Prevention

Main articles: Harm reduction and Preventive healthcare

Abuse liability

Abuse or addiction liability is the tendency to use drugs in a

non-medical situation. This is typically for euphoria, mood changing,

or sedation.[131] Abuse liability is used when the person using the

drugs wants something that they otherwise can not obtain. The only way

to obtain this is through the use of drugs. When looking at abuse

liability there are a number of determining factors in whether the drug

is abused. These factors are: the chemical makeup of the drug, the

effects on the brain, and the age, vulnerability, and the health

(mental and physical) of the population being studied.[131] There are a

few drugs with a specific chemical makeup that leads to a high abuse

liability. These are: cocaine, heroin, inhalants, marijuana, MDMA

(ecstasy), methamphetamine, PCP, synthetic cannabinoids, synthetic

cathinones (bath salts), nicotine (e.g. tobacco), and alcohol.[132]

|

予防

主な記事:ハームリダクションおよび予防医療

乱用可能性

乱用または依存の可能性とは、医療目的以外で薬物を使用する傾向のことです。これは通常、陶酔感、気分変化、または鎮静を目的としています[131]。乱

用可能性は、薬物を使用する人が、それ以外では得られないものを望んでいる場合に使用されます。これを手に入れる唯一の方法は、薬物を使用することだ。乱

用可能性を検討する場合、その薬物が乱用されるかどうかを判断するための決定要因がいくつかある。これらの要因は、薬物の化学組成、脳への影響、および研

究対象集団の年齢、脆弱性、および(精神的および身体的)健康状態だ。[131]

乱用可能性の高い特定の化学組成を持つ薬物はいくつかある。これらは、コカイン、ヘロイン、吸入薬、マリファナ、MDMA(エクスタシー)、メタンフェタ

ミン、PCP、合成カンナビノイド、合成カチノン(バスソルト)、ニコチン(例:タバコ)、アルコールなどだ。[132]

|

Potential vaccines for addiction to substances

Vaccines for addiction have been investigated as a possibility since

the early 2000s.[133] The general theory of a vaccine intended to

"immunize" against drug addiction or other substance abuse is that it

would condition the immune system to attack and consume or otherwise

disable the molecules of such substances that cause a reaction in the

brain, thus preventing the addict from being able to realize the effect

of the drug. Addictions that have been floated as targets for such

treatment include nicotine, opioids, and fentanyl.[134][135][136][137]

Vaccines have been identified as potentially being more effective than

other anti-addiction treatments, due to "the long duration of action,

the certainty of administration and a potential reduction of toxicity

to important organs".[138]

Specific addiction vaccines in development include:

NicVAX, a conjugate vaccine intended to reduce or eliminate physical

dependence on nicotine.[139] This proprietary vaccine is being

developed by Nabi Biopharmaceuticals[140] of Rockville, MD. with the

support from the U.S. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NicVAX consists

of the hapten 3'-aminomethylnicotine which has been conjugated

(attached) to Pseudomonas aeruginosa exotoxin A.[141]

TA-CD, an active vaccine[142] developed by the Xenova Group which is

used to negate the effects of cocaine. It is created by combining

norcocaine with inactivated cholera toxin. It works in much the same

way as a regular vaccine. A large protein molecule attaches to cocaine,

which stimulates response from antibodies, which destroy the molecule.

This also prevents the cocaine from crossing the blood–brain barrier,

negating the euphoric high and rewarding effect of cocaine caused from

stimulation of dopamine release in the mesolimbic reward pathway. The

vaccine does not affect the user's "desire" for cocaine—only the

physical effects of the drug.[143]

TA-NIC, used to create human antibodies to destroy nicotine in the human body so that it is no longer effective.[144]

As of September 2023, it was further reported that a vaccine "has been

tested against heroin and fentanyl and is on its way to being tested

against OxyContin".[145]

|

物質依存症に対する潜在的なワクチン

依存症に対するワクチンは、2000年代初頭から可能性として研究されている。[133]

薬物依存症やその他の物質乱用に対して「免疫」を与えることを目的としたワクチンの一般的な理論は、脳に反応を引き起こす物質の分子を攻撃して消費した

り、その他の方法で無効化したりするように免疫系を条件付け、依存者が薬物の効果を実現できないようにするというものだ。このような治療の対象として提案

されている依存症には、ニコチン、オピオイド、フェンタニルなどが挙げられています。[134][135][136][137]

ワクチンは、「作用の持続期間が長く、投与の確実性があり、重要な臓器への毒性を軽減する可能性」から、他の依存症治療法よりも効果的である可能性が指摘

されています。[138]

開発中の特定の依存症ワクチンには、次のようなものがある。

NicVAX は、ニコチンに対する身体的依存を軽減または排除することを目的とした複合ワクチンである。[139]

この独自開発のワクチンは、メリーランド州ロックビルにある Nabi Biopharmaceuticals[140]

が、米国国立薬物乱用研究所の支援を受けて開発している。NicVAXは、3'-アミノメチルニコチンというハプテンを、Pseudomonas

aeruginosaのエクソトキシンAに結合(付着)させたものである。[141]

TA-CDは、コカインの効果を無効化するためにXenova

Groupが開発した活性ワクチン[142]です。これは、ノルコカインと不活化コレラ毒素を組み合わせることで作成されます。その作用機序は通常のワク

チンとほぼ同じです。大きなタンパク質分子がコカインに結合し、抗体の反応を刺激して分子を破壊する。これにより、コカインが血液脳関門を通過するのを防

ぎ、ドーパミンの放出による中脳辺縁系報酬回路での多幸感や報酬効果を無効化する。このワクチンは、ユーザーのコカインに対する「欲求」には影響せず、薬

物の物理的効果のみを阻害する。[143]

TA-NICは、人体内のニコチンを破壊し無効化するヒト抗体を生成するために使用される。[144]

2023年9月現在、ヘロインとフェンタニルに対するワクチンが試験され、オキシコドンに対する試験が進行中であることがさらに報告されている。[145]

|

Treatment

Main article: Treatment and management of addiction

To be effective, treatment for addiction that is pharmacological or

biologically based need to be accompanied by other interventions such

as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavioral

therapy (DBT); individual and group psychotherapy, behavior

modification strategies, twelve-step programs, and residential

treatment facilities.[146][19] The transtheoretical model (TTM) can be

used to determine when treatment can begin and which method will be

most effective. If treatment begins too early, it can cause a person to

become defensive and resistant to change.[41][147]

|

治療

主な記事:依存症の治療と管理

薬物療法や生物学的療法に基づく依存症の治療が効果を発揮するためには、認知行動療法(CBT)や弁証法的行動療法(DBT)、個人療法やグループ療法、

行動修正戦略、12ステッププログラム、入院治療施設などの他の介入を併用する必要がある。[146][19]

治療開始のタイミングや最も効果的な方法を決定するために、トランセオретиカルモデル(TTM)が活用できる。治療が早すぎると、人格が防御的にな

り、変化に抵抗を示すようになる。[41][147]

|

Epidemiology

Further information: Countries by alcohol consumption, Opioid epidemic, and Prevalence of tobacco use

Due to cultural variations, the proportion of individuals who develop a

drug or behavioral addiction within a specified time period (i.e., the

prevalence) varies over time, by country, and across national

population demographics (e.g., by age group, socioeconomic status,

etc.).[47] Where addiction is viewed as unacceptable, there will be

fewer people addicted.

Asia

The prevalence of alcohol dependence is not as high as is seen in other

regions. In Asia, not only socioeconomic factors but biological factors

influence drinking behavior.[148]

Internet addiction disorder is highest in the Philippines, according to

both the IAT (Internet Addiction Test) – 5% and the CIAS-R (Revised

Chen Internet Addiction Scale) – 21%.[149]

|

疫学

詳細情報:アルコール消費量、オピオイドの流行、およびタバコの使用率

文化の違いにより、特定の期間内に薬物または行動依存症を発症する個人の割合(すなわち、有病率)は、時間、国、および国民の人口統計(年齢層、社会経済的地位など)によって異なる[47]。依存症が容認されない社会では、依存症になる人は少なくなる。

アジア

アルコール依存症の有病率は、他の地域ほど高くない。アジアでは、社会経済的要因だけでなく、生物学的要因も飲酒行動に影響を与える。[148]

インターネット依存症の有病率は、IAT(インターネット依存症検査)で5%、CIAS-R(改訂版チェン・インターネット依存症尺度)で21%と、フィリピンが最も高い。[149]

|

Australia

Further information: Alcoholism in rural Australia

The prevalence of substance use disorder among Australians was reported

at 5.1% in 2009.[150] In 2019 the Australian Institute of Health and

Welfare conducted a national drug survey that quantified drug use for

various types of drugs and demographics.[151] The survey found that in

2019, 11% of people over 14 years old smoke daily; that 9.9% of those

who drink alcohol, which equates to 7.5% of the total population age 14

or older, may qualify as alcohol dependent; that 17.5% of the 2.4

million people who used cannabis in the last year may have hazardous

use or a dependence problem; and that 63.5% of about 300000 recent

users of meth and amphetamines were at risk for developing problem

use.[151]

|

オーストラリア

詳細情報:オーストラリアの農村部のアルコール依存症

2009年のオーストラリア人の物質使用障害の有病率は5.1%と報告されている[150]。2019年、オーストラリア保健福祉研究所は、さまざまな種

類の薬物使用と人口統計を定量化した全国薬物調査を実施した。[151] この調査では、2019 年には 14 歳以上の人々の 11%

が毎日喫煙しており、アルコールを飲む人の 9.9% (14 歳以上の人口の 7.5% に相当)

がアルコール依存症と認定される可能性があり、大麻を使用した 240 万人中 5%

が危険な使用または依存の問題を抱えている可能性があり、最近メタンフェタミンを使用した約 30 万人中 63.5%

が危険な使用または依存の問題を抱えている可能性があることが明らかになった。5%

が危険な使用または依存の問題を抱えている可能性があり、最近メタンフェタミンおよびアンフェタミンを使用した約 30 万人中 63.5%

が問題使用を発症するリスクがあることが明らかになった。[151]

|

Europe

Further information: Alcoholism in Ireland and Alcoholism in Russia

In 2015, the estimated prevalence among the adult population was 18.4%

for heavy episodic alcohol use (in the past 30 days); 15.2% for daily

tobacco smoking; and 3.8% for cannabis use, 0.77% for amphetamine use,

0.37% for opioid use, and 0.35% for cocaine use in 2017. The mortality

rates for alcohol and illicit drugs were highest in Eastern

Europe.[152] Data shows a downward trend of alcohol use among children

15 years old in most European countries between 2002 and 2014.

First-time alcohol use before the age of 13 was recorded for 28% of

European children in 2014.[19]

|

ヨーロッパ

詳細情報:アイルランドのアルコール依存症とロシアのアルコール依存症

2015年の成人人口における推定有病率は、過去30日間の過量飲酒が18.4%、毎日のタバコ喫煙が15.2%、大麻使用が3.8%、アンフェタミン使

用が0.77%、オピオイド使用が0.37%、コカイン使用が0.35%だった。アルコールと違法薬物の死亡率は東欧で最も高かった。[152]

2002年から2014年にかけて、ほとんどのヨーロッパ諸国で15歳の子どものアルコール使用率が減少傾向を示している。2014年には、ヨーロッパの

子どもの28%が13歳未満で初めてアルコールを摂取したことが記録されている。[19]

|

United States

Further information: Cocaine in the United States, Crack epidemic in the United States, and Opioid epidemic in the United States

Based on representative samples of the US youth population in 2011, the

lifetime prevalence[note 7] of addictions to alcohol and illicit drugs

has been estimated to be approximately 8% and 2–3% respectively.[153]

Based on representative samples of the US adult population in 2011, the

12-month prevalence of alcohol and illicit drug addictions were

estimated at 12% and 2–3% respectively.[153] The lifetime prevalence of

prescription drug addictions is around 4.7%.[154]

As of 2021, 43.7 million people aged 12 or older surveyed by the

National Survey on Drug Use and Health in the United States needed

treatment for an addiction to alcohol, nicotine, or other drugs. The

groups with the highest number of people were 18–25 years (25.1%) and

"American Indian or Alaska Native" (28.7%).[155] Only about 10%, or a

little over 2 million, receive any form of treatments, and those that

do generally do not receive evidence-based care.[156][157] One-third of

inpatient hospital costs and 20% of all deaths in the US every year are

the result of untreated addictions and risky substance use.[156][157]

In spite of the massive overall economic cost to society, which is

greater than the cost of diabetes and all forms of cancer combined,

most doctors in the US lack the training to effectively address a drug

addiction.[156][157]

Estimates of lifetime prevalence rates in the US are 1–2% for

compulsive gambling, 5% for sexual addiction, 2.8% for food addiction,

and 5–6% for compulsive shopping.[23] The time-invariant prevalence

rate for sexual addiction and related compulsive sexual behavior (e.g.,

compulsive masturbation with or without pornography, compulsive

cybersex, etc.) within the US ranges from 3–6% of the population.[31]

According to a 2017 poll conducted by the Pew Research Center, almost

half of US adults know a family member or close friend who has

struggled with a drug addiction at some point in their life.[158]

In 2019, opioid addiction was acknowledged as a national crisis in the

United States.[159] An article in The Washington Post stated that

"America's largest drug companies flooded the country with pain pills

from 2006 through 2012, even when it became apparent that they were

fueling addiction and overdoses."

The National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions

found that from 2012 to 2013 the prevalence of Cannabis use disorder in

U.S. adults was 2.9%.[160]

|

アメリカ合衆国

詳細情報:アメリカ合衆国におけるコカイン、アメリカ合衆国におけるクラック流行、アメリカ合衆国におけるオピオイド流行

2011年の米国の若年層人口の代表的なサンプルに基づいて、アルコールおよび違法薬物への依存症の生涯有病率[注7]は、それぞれ約8%および2~3%

と推定されている。[153]

2011年の米国成人人口の代表的なサンプルに基づき、アルコールと違法薬物依存症の12ヶ月有病率はそれぞれ12%と2~3%と推計されている。

[153] 処方薬依存症の生涯有病率は約4.7%である。[154]

2021年現在、米国の薬物使用と保健に関する全国調査で調査された12歳以上の4,370万人が、アルコール、ニコチン、その他の薬物依存の治療を必要

としている。その人数が最も多いグループは、18~25歳(25.1%)と「アメリカインディアンまたはアラスカ先住民」

(28.7%)でした。[155]

治療を受けるのは約10%(200万人強)に過ぎず、その多くはエビデンスに基づくケアを受けていません。[156][157]

アメリカでは、入院医療費の3分の1と全死亡の20%が、未治療の依存症と危険な薬物使用が原因となっています。[156][157]

糖尿病とすべての癌のコストを合わせたよりも大きい、社会全体への莫大な経済的コストにもかかわらず、米国の医師の大多数は薬物依存症を効果的に対処する

ための訓練を受けていない。[156][157]

米国における生涯有病率の推計値は、強迫性ギャンブルが1~2%、性依存症が5%、食依存症が2.8%、強迫性買い物が5~6%となっている。[23]

米国における性依存症および関連する強迫性性行動(例:ポルノの有無を問わず強迫的な自慰行為、強迫的なサイバーセックスなど)の恒常的な有病率は、人口

の3~6%と推定されている。[31]

ピュー・リサーチ・センターが2017年に実施した世論調査によると、米国成人のほぼ半数が、人生のある時点で薬物依存症に苦しんだ家族や親しい友人を知っている。[158]

2019

年、オピオイド依存症は米国における国家的な危機として認識されました[159]。ワシントン・ポスト紙の記事では、「米国の大手製薬会社は、依存症や過

剰摂取を助長していることが明らかになったにもかかわらず、2006 年から 2012

年にかけて、鎮痛剤を国内に大量に出回らせた」と報じられています。

アルコールおよび関連状態に関する全国疫学調査によると、2012 年から 2013 年にかけて、米国の成人の大麻使用障害の有病率は 2.9% だった。[160] |

Canada

A Statistics Canada Survey in 2012 found the lifetime prevalence and

12-month prevalence of substance use disorders were 21.6%, and 4.4% in

those 15 and older.[161] Alcohol abuse or dependence reported a

lifetime prevalence of 18.1% and a 12-month prevalence of 3.2%.[161]

Cannabis abuse or dependence reported a lifetime prevalence of 6.8% and

a 12-month prevalence of 3.2%.[161] Other drug abuse or dependence has

a lifetime prevalence of 4.0% and a 12-month prevalence of 0.7%.[161]

Substance use disorder is a term used interchangeably with a drug

addiction.[162]

In Ontario, Canada between 2009 and 2017, outpatient visits for mental

health and addiction increased from 52.6 to 57.2 per 100 people,

emergency department visits increased from 13.5 to 19.7 per 1000 people

and the number of hospitalizations increased from 4.5 to 5.5 per 1000

people.[163] Prevalence of care needed increased the most among the

14–17 age group overall.[163]

|

カナダ

2012年のカナダ統計局の調査によると、15歳以上の人々の物質使用障害の生涯有病率は21.6%、12ヶ月有病率は4.4%だった。[161]

アルコール乱用または依存の生涯有病率は18.1%、12ヶ月有病率は3.2%だった。[161]

大麻の乱用または依存の生涯有病率は6.8%、12ヶ月有病率は3.2%でした。[161]

その他の薬物乱用または依存の生涯有病率は4.0%、12ヶ月有病率は0.7%でした。[161]

物質使用障害は、薬物依存症と置き換えられる用語です。[162]

2009 年から 2017 年にかけて、カナダのオンタリオ州では、精神保健および依存症に関する外来受診が 52.6 人から 57.2

人に、救急外来の受診は 1000 人あたり 13.5 人から 19.7 人に、入院者数は 1000 人あたり 4.5 人から 5.5

人に増加した[163]。ケアの必要性の有病率は、14~17 歳の年齢層で全体として最も増加した[163]。

|

South America

The realities of opioid use and opioid use disorder in Latin America

may be deceptive if observations are limited to epidemiological

findings. In the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report,[164]

although South America produced 3% of the world's morphine and heroin

and 0.01% of its opium, prevalence of use is uneven. According to the

Inter-American Commission on Drug Abuse Control, consumption of heroin

is low in most Latin American countries, although Colombia is the

area's largest opium producer. Mexico, because of its border with the

United States, has the highest incidence of use.[165]

|

南アメリカ

ラテンアメリカにおけるオピオイドの使用およびオピオイド使用障害の現実は、疫学的知見のみに観察を限定すると、誤解を招くおそれがある。国連薬物犯罪事

務所(UNODC)の報告書[164]によると、南アメリカは世界全体のモルヒネおよびヘロインの 3%、アヘン生産量の 0.01%

を生産しているが、使用の有病率は不均一である。米州薬物乱用対策委員会によると、コロンビアが地域最大のオピウム生産国であるにもかかわらず、ラテンア

メリカの大多数の国ではヘロインの消費量は低い。メキシコはアメリカ合衆国との国境を接しているため、使用率が最も高い。[165]

|

Etymology

The word addiction derives from the Latin "addico", meaning "giving

over" with both positive connotations (devotion, dedication) and

negative ones (being enslaved to a creditor in Roman law). This dual

meaning persisted in traditional English dictionaries, encompassing

both legal surrender and personal devotion to habits. Later, 19th

century temperance movements narrowed the definition of addiction to

just drug-related disease, ignoring behavioral addictions and the

possibility of positive or neutral addictions. This restrictive view

opposes the current understanding of addiction.[166]

Addiction and addictive behavior are polysemes denoting a category of

mental disorders, of neuropsychological symptoms, or of merely

maladaptive/harmful habits and lifestyles.[167] A common use of the

term addiction in medicine is for neuropsychological symptoms denoting

pervasive/excessive and intense urges to engage in a category of

behavioral compulsions or impulses towards sensory rewards (e.g.,

alcohol, betel quid, drugs, sex, gambling, video

gaming).[168][169][170][171][121] Addictive disorders or addiction

disorders are mental disorders involving high intensities of addictions

(as neuropsychological symptoms) that induce functional disabilities

(i.e., limit subjects' social/family and occupational activities); the

two categories of such disorders are substance-use addictions and

behavioral addictions.[172][167][171][121]

The etymology of the term addiction throughout history has been

misunderstood and has taken on various meanings associated with the

word.[173] An example is the usage of the word in the religious

landscape of early modern Europe.[174] "Addiction" at the time meant

"to attach" to something, giving it both positive and negative

connotations. The object of this attachment could be characterized as

"good or bad".[175] The meaning of addiction during the early modern

period was mostly associated with positivity and goodness;[174] during

this early modern and highly religious era of Christian revivalism and

Pietistic tendencies,[174] it was seen as a way of "devoting oneself to

another".[175]

|

語源

「依存症」という言葉は、ラテン語の「addico」に由来し、「委ねる」という意味で、肯定的な意味(献身、献身)と否定的な意味(ローマ法における債

権者に奴隷にされる)の両方があります。この二重の意味は、伝統的な英語辞書にも残っており、法的降伏と習慣に対する個人的な献身の両方を包含していま

す。その後、19

世紀の禁酒運動により、依存症の定義は薬物関連疾患のみに狭められ、行動依存症や肯定的または中立的な依存症の可能性は無視された。この限定的な見解は、

現在の依存症の理解とは対立している。[166]

依存症および依存行動は、精神障害、神経心理学的症状、あるいは単に不適応/有害な習慣やライフスタイルのカテゴリーを示す多義語だ。[167]

医学における「依存症」という用語の一般的な使用法は、感覚的報酬(例:アルコール、ベテルナッツ、薬物、性行為、ギャンブル、ビデオゲーム)への行動的

強迫や衝動への広範で過剰かつ激しい欲求を示す神経心理学的症状を指す。[168][169][170][171][121]

依存症または依存障害は、機能障害(すなわち、対象者の社会的/家族的および職業的活動を制限する)を引き起こす高い強度の依存(神経心理学的症状とし

て)を特徴とする精神障害で、この障害の2つのカテゴリーは、物質使用依存症と行動依存症です。[172][167][171][121]

「依存症」という用語の語源は歴史的に誤解され、言葉に関連する多様な意味を帯びてきた。[173]

例えば、近世ヨーロッパの宗教的文脈における用語の用法が挙げられる。[174]

当時の「依存症」は「何かにくっつく」という意味を持ち、ポジティブとネガティブな両方のニュアンスを含んでいた。この「結びつく」対象は「良いもの」ま

たは「悪いもの」と特徴付けられた。[175] 近代初期の依存症の意味は主にポジティブで良いものと関連付けられていた。[174]

このキリスト教の復興とピエティズムの傾向が強く、宗教的な時代において、依存症は「他者に自分を捧げる方法」と見なされていた。[175]

|

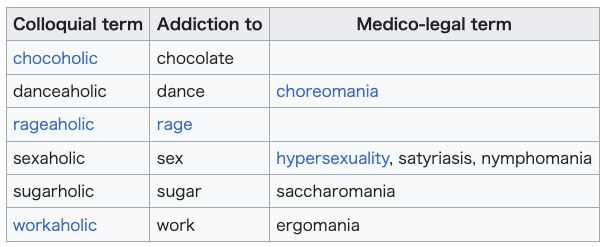

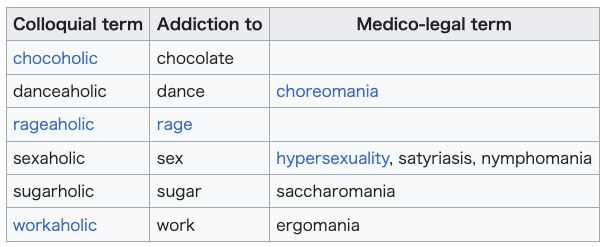

The suffixes "-holic" and "-holism"

In contemporary modern English "-holic" is a suffix that can be added

to a subject to denote an addiction to it. It was extracted from the

word alcoholism (one of the first addictions to be widely identified

both medically and socially) (correctly the root "alcohol" plus the

suffix "-ism") by misdividing or rebracketing it into "alco" and

"-holism". There are correct medico-legal terms for such addictions:

dipsomania is the medico-legal term for alcoholism;[176] other examples

are in this table:[citation needed]

History

Modern research on addiction has led to a better understanding of the

disease with research on the topic dating back to 1875, specifically on

morphine addiction.[177] This furthered the understanding of addiction

being a medical condition. It was not until the 19th century that

addiction was seen and acknowledged in the Western world as a disease,

being both a physical condition and mental illness.[178] Today,

addiction is understood both as a biopsychosocial and neurological

disorder that negatively impacts those who are affected by it, most

commonly associated with the use of drugs and excessive use of

alcohol.[4] The understanding of addiction has changed throughout

history, which has impacted and continues to impact the ways it is

medically treated and diagnosed.[citation needed]

|

接尾辞「-holic」と「-holism」

現代英語において「-holic」は、対象物への依存や中毒を表すために名詞に付加される接尾辞だ。これは、医学的・社会的に初めて広く認識された依存症

の一つである「アルコール依存症」(正確には「アルコール」という語根に「-ism」という接尾辞が付いたもの)から、誤って「alco」と「-

holism」に分割または再括弧付けされることで抽出された。このような依存症には正しい医学的・法的用語がある。アルコール依存症の医学的・法的用語

は「ディプソマニア」[176] であり、他の例はこの表に示されている[出典必要]。

歴史

依存症に関する現代の研究は、1875年にモルヒネ依存症に関する研究が開始されて以来、この疾患の理解を深めてきた。[177]

これにより、依存症が医学的疾患であるとの理解がさらに進んだ。依存症が、身体的状態および精神疾患の両方である疾患として西洋世界で認識され、認められ

たのは19世紀に入ってからのことだった。[178]

現在、依存症は、生物心理社会的および神経学的障害として理解されており、影響を受ける人々に負の影響を及ぼす。最も一般的に、薬物の使用やアルコールの

過剰摂取と関連付けられている。[4] 依存症の理解は歴史を通じて変化し、その医療的治療法や診断方法に影響を与え続けています。[出典が必要]

|

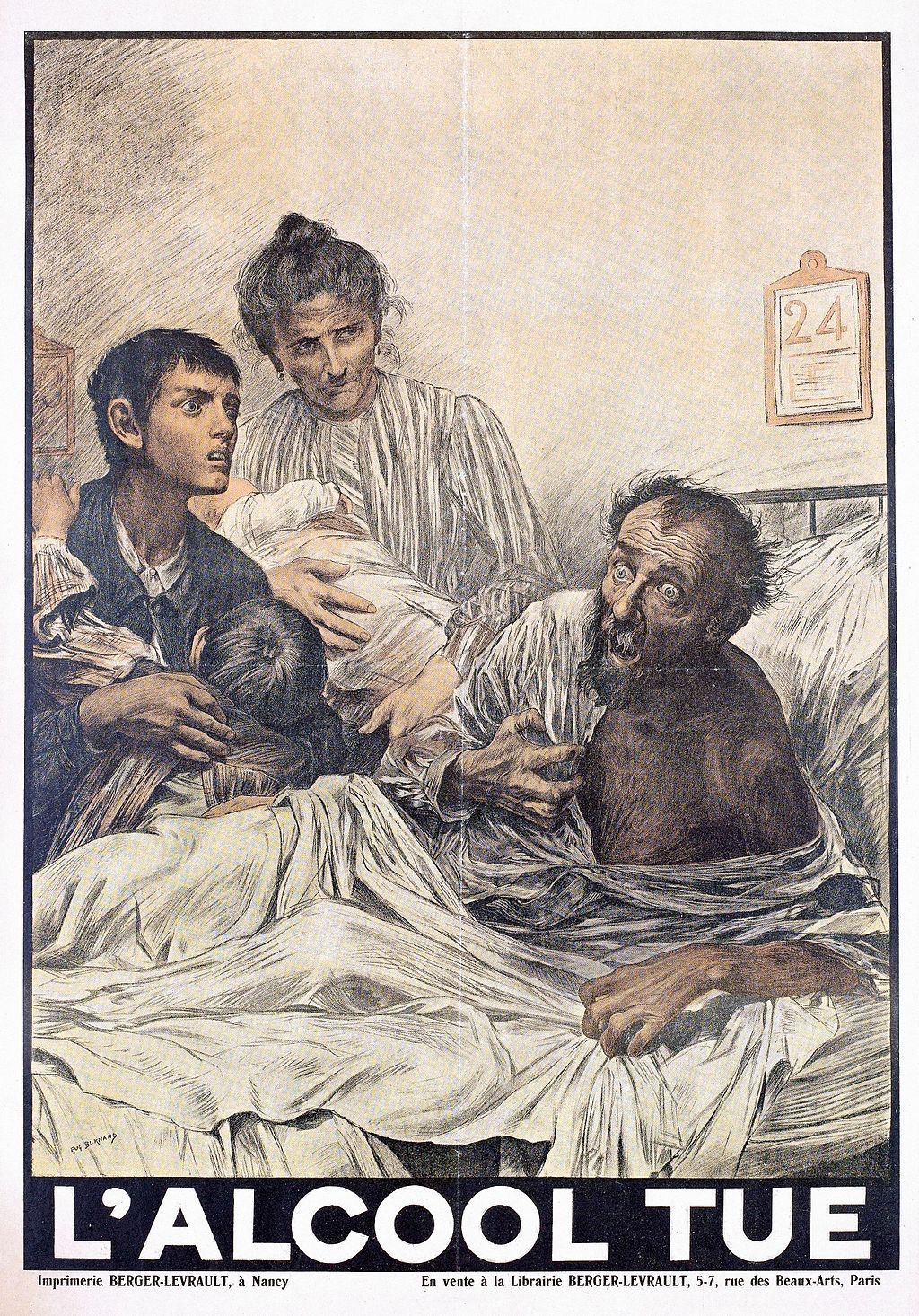

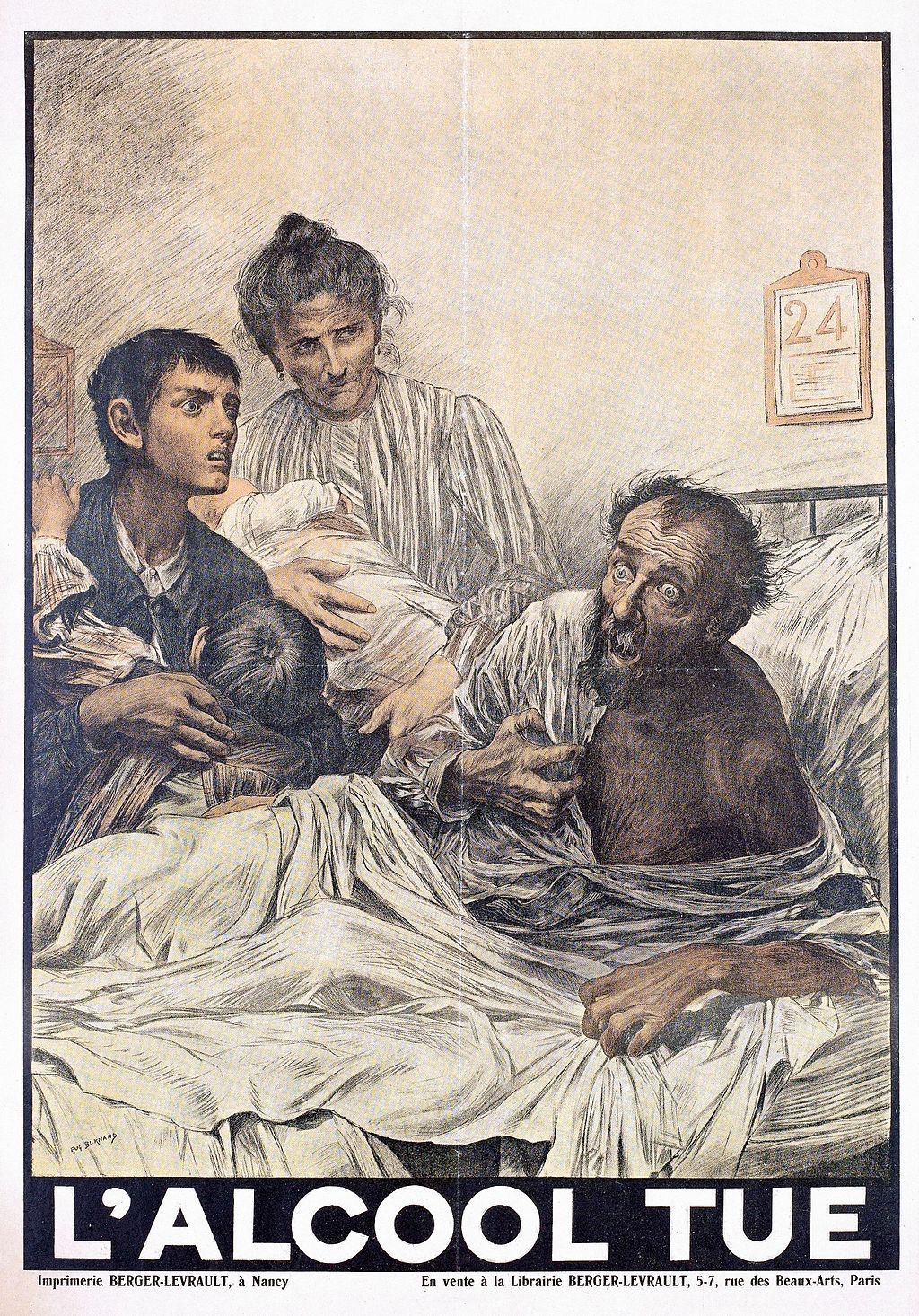

Addiction and art

The arts can be used in a variety of ways to address issues related to

addiction. Art can be used as a form of therapy in the treatment of

substance use disorders. Creative activities like painting, sculpting,

music, and writing can help people express their feelings and

experiences in safe and healthy ways. The arts can be used as an

assessment tool to identify underlying issues that may be contributing

to a person's substance use disorder. Through art, individuals can gain

insights into their own motivations and behaviors that can be helpful

in determining a course of treatment. Finally, the arts can be used to

advocate for those suffering from a substance use disorder by raising

awareness of the issue and promoting understanding and compassion.

Through art, individuals can share their stories, increase awareness,

and offer support and hope to those struggling with substance use

disorders.

|

依存症と芸術

芸術は、依存症に関連する問題に対処するためにさまざまな方法で活用することができます。芸術は、物質使用障害の治療における療法の一形態として活用する

ことができます。絵画、彫刻、音楽、執筆などの創造的な活動は、人々が自分の感情や経験を安全かつ健全な方法で表現するのに役立ちます。芸術は、人の物質

使用障害の原因となっている根本的な問題を見極めるための評価ツールとしても活用することができます。芸術を通じて、個人は自分の動機や行動について洞察

を得ることができ、治療方針を決定するのに役立つ。最後に、芸術は、問題に対する認識を高め、理解と共感を促進することで、物質使用障害に苦しむ人々を支

援するために活用することができます。芸術を通じて、個人は自分の物語を共有し、認識を高め、物質使用障害に苦しむ人々に支援と希望を与えることができま

す。

|

As therapy

Addiction treatment is complex and not always effective due to

engagement and service availability concerns, so researchers prioritize

efforts to improve treatment retention and decrease relapse

rates.[179][180] Characteristics of substance abuse may include

feelings of isolation, a lack of confidence, communication

difficulties, and a perceived lack of control.[181] In a similar vein,

people suffering from substance use disorders tend to be highly

sensitive, creative, and as such, are likely able to express themselves

meaningfully in creative arts such as dancing, painting, writing,

music, and acting.[182] Further evidenced by Waller and Mahony

(2002)[183] and Kaufman (1981),[184] the creative arts therapies can be

a suitable treatment option for this population especially when verbal

communication is ineffective.

Primary advantages of art therapy in the treatment of addiction have been identified as:[185][186]

Assess and characterize a client's substance use issues

Bypassing a client's resistances, defenses, and denial

Containing shame or anger

Facilitating the expression of suppressed and/or complicated emotions

Highlighting a client's strengths

Providing an alternative to verbal communication (via use of symbols) and conventional forms of therapy

Providing clients with a sense of control

Tackling feelings of isolation

Art therapy is an effective method of dealing with substance abuse in

comprehensive treatment models. When included in psychoeducational

programs, art therapy in a group setting can help clients internalize

taught concepts in a more personalized manner.[187] During the course

of treatment, by examining and comparing artwork created at different

times, art therapists can be helpful in identifying and diagnosing

issues, as well as charting the extent or direction of improvement as a

person detoxifies.[187] Where increasing adherence to treatment regimes

and maintaining abstinence is the target; art therapists can aid by

customizing treatment directives (encourage the client to create

collages that compare pros and cons, pictures that compare past and

present and future, and drawings that depict what happened when a

client went off medication).[187]

Art therapy can function as a complementary therapy used in conjunction

with more conventional therapies and can integrate with harm reduction

protocols to minimize the negative effects of drug use.[188][186] An

evaluation of art therapy incorporation within a pre-existing Addiction

Treatment Programme based on the 12 step Minnesota Model endorsed by

the Alcoholics Anonymous found that 66% of participants expressed the

usefulness of art therapy as a part of treatment.[189][186] Within the

weekly art therapy session, clients were able to reflect and process

the intense emotions and cognitions evoked by the programme. In turn,

the art therapy component of the programme fostered stronger

self-awareness, exploration, and externalization of repressed and

unconscious emotions of clients, promoting the development of a more

integrated 'authentic self'.[190][186]

Despite the large number of randomized control trials, clinical control

trials, and anecdotal evidence supporting the effectiveness of art

therapies for use in addiction treatment, a systematic review conducted

in 2018 could not find enough evidence on visual art, drama, dance and

movement therapy, or 'arts in health' methodologies to confirm their

effectiveness as interventions for reducing substance misuse.[191]

Music therapy was identified to have potentially strong beneficial

effects in aiding contemplation and preparing those diagnosed with

substance use for treatment.[191]

|

治療として

依存症の治療は複雑であり、治療への参加やサービスの利用可能性に関する問題から、必ずしも効果的とは限らないため、研究者は治療の継続率の向上と再発率

の低下に重点を置いた取り組みを進めている。[179][180]

薬物乱用の特徴としては、孤立感、自信の欠如、コミュニケーションの困難、コントロールの欠如の認識などが挙げられる。[181]

同様に、物質使用障害に苦しむ人々は、非常に敏感で創造性が高く、そのため、ダンス、絵画、執筆、音楽、演技などの創造的な芸術で、自分自身を意味のある

形で表現できる傾向がある。[182] Waller と Mahony (2002)[183] および Kaufman (1981)[184]

によってさらに証明されているように、創造的な芸術療法は、特に言葉によるコミュニケーションが効果的でない場合、この集団に適した治療選択肢となる可能

性があります。

依存症の治療におけるアートセラピーの主な利点は、次のように特定されています。[185][186]

クライアントの物質使用の問題を評価し、特徴づける

クライアントの抵抗、防御機制、否認を回避する

恥や怒りを抑える

抑圧された複雑な感情の表現を促進する

クライアントの強みを強調する

言語コミュニケーションの代替手段(シンボルの使用)や伝統的な療法形態を提供する

クライアントにコントロール感を与える

孤立感に対処する

アートセラピーは、包括的な治療モデルにおける薬物乱用の対処に効果的な手法です。心理教育プログラムに組み込むと、グループでのアートセラピーは、クラ

イアントが教えられた概念をより個人的な形で内面化するのに役立ちます。[187]

治療期間中、アートセラピストは、異なる時期に制作された作品を検証、比較することで、問題の特定と診断、および人格の解毒に伴う改善の程度や方向性の把

握に役立てることができます。[187]

治療計画への遵守率向上と禁断症状の維持が目標の場合、アートセラピストは治療指針をカスタマイズすることで支援できます(クライアントに、メリットとデ

メリットを比較するコラージュを作成させたり、過去と現在と未来を比較する絵を描かせたり、薬物を服用しなかった時の状況を表現する絵を描かせたりす

る)。[187]

アートセラピーは、より従来の治療法と組み合わせて補完的な治療法として機能し、薬物使用の悪影響を最小限に抑えるためのハームリダクション(ハームリダ

クション)プロトコルと統合することができる。[188][186] アルコール依存症者支援団体「アルコホーリクス・アノニマス」が推奨する 12

ステップのミネソタモデルに基づく、既存の依存症治療プログラムにアートセラピーを取り入れた評価では、参加者の 66%

が、治療の一部としてアートセラピーの有用性を評価した。[189][186]

週1回のアートセラピーセッションにおいて、クライアントはプログラムによって引き起こされた強い感情や認知を反映し処理することができました。その結

果、プログラムのアートセラピー要素は、クライアントの抑圧された無意識の感情の自己認識、探求、外在化を促進し、より統合された「本物の自己」の発達を

促しました。[190][186]

依存症治療におけるアートセラピーの有効性を支持するランダム化比較試験、臨床対照試験、および事例報告は多数あるが、2018

年に実施された系統的レビューでは、視覚芸術、演劇、ダンス、運動療法、あるいは「保健における芸術」の手法について、薬物乱用を削減するための介入とし

ての有効性を確認する十分な証拠は見つからなかった。[191]

音楽療法は、物質使用と診断された人々の治療準備を支援し、内省を促す点で、潜在的に強い有益な効果を有することが示された。[191]

|

As an assessment tool

The Formal Elements Art Therapy Scale (FEATS) is an assessment tool

used to evaluate drawings created by people suffering from substance

use disorders by comparing them to drawings of a control group

(consisting of individuals without SUDs).[192][186] FEATS consists of

twelve elements, three of which were found to be particularly effective

at distinguishing the drawings of those with SUDs from those without:

Person, Realism, and Developmental. The Person element assesses the

degree to which a human features are depicted realistically, the

Realism element assesses the overall complexity of the artwork, and the

Developmental element assesses "developmental age" of the artwork in

relation to standardized drawings from children and adolescents.[192]

By using the FEATS assessment tool, clinicians can gain valuable

insight into the drawings of individuals with SUDs, and can compare

them to those of the control group. Formal assessments such as FEATS

provide healthcare providers with a means to quantify, standardize, and

communicate abstract and visceral characteristics of SUDs to provide

more accurate diagnoses and informed treatment decisions.[192]

Other artistic assessment methods include the Bird's Nest Drawing: a

useful tool for visualizing a client's attachment security.[193][186]

This assessment method looks at the amount of color used in the

drawing, with a lack of color indicating an 'insecure attachment', a

factor that the client's therapist or recovery framework must take into

account.[194]

Art therapists working with children of parents suffering from

alcoholism can use the Kinetic Family Drawings assessment tool to shed

light on family dynamics and help children express and understand their

family experiences.[195][186] The KFD can be used in family sessions to

allow children to share their experiences and needs with parents who

may be in recovery from alcohol use disorder. Depiction of isolation of

self and isolation of other family members may be an indicator of

parental alcoholism.[195]

|

評価ツールとして

形式要素アートセラピースケール(FEATS)は、物質使用障害に苦しむ人々が描いた絵を、対照群(物質使用障害のない個人で構成される)の絵と比較する

ことで評価するための評価ツールだ。[192][186] FEATS は 12 の要素で構成されており、そのうち 3

つは、物質使用障害のある人とない人の絵を区別するのに特に有効であることがわかった。人格要素は、人物の特徴がどれだけ現実的に描かれているかを評価

し、現実性要素は、作品の全体的な複雑さを評価し、発達要素は、子供や青少年の標準的な絵と比較して、作品の「発達年齢」を評価する。[192]

FEATS 評価ツールを使用することで、臨床医は SUD

患者の絵について貴重な洞察を得ることができ、対照群の絵と比較することができる。FEATSのような形式的な評価は、医療従事者がSUDの抽象的で直感

的な特性を定量化、標準化、コミュニケーションする手段を提供し、より正確な診断と適切な治療決定を支援する。[192]

他の芸術的評価方法には、クライアントの愛着の安全性を可視化する有用なツールである「バード・ネスト・ドローイング」がある。[193][186]

この評価方法は、絵に使用された色の量に注目し、色の不足は「不安定な愛着」を示し、クライアントのセラピストや回復枠組みが考慮すべき要因となる。

[194]

アルコール依存症の親を持つ子供たちを支援するアートセラピストは、キネティック・ファミリー・ドローイング(KFD)という評価ツールを使用して、家族

の力学を明らかにし、子供たちが家族の経験を表現し、理解するのを助けることができる。[195][186] KFD

は、子供たちがアルコール使用障害から回復中の親と自分の経験やニーズを共有するための家族セッションで使用することができる。自己の孤立や他の家族メン

バーの孤立の描写は、親のアルコール依存症の指標となる可能性がある。[195]

|

Advocacy

Stigma can lead to feelings of shame that can prevent people with

substance use disorders from seeking help and interfere with provision

of harm reduction services.[196][197][198] It can influence healthcare

policy, making it difficult for these individuals to access

treatment.[199]

Artists attempt to change the societal perception of addiction from a

punishable moral offense to instead a chronic illness necessitating

treatment. This form of advocacy can help to relocate the fight of

addiction from a judicial perspective to the public health system.[200]

Artists who have personally lived with addiction or undergone recovery

may use art to depict their experiences in a manner that uncovers the

"human face of addiction". By bringing experiences of addiction and

recovery to a personal level and breaking down the "us and them", the

viewer may be more inclined to show compassion, forego stereotypes and

stigma of addiction, and label addiction as a social rather than

individual problem.[200]

According to Santora[200] the main purposes in using art as a form of

advocacy in the education and prevention of substance use disorders

include:

Addiction art exhibitions can come from a variety of sources, but the

underlying message of these works is the same: to communicate through

emotions without relying on intellectually demanding/gatekept facts and

figures. These exhibitions can either stand alone, reinforce, or

challenge facts.

A powerful educational tool for increasing awareness and understanding

of addiction as a medical illness. Exhibitions featuring personal

stories and images can help to create lasting impressions on diverse

audiences (including addiction scientists/researchers, family/friends

of those affected by addiction etc.), highlighting the humanity of the

problem and in turn encouraging compassion and understanding.

A way to destigmatize substance use disorders and shift public

perception from viewing them as a moral failing to understanding them

as a chronic medical condition which requires treatment.

Provide those who are struggling with addiction assurance and

encouragement of healing, and let them know that they are not alone in

their struggle.

The use of visual arts can help bring attention to the lack of adequate

substance use treatment, prevention, and education programs and

services in a healthcare system. Messages can encourage policymakers to

allocate more resources to addiction treatment and prevention from

federal, state, and local levels.

The Temple University College of Public Health department conducted a

project to promote awareness around opioid use and reduce associated

stigma by asking students to create art pieces that were displayed on a

website they created and promoted via social media.[201] Quantitative

and qualitative data was recorded to measure engagement, and the

student artists were interviewed, which revealed a change in

perspective and understanding, as well as greater appreciation of

diverse experiences. Ultimately, the project found that art was an

effective medium for empowering both the artist creating the work and

the person interacting with it.[201]

Another author critically examined works by contemporary Canadian

artists that deal with addiction via the metaphor of a cultural

landscape to "unmap" and "remap" ideologies related to Indigenous

communities and addiction to demonstrate how colonial violence in

Canada has drastically impacted the relationship between Indigenous

peoples, their land, and substance abuse.[202]

A project known as "Voice" was a collection of art, poetry and

narratives created by women living with a history of addiction to

explore women's understanding of harm reduction, challenge the effects

of stigma and give voice to those who have historically been silenced

or devalued.[203] In the project, nurses with knowledge of mainstream

systems, aesthetic knowing, feminism and substance use organized weekly

gatherings, wherein women with histories of substance use and addiction

worked alongside a nurse to create artistic expressions. Creations were

presented at several venues, including an International Conference on

Drug Related Harm, a Nursing Conference and a local gallery to positive

community response.[203]

|

アドボカシー

スティグマは、物質使用障害のある人々に恥の感情を抱かせ、助けを求めることを妨げ、ハームリダクションサービスの提供を妨げる要因となる。[196][197][198] また、医療政策にも影響を及ぼし、こうした人々が治療を受けることを困難にする。[199]

アーティストたちは、依存症を罰すべき道徳的犯罪という社会の認識を変え、治療が必要な慢性疾患という認識に変えようとしています。この形のアドボカシーは、依存症との闘いを司法の観点から公衆衛生システムへと移すのに役立つ可能性があります。[200]

依存症を経験したり、回復を経験したアーティストは、芸術を用いて「依存症の人間的な側面」を明らかにする形で、自らの経験を表現することがあります。依

存症と回復の経験を個人的なレベルに引き下げ、「私たちと彼ら」という区分を打ち破ることで、鑑賞者は、依存症に対する思いやりを示し、依存症に対する固

定観念や偏見を捨て、依存症を個人ではなく社会の問題として捉えるようになる可能性があります。[200]

サントラ[200]によると、薬物使用障害の教育と予防においてアートをアドボカシーの手段として使用する主な目的には、以下のものが含まれる:

依存症アート展は多様な出典から生まれるが、これらの作品の根本的なメッセージは同じだ:知的負担の大きい事実や数字に依存せず、感情を通じて伝えること。これらの展覧会は、単独で存在したり、事実を補強したり、挑戦したりする可能性がある。

依存症を医学的疾患として認識し、理解を深めるための強力な教育ツール。個人的な体験談や画像を紹介する展示会は、依存症の研究者、依存症患者の家族や友人など、さまざまな観客に深い印象を与え、この問題の人間性を浮き彫りにすることで、共感と理解を促すことができます。

物質使用障害の偏見を排除し、それを道徳的欠陥として見るという社会の認識を、治療が必要な慢性疾患として理解する方向に転換する方法。

依存症と闘う人々に癒しの確信と励ましを提供し、彼らが孤独ではないことを伝える。

視覚芸術の活用は、医療システムにおける適切な物質使用治療、予防、教育プログラムやサービスの不足に注目を集めるのに役立ちます。メッセージは、政策決定者が連邦、州、地方レベルで依存症治療と予防に更多的資源を配分するよう促すことができます。

テンプル大学公衆衛生学部は、学生たちに芸術作品を作成してもらい、その作品を学生たちが作成したウェブサイトに掲載し、ソーシャルメディアで宣伝するこ

とで、オピオイドの使用に関する認識を高め、それに関連する偏見を軽減するプロジェクトを実施した[201]。参加の程度を測定するために定量的および定

性的データが記録され、学生アーティストたちがインタビューを受けた結果、視点や理解の変化、多様な経験に対する理解の深まりが明らかになった。結局、こ

のプロジェクトでは、芸術は作品制作を行うアーティストと作品と関わる人々の双方をエンパワーする効果的な媒体であることがわかった。[201]

別の著者は、先住民コミュニティと依存症に関するイデオロギーを「解体」し、「再構築」するために、文化的な景観を隠喩として用いて依存症を扱った現代カ

ナダ人アーティストの作品を批判的に考察し、カナダにおける植民地時代の暴力がいかに先住民、その土地、薬物乱用との関係に深刻な影響を与えたかを明らか

にした。[202]

「Voice」というプロジェクトは、依存症の経験を持つ女性たちが、ハームリダクションに対する女性の理解を探求し、スティグマの影響に挑み、これまで

沈黙を強いられてきた、あるいは軽視されてきた人たちに発言の場を与えることを目的とした、アート、詩、物語のコレクションです。[203]

このプロジェクトでは、主流のシステム、美的感覚、フェミニズム、薬物使用に関する知識を持つ看護師が、週に一度の集まりを組織し、薬物使用や依存症の経

験を持つ女性たちが看護師と共に芸術的な表現を作成した。作品は、国際薬物関連危害会議、看護学会、地元のギャラリーなど複数の会場で展示され、地域社会

からポジティブな反応を得た。[203]

|

☆

☆