アクターネットワークセオリー

Actor Network Theory,

ANT

☆ アク ター・ネットワーク理論(ANT) とは、社会理論における理論的・方法論的アプローチであり、社会世界や自然界に存在するあらゆるものは、常に変化す る関係性のネットワーク(R)の中に存在しているとする。そのような関係の外には何も存在しないと仮定する。社会的状況に関与するすべての要因は同じレベ ルにあ り、したがって、ネットワーク参加者が現在どのように相互作用しているかを超える外部の社会的力は存在しない。したがって、モノ、アイデア、プロセス、そ の他関連するあらゆる要因は、社会状況を作り出す上で人間と同様に重要であると見なされる(→「ネットーワーク」「リゾーム(哲学)」「ミンスキー『こころの社会』」「アクターネットワークの結節点としての《宗教》」「解釈学」「詩学」)。

| アクター/アクタント (Actor/Actant) | 行為者(actant)とは、行為するもの、または他者から活動を与え

られるものである。アクター(行為者)とは、行為するもの、あるいは他者から活動を

与えられるもののことであり、人間個人の動機づけや人間一般の動機づけを意味するものではない。アクタントは、行動の源であることが認められれば、文字通

り何でもあり得る[7]。別の言葉で言えば、この状況においてアクターとは、物事を行うあらゆる存在と見なされる。例えば、「パスツール・ネットワーク」

において、微生物は不活性ではなく、滅菌されていない物質を発酵させる一方で、滅菌された物質には影響を与えない。もし彼らが他の行動を取ったとしたら、

つまりパスツールに協力しなかったとしたら、(少なくともパスツールの意図に従って)行動を起こさなかったとしたら、パスツールの話は少し違ってくるかも

しれない。ラトゥールが微生物を行為者と呼ぶことができるのは、このような意味においてである[7]。 ANTの枠組みの下では、一般化された対称性の原則[8]により、ネットワークを考える前に、すべての実体が同じ用語で記述されなければならない。実体間 の違いは関係のネットワークの中で生じるものであり、ネットワークが適用される前には存在しない。 |

| 人間の行為者・ヒューマンアクター(Human actors) | 通常、人間とは人間とその人間的行動を指す。 |

| 非人間的アクター・ノンヒューマンアクター(Nonhuman

actors) |

伝統的に、非人間的な主体は、植物、動物、地質学、自然力、および芸術

や言語の人間の集団的な創造を含む生き物である[9]。ANTでは、非人間的な主体

は、モノ、物体、動物、自然現象、物質的構造、輸送装置、テキスト、および経済財を含む複数の主体をカバーする。しかし、非人間的な行為者は、人間、超自

然的存在、自然界における他の象徴的対象などの実体を対象としていない[10]。 |

| アクター-ネットワーク(Actor-Network) |

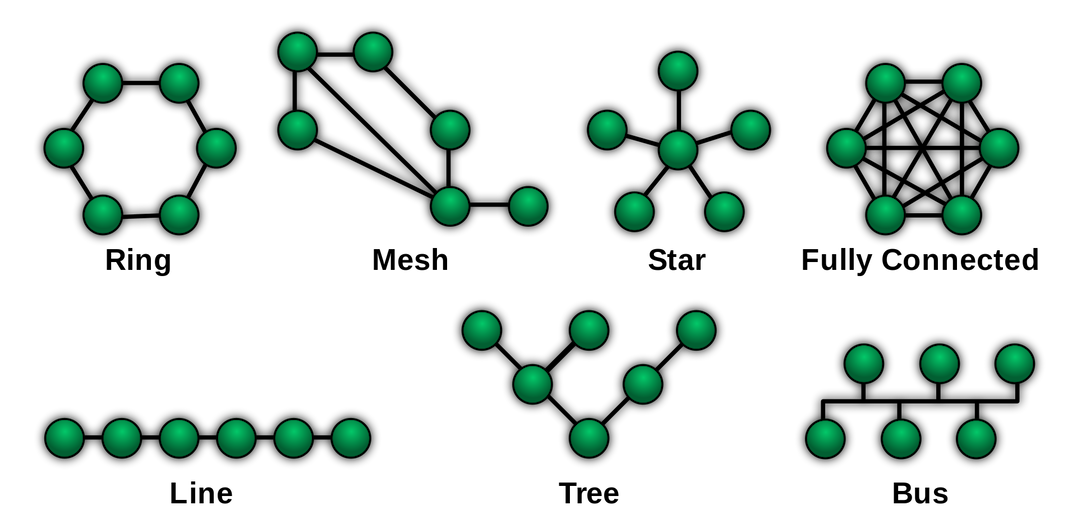

この用語が意味するように、行為者-ネットワークはANTの中心的概念

である。ネットワーク」という用語は、ラトゥール[1][11][12]が指摘する

ように、多くの好ましくない意味合いを持つという点でやや問題がある。第一に、この用語は、説明されるものがネットワークの形をとることを意味するが、そ

れは必ずしもそうではない。第二に、それは「変形を伴わない輸送」を意味するが、ANTにおいては、どのような行為者-ネットワークも膨大な数の翻訳を含

むため、それは不可能である。しかし、ラトゥール[12]は、「ネットワークは先験的な秩序関係を持たず、社会のトップとボトムという公理的な神話に縛ら

れることもなく、特定の場所がマクロであるかミクロであるかという仮定をまったく持たず、要素「a」や要素「b」を研究するための道具を修正することもな

い」ため、ネットワークという用語は使用するのにふさわしいと主張している。この「ネットワーク」という言葉の使い方は、ドゥルーズとガタリのリゾームと

非常によく似ている。ラトゥール[11]は、響きさえよければANTを「アクター・リゾーム存在論」と改名することに異論はないと皮肉さえ述べているが、

これはラトゥールが「理論」という言葉に不安を抱いていることを示唆している。 アクター・ネットワーク理論は、物質的-記号論的ネットワークがどのように組み合わさって全体として作用するかを説明しようとするものである。意味の創造 に関わるアクターのクラスターは、物質的であると同時に記号論的でもある。その一環として、異なる要素をネットワークに結びつけ、それらが見かけ上首尾一 貫した全体を形成するための明確な戦略に注目することもある。このようなネットワークは潜在的に一過性のものであり、絶え間ない創造と再創造の中に存在す る[1]。つまり、関係は繰り返し「実行」される必要があり、さもなければネットワークは溶解してしまう。彼らはまた、関係のネットワークは本質的に首尾 一貫しているわけではなく、実際に対立を含んでいる可能性があると仮定している。言い換えれば、社会関係は常にプロセスの中にあり、継続的に実行されなけ ればならないのである。 前述したパスツールの話は、多様な素材からなるパターン化されたネットワークを紹介したものであり、これは「異種ネットワーク」の考え方と呼ばれている [7]。パターン化されたネットワークの基本的な考え方は、社会やあらゆる社会活動やネットワークにおいて、人間だけが唯一の要因や貢献者ではないという ことである。したがって、ネットワークは機械、動物、モノ、その他のあらゆるオブジェクトから構成される[13]。人間以外のアクターにとって、ネット ワークにおける自分の役割を想像することは難しいかもしれない。例えば、ジェイコブとマイクという二人の人間が、テキストを通じて会話しているとする。現 在の技術では、彼らはお互いを直接見ることなくコミュニケーションをとることができる。したがって、タイプしたり書いたりするとき、コミュニケーションは 基本的に二人のどちらかによって媒介されるのではなく、コンピュータや携帯電話のようなオブジェクトのネットワークによって媒介される[13]。 論理的な結論を導き出せば、ほとんどすべての行為者は、他の、 より小さな行為者の総和に過ぎないと考えることができる。自動車は複雑系の一例である。自動 車には多くの電子部品や機械部品が搭載されているが、そのすべては基本的に運転手には見えないようになっており、運転手は単に自動車を1つの物体として扱 うだけである。この効果はパンクチャライゼーションと呼ばれ[13]、オブジェクト指向プログラミングにおけるカプセル化の考え方に似ている。 上記の自動車の例では、エンジンが動作しないと、ドライバーは自動車を、自分をあちこちに運んでくれる単なる乗り物としてではなく、部品の集合体として認 識するようになる。これは、ネットワークの構成要素がネットワーク全体と相反する行動をとる場合にも起こりうる。ラトゥールは著書『パンドラの希望』 [14]の中で、depunctualizationをブラックボックスの開封に例えている。閉じているとき、箱は単に箱として認識されるが、開けると中 のすべての要素が見えるようになる。 |

| 翻訳・トランスレーション(Translation) |

ANTの中心は翻訳の概念であり、翻訳社会学と呼ばれることもある。翻

訳社会学では、イノベーターがフォーラム、つまり、すべてのアクターがネットワーク

を構築し守る価値があると合意する中心的なネットワークを作ろうとする。海洋生物学者がより多くのホタテガイを生産するためにサンブリューク湾の資源回復

を試みた方法に関する1986年の研究において、ミシェル・カロン(Michel Callon)は翻訳の4つの瞬間を定義した[8]。 1. 問題化: 研究者たちは、ドラマの他のプレイヤーたちの性質や問題点を明らかにすることで、彼ら自身を重要な存在にしようとし、その後、アクターたちが研究者たちの 研究プログラムの「義務的な通過点」を交渉すれば、それらが改善されると主張する。 2. インタレスメント: 研究者が、他の行為者をそのプログラムにおいて割り当てられた役割に拘束するために用いる一連の手続き。 3. 参加: 研究者たちが他者に割り当てた数多くの役割を定義し、結びつけるために用いた戦術のコレクション。 4. 動員: 研究者たちは、さまざまな重要な集団の表向きの代弁者が、それらの集団を適切に代表し、後者に欺かれないようにするために、一連のアプローチを利用した。 この概念にとって重要なのは、ネットワーク・オブジェクトが、そうでなければ非常に困難な人々、組織、条件の間に等価性を生み出すことで、翻訳プロ セスを円滑に進める手助けをするという役割である。 |

| 問題化

(Problematisation) |

1.

研究者たちは、ドラマの他のプレイヤーたちの性質や問題点を明らかにすることで、彼ら自身を重要な存在にしようとし、その後、アクターたちが研究者たちの

研究プログラムの「義務的な通過点」を交渉すれば、それらが改善されると主張する。 |

| インタレスメント・利害関係化

(Interessement) |

2.

研究者が、他の行為者をそのプログラムにおいて割り当てられた役割に拘束するために用いる一連の手続き。 |

| 従事参加・エンロールメント

(Enrollment) |

3.

研究者たちが他者に割り当てた数多くの役割を定義し、結びつけるために用いた戦術のコレクション。 |

| 動員

(Mobilisation) |

4.

研究者たちは、さまざまな重要な集団の表向きの代弁者が、それらの集団を適切に代表し、後者に欺かれないようにするために、一連のアプローチを利用した。 |

| 準オブジェクト(Quasi-object) |

準オブジェクトとは、ネットワーク、社会的集合体、連合(バスケット

ボール、言語、パンなど)を結びつけ、織り成す方法によって特徴づけられる実体である [15]。 例えば「社会的秩序」と「機能する車」はそれぞれの行為者ネットワークの成功した相互作用を通して誕生し、行為者ネットワーク理論はこれらの創造 物をネットワーク内の行為者間で受け渡されるトークンまたは準物体として参照する。 トークンがネットワークを通じてますます伝達されたり、受け渡されたりするにつれて、トークンはますます時間化され、またますます再定義されるようにな る。トークンの伝達が減少したり、アクターがトークンの伝達に失敗したりすると(例えば、オイルポンプが壊れた)、時間厳守と再定義も減少する。 |

| 物質的記号論的手法(A material semiotic

method) |

ANTは「理論」と呼ばれてはいるが、通常、ネットワークが「なぜ」そ

のような形態をとるのかを説明することはない[1]。ラトゥールが述べているように

[11]、「説明は説明から生じるものではなく、説明からさらに踏み込んだものである」。言い換えれば、それは何かの「理論」ではなく、ラトゥール[1]

が言うように、むしろ方法、あるいは「ハウツー本」なのである。 このアプローチは、物質記号論の他のバージョン(特に哲学者のジル・ドゥルーズ、ミシェル・フーコー、フェミニスト学者のドナ・ハラウェイの仕事)と関連 している。また、エスノメソドロジー(ethnomethodology)の洞察や、一般的な活動、習慣、手順がどのように維持されているかについての詳 細な記述に忠実な方法ともいえる。ANTと、状況分析のような新しい形のグラウンデッド・セオリーのような象徴相互作用論的アプローチとの間には類似点が 存在するが[16]、ラトゥール[17]はこのような比較に異議を唱えている。 ANTは主に科学技術研究や科学社会学と関連しているが、社会学の他の分野でも着実に進歩を遂げている。ANTは断固として経験的であり、そのため社会学 的探究一般にとって有用な洞察やツールをもたらす。ANTはまた、政治社会学や歴史社会学においても着実な進歩を遂げている[19]。 |

| 仲介者と媒介者(Intermediaries and

mediators) |

仲介者と媒介者の区別はANT社会学の鍵である。仲介者は、(私たちが

研究しているある興味深い状態に対して)何の違いももたらさない存在であり、した

がって無視することができる。媒介者は、多かれ少なかれ、他の実体の力を変容させることなく運搬する存在であり、そのためあまり興味深い存在ではない。メ

ディエーターは差異を増大させる存在であり、研究の対象となるべきである。そのアウトプットは、そのインプットによって予測することはできない。ANTの

観点から見ると、社会学は世界の多くを媒介者として扱う傾向が強すぎる。 例えば、社会学者は絹とナイロンを仲介者とし、前者は上流階級を「意味」し、「反映」し、あるいは「象徴」し、後者は下層階級を「象徴」すると考えるかも しれない。このような見方では、現実世界のシルクとナイロンの違いは無関係である。シルクとナイロンの現実世界における内的な複雑性が突如として関連性を 帯び、かつては単に反映していたに過ぎないイデオロギー的な階級区別を積極的に構築していると見なされるのである。 献身的なANT分析者にとって、社会的なものは、シルクとナイロンの例における嗜好の階級的区別だけでなく、集団や権力のようなものであり、複雑な媒介者 との複雑な関わりを通して、常に新たに構築され、実行されなければならない。背景には、(仲介概念におけるように)相互作用の中で反映されたり、表現され たり、実証されたりするような、独立した社会的レパートリーは横たわっていない[1]。 |

| 反射性・反省性・リフレクシビティ(Reflexivity) |

相対主義理論では、反射性が問題とされる。それは観察者が他者に対して

否定する地位を要求するだけでなく、特権的な地位が否定される他者と同様に沈黙する

ことを要求する[12]。行為者(actants)が他者のことを説明できるのであれば、そうする。もしそれができなくても、彼らはそうしようとするだろ

う。 |

| 混成性・ハイブリディティ(Hybridity) |

人間も非人間も、絶対的な意味では人間でも非人間でもなく、むしろ両者

の相互作用によって生み出された存在であるという意味で、人間も非人間も純粋ではな

いという信念。したがって、人間は準主体、非人間は準対象とみなされる[7]。 |

| 再編成(Reassembling) |

ラトゥールは、彼の作品『Reassembling the

Social(社会的再構築)』[1]の中で、オブジェクトのこの特別な仕事について語っている。 |

| 共生の科学(science of living together) |

|

| 連関、あるいは繫がり(association) |

|

| エージェンシー(agecy) |

行為主体性 |

| 実体(substance) |

|

| 試行、あるいは試験(trial) |

|

| 循環する存在(circulating entity) |

|

| 社会的 |

|

| 強度の試験(traial of strength) |

|

| 批判的社会学(critical sociology) |

|

| 参照フレーム(frame of reference) |

|

| 参与するもの(participant) |

|

| モナド(monad) |

|

| モノ(object) |

|

| 報告(account) |

|

| エスノメソッド(ethnomethod) |

社会の成員がおこなう諸式あるいは報告 |

| 説明責任(accountability) |

|

| 外在(out-there) |

|

| 外在性(out-thereness) |

|

| メタ言語(meta-language) |

セカンドオーダーの言語あるいは説明 |

| 遂行的(performative) |

|

| 行為遂行性(parformativity) |

|

| 中間項(intermediary) |

|

| 媒介項(mediator) |

|

| 複雑性(complexity) |

|

| 立法者 |

|

| 解釈者 |

|

| 行為はアクターを超える(action is overtaken) |

|

| アクタン、アクタント(actant) |

|

| 可能的実在性(potentiality-reality) |

|

| 仮想的現実性(virtuality-actuality) |

|

| 基礎的な社交スキル(basic social skill) |

|

| 行為 |

|

| 作用 |

|

| 非人間(non-human) |

|

| 事実(fact) |

|

| 出来事(event) |

|

| 厳然たる事実(matter of fact) |

|

| 議論を呼ぶ事実(matter of concern) |

|

| 共通世界(common world) |

|

| 物体(thing) |

具体的な形相をもつ物体(thing)は、抽象的にモノ化 (objectification)されるモノ(object)と区別せよ。 |

| テクスト(text) |

|

| 命題(proposition) |

|

| 固有の妥当性(unique adequacy) |

|

| 分節化(articulation) |

|

| 襞(fold) |

|

| 書き込み(inscription) |

|

| 社交のツール(social tool) |

|

| 準客体(quasi-object) |

|

| 準主体(quasi-subject) |

|

| 存在様態(modes d'existence) |

|

| 政治認識(political epistemology) |

|

| 憲法(Constitution) |

|

| コスモポリティクス(cosmopolitics) |

|

key concepts of the ANT

| Outline Actor–network theory (ANT) is a theoretical and methodological approach to social theory where everything in the social and natural worlds exists in constantly shifting networks of relationships. It posits that nothing exists outside those relationships. All the factors involved in a social situation are on the same level, and thus there are no external social forces beyond what and how the network participants interact at present. Thus, objects, ideas, processes, and any other relevant factors are seen as just as important in creating social situations as humans. ANT holds that social forces do not exist in themselves, and therefore cannot be used to explain social phenomena. Instead, strictly empirical analysis should be undertaken to "describe" rather than "explain" social activity. Only after this can one introduce the concept of social forces, and only as an abstract theoretical concept, not something which genuinely exists in the world.[1] Although it is best known for its controversial insistence on the capacity of nonhumans to act or participate in systems or networks or both, ANT is also associated with forceful critiques of conventional and critical sociology. Developed by science and technology studies (STS) scholars Michel Callon, Madeleine Akrich and Bruno Latour, the sociologist John Law, and others, it can more technically be described as a "material-semiotic" method. This means that it maps relations that are simultaneously material (between things) and semiotic (between concepts). It assumes that many relations are both material and semiotic. The term actor-network theory was coined by John Law in 1992 to describe the work being done across case studies in different areas at the Centre de Sociologie de l'Innovation at the time.[2] The theory demonstrates that everything in the social and natural worlds, human and nonhuman, interacts in shifting networks of relationships without any other elements out of the networks. ANT challenges many traditional approaches by defining nonhumans as actors equal to humans. This claim provides a new perspective when applying the theory in practice. Broadly speaking, ANT is a constructivist approach in that it avoids essentialist explanations of events or innovations (i.e. ANT explains a successful theory by understanding the combinations and interactions of elements that make it successful, rather than saying it is true and the others are false).[3] Likewise, it is not a cohesive theory in itself. Rather, ANT functions as a strategy that assists people in being sensitive to terms and the often unexplored assumptions underlying them.[4] It is distinguished from many other STS and sociological network theories for its distinct material-semiotic approach. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Actor%E2%80%93network_theory |

全体の構想 アクター・ネットワーク理論(ANT)とは、社会理論における理論的・ 方法論的アプローチであり、社会世界や自然界に存在するあらゆるものは、常に変化する関係性のネットワークの中に存在しているとする。そのような関係の外 には何も存在しないと仮定する。社会的状況に関与するすべての要因は同じレベルにあり、したがって、ネットワーク参加者が現在どのように相互作用している かを超える外部の社会的力は存在しない。したがって、モノ、アイデア、プロセス、その他関連するあらゆる要因は、社会状況を作り出す上で人間と同様に重要 であると見なされる。 ANTは、社会的な力はそれ自体では存在しないため、社会現象を説明するために用いることはできないと考える。その代わりに、社会活動を「説明」するので はなく「記述」するために、厳密に経験的な分析を行うべきである。この後に初めて社会的諸力の概念を導入することができ、それは抽象的な理論的概念として のみであり、実際に世界に存在するものではない[1]。 ANTは、システムあるいはネットワーク、あるいはその両方において行動したり参加したりする非人間的な能力についての論争的な主張で最もよく知られてい るが、従来の社会学や批判的社会学の力強い批判とも関連している。科学技術研究(STS)の研究者であるミシェル・カロン、マドレーヌ・アクリッチ、ブ ルーノ・ラトゥール、社会学者のジョン・ローらによって開発されたANTは、より専門的には「物質-記号論的」手法と表現される。つまり、物質的な関係 (モノとモノの間)と記号論的な関係(概念と概念の間)を同時にマッピングするということである。多くの関係が物質的かつ記号的であると仮定している。ア クター・ネットワーク理論という用語は、1992年にジョン・ローによって、当時イノベーション社会学センターで行われていた様々な分野における事例研究 を説明するために作られたものである[2]。 この理論は、社会的世界と自然界に存在するすべてのもの、人間と人間以外のものは、ネットワークから他の要素を排除して、移り変わる関係のネットワークの 中で相互作用していることを実証している。ANTは、人間以外を人間と同等の行為者として定義することで、多くの伝統的なアプローチに挑戦している。この 主張は、理論を実践に応用する際に新たな視点を提供する。 大雑把に言えば、ANTは事象やイノベーションの本質論的な説明を避けるという点で構成主義的なアプローチである(すなわち、ANTは成功した理論につい て、それが真であり他が偽であると言うのではなく、それを成功させる要素の組み合わせや相互作用を理解することで説明する)[3]。むしろANTは、用語 やその根底にあるしばしば未解明な仮定に敏感になることを支援する戦略として機能する[4]。 |

If it is interactive, the actor can

be an object other than a human being, such as an animal or a machine.

We think of an actor as a unit that collects information from the

outside, negotiates with each other, and plans the next action in a

time series. Actors obtain information and derive actions based on it

[or independently of it]. Put another way, actors generate specific

information toward other actors. Actors are both the derivators and the

conduits through which chains of information and actions are derived

and transmitted. When we link these chains ad hoc, we see the formation

of a network. Today, while describing the networks woven by such

actors, a framework for studying (i) what each actor's perceptions and

actions produce, (ii) what the interaction of segments among actors

produces, and (iii) what the network as a whole produces is called

Actor Network Theory (ANT)" (Callon 2001). If it is interactive, the actor can

be an object other than a human being, such as an animal or a machine.

We think of an actor as a unit that collects information from the

outside, negotiates with each other, and plans the next action in a

time series. Actors obtain information and derive actions based on it

[or independently of it]. Put another way, actors generate specific

information toward other actors. Actors are both the derivators and the

conduits through which chains of information and actions are derived

and transmitted. When we link these chains ad hoc, we see the formation

of a network. Today, while describing the networks woven by such

actors, a framework for studying (i) what each actor's perceptions and

actions produce, (ii) what the interaction of segments among actors

produces, and (iii) what the network as a whole produces is called

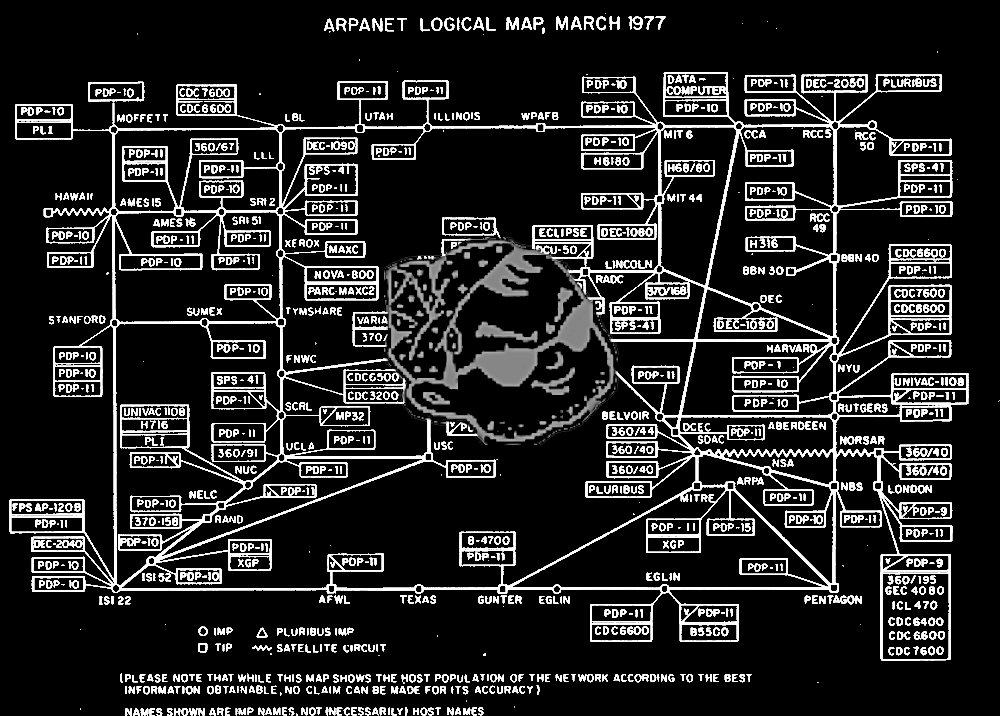

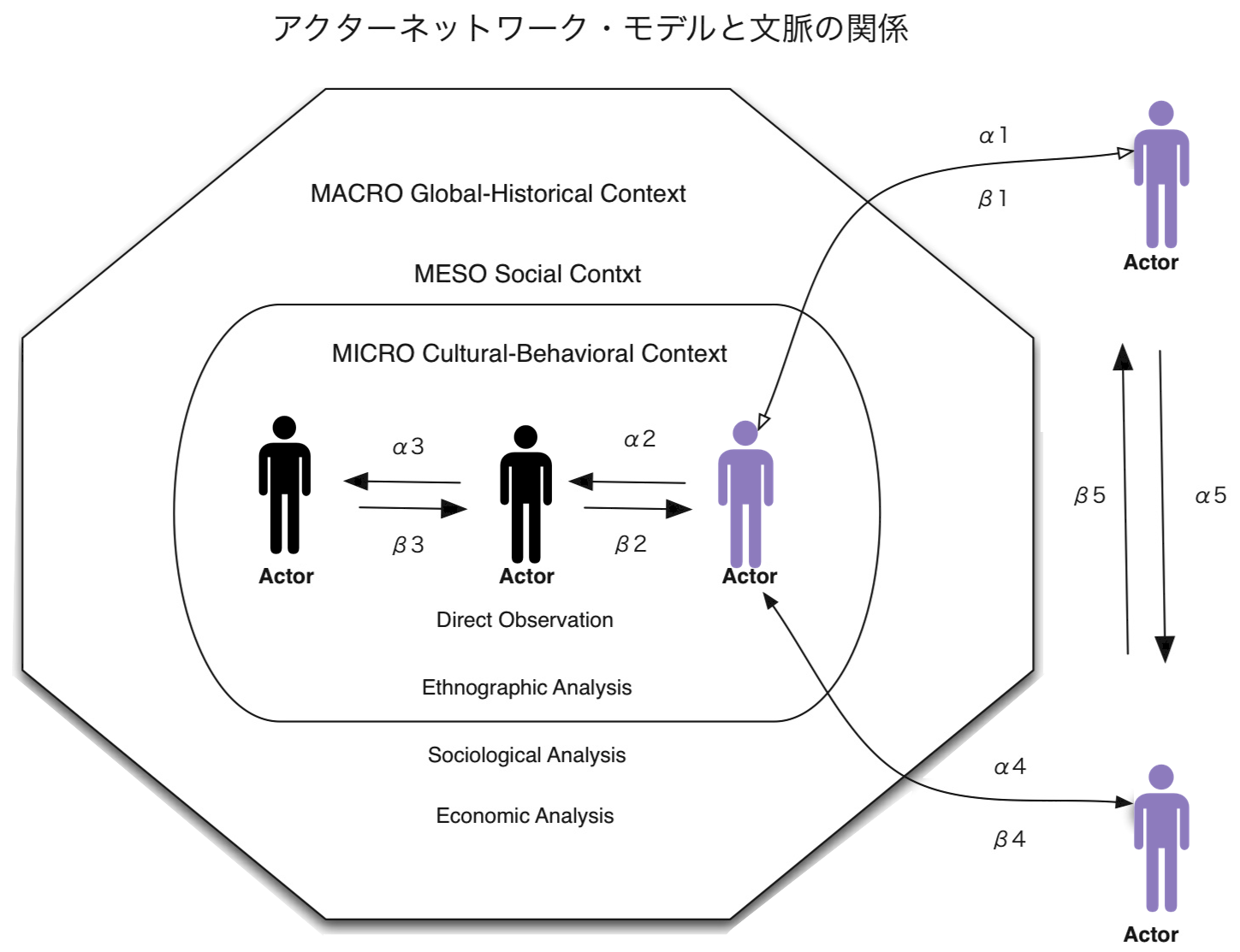

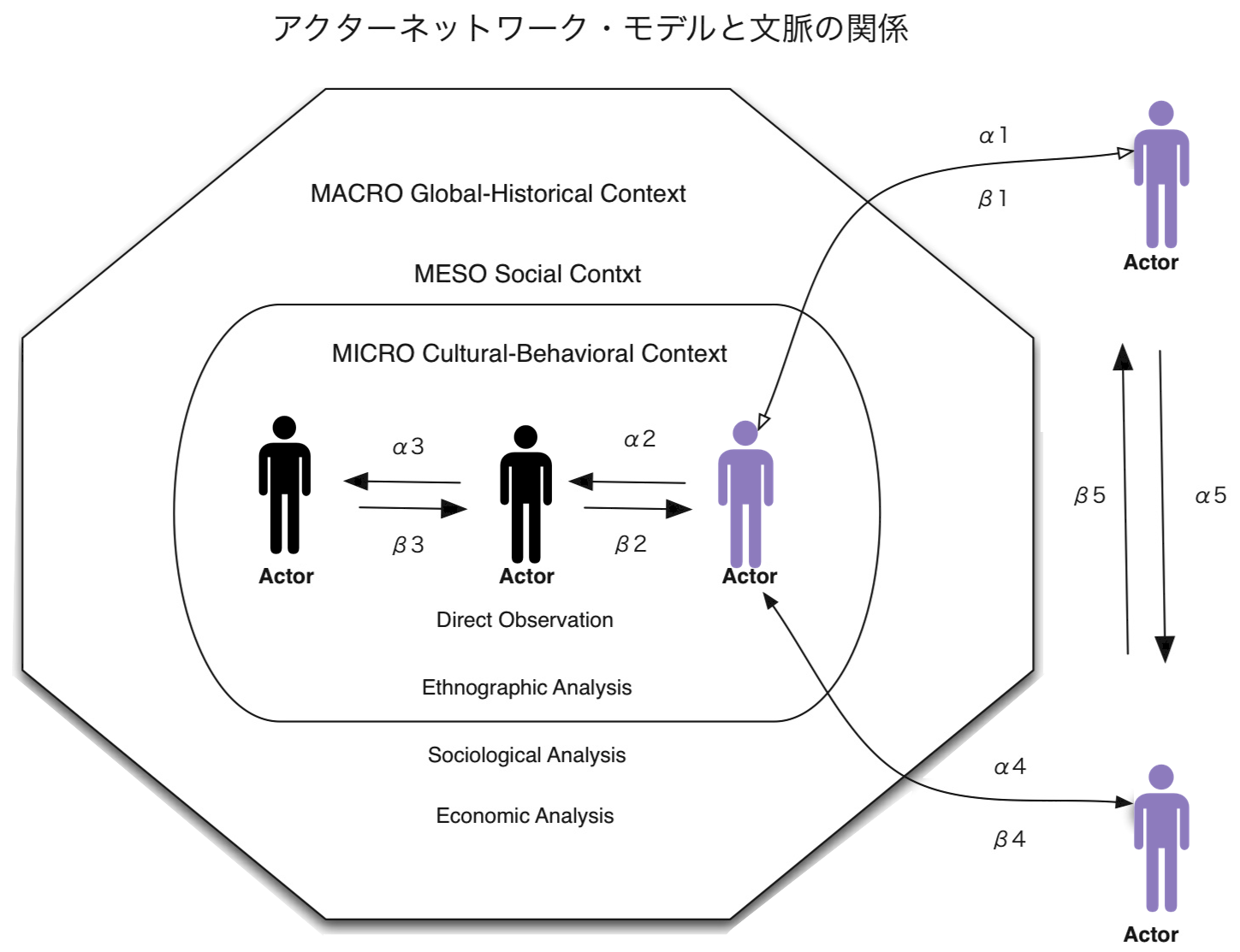

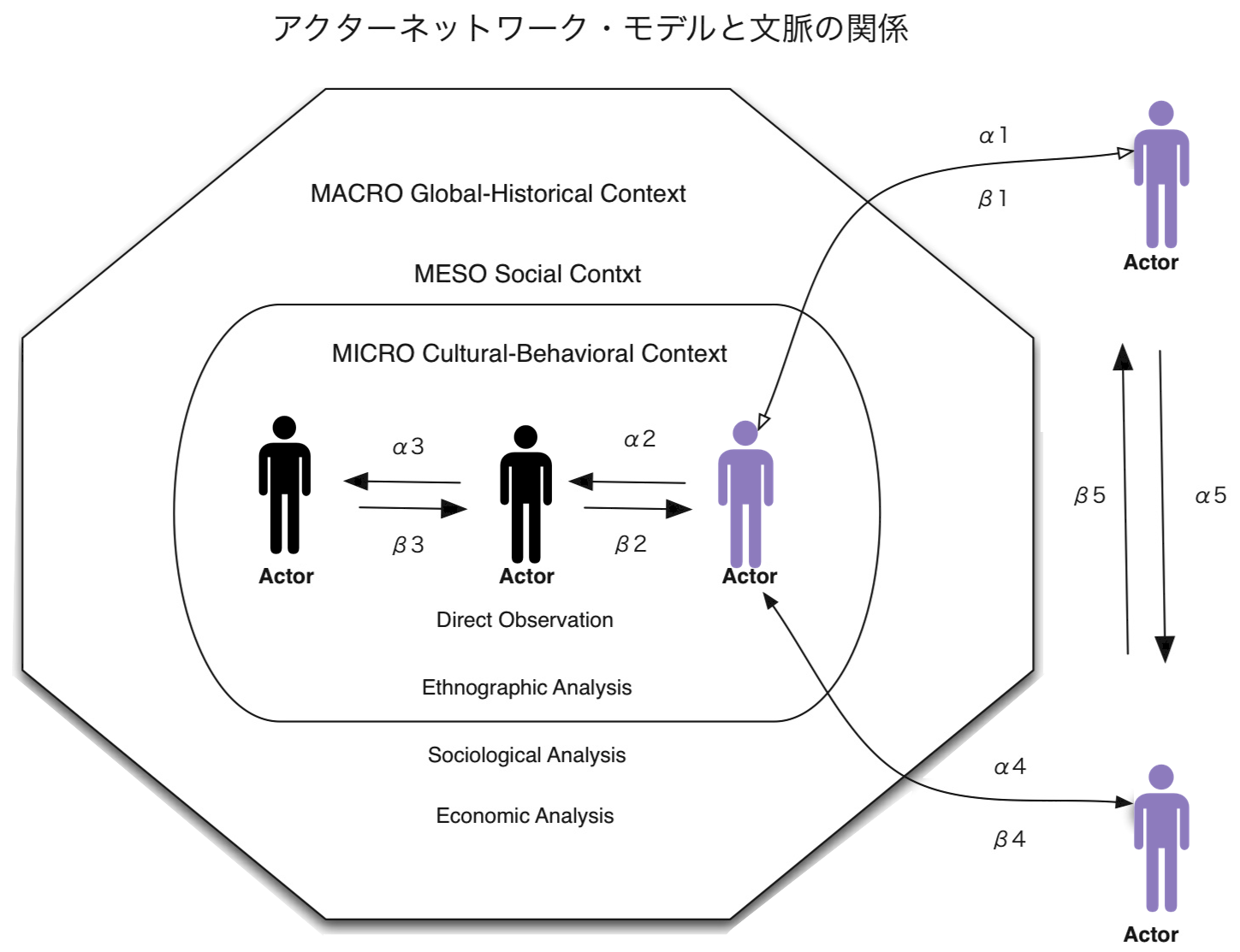

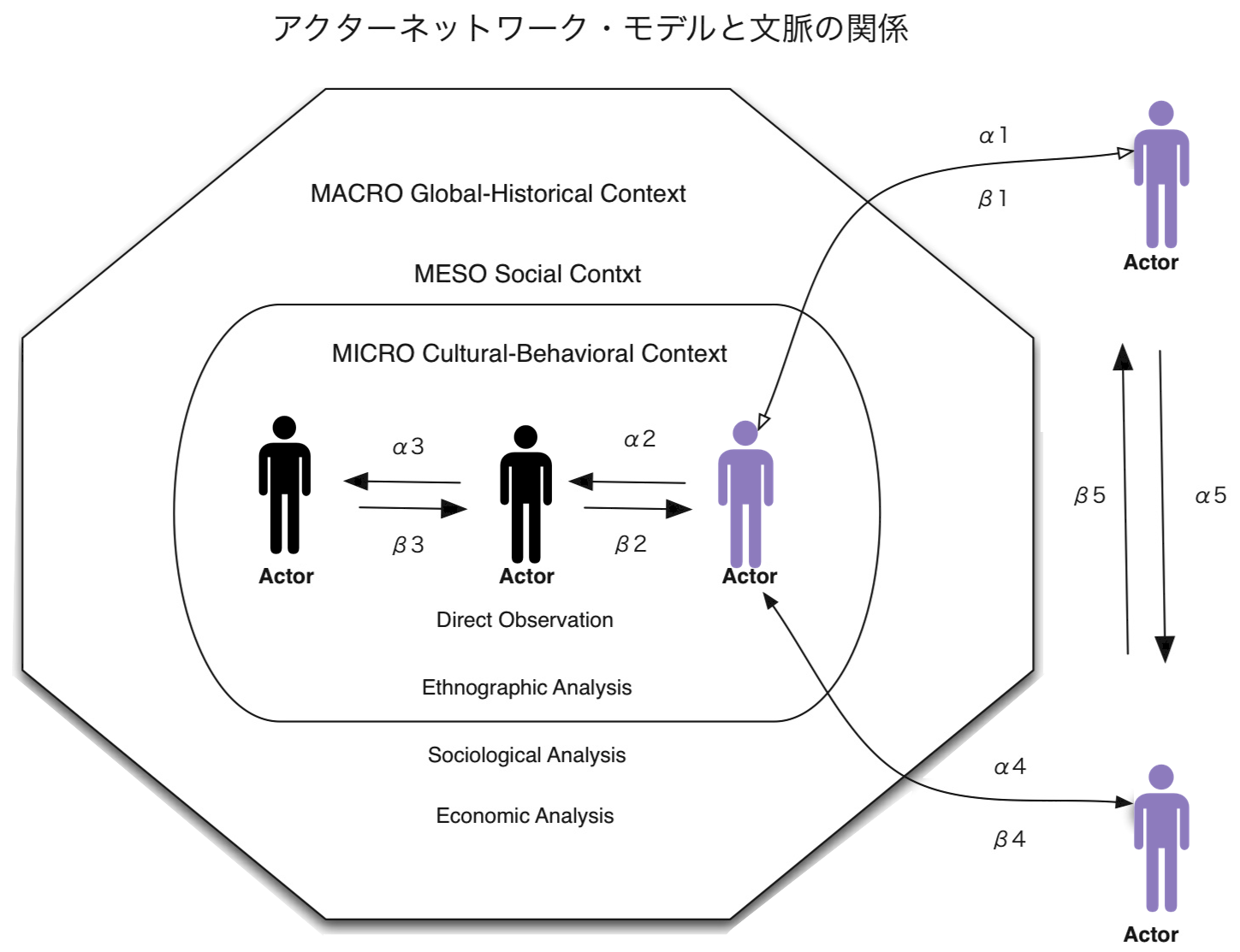

Actor Network Theory (ANT)" (Callon 2001). Figure B.1 shows a schematic representation of the interactions between actors and actors in a healthcare project based on the ideas of Actor Network Theory. The actor on the upper right is the initiator, who plans and implements the project itself. The initiator constructs the project design free from (or believing that it is free from) the specific historical and social context. However, a project cannot be said to have operated in reality unless it is practiced in a unique historically and socially conditioned specific social context (context). The actors on the upper right either go to the local society or interact with the people who go there to do the work. In the local society, there will be a variety of actors who are directly or indirectly related to the project. These actors include the target group of the project, local actors affiliated with the project on the local side (Ministry of Health officials, field practitioners, hospitals, clinics, and other facilities), other national and international organizations with which the project is allied or in competition, universities and research institutions, and, in politically charged areas and armed guerrilla groups that see the project as an agent of state or international capitalism and sabotage it, and countless other networks of interaction can be envisioned. An important point to keep in mind in any discussion of actor-networks is that when observing interactions among actors and considering their meaning, it is important to keep in mind the social context in which the interactions occur [or are made possible], i.e., the context. Actors do not perform their practices in a social vacuum. Actors may induce interactions that are ideal for them. In doing so, it is obvious that actors take into account the social context (context) in which they and their counterparts are placed. In Figure B.1, I have pointed out a very simple, formal, but necessary and minimal context in which the actors are placed. First, the most localized of the actors' surroundings is the micro-region (MICRO). This is the area where everyday language and gestures are the basis of communication, and where the actor's cultural and behavioral habits are frequently observed. At the opposite end of the spectrum is the global-historical context, which is the macro-region (MACRO), the largest thing that surrounds the place where the actors practice. The context that is delimited within a local society, community, or national framework is intermediate between these two, and we will call it the meso-area. The meso-area context, like the macro-area events, cannot be experienced directly - indeed, who can grasp "society" or "community" in a tangible, hands-on way? --We acquire an image of the community that each culture prepares us for, and we unwittingly learn [whether we realize it or not] the public and national stereotypes that are inculcated over the years through education. |

インタラクティブであればアクターは人間以外の動物や機械などの物

体でもかまわな

い。

外部から情報を収集し、相互に交渉しながら時系列の中で次の行動を投企する単位としてアクターを考えるのである。アクターが情報を入手し、それにもと

づいて[あるいはそれとは無関係に]行動を派生させる。別の見方をすれば、他のアクターに向かってアクターは特定の情報を発生する。アクターは情報と行動

の連鎖を派生させると同時に伝達する媒介にもなる。これらの連鎖をその場限りで(ad

hoc)結びつけるとネットワークを形成している様を我々はみることができる。今日ではそのようなアクターが織りなすネットワークを叙述しつつ、(i)ア

クターのそれぞれの認識と行為が生み出すもの、(ii)アクター間のセグメントの相互作用が生み出すもの、(iii)そしてネットワーク全体がもたらすも

のについて研究する枠組みは「アクターネットワーク理論(Actor Network Theory, ANT)」と呼ばれる(Callon

2001)。 インタラクティブであればアクターは人間以外の動物や機械などの物

体でもかまわな

い。

外部から情報を収集し、相互に交渉しながら時系列の中で次の行動を投企する単位としてアクターを考えるのである。アクターが情報を入手し、それにもと

づいて[あるいはそれとは無関係に]行動を派生させる。別の見方をすれば、他のアクターに向かってアクターは特定の情報を発生する。アクターは情報と行動

の連鎖を派生させると同時に伝達する媒介にもなる。これらの連鎖をその場限りで(ad

hoc)結びつけるとネットワークを形成している様を我々はみることができる。今日ではそのようなアクターが織りなすネットワークを叙述しつつ、(i)ア

クターのそれぞれの認識と行為が生み出すもの、(ii)アクター間のセグメントの相互作用が生み出すもの、(iii)そしてネットワーク全体がもたらすも

のについて研究する枠組みは「アクターネットワーク理論(Actor Network Theory, ANT)」と呼ばれる(Callon

2001)。アクターネットワーク理論の発想にもとづいて保健医療プ ロジェクトにおけるアクターとアクター間の相互作用を模式的に表したものが図B.である。右上のアクターがプロジェクトそのものを企画立案し、それを実行 に移す初発者(initiator)である。初発者は特定の歴史社会的文脈から自由になり(あるいはそう信じて)プロジェクトデザインを構築する。しかし ながら、固有の歴史的社会的に条件化された固有の社会的文脈(コンテクスト)で実践しないとプロジェクトは現実に作動したとは言えない。右上のアクター は、現地社会に赴くか、あるいはそこに赴いて仕事をする人間との相互作用をもちながら仕事をおこなう。現地社会には、そのプロジェクトに直接間接に関係を もつさまざまなアクターが生まれることになる。現地社会でのアクターには、プロジェクトのターゲットグループと呼ばれる集団、現地側でプロジェクトを提携 する現地のアクター(保健省役人、現場の実務担当者、病院や診療所などの施設)、同盟あるいは競合関係にある他の国内・国際的組織、大学や研究機関、政治 的係争地であれば、プロジェクトを国家や国際的資本主義のエージェントと見なして妨害する武装ゲリラグループ、など無数の相互作用のネットワークを想定す ることができる。アクターネットワークの議論の中で押さえておかねばなら ない重要なポイントは、アクター間の相互作用を観察したり、その意味を考えたりする際に、相互作用が生起した[あるいはそれを可能にした]社会的文脈すな わちコンテクストについて留意することである。 アクターは、社会的真空の中で行為実践をおこなうのではない。 またアクターは自分にとって理想的な状態にな るよう相互作用を誘導することがある。その際、アクターは自分と相手がおかれている社会的文脈(コンテクスト)を十分に計算に含めておこなっていること は、我々の身の回りを眺めてみても自明である。事例としてあげた図B.には、アクターが置かれるコンテクストについて、きわめて単純で形式的だが必要かつ 最小限のものを指摘しておいた。まず行為者の身の回りのもっとも局所的なものがミクロ領域(MICRO)である。これには、日常的言語や仕草などがコミュ ニケーションの基調とされ、行為者がもつ文化や行動学的癖のようなものが頻繁に観察さえる領域である。その対極には、行為者たちが実践する場所を取り囲む もっとも大きなもの、すなわちマクロ領域(MACRO)としての全地球的−歴史的文脈がある。地域社会やコミュニティ、あるいは国家的枠組みの中で仕切ら れる文脈は、それらの中間であるのでメゾ(MESO)領域と呼んでおこう。メゾ領域の文脈は、マクロ領域の事象と同様に、直接体験することができないが −−実際いったい誰が「社会」や「コミュニティ」というものを具体的に手にとって把握することができようか?−−我々はそれぞれの文化が準備するコミュニ ティのイメージを獲得し、教育を通して長年にわたって訓育される公共や国家のステレオタイプを[自覚の有無に関わらず]知らず知らずのうちに学んでいる。 |

| Background and context ANT was first developed at the Centre de Sociologie de l'Innovation (CSI) of the École nationale supérieure des mines de Paris in the early 1980s by staff (Michel Callon, Madeleine Akrich, Bruno Latour) and visitors (including John Law).[3] The 1984 book co-authored by John Law and fellow-sociologist Peter Lodge (Science for Social Scientists; London: Macmillan Press Ltd.) is a good example of early explorations of how the growth and structure of knowledge could be analyzed and interpreted through the interactions of actors and networks. Initially created in an attempt to understand processes of innovation and knowledge-creation in science and technology, the approach drew on existing work in STS, on studies of large technological systems, and on a range of French intellectual resources including the semiotics of Algirdas Julien Greimas, the writing of philosopher Michel Serres, and the Annales School of history. ANT appears to reflect many of the preoccupations of French post-structuralism, and in particular a concern with non-foundational and multiple material-semiotic relations.[3] At the same time, it was much more firmly embedded in English-language academic traditions than most post-structuralist-influenced approaches. Its grounding in (predominantly English) science and technology studies was reflected in an intense commitment to the development of theory through qualitative empirical case-studies. Its links with largely US-originated work on large technical systems were reflected in its willingness to analyse large scale technological developments in an even-handed manner to include political, organizational, legal, technical and scientific factors. Many of the characteristic ANT tools (including the notions of translation, generalized symmetry and the "heterogeneous network"), together with a scientometric tool for mapping innovations in science and technology ("co-word analysis") were initially developed during the 1980s, predominantly in and around the CSI. The "state of the art" of ANT in the late 1980s is well-described in Latour's 1987 text, Science in Action.[5] From about 1990 onwards, ANT started to become popular as a tool for analysis in a range of fields beyond STS. It was picked up and developed by authors in parts of organizational analysis, informatics, health studies, geography, sociology, anthropology, archaeology, feminist studies, technical communication, and economics. As of 2008, ANT is a widespread, if controversial, range of material-semiotic approaches for the analysis of heterogeneous relations. In part because of its popularity, it is interpreted and used in a wide range of alternative and sometimes incompatible ways. There is no orthodoxy in current ANT, and different authors use the approach in substantially different ways. Some authors talk of "after-ANT" to refer to "successor projects" blending together different problem-focuses with those of ANT.[6] |

背景と文脈 ANTは1980年代初頭にパリ国立高等鉱業学校のイノベーション社会学センター(CSI)で、スタッフ(ミシェル・カロン、マドレーヌ・アクリッチ、ブ ルーノ・ラトゥール)や訪問者(ジョン・ロウを含む)によって初めて開発された。 [3] ジョン・ローと同じ社会学者であるピーター・ロッジの共著である1984年の本(Science for Social Scientists; London: Macmillan Press Ltd.)は、アクターとネットワークの相互作用を通じて、知識の成長と構造がどのように分析され、解釈されうるかについての初期の探求の好例である。当 初は、科学技術におけるイノベーションと知識創造のプロセスを理解する試みとして創始されたこのアプローチは、STSにおける既存の研究、大規模な技術シ ステムの研究、そしてアルギルダス・ジュリアン・グレイマスの記号論、哲学者ミシェル・セレスの著作、歴史学のアナール学派を含むフランスの様々な知的資 源を利用した。 ANTは、フランスのポスト構造主義の関心の多くを反映しているように見え、特に非基礎的で多重的な物質的・記号的関係への関心を示している[3]。その (主に英語の)科学技術研究における基盤は、質的な経験的ケーススタディを通じて理論を発展させることへの強いコミットメントに反映されていた。政治的、 組織的、法的、技術的、科学的な要因を含む大規模な技術開発を公平な方法で分析しようとする姿勢には、主として米国発祥の大規模技術システムに関する研究 とのつながりが反映されている。 ANTの特徴的なツール(翻訳、一般化された対称性、「異質なネットワーク」の概念を含む)の多くは、科学技術におけるイノベーションをマッピングするた めのサイエントロメトリーツール(「共語分析」)とともに、1980年代に主にCSIとその周辺で開発された。1980年代後半におけるANTの「技術的 状況」は、ラトゥールの1987年のテキスト『行動する科学』(Science in Action)によく述べられている[5]。 1990年頃から、ANTはSTS以外の様々な分野の分析ツールとして普及し始めた。組織分析、情報学、健康学、地理学、社会学、人類学、考古学、フェミ ニスト研究、テクニカル・コミュニケーション、経済学などの著者によって取り上げられ、発展していった。 2008年現在、ANTは、異質な関係を分析するための物質・記号論的アプローチとして、議論の余地はあるにせよ、広く普及している。その人気の高さも あって、ANTはさまざまに解釈され、利用されている。現在のANTに正統性はなく、著者によってアプローチの使い方は大きく異なる。異なる問題意識を ANTのものと融合させた「後継プロジェクト」を指して「アフターANT」と語る著者もいる[6]。 |

| Key concepts Actor/Actant An actor (actant) is something that acts or to which activity is granted by others. It implies no motivation of human individual actors nor of humans in general. An actant can literally be anything provided it is granted to be the source of action.[7] In another word, an actor, in this circumstance, is considered as any entity that does things. For example, in the "Pasteur Network", microorganisms are not inert, they cause unsterilized materials to ferment while leaving behind sterilized materials not affected. If they took other actions, that is, if they did not cooperate with Pasteur – if they did not take action (at least according to Pasteur's intentions) – then Pasteur's story may be a bit different. It is in this sense that Latour can refer to microorganisms as actors.[7] Under the framework of ANT, the principle of generalized symmetry[8] requires all entities must be described in the same terms before a network is considered. Any differences between entities are generated in the network of relations, and do not exist before any network is applied. Human actors Human normally refers to human beings and their human behaviors. Nonhuman actors Traditionally, nonhuman entities are creatures including plants, animals, geology, and natural forces, as well as a collective human making of arts, languages.[9] In ANT, nonhuman covers multiple entities including things, objects, animals, natural phenomena, material structures, transportation devices, texts, and economic goods. But nonhuman actors do not cover entities such as humans, supernatural beings, and other symbolic objects in nature.[10] Actor-Network As the term implies, the actor-network is the central concept in ANT. The term "network" is somewhat problematic in that it, as Latour[1][11][12] notes, has a number of unwanted connotations. Firstly, it implies that what is described takes the shape of a network, which is not necessarily the case. Secondly, it implies "transportation without deformation," which, in ANT, is not possible since any actor-network involves a vast number of translations. Latour,[12] however, still contends that network is a fitting term to use, because "it has no a priori order relation; it is not tied to the axiological myth of a top and of a bottom of society; it makes absolutely no assumption whether a specific locus is macro- or micro- and does not modify the tools to study the element 'a' or the element 'b'." This use of the term "network" is very similar to Deleuze and Guattari's rhizomes; Latour[11] even remarks tongue-in-cheek that he would have no objection to renaming ANT "actant-rhizome ontology" if it only had sounded better, which hints at Latour's uneasiness with the word "theory". Actor–network theory tries to explain how material–semiotic networks come together to act as a whole; the clusters of actors involved in creating meaning are both material and semiotic. As a part of this it may look at explicit strategies for relating different elements together into a network so that they form an apparently coherent whole. These networks are potentially transient, existing in a constant making and re-making.[1] This means that relations need to be repeatedly "performed" or the network will dissolve. They also assume that networks of relations are not intrinsically coherent, and may indeed contain conflicts. Social relations, in other words, are only ever in process, and must be performed continuously. The Pasteur story that was mentioned above introduced the patterned network of diverse materials, which is called the idea of 'heterogenous networks'.[7] The basic idea of patterned network is that human is not the only factor or contributor in the society, or in any social activities and networks. Thus, the network composes machines, animals, things, and any other objects.[13] For those nonhuman actors, it might be hard for people to imagine their roles in the network. For example, say two people, Jacob and Mike, are speaking through texts. Within the current technology, they are able to communicate with each other without seeing each other in person. Therefore, when typing or writing, the communication is basically not mediated by either of them, but instead by a network of objects, like their computers or cell phones.[13] If taken to its logical conclusion, then, nearly any actor can be considered merely a sum of other, smaller actors. A car is an example of a complex system. It contains many electronic and mechanical components, all of which are essentially hidden from view to the driver, who simply deals with the car as a single object. This effect is known as punctualisation,[13] and is similar to the idea of encapsulation in object-oriented programming. When an actor network breaks down, the punctualisation effect tends to cease as well.[13] In the automobile example above, a non-working engine would cause the driver to become aware of the car as a collection of parts rather than just a vehicle capable of transporting him or her from place to place. This can also occur when elements of a network act contrarily to the network as a whole. In his book Pandora's Hope,[14] Latour likens depunctualization to the opening of a black box. When closed, the box is perceived simply as a box, although when it is opened all elements inside it become visible. Translation Main article: Translation (sociology) Central to ANT is the concept of translation which is sometimes referred to as sociology of translation, in which innovators attempt to create a forum, a central network in which all the actors agree that the network is worth building and defending. In his widely debated 1986 study of how marine biologists tried to restock the St Brieuc Bay in order to produce more scallops, Michel Callon defined 4 moments of translation:[8] Problematisation: The researchers attempted to make themselves important to the other players in the drama by identifying their nature and issues, then claiming that they could be remedied if the actors negotiated the 'obligatory passage point' of the researchers' study program. Interessement: A series of procedures used by the researchers to bind the other actors to the parts that had been assigned to them in that program. Enrollment: A collection of tactics used by the researchers to define and connect the numerous roles they had assigned to others. Mobilisation: The researchers utilized a series of approaches to ensure that ostensible spokespeople for various key collectivities were appropriately able to represent those collectivities and were not deceived by the latter. Also important to the notion is the role of network objects in helping to smooth out the translation process by creating equivalencies between what would otherwise be very challenging people, organizations or conditions to mesh together. Bruno Latour spoke about this particular task of objects in his work Reassembling the Social.[1] Quasi-object The quasi-object is an entity characterized by the way it is connective and weaves networks, social collectives, and associations (such as a basketball, language, or bread).[15] In the above examples, "social order" and "functioning car" come into being through the successful interactions of their respective actor-networks, and actor-network theory refers to these creations as tokens or quasi-objects which are passed between actors within the network. As the token is increasingly transmitted or passed through the network, it becomes increasingly punctualized and also increasingly reified. When the token is decreasingly transmitted, or when an actor fails to transmit the token (e.g., the oil pump breaks), punctualization and reification are decreased as well. |

キーコンセプト アクター/アクタント 行為者(actant)とは、行為するもの、または他者から活動を与えられるものである。アクター(行為者)とは、行為するもの、あるいは他者から活動を 与えられるもののことであり、人間個人の動機づけや人間一般の動機づけを意味するものではない。アクタントは、行動の源であることが認められれば、文字通 り何でもあり得る[7]。別の言葉で言えば、この状況においてアクターとは、物事を行うあらゆる存在と見なされる。例えば、「パスツール・ネットワーク」 において、微生物は不活性ではなく、滅菌されていない物質を発酵させる一方で、滅菌された物質には影響を与えない。もし彼らが他の行動を取ったとしたら、 つまりパスツールに協力しなかったとしたら、(少なくともパスツールの意図に従って)行動を起こさなかったとしたら、パスツールの話は少し違ってくるかも しれない。ラトゥールが微生物を行為者と呼ぶことができるのは、このような意味においてである[7]。 ANTの枠組みの下では、一般化された対称性の原則[8]により、ネットワークを考える前に、すべての実体が同じ用語で記述されなければならない。実体間 の違いは関係のネットワークの中で生じるものであり、ネットワークが適用される前には存在しない。 人間の行為者 通常、人間とは人間とその人間的行動を指す。 非人間的アクター 伝統的に、非人間的な主体は、植物、動物、地質学、自然力、および芸術や言語の人間の集団的な創造を含む生き物である[9]。ANTでは、非人間的な主体 は、モノ、物体、動物、自然現象、物質的構造、輸送装置、テキスト、および経済財を含む複数の主体をカバーする。しかし、非人間的な行為者は、人間、超自 然的存在、自然界における他の象徴的対象などの実体を対象としていない[10]。 行為者-ネットワーク この用語が意味するように、行為者-ネットワークはANTの中心的概念である。ネットワーク」という用語は、ラトゥール[1][11][12]が指摘する ように、多くの好ましくない意味合いを持つという点でやや問題がある。第一に、この用語は、説明されるものがネットワークの形をとることを意味するが、そ れは必ずしもそうではない。第二に、それは「変形を伴わない輸送」を意味するが、ANTにおいては、どのような行為者-ネットワークも膨大な数の翻訳を含 むため、それは不可能である。しかし、ラトゥール[12]は、「ネットワークは先験的な秩序関係を持たず、社会のトップとボトムという公理的な神話に縛ら れることもなく、特定の場所がマクロであるかミクロであるかという仮定をまったく持たず、要素「a」や要素「b」を研究するための道具を修正することもな い」ため、ネットワークという用語は使用するのにふさわしいと主張している。この「ネットワーク」という言葉の使い方は、ドゥルーズとガタリのリゾームと 非常によく似ている。ラトゥール[11]は、響きさえよければANTを「アクター・リゾーム存在論」と改名することに異論はないと皮肉さえ述べているが、 これはラトゥールが「理論」という言葉に不安を抱いていることを示唆している。 アクター・ネットワーク理論は、物質的-記号論的ネットワークがどのように組み合わさって全体として作用するかを説明しようとするものである。意味の創造 に関わるアクターのクラスターは、物質的であると同時に記号論的でもある。その一環として、異なる要素をネットワークに結びつけ、それらが見かけ上首尾一 貫した全体を形成するための明確な戦略に注目することもある。このようなネットワークは潜在的に一過性のものであり、絶え間ない創造と再創造の中に存在す る[1]。つまり、関係は繰り返し「実行」される必要があり、さもなければネットワークは溶解してしまう。彼らはまた、関係のネットワークは本質的に首尾 一貫しているわけではなく、実際に対立を含んでいる可能性があると仮定している。言い換えれば、社会関係は常にプロセスの中にあり、継続的に実行されなけ ればならないのである。 前述したパスツールの話は、多様な素材からなるパターン化されたネットワークを紹介したものであり、これは「異種ネットワーク」の考え方と呼ばれている [7]。パターン化されたネットワークの基本的な考え方は、社会やあらゆる社会活動やネットワークにおいて、人間だけが唯一の要因や貢献者ではないという ことである。したがって、ネットワークは機械、動物、モノ、その他のあらゆるオブジェクトから構成される[13]。人間以外のアクターにとって、ネット ワークにおける自分の役割を想像することは難しいかもしれない。例えば、ジェイコブとマイクという二人の人間が、テキストを通じて会話しているとする。現 在の技術では、彼らはお互いを直接見ることなくコミュニケーションをとることができる。したがって、タイプしたり書いたりするとき、コミュニケーションは 基本的に二人のどちらかによって媒介されるのではなく、コンピュータや携帯電話のようなオブジェクトのネットワークによって媒介される[13]。 論理的な結論を導き出せば、ほとんどすべての行為者は、他の、より小さな行為者の総和に過ぎないと考えることができる。自動車は複雑系の一例である。自動 車には多くの電子部品や機械部品が搭載されているが、そのすべては基本的に運転手には見えないようになっており、運転手は単に自動車を1つの物体として扱 うだけである。この効果はパンクチャライゼーションと呼ばれ[13]、オブジェクト指向プログラミングにおけるカプセル化の考え方に似ている。 上記の自動車の例では、エンジンが動作しないと、ドライバーは自動車を、自分をあちこちに運んでくれる単なる乗り物としてではなく、部品の集合体として認 識するようになる。これは、ネットワークの構成要素がネットワーク全体と相反する行動をとる場合にも起こりうる。ラトゥールは著書『パンドラの希望』 [14]の中で、depunctualizationをブラックボックスの開封に例えている。閉じているとき、箱は単に箱として認識されるが、開けると中 のすべての要素が見えるようになる。 翻訳 主な記事 翻訳(社会学) ANTの中心は翻訳の概念であり、翻訳社会学と呼ばれることもある。翻訳社会学では、イノベーターがフォーラム、つまり、すべてのアクターがネットワーク を構築し守る価値があると合意する中心的なネットワークを作ろうとする。海洋生物学者がより多くのホタテガイを生産するためにサンブリューク湾の資源回復 を試みた方法に関する1986年の研究において、ミシェル・カロン(Michel Callon)は翻訳の4つの瞬間を定義した[8]。 問題化: 研究者たちは、ドラマの他のプレイヤーたちの性質や問題点を明らかにすることで、彼ら自身を重要な存在にしようとし、その後、アクターたちが研究者たちの 研究プログラムの「義務的な通過点」を交渉すれば、それらが改善されると主張する。 インタレスメント: 研究者が、他の行為者をそのプログラムにおいて割り当てられた役割に拘束するために用いる一連の手続き。 参加: 研究者たちが他者に割り当てた数多くの役割を定義し、結びつけるために用いた戦術のコレクション。 動員: 研究者たちは、さまざまな重要な集団の表向きの代弁者が、それらの集団を適切に代表し、後者に欺かれないようにするために、一連のアプローチを利用した。 また、この概念にとって重要なのは、ネットワーク・オブジェクトが、そ うでなければ非常に困難な人々、組織、条件の間に等価性を生み出すことで、翻訳プロ セスを円滑に進める手助けをするという役割である。 ブルーノ・ラトゥールは、彼の作品『Reassembling the Social(社会的再構築)』[1]の中で、オブジェクトのこの特別な仕事について語っている。 準オブジェクト 準オブジェクトとは、ネットワーク、社会的集合体、連合(バスケットボール、言語、パンなど)を結びつけ、織り成す方法によって特徴づけられる実体である [15]。 上記の例では、「社会的秩序」と「機能する車」はそれぞれの行為者ネットワークの成功した相互作用を通して誕生し、行為者ネットワーク理論はこれらの創造 物をネットワーク内の行為者間で受け渡されるトークンまたは準物体として参照する。 トークンがネットワークを通じてますます伝達されたり、受け渡されたりするにつれて、トークンはますます時間化され、またますます再定義されるようにな る。トークンの伝達が減少したり、アクターがトークンの伝達に失敗したりすると(例えば、オイルポンプが壊れた)、時間厳守と再定義も減少する。 |

| Other central concepts A material semiotic method Although it is called a "theory", ANT does not usually explain "why" a network takes the form that it does.[1] Rather, ANT is a way of thoroughly exploring the relational ties within a network (which can be a multitude of different things). As Latour notes,[11] "explanation does not follow from description; it is description taken that much further." It is not, in other words, a theory "of" anything, but rather a method, or a "how-to book" as Latour[1] puts it. The approach is related to other versions of material-semiotics (notably the work of philosophers Gilles Deleuze, Michel Foucault, and feminist scholar Donna Haraway). It can also be seen as a way of being faithful to the insights of ethnomethodology and its detailed descriptions of how common activities, habits and procedures sustain themselves. Similarities between ANT and symbolic interactionist approaches such as the newer forms of grounded theory like situational analysis, exist,[16] although Latour[17] objects to such a comparison. Although ANT is mostly associated with studies of science and technology and with the sociology of science, it has been making steady progress in other fields of sociology as well. ANT is adamantly empirical, and as such yields useful insights and tools for sociological inquiry in general. ANT has been deployed in studies of identity and subjectivity, urban transportation systems, and passion and addiction.[18] It also makes steady progress in political and historical sociology.[19] Intermediaries and mediators The distinction between intermediaries and mediators is key to ANT sociology. Intermediaries are entities which make no difference (to some interesting state of affairs which we are studying) and so can be ignored. They transport the force of some other entity more or less without transformation and so are fairly uninteresting. Mediators are entities which multiply difference and so should be the object of study. Their outputs cannot be predicted by their inputs. From an ANT point of view sociology has tended to treat too much of the world as intermediaries. For instance, a sociologist might take silk and nylon as intermediaries, holding that the former "means", "reflects", or "symbolises" the upper classes and the latter the lower classes. In such a view the real world silk–nylon difference is irrelevant– presumably many other material differences could also, and do also, transport this class distinction. But taken as mediators these fabrics would have to be engaged with by the analyst in their specificity: the internal real-world complexities of silk and nylon suddenly appear relevant, and are seen as actively constructing the ideological class distinction which they once merely reflected. For the committed ANT analyst, social things—like class distinctions in taste in the silk and nylon example, but also groups and power—must constantly be constructed or performed anew through complex engagements with complex mediators. There is no stand-alone social repertoire lying in the background to be reflected off, expressed through, or substantiated in, interactions (as in an intermediary conception).[1] Reflexivity In relativist theory, reflexivity is considered as a problem. It requires not only the observer requests a status it denies to others, but also as silent as others to which any privileged status is denied.[12] There is no privileges or limits on knowledge. If actors, or actants are able to account for others, then they do so. If they cannot, they would still try. Hybridity The belief that neither a human nor a nonhuman is pure, in the sense that neither is human or nonhuman in an absolute sense, but rather beings created via interactions between the two. Humans are thus regarded as quasi-subjects, while nonhumans are regarded as quasi-objects.[7] Actor–network theory and specific disciplines Recently, there has been a movement to introduce actor network theory as an analytical tool to a range of applied disciplines outside of sociology, including nursing, public health, urban studies (Farias and Bender, 2010), and community, urban, and regional planning (Beauregard, 2012;[20] Beauregard and Lieto, 2015; Rydin, 2012;[21] Rydin and Tate, 2016, Tate, 2013).[22] International relations Actor–network theory has become increasingly prominent within the discipline of international relations and political science. Theoretically, scholars within IR have employed ANT in order to disrupt traditional world political binaries (civilised/barbarian, democratic/autocratic, etc.),[23] consider the implications of a posthuman understanding of IR,[24] explore the infrastructures of world politics,[25] and consider the effects of technological agency.[26] Empirically, IR scholars have drawn on insights from ANT in order to study phenomena including political violences like the use of torture and drones,[23] piracy and maritime governance,[27] and garbage.[28] Design The actor–network theory can also be applied to design, using a perspective that is not simply limited to an analysis of an object's structure. From the ANT viewpoint, design is seen as a series of features that account for a social, psychological, and economical world. ANT argues that objects are designed to shape human action and mold or influence decisions. In this way, the objects' design serves to mediate human relationships and can even impact our morality, ethics, and politics.[29] Literary criticism The literary critic Rita Felski has argued that ANT offers the fields of literary criticism and cultural studies vital new modes of interpreting and engaging with literary texts. She claims that Latour's model has the capacity to allow "us to wiggle out of the straitjacket of suspicion," and to offer meaningful solutions to the problems associated with critique.[30] The theory has been crucial to her formulation of postcritique. Felski suggests that the purpose of applying ANT to literary studies "is no longer to diminish or subtract from the reality of the texts we study but to amplify their reality, as energetic coactors and vital partners."[31] Anthropology of religion In the study of Christianity by anthropologists, the ANT has been employed in a variety of ways of understanding how humans interact with nonhuman actors. Some have been critical of the field of Anthropology of Religion in its tendency to presume that God is not a social actor. The ANT is used to problematize the role of God, as a nonhuman actor, and speak of how They affect religious practice.[32] Others have used the ANT to speak of the structures and placements of religious buildings, especially in cross-cultural contexts, which can see architecture as agents making God's presence tangible.[33] ANT in practice ANT has been considered more than just a theory, but also a methodology. In fact, ANT is a useful method that can be applied in different studies. Moreover, with the development of the digital communication, ANT now is popular in being applied in science field like IS research. In addition, it widen the horizon of researchers from arts field as well. ANT in arts ANT is a big influencer in the development of design. In the past, researchers or scholars from design field mainly view the world as a human interactive situation. No matter what design we [who?] applied, it is for human's action. However, the idea of ANT now applies into design principle, where design starts to be viewed as a connector. As the view of design itself has changed, the design starts to be considered more important in daily lives. Scholars [who?] analyze how design shapes, connects, reflects, interacts our daily activities.[34] ANT has also been widely applied in museums. ANT proposes that it is difficult to discern the 'hard' from the 'soft' components of the apparatus in curatorial practice; that the object 'in progress' of being curated is slick and difficult to separate from the setting of the experiment or the experimenter's identity.[35] ANT in science In recent years, actor-network theory has gained a lot of traction, and a growing number of IS academics are using it explicitly in their research. Despite the fact that these applications vary greatly, all of the scholars cited below agree that the theory provides new notions and ideas for understanding the socio-technical character of information systems.[36] Bloomfield present an intriguing case study of the development of a specific set of resource management information systems in the UK National Health Service, and they evaluate their findings using concepts from actor-network theory. The actor-network approach does not prioritize social or technological aspects, which mirrors the situation in the case study, where arguments about social structures and technology are intertwined within actors' discourse as they try to persuade others to align with their own goals. The research emphasizes the interpretative flexibility of information technology and systems, in the sense that seemingly similar systems produce drastically different outcomes in different locales as a result of the specific translation and network-building processes that occurred. They show how the boundary between the technological and the social, as well as the link between them, is the topic of constant battles and trials of strength in the creation of facts, rather than taking technology for granted.[36] |

その他の中心概念 物質的記号論的手法 ANTは「理論」と呼ばれてはいるが、通常、ネットワークが「なぜ」そのような形態をとるのかを説明することはない[1]。ラトゥールが述べているように [11]、「説明は説明から生じるものではなく、説明からさらに踏み込んだものである」。言い換えれば、それは何かの「理論」ではなく、ラトゥール[1] が言うように、むしろ方法、あるいは「ハウツー本」なのである。 このアプローチは、物質記号論の他のバージョン(特に哲学者のジル・ドゥルーズ、ミシェル・フーコー、フェミニスト学者のドナ・ハラウェイの仕事)と関連 している。また、エスノメソドロジー(ethnomethodology)の洞察や、一般的な活動、習慣、手順がどのように維持されているかについての詳 細な記述に忠実な方法ともいえる。ANTと、状況分析のような新しい形のグラウンデッド・セオリーのような象徴相互作用論的アプローチとの間には類似点が 存在するが[16]、ラトゥール[17]はこのような比較に異議を唱えている。 ANTは主に科学技術研究や科学社会学と関連しているが、社会学の他の分野でも着実に進歩を遂げている。ANTは断固として経験的であり、そのため社会学 的探究一般にとって有用な洞察やツールをもたらす。ANTはまた、政治社会学や歴史社会学においても着実な進歩を遂げている[19]。 仲介者と媒介者 仲介者と媒介者の区別はANT社会学の鍵である。仲介者は、(私たちが研究しているある興味深い状態に対して)何の違いももたらさない存在であり、した がって無視することができる。媒介者は、多かれ少なかれ、他の実体の力を変容させることなく運搬する存在であり、そのためあまり興味深い存在ではない。メ ディエーターは差異を増大させる存在であり、研究の対象となるべきである。そのアウトプットは、そのインプットによって予測することはできない。ANTの 観点から見ると、社会学は世界の多くを媒介者として扱う傾向が強すぎる。 例えば、社会学者は絹とナイロンを仲介者とし、前者は上流階級を「意味」し、「反映」し、あるいは「象徴」し、後者は下層階級を「象徴」すると考えるかも しれない。このような見方では、現実世界のシルクとナイロンの違いは無関係である。シルクとナイロンの現実世界における内的な複雑性が突如として関連性を 帯び、かつては単に反映していたに過ぎないイデオロギー的な階級区別を積極的に構築していると見なされるのである。 献身的なANT分析者にとって、社会的なものは、シルクとナイロンの例における嗜好の階級的区別だけでなく、集団や権力のようなものであり、複雑な媒介者 との複雑な関わりを通して、常に新たに構築され、実行されなければならない。背景には、(仲介概念におけるように)相互作用の中で反映されたり、表現され たり、実証されたりするような、独立した社会的レパートリーは横たわっていない[1]。 反射性(反省性) 相対主義理論では、反射性が問題とされる。それは観察者が他者に対して否定する地位を要求するだけでなく、特権的な地位が否定される他者と同様に沈黙する ことを要求する[12]。行為者(actants)が他者のことを説明できるのであれば、そうする。もしそれができなくても、彼らはそうしようとするだろ う。 ハイブリディティ 人間も非人間も、絶対的な意味では人間でも非人間でもなく、むしろ両者の相互作用によって生み出された存在であるという意味で、人間も非人間も純粋ではな いという信念。したがって、人間は準主体、非人間は準対象とみなされる[7]。 アクター・ネットワーク理論と特定の学問分野 近年、看護学、公衆衛生学、都市研究(Farias and Bender, 2010)、コミュニティ・都市・地域計画(Beauregard, 2012;[20] Beauregard and Lieto, 2015; Rydin, 2012;[21] Rydin and Tate, 2016, Tate, 2013)など、社会学以外の様々な応用分野に分析ツールとして行為者ネットワーク理論を導入する動きがある[22]。 国際関係 アクター・ネットワーク理論は、国際関係学や政治学の分野でますます顕著になってきている。 理論的には、IRの研究者たちは、伝統的な世界政治の二項対立(文明的/野蛮的、民主的/独裁的など)を破壊するためにANTを採用し[23]、IRのポ ストヒューマン理解の意味を検討し[24]、世界政治のインフラを探求し[25]、技術的エージェンシーの影響を検討してきた[26]。 経験的には、IR研究者は拷問やドローンの使用のような政治的暴力、[23]海賊行為や海洋統治、[27]ゴミ[28]などの現象を研究するためにANT からの洞察を活用している。 デザイン 行為者ネットワーク理論は、単に対象物の構造の分析に限定されない視点を用いて、デザインにも適用することができる。ANTの視点からは、デザインは社会 的、心理的、経済的な世界を説明する一連の特徴として捉えられる。ANTは、モノは人間の行動を形成し、意思決定に型や影響を与えるようにデザインされて いると主張する。このように、モノのデザインは人間関係を媒介する役割を果たし、私たちの道徳、倫理、政治に影響を与えることさえある[29]。 文学批評 文芸批評家のリタ・フェルスキーは、ANTは文芸批評やカルチュラル・スタディーズの分野に、文学テクストを解釈し、それに関与するための重要な新しい方 法を提供すると主張している。彼女はラトゥールのモデルが「疑惑の拘束から抜け出す」ことを可能にし、批評に関連する問題に対して意味のある解決策を提示 する能力を有していると主張している。フェルスキーは、ANTを文学研究に適用する目的は、「もはや、我々が研究するテクストのリアリティを減少させた り、引き下げたりすることではなく、エネルギッシュな共同体や重要なパートナーとして、そのリアリティを増幅させることである」と示唆している[31]。 宗教人類学 人類学者によるキリスト教研究において、ANTは、人間が人間以外の行為者とどのように相互作用するかを理解する様々な方法で用いられてきた。宗教人類学 の分野では、神が社会的行為者ではないと仮定する傾向があり、批判的な意見もある。ANTは、非人間的行為者としての神の役割を問題化し、それらが宗教的 実践にどのような影響を与えるかを語るために用いられている[32]。また、ANTを用いて、特に異文化の文脈における宗教的建造物の構造や配置について 語る者もおり、建築を神の存在を目に見えるものにする行為者とみなすことができる[33]。 実践におけるANT ANTは単なる理論ではなく、方法論であると考えられてきた。実際、ANTはさまざまな研究に応用できる有用な方法である。さらに、デジタル・コミュニ ケーションの発展に伴い、ANTは現在、IS研究のような科学分野での応用が盛んである。さらに、芸術分野の研究者にも視野を広げている。 芸術分野におけるANT ANTはデザインの発展に大きな影響を与えている。かつて、デザイン分野の研究者や学者は、主に世界を人間の相互作用的な状況として捉えていました。どの ようなデザインを適用しても、それは人間の行為のためのものです。しかし、今やANTの考え方はデザイン原理にも適用され、デザインはコネクターとして捉 えられるようになった。デザインそのものの見方が変わるにつれて、デザインは日常生活においてより重要視されるようになった。学者[誰?]は、デザインが どのように私たちの日々の活動を形成し、結びつけ、反映し、相互作用するかを分析している[34]。 ANTは博物館でも広く応用されている。ANTは、学芸員の実践において、装置の「ハード」な構成要素と「ソフト」な構成要素とを見分けることは困難であ り、学芸される「進行中」の対象は巧妙であり、実験の設定や実験者のアイデンティティから切り離すことは困難であると提唱している[35]。 科学におけるANT 近年、アクター・ネットワーク理論は多くの支持を得ており、それを研究において明確に用いるIS学者が増えている。これらの応用は実にさまざまであるにも かかわらず、以下に引用する学者はすべて、この理論が情報システムの社会技術的性格を理解するための新しい概念とアイデアを提供することに同意している [36]。ブルームフィールドは、英国の国民保健サービスにおける特定の資源管理情報システムの開発に関する興味深いケーススタディを提示し、アクター・ ネットワーク理論の概念を用いてその発見を評価している。アクター・ネットワーク・アプローチは、社会的側面や技術的側面に優先順位をつけないが、これ は、社会構造や技術に関する議論が、自らの目標に沿うように他者を説得しようとするアクターの言説の中で絡み合っているという、ケース・スタディの状況を 反映している。この研究は、一見似たようなシステムが、特定の翻訳やネットワーク構築のプロセスの結果として、異なる地域でまったく異なる結果を生み出す という意味で、情報技術やシステムの解釈の柔軟性を強調している。彼らは、技術的なものと社会的なものとの境界、そしてそれらの間のつながりが、技術を当 然視するのではなく、事実の創造における絶え間ない戦いや力の試練のテーマであることを示している[36]。 |

| Impact of ANT Contributions of nonhuman actors There are at least four contributions of nonhumans as actors in their ANT positions.[10] Nonhuman actors can be considered as a condition in human social activities. Through the human's formation of nonhuman actors such as durable materials, they provide a stable foundation for interactions in society.[37] Reciprocally, nonhumans' actions and capacities serve as a condition for the possibility of the formation of society.[38][10][39] In Latour's We Have Never Been Modern[39], his conceptual "parliament of things" consists of social, natural, and discourse together as hybrids. Although the interlocks between human actors and nonhumans effects the modernized society, this parliamentary setting based on nonhuman actors would eliminate such fake modernization, and changes the dichotomy between modern society and premodern society.[40] Nonhuman actors can be considered as mediators. On the one hand, nonhumans could constantly modify relations between actors.[14][41] On the other hand, nonhumans share the same features with other actors not solely as means for human actors.[42] In this circumstance, nonhuman actors impact human interactions. It either creates an atmosphere for humans to agree with each other, or lead to conflict as the mediators. It is noticeable that the status of mediation is more affiliated with intermediaries or means as a stable presence in the corpus of ANT,[43][44] while mediators function more powers to influence actors and networks.[10] Technical mediation exerts itself on four dimensions: interference, composition, the folding of time and space, and crossing the boundary between signs and things.[14] Nonhuman actors can be considered as members of moral and political associations. For example, noise is a nonhuman actor if the topic is applied to actor-network theory.[10] Noise is the criteria for humans to regulate themselves to morality, and subject to the limitations inherent in some legal rules for its political effects. After nonhumans are visible actors through their associations with morality and politics, these collectives become inherently regulative principles in social networks.[45] Nonhuman actors can be considered as gatherings. Alike nonhumans' impacts on morality and politics, they could gather actors from other times and spaces.[43] Interacted with variable ontologies, times, spaces, and durability, nonhumans exert subtle influences within a network.[38] |

ANTのインパクト 人間以外のアクターの貢献 ANTの立場において、アクターとしての非人間の貢献は少なくとも4つある[10]。 1. 非人間的アクターは、人間の社会活動における条件として考えることができる。耐久性のある素材のような非人間的アクターを人間が形成することを通して、非 人間的アクターは社会における相互作用のための安定した基盤を提供する[37]。 反比例的に、非人間的な行為や能力は社会が形成される可能性のための条件として機能する[38][10][39]。 ラトゥールの『We Have Never Been Modern』[39]において、彼の概念的な「物事の議会」は社会、自然、言説がハイブリッドとして一緒になって構成されている。人間的行為者と非人間 的行為者の相互作用は近代化社会に影響を与えるが、非人間的行為者に基づくこの議会設定はそのような偽の近代化を排除し、近代社会と前近代社会の間の二分 法を変えるだろう[40]。 2. 非人間的行為者は媒介者として考えることができる。一方では、非人間は行為者間の関係を常に修正しうる[14][41]。他方では、非人間は人間の行為者 のための手段としてだけでなく、他の行為者と同じ特徴を共有している[42]。このような状況において、非人間的行為者は人間の相互作用に影響を与える。 それは、人間同士が合意するための雰囲気を作り出すか、調停者として対立を導くかのどちらかである。 メディエーターがアクターやネットワークに影響を与える力として機能するのに対して、メディエーションの地位がANTのコーパスにおいて安定 した存在とし て仲介者や手段とより結びついていることは注目に値する[43][44]。技術的なメディエーションは干渉、構成、時間と空間の折りたたみ、記号と事物の 間の境界の横断という4つの次元でそれ自体を発揮する[14]。 3. 人間以外の行為者は、道徳的・政治的団体の構成員として考えるこ とができる。例えば、アクター・ネットワーク理論に当てはめれば、ノイズは非人間的な行為 者である[10]。ノイズは人間が道徳的に自らを規制するための基準であり、その政治的効果についてはいくつかの法的ルールに内在する制限を受ける。非人 間が道徳や政治との関連を通じて目に見えるアクターとなった後、これらの集合体は社会的ネットワークにおいて本質的に規制的な原理となる[45]。 4. 非人間的行為者は集まりとみなすことができる。非人間が道徳や政 治に与える影響と同様に、非人間は他の時間や空間から行為者を集める可能性がある [43]。可変的な存在論、時間、空間、耐久性と相互作用することで、非人間はネットワーク内で微妙な影響を及ぼす[38]。 |

| Criticism Some critics[46] have argued that research based on ANT perspectives remains entirely descriptive and fails to provide explanations for social processes. ANT—like comparable social scientific methods—requires judgement calls from the researcher as to which actors are important within a network and which are not. Critics[who?] argue that the importance of particular actors cannot be determined in the absence of "out-of-network" criteria, such as is a logically proven fact about deceptively coherent systems given Gödel's incompleteness theorems. Similarly, others[who?] argue that actor-networks risk degenerating into endless chains of association (six degrees of separation—we are all networked to one another). Other research perspectives such as social constructionism, social shaping of technology, social network theory, normalization process theory, and diffusion of innovations theory are held to be important alternatives to ANT approaches. From STS itself and organizational studies Key early criticism came from other members of the STS community, in particular the "Epistemological Chicken" debate between Collins and Yearley with responses from Latour and Callon as well as Woolgar. In an article in Science as Practice and Culture, sociologist Harry Collins and his co-writer Steven Yearley argue that the ANT approach is a step backwards towards the positivist and realist positions held by early theory of science.[47] Collins and Yearley accused ANTs approach of collapsing into an endless relativist regress.[48] Whittle and organization studies professor André Spicer note that "ANT has also sought to move beyond deterministic models that trace organizational phenomena back to powerful individuals, social structures, hegemonic discourses or technological effects. Rather, ANT prefers to seek out complex patterns of causality rooted in connections between actors." They argue that ANT's ontological realism makes it "less well equipped for pursuing a critical account of organizations—that is, one which recognises the unfolding nature of reality, considers the limits of knowledge and seeks to challenge structures of domination."[49] This implies that ANT does not account for pre-existing structures, such as power, but rather sees these structures as emerging from the actions of actors within the network and their ability to align in pursuit of their interests. Accordingly, ANT can be seen as an attempt to re-introduce Whig history into science and technology studies; like the myth of the heroic inventor, ANT can be seen as an attempt to explain successful innovators by saying only that they were successful. Likewise, for organization studies, Whittle and Spicer assert that ANT is, "ill suited to the task of developing political alternatives to the imaginaries of market managerialism." Human agency Actor–network theory insists on the capacity of nonhumans to be actors or participants in networks and systems. Critics including figures such as Langdon Winner maintain that such properties as intentionality fundamentally distinguish humans from animals or from "things" (see Activity Theory). ANT scholars [who?] respond with the following arguments: They do not attribute intentionality and similar properties to nonhumans. Their conception of agency does not presuppose intentionality. They locate agency neither in human "subjects" nor in nonhuman "objects", but in heterogeneous associations of humans and nonhumans. ANT has been criticized as amoral. Wiebe Bijker has responded to this criticism by stating that the amorality of ANT is not a necessity. Moral and political positions are possible, but one must first describe the network before taking up such positions. This position has been further explored by Stuart Shapiro who contrasts ANT with the history of ecology, and argues that research decisions are moral rather than methodological, but this moral dimension has been sidelined.[50] Misnaming In a workshop called "On Recalling ANT", Latour himself stated that there are four things wrong with actor-network theory: "actor", "network", "theory" and the hyphen.[51] In a later book, however, Latour reversed himself, accepting the wide use of the term, "including the hyphen."[1]: 9 He further remarked how he had been helpfully reminded that the ANT acronym "was perfectly fit for a blind, myopic, workaholic, trail-sniffing, and collective traveler"—qualitative hallmarks of actor-network epistemology.[1] |

批判 批評家[46]の中には、ANTの視点に基づく研究は完全に記述的であり、社会プロセスの説明を提供できていないと主張する者もいる。ANTは、同等の社 会科学的手法と同様に、ネットワーク内でどのアクターが重要で、どのアクターが重要でないかを研究者が判断する必要がある。批評家[who?]は、ゲーデ ルの不完全性定理が示すように、欺瞞的に首尾一貫したシステムについて論理的に証明された事実のような「ネットワーク外」の基準がない場合、特定のアク ターの重要性を決定することはできないと主張する。同様に、アクター・ネットワークが無限の連鎖的関連性(6度の隔たり-私たちはみな互いにネットワーク でつながっている)に堕落する危険性があると主張する人もいる。社会構築主義、技術の社会的形成、社会ネットワーク理論、正規化プロセス理論、イノベー ションの普及理論などの他の研究視点は、ANTアプローチに代わる重要なものであると考えられている。 STSそのものと組織研究から 初期の重要な批判は、STSコミュニティの他のメンバーからもたらされた。特に、コリンズとイアリーの間で交わされた「認識論的チキン (Epistemological Chicken)」論争では、ラトゥールやカロン、ウールガーがこれに反論している。社会学者のハリー・コリンズと彼の共同執筆者であるスティーヴン・イ ヤーリーは、『Science as Practice and Culture(実践と文化としての科学)』誌の論文の中で、ANTのアプローチは初期の科学理論が保持していた実証主義的、現実主義的な立場に対して後 退していると主張している[47]。 Whittleと組織学のAndré Spicer教授は「ANTはまた、組織現象を強力な個人、社会構造、覇権的な言説や技術的効果にまで遡及させる決定論的なモデルを超えていこうとしてき た」と指摘している。むしろANTは、行為者間のつながりに根ざした複雑な因果関係のパターンを追求することを好む。彼らは、ANTの存在論的実在論が、 「組織に関する批判的な説明、つまり、現実の展開する性質を認識し、知識の限界を考慮し、支配の構造に挑戦しようとする説明を追求するのに適していない」 [49]と論じている。このことは、ANTが権力のような既存の構造を説明せず、むしろ、これらの構造がネットワーク内の行為者の行動と、彼らの利益を追 求するために彼らが協調する能力から出現するとみなすことを意味している。したがって、ANTは科学技術研究にホイッグの歴史を再導入しようとする試みと みなすことができる。英雄的発明家の神話のように、ANTは成功したイノベーターを、彼らが成功したということだけで説明しようとする試みとみなすことが できる。同様に、組織研究についても、WhittleとSpicerは、ANTは「市場管理主義のイマジナリーに対する政治的な代替案を開発する作業に適 していない」と主張している。 人間の主体性 アクター・ネットワーク理論は、人間以外がネットワークやシステムのアクターや参加者になれることを主張する。ラングドン・ウィナーなどの批評家たちは、 意図性といった性質が、人間を動物や「モノ」から根本的に区別していると主張している(アクティビティ理論参照)。ANTの研究者たちは次のように反論し ている: 非人間には意図性や類似の特性を認めない。 彼らのエージェンシー概念は意図性を前提としない。 エージェンシーを人間の「主体」にも非人間の「対象」にも位置づけず、 人間と非人間の異質な連合に位置づける。 ANTは非道徳的であると批判されてきた。ウィービー・バイカーはこの批判に対して、ANTの非道徳性は必然ではないと述べている。道徳的、政治的な立場 は可能だが、そのような立場を取る前に、まずネットワークを記述しなければならない。この立場は、ANTを生態学の歴史と対比させ、研究の決定は方法論的 というよりもむしろ道徳的なものであると主張するスチュアート・シャピロによってさらに追求されているが、この道徳的な側面は傍観されている[50]。 誤ったネーミング ラトゥール自身は「ANTを想起する」というワークショップの中で、アクター・ネットワーク理論には「アクター」、「ネットワーク」、「理論」、そして 「ハイフン」という4つの間違いがあると述べている[51]。 「1]: 9 彼はさらに、ANTの頭字語は「盲目で、近視眼的で、仕事中毒で、痕跡を嗅ぎ分け、集団的な旅行者にぴったりである」-アクター・ネットワーク認識論の特 徴である-ことに気づかされたと述べている[1]。 |

| Annemarie Mol Helen Verran Mapping controversies Science and technology studies (STS) Obligatory passage point (OPP) Social construction of technology (SCOT) Technology dynamics Theory of structuration (according to which neither agents nor social structure have primacy) Outline of organizational theory |

アンネマリー・モル ヘレン・ヴェラン 論争のマッピング 科学技術研究(STS) 義務的通過点(OPP) 技術の社会的構築(SCOT) テクノロジー・ダイナミクス 構造化理論(エージェントにも社会構造にも優位性はな い) 組織論の概要 |

| Actor–network theory (ANT) | Actor–network theory (ANT) |

| Further reading Carroll, N., Whelan, E., and Richardson, I. (2012). Service Science – an Actor Network Theory Approach. International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation (IJANTTI), Volume 4, Number 3, pp. 52–70. Carroll, N. (2014). Actor-Network Theory: A Bureaucratic View of Public Service Innovation. Chapter 7, p. 115-144. In Ed Tatnall (ed). Technological Advancements and the Impact of Actor-Network Theory, IGI Global. Online version of the article "On Actor Network Theory: A Few Clarifications", in which Latour responds to criticisms. Archived 2021-04-26 at the Wayback Machine Introductory article "Dolwick, JS. 2009. The 'Social' and Beyond: Introducing Actor–Network Theory", which includes an analysis of other social theories ANThology. Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur–Netzwerk-Theorie, von Andréa Belliger und David Krieger, transcript Verlag (German) Transhumanism as Actor-Network Theory "N00bz & the Actor-Network: Transhumanist Traductions" Archived 2010-10-08 at the Wayback Machine (Humanity+ Magazine) by Woody Evans. John Law (1992). "Notes on the Theory of the Actor Network: Ordering, Strategy, and Heterogeneity." John Law (1987). "Technology and Heterogeneous Engineering: The Case of Portuguese Expansion." In W.E. Bijker, T.P. Hughes, and T.J. Pinch (eds.), The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). Gianpaolo Baiocchi, Diana Graizbord, and Michael Rodríguez-Muñiz. 2013. "Actor-Network Theory and the ethnographic imagination: An exercise in translation". Qualitative Sociology Volume 36, Issue 4, pp 323–341. Seio Nakajima. 2013. "Re-imagining Civil Society in Contemporary Urban China: Actor-Network-Theory and Chinese Independent Film Consumption." Qualitative Sociology Volume 36, Issue 4, pp 383–402. [1] Isaac Marrero-Guillamón. 2013. "Actor-Network Theory, Gabriel Tarde and the Study of an Urban Social Movement: The Case of Can Ricart, Barcelona." Qualitative Sociology Volume 36, Issue 4, pp 403–421. [2] John Law and Vicky Singleton. 2013. "ANT and Politics: Working in and on the World". Qualitative Sociology Volume 36, Issue 4, pp 485–502. |

さらに読む Carroll, N., Whelan, E., and Richardson, I. (2012). サービス科学-アクター・ネットワーク理論によるアプローチ。International Journal of Actor-Network Theory and Technological Innovation (IJANTTI), Volume 4, Number 3, pp.52-70. キャロル、N. (2014). アクター・ネットワーク理論: A Bureaucratic View of Public Service Innovation. 第7章、115-144頁。Ed Tatnall (ed). 技術の進歩とアクター・ネットワーク理論の影響』IGIグローバル。 論文「アクター・ネットワーク理論について」のオンライン版: ラトゥールが批判に反論している。Archived 2021-04-26 at the Wayback Machine 紹介記事「Dolwick, JS. 2009. The 『Social』 and Beyond: 他の社会理論の分析も含まれている。 ANThology。Ein einführendes Handbuch zur Akteur-Netzwerk-Theorie, von Andréa Belliger und David Krieger, transcript Verlag (German). アクター・ネットワーク理論としてのトランスヒューマニズム「N00bz & the Actor-Network: Archived 2010-10-08 at the Wayback Machine (Humanity+ Magazine) by Woody Evans. ジョン・ロー (1992). 「アクター・ネットワークの理論に関するノート: 秩序、戦略、異質性". ジョン・ロー (1987). 「技術と異質な工学: ポルトガル進出の事例". W.E. Bijker, T.P. Hughes, and T.J. Pinch (eds.), The Social Construction of Technological Systems: The Social Construction of Technological Systems: New Directions in the Sociology and History of Technology (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press). Gianpaolo Baiocchi, Diana Graizbord, and Michael Rodríguez-Muñiz. 2013. 「Actor-Network Theory and the ethnographic imagination: 翻訳の練習". 質的社会学36巻4号323-341頁。 中島征夫. 2013. 「現代中国都市における市民社会の再想像: アクター・ネットワーク理論と中国インディペンデント映画の消費". 質的社会学第36巻第4号、383-402頁。[1] Isaac Marrero-Guillamón. 2013. 「Actor-Network Theory, Gabriel Tarde and the Study of an Urban Social Movement: バルセロナのカン・リカルトの事例". 質的社会学36巻4号403-421頁。[2] John Law and Vicky Singleton. 2013. 「ANT and Politics: 世界における、そして世界に関する作業」。質的社会学36巻4号485-502頁。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Actor%E2%80%93network_theory |

| Reassembling

the social : an introduction to actor-network-theory, Bruno Latour,

Oxford University Press 2007, c2005 Clarendon lectures in management

studies |

社会的なものを組み直す : アクターネットワーク理論入門 / ブリュノ・ラトゥール [著] ; 伊藤嘉高訳, 東京 : 法政大学出版局 , 2019.1. - (叢書・ウニベルシタス ; 1090) |

| CONTENTS Acknowledgements ix Introduction: How to Resume the Task of Tracing Associations 1 Part I: How to Deploy Controversies About the Social World Introduction to Part I: Learning to Feed off Controversies 21 First Source of Uncertainty: No Group, Only Group Formation 27 Second Source of Uncertainty: Action Is Overtaken 43 Third Source of Uncertainty: Objects too Have Agency 63 Fourth Source of Uncertainty: Matters of Fact vs.Matters of Concern 87 Fifth Source of Uncertainty: Writing Down Risky Accounts 121 On the Difficulty of Being an ANT: An Interlude in the Form of a Dialog 141 Part II: How to Render Associations Traceable Again Introduction to Part II: Why is it so Difficult to Trace the Social? 159 How to Keep the Social Flat 165 First Move: Localizing the Global 173 Second Move: Redistributing the Local 191 Third Move: Connecting Sites 219 Conclusion: From Society to Collective—Can the Social Be Reassembled? 247 Bibliography 263 Index 281 |

目次 謝辞 ix はじめに 関連性を追跡する作業を再開するには 1 第一部:論争をどう展開するか 社会的世界について 序章:論争を糧にすることを学ぶ 21 不確実性の最初の源泉 グループなし、グループ形成のみ 27 不確実性の第二の源泉 行動が追い越される 43 第三の不確実性の源泉:物体にも主体性がある 63 不確実性の第四の源泉 事実の問題vs.懸念の問題 87 不確実性の第五の源泉 危険な勘定を書き留める 121 ANTであることの難しさについて:対話形式の幕間劇 141 ダイアロジック形式で 141 第II部 連想を再び追跡可能にする方法 再び追跡可能にする 序論:なぜ社会的なものを追跡することは難しいのか?159 ソーシャルをフラットに保つ方法 165 第一の手:グローバルなものをローカライズする 173 第二の手:ローカルを再分配する 191 第三の手:サイトをつなぐ 219 結論:社会から集団へ 社会から集団へ-社会は再構築できるか?247 参考文献 263 索引 281 |

★ アクターネットワークの結節点としての《宗教》

宗

教の実在を、それ自体で存在すると考えるのではな

く、「信じる人」がいることから論証しようとする研究者がいる。アンリ・ユーベルとマルセル・モースの『供犠論』がそれである。かれらはその研究の結論の

部分でこういう:「宗教的観念は信じられているがゆえに、存在する。しかもそれを、それは社会的事実のように、客観的に存在するのである」(小関訳

1983:109)Les notions religieuses, parce qu'elles sont crues, sont ;

elles existent objectivement, comme faits sociaux.

★ 死という概念もアクタント化する

ラ・

カレヴェラ・カタリナは、ホセ・グアダルーペ・ポサダによるカタリナの版画(1910年~1913年)の一つである。

★Global production network(グローバルな生産ネットワーク)

| Global Production

Networks (GPN) is a concept in developmental literature which refers to

"the nexus of interconnected functions, operations and transactions

through which a specific product or service is produced, distributed

and consumed."[1] |

グローバル生産ネットワーク(GPN)とは、開発学文献における概念であり、「特定の製品やサービスが生産、流通、消費される過程で相互に結びついた機能、業務、取引の連関」を指すものである。[1] |

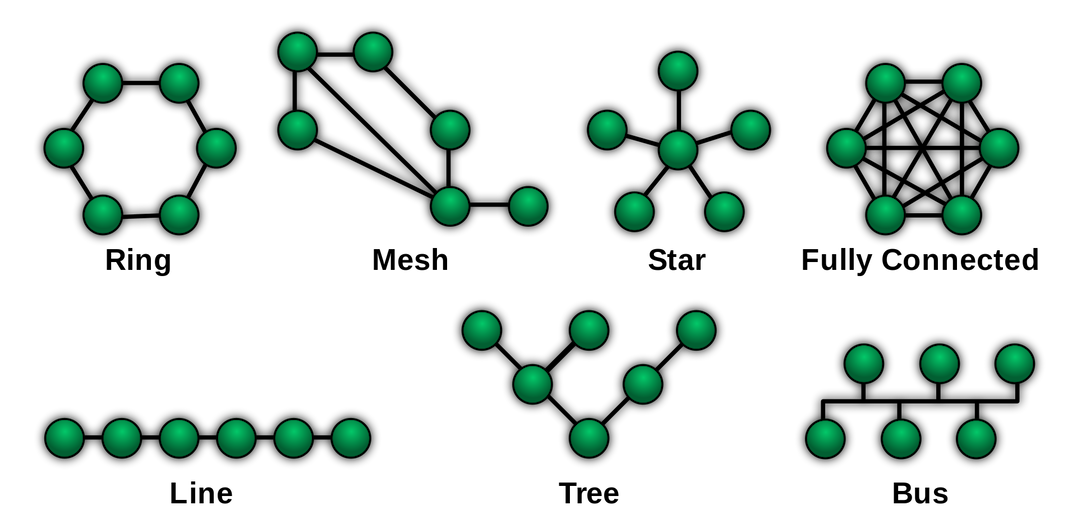

| Global Production Networks A global production network is one whose interconnected nodes and links extend spatially across national boundaries and, in so doing, integrates parts of disparate national and subnational territories".[1] GPN frameworks combines the insights from the global value chain analysis, actor–network theory and literature on Varieties of Capitalism. GPN provides a relational framework that aims to encompass all the relevant actors in the production systems. GPN framework provides analytical platform that relates sub-national regional development[2] with clustering dynamics.[3] |

グローバル生産ネットワーク グローバル生産ネットワークとは、相互接続されたノードとリンクが国家境界を越えて空間的に広がり、それによって異なる国家および地方の領域の一部を統合 するものである。[1] GPNフレームワークは、グローバルバリューチェーン分析、アクターネットワーク理論、資本主義の多様性に関する文献からの知見を統合する。GPNは生産 システムに関わる全ての主体を包含しようとする関係性フレームワークを提供する。GPNフレームワークは、地方レベルでの地域開発[2]とクラスター形成 の力学[3]を関連付ける分析的基盤を提供する。 |

| Historical development of concept In 1990s the concept of value chain gained its credit among economists and business scholars. (Its prominent developer Michael Porter). The concept combined sequenced and interconnected activities in the process of value creation. Value chain concept focused on business activities, but not on the corporate power and institutional context. In 1994 Garry Gereffi, together with Miguel Korzeniewicz introduced the concept of Global Commodity Chains (GCC): sets of interorganizational networks clustered around one commodity or product, linking households, enterprises, and states to one another within the world-economy. These networks are situationally specific, socially constructed, and locally integrated, underscoring the social embeddedness of economic organization — Gereffi[4] The concept was developed further by a number of authors that emphasized importance of chain governance in different commodities (e.g. automobiles, textile, electronics etc.) At the beginning of 2000s a group of authors Jeffrey Henderson, Peter Dicken, Martin Hess, Neil Coe and Henry Wai-Chung Yeung, introduced GPN framework, that builds on the development of previous approaches to international production processes. At the same time it expands beyond the linearity of GCC approach to incorporate all kinds of network configuration. Adopting clear network perspective allows to embrace the complexity of multidimensional layers of production moving beyond the "linear progression of the product or service"[5] |

概念の歴史的発展 1990年代、バリューチェーンの概念は経済学者や経営学者の間で評価を得た(その主要な提唱者はマイケル・ポーターである)。この概念は、価値創造プロ セスにおける一連の相互接続された活動を統合した。バリューチェーン概念は事業活動に焦点を当てたが、企業の力や制度的文脈には注目しなかった。1994 年、ギャリー・ゲレフィはミゲル・コルゼニエヴィッチと共にグローバル商品チェーン(GCC)概念を導入した: 特定の商品や製品を中心に形成される組織間ネットワーク群であり、世界経済の中で世帯、企業、国家を相互に結びつける。これらのネットワークは状況に依存し、社会的に構築され、地域的に統合されており、経済組織の社会的埋め込み性を強調する — ゲレフィ [4] この概念は、異なる商品(自動車、繊維、電子機器など)におけるチェーンガバナンスの重要性を強調する多くの著者によってさらに発展した。 2000年代の初め、ジェフリー・ヘンダーソン、ピーター・ディッケン、マーティン・ヘス、ニール・コー、ヘンリー・ワイチョン・ヤンらの一群の著者が、 国際的な生産プロセスに関するこれまでのアプローチの発展に基づいて構築された GPN フレームワークを導入した。同時に、GCC アプローチの直線性を超え、あらゆる種類のネットワーク構成を取り込むように拡大している。明確なネットワークの視点を採用することで、「製品やサービス の直線的な進展」[5] を超えた、多次元的な生産の複雑さを包括的に捉えることができる。 |

| Insights from the analysis of production networks Analysis of the global production networks relies on the use of the input-output tables that links firms through the transactions involved in the product creation. Commodity chain literature considers firms as the nodes in a number of chains that transform inputs into outputs through a series of interconnected stages of production, later linked to distribution and consumption activities. Andersen and Christensen define five major types of connective nodes in supply networks: Local integrator, Export base, Import base, International spanner and Global integrator [6] Hobday et al. argue that the core capability of the firms stem from their ability to manage network of components and subsystem suppliers.[7] To capture both vertical and horizontal links across the sequence of production process, Lazzarini introduced the concept of Netchain: "a set of networks comprised of horizontal ties between firms within a particular industry or group, which are sequentially arranged based on vertical ties between firms in different layers ... Netchain analysis explicitly differentiates between horizontal (transactions in the same layer) and vertical ties (transactions between layers), mapping how agents in each layer are related to each other and to agents in other layers".[8] Critical studies have explored production networks in the domain of ethics of production, for instance focusing on local effects or labor relations.[9] |

生産ネットワーク分析からの知見 グローバル生産ネットワークの分析は、製品創出に関わる取引を通じて企業を結びつける産業連関表の利用に依存する。商品チェーンの文献では、企業を複数の チェーンにおけるノードと見なす。これらのチェーンは、相互接続された一連の生産段階を通じて投入物を産出物に変換し、その後流通・消費活動と結びつく。 アンダーセンとクリステンセンは、供給ネットワークにおける主要な接続ノードを5種類定義している:ローカル・インテグレーター、輸出拠点、輸入拠点、国 際的スパンナー、グローバル・インテグレーターである[6]。ホブデイらは、企業の核心的能力は、部品やサブシステム供給業者からなるネットワークを管理 する能力に由来すると主張する。[7] 生産プロセスの連続性における垂直的・水平的連結を捉えるため、ラザリーニはネットチェーン概念を導入した:「特定産業またはグループ内の企業間における 水平的連結で構成されるネットワーク群であり、異なる層の企業間における垂直的連結に基づいて順次配置される... ネットチェーン分析は、水平的関係(同一層内での取引)と垂直的関係(層間での取引)を明確に区別し、各層の主体が相互に、また他層の主体とどう関連して いるかを可視化する」。[8] 批判的研究は、生産の倫理という領域において生産ネットワークを探究してきた。例えば、地域への影響や労働関係に焦点を当てた研究が挙げられる。[9] |

| References 1. Coe, N. M.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M. (2008), "Global production networks: Realizing the potential", Journal of Economic Geography, 8 (3): 271–295, doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002 2. Coe NM, Hess M, Yeung H. W-C, Dicken P, Henderson J (2004) Globalizing regional development: a global production networks perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29:468–484. 3. Harald Bathelt and Peng-Fei Li, “Global Cluster Networks—Foreign Direct Investment Flows from Canada to China,” Journal of Economic Geography 14, no. 1 (2014): 45–71. 4. Gereffi, G. (1994) ‘The organisation of buyer-driven global commodity chains: how US retailers shape overseas production networks’, in G. Gereffi and M. Korzeniewicz (eds), Commodity Chains and Global Development. Westport: Praeger, pp. 95–122: 2 5. Neil M. Coe, Peter Dicken, and Martin Hess, “Global Production Networks: Realizing the Potential,” Journal of Economic Geography 8, no. 3 (May 1, 2008): 271–95, doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002. 6. Poul Houman Andersen and Poul Rind Christensen, “Bridges over Troubled Water: Suppliers as Connective Nodes in Global Supply Networks,” Journal of Business Research 58, no. 9 (September 2005): 1261–73, doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.04.002. 7. Hobday, M., Davies, A., Prencipe, A. (2005) Systems integration: a core capability of the modern corporation. Industrial and Corporate Change, 14: 1109–1143. 8. Lazzarini, S., Chaddad, F. R., Cook, M. L. (2000) Integrating supply chain and network analysis: the study of netchains. Journal on Chain and Network Science, 1: 7–22. 9. Miszczynski, M. (2016-02-18). "Global Production in a Romanian Village: Middle-Income Economy, Industrial Dislocation and the Reserve Army of Labor". Critical Sociology. 43 (7–8): 1079–1092. doi:10.1177/0896920515623076. S2CID 146971797 |

参考文献 1. Coe, N. M.; Dicken, P.; Hess, M. (2008), 「グローバル生産ネットワーク:可能性の実現」, Journal of Economic Geography, 8 (3): 271–295, doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002 2. Coe NM, Hess M, Yeung H. W-C, Dicken P, Henderson J (2004) 地域開発のグローバル化:グローバル生産ネットワークの視点. 英国地理学会紀要 29:468–484. 3. Harald Bathelt and Peng-Fei Li, 「グローバル・クラスター・ネットワーク——カナダから中国への外国直接投資フロー」, Journal of Economic Geography 14, no. 1 (2014): 45–71. 4. Gereffi, G. (1994) 「バイヤー主導のグローバル商品チェーンの組織化:米国小売業者が海外生産ネットワークを形作る方法」, G. Gereffi および M. Korzeniewicz (編), Commodity Chains and Global Development. Westport: Praeger, pp. 95–122: 2 5. Neil M. Coe、Peter Dicken、Martin Hess、「グローバル生産ネットワーク:その可能性の実現」、『経済地理学雑誌』8、第3号(2008年5月1日):271-95、doi:10.1093/jeg/lbn002。 6. Poul Houman Andersen および Poul Rind Christensen、「困難な状況における架け橋:グローバル供給ネットワークにおける接続ノードとしてのサプライヤー」『Journal of Business Research』58、第 9 号(2005 年 9 月):1261–73、doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2003.04.002。 7. Hobday, M., Davies, A., Prencipe, A. (2005) システム統合:現代企業のコア能力。産業と企業の変化、14: 1109–1143。 8. Lazzarini, S., Chaddad, F. R., Cook, M. L. (2000) サプライチェーンとネットワーク分析の統合:ネットチェーンの研究。Journal on Chain and Network Science, 1: 7–22. 9. Miszczynski, M. (2016-02-18). 「ルーマニアの村におけるグローバル生産:中所得経済、産業の変容、および予備労働軍」. クリティカル・ソシオロジー. 43 (7–8): 1079–1092. doi:10.1177/0896920515623076. S2CID 146971797 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Global_production_network |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆