理論は、アジアがアメリカ大陸の先住民の起源であると主張している。しかし彼は、南アメリカへの移住は約6,000年前にオーストラリアから 行われ、やや遅れてメラネシアから行われたとも示唆した。1943年に出版された『アメリカ人の起源』(Les Origines de l'Homme Américain)には、彼の説を裏付ける言語学的、人類学的論拠が記されている。 栄誉 リヴェットは南米のヘビLeptophis riveti[1]とカエルPristimantis rivetiの学名に記念されている[5]。 著書 1921-1922年、ルネ・ヴェルノーと共著。エクアドルの古代民族誌。 1923. L'orfèvrerie du Chiriquí et de Colombie. パリ: Société des Américanistes de Paris. 1923. L'orfèvrerie précolombienne des Antilles, des Guyanes, et du Vénézuéla, dans its rapports with l'orfèvrerie et la métallurgie des other régions américaines. Paris: Au siège de la société des Américanistes de Paris. 1943. アメリカ人の起源。México: メキシコ: Cuadernos amerícanos. 1960. マヤの都市: 古代都市と神殿。ロンドン: Elek Books. Freund, Gisèle, 1954. Mexique précolombien. Neuchâtel: Éditions Ides et calendes. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Rivet |

|

The Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro

(Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro, also called simply the Musée du

Trocadéro) was the first anthropological museum in Paris, founded in

1878. It closed in 1935 when the building that housed it, the Trocadéro

Palace, was demolished; its descendant is the Musée de l'Homme, housed

in the Palais de Chaillot on the same site, and its French collections

formed the nucleus of the Musée National des Arts et Traditions

Populaires, also in the Palais de Chaillot. Numerous modern artists

visited it and were influenced by its "primitive" art, in particular

Picasso during the period when he was working on Les Demoiselles

d'Avignon (1907). The Musée d'Ethnographie du Trocadéro

(Ethnographic Museum of the Trocadéro, also called simply the Musée du

Trocadéro) was the first anthropological museum in Paris, founded in

1878. It closed in 1935 when the building that housed it, the Trocadéro

Palace, was demolished; its descendant is the Musée de l'Homme, housed

in the Palais de Chaillot on the same site, and its French collections

formed the nucleus of the Musée National des Arts et Traditions

Populaires, also in the Palais de Chaillot. Numerous modern artists

visited it and were influenced by its "primitive" art, in particular

Picasso during the period when he was working on Les Demoiselles

d'Avignon (1907). |

ト

ロカデロ民族学博物館(Musée d'Ethnographie du

Trocadéro)は、1878年に設立されたパリで最初の人類学博物館である。トロカデロ宮殿が取り壊されたため、1935年に閉館した。その後身

が、同じ敷地内のシャイヨー宮にある人間博物館であり、フランスのコレクションは、同じくシャイヨー宮にある国立民衆芸術伝統博物館の核となった。数多く

の近代芸術家たちがここを訪れ、その「原始的な」芸術に影響を受けた。特にピカソは、『アヴィニョンの娘』(1907年)の制作に取り組んでいた時期であ

る。 ト

ロカデロ民族学博物館(Musée d'Ethnographie du

Trocadéro)は、1878年に設立されたパリで最初の人類学博物館である。トロカデロ宮殿が取り壊されたため、1935年に閉館した。その後身

が、同じ敷地内のシャイヨー宮にある人間博物館であり、フランスのコレクションは、同じくシャイヨー宮にある国立民衆芸術伝統博物館の核となった。数多く

の近代芸術家たちがここを訪れ、その「原始的な」芸術に影響を受けた。特にピカソは、『アヴィニョンの娘』(1907年)の制作に取り組んでいた時期であ

る。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mus%C3%A9e_d%27Ethnographie_du_Trocad%C3%A9ro |

続きは「トロカデロ民族学博物館」 |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆