ペンテコステ派/ペンテコステ運動

Pentecostalism

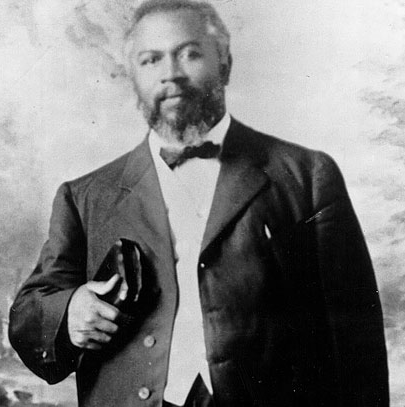

William

Seymour, leader of the Azusa Street Revival / Women in a Pentecostal

worship service

☆ ペンテコステ派、または古典的ペンテコステ派は、プロテスタントのキリスト教の幅広い福音派の一派[1][2][3] で、聖霊の洗礼による神との直接的な体験を重視する運動だ。[1] 「ペンテコステ派」という用語は、使徒行伝(使徒行伝2章1節から31節)に記述されている、イエス・キリストの弟子たちがエルサレムで七週の祭りを祝っ ていた際に、使徒たちや他の信者たちに聖霊が降臨した出来事を記念する「ペンテコステ」に由来する。 他の形態の福音主義プロテスタントと同様[5]、ペンテコステ派は、聖書の無誤性と「新生」の必要性を信奉している。新生とは、個人が自分の罪を悔い改 め、「イエス・キリストを自分の個人的な主であり救い主である」と受け入れることだ。ペンテコステ派は、「聖霊のバプテスマ」と水によるバプテスマの両方 を信じることで、キリスト教徒が「聖霊に満たされ、力を与えられた人生」を送ることができると信じている点で、他のプロテスタントと区別される。この力に は、異言や神の癒しなどの霊的賜物の使用が含まれる。[1] 聖書の権威、霊的賜物、奇跡へのコミットメントから、ペンテコステ派は自らの運動を、初期教会の使徒時代に見られた同じ種類の霊的力と教義を反映したもの と見なしている。このため、一部のペンテコステ派は、自らの運動を「使徒的」または「フル・ゴスペル」と表現することもある。[1] 聖潔ペンテコステ派は、キリスト教の復興運動とキリストの再臨の迫り来る期待に活気づけられたウェスレー聖潔運動の信者たちの中から、20 世紀初頭に誕生した。[6] 彼らは、自分たちが終末の時代に生きていると信じ、神がキリスト教教会を霊的に刷新し、霊的な賜物の回復と世界への伝道を実現すると期待していた。 1900年、アメリカの伝道者兼信仰治療家であるチャールズ・パーハムは、異言を話すことが聖霊のバプテスマの聖書的な証拠であると教え始めた。ウェス レー派のホーリネス派の説教者ウィリアム・J・シーモアと共に、彼はこれが「第三の恵みの業」であると教えた。[7] セイモアがカリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスで設立し指導した3年間に及ぶアズサ・ストリート・リバイバルは、アメリカ合衆国および世界中にペンテコステ派の 拡大をもたらした。訪問者はペンテコステ派の体験を故郷の教会に持ち帰ったり、宣教地に召されたと感じたりした。ほぼすべてのペンテコステ派教派はアズ サ・ストリートに起源をたどるが、この運動は複数の分裂と論争を経験してきた。初期の論争は、完全聖化教義への挑戦に焦点を当てていましたが、後には聖三 位一体教義への挑戦に移りました。その結果、ペンテコステ派は、三つの明確な恵みの業を肯定する「ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派」と、三位一体派と非三位一 体派に分かれた「フィニッシュド・ワーク・ペンテコステ派」に分割され、後者は「オネネス・ペンテコステ派」を生み出した。[8][9]

プロテスタント諸教派の系統概略

| Pentecostalism

or classical

Pentecostalism is a movement within the broader Evangelical

wing of Protestant Christianity[1][2][3] that emphasizes direct

personal experience of God through baptism with the Holy Spirit.[1] The

term Pentecostal is derived from Pentecost, an event that commemorates

the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles and other followers of

Jesus Christ while they were in Jerusalem celebrating the Feast of

Weeks, as described in the Acts of the Apostles (Acts 2:1–31).[4] Like other forms of evangelical Protestantism,[5] Pentecostalism adheres to the inerrancy of the Bible and the necessity of the New Birth: an individual repenting of their sin and "accepting Jesus Christ as their personal Lord and Savior". It is distinguished by belief in both the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" and baptism by water, that enables a Christian to "live a Spirit-filled and empowered life". This empowerment includes the use of spiritual gifts: such as speaking in tongues and divine healing.[1] Because of their commitment to biblical authority, spiritual gifts, and the miraculous, Pentecostals see their movement as reflecting the same kind of spiritual power and teachings that were found in the Apostolic Age of the Early Church. For this reason, some Pentecostals also use the term "Apostolic" or "Full Gospel" to describe their movement.[1] Holiness Pentecostalism emerged in the early 20th century among adherents of the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, who were energized by Christian revivalism and expectation of the imminent Second Coming of Christ.[6] Believing that they were living in the end times, they expected God to spiritually renew the Christian Church and bring to pass the restoration of spiritual gifts and the evangelization of the world. In 1900, Charles Parham, an American evangelist and faith healer, began teaching that speaking in tongues was the Biblical evidence of Spirit baptism. Along with William J. Seymour, a Wesleyan-Holiness preacher, he taught that this was the third work of grace.[7] The three-year-long Azusa Street Revival, founded and led by Seymour in Los Angeles, California, resulted in the growth of Pentecostalism throughout the United States and the rest of the world. Visitors carried the Pentecostal experience back to their home churches or felt called to the mission field. While virtually all Pentecostal denominations trace their origins to Azusa Street, the movement has had several divisions and controversies. Early disputes centered on challenges to the doctrine of entire sanctification, and later on, the Holy Trinity. As a result, the Pentecostal movement is divided between Holiness Pentecostals who affirm three definite works of grace,[6] and Finished Work Pentecostals who are partitioned into trinitarian and non-trinitarian branches, the latter giving rise to Oneness Pentecostalism.[8][9] Comprising over 700 denominations and many independent churches, Pentecostalism is highly decentralized.[10] No central authority exists, but many denominations are affiliated with the Pentecostal World Fellowship. With over 279 million classical Pentecostals worldwide, the movement is growing in many parts of the world, especially the Global South and Third World countries.[10][11][12][13][14] Since the 1960s, Pentecostalism has increasingly gained acceptance from other Christian traditions, and Pentecostal beliefs concerning the baptism of the Holy Spirit and spiritual gifts have been embraced by non-Pentecostal Christians in Protestant and Catholic churches through their adherence to the Charismatic movement. Together, worldwide Pentecostal and Charismatic Christianity numbers over 644 million adherents.[15] While the movement originally attracted mostly lower classes in the global South, there is a new appeal to middle classes.[16][17][18] Middle-class congregations tend to have fewer members.[19][20][21] Pentecostalism is believed to be the fastest-growing religious movement in the world.[22] |

ペンテコステ派、または古典的ペンテコステ派は、プロテスタントのキリ

スト教の幅広い福音派の一派[1][2][3] で、聖霊の洗礼による神との直接的な体験を重視する運動だ。[1]

「ペンテコステ派」という用語は、使徒行伝(使徒行伝2章1節から31節)に記述されている、イエス・キリストの弟子たちがエルサレムで七週の祭りを祝っ

ていた際に、使徒たちや他の信者たちに聖霊が降臨した出来事を記念する「ペンテコステ」に由来する。 他の形態の福音主義プロテスタントと同様[5]、ペンテコステ派は、聖書の無誤性と「新生」の必要性を信奉している。新生とは、個人が自分の罪を悔い改 め、「イエス・キリストを自分の個人的な主であり救い主である」と受け入れることだ。ペンテコステ派は、「聖霊のバプテスマ」と水によるバプテスマの両方 を信じることで、キリスト教徒が「聖霊に満たされ、力を与えられた人生」を送ることができると信じている点で、他のプロテスタントと区別される。この力に は、異言や神の癒しなどの霊的賜物の使用が含まれる。[1] 聖書の権威、霊的賜物、奇跡へのコミットメントから、ペンテコステ派は自らの運動を、初期教会の使徒時代に見られた同じ種類の霊的力と教義を反映したもの と見なしている。このため、一部のペンテコステ派は、自らの運動を「使徒的」または「フル・ゴスペル」と表現することもある。[1] 聖潔ペンテコステ派は、キリスト教の復興運動とキリストの再臨の迫り来る期待に活気づけられたウェスレー聖潔運動の信者たちの中から、20 世紀初頭に誕生した。[6] 彼らは、自分たちが終末の時代に生きていると信じ、神がキリスト教教会を霊的に刷新し、霊的な賜物の回復と世界への伝道を実現すると期待していた。 1900年、アメリカの伝道者兼信仰治療家であるチャールズ・パーハムは、異言を話すことが聖霊のバプテスマの聖書的な証拠であると教え始めた。ウェス レー派のホーリネス派の説教者ウィリアム・J・シーモアと共に、彼はこれが「第三の恵みの業」であると教えた。[7] セイモアがカリフォルニア州ロサンゼルスで設立し指導した3年間に及ぶアズサ・ストリート・リバイバルは、アメリカ合衆国および世界中にペンテコステ派の 拡大をもたらした。訪問者はペンテコステ派の体験を故郷の教会に持ち帰ったり、宣教地に召されたと感じたりした。ほぼすべてのペンテコステ派教派はアズ サ・ストリートに起源をたどるが、この運動は複数の分裂と論争を経験してきた。初期の論争は、完全聖化教義への挑戦に焦点を当てていましたが、後には聖三 位一体教義への挑戦に移りました。その結果、ペンテコステ派は、三つの明確な恵みの業を肯定する「ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派」と、三位一体派と非三位一 体派に分かれた「フィニッシュド・ワーク・ペンテコステ派」に分割され、後者は「オネネス・ペンテコステ派」を生み出した。[8][9] 700以上の教派と多くの独立教会で構成されるペンテコステ派は、非常に分散化している[10]。中央の権威は存在しないが、多くの教派はペンテコステ派 世界連盟に加盟している。世界中に2億7900万人以上の古典的ペンテコステ派が存在し、この運動は世界の多くの地域、特にグローバル・サウスや第三世界 諸国で成長している[10][11]。[12][13][14] 1960年代以降、ペンテコステ派は他のキリスト教伝統から徐々に受け入れられるようになり、ペンテコステ派の聖霊の洗礼と霊的賜物に関する信仰は、プロ テスタントやカトリック教会におけるカリスマ運動への参加を通じて、非ペンテコステ派のキリスト教徒にも受け入れられるようになった。世界中のペンテコス テ派とカリスマ派キリスト教徒の総数は6億4,400万人を超える。[15] 当初、この運動は主にグローバル・サウス(南半球の途上国)の低所得層を惹きつけたが、現在では中間層にも新たな魅力が生まれている。[16][17] [18] 中間層の教会は信徒数が少ない傾向にある。[19][20][21] ペンテコステ派は、世界で最も急速に成長している宗教運動とされている。[22] |

| History Background Early Pentecostals have considered the movement a latter-day restoration of the church's apostolic power, and historians such as Cecil M. Robeck Jr. and Edith Blumhofer write that the movement emerged from late 19th-century radical evangelical revival movements in America and in Great Britain.[23][24] Within this radical evangelicalism, expressed most strongly in the Wesleyan–holiness and Higher Life movements, themes of restorationism, premillennialism, faith healing, and greater attention on the person and work of the Holy Spirit were central to emerging Pentecostalism.[25] Believing that the second coming of Christ was imminent, these Christians expected an endtime revival of apostolic power, spiritual gifts, and miracle-working.[26] Figures such as Dwight L. Moody and R. A. Torrey began to speak of an experience available to all Christians which would empower believers to evangelize the world, often termed baptism with the Holy Spirit.[27] Certain Christian leaders and movements had important influences on early Pentecostals. The essentially universal belief in the continuation of all the spiritual gifts in the Keswick and Higher Life movements constituted a crucial historical background for the rise of Pentecostalism.[28] Albert Benjamin Simpson (1843–1919) and his Christian and Missionary Alliance (founded in 1887) was very influential in the early years of Pentecostalism, especially on the development of the Assemblies of God. Another early influence on Pentecostals was John Alexander Dowie (1847–1907) and his Christian Catholic Apostolic Church (founded in 1896). Pentecostals embraced the teachings of Simpson, Dowie, Adoniram Judson Gordon (1836–1895) and Maria Woodworth-Etter (1844–1924; she later joined the Pentecostal movement) on healing.[29] Edward Irving's Catholic Apostolic Church (founded c. 1831) also displayed many characteristics later found in the Pentecostal revival.[30]: 131 Isolated Christian groups were experiencing charismatic phenomena such as divine healing and speaking in tongues. The Holiness Pentecostal movement provided a theological explanation for what was happening to these Christians, and they adapted a modified form of Wesleyan soteriology to accommodate their new understanding.[31][32][33] |

歴史 背景 初期のペンテコステ派は、この運動を教会の使徒的権威の現代における回復と捉えており、セシル・M・ロベック・ジュニアやエディス・ブルムホーファーなど の歴史家は、この運動は19世紀後半のアメリカとイギリスで起こった急進的な福音主義の復興運動から生まれたと記述している。[23][24] この急進的な福音主義の中で、ウェスレーの聖性運動やハイヤーライフ運動に最も強く表現された、復古主義、前千年王国説、信仰による癒し、そして聖霊の人 格と働きへの注目は、新興のペンテコステ派の中心的なテーマとなった[25]。キリストの再臨が間近であると信じていたこれらのキリスト教徒たちは、使徒 の権威、霊的賜物、そして奇跡の復活を、終末の時代に期待していた[26]。ドワイト・L・ムーディやR・A・トーリーのような人物は、すべてのキリスト 教徒が体験できる、信者を世界宣教に駆り立てる力となる体験について語り始め、これはしばしば「聖霊のバプテスマ」と呼ばれた。[27] 特定のキリスト教指導者や運動は、初期のペンテコステ派に重要な影響を与えた。ケズウィック運動とハイヤー・ライフ運動における、すべての霊的賜物の継続 という本質的に普遍的な信念は、ペンテコステ派の台頭にとって重要な歴史的背景となった。[28] アルバート・ベンジャミン・シンプソン(1843-1919)と彼のキリスト教宣教同盟(1887年設立)は、ペンテコステ派の初期、特に神召会の発展に 大きな影響を与えた。ペンテコステ派に初期の影響を与えたもう一人の人物は、ジョン・アレクサンダー・ドウィ(1847-1907)と彼のキリスト教カト リック使徒教会(1896年設立)だ。。ペンテコステ派は、シンプソン、ドウイー、アドニラム・ジャドソン・ゴードン(1836-1895)、マリア・ ウッドワース・エター(1844-1924、後にペンテコステ派運動に参加)の癒しの教えを受け入れた。[29] エドワード・アーヴィングのカトリック使徒教会(1831年頃設立)も、後にペンテコステ派の復活に見られる多くの特徴を示していた。[30]: 131 孤立したキリスト教団体は、神の癒しや異言などのカリスマ的な現象を経験していた。ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派運動は、これらのキリスト教徒たちに起こっ ていることを神学的に説明し、彼らの新しい理解に合わせてウェスレーの救済論を修正した形を採用した。[31][32][33] |

Early revivals: 1900–1929 Charles Fox Parham, who associated glossolalia with the baptism in the Holy Spirit.  The Apostolic Faith Mission on Azusa Street, now considered to be the birthplace of Pentecostalism. Charles Fox Parham, an independent holiness evangelist who believed strongly in divine healing, was an important figure to the emergence of Pentecostalism as a distinct Christian movement. Parham, who was raised as a Methodist,[34] started a spiritual school near Topeka, Kansas in 1900, which he named Bethel Bible School. There he taught that speaking in tongues was the scriptural evidence for the reception of the baptism with the Holy Spirit. On January 1, 1901, after a watch night service, the students prayed for and received the baptism with the Holy Spirit with the evidence of speaking in tongues.[35] Parham received this same experience sometime later and began preaching it in all his services. Parham believed this was xenoglossia and that missionaries would no longer need to study foreign languages. Parham closed his Topeka school after 1901 and began a four-year revival tour throughout Kansas and Missouri.[36] He taught that the baptism with the Holy Spirit was a third experience, subsequent to conversion and sanctification. Sanctification cleansed the believer, but Spirit baptism empowered for service.[37] At about the same time that Parham was spreading his doctrine of initial evidence in the Midwestern United States, news of the Welsh Revival of 1904–1905 ignited intense speculation among radical evangelicals around the world and particularly in the US of a coming move of the Spirit which would renew the entire Christian Church. This revival saw thousands of conversions and also exhibited speaking in tongues.[38] Parham moved to Houston, Texas in 1905, where he started a Bible training school. One of his students was William J. Seymour, a one-eyed black preacher. Seymour traveled to Los Angeles where his preaching sparked the three-year-long Azusa Street Revival in 1906.[39] The revival first broke out on Monday April 9, 1906 at 214 Bonnie Brae Street and then moved to 312 Azusa Street on Friday, April 14, 1906.[40] Worship at the racially integrated Azusa Mission featured an absence of any order of service. People preached and testified as moved by the Spirit, spoke and sung in tongues, and fell (were slain) in the Spirit. The revival attracted both religious and secular media attention, and thousands of visitors flocked to the mission, carrying the "fire" back to their home churches.[41] Despite the work of various Wesleyan groups such as Parham's and D. L. Moody's revivals, the beginning of the widespread Pentecostal movement in the US is generally considered to have begun with Seymour's Azusa Street Revival.[42] |

初期の復興:1900年~1929年 チャールズ・フォックス・パーハムは、聖霊の洗礼と異言を関連付けた人物だ。  アズサ・ストリートのアポストル・フェイス・ミッションは、現在、ペンテコステ派の誕生地とされている。 チャールズ・フォックス・パーハムは、神の癒しを強く信じる独立系の聖潔伝道者で、ペンテコステ派が独自のキリスト教運動として台頭する上で重要な人物 だった。メソジスト派で育ったパーハムは、1900年にカンザス州トピカ近郊にベテル聖書学校と名付けた霊的学校を設立。そこで、舌で話すことが聖霊の洗 礼を受けた証拠だと教えた。1901年1月1日、徹夜礼拝の後、学生たちは祈り、舌で話すという証拠と共に聖霊のバプテスマを受けた[35]。パーハムも 後に同じ体験をし、全ての礼拝でこれを説教し始めた。パラムはこれをゼノグロッシア(異言現象)と信じ、宣教師は外国語を学ぶ必要がなくなると思った。パ ラムは1901年以降トペカの学校を閉鎖し、カンザス州とミズーリ州を回る4年間の復興巡回を開始した。[36] 彼は、聖霊のバプテスマは回心と聖化に続く第三の経験だと教えた。聖化は信者を清めるが、聖霊のバプテスマは奉仕のための力を与える。[37] パーハムが米国中西部で初期の証拠の教義を広めていた頃、1904年から1905年にかけてのウェールズリバイバルに関するニュースが、世界中の過激な福 音派、特に米国の福音派の間で、キリスト教教会全体を刷新する聖霊の働きが間もなく始まるという激しい憶測を巻き起こした。このリバイバルでは、何千人も の人々が改宗し、異言も発せられた。[38] 1905年、パーハムはテキサス州ヒューストンに移住し、聖書訓練学校を設立した。その生徒の一人に、片目の黒人牧師ウィリアム・J・シーモアがいた。 シーモアはロサンゼルスを訪れ、その説教がきっかけで1906年に3年間にわたるアズサ・ストリート・リバイバルが起こった。[39] 復興運動は1906年4月9日月曜日にボニー・ブレイ・ストリート214番地で始まり、1906年4月14日金曜日にアズサ・ストリート312番地に移っ た。[40] 民族的に統合されたアズサ・ミッションでの礼拝には、礼拝の順序が一切なかった。人々は御霊に動かされて説教し、証し、異言で話し、歌い、そして御霊に打 たれて倒れた。この復興運動は宗教界と世俗メディアの両方の注目を集め、数千人の訪問者がミッションに殺到し、その「火」を故郷の教会に持ち帰った。 [41] パラムやD.L.ムーディの復興運動を含むさまざまなウェスレー派の活動にもかかわらず、アメリカにおける広範なペンテコステ運動の始まりは、一般にセ ymourのアズサ・ストリート復興運動から始まったとされている。[42] |

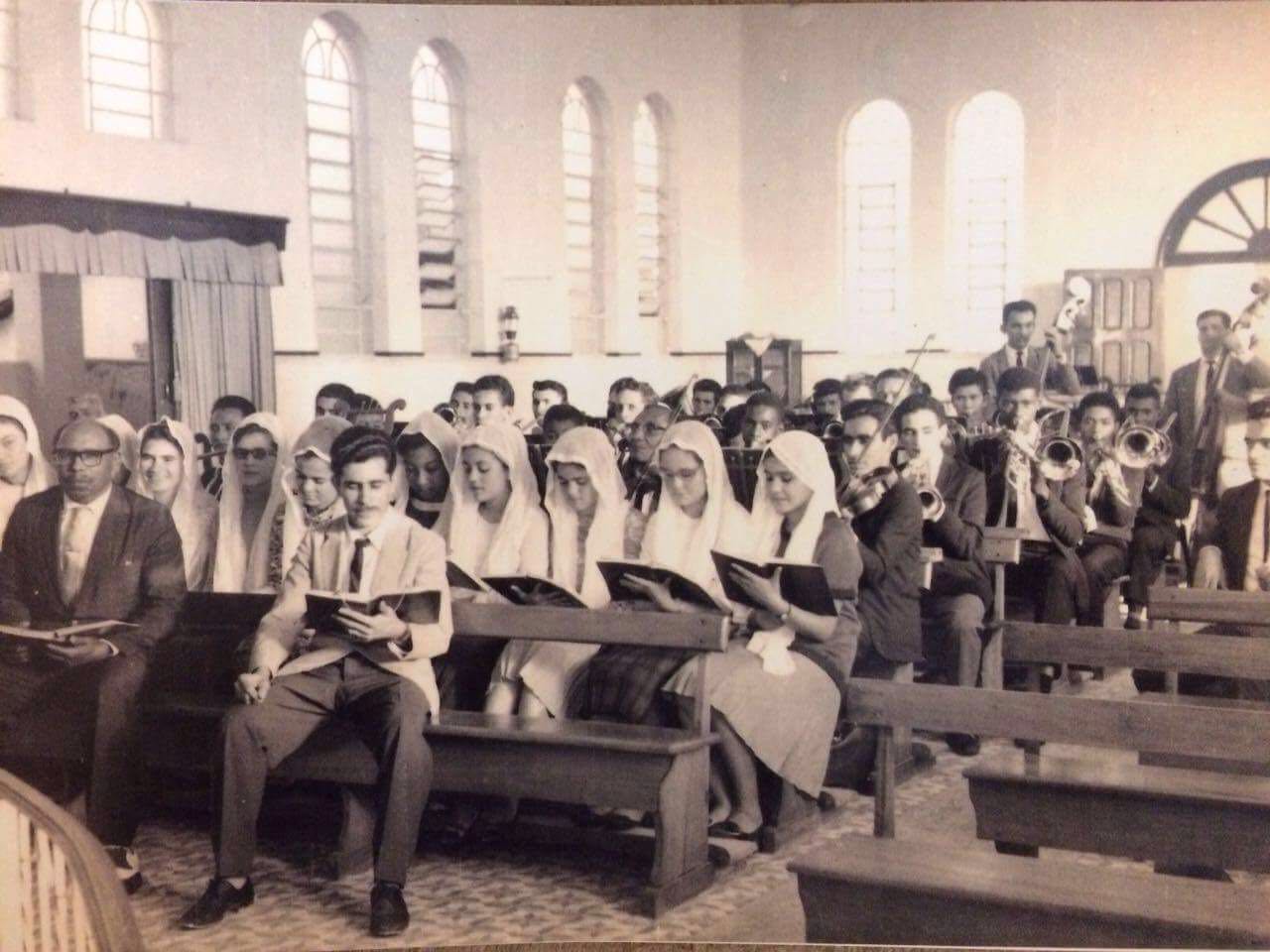

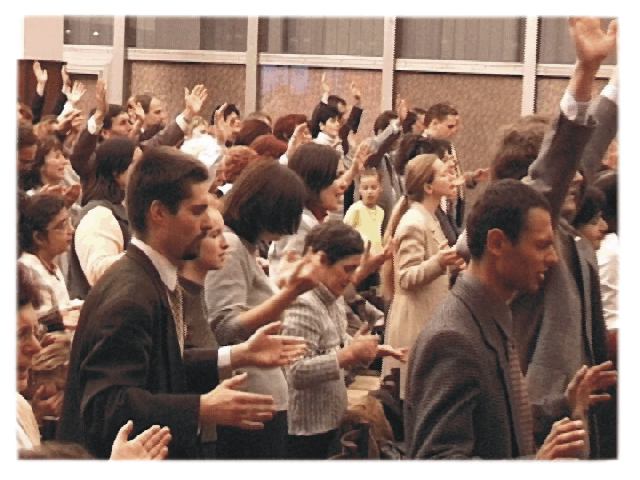

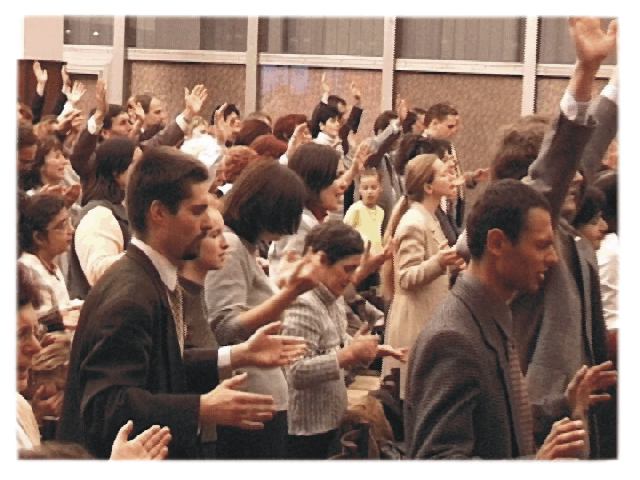

William Seymour, leader of the Azusa Street Revival The crowds of African-Americans and whites worshiping together at William Seymour's Azusa Street Mission set the tone for much of the early Pentecostal movement. During the period of 1906–1924, Pentecostals defied social, cultural and political norms of the time that called for racial segregation and the enactment of Jim Crow laws. The Church of God in Christ, the Church of God (Cleveland), the Pentecostal Holiness Church, and the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World were all interracial denominations before the 1920s. These groups, especially in the Jim Crow South were under great pressure to conform to segregation. Ultimately, North American Pentecostalism would divide into white and African-American branches. Though it never entirely disappeared, interracial worship within Pentecostalism would not reemerge as a widespread practice until after the civil rights movement.[43]  Women in a Pentecostal worship service Women were vital to the early Pentecostal movement.[44] Believing that whoever received the Pentecostal experience had the responsibility to use it towards the preparation for Christ's second coming, Pentecostal women held that the baptism in the Holy Spirit gave them empowerment and justification to engage in activities traditionally denied to them.[45][46] The first person at Parham's Bible college to receive Spirit baptism with the evidence of speaking in tongues was a woman, Agnes Ozman.[45][47][48] Women such as Florence Crawford, Ida Robinson, and Aimee Semple McPherson founded new denominations, and many women served as pastors, co-pastors, and missionaries.[49] Women wrote religious songs, edited Pentecostal papers, and taught and ran Bible schools.[50] The unconventionally intense and emotional environment generated in Pentecostal meetings dually promoted, and was itself created by, other forms of participation such as personal testimony and spontaneous prayer and singing. Women did not shy away from engaging in this forum, and in the early movement the majority of converts and church-goers were female.[51] Nevertheless, there was considerable ambiguity surrounding the role of women in the church. The subsiding of the early Pentecostal movement allowed a socially more conservative approach to women to settle in, and, as a result, female participation was channeled into more supportive and traditionally accepted roles. Auxiliary women's organizations were created to focus women's talents on more traditional activities. Women also became much more likely to be evangelists and missionaries than pastors. When they were pastors, they often co-pastored with their husbands.[52] The majority of early Pentecostal denominations taught Christian pacifism and adopted military service articles that advocated conscientious objection.[53] |

ウィリアム・シーモア、アズサ・ストリート・リバイバルの指導者 ウィリアム・シーモアのアズサ・ストリート・ミッションで、アフリカ系アメリカ人と白人が一緒に礼拝する群衆は、初期のペンテコステ運動の多くに大きな影 響を与えた。1906年から1924年にかけて、ペンテコステ派は、人種隔離とジム・クロウ法の制定を求める当時の社会的、文化的、政治的規範に反対し た。キリストの教会(Church of God in Christ)、クリーブランド・ペンテコステ派(Church of God (Cleveland))、ペンテコステ派ホーリネス教会(Pentecostal Holiness Church)、世界ペンテコステ派集会(Pentecostal Assemblies of the World)は、1920年代以前にはすべて人種混合の教派だった。これらのグループは、特にジム・クロウ法下の南部で、分離に順応する大きな圧力を受け ていた。最終的に、北米のペンテコステ派は白人とアフリカ系アメリカ人の派閥に分裂した。完全に消滅したわけではないが、ペンテコステ派内での人種混合の 礼拝は、公民権運動以降まで広範な実践として再興しなかった。[43]  ペンテコステ派の礼拝に参加する女性たち 女性は、初期のペンテコステ派運動において重要な役割を果たした。[44] ペンテコステ派の女性は、ペンテコステの体験を受けた者は、キリストの再臨の準備のためにその体験を活用する責任があると信じ、聖霊の洗礼によって、従来 は禁じられていた活動に従事する権限と正当性が与えられたと主張した。[45][46] パーハムの聖書大学で、異言を話すという証拠とともに聖霊の洗礼を受けた最初の人は、アグネス・オズマンという女性だった。[45][47][48] フローレンス・クロフォード、アイダ・ロビンソン、エイミー・センプル・マクファーソンなどの女性たちが新しい宗派を設立し、多くの女性が牧師、副牧師、 宣教師として活躍した。[49] 女性は宗教的な歌を作曲し、ペンテコステ派の新聞を編集し、聖書学校を運営し、教鞭をとった。[50] ペンテコステ派の集会では、型にはまらない、強烈で感情的な雰囲気が生まれ、個人的な証言や自発的な祈りや歌などの他の参加形態も促進され、またそれ自体 がそのような雰囲気を作り出していた。女性はこのような場への参加をためらわず、初期の運動では改宗者や教会出席者の大多数が女性だった。[51] しかし、女性の教会における役割には大きな曖昧さが残っていた。初期のペンテコステ派運動の衰退により、女性に対する社会的に保守的な態度が定着し、その 結果、女性の参加は支援的かつ伝統的に受け入れられる役割に導かれた。女性の才能を伝統的な活動に集中させるため、補助的な女性団体が設立された。女性は 牧師よりも伝道者や宣教師になる可能性がはるかに高くなった。牧師となった場合、多くの場合、夫と共に共同牧師を務めた。[52] 初期のペンテコステ派の教派の多くは、キリスト教の平和主義を教え、良心的兵役拒否を主張する軍事サービス条項を採用していた。[53] |

| Spread and opposition Main article: Christianity in the modern era Further information: Christian population growth and Christianity by country Azusa participants returned to their homes carrying their new experience with them. In many cases, whole churches were converted to the Pentecostal faith, but many times Pentecostals were forced to establish new religious communities when their experience was rejected by the established churches. One of the first areas of involvement was the African continent, where, by 1907, American missionaries were established in Liberia, as well as in South Africa by 1908.[54] Because speaking in tongues was initially believed to always be actual foreign languages, it was believed that missionaries would no longer have to learn the languages of the peoples they evangelized because the Holy Spirit would provide whatever foreign language was required. (When the majority of missionaries, to their disappointment, learned that tongues speech was unintelligible on the mission field, Pentecostal leaders were forced to modify their understanding of tongues.)[55] Thus, as the experience of speaking in tongues spread, a sense of the immediacy of Christ's return took hold, and that energy would be directed into missionary and evangelistic activity. Early Pentecostals saw themselves as outsiders from mainstream society, dedicated solely to preparing the way for Christ's return.[45][56] An associate of Seymour's, Florence Crawford, brought the message to the Northwest, forming what would become the Apostolic Faith Church—a Holiness Pentecostal denomination—by 1908. After 1907, Azusa participant William Howard Durham, pastor of the North Avenue Mission in Chicago, returned to the Midwest to lay the groundwork for the movement in that region. It was from Durham's church that future leaders of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Canada would hear the Pentecostal message.[57] One of the most well known Pentecostal pioneers was Gaston B. Cashwell (the "Apostle of Pentecost" to the South), whose evangelistic work led three Southeastern holiness denominations into the new movement.[58] The Pentecostal movement, especially in its early stages, was typically associated with the impoverished and marginalized of America, especially African Americans and Southern Whites. With the help of many healing evangelists such as Oral Roberts, Pentecostalism spread across America by the 1950s.[59] |

広まりと反対 主な記事:現代におけるキリスト教 詳細情報:キリスト教徒の人口増加と国別キリスト教徒の人口 アズサの参加者は、新しい体験を持ち帰って故郷に戻った。多くの場合、教会全体がペンテコステ派に改宗したが、既存の教会によってその体験が拒絶されたた め、ペンテコステ派は新たな宗教共同体を設立せざるを得なかった。最初の活動地域の一つはアフリカ大陸で、1907年までにアメリカの宣教師たちがリベリ ア、1908年までに南アフリカに拠点を設立した。[54] 当初、異言は常に実際の外国語であると信じられていたため、宣教師たちは、聖霊が必要な外国語をすべて与えてくれるので、伝道する人々の言語を学ぶ必要は もはやないだろうと考えられていた。(しかし、宣教師の大多数が、舌で話すことが宣教地で理解不能であることに失望したため、ペンテコステ派の指導者は舌 の理解を修正せざるを得なくなった。)[55] こうして、舌で話す経験が広まるにつれ、キリストの再臨の迫り来る感覚が広まり、そのエネルギーは宣教活動と伝道活動に注がれるようになった。初期のペン テコステ派は、主流社会から離れた存在であり、キリストの再臨の準備に専念する者たちだと自覚していた。[45][56] シーモア氏の仲間であるフローレンス・クロフォードは、そのメッセージを北西部に持ち込み、1908年までに、ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派の教派である使 徒信仰教会を設立した。1907年以降、アズサの参加者であったウィリアム・ハワード・ダーラム(シカゴのノース・アベニュー・ミッションの牧師)は、中 西部に戻り、その地域での運動の基盤を築いた。カナダのペンテコステ派アセンブリーの将来の指導者たちは、ダーラムの教会でペンテコステ派のメッセージを 聴いた。ペンテコステ派の最も有名な先駆者の一人に、ガストン・B・キャッシュウェル(南部では「ペンテコステの使徒」と呼ばれていた)がいる。彼の伝道 活動により、南東部の 3 つのホーリネス派が新しい運動に加わった。[58] ペンテコステ派運動は、特にその初期段階では、アメリカの貧困層や社会から疎外された人々、特にアフリカ系アメリカ人や南部白人と関連付けられていまし た。オーラル・ロバーツなどの多くの癒しの伝道者の助けを借りて、ペンテコステ派は 1950 年代までにアメリカ全土に広まりました。[59] |

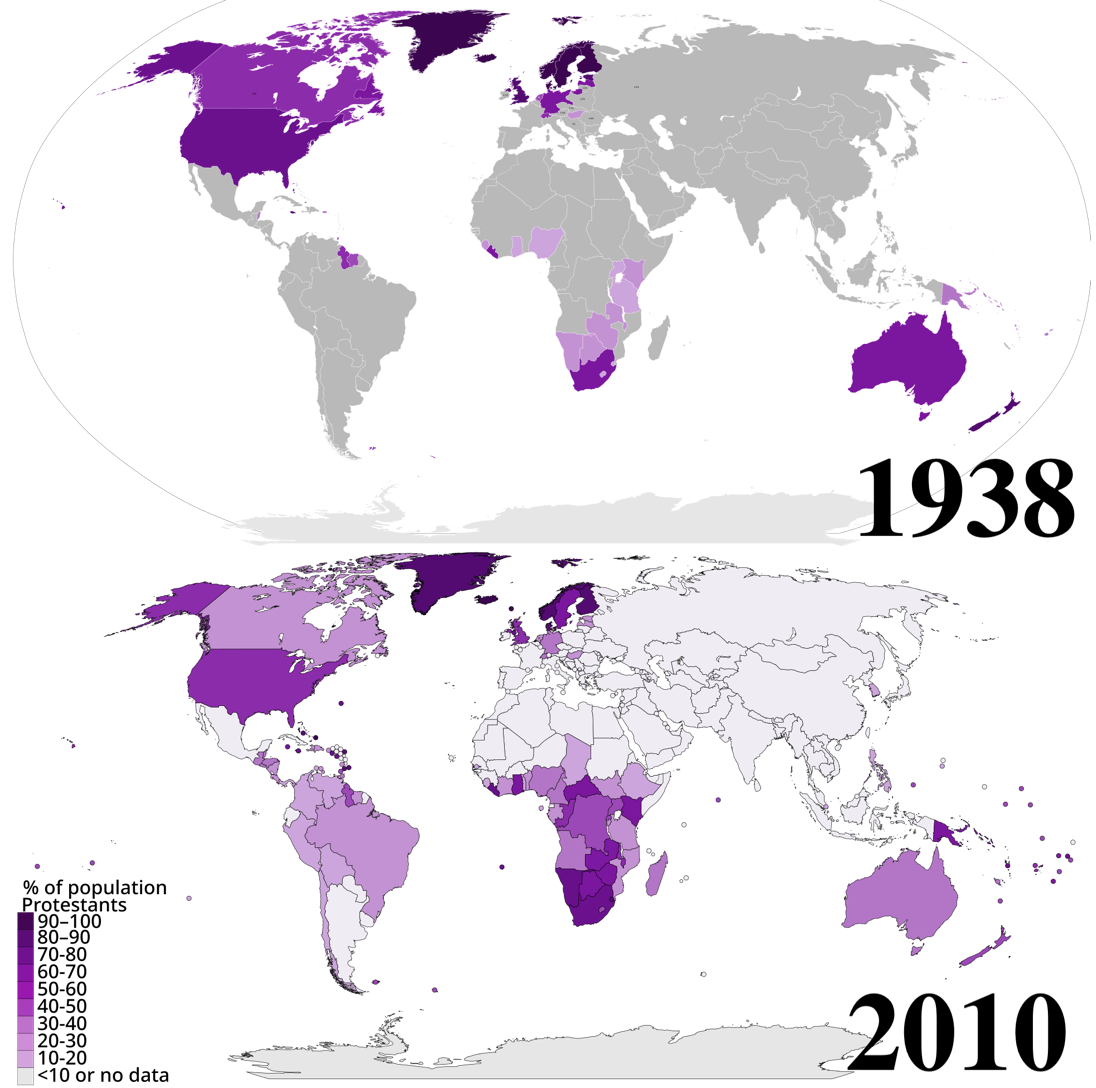

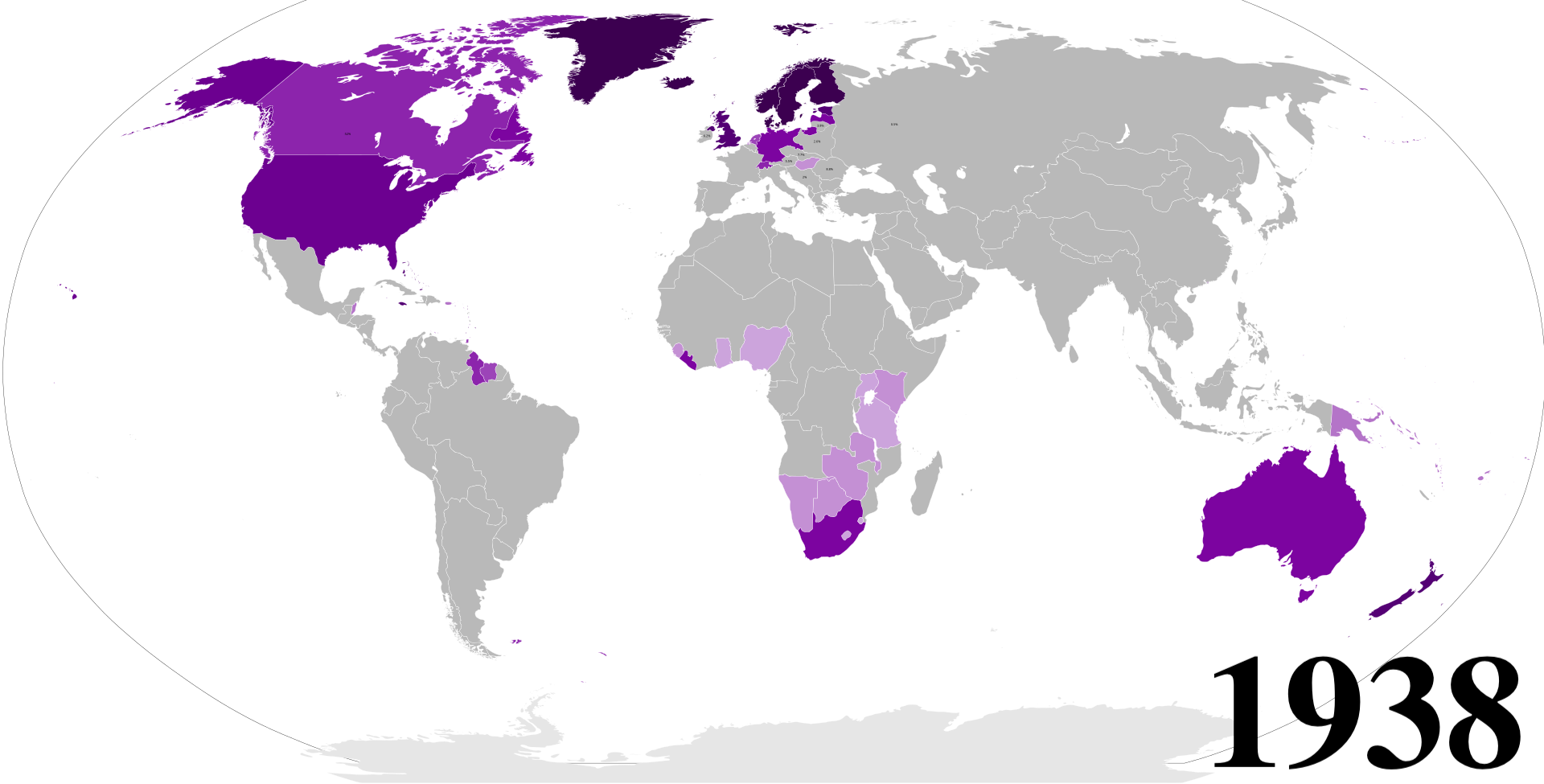

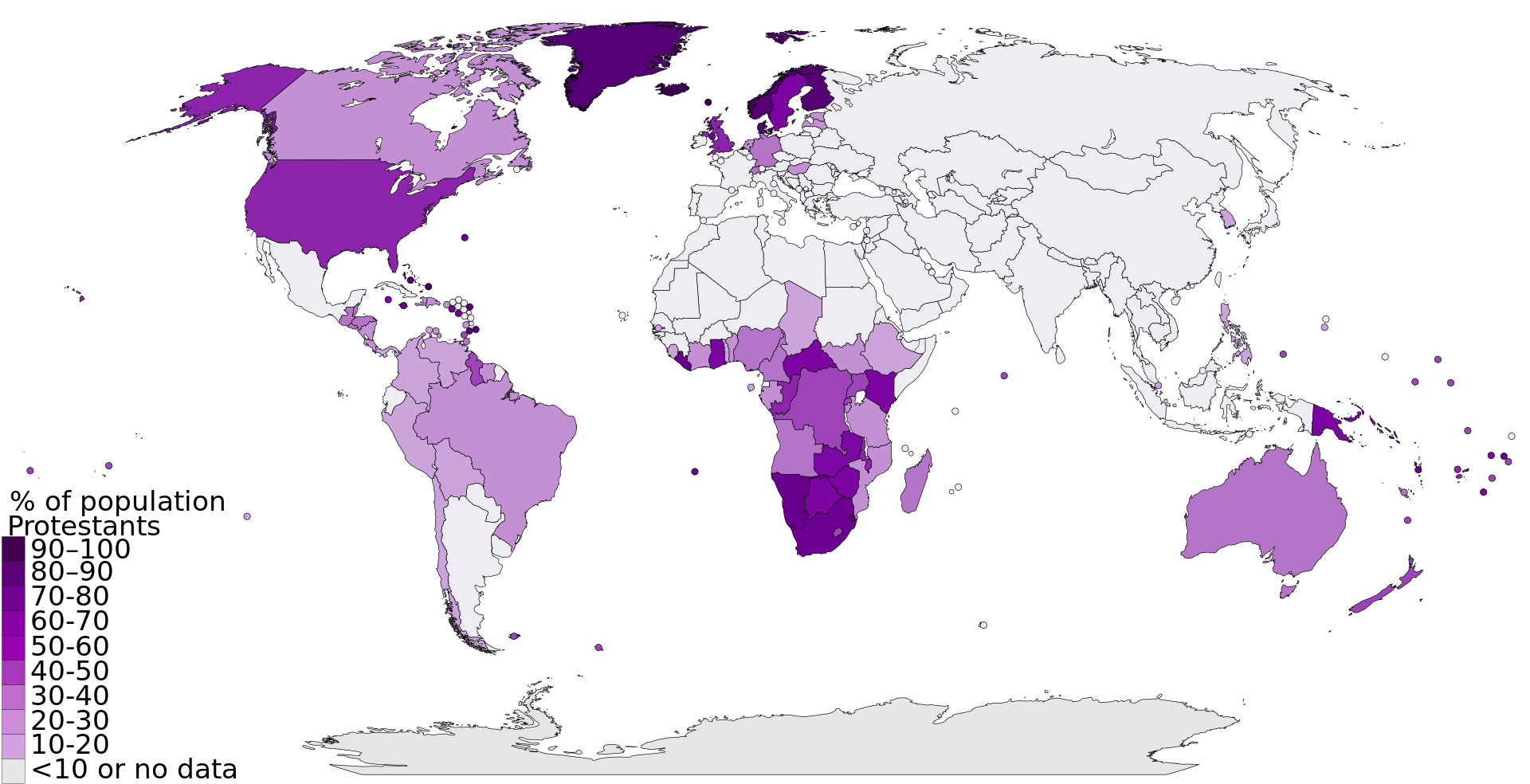

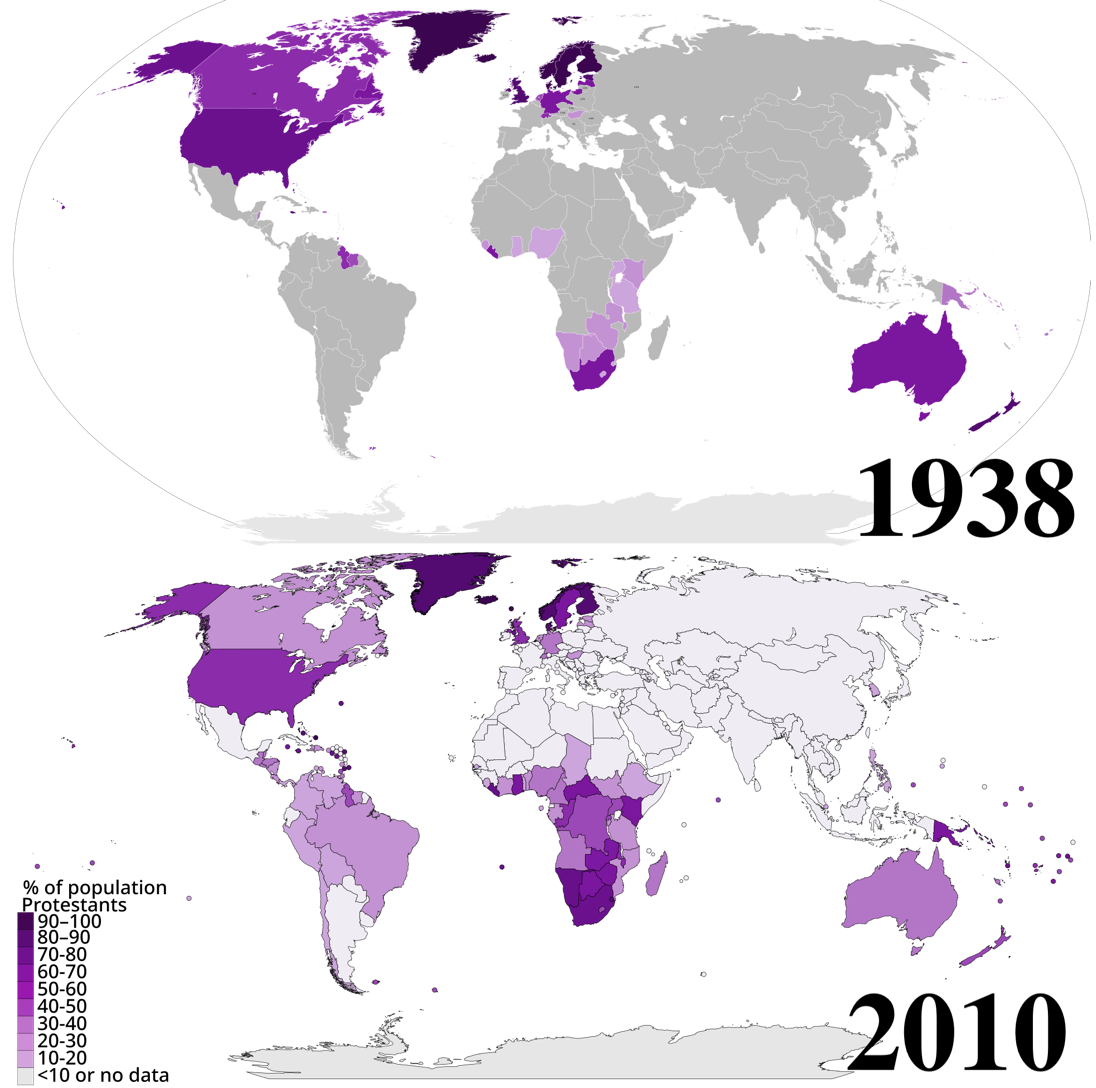

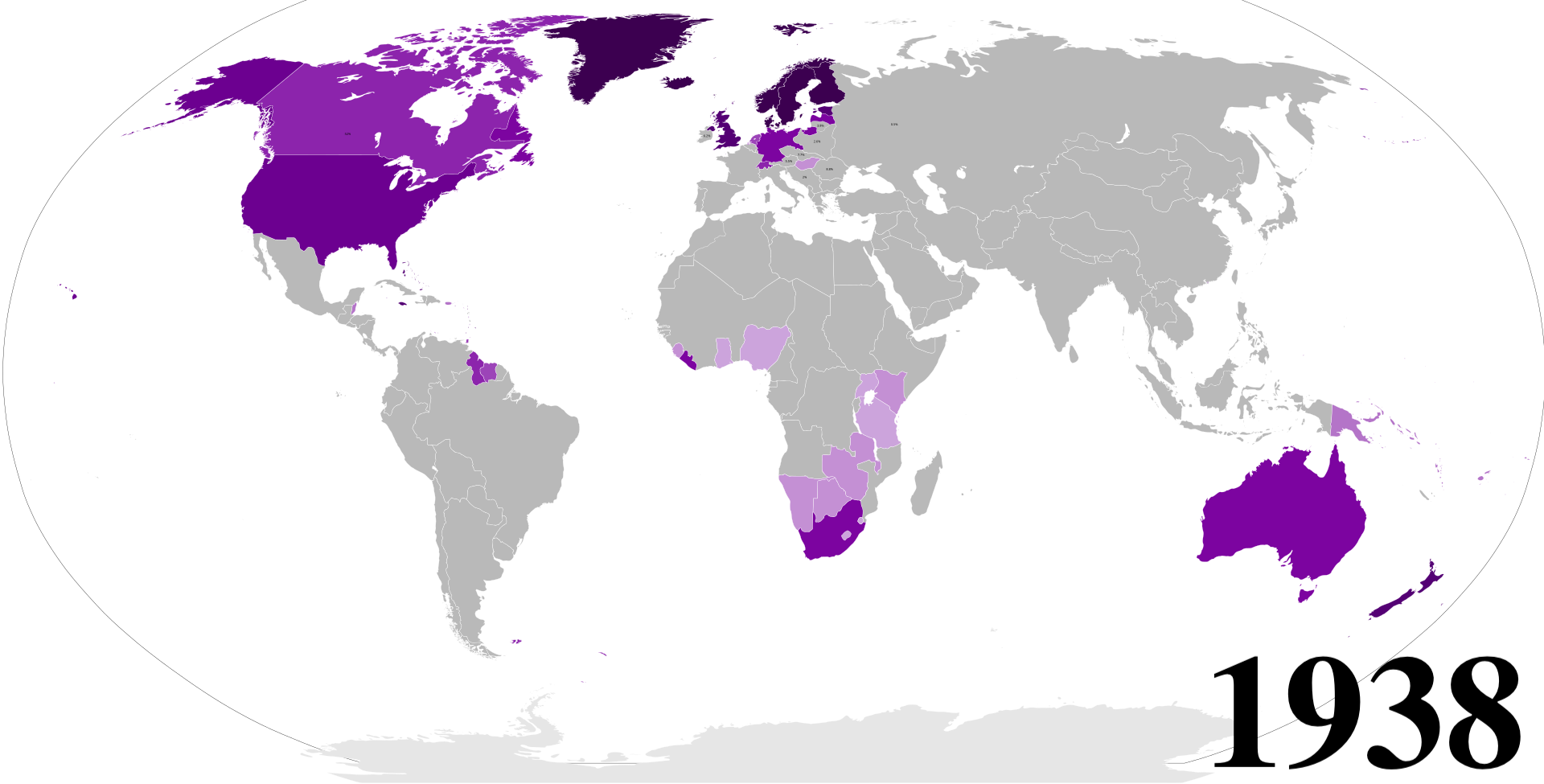

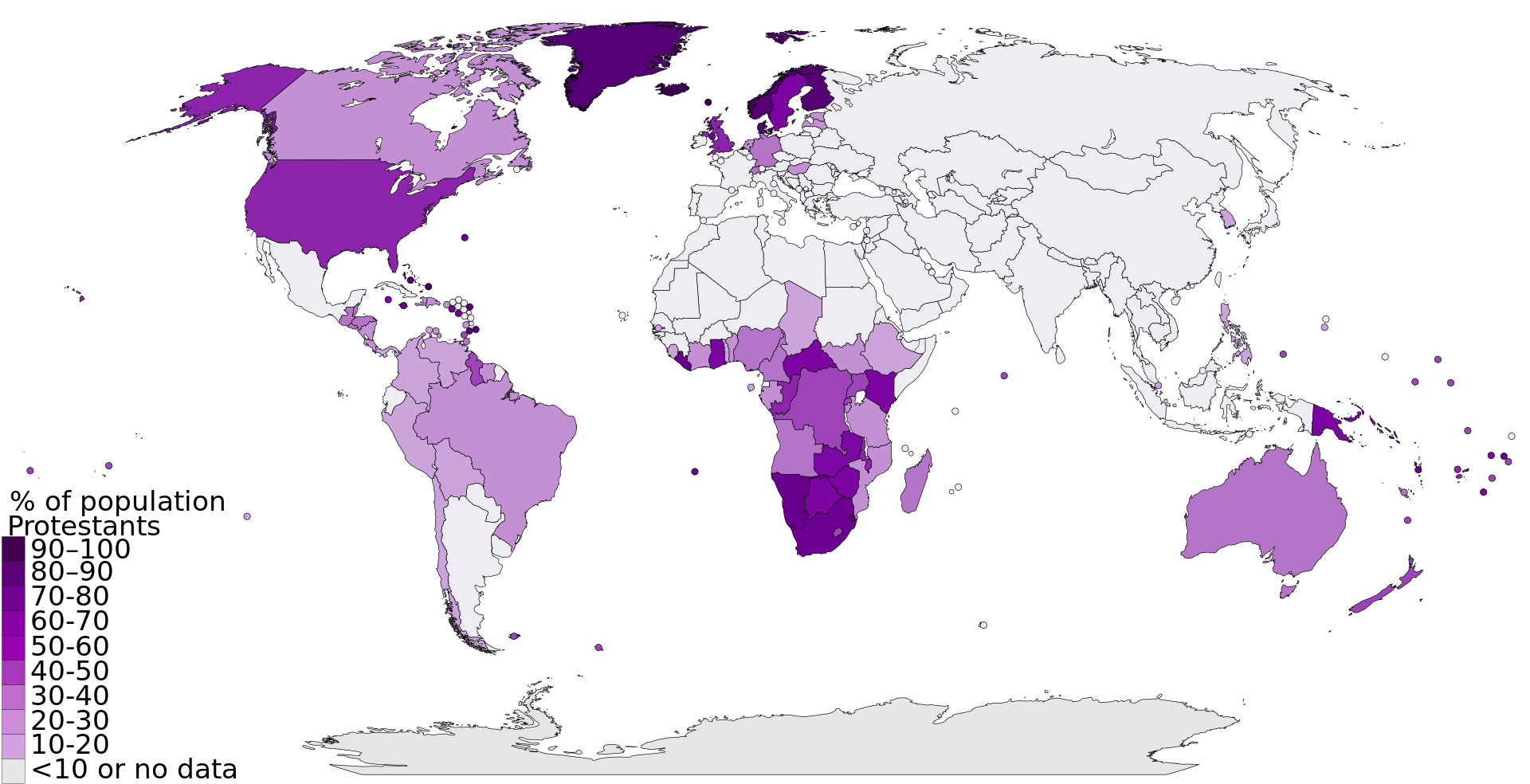

Countries by percentage of Protestant Christians in 1938 and 2010. Pentecostal and Evangelical denominations within Protestantism fueled much of the global growth of Christianity in Latin America, the Caribbean, Oceania, and Sub-Saharan Africa.[10][11][12][13][14]  Filadelfiakyrkan ('the Philadelphia Church') in Stockholm, Sweden, is part of the Swedish Pentecostal Movement International visitors and Pentecostal missionaries would eventually export the revival to other nations. The first foreign Pentecostal missionaries were Alfred G. Garr and his wife, who were Spirit baptized at Azusa and traveled to India and later Hong Kong.[60] On being Spirit baptized, Garr spoke in Bengali, a language he did not know, and becoming convinced of his call to serve in India came to Calcutta with his wife Lilian and began ministering at the Bow Bazar Baptist Church.[61] The Norwegian Methodist pastor T. B. Barratt was influenced by Seymour during a tour of the United States. By December 1906, he had returned to Europe, and he is credited with beginning the Pentecostal movement in Sweden, Norway, Denmark, Germany, France and England.[62] A notable convert of Barratt was Alexander Boddy, the Anglican vicar of All Saints' in Sunderland, England, who became a founder of British Pentecostalism.[63] Other important converts of Barratt were German minister Jonathan Paul who founded the first German Pentecostal denomination (the Mülheim Association) and Lewi Pethrus, the Swedish Baptist minister who founded the Swedish Pentecostal movement.[64] Through Durham's ministry, Italian immigrant Luigi Francescon received the Pentecostal experience in 1907 and established Italian Pentecostal congregations in the US, Argentina (Christian Assembly in Argentina), and Brazil (Christian Congregation of Brazil). In 1908, Giacomo Lombardi led the first Pentecostal services in Italy.[65] In November 1910, two Swedish Pentecostal missionaries arrived in Belem, Brazil and established what would become the Assembleias de Deus (Assemblies of God of Brazil).[66] In 1908, John G. Lake, a follower of Alexander Dowie who had experienced Pentecostal Spirit baptism, traveled to South Africa and founded what would become the Apostolic Faith Mission of South Africa and the Zion Christian Church.[67] As a result of this missionary zeal, practically all Pentecostal denominations today trace their historical roots to the Azusa Street Revival.[68] Eventually, the first missionaries realized that they definitely needed to learn the local language and culture, needed to raise financial support, and develop long-term strategies for the development of indigenous churches.[69] The first generation of Pentecostal believers faced immense criticism and ostracism from other Christians, most vehemently from the Holiness movement from which they originated. Alma White, leader of the Pillar of Fire Church—a Holiness Methodist denomination, wrote a book against the movement titled Demons and Tongues in 1910. She called Pentecostal tongues "satanic gibberish" and Pentecostal services "the climax of demon worship".[70] Famous Holiness Methodist preacher W. B. Godbey characterized those at Azusa Street as "Satan's preachers, jugglers, necromancers, enchanters, magicians, and all sorts of mendicants". To Dr. G. Campbell Morgan, Pentecostalism was "the last vomit of Satan", while Dr. R. A. Torrey thought it was "emphatically not of God, and founded by a Sodomite".[71] The Pentecostal Church of the Nazarene, one of the largest holiness groups, was strongly opposed to the new Pentecostal movement. To avoid confusion, the church changed its name in 1919 to the Church of the Nazarene.[72] A. B. Simpson's Christian and Missionary Alliance—a Keswickian denomination—negotiated a compromise position unique for the time. Simpson believed that Pentecostal tongues speaking was a legitimate manifestation of the Holy Spirit, but he did not believe it was a necessary evidence of Spirit baptism. This view on speaking in tongues ultimately led to what became known as the "Alliance position" articulated by A. W. Tozer as "seek not—forbid not".[72] |

1938年と2010年のプロテスタントキリスト教徒の割合による国別ランキング。プロテスタント内のペンテコステ派と福音派は、ラテンアメリカ、カリブ 海地域、オセアニア、サハラ以南のアフリカにおけるキリスト教の世界的な拡大を大きく後押しした。[10][11][12][13][14]  スウェーデンのストックホルムにあるフィラデルフィア教会(Filadelfiakyrkan)は、スウェーデンペンテコステ派運動の一部です。 海外からの訪問者やペンテコステ派の宣教師たちが、やがてこのリバイバルを他の国々にも広めていきました。最初の外国人ペンテコステ派宣教師は、アルフ レッド・G・ガーと彼の妻でした。彼らはアズサで聖霊のバプテスマを受け、インド、そして後に香港に渡りました。[60] 聖霊の洗礼を受けた後、ガーは知らない言語であるベンガル語で話し、インドで奉仕する召命に確信を持ち、妻のリリアンと共にカルカッタへ移り、ボウ・バ ザール・バプテスト教会で宣教を開始した。[61] ノルウェーのメソジスト派牧師T.B.バレットは、アメリカ合衆国を訪問中にセイモアに影響を受けた。1906年12月までに彼はヨーロッパに戻り、ス ウェーデン、ノルウェー、デンマーク、ドイツ、フランス、イギリスでペンテコステ運動を始めた人物として知られている。[62] バレットの注目すべき改宗者には、英国サザーランドにあるオールセインツ教会の英国国教会牧師であり、英国のペンテコステ派の創設者となったアレクサン ダー・ボディがいた。[63] バレットのその他の重要な改宗者には、最初のドイツのペンテコステ派(ミュールハイム協会)を設立したドイツの牧師ジョナサン・ポール、およびスウェーデ ンのペンテコステ派運動を設立したスウェーデンのバプテスト牧師ルウィ・ペトルスがいる。[64] ダーラムの宣教活動を通じて、イタリア移民のルイジ・フランチェスコンは 1907 年にペンテコステ派の体験をし、米国、アルゼンチン(アルゼンチンのキリスト教集会)、ブラジル(ブラジルのキリスト教集会)にイタリアのペンテコステ派 教会を設立した。1908 年、ジャコモ・ロンバルディがイタリアで最初のペンテコステ派の礼拝を導いた。[65] 1910年11月、2人のスウェーデンのペンテコステ派の宣教師がブラジルのベレンに到着し、後にアセンブレイアス・デ・デウス(ブラジル神召教会)とな る団体を設立した。[66] 1908年、ペンテコステ派の聖霊の洗礼を受けたアレクサンダー・ドウィの信奉者であったジョン・G・レイクは、南アフリカに渡り、後に南アフリカ使徒信 仰宣教団およびシオン・クリスチャン教会となる団体を設立した。[67] この宣教活動の結果、今日のペンテコステ派のほぼすべての宗派は、その歴史的ルーツをアズサ・ストリート・リバイバルに求めている。[68] 結局、最初の宣教師たちは、現地の言語と文化を習得し、財政的支援を集め、先住民教会を発展させるための長期的な戦略を立てる必要があると悟った。 [69] 最初の世代のペンテコステ派信者は、他のキリスト教徒、特に彼らが起源とするホーリネス運動から激しい批判と排斥を受けた。ホーリネス・メソジスト派の教 団である「ファイア・ピラー教会」のリーダー、アルマ・ホワイトは、1910年に『悪魔と言語』という反ペンテコステ派の書籍を出版した。彼女はペンテコ ステ派の言語を「悪魔の支離滅裂な言葉」と呼び、ペンテコステ派の礼拝を「悪魔崇拝の頂点」と非難した。[70] 有名なホーリネス・メソジストの説教者 W. B. ゴッドベイは、アズサ・ストリートの信者たちを「悪魔の説教者、雑技師、降霊師、魔術師、手品師、そしてあらゆる種類の托鉢僧」と表現した。G. キャンベル・モーガン博士は、ペンテコステ派を「サタンの最後の嘔吐物」と表現し、R. A. トーリー博士は「明らかに神のものではなく、ソドム人によって設立された」と批判した。[71]最大のホーリネス派団体の一つであるナザレのペンテコステ 教会は、新しいペンテコステ運動に強く反対した。混乱を避けるため、この教会は 1919 年に「ナザレ教会」に名称を変更した。[72] A. B. シンプソンのキリスト教宣教同盟(ケズウィック派)は、当時としてはユニークな妥協案を交渉した。シンプソンは、ペンテコステ派の異言は聖霊の正当な現れ であると信じていたが、それが聖霊のバプテスマの必要な証拠であるとは考えていなかった。この舌で話すことに関する見解は、最終的にA. W. トーザーが「求めず、禁じず」と表現した「同盟の立場」として知られるようになった。[72] |

| Early controversies The first Pentecostal converts were mainly derived from the Holiness movement and adhered to a Wesleyan understanding of entire sanctification as a definite, instantaneous experience and second work of grace.[6] Problems with this view arose when large numbers of converts entered the movement from non-Wesleyan backgrounds, especially from Baptist churches.[73] In 1910, William Durham of Chicago first articulated the Finished Work, a doctrine which located sanctification at the moment of salvation and held that after conversion the Christian would progressively grow in grace in a lifelong process.[74] This teaching polarized the Pentecostal movement into two factions: Holiness Pentecostalism and Finished Work Pentecostalism.[8] The Wesleyan doctrine was strongest in the Apostolic Faith Church, which views itself as being the successor of the Azusa Street Revival, as well as in the Calvary Holiness Association, Congregational Holiness Church, Church of God (Cleveland), Church of God in Christ, Free Gospel Church and the Pentecostal Holiness Church; these bodies are classed as Holiness Pentecostal denominations.[75] The Finished Work, however, would ultimately gain ascendancy among Pentecostals, in denominations such as the Assemblies of God, which was the first Finished Work Pentecostal denomination.[9] After 1911, most new Pentecostal denominations would adhere to Finished Work sanctification.[76] In 1914, a group of 300 predominately white Pentecostal ministers and laymen from all regions of the United States gathered in Hot Springs, Arkansas, to create a new, national Pentecostal fellowship—the General Council of the Assemblies of God.[77] By 1911, many of these white ministers were distancing themselves from an existing arrangement under an African-American leader. Many of these white ministers were licensed by the African-American, C. H. Mason under the auspices of the Church of God in Christ, one of the few legally chartered Pentecostal organizations at the time credentialing and licensing ordained Pentecostal clergy. To further such distance, Bishop Mason and other African-American Pentecostal leaders were not invited to the initial 1914 fellowship of Pentecostal ministers. These predominately white ministers adopted a congregational polity, whereas the COGIC and other Southern groups remained largely episcopal and rejected a Finished Work understanding of Sanctification. Thus, the creation of the Assemblies of God marked an official end of Pentecostal doctrinal unity and racial integration.[78] Among these Finished Work Pentecostals, the new Assemblies of God would soon face a "new issue" which first emerged at a 1913 camp meeting. During a baptism service, the speaker, R. E. McAlister, mentioned that the Apostles baptized converts once in the name of Jesus Christ, and the words "Father, Son, and Holy Ghost" were never used in baptism.[79] This inspired Frank Ewart who claimed to have received as a divine prophecy revealing a nontrinitarian conception of God.[80] Ewart believed that there was only one personality in the Godhead—Jesus Christ. The terms "Father" and "Holy Ghost" were titles designating different aspects of Christ. Those who had been baptized in the Trinitarian fashion needed to submit to rebaptism in Jesus's name. Furthermore, Ewart believed that Jesus's name baptism and the gift of tongues were essential for salvation. Ewart and those who adopted his belief, which is known as Oneness Pentecostalism, called themselves "oneness" or "Jesus's Name" Pentecostals, but their opponents called them "Jesus Only".[81][8] Amid great controversy, the Assemblies of God rejected the Oneness teaching, and many of its churches and pastors were forced to withdraw from the denomination in 1916.[82] They organized their own Oneness groups. Most of these joined Garfield T. Haywood, an African-American preacher from Indianapolis, to form the Pentecostal Assemblies of the World. This church maintained an interracial identity until 1924 when the white ministers withdrew to form the Pentecostal Church, Incorporated. This church later merged with another group forming the United Pentecostal Church International.[83] This controversy among the Finished Work Pentecostals caused Holiness Pentecostals to further distance themselves from Finished Work Pentecostals, who they viewed as heretical.[8] |

初期の論争 最初のペンテコステ派の改宗者は主にホーリネス運動から派生し、完全な聖化とは明確な瞬間的な体験であり、恵みの第二の働きであるとするウェスレーの理解 を支持していた。[6] この見解に対する問題は、ウェスレー派以外の背景、特にバプテスト教会から多くの改宗者がこの運動に参加したときに生じた。[73] 1910年、シカゴのウィリアム・ダーハムは「完了した業」という教義を初めて明確に述べた。この教義は、聖化を救いの瞬間に位置付け、改宗後、キリスト 教徒は生涯にわたるプロセスで恵みの中で徐々に成長すると主張した。[74] この教義はペンテコステ派運動を二つの派閥に分裂させた:ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派と完了した業ペンテコステ派。[8] ウェスレー派の教義は、アズサ・ストリート・リバイバルの継承者と自認するアポストロリック・フェイス・チャーチ、およびカルバリー・ホーリネス・アソシ エーション、コンゴゲーション・ホーリネス・チャーチ、チャーチ・オブ・ゴッド(クリーブランド)、チャーチ・オブ・ゴッド・イン・クライスト、フリー・ ゴスペル・チャーチ、ペンテコステ・ホーリネス・チャーチなどに最も強く根付いていた。これらの団体はホーリネス・ペンテコステ派の教派に分類される。 [75] しかし、完成の業は最終的にペンテコステ派の中で優位を占め、アッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッド(最初の完成の業ペンテコステ派教派)などの教派で採用され た。[9] 1911年以降、新たなペンテコステ派教派のほとんどは完成の業の聖化を支持するようになった。[76] 1914年、米国各地から300人の主に白人のペンテコステ派の牧師や信徒たちが、アーカンソー州ホットスプリングスに集まり、新しい全国的なペンテコス テ派の団体、神のアセンブリーズ総会議(General Council of the Assemblies of God)を設立した。[77] 1911年までに、これらの白人牧師たちの多くは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の指導者のもとでの既存の体制から距離を置くようになっていた。これらの白人牧師 の多くは、当時、ペンテコステ派の聖職者を認証・免許する数少ない合法的に認可されたペンテコステ派組織の一つである「キリストの教会」の傘下で、アフリ カ系アメリカ人のC.H.メイソンによって免許を受けていた。このような距離をさらに広げるため、メイソン主教を含むアフリカ系アメリカ人のペンテコステ 派指導者は、1914年の最初のペンテコステ派牧師の連合に招待されなかった。これらの主に白人牧師は会衆制を採用したのに対し、COGIC(キリスト教 神殿教会)を含む南部のグループは主に主教制を維持し、聖化に関する「完了した業」の理解を拒否した。 thus、アッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッドの設立は、ペンテコステ派の教義的統一と人種的統合の公式な終結を意味した。[78] これらの「完成した業」ペンテコステ派の中で、新しいアッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッドは、1913年のキャンプ集会で初めて浮上した「新たな問題」に直面 することになった。洗礼式の中で、講演者の R. E. マカリスターは、使徒たちは改宗者にイエス・キリストの名によって一度だけ洗礼を施し、「父、子、聖霊」という言葉は洗礼では決して使用されなかったと述 べた。[79] これは、三位一体説ではない神の概念を明らかにする神の予言を受けたと主張するフランク・エワートに影響を与えた。[80] エワートは、神にはイエス・キリストという唯一の人格しか存在しないと信じていた。「父」と「聖霊」という用語は、キリストの異なる側面を表す称号にすぎ ない。三位一体説に従って洗礼を受けた者は、イエスの名によって再洗礼を受ける必要があった。さらに、エワートは、イエスの名による洗礼と舌の賜物が救い にとって不可欠であると信じていた。エワートとその教えを採用した人々は、オネネス・ペンテコステリズムと呼ばれ、自身を「オネネス」または「イエスの 名」ペンテコステ派と称したが、反対派は彼らを「イエス・オンリー」と呼んだ。[81][8] 大きな論争の中で、神のアセンブリは「唯一神教」の教えを拒否し、その多くの教会と牧師たちは 1916 年に教団から脱退を余儀なくされた。[82] 彼らは独自の「唯一神教」の団体を結成した。そのほとんどは、インディアナポリスのアフリカ系アメリカ人牧師、ガーフィールド・T・ヘイウッドに加わり、 「世界ペンテコステ派アセンブリ」を結成した。この教会は1924年に白人牧師たちが離脱してペンテコステ教会(株式会社)を設立するまで、人種混合のア イデンティティを維持した。この教会は後に別のグループと合併し、国際ペンテコステ教会を設立した。[83] フィニッシュド・ワーク・ペンテコステ派内のこの論争は、彼らを異端と見なすホーリネス・ペンテコステ派がフィニッシュド・ワーク・ペンテコステ派からさ らに距離を置く原因となった。[8] |

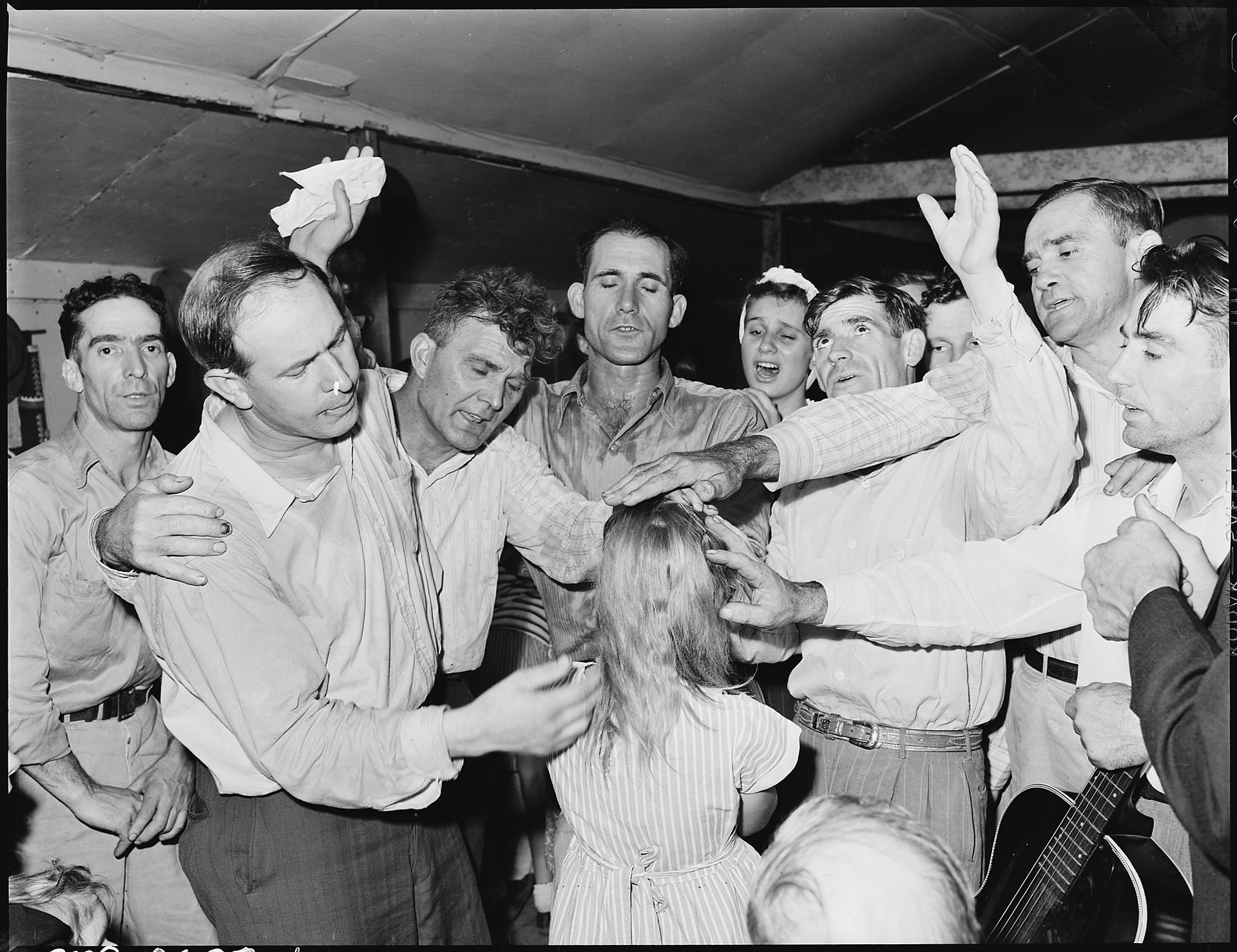

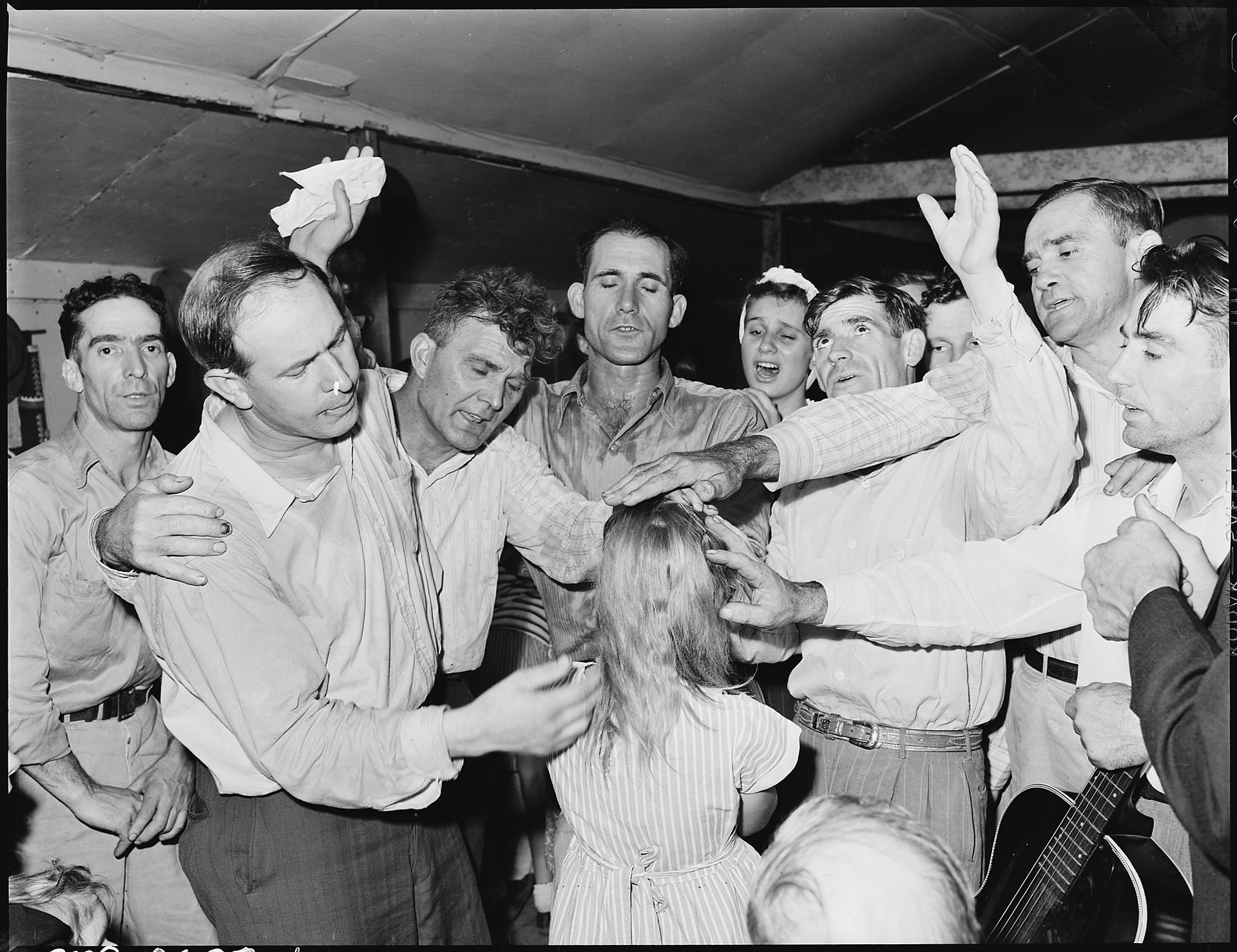

1930–1959 Members of the Pentecostal Church of God in Lejunior, Kentucky pray for a girl in 1946 While Pentecostals shared many basic assumptions with conservative Protestants, the earliest Pentecostals were rejected by Fundamentalist Christians who adhered to cessationism. In 1928, the World Christian Fundamentals Association labeled Pentecostalism "fanatical" and "unscriptural". By the early 1940s, this rejection of Pentecostals was giving way to a new cooperation between them and leaders of the "new evangelicalism", and American Pentecostals were involved in the founding of the 1942 National Association of Evangelicals.[84] Pentecostal denominations also began to interact with each other both on national levels and international levels through the Pentecostal World Fellowship, which was founded in 1947. Though Pentecostals began to find acceptance among evangelicals in the 1940s, the previous decade was widely viewed as a time of spiritual dryness, when healings and other miraculous phenomena were perceived as being less prevalent than in earlier decades of the movement.[85] It was in this environment that the Latter Rain Movement, the most important controversy to affect Pentecostalism since World War II, began in North America and spread around the world in the late 1940s. Latter Rain leaders taught the restoration of the fivefold ministry led by apostles. These apostles were believed capable of imparting spiritual gifts through the laying on of hands.[86] There were prominent participants of the early Pentecostal revivals, such as Stanley Frodsham and Lewi Pethrus, who endorsed the movement citing similarities to early Pentecostalism.[85] However, Pentecostal denominations were critical of the movement and condemned many of its practices as unscriptural. One reason for the conflict with the denominations was the sectarianism of Latter Rain adherents.[86] Many autonomous churches were birthed out of the revival.[85] A simultaneous development within Pentecostalism was the postwar Healing Revival. Led by healing evangelists William Branham, Oral Roberts, Gordon Lindsay, and T. L. Osborn, the Healing Revival developed a following among non-Pentecostals as well as Pentecostals. Many of these non-Pentecostals were baptized in the Holy Spirit through these ministries. The Latter Rain and the Healing Revival influenced many leaders of the charismatic movement of the 1960s and 1970s.[87] |

1930年~1959年 1946年、ケンタッキー州レジュニアーにあるペンテコステ派の教会で、教会員たちが少女のために祈っている様子。 ペンテコステ派は保守的なプロテスタントと多くの基本的な考え方を共有していましたが、初期のペンテコステ派は、聖霊の賜物の停止を信奉する原理主義キリ スト教徒たちから拒絶されていました。1928年、世界キリスト教原理主義者協会は、ペンテコステ派を「狂信的」かつ「非聖書的」と非難しました。 1940年代初頭までに、ペンテコステ派に対するこの拒絶は、彼らと「新しい福音主義」の指導者たちとの新たな協力関係に取って代わられ、アメリカのペン テコステ派は1942年の全米福音協会(National Association of Evangelicals)の設立に関わった。[84] ペンテコステ派の宗派も、1947年に設立されたペンテコステ世界フェローシップ(Pentecostal World Fellowship)を通じて、国内レベルおよび国際レベルの両方で相互交流を開始した。 1940年代、ペンテコステ派は福音派の間で受け入れられ始めたが、その前の10年間は、癒やしやその他の奇跡的な現象が、運動の初期の数十年よりもあま り見られなくなった、霊的に乾燥した時代と広く見なされていた。[85] このような背景の中、第二次世界大戦後ペンテコステ派に最も大きな影響を与えた論争である「レイター・レイン運動」が北米で始まり、1940年代後半に世 界中に広がった。レイター・レインの指導者たちは、使徒によって率いられる五重の奉仕の回復を教えた。これらの使徒は、手置きの儀式を通じて霊的賜物を授 ける能力があると信じられていた。[86] 初期のペンテコステ派の復興運動に参加した著名な人物には、スタンリー・フロッシュアムやレウィ・ペトゥルスなどがおり、彼らはこの運動を初期のペンテコ ステ派との類似性を理由に支持した。[85] しかし、ペンテコステ派の教派は、この運動を批判し、その多くの実践を聖書に反するものとして非難した。宗派間の対立の原因のひとつは、後雨信奉者の宗派 主義だった。[86] このリバイバルから、多くの自治教会が誕生した。[85] ペンテコステ派内で同時に起こった動きは、戦後のヒーリング・リバイバルだった。癒しの伝道者ウィリアム・ブランハム、オーラル・ロバーツ、ゴードン・リ ンゼイ、T. L. オズボーンが主導した癒しのリバイバルは、ペンテコステ派だけでなく、非ペンテコステ派の間でも支持者を増やした。これらの非ペンテコステ派の多くは、こ れらのミニストリーを通じて聖霊の洗礼を受けた。後雨と癒しのリバイバルは、1960年代と1970年代のカリスマ運動の多くの指導者に影響を与えた。 [87] |

1960–present Dmanisi Pentecostal Church in Georgia  Pentecostal Church in Belgrade, Serbia Before the 1960s, most non-Pentecostal Christians who experienced the Pentecostal baptism in the Holy Spirit typically kept their experience a private matter or joined a Pentecostal church afterward.[88] The 1960s saw a new pattern develop where large numbers of Spirit baptized Christians from mainline churches in the US, Europe, and other parts of the world chose to remain and work for spiritual renewal within their traditional churches. This initially became known as New or Neo-Pentecostalism (in contrast to the older classical Pentecostalism) but eventually became known as the Charismatic Movement.[89] While cautiously supportive of the Charismatic Movement, the failure of Charismatics to embrace traditional Pentecostal teachings, such as the prohibition of dancing, abstinence from alcohol and other drugs such as tobacco, as well as restrictions on dress and appearance following the doctrine of outward holiness, initiated an identity crisis for classical Pentecostals, who were forced to reexamine long held assumptions about what it meant to be Spirit filled.[90][91] The liberalizing influence of the Charismatic Movement on classical Pentecostalism can be seen in the disappearance of many of these taboos since the 1960s, apart from certain Holiness Pentecostal denominations, such as the Apostolic Faith Church, which maintain these standards of outward holiness. Because of this, the cultural differences between classical Pentecostals and charismatics have lessened over time.[92] The global renewal movements manifest many of these tensions as inherent characteristics of Pentecostalism and as representative of the character of global Christianity.[93] |

1960年~現在 ジョージアのドマニシ・ペンテコステ教会  セルビアのベオグラードのペンテコステ教会 1960年代以前は、聖霊のバプテスマを受けた非ペンテコステ派のキリスト教徒の多くは、その経験を秘密にしたり、その後ペンテコステ教会に入会したりし ていました。[88] 1960年代には、米国、ヨーロッパ、および世界の他の地域における主流の教会から、聖霊の洗礼を受けた多くのキリスト教徒が、伝統的な教会内に留まり、 霊的な刷新のために働くという新しいパターンが現れた。これは当初、新しいペンテコステ派または新ペンテコステ派(従来の古典的なペンテコステ派とは対照 的)として知られていたが、最終的にはカリスマ運動として知られるようになった。[89] チャリズマティック運動に対して慎重な支持を示した古典的ペンテコステ派は、チャリズマティック派が伝統的なペンテコステ派の教義(ダンスの禁止、アル コールやタバコを含む薬物の禁酒・禁断、外見の清浄さを求める教義に基づく服装や外見の制限など)を受け入れなかったため、アイデンティティ危機に直面し た。これにより、古典的ペンテコステ派は、聖霊に満たされることの意味について長年抱いてきた前提を再考せざるを得なくなった。[90][91] 1960年代以降、外見の聖さを重視する特定の聖霊ペンテコステ派(使徒信仰教会など)を除いて、これらのタブーの多くが消滅したことから、カリスマ運動 が古典的なペンテコステ派に与えた自由化の影響が見られます。このため、古典的なペンテコステ派とカリスマ派の文化的な違いは、時間の経過とともに縮小し ています。[92] グローバルな刷新運動は、これらの緊張をペンテコステ派の固有の特徴として、またグローバルなキリスト教の特性を代表するものとして表している。[93] |

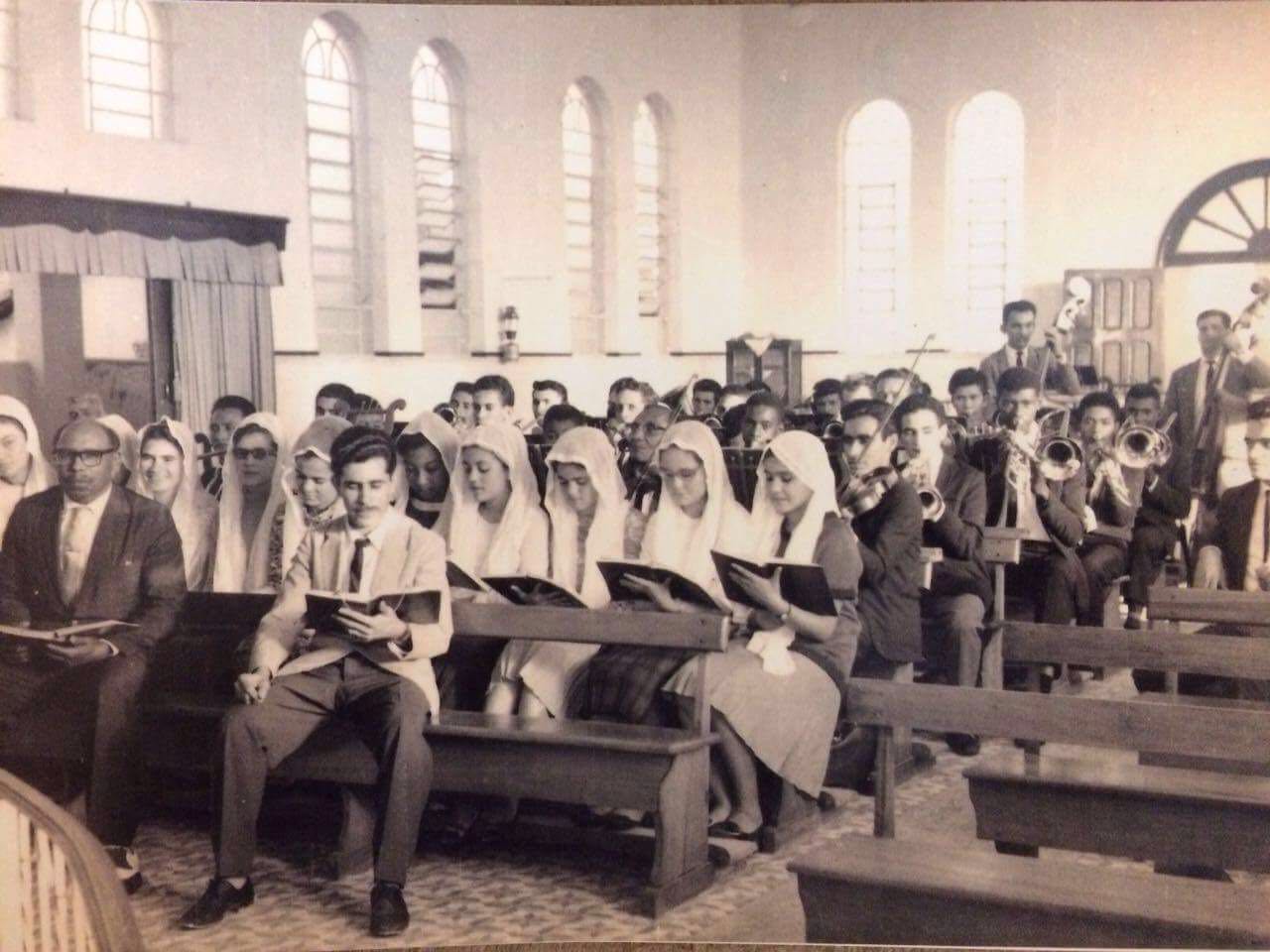

Beliefs A Pentecostal church in Jyväskylä, Finland Pentecostalism is an evangelical faith, emphasizing the reliability of the Bible and the need for the transformation of an individual's life through faith in Jesus.[31] Like other evangelicals, Pentecostals generally adhere to the Bible's divine inspiration and inerrancy—the belief that the Bible, in the original manuscripts in which it was written, is without error.[94] Pentecostals emphasize the teaching of the "full gospel" or "foursquare gospel". The term foursquare refers to the four fundamental beliefs of Pentecostalism: Jesus saves according to John 3:16; baptizes with the Holy Spirit according to Acts 2:4; heals bodily according to James 5:15; and is coming again to receive those who are saved according to 1 Thessalonians 4:16–17.[95] Salvation  Pentecostal worshippers belonging to the Christian Congregation in Brazil, with women wearing modest dress and headcoverings Main article: Christian soteriology The central belief of classical Pentecostalism is that through the death, burial, and resurrection of Jesus Christ, sins can be forgiven and humanity reconciled with God.[96] This is the Gospel or "good news". The fundamental requirement of Pentecostalism is that one be born again.[97] The new birth is received by the grace of God through faith in Christ as Lord and Savior.[98] In being born again, the believer is regenerated, justified, adopted into the family of God, and the Holy Spirit's work of sanctification is initiated.[99] Classical Pentecostal soteriology is generally Arminian rather than Calvinist.[100] The security of the believer is a doctrine held within Pentecostalism; nevertheless, this security is conditional upon continual faith and repentance.[101] Pentecostals believe in both a literal heaven and hell, the former for those who have accepted God's gift of salvation and the latter for those who have rejected it.[102] For most Pentecostals there is no other requirement to receive salvation. Baptism with the Holy Spirit and speaking in tongues are not generally required, though Pentecostal converts are usually encouraged to seek these experiences.[103][104][105] A notable exception is Jesus's Name Pentecostalism, most adherents of which believe both water baptism and Spirit baptism are integral components of salvation. |

信仰 フィンランド、ユヴァスキュラにあるペンテコステ派教会 ペンテコステ派は、聖書の信頼性と、イエスへの信仰による個人の人生の変化の必要性を強調する福音主義の信仰です。[31] 他の福音派同様、ペンテコステ派は一般的に聖書の神聖な啓示と無謬性を信奉しています——つまり、聖書が書かれた原典において誤りがないという信念です。 [94] ペンテコステ派は「完全な福音」または「四角い福音」の教えを強調しています。「フォースクエア」という用語は、ペンテコステ派の4つの基本的な信仰を指 す:ヨハネ3:16に従ってイエスが救う;使徒2:4に従って聖霊で洗礼を施す;ヤコブ5:15に従って肉体的に癒す;そして1テサロニケ4:16–17 に従って救われた者を迎えに来る。[95] 救い  ブラジルのキリスト教会に所属するペンテコステ派の礼拝者たち。女性は控えめな服装と頭巾を着用している。 主な記事:キリスト教の救い論 古典的なペンテコステ派の中心的な信念は、イエス・キリストの死、埋葬、そして復活によって、罪は赦され、人類は神と和解することができるというものであ る。[96] これが福音、すなわち「良き知らせ」である。ペンテコステ派の根本的な要件は、人が生まれ変わることであり[97]、この新しい誕生は、キリストを主と救 い主として信じる信仰を通じて神の恵みによって与えられる[98]。生まれ変わることで、信者は再生され、義とされ、神の家族に採用され、聖霊の聖化の仕 事が開始される。[99] 古典的なペンテコステ派の救済論は、カルヴァン主義よりもアルミニウス主義に近いです。[100] 信者の安全はペンテコステ派の教義ですが、この安全は継続的な信仰と悔い改めに条件付けられています。[101] ペンテコステ派は、文字通りの天国と地獄の両方を信じています。前者は神の救いの贈り物を受け入れた者たちのためのものであり、後者はそれを拒絶した者た ちのためのものです。[102] ほとんどのペンテコステ派にとって、救いを受けるための他の要件はない。聖霊のバプテスマと異言は一般的に必要とされないが、ペンテコステ派の改宗者は通 常、これらの体験を求めるよう奨励されている。[103][104][105] 顕著な例外は、イエスの名によるペンテコステ派で、その信者の多くは、水によるバプテスマと聖霊のバプテスマの両方が救いの不可欠な要素であると信じてい る。 |

| Baptism with the Holy Spirit Main article: Baptism with the Holy Spirit Pentecostals identify three distinct uses of the word "baptism" in the New Testament: Baptism into the body of Christ: This refers to salvation. Every believer in Christ is made a part of his body, the Church, through baptism. The Holy Spirit is the agent, and the body of Christ is the medium.[106] Water baptism: Symbolic of dying to the world and living in Christ, water baptism is an outward symbolic expression of that which has already been accomplished by the Holy Spirit, namely baptism into the body of Christ.[107] Baptism with the Holy Spirit: This is an experience distinct from baptism into the body of Christ. In this baptism, Christ is the agent and the Holy Spirit is the medium.[106] While the figure of Jesus Christ and his redemptive work are at the center of Pentecostal theology, that redemptive work is believed to provide for a fullness of the Holy Spirit of which believers in Christ may take advantage.[108] The majority of Pentecostals believe that at the moment a person is born again, the new believer has the presence (indwelling) of the Holy Spirit.[104] While the Spirit dwells in every Christian, Pentecostals believe that all Christians should seek to be filled with him. The Spirit's "filling", "falling upon", "coming upon", or being "poured out upon" believers is called the baptism with the Holy Spirit.[109] Pentecostals define it as a definite experience occurring after salvation whereby the Holy Spirit comes upon the believer to anoint and empower them for special service.[110][111] It has also been described as "a baptism into the love of God".[112] The main purpose of the experience is to grant power for Christian service. Other purposes include power for spiritual warfare (the Christian struggles against spiritual enemies and thus requires spiritual power), power for overflow (the believer's experience of the presence and power of God in their life flows out into the lives of others), and power for ability (to follow divine direction, to face persecution, to exercise spiritual gifts for the edification of the church, etc.).[113] Pentecostals believe that the baptism with the Holy Spirit is available to all Christians.[114] Repentance from sin and being born again are fundamental requirements to receive it. There must also be in the believer a deep conviction of needing more of God in their life, and a measure of consecration by which the believer yields themself to the will of God. Citing instances in the Book of Acts where believers were Spirit baptized before they were baptized with water, most Pentecostals believe a Christian need not have been baptized in water to receive Spirit baptism. However, Pentecostals do believe that the biblical pattern is "repentance, regeneration, water baptism, and then the baptism with the Holy Ghost". There are Pentecostal believers who have claimed to receive their baptism with the Holy Spirit while being water baptized.[115] It is received by having faith in God's promise to fill the believer and in yielding the entire being to Christ.[116] Certain conditions, if present in a believer's life, could cause delay in receiving Spirit baptism, such as "weak faith, unholy living, imperfect consecration, and egocentric motives".[117] In the absence of these, Pentecostals teach that seekers should maintain a persistent faith in the knowledge that God will fulfill his promise. For Pentecostals, there is no prescribed manner in which a believer will be filled with the Spirit. It could be expected or unexpected, during public or private prayer.[118] Pentecostals expect certain results following baptism with the Holy Spirit. Some of these are immediate while others are enduring or permanent. Most Pentecostal denominations teach that speaking in tongues is an immediate or initial physical evidence that one has received the experience.[119] Some teach that any of the gifts of the Spirit can be evidence of having received Spirit baptism.[120] Other immediate evidences include giving God praise, having joy, and desiring to testify about Jesus.[119] Enduring or permanent results in the believer's life include Christ glorified and revealed in a greater way, a "deeper passion for souls", greater power to witness to nonbelievers, a more effective prayer life, greater love for and insight into the Bible, and the manifestation of the gifts of the Spirit.[121] Holiness Pentecostals, with their background in the Wesleyan-Holiness movement, historically teach that baptism with the Holy Spirit, as evidenced by glossolalia, is the third work of grace, which follows the new birth (first work of grace) and entire sanctification (second work of grace).[6][7][8] While the baptism with the Holy Spirit is a definite experience in a believer's life, Pentecostals view it as just the beginning of living a Spirit-filled life. Pentecostal teaching stresses the importance of continually being filled with the Spirit. There is only one baptism with the Spirit, but there should be many infillings with the Spirit throughout the believer's life.[122] |

聖霊のバプテスマ 主な記事:聖霊のバプテスマ ペンテコステ派は、新約聖書における「バプテスマ」という言葉の 3 つの異なる用法を識別している。 キリストの体へのバプテスマ:これは救いを指す。キリストを信じる者は皆、バプテスマによってキリストの体である教会の一員となる。聖霊が媒介者であり、 キリストの体が媒体である。[106] 水によるバプテスマ:この世に死んでキリストに生きることを象徴する水によるバプテスマは、聖霊によってすでに成されたこと、すなわちキリストの体へのバ プテスマを、外的に象徴的に表現したものだ。[107] 聖霊によるバプテスマ:これは、キリストの体へのバプテスマとは別の体験だ。このバプテスマでは、キリストが媒介者であり、聖霊が媒体だ。[106] イエス・キリストの姿と彼の贖いの業はペンテコステ派の神学の中心にあるが、その贖いの業は、キリストを信じる者たちが享受できる聖霊の完全さを与えるも のと信じられている。[108] ペンテコステ派の大半は、人が新たに生まれ変わる瞬間、新しい信者は聖霊の存在(内住)を受けると信じている。[104] 聖霊はすべてのキリスト教徒の中に住んでいますが、ペンテコステ派は、すべてのキリスト教徒が聖霊に満たされることを求めるべきだと信じています。聖霊の 「満たし」、「降りかかる」、「臨む」、または「注がれる」ことは、聖霊のバプテスマと呼ばれています。[109] ペンテコステ派は、これを救い後に起こる明確な経験として定義し、聖霊が信者に臨み、特別な奉仕のために油を注ぎ、力を与えるものとしています。 [110][111] また、「神の愛へのバプテスマ」と表現されることもある。[112] この体験の主な目的は、キリスト教の奉仕のための力を与えることだ。他の目的には、霊的戦いのための力(キリスト教徒は霊的な敵と戦い、そのため霊的な力 が必要だ)、溢れ出る力(信者が人生において神の臨在と力を体験し、それが他者の人生に流れ出る)、能力のための力(神の導きに従うこと、迫害に直面する こと、教会の建設のために霊的賜物を行使することなど)がある。[113] ペンテコステ派は、聖霊のバプテスマはすべてのクリスチャンが受けることができると信じている。[114] 罪からの悔い改めと新生は、それを受けるための基本的な要件である。また、信者には、自分の人生においてより神を必要としているという深い確信と、神の御 心に従うというある程度の献身も必要な。使徒行伝で、信者が水で洗礼を受ける前に聖霊の洗礼を受けた例を引用し、ほとんどのペンテコステ派は、キリスト教 徒が水で洗礼を受けていなくても聖霊の洗礼を受けることができると信じています。しかし、ペンテコステ派は、聖書のパターンは「悔い改め、再生、水洗礼、 そして聖霊の洗礼」であると信じています。水洗礼を受けている最中に聖霊の洗礼を受けたとするペンテコステ派の信者もいます。[115] それは、信者を満たすという神の約束を信じ、自分の全存在をキリストに委ねることによって受けられる。[116] 信者の人生に「弱い信仰、不聖な生活、不完全な献身、自己中心的な動機」などの特定の条件が存在する場合、聖霊のバプテスマを受けるのが遅れることがあ る。[117] これらの条件が欠如している場合、ペンテコステ派は、求道者が神が約束を果たされるという知識に基づいて、持続的な信仰を維持すべきだと教えます。ペンテ コステ派にとって、信者が聖霊で満たされる方法に定められた形式はありません。それは予期せぬものや予期せぬもの、公の祈りや私的な祈りの際に起こる可能 性があります。[118] ペンテコステ派は、聖霊のバプテスマを受けた後に、特定の結果を期待している。その中には、即座に現れるものもあれば、永続的または永続的なものもある。 ほとんどのペンテコステ派は、異言を話すことが、その体験を受けたことの即座または最初の物理的な証拠であると教えている。[119] 聖霊の賜物であれば、どれでも聖霊のバプテスマを受けた証拠になると教える者もいる。[120] 他の即時の証拠には、神への賛美、喜び、イエスについて証ししたいという願望が含まれます。[119] 信者の人生における持続的または永久的な結果には、キリストがより大きな方法で栄光を受け現れること、魂へのより深い情熱、非信者への証しをするためのよ り大きな力、より効果的な祈りの生活、聖書へのより深い愛と理解、そして聖霊の賜物の現れが含まれます。[121] ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派は、ウェスレー・ホーリネス運動を背景として、歴史的に、異言を伴う聖霊のバプテスマは、新生(最初の恵みの働き)と完全な聖 化(第二の恵みの働き)に続く、第三の恵みの働きであると教えている。[6][7][8] 聖霊のバプテスマは信者の人生における明確な経験ですが、ペンテコステ派はそれを聖霊に満たされた人生のはじまりに過ぎないと見なしています。ペンテコス テ派の教えは、絶えず聖霊に満たされることの重要性を強調しています。聖霊のバプテスマは一度だけですが、信者の人生を通じて何度も聖霊に満たされるべき です。[122] |

| Divine healing Further information: Divine healing Pentecostalism is a holistic faith, and the belief that Jesus is Healer is one quarter of the full gospel. Pentecostals cite four major reasons for believing in divine healing: 1) it is reported in the Bible, 2) Jesus's healing ministry is included in his atonement (thus divine healing is part of salvation), 3) "the whole gospel is for the whole person"—spirit, soul, and body, 4) sickness is a consequence of the Fall of Man and salvation is ultimately the restoration of the fallen world.[123] In the words of Pentecostal scholar Vernon L. Purdy, "Because sin leads to human suffering, it was only natural for the Early Church to understand the ministry of Christ as the alleviation of human suffering, since he was God's answer to sin ... The restoration of fellowship with God is the most important thing, but this restoration not only results in spiritual healing but many times in physical healing as well."[124] In the book In Pursuit of Wholeness: Experiencing God's Salvation for the Total Person, Pentecostal writer and Church historian Wilfred Graves Jr. describes the healing of the body as a physical expression of salvation.[125] For Pentecostals, spiritual and physical healing serves as a reminder and testimony to Christ's future return when his people will be completely delivered from all the consequences of the fall.[126] However, not everyone receives healing when they pray. It is God in his sovereign wisdom who either grants or withholds healing. Common reasons that are given in answer to the question as to why all are not healed include: God teaches through suffering, healing is not always immediate, lack of faith on the part of the person needing healing, and personal sin in one's life (however, this does not mean that all illness is caused by personal sin).[127] Regarding healing and prayer Purdy states: On the other hand, it appears from Scripture that when we are sick we should be prayed for, and as we shall see later in this chapter, it appears that God's normal will is to heal. Instead of expecting that it is not God's will to heal us, we should pray with faith, trusting that God cares for us and that the provision He has made in Christ for our healing is sufficient. If He does not heal us, we will continue to trust Him. The victory many times will be procured in faith (see Heb. 10:35–36; 1 John 5:4–5).[128] Pentecostals believe that prayer and faith are central in receiving healing. Pentecostals look to scriptures such as James 5:13–16 for direction regarding healing prayer.[129] One can pray for one's own healing (verse 13) and for the healing of others (verse 16); no special gift or clerical status is necessary. Verses 14–16 supply the framework for congregational healing prayer. The sick person expresses their faith by calling for the elders of the church who pray over and anoint the sick with olive oil. The oil is a symbol of the Holy Spirit.[130] Besides prayer, there are other ways in which Pentecostals believe healing can be received. One way is based on Mark 16:17–18 and involves believers laying hands on the sick. This is done in imitation of Jesus who often healed in this manner.[131] Another method that is found in some Pentecostal churches is based on the account in Acts 19:11–12 where people were healed when given handkerchiefs or aprons worn by the Apostle Paul. This practice is described by Duffield and Van Cleave in Foundations of Pentecostal Theology: Many Churches have followed a similar pattern and have given out small pieces of cloth over which prayer has been made, and sometimes they have been anointed with oil. Some most remarkable miracles have been reported from the use of this method. It is understood that the prayer cloth has no virtue in itself, but provides an act of faith by which one's attention is directed to the Lord, who is the Great Physician.[131] During the initial decades of the movement, Pentecostals thought it was sinful to take medicine or receive care from doctors.[132] Over time, Pentecostals moderated their views concerning medicine and doctor visits; however, a minority of Pentecostal churches continues to rely exclusively on prayer and divine healing. For example, doctors in the United Kingdom reported that a minority of Pentecostal HIV patients were encouraged to stop taking their medicines and parents were told to stop giving medicine to their children, trends that placed lives at risk.[133] |

神の癒し 詳細情報:神の癒し ペンテコステ派は全体論的な信仰であり、イエスが癒し主であるという信念は、完全な福音の4分の1を占めています。ペンテコステ派は、神の癒しを信じる 4 つの主な理由を挙げています。1) 聖書に記されている、2) イエスの癒しの働きは彼の贖罪の一部である(したがって、神の癒しは救いの一部である)、3) 「福音は人格全体、つまり霊、魂、体すべてのためのもの」である、4) 病気は人間の堕落の結果であり、救いは最終的には堕落した世界の回復である。[123] ペンテコステ派の学者、ヴァーノン・L・パーディは、「罪は人間の苦悩につながるため、キリストは罪に対する神の答えであったことから、初期教会がキリス トの働きを人間の苦悩の緩和と理解したのは当然のことだった... 神との交わりの回復が最も重要だが、この回復は霊的な癒しだけでなく、多くの場合、肉体的な癒しももたらす」と述べています。[124] ペンテコステ派の作家であり教会史家でもあるウィルフレッド・グレイブス・ジュニアは、著書『In Pursuit of Wholeness: Experiencing God's Salvation for the Total Person』の中で、身体の癒しは救いの物理的な表現であると述べている。 ペンテコステ派にとって、霊的および肉体的な癒しは、キリストの民が堕落の結果から完全に解放される、キリストの将来の再臨を思い出させる証しとしての役 割を果たしている。[126] しかし、祈ったからといって、誰もが癒されるわけではない。癒すか癒さないかは、神の至高の知恵によるものだ。なぜすべての人々が癒されないのかという質 問に対する一般的な答えとしては、神は苦悩を通して教えを授ける、癒しは必ずしも即座に起こるわけではない、癒やしを必要とする人物の信仰の欠如、その人 物の個人的な罪(ただし、すべての病気は個人的な罪によって引き起こされるわけではない)などが挙げられる。[127] 癒しと祈りについて、パーディは次のように述べている。 一方、聖書からは、私たちが病気になったときは、祈られるべきであることがわかる。また、この章の後半で見るように、神の通常の御心は癒すことであるよう にも見える。神が私たちを癒す意志がないと期待するのではなく、神が私たちを顧みておられ、キリストにおいて私たちの癒しのために備えられたものが十分で あると信頼し、信仰をもって祈るべきだ。もし神が私たちを癒さない場合でも、私たちは神を信頼し続ける。勝利は多くの場合、信仰によって得られる(ヘブル 10:35–36;1ヨハネ5:4–5)。[128] ペンテコステ派は、祈りと信仰が癒しを受ける中心的な要素だと信じています。ペンテコステ派は、癒しの祈りに関する指針としてヤコブ5:13–16などの 聖書箇所を参照しています。[129] 自分自身の癒し(13節)や他者の癒し(16節)のために祈ることができます。特別な賜物や教職の地位は必要ありません。14–16節は、会衆の癒しの祈 りの枠組みを提供しています。病気の人は、教会の長老たちを呼び、その長老たちが祈り、オリーブオイルを塗って油を注ぐことで、自分の信仰を表現する。オ イルは聖霊の象徴だ。[130] 祈り以外にも、ペンテコステ派は癒しが受けられる方法をいくつか信じている。その一つは、マルコによる福音書 16:17-18 に基づいており、信者が病人に手を置くというものである。これは、この方法でしばしば癒やしを行ったイエスを模倣したものだ。[131] 一部のペンテコステ派教会で見られるもう一つの方法は、使徒パウロが着用したハンカチやエプロンを人々に渡すと、彼らが癒されたという使徒行伝 19:11-12 の記述に基づいている。この慣習は、ダフィールドとヴァン・クリーヴの『Foundations of Pentecostal Theology』で次のように説明されている。 多くの教会は同様のパターンに従い、祈りを捧げた小さな布片を配布し、時には油を塗ることもあります。この方法による驚くべき奇跡が報告されています。祈 りの布自体に力があるのではなく、大いなる医者である主への注意を向ける信仰の行為として機能すると理解されています。[131] 運動の初期の数十年、ペンテコステ派は、薬を服用したり、医師の治療を受けることは罪であると考えていた。[132] 時間の経過とともに、ペンテコステ派は、薬や医師の診察に関する見解を緩和したが、ペンテコステ派の教会の一部では、依然として祈りと神の癒しのみに頼っ ている。例えば、イギリスの医師たちは、ペンテコステ派のHIV患者の少数派が薬を飲むのをやめるよう促され、親たちは子供に薬を飲ませないよう指示され たと報告している。これらの傾向は命を危険にさらすものだった。[133] |

| Eschatology Further information: Christian eschatology, Dispensationalism, and Futurism (Christianity) The last element of the gospel is that Jesus is the "Soon Coming King". For Pentecostals, "every moment is eschatological" since at any time Christ may return.[134] This "personal and imminent" Second Coming is for Pentecostals the motivation for practical Christian living including: personal holiness, meeting together for worship, faithful Christian service, and evangelism (both personal and worldwide).[135] Globally, Pentecostal attitudes to the End Times range from enthusiastic participation in the prophecy subculture to a complete lack of interest through to the more recent, optimistic belief in the coming restoration of God's kingdom.[136] Historically, however, they have been premillennial dispensationalists believing in a pretribulation rapture.[137] Pre-tribulation rapture theology was popularized extensively in the 1830s by John Nelson Darby,[138] and further popularized in the United States in the early 20th century by the wide circulation of the Scofield Reference Bible.[139] |

終末論 詳細情報:キリスト教の終末論、ディスペンセーション主義、未来主義(キリスト教) 福音の最後の要素は、イエスが「間もなく到来する王」であるということだ。ペンテコステ派にとって、「あらゆる瞬間は終末論的」である。なぜなら、キリス トはいつでも再臨する可能性があるからだ。[134] この「個人的かつ差し迫った」再臨は、ペンテコステ派にとって、個人的な聖性、礼拝のための集会、忠実なキリスト教の奉仕、伝道(個人的および世界規模) など、実践的なキリスト教徒の生活の動機となっている。[135]世界的に見ると、終末に対するペンテコステ派の姿勢は、予言のサブカルチャーへの熱狂的 な参加から、まったくの無関心、そして最近では、神の王国の復活を信じる楽観的な信念まで多岐にわたっている。[136] しかし、歴史的には、彼らは前千年王国説のディスペンセーション主義者であり、大患難前の携挙を信じていた。[137] 大患難前の携挙神学は、1830年代にジョン・ネルソン・ダービーによって広く普及し、[138] 20世紀初頭にはスコフィールド参考聖書の広範な流通により、アメリカ合衆国でさらに普及した。[139] |

| Spiritual gifts Main article: Spiritual gifts Pentecostals are continuationists, meaning they believe that all of the spiritual gifts, including the miraculous or "sign gifts", found in 1 Corinthians 12:4–11, 12:27–31, Romans 12:3–8, and Ephesians 4:7–16 continue to operate within the Church in the present time.[140] Pentecostals place the gifts of the Spirit in context with the fruit of the Spirit.[141] The fruit of the Spirit is the result of the new birth and continuing to abide in Christ. It is by the fruit exhibited that spiritual character is assessed. Spiritual gifts are received as a result of the baptism with the Holy Spirit. As gifts freely given by the Holy Spirit, they cannot be earned or merited, and they are not appropriate criteria with which to evaluate one's spiritual life or maturity.[142] Pentecostals see in the biblical writings of Paul an emphasis on having both character and power, exercising the gifts in love. Just as fruit should be evident in the life of every Christian, Pentecostals believe that every Spirit-filled believer is given some capacity for the manifestation of the Spirit.[143] The exercise of a gift is considered to be a manifestation of the Spirit, not of the gifted person, and though the gifts operate through people, they are primarily gifts given to the Church.[142] They are valuable only when they minister spiritual profit and edification to the body of Christ. Pentecostal writers point out that the lists of spiritual gifts in the New Testament do not seem to be exhaustive. It is generally believed that there are as many gifts as there are useful ministries and functions in the Church.[143] A spiritual gift is often exercised in partnership with another gift. For example, in a Pentecostal church service, the gift of tongues might be exercised followed by the operation of the gift of interpretation. According to Pentecostals, all manifestations of the Spirit are to be judged by the church. This is made possible, in part, by the gift of discerning of spirits, which is the capacity for discerning the source of a spiritual manifestation—whether from the Holy Spirit, an evil spirit, or from the human spirit.[144] While Pentecostals believe in the current operation of all the spiritual gifts within the church, their teaching on some of these gifts has generated more controversy and interest than others. There are different ways in which the gifts have been grouped. W. R. Jones[145] suggests three categories, illumination (Word of Wisdom, word of knowledge, discerning of spirits), action (Faith, working of miracles and gifts of healings) and communication (Prophecy, tongues and interpretation of tongues). Duffield and Van Cleave use two categories: the vocal and the power gifts. |

霊的賜物 主な記事:霊的賜物 ペンテコステ派は継続主義者であり、1コリント12:4-11、12:27-31、ローマ12:3-8、エペソ4:7-16に見られる、奇跡や「しるしの 賜物」を含むすべての霊的賜物が、現在の教会でも引き続き機能していると信じている。[140] ペンテコステ派は、聖霊の賜物を聖霊の果実と関連付けています。[141] 聖霊の果実は、新生とキリストに留まり続ける結果です。霊的性格は、示される果実によって評価されます。霊的賜物は、聖霊のバプテスマによって与えられる ものです。聖霊によって自由に与えられる賜物であるため、それらを稼ぐことや得ることはできず、霊的な生活や成熟度を評価する適切な基準とはなりません。 [142] ペンテコステ派は、パウロの聖書記述において、性格と力、そして愛をもって賜物を用いることの重要性が強調されていると見ています。 すべてのクリスチャンの生活において実が明らかであるべきであるように、ペンテコステ派は、聖霊に満たされたすべての信者は、聖霊の現れを示す何らかの能 力を与えられていると信じています。[143] 賜物の行使は、その賜物を持つ人格の現れではなく、御霊の現れであるとみなされ、賜物は人々を通して働くものの、それは主に教会に与えられた賜物である。 [142] それらは、キリストの体に霊的な益と啓発をもたらす場合にのみ価値がある。ペンテコステ派の作家たちは、新約聖書にある霊的賜物のリストは網羅的ではない ようだと指摘している。一般的に、教会における有用な奉仕や機能の数だけ賜物があると考えられている。[143] 霊的賜物は、しばしば他の賜物と協力して行使される。例えば、ペンテコステ派の教会礼拝では、異言の賜物が行使された後、解釈の賜物が働くことがある。 ペンテコステ派によると、聖霊のすべての現れは教会によって判断されるべきである。これは、霊の現れの源(聖霊、悪霊、人間の霊のいずれか)を区別する能 力である「霊の区別」の賜物によって、一部可能となっています。[144] ペンテコステ派は、教会内ですべての霊的賜物が現在も機能していると信じていますが、これらの賜物の一部に関する教えは、他のものよりも多くの議論と関心 を引き起こしています。賜物はさまざまな方法で分類されている。W. R. ジョーンズ[145] は、3 つのカテゴリー、すなわち「啓示(知恵の言葉、知識の言葉、霊の識別)」、「行動(信仰、奇跡の行使、癒しの賜物)」、「コミュニケーション(預言、異 言、異言の解釈)」を提案している。ダフィールドとヴァン・クリーヴは、2 つのカテゴリー、すなわち「声の賜物」と「力の賜物」を使用している。 |

| Vocal gifts The gifts of prophecy, tongues, interpretation of tongues, and words of wisdom and knowledge are called the vocal gifts.[146] Pentecostals look to 1 Corinthians 14 for instructions on the proper use of the spiritual gifts, especially the vocal ones. Pentecostals believe that prophecy is the vocal gift of preference, a view derived from 1 Corinthians 14. Some teach that the gift of tongues is equal to the gift of prophecy when tongues are interpreted.[147] Prophetic and glossolalic utterances are not to replace the preaching of the Word of God[148] nor to be considered as equal to or superseding the written Word of God, which is the final authority for determining teaching and doctrine.[149] |

声の賜物 預言、異言、異言の解釈、知恵と言葉の賜物は、声の賜物と呼ばれている。[146] ペンテコステ派は、霊的賜物、特に声の賜物の適切な使用に関する指示を、コリント人への第一の手紙 14 章に求めている。ペンテコステ派は、預言が声の賜物の中で最も重要なものであると信じている。この見解は、コリント人への第一の手紙 14 章に由来している。一部の人々は、舌の賜物が解釈された場合、舌の賜物は預言の賜物と同等であると教えています。[147] 預言的な発言と舌の賜物による発言は、神の言葉の宣教に代わるものではなく[148]、また、教義や教理を決定する最終的な権威である書かれた神の言葉と 同等またはそれを超えるものと見なされるべきではありません。[149] |

| Word of wisdom and word of

knowledge Main articles: Word of wisdom and Word of knowledge Pentecostals understand the word of wisdom and the word of knowledge to be supernatural revelations of wisdom and knowledge by the Holy Spirit. The word of wisdom is defined as a revelation of the Holy Spirit that applies scriptural wisdom to a specific situation that a Christian community faces.[150] The word of knowledge is often defined as the ability of one person to know what God is currently doing or intends to do in the life of another person.[151] |

知恵の言葉と知識の言葉 主な記事:知恵の言葉と知識の言葉 ペンテコステ派は、知恵の言葉と知識の言葉は、聖霊による超自然的な知恵と知識の啓示であると理解している。知恵の言葉は、キリスト教コミュニティが直面 する特定の状況に対して、聖書の知恵を適用する聖霊の啓示と定義されている[150]。知識の言葉は、ある人物が、神が現在、別の人物の生活の中で何をし ているか、あるいは何をするつもりかを、その人物が知ることができる能力と定義されることが多い[151]。 |

| Prophecy Main article: Prophecy Pentecostals agree with the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura. The Bible is the "all sufficient rule for faith and practice"; it is "fixed, finished, and objective revelation".[152] Alongside this high regard for the authority of scripture is a belief that the gift of prophecy continues to operate within the Church. Pentecostal theologians Duffield and van Cleave described the gift of prophecy in the following manner: "Normally, in the operation of the gift of prophecy, the Spirit heavily anoints the believer to speak forth to the body not premeditated words, but words the Spirit supplies spontaneously in order to uplift and encourage, incite to faithful obedience and service, and to bring comfort and consolation."[144] Any Spirit-filled Christian, according to Pentecostal theology, has the potential, as with all the gifts, to prophesy. Sometimes, prophecy can overlap with preaching "where great unpremeditated truth or application is provided by the Spirit, or where special revelation is given beforehand in prayer and is empowered in the delivery".[153] While a prophetic utterance at times might foretell future events, this is not the primary purpose of Pentecostal prophecy and is never to be used for personal guidance. For Pentecostals, prophetic utterances are fallible, i.e. subject to error.[148] Pentecostals teach that believers must discern whether the utterance has edifying value for themselves and the local church.[154] Because prophecies are subject to the judgement and discernment of other Christians, most Pentecostals teach that prophetic utterances should never be spoken in the first person (e.g. "I, the Lord") but always in the third person (e.g. "Thus saith the Lord" or "The Lord would have...").[155] |

予言 主な記事:予言 ペンテコステ派は、プロテスタントの「聖書のみ」の原則に同意している。聖書は「信仰と実践のための完全な規範」であり、「固定され、完成され、客観的な 啓示」である。[152] 聖書の権威を高く評価する一方で、予言の賜物は教会内で引き続き機能していると信じられている。ペンテコステ派の神学者ダフィールドとヴァン・クリーヴ は、預言の賜物を次のように説明している:「通常、預言の賜物が働く際、聖霊は信者を深く油注ぎ、事前に計画された言葉ではなく、聖霊が自発的に与える言 葉を、教会に語りかけるようにする。その目的は、励ましと慰めを与え、忠実な従順と奉仕を促し、慰めと慰めをもたらすことである。」[144] ペンテコステ派の神学によると、聖霊に満たされたキリスト教徒は、他のすべての賜物と同様に、預言する可能性を秘めている。時折、預言は説教と重なること がある。「聖霊によって大きな予期せぬ真理や応用が与えられる場合、または祈りの中で事前に特別な啓示が与えられ、その伝達において力づけられる場合」で ある。[153] 預言的な発言は、時には将来の出来事を予言する場合もあるが、それはペンテコステ派の預言の主な目的ではなく、個人的な指針として用いてはならない。ペン テコステ派にとって、預言的な発言は誤りのある、つまり間違いのあるものである[148]。ペンテコステ派は、その発言が自分自身や地元の教会にとって啓 発的な価値があるかどうかを、信者は識別しなければならないと教えている。[154] 預言は他のキリスト教徒の判断と識別力によって左右されるため、ほとんどのペンテコステ派は、預言的発言は決して一人称(例えば「私、主は」)で発しては ならず、常に三人称(例えば「主はこう言われる」や「主は...であろう」)で発すべきだと教えている。[155] |

Tongues and interpretation Pentecostals pray in tongues at an Assemblies of God church in Cancún, Mexico A Pentecostal believer in a spiritual experience may vocalize fluent, unintelligible utterances (glossolalia) or articulate a natural language previously unknown to them (xenoglossy). Commonly termed "speaking in tongues", this vocal phenomenon is believed by Pentecostals to include an endless variety of languages. According to Pentecostal theology, the language spoken (1) may be an unlearned human language, such as the Bible claims happened on the Day of Pentecost, or (2) it might be of heavenly (angelic) origin. In the first case, tongues could work as a sign by which witness is given to the unsaved. In the second case, tongues are used for praise and prayer when the mind is superseded and "the speaker in tongues speaks to God, speaks mysteries, and ... no one understands him".[156] Within Pentecostalism, there is a belief that speaking in tongues serves two functions. Tongues as the initial evidence of the third work of grace, baptism with the Holy Spirit,[6] and in individual prayer serves a different purpose than tongues as a spiritual gift.[156][157] All Spirit-filled believers, according to initial evidence proponents, will speak in tongues when baptized in the Spirit and, thereafter, will be able to express prayer and praise to God in an unknown tongue. This type of tongue speaking forms an important part of many Pentecostals' personal daily devotions. When used in this way, it is referred to as a "prayer language" as the believer is speaking unknown languages not for the purpose of communicating with others but for "communication between the soul and God".[158] Its purpose is for the spiritual edification of the individual. Pentecostals believe the private use of tongues in prayer (i.e. "prayer in the Spirit") "promotes a deepening of the prayer life and the spiritual development of the personality". From Romans 8:26–27, Pentecostals believe that the Spirit intercedes for believers through tongues; in other words, when a believer prays in an unknown tongue, the Holy Spirit is supernaturally directing the believer's prayer.[159] Besides acting as a prayer language, tongues also function as the gift of tongues. Not all Spirit-filled believers possess the gift of tongues. Its purpose is for gifted persons to publicly "speak with God in praise, to pray or sing in the Spirit, or to speak forth in the congregation".[160] There is a division among Pentecostals on the relationship between the gifts of tongues and prophecy.[161] One school of thought believes that the gift of tongues is always directed from man to God, in which case it is always prayer or praise spoken to God but in the hearing of the entire congregation for encouragement and consolation. Another school of thought believes that the gift of tongues can be prophetic, in which case the believer delivers a "message in tongues"—a prophetic utterance given under the influence of the Holy Spirit—to a congregation. Whether prophetic or not, however, Pentecostals are agreed that all public utterances in an unknown tongue must be interpreted in the language of the gathered Christians.[148] This is accomplished by the gift of interpretation, and this gift can be exercised by the same individual who first delivered the message (if he or she possesses the gift of interpretation) or by another individual who possesses the required gift. If a person with the gift of tongues is not sure that a person with the gift of interpretation is present and is unable to interpret the utterance themself, then the person should not speak.[148] Pentecostals teach that those with the gift of tongues should pray for the gift of interpretation.[160] Pentecostals do not require that an interpretation be a literal word-for-word translation of a glossolalic utterance. Rather, as the word "interpretation" implies, Pentecostals expect only an accurate explanation of the utterance's meaning.[162] Besides the gift of tongues, Pentecostals may also use glossolalia as a form of praise and worship in corporate settings. Pentecostals in a church service may pray aloud in tongues while others pray simultaneously in the common language of the gathered Christians.[163] This use of glossolalia is seen as an acceptable form of prayer and therefore requires no interpretation. Congregations may also corporately sing in tongues, a phenomenon known as singing in the Spirit. Speaking in tongues is not universal among Pentecostal Christians. In 2006, a ten-country survey by the Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life found that 49 percent of Pentecostals in the US, 50 percent in Brazil, 41 percent in South Africa, and 54 percent in India said they "never" speak or pray in tongues.[105] |

舌と通訳 ペンテコステ派の信者がメキシコ・カンクンのアッセンブリーズ・オブ・ゴッド教会で舌で祈る 霊的な体験をしているペンテコステ派の信者は、流暢で理解不能な発声(グロソラリア)をしたり、これまで知らなかった自然言語を話したり(ゼノグロッ シー)することがある。一般的に「舌で話す」と呼ばれるこの音声現象は、ペンテコステ派によって、無限の言語のバリエーションを含むものと信じられてい る。ペンテコステ派の神学によると、話される言語は(1)聖書がペンテコステの日に起こったと述べるような、学習されていない人間の言語である可能性があ り、(2)天界(天使)起源の言語である可能性もある。前者では、舌は未信者への証しとして機能する。後者では、舌は心が超越され、「舌で話す者は神に語 り、神秘を語り、…誰も彼を理解しない」[156] ときに、賛美と祈りのために用いられる。 ペンテコステ派では、舌で話すことは二つの機能を持つと信じられている。聖霊のバプテスマ[6] という第三の恵みの働きの最初の証拠としての異言は、霊的賜物としての異言とは異なる目的を果たしている。[156][157] 最初の証拠の支持者によると、聖霊に満たされた信者は皆、聖霊のバプテスマを受けたときに異言を話し、それ以降、未知の言語で神への祈りと賛美を表現する ことができるようになる。この種の異言は、多くのペンテコステ派の信者の個人的な毎日の献身的な祈りの重要な部分を形成している。このように使用される場 合、信者は他者とコミュニケーションをとるためではなく、「魂と神とのコミュニケーション」のために未知の言語を話すため、これは「祈りの言語」と呼ばれ る。[158] その目的は、個人の霊的啓発にある。ペンテコステ派は、祈りの中で舌を私的に使うこと(すなわち「御霊による祈り」)は、「祈りの生活を深め、人格の霊的 成長を促進する」と信じている。ローマ人への手紙8章26~27節から、ペンテコステ派は、聖霊が舌を通して信者のために取り成し祈ると信じている。つま り、信者が未知の言語で祈る時、聖霊が超自然的に信者の祈りを導いていると考える。[159] 異言は、祈りの言語としての役割だけでなく、異言の賜物としても機能する。御霊に満たされた信者全員が異言の賜物を持っているわけではない。その目的は、 賜物を持つ者が「神を賛美し、御霊によって祈ったり歌ったり、会衆の中で声を上げて話す」ことにある。[160] ペンテコステ派の間では、異言の賜物と預言の賜物の関係について意見が分かれている。[161] 一つの学派は、舌の賜物は常に人間から神に向けられていると主張し、その場合、それは常に神への祈りや賛美であり、会衆全体が励ましや慰めを受けるために 聞くものだとする。別の学派は、舌の賜物は預言的である可能性があると主張し、その場合、信者は「舌によるメッセージ」——聖霊の影響下で与えられる預言 的な言葉——を会衆に伝えると主張する。 しかし、預言的であるかどうかにかかわらず、ペンテコステ派は、未知の舌によるすべての公の言辞は、集まったキリスト教徒の言語で解釈されなければならな いと一致している。[148] これは解釈の賜物によって行われ、この賜物は、メッセージを最初に伝えた者(その者が解釈の賜物を持っている場合)または必要な賜物を持つ別の者が行使す ることができる。異言の賜物を持つ人が、解釈の賜物を持つ人がその場にいないことを確信し、その発言を自分で解釈できない場合は、その人は話すべきではな い[148]。ペンテコステ派は、異言の賜物を持つ人は、解釈の賜物を祈るべきだと教えている[160]。ペンテコステ派は、解釈が、異言の発言を文字通 り一語一語翻訳したものとなることを要求していない。むしろ、「解釈」という言葉が示すように、ペンテコステ派は、その言葉の意味の正確な説明のみを期待 している。[162] 舌の賜物以外にも、ペンテコステ派は集団の場で賛美と礼拝の形態としてグロソラリアを用いることがある。教会礼拝において、ペンテコステ派は舌で声に出し て祈りながら、他の信者は集まったキリスト教徒の共通言語で同時に祈る。[163] このグロソラリアの用法は、祈りの適切な形態と見なされるため、解釈は不要だ。会衆は集団で舌で歌うこともでき、この現象は「聖霊による歌」と呼ばれる。 舌で話すことは、ペンテコステ派のキリスト教徒の間で普遍的なものではありません。2006年にピュー・フォーラム・オン・リリジョン・アンド・パブリッ ク・ライフが実施した10カ国調査では、米国で49%、ブラジルで50%、南アフリカで41%、インドで54%のペンテコステ派が「決して」舌で話したり 祈ったりしないと回答しました。[105] |

| Power gifts The gifts of power are distinct from the vocal gifts in that they do not involve utterance. Included in this category are the gift of faith, gifts of healing, and the gift of miracles.[164] The gift of faith (sometimes called "special" faith) is different from "saving faith" and normal Christian faith in its degree and application.[165] This type of faith is a manifestation of the Spirit granted only to certain individuals "in times of special crisis or opportunity" and endues them with "a divine certainty ... that triumphs over everything". It is sometimes called the "faith of miracles" and is fundamental to the operation of the other two power gifts.[166] |

力の賜物 力の賜物は、発話を含まないという点で、声の賜物とは異なります。このカテゴリーには、信仰の賜物、癒しの賜物、奇跡の賜物などが含まれます。[164] 信仰の賜物(「特別な」信仰とも呼ばれる)は、その程度と適用において、「救いの信仰」や通常のキリスト教の信仰とは異なります。[165] この種類の信仰は、特定の個人に「特別な危機や機会」においてのみ与えられる聖霊の現れであり、彼らに「すべてを打ち破る神聖な確信」を授ける。これは 「奇跡の信仰」とも呼ばれ、他の二つの力による賜物の機能の基盤を成す。[166] |

| Trinitarianism and Oneness During the 1910s, the Finished Work Pentecostal movement split over the nature of the Godhead into two camps – Trinitarian and Oneness.[8] The Oneness doctrine viewed the doctrine of the Trinity as polytheistic.[167] The majority of Pentecostal denominations believe in the doctrine of the Trinity, which is considered by them to be Christian orthodoxy; these include Holiness Pentecostals and Finished Work Pentecostals. Oneness Pentecostals are nontrinitarian Christians, believing in the Oneness theology about God.[168] In Oneness theology, the Godhead is not three persons united by one substance, but one God who reveals himself in three different modes. Thus, God relates himself to humanity as our Father within creation, he manifests himself in human form as the Son by virtue of his incarnation as Jesus Christ (1 Timothy 3:16), and he is the Holy Spirit (John 4:24) by way of his activity in the life of the believer.[169][170] Oneness Pentecostals believe that Jesus is the name of God and therefore baptize in the name of Jesus Christ as performed by the apostles (Acts 2:38), fulfilling the instructions left by Jesus Christ in the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19), they believe that Jesus is the only name given to mankind by which we must be saved (Acts 4:12). The Oneness doctrine may be considered a form of Modalism, an ancient teaching considered heresy by the Roman Catholic Church and other trinitarian denominations. In contrast, Trinitarian Pentecostals hold to the doctrine of the Trinity, that is, the Godhead is not seen as simply three modes or titles of God manifest at different points in history, but is constituted of three completely distinct persons who are co-eternal with each other and united as one substance. The Son is from all eternity who became incarnate as Jesus, and likewise the Holy Spirit is from all eternity, and both are with the eternal Father from all eternity.[171] |

三位一体論と唯一神論 1910年代、完成の業ペンテコステ派は、神の本質について三位一体論と唯一神論の2つの派閥に分裂した。[8] 唯一神論は、三位一体の教義を多神教的であると見なした。[167] ペンテコステ派の宗派の大半は、キリスト教の正統教義であるとする三位一体の教義を信じている。これには、ホーリネス・ペンテコステ派や完成の業ペンテコ ステ派などが含まれる。一神教ペンテコステ派は、神に関する一神教の神学を信じる、非三位一体のキリスト教徒である。[168] 一神教の神学では、神は一つの物質によって結合した三つの人格ではなく、三つの異なる形態で自らを現す一つの神である。したがって、神は創造物の中での私 たちの父として人間と関わり、イエス・キリストとしての受肉により人間の姿で現れ(1テモテ3:16)、信者の人生における活動を通じて聖霊として現れる [169]。[170] 一神教のペンテコステ派は、イエスが神の名前であると信じ、したがって、使徒たちが行ったように(使徒 2:38)、イエス・キリストの名によって洗礼を施し、イエス・キリストが大宣教命令で残した指示(マタイ 28:19)を果たす。彼らは、イエスが人類に与えられた、私たちが救われるために必要な唯一の名前であると信じている(使徒 4:12)。 一神教の教義は、ローマカトリック教会や他の三位一体説を信奉する宗派によって異端とみなされている、古代の教義であるモード主義の一形態とみなすことも できる。これとは対照的に、三位一体説を信奉するペンテコステ派は、三位一体の教義、すなわち、神は単に歴史上の異なる時点で現れた 3 つの形態や称号ではなく、互いに永遠に存在し、一つの実体として結ばれた 3 つの完全に別の人格で構成されていると信じている。子は永遠から存在し、イエスとして受肉した。同様に、聖霊も永遠から存在し、両者は永遠の父と共に永遠 から存在している。[171] |