政治経済[学]

Political economy, ポリティカル・エコノミー

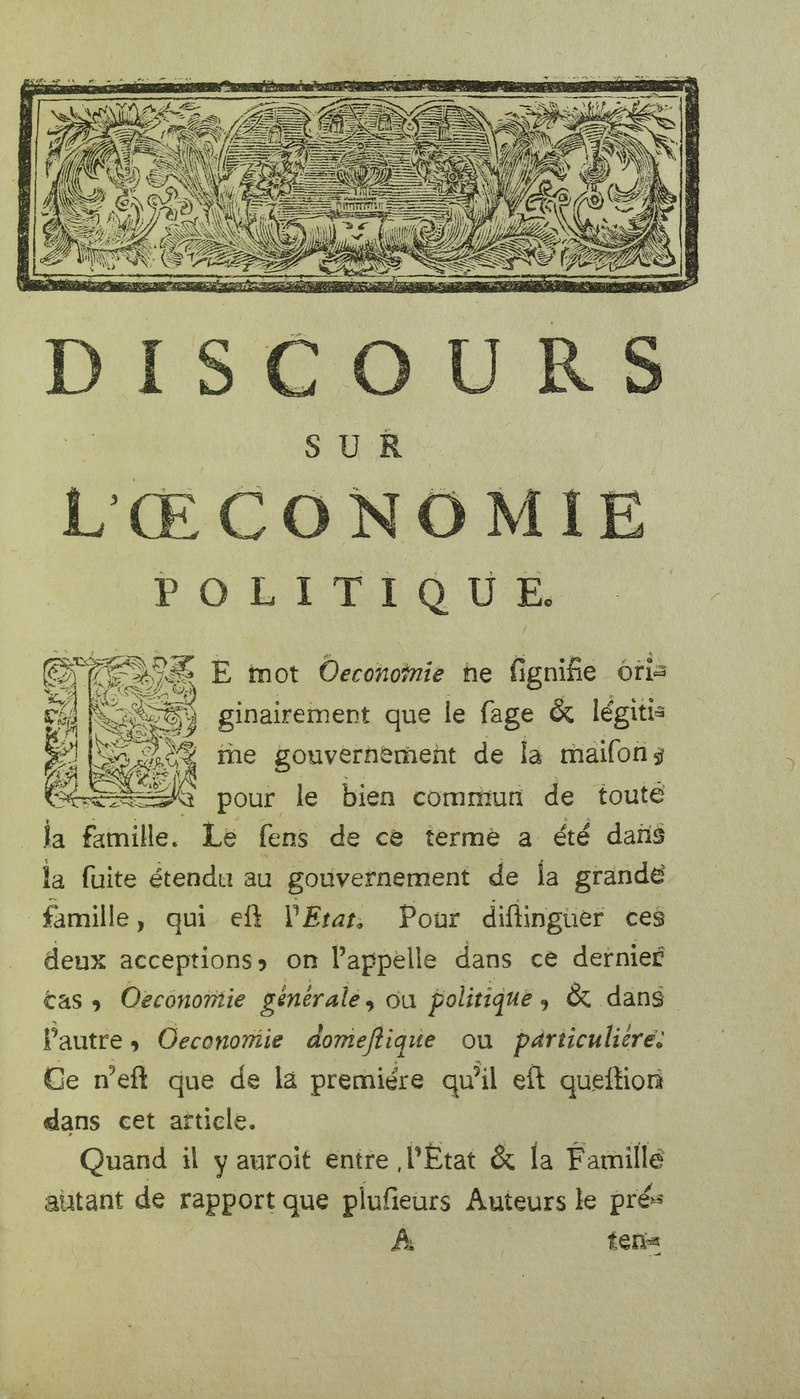

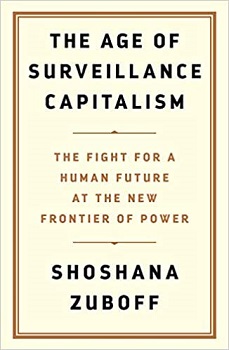

Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Discours sur l'oeconomie politique, 1758/ 国勢調査に協力しませう/ Surveillance capitalism, 2019

☆政治経済学あるいは比較経済学(Political or

comparative economy)

は、政治学と経済学の一分野であり、経済システム(例えば市場や国民経済)と、それらを統治する政治システム(例えば法、制度、政府)を研究する。[1]

[2][3][4]

この分野で広く研究される現象には、労働市場や国際市場といったシステム、成長・分配・不平等・貿易といった現象、そしてこれらがいかに制度・法律・政府

政策によって形作られるかが含まれる。18世紀に起源を持ち、現代経済学の前身である。[5][6]

現代的な形態の政治経済学は学際的分野と見なされ、政治学と現代経済学の両方の理論を基盤としている。[4]

政治経済学は16世紀の西洋道徳哲学に起源を持ち、国家の富の管理を探求する理論的著作から生まれた。ここで「政治」は政治体制を指し、「経済」はギリ

シャ語οἰκονομία(家計管理)に由来する。政治経済学の最も初期の著作は、通常、英国の学者であるアダム・スミス、トマス・マルサス、デヴィッ

ド・リカードによるものとされているが、その前に、フランソワ・ケネー、リシャール・カンティヨン、アンヌ=ロベール=ジャック・トゥルゴーなどのフラン

スの重農主義者たちの著作があった。[7]

さまざまな思想家、アダム・スミス、ジョン・スチュワート・ミル、カール・マルクスは、経済学と政治学は切り離せないものと考えていた。[8]

19世紀後半、アルフレッド・マーシャルによる影響力のある教科書『経済学原理』が1890年に出版されると同時に、数学的モデリングが台頭し、経済学と

いう用語が政治経済学という用語に徐々に取って代わり始めた。それより以前、この分野に数学的手法を適用した支持者であるウィリアム・スタンレー・ジェ

ヴォンズは、簡潔さと「科学の公認名」となることを期待して、経済学という用語を提唱していた。[9][10] Google Ngram

Viewerの引用頻度指標によれば、「経済学」という用語の使用頻度が「政治経済学」を上回り始めたのは1910年頃であり、1920年までにはこの分

野の主要用語となった。[11]

今日では、「経済学」という用語は通常、他の政治的考慮を排除した経済の狭義の研究を指すのに対し、「政治経済学」という用語は、それとは異なる競合する

アプローチを表す。

| Political or

comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics

studying economic systems (e.g. markets and national economies) and

their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and

government).[1][2][3][4] Widely-studied phenomena within the discipline

are systems such as labour and international markets, as well as

phenomena such as growth, distribution, inequality, and trade, and how

these are shaped by institutions, laws, and government policy.

Originating in the 18th century, it is the precursor to the modern

discipline of economics.[5][6] Political economy in its modern form is

considered an interdisciplinary field, drawing on theory from both

political science and modern economics.[4] Political economy originated within 16th century western moral philosophy, with theoretical works exploring the administration of states' wealth – political referring to polity, and economy derived from Greek οἰκονομία "household management". The earliest works of political economy are usually attributed to the British scholars Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo, although they were preceded by the work of the French physiocrats, such as François Quesnay, Richard Cantillon and Anne-Robert-Jacques Turgot.[7] Varied thinkers Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, and Karl Marx saw economics and politics as inseparable.[8] In the late 19th century, the term economics gradually began to replace the term political economy with the rise of mathematical modeling coinciding with the publication of the influential textbook Principles of Economics by Alfred Marshall in 1890. Earlier, William Stanley Jevons, a proponent of mathematical methods applied to the subject, advocated economics for brevity and with the hope of the term becoming "the recognised name of a science".[9][10] Citation measurement metrics from Google Ngram Viewer indicate that use of the term economics began to overshadow political economy around roughly 1910, becoming the preferred term for the discipline by 1920.[11] Today, the term economics usually refers to the narrow study of the economy absent other political and social considerations while the term political economy represents a distinct and competing approach. |

政治経済学あるいは比較経済学は、政治学と経済学の一分野であり、経済

システム(例えば市場や国民経済)と、それらを統治する政治システム(例えば法、制度、政府)を研究する。[1][2][3][4]

この分野で広く研究される現象には、労働市場や国際市場といったシステム、成長・分配・不平等・貿易といった現象、そしてこれらがいかに制度・法律・政府

政策によって形作られるかが含まれる。18世紀に起源を持ち、現代経済学の前身である。[5][6]

現代的な形態の政治経済学は学際的分野と見なされ、政治学と現代経済学の両方の理論を基盤としている。[4] 政治経済学は16世紀の西洋道徳哲学に起源を持ち、国家の富の管理を探求する理論的著作から生まれた。ここで「政治」は政治体制を指し、「経済」はギリ シャ語οἰκονομία(家計管理)に由来する。政治経済学の最も初期の著作は、通常、英国の学者であるアダム・スミス、トマス・マルサス、デヴィッ ド・リカードによるものとされているが、その前に、フランソワ・ケネー、リシャール・カンティヨン、アンヌ=ロベール=ジャック・トゥルゴーなどのフラン スの重農主義者たちの著作があった。[7] さまざまな思想家、アダム・スミス、ジョン・スチュワート・ミル、カール・マルクスは、経済学と政治学は切り離せないものと考えていた。[8] 19世紀後半、アルフレッド・マーシャルによる影響力のある教科書『経済学原理』が1890年に出版されると同時に、数学的モデリングが台頭し、経済学と いう用語が政治経済学という用語に徐々に取って代わり始めた。それより以前、この分野に数学的手法を適用した支持者であるウィリアム・スタンレー・ジェ ヴォンズは、簡潔さと「科学の公認名」となることを期待して、経済学という用語を提唱していた。[9][10] Google Ngram Viewerの引用頻度指標によれば、「経済学」という用語の使用頻度が「政治経済学」を上回り始めたのは1910年頃であり、1920年までにはこの分 野の主要用語となった。[11] 今日では、「経済学」という用語は通常、他の政治的考慮を排除した経済の狭義の研究を指すのに対し、「政治経済学」という用語は、それとは異なる競合する アプローチを表す。 |

| Etymology Originally, political economy meant the study of the conditions under which production or consumption within limited parameters was organized in nation-states. In that way, political economy expanded the emphasis on economics, which comes from the Greek oikos (meaning "home") and nomos (meaning "law" or "order"). Political economy was thus meant to express the laws of production of wealth at the state level, quite like economics concerns putting home to order. The phrase économie politique (translated in English to "political economy") first appeared in France in 1615 with the well-known book by Antoine de Montchrétien, Traité de l'economie politique. Other contemporary scholars attribute the roots of this study to the 13th Century Tunisian Arab Historian and Sociologist, Ibn Khaldun, for his work on making the distinction between "profit" and "sustenance", in modern political economy terms, surplus and that required for the reproduction of classes respectively. He also calls for the creation of a science to explain society and goes on to outline these ideas in his major work, the Muqaddimah. In Al-Muqaddimah Khaldun states, "Civilization and its well-being, as well as business prosperity, depend on productivity and people's efforts in all directions in their own interest and profit" – seen as a modern precursor to Classical Economic thought. Leading on from this, the French physiocrats were the first major exponents of political economy,[12] although the intellectual responses[13] of Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, David Ricardo, Henry George and Karl Marx to the physiocrats generally receive much greater attention.[14] The world's first professorship in political economy was established in 1754 at the University of Naples Federico II in southern Italy. The Neapolitan philosopher Antonio Genovesi was the first tenured professor. In 1763, Joseph von Sonnenfels was appointed a Political Economy chair at the University of Vienna, Austria. Thomas Malthus, in 1805, became England's first professor of political economy, at the East India Company College, Haileybury, Hertfordshire. At present, political economy refers to different yet related approaches to studying economic and related behaviours, ranging from the combination of economics with other fields to the use of different, fundamental assumptions challenging earlier economic assumptions. |

語源 もともと政治経済学とは、国民という枠組みの中で、限られた条件下における生産や消費がどのように組織化されるかを研究する学問を指していた。この意味で 政治経済学は、ギリシャ語のオイコス(家)とノモス(法や秩序)に由来する経済学の概念を拡張したものだ。したがって政治経済学は、国家レベルにおける富 の生産法則を表現する意図で用いられた。これは経済学が家屋の秩序化を扱うのとよく似ている。この「政治経済学」に相当するフランス語表現「経済政治学 (économie politique)」は、1615年にアントワーヌ・ド・モンクレティアンの著名な著作『政治経済論(Traité de l'economie politique)』で初めて登場した。他の同時代の学者たちは、この学問の起源を13世紀のチュニジアのアラブ人歴史家・社会学者イブン・ハルドゥー ンに帰している。彼は現代の政治経済学用語で言うところの「剰余」と「再生産に必要な分」——つまり「利益」と「生計」の区別を明確にした。また彼は社会 を説明する科学の創出を提唱し、その主要著作『序説』でこれらの思想を概説している。アル・ムカッディマの中で、ハルドゥーンは「文明とその繁栄、そして ビジネスの繁栄は、生産性と、あらゆる方面における人々の利益と利益のための努力に依存している」と述べている。これは、古典派経済思想の現代的な先駆者 と見なされている。 これに続き、フランスの重農主義者たちが政治経済学の最初の主要な提唱者となった[12]が、アダム・スミス、ジョン・スチュワート・ミル、デヴィッド・ リカード、ヘンリー・ジョージ、カール・マルクスによる重農主義者たちへの知的反応[13]の方が、一般的にはるかに大きな注目を集めている[14]。世 界初の政治経済学の教授職は、1754年に南イタリアのナポリ・フェデリコ2世大学に設立された。ナポリの哲学者アントニオ・ジェノヴェージが最初の終身 教授だった。1763年、ヨーゼフ・フォン・ゾンネンフェルスがオーストリアのウィーン大学で政治経済学の教授に任命された。1805年、トーマス・マル サスがハートフォードシャー州ヘイリーベリーにある東インド会社大学にて、イングランド初の政治経済学教授となった。現在、政治経済学とは、経済学と他分 野の融合から、従来の経済学の前提に異議を唱える根本的な仮定の採用に至るまで、経済および関連する行動を研究する、異なるが関連性のある様々なアプロー チを指す。 |

Current approaches Robert Keohane, international relations theorist Political economy most commonly refers to interdisciplinary studies drawing upon economics, sociology and political science in explaining how political institutions, the political environment, and the economic system—capitalist, socialist, communist, or mixed—influence each other.[15] The Journal of Economic Literature classification codes associate political economy with three sub-areas: (1) the role of government and/or class and power relationships in resource allocation for each type of economic system;[16] (2) international political economy, which studies the economic impacts of international relations;[17] and (3) economic models of political or exploitative class processes.[18] Within political science, a general distinction is made between international political economy typically examined by scholars of international relations and comparative political economy, which is primarily studied by scholars of comparative politics.[1] Public choice theory is a microfoundations theory closely intertwined with political economy. Both approaches model voters, politicians and bureaucrats as behaving in mainly self-interested ways, in contrast to a view, ascribed to earlier mainstream economists, of government officials trying to maximize individual utilities from some kind of social welfare function.[19] As such, economists and political scientists often associate political economy with approaches using rational-choice assumptions,[20] especially in game theory[21] and in examining phenomena beyond economics' standard remit, such as government failure and complex decision making in which context the term "positive political economy" is common.[22] Other "traditional" topics include analysis of such public policy issues as economic regulation,[23] monopoly, rent-seeking, market protection,[24] institutional corruption[25] and distributional politics.[26] Empirical analysis includes the influence of elections on the choice of economic policy, determinants and forecasting models of electoral outcomes, the political business cycles,[27] central-bank independence and the politics of excessive deficits.[28] An interesting example would be the publication in 1954 of the first manual of Political Economy in the Soviet Union, edited by Lev Gatovsky, which mixed the classic theoretical approach of the time with the soviet political discourse.[29]  Susan Strange, international relations scholar A rather recent focus has been put on modeling economic policy and political institutions concerning interactions between agents and economic and political institutions,[30] including the seeming discrepancy of economic policy and economist's recommendations through the lens of transaction costs.[31] From the mid-1990s, the field has expanded, in part aided by new cross-national data sets allowing tests of hypotheses on comparative economic systems and institutions.[32] Topics have included the breakup of nations,[33] the origins and rate of change of political institutions in relation to economic growth,[34] development,[35] financial markets and regulation,[36] the importance of institutions,[37] backwardness,[38] reform[39] and transition economies,[40] the role of culture, ethnicity and gender in explaining economic outcomes,[41] macroeconomic policy,[42] the environment,[43] fairness[44] and the relation of constitutions to economic policy, theoretical[45] and empirical.[46] Other important landmarks in the development of political economy include: New political economy which may treat economic ideologies as the phenomenon to explain, per the traditions of Marxian political economy. Thus, Charles S. Maier suggests that a political economy approach "interrogates economic doctrines to disclose their sociological and political premises.... in sum, [it] regards economic ideas and behavior not as frameworks for analysis, but as beliefs and actions that must themselves be explained".[47] This approach informs Andrew Gamble's The Free Economy and the Strong State (Palgrave Macmillan, 1988), and Colin Hay's The Political Economy of New Labour (Manchester University Press, 1999). It also informs much work published in New Political Economy, an international journal founded by Sheffield University scholars in 1996.[48] International political economy (IPE) an interdisciplinary field comprising approaches to the actions of various actors. According to International Relations scholar Chris Brown, University of Warwick professor, Susan Strange, was "almost single-handedly responsible for creating international political economy as a field of study."[49] In the United States, these approaches are associated with the journal International Organization, which in the 1970s became the leading journal of IPE under the editorship of Robert Keohane, Peter J. Katzenstein and Stephen Krasner. They are also associated with the journal The Review of International Political Economy. There also is a more critical school of IPE, inspired by thinkers such as Antonio Gramsci and Karl Polanyi; two major figures are Matthew Watson and Robert W. Cox.[50] The use of a political economy approach by anthropologists, sociologists, and geographers used in reference to the regimes of politics or economic values that emerge primarily at the level of states or regional governance, but also within smaller social groups and social networks. Because these regimes influence and are influenced by the organization of both social and economic capital, the analysis of dimensions lacking a standard economic value (e.g. the political economy of language, of gender, or of religion) often draws on concepts used in Marxian critiques of capital. Such approaches expand on neo-Marxian scholarship related to development and underdevelopment postulated by André Gunder Frank and Immanuel Wallerstein. Historians have employed political economy to explore the ways in the past that persons and groups with common economic interests have used politics to effect changes beneficial to their interests.[51] Political economy and law is a recent attempt within legal scholarship to engage explicitly with political economy literature. In the 1920s and 1930s, legal realists (e.g. Robert Hale) and intellectuals (e.g. John Commons) engaged themes related to political economy. In the second half of the 20th century, lawyers associated with the Chicago School incorporated certain intellectual traditions from economics. However, since the crisis in 2007 legal scholars especially related to international law, have turned to more explicitly engage with the debates, methodology and various themes within political economy texts.[52][53] Thomas Piketty's approach and call to action which advocated for the re-introduction of political consideration and political science knowledge more generally into the discipline of economics as a way of improving the robustness of the discipline and remedying its shortcomings, which had become clear following the 2008 financial crisis.[54] In 2010, the only Department of Political Economy in the United Kingdom formally established at King's College London. The rationale for this academic unit was that "the disciplines of Politics and Economics are inextricably linked", and that it was "not possible to properly understand political processes without exploring the economic context in which politics operates".[55] In 2012, the Sheffield Political Economy Research Institute (SPERI) was founded at The University of Sheffield by professors Tony Payne and Colin Hay. It was created as a means of combining political and economic analyses of capitalism which were viewed by the founders to be insufficient as independent disciplines in explaining the 2008 financial crisis.[56] In 2017, the Political Economy UK Group (abbreviated PolEconUK) was established as a research consortium in the field of political economy. It hosts an annual conference and counts among its member institutions Oxford, Cambridge, King's College London, Warwick University and the London School of Economics.[57] |

現在のアプローチ 国際関係理論家ロバート・キオハーン 政治経済学とは、経済学、社会学、政治学を基盤とし、政治制度、政治環境、そして資本主義、社会主義、共産主義、あるいは混血の経済システムが互いにどの ように影響し合うかを説明する学際的研究を指すことが多い。[15] 『経済文献ジャーナル』の分類コードでは、政治経済学を以下の3つのサブ領域に関連付けている:(1) 各経済システムにおける資源配分における政府および/または階級・権力関係の役割[16]、(2) 国際関係が経済に与える影響を研究する国際政治経済学[17]、(3) 政治的または搾取的な階級過程の経済モデル。[18] 政治学の分野では、国際関係論の研究者が主に扱う国際政治経済学と、比較政治学の研究者が主に扱う比較政治経済学との間に、一般的な区別がなされている。 [1] 公共選択理論は、政治経済学と密接に絡み合ったミクロ基礎理論である。両アプローチとも、有権者、政治家、官僚を主に自己利益を追求する形で行動する存在 としてモデル化する。これは、政府関係者が何らかの社会福祉関数から個人の効用を最大化しようとするという、従来の主流派経済学者の見解とは対照的であ る。[19] このため、経済学者や政治学者は、政治経済学を合理的選択仮定を用いるアプローチ[20]、特にゲーム理論[21]や、政府の失敗や複雑な意思決定といっ た経済学の標準的な範囲を超えた現象の分析と結びつけることが多い。この文脈では「実証的政治経済学」という用語が一般的である[22]。その他の「伝統 的」な主題には、経済規制[23]、独占、レントシーキング、市場保護[24]、制度的腐敗[25]、分配政治[26]といった公共政策問題の分析が含ま れる。実証分析には、選挙が経済政策選択に及ぼす影響、選挙結果の決定要因と予測モデル、政治的景気循環[27]、中央銀行の独立性、過剰赤字の政治学な どが含まれる。[28] 興味深い事例として、1954年にソ連で初となる政治経済学の教科書が刊行されたことが挙げられる。レフ・ガトフスキーが編集したこの教科書は、当時の古 典的理論的アプローチとソ連の政治的言説を混血のものとさせたものであった。[29]  スーザン・ストレンジ(国際関係学者) 比較的近年では、経済政策と政治制度のモデリングに焦点が当てられている。これは主体と経済・政治制度の相互作用[30]、特に取引費用の観点から見た経 済政策と経済学者の提言との見かけ上の乖離[31]を含む。1990年代半ば以降、この分野は拡大した。一因は、比較経済システムや制度に関する仮説の検 証を可能にする新たな国際比較データセットの出現である[32]。研究テーマには国民解体[33]、経済成長に関連する政治制度の起源と変化速度 [34]、開発[35]、金融市場と規制[36]、制度の重要性[37]、後進性[38]、改革[39]と移行経済[40]、経済成果を説明する上での文 化・民族・ジェンダーの役割[41]、マクロ経済政策、 [42] 環境[43]、公平性[44]、憲法と経済政策の関係、理論的[45]および実証的[46]研究などである。 政治経済学の発展におけるその他の重要な里程標には以下が含まれる: マルクス主義政治経済学の伝統に従い、経済イデオロギーを説明すべき現象として扱う新しい政治経済学。したがって、チャールズ・S・マイヤーは、政治経済 学のアプローチは「経済学説を問い詰め、その社会学的および政治学的前提を明らかにする」と示唆している。つまり、経済思想や行動を分析の枠組みとしてで はなく、それ自体が説明されるべき信念や行動として捉えるのである。[47] このアプローチは、アンドルー・ギャンブルの『自由経済と強力な国家』(Palgrave Macmillan、1988年)や、コリン・ヘイの『ニュー・レイバーの政治経済学』(Manchester University Press、1999年)に影響を与えている。また、1996年にシェフィールド大学の学者たちが創刊した国際誌『New Political Economy』に掲載された多くの研究にも影響を与えている。[48] 国際政治経済学(IPE)は、様々な行為者の行動に対するアプローチで構成される学際的な分野である。国際関係学者のクリス・ブラウンによれば、ウォリッ ク大学のスーザン・ストレンジ教授は「国際政治経済学を学問分野として確立したほぼ唯一の人物」である[49]。米国では、こうしたアプローチは学術誌 『International Organization』と結びついている。同誌は1970年代、ロバート・キーホーン、ピーター・J・カッツェンシュタイン、スティーブン・クラス ナーの編集下でIPEの主要誌となった。また学術誌『The Review of International Political Economy』とも関連している。さらに批判的な国際政治経済学の学派も存在する。アントニオ・グラムシやカール・ポラニーといった思想家に影響を受け たもので、主要な人物としてマシュー・ワトソンとロバート・W・コックスが挙げられる[50]。 人類学者、社会学者、地理学者による政治経済学的アプローチの活用は、主に国家や地域統治のレベルで、またより小規模な社会集団や社会ネットワーク内でも 生じる政治体制や経済的価値体系を指して用いられる。これらの体制は社会的資本と経済的資本の組織化に影響を与え、また影響を受けるため、標準的な経済的 価値を持たない次元(言語・ジェンダー・宗教の政治経済など)の分析では、マルクス主義的資本批判で用いられる概念が頻繁に援用される。こうしたアプロー チは、アンドレ・ガンダー・フランクやイマニュエル・ウォーラスティンが提唱した発展と未発展に関する新マルクス主義的研究を発展させたものである。 歴史家たちは政治経済学を用いて、過去において共通の経済的利益を持つ人格や集団が、自らの利益に有益な変化をもたらすために政治をどのように利用してきたかを探求してきた。[51] 政治経済学と法は、法学研究において政治経済学文献と明示的に関わる最近の試みである。1920年代から1930年代にかけて、法実証主義者(例:ロバー ト・ヘイル)や知識人(例:ジョン・コモンズ)が政治経済学に関連するテーマに取り組んだ。20世紀後半には、シカゴ学派に連なる法学者たちが経済学の知 的伝統を一部取り入れた。しかし2007年の金融危機以降、特に国際法に関連する法学者たちが、政治経済学の文献における議論・方法論・諸テーマとより明 確に向き合うようになった。[52] [53] トマ・ピケティのアプローチと行動要請は、2008年の金融危機後に明らかになった経済学の欠陥を補い、学問の堅牢性を高める手段として、政治的考察と政治学の知見を経済学の分野に再導入することを提唱したものである。[54] 2010年、英国で唯一の政治経済学部がキングス・カレッジ・ロンドンに正式に設立された。この学術部門の設立理由は「政治学と経済学の学問領域は不可分 である」こと、そして「政治が機能する経済的文脈を探究せずに政治プロセスを適切に理解することは不可能である」ことにある。[55] 2012年、トニー・ペイン教授とコリン・ヘイ教授によりシェフィールド大学にシェフィールド政治経済研究所(SPERI)が設立された。これは資本主義 に対する政治分析と経済分析を統合する手段として創設された。創設者らは、2008年の金融危機を説明するには、これらを独立した学問分野として捉えるだ けでは不十分だと考えていた。[56] 2017年には、政治経済学分野の研究コンソーシアムとして政治経済学英国グループ(略称PolEconUK)が設立された。年次会議を開催しており、加 盟機関にはオックスフォード大学、ケンブリッジ大学、キングス・カレッジ・ロンドン、ウォリック大学、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスが含まれ る。[57] |

| Related disciplines Because political economy is not a unified discipline, there are studies using the term that overlap in subject matter, but have radically different perspectives:[58] Politics studies power relations and their relationship to achieving desired ends. Philosophy rigorously assesses and studies a set of beliefs and their applicability to reality. Economics studies the distribution of resources so that the material wants of a society are satisfied; enhance societal well-being. Sociology studies the effects of persons' involvement in society as members of groups and how that changes their ability to function. Many sociologists start from a perspective of production-determining relation from Karl Marx.[citation needed] Marx's theories on the subject of political economy are contained in his book Das Kapital. Anthropology studies political economy by investigating regimes of political and economic value that condition tacit aspects of sociocultural practices (e.g. the pejorative use of pseudo-Spanish expressions in the U.S. entertainment media) by means of broader historical, political and sociological processes. Analyses of structural features of transnational processes focus on the interactions between the world capitalist system and local cultures.[citation needed] Archaeology attempts to reconstruct past political economies by examining the material evidence for administrative strategies to control and mobilize resources.[59] This evidence may include architecture, animal remains, evidence for craft workshops, evidence for feasting and ritual, evidence for the import or export of prestige goods, or evidence for food storage. Psychology is the fulcrum on which political economy exerts its force in studying decision making (not only in prices), but as the field of study whose assumptions model political economy. Geography studies political economy within the wider geographical studies of human-environment interactions wherein economic actions of humans transform the natural environment. Apart from these, attempts have been made to develop a geographical political economy that prioritises commodity production and "spatialities" of capitalism. History documents change, often using it to argue political economy; some historical works take political economy as the narrative's frame. Ecology deals with political economy because human activity has the greatest effect upon the environment, its central concern being the environment's suitability for human activity. The ecological effects of economic activity spur research upon changing market economy incentives. Additionally and more recently, ecological theory has been used to examine economic systems as similar systems of interacting species (e.g., firms).[60] Cultural studies examines social class, production, labor, race, gender and sex. Communications examines the institutional aspects of media and telecommunication systems. As the area of study focusing on aspects of human communication, it pays particular attention to the relationships between owners, labor, consumers, advertisers, structures of production and the state and the power relationships embedded in these relationships. |

関連分野 政治経済学は統一された学問分野ではないため、この用語を用いる研究には主題が重複するものもあるが、根本的に異なる視点を持つものもある:[58] 政治学は権力関係と、それが目的達成にどう関わるかを研究する。 哲学は一連の信念とその現実への適用可能性を厳密に評価・研究する。 経済学は社会の物質的欲求を満たすための資源配分、すなわち社会的福祉の向上を研究する。 社会学は、個人が集団の一員として社会に関与することの影響と、それが個人の機能能力をどう変えるかを研究する。多くの社会学者はカール・マルクスの生産関係決定論の視点から出発する[出典必要]。マルクスの政治経済学に関する理論は『資本論』に収められている。 人類学は、より広範な歴史的・政治的・社会学的プロセスを通じて、社会文化的実践の暗黙的側面(例:米国娯楽メディアにおける擬似スペイン語表現の蔑称的 用法)を規定する政治的・経済的価値体系を調査することで政治経済学を研究する。越境的プロセスの構造的特徴の分析は、世界資本主義システムと地域文化の 相互作用に焦点を当てる。[出典が必要] 考古学は、資源を管理・動員するための行政戦略の物的証拠を検証することで、過去の政治経済を再構築しようとする。[59] この証拠には、建築物、動物の遺骸、工芸工房の痕跡、宴会や儀礼の痕跡、威信財の輸出入の痕跡、食料貯蔵の痕跡などが含まれる。 心理学は、意思決定(価格だけでなく)を研究する上で政治経済学が力を発揮する支点であると同時に、その前提が政治経済学をモデル化する研究分野である。 地理学は、人間の経済活動が自然環境を変容させる人間と環境の相互作用に関する広範な地理学研究の中で政治経済学を研究する。これらとは別に、商品生産と資本主義の「空間性」を優先する地理的政治経済学を発展させようとする試みも行われている。 歴史学は変化を記録し、しばしばそれを政治経済学の論証に用いる。一部の歴史研究は政治経済学を物語の枠組みとして採用する。 生態学は、人間の活動が環境に最も大きな影響を与えるため、政治経済学を扱う。その中心的な関心は、環境が人間の活動に適しているかどうかである。経済活 動が生態系に与える影響は、市場経済のインセンティブの変化に関する研究を促す。さらに近年では、生態学的理論が、相互作用する種(例えば企業)の類似シ ステムとして経済システムを検証するために用いられている。[60] 文化研究は社会階級、生産、労働、人種、性別、性(セクシュアリティ)を検証する。 コミュニケーション学はメディアと通信システムの制度的側面を検証する。人間コミュニケーションの諸側面を研究対象とする分野として、所有者、労働者、消費者、広告主、生産構造、国家間の関係、およびこれらの関係に内在する権力関係に特に注目する。 |

| Constitutional Political Economy Economics & Politics. ISSN 0954-1985 European Journal of Political Economy. Latin American Perspectives International Journal of Political Economy Journal of Australian Political Economy. ISSN 0156-5826 New Political Economy Public Choice. Studies in Political Economy |

憲法政治経済学 経済学と政治学。ISSN 0954-1985 欧州政治経済ジャーナル ラテンアメリカ展望 国際政治経済ジャーナル オーストラリア政治経済ジャーナル。ISSN 0156-5826 新政治経済学 公共選択論 政治経済学研究 |

| Critique of political economy Economic sociology Economic study of collective action Constitutional economics European Association for Evolutionary Political Economy (EAEPE) Economic ideology Government debt Institutional economics Land value tax Law of rent Important publications in political economy Marxian political economy Perspectives on capitalism by school of thought Political ecology Political economy in anthropology Political economy of climate change Social model Social capital Socioeconomics Surplus economics |

政治経済批判 経済社会学 集団行動の経済学的研究 憲法経済学 欧州進化政治経済学会(EAEPE) 経済イデオロギー 政府債務 制度経済学 地価税 地代法則 政治経済学における重要文献 マルクス主義政治経済学 思想学派による資本主義の視点 政治生態学 人類学における政治経済学 気候変動の政治経済学 社会モデル 社会資本 社会経済学 剰余経済学 |

| Baran,

Paul A. (1957). The Political Economy of Growth. Monthly Review Press,

New York. Review extrract. Archived 2015-05-01 at the Wayback Machine Commons, John R. (1934 [1986]). Institutional Economics: Its Place in Political Economy, Macmillan. Description Archived 2011-05-10 at the Wayback Machine and preview. Archived 2023-04-12 at the Wayback Machine David, F., "Utopia and the Critique of Political Economy." Journal of Australian Political Economy, Australian Political Economy Movement, 1 Jan. 2017 Komls, John (2023). Foundations of Real-World Economics; What Every Economics Student Needs To Know (3rd edition) Routledge. Leroux, Robert (2011), Political Economy and Liberalism in France : The Contributions of Frédéric Bastiat, London, Routledge. Maggi, Giovanni, and Andrés Rodríguez-Clare (2007). "A Political-Economy Theory of Trade Agreements," American Economic Review, 97(4), pp. 1374–1406. O'Hara, Phillip Anthony, ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of Political Economy, 2 v. Routledge. 2003 review links. Pressman, Steven, Interactions in Political Economy: Malvern After Ten Years Routledge, 1996 Rausser, Gordon, Swinnen, Johan, and Zusman, Pinhas (2011). Political Power and Economic Policy. Cambridge University Press. Winch, Donald (1996). Riches and Poverty : An Intellectual History of Political Economy in Britain, 1750–1834 Cambridge University Press. |

バラン、ポール・A. (1957). 『成長の政治経済学』. ニューヨーク:マンスリー・レビュー・プレス. 書評抜粋. 2015-05-01 ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ コモンズ、ジョン・R. (1934 [1986]). 『制度経済学:政治経済学におけるその位置』. マクミラン. 説明 2011年5月10日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ 及び プレビュー。2023年4月12日ウェイバックマシンにアーカイブ デイヴィッド、F.、「ユートピアと政治経済批判」『オーストラリア政治経済ジャーナル』、オーストラリア政治経済運動、2017年1月1日 コムルス、ジョン(2023)。『現実世界経済学の基礎』; 経済学の学生が知るべきこと(第3版)ラウトレッジ社。 ルルー、ロベール(2011年)『フランスにおける政治経済学と自由主義:フレデリック・バスティアの貢献』ロンドン、ラウトレッジ社。 マッジ、ジョヴァンニ、アンドレス・ロドリゲス=クレア(2007年)「貿易協定の政治経済学理論」『アメリカン・エコノミック・レビュー』97巻4号、 pp. 1374–1406. オハラ、フィリップ・アンソニー編(1999)。『政治経済学事典』、全2巻。ラウトレッジ。2003年版レビューリンク。 プレスマン、スティーブン、『政治経済学における相互作用:マルバーン会議10年後』ラウトレッジ、1996年 ラウサー、ゴードン、スウィネン、ヨハン、ズスマン、ピンハス(2011)。『政治権力と経済政策』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 ウィンチ、ドナルド(1996)。『富と貧困:1750-1834年英国における政治経済学の知的歴史』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Political_economy |

|

| Knowledge and

Politics is a 1975 book by philosopher and politician Roberto

Mangabeira Unger. In it, Unger criticizes classical liberal doctrine,

which originated with European social theorists in the mid-17th century

and continues to exercise a tight grip over contemporary thought, as an

untenable system of ideas, resulting in contradictions in solving the

problems that liberal doctrine itself identifies as fundamental to

human experience. Liberal doctrine, according to Unger, is an

ideological prison-house that condemns people living under its spell to

lives of resignation and disintegration. In its place, Unger proposes

an alternative to liberal doctrine that he calls the "theory of organic

groups," elements of which he finds emergent in partial form in the

welfare-corporate state and the socialist state. The theory of organic

groups, Unger contends, offers a way to overcome the divisions in human

experience that make liberalism fatally flawed. The theory of organic

groups shows how to revise society so that all people can live in a way

that is more hospitable to the flourishing of human nature as it is

developing in history, particularly in allowing people to integrate

their private and social natures, achieving a wholeness in life that

has previously been limited to the experience of a small elite of

geniuses and visionaries. |

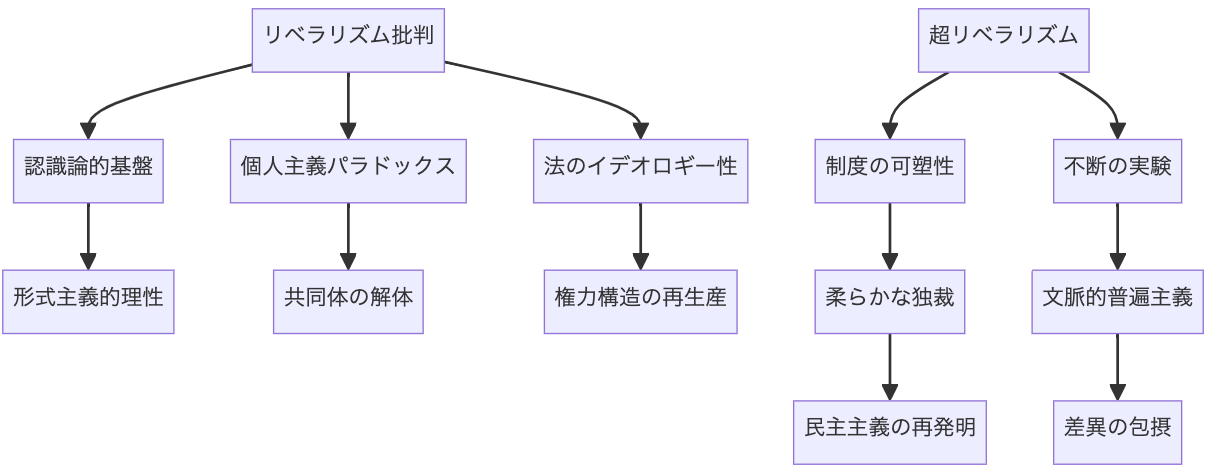

『知識と政治』は、哲学者であり政治家でもあるロベルト・マンガベイ

ラ・ウンガーによる1975年の著作である。本書においてウンガーは、17世紀中頃のヨーロッパ社会理論家たちに起源を持ち、現代思想に今なお強い影響力

を行使し続ける古典的自由主義の教義を、持続不可能な思想体系として批判する。自由主義教義自体が人間の経験にとって根本的と認める問題の解決において、

矛盾を生じさせる結果をもたらすからである。ウンガーによれば、自由主義教義はイデオロギー的な監獄であり、その呪縛下で生きる人民を諦観と崩壊の人生へ

と追いやる。その代わりにウンガーは「有機的集団の理論」と呼ぶ自由主義教義への代替案を提案する。その要素は福祉企業国家や社会主義国家において部分的

に現れていると彼は見出す。有機的集団理論は、自由主義を致命的に欠陥あるものとする人間経験の分裂を克服する道を提供するとウンガーは主張する。有機的

集団理論は、社会をどのように改変すべきかを示す。それは、歴史の中で発展しつつある人間性の開花により適した生き方を、全ての人々が実現できるようにす

るためである。特に、個人が私的性質と社会的性質を統合し、これまでごく少数の天才や先見者というエリート層の経験に限定されていた、人生における全体性

を達成することを可能にする。 |

| Overview Introduction Unger opens Knowledge and Politics by explaining how he intends to criticize liberal doctrine and how that criticism will help lead to, and elucidate, a positive program: the creation of a nonliberal doctrine of mind and society.[1] He explains that the rationale for this theoretical enterprise is rooted in the human desire to understand the “meaning of life,” specifically, the nature of the bond between the self and the world.[2] Unger contends that the contemporary human moral experience is one of division, between a side of the self that maintains allegiance to the dominant theoretical and political regimes of society, and another side that is drawn to ideals that current modes of thought reject. Under this experience of division, Unger contends, human experience demands “total criticism” of the kind he intends to apply to the doctrine of liberalism.[2] Unger describes classical liberal doctrine as both a ruling consciousness of society and a metaphysical system, a system of ideas which involves a particular organization of moral sentiments.[3] In human moral experience, liberalism's failure to satisfy the ideal of the self (which Unger later describes as the fullest expression of man's species nature) is experienced as the twin evils of resignation and disintegration. The early liberal thinkers and the classic social theorists understood the radical separations that mark human life, between self and nature, self and others, self and its own roles and works.[3] By undertaking a total criticism of liberal doctrine, particularly by repudiating its distinction between reason and desire, and Unger intends to lay the groundwork for his positive program, the nonliberal social theory that would help to overcome these divisions and give full expression to a range of human feelings and ideas.[4] |

概要 序論 ウンガーは『知識と政治』の冒頭で、自由主義的教義をいかに批判するつもりか、そしてその批判がいかにして積極的なプログラム——非自由主義的な精神と社 会の教義の構築——へと導き、それを解明するかを説明している[1]。彼は、この理論的試みの根拠が「人生の意味」、具体的には自己と世界との絆の本質を 理解したいという人間の欲求に根ざしていると述べる。[2] アンガーは、現代人の道徳的経験は分裂状態にあると主張する。つまり、社会における支配的な理論的・政治的体制への忠誠を保つ自己の一側面と、現在の思考 様式が拒絶する理想に引き寄せられる別の側面との分裂である。この分裂の経験のもとでは、人間の経験はリベラリズムの教義に対して彼が適用しようとする類 の「全面的な批判」を要求するとアンガーは論じる。[2] ウンガーは古典的自由主義の教義を、社会の支配的意識であると同時に形而上学的体系、すなわち道徳感情の特定の組織化を伴う思想体系であると描写する。 [3] 人間の道徳的経験において、自由主義が自己の理想(ウンガーは後にこれを人間の本性の最も完全な表現と説明する)を満たせないことは、諦観と解体の二つの 悪として経験される。初期の自由主義思想家や古典的社会理論家たちは、自己と自然、自己と他者、自己とその役割や行為との間に存在する、人間生活を特徴づ ける根本的な分離を理解していた。[3] 自由主義学説の徹底的批判、特に理性と欲望の区別を否定することで、ウンガーは自らの積極的プログラムの基盤を築こうとしている。それは非自由主義的社会 理論であり、これらの分裂を克服し、人間の感情や思想の多様性を完全に表現することを助けるものである。[4] |

| Chapter 1: Liberal Psychology The Antinomy of Theory and Fact The liberal doctrines of mind and society rejected the medieval view of knowledge which held that all things in nature have intelligible essences. Under the doctrine of intelligible essences, everything can be classified under the word that names its category. Liberal thinkers, in rejecting the doctrine of intelligible essences, realized that there is an infinite number of ways objects and events can be classified, infinite ways the world can be divided up by the mind. Liberalism's rejection of the doctrine of intelligible essences had far-reaching consequences for moral and political views. The rejection of intelligible essences also led to the antinomy of theory and fact, a seemingly insoluble conflict between two ideas that seemed equally plausible but led to equally absurd consequences. The antinomy of theory and fact is the conflict between, on the one hand, the realization that all understanding of facts is mediated by theory, and on the other hand, the belief in an independent comparison of theory and fact. Faced with the antinomy of theory and fact, we ask: how can we assess the power of competing theories, if there is no appeal to facts independently of theories? Kant's metaphysics offered a promising and ingenious solution—namely, locating the source of the antinomy in the division of universal and particular, form and substance, in human thought. The division between the universal and particular is at the heart of the contradictions of liberal thought. |

第1章:自由主義心理学 理論と事実の対立 自由主義的な精神と社会に関する教義は、自然界のあらゆる事物に知性的な本質が存在するとする中世の知識観を拒否した。知性的な本質という教義の下では、 あらゆるものはそのカテゴリーを名指す言葉の下に分類できる。自由主義思想家たちは、知性的な実体論を拒絶することで、物や出来事を分類する方法は無限に 存在し、世界が精神によって分割される方法も無限であることを認識した。自由主義による知性的な実体論の拒絶は、道徳観や政治観に広範な影響をもたらし た。知性的な本質論の否定はまた、理論と事実の二律背反へとつながった。これは二つの考えの間にある、一見解決不能な矛盾である。両者は等しく妥当に見え るが、等しく荒唐無稽な結果を招く。理論と事実の二律背反とは、一方では事実の理解は全て理論を介して行われるという認識と、他方では理論と事実の独立し た比較が可能だという信念との間の矛盾である。理論と事実の対立に直面して我々は問う:理論から独立した事実への訴えがなければ、競合する理論の力をどう 評価できるのか?カントの形而上学は有望かつ独創的な解決策を提示した。すなわち、この対立の根源を人間の思考における普遍と個別、形式と実体の区分に見 いだすという解決策である。普遍と個別との区別こそが、自由主義思想の矛盾の核心にある。 |

| The Principles of Liberal Psychology Unger describes the “unreflective view of mind” that characterizes liberal psychology. According to this unreflective view of mind, the mind is a machine that perceives and understands facts (object-events) through sensations. These sensations can be combined, or split until they are indivisible. Combining sensations does not change them. Facts that have been combined can be analyzed back into their constituent sensations. Hobbes explained that desire is what impels the “mind-machine” to its operations of combination and analysis. What leads desire to choose one course of action over another is the desire to seek pleasure and avoid pain. This account of liberal doctrine's unreflective view of the mind can be reduced to three principles: The principle of reason and desire. The principle that the self is divided between desire, which is the active, desiring, moving part of the self, and understanding, which is the knowing part of the self. The understanding wants nothing; desire can see nothing. What distinguishes human beings is that they desire different things, not that they understand the world differently. The principle of arbitrary desire. This principle holds that desires are arbitrary from the perspective of the understanding. We cannot determine what we should want simply by learning more about the world. Reason cannot be used to justify the content of desires. The principle of analysis. This principle holds that knowledge is the sum of its parts. Operations of the mind by which we acquire knowledge involve either joining discrete sensations into more complex ideas, or breaking these complex ideas down into their building blocks. Underlying the principle of analysis is an idea at the heart of liberal doctrine as a whole: confidence in the primacy of the simple. The principle of analysis, according to Unger, reveals liberalism's incomplete rejection of the doctrine of intelligible essences, and has pernicious effects on social theory, by demoralizing attempts to construct ambitious conceptual systems and discouraging us from trying to understand, and change, social situations as a whole. |

自由主義心理学の原理 ウンガーは自由主義心理学の特徴である「無反省的な心観」を説明する。この無反省的な心観によれば、心は感覚を通じて事実(対象事象)を知覚し理解する機 械である。これらの感覚は結合したり、分割して不可分になるまで分解できる。感覚を結合してもそれらは変化しない。結合された事実は、構成要素である感覚 へと分析し戻すことができる。ホッブズは、欲望こそが「精神機械」を結合と分析の操作へと駆り立てるものだと説明した。欲望がひとつの行動方針を他方より も選ぶように導くのは、快楽を求め苦痛を避けるという欲望である。自由主義学説のこの非反省的な精神観は、三つの原理に還元できる: 理性と欲望の原理。自己は、能動的で欲求し動く部分である欲望と、認識する部分である理解力とに分かれているという原理である。理解力は何も欲しない。欲望は何も見えない。人間を区別するのは、世界を理解する方法の違いではなく、異なるものを欲する点にある。 恣意的欲望の原理。この原理は、欲望が理解の視点から見て恣意的だと主張する。世界についてより多く学ぶだけでは、我々が何を望むべきかを決定できない。理性は欲望の内容を正当化するために用いられない。 分析の原理。この原理は、知識はその構成要素の総和だと主張する。知識を獲得する精神の作用は、離散的な感覚をより複雑な観念に結合するか、あるいはこれ らの複雑な観念を構成要素に分解するかのいずれかである。分析の原理の根底には、自由主義思想全体の中核をなす考えがある。すなわち、単純性の優位性への 確信である。ウンガーによれば、分析の原理は自由主義が知性的な本質論を不完全にしか拒絶していないことを露呈し、野心的な概念体系の構築を試みる意欲を 挫き、社会状況全体を理解し変革しようとする試みを阻害することで、社会理論に有害な影響を及ぼす。 |

| Reason and Desire Liberal psychology gives rise to two kinds of moral theory, each of which are caught up in a paradox that Unger calls the antinomy of reason and desire. Both of these moralities are destructive of a true conception of human personality. One moral theory generated under liberal psychology is the morality of desire. This morality defines the good as the satisfaction of desire, and asserts the primacy of the good over the right. Contentment is the condition in which desire is satisfied, and the task of moral theory is to show how we might organize our lives so that we can gain contentment, or happiness. The other moral theory bequeathed by liberal psychology is the morality of reason, which holds that reason alone establishes the standards of right conduct. Unger points out that, in light of liberal doctrine's conviction that reason wants nothing, it might strike us as strange to contend that reason alone is a basis of morality. The basis for the morality of reason is the belief that humans must accept certain rules, offered by reason, to move beyond the exercise of “naked desire” to the possibility of judging right and wrong and justifying our actions to our fellow men. When reason is believed to offer us universal rules for conduct, it is really telling us what principles we would have to accept to engage in moral criticism. The foremost example of the morality of reason is Kant's moral theory. The moralities of reason and desire are both vulnerable to serious objections. The morality of desire is deficient because it is incapable of passing from description to evaluation of conduct, and thus is unable to lay down standards of justification. Furthermore, the life to which morality of desire points is inadequate; contentment is elusive without any criteria to judge and order the ends of conduct. The morality of reason is inadequate, first, due to the inadequacy of reason to serve as a foundation for any moral judgments and, second, because the moral life as conceived by the moralist of reason is inadequate. The respective inadequacies of moralities of desire and reason generate an antinomy. If morality of desire abandons us to our random and changing appetites, morality of reason suppresses our existence as subjective beings with individual ends. The root of this antinomy of reason and desire is the separation between understanding and evaluation in liberal doctrine. |

理性と欲望 自由主義心理学は二種類の道徳理論を生み出すが、いずれもウンガーが理性と欲望の反論と呼ぶパラドックスに陥っている。これらの道徳観はいずれも人間人格 の真の概念を破壊する。自由主義心理学から生まれた一つの道徳理論は欲望の道徳である。この道徳は善を欲望の充足と定義し、善が権利に優先すると主張す る。満足とは欲望が満たされた状態であり、道徳理論の課題は、我々が満足、すなわち幸福を得るために如何に生活を組織すべきかを示すことにある。自由主義 心理学が遺したもう一つの道徳理論は理性道徳であり、正しい行為の基準は理性のみが確立すると主張する。ウンガーは指摘する。自由主義的教義が「理性は何 も欲しない」と確信していることを踏まえると、理性のみが道徳の基盤だと主張するのは奇妙に思えるかもしれないと。理性による道徳の基盤は、人間が「裸の 欲望」の行使を超えて、善悪を判断し、仲間に対して自らの行動を正当化する可能性へと進むためには、理性が提示する一定の規則を受け入れねばならないとい う信念にある。理性が普遍的な行動規範を提供するとされる時、それは実際には道徳的批判を行うために受け入れねばならない原理を示しているに過ぎない。理 性道徳の代表例はカントの道徳理論である。 理性と欲望の道徳観は双方とも深刻な反論に晒される。欲望道徳は行動の記述から評価へ移行できず、正当化の基準を確立できない点で不十分である。さらに、 欲望の道徳が指し示す人生は不十分だ。行動の目的を判断し秩序立てる基準がなければ、満足は得られない。理性の道徳も不十分である。第一に、理性が道徳的 判断の基盤として不十分だからだ。第二に、理性の道徳家が構想する道徳的生活自体が不十分だからだ。欲望と理性の道徳がそれぞれ不十分であることが、矛盾 を生む。欲望の道徳が我々を無秩序で移ろいやすい欲望に委ねるならば、理性の道徳は個別の目的を持つ主体的存在としての我々の存在を抑制する。この理性と 欲望の対立の根源は、自由主義的教義における理解と評価の分離にある。 |

| Personality Unger contends that the psychological principles of liberalism make it impossible to formulate an adequate conception of personality. Unger identifies four dimensions of the minimum idea of personality: continuing identity, common humanity with others, ability to change ends over time while acknowledging continuity of existence, and being a unique individual despite membership in species of like beings. But neither the morality of desire nor morality of reason does justice to these qualities. The morality of desire denies continuity and humanity of the self, seeing the human being led by desire to seek contentment without any criteria for ordering the ends of conduct, while the morality of reason denies the human capacity for moral innovation and individual identity, offering a formal, empty principle of reason as the only guidance to what we ought to do. The theoretical deficiencies of the liberal conception of personality are mirrored in the experience of the individual in the social world in which the liberal mode of consciousness prevails. The individual is condemned to a state of degradation and division, forced to deal with others in a social world that threatens the person with loss of individuality and loss of autonomy in directing his life, perpetually fleeing to private life for the chance to shed the mask of one's largely unchosen public role. People seek temporal unity in a public identity at the cost of their singularity and uniqueness. As Unger says, “Others save you from being nothing, but they do not allow you to become yourself.” Under liberalism, people are torn between roles that force them to sacrifice their private selves to their public ones, thus surrendering individual identity; or casting off convention and following their own courses, but risking disintegration of the self. |

人格(パーソナリティ) ウンガーは、自由主義の心理学的原理では、人格の適切な概念を構築することは不可能だと主張する。ウンガーは人格の最小限の概念として四つの次元を特定す る:継続的な同一性、他者との共通の人間性、存在の継続性を認めつつ時間の経過とともに目的を変更する能力、そして同種の存在に属しながらも独自の個人で あること。しかし欲望の道徳も理性の道徳も、これらの特質を正当に評価していない。欲望の道徳は、自己の継続性と人間性を否定する。人間は欲望に導かれ、 行動の目的を秩序づける基準なしに満足を求める存在だと見なす。一方、理性の道徳は、人間の道徳的革新能力と個人同一性を否定する。形式的で空虚な理性の 原理を、我々がなすべきことの唯一の指針として提示するに過ぎない。 リベラリズム的人格観の理論的欠陥は、リベラリズム的意識様式が支配する社会世界における個人の経験に反映される。個人は堕落と分裂の状態に陥り、社会世 界において他者と関わらざるを得ない。そこでは個性が失われ、自らの人生を自律的に導く能力が脅かされる。結局、個人は公的な役割という、ほとんど自ら選 んだものではない仮面を脱ぎ捨てる機会を求めて、常に私的生活へと逃げ込むことになる。人民は公的なアイデンティティにおいて一時的な統一を求めるが、そ の代償として独自性と唯一無二性を犠牲にする。ウンガーが言うように「他者はお前を無から救うが、お前自身になることを許さない」。自由主義のもとでは、 人民は二つの役割の間で引き裂かれる。公的な自己に私的な自己を犠牲にする役割か、慣習を捨てて自らの道を歩むが自己の崩壊を危険に晒す役割かの選択を迫 られるのだ。 |

| Chapter 2: Liberal Political Theory The Unreflective View of Society Unger outlines liberal political theory in much the same way that he described liberal psychology. He begins by describing the unreflective view of society that holds a central place in everyday thinking about social life, as well as in some specialized fields of study. According to this unreflective and widely held view of society, the individual is made up of reason and will. Reason is directed by will, the desiring element of personality. Human beings are blind creatures of appetite, but they are capable of objectively understanding the world, and some are more acute in their understanding than others. Despite their capacity for objective understanding, the things people desire are infinitely diverse. The universal desire for comfort and honor, under circumstances of scarcity, make mutual antagonism and mutual dependence inevitable and unavoidable. Freedom, or not being under the control of an alien will, is sought and experienced as a form of power. People form alliances to further their interests in hostility and collaboration. The two fundamental problems of politics, order and freedom, are consequences of this mutual antagonism and reciprocal need. Society's first task is to place restraints on the exercise of mutual antagonism, so that mutual need can be satisfied. Such restraints moderate the struggle for comfort, power and glory, so that everyone can be protected from the worst outcomes for a person—grave indignity, harsh penury, enslavement, or violent death. How to control hostility between people is the problem of order. As soon as limits are placed on mutual antagonism, men encounter the problem of freedom: how to order society so that no one's liberty is arbitrarily preferred over another's, so that no one's arbitrarily chosen means and ends of striving take unjustifiable precedence over another's? Society tries to solve the problems of order and freedom by making and applying impersonal laws. |

第2章:自由主義的政治理論 社会に対する無反省な見方 ウンガーは自由主義的政治理論を、自由主義的心理学を説明したのとほぼ同様の方法で概説する。彼はまず、日常生活における社会生活についての思考や、いく つかの専門的な研究分野において中心的な位置を占める、社会に対する無反省な見方を描写することから始める。この無反省で広く受け入れられている社会観に よれば、個人は理性と意志から成り立つ。理性は意志、すなわち人格の欲求要素によって導かれる。人間は欲望に駆られる盲目の生き物だが、世界を客観的に理 解する能力を持ち、その理解力は人によって鋭さを増す。客観的理解能力にもかかわらず、人民が求めるものは無限に多様である。不足の状況下では、快適さと 名誉への普遍的な欲求が、相互の敵対と相互依存を必然かつ避けがたいものにする。自由、すなわち他者の意志に支配されない状態は、一種の力として求めら れ、経験される。人民は敵対と協力の中で自らの利益を追求するために同盟を結ぶ。政治の二大課題である秩序と自由は、この相互敵対と相互依存の結果であ る。 社会の第一の課題は、相互の敵対行為に制約を設け、相互の必要性を満たせるようにすることだ。こうした制約は、安楽・権力・栄誉をめぐる争いを緩和し、あ らゆる人格を最悪の結果——深刻な屈辱、過酷な貧困、奴隷化、暴力的な死——から守る。人間同士の敵意をどう制御するかが秩序の問題である。相互敵対に制 限が課されるやいなや、人間は自由の問題に直面する。すなわち、誰の自由も他者の自由より恣意的に優先されないように、また誰の恣意的に選んだ手段や目的 が他者のそれより不当に優先されないように、社会を秩序づけるにはどうすべきか?社会は、非人格的な法律を制定し適用することで、秩序と自由の問題を解決 しようとする。 |

| The Principles of Liberal Political Thought Liberal political thought revolves around three core principles, according to Unger: The principle of rules and values. This principle holds that value is the social face of desire, referring to something wanted or sought by a person. Rules are necessary to restrain the mutual hostility and antagonism that arises as people pursue their arbitrarily chosen values. The distinction between rules and values as two basic elements of social order is the first principle of liberal social thought, and it stands at the heart of the unreflective liberal belief that the eternal hostility of men to each other requires that order and freedom be maintained by government under law. The principle of subjective value. This is the idea that all values are individual and subjective; the individuality of values is the basis of personal identity under liberalism, which does not recognize communal values. Values are subjective, determined by choice, a belief that goes against the ancient conception of objective value. Liberal thought represents a revolt against the conception of objective value. The principle of individualism holds that a group is simply a collection of individuals. Formally analogous to the principle of analysis, which maintains that a whole is just the sum of its parts, the principle of individualism implies that society is artificial, that groups, being merely the products of the will and interests of individuals, are less real than the individuals that comprise them. Unger suggests that individualism is so deeply rooted in Western liberal thought that it is hard to grasp the opposite view, the collectivist and organicist view held by romantics. Collectivists view the group as having an independent existence. The heart of the collectivist view is the idea of the spontaneity of social bonds and their priority over individual striving. |

自由主義的政治思想の原理 ウンガーによれば、自由主義的政治思想は三つの核心的原理を中心に展開する。 規則と価値の原理。この原理は、価値とは欲望の社会的側面であり、人格が望むものや求めるものを指すとする。規則は、人民が恣意的に選んだ価値を追求する 過程で生じる相互の敵意や対立を抑制するために必要である。社会秩序の二つの基本要素としての規則と価値の区別は、自由主義的社会思想の第一原理であり、 人間同士の永遠の敵意が法に基づく政府による秩序と自由の維持を必要とするという、自由主義者の無批判な信念の中核をなす。 主観的価値の原理。これは全ての価値が個人的かつ主観的であるという考えだ。価値の個別性は、共同体の価値を認めない自由主義における人格の同一性の基盤 である。価値は主観的で選択によって決定されるというこの信念は、客観的価値という古代の概念に反する。自由主義思想は客観的価値の概念に対する反逆を表 す。 個人主義の原理は、集団とは単に個人の集合体に過ぎないと主張する。形式的には分析の原理(全体は単なる部分の総和であるとする)と類似しているが、個人 主義の原理は社会が人工的であり、集団は個人の意志と利益の産物に過ぎないため、それを構成する個人よりも現実性に欠けることを示唆する。ウンガーによれ ば、個人主義は西洋自由主義思想に深く根ざしているため、ロマン主義者が抱く集団主義的・有機主義的見解という対極の立場を理解するのは困難だという。集 団主義者は集団を独立した存在と見なす。集団主義的見解の核心は、社会的絆の自発性と、それが個人の努力よりも優先されるという考えにある。 |

| The Problems of Legislation and Adjudication Unger contends that there can be no coherent theory of legislation or adjudication on liberal premises. Liberal thinkers believe society is held together by rules, so under liberal doctrine issues of legislation and adjudication are central to solving the problems of order and freedom. Unger shows that the problems of order and freedom collapse into each other (to know what standards laws would have to conform to, so as not to prefer arbitrarily one man's advantage over another's, one would also have to know how best to restrain antagonism in the interest of collaboration). Justification of laws, therefore, consists in showing that restraints on freedom are justified and no greater than necessary. Unger enumerates three main ways that modern political philosophy envisages the establishment of freedom through legislation. The first two, based on formal and substantive theories of freedom, are expressions of liberal doctrine. They have similar flaws that render them incoherent. The formal theory (represented most prominently by Kant) is too abstract to offer concrete guidance on legislation; once we try to derive specificity from its principles, we cannot avoid preferring some values over others. The substantive doctrine (with variations offered by utilitarianism, social contract theory, and Rawls) also fails because it cannot find a neutral way to legislate among individual and competing values. The third basis for legislation, based on a doctrine of shared values, is a partial attempt to escape liberal doctrine, one that does not go far enough. It has the merit of viewing freedom as something other than the liberal concept of freedom to do whatever one wants; freedom, under the doctrine of shared values, is a development of human capacities, talents, and powers, and the task of the state is to choose arrangements that foster this human flourishing. If taken to the hilt, the doctrine of shared values might be a coherent basis for lawmaking. Liberalism has failed to provide such a coherent theory; its attempts to offer one have failed because they could not avoid preferring some values over others, thus violating the demand for neutral laws that is at the heart of liberalism. Similarly, liberalism has failed to provide a coherent theory of adjudication. Unger describes two ways of ordering human relations under a judicial regime: legal justice and substantive justice. Legal justice establishes rules governing general categories of acts and persons, and settles particular disputes on the basis of the system's rules. Substantive justice determines goals of the system, and then, independent of rules, tries to decide cases by a judgment of which decision will likely contribute to the achievement of the goal, in other words, an exercise of instrumental rationality. In a system of legal justice, there is a possible distinction between legislation and adjudication, although the line may be hazy in some systems (such as under a common law system). In substantive justice regimes, there is no meaningful line between legislation and adjudication. In his account of the failure of liberalism to provide a coherent account of adjudication, Unger explores the two primary paths that jurists have taken in explaining regimes of legal justice: formalist and purposive accounts. Formalist accounts collapse because they depend upon a theory of plain meaning that can only be accepted if one accepts the doctrine of intelligible essences, which liberalism must reject. A purposive account of legal justice, which holds that judges must consider the purposes and policies of laws they apply, in order to apply them correctly and uniformly, results in judges applying their own subjective preferences, and there is no method of choice among the many policies that may compete for the judge's attention in finding a rationale for decision. Ultimately, purposive adjudication results in the exercise of instrumental rationality, which cannot pretend to have stability or generality, thus it is fatal to the aims of legal justice. Substantive justice does not offer hope for the liberal seeking a basis for a coherent theory of adjudication. A substantive justice regime, Unger explains, requires common values so firmly established that they can be taken for granted in deciding individual cases. Tribal societies and theocratic states have common values that can provide such a basis for adjudication. But in liberal thought, the centrality of the principles of subjective value and individualism destroy the possibility of a stable set of common ends. Thus, whether liberal doctrine appeals to legal justice or substantive justice in developing a theory of adjudication, it will fail, because the premises of liberalism make all such efforts collapse into incoherence. |

立法と裁判の問題 ウンガーは、自由主義の前提では立法や裁判の首尾一貫した理論は成り立たないと主張する。自由主義思想家は社会が規則によって維持されると考えるため、自 由主義の教義では秩序と自由の問題を解決する上で立法と裁判が核心となる。ウンガーは秩序と自由の問題が相互に内在化することを示す(ある人の利益を他人 の利益より恣意的に優先させないために、法律が従うべき基準を知るには、協働の利益のために敵対心をいかに抑制すべきかを知る必要もある)。したがって法 律の正当化とは、自由への制約が必要最小限であり正当化されることを示すことに帰着する。 ウンガーは、現代政治哲学が立法による自由の確立を構想する三つの主要な方法を列挙する。最初の二つは、形式的自由理論と実質的自由理論に基づく自由主義 的教義の表現である。これらは矛盾を招く類似の欠陥を持つ。形式的理論(カントが最も顕著な代表者)は抽象的すぎて立法への具体的指針を提供できず、その 原理から具体性を導こうとすれば、必然的にある価値を他の価値より優先せざるを得なくなる。実質的理論(功利主義、社会契約論、ロールズによる変種を含 む)もまた、競合する個別的価値の間で中立的な立法方法を見出せない点で失敗する。第三の立法基盤である共有価値の理論は、自由主義的教義からの部分的な 脱却を試みるものだが、その試みは不十分である。この立場の利点は、自由を「やりたい放題の自由」という自由主義的概念とは異なるものとして捉える点にあ る。共有価値の理論における自由とは、人間の能力・才能・力を発展させることであり、国家の役割はこうした人間の繁栄を促進する制度を選択することだ。徹 底的に追求されれば、共有価値の理論は法制定のための一貫した基盤となり得る。自由主義はこうした首尾一貫した理論を提供できなかった。その試みが失敗し たのは、特定の価値観を他より優先せざるを得ず、自由主義の核心である中立的な法律の要求に反したからだ。 同様に、自由主義は裁判に関する首尾一貫した理論も提供できなかった。ウンガーは司法体制下における人間関係の秩序付けを二つの方法、すなわち法的正義と 実質的正義で説明する。法的正義は、行為や人格の一般的なカテゴリーを統制する規則を確立し、その体系の規則に基づいて個別の紛争を解決する。実質的正義 は、体系の目標を決定し、その後、規則とは独立して、どの決定がその目標達成に貢献する可能性が高いかという判断、つまり手段的合理性の行使によって事件 を裁こうとする。法的正義の制度では、立法と裁判の間に区別が存在する可能性があるが、その境界線は(コモン・ロー制度など)一部の制度では曖昧である。 実質的正義の制度では、立法と裁判の間に意味のある境界線は存在しない。 ウンガーは、自由主義が裁判制度について首尾一貫した説明を提供できなかった理由を論じる中で、法学者たちが法的正義の体制を説明するために採ってきた二 つの主要な道筋、すなわち形式主義的説明と目的論的説明を探求している。形式主義的説明は、自由主義が拒否せざるを得ない「理解可能な本質」の教義を受け 入れる場合にのみ成立し得る平易な意味の理論に依存しているため、崩壊する。目的論的説明は、裁判官が法を正しく均一に適用するためには、適用する法の目 的や政策を考慮しなければならないとする。しかしこれは裁判官が自らの主観的好みを適用することになり、判決の根拠を見出す過程で裁判官の注意を引く可能 性のある多数の政策の中から選択する方法が存在しない。結局、目的論的裁判は手段的合理性の行使に帰着し、安定性や普遍性を装うことはできない。したがっ て、これは法的正義の目的にとって致命的である。 実質的正義は、一貫した裁判理論の基盤を求める自由主義者に希望を与えない。ウンガーが説明する通り、実質的正義の体制には、個々の事件を判断する際に当 然の前提として扱えるほど強固に確立された共通の価値観が必要である。部族社会や神権国家には、裁定の基盤となり得る共通の価値観が存在する。しかし自由 主義思想においては、主体性および個人主義の原則が中心的な位置を占めるため、安定した共通目的の確立は不可能となる。したがって自由主義の教義が裁定理 論を構築するにあたり、法的正義に訴えようが実質的正義に訴えようが、その試みは失敗に終わる。自由主義の前提条件が、あらゆる試みを矛盾に陥らせるから である。 |

| Shared Values Unger concludes his account of liberal political thought by exploring the idea of shared values as a possible solution to the problem of order and freedom that liberalism failed to solve. Unger sees the concept of shared values as a possible basis for saving formalism, a formalism based on plain meanings that derive from shared social life, not derived from the unsupportable doctrine of intelligible essences. Shared values could also serve as a basis for a regime of substantive justice, in which decisions would be made based on their ability to promote common ends. Rules could have plain meanings because that are backed by a common vision of the world. Unger sees the possibility of shared values, conceived in this way, as requiring group values that are neither individual nor subjective. A system of ideas and social life in which shared values would have this central role would be one in which the distinction between fact and value has been repudiated. But under liberalism, and the social experience that exists in the grip of liberal doctrine, shared values could not have this force. Unger believes shared values have this promise, but that this promise could only be realized under two conditions: the development of a new system of thought, and the occurrence of a political event that transforms the conditions of social life. The theory of organic groups, which he will explore at the end of Knowledge and Politics, describes a setting in which these conditions are satisfied. |

共有価値 ウンガーは自由主義的政治思想の考察を締めくくるにあたり、自由主義が解決できなかった秩序と自由の問題に対する一つの解決策として、共有価値という概念 を探求する。ウンガーは共有価値の概念を、形式主義を救う可能性のある基盤と見なしている。この形式主義は、理解可能な本質という支持できない教義から導 かれるのではなく、共有された社会生活から派生する平易な意味に基づくものである。共有価値は実質的正義の体制の基盤ともなり得る。そこでは共通の目的を 促進する能力に基づいて決定が行われる。規則は世界に対する共通のビジョンに裏打ちされるため、平易な意味を持つことができる。ウンガーは、このように構 想された共有価値の可能性が、個人でも主体性でもない集団的価値を必要とするものだと見ている。共有された価値観がこのような中心的な役割を担う思想体系 と社会生活は、事実と価値の区別が否定された世界である。しかし自由主義、そして自由主義的教義に支配された社会経験の下では、共有された価値観にそのよ うな力は持ち得ない。ウンガーは共有価値にこの可能性があると信じているが、その実現には二つの条件が必要だとする。新たな思想体系の発展と、社会生活の 条件を変革する政治的出来事の発生である。『知識と政治』の末尾で論じられる有機的集団の理論は、これらの条件が満たされる状況を記述している。 |

| Chapter 3: The Unity of Liberal Thought Having surveyed liberal psychology and liberal political thought, Unger then undertakes to show the underlying unity of liberal thought, and he seeks to locate the source of this unity in ideas even more fundamental than those discussed in previous chapters. |

第3章:自由主義思想の統一性 自由主義心理学と自由主義政治思想を概観した後、ウンガーは自由主義思想の根底にある統一性を示すことに着手する。そして彼は、この統一性の源泉を、これまでの章で論じた思想よりもさらに根本的な思想の中に位置づけようとする。 |

| The Methodological Challenge of Studying Liberalism Unger explains that much criticism of liberalism is directed at liberal doctrine only as it exists in the order of ideas, a level of discourse in which one can fruitfully apply the methods and procedures of formal logic. However, a full review of liberalism requires that it be examined not only as it exists in the order of ideas, but also as a form of social life, one that exists in the realm of consciousness. Studying liberalism as it exists in the realm of consciousness is not an inquiry susceptible of formal logical analysis; rather, a different method must be employed, one suited to symbolic analysis. Unger describes the method needed as a method of appositeness or symbolic interpretation. The method Unger contends is most suited to the examination of liberalism in the realm of consciousness, is one that has been driven to the periphery of intellectual life under liberalism, namely the method of the ancient humanistic, dogmatic disciplines, such as theology, grammar, and legal study. Such method assumes a community of intention between the interpreter and the interpreted. This method of symbolic interpretation has been largely abandoned under liberalism, since liberal principles of subjective value and individualism have destroyed the community of intentions required to make such doctrinal inquiry fruitful. Unger discusses how studying ideas such as those represented by liberalism can be challenging because ideas can exist in three senses of existence—in the mode of events, in the mode of social life, and in the mode of ideas. An idea can be a psychic event that can be studied by science; a belief wedded to human conduct that is amenable only to a symbolic, interpretive method; and as the content of thought, which can have truth or falsehood and is susceptible to logical analysis. This "stratified ontology," as Unger describes it, leads to some of the most intractable problems of philosophy, especially in understanding the relation of social life to the realms of ideas and events. Liberalism exists both as a philosophical system and as a type of consciousness that represents and dictates a kind of social life. Explaining that liberalism "is a 'deep structure' of thought, placed at the intersection of two modes of being, liberalism resists a purely logical analysis."[5] Unger makes this foray into methodology as a way of setting the stage for his explanation of the unity of liberalism, and his exploration of what might replace liberalism as a superior conception of culture and society. |

自由主義研究の方法論的課題 ウンガーは、自由主義への批判の多くが、観念の秩序における自由主義の教義のみに向けられていると説明する。この言説のレベルでは、形式論理学の方法と手 順を効果的に適用できる。しかし、自由主義を完全に検証するには、観念の秩序における存在だけでなく、意識の領域に存在する社会生活の形態としても検討す る必要がある。意識の領域に存在するリベラリズムを研究することは、形式論理学的分析の対象となり得る探究ではない。むしろ、象徴的分析に適した異なる方 法を採用しなければならない。ウンガーは、必要な方法を「適切性」あるいは「象徴的解釈」の方法と表現している。 ウンガーが主張する、意識の領域における自由主義の検証に最も適した方法は、自由主義のもとで知的生活の周辺に追いやられてきた、すなわち神学、文法学、 法学といった古代の人文的・教義的学問の方法である。この方法は、解釈者と解釈対象の間に意図の共同体を前提とする。この象徴的解釈法は自由主義のもとで ほぼ放棄されてきた。主観的価値と個人主義という自由主義の原理が、こうした教義的探究を実りあるものにするために必要な意図の共同体を破壊したからだ。 ウンガーは、自由主義に代表されるような思想を研究することがいかに困難かを論じている。思想は三つの存在様態——出来事の様態、社会生活の様態、思想の 様態——において存在しうるからだ。思想は、科学によって研究可能な精神的出来事となり得る。また、人間の行動と結びついた信念として、象徴的解釈法に よってのみ扱えるものとなり得る。さらに、真偽を持ち論理的分析の対象となり得る思考の内容として存在し得る。ウンガーが「階層化された存在論」と呼ぶこ の概念は、哲学における最も解決困難な問題、特に社会生活と思想・事象の領域との関係を理解する上で生じる問題へとつながる。 自由主義は、哲学体系としてだけでなく、ある種の社会生活を体現し規定する意識形態としても存在する。ウンガーは、自由主義が「二つの存在様態の交差点に 位置する思考の『深層構造』であるため、純粋に論理的な分析には抵抗する」と説明する[5]。この方法論への踏み込みは、自由主義の統一性を解明し、文化 と社会に関するより優れた概念として自由主義に取って代わる可能性を探るための布石としてなされている。 |

| The Interdependence of Psychological and Political Principles Unger describes how key principles of liberal psychology—the principle of reason and desire and the principle of arbitrary desire—have a reciprocal interdependence with the main principles of liberal political thought, the principle of rules and values and the principle of subjective value. The psychological principles, which apply to the individual, mirror the corresponding political principles that describe society. “Desire” describes the place of individual ends in the self, while “value” describes the place of individual ends in society. Under liberalism, in neither the psychological realm nor the political realm can the understanding guide people to what they ought to desire or value. A society in which understanding were capable of perceiving or establishing the ends of conduct would look very different from society under a liberal regime of social life. Values would be perceived as objective, they would be shared communally, and rules would no longer be needed as the main social bond. The theories of natural law and natural right, and the communal/organicist view of the romantics, both articulate a vision in which values are communal and evident to all members of society, a very different view from liberal thought which holds that men have no natural guides to the moral life and must be led around by threats and restrained by rules. Unger explains how the psychological principle of analysis and the political principle of individualism have an identical form and a relationship of reciprocal interdependence. They both stand for the idea that the whole is the sum of its parts. Individualism depends upon the principle of analysis, because it implies that one is able to decompose every aspect of group life into a feature of the lives of individuals. Analysis depends upon individualism, because individualism implies that all phenomena must be treated as aggregations of distinct individuals interacting with each other. But Unger, using the examples of artistic style and consciousness, concludes that analysis and individualism both fail to explain certain phenomena that resist reduction to individual belief and conduct. The concepts of collectivism and totality manage to explain phenomena of consciousness, and these anti-liberal concepts view the authors of these wholes as groups, classes, factions, and nations, not individuals. If we admit that consciousness is real, we must reject the principles of individualism and analysis, as unable to explain much of the world as we experience it. Unger contends that the implications of analytic thinking also give unmerited authority to the fact-value distinction; because the analytic thinker fragments forms of social consciousness, such as dividing beliefs into descriptive and normative beliefs, the analyst gives plausibility to the fact-value distinction which has been part of the damaging legacy of liberal doctrine. Because principles of analysis and individualism create obstacles for the understanding of mind and science, social theory has sought to escape these limitations and find a method of social study that respects the integrity of social wholes. Unger offers a suggestion of how analytic and individualist ideas can be overthrown, and he explains why some efforts to do so (such as structuralism) have failed. As Unger explained earlier in Knowledge and Politics, analysis and individualism reflect belief in the principle of aggregation, while synthesis and collectivism reflect a belief in totality. Modern social theory has repeatedly tried to formulate a plausible account of the idea of totality; examples of these efforts include Chomsky's linguistic theory, gestalt psychology, structuralism, and Marxism. But these efforts have often stumbled in defining exactly what the difference is between wholes and parts, and exactly what the idea of “part” means if it is something different in kind from the totality. Unger explains that the two main interpretations of the principle of totality are structuralism and realism. Structuralism finds it useful to regard certain things as totalities, but it errs in its conventionalist attitude toward totality; it doubts whether totalities correspond to real things. Realism is a more promising approach to totality because it regards unanalyzable wholes—totalities—as real things. But realism, too, falls short of the mark because it fails to resolve the antinomy of theory and fact. |

心理学的原理と政治的原理の相互依存性 ウンガーは、自由主義心理学の主要な原理——理性と欲望の原理、恣意的欲望の原理——が、自由主義政治思想の主要な原理——規則と価値の原理、主観的価値 の原理——と相互に依存し合っていることを説明している。個人に適用される心理学的原理は、社会を記述する対応する政治的原理を反映している。「欲望」は 自己における個人の目的の位置を記述し、「価値」は社会における個人の目的の位置を記述する。自由主義の下では、心理的領域においても政治的領域において も、理解は人々が何を欲望し価値あるとすべきかを導くことはできない。 行動の目的を認識または確立できる理解が存在する社会は、自由主義的な社会生活体制下の社会とは大きく異なるだろう。価値は客観的に認識され、共同体で共 有され、主要な社会的絆としての規則は不要となる。自然法・自然権の理論やロマン派の共同体的/有機的見解は、価値が共同体のものであり社会の全構成員に 自明であるというビジョンを提示する。これは、人間には道徳的生活への自然の指針がなく、脅威によって導かれ規則によって抑制されねばならないとする自由 主義思想とは全く異なる見解だ。 ウンガーは、分析という心理学的原理と個人主義という政治的原理が同一の形式を持ち、相互依存の関係にあることを説明する。両者は「全体は部分の総和であ る」という考えを体現している。個人主義は分析の原理に依存する。なぜならそれは、集団生活のあらゆる側面を個人の生活の特性へと分解できることを意味す るからだ。分析は個人主義に依存する。個人主義はあらゆる現象を、相互に作用する個別の個人の集合体として扱うことを前提とするからだ。しかしウンガー は、芸術的様式と意識の例を用いて、分析と個人主義の双方が、個人の信念や行動に還元できない特定の現象を説明し得ないと結論づける。集団主義と全体性の 概念は意識の現象を説明しうる。これらの反自由主義的概念は、こうした全体の生み手として個人ではなく集団・階級・派閥・国民を想定する。意識が実在する と認めるならば、我々が経験する世界の多くを説明できない個人主義と分析の原理は退けねばならない。ウンガーは、分析的思考の帰結が事実と価値の区別に不 当な権威を与えているとも主張する。分析的思考者は社会的意識の形態を断片化するため―例えば信念を記述的信念と規範的信念に分割する―分析者は自由主義 的教義の有害な遺産の一部である事実と価値の区別に妥当性を与えてしまうのだ。 分析と個人主義の原理が心と科学の理解に障害を生むため、社会理論はこれらの限界から脱却し、社会全体の統合性を尊重する社会科学の方法を探求してきた。 ウンガーは分析的・個人主義的観念を覆す方法を示唆し、その試み(構造主義など)が失敗した理由を説明する。ウンガーが『知識と政治』で先に説明したよう に、分析と個人主義は集積の原理への信仰を反映し、統合と集団主義は全体性への信仰を反映する。現代社会理論は繰り返し、全体性の概念について説得力のあ る説明を構築しようとしてきた。その試みの例には、チョムスキーの言語理論、ゲシュタルト心理学、構造主義、マルクス主義が含まれる。しかしこれらの試み は、全体と部分の差異を正確に定義すること、また「部分」という概念が全体とは本質的に異なるものだとすれば、その意味を正確に規定することにしばしばつ まずいてきた。ウンガーは、全体性の原理に対する二つの主要な解釈が構造主義と現実主義であると説明する。構造主義は特定のものを全体として捉えることに 有用性を見出すが、全体性に対する慣習主義的態度において誤っている。すなわち全体性が実在するものと対応するかどうかを疑うのだ。実在論は分析不能な全 体——すなわち全体性——を実在するものとして扱うため、全体性へのより有望なアプローチである。しかし実在論もまた、理論と事実の対立を解決できない点 で不十分である。 |

| The Antinomies of Liberal Thought Related to the Universal and the Particular Unger concludes his discussion of the unity of liberal thought by discussing the seemingly insoluble antinomies of liberal thought—theory and fact, reason and desire, rules and values—and their connection with the division between the universal and the particular. Under the antinomy of theory and fact, it appears that we can only discuss facts in the language of theory, but at the same time there appears to be some ability to appeal to the facts independently of theory, in order to judge the merits of competing theories. Reason and desire present a similarly intractable conflict; reason can clarify the relations among ends, never what ends we should choose; but falling back on a morality of desire seems to condemn us to action with no standards other than arbitrary choice. The antinomy of rules and values reveals that a system of legal justice or rules cannot dispense with a consideration of values, but also cannot be made consistent with them, and a system of substantive justice (or values) cannot do without rules but also cannot be made consistent with them. Unger contends that we will never resolve these antinomies until we find our way out of the "prison-house of liberal thought." Unger begins here to suggest the way we might create an alternative doctrine, one that is not bedeviled by the antinomies of liberalism, would be to start with a premise of the unity, or identity, of universals and particulars. Doing this plausibly, would require overcoming the division between ideas and events, reason and desire, rule and value, without denying their separateness, and without rejecting universality and particularity. Overcoming the seemingly intractable antagonism between universality and particularity, which is the source of so much tragedy in life according to Unger, may seem impossible, but Unger points to examples of how this unity can be understood. He maintains that universals must exist as particulars; in the way a person is inseparable from their body but is also more than their body, the universal and particular may represent different levels of reality. Unger contends that a kind of unity between the universal and the particular is evident in moral, artistic, and religious experience, and understanding the basis of this unity is a way past the antinomies of liberal thought. Understanding this unity between the universal and particular sets the stage for Unger's positive theory in Knowledge and Politics. |

普遍と個別に関する自由主義思想の矛盾 ウンガーは自由主義思想の統一性に関する議論を、自由主義思想に見られる一見解決不能な矛盾——理論と事実、理性と欲望、規則と価値——およびそれらが普 遍と個別との分裂と結びついている点について論じることで締めくくる。理論と事実の対立において、我々は事実を理論の言語でしか議論できないように見え る。しかし同時に、競合する理論の優劣を判断するために、理論とは独立して事実を訴える能力が多少なりとも存在するように思われる。理性と欲望も同様に解 決困難な対立を呈する。理性は目的間の関係を明晰化できるが、我々がどの目的を選ぶべきかは決して示せない。しかし欲望の道徳に退行すれば、恣意的な選択 以外の基準を持たない行動に陥ることを自ら招くように思われる。規則と価値の矛盾は、法的正義や規則の体系が価値の考慮を欠くことはできないが、それと整 合させることも不可能であり、実質的正義(または価値)の体系も規則なしでは成り立たないが、それと整合させることも不可能であることを明らかにする。ウ ンガーは、我々が「自由主義思想の牢獄」から脱する道を見出さない限り、これらの矛盾を決して解決できないと主張する。 ウンガーはここで、自由主義の矛盾に悩まされない代替的な教義を構築する道筋を示唆し始める。それは普遍と個別の一体性、あるいは同一性を前提とすること から始めるべきだという。これを説得力を持って行うには、理念と出来事、理性と欲望、規則と価値の間の分裂を克服しつつ、それらの分離性を否定せず、普遍 性と個別性を拒絶しないことが必要となる。ウンガーによれば、普遍性と個別性の間の一見解決不能な対立は、人生における多くの悲劇の根源である。この統一 性を理解する方法は不可能に思えるかもしれないが、ウンガーはその理解例を提示する。彼は、普遍性は個別性として存在しなければならないと主張する。人格 が身体から切り離せないが身体以上の存在であるように、普遍性と個別性は現実の異なる次元を表す可能性があるのだ。ウンガーは、普遍と個別の一種の統一が 道徳的・芸術的・宗教的経験に明らかであり、この統一の基盤を理解することが自由主義思想の矛盾を乗り越える道だと主張する。普遍と個別の一体性を理解す ることが、『知識と政治』におけるウンガーの積極的理論の基盤となるのである。 |

| Chapter 4: The Theory of the Welfare-Corporate State In this chapter, Unger expands his view and intends to consider liberal thought in view of its relationship to society. Liberalism, Unger explains, is a representation of a form of life in the language of speculative thought, and gains its unity and richness by being associated with a form of life. We must understand the nature of its association with a form of life in order to complete the task of total criticism. Unger contends that the underlying mode of social life has been changing in ways that both require a reconstruction of philosophical principles and guide us toward that reconstruction. Unger asserts that "the truth of knowledge and politics is both made and discovered in history." Every type of social life can be viewed from two complementary perspectives, both informed by the principle of totality: as a form of consciousness, and as a mode of order. Forms of social consciousness cannot be dissolved into constituent parts without a critical loss of understanding; this is the basis for Unger's assertion that the principle of totality governs the explanation of social consciousness. |

第4章:福祉企業国家論 本章においてウンガーは視点を広げ、リベラリズム思想を社会との関係性という観点から考察する。リベラリズムとは、思索的思考の言語による生活様態の表現 であり、生活様式との結びつきによってその統一性と豊かさを獲得する。総合的批判の課題を完遂するには、生活様式との結びつきの本質を理解せねばならな い。 ウンガーは、社会生活の根底にある様式が変化しており、その変化は哲学的原理の再構築を必要とすると同時に、我々をその再構築へと導いていると主張する。ウンガーは「知識と政治の真実は、歴史の中で作り出され、発見される」と断言する。 あらゆるタイプの社会生活は、総体性の原理によって導かれる二つの補完的な視点から捉えられる。すなわち、意識の形態として、そして秩序の様式としてであ る。社会意識の形態は、批判的な理解の喪失を伴わずに構成要素へと分解することはできない。これが、社会意識の説明を総体性の原理が支配するというウン ガーの主張の根拠である。 |

| Social Consciousness in the Liberal State Unger sees three major elements of social consciousness in the liberal state as instrumentalism, individualism, and a conception of social place as a role that is external to oneself. Each of these elements of liberal social consciousness are reflections of the ideal of transcendence, which, being opposed to the concept of immanence, originated in the religious concept of a separation between the divine and the mundane, heaven and earth, God and man. The divisions at the heart of liberalism reflect a secularized version of transcendence; liberals abandon the explicitly theological form of religiosity without completely discarding the implicitly religious meaning of the concept. Liberal consciousness, because it has abandoned the explicitly theological form of transcendence, leads to a seeming paradox: when the divine is secularized, part of the secular world becomes sanctified, which seems to lead to the position of immanence. For this reason, Unger sees liberal social consciousness as a transition between two modes of consciousness: from one in which transcendence is emphasized, to one that reasserts the earlier religious ideal of immanence. This uneasy balance between the pure theological form of transcendence and the affirmation of religious immanence is the basis for the key dichotomies of liberal thought. |

自由主義国家における社会的意識 ウンガーは自由主義国家の社会的意識に三つの主要要素を見出す。それは功利主義、個人主義、そして社会的立場を自己の外にある役割として捉える概念であ る。自由主義的社会意識のこれらの要素はそれぞれ、超越の理想を反映している。この超越の理想は内在性の概念に対立するものであり、神聖と世俗、天と地、 神と人の分離という宗教的概念に起源を持つ。自由主義の中核にある分断は、超越性の世俗化された形態を反映している。自由主義者は、概念の暗黙の宗教的意 味を完全に捨て去ることなく、明示的な神学的形態の宗教性を放棄するのだ。 自由主義的意識は、明示的な神学的形態の超越性を放棄したために、一見矛盾した結果をもたらす。神聖なものが世俗化されると、世俗世界の一部が聖別される ように見え、それは内在性の立場へと導くように思われるのだ。このためウンガーは、リベラルな社会意識を二つの意識形態の過渡期と見なす。超越性が強調さ れる形態から、以前の宗教的理想である内在性を再主張する形態への移行である。純粋な神学的形態の超越性と、宗教的内在性の肯定との間のこの不安定な均衡 こそが、リベラル思想の主要な二項対立の基盤となっている。 |

| Social Order in the Liberal State Unger argues that a social order is composed of elements, each defined by their relation to all other elements. The two types of elements are individuals and groups. One's position in the social order is one's social place. The types of social order are distinguished by their principle of order, the rule according to which the elements are arranged. Each individual lives in a social situation in which one or a few types of social order are dominant. According to Unger, the generative principles of the types of social order are the foremost determinants of how a person defines his identity. The most familiar principles of social order are kinship, estate, class, and role. Class and role are the most relevant to the social order of the liberal state. When determination of social place is governed by class, one's class membership tends to determine the job one holds. When determination of social place is by role, one's merit is the principle that determines the job one holds. Unger explains that the links between class and role can be so numerous that they appear indistinguishable. Unger points out that there could be a fundamental opposition between class and role—a role achieved by recognized merit could give access to consumption, power, and knowledge. Class would then become a consequence, not a cause, of role. Under the systems of kinship, estate, and class, there is a common reliance on personal dependence and personal domination as devices of social organization. By contrast with these earlier systems, the principle of role, at its fullest development, actualizes an ideal that moves away from personal dependence and domination. It embodies the ideal that power in the liberal state should be disciplined by prescriptive, impersonal rules. Power should not be held arbitrarily; in government, those with power must be chosen by election, and in private roles, by merit. Jobs are to be allocated by merit, namely the ability to get job done, by acquired skill, past efforts, and natural talent. Although the ascendance of role seems to imply the lessening of arbitrary power in society, Unger points out how class survives alongside role, pervading every aspect of social life, and functioning as a permanent refutation of ideal of impersonal roles. Natural talent and genetic gifts are distributed capriciously, and amount to a brute fact of natural advantage that is decisive in allocating power in a society governed by a principle of merit-based role. Unger concludes that superimposed on the conflict between class and role, there is a pervasive conflict between experience of personal dependency/dominance, and the ideal of organization by impersonal rules, and evidence of these two tensions touches every aspect of life in the liberal state. |

自由主義国家における社会秩序 ウンガーは、社会秩序は要素から成り立ち、各要素は他の全要素との関係によって定義されると論じる。要素には個人と集団の二種類がある。社会秩序における 個人の位置は、その人の社会的立場である。社会秩序の種類は、秩序の原理、すなわち要素が配置される規則によって区別される。 各個人は、一つまたは数種類の社会秩序が支配的な社会的状況に生きている。ウンガーによれば、社会秩序の類型を生み出す原理こそが、人格のアイデンティティ形成における最優先の決定要因である。 最も一般的な社会秩序の原理は、血縁、身分、階級、役割である。自由主義国家の社会秩序において最も関連性が高いのは階級と役割である。社会的地位の決定 が階級によって支配される場合、個人の階級所属が職業を決定する傾向がある。社会的地位の決定が役割によってなされる場合、個人の能力がその職位を決定す る原理となる。ウンガーは、階級と役割の関連性が非常に多岐にわたるため、両者が区別不能に見える場合があると説明する。 ウンガーは、階級と役割の間に根本的な対立が存在する可能性を指摘する。すなわち、認められた能力によって達成された役割は、消費、権力、知識へのアクセスをもたらしうる。その場合、階級は役割の結果となり、原因ではなくなる。 血縁制、身分制、階級制の下では、社会組織の手段として個人の依存と支配が共通して依存されている。これらの古い制度とは対照的に、役割の原理は、その最 も発展した形態において、個人の依存と支配から離れる理想を実現する。それは自由主義国家における権力が、規範的で非人格的な規則によって規律されるべき だという理想を体現している。権力は恣意的に保持されるべきではない。政府においては権力者は選挙によって選ばれ、私的役割においては能力によって選ばれ るべきだ。職務は能力、すなわち仕事を遂行する能力によって配分される。それは習得した技能、過去の努力、そして天賦の才によって決まる。 役割の台頭は社会における恣意的な権力の減退を暗示しているように見えるが、ウンガーは階級が役割と並存し、社会生活のあらゆる側面に浸透し、非人格的な 役割の理想に対する恒久的な反証として機能している点を指摘する。天賦の才や遺伝的資質は気まぐれに分配され、能力に基づく役割の原則で統治される社会に おいて権力を配分する上で決定的な、自然の優位性という残酷な事実となる。 ウンガーは結論として、階級と役割の対立の上に、個人の依存/支配の経験と非人格的規則による組織化の理想との普遍的な対立が重なり、この二つの緊張の痕跡が自由主義国家の生活のあらゆる側面に触れていると述べる。 |