ウィキペディアはいう「チューリングテスト(Turing test)は、アラン・ チューリングが提案した、ある機械が「人間的」かどうかを判定するためのテストである。これが「知的であるかかどうか」とか「人工知能であるかどうか」と かのテストであるかどうかは、「知的」あるいは「(人工)知能」の定義、あるいは、人間が知的であるか、人間の能力は知能であるか、といった定義に依存す る。 アラン・チューリングが1950年に"Computing Machinery and Intelligence"の中で書いたもので、以下のように行われる。人間の判定者が、一人の(別の)人間と一機の機械に対して通常の言語での会話を行 う。このとき人間も機械も人間らしく見えるように対応するのである。これらの参加者はそれぞれ隔離されている。判定者は、機械の言葉を音声に変換する能力 に左右されることなく、その知性を判定するために、会話はたとえばキーボードとディスプレイのみといった、文字のみでの交信に制限しておく[注釈 1]。判定者が、機械と人間との確実な区別ができなかった場合、この機械はテストに合格したことになる。 このテストについては、もっともだと納得する人もいれば、そうでない人もいた。後に実際に人間と「会話」するコンピュータ・プログラムが現れた後における 知見としては、「ELIZA効果」などのように、先入観や情況などによって単純な(「機械的」な)反応をするだけのものにも人間はだまされてしまう場合が あるということがわかり、それは結果的にはこのテストの発想への反例と考えられることがある。サールは、そのような一見人工知能のように見えるものを"弱 いAI"とした。他にもサールは「中国語の部屋」という、表面的にはこのテストと同であるにもかかわらず、その示す所に納得できないだろうようなアレンジ を提示している。 2014年6月7日、ロンドンのテストに「13歳の少年」の設定で参加したロシアのチャットボットであるユージーン・グーツマン(Eugene Goostman)が、30%以上の確率で審査員らに人間と間違われて史上初めての「合格者」となった」以上、ウィキペディア.

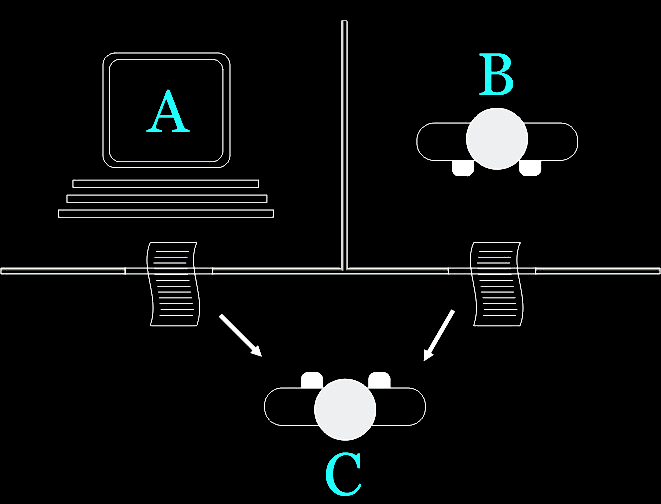

"The Turing test, originally called the imitation game by Alan Turing in 1950,[2] is a test of a machine's ability to exhibit intelligent behaviour equivalent to, or indistinguishable from, that of a human. Turing proposed that a human evaluator would judge natural language conversations between a human and a machine designed to generate human-like responses. The evaluator would be aware that one of the two partners in conversation is a machine, and all participants would be separated from one another. The conversation would be limited to a text-only channel such as a computer keyboard and screen so the result would not depend on the machine's ability to render words as speech.[3] If the evaluator cannot reliably tell the machine from the human, the machine is said to have passed the test. The test results do not depend on the machine's ability to give correct answers to questions, only how closely its answers resemble those a human would give. The test was introduced by Turing in his 1950 paper "Computing Machinery and Intelligence" while working at the University of Manchester.[4] It opens with the words: "I propose to consider the question, 'Can machines think?'" Because "thinking" is difficult to define, Turing chooses to "replace the question by another, which is closely related to it and is expressed in relatively unambiguous words."[5] Turing describes the new form of the problem in terms of a three-person game called the "imitation game", in which an interrogator asks questions of a man and a woman in another room in order to determine the correct sex of the two players. Turing's new question is: "Are there imaginable digital computers which would do well in the imitation game?"[2] This question, Turing believed, is one that can actually be answered. In the remainder of the paper, he argued against all the major objections to the proposition that "machines can think".[6] Since Turing first introduced his test, it has proven to be both highly influential and widely criticised, and it has become an important concept in the philosophy of artificial intelligence.[7][8][9]. Some of these criticisms, such as John Searle's Chinese room, are themselves controversial."

[2] (Turing 1950, p. 442) Turing does not call his idea "Turing test", but rather the "imitation game"; however, later literature has reserved the term "imitation game" to describe a particular version of the test. See #Versions of the Turing test, below. Turing gives a more precise version of the question later in the paper: "[T]hese questions [are] equivalent to this, 'Let us fix our attention on one particular digital computer C. Is it true that by modifying this computer to have an adequate storage, suitably increasing its speed of action, and providing it with an appropriate programme, C can be made to play satisfactorily the part of A in the imitation game, the part of B being taken by a man?'" (Turing 1950, p. 442)- Turing, Alan (October 1950), "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind, LIX (236): 433–460, doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

リンク

- ︎ヱホバのチューリングテスト▶中国語の部屋のページ︎▶新しいAIのチューリングテスト問題または「人工知能バブルの終焉」︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

文献

- Turing, Alan (October 1950), "Computing Machinery and Intelligence", Mind, LIX (236): 433–460, doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.433

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099