アブラム・ノーム・チョムスキー

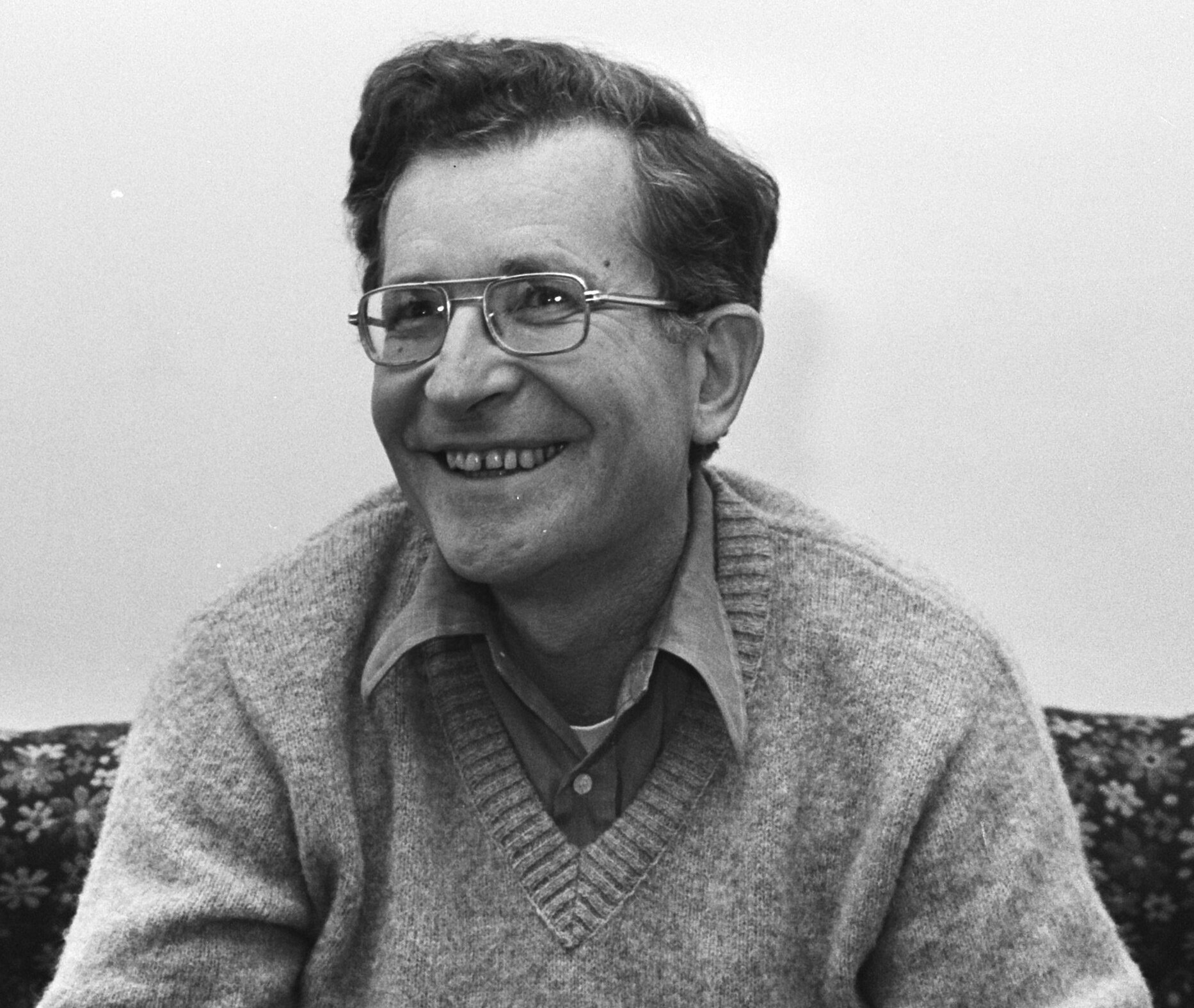

Noam Chomsky, 1928-

2017

年のチョムスキー

☆ アブラム・ノーム・チョムスキー(/noʊmski/ ˈ nohm CHOM-skee、1928年12月7日生まれ)は、言語学、政治活動、社会批評の分野で知られるアメリカの教授であり知識人である。現代言語学の父」 と呼ばれることもあり[a]、分析哲学の重鎮であり、認知科学分野の創始者の一人でもある。アリゾナ大学言語学名誉教授、マサチューセッツ工科大学 (MIT)名誉教授。言語学、戦争、政治などをテーマに150冊以上の著作がある。思想的には、アナルコ・サンディカリズムとリバタリアン社会主義に傾倒 している。 フィラデルフィアのアシュケナージ・ユダヤ系移民の子として生まれたチョムスキーは、ニューヨークのオルタナティブ書店でアナーキズムに早くから関心を抱 くようになる。ペンシルベニア大学で学ぶ。ハーバード大学フェロー・ソサエティに在籍中、変形文法の理論を構築し、1955年に博士号を取得した。同年、 マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭をとり始め、1957年、言語研究の改革に大きな役割を果たした画期的な著作『構文構造』で言語学の重要人物と して頭角を現す。1958年から1959年まで、チョムスキーは高等研究所で全米科学財団のフェローを務めた。普遍文法理論、生成文法理論、チョムス キー・ヒエラルキー、ミニマリスト・プログラムを創始、あるいは共同創始した。言語行動主義の衰退においても重要な役割を果たし、特にB.F.スキナーの 研究に批判的であった。 1967年、チョムスキーは反戦エッセイ『知識人の責任』で全米の注目を集めた。新左翼と関わりを持つようになった彼は、その活動で何度も逮捕され、リ チャード・ニクソン大統領の政敵リストに載った。その後数十年にわたり言語学の仕事を拡大する一方で、言語学戦争にも巻き込まれた。エドワード・S・ハー マンと共同で、後に『Manufacturing Consent』でメディア批評のプロパガンダ・モデルを明確にし、インドネシアによる東ティモール占領の暴露に取り組んだ。ホロコースト否定を含む無条 件の言論の自由の擁護は、1980年代のフォーリソン事件で大きな論争を巻き起こした。カンボジアの大虐殺やボスニアの大虐殺に関するチョムスキーの論評 も物議を醸した。マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭をとる現役を退いてからは、2003年のイラク侵攻に反対し、「占拠せよ」運動を支持するな ど、声高な政治活動を続けている。反シオニストであるチョムスキーは、イスラエルのパレスチナ人に対する扱いは南アフリカ型のアパルトヘイトよりもひどい と考え[20]、米国のイスラエル支援を批判している。 チョムスキーは人間科学における認知革命の火付け役として広く認知されており、言語と心の研究のための新しい認知論的枠組みの発展に貢献している。チョム スキーは、米国の外交政策、現代の資本主義、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争における米国の関与とイスラエルの役割、マスメディアに対する主要な批判者であり 続けている。チョムスキーとその思想は、反資本主義、反帝国主義運動において大きな影響力を持っている。2017年より、アリゾナ大学の環境と社会正義に おけるアグネーゼ・ヘルムス・ハウリー・プログラムのアグネーゼ・ヘルムス・ハウリー・チェアを務めている。

Noam Chomsky - Anarchism I (YouTube)

Noam Chomsky (2013) "What is Anarchism?"

Ecology, Ethics, Anarchism: In Conversation with Noam Chomsky

Noam Chomsky Interview 2010 - Never seen until now. Subjects: Antisemitism, Holocaust, Israel, etc.

| Avram Noam Chomsky

(/noʊm ˈtʃɒmski/ ⓘ nohm CHOM-skee; born December 7, 1928) is an

American professor and public intellectual known for his work in

linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called

"the father of modern linguistics",[a] Chomsky is also a major figure

in analytic philosophy and one of the founders of the field of

cognitive science. He is a laureate professor of linguistics at the

University of Arizona and an institute professor emeritus at the

Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). Among the most cited

living authors, Chomsky has written more than 150 books on topics such

as linguistics, war, and politics. Ideologically, he aligns with

anarcho-syndicalism and libertarian socialism. Born to Ashkenazi Jewish immigrants in Philadelphia, Chomsky developed an early interest in anarchism from alternative bookstores in New York City. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania. During his postgraduate work in the Harvard Society of Fellows, Chomsky developed the theory of transformational grammar for which he earned his doctorate in 1955. That year he began teaching at MIT, and in 1957 emerged as a significant figure in linguistics with his landmark work Syntactic Structures, which played a major role in remodeling the study of language. From 1958 to 1959 Chomsky was a National Science Foundation fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study. He created or co-created the universal grammar theory, the generative grammar theory, the Chomsky hierarchy, and the minimalist program. Chomsky also played a pivotal role in the decline of linguistic behaviorism, and was particularly critical of the work of B. F. Skinner. An outspoken opponent of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, which he saw as an act of American imperialism, in 1967 Chomsky rose to national attention for his anti-war essay "The Responsibility of Intellectuals". Becoming associated with the New Left, he was arrested multiple times for his activism and placed on President Richard Nixon's list of political opponents. While expanding his work in linguistics over subsequent decades, he also became involved in the linguistics wars. In collaboration with Edward S. Herman, Chomsky later articulated the propaganda model of media criticism in Manufacturing Consent, and worked to expose the Indonesian occupation of East Timor. His defense of unconditional freedom of speech, including that of Holocaust denial, generated significant controversy in the Faurisson affair of the 1980s. Chomsky's commentary on the Cambodian genocide and the Bosnian genocide also generated controversy. Since retiring from active teaching at MIT, he has continued his vocal political activism, including opposing the 2003 invasion of Iraq and supporting the Occupy movement. An anti-Zionist, Chomsky considers Israel's treatment of Palestinians to be worse than South African-style apartheid[20], and criticizes U.S. support for Israel. Chomsky is widely recognized as having helped to spark the cognitive revolution in the human sciences, contributing to the development of a new cognitivistic framework for the study of language and the mind. Chomsky remains a leading critic of U.S. foreign policy, contemporary capitalism, U.S. involvement and Israel's role in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, and mass media. Chomsky and his ideas are highly influential in the anti-capitalist and anti-imperialist movements. Since 2017, he has been Agnese Helms Haury Chair in the Agnese Nelms Haury Program in Environment and Social Justice at the University of Arizona. |

アブラム・ノーム・チョムスキー(/noʊmski/ ˈ nohm

CHOM-skee、1928年12月7日生まれ)は、言語学、政治活動、社会批評の分野で知られるアメリカの教授であり知識人である。現代言語学の父」

と呼ばれることもあり[a]、分析哲学の重鎮であり、認知科学分野の創始者の一人でもある。アリゾナ大学言語学名誉教授、マサチューセッツ工科大学

(MIT)名誉教授。言語学、戦争、政治などをテーマに150冊以上の著作がある。思想的には、アナルコ・サンディカリズムとリバタリアン社会主義に傾倒

している。 フィラデルフィアのアシュケナージ・ユダヤ系移民の子として生まれたチョムスキーは、ニューヨークのオルタナティブ書店でアナーキズムに早くから関心を抱 くようになる。ペンシルベニア大学で学ぶ。ハーバード大学フェロー・ソサエティに在籍中、変形文法の理論を構築し、1955年に博士号を取得した。同年、 マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭をとり始め、1957年、言語研究の改革に大きな役割を果たした画期的な著作『構文構造』で言語学の重要人物と して頭角を現す。1958年から1959年まで、チョムスキーは高等研究所で全米科学財団のフェローを務めた。普遍文法理論、生成文法理論、チョムス キー・ヒエラルキー、ミニマリスト・プログラムを創始、あるいは共同創始した。言語行動主義の衰退においても重要な役割を果たし、特にB.F.スキナーの 研究に批判的であった。 1967年、チョムスキーは反戦エッセイ『知識人の責任』で全米の注目を集めた。新左翼と関わりを持つようになった彼は、その活動で何度も逮捕され、リ チャード・ニクソン大統領の政敵リストに載った。その後数十年にわたり言語学の仕事を拡大する一方で、言語学戦争にも巻き込まれた。エドワード・S・ハー マンと共同で、後に『Manufacturing Consent』でメディア批評のプロパガンダ・モデルを明確にし、インドネシアによる東ティモール占領の暴露に取り組んだ。ホロコースト否定を含む無条 件の言論の自由の擁護は、1980年代のフォーリソン事件で大きな論争を巻き起こした。カンボジアの大虐殺やボスニアの大虐殺に関するチョムスキーの論評 も物議を醸した。マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)で教鞭をとる現役を退いてからは、2003年のイラク侵攻に反対し、「占拠せよ」運動を支持するな ど、声高な政治活動を続けている。反シオニストであるチョムスキーは、イスラエルのパレスチナ人に対する扱いは南アフリカ型のアパルトヘイトよりもひどい と考え[20]、米国のイスラエル支援を批判している。 チョムスキーは人間科学における認知革命の火付け役として広く認知されており、言語と心の研究のための新しい認知論的枠組みの発展に貢献している。チョム スキーは、米国の外交政策、現代の資本主義、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争における米国の関与とイスラエルの役割、マスメディアに対する主要な批判者であり 続けている。チョムスキーとその思想は、反資本主義、反帝国主義運動において大きな影響力を持っている。2017年より、アリゾナ大学の環境と社会正義に おけるアグネーゼ・ヘルムス・ハウリー・プログラムのアグネーゼ・ヘルムス・ハウリー・チェアを務めている。 |

| Life Childhood: 1928–1945 Chomsky was born on December 7, 1928, in the East Oak Lane neighborhood of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.[21] His parents, William Chomsky and Elsie Simonofsky, were Jewish immigrants.[22] William had fled the Russian Empire in 1913 to escape conscription and worked in Baltimore sweatshops and Hebrew elementary schools before attending university.[23] After moving to Philadelphia, William became principal of the Congregation Mikveh Israel religious school and joined the Gratz College faculty. He placed great emphasis on educating people so that they would be "well integrated, free and independent in their thinking, concerned about improving and enhancing the world, and eager to participate in making life more meaningful and worthwhile for all", a mission that shaped and was subsequently adopted by his son.[24] Elsie, who also taught at Mikveh Israel, shared her leftist politics and care for social issues with her sons.[24] Noam's only sibling, David Eli Chomsky (1934–2021), was born five years later, and worked as a cardiologist in Philadelphia.[24][25] The brothers were close, though David was more easygoing while Noam could be very competitive. They were raised Jewish, being taught Hebrew and regularly involved with discussing the political theories of Zionism; the family was particularly influenced by the Left Zionist writings of Ahad Ha'am.[26] He faced antisemitism as a child, particularly from Philadelphia's Irish and German communities.[27] Chomsky attended the independent, Deweyite Oak Lane Country Day School[28] and Philadelphia's Central High School, where he excelled academically and joined various clubs and societies, but was troubled by the school's hierarchical and domineering teaching methods.[29] He also attended Hebrew High School at Gratz College, where his father taught.[30] Chomsky has described his parents as "normal Roosevelt Democrats" with center-left politics, but relatives involved in the International Ladies' Garment Workers' Union exposed him to socialism and far-left politics.[31] He was substantially influenced by his uncle and the Jewish leftists who frequented his New York City newspaper stand to debate current affairs.[32] Chomsky himself often visited left-wing and anarchist bookstores when visiting his uncle in the city, voraciously reading political literature.[33] He became absorbed in the story of the 1939 fall of Barcelona and suppression of the Spanish anarchosyndicalist movement, writing his first article on the topic at the age of 10.[34] That he came to identify with anarchism first rather than another leftist movement, he described as a "lucky accident".[35] Chomsky was firmly anti-Bolshevik by his early teens.[36] University: 1945–1955  Carol Schatz married Chomsky in 1949. In 1945, at the age of 16, Chomsky began a general program of study at the University of Pennsylvania, where he explored philosophy, logic, and languages and developed a primary interest in learning Arabic.[37] Living at home, he funded his undergraduate degree by teaching Hebrew.[38] Frustrated with his experiences at the university, he considered dropping out and moving to a kibbutz in Mandatory Palestine,[39] but his intellectual curiosity was reawakened through conversations with the linguist Zellig Harris, whom he first met in a political circle in 1947. Harris introduced Chomsky to the field of theoretical linguistics and convinced him to major in the subject.[40] Chomsky's BA honors thesis, "Morphophonemics of Modern Hebrew", applied Harris's methods to the language.[41] Chomsky revised this thesis for his MA, which he received from the University of Pennsylvania in 1951; it was subsequently published as a book.[42] He also developed his interest in philosophy while at university, in particular under the tutelage of Nelson Goodman.[43] From 1951 to 1955, Chomsky was a member of the Society of Fellows at Harvard University, where he undertook research on what became his doctoral dissertation.[44] Having been encouraged by Goodman to apply,[45] Chomsky was attracted to Harvard in part because the philosopher Willard Van Orman Quine was based there. Both Quine and a visiting philosopher, J. L. Austin of the University of Oxford, strongly influenced Chomsky.[46] In 1952, Chomsky published his first academic article in The Journal of Symbolic Logic.[45] Highly critical of the established behaviorist currents in linguistics, in 1954, he presented his ideas at lectures at the University of Chicago and Yale University.[47] He had not been registered as a student at Pennsylvania for four years, but in 1955 he submitted a thesis setting out his ideas on transformational grammar; he was awarded a Doctor of Philosophy degree for it, and it was privately distributed among specialists on microfilm before being published in 1975 as part of The Logical Structure of Linguistic Theory.[48] Harvard professor George Armitage Miller was impressed by Chomsky's thesis and collaborated with him on several technical papers in mathematical linguistics.[49] Chomsky's doctorate exempted him from compulsory military service, which was otherwise due to begin in 1955.[50] In 1947, Chomsky began a romantic relationship with Carol Doris Schatz, whom he had known since early childhood. They married in 1949.[51] After Chomsky was made a Fellow at Harvard, the couple moved to the Allston area of Boston and remained there until 1965, when they relocated to the suburb of Lexington.[52] The couple took a Harvard travel grant to Europe in 1953.[53] He enjoyed living in Hashomer Hatzair's HaZore'a kibbutz while in Israel, but was appalled by his interactions with Jewish nationalism, anti-Arab racism and, within the kibbutz's leftist community, Stalinism.[54] On visits to New York City, Chomsky continued to frequent the office of the Yiddish anarchist journal Fraye Arbeter Shtime and became enamored with the ideas of Rudolf Rocker, a contributor whose work introduced Chomsky to the link between anarchism and classical liberalism.[55] Chomsky also read other political thinkers: the anarchists Mikhail Bakunin and Diego Abad de Santillán, democratic socialists George Orwell, Bertrand Russell, and Dwight Macdonald, and works by Marxists Karl Liebknecht, Karl Korsch, and Rosa Luxemburg.[56] His politics were reaffirmed by Orwell's depiction of Barcelona's functioning anarchist society in Homage to Catalonia (1938).[57] Chomsky read the leftist journal Politics, which furthered his interest in anarchism,[58] and the council communist periodical Living Marxism, though he rejected the Marxist orthodoxy of its editor, Paul Mattick.[59] Early career: 1955–1966 Chomsky befriended two linguists at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)—Morris Halle and Roman Jakobson—the latter of whom secured him an assistant professor position there in 1955. At MIT, Chomsky spent half his time on a mechanical translation project and half teaching a course on linguistics and philosophy.[60] He described MIT as open to experimentation where he was free to pursue his idiosyncratic interests.[61] MIT promoted him to the position of associate professor in 1957, and over the next year he was also a visiting professor at Columbia University.[62] The Chomskys had their first child, Aviva, that same year.[63] He also published his first book on linguistics, Syntactic Structures, a work that radically opposed the dominant Harris–Bloomfield trend in the field.[64] Responses to Chomsky's ideas ranged from indifference to hostility, and his work proved divisive and caused "significant upheaval" in the discipline.[65] The linguist John Lyons later asserted that Syntactic Structures "revolutionized the scientific study of language".[66] From 1958 to 1959 Chomsky was a National Science Foundation fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.[67]  The Great Dome at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT); Chomsky began working at MIT in 1955. Chomsky's provocative critique of B. F. Skinner, who viewed language as learned behavior, and its challenge to the dominant behaviorist paradigm thrust Chomsky into the limelight. Chomsky argued that behaviorism underplayed the role of human creativity in learning language and overplayed the role of external conditions in influencing verbal behavior.[68] He proceeded to found MIT's graduate program in linguistics with Halle. In 1961, Chomsky received tenure and became a full professor in the Department of Modern Languages and Linguistics.[69] He was appointed plenary speaker at the Ninth International Congress of Linguists, held in 1962 in Cambridge, Massachusetts, which established him as the de facto spokesperson of American linguistics.[70] Between 1963 and 1965 he consulted on a military-sponsored project to teach computers to understand natural English commands from military generals.[71] Chomsky continued to publish his linguistic ideas throughout the decade, including in Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (1965), Topics in the Theory of Generative Grammar (1966), and Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought (1966).[72] Along with Halle, he also edited the Studies in Language series of books for Harper and Row.[73] As he began to accrue significant academic recognition and honors for his work, Chomsky lectured at the University of California, Berkeley, in 1966.[74] These lectures were published as Language and Mind in 1968.[75] In the late 1960s, a high-profile intellectual rift later known as the linguistic wars developed between Chomsky and some of his colleagues and doctoral students—including Paul Postal, John Ross, George Lakoff, and James D. McCawley—who contended that Chomsky's syntax-based, interpretivist linguistics did not properly account for semantic context (general semantics). A post hoc assessment of this period concluded that the opposing programs ultimately were complementary, each informing the other.[76] Anti-war activism and dissent: 1967–1975 [I]t does not require very far-reaching, specialized knowledge to perceive that the United States was invading South Vietnam. And, in fact, to take apart the system of illusions and deception which functions to prevent understanding of contemporary reality [is] not a task that requires extraordinary skill or understanding. It requires the kind of normal skepticism and willingness to apply one's analytical skills that almost all people have and that they can exercise. —Chomsky on the Vietnam War[77] Chomsky joined protests against U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War in 1962, speaking on the subject at small gatherings in churches and homes.[78] His 1967 critique of U.S. involvement, "The Responsibility of Intellectuals", among other contributions to The New York Review of Books, debuted Chomsky as a public dissident.[79] This essay and other political articles were collected and published in 1969 as part of Chomsky's first political book, American Power and the New Mandarins.[80] He followed this with further political books, including At War with Asia (1970), The Backroom Boys (1973), For Reasons of State (1973), and Peace in the Middle East? (1974), published by Pantheon Books.[81] These publications led to Chomsky's association with the American New Left movement,[82] though he thought little of prominent New Left intellectuals Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm and preferred the company of activists to that of intellectuals.[83] Chomsky remained largely ignored by the mainstream press throughout this period.[84] Chomsky also became involved in left-wing activism. Chomsky refused to pay half his taxes, publicly supported students who refused the draft, and was arrested while participating in an anti-war teach-in outside the Pentagon.[85] During this time, Chomsky co-founded the anti-war collective RESIST with Mitchell Goodman, Denise Levertov, William Sloane Coffin, and Dwight Macdonald.[86] Although he questioned the objectives of the 1968 student protests,[87] Chomsky regularly gave lectures to student activist groups and, with his colleague Louis Kampf, ran undergraduate courses on politics at MIT independently of the conservative-dominated political science department.[88] When student activists campaigned to stop weapons and counterinsurgency research at MIT, Chomsky was sympathetic but felt that the research should remain under MIT's oversight and limited to systems of deterrence and defense.[89] Chomsky has acknowledged that his MIT lab's funding at this time came from the military.[90] He later said he considered resigning from MIT during the Vietnam War.[91] There has since been a wide-ranging debate about what effects Chomsky's employment at MIT had on his political and linguistic ideas.[92] External images Chomsky participating in the anti-Vietnam War March on the Pentagon, October 21, 1967 image icon Chomsky with other public figures image icon The protesters passing the Lincoln Memorial en route to the Pentagon Chomsky's anti-war activism led to his arrest on multiple occasions and he was on President Richard Nixon's master list of political opponents.[93] Chomsky was aware of the potential repercussions of his civil disobedience, and his wife began studying for her own doctorate in linguistics to support the family in the event of Chomsky's imprisonment or joblessness.[94] Chomsky's scientific reputation insulated him from administrative action based on his beliefs.[95] In 1970 he visited southeast Asia to lecture at Vietnam's Hanoi University of Science and Technology and toured war refugee camps in Laos. In 1973 he helped lead a committee commemorating the 50th anniversary of the War Resisters League.[96] Chomsky's work in linguistics continued to gain international recognition as he received multiple honorary doctorates.[97] He delivered public lectures at the University of Cambridge, Columbia University (Woodbridge Lectures), and Stanford University.[98] His appearance in a 1971 debate with French continental philosopher Michel Foucault positioned Chomsky as a symbolic figurehead of analytic philosophy.[99] He continued to publish extensively on linguistics, producing Studies on Semantics in Generative Grammar (1972),[95] an enlarged edition of Language and Mind (1972),[100] and Reflections on Language (1975).[100] In 1974 Chomsky became a corresponding fellow of the British Academy.[98] Edward S. Herman and the Faurisson affair: 1976–1980 See also: Cambodian genocide denial § Chomsky and Herman, and Faurisson affair  Chomsky in 1977 In the late 1970s and 1980s, Chomsky's linguistic publications expanded and clarified his earlier work, addressing his critics and updating his grammatical theory.[101] His political talks often generated considerable controversy, particularly when he criticized the Israeli government and military.[102] In the early 1970s Chomsky began collaborating with Edward S. Herman, who had also published critiques of the U.S. war in Vietnam.[103] Together they wrote Counter-Revolutionary Violence: Bloodbaths in Fact & Propaganda, a book that criticized U.S. military involvement in Southeast Asia and the mainstream media's failure to cover it. Warner Modular published it in 1973, but its parent company disapproved of the book's contents and ordered all copies destroyed.[104] While mainstream publishing options proved elusive, Chomsky found support from Michael Albert's South End Press, an activist-oriented publishing company.[105] In 1979, South End published Chomsky and Herman's revised Counter-Revolutionary Violence as the two-volume The Political Economy of Human Rights,[106] which compares U.S. media reactions to the Cambodian genocide and the Indonesian occupation of East Timor. It argues that because Indonesia was a U.S. ally, U.S. media ignored the East Timorese situation while focusing on events in Cambodia, a U.S. enemy.[107] Chomsky's response included two testimonials before the United Nations' Special Committee on Decolonization, successful encouragement for American media to cover the occupation, and meetings with refugees in Lisbon.[108] Marxist academic Steven Lukes most prominently publicly accused Chomsky of betraying his anarchist ideals and acting as an apologist for Cambodian leader Pol Pot.[109] Herman said that the controversy "imposed a serious personal cost" on Chomsky,[110] who considered the personal criticism less important than the evidence that "mainstream intelligentsia suppressed or justified the crimes of their own states".[111] Chomsky had long publicly criticized Nazism, and totalitarianism more generally, but his commitment to freedom of speech led him to defend the right of French historian Robert Faurisson to advocate a position widely characterized as Holocaust denial. Without Chomsky's knowledge, his plea for Faurisson's freedom of speech was published as the preface to the latter's 1980 book Mémoire en défense contre ceux qui m'accusent de falsifier l'histoire.[112] Chomsky was widely condemned for defending Faurisson,[113] and France's mainstream press accused Chomsky of being a Holocaust denier himself, refusing to publish his rebuttals to their accusations.[114] Critiquing Chomsky's position, sociologist Werner Cohn later published an analysis of the affair titled Partners in Hate: Noam Chomsky and the Holocaust Deniers.[115] The Faurisson affair had a lasting, damaging effect on Chomsky's career,[116] especially in France.[117] Critique of propaganda and international affairs External videos video icon Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media, a 1992 documentary exploring Chomsky's work of the same name and its impact In 1985, during the Nicaraguan Contra War—in which the U.S. supported the contra militia against the Sandinista government—Chomsky traveled to Managua to meet with workers' organizations and refugees of the conflict, giving public lectures on politics and linguistics.[118] Many of these lectures were published in 1987 as On Power and Ideology: The Managua Lectures.[119] In 1983 he published The Fateful Triangle, which argued that the U.S. had continually used the Israeli–Palestinian conflict for its own ends.[120] In 1988, Chomsky visited the Palestinian territories to witness the impact of Israeli occupation.[121] Chomsky and Herman's Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media (1988) outlines their propaganda model for understanding mainstream media. Even in countries without official censorship, they argued, the news is censored through five filters that greatly influence both what and how news is presented.[122] The book received a 1992 film adaptation.[123] In 1989, Chomsky published Necessary Illusions: Thought Control in Democratic Societies, in which he suggests that a worthwhile democracy requires that its citizens undertake intellectual self-defense against the media and elite intellectual culture that seeks to control them.[124] By the 1980s, Chomsky's students had become prominent linguists who, in turn, expanded and revised his linguistic theories.[125]  Chomsky speaking in support of the Occupy movement in 2011 In the 1990s, Chomsky embraced political activism to a greater degree than before.[126] Retaining his commitment to the cause of East Timorese independence, in 1995 he visited Australia to talk on the issue at the behest of the East Timorese Relief Association and the National Council for East Timorese Resistance.[127] The lectures he gave on the subject were published as Powers and Prospects in 1996.[127] As a result of the international publicity Chomsky generated, his biographer Wolfgang Sperlich opined that he did more to aid the cause of East Timorese independence than anyone but the investigative journalist John Pilger.[128] After East Timor attained independence from Indonesia in 1999, the Australian-led International Force for East Timor arrived as a peacekeeping force; Chomsky was critical of this, believing it was designed to secure Australian access to East Timor's oil and gas reserves under the Timor Gap Treaty.[129] Chomsky was widely interviewed after the September 11 attacks in 2001 as the American public attempted to make sense of the attacks.[130] He argued that the ensuing War on Terror was not a new development but a continuation of U.S. foreign policy and concomitant rhetoric since at least the Reagan era.[131] He gave the D.T. Lakdawala Memorial Lecture in New Delhi in 2001,[132] and in 2003 visited Cuba at the invitation of the Latin American Association of Social Scientists.[133] Chomsky's 2003 Hegemony or Survival articulated what he called the United States' "imperial grand strategy" and critiqued the Iraq War and other aspects of the War on Terror.[134] Chomsky toured internationally with greater regularity during this period.[133] During the 2014 Scottish independence referendum, Chomsky supported Scottish independence.[135] Retirement Chomsky retired from MIT in 2002,[136] but continued to conduct research and seminars on campus as an emeritus.[137] That same year he visited Turkey to attend the trial of a publisher who had been accused of treason for printing one of Chomsky's books; Chomsky insisted on being a co-defendant and amid international media attention, the Security Courts dropped the charge on the first day.[138] During that trip Chomsky visited Kurdish areas of Turkey and spoke out in favor of the Kurds' human rights.[138] A supporter of the World Social Forum, he attended its conferences in Brazil in both 2002 and 2003, also attending the Forum event in India.[139] Chomsky supported the 2011 Occupy movement, speaking at encampments and publishing on the movement, which he called a reaction to a 30-year class war.[140] The 2015 documentary Requiem for the American Dream summarizes his views on capitalism and economic inequality through a "75-minute teach-in".[141] Chomsky taught a short-term politics course at the University of Arizona in 2017[142] and was later hired as a part-time professor in the linguistics department there, his duties including teaching and public seminars.[143] His salary was covered by philanthropic donations.[144] |

人生 子供時代:1928-1945 チョムスキーは1928年12月7日、ペンシルベニア州フィラデルフィアのイースト・オーク・レーン地区で生まれた[21]。彼の両親、ウィリアム・チョ ムスキーとエルシー・シモノフスキーはユダヤ系移民であった[22]。ウィリアムは徴兵を逃れるために1913年にロシア帝国を逃れ、ボルチモアの搾取工 場やヘブライ語の小学校で働いた後、大学に通った[23]。彼は、人々が「よく統合され、自由で独立した考え方を持ち、世界を改善し向上させることに関心 を持ち、すべての人にとって人生をより有意義で価値あるものにするために参加することを熱望する」ようになるための教育を重視し、この使命は彼の息子を形 成し、その後息子も採用した[24]。ミクヴェ・イスラエルで教鞭をとっていたエルシーもまた、左翼的な政治と社会問題への関心を息子たちと共有していた [24]。 ノアムの唯一の兄弟であるデイヴィッド・エリ・チョムスキー(1934-2021)は5年後に生まれ、フィラデルフィアで心臓専門医として働いていた。彼 らはユダヤ教徒として育ち、ヘブライ語を教えられ、シオニズムの政治理論について定期的に議論していた。家族は特にアハド・ハームの左シオニストの著作に 影響を受けていた[26]。 チョムスキーは独立系でデューイ派のオーク・レーン・カントリー・デイ・スクール[28]とフィラデルフィアのセントラル・ハイスクールに通い、学業面で 優秀で様々なクラブや協会に所属していたが、学校の階層的で支配的な教授法に悩まされていた[29]。 チョムスキーは両親のことを中道左派の政治をする「普通のルーズベルト民主党員」であったと述べているが、国際婦人服労働組合に関わる親戚から社会主義や 極左政治に触れていた[31]。叔父や、叔父が経営するニューヨークの新聞スタンドに頻繁に出入りし、時事問題について議論していたユダヤ人左翼から大き な影響を受けた[32]。 [1939年のバルセロナ陥落とスペインのアナーコサンディカリスム運動の弾圧の物語に夢中になり、10歳の時にこのトピックに関する最初の記事を書いた [34]。他の左翼運動ではなく、アナーキズムに最初に共感するようになったことを、チョムスキーは「幸運な事故」と表現している[35]。 大学:1945-1955  1949年、キャロル・シャッツがチョムスキーと結婚。 1945年、16歳のチョムスキーはペンシルベニア大学で一般教養課程を開始し、哲学、論理学、言語について学び、アラビア語の習得に興味を持つようにな る[37]。 [しかし、1947年に政治サークルで初めて出会った言語学者ゼリグ・ハリスとの会話を通じて、彼の知的好奇心は再び目覚める。ハリスはチョムスキーに理 論言語学の分野を紹介し、この分野を専攻するよう説得した[40]。チョムスキーの学士号の優等論文「現代ヘブライ語の形態素論」は、ハリスの手法をヘブ ライ語に適用したものであった[41]。 1951年から1955年まで、チョムスキーはハーバード大学のソサエティ・オブ・フェローのメンバーであり、そこで博士論文となる研究を行った [44]。グッドマンから応募するように勧められた[45]チョムスキーは、哲学者ウィラード・ヴァン・オーマン・クワインがハーバード大学を拠点として いたこともあり、ハーバード大学に惹かれた。1952年、チョムスキーは最初の学術論文をThe Journal of Symbolic Logicに発表した[45]。1954年、言語学において確立された行動主義的な流れを強く批判し、シカゴ大学とイェール大学での講義で自身の考えを発 表した[47]。 [1975年に『言語理論の論理構造』の一部として出版される前に、マイクロフィルムで専門家の間で私的に配布された。 [ハーバード大学のジョージ・アーミテージ・ミラー教授はチョムスキーの論文に感銘を受け、数理言語学のいくつかの技術論文で彼と共同研究を行った [49]。チョムスキーは博士号を取得したことにより、1955年に始まるはずだった義務兵役を免除された[50]。 1947年、チョムスキーは幼い頃から知っていたキャロル・ドリス・シャッツと恋愛関係になる。チョムスキーがハーバードのフェローになった後、夫妻はボ ストンのオールストン地区に引っ越し、1965年に郊外のレキシントンに引っ越すまでそこに留まった[52]。 [イスラエル滞在中はハシュマー・ハツェアのキブツHazore'aでの生活を楽しんだが、ユダヤ民族主義、反アラブ人種差別主義、キブツの左翼コミュニ ティ内のスターリン主義との交流に愕然とした。 [ニューヨークを訪れると、チョムスキーはイディッシュ語のアナーキスト雑誌『Fraye Arbeter Shtime』のオフィスに頻繁に出入りし、ルドルフ・ロッカーの思想に夢中になった。 [アナーキストのミハイル・バクーニンやディエゴ・アバド・デ・サンティラン、民主社会主義者のジョージ・オーウェル、バートランド・ラッセル、ドワイ ト・マクドナルド、マルクス主義者のカール・リープクネヒト、カール・コルシュ、ローザ・ルクセンブルクなどの著作を読んだ。 [チョムスキーは、左翼雑誌『ポリティクス』(Politics)を読み、アナーキズムへの関心をさらに高めた[58]。また、共産主義定期刊行物『リビ ング・マルクス主義』(Living Marxism)を読んでいたが、編集者のポール・マティックのマルクス主義的な正統性を否定していた[59]。 初期のキャリア 1955-1966 チョムスキーは、マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)の2人の言語学者、モリス・ハレとローマン・ヤコブソンと親しくなり、後者から1955年に助教授の 地位を得る。マサチューセッツ工科大学では、チョムスキーは半分の時間を機械翻訳プロジェクトに費やし、半分の時間を言語学と哲学の講義に費やしていた [60]。彼はマサチューセッツ工科大学が実験に開かれており、自分の特異な興味を自由に追求することができると述べている[61]。 [チョムスキーの考えに対する反応は無関心なものから敵対的なものまで様々であった。 [言語学者のジョン・ライオンズは後に、構文構造は「言語の科学的研究に革命をもたらした」と主張している[66]。1958年から1959年まで、チョ ムスキーはニュージャージー州プリンストンにある高等研究所で全米科学財団のフェローを務めていた[67]。  マサチューセッツ工科大学(MIT)のグレートドーム:チョムスキーは1955年にMITで働き始めた。 言語を学習行動と見なしたB.F.スキナーに対する挑発的な批判と、支配的な行動主義パラダイムへの挑戦によって、チョムスキーは一躍脚光を浴びることに なる。チョムスキーは、行動主義は言語学習における人間の創造性の役割を過小評価し、言語行動に影響を与える外的条件の役割を過大評価していると主張した [68]。1962年、マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジで開催された第9回国際言語学者会議(International Congress of Linguists)において全体講演者に任命され、アメリカ言語学の事実上のスポークスパーソンとしての地位を確立した[70]。1963年から 1965年にかけては、軍の将軍からの自然な英語の命令を理解するためにコンピュータを教えるという軍が後援するプロジェクトでコンサルタントを務めた [71]。 チョムスキーはこの10年間、『統語論の諸相』(1965年)、『生成文法の理論におけるトピックス』(1966年)、『デカルト言語学』(1966年) など、言語学的なアイデアを発表し続けた: また、ハレとともにハーパー・アンド・ロウ社の『言語研究』シリーズを編集していた[73]。1966年、チョムスキーはカリフォルニア大学バークレー校 で講義を行った[74]。 [1960年代後半、チョムスキーと彼の同僚や博士課程の学生たち(ポール・ポスタル、ジョン・ロス、ジョージ・レイコフ、ジェームズ・D・マコーリーな ど)との間で、後に言語戦争として知られる有名な知的対立が勃発し、彼らはチョムスキーの統語論に基づく解釈論的言語学が意味文脈(一般意味論)を適切に 説明していないと主張した。この時期の事後評価では、対立するプログラムは最終的には補完的なものであり、それぞれが他方に情報を与えていたと結論づけて いる[76]。 反戦運動と反対運動 1967-1975 [アメリカが南ベトナムに侵攻していることを認識するのに、それほど広範で専門的な知識は必要ない。そして実際、現代の現実を理解できないように機能して いる幻想と欺瞞のシステムを解体することは、並外れた技術や理解を必要とする作業ではない。必要なのは、ほとんどすべての人が持っており、また行使できる ような、普通の懐疑心と、自分の分析能力を応用しようとする意欲なのである。 -ベトナム戦争についてのチョムスキー[77]。 チョムスキーは1962年に米国のベトナム戦争への関与に反対する抗議活動に参加し、教会や家庭での小規模な集会でこのテーマについてスピーチを行った [78]。1967年に『ニューヨーク・レビュー・オブ・ブックス』誌に寄稿した、米国の関与に対する彼の批評「知識人の責任」は、チョムスキーを公的な 反体制派としてデビューさせた。 [このエッセイとその他の政治的論考は、1969年にチョムスキー初の政治書『American Power and the New Mandarins』としてまとめられ出版された[80]。その後、『At War with Asia』(1970年)、『The Backroom Boys』(1973年)、『For Reasons of State』(1973年)、『Peace in the Middle East? (これらの出版物はチョムスキーがアメリカの新左翼運動と関わるきっかけとなった[81]が、彼は著名な新左翼知識人であるヘルベルト・マルクーゼやエー リッヒ・フロムのことをあまりよく思っておらず、知識人の仲間よりも活動家の仲間を好んでいた[83]。 チョムスキーはまた、左翼活動にも関わるようになった。この時期、チョムスキーはミッチェル・グッドマン、デニース・レヴァートフ、ウィリアム・スロー ン・コフィン、ドワイト・マクドナルドらと反戦団体RESISTを共同設立した。 [1968年の学生抗議運動の目的には疑問を呈していたが[87]、チョムスキーは学生活動家グループに対して定期的に講義を行い、同僚のルイス・カンプ フとともに、保守派が支配する政治学部とは別にMITで政治に関する学部講座を開講していた。 [88]学生活動家たちがMITでの武器や対反乱軍の研究を止めるよう運動したとき、チョムスキーは同調していたが、その研究はMITの監視下に置かれ、 抑止力と防衛のシステムに限定されるべきであると感じていた[89]。 チョムスキーはこの頃のMITの研究室の資金源が軍からのものであったことを認めている[90]。後に彼はベトナム戦争中にMITを辞職することも考えた と語っている[91]。その後、チョムスキーのMITでの雇用が彼の政治的、言語的思想にどのような影響を与えたかについて幅広い議論がなされている [92]。 外部画像 ペンタゴンへの反ベトナム戦争行進に参加するチョムスキー(1967年10月21日 イメージアイコン 他の公人とともにいるチョムスキー ペンタゴンに向かう途中、リンカーン・メモリアルを通過するデモ参加者たち。 チョムスキーは反戦活動によって何度も逮捕され、リチャード・ニクソン大統領の政治的反対者のマスターリストに載っていた[93]。チョムスキーは市民的 不服従の潜在的な影響を認識しており、彼の妻はチョムスキーが投獄されたり失業したりした場合に家族を支えるために、言語学の博士号を取得するための勉強 を始めた。 [1970年、チョムスキーは東南アジアを訪れ、ベトナムのハノイ科学技術大学で講義を行い、ラオスの戦争難民キャンプを視察した。1973年には戦争抵 抗者同盟の50周年を記念する委員会のリーダーを務めた[96]。 1971年、フランスの大陸哲学者ミシェル・フーコーとの討論会に出席し、チョムスキーは分析哲学の象徴的な人物となった。 [1972年には『言語と心』の増補版[100]、『言語についての考察』(1975)を出版している[100]。1974年、チョムスキーは英国アカデ ミーの特別研究員となった[98]。 エドワード・S・ハーマンとフォーリソン事件:1976年-1980年 以下も参照: カンボジア人虐殺否定論§チョムスキーとハーマン、フォーリソン事件  1977年のチョムスキー 1970年代後半から1980年代にかけて、チョムスキーの言語学に関する著作は、それまでの著作を拡大し、明確化し、批判に対処し、文法理論を更新した [101]。彼の政治的な発言はしばしば大きな論争を巻き起こし、特にイスラエル政府と軍を批判した[102]: この本は、東南アジアにおける米軍の関与と、それを報道しない主流メディアの失敗を批判したものである。ワーナー・モジュラーは1973年にこの本を出版 したが、親会社はこの本の内容を不承認とし、すべてのコピーの破棄を命じた[104]。 1979年、サウスエンドはチョムスキーとハーマンの改訂版『反革命的暴力』を2巻からなる『人権の政治経済学』として出版した[106]。インドネシア が米国の同盟国であったため、米国のメディアは東ティモールの状況を無視する一方で、米国の敵国であったカンボジアの出来事に焦点を当てたと論じている [107]。チョムスキーの反応には、国連の脱植民地化特別委員会での2つの証言、占領を報道するよう米国のメディアに働きかける成功、リスボンでの難民 との会合などが含まれる。 [108]マルクス主義者の学者であるスティーブン・ルークスは、最も顕著に、チョムスキーが無政府主義者の理想を裏切り、カンボジアの指導者ポル・ポト の謝罪者として行動していると公に非難した[109]。 ハーマンは、この論争がチョムスキーに「深刻な個人的犠牲を課した」と述べており[110]、彼は個人的批判を「主流派の知識人が自国の国家の犯罪を抑圧 したり正当化したりした」という証拠よりも重要でないと考えていた[111]。 チョムスキーは長い間、ナチズム、そしてより一般的な全体主義を公に批判していたが、言論の自由へのコミットメントから、フランスの歴史家ロベール・ フォーリソンがホロコースト否定として広く特徴づけられる立場を主張する権利を擁護することになった。チョムスキーが知らないうちに、フォーリソンの言論 の自由を擁護する彼の訴えは、1980年のフォーリソンの著書『Mémoire en défense contre ceuxi m'accusent de falsifier l'histoire』の序文として出版された[112]。チョムスキーはフォーリソンを擁護したことで広く非難され[113]、フランスの主要紙はチョ ムスキー自身がホロコースト否定論者であると非難し、彼らの非難に対する彼の反論を掲載することを拒否した。 [114]チョムスキーの立場を批評する社会学者ヴェルナー・コーンは後に『憎悪のパートナー:ノーム・チョムスキーとホロコースト否定論者たち』と題す るこの事件の分析を発表した[115]。フォーリソン事件はチョムスキーのキャリア、特にフランスにおけるキャリアに永続的なダメージを与えた [116]。 プロパガンダ批判と国際問題 外部ビデオ ビデオアイコン:Manufacturing Consent: 1992年のドキュメンタリーで、チョムスキーの同名の著作とその影響を探る。 1985年、ニカラグアのコントラ戦争(アメリカがサンディニスタ政府に対するコントラ民兵を支援していた)の最中、チョムスキーはマナグアを訪れ、労働 者団体や紛争難民と会い、政治や言語学について公開講義を行った[118]: 1983年、彼は『運命の三角形』を出版し、アメリカがイスラエルとパレスチナの紛争を自らの目的のために継続的に利用してきたと主張した[120]。 1988年、チョムスキーはパレスチナ自治区を訪れ、イスラエルによる占領の影響を目の当たりにした[121]。 チョムスキーとハーマンの『Manufacturing Consent: The Political Economy of the Mass Media』(1988年)は、主流メディアを理解するための彼らのプロパガンダ・モデルの概要を示している。公式の検閲がない国でさえ、ニュースは5つ のフィルターを通して検閲され、何がどのように報道されるかに大きく影響すると彼らは主張した[122]: 1980年代までに、チョムスキーの弟子たちは著名な言語学者となり、その弟子たちはチョムスキーの言語理論を拡張し、改訂していった[125]。  2011年、占拠運動を支持するチョムスキー 1990年代に入ると、チョムスキーは以前よりも政治的な活動を積極的に行うようになる[126]。東ティモールの独立という大義へのコミットメントを維 持したまま、1995年には東ティモール救援協会と東ティモール抵抗国民評議会の要請でオーストラリアを訪れ、この問題について講演を行った[127]。 このテーマで行った講演は1996年に『Powers and Prospects』として出版された。 [127]チョムスキーが巻き起こした国際的な宣伝の結果、彼の伝記作者であるヴォルフガング・スペルリッヒは、調査報道ジャーナリストのジョン・ピル ジャー以外の誰よりも東ティモールの独立の大義に貢献したとの見解を示した[128]。 1999年に東ティモールがインドネシアから独立した後、オーストラリア主導の東ティモール国際軍が平和維持軍として派遣されたが、チョムスキーはこれを 批判し、ティモール・ギャップ条約に基づく東ティモールの石油・ガス埋蔵量へのオーストラリアのアクセスを確保するためのものだと考えていた[129]。 チョムスキーは、2001年の9.11同時多発テロの後、アメリカ国民がこのテロを理解しようとする中で、広くインタビューを受けた[130]。彼は、続 く対テロ戦争は新しい展開ではなく、少なくともレーガン時代からのアメリカの外交政策とそれに付随するレトリックの継続であると主張した[131]。また 2003年にはラテンアメリカ社会科学者協会の招きでキューバを訪問している[133]。2003年のチョムスキーの『覇権か生存か』(Hegemony or Survival)は、彼がアメリカの「帝国的大戦略」と呼ぶものを明確にし、イラク戦争や対テロ戦争の他の側面を批判している[134]。 2014年のスコットランド独立の住民投票の際、チョムスキーはスコットランド独立を支持した[135]。 引退 同年、チョムスキーはトルコを訪れ、チョムスキーの著書を印刷したことで国家反逆罪に問われた出版社の裁判に出席した。 [138]。世界社会フォーラムの支持者であり、2002年と2003年にブラジルで開催された同フォーラムの会議に出席し、インドで開催された同フォー ラムのイベントにも参加した[139]。 時間 41分5秒 41:05 2014年、エコロジー、倫理、アナーキズムについて語るチョムスキー チョムスキーは2011年のオキュパイ運動を支持し、野営地で演説したり、30年にわたる階級戦争への反動と呼ばれるこの運動について出版したりした [140]。2015年のドキュメンタリー映画『アメリカン・ドリームのためのレクイエム』では、資本主義と経済的不平等についての彼の見解が「75分間 のティーチイン」を通してまとめられている[141]。 チョムスキーは2017年にアリゾナ大学で短期間の政治学の講義を担当し[142]、その後同大学の言語学部の非常勤教授として雇われ、その職務には教育 と公開セミナーが含まれていた[143]。 彼の給与は慈善団体の寄付によって賄われていた[144]。 |

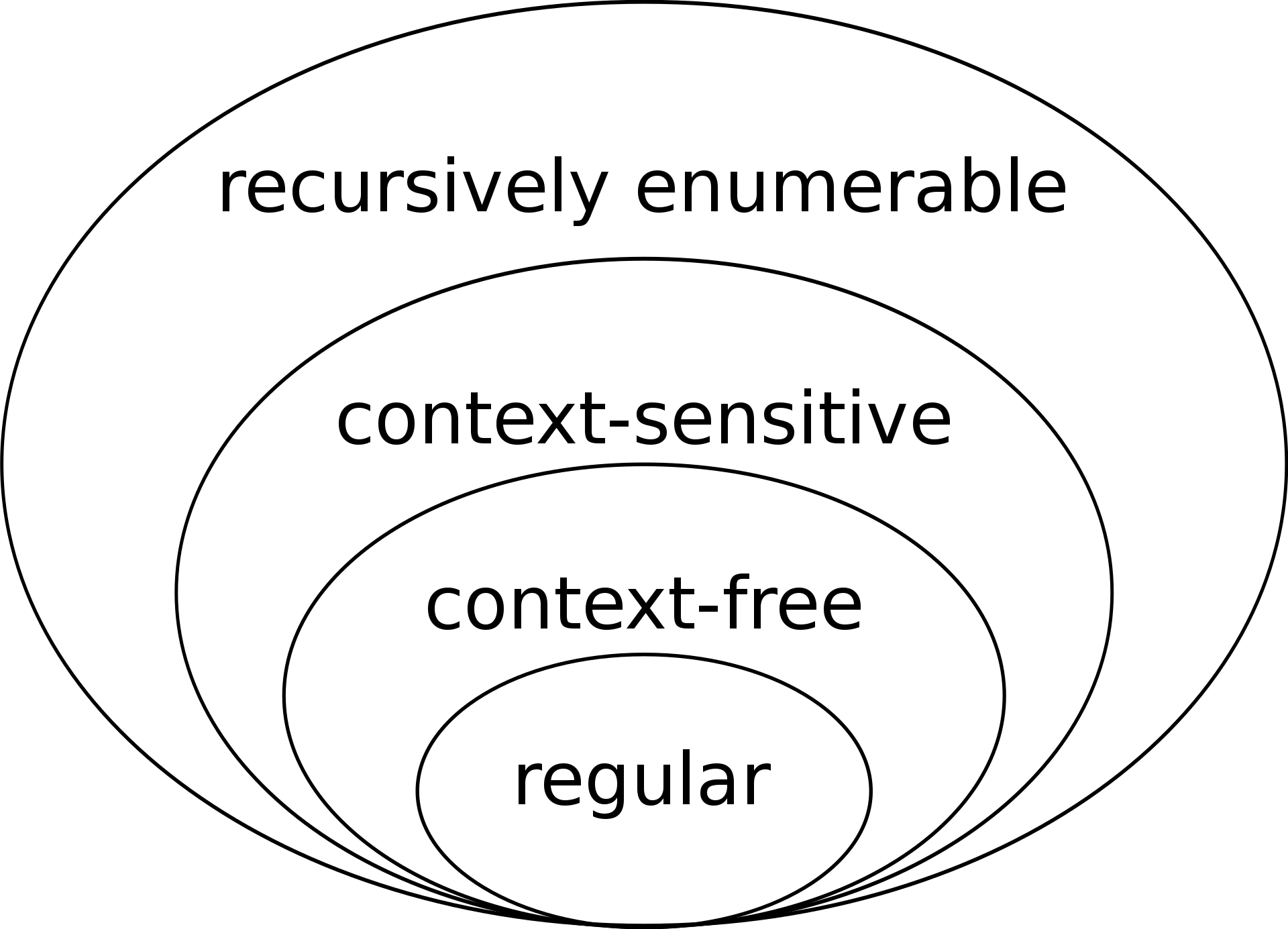

| Linguistic theory Main article: Linguistics of Noam Chomsky What started as purely linguistic research ... has led, through involvement in political causes and an identification with an older philosophic tradition, to no less than an attempt to formulate an overall theory of man. The roots of this are manifest in the linguistic theory ... The discovery of cognitive structures common to the human race but only to humans (species specific), leads quite easily to thinking of unalienable human attributes. —Edward Marcotte on the significance of Chomsky's linguistic theory[145] The basis of Chomsky's linguistic theory lies in biolinguistics, the linguistic school that holds that the principles underpinning the structure of language are biologically preset in the human mind and hence genetically inherited.[146] He argues that all humans share the same underlying linguistic structure, irrespective of sociocultural differences.[147] In adopting this position Chomsky rejects the radical behaviorist psychology of B. F. Skinner, who viewed speech, thought, and all behavior as a completely learned product of the interactions between organisms and their environments. Accordingly, Chomsky argues that language is a unique evolutionary development of the human species and distinguished from modes of communication used by any other animal species.[148][149] Chomsky argues that his nativist, internalist view of language is consistent with the philosophical school of "rationalism" and contrasts with the anti-nativist, externalist view of language consistent with the philosophical school of "empiricism",[150] which contends that all knowledge, including language, comes from external stimuli.[145] Historians have disputed Chomsky's claim about rationalism on the basis that his theory of innate grammar excludes propositional knowledge and instead focuses on innate learning capacities or structures.[151] Universal grammar Main article: Universal grammar Since the 1960s, Chomsky has maintained that syntactic knowledge is at least partially inborn, implying that children need only learn certain language-specific features of their native languages. He bases his argument on observations about human language acquisition and describes a "poverty of the stimulus": an enormous gap between the linguistic stimuli to which children are exposed and the rich linguistic competence they attain. For example, although children are exposed to only a very small and finite subset of the allowable syntactic variants within their first language, they somehow acquire the highly organized and systematic ability to understand and produce an infinite number of sentences, including ones that have never before been uttered, in that language.[152] To explain this, Chomsky reasoned that the primary linguistic data must be supplemented by an innate linguistic capacity. Furthermore, while a human baby and a kitten are both capable of inductive reasoning, if they are exposed to exactly the same linguistic data, the human will always acquire the ability to understand and produce language, while the kitten will never acquire either ability. Chomsky referred to this difference in capacity as the language acquisition device, and suggested that linguists needed to determine both what that device is and what constraints it imposes on the range of possible human languages. The universal features that result from these constraints would constitute "universal grammar".[153][154][155] Multiple scholars have challenged universal grammar on the grounds of the evolutionary infeasibility of its genetic basis for language,[156] the lack of universal characteristics between languages,[157] and the unproven link between innate/universal structures and the structures of specific languages.[158] Scholar Michael Tomasello has challenged Chomsky's theory of innate syntactic knowledge as based on theory and not behavioral observation.[159] Although it was influential from 1960s through 1990s, Chomsky's nativist theory was ultimately rejected by the mainstream child language acquisition research community owing to its inconsistency with research evidence.[160][161] It was also argued by linguists including Robert Freidin, Geoffrey Sampson, Geoffrey K. Pullum and Barbara Scholz that Chomsky's linguistic evidence for it had been false.[162] Transformational-generative grammar Main articles: Transformational grammar, Generative grammar, Chomsky hierarchy, and Minimalist program Transformational-generative grammar is a broad theory used to model, encode, and deduce a native speaker's linguistic capabilities.[163] These models, or "formal grammars", show the abstract structures of a specific language as they may relate to structures in other languages.[164] Chomsky developed transformational grammar in the mid-1950s, whereupon it became the dominant syntactic theory in linguistics for two decades.[163] "Transformations" refers to syntactic relationships within language, e.g., being able to infer that the subject between two sentences is the same person.[165] Chomsky's theory posits that language consists of both deep structures and surface structures: Outward-facing surface structures relate phonetic rules into sound, while inward-facing deep structures relate words and conceptual meaning. Transformational-generative grammar uses mathematical notation to express the rules that govern the connection between meaning and sound (deep and surface structures, respectively). By this theory, linguistic principles can mathematically generate potential sentence structures in a language.[145]  A set of 4 ovals inside one another, each resting at the bottom of the one larger than itself. There is a term in each oval; from smallest to largest: regular, context-free, context-sensitive, recursively enumerable. Set inclusions described by the Chomsky hierarchy Chomsky is commonly credited with inventing transformational-generative grammar, but his original contribution was considered modest when he first published his theory. In his 1955 dissertation and his 1957 textbook Syntactic Structures, he presented recent developments in the analysis formulated by Zellig Harris, who was Chomsky's PhD supervisor, and by Charles F. Hockett.[b] Their method is derived from the work of the Danish structural linguist Louis Hjelmslev, who introduced algorithmic grammar to general linguistics.[c] Based on this rule-based notation of grammars, Chomsky grouped logically possible phrase-structure grammar types into a series of four nested subsets and increasingly complex types, together known as the Chomsky hierarchy. This classification remains relevant to formal language theory[166] and theoretical computer science, especially programming language theory,[167] compiler construction, and automata theory.[168] Transformational grammar was the dominant research paradigm through the mid-1970s. The derivative[163] government and binding theory replaced it and remained influential through the early 1990s, [163] when linguists turned to a "minimalist" approach to grammar. This research focused on the principles and parameters framework, which explained children's ability to learn any language by filling open parameters (a set of universal grammar principles) that adapt as the child encounters linguistic data.[169] The minimalist program, initiated by Chomsky,[170] asks which minimal principles and parameters theory fits most elegantly, naturally, and simply.[169] In an attempt to simplify language into a system that relates meaning and sound using the minimum possible faculties, Chomsky dispenses with concepts such as "deep structure" and "surface structure" and instead emphasizes the plasticity of the brain's neural circuits, with which come an infinite number of concepts, or "logical forms".[149] When exposed to linguistic data, a hearer-speaker's brain proceeds to associate sound and meaning, and the rules of grammar we observe are in fact only the consequences, or side effects, of the way language works. Thus, while much of Chomsky's prior research focused on the rules of language, he now focuses on the mechanisms the brain uses to generate these rules and regulate speech.[149][171] |

言語理論 主な記事 ノーム・チョムスキーの言語学 純粋に言語学的な研究として始まったものが、政治的な大義への関与や古い哲学的伝統との同一化を通じて、人間についての全体的な理論を打ち立てようとする 試みへとつながっていった。そのルーツは言語理論にある。人類に共通する、しかし人間にしかない(種特異的な)認知構造が発見されると、人間の譲ることの できない属性について考えるようになる。 -エドワード・マーコットがチョムスキーの言語理論の意義について述べている[145]。 チョムスキーの言語理論の基礎は生物言語学にあり、言語の構造を支える原理は生物学的に人間の心にあらかじめ備わっており、それゆえ遺伝的に遺伝するとす る言語学派である[146]。従って、チョムスキーは、言語はヒトという種の独自の進化的発展であり、他の動物種が使用するコミュニケーション様式とは区 別されると主張している[148][149]。チョムスキーは、言語に関する彼の自然主義的、内面主義的な見解は「合理主義」の哲学的学派と一致してお り、言語を含むすべての知識は外部からの刺激に由来すると主張する「経験主義」の哲学的学派[150]と一致する言語に関する反自然主義的、外面主義的な 見解とは対照的であると主張している。 [145]歴史家たちは、チョムスキーの生得的文法理論が命題知識を除外し、代わりに生得的な学習能力や構造に焦点を当てているという根拠に基づいて、合 理主義に関するチョムスキーの主張に異議を唱えている[151]。 普遍文法 主な記事 普遍文法 1960年代以降、チョムスキーは統語論的知識は少なくとも部分的には先天的に備わっていると主張し、子供たちは母国語の特定の言語固有の特徴のみを学習 すればよいとしている。チョムスキーは、人間の言語習得に関する観察に基づき、「刺激の貧困」、すなわち、子どもが受ける言語刺激と、彼らが獲得する豊か な言語能力との間にある大きなギャップについて論じている。例えば、子どもは最初の言語内で許容される構文的変種のごくわずかで有限なサブセットにしか触 れないにもかかわらず、その言語で一度も発せられたことのない文も含め、無限の数の文を理解し生成する高度に組織的かつ体系的な能力を何らかの形で獲得す る[152]。これを説明するために、チョムスキーは、一次的な言語データは生得的な言語能力によって補完されなければならないと推論した。さらに、人間 の赤ちゃんと子猫はともに帰納的推論が可能であるが、まったく同じ言語データにさらされた場合、人間は必ず言語を理解し生成する能力を獲得するが、子猫は どちらの能力も獲得することはない。チョムスキーはこの能力の差を言語習得装置と呼び、言語学者はその装置が何であるか、そしてそれが人間の言語の可能性 の範囲にどのような制約を課すかを決定する必要があると示唆した。これらの制約から生じる普遍的な特徴は「普遍文法」を構成することになる[153] [154][155]。複数の学者が、言語の遺伝的基礎の進化論的非実現性[156]、言語間の普遍的特徴の欠如[157]、生得的/普遍的構造と特定の 言語の構造との間の証明されていない関連性[158]を理由に普遍文法に異議を唱えている。 [学者のマイケル・トマセロは、チョムスキーの生得的構文知識理論は理論に基づくものであり、行動観察に基づくものではないとして異議を唱えている [159]。 [160][161]また、ロバート・フレイディン、ジェフリー・サンプソン、ジェフリー・K・プラム、バーバラ・ショルツなどの言語学者によって、チョ ムスキーの言語学的根拠は誤りであったと主張された[162]。 変形生成文法 主な記事 変容生成文法、生成文法、チョムスキー階層、ミニマリスト・プログラム 変換-生成文法とは、ネイティブスピーカーの言語能力をモデル化し、符号化し、推論するために使用される広範な理論である[163]。これらのモデル、ま たは「形式文法」は、特定の言語の抽象的な構造を、それらが他の言語の構造に関連する可能性があるように示す[164]、 チョムスキーの理論では、言語は深層構造と表層構造の両方から構成されていると仮定している: 外向きの表層構造は音声規則を音に関連付け、内向きの深層構造は単語と概念的意味を関連付ける。変換生成文法は、意味と音(それぞれ深層構造と表層構造) の結びつきを支配する規則を数学的表記法で表現する。この理論によって、言語原理は言語における潜在的な文構造を数学的に生成することができる [145]。  互いに内側にある4つの楕円の集合で、それぞれが自分より大きい楕円の底にある。小さいものから順に、規則的、文脈自由、文脈依存、再帰的に列挙可能であ る。 チョムスキー・ヒエラルキーで説明される集合包含体 チョムスキーは一般的に、変形生成文法を発明したと信じられているが、彼が最初に理論を発表したときには、その貢献はささやかなものだったと考えられてい る。1955年の学位論文と1957年の教科書『統語構造』において、彼はチョムスキーの博士課程の指導教官であったゼリグ・ハリスとチャールズ・F・ホ ケットによって定式化された解析の最近の発展を紹介した[b]。彼らの方法は、一般言語学にアルゴリズム文法を導入したデンマークの構造言語学者ルイス・ ヒェルムスレフの研究に由来する。 [チョムスキーはこのルールベースの文法表記法に基づいて、論理的に可能な句構造文法を4つの入れ子になった部分集合と次第に複雑になっていく文法型に分 類し、これらを合わせてチョムスキー階層と呼んだ。この分類は形式言語理論[166]や理論計算機科学、特にプログラミング言語理論[167]、コンパイ ラ構築、オートマトン理論[168]に依然として関連している。 変形文法は1970年代半ばまで支配的な研究パラダイムであった。派生的な[163]政府と束縛理論がこれに取って代わり、言語学者が文法への「ミニマリ スト」アプローチに転じた1990年代初頭まで影響力を持ち続けた[163]。この研究は原理とパラメータのフレームワークに焦点を当てたものであり、子 どもが言語データに遭遇したときに適応するオープンパラメータ(普遍的な文法原理のセット)を満たすことによって、子どもがどのような言語でも学習する能 力を説明するものであった[169]。チョムスキーによって始められたミニマリストプログラム[170]は、どの最小限の原理とパラメータ理論が最もエレ ガントで、自然で、シンプルに適合するかを問うものであった。 [チョムスキーは言語を、可能な限り最小限の能力を用いて意味と音を関連付けるシステムへと単純化する試みにおいて、「深層構造」や「表層構造」といった 概念を排除し、代わりに脳の神経回路の可塑性を強調する。したがって、チョムスキーの先行研究の多くが言語のルールに焦点を当てていたのに対して、現在は 脳がこれらのルールを生成し、発話を制御するために使用するメカニズムに焦点を当てている[149][171]。 |

| Political views Main article: Political positions of Noam Chomsky The second major area to which Chomsky has contributed—and surely the best known in terms of the number of people in his audience and the ease of understanding what he writes and says—is his work on sociopolitical analysis; political, social, and economic history; and critical assessment of current political circumstance. In Chomsky's view, although those in power might—and do—try to obscure their intentions and to defend their actions in ways that make them acceptable to citizens, it is easy for anyone who is willing to be critical and consider the facts to discern what they are up to. —James McGilvray, 2014[172] Chomsky is a prominent political dissident.[d] His political views have changed little since his childhood,[173] when he was influenced by the emphasis on political activism that was ingrained in Jewish working-class tradition.[174] He usually identifies as an anarcho-syndicalist or a libertarian socialist.[175] He views these positions not as precise political theories but as ideals that he thinks best meet human needs: liberty, community, and freedom of association.[176] Unlike some other socialists, such as Marxists, Chomsky believes that politics lies outside the remit of science,[177] but he still roots his ideas about an ideal society in empirical data and empirically justified theories.[178] In Chomsky's view, the truth about political realities is systematically distorted or suppressed by an elite corporatocracy, which uses corporate media, advertising, and think tanks to promote its own propaganda. His work seeks to reveal such manipulations and the truth they obscure.[179] Chomsky believes this web of falsehood can be broken by "common sense", critical thinking, and understanding the roles of self-interest and self-deception,[180] and that intellectuals abdicate their moral responsibility to tell the truth about the world in fear of losing prestige and funding.[181] He argues that, as such an intellectual, it is his duty to use his social privilege, resources, and training to aid popular democracy movements in their struggles.[182] Although he has participated in direct action demonstrations—joining protests, being arrested, organizing groups—Chomsky's primary political outlet is education, i.e., free public lessons.[183] He is a longtime member of the Industrial Workers of the World international union,[184] as was his father.[185] United States foreign policy  Chomsky at the 2003 World Social Forum, a convention for counter-hegemonic globalization, in Porto Alegre Chomsky has been a prominent critic of American imperialism[186] but is not a pacifist, believing World War II was justified as America's last defensive war.[187] He believes that U.S. foreign policy's basic principle is the establishment of "open societies" that are economically and politically controlled by the U.S. and where U.S.-based businesses can prosper.[188] He argues that the U.S. seeks to suppress any movements within these countries that are not compliant with U.S. interests and to ensure that U.S.-friendly governments are placed in power.[181] When discussing current events, he emphasizes their place within a wider historical perspective.[189] He believes that official, sanctioned historical accounts of U.S. and British extraterritorial operations have consistently whitewashed these nations' actions in order to present them as having benevolent motives in either spreading democracy or, in older instances, spreading Christianity; by criticizing these accounts, he seeks to correct them.[190] Prominent examples he regularly cites are the actions of the British Empire in India and Africa and U.S. actions in Vietnam, the Philippines, Latin America, and the Middle East.[190] Chomsky's political work has centered heavily on criticizing the actions of the United States.[189] He has said he focuses on the U.S. because the country has militarily and economically dominated the world during his lifetime and because its liberal democratic electoral system allows the citizenry to influence government policy.[191] His hope is that, by spreading awareness of the impact U.S. foreign policies have on the populations affected by them, he can sway the populations of the U.S. and other countries into opposing the policies.[190] He urges people to criticize their governments' motivations, decisions, and actions, to accept responsibility for their own thoughts and actions, and to apply the same standards to others as to themselves.[192] Chomsky has been critical of U.S. involvement in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, arguing that it has consistently blocked a peaceful settlement.[181] He also criticizes the U.S.'s close ties with Saudi Arabia and involvement in Saudi Arabian-led intervention in Yemen, highlighting that Saudi Arabia has "one of the most grotesque human rights records in the world".[193] While calling the Russian invasion of Ukraine a "war crime" similar to the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq,[194] Chomsky has nevertheless argued that Russia was conducting the war less brutally than the U.S. did the Iraq war.[195] He considered support for Ukraine's self-defense legitimate, but also argued that the U.S. rejection of a compromise and negotiated settlement with Russia was an obstacle to the only likely way of achieving peace, might have contributed to the war breaking out in the first place, and meant sacrificing Ukraine's own well-being and survival for the sake of using it as a weapon against Russia.[194] Capitalism and socialism In his youth, Chomsky developed a dislike of capitalism and the pursuit of material wealth.[196] At the same time, he developed a disdain for authoritarian socialism, as represented by the Marxist–Leninist policies of the Soviet Union.[197] Rather than accepting the common view among U.S. economists that a spectrum exists between total state ownership of the economy and total private ownership, he instead suggests that a spectrum should be understood between total democratic control of the economy and total autocratic control (whether state or private).[198] He argues that Western capitalist countries are not really democratic,[199] because, in his view, a truly democratic society is one in which all persons have a say in public economic policy.[200] He has stated his opposition to ruling elites, among them institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and GATT (precursor to the WTO).[201] Chomsky highlights that, since the 1970s, the U.S. has become increasingly economically unequal as a result of the repeal of various financial regulations and the unilateral rescinding of the Bretton Woods financial control agreement by the U.S.[202] He characterizes the U.S. as a de facto one-party state, viewing both the Republican Party and Democratic Party as manifestations of a single "Business Party" controlled by corporate and financial interests.[203] Chomsky highlights that, within Western capitalist liberal democracies, at least 80% of the population has no control over economic decisions, which are instead in the hands of a management class and ultimately controlled by a small, wealthy elite.[204] Noting the entrenchment of such an economic system, Chomsky believes that change is possible through the organized cooperation of large numbers of people who understand the problem and know how they want to reorganize the economy more equitably.[204] Acknowledging that corporate domination of media and government stifles any significant change to this system, he sees reason for optimism in historical examples such as the social rejection of slavery as immoral, the advances in women's rights, and the forcing of government to justify invasions.[202] He views violent revolution to overthrow a government as a last resort to be avoided if possible, citing the example of historical revolutions where the population's welfare has worsened as a result of upheaval.[204] Chomsky sees libertarian socialist and anarcho-syndicalist ideas as the descendants of the classical liberal ideas of the Age of Enlightenment,[205] arguing that his ideological position revolves around "nourishing the libertarian and creative character of the human being".[206] He envisions an anarcho-syndicalist future with direct worker control of the means of production and government by workers' councils, who would select temporary and revocable representatives to meet together at general assemblies.[207] The point of this self-governance is to make each citizen, in Thomas Jefferson's words, "a direct participator in the government of affairs."[208] He believes that there will be no need for political parties.[209] By controlling their productive life, he believes that individuals can gain job satisfaction and a sense of fulfillment and purpose.[210] He argues that unpleasant and unpopular jobs could be fully automated, specially remunerated, or communally shared.[211] Israeli–Palestinian conflict A left-anarchist who believes in a radically different way of ordering society and of states and is largely critical of existing institutions, and an anti-war American Jewish socialist, Chomsky has nuanced and complex views on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.[212][better source needed][needs copy edit] He has written prolifically about the conflict, aiming to raise public awareness of it.[213] A labor Zionist who later became what is today considered an anti-Zionist, Chomsky has criticized the Israeli settlements in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, which he likens to a settler colony.[214] He has said that the 1947 United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a bad decision, but given the realpolitik of the situation, he has also considered a two-state solution on the condition that the nation-states exist on equal terms.[215] Chomsky has said that characterizing Israel's treatment of the Palestinians as apartheid, similar to the system that existed in South Africa, would be a "gift to Israel", as he has long held that "the Occupied Territories are much worse than South Africa".[216][217] South Africa depended on its black population for labor, but Chomsky argues the same is not true of Israel, which in his view seeks to make the situation for Palestinians under its occupation unlivable, especially in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip, where "atrocities" take place every day.[216] He also argues that, unlike South Africa, Israel has not sought the international community's approval, but rather relies solely on U.S. support.[216] Chomsky has said that the Israeli-led blockade of the Gaza Strip has turned it into a "concentration camp" and expressed similar fears to Israeli intellectual Yeshayahu Leibowitz's 1990s warning that the continued occupation of the Palestinian territories could turn Israeli Jews into "Judeo-Nazis". Chomsky has said that Leibowitz's warning "was a direct reflection of the continued occupation, the humiliation of people, the degradation, and the terrorist attacks by the Israeli government".[218] He has also called the U.S. a violent state that exports violence by supporting Israeli "atrocities" against the Palestinians and said that listening to American mainstream media, including CBS, is like listening to "Israeli propaganda agencies".[219] Chomsky was denied entry to the West Bank in 2010 because of his criticisms of Israel. He had been invited to deliver a lecture at Bir Zeit University and was to meet with Palestinian Prime Minister Salam Fayyad.[220][221][222][223] An Israeli Foreign Ministry spokesman later said that Chomsky was denied entry by mistake.[224] In his 1983 book The Fateful Triangle, Chomsky criticized the Palestinian Liberation Organization for its "self-destructiveness" and "suicidal character" and disapproved of its programs of "armed struggle" and "erratic violence". He also criticized the Arab governments as not "decent".[225][226] Given what he has described as his very Jewish upbringing with deeply Zionist activist parents, Chomsky's views have drawn controversy and criticism. They are rooted in the kibbutzim and socialist binational cooperation.[227] In a 2014 interview on Democracy Now!, Chomsky said that the charter of Hamas, which calls for Israel's destruction, "means practically nothing", having been created "by a small group of people under siege, under attack in 1988". He compared it to the electoral program of the Likud party, which, he said, "states explicitly that there can never be a Palestinian state west of the Jordan River. And they not only state it in their charter, that's a call for the destruction of Palestine, explicit call for it".[217] Mass media and propaganda Main article: Propaganda model External videos video icon Chomsky on propaganda and the manufacturing of consent, June 1, 2003 Chomsky's political writings have largely focused on ideology, social and political power, mass media, and state policy.[228] One of his best-known works, Manufacturing Consent, dissects the media's role in reinforcing and acquiescing to state policies across the political spectrum while marginalizing contrary perspectives. Chomsky asserts that this version of censorship, by government-guided "free market" forces, is subtler and harder to undermine than was the equivalent propaganda system in the Soviet Union.[229] As he argues, the mainstream press is corporate-owned and thus reflects corporate priorities and interests.[230] Acknowledging that many American journalists are dedicated and well-meaning, he argues that the mass media's choices of topics and issues, the unquestioned premises on which that coverage rests, and the range of opinions expressed are all constrained to reinforce the state's ideology:[231] although mass media will criticize individual politicians and political parties, it will not undermine the wider state-corporate nexus of which it is a part.[232] As evidence, he highlights that the U.S. mass media does not employ any socialist journalists or political commentators.[233] He also points to examples of important news stories that the U.S. mainstream media has ignored because reporting on them would reflect badly upon the country, including the murder of Black Panther Fred Hampton with possible FBI involvement, the massacres in Nicaragua perpetrated by U.S.-funded Contras, and the constant reporting on Israeli deaths without equivalent coverage of the far larger number of Palestinian deaths in that conflict.[234] To remedy this situation, Chomsky calls for grassroots democratic control and involvement of the media.[235] Chomsky considers most conspiracy theories fruitless, distracting substitutes for thinking about policy formation in an institutional framework, where individual manipulation is secondary to broader social imperatives.[236] He separates his Propaganda Model from conspiracy in that he is describing institutions following their natural imperatives rather than collusive forces with secret controls.[237] Instead of supporting the educational system as an antidote, he believes that most education is counterproductive.[238] Chomsky describes mass education as a system solely intended to turn farmers from independent producers into unthinking industrial employees.[238] Reactions of critics and counter-criticism: 1980s–present In the 2004 book The Anti-Chomsky Reader, Peter Collier and David Horowitz accuse Chomsky of cherry-picking facts to suit his theories.[239] Horowitz has also criticized Chomsky's anti-Americanism:[240] For 40 years Noam Chomsky has turned out book after book, pamphlet after pamphlet and speech after speech with one message, and one message alone: America is the Great Satan; it is the fount of evil in the world. In Chomsky's demented universe, America is responsible not only for its own bad deeds, but for the bad deeds of others, including those of the terrorists who struck the World Trade Center and the Pentagon. In this attitude he is the medium for all those who now search the ruins of Manhattan not for the victims and the American dead, but for the "root causes" of the catastrophe that befell them. For the conservative public policy think tank the Hoover Institution, Peter Schweizer wrote in January 2006, "Chomsky favors the estate tax and massive income redistribution—just not the redistribution of his income." Schweizer criticized Chomsky for setting up an estate plan and protecting his own intellectual property as it relates to his published works, as well as the high speaking fees that Chomsky received on a regular basis, around $9,000–$12,000 per talk at that time.[241][242] Chomsky has been accused of treating socialist or communist regimes with credulity and examining capitalist regimes with greater scrutiny or criticism:[243] Chomsky's analysis of U.S. actions plunged deep into dark U.S. machinations, but when traveling among the Communists he rested content with appearances. The countryside outside Hanoi, he reported in The New York Review of Books, displayed "a high degree of democratic participation at the village and regional levels." But how could he tell? Chomsky did not speak Vietnamese, and so he depended on government translators, tour guides, and handlers for information. In [Communist] Vietnamese hands, the clear-eyed skepticism turned into willing credulousness.[243] According to Nikolas Kozloff, writing for Al Jazeera in September 2012, Chomsky "has drawn the world's attention to the various misdeeds of the US and its proxies around the world, and for that he deserves credit. Yet, in seeking to avoid controversy at all costs Chomsky has turned into something of an ideologue. Scour the Chomsky web site and you won't find significant discussion of Belarus or Latin America's flirtation with outside authoritarian leaders, for that matter."[244] Political activist George Monbiot has argued that "Part of the problem is that a kind of cult has developed around Noam Chomsky and John Pilger, which cannot believe they could ever be wrong, and produces ever more elaborate conspiracy theories to justify their mistakes."[245] Anarchist and primitivist John Zerzan has accused Chomsky of not being a real anarchist, saying that he is instead "a liberal-leftist politically, and downright reactionary in his academic specialty, linguistic theory. Chomsky is also, by all accounts, a generous, sincere, tireless activist—which does not, unfortunately, ensure his thinking has liberatory value."[246] Defenders of Chomsky have countered that he has been censored or left out of public debate. Claims of this nature date to the Reagan era. Writing for The Washington Post in February 1988, Saul Landau wrote, "It is unhealthy that Chomsky's insights are excluded from the policy debate. His relentless prosecutorial prose, with a hint of Talmudic whine and the rationalist anarchism of Tom Paine, may reflect a justified frustration."[247] |

政治的見解 主な記事 ノーム・チョムスキーの政治的立場 チョムスキーが貢献した第二の主要分野であり、彼の聴衆の数や彼の著作や発言を理解しやすいという点で最もよく知られているのは間違いなく、社会政治分 析、政治・社会・経済史、現在の政治状況に対する批判的評価に関する彼の仕事である。チョムスキーの見解によれば、権力者はその意図を曖昧にし、市民に受 け入れられるような方法で自分たちの行動を擁護しようとするかもしれないが、批判的であることを厭わず、事実を考慮しようとする者であれば、彼らが何をし ようとしているのかを見分けることは容易である。 -ジェイムズ・マクギルブレイ、2014年[172]。 チョムスキーは著名な政治的反体制派である[d]。彼の政治的見解は、ユダヤ人労働者階級の伝統に根付いていた政治活動重視の影響を受けた幼少期からほと んど変わっていない[173]。 [マルクス主義者など他の社会主義者とは異なり、チョムスキーは政治は科学の範囲外にあると考えている[177]が、それでも理想的な社会についての考え を経験的データと経験的に正当化された理論に根付かせている[178]。 チョムスキーの見解では、政治的現実に関する真実は、企業メディア、広告、シンクタンクを利用して自らのプロパガンダを推進するエリート企業によって組織 的に歪曲されたり抑圧されたりしている。チョムスキーは、この虚偽の網は、「常識」、批判的思考、自己利益と自己欺瞞の役割を理解することによって断ち切 ることができると信じており[180]、知識人は名声と資金を失うことを恐れて、世界の真実を伝えるという道徳的責任を放棄していると主張している [181]。 抗議行動に参加したり、逮捕されたり、グループを組織したりと、直接行動デモに参加したこともあるが、チョムスキーの主な政治的出口は教育、つまり無料の 公開授業である[183]。父親と同様、世界産業別労働者国際組合の長年の組合員である[184]。 アメリカの外交政策  2003年、ポルト・アレグレで開催された反ヘゲモニー的グローバリゼーションのための世界社会フォーラムにて。 チョムスキーはアメリカ帝国主義を顕著に批判してきたが[186]、平和主義者ではなく、第二次世界大戦はアメリカの最後の防衛戦争として正当化されたと 考えている[187]。 米国はこれらの国の中で米国の利益に従わない動きを抑圧し、米国に友好的な政府が政権を握るようにしようとしていると主張する[188]。 現在の出来事について論じるとき、彼はより広い歴史的視野の中での位置づけを強調する[189]。彼が定期的に挙げる顕著な例は、インドとアフリカにおけ る大英帝国の行動と、ベトナム、フィリピン、ラテンアメリカ、中東におけるアメリカの行動である[190]。 チョムスキーの政治的活動は、米国の行動を批判することに重点を置いている[189]。彼が米国に焦点を当てるのは、米国が彼が生きている間に軍事的、経 済的に世界を支配してきたからであり、その自由民主的な選挙制度によって市民が政府の政策に影響を与えることができるからだと述べている[191]。 チョムスキーは人々に、自国の政府の動機、決定、行動を批判し、自らの考えや行動に責任を持ち、他者に対しても自分自身と同じ基準を適用するよう促してい る[192]。 チョムスキーはイスラエルとパレスチナの紛争へのアメリカの関与に批判的であり、それは一貫して平和的解決を妨げてきたと主張している[181]。彼はま た、アメリカとサウジアラビアとの緊密な関係や、サウジアラビアが主導するイエメンへの介入への関与を批判し、サウジアラビアが「世界で最もグロテスクな 人権記録のひとつ」であることを強調している[193]。 ロシアによるウクライナ侵攻を、アメリカ主導のイラク侵攻と同様の「戦争犯罪」と呼ぶ一方で[193]、サウジアラビアは「世界で最もグロテスクな人権記 録を持っている」と強調した。 チョムスキーは、ウクライナの自衛を支持することは正当であると考える一方で、米国がロシアとの妥協と交渉による解決を拒否したことは、平和を達成する唯 一の可能性のある方法に対する障害であり、そもそも戦争が勃発する一因となったかもしれず、ロシアに対する武器として使用するためにウクライナ自身の幸福 と生存を犠牲にすることを意味するとも主張している[194]。 資本主義と社会主義 若い頃、チョムスキーは資本主義と物質的な富の追求を嫌うようになった[196]。同時に、彼はソビエト連邦のマルクス・レーニン主義政策に代表される権 威主義的な社会主義を軽蔑するようになった[197]。チョムスキーは、経済の完全な国家所有と完全な私的所有の間にスペクトラムが存在するという米国の 経済学者の間で一般的な見解を受け入れるのではなく、経済の完全な民主的支配と完全な独裁的支配(国家であれ私的であれ)の間にスペクトラムが存在すると 理解すべきだと提案している。 [なぜなら、彼の見解では、真に民主的な社会とは、すべての人が公的な経済政策に対して発言権を持つ社会だからである[200]。 チョムスキーは、1970年代以降、様々な金融規制の撤廃やアメリカによるブレトンウッズ金融管理協定の一方的な破棄の結果として、アメリカが経済的にま すます不平等になっていることを強調している[202]。チョムスキーは、アメリカは事実上の一党独裁国家であり、共和党も民主党も、企業や金融の利害関 係者によってコントロールされている単一の「ビジネス・パーティー」の現れであるとみなしている[203]。チョムスキーは、欧米の資本主義自由民主主義 国家の中では、少なくとも人口の80%は経済的な意思決定をコントロールすることができず、その代わりに、経済的な意思決定は経営者層の手に委ねられ、最 終的には少数の裕福なエリートによってコントロールされていると強調している[204]。 チョムスキーは、このような経済体制が定着していることを指摘し、問題を理解し、経済をより公平に再編成する方法を知っている大勢の人々の組織的な協力に よって変革が可能であると信じている[204]。 [チョムスキーは、メディアや政府における企業の支配がこのような体制に対する大きな変化を阻害していることを認識しつつ、不道徳な奴隷制の社会的否定、 女性の権利の進歩、侵略を正当化するための政府の強制といった歴史的な事例に楽観的な理由を見出す[202]。チョムスキーは、政府を転覆させるための暴 力的な革命は、可能であれば避けるべき最後の手段であると見なしており、動乱の結果として住民の福祉が悪化した歴史的な革命の例を挙げている[204]。 チョムスキーは、リバタリアン社会主義やアナーコ・サンディカリストの思想を啓蒙時代の古典的な自由主義思想の末裔とみなしており[205]、彼の思想的 立場は「人間のリバタリアンで創造的な性格を養う」ことを中心に展開していると主張している[206]。 彼は、労働者が生産手段を直接管理し、労働者評議会によって政府が運営されるアナーコ・サンディカリストの未来を構想しており、労働者は一時的で取り消し 可能な代表者を選出し、総会で共に会合することになる。 [このセルフ・ガバナンスのポイントは、トーマス・ジェファーソンの言葉を借りれば、各市民を「問題の政府への直接の参加者」にすることである [208]。彼は、政党は必要なくなると考えている[209]。生産生活をコントロールすることによって、彼は、個人が仕事の満足感や充実感や目的意識を 得ることができると考えている[210]。 イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争 社会と国家を秩序づける根本的に異なる方法を信奉し、既存の制度を大きく批判する左翼アナーキストであり、反戦的なアメリカ系ユダヤ人社会主義者である チョムスキーは、イスラエル・パレスチナ紛争について微妙で複雑な見解を持っている[212][より良い情報源は必要][needs copy edit]。 [213]労働シオニストであり、後に反シオニストとみなされるようになったチョムスキーは、イスラエル占領下のヨルダン川西岸地区におけるイスラエルの 入植地を入植者の植民地とみなして批判している[214]。1947年の国連パレスチナ分割計画は誤った決定であったと述べているが、現実の政治状況を考 慮し、国民国家が対等な条件で存在することを条件とした2国家間解決策も検討している[215]。 チョムスキーは、イスラエルのパレスチナ人に対する扱いを、南アフリカに存在した制度と同様のアパルトヘイトとして特徴づけることは、「イスラエルへの贈 り物」であると述べている。 [216][217]南アフリカは労働力を黒人人口に依存していたが、チョムスキーは同じことはイスラエルには当てはまらないと主張し、イスラエルは占領 下にあるパレスチナ人の状況を、特にヨルダン川西岸地区とガザ地区において、毎日「残虐行為」が行われているような住みにくいものにしようとしていると彼 は見ている。 [チョムスキーは、イスラエル主導のガザ地区封鎖がガザ地区を「強制収容所」に変えてしまったと述べ、イスラエルの知識人であるイェシャヤフ・ライボ ヴィッツが1990年代にパレスチナ地域の占領を続ければ、イスラエルのユダヤ人が「ユダヤ・ナチス」になってしまうかもしれないと警告したのと同じよう な恐れを表明した。チョムスキーは、ライボヴィッツの警告は「イスラエル政府による継続的な占領、人々への屈辱、劣化、テロ攻撃の直接的な反映であった」 と述べている[218]。また、アメリカはイスラエルのパレスチナ人に対する「残虐行為」を支援することで暴力を輸出する暴力国家であると呼び、CBSを 含むアメリカの主流メディアの報道を聞くことは「イスラエルのプロパガンダ機関」の報道を聞くようなものだと述べている[219]。 チョムスキーは2010年、イスラエル批判を理由にヨルダン川西岸への入国を拒否された。彼はビル・ツァイト大学での講演に招かれ、パレスチナのサラム・ ファイヤド首相と会談する予定だった[220][221][222][223]。後にイスラエル外務省の報道官は、チョムスキーは誤って入国を拒否された と述べた[224]。 1983年の著書『運命の三角形』の中で、チョムスキーはパレスチナ解放機構をその「自己破壊性」と「自殺的性格」から批判し、その「武装闘争」と「不規 則な暴力」のプログラムを否定した。また、アラブ諸国の政府は「まとも」ではないと批判している[225][226]。シオニストの活動家である両親のも とで育ったチョムスキーは、その生い立ちを非常にユダヤ的であると語っており、チョムスキーの見解は論争と批判を呼んでいる。2014年のデモクラシー・ ナウ!でのインタビューで、チョムスキーは、イスラエルの破壊を求めるハマスの憲章は「実質的に何の意味もない」ものであり、「1988年に攻撃を受け、 四面楚歌の状態にある小さなグループによって」作られたものだと述べた。彼はこれをリクード党の選挙プログラムと比較し、「ヨルダン川以西にパレスチナ国 家が存在することはあり得ないと明言している。そして、彼らは綱領でそれを表明しているだけでなく、パレスチナの破壊を明確に呼びかけている」と述べた [217]。 マスメディアとプロパガンダ 主な記事 プロパガンダ・モデル 外部ビデオ ビデオアイコン プロパガンダと同意の製造に関するチョムスキー 2003年6月1日 チョムスキーの政治的著作は、主にイデオロギー、社会的・政治的権力、マスメディア、国家政策に焦点を当てている[228]。彼の最も有名な著作のひとつ である『Manufacturing Consent』は、政治的スペクトラム全体にわたって国家政策を強化し、容認する一方で、反対の視点を疎外するメディアの役割を解剖している。チョムス キーは、政府主導の「自由市場」勢力による検閲のこのバージョンは、ソビエト連邦における同等のプロパガンダ・システムよりも繊細で、弱体化させるのが難 しいと主張する[229]。 [マスメディアは個々の政治家や政党を批判することはあっても、その一部である国家と企業の結びつきを弱めることはない。 [その証拠として、彼はアメリカのマスメディアが社会主義者のジャーナリストや政治評論家を雇っていないことを強調している[233]。 彼はまた、ブラックパンサーであるフレッド・ハンプトンがFBIの関与の可能性によって殺害された事件や、アメリカが資金提供したコントラによってニカラ グアで行われた虐殺事件など、アメリカの主流メディアが国の印象を悪くするので無視してきた重要なニュースの例を挙げている。 このような状況を改善するために、チョムスキーは草の根民主主義によるメディアの統制と関与を呼びかけている[235]。 チョムスキーは、ほとんどの陰謀論は実を結ばず、個人の操作がより広範な社会的要請に対して二次的なものであるような制度的枠組みにおける政策形成につい て考えるための気をそらす代用品であると考えている[236]。 彼は、秘密裏に統制を行う癒着勢力ではなく、自然な要請に従う制度について述べているという点で、彼のプロパガンダ・モデルを陰謀論から切り離している。 [237]チョムスキーは、教育システムを解毒剤として支持する代わりに、ほとんどの教育は逆効果であると考えている[238]。 批評家の反応と反批判:1980年代-現在 2004年に出版された『The Anti-Chomsky Reader』の中で、ピーター・コリアーとデヴィッド・ホロヴィッツは、チョムスキーが自分の理論に合うように事実を選んでいると非難している [239]。 ホロヴィッツはまた、チョムスキーの反米主義を次のように批判している[240]。 ノーム・チョムスキーは40年もの間、本に次ぐ本、パンフレットに次ぐパンフレット、スピーチに次ぐスピーチで、ひとつのメッセージ、そしてひとつのメッ セージだけを発信してきた: アメリカは大悪魔であり、世界の悪の源泉である。チョムスキーの頭の悪い世界では、アメリカは自国の悪行だけでなく、世界貿易センターやペンタゴンを襲っ たテロリストを含む他者の悪行にも責任がある。このような態度において、彼はマンハッタンの廃墟を、犠牲者やアメリカ人の死者のためではなく、自分たちを 襲った大惨事の「根本原因」のために捜索するすべての人々の媒介者である。 保守的な公共政策シンクタンク、フーバー研究所のピーター・シュワイザーは2006年1月、「チョムスキーは相続税と大規模な所得再分配に賛成している。 シュワイザーは、チョムスキーが遺産分割計画を立て、出版された著作物に関する自身の知的財産を保護していること、またチョムスキーが定期的に受け取って いた高額な講演料(当時は1回あたり約9,000ドルから12,000ドル)を批判した[241][242]。 チョムスキーは社会主義体制や共産主義体制を信憑性をもって扱い、資本主義体制をより精査したり批判したりすることで非難されてきた。 米国の行動に対するチョムスキーの分析は、米国の暗躍に深く踏み込んでいたが、共産主義者の間を旅行する際には、外見に満足していた。ニューヨーク・レ ビュー・オブ・ブックス』誌で彼は、ハノイ郊外の田舎では「村や地域レベルで高度な民主的参加が見られる」と報告している。しかし、どうしてそう言えるの だろうか?チョムスキーはベトナム語を話せなかったので、情報を政府の通訳、ツアーガイド、ハンドラーに頼っていた。共産主義]ベトナム人の手にかかる と、明晰な目をした懐疑主義が、進んで信じるようになった[243]。 2012年9月にアルジャジーラに寄稿したニコラス・コズロフによれば、チョムスキーは「米国とその代理人が世界中で行っているさまざまな悪行に世界の関 心を集めてきた。しかし、論争を避けようとするあまり、チョムスキーはある種のイデオローグになってしまった。チョムスキーのウェブサイトを探し回って も、ベラルーシやラテンアメリカの権威主義的な指導者たちに関する重要な議論は見当たらない」[244]。 政治活動家のジョージ・モンビオットは、「問題の一部は、ノーム・チョムスキーとジョン・ピルジャーの周りに一種のカルト集団が発達していることである。 アナーキストで原始主義者のジョン・ゼルザンは、チョムスキーは本物のアナーキストではないと非難し、その代わりに「政治的にはリベラル・左翼であり、彼 の学問的専門である言語理論においてはまさに反動的である」と述べている。チョムスキーは、どう見ても、寛大で、誠実で、疲れを知らない活動家でもある- だからといって、残念ながら、彼の思考が解放的な価値を持つとは限らない」[246]。 チョムスキーを擁護する人々は、チョムスキーは検閲されてきた、あるいは公的な議論から取り残されてきたと反論してきた。このような主張はレーガン時代ま でさかのぼる。1988年2月にワシントン・ポスト紙に寄稿したソール・ランドーは、「チョムスキーの洞察が政策論争から排除されているのは不健全だ。タ ルムードの愚痴やトム・ペインの合理主義的アナーキズムを思わせる彼の執拗な検察的散文は、正当なフラストレーションを反映しているのかもしれない」 [247]。 |

| Philosophy Chomsky has also been active in a number of philosophical fields, including philosophy of mind, philosophy of language, and philosophy of science.[248] In these fields he is credited with ushering in the "cognitive revolution",[248] a significant paradigm shift that rejected logical positivism, the prevailing philosophical methodology of the time, and reframed how philosophers think about language and the mind.[170] Chomsky views the cognitive revolution as rooted in 17th-century rationalist ideals.[249] His position—the idea that the mind contains inherent structures to understand language, perception, and thought—has more in common with rationalism than behaviorism.[250] He named one of his key works Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought (1966).[249] This sparked criticism from historians and philosophers who disagreed with Chomsky's interpretations of classical sources and use of philosophical terminology.[e] In the philosophy of language, Chomsky is particularly known for his criticisms of the notion of reference and meaning in human language and his perspective on the nature and function of mental representations.[251] Chomsky's famous 1971 debate on human nature with the French philosopher Michel Foucault was a symbolic clash of the analytic and continental philosophy traditions, represented by Chomsky and Foucault, respectively.[99] It showed what appeared to be irreconcilable differences between two moral and intellectual luminaries of the 20th century. Foucault held that any definition of human nature is connected to our present-day conceptions of ourselves; Chomsky held that human nature contained universals such as a common standard of moral justice as deduced through reason.[252] Chomsky criticized postmodernism and French philosophy generally, arguing that the obscure language of postmodern, leftist philosophers gives little aid to the working classes.[253] He has also debated analytic philosophers, including Tyler Burge, Donald Davidson, Michael Dummett, Saul Kripke, Thomas Nagel, Hilary Putnam, Willard Van Orman Quine, and John Searle.[170] Chomsky's contributions span intellectual and world history, including the history of philosophy.[254] Irony is a recurring characteristic of his writing, such as rhetorically implying that his readers already know something to be true, which engages the reader more actively in assessing the veracity of his claims.[255] |

哲学 チョムスキーはまた、心の哲学、言語哲学、科学哲学を含む数多くの哲学分野でも活躍してきた[248]。これらの分野において彼は、当時主流であった哲学 的方法論である論理実証主義を否定し、哲学者が言語と心についてどのように考えるかを再構築した重要なパラダイムシフトである「認知革命」[248]の先 駆けとなったと評価されている。 [チョムスキーは認知革命を17世紀の合理主義の理想に根ざしていると考えている[249]。彼の立場、つまり心には言語、知覚、思考を理解するための固 有の構造が含まれているという考え方は、行動主義よりも合理主義と共通点が多い[250]: これは、チョムスキーの古典的な出典の解釈や哲学用語の使用に反対する歴史家や哲学者からの批判を巻き起こした[249]。言語哲学において、チョムス キーは人間の言語における参照と意味の概念に対する批判や、心的表象の性質と機能に関する彼の視点によって特に知られている[251]。 チョムスキーが1971年にフランスの哲学者ミシェル・フーコーと行った人間の本質に関する有名な論争は、チョムスキーとフーコーがそれぞれ代表する分析 哲学と大陸哲学の伝統の象徴的な衝突であった[99]。フーコーは、人間の本性についてのいかなる定義も、現在の自分自身についての概念と結びついている と主張し、チョムスキーは、人間の本性は、理性を通じて推論される道徳的正義の共通の基準といった普遍性を含んでいると主張していた。 [また、タイラー・バージ、ドナルド・デイヴィッドソン、マイケル・ダンメット、ソール・クリプキ、トーマス・ネーゲル、ヒラリー・パットナム、ウィラー ド・ヴァン・オーマン・クワイン、ジョン・サールなどの分析哲学者とも議論している[170]。 チョムスキーの貢献は哲学史を含む知的世界史に及んでいる[254]。アイロニーは彼の文章に繰り返し見られる特徴であり、例えば、読者がすでに何かを真 実であると知っていることをレトリック的にほのめかすことで、読者をより積極的に彼の主張の信憑性を評価するように仕向けている[255]。 |