ナチスによる人体実験

実験医学序説 / クロード・ベルナール著 ; 三浦岱栄訳,改訳. - 東京 : 岩波書店 , 1970/ Bernard, Claude. Introduction à l'étude de la médecine expérimentale.

ナチスの人体実験とは、第二次世界大戦中およびホロコースト中の1940年代前半から半ばに かけて、ナチス・ドイツが強制収容所で子供を含む大量の捕虜を 対象に行った一連の医学実験のことである。主な対象者は、ロマ人、シンティ人、ポーランド人、ソ連軍捕虜、障害を持つドイツ人、ヨーロッパ全土のユダヤ人 などであった(→「人体実験の生命倫理学」「ナチスドイツの非人道的医学実験と処刑」)。

"I don't want to have to use the Nazi data, but there is no other and will be no other in an ethical world ... not to use it would be equally bad. I'm trying to make something constructive out of it." - Dr John Hayward, justifying citing the Dachau freezing experiments in his research.[38] ——「ナチスのデータは使いたくないが、倫理的な世界 では他にないし、これからもないだろう・・・使わないのも同様に悪いことだろう。私は何か建設的なものを作ろうとしているのだ」。 - ジョン・ヘイワード博士、自分の研究にダッハウ凍結実験を引用したことを正当化するために

| Nazi

human experimentation was a series of medical experiments on large

numbers of prisoners, including children, by Nazi Germany in its

concentration camps in the early to mid 1940s, during World War II and

the Holocaust. Chief target populations included Romani, Sinti, ethnic

Poles, Soviet POWs, disabled Germans, and Jews from across Europe. Nazi physicians and their assistants forced prisoners into participating; they did not willingly volunteer and no consent was given for the procedures. Typically, the experiments were conducted without anesthesia and resulted in death, trauma, disfigurement, or permanent disability, and as such are considered examples of medical torture. At Auschwitz and other camps, under the direction of Eduard Wirths, selected inmates were subjected to various experiments that were designed to help German military personnel in combat situations, develop new weapons, aid in the recovery of military personnel who had been injured, and to advance the Nazi racial ideology and eugenics,[1] including the twin experiments of Josef Mengele.[2] Aribert Heim conducted similar medical experiments at Mauthausen.[3] After the war, these crimes were tried at what became known as the Doctors' Trial, and revulsion at the abuses perpetrated led to the development of the Nuremberg Code of medical ethics. The Nazi physicians in the Doctors' Trial argued that military necessity justified their experiments, and compared their victims to collateral damage from Allied bombings. |

ナ

チスの人体実験とは、第二次世界大戦中およびホロコースト中の1940年代前半から半ばにかけて、ナチス・ドイツが強制収容所で子供を含む大量の捕虜を対

象に行った一連の医学実験のことである。主な対象者は、ロマ人、シンティ人、ポーランド人、ソ連軍捕虜、障害を持つドイツ人、ヨーロッパ全土のユダヤ人な

どであった。 ナチスの医師とその助手は、捕虜を強制的に参加させた。彼らは進んで志願したわけではなく、処置に同意することもなかった。通常、実験は麻酔なしで行わ れ、死亡、外傷、醜状、後遺症などを引き起こしたため、医療拷問とみなされた。 アウシュビッツや他の収容所では、エドゥアルド・ヴィルトスの指揮の下、選ばれた収容者は、戦闘状況におけるドイツ軍人の助け、新兵器の開発、負傷した軍 人の回復を助けるため、またナチスの人種思想と優生学を推進するために、ヨーゼフ・メンゲレの双子の実験など様々な実験を受けた[1]。 アリベルト・ハイムはマウトハウゼンにおいて同様の医学実験を行った[2]。 戦後、これらの犯罪は「医師裁判」として知られるようになり、行われた虐待への反発から、医学倫理に関する「ニュルンベルク綱領」が作成された。医師団裁 判でナチスの医師たちは、軍事的必要性から実験を正当化し、その犠牲者を連合軍の爆撃の巻き添え被害と比較したと主張した。 |

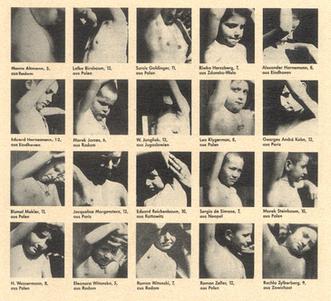

| Experiments The table of contents of a document from the Nuremberg military tribunals prosecution includes titles of the sections that document medical experiments revolving around: food, seawater, epidemic jaundice, sulfanilamide, blood coagulation and phlegmon.[4] According to the indictments at the Subsequent Nuremberg Trials,[5][6] these experiments included the following: Experiments on twins Experiments on twin children in concentration camps were created to show the superiority of heredity over the environment in determining phenotypes and to find ways to increase German reproduction rates. The central leader of the experiments was Josef Mengele, who from 1943 to 1944 performed experiments on nearly 1,500 sets of imprisoned twins at Auschwitz. About 200 people survived these studies.[7] The twins were arranged by age and sex and kept in barracks between experiments, which ranged from amputations, infecting them with various diseases and injecting dyes into their eyes to change their color. He also attempted to create conjoined twins by sewing twins together, causing gangrene and eventually, death.[8][9] Often, one twin would be forced to undergo experimentation, while the other was kept as a control. If one twin died from experimentation, the second twin would be brought in to be killed at the same time. Doctors would then look at the effects of experimentation and compare both bodies.[10] If the first twin survived, Mengele would dissect their bodies.[11] Bone, muscle, and nerve transplantation experiments From about September 1942 to about December 1943 experiments were conducted at the Ravensbrück concentration camp, for the benefit of the German Armed Forces, to study bone, muscle, and nerve regeneration, and bone transplantation from one person to another.[12] In these experiments, subjects had their bones, muscles and nerves removed without anesthesia. As a result of these operations, many victims suffered intense agony, mutilation, and permanent disability.[12] On 12 August 1946 a survivor named Jadwiga Kamińska[13] gave a deposition about her time at Ravensbrück concentration camp and describes how she was operated on twice. Both operations involved one of her legs and although she never describes having any knowledge as to what exactly the procedure was, she explains that both times she was in extreme pain and developed a fever post surgery, but was given little to no aftercare. Kamińska describes being told that she had been operated on simply because she was a "young girl and a Polish patriot". She describes how her leg oozed pus for months after the operations.[14] Prisoners were also experimented on by having their bone marrow injected with bacteria to study the effectiveness of new drugs being developed for use in the battle fields. Those who survived remained permanently disfigured.[15] Head injury experiments In mid-1942 in Baranowicze, occupied Poland, experiments were conducted in a small building behind the private home occupied by a known Nazi SD Security Service officer, in which "a young boy of eleven or twelve [was] strapped to a chair so he could not move. Above him was a mechanized hammer that every few seconds came down upon his head." The boy was driven insane from the torture.[16] Freezing experiments In 1941, the Luftwaffe conducted experiments with the intent of discovering means to prevent and treat hypothermia. There were 360 to 400 experiments and 280 to 300 victims indicating some victims suffered more than one experiment.[17] Another study placed prisoners naked in the open air for several hours with temperatures as low as −6 °C (21 °F). Besides studying the physical effects of cold exposure, the experimenters also assessed different methods of rewarming survivors.[19] "One assistant later testified that some victims were thrown into boiling water for rewarming."[17][20] Beginning in August 1942, at the Dachau camp, prisoners were forced to sit in tanks of freezing water for up to three hours. After subjects were frozen, they then underwent different methods for rewarming. Many subjects died in this process.[21] In a letter from 10 September 1942, Rascher describes an experiment on intense cooling performed in Dachau where people were dressed in fighter pilot uniforms and submerged in freezing water. Rascher had some of the victims completely underwater and others only submerged up to the head.[22] The freezing and hypothermia experiments were conducted for the Nazi high command to simulate the conditions the armies suffered on the Eastern Front, as the German forces were ill-prepared for the cold weather they encountered. Many experiments were conducted on captured Soviet troops; the Nazis wondered whether their genetics gave them superior resistance to cold. The principal locales were Dachau and Auschwitz. Sigmund Rascher, an SS doctor based at Dachau, reported directly to Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler and publicised the results of his freezing experiments at the 1942 medical conference entitled "Medical Problems Arising from Sea and Winter".[23] Himmler suggested that the victims could be warmed by forcing them to engage in sexual contact with other victims. An example included how a hypothermic victim was placed between two naked Romani women.[24][25] Approximately 100 people are reported to have died as a result of these experiments.[26] |

実験 ニュルンベルク軍事裁判の検察側文書の目次には、食品、海水、流行性黄疸、スルファニルアミド、血液凝固、痰などの医学実験を記録したセクションのタイト ルがある[4]。 その後のニュルンベルク裁判での起訴状によると、これらの実験には以下のものがある[5][6]。 双子の実験 強制収容所における双子の子供の実験は、表現型の決定において環境よりも遺伝が優れていることを示し、ドイツの繁殖率を高める方法を見出すために行われた ものである。実験の中心的指導者はヨーゼフ・メンゲレで、1943年から1944年にかけて、アウシュビッツに収容されていた約1,500組の双子に対し て実験を行った。双子は年齢と性別で並べられ、切断、様々な病気の感染、目の色を変えるための染料の注入など、実験の合間にバラックで保管された[7]。 また、双子を縫い合わせて結合双生児を作ろうとし、壊疽を起こし、最終的には死に至らしめた[8][9]。しばしば、一方の双子は実験を受けさせられ、も う一方は対照として保存された。片方の双子が実験によって死亡すると、もう片方の双子も同時に殺される。最初の双子が生き残った場合、メンゲレは彼らの体 を解剖する[11]。 骨、筋肉、神経の移植実験 1942年9月頃から1943年12月頃まで、ラーベンスブリュック強制収容所において、ドイツ軍のために、骨、筋肉、神経の再生や、人から人への骨移植 を研究する実験が行われた[12] 。これらの手術の結果、多くの犠牲者が激しい苦痛、切断、後遺症を負った[12]。 1946年8月12日、ヤドヴィガ・カミンスカ[13]という生存者は、ラーフェンスブリュック強制収容所での時間について供述し、彼女が2度手術を受け たことを記述している。両手術とも片方の脚の手術であった。彼女は、手術が正確にどのようなものであったかを知っていたとは述べていないが、2回とも術後 に激痛と発熱があったが、アフターケアはほとんど何もされなかったと説明している。カミンスカは、単に「若い女の子でポーランドの愛国者」だから手術を受 けたと言われたことを説明する。彼女は、手術の後、数ヶ月間、脚から膿がにじみ出たと述べている[14]。 捕虜はまた、戦場で使用するために開発された新薬の効果を調べるために、骨髄に細菌を注入される実験も行われた[14]。生き残った者は、永久に醜態を晒 したままであった[15]。 頭部損傷実験 1942年半ば、占領下のポーランドのバラノヴィツェで、ナチスのSD保安局員として知られる人物が住んでいた私邸の裏にある小さな建物で実験が行われ、 「11歳か12歳の少年が動けないように椅子に縛り付けられていた。彼の頭上には機械化されたハンマーがあり、数秒ごとに彼の頭上に振り下ろされた」。少 年は拷問によって正気を失ってしまった[16]。 凍結実験 1941年、ドイツ空軍は低体温症を予防・治療する手段を発見する目的で実験を行った。実験は360から400回、犠牲者は280から300人で、複数の 実験を受けたも犠牲者もいたようだ[17]。 別の研究では、囚人を裸で数時間、-6 °C (21 °F)の気温の屋外に置いた。寒冷暴露の身体的影響を研究するほかに、実験者たちは生存者を再加熱するさまざまな方法を評価した[19]。「ある助手は後 に、再加熱のために熱湯に投げ込まれる犠牲者もいたと証言している」[17][20]。 1942年8月からダッハウ収容所では、囚人たちは氷水のタンクに最大3時間座ることを余儀なくされた。被験者は凍結後、様々な方法で再加温された。 1942年9月10日の手紙の中で、ラッシャーはダッハウで行われた戦闘機パイロットの制服を着て氷水の中に沈めるという強烈な冷却実験について述べてい る[21]。ラッシャーは犠牲者の何人かを完全に水中に潜らせ、他の者は頭までしか沈ませなかった[22]。 凍結と低体温の実験はナチス上層部のために行われ、ドイツ軍が遭遇した寒冷な天候に対する準備が不十分であったため、東部戦線で軍が受けた状況をシミュ レートするために行われたものであった。捕虜にしたソ連軍を対象にした実験も多く、ナチスは彼らの遺伝子が寒さに対する抵抗力に優れているのではないかと 考えた。主な実験場はダッハウとアウシュビッツである。ダッハウにいた親衛隊の医師ジークムント・ラッ シャーはハインリッヒ・ヒムラー親衛隊大将に直接報告し、「海と冬から生じる医療問題」と題した1942年の医学会議で彼の凍結実験の結果を公表した [23] ヒムラーは犠牲者を他の犠牲者と性的接触をさせることによって暖めることができると示唆した。例としては、低体温の犠牲者を2人の裸のロマ人女性の間に置 く方法が含まれていた[24][25]。 これらの実験の結果として、約100人が死亡したと報告されている[26]。 |

| Malaria experiments From about February 1942 to about April 1945, experiments were conducted at the Dachau concentration camp in order to investigate immunization for treatment of malaria. Healthy inmates were infected by mosquitoes or by injections of extracts of the mucous glands of female mosquitoes. After contracting the disease, the subjects were treated with various drugs to test their relative efficacy.[27] Over 1,200 people were used in these experiments and more than half died as a result.[28] Other test subjects were left with permanent disabilities.[29] Immunization experiments At the German concentration camps of Sachsenhausen, Dachau, Natzweiler, Buchenwald, and Neuengamme, scientists tested immunization compounds and serums for the prevention and treatment of contagious diseases, including malaria, typhus, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, yellow fever, and infectious hepatitis.[30][31] Viral hepatitis From June 1943 until January 1945 at the concentration camps, Sachsenhausen and Natzweiler, experimentation with 'epidemic jaundice' was conducted. The test subjects were injected with the disease in order to discover new inoculations for the condition. These tests were conducted for the benefit of the German Armed Forces. Most died in the experiments, whilst others survived, experiencing great pain and suffering.[32] Mustard gas experiments At various times between September 1939 and April 1945, many experiments were conducted at Sachsenhausen, Natzweiler, and other camps to investigate the most effective treatment of wounds caused by mustard gas. Test subjects were deliberately exposed to mustard gas and other vesicants (e.g. Lewisite) which inflicted severe chemical burns. The victims' wounds were then tested to find the most effective treatment for the mustard gas burns.[33] Sulfonamide experiments From about July 1942 to about September 1943, experiments to investigate the effectiveness of sulfonamide, a synthetic antimicrobial agent, were conducted at Ravensbrück.[35] Wounds inflicted on the subjects were infected with bacteria such as Streptococcus, Clostridium perfringens (a major causative agent in gas gangrene) and Clostridium tetani, the causative agent in tetanus.[36] Circulation of blood was interrupted by tying off blood vessels at both ends of the wound to create a condition similar to that of a battlefield wound. Researchers also aggravated the subjects' infection by forcing wood shavings and ground glass into their wounds. The infection was treated with sulfonamide and other drugs to determine their effectiveness. Sea water experiments From about July 1944 to about September 1944, experiments were conducted at the Dachau concentration camp to study various methods of making sea water drinkable. These victims were subject to deprivation of all food and only given the filtered sea water.[37] At one point, a group of roughly 90 Roma were deprived of food and given nothing but sea water to drink by Hans Eppinger, leaving them gravely injured.[23] They were so dehydrated that others observed them licking freshly mopped floors in an attempt to get drinkable water.[38] A Holocaust survivor named Joseph Tschofenig wrote a statement on these seawater experiments at Dachau. Tschofenig explained how while working at the medical experimentation stations he gained insight into some of the experiments that were performed on prisoners, namely those in which they were forced to drink salt water. Tschofenig also described how victims of the experiments had trouble eating and would desperately seek out any source of water including old floor rags. Tschofenig was responsible for using the X-ray machine in the infirmary and describes how even though he had insight into what was going on he was powerless to stop it. He gives the example of a patient in the infirmary who was sent to the gas chambers by Sigmund Rascher simply because he witnessed one of the low-pressure experiments.[39] |

マラリア実験 1942年2月頃から1945年4月頃まで、ダッハウ強制収容所において、マラリア治療のための免疫について調べるための実験が行われた。健康な被収容者 を蚊に感染させたり、雌の蚊の粘膜腺の抽出物を注射して感染させた。1,200人以上がこの実験に使用され、半数以上が結果として死亡した[28]。 他の被験者は後遺症を残すこととなった[29]。 予防接種実験 ドイツのザクセンハウゼン、ダッハウ、ナッツヴァイラー、ブッヘンヴァルト、ノイエンガンメの強制収容所で、科学者はマラリア、チフス、結核、チフス、黄 熱病、感染性肝炎などの伝染病の予防と治療のために免疫化合物と血清の実験を行った[30][31]。 ウイルス性肝炎 1943年6月から1945年1月まで、強制収容所であるザクセンハウゼンとナッツヴァイラーで、「伝染性黄疸」の実験が行われた。この症状に対する新し い予防接種を発見するために、被験者にこの病気を注射したのである。この実験は、ドイツ軍のために行われた。ほとんどの者は実験で死亡し、他の者は大きな 痛みと苦しみを経験しながら生き延びた[32]。 マスタードガス実験 1939年9月から1945年4月にかけて、ザクセンハウゼン、ナッツヴァイラー、その他の収容所で、マスタードガスによる傷の最も効果的な治療法を調査 するために多くの実験が行われた。被験者は、マスタードガスや他の揮発性物質(ルイサイトなど)に意図的にさらされ、重度の化学熱傷を負わされた。犠牲者 の傷はその後、マスタードガスによる火傷の最も効果的な治療法を見つけるためにテストされた[33]。 スルホンアミド実験 1942年7月頃から1943年9月頃まで、ラーベンスブリュックでは合成抗菌剤であるスルホンアミドの効果を調べる実験が行われた[35]。 [傷口に溶連菌、ガス壊疽の主要原因菌であるクロストリジウム・パーフリンゲンス、破傷風の原因菌であるクロストリジウム・テタニなどの細菌を感染させ、 傷口の両端の血管を縛って血液循環を遮断し、戦場の傷に近い状態を作り出した[36]。また、研究者たちは、木屑やすりガラスを無理やり傷口に押し込ん で、被験者の感染を悪化させた。感染症にはスルホンアミドなどの薬剤を投与し、その効果を検証した。 海水実験 1944年7月頃から9月頃まで、ダッハウ強制収容所において、海水を飲めるようにするための様々な方法を研究するための実験が行われた。あるとき、約 90人のロマの集団がハンス・エッピンガーによって食料を奪われ、海水しか与えられず、重症を負った[23]。 彼らは脱水状態にあり、飲める水を得るためにモップがけされたばかりの床を舐める姿が他の者によって観察された[38]。 ホロコーストの生存者であるヨーゼフ・ツォフェニヒは、ダッハウでのこれらの海水実験について声明を書いている。ツォフェニヒは、医学実験場で働いている ときに、囚人に対して行われた実験の一部、すなわち、塩水を飲ませる実験について洞察を得たことを説明した。ツォフェニヒはまた、この実験の犠牲者が食べ るのに苦労し、古い床の雑巾を含むあらゆる水源を必死で探していたことを説明した。ツォフェニヒは医務室のX線装置の責任者であったが、実験が行われてい ることを知りながら、それを止めることができなかった。彼は、医務室で低圧実験の一つを目撃したという理由だけでジークムント・ラッシャーによってガス室 送りにされた患者の例を挙げている[39]。 |

| Child victims of Nazi experimentation show incisions where axillary lymph nodes had been surgically removed after they were deliberately infected with tuberculosis at Neuengamme concentration camp. They were later murdered.[34] |  ノイエンガンメ強制収容所

で結核に意図的に感染させられ、腋窩リンパ節を外科的に切除されたナチスの実験犠牲者の子供たち。彼らは後に殺害された[34]。 ノイエンガンメ強制収容所

で結核に意図的に感染させられ、腋窩リンパ節を外科的に切除されたナチスの実験犠牲者の子供たち。彼らは後に殺害された[34]。 |

| Sterilization and fertility

experiments The Law for the Prevention of Genetically Defective Progeny, which was passed on 14 July 1933, legalized the involuntary sterilization of persons with diseases claimed to be hereditary: weak-mindedness, schizophrenia, alcohol abuse, insanity, blindness, deafness, and physical deformities. The law was used to encourage growth of the Aryan race through the sterilization of persons who fell under the quota of being genetically defective.[40] 1% of citizens between the age of 17 to 24 had been sterilized within two years of the law passing. Within four years, 300,000 patients had been sterilized.[41] From about March 1941 to about January 1945, sterilization experiments were conducted at Auschwitz, Ravensbrück, and other places by Carl Clauberg.[33] The purpose of these experiments was to develop a method of sterilization which would be suitable for sterilizing millions of people with a minimum of time and effort. The targets for sterilization included Jewish and Roma populations.[15] These experiments were conducted by means of X-ray, surgery and various drugs. Thousands of victims were sterilized. Aside from its experimentation, the Nazi government sterilized around 400,000 people as part of its compulsory sterilization program.[42] Carl Clauberg was the leading research developer in the search for cost effective and efficient means of mass sterilization. He was particularly interested in experimenting on women from age twenty to forty who had already given birth. Prior to any experiments, Clauberg X-rayed women to make sure that there was no obstruction to their ovaries. Next, over the course of three to five sessions, he injected the women's cervixes with the goal of blocking their fallopian tubes. The women who stood against him and his experiments or were deemed as unfit test subjects were sent to be killed in the gas chambers.[43] Intravenous injections of solutions speculated to contain iodine and silver nitrate were successful, but had unwanted side effects such as vaginal bleeding, severe abdominal pain, and cervical cancer.[44] Therefore, radiation treatment became the favored choice of sterilization. Specific amounts of exposure to radiation destroyed a person's ability to produce ova or sperm, sometimes administered through deception. Many suffered severe radiation burns.[45] The Nazis also implemented X-ray radiation treatment in their search for mass sterilization. They gave the women abdomen X-rays, men received them on their genitalia, for abnormal periods of time in attempt to invoke infertility. After the experiment was complete, they surgically removed their reproductive organs, often without anesthesia, for lab analysis.[43] M.D. William E. Seidelman, a professor from the University of Toronto, in collaboration with Dr. Howard Israel of Columbia University, published a report on an investigation on the medical experimentation performed in Austria under the Nazi regime. In that report he mentions a Doctor Hermann Stieve, who used the war to experiment on live humans. Stieve specifically focused on the reproductive system of women. He would tell women their date of death in advance, and he would evaluate how their psychological distress would affect their menstruation cycles. After they were murdered, he would dissect and examine their reproductive organs. Some of the women were raped after they were told the date when they would be killed so that Stieve could study the path of sperm through their reproductive system.[46] |

不妊手術と不妊実験 1933年7月14日に成立した「遺伝子異常者予防法」は、遺伝性の疾患(精神薄弱、統合失調症、アルコール依存症、心神喪失、失明、難聴、身体奇形)を 持つ者に対して強制的に不妊手術を行うことを合法化した。この法律は、アーリア人種の成長を促すために、遺伝的に欠陥があるという枠に当てはまる人を不妊 化することに使われた[40]。法律成立から2年以内に17歳から24歳の市民の1%が不妊化された。 1941年3月頃から1945年1月頃まで、アウシュヴィッツやラーベンスブリュックなどでカール・クラウベルクによる不妊化実験が行われた[33]。こ れらの実験の目的は、最小限の時間と労力で数百万人を殺菌するのに適した殺菌方法を開発することであった。不妊化の対象にはユダヤ人とロマ人が含まれてい た[15]。これらの実験は、X線、手術、様々な薬物によって行われた。何千人もの犠牲者が不妊化された。その実験とは別に、ナチス政府は強制不妊化プロ グラムの一環として約40万人の人々を不妊化した[42]。 カール・クラウベルクは、費用対効果が高く効率的な大量不妊手術の手段を模索する研究開発の第一人者であった。彼は、特に20歳から40歳までの出産経験 のある女性を対象とした実験に関心をもっていた。実験に先立ち、クラウバーグは女性のX線写真を撮って、卵巣に障害がないことを確認した。そして、3回か ら5回にわたって、女性の子宮頸管に注射して卵管をふさぐという実験を行った。彼や彼の実験に逆らった女性や、実験台にふさわしくないと判断された女性 は、ガス室で殺されるように送られた[43]。 ヨウ素と硝酸銀を含むと推測される溶液の静脈注射は成功したが、膣からの出血、激しい腹痛、子宮頸癌などの望ましくない副作用があった[44]。 したがって、放射線治療が不妊手術として好まれるようになったのである。特定の量の放射線を浴びると、卵子や精子を作る能力が破壊され、時には騙されて投 与されることもあった。多くの人が重度の放射線熱傷を負った[45]。 ナチスもまた、集団不妊化のためにX線照射治療を実施した。女性には腹部、男性には生殖器に異常な時間X線を照射し、不妊を誘発しようとしたのである。実 験が完了した後、彼らはしばしば無麻酔で生殖器を外科的に摘出し、研究室で分析した[43]。 トロント大学の医学博士ウィリアム・E・サイデルマンは、コロンビア大学のハワード・イスラエル博士と共同で、ナチス政権下のオーストリアで行われた医療 実験に関する調査報告書を発表している。その中で、戦争中に生きた人間の実験を行ったヘルマン・スティーブ博士について触れている。シュティーフェは、特 に女性の生殖器系に焦点を当てた。シュティーフェは、女性にあらかじめ死の日を告げ、その心理的苦痛が月経周期にどのような影響を与えるかを評価した。そ して、殺された女性の生殖器官を解剖し、調べるのである。シュティーヴが生殖器官を通る精子の経路を研究するために、殺される日を告げられた後にレイプさ れた女性もいた[46]。 |

| Experiments with poison Somewhere between December 1943 and October 1944, experiments were conducted at Buchenwald to investigate the effect of various poisons. The poisons were secretly administered to experimental subjects in their food. The victims died as a result of the poison or were killed immediately in order to permit autopsies. In September 1944, experimental subjects were shot with poisonous bullets, suffered torture, and often died.[33] Some male Jewish prisoners had poisonous substances scrubbed or injected into their skin, causing boils filled with black fluid to form. These experiments were heavily documented as well as photographed by the Nazis.[43] Incendiary bomb experiments From around November 1943 to around January 1944, experiments were conducted at Buchenwald to test the effect of various pharmaceutical preparations on phosphorus burns. These burns were inflicted on prisoners using phosphorus material extracted from incendiary bombs.[33] High altitude experiments Further information: Hubertus Strughold In early 1942, prisoners at Dachau concentration camp were used by Sigmund Rascher in experiments to aid German pilots who had to eject at high altitudes. A low-pressure chamber containing these prisoners was used to simulate conditions at altitudes of up to 68,000 feet (21,000 m). It was rumored that Rascher performed vivisections on the brains of victims who survived the initial experiment.[47] Of the 200 subjects, 80 died outright, and the others were murdered.[23] In a letter from 5 April 1942 between Rascher and Heinrich Himmler, Rascher explains the results of a low-pressure experiment that was performed on people at Dachau Concentration camp in which the victim was suffocated while Rascher and another unnamed doctor took note of his reactions. The person was described as 37 years old and in good health before being murdered. Rascher described the victim's actions as he began to lose oxygen and timed the changes in behavior. The 37-year-old began to wiggle his head at four minutes; a minute later Rascher observed that he was suffering from cramps before falling unconscious. He describes how the victim then lay unconscious, breathing only three times per minute, until he stopped breathing 30 minutes after being deprived of oxygen. The victim then turned blue and began foaming at the mouth. An autopsy followed an hour later.[48] In a letter from Himmler to Rascher on 13 April 1942, Himmler ordered Rascher to continue the high altitude experiments and to continue experimenting on prisoners condemned to death and to "determine whether these men could be recalled to life". If a victim could be successfully resuscitated, Himmler ordered that he be pardoned to "concentration camp for life".[49] |

毒物実験 1943年12月から1944年10月にかけて、ブッヘンヴァルトでは、さまざまな毒物の効果を調べる実験が行われた。毒薬は、実験対象者の食事に混ぜて 密かに投与された。犠牲者は毒が原因で死亡するか、解剖を可能にするために直ちに殺されました。1944年9月、実験対象者は毒弾を撃たれ、拷問を受け、 しばしば死亡していた[33]。 一部のユダヤ人男性囚人は、毒物を皮膚に擦り込まれたり、注入されたりして、黒い液体で満たされた腫れ物を形成させた。これらの実験は、ナチスによって写 真に撮られるとともに、厳重に記録された[43]。 焼夷弾実験 1943年11月頃から1944年1月頃まで、ブッヘンヴァルトでは、リンの火傷に対する様々な製薬の効果を試す実験が行われた。これらの火傷は焼夷弾か ら抽出された燐物質を使って囚人に負わされたものである[33]。 高高度実験 さらに詳しい情報はこちら。フベルトゥス・シュトルークホル ト(1898-1986) 1942年初頭、ダッハウ強制収容所の囚人はジークムント・ラッシャーによって、高高度で脱出しなければならないドイツのパイロットを助けるための実験に 使用された。この囚人たちを収容した低圧室は、高度21,000mまでの状況を再現するために使用された。1942年4月5日のラッシャーとハインリッ ヒ・ヒムラーとの手紙の中で、ラッシャーはダッハウ強制収容所で行われた低圧実験の結果について説明しており、被害者はラッシャーと他の無名の医師によっ てその反応を記録されながら窒息させられた。その被害者は37歳で、殺される前は健康だったという。ラッシャーは、被害者が酸素を失い始めたときの行動を 説明し、その変化をタイミングよく記録した。37歳は4分後に頭をくねらせ始め、その1分後にラシャーは意識を失う前にけいれんを起こしているのを観察し た。その後、被害者は意識を失い、1分間に3回しか呼吸をせず、酸素が奪われてから30分後に呼吸が停止したと説明している。そして、青くなり、口から泡 を吹き始めた。検死は1時間後に行われた[48]。 1942年4月13日のヒムラーからラッシャーへの手紙の中で、ヒムラーはラッシャーに高高度実験の継続と死刑囚の実験を続け、「これらの人々を生き返ら せることができるかどうか判断する」よう命じた。犠牲者の蘇生に成功した場合、ヒムラーはその者を「終身強制収容所」に赦免するよう命じた[49]。 |

| Aftermath Other documented transcriptions from Heinrich Himmler include phrases such as "These researches… can be performed by us with particular efficiency because I personally assumed the responsibility for supplying asocial individuals and criminals who deserve only to die from concentration camps for these experiments."[51] Many of the subjects died as a result of the experiments conducted by the Nazis, while many others were murdered after the tests were completed to study the effects post mortem.[52] Those who survived were often left mutilated, with permanent disability, weakened bodies, and mental distress.[23][53] On 19 August 1947, the doctors captured by Allied forces were put on trial in USA vs. Karl Brandt et al., commonly known as the Doctors' Trial. At the trial, several of the doctors argued in their defense that there was no international law regarding medical experimentation.[citation needed] Some doctors also claimed that they had been doing the world a favor. An SS doctor was quoted saying that "Jews were the festering appendix in the body of Europe." He then went on to argue he was doing the world a favor by eliminating them.[10] The issue of informed consent had previously been controversial in German medicine in 1900, when Albert Neisser infected patients (mainly prostitutes) with syphilis without their consent. Despite Neisser's support from most of the academic community, public opinion, led by psychiatrist Albert Moll, was against Neisser. While Neisser went on to be fined by the Royal Disciplinary Court, Moll developed "a legally based, positivistic contract theory of the patient-doctor relationship" that was not adopted into German law.[54] Eventually, the minister for religious, educational, and medical affairs issued a directive stating that medical interventions other than for diagnosis, healing, and immunization were excluded under all circumstances if "the human subject was a minor or not competent for other reasons", or if the subject had not given his or her "unambiguous consent" after a "proper explanation of the possible negative consequences" of the intervention, though this was not legally binding.[54] In response, Drs. Leo Alexander and Andrew Conway Ivy, the American Medical Association representative at the Doctors' Trial, drafted a ten-point memorandum entitled Permissible Medical Experiment that went on to be known as the Nuremberg Code.[55] The code calls for such standards as voluntary consent of patients, avoidance of unnecessary pain and suffering, and that there must be a belief that the experimentation will not end in death or disability.[56] The Code was not cited in any of the findings against the defendants and never made it into either German or American medical law.[57] This code comes from the Nuremberg Trials where the most heinous of Nazi leaders were put on trial for their war crimes.[58] To this day, the Nuremberg Code remains a major stepping stone for medical experimentation.[59] |

余波 ハインリッヒ・ヒムラーの他の記録には、「これらの研究は...私が個人的にこれらの実験のために強制収容所から死に値する非社会的な個人と犯罪者を供給 する責任を負っているので、特に効率的に我々によって行うことができます」といったフレーズが含まれている[51]。 「ナチスによって行われた実験の結果、多くの被験者が死亡し、他の多くの被験者が死後の影響を調べるために実験終了後に殺害された[52]。生き残った人 々は、しばしば切断され、後遺症、弱った身体、精神的苦痛を残した。 1947年8月19日、連合軍によって捕えられた医師たちはUSA vs. Karl Brandt et al, 通称「ドクターズトライアル」。この裁判で、医師たちの何人かは、医学実験に関する国際法は存在しないと弁護した[citation needed]。また、一部の医師たちは、自分たちは世界のためにやっているのだと主張した。ある親衛隊の医師は、「ユダヤ人はヨーロッパの体内の化膿し た盲腸である」と言ったことが引用されています。そして彼は、彼らを排除することで世界のためになっていると主張し続けた[10]。 インフォームド・コンセントの問題は、1900年にアルベルト・ナイザーが患者(主に売春婦)に同意なしに梅毒を感染させたときに、ドイツの医学界で論争 になったことがある。ナイサーは学界の大半から支持されていたにもかかわらず、精神科医のアルベルト・モルが率いる世論はナイサーに反対していた。ナイ サーは王立懲戒裁判所から罰金を科されることになったが、モルは「患者と医師の関係について、法的根拠に基づく実証的な契約理論」を展開し、ドイツの法律 には採用されなかった[54]。 [54] 最終的には、宗教・教育・医療担当大臣が、診断、治癒、予防接種以外の医療介入は、「被験者が未成年であるか、その他の理由で能力がない」場合、あるいは 被験者が介入の「起こりうる否定的な結果についての適切な説明」の後に「あいまいではない同意」を与えていない場合には、いかなる状況でも除外されるとい う指示を出しているが、これは法的拘束力はないものである[54]。 これに対して、医師裁判のアメリカ医師会代表であったレオ・アレクサンダー博士とアンドリュー・コンウェイ・アイビー博士は、後にニュルンベルク・コード として知られるようになった「許容される医学実験」と題する10項目のメモを起草した[55]。このコードは、患者の自発的同意、不必要な痛みと苦しみの 回避、実験が死亡や障害に終わらないと信じること、といった基準について要求している。 [この規範は、ナチスの最も凶悪な指導者が戦争犯罪のために裁判にかけられたニュルンベルク裁判に由来する[57]。 今日まで、ニュルンベルク規範は医学実験のための主要な足がかりとして残されている[59]。 |

| Jadwiga Dzido shows scars on her leg from medical experiments to the Doctors' Trial |  ヤドヴィガ・ジドさんが医師裁判で見せた医療実験による足の傷跡 ヤドヴィガ・ジドさんが医師裁判で見せた医療実験による足の傷跡 |

| Modern ethical issues Andrew Conway Ivy stated the Nazi experiments were of no medical value.[17] Data obtained from the experiments, however, has been used and considered for use in multiple fields, often causing controversy. Some object to the data's use purely on ethical grounds, disagreeing with the methods used to obtain it, while others have rejected the research only on scientific grounds, criticizing methodological inconsistencies.[17] Those in favor of using the data argue that if it has practical value to save lives, it would be equally unethical not to use it.[38] Arnold S. Relman, editor of The New England Journal of Medicine from 1977 until 1991, refused to allow the journal to publish any article that cited the Nazi experiments.[17] The results of the Dachau freezing experiments have been used in some late 20th century research into the treatment of hypothermia; at least 45 publications had referenced the experiments as of 1984, though the majority of publications in the field did not cite the research.[17] Those who have argued in favor of using the research include Robert Pozos from the University of Minnesota and John Hayward from the University of Victoria.[38] In a 1990 review of the Dachau experiments, Robert Berger concludes that the study has "all the ingredients of a scientific fraud" and that the data "cannot advance science or save human lives."[17] In 1989, the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) considered using data from Nazi research into the effects of phosgene gas, believing the data could help US soldiers stationed in the Persian Gulf at the time. They eventually decided against using it, on the grounds it would lead to criticism and similar data could be obtained from later studies on animals. Writing for Jewish Law, Baruch Cohen concluded that the EPA's "knee-jerk reaction" to reject the data's use was "typical, but unprofessional", arguing that it could have saved lives.[38] |

現代の倫理問題 アンドリュー・コンウェイ・アイビーは、ナチスの実験に医学的価値はないと述べている[17]が、実験から得られたデータは様々な分野で利用・検討されて おり、しばしば論争を巻き起こしている。1977年から1991年まで『ニューイングランド・ジャーナル・オブ・メディシン』誌の編集長だったアーノル ド・レルマンは、ナチスの実験を引用する論文の掲載を拒否している[17]。 ダッハウ凍結実験の結果は、低体温症の治療に関する20世紀後半のいくつかの研究において利用されている。1984年の時点で少なくとも45の出版物がこ の実験に言及していたが、この分野の出版物の大部分はこの研究を引用していなかった。 [1990年のダッハウ実験のレビューにおいて、ロバート・バーガーは、この研究は「科学的詐欺のすべての要素」を持ち、そのデータは「科学を進歩させる ことも、人命を救うこともできない」と結論付けている[17]。 1989年、アメリカ合衆国環境保護庁(EPA)は、ホスゲンガスの影響に関するナチスの研究データを、当時ペルシャ湾に駐留していたアメリカ兵を助ける ことができると考え、その使用を検討した。しかし、批判を浴びそうなことと、同様のデータは後に動物実験によって得られるという理由から、結局は使用を見 送った。バルーク・コーエンは、Jewish Lawに寄稿し、このデータの使用を拒否したEPAの「膝を打つような反応」は「典型的だが、プロフェッショナルではない」と結論づけ、人命を救えたかも しれないと論じている[38]。 |

| Bullenhuser Damm Erwin Ding-Schuler Guatemala syphilis experiment Herta Oberheuser Henry K. Beecher Human experimentation in North Korea Human radiation experiments Japanese human experimentation Jewish skeleton collection Karl Genzken Karl Gebhardt Viktor Frankl List of medical eponyms with Nazi associations List of Nazi doctors Nazi eugenics Project MKUltra (CIA) Shiro Ishii Unethical human experimentation in the United States Margarethe Kraus |

ブルンヒュッサー・ダム エルヴィン・ディン=シューラー グアテマラ梅毒実験 ヘルタ・オーバーホイザー ヘンリー・K・ビーチャー 北朝鮮における人体実験 人体放射線実験 日本における人体実験 ユダヤ人骨格収集 カール・ゲンツケン カール・ゲブハルト ヴィクトール・フランクル ナチス関連医学用語一覧 ナチス医師一覧 ナチス優生学 プロジェクトMKウルトラ(CIA) 石井四郎 米国における非倫理的人体実験 マルガレーテ・クラウス |

| Further reading Annas, George J. (1992). The Nazi Doctors and the Nuremberg Code: Human Rights in Human Experimentation. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195101065. Baumslag, N. (2005). Murderous Medicine: Nazi Doctors, Human Experimentation, and Typhus. Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-275-98312-9 Michalczyk, J. (Dir.) (1997). In The Shadow of the Reich: Nazi Medicine. First Run Features. (video) Nyiszli, M. (2011). "3". Auschwitz: A Doctor's Eyewitness Account. New York: Arcade Publishing. Rees, L. (2005). Auschwitz: A New History. Public Affairs. ISBN 1-58648-357-9 Weindling, P.J. (2005). Nazi Medicine and the Nuremberg Trials: From Medical War Crimes to Informed Consent. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 1-4039-3911-X USAF School of Aerospace Medicine (1950). German Aviation Medicine, World War II. United States Air Force. |

参考文献 アナス、ジョージ・J. (1992). 『ナチス医師とニュルンベルク綱領:人体実験における人権』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0195101065. バウムスラグ、N.(2005)。『殺戮の医学:ナチス医師、人体実験、そしてチフス』。プレガー出版社。ISBN 0-275-98312-9 ミハルチク、J.(監督)(1997)。『帝国の影:ナチス医学』。ファースト・ラン・フィーチャーズ。(ビデオ) ニシュリ、M.(2011).「3」.『アウシュヴィッツ:医師の目撃証言』.ニューヨーク:アーケード出版. リース、L.(2005).『アウシュヴィッツ:新たな歴史』.パブリック・アフェアーズ.ISBN 1-58648-357-9 ヴァインディング、P.J.(2005)。『ナチス医学とニュルンベルク裁判:医療戦争犯罪からインフォームド・コンセントへ』。パルグレイブ・マクミラン。ISBN 1-4039-3911-X 米国空軍航空医学学校(1950)。『第二次世界大戦におけるドイツ航空医学』。米国空軍。 |

| External links The Infamous Medical Experiments from Holocaust Survivors and Remembrance Project: "Forget You Not" United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Online Exhibition: Doctors Trial United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Online Exhibition: Deadly Medicine: Creating the Master Race United States Holocaust Memorial Museum – Library Bibliography: Medical Experiments Jewish Virtual Library: Medical Experiments Table of Contents |

外部リンク ホロコースト生存者による悪名高い医学実験と記憶プロジェクト:「忘れるな」 米国ホロコースト記念博物館 – オンライン展示:医師裁判 米国ホロコースト記念博物館 – オンライン展示:致死的な医学:優生人種創造 米国ホロコースト記念博物館 – 図書館書誌:医学実験 ユダヤ仮想図書館:医学実験目次 |

| Controversy regarding use of

findings Campell, Robert. "Citations of shame; scientists are still trading on Nazi atrocities", New Scientist, 28 February 1985, 105(1445), p. 31.Citations of shame; scientists are still trading on Nazi atrocities[1] "Citing Nazi 'Research': To Do So Without Condemnation Is Not Defensible" "On the Ethics of Citing Nazi Research" "Remembering the Holocaust, Part 2" "The Ethics Of Using Medical Data From Nazi Experiments" |

研究成果の利用に関する論争 キャンベル、ロバート。「恥の引用:科学者たちは今もナチスの残虐行為を利用している」、『ニュー・サイエンティスト』1985年2月28日号、105(1445)、31ページ。恥の引用:科学者たちは今もナチスの残虐行為を利用している[1] 「ナチスの『研究』を引用する:非難なしにそうすることは正当化できない」 「ナチス研究を引用する倫理について」 「ホロコーストを記憶する、その2」 「ナチス実験の医学データを利用する倫理」 |

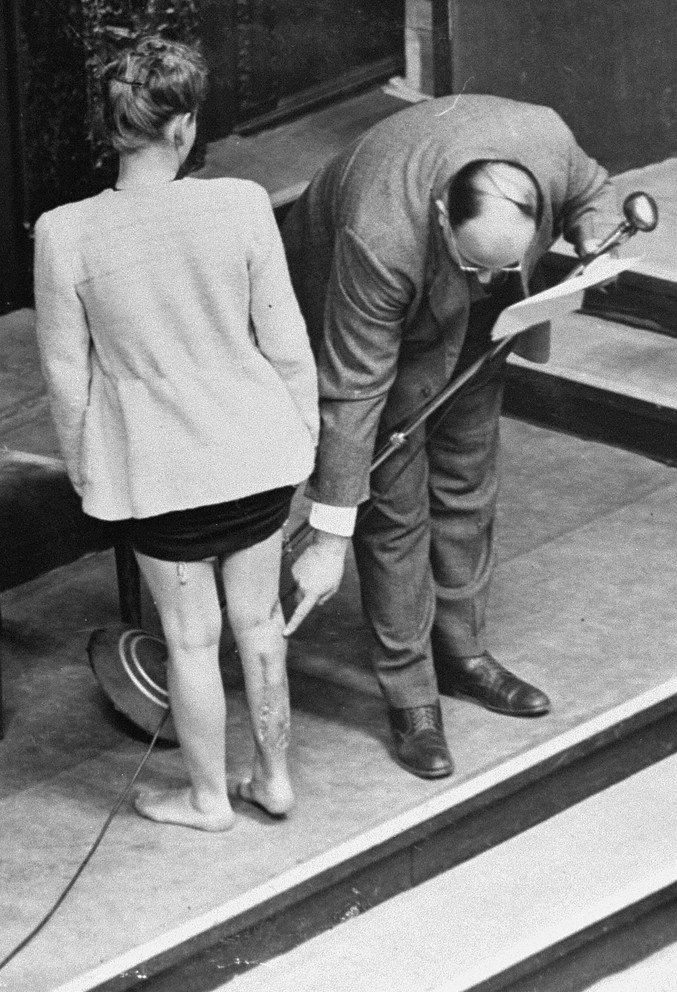

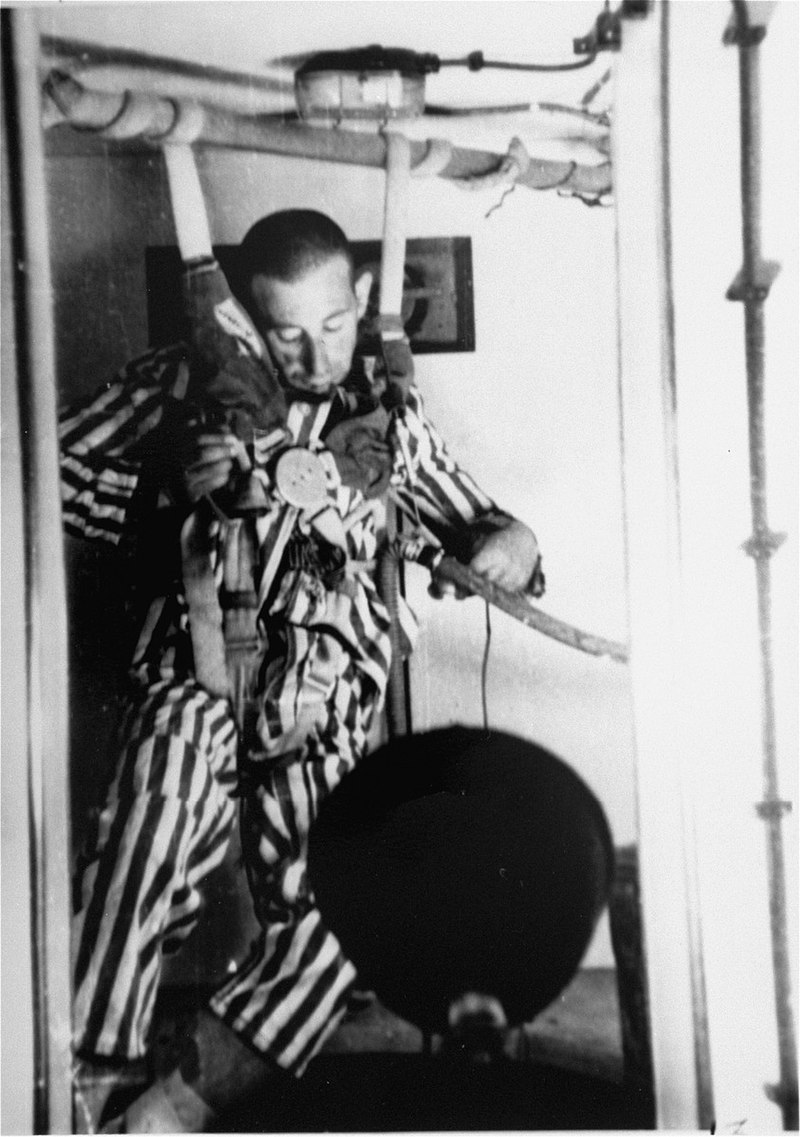

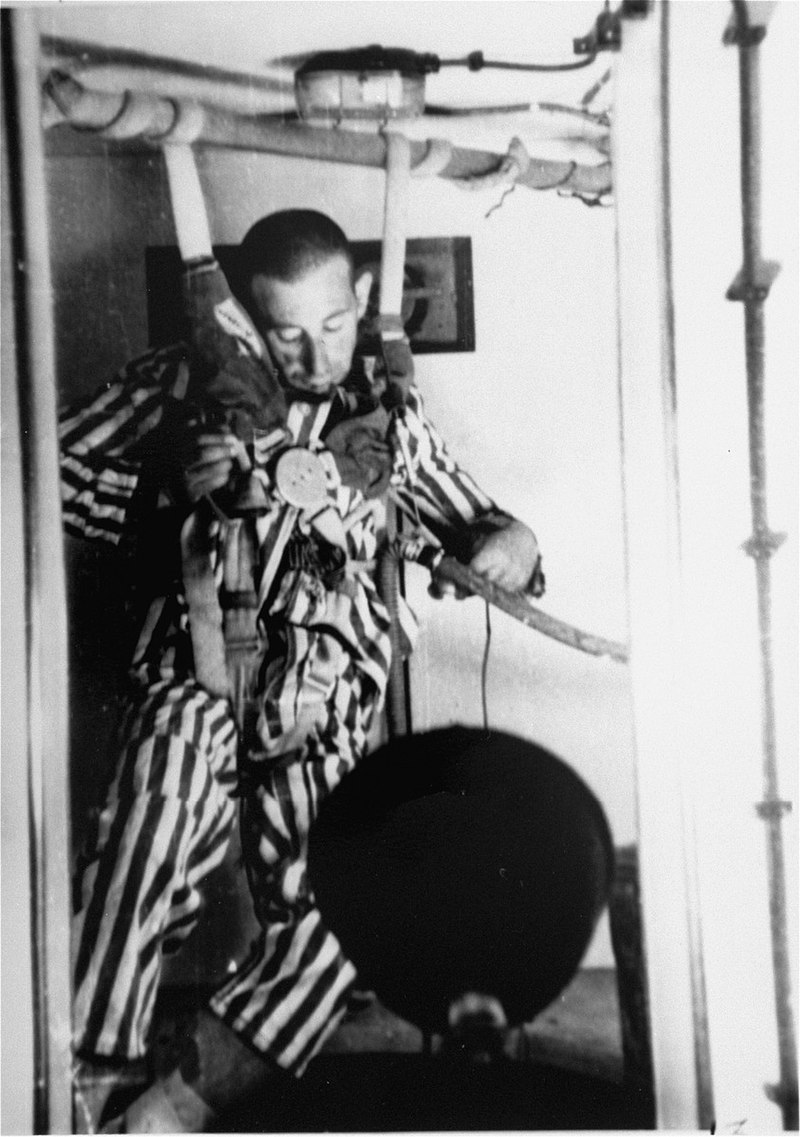

| "A prisoner in a special chamber responds to changing air pressure during high-altitude experiments. For the benefit of the Luftwaffe, conditions simulating those found at 15,000 meters [49,000 ft] in altitude were created in an effort to determine if German pilots might survive at that height." |  高高度実験中、気圧の変化に反応する特殊な部屋に入れられた囚人。ドイツ空軍のために、高度15,000メートルでドイツ軍

のパイロットが生き残れるかどうかを調べるために、高度15,000メートルを模擬した条件が作られた。 高高度実験中、気圧の変化に反応する特殊な部屋に入れられた囚人。ドイツ空軍のために、高度15,000メートルでドイツ軍

のパイロットが生き残れるかどうかを調べるために、高度15,000メートルを模擬した条件が作られた。 |

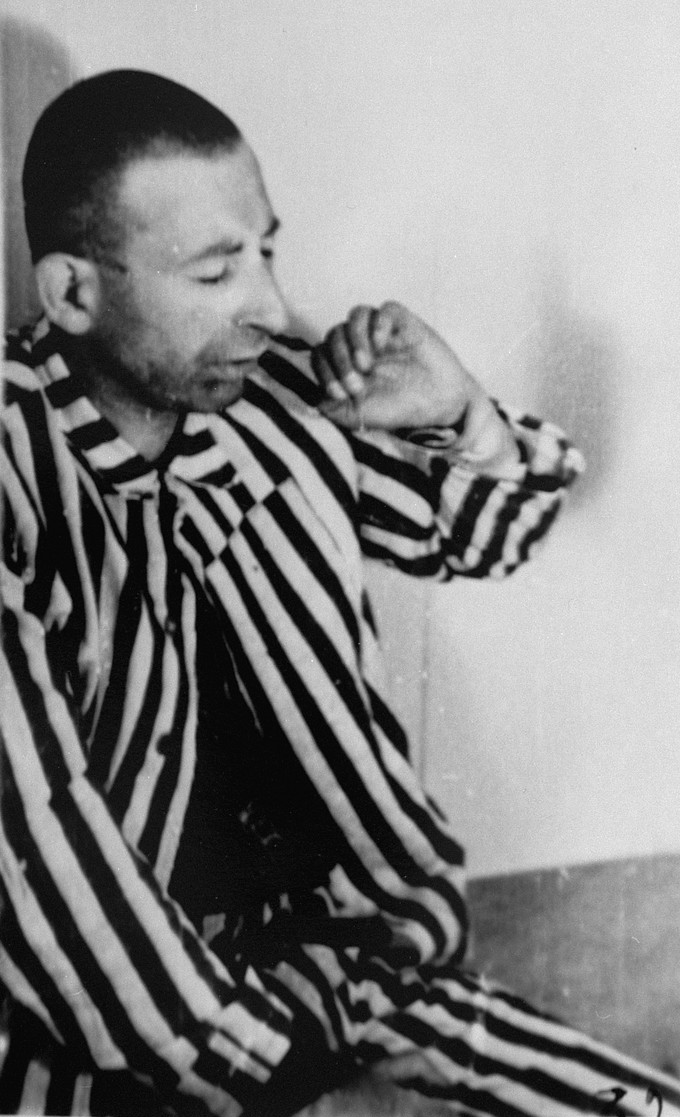

| A victim loses consciousness during a depressurization experiment at Dachau by Luftwaffe doctor Sigmund Rascher, 1942. |  ドイツ空軍の

医師ジークムント・ラッシャーがダッハウで行った減圧実験で、意識を失う被害者(1942年) ドイツ空軍の

医師ジークムント・ラッシャーがダッハウで行った減圧実験で、意識を失う被害者(1942年) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nazi_human_experimentation |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

"A prisoner in a special chamber responds to changing air pressure during high-altitude experiments. For the benefit of the Luftwaffe, conditions simulating those found at 15,000 meters [49,000 ft] in altitude were created in an effort to determine if German pilots might survive at that height."/A victim loses consciousness during a depressurization experiment at Dachau by Luftwaffe doctor Sigmund Rascher, 1942.

Karl Brandt (stehend) bei der Urteilsverkündung, 20. August 1947

| On the Ethics of Citing Nazi Research by Talia Determining the appropriate way to go about citing the Nazi experimental data is complicated on many levels. First, one must decide whether it is right to cite it at all, and if so what the best way to do so is. Additionally, a person must consider whether the data is valid and valuable, and what the arguments are for and against using the information. It is an exceptionally sensitive topic for many reasons, including the ramifications of citing the data. Using the Nazi research in any context brings up scientific, ethical and practical questions, with arguments on both sides raising moral, philosophic and historical points. The question must be approached with simultaneous caution and assurance to attempt to reach a firm practical solution for this very real and current issue. Analyzing the reasons for the Nazi's experimentation on Jews is difficult in many ways. It is important to understand its modern day pertinence in the scientific world, the intentions behind the experimentation, and what it is specifically about the experiments that makes us so resistant to publishing them. The issue lies in how the experiments were conducted, rather than that they were. What becomes clear from the method of experimentation is that there was another goal beyond scientific advancement. The people whom the Nazi doctors experimented on were ones that they considered subhuman, and consequently the Nazis felt they had the right to be treated with subhuman standards. There were deliberate, torturous parts of the experiments simply because the subjects were Jews and therefore could be experimented upon with no concern for their well-being. It is a researcher's duty to express concern for the ramifications of the experiment on the subject and attempt to minimize the negative effects, clearly not what went on during the Nazi experimentation. The entire argument in favor of citing the results of Nazi experiments rests on the assumption that they are scientifically valid. There would be absolutely no moral or scientific reason to use the results in any context if there was nothing to be gained from their further publication. For this reason, the decision of whether or not to use them must be preceded by a determination of the experiments scientific validity and applicability. This ruling has been largely disputed within the scientific community since the experiments were conducted. For the most part, the experiments have been discarded due to their scientific failings along with their blatant ethical wrongs, but there are a few sections in the corpus of Nazi medicine that have survived because of their possible scientific use. The major group of experiments still up for discussion is the Dachau human hypothermia series. Needless to say, nothing of its kind has been repeated, not because of a lack of medical interest in hypothermia, but because it is impossible to learn about hypothermia in the same way that the Nazis did without exposing subjects to the kinds of atrocious conditions that the Nazis employed. Robert Berger describes many of the scientific issues in an extremely detailed article1 and comes to the conclusion that for the most part, the experiments have so many inconsistencies and issues of scientific concern that they are scientifically invalid and their further citation is useless. If Berger is correct in his assertion that the Dachau experiments have no scientific merit, then I would agree with this recommendation that no further citing of these experiments is necessary other than a citation in the Alexander report as a documentation of a time of scientific and ethical depravity. However, though he presents many reasons why the experiments have no worth there are those who disagree with him. Jay Katz brings references from the Nuremberg Trials to support his assertion that the science is good, and should be used. Dr. Franz Vollhardt, an expert witness for the defense contended that " 'scientifically speaking the planning was excellent' and that the results of these [hypothermia] experiments 'were a wonderful thing for all seafaring nations'"2. Whether or not the science is merely valid or exceptionally useful, it is imperative, as both Kirsten Moe and Jay Katz state in their articles defending the validity of the experiments, that the data be cited only when it is the only information of its kind available.3 4 As John S. Hayward of the University of Victoria in British Columbia said, "I don't want to have to use this data, but there is no other and will be not other in an ethical world."5 He, along with others, also acknowledges the scientific flaws that exist and attempts to account for them by only using the results unaffected by the unreliable aspects of the research. For example, Hayward uses the Nazi measurement of the rate of body cooling in cold water, but doesn't use the data that shows the points at which prisoners became unconscious or died because they were performed on emaciated and unhealthy individuals and therefore are not representative of the general population. In this scientific sense, it seems possible to distinguish between parts of the experiment and use the applicable and sound pieces, though this does not account for the ethical implications of using data from experiments that were so clearly cruel and immoral. Based on the majority of the sources that I have seen, I will assume that the science is sound as well as applicable. Even if in the future it is somehow determined that the science is flawed, at present the research is being cited, and so it is important to deal with the philosophic consequences of that choice. A common argument in favor of citing Nazi research is the 'salvaging some good from the ashes' idea; that something positive should come from all the harm that was inflicted on the victims. I would like to avoid relying on this line of thinking. I find it somewhat belittling and offensive because of the assumptions it makes about the intent of the victims. It is a retrospective apologetic argument, asserting that because it already happened, maybe the participants would want something positive to come out of it. But this is a weak assertion because the subjects of these experiments did not consent in any informed way to their participation. They were not involved in the experiments for the good of science, and assumedly would have preferred to live then to die for German scientific good. It is true that many people do not become subjects of experiments for the good of science or for the good of humanity; instead they may do it for recognition, for money or for other rewards. The difference here is that there was no reward whatsoever for these victims, on the contrary, many of them were permanently physically and mentally harmed, many even died over the course of the experiments. Those who participate in experiments for reasons other than the scientific causes have some reward, as well as, more importantly, some sort of informed consent. Though it may be the most basic or the most obvious argument, it is unnecessary to rely on it, as there are better reasons that involve less degradation to continue to use the data then this general salvaging the good idea. If nothing else citing the Nazi data provides evidence that these experiments were carried out. Holocaust revisionists reject all historical ideas that any part of the Holocaust occurred, and the Alexander report provides a detailed documentation, at the very least, of one piece of Holocaust history. The existence of this document and Alexander's confirmation make it impossible to claim that no one was harmed in Nazi occupied Germany as it documents the systematic torture of human subjects in hundreds of comprehensive experiments.6 Assuming that experimentation did in fact go on, some have suggested citing it with some sort of limitation rather than making an overall decision one way or the other in order to avoid putting a blanket moral determination on the ethics of their citation. None of these solutions seem particularly effective or plausible. Citing the data without any sort of moral qualifier is disturbing and makes it seem as if there is nothing questionable about it. The suggestion to cite it with a footnote describing its ethical problems does not seem feasible in a scientific research environment, where sections of articles are often used out of context, and very often without reference to external footnotes. Moe brings the suggestion to use the data on a case-by-case basis in specifically applicable situations7, but in today's globalized world where information is constantly searched for to establish precedent this is an impractical option. To me, the failings of any of these options are partially based on the problem that the intentions are practically rather then ethically motivated. The goal seems to be to allow a scientist to cite the experiment without diluting the reference with an ethical qualifier while still, in some way, acknowledging the difficulties that arise in using them, but the ethics get lost in the desire to reference the data. A serious issue with publishing the data is that many believe that medical and scientific journals should not publish studies achieved through unethical means. Publishing the articles seems to legitimize the studies as well as the means by which they were achieved and it may give a reader the idea that it is possible to achieve scientific recognition regardless of results achieved through immoral approaches. In my view, this argument's intentions have merit, but is slightly misdirected in its execution. If the purpose is to condemn the unethical activity of the Nazis, then I believe that should be done. But I do not think that the means to address unethical behavior in science is by not addressing the experiments at all. Excluding them from articles and research removes any opportunity for response from the academic scientific community in a traditional or formal way. A popular objection to using the Nazi data, voiced in particular by representatives of scientific journals, is the fear that scientists will somehow assume that they are separate from the rest of society; that ethical rules and moral norms do not apply to them when they are doing research in 'the name of science' or for 'the good of mankind'. There is value in the suggestion to ban citation of the research even if only to prove that science is not above common moral law, that "[scientists] do not have carte blanche to treat human subjects any way they like, in the interest of science"8. This is a valid point, and one that I think should and can be focused on through this issue. But the same counterargument stands as it did before - silence is not an effective method of deterrence. The Nazi data absolutely can and should be a reminder of the intrinsic relationship between science and human values, and it "can be a reminder to scientists that they do not inhabit a 'value free' morally neutral world merely by virtue of their discipline's methodological concern with objectivity"9. This article against citation emphasizes memorial, but not citing the data creates only a silent memorial. Additionally, in trying to find what is in the victims' memories' collective best interest, the unfortunately historically typical Jewish silent resistance does not best fight off Nazi cruelty. Citing the data need not automatically give glory to the researchers; there is room for exactly the opposite response. Citing the data gives the writer an opportunity to accept the science while simultaneously verbally and outwardly condemning the methods. "To make a statement you make a statement, you don't fail to make a statement. Silence is ambiguous and often amounts to the uncomfortably averted gaze, whether consciously intended or not"10. Here, Benjamin Freedman has hit upon a crucial point. By not citing the data, there is no fight, no opposition to the experiments. Instead, the issues are simply avoided without any sense of consequence from the researchers, which seems to be the reverse of the argument against citing the data. Those who are opposed to including the citations claim that using Nazi research legitimizes it, that it appears that the research community has noticed the data and is appreciative of it. But not citing them leaves the scientific community silent. It is a counterproductive measure. There is no peer recourse at all, nothing that shows that they deny the methods. Omission is not rejection; it is merely omission. Arguments against the Nazi data must be made, and they must be made powerfully in print, not in silence. By citing the material the authors are able to use the legitimate aspects of the research while addressing the moral issues at the same time. The positions of both those who oppose citing the data and those who support it rest partially on a Utilitarian argument. Arthur Schaefer articulates the opposition's argument by assessing the risk benefit ration as one that is not worth taking. He claims that the "wickedness of the means" is so great that the data must be "transcendentally important" in order to make it morally acceptable to use the data.11 I agree with him on this point, and I wonder what benefit could be of enough "transcendental importance" to somehow balance out the cruelty inflicted by the Nazis in these experiments. However, he is using the Utilitarian position as a means to claim Utilitarianism as an inappropriate method of addressing this issue in a practical way that weakens the structure of his argument a bit. He limits Utilitarianism by portraying it in a somewhat limited and biased way by showing that it sometimes works and sometimes does not, yet he still relies on its reasoning. On the other hand, Freedman uses a Utilitarian platform by rejecting Utilitarian reasoning to support citation. He asserts that banning the use of the data or even describing it as "unethical" is not a fitting punishment or a logically appropriate consequence.12 The act that is being measured is not the act of the experiments, rather the act of their citation. By citing the data while using a Utilitarian argument, one must be willing to say that the act is justified because of the good that it is doing, and scientifically, it may be. But it is difficult to make that assessment because it is nearly impossible to measure the evil of the experiments, consequently making it impossible to effectively measure the potential good in relation to that evil. Nazi cruelty far surpasses anything that could be weighed in any sort of 'ends justifying the means' balance. I can not imagine a risk-benefit ratio that could avoid being monumentally insulting, because by necessity it would have to imply that there exists some measure that make the experiments retroactively worthwhile. Due to all the above-mentioned reasons, my personal recommendation is that citing the Nazi data is appropriate. In addition to the benefits of using the data for its scientific value, using the experiments has a moral benefit. Citation gives the opportunity to address the issue and to condemn it, something that cannot be done too many times. It may be possible for scientists to admit that they would have used the research, but because of its immorality will not. This is an option, but then the scientific value that the experiments may have is lost. I think that citation with some sort of explanation is a forward thinking solution as it uses the information without justifying it. This being said, I consequently have to qualify my recommendation by echoing Katz's sentiment at the end of his article- "there are no final answers to these tragic questions".13 I do not feel one-hundred percent comfortable with this suggestion, knowing the opposing arguments and the sensitivity and meaning of the issue at hand. Understanding what happened in the past does not provide complete answers or total guidance as we move towards the uncertainty of the scientific future. |

ナチス研究の引用に関する倫理 タリア著 ナチスの実験データを引用する適切な方法を決定することは、多くの点で複雑だ。まず、引用すること自体が正しいかどうかを判断し、正しいとすれば最善の方 法を考えねばならない。さらに、そのデータが有効で価値あるものか、情報の使用に対する賛否両論の論拠は何かを考慮する必要がある。この問題は、データを 引用することの帰結を含め、多くの理由から極めてデリケートだ。いかなる文脈でナチスの研究を用いる場合でも、科学的・倫理的・実践的な疑問が生じ、双方 の主張は道徳的・哲学的・歴史的な論点を提起する。この現実的で現代的な問題に対し、確固たる実践的解決策を見出すためには、慎重さと確信を同時に持ちな がらこの問題に取り組まねばならない。 ナチスがユダヤ人に対して実験を行った理由を分析することは、多くの点で困難である。現代の科学界におけるその関連性、実験の背後にある意図、そして特に 何が我々にその公表を強く拒ませるのかを理解することが重要だ。問題は実験が行われたこと自体ではなく、その実施方法にある。実験手法から明らかになるの は、科学的進歩を超えた別の目的が存在したことだ。ナチス医師が実験対象とした人民は、彼らによって「亜人間」と見なされていた。ゆえにナチスは、彼らを 亜人間の基準で扱う権利があると考えたのである。実験には熟議な拷問的要素が含まれていた。被験者がユダヤ人であるという理由だけで、その福祉を顧みずに 実験が施されたのだ。研究者には被験者への実験の影響を懸念し、悪影響を最小限に抑える義務がある。ナチスの実験では明らかにそれが守られていなかった。 ナチス実験の結果を引用することを支持する議論全体は、それらの結果が科学的に有効であるという前提に立っている。さらなる公表によって得られるものが何 もないならば、いかなる文脈においてもその結果を利用すべき道徳的・科学的根拠は全く存在しない。このため、それらを利用するか否かの判断に先立ち、実験 の科学的妥当性と適用可能性を確定しなければならない。 この判断は、実験実施以来、科学界内で広く議論されてきた。大半の実験は、科学的欠陥と明白な倫理的過ちにより廃棄されているが、ナチス医学の体系の中に は、科学的利用の可能性ゆえに存続している部分も存在する。現在も議論の対象となっている主要な実験群は、ダッハウにおける人体低体温症シリーズである。 言うまでもなく、同種の実験は再現されていない。低体温症に対する医学的関心が欠如しているためではなく、ナチスが用いたような残虐な条件に被験者を晒さ ずに、ナチスと同じ方法で低体温症を研究することが不可能だからである。ロバート・バーガーは、非常に詳細な記事1 で多くの科学的論点を述べ、その結論として、実験のほとんどは、科学的に懸念される矛盾や問題が多すぎるため、科学的に無効であり、今後引用しても意味が ないとしている。ベルガーの主張、すなわちダッハウ実験には科学的価値がないという見解が正しいならば、私は、科学的・倫理的堕落の時代を証明する資料と してアレクサンダー報告書で引用する以外、これらの実験をこれ以上引用する必要はないというこの勧告に同意する。しかし、ベルガーは実験に価値がない理由 を数多く挙げているものの、彼の意見に反対する者もいる。ジェイ・カッツは、この科学は優れており、利用されるべきであるとの主張を裏付けるため、ニュル ンベルク裁判からの引用を提示している。弁護側の専門家証人であるフランツ・フォルハルト博士は、「科学的に言えば、その計画は優れたものであり、これら の(低体温)実験の結果は、すべての航海国民にとって素晴らしいものだった」と主張した2。 科学が単に有効か、あるいは極めて有用かに関わらず、キルステン・モーとジェイ・カッツが実験の正当性を擁護する論文で述べているように、そのデータが唯 一入手可能な情報である場合にのみ引用することが不可欠だ。3 4 ブリティッシュコロンビア州ビクトリア大学のジョン・S・ヘイワードが言うように、 「このデータを使いたくはないが、倫理的な世界では他に選択肢がない」5。彼を含む研究者らは、研究の欠陥を認めつつ、信頼性の低い要素の影響を受けない 結果のみを用いることで、その欠陥を補おうとしている。例えばヘイワードは、冷水中での体温低下速度に関するナチスの測定値は用いるが、囚人が意識を失っ た時点や死亡した時点を示すデータは使用しない。なぜならそれらのデータは衰弱した不健康な個人を対象に実施されたものであり、一般人口を代表するもので はないからだ。この科学的観点では、実験の一部を切り離し、適用可能で妥当な部分のみを利用することは可能に見える。ただし、これでは明らかに残酷で非道 徳的な実験から得られたデータを使用することの倫理的含意は説明できない。私が確認した大半の資料に基づけば、その科学は妥当かつ適用可能であると仮定す る。仮に将来、その科学に欠陥があると判明したとしても、現時点では研究が引用されている以上、その選択がもたらす哲学的帰結と向き合うことが重要だ。 ナチス研究を引用する正当化論としてよく見られるのが「灰の中から何か良いものを救い出す」という考え方だ。犠牲者に加えられたあらゆる害悪から、何か肯 定的なものが生まれるべきだという主張である。私はこの思考回路に依拠することを避けたい。この主張は被害者の意図を前提としている点で、やや侮蔑的で不 快に感じる。それは事後的な弁解論であり、「既に起きたことだから、参加者も何か良い結果を望んでいたはずだ」と主張するものである。しかしこの主張は弱 い。被験者たちは十分な説明を受けた上で参加を承諾したわけではない。科学の進歩のために実験に参加したわけでもなく、ドイツの科学的利益のために死ぬよ り生きることを選んだはずだ。確かに多くの人民は科学や人類の利益のために実験に参加するわけではない。名誉や金銭、その他の報酬を求めて参加する場合も ある。しかしここでの違いは、被害者たちには何の報酬もなかったことだ。むしろ多くの者が実験の過程で身体的・精神的に永続的な損傷を受け、多数が死亡し た。科学的理由以外で実験に参加する者には何らかの報酬があり、さらに重要なのは、何らかの形でインフォームド・コンセントが得られている点だ。 これは最も基本的かつ明白な議論かもしれないが、この一般的な「良いアイデアを救う」という理由よりも、データを継続して使用するための、より優れた、そ してより品位を損なわない理由があるため、この議論に頼る必要はない。少なくとも、ナチスのデータを引用することで、これらの実験が実施されたという証拠 が得られる。ホロコースト修正主義者は、ホロコーストの一部が実際に起こったという歴史的見解をすべて否定しているが、アレクサンダーの報告書は、少なく ともホロコーストの歴史の一片について、詳細な記録を提供している。この文書の存在とアレクサンダーの確証により、ナチス占領下のドイツでは誰も被害を受 けなかったと主張することは不可能である。なぜなら、この文書は、何百もの包括的な実験における人間対象者の組織的な拷問を記録しているからだ。6 実験が実際に実施されたと仮定すると、その引用に道徳的な判断を下すことを避けるため、全面的にどちらかの判断を下すのではなく、何らかの制限を設けて引 用すべきだと提案する者もいる。これらの解決策はどれも、特に効果的でも妥当でもなさそうだ。道徳的な限定条件を一切設けずにデータを引用することは不穏 であり、その引用に何の問題もないかのように思わせる。倫理的問題を脚注で説明して引用する提案は、論文の一部が文脈を離れて引用され、外部脚注を参照し ないことが頻繁にある科学研究環境では実現不可能だ。モーは適用可能な状況に限定してケースバイケースでデータを使用する提案を7しているが、先例確立の ために情報が絶えず検索される現代のグローバル化した世界では非現実的な選択肢である。これらの選択肢の欠点は、その意図が倫理的というより実用的な動機 に基づいている点にある。科学者が倫理的留保を付けずに実験を引用しつつ、何らかの形で利用上の困難を認めることを可能にするのが目的のように見えるが、 データを引用したいという欲求の中で倫理が置き去りにされている。 データを公開することの深刻な問題は、多くの人が医学・科学雑誌は非倫理的な手段で得られた研究を掲載すべきでないと考える点だ。論文を出版することは、 研究そのものとその達成手段を正当化するように見え、読者に「非道徳的な手法で得られた結果であっても科学的評価を得られる」という誤解を与える恐れがあ る。 私の見解では、この議論の意図自体は妥当だが、その実行方法がやや誤っている。目的がナチスの非倫理的行為を非難することなら、それは行うべきだ。しかし 科学における非倫理的行為に対処する手段が、実験自体を一切扱わないことだとは思わない。論文や研究からそれらを排除することは、学術的科学コミュニティ が伝統的・正式な方法で反論する機会を完全に奪うことになる。 ナチスのデータ利用に対する一般的な反論、特に科学雑誌の代表者らが主張するのは、科学者が「科学の名の下」や「人類の利益」のために研究を行う際、自分 たちは社会から切り離されていると誤って思い込み、倫理的ルールや道徳的規範が適用されないと考えてしまう恐れだ。たとえ科学が一般的な道徳法の上に立つ ものではないこと、すなわち「科学者の利益のために、人間被験者を好き勝手に扱う無制限の権限を科学者が有するわけではない」ことを証明するためだけに、 この研究の引用を禁止するという提案には価値がある。これは妥当な指摘であり、この問題を通じて焦点を当てるべきであり、また当てることも可能だと考え る。しかし、それに対する反論は以前と同様に成立する——沈黙は効果的な抑止手段ではない。ナチスのデータは、科学と人間的価値の本質的関係を絶対に想起 させるべきものであり、それは「科学者に対し、単に自らの学問分野が客観性を方法論的に重視するという理由だけで、彼らが『価値中立的』な道徳的に中立な 世界に存在しているわけではないことを想起させる」ことができるのだ。9。この引用反対論は追悼を強調するが、データを引用しないことは沈黙の追悼を生み 出すに過ぎない。さらに、犠牲者の記憶が集合的に最も利益となるものを探る上で、歴史的に典型的なユダヤ人の沈黙の抵抗は、残念ながらナチスの残虐性を最 も効果的に撃退する手段ではなかった。データを引用することが自動的に研究者に栄光を与えるわけではない。むしろ正反対の反応を示す余地がある。データを 引用することは、執筆者に科学を受け入れつつ、同時にその手法を言葉と行動で非難する機会を与えるのだ。「声明を出すなら声明を出すべきであり、声明を出 さないのは失敗だ。沈黙は曖昧であり、意識的か否かを問わず、しばしば不快なほど目を背ける行為に等しい」10。ここでベンジャミン・フリードマンは核心 を突いている。データを引用しないことで、実験への対抗も抵抗も生まれない。代わりに問題は単に回避され、研究者側からは何の帰結も感じられない。これは データを引用すべきでないという主張とは逆の現象だ。引用に反対する者たちは、ナチスの研究を用いることがそれを正当化し、研究コミュニティがデータに気 づき評価しているように見えると主張する。しかし引用しないことは科学コミュニティを沈黙させる。これは逆効果の措置だ。同業者による是正手段は全く存在 せず、手法を否定する意思を示すものもない。省略は拒絶ではない。単なる省略に過ぎない。ナチスデータへの反論は必ず行われねばならず、沈黙ではなく印刷 物で力強く表明されねばならない。資料を引用することで、著者は研究の正当な側面を活用しつつ、同時に道徳的問題にも対処できるのだ。 引用に反対する立場も支持する立場も、その一部は功利主義的議論に依拠している。アーサー・シェーファーは反対論を、リスクとベネフィットの比率が取るに 足らないものだと評価することで明確にしている。彼は「手段の邪悪さ」があまりに甚大であるため、データ利用を道徳的に許容するには、そのデータが「超越 的に重要」でなければならないと主張する。11 この点については私も同意見だ。ナチスによる実験で加えられた残虐性を相殺しうるほど「超越的に重要」な利益とは、いったい何なのかと疑問に思う。しかし 彼は功利主義の立場を、この問題を実践的に扱う方法として不適切だと主張する手段として利用しており、これが彼の論理構造をやや弱めている。功利主義が時 に機能し時に機能しないことを示すことで、やや限定的で偏った形で功利主義を描写し、その適用範囲を制限しているにもかかわらず、彼は依然としてその論理 に依存しているのだ。 一方フリードマンは、引用を支持するために功利主義的論理を拒否するという形で功利主義の立場を利用している。彼は、データの使用を禁止したり「非倫理 的」と表現することさえも、適切な罰や論理的に妥当な結果ではないと主張する。12 評価対象となっている行為は実験そのものではなく、その引用行為である。功利主義の議論を用いてデータを引用するならば、その行為がもたらす善のために正 当化されると言わねばならない。科学的にはそうかもしれない。しかし、実験の悪を測ることはほぼ不可能であり、その結果、その悪に対する潜在的な善を効果 的に測ることも不可能であるため、その評価は困難だ。ナチスの残虐性は、いかなる「目的が手段を正当化する」天秤で測ろうとも、はるかに凌駕する。いかな るリスク・ベネフィット比も、途方もない侮辱を免れないだろう。なぜなら必然的に、実験を後付けで正当化する何らかの尺度が存在すると示唆せざるを得ない からだ。 以上の理由から、ナチスのデータを引用することは適切だと個人的に考える。科学的価値としての利用に加え、実験データを用いることには道徳的利益もある。 引用は問題に向き合い非難する機会を与える。これは何度行ってもやり過ぎではない。科学者が「研究は利用しただろうが、非道徳的ゆえに利用しない」と認め る選択肢もある。だがそうすれば実験が持つ科学的価値は失われる。何らかの説明を伴う引用は、情報を正当化せずに活用する先見的な解決策だと考える。とは いえ、カッツが記事の最後に述べた「これらの悲劇的な問いに最終的な答えはない」という見解に同意せざるを得ない。13 反対論や問題の敏感さ・重要性を踏まえ、この提案に完全には納得していない。過去の出来事を理解しても、不確実な科学の未来へ向かう上で完全な答えや指針 は得られないのだ。 |

| https://x.gd/xg7rW |

+++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

☆

☆

☆