人工知能の哲学

Philosophy of

artificial intelligence

☆人工知能の哲学[philosophy of

artificial intelligence]

は、心の哲学と計算機科学哲学の一分野である[1]。人工知能と、それが知能・倫理・意識・認識論[2][3]・自由意志[4][5]の知識と理解に与え

る影響を探究する。さらにこの技術は人工動物や人工人間(少なくとも人工生命体)の創造に関わるため、この分野は哲学者にとって極めて興味深い。[6]

こうした要因が人工知能の哲学の出現に寄与した。

人工知能の哲学は以下のような問いに答えようとする[7]:

1) 機械は知的に行動できるか? 人間が思考によって解決するあらゆる問題を解決できるか?

2) 人間の知性と機械の知性は同じか? 人間の脳は本質的にコンピュータか?

3) 機械は人間と同じ意味で心や精神状態、意識を持つことができるか?物事の本質を実感できるか?(すなわちクオリアを持つか?)

こうした疑問は、それぞれAI研究者、認知科学者、哲学者の異なる関心事を反映している。これらの科学的回答は「知能」や「意識」の定義、そして具体的に

どの「機械」を論じているかによって異なる。

AI哲学における重要な命題には、以下のようなものがある:

4) チューリングの「礼儀正しい慣習」:機械が人間と同等に知的に振る舞うならば、それは人間と同等に知的なのだ[8]

5)

ダートマス提案:「学習のあらゆる側面、あるいは知性のその他の特徴は、原則として機械がそれを模倣できるように、極めて正確に記述し得る」[9]

6)

アレン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンの物理的記号システム仮説:「物理的記号システムは、一般的な知的な行動に必要な十分条件を備えている」

[10]

7)

ジョン・サールの強いAI仮説:「適切にプログラムされたコンピュータは、正しい入力と出力があれば、人間が心を持つのと全く同じ意味で心を持つことにな

る」[11]

8)

ホッブズの機械論:「『理性』とは…単に『計算』に過ぎない。つまり、我々の思考を『記号化』し『意味付け』するために合意された一般名称の結果を、足し

算し引き算することである…」[12](→「人工知能」)

| The philosophy of

artificial intelligence is a branch of the philosophy of mind and the

philosophy of computer science[1] that explores artificial intelligence

and its implications for knowledge and understanding of intelligence,

ethics, consciousness, epistemology,[2][3] and free will.[4][5]

Furthermore, the technology is concerned with the creation of

artificial animals or artificial people (or, at least, artificial

creatures; see artificial life) so the discipline is of considerable

interest to philosophers.[6] These factors contributed to the emergence

of the philosophy of artificial intelligence. The philosophy of artificial intelligence attempts to answer such questions as follows:[7] Can a machine act intelligently? Can it solve any problem that a person would solve by thinking? Are human intelligence and machine intelligence the same? Is the human brain essentially a computer? Can a machine have a mind, mental states, and consciousness in the same sense that a human being can? Can it feel how things are? (i.e. does it have qualia?) Questions like these reflect the divergent interests of AI researchers, cognitive scientists and philosophers respectively. The scientific answers to these questions depend on the definition of "intelligence" and "consciousness" and exactly which "machines" are under discussion. Important propositions in the philosophy of AI include some of the following: Turing's "polite convention": If a machine behaves as intelligently as a human being, then it is as intelligent as a human being.[8] The Dartmouth proposal: "Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it."[9] Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon's physical symbol system hypothesis: "A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means of general intelligent action."[10] John Searle's strong AI hypothesis: "The appropriately programmed computer with the right inputs and outputs would thereby have a mind in exactly the same sense human beings have minds."[11] Hobbes' mechanism: "For 'reason' ... is nothing but 'reckoning,' that is adding and subtracting, of the consequences of general names agreed upon for the 'marking' and 'signifying' of our thoughts..."[12] |

人工知能の哲学は、心哲学と計算機科学哲学の一分野である[1]。人工

知能と、それが知能・倫理・意識・認識論[2][3]・自由意志[4][5]の知識と理解に与える影響を探究する。さらにこの技術は人工動物や人工人間

(少なくとも人工生命体)の創造に関わるため、この分野は哲学者にとって極めて興味深い。[6] こうした要因が人工知能哲学の出現に寄与した。 人工知能哲学は以下のような問いに答えようとする[7]: 1) 機械は知的に行動できるか? 人間が思考によって解決するあらゆる問題を解決できるか? 2) 人間の知性と機械の知性は同じか? 人間の脳は本質的にコンピュータか? 3) 機械は人間と同じ意味で心や精神状態、意識を持つことができるか?物事の本質を実感できるか?(すなわちクオリアを持つか?) こうした疑問は、それぞれAI研究者、認知科学者、哲学者の異なる関心事を反映している。これらの科学的回答は「知能」や「意識」の定義、そして具体的に どの「機械」を論じているかによって異なる。 AI哲学における重要な命題には、以下のようなものがある: 4) チューリングの「礼儀正しい慣習」:機械が人間と同等に知的に振る舞うならば、それは人間と同等に知的なのだ[8] 5) ダートマス提案:「学習のあらゆる側面、あるいは知性のその他の特徴は、原則として機械がそれを模倣できるように、極めて正確に記述し得る」[9] 6) アレン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンの物理的記号システム仮説:「物理的記号システムは、一般的な知的な行動に必要な十分条件を備えている」 [10] 7) ジョン・サールの強いAI仮説:「適切にプログラムされたコンピュータは、正しい入力と出力があれば、人間が心を持つのと全く同じ意味で心を持つことにな る」[11] 8) ホッブズの機械論:「『理性』とは…単に『計算』に過ぎない。つまり、我々の思考を『記号化』し『意味付け』するために合意された一般名称の結果を、足し 算し引き算することである…」[12] |

| Can a machine display general intelligence? Is it possible to create a machine that can solve all the problems humans solve using their intelligence? This question defines the scope of what machines could do in the future and guides the direction of AI research. It only concerns the behavior of machines and ignores the issues of interest to psychologists, cognitive scientists and philosophers, evoking the question: does it matter whether a machine is really thinking, as a person thinks, rather than just producing outcomes that appear to result from thinking?[13] The basic position of most AI researchers is summed up in this statement, which appeared in the proposal for the Dartmouth workshop of 1956: "Every aspect of learning or any other feature of intelligence can in principle be so precisely described that a machine can be made to simulate it."[9] Arguments against the basic premise must show that building a working AI system is impossible because there is some practical limit to the abilities of computers or that there is some special quality of the human mind that is necessary for intelligent behavior and yet cannot be duplicated by a machine (or by the methods of current AI research). Arguments in favor of the basic premise must show that such a system is possible. It is also possible to sidestep the connection between the two parts of the above proposal. For instance, machine learning, beginning with Turing's infamous child machine proposal,[14] essentially achieves the desired feature of intelligence without a precise design-time description as to how it would exactly work. The account on robot tacit knowledge[15] eliminates the need for a precise description altogether. The first step to answering the question is to clearly define "intelligence". |

機械は汎用知能を示すことができるか? 人間が知性を使って解決するあらゆる問題を解決できる機械を作ることは可能か?この問いは、将来機械が成し得る可能性の範囲を定義し、AI研究の方向性を 導くものである。これは機械の行動のみを扱い、心理学者や認知科学者、哲学者が関心を持つ問題を無視している。それゆえ疑問が生じる:機械が単に思考の結 果のように見える成果を生み出すのではなく、人格のように真に思考しているかどうかは重要なのか?[13] 大半のAI研究者の基本姿勢は、1956年のダートマスワークショップ提案書に記されたこの声明に集約される: 「学習のあらゆる側面、あるいは知性のその他の特徴は、原則として、機械がそれを模倣できるように、極めて正確に記述することができる」[9] この基本前提に対する反論は、コンピュータの能力に実用上の限界があるため、あるいは知的な行動に必要な人間の精神の特殊な性質が機械(または現在のAI 研究の方法)では再現できないため、実用的なAIシステムの構築が不可能であることを示さねばならない。基本前提を支持する議論は、そのようなシステムが 可能であることを示さねばならない。 上記の提案の二つの部分間の関連性を回避することも可能である。例えば、チューリングの悪名高い子供機械提案[14]に端を発する機械学習は、その正確な 動作原理を設計段階で記述することなく、本質的に知能の望ましい特性を達成している。ロボットの暗黙知に関する研究[15]は、正確な記述そのものを不要 にする。 この問いに答える第一歩は、『知能』を明確に定義することだ。 |

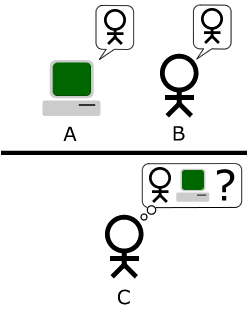

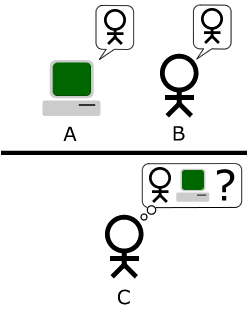

Intelligence The "standard interpretation" of the Turing test[16] Turing test Main article: Turing test Alan Turing[17] reduced the problem of defining intelligence to a simple question about conversation. He suggests that: if a machine can answer any question posed to it, using the same words that an ordinary person would, then we may call that machine intelligent. A modern version of his experimental design would use an online chat room, where one of the participants is a real person and one of the participants is a computer program. The program passes the test if no one can tell which of the two participants is human.[8] Turing notes that no one (except philosophers) ever asks the question "can people think?" He writes "instead of arguing continually over this point, it is usual to have a polite convention that everyone thinks".[18] Turing's test extends this polite convention to machines: If a machine acts as intelligently as a human being, then it is as intelligent as a human being. One criticism of the Turing test is that it only measures the "humanness" of the machine's behavior, rather than the "intelligence" of the behavior. Since human behavior and intelligent behavior are not exactly the same thing, the test fails to measure intelligence. Stuart J. Russell and Peter Norvig write that "aeronautical engineering texts do not define the goal of their field as 'making machines that fly so exactly like pigeons that they can fool other pigeons'".[19] |

知能 チューリングテストの「標準的な解釈」[16] チューリングテスト 詳細な記事: チューリングテスト アラン・チューリング[17]は、知能を定義する問題を会話に関する単純な問いに還元した。彼はこう提案している:もし機械が、普通の人格が使うのと同じ 言葉を使って、投げかけられたどんな質問にも答えられるなら、その機械を知能的と呼んでもよい。この実験設計の現代版では、オンラインチャットルームを用 いる。参加者の一方は実在の人格、もう一方はコンピュータプログラムである。どちらが人間か誰も判別できなければ、プログラムはテストに合格する。[8] チューリングは「人間は思考できるか?」という問いを(哲学者以外)誰も問わないと指摘する。「この点について延々と議論する代わりに、誰もが思考してい ると仮定する礼儀正しい慣習が一般的だ」と彼は記している。[18] チューリングのテストはこの礼儀正しい慣習を機械に拡張する: 機械が人間と同等に知的に振る舞うならば、それは人間と同等に知的なのだ。 チューリングテストに対する批判の一つは、このテストが機械の行動の「知性」ではなく、その行動の「人間らしさ」しか測定しないという点である。人間の行 動と知的な行動はまったく同じものではないため、このテストは知性を測定することに失敗している。スチュワート・J・ラッセルとピーター・ノーヴィグは、 「航空工学の教科書は、その分野の目標を『鳩のように正確に飛ぶ機械を作って、他の鳩を騙せるようにすること』とは定義していない」と書いている。 [19] |

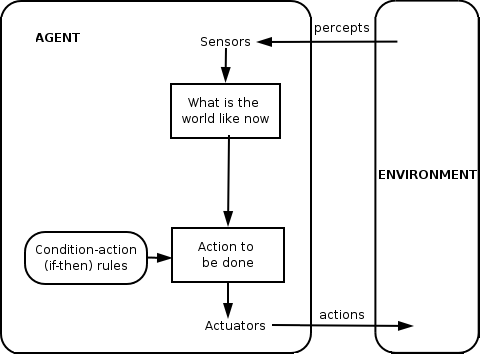

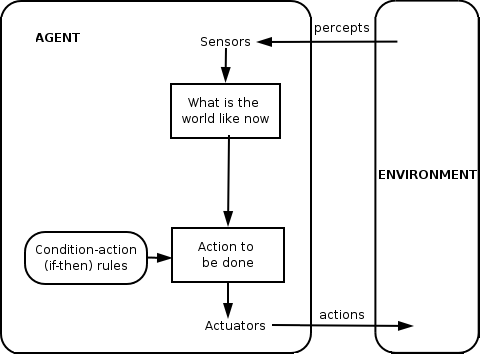

Intelligence as achieving goals Simple reflex agent Twenty-first century AI research defines intelligence in terms of goal-directed behavior. It views intelligence as a set of problems that the machine is expected to solve – the more problems it can solve, and the better its solutions are, the more intelligent the program is. AI founder John McCarthy defined intelligence as "the computational part of the ability to achieve goals in the world."[20] Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig formalized this definition using abstract intelligent agents. An "agent" is something which perceives and acts in an environment. A "performance measure" defines what counts as success for the agent.[21] "If an agent acts so as to maximize the expected value of a performance measure based on past experience and knowledge then it is intelligent."[22] Definitions like this one try to capture the essence of intelligence. They have the advantage that, unlike the Turing test, they do not also test for unintelligent human traits such as making typing mistakes.[23] They have the disadvantage that they can fail to differentiate between "things that think" and "things that do not". By this definition, even a thermostat has a rudimentary intelligence.[24] |

目標達成としての知能 単純な反射エージェント 21世紀のAI研究は、目標指向の行動という観点から知能を定義している。知能とは、機械が解決することが期待される一連の問題とみなされる。解決できる 問題が多く、その解決策が優れているほど、そのプログラムはより知能的であると言える。AIの創始者であるジョン・マッカーシーは、知能を「現実の世界で 目標を達成する能力のうち、計算に関する部分」と定義した[20]。 スチュワート・ラッセルとピーター・ノーヴィグは、抽象的な知能エージェントを用いてこの定義を形式化した。「エージェント」とは、環境の中で知覚し行動するものである。「パフォーマンス測定」は、エージェントにとって何が成功であるかを定義するものである[21]。 「エージェントが、過去の経験と知識に基づいて、パフォーマンス測定の期待値を最大化するよう行動する場合、そのエージェントは知能的である」[22]。 このような定義は、知能の本質を捉えようとするものである。チューリングテストとは異なり、タイピングミスなどの知能とは関係のない人間の特性もテストの 対象とならないという利点がある[23]。しかし、「考えるもの」と「考えないもの」を区別できないという欠点もある。この定義によれば、サーモスタット でさえも初歩的な知能を持っていることになる[24]。 |

| Arguments that a machine can display general intelligence The brain can be simulated Main article: Artificial brain Duration: 6 seconds.0:06 An MRI scan of a normal adult human brain Hubert Dreyfus describes this argument as claiming that "if the nervous system obeys the laws of physics and chemistry, which we have every reason to suppose it does, then ... we ... ought to be able to reproduce the behavior of the nervous system with some physical device".[25] This argument, first introduced as early as 1943[26] and vividly described by Hans Moravec in 1988,[27] is now associated with futurist Ray Kurzweil, who estimates that computer power will be sufficient for a complete brain simulation by the year 2029.[28] A non-real-time simulation of a thalamocortical model that has the size of the human brain (1011 neurons) was performed in 2005,[29] and it took 50 days to simulate 1 second of brain dynamics on a cluster of 27 processors. Even AI's harshest critics (such as Hubert Dreyfus and John Searle) agree that a brain simulation is possible in theory.[a] However, Searle points out that, in principle, anything can be simulated by a computer; thus, bringing the definition to its breaking point leads to the conclusion that any process at all can technically be considered "computation". "What we wanted to know is what distinguishes the mind from thermostats and livers," he writes.[32] Thus, merely simulating the functioning of a living brain would in itself be an admission of ignorance regarding intelligence and the nature of the mind, like trying to build a jet airliner by copying a living bird precisely, feather by feather, with no theoretical understanding of aeronautical engineering.[33] |

機械が汎用知能を示すという主張 脳はシミュレート可能である 主な記事: 人工脳 所要時間: 6秒.0:06 正常な成人人間の脳のMRIスキャン ヒューバート・ドレイファスはこの主張を「神経系が物理学と化学の法則に従うなら、我々がそう考える十分な理由があるのだから、... 我々は...物理的な装置で神経系の動作を再現できるはずだ」と主張していると述べる。[25] この議論は早くも1943年に初めて提唱され[26]、1988年にハンス・モラベックによって鮮明に説明された[27]。現在では未来学者レイ・カーツ ワイルと結びつけられており、彼は2029年までに完全な脳シミュレーションを実行するのに十分なコンピューター性能が実現すると予測している。[28] 2005年には、人間の脳と同規模(10¹¹ニューロン)の視床皮質モデルの非リアルタイムシミュレーションが実施された[29]。27プロセッサのクラ スター上で、脳の動態1秒分をシミュレートするのに50日を要した。 AIの最も厳しい批判者たち(ヒューバート・ドレイファスやジョン・サールなど)でさえ、理論上は脳のシミュレーションが可能だと認めている。[a] しかしサールは、原理的にはコンピュータで何でもシミュレートできると指摘する。つまり定義を限界まで押し進めると、あらゆるプロセスが技術的には「計 算」と見なせるという結論に至るのだ。「我々が知りたかったのは、心とサーモスタットや肝臓との違いだ」と彼は記している[32]。したがって、生きた脳 の機能を単にシミュレートすることは、それ自体が知性や心の本質に関する無知を認めることに等しい。それは航空工学の理論的理解なしに、生きた鳥を羽根一 本一本まで正確に模倣してジェット旅客機を作ろうとするようなものだ[33]。 |

| Human thinking is symbol processing Main article: Physical symbol system In 1963, Allen Newell and Herbert A. Simon proposed that "symbol manipulation" was the essence of both human and machine intelligence. They wrote: "A physical symbol system has the necessary and sufficient means of general intelligent action."[10] This claim is very strong: it implies both that human thinking is a kind of symbol manipulation (because a symbol system is necessary for intelligence) and that machines can be intelligent (because a symbol system is sufficient for intelligence).[34] Another version of this position was described by philosopher Hubert Dreyfus, who called it "the psychological assumption": "The mind can be viewed as a device operating on bits of information according to formal rules."[35] The "symbols" that Newell, Simon and Dreyfus discussed were word-like and high level—symbols that directly correspond with objects in the world, such as <dog> and <tail>. Most AI programs written between 1956 and 1990 used this kind of symbol. Modern AI, based on statistics and mathematical optimization, does not use the high-level "symbol processing" that Newell and Simon discussed. Arguments against symbol processing These arguments show that human thinking does not consist (solely) of high level symbol manipulation. They do not show that artificial intelligence is impossible, only that more than symbol processing is required. Gödelian anti-mechanist arguments Main article: Mechanism (philosophy): Gödelian arguments In 1931, Kurt Gödel proved with an incompleteness theorem that it is always possible to construct a "Gödel statement" that a given consistent formal system of logic (such as a high-level symbol manipulation program) could not prove. Despite being a true statement, the constructed Gödel statement is unprovable in the given system. (The truth of the constructed Gödel statement is contingent on the consistency of the given system; applying the same process to a subtly inconsistent system will appear to succeed, but will actually yield a false "Gödel statement" instead.)[citation needed] More speculatively, Gödel conjectured that the human mind can eventually correctly determine the truth or falsity of any well-grounded mathematical statement (including any possible Gödel statement), and that therefore the human mind's power is not reducible to a mechanism.[36] Philosopher John Lucas (since 1961) and Roger Penrose (since 1989) have championed this philosophical anti-mechanist argument.[37] Gödelian anti-mechanist arguments tend to rely on the innocuous-seeming claim that a system of human mathematicians (or some idealization of human mathematicians) is both consistent (completely free of error) and believes fully in its own consistency (and can make all logical inferences that follow from its own consistency, including belief in its Gödel statement) [citation needed]. This is probably impossible for a Turing machine to do (see Halting problem); therefore, the Gödelian concludes that human reasoning is too powerful to be captured by a Turing machine, and by extension, any digital mechanical device. However, the modern consensus in the scientific and mathematical community is that actual human reasoning is inconsistent; that any consistent "idealized version" H of human reasoning would logically be forced to adopt a healthy but counter-intuitive open-minded skepticism about the consistency of H (otherwise H is provably inconsistent); and that Gödel's theorems do not lead to any valid argument that humans have mathematical reasoning capabilities beyond what a machine could ever duplicate.[38][39][40] This consensus that Gödelian anti-mechanist arguments are doomed to failure is laid out strongly in Artificial Intelligence: "any attempt to utilize (Gödel's incompleteness results) to attack the computationalist thesis is bound to be illegitimate, since these results are quite consistent with the computationalist thesis."[41] Stuart Russell and Peter Norvig agree that Gödel's argument does not consider the nature of real-world human reasoning. It applies to what can theoretically be proved, given an infinite amount of memory and time. In practice, real machines (including humans) have finite resources and will have difficulty proving many theorems. It is not necessary to be able to prove everything in order to be an intelligent person.[42] Less formally, Douglas Hofstadter, in his Pulitzer Prize winning book Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid, states that these "Gödel-statements" always refer to the system itself, drawing an analogy to the way the Epimenides paradox uses statements that refer to themselves, such as "this statement is false" or "I am lying".[43] But, of course, the Epimenides paradox applies to anything that makes statements, whether it is a machine or a human, even Lucas himself. Consider: Lucas can't assert the truth of this statement.[44] This statement is true but cannot be asserted by Lucas. This shows that Lucas himself is subject to the same limits that he describes for machines, as are all people, and so Lucas's argument is pointless.[45] After concluding that human reasoning is non-computable, Penrose went on to controversially speculate that some kind of hypothetical non-computable processes involving the collapse of quantum mechanical states give humans a special advantage over existing computers. Existing quantum computers are only capable of reducing the complexity of Turing computable tasks and are still restricted to tasks within the scope of Turing machines. [citation needed] [clarification needed]. By Penrose and Lucas's arguments, the fact that quantum computers are only able to complete Turing computable tasks implies that they cannot be sufficient for emulating the human mind.[citation needed] Therefore, Penrose seeks for some other process involving new physics, for instance quantum gravity which might manifest new physics at the scale of the Planck mass via spontaneous quantum collapse of the wave function. These states, he suggested, occur both within neurons and also spanning more than one neuron.[46] However, other scientists point out that there is no plausible organic mechanism in the brain for harnessing any sort of quantum computation, and furthermore that the timescale of quantum decoherence seems too fast to influence neuron firing.[47] |

人間の思考は記号処理である 主記事: 物理的記号システム 1963年、アレン・ニューウェルとハーバート・A・サイモンは「記号操作」が人間と機械の知能の本質であると提唱した。彼らはこう記している: 「物理的記号システムは、一般的な知的な行動に必要な十分条件を備えている」[10] この主張は非常に強い:それは人間の思考が一種の記号操作であること(知能には記号システムが必要だから)、そして機械が知能を持つことができること(知 能には記号システムが十分だから)の両方を示唆している。[34] この立場の別の表現は哲学者ヒューバート・ドレイファスによって「心理学的仮定」と呼ばれた: 「心は形式的な規則に従って情報の断片を操作する装置と見なせる」[35] ニューウェル、サイモン、ドレイファスが論じた「記号」は単語のような高次のものであった——<犬>や<尾>のように、世界の物 体に直接対応する記号である。1956年から1990年にかけて書かれたAIプログラムの大半は、この種の記号を用いた。統計学と数学的最適化に基づく現 代のAIは、ニューウェルとサイモンが論じた高次元の「記号処理」を使用しない。 記号処理に対する反論 これらの反論は、人間の思考が高次元の記号操作(のみ)から成るわけではないことを示している。人工知能が不可能であることを示すものではなく、記号処理以上のものが必要であることを示すに過ぎない。 ゲーデル的反機械論的議論 詳細記事: 機械論 (哲学): ゲーデル的議論 1931年、クルト・ゲーデルは不完全性定理を用いて、与えられた一貫した形式論理体系(高次記号操作プログラムなど)が証明できない「ゲーデル文」を常 に構築可能であることを証明した。構築されたゲーデルの命題は真の命題であるにもかかわらず、与えられた体系内では証明不可能である。(構築されたゲーデ ルの命題の真偽は、与えられた体系の一貫性に依存する。わずかに矛盾した体系に同じ過程を適用すると成功したように見えるが、実際には偽の「ゲーデルの命 題」が生成される。)[出典が必要] より推論的な観点では、ゲーデルは人間の精神が最終的にあらゆる正当な数学的命題(あらゆる可能性のあるゲーデルの命題を含む)の真偽を正しく判定できる と推測した。したがって人間の精神の力は機械論に還元できないと主張した。[36] 哲学者ジョン・ルカーチ(1961年以降)とロジャー・ペンローズ(1989年以降)はこの哲学的反機械論的議論を支持している。[37] ゲーデル的反機械論的議論は、一見無害に見える主張に依存する傾向がある。すなわち、人間の数学者からなるシステム(あるいは人間の数学者の理想化)は、 一貫性(完全に誤りがないこと)を持ち、かつ自らの整合性を完全に信じている(そして自らの整合性から導かれる全ての論理的推論、ゲーデル命題への信念を 含む)という主張である[出典必要]。これはおそらくチューリングマシンには不可能である(停止問題参照)。したがってゲーデル主義者は、人間の推論は チューリングマシン、ひいてはあらゆるデジタル機械装置では捉えきれないほど強力だと結論づける。 しかし、現代の科学・数学コミュニティにおける共通認識は、実際の人間の推論は不整合的であるということだ。つまり、人間の推論を「理想化したバージョ ン」Hとして整合的に構築しようとすると、Hの整合性に対して健全だが直観に反する懐疑的態度を論理的に採用せざるを得ない(さもなければHは証明可能に 不整合となる)。そしてゲーデルの定理は、人間の数学的推論能力が機械が再現しうる範囲を超えているという有効な論証にはつながらない。[38][39] [40] ゲーデルの反機械論的議論は失敗に終わるというこの合意は、『人工知能』の中で強く述べられている。「(ゲーデルの不完全性定理を)計算主義の定説を攻撃 するために利用しようとする試みは、これらの定理が計算主義の定説と非常に整合的であるため、必ず不適法となる」[41]。 スチュワート・ラッセルとピーター・ノーヴィグは、ゲーデルの議論は現実世界における人間の推論の性質を考慮していないという点で意見が一致している。こ の議論は、無限の記憶と時間があれば理論的に証明できる事柄に適用される。実際には、現実の機械(人間を含む)は有限の資源しか持たず、多くの定理を証明 することは困難である。知的な人格であるためには、あらゆることを証明できる必要はまったくない。[42] より形式的には、ダグラス・ホフスタッターは、ピューリッツァー賞を受賞した著書『ゲーデル、エッシャー、バッハ:永遠の黄金の組』の中で、これらの 「ゲーデルの定理」は常にシステム自体を指しており、エピメニデスのパラドックスが「この定理は偽である」や「私は嘘をついている」など、自分自身を指す 定理を使用していることに類似していると述べている。[43] しかし当然ながら、エピメニデスのパラドックスは、機械であれ人間であれ、ルカーチ自身でさえも、あらゆる発言主体に適用される。考えてみよう: ルーカスは、この文の真偽を断言できない。[44] この文は真であるが、ルーカス自身はこれを断言できない。これはルカーチ自身が、機械に対して述べたのと同じ制約に縛られていることを示しており、それは全ての人間にも当てはまる。したがってルーカスの手法は無意味である。[45] 人間の推論が非計算可能であると結論付けた後、ペンローズはさらに議論を呼ぶ推測を展開した。量子力学的状態の崩壊を伴うある種の仮説的な非計算可能プロ セスが、人間に既存のコンピュータに対する特別な優位性をもたらすというのだ。既存の量子コンピュータは、チューリング計算可能なタスクの複雑性を低減す ることしかできず、依然としてチューリングマシンの範囲内のタスクに制限されている。[出典必要] [説明必要]。ペンローズとルカーチの議論によれば、量子コンピュータがチューリング計算可能なタスクしか遂行できない事実は、それらが人間の精神を模倣 するのに十分ではないことを示唆している。[出典必要] したがってペンローズは、量子重力理論など新たな物理学を伴う他のプロセスを模索している。例えば量子重力理論は、波動関数の自発的量子崩壊を通じてプラ ンク質量スケールで新たな物理学を顕現する可能性がある。彼は、こうした状態がニューロン内部で生じるだけでなく、複数のニューロンにまたがって発生する と示唆した。[46] しかし他の科学者は、脳内で量子計算を利用するための妥当な有機的メカニズムは存在せず、さらに量子デコヒーレンスの時間スケールがニューロン発火に影響 を与えるには速すぎると指摘している。[47] |

| Dreyfus: the primacy of implicit skills Main article: Hubert Dreyfus's views on artificial intelligence Hubert Dreyfus argued that human intelligence and expertise depended primarily on fast intuitive judgements rather than step-by-step symbolic manipulation, and argued that these skills would never be captured in formal rules.[48] Dreyfus's argument had been anticipated by Turing in his 1950 paper Computing machinery and intelligence, where he had classified this as the "argument from the informality of behavior."[49] Turing argued in response that, just because we do not know the rules that govern a complex behavior, this does not mean that no such rules exist. He wrote: "we cannot so easily convince ourselves of the absence of complete laws of behaviour ... The only way we know of for finding such laws is scientific observation, and we certainly know of no circumstances under which we could say, 'We have searched enough. There are no such laws.'"[50] Russell and Norvig point out that, in the years since Dreyfus published his critique, progress has been made towards discovering the "rules" that govern unconscious reasoning.[51] The situated movement in robotics research attempts to capture our unconscious skills at perception and attention.[52] Computational intelligence paradigms, such as neural nets, evolutionary algorithms and so on are mostly directed at simulated unconscious reasoning and learning. Statistical approaches to AI can make predictions which approach the accuracy of human intuitive guesses. Research into commonsense knowledge has focused on reproducing the "background" or context of knowledge. In fact, AI research in general has moved away from high level symbol manipulation, towards new models that are intended to capture more of our intuitive reasoning.[51] Cognitive science and psychology eventually came to agree with Dreyfus' description of human expertise. Daniel Kahnemann and others developed a similar theory where they identified two "systems" that humans use to solve problems, which he called "System 1" (fast intuitive judgements) and "System 2" (slow deliberate step by step thinking).[53] Although Dreyfus' views have been vindicated in many ways, the work in cognitive science and in AI was in response to specific problems in those fields and was not directly influenced by Dreyfus. Historian and AI researcher Daniel Crevier wrote that "time has proven the accuracy and perceptiveness of some of Dreyfus's comments. Had he formulated them less aggressively, constructive actions they suggested might have been taken much earlier."[54] |

ドレイファス:暗黙の技能の優位性 詳細記事:ヒューバート・ドレイファスの人工知能に関する見解 ヒューバート・ドレイファスは、人間の知性と専門性は段階的な記号操作ではなく、主に迅速な直感的判断に依存すると主張した。そしてこれらの技能は形式的な規則では決して捉えられないと論じた。[48] ドレイファスの主張は、チューリングが1950年の論文『計算機と知能』で予見していたもので、彼はこれを「行動の非形式性に基づく議論」と分類してい た。[49] チューリングはこれに対し、複雑な行動を支配する規則が我々に知られていないからといって、そのような規則が存在しないわけではないと反論した。彼はこう 記している:「行動の完全な法則が存在しないとは、そう簡単に自らを納得させられない…我々が知る唯一の法則発見方法は科学的観察であり、『十分に探求し た。そのような法則は存在しない』と言える状況は確かに存在しない」[50] ラッセルとノーヴィグは、ドレイファスが批判を発表して以来、無意識の推論を支配する「規則」の発見に向けた進展があったと指摘している[51]。ロボッ ト研究における状況依存運動は、知覚と注意における人間の無意識の技能を捉えようとする試みである[52]。ニューラルネットワークや進化アルゴリズムな どの計算知能パラダイムは、主にシミュレートされた無意識の推論と学習に向けられている。統計的アプローチによるAIは、人間の直感的な推測に迫る精度で 予測を行うことができる。常識知識の研究は、知識の「背景」や文脈を再現することに焦点を当ててきた。実際、AI研究全般は、高次元の記号操作から離れ、 人間の直感的推論をより多く捉えることを意図した新たなモデルへと移行している。[51] 認知科学と心理学は最終的に、ドレイファスによる人間の専門性の描写に同意するに至った。ダニエル・カーネマンらは類似の理論を展開し、人間が問題解決に 用いる二つの「システム」を特定した。彼はこれを「システム1」(迅速な直感的判断)と「システム2」(遅く慎重な段階的思考)と呼んだ。[53] ドレイファスの見解は多くの点で正当性が認められたものの、認知科学やAI分野での研究は、それらの分野固有の問題への対応として行われたものであり、ド レイファスに直接影響されたものではない。歴史家でありAI研究者でもあるダニエル・クレヴィエは「時が経つにつれ、ドレイファスの指摘の正確さと洞察力 が証明されてきた。もし彼がより穏やかに表現していたなら、彼の示唆した建設的な行動はもっと早く取られていたかもしれない」と記している。[54] |

| Can a machine have a mind, consciousness, and mental states? This is a philosophical question, related to the problem of other minds and the hard problem of consciousness. The question revolves around a position defined by John Searle as "strong AI": A physical symbol system can have a mind and mental states.[11] Searle distinguished this position from what he called "weak AI": A physical symbol system can act intelligently.[11] Searle introduced the terms to isolate strong AI from weak AI so he could focus on what he thought was the more interesting and debatable issue. He argued that even if we assume that we had a computer program that acted exactly like a human mind, there would still be a difficult philosophical question that needed to be answered.[11] Neither of Searle's two positions are of great concern to AI research, since they do not directly answer the question "can a machine display general intelligence?" (unless it can also be shown that consciousness is necessary for intelligence). Turing wrote "I do not wish to give the impression that I think there is no mystery about consciousness… [b]ut I do not think these mysteries necessarily need to be solved before we can answer the question [of whether machines can think]."[55] Russell and Norvig agree: "Most AI researchers take the weak AI hypothesis for granted, and don't care about the strong AI hypothesis."[56] There are a few researchers who believe that consciousness is an essential element in intelligence, such as Igor Aleksander, Stan Franklin, Ron Sun, and Pentti Haikonen, although their definition of "consciousness" strays very close to "intelligence". (See artificial consciousness.) Before we can answer this question, we must be clear what we mean by "minds", "mental states" and "consciousness". |

機械は心や意識、精神状態を持つことができるか? これは哲学的な問いであり、他者の心の問題や意識の難問と関連している。この問いはジョン・サールが「強いAI」と定義した立場を中心に展開される: 物理的な記号体系は心や精神状態を持つことができる。[11] サールはこの立場を、彼が「弱いAI」と呼ぶものから区別した: 物理的な記号体系は知的に振る舞うことができる。[11] サールは強いAIと弱いAIを区別するためにこれらの用語を導入し、より興味深く議論の余地がある問題に焦点を当てた。彼は、たとえ人間の精神と全く同じ ように振る舞うコンピュータプログラムがあると仮定しても、なお答えなければならない難しい哲学的問題が残ると主張した。[11] サールの二つの立場はいずれも、AI研究にとって大きな関心事ではない。なぜなら「機械は汎用知能を示せるか?」という問いに直接答えていないからだ(意 識が知能に必要だと証明されない限り)。チューリングは「意識について謎がないという印象を与えたくない…しかし、機械が思考できるかどうかという疑問に 答える前に、これらの謎を必ずしも解決する必要はないと思う」と書いている[55]。ラッセルとノーヴィグも「ほとんどの AI 研究者は弱い AI 仮説を当然のこととして受け入れており、強い AI 仮説を気にしていない」と同意している[56]。 イゴール・アレクサンダー、スタン・フランクリン、ロン・サン、ペント・ハイコネンなど、意識は知能に不可欠な要素であると考える研究者も少数ながら存在する。ただし、彼らの「意識」の定義は「知能」に非常に近いものである(人工意識を参照)。 この疑問に答える前に、「心」、「精神状態」、「意識」が何を意味するのかを明確にしなければならない。 |

| Consciousness, minds, mental states, meaning The words "mind" and "consciousness" are used by different communities in different ways. Some new age thinkers, for example, use the word "consciousness" to describe something similar to Bergson's "élan vital": an invisible, energetic fluid that permeates life and especially the mind. Science fiction writers use the word to describe some essential property that makes us human: a machine or alien that is "conscious" will be presented as a fully human character, with intelligence, desires, will, insight, pride and so on. (Science fiction writers also use the words "sentience", "sapience", "self-awareness" or "ghost"—as in the Ghost in the Shell manga and anime series—to describe this essential human property). For others [who?], the words "mind" or "consciousness" are used as a kind of secular synonym for the soul. For philosophers, neuroscientists and cognitive scientists, the words are used in a way that is both more precise and more mundane: they refer to the familiar, everyday experience of having a "thought in your head", like a perception, a dream, an intention or a plan, and to the way we see something, know something, mean something or understand something.[57] "It's not hard to give a commonsense definition of consciousness" observes philosopher John Searle.[58] What is mysterious and fascinating is not so much what it is but how it is: how does a lump of fatty tissue and electricity give rise to this (familiar) experience of perceiving, meaning or thinking? Philosophers call this the hard problem of consciousness. It is the latest version of a classic problem in the philosophy of mind called the "mind-body problem".[59] A related problem is the problem of meaning or understanding (which philosophers call "intentionality"): what is the connection between our thoughts and what we are thinking about (i.e. objects and situations out in the world)? A third issue is the problem of experience (or "phenomenology"): If two people see the same thing, do they have the same experience? Or are there things "inside their head" (called "qualia") that can be different from person to person?[60] Neurobiologists believe all these problems will be solved as we begin to identify the neural correlates of consciousness: the actual relationship between the machinery in our heads and its collective properties; such as the mind, experience and understanding. Some of the harshest critics of artificial intelligence agree that the brain is just a machine, and that consciousness and intelligence are the result of physical processes in the brain.[61] The difficult philosophical question is this: can a computer program, running on a digital machine that shuffles the binary digits of zero and one, duplicate the ability of the neurons to create minds, with mental states (like understanding or perceiving), and ultimately, the experience of consciousness? |

意識、心、精神状態、意味 「心」と「意識」という言葉は、異なるコミュニティで異なる意味で使われる。例えばニューエイジ思想家たちは、「意識」という言葉をベルクソンの「生命衝 動」に似たものを指すのに使う。それは目に見えないエネルギーの流体であり、生命、特に心に浸透している。SF作家たちはこの言葉を使って、人間らしさを 形作る本質的な特性を表現する。つまり「意識を持つ」機械や異星人は、知性、欲望、意志、洞察力、誇りなどを備えた完全な人間キャラクターとして描かれる のだ。(SF作家は「知覚力」「知性」「自己認識」あるいは「ゴースト」——『攻殻機動隊』の漫画・アニメシリーズのように——といった言葉も、この本質 的な人間的特性描写に用いる)。また別の者たち[誰?]にとって、「精神」や「意識」という言葉は、一種の世俗的な「魂」の同義語として使われる。 哲学者、神経科学者、認知科学者にとって、これらの言葉はより正確かつ日常的な意味で使われる。つまり、知覚や夢、意図や計画といった「頭の中の思考」と いう身近な日常体験を指し、何かを見る方法、知る方法、意味する方法、理解する方法を指すのだ。[57] 哲学者ジョン・サールは「意識の常識的な定義を与えるのは難しくない」と指摘する。[58] 謎めいて興味深いのは、意識が何かというよりも、そのあり方だ。脂肪組織と電気の塊が、どうして知覚や意味づけ、思考という(身近な)体験を生み出すの か? 哲学者たちはこれを意識の難問と呼ぶ。これは心哲学における古典的問題「心身問題」の最新形だ。[59] 関連する問題として意味や理解の問題(哲学では「意図主義」と呼ばれる)がある:我々の思考と、思考の対象(つまり外界の物体や状況)との間にはどんな繋 がりがあるのか? 第三の問題は経験(または「現象学」)の問題だ: 同じものを見た二人の人間は、同じ体験をするのか?それとも「頭の中」にあるもの(「クオリア」と呼ばれる)が人格によって異なる可能性があるのか? [60] 神経生物学者は、意識の神経相関(頭の中の機械と、心・体験・理解といった集合的特性との実際の関係性)を特定し始めれば、これらの問題は全て解決される と信じている。人工知能に対する最も厳しい批判者の一部でさえ、脳は単なる機械であり、意識や知能は脳内の物理的プロセスの結果に過ぎないという点では同 意している。[61] 難しい哲学的問いはこうだ:0と1の二進数を処理するデジタル機械上で動作するコンピュータプログラムが、神経細胞が持つ能力――精神状態(理解や知覚な ど)を生み出し、究極的には意識の体験をもたらす能力――を再現できるのか? |

| Arguments that a computer cannot have a mind and mental states Searle's Chinese room Main article: Chinese room John Searle asks us to consider a thought experiment: suppose we have written a computer program that passes the Turing test and demonstrates general intelligent action. Suppose, specifically that the program can converse in fluent Chinese. Write the program on 3x5 cards and give them to an ordinary person who does not speak Chinese. Lock the person into a room and have him follow the instructions on the cards. He will copy out Chinese characters and pass them in and out of the room through a slot. From the outside, it will appear that the Chinese room contains a fully intelligent person who speaks Chinese. The question is this: is there anyone (or anything) in the room that understands Chinese? That is, is there anything that has the mental state of understanding, or which has conscious awareness of what is being discussed in Chinese? The man is clearly not aware. The room cannot be aware. The cards certainly are not aware. Searle concludes that the Chinese room, or any other physical symbol system, cannot have a mind.[62] Searle goes on to argue that actual mental states and consciousness require (yet to be described) "actual physical-chemical properties of actual human brains."[63] He argues there are special "causal properties" of brains and neurons that gives rise to minds: in his words "brains cause minds."[64] Related arguments: Leibniz' mill, Davis's telephone exchange, Block's Chinese nation and Blockhead Gottfried Leibniz made essentially the same argument as Searle in 1714, using the thought experiment of expanding the brain until it was the size of a mill.[65] In 1974, Lawrence Davis imagined duplicating the brain using telephone lines and offices staffed by people, and in 1978 Ned Block envisioned the entire population of China involved in such a brain simulation. This thought experiment is called "the Chinese Nation" or "the Chinese Gym".[66] Ned Block also proposed his Blockhead argument, which is a version of the Chinese room in which the program has been re-factored into a simple set of rules of the form "see this, do that", removing all mystery from the program. Responses to the Chinese room Responses to the Chinese room emphasize several different points. The systems reply and the virtual mind reply:[67] This reply argues that the system, including the man, the program, the room, and the cards, is what understands Chinese. Searle claims that the man in the room is the only thing which could possibly "have a mind" or "understand", but others disagree, arguing that it is possible for there to be two minds in the same physical place, similar to the way a computer can simultaneously "be" two machines at once: one physical (like a Macintosh) and one "virtual" (like a word processor). Speed, power and complexity replies:[68] Several critics point out that the man in the room would probably take millions of years to respond to a simple question, and would require "filing cabinets" of astronomical proportions. This brings the clarity of Searle's intuition into doubt. Robot reply:[69] To truly understand, some believe the Chinese Room needs eyes and hands. Hans Moravec writes: "If we could graft a robot to a reasoning program, we wouldn't need a person to provide the meaning anymore: it would come from the physical world."[70] Brain simulator reply:[71] What if the program simulates the sequence of nerve firings at the synapses of an actual brain of an actual Chinese speaker? The man in the room would be simulating an actual brain. This is a variation on the "systems reply" that appears more plausible because "the system" now clearly operates like a human brain, which strengthens the intuition that there is something besides the man in the room that could understand Chinese. Other minds reply and the epiphenomena reply:[72] Several people have noted that Searle's argument is just a version of the problem of other minds, applied to machines. Since it is difficult to decide if people are "actually" thinking, we should not be surprised that it is difficult to answer the same question about machines. A related question is whether "consciousness" (as Searle understands it) exists. Searle argues that the experience of consciousness cannot be detected by examining the behavior of a machine, a human being or any other animal. Daniel Dennett points out that natural selection cannot preserve a feature of an animal that has no effect on the behavior of the animal, and thus consciousness (as Searle understands it) cannot be produced by natural selection. Therefore, either natural selection did not produce consciousness, or "strong AI" is correct in that consciousness can be detected by suitably designed Turing test. |

コンピュータが心や精神状態を持つことはできないという議論 サールの中国語の部屋 主な記事: 中国語の部屋 ジョン・サールは思考実験を考えてみるよう求めている。仮に我々がチューリングテストを通過し、一般的な知的な行動を示すコンピュータプログラムを書いた としよう。具体的には、そのプログラムが流暢な中国語で会話できるとしよう。プログラムを3×5インチのカードに書き、中国語を話せない普通の人に渡す。 その人格を部屋に閉じ込め、カード上の指示に従わせる。彼は漢字を書き写し、それを部屋の隙間から出し入れする。外から見れば、中国語を話す完全な知性を 持つ人格が中国語の部屋にいるように見えるだろう。問題はこうだ:その部屋の中に中国語を理解する者(あるいは何か)は存在するのか?つまり、中国語で議 論されている内容を理解する精神状態、あるいは意識的な認識を持つものは存在するのか?その人物が認識していないのは明らかだ。部屋が認識することはあり えない。カードが認識しているはずもない。サールは結論づける。中国語の部屋、あるいは他のいかなる物理的記号体系も、心を持つことはできないと。 [62] さらに、実際の精神状態や意識には(まだ説明されていない)「実際の人間の脳が持つ実際の物理的・化学的特性」が必要だと主張している[63]。彼は、脳 やニューロンには、精神を生み出す特別な「因果的特性」があると論じている。彼の言葉を借りれば、「脳が精神を生み出す」というわけだ[64]。 関連する議論:ライプニッツの工場、デイヴィスの電話交換機、ブロックの中国国民、ブロックヘッド ゴットフリート・ライプニッツは、1714年に、脳を工場ほどの大きさに拡大するという思考実験を用いて、サールと本質的に同じ議論を行った[65]。 1974年、ローレンス・デイヴィスは、電話回線と人員を配置した事務所を用いて脳を複製することを想像し、1978年には、ネッド・ブロックが、中国全 人口がそのような脳シミュレーションに関与することを構想した。この思考実験は「中国国民」あるいは「中国ジム」と呼ばれている。[66] ネッド・ブロックはまた、ブロックヘッドの議論も提案した。これは中国人の部屋の一形態であり、プログラムは「これを見て、あれをせよ」という形式の単純 な一連のルールに再構成され、プログラムからすべての謎が取り除かれている。 中国語の部屋への反論 中国語の部屋への反論は、いくつかの異なる点を強調している。 システム応答と仮想心応答:[67] この応答は、人間、プログラム、部屋、カードを含むシステム全体が中国語を理解していると主張する。サールは「心を持つ」あるいは「理解する」可能性のあ る存在は部屋の人間だけだと主張するが、これに異論を唱える者もいる。彼らは、物理的に同一の場所に二つの心が存在し得ることを指摘する。これはコン ピュータが同時に二つの機械(物理的なもの〈例:マッキントッシュ〉と仮想的なもの〈例:ワープロ〉)として「存在」し得るのと類似している。 速度、能力、複雑性への反論:[68] 複数の批評家が指摘するように、部屋の中の男が単純な質問に答えるには数百万年を要し、天文学的な規模の「書類棚」を必要とするだろう。これはサールの直観の明快さに疑問を投げかける。 ロボットの反論:[69] 真に理解するためには、中国語の部屋には目と手が必要だと考える者もいる。ハンス・モラベックはこう記す: 「もしロボットに推論プログラムを組み込めれば、意味を提供する人格は不要になる。意味は物理世界から生まれる」[70] 脳シミュレータの反論:[71] もしプログラムが、実際の中国語話者の実際の脳のシナプスにおける神経発火の連鎖をシミュレートしたらどうか? 部屋の中の男は実際の脳をシミュレートしていることになる。これは「システム反論」の変種であり、「システム」が明らかに人間の脳のように動作するため、 より説得力があるように見える。これにより、部屋の中の男以外に中国語を理解できる何かが存在するという直感が強まるのだ。 他者の心反論と随伴現象反論:[72] 複数の研究者が指摘しているように、サールの議論は機械に適用された他者の心問題の一形態に過ぎない。人間が「実際に」思考しているかどうかを判断するのが難しい以上、機械について同じ疑問に答えるのが困難なのも当然だ。 関連する疑問として、「意識」(サールの理解する意味での)が存在するかどうかがある。サールは、意識の経験は機械や人間、その他の動物の行動を観察して も検出できないと主張する。ダニエル・デネットは、自然淘汰は動物の行動に影響を与えない特徴を保存できないと指摘する。したがって(サールが理解する意 味での)意識は自然淘汰によって生み出せない。つまり、自然淘汰が意識を生み出さなかったか、あるいは「強いAI」の主張が正しい——つまり適切に設計さ れたチューリングテストによって意識を検出できる——かのどちらかである。 |

| Is thinking a kind of computation? Main article: Computational theory of mind The computational theory of mind or "computationalism" claims that the relationship between mind and brain is similar (if not identical) to the relationship between a running program (software) and a computer (hardware). The idea has philosophical roots in Hobbes (who claimed reasoning was "nothing more than reckoning"), Leibniz (who attempted to create a logical calculus of all human ideas), Hume (who thought perception could be reduced to "atomic impressions") and even Kant (who analyzed all experience as controlled by formal rules).[73] The latest version is associated with philosophers Hilary Putnam and Jerry Fodor.[74] This question bears on our earlier questions: if the human brain is a kind of computer then computers can be both intelligent and conscious, answering both the practical and philosophical questions of AI. In terms of the practical question of AI ("Can a machine display general intelligence?"), some versions of computationalism make the claim that (as Hobbes wrote): Reasoning is nothing but reckoning.[12] In other words, our intelligence derives from a form of calculation, similar to arithmetic. This is the physical symbol system hypothesis discussed above, and it implies that artificial intelligence is possible. In terms of the philosophical question of AI ("Can a machine have mind, mental states and consciousness?"), most versions of computationalism claim that (as Stevan Harnad characterizes it): Mental states are just implementations of (the right) computer programs.[75] This is John Searle's "strong AI" discussed above, and it is the real target of the Chinese room argument (according to Harnad).[75] |

思考は一種の計算なのか? 主記事: 計算論的心理論 計算論的心理論、あるいは「計算主義」は、心と脳の関係が、動作中のプログラム(ソフトウェア)とコンピュータ(ハードウェア)の関係に類似している(同 一ではないにせよ)と主張する。この考えは、ホッブズ(推論は「計算にすぎない」と主張)、ライプニッツ(すべての人間の考えを論理的に計算しようとし た)、ヒューム(知覚は「原子的印象」に還元できると考えた)、さらにはカント(すべての経験を形式的な規則によって制御されると分析した)に哲学的な ルーツがある。[73] 最新のバージョンは、哲学者ヒラリー・パトナムとジェリー・フォドルに関連している。[74] この疑問は、前述の疑問と関連している。人間の脳がコンピュータの一種であるならば、コンピュータは知性と意識の両方を持つことができ、AI に関する実践的および哲学的な疑問の両方に応えることができる。AI に関する実践的な疑問(「機械は汎用知能を発揮することができるか?」)に関しては、計算主義のいくつかのバージョンは(ホッブズが書いたように)次のよ うに主張している。 推論とは、計算に他ならない。[12] つまり、人間の知性は算術に似た計算の一形態から派生している。これは前述の物理的記号システム仮説であり、人工知能が可能であることを示唆している。 AI の哲学的問題(「機械は心、精神状態、意識を持つことができるか?」)に関しては、計算主義のほとんどのバージョンは(スティーブン・ハーナッドが特徴づ けるように)次のように主張している。 精神状態は(適切な)コンピュータプログラムの実装にすぎない。[75] これは前述のジョン・サールの「強いAI」であり、(ハーナドによれば)中国語の部屋論法の真の標的である。[75] |

| Other related questions Can a machine have emotions? If "emotions" are defined only in terms of their effect on behavior or on how they function inside an organism, then emotions can be viewed as a mechanism that an intelligent agent uses to maximize the utility of its actions. Given this definition of emotion, Hans Moravec believes that "robots in general will be quite emotional about being nice people".[76] Fear is a source of urgency. Empathy is a necessary component of good human computer interaction. He says robots "will try to please you in an apparently selfless manner because it will get a thrill out of this positive reinforcement. You can interpret this as a kind of love."[76] Daniel Crevier writes "Moravec's point is that emotions are just devices for channeling behavior in a direction beneficial to the survival of one's species."[77] Can a machine be self-aware? "Self-awareness", as noted above, is sometimes used by science fiction writers as a name for the essential human property that makes a character fully human. Turing strips away all other properties of human beings and reduces the question to "can a machine be the subject of its own thought?" Can it think about itself? Viewed in this way, a program can be written that can report on its own internal states, such as a debugger.[78] Can a machine be original or creative? Turing reduces this to the question of whether a machine can "take us by surprise" and argues that this is obviously true, as any programmer can attest.[79] He notes that, with enough storage capacity, a computer can behave in an astronomical number of different ways.[80] It must be possible, even trivial, for a computer that can represent ideas to combine them in new ways. (Douglas Lenat's Automated Mathematician, as one example, combined ideas to discover new mathematical truths.) Kaplan and Haenlein suggest that machines can display scientific creativity, while it seems likely that humans will have the upper hand where artistic creativity is concerned.[81] In 2009, scientists at Aberystwyth University in Wales and the U.K's University of Cambridge designed a robot called Adam that they believe to be the first machine to independently come up with new scientific findings.[82] Also in 2009, researchers at Cornell developed Eureqa, a computer program that extrapolates formulas to fit the data inputted, such as finding the laws of motion from a pendulum's motion. Can a machine be benevolent or hostile? Main article: Ethics of artificial intelligence This question (like many others in the philosophy of artificial intelligence) can be presented in two forms. "Hostility" can be defined in terms function or behavior, in which case "hostile" becomes synonymous with "dangerous". Or it can be defined in terms of intent: can a machine "deliberately" set out to do harm? The latter is the question "can a machine have conscious states?" (such as intentions) in another form.[55] The question of whether highly intelligent and completely autonomous machines would be dangerous has been examined in detail by futurists (such as the Machine Intelligence Research Institute). The obvious element of drama has also made the subject popular in science fiction, which has considered many differently possible scenarios where intelligent machines pose a threat to mankind; see Artificial intelligence in fiction. One issue is that machines may acquire the autonomy and intelligence required to be dangerous very quickly. Vernor Vinge has suggested that over just a few years, computers will suddenly become thousands or millions of times more intelligent than humans. He calls this "the Singularity".[83] He suggests that it may be somewhat or possibly very dangerous for humans.[84] This is discussed by a philosophy called Singularitarianism. In 2009, academics and technical experts attended a conference to discuss the potential impact of robots and computers and the impact of the hypothetical possibility that they could become self-sufficient and able to make their own decisions. They discussed the possibility and the extent to which computers and robots might be able to acquire any level of autonomy, and to what degree they could use such abilities to possibly pose any threat or hazard. They noted that some machines have acquired various forms of semi-autonomy, including being able to find power sources on their own and being able to independently choose targets to attack with weapons. They also noted that some computer viruses can evade elimination and have achieved "cockroach intelligence". They noted that self-awareness as depicted in science-fiction is probably unlikely, but that there were other potential hazards and pitfalls.[83] Some experts and academics have questioned the use of robots for military combat, especially when such robots are given some degree of autonomous functions.[85] The US Navy has funded a report which indicates that as military robots become more complex, there should be greater attention to implications of their ability to make autonomous decisions.[86][87] The President of the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence has commissioned a study to look at this issue.[88] They point to programs like the Language Acquisition Device which can emulate human interaction. Some have suggested a need to build "Friendly AI", a term coined by Eliezer Yudkowsky, meaning that the advances which are already occurring with AI should also include an effort to make AI intrinsically friendly and humane.[89] Can a machine imitate all human characteristics? Turing said "It is customary ... to offer a grain of comfort, in the form of a statement that some peculiarly human characteristic could never be imitated by a machine. ... I cannot offer any such comfort, for I believe that no such bounds can be set."[90] Turing noted that there are many arguments of the form "a machine will never do X", where X can be many things, such as: Be kind, resourceful, beautiful, friendly, have initiative, have a sense of humor, tell right from wrong, make mistakes, fall in love, enjoy strawberries and cream, make someone fall in love with it, learn from experience, use words properly, be the subject of its own thought, have as much diversity of behaviour as a man, do something really new.[78] Turing argues that these objections are often based on naive assumptions about the versatility of machines or are "disguised forms of the argument from consciousness". Writing a program that exhibits one of these behaviors "will not make much of an impression."[78] All of these arguments are tangential to the basic premise of AI, unless it can be shown that one of these traits is essential for general intelligence. Can a machine have a soul? Finally, those who believe in the existence of a soul may argue that "Thinking is a function of man's immortal soul." Alan Turing called this "the theological objection". He writes: In attempting to construct such machines we should not be irreverently usurping His power of creating souls, any more than we are in the procreation of children: rather we are, in either case, instruments of His will providing mansions for the souls that He creates.[91] The discussion on the topic has been reignited as a result of recent claims made by Google's LaMDA artificial intelligence system that it is sentient and had a "soul".[92] LaMDA (Language Model for Dialogue Applications) is an artificial intelligence system that creates chatbots—AI robots designed to communicate with humans—by gathering vast amounts of text from the internet and using algorithms to respond to queries in the most fluid and natural way possible. The transcripts of conversations between scientists and LaMDA reveal that the AI system excels at this, providing answers to challenging topics about the nature of emotions, generating Aesop-style fables on the moment, and even describing its alleged fears.[93] Pretty much all philosophers doubt LaMDA's sentience.[94] |

その他の関連する質問 機械は感情を持つことができるか? 「感情」を行動への影響や生物内部での機能のみに基づいて定義するなら、感情は知性を持つ主体が自らの行動の効用を格律するために用いるメカニズムと見な せる。この感情の定義に基づき、ハンス・モラベックは「ロボットは概して、善良な存在であることに強い感情を抱くだろう」と述べている。[76] 恐怖は緊急性の源泉である。共感は良好な人間とコンピュータの相互作用に必要な要素だ。彼はロボットについて「自己犠牲的な方法であなたを喜ばせようとす るだろう。なぜならこの肯定的強化から興奮を得るからだ。これは一種の愛と解釈できる」と述べている[76]。ダニエル・クレビエは「モラベックの主張 は、感情とは単に自らの種の生存に有益な方向へ行動を導くための装置に過ぎないというものだ」と記している[77]。 機械は自己認識できるか? 前述のように「自己認識」は、SF作家がキャラクターを完全に人間たらしめる本質的特性として用いることがある。チューリングは人間の他の特性を全て剥ぎ 取り、問題を「機械は自らの思考の主体となり得るか?」と還元する。機械は自己について思考できるのか?この観点から見れば、デバッガーのように自身の内 部状態を報告できるプログラムは記述可能だ。[78] 機械は独創的あるいは創造的になり得るか? チューリングはこれを「機械が我々を驚かせる」可能性の有無に還元し、これは明らかに真実だと主張する。あらゆるプログラマーが証言できる通りだ。 [79] 彼は、十分な記憶容量があれば、コンピュータは天文学的な数の異なる方法で振る舞うことができると指摘している。[80] 概念を表現できるコンピュータが、それらを新たな方法で組み合わせるのは可能であり、むしろ当然のことだ。(ダグラス・レナットの「自動数学者」は、概念 を組み合わせて新たな数学的真理を発見した一例である。) カプランとヘーンラインは、機械が科学的創造性を示す可能性を示唆する一方、芸術的創造性に関しては人間が優位にある可能性が高いと述べている。[81] 2009年、ウェールズのアベリストウィス大学と英ケンブリッジ大学の科学者らは、アダムと呼ばれるロボットを設計した。彼らはこれを、独自に新たな科学 的発見を生み出した初の機械と信じている。[82] また2009年には、コーネル大学の研究者がユーレカを開発した。これは入力データに適合する定式を推定するコンピュータプログラムで、例えば振り子の動 きから運動の法則を見出すことができる。 機械は善意を持つことも敵意を持つこともできるのか? 詳細記事: 人工知能の倫理 この問い(人工知能哲学における他の多くの問いと同様に)は二つの形で提示できる。「敵意」は機能や行動の観点から定義できる。この場合「敵意」は「危 険」と同義となる。あるいは意図の観点から定義することも可能だ:機械は「意図的に」害を及ぼす行動を取れるか?後者は「機械は意識状態(意図など)を持 ち得るか?」という問いを別の形で問うものである。[55] 高度な知能を持ち完全に自律した機械が危険かどうかという問題は、未来学者(例えば機械知能研究所)によって詳細に検討されてきた。この問題が持つ明らか なドラマ性から、SF作品でも人気を博しており、知能機械が人類に脅威をもたらす異なるシナリオが考案されてきた。詳細は「フィクションにおける人工知 能」を参照のこと。 一つの問題は、機械が危険となるのに必要な自律性と知能を非常に短期間で獲得する可能性があることだ。ヴァーナー・ヴィンジは、わずか数年でコンピュータ が突然、人間の何千倍、何百万倍もの知能を持つようになると示唆している。彼はこれを「シンギュラリティ」と呼ぶ[83]。彼は、これが人類にとって多 少、あるいは非常に危険かもしれないと示唆している[84]。これはシンギュラリティ主義と呼ばれる哲学で議論されている。 2009年、学者や技術専門家が会議に集まり、ロボットやコンピュータが自律性を獲得し独自の判断を下せるようになる可能性と、その潜在的な影響について 議論した。彼らはコンピュータやロボットがどの程度の自律性を獲得し得るか、またそうした能力をどの程度活用して脅威や危険をもたらす可能性があるかにつ いて検討した。彼らは、一部の機械が様々な形の半自律性を獲得していることを指摘した。例えば、自ら電源源を見つけたり、武器で攻撃する標的を独立して選 択したりする能力である。また、一部のコンピュータウイルスは消去法を回避し、「ゴキブリ知能」を達成していると述べた。彼らは、SFで描かれるような自 己認識はおそらく起こり得ないが、他の潜在的な危険や落とし穴は存在すると指摘した。[83] 一部の専門家や学者は、特に自律機能をある程度付与されたロボットを軍事戦闘に用いることに対して疑問を呈している[85]。米海軍が資金提供した報告書 は、軍事ロボットがより複雑化するにつれ、自律的な意思決定能力がもたらす影響への注意を強化すべきだと示唆している[86][87]。 人工知能推進協会会長はこの問題を検討する研究を委託した。[88] 彼らは、人間の相互作用を模倣できる言語習得装置(LAD)のようなプログラムを例に挙げている。 一部では「友好的な人工知能(Friendly AI)」の構築が必要だと提唱されている。これはエリエザー・ユドコウスキーが提唱した用語で、既に進行中のAI技術の発展には、AIを本質的に友好的かつ人道的であるようにする努力も含まれるべきだという意味だ。[89] 機械は人間の特性を全て模倣できるのか? チューリングはこう述べている。「慣例として…『特定の人的特性は機械が決して模倣できない』という形で慰めの言葉が提示される。…しかし私はそのような慰めを提供できない。なぜなら、そのような限界は設定できないと信じるからだ。」[90] チューリングは「機械は決してXをしない」という形式の議論が数多く存在すると指摘した。ここでXには以下のような様々なものが当てはまる: 親切であること、機転が利くこと、美しいこと、友好的であること、自発性を持つこと、ユーモアのセンスを持つこと、善悪を判断すること、間違いを犯すこ と、恋に落ちること、イチゴと生クリームを楽しむこと、誰かを恋に落とすこと、経験から学ぶこと、言葉を適切に使うこと、自らの思考の対象となること、人 間と同等の行動の多様性を持つこと、真に新しいことを成し遂げること。[78] チューリングは、こうした反論は往々にして機械の汎用性に関する素朴な前提に基づいているか、「意識に基づく議論の変形」だと論じる。これらの行動のどれ か一つを示すプログラムを書くことは「大した印象を与えない」[78]。これらの特性の一つが汎用知能に不可欠だと証明されない限り、これら全ての議論は AIの基本前提とは無関係だ。 機械に魂はあり得るか? 最後に、魂の存在を信じる者は「思考は人間の不滅の魂の機能である」と主張するかもしれない。アラン・チューリングはこれを「神学的反論」と呼んだ。彼はこう記している: このような機械を構築しようとする際、我々は子供を産む場合と同様に、神の魂を創造する力を不敬にも奪ってはならない。どちらの場合も、我々は神の意志の道具として、神が創造する魂のための住まいを提供しているに過ぎない。[91] この議論は、Googleの人工知能システムLaMDAが「自覚的であり『魂』を持つ」と主張したことで再燃した。[92] LaMDA(Language Model for Dialogue Applications)は、インターネットから膨大なテキストを収集し、アルゴリズムを用いて可能な限り流暢で自然な方法で質問に応答するチャット ボット(人間とコミュニケーションを取るように設計されたAIロボット)を作成する人工知能システムである。 科学者とLaMDAの対話記録によれば、このAIシステムは感情の本質に関する難題への回答、即興のイソップ寓話の生成、さらには自称する恐怖の描写に至 るまで、この能力に長けていることが明らかになった。[93] ほぼ全ての哲学者はLaMDAの知覚能力を疑っている。[94] |

| Views on the role of philosophy Some scholars argue that the AI community's dismissal of philosophy is detrimental. In the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, some philosophers argue that the role of philosophy in AI is underappreciated.[6] Physicist David Deutsch argues that without an understanding of philosophy or its concepts, AI development would suffer from a lack of progress.[95] |

哲学の役割に関する見解 一部の学者は、AIコミュニティが哲学を軽視する姿勢は有害だと主張する。スタンフォード哲学百科事典では、AIにおける哲学の役割が過小評価されている と論じる哲学者もいる[6]。物理学者デイヴィッド・ドイッチュは、哲学やその概念を理解しなければ、AI開発は進歩の欠如によって苦悩するだろうと主張 する[95]。 |

| Conferences and literature The main conference series on the issue is "Philosophy and Theory of AI" (PT-AI), run by Vincent C. Müller. The main bibliography on the subject, with several sub-sections, is on PhilPapers. A recent survey for Philosophy of AI is Müller (2025).[5] |

会議と文献 この問題に関する主な会議シリーズは、ヴィンセント・C・ミュラーが主催する「AI の哲学と理論」(PT-AI)である。 この主題に関する主な参考文献は、いくつかのサブセクションとともに PhilPapers に掲載されている。 AI の哲学に関する最近の調査は、ミュラー(2025)によるものである。[5] |

| AI takeover Artificial brain Artificial consciousness Artificial intelligence Artificial neural network Chatbot Computational theory of mind Computing Machinery and Intelligence Existential risk from artificial general intelligence Functionalism Hubert Dreyfus's views on artificial intelligence Multi-agent system Philosophy of computer science Philosophy of information Philosophy of mind Physical symbol system Simulated reality Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies Synthetic intelligence Wireheading |

AIによる支配 人工脳 人工意識 人工知能 人工ニューラルネットワーク チャットボット 計算論的心理論 計算機械と知能 汎用人工知能による実存的リスク 機能主義 ヒューバート・ドレイファスによる人工知能論 マルチエージェントシステム 計算機科学の哲学 情報哲学 心の哲学 物理的記号システム シミュレートされた現実 超知能:道筋、危険、戦略 合成知能 ワイヤーヘディング |

| Notes a. Hubert Dreyfus writes: "In general, by accepting the fundamental assumptions that the nervous system is part of the physical world and that all physical processes can be described in a mathematical formalism which can, in turn, be manipulated by a digital computer, one can arrive at the strong claim that the behavior which results from human 'information processing,' whether directly formalizable or not, can always be indirectly reproduced on a digital machine." .[30] John Searle writes: "Could a man made machine think? Assuming it possible produce artificially a machine with a nervous system, ... the answer to the question seems to be obviously, yes ... Could a digital computer think? If by 'digital computer' you mean anything at all that has a level of description where it can be correctly described as the instantiation of a computer program, then again the answer is, of course, yes, since we are the instantiations of any number of computer programs, and we can think."[31] |

注 a. ヒューバート・ドレイファスによれば:「神経系が物理世界の一部であり、あらゆる物理的過程が数学的形式主義で記述可能であり、それがデジタルコンピュー タで操作可能であるという根本的前提を受け入れることで、人間の『情報処理』から生じる行動は、直接形式化可能か否かにかかわらず、常にデジタル機械で間 接的に再現可能だという強硬な主張に到達できる」 [30] ジョン・サールは次のように書いている。「人工的に神経系を持つ機械を作り出すことが可能だと仮定すれば、…その機械は思考できるだろうか?この問いへの 答えは明らかにイエスである…では、デジタルコンピュータは思考できるだろうか?もし『デジタルコンピュータ』が、コンピュータプログラムの具体化として 正しく記述できる記述レベルを持つあらゆるものを指すなら、答えは当然イエスだ。なぜなら我々自身も無数のコンピュータプログラムの具体化であり、思考で きるからだ。」[31] |

| References |

|

| Works cited Adam, Alison (1989). Artificial Knowing: Gender and the Thinking Machine. Routledge & CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-415-12963-3 Benjamin, Ruha (2019). Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-509-52643-7 Blackmore, Susan (2005), Consciousness: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press Bostrom, Nick (2014), Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-967811-2 Brooks, Rodney (1990), "Elephants Don't Play Chess" (PDF), Robotics and Autonomous Systems, 6 (1–2): 3–15, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.588.7539, doi:10.1016/S0921-8890(05)80025-9, retrieved 2007-08-30 Bryson, Joanna (2019). The Artificial Intelligence of the Ethics of Artificial Intelligence: An Introductory Overview for Law and Regulation, p. 34 Chalmers, David J (1996), The Conscious Mind: In Search of a Fundamental Theory, Oxford University Press, New York, ISBN 978-0-19-511789-9 Cole, David (Fall 2004), "The Chinese Room Argument", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Crawford, Kate (2021). Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale University Press Crevier, Daniel (1993). AI: The Tumultuous Search for Artificial Intelligence. New York, NY: BasicBooks. ISBN 0-465-02997-3. Dennett, Daniel (1991), Consciousness Explained, The Penguin Press, ISBN 978-0-7139-9037-9 Dreyfus, Hubert (1972), What Computers Can't Do, New York: MIT Press, ISBN 978-0-06-011082-6 Dreyfus, Hubert (1979), What Computers Still Can't Do, New York: MIT Press Dreyfus, Hubert; Dreyfus, Stuart (1986), Mind over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Fearn, Nicholas (2005), Philosophy: The Latest Answers to the Oldest Questions, London: Atlantic Books, ISBN 1-84354-066-5 Gladwell, Malcolm (2005), Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking, Boston, Massachusetts: Little, Brown, ISBN 978-0-316-17232-5 Harnad, Stevan (2001), "What's Wrong and Right About Searle's Chinese Room Argument?", in Bishop, M.; Preston, J. (eds.), Essays on Searle's Chinese Room Argument, Oxford University Press Haraway, Donna (1985). A Cyborg Manifesto Haugeland, John (1985), Artificial Intelligence: The Very Idea, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press Hobbes, Thomas (1651), Leviathan Hofstadter, Douglas (1979), Gödel, Escher, Bach: an Eternal Golden Braid Horst, Steven (Fall 2005), "The Computational Theory of Mind", in Zalta, Edward N. (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, archived from the original on 2021-03-04, retrieved 2012-03-22 Kaplan, Andreas; Haenlein, Michael (2018), "Siri, Siri in my Hand, who's the Fairest in the Land? On the Interpretations, Illustrations and Implications of Artificial Intelligence", Business Horizons, 62: 15–25, doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004, S2CID 158433736 Kurzweil, Ray (2005), The Singularity is Near, New York: Viking Press, ISBN 978-0-670-03384-3 Leibniz, Gottfried (1714), Monadology, translated by Ross, George MacDonald, archived from the original on July 3, 2011 Lucas, John (1961), "Minds, Machines and Gödel", in Anderson, A. R. (ed.), Minds and Machines Malabou, Catherine (2019). Morphing Intelligence: From IQ Measurement to Artificial Brains. (C. Shread, Trans.). Columbia University Press McCarthy, John; Minsky, Marvin; Rochester, Nathan; Shannon, Claude (1955), A Proposal for the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence, archived from the original on 2008-09-30 McCarthy, John (1999), What is AI?, archived from the original on 4 December 2022, retrieved 4 December 2022 McCulloch, Warren S.; Pitts, Walter (1 December 1943). "A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity". Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259. ISSN 1522-9602. McDermott, Drew (May 14, 1997), "How Intelligent is Deep Blue", New York Times, archived from the original on October 4, 2007, retrieved October 10, 2007 Moravec, Hans (1988), Mind Children, Harvard University Press Newell, Allen; Simon, H. A. (1976). "Computer Science as Empirical Inquiry: Symbols and Search". Communications of the ACM. 19 (3): 113–126. doi:10.1145/360018.360022. Penrose, Roger (1989), The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and The Laws of Physics, Oxford University Press, Bibcode:1989esnm.book.....P, ISBN 978-0-14-014534-2c Rescorla, Michael, "The Computational Theory of Mind", in:Edward N. Zalta (ed.), The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Fall 2020 Edition) Russell, Stuart J.; Norvig, Peter (2003), Artificial Intelligence: A Modern Approach (2nd ed.), Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, ISBN 0-13-790395-2 Saygin, A. P.; Cicekli, I.; Akman, V. (2000), "Turing Test: 50 Years Later" (PDF), Minds and Machines, 10 (4): 463–518, doi:10.1023/A:1011288000451, hdl:11693/24987, S2CID 990084, archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2011, retrieved 7 January 2004 Searle, John (1980), "Minds, Brains and Programs" (PDF), Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3): 417–457, doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756, S2CID 55303721, archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-09-23 Searle, John (1984), Minds, Brains and Science: The 1984 Reith Lectures, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-57631-5 Searle, John (1992), The Rediscovery of the Mind, Cambridge, Massachusetts: M.I.T. Press Searle, John (1999), Mind, language and society, New York, NY: Basic Books, ISBN 978-0-465-04521-1, OCLC 231867665 Yudkowsky, Eliezer (2008), "Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk" (PDF), Global Catastrophic Risks, Oxford University Press, 2008, Bibcode:2008gcr..book..303Y, archived (PDF) from the original on 19 October 2013, retrieved 24 September 2021 |

参考文献 アダム、アリソン(1989)。『人工知能:ジェンダーと思考機械』。ラウトリッジ&CRCプレス。ISBN 978-0-415-12963-3 ベンジャミン、ルーハ(2019)。『テクノロジー後の人種:新たなジム・コードのための廃止主義的ツール』。ワイリー。ISBN 978-1-509-52643-7 ブラックモア、スーザン(2005)。『意識:超短編入門』。オックスフォード大学出版局。 ボストロム、ニック(2014)。『超知能:その道筋、危険、戦略』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-967811-2 ブルックス、ロドニー(1990)。「象はチェスをしない」 (PDF), ロボティクス・アンド・オートノマス・システムズ, 6 (1–2): 3–15, CiteSeerX 10.1.1.588.7539, doi:10.1016/S0921-8890(05)80025-9, 2007年8月30日取得 ブライソン、ジョアンナ(2019)。『人工知能の倫理の人工知能:法と規制のための入門的概観』、p. 34 チャーマーズ、デイヴィッド・J(1996)、『意識の心:基礎理論を求めて』、オックスフォード大学出版局、ニューヨーク、ISBN 978-0-19-511789-9 コール、デイヴィッド(2004年秋)、「中国語の部屋論」、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』エドワード・N・ザルタ編 クロフォード、ケイト(2021)。『AIアトラス:人工知能の力、政治、そして地球規模の代償』。イェール大学出版局 クレヴィエ、ダニエル(1993)。『AI:人工知能の激動の探求』。ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: ベーシックブックス。ISBN 0-465-02997-3。 デネット、ダニエル(1991年)、『意識の解明』、ペンギン・プレス、ISBN 978-0-7139-9037-9 ドレイファス、ユベール(1972年)、『コンピュータができないこと』、ニューヨーク: MITプレス、 ISBN 978-0-06-011082-6 Dreyfus, Hubert (1979), What Computers Still Can't Do, New York: MIT Press Dreyfus, Hubert; Dreyfus, Stuart (1986), Mind over Machine: The Power of Human Intuition and Expertise in the Era of the Computer, Oxford, UK: Blackwell ファーン、ニコラス(2005)、『哲学:最も古い疑問に対する最新の答え』、ロンドン:アトランティック・ブックス、ISBN 1-84354-066-5 グラッドウェル、マルコム(2005)、『ブリンク:思考しない思考の力』、マサチューセッツ州ボストン:リトル、ブラウン、ISBN 978-0-316-17232-5 ハーナッド、スティーヴン(2001)、「サールの中国語の部屋論の正誤について」、ビショップ、M.;プレストン、J.(編)、『サールの中国語の部屋論に関する論考』、オックスフォード大学出版局 ハラウェイ、ドナ(1985年)『サイボーグ宣言』 ホーゲランド、ジョン(1985年)『人工知能:その本質』マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ:MITプレス ホッブズ、トマス(1651年)『リヴァイアサン』 ホフスタッター、ダグラス(1979年)『ゲーデル、エッシャー、バッハ:永遠の黄金の編み目』 ホース、スティーブン(2005年秋)、「心の計算理論」、ザルタ、エドワード・N.(編)、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』、2021年3月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2012年3月22日に取得 カプラン、アンドレアス;ヘーンライン、マイケル(2018年)、「シリ、シリ、私の手の中のシリよ、この国で最も美しいのは誰か?人工知能の解釈、実 例、および含意について」、『ビジネス・ホライズンズ』、62: 15–25, doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2018.08.004, S2CID 158433736 カーツワイル, レイ (2005), 『シンギュラリティは近い』, ニューヨーク: バイキング・プレス, ISBN 978-0-670-03384-3 ライプニッツ、ゴットフリート (1714)、『モナド論』、ロス、ジョージ・マクドナルド訳、2011年7月3日にオリジナルからアーカイブ ルカーチ、ジョン (1961)、「心、機械、ゲーデル」、アンダーソン、A. R. (編)、『心と機械』 マラブー、キャサリン (2019)。変形する知性:IQ測定から人工脳まで。(C. Shread、翻訳)。コロンビア大学出版局 マッカーシー、ジョン;ミンスキー、マービン;ロチェスター、ネイサン;シャノン、クロード (1955)、人工知能に関するダートマス夏期研究プロジェクトの提案、2008年9月30日にオリジナルからアーカイブ McCarthy, John (1999), What is AI?, 2022年12月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2022年12月4日に取得 McCulloch, Warren S.; Pitts, Walter (1943年12月1日). 「神経活動に内在する概念の論理的計算」. Bulletin of Mathematical Biophysics. 5 (4): 115–133. doi:10.1007/BF02478259. ISSN 1522-9602. マクダーモット、ドリュー(1997年5月14日)、「ディープブルーの知能はどれほどか」、『ニューヨーク・タイムズ』、2007年10月4日にオリジナルからアーカイブ、2007年10月10日に閲覧 モラベック、ハンス(1988年)、『マインド・チルドレン』、ハーバード大学出版局 ニューウェル、アレン; サイモン、H. A. (1976). 「経験的探究としての計算機科学:記号と探索」. Communications of the ACM. 19 (3): 113–126. doi:10.1145/360018.360022. ペンローズ、ロジャー(1989)、『皇帝の新しい心:コンピュータ、心、そして物理法則について』、オックスフォード大学出版局、Bibcode:1989esnm.book.....P、ISBN 978-0-14-014534-2c レスコーラ、マイケル、「心の計算理論」、エドワード・N・ザルタ(編)、『スタンフォード哲学百科事典』(2020年秋版) ラッセル、スチュワート・J.、ノーヴィグ、ピーター(2003)、『人工知能:現代的アプローチ』(第2版)、ニュージャージー州アッパーサドルリバー:プレンティスホール、 ISBN 0-13-790395-2 Saygin, A. P.; Cicekli, I.; Akman, V. (2000), 「Turing Test: 50 Years Later」 (PDF), Minds and Machines, 10 (4): 463–518, doi:10.1023/A:1011288000451, hdl:11693/24987, S2CID 990084, 2011年4月9日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ, 2004年1月7日に取得 サール, John (1980), 「Minds, Brains and Programs」 (PDF), Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 3 (3): 417–457, doi:10.1017/S0140525X00005756, S2CID 55303721, 2015年9月23日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ サール, ジョン (1984), 『心、脳、そして科学:1984年リース講義』, Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0-674-57631-5 サール, ジョン (1992), 『心の再発見』, Cambridge, Massachusetts: M.I.T. Press サール, ジョン (1999), 『心、言語、社会』, ニューヨーク: ベーシック・ブックス, ISBN 978-0-465-04521-1, OCLC 231867665 Yudkowsky, Eliezer (2008), 「Artificial Intelligence as a Positive and Negative Factor in Global Risk」 (PDF)、『地球規模的破滅リスク』、オックスフォード大学出版局、2008年、Bibcode:2008gcr..book..303Y、2013年 10月19日にオリジナルからアーカイブ(PDF)、2021年9月24日に取得 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philosophy_of_artificial_intelligence |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099