キューバの音楽

Music of Cuba

☆ キューバの音楽( music of Cuba) は、楽器、パフォーマティビティ、ダンスを含め、主に西アフリカとヨーロッパ(特にスペイン)の音楽の影響を受けた独自の伝統的な音楽で構成されている。 例えば、ソン・クバーノは、スペインのギター(トレス)、メロディー、ハーモニー、叙情的な伝統と、アフロ・キューバのパーカッションやリズムを融合させ たものである。16世紀に原住民が絶滅したため、原住民の伝統はほとんど残っていない。 19世紀以降、キューバ音楽は世界中で絶大な人気と影響力を持っている。19世紀以降、キューバ音楽は世界中で絶大な人気と影響力を持つようになり、録音 技術が導入されて以来、おそらく最も人気のある地域音楽の形態となっている。キューバ音楽は、ラテンアメリカ、カリブ海諸国、西アフリカ、ヨーロッパを中 心に、世界中のさまざまなジャンルや音楽スタイルの発展に貢献してきた。例えば、ルンバ、アフロ・キューバン・ジャズ、サルサ、スークー、アフロ・キュー バン・ミュージックを西アフリカに再アダプトしたもの(オーケストラ・バオバブ、アフリカンド)、スペインのフュージョン・ジャンル(特にフラメンコとの フュージョン)、ラテン・アメリカの多種多様なジャンルなどが挙げられる。

| The music of Cuba,

including its instruments, performance, and dance, comprises a large

set of unique traditions influenced mostly by west African and European

(especially Spanish) music.[1] Due to the syncretic nature of most of

its genres, Cuban music is often considered one of the richest and most

influential regional music in the world. For instance, the son cubano

merges an adapted Spanish guitar (tres), melody, harmony, and lyrical

traditions with Afro-Cuban percussion and rhythms. Almost nothing

remains of the original native traditions, since the native population

was exterminated in the 16th century.[2] Since the 19th-century Cuban music has been hugely popular and influential throughout the world. It has been perhaps the most popular form of regional music since the introduction of recording technology. Cuban music has contributed to the development of a wide variety of genres and musical styles around the globe, most notably in Latin America, the Caribbean, West Africa, and Europe. Examples include rhumba, Afro-Cuban jazz, salsa, soukous, many West African re-adaptations of Afro-Cuban music (Orchestra Baobab, Africando), Spanish fusion genres (notably with flamenco), and a wide variety of genres in Latin America. |

キューバの音楽は、楽器、パフォーマティビ

ティ、ダンスを含め、主に西アフリカとヨーロッパ(特にスペイン)の音楽の影響を受けた独自の伝統的な音楽で構成されている。例えば、ソン・クバーノは、

スペインのギター(トレス)、メロディー、ハーモニー、叙情的な伝統と、アフロ・キューバのパーカッションやリズムを融合させたものである。16世紀に原

住民が絶滅したため、原住民の伝統はほとんど残っていない[2]。 19世紀以降、キューバ音楽は世界中で絶大な人気と影響力を持っている。19世紀以降、キューバ音楽は世界中で絶大な人気と影響力を持つようになり、録音 技術が導入されて以来、おそらく最も人気のある地域音楽の形態となっている。キューバ音楽は、ラテンアメリカ、カリブ海諸国、西アフリカ、ヨーロッパを中 心に、世界中のさまざまなジャンルや音楽スタイルの発展に貢献してきた。例えば、ルンバ、アフロ・キューバン・ジャズ、サルサ、スークー、アフロ・キュー バン・ミュージックを西アフリカに再アダプトしたもの(オーケストラ・バオバブ、アフリカンド)、スペインのフュージョン・ジャンル(特にフラメンコとの フュージョン)、ラテン・アメリカの多種多様なジャンルなどが挙げられる。 |

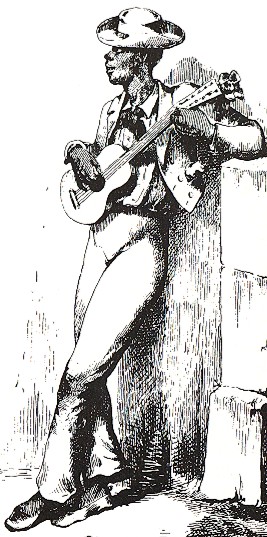

Overview Ancient print of colonial Havana Large numbers of enslaved Africans and European, mostly Spanish, immigrants came to Cuba and brought their own forms of music to the island. European dances and folk musics included zapateo, fandango, paso doble and retambico. Later, northern European forms like minuet, gavotte, mazurka, contradanza, and the waltz appeared among urban whites. There was also an immigration of Chinese indentured laborers later in the 19th century. Fernando Ortiz, the first great Cuban folklorist, described Cuba's musical innovations as arising from the interplay ('transculturation') between enslaved Africans settled on large sugar plantations and Spaniards from different regions such as Andalusia and Canary Islands. The enslaved Africans and their descendants made many percussion instruments and preserved rhythms they had known in their homeland.[3] The most important instruments were the drums, of which, there were originally about fifty different types; today only the bongos, congas and batá drums are regularly seen (the timbales are descended from kettle drums in Spanish military bands). Also important are the claves, two short hardwood batons, and the cajón, a wooden box, originally made from crates. Claves are still used often, and wooden boxes (cajones) were widely used during periods when the drum was banned. In addition, there are other percussion instruments in use for African-origin religious ceremonies. Chinese immigrants contributed the corneta china (Chinese cornet), a Chinese reed instrument still played in the comparsas, or carnival groups, of Santiago de Cuba. The great instrumental contribution of the Spanish was their guitar, but even more important was the tradition of European musical notation and techniques of musical composition. Hernando de la Parra's archives give some of our earliest available information on Cuban music. He reported instruments including the clarinet, violin and vihuela. There were few professional musicians at the time, and fewer still of their songs survive. One of the earliest is Ma Teodora, supposed to be related to a freed slave, Teodora Ginés of Santiago de Cuba, who was famous for her compositions. The piece is said to be similar to 16th-, 17th- and 18th-century Spanish popular songs and dances.[4] Cuban music has its principal roots in Spain and West Africa, but over time has been influenced by diverse genres from different countries. Important among these are France (and its colonies in the Americas), and the United States. Cuban music has been immensely influential[citation needed] in other countries. It contributed not only to the development of jazz and salsa, but also to the Argentine tango, Ghanaian high-life, West African Afrobeat, Dominican Bachata and Merengue, Colombian Cumbia and Spanish Nuevo flamenco and to the Arabo-Cuban music (Hanine Y Son Cubano)[5] developed by Michel Elefteriades in the 1990s. The African beliefs and practices certainly influenced Cuba's music. Polyrhythmic percussion is an inherent part of African music, as the melody is part of European music. Also, in African tradition, percussion is always joined to song and dance, and a particular social setting.[6] The result of the meeting of European and African cultures is that most Cuban popular music is creolized. This creolization of Cuban life has been happening for a long time, and by the 20th century, elements of African belief, music, and dance were well integrated into popular and folk forms. |

概要 植民地時代のハバナの古代版画 奴隷にされた大勢のアフリカ人とヨーロッパ人(主にスペイン人)がキューバに移住し、独自の音楽様式を持ち込んだ。ヨーロッパのダンスや民族音楽には、サ パテオ、ファンダンゴ、パソ・ドブレ、レタンビコなどがあった。その後、メヌエット、ガボット、マズルカ、コントラバンザ、ワルツといった北欧の形式が都 市部の白人の間に登場した。19世紀後半には、中国人年季奉公労働者の移民もあった。 キューバ初の偉大な民俗学者フェルナンド・オルティスは、キューバの音楽的革新は、大規模な砂糖プランテーションに定住した奴隷アフリカ人と、アンダルシ アやカナリア諸島など異なる地域から来たスペイン人との相互作用(「トランスカルチュレーション」)から生じたと述べている。最も重要な楽器はドラムで、 元々は50種類ほどあったが、現在ではボンゴ、コンガ、バタ・ドラムのみが一般的である(ティンバレスはスペインの軍楽隊のケトル・ドラムの子孫)。ま た、クラベスという2本の短い広葉樹のバトンと、カホンという木製の箱も重要で、もともとは木箱で作られていた。クラーベは今でもよく使われ、木製の箱 (カホン)はドラムが禁止されていた時期にも広く使われていた。さらに、アフリカ起源の宗教儀式に使われる打楽器もある。中国からの移民は、サンティア ゴ・デ・クーバのコンパーサ(カーニバルのグループ)で今でも演奏されている中国のリード楽器、コルネータ・チャイナ(中国のコルネット)をもたらした。 スペイン人の楽器面での大きな貢献はギターであったが、それ以上に重要だったのは、ヨーロッパ楽譜の伝統と作曲技術であった。エルナンド・デ・ラ・パラの アーカイブには、キューバ音楽に関する最も古い情報が残されている。彼は、クラリネット、バイオリン、ビウエラなどの楽器を報告している。当時、プロの音 楽家はほとんどおらず、彼らの歌はほとんど残っていない。最も古い曲のひとつは「マ・テオドラ」で、解放奴隷だったサンティアゴ・デ・クーバのテオドラ・ ジネスが作曲したことで有名だ。この曲は、16世紀、17世紀、18世紀のスペインのポピュラーソングやダンスに似ていると言われている[4]。 キューバ音楽の主なルーツはスペインと西アフリカにあるが、長い時間をかけて様々な国の多様なジャンルの影響を受けてきた。中でも重要なのは、フランス(とアメリカ大陸の植民地)、アメリカである。 キューバ音楽は他国にも多大な影響力[要出典]を持っている。ジャズやサルサの発展だけでなく、アルゼンチン・タンゴ、ガーナのハイ・ライフ、西アフリカ のアフロビート、ドミニカのバチャータとメレンゲ、コロンビアのクンビア、スペインのヌエボ・フラメンコ、そして1990年代にミシェル・エレフテリアデ スが発展させたアラボ・キューバ音楽(Hanine Y Son Cubano)[5]にも貢献した。 アフリカの信仰と慣習がキューバの音楽に影響を与えたのは確かである。ポリリズムのパーカッションは、メロディがヨーロッパ音楽の一部であるように、アフ リカ音楽に固有のものである。また、アフリカの伝統では、パーカッションは常に歌や踊り、特定の社会的環境と結びついている[6]。ヨーロッパとアフリカ の文化が出会った結果、キューバのポピュラー音楽のほとんどはクレオール化している。キューバ人の生活におけるこのクレオール化は長い間起こっており、 20世紀までには、アフリカの信仰、音楽、ダンスの要素は、ポピュラーや民俗の形態によく溶け込んでいた。 |

18th and 19th centuries Manuel Saumell  Ignacio Cervantes  L. M. Gottschalk Among internationally heralded composers of the "serious" genre can be counted the Baroque composer Esteban Salas y Castro (1725–1803), who spent much of his life teaching and writing music for the Church.[7] He was followed in the Cathedral of Santiago de Cuba by the priest Juan París (1759–1845). París was an exceptionally industrious man and an important composer. He encouraged continuous and diverse musical events.[8]p181 Aside from rural music and Afro-Cuban folk music, the most popular kind of urban Creole dance music in the 19th century was the contradanza, which commenced as a local form of the English country dance and the derivative French contredanse and Spanish contradanza. While many contradanzas were written for dance, from the mid-century several were written as light-classical parlor pieces for piano. The first distinguished composer in this style was Manuel Saumell (1818–1870), who is sometimes accordingly hailed as the father of Cuban creole musical development. According to Helio Orovio, "After Saumell's visionary work, all that was left to do was to develop his innovations, all of which profoundly influenced the history of Cuban nationalist musical movements."[9] In the hands of his successor, Ignacio Cervantes Kavanagh, the piano idiom related to the contradanza achieved even greater sophistication. Cervantes was called by Aaron Copland a "Cuban Chopin" because of his Chopinesque piano compositions. Cervantes' reputation today rests almost solely upon his famous forty-one Danzas Cubanas, which Carpentier said, "occupy the place that the Norwegian Dances of Grieg or the Slavic Dances of Dvořák occupy in the music of their respective countries". Cervantes' never-finished opera, Maledetto, is forgotten.[8] In the 1840s, the habanera emerged as a languid vocal song using the contradanza rhythm. (Non-Cubans sometimes called Cuban contradanzas "habaneras.") The habanera went on to become popular in Spain and elsewhere. The Cuban contradanza/Danza was also an important influence on the Puerto Rican Danza, which went on to enjoy its own dynamic and distinctive career lasting through the 1930s. In Cuba, in the 1880s the contradanza/Danza gave birth to the danzón, which effectively superseded it in popularity.[10] Laureano Fuentes (1825–1898) came from a family of musicians and wrote the first opera to be composed on the island, La Hija de Jefté (Jefte's daughter). This was later lengthened and staged under the title Seila. His numerous works spanned all genres. Gaspar Villate (1851–1891) produced abundant and wide-ranging work, all centered on opera.[8]p239 José White (1836–1918), a mulatto of a Spanish father and an Afrocuban mother, was a composer and a violinist of international merit. He learned to play sixteen instruments, and lived, variously, in Cuba, Latin America, and Paris. His most famous work is La Bella Cubana, a habanera. During the middle years of the 19th century, a young American musician Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829–1869) came to Cuba. Gottschalk's father was a Jewish businessman from London, and his mother a white creole of French Catholic background.[11] Gottschalk was brought up mostly by his black grandmother and nurse Sally, both from Saint-Domingue. He was a piano prodigy who had listened to the music and seen the dancing in Congo Square, New Orleans from childhood. His period in Cuba lasted from 1853 to 1862, with visits to Puerto Rico and Martinique squeezed in. He composed many creolized pieces, such as the habanera Bamboula, Op. 2 (Danse de negres) (1845), the title referring to a bass Afro-Caribbean drum; El cocoye (1853), a version of a rhythmic melody already present in Cuba; the contradanza Ojos criollos (Danse cubaine) (1859) and a version of María de la O, which refers to a Cuban mulatto singer. These numbers made use of typical Cuban rhythmic patterns. At one of his farewell concerts he played his Adiós a Cuba to huge applause and shouts of 'bravo!' Unfortunately, his score for the work has not survived.[12] In February 1860 Gottschalk produced a huge work La nuit des tropiques in Havana. The work used about 250 musicians and a choir of 200 singers plus a tumba francesa group from Santiago de Cuba. He produced another huge concert the following year, with new material. These shows probably dwarfed anything seen in the island before or since, and no doubt were unforgettable for those who attended.[13]p147 |

18世紀と19世紀 マヌエル・サウメル  イグナシオ・セルバンテス  L. M.ゴットシャルク 「シリアスな」ジャンルの国際的に著名な作曲家の中には、バロック時代の作曲家エステバン・サラス・イ・カストロ(1725~1803年)を挙げることがで き、彼は生涯の大半を教会のための教育と作曲に費やした[7]。パリスは非常に勤勉な人物で、重要な作曲家でもあった。農村音楽やアフロ・キューバの民俗 音楽は別として、19世紀の都市クレオールのダンス音楽で最も人気があったのはコントラダンツァであった。コントラダンツァは、イギリスのカントリーダン スや、そこから派生したフランスのコントレダンツァ、スペインのコントラダンツァのローカルな形態として始まった。多くのコントラダンザはダンスのために 書かれたが、世紀半ばからはピアノのための軽いクラシカルなパーラー曲として書かれるようになった。このスタイルの最初の著名な作曲家はマヌエル・サウメ ル(1818-1870)で、彼はキューバ・クレオール音楽発展の父と称されることもある。ヘリオ・オロビオによれば、「サウメルの先見的な仕事の後、残 されたのは彼の革新的な作品を発展させることだけであり、そのすべてがキューバの民族主義音楽運動の歴史に大きな影響を与えた」[9]。 彼の後継者であるイグナシオ・セルバンテス・カヴァナーの手にかかると、コントラフォルツァに関連するピアノのイディオムはさらに洗練されたものとなっ た。セルバンテスは、そのショパン風のピアノ曲から、アーロン・コープランドに「キューバのショパン」と呼ばれた。セルバンテスの今日の名声は、ほとんど 彼の有名な41の「キューバ舞曲」だけにかかっている。この舞曲は、「グリーグのノルウェー舞曲やドヴォルザークのスラブ舞曲がそれぞれの国の音楽で占め る位置を占めている」とカルペンティエは述べている。セルバンテスの未完のオペラ『マレデット』は忘れ去られた[8]。 1840年代には、ハバネラはコントラバンザのリズムを使った物憂げな声楽曲として登場した。(非キューバ人はキューバのコントラフォルツァを「ハバネ ラ」と呼ぶこともあった。キューバのコンコンダンサ/ダンツァは、プエルトリコのダンツァにも重要な影響を与え、1930年代まで続くダイナミックで独特 なキャリアを謳歌した。キューバでは、1880年代にコンディトランサ/ダンツァがダンツォンを誕生させ、事実上ダンツォンに人気が取って代わられた [10]。 ラウレアノ・フエンテス(1825-1898)は音楽家の家系に生まれ、キューバで最初に作曲されたオペラLa Hija de Jefté(ジェフテの娘)を書いた。この作品は後に長大化され、『セイラ』というタイトルで上演された。彼の作品はあらゆるジャンルに及んだ。ホセ・ホ ワイト(1836-1918)は、スペイン人の父とアフロキューバ人の母をもつ混血児で、作曲家であると同時に国際的なヴァイオリニストでもあった。彼は 16の楽器を習得し、キューバ、ラテンアメリカ、パリでさまざまな生活を送った。彼の最も有名な作品は、ハバネラ「ラ・ベッラ・クバーナ」である。 19世紀中頃、若きアメリカ人音楽家ルイ・モロー・ゴットシャルク(1829-1869)がキューバにやってきた。ゴットチョークの父はロンドン出身のユ ダヤ人実業家、母はフランス系カトリックの白人クレオール人であった[11]。ゴットチョークは、主にサン=ドマング出身の黒人の祖母と看護婦のサリーに 育てられた。幼い頃からニューオーリンズのコンゴ・スクエアで音楽を聴き、踊りを見ていたピアノの天才だった。キューバでの生活は1853年から1862 年まで続き、プエルトリコとマルティニークも訪れた。例えば、ハバネラ『バンブーラ』作品2(Danse de negres)(1845年)、『エル・ココイエ』(1853年)、キューバにすでにあったリズムのメロディーのヴァージョン、コントラバンザ『Ojos criollos(Danse cubaine)』(1859年)、キューバの混血歌手マリア・デ・ラ・オーのヴァージョンなどである。これらのナンバーは、典型的なキューバのリズム・ パターンを用いている。1860年2月、ゴットシャルクはハバナで大作La nuit des tropiquesを作曲した。この作品には、約250人の音楽家と200人の合唱団、それにサンティアゴ・デ・クーバのトゥンバ・フランセーサ・グルー プが起用された。翌年もまた、新曲を含む大規模なコンサートを開催した。これらのショーは、おそらくそれ以前にもそれ以降にもキューバで見られたものを凌 ぐものであり、参加した人々にとって忘れがたいものであったことは間違いない[13]p147。 |

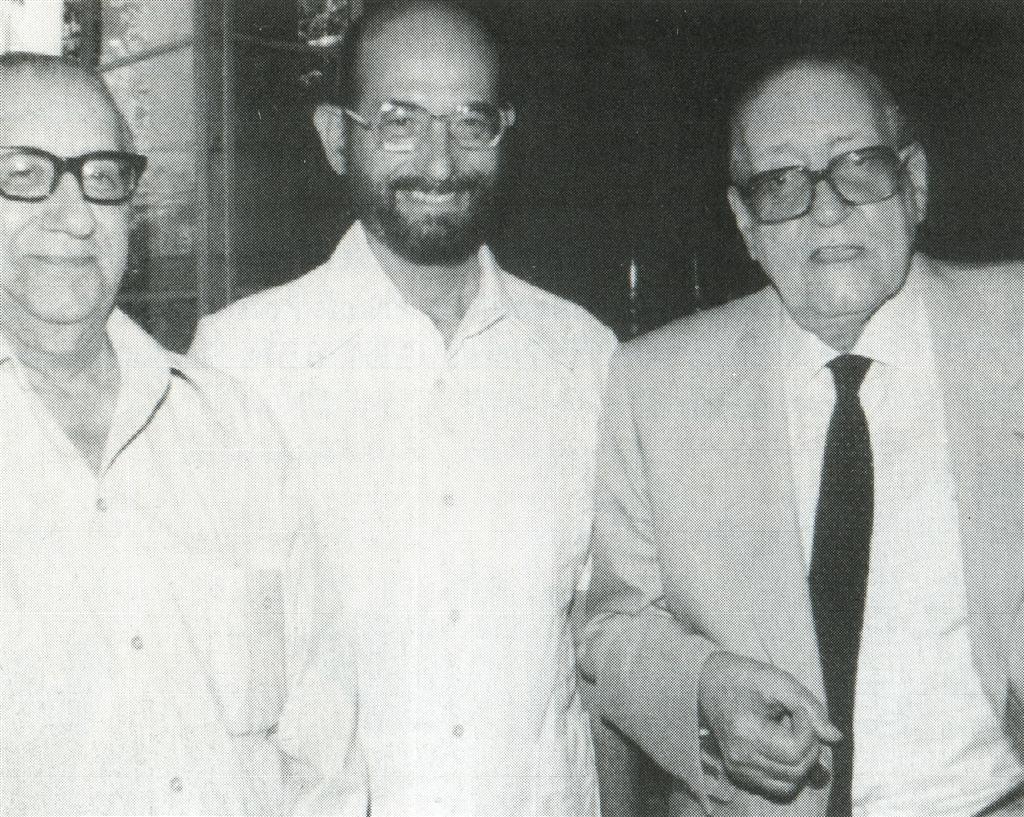

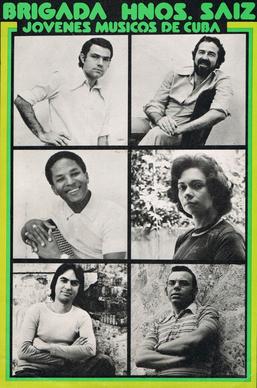

20th-century classical and art music José Marín Varona. Between the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th a number of composers excel within the Cuban music panorama. They cultivated genres such as the popular song and the concert lied, dance music, the zarzuela and the vernacular theatre, as well as symphonic music. Among others, we should mention Hubert de Blanck (1856-1932); José Mauri (1856-1937); Manuel Mauri (1857-1939); José Marín Varona; Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes (1874-1944); Jorge Anckermann (1877-1941); Luis Casas Romero (1882-1950) and Mario Valdés Costa (1898-1930).[14]  Gonzalo Roig. The work of José Marín Varona links the Cuban musical activity from the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century. In 1896, the composer included in his zarzuela "El Brujo" the first Cuban guajira which has been historically documented.[15][16] About this piece, composer Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes said: "The honest critique of a not very far day will bestow the author of the immortal guajira of "El Brujo" the honor to which he is undoubtedly entitled at any time".[17] Gonzalo Roig (1890–1970) was a major force in the first half of the century.[18] A composer and orchestral director, he qualified in piano, violin and composition theory. In 1922 he was one of the founders of the National Symphony Orchestra, which he conducted. In 1927 he was appointed Director of the Havana School of Music. As a composer he specialized in the zarzuela, a musical theatre form, very popular up to World War II. In 1931 he co-founded a bufo company (comic theatre) at the Teatro Martí in Havana. He was the composer of the most well-known Cuban zarzuela, Cecilia Valdés, based on the famous 19th-century novel about a Cuban mulata. It was premiered in 1932. He founded various organizations and wrote frequently on musical topics.[19] One of the greatest Cuban pianist/composers of the 20th century was Ernesto Lecuona (1895–1963).[20] Lecuona composed over six hundred pieces, mostly in the Cuban vein, and was a pianist of exceptional quality. He was a prolific composer of songs and music for stage and film. His works consisted of zarzuela, Afro-Cuban and Cuban rhythms, suites and many songs that became Latin standards. They include Siboney, Malagueña and The Breeze And I (Andalucía). In 1942 his great hit Always in my heart (Siempre en mi Corazon) was nominated for an Oscar for Best Song; it lost out to White Christmas. The Ernesto Lecuona Symphonic Orchestra performed the premiere of Lecuona's Black Rhapsody in the Cuban Liberation Day Concert at Carnegie Hall on 10 October 1943.[21] Although their music is rarely played today, "Amadeo Roldán (1900–1939) and Alejandro García Caturla (1906–1940) were Cuba's symphonic revolutionaries during the first half of the 20th Century.[13] They both played a part in Afrocubanismo: the movement in black-themed Cuban culture with origins in the 1920s, and extensively analysed by Fernando Ortiz. Roldan, born in Paris to a Cuban mulatta and a Spanish father, came to Cuba in 1919 and became the concert-master (first-chair violin) of the new Orquesta Sinfónica de La Habana in 1922. There he met Caturla, at sixteen a second violin. Roldan's compositions included Overture on Cuban themes (1925), and two ballets: La Rebambaramba (1928) and El milagro de Anaquille (1929). There followed a series of Ritmicas and Poema negra (1930) and Tres toques (march, rites, dance) (1931). In Motivos de son (1934) he wrote eight pieces for voice and instruments based on the poet Nicolás Guillén's set of poems with the same title. His last composition was two Piezas infantiles for piano (1937). Roldan died young, at 38, of a disfiguring facial cancer (he had been an inveterate smoker).  Alejandro García Caturla After his student days, Caturla lived all his life in the small central town of Remedios, where he became a lawyer to support his growing family. His Tres danzas cubanas for symphony orchestra was first performed in Spain in 1929. Bembe was premiered in Havana the same year. His Obertura cubana won first prize in a national contest in 1938. Caturla was murdered at 34 by a young gambler.[8]  José Ardévol, Harold Gramatges, Alejo Carpentier Founded in 1942 under the guidance of José Ardévol (1911–1981), a Catalan composer established in Cuba since 1930, the "Grupo de Renovación Musical" served as a platform for a group of young composers to develop a proactive movement with the purpose of improving and literally renovating the quality of the Cuban musical environment. During its existence from 1942 to 1948, the group organized numerous concerts at the Havana Lyceum in order to present their avant-garde compositions to the general public and fostered within its members the development of many future conductors, art critics, performers and professors. They also started a process of investigation and reevaluation of the Cuban music in general, discovering the outstanding work of Carlo Borbolla[22] and promoting the compositions of Saumell, Cervantes, Caturla and Roldán. The "Grupo de Renovación Musical" included the following composers: Hilario González, Harold Gramatges, Julián Orbón, Juan Antonio Cámara, Serafín Pro, Virginia Fleites, Gisela Hernández, Enrique Aparicio Bellver, Argeliers León, Dolores Torres and Edgardo Martín.[citation needed] Other contemporary Cuban composers that were little or no related at all to the "Groupo de Renovación Musical" were: Aurelio de la Vega, Joaquín Nin-Culmell, Alfredo Diez Nieto[23] and Natalio Galán.[24] Although, in Cuba, many composers have written both classical and popular creole types of music, the distinction became clearer after 1960, when (at least initially) the regime frowned on popular music and closed most of the night-club venues, whilst providing financial support for classical music rather than creole forms. From then on, most musicians have kept their careers on one side of the invisible line or the other. After the Cuban Revolution in 1959, a new crop of classical musicians came onto the scene. The most important of these is guitarist Leo Brouwer, who have made significant contributions to the technique and repertoire of the modern classical guitar, and has been the director of the National Symphony Orchestra of Cuba. His directorship in the early 1970s of the "Grupo de Experimentacion Sonora del ICAIC" was instrumental in the formation and consolidation of the Nueva trova movement. Other important composers from the early post-revolution period that began in 1959 were: Carlos Fariñas and Juan Blanco, a pioneer of "concrete" and "electroacoustic music" in Cuba.[25]  Left column, top to bottom: Armando Rodríguez Ruidíaz, Carlos Malcolm, Juan Piñera. Right column, top to bottom: Flores Chaviano, Magali Ruiz, Danilo Avilés. Closely following the early post-revolution generation, a group of young composers started to attract the attention of the public that attended classical music concerts. Most of them had obtained degrees in reputable Schools outside the country thanks to scholarships granted by the government, like Sergio Fernández Barroso (also known as Sergio Barroso), that received a post-graduate degree from the Superior Academy of Music in Prague,[26] and Roberto Valera, who studied with Witold Rudziński and Andrzej Dobrowolski in Poland.[27] Three other composers belong to this group: Calixto Alvarez,[28] Carlos Malcolm[citation needed] and Héctor Angulo.[29] In 1962, the North American composer Federico Smith arrives in Havana. He embraced the Cuban nation as his own country and became one of the most accomplished musicians living and working in Cuba at that time. He remained in Cuba until his death, and made an important contribution to the Cuban musical patrimony. During the early 1970s, a group of musicians and composers, most of them graduated from the National School of Arts and the Havana Conservatory, gathered around an organization recently created by the government as the junior section of UNEAC (National Union of Writers and Artists of Cuba), the "Brigada Hermanos Saíz.[30][31] Some of its member were composers Juan Piñera (nephew of the renowned Cuban writer Virgilio Piñera),[23] Flores Chaviano, Armando Rodriguez Ruidiaz, Danilo Avilés,[23] Magaly Ruiz, Efraín Amador Piñero and José Loyola . Other contemporary composers less involved with the organization were José María Vitier, Julio Roloff,[23] and Jorge López Marín.[32]  Tania León After the Cuban Revolution (1959), many future Cuban composers emigrated at a very young age and developed most of their careers outside the country. Within this group are the composers Tania León, Orlando Jacinto García, Armando Tranquilino,[23] Odaline de la Martinez, José Raul Bernardo,[32] Jorge Martín (composer) and Raul Murciano.[33] |

20世紀のクラシック音楽と芸術音楽 ホセ・マリーン・ヴァローナ 19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけて、キューバ音楽界では多くの作曲家が活躍した。彼らは、ポピュラーソング、リート、ダンスミュージック、サルスエラ、 地方演劇、交響曲などのジャンルを開拓した。中でも、ユベール・デ・ブランク(1856~1932)、ホセ・マウリ(1856~1937)、マヌエル・マ ウリ(1857~1939)、ホセ・マリーン・ヴァローナ、エドゥアルド・サンチェス・デ・フエンテス(1874~1944)、ホルヘ・アンカーマン (1877~1941)、ルイス・カサス・ロメロ(1882~1950)、マリオ・バルデス・コスタ(1898~1930)を挙げることができる [14]。  ゴンサロ・ロイグ ホセ・マリーン・ヴァローナの作品は、19世紀末から20世紀初頭にかけてのキューバの音楽活動をつなぐものである。1896年、この作曲家は自身のサルスエラ「エル・ブルホ」に、歴史的に記録されているキューバ初のグアヒーラを取り入れた[15][16]。 この作品について、作曲家のエドゥアルド・サンチェス・デ・フエンテスはこう語っている: 「そう遠くない日の率直な批評は、「エル・ブルホ 」という不朽のグアヒーラの作者に、いつでも間違いなく受けるべき名誉を与えるだろう」[17]。 ゴンサロ・ロイグ(1890-1970)は、今世紀前半の主要人物であった[18]。作曲家、オーケストラのディレクターとして活躍し、ピアノ、ヴァイオ リン、作曲理論の資格を得た。1922年、彼は国立交響楽団の創設者の一人であり、同オーケストラを指揮した。1927年にはハバナ音楽院院長に任命され た。作曲家としては、第二次世界大戦まで人気を博した音楽劇の形式であるサルスエラを専門とした。1931年には、ハバナのマルティ劇場でブフォ・カンパ ニー(喜劇)を共同設立した。キューバで最も有名なサルスエラ『セシリア・バルデス』の作曲者であり、キューバのムラータを題材にした19世紀の有名な小 説が原作である。この作品は1932年に初演された。彼は様々な団体を設立し、音楽的なテーマについて頻繁に執筆した[19]。 20世紀最大のキューバ人ピアニスト/作曲家の一人はエルネスト・ルクオナ(1895-1963)である[20]。歌曲や舞台音楽、映画音楽の作曲家とし ても多作であった。彼の作品は、サルスエラ、アフロ・キューバン、キューバのリズム、組曲、そしてラテンのスタンダードとなった多くの歌曲で構成されてい る。シボニー』、『マラゲーニャ』、『そよ風と私(アンダルシア)』などである。1942年には大ヒット曲「いつも心に(Siempre en mi Corazon)」がアカデミー賞歌曲賞にノミネートされたが、ホワイト・クリスマスに敗れた。エルネスト・レクオーナ交響楽団は、1943年10月10 日にカーネギー・ホールで行われたキューバ解放記念コンサートで、レクオーナの『黒い狂詩曲』を初演した[21]。 今日、彼らの音楽が演奏されることはほとんどないが、「アマデオ・ロルダン(1900-1939)とアレハンドロ・ガルシア・カトゥーラ(1906-1940)は、20世紀前半のキューバの交響楽革命家であった[13]」。 ロルダンはキューバのムラータとスペイン人の父の間にパリで生まれ、1919年にキューバに渡り、1922年に新オルケスタ・シンフォニカ・デ・ラ・ハバ ナのコンサートマスター(首席ヴァイオリン奏者)となった。そこで16歳で第2ヴァイオリンのカトゥーラと出会う。ロルダンの作曲作品には、キューバの主 題による序曲(1925年)、2つのバレエがある: La Rebambaramba(1928年)とEl milagro de Anaquille(1929年)である。続いて、一連のリトミカスとポエマ・ネグラ(1930年)、Tres toques(行進曲、儀式、ダンス)(1931年)がある。Motivos de son』(1934年)では、詩人ニコラス・ギジェンの同タイトルの詩集に基づき、声楽と楽器のための8曲を作曲した。最後に作曲したのは、ピアノのため の2つの幼児向け小品(1937年)である。ロルダンは、38歳の若さで、醜い顔面の癌(彼は常習的な喫煙者であった)で亡くなった。  アレハンドロ・ガルシア・カトゥーラ 学生時代を過ごした後、カトゥーラは中央部の小さな町レメディオスで生涯を過ごし、成長する家族を養うために弁護士となった。交響楽団のための《Tres danzas cubanas》は1929年にスペインで初演された。同年、ハバナで「ベンベ」が初演された。オベルトゥーラ・クバーナは1938年に全国コンクールで 1位を獲得した。カトゥーラは34歳の時に若いギャンブラーに殺害された[8]。  ホセ・アルデヴォル、ハロルド・グラマッジス、アレホ・カルペンティエ 1930年からキューバで活動していたカタルーニャ出身の作曲家、ホセ・アルデヴォル(1911~1981)の指導のもと1942年に設立された 「Grupo de Renovación Musical 」は、キューバの音楽環境の質を向上させ、文字通り刷新することを目的とした積極的な運動を展開する若手作曲家グループのプラットフォームとして機能し た。1942年から1948年までの活動期間中、このグループはハバナ・リセウムで数多くのコンサートを開催し、前衛的な楽曲を一般大衆に披露するととも に、メンバーの中に将来の指揮者、芸術評論家、パフォーマビティ、教授を多数輩出した。彼らはまた、キューバ音楽全般の調査と再評価のプロセスを開始し、 カルロ・ボルボラ[22]の優れた作品を発見し、サウメル、セルバンテス、カトゥーラ、ロルダンの作曲を推進した。音楽改革グループ」には以下の作曲家が 含まれていた: ヒラリオ・ゴンサレス、ハロルド・グラマッジス、フリアン・オルボン、フアン・アントニオ・カマラ、セラフィン・プロ、ヴァージニア・フライテス、ジゼ ラ・エルナンデス、エンリケ・アパリシオ・ベリバー、アルゲリエス・レオン、ドロレス・トーレス、エドガルド・マルティンなどである: アウレリオ・デ・ラ・ベガ、ホアキン・ニン=クルメル、アルフレド・ディエス・ニエト[23]、ナタリオ・ガラン[24]である。 キューバでは、多くの作曲家がクラシックとポピュラー・タイプのクレオール音楽の両方を書いてきたが、1960年以降、(少なくとも当初は)政権がポピュ ラー音楽を嫌悪し、ナイトクラブの会場のほとんどを閉鎖したことで、その区別が明確になった。それ以来、ほとんどの音楽家は、見えない線のどちらか一方に 自分のキャリアを置いている。1959年のキューバ革命後、新しいクラシック音楽家が登場した。その最たるものがギタリストのレオ・ブローウェルで、彼は モダン・クラシック・ギターのテクニックとレパートリーに多大な貢献をし、キューバ国立交響楽団のディレクターも務めている。1970年代初頭に 「ICAICソノラ実験グループ」のディレクターを務めたことは、ヌエバ・トロヴァ・ムーブメントの形成と定着に貢献した。 1959年に始まった革命後初期の重要な作曲家は他にいる: カルロス・ファリニャスと、キューバにおける「具象音楽」と「電子音響音楽」の先駆者であるフアン・ブランコである[25]。  左列、上から下へ: アルマンド・ロドリゲス・ルイディアス、カルロス・マルコム、フアン・ピニェラ。右列、上から下へ: フローレス・チャビアーノ、マガリ・ルイス、ダニーロ・アビレス。 革命後間もない世代に続いて、若い作曲家たちがクラシック音楽コンサートに足を運ぶ人々の注目を集め始めた。彼らのほとんどは、政府から支給された奨学金 のおかげで、国外の評判の高い学校で学位を取得していた。例えば、セルヒオ・フェルナンデス・バロソ(セルヒオ・バロソとしても知られる)は、プラハの高 等音楽アカデミーの大学院で学位を取得し[26]、ロベルト・バレラは、ポーランドでヴィトルド・ルドジンスキとアンジェイ・ドブロヴォルスキに師事した [27]: カリクスト・アルバレス、カルロス・マルコム[要出典]、エクトル・アングーロである[29]。 1962年、北米の作曲家フェデリコ・スミスがハバナに到着する。彼はキューバという国を自分の国として受け入れ、当時キューバに住み、活動していた最も優れた音楽家の一人となった。彼は亡くなるまでキューバに留まり、キューバの音楽遺産に重要な貢献をした。 1970年代初頭、国立芸術学校とハバナ音楽院を卒業した音楽家と作曲家のグループが、UNEAC(キューバ全国作家芸術家連合)のジュニア部門として政 府によって設立されたばかりの組織「ブリガダ・エルマノス・サイス」に集まった。 [30][31]メンバーの中には、作曲家のフアン・ピニェラ(有名なキューバの作家ヴィルジリオ・ピニェラの甥)、[23]フローレス・チャビアーノ、 アルマンド・ロドリゲス・ルイディアス、ダニロ・アビレス、[23]マガリ・ルイス、エフライン・アマドール・ピニェロ、ホセ・ロヨラなどがいた。この組 織との関わりが薄かった現代作曲家としては、ホセ・マリア・ヴィティエ、フリオ・ロロフ[23]、ホルヘ・ロペス・マリンがいる[32]。  タニア・レオン キューバ革命(1959年)後、多くの未来のキューバ人作曲家が若くして移住し、キャリアのほとんどを国外で築いた。このグループの中には、タニア・レオ ン、オルランド・ハシント・ガルシア、アルマンド・トランキリーノ、[23] オダリーヌ・デ・ラ・マルティネス、ホセ・ラウル・ベルナルド、[32] ホルヘ・マルティン(作曲家)、ラウル・ムルシアーノといった作曲家がいる[33]。 |

| 21st-century classical and art music During the last decades of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century a new generation of composers emerged into the Cuban classical music panorama. Most of them received a solid musical education provided by the official arts school system created by the Cuban government and graduated from the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA). Some of those composers are Louis Franz Aguirre,[34] Ileana Pérez Velázquez, Keila María Orozco,[32] Viviana Ruiz,[23] Fernando (Archi) Rodríguez Alpízar,[35] Yalil Guerra, Eduardo Morales Caso,[36] Ailem Carvajal Gómez, Irina Escalante Chernova and Evelin Ramón. All of them have emigrated and currently live and have worked in other countries.[citation needed] |

21世紀のクラシック音楽と芸術音楽 20世紀末から21世紀初頭にかけて、キューバのクラシック音楽界に新しい世代の作曲家が登場した。彼らのほとんどは、キューバ政府によって設立された公 的な芸術学校制度によってしっかりとした音楽教育を受け、高等芸術学院(ISA)を卒業した。それらの作曲家の中には、ルイス・フランツ・アギーレ、 [34] イレアナ・ペレス・ベラスケス、ケイラ・マリア・オロスコ、[32] ビビアナ・ルイス、[23] フェルナンド(アルチ)・ロドリゲス・アルピサル、[35] ヤリル・ゲラ、エドゥアルド・モラレス・カソ、[36] アイレム・カルバハル・ゴメス、イリーナ・エスカランテ・チェルノヴァ、エヴェリン・ラモンなどがいる。彼ら全員が移住し、現在は他国に住み、仕事をして いる[要出典]。 |

| Electroacoustic music in Cuba This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Juan Blanco was the first Cuban composer to create an electroacoustic piece in 1961. This first composition, titled "Musica Para Danza", was produced with just an oscillator and three common tape recorders. However, it was not until 1969 that another Cuban composer, Sergio Barroso, dedicated himself to the creation of electroacoustic musical compositions. In 1970, Juan Blanco began to work as a music advisor for the Department of Propaganda of ICAP (Insituto Cubano de Amistad con Los Pueblos). In this capacity, he created electroacoustic music for all the audiovisual materials produced by ICAP. After nine years working without restitution, Blanco finally obtained financing to set up an Electroacoustic Studio to be used for his work. He was appointed as Director of the Studio, but under the condition that he should be the only one to use the facility. After a few months, and without asking for permission, he opened the Electroacoustic Studio to all composers interested in working with electroacoustic technology, thus creating the ICAP Electroacoustsic Music Workshop (TIME), where he himself provided training to all participants. In 1990, the ICAP Workshop changed its name to Laboratorio Nacional de Música Electroacústica (LNME) and its main objective was to support and promote the work of Cuban electroacoustic composers and sound artists. Some years later, another electroacoustic music studio was created at the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA). The Estudio de Música Electroacústica y por Computadoras (EMEC), currently named Estudio Carlos Fariñas de Arte Musical (Carlos Fariñas Studio of Musical Electroacoustic Art), is intended to provide electroacoustic music training to the composition students during the last years of their careers. After 1970, Cuban composers such as Leo Brouwer, Jesús Ortega, Carlos Fariñas and Sergio Vitier began also creating electroacoustic pieces; and in the 1980s a group of composers that included Edesio Alejandro, Fernando (Archi) Rodríguez Alpízar, Marietta Véulens, Mirtha de la Torre, Miguel Bonachea and Julio Roloff, started receiving instruction and working at the ICAP Electroacoustic Studio. A list of Cuban composers that have utilized elecotroacoustics technology include Argeliers León, Juan Piñera, Roberto Valera, José Loyola, Ileana Pérez Velázquez and José Angel Pérez Puentes.[37] Most Cuban composers that established their residence outside Cuba have worked with electroacoustic technology. These include composers Aurelio de la Vega, Armando Tranquilino, Tania León, Orlando Jacinto García, Armando Rodriguez Ruidiaz, Ailem Carvajal Gómez and Irina Escalante Chernova.[38] |

キューバの電子音響音楽 このセクションでは、検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセク ションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性があ る。(2018年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) フアン・ブランコは1961年、キューバ人作曲家として初めて電子音響作品を制作した。Musica Para Danza」と題されたこの最初の作品は、オシレーターと3台の一般的なテープレコーダーだけで制作された。しかし、同じくキューバの作曲家セルヒオ・バ ローゾが電子音響音楽の創作に専念したのは1969年のことだった。 1970年、フアン・ブランコはICAP(Insituto Cubano de Amistad con Los Pueblos)の宣伝部の音楽アドバイザーとして働き始めた。ICAPが制作するすべての視聴覚資料のための電子音響音楽を制作した。9年間、何の報酬 も得られないまま働き続けたブランコは、ついに資金を得て、自分の仕事に使うための電気音響スタジオを設立した。彼はスタジオのディレクターに任命された が、その施設を使うのは自分だけという条件付きだった。 数ヵ月後、彼は許可を得ることなく、電子音響スタジオを電子音響技術を使った作品に興味のある作曲家全員に開放し、ICAP電子音響音楽ワークショップ (TIME)を創設した。1990年、ICAPワークショップはラボラトリオ・ナシオナル・デ・ムジカ・エレクトロアコースティカ(LNME)と名称を変 え、キューバの電子音響作曲家やサウンド・アーティストの活動を支援・促進することを主な目的とした。 数年後、もうひとつの電子音響音楽スタジオがInstituto Superior de Arte(ISA)に設立された。EMEC(Estudio de Música Electroacústica y por Computadoras)は現在、カルロス・ファリニャス音楽電子音響スタジオ(Estudio Carlos Fariñas de Arte Musical)と名付けられ、作曲を学ぶ学生たちのキャリアの最後の時期に、電子音響音楽のトレーニングを提供することを目的としている。 1970年以降、レオ・ブローウェル、ヘスス・オルテガ、カルロス・ファリニャス、セルジオ・ヴィティエといったキューバの作曲家たちも電子音響作品を作 り始め、1980年代には、エデシオ・アレハンドロ、フェルナンド・ロドリゲス・アルピサル、マリエッタ・ベウレンス、ミルタ・デ・ラ・トーレ、ミゲル・ ボナヘア、フリオ・ロロフといった作曲家たちがICAP電子音響スタジオで指導を受け、活動を始めた。電気音響技術を利用したキューバの作曲家のリストに は、アルゲリエス・レオン、フアン・ピニェラ、ロベルト・バレラ、ホセ・ロヨラ、イレアナ・ペレス・ベラスケス、ホセ・アンヘル・ペレス・プエンテスなど がいる[37]。 キューバ国外に居を構えたキューバ人作曲家のほとんどは、電子音響技術を用いた作品を残している。その中には、アウレリオ・デ・ラ・ベガ、アルマンド・ト ランキリーノ、タニア・レオン、オルランド・ハシント・ガルシア、アルマンド・ロドリゲス・ルイディアス、アイレム・カルバハル・ゴメス、イリーナ・エス カランテ・チェルノヴァなどの作曲家が含まれる[38]。 |

| Classical guitar in Cuba Main article: Classical Guitar in Cuba From the 16th to the 19th century The guitar (as it is known today or in one of its historical versions) has been present in Cuba since the discovery of the island by Spain. As early as the 16th century, a musician named Juan Ortiz, from the village of Trinidad, is mentioned by famous chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo as "gran tañedor de vihuela y viola" ("a great performer of the vihuela and the guitar"). Another "vihuelista", Alonso Morón from Bayamo, is also mentioned in the Spanish conquest chronicles during the 16th century.[39][40] A disciple of famous Spanish guitarist Dionisio Aguado, José Prudencio Mungol was the first Cuban guitarist trained in the Spanish guitar tradition. In 1893 he performed at a much acclaimed concert in Havana, after returning from Spain. Mungol actively participated in the musical life of Havana and was a professor at the Hubert de Blanck conservatory.[41] 20th century and beyond Severino López was born in Matanzas. He studied guitar in Cuba with Juan Martín Sabio and Pascual Roch, and in Spain with renowned Catalan guitarist Miguel Llobet. Severino López is considered the initiator in Cuba of the guitar school founded by Francisco Tárrega in Spain.[42] Clara Romero (1888-1951), founder of the modern Cuban School of Guitar, studied in Spain with Nicolás Prats and in Cuba with Félix Guerrero. She inaugurated the guitar department at the Havana Municipal Conservatory in 1931, where she also introduced the teachings of the Cuban folk guitar style. She created the Guitar Society of Cuba (Sociedad Guitarrística de Cuba) in 1940, and also the "Guitar" (Guitarra) magazine, with the purpose of promoting the Society's activities. She was the professor of many Cuban guitarists including her son Isaac Nicola and her daughter Clara (Cuqui) Nicola.[43] After studying with his mother, Clara Romero, at the Havana Municipal Conservatory, Isaac Nicola (1916 – 1997) continued his training in Paris with Emilio Pujol, a disciple of Francisco Tárrega. He also studied the vihuela with Pujol and researched about the guitar's history and literature.[44] Modern Cuban Guitar School  Leo Brouwer After the Cuban revolution in 1959, Isaac Nicola and other professors such as Marta Cuervo, Clara (Cuqui) Nicola, Marianela Bonet and Leopoldina Núñez were integrated to the national music schools system, where a unified didactical method was implemented. This was a nucleus for the later development of a national Cuban Guitar School with which a new generation of guitarists and composers collaborated. Maybe the most important contribution to the modern Cuban guitar technique and repertoire comes from Leo Brouwer (born 1939). The grandson of Ernestina Lecuona, sister of Ernesto Lecuona, Brouwer began studying the guitar with his father and after some time continued with Isaac Nicola. He taught himself harmony, counterpoint, musical forms and orchestration before completing his studies at the Juilliard School and the University of Hartford. New generations Since the 1960s, several generations of guitar performers, professors and composers have been formed under the Cuban Guitar School at educational institutions such as the Havana Municipal Conservatory, the National School of Arts, and the Instituto Superior de Arte. Others, such as Manuel Barrueco, a concertist of international renown, developed their careers outside the country. Among many other guitarists related to the Cuban Guitar School are Carlos Molina, Sergio Vitier, Flores Chaviano, Efraín Amador Piñero, Armando Rodriguez Ruidiaz, Martín Pedreira, Lester Carrodeguas, Mario Daly, José Angel Pérez Puentes and Teresa Madiedo. A younger group includes guitarists Rey Guerra, Aldo Rodríguez Delgado, Pedro Cañas, Leyda Lombard, Ernesto Tamayo, Miguel Bonachea,[45] Joaquín Clerch[46][47] and Yalil Guerra. |

キューバのクラシックギター 主な記事 キューバのクラシック・ギター 16世紀から19世紀まで キューバでは、スペインがキューバを発見して以来、ギター(現在または歴史的に知られているもの)は存在していた。16世紀には、トリニダッド村出身のフ アン・オルティスという音楽家が、有名な年代記作家ベルナル・ディアス・デル・カスティージョによって 「gran tañedor de vihuela y viola」(「ヴィウエラとギターの偉大な演奏者」)として言及されている。また、バヤモ出身のアロンソ・モロンも16世紀のスペイン征服年代記に登場 する[39][40]。 有名なスペイン人ギタリスト、ディオニシオ・アグアドの弟子であるホセ・プルデンシオ・マンゴルは、スペインギターの伝統に習った最初のキューバ人ギタリ ストである。1893年、スペインから帰国した彼はハバナでコンサートを開き、高い評価を得た。ムンゴルはハバナの音楽生活に積極的に参加し、ユベール・ デ・ブランク音楽院の教授も務めた[41]。 20世紀以降 セヴェリーノ・ロペスはマタンサスに生まれる。キューバではフアン・マルティン・サビオとパスクアル・ロッホに、スペインでは著名なカタルーニャ人ギタリ スト、ミゲル・ロベにギターを師事した。セヴェリーノ・ロペスは、スペインのフランシスコ・タルレガが創設したギター・スクールのキューバにおける創始者 とされている[42]。 近代キューバギター学校の創始者であるクララ・ロメロ(1888-1951)は、スペインでニコラス・プラッツに、キューバでフェリックス・ゲレーロに師 事した。1931年にハバナ市立音楽院にギター科を開設し、キューバのフォーク・ギター・スタイルの教えも紹介した。1940年にはキューバ・ギター協会 (Sociedad Guitarrística de Cuba)を設立し、協会の活動を促進する目的で「ギター」(Guitarra)誌も創刊した。彼女は息子のアイザック・ニコラや娘のクララ(クキ)・ニ コラを含む多くのキューバ人ギタリストの教授であった[43]。 ハバナ市立音楽院で母クララ・ロメロに師事した後、イサク・ニコラ(1916年 - 1997年)はパリでフランシスコ・タルレガの弟子エミリオ・プジョルに師事した。また、プジョールのもとでヴィウエラを学び、ギターの歴史や文献についても研究した[44]。 現代キューバギター派  レオ・ブローウェル 1959年のキューバ革命後、イサク・ニコラをはじめ、マルタ・クエルボ、クララ(クキ)・ニコラ、マリアネラ・ボネ、レオポルディナ・ヌニェスといった 教授陣が国立音楽学校のシステムに統合され、統一された教授法が実施された。これは後にキューバ国立ギター学校を発展させる核となり、新しい世代のギタリ ストや作曲家たちが協力することになった。 現代キューバ・ギターのテクニックとレパートリーへの最も重要な貢献は、レオ・ブローウェル(1939年生まれ)だろう。エルネスト・ルクオナの姉エルネ スティナ・ルクオナの孫であるブローウェルは、父にギターを習い始め、しばらくしてアイザック・ニコラに師事した。独学で和声、対位法、音楽形式、オーケ ストレーションを学んだ後、ジュリアード音楽院とハートフォード大学で学んだ。 新しい世代 1960年代以降、ハバナ市立音楽院、国立芸術学校、高等芸術学院などの教育機関で、キューバ・ギター・スクールのもと、数世代のギター演奏家、教授、作 曲家が形成された。また、国際的に有名なコンチェルト奏者マヌエル・バルエコのように、国外でキャリアを積んだ者もいる。キューバ・ギター学校に関係する ギタリストとしては、カルロス・モリーナ、セルジオ・ヴィティエ、フローレス・チャビアーノ、エフライン・アマドール・ピニェーロ、アルマンド・ロドリゲ ス・ルイディアス、マルティン・ペドレイラ、レスター・カロデガス、マリオ・ダリー、ホセ・アンヘル・ペレス・プエンテス、テレサ・マディエドなどがい る。若いグループには、レイ・ゲラ、アルド・ロドリゲス・デルガド、ペドロ・カニャス、レイダ・ロンバード、エルネスト・タマヨ、ミゲル・ボナケア [45]、ホアキン・クレルチ[46][47]、ヤリル・ゲラなどのギタリストがいる。 |

| Classical piano in Cuba Main article: Classical piano in Cuba Ernesto Lecuona After its arrival in Cuba at the end of the 18th century, the pianoforte (commonly called piano) rapidly became one of the favorite instruments among the Cuban population. Along with the humble guitar, the piano accompanied the popular Cuban "guarachas" and "contradanzas" (derived from the European Country Dances) at salons and ballrooms in Havana and all over the country.[48] As early as in 1804, a concert program in Havana announced a vocal concert "accompanied at the fortepiano by a distinguished foreigner recently arrived"[49] and in 1832, Juan Federico Edelmann (1795-1848), a renowned pianist, son of a famous Alsatian composer and pianist, arrived in Havana and gave a very successful concert at the Teatro Principal. Encouraged by the warm welcome, Edelmann decided to stay in Havana, and he was very soon promoted to an important position within the Santa Cecilia Philharmonic Society. In 1836, he opened a music store and publishing company.[50] One of the most prestigious Cuban musicians, Ernesto Lecuona (1895-1963), began studying piano with his sister Ernestina and continued with Peyrellade, Saavedra, Nin and Hubert de Blanck. A child prodigy, Lecuona gave a concert, at just five, at the Círculo Hispano. When he graduated from the National Conservatory, he was awarded the First Prize and the Gold Medal of his class by unanimous decision of the board. He is by far the Cuban composer of greatest international recognition and his contributions to the Cuban piano tradition are considered exceptional.[21] |

キューバのクラシックピアノ 主な記事 キューバのクラシックピアノ エルネスト・レクオナ 18世紀末にキューバに到着したピアノフォルテ(通称ピアノ)は、キューバの人々の間で急速に愛用されるようになった。地味なギターとともに、ピアノはハ バナやキューバ全土のサロンや舞踏場で、キューバで人気のある「グアラチャス」や「コントラヴァンツァス」(ヨーロッパのカントリーダンスに由来する)の 伴奏を務めた。 [また1832年には、アルザスの有名な作曲家兼ピアニストの息子で、著名なピアニストであったフアン・フェデリコ・エデルマン(1795-1848)が ハバナに到着し、テアトロ・プリンシパルでコンサートを開き、大成功を収めた。温かい歓迎に励まされ、エーデルマンはハバナに留まることを決め、すぐにサ ンタ・チェチーリア・フィルハーモニック協会の重要なポジションに昇進した。1836年には、楽器店と出版社を開いた[50]。 キューバで最も有名な音楽家の一人であるエルネスト・ルクオナ(1895-1963)は、姉のエルネスティナにピアノを習い始め、ペイレラード、サーヴェ ドラ、ニン、ユベール・デ・ブランクに師事した。神童だったルクオナは、わずか5歳でシルクロ・イスパノでコンサートを開いた。国立音楽院を卒業した時に は、審査員全員一致で最優秀賞と金賞を受賞した。キューバ人作曲家の中で最も国際的な知名度が高く、キューバのピアノの伝統に対する彼の貢献は並大抵のも のではないと考えられている[21]。 |

| Classical violin in Cuba Main article: Classical violin in Cuba From the 16th to the 18th century Bowed stringed instruments have been present in Cuba since the 16th century. Musician Juan Ortiz from the Ville of Trinidad is mentioned by chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo as a "great performer of "vihuela" and "viola".[42] On In 1764, Esteban Salas y Castro, became the new chapel master of the Santiago de Cuba Cathedral, and to fulfill his musical duties he counted with a small vocal-instrumental group that included two violins.[51] In 1793, numerous colonists fleeing from the slave revolt in Saint Domingue arrived in Santiago de Cuba, and an orchestra consisting of a flute, oboe, clarinet, trumpet, three horns, three violins, viola, two violoncellos, and percussion was founded.[52] From the 18th to the 19th century During the transition from the 18th to the 19th centuries, the Havanese Ulpiano Estrada (1777–1847) offered violin lessons and conducted the Teatro Principal orchestra from 1817 to 1820. Apart from his activity as a violinist, Estrada kept a very active musical career as a conductor of numerous orchestras, bands and operas, and composing many contradanzas and other dance pieces, such as minuets and valses.[53] José Vandergutch, Belgian violinist, arrived at Havana along with his father Juan and brother Francisco, also violinists. They returned at a later time to Belgium, but José established his permanent residence in Havana, where he acquired great recognition. Vandergutch offered numerous concerts as a soloist and accompanied by several orchestras, around the mid-19th century. He was a member of the Classical Music Association and also a Director of The "Asociación Musical de Socorro Mutuo de La Habana."[54] Within the universe of the classical Cuban violin during the 19th century, there are two outstanding Masters that may be considered among the greatest violin virtuosos of all time; they are José White Lafitte y Claudio Brindis de Salas Garrido.  José White in 1856, after receiving ana award from the Conservatoire de Paris After receiving his first musical instruction from his father, the virtuoso Cuban violinist José White Lafitte (1835–1918) offered his first concert in Matanzas on March 21, 1854. In that presentation he was accompanied by the famous American pianist and composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk, whom encouraged him to further his musical instruction in Paris, and also collected funds for that purpose.[55] José White studied musical composition in the Conservatoire de Paris from 1855 to 1871. Just ten months after his arrival he won the first prize in the violin category on the Conservatorie's contest and was highly praised by Gioachino Rossini. At a later time he was a professor of the renowned violinists George Enescu and Jacques Thibaud. From 1877 to 1889, White was appointed as Director of the Imperial Conservatory in Rio de Janeiro, Brasil, where he also served as court musician of the Emperor Pedro II.[56] At a later time he returned to Paris where he stayed until his death. The famous violin named "Swan's song" was his preferred instrument and his most famous composition is the Habanera "La bella cubana". White also composed many other pieces, including a concert for violin and orchestra.[57]  Claudio José Domingo Brindis de Salas y Garrido, called the "Black "Paganini" posing with his famous Stradivarius Claudio José Domingo Brindis de Salas y Garrido (1852–1911) was a renowned Cuban violinist, son of the also famous violinist, double-bassist and conductor Claudio Brindis de Salas (1800-1972), which conducted one of the most popular orchestras of Havana during the first half of the 19th century, named "La Concha de Oro" (The Golden Conch). Claudio José surpassed the fame and expertise of his father and came to acquire international recognition.[58][59][60] Claudio Brindis de Salas Garrido began his musical studies with his father and continued with Maestros José Redondo and the Belgian José Vandergutch. He offered his first concert in Havana in 1863, in which Vandegutch participated as accompanist. The famous pianist and composer Ignacio Cervantes also participated in that event. According with the contemporary critique, Brindis de Salas was considered one of the most outstanding violinists of his time at an international level. Alejo Carpentier referred to him as: "The most outstanding black violinist from the 19th century... something without any precedent in the musical history of the continent".[61] The French government named him member of the Légion d'Honneur, and gave him a nobility title of "Baron". In Buenos Aires he received a genuine Stradivarius, and while living in Berlin he married a German lady, was named Chamber Musician of the Emperor and received an honorary citizenship from that country. Brindis de Salas died poor and forgotten in 1911 from tuberculosis, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. In 1930 his remains were transferred to Havana with great honors.[62] Another outstanding Cuban violinist from the 19th century was Rafael Díaz Albertini (1857–1928). He studied violin with José Vandergutch and Anselmo López (1841-1858), well known Havanese violinist that was dedicated also to music publishing. In 1870, Albertini travelled to Paris with the purpose of perfecting his technique with famous violinist Jean-Delphin Alard, and in 1875 received First prize in the Paris Contest, in which he subsequently participated as a Juror. He toured extensively through the world, accompanied some times by prestigious Masters such as Hugo Wolf and Camille Saint-Saëns. In 1894 he made presentations, along with Ignacion Cervantes, through the most important cities of Cuba.[63] A list of prominent Cuban violinist from the second half of the 19th century and the first of the 20th may include: Manuel Muñoz Cedeño (b. 1813), José Domingo Bousquet (b. 1823), Carlos Anckermann (b. 1829), Antonio Figueroa (b. 1852), Ramón Figueroa (b. 1862), Juan Torroella (b.1874), Casimiro Zertucha (b. 1880), Joaquín Molina (b. 1884), Marta de La Torre (1888), Catalino Arjona (b. 1895) and Diego Bonilla (1898-).[64] From the 20th to the 21st century During the first half of the 20th century the name of Amadeo Roldán stands out (1900–1939), because apart from an excellent violinist, professor and conductor, Roldán is considered one of the most important Cuban composers of all time. After his graduation at the Conservatoire de Paris in 1935 with just 16 years old, the renowned Cuban violinist Ángel Reyes (1919–1988) developed a very successful career as a soloist and also accompanied by prestigious orchestras of many countries. He established his residence in the United States at a very young age, obtained an award in the Ysaÿe Contest in Brussels and was a professor at the Michigan and Northwestern Universities, until his retirement in 1985.[65] Eduardo Hernández Asiaín (1911-2010) was born in Havana, began his musical studies at a very early age and offered his first concert with just seven years old. When he was 14, he obtained the First Award at the Municipal Conservatory of Havana and was appointed as Concertino of the Havana Symphony Orchestra. In 1932, he travelled to Madrid to further his musical education with professors Enrique Fernández Arbós and Antonio Fernández Bordas. Since 1954, Hernández Asiaín performed as a soloist with the orchestras from the Pasdeloup Concert Society and the Radiodiffusion française in Paris, the "Orquesta Nacional de España", the "Orquesta Sinfónica de Bilbao", the "Orquesta de Cámara de Madrid" and the "Orquesta Sinfónica y de Cámara de San Sebastián", of which he is the founder. In 1968, he was appointed as First Violin of the "Cuarteto Clásico" of RTVE, participating with pianist Isabel Picaza González in the "Quinteto Clásico de RNE", with which he offered concerts and made numerous recordings in Spain and other countries. He also toured extensively through the US.[66] Other prominent Cuban violinists from the first half of the 20th century are: Robero Valdés Arnau (1919-1974), Alberto Bolet and Virgilio Diago.[67] After 1959, already in the post revolutionary period, stands out a Cuban violinist that has made a substantial contribution, not just to the development of the violin and the bowed string instruments, but also to the national musical culture in general. Evelio Tieles began to study music in Cuba with his father, Evelio Tieles Soler, when he was just seven years old,[68] and continued at a later time with professor Joaquín Molina. Between 1952 and 1954, Tieles studied violin in Paris, France, with Jacques Thibaud and René Benedetti. In 1955 he returned to Paris and studied at the National Superior Music Conservatory in that city, and in 1958, he continued his musical training at Conservatorio Tchaikovsky in Moscú, where he was a disciple of renowned violinists David Oistrakh and Igor Oistrakh. Tieles graduated in 1963 and by recommendation of the Conservatory he pursued his master's degree from 1963 to 1966, with the same mentioned professors.[68] Tieles received also professional training from the prestigious violinists Henryk Szeryng and Eduardo Hernández Asiaín.[69] Evelio Tieles has offered numerous presentations as a concert performer, in a duo with his brother, pianist Cecilio Tieles, or accompanied by the Cuban National Symphony Orchestra and other symphonic and chamber ensembles. He has performed along with prestigious conductors such as Thomas Sanderling, Boris Brott, Enrique González Mántici y Manuel Duchesne Cuzán, among others.[citation needed] Tieles has established his residence in Spain since 1984, and he teaches violin in the Vila-Seca Conservatory, in the province of Tarragona, where he has been appointed as "Professor Emeritus".[citation needed] He has also served at the Superior Conservatory of the Barcelona Lyceum as Chief of the Chamber Music Department (1991–1998), Head of the Division of Bowed String Instruments (1986-2002) and Academic Director (2000–2002).[69] Apart from his outstanding career as a concert performer and professor, during the Post-Revolutionary period, Tieles promoted and organized in Cuba the bowed string instruments training, fundamentally for the violin.[69] Another prominent violinist is professor Alla Tarán (1941). She was formed as a violinist in her native Ukraine and worked as a professor of Chamber Ensemble Practice. Tarán established her residence in Cuba since 1969.[citation needed] Alfredo Muñoz (1949) began studying the violin at Conservatorio Orbon in Havana, Cuba, and subsequently continued at the National School of Arts and the Instituto Superior de Arte (ISA). He joined the National Symphony Orchestra as a violinist in 1972 and since then has been very active as a soloist and a member of the White Trio, in Cuba and abroad. He is currently a professor at the Instituto Superior de Artes (ISA).[70] Other Cuban violinists that have developed their careers between the 20th and the 21st century are: Armando Toledo (1950), Julián Corrales (1954), Miguel del Castillo and Ricardo Jústiz.[64] 21st century This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Already at the beginning of the 21st century the violinists Ilmar López-Gavilán, Mirelys Morgan Verdecia, Ivonne Rubio Padrón, Patricia Quintero and Rafael Machado are worthy of note. |

キューバのクラシック・ヴァイオリン 主な記事 キューバのクラシック・ヴァイオリン 16世紀から18世紀まで 弓を使った弦楽器は16世紀からキューバに存在していた。1764年、エステバン・サラス・イ・カストロがサンティアゴ・デ・クーバ大聖堂の新しい礼拝堂 司祭となり、音楽的任務を果たすために2台のヴァイオリンを含む小さな声楽と楽器のグループを数えた。 [1793年、サン・ドミンゲの奴隷反乱から逃れてきた多くの植民者たちがサンティアゴ・デ・クーバに到着し、フルート、オーボエ、クラリネット、トラン ペット、3本のホルン、3本のヴァイオリン、ヴィオラ、2本のヴィオロンチェロ、打楽器から成るオーケストラが設立された[52]。 18世紀から19世紀へ 18世紀から19世紀への移行期には、ハヴァネス出身のウルピアーノ・エストラーダ(1777-1847)がヴァイオリンのレッスンを行い、1817年か ら1820年までテアトロ・プリンシパルのオーケストラを指揮した。ヴァイオリニストとしての活動とは別に、エストラーダは数多くのオーケストラ、楽団、 オペラの指揮者として非常に活発な音楽活動を続け、メヌエットやヴァルスのようなコントランサやその他の舞曲を数多く作曲した[53]。 ベルギー人ヴァイオリニストのホセ・ヴァンダーガッチは、同じくヴァイオリニストの父フアンと弟フランシスコとともにハバナに到着した。彼らは後にベル ギーに戻ったが、ホセはハバナに定住し、そこで大きな評価を得た。ヴァンデルガッチは、19世紀半ば頃、ソリストとして、またいくつかのオーケストラの伴 奏者として、数多くのコンサートを開いた。彼はクラシック音楽協会のメンバーであり、ラ・ハバナ音楽協会(Asociación Musical de Socorro Mutuo de La Habana)の理事でもあった[54]。 19世紀におけるキューバのクラシック・ヴァイオリンの世界には、史上最高のヴァイオリン・ヴィルトゥオーゾとみなされる2人の傑出した巨匠がいる。  1856年、パリ国立高等音楽院から勲章を授与されたホセ・ホワイト 父親から初めて音楽の手ほどきを受けたキューバの名ヴァイオリニスト、ホセ・ホワイト・ラフィット(1835-1918)は、1854年3月21日にマタ ンサスで最初のコンサートを開いた。その演奏会では、有名なアメリカ人ピアニスト兼作曲家のルイス・モロー・ゴットシャルクが同伴し、彼は彼にパリで音楽 教育を受けることを勧め、そのための資金も集めた[55]。 ジョゼ・ホワイトは1855年から1871年までパリ音楽院で作曲を学んだ。到着してわずか10ヶ月後、彼はコンセルヴァトワールのコンクールのヴァイオ リン部門で優勝し、ジョアキーノ・ロッシーニに高く評価された。その後、著名なヴァイオリニスト、ジョージ・エネスクとジャック・ティボーの教授を務め た。 1877年から1889年にかけて、ホワイトはブラジルのリオ・デ・ジャネイロにある帝国音楽院の院長に任命され、皇帝ペドロ2世の宮廷音楽家も務めた [56]。白鳥の歌」と名付けられた有名なヴァイオリンは彼の好んだ楽器であり、最も有名な曲はハバネラ「ラ・ベッラ・クバーナ」である。ホワイトは、 ヴァイオリンとオーケストラのための協奏曲など、他にも多くの作品を作曲した[57]。  黒い 「パガニーニ」」と呼ばれたクラウディオ・ホセ・ドミンゴ・ブリンディス・デ・サラス・イ・ガリドは、有名なストラディヴァリウスを手にポーズをとっている。 クラウディオ・ホセ・ドミンゴ・ブリンディス・デ・サラス・イ・ガリード(1852-1911)は、キューバの有名なヴァイオリニストであり、同じく有名 なヴァイオリニスト、コントラバス奏者、指揮者であるクラウディオ・ブリンディス・デ・サラス(1800-1972)の息子である。クラウディオ・ホセ は、父の名声と専門知識を凌駕し、国際的な評価を得るようになった[58][59][60]。 クラウディオ・ブリンディス・デ・サラス・ガリードは父のもとで音楽の勉強を始め、マエストロであるホセ・レドンドとベルギー人のホセ・ヴァンダーガッチ に師事した。1863年にハバナで最初のコンサートを開き、ヴァンデルガッチも伴奏者として参加した。有名なピアニストで作曲家のイグナシオ・セルバンテ スもこのコンサートに参加した。 同時代の批評によると、ブリンディス・デ・サラスは、国際的なレベルで当時最も優れたヴァイオリニストの一人とみなされていた。アレホ・カルペンティエは彼をこう呼んだ: 「19世紀で最も傑出した黒人ヴァイオリニスト......大陸の音楽史上、前例がない」[61]。 フランス政府は彼にレジオン・ドヌール勲章を授与し、「男爵」の貴族称号を与えた。ブエノスアイレスでは本物のストラディヴァリウスを手に入れ、ベルリン 在住時にはドイツ人女性と結婚し、皇帝の室内楽奏者に任命され、同国の名誉市民権を得た。ブリンディス・デ・サラスは1911年、アルゼンチンのブエノス アイレスで結核のため貧しく忘れられた存在となっていた。1930年、彼の遺骨はハバナに移された。 19世紀に活躍したもう一人の傑出したキューバのヴァイオリニストは、ラファエル・ディアス・アルベルティーニ(1857-1928)である。アルベル ティーニは、ホセ・ヴァンデルガッチとアンセルモ・ロペス(1841-1858)にヴァイオリンを師事した。1870年、アルベルティーニは、有名なヴァ イオリニスト、ジャン・デルフィン・アラールのもとで技巧を磨くためにパリに渡り、1875年にはパリ・コンクールで一等賞を受賞、その後審査員として参 加した。ユーゴ・ウルフやカミーユ・サン=サーンスといった一流の巨匠の伴奏で世界各地を演奏旅行した。1894年には、イグナシオン・セルバンテスとと もにキューバの主要都市で公演を行った[63]。 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてのキューバの著名なヴァイオリニストのリストには、以下のようなものがある: マヌエル・ムニョス・セデーニョ(1813年生まれ)、ホセ・ドミンゴ・ブスケ(1823年生まれ)、カルロス・アンケルマン(1829年生まれ)、アン トニオ・フィゲロア(1852年生まれ)、ラモン・フィゲロア(1862年生まれ)、フアン・トロエラ(1874年生まれ )、カジミロ・ゼルチャ(1880年生)、ホアキン・モリナ(1884年生)、マルタ・デ・ラ・トーレ(1888年生)、カタリノ・アルホナ(1895年 生)、ディエゴ・ボニーリャ(1898-)である[64]。 20世紀から21世紀 20世紀前半には、アマデオ・ロルダン(1900-1939)の名が際立っている。優れたヴァイオリニスト、教授、指揮者であると同時に、ロルダンはキューバで最も重要な作曲家の一人とみなされているからである。 キューバの著名なヴァイオリニスト、アンヘル・レイエス(1919-1988)は、1935年にわずか16歳でパリ音楽院を卒業した後、ソリストとして、 また各国の一流オーケストラの伴奏者として大成功を収めた。彼は若くしてアメリカに居を構え、ブリュッセルのイザイ・コンテストで受賞し、1985年に引 退するまでミシガン大学とノースウェスタン大学で教授を務めた[65]。 エドゥアルド・エルナンデス・アジアイン(1911-2010)はハバナで生まれ、幼い頃から音楽の勉強を始め、わずか7歳で最初のコンサートを開いた。 14歳の時、ハバナ市立音楽院で一等賞を受賞し、ハバナ交響楽団のコンチェルティーノに任命された。1932年、マドリードに渡り、エンリケ・フェルナン デス・アルボスとアントニオ・フェルナンデス・ボルダスの両教授のもとで音楽教育を受ける。1954年以来、エルナンデス・アジアインは、ソリストとして パリのパスデループ・コンサート協会やラジオディフュージョン・フランセーズ、スペイン国立管弦楽団、ビルバオ交響楽団、マドリッド・カマラ管弦楽団、そ して自身が創設者であるサン・セバスティアン・シンフォニカ管弦楽団と共演している。1968年、RTVEの 「クァルテート・クラシコ 」のファースト・ヴァイオリンに任命され、ピアニストのイサベル・ピカサ・ゴンサレスとともに 「クインテート・クラシコ・デ・RNE 」に参加し、スペインやその他の国々でコンサートを開き、数多くのレコーディングを行った。また、アメリカ国内でも大規模なツアーを行った[66]。 20世紀前半に活躍した他の著名なキューバ人ヴァイオリニストは以下の通りである: ロベロ・バルデス・アルナウ(1919-1974)、アルベルト・ボレット、ヴィルジリオ・ディアゴなどがいる[67]。 1959年以降、革命後の時代にはすでに、ヴァイオリンと弦楽器の発展だけでなく、国の音楽文化全般に多大な貢献をしたキューバのヴァイオリニストがいる。 エヴェリオ・ティエレスは、わずか7歳の時に父であるエヴェリオ・ティエレス・ソレールにキューバで音楽を習い始め[68]、その後、ホアキン・モリーナ 教授に師事した。1952年から1954年にかけて、ティエレスはフランスのパリでジャック・ティボーとルネ・ベネデッティにヴァイオリンを師事した。 1955年にパリに戻り、同市の国立高等音楽院で学び、1958年にはモスクーのチャイコフスキー音楽院で音楽教育を受け、著名なヴァイオリニスト、ダ ヴィッド・オイストラフとイーゴリ・オイストラフの弟子となった。ティエルスは1963年に卒業し、音楽院の推薦により、1963年から1966年まで修 士課程に進み、同じ教授陣のもとで研鑽を積んだ[68]。ティエルスは、著名なヴァイオリニスト、ヘンリク・セリンとエドゥアルド・エルナンデス・アジア インからも専門的な指導を受けた[69]。 弟でピアニストのセシリオ・ティエレスとのデュオや、キューバ国立交響楽団をはじめとする交響楽団や室内楽団との共演など、コンサートパフォーマーとして 数多くの作品を発表している。トーマス・サンデルリング、ボリス・ブロット、エンリケ・ゴンサレス・マーンティチ、マヌエル・ドゥチェスネ・クザンなど一 流の指揮者と共演している[要出典]。 ティエルスは1984年からスペインに居を構え、タラゴナ県にあるヴィラ=セカ音楽院でヴァイオリンを教えており、「名誉教授」に任命されている[要出 典]。また、バルセロナ高等音楽院では、室内楽科主任(1991-1998)、弓奏弦楽器科主任(1986-2002)、アカデミック・ディレクター (2000-2002)を務めている[69]。 コンサート演奏家、教授としての卓越したキャリアとは別に、革命後のキューバでは、ティエルスは、基本的にヴァイオリンのための弓付き弦楽器の訓練を推進し、組織した[69]。 もう一人の著名なヴァイオリニストは、アラ・タラン教授(1941年)である。彼女は母国ウクライナでヴァイオリニストとして結成され、室内アンサンブルの教授として活動していた。タランは1969年からキューバに居を構えている[要出典]。 アルフレード・ムニョス(1949年)は、キューバ・ハバナのオルボン音楽院でヴァイオリンを学び始め、国立芸術学校と高等芸術学院(ISA)で学んだ。 1972年に国立交響楽団にヴァイオリニストとして入団して以来、ソリストとして、またホワイト・トリオのメンバーとして、キューバ国内外で精力的に活動 している。現在はISA(Instituto Superior de Artes)の教授を務めている[70]。 20世紀から21世紀にかけてキャリアを積んだキューバのヴァイオリニストは他にもいる: アルマンド・トレド(1950年)、フリアン・コラレス(1954年)、ミゲル・デル・カスティーリョ、リカルド・フスティスである[64]。 21世紀 このセクションは、検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2018年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 21世紀初頭にはすでに、イルマール・ロペス=ガビラン、ミレリス・モルガン・ベルデシア、イヴォンヌ・ルビオ・パドロン、パトリシア・キンテロ、ラファエル・マチャドのヴァイオリニストが注目に値する。 |

| Opera in Cuba Main article: Opera in Cuba Opera has been present in Cuba since the latest part of the 18th century, when the first full-fledged theater, called Coliseo, was built. Since then to present times, the Cuban people have highly enjoyed opera, and many Cuban composers have cultivated the operatic genre, sometimes with great success at an international level. The best Cuban lyrical singer in the 20th century was the operatic tenor Francisco Fernandez Dominicis (Italian name: Francesco Dominici) (1885-1968). The best Cuban female lyrical singer in the 20th century was the mezzo-soprano Marta Perez (1924-2009). She sang at La Scala in Milan, Italy in 1955.[71] The 19th century The first documented operatic event in Havana took place in 1776. That presentation was mentioned in a note published in the newspaper Diario de La Habana on December 19, 1815: "Today, Wednesday 19th of the current, if the weather allows, the new tragic opera of merit in three acts that contains 17 pieces of music, titled Dido Abandoned will be performed ... This is one of the premiere dramas from the French theater. In Italy, the one composed by renowned Metastasio deserved a singular applause, and was sung in this city on October 12, 1776."[72] Cristóbal Martínez Corrés was the first Cuban opera composer, but his Works, such as El diablo contrabandista and Don papanero were never premiered and have not been preserved until the present time. Born in Havana, in 1822, composer and pianist Martínez Corrés established his residence together with his family in France when he was just nine years old; and at a later tame they went to Italy. Due to his premature death, a third opera named Safo, never surpassed an early creative stage. Martínez Corrés died in Genoa, in 1842.[16] Gaspar Villate y Montes was born in Havana, in 1851 and since an early age he showed a great musical talent. As a child, he began to study piano with Nicolás Ruiz Espadero and in 1867, when he was just 16 years old, he composed his first opera on a drama by Victor Hugo, titled Angelo, tirano de Padua. A year later, at the beginning of the 1868 war, he travelled to the United States with his family and upon his return to Havana in 1871 he wrote another opera called Las primeras armas de Richelieu. Villate travelled to France with the purpose to continue his music studies in the Paris Conservatory, where he received classes from François Bazin, Victorien de Joncieres and Adolphe Danhauser. He composed numerous instrumental pieces such as contradanzas, habaneras, romances and waltzes, and in 1877 he premiered with great audience acclaim his opera Zilia in Paris, which was presented in Havana in 1881. Since then, Villate focused his efforts mainly in opera and composed pieces such as La Zarina and Baltazar, premiered at La Haya and Teatro Real de Madrid respectively. It is known that he worked on an opera with a Cuban theme called Cristóbal Colón, but its manuscript has been lost. Villate died in Paris in 1891, soon after starting to compose a lyrical drama called Lucifer, from which some fragments have been preserved.[73] From 1901 to 1959 Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes was born in Havana, in 1874, within an artistic family; his father was a writer and his mother a pianist and singer. He began his musical studies at Conservatorio Hubert de Blanck and at a later time took classes from Carlos Anckermann. He received also a Law Degree in 1894.[74] When Sánchez de Fuentes was just 18 years old, he composed the famous Habanera "Tú", which became an extraordinary international success. Alejo Carpentier said it was: "the most famous Habanera".[75] On October 26, 1898, Sánchez de Fuentes premiered at the Albisu Theater in Havana his first opera called Yumuri, based on the Island's colonization theme. In it, an aborigine princess falls in love with a handsome Spanish conqueror, which abducts her at the wedding ceremony with another indigenous character. At the end, while escaping, both suffer a tragic death during an earthquake.[76] Sánchez de Fuentes would go on to compose another five operas: El Náufrago (1901), Dolorosa (1910), Doreya (1918), El Caminante (1921) and Kabelia (1942).[77] From 1960 to present time This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this message) One of the most active and outstanding composers of his generation, Sergio Fernández Barroso (also known as Sergio Barroso) (1946), is the author of an opera called La forma del camino, which also possesses the complementary title of s-XIV-69 (which means Siglo XIV – 1969). With an approximate duration of 60 minutes, this piece utilizes as a script a story from the Popol Vuh (the sacred text of the Maya culture) about the mythic brothers Hunahpu and Ixbalanqué. The score includes soloists and a choir of nine mixed voices, accompanied by an instrumental group and an electro-acoustic quadraphonic system. The scene requires a stage elevated over the choir spatial position, which members wear dinner jackets, in opposition to the more casual attire of the soloists. All singers wear Indian masks.[78] Most recently the work of two young Cuban composers stand out, Jorge Martín (composer) and Louis Franz Aguirre. Jorge Martín (1959) was born in Santiago de Cuba and established his residence in the US at a very young age. He studied musical composition at the Yale and Columbia Universities. He has composed three lyric pieces: Beast and Superbeast, a series of four operas in one act each, based on short stories by Saki; Tobermory, opera in one act that obtained first prize in the Fifth Biennial of the National Opera Association (USA), and has been presented in several cities of the United States; and Before Night Falls, an opera based on the famous autobiography of the Cuban novelist, playwright and poet Reinaldo Arenas, renowned dissident from the Fidel Castro government.[79] Louis Franz Aguirre (1968) is currently one of the most prolific and renowned Cuban composers at an international level. His catalog includes four operatic works: Ebbó (1998), premiered on January 17, 1999, at the Brotfabrik Theater in Bonn, Germany; Ogguanilebbe (Liturgy of the divine word) (2005), premiered in the Salla dil Parlamento d'il Castello di Udine, Italy. Yo el Supremo (Comic play with Dictator in one Act), premiered on October 27, 2015, in the Teatro Galileo, Madrid, Spain and The way the dead love (Theogony: an operatic manifest), commissioned by the Lydenskab Ensemble and financed by KODA, Denmark. Premiered on February 24, 2017, in Godsbanen, Aarhus, Denmark, as part of the Århus European Capital of Culture 2017. |

キューバのオペラ 主な記事 キューバのオペラ キューバには、18世紀末にコリセオと呼ばれる本格的な劇場が建設されて以来、オペラが存在している。それ以来現在に至るまで、キューバ国民はオペラを大 いに楽しみ、多くのキューバ人作曲家がオペラのジャンルを開拓し、時には国際的なレベルで大成功を収めている。20世紀最高のキューバ人叙情歌手は、オペ ラのテノール歌手フランシスコ・フェルナンデス・ドミニチ(イタリア名:フランチェスコ・ドミニチ)(1885-1968)である。20世紀最高のキュー バ人女性叙情歌手は、メゾ・ソプラノのマルタ・ペレス(1924-2009)である。彼女は1955年にイタリアのミラノ・スカラ座で歌っている [71]。 19世紀 ハバナで初めてオペラが上演されたのは1776年のことである。その上演は、1815年12月19日にDiario de La Habana紙に掲載されたメモに記載されている: 本日19日水曜日、天候が許せば、17曲からなる3幕の悲劇的オペラ『見捨てられたディド』が上演される。これはフランス演劇の初演作品のひとつである。 イタリアでは、高名なメタスタシオが作曲したものが特筆すべき喝采を浴び、1776年10月12日にこの街で歌われた」[72]。 クリストバル・マルティネス・コレスはキューバ初のオペラ作曲家であったが、彼の作品であるEl diablo contrabandistaやDon papaneroは初演されることなく、現在まで保存されていない。1822年にハバナで生まれた作曲家でピアニストのマルティネス・コレスは、わずか9 歳の時に家族とともにフランスに居を構え、その後イタリアに渡った。夭折のため、サフォと名付けられた3作目のオペラは、初期の創作段階を超えることはな かった。マルティネス・コレスは1842年にジェノヴァで死去した[16]。 ガスパル・ビジャテ・イ・モンテスは1851年にハバナで生まれ、幼い頃から音楽の才能を発揮した。幼い頃からニコラス・ルイス・エスパデロにピアノを習 い、1867年、弱冠16歳でヴィクトル・ユーゴーの戯曲を題材にした最初のオペラ『パドヴァのティラノ、アンジェロ』を作曲した。その1年後、1868 年の戦争が始まると、彼は家族とともにアメリカに渡り、1871年にハバナに戻ると、また『リシュリューの武器』というオペラを作曲した。 ヴィラートは、パリ音楽院で音楽の勉強を続けるためにフランスに渡り、フランソワ・バザン、ヴィクトリアン・ド・ヨンシエール、アドルフ・ダンハウザーか ら指導を受けた。1877年、オペラ『ジリア』をパリで初演し、聴衆の大喝采を浴びた。それ以来、ビジャテは主にオペラに力を入れ、『ラ・ザリーナ』や 『バルタザール』といった作品を作曲し、それぞれラ・ハヤやマドリード・レアル劇場で初演された。クリストバル・コロン(Cristóbal Colón)というキューバをテーマにしたオペラに取り組んだことも知られているが、その原稿は失われている。 1891年、ヴィラートは『ルシファー』という叙情劇の作曲に着手した直後にパリで死去したが、その断片が残っている[73]。 1901年から1959年まで 父は作家で、母はピアニスト兼歌手であった。父は作家、母はピアニストで歌手であった。フベール・デ・ブランク音楽院で音楽の勉強を始め、後にカルロス・ アンカーマンのレッスンを受ける。1894年には法律の学位も取得した[74]。サンチェス・デ・フエンテスがまだ18歳のとき、有名なハバネラ「Tú」 を作曲し、世界的に大成功を収めた。アレホ・カルペンティエはこの曲をこう評した: 「最も有名なハバネラである」と述べている[75]。 1898年10月26日、サンチェス・デ・フエンテスはハバナのアルビス劇場で、島の植民地化をテーマにした最初のオペラ「ユムリ」を初演した。このオペ ラでは、原住民の王女がハンサムなスペイン人征服者と恋に落ちるが、そのスペイン人征服者は、別の原住民との結婚式で彼女を誘拐する。サンチェス・デ・フ エンテスはその後も5つのオペラを作曲する: El Náufrago』(1901年)、『Dolorosa』(1910年)、『Doreya』(1918年)、『El Caminante』(1921年)、『Kabelia』(1942年)である[77]。 1960年から現在まで このセクションは、検証のために追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきた い。ソースのないものは異議申し立てされ、削除される可能性がある。(2018年10月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 同世代で最も活動的で傑出した作曲家の一人であるセルヒオ・フェルナンデス・バローゾ(セルヒオ・バローゾとしても知られる)(1946年)は、「La forma del camino」というオペラの作者であり、s-XIV-69(Siglo XIV - 1969の意)という補完的なタイトルも持っている。約60分のこの作品は、ポポル・ヴフ(マヤ文化の聖典)にある神話の兄弟フナプとイクスバランケの物 語を台本としている。楽譜にはソリストと9人の混声合唱団が含まれ、楽器隊と電子音響クアドラフォニック・システムが伴う。この場面では、合唱団の空間的 な位置よりも高いステージが必要で、メンバーはディナージャケットを着ており、ソリストたちのカジュアルな服装とは対照的である。歌手は全員インドの仮面 をつけている[78]。 最近では、ホルヘ・マルティン(作曲家)とルイス・フランツ・アギーレという2人の若いキューバの作曲家の作品が際立っている。 ホルヘ・マルティン(1959)はサンティアゴ・デ・クーバで生まれ、若くしてアメリカに居を構えた。エール大学とコロンビア大学で作曲を学ぶ。これまで に3曲の抒情詩を作曲している: サキの短編小説をもとにした1幕完結の4つのオペラからなる《野獣》と《超野獣》、全米オペラ協会第5回ビエンナーレで1位を獲得し、アメリカ国内のいく つかの都市で上演された1幕完結のオペラ《トバモリー》、フィデル・カストロ政権の反体制派として知られるキューバの小説家、劇作家、詩人レイナルド・ア レナスの有名な自伝をもとにしたオペラ《Before Night Falls》である[79]。 ルイス・フランツ・アギーレ(1968)は、現在、国際的に最も多作で有名なキューバの作曲家の一人である。彼のカタログには4つのオペラ作品が含まれて いる: 1999年1月17日にドイツのボンのブロートファブリーク劇場で初演された「エッボー」(1998年)、イタリアのウディネのカステッロ劇場で初演され た「オグワニレッベ」(2005年)、「神の言葉の典礼」(2005年)である。Yo el Supremo(一幕の独裁者を伴う喜劇)』(2015年10月27日、スペイン、マドリードのガリレオ劇場で初演)、『The way the dead love(テオゴニー:オペラ的マニフェスト)』(ライデンスカブ・アンサンブルの委嘱、デンマークのKODAの出資)。2017年2月24日、オーフス 欧州文化首都2017の一環として、デンマーク、オーフスのGodsbanenで初演された。 |

| Musicology in Cuba Main article: Musicology in Cuba  Alejo Carpentier Throughout the years, the Cuban nation has developed a wealth of musicological material created by numerous investigators and experts on this subject. The work of some authors who provided information about the music in Cuba during the 19th century was usually included in chronicles covering a more general subject. The first investigations and studies specifically dedicated to the musical art and practice did not appear in Cuba until the beginning of the 20th century.[80] A list of important personalities that have contributed to musicological studies in Cuba includes Fernando Ortiz, Eduardo Sánchez de Fuentes, Emilio Grenet, Alejo Carpentier, Argeliers León, Maria Teresa Linares, Pablo Hernández Balaguer, Alberto Muguercia and Zoila Lapique. A second generation of musicologists formed after de Cuban revolution of 1959 include: Zoila Gómez, Victoria Elí, Alberto Alén Pérez, Rolando Antonio Pérez Fernández and Leonardo Acosta. Most recently, a group of young Cuban musicologists have earned a well deserved reputation within the international academic field, due to their solid investigative work. Some of the most prominent members of this group are: Miriam Escudero Suástegui, Liliana González Moreno,[citation needed] Iván César Morales Flores[81] and Pablo Alejandro Suárez Marrero.[82] |

キューバの音楽学 主な記事 キューバの音楽学  アレホ・カルペンティエ キューバでは長年にわたり、音楽学に関する多くの研究者や専門家によって、豊富な音楽学的資料が作成されてきた。19世紀にキューバの音楽に関する情報を 提供した何人かの著者の仕事は、通常、より一般的なテーマを扱った年代記の中に含まれていた。音楽芸術と実践に特化した最初の調査や研究は、20世紀初頭 までキューバに現れなかった[80]。 キューバの音楽学研究に貢献した重要な人物のリストには、フェルナンド・オルティス、エドゥアルド・サンチェス・デ・フエンテス、エミリオ・グレネ、アレ ホ・カルペンティエ、アルゲリエス・レオン、マリア・テレサ・リナレス、パブロ・エルナンデス・バラゲール、アルベルト・ムゲルシア、ゾイラ・ラピケなど がいる。 1959年のキューバ革命後に結成された第二世代の音楽学者には、次のような人々がいる: ゾイラ・ゴメス、ビクトリア・エリ、アルベルト・アレン・ペレス、ロランド・アントニオ・ペレス・フェルナンデス、レオナルド・アコスタなどである。 最近では、キューバの若手音楽学者のグループが、その堅実な調査活動により、国際的な学術分野で正当な評価を得ている。このグループの最も著名なメンバー は以下の通りである: ミリアム・エスクデロ・スアステギ、リリアナ・ゴンサレス・モレノ、イバン・セサル・モラレス・フローレス[81]、パブロ・アレハンドロ・スアレス・マ レーロ[82]である。 |

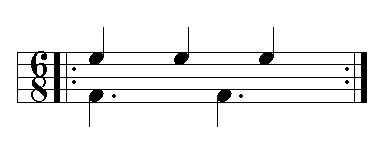

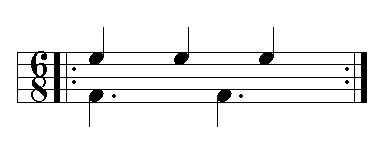

| Popular music Hispanic heritage The first popular music played in Cuba after the Spanish conquest was brought by the Spanish conquerors themselves, and was most likely borrowed from the Spanish popular music in vogue during the 16th century. From the 16th to the 18th century some danceable songs that emerged in Spain were associated with Hispanic America, or considered to have originated in America. Some of these songs with picturesque names such as Sarabande, Chaconne, Zambapalo, Retambico and Gurumbé, among others,[83] shared a common trait, its characteristic rhythm called Hemiola or Sesquiáltera (in Spain).  Vertical hemiola. Playⓘ This rhythm has been described as the alternation or superposition of a duple meter and a triple meter (6/8 + 3/4), and its utilization was widespread in the Spanish territory since at least the 13th century, where it appears in one of the Cantigas de Santa María (Como poden per sas culpas).[84] Hemiola or Sesquiáltera is also a typical rhythm within the African musical traditions, both from the North of the Continent as from the South.[85] Therefore, it is quite probable that the original song-dances brought by the Spanish to America already included elements from the African culture with which the enslaved Africans that arrived to the Island were familiar; and they further utilized them in order to create new creole genres.[86] The well known Son de la Ma Teodora, an ancient Cuban song, as well as the first Cuban autochthonous genres, Punto and Zapateo, show the Sesquiáltera rhythm on their accompaniment, which greatly associate those genres to the Spanish song-dances from the 16th to the 18th centuries.[87] |

ポピュラー音楽 ヒスパニックの遺産 スペインによる征服後、キューバで最初に演奏されたポピュラー音楽は、スペイン人征服者たち自身によってもたらされたもので、16世紀に流行したスペイン のポピュラー音楽を借用した可能性が高い。16世紀から18世紀にかけて、スペインで生まれたダンサブルな曲の中には、ヒスパニック・アメリカにちなんだ ものや、アメリカ発祥と思われるものもあった。サラバンド、シャコンヌ、ザンバパロ、レタンビコ、グルンベなど、絵に描いたような名前のこれらの曲のいく つか[83]には、ヘミオラまたはセスキアルテラ(スペイン語)と呼ばれる特徴的なリズムという共通の特徴があった。  縦のヘミオラ プレイⓘ。 このリズムは二重拍子と三重拍子(6/8+3/4)の交互または重ね合わせとして説明され、その利用は少なくとも13世紀以降スペイン領内で広まり、サンタ・マリアのカンティーガのひとつ(Como poden per sas culpas)に登場する[84]。 ヘミオラまたはセスキアルテラもまた、アフリカ大陸の北部と南部の両方のアフリカ音楽の伝統における典型的なリズムである[85]。したがって、スペイン 人がアメリカに持ち込んだオリジナルの歌舞曲には、島に到着した奴隷にされたアフリカ人が慣れ親しんでいたアフリカ文化の要素がすでに含まれていた可能性 が高く、彼らは新しいクレオールのジャンルを作り出すためにそれらをさらに利用した[86]。 よく知られているキューバ古来の歌であるソン・デ・ラ・マ・テオドラや、キューバ初の自国語ジャンルであるプントやサパテオには、伴奏にセスキアルテラの リズムが使われており、これらのジャンルは16世紀から18世紀にかけてのスペインの歌舞曲に大きく関連している[87]。 |

Música campesina (peasant music) Cuban rural landscape It seems that Punto and Zapateo Cubano were the first autochthonous musical genres of the Cuban nation. Although the first printed sample of a Cuban Creole Zapateo (Zapateo Criollo) was not published until 1855 in the "Álbum Regio of Vicente Díaz de Comas",[88] it is possible to find references about the existence of those genres since long time before.[89] Its structural characteristics have survived almost unaltered through a period of more than two hundred years and they are usually considered the most typically Hispanic Cuban popular music genres. Cuban musicologists María Teresa Linares, Argeliers León and Rolando Antonio Pérez coincide in thinking that Punto and Zapateo are based on Spanish dance –songs (such as chacone and sarabande) that arrived first at the most important population centers such as Havana and Santiago de Cuba and then spread throughout the surrounding rural areas where they were adopted and modified by the peasant (campesino) population at a later time.[88] Punto guajiro Punto guajiro or Punto Cubano, or simply Punto is a sung genre of Cuban music, an improvised poetic-music art that emerged in the western and central regions of Cuba during the 19th century.[90] Although Punto appears to come from an Andalusian origin, it is a true Cuban genre because of its creole modifications.[91] Punto is played by a group with various types of plucked string instruments: the tiple (a treble guitar currently in disuse), the Spanish guitar, the Cuban tres, and the laúd. The word punto refers to the use of a plucked technique (punteado), rather than strumming (rasgueado). Also some percussion instruments have been utilized such as the clave, the güiro and the guayo ( a metallic scraper). Singers gather themselves in contending teams, and improvise their lines. They sing fixed melodies called "tonadas" which are based on a meter of ten strophe verses called "décimas", with intervals between stanzas to give the singers some time to prepare the next verse.[92] Early compositions were sometimes recorded and published, as were the names of some of the singers and composers. Beginning around 1935, Punto reached a peak of popularity on Cuban radio. Punto was one of the first Cuban genres recorded by American companies at the beginning of the 20th century, but at a later time the interest decayed and little effort was made to continue recording the live radio performances. A fan of this genre, stenographer Aida Bode, wrote down many verses as they were broadcast and finally, in 1997, her transcriptions were published in book form.[93] Celina González and Albita Rodríguez both sang Punto at the beginning of their careers, proving that the genre is still alive. Celina had one of the greatest voices in popular music, and her supporting group Campo Alegre was outstanding. For aficionados, however, Indio Naborí (Sabio Jesús Orta Ruiz, b. 30 September 1922) is the greatest name in Punto for his "decima" poetry, which he wrote daily for the radio and newspapers. He is also a published author with several collections of his poetry, much of which has a political nueva trova edge.[94] Zapateo Main article: Zapateo  Cuban güiro Zapateo is a typical dance of the Cuban "campesino" or "guajiro," of Spanish origin. It is a dance of pairs, involving tapping of the feet, mostly performed by the male partner. Illustrations exist from previous centuries and today it survives cultivated by Folk Music Groups as a fossil genre. It was accompanied by tiple, guitar and güiro, in combined 6/8 and 3/4 rhythm (hemiola), accented on the first of every three quavers. Guajira Main article: Guajira (music) A genre of Cuban song similar to the Punto cubano and the Criolla.[95] It contains bucolic countryside lyrics, similar to décima poetry. Its music shows a mixture of 6/8 and 3/4 rhythms called Hemiola. According to Sánchez de Fuentes, its first section is usually presented in a minor key, and its second section in its direct major relative key.[96] The term Guajira is now used mostly to describe a slow dance music in 4/4 time, a fusion of the Guajira and the Son (called Guajira-Son). Singer and guitarist Guillermo Portabales was the most outstanding representative of this genre. Criolla Main article: Criolla Criolla is a genre of Cuban music which is closely related to the music of the Cuban Coros de Clave and a genre of Cuban popular music called Clave. The Clave became a very popular genre in the Cuban vernacular theater and was created by composer Jorge Anckermann based on the style of the Coros de Clave.[97] The Clave served, in turn, as a model for the creation of a new genre called Criolla. According to musicologist Helio Orovio, "Carmela", the first Criolla, was composed by Luis Casas Romero in 1909, which also created one of the most famous Criollas of all time, "El Mambí".[98] |

カンペシーナ音楽(農民音楽) キューバの田園風景 プントとサパテオ・クバーノは、キューバ民族の最初の自国音楽ジャンルだったようだ。キューバ・クレオールのサパテオ(サパテオ・クリオーリョ)の最初の 印刷サンプルは、1855年の 「Álbum Regio of Vicente Díaz de Comas 」に掲載されるまで出版されなかったが[88]、これらのジャンルの存在に関する文献を見つけることは可能である。キューバの音楽学者であるマリア・テレ サ・リナレス、アルゲリエス・レオン、ロランド・アントニオ・ペレスの見解は一致しており、プントとサパテオは、ハバナやサンティアゴ・デ・クーバといっ た最も重要な人口の中心地に最初に到着したスペインのダンス・ソング(チャコーンやサラバンドなど)を基にしており、その後、周辺の農村地域全体に広ま り、後に農民(カンペシーノ)によって取り入れられ、修正されたものであるとしている[88]。 プント・グアヒーロ プント・グアヒーロ(Punto guajiro)またはプント・クバーノ(Punto Cubano)、あるいは単にプント(Punto)は、キューバ音楽の歌唱ジャンルであり、19世紀にキューバの西部および中部地方で生まれた即興の詩的音楽芸術である[90]。 プントは、ティプル(現在では使われなくなった高音ギター)、スパニッシュ・ギター、キューバ・トレス、ラウードといった様々な種類の撥弦楽器を持ったグ ループによって演奏される。プントという言葉は、打ち込み(ラスゲアード)ではなく、撥弦楽器(プンテアード)の奏法を指す。また、クラーベ、グイロ、グ アヨ(金属製スクレーパー)などの打楽器も使われる。歌い手たちはチーム対抗で集まり、即興で歌う。 トナーダ」と呼ばれる決まったメロディーを歌うが、これは「デシマス」と呼ばれる10節からなる拍子に基づくもので、節と節の間には次の節を準備する時間を与えるためのインターバルがある[92]。1935年頃から、プントはキューバのラジオで人気のピークに達した。 プントは、20世紀初頭にアメリカの会社によって録音された最初のキューバジャンルのひとつであったが、その後、関心は薄れ、ラジオの生演奏を録音し続け る努力はほとんどなされなかった。このジャンルのファンであった速記者のアイーダ・ボデは、放送されるたびに多くの詩を書き留め、1997年、ついに彼女 の書き起こしが本の形で出版された[93]。 セリーナ・ゴンサレスとアルビータ・ロドリゲスは、キャリアの初期にプントを歌い、このジャンルがまだ生きていることを証明した。セリーナはポピュラー音 楽界で最も素晴らしい声の持ち主で、彼女のサポート・グループであるカンポ・アレグレは傑出していた。しかし、愛好家にとっては、インディオ・ナボリ(サ ビオ・ヘスス・オルタ・ルイス、1922年9月30日生まれ)は、ラジオや新聞に毎日書いた「デシマ」の詩で、プントで最も偉大な名前である。彼はまた、 いくつかの詩集を出版している作家でもあり、その多くは政治的なヌエバ・トロヴァのエッジを持っている[94]。 サパテオ 主な記事 サパテオ  キューバのグイロ サパテオはキューバの「カンペシーノ」または「グアヒーロ」の典型的なダンスで、スペインに起源を持つ。2人1組で踊るもので、足をたたくのが特徴で、主 に男性のパートナーが踊る。何世紀も前の挿絵が残っており、今日でも化石的なジャンルとして民族音楽グループによって育てられている。ティプル、ギター、 グイロの伴奏で、6/8と3/4の複合リズム(ヘミオラ)で、3つのクォーバーのうち最初のクォーバーにアクセントがある。 グアヒーラ 主な記事 グアヒーラ(音楽) プント・クバーノ(Punto cubano)やクリオージャ(Criolla)に似たキューバの歌のジャンル[95]。ヘミオラと呼ばれる8分の6拍子と4分の3拍子のリズムが混ざっ た音楽である。サンチェス・デ・フエンテスによると、その第1部は通常短調で、第2部は直接長調の相対調で演奏される[96]。グアヒーラという用語は、 現在では主に、グアヒーラとソン(グアヒーラ・ソンと呼ばれる)の融合である4/4拍子のスロー・ダンス・ミュージックを表すのに使われる。歌手でギタリ ストのギジェルモ・ポルタバレスは、このジャンルの最も傑出した代表者である。 クリオージャ 主な記事 クリオージャ クリオージャはキューバ音楽のジャンルのひとつで、キューバのコーロス・デ・クラーヴェの音楽や、クラーヴェと呼ばれるキューバのポピュラー音楽のジャンルと密接な関係がある。 クラーベはキューバの地方演劇で非常に人気のあるジャンルとなり、作曲家のホルヘ・アンカーマンによってコーロス・デ・クラーベのスタイルに基づいて創作 された[97]。音楽学者のヘリオ・オロビオによれば、最初のクリオージャである「カルメラ」はルイス・カサス・ロメロによって1909年に作曲され、ク リオージャの中で最も有名な曲のひとつである「エル・マンビ」もこの曲によって生み出された[98]。 |