Potentiality and actuality, 潜

勢力と現実力

可能態と現実態

Potentiality and actuality, 潜

勢力と現実力

池田光穂

★哲学において、可能態と現実態[1]は密接に関連する一対の原理である。アリストテレスは

『物理学』『形而上学』『ニコマコス倫理学』『魂について』において、運動・因果関係・倫理・生理学を分析するためにこの原理を用いた[2]。

この文脈における可能態の概念は、一般的に、あるものが持つと言えるあらゆる「可能性」を指す。アリストテレスは全ての可能態を同等に扱わず、条件が整い

妨げるものが何もない時に自ずから現実となるものの重要性を強調した[3]。これに対し、現実態は可能態とは対照的に、可能態が最も完全な意味で現実とな

る時、すなわち可能態の行使や実現を表す運動、変化、活動である。したがって、これらの概念はいずれも、自然界の事象が真の意味で全て自然的ではないとい

うアリストテレスの信念を反映している。彼の見解では、多くの事象は偶然的に発生し、したがって物事の自然な目的に従って起こっているわけではない。

これらの概念は、修正版ながら中世に至るまで非常に重要であり続け、中世神学の発展に幾つかの形で影響を与えた。近代において、自然と神に対する理解が変

化するにつれ、この二分法は次第に重要性を失った。しかし、この用語体系は新たな用途にも適応されてきた。最も顕著なのは「エネルギー」や「ダイナミッ

ク」といった言葉である。これらはドイツの科学者・哲学者ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツが近代物理学で初めて用いた言葉だ。より議論を呼ぶ

点では、アリストテレスのエンテレケイア概念が生物学において「エンテレケイア」の使用を求める声に時折影響を与え続けている。

★可能態と現実態::潜勢力=ポテンシアリティと現実性(Potentiality and actuality)→このページは「具体化した=身体化したコミュニケーション技術」よりスピンオンしました

| In philosophy, potentiality

and actuality[1] are a pair of closely connected principles which

Aristotle used to analyze motion, causality, ethics, and physiology in

his Physics, Metaphysics, Nicomachean Ethics, and On the Soul.[2] The concept of potentiality, in this context, generally refers to any "possibility" that a thing can be said to have. Aristotle did not consider all possibilities the same, and emphasized the importance of those that become real of their own accord when conditions are right and nothing stops them.[3] Actuality, in contrast to potentiality, is the motion, change or activity that represents an exercise or fulfillment of a possibility, when a possibility becomes real in the fullest sense.[4] Both these concepts therefore reflect Aristotle's belief that events in nature are not all natural in a true sense. As he saw it, many things happen accidentally, and therefore not according to the natural purposes of things. These concepts, in modified forms, remained very important into the Middle Ages, influencing the development of medieval theology in several ways. In modern times the dichotomy has gradually lost importance, as understandings of nature and deity have changed. However the terminology has also been adapted to new uses, as is most obvious in words like energy and dynamic. These were words first used in modern physics by the German scientist and philosopher, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. More controversially, Aristotle's concept of entelechy retains influence on occasional calls for the use of "entelechy" in biology. |

哲学において、可能態と現実態[1]は密接に関連する一対の原理であ

る。アリストテレスは『物理学』『形而上学』『ニコマコス倫理学』『魂について』において、運動・因果関係・倫理・生理学を分析するためにこの原理を用い

た[2]。 この文脈における可能態の概念は、一般的に、あるものが持つと言えるあらゆる「可能性」を指す。アリストテレスは全ての可能態を同等に扱わず、条件が整い 妨げるものが何もない時に自ずから現実となるものの重要性を強調した[3]。これに対し、現実態は可能態とは対照的に、可能態が最も完全な意味で現実とな る時、すなわち可能態の行使や実現を表す運動、変化、活動である。したがって、これらの概念はいずれも、自然界の事象が真の意味で全て自然的ではないとい うアリストテレスの信念を反映している。彼の見解では、多くの事象は偶然的に発生し、したがって物事の自然な目的に従って起こっているわけではない。 これらの概念は、修正版ながら中世に至るまで非常に重要であり続け、中世神学の発展に幾つかの形で影響を与えた。近代において、自然と神に対する理解が変 化するにつれ、この二分法は次第に重要性を失った。しかし、この用語体系は新たな用途にも適応されてきた。最も顕著なのは「エネルギー」や「ダイナミッ ク」といった言葉である。これらはドイツの科学者・哲学者ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツが近代物理学で初めて用いた言葉だ。より議論を呼ぶ 点では、アリストテレスのエンテレケイア概念が生物学において「エンテレケイア」の使用を求める声に時折影響を与え続けている。 |

| Potentiality Look up potentiality, potentia, or δύναμις in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. "Potentiality" and "potency" are translations of the Ancient Greek word dunamis (δύναμις). They refer especially to the way the word is used by Aristotle, as a concept contrasting with "actuality". The Latin translation of dunamis is potentia, which is the root of the English word "potential"; it is also sometimes used in English-language philosophical texts. In early modern philosophy, English authors like Hobbes and Locke used the English word power as their translation of Latin potentia.[5] Dunamis is an ordinary Greek word for possibility or capability. Depending on the context, it could be translated as 'potency', 'potential', 'capacity', 'ability', 'power', 'capability', 'strength', 'possibility', or 'force' and is the root of modern English words dynamic, dynamite, and dynamo.[6] In his philosophy, Aristotle distinguished two meanings of the word dunamis. According to his understanding of nature there was both a weak sense of potential, meaning simply that something "might chance to happen or not to happen", and a stronger sense, to indicate how something could be done well. For example, "sometimes we say that those who can merely take a walk, or speak, without doing it as well as they intended, cannot speak or walk." This stronger sense is mainly said of the potentials of living things, although it is also sometimes used for things like musical instruments.[7] Throughout his works, Aristotle clearly distinguishes things that are stable or persistent, which hold their own strong natural tendency to a specific type of change, from things that appear to occur by chance. He treats these as having a different and more real existence. "Natures which persist" are said by him to be one of the causes of all things, while natures that do not persist, "might often be slandered as not being at all by one who fixes his thinking sternly upon it as upon a criminal." The potencies which persist in a particular material are one way of describing "the nature itself" of that material, an innate source of motion and rest within that material. In terms of Aristotle's theory of four causes, a material's non-accidental potential is the material cause of the things that can come to be from that material, and one part of how we can understand the substance (ousia, sometimes translated as "thinghood") of any separate thing. (As emphasized by Aristotle, this requires his distinction between accidental causes and natural causes.)[8] According to Aristotle, when we refer to the nature of a thing, we are referring to the form or shape of a thing, which was already present as a potential, an innate tendency to change, in that material before it achieved that form. When things are most "fully at work" we can see more fully what kind of thing they really are.[9] |

潜在性 ウィクショナリー(無料辞書)で「潜在 性」「potentia」「δύναμις」を検索せよ。 「潜在性」と「潜在力」は古代ギリシャ語の「dunamis(δύναμις)」の訳語である。特にアリストテレスが「現実態」と対比する概念として用い た用法を指す。「δύναμις」のラテン語訳は「potentia」であり、これが英語の「potential」の語源である。英語圏の哲学文献でも時 折使用される。近世哲学では、ホッブズやロックといった英国の著者が、ラテン語の「potentia」を英語の「power」で訳した。[5] デュナミスは可能態や能力を表す一般的なギリシャ語である。文脈に応じて「潜在力」「可能態」「能力」「力量」「力」「強さ」「可能態」「作用力」などと 訳され、現代英語の「ダイナミック」「ダイナマイト」「ダイナモ」の語源となっている。[6] アリストテレスは哲学において、dunamisという言葉に二つの意味を区別した。彼の自然観によれば、単に「偶然に起こり得るか否か」を意味する弱い潜 在性の意味と、物事が如何に良く為し得るかを示す強い意味の両方が存在した。例えば「単に歩くことや話すことが可能であっても、意図した通りに上手く行え ない者を、我々は話すことも歩くこともできないと言うことがある」と彼は述べている。この強い意味は主に生物の潜在能力について言われるが、楽器のような ものにも時折用いられる。[7] アリストテレスは著作全体を通じて、安定した持続的なもの(特定の変化への強い自然傾向を保持するもの)と、偶然に起こるように見えるものを明確に区別し ている。彼は前者をより現実的な存在として扱う。「持続する性質」は万物の原因の一つとされ、持続しない性質は「それを犯罪者のように厳しく見つめる者 が、全く存在しないと誹謗するかもしれない」と述べられている。特定の物質に持続する潜在性は、その物質の「本質そのもの」を説明する一つの方法であり、 その物質内に内在する運動と静止の源である。アリストテレスの四原因説において、物質の非偶因的な潜在性は、その物質から生じうるものの物質的原因であ り、あらゆる個別のものの実体(ousia、時に「物性」と訳される)を理解する一つの要素である。(アリストテレスが強調したように、これは偶因と自然 因の区別を前提とする)[8]。アリストテレスによれば、あるものの本質に言及するとき、我々はすでに潜在的な可能態として、つまりその形態を獲得する前 からその物質に内在していた変化への傾向として存在していた、そのものの形態や形状を指している。ものが最も「完全に作用している」とき、我々はそのもの が本当にどのようなものであるかをより完全に知ることができるのだ[9]。 |

| Actuality Actuality is often used to translate both energeia (ἐνέργεια) and entelecheia (ἐντελέχεια) (sometimes rendered in English as entelechy). Actuality comes from Latin actualitas and is a traditional translation, but its normal meaning in Latin is 'anything which is currently happening.' The two words energeia and entelecheia were coined by Aristotle, and he stated that their meanings were intended to converge.[10] In practice, most commentators and translators consider the two words to be interchangeable.[11][12] They both refer to something being in its own type of action or at work, as all things are when they are real in the fullest sense, and not just potentially real. For example, "to be a rock is to strain to be at the center of the universe, and thus to be in motion unless constrained otherwise."[2] Energeia Energeia is a word based upon ἔργον (ergon), meaning 'work'.[11][13] It is the source of the modern word energy but the term has evolved so much over the course of the history of science that reference to the modern term is not very helpful in understanding the original as used by Aristotle. It is difficult to translate his use of energeia into English with consistency. Joe Sachs renders it with the phrase "being-at-work" and says that "we might construct the word is-at-work-ness from Anglo-Saxon roots to translate energeia into English".[14] Aristotle says the word can be made clear by looking at examples rather than trying to find a definition.[15] Two examples of energeiai in Aristotle's works are pleasure and happiness (eudaimonia). Pleasure is an energeia of the human body and mind whereas happiness is more simply the energeia of a human being a human.[16] Kinesis, translated as movement, motion, or in some contexts change, is also explained by Aristotle as a particular type of energeia. See below. Entelechy (entelechia) Entelechy, in Greek entelécheia, was coined by Aristotle and transliterated in Latin as entelechia. According to Sachs (1995, p. 245): Aristotle invents the word by combining entelēs (ἐντελής, 'complete, full-grown') with echein (= hexis, to be a certain way by the continuing effort of holding on in that condition), while at the same time punning on endelecheia (ἐνδελέχεια, 'persistence') by inserting telos (τέλος, 'completion'). This is a three-ring circus of a word, at the heart of everything in Aristotle's thinking, including the definition of motion. Sachs therefore proposed a complex neologism of his own, "being-at-work-staying-the-same."[17] Another translation in recent years is "being-at-an-end" (which Sachs has also used).[2] Entelecheia, as can be seen by its derivation, is a kind of completeness, whereas "the end and completion of any genuine being is its being-at-work" (energeia). The entelecheia is a continuous being-at-work (energeia) when something is doing its complete "work". For this reason, the meanings of the two words converge, and they both depend upon the idea that every thing's "thinghood" is a kind of work, or in other words a specific way of being in motion. All things that exist now, and not just potentially, are beings-at-work, and all of them have a tendency towards being-at-work in a particular way that would be their proper and "complete" way.[17] Sachs explains the convergence of energeia and entelecheia as follows, and uses the word actuality to describe the overlap between them:[2] Just as energeia extends to entelecheia because it is the activity which makes a thing what it is, entelecheia extends to energeia because it is the end or perfection which has being only in, through, and during activity. |

現実態 現実態という言葉は、しばしばエネルギーア(ἐνέργεια)とエンテレケイア(ἐντελέχεια)(英語ではエンテレキーと訳されることもある) の両方を訳すのに用いられる。現実態はラテン語のactualitasに由来する伝統的な訳語だが、ラテン語における通常の意味は「現在起きているあらゆ る事象」である。 energeia と entelecheia の二語はアリストテレスによって造語され、彼は両者の意味が収束するよう意図したと述べている[10]。実際には、ほとんどの注釈者や翻訳者はこの二語を 互換性があると見なしている[11][12]。両者とも、物事が潜在的に実在するだけでなく、最も完全な意味で現実であるとき、すなわちその種別における 活動状態にあることを指す。例えば、「岩であるとは、宇宙の中心になろうと努力することであり、それゆえに他の制約がない限り運動している状態である」と 言える[2]。 エネルゲイア エネルゲイアは「仕事」を意味するἔργον(エルゴン)に基づく語である。[11][13] 現代語の「エネルギー」の語源だが、科学史の過程でこの用語は大きく変遷したため、アリストテレスが用いた本来の概念を理解する上で現代語を参照してもあ まり役立たない。彼のエネルゲイアの用法を一貫して英語に翻訳するのは困難である。ジョー・サックスはこれを「being-at-work(作用状態)」 と訳し、「アングロサクソン語源から『is-at-work-ness(作用状態性)』という語を造語してenergeiaを英語に翻訳できるかもしれな い」と述べている。[14] アリストテレスは、定義を探すよりも具体例を見ることでこの言葉が明確になると述べている。[15] アリストテレスの著作におけるエネルゲイアの二つの例は、快楽と幸福(ユーダイモニア)である。快楽は人体と精神のエネルゲイアであるのに対し、幸福はよ り単純に人間という存在のエネルゲイアである。[16] キネシス(kinesis)は、動き、運動、あるいは文脈によっては変化と訳されるが、アリストテレスはこれも特定の種類のエネルギーアとして説明してい る。詳細は後述。 エンテレキー(entelechia) エンテレキー(ギリシャ語:entelécheia)はアリストテレスが造語し、ラテン語でentelechiaと音訳された。サックス(1995, p. 245)によれば: アリストテレスはこの語を、entelēs(ἐντελής、「完全な、成長した」)と echein(= hexis、「その状態を維持し続ける努力によって特定のあり方であること」)を組み合わせることで創出した。同時に、endelecheia (ἐνδελέχεια、「持続」)を掛詞として用いるため、telos(τέλος、「完成」)を挿入している。これは三重の意味を持つ言葉であり、運 動の定義を含むアリストテレスの思考の核心をなす。 サックスはそこで独自の複雑な新語「働きつつ同じままであること」を提案した[17]。近年では「終わりにある存在」という訳も用いられている(サックス もこの訳を採用している)。[2] エンテレケイアは、その語源からも分かるように、一種の完全性である。一方、「あらゆる真の存在の終点かつ完成は、その働き(エネルゲイア)である」。エ ンテレケイアとは、何かが完全な「働き」を遂行している状態における、継続的な働き(エネルゲイア)である。このため両語の意味は収束し、あらゆるものの 「ものとしてのあり方」が一種の営み、すなわち特定の運動状態であるという観念に依存する。潜在的に存在するだけでなく現在存在する全てのものは営みとし ての存在であり、それぞれが固有の「完全な」営み方へと向かう傾向を持つ。[17] ザックスはエネルゲイアとエンテレケイアの収束を次のように説明し、両者の重なりを「現実態」という言葉で表現している:[2] エネルゲイアがエンテレケイアへと拡張するのは、それが物事をその物たらしめる活動であるからである。同様に、エンテレケイアがエネルゲイアへと拡張する のは、それが活動の中において、活動を通じて、活動の中でしか存在し得ない終点あるいは完成であるからである。 |

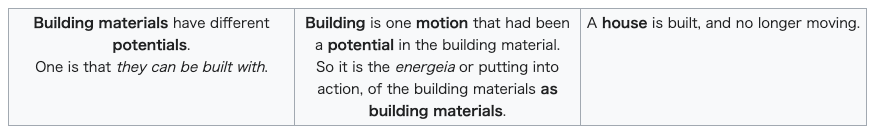

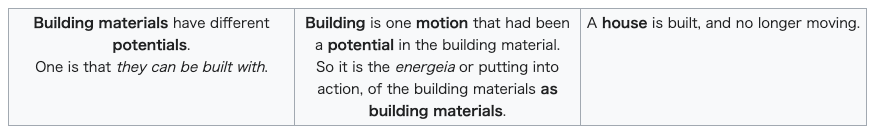

| Motion Aristotle discusses motion (kinēsis) in his Physics quite differently from modern science. Aristotle's definition of motion is closely connected to his actuality-potentiality distinction. Taken literally, Aristotle defines motion as the actuality (entelecheia) of a "potentiality as such".[18] What Aristotle meant however is the subject of several different interpretations. A major difficulty comes from the fact that the terms actuality and potentiality, linked in this definition, are normally understood within Aristotle as opposed to each other. On the other hand, the "as such" is important and is explained at length by Aristotle, giving examples of "potentiality as such". For example, the motion of building is the energeia of the dunamis of the building materials as building materials as opposed to anything else they might become, and this potential in the unbuilt materials is referred to by Aristotle as "the buildable". So the motion of building is the actualization of "the buildable" and not the actualization of a house as such, nor the actualization of any other possibility which the building materials might have had.[19]  In an influential 1969 paper, Aryeh Kosman divided up previous attempts to explain Aristotle's definition into two types, criticised them, and then gave his own third interpretation. While this has not become a consensus, it has been described as having become "orthodox".[20] This and similar more recent publications are the basis of the following summary. |

運動性 アリストテレスは『物理学』において、運動(キネーシス)を現代科学とは全く異なる形で論じている。アリストテレスの運動の定義は、彼の「現実態」と「可 能態」の区別と密接に関連している。文字通り解釈すれば、アリストテレスは運動を「可能態そのもの」の現実態(エンテレケイア)と定義している[18]。 しかしアリストテレスが意図したことは、いくつかの異なる解釈の対象となっている。大きな難点は、この定義で結びつけられた「現実態」と「可能態」という 用語が、アリストテレスの文脈では通常、対立概念として理解される点にある。一方で「それ自体として」という表現が重要であり、アリストテレスは「それ自 体としての可能態」の例を挙げて詳細に説明している。例えば、建築の運動とは、建築材料が建築材料として持つ可能態(dunamis)のエネルギー (energeia)であり、それ以外の何かに変容する可能態ではない。未加工の材料に内在するこの可能態を、アリストテレスは「建築可能なもの」と呼ん でいる。したがって建築の運動とは、「建築可能なもの」の実現であり、家そのものの実現でもなければ、建築材料が持つ可能態の他のいかなる実現でもない。 [19]  1969年の影響力のある論文で、アリエ・コスマンはアリストテレスの定義を説明しようとするこれまでの試みを二種類に分類し、それらを批判した上で、独 自の第三の解釈を示した。これはコンセンサスには至っていないが、「正統的」と見なされるようになったと評されている[20]。この論文と、それに類似し た近年の出版物が、以下の要約の基礎となっている。 |

Building materials have different potentials. One is that they can be built with. |

建材には異なる可能態がある。 一つは、それを使って建造物を作れるということだ。 |

| Building is one motion that had

been a potential in the building material. So it is the energeia or putting into action, of the building materials as building materials. |

建築とは、建材が本来持つ可能態の一つであった。 つまり建材が建材として発揮するエネルギー、すなわち実践なのである。 |

| A house is built, and no longer

moving. |

家は建てられ、もはや動かない(=運動性をもたない)。 |

| 1. The "process" interpretation Kosman (1969) and Coope (2009) associate this approach with W. D. Ross. Sachs (2005) points out that it was also the interpretation of Averroes and Maimonides. This interpretation is, to use the words of Ross that "it is the passage to actuality that is kinesis" as opposed to any potentiality being an actuality.[21] Opponents argue that this interpretation requires Ross to assert that Aristotle actually used his own word entelecheia wrongly, or inconsistently, only within his definition, making it mean "actualization", which is in conflict with Aristotle's normal use of words. According to Sachs (2005) this explanation also can't account for the "as such" in Aristotle's definition. |

1. 「過程」解釈 コスマン(1969)とクープ(2009)はこの解釈をW. D. ロスに関連づける。サックス(2005)は、アヴェロエスとマイモニデスも同様の解釈をしていたと指摘している。 この解釈は、ロス自身の言葉を借りれば「運動(kinesis)とは、潜在性が現実態となる過程そのものである」というものであり、いかなる潜在性も現実 態そのものを指すものではない。[21] 反対論者は、この解釈がロスに、アリストテレスが自身の用語「エンテレケイア」を、その定義においてのみ誤用あるいは矛盾して使用し、「実現化」を意味さ せたと主張することを要求すると論じる。これはアリストテレスの通常の用語使用と矛盾する。サックス(2005)によれば、この説明はアリストテレスの定 義における「そのものとして」という表現も説明できない。 |

| 2. The "product" interpretation Sachs (2005) associates this interpretation with Thomas Aquinas and explains that by this explanation "the apparent contradiction between potentiality and actuality in Aristotle's definition of motion" is resolved "by arguing that in every motion actuality and potentiality are mixed or blended." Motion is therefore "the actuality of any potentiality insofar as it is still a potentiality." Or in other words: The Thomistic blend of actuality and potentiality has the characteristic that, to the extent that it is actual it is not potential and to the extent that it is potential it is not actual; the hotter the water is, the less is it potentially hot, and the cooler it is, the less is it actually, the more potentially, hot. As with the first interpretation however, Sachs (2005) objects that: One implication of this interpretation is that whatever happens to be the case right now is an entelechia, as though something that is intrinsically unstable as the instantaneous position of an arrow in flight deserved to be described by the word that everywhere else Aristotle reserves for complex organized states that persist, that hold out against internal and external causes that try to destroy them. In a more recent paper on this subject, Kosman associates the view of Aquinas with those of his own critics, David Charles, Jonathan Beere, and Robert Heineman.[22] |

2. 「産物」解釈 Sachs (2005)はこの解釈をトマス・アクィナスに関連付け、「アリストテレスの運動定義における可能態と現実態の見かけの矛盾」が「あらゆる運動において現 実態と可能態が混血の」と論じることで解決されると説明する。したがって運動とは「可能態が依然として可能態である限りにおける、あらゆる可能態の現実 態」である。あるいは言い換えれば: トマス主義における現実態と可能態の混合は、次のような特徴を持つ。すなわち、現実である限り可能態ではなく、可能態である限り現実ではない。水は熱けれ ば熱いほど、潜在的に熱い状態ではなくなり、冷たければ冷たいほど、現実的には熱くなく、潜在的にはより熱くなる。 しかし最初の解釈と同様に、サックス(2005)は次のように反論する: この解釈が示唆するのは、現在たまたま起こっている事象がすべてエンテレケイアであるという主張だ。あたかも、飛行中の矢の瞬間的な位置のように本質的に 不安定なものが、アリストテレスが他のあらゆる場面で持続する複雑な組織状態、すなわち内部・外部の破壊要因に耐えうる状態にのみ用いる言葉を、不当に用 いられているかのようだ。 この主題に関するより最近の論文で、コスマンはアクィナスの見解を、自身の批判者であるデイヴィッド・チャールズ、ジョナサン・ビア、ロバート・ハイネマ ンの見解と結びつけている。[22] |

| 3. The interpretation of Kosman,

Coope, Sachs and others Sachs (2005), amongst other authors (such as Aryeh Kosman and Ursula Coope), proposes that the solution to problems interpreting Aristotle's definition must be found in the distinction Aristotle makes between two different types of potentiality, with only one of those corresponding to the "potentiality as such" appearing in the definition of motion. He writes: The man with sight, but with his eyes closed, differs from the blind man, although neither is seeing. The first man has the capacity to see, which the second man lacks. There are then potentialities as well as actualities in the world. But when the first man opens his eyes, has he lost the capacity to see? Obviously not; while he is seeing, his capacity to see is no longer merely a potentiality, but is a potentiality which has been put to work. The potentiality to see exists sometimes as active or at-work, and sometimes as inactive or latent. Coming to motion, Sachs gives the example of a man walking across the room and explains as follows: "Once he has reached the other side of the room, his potentiality to be there has been actualized in Ross' sense of the term". This is a type of energeia. However, it is not a motion, and not relevant to the definition of motion. While a man is walking his potentiality to be on the other side of the room is actual just as a potentiality, or in other words the potential as such is an actuality. "The actuality of the potentiality to be on the other side of the room, as just that potentiality, is neither more nor less than the walking across the room." Sachs (1995, pp. 78–79), in his commentary of Aristotle's Physics Book III gives the following results from his understanding of Aristotle's definition of motion: The genus of which motion is a species is being-at-work-staying-itself (entelecheia), of which the only other species is thinghood. The being-at-work-staying-itself of a potency (dunamis), as material, is thinghood. The being-at-work-staying-the-same of a potency as a potency is motion. |

3. コスマン、クープ、サックスらによる解釈 サックス(2005)は、アリアエ・コスマンやウルスラ・クープら他の著者と同様に、アリストテレスの定義解釈における問題の解決は、アリストテレスが異 なる二種類の可能態を区別している点に見出されねばならないと提案する。そのうちの片方だけが、運動の定義に現れる「可能態そのもの」に対応するのだ。彼 はこう記す: 目が見えるが目を閉じている男は、盲目の男とは異なる。どちらも見てはいないが、前者は見る能力を持ち、後者はそれを欠いている。つまり世界には可能態も 現実も存在するのだ。しかし、前者の男が目を開けたとき、見る能力を失ったか?明らかにそうではない。彼が見ている間、見る能力はもはや単なる可能態では なく、働かせられた可能態となる。見る可能態は時に活動的または働いている状態で、時に非活動的または潜在的な状態で存在する。 運動について、サックスは部屋を横切る男の例を挙げ、次のように説明する: 「彼が部屋の反対側に到達した時点で、そこに在るという彼の潜在性は、ロスが用いる意味において実現された」これは一種のエネルギーである。しかしそれは 運動ではなく、運動の定義とは無関係だ。 人が歩いている間、部屋の反対側に在るという彼の潜在性は、潜在性としてまさに現実的である。言い換えれば、潜在性そのものが現実態なのである。「部屋の 反対側にいる可能態としてのその可能態の現実態は、単に部屋を横切る行為そのものに他ならない」 サックス(1995年、78-79頁)は、アリストテレスの『物理学』第三巻の解説において、アリストテレスの運動の定義に関する自身の理解から以下の結 論を導いている: 運動がその種である属は、自己を保ちつつ作用する存在(エンテレケイア)であり、その唯一の他の種は物性である。可能態(デュナミス)としての自己を保ち つつ作用する存在は、物質として物性である。可能態としての可能態が自己を保ちつつ作用する存在は、運動である。 |

| The importance of actuality in

Aristotle's philosophy The actuality-potentiality distinction in Aristotle is a key element linked to everything in his physics and metaphysics.[23]  A marble block in Carrara. Could there be a particular sculpture already existing in it as a potentiality? Aristotle wrote approvingly of such ways of talking, and felt it reflected a type of causation in nature which is often ignored in scientific discussion. Aristotle describes potentiality and actuality, or potency and action, as one of several distinctions between things that exist or do not exist. In a sense, a thing that exists potentially does not exist; but, the potential does exist. This type of distinction is expressed for several different types of being within Aristotle's categories of being. For example, from Aristotle's Metaphysics, 1017a:[24] We speak of an entity being a "seeing" thing whether it is currently seeing or just able to see. We speak of someone having understanding, whether they are using that understanding or not. We speak of corn existing in a field even when it is not yet ripe. People sometimes speak of a figure being already present in a rock which could be sculpted to represent that figure. Within the works of Aristotle the terms energeia and entelecheia, often translated as actuality, differ from what is merely actual because they specifically presuppose that all things have a proper kind of activity or work which, if achieved, would be their proper end. Greek for end in this sense is telos, a component word in entelecheia (a work that is the proper end of a thing) and also teleology. This is an aspect of Aristotle's theory of four causes and specifically of formal cause (eidos, which Aristotle says is energeia[25]) and final cause (telos). In essence this means that Aristotle did not see things as matter in motion only, but also proposed that all things have their own aims or ends. In other words, for Aristotle (unlike modern science), there is a distinction between things with a natural cause in the strongest sense, and things that truly happen by accident. He also distinguishes non-rational from rational potentialities (e.g. the capacity to heat and the capacity to play the flute, respectively), pointing out that the latter require desire or deliberate choice for their actualization.[26] Because of this style of reasoning, Aristotle is often referred to as having a teleology, and sometimes as having a theory of forms. While actuality is linked by Aristotle to his concept of a formal cause, potentiality (or potency) on the other hand, is linked by Aristotle to his concepts of hylomorphic matter and material cause. Aristotle wrote for example that "matter exists potentially, because it may attain to the form; but when it exists actually, it is then in the form."[27] Teleology is a crucial concept throughout Aristotle's philosophy.[28] This means that as well as its central role in his physics and metaphysics, the potentiality-actuality distinction has a significant influence on other areas of Aristotle's thought such as his ethics, biology and psychology.[29] |

アリストテレス哲学における現実態の重要性 アリストテレスにおける現実態と可能態の区別は、彼の物理学と形而上学のあらゆる要素と結びついた核心的な要素である。[23]  カララ産の大理石の塊。そこにはすでに特定の彫刻が可能態として存在しているのだろうか?アリストテレスはこうした言い方を肯定的に論じ、それが自然界に おける一種の因果関係を反映していると感じていた。この因果関係は科学的議論ではしばしば無視される。 アリストテレスは、潜在性と現実態、あるいは潜在力と作用を、存在するものと存在しないものの間の幾つかの区別の一つとして説明する。ある意味で、潜在的 に存在するものは存在しないが、その潜在性は存在する。この種の区別は、アリストテレスの存在の範疇における幾つかの異なる存在類型に対して表現される。 例えば、『形而上学』1017aより: [24] 我々は、ある実体が現在見ているか、単に視覚を持つ能力があるかにかかわらず、それを「見る」ものと呼ぶ。 我々は、その理解力を使っているかどうかにかかわらず、誰かが理解力を持っていると言う。 畑のトウモロコシは、まだ実っていない段階でも存在していると言う。 岩の中に彫刻によって表現されるべき図像が既に存在していると言うこともある。 アリストテレスの著作において、energeia(エネルギーア)とentelecheia(エンテレケイア)という用語は、しばしば「現実態」と訳され るが、単に現実的なものとは異なる。なぜなら、これらは特に、あらゆるものが達成されればその適切な終点となるべき、固有の活動や働きを有することを前提 としているからだ。この意味での「目的」をギリシャ語で表すのは「テロス」であり、これは「エンテレケイア」(物事の適切な目的である営み)や「目的論」 を構成する語根でもある。これはアリストテレスの四原因論、特に形式原因(イードス、アリストテレスによればこれはエネルギーである[25])と目的原因 (テロス)の一側面である。 本質的にこれは、アリストテレスが物事を単なる運動する物質と見なさず、全ての物には独自の目的や終末があると提唱したことを意味する。言い換えれば、ア リストテレスにとって(現代科学とは異なり)、最も強い意味での自然的原因を持つ物と、真に偶然に起こる物との間には区別がある。彼はまた、非理性的潜在 性と理性的潜在性(例えば、加熱する能力とフルートを演奏する能力)を区別し、後者の実現には欲望や意図的な選択が必要だと指摘している[26]。この推 論様式ゆえに、アリストテレスはしばしば目的論的であると言われ、時にはイデア論を持つとも呼ばれる。 アリストテレスは、現実態を形式原因の概念と結びつける一方で、可能態(あるいは潜在性)を物質と物質原因の概念と結びつけている。例えば彼は「物質は潜 在的に存在する。なぜならそれは形式に到達し得るからである。しかし実際に存在する時、それは形式の中にある」と記している[27]。 目的論はアリストテレス哲学全体を通じて重要な概念である[28]。これは、物理学や形而上学における中心的な役割に加え、可能態と現実態の区別が倫理 学、生物学、心理学といったアリストテレスの思想の他の領域にも大きな影響を与えていることを意味する[29]。 |

| The active intellect Main article: Active Intellect The active intellect was a concept Aristotle described that requires an understanding of the actuality-potentiality dichotomy. Aristotle described this in his De Anima (Book 3, Chapter 5, 430a10-25) and covered similar ground in his Metaphysics (Book 12, Chapter 7-10). The following is from the De Anima, translated by Joe Sachs,[30] with some parenthetic notes about the Greek. The passage tries to explain "how the human intellect passes from its original state, in which it does not think, to a subsequent state, in which it does." He inferred that the energeia/dunamis distinction must also exist in the soul itself:[31] ...since in nature one thing is the material [hulē] for each kind [genos] (this is what is in potency all the particular things of that kind) but it is something else that is the causal and productive thing by which all of them are formed, as is the case with an art in relation to its material, it is necessary in the soul [psuchē] too that these distinct aspects be present; the one sort is intellect [nous] by becoming all things, the other sort by forming all things, in the way an active condition [hexis] like light too makes the colors that are in potency be at work as colors [to phōs poiei ta dunamei onta chrōmata energeiai chrōmata]. This sort of intellect is separate, as well as being without attributes and unmixed, since it is by its thinghood a being-at-work, for what acts is always distinguished in stature above what is acted upon, as a governing source is above the material it works on. Knowledge [epistēmē], in its being-at-work, is the same as the thing it knows, and while knowledge in potency comes first in time in any one knower, in the whole of things it does not take precedence even in time. This does not mean that at one time it thinks but at another time it does not think, but when separated it is just exactly what it is, and this alone is deathless and everlasting (though we have no memory, because this sort of intellect is not acted upon, while the sort that is acted upon is destructible), and without this nothing thinks. This has been referred to as one of "the most intensely studied sentences in the history of philosophy."[31] In the Metaphysics, Aristotle wrote at more length on a similar subject and is often understood to have equated the active intellect with being the "unmoved mover" and God. Nevertheless, as Davidson remarks: Just what Aristotle meant by potential intellect and active intellect – terms not even explicit in the De Anima and at best implied – and just how he understood the interaction between them remains moot to this day. Students of the history of philosophy continue to debate Aristotle's intent, particularly the question whether he considered the active intellect to be an aspect of the human soul or an entity existing independently of man.[31] |

能動的知性 主な記事: 能動的知性 能動的知性とは、アリストテレスが説明した概念であり、現実態と可能態の二分法を理解する必要がある。アリストテレスはこれを『魂について』(第3巻第5 章、430a10-25)で説明し、『形而上学』(第12巻第7-10章)でも同様の論点を扱った。以下はジョー・サックス訳『魂について』からの引用 [30]であり、ギリシャ語に関する補足注記を付す。この箇所は「人間の知性が、思考しない初期状態から、思考する後の状態へいかに移行するか」を説明し ようとするものである。彼は、エンレーギア/ドゥーナミスの区別が魂そのものにも存在すると推論した[31]: …自然において、ある種の物質(フレー)は各類(ゲノス)の材料となる(これはその類のあらゆる個別のものが潜在的に存在するものである)。しかし、それ ら全てを形成する原因的・生産的なものは別のものである。これは技術がその材料との関係においてそうであるように、魂(プシュケー)においてもまた、これ らの異なる側面が存在する必要がある。 一方の種別は万物となることによって知性[nous]となり、他方の種別は万物を形成することによって知性となる。これは、光のような能動的状態 [hexis]が、潜在的に存在する色彩を実際に色彩として作用させるのと同様である[to phōs poiei ta dunamei onta chrōmata energeiai chrōmata]。 この種の知性は分離している。また属性を持たず混じりけもない。なぜならその存在そのものが作用する存在だからだ。作用するものは常に作用されるものより 格上にある。統治する源が作用する材料より上にあるように。 知(エピステメー)は、その作用において、それが知るものと同一である。そして、知は、ある知者においては、潜在的な状態で時間的に先立つが、万物の全体 においては、時間的にさえも優先しない。 これは、ある時は思考し、別の時は思考しないという意味ではない。分離された時、それはまさにそれ自体であり、これだけが不死で永遠である(我々は記憶を 持たないが、この種の知性は作用される対象ではなく、作用される知性は滅びるからだ)。そしてこれなしには何も思考しない。 これは「哲学史上最も深く研究された一節」の一つと評されてきた[31]。『形而上学』においてアリストテレスは類似の主題についてより詳細に論じ、能動 的知性を「不動の動者」すなわち神と同一視したと解釈されることが多い。しかしながら、デイヴィッドソンが指摘するように: アリストテレスが潜在知性や能動的知性(『魂について』では明示されておらず、せいぜい暗示されているに過ぎない用語)をどう定義したか、またそれらの相 互作用をどう理解したかは、今日に至るまで議論の余地がある。哲学史の研究者たちは、特に能動的知性を人間の魂の一側面と考えたのか、それとも人間とは独 立して存在する実体と考えたのかという点について、アリストテレスの意図を巡り議論を続けている。[31] |

| Post-Aristotelian usage New meanings of energeia or energy Already in Aristotle's own works, the concept of a distinction between energeia and dunamis was used in many ways, for example to describe the way striking metaphors work,[32] or human happiness. Polybius about 150 BC, in his work the Histories uses Aristotle's word energeia in both an Aristotelian way and also to describe the "clarity and vividness" of things.[33] Diodorus Siculus in 60-30 BC used the term in a very similar way to Polybius. However, Diodorus uses the term to denote qualities unique to individuals. Using the term in ways that could translated as 'vigor' or 'energy' (in a more modern sense); for society, 'practice' or 'custom'; for a thing, 'operation' or 'working'; like vigor in action.[34] Platonism and neoplatonism Already in Plato it is found implicitly the notion of potency and act in his cosmological presentation of becoming (kinēsis) and forces (dunamis),[35] linked to the ordering intellect, mainly in the description of the Demiurge and the "Receptacle" in his Timaeus.[36][37] It has also been associated to the dyad of Plato's unwritten doctrines,[38] and is involved in the question of being and non-being since from the pre-socratics,[39] as in Heraclitus's mobilism and Parmenides' immobilism. The mythological concept of primordial Chaos is also classically associated with a disordered prime matter (see also prima materia), which, being passive and full of potentialities, would be ordered in actual forms, as can be seen in Neoplatonism, especially in Plutarch, Plotinus, and among the Church Fathers,[39] and the subsequent medieval and Renaissance philosophy, as in Ramon Lllull's Book of Chaos[40] and John Milton's Paradise Lost.[41] Plotinus was a late classical pagan philosopher and theologian whose monotheistic re-workings of Plato and Aristotle were influential amongst early Christian theologians. In his Enneads he sought to reconcile ideas of Aristotle and Plato together with a form of monotheism, that used three fundamental metaphysical principles, which were conceived of in terms consistent with Aristotle's energeia/dunamis dichotomy, and one interpretation of his concept of the Active Intellect (discussed above): The Monad or "the One" sometimes also described as "the Good". This is the dunamis or possibility of existence. The Intellect, or Intelligence, or, to use the Greek term, Nous, which is described as God, or a Demiurge. It thinks its own contents, which are thoughts, equated to the Platonic ideas or forms (eide). The thinking of this Intellect is the highest activity of life. The actualization of this thinking is the being of the forms. This Intellect is the first principle or foundation of existence. The One is prior to it, but not in the sense that a cause is prior to an effect, but instead Intellect is called an emanation of the One. The One is the possibility of this foundation of existence. Soul or, to use the Greek term, Psyche. The soul is also an energeia: it acts upon or actualizes its own thoughts and creates "a separate, material cosmos that is the living image of the spiritual or noetic Cosmos contained as a unified thought within the Intelligence." This was based largely upon Plotinus' reading of Plato, but also incorporated many Aristotelian concepts, including the unmoved mover as energeia.[42] |

アリストテレス以降の用法 エネルゲイア(energeia)またはエネルギーの新たな意味 アリストテレス自身の著作においてさえ、エネルゲイアとデュナミス(dunamis)の区別という概念は様々な形で用いられていた。例えば、印象的な隠喩 の作用を説明するため[32]、あるいは人間の幸福を説明するためである。紀元前150年頃のポリュビオスは、著書『歴史』において、アリストテレスの用 語であるエネルゲイアを、アリストテレス的な用法と、物事の「明瞭さと鮮やかさ」を記述する用法の両方で用いている[33]。紀元前60-30年のディオ ドロス・シクルスは、ポリュビオスと非常に似た用法でこの用語を用いた。ただしディオドロスは、個人に特有の性質を示すためにこの用語を使用している。こ の用語は、より現代的な意味で「活力」や「エネルギー」と訳せる用法、社会に対しては「慣行」や「習俗」、事物に対しては「作用」や「働き」として用いら れる。行動における活力のようなものだ。[34] プラトン主義と新プラトン主義 プラトンにおいて既に、生成(キネーシス)と力(デュナミス)の宇宙論的提示の中に、潜在性と実現性の概念が暗黙的に見出される。[35] これは主に『ティマイオス』におけるデミウルゴスと「容器」の記述において、秩序を与える知性に関連付けられている。[36] [37] また、プラトンの「書かれざる教義」の二項対立[38]とも関連付けられ、ヘラクレイトスの流動説やパルメニデスの不動説に見られるように、前ソクラテス 派[39]以来の「存在と非存在」の問題にも関与している。神話的な原初のカオスの概念は、古典的には無秩序な第一物質(プリマ・マテリアも参照)とも結 びつけられる。この第一物質は受動的で可能態に満ちており、ネオプラトニズム、特にプルタルコス、 プロティノス、教父たち[39]、そして中世・ルネサンス期の哲学(ラモン・リュイユの『カオスの書』[40]やジョン・ミルトンの『失楽園』[41]な ど)においても同様である。 プロティノスは後期古典時代の異教哲学者・神学者であり、プラトンとアリストテレスを基にした一神教的再解釈は初期キリスト教神学者に影響を与えた。彼の 『エネーゲイス』では、アリストテレスとプラトンの思想を、三つの根本的な形而上学的原理を用いた一神教と調和させようとした。これらの原理は、アリスト テレスのエネルゲイア/ドゥナミス二分法と整合する形で構想され、彼の能動的知性概念(前述)の一解釈に基づいている: 単子(モノアド)あるいは「一者(ワン)」は、時に「善(グッド)」とも称される。これは存在の可能態(デュナミス)である。 知性(インテレクテ)あるいは知性(インテリジェンス)、あるいはギリシャ語でノウス(Nous)と呼ばれるものは、神あるいはデミウルゴス(創造主)と 説明される。それは自らの内容、すなわちプラトンのイデア(理念)や形式(エイドス)に等しい思考(思想)を思考する。この知性による思考は生命の最高活 動である。この思考の実現がイデアの存在である。この知性は存在の第一原理あるいは基盤である。「一者」はこれに先行するが、原因が結果に先行する意味で はなく、知性は「一者」の流出(エマナシオン)と呼ばれる。一者はこの存在基盤の可能態である。 魂、あるいはギリシャ語でプシュケー。魂もまたエネルギーである:それは自らの思考に作用し、それを実現し、「知性の中に統一された思考として内包される 精神的あるいは知的な宇宙の生きた像である、分離した物質的宇宙」を創造する。 これは主にプロティノスがプラトンを解釈した内容に基づいているが、不動の動者(unmoved mover)をエネルギーとして捉えるなど、多くのアリストテレス的概念も取り入れている。[42] |

| New Testament usage This section possibly contains original research. New Testament concordances are not evidence that this concept is used in the New Testament. Please improve it by verifying the claims made and adding inline citations. Statements consisting only of original research should be removed. (August 2021) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Other than incorporation of Neoplatonic into Christendom by early Christian theologians such as St. Augustine, the concepts of dunamis and ergon (the morphological root of energeia[43]) are frequently used in the original Greek New Testament.[44] Dunamis is used 119 times[45] and ergon is used 161 times,[46] usually with the meaning 'power/ability' and 'act/work', respectively. Essence-energies debate in medieval Christian theology Further information: Essence-Energies distinction In Eastern Orthodox Christianity, St Gregory Palamas wrote about the "energies" (actualities; singular energeia in Greek, or actus in Latin) of God in contrast to God's "essence" (ousia). These are two distinct types of existence, with God's energy being the type of existence which people can perceive, while the essence of God is outside of normal existence or non-existence or human understanding, i.e. transcendental, in that it is not caused or created by anything else. Palamas gave this explanation as part of his defense of the Eastern Orthodox ascetic practice of hesychasm. Palamism became a standard part of Orthodox dogma after 1351.[47] In contrast, the position of Western Medieval (or Catholic) Christianity, can be found for example in the philosophy of Thomas Aquinas, who relied on Aristotle's concept of entelechy, when he defined God as actus purus, pure act, actuality unmixed with potentiality. The existence of a truly distinct essence of God which is not actuality, is not generally accepted in Catholic theology. Influence on modal logic The notion of possibility was greatly analyzed by medieval and modern philosophers. Aristotle's logical work in this area is considered by some to be an anticipation of modal logic and its treatment of potentiality and time. Indeed, many philosophical interpretations of possibility are related to a famous passage on Aristotle's On Interpretation, concerning the truth of the statement: "There will be a sea battle tomorrow."[48] Contemporary philosophy regards possibility, as studied by modal metaphysics, to be an aspect of modal logic. Modal logic as a named subject owes much to the writings of the Scholastics, in particular William of Ockham and John Duns Scotus, who reasoned informally in a modal manner, mainly to analyze statements about essence and accident. |

新約聖書における用法 この節はおそらく独自研究を含んでいる。新約聖書のコンコーダンスは、この概念が新約聖書で使われている証拠とはならない。主張を検証し、インライン引用 を追加することで改善してほしい。独自研究のみで構成された記述は削除すべきである。(2021年8月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) 聖アウグスティヌスなどの初期キリスト教神学者による新プラトン主義のキリスト教への取り込み以外に、デュナミス(dunamis)とエルゴン (ergon)(エネルゲイア[43]の形態学的語根)の概念は、原語であるギリシャ語の新約聖書で頻繁に使用されている。[44] ダナミスは119回[45]、エルゴンは161回[46]使用されており、それぞれ通常「力/能力」と「行為/働き」の意味で用いられている。 中世キリスト教神学における本質-エネルギー論争 詳細情報: 本質-エネルギーの区別 東方正教会において、聖グレゴリオス・パラマスは、神の本質(ウーシア)とは対照的な神の「エネルギー」(現実態;ギリシャ語で単数形はエネルゲイア、ラ テン語でアクタス)について論じた。これらは二つの異なる存在形態であり、神のエネルギーは人間が知覚可能な存在形態であるのに対し、神の本質は通常の意 味での存在・非存在や人間の理解を超越している。すなわち、他の何ものにも起因せず、創造されない超越的な存在である。 パラマスはこの説明を、東方正教会の修道実践であるヘシカズムを擁護する一環として行った。パラマスの思想は1351年以降、正教会の教義の標準的な一部 となった。[47] これに対し、西洋中世(カトリック)キリスト教の立場は、例えばトマス・アクィナスの哲学に見られる。彼はアリストテレスのエンテレキー概念に依拠し、神 をactus purus(純粋な行為)、すなわち可能態と混ざらない純粋な実在と定義した。カトリック神学では、実在ではない真に別個の神の本質の存在は、一般的に受 け入れられていない。 様相論理への影響 可能態の概念は中世および近代の哲学者によって深く分析された。アリストテレスのこの分野における論理学的研究は、様相論理とその潜在性・時間への取扱い に対する先駆と見なされることもある。実際、可能態に関する多くの哲学的解釈は、アリストテレスの『解釈論』における「明日、海戦が起こるだろう」という 命題の真偽に関する有名な一節に関連している。[48] 現代哲学では、様相形而上学が扱う可能態は様相論理学の一側面と見なされている。様相論理学という分野の確立は、特にウィリアム・オブ・オッカムやジョ ン・ダンズ・スコトゥスといったスコラ哲学者の著作に大きく依存している。彼らは本質と偶有性に関する命題を分析するため、主に様相的な方法で非形式的に 推論したのである。 |

| Influence on early modern physics Aristotle's metaphysics, his account of nature and causality, was for the most part rejected by the early modern philosophers. Francis Bacon in his Novum Organon in one explanation of the case for rejecting the concept of a formal cause or "nature" for each type of thing, argued for example that philosophers must still look for formal causes but only in the sense of "simple natures" such as colour, and weight, which exist in many gradations and modes in very different types of individual bodies.[49] In the works of Thomas Hobbes then, the traditional Aristotelian terms, "potentia et actus", are discussed, but he equates them simply to "cause and effect".[50]  Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was the source of the modern adaptations of Aristotle's concepts of potentiality and actuality. There was an adaptation of at least one aspect of Aristotle's potentiality and actuality distinction, which has become part of modern physics, although as per Bacon's approach, it is a generalized form of energy, not one connected to specific forms for specific things. The definition of energy in modern physics as the product of mass and the square of velocity, was derived by Leibniz, as a correction of Descartes, based upon Galileo's investigation of falling bodies. He preferred to refer to it as an entelecheia or 'living force' (Latin vis viva), but what he defined is today called kinetic energy, and was seen by Leibniz as a modification of Aristotle's energeia, and his concept of the potential for movement which is in things. Instead of each type of physical thing having its own specific tendency to a way of moving or change, as in Aristotle, Leibniz said that force, power, or motion itself could be transferred between things of different types, in such a way that there is a general conservation of this energy. In other words, Leibniz's modern version of entelechy or energy obeys its own laws of nature, whereas different types of things do not have their own separate laws of nature.[51] Leibniz wrote:[52] ...the entelechy of Aristotle, which has made so much noise, is nothing else but force or activity; that is, a state from which action naturally flows if nothing hinders it. But matter, primary and pure, taken without the souls or lives which are united to it, is purely passive; properly speaking also it is not a substance, but something incomplete. Leibniz's study of the "entelechy" now known as energy was part of what he called his new science of "dynamics", based on the Greek word dunamis and his understanding that he was making a modern version of Aristotle's old dichotomy. He also referred to it as the "new science of power and action", (Latin potentia et effectu and potentia et actione). And it is from him that the modern distinction between statics and dynamics in physics stems. The emphasis on dunamis in the name of this new science comes from the importance of his discovery of potential energy which is not active, but conserves energy nevertheless. "As 'a science of power and action', dynamics arises when Leibniz proposes an adequate architectonic of laws for constrained, as well as unconstrained, motions."[53] For Leibniz, like Aristotle, this law of nature concerning entelechies was also understood as a metaphysical law, important not only for physics, but also for understanding life and the soul. A soul, or spirit, according to Leibniz, can be understood as a type of entelechy (or living monad) which has distinct perceptions and memory. Influence on modern physics Ideas about potentiality have been related to quantum mechanics, where a wave function in a superposition of potential values (before measurement) has the potential to collapse into one of those values, under the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics. In particular, the German physicist Werner Heisenberg called this "a quantitative version of the old concept of 'potentia' in Aristotelian philosophy".[54][55] Entelecheia in modern philosophy and biology As discussed above, terms derived from dunamis and energeia have become parts of modern scientific vocabulary with a very different meaning from Aristotle's. The original meanings are not used by modern philosophers unless they are commenting on classical or medieval philosophy. In contrast, entelecheia, in the form of entelechy is a word used much less in technical senses in recent times. As mentioned above, the concept had occupied a central position in the metaphysics of Leibniz, and is closely related to his monad in the sense that each sentient entity contains its own entire universe within it. But Leibniz' use of this concept influenced more than just the development of the vocabulary of modern physics. Leibniz was also one of the main inspirations for the important movement in philosophy known as German idealism, and within this movement and schools influenced by it entelechy may denote a force propelling one to self-fulfillment. In the biological vitalism of Hans Driesch, living things develop by entelechy, a common purposive and organising field. Leading vitalists like Driesch argued that many of the basic problems of biology cannot be solved by a philosophy in which the organism is simply considered a machine.[56] Vitalism and its concepts like entelechy have since been discarded as without value for scientific practice by the overwhelming majority of professional biologists.[citation needed] Important to the philosophy of Giorgio Agamben is potentiality and the notion that tied in every potentiality is the potentiality to not do something as well, and that actuality is actually the not not doing of a potentiality; Agamben notes that thought is unique in that it is the ability to reflect on this potentiality in itself rather than in a relation to an object making the mind a sort of tabula rasa.[57] However, in philosophy aspects and applications of the concept of entelechy have been explored by scientifically interested philosophers and philosophically inclined scientists alike. One example was the American critic and philosopher Kenneth Burke (1897–1993) whose concept of the "terministic screen" illustrates his thought on the subject. Prof. Denis Noble argues that, just as teleological causation is necessary to the social sciences, specific teleological causation in biology, expressing functional purpose, should be restored and that it is already implicit in neo-Darwinism (e.g. "selfish gene"). Teleological analysis proves parsimonious when the level of analysis is appropriate to the complexity of the required 'level' of explanation (e.g. whole body or organ rather than cell mechanism).[58] |

近世物理学への影響 アリストテレスの形而上学、すなわち自然や因果性に関する彼の説明は、近世の哲学者たちによってほぼ全面的に否定された。フランシス・ベーコンは『新器具 論』において、各事物の形式的原因あるいは「本性」という概念を拒否する理由の一つとして、例えば、哲学者は依然として形式的原因を探求すべきだが、それ は色や重量といった「単純な本性」の意味においてのみであり、それらは非常に異なる個々の物体に多くの段階や様式で存在すると論じた。[49] トマス・ホッブズの著作では、伝統的なアリストテレス用語「潜在(potentia)と実現(actus)」が論じられるが、彼はこれを単純に「原因と結 果」に等しいとみなした。[50]  ゴットフリート・ヴィルヘルム・ライプニッツは、アリストテレスの潜在性と実現性の概念を現代的に適応させた源流である。 アリストテレスの潜在性と現実態の区別は、少なくとも一つの側面が現代物理学に取り入れられた。ただしベーコンのアプローチと同様、特定の事物に結びつい た形態ではなく、エネルギーの一般化された形態としてである。現代物理学におけるエネルギーの定義——質量と速度の二乗の積——は、ガリレオの落下体研究 に基づき、デカルトの修正としてライプニッツによって導かれた。彼はこれを「エンテレケイア」あるいは「生ける力」(ラテン語でビス・ヴィーヴァ)と呼ぶ ことを好んだが、彼が定義したものは今日「運動エネルギー」と呼ばれ、ライプニッツはこれをアリストテレスの「エネルギーア」の修正、すなわち物の中に内 在する運動の潜在的可能態の概念と見なした。アリストテレスのように、あらゆる物理的事物がそれぞれ固有の運動や変化への傾向を持つのではなく、ライプ ニッツは力や運動そのものが異なる種類の事物間で転移し得ることを主張した。この転移において、エネルギーは全体として保存されるのである。言い換えれ ば、ライプニッツのエンテレケイア(エネルギー)の現代的解釈は独自の自然法則に従うが、異なる種類の事物にはそれぞれ固有の自然法則は存在しないのであ る[51]。ライプニッツはこう記している: [52] ...アリストテレスのエンテレキーは、これほど騒がれたが、結局のところ力や活動に他ならない。つまり、妨げられることがなければ自然に作用が流れ出る 状態である。しかし物質は、それ自体に結合した魂や生命を除けば、純粋に受動的である。厳密に言えば、それは実体ではなく、不完全な何かである。 ライプニッツの「エンテレケイア」(現代ではエネルギーとして知られる)の研究は、彼が「力学」と呼んだ新科学の一部であった。これはギリシャ語の「デュ ナミス」に由来し、彼がアリストテレスの古い二分法を現代的に再構築していると理解していた。彼はこれを「力と作用の新科学」(ラテン語で potentia et effectu、potentia et actione)とも呼んだ。物理学における静力学と動力学の現代的な区別は、彼に由来する。この新科学の名前に「dunamis」を強調したのは、活動 的ではないがエネルギーを保存する潜在エネルギーの発見が重要だったからだ。「『力と作用の科学』として、動力学はライプニッツが制約された運動と制約さ れない運動の両方に対する適切な構造的法則を提案した時に生まれる」[53] ライプニッツにとって、アリストテレスと同様に、エンテレキーに関するこの自然法則は形而上学的法則としても理解され、物理学だけでなく生命や魂の理解に おいても重要であった。ライプニッツによれば、魂あるいは精神は、独自の知覚と記憶を持つ一種のエンテレキー(あるいは生けるモナド)として理解できる。 現代物理学への影響 潜在性に関する考え方は量子力学と関連付けられてきた。コペンハーゲン解釈によれば、測定前の波動関数は複数の潜在値の重ね合わせ状態にあり、いずれかの 値へ収束する潜在性を持つ。特にドイツの物理学者ヴェルナー・ハイゼンベルクはこれを「アリストテレス哲学における『ポテンティア』の古い概念の定量的解 釈」と呼んだ。[54] [55] 現代哲学と生物学におけるエンテレケイア 前述のように、デュナミスやエネルゲイアに由来する用語は、アリストテレスの概念とは大きく異なる意味で現代科学語彙の一部となっている。古典哲学や中世 哲学を論評する場合を除き、現代哲学者が本来の意味でこれらの用語を用いることはない。対照的に、エンテレケイア(エンテレキーの形態)は近年、技術的な 意味で使用されることが極めて少なくなっている。 前述のように、この概念はライプニッツの形而上学において中心的な位置を占め、各知覚的実体がその内部に完全な宇宙を内包するという意味で、彼のモナドと 密接に関連している。しかしライプニッツによるこの概念の用法は、現代物理学の語彙の発展以上に影響を与えた。ライプニッツはドイツ観念論として知られる 重要な哲学運動の主要な啓発源の一つでもあり、この運動及びそれに影響を受けた学派においては、エンテレキーは自己実現へと駆り立てる力を示すことがあ る。 ハンス・ドリーシュの生物学的生命論では、生物はエンテレケイア、すなわち共通の目的的・組織的場によって発達する。ドリーシュのような主要な生命論者 は、生物を単なる機械と見なす哲学では生物学の基本的問題の多くは解決できないと主張した[56]。その後、生命論やエンテレケイアのような概念は、科学 的な実践にとって価値がないとして、圧倒的多数の専門生物学者によって廃棄された[出典必要]。 ジョルジョ・アガンベンの哲学において重要なのは、可能態と、あらゆる可能態には「何かをしない」可能態も内在しているという概念である。また、現実態と は実際には「可能態をしないこと」をしないことだとする。アガンベンは、思考が唯一無二であるのは、対象との関係ではなく、この可能態そのものを内省する 能力であり、それによって精神が一種の白紙状態(タブラ・ラサ)となる点にあると指摘する。[57] しかし哲学においては、エンテレケイア概念の側面と応用が、科学に関心を持つ哲学者と哲学的傾向を持つ科学者の双方によって探求されてきた。一例がアメリ カの批評家・哲学者ケネス・バーク(1897–1993)であり、彼の「テリニスティック・スクリーン」概念はこの主題に関する彼の思想を説明している。 デニス・ノーブル教授は、社会科学において目的論的因果関係が不可欠であるのと同様に、機能的目的を表現する生物学における特定の目的論的因果関係も回復 されるべきであり、それはすでに新ダーウィニズム(例:「利己的な遺伝子」)に暗黙的に含まれていると主張する。目的論的分析は、分析レベルが要求される 説明の「レベル」の複雑さに適切である場合(例えば細胞機構ではなく全身や器官レベル)、簡潔さを証明する。[58] |

| Actual infinity Actus purus Alexander of Aphrodisias Essence–Energies distinction First cause Henosis Hylomorphism Hypokeimenon Hypostasis (philosophy and religion) Sumbebekos Theosis Unmoved movers |

実際の無限 アクタス・プルス アフロディシアスのアレクサンダー 本質とエネルギーの区別 第一原因 ヘノーシス 物質形態論 ヒポケイメノン ハイポスタシス(哲学および宗教) スンベベコス 神化 不動の動者 |

| References |

|

| Bibliography Aristotle (1999), Aristotle's Metaphysics, a new translation by Joe Sachs, Santa Fe, NM: Green Lion Books, ISBN 1-888009-03-9 Beere, Jonathan (1990), Doing and Being: An Interpretation of Aristotle's Metaphysics Theta, Oxford Bradshaw, David (2004). Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82865-9. Charles, David (1984), Aristotle's Philosophy of Action, Duckworth Coope, Ursula (2009), "Change and its Relation to Actuality and Potentiality", in Anagnostopoulos, Georgios (ed.), A Companion to Aristotle, Blackwell, p. 277, ISBN 978-1-4443-0567-8 Davidson, Herbert (1992), Alfarabi, Avicenna, and Averroes, on Intellect, Oxford University Press Duchesneau, François (1998), "Leibniz's Theoretical Shift in the Phoranomus and Dynamica de Potentia", Perspectives on Science, 6 (1&2): 77–109, doi:10.1162/posc_a_00545, S2CID 141935224 Durrant, Michael (1993). Aristotle's De Anima in Focus. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-05340-2. Jaeger, Gregg (2017), "Quantum potentiality revisited", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A, 375 (2106) 20160390, Bibcode:2017RSPTA.37560390J, doi:10.1098/rsta.2016.0390, PMID 28971942 Klein, Jacob (1985), "Leibnitz, an Introduction", Lectures and Essays, St Johns College Press Kosman, Aryeh (1969), "Aristotle's Definition of Motion", Phronesis, 14 (1): 40–62, doi:10.1163/156852869x00037 Kosman, Aryeh (2013), The Activity of Being: an Essay on Aristotle's Ontology, Harvard University Press Heinaman, Robert (1994), "Is Aristotle's definition of motion circular?", Apeiron (27), doi:10.1515/APEIRON.1994.27.1.25, S2CID 171013812 Leibniz, Gottfried (1890) [1715], "On the Doctrine of Malebranche. A Letter to M. Remond de Montmort, containing Remarks on the Book of Father Tertre against Father Malebranche", The Philosophical Works of Leibnitz, p. 234 Locke, John (1689). "Book II Chapter XXI "Of Power"". An Essay concerning Human Understanding and Other Writings, Part 2. The Works of John Locke in Nine Volumes. Vol. 2. Rivington. Mayr, Ernst (2002). The Walter Arndt Lecture: The Autonomy of Biology. Sachs, Joe (1995), Aristotle's Physics: a Guided Study, Rutgers University Press Sachs, Joe (1999), Aristotle's Metaphysics, a New Translation by Joe Sachs, Santa Fe, NM: Green Lion Books, ISBN 1-888009-03-9 Sachs, Joe (2001), Aristotle's On the Soul and On Memory and Recollection, Green Lion Books Sachs, Joe (2005), "Aristotle: Motion and its Place in Nature", Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy Warnock, Mary (1950). "A Note on Aristotle: Categories 6a 15". Mind. New Series (59): 552–554. doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.552. |

参考文献 アリストテレス (1999), 『アリストテレス形而上学』ジョー・サックス新訳, サンタフェ, NM: グリーン・ライオン・ブックス, ISBN 1-888009-03-9 ビール, ジョナサン (1990), 『行為と存在:アリストテレス形而上学シータの解釈』, オックスフォード ブラッドショー, デイヴィッド (2004). アリストテレス東西:形而上学とキリスト教世界の分裂。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-82865-9。 チャールズ、デイヴィッド(1984)、『アリストテレスの行為哲学』、ダックワース クープ、ウルスラ(2009)、「変化と実在性・可能態との関係」、アナグノストプロス、ゲオルギオス(編)、『アリストテレス研究事典』、ブラックウェ ル、p. 277、ISBN 978-1-4443-0567-8 デイヴィッドソン、ハーバート(1992)、『知性に関するアルファラビ、アヴィセンナ、アヴェロエス』、オックスフォード大学出版局 デュシェノー、フランソワ(1998)、「『フォラノムス』と『力動論』におけるライプニッツの理論的転換」、『科学の展望』、6巻(1&2 号):77–109頁、 doi:10.1162/posc_a_00545, S2CID 141935224 デュラント、マイケル(1993)。『アリストテレスの「魂について」を焦点に』テイラー&フランシス。ISBN 978-0-415-05340-2。 イェーガー、グレッグ(2017年)、「量子可能態の再考」、『王立協会哲学紀要A』375巻2106号 20160390, Bibcode:2017RSPTA.37560390J, doi:10.1098/rsta.2016.0390, PMID 28971942 クライン, ジェイコブ (1985), 「ライプニッツ入門」, 『講義と論考』, セント・ジョンズ・カレッジ出版 コスマン、アリエ(1969)、「アリストテレスの運動の定義」、『フロンエシス』14巻1号:40–62頁、doi: 10.1163/156852869x00037 コスマン、アリエ(2013)、『存在の活動:アリストテレスの存在論に関するエッセイ』、ハーバード大学出版局 ハイナマン、ロバート(1994)、「アリストテレスの運動の定義は循環的か?」、『アペイロン』27号、 doi:10.1515/APEIRON.1994.27.1.25, S2CID 171013812 ライプニッツ、ゴットフリート(1890)[1715]、「マレブランシュの教義について。レモンド・ド・モンモル氏への書簡:テルトル神父によるマレブ ランシュ神父批判書への所見」『ライプニッツ哲学著作集』234頁 ロック、ジョン(1689年)『人間知性論およびその他の著作』第2部第2巻第21章「力について」『ジョン・ロック著作集全9巻』第2巻 リヴィントン社。 マイヤー、エルンスト(2002)。『ウォルター・アーント記念講演:生物学の自律性』。 サックス、ジョー(1995)、『アリストテレスの物理学:ガイド付き研究』、ラトガース大学出版局 サックス、ジョー(1999)、『アリストテレスの形而上学、ジョー・サックスによる新訳』、ニューメキシコ州サンタフェ:グリーンライオンブックス、 ISBN 1-888009-03-9 サックス、ジョー(2001年)『アリストテレスの「魂について」と「記憶と想起について」』グリーン・ライオン・ブックス サックス、ジョー(2005年)「アリストテレス:運動と自然におけるその位置」インターネット哲学百科事典 ワーノック、メアリー(1950)。「アリストテレスに関する注記:『範疇論』6a 15」。『マインド』新シリーズ(59):552–554。doi:10.1093/mind/LIX.236.552。 |

| Old translations of Aristotle Aristotle (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive - Aristotle On the Soul, J.A. Smith translator". MIT. Aristotle (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive - Aristotle Categories, E.M. Edghill translator". MIT. Aristotle (2009). "The Internet Classics Archive - Aristotle Physics, R.P. Hardie & Gaye, R.K. translators". MIT. Aristotle (1908). Metaphysica translated by W.D. Ross. The Works of Aristotle. Vol. VIII. Oxford: Clarendon Press. Aristotle (1989). "Metaphysics, Hugh Tredennick trans.". Aristotle in 23 Volumes. Vol. 17, 18. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; (London: William Heinemann Ltd.). This 1933 translation is reproduced online at the Perseus Project. |

アリストテレスの古い翻訳 アリストテレス (2009). 「インターネット古典アーカイブ - アリストテレス『魂について』、J.A. スミス訳」. MIT. アリストテレス (2009). 「インターネット古典アーカイブ - アリストテレス『範疇論』、E.M. エッジヒル訳」. MIT. アリストテレス (2009). 「インターネット古典アーカイブ - アリストテレス『物理学』、R.P.ハーディー&ゲイ、R.K.訳」. MIT. アリストテレス (1908). 『形而上学』、W.D.ロス訳. 『アリストテレス全集』第VIII巻. オックスフォード: クラレンドン・プレス. アリストテレス (1989). 「形而上学、ヒュー・トレデンニック訳」. 『アリストテレス全集23巻』第17・18巻. ケンブリッジ: ハーバード大学出版局; (ロンドン: ウィリアム・ハイネマン社). この1933年訳はペルセウス・プロジェクトでオンライン公開されている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Potentiality_and_actuality |

ブレンターノ学位論文、Franz Brentano, Von der mannigfachen Bedeutung des Seienden nach Aristoteles. 1862年は、113年後にRolf George により英訳"On the several senses of being in Aristotle"として、カリフォルニア大学出版会から出版されました。「私の仕事の途上において、最初に出会った本が、1907年以来何度も何度 も、Franz Brentano の Von der mannigfachen Bedeutung des Seienden nach Aristoteles だったのです」——このハイデガーの言葉は『言葉への途上』に収載されています。(ブレンターノの本の英訳の解説より)。ブレンターノが整理した、4つの 存在(様式)とは、1. Accidental Being, 2. Being in the Sense of Being True, 3. Potential and Actual Being, 4. Being According to the Figure of the Categories. ですが、最後の4つ目のものについては、15の命題を立てて、存在とカテゴリーの関係(後者は、語の存在様式=秩序という観点から「文法概念」が多用され て)を詳しく検討しています。下記の2つの図は、そこからとられたものです。

___________________

クレジット:具体化した=身体化したコミュニケー ション技術; Embodied Communication Technology, ECT

このページは、最初(2012年6月4日に[http://d.hatena.ne.jp/mitzubishi/20120604] のページで構築され、同じ場所にて改造を受けた後に、このページに移植されました:同年8月10日)[仮想・医療人類学辞典]

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Do not paste, but [re]think this message for all undergraduate students!!!

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099