新植民地主義

Neocolonialism

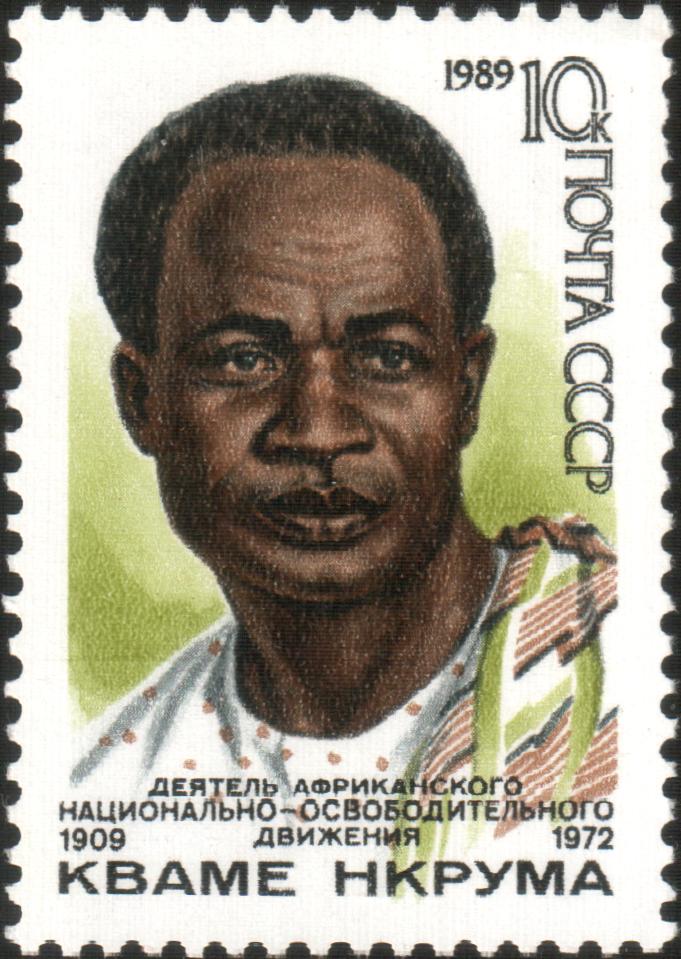

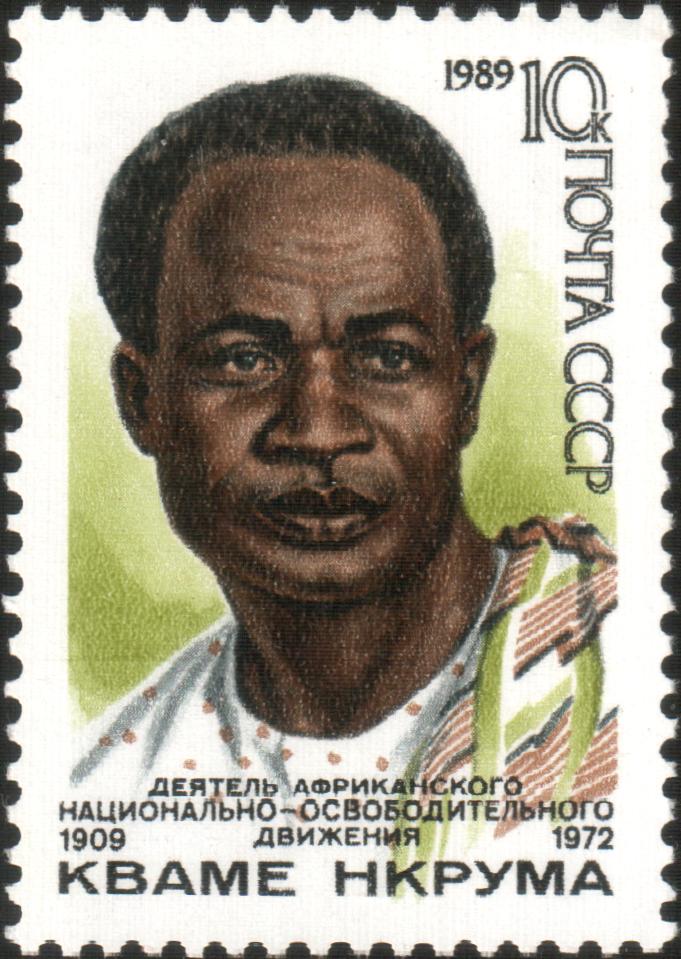

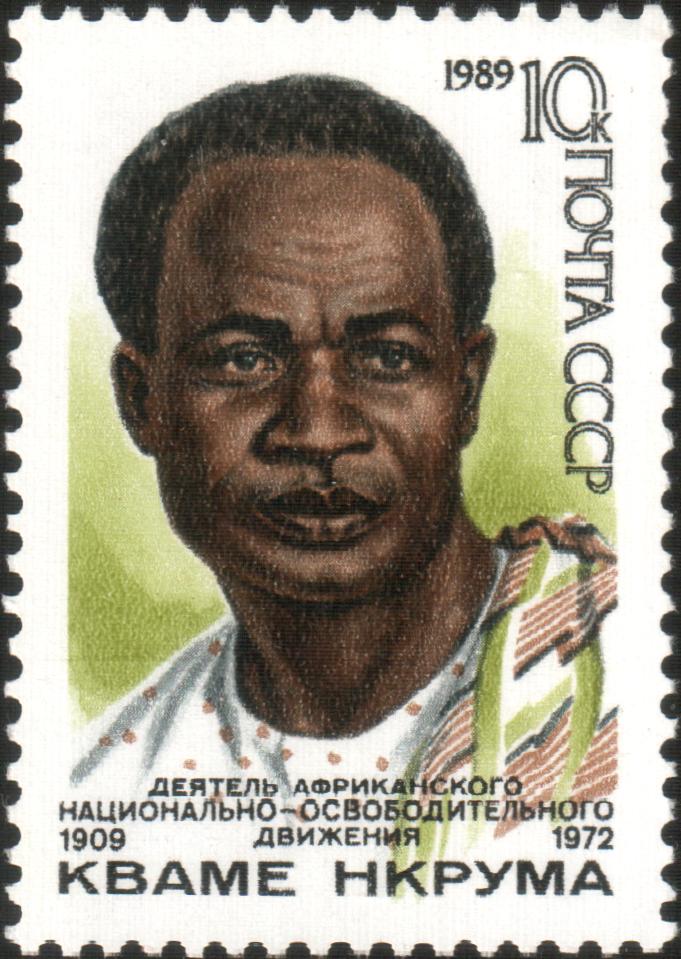

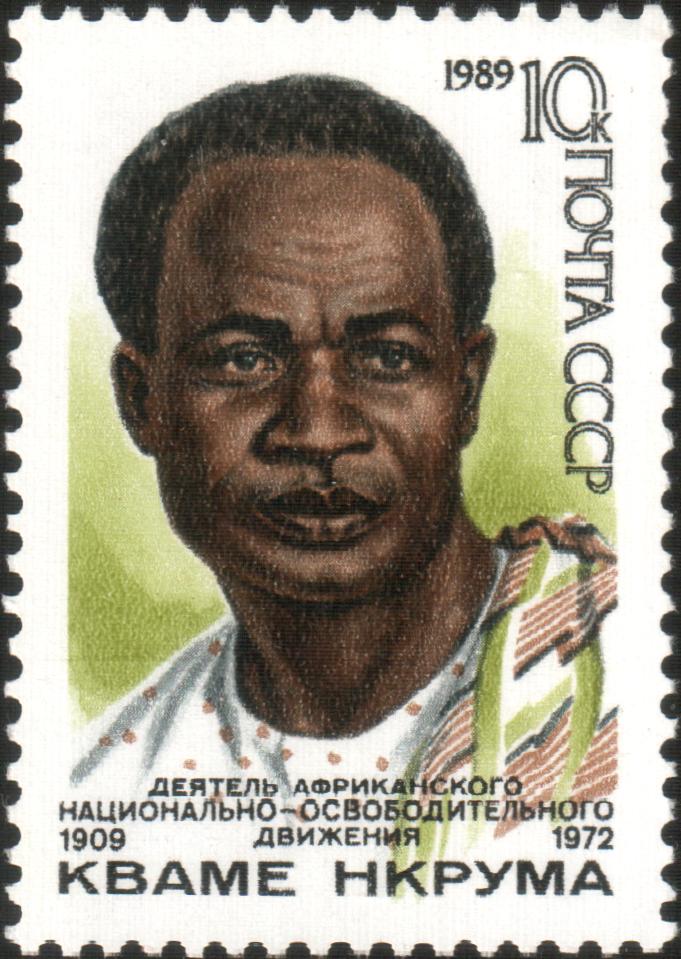

Kwame

Nkrumah (pictured on a Soviet postage stamp), president of Ghana

(1960–1966), coined the term "neocolonialism".

☆ 新植民地主義(Neocolonialism) とは、国家(通常は旧植民地国)が間接的な手段によって他の名目上独立した国家(通常は旧植民地国)を支配することである[1][2][3]。新植民地主 義という用語は、第二次世界大戦後、旧植民地国が外国に依存し続けていることを指す言葉として使われ始めたが、その意味はすぐに広がり、より一般的に、先 進国の力が植民地的な搾取を生み出すために使われている場所に適用されるようになった[3]。 新植民地主義は、直接的な軍事的支配や間接的な政治的支配(覇権)という以前の植民地的手法の代わりに、経済的帝国主義、グローバリゼーション、文化的帝 国主義、発展途上国に影響を与えたり支配したりするための条件付き援助という形をとる。ナショナリズムが標準的なグローバリゼーションや開発援助と異なる のは、一般的に新植民地主義国家に対する依存、従属、または経済的義務の関係をもたらす点である。 1956年にフランスの哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルによって造語され[4][5]、1960年代に脱植民地化が進むアフリカ諸国の文脈でクワメ・ンク ルマによって初めて使用された。新植民地主義は、サルトル(『植民地主義と新植民地主義』1964年)やノーム・チョムスキー(『ワシントン・コネクショ ンと第三世界のファシズム』1979年)といった西洋の思想家の著作でも論じられている[7]。

新植民地主義を語る用語群:1)従属理論、2)冷戦、3)多国籍企業、4)国際的な借入(借款)、5)従属を生み出す第三世界に対する自然保護の発想、6)科学的な収奪。

| Neocolonialism is

the control by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another

nominally independent state (usually, a former colony) through indirect

means.[1][2][3] The term neocolonialism was first used after World War

II to refer to the continuing dependence of former colonies on foreign

countries, but its meaning soon broadened to apply, more generally, to

places where the power of developed countries was used to produce a

colonial-like exploitation.[3] Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, globalization, cultural imperialism and conditional aid to influence or control a developing country instead of the previous colonial methods of direct military control or indirect political control (hegemony). Neocolonialism differs from standard globalisation and development aid in that it typically results in a relationship of dependence, subservience, or financial obligation towards the neocolonialist nation. Coined by the French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre in 1956,[4][5] it was first used by Kwame Nkrumah in the context of African countries undergoing decolonisation in the 1960s. Neocolonialism is also discussed in the works of Western thinkers such as Sartre (Colonialism and Neocolonialism, 1964)[6] and Noam Chomsky (The Washington Connection and Third World Fascism, 1979).[7] |

新植民地主義とは、国家(通常は旧植民地国)が間接的な手段によって他

の名目上独立した国家(通常は旧植民地国)を支配することである[1][2][3]。新植民地主義という用語は、第二次世界大戦後、旧植民地国が外国に依

存し続けていることを指す言葉として使われ始めたが、その意味はすぐに広がり、より一般的に、先進国の力が植民地的な搾取を生み出すために使われている場

所に適用されるようになった[3]。 新植民地主義は、直接的な軍事的支配や間接的な政治的支配(覇権)という以前の植民地的手法の代わりに、経済的帝国主義、グローバリゼーション、文化的帝 国主義、発展途上国に影響を与えたり支配したりするための条件付き援助という形をとる。ナショナリズムが標準的なグローバリゼーションや開発援助と異なる のは、一般的に新植民地主義国家に対する依存、従属、または経済的義務の関係をもたらす点である。 1956年にフランスの哲学者ジャン=ポール・サルトルによって造語され[4][5]、1960年代に脱植民地化が進むアフリカ諸国の文脈でクワメ・ンク ルマによって初めて使用された。新植民地主義は、サルトル(『植民地主義と新植民地主義』1964年)やノーム・チョムスキー(『ワシントン・コネクショ ンと第三世界のファシズム』1979年)といった西洋の思想家の著作でも論じられている[7]。 |

| Term Origins When first proposed, the term neocolonialism was applied to European countries' continued economic and cultural relationships with their former colonies, those African countries that had been liberated in the aftermath of Second World War. At the 1962 National Union of Popular Forces conference, Mehdi Ben Barka, the Moroccan political organizer and later chair of the Tricontinental Conference 1966, used the term al-isti'mar al-jadid (Arabic: الاستعمار الجديد "the new colonialism") to describe the political trends in Africa in the early sixties.[8] الاستعمار الجديد عبارة عن سياسة تعمل من جهة على منح الاستقلال السياسي، وعند الاقتضاء إنشاء دول مصطنعة لا حظ لها في وجود ذاتي، ومن جهة أخرى، تعمل على تقديم مساعدات مصحوبة بوعود تحقيق رفاهية تكون قواعدها في الحقيقة خارج القارة الإفريقية. "Neo-colonialism is a policy that functions on one hand through granting political independence and, when necessary, creating artificial states that have no chance of sovereignty, and on the other hand, through providing 'assistance' accompanied by promises of achieving prosperity, though its bases are in fact outside the African continent." Mehdi Ben Barka, The Revolutionary Option in Morocco (May 1962)  Kwame Nkrumah (pictured on a Soviet postage stamp), president of Ghana (1960–1966), coined the term "neocolonialism". Kwame Nkrumah, president of Ghana from 1960 to 1966, is credited with coining the term, which appeared in the 1963 preamble of the Organisation of African Unity Charter, and was the title of his 1965 book, Neo-Colonialism, The Last Stage of Imperialism.[9] In his book the President of Ghana exposes the workings of International monopoly capitalism in Africa. For him Neo-colonialism, insidious and complex, is even more dangerous than the old colonialism and shows how meaningless political freedom can be without economic independence. Nkrumah theoretically developed and extended to the post–World War II 20th century the socio-economic and political arguments presented by Lenin in the pamphlet Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1917). The pamphlet frames 19th-century imperialism as the logical extension of geopolitical power, to meet the financial investment needs of the political economy of capitalism.[10] In Neo-Colonialism, the Last Stage of Imperialism, Kwame Nkrumah wrote: In place of colonialism, as the main instrument of imperialism, we have today neo-colonialism ... [which] like colonialism, is an attempt to export the social conflicts of the capitalist countries. ... The result of neo-colonialism is that foreign capital is used for the exploitation rather than for the development of the less developed parts of the world. Investment, under neo-colonialism, increases, rather than decreases, the gap between the rich and the poor countries of the world. The struggle against neo-colonialism is not aimed at excluding the capital of the developed world from operating in less developed countries. It is also dubious in consideration of the name given being strongly related to the concept of colonialism itself. It is aimed at preventing the financial power of the developed countries being used in such a way as to impoverish the less developed.[11] The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside. |

用語 起源 新植民地主義という言葉が最初に提唱されたとき、ヨーロッパ諸国が旧植民地(第二次世界大戦後に解放されたアフリカ諸国)との経済的・文化的関係を継続し ていることに適用された。1962年の国民民衆勢力連合会議で、モロッコの政治組織者で後に三大陸会議1966の議長であったメフディ・ベン・バルカは、 al-isti'mar al-jadid(アラビア語:الاستعمار الجديد「新たな植民地主義」)という言葉を使い、60年代初頭のアフリカの政治動向を表現した[8]。 الاستعمار الجديد عبارة عن سياسة تعمل من جهة على منح الاستقلال السياسي وعند الاقتضاء إنشاء دول مصطنعة لاحظ لها في وجود ذاتي، ومن جهة أخرى تعمل على تقديم مساعدات مصحوبة بوعود تحقيق رفاهية تكون قواعدها في الحقيقة خارج القارة الإفريقية. 「新植民地主義とは、一方では政治的独立を認め、必要であれば、主権の見込みのない人工国家を創設することによって機能し、他方では、その拠点は実際にはアフリカ大陸の外にあるが、繁栄を達成するという約束を伴った「援助」を提供することによって機能する政策である。」 メフディ・ベン・バルカ『モロッコにおける革命の選択』(1962年5月)  「新植民地主義」という言葉を生み出したのは、ガーナ大統領(1960-66年)のクワメ・ンクルマ(写真はソ連の切手)である。 この言葉は1963年のアフリカ統一機構憲章の前文に登場し、1965年の著書『新植民地主義、帝国主義の最終段階』のタイトルにもなっている[9]。彼 にとって、陰湿で複雑な新植民地主義は、旧植民地主義よりもさらに危険なものであり、経済的独立なくして政治的自由がいかに無意味なものであるかを示して いる。ンクルマは、レーニンがパンフレット『帝国主義、資本主義の最高段階』(1917年)で提示した社会経済的、政治的議論を理論的に発展させ、第二次 世界大戦後の20世紀にまで拡張した。このパンフレットは、19世紀の帝国主義を、資本主義の政治経済の金融投資の必要性を満たすための、地政学的権力の 論理的拡張として組み立てている[10]。 新植民地主義、帝国主義の最終段階』の中で、クワメ・ンクルマはこう書いている: 帝国主義の主要な手段としての植民地主義に代わって、今日、われわれは新植民地主義を有している......[植民地主義のように]資本主義諸国の社会的対立を輸出しようとする試みである。... 新植民地主義の結果は、外国資本が世界の後発開発地域の発展のためではなく搾取のために使われることである。新植民地主義のもとでの投資は、世界の富める 国と貧しい国との格差を縮小させるどころか、むしろ拡大させる。新植民地主義との闘いは、先進国の資本が後発開発途上国で活動することを排除することが目 的ではない。また、その名称が植民地主義の概念そのものと強く関連していることを考慮すると、それは疑わしい。それは、先進国の資金力が後進国を貧困化さ せるような形で使われるのを防ぐことを目的としている[11]。 新植民地主義の本質は、その対象となる国家が、理論的には独立しており、国際的な主権を外見上すべて備えているということである。現実には、その経済システム、ひいては政治政策は外部から指示されている。 |

Neocolonial economic dominance People in Brisbane protesting Australia's claim on East Timorese oil, in May 2017 In 1961, regarding the economic mechanism of neocolonial control, in the speech Cuba: Historical Exception or Vanguard in the Anti-colonial Struggle?, Argentine revolutionary Che Guevara said: We, politely referred to as "underdeveloped", in truth, are colonial, semi-colonial or dependent countries. We are countries whose economies have been distorted by imperialism, which has abnormally developed those branches of industry or agriculture needed to complement its complex economy. "Underdevelopment", or distorted development, brings a dangerous specialisation in raw materials, inherent in which is the threat of hunger for all our peoples. We, the "underdeveloped", are also those with the single crop, the single product, the single market. A single product whose uncertain sale depends on a single market imposing and fixing conditions. That is the great formula for imperialist economic domination.[12] Dependency theory Main article: Dependency theory Dependency theory is the theoretical description of economic neocolonialism. It proposes that the global economic system comprises wealthy countries at the centre, and poor countries at the periphery. Economic neocolonialism extracts the human and natural resources of a poor country to flow to the economies of the wealthy countries. It claims that the poverty of the peripheral countries is the result of how they are integrated in the global economic system. Dependency theory derives from the Marxist analysis of economic inequalities within the world's system of economies, thus, under-development of the periphery is a direct result of development in the centre. It includes the concept of the late 19th century semi-colony.[13] It contrasts the Marxist perspective of the theory of colonial dependency with capitalist economics. The latter proposes that poverty is a development stage in the poor country's progress towards full integration in the global economic system. Proponents of dependency theory, such as Venezuelan historian Federico Brito Figueroa, who investigated the socioeconomic bases of neocolonial dependency, influenced the thinking of the former President of Venezuela, Hugo Chávez.[citation needed] Cold War Main article: Cold War During the mid-to-late 20th century, in the course of the ideological conflict between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R., each country and its satellite states accused each other of practising neocolonialism in their imperial and hegemonic pursuits.[14][15][16][17][18][19][20] The struggle included proxy wars, fought by client states in the decolonised countries. Cuba, the Warsaw Pact bloc, Egypt under Gamal Abdel Nasser (1956–1970) et al. accused the U.S. of sponsoring anti-democratic governments whose regimes did not represent the interests of their people and of overthrowing elected governments (African, Asian, Latin American) that did not support U.S. geopolitical interests.[citation needed] In the 1960s, under the leadership of Chairman Mehdi Ben Barka, the Cuban Tricontinental Conference (Organisation of Solidarity with the People of Asia, Africa and Latin America) recognised and supported the validity of revolutionary anti-colonialism as a means for colonised peoples of the Third World to achieve self-determination, a policy which angered the U.S. and France. Moreover, Chairman Barka headed the Commission on Neocolonialism, which dealt with the work to resolve the neocolonial involvement of colonial powers in decolonised counties; and said that the U.S., as the leading capitalist country of the world, was, in practise, the principal neocolonialist political actor.[citation needed] Multinational corporations Main article: Multinational corporation Critics of the practice of neocolonialism also argue that investment by multinational corporations enriches few in underdeveloped countries and causes humanitarian, environmental and ecological damage to their populations. They argue that this results in unsustainable development and perpetual underdevelopment. These countries remain reservoirs of cheap labor and raw materials, while restricting access to advanced production techniques to develop their own economies. In some countries, monopolization of natural resources, while initially leading to an influx of investment, is often followed by increases in unemployment, poverty and a decline in per-capita income.[21] In the West African nations of Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and Mauritania, fishing was historically central to the economy. Beginning in 1979, the European Union began negotiating contracts with governments for fishing off the coast of West Africa. Unsustainable commercial over-fishing by foreign fleets played a significant role in large-scale unemployment and migration of people across the region.[22] This violates the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which recognises the importance of fishing to local communities and insists that government fishing agreements with foreign companies should target only surplus stocks.[23] Oxfam's 2024 report "Inequality, Inc" concludes that multinational corporations located in the Global North are "perpetuating a colonial style 'extractivist' model" across the Global South as the economies of the latter "are locked into exporting primary commodities, from copper to coffee" to these multinationals.[24] International borrowing See also: Criticism of the International Monetary Fund American economist Jeffrey Sachs recommended that the entire African debt (c. US$200 billion) be dismissed, and recommended that African nations not repay either the World Bank or the International Monetary Fund (IMF):[25] The time has come to end this charade. The debts are unaffordable. If they won't cancel the debts, I would suggest obstruction; you do it, yourselves. Africa should say: "Thank you very much, but we need this money to meet the needs of children who are dying, right now, so, we will put the debt-servicing payments into urgent social investment in health, education, drinking water, the control of AIDS, and other needs". Conservation and neocolonialism Wallerstein, and separately Frank, claim that the modern conservation movement, as practiced by international organisations such as the World Wide Fund for Nature, inadvertently developed a neocolonial relationship with underdeveloped nations.[26] Science This section is an excerpt from Neo-colonial science.[edit] Neo-colonial research or neo-colonial science,[27][28] frequently described as helicopter research,[27] parachute science[29][30] or research,[31] parasitic research,[32][33] or safari study,[34] is when researchers from wealthier countries go to a developing country, collect information, travel back to their country, analyze the data and samples, and publish the results with no or little involvement of local researchers. A 2003 study by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences found that 70% of articles in a random sample of publications about least-developed countries did not include a local research co-author.[28] Frequently, during this kind of research, the local colleagues might be used to provide logistics support as fixers but are not engaged for their expertise or given credit for their participation in the research. Scientific publications resulting from parachute science frequently only contribute to the career of the scientists from rich countries, thus limiting the development of local science capacity (such as funded research centers) and the careers of local scientists.[27] This form of "colonial" science has reverberations of 19th century scientific practices of treating non-Western participants as "others" in order to advance colonialism—and critics call for the end of these extractivist practices in order to decolonize knowledge.[35][36] This kind of research approach reduces the quality of research because international researchers may not ask the right questions or draw connections to local issues.[37] The result of this approach is that local communities are unable to leverage the research to their own advantage.[30] Ultimately, especially for fields dealing with global issues like conservation biology which rely on local communities to implement solutions, neo-colonial science prevents institutionalization of the findings in local communities in order to address issues being studied by scientists.[30][35] |

新植民地経済支配 2017年5月、ブリスベンで東ティモールの石油をめぐるオーストラリアの主張に抗議する人民たち 1961年、新植民地支配の経済的メカニズムについて、アルゼンチンの革命家チェ・ゲバラは『キューバ:歴史的例外か、反植民地闘争の前衛か』という演説の中で、次のように述べている: われわれは、礼儀正しく 「低開発国 」と呼ばれているが、その実、植民地、半植民地、あるいは従属国である。われわれは、帝国主義によって経済がゆがめられ、その複雑な経済を補完するために 必要な工業や農業の部門を異常に発展させてきた国々である。「低開発」、すなわち歪んだ開発は、原材料の危険な特化をもたらし、その特化には、すべての人 民にとっての飢餓の脅威が内在している。私たち「低開発国」は、単一作物、単一製品、単一市場を持つ国でもある。単一の製品は、その不確かな販売が、単一 の市場が条件を課し、固定するかどうかにかかっている。それが帝国主義経済支配の偉大な定式である。 従属理論 主な記事 従属理論 従属理論は、経済的新植民地主義を理論的に説明するものである。世界経済システムは、中心部に裕福な国、周辺部に貧しい国から構成されていると提唱してい る。経済的新植民地主義は、貧困国の人的・天然資源を富裕国の経済に流入させるために抽出する。周辺国の貧困は、グローバル経済システムに組み込まれた結 果であると主張する。従属理論は、世界経済システム内の経済的不平等に関するマルクス主義的分析から派生したものであり、したがって、周辺国の低開発は中 央の開発の直接的な結果である。19世紀末の半植民地という概念も含まれている[13]。植民地依存論というマルクス主義の視点を資本主義経済学と対比さ せている。後者は、貧困は貧しい国がグローバル経済システムへの完全な統合に向けて前進するための発展段階であると提唱している。新植民地依存の社会経済 的基盤を調査したベネズエラの歴史家フェデリコ・ブリト・フィゲロアなどの依存理論の支持者は、ベネズエラの前大統領ウゴ・チャベスの考え方に影響を与え た[要出典]。 冷戦 主な記事 冷戦 20世紀半ばから後半にかけて、アメリカとソビエト連邦の間のイデオロギー対立の過程で、それぞれの国とその衛星国は、帝国主義的・覇権主義的な追求にお いて新植民地主義を実践しているとお互いを非難した[14][15][16][17][18][19][20]。この闘争には、脱植民地化された国々のク ライアント国家によって戦われた代理戦争も含まれていた。キューバ、ワルシャワ条約機構圏、ガマル・アブデル・ナセル政権下のエジプト(1956- 1970年)などは、政権が人民の利益を代表しない反民主主義政府を後援し、米国の地政学的利益を支持しない選挙で選ばれた政府(アフリカ、アジア、ラテ ンアメリカ)を転覆させたとして米国を非難した[要出典]。 1960年代、メフディ・ベン・バルカ議長の指導の下、キューバ三大陸会議(アジア、アフリカ、ラテンアメリカの人民と連帯する組織)は、第三世界の植民 地化された人民が自決を達成する手段としての革命的反植民地主義の有効性を認め、支持したが、この政策はアメリカとフランスを怒らせた。さらに、バルカ委 員長は、脱植民地化された国々における植民地大国の新植民地主義的関与を解決する作業を扱う新植民地主義委員会の委員長を務め、世界の主要な資本主義国で あるアメリカは、実際上、主要な新植民地主義的政治主体であると述べた[要出典]。 多国籍企業 主な記事 多国籍企業 新植民地主義の実践を批判する人々はまた、多国籍企業による投資は低開発国の少数派を富ませ、その国の人々に人道的、環境的、生態学的な損害をもたらすと 主張している。その結果、持続不可能な開発と永続的な低開発がもたらされると主張する。これらの国々は、自国の経済を発展させるための高度な生産技術への アクセスを制限する一方で、安価な労働力と原材料の貯蔵庫であり続けている。一部の国では、天然資源の独占は、当初は投資の流入につながるものの、失業、 貧困の増加、一人当たり所得の減少を招くことが多い[21]。 西アフリカのギニアビサウ、セネガル、モーリタニアでは、歴史的に漁業が経済の中心であった。1979年に始まり、欧州連合(EU)は西アフリカ沿岸の漁 業について各国政府と交渉するようになった。外国船団による持続不可能な商業的乱獲は、この地域全体の大規模な失業と人民の移住に大きな役割を果たした [22]。これは、地域社会にとっての漁業の重要性を認識し、外国企業との政府漁業協定は余剰資源のみを対象とすべきであると主張する、国連海洋法条約に 違反している[23]。 オックスファムの2024年版報告書『不平等、株式会社』は、北半球に位置する多国籍企業が、南半球全域で「植民地スタイルの 「抽出主義 」モデルを永続させている」と結論付けている。 国際的な借入(借款) 以下も参照のこと: 国際通貨基金への批判 アメリカの経済学者ジェフリー・サックスは、アフリカの債務(約2,000億米ドル)の全額を放棄するよう勧告し、アフリカ国民は世界銀行にも国際通貨基金(IMF)にも返済しないよう勧告した[25]。 この茶番劇を終わらせる時が来た。借金は手に負えない。もし彼らが借金を帳消しにしないのであれば、私は妨害することを提案する。アフリカはこう言うべき だ: 「ありがとうございます。しかし、今まさに死につつある子どもたちのニーズを満たすために、このお金が必要なのです。だから、債務返済分を保健、教育、飲 料水、エイズ対策など、緊急の社会投資に回します」と言うべきだ。 自然保護と新植民地主義 ウォーラーステインと、それとは別にフランクは、世界自然保護基金などの国際組織によって実践されている現代の自然保護運動は、不注意にも低開発国家と新植民地主義的な関係を築いてしまったと主張している[26]。 科学(科学的な収奪) このセクションは新植民地主義科学からの抜粋である[編集]。 新植民地研究または新植民地科学[27][28]は、ヘリコプター研究[27]、パラシュート科学[29][30]、寄生虫研究[31][32] [33]、サファリ研究[34]などと形容されることが多いが、裕福な国の研究者が発展途上国に行き、情報を収集し、自国に戻り、データやサンプルを分析 し、現地の研究者が全く、またはほとんど関与せずに結果を発表することである。ハンガリー科学アカデミーの2003年の調査によると、後発開発途上国に関 する出版物の無作為サンプルのうち、70%の論文に現地の研究者の共著者が含まれていなかった[28]。 この種の研究において、現地の同僚は、フィクサーとして後方支援に使われることはあっても、その専門知識に対して関与されたり、研究への参加に対して信用 を与えられたりすることは、しばしばない。このような「植民地」科学の形態は、植民地主義を推し進める ために非西洋の参加者を「他者」として扱うという19世紀の科学的慣 行を想起させ、批評家たちは知識を脱植民地化するためにこのよう な抽出主義的慣行の終焉を求めている[35][36]。 このような研究アプローチは、国際的な研究者が適切な質問をしなかったり、現地の問題との関連性を引き出せなかったりするため、研究の質を低下させる [37]。このようなアプローチの結果、現地のコミュニティは研究を自分たちに有利なように活用することができない[30]。結局のところ、特に保全生物 学のような、解決策を実行するために現地のコミュニティに依存しているグローバルな問題を扱う分野では、新植民地主義的な科学は、科学者が研究している問 題に対処するために、現地のコミュニティにおける知見の制度化を妨げる[30][35]。 |

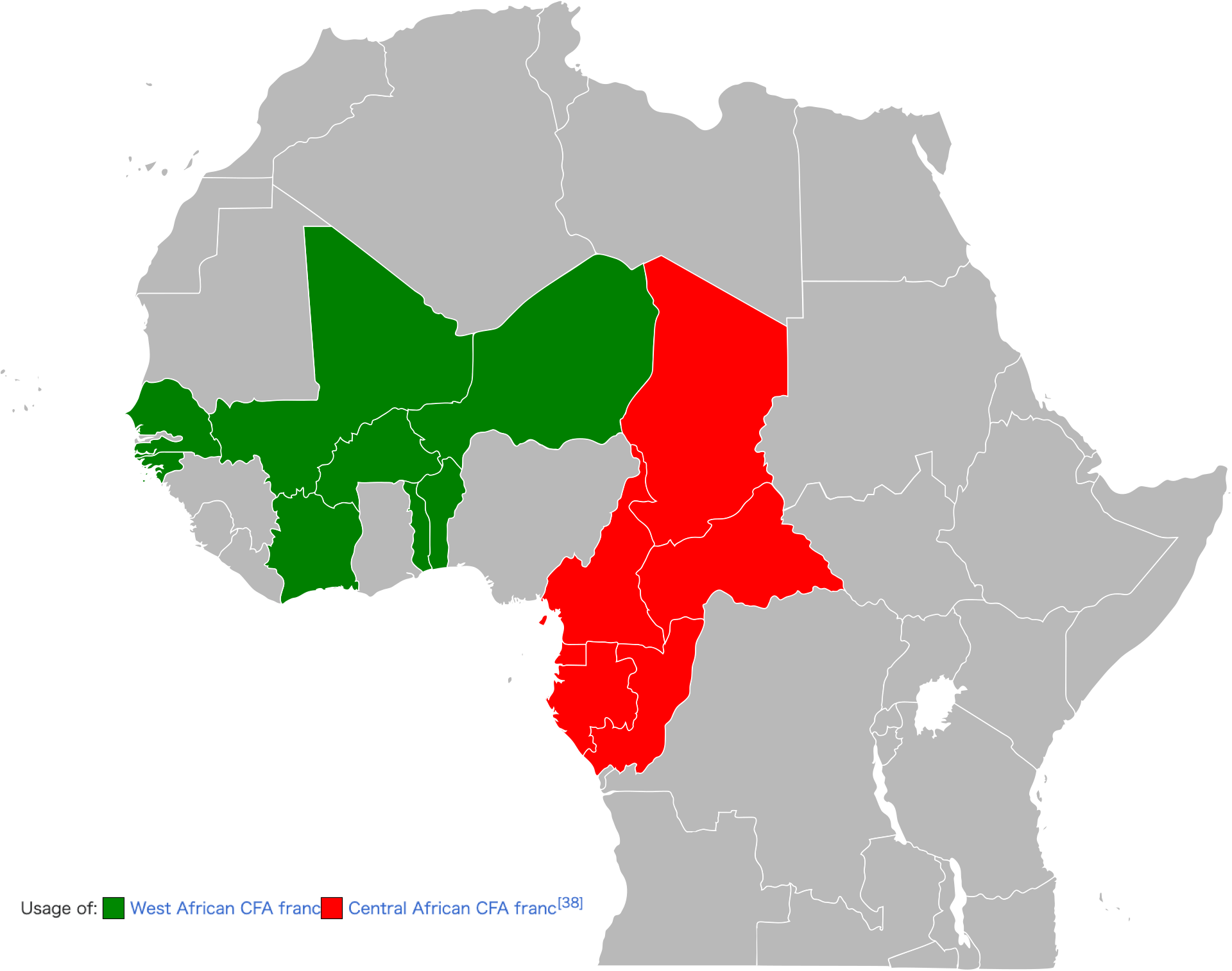

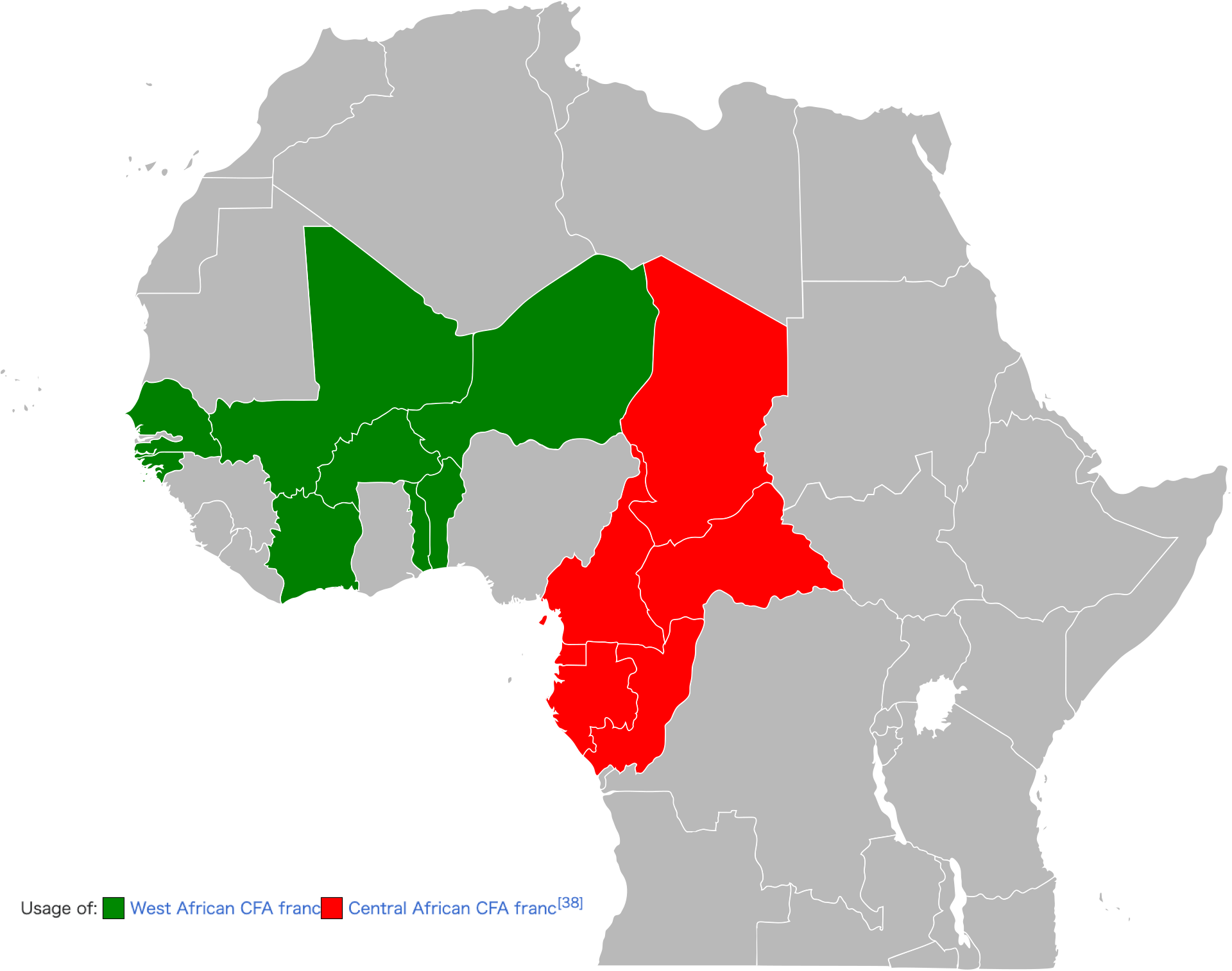

| Former colonial powers and Africa Françafrique See also: CFA franc  Usage of: West African CFA franc Central African CFA franc[38] The representative example of European neocolonialism is Françafrique, the "France-Africa" constituted by the continued close relationships between France and its former African colonies.[citation needed] In 1955, the initial usage of the term "French Africa", by President Félix Houphouët-Boigny of Ivory Coast, denoted positive social, cultural and economic Franco–African relations. It was later applied by neocolonialism critics to describe an imbalanced international relation.[citation needed] Neocolonialism was used to describe a type of foreign intervention in countries belonging to the Pan-Africanist movement, as well as the Asian–African Conference of Bandung (1955), which led to the Non-Aligned Movement (1961). Neocolonialism was formally defined by the All-African Peoples' Conference (AAPC) and published in the Resolution on Neo-colonialism. At both the Tunis conference (1960) and the Cairo conference (1961), AAPC described the actions of the French Community of independent states, organised by France, as neocolonial.[39][40] The politician Jacques Foccart, the principal adviser for African matters to French presidents Charles de Gaulle (1958–1969) and Georges Pompidou (1969–1974), was the principal proponent of Françafrique.[41] The works of Verschave and Beti reported a forty-year, post-independence relationship with France's former colonial peoples, which featured colonial garrisons in situ and monopolies by French multinational corporations, usually for the exploitation of mineral resources. It was argued that the African leaders with close ties to France—especially during the Soviet–American Cold War (1945–1992)—acted more as agents of French business and geopolitical interests than as the national leaders of sovereign states. Cited examples are Omar Bongo (Gabon), Félix Houphouët-Boigny (Ivory Coast), Gnassingbé Eyadéma (Togo), Denis Sassou-Nguesso (Republic of the Congo), Idriss Déby (Chad), and Hamani Diori (Niger).[citation needed] Belgian Congo Belgium's approach to Belgian Congo has been characterized as a quintessential example of neocolonialism, as the Belgians embraced rapid decolonization of the Congo with the expectation that the newly independent state would become dependent on Belgium. This dependence would allow the Belgians to exert control over Congo, even though Congo was formally independent.[1] After the decolonisation of Belgian Congo, Belgium continued to control, through the Société Générale de Belgique, an estimated 70% of the Congolese economy following the decolonisation process. The most contested part was in the province of Katanga where the Union Minière du Haut Katanga, part of the Société, controlled the mineral-resource-rich province. After a failed attempt to nationalise the mining industry in the 1960s, it was reopened to foreign investment.[citation needed] |

旧植民地大国とアフリカ フランス こちらも参照のこと: CFAフラン  の使用法: 西アフリカCFAフラン 中央アフリカCFAフラン[38] ヨーロッパの新植民地主義の代表例は、フランスとその旧アフリカ植民地との間の継続的な緊密な関係によって構成される「フランス・アフリカ」であるフランサフリックである[要出典]。 1955年、コートジボワールのフェリックス・ウフエ・ボワニー大統領によって、「フランス領アフリカ」という用語が最初に使用され、積極的な社会的、文 化的、経済的なアフリカとフランスの関係が示された。その後、新植民地主義批判者たちによって、不均衡な国際関係を表現するために適用された[要出典]。 新植民地主義は、非同盟運動(1961年)につながったバンドンのアジア・アフリカ会議(1955年)と同様に、汎アフリカ主義運動に属する国々への一種 の外国介入を表現するために使用された。新植民地主義は、全アフリカ人民会議(AAPC)によって正式に定義され、「新植民地主義に関する決議」として発 表された。チュニス会議(1960年)とカイロ会議(1961年)の両方において、AAPCはフランスによって組織された独立国家共同体の行動を新植民地 主義として記述した[39][40]。 フランスのシャルル・ド・ゴール大統領(1958年-1969年)とジョルジュ・ポンピドゥー大統領(1969年-1974年)のアフリカ問題の主要な顧問であった政治家のジャック・フォカールは、フランサフリックの主要な支持者であった[41]。 ヴェルシャーヴとベティの著作は、フランスの旧植民地人民との独立後の40年にわたる関係を報告しており、植民地駐留とフランスの多国籍企業による独占 (通常は鉱物資源の開発)を特徴としていた。フランスと密接な関係を持つアフリカの指導者たちは、特に米ソ冷戦時代(1945年~1992年)には、主権 国家の国民指導者としてよりも、フランスのビジネスや地政学的利益の代理人として行動していたと論じられた。オマール・ボンゴ(ガボン)、フェリックス・ ウフエ・ボワニー(コートジボワール)、グナシンベ・エヤデマ(トーゴ)、デニス・サッスー=ヌゲッソ(コンゴ共和国)、イドリス・デビ(チャド)、ハマ ニ・ディオリ(ニジェール)などがその例である[要出典]。 ベルギー領コンゴ ベルギーのベルギー領コンゴに対するアプローチは、新植民地主義の典型的な例として特徴づけられている。この依存によって、コンゴは形式的には独立していても、ベルギーはコンゴを支配することができるようになった[1]。 ベルギー領コンゴの非植民地化後も、ベルギーはベルギー社会主義協会(Société Générale de Belgique)を通じて、コンゴ経済の推定70%を支配し続けた。最も争奪戦が繰り広げられたのはカタンガ州で、ソシエテの一部であるユニオン・ミニ エール・デュ・オー・カタンガが鉱物資源の豊富な州を支配していた。1960年代に鉱業を国有化する試みが失敗した後、外資に再開された[要出典]。 |

| United States Main articles: American imperialism and Criticism of United States foreign policy There is an ongoing debate about whether certain actions by the United States should be considered neocolonialism.[42] Nayna J. Jhaveri, writing in Antipode, views the 2003 invasion of Iraq as a form of "petroimperialism", believing that the U.S. was motivated to go to war to attain vital oil reserves, rather than to pursue the U.S. government's official rationale for the Iraq War.[43] Noam Chomsky has been a prominent critic of "American imperialism";[44] he believes that the basic principle of the foreign policy of the United States is the establishment of "open societies" that are economically and politically controlled by the United States and where U.S.-based businesses can prosper.[45] He argues that the U.S. seeks to suppress any movements within these countries that are not compliant with U.S. interests and to ensure that U.S.-friendly governments are placed in power.[46] He believes that official accounts of U.S. operations abroad have consistently whitewashed U.S. actions in order to present them as having benevolent motives in spreading democracy.[47] Examples he regularly cites are the actions of the United States in Vietnam, the Philippines, Latin America, and the Middle East.[47] Chalmers Johnson argued in 2004 that America's version of the colony is the military base.[48] Johnson wrote numerous books, including three examinations of the consequences of what he called the "American Empire".[49] Chip Pitts argued similarly in 2006 that enduring United States bases in Iraq suggested a vision of "Iraq as a colony".[50] David Vine, author of Base Nation: How U.S. Military Bases Overseas Harm America and the World (2015), said the US had bases in 45 "less-than-democratic" countries and territories. He quotes political scientist Kent Calder: "The United States tends to support dictators [and other undemocratic regimes] in nations where it enjoys basing facilities".[51] |

アメリカ 主な記事 アメリカ帝国主義、アメリカ外交政策批判 アメリカによるある行動が新植民地主義とみなされるべきかどうかについては、現在も議論が続いている[42]。 Nayna J. Jhaveriは『Antipode』に寄稿し、2003年のイラク侵攻を「石油帝国主義」の一形態とみなしており、アメリカはイラク戦争に対するアメリ カ政府の公式な根拠を追求するためではなく、重要な石油埋蔵量を獲得するために戦争に踏み切ったのだと考えている[43]。 ノーム・チョムスキーは「アメリカ帝国主義」の著名な批判者である[44]。彼は、アメリカの外交政策の基本原則は、アメリカによって経済的・政治的に支 配され、アメリカに本拠を置く企業が繁栄できる「開かれた社会」の確立であると考えている[45]。 彼は、アメリカはこれらの国の中でアメリカの利益に従わない動きを抑圧し、アメリカにとって友好的な政府が政権を握るようにしようとしていると主張してい る[45]。 彼は、米国の海外での活動に関する公式の説明は、民主主義を広めるという善意的な動機があるかのように見せるために、一貫して米国の行動を美化してきたと 考えている。 チャルマーズ・ジョンソンは2004年に、アメリカの植民地バージョンは軍事基地であると主張した[48]。ジョンソンは、彼が「アメリカ帝国」と呼ぶも のの結果についての3つの検証を含む数多くの著書を書いた[49]。 チップ・ピッツは2006年に、イラクにおけるアメリカの基地の存続は「植民地としてのイラク」のビジョンを示唆していると同様に主張した[50]。 デイヴィッド・ヴァインは『ベース・ネーション』の著者である: How U.S. Military Bases Overseas Harm America and the World』(2015年)の著者デイヴィッド・ヴァインは、アメリカは45の「民主的ではない」国や地域に基地を有していると述べた。彼は政治学者のケ ント・カルダーの言葉を引用している: 「アメリカは、基地を享受している国民において、独裁者(やその他の非民主的な政権)を支持する傾向がある」[51]。 |

| China See also: Sino-African relations, Belt and Road Initiative, and Sinicization The People's Republic of China has built increasingly strong ties with some African, Asian, European and Latin American nations which has led to accusations of colonialism,[52][53] As of August 2007, an estimated 750,000 Chinese nationals were working or living for extended periods in Africa.[54][55] In the 1980s and 90s, China continued to purchase natural resources—petroleum and minerals—from Africa to fuel the Chinese economy and to finance international business enterprises.[56][57] In 2006, trade had increased to $50 billion expanding to $500 billion by 2016.[58] In Africa, China has loaned $95.5 billion to various countries between 2000 and 2015, the majority being spent on power generation and infrastructure.[59] Cases in which this has ended with China acquiring foreign land have led to accusations of "debt-trap diplomacy".[60][61][62] Other analysts say that China's activities "are goodwill for later investment opportunities or an effort to stockpile international support for contentious political issues".[63] In 2018, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad cancelled two China-funded projects. He also talked about fears of Malaysia becoming "indebted" and of a "new version of colonialism".[64][65] He later clarified that he did not refer to the Belt and Road Initiative or China with this.[66][67] According to Mark Langan in 2017, China, Western actors, and other emerging powers pursue their own interests at the expense of African interests. Western actors depict China as a threat to Africa, while depicting European and American involvement in Africa as being virtuous.[68] |

中国 こちらも参照のこと: 中アフリカ関係、一帯一路構想、中国化 中華人民共和国は、アフリカ、アジア、ヨーロッパ、ラテンアメリカの一部の国々とますます強固な関係を築いており、植民地主義への非難につながっている [52][53] 。 [1980年代から90年代にかけて、中国は中国経済を活性化させ、国際的なビジネス企業に資金を供給するために、アフリカから天然資源である石油や鉱物 を購入し続けた[56][57]。2006年には、貿易額は500億ドルに増加し、2016年には5000億ドルに拡大した[58]。 アフリカでは、中国は2000年から2015年の間に様々な国に955億ドルを貸し付けており、その大部分は発電とインフラに費やされている[59]。中 国が外国の土地を取得することでこれが終わったケースは、「債務トラップ外交」という非難につながっている[60][61][62]。他のアナリストは、 中国の活動は「後の投資機会のための善意であるか、争点となる政治問題に対する国際的な支持を蓄えるための努力である」と述べている[63]。 2018年、マレーシアのマハティール・モハマド首相は、中国が資金提供した2つのプロジェクトをキャンセルした。彼はまた、マレーシアが「負い目」を負 い、「植民地主義の新バージョン」になる恐れについて語った[64][65]。彼は後に、一帯一路構想や中国についてこのように言及したのではないことを 明らかにした[66][67]。 2017年のマーク・ランガンによれば、中国、欧米のアクター、その他の新興勢力は、アフリカの利益を犠牲にして自らの利益を追求している。欧米のアクターは中国をアフリカの脅威として描く一方で、欧米のアフリカへの関与を美徳として描いている[68]。 |

| Russia Russia currently occupies parts of neighboring states. These occupied territories are Transnistria (part of Moldova); Abkhazia and South Ossetia (part of Georgia); and five provinces of Ukraine, which it has illegally annexed. Russia has also established effective political domination over Belarus, through the Union State.[69] Historian Timothy Snyder defines Russia's war against Ukraine as "a colonial war, in the sense that Russia meant to conquer, dominate, displace and exploit" the country and its people.[70] Russia has been accused of colonialism in Crimea, which it annexed in 2014, by enforced Russification, passportization, and by settling Russian citizens on the peninsula and forcing out Ukrainians and Crimean Tatars.[71]  Russian mercenaries standing guard near an armored vehicle in the Central African Republic The Wagner Group, a Russian state-funded[72] private military company (PMC), has provided military support, security and protection for several autocratic regimes in Africa since 2017. In return, Russian and Wagner-linked companies have been given privileged access to those countries' natural resources, such as rights to gold and diamond mines, while the Russian military has been given access to strategic locations such as airbases and ports.[73][74] This has been described as a neo-colonial and neo-imperialist kind of state capture, whereby Russia gains sway over countries by helping to keep the ruling regime in power and making them reliant on its protection, while generating economic and political benefits for Russia, without benefitting the local population.[75][76][77] Russia has also gained geopolitical influence in Africa through election interference and spreading pro-Russian propaganda and anti-Western disinformation.[78][79] Russian PMCs have been active in the Central African Republic, Sudan, Libya, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger and Mozambique, among other countries. They have been accused of human rights abuses and killing civilians.[73] In 2024, the Wagner Group in Africa was merged into a new 'Africa Corps' under the direct control of Russia's Ministry of Defense.[80] Analysts for the Russian government have privately acknowledged the neo-colonial nature of Russia's policy towards Africa.[81] The "Russian world" is a term used by the Russian government and Russian nationalists for territories and communities with a historical, cultural, or spiritual tie to Russia.[69] The Kremlin meanwhile refers to the Russian diaspora and Russian-speakers in other countries as "Russian compatriots". In her book Beyond Crimea: The New Russian Empire (2016), Agnia Grigas highlights how ideas like the "Russian world" and "Russian compatriots" have become an "instrument of Russian neo-imperial aims".[82] The Kremlin has sought influence over its "compatriots" by offering them Russian citizenship and passports (passportization), and in some cases eventually calling for their military protection.[82] Grigas writes that the Kremlin uses the existence of these "compatriots" to "gain influence over and challenge the sovereignty of foreign states and at times even take over territories".[82] |

ロシア ロシアは現在、近隣諸国の一部を占領している。これらの占領地は、トランスニストリア(モルドバの一部)、アブハジアと南オセチア(グルジアの一部)、そ してウクライナの5つの州であり、これらを不法に併合している。歴史家のティモシー・スナイダーは、ロシアの対ウクライナ戦争を「ロシアがウクライナとそ の人民を征服し、支配し、移住させ、搾取するという意味での植民地戦争」と定義している[70]。ロシアは2014年に併合したクリミアにおいて、強制的 なロシア化、パスポート化、ロシア市民を半島に定住させ、ウクライナ人とクリミア・タタール人を強制排除することによって、植民地主義を非難されている [71]。  中央アフリカ共和国で装甲車の近くで警備するロシアの傭兵たち ロシアの国営[72]民間軍事会社(PMC)であるワグナー・グループは、2017年以降、アフリカのいくつかの独裁政権に軍事支援、警備、保護を提供し てきた。その見返りとして、ロシアとワグナーに関連する企業は、金鉱やダイヤモンド鉱山の権利など、それらの国の天然資源への特権的なアクセスを与えられ ており、ロシア軍は空軍基地や港湾などの戦略的な場所へのアクセスを与えられている[73][74]。これは新植民地主義的、新帝国主義的な国家捕捉とし て説明されており、ロシアは、支配体制を維持し、その保護に依存させることを支援することによって、国々に対する影響力を獲得する。 [75][76][77]ロシアはまた、選挙干渉や親ロシア的なプロパガンダや反欧米的な偽情報の拡散を通じて、アフリカにおける地政学的影響力を獲得し てきた[78][79]。ロシアのPMCは、中央アフリカ共和国、スーダン、リビア、マリ、ブルキナファソ、ニジェール、モザンビークなどで活動してき た。彼らは人権侵害や民間人の殺害で告発されている[73]。2024年、アフリカのワグネル・グループは、ロシア国防省直轄の新たな「アフリカ軍団」に 統合された[80]。ロシア政府のアナリストたちは、ロシアの対アフリカ政策の新植民地主義的性質を内々に認めている[81]。 ロシア世界」とは、ロシアと歴史的、文化的、あるいは精神的な結びつきを持つ地域や共同体に対して、ロシア政府やロシアのナショナリストが使用する用語で ある[69]。一方クレムリンは、ロシアのディアスポラや他国のロシア語話者を「ロシア同胞」と呼んでいる。彼女の著書『クリミアを越えて』(2016 年)では、「新しいロシア帝国」が紹介されている: アグニア・グリガスは、その著書『クリミアを越えて:新しいロシア帝国』(2016年)の中で、「ロシア世界」や「ロシア同胞」といった考え方がいかに 「ロシアの新帝国主義的な目的の道具」となっているかを強調している[82]。クレムリンは、彼らにロシア市民権やパスポート(パスポート化)を提供し、 場合によっては最終的に彼らの軍事的保護を求めることによって、「同胞」に対する影響力を求めてきた。 [82]グリガスは、クレムリンはこうした「同胞」の存在を利用して、「外国に対して影響力を獲得し、外国の主権に挑戦し、時には領土を占領することさえ ある」と書いている[82]。 |

| Other countries and entities Iran The Iranian government has been called an example of neocolonialism.[83] The motivation for Iran is not economic, but religious.[84] After its establishment in 1979, Iran sought to export Shia Islam globally and position itself as a force in world political structures.[84] Africa's Muslims present a unique opportunity in Iran's dominance in the Muslim world.[84] Iran is able to use these African communities to circumvent economic sanctions and move arms, man power, and nuclear technology.[84] Iran exerts its influence through humanitarian initiatives, such as those seen in Ghana.[85] Through the building of hospitals, schools, and agricultural projects Iran uses "soft power" to assert its influence in Western Africa.[85] Niue The government of Niue has been trying to get back access to its domain name, .nu.[86] The country signed a deal with a Massachusetts-based non-profit in 1999 that gave away rights to the domain name. Management of the domain name has since shifted to a Swedish organisation. The Niue government is currently fighting on two fronts to get back control on its domain name, including with the ICANN.[87] Toke Talagi, the long-serving Premier of Niue who died in 2020, called it a form of neocolonialism.[88] South Korea To ensure a reliable, long-term supply of food, the South Korean government and powerful Korean multinationals bought farming rights to millions of hectares of agricultural land in under-developed countries.[89] South Korea's RG Energy Resources Asset Management CEO Park Yong-soo stressed that "the nation does not produce a single drop of crude oil and other key industrial minerals. To power economic growth and support people's livelihoods, we cannot emphasise too much that securing natural resources in foreign countries is a must for our future survival."[90] The head of the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), Jacques Diouf, stated that the rise in land deals could create a form of "neocolonialism", with poor states producing food for the rich at the expense of their own hungry people.[91] In 2008, South Korean multinational Daewoo Logistics secured 1.3 million hectares of farmland in Madagascar to grow maize and crops for biofuels. Roughly half of the country's arable land, as well as rainforests were to be converted into palm and corn monocultures, producing food for export from a country where a third of the population and 50 percent of children under five are malnourished, using South African workers instead of locals. Local residents were not consulted or informed, despite being dependent on the land for food and income. The controversial deal played a major part in prolonged anti-government protests that resulted in over a hundred deaths.[89] This was a source of popular resentment that contributed to the fall of then-President Marc Ravalomanana. The new president, Andry Rajoelina, cancelled the deal.[92] Tanzania later announced that South Korea was in talks to develop 100,000 hectares for food production and processing for 700 to 800 billion won. Scheduled to be completed in 2010, it was to be the largest single piece of overseas South Korean agricultural infrastructure ever built.[89] In 2009, Hyundai Heavy Industries acquired a majority stake in a company cultivating 10,000 hectares of farmland in the Russian Far East and a South Korean provincial government secured 95,000 hectares of farmland in Oriental Mindoro, central Philippines, to grow corn. The South Jeolla province became the first provincial government to benefit from a new central government fund to develop farmland overseas, receiving a loan of $1.9 million. The project was expected to produce 10,000 tonnes of feed in the first year.[93] South Korean multinationals and provincial governments purchased land in Sulawesi, Indonesia, Cambodia and Bulgan, Mongolia. The national South Korean government announced its intention to invest 30 billion won in land in Paraguay and Uruguay. As of 2009 discussions with Laos, Myanmar and Senegal were underway.[89] |

その他の国・団体 イラン イラン政府は新植民地主義の一例と呼ばれている[83]。 イランにとっての動機は経済的なものではなく、宗教的なものである[84]。1979年の建国後、イランはシーア派イスラム教を世界的に輸出し、自らを世 界の政治構造における勢力として位置づけようとした[84]。アフリカのイスラム教徒は、イスラム世界におけるイランの支配において、またとない機会を提 供している[84]。イランはこうしたアフリカのコミュニティを利用して、経済制裁を回避し、武器、人的資源、核技術を移動させることができる。 イランは、ガーナで見られるような人道的イニシアティブを通じて影響力を行使している[85]。病院、学校、農業プロジェクトの建設を通じて、イランは「ソフトパワー」を利用して西アフリカにおける影響力を主張している[85]。 ニウエ ニウエ政府は、ドメイン名である.nuへのアクセスを取り戻そうとしている[86]。同国は1999年にマサチューセッツに拠点を置く非営利団体と契約を 結び、ドメイン名の権利を譲り受けた。その後、ドメイン名の管理はスウェーデンの団体に移った。ニウエ政府は現在、ICANNを含め、ドメイン名の管理権 を取り戻すために2つの面で戦っている[87]。2020年に死去したニウエの長年の首相であったトケ・タラギは、これを新植民地主義の一形態と呼んだ [88]。 韓国 信頼できる長期的な食糧供給を確保するため、韓国政府と韓国の有力多国籍企業は、低開発国の数百万ヘクタールの農地の耕作権を購入した[89]。 韓国のRGエナジー・リソース・アセット・マネジメントのCEOである朴容洙(パク・ヨンス)は、「国民は原油やその他の主要工業鉱物を一滴も生産してい ない」と強調した。経済成長の原動力となり、人びとの生活を支えるためには、外国の天然資源を確保することが将来の生存のために必須であることは、いくら 強調してもしすぎることはない」[90]。国連食糧農業機関(FAO)のジャック・ディウフ所長は、土地取引の増加は、貧しい国家が自国の飢えた人民を犠 牲にして富裕層のために食糧を生産するという、一種の「新植民地主義」を生み出しかねないと述べた[91]。 2008年、韓国の多国籍企業である大宇ロジスティクスは、トウモロコシとバイオ燃料用の作物を栽培するため、マダガスカルに130万ヘクタールの農地を 確保した。マダガスカルの耕地の約半分と熱帯雨林が、ヤシとトウモロコシの単一栽培に転換され、人口の3分の1、5歳未満の子どもの50%が栄養不良のこ の国で、地元住民の代わりに南アフリカ人労働者を使って輸出用の食糧を生産することになった。食料と収入をその土地に依存しているにもかかわらず、地元住 民には何の相談も情報も与えられなかった。物議を醸したこの取引は、100人以上の死者を出した長期にわたる反政府デモに大きな役割を果たした[89]。 これが民衆の憤りの源となり、当時のマルク・ラバロマナナ大統領の失脚につながった。新大統領のアンドリー・ラジョエリナは、この契約を取り消した [92]。タンザニアはその後、韓国が7,000億~8,000億ウォンで10万ヘクタールの食料生産・加工開発を行う交渉を進めていると発表した。 2010年に完成する予定であり、韓国が海外に建設した単一の農業インフラとしては過去最大規模となる予定であった[89]。 2009年、現代重工業はロシア極東で1万ヘクタールの農地を耕作している会社の株式の過半数を取得し、韓国の地方政府はフィリピン中部の東洋ミンドロで トウモロコシを栽培するために9万5,000ヘクタールの農地を確保した。全羅南道は、海外で農地を開発するための新しい中央政府基金の恩恵を受けた最初 の地方政府となり、190万ドルの融資を受けた。このプロジェクトでは、初年度に1万トンの飼料生産が見込まれていた[93]。韓国の多国籍企業と地方政 府は、インドネシアのスラウェシ島、カンボジア、モンゴルのブルガンで土地を購入した。韓国国民政府は、パラグアイとウルグアイの土地に300億ウォンを 投資する意図を表明した。2009年の時点では、ラオス、ミャンマー、セネガルとの話し合いが進められていた[89]。 |

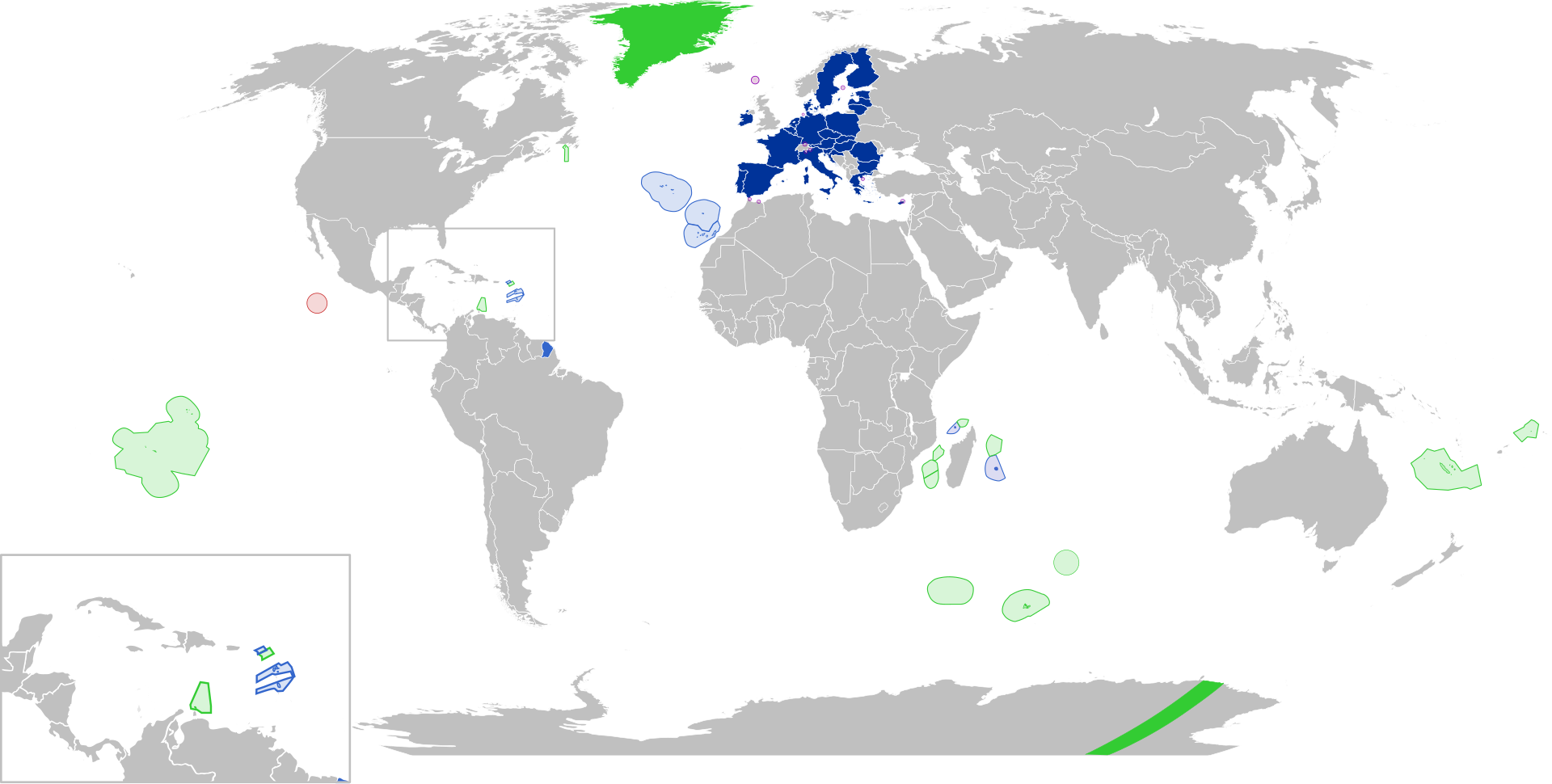

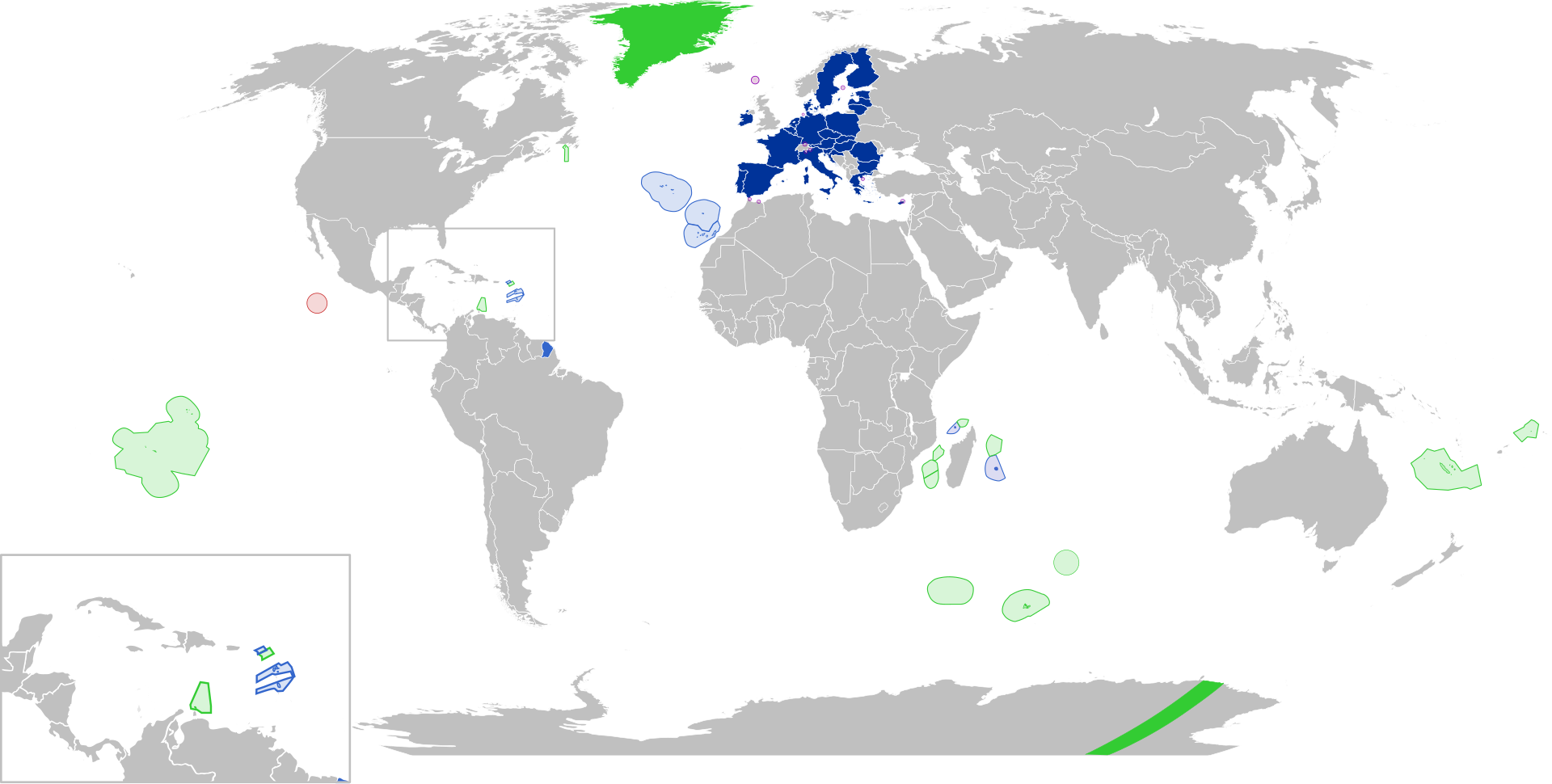

| Cultural approaches Although the concept of neocolonialism was originally developed within a Marxist theoretical framework and is generally employed by the political left, the term "neocolonialism" is found in other theoretical frameworks. Coloniality "Coloniality" claims that knowledge production is strongly influenced by the context of the person producing the knowledge and that this has further disadvantaged developing countries with limited knowledge production infrastructure. It originated among critics of subaltern theories, which, although strongly de-colonial, are less concerned with the source of knowledge.[94] Cultural theory  Map of the European Union in the world, with Overseas Countries and Territories (OCT) in green and Outermost Regions (OMR) in blue One variant of neocolonialism theory critiques cultural colonialism, the desire of wealthy nations to control other nations' values and perceptions through cultural means such as media, language, education[95] and religion, ultimately for economic reasons. One impact of this is "colonial mentality", feelings of inferiority that lead post-colonial societies to latch onto physical and cultural differences between the foreigners and themselves. Foreign ways become held in higher esteem than indigenous ways. Given that colonists and colonisers were generally of different races, the colonised may over time hold that the colonisers' race was responsible for their superiority. Rejections of the colonisers culture, such as the Negritude movement, have been employed to overcome these associations. Post-colonial importation or continuation of cultural mores or elements may be regarded as a form of neocolonialism.[citation needed] Postcolonialism Main article: Postcolonialism Post-colonialism theories in philosophy, political science, literature and film deal with the cultural legacy of colonial rule. Post-colonialism studies examine how once-colonised writers articulate their national identity; how knowledge about the colonised was generated and applied in service to the interests of the coloniser; and how colonialist literature justified colonialism by presenting the colonised people as inferior whose society, culture and economy must be managed for them. Post-colonial studies incorporate subaltern studies of "history from below"; post-colonial cultural evolution; the psychopathology of colonisation (by Frantz Fanon); and the cinema of film makers such as the Cuban Third Cinema, e.g. Tomás Gutiérrez Alea, and Kidlat Tahimik.[citation needed] Critical theory Critiques of postcolonialism/neocolonialism are evident in literary theory. International relations theory defined "postcolonialism" as a field of study. While the lasting effects of cultural colonialism are of central interest, the intellectual antecedents in cultural critiques of neocolonialism are economic. Critical international relations theory references neocolonialism from Marxist positions as well as postpositivist positions, including postmodernist, postcolonial and feminist approaches. These differ from both realism and liberalism in their epistemological and ontological premises. The neoliberalist approach tends to depict modern forms of colonialism as a benevolent imperialism.[citation needed] Neocolonialism and gender construction Concepts of neocolonialism can be found in theoretical works investigating gender outside the global north. Often these conceptions can be seen as erasing gender norms within communities in the global south[96] to create conceptions of gender that align with the global north. Gerise Herndon argues that applying feminism or other theoretical frameworks around gender must look at the relationship between the individual subject, their home country or culture, and the country and culture that exerts neocolonial control over the country. In her piece "Gender Construction and Neocolonialism", Herndon presents the writings of Maryse Condé as an example of grappling with what it means to have your identity constructed by neocolonial powers. Her work explores how women in burgeoning nations rebuilt their identities in the postcolonial period. The task of creating new identities was met with challenges from not only an internal view of what the culture was in these places but also from the external expectations of ex-colonial powers.[97] An example of the construction of gender norms and conceptions by neocolonial interests is made clear in the Ugandan Anti-Homosexuality Act introduced in 2009 and passed in 2014. The act expanded upon previously existing laws against sodomy to make gay relationships punishable by life imprisonment. The call for this bill came from Ugandans who claimed traditional African values that did not include homosexuality. This act faced backlash from western countries, citing human rights violations. The United States imposed economic sanctions against Uganda in June 2014 in response to the law, the World Bank indefinitely postponed a $90 million aid loan to Uganda and the governments of Denmark, the Netherlands, Sweden and Norway halted aid to Uganda in opposition to the law; the Ugandan government defended the bill and rejected condemnation of it, with the country's authorities stating President Museveni wanted "to demonstrate Uganda's independence in the face of Western pressure and provocation".[98] The Ugandan response was to claim that this was a neocolonialist attack on their culture. Kristen Cheney argued that this is a misrepresentation of neocolonialism at work and that this conception of gender and anti-homosexuality erased historically diverse gender identities in Africa. To Cheney, neocolonialism was found in accepting conservative gender identity politics, specifically those of U.S.-based Evangelical Christians. Before the introduction of this act, conservative Christian groups in the United States had put African religious leaders and politicians on their payroll, reflecting the talking points of U.S.-based Christian evangelism. Cheney argues that this adoption and bankrolling of U.S. conservative Christian evangelist thought in Uganda is the real neocolonialism and effectively erodes any historical gender diversity in Africa.[96] |

文化的アプローチ 新植民地主義の概念は、もともとマルクス主義の理論的枠組みの中で発展したものであり、一般的に政治的左派によって用いられているが、「新植民地主義」という用語は他の理論的枠組みにも見られる。 植民地性 「植民地主義」は、知識生産は知識を生産する人格の文脈に強く影響され、このことが知識生産のインフラが限られている発展途上国をさらに不利にしていると 主張する。これはサバルタン理論に対する批判者の間で生まれたものであり、強く脱植民地的であるにもかかわらず、知識の源泉にはあまり関心がない [94]。 文化理論  欧州連合(EU)の世界地図。緑が海外諸国・地域(OCT)、青が最外地域(OMR)である。 新植民地主義理論のバリエーションのひとつは、文化的植民地主義を批判している。文化的植民地主義とは、メディア、言語、教育[95]、宗教といった文化 的手段を通じて、他国の価値観や認識を支配しようとする富裕国の欲望であり、最終的には経済的理由によるものである。この影響のひとつが「植民地メンタリ ティ」であり、植民地支配後の社会が外国人と自分たちとの物理的・文化的差異にとらわれるようになる劣等感である。外国のやり方は、土着のやり方よりも高 く評価されるようになる。植民者と被植民者は一般的に異なる人種であったため、被植民者は植民者の人種が自分たちの優位性の原因であると考えるようにな る。このような連想を克服するために、ネグリチュード運動のような植民地人文化の拒絶が行われてきた。ポストコロニアルによる文化的風俗や要素の輸入や継 続は、新植民地主義の一形態と見なされることもある[要出典]。 ポストコロニアリズム 主な記事 ポストコロニアリズム 哲学、政治学、文学、映画におけるポストコロニアリズムの理論は、植民地支配の文化的遺産を扱っている。ポストコロニアリズム研究では、かつて植民地化さ れた作家がどのようにナショナリズムを表現したか、植民地化された人びとに関する知識がどのように生み出され、植民地化した側の利益のために応用された か、植民地主義文学がどのように植民地化された人びとを社会、文化、経済が管理されるべき劣った存在として提示することで植民地主義を正当化したかを検証 する。ポストコロニアル研究は、「下からの歴史」のサバルタン研究、ポストコロニアル文化の発展、植民地化の精神病理学(フランツ・ファノンによる)、 キューバ第3の映画(トマス・グティエレス・アレア、キドラット・タヒミックなど)のような映画制作者の映画を取り込んでいる[要出典]。 批評理論 ポストコロニアリズム/新植民地主義への批判は文学理論において顕著である。国際関係論は「ポストコロニアリズム」を研究分野として定義した。文化的植民 地主義の永続的な影響が中心的な関心事である一方で、新植民地主義に対する文化的批評の知的な先行要因は経済的なものである。批判的国際関係論は、マルク ス主義の立場からだけでなく、ポストモダニズム、ポストコロニアル、フェミニズムのアプローチを含む後実証主義の立場からも、新植民地主義に言及してい る。これらは認識論的、存在論的前提において、リアリズムともリベラリズムとも異なる。新自由主義的アプローチは、現代の植民地主義の形態を慈悲深い帝国 主義として描く傾向がある[要出典]。 新植民地主義とジェンダー構築 新植民地主義の概念は、グローバル・ノース以外のジェンダーを研究する理論的著作に見出すことができる。多くの場合、これらの概念はグローバル・ノースに 沿ったジェンダーの概念を作り出すために、グローバル・サウス[96]のコミュニティ内のジェンダー規範を消去していると見ることができる。Gerise Herndonは、フェミニズムやジェンダーをめぐる他の理論的枠組みを適用することは、個々の主体、彼らの母国や文化、そして新植民地支配を及ぼしてい る国や文化との関係を見なければならないと主張している。ハーンドンは「ジェンダー構築と新植民地主義」の中で、新植民地権力によってアイデンティティを 構築されることが何を意味するのかに取り組む例として、マリーズ・コンデの著作を紹介している。彼女の著作は、急成長する国民の女性たちが、ポストコロニ アル時代にどのようにアイデンティティを再構築したかを探求している。新たなアイデンティティを創造する作業は、これらの場所の文化が何であったかという 内面的な視点だけでなく、元植民地大国の外的な期待からも課題に直面した[97]。 新植民地的利益によるジェンダー規範と概念の構築の例は、2009年に導入され2014年に可決されたウガンダの反同性愛法に明確に示されている。この法 律は、以前からあったソドミーに対する法律を拡大し、同性愛者の関係を無期懲役で罰するものとした。この法案を求めたのは、同性愛を含まない伝統的なアフ リカの価値観を主張するウガンダ人だった。この法律は、人権侵害を理由に西側諸国からの反発に直面した。アメリカは2014年6月、この法律に対抗してウ ガンダに対して経済制裁を課し、世界銀行はウガンダへの9000万ドルの援助融資を無期限に延期し、デンマーク、オランダ、スウェーデン、ノルウェーの政 府はこの法律に反対してウガンダへの援助を停止した。ウガンダ政府はこの法案を擁護し、ムセベニ大統領は「欧米の圧力と挑発に直面してウガンダの独立性を 示したかった」と述べ、この法案に対する非難を拒否した。 [98]ウガンダの反応は、これは自国の文化に対する新植民地主義的な攻撃であると主張するものであった。クリステン・チェイニーは、これは新植民地主義 が働いていることの誤った表現であり、このジェンダーと反同性愛の概念は、アフリカにおける歴史的に多様なジェンダーのアイデンティティを消し去っている と主張した。チェイニーに言わせれば、新植民地主義は保守的なジェンダー・アイデンティティ政治、特に米国を拠点とする福音派キリスト教徒のそれを受け入 れることに見出された。この法律が導入される以前から、米国の保守的なキリスト教グループは、アフリカの宗教指導者や政治家たちを、米国を拠点とするキリ スト教伝道主義の論点を反映させながら、自分たちの給与支払者にしてきた。チェイニーは、ウガンダにおける米国の保守的キリスト教伝道者の思想の採用と資 金提供こそが真の新植民地主義であり、アフリカにおける歴史的なジェンダーの多様性を効果的に侵食していると主張している[96]。 |

| Academic imperialism Americanization Colonialism Cultural hegemony Cultural imperialism Dependency theory Ecological imperialism François-Xavier Verschave's book on Françafrique Gatekeeper state: the concept of neocolonial "successor states", introduced by the African historian Frederick Cooper in Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present. Global apartheid Hegemony Impact of Western European colonialism and colonisation Imperialism List of coups d'état and coup attempts Modernization theory Neocolonial racism Neoliberalism New imperialism Postcolonialism Sino-African relations Trans-Pacific Partnership Washington Consensus |

学術的帝国主義 アメリカ化 植民地主義 文化的覇権主義 文化的帝国主義 依存理論 生態学的帝国主義 フランソワ=グザヴィエ・ヴェルシャーヴのフランサフリックに関する著書 ゲートキーパー国家:アフリカの歴史家フレデリック・クーパーが『1940年以降のアフリカ』で紹介した新植民地「後継国家」の概念: の中でアフリカの歴史家フレデリック・クーパーによって紹介された。 グローバル・アパルトヘイト ヘゲモニー 西欧の植民地主義と植民地化の影響 帝国主義 クーデターとクーデター未遂のリスト 近代化理論 新植民地人種主義 新自由主義 新帝国主義 ポストコロニアリズム 中アフリカ関係 環太平洋パートナーシップ ワシントン・コンセンサス |

| Bibliography McGilvray, James (2014). Chomsky: Language, Mind, Politics (Second ed.). Cambridge: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-4989-4. Sperlich, Wolfgang B. (2006). Noam Chomsky. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-269-0 – via Internet Archive. Further reading Agyeman, Opoku (1992). Nkrumah's Ghana and East Africa: Pan-Africanism and African interstate relations. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. Ankerl, Guy (2000). Global communication without universal civilisation. INU societal research. Vol. 1: Coexisting contemporary civilisations : Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. Geneva: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5. Ashcroft, Bill, ed. (1995). The post-colonial studies reader. et al. London: Routledge. Barongo, Yolamu R. (1980). Neo-colonialism and African politics: A survey of the impact of neo-colonialism on African political behavior. New York: Vantage Press. Mongo Beti, Main basse sur le Cameroun. Autopsie d'une décolonisation (1972), new edition La Découverte, Paris 2003 [A classical critique of neo-colonialism. Raymond Marcellin, the French Minister of the Interior at the time, tried to prohibit the book. It could only be published after fierce legal battles.] Frédéric Turpin. De Gaulle, Pompidou et l'Afrique (1958–1974): décoloniser et coopérer (Les Indes savantes, Paris, 2010. [Grounded on Foccart's previously inaccessibles archives] Kum-Kum Bhavnani. (ed., et al.) Feminist futures: Re-imagining women, culture and development (Zed Books, NY, 2003). See: Ming-yan Lai's "Of Rural Mothers, Urban Whores and Working Daughters: Women and the Critique of Neocolonial Development in Taiwan's Nativist Literature", pp. 209–225. David Birmingham. The decolonisation of Africa (Ohio University Press, 1995). Charles Cantalupo(ed.). The world of Ngugi wa Thiong'o (Africa World Press, 1995). Laura Chrisman and Benita Parry (ed.) Postcolonial theory and criticism (English Association, Cambridge, 2000). Renato Constantino. Neocolonial identity and counter-consciousness: Essays on cultural decolonisation (Merlin Press, London, 1978). George A. W. Conway. A responsible complicity: Neo/colonial power-knowledge and the work of Foucault, Said, Spivak (University of Western Ontario Press, 1996). Julia V. Emberley. Thresholds of difference: feminist critique, native women's writings, postcolonial theory (University of Toronto Press, 1993). Nikolai Aleksandrovich Ermolov. Trojan horse of neo-colonialism: U.S. policy of training specialists for developing countries (Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1966). Thomas Gladwin. Slaves of the white myth: The psychology of neo-colonialism (Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1980). Lewis Gordon. Her Majesty's Other Children: Sketches of Racism from a Neocolonial Age (Rowman & Littlefield, 1997). Ankie M. M. Hoogvelt. Globalisation and the postcolonial world: The new political economy of development (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). J. M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge University Press, 2004). M. B. Hooker. Legal pluralism; an introduction to colonial and neo-colonial laws (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1975). E.M. Kramer (ed.) The emerging monoculture: assimilation and the "model minority" (Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2003). See: Archana J. Bhatt's "Asian Indians and the Model Minority Narrative: A Neocolonial System", pp. 203–221. Geir Lundestad (ed.) The fall of great powers: Peace, stability, and legitimacy (Scandinavian University Press, Oslo, 1994). Jean-Paul Sartre. 'Colonialism and neo-colonialism. Translated by Steve Brewer, Azzedine Haddour, Terry McWilliams Republished in the 2001 edition by Routledge France. ISBN 0-415-19145-9. Peccia, T., 2014, "The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks: A New Sphere of Influence 2.0", Jura Gentium – Rivista di Filosofia del Diritto Internazionale e della Politica Globale, Sezione "L'Afghanistan Contemporaneo", The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks Stuart J. Seborer. U.S. neo-colonialism in Africa (International Publishers, NY, 1974). D. Simon. Cities, capital and development: African cities in the world economy (Halstead, NY, 1992). Phillip Singer(ed.) Traditional healing, new science or new colonialism": (essays in critique of medical anthropology) (Conch Magazine, Owerri, 1977). Jean Suret-Canale. Essays on African history: From the slave trade to neo-colonialism (Hurst, London 1988). Ngũgĩ wa Thiong'o. Barrel of a pen: Resistance to repression in neo-colonial Kenya (Africa Research & Publications Project, 1983). Carlos Alzugaray Treto. El ocaso de un régimen neocolonial: Estados Unidos y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958,(The twilight of a neocolonial regime: The United States and Batista during 1958), in Temas: Cultura, Ideología y Sociedad, No.16-17, October 1998/March 1999, pp. 29–41 (La Habana: Ministry of Culture). Uzoigw, Godfrey N. "Neocolonialism Is Dead: Long Live Neocolonialism." Journal of Global South Studies 36.1 (2019): 59–87. Reports of International Arbitral Awards. Vol. XXVII. United Nations Publication. 2007. p. 188. ISBN 978-92-1-033098-5. Richard Werbner (ed.) Postcolonial identities in Africa (Zed Books, NJ, 1996). External links |

書誌情報 McGilvray, James (2014). チョムスキー: Language, Mind, Politics (Second ed.). ケンブリッジ: Polity. ISBN 978-0-7456-4989-4. Sperlich, Wolfgang B. (2006). Noam Chomsky. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1-86189-269-0 - via Internet Archive. さらに読む Agyeman, Opoku (1992). ンクルマのガーナと東アフリカ: 汎アフリカ主義とアフリカの国家間関係. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. Ankerl, Guy (2000). 普遍文明なきグローバル・コミュニケーション. INU 社会研究。第1巻:共存する現代文明: 第1巻:共存する現代文明:アラブ・イスラム、バーラティ、中国、西洋。ジュネーブ: INU Press. ISBN 2-88155-004-5. Ashcroft, Bill, ed. (1995). ポストコロニアル・スタディーズ・リーダー: Routledge. Barongo, Yolamu R. (1980). 新植民地主義とアフリカ政治: 新植民地主義がアフリカの政治行動に与えた影響の調査。New York: Vantage Press. Mongo Beti, Main basse sur le Cameroun. Autopsie d'une décolonisation (1972), new edition La Découverte, Paris 2003 [新植民地主義に対する古典的批判。当時のフランス内務大臣であったレイモン・マルセランは、この本の出版を禁止しようとした。熾烈な法廷闘争の末に初め て出版された。] フレデリック・トゥルパン ドゴール、ポンピドゥーとアフリカ(1958-1974):脱植民地化と協力』(Les Indes savantes, Paris, 2010. [以前はアクセスできなかったフォカールのアーカイブに基づく]。 Kum-Kum Bhavnani. (フェミニストの未来: Feminist futures: Re-imagining women, culture and development (Zed Books, NY, 2003). 参照: ミンヤン・ライの「農村の母、都市の娼婦、働く娘たち」(Of Rural Mothers, Urban Whores and Working Daughters: 台湾先住民文学における女性と新植民地開発批判」、209-225頁。 デイヴィッド・バーミンガム The decolonisation of Africa (Ohio University Press, 1995). チャールズ・カンタルポ編. The world of Ngugi wa Thiong'o (Africa World Press, 1995). Laura Chrisman and Benita Parry (ed.) Postcolonial theory and criticism (English Association, Cambridge, 2000). レナート・コンスタンティーノ 新植民地アイデンティティと反意識: Essays on cultural decolonisation (Merlin Press, London, 1978). ジョージ・A・W・コンウェイ 責任ある共犯関係: Neo/colonial power-knowledge and the work of Foucault, Said, Spivak (University of Western Ontario Press, 1996). Julia V. Emberley. フェミニズム批評、先住民女性の著作、ポストコロニアル理論(トロント大学出版、1993年)。 Nikolai Aleksandrovich Ermolov. 新植民地主義のトロイの木馬: 新植民地主義のトロイの木馬:発展途上国のための専門家養成というアメリカの政策(プログレス出版社、モスクワ、1966年)。 トーマス・グラドウィン 白人神話の奴隷: 新植民地主義の心理学(Humanities Press, Atlantic Highlands, NJ, 1980)。 ルイス・ゴードン Her Majesty's Other Children: Her Majesty's Other Children: Sketches of Racism from a Neocolonial Age (Rowman & Littlefield, 1997). Ankie M. M. Hoogvelt. グローバリゼーションとポストコロニアル世界: The new political economy of development (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001). J. M. Hobson, The Eastern Origins of Western Civilisation (Cambridge University Press, 2004). M. B. フッカー。Legal pluralism; an introduction to colonial and neo-colonial laws (Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1975). E.M. Kramer (ed.) The emerging monoculture: assimilation and the 「model minority」 (Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2003). 参照: Archana J. Bhattの「アジア・インディアンとモデル・マイノリティの物語」、pp: A Neocolonial System」, pp.203-221. Geir Lundestad (ed.) The fall of great powers: Peace, stability, and legitimacy (Scandinavian University Press, Oslo, 1994). ジャン=ポール・サルトル 植民地主義と新植民地主義」。スティーブ・ブリュワー、アズディーヌ・ハドゥール、テリー・マクウィリアムズ訳 ラウトレッジ・フランス社より2001年版として再出版。ISBN 0-415-19145-9. Peccia, T., 2014, "Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks: A New Sphere of Influence 2.0「, Jura Gentium - Rivista di Filosofia del Diritto Internazionale eella Politica Globale, Sezione 」L'Afghanistan Contemporaneo」, The Theory of the Globe Scrambled by Social Networks. スチュアート・J・セボラー アフリカにおけるアメリカの新植民地主義』(インターナショナル・パブリッシャーズ、NY、1974年) D. サイモン 都市、資本、開発: 世界経済におけるアフリカの都市 (Halstead, NY, 1992). フィリップ・シンガー(編)伝統的治癒、新しい科学、あるいは新しい植民地主義」:(医療人類学批判エッセイ)(コンク誌、オウェリ、1977年)。 ジャン・スレット=カナール アフリカ史エッセイ: From the slave trade to neo-colonialism (Hurst, London 1988). Ngũ wa Thiong'o. Barrel of a pen: Barrel of the pen: Resistance to repression in neo-colonial Kenya (Africa Research & Publications Project, 1983). Carlos Alzugaray Treto. El ocaso de un régimen neocolonial: Estados Union y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958,(The twilight of a neocolonial regime: The twilight of neocolonial regime: The Estados Unidos y la dictadura de Batista durante 1958,), in Temas: Cultura, Ideología y Sociedad, No.16-17, October 1998/March 1999, pp.29-41 (La Habana: Ministry of Culture). Uzoigw, Godfrey N. 「Neocolonialism Is Dead: Long Live Neocolonialism.」. Journal of Global South Studies 36.1 (2019): 59-87. Report of International Arbitral Awards. 第 XXVII 巻。国連出版。2007. p. 188. ISBN 978-92-1-033098-5. Richard Werbner (ed.) Postcolonial identities in Africa (Zed Books, NJ, 1996). 外部リンク |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Neocolonialism |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆