じんこう・ちのう artificial intelligence, AI

人工知能

じんこう・ちのう artificial intelligence, AI

解説:池田光穂

人工知能 (AI)とは、計算科学では、連合学習 (Federated learning)を機械におこなわせることである。また、一般的には、人工知能とは、(1)人間の知性・ 知能を計算機によって作り出すこと、(2)作り出され た〈実体〉、あるいは、(3)このことに関 する学問分野や実践、さらには欲望など、を指す多義的な意味をもつ言葉である。俗にいう人工知能(artificial intelligence)とは、コンピュータ科学が定義する、「機械学習」+ 「デープラーニング」+「連合学習=フェデレーティッド・ラーニング」の3つの様態の人工的な学習プロセスのことであり、これは有機体としての人間がおこ なっている「人間学習(human learning)」とは根本的異なっている代物である。その意味で、人間学習は、非人工知能学習(natural learning)のことであり、人工知能がシリコンチップによる無機学 習だとすれば、有機学習であるとも言える。英 語のウィキペディアはそのことを正しく定義している;"Artificial intelligence (AI) is intelligence demonstrated by machines, as opposed to the natural intelligence displayed by humans or animals."(人工知能(AI)とは、人間や動物が示す自然な知能とは異なり、機械が示す知能のことである)(→「人工知能(辞書的定義)」「人工知能の定義をめぐる支離滅裂さ」「人工知能・機械学習・深層学習・連合=協調学習」)

こ こで言う知性・知能とは、単に計算能力だけでなく、推論や学習などの高度の知的能力(それゆえ インテリジェンスの語がつく)のことである。この知的能力の様式をもった[あるいは類似の]活動が計算機=コンピュータにある時[あるいは、あるように思 える時]、技術者は人工知能(AI)を使っていると表現する。計算科学者のジャン=ガブリエル・ガナシアはこういう:「そもそも知能とは、単純作業を実施 するスピードのことでも、メモリに保存された情報量のことでもない。演算能力が向上したり記憶容量が増えたりしたからといって、自動的に知能が生じるわけ ではない」(ガナシア 2019:60)。

人間の知性・知能と計算機のそれは、同じであるのか、そうでないのか。あるいは、将来可能になる のか、ならないのかという学問的議論は、人工知能論争(じんこうちのう・ろんそう, AI論争)と呼ばれており、その決着はついていない(知性・知能の定義次第で、議論は大幅に変わりうるので、永遠に決着が着かないという表現も、もう決着 はついているという表現もともに可能である)。人間と同じ能力をもつ人工知能は、汎用人工知能(Artificial general intelligence)と呼ばれる。

人工知能(AI)とは、計算科学では、連合学習 (Federated

learning)を機械におこなわせることである。また、一般的には、人工知能とは、(1)人間の知性・知能を計算機によって作り出すこ

と、(2)作り

出され た〈実体〉、あるいは、(3)このことに関

する学問分野や実践、さらには欲望など、を指す多義的な意味をもつ言葉である。俗にいう人工知能(artificial

intelligence)とは、コンピュータ科学が定義する、「機械学習」+

「デープラーニング」+「連合学習=フェデレーティッド・ラーニング」の3つの様態の人工的な学習プロセスのことであり、これは有機体としての人間がおこ

なっている「人間学習(human

learning)」とは根本的異なっている代物である。その意味で、人間学習は、非=人工知能学習のことであり、人工知能がシリコンチップによる無機学

習だとすれば、有機学習であるとも言える。英 語のウィキペディアはそのことを正しく定義している;"Artificial intelligence

(AI) is intelligence demonstrated by machines, as opposed to the

natural intelligence displayed by humans or

animals."(人工知能(AI)とは、人間や動物が示す自然な知能とは異なり、機械が示す知能のことである)(→「人工知能の定義をめぐる支離滅裂さ」) 人工知能(AI)とは、計算科学では、連合学習 (Federated

learning)を機械におこなわせることである。また、一般的には、人工知能とは、(1)人間の知性・知能を計算機によって作り出すこ

と、(2)作り

出され た〈実体〉、あるいは、(3)このことに関

する学問分野や実践、さらには欲望など、を指す多義的な意味をもつ言葉である。俗にいう人工知能(artificial

intelligence)とは、コンピュータ科学が定義する、「機械学習」+

「デープラーニング」+「連合学習=フェデレーティッド・ラーニング」の3つの様態の人工的な学習プロセスのことであり、これは有機体としての人間がおこ

なっている「人間学習(human

learning)」とは根本的異なっている代物である。その意味で、人間学習は、非=人工知能学習のことであり、人工知能がシリコンチップによる無機学

習だとすれば、有機学習であるとも言える。英 語のウィキペディアはそのことを正しく定義している;"Artificial intelligence

(AI) is intelligence demonstrated by machines, as opposed to the

natural intelligence displayed by humans or

animals."(人工知能(AI)とは、人間や動物が示す自然な知能とは異なり、機械が示す知能のことである)(→「人工知能の定義をめぐる支離滅裂さ」)

|

☆人工知能(Artificial intelligence, AI)

| Artificial intelligence

(AI) is the capability of computational systems to perform tasks

typically associated with human intelligence, such as learning,

reasoning, problem-solving, perception, and decision-making. It is a

field of research in computer science that develops and studies methods

and software that enable machines to perceive their environment and use

learning and intelligence to take actions that maximize their chances

of achieving defined goals.[1] High-profile applications of AI include advanced web search engines (e.g., Google Search); recommendation systems (used by YouTube, Amazon, and Netflix); virtual assistants (e.g., Google Assistant, Siri, and Alexa); autonomous vehicles (e.g., Waymo); generative and creative tools (e.g., language models and AI art); and superhuman play and analysis in strategy games (e.g., chess and Go). However, many AI applications are not perceived as AI: "A lot of cutting edge AI has filtered into general applications, often without being called AI because once something becomes useful enough and common enough it's not labeled AI anymore."[2][3] Various subfields of AI research are centered around particular goals and the use of particular tools. The traditional goals of AI research include learning, reasoning, knowledge representation, planning, natural language processing, perception, and support for robotics.[a] To reach these goals, AI researchers have adapted and integrated a wide range of techniques, including search and mathematical optimization, formal logic, artificial neural networks, and methods based on statistics, operations research, and economics.[b] AI also draws upon psychology, linguistics, philosophy, neuroscience, and other fields.[4] Some companies, such as OpenAI, Google DeepMind and Meta,[5] aim to create artificial general intelligence (AGI)—AI that can complete virtually any cognitive task at least as well as a human. Artificial intelligence was founded as an academic discipline in 1956,[6] and the field went through multiple cycles of optimism throughout its history,[7][8] followed by periods of disappointment and loss of funding, known as AI winters.[9][10] Funding and interest vastly increased after 2012 when graphics processing units started being used to accelerate neural networks and deep learning outperformed previous AI techniques.[11] This growth accelerated further after 2017 with the transformer architecture.[12] In the 2020s, an ongoing period of rapid progress in advanced generative AI became known as the AI boom. Generative AI's ability to create and modify content has led to several unintended consequences and harms, which has raised ethical concerns about AI's long-term effects and potential existential risks, prompting discussions about regulatory policies to ensure the safety and benefits of the technology. |

人工知能(AI)とは、学習、推論、問題解決、知覚、意思決定など、通

常人間の知能に関連するタスクを実行する計算システムの能力のことです。これは、機械が環境を知覚し、学習と知能を用いて、定義された目標を達成する可能

性を最大限に高める行動を取ることを可能にする手法やソフトウェアを開発、研究するコンピュータサイエンスの研究分野です。[1] AI の注目すべき応用例としては、高度なウェブ検索エンジン(Google 検索など)、レコメンデーションシステム(YouTube、Amazon、Netflix で使用)、 バーチャルアシスタント(例:Googleアシスタント、Siri、Alexa)、自律走行車(例:Waymo)、生成型・創造的ツール(例:言語モデ ル、AIアート)、戦略ゲーム(例:チェス、囲碁)における超人的なプレイと分析などがあります。しかし、多くのAIアプリケーションはAIとして認識さ れていません:「最先端のAIの多くは、一般アプリケーションに浸透していますが、有用で一般的になるとAIと呼ばれなくなるため、AIと呼ばれないこと が多いのです。」[2][3] AI 研究のさまざまなサブフィールドは、特定の目標と特定のツールの使用を中心に展開されている。AI 研究の伝統的な目標には、学習、推論、知識表現、計画、自然言語処理、知覚、ロボット工学の支援などがある。[a] これらの目標を達成するために、AI 研究者は、検索や数学的最適化、形式論理、人工ニューラルネットワーク、統計、オペレーションズリサーチ、経済学に基づく手法など、幅広い技術を適応、統 合してきた。[b] AIは、心理学、言語学、哲学、神経科学、その他の分野からも影響を受けている。[4] OpenAI、Google DeepMind、Meta[5]などの企業は、人工汎用知能(AGI)——人間と同等以上の認知タスクをほぼすべて実行できるAI——の創造を目指して いる。 人工知能は1956年に学術分野として設立され[6]、その歴史を通じて複数の楽観的なサイクルを経て[7][8]、失望と資金不足の時期(AIの冬)を 経験してきました[9][10]。2012年以降、グラフィック処理ユニットがニューラルネットワークの加速に利用され、ディープラーニングが従来のAI 技術を凌駕したことで、資金と関心は急増しました。[11] 2017年以降、トランスフォーマーアーキテクチャの登場により、この成長はさらに加速した。[12] 2020年代には、高度な生成AIの急速な進展が続く期間が「AIブーム」として知られるようになった。生成AIがコンテンツを作成・改変する能力は、い くつかの予期せぬ結果や害を引き起こし、AIの長期的な影響や潜在的な存在リスクに関する倫理的な懸念を招き、技術の安全性と利益を確保するための規制政 策に関する議論を促している。 |

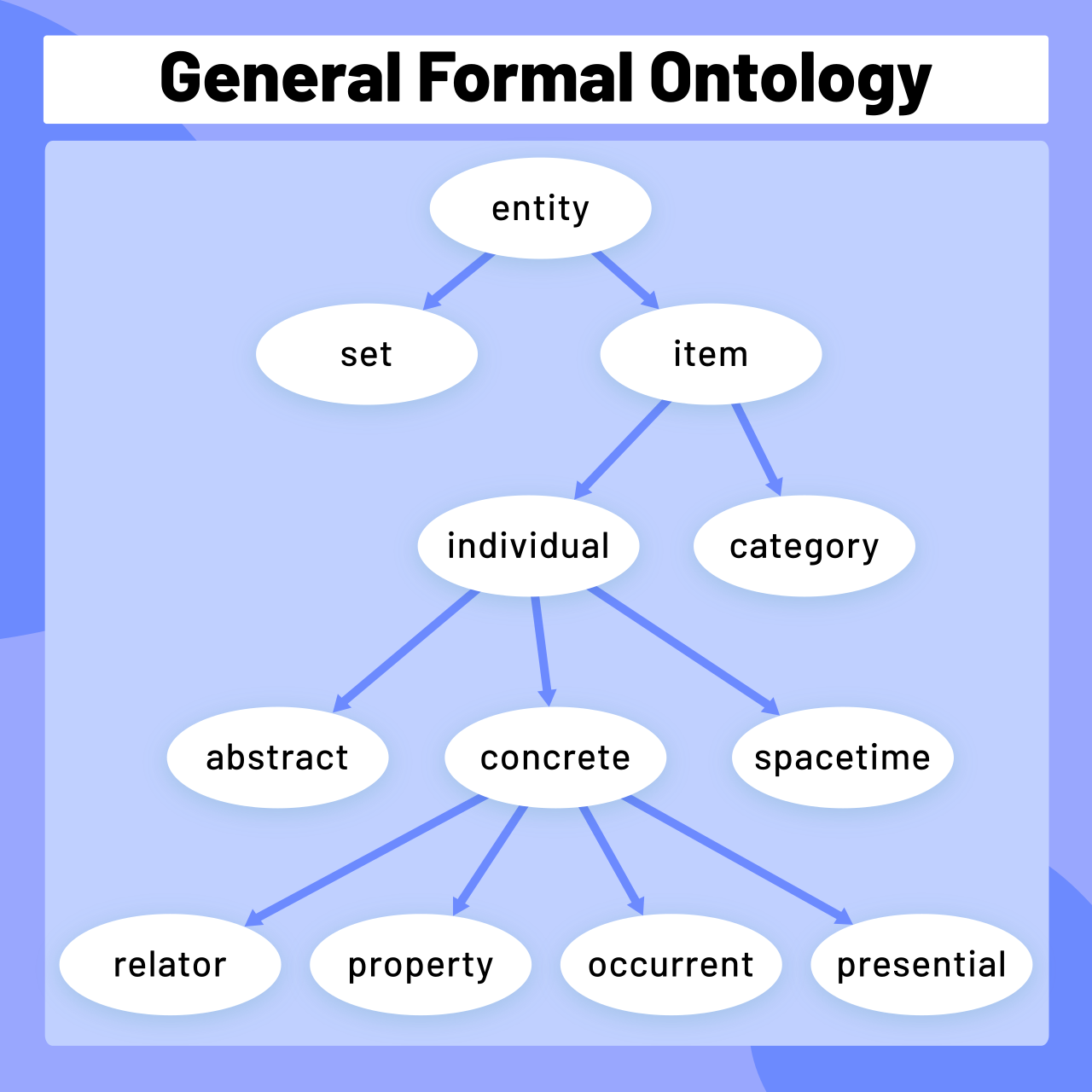

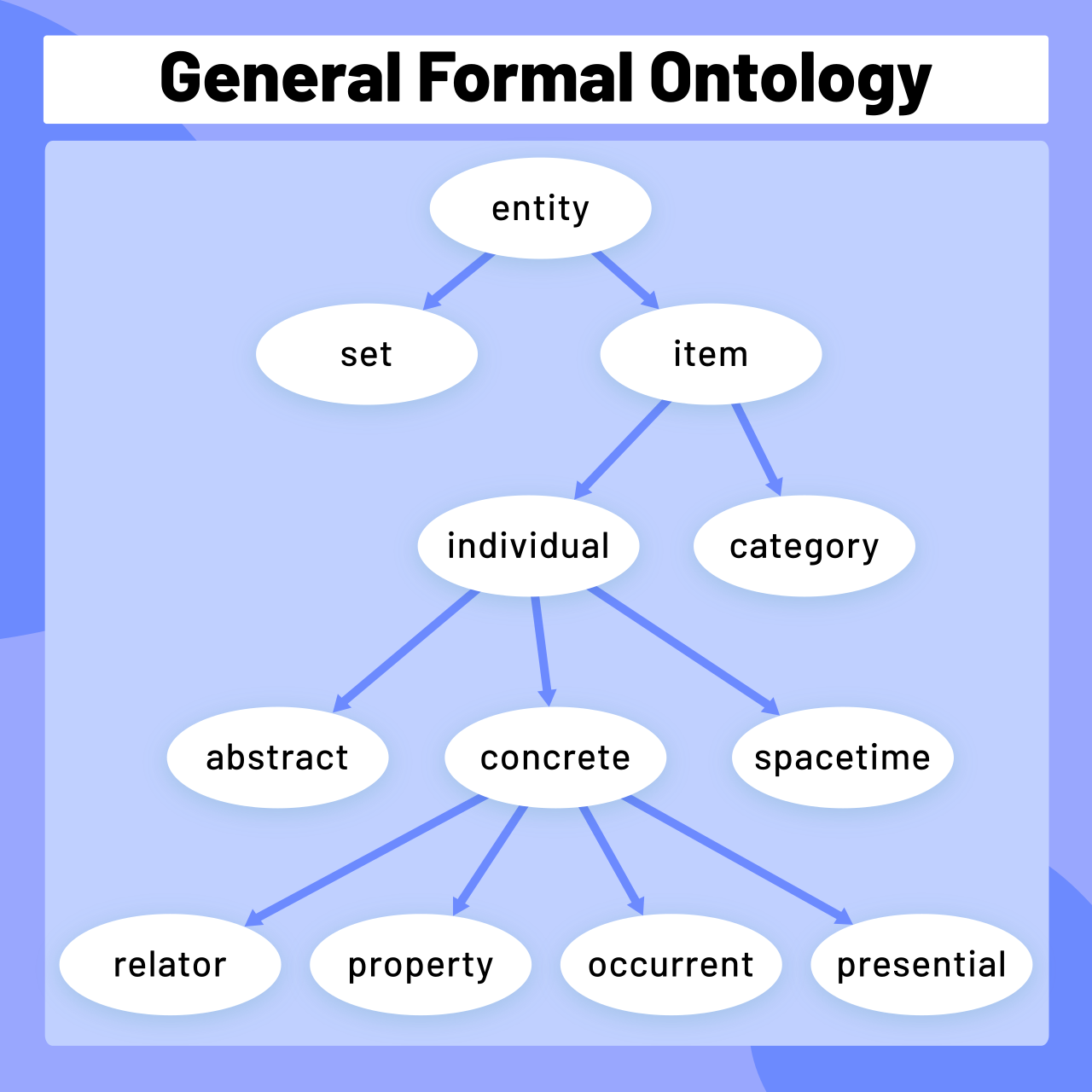

| Goals The general problem of simulating (or creating) intelligence has been broken into subproblems. These consist of particular traits or capabilities that researchers expect an intelligent system to display. The traits described below have received the most attention and cover the scope of AI research.[a] Reasoning and problem-solving Early researchers developed algorithms that imitated step-by-step reasoning that humans use when they solve puzzles or make logical deductions.[13] By the late 1980s and 1990s, methods were developed for dealing with uncertain or incomplete information, employing concepts from probability and economics.[14] Many of these algorithms are insufficient for solving large reasoning problems because they experience a "combinatorial explosion": They become exponentially slower as the problems grow.[15] Even humans rarely use the step-by-step deduction that early AI research could model. They solve most of their problems using fast, intuitive judgments.[16] Accurate and efficient reasoning is an unsolved problem. Knowledge representation  An ontology represents knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain and the relationships between those concepts. Knowledge representation and knowledge engineering[17] allow AI programs to answer questions intelligently and make deductions about real-world facts. Formal knowledge representations are used in content-based indexing and retrieval,[18] scene interpretation,[19] clinical decision support,[20] knowledge discovery (mining "interesting" and actionable inferences from large databases),[21] and other areas.[22] A knowledge base is a body of knowledge represented in a form that can be used by a program. An ontology is the set of objects, relations, concepts, and properties used by a particular domain of knowledge.[23] Knowledge bases need to represent things such as objects, properties, categories, and relations between objects;[24] situations, events, states, and time;[25] causes and effects;[26] knowledge about knowledge (what we know about what other people know);[27] default reasoning (things that humans assume are true until they are told differently and will remain true even when other facts are changing);[28] and many other aspects and domains of knowledge. Among the most difficult problems in knowledge representation are the breadth of commonsense knowledge (the set of atomic facts that the average person knows is enormous);[29] and the sub-symbolic form of most commonsense knowledge (much of what people know is not represented as "facts" or "statements" that they could express verbally).[16] There is also the difficulty of knowledge acquisition, the problem of obtaining knowledge for AI applications.[c] Planning and decision-making An "agent" is anything that perceives and takes actions in the world. A rational agent has goals or preferences and takes actions to make them happen.[d][32] In automated planning, the agent has a specific goal.[33] In automated decision-making, the agent has preferences—there are some situations it would prefer to be in, and some situations it is trying to avoid. The decision-making agent assigns a number to each situation (called the "utility") that measures how much the agent prefers it. For each possible action, it can calculate the "expected utility": the utility of all possible outcomes of the action, weighted by the probability that the outcome will occur. It can then choose the action with the maximum expected utility.[34] In classical planning, the agent knows exactly what the effect of any action will be.[35] In most real-world problems, however, the agent may not be certain about the situation they are in (it is "unknown" or "unobservable") and it may not know for certain what will happen after each possible action (it is not "deterministic"). It must choose an action by making a probabilistic guess and then reassess the situation to see if the action worked.[36] In some problems, the agent's preferences may be uncertain, especially if there are other agents or humans involved. These can be learned (e.g., with inverse reinforcement learning), or the agent can seek information to improve its preferences.[37] Information value theory can be used to weigh the value of exploratory or experimental actions.[38] The space of possible future actions and situations is typically intractably large, so the agents must take actions and evaluate situations while being uncertain of what the outcome will be. A Markov decision process has a transition model that describes the probability that a particular action will change the state in a particular way and a reward function that supplies the utility of each state and the cost of each action. A policy associates a decision with each possible state. The policy could be calculated (e.g., by iteration), be heuristic, or it can be learned.[39] Game theory describes the rational behavior of multiple interacting agents and is used in AI programs that make decisions that involve other agents.[40] |

目標 知能のシミュレーション(または創造)という一般的な問題は、いくつかのサブ問題に分かれている。これらは、研究者が知能システムに期待する特定の特性や能力で構成されている。以下で説明する特性は、最も注目されているもので、AI 研究の範囲を網羅している。 推論と問題解決 初期の研究者は、人間がパズルを解いたり、論理的な推論を行う際に使用する段階的な推論を模倣したアルゴリズムを開発した。1980年代後半から1990年代にかけて、不確実または不完全な情報を扱うための手法が、確率論や経済学の概念を用いて開発された。[14] これらのアルゴリズムの多くは、大規模な推論問題を解決するには不十分である。なぜなら、これらは「組み合わせの爆発」に直面するからだ。つまり、問題が 大きくなるにつれて、その処理速度は指数関数的に低下する。[15] 人間でさえ、初期のAI研究でモデル化されたような段階的な推論をほとんど使用しない。人間は、ほとんどの問題を、迅速で直感的な判断によって解決してい る[16]。正確かつ効率的な推論は、未解決の問題である。 知識表現  オントロジーは、ある領域内の概念の集合と、それらの概念間の関係として知識を表す 知識表現と知識工学[17]により、AI プログラムは、質問に対してインテリジェントに答え、現実世界の事実について推論を行うことが可能になる。形式的な知識表現は、コンテンツベースの索引付 けと検索[18]、シーン解釈[19]、臨床意思決定支援[20]、知識発見(大規模データベースから「興味深い」かつ実用的な推論を抽出する) [21]、その他の分野で使用されている[22]。 知識ベースは、プログラムで使用できる形式で表現された知識の集合体だ。オントロジーは、特定の知識領域で使用されるオブジェクト、関係、概念、およびプ ロパティのセットだ。[23] 知識ベースは、オブジェクト、プロパティ、カテゴリ、オブジェクト間の関係などのものを表現する必要がある。[24] 状況、イベント、状態、および時間。[25] 原因と結果。[26] 知識に関する知識(他の人が知っていることについて私たちが知っていること)。[27] デフォルト推論(人間が、異なる情報が得られるまで真実であると想定し、他の事実が変化しても真実であり続けると想定する事柄)[28]、およびその他の 多くの側面や知識領域。 知識表現における最も困難な問題としては、常識知識の広範さ(平均的な人が知っている原子的な事実の集合は膨大である)[29]、およびほとんどの常識知 識が記号以下の形式である(人々が知っていることの多くは、言葉で表現できる「事実」や「文」として表現できない)ことが挙げられる。[16] また、AI アプリケーションのために知識を取得する、知識獲得の問題もある。[c] 計画と意思決定 「エージェント」とは、世界を知覚し、行動するあらゆるもののことだ。合理的なエージェントは目標や好みを持っており、それらを実現するために行動する。 [d][32] 自動計画では、エージェントは特定の目標を持つ。[33] 自動意思決定では、エージェントは好みを持つ——ある状況は好むし、ある状況は避けたい。意思決定エージェントは、各状況に数値(ユーティリティと呼ばれ る)を割り当て、エージェントがその状況をどれだけ好むかを測定する。各可能な行動について、その行動の結果として生じるすべての結果のユーティリティ に、その結果が生じる確率を乗じた「期待ユーティリティ」を計算することができる。そして、期待ユーティリティが最大の行動を選択することができる。 [34] 古典的な計画では、エージェントはあらゆる行動の結果を正確に知っている。[35] しかし、現実世界の多くの問題では、エージェントは自分が置かれている状況について確信を持っていない(状況は「未知」または「観測不能」である)場合が あり、各可能な行動後に何が起こるかについても確信を持っていない(状況は「決定論的」ではない)場合がある。そのため、確率的な推測に基づいて行動を選 択し、その後、その行動が機能したかどうかを再評価する必要がある。[36] 一部の問題では、特に他のエージェントや人間が関与している場合、エージェントの好みが不確実である場合があります。これらは学習可能(例えば、逆強化学 習)である場合もあれば、エージェントが自分の好みを改善するための情報を求める場合もあります。[37] 情報価値理論は、探索的または実験的な行動の価値を評価するために使用できます。[38] 将来起こりうる行動や状況の空間は通常、非常に広大であるため、エージェントは結果が不確かなまま行動を取り、状況を評価しなければならない。 マルコフ決定過程には、特定の行動が特定の方法で状態を変化させる確率を表す遷移モデルと、各状態の効用と各行動のコストを提供する報酬関数がある。ポリ シーは、各可能な状態に決定を関連付けます。ポリシーは、反復によって計算される、ヒューリスティックである、または学習される場合があります。[39] ゲーム理論は、複数の相互作用するエージェントの合理的な行動を記述し、他のエージェントを含む決定を行う AI プログラムで使用されます。[40] |

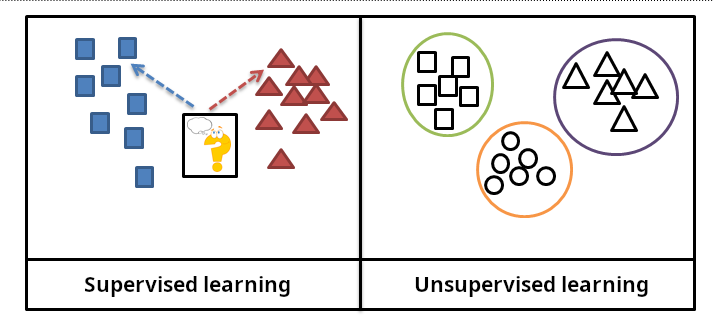

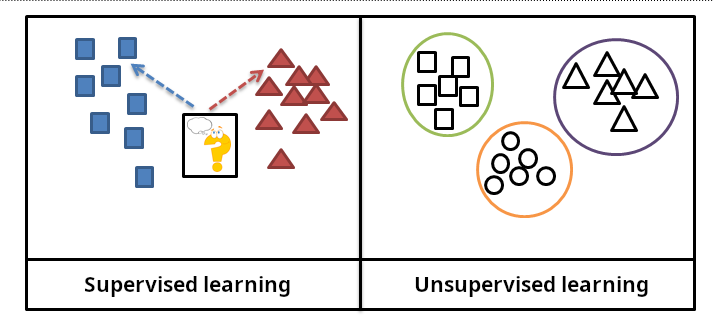

| Learning Machine learning is the study of programs that can improve their performance on a given task automatically.[41] It has been a part of AI from the beginning.[e]  In supervised learning, the training data is labelled with the expected answers, while in unsupervised learning, the model identifies patterns or structures in unlabelled data. There are several kinds of machine learning. Unsupervised learning analyzes a stream of data and finds patterns and makes predictions without any other guidance.[44] Supervised learning requires labeling the training data with the expected answers, and comes in two main varieties: classification (where the program must learn to predict what category the input belongs in) and regression (where the program must deduce a numeric function based on numeric input).[45] In reinforcement learning, the agent is rewarded for good responses and punished for bad ones. The agent learns to choose responses that are classified as "good".[46] Transfer learning is when the knowledge gained from one problem is applied to a new problem.[47] Deep learning is a type of machine learning that runs inputs through biologically inspired artificial neural networks for all of these types of learning.[48] Computational learning theory can assess learners by computational complexity, by sample complexity (how much data is required), or by other notions of optimization.[49] |

学習 機械学習とは、与えられたタスクのパフォーマンスを自動的に向上させることができるプログラムの研究だ[41]。これは当初から AI の一部として取り入れられてきた[e]。  教師あり学習では、トレーニングデータに予想される答えがラベル付けされるのに対し、教師なし学習では、モデルがラベルのないデータからパターンや構造を識別する。 機械学習にはいくつかの種類がある。教師なし学習は、データの流れを分析し、他の指示なしにパターンを発見し、予測を行う。[44] 教師あり学習では、トレーニングデータに期待される回答をラベル付けする必要があり、主に2つの種類に分類される:分類(プログラムが入力データが属する カテゴリを予測するように学習する)と回帰(プログラムが数値入力に基づいて数値関数を導き出す)。[45] 強化学習では、エージェントは良い反応に対して報酬を受け、悪い反応に対して罰を受ける。エージェントは、「良い」と分類される反応を選択することを学習 する。[46] 転移学習とは、ある問題から得た知識を新しい問題に適用することである。[47] ディープラーニングは、これらの学習のすべてについて、生物にヒントを得た人工ニューラルネットワークに入力を通す機械学習の一種である。[48] 計算学習理論は、計算の複雑さ、サンプルの複雑さ(必要なデータ量)、またはその他の最適化の概念によって学習者を評価することができる。[49] |

| Natural language processing Natural language processing (NLP) allows programs to read, write and communicate in human languages.[50] Specific problems include speech recognition, speech synthesis, machine translation, information extraction, information retrieval and question answering.[51] Early work, based on Noam Chomsky's generative grammar and semantic networks, had difficulty with word-sense disambiguation[f] unless restricted to small domains called "micro-worlds" (due to the common sense knowledge problem[29]). Margaret Masterman believed that it was meaning and not grammar that was the key to understanding languages, and that thesauri and not dictionaries should be the basis of computational language structure. Modern deep learning techniques for NLP include word embedding (representing words, typically as vectors encoding their meaning),[52] transformers (a deep learning architecture using an attention mechanism),[53] and others.[54] In 2019, generative pre-trained transformer (or "GPT") language models began to generate coherent text,[55][56] and by 2023, these models were able to get human-level scores on the bar exam, SAT test, GRE test, and many other real-world applications.[57] Perception Machine perception is the ability to use input from sensors (such as cameras, microphones, wireless signals, active lidar, sonar, radar, and tactile sensors) to deduce aspects of the world. Computer vision is the ability to analyze visual input.[58] The field includes speech recognition,[59] image classification,[60] facial recognition, object recognition,[61] object tracking,[62] and robotic perception.[63] |

自然言語処理 自然言語処理(NLP)は、プログラムが人間の言語を読み、書き、コミュニケーションすることを可能にする。[50] 具体的な問題としては、音声認識、音声合成、機械翻訳、情報抽出、情報検索、質問応答などが挙げられる。[51] 初期の研究は、ノーム・チョムスキーの生成文法と意味ネットワークに基づいており、一般的な知識の問題[29]のため、「マイクロワールド」と呼ばれる小 さな領域に限定されない限り、単語の意味の曖昧性解消[f]に困難を伴った。マーガレット・マスターマンは、言語を理解する鍵は文法ではなく意味であり、 計算言語構造の基盤は辞書ではなく類語辞典であるべきだと主張した。 現代のNLPにおける深層学習技術には、単語埋め込み(単語を、その意味を符号化したベクトルとして表す手法)[52]、トランスフォーマー(注意メカニ ズムを用いた深層学習アーキテクチャ)[53]などがある[54]。2019年、生成型事前訓練トランスフォーマー(または「GPT」)言語モデルが、一 貫性のあるテキストを生成し始めた。[55][56]、2023 年には、これらのモデルは司法試験、SAT 試験、GRE 試験、およびその他の多くの実世界アプリケーションで人間レベルのスコアを獲得できるようになりました。[57] 知覚 機械知覚とは、センサー(カメラ、マイク、無線信号、アクティブライダー、ソナー、レーダー、触覚センサーなど)からの入力を使用して、世界に関する側面を推測する能力です。コンピュータビジョンは、視覚的な入力を分析する能力だ。[58] この分野には、音声認識[59]、画像分類[60]、顔認識、物体認識[61]、物体追跡[62]、ロボット知覚[63]などが含まれる。 |

| Social intelligence Kismet, a robot head which was made in the 1990s; it is a machine that can recognize and simulate emotions.[64] Affective computing is a field that comprises systems that recognize, interpret, process, or simulate human feeling, emotion, and mood.[65] For example, some virtual assistants are programmed to speak conversationally or even to banter humorously; it makes them appear more sensitive to the emotional dynamics of human interaction, or to otherwise facilitate human–computer interaction. However, this tends to give naïve users an unrealistic conception of the intelligence of existing computer agents.[66] Moderate successes related to affective computing include textual sentiment analysis and, more recently, multimodal sentiment analysis, wherein AI classifies the effects displayed by a videotaped subject.[67] General intelligence A machine with artificial general intelligence would be able to solve a wide variety of problems with breadth and versatility similar to human intelligence.[68] |

社会的知能 1990年代に製作されたロボットの頭部「キスメット」は、感情を認識し、シミュレートすることができる機械だ。[64] 感情コンピューティングは、人間の感情、感情、気分を認識、解釈、処理、またはシミュレートするシステムで構成される分野だ。[65] 例えば、一部の仮想アシスタントは、会話のように話したり、ユーモラスな冗談を言ったりするようにプログラムされており、人間同士の感情のやり取りに敏感 であるように見える、あるいは人間とコンピュータの相互作用を促進するように見える。 しかし、これは、経験の浅いユーザーに、既存のコンピュータエージェントの知能について非現実的な概念を与える傾向がある。[66] 感情コンピューティングに関連する中程度の成功例としては、テキストの感情分析、そして最近では、AI がビデオに録画された対象者が示す感情を分類するマルチモーダル感情分析がある。 汎用知能 汎用人工知能を備えた機械は、人間の知能と同様の幅広さと汎用性をもって、さまざまな問題を解決することができるだろう。[68] |

| Techniques AI research uses a wide variety of techniques to accomplish the goals above.[b] Search and optimization AI can solve many problems by intelligently searching through many possible solutions.[69] There are two very different kinds of search used in AI: state space search and local search. State space search State space search searches through a tree of possible states to try to find a goal state.[70] For example, planning algorithms search through trees of goals and subgoals, attempting to find a path to a target goal, a process called means-ends analysis.[71] Simple exhaustive searches[72] are rarely sufficient for most real-world problems: the search space (the number of places to search) quickly grows to astronomical numbers. The result is a search that is too slow or never completes.[15] "Heuristics" or "rules of thumb" can help prioritize choices that are more likely to reach a goal.[73] Adversarial search is used for game-playing programs, such as chess or Go. It searches through a tree of possible moves and countermoves, looking for a winning position.[74] Local search  Illustration of gradient descent for 3 different starting points; two parameters (represented by the plan coordinates) are adjusted in order to minimize the loss function (the height) Local search uses mathematical optimization to find a solution to a problem. It begins with some form of guess and refines it incrementally.[75] Gradient descent is a type of local search that optimizes a set of numerical parameters by incrementally adjusting them to minimize a loss function. Variants of gradient descent are commonly used to train neural networks,[76] through the backpropagation algorithm. Another type of local search is evolutionary computation, which aims to iteratively improve a set of candidate solutions by "mutating" and "recombining" them, selecting only the fittest to survive each generation.[77] Distributed search processes can coordinate via swarm intelligence algorithms. Two popular swarm algorithms used in search are particle swarm optimization (inspired by bird flocking) and ant colony optimization (inspired by ant trails).[78] Logic Formal logic is used for reasoning and knowledge representation.[79] Formal logic comes in two main forms: propositional logic (which operates on statements that are true or false and uses logical connectives such as "and", "or", "not" and "implies")[80] and predicate logic (which also operates on objects, predicates and relations and uses quantifiers such as "Every X is a Y" and "There are some Xs that are Ys").[81] Deductive reasoning in logic is the process of proving a new statement (conclusion) from other statements that are given and assumed to be true (the premises).[82] Proofs can be structured as proof trees, in which nodes are labelled by sentences, and children nodes are connected to parent nodes by inference rules. Given a problem and a set of premises, problem-solving reduces to searching for a proof tree whose root node is labelled by a solution of the problem and whose leaf nodes are labelled by premises or axioms. In the case of Horn clauses, problem-solving search can be performed by reasoning forwards from the premises or backwards from the problem.[83] In the more general case of the clausal form of first-order logic, resolution is a single, axiom-free rule of inference, in which a problem is solved by proving a contradiction from premises that include the negation of the problem to be solved.[84] Inference in both Horn clause logic and first-order logic is undecidable, and therefore intractable. However, backward reasoning with Horn clauses, which underpins computation in the logic programming language Prolog, is Turing complete. Moreover, its efficiency is competitive with computation in other symbolic programming languages.[85] Fuzzy logic assigns a "degree of truth" between 0 and 1. It can therefore handle propositions that are vague and partially true.[86] Non-monotonic logics, including logic programming with negation as failure, are designed to handle default reasoning.[28] Other specialized versions of logic have been developed to describe many complex domains. |

手法 AI 研究では、上記の目標を達成するためにさまざまな手法が用いられている[b]。 検索と最適化 AI は、考えられる多くの解決策をインテリジェントに検索することで、多くの問題を解決することができる[69]。AI で用いられる検索には、状態空間検索と局所検索という 2 つのまったく異なる種類がある。 状態空間検索 状態空間検索は、考えられる状態のツリーを検索して、目標状態を見つけようとする。[70] 例えば、計画アルゴリズムは、目標とサブ目標のツリーを検索し、目標への経路を見つけようとする、手段-目的分析と呼ばれるプロセスを行う。 単純な網羅的検索[72] は、ほとんどの現実の問題にはほとんど不十分だ。検索空間(検索する場所の数)は、すぐに天文学的な数に膨れ上がるからだ。その結果、検索が過度に遅く なったり、完了しなくなったりする[15]。「ヒューリスティック」や「経験則」は、目標に到達する可能性の高い選択肢の優先順位付けに役立つ[73]。 敵対的検索は、チェスや囲碁などのゲームプログラムで使用される。可能な手と反手の手のツリーを検索し、勝利の位置を探す[74]。 局所検索  3 つの異なる開始点に対する勾配降下法の図。損失関数(高さ)を最小化するために、2 つのパラメータ(計画座標で表される)が調整される。 ローカル検索は、数学的最適化を用いて問題の解決策を見つける。まず、何らかの推測から始め、それを段階的に改良していく。[75] 勾配降下法は、損失関数を最小化するために一連の数値パラメータを段階的に調整して最適化する、ローカル検索の一種である。勾配降下法の変種は、バックプロパゲーションアルゴリズムを通じて、ニューラルネットワークのトレーニングに広く使われている。[76] ローカル検索のもう1つのタイプは、進化計算で、候補解のセットを「突然変異」および「再結合」して、各世代で最も適した解のみを選択することで、そのセットを反復的に改善することを目的としている。[77] 分散検索プロセスは、群知能アルゴリズムによって調整することができます。検索で使用される 2 つの一般的な群アルゴリズムは、粒子群最適化(鳥の群れから着想)と蟻群最適化(蟻の群れから着想)です。[78] 論理 形式論理は、推論や知識表現に使用されます。[79] 形式論理は主に2つの形態に分けられる:命題論理(真または偽の文を操作し、「かつ」「または」「否定」「含意」などの論理接続詞を使用する)[80]と 述語論理(対象、述語、関係も操作し、「すべてのXはYである」や「XのうちYであるものが存在する」などの量化詞を使用する)。[81] 論理における演繹的推論とは、与えられた、かつ真であると仮定される他の文(前提)から、新しい文(結論)を証明するプロセスだ。[82] 証明は、ノードが文でラベル付けされ、子ノードが推論規則によって親ノードに接続された証明ツリーとして構造化することができる。 問題と前提の集合が与えられた場合、問題解決は、問題の解でラベル付けされた根ノードを持ち、葉ノードが前提または公理でラベル付けされた証明木を検索す る作業に還元される。ホーン節の場合、問題解決の検索は、前提から順方向に推論するか、問題から逆方向に推論することで実行できる。[83] より一般的な一階論理の節形式の場合、解決は、解決すべき問題を含む否定を含む前提から矛盾を証明することで問題を解決する、単一の公理のない推論規則で ある。[84] ホーン節論理と一階論理の両方における推論は決定不能であり、したがって扱いが難しい。しかし、論理プログラミング言語 Prolog の計算の基礎となるホーン節を用いた逆推論は、チューリング完全である。さらに、その効率は他の記号プログラミング言語の計算と競合する。[85] ファジー論理は、0 から 1 までの「真度」を割り当てる。したがって、曖昧で部分的に真である命題を扱うことができる。[86] 失敗を否定とする論理プログラミングを含む非単調論理は、デフォルト推論を扱うために設計されている。[28] 多くの複雑な領域を記述するために、他の特殊な論理が開発されている。 |

| Probabilistic methods for uncertain reasoning A simple Bayesian network, with the associated conditional probability tables Many problems in AI (including reasoning, planning, learning, perception, and robotics) require the agent to operate with incomplete or uncertain information. AI researchers have devised a number of tools to solve these problems using methods from probability theory and economics.[87] Precise mathematical tools have been developed that analyze how an agent can make choices and plan, using decision theory, decision analysis,[88] and information value theory.[89] These tools include models such as Markov decision processes,[90] dynamic decision networks,[91] game theory and mechanism design.[92] Bayesian networks[93] are a tool that can be used for reasoning (using the Bayesian inference algorithm),[g][95] learning (using the expectation–maximization algorithm),[h][97] planning (using decision networks)[98] and perception (using dynamic Bayesian networks).[91] Probabilistic algorithms can also be used for filtering, prediction, smoothing, and finding explanations for streams of data, thus helping perception systems analyze processes that occur over time (e.g., hidden Markov models or Kalman filters).[91] Expectation–maximization clustering of Old Faithful eruption data starts from a random guess but then successfully converges on an accurate clustering of the two physically distinct modes of eruption. Classifiers and statistical learning methods The simplest AI applications can be divided into two types: classifiers (e.g., "if shiny then diamond"), on one hand, and controllers (e.g., "if diamond then pick up"), on the other hand. Classifiers[99] are functions that use pattern matching to determine the closest match. They can be fine-tuned based on chosen examples using supervised learning. Each pattern (also called an "observation") is labeled with a certain predefined class. All the observations combined with their class labels are known as a data set. When a new observation is received, that observation is classified based on previous experience.[45] There are many kinds of classifiers in use.[100] The decision tree is the simplest and most widely used symbolic machine learning algorithm.[101] K-nearest neighbor algorithm was the most widely used analogical AI until the mid-1990s, and Kernel methods such as the support vector machine (SVM) displaced k-nearest neighbor in the 1990s.[102] The naive Bayes classifier is reportedly the "most widely used learner"[103] at Google, due in part to its scalability.[104] Neural networks are also used as classifiers.[105] Artificial neural networks A neural network is an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of neurons in the human brain. An artificial neural network is based on a collection of nodes also known as artificial neurons, which loosely model the neurons in a biological brain. It is trained to recognise patterns; once trained, it can recognise those patterns in fresh data. There is an input, at least one hidden layer of nodes and an output. Each node applies a function and once the weight crosses its specified threshold, the data is transmitted to the next layer. A network is typically called a deep neural network if it has at least 2 hidden layers.[105] Learning algorithms for neural networks use local search to choose the weights that will get the right output for each input during training. The most common training technique is the backpropagation algorithm.[106] Neural networks learn to model complex relationships between inputs and outputs and find patterns in data. In theory, a neural network can learn any function.[107] In feedforward neural networks the signal passes in only one direction.[108] The term perceptron typically refers to a single-layer neural network.[109] In contrast, deep learning uses many layers.[110] Recurrent neural networks (RNNs) feed the output signal back into the input, which allows short-term memories of previous input events. Long short-term memory networks (LSTMs) are recurrent neural networks that better preserve longterm dependencies and are less sensitive to the vanishing gradient problem.[111] Convolutional neural networks (CNNs) use layers of kernels to more efficiently process local patterns. This local processing is especially important in image processing, where the early CNN layers typically identify simple local patterns such as edges and curves, with subsequent layers detecting more complex patterns like textures, and eventually whole objects.[112] Deep learning Deep learning is a subset of machine learning, which is itself a subset of artificial intelligence.[113] Deep learning uses several layers of neurons between the network's inputs and outputs.[110] The multiple layers can progressively extract higher-level features from the raw input. For example, in image processing, lower layers may identify edges, while higher layers may identify the concepts relevant to a human such as digits, letters, or faces.[114] Deep learning has profoundly improved the performance of programs in many important subfields of artificial intelligence, including computer vision, speech recognition, natural language processing, image classification,[115] and others. The reason that deep learning performs so well in so many applications is not known as of 2021.[116] The sudden success of deep learning in 2012–2015 did not occur because of some new discovery or theoretical breakthrough (deep neural networks and backpropagation had been described by many people, as far back as the 1950s)[i] but because of two factors: the incredible increase in computer power (including the hundred-fold increase in speed by switching to GPUs) and the availability of vast amounts of training data, especially the giant curated datasets used for benchmark testing, such as ImageNet.[j] |

不確実な推論のための確率的手法 AI(人工知能)の多くの問題(推論、計画、学習、知覚、ロボット工学など)では、エージェントが不完全または不確実な情報に基づいて動作する必要があり ます。AI 研究者は、確率論や経済学の手法を用いてこれらの問題を解決するための数多くのツールを考案してきた。[87] 意思決定理論、意思決定分析[88]、情報価値理論[89] を使用して、エージェントが選択を行い計画を立てる方法を分析する精密な数学的ツールが開発されている。これらのツールには、マルコフ決定過程[90]、 動的意思決定ネットワーク[91]、ゲーム理論、メカニズム設計などのモデルが含まれる。[92] ベイズネットワーク[93] は、推論(ベイズ推定アルゴリズムを使用)、[g][95] 学習(期待値最大化アルゴリズムを使用)、[h][97] 計画(決定ネットワークを使用)、[98] 認識(動的ベイズネットワークを使用)に使用できるツールです。[91] 確率アルゴリズムは、フィルタリング、予測、平滑化、およびデータストリームの説明の発見にも使用でき、これにより、知覚システムが時間経過とともに発生するプロセス(隠れたマルコフモデルやカルマンフィルタなど)を分析するのに役立つ。[91] オールド・フェイスフル火山の噴火データの期待値最大化クラスタリングは、ランダムな推測から始まりますが、最終的には、物理的に異なる 2 つの噴火モードの正確なクラスタリングにうまく収束しています。 分類器と統計的学習手法 最も単純なAIアプリケーションは、分類器(例:「光っているならダイヤモンド」)とコントローラー(例:「ダイヤモンドなら拾う」)の2種類に分類でき る。分類器[99]は、パターンマッチングを使用して最も近い一致を決定する関数です。これらは、選択された例に基づいて監督学習により微調整可能です。 各パターン(観測値とも呼ばれる)は、事前に定義されたクラスでラベル付けされます。すべての観測値とそのクラスラベルの組み合わせはデータセットと呼ば れます。新しい観測値が受信されると、その観測値は過去の経験に基づいて分類されます。[45] 使用されている分類器には多くの種類がある。[100] 決定木は、最も単純で広く使用されている記号的機械学習アルゴリズムである。[101] K 最近傍アルゴリズムは、1990 年代半ばまで最も広く使用されていた類推 AI だったが、1990 年代にはサポートベクターマシン (SVM) などのカーネル手法が K 最近傍に取って代わった。[102] ナイーブベイズ分類器は、そのスケーラビリティもあって、Google で「最も広く使用されている学習器」[103] であると報告されている。[104] ニューラルネットワークも分類器として使用されている。[105] 人工ニューラルネットワーク ニューラルネットワークは、人間の脳内の広大なニューロンのネットワークに似た、相互に接続されたノードのグループだ。 人工ニューラルネットワークは、生物の脳内のニューロンを大まかに模倣した、人工ニューロンとも呼ばれるノードの集合体に基づいています。パターン認識の ために訓練され、訓練後は新しいデータ内のパターンを認識することができます。入力、少なくとも1つの隠れたノード層、および出力があります。各ノードは 関数を適用し、重みが指定された閾値を超えると、データは次の層に伝達されます。ネットワークは、少なくとも 2 つの隠れ層を持つ場合、通常、深層神経ネットワークと呼ばれる。[105] ニューラルネットワークの学習アルゴリズムは、トレーニング中に各入力に対して正しい出力を得る重みを選択するために、局所探索を使用する。最も一般的な トレーニング手法は、バックプロパゲーションアルゴリズムである。[106] ニューラルネットワークは、入力と出力の間の複雑な関係をモデル化し、データ内のパターンを見つけることを学習する。理論的には、ニューラルネットワーク はあらゆる関数を学習することができる。[107] フィードフォワードニューラルネットワークでは、信号は一方向のみに伝達される。[108] パーセプトロンという用語は、通常、単層ニューラルネットワークを指す。[109] 対照的に、ディープラーニングは多くの層を使用する。[110] リカレントニューラルネットワーク(RNN)は、出力信号を入力に戻し、以前の入力イベントの短期記憶を可能にする。長短期記憶ネットワーク(LSTM) は、長期依存性をよりよく保持し、勾配消失問題に敏感でない再帰型ニューラルネットワークだ。[111] 畳み込みニューラルネットワーク(CNN)は、カーネルの層を使用して局所的なパターンを効率的に処理する。この局所的な処理は、画像処理において特に重 要だ。画像処理では、CNN の初期層では通常、エッジや曲線などの単純な局所パターンが識別され、その後の層でテクスチャなどのより複雑なパターンが検出され、最終的には物体全体が 検出される。[112] ディープラーニング ディープラーニングは、人工知能の一分野である機械学習の一分野だ。[113] ディープラーニングは、ネットワークの入力と出力の間に複数のニューロン層を使用する。[110] 複数の層により、生入力からより高レベルの特性を段階的に抽出することができます。例えば、画像処理では、下層はエッジを識別し、上層は数字、文字、顔な ど、人間に関連する概念を識別します。[114] ディープラーニングは、コンピュータビジョン、音声認識、自然言語処理、画像分類[115] など、人工知能の多くの重要なサブフィールドにおけるプログラムのパフォーマンスを飛躍的に向上させました。ディープラーニングがこれほど多くのアプリ ケーションで優れたパフォーマンスを発揮する理由は、2021 年の時点ではまだ不明だ。[116] 2012 年から 2015 年にかけてディープラーニングが突然成功を収めたのは、何らかの新しい発見や理論上の飛躍的進歩があったからではない(ディープニューラルネットワークや バックプロパゲーションは、1950 年代にはすでに多くの人々によって説明されていた)。[i] 成功の要因は 2 つある。コンピュータの処理能力の驚異的な向上(GPUへの移行による速度の100倍以上の向上を含む)と、大量のトレーニングデータの可用性、特に ImageNetのようなベンチマークテスト用に整備された大規模なデータセットの可用性[j]。 |

| GPT Generative pre-trained transformers (GPT) are large language models (LLMs) that generate text based on the semantic relationships between words in sentences. Text-based GPT models are pre-trained on a large corpus of text that can be from the Internet. The pretraining consists of predicting the next token (a token being usually a word, subword, or punctuation). Throughout this pretraining, GPT models accumulate knowledge about the world and can then generate human-like text by repeatedly predicting the next token. Typically, a subsequent training phase makes the model more truthful, useful, and harmless, usually with a technique called reinforcement learning from human feedback (RLHF). Current GPT models are prone to generating falsehoods called "hallucinations". These can be reduced with RLHF and quality data, but the problem has been getting worse for reasoning systems.[124] Such systems are used in chatbots, which allow people to ask a question or request a task in simple text.[125][126] Current models and services include ChatGPT, Claude, Gemini, Copilot, and Meta AI.[127] Multimodal GPT models can process different types of data (modalities) such as images, videos, sound, and text.[128] |

GPT 生成型事前学習済みトランスフォーマー(GPT)は、文中の単語間の意味関係に基づいてテキストを生成する大規模言語モデル(LLM)です。テキストベー スの GPT モデルは、インターネットなどから取得した大規模なテキストコーパスを用いて事前学習されます。事前学習では、次のトークン(トークンは通常、単語、サブ ワード、または句読点)を予測します。この事前学習を通じて、GPTモデルは世界に関する知識を蓄積し、次のトークンを繰り返し予測することで人間のよう なテキストを生成できるようになる。通常、その後のトレーニングフェーズでは、強化学習から人間フィードバック(RLHF)と呼ばれる技術を用いて、モデ ルをより真実性が高く、有用で、無害なものにする。現在の GPT モデルは、「幻覚」と呼ばれる虚偽の生成を起こしやすい傾向がある。これは RLHF と高品質のデータによって軽減できるが、推論システムではこの問題が悪化している。[124] このようなシステムは、人々が簡単なテキストで質問をしたり、タスクを依頼したりできるチャットボットで使用されている。[125][126] 現在のモデルおよびサービスには、ChatGPT、Claude、Gemini、Copilot、Meta AI などがある。[127] マルチモーダル GPT モデルは、画像、動画、音声、テキストなど、さまざまなタイプのデータ(モダリティ)を処理することができる。[128] |

| Hardware and software Main articles: Programming languages for artificial intelligence and Hardware for artificial intelligence In the late 2010s, graphics processing units (GPUs) that were increasingly designed with AI-specific enhancements and used with specialized TensorFlow software had replaced previously used central processing unit (CPUs) as the dominant means for large-scale (commercial and academic) machine learning models' training.[129] Specialized programming languages such as Prolog were used in early AI research,[130] but general-purpose programming languages like Python have become predominant.[131] The transistor density in integrated circuits has been observed to roughly double every 18 months—a trend known as Moore's law, named after the Intel co-founder Gordon Moore, who first identified it. Improvements in GPUs have been even faster,[132] a trend sometimes called Huang's law,[133] named after Nvidia co-founder and CEO Jensen Huang. |

ハードウェアとソフトウェア 主な記事:人工知能のためのプログラミング言語、人工知能のためのハードウェア 2010年代後半、AIに特化した機能強化がますます進んだグラフィックスプロセッシングユニット(GPU)が、専用のTensorFlowソフトウェア とともに、大規模(商業および学術)の機械学習モデルのトレーニングの主流手段として、これまで使用されていた中央処理装置(CPU)に取って代わった。 [129] 初期の人工知能研究ではPrologのような専門的なプログラミング言語が使用されていましたが、[130] Pythonのような汎用プログラミング言語が主流となっています。[131] 集積回路のトランジスタ密度は、およそ18ヶ月ごとに2倍になる傾向が見られ、この傾向は、それを最初に指摘したインテル社の共同創設者ゴードン・ムーア にちなんで「ムーアの法則」と呼ばれている。GPUの進歩はさらに急速で[132]、この傾向は、Nvidia社の共同創設者兼CEOであるジェンセン・ フアンにちなんで「フアンの法則」と呼ばれることもある。 |

| Applications Main article: Applications of artificial intelligence AI and machine learning technology is used in most of the essential applications of the 2020s, including: search engines (such as Google Search), targeting online advertisements, recommendation systems (offered by Netflix, YouTube or Amazon), driving internet traffic, targeted advertising (AdSense, Facebook), virtual assistants (such as Siri or Alexa), autonomous vehicles (including drones, ADAS and self-driving cars), automatic language translation (Microsoft Translator, Google Translate), facial recognition (Apple's FaceID or Microsoft's DeepFace and Google's FaceNet) and image labeling (used by Facebook, Apple's Photos and TikTok). The deployment of AI may be overseen by a chief automation officer (CAO). Health and medicine Main article: Artificial intelligence in healthcare The application of AI in medicine and medical research has the potential to increase patient care and quality of life.[134] Through the lens of the Hippocratic Oath, medical professionals are ethically compelled to use AI, if applications can more accurately diagnose and treat patients.[135][136] For medical research, AI is an important tool for processing and integrating big data. This is particularly important for organoid and tissue engineering development which use microscopy imaging as a key technique in fabrication.[137] It has been suggested that AI can overcome discrepancies in funding allocated to different fields of research.[137][138] New AI tools can deepen the understanding of biomedically relevant pathways. For example, AlphaFold 2 (2021) demonstrated the ability to approximate, in hours rather than months, the 3D structure of a protein.[139] In 2023, it was reported that AI-guided drug discovery helped find a class of antibiotics capable of killing two different types of drug-resistant bacteria.[140] In 2024, researchers used machine learning to accelerate the search for Parkinson's disease drug treatments. Their aim was to identify compounds that block the clumping, or aggregation, of alpha-synuclein (the protein that characterises Parkinson's disease). They were able to speed up the initial screening process ten-fold and reduce the cost by a thousand-fold.[141][142] Games Main article: Artificial intelligence in video games Game playing programs have been used since the 1950s to demonstrate and test AI's most advanced techniques.[143] Deep Blue became the first computer chess-playing system to beat a reigning world chess champion, Garry Kasparov, on 11 May 1997.[144] In 2011, in a Jeopardy! quiz show exhibition match, IBM's question answering system, Watson, defeated the two greatest Jeopardy! champions, Brad Rutter and Ken Jennings, by a significant margin.[145] In March 2016, AlphaGo won 4 out of 5 games of Go in a match with Go champion Lee Sedol, becoming the first computer Go-playing system to beat a professional Go player without handicaps. Then, in 2017, it defeated Ke Jie, who was the best Go player in the world.[146] Other programs handle imperfect-information games, such as the poker-playing program Pluribus.[147] DeepMind developed increasingly generalistic reinforcement learning models, such as with MuZero, which could be trained to play chess, Go, or Atari games.[148] In 2019, DeepMind's AlphaStar achieved grandmaster level in StarCraft II, a particularly challenging real-time strategy game that involves incomplete knowledge of what happens on the map.[149] In 2021, an AI agent competed in a PlayStation Gran Turismo competition, winning against four of the world's best Gran Turismo drivers using deep reinforcement learning.[150] In 2024, Google DeepMind introduced SIMA, a type of AI capable of autonomously playing nine previously unseen open-world video games by observing screen output, as well as executing short, specific tasks in response to natural language instructions.[151] Mathematics Large language models, such as GPT-4, Gemini, Claude, Llama or Mistral, are increasingly used in mathematics. These probabilistic models are versatile, but can also produce wrong answers in the form of hallucinations. They sometimes need a large database of mathematical problems to learn from, but also methods such as supervised fine-tuning[152] or trained classifiers with human-annotated data to improve answers for new problems and learn from corrections.[153] A February 2024 study showed that the performance of some language models for reasoning capabilities in solving math problems not included in their training data was low, even for problems with only minor deviations from trained data.[154] One technique to improve their performance involves training the models to produce correct reasoning steps, rather than just the correct result.[155] The Alibaba Group developed a version of its Qwen models called Qwen2-Math, that achieved state-of-the-art performance on several mathematical benchmarks, including 84% accuracy on the MATH dataset of competition mathematics problems.[156] In January 2025, Microsoft proposed the technique rStar-Math that leverages Monte Carlo tree search and step-by-step reasoning, enabling a relatively small language model like Qwen-7B to solve 53% of the AIME 2024 and 90% of the MATH benchmark problems.[157] Alternatively, dedicated models for mathematical problem solving with higher precision for the outcome including proof of theorems have been developed such as AlphaTensor, AlphaGeometry, AlphaProof and AlphaEvolve[158] all from Google DeepMind,[159] Llemma from EleutherAI[160] or Julius.[161] When natural language is used to describe mathematical problems, converters can transform such prompts into a formal language such as Lean to define mathematical tasks. The experimental model Gemini Deep Think accepts natural language prompts directly and achieved gold medal results in the International Math Olympiad of 2025.[162] Some models have been developed to solve challenging problems and reach good results in benchmark tests, others to serve as educational tools in mathematics.[163] Topological deep learning integrates various topological approaches. Finance Finance is one of the fastest growing sectors where applied AI tools are being deployed: from retail online banking to investment advice and insurance, where automated "robot advisers" have been in use for some years.[164] According to Nicolas Firzli, director of the World Pensions & Investments Forum, it may be too early to see the emergence of highly innovative AI-informed financial products and services. He argues that "the deployment of AI tools will simply further automatise things: destroying tens of thousands of jobs in banking, financial planning, and pension advice in the process, but I'm not sure it will unleash a new wave of [e.g., sophisticated] pension innovation."[165] Military Main article: Military applications of artificial intelligence Various countries are deploying AI military applications.[166] The main applications enhance command and control, communications, sensors, integration and interoperability.[167] Research is targeting intelligence collection and analysis, logistics, cyber operations, information operations, and semiautonomous and autonomous vehicles.[166] AI technologies enable coordination of sensors and effectors, threat detection and identification, marking of enemy positions, target acquisition, coordination and deconfliction of distributed Joint Fires between networked combat vehicles, both human-operated and autonomous.[167] AI has been used in military operations in Iraq, Syria, Israel and Ukraine.[166][168][169][170] |

アプリケーション 主な記事:人工知能の応用 AIと機械学習技術は、2020年代の重要なアプリケーションのほとんどで使用されている。その例としては、検索エンジン(Google検索など)、オン ライン広告のターゲティング、レコメンデーションシステム(Netflix、YouTube、Amazonなどが提供)、インターネットトラフィックの誘 導、ターゲット広告(AdSense、Facebook)、仮想アシスタント(SiriやAlexaなど)、 自律走行車両(ドローン、ADAS、自動運転車を含む)、自動言語翻訳(Microsoft Translator、Google Translate)、顔認識(AppleのFaceID、MicrosoftのDeepFace、GoogleのFaceNet)、画像ラベル付け (Facebook、AppleのPhotos、TikTokで利用されている)など。AIの展開は、チーフオートメーションオフィサー(CAO)によっ て監督される場合があります。 保健および医療 主な記事:医療における人工知能 医療および医学研究における AI の応用は、患者ケアと生活の質を向上させる可能性を秘めている。[134] ヒポクラテスの誓いという観点からは、医療従事者は、AI の応用によって患者の診断と治療がより正確になるのであれば、倫理的に AI を使用することが義務付けられている。[135][136] 医学研究において、AI はビッグデータを処理・統合するための重要なツールです。これは、製造の主要技術として顕微鏡画像診断を用いるオルガノイドおよび組織工学の開発において 特に重要です。[137] AI は、異なる研究分野に割り当てられる資金格差を克服できると示唆されています。[137][138] 新しい AI ツールは、生物医学に関連する経路の理解を深めることができます。例えば、AlphaFold 2 (2021) は、タンパク質の 3D 構造を数ヶ月ではなく数時間で近似する能力を発揮しました。[139] 2023 年、AI による創薬が、2 種類の薬剤耐性菌を殺すことのできる抗生物質の発見に貢献したと報告されました。[140] 2024年、研究者は機械学習を用いてパーキンソン病の治療薬探索を加速させた。その目的は、パーキンソン病の特徴的なタンパク質であるアルファシヌクレ インの凝集を阻害する化合物を特定することだった。彼らは初期スクリーニングプロセスを10倍速くし、コストを1000分の1に削減した。[141] [142] ゲーム 主な記事:ビデオゲームにおける人工知能 ゲームプレイプログラムは、1950年代からAIの最先端技術を実証・試験するために使用されてきた。[143] 1997年5月11日、ディープブルーは、世界チェスチャンピオンであるガリ・カスパロフを破った、チェスをプレイする最初のコンピュータシステムとなっ た。[144] 2011 年、クイズ番組「Jeopardy! 」のエキシビションマッチで、IBM の質問応答システム「Watson」は、Jeopardy! の 2 大チャンピオンであるブラッド・ラッターとケン・ジェニングスを、大きな差をつけて破った。[145] 2016年3月、AlphaGoは囲碁チャンピオンの李世ドルとの5局中4局を制し、ハンディキャップなしでプロの囲碁プレイヤーを破った最初のコン ピュータ囲碁システムとなった。その後、2017年には世界一の囲碁プレイヤーだった柯潔を破った。[146] 他のプログラムは不完全情報ゲームにも対応しており、ポーカープレイプログラムのPluribusなどがその例だ。[147] DeepMind は、チェス、囲碁、アタリ社のゲームなどをプレイするように訓練できる MuZero など、ますます汎用性の高い強化学習モデルを開発した。[148] 2019 年、DeepMind の AlphaStar は、マップ上で何が起こっているのかが不完全な情報しか得られない、特に難易度の高いリアルタイム戦略ゲーム「スタークラフト II」で、グランドマスターレベルを達成した。[149] 2021年、AIエージェントがPlayStation Gran Turismoの競技会で、深層強化学習を用いて世界トップクラスのGran Turismoドライバー4人を破って優勝した。[150] 2024年、Google DeepMindはSIMAというAIを導入した。これは、画面出力を観察して9つの未見のオープンワールドビデオゲームを自律的にプレイし、自然言語の 指示に応じて短い特定のタスクを実行できるAIだ。[151] 数学 GPT-4、Gemini、Claude、Llama、Mistral などの大規模言語モデルは、数学でますます利用されるようになっている。これらの確率モデルは汎用性があるが、幻覚という形で間違った答えを出すこともあ る。これらのモデルは、学習のために大規模な数学問題データベースを必要とする場合もありますが、新しい問題に対する答えを改善し、修正から学習するため に、教師ありの微調整[152] や、人間が注釈を付けたデータを用いて訓練した分類器などの手法も必要です[153]。2024年2月の研究では、トレーニングデータに含まれていない数 学の問題を解く推論能力について、一部の言語モデルのパフォーマンスは、トレーニングデータからわずかな偏差がある問題でも低かったことが示されました。 [154] これらのパフォーマンスを向上させるための 1 つの手法は、正しい結果だけでなく、正しい推論手順を生成するようにモデルをトレーニングすることだ。[155] Alibaba Group は、Qwen モデルのバージョンである Qwen2-Math を開発し、数学のコンテスト問題データセット MATH データセットで 84% の精度を達成するなど、いくつかの数学ベンチマークで最先端のパフォーマンスを達成した。[156] 2025年1月、マイクロソフトはモンテカルロ木探索とステップバイステップ推論を活用するrStar-Mathという技術を提案し、Qwen-7Bのよ うな比較的小さな言語モデルでAIME 2024の53%とMATHベンチマーク問題の90%を解決可能にした。[157] あるいは、定理の証明など、より正確な結果を求める数学の問題解決に特化したモデルも開発されている。Google DeepMind の AlphaTensor、AlphaGeometry、AlphaProof、AlphaEvolve[158]、EleutherAI の Llemma[160]、Julius[161] などだ。 自然言語が数学の問題を記述するために使用される場合、コンバーターは、そのようなプロンプトを Lean などの形式言語に変換して、数学的なタスクを定義することができる。実験的なモデル Gemini Deep Think は、自然言語のプロンプトを直接受け付け、2025 年の国際数学オリンピックで金メダルを獲得した。[162] いくつかのモデルは、困難な問題を解決し、ベンチマークテストで良い結果を達成するために開発されており、他のモデルは数学の教育ツールとして活用されている。[163] トポロジカルディープラーニングは、さまざまなトポロジカルアプローチを統合したものだ。 金融 金融は、応用 AI ツールが導入されている最も急成長している分野のひとつだ。小売オンラインバンキングから投資アドバイス、保険まで、自動化された「ロボットアドバイザー」が数年前から使用されている。[164] ワールド・ペンションズ・アンド・インベスターズ・フォーラムのディレクター、ニコラス・フィルズリ氏は、高度に革新的なAIを活用した金融商品やサービ スの出現は、まだ時期尚早かもしれないと指摘している。彼は「AIツールの展開は単に既存の業務をさらに自動化させるだけで、銀行、金融計画、年金アドバ イス分野で数万人の雇用を破壊するだろうが、それが[例えば高度な]年金イノベーションの新たな波を引き起こすかどうかは不明だ」と主張している。 [165] 軍事 主な記事:人工知能の軍事利用 さまざまな国が AI の軍事利用を展開している。[166] 主な用途は、指揮統制、通信、センサー、統合、相互運用性の強化だ。[167] 研究は、情報収集と分析、ロジスティクス、サイバー作戦、情報作戦、半自律型および自律型車両を対象としている。[166] AI 技術は、センサーとエフェクターの連携、脅威の検出と識別、敵の位置のマーク付け、目標の捕捉、ネットワーク化された戦闘車両(人間操作および自律型)間 の分散型共同射撃の連携と調整を可能にする。 AI は、イラク、シリア、イスラエル、ウクライナでの軍事作戦で使用されている。[166][168][169][170] |

Generative AI Vincent van Gogh in watercolour created by generative AI software These paragraphs are an excerpt from Generative artificial intelligence.[edit] Generative artificial intelligence (Generative AI, GenAI,[171] or GAI) is a subfield of artificial intelligence that uses generative models to produce text, images, videos, or other forms of data.[172][173][174] These models learn the underlying patterns and structures of their training data and use them to produce new data[175][176] based on the input, which often comes in the form of natural language prompts.[177][178] Generative AI tools have become more common since the AI boom in the 2020s. This boom was made possible by improvements in transformer-based deep neural networks, particularly large language models (LLMs). Major tools include chatbots such as ChatGPT, Copilot, Gemini, Claude, Grok, and DeepSeek; text-to-image models such as Stable Diffusion, Midjourney, and DALL-E; and text-to-video models such as Veo and Sora.[179][180][181][182][183] Technology companies developing generative AI include OpenAI, xAI, Anthropic, Meta AI, Microsoft, Google, DeepSeek, and Baidu.[177][184][185] Generative AI is used across many industries, including software development,[186] healthcare,[187] finance,[188] entertainment,[189] customer service,[190] sales and marketing,[191] art, writing,[192] fashion,[193] and product design.[194] The production of Generative AI systems requires large scale data centers using specialized chips which require high levels of energy for processing and water for cooling.[195] |

生成型 AI 生成型 AI ソフトウェアによって作成された水彩画のヴィンセント・ヴァン・ゴッホ これらの段落は、生成型人工知能からの抜粋です。[編集] 生成型人工知能(Generative AI、GenAI、[171]、または GAI)は、生成モデルを使用してテキスト、画像、動画、その他の形式のデータを生成する人工知能のサブ分野です。[172][173][174] これらのモデルは、トレーニングデータの根本的なパターンと構造を学習し、入力に基づいて新しいデータを生成する[175][176]。入力は、多くの場 合、自然言語の 프롬프트 の形式で与えられる[177][178]。 生成AIツールは、2020年代のAIブーム以来、より一般的になってきた。このブームは、トランスフォーマーベースの深層ニューラルネットワーク、特に 大規模言語モデル(LLM)の改良によって可能になった。主なツールとしては、ChatGPT、Copilot、Gemini、Claude、Grok、 DeepSeek などのチャットボット、Stable Diffusion、Midjourney、DALL-E などのテキストから画像への変換モデル、Veo や Sora などのテキストから動画への変換モデルがある。[179][180][181][182][183] 生成AIを開発するテクノロジー企業には、OpenAI、xAI、Anthropic、Meta AI、Microsoft、Google、DeepSeek、Baiduがある。[177][184][185] 生成 AI は、ソフトウェア開発[186]、医療[187]、金融[188]、エンターテイメント[189]、顧客サービス[190]、販売およびマーケティング [191]、芸術、執筆[192]、ファッション[193]、製品設計など、多くの業界で使用されている。[194] 生成AIシステムの生産には、処理に高いエネルギーと冷却に水が必要な専用チップを使用する大規模データセンターが必要だ。[195] |

| Agents Main article: Agentic AI AI agents are software entities designed to perceive their environment, make decisions, and take actions autonomously to achieve specific goals. These agents can interact with users, their environment, or other agents. AI agents are used in various applications, including virtual assistants, chatbots, autonomous vehicles, game-playing systems, and industrial robotics. AI agents operate within the constraints of their programming, available computational resources, and hardware limitations. This means they are restricted to performing tasks within their defined scope and have finite memory and processing capabilities. In real-world applications, AI agents often face time constraints for decision-making and action execution. Many AI agents incorporate learning algorithms, enabling them to improve their performance over time through experience or training. Using machine learning, AI agents can adapt to new situations and optimise their behaviour for their designated tasks.[196][197][198] Sexuality Applications of AI in this domain include AI-enabled menstruation and fertility trackers that analyze user data to offer predictions,[199] AI-integrated sex toys (e.g., teledildonics),[200] AI-generated sexual education content,[201] and AI agents that simulate sexual and romantic partners (e.g., Replika).[202] AI is also used for the production of non-consensual deepfake pornography, raising significant ethical and legal concerns.[203] AI technologies have also been used to attempt to identify online gender-based violence and online sexual grooming of minors.[204][205] Other industry-specific tasks There are also thousands of successful AI applications used to solve specific problems for specific industries or institutions. In a 2017 survey, one in five companies reported having incorporated "AI" in some offerings or processes.[206] A few examples are energy storage, medical diagnosis, military logistics, applications that predict the result of judicial decisions, foreign policy, or supply chain management. AI applications for evacuation and disaster management are growing. AI has been used to investigate patterns in large-scale and small-scale evacuations using historical data from GPS, videos or social media. Furthermore, AI can provide real-time information on the evacuation conditions.[207][208][209] In agriculture, AI has helped farmers to increase yield and identify areas that need irrigation, fertilization, pesticide treatments. Agronomists use AI to conduct research and development. AI has been used to predict the ripening time for crops such as tomatoes, monitor soil moisture, operate agricultural robots, conduct predictive analytics, classify livestock pig call emotions, automate greenhouses, detect diseases and pests, and save water. Artificial intelligence is used in astronomy to analyze increasing amounts of available data and applications, mainly for "classification, regression, clustering, forecasting, generation, discovery, and the development of new scientific insights." For example, it is used for discovering exoplanets, forecasting solar activity, and distinguishing between signals and instrumental effects in gravitational wave astronomy. Additionally, it could be used for activities in space, such as space exploration, including the analysis of data from space missions, real-time science decisions of spacecraft, space debris avoidance, and more autonomous operation. During the 2024 Indian elections, US$50 million was spent on authorized AI-generated content, notably by creating deepfakes of allied (including sometimes deceased) politicians to better engage with voters, and by translating speeches to various local languages.[210] |

エージェント 主な記事:エージェント型 AI AI エージェントは、環境を知覚し、意思決定を行い、特定の目標を達成するために自律的に行動するように設計されたソフトウェアエンティティである。これらのエー ジェントは、ユーザー、その環境、または他のエージェントと対話することができる。AI エージェントは、仮想アシスタント、チャットボット、自動運転車、ゲームプレイシステム、産業用ロボットなど、さまざまなアプリケーションで使用されてい る。AI エージェントは、そのプログラミング、利用可能な計算リソース、およびハードウェアの制限の範囲内で動作する。つまり、定義された範囲内のタスクの実行に 制限され、メモリや処理能力にも限りがある。現実世界のアプリケーションでは、AI エージェントは意思決定や行動の実行において時間的制約に直面することが多い。多くの AI エージェントは学習アルゴリズムを組み込んでおり、経験やトレーニングを通じて、時間の経過とともにパフォーマンスを向上させることができる。機械学習を 使用することで、AI エージェントは新しい状況に適応し、指定されたタスクに合わせて行動を最適化することができる。[196][197][198] セクシュアリティ この分野における AI の応用例としては、ユーザーデータを分析して予測を提供する AI 搭載の月経・妊娠追跡アプリ[199]、AI を組み込んだ大人のおもちゃ(テレディルドニクスなど)[200]、AI によって生成された性教育コンテンツ[201]、性的パートナーや恋愛パートナーをシミュレートする AI エージェント(Replika など)がある。[202] AI は、同意のないディープフェイクポルノの制作にも使用されており、重大な倫理的および法的問題を引き起こしている。[203] AI 技術は、オンラインでのジェンダーに基づく暴力や未成年者に対するオンラインでの性的誘惑の特定にも使用されている。[204][205] その他の業界固有のタスク 特定の業界や機関の特定の課題を解決するために、数千ものAIアプリケーションが成功裏に活用されている。2017年の調査では、5社に1社が、一部の製 品やプロセスに「AI」を組み込んでいると回答している。[206] 例としては、エネルギー貯蔵、医療診断、軍事物流、司法判断の結果を予測するアプリケーション、外交政策、サプライチェーンマネジメントなどが挙げられ る。 避難および災害管理のためのAIアプリケーションが拡大している。AI は、GPS、ビデオ、ソーシャルメディアからの履歴データを用いて、大規模および小規模の避難のパターンを調査するために使用されている。さらに、AI は避難状況に関するリアルタイムの情報を提供することができる。[207][208][209] 農業分野では、AI は農家の収穫量の増加や、灌漑、施肥、農薬散布が必要な地域の特定に役立っている。農学者は AI を研究開発に活用している。AI は、トマトなどの作物の成熟時期の予測、土壌水分モニタリング、農業用ロボットの操作、予測分析、家畜の感情の分類、温室の自動化、病気や害虫の検出、節 水などに活用されている。 人工知能は、主に「分類、回帰、クラスタリング、予測、生成、発見、および新しい科学的知見の開発」のために、利用可能なデータやアプリケーションの増加 を分析するために天文学で活用されている。例えば、系外惑星の発見、太陽活動の予測、重力波天文学における信号と機器の影響の区別などに活用されていま す。さらに、宇宙探査を含む宇宙活動、例えば宇宙ミッションからのデータ分析、宇宙船のリアルタイム科学判断、宇宙ごみの回避、より自律的な運用などにも 活用される可能性があります。 2024年のインドの選挙では、有権者の関心を高めるため、同盟国の政治家(時には故人を含む)のディープフェイクを作成したり、演説をさまざまな現地言語に翻訳したりするなど、認可された AI 生成コンテンツに 5,000 万米ドルが費やされた。 |