ポリフォニー

Polyphony

★ポリフォニーとは、2つ以上の独立した旋律からなる音楽のテクスチャーの一種で、1つの声 部を持つ音楽(モノフォニー)や、和音を伴う1つの主旋律を持つ音楽(ホモフォニー)とは対照的なテクスチャーのことである。

| Polyphony

is a type of musical texture consisting of two or more simultaneous

lines of independent melody, as opposed to a musical texture with just

one voice, monophony, or a texture with one dominant melodic voice

accompanied by chords, homophony. Within the context of the Western musical tradition, the term polyphony is usually used to refer to music of the late Middle Ages and Renaissance. Baroque forms such as fugue, which might be called polyphonic, are usually described instead as contrapuntal. Also, as opposed to the species terminology of counterpoint,[clarification needed] polyphony was generally either "pitch-against-pitch" / "point-against-point" or "sustained-pitch" in one part with melismas of varying lengths in another.[1] In all cases the conception was probably what Margaret Bent (1999) calls "dyadic counterpoint",[2] with each part being written generally against one other part, with all parts modified if needed in the end. This point-against-point conception is opposed to "successive composition", where voices were written in an order with each new voice fitting into the whole so far constructed, which was previously assumed. The term polyphony is also sometimes used more broadly, to describe any musical texture that is not monophonic. Such a perspective considers homophony as a sub-type of polyphony.[3] |

ポリフォニーとは、2つ以上の独立した旋律からなる音楽のテクスチャーの一種で、1つの声部を持つ音楽(モノフォ

ニー)や、和音を伴う1つの主旋律を持つ音楽(ホモフォニー)とは対照的なテクスチャーのことである。 西洋音楽の伝統の中で、ポリフォニーという言葉は通常、中世後期からルネサンス期の音楽を指す言葉として使われている。フーガのようなバロック音楽はポリ フォニーと呼ばれることもあるが、通常はコントラプンタルと呼ばれる。また、対位法の種の用語とは対照的に[clarification needed]、ポリフォニーは一般に、あるパートでは「ピッチ-アゲンスト-ピッ チ」/「ポイント-アゲンスト-ポイント」または「持続-ピッチ」、別 のパートでは様々な長さのメリスマであった[1] いずれの場合も、おそらくマーガレット・ベント(1999)が「二項対位」と呼ぶ概念で、各パートは概ね他のパートに対して書かれており、最後に必要に応 じてすべてのパートが変更された[2]。この点対点の発想は,声部が順番に書かれ,それぞれの新しい声部がこれまでに構築された全体像に適合するという, 事前に想定されていた「逐次作曲」とは対照的である. また、ポリフォニーという言葉は、より広義に、単旋律でない音楽のテクスチャーを表す言葉として使われることもある。このような観点では、ホモフォニーを ポリフォニーのサブタイプとして考える[3]。 |

| Origins Traditional (non-professional) polyphony has a wide, if uneven, distribution among the peoples of the world.[4] Most polyphonic regions of the world are in sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and Oceania. It is believed that the origins of polyphony in traditional music vastly predate the emergence of polyphony in European professional music. Currently there are two contradictory approaches to the problem of the origins of vocal polyphony: the Cultural Model, and the Evolutionary Model.[5] According to the Cultural Model, the origins of polyphony are connected to the development of human musical culture; polyphony came as the natural development of the primordial monophonic singing; therefore polyphonic traditions are bound to gradually replace monophonic traditions.[6] According to the Evolutionary Model, the origins of polyphonic singing are much deeper, and are connected to the earlier stages of human evolution; polyphony was an important part of a defence system of the hominids, and traditions of polyphony are gradually disappearing all over the world.[7]: 198–210 Although the exact origins of polyphony in the Western church traditions are unknown, the treatises Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, both dating from c. 900, are usually considered the oldest extant written examples of polyphony. These treatises provided examples of two-voice note-against-note embellishments of chants using parallel octaves, fifths, and fourths. Rather than being fixed works, they indicated ways of improvising polyphony during performance. The Winchester Troper, from c. 1000, is the generally considered to be the oldest extant example of notated polyphony for chant performance, although the notation does not indicate precise pitch levels or durations.[8] However, a two-part antiphon to Saint Boniface recently discovered in the British Library, is thought to have originated in a monastery in north-west Germany and has been dated to the early tenth century.[9] |

起源 伝統的な(非専門的な)ポリフォニーは、世界の人々の間で不均一ではあるが広く分布している[4]。 世界のほとんどのポリフォニー地域はサハラ以南のアフリカ、ヨーロッパ、オセアニアにある。伝 統音楽におけるポリフォニーの起源は、ヨーロッパの専門音楽におけるポリフォニーの出現よりはるかに先であると考えられている。 現在、声楽のポリフォニーの起源という問題には、文化モデルと進化モデルの2つの矛盾するアプローチがある[5]。文化モデルによると、ポリフォニーの起 源は人類の音楽文化の発展と関係があり、ポリフォニーは原初の単旋律歌唱の自然な発展として生まれた。 [ポリフォニーはヒト科動物の防御システムの重要な一部であり、ポリフォニーの伝統は世界中で徐々に失われつつある[6]。 198-210 西方教会の伝統におけるポリフォニーの正確な起源は不明だが、900年 頃に書かれた『Musica enchiriadis』と『Scolica enchiriadis』が現存する最古のポリフォニーの例とされるのが普通である。これらの論文では、聖歌をオクターブ、5分音符、4分音符を平行して 使い、2声による音符対音符の装飾を例示している。これらは固定された作品ではなく、演奏中に即興でポリフォニーを演奏する方法を示してい ます。1000年頃に作られた『ウィンチェスター・トローパー』は、現存する聖歌演奏のためのポリフォニー楽譜の最古の例とされていますが、楽譜には正確 な音程や長さが示されていない[8]。しかし、最近大英図書館で発見された聖ボニファティウスの2部構成のアンティフォンは、北西ドイツの僧院で作られた と考えられ、10世紀初頭に作られました[9]。 |

| European polyphony Historical context European polyphony rose out of melismatic organum, the earliest harmonization of the chant. Twelfth-century composers, such as Léonin and Pérotin developed the organum that was introduced centuries earlier, and also added a third and fourth voice to the now homophonic chant. In the thirteenth century, the chant-based tenor was becoming altered, fragmented, and hidden beneath secular tunes, obscuring the sacred texts as composers continued to play with this new invention called polyphony. The lyrics of love poems might be sung above sacred texts in the form of a trope, or the sacred text might be placed within a familiar secular melody. The oldest surviving piece of six-part music is the English rota Sumer is icumen in (c. 1240).[10] These musical innovations appeared in a greater context of societal change. After the first millennium, European monks started translating Greek philosophy into the vernacular. In the Middle Ages Western Europeans' ignorance of ancient Greek meant they lost touch with works by Plato, Socrates, and Hippocrates. Translations into Latin from Arabic allowed these philosophical works to impact Western Europe. This sparked a number of innovations in medicine, science, art, and music. |

ヨーロッパのポリフォニー 歴史的背景 ヨーロッパのポリフォニーは、聖歌の最古の和声化であるメリスマティック・オルガヌムから発展したものである。12世紀のレオナンやペロタンなどの作曲家 は、数世紀前に導入されたオルガヌムを発展させ、現在は同声聖歌となっているものに第3声や第4声を加えました。13世紀には、聖歌をベースにしたテノー ルは変化し、断片化し、世俗的な曲の下に隠れてしまい、聖なるテキストが見えなくなっていました。愛の詩の歌詞は、聖なるテキストの上にトロフィーという 形で歌われたり、聖なるテキストが親しみやすい世俗のメロディーの中に置かれたりすることもあった。現存する6部構成の音楽で最も古いものは、イギリスの 『rota Sumer is icumen in』(1240年頃)である[10]。 このような音楽の革新は、社会の変化という大きな文脈の中で現れた。最初の千年紀以降、ヨーロッパの修道士たちは、ギリシャ哲学を現地語に翻訳し始めた。 中世の西ヨーロッパでは、古代ギリシア語を知らないために、プラトン、ソクラテス、ヒポクラテスの著作に触れる機会がなかった。アラビア語からラテン語へ の翻訳によって、これらの哲学的著作が西欧に影響を与えるようになった。そして、医学、科学、芸術、音楽などの分野で、さまざまな革新が起こりました。 |

| Western Europe and Roman

Catholicism European polyphony rose prior to, and during the period of the Western Schism. Avignon, the seat of popes and then antipopes, was a vigorous center of secular music-making, much of which influenced sacred polyphony.[11] The notion of secular and sacred music merging in the papal court also offended some medieval ears. It gave church music more of a jocular performance quality supplanting the solemnity of worship they were accustomed to. The use of and attitude toward polyphony varied widely in the Avignon court from the beginning to the end of its religious importance in the fourteenth century. Harmony was considered frivolous, impious, lascivious, and an obstruction to the audibility of the words. Instruments, as well as certain modes, were actually forbidden in the church because of their association with secular music and pagan rites. After banishing polyphony from the Liturgy in 1322, Pope John XXII warned against the unbecoming elements of this musical innovation in his 1324 bull Docta Sanctorum Patrum.[12] In contrast Pope Clement VI indulged in it. The oldest extant polyphonic setting of the mass attributable to one composer is Guillaume de Machaut's Messe de Nostre Dame, dated to 1364, during the pontificate of Pope Urban V. The Second Vatican Council said Gregorian chant should be the focus of liturgical services, without excluding other forms of sacred music, including polyphony.[13] Notable works and artists Tomás Luis de Victoria William Byrd, Mass for Five Voices Thomas Tallis, Spem in alium Orlandus Lassus, Missa super Bella'Amfitrit'altera Guillaume de Machaut, Messe de Nostre Dame Geoffrey Chaucer[14] Jacob Obrecht Palestrina, Missa Papae Marcelli Josquin des Prez, Missa Pange Lingua Gregorio Allegri, Miserere |

西ヨーロッパとローマ・カトリック 西ヨーロッパのポリフォニーは、西方分裂以前から西方分裂の期間中に隆盛を極めた。ローマ教皇と反教皇の所在地であったアヴィニョンは、世俗的な音楽制作 が盛んであり、その多くが聖なるポリフォニーに影響を与えた[11]。 また、教皇庁で世俗音楽と聖楽が融合するという考え方は、中世の一部の人々の耳には不快に映った。それは、教会音楽が、彼らが慣れ親しんだ礼拝の厳粛さに 代わって、より陽気な演奏の質を持つようになったからである[11]。14世紀のアヴィニョン宮廷では、ポリフォニーの宗教的重要性の始まりから終わりま で、ポリフォニーの使い方や態度が大きく変化した。 和声は軽薄で、不敬で、淫らで、言葉の聞き取りやすさを阻害するものとされた。楽器や特定の旋法は、世俗的な音楽や異教徒の儀式と結びついていたため、教 会では実際に禁止されていた。1322年に典礼からポリフォニーを追放した教皇ヨハネ22世は、1324年の教書「Docta Sanctorum Patrum」で、この音楽的革新の不適切な要素に警告した[12]が、教皇クレメンス6世はこれに甘んじている。 現存する最古のポリフォニーによるミサ曲は、ギョーム・ド・マショー(Guillaume de Machaut)の『Messe de Nostre Dame』で、教皇ウルバン5世の時代、1364年に作られた。第2バチカン公会議は、ポリフォニーなど他の形式の聖楽を排除せず、典礼の焦点はグレゴリ オ聖歌であるべきだと述べている[13]。 代表的な作品・作家 トーマス・ルイス・デ・ヴィクトリア ウィリアム・バード 5声のためのミサ曲 トマス・タリス《Spem in alium》より オルランドゥス・ラッスス作曲 ミサ・スーパー・ベラ'アンフィトリ'アッテルラ ギョーム・ド・マショー ノスタル・ダムのミサ曲 ジェフリー・チョーサー[14](Geoffrey Chaucer ジェイコブ・オブレヒト パレストリーナ「ミサ・パパエ・マルチェッリ ジョスカン・デ・プレ「ミサ・パンゲ・リングア グレゴリオ・アレグリ、ミゼレーレ |

| Protestant Britain and the

United States English Protestant west gallery music included polyphonic multi-melodic harmony, including fuguing tunes, by the mid-18th century. This tradition passed with emigrants to North America, where it was proliferated in tunebooks, including shape-note books like The Southern Harmony and The Sacred Harp. While this style of singing has largely disappeared from British and North American sacred music, it survived in the rural Southern United States, until it again began to grow a following throughout the United States and even in places such as Ireland, the United Kingdom, Poland, Australia and New Zealand, among others.[citation needed] |

プロテスタントのイギリスとアメリカ イギリスのプロテスタント系ウェストギャラリーでは、18世紀半ばまでに、フーガを含む多声部和声の音楽が作られた。この伝統は移民とともに北米に渡り、 『The Southern Harmony』や『The Sacred Harp』などの形声楽譜を含むチューンブックに盛んに掲載されるようになった。この歌唱スタイルはイギリスや北アメリカの聖楽からほとんど姿を消した が、アメリカ南部の農村では生き残り、再びアメリカ全土、さらにはアイルランド、イギリス、ポーランド、オーストラリア、ニュージーランドなどでも信奉者 が増え始めた[citation needed]。 |

| Balkan region Polyphonic singing in the Balkans is traditional folk singing of this part of southern Europe. It is also called ancient, archaic or old-style singing.[15][16] Byzantine chant Ojkanje singing, in Croatia, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina Ganga singing, in Croatia, Montenegro and Bosnia and Herzegovina Epirote singing, in northern Greece and southern Albania (see below) Iso-polyphony, in southern Albania (see below) Gusle singing, in Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia and Albania Izvika singing, in Serbia Woman choirs of Shopi (Bistritsa Babi) and Pirin, in Bulgaria and those in North Macedonia Incipient polyphony (previously primitive polyphony) includes antiphony and call and response, drones, and parallel intervals. Balkan drone music is described as polyphonic due to Balkan musicians using a literal translation of the Greek polyphōnos ('many voices'). In terms of Western classical music, it is not strictly polyphonic, due to the drone parts having no melodic role, and can better be described as multipart.[17] The polyphonic singing tradition of Epirus is a form of traditional folk polyphony practiced among Aromanians, Albanians, Greeks, and ethnic Macedonians in southern Albania and northwestern Greece.[18][19] This type of folk vocal tradition is also found in North Macedonia and Bulgaria.  Albanian polyphonic folk group wearing qeleshe and fustanella in Skrapar. Albanian polyphonic singing can be divided into two major stylistic groups as performed by the Tosks and Labs of southern Albania. The drone is performed in two ways: among the Tosks, it is always continuous and sung on the syllable 'e', using staggered breathing; while among the Labs, the drone is sometimes sung as a rhythmic tone, performed to the text of the song. It can be differentiated between two-, three- and four-voice polyphony. In Aromanian music, polyphony is common, and polyphonic music follows a set of common rules.[20] The phenomenon of Albanian folk iso-polyphony (Albanian iso-polyphony) has been proclaimed by UNESCO a "Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity". The term iso refers to the drone, which accompanies the iso-polyphonic singing and is related to the ison of Byzantine church music, where the drone group accompanies the song.[21][22] |

バルカン地域 バルカン半島のポリフォニックな歌唱は、南ヨーロッパのこの地域の伝統的な民謡である。古代歌謡、アルカイック歌謡、旧式歌謡とも呼ばれる[15] [16]。 ビザンチン聖歌 Ojkanje歌唱(クロアチア、セルビア、ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナにて ガンガ歌唱(クロアチア、モンテネグロ、ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナにて エピロテ歌唱、ギリシャ北部とアルバニア南部で(下記参照) アイソポリフォニー(アルバニア南部)(下記参照 グスレ歌唱:セルビア、モンテネグロ、ボスニア・ヘルツェゴビナ、クロアチア、アルバニアに分布 イズヴィカ(Izvika)歌唱(セルビア ブルガリアのショピ(ビストリツァ・バビ)とピリンの女声合唱団、および北マケドニアの女声合唱団。 初期ポリフォニー(以前は原始ポリフォニー)には、アンチフォニーやコール&レスポンス、ドローン、平行音程などがある。 バルカンのドローン音楽は、バルカンの音楽家がギリシャ語のpolyphōnos(「多くの声」)を直訳して使っているため、ポリフォニックと表現され る。西洋クラシック音楽の観点からは、ドローンパートが旋律的な役割を持たないため、厳密には多声部とは言えず、多声部と表現した方が良い[17]。 エピルスの多声部歌唱の伝統は、アルバニア南部とギリシャ北西部のアロマニア人、アルバニア人、ギリシャ人、マケドニア民族の間で行われている伝統的な民 族多声部の形式である[18][19] この種の民族声楽伝統は北マケドニアとブルガリアでも見られる。  スクラパルでケレシェとフスタネッラを身につけたアルバニアのポリフォニックフォークグループ。 アルバニアの多声部歌唱は、アルバニア南部のトスク族とラブ族によって演奏される2つの主要な様式群に分けることができる。トスクでは、ドローンは常に連 続的で、音節「e」の上で千鳥呼吸で歌われます。一方、ラボでは、ドローンはリズム音として歌われることもあり、曲のテキストに合わせて演奏されます。2 声、3声、4声のポリフォニーに区別することができる。 アロマニア音楽ではポリフォニーは一般的であり、ポリフォニックな音楽は共通のルールに則っている[20]。 アルバニア民謡のアイソポリフォニー(Albanian iso-polyphony)の現象は、ユネスコによって「人類の口承及び無形遺産の傑作」と宣言されている。イソとはイソ・ポリフォニー歌唱に伴うド ローンのことであり、ドローン群が歌に伴うビザンチン教会音楽のイソンと関係がある[21][22]。 |

| Corsica The French island Corsica has a unique style of music called Paghjella that is known for its polyphony. Traditionally, Paghjella contains a staggered entrance and continues with the three singers carrying independent melodies. This music tends to contain much melisma and is sung in a nasal temperament. Additionally, many paghjella songs contain a picardy third. After paghjella's revival in the 1970s, it mutated. In the 1980s it had moved away from some of its more traditional features as it became much more heavily produced and tailored towards western tastes. There were now four singers, significantly less melisma, it was much more structured, and it exemplified more homophony. To the people of Corsica, the polyphony of paghjella represented freedom; it had been a source of cultural pride in Corsica and many felt that this movement away from the polyphonic style meant a movement away from paghjella's cultural ties. This resulted in a transition in the 1990s. Paghjella again had a strong polyphonic style and a less structured meter.[23][24] Sardinia Cantu a tenore is a traditional style of polyphonic singing in Sardinia. |

コルシカ島 フランスのコルシカ島には、ポリフォニーで知られるパジェッラという独特の音楽スタイルがある。伝統的にパジェッラでは、入場のタイミングをずらし、3人 の歌い手がそれぞれ独立した旋律を担って歌い続ける。この音楽はメリスマを多く含み、鼻音で歌われる傾向がある。また、多くのパジェーラの曲にはピカル ディ3分の1が含まれる。1970年代にパージェラが復活した後、パージェラは変異した。1980年代には、より伝統的な特徴から離れ、より重厚に、西洋 的なテイストに合うように制作されるようになりました。歌手は4人になり、メリスマは大幅に減少し、より構造化され、より同音異義性を示すようになった。 コルシカ島の人々にとって、パージェラのポリフォニーは自由を代表するものであり、コルシカ島の文化的な誇りでもありました。その結果、1990年代に移 行することになった。パジェッラは再び強いポリフォニックなスタイルと、あまり構造化されていないメーターを持つようになった[23][24]。 サルデーニャ Cantu a tenoreはサルデーニャの伝統的なポリフォニック歌唱のスタイルである。 |

| Caucasus region Georgia Polyphony in the Republic of Georgia is arguably (but no any strong confirmation) the oldest polyphony in the Christian world. Georgian polyphony is traditionally sung in three parts with strong dissonances, parallel fifths, and a unique tuning system based on perfect fifths.[25] Georgian polyphonic singing has been proclaimed by UNESCO an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. Popular singing has a highly valued place in Georgian culture. There are three types of polyphony in Georgia: complex polyphony, which is common in Svaneti; polyphonic dialogue over a bass background, prevalent in the Kakheti region in Eastern Georgia; and contrasted polyphony with three partially improvised sung parts, characteristic of western Georgia. The Chakrulo song, which is sung at ceremonies and festivals and belongs to the first category, is distinguished by its use of metaphor and its yodel, the krimanchuli and a “cockerel’s crow”, performed by a male falsetto singer. Some of these songs are linked to the cult of the grapevine and many date back to the eighth century. The songs traditionally pervaded all areas of everyday life, ranging from work in the fields (the Naduri, which incorporates the sounds of physical effort into the music) to songs to curing of illnesses and to Christmas Carols (Alilo). Byzantine liturgical hymns also incorporated the Georgian polyphonic tradition to such an extent that they became a significant expression of it.[26] Chechens and Ingushes Chechen and Ingush traditional music can be defined by their tradition of vocal polyphony. Chechen and Ingush polyphony is based on a drone and is mostly three-part, unlike most other north Caucasian traditions' two-part polyphony. The middle part carries the main melody accompanied by a double drone, holding the interval of a fifth around the melody. Intervals and chords are often dissonances (sevenths, seconds, fourths), and traditional Chechen and Ingush songs use sharper dissonances than other North Caucasian traditions. The specific cadence of a final, dissonant three-part chord, consisting of fourth and the second on top (c-f-g), is almost unique. (Only in western Georgia do a few songs finish on the same dissonant c-f-g chord).[7]: 60–61 |

コーカサス地方 グルジア共和国 グルジア共和国のポリフォニーは、間違いなく(しかし、どんな強い確証もない)キリスト教世界で最も古いポリフォニーである。グルジアのポリフォニーは、 強い不協和音、平行五度、および完全五度に基づくユニークなチューニングシステムを持つ3つのパートで伝統的に歌われる[25]。グルジアのポリフォニー の歌は、ユネスコによって人類の無形文化遺産に宣言されている。ポピュラーな歌は、グルジアの文化で高く評価されている場所を持っている。スヴァネティ (Svaneti)と言う地方で一般的な複雑なポリフォニ ー、東グルジアのカへティ(Kakheti)と言う地方で一般的な低音の 背景にポリフォニーの対話、西グルジアの特徴として、3つの部分 的に即興の歌の部分を持つ対照的なポリフォニーがある。儀式や祭りで歌われ、最初のカテゴリーに属するチャク ルロの歌は、比喩の使用と、男性のファルセット歌手によって演じられるヨーデル、クリマンチュリと "コッケルのカラス "で区別されている。これらの歌の中には、ブドウの木の信仰に関連するものもあり、多くは8世紀にさかのぼる。伝統的に歌は日常生活のあらゆる分野に浸透 しており、畑仕事(ナドゥーリ:肉体労働の音を音楽に取り入れる)から病気を治すための歌、クリスマス・キャロル(アリロ)に至るまで、様々な歌がある。 ビザンチンの典礼の賛美歌も、グルジアの多声部の伝統を重要な表現になる程に取り入れた[26]。 チェチェン人とイングーシ人 チェチェンとイングーシの伝統音楽は、声楽のポリフォニーという伝統によって定義することができる。チェチェンとイングーシのポリフォニーは、他の多くの 北コーカサス地方の伝統的な2部構成のポリフォニーとは異なり、ドローンを基本とした3部構成がほとんどです。中間部は主旋律に二重のドローンを伴わせ、 旋律の周りに5分の1の音程を保持する。音程と和音はしばしば不協和音(7分の1、2分の1、4分の1)であり、チェチェンとイングーシの伝統的な歌は他 の北カフカスの伝統よりも鋭い不協和音を使用する。最後の、4番目と2番目を上にした不協和音の3部和音(c-f-g) の特定のカデンツは、ほとんど独特である。(ジョージア州西部でのみ、いくつかの歌が同じ不協和音のc-f-gの和音で終わる)[7]: 60-61 |

| Oceania Parts of Oceania maintain rich polyphonic traditions. Melanesia The peoples of New Guinea Highlands including the Moni, Dani, and Yali use vocal polyphony, as do the people of Manus Island. Many of these styles are drone-based or feature close, secondal harmonies dissonant to western ears. Guadalcanal and the Solomon Islands are host to instrumental polyphony, in the form of bamboo panpipe ensembles.[27][28] Polynesia Europeans were surprised to find drone-based and dissonant polyphonic singing in Polynesia. Polynesian traditions were then influenced by Western choral church music, which brought counterpoint into Polynesian musical practice.[29][30] Africa See Also Traditional sub-Saharan African harmony Numerous Sub-Saharan African music traditions host polyphonic singing, typically moving in parallel motion.[31] East Africa While the Maasai people traditionally sing with drone polyphony, other East African groups use more elaborate techniques. The Dorze people, for example, sing with as many as six parts, and the Wagogo use counterpoint.[31] Central Africa The music of African Pygmies (e.g. that of the Aka people) is typically ostinato and contrapuntal, featuring yodeling. Other Central African peoples tend to sing with parallel lines rather than counterpoint.[32] Southern Africa The singing of the San people, like that of the pygmies, features melodic repetition, yodeling, and counterpoint. The singing of neighboring Bantu peoples, like the Zulu, is more typically parallel.[32] West Africa The peoples of tropical West Africa traditionally use parallel harmonies rather than counterpoint.[33] |

オセアニア オセアニアの一部には、豊かなポリフォニックの伝統が残されている。 メラネシア ニューギニア高地のモニ族、ダニ族、ヤリ族、マヌス島の人々は、声楽のポリフォニーを使用しています。これらのスタイルの多くは、ドローンを用いたり、西 洋の耳には不協和な二次的ハーモニーを特徴としています。ガダルカナル島とソロモン諸島では、バンブーパイプのアンサンブルという形で器楽のポリフォニー が行われている[27][28]。 ポリネシア ヨーロッパ人はポリネシアでドローンを使った不協和音のポリフォニックな歌声を発見し、驚いた。その後、ポリネシアの伝統は西洋の合唱教会音楽の影響を受 け、ポリネシアの音楽実践に対位法が持ち込まれた[29][30]。 アフリカ 参照 サハラ以南のアフリカの伝統的な和声 サハラ以南アフリカの数多くの音楽伝統では多声部による歌唱が行われており、典型的には平行移動している[31]。 東アフリカ マサイ族は伝統的にドローン・ポリフォニーで歌うが、他の東アフリカのグループはより精巧な技法を用いている。例えばドルゼ族は6つのパートで歌い、ワゴ ゴ族は対位法を用いる[31]。 中央アフリカ アフリカのピグミー族(アカ族など)の音楽は典型的なオスティナートと対位法であり、ヨーデルが特徴である。他の中央アフリカの民族は対位法よりも平行線 を用いて歌う傾向がある[32]。 南部アフリカ サン族の歌唱はピグミー族と同様、旋律の繰り返し、ヨーデル、対位法を特徴とする。ズールー族のような近隣のバンツー族の歌唱は、より典型的な平行線であ る[32]。 西アフリカ 西アフリカの熱帯の民族は伝統的に対位法よりも平行和音を用いる[33]。 |

| Micropolyphony Polyphonic Era Venetian polychoral style |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Polyphony |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

| Micropolyphony Micropolyphony is a kind of polyphonic musical texture developed by György Ligeti which consists of many lines of dense canons moving at different tempos or rhythms, thus resulting in tone clusters vertically.[citation needed] According to David Cope, "micropolyphony resembles cluster chords, but differs in its use of moving rather than static lines"; it is "a simultaneity of different lines, rhythms, and timbres".[1] Differences between micropolyphonic texture and conventional polyphonic texture can be explained by Ligeti's own description: Technically speaking I have always approached musical texture through part-writing. Both Atmosphères and Lontano have a dense canonic structure. But you cannot actually hear the polyphony, the canon. You hear a kind of impenetrable texture, something like a very densely woven cobweb. I have retained melodic lines in the process of composition, they are governed by rules as strict as Palestrina's or those of the Flemish school, but the rules of this polyphony are worked out by me. The polyphonic structure does not come through, you cannot hear it; it remains hidden in a microscopic, underwater world, to us inaudible. I call it micropolyphony (such a beautiful word!). (Ligeti, quoted in Bernard 1994, 238). The earliest example of micropolyphony in Ligeti's work occurs in the second movement (mm 25–37) of his orchestral composition Apparitions.[2] He used the technique in a number of his other works, including Atmosphères for orchestra; the first movement of his Requiem for soprano, mezzo-soprano, mixed choir, and orchestra; the unaccompanied choral work Lux aeterna; and Lontano for orchestra. Micropolyphony is easier with larger ensembles or polyphonic instruments such as the piano,[1] though the Poème symphonique for a hundred metronomes creates "micropolyphony of unparallelled complexity".[3] Many of Ligeti's piano pieces are examples of micropolyphony applied to complex "minimalist" Steve Reich and Pygmy music derived rhythmic schemes. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Micropolyphony |

マイクロポリフォニー マイクロポリフォニー(Micropolyphony)は、ギョルジ・リゲティが開発したポリフォニックな音楽テクスチャの一種で、異なるテンポやリズム で動く密なカノンの多くのラインからなり、それによって垂直方向にトーンクラスターが生じる[citation needed] 。 デイビッド・コープによると、「マイクロポリフォニーはクラスター和音に似ているが、静的ではなく動くラインの使用で異なる」、それは「異なるライン、リ ズム、音色の同時性」[1] である、という。 マイクロポリフォニック・テクスチャーと従来のポリフォニック・テクスチャーとの違いは、リゲティ自身の記述によって説明することができる。 技術的に言えば、私は常にパート・ライティングによって音楽のテクスチャーにアプローチしてきた。アトモスフェール』も『ロンターノ』も濃密なカノン的構 造を持っている。しかし、実際にポリフォニー、カノンを聴くことはできません。非常に密に織られたクモの巣のような、不可解なテクスチャーが聴こえるので す。私は作曲の過程でメロディラインを保持し、それらはパレストリーナやフランドル楽派のような厳格な規則によって支配されていますが、このポリフォニー の規則は私が作り出したものです。ポリフォニーの構造は、私たちには聞こえない、ミクロの水面下の世界に潜んでいる。私はそれをマイクロポリフォニーと呼 んでいる(なんて美しい言葉だ!)。(リゲティ、ベルナール1994, 238より引用)。 リゲティの作品におけるマイクロポリフォニーの最も古い例は、管弦楽曲《Apparitions》の第2楽章(25-37mm)である[2]。 彼はこの手法を他の多くの作品でも用いており、管弦楽曲《Atmosphères》、ソプラノ、メゾソプラノ、混声合唱およびオーケストラのための 《Requiem》第1楽章、無伴奏合唱曲《Lux aeterna》およびオーケストラ曲《Lontano》などでも用いている。リゲティのピアノ曲の多くは、マイクロポリフォニーをスティーヴ・ライヒや ピグミー音楽由来の複雑な「ミニマル」なリズム体系に適用した例である[3]。 |

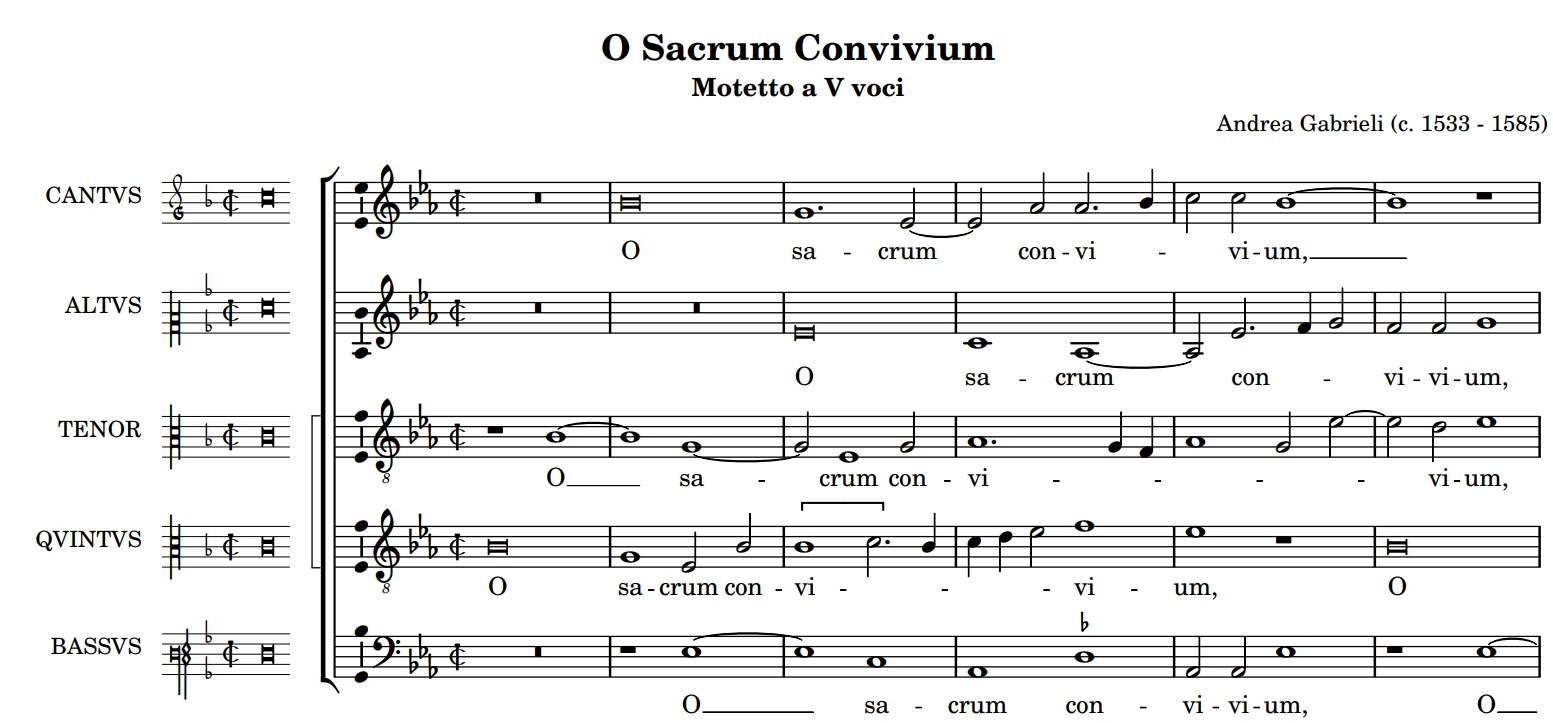

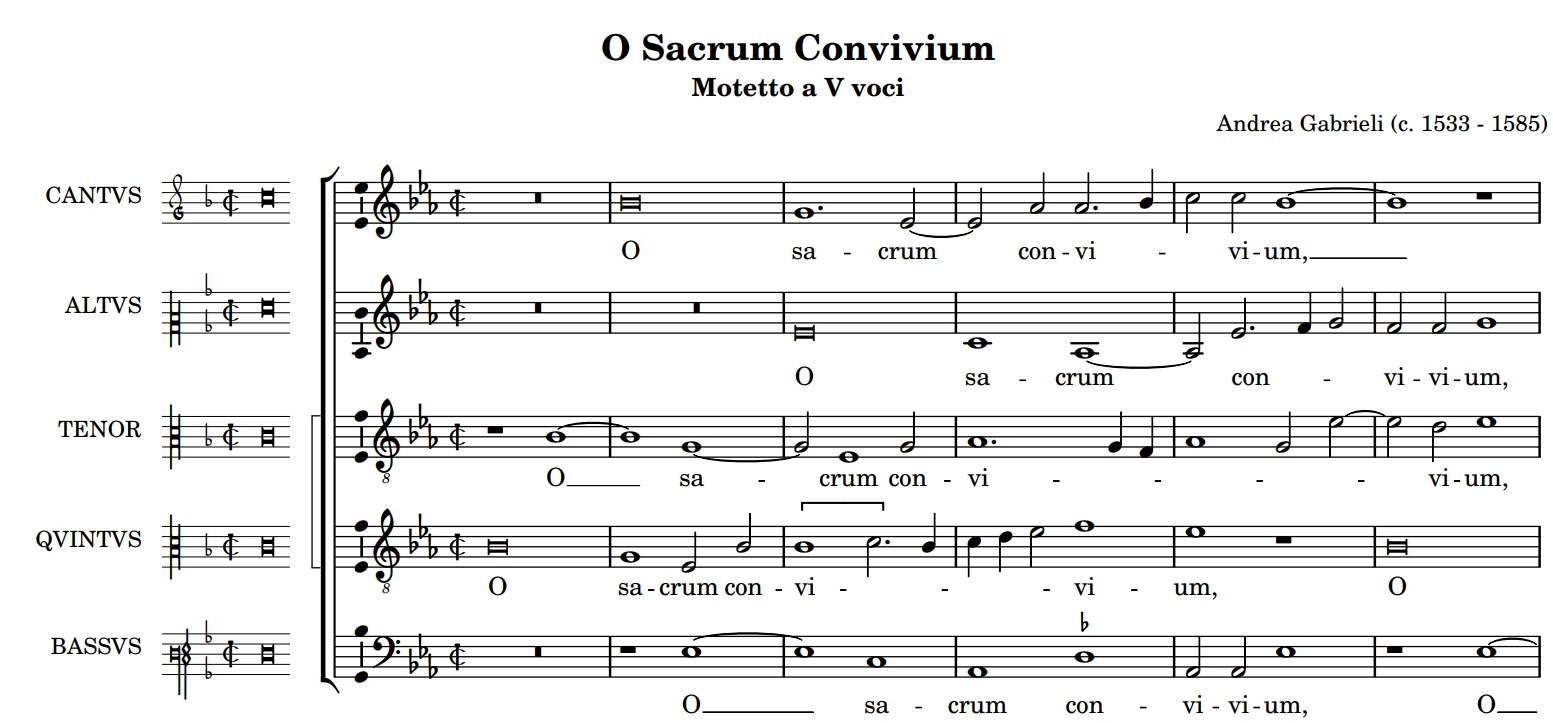

| Venetian polychoral style The Venetian polychoral style was a type of music of the late Renaissance and early Baroque eras which involved spatially separate choirs singing in alternation. It represented a major stylistic shift from the prevailing polyphonic writing of the middle Renaissance, and was one of the major stylistic developments which led directly to the formation of what is now known as the Baroque style. A commonly encountered term for the separated choirs is chori spezzati—literally, "broken choruses" as they were called, added the element of spatial contrast to Venetian music.These included the echo device, so important in the entire baroque tradition;the alternation of two contrasting bodies of sound, such as chorus against chorus, single line versus a full choir, solo voice opposing full choir, instruments outed against voices and contrasting instrumental groups; the alternation of high and low voices; soft level of sound alternated with a loud one; the fragmentary versus the continuous; and blocked chords contrasting with flowing counterpoint. Principle of duality , or opposing elements, is the basis for the concertato or concerning style, both words being derived from concertare, meaning "to compete with or to strive against." The word appears in the title of some works Giovanni published jointly with his uncle Andrea Gabrieli in 1587: Concerti...per voice at stromenti ("Concertos...for voices and instruments"). The term later came to be widely used, with such titles as Concerti Ecclesiastici (Church Concertos) appearing frequently. |

ベネチアン・ポリコーラル・スタイル ヴェネツィアの多声合唱は、ルネサンス後期からバロック初期にかけての音楽の一種で、空間的に分離した合唱団が交互に歌うものである。ルネサンス中期に主 流であったポリフォニックな様式から大きく変化し、現在バロック様式として知られているものの形成に直接つながる大きな様式上の展開の一つであった。分離 された合唱団は、一般に「コリ・スペッツァーティ」と呼ばれ、「壊れた合唱団」として、ヴェネチアの音楽に空間のコントラストという要素を加えた。 合唱と合唱、単音と全合唱、独唱と全合唱、楽器と声楽、楽器群と声楽の対比、高音と低音の交代、柔らかい音と大きい音の交代、断片と連続、閉じた和音と流 麗な対位法など、バロックの伝統に欠かせないエコー装置である。 二重性の原理、すなわち対立する要素は、コンチェルタートまたはコンゴーニング・スタイルの基礎であり、どちらの言葉も「競い合う、努力する」という意味 のconcertareから派生したものである。この言葉は、ジョバンニが1587年に叔父のアンドレア・ガブリエリと共同で出版したいくつかの作品のタ イトルに登場する。この言葉は、1587年にジョヴァンニが叔父のアンドレア・ガブリエリと共同で出版した「声楽と楽器のための協奏曲 (Concerto...per voice at stromenti)」という作品のタイトルにも使われている。その後、この言葉は広く使われるようになり、Concerti Ecclesiastici(教会協奏曲)のようなタイトルが頻繁に登場するようになった。 |

| The style arose in Northern

Italian churches in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and proved

to be a good fit for the architectural peculiarities of the imposing

Basilica San Marco di Venezia in Venice.[1] Composers such as Adrian

Willaert, the maestro di cappella of St. Mark's in the 1540s, wrote

antiphonal music, in which opposing choirs sang successive, often

contrasting phrases of the music from opposing choir lofts, from

specially constructed wooden platforms, and from the octagonal bigonzo

across from the pulpit.[2] This was a rare but interesting case of the

architectural peculiarities of a single building encouraging the

proliferation of a style which had become popular all over Europe, and

helped define the shift from the Renaissance to the Baroque era. The

idea of different groups singing in alternation contributed to the

evolution of the concertato style, which in its different instrumental

and vocal manifestations eventually led to such diverse musical ideas

as the chorale cantata, the concerto grosso, and the sonata. The peak of development of the style was in the late 1580s and 1590s, while Giovanni Gabrieli was organist at San Marco and principal composer, and while Gioseffo Zarlino was still maestro di cappella. Gabrieli seems to have been the first to specify instruments in his published works, including large choirs of cornetti and sackbuts; he also seems to be one of the earliest to specify dynamics (as in his Sonata pian' e forte), and to develop the "echo" effects for which he became famous. The fame of the spectacular, sonorous music of San Marco at this time spread across Europe, and numerous musicians came to Venice to hear, to study, to absorb and bring back what they learned to their countries of origin. Germany, in particular, was a region where composers began to work in a locally-modified form of the Venetian style—most notably Heinrich Schütz—though polychoral works were also composed elsewhere, such as the many masses written in Spain by Tomás Luis de Victoria. After 1603, a basso continuo was added to the already considerable forces at San Marco—orchestra, soloists, choir—a further step toward the Baroque cantata. Music at San Marco went through a period of growth and decline, but the fame of the institution spread far. Although the repertoire eventually included music in the concertato style, as well as the conservative stile antico, works in the polychoral style maintained a secure place in the San Marco repertoire into the 1800s. |

この様式は、16世紀から17世紀にかけて北イタリアの教会で生まれ、

ヴェネチアの堂々としたサン・マルコ寺院の建築的な特殊性によく合うことが証明された[1]。1540年代にサン・マルコ寺院のマエストロ・ディ・カペラ

であったアドリアン・ウィラートなどの作曲家がアンティフォナル音楽を書き、対立する聖歌隊が、対立する聖歌隊のロフト、特製の木の台、講壇の向かいにあ

る八角形のビゴンゾから連続して、しばしば対照的に曲を歌いました[2]

これは、一つの建物の建築上の特殊性がヨーロッパ中に普及したスタイルの普及を促進した珍しいケースですが興味深い例で、ルネッサンスからバロックへの時

代の移行を決定づける一翼を担ったのです。コンチェルトは、異なる集団が交互に歌うことで発展し、楽器や声楽の形態も変化して、コラール・カンタータ、コ

ンチェルト・グロッソ、ソナタなど、さまざまな音楽的アイディアが生み出された。 コンチェルト様式の発展のピークは、Giovanni GabrieliがSan Marcoのオルガニスト兼作曲家、Gioseffo Zarlinoがまだマエストロ・ディ・カペラだった1580年代後半から1590年代にかけてであった。ガブリエリは、コルネッティやサックバットの大 合唱など、出版された作品の中で初めて楽器を特定したようである。また、ダイナミクス(Sonata pian' e forteなど)や、彼が有名になった「エコー」効果を開発したのも早かったと思われる。この頃、サンマルコの華やかで音色のよい音楽の名声はヨーロッパ 中に広まり、多くの音楽家がヴェネツィアを訪れ、演奏を聴き、学び、吸収して、それぞれの国に持ち帰っていった。特にドイツでは、ハインリッヒ・シュッツ を筆頭に、ヴェネチア様式を現地で改良した作曲家が現れたが、スペインではトマス・ルイス・デ・ビクトリアが多くのミサ曲を作曲するなど、ポリコロールの 作品も作られた。 1603年以降、サンマルコでは、オーケストラ、ソリスト、合唱団という強力な編成に、通奏低音が加わり、バロック・カンタータへのさらなる一歩を踏み出 した。サンマルコの音楽は成長期と衰退期を繰り返したが、その名声は広く知れ渡ることになった。レパートリーもコンチェルタンテ形式や保守的なスティレ・ アンコ形式からポリコラール形式へと変化していったが、ポリコラール形式の作品は1800年代までサンマルコのレパートリーとして安定した地位を保ってい た。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Venetian_polychoral_style |

+++

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆