プラトン

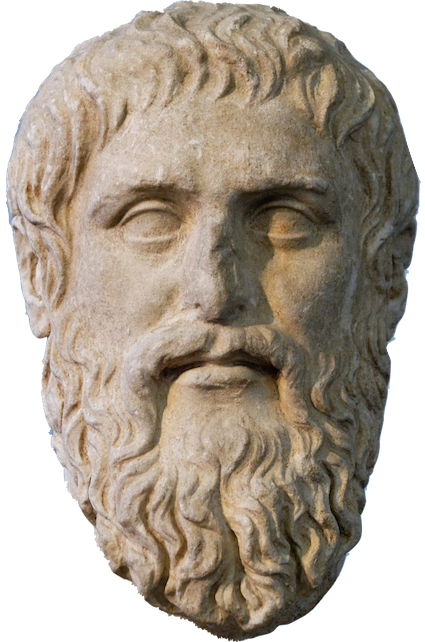

Plato, c.427-348 BC

☆ プラトン( Plato /ˈ PLAY-toe、[1] ギリシア語: Πλάτων)は、アリストクレス(Ἀριστοκλῆς、紀元前427年頃 - 348年頃)出身の古典期の古代ギリシアの哲学者で、西洋哲学の基礎となる思想家であり、対話文や弁証法形式の革新者と考えられている。プラトンは、後に プラトン主義として知られるようになる教義を教えたアテネの哲学学校、プラトン・アカデミーの創設者である。 プラトンの最も有名な貢献は形式(またはイデア)の理論であり、これは現在普遍の問題として知られているものに対する解決策を提示したものと解釈されてい る。プラトンはソクラテス以前の思想家であるピュタゴラス、ヘラクレイトス、パルメニデスから決定的な影響を受けたが、彼らについて知られていることの多 くはプラトン自身から得たものである[a]。 プラトンは、師であるソクラテス、弟子のアリストテレスとともに、哲学史の中心人物である。プラトンの全著作は、同時代のほぼすべての著作とは異なり、 2,400年以上そのままの形で残っていると考えられている。プラトンの著作の人気は変動しているものの、時代を超えて一貫して読み継がれ、研究されてき た。現代では、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドが有名な言葉を残している:現代において、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドは有名な言葉を残し ている。"ヨーロッパの哲学的伝統の最も安全な一般的特徴は、それがプラトンへの一連の脚注で構成されているということである"。

★プラトンの作品

| Phaedo Meno Protagoras Gorgias Symposium Phaedrus Parmenides Theaetetus Republic Timaeus Laws |

フェードン(パイドン/パイドーン)(対話体) メノン(ソクラテス的対話体) プロタゴラス(対話体) ゴルギアス(対話体) 饗宴(ソクラテス的対話体) フェードロス(パイドロス)(対話体) パルメニデス(対話体) テアイテトス(対話体) 国家(共和国) ティマイオス 法律(対話体) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plato |

★プラトンの哲学

★生涯や、評価など

| Plato

(/ˈpleɪtoʊ/ PLAY-toe;[1] Greek: Πλάτων), born Aristocles

(Ἀριστοκλῆς;

c. 427 – 348 BC), was an ancient Greek philosopher of the Classical

period who is considered a foundational thinker in Western philosophy

and an innovator of the written dialogue and dialectic forms. He raised

problems for what became all the major areas of both theoretical

philosophy and practical philosophy, and was the founder of the

Platonic Academy, a philosophical school in Athens where Plato taught

the doctrines that would later become known as Platonism. Plato's most famous contribution is the theory of forms (or ideas), which has been interpreted as advancing a solution to what is now known as the problem of universals. He was decisively influenced by the pre-Socratic thinkers Pythagoras, Heraclitus, and Parmenides, although much of what is known about them is derived from Plato himself.[a] Along with his teacher Socrates, and Aristotle, his student, Plato is a central figure in the history of philosophy.[b] Plato's entire body of work is believed to have survived intact for over 2,400 years—unlike that of nearly all of his contemporaries.[5] Although their popularity has fluctuated, they have consistently been read and studied through the ages.[6] Through Neoplatonism, he also greatly influenced both Christian and Islamic philosophy.[c] In modern times, Alfred North Whitehead famously said: "the safest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato."[7] |

プラトン(/ˈ PLAY-toe、[1] ギリシア語:

Πλάτων)は、アリストクレス(Ἀριστοκλῆς、紀元前427年頃 -

348年頃)出身の古典期の古代ギリシアの哲学者で、西洋哲学の基礎となる思想家であり、対話文や弁証法形式の革新者と考えられている。プラトンは、後に

プラトン主義として知られるようになる教義を教えたアテネの哲学学校、プラトン・アカデミーの創設者である。 プラトンの最も有名な貢献は形式(またはイデア)の理論であり、これは現在普遍の問題として知られているものに対する解決策を提示したものと解釈されてい る。プラトンはソクラテス以前の思想家であるピュタゴラス、ヘラクレイトス、パルメニデスから決定的な影響を受けたが、彼らについて知られていることの多 くはプラトン自身から得たものである[a]。 プラトンは、師であるソクラテス、弟子のアリストテレスとともに、哲学史の中心人物である。プラトンの全著作は、同時代のほぼすべての著作とは異なり、 2,400年以上そのままの形で残っていると考えられている。プラトンの著作の人気は変動しているものの、時代を超えて一貫して読み継がれ、研究されてき た。現代では、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドが有名な言葉を残している: 現代において、アルフレッド・ノース・ホワイトヘッドは有名な言葉を残している。"ヨーロッパの哲学的伝統の最も安全な一般的特徴は、それがプラトンへの 一連の脚注で構成されているということである"。 |

| Names Plato (Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn, from Ancient Greek: πλατύς, romanized: platys, lit. 'broad') is actually a nickname. Although it is a fact that the philosopher called himself Platon in his maturity, the origin of this name remains mysterious. Platon was a fairly common name (31 instances are known from Athens alone),[8] but the name does not occur in Plato's known family line.[9] The sources of Diogenes Laertius account for this by claiming his wrestling coach, Ariston of Argos, dubbed him "broad" on account of his chest and shoulders, or that Plato derived his name from the breadth of his eloquence, or his wide forehead.[10][11] Philodemus, in extracts from the Herculaneum papyri, corroborates the claim that Plato was named for his "broad forehead".[12] While recalling a moral lesson about frugal living, Seneca mentions the meaning of Plato's name: "His very name was given him because of his broad chest."[13] According to Diogenes Laertius,[14] his birth name was Aristocles (Ἀριστοκλῆς), meaning 'best reputation'.[d] |

名前 プラトン(ギリシャ語:Πλάτων,Plátōn,古代ギリシャ語: πλατύς,ローマ字表記:platys,lit. ギリシャ語: Πλατύς, ローマ字表記: platys, lit. 哲学者が円熟期にプラトンと名乗ったのは事実だが、この名前の由来は謎のままである。プラトンはかなり一般的な名前であったが(アテネだけで31例が知ら れている)[8]、この名前はプラトンの家系には登場しない[9]。 ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスの資料では、彼のレスリングのコーチであったアルゴスのアリストンが、彼の胸と肩の広さを理由に「広い」と呼んだと主張した り、プラトンの名前の由来は彼の雄弁の広さ、あるいは彼の額の広さであると主張したりして、このことを説明している[10][11]。フィロデモスは ヘルクラネウムのパピルスからの抜粋の中で、プラトンが「広い額」から名付けられたという主張を裏付けている[12]。 セネカは質素な生活についての道徳的教訓を思い起こしながら、プラトンの名前の意味について言及している:「彼の名前はまさにその広い胸のゆえに与えられ た」[13] ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによれば[14]、彼の出生名はアリストクレス(Ἀριστοκλῆς)で、「最高の評判」を意味する[d]。 |

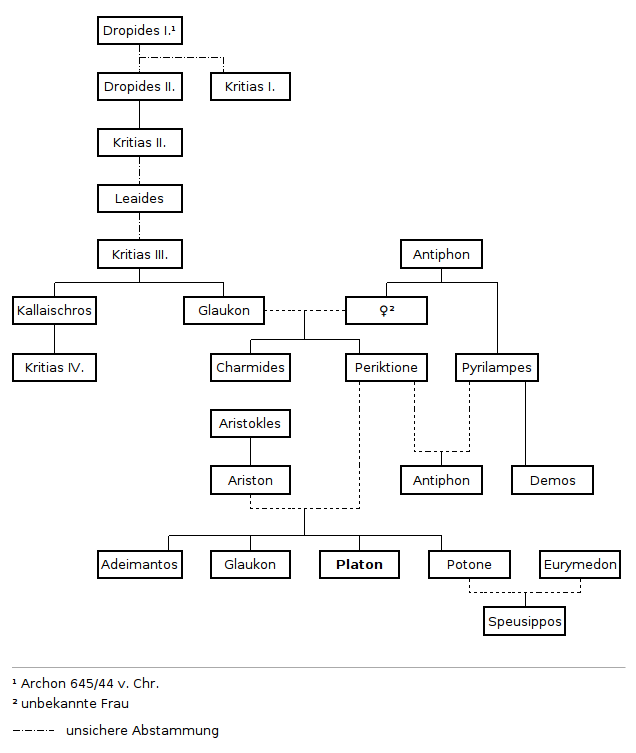

Biography Further information: Life of Plato Plato, whose actual name was Aristocles, was born in Athens or Aegina, between 428[15] and 423 BC.[16] He was a member of an aristocratic and influential family.[17][e][20] His father was Ariston,[f][20] who may have been a descendant of two kings—Codrus and Melanthus.[g][21] His mother was Perictione, descendant of Solon,[22][23] a statesman credited with laying the foundations of Athenian democracy.[24][25][26] Plato had two brothers, Glaucon and Adeimantus, a sister, Potone,[23] and a half brother, Antiphon.[27] Plato may have travelled to Italy, Sicily, Egypt, and Cyrene.[28] At 40, he founded a school of philosophy, the Academy. It was located in Athens, on a plot of land in the Grove of Hecademus or Academus,[29] named after an Attic hero in Greek mythology. The Academy operated until it was destroyed by Sulla in 84 BC. Many philosophers studied at the Academy, the most prominent being Aristotle.[30][31] According to Diogenes Laertius, throughout his later life, Plato became entangled with the politics of the city of Syracuse, where he attempted to replace the tyrant Dionysius,[32] with Dionysius's brother-in-law, Dion of Syracuse, whom Plato had recruited as one of his followers, but the tyrant himself turned against Plato. Plato almost faced death, but was sold into slavery. Anniceris, a Cyrenaic philosopher, bought Plato's freedom for twenty minas,[33] and sent him home. Philodemus however states that Plato was sold as a slave as early as in 404 BC, when the Spartans conquered Aegina, or, alternatively, in 399 BC, immediately after the death of Socrates.[34] After Dionysius's death, according to Plato's Seventh Letter, Dion requested Plato return to Syracuse to tutor Dionysius II, who seemed to accept Plato's teachings, but eventually became suspicious of their motives, expelling Dion and holding Plato against his will. Eventually Plato left Syracuse and Dion would return to overthrow Dionysius and rule Syracuse, before being usurped by Callippus, a fellow disciple of Plato. A variety of sources have given accounts of Plato's death. One story, based on a mutilated manuscript,[35] suggests Plato died in his bed, whilst a young Thracian girl played the flute to him.[36] Another tradition suggests Plato died at a wedding feast. The account is based on Diogenes Laertius's reference to an account by Hermippus, a third-century Alexandrian.[37] According to Tertullian, Plato simply died in his sleep.[37] According to Philodemus, Plato was buried in the garden of his academy in Athens, close to the sacred shrine of the Muses.[34] |

バイオグラフィー さらに詳しい情報 プラトンの生涯 プラトンは実名をアリストクレスといい、紀元前428年[15]から423年の間にアテネかエギナで生まれた[16]。父親はアリストンで[f] [20]、コドルスと メランサスの2人の王の子孫であった可能性がある。 [g][21]母はアテナイ民主主義の基礎を築いたとされる政治家ソロンの子孫であるペリクショネ[22][23]であった[24][25][26]プラ トンにはグラウコンと アデイマントスの2人の兄弟、妹のポトネ[23]、異母弟のアンティフォン[27]がいた。 プラトンはイタリア、シチリア、エジプト、キュレネを旅した可能性がある[28]。アカデミーはアテネのヘカデムスの木立の一画にあり、ギリシャ神話に登 場するアッティカ人の英雄にちなんで名付けられた[29]。アカデミーは紀元前84年にスッラによって破壊されるまで運営された。多くの哲学者がアカデ ミーで学んだが、最も著名なのはアリストテレスである[30][31]。 ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによれば、プラトンは晩年を通じてシラクサの政治に関わるようになり、暴君ディオニシウスに代わって、プラトンが従者の一人 としてスカウトしたディオニシウスの義弟であるシラクサのディオンをシラクサに擁立しようとしたが[32]、暴君ディオニシウス自身がプラトンに反旗を翻 した。プラトンは死に直面しそうになったが、奴隷として売られた。キレナイの哲学者アンニセリスは20ミナでプラトンの自由を買い取り、彼を故郷に送った [33]。しかしフィロデモスは、プラトンが奴隷として売られたのはスパルタ軍がエギナを征服した紀元前404年か、あるいはソクラテスの死後すぐの紀元 前399年であったと述べている[34]。 プラトンの『第七書簡』によれば、ディオニシウスの死後、ディオンはディオニシウス2世の家庭教師としてシラクサに戻るようプラトンに要請し、ディオニシ ウス2世はプラトンの教えを受け入れたようであったが、やがてその動機に疑念を抱き、ディオンを追放し、プラトンの意思に反してプラトンを拘束した。やが てプラトンはシラクサを去り、ディオニシウスはディオニシウスを打倒してシラクサを統治するために戻ってくるが、プラトンの弟子仲間であったカリッポスに 簒奪される。 プラトンの死については、さまざまな資料が伝えている。ある説では、プラトンはベッドで若いトラキア娘にフルートを吹かれながら死んだとされ[35]、ま た別の説では、プラトンは婚礼の宴で死んだとされている。テルトゥリアヌスによれば、プラトンは単に眠っている間に死んだとされる[37]。 フィロデモスによれば、プラトンはアテネのアカデミーの庭に埋葬され、ミュゼスの聖廟の近くにあったとされる[34]。 |

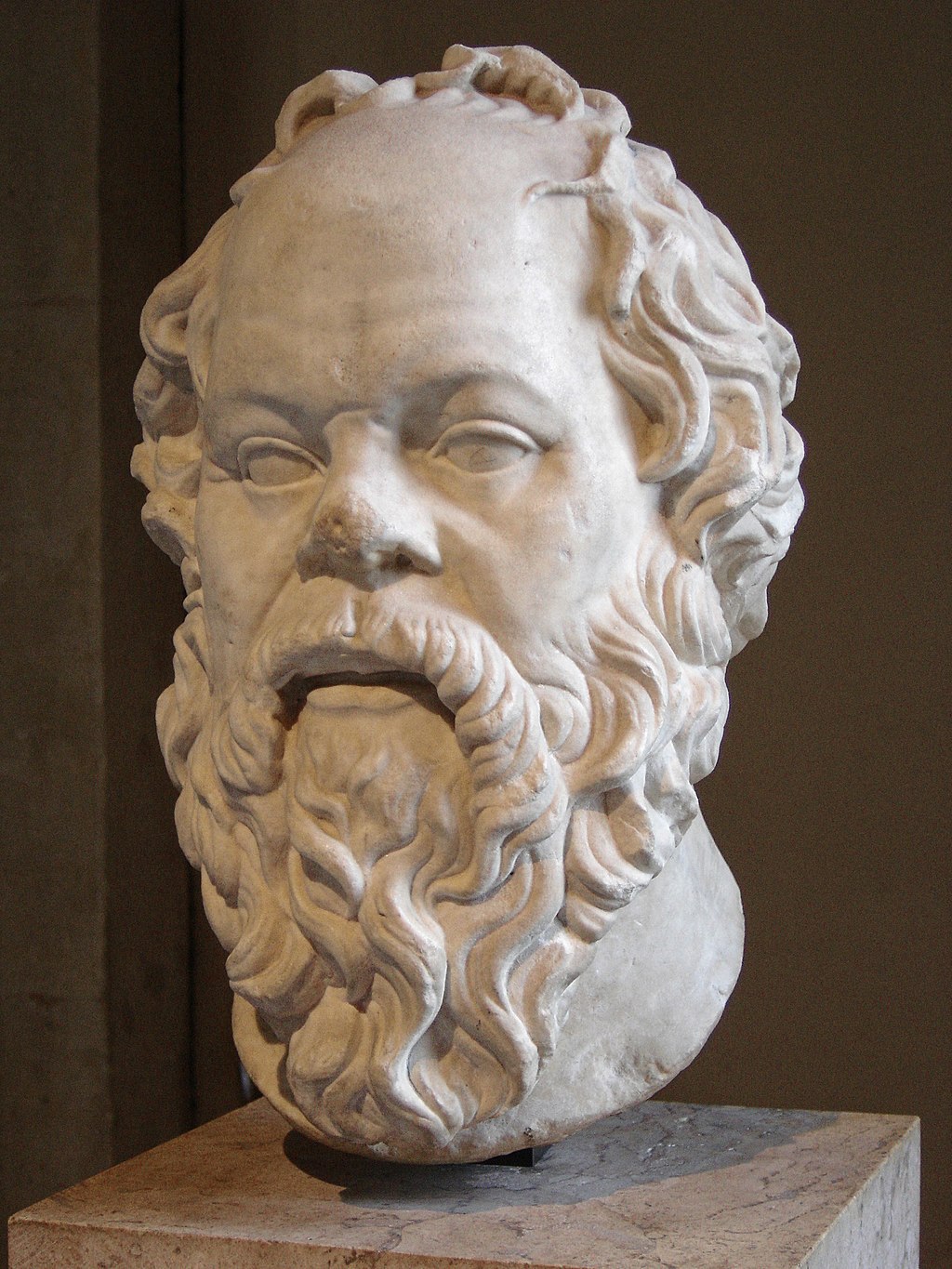

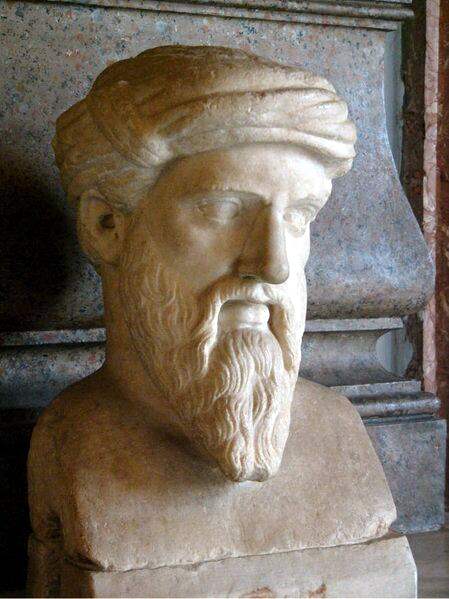

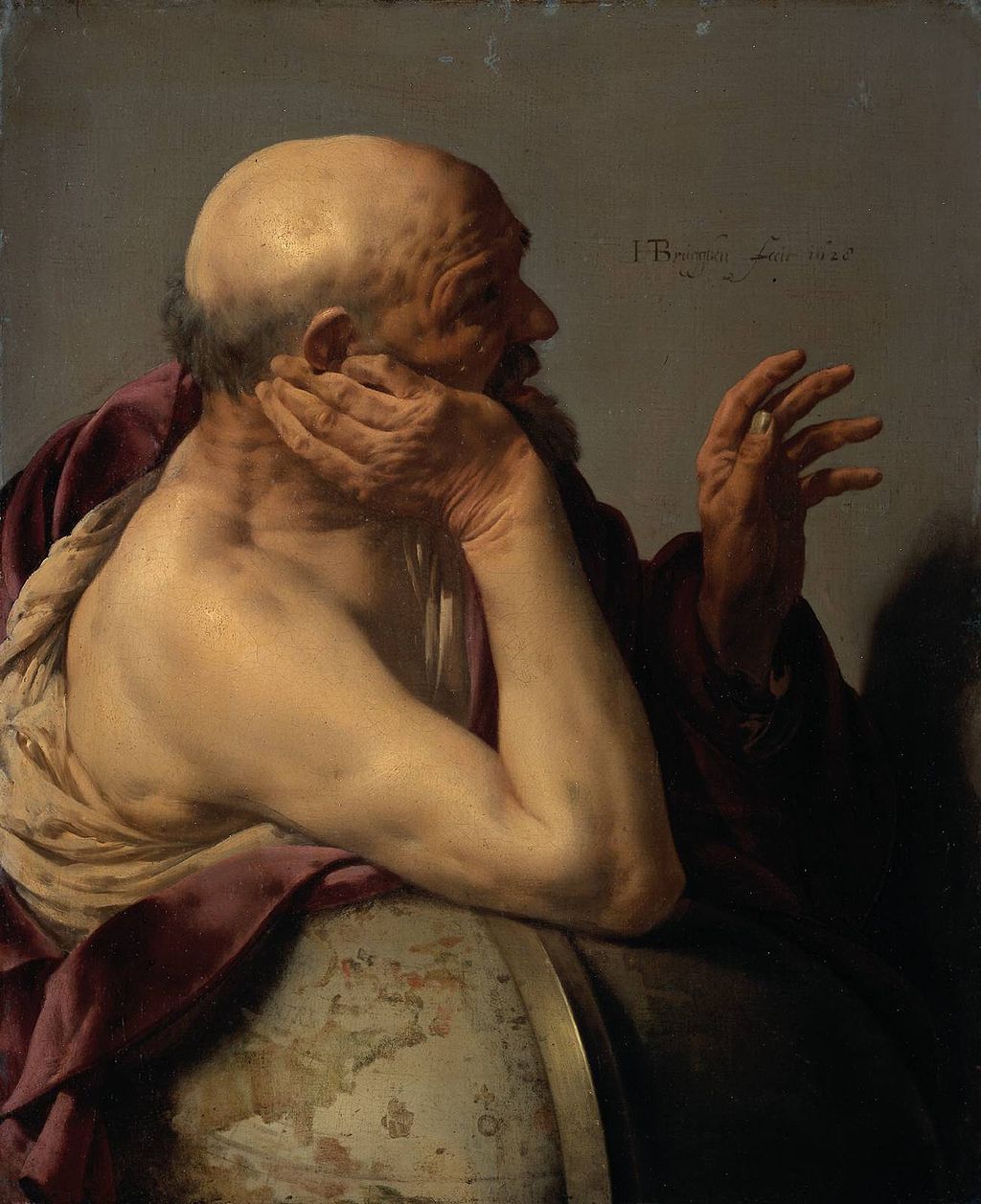

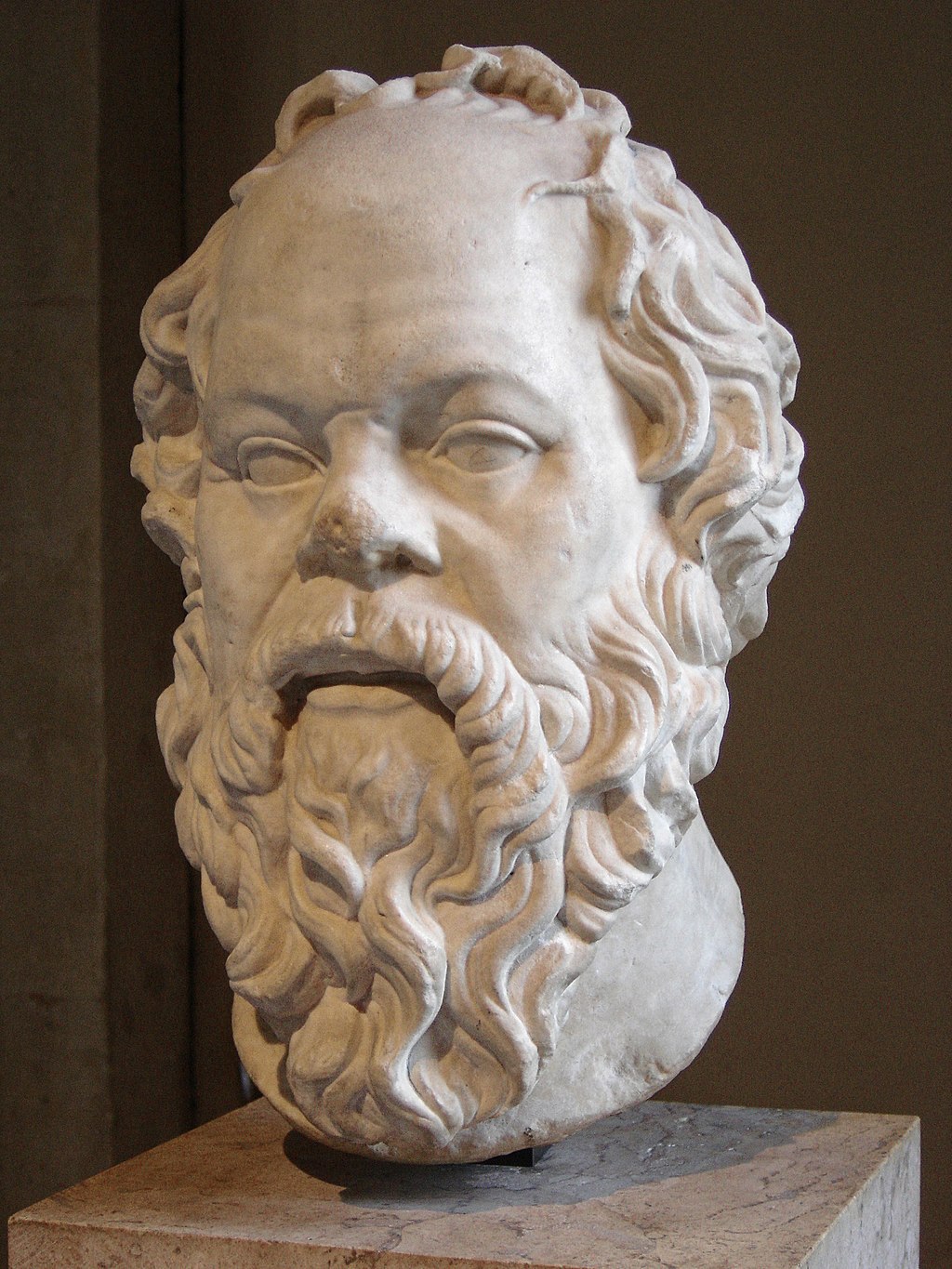

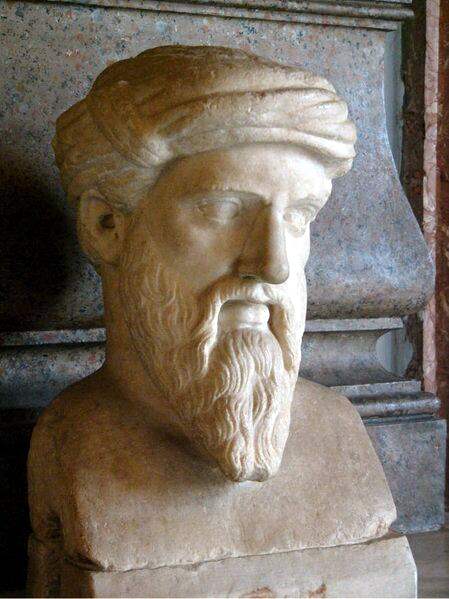

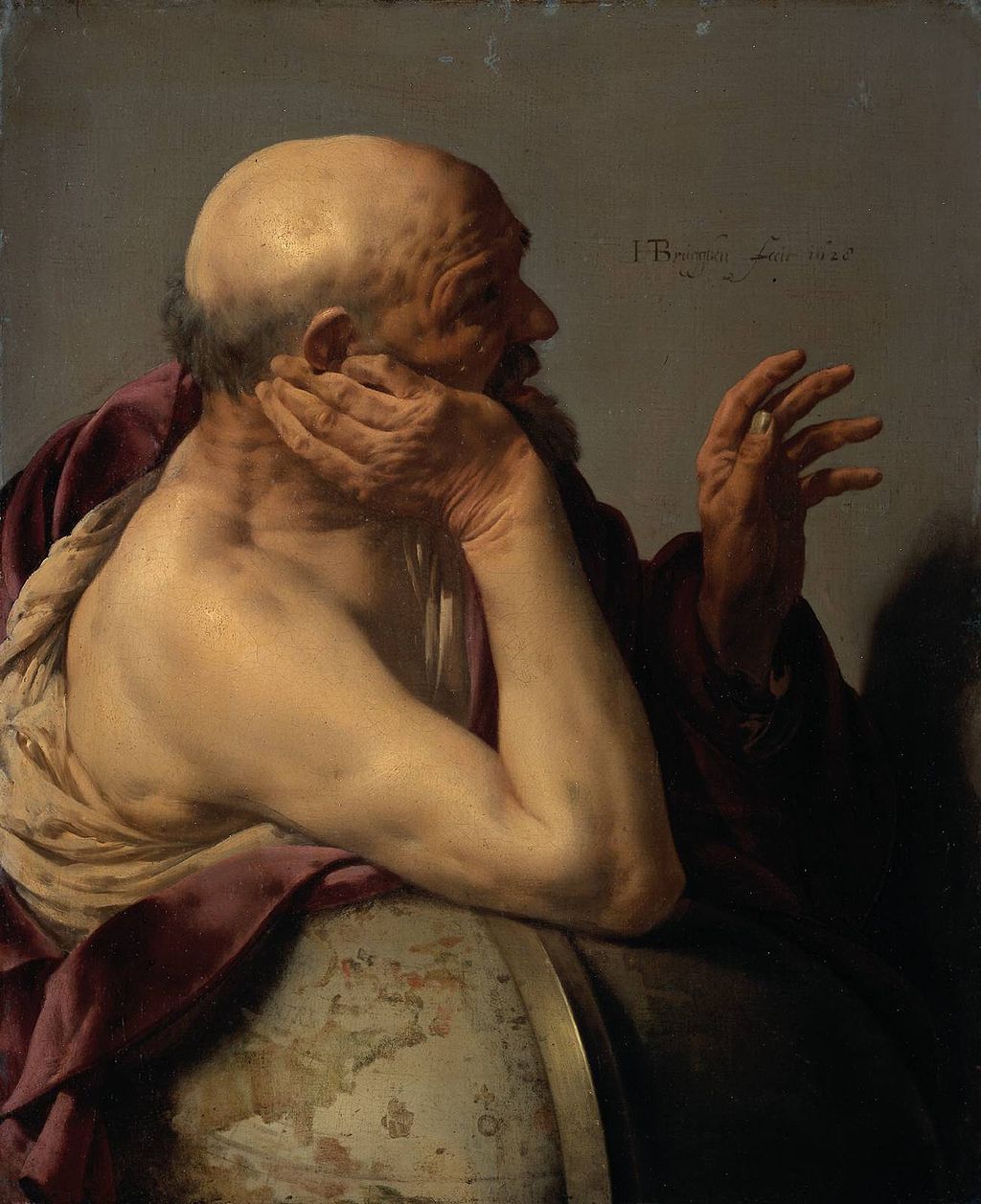

| Influences Plato was one of the devoted young followers of Socrates, whose bust is pictured above.  Socrates Main article: Socratic problem Plato never speaks in his own voice in his dialogues; every dialogue except the Laws features Socrates, although many dialogues, including the Timaeus and Statesman, feature him speaking only rarely. Leo Strauss notes that Socrates' reputation for irony casts doubt on whether Plato's Socrates is expressing sincere beliefs.[38] Xenophon's Memorabilia and Aristophanes's The Clouds seem to present a somewhat different portrait of Socrates from the one Plato paints. Aristotle attributes a different doctrine with respect to Forms to Plato and Socrates.[39] Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms that exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding.[40] The Socratic problem concerns how to reconcile these various accounts. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of contention among scholars.[41][page needed] Pythagoreanism Main article: Pythagoreanism  The mathematical and mystical teachings of the followers of Pythagoras, pictured above, exerted a strong influence on Plato. Although Socrates influenced Plato directly, the influence of Pythagoras, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as Archytas also appears to have been significant. Aristotle and Cicero both claimed that the philosophy of Plato closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans.[42][43] According to R. M. Hare, this influence consists of three points: The platonic Republic might be related to the idea of "a tightly organized community of like-minded thinkers", like the one established by Pythagoras in Croton. The idea that mathematics and, generally speaking, abstract thinking is a secure basis for philosophical thinking as well as "for substantial theses in science and morals". They shared a "mystical approach to the soul and its place in the material world".[44][45] Pythagoras held that all things are number, and the cosmos comes from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as distinct from matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world. These ideas were very influential on Heraclitus, Parmenides and Plato.[46][47]  Heraclitus  Parmenides Main articles: Heraclitus and Parmenides Heraclitus (1628) by Hendrick ter Brugghen. Heraclitus saw a world in flux, with everything always in conflict, constantly changing. Bust of Parmenides from Velia. Parmenides saw the world as eternal and unchanging, that all change was an illusion. The two philosophers Heraclitus and Parmenides, influenced by earlier pre-Socratic Greek philosophers such as Pythagoras and Xenophanes,[48] departed from mythological explanations for the universe and began the metaphysical tradition that strongly influenced Plato and continues today.[47] Heraclitus viewed all things as continuously changing, that one cannot "step into the same river twice" due to the ever-changing waters flowing through it, and all things exist as a contraposition of opposites. According to Diogenes Laertius, Plato received these ideas through Heraclitus' disciple Cratylus.[49] Parmenides adopted an altogether contrary vision, arguing for the idea of a changeless, eternal universe and the view that change is an illusion.[47] Plato's most self-critical dialogue is the Parmenides, which features Parmenides and his student Zeno, which criticizes Plato's own metaphysical theories. Plato's Sophist dialogue includes an Eleatic stranger. These ideas about change and permanence, or becoming and Being, influenced Plato in formulating his theory of Forms.[49] |

影響 プラトンはソクラテスの若い熱心な信奉者の一人であった。  ソクラテス 主な記事 ソクラテスの問題 プラトンは対話の中で自分の声で話すことはない。『法学』を除くすべての対話にソクラテスが登場するが、『ティマイオス』や『ステーツマン』を含む多くの 対話では、ソクラテスが話すことはまれである。レオ・シュトラウスは、ソクラテスの皮肉に対する評判が、プラトンのソクラテスが誠実な信念を表明している かどうかに疑問を投げかけていると指摘している[38]。クセノフォンの『メモラビリア』とアリストファネスの『雲』は、プラトンの描くソクラテス像とは やや異なるソクラテス像を提示しているようである。アリストテレスは、プラトンとソクラテスの形相に関する教義は異なるとしている[39]。アリストテレ スは、ソクラテスの形相の考えは、プラトンの形相とは異なり、自然界を調査することによって発見することができると示唆している。プラトンとソクラテスの 正確な関係については、学者たちの間で論争が続いている[41][要出典]。 ピタゴラス主義 主な記事 ピタゴラス主義  上の写真のピタゴラスの信奉者たちの数学的・神秘的な教えは、プラトンに強い影響を与えた。 ソクラテスはプラトンに直接影響を与えたが、アルキタスなどの ピタゴラス、あるいは広義のピタゴラス派の影響も大きかったようだ。アリストテレスと キケロは、プラトンの哲学はピュタゴラス派の教えを忠実に踏襲していると主張している[42][43]: プラトン共和国は、ピタゴラスがクロトンに設立したような「志を同じくする思想家たちの緊密に組織された共同体」という考え方に関連しているかもしれな い。 数学と、一般的に言えば抽象的な思考が、哲学的思考だけでなく「科学と 道徳における実質的なテーゼの」確実な基礎となるという考え。 彼らは「魂と物質世界におけるその位置に対する神秘主義的なアプローチ」を共有していた[44][45]。 ピタゴラスは万物は数であり、宇宙は数の原理から生まれるとした。彼は物質とは異なる形の概念を導入し、物理的世界は永遠の数学的世界の模倣であるとし た。これらの考えはヘラクレイトス、パルメニデス、プラトンに大きな影響を与えた[46][47]。  ヘラクレイトス  パルメニデス 主な記事 ヘラクレイトスと パルメニデス ヘンドリック・テル・ブルッヘン作『ヘラクレイトス』(1628年)。ヘラクレイトスは、あらゆるものが常に対立し、絶えず変化する流動的な世界を見てい た。 ヴェリアのパルメニデスの胸像。パルメニデスは、世界は永遠で不変であり、すべての変化は幻想であると考えた。 ヘラクレイトスと パルメニデスの2人の哲学者は、ピタゴラスやクセノファネスといった ソクラテス以前のギリシアの哲学者の影響を受け[48]、宇宙に関する神話的な説明から離れ、プラトンに強い影響を与え、今日まで続いている形而上学的な 伝統を始めた[47]。ディオゲネス・ラエルティウスによれば、プラトンはヘラクレイトスの弟子クラティロスを通じてこれらの考えを得た[49]。パルメ ニデスは全く逆の考えを採用し、変化のない永遠の宇宙という考えと、変化は幻想であるという見解を主張した[47]。プラトンの最も自己批判的な対話は、 パルメニデスとその弟子ゼノが登場する『パルメニデス』であり、プラトン自身の形而上学的理論を批判している。プラトンの『ソフィスト』の対話には、エレ アスの異端者が登場する。変化と永続性、あるいは「なること」と「存在すること」に関するこれらの考え方は、プラトンが形相論を定式化する際に影響を与え た[49]。 |

| Rhetoric and poetry Several dialogues tackle questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says that poetry is inspired by the muses, and is not rational. He speaks approvingly of this, and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreaming) in the Phaedrus,[66] and yet in the Republic wants to outlaw Homer's great poetry, and laughter as well. Scholars often view Plato's philosophy as at odds with rhetoric due to his criticisms of rhetoric in the Gorgias and his ambivalence toward rhetoric expressed in the Phaedrus. But other contemporary researchers contest the idea that Plato despised rhetoric and instead view his dialogues as a dramatization of complex rhetorical principles.[67][68][69] Plato made abundant use of mythological narratives in his own work;[70] It is generally agreed that the main purpose for Plato in using myths was didactic.[71] He considered that only a few people were capable or interested in following a reasoned philosophical discourse, but men in general are attracted by stories and tales. Consequently, then, he used the myth to convey the conclusions of the philosophical reasoning.[72] Notable examples include the story of Atlantis, the Myth of Er, and the Allegory of the Cave. |

修辞と詩作 いくつかの対話は、修辞学や狂詩曲を含む芸術に関する問題に取り組んでいる。ソクラテスは、詩はミューズに触発されたもので、理性的なものではないと言 う。ソクラテスは『パイドロス』において、この詩や他の神の狂気(酩酊、エロティシズム、夢想)を肯定的に語っているが[66]、『共和国』ではホメロス の偉大な詩や笑いを禁止しようとしている。ゴルギアス』での修辞学批判や『パイドロス』での修辞学に対する両義的な態度から、学者たちはプラトンの哲学を 修辞学と対立するものとみなすことが多い。しかし他の現代の研究者たちは、プラトンが修辞学を軽んじていたという考えに異議を唱え、その代わりに彼の対話 篇を複雑な修辞学的原理の劇化と見なしている[67][68][69]。プラトンは自身の著作の中で神話的物語をふんだんに用いている[70]。プラトン が神話を用いる主な目的は教訓的なものであったというのが一般的な見解である[71]。彼は、理路整然とした哲学的言説に従うことができたり興味を持った りする人間はごく少数であるが、一般的な人間は物語や物語に惹かれると考えた。その結果、プラトンは哲学的推論の結論を伝えるために神話を用いた。 |

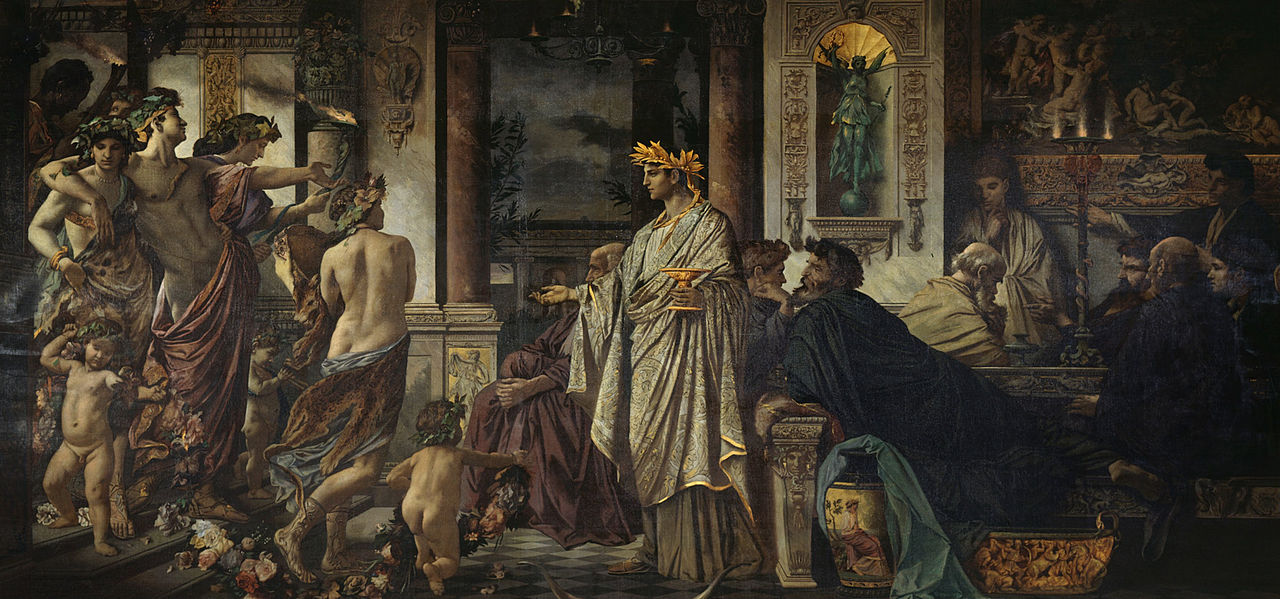

| Works Themes  Painting of a scene from Plato's Symposium (Anselm Feuerbach, 1873) See also: List of speakers in Plato's dialogues Plato never presents himself as a participant in any of the dialogues, and with the exception of the Apology, there is no suggestion that he heard any of the dialogues firsthand. Some dialogues have no narrator but have a pure "dramatic" form, some dialogues are narrated by Socrates himself, who speaks in the first person. The Symposium is narrated by Apollodorus, a Socratic disciple, apparently to Glaucon. Apollodorus assures his listener that he is recounting the story, which took place when he himself was an infant, not from his own memory, but as remembered by Aristodemus, who told him the story years ago. The Theaetetus is also a peculiar case: a dialogue in dramatic form embedded within another dialogue in dramatic form. Some scholars take this as an indication that Plato had by this date wearied of the narrated form.[73] In most of the dialogues, the primary speaker is Socrates, who employs a method of questioning which proceeds by a dialogue form called dialectic. The role of dialectic in Plato's thought is contested but there are two main interpretations: a type of reasoning and a method of intuition.[74] Simon Blackburn adopts the first, saying that Plato's dialectic is "the process of eliciting the truth by means of questions aimed at opening out what is already implicitly known, or at exposing the contradictions and muddles of an opponent's position."[74] Karl Popper, on the other hand, claims that dialectic is the art of intuition for "visualising the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas, of unveiling the Great Mystery behind the common man's everyday world of appearances".[75] |

作品紹介 テーマ  プラトンの『シンポジウム』の一場面を描いた絵(アンゼルム・フォイエルバッハ、1873年) 以下も参照のこと: プラトンの対話における発言者のリスト プラトンは、どの対話篇においても、自分自身を参加者として示すことはなく、『弁明』を除いては、対話篇のどれかを直接聞いたという事実はない。語り手が いない純粋な「劇」形式の対話もあれば、ソクラテス自身が一人称で語る対話もある。シンポジウム』は、ソクラテスの弟子アポロドロスがグラウコンに語りか けたものである。アポロドルスは、自分自身の記憶ではなく、数年前にアリストデモスから聞いた話を、自分が幼い頃の出来事として語っているのだと、聞き手 に保証している。テアエテトス』もまた特殊なケースである。劇形式の対話の中に、別の劇形式の対話が埋め込まれているのだ。ほとんどの対話篇において、主 な話し手はソクラテスであり、ソクラテスは弁証法と呼ばれる対話形式によって進行する質問法を用いている。プラトンの思想における弁証法の役割については 論争があるが、推論の一種と直観の方法という2つの主な解釈がある[74]。サイモン・ブラックバーンは前者を採用し、プラトンの弁証法は「すでに暗黙の うちに知られていることを開陳すること、あるいは相手の立場の矛盾や混迷を暴露することを目的とした質問によって真理を引き出すプロセス」であると述べて いる。 「一方、カール・ポパーは、弁証法は「神的な起源である形態やイデアを視覚化し、庶民の日常的な見かけの世界の背後にある大いなる謎を解き明かす」ための 直観の技術であると主張している[75]。 |

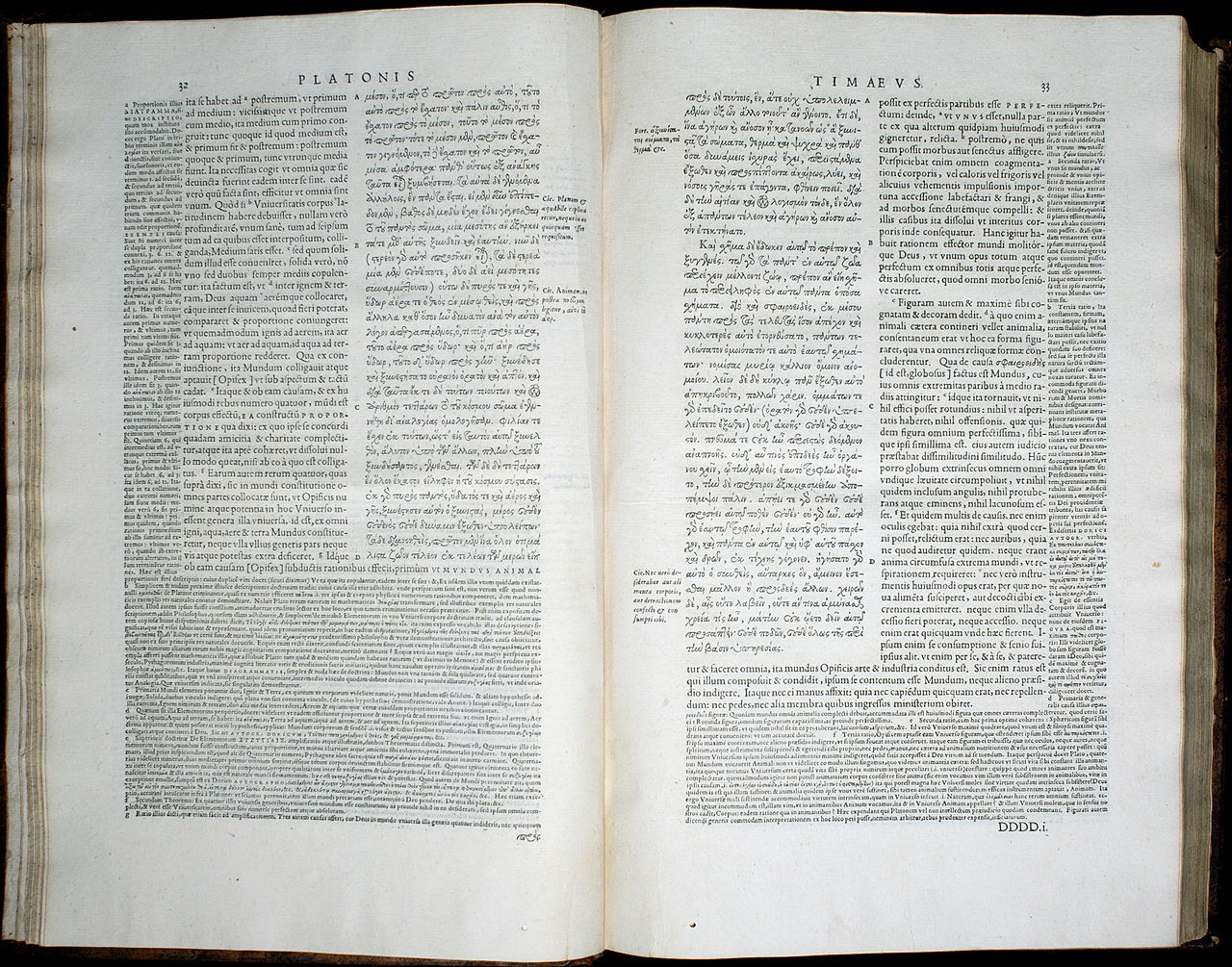

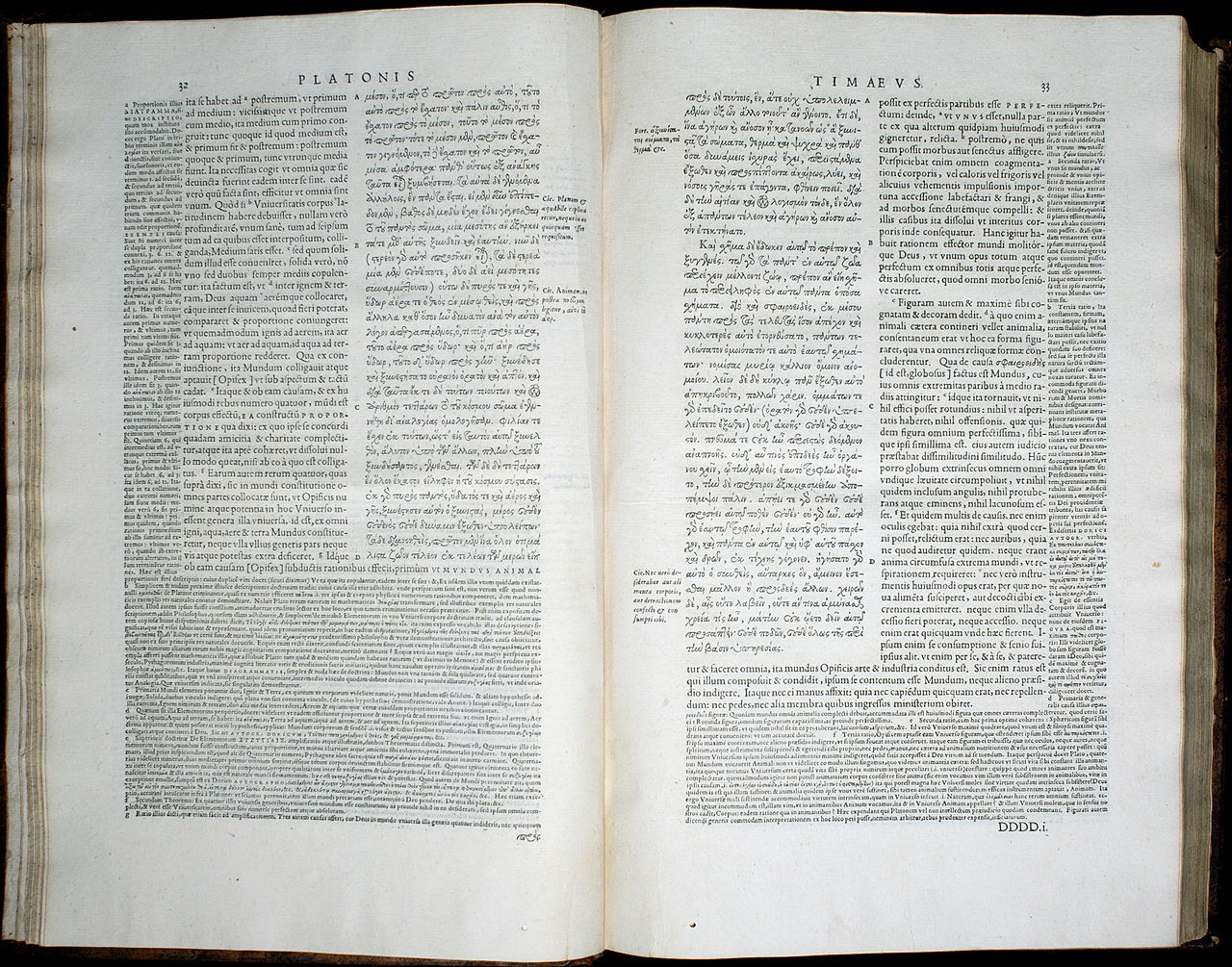

Textual sources and history Volume 3, pp. 32–33, of the 1578 Stephanus edition of Plato, showing a passage of Timaeus with the Latin translation and notes of Jean de Serres See also: List of manuscripts of Plato's dialogues During the early Renaissance, the Greek language and, along with it, Plato's texts were reintroduced to Western Europe by Byzantine scholars. Some 250 known manuscripts of Plato survive.[76] In September or October 1484 Filippo Valori and Francesco Berlinghieri printed 1025 copies of Ficino's translation, using the printing press [it] at the Dominican convent of San Jacopo di Ripoli [it].[77] The 1578 edition[78] of Plato's complete works published by Henricus Stephanus (Henri Estienne) in Geneva also included parallel Latin translation and running commentary by Joannes Serranus (Jean de Serres). It was this edition which established standard Stephanus pagination, still in use today.[79] The text of Plato as received today apparently represents the complete written philosophical work of Plato, based on the first century AD arrangement of Thrasyllus of Mendes.[80][81] The modern standard complete English edition is the 1997 Hackett Plato: Complete Works, edited by John M. Cooper.[82][83] |

典拠と歴史 1578年ステファヌス版『プラトン』第3巻、32-33頁。『ティマイオス』の一節をジャン・ド・セレスのラテン語訳と注釈で示す。 こちらも参照のこと: プラトン対話篇の写本リスト ルネサンス初期、ビザンチンの学者たちによって、ギリシア語とプラトンのテキストが西ヨーロッパに再び紹介された。1484年9月か10月、フィリッポ・ ヴァローリと フランチェスコ・ベルリンギエリは、サン・ヤコポ・ディ・リポリのドミニコ会修道院の印刷機[it]を使って、フィチーノの翻訳を1025部印刷した [77]。 1578年、ジュネーヴでヘンリクス・ステファヌス(アンリ・エスティエンヌ)によって出版されたプラトン全集[78]には、ジョアン・セラヌス(ジャ ン・ド・セレス)によるラテン語の並行訳と注釈も含まれていた。この版によって、今日でも使用されている標準的なステファヌスのページネーションが確立さ れた[79]。今日受け入れられているプラトンのテキストは、紀元1世紀にメンデスのトラシルスによって編まれたプラトンの完全な哲学的著作であるらしい [80][81]。現代の標準的な英語完全版は1997年のハケット・プラトンである: ジョン・M・クーパー編『プラトン全集』である[82][83]。 |

|

Authenticity Further information: Pseudo-Platonica Thirty-five dialogues and thirteen letters (the Epistles) have traditionally been ascribed to Plato, though modern scholarship doubts the authenticity of at least some of these. Jowett[84] mentions in his Appendix to Menexenus, that works which bore the character of a writer were attributed to that writer even when the actual author was unknown. The works taken as genuine in antiquity but are now doubted by at least some modern scholars are: Alcibiades I (*),[h] Alcibiades II (‡), Clitophon (*), Epinomis (‡), Letters (*), Hipparchus (‡), Menexenus (*), Minos (‡), Lovers (‡), Theages (‡) The following works were transmitted under Plato's name in antiquity, but were already considered spurious by the 1st century AD: Axiochus, Definitions, Demodocus, Epigrams, Eryxias, Halcyon, On Justice, On Virtue, Sisyphus. |

真正性(真贋について) 更なる情報 偽プラトンニカ 35の対話篇と13の書簡(書簡集)は伝統的にプラトンの著作とされてきたが、現代の学問はこれらの少なくともいくつかの信憑性を疑っている。ジョウェッ ト[84]は『メネクセヌス』の付録の中で、ある作家の名を冠した作品は、実際の作者が不明であっても、その作家のものとされたと述べている。古代には真 作とされていたが、現在では少なくとも何人かの現代学者によって疑問視されている作品は以下の通りである: アルキビアデス一世(*)、[h] アルキビアデス二世(‡)、クリトフォン(*)、エピノミス(‡)、書簡(*)、ヒッパルコス(‡)、メネクセヌス(*)、ミノス(‡)、恋人たち(‡) である、 Theages(‡) 以下の著作は古代にはプラトンの名で伝えられていたが、紀元1世紀にはすでに偽書とみなされていた: アクシオコス』、『定義』、『デモドクス』、『エピグラム』、『エリクシアス』、『ハルシオン』、『正義について』、『徳について』、『シジフォス』であ る。 |

|

Chronology No one knows the exact order Plato's dialogues were written in, nor the extent to which some might have been later revised and rewritten. The works are usually grouped into Early (sometimes by some into Transitional), Middle, and Late period; The following represents one relatively common division.[85] Early: Apology, Charmides, Crito, Euthyphro, Gorgias, Hippias Minor, Hippias Major, Ion, Laches, Lysis, Protagoras Middle: Cratylus, Euthydemus, Meno, Parmenides, Phaedo, Phaedrus, Republic, Symposium, Theatetus Late: Critias, Sophist, Statesman, Timaeus, Philebus, Laws.[86] Whereas those classified as "early dialogues" often conclude in aporia, the so-called "middle dialogues" provide more clearly stated positive teachings that are often ascribed to Plato such as the theory of Forms. The remaining dialogues are classified as "late" and are generally agreed to be difficult and challenging pieces of philosophy.[87] It should, however, be kept in mind that many of the positions in the ordering are still highly disputed, and also that the very notion that Plato's dialogues can or should be "ordered" is by no means universally accepted,[88][i] though Plato's works are still often characterized as falling at least roughly into three groups stylistically.[2] |

年表 プラトンの対話篇がどのような順序で書かれたのか、またどの程度改訂され書き直されたのか、正確なことは誰にもわからない。作品は通常、初期(一部には過 渡期)、中期、後期に分類されるが、以下は比較的一般的な区分の一つである[85]。 初期: 前期:『弁証論』、『カルミデス』、『クリト』、『エウテュフロ』、『ゴルギアス』、『ヒッピアス小論』、『ヒッピアス大論』、『イオン』、『ラケス』、 『リシス』、『プロタゴラス』 中期: クラテュロス、エウティデモス、メノ、パルメニデス、パイドゥ、パイドロス、共和国、シンポジウム、テアテトス 後期:クリティアス、ソフィスト、ステーツマン、ティマイオス、フィレバス、法学[86]。 「初期の対話篇」に分類される対話篇がしばしばアポリアで完結するのに対し、いわゆる「中期の対話篇」は、形相論のようなプラトンにしばしば帰属する肯定的 な教えをより明確に述べている。残りの対話篇は「後期」に分類され、哲学の難解で挑戦的な作品であることが一般的に認められている[87]。しかし、順序 づけの立場の多くはいまだに非常に論争が多いこと、またプラトンの対話篇が「順序づけ」られる、あるいは「順序づけ」られるべきであるという概念そのもの が決して普遍的に受け入れられているわけではない[88][i]ことを心に留めておく必要がある[2]。 |

Legacy Plato's Academy mosaic in the villa of T. Siminius Stephanus in Pompeii, around 100 BC to 100 CE |

遺産 ポンペイのT.シミニウス・ステファヌスの別荘にあるプラトンのアカデミーのモザイク画(紀元前100年から紀元後100年頃 |

|

Unwritten doctrines Main articles: Plato's unwritten doctrines and Allegorical interpretations of Plato Plato's unwritten doctrines are,[90][91][92] according to some ancient sources, the most fundamental metaphysical teaching of Plato, which he disclosed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted fellows, and which he may have kept secret from the public, although many modern scholars[who?] doubt these claims. A reason for not revealing it to everyone is partially discussed in Phaedrus where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as faulty, favouring instead the spoken logos: "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and beautiful ... will not, when in earnest, write them in ink, sowing them through a pen with words, which cannot defend themselves by argument and cannot teach the truth effectually."[93] It is, however, said that Plato once disclosed this knowledge to the public in his lecture On the Good (Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle. The first witness who mentions its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus] of the participant is different from what he says in his so-called unwritten teachings (Ancient Greek: ἄγραφα δόγματα, romanized: agrapha dogmata)."[94] In Metaphysics he writes: "Now since the Forms are the causes of everything else, he [i.e. Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Accordingly, the material principle is the Great and Small [i.e. the Dyad], and the essence is the One (τὸ ἕν), since the numbers are derived from the Great and Small by participation in the One".[95] "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence, and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in everything else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also tells us what the material substrate is of which the Forms are predicated in the case of sensible things, and the One in that of the Forms – that it is this the duality (the Dyad, ἡ δυάς), the Great and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν). Further, he assigned to these two elements respectively the causation of good and of evil".[95] The most important aspect of this interpretation of Plato's metaphysics is the continuity between his teaching and the Neoplatonic interpretation of Plotinus[j] or Ficino[k] which has been considered erroneous by many but may in fact have been directly influenced by oral transmission of Plato's doctrine. A modern scholar who recognized the importance of the unwritten doctrine of Plato was Heinrich Gomperz who described it in his speech during the 7th International Congress of Philosophy in 1930.[96] All the sources related to the ἄγραφα δόγματα have been collected by Konrad Gaiser and published as Testimonia Platonica.[97] |

書かれなかった教義 主な記事 プラトンの不文律、プラトンの寓意的解釈 いくつかの古代の資料によれば、プラトンの書かれざる教義とは[90][91][92]、プラトンの最も根本的な形而上学的教えであり、彼は口頭でのみ開 示し、最も信頼できる仲間にのみ開示したとする説もある。プラトンは知識の文字による伝達を誤りであると批判し、代わりに話し言葉によるロゴスを支持して いる: 「正しいこと、善いこと、美しいことについての知識を持っている者は......真剣なときには、それをインクで書くことはしない。 プラトンは、その講義『善について』(Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ)の中で、この知識を公衆に開示したと言われている。 その存在に言及した最初の証人はアリストテレスであり、彼は『物理学』の中で次のように書いている。「彼がそこ(すなわち『ティマイオス』)で述べた参加 者の説明は、彼がいわゆる不文律(古代ギリシア語: ἄγραφα δόγματα、ローマ字表記:agrapha dogmata)で述べていることとは異なっているのは事実である。 形而上学』の中で、彼は次のように書いている。「形相は他のすべてのものの原因であるから、彼[すなわちプラトン]はその要素が万物の要素であると考え た。したがって、物質的な原理は大小(すなわちダイアド)であり、数は大小から一への参加によって派生するので、本質は一(τὸ ἕν)である」[95]「この説明から、彼が二つの原因、すなわち本質の原因と物質的な原因のみを用いていたことは明らかである。彼はまた、形相の場合は 形相が、形相の場合は形相が述懐する物質的な基体とは何か、それは二元性(二重性、ἡ δυάς)であり、大小(τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν)であると語る。さらに、彼はこの二つの要素にそれぞれ善と悪の因果を割り当てている」[95]。 プラトンの形而上学に関するこの解釈の最も重要な側面は、プラトンの教えとプロティノス[j]やフィチーノ[k]の新プラトン主義的解釈との連続性であ る。プラトンの不文律の重要性を認識していた現代の学者はハインリッヒ・ゴンペルツであり、彼は1930年に開催された第7回国際哲学会議の演説の中でプ ラトンの不文律について述べている[96]。ἄγραφα δόγματαに関連するすべての資料はコンラート・ガイザーによって収集され、『テスティモニア・プラトニカ』として出版されている[97]。 |

|

Reception See also: Transmission of the Greek Classics Plato's thought is often compared with that of his most famous student, Aristotle, whose reputation during the Western Middle Ages so completely eclipsed that of Plato that the Scholastic philosophers referred to Aristotle as "the Philosopher". The only Platonic work known to western scholarship was Timaeus, until translations were made after the fall of Constantinople, which occurred during 1453.[98] However, the study of Plato continued in the Byzantine Empire, the Caliphates during the Islamic Golden Age, and Spain during the Golden age of Jewish culture. Plato is also referenced by Jewish philosopher and Talmudic scholar Maimonides in his The Guide for the Perplexed. The works of Plato were again revived at the times of Islamic Golden ages with other Greek contents through their translation from Greek to Arabic. Neoplatonism was revived from its founding father, Plotinus.[99] Neoplatonism, a philosophical current that permeated Islamic scholarship, accentuated one facet of the Qur’anic conception of God—the transcendent—while seemingly neglecting another—the creative. This philosophical tradition, introduced by Al-Farabi and subsequently elaborated upon by figures such as Avicenna, postulated that all phenomena emanated from the divine source.[100][101] It functioned as a conduit, bridging the transcendental nature of the divine with the tangible reality of creation. In the Islamic context, Neoplatonism facilitated the integration of Platonic philosophy with mystical Islamic thought, fostering a synthesis of ancient philosophical wisdom and religious insight.[100] Inspired by Plato's Republic, Al-Farabi extended his inquiry beyond mere political theory, proposing an ideal city governed by philosopher-kings.[102] Many of these commentaries on Plato were translated from Arabic into Latin and as such influenced Medieval scholastic philosophers.[103]  The School of Athens fresco by Raphael features Plato (left) also as a central figure, holding his Timaeus while he gestures to the heavens. Aristotle (right) gestures to the earth while holding a copy of his Nicomachean Ethics in his hand. During the Renaissance, George Gemistos Plethon brought Plato's original writings to Florence from Constantinople in the century of its fall. Many of the greatest early modern scientists and artists who broke with Scholasticism, with the support of the Plato-inspired Lorenzo (grandson of Cosimo), saw Plato's philosophy as the basis for progress in the arts and sciences. The 17th century Cambridge Platonists, sought to reconcile Plato's more problematic beliefs, such as metempsychosis and polyamory, with Christianity.[104] By the 19th century, Plato's reputation was restored, and at least on par with Aristotle's. Plato's influence has been especially strong in mathematics and the sciences. Plato's resurgence further inspired some of the greatest advances in logic since Aristotle, primarily through Gottlob Frege. Albert Einstein suggested that the scientist who takes philosophy seriously would have to avoid systematization and take on many different roles, and possibly appear as a Platonist or Pythagorean, in that such a one would have "the viewpoint of logical simplicity as an indispensable and effective tool of his research."[105] British philosopher Alfred N. Whitehead is often misquoted of uttering the famous saying of "All of Western philosophy is a footnote to Plato."[106] |

受容 以下も参照のこと: ギリシア古典の継承 プラトンの思想は、彼の最も有名な弟子であるアリストテレスとしばしば比較されるが、西方中世におけるアリストテレスの名声はプラトンを完全に凌駕し、ス コラ哲学者たちはアリストテレスを「哲学者」と呼んだ。しかし、プラトンの研究はビザンティン帝国、イスラム黄金時代のカリフ帝国、ユダヤ文化黄金時代の スペインで続けられた。プラトンは、ユダヤの哲学者でありタルムード学者でもあるマイモニデスの 『当惑者への手引き』でも言及されている。 プラトンの著作は、ギリシア語からアラビア語への翻訳を通じて、他のギリシア語の内容とともにイスラム黄金時代に再びよみがえった。新プラトン主義は、そ の創始者であるプロティノスから復活した[99]。イスラムの学問に浸透した哲学的潮流である新プラトン主義は、クルアーンにおける神の概念(超越的なも の)の一面を強調する一方で、もう一つの創造的なものを軽視しているように見えた。この哲学的伝統はアル=ファラービーによって導入され、その後アヴィセ ンナなどによって精緻化され、すべての現象は神の源から発していると仮定した[100][101]。イスラムの文脈では、新プラトン主義はプラトン哲学と 神秘主義的なイスラム思想の統合を促進し、古代の哲学的な知恵と宗教的な洞察力の統合を促進した[100]。プラトンの『共和国』に触発されたアル=ファ ラービーは、彼の探究を単なる政治理論を超えて拡張し、哲学者の王によって統治される理想都市を提案した[102]。 プラトンに関するこれらの注釈書の多くはアラビア語からラテン語に翻訳され、中世のスコラ哲学者たちに影響を与えた[103]。  ラファエロによるアテネの学校のフレスコ画では、プラトン(左)も中心人物として描かれており、天に向かって身振りをしながら『ティマイオス』を手にして いる。アリストテレス(右)は『ニコマコス倫理学』を手にしながら大地に向かって身振りをする。 ルネサンス期、ジョージ・ジェミストス・プレトンは、コンスタンティノープルが滅亡した世紀に、プラトンの原著をコンスタンティノープルからフィレンツェ に持ち帰った。スコラ哲学と決別した近世の偉大な科学者や芸術家の多くは、プラトンに影響を受けたロレンツォ(コジモの孫)の支援を受けて、プラトン哲学 を芸術と科学の進歩の基礎と見なした。17世紀のケンブリッジ・プラトン主義者たちは、プラトンのより問題の多い信念、例えば、超神論やポリアモリーなど をキリスト教と調和させようとした[104]。19世紀になると、プラトンの評判は回復し、少なくともアリストテレスと肩を並べるようになった。プラトン の影響は、数学と科学において特に強かった。プラトンの復活はさらに、主にゴットローブ・フレーゲを通して、アリストテレス以来の論理学の偉大な進歩に影 響を与えた。アルベルト・アインシュタインは、哲学を真摯に受け止める科学者は体系化を避け、様々な役割を担わなければならず、そのような科学者は「論理 的な単純さという視点を自分の研究に不可欠で効果的な道具として持っている」という点で、プラトン主義者やピタゴラス主義者のように見えるかもしれないと 示唆した[105]。イギリスの哲学者アルフレッド・N・ホワイトヘッドは、「西洋哲学の全てはプラトンの脚注である」という有名な言葉を口にしたという 誤った引用をされることが多い[106]。 |

|

Criticism Many recent philosophers have also diverged from what some would describe as ideals characteristic of traditional Platonism. Friedrich Nietzsche notoriously attacked Plato's "idea of the good itself" along with many fundamentals of Christian morality, which he interpreted as "Platonism for the masses" in Beyond Good and Evil (1886). Martin Heidegger argued against Plato's alleged obfuscation of Being in his incomplete tome, Being and Time (1927), and the philosopher of science Karl Popper argued in the first volume of The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945) that Plato's alleged proposal for a utopian political regime in the Republic was prototypically totalitarian. Edmund Gettier famously demonstrated the Gettier problem for the justified true belief account of knowledge. That the modern theory of justified true belief as knowledge, which Gettier addresses, is equivalent to Plato's is, however, accepted only by some scholars but rejected by others.[107] |

批判 最近の哲学者の多くもまた、伝統的なプラトン主義に特徴的な理想とされるものから逸脱している。フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、『善悪の彼岸』(1886年) の中で、プラトンの「善そのものの思想」をキリスト教道徳の多くの基本とともに攻撃し、「大衆のためのプラトン主義」と解釈したことは有名である。マル ティン・ハイデガーは、未完の大著『存在と時間』(1927年)の中で、プラトンの「存在」の難解さについて論じ、科学哲学者のカール・ポパーは、『開か れた社会とその敵』(1945年)の第1巻で、『共和国』におけるプラトンのユートピア的な政治体制の提案は、典型的な全体主義的なものであると論じた。 エドマンド・ゲッティアは、知識に関する正当化された真の信念の説明に対するゲッティア問題を証明したことで有名である。しかし、ゲッティアが取り上げた 知識としての正当化された真の信念の現代理論がプラトンと同等であることは、一部の学者によってのみ受け入れられているが、他の学者によって否定されてい る[107]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plato |

★

| References Allen, Michael J.B. (1975). "Introduction". Marsilio Ficino: The Philebus Commentary. University of California Press. pp. 1–58. Aminrazavi, Mehdi (2021). "Mysticism in Arabic and Islamic Philosophy". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Baird, Forrest E.; Kaufmann, Walter, eds. (2008). Philosophic Classics: From Plato to Derrida (Fifth ed.). Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0-13-158591-1. Blössner, Norbert (2007). "The City-Soul Analogy". In Ferrari, G.R.F. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to Plato's Republic. Translated by G.R.F. Ferrari. Cambridge University Press. Brumbaugh, Robert S.; Wells, Rulon S. (October 1989). "Completing Yale's Microfilm Project". The Yale University Library Gazette. 64 (1/2): 73–75. JSTOR 40858970. Burrell, David (1998). "Platonism in Islamic Philosophy". In Craig, Edward (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Vol. 7. Routledge. pp. 429–430. Cooper, John M.; Hutchinson, D.S., eds. (1997). Plato: Complete Works. Hackett Publishing. Dillon, John (2003). The Heirs of Plato: A Study of the Old Academy. Oxford University Press. Dorter, Kenneth (2006). The Transformation of Plato's Republic. Lexington Books. Einstein, Albert (1949). "Remarks to the Essays Appearing in this Collective Volume". In Schilpp (ed.). Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist. The Library of Living Philosophers. Vol. 7. MJF Books. pp. 663–688. Fine, Gail (1999a). "Selected Bibliography". Plato 1: Metaphysics and Epistemology. Oxford University Press. pp. 481–494. Fine, Gail (1999b). "Introduction". Plato 2: Ethics, Politics, Religion, and the Soul. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–33. Fine, Gail (2003). "Introduction". Plato on Knowledge and Forms: Selected Essays. Oxford University Press. Gaiser, Konrad (1998). Reale, Giovanni (ed.). Testimonia Platonica: Le antiche testimonianze sulle dottrine non scritte di Platone. Milan: Vita e Pensiero. Guthrie, W.K.C. (1986). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 4, Plato: The Man and His Dialogues: Earlier Period. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-31101-4. Hasse, Dag Nikolaus (2002). "Plato Arabico-latinus". In Gersh; Hoenen (eds.). The Platonic Tradition in the Middle Ages: A Doxographic Approach. De Gruyter. pp. 33–66. Jorgenson, Chad (5 April 2018). The Embodied Soul in Plato's Later Thought. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-316-80052-2. Retrieved 15 May 2025. Kastely, James L. (25 August 2015). The Rhetoric of Plato's Republic: Democracy and the Philosophical Problem of Persuasion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-27876-6. Retrieved 15 May 2025. Kraut, Richard (11 September 2013). Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). "Plato". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University. Archived from the original on 6 September 2018. Retrieved 3 April 2014. Lee, M.-K. (2011). "The Theaetetus". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 411–436. McDowell, J. (1973). Plato: Theaetetus. Oxford University Press. Nails, Debra (2002). The People of Plato: A Prosopography of Plato and Other Socratics. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87220-564-2. Nails, Debra (2006). "The Life of Plato of Athens". A Companion to Plato edited by Hugh H. Benson. Blackwell Publishing. pp. 1–12. doi:10.1002/9780470996256.ch1. ISBN 1-4051-1521-1. Notopoulos, A. (April 1939). "The Name of Plato". Classical Philology. 34 (2): 135–145. doi:10.1086/362227. S2CID 161505593. Reale, Giovanni (1990). Catan, John R. (ed.). Plato and Aristotle. A History of Ancient Philosophy. Vol. 2. State University of New York Press. Riginos, Alice (1976). Platonica : the anecdotes concerning the life and writings of Plato. Leiden: E.J. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-04565-1. Strauss, Leo (1964). The City and the Man. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Taylor, C.C.W. (2011). "Plato's Epistemology". In Fine, G. (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Plato. Oxford University Press. pp. 165–190. Vlastos, Gregory (1991). Socrates: Ironist and Moral Philosopher. Cambridge University Press. Waterfield, Robin (2023). Plato of Athens: A Life in Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-756475-2. Retrieved 5 May 2025. Whitehead, Alfred North (1978). Process and Reality. New York: The Free Press. |

作品 1602年。エウリピデスの『メデア』のラテン語訳(現存せず)。 1620年。『タキトゥス論』『ローマ論』『法論』。収録『ホラエ・サブセキヴァエ:観察と論考』[51] 1626年。「ダービーシャーの峰の驚異について」(1636年刊行)-ピークの七不思議を詠んだ詩 1629年。『ペロポネソス戦争八書』-トゥキディデスの『ペロポネソス戦争史』の翻訳と序文 1630年。『第一原理に関する小論』[52] [53] 著作者は疑わしい。主要な批評家たちはこの著作をロバート・ペインに帰属させている。[54] 1637年. 『修辞学の技法要約』[55] モレスワース版タイトル: 『修辞学の全技法』 著作者可能性あり:シューマン(1998)はこの著作のホッブズ帰属を断固否定しているが[56]、学界の大勢はシューマンの特異な評価に同意しない。 シューマンは歴史家クエンティン・スキナーと対立するが、スキナーは後にシューマンの見解に同意するようになる[57]。[58] 1639年. 光学論 II(別名:ラテン語光学原稿)[59][60] 1640年. 自然法と政治法の要素 当初は写本のみで流通。ホッブズの許可なく初版が印刷されたのは1650年である。 1641年 『デカルトの第一哲学に関する省察への異議』第三系列の異議 1642年 『哲学要素 第三部 市民論』(ラテン語、初版限定版) 1643年 『運動・位置・時間について』[61] 初版(1973年)のタイトル:トマス・ホワイトの『世界論』検証 1644年。『メルセンヌ弾道論』序文の一部。F. マリニ『メルセンヌ小論集 物理数学考』所収。自然界と人工物の驚異的現象を厳密な証明で解明する。 1644年。「光学、第七巻」(別名『光学論I』、1640年執筆)。マリヌス・メルセンヌ編『幾何学と混合数学の総覧』所収。 モレスワース版(OL V, pp. 215–248)題名:「光学論」 1646年。『光学論』の草稿あるいは初稿 [62] モレスワースは『オプティクス』の序文(キャベンディッシュへの献辞)と結論のみをEW VII, pp. 467–471に掲載した。 1646年。『自由と必然について』(1654年刊行) ホッブズの許可なく出版 1647年。『市民に関する哲学的基礎』 新たな読者への序文を付した第二拡張版 1650年。ウィリアム・ダヴェナント卿の『ゴンディベルト序文』への反論 1650年。人間本性、あるいは政治学の基礎要素 『自然法および政治法の本質』の最初の13章を含む ホッブズの許可なく出版 1650年。『自然法および政治法の本質』(海賊版) 再構成版として二部構成で収録: 「人間本性、あるいは政治学の基礎要素」:『法・自然・政治の要素』第一部(1640年)第14~19章 「国家論」:『法・自然・政治の要素』第二部(1640年) 1651年。『政府と社会に関する哲学的基礎』―『市民論』の英訳[63] 1651年 『リヴァイアサン、あるいは教会と市民の共同体の本質、形態、権力について』 1654年 『自由と必然性に関する論考』 1655年 『国家論(ラテン語)』 1656年. 『哲学の要素』第一部 身体に関するもの – 『デ・コルポレ』の匿名英訳 1656年. 数学教授への六講 1656年. 『自由、必然、偶然に関する諸問題』 – 『自由と必然に関する論考』の再版。ブラムホールの反論と、それに対するホッブズの反論を追加。 1657年. ジョン・ウォリスの不合理幾何学、田舎言葉、スコットランド教会政治、野蛮行為の烙印 1658年. 哲学要素 第二部 人間について 1660年. ジョン・ウォリスの著作に説明される現代数学の検証と修正 1661. 物理的対話、あるいは空気の性質について 1662. 物理学問題集 英訳題:七つの哲学的問題(1682年) 1662. 七つの哲学的問題と幾何学の二命題 – 死後刊行 1662. ホッブズ氏の忠誠心、宗教観、評判、品性に関する考察。ウォリス博士への書簡形式による自伝 1666. 幾何学の原理と推論について 1666. 哲学者とイングランド普通法の学生との対話(1681年刊行) 1668年。『リヴァイアサン』 – ラテン語訳 1668年。『デリー前主教ブラムホール博士著書「リヴァイアサンの捕獲」への反論。異端とその処罰に関する歴史的叙述を併せて』(1682年刊行) 1671年。『王立協会に提出されたウォリス博士批判三論文。ウォリス博士のそれに対する回答に関する考察を添えて 1671年 『幾何学の薔薇、あるいはこれまで徒労に終わった幾つかの命題。ウォリスの運動論に関する簡潔な批判を添えて』 1672年 『数学の光。ヨハネス・ウォリスの衝突論から導かれた』 1673年 ホメロスの『イリアス』と『オデュッセイア』の英訳 幾何学上の原理と問題集(1674年) 自然哲学十篇(1678年) トマス・ホッブズ自伝(1679年) 1680年に英訳 死後出版作品 1680年 『異端とその処罰に関する歴史的叙述』 1681年 『ベヒーモス、あるいは長期議会』 1668年執筆。国王の要請により未出版 初海賊版:1679年 1682年 『七つの哲学的問題』(『物理学問題集』1662年の英訳) 1682年 『幾何学の薔薇園』(『ロゼトゥム・ゲオメトリクム』1671年 英語訳) 1682年 『幾何学の原理と問題集』(『プリンキピア・エト・プロブレマタ』1674年 英語訳) 1688年 『哀歌調で綴られた教会史』 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plato |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆