Squanto effect

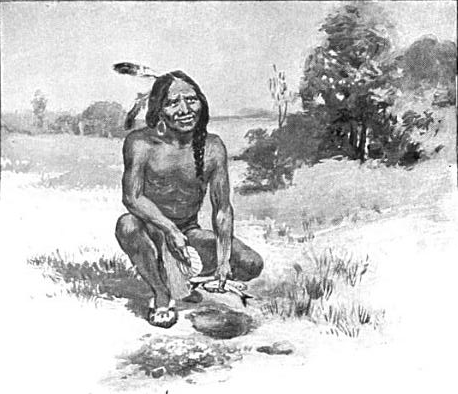

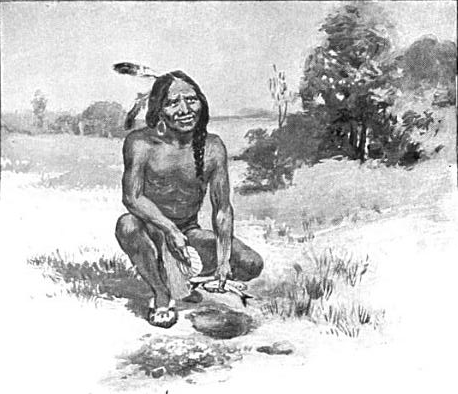

Squanto or Tisquantum teaching

the Plymouth colonists to plant corn

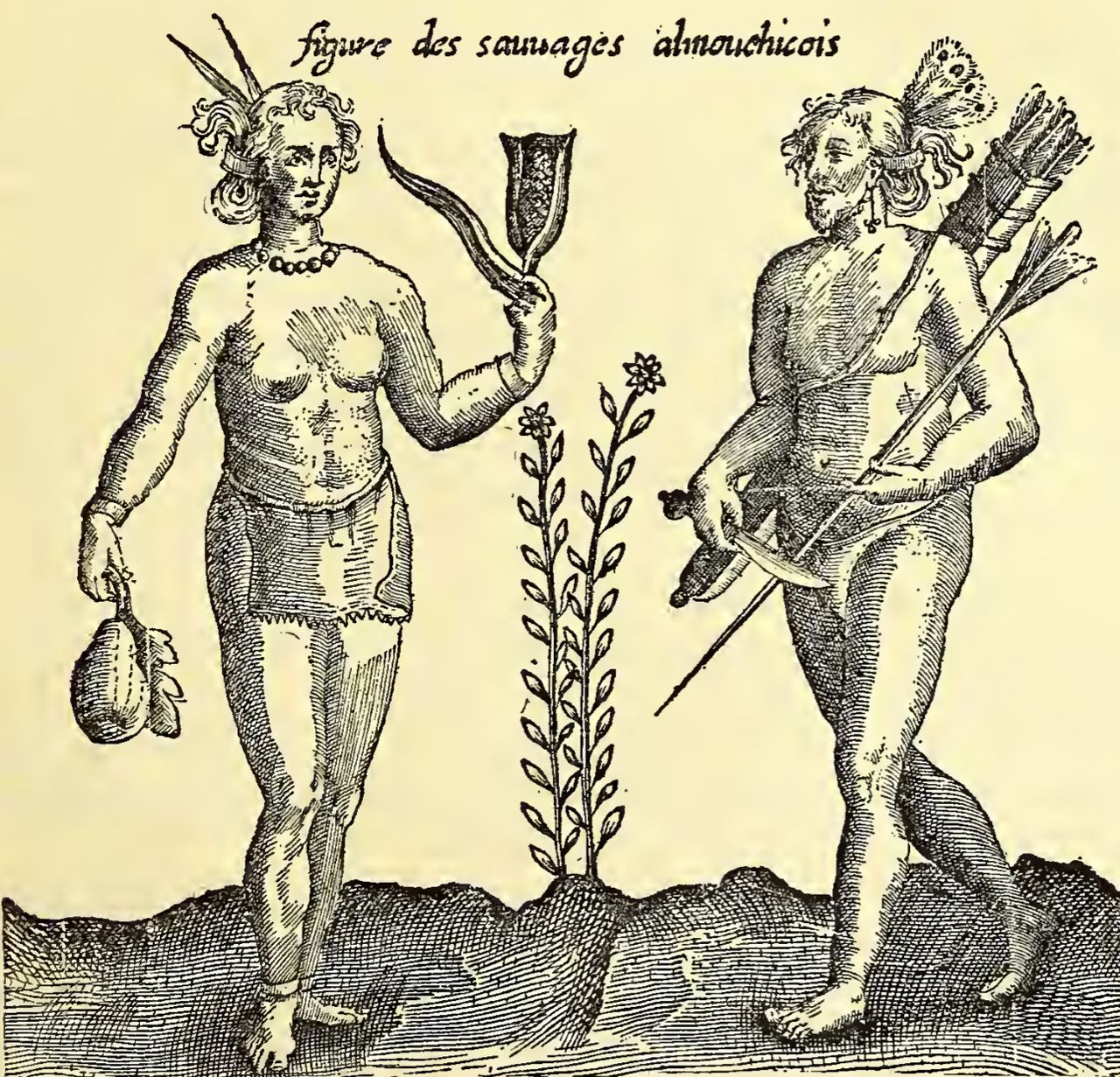

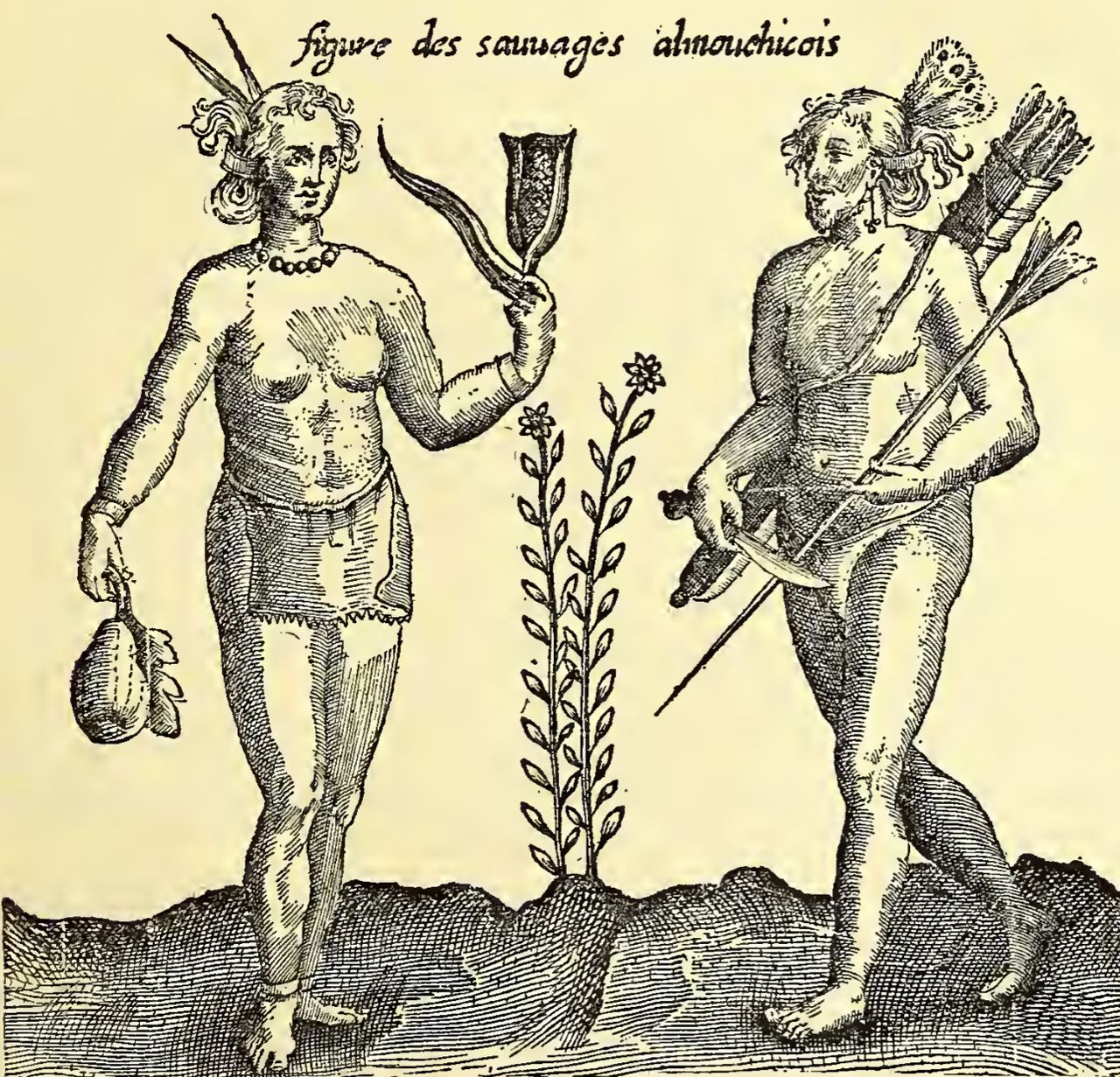

with fish./ Champlain's drawing of Southern New England Algonquians

emphasizing their pacific nature and sedentary and agricultural

lifestyle

はじめによ

んでください

〈スクワント効果〉

Squanto effect

Squanto or Tisquantum teaching

the Plymouth colonists to plant corn

with fish./ Champlain's drawing of Southern New England Algonquians

emphasizing their pacific nature and sedentary and agricultural

lifestyle

・スクアント[スクワント Squanto]効果(クリフォード 2002:29)

ス クアント(あるいは ティスクワントゥム[Tisquantum, 1585?-1622])は1620年ピルグリム・ファーザーズを迎え入れた先住民族パチュケト(Patuxet tribe)のひとり。彼らのうちの一人ティスクワントゥムはちょうどヨーロッパから帰還した ばかりで流暢な英語を話し、巡礼たちを歓待した。クリフォードは、スクアントの中に、現代の文化人類学のインフォーマントにおけるさまざまな属性を見いだ し文化の媒介者〈兼〉移動者として先住民=インフォーマントを再考することを促すために、この用語(=スクアント効果)を提唱している(ク リフォード 2002:29)。

| Tisquantum Tisquantum (/tɪsˈkwɒntəm/; c. 1585 (±10 years?) – November 30, 1622 O.S.), more commonly known as Squanto (/ˈskwɒntoʊ/), was a member of the Wampanoag Patuxet tribe best known for being an early liaison between the Native American population in Southern New England and the Mayflower Pilgrims who made their settlement at the site of Tisquantum's former summer village, now Plymouth, Massachusetts. The Patuxet tribe had lived on the western coast of Cape Cod Bay, but an epidemic infection wiped them out, likely brought by previous European explorers. Tisquantum was kidnapped by English explorer and slaver Captain Thomas Hunt, who trafficked him to Spain, where he sold him in the city of Málaga. He was among several captives traditionally claimed to have been ransomed[1] by local Franciscan monks who focused on their education and evangelization. Tisquantum is said to have been baptized a Catholic, although no known primary sources support this claim. He eventually travelled to England and from there returned to his native village in America in 1619, baptised Catholic and eventually traveled to England. He then returned to America in 1619 to his native village, only to find that an epidemic infection had wiped out his tribe; Tisquantum was the last of the Patuxet and went to live with the Wampanoags. The Mayflower landed in Cape Cod Bay in 1620, and Tisquantum worked to broker peaceable relations between the Pilgrims and the local Pokanokets. He played a crucial role in the early meetings in March 1621, partly because he spoke English. He then lived with the Pilgrims for 20 months as an interpreter, guide, and advisor. He introduced the settlers to the fur trade and taught them how to sow and fertilize native crops; this proved vital because the seeds the Pilgrims had brought from England mostly failed. As food shortages worsened, Plymouth Colony Governor William Bradford relied on Tisquantum to pilot a ship of settlers on a trading expedition around Cape Cod and through dangerous shoals. During that voyage, Tisquantum contracted what Bradford called an "Indian fever". Bradford stayed with him for several days until he died, which Bradford described as a "great loss". |

ティスカンタム ティスカンタム(/tɪntəm/; 1585年頃(±10年? スクワント(/ˈskwɒnto↪Ll_28A/ )としてより一般的に知られているワンパノアグ族パトゥクセット(Patuxet)部族の一員で、南ニューイングランドのネイティブ・アメリカンとメイフ ラワー号のピルグリムとの初期の連絡役として知られる。パトゥセット族はケープ・コッド湾の西海岸に住んでいたが、ヨーロッパ人探検家によってもたらされ たと思われる伝染病が彼らを絶滅させた。 ティスカンタムは、イギリスの探検家で奴隷商人のキャプテン・トーマス・ハントに誘拐され、スペインに密売された。彼は、教育と伝道に力を注いだ地元のフ ランシスコ会修道士によって身代金[1]を手に入れたと伝統的に主張されている何人かの捕虜の一人であった。ティスカンタムはカトリックの洗礼を受けたと 言われているが、この主張を裏付ける一次資料は知られていない。彼はやがてイギリスに渡り、そこから1619年にアメリカの故郷の村に戻り、カトリックの 洗礼を受け、やがてイギリスに渡った。ティスカンタムはパトゥクセット族の最後の一人となり、ワンパノアグ族と共に暮らすことになった。 1620年にメイフラワー号がケープ・コッド湾に上陸すると、ティスカンタムはピルグリムと地元のポカノケッツ族との平和的な関係の仲介に努めた。 1621年3月の初期の会議では、英語が話せたこともあり、重要な役割を果たした。その後、彼は通訳、ガイド、アドバイザーとして20ヵ月間ピルグリムと ともに暮らした。彼は入植者たちに毛皮貿易を紹介し、土着の作物の種まきと肥料の与え方を教えた。ピルグリムたちがイギリスから持ち込んだ種はほとんど失 敗したため、これは極めて重要なことであった。食糧不足が深刻化する中、プリマス植民地総督ウィリアム・ブラッドフォードは、コッド岬周辺の危険な浅瀬を 通過する貿易遠征に向かう入植者の船の操縦をティスカンタムに任せた。その航海中、ティスカンタムはブラッドフォードが「インディアン熱」と呼ぶ病気にか かった。ブラッドフォードはティスカンタムが亡くなるまで数日間彼のそばにいたが、ティスカンタムはそれを「大きな損失」と表現した。 |

| Name Documents from the 17th century variously render the spelling of Tisquantum's name as Tisquantum, Tasquantum, and Tusquantum, and alternately call him Squanto, Squantum, Tantum, and Tantam.[2] Even the two Mayflower settlers who dealt with him closely spelled his name differently; Bradford nicknamed him "Squanto", while Edward Winslow invariably referred to him as Tisquantum, which historians believe was his proper name.[3] One suggestion of the meaning is that it is derived from the Algonquian expression for the rage of the Manitou, "the world-suffusing spiritual power at the heart of coastal Indians' religious beliefs".[4] Manitou was "the spiritual potency of an object" or "a phenomenon", the force which made "everything in Nature responsive to man".[5] Other suggestions have been offered,[a] but all involve some relationship to beings or powers that the colonists associated with the devil or evil.[b] It is, therefore, unlikely that it was his birth name rather than one that he acquired or assumed later in life, but there is no historical evidence on this point. The name may suggest, for example, that he underwent special spiritual and military training and was selected for his role as liaison with the settlers in 1620 for that reason.[8] |

名前 17世紀の文献では、ティスカンタムの名前の綴りはTisquantum、Tasquantum、Tusquantumと様々に表記され、 Squanto、Squantum、Tantum、Tantamと交互に呼ばれている[2]。ブラッドフォードが彼を「Squanto」とあだ名したのに 対し、エドワード・ウィンズロウは必ずティスカンタムと呼んだ。 [3]その意味の1つの示唆は、「沿岸インディアンの宗教的信念の中心にある、世界を粛清する霊的な力」であるマニトウの怒りを表すアルゴンキン語の表現 に由来するというものである。 [4]マニトウは「ある物体の霊的な力」または「ある現象」であり、「自然界のあらゆるものを人間に反応させる力」であった[5]。他の説もある[a] が、いずれも植民地人が悪魔や邪悪なものと関連付けていた存在や力との関係が指摘されている[b]。この名前は、例えば、彼が特別な精神的・軍事的訓練を 受け、そのために1620年に入植者との連絡役として選ばれたことを示唆しているのかもしれない[8]。 |

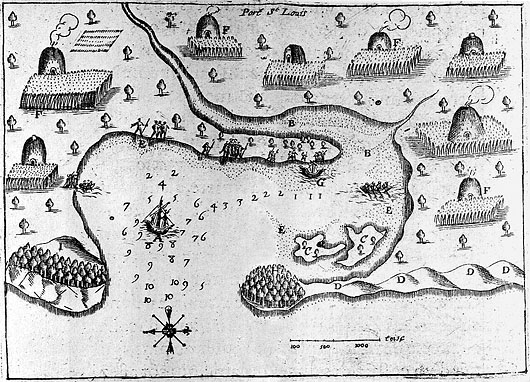

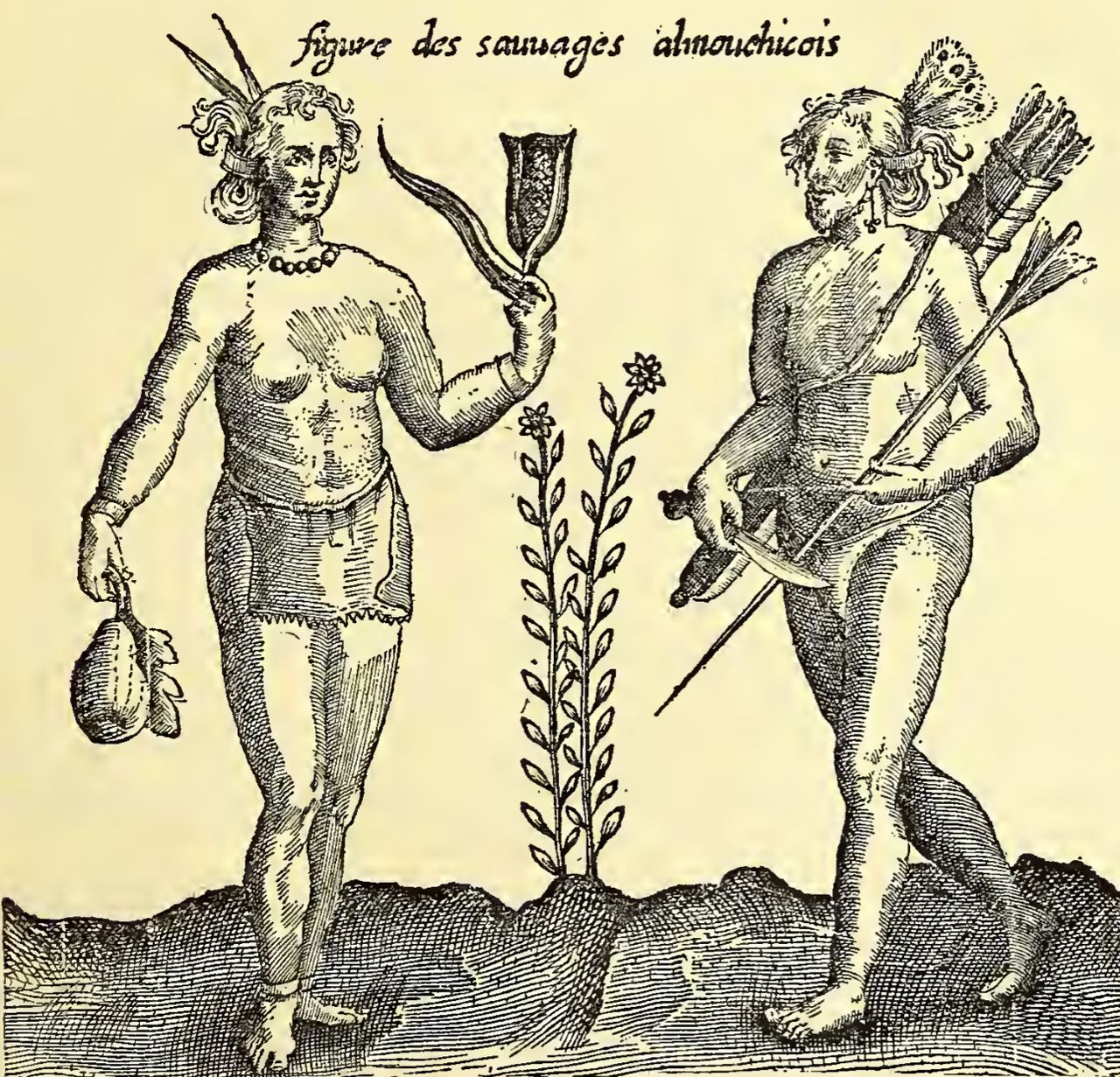

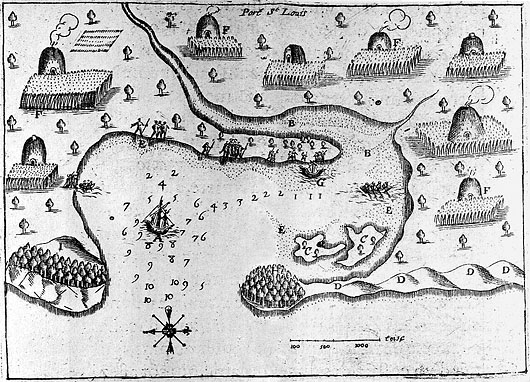

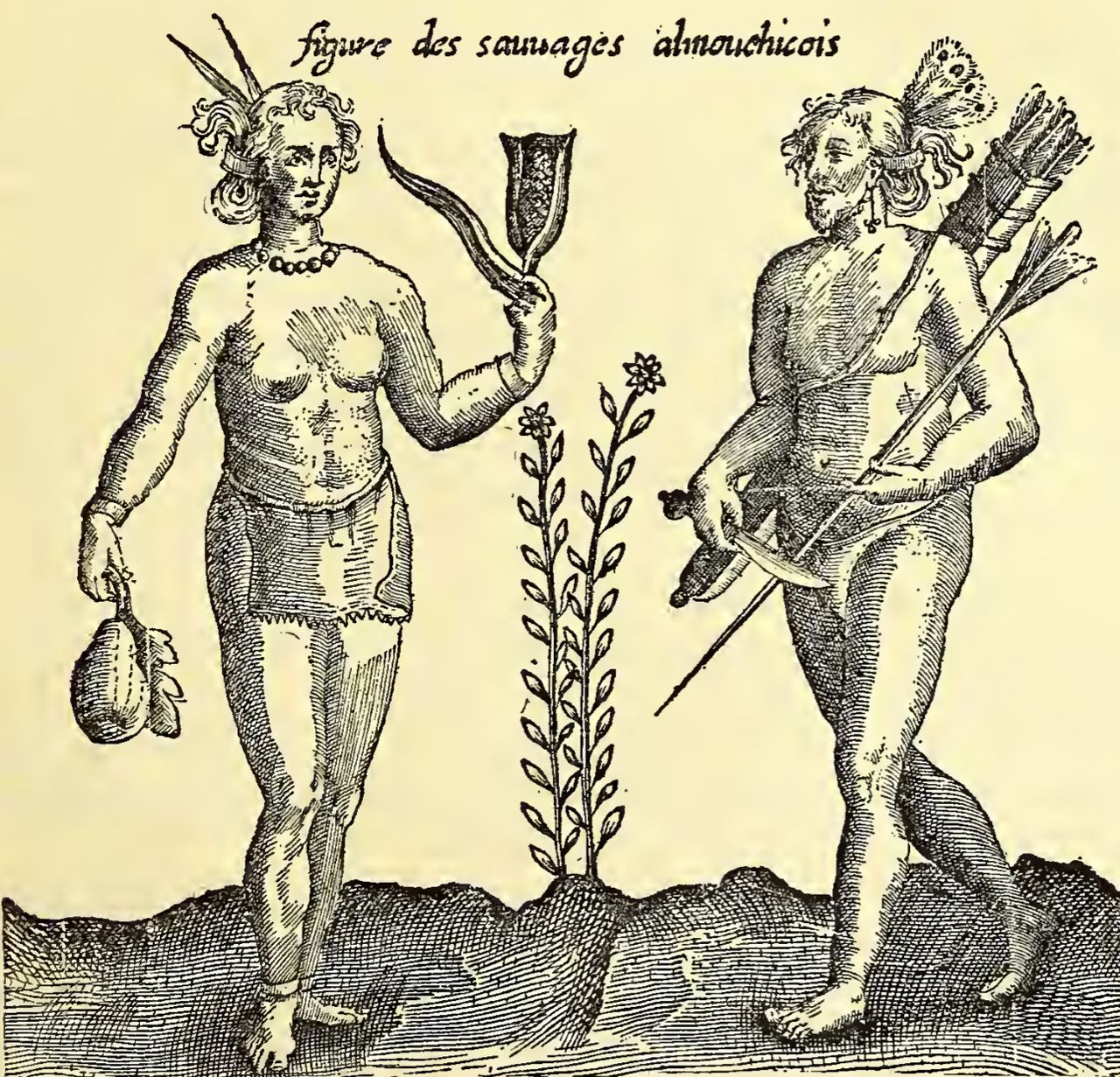

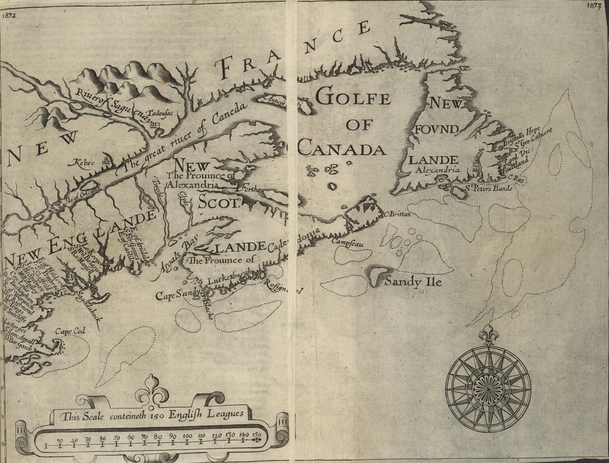

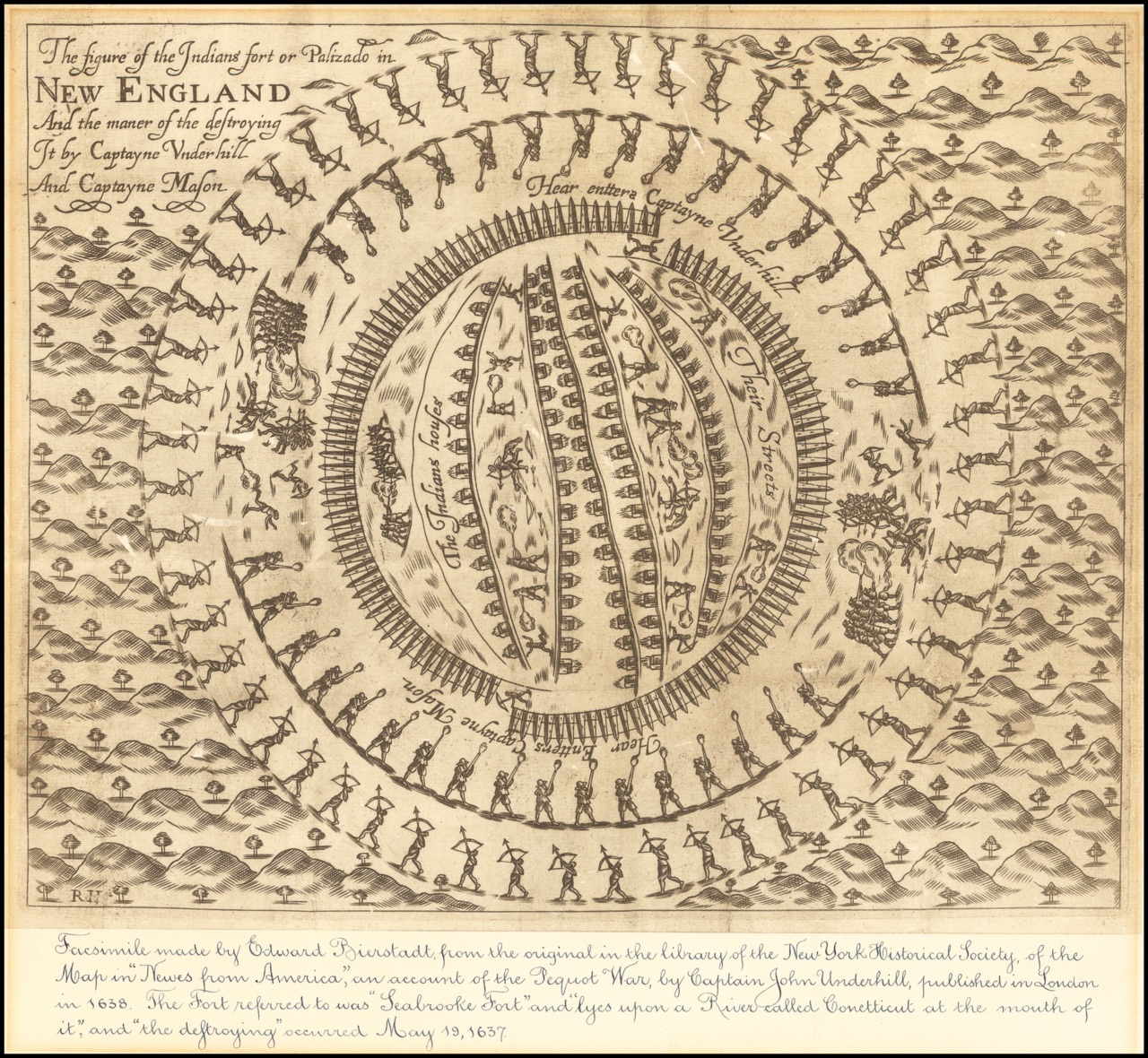

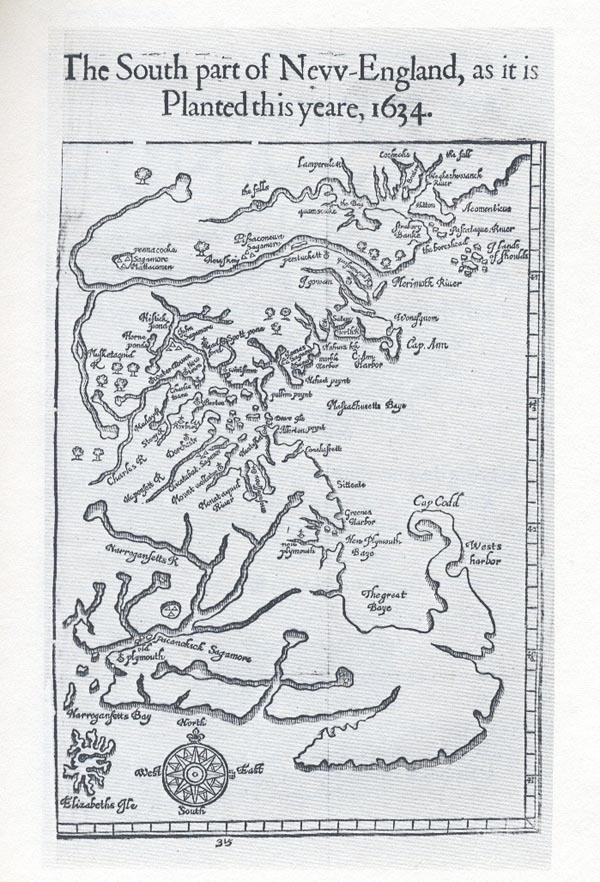

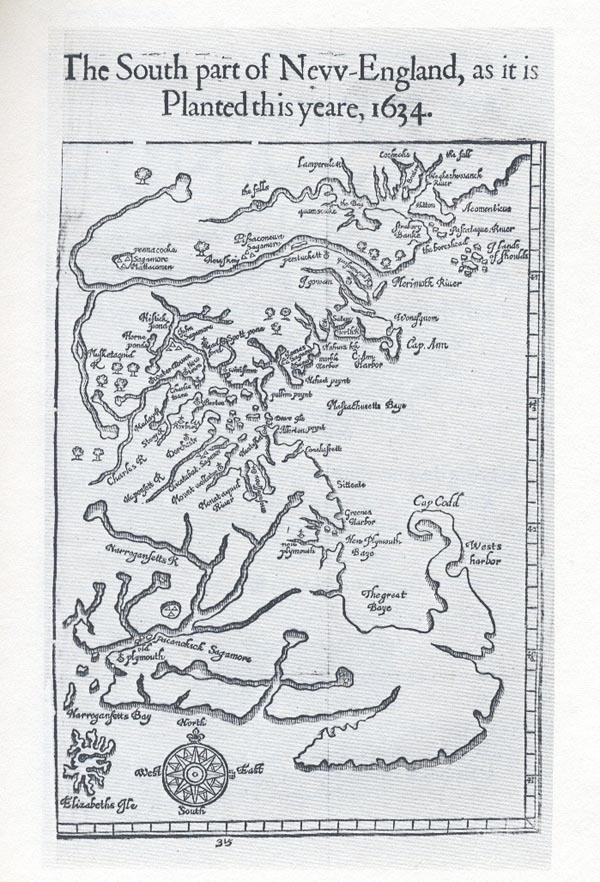

| Early life Almost nothing is known of Tisquantum's life before his first contact with Europeans, and even when and how that first encounter took place is subject to contradictory assertions.[9] First-hand descriptions of him written between 1618 and 1622 do not remark on his youth or old age, and Salisbury has suggested that he was in his twenties or thirties when he was captured and taken to Spain in 1614.[10] If that was the case, he would have been born around 1585 (±10 years). Native culture Main article: Ninnimissinuok  1605 map drawn by Samuel de Champlain of Plymouth Harbor (which he called Port St. Louis); "F" designates wigwams and cultivated fields. The tribes who lived in southern New England at the beginning of the 17th century referred to themselves as Ninnimissinuok, a variation of the Narragansett word Ninnimissinnȗwock meaning "people" and signifying "familiarity and shared identity".[11] Tisquantum's tribe of the Patuxets occupied the coastal area west of Cape Cod Bay, and he told an English trader that the Patuxets once numbered 2,000.[12] They spoke a dialect of Eastern Algonquian common to tribes as far west as Narragansett Bay.[c] The various Algonquian dialects of Southern New England were sufficiently similar to allow effective communications.[d] The term patuxet refers to the site of Plymouth, Massachusetts, and means "at the little falls"[e] referencing Morison.[17] Morison gives Mourt's Relation as authority for both assertions. The annual growing season in southern Maine and Canada was not long enough to produce maize harvests. Indian tribes in those areas were required to live a fairly nomadic existence,[18] while the southern New England Algonquins were "sedentary cultivators" by contrast.[19] They grew enough for their own winter needs and for trade, especially to northern tribes, and enough to relieve the colonists' distress for many years when their harvests were insufficient.[20]  Champlain's drawing of Southern New England Algonquians emphasizing their pacific nature and sedentary and agricultural lifestyle The groups that made up the Ninnimissinuok were presided over by one or two sachems.[21] The chief functions of the sachems were to allocate land for cultivation,[22] to manage the trade with other sachems or more distant tribes,[23] to dispense justice (including capital punishment),[24] to collect and store tribute from harvests and hunts,[25] and leading in war.[26] Sachems were advised by "principal men" of the community called ahtaskoaog, generally called "nobles" by the colonists. Sachems achieved consensus through the consent of these men, who probably also were involved in the selection of new sachems. One or more principal men were generally present when sachems ceded land.[27] There was a class called the pniesesock among the Pokanokets which collected the annual tribute to the sachem, led warriors into battle, and had a special relationship with their god Abbomocho (Hobbomock) who was invoked in pow wows for healing powers, a force that the colonists equated with the devil.[f] The priest class came from this order, and the shamans also acted as orators, giving them political power within their societies.[32] Salisbury has suggested that Tisquantum was a pniesesock.[8] This class may have produced something of a praetorian guard, equivalent to the "valiant men" described by Roger Williams among the Narragansetts, the only Southern New England society with an elite class of warriors.[33] In addition to the class of commoners (sanops), there were outsiders who attached themselves to a tribe. They had few rights except the expectation of protection against any common enemy.[32] |

初期の生活 1618年から1622年にかけて書かれたティスカンタムの最初の手による記述には、ティスカンタムが若かったとも老いていたとも記されておらず、ソール ズベリーは、1614年に捕らえられスペインに連れて行かれた時、ティスカンタムは20代か30代であったと示唆している[10]。 先住民の文化 主な記事 ニンニミシヌオク  1605年、サミュエル・ド・シャンプランが描いたプリマス港(彼はポート・セントルイスと呼んだ)の地図。 17世紀初頭にニューイングランド南部に住んでいた部族は、ナラガンセット語で「人々」を意味するNinnimissinnȗwockが変化した Ninnimissinuokと呼ばれ、「親しみやすさとアイデンティティの共有」を意味した[11]。ティスカンタムの部族であるパトゥクセッツ族は、 ケープコッド湾の西の沿岸地域を占めており、彼はイギリス人商人にパトゥクセッツ族はかつて2,000人であったと語った[12]。 [12]彼らはナラガンセット湾より西の部族に共通する東アルゴンキア語の方言を話していた[c]。南ニューイングランドの様々なアルゴンキア語の方言 は、効果的なコミュニケーションを可能にするほど十分に類似していた[d]。パトゥクセットという用語はマサチューセッツ州プリマスの場所を指し、「小さ な滝で」[e]という意味である。 メイン州南部とカナダの年間生育期間は、トウモロコシを収穫するのに十分な長さではなかった。これらの地域のインディアン部族はかなり遊牧的な生活を強い られたが[18]、ニューイングランド南部のアルゴンキン族は対照的に「定住的な耕作者」であった[19]。彼らは自分たちが冬に必要とする分と、特に北 部部族との交易のために十分な量のトウモロコシを栽培し、収穫が不十分であった何年もの間、植民者たちの苦痛を和らげるのに十分な量のトウモロコシを栽培 していた[20]。  シャンプランが描いたニューイングランド南部アルゴン人の図面。太平洋的な性質と定住的で農耕的な生活様式が強調されている。 ニンニミシヌオクを構成する集団は、1人か2人のachemによって統率されていた[21]。achemの主な役割は、耕作地の割り当て、[22]他の achemやより遠方の部族との交易の管理、[23](死刑を含む)司法の執行、[24]収穫や狩猟からの貢物の徴収と貯蔵、[25]戦争の指揮であった [26]。 Sachemsは、一般的に植民者たちから「貴族」と呼ばれる、ahtaskoaogと呼ばれる共同体の「主要人物」によって助言されていた。 achemsはこれらの男性の同意によってコンセンサスを得ており、おそらく彼らは新しいachemsの選定にも関与していた。ポカノケッツ族にはプニー ソックと呼ばれる階級があり、サケムへの年貢を徴収し、戦士を率いて戦いに赴き、彼らの神アッボモチョ(ホッボモック)と特別な関係にあった。 [32]ソールズベリーはティスカンタムがプニーソックであったことを示唆している[8]。この階級は、ニューイングランド南部の社会で唯一戦士のエリー ト階級を持つナラガンセッツ族においてロジャー・ウィリアムズが記述した「勇士」に相当する、プラエトリアンガードのようなものを生み出していたのかもし れない[33]。平民(サノプス)の階級に加えて、部族に帰属する部外者がいた。彼らには共通の敵からの保護を期待する以外にはほとんど権利がなかった [32]。 |

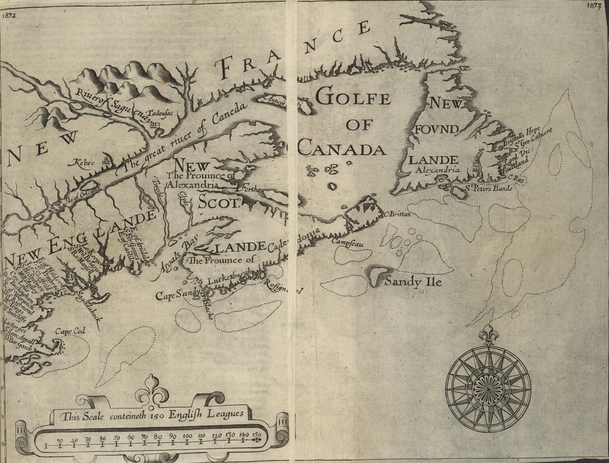

| Contact with Europeans The Ninnimissinuok had sporadic contact with European explorers for nearly a century before the landing of the Mayflower in 1620. The fishermen off the Newfoundland banks from Bristol, Normandy, and Brittany began making annual spring visits beginning as early as 1581 to bring cod to Southern Europe.[34] These early encounters had long-term effects. Europeans very likely introduced diseases[g] for which the Indian population had no resistance. When the Mayflower arrived, the Pilgrims discovered that an entire village was devoid of inhabitants.[36] European fur traders traded goods with different tribes, and this exacerbated intertribal rivalries and hostilities.[37] The first kidnappings Main article: George Weymouth  Captain Weymouth impressing Natives of Pemaquid, Maine, with a sword he magnetized by means of a lodestone. In 1605, George Weymouth set out on an expedition to explore the possibility of settlement in upper New England, sponsored by Henry Wriothesley and Thomas Arundell.[38] They had a chance encounter with a hunting party, then decided to kidnap a number of Indians. The capture of Indians was "a matter of great importance for the full accomplement of our voyage".[39] They took five captives to England and gave three to Sir Ferdinando Gorges. Gorges was an investor in the Weymouth voyage and became the chief promoter of the scheme when Arundell withdrew from the project.[40] Gorges wrote of his delight in Weymouth's kidnapping, and named Tisquantum as one of the three given to him. Captain George Weymouth, having failed at finding a Northwest Passage, happened into a River on the Coast of America, called Pemmaquid, from whence he brought five of the Natives, three of whose names were Manida, Sellwarroes, and Tasquantum, whom I seized upon, they were all of one Nation, but of severall parts, and severall Families; This accident must be acknowledged the meanes under God of putting on foote, and giving life to all our Plantations.[41] However, it is unlikely that the "Tasquantum" identified by Gorges refers to the same man. Circumstantial evidence makes this nearly impossible. The Indians taken by Weymouth and given to Gorges were Eastern Abenaki from Maine, whereas the subject Tisquantum was Patuxet, a Southern New England Algonquin. He lived in Plymouth, and the Archangel did not sail that far south on the voyage of 1605. Adams maintains that "it is not supposable that a member of the Pokánoket [Patuxet] tribe would be passing the summer of 1605 in a visit among his deadly enemies the Tarratines, whose language was not even intelligible to him ... and be captured as one of a party of them in the way described by Rosier."[42] No modern historian entertains this supposition.[h] Abduction  John Smith's 1614 Map of New England. In 1614, an English expedition headed by John Smith sailed along the coast of Maine and Massachusetts Bay collecting fish and furs. Smith returned to England in one of the vessels and left Thomas Hunt in command of the second ship. Hunt was to complete the haul of cod and proceed to Málaga, Spain, where there was a market for dried fish,[43] but Hunt decided to enhance the value of his shipment by adding human cargo. He sailed to Plymouth harbor ostensibly to trade with the village of Patuxet, where he lured 20 Indians aboard his vessel under promise of trade, including Tisquantum.[43] Once aboard, they were confined and the ship sailed across Cape Cod Bay where Hunt abducted seven more from the Nausets.[44] He then set sail for Málaga. Smith and Gorges both disapproved of Hunt's decision to enslave the Indians.[45] Gorges worried about the prospect of "a warre now new begun between the inhabitants of those parts, and us",[46] although he seemed mostly concerned about whether this event had upset his gold-finding plans with Epenow on Martha's Vineyard.[47] Smith suggested that Hunt got his just desserts because "this wilde act kept him ever after from any more imploiment to those parts."[43]  Málaga in 1572, 40 years before Tisquantum was delivered there in slavery According to Gorges, Hunt took the Indians to the Strait of Gibraltar where he sold as many as he could. But the "Friers (sic) of those parts" discovered what he was doing, and they took the remaining Indians to be "instructed in the Christian Faith; and so disappointed this unworthy fellow of his hopes of gaine".[48] No truly primary sources of Tisquantum's arrival in Spain were known to exist until Spanish researcher Ms. Purificación Ruiz uncovered two deeds in public archives in Málaga, documenting the facts with original notarial records.[49] It turns out that on October 22nd, 1614 one Thomas Hunt sold a grand total of twenty-five Native Americans to Juan Bautista Reales, a larger-than-life adventurer well known to historians for having been at the same time Catholic priest, businessman and spy. The sale of the captives was thinly disguised owing to its illegal nature, because while slavery of North African captives was rampant, enslavement of Native Americans was against the law. Further research by Ms. Ruiz indeed found two more notarial records showing that only two weeks later Málaga's Corregidor had regained control of twenty captives and distributed them among a number of local notables, with orders to have them educated in the Catholic faith and local mores. No further documents have been found but research continues and there is some hope that any hitherto undocumented involvement of Spanish friars or other individuals may be brought to light. No records show how long Tisquantum lived in Spain, what he did there, or how he "got away for England", as Bradford puts it.[50] Prowse asserts that he spent four years in slavery in Spain and was then smuggled aboard a ship belonging to Guy's colony, taken to England, and then to Newfoundland.[51] Smith attested that Tisquantum lived in England "a good time", although he does not say what he was doing there.[52] Plymouth Governor William Bradford knew him best and recorded that he lived in Cornhill, London with "Master John Slanie".[53] Slany was a merchant and shipbuilder who became another of the merchant adventurers of London hoping to make money from colonizing projects in America and was an investor in the East India Company. Return to New England According to the report by the Plymouth Council for New England in 1622, Tisquantum was in Newfoundland "with Captain Mason Governor there for the undertaking of that Plantation".[54] Thomas Dermer was at Cuper's Cove in Conception Bay,[55] an adventurer who had accompanied Smith on his abortive 1615 voyage to New England. Tisquantum and Dermer talked of New England while in Newfoundland, and Tisquantum persuaded him that he could make his fortune there, and Dermer wrote Gorges and requested that Gorges send him a commission to act in New England.  Map of New England from Newfoundland to Cape Cod in Purchas 1625, pp. IV:1880–81 Toward the end of 1619, Dermer and Tisquantum sailed down the New England coast to Massachusetts Bay. They discovered that all inhabitants had died in Tisquantum's home village at Patucket, so they moved inland to the village of Nemasket. Dermer sent Tisquantum[56] to the village of Pokanoket near Bristol, Rhode Island, seat of Chief Massasoit. A few days later, Massasoit arrived at Nemasket along with Tisquantum and 50 warriors. It is not known whether Tisquantum and Massasoit had met prior to these events, but their interrelations can be traced at least to this date. Dermer returned to Nemasket in June 1620, but this time he discovered that the Indians there bore "an inveterate malice to the English", according to a June 30, 1620, letter transcribed by Bradford. This sudden and dramatic change from friendliness to hostility was due to an incident the previous year, when a European coastal vessel lured some Indians on board with the promise of trade, only to mercilessly slaughter them. Dermer wrote that "Squanto cannot deny but they would have killed me when I was in Nemask, had he not entreated hard for me."[57] Some time after this encounter, Indians attacked Dermer, Tisquantum and their party on Martha's Vineyard. Dermer received "14 mortal wounds in the process".[58] He fled to Virginia where he died. Sometime after this, Tisquantum fell in with the Pokanokets (neighbors of his native village), and was living with them by March 1622 when he was introduced to the Pilgrims. |

ヨーロッパ人との接触 ニンニミシヌオック族は、1620年にメイフラワー号が上陸するまでの約1世紀間、ヨーロッパの探検家たちと散発的に接触していた。ブリストル、ノルマン ディー、ブルターニュの漁師たちは、南ヨーロッパにタラを運ぶために、1581年から毎年春にニューファンドランドの堤防を訪れていた[34]。ヨーロッ パ人は、インディアンの人々が抵抗力を持たない病気[g]を持ち込んだ可能性が非常に高かった。メイフラワー号が到着したとき、ピルグリムたちは村全体か ら住民がいなくなっているのを発見した[36]。ヨーロッパの毛皮商人たちは異なる部族と商品を取引し、これが部族間の対立や敵対関係を悪化させた [37]。 最初の誘拐 主な記事 ジョージ・ウェイマス  メイン州ペマキッドの先住民に、ロッジストーンで磁化した剣で感銘を与えるウェイマス船長。 1605年、ジョージ・ウェイマスは、ヘンリー・ウリオセスリーとトーマス・アランデルの後援で、ニューイングランド上部に入植する可能性を探る探検に出 発した[38]。インディアンの捕獲は「我々の航海を完全に遂行するために非常に重要な問題」であった[39]。 彼らは5人の捕虜をイギリスに連れ帰り、3人をフェルディナンド・ゴージズ卿に渡した。ゴルジェスはウェーマス航海の出資者であり、アランデルがこの計画 から撤退した際には、この計画の主席推進者となった[40]。ゴルジェスはウェーマス誘拐の喜びを綴り、与えられた3人のうちの1人としてティスカンタム の名を挙げた。 ジョージ・ウェイマス船長は北西航路を見つけることに失敗し、ペンマキッドと呼ばれるアメリカ沿岸の川に入り、そこから5人の原住民を連れてきた。 しかし、ゴルジュが特定した「タスカンタム」が同一人物を指しているとは考えにくい。状況証拠からして、これは不可能に近い。ウェイマスによって連れ去ら れ、ゴルジュに渡されたインディアンはメイン州出身のイースタン・アベナキであったのに対し、ティスカンタムの主体は南ニューイングランド地方のアルゴン キン族であるパトゥクセットであった。彼はプリマスに住んでおり、大天使号は1605年の航海ではそこまで南下していない。アダムスは、「ポカノケット (パトゥセット)族の一員が1605年の夏を、言語すら理解できない宿敵タラティン族の間を訪問して過ごし、ロジエが述べたような方法で、その一隊として 捕らえられるということは考えられない」と主張している[42]。 拉致  ジョン・スミスの1614年のニューイングランドの地図。 1614年、ジョン・スミスが率いるイギリスの探検隊がメイン州とマサチューセッツ湾の沿岸を航海し、魚と毛皮を収集した。スミスは1隻の船でイングラン ドに戻り、2隻目の船の指揮をトーマス・ハントに任せた。ハントはマダラの漁獲を完了し、乾燥魚の市場があるスペインのマラガに向かう予定であったが [43]、ハントは人間の積荷を加えて積荷の価値を高めることにした。彼は、表向きはパトゥセット村との交易のためにプリマス港へ航海し、そこでティスカ ンタムを含む20人のインディアンを交易の約束で船に誘い込んだ。 スミスとゴルジェスは、インディアンを奴隷にするというハントの決断に反対していた[45]。ゴルジェスは、「あの地域の住民と我々との間に新たな戦争が 始まる」[46]のではないかと心配していたが、彼はこの出来事によってマーサズ・ヴィニヤードでのエペノウとの金鉱探しの計画が狂ってしまうのではない かと心配していたようであった[47]。スミスは、「この乱暴な行為によって、ハントはそれ以降あの地域に対してこれ以上干渉しないようになった」 [43]ため、ハントは正当な報いを受けたと示唆した。  ティスカンタムが奴隷として引き渡される40年前、1572年のマラガ ゴルジュによれば、ハントはインディオたちをジブラルタル海峡に連れて行き、そこでできるだけ多くのインディオたちを売った。しかし、「その地域の修道士 (sic)」が彼のしていることを発見し、彼らは残りのインディオたちを「キリスト教の信仰を指導する」ために連れて行った。 スペインの研究者ピュリフィカシオン・ルイス女史がマラガの公文書館で2つの証書を発見し、オリジナルの公証記録で事実を文書化するまで、ティスカンタム がスペインに到着した真に一次的な資料が存在することは知られていなかった[49]。 1614年10月22日、トーマス・ハント1人が、カトリック司祭であり、ビジネスマンであり、スパイでもあったことで歴史家によく知られている大物冒険 家フアン・バウティスタ・レアルスに、合計25人のネイティブ・アメリカンを売却したことが判明した。捕虜の売買は、北アフリカの捕虜の奴隷化が横行して いた一方で、ネイティブ・アメリカンの奴隷化は法律違反であったため、その違法性を薄々気づいていた。ルイズ女史がさらに調査したところ、わずか2週間後 にマラガのコレヒドールが20人の捕虜の支配権を取り戻し、カトリックの信仰とその土地の風俗を教育するよう命じて、地元の名士たちに分配したことを示す 公証記録がさらに2つ見つかった。それ以上の文書は見つかっていないが、調査は続けられており、スペインの修道士やその他の人物による、これまで文書化さ れていない関与が明るみに出るかもしれないという期待もある。 ブラッドフォードが言うように、ティスカンタムがスペインでどれくらいの期間暮らし、そこで何をしていたのか、どのようにして「イングランドに逃れた」の かを示す記録はない[50]。 プロウスは、ティスカンタムはスペインで4年間奴隷として過ごし、その後ガイの植民地の船に密航し、イングランドに連れて行かれ、さらにニューファンドラ ンドに連れて行かれたと主張している[51]。 [52]プリマス総督ウィリアム・ブラッドフォードは彼を最もよく知っており、ロンドンのコーンヒルに「ジョン・スラニー師匠」と住んでいたと記録してい る[53]。スラニーは商人であり造船業者であったが、アメリカの植民地化事業で金儲けをしようとするロンドンの商人冒険家の一人となり、東インド会社の 投資家でもあった。 ニューイングランドへの帰還 1622年のプリマスのニューイングランド評議会の報告書によれば、ティスカンタムはニューファンドランドにおり、「そのプランテーションの事業のために そこのメイスン総督船長と共に」[54]、トーマス・ダーマーはコンセプション湾のキュパーズ・コーブにおり[55]、スミスのニューイングランドへの 1615年の航海に同行した冒険家であった。ティスカンタムとダーマーはニューファンドランドでニューイングランドの話をし、ティスカンタムはそこで財産 を築くことができると彼を説得し、ダーマーはゴルジュに手紙を書き、ゴルジュからニューイングランドでの活動の依頼を受けるよう要請した。  ニューファンドランドからケープコッドに至るニューイングランドの地図(Purchas 1625, pp.) 1619年末、ダーマーとティスカンタムはニューイングランド沿岸をマサチューセッツ湾まで航海した。ティスカンタムの故郷であるパタケット村ではすべて の住民が死亡していたため、彼らは内陸のネマスケット村に移動した。ダーマーはティスカンタム[56]をマサソイト酋長の居城であるロードアイランド州ブ リストル近郊のポカノケット村に送った。数日後、マサソイトはティスカンタムと50人の戦士とともにネマスケットに到着した。ティスカンタムとマサソイト がこの出来事以前に会っていたかどうかは定かではないが、少なくともこの日まで二人の関係は遡ることができる。 ダーマーは1620年6月にネマスケットに戻ったが、ブラッドフォードが書き写した1620年6月30日の書簡によると、今度はそこのインディアンが「イ ングランド人に根強い悪意」を抱いていることを知った。この友好から敵意への突然の劇的な変化は、前年にヨーロッパ沿岸の船が貿易の約束で数人のインディ アンを船に誘い込んだが、容赦なく虐殺した事件が原因だった。ダーマーは「スクワントは否定できないが、私がネマスクにいたとき、彼が私のために懸命に懇 願しなければ、彼らは私を殺していただろう」と書いている[57]。 この遭遇からしばらくして、インディアンはマーサズ・ヴィニヤードでダーマーとティスカンタムとその一行を襲撃した。ダーマーは「その過程で14の致命 傷」を負った[58]。この後しばらくして、ティスカンタムはポカノケッツ族(生まれ故郷の村の隣人)と親しくなり、1622年3月にピルグリムたちに紹 介されるまでは彼らと暮らしていた。 |

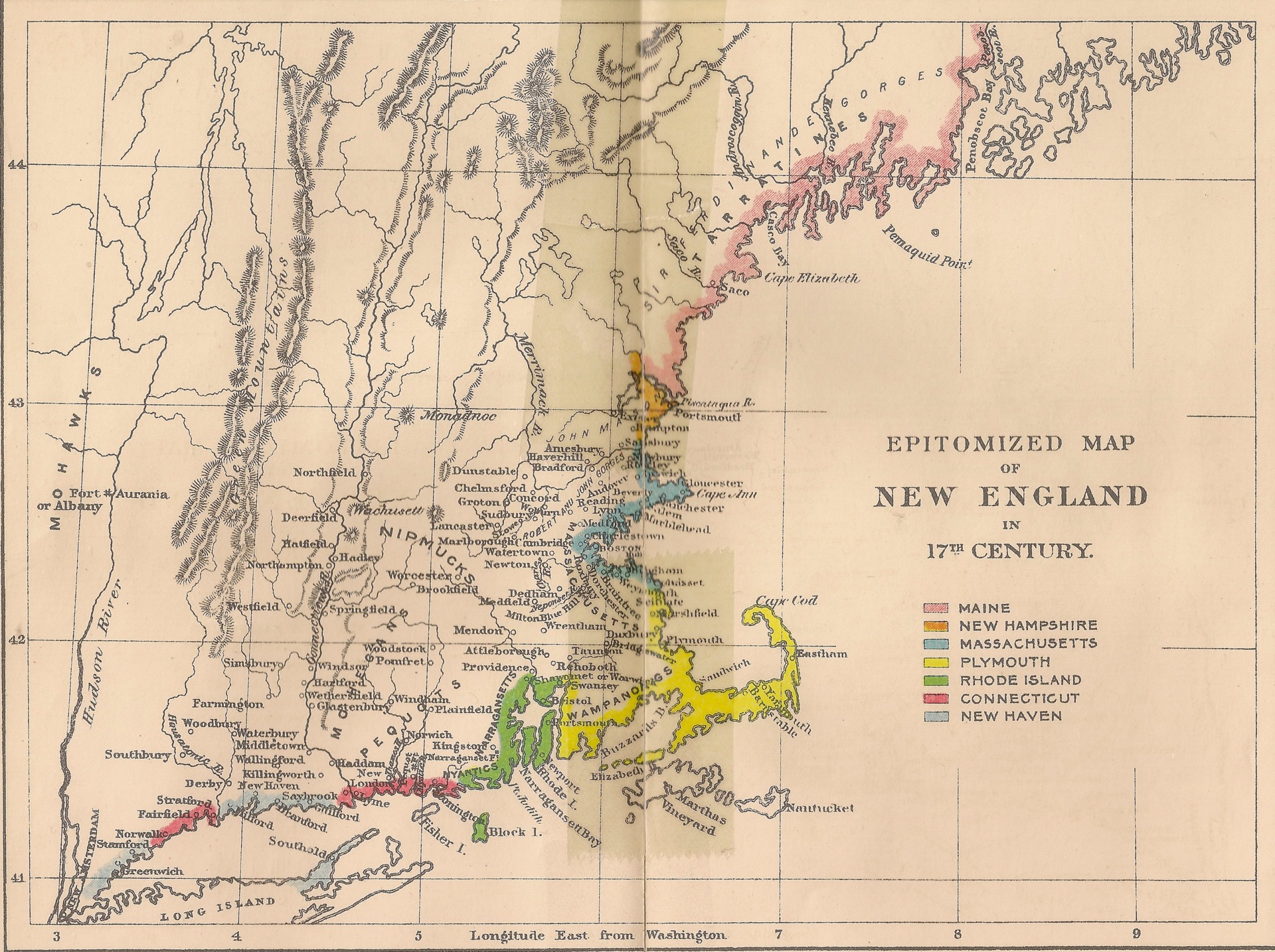

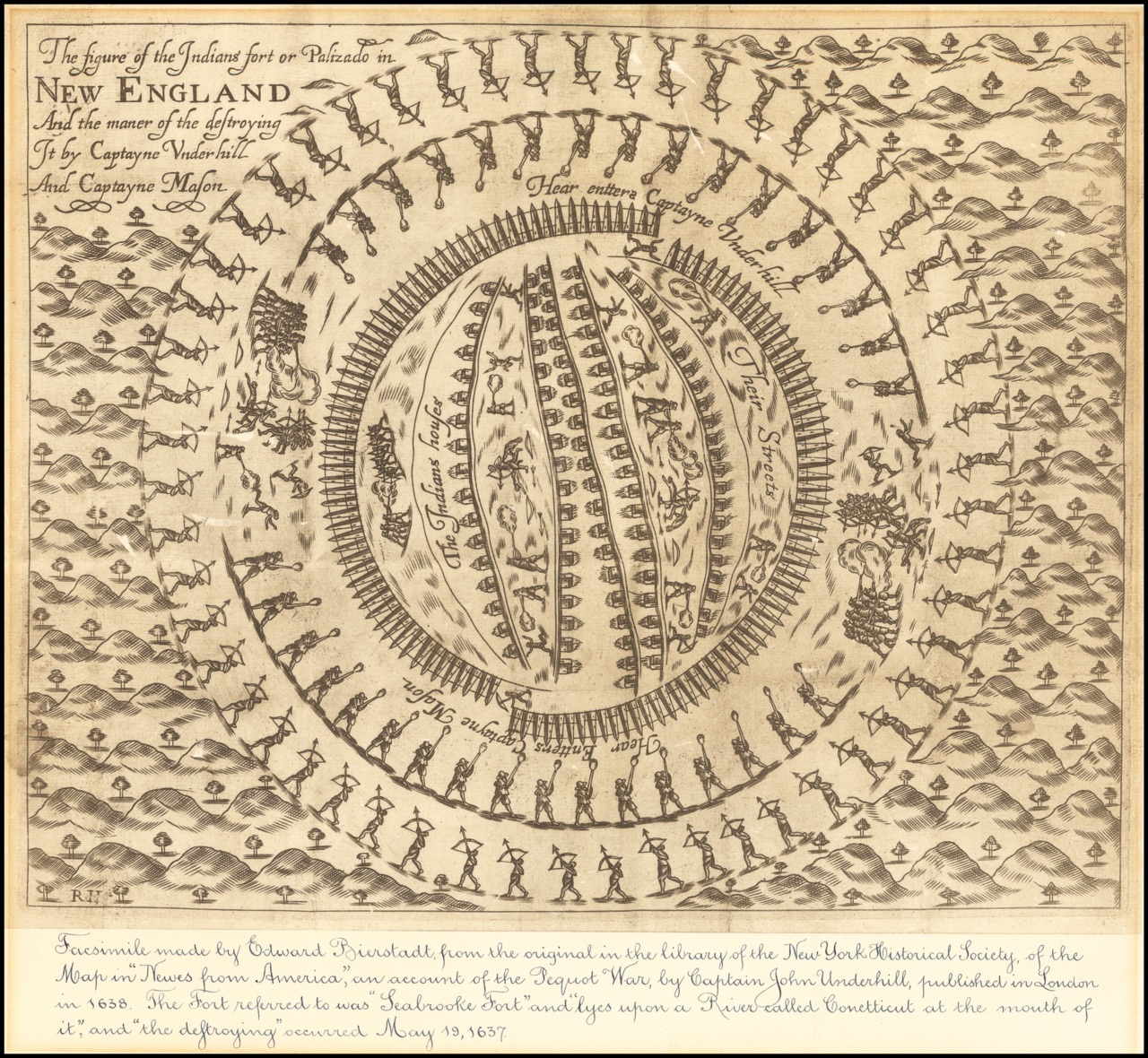

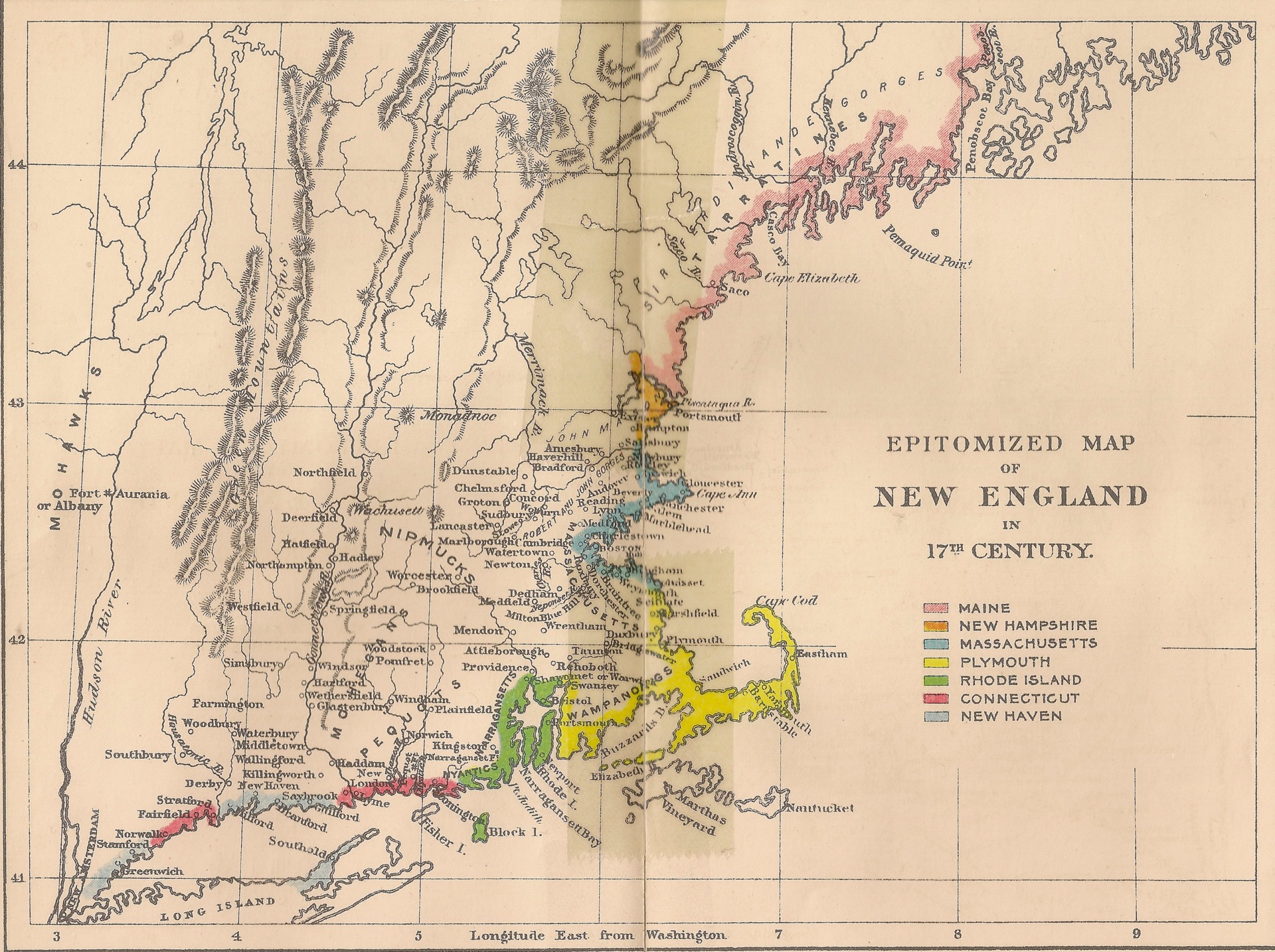

Plymouth Colony Map of Southern New England, 1620–22 showing Indian tribes, settlements, and exploration sites The Massachusett Indians were north of Plymouth Colony, led by Chief Massasoit, and the Pokanoket tribe were north, east, and south. Tisquantum was living with the Pokanokets, as his native tribe of the Patuxets had been effectively wiped out prior to the arrival of the Mayflower; indeed, the Pilgrims had established the Patuxets former habitation as the site of Plymouth Colony.[59] The Narragansett tribe inhabited Rhode Island. Massasoit was faced with the dilemma whether to form an alliance with the Plymouth colonists, who might protect him from the Narragansetts, or try to put together a tribal coalition to drive out the colonists. To decide the issue, according to Bradford's account, "they got all the Powachs of the country, for three days together in a horrid and devilish manner, to curse and execrate them with their conjurations, which assembly and service they held in a dark and dismal swamp."[60] Philbrick sees this as a convocation of shamans brought together to drive the colonists from the shores by supernatural means.[i] Tisquantum had lived in England, and he told Massassoit "what wonders he had seen" there. He urged Massasoit to become friends with the Plymouth colonists, because his enemies would then be "Constrained to bowe to him".[61] Also connected to Massasoit was Samoset, a minor Abenaki sachem who hailed from the Muscongus Bay area of Maine. Samoset (a mispronunciation of Somerset) had learned English in England as a captive of the Merchant Tailors Guild.  Samoset comes "boldly" into Plymouth settlement; woodcut designed by A.R. Waud and engraved by J.P. Davis (1876) On Friday, March 16, 1621 (Old Style), the settlers were conducting military training when Samoset "boldly came alone" into the settlement.[62] The colonists were initially alarmed, but he immediately set their fears at ease by asking for beer.[63] He spent the day giving them intelligence of the surrounding tribes, then stayed for the night, leaving on Saturday morning. The next day, Samoset returned with five men all bearing deer skins and one cat skin. The settlers entertained them but refused to trade with them because it was Sunday, although they encouraged them to return with more furs. All left but Samoset who lingered until Wednesday, feigning illness.[64] He returned once more on Thursday, March 22, 1622, this time with Tisquantum. The men brought important news: Massasoit, his brother Quadrquina, and all of their men were close by. After an hour's discussion, the sachem and his train of 60 men appeared on Strawberry Hill. Both the colonists and Massasoit's men were unwilling to make the first move, but Tisquantum shuttled between the groups and effected the simple protocol which permitted Edward Winslow to approach the sachem. Winslow, with Tisquantum as translator, proclaimed the loving and peaceful intentions of King James and the desire of their governor to trade and make peace with him.[65] After Massasoit ate, Miles Standish led him to a house which was furnished with pillows and a rug. Governor Carver then came "with Drumme and Trumpet after him" to meet Massasoit. The parties ate together, then negotiated a treaty of peace and mutual defense between the Plymouth settlers and the Pokanoket people.[66] According to Bradford, "all the while he sat by the Governour, he trembled for feare".[67] Massasoit's followers applauded the treaty,[67] and the peace terms were kept by both parties during Massasoit's lifetime. Guide to frontier survival Massasoit and his men left the day after the treaty, but Samoset and Tisquantum remained.[68] Tisquantum and Bradford developed a close friendship, and Bradford relied on him heavily during his years as governor of the colony. Bradford considered him "a special instrument sent of God for their good beyond their expectation".[69] Tisquantum instructed them in survival skills and acquainted them with their environment. "He directed them how to set their corn, where to take fish, and to procure other commodities, and was also their pilot to bring them to unknown places for their profit, and never left them till he died."[69] The day after Massasoit left Plymouth, Tisquantum spent the day at Eel River treading eels out of the mud with his feet. The bucketful of eels he brought back were "fat and sweet".[70] Collection of eels became part of the settlers' annual practice. But Bradford makes special mention of Tisquantum's instruction concerning local horticulture. He had arrived at the time of planting for that year's crops, and Bradford said that "Squanto stood them in great stead, showing them both the manner how to set it, and after how to dress and tend it."[71] Bradford wrote that Squanto showed them how to fertilize exhausted soil: He told them, except they got fish and set with it [corn seed] in these old grounds it would come to nothing. And he showed them that in the middle of April they should have store enough [of fish] come up the brook by which they began to build, and taught them how to take it, and where to get other provisions necessary for them. All of which they found true by trial and experience.[72] Edward Winslow made the same point about the value of Indian cultivation methods in a letter to England at the end of the year: We set the last Spring some twentie Acres of Indian Corne, and sowed some six Acres of Barly and Pease; and according to the manner of the Indians, we manured our ground with Herings or rather Shadds, which we have in great abundance, and take with great ease at our doores. Our Corn did prove well, & God be praysed, we had a good increase of Indian-Corne, and our Barly indifferent good, but our Pease were not worth the gathering, for we feared they were too late sowne.[73] The method shown by Tisquantum became the regular practice of the settlers.[74] Tisquantum also showed the Plymouth colonists how they could obtain pelts with the "few trifling commodities they brought with them at first". Bradford reported that there was not "any amongst them that ever saw a beaver skin till they came here and were informed by Squanto".[75] Fur trading became an important way for the colonists to pay off their financial debt to their financial sponsors in England. Role in settler diplomacy Thomas Morton stated that Massasoit was freed as a result of the peace treaty and "suffered [Tisquantum] to live with the English",[76] and Tisquantum remained loyal to the colonists. One commentator has suggested that the loneliness occasioned by the wholesale extinction of his people was the motive for his attachment to the Plymouth settlers.[77] Another has suggested that it was self-interest that he conceived while in the captivity of the Pokanoket.[78] The settlers were forced to rely on Tisquantum because he was the only means by which they could communicate with the surrounding Indians, and he was involved in every contact for the 20 months that he lived with them. Mission to Pokanoket Plymouth Colony decided in June that a mission to Massasoit in Pokatoket would enhance their security and reduce visits by Indians who drained their food resources. Winslow wrote that they wanted to ensure that the peace treaty was still valued by the Pokanoket and to reconnoiter the surrounding country and the strength of the various tribes. They also hoped to show their willingness to repay the grain that they took on Cape Cod the previous winter, in the words of Winslow to "make satisfaction for some conceived injuries to be done on our parts".[79]  Sculpture of Massasoit in Mill Creek Park, Kansas City, Missouri by Cyrus E. Dallin (1920) Governor Bradford selected Edward Winslow and Stephen Hopkins to make the journey with Tisquantum. They set off on July 2[j] carrying a "Horse-mans coat" as a gift for Massasoit made of red cotton and trimmed "with a slight lace". They also took a copper chain and a message expressing their desire to continue and strengthen the peace between the two peoples and explaining the purpose of the chain. The colony was uncertain of their first harvest, and they requested that Massasoit restrain his people from visiting Plymouth as frequently as they had—though they wished always to entertain any guest of Massasoit. So if he gave anyone the chain, they would know that the visitor was sent by him and they would always receive him. The message also attempted to explain the settlers' conduct on Cape Cod when they took some corn, and they requested that he send his men to the Nauset to express the settlers' wish to make restitution. They departed at 9 a.m.,[83] and traveled for two days meeting friendly Indians along the way. When they arrived at Pokanoket, Massasoit had to be sent for, and Winslow and Hopkins gave him a salute with their muskets when he arrived, at Tisquantum's suggestion. Massasoit was grateful for the coat and assured them on all points that they made. He assured them that his 30 tributary villages would remain in peace and would bring furs to Plymouth. The colonists stayed for two days,[84] then sent Tisquantum off to the various villages to seek trading partners for the English while they returned to Plymouth. Mission to the Nauset Winslow writes that young John Billington had wandered off and had not returned for five days. Bradford sent word to Massasoit, who made inquiry and found that the child had wandered into a Manumett village, who turned him over to the Nausets.[85] Ten settlers set out and took Tisquantum as a translator and Tokamahamon as "a special friend," in Winslow's words. They sailed to Cummaquid by evening and spent the night anchored in the bay. In the morning, the two Indians on board were sent to speak to two Indians who were lobstering. They were told that the boy was at Nauset, and the Cape Cod Indians invited all the men to take food with them. The Plymouth colonists waited until the tide allowed the boat to reach the shore, and then they were escorted to sachem Iyanough who was in his mid-20s and "very personable, gentle, courteous, and fayre conditioned, indeed not like a Savage", in Winslow's words. The colonists were lavishly entertained, and Iyanough even agreed to accompany them to the Nausets.[86] While in this village, they met an old woman, "no lesse then an hundred yeeres old", who wanted to see the colonists, and she told them of how her two sons were kidnapped by Hunt at the same time that Tisquantum was, and she had not seen them since. Winslow assured her that they would never treat Indians that way and "gave her some small trifles, which somewhat appeased her".[87] After their lunch, the settlers took the boat to Nauset with the sachem and two of his band, but the tide prevented the boat from reaching shore, so the colonists sent Inyanough and Tisquantum to meet Nauset sachem Aspinet. The colonists remained in their shallop and Nauset men came "very thick" to entreat them to come ashore, but Winslow's party was afraid because this was the very spot of the First Encounter. One of the Indians whose corn they had taken the previous winter came out to meet them, and they promised to reimburse him.[k] That night, the sachem came with more than 100 men, the colonists estimated, and he bore the boy out to the shallop. The colonists gave Aspinet a knife and one to the man who carried the boy to the boat. By this, Winslow considered that "they made peace with us." The Nausets departed, but the colonists learned (probably from Tisquantum) that the Narragansetts had attacked the Pokanokets and taken Massasoit. This caused great alarm because their own settlement was not well guarded given that so many were on this mission. The men tried to set off immediately, but they had no fresh water. After stopping again at Iyanough's village, they set off for Plymouth.[89] This mission resulted in a working relationship between the Plymouth settlers and the Cape Cod Indians, both the Nausets and the Cummaquid, and Winslow attributed that outcome to Tisquantum.[90] Bradford wrote that the Indians whose corn they had taken the previous winter came and received compensation, and peace generally prevailed.[91] Action to save Tisquantum in Nemasket The men returned to Plymouth after rescuing the Billington boy, and it was confirmed to them that Massasoit had been ousted or taken by the Narragansetts.[92] They also learned that Corbitant, a Pocasset[93] sachem formerly tributary to Massasoit, was at Nemasket attempting to pry that band away from Massasoit. Corbitant was reportedly also railing against the peace initiatives that the Plymouth settlers had just had with the Cummaquid and the Nauset. Tisquantum was an object of Corbitant's ire because of his role in mediating peace with the Cape Cod Indians, but also because he was the principal means by which the settlers could communicate with the Indians. "If he were dead, the English had lost their tongue," he reportedly said.[94] Hobomok was a Pokanoket pniese residing with the colonists,[l] and he had also been threatened for his loyalty to Massasoit.[96] Tisquantum and Hobomok were evidently too frightened to seek out Massasoit, and instead went to Nemasket to find out what they could. Tokamahamon, however, went looking for Massasoit. Corbitant discovered Tisquantum and Hobomok at Nemasket and captured them. He held Tisquantum with a knife to his breast, but Hobomok broke free and ran to Plymouth to alert them, thinking that Tisquantum had died.[97] Governor Bradford organized an armed task force of about a dozen men under the command of Miles Standish,[98][99] and they set off before daybreak on August 14[100] under the guidance of Hobomok. The plan was to march the 14 miles to Nemasket, rest, and then take the village unawares in the night. The surprise was total, and the villagers were terrified. The colonists could not make the Indians understand that they were only looking for Corbitant, and there were "three sore wounded" trying to escape the house.[101] The colonists realized that Tisquantum was unharmed and staying in the village, and that Corbitant and his men had returned to Pocaset. The colonists searched the dwelling, and Tisquantum came out after Hobomok called him from the top of the building. The settlers commandeered the house for the night. The next day, they explained to the village that they were interested only in Corbitant and those supporting him. They warned that they would exact retribution if Corbitant continued threatening them, or if Massasoit did not return from the Narragansetts, or if anyone attempted harm to any of Massasoit's subjects, including Tisquantum and Hobomok. They then marched back to Plymouth with Nemasket villagers helping bear their equipment.[102] Bradford wrote that this action resulted in a firmer peace, and that "divers sachems" congratulated the settlers and more came to terms with them. Even Corbitant made his peace through Massasoit.[100] Nathaniel Morton later recorded that nine sub-sachems came to Plymouth on September 13, 1621, and signed a document declaring themselves "Loyal Subjects of King James, King of Great Britain, France and Ireland".[103] Mission to the Massachuset people The Plymouth colonists resolved to meet with the Massachusetts Indians who had frequently threatened them.[104] On August 18, a crew of ten settlers set off around midnight, with Tisquantum and two other Indians as interpreters, hoping to arrive before daybreak. But they misjudged the distance and were forced to anchor off shore and stay in the shallop over the next night.[105] Once ashore, they found a woman coming to collect the trapped lobsters, and she told them where the villagers were. Tisquantum was sent to make contact, and they discovered that the sachem presided over a considerably reduced band of followers. His name was Obbatinewat, and he was a tributary of Massasoit. He explained that his current location within Boston harbor was not a permanent residence since he moved regularly to avoid the Tarentines[m] and the Squa Sachim (the widow of Nanepashemet).[107] Obbatinewat agreed to submit himself to King James in exchange for the colonists' promise to protect him from his enemies. He also took them to see the squa sachem across the Massachusetts Bay.  Engraving of a Pequot fort on Block Island in 1637 with design similar to the description of Nenepashemet's fort observed by Plymouth settlers in 1621 On Friday, September 21, the colonists went ashore and marched a house where Nanepashemet was buried.[108] They remained there and sent Tisquantum and another Indian to find the people. There were signs of hurried removal, but they found the women together with their corn and later a man who was brought trembling to the settlers. They assured him that they did not intend harm, and he agreed to trade furs with them. Tisquantum urged the colonists to simply "rifle" the women and take their skins on the ground, that "they are a bad people and oft threatned you,"[109] but the colonists insisted on treating them fairly. The women followed the men to the shallop, selling them everything that they had, including the coats off their backs. As the colonists shipped off, they noticed that the many islands in the harbor had been inhabited, some cleared entirely, but all the inhabitants had died.[110] They returned with "a good quantity of beaver", but the men who had seen Boston Harbor expressed their regret that they had not settled there.[100] Peace regime During the fall of 1621, the Plymouth settlers had every reason to be contented with their condition, less than one year after the "starving times". Bradford expressed the sentiment with biblical allusion[n] that they found "the Lord to be with them in all their ways, and to bless their outgoings and incomings ..."[111] Winslow was more prosaic when he reviewed the political situation with respect to surrounding natives in December 1621: "Wee have found the Indians very faithfull in their Covenant of Peace with us; very loving and readie to pleasure us ...," not only the greatest, Massasoit, "but also all the Princes and peoples round about us" for fifty miles. Even a sachem from Martha's Vineyard, who they never saw, and also seven others came in to submit to King James "so that there is now great peace amongst the Indians themselves, which was not formerly, neither would have bin but for us ..."[112] Thanksgiving Bradford wrote in his journal that come fall together with their harvest of Indian corn, they had abundant fish and fowl, including many turkeys they took in addition to venison. He affirmed that the reports of plenty that many report "to their friends in England" were not "feigned but true reports".[113] He did not, however, describe any harvest festival with their native allies. Winslow, however, did, and the letter which was included in Mourt's Relation became the basis for the tradition of "the first Thanksgiving".[o] Winslow's description of what was later celebrated as the first Thanksgiving was quite short. He wrote that after the harvest (of Indian corn, their planting of peas were not worth gathering and their harvest of barley was "indifferent"), Bradford sent out four men fowling "so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours ..."[115] The time was one of recreation, including the shooting of arms, and many Natives joined them, including Massasoit and 90 of his men,[p] who stayed three days. They killed five deer which they presented to Bradford, Standish and others in Plymouth. Winslow concluded his description by telling his readers that "we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie."[117] The Narragansett threat The various treaties created a system where the English settlers filled the vacuum created by the epidemic. The villages and tribal networks surrounding Plymouth now saw themselves as tributaries to the English and (as they were assured) King James. The settlers also viewed the treaties as committing the Natives to a form of vassalage. Nathaniel Morton, Bradford's nephew, interpreted the original treaty with Massasoit, for example, as "at the same time" (not within the written treaty terms) acknowledging himeself "content to become the Subject of our Sovereign Lord the King aforesaid, His Heirs and Successors, and gave unto them all the Lands adjacent, to them and their Heirs for ever".[118] The problem with this political and commercial system was that it "incurred the resentment of the Narragansett by depriving them of tributaries just when Dutch traders were expanding their activities in the [Narragansett] bay".[119] In January 1622 the Narraganset responded by issuing an ultimatum to the English.  Map of Southern New England in the 17th century with locations of prominent societies of Ninnimissinuok. In December 1621 the Fortune (which had brought 35 more settlers) had departed for England.[q] Not long afterwards rumors began to reach Plymouth that the Narragansett were making warlike preparations against the English.[r] Winslow believed that that nation had learned that the new settlers brought neither arms nor provisions and thus in fact weakened the English colony.[123] Bradford saw their belligerency as a result of their desire to "lord it over" the peoples who had been weakened by the epidemic (and presumably obtain tribute from them) and the colonists were "a bar in their way".[124] In January 1621/22 a messenger from Narraganset sachem Canonicus (who travelled with Tokamahamon, Winslow's "special friend") arrived looking for Tisquantum, who was away from the settlement. Winslow wrote that the messenger appeared relieved and left a bundle of arrows wrapped in a rattlesnake skin. Rather than let him depart, however, Bradford committed him to the custody of Standish. The captain asked Winslow, who had a "speciall familiaritie" with other Indians, to see if he could get anything out of the messenger. The messenger would not be specific but said that he believed "they were enemies to us." That night Winslow and another (probably Hopkins) took charge of him. After his fear subsided, the messenger told him that the messenger who had come from Canonicus last summer to treat for peace, returned and persuaded the sachem on war. Canonicus was particularly aggrieved by the "meannesse" of the gifts sent him by the English, not only in relation to what he sent to colonists but also in light of his own greatness. On obtaining this information, Bradford ordered the messenger released.[125] When Tisquantum returned he explained that the meaning of the arrows wrapped in snake skin was enmity; it was a challenge. After consultation, Bradford stuffed the snake skin with powder and shot and had a Native return it to Canonicus with a defiant message. Winslow wrote that the returned emblem so terrified Canonicus that he refused to touch it, and that it passed from hand to hand until, by a circuitous route, it was returned to Plymouth.[126] Double dealing Notwithstanding the colonists' bold response to the Narragansett challenge, the settlers realized their defenselessness to attack.[127] Bradford instituted a series of measures to secure Plymouth. Most important they decided to enclose the settlement within a pale (probably much like what was discovered surrounding Nenepashemet's fort). They shut the inhabitants within gates that were locked at night, and a night guard was posted. Standish divided the men into four squadrons and drilled them in where to report in the event of alarm. They also came up with a plan of how to respond to fire alarms so as to have a sufficient armed force to respond to possible Native treachery.[128] The fence around the settlement required the most effort since it required felling suitable large trees, digging holes deep enough to support the large timbers and securing them close enough to each other to prevent penetration by arrows. This work had to be done in the winter and at a time too when the settlers were on half rations because of the new and unexpected settlers.[129] The work took more than a month to complete.[130] False alarms By the beginning of March, the fortification of the settlement had been accomplished. It was now time when the settlers had promised the Massachuset they would come to trade for furs. They received another alarm however, this time from Hobomok, who was still living with them. Hobomok told of his fear that the Massachuset had joined in a confederacy with the Narraganset and if Standish and his men went there, they would be cut off and at the same time the Narraganset would attack the settlement at Plymouth. Hobomok also told them that Tisquantum was part of this conspiracy, that he learned this from other Natives he met in the woods and that the settlers would find this out when Tisquantum would urge the settlers into the Native houses "for their better advantage".[131] This allegation must have come as a shock to the English given that Tisquantum's conduct for nearly a year seemed to have aligned him perfectly with the English interest both in helping to pacify surrounding societies and in obtaining goods that could be used to reduce their debt to the settlers' financial sponsors. Bradford consulted with his advisors, and they concluded that they had to make the mission despite this information. The decision was made partly for strategic reasons. If the colonists cancelled the promised trip out of fear and instead stayed shut up "in our new-enclosed towne", they might encourage even more aggression. But the main reason they had to make the trip was that their "Store was almost emptie" and without the corn they could obtain by trading "we could not long subsist ..."[132] The governor therefore deputed Standish and 10 men to make the trip and sent along both Tisquantum and Hobomok, given "the jealousy between them".[133] Not long after the shallop departed, "an Indian belonging to Squanto's family" came running in. He betrayed signs of great fear, constantly looking behind him as if someone "were at his heels". He was taken to Bradford to whom he told that many of the Narraganset together with Corbitant "and he thought Massasoit" were about to attack Plymouth.[133] Winslow (who was not there but wrote closer to the time of the incident than did Bradford) gave even more graphic details: The Native's face was covered in fresh blood which he explained was a wound he received when he tried speaking up for the settlers. In this account he said that the combined forces were already at Nemasket and were set on taking advantage of the opportunity supplied by Standish's absence.[134] Bradford immediately put the settlement on military readiness and had the ordnance discharge three rounds in the hope that the shallop had not gone too far. Because of calm seas Standish and his men had just reached Gurnet's Nose, heard the alarm and quickly returned. When Hobomok first heard the news he "said flatly that it was false ..." Not only was he assured of Massasoit's faithfulness, he knew that his being a pniese meant he would have been consulted by Massasoit before he undertook such a scheme. To make further sure Hobomok volunteered his wife to return to Pokanoket to assess the situation for herself. At the same time Bradford had the watch maintained all that night, but there were no signs of Natives, hostile or otherwise.[135] Hobomok's wife found the village of Pokanoket quiet with no signs of war preparations. She then informed Massasoit of the commotion at Plymouth. The sachem was "much offended at the carriage of Tisquantum" but was grateful for Bradford's trust in him [Massasoit]. He also sent word back that he would send word to the governor, pursuant to the first article of the treaty they had entered, if any hostile actions were preparing.[136] Allegations against Tisquantum Winslow writes that "by degrees wee began to discover Tisquantum," but he does not describe the means or over what period of time this discovery took place. There apparently was no formal proceeding. The conclusion reached, according to Winslow, was that Tisquantum had been using his proximity and apparent influence over the English settlers "to make himselfe great in the eyes of" local Natives for his own benefit. Winslow explains that Tisquantum convinced locals that he had the ability to influence the English toward peace or war and that he frequently extorted Natives by claiming that the settlers were about to kill them in order "that thereby hee might get gifts to himself to work their peace ..."[137] Bradford's account agrees with Winslow's to this point, and he also explains where the information came from: "by the former passages, and other things of like nature",[138] evidently referring to rumors Hobomok said he heard in the woods. Winslow goes much further in his charge, however, claiming that Tisquantum intended to sabotage the peace with Massasoit by false claims of Massasoit aggression "hoping whilest things were hot in the heat of bloud, to provoke us to march into his Country against him, whereby he hoped to kindle such a flame as would not easily be quenched, and hoping if that blocke were once removed, there were no other betweene him and honour" which he preferred over life and peace.[139] Winslow later remembered "one notable (though) wicked practice of this Tisquantum"; namely, that he told the locals that the English possessed the "plague" buried under their storehouse and that they could unleash it at will. What he referred to was their cache of gunpowder.[s] Massasoit's demand for Tisquantum Captain Standish and his men eventually did go to the Massachuset and returned with a "good store of Trade". On their return, they saw that Massasoit was there and he was displaying his anger against Tisquantum. Bradford did his best to appease him, and he eventually departed. Not long afterward, however, he sent a messenger demanding that Tisquantum be put to death. Bradford responded that although Tisquantum "deserved to die both in respect of him [Massasoit] and us", but said that Tisquantum was too useful to the settlers because otherwise, he had no one to translate. Not long afterward, the same messenger returned, this time with "divers others", demanding Tisquantum. They argued that Tisquantum being a subject of Massasoit, was subject, pursuant to the first article of the Peace Treaty, to the sachem's demand, in effect, rendition. They further argued that if Bradford would not produce pursuant to the Treaty, Massasoit had sent many beavers' skins to induce his consent. Finally, if Bradford still would not release him to them, the messenger had brought Massasoit's own knife by which Bradford himself could cut off Tisquantum's head and hands to be returned with the messenger. Bradford avoided the question of Massasoit's right under the treaty[t] but refused the beaver pelts saying that "It was not the manner of the English to sell men's lives at a price ..." The governor called Tisquantum (who had promised not to flee), who denied the charges and ascribed them to Hobomok's desire for his downfall. He nonetheless offered to abide by Bradford's decision. Bradford was "ready to deliver him into the hands of his Executioners" but at that instance, a boat passed before the town in the harbor. Fearing that it might be the French, Bradford said he had to first identify the ship before dealing with the demand. The messenger and his companions, however, "mad with rage, and impatient at delay" left "in great heat".[142] Final mission with the settlers Arrival of the Sparrow The ship the English saw pass before the town was not French, but rather a shallop from the Sparrow, a shipping vessel sponsored by Thomas Weston and one other of the Plymouth settlement's sponsors, which was plying the eastern fishing grounds.[143] This boat brought seven additional settlers but no provisions whatsoever "nor any hope of any".[144] In a letter they brought, Weston explained that the settlers were to set up a salt pan operation on one of the islands in the harbor for the private account of Weston. He asked the Plymouth colony, however, to house and feed these newcomers, provide them with seed stock and (ironically) salt, until he was able to send the salt pan to them.[145] The Plymouth settlers had spent the winter and spring on half rations in order to feed the settlers that had been sent nine months ago without provisions.[146] Now Weston was exhorting them to support new settlers who were not even sent to help the plantation.[147] He also announced that he would be sending another ship that would discharge more passengers before it would sail on to Virginia. He requested that the settlers entertain them in their houses so that they could go out and cut down timber to lade the ship quickly so as not to delay its departure.[148] Bradford found the whole business "but cold comfort to fill their hungry bellies".[149] Bradford was not exaggerating. Winslow described the dire straits. They now were without bread "the want whereof much abated the strength and the flesh of some, and swelled others".[150] Without hooks or seines or netting, they could not collect the bass in the rivers and cove, and without tackle and navigation rope, they could not fish for the abundant cod in the sea. Had it not been for shellfish which they could catch by hand, they would have perished.[151] But there was more, Weston also informed them that the London backers had decided to dissolve the venture. Weston urged the settlers to ratify the decision; only then might the London merchants send them further support, although what motivation they would then have he did not explain.[152] That boat also, evidently,[u] contained alarming news from the South. John Huddleston, who was unknown to them but captained a fishing ship that had returned from Virginia to the Maine fishing grounds, advised his "good friends at Plymouth" of the massacre in the Jamestown settlements by the Powhatan in which he said 400 had been killed. He warned them: "Happy is he whom other men's harms doth make to beware."[156] This last communication Bradford decided to turn to their advantage. Sending a return for this kindness, they might also seek fish or other provisions from the fishermen. Winslow and a crew were selected to make the voyage to Maine, 150 miles away, to a place they had never been.[159] In Winslow's reckoning, he left at the end of May for Damariscove.[v] Winslow found the fishermen more than sympathetic and they freely gave what they could. Even though this was not as much as Winslow hoped, it was enough to keep them going until the harvest.[164] When Winslow returned, the threat they felt had to be addressed. The general anxiety aroused by Huddleston's letter was heightened by the increasingly hostile taunts they learned of. Surrounding villagers were "glorying in our weaknesse", and the English heard threats about how "easie it would be ere long to cut us off". Even Massasoit turned cool towards the English, and could not be counted on to tamp down this rising hostility. So they decided to build a fort on burying hill in town. And just as they did when building the palisade, the men had to cut down trees, haul them from the forest and up the hill and construct the fortified building, all with inadequate nutrition and at the neglect of dressing their crops.[165] Weston's English settlers They might have thought they reached the end of their problems, but in June 1622 the settlers saw two more vessels arrive, carrying 60 additional mouths to feed. These were the passengers that Weston had written would be unloaded from the vessel going on to Virginia. That vessel also carried more distressing news. Weston informed the governor that he was no longer a part of the company sponsoring the Plymouth settlement. The settlers he sent just now, and requested the Plymouth settlement to house and feed, were for his own enterprise. The "sixty lusty men" would not work for the benefit of Plymouth; in fact he had obtained a patent and as soon as they were ready they would settle an area in Massachusetts Bay. Other letters also were brought. The other venturers in London explained that they had bought out Weston, and everyone was better off without him. Weston, who saw the letter before it was sent, advised the settlers to break off from the remaining merchants, and as a sign of good faith delivered a quantity of bread and cod to them. (Although, as Bradford noted in the margin, he "left not his own men a bite of bread.") The arrivals also brought news that the Fortune had been taken by French pirates, and therefore all their past effort to export American cargo (valued at £500) would count for nothing. Finally Robert Cushman sent a letter advising that Weston's men "are no men for us; wherefore I prey you entertain them not"; he also advised the Plymouth Separatists not to trade with them or loan them anything except on strict collateral."I fear these people will hardly deal so well with the savages as they should. I pray you therefore signify to Squanto that they are a distinct body from us, and we have nothing to do with them, neither must be blamed for their faults, much less can warrant their fidelity." As much as all this vexed the governor, Bradford took in the men and fed and housed them as he did the others sent to him, even though Weston's men would compete with his colony for pelts and other Native trade.[166] But the words of Cushman would prove prophetic.  Map contained as frontispiece to Wood 1634. Weston's men, "stout knaves" in the words of Thomas Morton,[167] were roustabouts collected for adventure[168] and they scandalized the mostly strictly religious villagers of Plymouth. Worse, they stole the colony's corn, wandering into the fields and snatching the green ears for themselves.[169] When caught, they were "well whipped", but hunger drove them to steal "by night and day". The harvest again proved disappointing, so that it appeared that "famine must still ensue, the next year also" for lack of seed. And they could not even trade for staples because their supply of items the Natives sought had been exhausted.[170] Part of their cares were lessened when their coasters returned from scouting places in Weston's patent and took Weston's men (except for the sick, who remained) to the site they selected for settlement, called Wessagusset (now Weymouth). But not long after, even there they plagued Plymouth, who heard, from Natives once friendly with them, that Weston's settlers were stealing their corn and committing other abuses.[171] At the end of August a fortuitous event staved off another starving winter: the Discovery, bound for London, arrived from a coasting expedition from Virginia. The ship had a cargo of knives, beads and other items prized by Natives, but seeing the desperation of the colonists the captain drove a hard bargain: He required them to buy a large lot, charged them double their price and valued their beaver pelts at 3s. per pound, which he could sell at 20s. "Yet they were glad of the occasion and fain to buy at any price ..."[172] Trading expedition with Weston's men The Charity returned from Virginia at the end of September–beginning of October. It proceeded on to England, leaving the Wessagusset settlers well provisioned. The Swan was left for their use as well.[173] It was not long after they learned that the Plymouth settlers had acquired a store of trading goods that they wrote Bradford proposing that they jointly undertake a trading expedition, they to supply the use of the Swan. They proposed equal division of the proceeds with payment for their share of the goods traded to await arrival of Weston. (Bradford assumed they had burned through their provisions.) Bradford agreed and proposed an expedition southward of the Cape.[174] Winslow wrote that Tisquantum and Massasoit had "wrought" a peace (although he doesn't explain how this came about). With Tisquantum as guide, they might find the passage among the Monomoy Shoals to Nantucket Sound;[w] Tisquantum had advised them he twice sailed through the shoals, once on an English and once on a French vessel.[176] The venture ran into problems from the start. When in Plymouth Richard Green, Weston's brother-in-law and temporary governor of the colony, died. After his burial and receiving directions to proceed from the succeeding governor of Wessagusset, Standish was appointed leader but twice the voyage was turned back by violent winds. On the second attempt, Standish fell ill. On his return Bradford himself took charge of the enterprise.[177] In November they set out. When they reached the shoals, Tisquantum piloted the vessel, but the master of the vessel did not trust the directions and bore up. Tisquantum directed him through a narrow passage, and they were able to harbor near Mamamoycke (now Chatham). That night Bradford went ashore with a few others, Tisquantum acting as translator and facilitator. Not having seen any of these Englishmen before, the Natives were initially reluctant. But Tisquantum coaxed them and they provided a plentiful meal of venison and other victuals. They were reluctant to allow the English to see their homes, but when Bradford showed his intention to stay on shore, they invited him to their shelters, having first removed all their belongings. As long as the English stayed, the Natives would disappear "bag and baggage" whenever their possessions were seen. Eventually Tisquantum persuaded them to trade and as a result, the settlers obtained eight hogsheads of corn and beans. The villagers also told them that they had seen vessels "of good burthen" pass through the shoals. And so, with Tisquantum feeling confident, the English were prepared to make another attempt. But suddenly Tisquantum became ill and died.[178] |