詩学

Poetics

☆

詩学(Poetics)は詩の研究または理論であり、具体的には詩に関する装置、構造、形式、型、効果についての研究または理論である[1]が、この用語の用法は広く文学を

指すこともある[2][3]。詩学は、意味的解釈よりもむしろテクスト内の非意味的要素の統合に焦点を当てることによって、解釈学と区別される[4]。ほ

とんどの文芸批評は詩学と解釈学を組み合わせて一つの分析を行っているが、テクストや読解を行う者の目的によっては、どちらかが優勢になることもある(→アリストテレス「詩学」)。

| Poetics is the study

or theory of poetry, specifically the study or theory of device,

structure, form, type, and effect with regards to poetry,[1] though

usage of the term can also refer to literature broadly.[2][3] Poetics

is distinguished from hermeneutics by its focus on the synthesis of

non-semantic elements in a text rather than its semantic

interpretation.[4] Most literary criticism combines poetics and

hermeneutics in a single analysis; however, one or the other may

predominate given the text and the aims of the one doing the reading. |

詩学は詩の研究または理論であり、具体的には詩に関する装置、構造、形

式、型、効果についての研究または理論である[1]が、この用語の用法は広く文学を指すこともある[2][3]。詩学は、意味的解釈よりもむしろテクスト

内の非意味的要素の統合に焦点を当てることによって、解釈学と区別される[4]。ほとんどの文芸批評は詩学と解釈学を組み合わせて一つの分析を行っている

が、テクストや読解を行う者の目的によっては、どちらかが優勢になることもある。 |

| History of Poetics Western Poetics Generally speaking, poetics in the western tradition emerged out of Ancient Greece. Fragments of Homer and Hesiod represent the earliest Western treatments of poetic theory, followed later by the work of the lyricist Pindar.[5] The term poetics derives from the Ancient Greek ποιητικός poietikos "pertaining to poetry"; also "creative" and "productive".[6] It stems, not surprisingly, from the word for poetry, "poiesis" (ποίησις) meaning "the activity in which a person brings something into being that did not exist before." ποίησις itself derives from the Doric word "poiwéō" (ποιέω) which translates, simply, as "to make."[7] In the Western world, the development and evolution of poetics featured three artistic movements concerned with poetical composition: (i) the formalist, (2) the objectivist, and (iii) the Aristotelian.[8] Plato's Republic The Republic by Plato represents the first major Western work to treat the theory of poetry. In Book III Plato defines poetry as a type of narrative which takes one of three forms: the "simple," the "imitative" (mimetic), or any mix of the two.[9] In Book X, Plato argues that poetry is too many degrees removed from the ideal form to be anything other than deceptive and, therefore, dangerous. Only capable of producing these ineffectual copies of copies, poets had no place in his utopic city.[5][10] |

詩学の歴史 西洋の詩学 一般的に言って、西洋の伝統における詩学は古代ギリシャから生まれた。ホメロスやヘシオドスの断片が西洋最古の詩学理論であり、後に抒情詩人ピンダルの作 品がそれに続く[5]。詩学という用語は、古代ギリシャ語のποιητικός poietikos「詩に関する」、また「創造的な」「生産的な」に由来する[6]。 また、「創造的な」「生産的な」という意味もある。[6] 当然のことながら、詩を意味する「ポイエーシス」(ποίησις)に由来する。ποίησις自体はドーリア語の 「poiwéō」(ποιέω)に由来しており、簡単に訳せば「作る」という意味である[7]。西洋世界において、詩学の発展と進化は、詩の構成に関わる 3つの芸術運動、すなわち(i)形式主義、(2)客観主義、(iii)アリストテレス主義を特徴としていた[8]。 プラトンの『共和国』 プラトンの『共和国』は、詩の理論を扱った最初の西洋の主要著作である。プラトンは第III巻で詩を、「単純な」、「模倣的な」(mimetic)、ある いはその2つの組み合わせの3つの形態のうちの1つをとる物語の一種と定義している[9]。第X巻でプラトンは、詩は理想的な形態からあまりにも何段階も かけ離れているため、欺瞞的であり、それゆえ危険であるというほかはないと論じている。このような非効果的な模倣の模倣を生み出すことしかできない詩人 は、彼のユートピアの都市には居場所がなかった[5][10]。 |

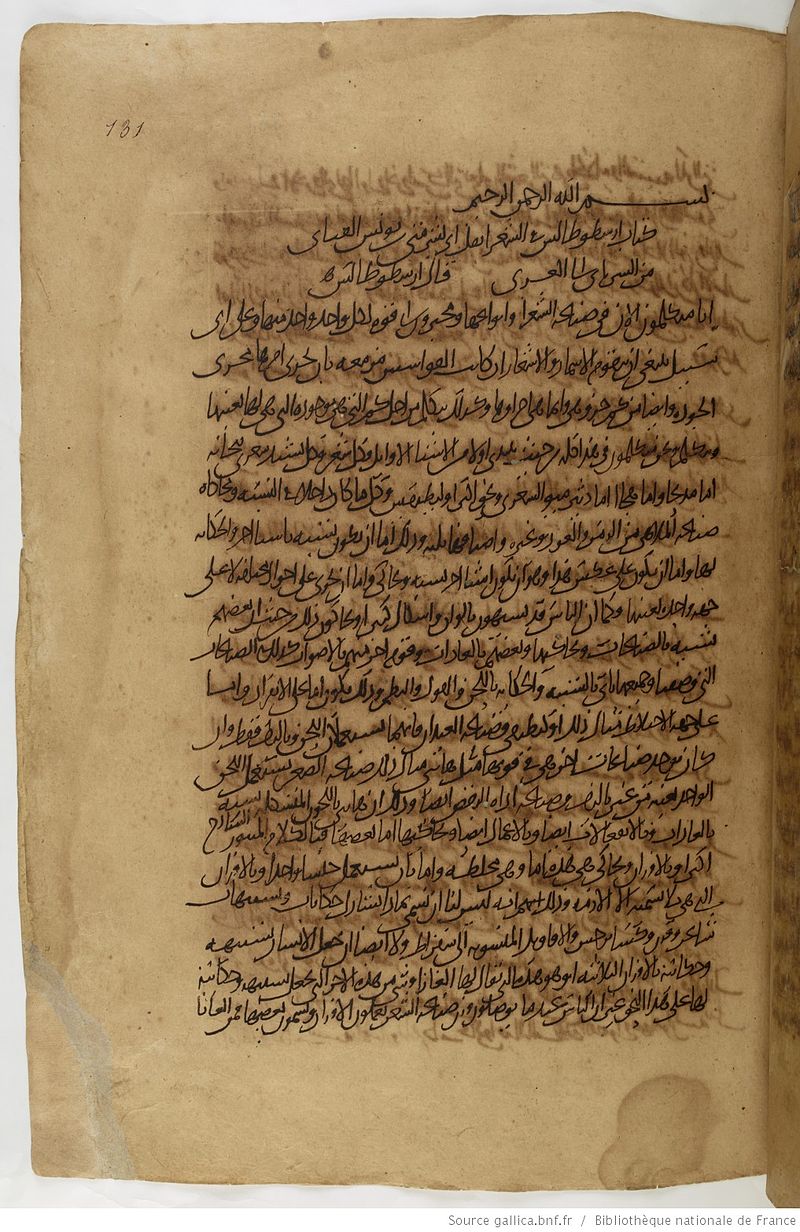

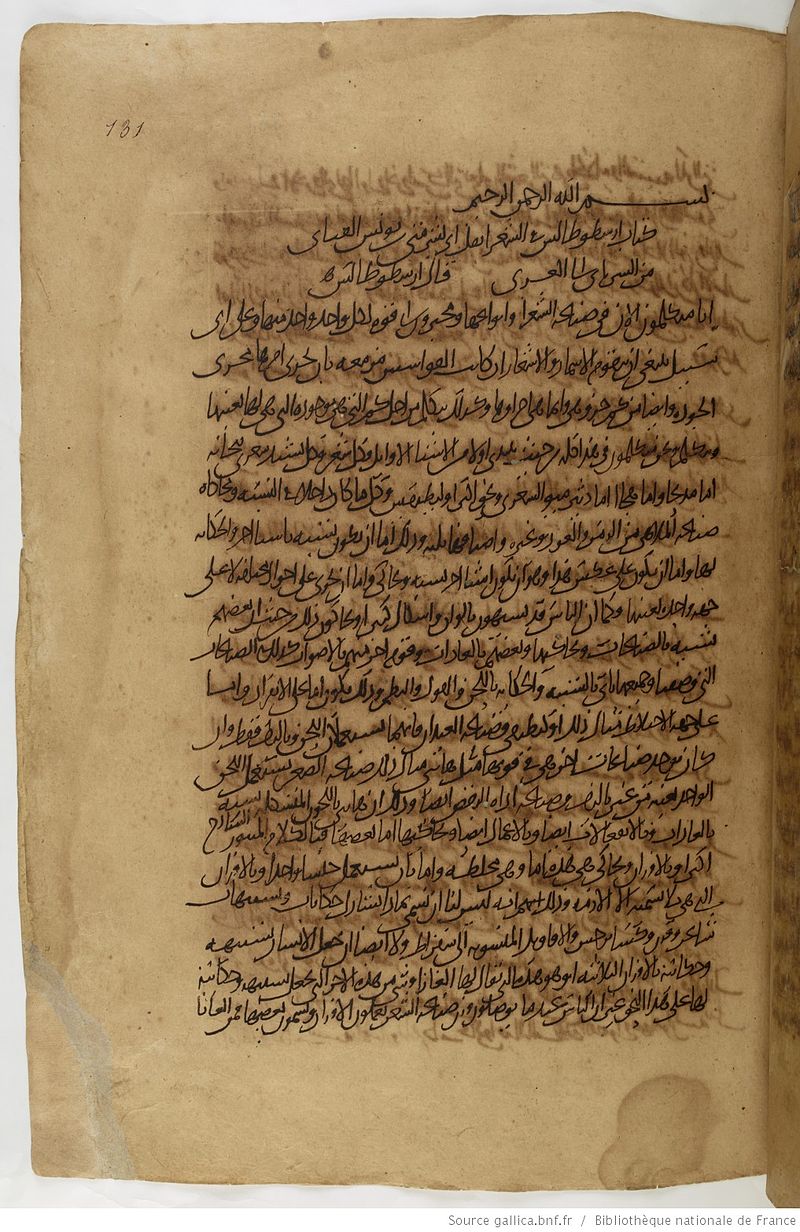

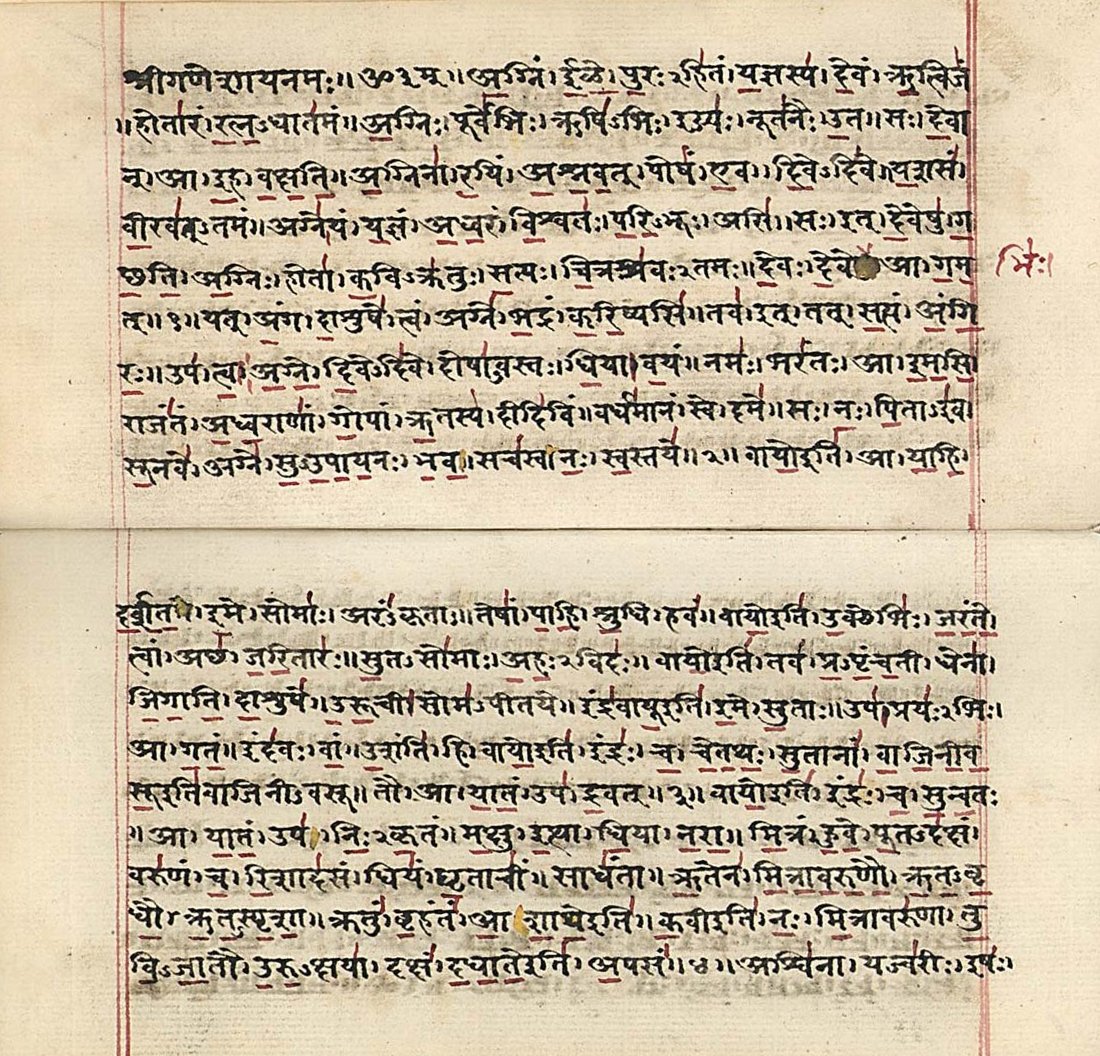

Aristotle's Poetics Arabic translation of Aristotle's Poetics by Abu Bishr Matta ibn Yunus Aristotle's Poetics is one of the first extant philosophical treatise to attempt a rigorous taxonomy of literature.[5] The work was lost to the Western world for a long time. It was available in the Middle Ages and early Renaissance only through a Latin translation of an Arabic commentary written by Averroes and translated by Hermannus Alemannus in 1256. The accurate Greek-Latin translation made by William of Moerbeke in 1278 was virtually ignored. The Arabic translation departed widely in vocabulary from the original Poetics and it initiated a misinterpretation of Aristotelian thought that continued through the Middle Ages. The Poetics itemized the salient genres of ancient Greek drama into three categories (comedy, tragedy, and the satyr play) while drawing a larger-scale distinction between drama, lyric poetry, and the epic.[11] Aristotle also critically revised Plato's interpretation of mimesis which Aristotle believed represented a natural human instinct for imitation, an instinct which could be found at the core of all poetry.[5] Modern poetics developed in Renaissance Italy. The need to interpret ancient literary texts in the light of Christianity, to appraise and assess the narratives of Dante, Petrarch, and Boccaccio, contributed to the development of complex discourses on literary theory. Thanks first of all to Giovanni Boccaccio's Genealogia Deorum Gentilium (1360), the literate elite gained a rich understanding of metaphorical and figurative tropes. Giorgio Valla's 1498 Latin translation of Aristotle's text (the first to be published) was included with the 1508 Aldine printing of the Greek original as part of an anthology of Rhetores graeci. There followed an ever-expanding corpus of texts on poetics in the later fifteenth century and throughout the sixteenth, a phenomenon that began in Italy and spread to Spain, England, and France. Among the most important Renaissance works on poetics are Marco Girolamo Vida's De arte poetica (1527) and Gian Giorgio Trissino's La Poetica (1529, expanded edition 1563). By the early decades of the sixteenth century, vernacular versions of Aristotle's Poetics appeared, culminating in Lodovico Castelvetro's Italian editions of 1570 and 1576. Luis de Góngora (1561–1627) and Baltasar Gracián (1601–58) brought a different kind of sophistication to poetic. Emanuele Tesauro wrote extensively in his Il Cannocchiale Aristotelico (The Aristotelian Spyglass, 1654), on figure ingeniose and figure metaforiche.[12] During the Romantic era, poetics tended toward expressionism and emphasized the perceiving subject. Twentieth-century poetics returned to the Aristotelian paradigm, followed by trends toward meta-criticality, and the establishment of a contemporary theory of poetics.[13] Eastern poetics developed lyric poetry, rather than the representational mimetic poetry of the Western world.[8] |

ア

リストテレスの詩学 アブ・ビシュル・マッタ・イブン・ユヌスによるアリストテレス『詩学』のアラビア語訳 アリストテレスの『詩学』は、文学の厳密な分類を試みた現存する最初の哲学書のひとつである。中世とルネサンス初期には、1256年にアヴェロエスによっ て書かれ、ヘルマヌス・アレマンヌスによって翻訳されたアラビア語注釈のラテン語訳によってのみ入手可能であった。1278年にモアベケのウィリアムに よって作られた正確なギリシャ語・ラテン語訳は、事実上無視された。アラビア語訳は原典の『詩学』から語彙の面で大きく逸脱しており、中世を通じて続くア リストテレス思想の誤訳の発端となった。 『詩学』は古代ギリシア演劇の主要なジャンルを3つのカテゴリー(喜劇、悲劇、サテュロス劇)に分類する一方で、戯曲、抒情詩、叙事詩をより大規模に区別 した[11]。アリストテレスはまたプラトンのミメーシス(模倣)の解釈を批判的に修正した。 近代詩学はルネサンス期のイタリアで発展した。キリスト教に照らして古代の文学テクストを解釈し、ダンテ、ペトラルカ、ボッカッチョの物語を評価する必要 性が、文学理論に関する複雑な言説の発展に寄与した。まず、ジョヴァンニ・ボッカッチョの『Genealogia Deorum Gentilium』(1360年)のおかげで、識字階級のエリートたちは隠喩的・比喩的表現に対する豊かな理解を得た。ジョルジョ・ヴァッラによる 1498年のアリストテレス・テキストのラテン語訳(出版されたのはこれが初めて)は、1508年のアルディン版ギリシア語原典とともに、 Rhetores graeciのアンソロジーの一部として収録された。この現象はイタリアで始まり、スペイン、イギリス、フランスへと広がっていった。ルネサンス期の詩学 に関する最も重要な著作には、マルコ・ジローラモ・ヴィーダの『De arte poetica』(1527年)とジャン・ジョルジョ・トリッシーノの『La Poetica』(1529年、増補版1563年)がある。16世紀初頭には、アリストテレスの『詩学』の現地語版が登場し、1570年と1576年のロ ドヴィコ・カステルヴェトロのイタリア語版がその頂点に達した。ルイス・デ・ゴンゴラ(1561-1627)とバルタサル・グラシアン(1601-58) は、詩学に別の種類の洗練をもたらした。エマヌエーレ・テサウロは『アリストテレスの覗き眼鏡』(Il Cannocchiale Aristotelico, 1654)の中で、独創的な姿とメタフォリッチな姿について幅広く書いている[12]。ロマン主義時代には、詩学は表現主義に傾き、知覚する主体を強調し た。20世紀の詩学はアリストテレス的なパラダイムに戻り、メタ批評性への傾向が続き、現代的な詩学理論が確立された[13]。東洋の詩学は西洋世界の表 象的な模倣詩ではなく、抒情詩を発展させた[8]。 |

| Outline of

poetry Cognitive poetics Descriptive poetics Historical poetics Figure of speech Poetry analysis Stylistic device Rhetorical device Meter (poetry) Allegory Allusion Imagery Musical form Symbolist poetry Sound poetry Refrain Literary theory History of poetry Poetics and Linguistics Association Theopoetics |

詩の概要 認知詩学 記述詩学 歴史詩学 言葉の形 詩の分析 文体の工夫 修辞的装置 メーター(詩) 寓意 アリュージョン 想像 音楽形式 象徴主義詩 音詩 リフレイン 文学理論 詩の歴史(以下) 詩学・言語学協会 テオポエティクス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Poetics |

|

| Poetry as an oral art form

likely predates written text.[1] The earliest poetry is believed to

have been recited or sung, employed as a way of remembering oral

history, genealogy, and law. Poetry is often closely related to musical

traditions, and the earliest poetry exists in the form of hymns (such

as Hymn to the Death of Tammuz), and other types of song such as

chants. As such, poetry is often a verbal art. Many of the poems

surviving from the ancient world are recorded prayers, or stories about

religious subject matter, but they also include historical accounts,

instructions for everyday activities, love songs,[2] and fiction. Many scholars, particularly those researching the Homeric tradition and the oral epics of the Balkans, suggest that early writing shows clear traces of older oral traditions, including the use of repeated phrases as building blocks in larger poetic units. A rhythmic and repetitious form would make a long story easier to remember and retell, before writing was available as a reminder. Thus, to aid memorization and oral transmission, surviving works from prehistoric and ancient societies appear to have been first composed in a poetic form – from the Vedas (1500–1000 bce) to the Odyssey (800–675 bce).[a] Poetry appears among the earliest records of most literate cultures, with poetic fragments found on early monoliths, runestones, and stelae. |

口承芸術としての詩は、文字で書かれたものよりも古いと考えられる

[1]。最古の詩は朗読されたり歌われたりしていたと考えられ、口承史、系図、法律を記憶する方法として用いられた。詩はしばしば音楽の伝統と密接に関連

しており、最古の詩は賛美歌(『タンムズの死への賛歌』など)や、聖歌などの他のタイプの歌の形で存在している。このように、詩はしばしば言語芸術であ

る。古代世界に残る詩の多くは、祈りや宗教的な主題に関する物語を記録したものであるが、歴史的な記述、日常的な活動の指示、愛の歌[2]、フィクション

なども含まれる。 多くの学者、特にホメロス伝承やバルカン半島の口承叙事詩を研究している学者たちは、初期の文章には、より大きな詩的単位の構成要素として繰り返されるフ レーズの使用など、より古い口承伝承の痕跡がはっきりと見られると指摘している。リズミカルで繰り返しの多い形式は、長い物語を記憶しやすくし、再話しや すくする。ヴェーダ(1500-1000 bce)からオデュッセイア(800-675 bce)に至るまで、先史時代や古代の社会で現存する作品は、暗記や口承による伝達を助けるために、詩的な形式で最初に作曲されたようである。 |

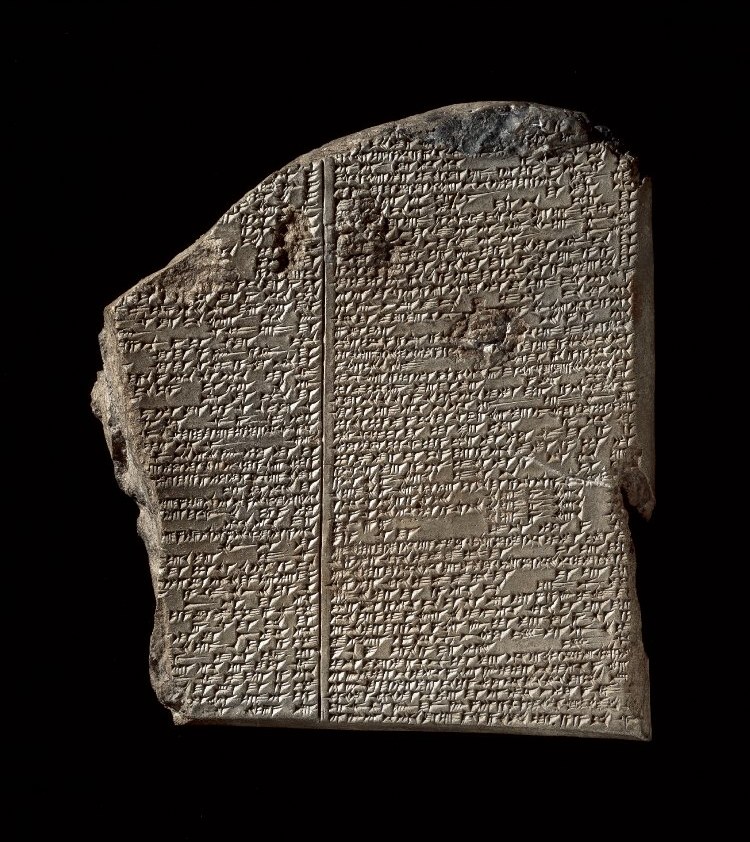

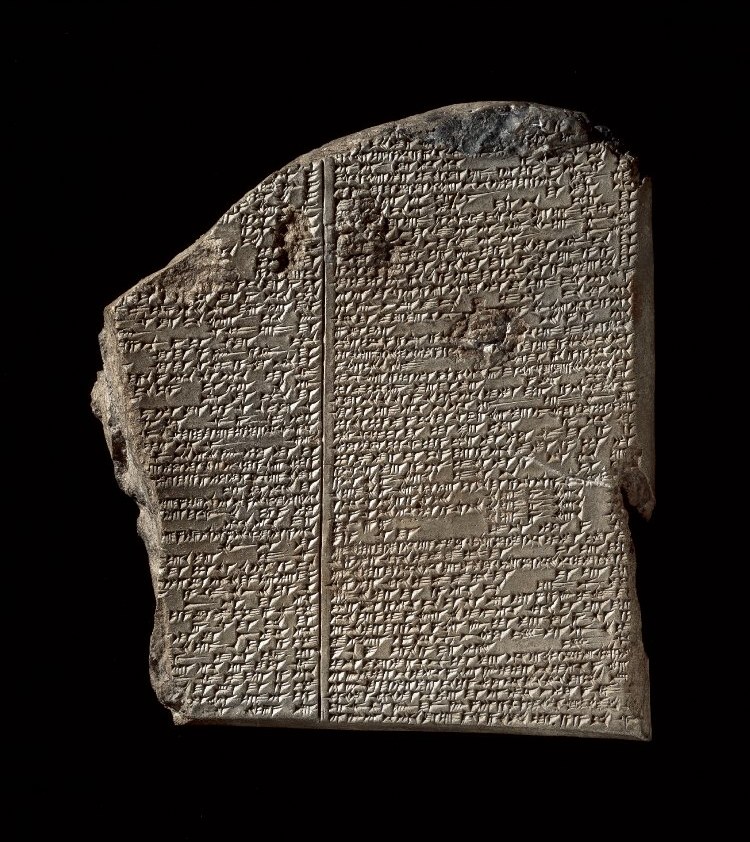

The Deluge tablet, carved in stone, of the Gilgamesh epic in Akkadian, circa 2nd millennium BC. |

紀元前2千年頃、大洪水のようすが書かれたギルガメシュ叙事詩の石板(アッカド語)。 |

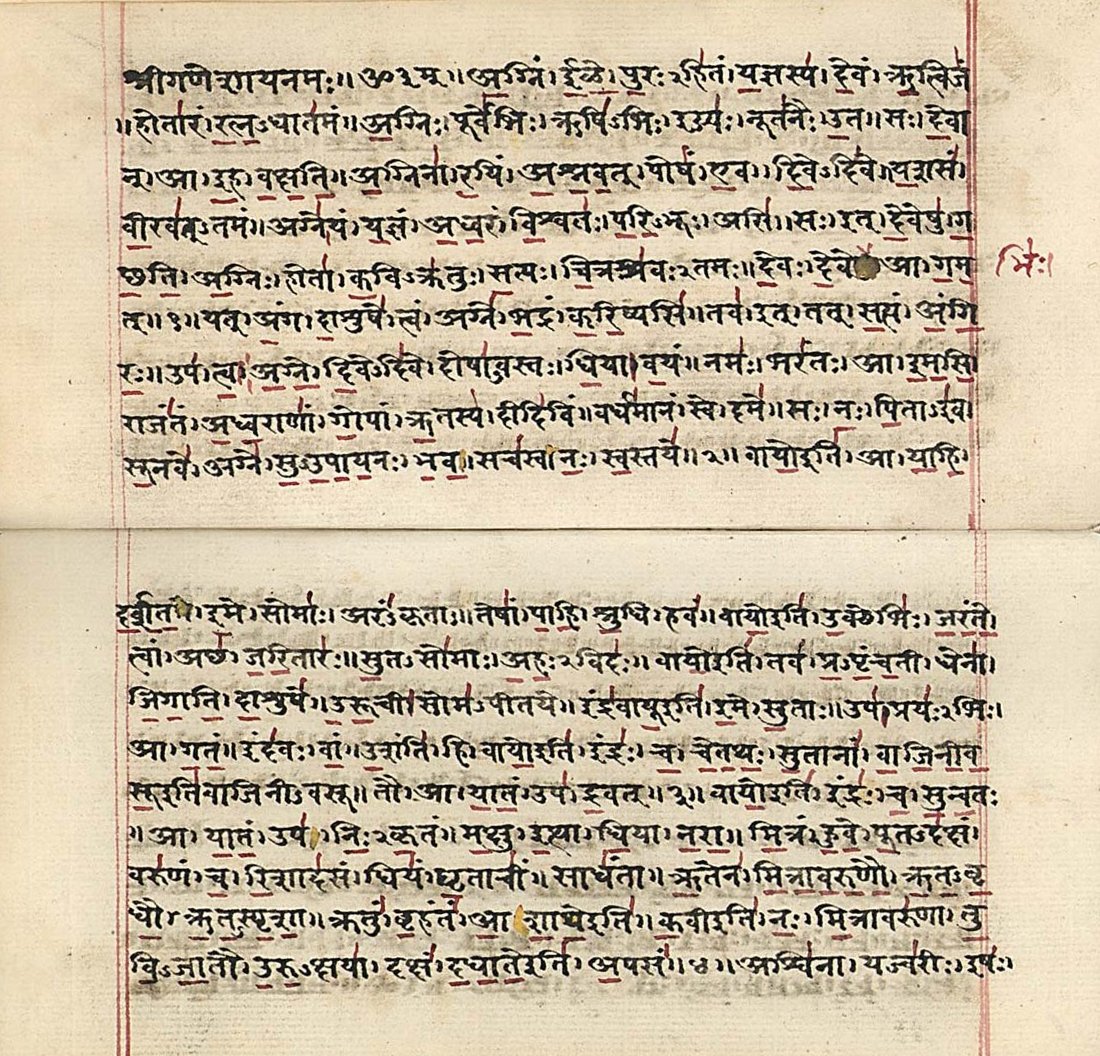

| Early poetry Some scholars believe that the art of poetry may predate literacy, and developed from folk epics and other oral genres.[5][6] Others, however, suggest that poetry did not necessarily predate writing.[7] The oldest surviving speculative fiction poem is the Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor,[8][better source needed] written in Hieratic and ascribed a date around 2500 bce. The oldest surviving epic poem, the Epic of Gilgamesh, dates from the 3rd millennium BCE in Sumer (in Mesopotamia, present-day Iraq), and was written in cuneiform script on clay tablets and, later, on papyrus.[9] The Istanbul tablet#2461, dating to c. 2000 BCE, describes an annual rite in which the king symbolically married and mated with the goddess Inanna to ensure fertility and prosperity; some have labelled it the world's oldest love poem.[10][11] An example of Egyptian epic poetry is The Story of Sinuhe (c. 1800 BCE).[12] Other ancient epics includes the Greek Iliad and the Odyssey; the Persian Avestan books (the Yasna); the Roman national epic, Virgil's Aeneid (written between 29 and 19 BCE); and the Indian epics, the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Epic poetry appears to have been composed in poetic form as an aid to memorization and oral transmission in ancient societies.[7][13] Other forms of poetry, including such ancient collections of religious hymns as the Indian Sanskrit-language Rigveda, the Avestan Gathas, the Hurrian songs, and the Hebrew Psalms, possibly developed directly from folk songs. The earliest entries in the oldest extant collection of Chinese poetry, the Classic of Poetry (Shijing), were initially lyrics.[14] The Shijing, with its collection of poems and folk songs, was heavily valued by the philosopher Confucius and is considered to be one of the official Confucian classics. His remarks on the subject have become an invaluable source in ancient music theory.[15] The efforts of ancient thinkers to determine what makes poetry distinctive as a form, and what distinguishes good poetry from bad, resulted in "poetics"—the study of the aesthetics of poetry.[16] Some ancient societies, such as China's through the Shijing, developed canons of poetic works that had ritual as well as aesthetic importance.[17] More recently, thinkers have struggled to find a definition that could encompass formal differences as great as those between Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and Matsuo Bashō's Oku no Hosomichi, as well as differences in content spanning Tanakh religious poetry, love poetry, and rap.[18] Until recently, the earliest examples of stressed poetry had been thought to be works composed by Romanos the Melodist (fl. 6th century CE). However, Tim Whitmarsh writes that an inscribed Greek poem predated Romanos' stressed poetry. [19][20][21] |

初期の詩 一部の学者は、詩の芸術は識字よりも古く、民間叙事詩やその他の口承ジャンルから発展したと考えている[5][6]。 現存する最古の推理小説詩は『難破船乗り物語』であり[8][要出典]、ヒエラティック語で書かれ、紀元前2500年頃とされている。現存する最古の叙事 詩であるギルガメシュ叙事詩は、紀元前3千年紀のシュメール(メソポタミア、現在のイラク)のもので、粘土板に楔形文字で書かれ、後にパピルスにも書かれ た[9]。紀元前2000年頃のイスタンブール・タブレット#2461には、豊穣と繁栄を保証するために、王が女神イナンナと象徴的に結婚・交配する年中 行事が描かれており、これを世界最古の愛の詩と評する者もいる[10][11]。エジプトの叙事詩の例としては、『シヌヘの物語』(紀元前1800年頃) がある[12]。 その他の古代叙事詩には、ギリシアの『イーリアス』や『オデュッセイア』、ペルシアの『アヴェスターンの書』(ヤスナ)、ローマの国民叙事詩であるヴァー ジルの『アエネーイス』(紀元前29年から19年の間に書かれた)、インディアンの叙事詩である『ラーマーヤナ』や『マハーバーラタ』などがある。叙事詩 は、古代社会における暗記や口承伝達の補助として詩の形式で作曲されたようである[7][13]。 インディアンのサンスクリット語『リグヴェーダ』、アヴェスターンの『ガータ』、ヒュリア人の歌、ヘブライ語の『詩篇』など、古代の宗教的賛美歌集を含む 他の形式の詩は、おそらく民謡から直接発展したものであろう。現存する中国最古の詩集である『詩経』の最古の項目は、当初は歌詞であった[14]。詩と民 謡を集めた『詩経』は、哲学者の孔子によって重用され、儒教の公式な古典のひとつとみなされている。この主題に関する彼の発言は、古代の音楽理論における 貴重な資料となっている[15]。 詩を形式として際立たせるものは何か、良い詩と悪い詩を区別するものは何かを見極めようとする古代の思想家たちの努力の結果、「詩学」-詩の美学を研究す る学問-が生まれた。 [17]最近では、チョーサーの『カンタベリー物語』と松尾芭蕉の『奥の細道』のような形式的な違いや、タナフの宗教詩、恋愛詩、ラップにまたがる内容の 違いを包含できるような定義を見出すことに、思想家たちは苦心している[18]。 最近まで、ストレス詩の最も古い例は、メロディストのロマノス(CE6世紀頃)によって作曲された作品であると考えられていた。しかし、ティム・ウィット マーシュは、ロマノスの強調詩よりも前にギリシャ語の詩が刻まれていたと書いている。[19][20][21] |

| Ancient African poetry In Africa, poetry has a history dating back to prehistorical times with the creation of hunting poetry, and panegyric and elegiac court poetry were developed extensively throughout the history of the empires of the Nile, Niger, and Volta river valleys.[22] Some of the earliest written poetry in Africa can be found among the Pyramid Texts written during the 25th century bce, while the Epic of Sundiata is one of the most well-known examples of griot court poetry. In African cultures, performance poetry is traditionally a part of theatrics, which was present in all aspects of pre-colonial African life[23] and whose theatrical ceremonies had many different functions, including political, educative, spiritual and entertainment. Poetics were an element of theatrical performances of local oral artists, linguists and historians, accompanied by local instruments of the people such as the kora, the xalam, the mbira and the djembe drum. Drumming for accompaniment is not to be confused with performances of the talking drum, which is a literature of its own, since it is a distinct method of communication that depends on conveying meaning through non-musical grammatical, tonal and rhythmic rules imitating speech.[22](pp 467–484)[24] Although, these performances could be included in those of griots. |

古代アフリカの詩 アフリカでは、詩の歴史は先史時代の狩猟詩の創作にまで遡り、ナイル川、ニジェール川、ヴォルタ川流域の帝国の歴史を通じて、パネジェリック詩やエレジ アックな宮廷詩が広く発展した[22]。アフリカで書かれた最古の詩のいくつかは、紀元前25世紀に書かれたピラミッド文書の中に見出すことができ、スン ディアタ叙事詩はグリオの宮廷詩の最もよく知られた例の一つである。アフリカの文化において、パフォーマティビティは伝統的に演劇の一部であり、植民地時 代以前のアフリカの生活のあらゆる側面に存在していた[23]。 パフォーマティビティは、コラ、クサラム、ムビラ、ジャンベドラムといった地元の楽器を伴奏にした、地元の口承芸術家、言語学者、歴史家による演劇の要素 であった。伴奏のための太鼓の演奏は、それ自体が文学であるトーキング・ドラムの演奏と混同してはならない。トーキング・ドラムは、発話を模倣した非音楽 的な文法、調性、リズムの規則によって意味を伝えることに依存する、独特のコミュニケーション方法だからである[22](pp.467-484)[24] が、これらの演奏はグリオの演奏に含まれうる。 |

Classical and early modern

Western traditions Calliope, the muse of heroic poetry Classical thinkers employed classification as a way to define and assess the quality of poetry. In book III of the Republic, Plato defined poetry as a narrative genre separated into three types: the "simple," the "imitative," or some mix of the two. He also famously, in book X, condemned poetry as evil, being only capable of creating deceptive and ineffectual copies of real-world corollaries.[25] In his Poetics, Aristotle taxonomized ancient Greek drama[26] (which he called "poetry") into three subcategories: epic, comic, and tragic. Aristotle developed rules to distinguish the highest-quality poetry of each genre, based on the underlying purposes of that genre.[27][full citation needed] Later aestheticians identified three major genres: Epic poetry, lyric poetry, and dramatic poetry (treating comedy and tragedy as subgenres of dramatic poetry). Aristotle's work was influential throughout the Middle East during the Islamic Golden Age,[b] as well as in Europe during the Renaissance.[30] Like Aristotle,[31] subsequent poets and aestheticians often distinguished poetry from, and defined it in opposition to, prose, which was generally understood as writing with a proclivity to logical explication and global trade.[citation needed] In addition to a boom in translation, during the Romantic period numerous ancient works were rediscovered.[citation needed] |

古典と近世西洋の伝統 英雄詩のミューズ、カリオペ 古典派の思想家たちは、詩の質を定義し評価する方法として分類を用いた。プラトンは『共和国』第III巻で、詩を「単純なもの」、「模倣的なもの」、ある いはその2つのミヘの3種類に分けられる物語ジャンルとして定義した。彼はまた有名なことに、第X巻において、詩は悪であり、現実世界の従属物の欺瞞的で 効果のないコピーを作り出すことしかできないと非難している[25]。 アリストテレスは『詩学』において、古代ギリシアの戯曲[26](彼は「詩」と呼んでいた)を叙事詩、喜劇、悲劇の3つのサブカテゴリーに分類した。アリ ストテレスはそのジャンルの根本的な目的に基づいて、各ジャンルの最も質の高い詩を区別するための規則を開発した[27][完全な引用は必要]。後の美学 者は3つの主要なジャンルを特定した:叙事詩、抒情詩、劇詩(喜劇と悲劇を劇詩のサブジャンルとして扱う)。アリストテレスの著作は、ルネサンス期のヨー ロッパだけでなく、イスラム黄金時代の中東全域[b]に影響を与えた[30]。 アリストテレスと同様に[31]、その後の詩人や美学者たちはしばしば詩を散文と区別し、散文と対立するものとして定義した。ロマン主義時代には翻訳ブー ムに加え、数多くの古代作品が再発見された[要出典]。 |

| History and development of

Chinese poetry See also: Classical Chinese poetry and Classical Chinese poetry forms The character which means "poetry", in the ancient Chinese Great Seal script style. The modern character is 詩/诗 (shī). The Classic of Poetry, often known by its original name of the Odes or Poetry is the earliest existing collection of Chinese poems and songs. This poetry collection comprises 305 poems and songs dating from the 11th to the 7th century bce. The stylistic development of Classical Chinese poetry consists of both literary and oral cultural processes, which are conventionally assigned to certain standard periods or eras, corresponding with Chinese Dynastic Eras, the traditional chronological process for Chinese historical events. The poems preserved in written form constitute the poetic literature. Furthermore, there is or were parallel traditions of oral and traditional poetry also known as popular or folk poems or ballads. Some of these poems seem to have been preserved in written form. Generally, the folk type of poems they are anonymous, and may show signs of having been edited or polished in the process of fixing them in written characters. Besides the Classic of Poetry, or Shijing, another early text is the Songs of the South (or, Chuci), although some individual pieces or fragments survive in other forms, for example embedded in classical histories or other literature. |

漢詩の歴史と発展 こちらも参照のこと: 中国古典の詩、中国古典の詩の形式 「詩」を意味する文字で、古代中国の大篆書体である。現代の文字は詩/诗(shī)である。 漢詩の古典である『詩経』は、『詩経』または『詩歌』の原名で知られ、現存する中国最古の詩歌集である。この詩集は、紀元前11世紀から7世紀までの 305篇の詩と歌で構成されている。中国古典詩の文体的発展には、文学的過程と口承文化的過程の両方があり、それらは従来、中国の歴史的出来事の伝統的な 年代過程である中国王朝時代に対応する、ある標準的な時代や時期に割り当てられている。 書き言葉で残された詩は、詩文学を構成している。さらに、民衆詩やバラッドとして知られる口承詩や伝統詩の伝統も並行して存在し、あるいは存在していた。 これらの詩の中には、文字として残っているものもあるようだ。一般に、民間の詩は無名であり、文字に直す過程で編集されたり磨かれたりした形跡がある。詩 経』のほかに、初期のテキストとして『楚辞』がある。 |

| Medieval poetry Main article: Medieval poetry Poetry took numerous forms in medieval Europe, for example, lyric and epic poetry. The troubadours, trouvères, and the minnesänger are known for composing their lyric poetry about courtly love usually accompanied by an instrument.[32] Old English poetry Old English religious poetry includes the poem Christ by Cynewulf and the poem The Dream of the Rood, preserved in both manuscript form and on the Ruthwell Cross. We do have some secular poetry; in fact a great deal of medieval literature was written in verse, including the Old English epic Beowulf. Scholars are fairly sure, based on a few fragments and on references in historic texts, that much lost secular poetry was set to music, and was spread by traveling minstrels, or bards, across Europe. Thus, the few poems written eventually became ballads or lays, and never made it to being recited without song or other music. Medieval Latin poetry In medieval Latin, while verse in the old quantitative meters continued to be written, a new more popular form called the sequence arose, which was based on accentual metres in which metrical feet were based on stressed syllables rather than vowel length. These metres were associated with Christian hymnody. However, much secular poetry was also written in Latin. Some poems and songs, like the Gambler's Mass (officio lusorum) from the Carmina Burana, were parodies of Christian hymns, while others were student melodies: folksongs, love songs and drinking ballads. The famous commercium song Gaudeamus igitur is one example. There are also a few narrative poems of the period, such as the unfinished epic Ruodlieb, which tells us the story of a knight's adventures. |

中世の詩 主な記事 中世の詩 中世ヨーロッパでは、抒情詩や叙事詩など、さまざまな形式の詩が生まれた。トルバドゥール、トゥルヴェール、ミンネゼンガーは、宮廷恋愛をテーマにした抒 情詩を作曲したことで知られている。 古英語詩 古英語の宗教詩には、シネウルフの詩『キリスト』や、写本やルースウェル・クロスに残されている詩『血の夢』などがある。実際、古英語の叙事詩『ベオウル フ』をはじめ、多くの中世文学が詩で書かれている。学者たちは、いくつかの断片や歴史的な文献の記述から、失われた世俗詩の多くが音楽につけられ、吟遊詩 人(吟遊詩人)によってヨーロッパ全土に広められたことを確信している。こうして書かれた数少ない詩は、やがてバラッドやレイとなり、歌や他の音楽なしに 朗読されることはなかった。 中世ラテン語の詩 中世ラテン語では、旧来の量的メートルによる詩が書かれ続けた一方で、シークエンスと呼ばれる、より一般的な新しい形式が生まれた。この形式は、アクセン ト音律に基づくもので、母音の長さではなく、強調音節に基づく音律であった。これらの音律はキリスト教の賛美歌と結びついていた。 しかし、多くの世俗詩もラテン語で書かれた。カルミナ・ブラーナ』の「ギャンブラーのミサ(officio lusorum)」のように、キリスト教賛美歌のパロディである詩や歌もあれば、フォークソング、ラブソング、酒飲みバラードなど、学生向けのメロディも あった。有名な商業歌曲Gaudeamus igiturはその一例である。また、騎士の冒険を描いた未完の叙事詩『ルオドリーブ』など、この時代の物語詩もいくつかある。 |

| Lyric poetry Main article: Lyric Poetry § History Lyric poetry grew to be popular in around the 19th century, with the addition of radio as they could broadcast to the world the earliest 'songs'. Lyric poetry is very similar to songs / song lyrics. They could have as many stanzas as they wanted, which was different to different forms of poetry at the time. There were no real regulations to this new form of poetry, which was invented by Sir Robert Cite in 1789. This form of poetry is known for being the quickest growing type of the past millennium. To this day, lyric poetry is the most used and important of poetries, and is used throughout the world. |

叙情詩 主な記事 抒情詩 § 歴史 抒情詩は19世紀ごろに流行し、ラジオが加わったことで、初期の「歌」を世界中に放送できるようになった。抒情詩は歌や歌の歌詞に非常に似ている。抒情詩 は、歌や歌の歌詞にとても似ている。1789年にロバート・カイト卿によって考案されたこの新しい詩の形式には、特に規制はなかった。この詩の形式は、過 去千年間で最も急速に成長した詩の形式として知られている。今日に至るまで、抒情詩は詩の中で最も使われ、重要なものであり、世界中で使われている。 |

| Modern developments See also: Modernist poetry and Postmodern American Poetry The development of modern poetry is generally seen as having started at the beginning of the 20th century and extends into the 21st century. Among its major American practitioners who write in English are T.S. Eliot, Robert Frost, Wallace Stevens, Maya Angelou, June Jordan, Allen Ginsberg, and Nobel laureate Louise Glück. Among the modern epic poets are Ezra Pound, H.D., Derek Walcott, and Giannina Braschi. Contemporary poets Joy Harjo, Kevin Young (poet), and Natasha Trethewey write poetry in the lyric form. |

現代の発展 こちらも参照のこと: モダニズム詩とポストモダン・アメリカ詩 現代詩の発展は、一般的に20世紀初頭に始まり、21世紀まで続いていると考えられている。現代詩の主要な実践者としては、T.S.エリオット、ロバー ト・フロスト、ウォレス・スティーヴンス、マヤ・アンジェロウ、ジューン・ジョーダン、アレン・ギンズバーグ、ノーベル賞受賞者のルイーズ・グリュックな どが挙げられる。現代の叙事詩家には、エズラ・パウンド、H.D.、デレク・ウォルコット、ジャンニーナ・ブラスキがいる。現代詩人のジョイ・ハージョ、 ケヴィン・ヤング(詩人)、ナターシャ・トレテウェイは抒情詩の形式で詩を書いている。 |

Manuscript of the Rig Veda, Sanskrit verse composed in the 2nd millennium BC. |

リグ・ヴェーダの写本で、紀元前2千年紀に作られたサンスクリット語の詩である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_poetry |

**☆Outline of poetry(詩の概要)

| Poetry – a form of art in which language is used for its aesthetic qualities, in addition to, or instead of, its apparent meaning. What type of thing is poetry? Poetry can be described as all of the following things: One of the arts – as an art form, poetry is an outlet of human expression, that is usually influenced by culture and which in turn helps to change culture. Poetry is a physical manifestation of the internal human creative impulse. A form of literature – literature is composition, that is, written or oral work such as books, stories, and poems. Fine art – in Western European academic traditions, fine art is art developed primarily for aesthetics, distinguishing it from applied art that also has to serve some practical function. The word "fine" here does not so much denote the quality of the artwork in question, but the purity of the discipline according to traditional Western European canons. |

詩-芸術の一形態で、明白な意味に加えて、あるいはその代わりに、その美的特質のために言語が使われる。 詩とはどのようなものか? 詩は、以下のすべてのものと言える: 芸術の一つである。芸術の一形態として、詩は人間の表現のはけ口であり、通常は文化の影響を受け、ひいては文化を変えるのに役立つ。詩は、人間の内的な創造的衝動の物理的な現れである。 文学の一形態 - 文学とは構成、つまり本、物語、詩のような文章や口頭による作品を指す。 ファインアート - 西ヨーロッパの学問的伝統において、ファインアートとは主に美学のために開発された芸術のことであり、実用的な機能を果たす必要のある応用芸術とは区別さ れる。ここでいう「ファイン」とは、問題の芸術作品の質ではなく、西欧の伝統的な規範に従った学問の純粋性を意味する。 |

| Types of poetry Common poetic forms Epic – lengthy narrative poem, ordinarily concerning a serious subject containing details of heroic deeds and events significant to a culture or nation. Milman Parry and Albert Lord have argued that the Homeric epics, the earliest works of Western literature, were fundamentally an oral poetic form. These works form the basis of the epic genre in Western literature. Sonnet – poetic form which originated in Italy; Giacomo da Lentini is credited with its invention. Jintishi – literally "Modern Poetry", was actually composed from the 5th century onwards and is considered to have been fully developed by the early Tang dynasty. The works were principally written in five- and seven-character lines and involve constrained tone patterns, intended to balance the four tones of Middle Chinese within each couplet. Villanelle – nineteen-line poetic form consisting of five tercets followed by a quatrain. There are two refrains and two repeating rhymes, with the first and third line of the first tercet repeated alternately until the last stanza, which includes both repeated lines. The villanelle is an example of a fixed versed form. Tanka – a classical Japanese poem, composed in Japanese (rather than Chinese, as with kanshi) Ode – a poem written in praise of a person (e.g. Psyche), thing (e.g. a Grecian urn), or event Ghazal – an Arabic poetic form with rhyming couplets and a refrain, each line in the same meter Haiku – a poem, normally in Japanese but also in other languages (particularly English), normally with 17 syllables arranged as 5 + 7 + 5 Free verse - an open form of poetry which does not use consistent meter patterns or rhyme, tending to follow the rhythm of natural speech |

詩の種類 一般的な詩の形式 叙事詩 - 長編の物語詩で、通常、ある文化や国民にとって重要な英雄的行為や出来事の詳細を含む、重大な主題に関するものである。ミルマン・パリーとアルバート・ ロードは、西洋文学の最初期の作品であるホメロス叙事詩は、基本的に口承詩の形式であったと主張している。これらの作品は、西洋文学における叙事詩という ジャンルの基礎を形成している。 ソネット - イタリアで生まれた詩的形式。ジャコモ・ダ・レンティーニが発明したとされている。 神代文字 - 文字どおり「近代の詩」で、実際には5世紀以降に作曲され、唐代初期には完全に発展したと考えられている。作品は主に5字と7字の行で書かれ、各連句の中で中国語中期の4つの音調のバランスをとることを意図した、制約のある音調パターンが含まれる。 ヴィラネル(Villanelle) - 19行の詩形で、5つの3連の後に4連が続く。2つのリフレインと2つの繰り返し韻があり、最後のスタンザまで、最初のターセットの1行目と3行目が交互に繰り返される。ヴィラネルは固定詩型の一例である。 短歌 - 古典的な和歌で、(漢詩のように漢文ではなく)日本語で詠まれる。 頌歌 - 人物(プシュケなど)、物(グレシアの壷など)、出来事を賛美して書かれた詩。 Ghazal - アラビア語の詩形で、韻を踏んだ連句とリフレインがあり、各行が同じメーターで書かれている。 俳句 - 通常は日本語だが、他の言語(特に英語)でも使われる詩で、17音節が5+7+5のように配置されている。 自由詩 - 自然な話し言葉のリズムに従う傾向があり、一貫したメーターパターンや韻を踏まない自由な詩の形式。 |

| Periods, styles and movements For movements, see List of poetry groups and movements. Augustan poetry – poetry written during the reign of Caesar Augustus as Emperor of Rome, particularly Virgil, Horace, and Ovid. Automatic poetry – Surrealist poetry written using the automatic method. Black Mountain – postmodern American poetry written in the mid-20th century, in Black Mountain College in North Carolina. Chanson de geste Classical Chinese poetry Concrete poetry Cowboy poetry Digital poetry Epitaph Fable Found poetry Haptic poetry Imagism Libel Limerick poetry Lyric poetry Metaphysical poetry Medieval poetry Microstory Minnesinger Modern Chinese poetry Modernist poetry The Movement Narrative poetry Objectivist Occasional poetry Odes and elegies Parable Parnassian Pastoral Performance poetry Post-modernist Prose poetry Romanticism San Francisco Renaissance Sound poetry Symbolism Troubadour Trouvère Visual poetry |

時代、スタイル、運動 運動については、詩のグループと運動のリストを参照のこと。 アウグストゥス詩 - ローマ皇帝カエサル・アウグストゥスの時代に書かれた詩。 自動詩 - 自動法を用いて書かれたシュルレアリスムの詩。 ブラック・マウンテン - ノースカロライナ州のブラック・マウンテン・カレッジで20世紀半ばに書かれたポストモダン・アメリカの詩。 シャンソン・ド・ジェスト 中国古典詩 具象詩 カウボーイの詩 デジタル詩 墓碑銘 寓話 ファウンド・ポエトリー 触覚詩 イマジズム リベル リメリック詩 抒情詩 形而上学的詩 中世詩 マイクロストーリー ミンネジンガー 現代中国の詩 モダニズムの詩 運動 物語詩 客観主義者 折々の詩 オードとエレジー たとえ話 パルナシアン 牧歌 パフォーマティビティ詩 ポストモダニズム 散文詩 ロマン主義 サンフランシスコ・ルネサンス 音詩 象徴主義 トルバドゥール トルベール 視覚詩 |

| History of poetry History of poetry – the earliest poetry is believed to have been recited or sung, such as in the form of hymns (such as the work of Sumerian priestess Enheduanna), and employed as a way of remembering oral history, genealogy, and law. Many of the poems surviving from the ancient world are recorded prayers, or stories about religious subject matter, but they also include historical accounts, instructions for everyday activities, love songs, and fiction. List of years in poetry |

詩の歴史 詩の歴史 - 最古の詩は、讃美歌(シュメールの巫女エンヘドゥアンナの作品など)の形で朗読されたり歌われたりし、口承史、系図、法律を記憶する方法として用いられた と考えられている。古代世界に現存する詩の多くは、祈りや宗教的主題に関する物語が記録されたものであるが、歴史的記述、日常的活動の指示、愛の歌、フィ クションなども含まれる。 詩の年号一覧 |

| Elements of poetry Main article: Meter (poetry) Accents Caesura Couplets – a pair of lines of meter in poetry. It usually consists of two lines that rhyme and have the same meter. While traditionally couplets rhyme, not all do. Elision Foot Intonation Meter Mora Prosody Rhythm Scansion Stanza Syllable Methods of creating rhythm Main articles: Timing (linguistics), tone (linguistics), and pitch accent See also: Parallelism, inflection, intonation, and foot Scanning meter Main article: Systems of scansion spondee – two stressed syllables together iamb – unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable trochee – one stressed syllable followed by an unstressed syllable dactyl – one stressed syllable followed by two unstressed syllables anapest – two unstressed syllables followed by one stressed syllable The number of metrical feet in a line are described in Greek terminology as follows: dimeter – two feet trimeter – three feet tetrameter – four feet pentameter – five feet hexameter – six feet heptameter – seven feet octameter – eight feet |

詩の要素 主な記事 メーター(詩) アクセント シースーラ 連音符(れんおんぷ) - 詩における一対の拍子。通常、韻を踏み、同じ音律を持つ2行で構成される。伝統的に連句は韻を踏むが、すべてが韻を踏むわけではない。 エリジョン 足音 イントネーション メーター モーラ プロソディー リズム 音階 スタンザ 音節 リズムの作り方 主な記事 タイミング(言語学)、トーン(言語学)、ピッチアクセント 以下も参照のこと: 平行調、抑揚、イントネーション、フィート スキャニングメーター 主な記事 拍節法 spondee - 2つの強調音節が一緒になる iamb - 非ストレス音節の後にストレス音節が続く トローチ(trochee) - 1つの強調音節の後に非強調音節が続く dactyl - 1つの強調された音節に2つの強調されていない音節が続く アナペスト(anapest) - 2つの非ストレス音節に1つのストレス音節が続く 1行に含まれる音節の数は、ギリシア語の専門用語で次のように表現される: dimeter - 2フィート トリメーター - 3フィート テトラメートル - 4フィート ペンタメートル - 5フィート ヘキサメートル - 6フィート ヘプタメートル-7フィート 八分音符-八フィート |

| Common metrical patterns Main article: Meter (poetry) Iambic pentameter Example: Paradise Lost,[1] by John Milton Dactylic hexameter Examples: Iliad,[2] by Homer The Metamorphoses, by Ovid Iambic tetrameter Examples: To His Coy Mistress, by Andrew Marvell Eugene Onegin,[3] by Aleksandr Pushkin Trochaic octameter Example: The Raven,[4] by Edgar Allan Poe Anapestic tetrameter Examples: The Hunting of the Snark,[5] by Lewis Carroll Don Juan,[6] by Lord Byron Alexandrine – also known as iambic hexameter. Example: Phèdre,[7] by Jean Racine Rhyme, alliteration and assonance Alliteration Alliterative verse Assonance Consonance Internal rhyme Rhyme Rhyming schemes Main article: Rhyme scheme Chant royal Ottava rima Rubaiyat Stanzas and verse paragraphs Main article: stanza 2-line stanza: couplet or distich 3-line stanza: triplet or tercet 4-line stanza: quatrain 5-line stanza: quintain or cinquain) 6-line stanza: sestet 8-line stanza: octet verse paragraph Poetic diction Main article: Poetic diction Poetics Main article: Poetics |

一般的な計量パターン 主な記事 拍子(詩) イアンビック・ペンタメートル 例 失楽園』[1](ジョン・ミルトン作 ダクティリック・ヘキサメートル 例 ホメロス作『イーリアス』[2] メタモルフォーゼ』(オウィッド作 イアンビック・テトラメートル 例 アンドリュー・マーヴェル作『愛しい人へ ウジェーヌ・オネーギン』[3](アレクサンドル・プーシキン作 トロキア八分音符 例 エドガー・アラン・ポー作『ワタリガラス』[4] アナペスティック四段 例 The Hunting of the Snark,[5] ルイス・キャロル作 ドン・ファン』[6] バイロン卿著 Alexandrine - iambic hexameterとしても知られる。 例 フェードル』[7] ジャン・ラシーヌ作 韻文、叙事詩、同音異義語 叙述 叙事詩 アソナンス 子音 内韻 韻 韻律 主な記事 韻律 チャント・ロワイヤル オッターヴァ・リマ ルバイヤート スタンザと詩段落 主な記事:スタンザ 2行スタンザ:連符またはディスティク 3行スタンザ:トリプレット(triplet)またはテルテット(tercet 4行スタンザ: クワトレイン 5行スタンザ: クインタン(quintain)またはシンカン(cinquain) 6行スタンザ: セステット 8行スタンザ: オクテット 段落 詩の語法 主な記事 詩の語法 詩学 主な記事 詩学 |

| Some famous poets and their poems Main articles: List of poets and List of poems Anna Akhmatova Requiem Maya Angelou On the Pulse of Morning Ludovico Ariosto Orlando Furioso W. H. Auden Musée des Beaux Arts September 1, 1939 Matsuo Bashō Natsu no Tsuki (Summer Moon) Charles Baudelaire Les Fleurs du Mal William Blake The Chimney Sweeper The Sick Rose London Geoffrey Chaucer The Complaint of Mars Samuel Coleridge The Rime of the Ancient Mariner Dante Divine Comedy Kamala Das The Descendants Emily Dickinson "Hope" is the thing with feathers "Why do I love" You, Sir "Faith" is a fine invention John Donne Devotions upon Emergent Occasions Elegy XIX: To His Mistress Going to Bed Rita Dove Thomas and Beulah (collection) John Dryden Absalom and Achitophel Mac Flecknoe T. S. Eliot The Waste Land Ferdowsi Shahnameh Robert Frost The Road Not Taken Nothing Gold Can Stay Mirza Ghalib Goethe Homer Iliad Odyssey Gerard Manley Hopkins Binsey Poplars Horace Epistles (collection) Victor Hugo Les Contemplations Alfred Edward Housman To An Athlete Dying Young Omar Khayyám Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam (Translated Collection) John Keats Sleep and Poetry Jan Kochanowski Laments (Translated Collection) Ignacy Krasicki Fables and Parables Jean de La Fontaine Mikhail Lermontov Boyarin Orsha Li Bai Quiet Night Thought Stéphane Mallarmé L'après-midi d'un faune W.S. Merwin Czesław Miłosz John Milton Paradise Lost Pablo Neruda Twenty Love Poems and a Song of Despair (Collection) Ovid Ars Amatoria (Collection) Petrarch Il Canzoniere (Collection) Sylvia Plath Lady Lazarus Edgar Allan Poe The Raven Alexander Pope The Rape of the Lock Ezra Pound The Cantos Alexander Pushkin Ruslan and Ludmila Rainer Maria Rilke Duino Elegies Arthur Rimbaud Le Bateau ivre (The Drunken Boat) Jalal ad-Din Rumi Masnavi William Shakespeare Shakespeare's sonnets Shel Silverstein Where the Sidewalk Ends (Collection) Edmund Spenser The Faerie Queene Philip Sidney The Countess of Pembroke's Arcadia Tasso Jerusalem Delivered Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson Break, Break, Break The Charge of the Light Brigade Tears, Idle Tears François Villon Virgil Aeneid Derek Walcott Omeros Walt Whitman Song of Myself Out of the Cradle Endlessly Rocking William Wordsworth The Prelude William Butler Yeats Sailing to Byzantium Swift's Epitaph (Translation) |

有名な詩人とその詩 主な記事 詩人のリスト、詩のリスト アンナ・アフマートワ レクイエム マヤ・アンジェロウ 朝の鼓動について ルドヴィコ・アリオスト オーランド・フュリオーソ W. オーデン ボザール美術館 1939年9月1日 松尾芭蕉 夏の月 シャルル・ボードレール 悪の華 ウィリアム・ブレイク 煙突掃除人 病気のバラ ロンドン ジェフリー・チョーサー 火星の訴え サミュエル・コールリッジ 太古の海人(The Rime of the Ancient Mariner ダンテ 神曲 カマラ・ダス 末裔 エミリー・ディキンソン 「希望」は羽のあるものだ 「なぜ私はあなたを愛するのか 「信仰」は立派な発明だ ジョン・ドンネ ふとした時の献身 エレジー XIX: ベッドに入る愛人へ リタ・ダヴ トーマスとビーラ(作品集) ジョン・ドライデン アブサロムとアキトフェル マック・フレクノー T. S.エリオット 荒れ地 フェルドウィー シャハメ ロバート・フロスト 行かれなかった道 黄金のものは何も残らない ミルザ・ガーリブ ゲーテ ホメロス イリアス オデュッセイア ジェラルド・マンリー・ホプキンス ビンジー・ポプラース ホレス 書簡集 ヴィクトル・ユーゴー 思索 アルフレッド・エドワード・ハウスマン 若くして死ぬ選手へ オマル・ハイヤーム オマル・ハイヤームのルバイヤート(翻訳集) ジョン・キーツ 眠りと詩 ヤン・コチャノフスキ 嘆き(翻訳詩集) イグナシー・クラシツキ 寓話とたとえ話 ジャン・ド・ラ・フォンテーヌ ミハイル・レールモントフ ボヤリン・オルシャ 李白 静かな夜の思想 ステファン・マラルメ ある動物たちの午後 W.S.マーウィン チェツワフ・ミウォシュ ジョン・ミルトン 失楽園 パブロ・ネルーダ 20の愛の詩と絶望の歌(全集) オヴィッド アルス・アマトリア(全集) ペトラルカ カンツォニエーレ(作品集) シルヴィア・プラス ラザロ夫人 エドガー・アラン・ポー 鴉 アレクサンダー・ポープ ザ・レイプ・オブ・ザ・ロック エズラ・パウンド カント アレクサンドル・プーシキン ルスランとリュドミラ ライナー・マリア・リルケ ドゥイノ哀歌 アルチュール・ランボー 酔いどれ船 ジャラル・アディン・ルーミー マスナヴィ ウィリアム・シェイクスピア シェイクスピアのソネット シェル・シルヴァスタイン 歩道の終わる場所(作品集) エドモンド・スペンサー フェアリークイーン フィリップ・シドニー ペンブローク伯爵夫人のアルカディア タッソ エルサレムを届けよ アルフレッド・テニスン(テニスン男爵1世 破れ、破れ、破れ 軽騎兵の突撃 涙、涙、涙 フランソワ・ヴィヨン バージル エニード デレク・ウォルコット オメロス ウォルト・ホイットマン 自分の歌 揺りかごの中から ウィリアム・ワーズワース 前奏曲 ウィリアム・バトラー・イェイツ ビザンチウムへの船出 スウィフトの墓碑銘(翻訳) |

| Glossary of poetry terms Glossary of literary terms |

Glossary of poetry terms Glossary of literary terms |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Outline_of_poetry |

《メ タ詩学を夢見る》

Das Große Lalulá (1905) by Christian Morgenstern

僕

たちの知らない詩人がたくさんいる。その訳詞というのもひとるの立派な創作ジャンルだが、また、その言語に精通したらもっと面白い世界が広がるのだろう。

世界の詩人と詩の愛好者たちが、国際会議をしてメタ詩学という新しいジャンルをつくって、次世代に伝えるのも、それぞれの言語使用者の責務なんじゃないか

な?

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆