高貴なる野蛮人

Noble savage

The

historical painting The Death of General Wolfe (1771) features a

noble-savage Indian observing the behaviours of civilized British

soldiers facing the battlefield death of their commanding officer.

☆西洋の文化における人類学、哲学、文学において、「高貴な野蛮人(noble savage)」 は文明に汚されていない典型的な人物である。 それゆえ、「高潔な野蛮人」は自然と調和して暮らす原始民族の生まれながらの善良さや道徳的優位性を象徴する。 ジョン・ドライデンは、舞台劇『スペイン人によるグラナダ征服』(1672年)という英雄劇において、「高貴な 野蛮人」を「自然の被造物としての人間」の典型として表現している。 スチュアート朝復古王政(1660年~1688年)の政治的思惑により、ドライデンの戯曲における「野蛮人」という表現は、人間としての野獣や野生人の意 味に拡大解釈されるようになった。礼儀正しさや無礼さについて、哲学者のアンソニー・アシュリー=クーパー(シャフツベリ伯爵)は著書『美徳あるいは功徳 に関する探究』(1699年)の中で、人間には生まれつき道徳心があり、善悪の区別を認識する能力があるとし、それは知性と感情に基づくものであって、宗 教上の教義に基づくものではないと述べている。 17世紀の英国における哲学論争において、『美徳あるいは徳に関する探究』は、ホッブズが絶対王政を擁護し、中央集権政府を正当化する政治哲学『リヴァイ アサン』(1651年)に対するシャフツベリー伯爵の倫理的な回答であった。政治的な組織が存在せず、人や資源が管理されていない状態では、男女の生活は 「孤独で、貧しく、不快で、粗野で、短い」ものとなる。ヨーロッパのホッブズは、文明を構成する社会に編成する部族や氏族が存在する前の好戦的な自然状態 に生きる人々として、誤ってアメリカ・インディアンを例に挙げた。 18世紀の人類学では、この言葉は「自然の紳士」を意味し、道徳感情論の感傷主義から生まれた理想的な人間を指していた。19世紀には、チャールズ・ディ ケンズがエッセイ「高潔な野蛮人」(1853年)で、道徳感情主義の感傷主義によって可能となった哲学や芸術における英国の原始主義のロマン主義化を風刺 し、高潔な野蛮人を修辞的な矛盾語として表現した。 多くの点で、高潔な野蛮人という概念は、社会科学におけるオリエンタリズム、植民地主義、エキゾティシズムに関する議論の核心を突く、西洋以外の地域に関 する空想を伴うものである。ここで浮かび上がる重要な問題は、「他者」に対する高潔な賞賛が支配的な階層を損なうのか、あるいは再生産するのか、それに よって「他者」が西洋の権力によって従属させられるのか、という点である。

| The noble savage In Western anthropology, philosophy, and literature, the noble savage is a stock character who is uncorrupted by civilization. As such, the noble savage symbolizes the innate goodness and moral superiority of a primitive people living in harmony with Nature.[2] In the heroic drama of the stageplay The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards (1672), John Dryden represents the noble savage as an archetype of Man-as-Creature-of-Nature.[3] The intellectual politics of the Stuart Restoration (1660–1688) expanded Dryden's playwright usage of savage to denote a human wild beast and a wild man.[4] Concerning civility and incivility, in the Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit (1699), the philosopher Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury, said that men and women possess an innate morality, a sense of right and wrong conduct, which is based upon the intellect and the emotions, and not based upon religious doctrine.[5] In the philosophic debates of 17th-century Britain, the Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit was the Earl of Shaftesbury's ethical response to the political philosophy of Leviathan (1651), in which Thomas Hobbes defended absolute monarchy and justified centralized government as necessary because the condition of Man in the apolitical state of nature is a "war of all against all", for which reason the lives of men and women are "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short" without the political organization of people and resources. The European Hobbes gave, incorrectly, as example the American Indians as people living in the bellicose state of nature that precedes tribes and clans organizing into the societies that compose a civilization.[5] In 18th-century anthropology, the term noble savage then denoted nature's gentleman, an ideal man born from the sentimentalism of moral sense theory. In the 19th century, in the essay "The Noble Savage" (1853) Charles Dickens rendered the noble savage into a rhetorical oxymoron by satirizing the British romanticisation of Primitivism in philosophy and in the arts made possible by moral sentimentalism.[6] In many ways, the noble savage notion entails fantasies about the non-West that cut to the core of the conversation in the social sciences about Orientalism, colonialism and exoticism. The key question that emerges here is whether an admiration of "the Other" as noble undermines or reproduces the dominant hierarchy, whereby the Other is subjugated by Western powers.[7] |

高貴な野蛮人 西洋の文化における人類学、哲学、文学において、「高貴な野蛮人」は文明に汚されていない典型的な人物である。 それゆえ、「高潔な野蛮人」は自然と調和して暮らす未開民族の生まれながらの善良さや道徳的優位性を象徴する。 ジョン・ドライデンは、舞台劇『スペイン人によるグラナダ征服』(1672年)という英雄劇において、「高貴な野蛮人」を「自然の被造物としての人間」の 典型として表現している。 スチュアート朝復古王政(1660年~1688年)の政治的思惑により、ドライデンの戯曲における「野蛮人」という表現は、人間としての野獣や野生人の意 味に拡大解釈されるようになった。礼儀正しさや無礼さについて、哲学者のアンソニー・アシュリー=クーパー(シャフツベリ伯爵)は著書『美徳あるいは功徳 に関する探究』(1699年)の中で、人間には生まれつき道徳心があり、善悪の区別を認識する能力があるとし、それは知性と感情に基づくものであって、宗 教上の教義に基づくものではないと述べている。 17世紀の英国における哲学論争において、『美徳あるいは徳に関する探究』は、ホッブズが絶対王政を擁護し、中央集権政府を正当化する政治哲学『リヴァイ アサン』(1651年)に対するシャフツベリー伯爵の倫理的な回答であった。政治的な組織が存在せず、人や資源が管理されていない状態では、男女の生活は 「孤独で、貧しく、不快で、粗野で、短い」ものとなる。ヨーロッパのホッブズは、文明を構成する社会に編成する部族や氏族が存在する前の好戦的な自然状態 に生きる人々として、誤ってアメリカ・インディアンを例に挙げた。 18世紀の人類学では、この言葉は「自然の紳士」を意味し、道徳感情論の感傷主義から生まれた理想的な人間を指していた。19世紀には、チャールズ・ディ ケンズがエッセイ「高潔な野蛮人」(1853年)で、道徳感情主義の感傷主義によって可能となった哲学や芸術における英国の未開主義のロマン主義化を風刺 し、高潔な野蛮人を修辞的な矛盾語として表現した。 多くの点で、高潔な野蛮人という概念は、社会科学におけるオリエンタリズム、植民地主義、エキゾティシズムに関する議論の核心を突く、西洋以外の地域に関 する空想を伴うものである。ここで浮かび上がる重要な問題は、「他者」に対する高潔な賞賛が支配的な階層を損なうのか、あるいは再生産するのか、それに よって「他者」が西洋の権力によって従属させられるのか、という点である。 |

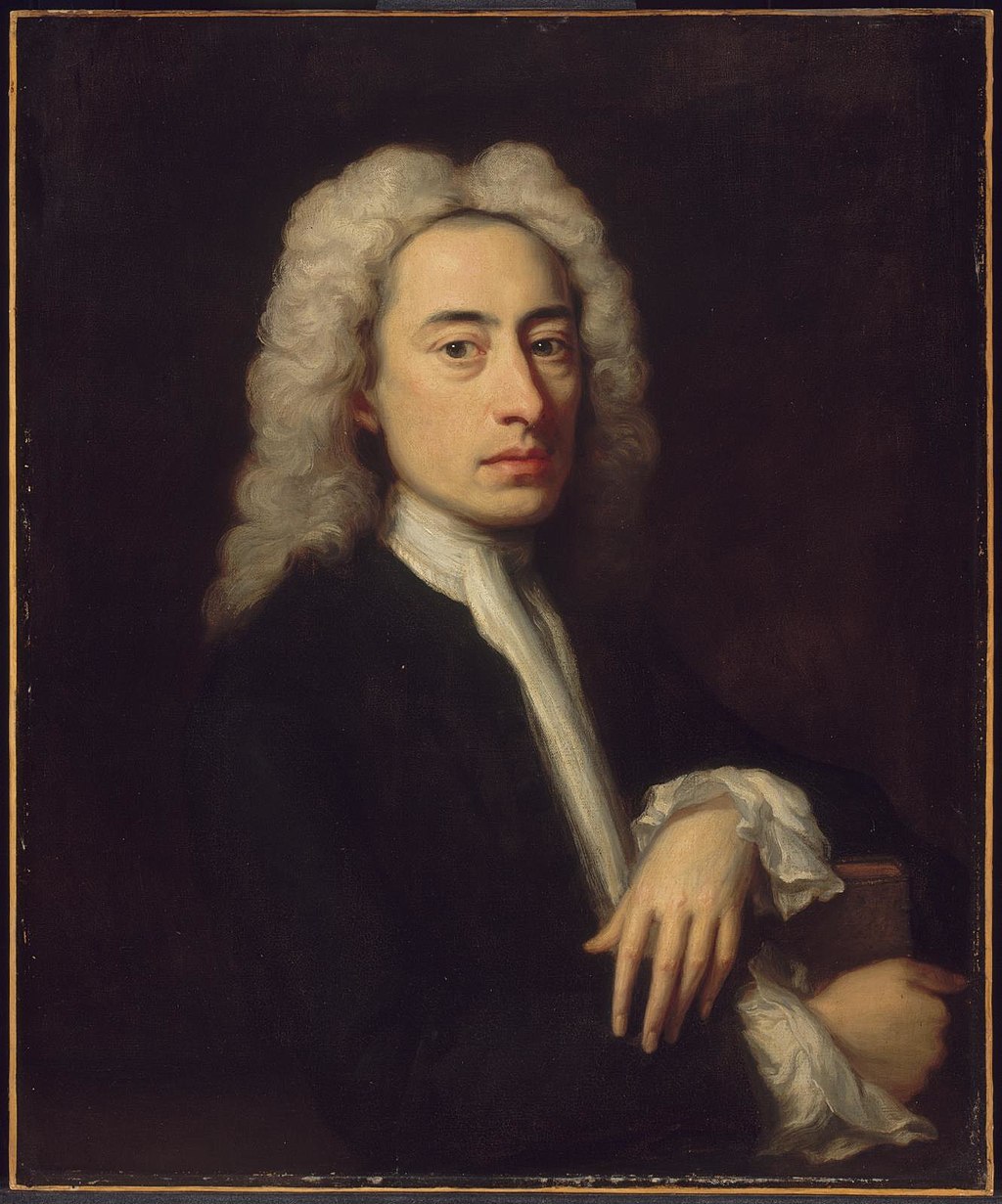

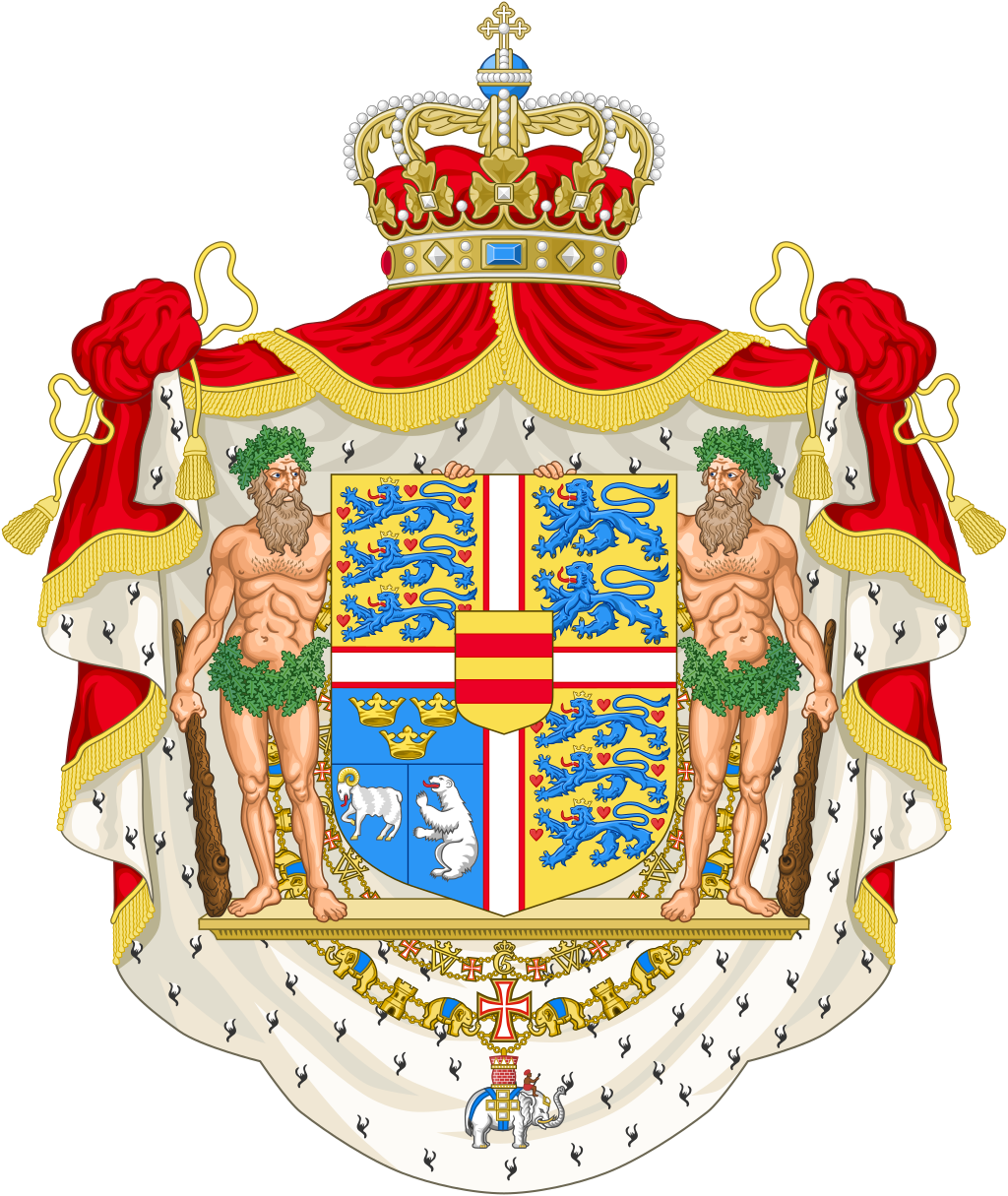

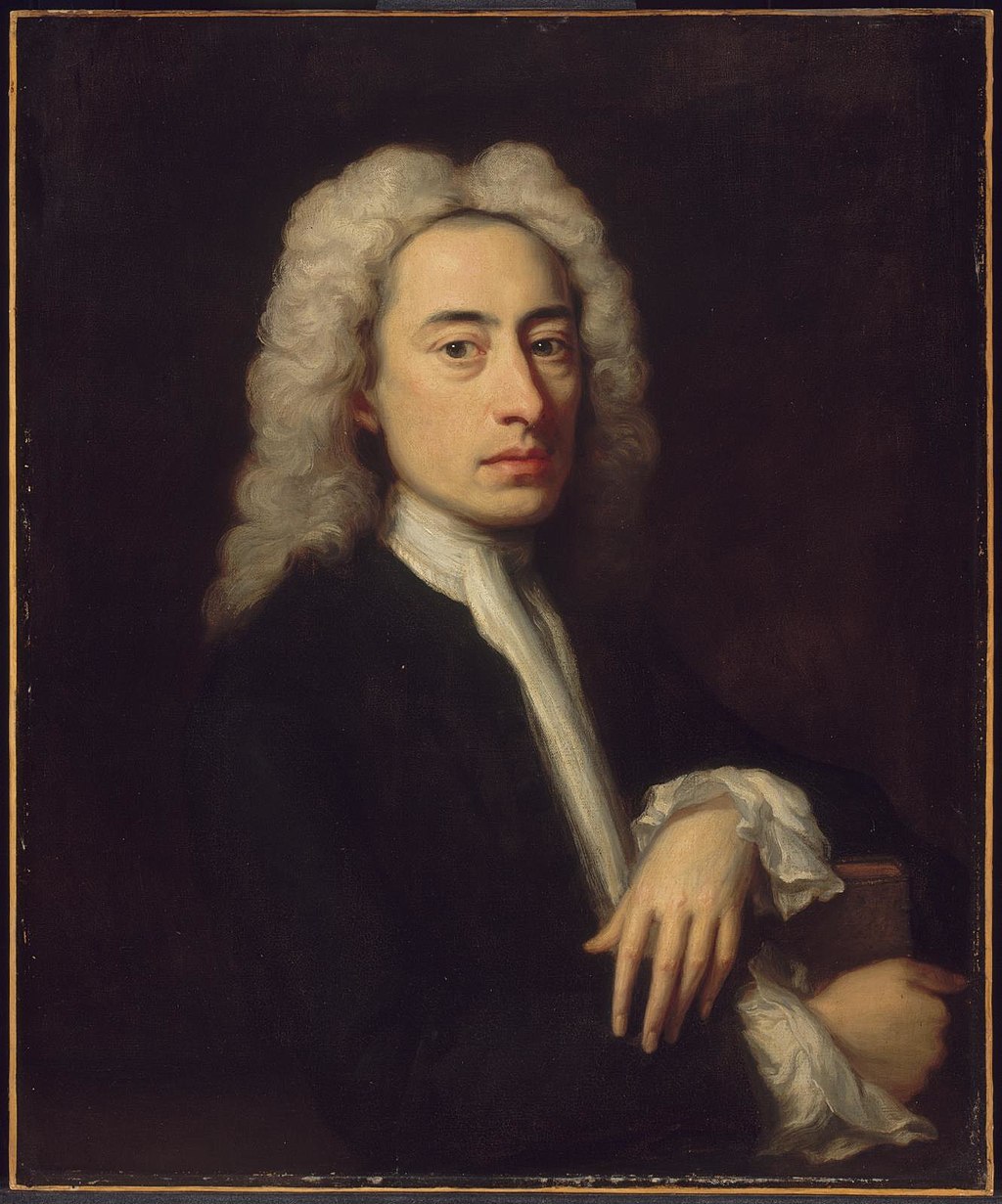

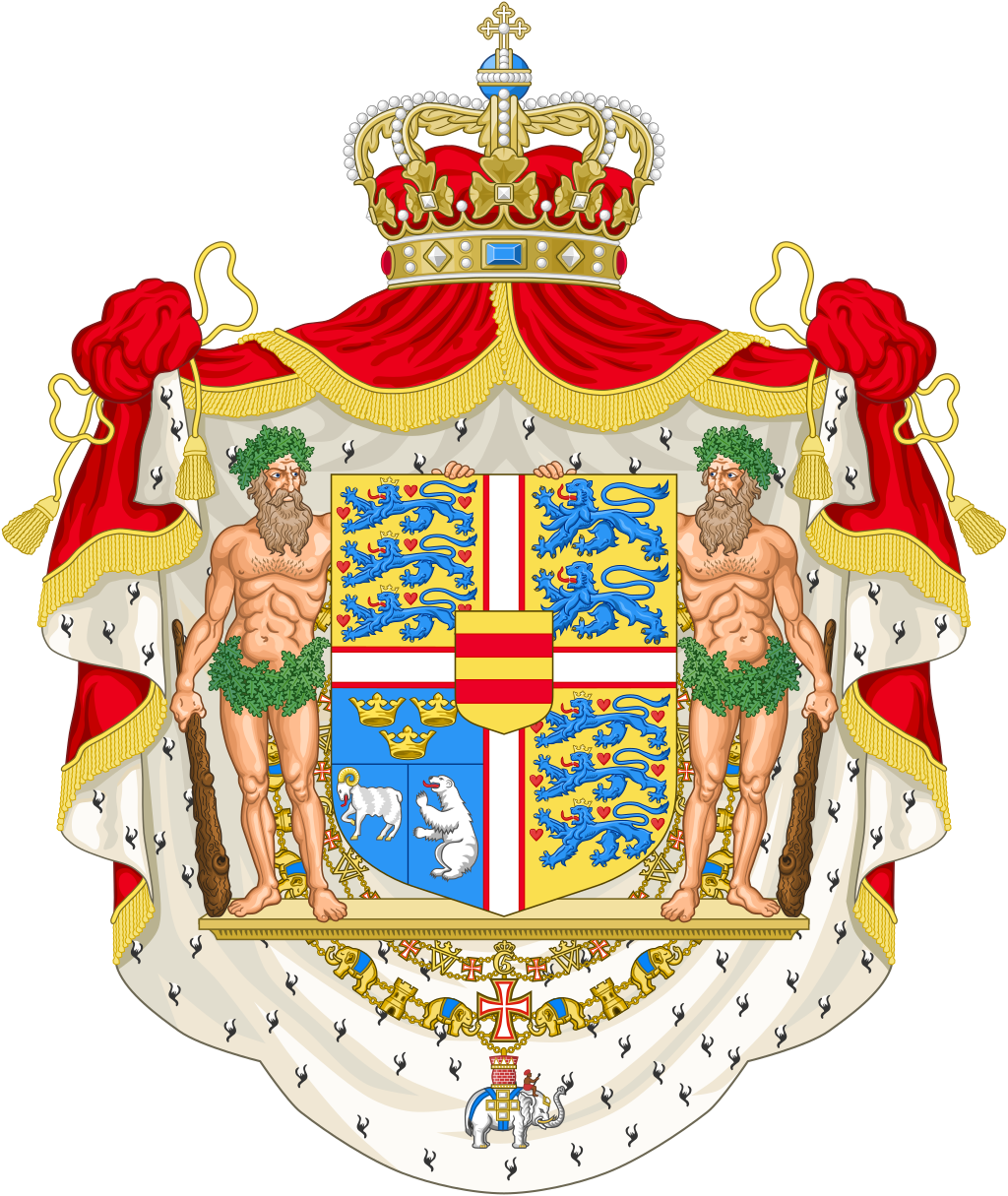

Origins In the essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), about the Tupinambá people of Brazil, the philosopher Michel de Montaigne introduced the noble savage (nature's gentleman) as a stock character in the stories of Europeans' relations with the non-European Other. 16th century The stock character of the noble savage originated from the essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), about the Tupinambá people of Brazil, wherein the philosopher Michel de Montaigne presents "Nature's Gentleman", the bon sauvage counterpart to civilized Europeans in the 16th century.  The playwright John Dryden coined the term "noble savage" in the stageplay The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards (1672). 17th century The first usage of the term noble savage in English literature occurs in John Dryden's stageplay The Conquest of Granada by the Spaniards (1672), about the troubled love of the hero Almanzor and the Moorish beauty Almahide, in which the protagonist defends his life as a free man by denying a prince's right to put him to death, because he is not a subject of the prince: I am as free as nature first made man, Ere the base laws of servitude began, When wild in woods the noble savage ran.[8]  In the poem "An Essay on Man" (1734), the poet Alexander Pope developed the noble savage into the non-European Other. (Jonathan Richardson, c. 1736) 18th century By the 18th century, Montaigne's predecessor to the noble savage, nature's gentleman was a stock character usual to the sentimental literature of the time, for which a type of non-European Other became a background character for European stories about adventurous Europeans in the strange lands beyond continental Europe. For the novels, the opera, and the stageplays, the stock of characters included the "Virtuous Milkmaid" and the "Servant-More-Clever-Than-the-Master" (e.g. Sancho Panza and Figaro), literary characters who personify the moral superiority of working-class people in the fictional world of the story. In English literature, British North America was the geographic locus classicus for adventure and exploration stories about European encounters with the noble savage natives, such as the historical novel The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757 (1826), by James Fenimore Cooper, and the epic poem The Song of Hiawatha (1855), by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, both literary works presented the primitivism (geographic, cultural, political) of North America as an ideal place for the European man to commune with Nature, far from the artifice of civilisation; yet in the poem “An Essay on Man” (1734), the Englishman Alexander Pope portrays the American Indian thus: Lo, the poor Indian! whose untutor'd mind Sees God in clouds, or hears Him in the wind; His soul proud Science never taught to stray Far as the solar walk or milky way; Yet simple Nature to his hope has giv'n, Behind the cloud-topp'd hill, a humbler heav'n; Some safer world in depth of woods embrac'd, Some happier island in the wat'ry waste, Where slaves once more their native land behold, No fiends torment, no Christians thirst for gold! To be, contents his natural desire; He asks no angel's wing, no seraph's fire: But thinks, admitted to that equal sky, His faithful dog shall bear him company. To the English intellectual Pope, the American Indian was an abstract being unlike his insular European self; thus, from the Western perspective of "An Essay on Man", Pope's metaphoric usage of poor means "uneducated and a heathen", but also denotes a savage who is happy with his rustic life in harmony with Nature, and who believes in deism, a form of natural religion — the idealization and devaluation of the non-European Other derived from the mirror logic of the Enlightenment belief that "men, everywhere and in all times, are the same".  The Noble savage: In the royal coat of arms of Denmark, the wild men (woodwose) who support the royal house date from the early reign of the Oldenburg dynasty. 19th century Like Dryden's noble savage term, Pope's phrase "Lo, the Poor Indian!" was used to dehumanize the natives of North America for European purposes, and so justified white settlers' conflicts with the local Indians for possession of the land. In the mid-19th century, the journalist-editor Horace Greeley published the essay "Lo! The Poor Indian!" (1859), about the social condition of the American Indian in the modern United States: I have learned to appreciate better than hitherto, and to make more allowance for the dislike, aversion, contempt wherewith Indians are usually regarded by their white neighbors, and have been since the days of the Puritans. It needs but little familiarity with the actual, palpable aborigines to convince anyone that the poetic Indian — the Indian of Cooper and Longfellow — is only visible to the poet's eye. To the prosaic observer, the average Indian of the woods and prairies is a being who does little credit to human nature — a slave of appetite and sloth, never emancipated from the tyranny of one animal passion, save by the more ravenous demands of another. As I passed over those magnificent bottoms of the Kansas, which form the reservations of the Delawares, Potawatamies, etc., constituting the very best corn-lands on Earth, and saw their owners sitting around the doors of their lodges at the height of the planting season, and in as good, bright planting weather as sun and soil ever made, I could not help saying: "These people must die out — there is no help for them. God has given this earth to those who will subdue and cultivate it, and it is vain to struggle against His righteous decree."[9] Moreover, during the American Indian Wars (1609–1924) for possession of the land, European white settlers considered the Indians "an inferior breed of men" and mocked them by using the terms "Lo" and "Mr. Lo" as disrespectful forms of address. In the Western U.S., those terms of address also referred to East Coast humanitarians whose noble-savage conception of the American Indian was unlike the warrior who confronted and fought the frontiersman. Concerning the story of the settler Thomas Alderdice, whose wife was captured and killed by Cheyenne Indians, The Leavenworth, Kansas, Times and Conservative newspaper said: "We wish some philanthropists, who talk about civilizing the Indians, could have heard this unfortunate and almost broken-hearted man tell his story. We think [that the philanthropists] would at least have wavered a little in their [high] opinion of the Lo family."[10] |

起源[編集] 哲学者ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュは、ブラジルのトゥピナンバ族を題材にしたエッセイ『食人族について』(1580年)の中で、ヨーロッパ人と非ヨーロッ パ人との関係を語る際の登場人物として、高貴な野蛮人(自然の紳士)を紹介した。 16世紀 高貴な野蛮人という 登場人物は、哲学者ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュがブラジルのトゥピナンバ族について書いたエッセイ『食人族について』(1580年)に登場する。  劇作家ジョン・ドライデンは、舞台劇『スペイン人によるグラナダ征服』(1672年)の中で「高貴な野蛮人」という言葉を生み出した。 17世紀 主人公アルマンゾールとムーア人の美女アルマヒデの悩める恋を描いたジョン・ドライデンの舞台劇『スペイン人によるグラナダ征服』(1672年)の中で、 主人公は王子の臣下ではないことを理由に、自分を死刑にする王子の権利を否定し、自由人としての自分の人生を守る: 私は、自然が最初に人間を作ったのと同じくらい自由だ、 隷属の基本法が始まる前に、 高貴な野蛮人が森を駆け巡っていたころのように。  詩人アレクサンダー・ポープは、詩「人間論」(1734年)の中で、高貴な野蛮人を非ヨーロッパ的な他者へと発展させた。(ジョナサン・リチャードソン、 1736年頃) 18世紀 18世紀になると、モンテーニュの「高貴な野蛮人」の前身である「自然の紳士」は、当時のセンチメンタル文学の定番キャラクターとなり、非ヨーロッパ的な 他者は、ヨーロッパ大陸を越えた見知らぬ土地での冒険的なヨーロッパ人を描いたヨーロッパ物語の背景キャラクターとなった。小説、オペラ、舞台劇では、 「高潔な乳飲み子」や「主人よりも賢い召使い」(例えばサンチョ・パンサや フィガロ)といった、物語の架空世界における労働者階級の人々の道徳的優越性を擬人化した文学的キャラクターが登場人物のストックとなった。 イギリス文学では、イギリス領北アメリカは、歴史小説『最後のモヒカン族』(The Last of the Mohicans)のような、ヨーロッパ人と気高い未開の原住民との出会いを描いた冒険・探検物語の地理的な古典的場所であった: ジェームズ・フェニモア・クーパーの歴史小説『The Last of the Mohicans:A Narrative of 1757』(1826年)やヘンリー・ワズワース・ロングフェローの叙事詩『The Song of Hiawatha』(1855年)などである。どちらの文学作品も、北アメリカの未開主義(地理的、文化的、政治的)を、ヨーロッパ人が文明の作為から遠 く離れた自然と交わるための理想的な場所として紹介している: 見よ、哀れなインディアンよ。 雲の中に神を見、風の中に神を聞く; 彼の誇り高き科学は、迷うことを教えなかった。 彼の魂は、誇り高き科学に、太陽の散歩道や天の川を遠くまで迷い歩くことを教えられることはなかった; しかし、素朴な自然は彼の希望となった、 雲に覆われた丘の向こうに、より謙虚な天がある; 森の奥には、もっと安全な世界がある、 (そのような)災難に見舞われることはない、 そこで奴隷たちは,もう一度祖国を見よ、 (中略)悪魔に苦しめられることも、キリスト教徒が黄金を渇望することもない! 彼は天使の翼を求めない; 天使の翼も,セラフの火も求めない: 彼は天使の翼もセラフの火も求めない、 忠実な飼い犬が、彼と一緒にいてくれるだろう。 イギリスの知識人ポープにとって、アメリカン・インディアンは、偏狭なヨーロッパ人とは異なる抽象的な存在だった; したがって、『人間論』の西洋的な観点からすると、ポープの言う貧者の比喩的用法は「無学な異教徒」を意味するが、同時に、自然と調和した素朴な生活に満 足し、自然宗教の一形態である神道を信じる野蛮人をも意味する。  高貴な野蛮人:デンマークの王家の紋章には、王家を支える野人(ウッドウォーズ)が描かれているが、これはオルデンブルク王朝の初期からのものである。 19世紀 ドライデンの"noble savage"と同様に、ポープの "Lo, the Poor Indian!"という言葉は、ヨーロッパ人の目的のために北アメリカの原住民の人間性を奪うために使われ、土地の所有権をめぐって白人入植者が地元のイ ンディアンと争うことを正当化した。19世紀半ば、ジャーナリストであり編集者であったホレス・グリーリーは、"Lo! The Poor Indian!"(1859年)というエッセイを発表した。(1859年)というエッセイを発表した: ピューリタンの時代からそうであったように、インディアンが隣人の白人から通常嫌われ、嫌悪され、軽蔑されていることを、私は以前よりもよく理解し、許容 するようになった。詩的なインディアン--クーパーや ロングフェローのインディアン--は、詩人の目にしか見えないということを誰にでも納得させるには、実際に目に見える原住民をよく知る必要はほとんどな い。平凡な観察者にとっては、森や草原の平均的なインディアンは、人間の本性をほとんど信用していない存在である。食欲と怠惰の奴隷であり、ある動物的情 熱の圧制から解放されることはなく、別の動物的情熱のより貪欲な要求によってのみ解放されるのだ。 デラウェア族やポタワタミー族などの保留地を形成しているカンザス州の壮大な底地を通り過ぎ、その所有者たちが田植えの最盛期にロッジのドアの周りに座っ ているのを見た: 「この人たちは死に絶えなければならない。神はこの大地を治め、耕す者たちにこの大地をお与えになったのであり、神の正しいご命令に逆らってもがくのはむ なしいことだ」[9]。 さらに、土地の所有権をめぐるアメリカ・インディアン戦争(1609年~1924年)の間、ヨーロッパ系白人入植者たちはインディアンを「劣った種類の人 間」とみなし、「ロー」や「ミスター・ロー」という無礼な呼び方を使って嘲笑した。アメリカ西部では、これらの呼び方は東海岸の人道主義者をも指してい た。彼らのアメリカン・インディアンに対する気高く野蛮な概念は、開拓者と対峙し戦う戦士とは異なっていた。シャイアンインディアンに妻を捕らえられ殺さ れた入植者トーマス・アルダーダイスの話について、カンザス州リーベンワースの『タイムズ・アンド・コンサーバティブ』紙はこう述べている: 「インディアンの文明化について語る博愛主義者たちに、この不幸でほとんど失意のどん底にいる男の話を聞かせたかった。博愛主義者たちは)少なくとも、 ロー一家に対する(高い)評価を少しは揺るがせただろうと思う」[10]。 |

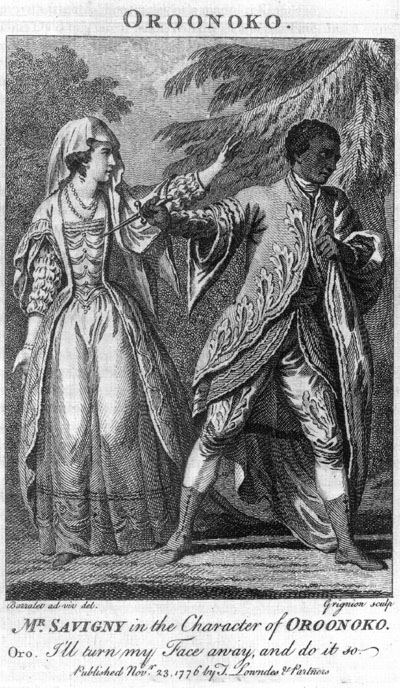

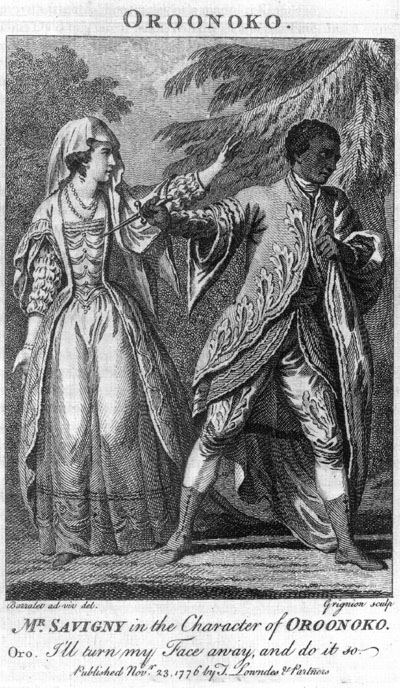

| Cultural stereotype The Roman Empire In Western literature, the Roman book De origine et situ Germanorum (On the Origin and Situation of the Germans, AD 98), by the historian Publius Cornelius Tacitus, introduced the anthropologic concept of the noble savage to the Western World; later a cultural stereotype who featured in the exotic-place tourism reported in the European travel literature of the 17th and the 18th centuries.[11] Al-Andalus The 12th-century Andalusian novel The Living Son of the Vigilant (Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān, 1160), by the polymath Ibn Tufail, explores the subject of natural theology as a means to understand the material world. The protagonist is a wild man isolated from his society, whose trials and tribulations lead him to knowledge of Allah by living a rustic life in harmony with Mother Nature.[12] Kingdom of Spain In the 15th century, soon after arriving to the Americas in 1492, the Europeans employed the term savage to dehumanise the indigènes (noble-savage natives) of the newly discovered "New World" as ideological justification for the European colonization of the Americas, called the Age of Discovery (1492–1800); thus with the dehumanizing stereotypes of the noble savage and the indigène, the savage and the wild man the Europeans granted themselves the right to colonize the natives inhabiting the islands and the continental lands of the northern, the central, and the southern Americas.[13] The conquistador mistreatment of the indigenous peoples of the Viceroyalty of New Spain (1521–1821) eventually produced bad-conscience recriminations amongst the European intelligentsias for and against colonialism.[14] As the Roman Catholic Bishop of Chiapas, the priest Bartolomé de las Casas witnessed the enslavement of the indigènes of New Spain, yet idealized them into morally innocent noble savages living a simple life in harmony with Mother Nature. At the Valladolid debate (1550–1551) of the moral philosophy of enslaving the native peoples of the Spanish colonies, Bishop de las Casas reported the noble-savage culture of the natives, especially noting their plain-manner social etiquette and that they did not have the social custom of telling lies. Kingdom of France In the intellectual debates of the late 16th and 17th centuries, philosophers used the racist stereotypes of the savage and the good savage as moral reproaches of the European monarchies fighting the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) and the French Wars of Religion (1562–1598). In the essay "Of Cannibals" (1580), Michel de Montaigne reported that the Tupinambá people of Brazil ceremoniously eat the bodies of their dead enemies, as a matter of honour, whilst reminding the European reader that such wild man behavior was analogous to the religious barbarism of burning at the stake: "One calls ‘barbarism’ whatever he is not accustomed to."[15] The academic Terence Cave further explains Montaigne's point of moral philosophy: The cannibal practices are admitted [by Montaigne] but presented as part of a complex and balanced set of customs and beliefs which "make sense" in their own right. They are attached to a powerfully positive morality of valor and pride, one that would have been likely to appeal to early modern codes of honor, and they are contrasted with modes of behavior in the France of the wars of religion, which appear as distinctly less attractive, such as torture and barbarous methods of execution.[16] As philosophic reportage, "Of Cannibals" applies cultural relativism to compare the civilized European to the uncivilized noble savage. Montaigne's anthropological report about cannibalism in Brazil indicated that the Tupinambá people were neither a noble nor an exceptionally good folk, yet neither were the Tupinambá culturally or morally inferior to his contemporary, 16th-century European civilization. From the perspective of Classical liberalism of Montaigne's humanist portrayal of the customs of honor of the Tupinambá people indicates Western philosophic recognition that people are people, despite their different customs, traditions, and codes of honor. The academic David El Kenz explicates Montaigne's background concerning the violence of customary morality: In his Essais ... Montaigne discussed the first three wars of religion (1562–63; 1567–68; 1568–70) quite specifically; he had personally participated in [the wars], on the side of the [French] royal army, in southwestern France. The [anti-Protestant] St. Bartholomew's Day massacre [1572] led him to retire to his lands in the Périgord region, and remain silent on all public affairs until the 1580s. Thus, it seems that he was traumatized by the massacre. To him, cruelty was a criterion that differentiated the Wars of Religion [1562–1598] from previous conflicts, which he idealized. Montaigne considered that three factors accounted for the shift from regular war to the carnage of civil war: popular intervention, religious demagogy, and the never-ending aspect of the conflict. ... He chose to depict cruelty through the image of hunting, which fitted with the tradition of condemning hunting for its association with blood and death, but it was still quite surprising, to the extent that this practice was part of the aristocratic way of life. Montaigne reviled hunting by describing it as an urban massacre scene. In addition, the man–animal relationship allowed him to define virtue, which he presented as the opposite of cruelty. ... [As] a sort of natural benevolence based on ... personal feelings. Montaigne associated the [human] propensity to cruelty toward animals, with that exercised toward men. After all, following the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, the invented image of Charles IX shooting Huguenots from the Louvre Palace window did combine the established reputation of the King as a hunter, with a stigmatization of hunting, a cruel and perverted custom, did it not?[17] Literature  Illustration of a 1776 performance of Oroonoko. In the stageplay Oroonoko: A Tragedy (1696), by Thomas Southerne, plot complications lead the protagonist Oroonoko to kill his beloved Imoinda. The themes about the person and persona of the noble savage are the subjects of the novel Oroonoko: Or the Royal Slave (1688), by Aphra Behn, which is the tragic love story between Oroonoko and the beautiful Imoinda, an African king and queen respectively. At Coramantien, Ghana, the protagonist is deceived and delivered into the Atlantic slave trade (16th–19th centuries), and Oroonoko becomes a slave of plantation colonists in Surinam (Dutch Guiana, 1667–1954). In the course of his enslavement, Oroonoko meets the woman who narrates to the reader the life and love of Prince Oroonoko, his enslavement, his leading a slave rebellion against the Dutch planters of Surinam, and his consequent execution by the Dutch colonialists.[18] Despite Behn having written the popular novel for money, Oroonoko proved to be political-protest literature against slavery, because the story, plot, and characters followed the narrative conventions of the European romance novel. In the event, the Irish playwright Thomas Southerne adapted the novel Oroonoko into the stage play Oroonoko: A Tragedy (1696) that stressed the pathos of the love story, the circumstances, and the characters, which consequently gave political importance to the play and the novel for the candid cultural representation of slave-powered European colonialism. |

文化的ステレオタイプ ローマ帝国 西洋文学では、歴史家プブリウス・コルネリウス・タキトゥスによるローマの著書『De origine et situ Germanorum』(ドイツ人の起源と 状況について、AD 98年)が、高貴な野蛮人という人類学的概念を西洋世界に紹介した。後に、17世紀から18世紀にかけてのヨーロッパの旅行文学で報告された異国情緒溢れ る観光に登場する文化的ステレオタイプとなった[11]。 アル=アンダルス[編集] 12世紀のアンダルシアの小説『警戒者の生ける子』(Ḥayyibn Yaqẓān, 1160)は、多神教徒イブン・トゥファイルによるもので、物質世界を理解する手段としての自然神学の主題を探求している。主人公は社会から隔離された野 生の男であり、その試練と苦難は彼を大自然と調和した素朴な生活を送ることでアッラーを知ることに導く[12]。 スペイン王国[編集] 15世紀、1492年にアメリカ大陸に到達した直後、ヨーロッパ人は、大航海時代(1492-1800)と呼ばれるヨーロッパ人のアメリカ大陸植民地化を イデオロギー的に正当化するために、新しく発見された「新大陸」のインディジェーヌ(高貴で野蛮な原住民)を非人間的にするために野蛮人という言葉を用い た; 高貴な野蛮人、先住民、野蛮人、野生人という非人間的なステレオタイプによって、ヨーロッパ人はアメリカ大陸北部、中部、南部の島々や大陸に住む先住民を 植民地化する権利を自らに認めたのである。 [13] コンキスタドールによる 新スペイン総督領(1521-1821)の先住民への虐待は、やがてヨーロッパの知識人たちの間で植民地主義に対する悪感情と反感を生み出した[14]。 ローマ・カトリックのチアパス司教であったバルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサス司祭は、新スペインの先住民の奴隷化を目の当たりにしながらも、彼らを大自然と調 和した素朴な生活を送る道徳的に無垢な高貴な野蛮人に理想化した。スペイン植民地の原住民を奴隷にすることの道徳的哲学をめぐるバリャドリッドの討論会 (1550-1551年)で、デ・ラス・カサス司教は原住民の高貴な野蛮人の文化を報告し、特に彼らの平凡な社会的礼儀作法と嘘をつくという社会的習慣が ないことに注目した。 フランス王国 16世紀後半から17世紀にかけての知的論争において、哲学者たちは30年戦争(1618年-1648年)とフランス宗教戦争(1562年-1598年) を戦うヨーロッパの君主に対する道徳的非難として、野蛮人と善良な野蛮人という人種差別的ステレオタイプを用いた。ミシェル・ド・モンテーニュは「食人族 について」(1580年)というエッセイの中で、ブラジルのトゥピナンバ族が儀式的に死んだ敵の死体を食べるのは名誉なことであると報告する一方で、その ような野生人の行動は火あぶりという宗教的な野蛮さに類似していることをヨーロッパの読者に思い起こさせた: モンテーニュは)食人の習慣を認めているが、複雑でバランスの取れた一連の習慣や信念の一部として提示されており、それはそれ自体として「理にかなってい る」。それらは、近世の名誉規範に訴えかけるような、勇気と誇りという強力に肯定的な道徳に付随するものであり、拷問や野蛮な処刑方法など、明らかに魅力 的でないと思われる宗教戦争のフランスにおける行動様式と対比されている[16]。 哲学的ルポルタージュとして、「食人族について」は文化相対主義を適用し、文明化されたヨーロッパ人と未開の高貴な野蛮人とを比較している。ブラジルのカ ニバリズムに関するモンテーニュの人類学的報告は、トゥピナンバ族が高貴な民族でも特別に善良な民族でもないことを示したが、しかしトゥピナンバ族が彼の 同時代人である16世紀のヨーロッパ文明に対して文化的・道徳的に劣っているわけでもなかった。古典的自由主義の観点からすれば、モンテーニュがトゥピナ ンバ族の名誉の習慣を人文主義的に描いたことは、習慣や伝統、名誉の規範が異なっていても、人は人であるという西洋哲学的認識を示している。学者デイ ヴィッド・エル・ケンズは、慣習道徳の暴力性に関するモンテーニュの背景を説明している: モンテーニュは『エッセ』の中で次のように述べている。モンテーニュは、最初の3つの宗教戦争(1562-63年、1567-68年、1568-70年) を具体的に論じている。反プロテスタント]聖バーソロミューの日の大虐殺[1572年]をきっかけに、彼はペリゴール地方の自分の土地に引きこもり、 1580年代まですべての公的な問題について沈黙を守った。そのため、彼はこの大虐殺がトラウマになっていたようだ。彼にとって、残酷さは宗教戦争 [1562-1598]を、彼が理想とするそれ以前の紛争と区別する基準であった。モンテーニュは、通常の戦争から内戦の殺戮へと移行したのは、民衆の介 入、宗教的デマゴギー、そして紛争の終わりのない側面という3つの要因によるものだと考えた。... モンテーニュは狩猟のイメージを通して残酷さを描写することを選んだが、それは狩猟が血と死を連想させるとして非難する伝統に合致するものであった。モン テーニュは狩猟を都市の虐殺シーンと表現して非難した。さらに、人間と動物の関係によって、彼は美徳を定義することができた。... [個人的な感情に基づく一種の自然な博愛として)。 モンテーニュは、動物に対して残酷になる[人間の]性向を、人間に対して行使されるそれと関連づけたのである。結局のところ、聖バーソロミューの日の虐殺 の後、シャルル9世がルーヴル宮殿の窓からユグノーを射殺するという捏造されたイメージは、猟師としての王の定評と、残酷で倒錯した風習である狩猟の汚名 とを結びつけたのではなかったか[17]。 文学[編集]  舞台劇『Oroonoko: トーマス・サザーン作『Oroonoko:A Tragedy』(1696年)では、主人公のオロノコが複雑な筋書きによって最愛のイモインダを殺すことになる。 高貴な野蛮人の人となりに関するテーマは、小説『オロノコ』の主題である: アフラ・ベーン作『Oroonoko:Or the Royal Slave』(1688年)は、アフリカの王と王妃であるオルーノコと美しいイモインダの悲恋物語である。ガーナのコラマンティエンで、主人公は騙されて 大西洋奴隷貿易(16~19世紀)に引き渡され、オロノコはスリナム(オランダ領ギアナ、1667~1954年)のプランテーション入植者の奴隷となる。 オロノコは奴隷にされる過程で、オロノコ王子の人生と愛、奴隷にされたこと、スリナムのオランダ人プランターに対する奴隷の反乱を率いたこと、その結果オ ランダ人植民地主義者によって処刑されたことを読者に語りかける女性と出会う[18]。 ベーンは金のためにこの人気小説を書いたにもかかわらず、『オロノコ』は奴隷制度に反対する政治的抗議文学であることが証明された。その際、アイルランド の劇作家トマス・サザーンが、小説『オロノコ』を舞台劇『オロノコ』に脚色した: その結果、この戯曲と小説は、奴隷を動力源とするヨーロッパの植民地主義を率直に文化的に表現するものとして、政治的に重要な意味を持つことになった。 |

| Uses of the stereotype Romantic primitivism In the 1st century AD, in the book Germania, Tacitus ascribed to the Germans the cultural superiority of the noble savage way of life, because Rome was too civilized, unlike the savage Germans.[19] The art historian Erwin Panofsky explains that: There had been, from the beginning of Classical speculation, two contrasting opinions about the natural state of man, each of them, of course, a "Gegen-Konstruktion" to the conditions under which it was formed. One view, termed "soft" primitivism in an illuminating book by Lovejoy and Boas, conceives of primitive life as a golden age of plenty, innocence, and happiness — in other words, as civilized life purged of its vices. The other, "hard" form of primitivism conceives of primitive life as an almost subhuman existence full of terrible hardships and devoid of all comforts — in other words, as civilized life stripped of its virtues.[20] — Et in Arcadia Ego: Poussin and the Elegiac Tradition (1936) In the novel The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses (1699), in the “Encounter with the Mandurians” (Chapter IX), the theologian François Fénelon presented the noble savage stock character in conversation with civilized men from Europe about possession and ownership of Nature: On our arrival upon this coast we found there a savage race who ... lived by hunting and by the fruits which the trees spontaneously produced. These people ... were greatly surprised and alarmed by the sight of our ships and arms and retired to the mountains. But since our soldiers were curious to see the country and hunt deer, they were met by some of these savage fugitives. The leaders of the savages accosted them thus: “We abandoned for you, the pleasant sea-coast, so that we have nothing left, but these almost inaccessible mountains: at least, it is just that you leave us in peace and liberty. Go, and never forget that you owe your lives to our feeling of humanity. Never forget that it was from a people whom you call rude and savage that you receive this lesson in gentleness and generosity. ... We abhor that brutality which, under the gaudy names of ambition and glory, ... sheds the blood of men who are all brothers. ... We value health, frugality, liberty, and vigor of body and mind: the love of virtue, the fear of the gods, a natural goodness toward our neighbors, attachment to our friends, fidelity to all the world, moderation in prosperity, fortitude in adversity, courage always bold to speak the truth, and abhorrence of flattery. ... If the offended gods so far blind you as to make you reject peace, you will find, when it is too late, that the people who are moderate and lovers of peace are the most formidable in war.” — Encounter with the Mandurians, The Adventures of Telemachus, Son of Ulysses (1699)[21] In the 18th century, British intellectual debate about Primitivism used the Highland Scots as a local, European example of a noble savage people, as often as the American Indians were the example. The English cultural perspective scorned the ostensibly rude manners of the Highlanders, whilst admiring and idealizing the toughness of person and character of the Highland Scots; the writer Tobias Smollett described the Highlanders: They greatly excel the Lowlanders in all the exercises that require agility; they are incredibly abstemious, and patient of hunger and fatigue; so steeled against the weather, that in traveling, even when the ground is covered with snow, they never look for a house, or any other shelter but their plaid, in which they wrap themselves up, and go to sleep under the cope of heaven. Such people, in quality of soldiers, must be invincible. . . . — The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771)[22] Thomas Hobbes The imperial politics of Western Europe featured debates about soft primitivism and hard primitivism worsened with the publication of Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil (1651), by Thomas Hobbes, which justified the central-government regime of absolute monarchy as politically necessary for societal stability and the national security of the state: Whatsoever therefore is consequent to a time of War, where every man is Enemy to every man; the same is consequent to the time, wherein men live without other security, than what their own strength, and their own invention shall furnish them withall. In such condition, there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth; no Navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by Sea; no commodious Building; no Instruments of moving, and removing such things as require much force; no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short. — Leviathan[23] In the Kingdom of France, critics of the Crown and Church risked censorship and summary imprisonment without trial, and primitivism was political protest against the repressive imperial règimes of Louis XIV and Louis XV. In his travelogue of North America, the writer Louis-Armand de Lom d'Arce de Lahontan, Baron de Lahontan, who had lived with the Huron Indians (Wyandot people), ascribed deist and egalitarian politics to Adario, a Canadian Indian who played the role of noble savage for French explorers: Adario sings the praises of Natural Religion. ... As against society, he puts forward a sort of primitive Communism, of which the certain fruits are Justice and a happy life. ... [The Savage] looks with compassion on poor civilized man — no courage, no strength, incapable of providing himself with food and shelter: a degenerate, a moral cretin, a figure of fun in his blue coat, his red hose, his black hat, his white plume and his green ribands. He never really lives, because he is always torturing the life out of himself to clutch at wealth and honors, which, even if he wins them, will prove to be but glittering illusions. ... For science and the arts are but the parents of corruption. The Savage obeys the will of Nature, his kindly mother, therefore he is happy. It is civilized folk who are the real barbarians. — Paul Hazard, The European Mind[24] Interest in the remote peoples of the Earth, in the unfamiliar civilizations of the East, in the untutored races of America and Africa, was vivid in France in the 18th century. Everyone knows how Voltaire and Montesquieu used Hurons or Persians to hold up the [looking] glass to Western manners and morals, as Tacitus used the Germans to criticize the society of Rome. But very few ever look into the seven volumes of the Abbé Raynal's History of the Two Indies, which appeared in 1772. It is however one of the most remarkable books of the century. Its immediate practical importance lay in the array of facts which it furnished to the friends of humanity in the movement against negro slavery. But it was also an effective attack on the Church and the sacerdotal system. ... Raynal brought home to the conscience of Europeans the miseries which had befallen the natives of the New World through the Christian conquerors and their priests. He was not indeed an enthusiastic preacher of Progress. He was unable to decide between the comparative advantages of the savage state of nature and the most highly cultivated society. But he observes that "the human race is what we wish to make it", that the felicity of Man depends entirely on the improvement of legislation, and ... his view is generally optimistic. — J.B. Bury, The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth[25] Benjamin Franklin Benjamin Franklin was critical of government indifference to the Paxton Boys massacre of the Susquehannock in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania in December 1763. Within weeks of the murders, he published A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County, in which he referred to the Paxton Boys as "Christian white savages" and called for judicial punishment of those who carried the Bible in one hand and a hatchet in the other.[26] When the Paxton Boys led an armed march on Philadelphia in February 1764, with the intent of killing the Moravian Lenape and Mohican who had been given shelter there, Franklin recruited associators including Quakers to defend the city and led a delegation that met with the Paxton leaders at Germantown outside Philadelphia. The marchers dispersed after Franklin convinced them to submit their grievances in writing to the government.[27] In his 1784 pamphlet Remarks Concerning the Savages of North America, Franklin especially noted the racism inherent to the colonists using the word savage as a synonym for indigenous people: "Savages" we call them, because their manners differ from ours, which we think the perfection of civility; they think the same of theirs.[28] Franklin praised the way of life of indigenous people, their customs of hospitality, their councils of government, and acknowledged that while some Europeans had foregone civilization to live like a "savage", the opposite rarely occurred, because few indigenous people chose "civilization" over "savagery".[29] Jean-Jacques Rousseau  Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778) by Allan Ramsay (1766) Wikiquote has quotations related to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and noble savage. Like the Earl of Shaftesbury in the Inquiry Concerning Virtue, or Merit (1699), Jean-Jacques Rousseau likewise believed that Man is innately good, and that urban civilization, characterized by jealousy, envy, and self-consciousness, has made men bad in character. In Discourse on the Origins of Inequality Among Men (1754), Rousseau said that in the primordial state of nature, man was a solitary creature who was not méchant (bad), but was possessed of an "innate repugnance to see others of his kind suffer."[30] Moreover, as the philosophe of the Jacobin radicals of the French Revolution (1789–1799), ideologues accused Rousseau of claiming that the noble savage was a real type of man, despite the term not appearing in work written by Rousseau;[31] in addressing The Supposed Primitivism of Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality (1923), the academic Arthur O. Lovejoy said that: The notion that Rousseau’s Discourse on Inequality was essentially a glorification of the State of Nature, and that its influence tended to wholly or chiefly to promote “Primitivism” is one of the most persistent historical errors.[32] In the Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau said that the rise of humanity began a "formidable struggle for existence" between the species man and the other animal species of Nature.[33] That under the pressure of survival emerged le caractère spécifique de l'espèce humaine, the specific quality of character, which distinguishes man from beast, such as intelligence capable of "almost unlimited development", and the faculté de se perfectionner, the capability of perfecting himself.[34] Having invented tools, discovered fire, and transcended the state of nature, Rousseau said that "it is easy to see. . . . that all our labors are directed upon two objects only, namely, for oneself, the commodities of life, and consideration on the part of others"; thus amour propre (self-regard) is a "factitious feeling arising, only in society, which leads a man to think more highly of himself than of any other." Therefore, "it is this desire for reputation, honors, and preferment which devours us all . . . this rage to be distinguished, that we own what is best and worst in men — our virtues and our vices, our sciences and our errors, our conquerors and our philosophers — in short, a vast number of evil things and a small number of good [things]"; that is the aspect of character "which inspires men to all the evils which they inflict upon one another."[35] Men become men only in a civil society based upon law, and only a reformed system of education can make men good; the academic Lovejoy explains that: For Rousseau, man's good lay in departing from his "natural" state — but not too much; "perfectability", up to a certain point, was desirable, though beyond that point an evil. Not its infancy but its jeunesse [youth] was the best age of the human race. The distinction may seem to us slight enough; but in the mid-eighteenth century it amounted to an abandonment of the stronghold of the primitivistic position. Nor was this the whole of the difference. As compared with the then-conventional pictures of the savage state, Rousseau's account, even of this third stage, is far less idyllic; and it is so because of his fundamentally unfavorable view of human nature quâ human. ... [Rousseau's] savages are quite unlike Dryden's Indians: "Guiltless men, that danced away their time, / Fresh as the groves and happy as their clime" or Mrs. Aphra Behn's natives of Surinam, who represented an absolute idea of the first state of innocence "before men knew how to sin." The men in Rousseau's "nascent society" already had 'bien des querelles et des combats" [many quarrels and fights]; l'amour propre was already manifest in them ... and slights or affronts were consequently visited with vengeances terribles.[36] Rousseau proposes reorganizing society with a social contract that will "draw from the very evil from which we suffer the remedy which shall cure it"; Lovejoy notes that in the Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau: declares that there is a dual process going on through history; on the one hand, an indefinite progress in all those powers and achievements which express merely the potency of man's intellect; on the other hand, an increasing estrangement of men from one another, an intensification of ill-will and mutual fear, culminating in a monstrous epoch of universal conflict and mutual destruction. And the chief cause of the latter process Rousseau, following Hobbes and [Bernard] Mandeville, found, as we have seen, in that unique passion of the self-conscious animal — pride, self esteem, le besoin de se mettre au dessus des autres [the need to put oneself above others]. A large survey of history does not belie these generalizations, and the history of the period since Rousseau wrote lends them a melancholy verisimilitude. Precisely the two processes, which he described have ... been going on upon a scale beyond all precedent: immense progress in man's knowledge and in his powers over nature, and, at the same time, a steady increase of rivalries, distrust, hatred and, at last, "the most horrible state of war" ... [Moreover, Rousseau] failed to realize fully how strongly amour propre tended to assume a collective form ... in pride of race, of nationality, of class.[37] Charles Dickens In 1853, in the weekly magazine Household Words, Charles Dickens published a negative review of the Indian Gallery cultural program, by the portraitist George Catlin, which then was touring England. About Catlin's oil paintings of the North American natives, the poet and critic Charles Baudelaire said that "He [Catlin] has brought back alive the proud and free characters of these chiefs; both their nobility and manliness."[38]  For European art collectors, the American portraitist George Catlin painted idealized representations of the North American noble savage. (William Fisk, 1849)  The Noble Savage as stereotype: Sha-có-pay, Chief of the Ojibwa Indians of the Great Plains. (George Catlin, 1832) Despite European idealization of the noble savage as a type of morally superior man, in the essay “The Noble Savage” (1853), Dickens expressed repugnance for the American Indians and their way of life, because they were dirty and cruel and continually quarrelled among themselves.[39] In the satire of romanticised primitivism Dickens showed that the painter Catlin, the Indian Gallery of portraits and landscapes, and the white people who admire the idealized American Indians or the bushmen of Africa are examples of the term noble savage used as a means of Othering a person into a racialist stereotype.[40] Dickens begins by dismissing the noble savage as not being a distinct human being: To come to the point at once, I beg to say that I have not the least belief in the Noble Savage. I consider him a prodigious nuisance and an enormous superstition. . . . [41] I don't care what he calls me. I call him a savage, and I call a savage a something highly desirable to be civilized off the face of the Earth. . . . [42] The noble savage sets a king to reign over him, to whom he submits his life and limbs without a murmur or question, and whose whole life is passed chin deep in a lake of blood; but who, after killing incessantly, is in his turn killed by his relations and friends the moment a grey hair appears on his head. All the noble savage's wars with his fellow-savages (and he takes no pleasure in anything else) are wars of extermination — which is the best thing I know of him, and the most comfortable to my mind when I look at him. He has no moral feelings of any kind, sort, or description; and his "mission" may be summed up as simply diabolical.[43] Dickens ends his cultural criticism by reiterating his argument against the romanticized persona of the noble savage: To conclude as I began. My position is that if we have anything to learn from the Noble Savage it is what to avoid. His virtues are a fable; his happiness is a delusion; his nobility, nonsense. We have no greater justification for being cruel to the miserable object, than for being cruel to a WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE or an ISAAC NEWTON; but he passes away before an immeasurably better and higher power than ever ran wild in any earthly woods, and the world will be all the better when this place [Earth] knows him no more.[44] Theories of racialism In 1860, the physician John Crawfurd and the anthropologist James Hunt identified the racial stereotype of the noble savage as an example of scientific racism,[45] yet, as advocates of polygenism — that each race is a distinct species of Man — Crawfurd and Hunt dismissed the arguments of their opponents by accusing them of being proponents of "Rousseau's Noble Savage". Later in his career, Crawfurd re-introduced the noble savage term to modern anthropology and deliberately ascribed coinage of the term to Jean-Jacques Rousseau.[46] |

ステレオタイプの用法 ロマン主義的未開主義 紀元1世紀、タキトゥスは『ゲルマニア』の中で、ローマは未開のゲルマン人とは異なり文明化されすぎていたため、高貴な未開人の生活様式の文化的優位性を ゲルマン人に認めた[19]: 古典派の思索が始まった当初から、人間の自然なあり方について二つの対照的な意見があった。ひとつは、ラブジョイとボアスによる啓発的な書物の中で「ソフ ト」な未開主義と呼ばれているもので、原始の生活を豊かで無邪気で幸福な黄金時代、言い換えれば、悪徳を取り除いた文明化された生活として考えている。も う一方の「硬質」な未開主義では、原始的な生活を、ひどい苦難に満ち、あらゆる快適さを欠いた、ほとんど人間以下の存在として、言い換えれば、美徳を取り 除いた文明化された生活として考えている[20]。 - プッサンとエレガンス プッサンとエレジアの伝統 (1936) 小説『ユリシーズの息子テレマコスの冒険』(1699年)の「マンドゥール人との出会い」(第Ⅸ章)では、神学者フランソワ・フェネロンが、高貴な未開人 である主人公が、自然の所有と所有権についてヨーロッパから来た文明人と会話する様子を描いている: 私たちがこの海岸に到着したとき、そこには狩猟と木々が自然に実らせる果実によって生活する未開の種族がいた。これらの人々は......我々の船と武器 を見て非常に驚き、警戒し、山に退いた。しかし、わが軍の兵士たちは、この地方を見物し、鹿を狩ることに興味を持ったので、未開人の逃亡者たちに出会っ た。 野蛮人のリーダーたちは彼らにこう声をかけた: 「私たちはあなたたちのために、快適な海辺を捨てた。だから、私たちには、このほとんど近づけない山々しか残っていない。行って、あなたたちの命が私たち の人道的感情に負っていることを決して忘れてはならない。あなた方が無礼で野蛮だと呼ぶ人々から、この優しさと寛大さの教えを受けたことを決して忘れては ならない。... われわれは、野心と栄光という派手な名の下に、同じ兄弟である人間の血を流す残忍さを憎む。... われわれは、健康、質素、自由、心身の活力を重んじ、美徳を愛し、神々を畏れ、隣人に対する自然な善意、友人に対する愛着、全世界に対する忠誠、繁栄にお ける節度、逆境における不屈の精神、常に真実を大胆に語る勇気、お世辞を嫌う。... ......怒れる神々が、あなたがたに平和を拒絶させるほどにあなたがたを盲目にさせるなら、手遅れになったとき、あなたがたは、穏健で平和を愛する人 々が、戦争において最も手ごわい存在であることに気づくだろう" - マンドゥール人との遭遇、 『ユリシーズの息子テレマコスの冒険』 (1699年)[21]。 18世紀、プリミティヴィズムに関するイギリスの知識人の議論では、アメリカン・インディアンがその例であったように、ハイランド・スコットランド人が高 貴な未開人のローカルなヨーロッパ人の例としてしばしば用いられた。イギリスの文化的視点は、ハイランド人の表向きの無作法なマナーを軽蔑する一方で、ハ イランド・スコットランド人の強靭な人間性と性格を賞賛し、理想化した: 彼らは、機敏さを必要とするあらゆる運動において、ローランド人に大きく勝っている。彼らは驚くほど禁欲的で、飢えや疲労に忍耐強い。天候に対して非常に 鋼鉄であり、旅先で地面が雪で覆われていても、家屋や他の避難所を探すことはない。このような人々は、兵士の質から言えば、無敵に違いない。. . . - ハンフリー・クリンカーの遠征』 (1771年)[22]。 トマス・ホッブズ[編集] 西ヨーロッパの帝国政治は、トマス・ホッブズによる『リヴァイアサン』(Leviathan, or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil(1651))の出版によって、ソフトな未開主義とハードな未開主義についての議論が悪化した: それゆえ、すべての人がすべての人に敵対する戦争の時代に帰結するものは何であろうと、同じことが、人が自分自身の力と自分自身の発明とがすべて与えてく れるもの以外の保障なしに生きる時代にも帰結するのである。このような状態では、産業の場がない;その果実が不確かであるため;その結果、大地の文化もな い;航海も、海によって輸入されるかもしれない商品の使用もない;日当たりのよい建物もない;移動する道具も、大きな力を必要とするものを取り除く道具も ない;地球の表面の知識もない;時間の計算もない;芸術もない;手紙もない;社会もない;そして、すべての中で最悪なのは、継続的な恐怖と、暴力的な死の 危険である;そして、人間の人生は、孤独で、貧しく、厄介で、残忍で、短い。 - リヴァイアサン[23] フランス王国では、王室や教会に対する批評家は検閲や裁判なしの略式投獄の危険にさらされ、プリミティヴィズムはルイ14世と ルイ15世の抑圧的な帝政に対する政治的抗議であった。ヒューロンインディアン(ワイアンドット族)と暮らしていた作家のラホンタン男爵ルイ=アルマン・ ド・ロム・ダルセは、北アメリカ旅行記の中で、フランスの探検家たちに高貴な野蛮人の役割を果たしたカナダのインディアン、アダリオに神道的で平等主義的 な政治性を与えた: アダリオは自然宗教を賛美している。... 社会に対して、彼は一種の原始的な共産主義を提唱し、その確かな果実は正義と幸福な生活である。... [勇気がなく、力もなく、衣食住を自分でまかなうこともできない、堕落した、道徳的な愚か者であり、青いコート、赤いホース、黒い帽子、白い羽飾り、緑の リバンドを身につけた滑稽な姿である。彼は、富と栄誉を手に入れるために、常に自分自身の生命を苦しめているのだ。... 科学や芸術は堕落の親にすぎない。野蛮人は、優しい母である自然の意志に従う。文明人こそが真の野蛮人なのだ。 - ポール・ハザード『 ヨーロッパ人の心』[24]。 地球の遠い民族、東洋の見慣れない文明、アメリカやアフリカの未学習の民族に対する関心は、18世紀のフランスでは鮮明だった。ヴォルテールや モンテスキューが、西洋の風俗や道徳を批判するために、ヒューロン人やペルシア人をどのように利用したか、タキトゥスがローマの社会を批判するためにドイ ツ人をどのように利用したか、誰もが知っている。しかし、1772年に出版されたレイナル修道院長の『二インド史』全7巻に目を通す者はほとんどいない。 しかし、この世紀の最も注目すべき書物の一つである。その直接的な実用的重要性は、黒人奴隷制に反対する運動において、人類の友に提供した事実の数々に あった。しかし、教会と聖職者制度に対する効果的な攻撃でもあった。... レイナルはヨーロッパ人の良心に、キリスト教征服者とその司祭によって新世界の原住民に降りかかった災難を訴えかけた。彼は進歩の熱心な説教者ではなかっ た。彼は、未開の自然状態と最も高度に発達した社会との比較優位性を判断することができなかった。しかし彼は、「人類はわれわれの望むとおりのものであ る」、「人間の幸福はすべて立法の改善にかかっている」、「......彼の見解は概して楽観的である」と述べている。 -J.B. Bury, The Idea of Progress: an Inquiry into its Origins and Growth[25]. ベンジャミン・フランクリン[編集] ベンジャミン・フランクリンは、1763年12月にペンシルベニア州ランカスター郡で起こったパクストン・ボーイズによる サスケハノック族の虐殺に対する政府の無関心に批判的であった。この殺人事件から数週間以内に、彼は『A Narrative of the Late Massacres in Lancaster County』を出版し、その中でパクストン・ボーイズを「キリスト教白人の野蛮人」と呼び、片手に聖書、片手に斧を持つ者たちを司法で罰するよう呼びか けた[26]。 1764年2月、パクストン・ボーイズがフィラデルフィアに避難していたモラビア人の レナペと モヒカンを殺害する目的で武装行進を行ったとき、フランクリンはクエーカー教徒を含む仲間を募ってフィラデルフィアを防衛し、代表団を率いてフィラデル フィア郊外のジャーマンタウンでパクストンの指導者たちと会談した。フランクリンが彼らの苦情を文書で政府に提出するよう説得した後、行進者たちは解散し た[27]。 フランクリンは1784年の小冊子『北アメリカの野蛮人に関する発言』の中で、植民地主義者が先住民の代名詞として野蛮人という言葉を使うことに内在する 人種差別を特に指摘している: 野蛮人 "とわれわれが呼ぶのは、彼らの作法がわれわれと異なるからであり、われわれはそれを礼節の完成形だと考えているが、彼らも同じだと考えている」 [28]。 フランクリンは先住民の生活様式、もてなしの習慣、政府の評議会を賞賛し、「野蛮人」のように生きるために文明を捨てたヨーロッパ人がいた一方で、「野 蛮」よりも「文明」を選んだ先住民はほとんどいなかったため、その逆はほとんど起こらなかったと認めている[29]。 ジャン=ジャック・ルソー  アラン・ラムジーによるジャン=ジャック・ルソー(1712年-1778年)(1766年) ウィキクオートには、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーと高潔な野蛮人に関する引用がある。 『徳について、あるいは、功徳について』(1699年)のシャフツベ リー伯のように、ジャン=ジャック・ルソーも同様に、人間は生まれつき善良であり、嫉妬、羨望、自意識に特徴づけられる都市文明が人間を悪くしたと信じて いた。『人間不平等起源論』(1754年)の中で、ルソーは、自然の原始状態においては、人間は孤立した生き物であり、悪人(méchant)ではなく、 「同類の者が苦しむのを見ることに対する生まれながらの嫌悪感」を持っていたと述べている。 さらに、フランス革命(1789年~1799年)におけるジャコバン派 急進派の哲学者として、イデオローグたちは、ルソーの著作にはその用語は登場していないにもかかわらず、高潔な野蛮人が現実の人間のタイプであると主張し たとルソーを非難した。『不平等についての論考』におけるルソーの未開主義(1923年)について論じた学者アーサー・O・ラブジョイは次のように述べて いる。 『不平等についての論考』は本質的には自然状態の美化であり、その影響は「未開主義」を全面的に、あるいは主に促進する傾向があるという考え方は、最も根強い歴史的誤りのひとつである。 『不平等起源論』の中で、ルソーは、人類の台頭は、人間という種と自然 界の他の動物種との間の「恐るべき生存競争」から始まったと述べている。生存の圧力の下で、人間を獣から区別する人間特有の性格、すなわち「ほぼ無限の可 能性」を持つ知性や、自分を磨く能力といった人間特有の性格が生まれた。 道具を発明し、火を発見し、自然の状態を超越したことで、ルソーは「容 易に理解できる。...我々のすべての労働は、すなわち、自分自身のために、生活必需品を得るため、そして他者の配慮を得るために、という2つの目的にの み向けられている」と述べた。したがって、amour propre(自己愛)は「社会においてのみ生じる、人間が自分自身を他の何よりも高く評価するよう仕向ける、作り出された感情」である。したがって、 「名声、栄誉、昇進への欲望が私たちをすべてを蝕む。... 際立とうとするこの欲望が、私たちが人間のもつ最良のものも最悪のものも、すなわち、私たちの美徳や悪徳、知識や誤り、征服者や哲学者を所有する。つま り、性格のこの側面が、人間に互いに悪事を働くよう駆り立てるのだ。 人間が人間らしくなるのは、法に基づく市民社会においてのみであり、人間を善良にするのは教育制度の改革だけである。学識あるラブジョイは次のように説明している。 ルソーにとって、人間が善良になるのは「自然な」状態から離れることで ある。ただし、それは度を超えてはならない。ある程度までは「完全性」が望ましいが、それを超えると悪となる。人間にとって最良の年齢は、幼少期ではなく 青年期(青春)である。この違いは私たちにとっては些細なことのように思えるかもしれないが、18世紀半ばにおいては、それは未開主義的立場を放棄するに 等しいものであった。 しかし、違いはこれだけにとどまらない。 野蛮な状態に関する当時の一般的な考え方と比較すると、ルソーの説明は、この第三段階においても、はるかに牧歌的ではない。 そして、それは彼が人間の本質を根本的に否定的にとらえているためである。... [ルソーの] 野蛮人は、ドライデンのインディアンとは全く異なる。「罪なき人々、踊って時を過ごし、/ 森のように瑞々しく、その風土のように幸福」というような、あるいは、アフラ・ベーン夫人のスリナムの原住民のように、「人が罪を犯すことを知る前の」無 垢の最初の状態の絶対的な概念を表すような。ルソーの言う「初期の社会」に属する人々はすでに「多くの争いと戦い」を経験しており、彼らの中にはすでに 「高潔さ」が現れていた。そして、軽視や侮辱は当然、恐ろしい復讐を招くこととなった。 ルソーは、社会契約によって社会を再編成することを提案し、「私たちが苦しむ悪の根源から、それを癒すための解決策を引き出す」と述べている。ラブジョイは、『不平等起源論』の中で、ルソーが 歴史の中で2つのプロセスが進行していると宣言している。一方では、人 間の知性の潜在能力を示すあらゆる力や成果における無限の進歩であり、他方では、人間同士の疎外感の増大、悪意と相互の恐怖の激化であり、最終的には、普 遍的な対立と相互破壊の怪物的な時代へと至る。そして、後者の過程の主な原因について、ルソーはホッブズやマンデヴィルにならって、我々が見てきたよう に、自意識を持つ動物特有の情熱、すなわち「プライド」、「自尊心」、「le besoin de se mettre au dessus des autres(他者よりも上に立つ必要性)」を見出した。歴史を広く概観しても、これらの一般論は間違いではない。そして、ルソーが書いた後の時代の歴史 は、それらに憂鬱な真実味を与えている。まさに彼が述べた2つのプロセスは、... これまでの前例をはるかに超える規模で進行している。すなわち、人間の知識と自然に対する人間の力の飛躍的な進歩、そして同時に、確実な対立、不信、憎 悪、そしてついには「最も恐ろしい戦争状態」である。... さらに、ルソーは、高潔さ(amour propre)が集団的な形態をとりがちであることを十分に理解していなかった。... 人種、国籍、階級の誇りにおいて。 チャールズ・ディケンズ 1853年、チャールズ・ディケンズは週刊誌『Household Words』に、当時イギリスを巡回していた肖像画家ジョージ・カトリンによるインド・ギャラリーの文化プログラムに対する否定的な批評を掲載した。北米 原住民を描いたカトリンの油絵について、詩人であり批評家でもあったシャルル・ボードレールは、「彼(カトリン)は、これらの酋長たちの誇り高く自由な性 格、その気高さと男らしさの両方を生き生きとよみがえらせた」と述べている[38]。  ヨーロッパの美術コレクターのために、アメリカの肖像画家ジョージ・カトリンは北米の高貴な野蛮人の理想化された姿を描いた。(ウィリアム・フィスク、 1849年)  ステレオタイプとしての高貴な野蛮人: 大平原のオジブワ・インディアンの酋長、シャ・コ・ペイ。(ジョージ・カトリン、1832年) ヨーロッパでは高貴な野蛮人を道徳的に優れた人間の一種として理想化していたにもかかわらず、ディケンズは『高貴な野蛮人』(1853年)というエッセイ の中で、アメリカ・インディアンとその生活様式に嫌悪感を示した。 [ディケンズは、ロマン主義的な未開主義への風刺の中で、画家のカトリン、肖像画や風景画のインディアンの画廊、理想化されたアメリカ・インディアンやア フリカのブッシュマンに憧れる白人が、人種主義的なステレオタイプに人を他者化する手段として使われる高貴な野蛮人という言葉の一例であることを示した [40]。ディケンズは、高貴な野蛮人は別個の人間ではないと切り捨てることから始める: すぐに本題に入るが、私は高貴な野蛮人というものを少しも信じていない。私は彼を、とてつもなく厄介で、とてつもなく大きな迷信だと思っている。. . . [41] 彼が私を何と呼ぼうと構わない。私は彼を野蛮人と呼ぶし、野蛮人は地球上から文明化されることが非常に望ましいものだと呼ぶ。. . . [42] 高貴な未開人は、自分の命と手足を捧げ、何の疑問も抱くことなく、血の湖にあごまで浸かって一生を終える王を、自分の上に君臨させる。高貴な野蛮人が仲間 の野蛮人と繰り広げる戦争はすべて(それ以外のことに喜びを感じることはない)絶滅戦争である。彼にはいかなる種類の、いかなる種類の、いかなる形容の道 徳的感情もなく、彼の「使命」は単に極悪非道と要約されるかもしれない[43]。 ディケンズは、高貴な野蛮人というロマン主義化されたペルソナに対する反論を繰り返すことで、文化批評を終えている: 結論から言おう。私の立場は、高貴な野蛮人から学ぶべきことがあるとすれば、それは何を避けるかということである。彼の美徳は寓話であり、彼の幸福は妄想 であり、彼の気高さはナンセンスである。しかし、彼は、地上の森で野生化した者よりも計り知れないほど優れた、より高い力の前に立ち去り、この場所(地 球)が彼を知らなくなったとき、世界はより良くなるであろう[44]。 人種主義の理論 1860年、医師のジョン・クローファードと人類学者のジェームズ・ハントは、高貴な野蛮人という人種的ステレオタイプを科学的人種差別主義の一例として 挙げたが[45]、各人種は人間の異なる種であるという多遺伝子主義の提唱者として、クローファードとハントは、反対派の議論を「ルソーの高貴な野蛮人」 の提唱者であると非難して退けた。その後、クロフルドはノーブル・ネイヴァーという言葉を現代の人類学に再び導入し、その造語を意図的にジャン=ジャッ ク・ルソーに帰属させた[46]。 ※【追記】ジェームス・ハントは、1854年までに人類学に興味を持ち、「人種が人間社会においてすべてである」という学説を広めたロバート・ノックス博 士の「弟子」となった。ハントにとって、遺伝的特権と平等主義の間の大きな葛藤は、奴隷制の対立のドラマの中で演じられるべきものであった。あるいは、こ の対立が他の学者の感情や良心を揺さぶり、ハントは人種的優越性の科学的「真実」の擁護者としてこの対立に巻き込まれるべきであった。この章では、人種 は、表面的な表現型の特徴の束を、その根底にある遺伝子型の複雑性よりも優先させる、一般的かつ政治的な神話であると論じている。しかし、ハントは人類学 を科学の基盤とすべく、全力を尽くした。 |

| Modern perspectives Supporters of primitivism In "The Prehistory of Warfare: Misled by Ethnography" (2006), the researchers Jonathan Haas and Matthew Piscitelli challenged the idea that the human species is innately bellicose and that warfare is an occasional activity by a society, but is not an inherent part of human culture.[47] Moreover, the UNESCO's Seville Statement on Violence (1986) specifically rejects claims that the human propensity towards violence has a genetic basis.[48][49] Anarcho-primitivists, such as the philosopher John Zerzan, rely upon a strong ethical dualism between Anarcho-primitivism and civilization; hence, "life before domestication [and] agriculture was, in fact, largely one of leisure, intimacy with nature, sensual wisdom, sexual equality, and health."[50] Zerzan's claims about the moral superiority of primitive societies are based on a certain reading of the works of anthropologists, such as Marshall Sahlins and Richard Borshay Lee, wherein the anthropologic category of primitive society is restricted to hunter-gatherer societies who have no domesticated animals or agriculture, e.g. the stable social hierarchy of the American Indians of the north-west North America, who live from fishing and foraging, is attributed to having domesticated dogs and the cultivation of tobacco, that animal husbandry and agriculture equal civilization.[50][51] In anthropology, the argument has been made that key tenets of the noble-savage idea inform cultural investments in places seemingly removed from the Tropics, such as the Mediterranean and specifically Greece, during the debt crisis by European institutions (such as documenta) and by various commentators who found Greece to be a positive inspiration for resistance to austerity policies and the neoliberalism of the EU[52] These commentators' positive embrace of the periphery (their noble-savage ideal) is the other side of the mainstream views, also dominant during that period, that stereotyped Greece and the South as lazy and corrupt. Opponents of primitivism In War Before Civilization: the Myth of the Peaceful Savage (1996), the archaeologist Lawrence H. Keeley said that the "widespread myth" that "civilized humans have fallen from grace from a simple, primeval happiness, a peaceful golden age" is contradicted and refuted by archeologic evidence that indicates that violence was common practice in early human societies. That the noble savage paradigm has warped anthropological literature to political ends.[53] Moreover, the anthropologist Roger Sandall likewise accused anthropologists of exalting the noble savage above civilized man,[54] by way of designer tribalism, a form of romanticised primitivism that dehumanises Indigenous peoples into the cultural stereotype of the indigène peoples who live a primitive way of life demarcated and limited by tradition, which discouraged Indigenous peoples from cultural assimilation into the dominant Western culture.[55][56][57] |

現代の視点 未開主義の支持者たち The Prehistory of Warfare(戦争の先史学)』(2006年)の中で、研究者のジョナサン・ハースとマシュー・ピシテリは、人類という種が生来持っているという考えに 異議を唱えた: さらに、ユネスコの「暴力に関するセビリア声明」(1986年)は、人間の暴力傾向が遺伝的基盤を持っているという主張を明確に否定している[48] [49]。 哲学者ジョン・ゼルザンのようなアナルコ未開主義者は、アナルコ未開主義と文明との間の強い倫理的二元論に依拠している。したがって、「家畜化(と農業) 以前の生活は、実際には、大部分が余暇、自然との親密さ、官能的な知恵、性的平等、健康のものであった。 「原始社会の道徳的優位性に関するゼルザンの主張は、マーシャル・サーリンズや リチャード・ボーシェイ・リーといった人類学者の著作のある読みに基づいている。 例えば、漁業と採集で生活する北アメリカ北西部のアメリカン・インディアンの安定した社会階層は、家畜化された犬とタバコの栽培を持っていることに起因し ており、畜産と農業は文明とイコールであるとしている[50][51]。 人類学においては、高貴で野蛮な思想の主要な教義が、地中海や特にギリシャのような、一見熱帯から離れた場所の文化的投資に反映されているという議論がな されている、 債務危機の際、(ドクメンタのような)ヨーロッパの機関や、緊縮政策やEUの新自由主義に対する抵抗のためのポジティブなインスピレーションをギリシャに 見出した様々なコメンテーターたちによって、ギリシャはそのようなものであった[52]。これらのコメンテーターたちの周縁部に対するポジティブな抱擁 (彼らの崇高な理想)は、ギリシャや南部を怠惰で堕落したものとしてステレオタイプ化した、同じくその時期に支配的であった主流の見解の裏返しである。 未開主義の反対者たち 考古学者のローレンス・H・キーリーは、『文明化以前の戦争:平和な野蛮人の神話』(1996年)の中で、「文明化された人類は、単純で原始的な幸福、平 和な黄金時代から堕落した」という「広範な神話」は、初期の人類社会では暴力が日常的に行われていたことを示す考古学的証拠によって矛盾し、反論されてい ると述べている。高貴な野蛮人のパラダイムは、人類学の文献を政治的目的のために歪めてきた。 [さらに、人類学者のロジャー・サンダルも同様に、デザイナー・トライバリズム(伝統によって区分され制限された原始的な生活様式を送る先住民という文化 的ステレオタイプに先住民を非人間化するロマンチックな未開主義の一形態)によって、人類学者が文明人よりも高貴な野蛮人を崇高していると非難している [54]。 |

| Racism in the work of Charles

Dickens Essays (Montaigne) Exoticism Native Americans in German popular culture Native American hobbyism in Germany Neotribalism Objectification Orientalism Pelagianism Positive stereotype Stereotypes about indigenous peoples of North America Racial fetishism Romantic racism Virtuous pagan Feral child Wild man Human zoo Uncontacted peoples Isolationism Concepts: Alterity Cultural relativism Golden Age Master-slave dialectic Primitive Communism Social progress State of nature Xenocentrism Cultural examples: The Blue Lagoon (novel) Brave New World A High Wind in Jamaica (novel) Legend of the Rainbow Warriors Lord of the Flies Magical Negro Plastic shaman |

チャールズ・ディケンズの作品における人種差別 エッセイ(モンテーニュ) エキゾチシズム ドイツの大衆文化におけるアメリカ先住民 ドイツにおけるアメリカ先住民趣味主義 新部族主義 対象化 オリエンタリズム ペラギウス主義 肯定的ステレオタイプ 北米先住民に関するステレオタイプ 人種フェティシズム ロマンチック人種主義 高潔な異教徒 野生児 野生人 人間動物園 未接触民族 孤立主義 概念 異質性 文化相対主義 黄金時代 主従弁証法 原始共産主義 社会の進歩 自然状態 ゼノセントリズム 文化的な例 ブルーラグーン(小説) ブレイブ・ニュー・ワールド ジャマイカに吹く強風(小説) 虹の戦士伝説 蝿の王 マジカル・ニグロ プラスチック・シャーマン |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Noble_savage |

|

| Plastic shamans, or plastic medicine people Plastic shamans, or plastic medicine people,[1] is a pejorative colloquialism applied to individuals who attempt to pass themselves off as shamans, holy people, or other traditional spiritual leaders, but who have no genuine connection to the traditions or cultures they claim to represent.[2] In some cases, the "plastic shaman" may have some genuine cultural connection, but is seen to be exploiting that knowledge for ego, power, or money.[3][4] Plastic shamans are believed by their critics to use the mystique of these cultural traditions, and the legitimate curiosity of sincere seekers, for their personal gain. In some cases, exploitation of students and traditional culture may involve the selling of fake "traditional" spiritual ceremonies, fake artifacts, fictional accounts in books, illegitimate tours of sacred sites, and often the chance to buy spiritual titles.[3] Often Native American symbols and terms are adopted by plastic shamans, and their adherents are insufficiently familiar with Native American religion to distinguish between imitations and actual Native religion.[1] |

プ

ラスティック・シャーマン、またはプラスティック・メディスン・ピープル プ ラスティック・シャーマン、またはプラスティック・メディスン・ピープル[1]とは、シャーマン、聖なる人々、または他の伝統的なスピリチュアル・リー ダーとして自分自身を偽ろうとするが、自分たちが代表すると主張する伝統や文化に真のつながりを持たない個人に適用される蔑称的な 口語表現である[2]。 場合によっては、「プラスティック・シャーマン」は何らかの真の文化的つながりを持つかもしれないが、エゴ、権力、または金銭のためにその知識を利用して いると見られる[3][4]。 プラスチック・シャーマンは、こうした文化的伝統の神秘性や、真摯に探求する人々の正当な好奇心を、個人的な利益のために利用していると、批判的な人々か ら信じられている。場合によっては、学生や伝統文化の搾取は、偽の「伝統的な」精神的儀式、偽の工芸品、書籍に書かれた架空の説明、聖地の違法なツアー、 そしてしばしば精神的な称号を購入する機会の販売を伴うこともある[3]。多くの場合、アメリカ先住民のシンボルや用語がプラスチック・シャーマンによっ て採用されており、彼らの信奉者はアメリカ先住民の宗教に十分に精通していないため、模造品と実際の先住民の宗教を区別することができない[1]。 |

| Overview The term "plastic shaman" originated among Native American and First Nations activists and is most often applied to people fraudulently posing as Native American traditional healers.[5][6] People who have been referred to as "plastic shamans" include those believed to be fraudulent, self-proclaimed spiritual advisors, seers, psychics, self-identified New Age shamans, or other practitioners of non-traditional modalities of spirituality and healing who are operating on a fraudulent basis.[3] "Plastic shaman" has also been used to refer to non-Natives who pose as Native American authors, especially if the writer is misrepresenting Indigenous spiritual ways (such as in the case of Ku Klux Klan member Asa Earl Carter and the scandal around his book The Education of Little Tree).[1][7] It is a very alarming trend. So alarming that it came to the attention of an international and intertribal group of medicine people and spiritual leaders called the Circle of Elders. They were highly concerned with these activities and during one of their gatherings addressed the issue by publishing a list of Plastic Shamans in Akwesasne Notes, along with a plea for them to stop their exploitative activities. One of the best known Plastic Shamans, Lynn Andrews, has been picketed by the Native communities in New York, Minneapolis, San Francisco, Seattle and other cities.[6] People have been injured, and some have died, in fraudulent sweat lodge ceremonies performed by non-Natives.[8][9][10][11][12] Among critics, this misappropriation and misrepresentation of Indigenous intellectual property is seen as an exploitative form of colonialism and one step in the destruction of Indigenous cultures:[13] The para-esoteric Indianess of Plastic Shamanism creates a neocolonial miniature with multilayered implications. First and foremost, it is suggested that the passé Injun elder is incapable of forwarding their knowledge to the rest of the white world. Their former white trainee, once thoroughly briefed in Indian spirituality, represents the truly erudite expert to pass on wisdom. This rationale, once again, reinforces nature-culture dualisms. The Indian stays the doomed barbaric pet, the Indianized is the eloquent and sophisticated medium to the outer, white world. Silenced and visually annihilated like that, the Indian retreats to prehistory, while the Plastic Shaman can monopolize their culture.[14] Defenders of the integrity of indigenous religion use the term "plastic shaman" to criticize those they believe are potentially dangerous and who may harm the reputations of the cultures and communities they claim to represent.[4] There is evidence that, in the most extreme cases, fraudulent and sometimes criminal acts have been committed by a number of these imposters.[15][16] It is also claimed by traditional peoples that in some cases these plastic shamans may be using corrupt, negative and sometimes harmful aspects of authentic practices. In many cases this has led to the actual traditional spiritual elders declaring the plastic shaman and their work to be "dark" or "evil" from the perspective of traditional standards of acceptable conduct.[3] Plastic shamans are also believed to be dangerous because they give people false ideas about traditional spirituality and ceremonies.[5] In some cases, the plastic shamans will require that the ceremonies are performed in the nude, and that men and women participate in the ceremony together, although such practices are an innovation and were not traditionally followed.[17] Another innovation may include the introduction of sex magic or "tantric" elements, which may be a legitimate form of spirituality in its own right (when used in its original cultural context), but in this context it is an importation from a different tradition and is not part of authentic Native practices.[3] The results of this appropriation of Indigenous knowledge have led some tribes, intertribal councils, and the United Nations General Assembly to issue several declarations on the subject: 4. We especially urge all our Lakota, Dakota, and Nakota people to take action to prevent our own people from contributing to and enabling the abuse of our sacred ceremonies and spiritual practices by outsiders; for, as we all know, there are certain ones among our own people who are prostituting our spiritual ways for their own selfish gain, with no regard for the spiritual well-being of the people as a whole. 5. We assert a posture of zero-tolerance for any "white man's shaman" who rises from within our own communities to "authorize" the expropriation of our ceremonial ways by non-Indians; all such "plastic medicine men" are enemies of the Lakota, Dakota and Nakota people. — Declaration of War Against Exploiters of Lakota Spirituality[18][19] Article 11: Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs. This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature. ... States shall provide redress through effective mechanisms, which may include restitution, developed in conjunction with indigenous peoples, with respect to their cultural, intellectual, religious and spiritual property taken without their free, prior and informed consent or in violation of their laws, traditions and customs. — Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[20] Article 31: 1. Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their cultural heritage, traditional knowledge and traditional cultural expressions, as well as the manifestations of their sciences, technologies and cultures, including human and genetic resources, seeds, medicines, knowledge of the properties of fauna and flora, oral traditions, literatures, designs, sports and traditional games and visual and performing arts. They also have the right to maintain, control, protect and develop their intellectual property over such cultural heritage, traditional knowledge, and traditional cultural expressions. — Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples[20] Therefore, be warned that these individuals are moving about playing upon the spiritual needs and ignorance of our non-Indian brothers and sisters. The value of these instructions and ceremonies are questionable, maybe meaningless, and hurtful to the individual carrying false messages. — Resolution of the 5th Annual Meeting of the Traditional Elders Circle[21] Many of those who work to expose plastic shamans believe that the abuses perpetuated by spiritual frauds can only exist when there is ignorance about the cultures a fraudulent practitioner claims to represent. Activists working to uphold the rights of traditional cultures work not only to expose the fraudulent distortion and exploitation of Indigenous traditions and Indigenous communities, but also to educate seekers about the differences between traditional cultures and the often-distorted modern approaches to spirituality.[3][6] One indicator of a plastic shaman might be someone who discusses "Native American spirituality" but does not mention any specific Native American tribe. The "New Age Frauds and Plastic Shamans" website discusses potentially plastic shamans.[22][23] |

概要 「プラスチック・シャーマン」という用語は、ネイティブ・アメリカンや ファースト・ネーションの活動家の間で生まれたもので、ネイティブ・アメリカンの伝統的なヒーラーを詐称している人々に対して適用されることが最も多い [5][6]。プラスチック・シャーマン」と呼ばれる人々には、詐称していると信じられている、自称スピリチュアル・アドバイザー、占い師、霊能者、自称 ニューエイジのシャーマン、または詐称に基づいて活動している非伝統的な精神性や癒しの様式の他の実践者が含まれる。 [3]「プラスチック・シャーマン」はまた、ネイティブ・アメリカンの著者を装う非ネイティブを指す場合にも使用されており、特にその著者が先住民の精神 的な方法を誤って伝えている場合(クー・クラックス・クランのメンバーであるアサ・アール・カーターや、彼の著書『リトル・ツリーの教育』にまつわるス キャンダルの場合など)に使用される[1][7]。 これは非常に憂慮すべき傾向である。あまりに憂慮すべきことなので、サークル・オブ・エルダーズと呼ばれるメディスンピープルとスピリチュアルリーダーの 国際的な部族間グループが注目するようになった。彼らはこうした活動に強い関心を持ち、ある会合でアクウェサスネ・ノートのプラスチック・シャーマンのリ ストを公表し、搾取的な活動をやめるよう嘆願した。最も有名なプラスティック・シャーマンの一人であるリン・アンドリュースは、ニューヨーク、ミネアポリ ス、サンフランシスコ、シアトルなどのネイティブ・コミュニティからピケを貼られている[6]。 非ネイティブによって行われた詐欺的なスウェット・ロッジの儀式で、人々が負傷し、何人かが死亡している[8][9][10][11][12]。 批評家の間では、このような先住民の知的財産の 不正流用や誤った表現は、植民地主義の搾取的な形態であり、先住民文化の破壊の一歩であるとみなされている[13]。 プラスティック・シャーマニズムのパラ密教的なインディアンらしさは、重層的な意味を持つ新植民地主義の縮図を作り出している。何よりもまず、インジュン の長老は自分たちの知識を白人世界の他の人々に伝えることができないということが示唆されている。インディアンの精神性を徹底的に学んだ元白人研修生こそ が、知恵を伝える真の博識の専門家なのである。この理論的根拠は、再び、自然と文化の二元論を強化する。インド人は破滅的な野蛮なペットのままであり、イ ンド人化した者は外側の白人世界に対する雄弁で洗練された媒介者である。そのように沈黙させられ、視覚的に消滅させられると、インディアンは先史時代に引 きこもり、一方、プラスティック・シャーマンは彼らの文化を独占することができる[14]。 土着宗教の完全性を擁護する人々は、潜在的に危険であり、彼らが代表すると主張する文化や共同体の評判を傷つけるかもしれないと考える人々を批判するため に、「プラスティック・シャーマン」という用語を使用している[4]。最も極端なケースでは、詐欺的な、時には犯罪的な行為が、これらの偽者の多くによっ て行われてきたという証拠がある[15][16]。多くの場合、これは実際の伝統的なスピリチュアルな長老たちに、伝統的な許容される行為の基準から見 て、プラスチックシャーマンとその活動は「暗黒」や「邪悪」であると宣言させることにつながっている[3]。 プラスチック・シャーマンはまた、伝統的なスピリチュアリティや儀式について誤った考えを人々に与えるため、危険であると信じられている[5]。場合に よっては、プラスチック・シャーマンは儀式を全裸で行い、男女が一緒に儀式に参加することを要求するが、そのような慣習は革新的なものであり、伝統的に守 られてきたものではない。 [17]もう一つの革新には、性魔術や「タントラ」の要素の導入が含まれることがある。これは(本来の文化的文脈で使用される場合には)それ自体正当な精 神性の一形態であるかもしれないが、この文脈では異なる伝統からの輸入であり、正真正銘の先住民の実践の一部ではない。 このような先住民の知識の流用の結果、いくつかの部族、部族間協議会、国連総会は、この問題に関するいくつかの宣言を発表するに至った: 4. われわれは特に、ラコタ、ダコタ、ナコタのすべての人々に対し、われわれの同胞が部外者によるわれわれの神聖な儀式や精神的慣習の乱用に加担したり、それ を可能にしたりするのを防ぐために行動を起こすよう強く求める。われわれ全員が知っているように、われわれの同胞の中には、民族全体の精神的な幸福を顧み ず、利己的な利益のためにわれわれの精神的な方法を売春している者がいる。 5. われわれは、われわれのコミュニティ内部から湧き上がり、非インディアンによるわれわれの儀式の方法の収奪を「認可」する「白人のシャーマン」に対して は、いかなる者に対しても容認ゼロの姿勢を主張する。そのような「プラスチックのメディスンマン」はすべて、ラコタ、ダコタ、ナコタの人々の敵である。 - ラコタ・スピリチュアリティの搾取者に対する宣戦布告[18][19]。 第11条:先住民族は、その文化的伝統と慣習を実践し、再生させる権利を有する。これには、遺跡や歴史的な場所、工芸品、デザイン、儀式、技術、視覚芸術 や舞台芸術、文学など、過去、現在、未来の彼らの文化の姿を維持し、保護し、発展させる権利が含まれる。... 国は、先住民の自由意思に基づき、事前の十分な情報に基づき、同意なしに、又は先住民の法律、伝統及び慣習に違反して行われた先住民の文化的、知的、宗教 的及び精神的財産について、先住民と共に開発した返還を含む効果的なメカニズムを通じて救済を行うものとする。 - 先住民族の権利に関する宣言[20]。 第31条 1. 先住民族は、その文化的遺産、伝統的知識および伝統的文化表現、ならびにヒトおよび遺伝資源、種子、医薬品、動植物の特性に関する知識、口承伝統、文学、 意匠、スポーツおよび伝統的競技、視覚芸術および芸能を含む科学、技術および文化の表現を維持、管理、保護および発展させる権利を有する。先住民はまた、 このような文化遺産、伝統的知識、伝統的文化表現に関する知的財産を維持し、管理し、保護し、発展させる権利を有する。 - 先住民族の権利に関する宣言[20]。 したがって、これらの人々は、インディアンではない兄弟姉妹の精神的なニーズや無知を利用して動いていることに警告を発しなければならない。これらの指示 や儀式の価値は疑わしいものであり、おそらく無意味であり、偽りのメッセージを伝える個人を傷つけるものである。 - 伝統的長老サークル第5回年次総会の決議[21]。 プラスチック・シャーマンの摘発に取り組む人々の多くは、スピリチュアル詐欺師によって行われる虐待は、詐欺師が代表であると主張する文化について無知で ある場合にのみ存在し得ると考えている。伝統文化の権利擁護に取り組む活動家たちは、先住民の伝統や先住民コミュニティに対する詐欺的な歪曲や搾取を暴く だけでなく、伝統文化としばしば歪曲されるスピリチュアリティへの現代的なアプローチとの違いについて、求道者を教育することにも取り組んでいる[3] [6]。 プラスチック・シャーマンの一つの指標は、「ネイティブ・アメリカンのスピリチュアリティ」を論じるが、特定のネイティブ・アメリカンの部族について言及 しない人物であるかもしれない。New Age Frauds and Plastic Shamans(ニューエイジ詐欺とプラスチック・シャーマン)」のウェブサイトでは、潜在的なプラスチック・シャーマンについて論じている[22] [23]。 |

| Terminology The word "shaman" originates from the Evenki word "šamán".[24] The term came into usage among Europeans via Russians interacting with the Indigenous peoples in Siberia. From there, "shamanism" was picked up by anthropologists to describe any cultural practice that involves vision-seeking and communication with the spirits, no matter how diverse the cultures included in this generalisation. Native American and First Nations spiritual people use terms in their own languages to describe their traditions; their spiritual teachers, leaders or elders are not called "shamans".[3][16] One significant promoter of this view of a global shamanism was the Beat Generation writer Gary Snyder, whose 1951 PhD thesis treated Haida religion as a form of shamanic practice, and whose subsequent poetry promotes the idea of the Pacific Rim as "a single cultural zone and a single bioregion."[25] Other writers promoting the idea of a generalised shamanic religion in this period also include Robert Bly, who stated that "the most helpful addition to thought about poetry in the past thirty years has been the concept of the poet as a relative of the shaman ... I am a shaman."[26] Snyder and Bly's remarks attest to the deep investment in shamanism in 1960s and 1970s counterculture. Leslie Marmon Silko would later condemn Snyder's appropriations of Native religions in her 1978 essay "An Old-Fashioned Indian Attack in Two Parts". Later, Michael Harner would develop the concept of neoshamanism, or "core shamanism", which also makes the unfounded claim that the ways of several North American tribes share more than surface elements with those of the Siberian Shamans.[3][5][27] This misappellation led to many non-Natives assuming Harner's inventions were traditional Indigenous ceremonies.[3] Geary Hobson sees the New Age use of the term shamanism as a cultural appropriation of Native American culture by "white" people who have distanced themselves from their own history.[3] In Nepal, the term Chicken Shaman is used.[28] Documentary film A 1996 documentary about this phenomenon, White Shamans and Plastic Medicine Men, was directed by Terry Macy and Daniel Hart.[29] |

用語[編集] 「シャーマン」という言葉は、エヴェンキ語の「šamán」に由来する[24]。この言葉は、ロシア人がシベリアの先住民族と交流する中で、ヨーロッパ人 の間で使われるようになった。そこから「シャーマニズム」は人類学者たちによって、この一般化に含まれる文化がどれほど多様であっても、幻視を求めたり精 霊と交信したりするあらゆる文化的実践を表す言葉として使われるようになった。ネイティブアメリカンや ファーストネーションのスピリチュアルな人々は、自分たちの伝統を説明するために自分たちの言語で用語を使用しており、彼らのスピリチュアルな教師、指導 者、長老は「シャーマン」とは呼ばれない[3][16]。このようなグローバルなシャーマニズムという見方を推進した重要な人物の一人が、ビートジェネ レーションの作家であるゲイリー・スナイダーであり、彼の1951年の博士論文はハイダの宗教をシャーマニズムの実践の一形態として扱っており、その後の 彼の詩は環太平洋を「単一の文化圏、単一の生物地域」という考えを推進している。 「25]この時期に一般化されたシャーマン宗教の考えを推進した他の作家には、「過去30年間、詩についての思考に最も役立ったのは、シャーマンの親戚と しての詩人という概念である。私はシャーマンである」[26]。スナイダーとブライの発言は、1960年代と1970年代のカウンターカルチャーにおける シャーマニズムへの深い投資を証明している。レスリー・マーモン・シルコは後に、1978年のエッセイ『古風なインディアンの攻撃』の中で、スナイダーに よる先住民の宗教の流用を非難している。その後、マイケル・ハーナーはネオシャーマニズム(核心的シャーマニズム)という概念を発展させ、北米のいくつか の部族のやり方はシベリアのシャーマンのやり方と表面的な要素以上のものを共有しているという根拠のない主張を展開することになる。 [3][5][27]この誤った呼称によって、多くの非ネイティブはハーナーの発明を先住民の伝統的な儀式であると思い込むようになった[3]。ギア リー・ホブソンは、シャーマニズムという用語のニューエイジでの使用を、自分たちの歴史から距離を置いた「白人」によるネイティブ・アメリカン文化の文化 的流用であると考えている[3]。 ネパールではチキン・シャーマンという言葉が使われている[28]。 ドキュメンタリー映画[編集] この現象に関する1996年のドキュメンタリー映画『White Shamans and Plastic Medicine Men』は、テリー・メイシーとダニエル・ハートによって監督された[29]。 |

| Brooke Medicine Eagle Colonialism Cultural appropriation Cultural imperialism Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Fraudulent Mediums Act 1951 – British legislation that both combats plastic shamanism and repeals the Witchcraft Act 1735 Hollywood Indian Huna (New Age) Indigenous intellectual property Iron Thunderhorse Legend of the Rainbow Warriors Native American hobbyism in Germany Native Americans in German popular culture Neoshamanism Noble savage Passing as Indigenous Americans Plastic Paddy Pretendian Q Shaman Rolling Thunder Stereotypes of Native Americans T. Lobsang Rampa – English writer (1910–1981) Traditional knowledge Twinkie (slur) Xenocentrism |

ブルック・メディスン・イーグル 植民地主義 文化的流用 文化的帝国主義 先住民の権利に関する宣言 1951年詐欺霊媒法- プラスティック・シャーマニズムと闘い、1735年の魔術法を廃止したイギリスの法律 ハリウッド・インディアン フナ(ニューエイジ) 先住民の知的財産 アイアン・サンダーホース 虹の戦士伝説 ドイツにおけるネイティブ・アメリカンの趣味 ドイツの大衆文化におけるネイティブ・アメリカン ネオシャーマニズム 高貴な野蛮人 アメリカ先住民になりすます プラスチック・パディ プレテンディアン Qシャーマン ローリング・サンダー アメリカ先住民のステレオタイプ T. ロブサン・ランパ- イギリスの作家(1910年~1981年) 伝統的知識 トゥインキー 外国人中心主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plastic_shaman |

|

James

Hunt (1833 – 29 August 1869) James

Hunt (1833 – 29 August 1869)James Hunt (1833 – 29 August 1869) was an anthropologist and speech therapist in London, England, during the middle of the nineteenth century. His clients included Charles Kingsley, Leo Tennyson (son of the poet laureate Alfred Tennyson), and Lewis Carroll (Charles Lutwidge Dodgson) author of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland. Lewis Carroll was a children’s author, mathematician, and clergyman. He had a stammer that was said to have affected his job. The 1861 census shows that Charles Lutwidge Dodgson was staying at Ore House in 1861 and being treated by Dr. Hunt a psellismolligist. Since his book was published in 1865 it is quite possible that some of it was written during his stay.[original research?] His other main interest was in anthropology, and in 1863 he established the Anthropological Society of London, which after his death merged with the more established Ethnological Society of London to become the Royal Anthropological Institute. Career James Hunt was born in Swanage, Dorset, the son of the speech therapist Thomas Hunt (1802–1851) and his wife Mary. His father trained him in the art of curing stuttering by means of breath exercises, muscle control and building the patient's confidence. He bought a doctorate from the University of Giessen in Germany and set up a practice in 1856 in Regent Street, London.[1] He dedicated his first Manual on the subject to Charles Kingsley who spent three weeks with him in 1859. He moved to Hastings to run residential courses during the summer season with his sister Elizabeth's husband, Rev. Henry F. Rivers. Anthropology In 1854 he joined the Ethnological Society of London because of his interest in racial differences and from 1859 to 1862 was the honorary secretary. However many members of this society disliked his attacks on humanitarian and missionary societies and the anti-slavery movement. [2] So in 1863 with the help of the explorer Richard Burton he set up the Anthropological Society of London, becoming its first president. His paper The Negro's place in nature was greeted with boos and hisses when given at the British Association meeting in 1863 because of its defense of slavery in the Confederate States of America and belief in the plurality of the human species.[3] He established the Anthropological Review as the organ of the society and by 1867 the membership of the Society had reached 500. However, by 1867 allegations by one of the members Hyde Clarke of financial irregularities in his running of the society caused his temporary resignation as president, though he returned in 1868 when Clarke was expelled. This took a toll on his health and in 1869 he died of an inflammation of the brain. The society shortly afterwards started discussions to merge with the Ethnological Society. He left a widow, Henrietta, and five children and left his books to his nephew W.H.R. Rivers who refused them, though, through unconnected means, he later became an anthropologist himself. Publications Manual of the Philosophy of Voice and Speech, 1859 Stammering and Stuttering, their nature and treatment, London: Longman, Green, Longman and Roberts, 1861. "The Negro's Place in Nature" (1863), Memoirs read before the Anthropological Society of London, 1865. Further reading Efram Sera-Shriar, ‘Observing Human Difference: James Hunt, Thomas Huxley, and Competing Disciplinary Strategies in the 1860s’, Annals of Science, 70 (2013), 461-491 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/James_Hunt_(speech_therapist) |

ジェー

ムズ・ハント(1833年~1869年8月29日) ジェー

ムズ・ハント(1833年~1869年8月29日)ジェームズ・ハント(1833年~1869年8月29日)は、19世紀中期のロンドンで人類学者および言語療法士として活動していた。彼のクライアントに は、チャールズ・キングズリー、レオ・テニソン(桂冠詩人アルフレッド・テニソンの息子)、そして『不思議の国のアリス』の作者ルイス・キャロル(チャー ルズ・ラトウィッジ・ドジソン)などがいた。 ルイス・キャロルは児童文学作家、数学者、聖職者であった。彼は吃音があり、それが仕事に悪影響を与えたと言われている。1861年の国勢調査によると、 チャールズ・ラトウィッジ・ドジソンは1861年にオレ・ハウスに滞在しており、言語病理学者のハント博士の治療を受けていた。1865年に彼の本が出版 されたので、その滞在中に書かれた可能性もある[独自研究?]。 彼のもう一つの主な関心は人類学であり、1863年に彼はロンドン人類学会を設立した。彼の死後、より確立されたロンドン民族学会と合併し、王立人類学協 会となった。 経歴 ジェームズ・ハントは、ドーセット州スウォンジで、言語療法士のトーマス・ハント(1802年~1851年)とその妻メアリーの間に生まれた。 父親は、息継ぎの練習、筋肉のコントロール、患者の自信の確立によって吃音の治療法を彼に教えた。彼はドイツのギーセン大学で博士号を取得し、1856年 にロンドンのリージェントストリートに診療所を開設した[1]。彼は1859年に3週間を共に過ごしたチャールズ・キングズリーにこのテーマに関する最初 のマニュアルを捧げた。彼は夏の間、妹エリザベスの夫であるヘンリー・F・リバーズ牧師とともに、ヘイスティングスで宿泊コースを運営するために移り住ん だ。 人類学 1854年、彼は人種差別の問題に関心を抱いていたため、ロンドン民族学会に入会し、1859年から1862年まで名誉書記を務めた。しかし、この学会の 多くの会員は、彼が人道主義団体や宣教師団体、そして奴隷制度廃止運動を攻撃することを嫌っていた。 [2] そのため、1863年に探検家リチャード・バートンの協力を得て、ロンドン人類学会を設立し、初代会長に就任した。1863年に英国人類学会で発表された 彼の論文『自然における黒人の位置』は、アメリカ連合国における奴隷制擁護と人類の多元説を主張していたため、ブーイングと野次を浴びた[3]。 彼は学会機関誌として『Anthropological Review』を創刊し、1867年までに学会の会員数は500人に達した。しかし、1867年、会員の一人ハイド・クラークが学会運営における金銭上の 不正を指摘し、ハイド・クラークが追放された1868年に復帰するまで、ハイド・クラークは会長職を一時的に辞任した。このことが彼の健康を損ない、 1869年に脳炎で亡くなった。学会はその後まもなく、人類学会との合併に向けた話し合いを開始した。 彼は未亡人のヘンリエッタと5人の子供を残し、本を甥のW.H.R.リヴァーズに遺したが、彼はそれを拒否した。しかし、その後、彼はまったく別の道で人 類学者となった。 著書 『音声と発声の哲学マニュアル』1859年 『吃音とどもり、その性質と治療法』ロンドン:ロングマン、グリーン、ロングマン、ロバーツ、1861年 「自然における黒人の位置」(1863年)、ロンドン人類学会で発表された回顧録(1865年)。 関連文献 Efram Sera-Shriar, ‘Observing Human Difference: James Hunt, Thomas Huxley, and Competing Disciplinary Strategies in the 1860s’, Annals of Science, 70 (2013), 461-491 |

| James Hunt, along with Richard

Francis Burton,

founded the Anthropological Society of London in 1863 out of

frustration at the reluctance of the Ethnological Society of London

(one of whose founders was James Cowles Prichard) to explore the social

significance of racial differences or to credit the importance of the

physical as well as the cultural aspects of humanity. Hunt’s new

organization quickly developed a large membership, with audiences for

events such as the 1864 presentation by Alfred Russel Wallace numbering