依存症

Addiction

☆依存症は、実質的な害やその他の否定的な結果にもかかわらず、薬物を使 用したり、自然な報酬をもたらす行動に関与したりしたいという持続的で強い衝動を特徴とする神経心理学的障害である。薬物の反復使用は、食物や恋愛のような自然な報酬と同様に、シ ナプスにおける脳機能を変化させ、渇望を持続させ、既存の脆弱性を持つ人々の自制心を弱める。この現象——薬物が脳機能を再形成する——は、依存症の発症 に関与する神経生物学的要因だけでなく、複雑で多様な心理社会的要因を伴う脳疾患としての依存症の理解につながっている(→「依存症の分子メカニズム」)。

★ 基本語彙集(Addiction and dependence glossary)

| 嗜癖(アディクション) Addiction |

・有害な結果にもかかわらず、報酬刺激に対しての強迫的関与

を特徴とする脳障害。1950年代に世界保健機関WHOにより依存症のような意味で定義されたが、異なる意味である乱用の意味でも用いられるため、WHO

の専門用語から除外した。2013年のDSM-5において大分類名に登場し、その下位にDSM-IVの依存症と乱用が統合された物質使用障害がある ・薬物(アルコールを含む)の持続的な使用によって特徴づけられる生物心理社会的障害である。 |

| 嗜癖性薬物 addictive drug |

・報酬と強化をもたらす薬物 ・脳の報酬系に薬物が作用することが主な原因で、反復使用によって薬物使用障害の割合が有意に高くなる精神作用物質。 |

| 物質使用障害 substance use disorder |

物・質使用が臨床的・機能的に重大な障害または苦痛をもたらす状態 |

| 依存症(Dependence) |

・反復暴露している刺激の中止時に、離脱を引き起こすような適応状態 ・ある刺激(例:薬物摂取)への反復曝露を中止した際に、離脱症候群を伴う適応状態。 |

| 乱用(Abuse) |

依存の状態を満たさないが繰り返して薬物による問題を起こす状態 |

| 習慣(Habit) |

WHOは摂取量が増えず身体依存もない状態と定義し[6]、その後破棄した[7]。日本の薬事法において身体依存のある薬物も含めて分類している。 |

| 中毒・依存 dependence |

・日本で過去に依存症のような意味で使われたが、現行の医学的には大量摂取などで毒性が生じている状態 ・ある刺激(例:薬物摂取)への反復曝露を中止した際に、離脱症候群を伴う適応状態。 |

| 離脱 drug withdrawal |

・反復使用している薬物の中断時に起こる症状 ・薬物の反復使用を中止したときに生じる症状。 |

| 身体的依存 physical dependence |

・身体的・心身的症状が持続して発生する依存状態 ・身体的・身体的離脱症状(振戦せん妄、吐き気など)が持続する依存。 |

| 精神的依存 psychological dependence |

・感情的・動機的な離脱症状が発生する依存状態 ・認知機能に影響を及ぼす情動-意欲的な離脱症状(例えば、無感覚症や不安)を特徴とする依存。 |

| 強化刺激 reinforcing stimuli |

・対象行動を繰り返す確率を高める刺激 ・その刺激と対になる行動を繰り返す確率を高める刺激。 |

| 報酬刺激 rewarding stimuli |

・本質的に脳がポジティブまたは取り入れるべきと解釈する刺激 ・脳が本質的に肯定的で望ましいもの、または近づくべきものとして解釈する刺激。 |

| 耐性 tolerance |

・与えられた用量での反復投与に起因する、薬物効果の減少 ・ある量を繰り返し投与した結果、薬物の効果が減弱すること。 |

| 逆耐性,感作 sensitization |

・薬剤の反復投与によって、その効用が漸増していくこと ・ある刺激に繰り返しさらされることによって、その刺激に対する反応が増幅されること。 |

☆語彙集(Addiction and

dependence glossary[3][14][15]——依存と依存の用語集[3][14][15]。)

| addiction – a biopsychosocial disorder characterized by persistent use

of drugs (including alcohol) despite substantial harm and adverse

consequences addictive drug – psychoactive substances that with repeated use are associated with significantly higher rates of substance use disorders, due in large part to the drug's effect on brain reward systems dependence – an adaptive state associated with a withdrawal syndrome upon cessation of repeated exposure to a stimulus (e.g., drug intake) drug sensitization or reverse tolerance – the escalating effect of a drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose drug withdrawal – symptoms that occur upon cessation of repeated drug use **** physical dependence – dependence that involves persistent physical–somatic withdrawal symptoms (e.g., delirium tremens and nausea) psychological dependence – dependence that is characterised by emotional-motivational withdrawal symptoms (e.g., anhedonia and anxiety) that affect cognitive functioning. reinforcing stimuli – stimuli that increase the probability of repeating behaviors paired with them rewarding stimuli – stimuli that the brain interprets as intrinsically positive and desirable or as something to approach sensitization – an amplified response to a stimulus resulting from repeated exposure to it substance use disorder – a condition in which the use of substances leads to clinically and functionally significant impairment or distress tolerance – the diminishing effect of a drug resulting from repeated administration at a given dose |

依存症 - 薬物(アルコールを含む)の持続的な使用によって特徴づけられる生物心理社会的障害である。 依存性薬物 - 脳の報酬系に薬物が作用することが主な原因で、反復使用によって薬物使用障害の割合が有意に高くなる精神作用物質。 依存 - ある刺激(例:薬物摂取)への反復曝露を中止した際に、離脱症候群を伴う適応状態。 薬物鋭敏化または逆耐性 - 与えられた用量で薬物を反復投与した結果、薬物の作用がエスカレートすること。 薬物の離脱-薬物の反復使用を中止したときに生じる症状。 **** 身体的依存 - 身体的・身体的離脱症状(振戦せん妄、吐き気など)が持続する依存。 心理的依存 - 認知機能に影響を及ぼす情動-意欲的な離脱症状(例えば、無感覚症や不安)を特徴とする依存。 強化刺激 - その刺激と対になる行動を繰り返す確率を高める刺激。 報酬刺激 - 脳が本質的に肯定的で望ましいもの、または近づくべきものとして解釈する刺激。 感作 - ある刺激に繰り返しさらされることによって、その刺激に対する反応が増幅されること。 物質使用障害 - 物質の使用が臨床的・機能的に重大な障害や苦痛をもたらす状態。 耐性 - ある量を繰り返し投与した結果、薬物の効果が減弱すること。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addiction |

★

依存症は、実質的な害やその他の否定的な結果にもかかわらず、薬物を使用したり、自然な報酬をもたらす行動に関与したりしたいという持続的で強い衝動を特

徴とする神経心理学的障害である。薬物の反復使用は、食物や恋愛のような自然な報酬[1]と同様に、シナプスにおける脳機能を変化させ、渇望を持続させ、

既存の脆弱性を持つ人々の自制心を弱める。[2]

この現象——薬物が脳機能を再形成する——は、依存症の発症に関与する神経生物学的要因だけでなく、複雑で多様な心理社会的要因を伴う脳疾患としての依存症の

理解につながっている[3][4][5]。コカインを与えられたマウスは依存症の強迫的で不随意的な性質を示したが[a]、人格[6]または人格特性に関

連するヒトにとっては、これはより複雑である[7]。

典型的な依存の徴候には、報酬刺激への強迫的な関与、物質や行動へのこだわり、否定的な結果にもかかわらず使用を続けることなどがある。依存症に関連する

習慣やパターンは、一般的に即時的な満足(短期的な報酬)[8][9]と、遅延した有害な影響(長期的なコスト)とが組み合わさって特徴づけられる[4]

[10]。

薬物依存の例としては、アルコール依存、大麻依存、アンフェタミン依存、コカイン依存、ニコチン依存、オピオイド依存、摂食または食物依存がある。行動依

存症には、ギャンブル依存症、買い物依存症、ストーカー行為、ポルノ依存症、インターネット依存症、ソーシャルメディア依存症、ビデオゲーム依存症、性的

依存症などがある。DSM-5とICD-10は、行動依存症としてギャンブル依存症のみを認めているが、ICD-11ではゲーム依存症も認めている

[11]。

☆【留意点】こ の項目の問題点:「この記事は、新しい記事「依存症のメカニズム」に分割することが提案されています。(議論) (2025年4月)」

★「依存症の予防とその歴史」はこちらです。

| Addiction is a

neuropsychological disorder characterized by a persistent and intense

urge to use a drug or engage in a behavior that produces natural

reward, despite substantial harm and other negative consequences.

Repetitive drug use can alter brain function in synapses similar to

natural rewards like food or falling in love[1] in ways that perpetuate

craving and weakens self-control for people with pre-existing

vulnerabilities.[2] This phenomenon – drugs reshaping brain function –

has led to an understanding of addiction as a brain disorder with a

complex variety of psychosocial as well as neurobiological factors that

are implicated in the development of addiction.[3][4][5] While mice

given cocaine showed the compulsive and involuntary nature of

addiction,[a] for humans this is more complex, related to behavior[6]

or personality traits.[7] Classic signs of addiction include compulsive engagement in rewarding stimuli, preoccupation with substances or behavior, and continued use despite negative consequences. Habits and patterns associated with addiction are typically characterized by immediate gratification (short-term reward),[8][9] coupled with delayed deleterious effects (long-term costs).[4][10] Examples of substance addiction include alcoholism, cannabis addiction, amphetamine addiction, cocaine addiction, nicotine addiction, opioid addiction, and eating or food addiction. Behavioral addictions may include gambling addiction, shopping addiction, stalking, pornography addiction, internet addiction, social media addiction, video game addiction, and sexual addiction. The DSM-5 and ICD-10 only recognize gambling addictions as behavioral addictions, but the ICD-11 also recognizes gaming addictions.[11] |

依存症は、実質的な害やその他の否定的な結果にもかかわらず、薬物を使

用したり、自然な報酬をもたらす行動に関与したりしたいという持続的で強い衝動を特徴とする神経心理学的障害である。薬物の反復使用は、食物や恋愛のよう

な自然な報酬[1]と同様に、シナプスにおける脳機能を変化させ、渇望を持続させ、既存の脆弱性を持つ人々の自制心を弱める。[2]

この現象-薬物が脳機能を再形成する-は、依存症の発症に関与する神経生物学的要因だけでなく、複雑で多様な心理社会的要因を伴う脳疾患としての依存症の

理解につながっている[3][4][5]。コカインを与えられたマウスは依存症の強迫的で不随意的な性質を示したが[a]、人格[6]または人格特性に関

連するヒトにとっては、これはより複雑である[7]。 典型的な依存の徴候には、報酬刺激への強迫的な関与、物質や行動へのこだわり、否定的な結果にもかかわらず使用を続けることなどがある。依存症に関連する 習慣やパターンは、一般的に即時的な満足(短期的な報酬)[8][9]と、遅延した有害な影響(長期的なコスト)とが組み合わさって特徴づけられる[4] [10]。 薬物依存の例としては、アルコール依存、大麻依存、アンフェタミン依存、コカイン依存、ニコチン依存、オピオイド依存、摂食または食物依存がある。行動依 存症には、ギャンブル依存症、買い物依存症、ストーカー行為、ポルノ依存症、インターネット依存症、ソーシャルメディア依存症、ビデオゲーム依存症、性的 依存症などがある。DSM-5とICD-10は、行動依存症としてギャンブル依存症のみを認めているが、ICD-11ではゲーム依存症も認めている [11]。 |

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addiction |

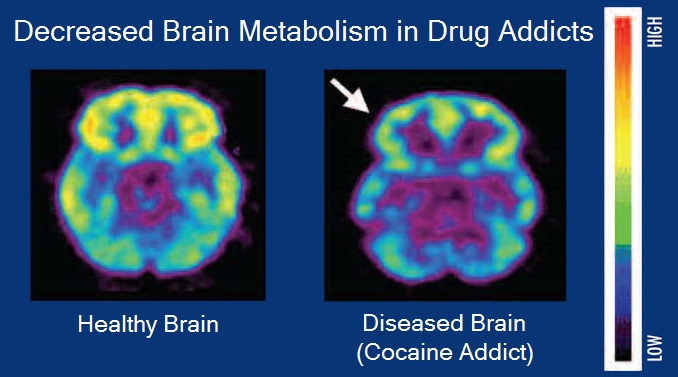

健常者とコカイン依存者の脳代謝を比較した脳ポジトロン断層撮影画像 |

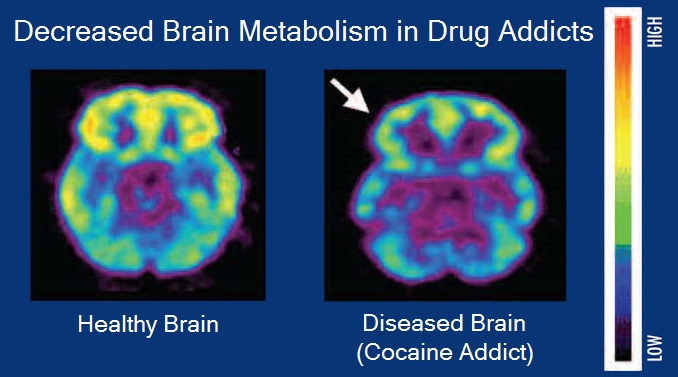

| Signs and symptoms Signs and symptoms of drug addiction can vary depending on the type of addiction. Symptoms may include: Continuation of drug use despite the knowledge of consequences[12] Disregarding financial status when it comes to drug purchases Ensuring a stable supply of the drug Needing more of the drug over time to achieve similar effects[12] Social and work life impacted due to drug use[12] Unsuccessful attempts to stop drug use[12] Urge to use drug regularly Other signs and symptoms can be categorized across relevant dimensions:  |

兆候と症状 薬物依存の兆候と症状は、依存の種類によって異なる。症状には以下のようなものがある: 結果がわかっているにもかかわらず薬物を使用し続ける[12]。 薬物を購入する際に経済状態を無視する。 薬物の安定供給を確保する。 同じような効果を得るために、時間をかけてより多くの薬物を必要とする[12]。 薬物使用によって社会生活や仕事生活に影響が出る[12]。 薬物使用を止めようとしてもうまくいかない[12]。 薬物を定期的に使用したいという衝動 その他の徴候や症状は、関連する次元にわたって分類することができる: |

| Substance addiction Main article: Substance use disorder (SUD) Further information: Substance abuse and Substance-related disorder |

物質依存 主な記事 物質使用障害 さらに詳しい情報 物質乱用および物質関連障害 |

| Drug addiction Drug addiction, which belongs to the class of substance-related disorders, is a chronic and relapsing brain disorder that features drug seeking and drug abuse, despite their harmful effects.[16] This form of addiction changes brain circuitry such that the brain's reward system is compromised,[17] causing functional consequences for stress management and self-control.[16] Damage to the functions of the organs involved can persist throughout a lifetime and cause death if untreated.[16] Substances involved with drug addiction include alcohol, nicotine, marijuana, opioids, cocaine, amphetamines, and even foods with high fat and sugar content.[18] Addictions can begin experimentally in social contexts[19] and can arise from the use of prescribed medications or a variety of other measures.[20] Drug addiction has been shown to work in phenomenological, conditioning (operant and classical), cognitive models, and the cue reactivity model. However, no one model completely illustrates substance abuse.[21] Risk factors for addiction include: Aggressive behavior (particularly in childhood) Availability of substance[19] Community economic status[citation needed] Experimentation[19] Epigenetics Impulsivity (attentional, motor, or non-planning)[22] Lack of parental supervision[19] Lack of peer refusal skills[19] Mental disorders[19] Method substance is taken[16] Usage of substance in youth[19] |

薬物依存症 薬物依存症は、物質関連障害の一群に属し、有害な作用があるにもかかわらず薬物を求め、薬物を乱用する慢性的かつ再発性の脳疾患である[16]。この種の 依存症は、脳の報酬系が損なわれるように脳回路を変化させ[17]、ストレス管理や自制心に機能的な影響を及ぼす。[薬物依存症に関与する物質には、アル コール、ニコチン、マリファナ、オピオイド、コカイン、アンフェタミン、さらには脂肪分や糖分を多く含む食品が含まれる[18]。依存症は、社会的文脈の 中で実験的に始まることもあれば[19]、処方された薬物や他の様々な手段の使用によって生じることもある[20]。 薬物依存症は、現象学的、条件づけ(オペラントおよび古典的)、認知モデル、および手がかり反応性モデルにおいて機能することが示されている。しかし、薬物乱用を完全に説明するモデルはひとつもない[21]。 依存の危険因子には以下が含まれる: 攻撃的行動(個別主義において) 物質の入手可能性[19]。 地域社会の経済状況[要出典]。 実験[19] エピジェネティクス 衝動性(注意力、運動、または非計画性)[22]。 親の監督[19]の欠如 仲間を拒否するスキルの欠如[19]。 精神障害[19] 物質の摂取方法[16]。 青少年における物質の使用[19] |

| Food addiction Main article: Food addiction The diagnostic criteria for food or eating addiction has not been categorized or defined in references such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM or DSM-5) and is based on subjective experiences similar to substance use disorders.[12][22] Food addiction may be found in those with eating disorders, though not all people with eating disorders have food addiction and not all of those with food addiction have a diagnosed eating disorder.[12] Long-term frequent and excessive consumption of foods high in fat, salt, or sugar, such as chocolate, can produce an addiction[23][24] similar to drugs since they trigger the brain's reward system, such that the individual may desire the same foods to an increasing degree over time.[25][12][22] The signals sent when consuming highly palatable foods have the ability to counteract the body's signals for fullness and persistent cravings will result.[25] Those who show signs of food addiction may develop food tolerances, in which they eat more, despite the food becoming less satisfactory.[25] Chocolate's sweet flavor and pharmacological ingredients are known to create a strong craving or feel 'addictive' by the consumer.[26] A person who has a strong liking for chocolate may refer to themselves as a chocoholic. Risk factors for developing food addiction include excessive overeating and impulsivity.[22] The Yale Food Addiction Scale (YFAS), version 2.0, is the current standard measure for assessing whether an individual exhibits signs and symptoms of food addiction.[27][12][22] It was developed in 2009 at Yale University on the hypothesis that foods high in fat, sugar, and salt have addictive-like effects which contribute to problematic eating habits.[28][25] The YFAS is designed to address 11 substance-related and addictive disorders (SRADs) using a 25-item self-report questionnaire, based on the diagnostic criteria for SRADs as per DSM-5.[29][12] A potential food addiction diagnosis is predicted by the presence of at least two out of 11 SRADs and a significant impairment to daily activities.[30] The Barratt Impulsiveness Scale, specifically the BIS-11 scale, and the UPPS-P Impulsive Behavior subscales of Negative Urgency and Lack of Perseverance have been shown to have relation to food addiction.[22] |

食品依存 主な記事 食物依存 食物依存または摂食依存の診断基準は、『精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル』(DSMまたはDSM-5)などの文献では分類または定義されておらず、物質使 用障害と同様の主観的体験に基づいている[12][22]。食物依存は摂食障害の人々に見られることがあるが、摂食障害のすべての人々が食物依存であるわ けではなく、また食物依存のすべての人々が摂食障害と診断されているわけでもない。[12] チョコレートなど脂肪、塩分、または糖分を多く含む食品の長期にわたる頻繁な過剰摂取は、脳の報酬系を誘発するため、薬物に類似した依存 [23] [24] を引き起こす可能性があり、時間の経過とともに同じ食品を欲する程度が増す可能性がある。[25][12][22]嗜好性の高い食品を摂取する際に送られ るシグナルは、満腹を求める身体のシグナルを打ち消す能力があり、持続的な渇望が生じる[25]。食物依存の徴候を示す人は、食品の満足度が低くなってい るにもかかわらず、より多く食べるという食物耐性を発達させることがある[25]。 チョコレートの甘い風味と薬理学的成分は、消費者に強い渇望を生じさせたり、「依存性」を感じさせたりすることが知られている[26]。チョコレートを強く好む人格は、自分自身をチョコホリックと呼ぶことがある。 食品依存を発症する危険因子には、過度の過食と衝動性がある[22]。 エール依存尺度(YFAS)バージョン2.0は、個人が食依存の徴候および症状を示すかどうかを評価するための現在の標準的な尺度である。[28] [25]YFASは、DSM-5によるSRADsの診断基準に基づき、25項目の自己報告式質問票を用いて11の物質関連・嗜癖性障害(SRADs)に対 応するように設計されている。[29][12]潜在的な食依存の診断は、11のSRADsのうち少なくとも2つのSRADsが存在し、日常生活に重大な障 害があることで予測される[30]。 Barratt Impulsiveness Scale、特にBIS-11尺度、およびUPPS-P Impulsive Behaviorの下位尺度であるNegative UrgencyとLack of Perseveranceは、食物依存と関係があることが示されている[22]。 |

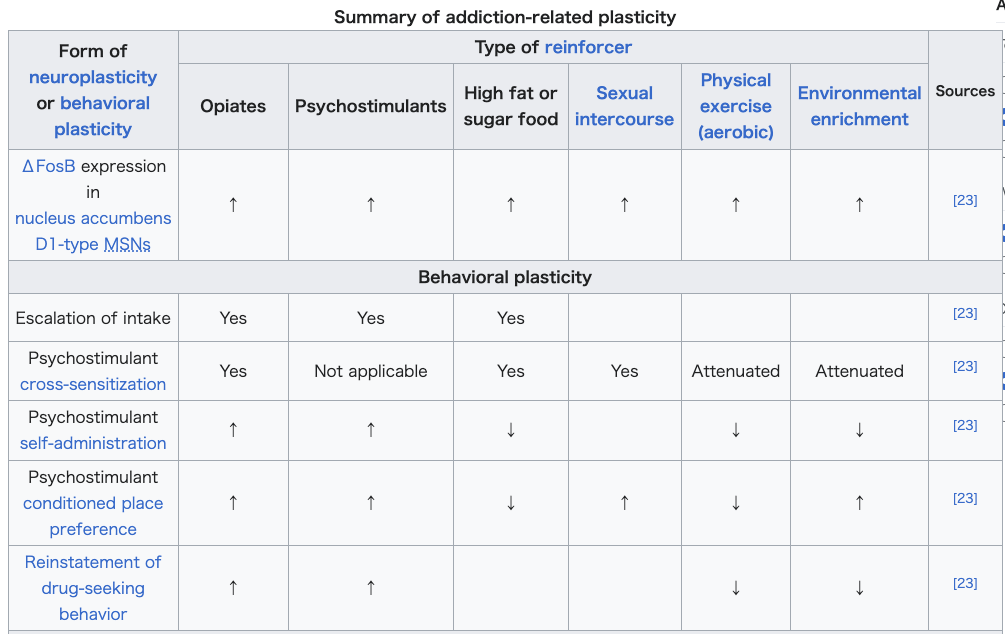

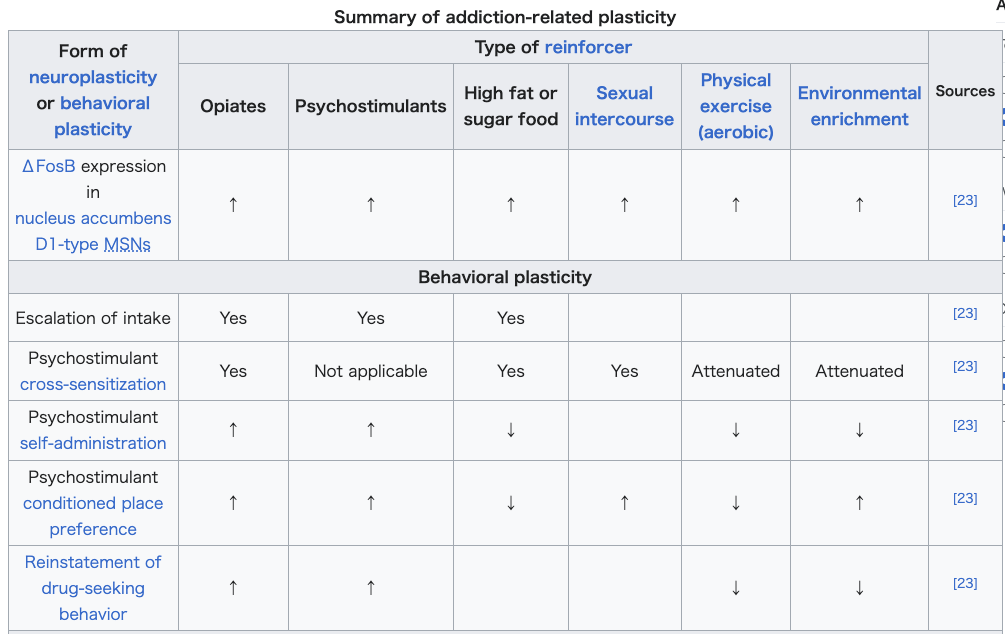

| Behavioral addiction Main article: Behavioral addiction The term behavioral addiction refers to a compulsion to engage in a natural reward – which is a behavior that is inherently rewarding (i.e., desirable or appealing) – despite adverse consequences.[9][23][24] Preclinical evidence has demonstrated that marked increases in the expression of ΔFosB through repetitive and excessive exposure to a natural reward induces the same behavioral effects and neuroplasticity as occurs in a drug addiction.[23][31][32][33] Addiction can exist without psychotropic drugs, an idea that was popularized by psychologist Stanton Peele.[34] These are termed behavioral addictions. Such addictions may be passive or active, but they commonly contain reinforcing features, which are found in most addictions.[34] Sexual behavior, eating, gambling, playing video games, and shopping are all associated with compulsive behaviors in humans and have been shown to activate the mesolimbic pathway and other parts of the reward system.[23] Based on this evidence, sexual addiction, gambling addiction, video game addiction, and shopping addiction are classified accordingly.[23] |

行動依存 主な記事 行動依存 行動依存症という用語は、有害な結果にもかかわらず、自然報酬(本来的に報酬が得られる(すなわち、望ましい、または魅力的である)行動)に従事しなけれ ばならないという強迫観念を指す[9][23][24]。前臨床試験では、自然報酬への反復的かつ過剰な曝露によってΔFosBの発現が著しく増加するこ とで、薬物依存症で起こるのと同じ行動効果と神経可塑性が誘導されることが実証されている[23][31][32][33]。 向精神薬がなくても依存症は存在しうるという考え方は、心理学者のスタントン・ピールによって広められた[34]。このような嗜癖は受動的である場合も能 動的である場合もあるが、一般的にほとんどの嗜癖にみられる強化的な特徴を含んでいる[34]。性行動、摂食、ギャンブル、ビデオゲーム、買い物はすべて ヒトの強迫行動と関連しており、中脳辺縁系経路や報酬系の他の部分を活性化することが示されている[23]。この証拠に基づいて、性的嗜癖、ギャンブル嗜 癖、ビデオゲーム嗜癖、買い物嗜癖が分類されている[23]。 |

| Causes Personality theories Main article: Personality theories of addiction Personality theories of addiction are psychological models that associate personality traits or modes of thinking (i.e., affective states) with an individual's proclivity for developing an addiction. Data analysis demonstrates that psychological profiles of drug users and non-users have significant differences and the psychological predisposition to using different drugs may be different.[35] Models of addiction risk that have been proposed in psychology literature include: an affect dysregulation model of positive and negative psychological affects, the reinforcement sensitivity theory of impulsiveness and behavioral inhibition, and an impulsivity model of reward sensitization and impulsiveness.[36][37][38][39][40] |

原因 人格理論 主な記事 依存症の人格理論 依存症のパーソナリティ理論とは、人格特性や思考様式(すなわち感情状態)を、依存症を発症する個人の傾向と関連付ける心理学的モデルである。データ分析 によると、薬物使用者と非使用者の心理的プロファイルには大きな相違があり、異なる薬物を使用する心理的素因は異なる可能性があることが示されている [35]。心理学の文献で提案されている依存症リスクのモデルには、肯定的心理的影響と否定的心理的影響の影響調節障害モデル、衝動性と行動抑制の強化感 受性理論、報酬感作と衝動性の衝動性モデルなどがある[36][37][38][39][40]。 |

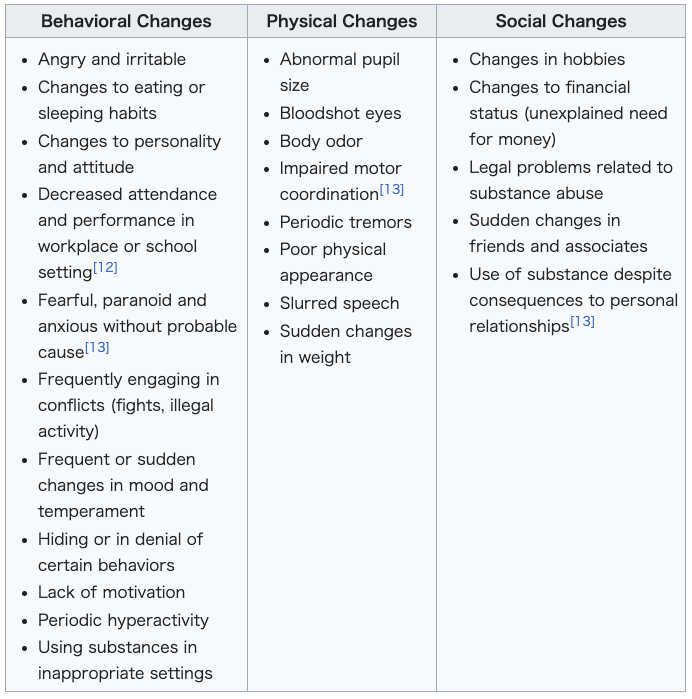

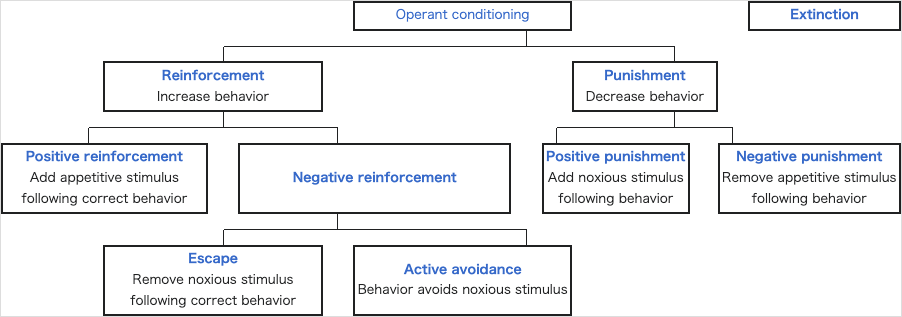

| Neuropsychology The transtheoretical model of change (TTM) can point to how someone may be conceptualizing their addiction and the thoughts around it, including not being aware of their addiction.[41] Cognitive control and stimulus control, which is associated with operant and classical conditioning, represent opposite processes (i.e., internal vs external or environmental, respectively) that compete over the control of an individual's elicited behaviors.[42] Cognitive control, and particularly inhibitory control over behavior, is impaired in both addiction and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.[43][44] Stimulus-driven behavioral responses (i.e., stimulus control) that are associated with a particular rewarding stimulus tend to dominate one's behavior in an addiction.[44] |

神経心理学 変化に関する超理論的モデル(TTM)は、ある人がどのように自分の依存症やその周囲の思考を概念化しているかを指し示すことができ、これには自分の依存症に気づいていないことも含まれる[41]。 認知制御と刺激制御は、オペラント条件づけと古典的条件づけに関連しており、正反対の過程(すなわち、それぞれ内部対外部または環境)を表している、 認知的制御、特に行動に対する抑制的制御は、依存症と注意欠陥多動性障害の両方で損なわれている[43][44]。 依存症では、特定の報酬刺激に関連する刺激主導型の行動反応(すなわち刺激制御)が行動を支配する傾向がある[44]。 |

| Stimulus control of behavior See also: Stimulus control.  In operant conditioning, behavior is influenced by outside stimulus, such as a drug. The operant conditioning theory of learning is useful in understanding why the mood-altering or stimulating consequences of drug use can reinforce continued use (an example of positive reinforcement) and why the addicted person seeks to avoid withdrawal through continued use (an example of negative reinforcement). Stimulus control is using the absence of the stimulus or presence of a reward to influence the resulting behavior.[41] |

行動の刺激制御 [刺激の制御.]  オペラント条件づけでは、薬物などの外部刺激によって行動が影響を受ける。学習のオペラント条件付け理論は、薬物使用による気分転換または刺激的な結果が なぜ継続的な使用を強化するのか(正の強化の例)、また依存人格がなぜ継続的な使用によって離脱を回避しようとするのか(負の強化の例)を理解するのに有 用である。刺激制御とは、刺激の不在または報酬の存在を利用して、結果として生じる行動に影響を及ぼすことである[41]。 |

| Cognitive control of behavior See also: Cognitive control Cognitive control is the intentional selection of thoughts, behaviors, and emotions, based on our environment. It has been shown that drugs alter the way our brains function, and its structure.[45][17] Cognitive functions such as learning, memory, and impulse control, are affected by drugs.[45] These effects promote drug use, as well as hinder the ability to abstain from it.[45] The increase in dopamine release is prominent in drug use, specifically in the ventral striatum and the nucleus accumbens.[45] Dopamine is responsible for producing pleasurable feelings, as well driving us to perform important life activities. Addictive drugs cause a significant increase in this reward system, causing a large increase in dopamine signaling as well as increase in reward-seeking behavior, in turn motivating drug use.[45][17] This promotes the development of a maladaptive drug to stimulus relationship.[46] Early drug use leads to these maladaptive associations, later affecting cognitive processes used for coping, which are needed to successfully abstain from them.[45][41] |

行動の認知制御 参照:認知制御 認知制御とは、私たちの環境に基づいて、思考、行動、感情を意図的に選択することである。薬物は、私たちの脳の機能や構造を変化させることが示されてい る。[45][17] 学習、記憶、衝動制御などの認知機能は、薬物の影響を受ける。[45] これらの影響は、薬物使用を促進するだけでなく、薬物使用を控える能力を妨げる。[45] 薬物使用では、ドーパミンの放出の増加が顕著で、特に腹側線条体および側坐核で顕著である。[45] ドーパミンは、快楽の感情を生み出すだけでなく、重要な生活活動を遂行する原動力ともなっている。依存性薬物は、この報酬系に著しい増加を引き起こし、 ドーパミン信号の増加および報酬追求行動の増加を引き起こし、その結果、薬物使用を動機付けます。[45][17] これは、不適応な薬物と刺激の関係の発達を促進する。[46] 早期の薬物使用は、これらの不適応な関連性を引き起こし、後に薬物使用を断つために必要な認知プロセスに影響を及ぼす。[45][41] |

| Risk factors Further information: Addiction vulnerability. A number of genetic and environmental risk factors exist for developing an addiction.[3][47] Genetic and environmental risk factors each account for roughly half of an individual's risk for developing an addiction;[3] the contribution from epigenetic risk factors to the total risk is unknown.[47] Even in individuals with a relatively low genetic risk, exposure to sufficiently high doses of an addictive drug for a long period of time (e.g., weeks–months) can result in an addiction.[3] Adverse childhood events are associated with negative health outcomes, such as substance use disorder. Childhood abuse or exposure to violent crime is related to developing a mood or anxiety disorder, as well as a substance dependence risk.[48] |

リスク要因 詳細情報:依存症の発症リスク 依存症を発症するリスク要因には、遺伝的要因と環境的要因がいくつかある。[3][47] 遺伝的要因と環境的要因は、それぞれ依存症を発症するリスクの約半分を占めている。[3] エピジェネティックなリスク要因が総リスクに与える影響は不明だ。[47] 遺伝的リスクが比較的低い個人でも、依存性薬物を長期間(数週間から数ヶ月など)にわたり高用量で摂取すると、依存症になる可能性がある。[3] 幼少期のトラウマ的な経験は、物質使用障害などの健康上の悪影響と関連している。幼少期の虐待や暴力犯罪への曝露は、気分障害や不安障害の発症、および物 質依存のリスクと関連している。[48] |

| Genetic factors Main articles: Epigenetics of cocaine addiction and Molecular and epigenetic mechanisms of alcoholism Further information: Alcoholism § Genetic variation, History of drinking, History of smoking, and Prevalence of tobacco use Genetic factors, along with socio-environmental (e.g., psychosocial) factors, have been established as significant contributors to addiction vulnerability.[3][47][49][12] Studies done on 350 hospitalized drug-dependent patients showed that over half met the criteria for alcohol abuse, with a role of familial factors being prevalent.[50] Genetic factors account for 40–60% of the risk factors for alcoholism.[51] Similar rates of heritability for other types of drug addiction have been indicated, specifically in genes that encode the Alpha5 Nicotinic Acetylcholine Receptor.[52] Knestler hypothesized in 1964 that a gene or group of genes might contribute to predisposition to addiction in several ways. For example, altered levels of a normal protein due to environmental factors may change the structure or functioning of specific brain neurons during development. These altered brain neurons could affect the susceptibility of an individual to an initial drug use experience. In support of this hypothesis, animal studies have shown that environmental factors such as stress can affect an animal's genetic expression.[52] In humans, twin studies into addiction have provided some of the highest-quality evidence of this link, with results finding that if one twin is affected by addiction, the other twin is likely to be as well, and to the same substance.[53] Further evidence of a genetic component is research findings from family studies which suggest that if one family member has a history of addiction, the chances of a relative or close family developing those same habits are much higher than one who has not been introduced to addiction at a young age.[54] The data implicating specific genes in the development of drug addiction is mixed for most genes. Many addiction studies that aim to identify specific genes focus on common variants with an allele frequency of greater than 5% in the general population. When associated with disease, these only confer a small amount of additional risk with an odds ratio of 1.1–1.3 percent; this has led to the development the rare variant hypothesis, which states that genes with low frequencies in the population (<1%) confer much greater additional risk in the development of the disease.[55] Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are used to examine genetic associations with dependence, addiction, and drug use.[49] These studies rarely identify genes from proteins previously described via animal knockout models and candidate gene analysis. Instead, large percentages of genes involved in processes such as cell adhesion are commonly identified. The important effects of endophenotypes are typically not capable of being captured by these methods. Genes identified in GWAS for drug addiction may be involved either in adjusting brain behavior before drug experiences, subsequent to them, or both.[56] |

遺伝的要因 主な記事:コカイン依存症のエピジェネティクス、アルコール依存症の分子およびエピジェネティックなメカニズム 詳細情報:アルコール依存症 § 遺伝的変異、飲酒の歴史、喫煙の歴史、およびタバコの使用の有病率 遺伝的要因は、社会環境的要因(例:心理社会的要因)と共に、依存症の脆弱性における重要な要因として確立されている。[3][47][49][12] 350人の入院中の薬物依存患者を対象とした研究では、過半数がアルコール乱用の基準を満たし、家族的要因が主要な役割を果たしていた。[50] 遺伝的要因は、アルコール依存症のリスク要因の40~60%を占める。[51] 他の種類の薬物依存症においても同様の遺伝率を示唆する報告があり、特にアルファ5ニコチン性アセチルコリン受容体をコードする遺伝子において指摘されて いる。[52] ケネストラーは1964年に、遺伝子または遺伝子群が依存症の素因に複数のメカニズムで寄与する可能性を提唱した。例えば、環境要因による正常なタンパク 質のレベル変化が、発達過程で特定の脳神経細胞の構造や機能を変える可能性がある。これらの変化した脳神経細胞は、個人が薬物使用を初めて経験した際の感 受性に影響を与える可能性がある。この仮説を支持する動物実験では、ストレスなどの環境要因が動物の遺伝子発現に影響を与えることが示されている。 [52] 人間における依存症に関する双生児研究は、この関連性を示す最も質の高い証拠の一部を提供しており、一方の双生児が依存症に罹患している場合、もう一方の 双生児も同様の依存症に罹患する可能性が高く、同じ物質に依存する傾向があることが示されている。[53] 遺伝的要因のさらなる証拠としては、家族研究による研究結果があり、家族の一員に依存症の病歴がある場合、その親戚や近親者が同じ習慣を発症する可能性 は、幼少期に依存症に接触したことがない人よりもはるかに高いことが示唆されている。[54] 薬物依存症の発症に関与する特定の遺伝子に関するデータは、ほとんどの遺伝子について混血のものである。特定の遺伝子を特定することを目的とした多くの依 存症研究は、一般人口でアレル頻度が5%を超える共通変異に焦点を当てている。これらの変異は疾患と関連する場合、オッズ比1.1~1.3%というわずか な追加リスクしか付与しない。これにより、人口における頻度が低い遺伝子(<1%)が疾患の発症に著しく高い追加リスクを付与するという「稀な変異 仮説」が提唱された。[55] ゲノムワイド関連研究(GWAS)は、依存症、依存症、薬物使用との遺伝的関連を調査するために使用されています。[49] これらの研究では、動物のノックアウトモデルや候補遺伝子解析で以前に同定されたタンパク質から遺伝子を同定することはほとんどありません。代わりに、細 胞接着などのプロセスに関与する遺伝子の大きな割合が一般的に同定されます。エンドフェノタイプの重要な効果は、これらの方法では通常捕捉できません。薬 物依存症に関するGWASで同定された遺伝子は、薬物経験前の脳の行動調整、経験後の調整、またはその両方に携わっている可能性があります。[56] |

| Environmental factors Environmental risk factors for addiction are the experiences of an individual during their lifetime that interact with the individual's genetic composition to increase or decrease his or her vulnerability to addiction.[3] For example, after the nationwide[where?] outbreak of COVID-19, more people quit (vs. started) smoking; and smokers, on average, reduced the quantity of cigarettes they consumed.[57] More generally, a number of different environmental factors have been implicated as risk factors for addiction, including various psychosocial stressors. The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and studies cite lack of parental supervision, the prevalence of peer substance use, substance availability, and poverty as risk factors for substance use among children and adolescents.[58][19] The brain disease model of addiction posits that an individual's exposure to an addictive drug is the most significant environmental risk factor for addiction.[59] Many researchers, including neuroscientists, indicate that the brain disease model presents a misleading, incomplete, and potentially detrimental explanation of addiction.[60] The psychoanalytic theory model defines addiction as a form of defense against feelings of hopelessness and helplessness as well as a symptom of failure to regulate powerful emotions related to adverse childhood experiences (ACEs), various forms of maltreatment and dysfunction experienced in childhood. In this case, the addictive substance provides brief but total relief and positive feelings of control.[41] The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has shown a strong dose–response relationship between ACEs and numerous health, social, and behavioral problems throughout a person's lifespan, including substance use disorder.[61] Children's neurological development can be permanently disrupted when they are chronically exposed to stressful events such as physical, emotional, or sexual abuse, physical or emotional neglect, witnessing violence in the household, or a parent being incarcerated or having a mental illness. As a result, the child's cognitive functioning or ability to cope with negative or disruptive emotions may be impaired. Over time, the child may adopt substance use as a coping mechanism or as a result of reduced impulse control, particularly during adolescence.[61][19][41] Vast amounts of children who experienced abuse have gone on to have some form of addiction in their adolescence or adult life.[62] This pathway towards addiction that is opened through stressful experiences during childhood can be avoided by a change in environmental factors throughout an individual's life and opportunities of professional help.[62] If one has friends or peers who engage in drug use favorably, the chances of them developing an addiction increases. Family conflict and home management is a cause for one to become engaged in drug use.[63] |

環境要因 依存症の環境的危険因子は、個人の生涯における経験であり、その個人の遺伝的構成と相互作用して、依存症への脆弱性を増減させるものです。[3] 例えば、全国的な[どこ?] COVID-19 の流行後、より多くの人々が喫煙をやめ(喫煙を始めた人よりも)、喫煙者は平均して喫煙量を減らしました。[57] より一般的には、さまざまな心理社会的ストレス要因など、多くの異なる環境要因が依存症の危険因子として挙げられています。国立薬物乱用研究所 (NIDA)および複数の研究では、親による監督の不十分さ、仲間による薬物使用の蔓延、薬物の入手容易さ、貧困などが、子供や青少年の薬物使用の危険因 子として挙げられています。[58][19] 依存症の脳疾患モデルは、個人が依存性物質に曝露することが、依存症の最も重要な環境的リスク要因であると主張しています。[59] 神経科学者を含む多くの研究者は、脳疾患モデルが依存症の誤解を招く、不完全で、潜在的に有害な説明を提供していると指摘しています。[60] 精神分析理論モデルは、依存症を絶望感や無力感に対する防御機制の一種であり、幼少期の逆境体験(ACEs)、幼少期に経験した様々な虐待や機能不全に関 連する強力な感情の調節失敗の症状と定義しています。この場合、依存性物質は、短時間の完全な安堵感と、コントロール感というポジティブな感情をもたらし ます[41]。米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)による「子供時代の不利な経験(ACE)研究」では、ACE と、物質使用障害を含む、人格の生涯にわたる数多くの健康、社会、行動の問題との間に、強い用量反応関係があることが示されています。[61] 子どもが身体的、感情的、または性的虐待、身体的または感情的な放置、家庭内暴力の目撃、親の収監や精神疾患など、慢性的なストレスfulな出来事への曝 露を受けると、神経発達に永久的な障害が生じる可能性があります。その結果、子どもの認知機能や、負の感情や混乱を招く感情に対処する能力が損なわれる可 能性があります。時間の経過とともに、子供は、特に思春期に、対処メカニズムとして、あるいは衝動制御の低下の結果として、薬物使用を採用する可能性があ る。[61][19][41] 虐待を経験した子供たちの多くは、思春期または成人期に何らかの依存症に陥っている。[62] 子供時代のストレスの多い経験によって開かれる依存症への道筋は、個人の生涯にわたる環境要因の変化や専門家の支援を受ける機会によって回避することがで きる。[62] 薬物使用を好意的に行う友人や同年代の仲間がいる場合、依存症を発症する可能性が高まる。家族間の衝突や家庭の管理は、薬物使用に巻き込まれる要因とな る。[63] |

| Social control theory Main article: Social control theory According to Travis Hirschi's social control theory, adolescents with stronger attachments to family, religious, academic, and other social institutions are less likely to engage in delinquent and maladaptive behavior such as drug use leading to addiction.[64] |

社会統制理論 主な記事:社会統制理論 トラヴィス・ハーシの社会統制理論によると、家族、宗教、学業、その他の社会制度との結びつきが強い青少年は、薬物使用による依存症などの非行や不適応行動に陥る可能性が低いとされている。[64] |

| Age Adolescence represents a period of increased vulnerability for developing an addiction.[65] In adolescence, the incentive-rewards systems in the brain mature well before the cognitive control center. This consequentially grants the incentive-rewards systems a disproportionate amount of power in the behavioral decision-making process. Therefore, adolescents are increasingly likely to act on their impulses and engage in risky, potentially addicting behavior before considering the consequences.[66] Not only are adolescents more likely to initiate and maintain drug use, but once addicted they are more resistant to treatment and more liable to relapse.[67][68] Most individuals are exposed to and use addictive drugs for the first time during their teenage years.[69] In the United States, there were just over 2.8 million new users of illicit drugs in 2013 (7,800 new users per day);[69] among them, 54.1% were under 18 years of age.[69] In 2011, there were approximately 20.6 million people in the United States over the age of 12 with an addiction.[70] Over 90% of those with an addiction began drinking, smoking or using illicit drugs before the age of 18.[70] |

年齢 思春期は、依存症を発症しやすい脆弱な時期です。[65] 思春期には、脳内の報酬系が認知制御中枢よりも早く成熟します。その結果、報酬系が行動の意思決定プロセスにおいて不釣り合いなほどの大きな影響力を持つ ようになります。そのため、思春期は衝動に従って行動し、結果を考慮する前にリスクの高い、依存症を引き起こす可能性のある行動に及ぶ可能性が高くなる。 [66] 思春期は薬物使用を開始し維持する可能性が高いだけでなく、依存症になった場合、治療への抵抗性が強く、再発のリスクも高い。[67][68] 大多数の個人が、思春期に初めて依存性薬物に曝露し、使用します。[69] アメリカ合衆国では、2013年に違法薬物の新規使用者数が280万人を超え(1日あたり7,800人);[69] そのうち54.1%が18歳未満でした。[69] 2011年には、アメリカ合衆国で12歳以上の依存症患者が約20.600 万人以上が依存症でした。[70] 依存症患者の 90%以上は、18 歳以前に飲酒、喫煙、違法薬物の使用を開始しています。[70] |

| Comorbid disorders Individuals with comorbid (i.e., co-occurring) mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) or post-traumatic stress disorder are more likely to develop substance use disorders.[71][72][73][19] The NIDA cites early aggressive behavior as a risk factor for substance use.[58] The National Bureau of Economic Research found that there is a "definite connection between mental illness and the use of addictive substances" and a majority of mental health patients participate in the use of these substances: 38% alcohol, 44% cocaine, and 40% cigarettes.[74] |

併存障害 うつ病、不安障害、注意欠陥多動性障害(ADHD)、心的外傷後ストレス障害(PTSD)などの精神疾患を併発(同時に発症)している人は、物質使用障害 を発症しやすい傾向がある[71][72][73][19]。NIDA は、物質使用の危険因子として、幼少期の攻撃的な行動を挙げている。[58] 米国国立経済研究局は、「精神疾患と依存性物質の使用には明確な関連性がある」こと、および精神疾患患者の大半がこれらの物質を使用している(アルコール 38%、コカイン 44%、タバコ 40%)ことを明らかにしている。[74] |

| Epigenetic Epigenetics is the study of stable phenotypic changes that do not involve alterations in the DNA sequence.[75] Illicit drug use has been found to cause epigenetic changes in DNA methylation, as well as chromatin remodeling.[76] The epigenetic state of chromatin may pose as a risk for the development of substance addictions.[76] It has been found that emotional stressors, as well as social adversities may lead to an initial epigenetic response, which causes an alteration to the reward-signalling pathways.[76] This change may predispose one to experience a positive response to drug use.[76] |

エピジェネティクス エピジェネティクスは、DNA シーケンスの変化を伴わない安定した表現型の変化を研究する学問です。[75] 違法薬物の使用は、DNA メチル化およびクロマチンリモデリングにおけるエピジェネティックな変化を引き起こすことがわかっています。[76] クロマチンのエピジェネティックな状態は、物質依存症の発症リスクとなる可能性があります。[76] 感情的なストレス要因や社会的逆境が、報酬信号経路の変容を引き起こす初期エピジェネティック反応を引き起こすことが判明しています。[76] この変化は、薬物使用に対するポジティブな反応を経験する傾向を高める可能性があります。[76] |

| Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance Main article: Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance Epigenetic genes and their products (e.g., proteins) are the key components through which environmental influences can affect the genes of an individual:[47] they serve as the mechanism responsible for transgenerational epigenetic inheritance, a phenomenon in which environmental influences on the genes of a parent can affect the associated traits and behavioral phenotypes of their offspring (e.g., behavioral responses to environmental stimuli).[47] In addiction, epigenetic mechanisms play a central role in the pathophysiology of the disease;[3] it has been noted that some of the alterations to the epigenome which arise through chronic exposure to addictive stimuli during an addiction can be transmitted across generations, in turn affecting the behavior of one's children (e.g., the child's behavioral responses to addictive drugs and natural rewards).[47][77] The general classes of epigenetic alterations that have been implicated in transgenerational epigenetic inheritance include DNA methylation, histone modifications, and downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs.[47] With respect to addiction, more research is needed to determine the specific heritable epigenetic alterations that arise from various forms of addiction in humans and the corresponding behavioral phenotypes from these epigenetic alterations that occur in human offspring.[47][77] Based on preclinical evidence from animal research, certain addiction-induced epigenetic alterations in rats can be transmitted from parent to offspring and produce behavioral phenotypes that decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[note 1][47] More generally, the heritable behavioral phenotypes that are derived from addiction-induced epigenetic alterations and transmitted from parent to offspring may serve to either increase or decrease the offspring's risk of developing an addiction.[47][77] |

世代間エピジェネティック遺伝 主な記事:世代間エピジェネティック遺伝 エピジェネティック遺伝子とその産物(タンパク質など)は、環境の影響が個人の遺伝子に影響を与えるための重要な要素です[47]。これらは、親遺伝子の 環境の影響が、その子孫の関連する形質や行動表現型(環境刺激に対する行動反応など)に影響を与える現象である、世代間エピジェネティック遺伝のメカニズ ムとして機能しています。[47] 依存症において、エピジェネティックなメカニズムは疾患の病態生理学において中心的な役割を果たしています;[3] 依存症の慢性的な依存刺激への曝露を通じて生じるエピゲノムの変異の一部が世代を超えて伝達され、その結果、子供の行動(例:依存性薬物や自然報酬に対す る子供の行動反応)に影響を与えることが指摘されています。[47][77] 世代間エピジェネティックな遺伝に関与するとされるエピジェネティックな変化の一般的な分類には、DNAメチル化、ヒストン修飾、マイクロRNAのダウン レギュレーションまたはアップレギュレーションが含まれます。[47] 依存症に関しては、人間におけるさまざまな依存症形態から生じる特定の遺伝可能なエピジェネティックな変化と、これらのエピジェネティックな変化が人間の 子供に及ぼす行動的表現型を特定するためのさらなる研究が必要です。[47][77] 動物研究の非臨床的証拠に基づき、ラットにおける特定の依存症誘発性エピジェネティックな変化は親から子孫に伝達され、子孫の依存症発症リスクを低下させ る行動表現型を引き起こすことが示されています。[note 1][47] より一般的には、依存症誘発性エピジェネティックな変化から派生し、親から子孫に伝達される遺伝可能な行動表現型は、子孫の依存症発症リスクを増加または 減少させる役割を果たす可能性があります。[47][77] |

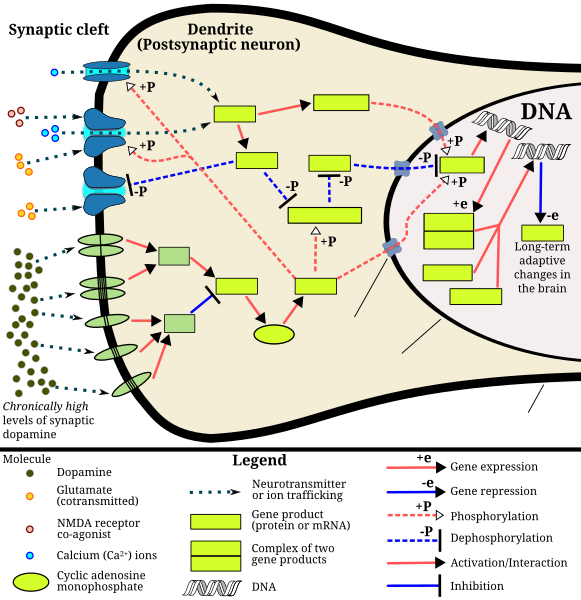

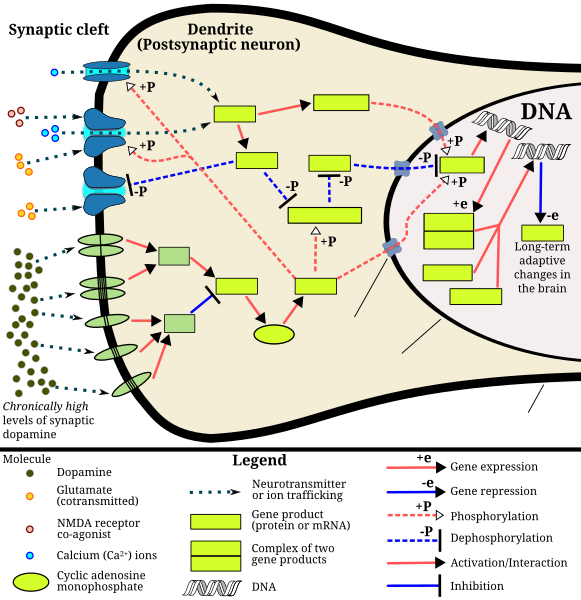

| Mechanisms Addiction is a disorder of the brain's reward system developing through transcriptional and epigenetic mechanisms as a result of chronically high levels of exposure to an addictive stimulus (e.g., eating food, the use of cocaine, engagement in sexual activity, participation in high-thrill cultural activities such as gambling, etc.) over extended time.[3][78][23] DeltaFosB (ΔFosB), a gene transcription factor, is a critical component and common factor in the development of virtually all forms of behavioral and drug addictions.[78][23][79][24] Two decades of research into ΔFosB's role in addiction have demonstrated that addiction arises, and the associated compulsive behavior intensifies or attenuates, along with the overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens.[3][78][23][79] Due to the causal relationship between ΔFosB expression and addictions, it is used preclinically as an addiction biomarker.[3][78][79] ΔFosB expression in these neurons directly and positively regulates drug self-administration and reward sensitization through positive reinforcement, while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][78] |

メカニズム 依存症は、依存性刺激(例えば、食事、コカインの使用、性行為、ギャンブルなどのスリルのある文化活動への参加など)に長期間にわたって慢性的に高レベル で曝露される結果、転写およびエピジェネティックなメカニズムを通じて脳の報酬系に障害が生じる疾患です。[3][78][23] DeltaFosB(ΔFosB)は、遺伝子転写因子であり、ほぼすべての形態の行動依存症と薬物依存症の発症において、重要な構成要素であり共通因子で す。[78][23][79][24] ΔFosBの依存症における役割に関する20年間の研究は、依存症の発症および関連する強迫的行動の増強または軽減が、腹側被蓋核のD1型中型有棘神経細 胞におけるΔFosBの発現過剰と連動して起こることを示しています。[3][78][23][79] ΔFosBの発現と依存症の因果関係から、ΔFosBは依存症のバイオマーカーとして前臨床的に利用されています。[3][78][79] これらの神経細胞におけるΔFosBの発現は、正の強化を通じて薬物自己投与と報酬感受性の増強を直接かつ正に調節し、嫌悪感の感受性を低下させます。 [note 2][3][78] |

| Chronic addictive drug use

causes alterations in gene expression in the mesocorticolimbic

projection.[24][87][88] The most important transcription factors that

produce these alterations are ΔFosB, cAMP response element binding

protein (CREB), and nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB).[24] ΔFosB is the

most significant biomolecular mechanism in addiction because the

overexpression of ΔFosB in the D1-type medium spiny neurons in the

nucleus accumbens is necessary and sufficient for many of the neural

adaptations and behavioral effects (e.g., expression-dependent

increases in drug self-administration and reward sensitization) seen in

drug addiction.[24] ΔFosB expression in nucleus accumbens D1-type

medium spiny neurons directly and positively regulates drug

self-administration and reward sensitization through positive

reinforcement while decreasing sensitivity to aversion.[note 2][3][78]

ΔFosB has been implicated in mediating addictions to many different

drugs and drug classes, including alcohol, amphetamine and other

substituted amphetamines, cannabinoids, cocaine, methylphenidate,

nicotine, opiates, phenylcyclidine, and propofol, among

others.[78][24][87][89][90] ΔJunD, a transcription factor, and G9a, a

histone methyltransferase, both oppose the function of ΔFosB and

inhibit increases in its expression.[3][24][91] Increases in nucleus

accumbens ΔJunD expression (via viral vector-mediated gene transfer) or

G9a expression (via pharmacological means) reduces, or with a large

increase can even block, many of the neural and behavioral alterations

that result from chronic high-dose use of addictive drugs (i.e., the

alterations mediated by ΔFosB).[79][24] ΔFosB plays an important role in regulating behavioral responses to natural rewards, such as palatable food, sex, and exercise.[24][92] Natural rewards, like drugs of abuse, induce gene expression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens, and chronic acquisition of these rewards can result in a similar pathological addictive state through ΔFosB overexpression.[23][24][92] Consequently, ΔFosB is the key transcription factor involved in addictions to natural rewards (i.e., behavioral addictions) as well;[24][23][92] in particular, ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is critical for the reinforcing effects of sexual reward.[92] Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess bidirectional cross-sensitization effects that are mediated through ΔFosB.[23][32][33] This phenomenon is notable since, in humans, a dopamine dysregulation syndrome, characterized by drug-induced compulsive engagement in natural rewards (specifically, sexual activity, shopping, and gambling), has been observed in some individuals taking dopaminergic medications.[23] ΔFosB inhibitors (drugs or treatments that oppose its action) may be an effective treatment for addiction and addictive disorders.[93] The release of dopamine in the nucleus accumbens plays a role in the reinforcing qualities of many forms of stimuli, including naturally reinforcing stimuli like palatable food and sex.[94][95][12] Altered dopamine neurotransmission is frequently observed following the development of an addictive state.[23][17] In humans and lab animals that have developed an addiction, alterations in dopamine or opioid neurotransmission in the nucleus accumbens and other parts of the striatum are evident.[23] Use of certain drugs (e.g., cocaine) affect cholinergic neurons that innervate the reward system, in turn affecting dopamine signaling in this region.[96] A recent study in Addiction reports that GLP-1 agonist medications, such as semaglutide, which are commonly used for diabetes and weight management, may also reduce the risk of overdose and alcohol intoxication in people with substance use disorders.[97] The study analyzed nearly nine years of health records from 1.3 million individuals across 136 U.S. hospitals, including 500,000 with opioid use disorder and over 800,000 with alcohol use disorder.[98] Researchers found that those who used Ozempic or similar medications had a 40% lower risk of opioid overdose and a 50% lower risk of alcohol intoxication compared to those not using these drugs. |

慢性的な薬物依存は、中脳皮質辺縁系投射における遺伝子発現の変化を引

き起こします。[24][87][88]

これらの変化を引き起こす最も重要な転写因子は、ΔFosB、cAMP応答要素結合タンパク質(CREB)、および核因子カッパB(NF-κB)です。

[24]

ΔFosBは、依存症における最も重要な生体分子メカニズムです。なぜなら、腹側被蓋核のD1型中型有棘神経細胞におけるΔFosBの過剰発現は、薬物依

存症で観察される多くの神経適応と行動効果(例えば、発現依存性の薬物自己投与の増加や報酬感受性の増強)に必要かつ十分だからです。[24]

ΔFosBの腹側被蓋核D1型中型棘細胞における発現は、正の強化を通じて薬物自己投与と報酬感受性増強を直接かつ正に調節し、嫌悪刺激に対する感受性を

低下させます。[注 2][3][78] ΔFosB

は、アルコール、アンフェタミンおよびその他の置換アンフェタミン、カンナビノイド、コカイン、メチルフェニデート、ニコチン、アヘン剤、フェニルシクリ

ジン、プロポフォールなど、多くの異なる薬物および薬物クラスへの依存を媒介に関与していることが示唆されている。[78][24][87][89]

[90]

転写因子であるΔJunDとヒストンメチル転移酵素であるG9aは、どちらもΔFosBの機能を阻害し、その発現増加を抑制する。[3][24][91]

ウイルスベクター媒介遺伝子導入による ΔJunD の発現増加または薬理学的手段による G9a の発現増加は、慢性高用量薬物使用(例えば

ΔFosB 介在の神経・行動変化)による多くの神経・行動変化を減少させ、または大幅な増加では完全に阻害する。[79][24] ΔFosBは、おいしい食べ物、性行為、運動などの自然報酬に対する行動反応の調節に重要な役割を果たしている。[24][92] 薬物乱用物質と同様に、自然報酬は腹側被蓋核におけるΔFosBの発現を誘導し、これらの報酬の慢性的な獲得は、ΔFosBの過剰発現を通じて同様の病理 学的依存状態を引き起こす可能性がある。[23][24][92] その結果、ΔFosB は、自然報酬(すなわち行動依存症)への依存にも関与する重要な転写因子である。[24][23][92] 特に、側坐核の ΔFosB は、性的報酬の強化効果に重要な役割を果たしている。[92] 自然報酬と薬物報酬の相互作用に関する研究は、ドーパミン作動性心理刺激薬(例:アンフェタミン)と性行動が、腹側被蓋核におけるΔFosBの発現を誘導 する類似の生物分子メカニズムを介し、ΔFosBを介した双方向の交差感受性効果を有することを示唆しています。[23][32][33] この現象は、人間において、ドーパミン調節障害症候群(薬物誘発性の自然報酬(具体的には性行為、買い物、ギャンブル)への強迫的な関与を特徴とする) が、ドーパミン作動薬を服用している一部の個人で観察されていることから、注目に値する。[23] ΔFosB阻害剤(その作用を阻害する薬剤や治療法)は、依存症および依存性障害の有効な治療法となる可能性がある。[93] 腹側被蓋核におけるドーパミンの放出は、おいしい食べ物や性行為のような自然に強化される刺激を含む、多くの刺激の強化特性に役割を果たしています。 [94][95][12] 依存状態の発達後に、ドーパミン神経伝達の異常が頻繁に観察されます。[23][17] 人間と実験動物で依存症を発症した個体では、腹側被蓋核や線条体他の部位におけるドーパミンやオピオイドの神経伝達に変化が認められる。[23] 特定の薬物(例:コカイン)の使用は、報酬系を支配するコリン作動性神経細胞に影響を及ぼし、その結果、この領域のドーパミンシグナル伝達に変化を引き起 こす。[96] Addiction 誌の最近の研究では、糖尿病や体重管理に一般的に使用されているセマグルチドなどの GLP-1 アゴニスト薬も、物質使用障害のある人々の過剰摂取やアルコール依存のリスクを軽減する可能性があることが報告されています。[97] この研究では、米国の 136 の病院における 130 万人(うち 50 万人はオピオイド使用障害、80 万人以上はアルコール使用障害)の 9 年間にわたる保健記録を分析した。[98] 研究者らは、オズエムピックまたは類似の薬剤を使用していた人は、これらの薬剤を使用していない人と比べて、オピオイド過剰摂取のリスクが40%低く、ア ルコール依存のリスクが50%低いことを発見した。 |

| Transcription factor glossary gene expression – the process by which information from a gene is used in the synthesis of a functional gene product such as a protein transcription – the process of making messenger RNA (mRNA) from a DNA template by RNA polymerase transcription factor – a protein that binds to DNA and regulates gene expression by promoting or suppressing transcription transcriptional regulation – controlling the rate of gene transcription for example by helping or hindering RNA polymerase binding to DNA upregulation, activation, or promotion – increase the rate of gene transcription downregulation, repression, or suppression – decrease the rate of gene transcription coactivator – a protein (or a small molecule) that works with transcription factors to increase the rate of gene transcription corepressor – a protein (or a small molecule) that works with transcription factors to decrease the rate of gene transcription response element – a specific sequence of DNA that a transcription factor binds to |

転写因子用語集 遺伝子発現 – 遺伝子から得た情報が、タンパク質などの機能的な遺伝子産物の合成に利用されるプロセス 転写 – DNAをテンプレートとしてRNAポリメラーゼによってメッセンジャーRNA(mRNA)を合成するプロセス 転写因子 – DNAに結合し、転写を促進または抑制することで遺伝子発現を調節するタンパク質 転写調節 – 例えばRNAポリメラーゼのDNAへの結合を助けるまたは妨げることで、遺伝子転写の速度を制御すること アップレギュレーション、活性化、または促進 – 遺伝子転写の速度を増加させる ダウンレギュレーション、抑制、または抑制 – 遺伝子転写の速度を減少させる コアクチベーター – 転写因子と協力して遺伝子転写の速度を増加させるタンパク質(または小分子) コアプレッサー – 転写因子と協力して遺伝子転写の速度を減少させるタンパク質(または小分子) 応答要素 – 転写因子が結合するDNAの特定の配列 |

Signaling cascade in the nucleus accumbens that results in psychostimulant addiction This diagram depicts the signaling events in the brain's reward center that are induced by chronic high-dose exposure to psychostimulants that increase the concentration of synaptic dopamine, like amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phenethylamine. Following presynaptic dopamine and glutamate co-release by such psychostimulants,[80][81] postsynaptic receptors for these neurotransmitters trigger internal signaling events through a cAMP-dependent pathway and a calcium-dependent pathway that ultimately result in increased CREB phosphorylation.[80][82][83] Phosphorylated CREB increases levels of ΔFosB, which in turn represses the c-Fos gene with the help of corepressors;[80][84][85] c-Fos repression acts as a molecular switch that enables the accumulation of ΔFosB in the neuron.[86] A highly stable (phosphorylated) form of ΔFosB, one that persists in neurons for 1–2 months, slowly accumulates following repeated high-dose exposure to stimulants through this process.[84][85] ΔFosB functions as "one of the master control proteins" that produces addiction-related structural changes in the brain, and upon sufficient accumulation, with the help of its downstream targets (e.g., nuclear factor kappa B), it induces an addictive state.[84][85] |

核内側前頭前野における精神刺激薬依存症を引き起こすシグナル伝達カスケード 「この図は、アンフェタミン、メタンフェタミン、フェネチルアミンなどの心理刺激薬による慢性的な高用量曝露により、脳の報酬系で誘発されるシグナル伝達 イベントを示している。このような心理刺激薬によるシナプス前ドーパミンとグルタメートの共放出後[80][81]、これらの神経伝達物質のシナプス後 受容体は、cAMP依存性経路とカルシウム依存性経路を通じて内部シグナル伝達イベントを誘発し、最終的にCREBのリン酸化増加を引き起こします。 [80][82][83] リン酸化されたCREBはΔFosBのレベルを増加させ、ΔFosBはコアプレッサーの助けを借りてc-Fos遺伝子の発現を抑制する;[80] [84][85] c-Fosの抑制は、神経細胞内でΔFosBの蓄積を可能にする分子スイッチとして機能する。[86] ΔFosBの高度に安定な(リン酸化された)形態は、刺激物質の反復高用量曝露を通じてこのプロセスを経て、神経細胞内で1~2ヶ月間持続し、徐々に蓄積 する。[84][85] ΔFosBは、脳における依存症関連構造変化を引き起こす「主要な制御タンパク質の一つ」として機能し、十分な蓄積量に達すると、下流の標的(例:核因子 カッパB)の助けを借りて依存状態を引き起こす。[84][85]」 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addiction |

This diagram depicts the signaling events in the brain's reward center that are induced by chronic high-dose exposure to psychostimulants that increase the concentration of synaptic dopamine, like amphetamine, methamphetamine, and phenethylamine. Following presynaptic dopamine and glutamate co-release by such psychostimulants,[80][81] postsynaptic receptors for these neurotransmitters trigger internal signaling events through a cAMP-dependent pathway and a calcium-dependent pathway that ultimately result in increased CREB phosphorylation.[80][82][83] Phosphorylated CREB increases levels of ΔFosB, which in turn represses the c-Fos gene with the help of corepressors;[80][84][85] c-Fos repression acts as a molecular switch that enables the accumulation of ΔFosB in the neuron.[86] A highly stable (phosphorylated) form of ΔFosB, one that persists in neurons for 1–2 months, slowly accumulates following repeated high-dose exposure to stimulants through this process.[84][85] ΔFosB functions as "one of the master control proteins" that produces addiction-related structural changes in the brain, and upon sufficient accumulation, with the help of its downstream targets (e.g., nuclear factor kappa B), it induces an addictive state.[84][85]

「この図は、アンフェタミン、メタンフェタミン、フェネチルアミンなどの心理刺激薬による慢性的な高用量曝露により、脳の報酬系で誘発されるシグナル伝達 イベントを示している。このような心理刺激薬によるシナプス前ドーパミンとグルタメートの共放出後[80][81]、これらの神経伝達物質のシナプス後 受容体は、cAMP依存性経路とカルシウム依存性経路を通じて内部シグナル伝達イベントを誘発し、最終的にCREBのリン酸化増加を引き起こします。 [80][82][83] リン酸化されたCREBはΔFosBのレベルを増加させ、ΔFosBはコアプレッサーの助けを借りてc-Fos遺伝子の発現を抑制する;[80] [84][85] c-Fosの抑制は、神経細胞内でΔFosBの蓄積を可能にする分子スイッチとして機能する。[86] ΔFosBの高度に安定な(リン酸化された)形態は、刺激物質の反復高用量曝露を通じてこのプロセスを経て、神経細胞内で1~2ヶ月間持続し、徐々に蓄積 する。[84][85] ΔFosBは、脳における依存症関連構造変化を引き起こす「主要な制御タンパク質の一つ」として機能し、十分な蓄積量に達すると、下流の標的(例:核因子 カッパB)の助けを借りて依存状態を引き起こす。[84][85]」

| Reward system Main article: Reward system Mesocorticolimbic pathway ΔFosB accumulation from excessive drug use ΔFosB accumulation graph Top: this depicts the initial effects of high dose exposure to an addictive drug on gene expression in the nucleus accumbens for various Fos family proteins (i.e., c-Fos, FosB, ΔFosB, Fra1, and Fra2). Bottom: this illustrates the progressive increase in ΔFosB expression in the nucleus accumbens following repeated twice daily drug binges, where these phosphorylated (35–37 kilodalton) ΔFosB isoforms persist in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens for up to 2 months.[85][99] Understanding the pathways in which drugs act and how drugs can alter those pathways is key when examining the biological basis of drug addiction. The reward pathway, known as the mesolimbic pathway,[17] or its extension, the mesocorticolimbic pathway, is characterized by the interaction of several areas of the brain. The projections from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) are a network of dopaminergic neurons with co-localized postsynaptic glutamate receptors (AMPAR and NMDAR). These cells respond when stimuli indicative of a reward are present.[12] The VTA supports learning and sensitization development and releases dopamine (DA) into the forebrain.[100] These neurons project and release DA into the nucleus accumbens,[101] through the mesolimbic pathway. Virtually all drugs causing drug addiction increase the DA release in the mesolimbic pathway.[102][17] The nucleus accumbens (NAcc) is one output of the VTA projections. The nucleus accumbens itself consists mainly of GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs).[103] The NAcc is associated with acquiring and eliciting conditioned behaviors, and is involved in the increased sensitivity to drugs as addiction progresses.[100][22] Overexpression of ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens is a necessary common factor in essentially all known forms of addiction;[3] ΔFosB is a strong positive modulator of positively reinforced behaviors.[3] The prefrontal cortex, including the anterior cingulate and orbitofrontal cortices,[104][22] is another VTA output in the mesocorticolimbic pathway; it is important for the integration of information which helps determine whether a behavior will be elicited.[105] It is critical for forming associations between the rewarding experience of drug use and cues in the environment. Importantly, these cues are strong mediators of drug-seeking behavior and can trigger relapse even after months or years of abstinence.[106][17] Other brain structures that are involved in addiction include: The basolateral amygdala projects into the NAcc and is thought to be important for motivation.[105] The hippocampus is involved in drug addiction, because of its role in learning and memory. Much of this evidence stems from investigations showing that manipulating cells in the hippocampus alters DA levels in NAcc and firing rates of VTA dopaminergic cells.[101] |

報酬システム メイン記事:報酬システム メソコルティコリムビック経路 過剰な薬物使用によるΔFosBの蓄積 ΔFosBの蓄積グラフ 上:これは、依存性薬物の高用量曝露が、腹側被蓋核におけるFosファミリータンパク質(c-Fos、FosB、ΔFosB、Fra1、Fra2など)の遺伝子発現に及ぼす初期の影響を示しています。 下:これは、1日2回の薬物乱用を繰り返した後に、腹側被蓋核におけるΔFosBの発現が徐々に増加する様子を示しています。これらのリン酸化された (35~37キロダルトン)ΔFosBアイソフォームは、腹側被蓋核のD1型中型有棘神経細胞に最大2ヶ月間持続します。[85][99] 薬物が作用する経路を理解し、薬物がそれらの経路をどのように変化させるかを理解することは、薬物依存の生物学的基盤を調査する際の鍵となる。報酬経路 (メソリムビック経路[17])またはその延長であるメソコルティコリムビック経路は、脳の複数の領域の相互作用によって特徴付けられる。 腹側被蓋野(VTA)からの投射は、共局在する後シナプスグルタミン酸受容体(AMPARとNMDAR)を有するドーパミン神経細胞のネットワークです。 これらの細胞は、報酬を示す刺激が存在すると反応します。[12] VTAは学習と感作の発達を支え、前脳にドーパミン(DA)を放出します。[100] これらの神経細胞は、メソリミビック経路を通じて核内側核(NAcc)に投射し、DAを放出します。[101] 薬物依存を引き起こすほぼすべての薬物は、メソリミビック経路におけるDAの放出を増大させます。[102][17] 腹側被蓋野(NAcc)は、VTAの投射の出力の一つです。NAcc自体は主にGABA作動性中型有棘神経細胞(MSN)から構成されています。 [103] NAccは条件付け行動の獲得と誘発に関与し、依存症の進行に伴い薬物に対する感受性が増加するプロセスにも関与しています。[100][22] 腹側被蓋核におけるΔFosBの過剰発現は、既知のほぼすべての依存症の必須の共通要因です。[3] ΔFosBは、正の強化を受けた行動の強力な正のモジュレーターです。[3] 前頭前皮質(前帯状皮質と眼窩前頭皮質を含む)[104][22]は、中脳皮質辺縁系経路におけるVTAのもう一つの出力部位であり、行動が誘発されるか どうかを決定する情報統合に重要です。[105] 薬物使用の報酬体験と環境の刺激との関連形成に不可欠です。重要なのは、これらの手がかりは薬物探索行動の強力な仲介因子であり、数ヶ月から数年もの禁断 期間を経ても再発を引き起こす可能性があることだ。[106][17] 依存症に関与するその他の脳構造には、次のようなものがある。 基底外側扁桃体は NAcc に投射し、動機付けに重要であると考えられている。[105] 海馬は、学習と記憶の役割から薬物依存に関与しています。この証拠の多くは、海馬の細胞を操作することでNAccのドーパミン(DA)濃度とVTAのドーパミン神経細胞の放電率が変化することを示す研究から得られています。[101] |

| Role of dopamine and glutamate Dopamine is the primary neurotransmitter of the reward system in the brain. It plays a role in regulating movement, emotion, cognition, motivation, and feelings of pleasure.[107] Natural rewards, like eating, as well as recreational drug use cause a release of dopamine, and are associated with the reinforcing nature of these stimuli.[107][108][12] Nearly all addictive drugs, directly or indirectly, act on the brain's reward system by heightening dopaminergic activity.[109][17] Excessive intake of many types of addictive drugs results in repeated release of high amounts of dopamine, which in turn affects the reward pathway directly through heightened dopamine receptor activation. Prolonged and abnormally high levels of dopamine in the synaptic cleft can induce receptor downregulation in the neural pathway. Downregulation of mesolimbic dopamine receptors can result in a decrease in the sensitivity to natural reinforcers.[107] Drug seeking behavior is induced by glutamatergic projections from the prefrontal cortex to the nucleus accumbens. This idea is supported with data from experiments showing that drug seeking behavior can be prevented following the inhibition of AMPA glutamate receptors and glutamate release in the nucleus accumbens.[104] |

ドーパミンとグルタミン酸の役割 ドーパミンは、脳内の報酬系の主要な神経伝達物質です。運動、感情、認知、動機付け、快楽の調節に役割を果たしています。[107] 食事のような自然な報酬や、娯楽目的の薬物使用はドーパミンの放出を引き起こし、これらの刺激の強化作用と関連しています。[107][108][12] ほぼすべての依存性薬物は、直接的または間接的に、ドーパミン系活動を高めることで脳の報酬系に作用します。[109][17] 多くの種類の依存性薬物の過剰摂取は、高濃度のドーパミンの反復放出を引き起こし、これがドーパミン受容体の活性化を強化することで報酬経路に直接影響を 及ぼします。シナプス間隙におけるドーパミンの持続的かつ異常な高濃度は、神経経路における受容体のダウンレギュレーションを引き起こす可能性がありま す。中脳辺縁系ドーパミン受容体のダウンレギュレーションは、自然報酬に対する感受性の低下を引き起こす可能性があります。[107] 薬物探索行動は、前頭前野から腹側被蓋核へのグルタミン酸系投射によって誘発されます。この考えは、腹側被蓋核におけるAMPAグルタミン酸受容体の阻害 とグルタミン酸の放出を抑制することで、薬物探索行動を防止できることを示す実験データによって支持されています。[104] |

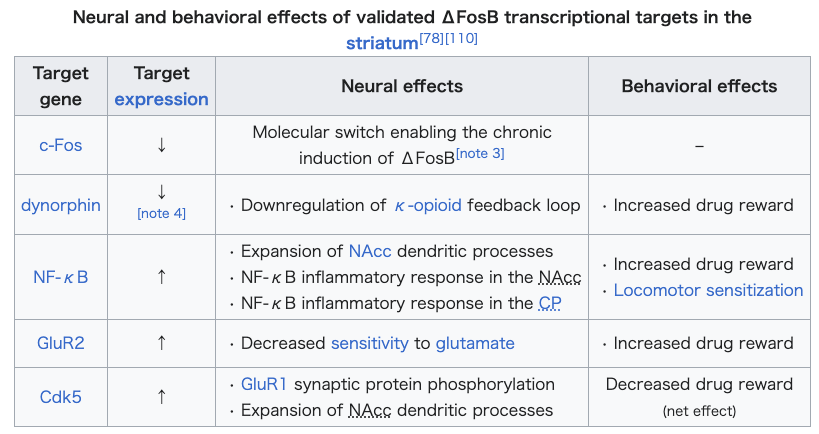

| Reward sensitization |

報酬感作 |

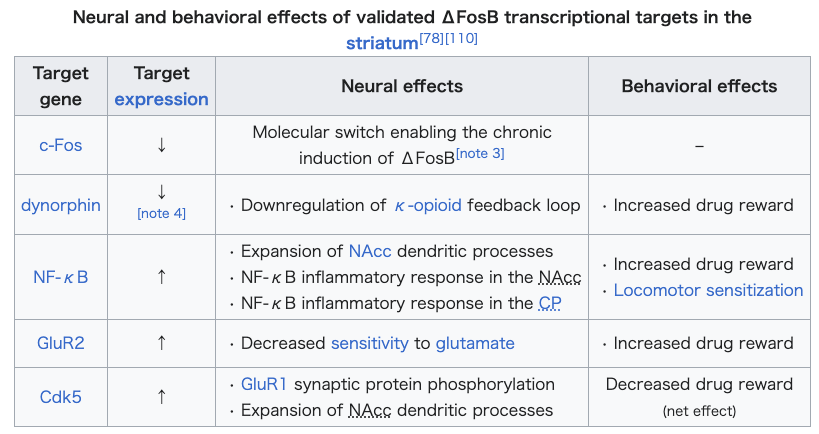

Neural and behavioral effects of validated ΔFosB transcriptional targets in the striatum[78][110] |

線条体における検証済みのΔFosB転写標的の神経および行動への影響[78][110] |

| Reward sensitization is a

process that causes an increase in the amount of reward (specifically,

incentive salience[note 5]) that is assigned by the brain to a

rewarding stimulus (e.g., a drug). In simple terms, when reward

sensitization to a specific stimulus (e.g., a drug) occurs, an

individual's "wanting" or desire for the stimulus itself and its

associated cues increases.[112][111][113] Reward sensitization normally

occurs following chronically high levels of exposure to the

stimulus.[17] ΔFosB expression in D1-type medium spiny neurons in the

nucleus accumbens has been shown to directly and positively regulate

reward sensitization involving drugs and natural rewards.[3][78][79] "Cue-induced wanting" or "cue-triggered wanting", a form of craving that occurs in addiction, is responsible for most of the compulsive behavior that people with addictions exhibit.[111][113] During the development of an addiction, the repeated association of otherwise neutral and even non-rewarding stimuli with drug consumption triggers an associative learning process that causes these previously neutral stimuli to act as conditioned positive reinforcers of addictive drug use (i.e., these stimuli start to function as drug cues).[111][114][113] As conditioned positive reinforcers of drug use, these previously neutral stimuli are assigned incentive salience (which manifests as a craving) – sometimes at pathologically high levels due to reward sensitization – which can transfer to the primary reinforcer (e.g., the use of an addictive drug) with which it was originally paired.[111][114][113] Research on the interaction between natural and drug rewards suggests that dopaminergic psychostimulants (e.g., amphetamine) and sexual behavior act on similar biomolecular mechanisms to induce ΔFosB in the nucleus accumbens and possess a bidirectional reward cross-sensitization effect[note 6] that is mediated through ΔFosB.[23][32][33] In contrast to ΔFosB's reward-sensitizing effect, CREB transcriptional activity decreases user's sensitivity to the rewarding effects of the substance. CREB transcription in the nucleus accumbens is implicated in psychological dependence and symptoms involving a lack of pleasure or motivation during drug withdrawal.[3][99][110] Summary of addiction-related plasticity  Neurochemical plasticity, Mesocorticolimbic synaptic plasticity  |

報酬感受性増強は、脳が報酬刺激(例えば薬物)に付与する報酬の量(具

体的には、報酬の誘因性[注5])が増加するプロセスです。単純に言うと、特定の刺激(例えば薬物)に対する報酬感受性増強が発生すると、その刺激自体と

その関連する手がかりに対する個人の「欲求」や欲望が増加します。[112][111][113]

報酬感受性増強は、通常、刺激への慢性的な高レベルの曝露後に発生します。[17]

腹側被蓋核のD1型中型有棘神経細胞におけるΔFosBの発現は、薬物と自然報酬に関連する報酬感受性増強を直接かつ正に調節することが示されています。

[3][78][79] 「キュー誘発欲求」または「キュー誘発欲求」は、依存症で生じる一種の渇望であり、依存症の人々が示す強迫的な行動のほとんどの原因となっている。 [111][113] 依存症の発達过程中、本来中立的で報酬を伴わない刺激と薬物摂取の反復的な関連付けは、関連学習プロセスを引き起こし、これらの以前は中立的だった刺激が 依存性薬物使用の条件付けされた正の強化因子として機能し始める(つまり、これらの刺激が薬物キューとして機能し始める)。[111][114] [113] 薬物使用の条件付けられた正の強化因子として、これらの以前は中立的な刺激はインセンティブ・サリエンシー(渇望として現れる)を付与される – 報酬感作により病理学的に高いレベルに達することもある – これが、当初ペアリングされていた一次強化因子(例:依存性薬物の使用)に移行する可能性がある。[111][114][113] 自然報酬と薬物報酬の相互作用に関する研究は、ドーパミン作動性心理刺激薬(例:アンフェタミン)と性行動が、腹側被蓋核におけるΔFosBの発現を誘導 する類似の生物分子メカニズムを介し、ΔFosBを介した双方向の報酬交差感受性効果[注6]を有することを示唆している。[23][32][33] ΔFosBの報酬感受性増強効果とは対照的に、CREBの転写活性は、物質の報酬効果に対する感受性を低下させる。腹側被蓋核におけるCREBの転写は、 薬物離脱時の快楽や動機付けの欠如に関連する心理的依存と症状に関与している。[3][99][110] 依存症に関連する可塑性の概要  神経化学的可塑性、中皮質辺縁系シナプス可塑性  |

| Neuroepigenetic mechanisms Further information: Neuroepigenetics and Chromatin remodeling Altered epigenetic regulation of gene expression within the brain's reward system plays a significant and complex role in the development of drug addiction.[91][115] Addictive drugs are associated with three types of epigenetic modifications within neurons.[91] These are (1) histone modifications, (2) epigenetic methylation of DNA at CpG sites at (or adjacent to) particular genes, and (3) epigenetic downregulation or upregulation of microRNAs which have particular target genes.[91][24][115] As an example, while hundreds of genes in the cells of the nucleus accumbens (NAc) exhibit histone modifications following drug exposure – particularly, altered acetylation and methylation states of histone residues[115] – most other genes in the NAc cells do not show such changes.[91] |

神経エピジェネティクス機構 詳細情報:神経エピジェネティクスとクロマチンリモデルリング 脳内の報酬系における遺伝子発現のエピジェネティックな調節の異常は、薬 物依存症の発症に重要な複雑な役割を果たしている。[91][115] 依存性薬物は、ニューロン内の 3 種類のエピジェネティックな変化と関連している。[91] これらは (1) ヒストン修飾、(2) 特定の遺伝子(またはその隣接部位)の CpG 部位における DNA のエピジェネティックなメチル化、および (3) 特定の標的遺伝子を持つマイクロ RNA のエピジェネティックなダウンレギュレーションまたはアップレギュレーションである。[91][24][115] 例えば、核内側前頭前皮質(NAc)の細胞では、薬物曝露後に数百の遺伝子がヒストン修飾(特に、ヒストン残基のアセチル化およびメチル化の状態の変化 [115])を示すが、NAc 細胞内の他のほとんどの遺伝子ではそのような変化は見られない。[91] |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addiction |

★Gateway Drug Hypothesis(ゲートウェイドラッグ仮説)

Gateway Drug Hypothesis(ゲートウェイドラッグ仮説)

概要

Gateway Drug Hypothesisは、特定の薬物(ゲートウェイドラッグ)が、より強力な薬物(ハードドラッグ)への使用を促進する可能性があるという理論です。この仮説は、特に若者の間でのドラッグ使用のパターンを理解するために重要です。

主なポイント

定義:

ゲートウェイドラッグとは、アルコール、タバコ、マリファナなど、比較的軽い薬物を指します。これらの薬物の使用が、より危険な薬物(例:コカイン、ヘロイン)への移行を引き起こす可能性があるとされています。

メカニズム:

初めての薬物使用が、依存症や薬物への興味を高めることがあります。この初期の経験が、より強力な薬物に対する好奇心を引き起こすと考えられています。

研究結果:

多くの研究が、若者がゲートウェイドラッグを使用することで、後にハードドラッグを使用するリスクが高まることを示しています。ただし、この仮説には異論もあり、すべての使用者が必ずしもハードドラッグに進むわけではないことも指摘されています。

批判:

一部の専門家は、ゲートウェイドラッグ仮説が薬物使用の原因を単純化しすぎていると主張しています。個人の背景、環境、心理的要因など、他の要因も重要です。

予防策:

この仮説に基づいて、教育プログラムや政策が展開され、軽い薬物の使用を防ぐことで、より重い薬物への移行を防ぐことを目指しています。

結論

Gateway Drug Hypothesisは、薬物依存症の理解において重要な理論ですが、個々のケースは多様であり、他の要因も考慮する必要があります。この仮説を基にした予防策は、特に若者に対して有効であるとされています。

Gateway Drug Hypothesis を解説したHPはありますか?

Monica

Gateway Drug Hypothesisに関する情報を提供しているウェブサイトはいくつかあります。以下は、信頼性の高い情報源を含むいくつかの例です。

参考ウェブサイト

国立薬物乱用研究所 (NIDA)

URL: nida.nih.gov

概要: 薬物乱用に関する研究や教育資料を提供しており、ゲートウェイドラッグ仮説についても触れています。

アメリカ精神医学会 (APA)

URL: psychiatry.org

概要: 精神的健康と薬物使用に関する情報が掲載されており、ゲートウェイドラッグに関する研究の概要もあります。

メイヨークリニック (Mayo Clinic)

URL: mayoclinic.org

概要: 薬物依存症に関する情報が豊富で、ゲートウェイドラッグについての解説も含まれています。

世界保健機関 (WHO)

URL: who.int

概要: 健康に関する広範な情報を提供しており、薬物使用に関する国際的な視点を持っています。

検索のヒント

これらのウェブサイトで「Gateway Drug Hypothesis」や「ゲートウェイドラッグ仮説」というキーワードで検索すると、関連する情報を見つけやすくなります。また、学術論文やレビュー記事も参考にすると、より深い理解が得られるでしょう。

★診断

| Diagnosis Further information: Substance use disorder § Diagnosis, and Problem gambling § Diagnosis Classification DSM-5 The fifth edition of the DSM uses the term substance use disorder to refer to a spectrum of drug use-related disorders. The DSM-5 eliminates the terms abuse and dependence from diagnostic categories, instead using the specifiers of mild, moderate and severe to indicate the extent of disordered use. These specifiers are determined by the number of diagnostic criteria present in a given case. In the DSM-5, the term drug addiction is synonymous with severe substance use disorder.[116][15] The DSM-5 introduced a new diagnostic category for behavioral addictions. Problem gambling is the only condition included in this category in the fifth edition.[117] Internet gaming disorder is listed as a "condition requiring further study" in the DSM-5.[118] Past editions have used physical dependence and the associated withdrawal syndrome to identify an addictive state. Physical dependence occurs when the body has adjusted by incorporating the substance into its "normal" functioning – i.e., attains homeostasis – and therefore physical withdrawal symptoms occur on cessation of use.[119] Tolerance is the process by which the body continually adapts to the substance and requires increasingly larger amounts to achieve the original effects. Withdrawal refers to physical and psychological symptoms experienced when reducing or discontinuing a substance that the body has become dependent on. Symptoms of withdrawal generally include but are not limited to body aches, anxiety, irritability, intense cravings for the substance, dysphoria, nausea, hallucinations, headaches, cold sweats, tremors, and seizures. During acute physical opioid withdrawal, symptoms of restless legs syndrome are common and may be profound. This phenomenon originated the idiom "kicking the habit". Medical researchers who actively study addiction have criticized the DSM classification of addiction for being flawed and involving arbitrary diagnostic criteria.[120] |

診断 詳細情報:物質使用障害 § 診断、および問題ギャンブル § 診断 分類 DSM-5 DSM の第 5 版では、物質使用障害という用語を使用して、薬物使用に関連する一連の障害を指しています。DSM-5 では、診断カテゴリーから「乱用」および「依存」という用語が削除され、その代わりに、障害の使用の程度を示すために「軽度」、「中等度」、「重度」とい う指定語が使用されています。これらの指定は、特定の症例に存在する診断基準の数によって決定される。DSM-5 では、「薬物依存症」という用語は「重度物質使用障害」と同義である。[116][15] DSM-5では、行動依存症の新しい診断カテゴリーが導入された。第5版では、このカテゴリーに問題ギャンブルのみが含まれている。[117] インターネットゲーム障害は、DSM-5で「さらに研究が必要な状態」として記載されている。[118] 過去の版では、身体的依存と関連する離脱症候群を用いて依存状態を特定していました。身体的依存は、身体が物質を「正常な」機能に取り込み、恒常性を維持 する状態に達した際に生じ、使用を中止すると身体的離脱症状が現れます。[119] 耐性は、身体が物質に継続的に適応し、元の効果を得るために徐々に量を増やす必要があるプロセスです。離脱とは、身体が依存している物質の使用を減少また は中止した際に経験する身体的および心理的な症状を指す。離脱症状には、身体の痛み、不安、 irritability、物質への強い渇望、dysphoria、吐き気、幻覚、頭痛、冷汗、震え、けいれんなどが含まれるが、これらに限定されない。 急性身体的オピオイド離脱症状では、むずむず脚症候群の症状がよく見られ、その程度は深刻になることがあります。この現象は「習慣を断つ」という慣用句の 由来となっています。 依存症を積極的に研究している医学研究者は、DSM の依存症分類が欠陥があり、恣意的な診断基準を含んでいると批判しています。[120] |

| ICD-11 The eleventh revision of the International Classification of Diseases, commonly referred to as ICD-11, conceptualizes diagnosis somewhat differently. ICD-11 first distinguishes between problems with psychoactive substance use ("Disorders due to substance use") and behavioral addictions ("Disorders due to addictive behaviours").[121] With regard to psychoactive substances, ICD-11 explains that the included substances initially produce "pleasant or appealing psychoactive effects that are rewarding and reinforcing with repeated use, [but] with continued use, many of the included substances have the capacity to produce dependence. They have the potential to cause numerous forms of harm, both to mental and physical health."[122] Instead of the DSM-5 approach of one diagnosis ("Substance Use Disorder") covering all types of problematic substance use, ICD-11 offers three diagnostic possibilities: 1) Episode of Harmful Psychoactive Substance Use, 2) Harmful Pattern of Psychoactive Substance Use, and 3) Substance Dependence.[122] |

ICD-11(国際疾病分類) ICD-11 として一般に知られる国際疾病分類の第 11 版では、診断の概念が多少異なっており、精神活性物質の使用に関する問題(「物質使用による障害」)と行動依存(「依存性行動による障害」)が最初に区別 されている。ICD-11ではまず、精神活性物質の使用に関する問題(「物質使用障害」)と行動依存症(「依存性行動障害」)を区別している。[121] 精神活性物質に関しては、ICD-11では、対象物質は当初「快楽や魅力のある精神作用をもたらし、反復使用により報酬的・強化的効果をもたらすが、継続 使用により、多くの対象物質は依存症を引き起こす可能性がある」と説明している。これらは、精神的および身体的健康の両方にさまざまな害をもたらす可能性 がある」と説明している。[122] DSM-5 では、あらゆる種類の問題のある物質使用を 1 つの診断(「物質使用障害」)で網羅しているが、ICD-11 では 3 つの診断の可能性を提示している。1) 有害な精神活性物質使用エピソード、2) 有害な精神活性物質使用パターン、および3) 物質依存。[122] |

| Screening and assessment Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment The Addictions Neuroclinical Assessment is used to diagnose addiction disorders. This tool measures three different domains: executive function, incentive salience, and negative emotionality.[123][124] Executive functioning consists of processes that would be disrupted in addiction.[124] In the context of addiction, incentive salience determines how one perceives the addictive substance.[124] Increased negative emotional responses have been found with individuals with addictions.[124] Tobacco, Alcohol, Prescription Medication, and Other Substance Use (TAPS) This is a screening and assessment tool in one, assessing commonly used substances. This tool allows for a simple diagnosis, eliminating the need for several screening and assessment tools, as it includes both TAPS-1 and TAPS-2, screening and assessment tools respectively. The screening component asks about the frequency of use of the specific substance (tobacco, alcohol, prescription medication, and other).[125] If an individual screens positive, the second component will begin. This dictates the risk level of the substance.[125] |

スクリーニングと評価 依存症神経臨床評価 依存症神経臨床評価は、依存症障害の診断に使用されます。このツールは、実行機能、動機付けの顕著性、および負の感情という 3 つの異なる領域を測定します。[123][124] 実行機能は、依存症で障害を受けるプロセスで構成されています。[124] 依存症の場合、動機付けの顕著性は、依存性物質をどのように認識するかを決定します。[124] 依存症の人では、負の感情的反応の増加が見られます。[124] タバコ、アルコール、処方薬、その他の物質使用 (TAPS) これは、一般的に使用される物質を評価する、スクリーニングと評価の 2 つの機能を 1 つにまとめたツールです。このツールは、スクリーニングツールである TAPS-1 と評価ツールである TAPS-2 の両方を備えているため、複数のスクリーニングおよび評価ツールを使用する必要がなく、簡単な診断が可能です。スクリーニングの要素では、特定の物質(タ バコ、アルコール、処方薬、その他)の使用頻度を尋ねます。[125] スクリーニングで陽性反応が出た場合、2つ目の要素に進みます。これにより、物質のリスクレベルが判定されます。[125] |

| CRAFFT The CRAFFT (Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble) is a screening tool that is used in medical centers. The CRAFFT is in version 2.1 and has a version for nicotine and tobacco use called the CRAFFT 2.1+N.[126] This tool is used to identify substance use, substance related driving risk, and addictions among adolescents. This tool uses a set of questions for different scenarios.[127] In the case of a specific combination of answers, different question sets can be used to yield a more accurate answer. After the questions, the DSM-5 criteria are used to identify the likelihood of the person having substance use disorder.[127] After these tests are done, the clinician is to give the "5 RS" of brief counseling. The five Rs of brief counseling includes:[127] REVIEW screening results RECOMMEND to not use RIDING/DRIVING risk counseling RESPONSE: elicit self-motivational statements REINFORCE self-efficacy |

CRAFFT CRAFFT(Car-Relax-Alone-Forget-Family and Friends-Trouble)は、医療センターで使用されているスクリーニングツールだ。CRAFFT はバージョン 2.1 で、ニコチンおよびタバコの使用に関するバージョンである CRAFFT 2.1+N がある。[126] このツールは、青少年の物質使用、物質に関連する運転リスク、および依存症を識別するために使用される。このツールは、さまざまなシナリオに対する一連の 質問を使用している。[127] 特定の回答の組み合わせの場合、より正確な回答を得るために、異なる質問セットを使用することができる。質問の後、DSM-5 の基準を用いて、その人物が物質使用障害である可能性を判断する。[127] これらの検査が完了した後、臨床医は「5 RS」という簡単なカウンセリングを行う。 簡略化されたカウンセリングの「5つのR」には、以下の内容が含まれる。[127] REVIEW(スクリーニング結果の確認) RECOMMEND(使用しないよう推奨) RIDING/DRIVING(運転リスクに関するカウンセリング) RESPONSE(自己動機付けの表明を引き出す) REINFORCE(自己効力感を強化する) |

| Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST-10) The Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) is a self-reporting tool that measures problematic substance use.[128] Responses to this test are recorded as yes or no answers, and scored as a number between zero and 28. Drug abuse or dependence, are indicated by a cut off score of 6.[128] Three versions of this screening tool are in use: DAST-28, DAST-20, and DAST-10. Each of these instruments are copyrighted by Dr. Harvey A. Skinner.[128] Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) The Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Test (ASSIST) is an interview-based questionnaire consisting of eight questions developed by the WHO.[129] The questions ask about lifetime use; frequency of use; urge to use; frequency of health, financial, social, or legal problems related to use; failure to perform duties; if anyone has raised concerns over use; attempts to limit or moderate use; and use by injection.[130] |

薬物乱用スクリーニングテスト(DAST-10) 薬物乱用スクリーニングテスト(DAST)は、問題のある物質使用を測定する自己報告式ツールです。[128] このテストの回答は「はい」または「いいえ」で記録され、0 から 28 までの点数で評価されます。薬物乱用または依存は、カットオフスコア 6 で示される。[128] このスクリーニングツールには、DAST-28、DAST-20、DAST-10 の 3 つのバージョンがある。これらの各ツールは、ハーヴェイ・A・スキナー博士によって著作権が保護されている。[128] アルコール、喫煙、薬物使用関与テスト(ASSIST) アルコール、喫煙、薬物使用に関する質問票(ASSIST)は、WHO が開発した 8 問の質問からなる面接形式の質問票だ。[129] 質問は、生涯の使用経験、使用頻度、使用への衝動、使用に関連する健康、経済、社会、法律上の問題の発生頻度、職務の遂行不能、使用について誰かが懸念を 表明したかどうか、使用を制限または節度ある使用を試みたかどうか、注射による使用の有無について尋ねている。[130] |

| Prevention Main articles: Harm reduction and Preventive healthcare |

予防(→依存症の予防と歴史) 主な記事:ハームリダクション、予防医療 |

| Autonomic nervous system Binge drinking Binge eating disorder Cognitive liberty Darwinian hedonism Discrimination against drug addicts Dopaminergic pathways Pavlovian-instrumental transfer Philosophy of medicine Substance dependence |

自律神経系 過度の飲酒 過食症 認知の自由 ダーウィニアン快楽主義 薬物依存者に対する差別 ドーパミン作動経路 パブロフの道具的転移 医学哲学 物質依存 |

| Further reading Pelchat ML (March 2009). "Food Addiction in Humans". The Journal of Nutrition. 139 (3): 620–622. doi:10.3945/jn.108.097816. PMID 19176747. Gordon HW (April 2016). "Laterality of Brain Activation for Risk Factors of Addiction". Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 9 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2174/1874473709666151217121309. PMC 4811731. PMID 26674074. Szalavitz M (2016). Unbroken Brain. St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-05582-8. Courtwright DT (2019). The Age of Addiction: How Bad Habits Became Big Business. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674248229. |

さらに読む Pelchat ML (2009年3月). 「ヒトにおける食物依存症」. The Journal of Nutrition. 139 (3): 620–622. doi:10.3945/jn.108.097816. PMID 19176747. Gordon HW (2016年4月). 「依存症の危険因子に関する脳活動の左右差」. Current Drug Abuse Reviews. 9 (1): 1–18. doi:10.2174/1874473709666151217121309. PMC 4811731. PMID 26674074. Szalavitz M (2016). Unbroken Brain. セント・マーティンズ・プレス。ISBN 978-1-250-05582-8。 Courtwright DT (2019). The Age of Addiction: How Bad Habits Became Big Business. マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: ハーバード大学出版局。ISBN 9780674248229。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Addiction |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099